Twelfth Night on the stage of the Théâtre du Vieux Colombier, New York.

Title: One-Act Plays by Modern Authors

Editor: Helen Louise Cohen

Release date: October 24, 2010 [eBook #33907]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Joseph R. Hauser, Christine P. Travers and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber's note: Obvious printer's errors have been corrected, all other inconsistencies are as in the original. The author's spelling has been maintained.

ONE-ACT PLAYS

BY

MODERN AUTHORS

EDITED BY

Chairman of the Department of English in the

Washington Irving High School in the

City of New York

Author of "The Ballade"

NEW YORK

HARCOURT, BRACE AND COMPANY

COPYRIGHT, 1921, BY

HARCOURT, BRACE AND COMPANY, INC.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by mimeograph or any other means, without permission in writing from the publisher.

PRINTED IN THE U.S.A. BY

QUINN & BODEN COMPANY, INC.

RAHWAY, N. J.

To

M. S. S.

Had not both authors and publishers acted with the greatest generosity, this collection could not have been made. Though the editor cannot adequately express her sense of obligation, she wishes at least to record explicitly her indebtedness to Mr. Harold Brighouse, Lord Dunsany, Mr. John Galsworthy, Lady Gregory, Mr. Percy MacKaye, Miss Jeannette Marks, Miss Josephine Preston Peabody, Professor Robert Emmons Rogers, Mr. Booth Tarkington, and Professor Stark Young. The editor also desires to thank Chatto & Windus, Duffield & Company, Gowans & Gray, Ltd., Harper & Brothers, Little, Brown & Company, John W. Luce & Company, G. P. Putnam's Sons, Charles Scribner's Sons, and The Sunwise Turn, for permissions granted ungrudgingly.

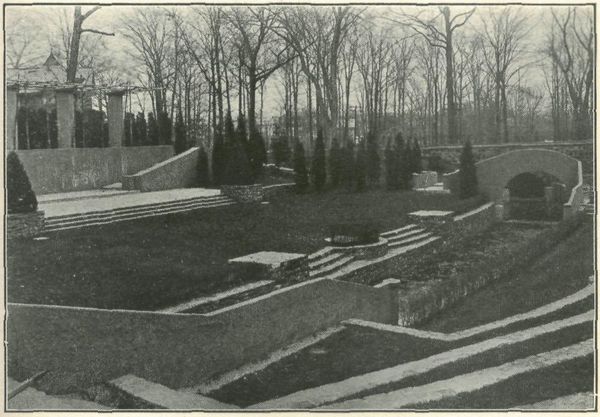

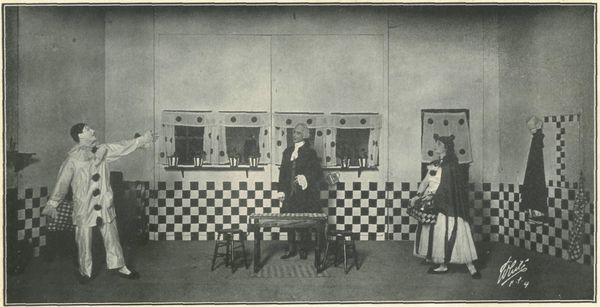

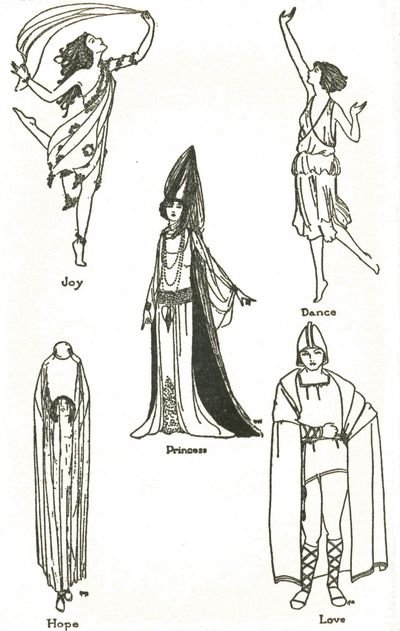

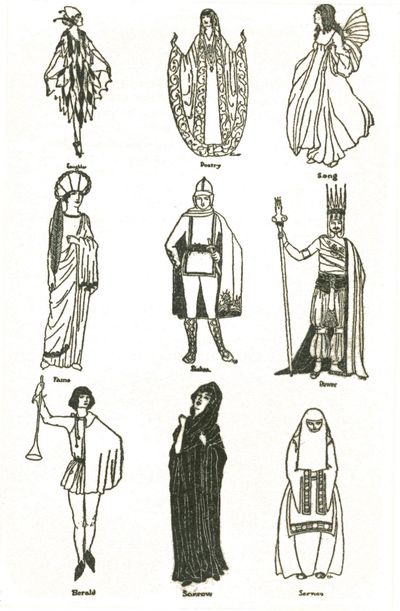

Through the courtesy of Mr. T. M. Cleland, director of the Beechwood Players, the pictures of the Beechwood Theatre appear. Miss Mary W. Carter, chairman of the Department of English in the High School in Montclair, New Jersey, contributed the photographs of the Garden Theatre. Other illustrations appear through the kindness of Theatre Arts Magazine, and of The Neighborhood Playhouse.

The editor is grateful to Mrs. John W. Alexander, Mr. B. Iden Payne, and Mrs. T. Bernstein for the privilege of personal conferences on the subject of the book. To Mr. Robert Edmond Jones, who has allowed three of his designs to be reproduced and who has read and corrected that part of the Introduction that deals with The New Art of the Theatre, the editor takes this opportunity of expressing her warm appreciation. Finally, the editor wishes to thank her friend, Helen Hopkins Crandell for her indefatigable work on the proofs of this book.

Perhaps the student who is going to read the plays in this collection may have felt at some time or other a gap between the "classics" that he was working over in school and the contemporary literature that he heard commonly discussed, but he does not know that until recently few books were studied in the high school that were less than half a century old. Consciousness of the gap often drove him to trashy reading. He recognized Addison as respectable but remote, and yet he had no guide to the good literature which the writers of his own day were producing and which would be especially interesting to him, because its ideas and language would be more nearly contemporary with his own.

Even though the greatest literature has the quality of universality, it has been almost invariably my experience that, only as one grows older, is one quite ready to appreciate this quality. When one is young, it is easier to enjoy literature written from a point of view nearer to one's own life and times. Reading good contemporary literature is likely also to pave the way for a deeper appreciation of the great masterpieces of all time.

This is a collection of one-act plays, some of them less than five years old, chosen both because their appeal seems not to be limited to the adult audiences for which they were originally written, and because they may well serve the purpose of introducing the student to contemporary dramatists of standing. Some of them, it is true, make use of old stories and traditions, but the treatment is in all cases modern, if we except the literary fashion that we find in Josephine Preston Peabody's Fortune and Men's Eyes. This, though it is a one-act play, a modern development, is written more or less in the Shakespearian convention; but whether we are bookish or not, we can hardly help having a knowledge of Shakespeare's plays, because, popular with all kinds of people, they are continually being revived on the stage, and quoted in conversation.

The plays in this book, though intended for class-room study, may be acted as well as read. The general introduction will (p. viii) be found helpful to groups who produce plays, to those who live in cities and go to the theatre often, and to those who like to experiment with dramatic composition. For this book was planned to encourage an understanding attitude towards the theatre, to deepen the love that is latent in the majority of us for what is beautiful and uplifting in the drama, and to make playgoing a less expensive, more regular, and more intelligent diversion for the generation that is growing up.

H. L. C.

Washington Irving High School,

New York, 1 February, 1921.

The one-act play is a new form of the drama and more emphatically a new form of literature. Its possibilities began to attract the attention of European and American writers in the last decade of the nineteenth century, those years when so many dramatic traditions lapsed and so many precedents were established. It is significant that the oldest play in the present collection is Maeterlinck's The Intruder, published in 1890.

The history of this new form is of necessity brief. Before its vogue became general, one-act plays were being presented in vaudeville houses in this country and were being used as curtain raisers in London theatres for the purpose of marking time until the late-dining audiences should arrive. With the exception of the famous Grand Guignol Theatre in Paris, where the entertainment for an evening might consist of several one-act plays, all of the hair-raising, blood-curdling variety, programs composed entirely of one-act plays were rare. Sir James Matthew Barrie is usually credited with being the first in England to write one-act plays intended to be grouped in a single production. A program of this character has been uncommon in the commercial theatre in America, but three of Barrie's one-act plays, constituting a single program, have met with enthusiastic response from American audiences.

There are two new developments in the history of the theatre that have encouraged and promoted the writing of one-act plays: the one is the Repertory Theatre abroad and the other is the Little Theatre movement on both sides of the Atlantic. The repertory of the Irish Players, for example, is composed largely of one-act plays, and American Little Theatres are given over almost exclusively to the one-act play.

