Transcriber's Note: Original spelling and punctuation have been

retained. In particular, both Eutainia and Eutaenia are used in

the original, as are both pickeringi and pickeringii.

University of Kansas Publications

Museum of Natural History

Volume 13, No. 5, pp. 289-308, 4 figs.

February 10, 1961

Occurrence of the Garter Snake,

Thamnophis sirtalis,

in the Great Plains and Rocky Mountains

BY

HENRY S. FITCH AND T. PAUL MASLIN

University of Kansas

Lawrence

1961

University of Kansas Publications, Museum of Natural History

Editors: E. Raymond Hall, Chairman, Henry S. Fitch,

Robert W. Wilson

Volume 13, No. 5, pp. 289-308, 4 figs.

Published February 10, 1961

University of Kansas

Lawrence, Kansas

PRINTED IN

THE STATE PRINTING PLANT

TOPEKA, KANSAS

1961

Occurrence of the Garter Snake,

Thamnophis sirtalis,

in the Great Plains and Rocky Mountains

BY

HENRY S. FITCH AND T. PAUL MASLIN

Introduction

The common garter snake (Thamnophis sirtalis) has by far the

most extensive geographic range of any North American reptile,

covering most of the continental United States from the Atlantic to

the Pacific and from south of the Mexican boundary far north into

Canada and southeastern Alaska. Of the several recognized subspecies,

the eastern T. s. sirtalis has the most extensive range, but

that of T. s. parietalis in the region between the Mississippi River

and the Rocky Mountains is almost as large. The more western

T. s. fitchi occurring from the Oregon and California coasts east

through the northern Great Basin, has the third largest range, while

the far western subspecies pickeringi, concinnus,

infernalis and tetrataenia,

and the Texan T. s. annectens all have relatively small ranges.

Since the publication of Ruthven's revision of the genus Thamnophis

more than 50 years ago, little attention has been devoted to

the study of this widespread and variable species, except in the

Pacific Coast states (Van Denburgh, 1918; Fitch, 1941; Fox, 1951).

However, Brown (1950) described the new subspecies annectens

in eastern Texas, and many local studies have helped to clarify the

distribution of the species in the eastern part of the continent and

to define the zone of intergradation between the subspecies sirtalis

and parietalis. In our study attention has been focused upon

parietalis

in an attempt to determine its western limits and its relationships

to the subspecies that replace it farther west.

Taxonomic History

Thamnophis sirtalis parietalis Say was described (as Coluber

parietalis) in 1823 from a specimen obtained in what is now Washington

County, Nebraska, on the west side of the Missouri River

three miles upstream from the mouth of Boyer's River [Iowa], or

approximately eight miles north of Omaha. Although the type locality

was unequivocally stated in the original description, Nebraska

was not mentioned since the state was not yet in existence. Because

[pg 292]

the mouth of Boyer's River, the landmark by means of which the

type locality is defined, is in Iowa, the impression has been imparted

that the type locality itself is in Iowa (Schmidt, 1953:175), and to

our knowledge the type locality has never been associated with Nebraska

in the literature.

Like all the more western subspecies, parietalis is strikingly different

from typical sirtalis in having conspicuous red markings. The

relationship between the two was early recognized. Several of the

other subspecies were originally described as distinct species. Coluber

infernalis Blainville, 1835; Tropidonotus concinnus Hallowell,

1852; Eutainia pickeringi Baird and Girard, 1853; and others now

considered synonyms eventually came to be recognized as conspecific

with Thamnophis sirtalis. Ruthven (1908:166-173) allocated

all western sirtalis to either parietalis or concinnus, the

latter

including the populations of the northwest coast in Oregon, Washington

and British Columbia.

Subsequent more detailed studies by later workers with more

abundant material led to the recognition of some subspecies that

Ruthven thought invalid and led to the resurrection of some names

that he had placed in synonomy. Van Denburgh and Slevin (1918:198)

recognized infernalis as the subspecies occurring over most

of California and southern Oregon, differing from more northern

populations in having more numerous ventrals and caudals and a

paler ground color. Fitch (1941:575) revived the name pickeringii

for a melanistic population of western Washington and southwestern

British Columbia, restricting the name concinnus to a red-headed

and melanistic population of northwestern Oregon, and restricting

the name infernalis to a pale-colored population in the coastal strip

of California.

These changes left most of the populations formerly included in

concinnus and infernalis without a name, and Fitch (op.

cit.) revived

Thamnophis sirtalis tetrataenia (Cope) to apply to them. However,

Fox (1951:257) demonstrated that the type of T. s. tetrataenia came

from the San Francisco peninsula (rather than from "Pit River, California"

as erroneously stated in the original description) and that

the name was applicable to a localized peninsular population rather

than to the wide-ranging far western subspecies, which he named

T. s. fitchi. The range of fitchi includes California west of the

Colorado

and Mohave deserts (except for the narrow strip of coast

occupied by infernalis and tetrataenia), Oregon except the northwestern

[pg 293]

part, Washington east of the Cascade Range, most of British

Columbia, extreme southeastern Alaska (occurring farther north

than any other terrestrial reptile of North America) and parts of

Idaho.

Neither Fox (1951) nor Fitch (1941) defined the eastern limits

of fitchi or discussed its relationship to the subspecies

parietalis.

Wright and Wright (1957:849) stated: "Fitch ... did not

even mention the big scrap basket form parietalis, from which he

pulled T. s. fitchi (old tetrataenia). That comparison remains to

be

made, and the east boundary of fitchi and the west boundary of

parietalis are still nebulous." We have undertaken to define better

than has been done before the ranges of parietalis and fitchi and

to list the diagnostic characters separating these two subspecies.

