I

INTRODUCTORY

The People and City of Rome

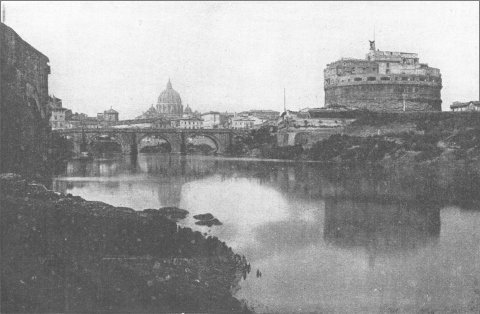

More than two thousand years ago, at a time when the people in the British Isles and in most parts of Western Europe were living the lives of savages, occupied in fighting, hunting, and fishing, dwelling in rude huts, clad in skins, ignorant of everything that we call civilization, Rome was the centre of a world in many ways as civilized as ours is now, over which the Roman people ruled. The men who dwelt in this one city, built on seven hills on the banks of the river Tiber, gradually conquered all Italy. Then they became masters of the lands round the Mediterranean Sea: of Northern Africa and of Spain, of Greece, Egypt, Asia Minor and the Near East, and of Western Europe. The greatness of Rome and of the Roman people does not lie, however, in their conquests. In the end their conquests ruined them. It lies in the character, mind, and will of the Romans themselves.

In the history of the ancient world the Romans played the part that men of our race have played in the history of the modern world. They knew, as we claim to know, how to govern: how to govern themselves, and how to govern other people. To this day much in our laws and in our system of government bears a Roman stamp. They were great soldiers and could conquer: they could also hold and keep their conquests and impress the Roman stamp on all the peoples over whom they ruled. Their stamp is still upon us. Much that belongs to our common life to-day comes to us from them: in their day they lived a life not much unlike ours now. And in many respects the Roman character was like the British. We can see the faults of the Romans, if we cannot see our own; we can also see the virtues. We can see, too—looking back at them over the distance 7 of time, judging them by their work and by what is left to us of their writings—how the mixture of faults in their virtues explains the fall as well as the rise of the great power of Rome.

The Romans were men of action, not dreamers. They were more interested in doing things than in understanding them. They were men of strong will and cool mind, who looked out upon the world as they saw it and, for the most part, did not wonder much about how and why it came to be there. It was there for them to rule. That was what interested them. Ideas they mostly got from other people, especially from the Greeks. When they had got them they could use them and turn them to something of their own. But they were not distracted by puzzling over ideas. Their religion was that of a practical people. In the later days of Rome few educated men believed in the gods. But all the ceremonies and festivals were dedicated to them; and magnificent temples in their honour were erected in which their spirits were supposed to dwell. In the old days every Roman household had its particular images—the Lares and Penates which the head of the family tended and guarded. Connected with this office was the sacred authority of the head of the family—the paterfamilias. His word was law for the members of the household. And the City of Rome stood to its citizens in the place of the paterfamilias. The first laws of a Roman’s life were his duty to his father and to the State. They had an absolute claim on him for all that he could give. The Roman’s code of honour, like the Englishman’s, rested on this sense of duty. A man must be worthy of his ancestors and of Rome. His own life was short, and without honour nothing; the life of Rome went on.

Courage, devotion to duty, strength of will, a great power of silence, a sense of justice rather than any sympathy in his dealings with other men: these were the characteristic Roman virtues. The Roman was proud: he had a high idea of what 8 was due from himself. This was the groundwork out of which his other qualities grew, good and bad. Proud men are not apt to understand the weakness of other people or to appreciate virtues different from their own. The defects of the Romans were therefore hardness, sometimes amounting to cruelty both in action and in judgement; lack of imagination; a blindness to the things in life that cannot be seen or measured. They were just rather than generous. They trampled on the defeated and scorned what they could not understand. They worshipped success and cared little for human suffering. About this, however, they were honest. Sentimentalism was not a Roman vice, nor hypocrisy. When great wealth poured into the city, after the Eastern conquests of Lucullus and Pompeius, the simplicity of the old Roman life was destroyed and men began to care for nothing but luxury, show, and all the visible signs of power. They were quite open about it: they did not pretend that they really cared for other things, or talk about the ‘burden of Empire’.

The heroes of Roman history are men of action. As they pass before us, so far as we can see their faces, hear their voices, know their natures from the stories recorded by those who wrote them down at the time or later, these men stand out in many respects astonishingly like the men of our own day, good and bad. Centuries of dust lie over them. Their bones are crumbled to the dust. Yet in a sense they live still and move among us. Between them and us there lie not only centuries but the great tide of ruin that swept the ancient world away: destroyed it so that the men who came after had to build the house of civilization, stone by stone anew, from the foundation. The Roman world was blotted out by the barbarians. For hundreds of years the kind of life men had lived in Rome disappeared altogether and the very records of it seemed to be lost. Gradually, bit by bit, the story has been pieced together, and the men of two thousand years ago stand before us: we see them across the gulf. The faces of those belonging to the earliest story of Rome are rather dim. But they, too, help us to understand what the Romans were like. We learn to know a people from the men it 9 chooses as its heroes; about whom fathers tell stories to their children. They show what are the deeds and qualities they admire: what kind of men they are trying to be.

II

The Early Heroes

The oldest Roman stories give a description of the coming of the people who afterwards inhabited the city, from across the seas. They tell of the founding of the first township round the Seven Hills, and of the kings, especially of the last seven, who ruled over the people until, for their misdeeds, they were driven out and the very name of King became hateful in Roman ears. Then there are many tales of the wars between the people of Rome and the neighbours dwelling round them on the plains of Latium and among the hills of Etruria and Samnium; and the fierce battles fought against the Gauls who, from time to time, swept down on Italy from the mountains of the north.

These stories do not tell us much that can be considered as actual history. But they do help us to understand what the Romans wished to be like, by showing us the sort of pictures they held up before themselves.

In later times the Romans learned to admire intensely all that came from Greece. The Greeks had been a great ruling people when the Roman State hardly existed: and from them much in Roman life and thought was borrowed. They liked to think that the first settlers on the Tiber bank came from an older finer world than that of the other tribes dwelling in Italy. So they told how, after the great siege of Troy by the Greek heroes, Aeneas, one of the Trojan leaders, fled from his ruined city across the seas, bearing his father and his household gods upon his shoulders, and after many adventures, and some time passed in the great city of Carthage, on the African coast, came with a few trusty companions to the shores of Latium and there founded a new home.

The descendants of Aeneas ruled over their people as kings. In later days, however, the Romans, who held that all citizens 10 were free and equal, hated the name of King. Rome was a republic: its government was carried on by men elected by the citizens from among themselves, and by assemblies in which all citizens could take part. The first duty of every citizen was to the republic: its claim on him stood before all other claims.

The story of the fall of the last king and of Lucius Junius Brutus, one of the first Consuls, as the chief magistrates of the new republic were called, shows clearly how far the idea of duty to the republic could go in the minds of Romans.

Brutus and Tarquin

The last King of Rome was Tarquin the Proud. His misrule, and the insolent heartlessness of his family, especially of his son Sextus, brought about their expulsion from Rome and the end of the kingship. Sextus had, by guile, got into the town of Gabii but was at a loss how to make himself master there. He managed to send out a messenger to his father. It was summer. In the garden where the King was walking, poppies—white and purple—were growing in long ranks. Tarquin said nothing to the messenger: only as he walked he struck off with his staff the heads of the tallest poppies, one after another, without saying a word. Sextus, when the messenger came back and described to him his father’s action, understood. Pitilessly he put the leading men of Gabii to the sword.

It was the misdeeds of this Sextus that brought the proud house of Tarquin to the ground. He tried to force his brutal love on the fair Lucretia, the wife of his cousin Collatinus, and so shamed her that, after telling her husband how she had been wronged, Lucretia killed herself before his eyes and those of his friend Brutus. Stirred to deepest wrath, Collatinus and Brutus then swore a great oath to drive the house of Tarquin from Rome and henceforth allow no king to rule over the free people of the city. When they had told their fellow citizens how Sextus had wronged Lucretia, a daughter of one of the proudest families in the city, and reminded them of the oppression and injustice they had all suffered at the hands of his family, the leading men of Rome rose up and drove the Tarquins out. The city was 11 proclaimed for ever a republic to be ruled not by any one man but by the will and for the good of all free men who dwelt in it. Some there were, however, who took the side of Tarquin and tried to bring him back. Among them were the two sons of Brutus. They were captured and brought up for judgement, and like the others condemned to death. Brutus was the judge. Though they were his sons and he loved them he condemned them unflinchingly. Without any sign of feeling he saw them go to their death. An action for which he would have sentenced another man seemed to him no less wrong when committed by his own children.