The one-act play is in reality so new a phenomenon, in spite of the use that has been made of the form by playwrights like Pinero, Hauptmann, Chekov, Shaw, and others of the first (p. xiv) rank, that it is still generally ignored in books on dramatic workmanship.[1] None the less, the status of the one-act play is established and a study of the plays of this length, which are rapidly increasing in number, discloses certain tendencies and laws which are exemplified in the form itself. Clayton Hamilton sums up the matter well when he says: "The one-act play is admirable in itself, as a medium of art. It shows the same relation to the full-length play as the short-story shows to the novel. It makes a virtue of economy of means. It aims to produce a single dramatic effect with the greatest economy of means that is consistent with the utmost emphasis. The method of the one-act play at its best is similar to the method employed by Browning in his dramatic monologues. The author must suggest the entire history of a soul by seizing it at some crisis of its career and forcing the spectator to look upon it from an unexpected and suggestive point of view. A one-act play in exhibiting the present should imply the past and intimate the future. The author has no leisure for laborious exposition; but his mere projection of a single situation should sum up in itself the accumulated results of many antecedent causes.... The form is complete, concise and self-sustaining; it requires an extraordinary force of imagination."[2]

To follow for a moment a train of thought suggested by Mr. Hamilton's timely and appreciative comment on the technique of the one-act play: All writers on the short-story agree that, to use Poe's phrase, "the vastly important artistic element, totality, or unity of effect" is indispensable to the successful short-story. This singleness of effect is an equally important consideration in the structure of the one-act play. A short-story is not a condensed novel any more than a one-act play is a condensed full-length play. There is no fixed length for the one-act play any more than there is for the short-story. The one-act play must have its "dominant incident" and "dominant character" like the short-story. The effect of the one-act play, as of the short-story, is measured by the way it makes its readers and spectators feel. Neither the short-story (p. xv) nor the one-act play need necessarily "be founded on one of the passionate cruces of life, where duty and inclination come nobly to the grapple." One has but to consider the short-stories of Henry James or the one-act plays of Galsworthy or of Maeterlinck to be convinced that a violent struggle is not necessary to the art of either form.

This point is further illustrated in what Galsworthy himself says in general about drama in his famous essay, Some Platitudes Concerning the Drama, which should be read in connection with his satirical comedy, The Little Man. In that essay Galsworthy writes: "The plot! A good plot is that sure edifice which slowly rises out of the interplay of circumstance on temperament, and temperament on circumstance, within the enclosing atmosphere of an idea. A human being is the best plot there is.... Now true dramatic action is what characters do, at once contrary, as it were, to expectation, and yet because they have already done other things.... Good dialogue again is character, marshaled so as continually to stimulate interest or excitement." This commentary of Galsworthy's on dramatic technique offers to the student of The Little Man an unusual opportunity to verify a great critic's theory by a great playwright's practice. It is indeed the character of the Little Man that is the plot in this case; the plot may be said to begin when, according to stage direction, the hapless Baby wails, and to be well launched with the Little Man's deprecatory, "Herr Ober! Might I have a glass of beer?" These words distinguish him immediately from his bullying companions in the buffet. The highest point of interest, like the beginning of the plot, is to be found in the play of the Little Man's personality, at the point where he is left alone with the Baby, now a typhus suspect, and after an instant's wavering, bends all his puny energies to pacifying its uneasy cry. Again, the end of the plot comes with the tribute of the bewildered but adoring mother to the ineffably gentle Little Man.

But a one-act play that has any pretensions to literature must be looked upon as a law unto itself and should not be expected to conform to any set of arbitrary requirements. As a matter of fact, there are only a very few generalizations that can be made with regard to the structure or to the classification of the one-act play. Even this book contains plays that are (p. xvi) not susceptible of any hard and fast classification. The Intruder and Riders to the Sea are indubitably tragedies, but Fortune and Men's Eyes, dealing, as it does, with the tragic theme of love's disillusionment, belongs not at all with the plays of Maeterlinck and Synge, shadowed, as they are, by death. And though the deaths are many and bloody in A Night at an Inn, the unreality of the romance is so strong that there is no such wrenching of the human sympathies as we associate with tragedy. The Pierrot of the Minute is superficially a Harlequinade, but Dowson's insistence on the theme of satiety brings it narrowly within the range of satire. Beauty and the Jacobin is rich in comedy; so is Lady Gregory's Spreading the News, and in both, the situations change imperceptibly from comedy to farce and from farce back to comedy.

The laws of the structure of the one-act play are in the nature of dramatic art no less flexible. It can be said that in order to secure that singleness of impression that is as essential to the one-act play as to the short-story, a single well sustained theme is necessary, a theme announced in some fashion early in the play. Indeed since the one-act play is a short dramatic form, it may be said in regard to the announcing of the theme that, "'Twere well it were done quickly." In Spreading the News, the curtain is barely up before Mrs. Tarpey is telling the magistrate: "Business, is it? What business would the people here have but to be minding one another's business?" And at approximately the same moment in the action of The Intruder, the uncle, foreshadowing the theme of the mysterious coming of death, says: "When once illness has come into a house, it is as though a stranger had forced himself into the family circle."

The single dominant theme for its dramatic expression calls also for a single situation developing to a single climax. In the case of Fortune and Men's Eyes, it is the ballad-monger, who in crying his wares,

"Plays, Play not Fair,

Or how a gentlewoman's heart was took

By a player, that was King in a stage-play,"

gives us in the first few minutes of the play his ironical clue to the theme. And this theme is worked out in Mary Fytton's (p. xvii) shallow intrigue with William Herbert, which culminates in the shattering of the Player's dream on that autumn day in South London at "The Bear and the Angel."

The single situation exemplifying the theme of The Intruder is found in the repeatedly expressed premonitions of the blind Grandfather, stationary in his armchair, whose heightened senses detect the presence of the Mysterious Stranger. The unity of effect secured in this play is only rivaled, not surpassed, by the wonderful totality of impression experienced by the reader of The Fall of the House of Usher. The unity of effect in The Intruder is secured also by Maeterlinck's description of the setting, which reminds the playgoer or the reader inevitably of Stevenson's familiar words: "Certain dark gardens cry aloud for murder; certain old houses demand to be haunted."

In general, as has been said, the plot of the one-act play, because of the time limitations, admits of no distracting incidents. For the same reason the characterization must be swift and direct. By Bartley Fallon's first speech in Spreading the News, Lady Gregory characterizes him completely. He needs but say: "Indeed it's a poor country and a scarce country to be living in. But I'm thinking if I went to America it's long ago the day I'd be dead," and the fundamental part of his character is fixed in the minds of the audience. From that moment it is just a question of filling in the picture with pantomime and further dialogue.

The characterization of the Player in Fortune and Men's Eyes begins at the moment that he enters the tavern, when Wat, the bear-ward, calls out:

"I say, I've played.... There's not one man

Of all the gang—save one.... Ay, there be one

I grant you, now!... He used me in right sort;

A man worth better trades."

Wat's verdict on the fair-mindedness of Master William Shakespeare of the Lord Chamberlain's company is borne out by the Player's own,

"High fortune, man!

Commend me to thy bear."

[Drinks and passes him the cup.]

(p. xviii) The entrance of the ballad-monger gives Master Will an opening for a punning jest and, the action continuing, shows him sympathetic to the strayed lady-in-waiting, tender to the tavern boy, magnanimous to the false friend and falser love.

One method of characterization which the author allows herself to use in this play, no doubt to heighten the Elizabethan illusion, is rare in the contemporary drama: when this "dark lady of the sonnets" flees "The Bear and the Angel," the Player breaks forth into the self-revealing soliloquy, found so frequently in his own plays, and continuing as a dramatic convention until the last quarter of the nineteenth century.[3]

Characterization rests in part on pantomime. In The Little Man, the Dutch Youth is dumb throughout the play, but he is sufficiently characterized by his foolish demeanor and his recurrent laugh. The part of the Little Man himself is one long gesture of humility and dedication. In those one-act plays in which the old characters of the Harlequinade reappear, like The Maker of Dreams and The Pierrot of the Minute, pantomime transcends dialogue as a method of characterization. In the plays of the Irish dramatists, Synge, Yeats, and Lady Gregory, pantomime and dialogue contribute equally to the characterization, which is of a very high order, since all these dramatists were close observers of the Irish peasant characters of their plays.

