Title: Higgins, a Man's Christian

Author: Norman Duncan

Release date: November 2, 2010 [eBook #34194]

Most recently updated: January 7, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Roger Frank

HIGGINS

A MAN’S CHRISTIAN

BY

NORMAN DUNCAN

HARPER & BROTHERS

NEW YORK AND LONDON

M–C–M–I–X

BOOKS BY NORMAN DUNCAN

| DR. GRENFELL’S PARISH: A Tract in Description of the Deep Sea Mission Work | |

| GOING DOWN PROM JERUSALEM: The Narrative of a Journey | Net $1.50 |

| EVERY MAN FOR HIMSELF: A Book of Short Stories | 1.50 |

| THE CRUISE OF THE “SHINING LIGHT”: A Novel of the Sea | 1.50 |

| DOCTOR LUKE OF THE “LABRADOR”: A Novel | |

| THE SUITABLE CHILD: A Christmas Story | |

| THE MOTHER: A Short Novel | |

| THE ADVENTURES OF BILLY TOPSAIL: A Story for Boys | |

| THE WAY OF THE SEA: A Book of Short Stories | |

| THE SOUL OF THE STREET: A Book of Short Stories | |

| HIGGINS–A MAN’S CHRISTIAN | .50 |

HARPER & BROTHERS, Publishers, N. Y.

Copyright, 1909, by Harper & Brothers.

All rights reserved.

Published November, 1909.

| CONTENTS | ||

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Hell Bent | 1 |

| II. | The Pilot of Souls | 4 |

| III. | In the Snake-Room | 8 |

| IV. | The Cloth in Queer Places | 11 |

| V. | Jack in Camp | 20 |

| VI. | “To the Tall Timber!” | 25 |

| VII. | Robbing the Blind | 32 |

| VIII. | Touching Pitch | 43 |

| IX. | In Spite of Laughter | 54 |

| X. | The Voice of the Lord | 57 |

| XI. | Fist-Play | 65 |

| XII. | Making the Grade | 72 |

| XIII. | Straight from the Shoulder | 78 |

| XIV. | The Shoe on the Other Foot | 85 |

| XV. | Cause and Effect | 97 |

| XVI. | The Wages of Sacrifice | 109 |

TO THE READER

What this book contains was learned by the writer in the course of two visits with Mr. Higgins in the Minnesota woods–one in the lumber-camps and lumber-towns at midwinter, and again at the time of the drive. Upon both occasions Mr. Higgins was accompanied by his devoted and admirable friend, the Rev. Thomas D. Whittles, to whose suggestions and leading he responded with many a tale of his experiences, some of which are here related. Mr. Whittles was at the same time good enough to permit the writer to draw whatever information might seem necessary from a more extended description of Mr. Higgins’s work, called The Lumber-jack’s Sky Pilot, which he had written.

HIGGINS

A MAN’S CHRISTIAN

Twenty thousand of the thirty thousand lumber-jacks and river-pigs of the Minnesota woods are hilariously in pursuit of their own ruin for lack of something better to do in town. They are not nice, enlightened men, of course; the debauch is the traditional diversion–the theme 2 of all the brave tales to which the youngsters of the bunk-houses listen in the lantern-light and dwell upon after dark. The lumber-jacks proceed thus–being fellows of big strength in every physical way–to the uttermost of filth and savagery and fellowship with every abomination. It is done with shouting and laughter and that large good-humor which is bedfellow with the bloodiest brawling, and it has for a bit, no doubt, its amiable aspect; but the merry shouters are presently become like Jimmie the Beast, that low, notorious brute, who, emerging drunk and hungry from a Deer River saloon, robbed a bulldog of his bone and gnawed it himself–or like Damned Soul Jenkins, who goes moaning into the forest, after the spree in town, 3 conceiving himself condemned to roast forever in hell, without hope, nor even the ease which his mother’s prayers might win from a compassionate God.

They can’t help themselves, it seems. Not all of them, of course; but most.

A big, clean, rosy-cheeked man in a Mackinaw coat and rubber boots–hardly distinguishable from the lumber-jack crew except for his quick step and high glance and fine resolute way–went swiftly through a Deer River saloon toward the snake-room in search of a lad from Toronto who had in the camps besought to be preserved from the vicissitudes of the town.

“There goes the Pilot,” said a lumber-jack at the bar. “Hello, Pilot!”

“Ain’t ye goin’ t’ preach no more at Camp Six?”

“Sure, Tom!”

“Well–when the hell?”

“Week from Thursday, Tom,” the vanishing man called back; “tell the boys I’m coming.”

“Know the Pilot?” the lumber-jack asked.

I nodded.

“Higgins’s job,” said he, earnestly, “is keepin’ us boys out o’ hell; an’ he’s the only man on the job.”

Of this I had been informed.

“I want t’ tell ye, friend,” the lumber-jack added, with honest reverence, “that he’s a damned good Christian, if ever there was one. Ain’t that right, Billy?”

6“Higgins,” the bartender agreed, “is a square man.”

The lumber-jack reverted to the previous interest. All at once he forgot about the Pilot.

“Hey, Billy!” he cried, severely, “where’d ye put that bottle?”

Higgins was then in the snake-room of the place–a foul compartment into which the stupefied and delirious are thrown when they are penniless–searching the pockets of the drunken boy from Toronto for some leavings of his wages. “Not a cent!” said he, bitterly. “They haven’t left him a cent! They’ve got every penny of three months’ wages! Don’t blame the boy,” he pursued, in pain and infinite sympathy, easing the lad’s head on the floor; “it isn’t all his fault. He came out of the camps 7 without telling me–and some cursed tin-horn gambler met him, I suppose–and he’s only a boy–and they didn’t give him a show–and, oh, the pity of it! he’s been here only two days!”

The boy was in a stupor of intoxication, but presently revived a little, and turned very sick.

“That you, Pilot?” he said.

“Yes, Jimmie.”

“A’ right.”

“Feel a bit better now?”

“Uh-huh.”

The boy sighed and collapsed unconscious: Higgins remained in the weltering filth of the room to ease and care for him. “Don’t wait for me, old man,” said he, looking up from the task. “I’ll be busy for a while.”

Frank necessity invented the snake-room of the lumber-town saloon. There are times of gigantic debauchery–the seasons of paying off. A logger then once counted one hundred and fifty men drunk in a single hotel of a town of twelve hundred inhabitants where fourteen other bar-rooms heartily flourished. They overflowed the snake-rooms–they lay snoring on the bar-room floor–they littered the office–they were doubled up on the stair-landings and stretched 9 out in the corridors. Drunken men stumbled over drunken men and fell helpless beside them; and still, in the bar-room (said he)–beyond the men who slept or writhed on the floor and had been kicked out of the way–the lumber-jacks were clamoring three deep for whiskey at the bar. Hence the snake-room: one may not eject drunken men into bitter weather and leave them to freeze. Bartenders and their helpers carry them off to the snake-room when they drop; others stagger in of their own notion and fall upon their reeking fellows. There is no arrangement of the bodies–but a squirming heap of them, from which legs and arms protrude, wherein open-mouthed bearded faces appear in a tangle of contorted limbs. Men moan and 10 laugh and sob and snore; and some cough with early pneumonia, some curse, some sing, some horribly grunt; and some, delirious, pick at spiders in the air, and talk to monkeys, and scream out to be saved from dogs and snakes. Men reel in yelling groups from the bar to watch the spectacle of which they will themselves presently be a part.

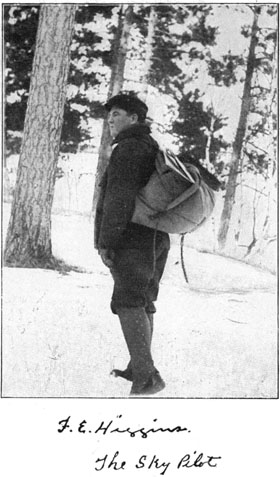

This is the simple and veracious narrative of the singular ministerial activities of the Rev. Francis Edmund Higgins, a Presbyterian, who regularly ministers, without a church, acting under the Board of Home Missions, to the lumber-jacks of the remoter Minnesota woods. Singular ministerial activities these are, truly, appealing alike to those who believe in God and to such as may deny Him. They are particularly robust. When we walked from 12 Camp Two to Camp Four of a midwinter day, with the snow crackling underfoot and the last sunset light glowing like heavenly fire beyond the great green pines–

“Boys,” said Higgins, gravely, “there’s just one thing that I regret; and if I had to prepare for the ministry over again, I wouldn’t make the same mistake: I ought to have taken boxing lessons.”