Freshly collected material of both has been compared. At the time

of his 1941 revision the senior author had never seen a live or recently

preserved specimen of parietalis.

Discontinuity of Range

Wherever it occurs at all, the common garter snake is usually

abundant. Because of its diurnal habits and the concentration of

its populations along watercourses, it is not likely to be overlooked.

There are few, if any, remaining large areas in the United States

where herpetologists have not carried on field work. It may be

anticipated that certain rare and secretive species will still be found

far from any known stations of occurrence, and seeming gaps in the

ranges of these species will eventually be filled. But for the common

garter snake the negative evidence provided by the lack of records

from extensive areas should be taken into account in mapping the

range.

Most large collections of garter snakes contain misidentified specimens.

The diagnostic differences in color and pattern are often

obscured, especially if the specimens are poorly preserved. Many

specimens deviate from the scalation typical of the form they represent,

and key out to other species. Isolated records should therefore

be accepted with caution. A case in point is Colorado University

Museum No. 46, from Buford, Rio Blanco County, Colorado, originally

identified by Cockerell (1910:131) as Thamnophis sirtalis

parietalis. This specimen, and another, now lost, from Meeker in the

same county seemingly served as the basis for mapping the range

of sirtalis across the western half of Colorado, for there seem to be

[pg 294]

no other records from this part of the state. However, a re-examination

of the specimen from Buford shows it to be an atypical individual

of another species, T. elegans vagrans. A specimen of T.

radix haydeni (Col. U. Mus. No. 3165) was the basis for Maslin's

(1959:53) record of parietalis in Baca County on the north fork of

the Cimarron River in southeastern Colorado. Brown (1950:203)

has mentioned the difficulty of defining the range of sirtalis in the

southern Great Plains because of misidentifications of the similar

T. radix.

The range of the common garter snake has never been adequately

mapped in the Rocky Mountain and Great Basin states. Recent general

works (Smith, 1956:291; Wright and Wright 1957:834; Stebbins

1954:505; Conant 1958:328) which have shown maps of the over-all

range of sirtalis, differ sharply as to the extent of its distribution in

Texas, New Mexico and Arizona, but all show its distribution as

continuous over the more northern Great Basin and Rocky Mountain

states. However, specimens and specific locality records from this

extensive area seem to be scarce and some are based on early collections

of doubtful provenance. Throughout this region the low

rainfall, fluctuating and uncertain water supply, and general lack of

mesic vegetation along many of the streams render the habitat rather

hostile to garter snakes in general. Thamnophis elegans vagrans,

highly adapted to conditions in this region and generally distributed

over it, doubtless offers intensive competition to the species sirtalis

wherever they overlap and perhaps constitutes a limiting factor for

sirtalis in some drainage basins.

Convincing records of sirtalis are lacking from all of Colorado—except

for those in the drainage basins of the South Platte, and the

Río Grande east of the Continental Divide—from the eastern half

of Utah (east of the Wasatch Range), from New Mexico except for

the Río Grande drainage (with one record each for the Canadian

and Pecos river drainages), from southwestern Wyoming (at least

that part in the Colorado River drainage basin), from the western

half of Oklahoma, and from Texas, except the eastern and extreme

western and northern parts. The species occurs in Nevada only

near that state's western and northern boundaries. The range is

therefore much different than it has been depicted heretofore, with

the populations living east of the Continental Divide widely separated

from those to the west for the entire length of the Rocky

Mountains south of the Yellowstone National Park region. The populations

of northern Utah, southern Idaho, and Nevada, which have

[pg 295]

been considered parietalis are thus far removed from the main

population of that subspecies to the east and are isolated from them

by the barrier of the Continental Divide and arid regions farther

west.

Although some of the records published for Thamnophis sirtalis

are erroneous, being based on misidentifications of other species,

various outlying records, including those in western Kansas, the

Panhandle of Texas, and southeastern New Mexico probably represent

localized relict populations that have survived from a time when

the species was more generally distributed in this region. The population

of T. sirtalis in the Río Grande drainage of New Mexico is

geographically isolated and remote from other populations of the

species. Except for a few isolated and highly localized populations

the species is absent from the Republican, Smoky Hill, Arkansas,

Cimarron, Canadian, Red, Brazos, Colorado and Pecos rivers and

their tributaries west of the one hundredth meridian in the arid High

Plains.

Streams in this region of High Plains are in most instances unsuitable

habitats because they are in eroded channels, have a variable

and uncertain water supply, and have poorly developed riparian

communities. The marsh and wet meadow habitat preferred by

sirtalis in most parts of its range is almost absent. T. radix and

T.

marcianus, well adapted to conditions in this region, perhaps provide

competition that is limiting to T. sirtalis. However, several

well-isolated

populations of sirtalis have survived as relicts in the southern

Great Plains, presumably from a time several thousand years ago

when mesic conditions were more prevalent, perhaps in an early

postglacial stage.