Synge, especially, illustrates the following critical theory of Galsworthy: "The art of writing true dramatic dialogue is an austere art, denying itself all license, grudging every sentence devoted to the mere machinery of the play, suppressing all jokes and epigrams severed from character, relying for fun and pathos on the fun and tears of life. From start to finish good dialogue is hand-made, like good lace; clear, of fine texture, furthering with each thread the harmony and strength of a design to which all must be subordinated." A study of the dialogue of Riders to the Sea reveals just this harmony (p. xix) between the dialogue and the inevitability of the plot, the dialogue and the simplicity of the characters.

The dialogue in The Little Man is the very idiom one would expect to issue from the mouth of the German colonel, the Englishman with the Oxford voice, or the intensely national American, as the case may be. The characters, though they have type names, are, as Mr. Galsworthy would probably be the first to explain, highly individualized. The author does not intend us to think that all Americans are like this loud-voiced traveler, or all Englishmen like the pharisaical gentleman who gives his wife the advertisements to read while he secures the news sheet for himself.

The function of dialogue is the same both in the long and in the short play. For, of course, both forms have many things in common. For instance, as in the full-length play it is necessary for the dramatist to carry forward the interest from act to act, to provide a "curtain" that will leave the audience in a state of suspense, so in the one-act play, the interest must be similarly relayed though the plot is confined to a single act. In The Intruder, every premonition expressed by the Grandfather grips the audience in such a way that they await from minute to minute the coming of the mysterious stranger. The tension is high in A Night at an Inn from the moment the curtain rises. In Riders to the Sea, the beginning of the suspense coincides with the opening of the play and lasts. "They're all gone now, and there isn't anything more the sea can do to me," says Maurya, and the audience experiences a rush of relief and a sense of release that the last words, "No man at all can be living for ever, and we must be satisfied," seem only to deepen.

A one-act play, then, has many structural features in common with the short-story; its plot must from beginning to end be dominated by a single theme; its crises may be crises of character as well as conflicts of will or physical conflicts; it must by a method of foreshadowing sustain the interest of the audience unflaggingly, but ultimately relieve their tension; it must achieve swift characterization by means of pantomime and dialogue; and its dialogue must achieve its effects by the same methods as the dialogue of longer plays, but by even greater economy of means. But when all is said and done, the success of a one-act play is judged not by its conformity to any set (p. xx) of hard and fast rules, but by its power to interest, enlighten, and hold an audience.

The term "Commercial Theatre" is rarely used without disparagement. The critic or the playwright who speaks of the Commercial Theatre usually does so either for the purpose of reflecting on the cheapness of the entertainment afforded, or in order to call attention to spectacular receipts.

In this country the Commercial Theatre stands for that form of big business in the theatrical world that produces dividends on the money invested comparable to those earned by the most prosperous of the large industries. This system has been, on the whole, a bad thing for the drama, because managers with their eye on attractions that should yield a return, let us say, of over ten per cent on the investment, have been unable to produce the superior play with an appeal to a definite, though perhaps limited audience, and have had to offer to the public the kind of play that would draw large audiences over a long period of time. The "longest run for the safest possible play" is thus conspicuously associated with the Commercial Theatre. As Clayton Hamilton says: "The trouble with the prevailing theatre system in America to-day is not that this system is commercial; for in any democratic country, it is not unreasonable to expect the public to defray the cost of the sort of drama that it wishes, and that, therefore, it deserves. The trouble is, rather, that our theatre system is devoted almost entirely to big business; and that in ignoring the small profits of small business it tends to exclude not only the uncommercial drama, but the non-commercial drama as well."[4] Here he makes a distinction between an "uncommercial" play, that is, a play that is a failure with all kinds of audiences, and the "noncommercial" play, which is capable of holding its own financially and yielding modest returns.

In the days before the pooling of theatrical interests in this (p. xxi) country there were indeed long runs, but in many of the large American cities "stock companies," composed of groups of actors and actresses all of about the same reputation and ability, were maintained that kept a number of plays, a "repertory," before the public in the course of a season and gave scope for experiment with various kinds of plays. But the "star system," which has now become common, has tended to drive out the "stock company" idea, with the result that the average company rests on the reputation of the "star" and dispenses with distinction in the "support." With the decay of the stock company, the repertory system, in the form in which it did once exist here in the Commercial Theatre, has also declined.

Both in Great Britain and in America the repertory system, long established on the Continent, has been reintroduced in order to combat the practices of the Commercial Theatre. For the most part the new repertory theatres have been endowed either by the State or by private individuals. "Absolute endowment for absolute freedom,"[5] has seemed to at least one American the only means of delivering the drama from commercial bondage. This phrase of Percy MacKaye's expresses his cherished belief that endowed civic theatres, which should encourage the participation of whole communities in a community form of drama, are what is needed in a democracy. John Masefield, in the following lines from the prologue written for the opening of the Liverpool Repertory Theatre, has found a poetic theme in this idea of an endowed theatre:

"Men will not spend, it seems, on that one art

Which is life's inmost soul and passionate heart;

They count the theatre a place for fun,

Where man can laugh at nights when work is done.

If it were only that, 'twould be worth while

To subsidize a thing which makes men smile;

But it is more; it is that splendid thing,

A place where man's soul shakes triumphant wing;

A place of art made living, where men may see

What human life is and has seemed to be

To the world's greatest brains....

(p. xxii)

O you who hark

Fan to a flame through England this first spark,

Till in this land there's none so poor of purse

But he may see high deeds and hear high verse,

And feel his folly lashed, and think him great

In this world's tragedy of Life and Fate."[6]

In Great Britain repertory is associated with the interest and generosity of Miss A. E. F. Horniman, who will be mentioned in connection with the Irish National Theatre, and through whom, after some preliminary experiment, the Gaiety Theatre at Manchester was opened as the first repertory house in England, in the spring of 1908. Fifty-five different plays were produced in a little over two years—"twenty-eight new, seventeen revivals of modern English plays, five modern translations, and five classics."[7] In Miss Horniman's own words, her interest was in a Civilized Theatre. "A Civilized Theatre," she has written, "means that a city has something of cultivation in it, something to make literature grow; a real theatre, not a mere amusing toy. What we want is the opportunity for our men and women, our boys and girls to get a chance to see the works of the greatest dramatists of modern times, as well as the classics, for their pleasure as well as their cultivation.... Young dramatists should have a theatre where they can see the ripe works of the masters and see them well acted at a moderate price. There should be in every city a theatre where we can see the best drama worthily treated."[8] Owing to war conditions, the Manchester project has had to be abandoned, and so, for the most part, have other similar enterprises. They rarely became self-supporting, but depended on subsidy of one kind or another, which under new economic conditions is no longer forthcoming. The Birmingham Repertory Theatre continues, however, under the direction of John Drinkwater, and has become famous through its production of his Abraham Lincoln. "John Drinkwater, I see, has recently defined a Repertory Theatre," writes William Archer, in his latest article on the subject, "as one which 'puts plays into (p. xxiii) stock which are good enough to stay there.'" Enlarging this definition, I should call it a theatre which excluded the long unbroken run; which presents at least three different programs in each week (though a popular success may be performed three or even four times a week throughout a whole season); which can produce plays too good to be enormously popular; which makes a principle of keeping alive the great drama of the past, whether recent or remote; which has a company so large that it can, without overworking its actors, keep three or four plays ready for instant presentation; which possesses an ample stage equipped with the latest artistic and labor-saving appliances; and which offers such comfort in front of the house as to encourage an intelligent public to make it an habitual place of resort.

"That there exists in every great American city an intelligent public large enough to support one or more such playhouses is to my mind indisputable. But the theatre might have to be run at a loss for two or three opening seasons, until it had attracted and educated its habitual supporters. For even a public of high general intelligence needs a certain amount of special education in things of the theatre." This testimony is in a highly optimistic vein.

A talk with B. Iden Payne, once director of the Manchester Players, reveals the fact that in England at the present time the repertory idea is being taken over with more promise of success by the small groups that represent the Little Theatre movement in that country. The repertory theatre there did succeed in arousing in the locality in which, for the time being, it existed an interest in intelligent plays, but it was not equally successful in confirming a distaste for unintelligent plays. The study of these experiments will repay Americans who are interested in seeing the repertory idea fostered over here by endowment or otherwise.

The year 1911 saw the beginning in the United States of the Little Theatre movement, which has grown with phenomenal rapidity and has spread in all directions. The first Little Theatres in this country were located in large cities; but in the course of time the idea has penetrated to small towns (p. xxiv) and rural communities all over the United States. Barns, wharves, saloons, and school assembly halls have been transformed into intimate little playhouses. There were European precedents for this idea. The Théâtre Libre, opened in Paris in 1887 by André Antoine as a protest against the kind of play then in favor, is generally called the first of this type. In the years from 1887 to 1911 Little Theatres were opened in Russia, in Belgium, in Germany, in Sweden, in Hungary, in England, in Ireland, and in France. In Europe these theatres came into being, generally speaking, in order to give freer play to the new arts of the theatre or for the purpose of encouraging a more intellectual type of drama than was being produced in the larger houses.