No other minister of the gospel, possibly, could with perfect propriety, in the sight of the unrighteous, who are the most severe critics of propriety in this respect, lean easily over a bar (his right foot having of long habit found the rail), and in terms of soundest common sense reasonably urge upon the man behind the wet mahogany the shame of 13 his situation and the virtue of abandoning it; nor could any other whom I know truculently crowd into the howling, brawling, drunken throng of lumber-jacks, all gone mad of adulterated liquor, and with any confident show of authority command the departure of some weakling who had followed the debauch of his mates far beyond his little strength.

“Come out o’ this!” says Higgins.

“Ah, go chase yerself, Pilot!” is the indulgent response, most amiably delivered, with a loose, kind smile.

“Come on!” says Higgins, in wrath.

“Ah, Pilot,” the youngster pleads, “I’m on’y havin’ a little fun. You go chase yerself, Pilot,” says he, affectionately, with no offence whatsoever, “an’ le’ me alone.”

The Rev. Francis Edmund 14 Higgins, in the midst of an unholy up-roar–the visible manifestation, this environment and behavior, it seems to me, of the noise and smell and very abandonment of hell–is privileged to seize the youngster by the throat and in no unnecessarily gentle way to jerk him into the clean, frosty air of the winter night. In these days of his ministry, nobody–the situation being an ordinary one–would interfere. If, however, it seemed unwise to proceed in this way, Higgins would at least strip the boy of his savings.

“Hand over!” says he.

The boy hands over every cent he possesses. If Higgins suspects, he will turn out the pockets. And later–late in the night–with the wintry dawn breaking, it may be–the sleepless Pilot carries the boy off on his 15 back to such saving care as he may be able to exercise. To a gentle care–a soft, tender solicitude, all separate from the wild doings of the bar-room, and all under cover, even as between the boy and the Pilot. I have been secretly told that the good Pilot is at such times like a brooding mother to the lusty, wayward youngsters of the camps, who, in their prodigality, do but manfully emulate the most manly behavior of which they are aware.

To confuse Higgins with cranks and freaks would be most injuriously to wrong him. He is not an eccentric; his hair is cropped, his finger nails are clean, there is a commanding achievement behind him, he has manners, a mind variously 16 interested, as the polite world demands. Nor is he a fanatic; he would spit cant from his mouth in disgust if ever it chanced within. He is a reasonable and highly efficient worker–a man dealing with active problems in an intelligent and thoroughly practical way; and he is as self-respecting and respected in his peculiar field as any pulpit parson of the cities–and as sane as an engineer. He is a big, jovial, rotund, rosy-cheeked Irish-Canadian (pugnacious upon occasion), with a boy’s smile and eyes and laugh, with a hearty voice and way, with a head held high, with a man’s clean, confident soul gazing frankly from unwavering eyes: five foot nine and two hundred pounds to him (which allows for a little rippling fat). He is big of body and heart and faith and 17 outlook and charity and inspiration and belief in the work of his hands; and his life is lived joyously–notwithstanding the dirty work of it–though deprived of the common delights of life. He has no church: he straps a pack on his back and tramps the logging-roads from camp to camp, whatever the weather–twelve miles in a blizzard at forty below–and preaches every day–and twice and three times a day–in the bunk-houses; and he buries the boys–and marries them to the kind of women they know–and scolds and beseeches and thrashes them, and banks for them.

God knows what they would do without Higgins! He is as necessary to them now–as much sought in trouble and as heartily regarded–as a Presbyterian minister of the old 18 school; he is as close and helpful and dogmatic in intimate affairs.

“Pilot,” said Ol’ Man Johnson, “take this here stuff away from me!”

The Sky Pilot rose astounded. Ol’ Man Johnson, in the beginnings of his spree in town–half a dozen potations–was frantically emptying his pockets of gold (some hundreds of dollars) on the preacher’s bed in the room above the saloon; and he blubbered like a baby while he threw the coins from him.

“Keep it away from me!” Ol’ Man Johnson wept, drawing back from the money with a gesture of terror. “For Christ’s sake, Pilot!––keep it away from me!”

The Pilot understood.

“If you don’t,” cried Ol’ Man Johnson, “it’ll kill me!”

19Higgins sent a draft for the money to Ol’ Man Johnson when Ol’ Man Johnson got safely home to his wife in Wisconsin. Another spree in town would surely have killed Ol’ Man Johnson.

The lumber-jack in camp can, in his walk and conversation, easily be distinguished from the angels; but at least he is industrious and no wild brawler. He is up and heartily breakfasted and off to the woods, with a saw or an axe, at break of day; and when he returns in the frosty dusk he is worn out with a man’s labor, and presently ready to turn in for sound sleep. They are all in the pink of condition then–big and healthy and clear-eyed, and wholly 21 able for the day’s work. A stout, hearty, kindly, generous crew, of almost every race under the sun–in behavior like a pack of boys. It is the Saturday in town–and the occasional spree–and the final debauch (which is all the town will give them for their money) that litters the bar-room floor with the wrecks of these masterful bodies.

Walking in from Deer River of a still, cold afternoon–with the sun low and the frost crackling under foot and all round about–we encountered a strapping young fellow bound out to town afoot.

“Look here, boy!” said Higgins; “where you going?”

“Deer River, sir.”

“What for?”

22There was some reply to this. It was a childish evasion; the boy had no honest business out of camp, with the weather good and the work pressing, and he knew that Higgins understood. Meanwhile, he kicked at the snow, with a sheepish grin, and would not look the Pilot in the eye.

“You’re from Three, aren’t you?”

“Yes, sir.”

“I thought I saw you there in the fall,” said the Pilot. “Well, boy,” he continued, putting a strong hand on the other’s shoulder, “look me in the eye.”

The boy looked up.

“God help you!” said the Pilot, from his heart; “nobody else ’ll give you a show in Deer River.”

We walked on, Higgins in advance, downcast. I turned, presently, and 23 discovered that the young lumber-jack was running.

“Can’t get there fast enough,” said Higgins. “I saw that his tongue was hanging out.”

“He seeks his pleasure,” I observed.

“True,” Higgins replied; “and the only pleasure the men of Deer River will let him have is what he’ll buy and pay for over a bar, until his last red cent is gone. It isn’t right, I tell you,” he exploded; “the boy hasn’t a show, and it isn’t right!”

It was twelve miles from Camp Three to Deer River. We met other men on the road to town–men with wages in their pockets, trudging blithely toward the lights and liquor and drunken hilarity of the place. It was Saturday; and on Monday, 24 ejected from the saloons, they would inevitably stagger back to the camps. I have heard of one kindly logger who dispatches a team to the nearest town every Monday morning to gather up his stupefied lumber-jacks from the bar-room floors and snake-rooms and haul them into the woods.

It is “back to the tall timber” for the penniless lumber-jack. Perhaps the familiar slang is derived from the necessity. I recall an intelligent Cornishman–a cook with a kitchen kept sweet and clean–who with a laugh contemplated the catastrophe of the snake-room, and the nervous collapse, and the bedraggled return to the woods.

“Of course,” said he, “that’s where I’ll land in the spring!”

It amazed me.

26“Can’t help it,” said he. “That’s where my stake ’ll go. Jake Boore ’ll get the most of it; and among the lot of them they’ll get every cent. I’ll blow four hundred dollars in two weeks–if I’m lucky enough to make it go that far.”

“When you know that they rob you?”

“Certainly they will rob me; everybody knows that! But every year for nine years, now, I’ve tried to get out of the woods with my stake, and haven’t done it. I intend to this year; but I know I won’t. I’ll strike for Deer River when I get my money; and I’ll have a drink at Jake Boore’s saloon, and when I get that drink down I’ll be on my way. It isn’t because I want to; it’s because I have to.”

“But why?”

“They won’t let you do anything 27 else,” said the cook. “I’ve tried it for nine years. Every winter I’ve said to myself that I’ll get out of the woods in the spring, and every spring I’ve been kicked out of a saloon dead broke. It’s always been back to the tall timber for me.”

“What you need, Jones,” said Higgins, who stood by, “is the grace of God in your heart.”

Jones laughed.