The Death of Lucretia

They tried to soothe her grief, laying the blame, not on the unwilling victim, but on the perpetrator of the offence. ‘It is the mind,’ they said, ‘not the body that sins. Where there is no intention, there is no fault,’ ‘It is for you,’ she replied, ‘to consider the punishment that is his due; I acquit myself of guilt, but I do not free myself from the penalty; no woman who lives after her honour is lost shall appeal to the example of Lucretia,’ Then she took a knife which she had hidden under her dress, plunged it into her heart, and dropping down soon expired. Her husband and father made the solemn invocation of the dead.

While the others were occupied in mourning, Brutus drew the knife from the wound, held it still reeking before him, and exclaimed, ‘I swear by this blood, pure and undefiled before the prince’s outrage, and I call you, gods, to witness, that I will punish Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, his impious wife, and all his children with fire and sword to the utmost of my power, and that I will not allow them or any other to rule in Rome.’ After this, he handed the knife to Collatinus, next to Lucretius and Valerius, all amazed at Brutus and perplexed to account for his new spirit of authority. They took the oath as he directed and, changing wholly from grief to anger, they obeyed his summons to follow him and make an immediate end of the royal power.

The body of Lucretia was brought from her house and carried to the Forum, the people thronging round, as was natural, in wonder at this strange and cruel sight, and loud in condemning the crime of Tarquinius. They were deeply moved by the father’s sorrow, and still more by the words of Brutus, who rebuked their tears and idle laments, urging them to act like men and Romans by taking up arms against the common enemy.

12Mucius and Cloelia

The same spirit was shown by Caius Mucius and the maiden Cloelia and many others in the long and bitter wars that followed. Tarquin found refuge with Lars Porsena, King of the Etruscans, who pretended to be eager to restore him while he really wanted to submit the Roman people to his own rule. Porsena laid siege to the city and the people were reduced to the hardest straits. A young man named Caius Mucius determined to kill Lars Porsena. He succeeded in passing through the enemy’s lines and made his way into their camp. There he saw a man clad in purple whom he took to be Lars Porsena. In his heart he plunged the dagger he had hidden under the folds of his toga. The man fell dead. But he was not the King. Mucius was carried before Lars and to him he said, ‘I am a Roman, my name Caius Mucius. There are in Rome hundreds of young men resolved, as I was, to take your life or perish in the attempt. You may slay me but you cannot escape them all.’ Porsena demanded the names of the others: Mucius refused to speak. When Porsena said he would compel him to speak by torture Mucius merely smiled. On the altar a flame was burning. To prove to the ally of Tarquin of what stuff the young men of Rome were made, he thrust his right arm into the flame and held it so without flinching until the flesh was charred away. Such, his action showed the King, was the spirit of Rome.

13Mucius: The Spirit of Rome

Mucius was escaping through the scared throng, that fell away before his bloody dagger, when, summoned by the shouts, the King’s guards seized him and dragged him back. Standing helpless before the throne, but even in such desperate position more formidable than afraid, he cried out, ‘I am a Roman citizen; my name is Caius Mucius. My purpose was to kill an enemy of my country; I have as much courage to die as I had to slay; a Roman should be ready for great deeds and great suffering. Nor have I alone been emboldened to strike this blow; behind me is a long line of comrades who seek the same honour. Therefore, if you choose, prepare for a struggle in which you will fight for your life every hour of the day and have the sword of an enemy at your palace door. Such is the war that we, the youth of Rome, proclaim against you. You need not fear armies and battles; by yourself you will meet us one by one.’ When the King, enraged and terrified, was threatening to have him thrown into the flames unless he explained the hints of assassination thus vaguely uttered, he replied, ‘See how worthless the body is to those whose gaze is fixed on glory.’ With these words he laid his right hand on a brazier already lighted for the sacrifice and let it burn, too resolute, as it seemed, to feel pain. Then Porsena, astounded at the sight, ordered Mucius to be removed from the altar and exclaimed, ‘Begone, your own desperate enemy more than mine. I would wish well to your valour, if that valour was on the side of my country. As it is, I send you hence unharmed and free from the penalties of war.’

14Later in the same war the Romans were compelled to give hostages, twenty-four men and maidens. Cloelia, a highborn maiden sent among them, escaped at night and on horseback swam across the foaming Tiber to Rome. But since she had been given as a hostage and faith once given was sacred, the Roman leaders sent her back.

Cloelia’s Heroism

This reward granted to the heroism of Mucius inspired women also with ambition to win honour from the people. The maiden Cloelia, one of the hostages, escaped the sentries of the Etruscan camp, which had been pitched near the Tiber, and amid a shower of missiles swam across the river, leading a band of maidens whom she brought back safe to their families in Rome. When Porsena heard of it, he was at first enraged, and sent envoys to the city with a demand for the return of his hostage Cloelia; he made no great account of the others. Afterwards, his anger being changed to admiration, he said that her exploit surpassed anything done by Horatius or Mucius, and declared that he would consider the treaty broken if the hostage was not surrendered, but that if she was, he would send her back unharmed to her people. Faith was kept on both sides; the Romans returned the guarantee of peace in accordance with the terms of the treaty, and the King not only protected but honoured the heroine, making her a present of half the hostages and bidding her choose as she pleased. The story is that when they were brought before her, she picked out the youngest, a choice at once creditable to her modesty and approved by the unanimous wish of the rest that those whose age made them most helpless should be liberated first. After the restoration of peace the Romans recognized this unexampled heroism in a woman with the honour, also unexampled, of an equestrian statue. It was placed at the top of the Sacred Way, a maiden sitting on a horse.

This same high temper and unflinching sense of honour was shown two hundred years later in an even more splendid way by Atilius Regulus.

Regulus

In the first war against Carthage (255 B.C.) Regulus, a Roman general, was heavily defeated and taken prisoner with a large part of his army. Shortly afterwards the Roman fleet was destroyed by a terrible storm. Nevertheless, the events of the 15 next year’s campaign went against the Carthaginians. They determined to offer peace and for this purpose sent an embassy to Rome. With this embassy Regulus was sent, on the understanding that if he failed to induce his countrymen to make peace and to agree to an exchange of prisoners he would return to Carthage, where, as he well knew, a terrible fate certainly awaited him. Nevertheless, despite the appeals of his wife and children, Regulus urged his countrymen not to make peace. His body might belong to the Carthaginians who had captured it, but his spirit was Roman and no Roman could urge his countrymen to accept defeat and give up fighting until they had won. True to his vow, he went back to Carthage and there he was put to dreadful tortures. His eyelids were cut off and he was then exposed to the full glare of the sun. But the story of his devotion remained strong in the minds of his countrymen, and Horace, one of their great poets, later put it into lines of imperishable verse.

The Honour of Regulus

Such a downfall had the prescient soul of Regulus feared, when he refused assent to dishonourable terms and maintained that the precedent would be fatal in time to come if the prisoners did not die unpitied. ‘I have seen’, he said, ‘our eagles hanging on Carthaginian shrines, and weapons of our soldiers surrendered without bloodshed; I have seen arms bound behind the back of the free, and gates thrown open in security, and lands tilled that our armies had wasted. Think you that the soldier, ransomed with gold, will return the braver? You do but add loss to disgrace. Wool, tinctured by dye, never regains its old purity; nor does true courage, if once it is lost, deign to be restored to the degraded. If the stag fights after being freed from the meshes of the net, he will be brave who has surrendered to a treacherous foe, and he will crush the Carthaginians in a second fight who without resentment has felt the thongs binding his arms, and has feared death. Such a man, all ignorant of the way to win a soldier’s life, has confused peace and war. Oh lost honour! Oh mighty Carthage, exalted by the shameful downfall of Italy!’ It is said that he put from him the lips of his virtuous wife and his little children, a free citizen no longer, and with grim resolution turned his eyes to the ground, till with the weight of advice never given by any before him he strengthened the wavering purpose of the Fathers, and amid the mourning of 16 his friends hurried into a noble exile. Yet, though he knew what the barbarian tormentor had in store for him, he set aside opposing kinsmen and people that would delay his return as quietly as if he were leaving the business of some client’s suit at last decided, and were journeying to his estate in Venefrum or to Tarentum that the Spartan built.

Marcus Curtius

What were Rome’s most precious possessions? To this question a splendid answer was given by Marcus Curtius. In the midst of the Forum—the market-place in the heart of the city where public business was transacted and men met daily to discuss politics and listen to speeches—the citizens found one morning that a yawning gulf had opened. This, so the priests declared, would not close until the most precious thing that Rome possessed had been thrown into it. Then the republic would be safe and everlasting. For a time men puzzled and pondered over the meaning of this dark saying. Marcus Curtius, a youth who had covered himself with honour in many battles, solved the riddle. Brave men, he said, had made Rome great: the city had nothing so precious. Clad in full armour and mounted on his war-horse he leaped into the gulf. It closed over him at once, nor ever opened again.