There are two conceptions of the Little Theatre current in the United States. According to one, it is a theatrical organization housed in a simple building, that makes its productions in the most economical way, does not pay its actors, does not charge admission, and uses scenery and properties that are cheaply manufactured at home.

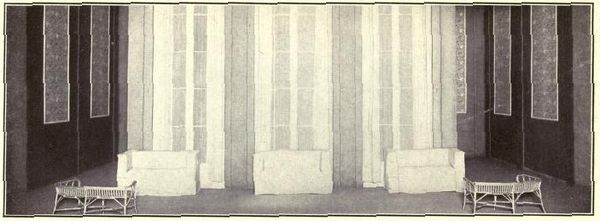

Twelfth Night on the stage of the Théâtre du Vieux Colombier, New York.

The Little Theatre is, however, more commonly conceived of as a repertory theatre supported by the subscription system, producing its plays on a small stage in a small hall, selecting for production the kind of play not likely to be used by the Commercial Theatre, most frequently the one-act play, and committed to experiments in stage decoration, lighting, and the other stage arts. The Little Theatre and the one-act play have developed each other reciprocally, for the Little Theatre has encouraged the writing of one-act plays in Europe and in this country. The one-act play is the natural unit of production in the Little Theatre, both because it requires a less sustained performance from the actors, who have frequently been amateurs, and because it has offered in the same evening several opportunities to the various groups of artists collaborating in the productions of the Little Theatre. Though the movement has had the effect of stimulating community spirit and has been the means of solving grave community problems, the Little Theatre is not, in the technical sense, a community theatre; in the sense, that is, in which Percy MacKaye uses the word. It is not, in fact, so portentous an enterprise, because it does not enlist the participation of every member of a community. The community theatre is an example of civic co-operation (p. xxv) on a large scale; the Little Theatre, of the same kind of co-operation on a small scale.

Notably artistic results have been achieved by such Little Theatres as The Neighborhood Playhouse in New York, built in 1914 by the Misses Irene and Alice Lewisohn, in connection with the social settlement idea, to provide expression for the talents of a community that had been previously trained in dramatic classes for some years; by the Chicago Little Theatre, founded in 1911, now no longer in existence, but for a few years under the direction of Maurice Browne, a disciple of Gordon Craig's; by the Detroit Theatre of Arts and Crafts, once under the direction of Mr. Sam Hume, also a follower of Gordon Craig's; by the Washington Square Players, who during several seasons in New York gave a remarkable impetus to the writing of one-act plays in America; by the Provincetown Players, whose first productions were made on Cape Cod, who later opened a small playhouse in New York, and who gave the public an opportunity to know the plays of Eugene O'Neill; by the Portmanteau Theatre of Stuart Walker, that uses but one setting in its productions, but varies the effect with different colored lights, and as its name implies, is portable, one of the few of its kind in the world; by the 47 Workshop Theatre that has arisen as the result of the course in playwriting given at Harvard University by Professor George Pierce Baker, and the productions of which have served to introduce many new writers; and by the Théâtre du Vieux Colombier, that came to New York from Paris in 1917, and remained for two seasons to illustrate the best French practice. These theatres also enjoy the distinction of having experimented with repertory.

The Théâtre du Vieux Colombier was organized and is directed by Jacques Copeau. It is no casual amateur experiment. Its actors are professionals and its director is a scholar and an artist. In preparation for the original opening the company went into the country and established a little colony. "During five hours of each day they studied repertoire but they did far more. They performed exercises in physical culture and the dance: they read aloud and acted improvised dramatic scenes. They worked thus upon their bodies, their voices and their actions: made them subtle instruments in their command." They learned that in an artistic production every (p. xxvi) gesture, every word, every line, and every color counted. Naturally no group of amateurs or semi-professionals can approach the results of a company trained as M. Copeau's is. When he was over here, he was much interested in our Little Theatres. He said in one of his addresses: "All the little theatres which now swarm in America, ought to come to an understanding among themselves and unite, instead of trying to keep themselves apart and distinctive. The ideas which they possess in common have not even begun to be put into execution. They must be incorporated into life."[9]

The native Little Theatres, much simpler affairs than the Vieux Colombier, persist. They have made a place for themselves in American life, among the farms, in the suburbs, in the small towns, and in the cities. Sometimes, no doubt, they are like the one in Sinclair Lewis's Gopher Prairie; or they hardly outlast a season. But new ones spring up to replace those that have gone out of existence, and meanwhile the ends of wholesome community recreation are being served.

About 1890 began the movement which has since been known as the Celtic Renaissance, a movement that had for its object the lifting into literature of the songs, myths, romances, and legends treasured for countless generations in the hearts (p. xxvii) of the Irish peasantry. In the same decade in Great Britain and on the Continent, tendencies were at work looking to the reform of the drama and its rescue from commercial formulas. The genesis of the Irish National Theatre, a pioneer in the field of repertory in Great Britain, and one of the first of the Little Theatres, is due to both of these influences.

Its first form was the Irish Literary Theatre, founded in 1899 by Edward Martyn, the author of The Heather Field and Maeve, George Moore, and William Butler Yeats. The first play produced by this organization was Yeats's Countess Cathleen. This enterprise employed only English actors, and did not assume to be purely national in scope. It came to an end in October, 1901. It was in October, 1902, that in Samhain, the organ of the Irish National Theatre, William Butler Yeats made the following announcement: "The Irish Literary Theatre has given place to a company of Irish actors." The nucleus of this new Irish National Theatre was certain companies of amateurs that W. G. Fay had assembled. These companies were composed of people who were unable to give full time to their interest in the drama, but who came from the office or the shop to rehearse at odd moments during the day and in the evening. The Irish National Theatre really developed from these amateur companies. It was strictly national in scope. The advisers, who were to include Synge, Lady Gregory, Padraic Colum, William Butler Yeats, and others, looked to the Irish National Theatre to bring the drama back to the people, to whom plays dealing with society life meant nothing. They intended also that their plays "should give them [the people] a quite natural pleasure, should either tell them of their own life, or of that life of poetry where every man can see his own magic, because there alone does human nature escape from arbitrary conditions." This program has been carried out with remarkable success.

October, 1902, is the date for the beginning of the Irish National Theatre. At first W. G. Fay, and his brother, Frank Fay, were in charge of the productions, the former as stage manager. Frank Fay had charge of training a company, in which the star system was unknown. He had studied French methods of stage diction and gesture, and the Irish Players are generally said to show the results of his familiarity with great French models. In 1913 a school of acting was (p. xxviii) organized in order to perpetuate the tradition created by the Fays.

Among the most famous playwrights who have written for the Irish National Theatre are Padraic Colum, John Millington Synge, William Butler Yeats, Lady Gregory, St. John G. Ervine, Æ (George W. Russell), and Lord Dunsany. At one time the theatre sent out, in a circular addressed to aspiring authors who showed promise, the following counsel: "A play to be suitable for performance at the Abbey should contain some criticism of life, founded on the experience or personal observation of the writer, or some vision of life, of Irish life by preference, important from its beauty or from some excellence of style, and this intellectual quality is not more necessary to tragedy than to the gayest comedy."[10]

In 1904 the Irish National Theatre was housed for the first time in its own playhouse, the Abbey Theatre. This change was made possible by the generosity of Miss A. E. F. Horniman, who saw the Irish Players when they first went to London in 1903. It was she who obtained the lease of the Mechanics' Institute in Dublin, increased its capacity, and rebuilt it, giving it rent free to the Players from 1904 to 1909, in addition to an annual subsidy which she allowed them. In 1910 the Abbey Theatre was bought from her by public subscription. The next year, the Irish Players paid their famous visit to the United States.

The Irish National Dramatic Company was organized as a protest against current theatrical practices. Its founders purposed to reform the various arts of the theatre. By encouraging native playwrights they hoped to do for the drama of Ireland what Ibsen and other writers had done for the drama in Scandinavian countries, where people go to the theatre to think as well as to feel. It was not intended in any sense that these new Irish players were to serve the purpose of propaganda; truth was not to be compromised in the service of a cause. Acting, too, was to be improved: redundant gesture was to be suppressed; repose was to be given its full value; speech was to be made more important than gesture. Yeats in particular had theories as to the way in which verse should be spoken on the stage; he advocated a cadenced chant, (p. xxix) monotonous but not sing-song, for the delivery of poetry. The simplification of costume and setting was also included in their scheme, for both were to be strictly accessory to the speech and movement of the characters.