“You hear me, Jones?” the Pilot repeated. “What you need is the grace of God in your heart.”

“The Pilot’s mad,” the cook laughed, but not unkindly. “The Pilot and I don’t agree about religion,” he explained; “and now he’s mad because I won’t go to church.”

This banter did not disturb the Pilot in the least.

28“I’m not mad, Jones,” said he. “All I’m saying,” he repeated, earnestly, fetching the cook’s flour-board a thwack with his fist, “is that what you need is the grace of God in your heart.”

Again Jones laughed.

“That’s all right, Jones!” cried the indignant preacher. “But I tell you that what you need is the grace of God in your heart. And you know it! And when I get you in the snake-room of Jake Boore’s saloon in Deer River next spring,” he continued, in righteous anger, “I’ll rub it into you! Understand me, Jones? When I haul you out of the snake-room, and wash you, and get you sobered up, I’ll rub it into you that what you need is the grace of God in your heart to give you the first splinter of a man’s backbone.”

29“I’ll be humble–then,” said Jones.

“You’ll have to be a good deal more than humble, friend,” Higgins retorted, “before there’ll be a man in the skin that you wear.”

“I don’t doubt it, Pilot.”

“Huh!” the preacher sniffed, in fine scorn.

The story fortunately has an outcome. I doubt that the cook took the Pilot’s prescription; but, at any rate, he had wisdom sufficient to warn the Pilot when his time was out, and his money was in his pocket, and he was bound out of the woods in another attempt to get through Deer River. It was midwinter when the Pilot prescribed the grace of God; it was late in the spring when the cook secretly warned him to stand 30 by the forlorn essay; and it was later still–the drive was on–when, one night, as we watched the sluicing, I inquired.

“Jones?” the Pilot replied, puzzled. “What Jones?”

“The cook who couldn’t get through.”

“Oh,” said the Pilot, “you mean Jonesy. Well,” he added, with satisfaction, “Jonesy got through this time.”

I asked for the tale of it.

“You’d hardly believe it,” said the Pilot, “but we cashed that big check right in Jake Boore’s saloon. I wouldn’t have it any other way, and neither would Jonesy. In we went, boys, brave as lions; and when Jake Boore passed over the money Jonesy put it in his pocket. Drink? Not 31 he! Not a drop would he take. They tried all the tricks they knew, but Jonesy wouldn’t fall to them. They even put liquor under his nose; and Jonesy let it stay there, and just laughed. I tell you boys, it was fine! It was great! Jonesy and I stuck it out night and day together for two days; and then I put Jonesy aboard train, and Jonesy swore he’d never set foot in Deer River again. He was going South, somewhere, to see–somebody.”

It was doubtless the grace of God, after all, that got the cook through: if not the grace of God in the cook’s heart, then in the Pilot’s.

It it a perfectly simple situation. There are thirty thousand men-more or less of them, according to the season–making the wages of men in the woods. Most of them accumulate a hot desire to wring some enjoyment from life in return for the labor they do. They have no care about money when they have it. They fling it in gold over the bars (and any sober man may rob their very pockets); they waste in a night what they earn in a winter–and then crawl back to 33 the woods. Naturally the lumber-towns are crowded with parasites upon their lusts and prodigality–with gamblers and saloon-keepers and purveyors of low passion. Some larger capitalists, more acute and more acquisitive, of a greed less nice -profess the three occupations at once. They are the men of real power in the remoter communities, makers of mayors and chiefs of police and magistrates–or were until Higgins came along to dispute them. And their operations have been simple and enormously profitable–so easy, so free from any fear of the law, that I should think they would (in their own phrase) be ashamed to take the money. It seems to be no trouble at all to abstract a drunken lumber-jack’s wages.

34It takes a big man to oppose these forces–a big heart and a big body, and a store of hope and courage not easily depleted. It takes, too, a good minister; it takes a loving heart and a fist quick to find the point of the jaw to preach the gospel after the manner of Higgins. And Higgins conceives it to be one of his sacred ministerial duties to protect his parishioners in town. Behind the bunk-houses, in the twilight, they say to him: “When you goin’ t’ be in Deer River, Pilot? Friday? All right. I’m goin’ home. See me through, won’t you?” Having committed themselves in this way, nothing can save them from Higgins–neither their own drunken will (if they escape him for an interval) nor the antagonism of the keepers of places. This is 35 perilous and unscholarly work; systematic theology has nothing to do with escorting through a Minnesota lumber-town a weak-kneed boy who wants to take his money home to his mother in Michigan.

Once the Pilot discovered such a boy in the bar-room of a Bemidji saloon.

“Where’s your money?” he demanded.

“’N my pocket.”

“Hand it over,” said the Pilot.

“Ain’t going to.”

“Yes, you are; and you’re going to do it quick. Come out of this!”

Cowed by these large words, the boy yielded to the grip of Higgins’s big hand, and was led away a little. Then the bartender leaned over the bar. A gambler or two lounged toward 36 the group. There was a pregnant pause.

“Look here, Higgins,” said the bartender, “what business is this of yours, anyhow?”

“What business–of mine?” asked the astounded Pilot.

“Yes; what you buttin’ in for?”

“This,” said Higgins, “is my job!”

The Pilot was leaning wrathfully over the bar, his face thrust belligerently forward, alert for whatever might happen. The bartender struck at him. Higgins had withdrawn. The bartender came over the bar at a bound. The preacher caught him on the jaw in mid-air with a stiff blow, and he fell headlong and unconscious. They made friends next day–the boy being then safely out 37 of town. It is not hard for Higgins to make friends with bartenders. They seem to like it; Higgins really does.

It was in some saloon of the woods that the watchful Higgins observed an Irish lumber-jack empty his pockets on the bar and, in a great outburst of joy, order drinks for the crowd. The men lined up; and the Pilot, too, leaned over the bar, close to the lumber-jack. The bartender presently whisked a few coins from the little heap of gold and silver. Higgins edged nearer. In a moment, as he knew–just as soon as the lumber-jack would for an instant turn his back–the rest of the money would be deftly swept away.

The thing was about to happen, 38 when Higgins’s big hand shot out and covered the heap.

“Pat,” said he, quietly, “I’ll not take a drink. This,” he added, as he put the money in his pocket, “is my treat.”

The Pilot stood them all off–the hangers on, the runners, the gamblers, the bartender (with a gun), and the Irish lumber-jack himself. To the bartender he remarked (while he gazed contemptuously into the muzzle of the gun) that should ever the fellow grow into the heavy-weight class he would be glad to “take him on.” As it was, he was really not worth considering in any serious way, and had better go get a reputation. It was a pity–for the Pilot (said he) was fit and able–but the thrashing must be postponed for the time.

Further to illustrate the ease with which the lumber-jack may be robbed, I must relate that last midwinter, in the office of a Deer River hotel, the Pilot was greeted with hilarious affection by a boy of twenty or thereabouts who had a moment before staggered out from the bar-room. The youngster was having an immensely good time, it seemed; he was full of laughter and wit and song–not yet quite full of liquor. It was snowing outside, I recall, and a bitter wind was blowing from the north; but it was warm and light in the office–bright, and cosy, and companionable: very different, indeed, from the low, stifling, crowded, ill-lit bunk-houses of the camps, nor 40 was his elation like the weariness of those places. There were six men lying drunk on the office floor-in grotesque attitudes, very drunk, stretched out and snoring where they had fallen.

“Boy,” demanded the Pilot, “where’s your money?”

The young lumber-jack said that it was in the safe-keeping of the bartender.

“How much you got left?”

“Oh, I got lots yet,” was the happy reply.

Presently the boy went away, and presently he reeled back again, and put a hand on the Pilot’s shoulder.

“Near all in?” asked the Pilot.

“I came here yesterday morning with a hundred and twenty-three dollars,” said the boy, very drunkenly, 41 “and I give it to the bartender to keep for me, and I’m told I got two-thirty left.”

He was quite content; but Higgins knew that the money of which they were robbing him was needed at his home, a day’s journey to the east of Deer River.

There is no pleasure thereabout (they say) but the spree, and the end of the spree is the snake-room for by far the most of the merry-makers–r a penniless condition for all–pneumonia for many–and for the survivors a beggared, reeling return to the hard work of the woods.