The Devotion of Marcus Curtius

During the same year, as the story goes, a cavern of measureless depth was opened in the middle of the Forum, either from the shock of an earthquake or from some other hidden force; and though all did their best by throwing soil into it, the gulf could not be filled up till, warned by the gods, the people began to inquire what was Rome’s greatest treasure. For that treasure, so the prophets declared, must be offered in it, if the Roman commonwealth was to be safe and lasting. Whereupon Marcus Curtius, a warrior renowned in war, rebuked them for doubting whether the Romans had any greater blessing than arms and valour. Amid a general silence he devoted himself, looking to the Capitol and the temples of the immortal gods that overhang the Forum, and stretching out his hands, at one time to the sky, at another to the yawning chasm that reached to the world below. Then, fully armed and seated on a horse splendidly caparisoned, 17 he plunged into its depths, while a crowd of men and women showered corn and other offerings after him. Thus we may suppose that the Curtian Lake got its name from him, and not from Curtius Mettus, in old time the famous soldier of Titus Tatius.

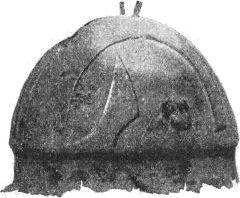

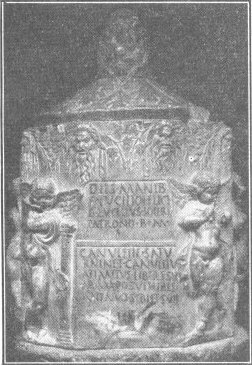

LACUS CURTIUS

Restored

In Mucius Scaevola, in Regulus, in Marcus Curtius, and many others the fine qualities of the old Roman temper, pride, courage, will, devotion, a love of their country that went beyond all other feelings, even unto death, stand out. One can see the main lines of the character that made the Romans what they afterwards became—the conquerors and law-givers first of a single city, Rome, then of the whole plain of Latium in which that city stood: then, after driving back barbarian invaders from the north and Greek invaders from the south, of all Italy: later of the known world.

Coriolanus

To understand this character better one may look at it from another angle, studying a man in whom these qualities were spoiled by the faults that belong to them. Courage may become cruelty: pride fall into arrogance: high contempt for others will grow to selfishness and hardness; even a high devotion to one’s country may be spoiled if it comes to mean a devotion to one’s own idea of what that country should be like and how it should treat oneself. It may then be mere selfishness. Many men love their country not as it is but as they think it ought to be. This may be a good and helpful feeling if what they think it 18 ought to be depends not on their own private wishes and welfare only, but on that of the people as a whole. A love of country of this kind makes men strive incessantly to make it better. But some Romans forgot the welfare of the people as a whole. The men belonging to the old families, men who claimed to be descended from the early settlers, who called themselves ‘patricians’, that is, the fathers of the State, were apt to consider that what they thought must be so: that they alone knew what was right and good. The welfare of the State depended on them. They were the leaders in the army and in the government. They had no patience with those who said that they should not settle everything in Rome, that their idea of what was right and patriotic was not the end of the matter; men who said that Rome was not this class or that but the whole people. The city was growing fast; new settlers had come in, men not counted as citizens, but men whose happiness and comfort depended on the way the State treated them. These people, the ‘plebs’ as they were called, were despised by many patricians. They looked upon them not as Romans, but as creatures who could be made into soldiers when the city needed soldiers, but at other times should keep quiet.

The faults and virtues of the patricians—and nearly all the heroes of Roman story belong to patrician families—are well shown in the life of Caius Marcius, called Coriolanus in honour of his victory outside the town of Corioli.

The Capture of Corioli

One of the leading men in the camp was C. Marcius, who afterwards received the name of Coriolanus, a youth of equal vigour in counsel and in action. The Roman army was besieging Corioli and, occupied with its people shut up behind their walls, had no fear of attack from without, when the Volscian troops from Antium swept down upon it, and at the same time the enemy sallied out of the town. Marcius happened to be on duty, and with some picked troops not only repelled the sally, but fearlessly rushed in through the open gate and, after slaughtering the enemy in the neighbourhood, chanced to come across some lighted brands and flung them on to the buildings that adjoined the wall. Then the cries of the townsmen, mingled with the 19 shrieks of women and children that quickly arose, as usual, when the alarm was given, encouraged the Romans and dismayed the Volscians, inasmuch as they found that the city which they had come to help was in the hands of the enemy. Thus the Volscians from Antium were routed and Corioli was taken.

Caius Marcius belonged to one of the oldest and proudest families in the Republic. A member of this family had been one of the Seven Kings. His father died when Caius was but a boy and he was left in the charge of his mother Volumnia. Volumnia was a woman of noble character and fine mind. Her house was admirably ordered: everything in it was beautiful and yet simple. She brought up her son well: he excelled in all manly exercises, was of a courage that nothing could shake, scorned idleness, luxury, and wealth: believed that the one life for a Roman was a life of service to the death. But Volumnia did not succeed, as a father might have done, in curbing the faults of the lad’s character. Caius grew up headstrong, obstinate, and excessively proud. Personally highly gifted in mind and body, he was disposed to look down upon others less firm and resolute. He set, for himself, a high standard of uprightness and courage, and cared nothing for what other people thought of him. Among the youths with whom he grew up he was the natural leader: his will brooked no contradiction. Few dared to criticize or oppose him. Those less firm in mind, less brave in action, less indifferent to the opinion of others, he despised. Any one who failed in courage, endurance, or devotion he condemned without sympathy.

When but a lad he won, for bravery in battle, the crown of oak leaves given to soldiers who saved the life of a comrade in action. In all the fighting of the hard years in which Rome was defending itself against the other Italian peoples, Marcius was ever to the fore. He shrank from no fatigue, no danger: he was always in the hottest of the fight: first as a simple soldier, then as a general. In the field his soldiers adored him because he shared all their hardships and always led them to victory. Always, too, he refused to take any reward in money or riches. But when these same soldiers got back to Rome Coriolanus had 20 no sympathy with them. Fighting was life to him: he did not see why it should not satisfy every one or understand the hardships of the common man whose wife and children were left behind in wretched poverty. There were indeed many things Coriolanus did not see. His harsh mind condemned without understanding the complaints of the poor. To him it seemed that they thought of themselves, instead of thinking about Rome. He did not realize that their hard lot compelled them to do so. His wealth and birth made him free, but they were not free.

All the land belonged to the patricians. Wars made them richer because the things their land produced fetched high prices, but the poor family starved while the father was away at the wars, unable to earn, and they had no money with which to purchase things. They had to pay taxes—and wars always mean heavy taxes. They fell into debt and, under the harsh Roman law, a debtor could be first imprisoned and then, unless some one helped him by paying off what he owed, sold as a slave. Even a man serving in the army might have his house and all the poor household goods he had left at home seized because he or his wife had got into debt. This harsh law finally produced a mutiny. The whole army marched out of Rome and, taking up a position on the Sacred Mount outside, stayed there until the Senate (this was the ruling body of the State, at the time composed only of patricians) agreed first to change the harsh laws about debt, and second to give to the poorer people a body of men to look after their interests. These were the Tribunes. The appointment of these tribunes angered many patricians, and especially Coriolanus. Not understanding the sufferings of the people—he had always been far removed himself from any such difficulties, belonging as he did to a family of wealth and dignity—he thought that their discontents were created by talk and idleness. And since there were men in Rome who got a cheap popularity by perpetually reminding the people of their wrongs, he sometimes seemed to be right. The tribunes he regarded as noxious busybodies, whose loose talk was dividing Rome into two parties. In fact there were two parties. Coriolanus could not see 21 that the real cause of the division was not what the tribunes said but what the people suffered. He could see no right but his own, and all his powerful will was set to driving that right through. To yield seemed to him pusillanimous. There was bound to be a fierce struggle and it soon came. Coriolanus made bitter scornful speeches, which enraged the people. They smarted under his biting words and forgot all his great deeds. He became more and more unpopular. This unpopularity only made him despise the people, who judged men by words and not by deeds. At last the tribunes accused him of trying to prevent their receiving the corn that had been sent to them by the city of Syracuse and of aiming at making himself ruler in the city. Finally they demanded that he should be banished. Coriolanus scorned to defend himself. Instead of that he attacked the tribunes and abused the people in terms of cruel scorn and contempt. When the vote banishing him was carried he turned on them, declaring that they made him despise not only them but Rome. He banished them: there was a world elsewhere.

But though Coriolanus had always declared that he cared more for Rome than for anything and desired not his own greatness but that of the city and now pretended to scorn the people and the sentence they had passed upon him, his actions showed how far his bitterness had eaten into his own soul. He turned his back on Rome and betook himself to the camp of Tullus Aufidius, the leader of the people of Antium, then engaged in war against the Republic, and prepared to assist him in order to punish the ungrateful Romans.

