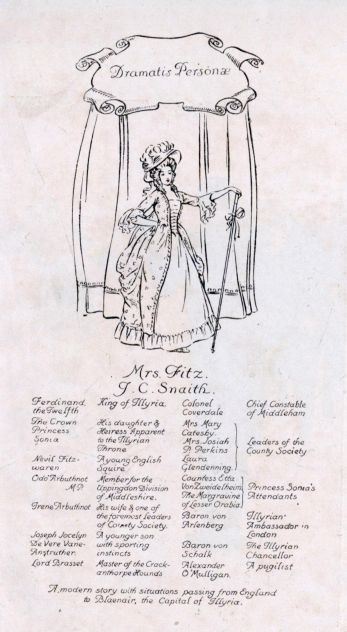

Title: Mrs. Fitz

Author: J. C. Snaith

Release date: February 13, 2011 [eBook #34398]

Most recently updated: October 11, 2022

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Al Haines

MRS. FITZ

BY

J. C. SNAITH

HODDER & STOUGHTON'S

SEVENPENNY LIBRARY

HODDER AND STOUGHTON

LONDON — NEW YORK — TORONTO

1912

CONTENTS

ACCORDING TO REUTER

TRIBULATIONS OF A M.F.H.

THE CASE FOR THE PROSECUTION

THE MIDDLE COURSE

ABOUNDS IN SENSATION

EXPERT OPINION

COVERDALE'S REPORT

PREPARATIONS FOR THE CAMPAIGN

ON THE EVE

ALARUMS AND EXCURSIONS

THE ORDERS FOR THE DAY

THE MAN OF DESTINY

FURTHER PASSAGES AT NO. 300 PORTLAND PLACE

A DEPLORABLE INCIDENT

AN INTERNATIONAL ISSUE

HORSE AND HOUND

A GLARE IN THE SKY

MRS. ARBUTHNOT BEGINS TO TAKE NOTICE

HER ROYAL HIGHNESS RECEIVES A LETTER

A LITTLE DIPLOMACY

THE EXPECTED GUEST

A VISIT TO BRYANSTON SQUARE

PROVIDES AN ILLUSTRATION OF THE THEORY THAT

THINGS ARE NOT ALWAYS WHAT THEY SEEM

HIS ILLYRIAN MAJESTY FERDINAND THE TWELFTH

THE FATHER OF HIS PEOPLE

A WALK IN THE GARDEN

PROVIDES A LITTLE FEMININE DIVERSION

THE WRITING ON THE WALL

THE CAST OF THE DIE

REACTION

NEWS FROM ILLYRIA

MORE ALARUMS AND EXCURSIONS

IN THE BALANCE

THE CREATURES OF PERRAULT

"It is snowing," said Mrs. Arbuthnot.

"Worse luck!" growled I from behind my newspaper. "This unspeakable climate! Why can't we sack the Clerk of the Weather?"

"Because he is a permanent official," said Joseph Jocelyn De Vere Vane-Anstruther, who was coming into the room. "And those are the people who run the benighted country."

Joseph Jocelyn De Vere Vane-Anstruther was in rather smart kit. It was December the First, and the hounds—there is only one pack in the United Kingdom—were about to pay an annual visit to the country of a neighbour. With conscious magnificence my relation by marriage took a bee-line to the sideboard. He paused a moment to debate to which of two imperative duties he should give the precedence: i.e. to make his daily report upon the personal appearance of his host, or to find out what there was to eat. The state of the elements enabled Mother Nature "to get a cinch" on an honourable æstheticism. Jodey began to forage slowly but resolutely among the dish covers.

"Kedgeree! Twice in a fortnight. Look here, Mops, it won't do."

Mrs. Arbuthnot was perusing that journal which for the modest sum of one halfpenny purveys the glamour of history with only five per cent. of its responsibilities. She merely turned over a page. Her brother, having heaped enough kedgeree upon his plate to make a meal for the average person, peppered and salted it on a scale equally liberal and then suggested coffee.

"Tea is better for the digestion," said Mrs. Arbuthnot, with her natural air of simple authority.

"I know," said Jodey, "that is why I prefer the other stuff."

"Men are so reasonable!"

"Do you mind 'andin' the sugar?"

"Sugar will make you a welter and ruin your appearance."

A cardinal axiom of my friend Mrs. Josiah P. Perkins, née Ogbourne, late of Brownville, Mass., is "Horse-sense always tells." Among the daughters of men I know none whose endowment of this felicitous quality can equal that of the amiable participator in my expenditure. It told in this case.

"Better give me tea."

"Without sugar?" said Mrs. Arbuthnot, with great charm of manner.

"A small lump," said Jodey as a concession to his force of character.

The young fellow stirred his tea with so much diligence that the small lump really seemed like a large one. And then, with a gravity that was somewhat sinister, he fixed his gaze on my coat and leathers.

"By a local artist of the name of Jobson," said I, humbly. "The second shop on the right as you enter Middleham High Street."

"They speak for themselves."

"My father went there," said I. "My grandfather also. In my grandfather's day I believe the name of the firm was Wiseman and Grundy."

"It's not fair to 'ounds. If I was Brasset I should take 'em 'ome."

"If you were Brasset," I countered, "that would hardly be necessary. They would find their way home by themselves."

"Mops is to blame. She has been brought up properly."

"It comes to this, my friend. We can't both wear the breeches. Hers cost a pretty penny from those thieves in Regent Street."

"Maddox Street," said a bland voice from the recesses of the Daily Courier.

"Those bandits in Maddox Street," said I, with pathos. "But for all I know it might be those sharks in the Mile End Road. I am a babe in these things."

"No, my dear Odo," said the young fellow, making his point somewhat elaborately, "in those things you are a perisher. An absolute perisher. I'm ashamed to be seen 'untin' the same fox with you. I should be ashamed to be found dead in the same ditch. I hate people who are not serious about clothes. It's so shallow."

My relation by marriage produced an extremely vivid yellow silk handkerchief, and pensively flicked a speck of invisible dust off an immaculate buckskin.

"My God, those tops!"

"By a local draughtsman," said I, "of the name of Bussey. He is careful in the measurements and takes a drawing of the foot."

"'Orrible. You look like a Cossack at the Hippodrome."

"The Madam patronises an establishment in Bond Street. One is given to understand that various royalties follow her example."

"They make for the King of Illyria," said Mrs. Arbuthnot.

"That is interesting," said I, in response to a quizzical glance from the breakfast table. "The fact is, my amiable coadjutor in the things of this life has a decided weakness for royalty. She denies it vehemently and betrays it shamelessly on every possible occasion."

"Very interestin' indeed," said her brother.

In the next moment a cry of surprise floated out of the depths of the halfpenny newspaper.

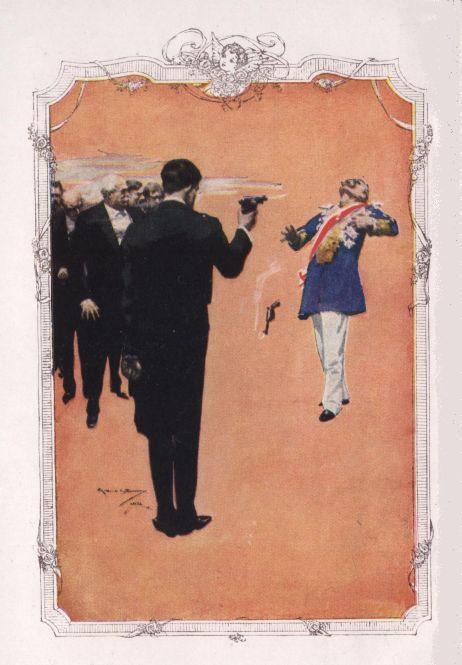

"What a coincidence!" exclaimed Mrs. Arbuthnot. "There has been an attempt on the life of the King of Illyria. They have thrown a bomb into his palace and killed the brother of the Prime Minister."

"In the interests of the shareholders of the Daily Courier," said I.

"Be serious, Odo," said Mrs. Arbuthnot. "To think of that dear old king being in danger!"

"Yes, the dear old king," said Jodey.

"I think you are horrid, both of you," said Mrs. Arbuthnot with the spirit that made her an admired member of the Crackanthorpe Hunt. "Those horrid Illyrians! They don't deserve to have a king. They ought to be like France and America and Switzerland."

"They will soon be in that unhappy position," said I, turning to page four of the Times newspaper. "According to Reuter, it appears to have been a bonâ fide attempt. Count Cyszysc——"

"You sneeze twice," suggested Jodey.

"Count Cyszysc was blown to pieces on the threshold of the Zweisgarten Palace, the whole of the south-west front of which was wrecked."