Higgins is used to picking over the bodies of drunken men in the snake-room heaps–of entering sadly, but never reluctantly (he said), in search 42 of men who have been sorely wounded in brawls, or are taken with pneumonia, or in whom there remains hope of regeneration. He carries them off on his back to lodgings–or he wheels them away in a barrow–and he washes them and puts them to bed and (sometimes angrily) restrains them until their normal minds return. It has never occurred to him, probably, that this is an amazing exhibition of primitive Christian feeling and practice. He may have thought of it, however, as a glorious opportunity for service, for which he should devoutly and humbly give thanks to Almighty God.

Not long ago Bemidji was what the Pilot calls “the worst town on the map.” It was indescribably lawless and vicious. An adequate description would be unprintable. The government–the police and magistrates–was wholly in the hands of the saloon-keeping element. It was a thoroughly noisome settlement. The town authorities laughed at the Pilot; the state authorities gently listened to him and conveniently forgot him, for political 44 reasons. But he was determined to cleanse the place of its established and flaunting wickednesses. He organized a W. C. T. U.; and then–“Boys,” said he to the keepers of places, “I’m going to clean you out. I want to be fair to you–and so I tell you. Don’t you ever come sneaking up to me and say I didn’t give you warning!” They laughed at him when he stripped off his coat and got to work. In the bar-rooms the toast was, “T’ Higgins–and t’ hell with Higgins!” and down went the red liquor. But when the fight was over, when the shutters were up for good–so had he compelled the respect of these men–they came to the preacher, saying: “Higgins, you gave us a show; you fought us fair–and we want to shake hands.”

45“That’s all right, boys,” said Higgins.

“Will you shake hands?”

“Sure, I’ll shake hands, boys!”

Jack Worth–that notorious gambler and saloon-keeper of Bemidji–quietly approached Higgins.

“Frank,” said he, “you win; but I’ve no hard feelings.”

“That’s all right, Jack,” said Higgins.

The Pilot remembered that he had sat close to the death-bed of the young motherless son of this same Jack Worth in the room above the saloon. They had been good friends–the big Pilot and the boy. And Jack Worth had loved the boy in a way that only Higgins knew. “Papa,” said the boy, at this time, death being then very near, “I want 46 you to promise me something.” Jack Worth listened. “I want you to promise me, papa,” the boy went on, “that you’ll never drink another drop in all your life.” Jack Worth promised, and kept his promise; and Jack Worth and the preacher had preserved a queer friendship since that night.

“Jack,” said the Pilot, now, “what you going to do?”

“I don’t know, Frank.”

“Aren’t you going to quit this dirty business.”

“I ran a square game in my house, and you know it,” the gambler replied.

“That’s all right, Jack,” Higgins said; “but look here, old man, isn’t little Johnnie ever going to pull you out of this?”

47“Maybe, Frank,” was the reply. “I don’t know.”

The gamblers, the bartenders, the little pickpockets are as surely the Pilot’s parishioners as anybody else, and they like and respect him. Nobody is excluded from his ministry. I recall that Higgins was late one night writing in his little room. There came a knock on the door-a loud, angry demand–a forewarning of trouble, to one who knows about knocks (as the Pilot says). Higgins opened, of course, and discovered a big bartender, new to the town–a bigger man than he, and a man with a fighting reputation. The object of the quarrelsome visit was perfectly plain: the preacher braced himself for combat.

“Higgins is my name.”

“Did you ever say that if it came to a row between the gamblers of this town and the lumber-jacks that you’d fight with the lumber-jacks?”

Higgins looked the man over.

“Well,” snarled the visitor, “how about it?”

“Well, my friend,” replied the Pilot, laying off his coat, “I guess you’re my man!” and advanced with guard up.

“I’m no gambler,” the visitor hastily explained. “I’m a bartender.”

“Don’t matter,” said Higgins. “You’re my man just the same. I meant bartenders, too.”

“Well,” said the bartender, “I just come up to ask you a question.”

“Are men made by conditions,” the bartender propounded, “or do conditions make men?”

There ensued the hottest kind of an argument. It turned out that the man was a Socialist–a propagandist who had come to Deer River to sow the seed (he said). I have forgotten what the Pilot’s contention was; but, at any rate, it dodged the general issue and concerned itself with the specific question of whether or not conditions at Deer River made saloon-keepers and gamblers and worse and bartenders–the affirmative of which he held to be an abominable opinion. They carried the argument to the bar-room, where, one on each side of the dripping bar, they disputed until daylight, Higgins at times loudly 50 taunting his opponent with the assertion that a bartender could do nothing but shame Socialism in the community. It ended in this amicable agreement: that the bartender was privileged to attempt the persuasion of Higgins to Socialism, and that Higgins was permitted to practise upon the bartender without let or hindrance with a view to his conversion.

“Have a drink?” said the bartender.

“Wh–what!” exclaimed the Pilot.

“Have a little something soft?”

“I wouldn’t take a glass of water over your dirty bar,” Higgins is said to have roared, “if I died of thirst!”

The man will not compromise.

To all these men, as well as to the lumber-jacks, the Pilot gives his help 51 and carries his message: to all the loggers and lumber-jacks and road-monkeys and cookees and punk-hunters and wood-butchers and swamp-men and teamsters and bull-cooks and the what-nots of the woods, and the gamblers and saloon-keepers and panderers and bartenders (and a host of filthy little runners and pullers-in and small thieves) of the towns. He has no abode near by, no church; he preaches in bunk-houses, and sleeps above saloons and in the little back rooms of hotels and in stables and wherever a blanket may be had in the woods. He ministers to nobody else: just to men like these. To women, too: not to many, perhaps, but still to those whom the pale men of the towns find necessary to their gain. To women like Nellie, in swiftly failing 52 health, who could not escape (she said) because she had lost the knack of dressing in any other way. She beckoned him, aboard train, well aware of his profession; and when Higgins had listened to her ordinary little story, her threadbare, pathetic little plea to be helped, he carried her off to some saving Refuge for such as she. To women like little Liz, too, whose consumptive hand Higgins held while she lay dying alone in her tousled bed in the shuttered Fifth Red House.

“Am I dyin’, Pilot?” she asked.

“Yes, my girl,” he answered.

“Dyin’–now?”

Higgins said again that she was dying; and little Liz was dreadfully frightened then–and began to sob for her mother with all her heart.

53I conceive with what tenderness the big, kind, clean Higgins comforted her–how that his big hand was soft and warm enough to serve in that extremity. It is not known to me, of course; but I fancy that little Liz of the Fifth Red House died more easily–more hopefully–because of the proximity of the Pilot’s clear, uplifted soul.

Higgins was born on August 19, 1865, in Toronto, Ontario, the son of a hotel-keeper. When he was seven years old his father died, and two years later his mother remarried and went pioneering to Shelburne, Dufferin County, Ontario, which was then a wilderness. There was no school; consequently there was no schooling. Higgins went through the experience of conversion when he was eighteen. Presently, thereafter, he determined to be a 55 minister; and they laughed at him. Everybody laughed. Obviously, what he must have was education; but he had no money, and (as they fancied) less capacity. At any rate, the dogged Higgins began to preach; he preached–and right vigorously, too, no doubt–to the stumps on his stepfather’s farm; and he kept on preaching until, one day, laughing faces slowly rose from behind the stumps, whereupon he took to his heels. At twenty he started to school with little children in Toronto. It was hard (he was still a laughing-stock); and there were three years of it–and two more in the high school. Then off went Higgins as a lay preacher of the Methodist Episcopal Church to Annandale, Minnesota. Following this came two years at Hamline University. 56 In 1895 he was appointed to the charge of the little Presbyterian church at Barnum, Minnesota, a town of four hundred, where, subsequently, he married Eva L. Lucas, of Rockford, Minnesota.

It was here (says he) that the call came.

It was on the way between camps, of a Sunday afternoon in midwinter, when the Pilot related the experience which led to the singular ministerial activities in which he is engaged. He was wrapped in a thick Mackinaw coat, with a cloth cap pulled down over his ears; and he wore big overshoes, which buckled near to his knees. There was a heavy pack on his pack; it contained a change of socks (for himself), and many pounds of “readin’ matter” 58 (for “the boys”). He had preached in the morning at one camp, in the afternoon at another, and was now bound to a third, where (as it turned out) a hearty welcome was waiting. The day–now drawn far toward evening–was bitterly cold. There was no wind. It was still and white and frosty on the logging-road.