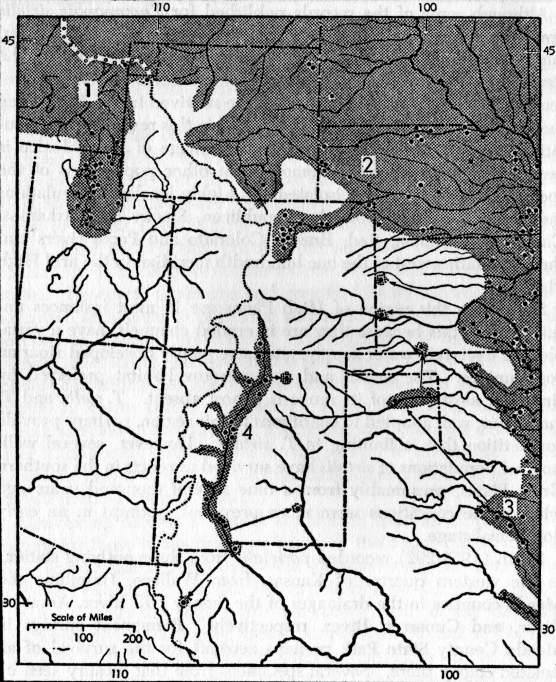

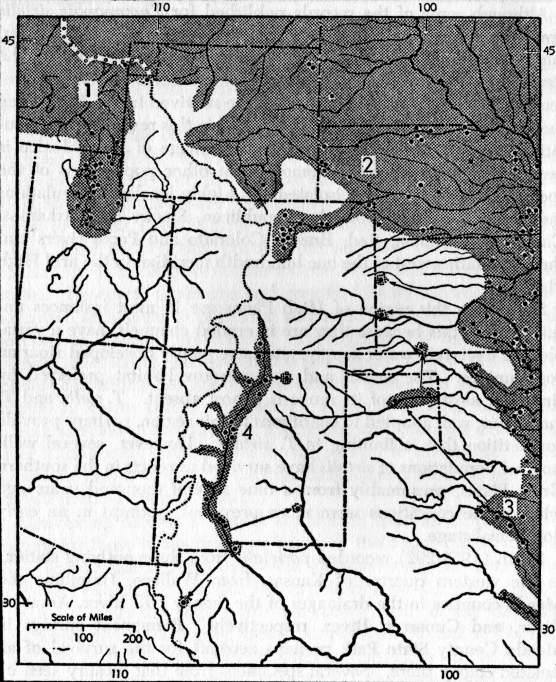

Fig. 1. Map of a part of the United States in the

region of the Great Plains and

Rocky Mountains, and adjacent northwestern Mexico showing supposed range

(shaded) and localities of authenticated occurrence (dots) of Thamnophis

sirtalis. 1. T. s. fitchi, 2. T. s. parietalis, 3. T. s.

annectens, 4. T. s. ornata. Records

from Idaho and Wyoming are based on specimens in the University of

Kansas Museum of Natural History collection. Other records are based on

Woodbury (1931) for Utah, Hudson (1942) for Nebraska, Maslin (1959) for

Colorado, Smith (1956) for Kansas, R. G. Webb (MS) for Oklahoma, Brown

(1950) and Fouquette and Lindsay (1955) for Texas, Cope (1900), Van Denburgh

(1924), Little and Keller (1937) for New Mexico, and Smith and Taylor

(1945) for Mexico.

Smith (1956:292) recorded parietalis from three outlying stations

in the western quarter of Kansas, from Wallace, Hamilton and

Meade counties in the drainages of the Smoky Hill River, Arkansas

River, and Cimarron River, respectively. Permanent springs in

Meade County State Park perhaps account for the survival of an

isolated colony there. Several specimens from that locality seen by

Fitch in August, 1960, when recently collected by a University of

Michigan field party, seemed to be of the Texas subspecies annectens,

as their dorsal stripes were reddish orange, and markings on

the dorsolateral area were pale yellow rather than red. Specimens

from the Texas Panhandle, from Hemphill County (Brown, 1950:207)

and nine miles east of Stinnet, Hutchison County (Fouquette

and Lindsay, 1955:417) likewise are most nearly like annectens

[pg 296]

judging from the authors' descriptions. The specimens from nine

miles east of Stinnet averaged large; the two largest would have

attained or slightly exceeded four feet in length if they had had complete

[pg 297]

tails. No sirtalis so long as four feet has been recorded

elsewhere.

Records are lacking from the drainages of the Republican, North

Canadian, Brazos and Colorado River drainages in the High Plains,

but possibly isolated populations occur in some of these also. The

only record from the Pecos River drainage is that of Bundy (1951:314)

from Wade's Swamp near Artesia, Eddy County, New Mexico.

This locality is separated by some 140 miles from any other known

station of occurrence.

From extreme southern Colorado south across New Mexico to the

Mexican border T. sirtalis occurs in continuous or nearly continuous

populations in the Río Grande Valley, and has been recorded from

many localities. It has been recorded from relatively few localities

of tributary streams (Los Pinos, Abiqui, Santa Fe) all near the main

valley. There is one record from the Ocate River, a headwaters

tributary of the Canadian River, in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains

near other localities in the Río Grande drainage. The southwestern-most

known locality of occurrence is Casas Grandes in the Mexican

state of Chihuahua some 130 miles southwest of El Paso, Texas, and

near the Continental Divide. The Río Casas Grandes must have

once been a tributary of the Río Grande, but now its desert drainage

basin is isolated.

Re-description of a Subspecies from New Mexico

Most specimens of a population of sirtalis occurring in New Mexico

are recognizably different from most specimens of other populations.

This New Mexican population is therefore here recognized

as a distinct subspecies:

Thamnophis sirtalis ornata Baird

Eutaenia ornata Baird, 1859:16.

Eutaenia sirtalis dorsalis Cope, 1900:1076.

Thamnophis sirtalis parietalis (part) Van Denburgh, 1924:222.

Type.—U. S. Nat. Mus. No. 960, obtained at El Paso, Texas, at some time in

the eighteen fifties by Col. J. D. Graham.

Range.—Río Grande and vicinity, from Conejos and Costilla counties in extreme

south-central Colorado south across New Mexico to Mexican border.