"The wretches!" said Mrs. Arbuthnot. "They are only fit to have a republic. Such a dear old man, the ideal of what a king ought to be. Don't you remember him in the state procession riding next to the Kaiser?"

"The old Johnny with the white hair," said Jodey, reaching for the marmalade.

"He looked every inch a king," said Mrs. Arbuthnot, "and Illyria is not a very large place either."

"In a small and obscure country," I ventured to observe, "you have to look every inch a king, else nobody will believe that you are one. In a country as important as ours it doesn't matter if a king looks like a commercial traveller."

"By the way," said Jodey, who had a polite horror of anything that could be construed as lèse majesté, "where is Illyria?"

"My dear fellow," said I, "don't you know where Illyria is?"

"I'll bet you a pony that you don't either," said Jodey, striving, as young fellows will, to cover his ignorance by a display of effrontery.

"Haven't you been to Blaenau? Don't you know the Sveltkes?—hoch! hoch!"

"No; do you?" said the young fellow, brazenly.

"They are the oldest reigning family in Europe," said Mrs. Arbuthnot, severely.

"How do you know that, Mops?" said the sceptical youth.

"It says so in the German 'Who's Who,'" said the Madam, sternly, "I looked them up on purpose."

"My dear fellow," said I, "if you knew a little less about polo, and a little less about hunting the fox, and a little more about geography and foreign languages and the things that make for efficiency, you would be au courant with the kingdom of Illyria and its reigning family. Tell the young fellow where that romantic country is, old lady."

"First you go to Paris," said the Madam, with admirable lucidity. "And then, I'm not sure, but I think you come to Vienna, and then I believe you cut across and you come to Illyria. And then you come to Blaenau, the capital, where the king lives, which is five hundred miles from St. Petersburg as the crow flies, because I've marked it on the map."

"Well, if you've really marked it on the map," said I, "it is only reasonable to assume that the kingdom of Illyria is in a state of being."

"You are too absurd," said Mrs. Arbuthnot. "The place is well known and its king is famous."

"I wonder if there is decent shootin' in Illyria," said Joseph Jocelyn De Vere, with that air of tacit condescension which gained him advancement throughout the English-speaking world. "One might try it for a week to show one has no feelin' against it."

"Where there is a king there is always decent shooting," I ventured to observe.

Mrs. Arbuthnot returned to her newspaper.

"They want to form a republic in Illyria," she announced, "but the old king is determined to thwart them."

"A bit of a sportsman, evidently," said her brother. "But never mind Illyria. Give me some more coffee. We've got to be at the Cross Roads by eleven."

"No mortal use, I am afraid," said I. "The glass has gone right back. And look through the window."

"Good old British climate! And on that side they've got one of the best bits o' country in the shires, and Morton's covers are always choke-full of foxes."

In spite of his pessimism, however, my relation by marriage continued to deal faithfully with the modest repast that had been offered him. Also he was fain to inquire of the mistress of the house whether enough sandwiches had been cut and whether both flasks had been filled; and from the nominal head of our modest establishment he sought to learn what arrangements had been made for the second horsemen.

"They will not be wanted to-day, I fear."

"Pooh, a few flakes o' snow!"

It was precisely at this moment that the toot of a motor horn was heard. A sixty-horse-power six-cylindered affair of the latest design was seen to steal through the shrubbery en route to the front door.

"Why, wasn't that Brasset?"

"His car certainly."

"What does the blighter want?"

"He has brought us the information that Morton has telephoned through to say that there is a foot of snow on the wolds and that hounds had better stay at the kennels."

"Pooh," said Jodey, "he wouldn't have troubled to come himself. You've got a telephone, ain't you?"

"Doubtless he also wishes to confer with Mrs. Arbuthnot upon the state of things in Illyria. He is a very serious fellow with political ambitions."

Further I might have added—which, however, I did not—that the Master of the Crackanthorpe was somewhat assiduous in his attitude of respectful attention towards my seductive co-participator in this vale of tears, who on her side was rather apt to pride herself upon an old-fashioned respect for the peerage. The prospect of a visit from the noble Master caused her to discard the affairs of the Illyrian monarchy in favour of a subject even more pregnant with interest.

"If it is Reggie Brasset," said she, renouncing the Daily Courier, "he has come about Mrs. Fitz."

"Get out!" said the scornful Jodey. "You people down here have got Mrs. Fitz on the brain."

Out of the mouths of babes! It was perfectly true that, in our own little corner of the world, people had got Mrs. Fitz on the brain.

Brasset it certainly was. And when he came into the room looking delightfully healthy, decidedly handsome, and a great deal more serious than a minister of the Crown, his first words were to the effect that Morton had telephoned through to say that they had a foot of snow on the wolds and that hounds had better stay where they were.

"Awfully good of you, Brasset, to come and tell us," said I, heartily. "Have some breakfast?"

"No, thanks," said Brasset. "The fact is, as we are not going over to Morton's, I thought this would be a good opportunity to—to——"

For some reason the noble Master did not appear to know how to complete his sentence.

"Yes, Lord Brasset," said Mrs. Arbuthnot, with an air of acute intelligence.

"A good opportunity to—to——" said Brasset, who in spite of his seriousness really looked absurdly young to be the master of such a pack as ours.

"Yes, Lord Brasset," said Mrs. Arbuthnot again.

"Yes, quite so, my dear fellow," said I, without, as I hope and believe, the least appearance of levity, for the uncompromising eye of authority was upon me.

"What's up, Brasset?" said Jodey, who contrary to the regulations was lighting his pipe at the breakfast table, and who combined with his many engaging qualities an extremely practical mind. "You want a glass of beer. Parkins, bring his lordship a glass of beer."

With this aid to the body corporeal in his hand, and with a pair of large, serious and admirably solicitous eyes fixed upon him, the noble Master made a third attempt to complete his sentence. This time he succeeded.

"The fact is," said he, "I thought this would be a good opportunity to—to"—here the noble Master made a heroic dash for England, home and glory—"to talk over this confounded business of Mrs. Fitz."

Mrs. Arbuthnot sat bolt upright with an air of ecstasy and the expression "There, what did I tell you!" written all over her

"Quite so, my dear fellow," said I, in simple good faith, but happening at that moment to intercept a glance from a feminine eye, had perforce to smother my countenance somewhat hastily in the voluminous folds of the Times.

"What about her?" inquired the occupant of the breakfast table, who, whatever the angels might happen to be doing at any given moment, never hesitated to walk right in with both feet. "I was saying to Arbuthnot and my sister just as you came in, that you people down here have got Mrs. Fitz on the brain."

"Yes, I am afraid we have," said Brasset, ruefully. "The fact is, things are coming to such a pass that they can't go on."

"I agree with you, Lord Brasset," said Mrs. Arbuthnot, with conviction.

"Something must be done."

"It is so uncomfortable for everybody," said Mrs. Arbuthnot. "And I can promise this, Lord Brasset"—the fair speaker looked ostentatiously away from the vicinity of the leading morning journal—"whatever steps you decide to take in the matter will have the entire sympathy and support of every woman subscriber to the Hunt."

"Thank you very much indeed, Mrs. Arbuthnot," said the noble Master, with feeling, "I am very grateful to you. It will help me very much."

"We held a meeting in Mrs. Catesby's drawing-room on Sunday afternoon. We passed a resolution expressing the fullest confidence in you—I wish, Lord Brasset, you could have heard what was said about you." The Master's picturesque complexion achieved a more roseate tinge. "Our unanimous support and approval was voted to you in all that you may feel called upon to do."

"A thousand thanks, my dear Mrs. Arbuthnot."

"And we hope you will turn Mrs. Fitz out of the Hunt. I also brought forward an amendment that Fitz be turned out as well, but it was decided by six votes to four to give him another chance. But in the case of Mrs. Fitz the meeting was absolutely unanimous."

"My God," said the occupant of the breakfast table. "If that ain't the limit!"

"Mrs. Fitz is a good deal more than the limit." Mrs. Arbuthnot's eyes sparkled with truculence.

"Have a cigarette, my dear fellow," said I, offering my case to the unfortunate Brasset as soon as the state of my emotions would permit me to do so.

Brasset selected a cigarette with an air of intense melancholy. As he applied the lighted match that was also offered him he favoured me with an eye that was so woebegone that it must have moved a heart of stone to pity. On the contrary, my fellow-pilgrim through this vale of tears had turned a most becoming shade of pink, which she invariably does when she is really out upon the warpath. Also in her china-blue eyes—I hope such a description of these weapons will pass the censor—was a look of grim, unalterable ruthlessness, before which men quite as stout as Brasset have had to quail.

The noble Master took a nervous draw at his Egyptian.

"Look here, Arbuthnot," said he, "you are a wise chap, ain't you?"

"He thinks he's wise," said my helpmeet.

"Every man does," said I, modestly, "not necessarily as an article of faith but as a point of ritual."