It seems that once from Barnum the Pilot went vacating into the woods to see the log-drive.

“You’re a preacher,” said the boys. “Give us a sermon.”

Higgins preached that evening, and the boys liked it. They liked the sermon; they fancied their own singing of Rock of Ages and Jesus, Lover of My Soul. They asked Higgins to come again. Frequently after 59 that–and ever oftener–Higgins walked into the woods when the drive was on, or into the camps in winter, to preach to the boys. They welcomed him; they were always glad to see him–and with great delight they sang Jesus, Lover of My Soul and Throw Out the Life-Line. Nobody else preached to them in those days; a great body of men–almost a multitude in all those woods: the Church had quite forgotten them.

“Boys,” said Higgins, “you’ve always treated me right, here. Come in to see me when you’re in town. The wife ’ll be glad to have you.”

They took him at his word. Without warning, one day, thirty lumber-jacks crowded into the little parlor. They were hospitably received.

“Pilot,” said the spokesman, all 60 now convinced of Higgins’s genuineness, “here’s something for you from the boys.”

A piece of paper (a check for fifty-one dollars) was thrust into the Pilot’s hand, and the whole crew decamped on a run, with howls of bashful laughter, like a pack of half-grown school-boys. And so the relationship was first established.

It was in winter, Higgins says, that the call came; and the voice of the Lord, as he says, was clear in direction. Two lumber-jacks came out of the woods to fetch him to the bedside of a sick homesteader who had been at work in the lumber-camps. The homesteader was a sick man (said they), and he had asked for the Pilot. The doctor was first to the 61 man’s mean home. There was no help for him, said he, in a log-cabin deep in the woods; if he could be taken to the hospital in Duluth there might be a chance. It was doubtful, of course; but to remain was death.

“All right,” said Higgins. “I’ll take him to the hospital.”

The hospital doctor in Duluth said that the man was dying. The Pilot so informed the homesteader and bade him prepare. But the man smiled. He had already prepared. “I heard you preach–that night–in camp–on the river,” said he. It seems that he had been reared in a Christian home, but had not for twenty years heard the voice of a minister in exhortation until Higgins chanced that way. And afterward–when the lights in the wannigan were out and 62 the crew had gone to sleep–he could not banish the vision of his mother. Life had been sweeter to him since that night. The Pilot’s message (said he) had saved him.

“Mr. Higgins,” said he, “go back to the camp and tell the boys about Jesus.”

Higgins wondered if the Lord had spoken.

“Go back to the camps,” the dying man repeated, “and tell the boys about Jesus.”

Nobody else was doing it. Why shouldn’t Higgins? The boys had no minister. Why shouldn’t Higgins be that minister? Was not this the very work the Lord had brought him to this far place to do? Had not the Lord spoken with the tongue of this dying man? “Go back to the camps 63 and tell the boys about Jesus.” The phrase was written on his heart. “Go back to the camp and tell the boys about Jesus.” How it appealed to the young preacher–the very form of it! All that night, the homesteader having died, Higgins–not then the beloved Pilot–walked the hospital corridor. When day broke he had made up his mind. Whatever dreams of a city pulpit he had cherished were gone. He would go back to the camps for good and all.

And back he went.

We had now come over the logging-road near to the third camp. The story of the call was finished at sunset.

“Well,” said the Pilot, heartily, with half a smile, “here I am, you see.”

64“On the job,” laughed one of the company.

“For good and all,” Higgins agreed. “It’s funny about life,” he added, gravely. “I’m a great big wilful fellow, naturally evil, I suppose; but it seems to me that all my lifelong the Lord has just led me by the hand as if I were nothing but a little child. And I didn’t know what was happening to me! Now isn’t that funny? Isn’t the whole thing funny?”

It used sometimes to be difficult for Higgins to get a hearing in the camps; this was before he had fought and preached his way completely into the trust of the lumber-jacks. There was always a warm welcome for him in the bunk-houses, to be sure, and for the most part a large eagerness for the distraction of his discourses after supper; but here and there in the beginning he encountered an obstreperous fellow (and does to this day) who interrupted for the fun of 66 the thing. It is related that upon one occasion a big Frenchman began to grind his axe of a Sunday evening precisely as Higgins began to preach.

“Some of the boys here,” Higgins drawled, “want to hear me preach, and if the boys would just grind their axes some other time I’d be much obliged.”

The grinding continued.

“I say,” Higgins proceeded, his voice rising a little, “that a good many of the boys have asked me to preach a little sermon to them; but I can’t preach while one of the boys grinds his axe.”

No impression was made.

“Now, boys,” Higgins went on, “most of you want to hear me preach, and I’m going to preach, all right; 67 but I cant preach if anybody grinds an axe.”

The Frenchman whistled a tune.

“Friend, back there!” Higgins called out, “can’t you oblige the boys by grinding that axe another time?”

There was some tittering in the bunk-house–and the grinding went on–and the tune came saucily up from the door where the Frenchman stood. Higgins walked slowly back; having come near, he paused–then put his hand on the Frenchman’s shoulder in a way not easily misunderstood.

“Friend,” he began, softly, “if you–”

The Frenchman struck at him.

“Keep back, boys!” an old Irishman yelled, catching up a peavy-pole. 68 “Give the Pilot a show! Keep out o’ this or I’ll brain ye!”

The Sky Pilot caught the Frenchman about the waist–flung him against a door–caught him again on the rebound–put him head foremost in a barrel of water–and absent-mindedly held him there until the old Irishman asked, softly, “Say, Pilot, ye ain’t goin’ t’ drown him, are ye?” It was all over in a flash: Higgins is wisely no man for half-way measures in an emergency; in a moment the Frenchman lay cast, dripping and gasping, on the floor, and the bunk-house was in a tumult of jeering. Then Higgins proceeded with the sermon; and–strangely–he is of an earnestness and frankly mild and loving disposition so impressive that this passionate incident had doubtless 69 no destructive effect upon the solemn service following. It is easy to fancy him passing unruffled to the upturned cask which served him for a pulpit, readjusting the blanket which was his altar-cloth, raising his dog-eared little hymn-book to the smoky light of the lantern overhead, and beginning, feelingly: “Boys, let’s sing Number Fifty-six: ‘Jesus, lover of my soul, let me to thy bosom fly.’ You know the tune, boys; everybody sing–‘While the nearer waters roll and the tempest still is high.’ All ready, now!” A fight in a church would be a seriously disturbing commotion; but a fight in a bunk-house–well, that is commonplace. There is more interest in singing Jesus, Lover of My Soul, than in dwelling upon the affair afterward. And the 70 boys sang heartily, I am sure, as they always do, the Frenchman quite forgotten.

Next day Higgins was roused by the selfsame man; and he jumped out of his bunk in a hurry (says he), like a man called to fire or battle.

“Well,” he thought, as he sighed, “if I am ever to preach in these camps again, I suppose, this man must be satisfactorily thrashed; but”–more cheerfully–“he needs a good thrashing, anyhow.”

“Pilot,” said the Frenchman, “I’m sorry about last night.”

Higgins shook hands with him.

Fully to describe Higgins’s altercations with lumber-jacks and tin-horn gamblers and the like in pursuit of clean opportunity for other men would be to pain him. It is a phase of ministry he would conceal. Perhaps he fears that unknowing folk might mistake him for a quarrelsome fellow. He is nothing of the sort, however; he is a wise and efficient minister of the gospel–but fights well, upon good occasion, notwithstanding his forty-odd years. In the Minnesota 72 woods fighting is as necessary as praying–just as tender a profession of Christ. Higgins regrets that he knows little enough of boxing; he shamefacedly feels that his preparation for the ministry has in this respect been inadequate. Once, when they examined him before the Presbytery for ordination, a new-made seminary graduate from the East, rising, quizzed thus: “Will the candidate not tell us who was Cæsar of Rome when Paul preached?” It stumped Higgins; but–he told us on the road from Six to Four–“I was confused, you see. The only Cæsar I could think of was Julius, and I knew that that wasn’t right. If he’d only said Emperor of Rome, I could have told him, of course! Anyhow, it didn’t matter much.” Boxing, according to the 73 experience of Higgins, was an imperative preparation for preaching in his field; a little haziness concerning an Emperor of Rome really didn’t matter so very much. At any rate, the boys wouldn’t care.