They have been faithful to their ideals. The performances at the Abbey Theatre continue, although from time to time certain of the most eminent actors of the company have withdrawn, some to migrate to America. Among the plays produced in 1919 and 1920 by the National Theatre Society at the Abbey Theatre are W. B. Yeats's The Land of Heart's Desire, G. B. Shaw's Androcles and the Lion, Lady Gregory's The Dragon, and Lord Dunsany's The Glittering Gate.

There are certain facts about the artistic transformation that the theatre is undergoing in the twentieth century with which students of the drama need to be familiar in order to picture for themselves how plays can be interpreted by means of design, color, and light. The transformation is definitely connected with a few famous names. In Europe two men, Edward Gordon Craig and Max Reinhardt, stand out as reformers in matters connected with the construction, the lighting, and the design of stage settings. In this country the artists of the theatre are, generally speaking, disciples of one or both of these great Europeans and their colleagues. The new stage artist studies the characterization and the situations in the play, the production of which he is directing, and tries to make his setting suggestive of the physical and emotional atmosphere in which the action of the drama moves.

Gordon Craig has written several books and many articles embodying his ideas on play production. In all his writings he emphasizes the importance of having one individual with complete authority and complete knowledge in charge of coordinating and subordinating the various arts that go to make the production of a play a symmetrical whole, his theory being that there is no one art that can be called to the exclusion of all others the Art of the Theatre: not the acting, not the play, not the setting, not the dance; but that all these properly harmonized through the personality of the director become the Art of the Theatre.

(p. xxx) The kind of setting that has become identified in the popular mind with Gordon Craig is the simple monochrome background composed either of draperies or of screens. It is unfortunate that this popular idea should be so limited because, of course, the name of Gordon Craig should carry with it the suggestion of an infinite variety of ways of interpreting the play through design. His screens, built to stand alone, vary in number from one to four and sometimes have as many as ten leaves. They are either made of solid wood or are wooden frames covered with canvas. The screens with narrow leaves may be used to produce curved forms, and screens with broad leaves to enclose large rectangular spaces. The screens are one form of the setting composed of adjustable units, which can be adapted in an infinite variety of ways to the needs of the play.

The new ideas in European stagecraft began to be popularized in America in the year 1914-15, when under the auspices of the Stage Society, Sam Hume, now teaching the arts of the theatre at the University of California, and Kenneth Macgowan, the dramatic critic, arranged an exhibition that was shown in New York, Chicago, and other great centres, of new stage sets designed by Robert Edmond Jones, Sam Hume, and others who have since become famous. The models displayed on this occasion brought before the public for the first time the new method of lighting which, as much as anything else, differentiates the new theatre art from the old. It introduced the device of a concave back wall made of plaster, sometimes called by its German name "horizont," and a lighting equipment that would dye this plaster horizon with colors that melted into one another like the colors in the sky; a stage with "dimmers" for every circuit of lights, and sockets for high-power lamps at any spot from the stage.

In the same year that the Stage Society showed Robert Edmond Jones's models, he was given an opportunity to design the settings and costumes for Granville Barker's production of Anatole France's The Man Who Married a Dumb Wife, which may be said to have advertised the new practices in America more than any other single production.

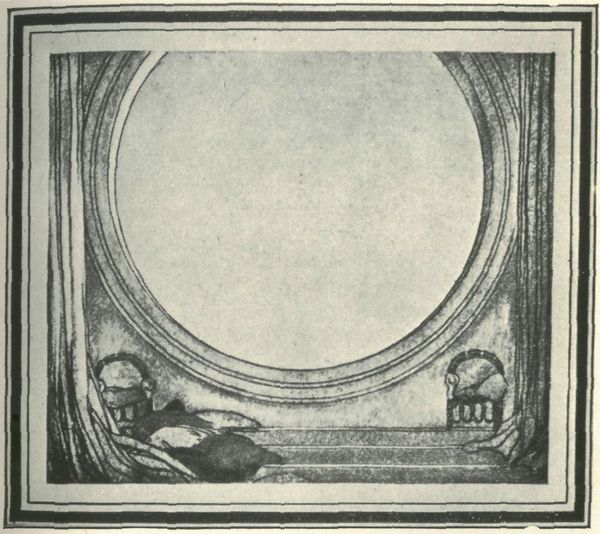

The Merchant of Venice. A room in Belmont. Design by Robert Edmond Jones. A great round window framed in the heavy molding of Mantegna and the pale clear sky of Northern Italy.

Writing of his own work shortly after, Mr. Jones says: "While the scenery of a play is truly important, it should be so important that the audience should forget that it is present. (p. xxxi) There should be fusion between the play and the scenery. Scenery isn't there to be looked at, it's really there to be forgotten. The drama is a fire, the scenery is the air that lifts the fire and makes it bright.... The audience that is always conscious of the back drop is paying a doubtful compliment to the painter.... Even costumes should be the handiwork of the scenic artist. Yes, and if possible, he should build the very furniture."[11] Robert Edmond Jones has not only designed settings and costumes for poetic and fantastic forms of drama, but he has also been called upon to plan the productions of realistic modern plays.

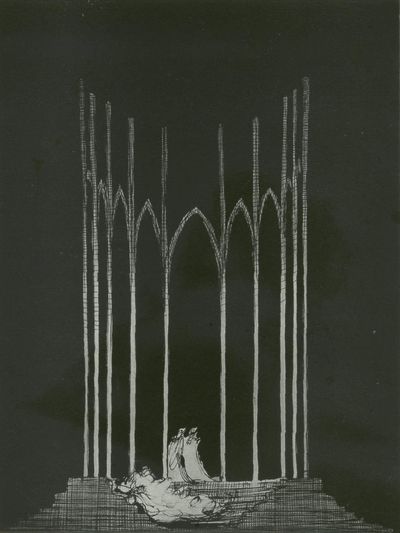

Three of his designs introducing three different aspects of his work have been here reproduced. The model for Maeterlinck's The Seven Princesses is an example of an attempt to present the essential significant structure of a setting in the simplest way conceivable and by so doing to stimulate the imagination of the spectator to create for itself the imaginative environment of the play. His design for a room in Belmont for The Merchant of Venice shows a great round window framed in the heavy molding of Mantegna and the pale, clear sky of Northern Italy. The scene for Good Gracious Annabelle is a corridor in an hotel. This scene is a typical example of a more or less abstract rendering of a literal scene. It was designed primarily with the idea of giving as many different exits and entrances as possible, in order that the action of the drama might be swift and varied.[12]

When Sam Hume was connected with the Detroit Theatre of Arts and Crafts, he used a symbolic and suggestive method for the setting of poetic plays the scene of which was laid in no definite locality. In this theatre he installed a permanent setting, including the following units: "Four pylons [square pillars], constructed of canvas on wooden frames, each of the three covered faces measuring two and one-half by eighteen feet; two canvas flats each three by eighteen feet; two sections of stairs three feet long, and one section eight feet long, of uniform eighteen-inch height; three platforms of the same height, respectively six, eight, and twelve feet long; dark green (p. xxxii) hangings as long as the pylons; two folding screens for masking, covered with the same cloth as that used in the hangings, and as high as the pylons; and two irregular tree forms in silhouette.

"The pylons, flats, and stairs, and such added pieces as the arch and window, were painted in broken color ...[13] so that the surfaces would take on any desired color under the proper lighting."[14] The economy of this method is illustrated by the fact that in one season nineteen plays were given in the Arts and Crafts Theatre at Detroit, and the settings for eleven of these were merely rearrangements of the permanent setting. This kind of setting is sometimes called "plastic"—a term which refers to the fact that the separate units are in the round, and not flat. The effect secured in settings representing outdoor scenes was made possible only by the use of a plaster horizon of the general type described in connection with the exhibition of the Stage Society.

Good Gracious Annabelle. A corridor in a hotel. Design by Robert Edmond Jones. A typical example of a more or less abstract rendering of a literal scene. It was designed primarily with the idea of giving as many different exits and entrances as possible in order that the action of the drama might be swift and varied.

Robert Edmond Jones and Sam Hume are two of an increasingly large number of artists in America, among whom should be mentioned Norman-bel Geddes, Maurice Browne, and Lee Simonson, who are experimenting with design, color, and light. Underlying the work of all of these is the belief that the whole production, the play, the acting, the lighting, and the setting, should be unified by some one dominating mood. In the work of these new artists, there is no place for the old-fashioned painted back drop, the use of which emphasizes the disparity between the painted and the actual perspective, though their backgrounds are by no means necessarily either screens or draperies. Another new style of background is the skeleton setting, a permanent structural foundation erected on the stage, which through the addition of draperies and movable properties, or the variation of lights, or the manipulation of screens, may serve for all the scenes of a play. A permanent structure of this sort, representing the Tower of London, was used by Robert Edmond Jones in a recent production of Richard III in New York, at the Plymouth Theatre. When Jacques Copeau conducted the Théâtre du Vieux Colombier in New York he had a permanent structure built on the stage of the Garrick Theatre, (p. xxxiii) that he used for all the plays he produced; at times the upper half of the stage was masked, at times the recess back of the two central columns was used. The aspect of the stage was often completely changed by the addition of tapestries, stairs, panels, screens, and furniture.