"Yes, of course," said Brasset, with an air of intelligence that imposed upon nobody. "But everybody says you are a wise chap. That little Mrs. Perkins says you are the wisest chap she has met out of London."

This indiscretion on the part of Brasset—some men have so little tact!—provoked a stiffening of plumage; and if the china-blue eyes did not shoot forth a spark this chronicle is not likely to be of much account.

"Stick to the point, if you please," said I. "I plead guilty to being a Solomon."

"Well, as you are a wise chap," said the blunderer, "and I'm by way of being an ass——"

"I don't agree with you at all, Lord Brasset," piped a fair admirer.

"Oh, but I am, Mrs. Arbuthnot," said Brasset, dissenting with that courtesy in which he was supreme. "It's awfully good of you to say I'm not, but everybody knows I am not much of a chap at most things."

"You may not be so clever as Odo," said the wife of my bosom, "because Odo's exceptional. But you are an extremely able man all the same, Lord Brasset."

"She means to attend that sale at Tatt's on Wednesday," said the occupant of the breakfast table in an aside to the marmalade.

"Well, if I am not such a fool as I think I am"—so perfect a sincerity disarmed criticism—"it is awfully good of you, Mrs. Arbuthnot, to say so. But what I mean is, I should like Arbuthnot's advice on the subject of—on the subject of——"

"On the subject of Mrs. Fitz," said Mrs. Arbuthnot, with the coo of the dove and the glance of the rattlesnake.

"Ye-es," said the noble Master, nervously dropping the ash from his cigarette on to a very expensive tablecloth.

"Odo will be very pleased indeed, Lord Brasset," said the superior half of my entity, "to give you advice about Mrs. Fitz. He agrees with me and Mary Catesby and Laura Glendinning, that she must be turned out of the Hunt."

Poor Brasset removed a bead of perspiration from the perplexed melancholy of his features with a silk handkerchief of vivid hue, own brother to the one sported by the Bayard at the breakfast table, in a futile attempt to cope with his dismay.

"Is it usual, Mrs. Arbuthnot?"

"It may not be usual, Lord Brasset, but Mrs. Fitz is not a usual woman."

"My dear Irene," said I, judicially—Mrs. Arbuthnot rejoices in the classical name of Irene—"my dear Irene, I understand Brasset to mean that there is nothing in the articles of association of the Crackanthorpe Hunt to provide against the contingency of Mrs. Fitz or any other British matron overriding hounds as often as she likes."

Although I have had no regular legal training beyond having once lunched in the hall of Gray's Inn, everybody knows my uncle the judge. But I regret to say that this weighty deliverance did not meet with entire respect in the quarter in which it was entitled to look for it.

"That is nonsense, Odo," said Mrs. Arbuthnot. "I am sure the Quorn——"

Brasset's misery assumed so acute a phase at the mention of the Quorn that Mrs. Arbuthnot paused sympathetically.

"The Quorn—my God!" muttered the Bayard at the breakfast table in an aside to the tea-kettle.

"Or the Cottesmore," continued the undefeated Mrs. Arbuthnot, "would not stand such behaviour from a person like Mrs. Fitz."

"Do you think so, Mrs. Arbuthnot?" said the noble Master. "You see, we shouldn't like to get our names up by doing something unusual."

"An unusual person must be dealt with in an unusual way," said Mrs. Arbuthnot, with great sententiousness.

"Mary Catesby thinks——"

The long arm of coincidence is sometimes very startling, and I can vouch for it that the entrance of Parkins at this psychological moment, to herald the appearance of Mary Catesby in the flesh, greatly impressed us all as something quite beyond the ordinary.

"Why, here is Mary," said Mrs. Arbuthnot, giving that source of light and authority a cross-over kiss on both checks. It is the hall-mark of the married ladies of our neighbourhood that they all delight to exhibit an almost exaggerated reverence for Mary Catesby.

I have great esteem for Mary Catesby myself. For one thing, she has deserved well of her country. The mother of three girls and five boys, she is the British matron in excelsis; and apart from the habit she has formed of riding in her horse's mouth, she has every attribute of the best type of Christian gentlewoman. She owns to thirty-nine—to follow the ungallant example of Debrett!—is the eldest daughter of a peer, and is extremely authoritative in regard to everything under the sun, from the price of eggs to the table of precedence.

The admirable Mary—her full name is Mary Augusta—may be a trifle over-elaborated. Her horses are well up to fourteen stone. And as matter and mind are one and the same, it is sometimes urged against her that her manner is a little overwhelming. But this is to seek for blemishes on the noonday sun of female excellence. One of a more fragile cast might find such a weight of virtue a burden. But Mary Catesby wears it like a flower.

In addition to her virtue she was also wearing a fur cloak which was the secret envy of the entire feminine population of the county, although individual members thereof made it a point of honour to proclaim for the benefit of one another, "Why does Mary persist in wearing that ermine-tailed atrocity! She really can't know what a fright she looks in it."

As a matter of fact, Mary Catesby in her fur cloak is one of the most impressive people the mind of man can conceive. That fur cloak of hers can stop the Flying Dutchman at any wayside station between Land's End and Paddington; and on the platform at the annual distribution of prizes at Middleham Grammar School, I have seen more than one small boy so completely overcome by it, that he has dropped "Macaulay's Essays" on the head of the reporter of the Advertiser.

Besides this celebrated garment, Mary was adorned with a bowler hat with enormous brims, not unlike that affected by Mr. Weller the Elder as Cruikshank depicted him, and so redoubtable a pair of butcher boots as literally made the earth tremble under her.

Her first remark was addressed, quite naturally, to the unfortunate Brasset, who had been rendered a little pinker and a little more perplexed than he already was by this notable woman's impressive entry.

"I consider this weather disgraceful," said she. "It always is when we go over to Morton's. Why is it, Reggie?"

She spoke as though the luckless Reggie was personally responsible for the weather and also for the insulting manner in which that much-criticised British institution had deranged her plans.

"I am awfully sorry, Mrs. Catesby. Not much of a day, is it?"

"Disgraceful. If one can't have better weather than this, one might as well go and have a week's skating at Prince's."

The idea of Mary Catesby having a week's skating at Prince's seemed to appeal to Joseph Jocelyn De Vere. At least that sportsman was pleased not a little.

"English style or Continental?" said he.

Mary Catesby did not deign to heed.

"I am awfully sorry, Mrs. Catesby," said Brasset again, with really beautiful humility.

Mrs. Catesby declined to accept this delightfully courteous apology, but gazed down her chin at the unfortunate Brasset with that ample air which invariably makes her look like Minerva as Titian conceived that deity. Silently, pitilessly, she proceeded to fix the whole responsibility for the weather upon the Master of the Crackanthorpe.

She had just performed this feat with the greatest efficiency, when by no means the least of her admirers put in an oar.

"I'm so glad you've come, Mary," said Mrs. Arbuthnot. "We were just having it out with Lord Brasset about Mrs. Fitz."

An uncomfortable silence followed.

"Is she a subject for discussion in a mixed company?" said I, to relieve the tension.

"I should say not," said Mary. "But Reggie has been so weak that there is no help for it."

"The victim of circumstances, perhaps," said I, with generous unwisdom.

"People who are weak always are the victims of circumstances. If Reggie had only been firmer at the beginning, we should not now be a laughing-stock for everybody. To my mind the first requisite in a master of hounds is resolution of character."

"Hear, hear," said the occupant of the breakfast table, sotto voce.

The miserable Brasset, whose pinkness and perplexity were ever increasing, fairly quailed before the Great Lady's forensic power.

"Do you think, Mrs. Catesby, I ought to resign?" said he, with the humility that invites a kicking.

"Not now, surely; it would be too abject. If you felt the situation was beyond you, you should have resigned at the beginning. You must show spirit, Reggie. You must not submit to being trampled on publicly by—by——"

The Great Lady paused here, not because she was at a loss for a word, but because, like all born orators, she had an instinctive knowledge of the value of a pause in the right place.

"By a circus rider from Vienna," she concluded in a level voice.

"I know, Mrs. Catesby, I'm not much of a chap," said Brasset, "but what's a feller to do? I did drop a hint to Fitz, you know."

"Fitz!!" The art of the littérateur can only render a scorn so sublime by two marks of exclamation.

"What did Fitz say?" I ventured to inquire.

"Scowled like blazes," said Brasset, miserably. "Thought the cross-grained, three-cornered devil would eat me. Beg pardon, Mrs. Catesby."

The noble Master subsided into his glass of beer in the most lamentably ineffectual manner.

I cleared my voice in the consciousness that I had an uncle a judge.

"Brasset," said I, "will you kindly inform the court what are the specific grounds of complaint against this much-maligned and unfortunate—er—female?"