From this dreadful action he was saved by his mother Volumnia. Her patriotism was truer and more unselfish than his. With his wife and his young children she came to the camp, clad in the garb of deepest mourning, dust scattered upon her grey hairs, and went on her knees to her son to implore him not to dishonour himself by fighting against his country. At last the true nobleness in the soul of Coriolanus made its way through the anger and bitterness that had darkened it: he acceded to Volumnia’s prayers, though he well knew what the price for himself would be. Rome was saved from a great danger, since the city had no 22 general to equal Coriolanus. He himself, however, was assassinated by the orders of Aufidius, who soon afterwards was badly defeated in the field. Coriolanus said to his mother, when she at last persuaded him to yield, that she had won a noble victory for Rome, but one that was fatal to her son. He was right. His very words showed that in some part of his mind he realized how wrong and really unpatriotic his action had been; in joining with the enemies of Rome he had shown clearly that what he loved was not his country but his own pride. In the end, thanks to Volumnia, he bent his head. The lesson to the Romans was a clear one: and in the years that followed it was not forgotten. Coriolanus was remembered as a hero, but also as a warning. When real danger threatened Rome the people stood unshaken from without and from within. In the Roman camp there were never any traitors.

The Mother’s Appeal

Distracted by the sight of his mother, Coriolanus leapt wildly from his seat and was advancing to embrace her when, turning from supplication to anger, she exclaimed, ‘Before I allow your embrace, let me know whether I have come to an enemy or a son, whether I am a prisoner or a mother in your camp. Has a long life and helpless old age brought me to such a pass that I see you, first as an exile, and afterwards as an enemy? Could you bear to devastate this land that bore and nurtured you? However hostile and threatening the spirit in which you came, did not your anger fail when you crossed its border? When Rome was in sight, did you not reflect, “Inside those walls are my home and its gods, my mother, wife, and children?” If I had not been a mother, as it seems, Rome would not have been besieged; if I had not a son, I should have died free in a free country. But as for me, I can no longer suffer anything that will add to my wretchedness or to your disgrace and, wretched though I am, it will not be for long. These younger ones have the claim upon you, for, if you persist, you will bring them to a premature death or to a life of slavery.’ Then his wife and children embraced him, and the wailing that arose from all the throng of women, and lamentations for themselves and their country, at length broke his resolution. He embraced them and sent them away, and at once withdrew his forces from the city.

23A Happy Victory

Coriolanus. O, mother, mother!

What have you done? Behold! the heavens do ope,

The gods look down, and this unnatural scene

They laugh at. O my mother! mother! O!

You have won a happy victory to Rome;

But, for your son, believe it, O! believe it,

Most dangerously you have with him prevail’d,

If not most mortal to him. But let it come.

Aufidius, though I cannot make true wars,

I’ll frame convenient peace. Now, good Aufidius,

Were you in my stead, would you have heard

A mother less, or granted less, Aufidius?

Auf. I was mov’d withal.

Cor. I dare be sworn you were:

And, sir, it is no little thing to make

Mine eyes to sweat compassion. But, good sir,

What peace you’ll make, advise me: for my part,

I’ll not to Rome, I’ll back with you; and pray you,

Stand to me in this cause.

CHAPTER III

The Great Enemies of Rome

The early history of Rome is a history of war. Its heroes are soldiers. When the city was founded and throughout its early life Italy was divided among different peoples, ruling over different parts of the country. With these peoples—the Latins, the Etruscans, the Volscians, the Samnites—the Romans fought. War with one or other of them was always going on. Its fortune varied, but in the end the Roman spirit and the Roman organization told. One by one the other Italian tribes submitted and accepted Roman overlordship. This was a long and slow business, extending over hundreds of years. While it was still going on the Romans had to meet another danger: the danger of invasion from without. Again and again the Gauls swept down upon Italy from the north. Once (390) they actually occupied parts of the city of Rome itself. After that they 24 were finally driven out and defeated by Camillus. Later, though they came again across the northern hills, they were always beaten and driven back. When on the march, their armies were dangerous; but the Gauls had no plan of permanent conquest: after a defeat, they retired to their northern plains and hills.

Within the space of a hundred years, in the third century before the birth of Christ, the Romans had to meet two invaders of a very different and far more dangerous kind: invaders with a settled plan of conquest, who came against them in order to subdue and rule Rome and Italy. These were Pyrrhus and Hannibal. Had either of them succeeded, the whole history of Rome and of the world might have been different. In a very real sense Pyrrhus and Hannibal are heroes in the story of Rome. They were the greatest enemies the Roman people ever had to meet. They were defeated because of qualities in the Roman people as a whole, rather than by the genius of any single general. No single Roman leader at the time was a first-rate commander like Pyrrhus, still less a genius like Hannibal, a much greater man than he. It is during their struggle with Pyrrhus, in the war with Carthage that followed Pyrrhus’s defeat, and in the long war with Hannibal that ended in his defeat and the destruction of Carthage as a great power that we can see the Roman character at its best. We can appreciate it and understand it only by understanding the enemies whom it met and broke.

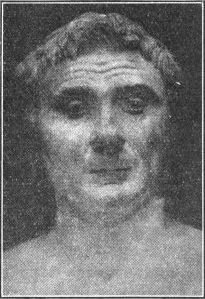

Pyrrhus

At the time of his attack upon Italy Pyrrhus, King of Epirus, was the most brilliant soldier of his day: and his ambition was to rule, like Alexander, over a world greater than that of his own Greek kingdom. From babyhood he breathed and grew up amid storm and adventure, all his life he was most at home in camps and on the battlefield. His father was killed in battle when Pyrrhus was but five years old: he himself was only saved from death by a faithful slave who carried him to the house of the King of the Illyrians and laid him at his feet. The baby Pyrrhus clasped the knees of the monarch who, looking into his 25 face, could not resist the appeal of the child’s eyes, but kept him safe till he was twelve years old and then helped to put him on his father’s throne. Though only a boy, Pyrrhus held it for five years. He was driven out, but later he recovered his kingdom again. As he grew up he studied the art of war constantly and wrote a handbook on tactics. As Plutarch, who wrote his life, puts it, ‘he was persuaded that neither to annoy others nor be annoyed by them was a life insufferably languishing and tedious’. Pyrrhus’s appearance expressed the strong, generous simplicity and directness of his character and his singleness of aim. The most remarkable feature in his face was his mouth, for his front teeth were formed of a continuous piece of bone, marked only with small lines resembling the divisions of a row of teeth. Fear was absolutely unknown to him. His weakness was that he did not understand men: though a brilliant soldier he knew nothing about government. He was a soldier only. He could win battles but not rule men.

Pyrrhus came to Italy on the invitation of the people of Tarentum. Tarentum was a wealthy and flourishing city in the south. Originally a Greek settlement, its people were famous for the luxury and elegance of their houses and lives, and scorned the rude, hardy, and simple Romans as untutored barbarians. When some Roman ships appeared in their harbour they were sunk by the Tarentines, who thought that as the Romans were at that time busy—the Gauls had swept down from the north and they were engaged with a war against the Samnites—Tarentum was safe from them. But the Romans at once declared war (281). The Tarentines took fright: they had no mind for fighting themselves and looked about for some one who would do it for them. Thus they called to 26 Pyrrhus to save the Greeks in Italy. Pyrrhus saw in their appeal his chance of realizing what for the great Alexander had remained a dream—an empire in the West. He took sail at once. He was indeed so eager that he started in mid-winter despite the storms, and lost part of his fleet on the way. Nevertheless he brought a great army with him: Macedonian foot soldiers, then considered the best in the world, horsemen, archers, and slingers; and elephants, never before seen in Italy. In Tarentum he found nothing ready. His first task was to make the idle, luxurious city into a camp. The inhabitants, who cared for nothing but feasting, drinking, and games, did not like this, but it was too late to be sorry. Pyrrhus had come, and since no other towns in Italy gave any sign of joining him, he had to make the most of Tarentum. The Tarentines, who had been used to having all their fighting done for them by slaves, now had to go into training themselves.

In the spring the Roman army took the field and marched south against the invader. When Pyrrhus surveyed from a hill the Roman camp and line of battle he exclaimed in surprise: ‘These are no barbarians!’ In the end he won a victory at Heraclea (280), partly by reason of the panic caused among the Roman soldiers by the elephants—they had never seen such beasts before—but the victory was a very expensive one. Pyrrhus’s own losses were so heavy that he said, ‘One more victory like this and I shall be ruined.’ As he walked over the field at night and saw the Roman dead, all their wounds in front, lying where they had fallen in their own lines, he cried: ‘Had I been king of these people I should have conquered the world.’