In the description of the equipment of the Detroit Theatre of Arts and Crafts, reference has been made to a method of painting the plastic units in broken color. This is so important a principle that it should be more generally understood by those who are interested in the theatre. The principle was put into operation by the Viennese designer, Joseph Urban. In practice it means that a canvas painted with red and with green spots upon which a red light is played, throws up only the red spots blended so as to produce a red surface, and that the same canvas under a green light shows a green surface; and, if both kinds of lights are used, then both the green and red spots are brought out, according to the proportion of the mixture of green and red in the light.

Color is being used now not only for decorative purposes, but also symbolically. The decorative use of color on the stage is, obviously, like the decorative use of color in the design of textiles, or stained glass, or posters. The symbolic use of color is less easy to interpret, but it is plain that in most people's minds red is connected with excitement and frenzy, and blues and grays, with an atmosphere of mystery. This is a very bald suggestion of some of the very subtle things that have been done with color on the modern stage.

The new methods of stage lighting make possible all kinds of color combinations and effects. The use of the plaster horizon (or of the cyclorama, a cheaper substitute, usually a straight semi-circular curtain enclosing the stage, made of either white or light blue cloth), combined with high-powered lights set at various angles on the stage, makes outdoor effects possible, the beauty of which is new to the theatre.[15] Nowadays footlights are not invariably discarded, but where they are used they are wired so that groups of them can be lighted when other sections are dimmed or darkened. When the setting shows an interior scene with a window, though the scene may be lighted from all sides, the window seems to be the (p. xxxiv) source of all light. A good deal of the lighting on the stage is what is known in the interior decoration of houses as indirect lighting; colored lights are produced most simply by the interposition between the source of light and the stage of transparent colored slides, gelatine or glass.

In any production that is made under the influence of the new stagecraft, the costumes, like the setting of the play, are considered in connection with the resources of lighting. The costumes, whether historically correct or historically suggestive, whether of a period or conventionalized, are conceived in their three-fold relation to the characters of the play, the background, and the scheme of lights, by the designer or the director under whose general supervision the play is staged.

In general, American audiences are hardly conscious of the existence of these reforms. Here and there, it is true, the manager of a commercial theatre or an opera house has called in an artist to supervise his productions and has thus given publicity to the new way of making the arts of the theatre work together. Certain Little Theatres, also, have educated their followers in the significance of the new use of light and design to represent the mood of a play. The demands that the new method makes on craftsmanship have also commended it to students in schools and colleges interested in play production. Both the Little Theatres and the school theatres are doing a real service when they educate their communities in these new arts, for not only will this education increase the capacity of these particular audiences to enjoy the good things of the theatre, but the influence of these groups is bound in the long run to popularize the new stagecraft.

Shortly before the death of William Dean Howells, he related the experience that he had had of being circularized by a correspondence school that offered to teach him the art of writing fiction in a phenomenally short time at a ridiculously low rate. In this instance, there was something wrong with the mailing list, but the fact remains that in universities successful courses in writing short-stories and plays are given and the best of these courses actually have turned out writers who achieve various degrees of success financially and artistically (p. xxxv) It is plain that a brief treatise like the present one makes no such pretensions; it means merely to suggest some of the most obvious points of departure for students in the drama who wish to exercise themselves in the composition of the one-act play, much as a student of poetry will try his hand at a ballade or a sonnet without taking himself or his metrical exercises too seriously.

Courtesy of Theatre Arts Magazine

The Seven Princesses. Design by Robert Edmond Jones. An example of the attempt to present the essential significant structure of a setting in the simplest way conceivable and by so doing to stimulate the imagination of the spectator to create for itself the imaginative environment of the play.

In the famous Perse School in Cambridge, England, the boys begin at the age of twelve to practise playmaking as an aid to the fuller understanding of Shakespeare's dramatic workmanship, and this work is developed throughout the rest of the course. The boys, having learned that Shakespeare himself used stories that he found ready to hand, discover in their own reading a story that will lend itself to dramatization. The story is told and retold from every angle. The class is then divided up into committees to every one of which is entrusted some part of the dramatization. One little committee busies itself with the setting, another with the structure, another with the comic characters, another with the songs that are interspersed and so on. These committees prepare rough notes to be presented in class. These notes may propose an outline of successive scenes, present the part of some principal character, or the "business" (illustrative action) of some minor part. Lessons of this sort are followed by composition rehearsals, where the dramatic and literary value of the proposed plot, characterization, pantomime, and dialogue are tested, and subjected to the criticism of teacher and boys. In the next lessons, the teacher brings to bear on the special problems on which the boys are working all the criticism that his wider range of reading and experience can suggest. In the light of his suggestions the various points are debated and the boys then proceed to careful fashioning, shaping, and writing. A rehearsal of the nearly finished product is held, followed by a final revision of the text. The work then goes forward to a public performance given with all due ceremony. In the higher classes playmaking is taught more especially in connection with writing and the boys are trained to imitate the style of various dramatists. Synge was used as a model at one time for, as one of the masters of the school explained: "The style of Synge is easy to copy because it is so largely composed of a certain phraseology. The same words, phrases, and turns of (p. xxxvi) sentence occur again and again. Here are a few taken at random; the reader will find them in a context on almost any page of the plays: It's myself—Is it me fight him?—I'm thinking—It's a poor (fine, great, hard, etc.) thing—A little path I have—Let you come—God help us all—Till Tuesday was a week—The end of time—The dawn of day—Let on—Kindly—Now, as in Walk out now—Surely—Maybe—Itself—At all—Afeard—Destroyed—It curse. Synge is also mighty fond of the words ditch and ewe. And there are certain forms of rhythm about Synge's prose which are used with equal frequency, and are quick and easy to catch. So far from this imitation of style being an artificial method, the fact is that once a boy of sixteen or over has read a play or two of Synge's, if he has any power of style in him, it will be all but impossible to stop him writing like Synge for a few weeks." Learning playwriting from models recalls the method of Benjamin Franklin and Robert Louis Stevenson who in their youth wrote slavish imitations of the great masters in order to form their own prose style. Of course, it is not claimed that this work at the Perse School makes playwrights, only that it gives the boys a deeper appreciation of dramatic workmanship and furnishes a new kind of intellectual game to add to the joy of school life.

The one-act plays contained in this collection are, as has been suggested in what has been said about their construction, illustrative of various kinds of workmanship. Certain of them are excellent models for those who are experimenting with playwriting. The one-act play, not nearly so difficult a form as the full-length play, offers undergraduates in school and college and inexperienced writers generally unlimited scope for experiment.

The testimony of Lord Dunsany is to the effect that his play is made when he has discovered a motive. Asked whether he always began with a motive, "'Not always,' he said; 'I begin with anything or next to nothing. Then suddenly, I get started, and go through in a hurry. The main point is not to interrupt a mood. Writing is an easy thing when one is going strong and going fast; it becomes a hard thing only when the onward rush is impeded. Most of my short plays have been written in a sitting or two.'"[16] This passage is quoted because insight (p. xxxvii) into the practice of professional writers is always helpful to amateurs. Dunsany uses "motive," it seems, as a convenient term for denoting the idea, the character, the incident or the mood that impels the dramatist to start writing a play. Such material is to be found everywhere. Many professional writers accumulate vast stores of such themes against the day when they may have the necessary leisure, energy, and insight to develop them.