Higgins’s ministry, however, knows a gentler service than that which a strong arm can accomplish in a bar-room. When Alex McKenzie lay dying in the hospital at Bemidji–a screen around his cot in the ward–the Pilot sat with him, as he sits with all dying lumber-jacks. It was the Pilot who told him that the end was near.

“Nearing the landing, Pilot?”

“Almost there, Alex.”

“I’ve a heavy load, Pilot–a heavy load!”

McKenzie was a four-horse teamster, 74 used to hauling logs from the woods to the landing at the lake–forty thousand pounds of new-cut timber to be humored over the logging-roads.

“Pilot,” he asked, presently, “do you think I can make the grade?”

“With help, Alex.”

McKenzie said nothing for a moment. Then he looked up. “You mean,” said he, “that I need another team of leaders?”

“The Great Leader, Alex.”

“Oh, I know what you mean,” said McKenzie: “you mean that I need the help of Jesus Christ.”

No need to tell what Higgins said then–what he repeated about repentance and faith and the infinite love of God and the power of Christ for salvation. Alex McKenzie had heard 75 it all before–long before, being Scottish born, and a Highlander–and had not utterly forgotten, prodigal though he was. It was all recalled to him, now, by a man whose life and love and uplifted heart were well known to him–his minister.

“Pray for me,” said he, like a child.

McKenzie died that night. He had said never a word in the long interval; but just before his last breath was drawn–while the Pilot still held his hand and the Sister of Charity numbered her beads near by–he whispered in the Pilot’s ear:

“Tell the boys I made the grade!”

Pat, the old road-monkey–now come to the end of a long career of furious living–being about to die, 76 sent for Higgins. He was desperately anxious concerning the soul that was about to depart from his ill-kept and degraded body; and he was in pain, and turning very weak.

Higgins waited.

“Pilot,” Pat whispered, with a knowing little wink, “I want you to fix it for me.”

“To fix it, Pat?”

“Sure, you know what I mean, Pilot,” Pat replied. “I want you to fix it for me.”

“Pat,” said Higgins, “I can’t fix it for you.”

“Then,” said the dying man, in amazement, “what the hell did you come here for?”

“To show you,” Higgins answered, gently, “how you can fix it.”

“Me fix it?”

77Higgins explained, then, the scheme of redemption, according to his creed–the atonement and salvation by faith. The man listened–and nodded comprehendingly–and listened, still with amazement–all the time nodding his understanding. “Uh-huh!” he muttered, when the preacher had done, as one who says, I see! He said no other word before he died. Just, “Uh-huh!”–to express enlightenment. And when, later, it came time for him to die, he still held tight to Higgins’s finger, muttering, now and again, “Uh-huh! Uh-huh!”–like a man to whom has come some great astounding revelation.

In the bunk-house, after supper, Higgins preaches. It is a solemn service: no minister of them all so punctilious as Higgins in respect to reverent conduct. The preacher is in earnest and single of purpose. The congregation is compelled to reverence. “Boys,” says he, in cunning appeal, “this bunk-house is our church–the only church we’ve got.” No need to say more! And a queer church: a low, long hut, stifling and ill-smelling and unclean and 79 infested, a row of double-decker bunks on either side, a great glowing stove in the middle, socks and Mackinaws steaming on the racks, boots put out to dry, and all dim-lit with lanterns. Half-clad, hairy men, and boys with young beards, lounge everywhere–stretched out on the benches, peering from the shadows of the bunks, squatted on the fire-wood, cross-legged on the floor near the preacher. Higgins rolls out a cask for a pulpit and covers it with a blanket. Then he takes off his coat and mops his brow.

Presently, hymn-book or Testament in hand, he is sitting on the pulpit.

“Not much light here,” says he, “so I won’t read to-night; but I’ll say the First Psalm. Are you all ready?”

“All right. ‘Blessed is the man that walketh not in the counsel of the ungodly,’ boys, ‘nor standeth in the way of sinners.’”

The door opens and a man awkwardly enters.

“Got any room back there for Bill, boys?” the preacher calls.

There seems to be room.

“I want to see you after service, Bill. You’ll find a seat back there with the boys. ‘For the Lord knoweth the way of the righteous; but the way of the ungodly,’ gentlemen, ‘shall perish.’”

There is a prayer, restrained, in the way of the preacher’s church–a petition terrible with earnestness. One wonders how a feeling God could turn a deaf ear to the beseeching 81 eloquence of it! And the boys sing–lustily, too–led by the stentorian preacher. An amazing incongruity: these seared, blasphemous barbarians bawling, What a Friend I Have in Jesus!

Enjoy it?

“Pilot,” said one of them, in open meeting, once, with no irreverence whatsoever, “that’s a damned fine toon! Why the hell don’t they have toons like that in the shows? Let’s sing her again!”

“Sure!” said the preacher, not at all shocked; “let’s sing her again!”

There is a sermon–composed on the forest roads from camp to camp: for on those long, white, cold, blustering roads Higgins either whistles his blithe way (like a boy) or fashions his preaching. It is a 82 searching, eloquent sermon: none other so exactly suited to environment and congregation–none other so simple and appealing and comprehensible. There isn’t a word of cant in it; there isn’t a suggestion of the familiar evangelistic rant. Higgins has no time for cant (he says)–nor any faith in ranting. The sermon is all orthodox and significant and reasonable; it has tender wisdom, and it is sometimes terrible with naked truth. The phrasing? It is as homely and brutal as the language of the woods. It has no affectation of slang. The preacher’s message is addressed with wondrous cunning to men in their own tongue: wherefore it could not be repeated before a polite congregation. Were the preacher to ejaculate an oath (which 83 he never would do)–were he to exclaim, “By God! boys, this is the only way of salvation!”–the solemnity of the occasion would not be disturbed by a single ripple.

“And what did the young man do?” he asked, concerning the Prodigal; “why, he packed his turkey and went off to blow his stake–just like you!” Afterward, when the poor Prodigal was penniless: “What about him then, boys? You know. I don’t need to tell you. You learned all about it at Deer River. It was the husks and the hogs for him–just like it is for you! It’s up the river for you–and it’s back to the woods for you–when they’ve cleaned you out at Deer River!” Once he said, in a great passion of pity: “Boys, you’re out here, floundering to your waists, 84 picking diamonds from the snow of these forests, to glitter, not in pure places, but on the necks of the saloon-keepers’ wives in Deer River!” There is applause when the Pilot strikes home. “That’s damned true!” they shout. And there is many a tear shed (as I saw) by the young men in the shadows when, having spoken long and graciously of home, he asks: “When did you write to your mother last? You, back there–and you! Ah, boys, don’t forget her!”

There was pause while the preacher leaned earnestly over the blanketed barrel.

“Write home to-night,” he besought them. “She’s–waiting–for–that–letter!”

They listened.

The Pilot is a fearless preacher–fearless of blame and violence–and he is the most downright and pugnacious of moral critics. He speaks in mighty wrath against the sins of the camps and the evil-doers of the towns–naming the thieves and gamblers by name and violently characterizing their ways: until it seems he must in the end be done to death in revenge. “Boys,” said he, in a bunk-house denunciation, “that tin-horn gambler Jim Leach is back 86 in Deer River from the West with a crooked game–just laying for you. I watched his game, boys, and I know what I’m talking about; and you know I know!” Proceeding: “You know that saloon-keeper Tom Jenkins? Of course you do! Well, boys, the wife of Tom Jenkins nodded toward the camps the other day, and, ‘Pshaw!’ says she; ‘what do I care about expense? My husband has a thousand men working for him in the woods!’ She meant you, boys! A thousand of you–think of it!–working for the wife of a brute like Tom Jenkins.” Again: “Boys, I’m just out from Deer River. I met ol’ Bill Morgan yesterday. ‘Hello, Bill!’ says I; ‘how's business?’ ‘Slow, Pilot,’ says he; ‘but I ain’t worryin’ none–it’ll pick up when the boys come in with their stake in the 87 spring.’ There you have it! That’s what you’ll be up against, boys, God help you! when you go in with your stake–a gang of filthy thieves like Jim Leach and Tom Jenkins and Bill Morgan!” It takes courage to attack, in this frank way, the parasites of a lawless community, in which murder may be accomplished in secret, and perjury is as cheap as a glass of whiskey.

It takes courage, too, to denounce the influential parishioner.