Records from neighboring drainage systems, Casas Grandes in Chihuahua and

Artesia and Ocate River in New Mexico, probably also pertain to ornata.

Description.—A specimen in the University of New Mexico Natural History

Museum (E. D. Flaherty No. 560, obtained one mile west and one-half mile

south of Isleta, Bernalillo County, New Mexico, on May 31, 1959) was described

as follows while its colors were still but little altered by preservatives:

Top of head olive, supralabials pale gray, edged with black posteriorly; chin

milky white, with dark edges posteriorly on fifth, sixth and seventh infralabials;

[pg 298]

dorsal stripe yellow; including middorsal row of scales and little more than adjacent

half of row on either side of it; dorsolateral area olive-brown with row of

black spots on its lower half, these spots elliptical, averaging about size of one

scale on anterior part of body, smaller posteriorly; adjacent spots separated by

interspaces of approximately their own length, irregular black markings on upper

half of dorsolateral area not forming definite spots but fused longitudinally to

form continuous black border to dorsal stripe; crescent-shaped red markings in

areas between scale rows three to nine, these markings invading edges of scales,

and themselves having ill-defined edges blending into the darker ground color;

lateral stripe pale, yellowish gray, limited to scale rows two and three for most

of its length, but including rows four and five in neck region; row of irregular

black marks low on each side, with each mark centering on anterior part of

lower half of scale of first row but overlapping onto corners of adjacent ventrals;

approximately every other scale of first row so marked; ventral surface pale,

suffused with bluish tint; most of ventrals marked on anterior edges with pair of

semicircular black spots, each situated about two-thirds of distance from mid-line

to lateral edge of ventral; these marks diminishing in size and finally disappearing

on posterior part of body; ventral surface otherwise immaculate.

Lepidosis normal for genus and species, with preoculars single on each side,

supralabials 7-7, infralabials 8-8, ventrals 159, anal entire, subcaudals 77 (including

terminal spine), paired except for second, third and fourth; scale rows

19 from neck slightly beyond mid-body, fifth on left side ending opposite 86th

ventral; length from snout to vent 670 mm., tail 202 mm.

Comparisons.—From T. s. parietalis, T. s. ornata differs in its consistently pale

ground color, olive instead of dark brown or black. In respect to color-pattern

ornata stands in approximately the same relation to parietalis as, farther west,

T. s. infernalis, a pale subspecies of the California coast, stands in relation to

T. s. fitchi. Nevertheless, fitchi consistently has a dark ground color, whereas

parietalis is highly variable, and the color of an occasional specimen (for example

KU 17032 from Douglas County, Kansas) matches ornata in olive coloration.

These unusually pale specimens of parietalis differ from ornata in not

having a continuous black edge along each side of dorsal stripe; black pigment

of this area is concentrated into rows of spots alternating with those of lower

series. From T. s. infernalis, ornata differs in having paired black spots on the

ventrals and in having more than three series of red crescents on dorsolateral

area of each side.

Remarks.—The type of ornata seems to have been lost, and the

available information concerning it is far from satisfactory. In the

original description, Baird listed three specimens, purportedly from

"Indianola, Texas" (J. H. Clark, 438), from the Río Grande, Texas

(J. H. Clark, 768), and from near San Antonio, Texas (Dr. Kennerley,

no number). None of these three specimens could have been

ornata as conceived of by us because all were collected outside the

geographic range of ornata. However, there was also included a

plate with a drawing of a specimen and a reference to an earlier

paper (Baird and Girard, 1853) in which a specimen obtained by

Col. Graham "Between San Antonio and El Paso" was described.

Smith and Brown (1946:72) have presented evidence that this specimen

[pg 299]

figured (rather than any of the three specifically mentioned)

served as a basis for the plate, and they therefore considered it to

be the holotype of ornata, even though Baird referred this specimen

to "Eutaenia parietalis Say" in the same paper (1859) in which the

original description of ornata was published. Cope (1900:1079)

listed under Eutaenia sirtalis parietalis a specimen, U. S. Nat. Mus.

No. 960, from El Paso, obtained by Col. Graham, and referred to it

as a type (without specifying of what it was the type). Smith and

Brown (loc. cit.) interpreted this statement by Cope as further evidence

that the specimen in question should be considered the type

of ornata, and they restricted the type locality, originally stated as

"between San Antonio and El Paso" to "El Paso." Actually all valid

records of the species sirtalis from the vicinity of the Río Grande are

from the El Paso region or from farther north.

It is with some misgivings that we herewith accept the interpretation

proposed by Smith and Brown regarding the applicability of

the name ornata and the designation by these authors of the now

missing specimen from the region of El Paso as the holotype of that

form. The evidence linking the name ornata with the New Mexican

subspecies is tenuous; there is some doubt as to the provenance of

U. S. Nat. Mus. No. 960 (the supposed type), and even more doubt

as to whether this is the specimen depicted in the plate that formed

part of the original description.

Cope (1900:1076) recognized as a distinct subspecies, Eutaenia

sirtalis dorsalis, the same population that we recognize herein as

T. s. ornata, and Smith (1942:98) considered the name dorsalis to

be a synonym of T. s. parietalis. However, it is almost certain that

both authors misapplied the name, since the type of Baird's and

Girard's (1853:31) Eutainia dorsalis was obtained

in Coahuila, Mexico,

between Monclova and the Río Grande, far south of the known

range limits of T. sirtalis in Texas. The description does not fit T.

sirtalis and almost certainly pertains to another species.