It has been pointed out that there are only thirty-six possible dramatic situations in any case, and that no matter how the plot shapes itself, it is bound to classify itself somehow or other as one of the inescapable thirty-six. There is comfort also in the suggestion that Shakespeare drew practically all the dramatic material that he used so transcendently direct from the familiar and accessible narrative stores of his day. The young or inexperienced playwright need have no hesitation, then, in turning to such sources as the Greek myths for inspiration. Quite recently a highly successful one-act play of Phillip Moeller's proved that Helen of Troy is as eternally interesting as she is perennially beautiful. Maurice Baring draws on the old Greek stories, too, for several of his Diminutive Dramas. The Bible has proved dramatically suggestive to Lord Dunsany and to Stephen Phillips. The old ballads of Fair Annie and The Wife of Usher's Well have been found dramatically available. The myths of the old Norse Gods, used by Richard Wagner for his music dramas, contain much unmined dramatic gold. John Masefield and Sigurjónsson have converted Saga material to the uses of the drama. In old English literature, in Widsith, in the Battle of Brunanburh, the seeking dramatist may find. The romances of the Middle Ages, the fairy lore of all peoples, and the old Hindu animal fables are fertile in suggestion to the intending dramatist. What a wonderful one-act play, steeped in the mellow atmosphere of the Renaissance in Italy, might be made out of Browning's My Last Duchess! At least one new literary precedent has recently been created by the author who wrote a sequel to Dombey and Son. Certainly many famous novels and plays may be conceived as calling out for similar treatment at the hands of the experimental playwright. Famous literary and historic characters offer themselves as promising dramatic material. When Robert Emmons Rogers, author of the well-known (p. xxxviii) play, Behind a Watteau Picture, was a sophomore at Harvard, he wrote the following charming little play on Shakespeare which is reprinted here, with the author's permission, as a pleasing example of a promising piece of apprentice work:[17]

Within the White Luces Inn on a late afternoon in spring, 1582. The room is of heavy-beamed dark oak, stained by age and smoke, with a great, hooded fireplace on the left. At the back is a door with the upper half thrown back, and two wide windows through whose open lattices, overgrown with columbine, one can see the fresh country side in the setting sun. Under them are broad window seats. At the right, a door and a tall dresser filled with pewter plates and tankards. A couple of chairs, a stool and a low table stand about. Anne, a slim girl of sixteen, is mending the fire. Master George Peele, a bold and comely young man, in worn riding dress and spattered boots, sprawls against the disordered table. Giles, a plump and peevish old rogue in tapster's cap and apron, stands by the door looking out.

Peele [rousing himself]. Giles! Gi-les!

Giles [hurries to him]. What more, zur? Wilt ha' the pastry or—?

Peele. Another quart of sack.

Giles. Yus, zur! Anne, bist asleep? [The girl rises slowly.]

Anne [takes the tankard]. He hath had three a'ready.

Peele [cheerfully]. And shall have three more so I will. This player's life of mine is a weary one.

Anne [pertly]. And a thirsty one, too, methinks.

(p. xxxix) Giles [scandalized]. Come, wench! Ha' done gawking about, and haste! [Anne goes at right.] 'Er be a forrard gel, zur, though hendy. I be glad 'er's none o' mine, but my brother's in Shottery. He canna say I love 'is way o' making wenches so saucy.

Peele. A pox on you! The best-spirited maid I ha' seen in Warwickshire, I say. Forward? Man alive, wouldst have her like your blowsy wenches here, that lie i' the sun all day? I have seen no one so comely since I left London.

Giles [feebly]. But 'ere, zur, in Stratford—

Peele [hotly]. Stratford? I doubt if God made Stratford! Another day here and I should die in torment. Your grass lanes, your rubbly houses, fat burgesses, old women, your young clouter-heads who have no care for a bravely acted stage-play. [Bitingly.] "Can any good come out of Stratford?"

Giles. Noa, Maister Peele! Others ha' spoke more fairly—

Peele [impatiently]. My sack, man! Is the girl a-brewing it?

Giles. Anne! Anne! (I'll learn she to mess about.) Anne!

Anne [hurries in and serves Peele]. I heard you.

Giles. Then whoi cunst thee not bustle? Be I to lose my loongs over 'ee?

Anne [simply]. Mistress Shakespeare called me to the butt'ry door. Will hath not been home all day, and she is fair anxious. She bade me send him home once I saw him.

Peele [drinking noisily]. Who is it? [Anne is clearing the table.]

Giles [shortly]. Poor John Shakespeare's son Will.

Peele. A Stratford lad? A straw-headed beater of clods!

Giles. Nay, zur. A wild young un, as 'ull do noa honest work, but dreams the day long, or poaches the graät woods wi' young loons o' like stomach.

Anne [indignantly, dropping a dish]. It's not true! He is no poacher.

Peele [grinning]. What a touchy lass! No poacher, eh?

Anne. Nay, sir, but the brightest lad in Stratford. He hath learning beyond the rest of us—and if he likes to wander i' the woods, 'tis for no ill—he loves the open air—and you should hear the little songs he makes!

Peele. Do all the lads find in you such a defender, or (p. xl) only—? [She turns away.] Nay, no offense! I should like to see this Will.

Giles [grumpily]. 'E 'ave noa will to help 'is father in these sorry times, but ever gawks at stage-plays. 'E 'ull come to noa good end. [The player starts up.]

Peele. Stage-plays—no good end? Have a care, man!

Giles. Nay, zur—noa harm, zur! I—I—canna bide longer. [Backs out.]

Anne [at the window, wonderingly]. He should be here. He hath never lingered till sunset before. [Peele comes up behind her.]

Peele. Troubled, lass?

Anne. Nay, sir, but—but—[Suddenly] Listen!

Peele [blankly]. To what? [A faint singing without.]

Anne [eagerly]. Canst hear nothing—a lilt afar off?

Peele [nodding]. Like a May-day catch? I hear it.

Anne. 'Tis Will! Cousin, Will is coming. [Giles comes back.]

Giles [peevishly]. I canna help it. Byunt 'e later'n common?

A Voice. [The clear, boyish singing is coming very near.]

When springtime frights the winter cold, 5

(Hark to the children singing!)

The cowslip turns the fields to gold,

The bird from 's nest is winging—

Peele. Look you! There the boy comes.

Anne [leaning out the window]. Isn't he coming here? Will! Will! [He passes by the window singing the last words

Young hearts are gay, while yet 'tis May,

Hark to the children singing!

and leaps in over the lower part of the door, a sturdy, ruddy boy, with merry face and a mop of brown hair. Anne greets him with outstretched hands.]

Anne [reproachfully]. Will! Thy mother was so anxious!

Will. I did na' think. I ha' been in the woods all day and forgot everything till the sun set.

Anne. All the day long? Thou must be weary.

Will [frankly]. Nay, not very weary—but hungry.

Anne. Poor boy. He shall have his supper now.

(p. xli) Giles [protesting]. 'E be allus eating 'ere, and I canna a-bear it. Let him sup at his own whoam.

Will [shaking his head]. I dare na go home, for na doubt my father'll beat me rarely. I'll bide here till he be asleep. [He places himself easily in the armchair by the fire.]

Giles [going sulkily]. Thriftless young loon!

Anne [laying the table]. Hast had a splendid day?

Will [absently]. Aye. In the great park at Charlecote. There you can lie on your back in the grass under the high arches of the trees, where the sun rarely peeps in, and you can listen to the wind in the trees, and see it shake the blossoms about you, and watch the red deer and the rabbits and the birds—where everything is lovely and still. [His voice trails off into silence. Anne smiles knowingly.]

Anne. Thou'lt be making poetry before long, eh, Will?—Will? [To Peele] The boy hath not heard a word I spoke.

Peele [coming forward]. Would he hear me, I wonder! Boy!

Will [starting]. Sir? [Peele looks down on him sternly.]

Peele. Dost know thou'rt in my chair?

Will [coolly]. Thine? Indeed, 'tis very easy.

Peele. Hark 'ee! Dost know my name?

Will. I canna say I do.

Peele [distinctly]. Master George Peele.

Will. I thank thee, sir.

Peele. Player in my Lord Admiral's Company.

Will. [His whole manner changes and he jumps up eagerly.] A player? Oh—I did not know. Pray, take the seat.

Peele [amused]. Dost think players are as lords? Most men have other views. [Sits. Will watches him, fascinated.]

Will. Nay, but—oh, I love to see stage-plays! Didst not play in Coventry three days agone, "The History of the Wicked King Richard"?

Peele. Aye, aye. Behold in me the tyrant.

Will. Thou? Rarely done! I mind me yet how the hump-backed king frowned and stamped about—thus [imitating]. Ha! Ha! 'Twas a brave play!

Anne. Thy supper is ready, Will.

Peele [amused]. The true player-instinct, on my soul!

(p. xlii) Will [flattered]. Dost truly think so? [Anne plucks his sleeve.]

Anne. Will, where are thy wits? Supper waits.

Will [apologetically]. Oh—I—I—did na hear thee. [He tries to eat, but his attention is ever distracted by the player's words.]

Peele. Is my reckoning ready, girl?

Anne. Reckoning now, sir? Wilt thou—?

Peele. Yes, yes, I go to-night. To-morrow Warwick, then the long road to Oxford, playing by the way—and London at last!

Anne. And then? [Will listens intently.]

Peele. Then back to the old Blackfriars, where all the city will flock to our tragedies and chronicles—a long, merry life of it.

Anne [interested]. And does the Queen ever come?

Peele. Nay, child, we go to her. Last Christmas I played before her at court, in the great room at Whitehall, before the nobles and ambassadors and ladies—oh, a gay time—and the Queen said—

Will [starting up]. What was the play?