A deep impression was made on him by the envoy Fabricius. Plutarch tells the story:

Pyrrhus and Fabricius

Presently envoys came to negotiate about the fate of the prisoners, and among them Gaius Fabricius, who was famed among the Romans, as Cineas told the King, for uprightness and military talent, and for extreme poverty as well. Therefore 27 Pyrrhus received him kindly, apart from the rest, and urged him to accept a present, of course not corruptly, but as a so-called token of friendship and intimacy. When Fabricius refused, the King did no more for the moment, but next day, wishing to try his nerves as he had never seen an elephant, he had the largest of these beasts put behind a curtain close to them as they conversed. This was done, and at a signal the curtain was drawn aside, and the beast suddenly raised its trunk and held it over the head of Fabricius, uttering a harsh and terrifying cry. Undisturbed, he turned round and, smiling, said to Pyrrhus, ‘Yesterday your gold did not move me, nor does your elephant to-day.’

At dinner all sorts of subjects were discussed, and as a great deal was said about Greece and its philosophers, Cineas happened to mention Epicurus and explained the doctrines of his disciples about the gods and service to the state and the chief end of life. This last, as he said, they identified with pleasure, while they avoided service to the state as interrupting and marring their happiness, and banished the gods far away from love and anger and care for mankind to an untroubled life of ceaseless enjoyment. Before he had finished, Fabricius interrupted him and said, ‘By Hercules, I hope that Pyrrhus and the Samnites will hold these doctrines as long as they are at war with us.’

This filled Pyrrhus with such admiration of his high spirit and character that he was more anxious than before to be on terms of friendship instead of hostility with the Romans, and he privately urged Fabricius to arrange a peace and to take service with him and live as the first of all his comrades and generals. It is said that he quietly replied, ‘O king, you would gain nothing; for these very men who now honour and admire you will prefer my rule to yours if they once get to know me.’ Such were his words; and Pyrrhus did not receive them with anger or in a spirit of offended majesty, but he actually told his friends of the nobility of Fabricius and gave him sole charge of the prisoners on the understanding that, if the Senate refused the peace, they should be sent back after greeting their friends and keeping the festival of Saturn. As it happened, they were sent back after the festival, the Senate ordaining the penalty of death for anyone who stayed behind.

He was yet more deeply impressed by the strength of the Roman character a little later. When he found that none of the Latins were going to join him Pyrrhus sent an ambassador 28 to the Senate, offering terms of peace. This ambassador was loaded with costly presents for the leading Romans and their wives. All these gifts were refused. Then Pyrrhus’s envoy came before the Senate, to see whether eloquence could not do what bribes had failed to effect. He had been a pupil of the great Demosthenes, the most wonderful orator of Greece, and his golden words moved many of the senators; they thought it would be wise to make terms. But old Appius Claudius, one of the most distinguished men in Rome, the builder of the great military road known as the Appian way, had been carried into the Senate House by his sons and servants, for he was very old and nearly blind. He now rose to his feet and his speech made these senators ashamed of themselves. ‘Hitherto’, he cried, ‘I have regarded my blindness as a misfortune; but now, Romans, I wish I had been deaf as well as blind, for then I should not have heard these shameful counsels. Who is there who will not despise you and think you an easy conquest, if Pyrrhus not only escapes unconquered but gains Tarentum as a reward for insulting the Romans?’ His words stirred the senators deeply. They voted as one man to continue the war. Pyrrhus’s ambassador was told to tell his master that the Romans could not treat so long as there was an enemy on Italian soil. He told Pyrrhus that the Senate seemed to him an assembly of kings.

The firm mind of the Romans did not change when Pyrrhus marched north. Though he got within forty miles of the city there was no panic: only a rush of men to join the armies standing outside the walls to guard it. He had to retire south again. Even after another victory in the next campaign—at Asculum (279)—Rome was not shaken: the Italians stood firm. Pyrrhus knew that to win battles was not enough; he could not conquer Rome unless he could shake the solid resistance of a whole people. This he could not do. Nor did he know how to appeal to the Italians and unite them against Rome. To the Italians Pyrrhus was a foreigner, called in by the Tarentine Greeks whom they rightly despised. Against him they rallied round Rome. And the Romans never wavered for an instant. 29 At the darkest hour there had been no break in the will of the whole people. Pyrrhus saw this: he saw that the Romans would last him out. After Asculum he crossed to Sicily and defeated the Carthaginians, the allies of Rome who were gradually capturing the island from Agathocles the king. But though he soon overran a large part of this island, the Greeks in Sicily liked his iron rule no better than the Greeks of Tarentum had done. He returned to Italy, leaving the great fortress of Lilybaeum still in Carthaginian hands, crying as he sailed away, ‘What a battleground for Romans and Carthaginians I am leaving.’ In Italy he fought one more big battle, at Beneventum (275); but it was a defeat. His hopes were ended. He had won glory for himself, but he had, and this he knew, helped to unite Italy under Rome; and, as he saw, to prepare the way for a great struggle between Rome and Carthage. Pyrrhus saw, sooner than any Roman, the great struggle coming in which the fate of Rome was to be decided. He had shown the Romans the way: had made their strength visible to them and turned their eyes beyond Italy, across the seas.

Carthage

The power of Carthage, to the men of the age of Pyrrhus, seemed infinitely greater than that of Rome. Rome at that time was but a single city whose rule did not extend even over the whole of Italy. Carthage was the head of an empire, built up on a trade which spread its name over the whole of the known world. The Punic or Phoenician people, as the ruling race in Carthage was called because of their dark skins, came from the East. Their earliest homes were in Arabia and Syria. It was from Tyre and Sidon, great and rich towns when Rome was hardly a village, that the traders came and settled in North Africa. Their ships, laden with woven stuffs in silk and cotton, dyed in rich colours, with perfumes and spices, ivory and gold, ornaments and implements in metal, sailed all the navigable seas, and brought home from distant places the goods and raw materials of different lands. At a time when the Romans had 30 hardly begun to sail the seas at all, their vessels passed out of the Mediterranean, through the Straits and up to the little-known lands of the Atlantic. They brought home tin from distant Cornwall, silver from Spain, iron from Elba, copper from Cyprus. Carthage itself was a magnificent city and the richest in the world. Its citizens lived in wealth and idleness on the labour of others. Trade supplied them with riches: the hardy tribes of Africa, Numidians and Libyans, were their slaves, manned their fleets and armies. Their navy ruled the seas. They had settlements in Spain; Corsica and Sardinia were owned by Carthage; all the west of Sicily was in their hands.

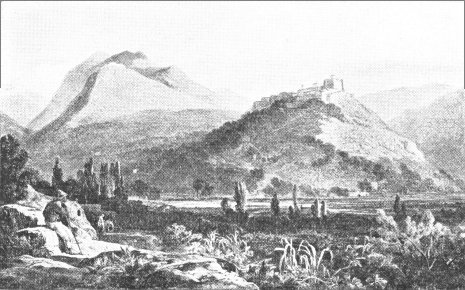

THE DESOLATION OF CARTHAGE TO-DAY

In Sicily the Carthaginians and the Romans first met. The eastern part of the island was ruled by King Hiero of Syracuse; but raids on it were constantly made by the people of Messina. After one of these Hiero attacked Messina. His force was driven off by the Carthaginians who then occupied the citadel. The people of the town looked round for assistance and finally appealed to Rome (265).

Messina was not a Roman city; but the Romans saw that 31 if the Carthaginians were left in possession they would hold a bridge from which they could easily cross into Italy. That was the question that had to be faced when the Senate met to consider whether they should help the people of Messina. To do so meant war with Carthage at once. Not to do so might mean war with Carthage later on. The Senate called upon the people to decide. The people voted for war now.

No man could then have foreseen how long and severe the war was going to be. It lasted three and twenty years (264-241); and at the beginning all the advantage seemed to be on the Carthaginian side. In the first place Carthage had the strongest navy in the world. The Carthaginian army was much the larger, though it was composed of paid soldiers of foreign race. There was no outstanding leader on the Roman side equal to Hamilcar, who commanded the Carthaginians in its later stages.

When the war began the Romans had no fleet. They had never had more than a few transport vessels: no fighting ships. They did not know how they were constructed. This did not daunt them, however. A Carthaginian man-of-war was driven ashore. Roman carpenters and shipwrights at once set to work, studying how it was put together, and thinking out devices by which it could be improved. While the shipwrights were busy the men practised rowing on dry land. The most famous improvement invented by the Romans was the ‘crow’. This was an attachment to the prow, worked by a pulley, consisting of a long pole with a sharp and strong curved iron spike at the end. As soon as an enemy ship came within range this pole was swung round so that the spike caught the vessel and held it in an iron grip. A bridge was fastened to the pole: the soldiers ran along and boarded, forcing a hand-to-hand fight. To this the Carthaginian 32 sailors were not used. They were better navigators than the Romans, but not such good fighters. In hand-to-hand encounters the Romans got the best of it. But they did not know so much of wind and weather, and again and again the storms made havoc with them. Four great fleets were destroyed or captured in the first sixteen years of the war, which lasted for twenty-three. In the year 249 Claudius the Consul lost 93 vessels at a stroke in the disastrous battle of Drepana and killed himself rather than live on under the disgrace. Later in the same year another great fleet was dashed to pieces in a storm.