"Don't make yourself ridiculous, Odo!"

"Odo, you know perfectly well!"

It was a dead heat between Mrs. Arbuthnot and the Great Lady.

"Order, order," said I, sternly. "This scene belongs to Brasset. Now, Brasset, answer the question, and then perhaps something may be done."

It was not to be, however. The nephew of my uncle failed lamentably to exact obedience to the chair.

"My dear Odo," said Mary Catesby, in what I can only describe as her Albert Hall manner, with her voice going right up to the top like a flag going up a pole, "do you mean to tell me——?"

"That you don't know how Mrs. Fitz has been carrying on!" the Madam chipped in with really wonderful cleverness.

"I don't, upon oath," said I, solemnly. "You appear to forget that I have been giving my time to the nation during this abominable autumn session."

"So he has, poor dear," said the partner of my joys.

"Like a good citizen," said Mary Catesby, most august of Primrose Dames.

"Thank you, Mary, I deserve it. But am I to understand that Mrs. Fitz has flung her cap over the mill, or that she has taken to riding astride, or is it that she continues to affect that scarlet coat which last season hastened the end of the Dowager?"

"No, Arbuthnot." It was the voice of Brasset, vibrating with such deep emotion that it can only be compared to the Marche Funèbre performed upon a cathedral organ. "But it was only by God's mercy that last Tuesday morning she didn't override Challenger."

"Allah is great," said I.

"Upon my solemn word of honour," said the noble Master, speaking from the depths, "she was within two inches of the old gal's stern."

"Parkins," said a voice from the breakfast table, "bring another glass of beer for his lordship."

To be perfectly frank, liquid sustenance was no longer a vital necessity to the noble Master. He was already rosy with indignation at the sudden memory of his wrongs. Only one thing can induce Brasset to display even a normal amount of spirit. That is the welfare of the sacred charges over which he presides for the public weal. He will suffer you to punch his head, to tread on his toe, or to call him names, and as likely as not he will apologise sweetly for any inconvenience you may have incurred in the process. But if you belittle the Crackanthorpe Hounds or in any way endanger the humblest member of the Fitzwilliam strain, woe unto you. You transform Brasset into a veritable man of blood and iron. He is invested with pathos and dignity. The lightnings of heaven flash from beneath his long-lashed orbs; and from his somewhat narrow chest there is bodied forth a far richer vocabulary than the general inefficiency of his appearance can possibly warrant in any conceivable circumstances.

Mere feminine clamour was silenced by Brasset transformed. His blue eyes glowed, his cheeks grew rosier, each particular hair of his perfectly charming little blond moustache—trimmed by Truefitt once a fortnight—stood up on end like quills upon the fretful porpentine. In lieu of pink abasement was tawny denunciation.

"I'll admit, Arbuthnot," said the Man of Blood and Iron, "I looked at the woman as no man ought to look at a lady."

"Didn't you say 'damn,' Lord Brasset?" piped a demure seeker after knowledge.

"I may have done, Mrs. Arbuthnot, I admit I may have done."

"I think that ought to go down on the depositions," said I, with an approximation to the manner of my uncle, the judge, that was very tolerable for an amateur.

"I honour you for it, Lord Brasset. Don't you, Mary?"

"Endeavour not to embarrass the witness," said I. "Go on, Brasset."

"Brasset, here's your beer," said Jodey, rising from the table and personally handing the Burton brew with vast solemnity.

"I may have damned her eyes," proceeded the witness, "or I mayn't have done. You see, she was within two inches of the old gal, and I may have lost my head for a bit. I'll admit that no man ought to damn the eyes of a lady. Mind, I don't say I did. And yet I don't say I didn't. It all happened before you could say 'knife,' and I'll admit I was rattled."

"The witness admits he was rattled," said I.

"So would you have been, old son," the witness continued magniloquently. "Within two inches, upon my oath."

"Were there reprisals on the part of the lady whose eyes you had damned in a moment of mental duress?"

"Rather. She damned mine in Dutch."

Sensation.

"How did you know it was Dutch, Lord Brasset?" piped a seeker of knowledge.

"By the behaviour of the hounds, Mrs. Arbuthnot."

"How did they behave?"

"The beggars bolted."

Sensation.

"My aunt!" said the occupant of the breakfast table with solemn irrelevance.

"So would you," said the noble Master. "I never heard anything like it. In my opinion there is no language like Dutch when it comes to cursing. And then, before I could blink, up went her hand, and she gave me one over the head with her crop."

Sensation.

"Upon my solemn word of honour. I don't mind showing the mark to anybody."

"Where is it, Lord Brasset?"

Mrs. Arbuthnot rose from her chair in the ecstatic pursuit of first-hand information. Her eyes were wide and glowing like those of her small daughter, Miss Lucinda, when she hears the story of "The Three Bears."

"Show me the scar, Reggie," said a Minerva-like voice.

"Let's see it, Brasset," said the occupant of the breakfast table, kicking over a piece of Chippendale of the best period and incidentally breaking the back of it.

The somewhat melodramatic investigations of a thick layer of Rowland's Macassar oil and a thin layer of fair hair disclosed an unmistakable weal immediately above the left temple of the noble martyr in the cause of public duty.

"If it don't beat cockfighting!" said Jodey in a tone of undisguised admiration.

"If it hadn't been for the rim of my cap," said the noble martyr in response to the public enthusiasm, "it must have laid my head clean open."

"In my opinion," said Mary Catesby, speaking ex cathedra, "that woman is a perfect devil. Reggie, if you only show firmness you can count upon support. They may stand that sort of thing in a Continental circus, but we don't stand it in the Crackanthorpe Hunt."

"Firmness, Brasset," said I, anxious, like all the world, to echo the oracle.

The little blond moustache was subjected to inhuman treatment.

"It's all very well, you know, but what's the use of being firm with a person who is just as firm as yourself?"

The Great Lady snorted.

"For three years, Reggie, you have filled a difficult office passably well. Don't let a little thing like this be your undoing."

"All very well, Mrs. Catesby, but I can't hit her over the head, can I?"

"No, but what about Fitz?" said a voice from the breakfast table.

"Ye-es, I hadn't thought of that."

"And I shouldn't think of it if I were you," said I, cordially. "Fitz with all his errors is a heftier chap than you are, my son."

Brasset's jaw dropped doubtfully—it is quite a good jaw, by the way.

"Practise the left a bit, Brasset," was the advice of the breakfast table. "I know a chap in Jermyn Street who has had lessons from Burns. We might trot up and see him after lunch. Bring a Bradshaw, Parkins. And I think we had better send a wire."

"I wasn't so bad with my left when I was up at Trinity," said Brasset.

Mrs. Arbuthnot shuddered audibly. She has long been an out-and-out admirer of the noble Master's nose. Certainly its contour has great elegance and refinement.

"Brasset," said I, "let me urge you not to listen to evil communications. If you were Burns himself you would do well to play very lightly with Fitz. He was my fag at school, and although sometimes there was occasion to visit him with an ash plant or a toasting fork in the manner prescribed by the house regulations at that ancient seat of learning, I shouldn't advise you or anybody else to undertake a scheme of personal chastisement."

"Certainly not, Reggie," said Mary Catesby, in response to Mrs. Arbuthnot's imploring gaze. "Odo is perfectly right. Besides, you must behave like a gentleman. It is the woman with whom you must deal."

"Well, I can't hit her, can I?" said Brasset, plaintively.

"If a cove's wife hit me over the head with a crop," said the voice of youth, "I should want to hit the cove that had the wife that hit me, and so would Odo. I see there's a train at two-fifteen gets to town at five."

Brasset's eyes are as softly, translucently blue as those of Miss Lucinda, but in them was the light of battle. He no longer tugged at his upper lip, but stroked it gently. To those conversant with these mysteries this portent was sinister.

"Is Genée on at the Empire?" said he.

"Parkins knows," said Jodey.

Parkins did know.

"Yes, my lord," said that peerless factotum, "she is."

In parenthesis, I ought to mention that Parkins is the pièce de resistance of our modest establishment. Not only is he highly accomplished in all the polite arts practised by man, but also he is a walking compendium of exact information.

"How's this?" said Jodey, proceeding to read aloud the telegram he had composed with studious care. "Dine self and pal Romano's 7.30. Empire afterwards. Book three stalls in centre."

"Wouldn't the side be better?" said Brasset. "Then you are out of the draught."

Before this important correction could be made Mary Catesby lifted up her voice in all its natural majesty.

"Reginald Philip Horatio," said the most august of her sex, "as one who dressed dolls and composed hymns with your poor dear mother before she made her imprudent marriage, I forbid you absolutely to fight with such a man as Nevil Fitzwaren. It is not seemly, it is not Christian, and Nevil Fitzwaren is a far more powerful man than yourself."