Specimens examined.—Univ. of Kansas Mus. Nat. Hist. (hereafter abbreviated

to "KU") Nos. 5479 to 5497, from the north end of Elephant Butte

Reservoir, Sierra County, New Mexico, and 8592 and 8593 from near Las Lunas,

Valencia County, New Mexico; Univ. of New Mexico Mus. Nos. 571 and 572

(J. S. Findley) from 2 miles west and 1/4 mile north of Albuquerque, Bernalillo

County, New Mexico, and No. 4021 (E. D. Flaherty) from 1 mile west and 1/2

mile south of Isleta, Bernalillo County, New Mexico.

Description of T. s. parietalis

From most of the vast area occupied by parietalis, material has

not been available to us, and our concept of this subspecies is based

chiefly on specimens and living material from Kansas and northeastern

[pg 300]

Colorado. A total of 520 live parietalis has been examined

from the University of Kansas Natural History Reservation some 130

miles south and a little east of the type locality in Nebraska. These

probably differ but little from typical specimens. The range of individual

variation in pattern is especially notable. In those from

the Reservation, the ground color varies from dull olive-brown to

almost jet black. The markings on the dorsolateral area vary in

color, in shade and in extent. These marks are chiefly confined to

the skin between the scales of rows three to nine. Although most

typically these marks are of some shade of red (hence the name

"red-sided garter snake"), they may be pale buff, or pale greenish

yellow, or may even have a bluish tint. In approximately ten per

cent of the specimens from the Reservation there is no red at all in

the pattern, which hence is similar to that of T. s. sirtalis in the

eastern

United States. Only a minority have all the dorsolateral marks

red, and in some of these specimens the marks higher on the sides

are progressively paler red, having a bleached out appearance. Most

typically the marks between rows three to six are some shade of red

while the smaller marks between rows six to nine are pale—yellowish,

greenish, or buffy. In some the pale area of the lateral stripe is

in varying degrees suffused with red, which may extend onto the

edges of the ventrals and even to the underside of the tail.

T. s. parietalis may be diagnosed, on the basis of these snakes from

northeastern Kansas, as follows: Size medium large (length 23.5 to

34.5, or, exceptionally 43.5 inches in adult males; 32.5 to 46.0 inches

in adult females), dorsolateral color olive to black. Approximately

every other scale of the third row is bordered above and anteriorly

by a crescent-shaped area of scarlet colored skin. Similar crescent-shaped

areas border the scales of the fourth and fifth rows and often

two adjacent crescents meet at the ends of an intervening scale and

fuse forming an H-shaped mark. Placed alternately with these markings

are similar but smaller crescent-shaped markings on the skin

of the upper half of the dorsolateral area on each side bordering

every other scale of the sixth, seventh and eighth rows. The crescents

of this upper series also may fuse to form series of H-shaped

markings alternating with those of the lower series. The dorsal stripe

is yellow with a faint dusky suffusion; it involves all of the middorsal

scale row and approximately the adjacent half of the row on either

side. The lateral stripe is faint, yellowish gray, chiefly on the upper

half of the second scale row, lower half of third, and the intervening

skin, and is often invaded or suffused by the red marks of the dorsolateral

area. The first scale row, adjacent corners of the ventrals,

[pg 301]

and lower half of the second scale row are suffused with dark pigment

and appear dusky, but this area is often marked with black,

setting off the paler area of the lateral stripe. The ventrals are dull,

whitish, faintly suffused with yellowish, greenish or bluish, each

ventral having a black dot usually of semicircular shape on its anterior

margin near the anterolateral corner.

Comparison of T. s. parietalis and T. s. fitchi

Like most widely ranging subspecies, parietalis and fitchi vary

geographically and local populations often are noticeably different

from typical material. It is possible that future revisors will recognize

additional subspecies, but in the variant populations known

to us the degree of differentiation is slight as compared, for instance,

with that in the subspecies of Thamnophis elegans. Scalation is

remarkably

uniform in all the subspecies of sirtalis, but coastal and

northern populations tend to have fewer ventrals and subcaudals

than do their counterparts farther inland and farther south. In their

geographic variation the ventrals and subcaudals follow clines, and

do not in themselves warrant subspecific divisions. Variation occurs

chiefly in the color and pattern including the intensity of dark pigmentation

of the dorsolateral area, head, ventral surface and lower

edge of the lateral stripe; in extent, position and shade of red or pale

colored markings on the dorsolateral area; in presence and extent of

reddish suffusion on the head, in the region of the lateral stripe, and

on the ventral surface of the tail. Most of these same characters

[pg 302]

vary within the subspecies fitchi, but the range of variation is

relatively

minor. Fitch (op. cit.:582-584) described typical populations

and also described briefly several small series from British Columbia,

Idaho, Oregon, and California which were not entirely typical. Most

[pg 303]

frequent variation was in heavy reddish suffusion on the sides of the

head not found in typical fitchi. In each local population of this

subspecies the characters seem to be remarkably uniform and stable.