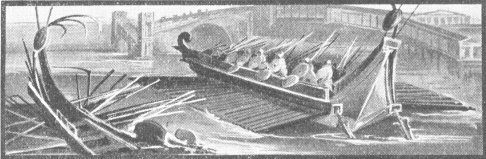

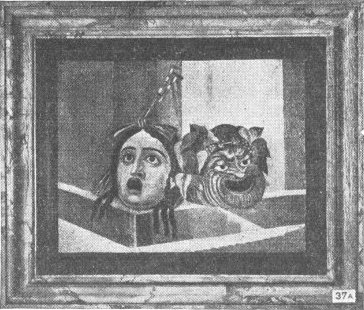

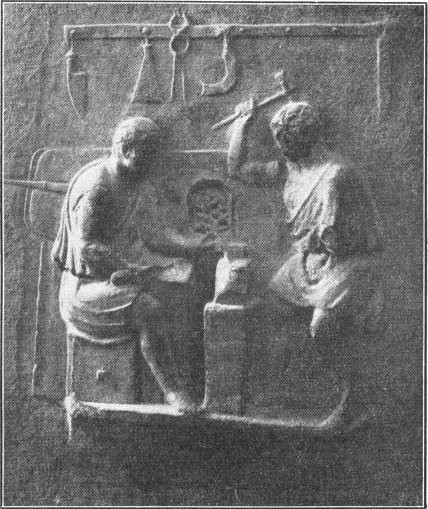

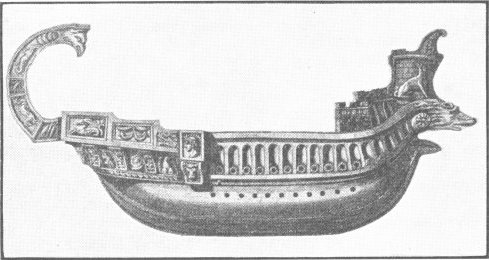

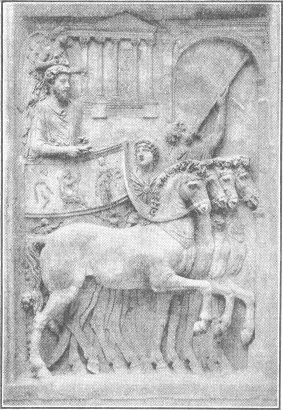

PICTURES FROM POMPEII—

The year ended with the Carthaginians masters of the seas and on land. Four Roman armies had been lost almost to a man. In five years one man in every six of the population of Rome had perished in battle or on the sea. After sixteen years’ hard fighting and extraordinary efforts the end of the war seemed further off than ever, unless the Romans were to admit defeat. But it was no part of their character to admit defeat. As Polybius, the great Greek historian who knew them well, said some years later, ‘The Romans are never so dangerous as when they seem to be reduced to desperation.’ So it proved. No one had any thought of giving in. Regulus, captured by the Carthaginians and sent by them to Rome to urge his countrymen to surrender, urged them to go on fighting, though he knew he must pay the penalty for such words with his life. Had the Carthaginians been made of the same metal they might have used the hour to strike the fatal blow; but they were not. On land they did not trust the one really great general whom 33 they had—Hamilcar Barca. For six years nothing serious was done in Sicily. On sea they let the fleet fall into disrepair because they were confident that the Romans, after their tremendous losses, could do nothing much. They did not know the Roman temper. In the coffers of the State there was no money to build ships. But there were rich men in Rome who put their country’s needs before their own comfort. A number of them sold all they had and gave the money for shipbuilding. Shipwrights and carpenters worked night and day, and in a wonderfully short time a fleet of 250 vessels was constructed and given to the State. And this fleet ended the war. Every man in it was alive with enthusiasm, ready to die for Rome. The Consul Lutatius Catulus, who was put in command of it, utterly defeated the Carthaginian navy in a great battle off the Aegatian Islands (241). In Sicily Hamilcar could do nothing; no supplies could reach him. With bitterness in his heart he had to make a peace which gave Sicily to Rome. The real heroes are the Roman people who, whether in the armies or the navies or at home, never yielded or lost courage in spite of defeat and disaster but held on to the end. They won the victory. They defeated Hamilcar. In this, the first Punic War, the Carthaginian Government was glad to make peace; Hamilcar was not. He was determined that Carthage should defeat Rome yet: he made his young son Hannibal swear never to be friends with Rome.

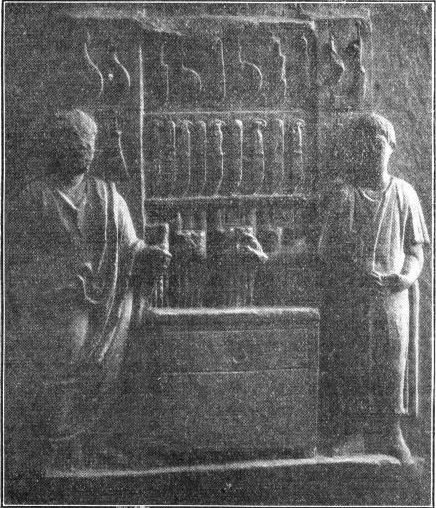

—OF A MIMIC NAVAL BATTLE

34Hannibal

This son of Hamilcar was the most dangerous enemy the Romans ever had to face. He was not only, like Pyrrhus, a brilliant soldier and general: he was much more than this. He was a genius in all the arts of war, and in the leadership of men; great as Napoleon and Julius Caesar were great. He had the power to fill the hearts of his followers with a devotion that asked no questions; they were ready to die for him, to endure any and every hardship. No Roman general of the time was a match for him: few in any time. Yet he was defeated. The reason was simple. He was defeated not by this or that Roman general but by the Roman people. His genius broke against their steady endurance, grim patience, and devotion to Rome. Hannibal could and did win battles, but no victory brought him nearer to his great object, that of dividing Italy and breaking the dominance of Rome. Except for the southern tribes and Capua the Italians stood solid; in Rome there was never any talk of giving in. When Varro, after a rout, partly due to his own recklessness, which left the road to Rome open to Hannibal, brought his remnant back to the city, the senators came out to meet him, and instead of uttering reproaches or lamentations, thanked him because he had not despaired of the Republic. This spirit Hannibal could not break. Behind him there was nothing of this kind. He had his genius and the soldiers he had made; but the people of Carthage only gave him grudging support.

Hannibal’s invasion of Italy failed: but it is one of the most wonderful stories in the whole history of war, and he is one of the great men of history.

His father, Hamilcar Barca (‘Barca’ means ‘lightning’), was a brilliant general; that the Carthaginians lost their first war with Rome was their fault, not his. Of his three sons, Hannibal, Hasdrubal, and Mago, Hannibal the eldest was the dearest to him and most like himself in strength of will, in the power to form a purpose and hold to it unshaken by all that happened to him or that other people said. Soon after the war with Rome was ended Hamilcar left Carthage, taking his sons 35 with him. Before he left he made young Hannibal, then nine years old, swear on the altars never to be friends with Rome. They sailed for Spain. Spain, Hamilcar saw, could be worth more than Sicily, if the people were trained as soldiers and taught the arts of agriculture and mining. The country was rich in metals. His sons helped him, and he meantime taught them not only everything connected with war and the training and handling of men, but languages and all that was then known of history and of art, so that although their boyhood was spent in camps they were as well taught as the noblest Roman.

At the age of six-and-twenty Hannibal was chosen by the army to command the Carthaginian forces in Spain. Although young in years Hannibal’s purpose in life had long been clear to him: since his father’s death he had lived and thought for nothing else. He had trained the army in Spain for this purpose; his captains knew and shared it; and they and the men were filled with a passionate love for and belief in their young commander. Hannibal could make himself feared. The discipline in his army was strict, though he never asked men to do or suffer what he would not do or suffer himself. It was not through fear, however, that he made men devoted to him. They followed him because they believed in him, believed that he had a clear plan and the will to carry it through, and because they loved him. He was the elder brother and companion of his soldiers, and never forgot that they were men.

Three years after he had been made general in Spain Hannibal’s plans were complete. Everything was ready. He knew what he was going to do. Suddenly he laid siege to Saguntum (219), a town in Spain allied to Rome, and took it. This was a declaration of war on Rome. A few months later news came to Rome; news which at first could hardly be believed. Hannibal had left New Carthage, his great base in Spain, with a large army. He had defeated the northern Spaniards and was preparing to cross the Alps and descend on Italy. The Roman army sent to stop him on the Rhone arrived too late to do so. But to cross the Alps with troops and baggage when the winter snows were beginning to fall upon the mountain passes and the streams 36 were freezing into ice was believed to be impossible: no army had ever done it. The paths were precipitous, at places there were no tracks at all. Wild fighting tribes of Gauls held the passes. There was no food: not even dry grass for the animals. Fierce storms of hail and snow swept the mountain tops.