“You grown-up men, here,” Higgins complained to his congregation, “ought to give the young fellows a chance to live decent lives. Shame to you that you don’t! You’ve lived in filth and blasphemy and whiskey so long that maybe you don’t know any 88 better; but I want to tell you–every one of you–that these boys don’t want that sort of thing. They remember their mothers and their sisters, and they want what’s clean! Now, you leave ’em alone. Give ’em a show to be decent. And I’m talking to you, Scotch Andrew”–with an angry thump of the pulpit and a swift belligerent advance–“and to you, Gin Thompson, sneaking back there in your bunk!”

“Oh, hell!” said Gin Thompson.

The Pilot was instantly confronting the lazy-lying man. “Gin,” said he, “you’ll take that back!”

Gin laughed.

“Understand me?” the wrathful preacher shouted.

Gin Thompson understood. Very wisely–however unwillingly–he 89 apologized. “That’s all right, Pilot,” said he; “you know I didn’t mean nothin’.”

“Anyhow,” the preacher muttered, returning to his pulpit and his sermon, “I’d rather preach than fight.”

Not by any means all Higgins’s sermons are of this nature; most are conventional enough, perhaps–but always vigorous and serviceable–and present the ancient Christian philosophy in an appealing and deeply reverent way. I recall, however, another downright and courageous display of dealing with the facts without gloves. It was especially fearless because the Pilot must have the permission of the proprietors before he may preach in the camps. It is 90 related that a drunken logger–the proprietor of the camp–staggered into Higgins’s service and sat down on the barrel which served for the pulpit. The preacher was discoursing on the duties of the employed to the employer. It tickled the drunken logger.

“Hit ’em again, Pilot!” he applauded. “It’ll do ’em good.”

Higgins pointed out the wrong worked the owners by the lumber-jacks’ common custom of “jumping camp.”

“Give ’em hell!” shouted the logger. “It’ll do ’em good.”

Higgins proceeded calmly to discuss the several evils of which the lumber-jacks may be accused in relation to their employers.

“You’re all right, Pilot,” the logger 91 agreed, clapping the preacher on the back. “Hit the –– rascals again! It’ll do ’em good.”

“And now, boys,” Higgins continued, gently, “we come to the other side of the subject. You owe a lot to your employers, and I’ve told you frankly what your minister thinks about it. But what can be expected of you, anyhow? Who sets you a good example of fair dealing and decent living? Your employers? Look about you and see! What kind of an example do your employers set? Is it any wonder,” he went on, in a breathless silence, “that you go wrong? Is it any wonder that you fail to consider those who fail to consider you? Is it any wonder that you are just exactly what you are, when the men to whom you ought to be 92 able to look for better things are themselves filthy and drunken loafers?”

The logger was thunderstruck.

“And how d’ye like that, Mister Woods?” the preacher shouted, turning on the man, and shaking his fist in his face. “How d’ye like that? Does it do you any good?”

The logger wouldn’t tell.

“Let us pray!” said the indignant preacher.

Next morning the Pilot was summoned to the office. “You think it was rough on you, do you, Mr. Woods?” said he. “But I didn’t tell the boys a thing that they didn’t know already. And what’s more,” he continued, “I didn’t tell them a thing that your own son doesn’t know. You know just as well as I do what road 93 he’s travelling; and you know just as well as I do what you are doing to help that boy along.”

Higgins continued to preach in those camps.

One inevitably wonders what would happen if some minister of the cities denounced from his pulpit in these frank and indignantly righteous terms the flagrant sinners and hypocrites of his congregation. What polite catastrophe would befall him?–suppose he were convinced of the wisdom and necessity of the denunciation and had no family dependent upon him. The outburst leaves Higgins established in the hearts of his hearers; and it leaves him utterly exhausted. He mingles with the boys afterward; he encourages and scolds them, he hears 94 confession, he prays in some quiet place in the snow with those whose hearts he has touched, he confers with men who have been seeking to overcome themselves, he writes letters for the illiterate, he visits the sick, he renews old acquaintanceship, he makes new friends, he yarns of the “cut” and the “big timber” and the “homesteading” of other places, and he distributes the “readin’ matter,” consisting of old magazines and tracts which he has carried into camp.

At last he quits the bunk-house, worn out and discouraged and downcast.

“I failed to-night,” he said, once, at the superintendent’s fire. “It was awfully kind of the boys to listen to me so patiently. Did you notice how attentive they were? I tell you, the 95 boys are good to me! Maybe I was a little rough on them to-night. But somehow all this unnecessary and terrible wickedness enrages me. And nobody else much seems to care about it. And I’m their minister. And I yearn to have the souls of these boys awakened. I’ve just got to stand up and tell them the truth about themselves and give them the same old Message that I heard when I was a boy. I don’t know, but it’s kind of queer about ministers of the gospel,” he went on. “We’ve got two Creations now, and three Genesises. But take a minister. It wouldn’t matter to me if a brother minister fell from grace. I’d pick him out of the mud and never think of it again. It wouldn’t cost me much to forgive him. I know that we’re all human and 96 liable to sin. But when an ordained minister gets up in his pulpit and dodges his duty–when he gets up and dodges the truth–why, bah! I’ve got no time for him!”

This sort of preaching–this genuine and practical ministry consistently and unremittingly carried on for love of the men, and without prospect of gain–wins respect and loyal affection. The dogged and courageous method will be sufficiently illustrated in the tale of the Big Scotchman of White Pine–to Higgins almost a forgotten incident of fourteen years’ service. The Big Scotchman was discovered drunk and shivering with apprehension–he was 98 in the first stage of delirium tremens–in a low saloon of White Pine, some remote and God-forsaken settlement off the railroad, into which the Pilot had chanced on his rounds. The man was a homesteader, living alone in a log-cabin on his grant of land, some miles from the village.

“Well,” thought the Pilot, quite familiar with the situation, “first of all I’ve got to get him home.”

There was only one way of accomplishing this, and the Pilot employed it; he carried the Big Scotchman.

“Well,” thought the Pilot, “what next?”

The next thing was to wrestle with the Big Scotchman, upon whom the “whiskey sickness” had by that time fallen–to wrestle with him in the lonely little cabin in the woods, and 99 to get him down, and to hold him down. There was no congregation to listen to the eloquent sermon which the Pilot was engaged in preaching; there was no choir, there was no report in the newspapers. But the sermon went on just the same. The Pilot got the Big Scotchman down, and kept him down, and at last got him into his bunk. For two days and nights he sat there ministering–hearing, all the time, the ravings of a horrible delirium. There was an interval of relief then, and during this the Pilot gathered up every shred of the Big Scotchman’s clothing and safely hid it. There was not a garment left in the cabin to cover his nakedness.

The Big Scotchman presently wanted whiskey.

100“No,” said the Pilot; “you stay right here.”

The Big Scotchman got up to dress.

“Nothing to wear,” said the Pilot.

Then the fight was on again. It was a long fight–merely a physical thing in the beginning, but a fight of another kind before the day was done. And the Pilot won. When the Big Scotchman got up from his knees he took the Pilot’s hand and said that, by God’s help, he would live better than he had lived. Moreover, he was as good as his word. Presently White Pine knew him no more; but news of his continuance in virtue not long ago came down to the Pilot from the north. It was what the Pilot calls a real reformation and conversion. It seems that there is a difference.

101We had gone the rounds of the saloons in Deer River, and had returned late at night to the hotel. The Pilot was very busy–he is always busy, from early morning until the last sot drops unconscious to the bar-room floor, when, often, the real day’s work begins; he is one of the hardest workers in any field of endeavor. And he was now heart-sick because of what he had seen that night; but he was not idle–he was still shaking hands with his parishioners in the bar-room, still advising, still inspiring, still scolding and beseeching, still holding private conversations in the corners, for all the world like a popular and energetic politician on primary day.

A curious individual approached me.

102“Friend of the Pilot’s?” said he.

I nodded.

“He’s a good man.”

I observed that the stranger was timid and slow–a singular fellow, with a lean face and nervous hands and clear but most unsteady eyes. He was like an old hulk repainted.

“He done me a lot of good,” he added, in a slow, soft drawl, hardly above a whisper, at the same time slowly smoothing his chin.

It was a pleasant thing to hear.