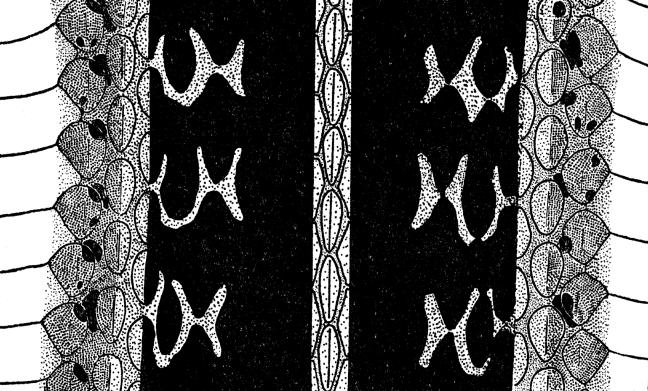

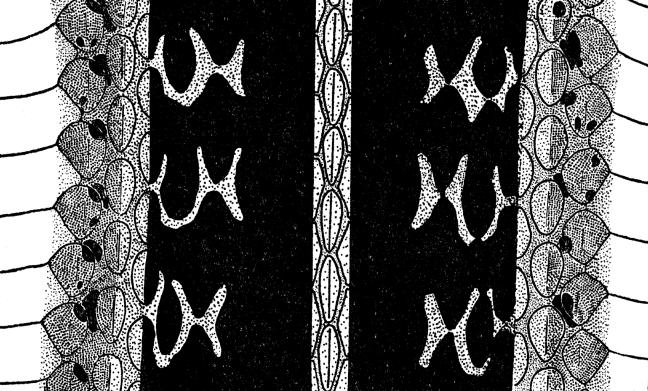

Fig. 2. Diagrammatic drawing of pattern in stretched

skin of T. s. fitchi; the

pale markings on the black dorsolateral area are scarlet (× 2-1/2).

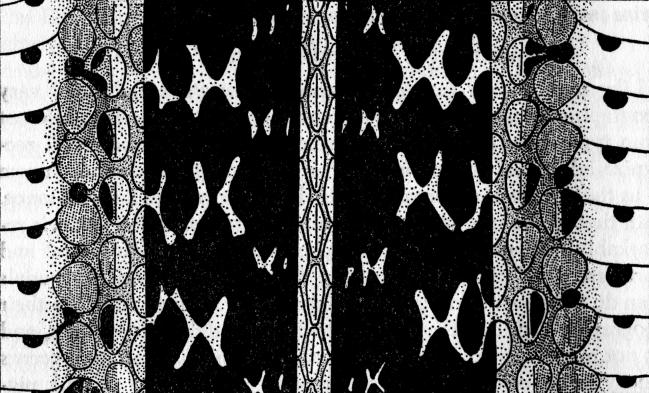

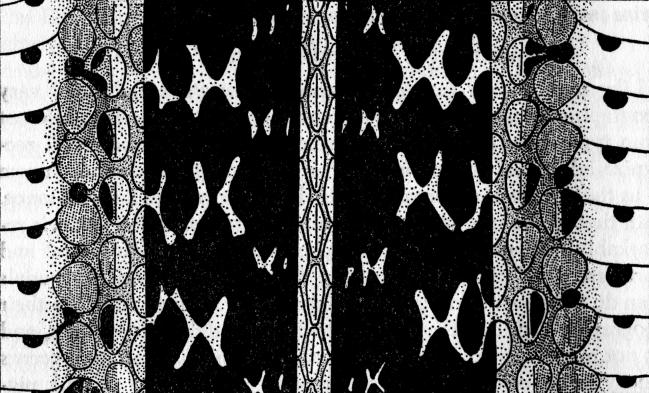

Fig. 3. Diagrammatic drawing of stretched skin of T.

s. parietalis; the scarlet

markings extend farther dorsally than in T. s. fitchi and black spots are

prominent

on the ventrals laterally. Some individuals of parietalis have much paler

ground color, resembling ornata except in minor details (× 2-1/2).

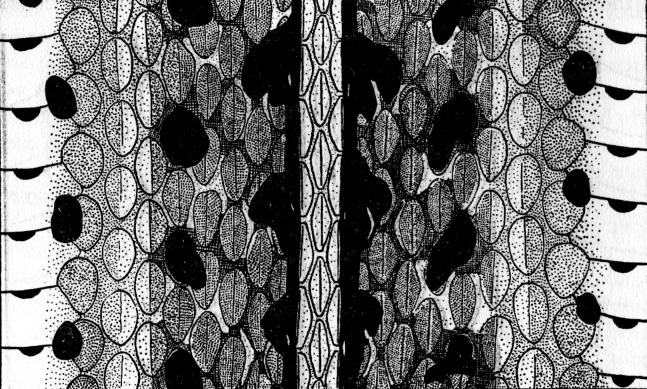

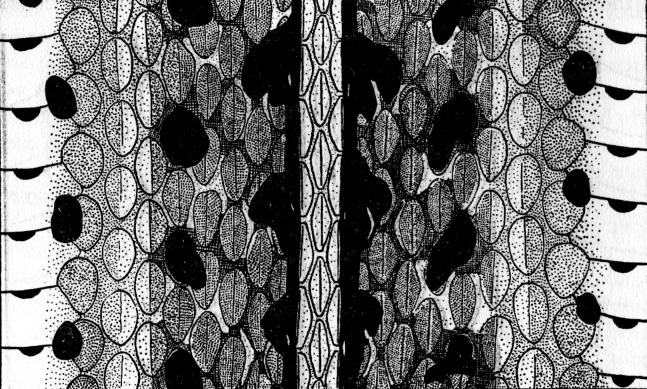

Fig. 4. Diagrammatic drawing of stretched skin of T.

s. ornata. The ground

color is like that of parietalis but paler with a continuous black area

bordering

the dorsal stripe (× 2-1/2).