Nevertheless, before winter had fully set in Hannibal had brought his army over. The losses of men and animals had been severe; but a thing thought impossible had been done. The season was still early for fighting: Hannibal could let his suffering troops rest in the fertile North Italian plains. Livy describes the last stage of the journey:

Hannibal’s March: the Sight of the Promised Land

On the ninth day they reached the crest of the Alps, pushing on over trackless steeps, and sometimes compelled to retrace their steps owing to the treachery of the guides or, where they were not trusted, to the random choice of some route through a valley. For two days they encamped on the top, and the soldiers, exhausted by marching and fighting, were allowed to rest. A number of baggage animals, too, that had slipped on the rocks, reached the camp by following the tracks of the army. Tired as the men were, and wearied by so many hardships, a further dismay was caused by a fall of snow, which the setting of the Pleiades brought with it. They started again at dawn, and the army was slowly advancing through ways blocked with snow, listlessness and despair visible on the faces of all, when Hannibal hurried in front of his men and ordered them to stop on a ridge commanding a wide and distant view, from which he pointed out Italy and the plains of the Po lying at the foot of the Alps. ‘Here’, he exclaimed, ‘you are scaling the walls, not merely of Italy, but of Rome; the rest of the way will be smooth and sloping; one or at most two battles will make you masters of the fortress and capital of Italy.’

Just across the river Ticinus a Roman army came to meet him under Cornelius Scipio (218). It was defeated; a month later the other consul, Sempronius, was out-generalled and defeated on the river Trebia. These two victories meant that Italy north of the Po was in Hannibal’s hands. Moreover the 37 Gauls had risen and joined him. Hannibal at once set to work training them, and filling the thinned ranks of his own army with fresh men. His hope was that not only the Gauls—poor allies, for they could never be trusted—but the Italians generally would rise and join him. He counted on their being eager to shake off the yoke of Rome.

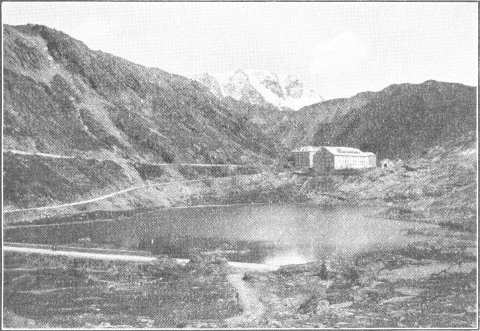

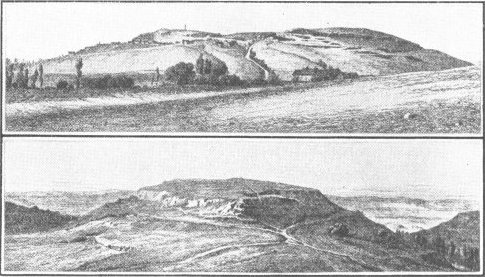

GREAT ST. BERNARD PASS

In Rome men were anxious and excited, but not dismayed. There were two main parties among the people and among the soldiers, led by men of very differing type. On one side stood those who believed that the way to treat Hannibal was by a waiting game. If Rome stood fast they could wear him out as they had worn Pyrrhus out. He was far away from his base of supplies. His new troops could not be so good as his old. The Italians would not rise to help him in any great numbers. The centre of Italy was safe, anyhow. So long as he stayed in the north the south would not rise; if he moved south the Gauls would soon tire of fighting. The leader of this party was Quintus Fabius, a member of one of the proudest Roman families, and a man of what was already beginning to be called the old 38 school. That the common people might suffer if the war dragged out for years did not disturb him much.

On the other side stood men like Caius Flaminius and Terentius Varro, younger both in years and in mind, eager, impatient for action.

Caius Flaminius had opposed Fabius before. He had been elected a tribune of the people—one of those magistrates appointed at the time of Coriolanus to speak for them. He was a man of great ability and warm enthusiasm, a man with more imagination than Fabius. He was as truly devoted to his country, but to his mind the greatness of Rome depended not only on conquest and fine laws and honesty and honour in its leading citizens. These were all good things. But there was another question to ask. Were the ordinary common people happy? Fifteen years before Hannibal’s invasion, Flaminius had brought in a Bill intended to help the poorer Romans by making land settlements for small cultivators in the north. Fabius and most of the old patricians were hot against this. Fabius said to give land to the poor people of Rome encouraged men who could find work in the city but did not take the trouble. They would not cultivate the land if they got it: they would sell it and come back for more. Flaminius denied this. There were men in numbers, he said, men who had served in the armies, who wanted to work but could not do it because they could not get land. To put more men on the land would enrich the whole country. His law was finally carried. Another work done by Flaminius stands to this day as a memorial of him. It, too, shows the imagination of the man. This is the Via Flaminia, a magnificent road that ran right across the Apennine Mountains from sea to sea. It took twenty years to build, but when built it stood for centuries, useful in time of war, even more useful in time of peace.

Flaminius, already popular on account of these achievements, dreamed of doing yet more striking things as a soldier. This was his danger. In the year after the battle of the Trebia he was put in command of one of the two new Roman armies. He was all for a bold policy and believed that he could defeat 39 Hannibal and thus add military glory to himself. He did not know Hannibal. Hannibal, however, had made it his business to know his enemies; he did know what Flaminius was like and used that knowledge for his undoing. Flaminius’s views and character are given by Livy.

Flaminius before Trasimene

Flaminius would not have refrained from action even if his enemy had been inactive; but when the lands of the allies were harried almost before his eyes, he thought it a personal disgrace that Hannibal should range through the heart of Italy and advance unopposed to attack the walls of Rome. In the council all the rest urged a safe rather than an ambitious policy. ‘Wait for your colleague,’ they exclaimed, ‘and then, joining the two armies, carry on the war with a common spirit and purpose; meantime use the cavalry and light-armed infantry to check the reckless plundering of the enemy.’ In a rage he flung himself out of the council and, bidding the trumpet give at once the signal for march and battle, he cried, ‘Rather let us sit still before the walls of Arretium, for here is our country and our home. Hannibal is to slip away from our hands and devastate Italy and, plundering and burning, to reach the walls of Rome, while we are not to move a step till C. Flaminius is summoned by the Fathers from Arretium, as Camillus of old was summoned from Veii.’ Amid these angry words he ordered the standards to be pulled up with all speed and leapt into the saddle, but the horse suddenly fell and threw the consul over his head. While the bystanders were alarmed by this gloomy omen for the beginning of a campaign, a further message arrived that, in spite of all the standard-bearer’s exertions, the standard could not be pulled up. Turning to the messenger, he said, ‘Do you also bring a dispatch from the Senate forbidding me to fight? Go, tell them to dig out the standard if their hands are so numbed with fear that they cannot pull it up.’ Then the advance began; the chief officers, apart from their previous disagreement, were further alarmed by the double portent; the soldiers were delighted with their high-spirited leader, as they thought more about his confidence than any grounds on which it might rest.

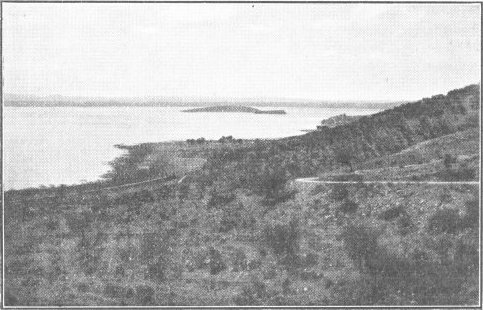

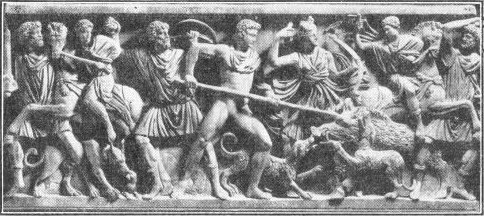

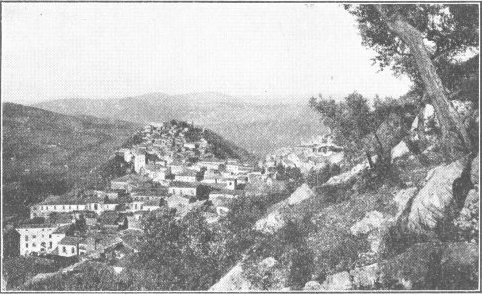

TRASIMENE

When Flaminius took the field he found that Hannibal, despite the melting snow that flooded the fields and made them into marshes and the rivers into torrents, had crossed the 40 Apennines. It had been a terrible crossing: men, horses, and animals fell ill and died. Hannibal himself lost an eye. But he had crossed the mountains and marched right past Flaminius, who was not strong enough to attack him, on the road to Rome. This was done on purpose to lure Flaminius on; for Hannibal knew that he longed to fight before the other consul, Servilius, could join him with his army and share the glory. Hannibal had learned a great deal about the country and he succeeded in misleading Flaminius as to his movements, drawing him on into a deadly trap. Along the high hills standing round the shores of Lake Trasimene he posted his men one night on either side of the pass that closed the entrance. In the morning the heavy mists concealed them absolutely. Flaminius marched his army right in, unsuspecting. Hannibal’s soldiers swept down the slopes and closed the Romans in on every side. They were doomed. There was no escape: they were entrapped between the marshes and the lake; only the vanguard cut their way through, and they were surrounded later. Fifteen thousand men perished, among them Flaminius himself, who died fighting. As many were taken prisoners. Hannibal’s losses were far less. Livy comments:

41After Trasimene

Such was the famous battle of Trasimene, one of the most memorable disasters of the Roman people. Fifteen thousand men were slain on the field; ten thousand, scattered in flight all over Etruria, made for Rome by different ways. Two thousand five hundred of the enemy fell in the battle; many afterwards died of wounds. Hannibal released without ransom the prisoners who belonged to the Latin allies, and threw the Romans into chains. He separated the bodies of his own men from the heaps of the enemy’s dead and gave orders for their burial. A long search was made for the body of Flaminius, which he wished to honour with a funeral; but it could not be found.

After this disaster old Fabius was called to the helm and he carried out his own totally different policy; a policy of endless waiting. During the whole of the rest of the year Hannibal could not force Fabius to give battle. Hannibal moved gradually south, along the western coast. But the Italians did not rise in any great numbers. Hannibal believed that a crushing defeat of Rome would make them do so, and prepared to that end. This is Livy’s account of Fabius’s plan of campaign, and of some of the difficulties he met with in carrying it out: difficulties not only from Hannibal but from his own captains. Thus Varro, his master of the horse, was constantly stirring up discontent.

The Strategy of Fabius

The dictator took over the consul’s army from his deputy, Fulvius Fleccus, and marching through the Sabine land came to Tibur on the day which he had fixed for the gathering of the new recruits. From Tibur he moved to Praeneste, and by cross roads to the Latin way. Thence, after very careful scouting, he led his army against the enemy, determined not to risk an engagement anywhere if he could avoid it. On the day that Fabius first encamped within view of the enemy, not far from Arpi, Hannibal at once formed his army into line and offered battle; but when he saw no movement of troops and no stir in the camp, he retired exclaiming that the ancestral spirit of the Romans was broken, that they were finally conquered, and that they admitted their inferiority in valour and renown. But an 42 unspoken anxiety invaded his mind that he would now have to deal with a general very unlike Flaminius and Sempronius, and that the Romans, taught by their disasters, had at last sought out a leader equal to himself.

Thus Hannibal at once saw reason to fear the wariness of the new dictator, but as he had not yet put his determination to the proof, he began to worry and harass him by constantly moving his camp and pillaging the lands of the allies actually before his eyes. Sometimes he would hurriedly march out of sight, sometimes he would wait concealed beyond a bend of the road, in the hope that he might catch him on the level. Fabius, however, led his troops along the high ground, neither losing touch with his enemy nor giving him battle. The soldiers were kept in the camp unless some necessary service called them out. If fodder and wood were wanted, they went in strong parties that did not scatter. A force of cavalry and light-armed infantry, formed and posted to meet sudden attacks, protected their own comrades and threatened the scattered plunderers of the enemy. The safety of the army was never staked on one pitched battle, while small successes in trivial engagements, begun without risk and with a retreat at hand, taught the soldiers, demoralized by previous disasters, to think better of their own valour and the chances of victory. But he did not find Hannibal such a formidable enemy of this sound strategy as the master of the horse, who was only prevented by his subordinate position from ruining the country, being headstrong and rash in action and unrestrained in speech. First with a few listeners, afterwards openly among the soldiers, he described the deliberation of his commander as indolence and his caution as cowardice, attributing to him faults that were akin to his virtues, and tried to exalt himself by depreciation of his superior, a detestable practice that has become common because it has been too successful.

In the following year, Varro, this same master of the horse, was made consul, sharing the command with Aemilius Paulus. Aemilius was an experienced soldier; but he was on the worst of terms with Varro, and Fabius did not mend matters by warning him that Varro’s rashness was likely to be more dangerous to Rome than Hannibal himself.

The Roman army was the largest yet put in the field and especially strong in infantry. The Plain of Cannae, where Hannibal was encamped, was not favourable for infantry, 43 Aemilius therefore wanted to put off battle. Varro was eager for it. They could not agree. In the end they decided to take command alternately. As soon as Varro’s day came the soldiers saw, to their delight, the red flag of battle flying from the general’s tent.

The battle of Cannae (216) was Hannibal’s greatest victory and the most terrible defeat for Rome in all its history. The Roman charge drove right through the Carthaginian centre: too far, so that the Carthaginians turned and attacked on all sides. The slaughter was terrible. Of 76,000 Romans who fought in the battle the bodies of 70,000 lay upon the field, among them Aemilius himself and the flower of the noblest families in Rome. It was said that a seventh of all the men of military age in Italy perished. Of the higher officers Varro was the only one who escaped; with him was a tiny handful of men, all that was left of the mighty army.

The news of Cannae came to Rome and the city was plunged in mourning. Yet despite the hideous losses and the extreme danger no one gave way to weakness or despair. The strife of parties died down. Men and women turned from weeping for their dead to working for their country. Rome still stood and to every Roman the city’s life was more important than his own. Not a reproach was uttered against Varro, even by those who before had distrusted and blamed him. After the battle he had done well. With great courage and energy he collected together and inspired with new faith the scattered units that remained, and at their head he marched back to Rome. The Senate and people went in procession to the city gate to meet him and the scattered remnant of travel-worn, bloodstained men who had escaped with him from Cannae. Before them all 44 Varro was thanked because he had not despaired of the Republic. Well might Hannibal feel that even after Cannae Rome was not conquered. It was not conquered because the spirit of its people was unbroken. Rome stood firm. The rich came forward giving or lending all they had to the State; men of all classes flocked to the new armies; heavy taxes were put on and no one complained. If the ordinary man was ready to give his life, the least the well-to-do could do was to give his money. The people of Central Italy stood by Rome. In the south rich cities like Capua opened their gates to Hannibal; some of the southern peoples joined him. But there was no big general rising. Nor did the help Hannibal needed come from home, Carthage, or from his other allies in Sicily and Macedonia. The people of Carthage were not like those of Rome. They were sluggish and a big party there was jealous of Hannibal and would do nothing to support him.

Marcellus, the general who took the field after Cannae, was a fine soldier who believed with Fabius that the way to defeat Hannibal was to wear him down. In Marcellus Hannibal found an enemy he must respect. When Marcellus was killed at last and brought into the Carthaginian camp Hannibal stood for a long time silent, looking at his dead enemy’s face. Then he ordered the body to be clothed in splendid funeral garments and burned with all the honours of war. He had the ashes placed in a silver urn and sent to Marcellus’s son. He had in the same way buried Aemilius with all honourable ceremony.

Time was on the Roman side. Yet for eleven years Hannibal, with a small army, kept the whole might of Rome at bay. He was driven further south, that was all. His great hope was that though the Carthaginians would not stir, his brothers Hasdrubal and Mago would send him help from Spain. In Spain after his own departure the Romans had reconquered most of the country, but four years after Cannae Publius Scipio (defeated on the Ticinus) and his brother Cneus were both defeated and killed, and during the next few years Hasdrubal won nearly the whole of Spain. In 208 he was able to move north. He crossed the Pyrenees; spent the winter in Gaul; and in the 45 spring, as soon as the snows melted, crossed the Alps by an easier pass than that taken by his great brother. Before any one expected him he was in Italy. The danger, if he could join Hannibal, was extreme. So serious was it indeed that Fabius, now a very old man, went to the two consuls, Livius and Claudius Nero, and begged them to act together. They hated one another. Fabius had learned how dangerous such quarrels might be to the State, and what harm his own advice had done between Varro and Aemilius Paulus; he now used all his great influence to get the consuls to put an end to personal strife. They agreed and joined their armies. Together they were much stronger than Hasdrubal. On the river Metaurus he was defeated (207). There Hasdrubal himself, fighting like a lion, was killed with ten thousand of his men.

Unhappily the victorious Nero showed in his treatment of his dead enemy a spirit very different from that of Hannibal. He threw the bloody head of Hasdrubal in front of Hannibal’s lines. It was the first news he had of the fate of his brother. He had lost not only a man dearer to him than any on earth but, with him, his last hope of success. He knew that all was over; the fortune of Carthage was at an end. For a moment he hid his face in his mantle. What deep bitterness and pain held his heart in that moment none may guess.