Anne. Eat thy supper, Will.

Will [impatiently]. I want no more.

Peele. So my young cockerel is awake again. Will, a boy of thy stamp is lost here in Stratford. Thou shouldst be in London with us. By cock and pie, I have a mind to steal thee for the company! [Rises to pace the floor.]

Will [breathlessly]. To play in London?

Anne. Nay, Will, he but jests. Thou'rt happier here than traipsing about wi' the players. [Giles appears at back.]

Giles. Nags be ready, zur, at sunset as thee'st bid. Shall I put the gear on?

Peele [sharply]. Well fed and groomed? Nay, I will see them myself. [Giles vanishes. Peele turns at the door.] Hark'ee, lass. Thy lad could do far worse than become a player. Good meat and drink, gold in 's pouch, favor at court, and true friends. I like the lad's spirit. [He goes. Anne drops into his chair by the fire. Twilight is coming on rapidly. Will stands silent at the window looking after the player.]

Anne [troubled]. Will, what is it? Thou'rt very strange to-night.

(p. xliii) Will [wistfully]. I—I—Oh, Anne, I want to go to London. I am a-weary of rusting in Stratford, where I can learn nothing new, save to grow old, following my father's trade.

Anne. But in London?

Will [kindling]. In London one can learn more marvels in a day than in a lifetime here; for there the streets are in a bustle all day long, and the whole world meets in them, soldiers and courtiers and men of war, from France and Spain and the new lands beyond the sea, all full of learning and pleasant tales of foreign wars and the wondrous things in the colonies. My schoolmaster told me of it. You can stand in St. Paul's and the whole world passes by, mad for knowledge and adventure. And then the stage-plays—!

Anne. Oh, Will, why long for them?

Will. Think how splendid they must be when the Queen herself loves to see 'em. If I were like this player-fellow, and acted with the Admiral's company! He laughed that he would take me with him—to be a player and perchance write plays, interludes, and noble tragedies! Think of it, Anne—to live in London and be one of all the rare company there, to write brave plays wi' sounding lines for all to wonder at, and have folk turn on the streets when I passed and whisper, "That be Will Shakespeare, the play-maker"—to act them even at court and gain the Queen's own thanks! Anne, London is so great and splendid! It beckons me wi' all its turmoil of affairs and its noble hearts ready to love a new comrade. [Disconsolately] And I must bide in Stratford?

Anne [gently]. Come now, Will. No need to be so feverish. Sit down by me. What canst thou know of play-making? What canst thou do in London?

Will [he sits down by the hearth at her feet, looking into the firelight]. I'll tell thee, Anne. Thy father and half the village call me a lazy oaf, that I stray i' the woods some days instead of helping my father. I canna help it. The fit comes on me, and I must be alone, out i' the great woods.

Anne [gladly]. Then thou dost not poach?

Will [hastily]. No, no—that is—sometimes I am with Hodge and Diccon and John a' Field, and 'tis hard not to chase the deer. Nay, look not so grave—I try to do no harm.

Anne [quietly]. And when thou'rt alone?

Will. Then I lie under the trees or wander through the (p. xliv) fields, and make plays to myself, as though I writ them in my mind, and cry the lines forth to the birds—they sound nobly, too—or make little songs and sing them i' the sunshine. They are but dreams, I know, but splendid ones—and the player looked wi' favor on me, and said I might make a good player, and he would take me with him.

Anne. But he only jested.

Will. No jest to me! I'll take him at his word and go with him to London. [He starts up eagerly.]

Anne [troubled]. Will, Will! [Peele enters at the back.]

Peele. Hark 'ee, Giles, I go in half an hour!

Will. Master Peele! [Catches at his arm.]

Peele. Well, youngster?

Will [slowly]. Thou—thou saidst I had a good spirit and would do well in London—in a stage company. Thou wert in jest, but—I will go with thee, if I may.

Peele [taken all aback]. Go with me?

Will [earnestly]. With the player's company—to London.

Peele [laughing]. 'S wounds! Thou hast assurance! Dost think to become a great player at once?

Will [impatiently]. Oh, I care not for the playing. Let me but be in London, to see the people there and be near the theatre. I'll be the players' servant, I'll hold the nobles' horses in the street—I'll do anything!

Peele [seriously]. And go with us all over England on hard journeys to play to ignorant rustics?

Will. Anywhere—I'll follow on to the world's end—only take me with you to London! [As he speaks Giles and Mistress Shakespeare, a kindly faced woman of middle age, dressed in housewife's cap and gown, appear at the door.]

Giles. There 'e be, Mistress Shixpur.

Mistress S. [as she enters]. Oh, Will. [He turns sharply.]

Will [confusedly]. Mother! I—I—did not know thou wert here.

Mistress S. Why didst not come home—and what dost thou want with this stranger?

Anne. He would go to London with him.

Mistress S. [aghast]. To London. My Will?

Will [quietly]. Thou knowest, mother, what I ha' told thee, things I told to no other, and now the good time has come that I can see more of England.

(p. xlv) Mistress S. But I canna let thee go. Oh, Anne, I knew the boy was restless, but I did not think for it so soon. He is only a boy.

Will [coloring]. In two years I shall be a man—I am a man now in spirit. I canna stay in Stratford. [Mistress Shakespeare sinks down in a chair.]

Mistress S. What o' me? And, Will, 'twill break thy father's heart! [Will looks ashamed.]

Will. I know, he would not understand. 'Tis hard. He must not know till I be gone.

Mistress S. [To Peele]. Oh, sir, how could you wish to lead the lad away? Hath not London enough a'ready?

Peele [who has been listening uncomfortably, faces her gravely]. I but played with the lad at first, till I saw how earnest he was; then I would take him, for I loved his boldness. But, boy, I'll tell thee fairly, thou'lt do better here. Thou'st seen the brave side of it, the gay dresses, the good horses, the cheering crowds and the court-favor. But 'tis dark sometimes, too. The pouches often hang empty when the people turn away—the lords are as the clouded sun, now smiling, now cold—and there come the bitter days, when a man has no friends but the pot-mates of the moment, when every man's hand is against him for a vagabond and a rascal, when the prison-gates lay ever wide before him, and the fickle folk, crying after a new favorite, leave the old to starve.

Anne. Will, canst not see? Thou'rt better here—

Will [bravely]. I know—all this may wait me—but I must go.

Mistress S. [alarmed]. Must go, Will? [He kneels by her side.]

Will. [tenderly]. Hush, mother, I'll tell thee. 'Tis not entirely my longing, for this morning the keeper of old Lucy—

Giles. Ha, poaching again, young scamp!

Will. Brought me before him—I was na poaching, I'll swear it, not so much as chasing the deer—but Sir Thomas had no patience, and bade me clear out, else he would seize me. I—I—dare na stay.

Mistress S. I feared it; thy father forbade thee in the great park. And now—Oh, Will, Will—I know well how thou'st longed to go from here—and now thou must—what shall I do, lacking thee?

(p. xlvi) Peele [frankly]. Will, if thou must go, thou must. London is greater than Stratford, and there is much evil there, but thou'rt true-hearted, and—by my player's honor—I will stand by thee, till the hangman get me. But we must go soon. 'Tis a dark road to Warwick—I'll see to the horses. Is it a compact? [Will gives him his hands.]

Will [huskily]. A compact, sir—to the end. [Peele hurries out.]

Giles. Look at 'e now, breaking 'is mother's heart, and mad wi' joy to revel in London. 'Tis little 'e recks of she.

Will [hotly]. Thou liest. [Bending over her] Mother, 'tis not true. I do love thee and father, I love Stratford. I'll never forget it. But 'tis so little here, and I must get away to gain learning and do things i' the world, that I may bring home all I get; fame, if God grant it, money, if I gain it, all to those at home.

Anne. Thou'rt over-confident.

Will. Aye, because I'm young. God knows there is enough pain in London, and I'll get my share—but I'm young! Mother, thou'rt not angry?

Mistress S. I knew 'twas coming, and 'tis not so hard. We will always wait for thee at home, when thou'rt weary.

Giles [at the door]. The horses are waiting. 'Tis dark, Will.

Will [breaking down]. Mother, mother!

Mistress S. The good God keep thee safe. Kiss me, Will. [He bends over her, then stumbles to the door, Anne following.]

Will [turning]. Anne—Anne—thou dost not despise me for deserting Stratford. I must go.

Anne. Oh, I know. Thou'lt go to London and forget us all.

Will. No, no, thou—I couldn't forget. I'll remember thee, Anne—I'll put thee in my plays; all my young maids and lovers shall be thee, as thou'rt now—and I'll bring thee rare gifts when I come home.