T. s. parietalis differs from fitchi in several trenchant

characters,

and there are additional slight or average differences between the

two. In approximate order of their importance the differences are

as follows: 1) The red (or pale yellow or green or buffy) marks on

skin between the scales on the upper half of the dorsolateral area

(that is between the sixth and seventh, seventh and eighth and

eighth and ninth scale rows) present in parietalis are missing in

fitchi or are represented by only an occasional small fleck. 2) The

dorsolateral area is black or nearly so in fitchi but averages paler in

parietalis, in which a wide range of shades may be found from black

to olive brown. 3) The red of the dorsolateral area frequently invades

the lateral stripe, which sometimes is mostly red, and may

even invade the ventrals in parietalis, but in fitchi the red

marks are

usually confined to the dorsolateral area, and do not invade the

lateral stripe. 4) The prominent paired black dots or semicircular

marks on the anterior edge of each ventral in parietalis are largely

lacking in fitchi, which rarely has any dark marks on the ventral

surface. 5) The dorsal stripe consistently involves the middorsal

scale row and the adjacent half of the next row on each side, and is

bright yellow in fitchi, but in parietalis it may be slightly

wider, may

be duller with more dusky suffusion, and its edges may be less

sharply defined.

Intermediate and Atypical Populations

Of many specimens examined from eastern Oregon, Idaho, Utah,

Wyoming and Colorado, few were typical of either parietalis or

fitchi. Many were intermediate in some respects or showed a composite

of characters of the two subspecies. No well-defined belt of

intergradation exists, but the transition extends over more than a

thousand miles, with local populations somewhat isolated and

slightly differentiated along divergent lines. In view of this situation

some plausibility could be claimed for any of several dividing lines

between the subspecies. However, by far the most logical division

is the Continental Divide; south of the Teton Range it constitutes

a broad barrier separating eastern and western populations. Across

Montana and Canada also it constitutes a more or less formidable

barrier, with high altitudes and cold climates that probably are limiting

to garter snakes. With few exceptions the snakes from east of

the Continental Divide are more nearly like parietalis in the sum of

[pg 304]

their characters whereas those from west of the Divide are more

nearly like fitchi.

In the Teton Range and in Yellowstone National Park these garter

snakes occur in headwater streams up to the Continental Divide.

KU 27956 from Two Ocean Lake 3-1/2 miles northeast of Moran, Teton

County, Wyoming, agrees in its characters with fitchi, having the

red lateral marks small and inconspicuous, discernible only on the

anterior half of the body. The dorsolateral area is dark, almost

black. The ventrals lack dark markings.

In Utah, populations of sirtalis occur in the drainages of the Bear,

Weber and Sevier rivers and other smaller streams of the western

half of the state. Obviously the species invaded Utah from the

north, probably at a time when Lake Bonneville, the predecessor

of the present Great Salt Lake, drained into the Snake River of

Idaho. Van Denburgh and Slevin (1918:190) separated from their

western "concinnus" and "infernalis" and allocated to

parietalis the

populations of Utah and southeastern Idaho, but presumably these

authors were not familiar with typical parietalis of the Mid-west.

Subsequent authors (Wright and Wright, 1957:834; Stebbins, 1954:505;

Conant, 1958:328) have followed this arrangement. A re-examination

of specimens from Utah, including living individuals

collected at Bear Lake in the summer of 1959, indicates that they

should be assigned to fitchi rather than to parietalis.

Likewise various specimens from the drainage basin of the Snake

River in Idaho are predominantly fitchi in the sum of their characters,

although they differ from that subspecies in its most typical

form and resemble parietalis in some respects. KU 23133 from two

miles east of Notus, Canyon County, Idaho, has the red crescents

on the lower part of the sides (between scale rows six and seven)

consistently developed on the anterior half of the body. KU 21873,

a large female from Bannock County, Idaho, is exceptional in having

small lateral black spots on the ventrals, resembling parietalis most

closely in this respect. Also, it has the red lateral crescents unusually

well developed; the first three series are conspicuous, those

of the fourth series are consistently developed, and those of the fifth

series show occasionally.

Forty-five specimens in the University of Colorado Museum from

northwestern Colorado were subjected to pattern analysis. In three

specimens the dorsolateral black area between the dorsal stripe and

the lateral stripe on each side has no markings, and in eight others

there is only an occasional fleck or crescent on the skin between the

[pg 305]

sixth and seventh scale rows. All others have the normal complement

of dorsolateral crescents or flecks between the scales of rows

three and four, four and five, and five and six. But, these specimens

vary in extent of development of the crescents in the upper half of

the dorsolateral area on each side—between scale rows six and seven,

seven and eight, and eight and nine. Only six snakes show traces of

the crescents of the uppermost series (between scale rows eight and

nine). Development of these crescents is variable but in all the

specimens the crescents are confined to the anterior half of the body.

The crescents between rows six and seven and between seven and

eight are present in 20 specimens and in ten of these the crescents

are conspicuous and regularly arranged, often meeting and consequently

form H-shaped markings. In most of the snakes the crescents

are best developed in the second fifth of the body and disappear

posteriorly. In five of the twenty, crescents between rows six and

seven are fairly regular, but those between rows seven and eight are

few and appear only sporadically. In eight specimens there are no

crescents between either rows seven and eight or eight and nine. In

eight others the crescents between rows six and seven are likewise

absent, and only the crescents between rows three to six are present.

These specimens from Colorado also differ from typical parietalis

in having the black spots on the anterolateral edges of the ventrals

less developed. In three of the 45 these spots are lacking entirely

and in four others they are few and small. In the majority of specimens

the spots are from 1/4 to 1/5 the length of the ventrals. In approximately

one-third of the specimens the spots are absent posterior to

mid-body. In five specimens obtained at Sheridan Lake, Pennington

County, South Dakota, in the Black Hills in August, 1960, dorsolateral

areas are dark with red crescents small and inconspicuous,

and with black spots either lacking from the ventrals or only faintly

developed. In two specimens from Sundance, Crook County, northeastern

Wyoming, the red crescents are small and inconspicuous

also. In one of these specimens, KU 28028, small black spots are

present in the corners of the ventrals, but in the other, KU 23654, the

spots are absent.