"Science will beat brute force at any hour of the day or night," was the opinion of the breakfast table.

Mrs. Catesby fixed the breakfast table with her invincible north eye.

"Joseph, pray hold your tongue. This is very wrong advice you are giving to a man who is rather older and quite as foolish as yourself."

The Bayard of the breakfast table rebutted the indictment.

"The advice is sound enough," said he. "My pal in Jermyn Street has won no end of pots as a middle-weight, and he'll soon have a go at the heavies now he's taken to supping at the Savoy. He'll put Brasset all right. He's as clever as daylight, a pupil of Burns. I tell you what, Mrs. C., if Brasset leads off with a left and a right and follows up with a half-arm hook on the point, in my opinion he'll have a walk over."

"Reggie, I forbid you absolutely," said the early collaborator with the noble Master's mother. "It is so uncivilised; besides, if Nevil Fitzwaren happened to be the first to lead off with a half-arm hook on the point, we should probably require a new Master. And that would be so awkward. It was always a maxim of my dear father's that foxes were the only things that profited by a change of mastership in the middle of December."

"Your dear father was right, Mary," said I, gravely.

"Dear father was infallible. But seriously, Reggie, if anything happened to you we should really have nobody to take the hounds now that for some obscure reason they have made Odo a member of Parliament."

"If a cove's wife hit me," came the refrain from the breakfast table in a kind of drone, "I should want to hit the cove that had the wife that hit me. See that this wire is sent, Parkins, and tell Kelly that I am running up to town by the 2.15 and shall stay the night."

"Jodey, don't be a fool," said I. "Brasset, I want to say this. I hope you are listening, Mary, and you too, Irene. Where Fitz and his wife are concerned, we have all got to play lightly."

I summoned all the earnestness of which I am capable. Even Mary Catesby was impressed by such an air of conviction.

"I fail to see," said she, "why we should be so especially considerate of the feelings of the Fitzwarens, when they are the last to consider the feelings of others."

"You can take it from me, Mary, that Fitz and his wife are not to be judged altogether by ordinary standards. They are extraordinary people."

"Tell me what you mean by the term extraordinary?" said my inquisitorial spouse.

"Does it really require explanation, mon enfant?"

"It means," said the plain-spoken Mary, "that Nevil Fitzwaren is an extraordinarily reckless and dissolute type of fellow, and that Mrs. Nevil is an extraordinarily unpleasant type of woman."

I am the first to admit that that ineffectual thing, the mere human male, is not of the calibre openly to dissent from a considered judgment of the Great Lady. But to the amazement of men and doubtless of gods, for once in a way her opinion was publicly challenged.

You could have heard a pin drop in the room when the occupant of the breakfast table took up the gage.

"Fitz is a bad hat." Joseph Jocelyn De Vere removed the pipe from his lips. "Everybody knows it. But Mrs. Fitz is a thousand times too good for the cove that's married her."

Such an expression of opinion left his sister open-mouthed. Mary Catesby lowered her chin and her eyelashes at an indiscretion so portentous.

"The Fitzwarens," said that great authority, "are a very old family, and Nevil has the education, if not the instincts, of a gentleman, but as for this circus rider he has brought from Vienna, she has neither the birth, the education nor the instincts of a lady."

This tremendous pronouncement would have put most people out of action at once. But here was a man of mettle.

"She's tophole," said that Bayard. "I've never seen her equal. If you ask my opinion there's not a chap in the Hunt who is fit to open a gate for Mrs. Fitz."

The young fellow had fairly got the bit between his teeth and no mistake.

"One doesn't ask your opinion, Joseph," said Mary Catesby, with a bluntness that would have felled a bullock. "Why should one, pray? I know no person less fitted to express an opinion on any subject."

"I've followed her line anyhow, and I've been proud to follow it. She can ride cunning, too, mind you. I've never seen her equal anywhere, and don't suppose I ever shall."

"No one questions her riding. She was born and bred in a circus. But a more unmitigated female bounder never jumped through a hoop in pink tights."

It was below the belt, and not only Jodey but Brasset, who, inefficient as he is in most things, is unmistakably a sportsman of the first class, also felt it to be so.

"Mrs. Fitz has foreign ways," said the noble Master, "but she can be as nice as anybody when she likes. I've known her be awfully civil."

"She is not without charm," said I, feeling that it was up to me to play up a bit.

"She's it," said Jodey. "She's the sort of woman that would make a chap——"

"Shoot himself," chirruped the noble Master.

Disgust and indignation are mild terms to apply to Mrs. Catesby's wrath.

"Pair of boobies! You are as bad as he is, Reggie. But it was always so like your poor mother to take things lying down."

"Oh, come now, Mrs. Catesby, haven't I said all along that she had no right to hit me over the head with her crop?"

"The safest place in which to hit you, anyway." The Great Lady was in peril of losing her temper.

The question of Mrs. Fitz was a very vexed one in the Crackanthorpe Hunt. It had already divided that proud institution into two sections: i.e. the thick and thin supporters of that lady and those who would not have her at any price. It need excite no remark in the minds of the judicious that the male followers of the Hunt, almost to a man, admired, as much as they dared in the circumstances, a very remarkable personality; while its feminine patrons, with a unanimity quite without precedent in that august body, were conspiring to humiliate, as deeply as it lay in their power, a personage who had set three counties by the ears.

The Great Lady proceeded to temper her wrath with some extremely dignified pathos.

"It is a mystery to me," said she, "how men who call themselves gentlemen can attempt to defend a creature who offered a public affront to the Duke and dear Evelyn."

"I presume you mean the affair of the bazaar?" said I.

"I do; a lamentable fracas. Dear Evelyn never left her bed for a fortnight."

"Dear me! Are we to understand that actual physical violence was offered to her Grace?"

"Don't be childish, Odo! I was present and saw everything, and I can answer for it that no such thing as violence was used."

"Then why did the great lady take to her bed?"

"Through sheer vexation. And really one doesn't wonder. It was nothing less than a public insult."

"Tell me, Mary, precisely in three words what did happen at the bazaar. All the world agrees that it was a desperate affair, yet nobody seems to know exactly what it was that occurred."

Mrs. Catesby enveloped herself in that mantle of high diplomacy that she is pleased so often to assume.

"No, my dear Odo, I don't think it would be kind to the Duke and dear Evelyn to say actually what did occur. To my mind it is not a thing to be spoken of, but I may tell you this—it has been mentioned at Windsor!"

It was clear from the Great Lady's demeanour that at this announcement we were all expected to cross ourselves. Only Mrs. Arbuthnot did so, however.

"Oh, Mary!" The china-blue eyes swam with ecstasy.

"If you wish to convey to us, my dear Mary," said I, "that a royal commission has been appointed to inquire into the subject, all experience tends to teach that there will be less prospect than ever of finding out what did happen at the bazaar."

"Tell us what really did happen at the bazaar, Mrs. Catesby," said Brasset. "I am sorry I wasn't there."

"No, Reggie, I am much too fond of dear Evelyn to disclose the truth to a living soul. But I may tell you this: the incident was far worse than has been reported."

"I understand," said I, solemnly lying, at the instance of the histrionic sense, "that Windsor earnestly desired that the incident, whatever it was, should be minimised as much as possible."

The bait was gobbled, hook and all.

"How did you come to hear that, Odo? Even I was not told that."

"Who told you that, Odo?" Mrs. Arbuthnot twittered breathlessly.

"There was a rumour the other day in the House."

"The idle gossip of the lobbies," the Great Lady was moved to affirm.

But we were straying away from the point. And the point was, in what manner was public decency to mark its sense of outrage at the conduct of Mrs. Fitz?

Although so many conflicting rumours were abroad as to the unparalleled affront that had been offered to the Strawberry Leaf—some accounts had it that "dear Evelyn" had been called "a cat" within the hearing of the Mayor and other civic dignitaries of Middleham, while others were pleased to affirm that she had had her ears boxed before the eyes of the horrified reporter for the Advertiser—there was the implicit word of Brasset that he had been subjected not only to unchaste expressions in a foreign tongue, but had actually been in receipt of physical violence in his honourable endeavour to uphold the dignity and the discipline of the Crackanthorpe Hunt.

I hope and believe I am a lenient judge of the offences of others—fellow-occupants of our local bench delight to tell me so—but even I was so imbued with the spirit of the meeting as to allow that some kind of official notice ought to be taken of the outrageous conduct of Mrs. Nevil Fitzwaren. From the first hour of her appearance among us, a short fifteen months ago, she had gathered the storm-clouds of controversy about her. Almost as soon as she appeared out cubbing she became the most discussed person in the shire. Her ways were unmistakably foreign and "unconventional"; and certainly, in the saddle and out of it, her personality can only be described as a little overpowering.