“They used to call me Brandy Bill,” he continued. He pointed to a group of drunkards lying on the floor. “I used to be like that,” said he, looking up like a child who perceives that he is interesting. After a pause, he went on: “But once when the snakes broke out on me I made up my mind 103 to quit. And then I went to the Pilot and he stayed with me for a while, and told me I had to hang on. I thought I could do it if the boys would leave me alone. So the Pilot told me what to do. ‘Whenever you come into town,’ says he, ‘you go on to your sister’s and borrow her little girl.’ Her little girl was just four years old then. ‘And,’ says the Pilot, ‘don’t you never come down street without her.’ Well, I done what the Pilot said. I never come down street without that little girl hanging on to my hand; and when she was with me not one of the boys ever asked me to take a drink. Yes,” he drawled, glancing at the drunkards again, “I used to be like that. Pretty near time,” he added, like a man displaying an experienced knowledge, 104 “to put them fellows in the snake-room.”

Such a ministry as the Pilot’s springs from a heart of kindness–from a pure and understanding love of all mankind. “Boys,” said he, once, in the superintendent’s office, after the sermon in the bunk-house, “I’ll never forget a porterhouse steak I saw once. It was in Duluth. I’d been too busy to have my breakfast, and I was hungry. I’m a big man, you know, and when I get hungry I’m hungry. Anyhow, I wasn’t thinking about that when I saw the steak. It didn’t occur to me that I was hungry until I happened to glance into a restaurant window as I walked along. And there I saw the steak. You know how they fix those windows up: a chunk of 105 ice and some lettuce and a steak or two and some chops. Well, boys, all at once I got so hungry that I ached. I could hardly wait to get in there.

“But I stopped.

“‘Look here, Higgins,’ thought I, ‘what if you didn’t have a cent in your pocket?’

“Well, that was a puzzler. ‘What if you were a dead-broke lumber-jack, and hungry like this?’

“Boys, it frightened me. I understood just what those poor fellows suffer. And I couldn’t go in the restaurant until I had got square with them.

“‘Look here, Higgins,’ I thought, ‘the best thing you can do is to go and find a hungry lumber-jack somewhere and feed him.’

106“And I did, too; and I tell you, boys, I enjoyed my dinner.”

It is a ministry that wins good friends, and often in unexpected places: friends like the lumber-jack (once an enemy) who would clear a way for the Pilot in town, shouting, “I’m road-monkeying for the Pilot!” and friends like the Blacksmith.

Higgins came one night to a new camp where an irascible boss was in complete command.

“You won’t mind, will you,” said he, “if I hold a little service for the boys in the bunk-house to-night?”

The boss ordered him to clear out.

“All I want to do,” Higgins protested, mildly, “is just to hold a little service for the boys.”

Again the boss ordered him to clear out: but Higgins had come 107 prepared with the authority of the proprietor of the camp.

“I’ve a pass in my pocket,” he suggested.

“Don’t matter,” said the boss; “you couldn’t preach in this camp if you had a pass from God Almighty!”

To thrash or not to thrash? that was the Pilot’s problem; and he determined not to thrash, for he knew very well that if he thrashed the boss the lumber-jacks would lose respect for the boss and jump the camp. The Blacksmith, however, had heard–and had heard much more than is here written. Next morning he involved himself in a quarrel with the boss; and having thrashed him soundly, and having thrown him into a snowbank, he departed, but returned, and, addressing himself to that 108 portion of the foreman which protruded from the snow, kicked it heartily, saying: “There’s one for the Pilot. And there’s another–and another. I’ll learn you to talk to the Pilot like a drunken lumber-jack. There’s another for him. Take that–and that–for the Pilot.”

Subsequently Higgins preached in those camps.

One asks, Why does Higgins do these things? The answer is simple: Because he loves his neighbor as himself–because he actually does, without self-seeking or any pious pretence. One asks, What does he get out of it? I do not know what Higgins gets. If you were to ask him, he would say, innocently, that once, when he preached at Camp Seven of the Green River Works, the boys fell in love with the singing. Jesus, Lover of My Soul, was the 110 hymn that engaged them. They sang it again and again; and when they got up in the morning, they said: “Say, Pilot, let’s sing her once more!” They sang it once more–in the bunk-house at dawn–and the boss opened the door and was much too amazed to interrupt. They sang it again. “All out!” cried the boss; and the boys went slowly off to labor in the woods, singing, Let me to Thy bosom fly! and, Oh, receive my soul at last!–diverging here and there, axes and saws over shoulder, some to the deeper forest, some making out upon the frozen lake, some pursuing the white roads–all passing into the snow and green and great trees and silence of the undefiled forest which the Pilot loves–all singing as they went, Other refuge have I none; hangs my 111 helpless soul on Thee–until the voices were like sweet and soft-coming echoes from the wilderness.

Poor Higgins put his face to the bunk-house door and wept.

“I tell you, boys,” he told us, on the road from Six to Four, “it was pay for what I’ve tried to do for the boys.”

Later–when the Sky Pilot sat with his stockinged feet extended to a red fire in the superintendent’s log-cabin of that bitterly cold night–he betrayed himself to the uttermost. “Do you know, boys,” said he, addressing us, the talk having been of the wide world and travel therein, “I believe you fellows would spend a dollar for a dinner and never think twice about it!”

We laughed.

112“If I spent more than twenty-five cents,” said he, accusingly, “I’d have indigestion.”

Again we laughed.

“And if I spent fifty cents for a hotel bed,” said he, with a grin, “I’d have the nightmare.”

That is exactly what Higgins gets out of it.

Higgins gets more than that out of it: he gets a clean eye and sound sleep and a living interest in life. He gets even more: he gets the trust and affection of almost–almost–every lumber-jack in the Minnesota woods. He wanders over two hundred square miles of forest, and hardly a man of the woods but would fight for his Christian reputation at a word. For example, he had pulled Whitey 113 Mooney out of the filth and nervous strain of the snake-room, and reestablished him, had paid his board, had got him a job in a near-by town, had paid his fare, had taken him to his place; but Whitey Mooney had presently thrown up his job (being a lazy fellow), and had fallen into the depths again, had asked Higgins for a quarter of a dollar for a drink or two, and had been denied. Immediately he took to the woods; and in the camp he came to be complained that Higgins had “turned him down.”

“You’re a liar,” they told him. “The Pilot never turned a lumber-jack down. Wait till he comes.”

Higgins came.

“Pilot,” said a solemn jack, rising, when the sermon was over, as he had 114 been delegated, “do you know Mooney?”

“Whitey Mooney?”

“Yes. Do you know Whitey Mooney?”

“You bet I do, boys!”

“Did–you–turn–him–down?”

“You bet I did, boys!”

“Why?”

Higgins informed them.

“Come out o’ there, Whitey!” they yelled; and they took Whitey Mooney from his bunk, and tossed him in a blanket, and drove him out of camp.

Higgins is doing a hard thing–correcting and persuading such men as these; and he could do infinitely better if he had more money to serve his ends. They are not all drunkards and savage beasts, of course. It would 115 wrong them to say so. Many are self-respecting, clean-lived, intelligent, sober; many have wives and children, to whom they return with clean hands and mouths when the winter is over. They all–without any large exception (and this includes the saloon-keepers and gamblers of the towns)–respect the Pilot. It is related of him that he was once taken sick in the woods. It was a case of exposure–occurring in cold weather after months of bitter toil, with a pack on his back and in deep trouble of spirit. There was a storm of snow blowing, at far below zero, and Higgins was miles from any camp. He managed, however, after hours of plodding through the snow, to reach the uncut timber, where he was somewhat sheltered from the wind. He remembers that 116 he was then intent upon the sermon for the evening; but beyond–even trudging through these tempered places–he has forgotten what occurred. The lumber-jacks found him at last, lying in the snow near the cook-house; and they carried him to the bunk-house, and put him to bed, and consulted concerning him. “The Pilot’s an almighty sick man,” said one. Another prescribed: “Got any whiskey in camp?” There was no whiskey–there was no doctor within reach–there was no medicine of any sort. And the Pilot, whom they had taken from the snow, was a very sick man. They wondered what could be done for him. It seemed that nobody knew. There was nothing to be done–nothing but keep him covered up and warm.

117“Boys,” a lumber-jack proposed, “how’s this for an idea?”

They listened.

“We can pray for the man,” said he, “who’s always praying for us.”

They managed to do it somehow; and when Higgins heard that the boys were praying for him–praying for him!–he turned his face to the wall, and covered up his head, and wept like a fevered boy.

THE END