In having the dorsolateral area consistently black, with the three

uppermost series of red crescents reduced or absent, and in having

the ventral black spots reduced or absent, these specimens from

Colorado, Wyoming, and South Dakota differ from more eastern and

more typical parietalis, and tend toward fitchi, even more

strongly

than some Idaho specimens tend toward parietalis. Nevertheless,

[pg 306]

all things considered, the Continental Divide is the most logical

boundary between the two subspecies, even though occasional individuals

and even local populations deviate from the general trend

of characters from east to west.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Doris M. Cochran of the United States National Museum kindly furnished

information concerning the type specimen of Eutainia dorsalis formerly in the

National Museum collection but now lost. Dr. James S. Findley of the University

of New Mexico and Dr. Ralph J. Raitt of New Mexico State University

contributed habitat notes and records of specimens and loaned us critical specimens

of T. sirtalis from New Mexico. Drs. George F. Baxter of the University

of Wyoming, John M. Legler of the University of Utah, and Wilmer W. Tanner

of Brigham Young University kindly provided us with information concerning

the specimens in the collections of their respective institutions, and their personal

observations concerning the distribution of garter snakes in their states.

Alice V. Fitch, Chester W. Fitch and Donald S. Fitch assisted in the collection

of fresh specimens in Oregon and Utah and the unsuccessful search of many

a mosquito-infested meadow in southern Wyoming and northwestern Colorado

in July, 1959. Dr. R. G. Webb made available his MS on reptiles of Oklahoma.

This taxonomic study of garter snakes originated as a by-product of the

senior author's study of ecology and economic bearing of snakes in the central

Plains Region of the United States, for which support received from the National

Science Foundation is gratefully acknowledged.

Literature Cited

Baird, S. F.

1859. Reptiles of the boundary. United States and Mexican Bound. Surv.,

2, 1-35, 41 pls.

Baird, S. F., and Girard, C.

1853. Catalogue of North American reptiles in the Museum of the Smithsonian

Institution. Smithson. Miscl. Col., part 1, Serpents., pp. xvi

+ 172.

Brown, B. C.

1950. An annotated check list of the reptiles and amphibians of Texas.

Baylor Univ. Studies, pp. xii + 259.

Bundy, R. E.

1951. New locality records of reptiles in New Mexico. Copeia, 1951 (4):314.

Cockerell, T. D. A.

1910. Zoology of Colorado. Univ. of Colorado, Boulder, vii + 262 pp.

Conant, R.

1958. A field guide to the reptiles and amphibians of the United States and

Canada east of the 100th Meridian. Houghton Mifflin Co., Boston,

xviii + 366 pp.

Cope, E. D.

1900. The crocodilians, lizards and snakes of North America. Rept. U. S.

Nat. Mus. for 1898, pp. 153-1270.

Fitch, H. S.

1941. Geographic variation in garter snakes of the species Thamnophis

sirtalis in the Pacific Coast region of North America. Amer. Midland

Nat., 26:570-592.

Fox, W.

1951. The status of the gartersnake, Thamnophis sirtalis tetrataenia.

Copeia, 1951:257-267.

Fouquette, M. J., and Lindsay, H. L., Jr.

1955. An ecological survey of reptiles in parts of northwestern Texas.

Texas Jour. Sci., 7(4):402-421.

Hudson, G. E.

1942. The amphibians and reptiles of Nebraska. Nebraska Conserv. Bull.

No. 24, pp. 1-146.

Little, E. L., Jr., and Keller, J. G.

1937. Amphibians and reptiles from the Jornada Experimental Range,

New Mexico. Copeia, 1937 (4):402-421.

Maslin, T. P.

1959. An annotated check list of the amphibians and reptiles of Colorado.

Univ. Colorado Studies, Ser. Biol. No. 6, 98 pp.

Ruthven, A. G.

1908. Variations and genetic relationships of the garter-snakes. Bull. U. S.

Nat. Mus., 61:xii + 201 pp.

Schmidt, K. P.

1953. A check list of North American amphibians and reptiles. Univ.

Chicago Press, vii + 280 pp.

Smith, H. M.

1942. The synonymy of the garter snakes (Thamnophis), with notes on

Mexican and Central American species. Zoologica, 27(17):97-123.

1956. Handbook of amphibians and reptiles of Kansas (2nd ed.). Univ.

Kansas Mus. Nat. Hist. Misc. Publ. No. 9, 356 pp.

Smith, H. M., and Brown, B. B.

1946. The identity of certain specific names in Thamnophis. Herpetologica,

3:71-72.

Smith, H. M., and Taylor, E. H.

1945. An annotated check list and key to the snakes of Mexico. Bull. U. S.

Nat. Mus., 187, 239 pp.

Stebbins, R. C.

1954. Amphibians and reptiles of western North America. McGraw-Hill

Book Co., Inc., xxiv + 528 pp.

Van Denburgh, J.

1924. Notes on the herpetology of New Mexico, with a list of the species

known from the state. Proc. California Acad. Sci., 4th ser., 13(12):189-250.

Van Denburgh, J., and Slevin, J.

1918. The garter-snakes of Western North America. Proc. California

Acad. Sci., 4th ser., 8:181-270.

Woodbury, A. M.

1931. A descriptive catalog of the reptiles of Utah. Univ. Utah Biol.

Ser., 1(4):1-129.

Wright, A. H., and Wright, A. A.

1957. Handbook of snakes of the United States and Canada. Comstock

Publ. Associates, Cornell Univ. Press, vol. 2, pp. i + ix and 565-1106.

Transmitted November 8, 1960.