In the beginning it may have been Fitz himself who contributed as much as anything to the notoriety of his continental wife. Five years before, the only surviving son of a disreputable father had let the house of his ancestors in a state of gross disrepair, together with the paternal acres, to a City magnate, and betook himself, Heaven alone knew where. Wise people, however, were more than willing that the President of the Destinies should retain the sole and exclusive possession of this information. Nobody had the least desire to know where Fitz the Younger, unmistakable scion of a somewhat deplorable dynasty, was to be found, except, perhaps, a few London tradesmen, who, if wise men, would be sparing of their tears. They might have been hit so much harder than proved to be the case. Wherever Fitz had gone, those who knew most of him, and the stock from which he sprang, devoutly hoped that there he would stay.

For five years we knew him not. And then one fine September afternoon he turned up at the Grange with a motor car and a French chauffeur and a foreign wife. It may not seem kind to say so, but in the interests of this strange but ower-true tale, it is well to state clearly that his return was highly disconcerting to all sections of the community. His name was still an offence in the ears of an obsequious and by no means over-censorious countryside. Rural England is astonishingly lenient "to Squoire and his relations," but Master Nevil had proved too stiff a proposition even for its forbearance.

Howbeit, Fitz had hardly been a week at his ancestral home with his foreign wife and his motor car when there began to be signs of a rise in Fitzwaren stock. It was bruited abroad that he was paying his debts, fulfilling long-neglected obligations, that he had given up the bowl, and that, in a word, he was doing his best to clear a pretty black record. Indeed, the upward tendency of the Fitzwaren stock was so well maintained, that it was decided by the Committee for the Maintenance of the Public Decency that the august Mrs. Catesby should call on his wife and so pave the way for the entente. After all, the Fitzwarens were the Fitzwarens, and our revered Vicar—the hardest riding parson in five counties—clinched the matter with the most apposite quotation from Holy Writ in which he has ever indulged.

The august Mrs. Catesby bore the olive branch in the form of a couple of pieces of pasteboard to the Grange in due course; Mrs. Arbuthnot, the Vicar's wife, Laura Glendinning, and the rank and file of the custodians of the public decency followed suit; and such an atmosphere of the best type of Christian magnanimity prevailed, that it was quite on the tapis that "dear Evelyn" herself, the Perpetual President and Past Grand Mistress of this strenuous society, would shoot a card at the Grange. To show that this is not the idle gossip of an empty tale, there is Mrs. Catesby's own declaration, made in Mrs. Arbuthnot's own drawing-room in the presence of Laura Glendinning and the Vicar's wife, "that had Mrs. Fitz only been presented she was in a position to know that dear Evelyn would have called upon her."

That was the hour in which the Fitzwaren stock touched its zenith. Thenceforward there was a fall in price. Nevertheless, it was agreed that Fitz was a reformed character. A glass of beer for luncheon, a glass of wine for dinner, and a maximum of three whiskies and sodas per diem; handsome indemnity paid to the daughter of the landlord of the Fitzwaren Arms; propitiation galore to persons of all degrees and shades of opinion; appearance with the ducal party at the Cockfoster shoot; regular attendance at church every Sunday forenoon. Fitz made the pace so hot that the wise declared it could not possibly last. They were wrong, however, as the wise are occasionally. Fitz had more staying power than friends and neighbours were prepared to concede to the son of his father. But in spite of all this, once the slump set in it continued steadily.

Those who had known Fitz before the reformation were not slow to believe that it was no strength of the inner nature that had rendered him a vessel of grace. It was excessively creditable, of course, to the black sheep of the fold, but the whole merit of the reclamation belonged not to the prodigal, but to the nondescript lady from the continent who had not been presented at Court. The depth of Fitz's infatuation for that unconventional creature was really grotesque.

To the merely masculine intelligence it would have seemed that an influence so beneficent over one so besmirched as poor Fitz must have counted to that lady for righteousness on the high court scale. But the Committee for the Maintenance of the Public Decency came to quite another conclusion. The mere male cannot do better than give in extenso the Committee's report upon the matter, and for the text of this judicial pearl our thanks are due to the august Mrs. Catesby. "If she had been Anybody," that great and good woman announced, "one would have felt it only right to encourage Nevil Fitzwaren in his praise-worthy effort, but as dear Evelyn has been informed, on unimpeachable authority, that she used to ride bareback in a circus in Vienna, it is quite clear that the wretched fellow is in the toils of an infatuation."

After this finding by the Committee, holders of Fitzwaren stock unloaded quickly. Yet there were some of these speculators who were loth to take that course. Fitz, the harum-scarum, with his nails trimmed, was a less picturesque figure than the provincial Don Juan; but there were those who were not slow to aver that the fair equestrienne he had had the audacity to import from Vienna was quite the most romantic figure that had ever hunted with the Crackanthorpe Hounds.

Doubtless she had been born in a stable and reared upon mares' milk, but to behold her mounted upon the strain of the Godolphin Arabian, in a tall hat, military gauntlets and a scarlet coat was a spectacle that few beholders were able to forget. In the opinion of the Committee, there can be no doubt whatever that it hastened the end of the Dowager. The old lady drove to the meet at the Cross Roads, behind her fat old ponies and her fat old coachman John Timmins, in the full enjoyment of all her faculties, with a shrewd wit, an easy conscience and a good appetite, took one glance at Mrs. Nevil Fitzwaren, told John Timmins in a hoarse whisper to go home immediately, had a stroke before she arrived, and passed away without regaining consciousness, in the presence of her spiritual, her medical, and her legal advisers.

In the inflamed state of the public mind, it was necessary that persons of moderate views should be wary. I had seen Mrs. Fitz out hunting, and in this place I am open to confess that I was sealed of the tribe of her admirers. Not from the athletic standpoint merely, but from the æsthetic one. Quite a young woman, with superb black eyes and a forest of raven hair, a skin of lustrous olive, a nose and chin of extraordinary decision and character; a more imperiously challenging personality I cannot remember to have seen. Professional Viennese equestriennes are doubtless a race apart. They may be accustomed to exact a homage from their world which in ours is reserved more or less for the "dear Evelyns" and their compeers. But the gaze of this haughty queen of the sawdust, when she condescended to exert it, was the most direct and arresting thing that ever exacted tribute from the English male or fluttered the devecotes of the scandalised English female. Her "what-pray-are-you-doing-on-the-earth?" air was so vital that it sent a thrill through the veins. Small wonder was it that the hapless Fitz had struggled so gamely to pull himself together. She was a woman to make a man or mar him. As Fitz was marred already, the sphere of her activities were limited accordingly.

Like most men of moderate views, at heart I own to being a bit of a coward. At any rate it would have taken wild horses to drag the admission from me that I was an out-and-out admirer of the "Stormy Petrel," as with rare felicity the Vicar of the parish had christened her. For by this time our little republic was cloven in twain. There were the Mrs. Fitzites, her humble admirers and willing slaves, whose sex you will easily guess; and there were the Anti-Mrs.-Fitzites, ruthless adversaries who had sworn to have her blood, or failing that, since Atalanta was an amazon indeed, to make the place so hot for her that, in the words of my friend Mrs. Josiah P. Perkins, "she would have to quit."

How to dislodge her, that was the problem for the ladies of the Crackanthorpe Hunt. It was in the quest of a solution that the illustrious Mrs. Catesby had honoured us with a morning call.

"Odo Arbuthnot," said that notable woman, "it is my intention to speak plainly. Mrs. Fitz must leave the neighbourhood. We look to you, as a married man, a father of a family and a county member, to devise a means for her removal."

"Issue a writ," said I. "That seems the most straightforward course. If our assaulted and battered friend, Brasset, will swear an information, I shall be glad to sign the warrant."

"Do you think she could be taken to prison?" said Mrs. Arbuthnot, hopefully.

"Don't attempt to beg the question." The Great Lady was not to be diverted from the scent. "Be more manly. We expect public spirit from you. Certainly this business is extremely disagreeable, but it does not excuse your pusillanimity. To my mind, your attitude all along has suggested that you are trying to run with the hare and to hunt with the hounds."

This was a terrible home-thrust for a confirmed lover of the middle course. I hope I am not wholly lacking in spirit, but such a charge was not easy to rebut. While I assumed a statesmanlike port, if only to gain a little time in which to cover my exposed position, my relation by marriage, with a daring which was certainly remarkable in one who is not by nature a thruster, took up the cudgels yet again.

"If I were you, Odo," said he, "I should let 'em do their own dirty work."

I felt Mary Catesby's glance flash past me like the lightning of heaven.

"Dirty work, Joseph? I demand an explanation."

"I call it dirty," said that gladiator. "I like things straightforrard myself. If you think a cove is askin' for trouble hand it out to him personally. Don't set on others."

Before the woman of impregnable virtue to whom this gem of morality was addressed, could visit the Bayard at the breakfast table according to his merit, we found ourselves suddenly precipitated into the realms of drama.

For this was the moment in which I became aware that Parkins was hovering about my chair and that a sensational announcement was on his lips.

"Mr. Fitzwaren desires to see you, sir, on most urgent business."

The effect was electrical. Mary Catesby suspended her indictment with a gesture like Boadicea's, queenly but ferocious. Brasset's pink perplexity approximated to a shade of green; the eyes of the Madam were like moons—in the circumstances a little poetic license is surely to be pardoned—while as for the demeanour of the narrator of this ower-true tale, I can answer for it that it was one of total discomfiture.

"Mr. Fitzwaren here?" were my first incredulous words.

"I have shown him into the library, sir," said Parkins, solemnly.

"You cannot see him, Odo," said the despot of our household. "He must not come here."

"Important business, Parkins?" said I.

"Most urgent business, sir."

"Highly mysterious!" Mrs. Catesby was pleased to affirm.

Highly mysterious the coming of Nevil Fitzwaren certainly was. A moment's reflection convinced me of the need of appeasing the general curiosity. I took my way to the library with many speculations rising in my mind. Nothing was further from my expectation than to be consulted by Nevil Fitzwaren on urgent business.

Astonished as I was by the coming of such a visitor, the appearance and the manner of that much-discussed personage did nothing to lessen my interest.

I found him pacing the room in a state of agitation. His face was haggard, his eyes were bloodshot, he was unkempt and almost piteous to look upon. And yet more strangely his open overcoat, which his distress could not suffer to keep buttoned, disclosed a rumpled shirt front, a tie askew and a dinner jacket which evidently had been donned the evening before.

"Hallo, Fitz," said I, as unconcernedly as I could.

He did not answer me, but immediately closed the door of the room. Somehow, the action gave me a thrill.

"There is no possibility of our being overheard?" he said in a hoarse whisper.

"None whatever. Let me help you off with your coat. Then sit down in that chair next the fire and have a drink."

Fitz submitted, doubtless under a sense of compulsion. My four years' seniority at school had generally enabled me to get my way with him. It was rather painful to witness the effort the unfortunate fellow put forth to pull himself together; and when I measured out a pretty stiff brandy-and-soda his refusal of it was distinctly poignant.

"I oughtn't to have it, old chap," he said, with his wild eyes looking into mine like those of a dumb animal. "It doesn't do, you know."

"Drink it straight off at once," said I, "and do as you are told."

Fitz did so with reluctance. The effect upon him was what I had not foreseen. His haggard wildness yielded quite suddenly to an outburst of tears. He covered his face with his hands and wept in a painfully overwrought manner.

I waited in silence for this outburst to pass.

"I've been scouring the country since nine o'clock last night," he said, "and I feel like going out of my mind."

"What's the trouble, old son?" said I, taking a chair beside him.

"They've got my wife."

"Whom do you mean by 'they'?"

"I can't, I mustn't tell you," said Fitz, excitedly, "but they have got her, and—and I expect she is dead by now."

Words as wild as these to the accompaniment of that overwrought demeanour suggested an acute form of mental disturbance only too clearly.

"You had better tell me everything," said I, persuasively. "Perhaps I might be able to help a little. Two heads are better than one, you know."

I must confess that I had no great hope of being able to help the unlucky fellow very materially, but somewhat to my surprise he answered in a perfectly rational manner.

"I have come here with the intention of telling you everything. I must have help, and you are the only friend I've got."

"One of many," said I, lying cordially.

"It's true," said Fitz. "The only one. Like that chap in the Bible, the hand of every man is against me. I deserve it; I know I've not played the game; but now I must have somebody to stand by me, and I've come to you."

"Well," said I, "that is no more than you would do by me in similar circumstances."

"You don't mean that," said Fitz, with an expression of keen misery. "But you are a genuine chap, all the same."

"Let's hear the trouble."

"The trouble is this," said Fitz, and as he spoke the look of wildness returned to his eyes. "My wife went in the car to do some shopping at Middleham at three o'clock yesterday afternoon expecting to be back at five, and neither she nor the car has returned.

"And nothing has been heard of her?"

"Not a word."

"Had she a chauffeur?"

"Yes, a Frenchman of the name of Moins whom we picked up in Paris."

"I suppose you have communicated with the police?"

"No; you see, the whole affair must be kept as dark as possible."

"They are certainly the people to help you, particularly if you have reason to suspect foul play."

"There is every reason to suspect it. I am afraid she is already beyond the help of the police."

"Why should you think that?"

Fitz hesitated. His distraught air was very painful.

"Arbuthnot," said he, slowly and reluctantly, "before I tell you everything I must pledge you to absolute secrecy. Other lives, other interests, more important than yours and mine, are involved in this."

I gave the pledge, and in so doing was impressed by a depth of responsibility in the manner of my visitor, of which I should hardly have expected it to be capable.

"Did you see in the papers last evening that there had been an attempt on the life of the King of Illyria?"

"I read it in this morning's paper."

"It will surprise you to learn," said Fitz, striving for a calmness he could not achieve, "that my wife is the only child of Ferdinand XII, King of Illyria. She is, therefore, Crown Princess and Heiress Apparent to the oldest monarchy in Europe."

"It certainly does surprise me," was the only rejoinder that for the moment I could make.

"I want help and I want advice; I feel that I hardly dare do anything on my own initiative. You see, it is most important that the world at large should know nothing of this."

"Why, may I ask?"

"There are two parties at war in Illyria. There is the King's party, the supporters of the monarchy, and there is the Republican party, which has made three attempts on the life of Ferdinand XII and two on that of his daughter."

"But I assume, my dear fellow, that the whereabouts in England of the Crown Princess are known to her father the King?"

"No; and it is essential that he should remain in ignorance. Our elopement from Illyria was touch and go. Ferdinand has moved heaven and earth to find out where she is, because she has been formally betrothed to a Russian Grand Duke, and if she does not return to Blaenau he will not be able to secure the succession."

"Depend upon it," said I, "the Crown Princess is on the way to Blaenau. Not of her own free will, of course. But his Majesty's agents have managed to play the trick."

"You may be right, Arbuthnot. But one thing is certain; my poor brave Sonia will never return to Blaenau alive."

Fitz buried his face in his hands tragically.

"She promised that, you know, in case anything of this kind happened, and I consented to it." The simplicity of his utterance had in it a certain grandeur which few would have expected to find in a man with the reputation of Nevil Fitzwaren. "Everybody doesn't believe in this sort of thing, Arbuthnot, but I and my princess do. She will never lie in the arms of another. God help her, brave and noble and unluckly soul!"

This was not the Fitz the world had always known. I suddenly recalled the flaxen-haired, odd, intense, somewhat twisted, wholly unhappy creature who had rendered me willing service in our boyhood. I had always enjoyed the reputation in our house at school that I alone, and none other, could manage Fitz. I recalled his passion for the "Morte d'Arthur," his angular vehemence, his sombre docility. In those distant days I had felt there was something in him; and now in what seemed curiously poignant circumstances there came the fulfilment of the prophecy.

"Let us assume, my dear fellow," said I, making an attempt to be of practical use in a situation of almost ludicrous difficulty, "that it is not her father who has abducted the Princess Sonia. Let us take it to be the other side, the Republican party.

"It would still mean death; not by her own hand, but by theirs. They twice attempted her life in Blaenau."

"In any case, it is reasonably clear that not a moment is to be lost if we are to help her."

"I don't know what to do," said Fitz, "and that's the truth."

I confessed that I too had no very clear idea of the course of action. It occurred to me that the wisest thing to be done was to take a third person into our counsels.

"You ask my advice," said I; "it seems to me that the best thing to do is to see if Coverdale will help us."

"That will mean publicity. At all costs I feel that that must be avoided."

"Coverdale is a shrewd fellow. He will know what to do; he is a man you can trust; and he will be able to set the proper machinery in motion."

My insistence on the point, and Fitz's unwilling recognition of the need for a desperate remedy, goaded him into a half-hearted consent. In my own mind I was persuaded of the value of Coverdale's advice, in whatever it might consist. He was the head of the police in our shire, and apart from a little external pomposity, without which one is given to understand it is hardly possible for a Chief Constable to play the part, he was a shrewd and kind-hearted fellow, who knew a good deal about things in general.

Poor Fitz would listen to no suggestion of food. Therefore I ordered the car round at once, and incidentally informed the ruler of the household, and the expectant assembly by whom she was surrounded, that Fitz and I had some private business to transact which required our immediate presence in the city of Middleham.

"Odo," said she whose word is law, with a mien of dark suspicion, "if Nevil Fitzwaren is persuading you to lend him money, I forbid you to entertain the idea. You are really so weak in such matters. You have really no idea of the value of money."

"It will do you no good with your constituents either," said Mary Catesby, "to be seen in Middleham with Nevil Fitzwaren."

To these warning voices I turned deaf ears, and fled from the room in a fashion so precipitate that it suggested guilt.

No time was lost in setting forth. As we glided past the front of the house, I at least was uncomfortably conscious of a battery of hostile eyes in ambush behind the window panes. There could be no doubt that every detail of our going was duly marked. Heaven knew what theories were being propounded! Yet whatever shape they assumed I was sure that all the ingenuity in the world would not hit the truth. No feat of pure imagination was likely to disclose what the business really was that had caused me to be identified in this open and flagrant manner with the husband of the luckless circus rider from Vienna.

Every mile of the eight to Middleham, Fitz was as gloomy as the grave. In spite of the confidence he had been led to repose in my judgment, he seemed wholly unable to extend it to that of Coverdale. He had a morbid dread of the police and of the publicity that would invest any dealings with them. The preservation of his wife's incognito was undoubtedly a matter of paramount importance.

It was half-past twelve when we reached Middleham. We were lucky enough to find Coverdale at his office at the sessions hall.

"Well, what can I do for you?" said the Chief Constable, heartily.

"You can do a great deal for us, Coverdale," said I. "But the first thing we shall ask you to do is to forget that you are an official. We come to you in your capacity of a personal friend. In that capacity we seek any advice you may feel able or disposed to give us. But before we give you any information, we should like to have your assurance that you will treat the whole matter as being told to you in the strictest secrecy."

Coverdale has as active a sense of humour as his exalted station allows him to sustain. There was something in my mode of address that seemed to appeal to it.

"I will promise that on one condition, Arbuthnot," said he; "which is that you do not seek to involve me in the compounding of a felony."

"Oh no, no, no, no!" Fitz burst out.

Fitz's exclamation and his tragic face banished the smile that lurked at the corners of Coverdale's lips.

I deemed it best that Fitz should re-tell the story of his tragedy, and this he did. In the course of his narrative the sweat ran down his face, his hands twitched painfully, and his bloodshot eyes grew so wild that neither Coverdale nor I cared to look at them.

Coverdale sat mute and grave at the conclusion of Fitz's remarkable story. He had swung round in his revolving chair to face us. His legs were crossed and the tips of his fingers were placed together, after the fashion that another celebrity in a branch of his calling is said to affect.

"It's a queer story of yours, Fitzwaren," he said at last. "But the world is full of 'em—what?"

"Help me," said Fitz, piteously. His voice was that of a drowning man.

"I think we shall be able to do that," said Coverdale. He spoke in the soothing tones of a skilful surgeon.

"The first thing to know," said the Chief Constable, "is the number of the car."

"G.Y. 70942 is the number."

Coverdale jotted it down pensively upon his blotting-pad.

"Have you a portrait of Mrs. Fitzwaren?" he asked.

"I have this," said Fitz.

In the most natural manner he flung open his overcoat, pulled away his evening tie, tore open his collar, and produced from under the rumpled shirt front a locket suspended by a fine gold chain round his neck. It contained a miniature of the Princess, executed in Paris. Both Coverdale and I examined it curiously, but as we did so I fear our minds had a single thought. It was that Fitz was a little mad.

"Will you entrust it to me?" said Coverdale.

Fitz's indecision was pathetic.

"It's the only one I've got," he mumbled. "I don't suppose I shall ever be able to get another. I ought to have had a replica while I had the chance."

"I undertake to return it within three days," said Coverdale, with a simple kindliness for which I honoured him.

Fitz handed the locket to him impulsively,

"Of course take it, by all means," he said, hurriedly. "I know you will take care of it. Fact is, you know, I'm a bit knocked over."

"Naturally, my dear fellow," said Coverdale. "So should we all be. But I shall go up to town this afternoon and have a talk with them at Scotland Yard.

"I was afraid that would have to happen. I wanted it to be kept an absolute secret, you know."

"You can depend upon the Yard to be the soul of discretion. It is not the first time they have been entrusted with the internal affairs of a reigning family. If the Princess is still in this country and she is still alive, and there is no reason to think otherwise, I believe we shall not have to wait long for news of her."

Coverdale spoke in a tone of calm reassurance, which at least was eloquent of his tact and his knowledge of men. Overwrought as Fitz was, it was not without its effect upon him.

"Ought not the ports to be watched?" he said.

"I hardly think it will be necessary. But if Scotland Yard thinks otherwise, they will be watched of course. Whatever happens, Fitzwaren, you can be quite sure that nothing will be left undone in our endeavour to find out what has really happened to the lady we shall agree to call Mrs. Fitzwaren. Further, you can depend upon it that absolute discretion will be used."

We left Coverdale, imbued with a sense of gratitude for his cordial optimism, and I think we both felt that a peculiarly delicate business could not be in more competent hands. He was a man of sound judgment and infinite discretion. Throughout this singular interview he had emerged as a shrewd, tactful and eminently kind-hearted fellow.

As a result of this visit to the sessions hall at Middleham, poor Fitz allowed himself a little hope. He had been duly impressed by the man of affairs who had taken the case in hand. However, he was still by no means himself. He was still in a strangely excited and gloomy condition; and this was aggravated by his friendlessness and the feeling that the hand of every man was against him.

In the circumstances, I felt obliged to yield to his expressed wish that I should accompany him to the Grange. As the crow flies it is less than four miles from my house.

The home of the Fitzwarens is a rambling, gloomy and dilapidated place enough. An air pervades it of having run to seed. Every Fitzwaren who has inhabited it within living memory has been a gambler and a roué in one form or another. The Fitzwarens are by long odds the oldest family in our part of the world, and by odds equally long their record is the most unfortunate. Coming of a long line of ill-regulated lives, the heavy bills drawn by his forbears upon posterity seemed to have become payable in the person of the unhappy Fitz. Doubtless it was not right that one who in Mrs. Catesby's phrase was a married man, a father of a family, and a county member, should constitute himself as the apologist of such a man as Fitz. But, in spite of his errors, I had never found it in my heart to act towards him as so many of his neighbours did not hesitate to do. The fact that he had fagged for me at school and the knowledge that there was a lovable, a pathetic and even a heroic side to one to whom fate had been relentlessly cruel, made it impossible for me to regard him as wholly outside the pale.

I can never forget our arrival at the Grange on this piercing winter afternoon. My car belonged to that earlier phase of motoring when the traveller was more exposed to the British climate than modern science considers necessary. The snow, at the beck of a terrible north-easter, beat in our faces pitilessly. And when we came half frozen into the house, we were met on its threshold by a mite of four. She was the image of her mother, with the same skin of lustrous olive, the same mass of raven hair, and the same challenging black eyes. In her hand was a mutilated doll. It was carried upside down and it had been decapitated.

"I want my mama," she said with an air of authority which was ludicrously like that of the circus rider from Vienna. "Have you brought my mama?"

"No, my pearl of price," said Fitz, swinging the mite up to his snow-covered face, "but she will be here soon. She has sent you this."

He kissed the small elf, who had all the disdain of a princess and the witchery of a fairy.

"Who is dis?" said she, pointing at me with her doll.

"Dis, my jewel of the east, is our kind friend Mr. Arbuthnot. If you are very nice to him he will stay to tea."

"Do you like my mama, Mistah 'Buthnot?" said the latest scion of Europe's oldest dynasty, with a directness which was disconcerting from a person of four.

"Very much indeed," said I, warmly.

"You can stay to tea, Mistah 'Buthnot. I like you vewy much."

The prompt cordiality of the verdict was certainly pleasant to a humble unit of a monarchical country. The creature extended her tiny paw with a gesture so superb that there was only one thing left for a courtier to do. That was to kiss it.

The owner of the paw seemed to be much gratified by this discreet action.

"I like you vewy much, Mistah 'Buthnot; I will tell you my name."

"Oh, do, please!"

"My name is Marie Sophie Louise Waren Fitzwaren."

"Phoebus, what a name!"

"And dis, Mistah 'Buthnot, is my guv'ness, Miss Green. She is a tarn fool."

The lady thus designated had come unexpectedly upon the scene. An estimable and bespectacled gentlewoman of uncompromising mien, she gazed down upon her charge with the gravest austerity.

"Marie Louise, if I hear that phrase again you will go to bed."

As Miss Green spoke, however, she gazed at me over her spectacles in a humorously reflective fashion.

Marie Louise shrugged her small shoulders disdainfully, and in a tone that, to say the least, was peremptory, ordered the butler, who looked venerable enough to be her great-grandfather, to bring the tea. The congé that the venerable servitor performed upon receiving this order rendered it clear that upon a day he had been a confidential retainer in the royal house of Illyria.