Title: In Love With the Czarina, and Other Stories

Author: Mór Jókai

Translator: Louis Felbermann

Release date: December 5, 2010 [eBook #34574]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Steven desJardins and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

SPECIAL AUTHORISED EDITION

TRANSLATED FROM THE ORIGINAL HUNGARIAN

WITH THE AUTHOR'S SPECIAL PERMISSION

BY

LOUIS FELBERMANN

AUTHOR OF "HUNGARY AND ITS PEOPLE"

ETC.

LONDON

FREDERICK WARNE & CO.

AND NEW YORK

[All rights reserved]

| PAGE | |

| Introduction | 9 |

| In Love with the Czarina | 17 |

| Tamerlan the Tartar | 57 |

| Valdivia | 111 |

| Bizeban | 141 |

| The Moonlight Somnambulist | 151 |

DEDICATED TO

HUNGARY'S GREATEST WRITER

MAURICE JÓKAI

BY LOUIS FELBERMANN

"From him I took it; to him I give it"

EASTERN PROVERB

London 1894

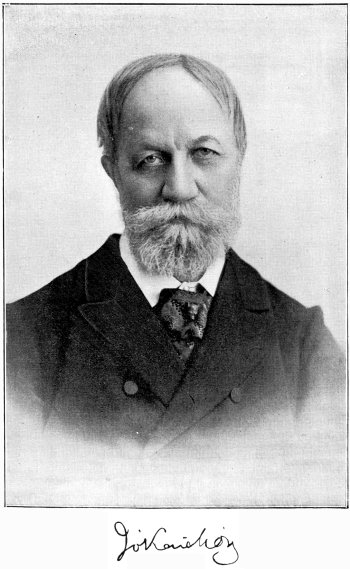

The entire Hungarian nation—king and people—have recently been celebrating the jubilee of Hungary's greatest writer, Maurice Jókai, whose pen, during half a century of literary activity, has given no less than 250 volumes to the world. Admired and beloved by his patriotic fellow-countrymen, Jókai has displayed that kind of genius which fascinates the learned and unlearned alike, the old and the young. He enchants the children of Hungary by his fairy-tales, and as they grow up into men and women he implants within them a passion for their native land and a knowledge of its splendid history such as only his poetic and dramatic pen could engrave upon their memory. His versatility of talent—for, besides being the Hungarian poet-laureate, he is a novelist, playwright, historian, and orator—enables the Hungarians to see in him their Heine, their Byron, their Walter Scott, and their Victor Hugo.

Jókai began his career at a period when Hungary aspired to political freedom, and his powerful pen,[Pg 10] in combination with that of his familiar friend, Alexander Petőfi, Hungary's greatest lyric poet, was mainly instrumental in rousing the nation to arms. In 1849, when the Hungarian nation had sustained a cruel defeat, it was Jókai who cheered the flagging spirits of the Magyars, and by the potency and skill of his extraordinary pen influenced that reconciliation between Sovereign and people which was ultimately accomplished by Hungary's greatest statesman, Francis Deák.

The Hungarian language is one of the richest of Turanian tongues, and particularly lends itself to the didactic and romantic styles. So far back as the beginning of the thirteenth century we find traces of Hungarian literature, and, if it had been permitted to develop, Hungary might now have possessed a literature second to none in the modern world. But in consequence of political struggles the Hungarian language and literature had to give way, at times, either to the Latin or German races, so much so that as late as 1849 all scientific subjects had to be taught either in German or in Latin. It was then that a few patriotic Magyars took the matter acutely to heart, and strove to restore the language and literature of their country, with the happy result that Hungary now, in proportion to its population, comes immediately after Germany in the number of its universities, colleges,[Pg 11] and scientific institutions, where all subjects are taught in the Hungarian language only.

Maurice Jókai is not only one of those who restored Hungarian literature, but is the creator of a particular style of romance, which stamps his works as unique, and has caused them to be eagerly read, and translated into almost every modern language. It is no wonder, therefore, that the Hungarians, who are a cultured race, should delight in showing all honour and respect to the veteran author, who has given to the world over a hundred splendid works on all subjects, comprising 250 volumes.

Jókai is descended from a middle-class family, a fact which he is always proud to own, and has no ambition to rise in higher spheres of society, although the greatest people in the land, including the Empress-Queen herself, favour him with their personal friendship.

He is a tall, fine-looking man, and carries himself well. He generally dresses in a black-braided costume, which is the favourite national Hungarian uniform of those patriots who belong to the forty-eight period, which marks such an epoch in the history of Hungary. In his younger days his beard was dark and silky, but now he is quite grey. He occupies a modest house, and leads a very simple life.

[Pg 12]To give the full history of such a great writer as Maurice Jókai, the titles of whose works fill nine pages of the British Museum catalogue, would be a task of considerable research, and would itself extend to volumes. I therefore only propose to touch upon a few of the salient points of his career.

Jókai was born on February 19, 1825, at Komárom, which city, by-the-by, is known as the "Virgin Fortress of Hungary."

He received his education partly in his native town and at Pozsony, the ancient capital of Hungary, Pápa and Kecskemét; and in 1846 he passed an examination as an advocate, though he did not follow the profession afterwards.

In the same year he took up his abode at Budapest, where in the following year he assumed the editorship of a paper called Életképek (Pictures of Life).

In 1848 he played an important part in the revolution, both in inciting the people by his literary writings and as a soldier. In 1849 he married Rose Laborfalvi, the famous actress. In the same year he followed the National Hungarian Government, which removed its seat to Debreczen, and became the editor of the Esti Lapok (Evening News). From that time activity characterised his literary and general career.

[Pg 13]In the political movements of 1861 he was to the front both as member of parliament and as newspaper editor. In 1860 he was elected member of the Kisfaludy Society, and in 1861 he became a member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, of which institute he is now a member of the executive committee. He is also the president of the Petőfi Society.

His first novel was "A Hétköznapok" (Days of the Week), which appeared in 1846, and since then hardly a year elapsed without the issue of several volumes from his pen.

Amongst his novels the most celebrated are:

"Egy Magyar Nábob" (The Hungarian Nabob).

"Kárpáthy Zoltán."

"A Kőszívű Ember Fiai" (The Sons of the Stonehearted Man).

"Szerelem Bolondjai" (Love's Puppet).

"Névtelen Vár" (The Nameless Fortress).

"Erdély Aranykora" (The Golden Period of Transylvania).

"Bálványosvár" (Idol Fortunes).

"Fekete Gyémántok" (Black Diamonds).

"A Jövő Század Regénye" (The Romance of the Future Century).

"Az Új Földesúr" (The New Landlord).

"Nincsen Ördög" (There is no Devil).

"Az Arany Ember" (The Gold Man).

[Pg 14]"A Szép Mikhál" (Pretty Michael).

Of his recent novels the most famous is the one published in 1892, in which Monk Gregory is the hero.

The short stories that we are presenting in this volume belong to his earliest writings.

Jókai's novels—in which his own strong personality everywhere reveals itself—are characterised by great imaginative power and by a light, humorous style which fascinates the reader. It may be said, without much exaggeration, that in point of wit and humour few living writers can compare with him. His subjects are principally drawn from history; but many of his works are remarkable for their vivid descriptions of Hungarian life, both past and present. In one word it might justly be said that in reading Jókai's novels one reads the history of Europe, and in reading Jókai's history one reads a novel drawn from actual life.

As a poet he occupies a unique position, and stands altogether alone: for his lyrics, ballads, and heroic verse are even sung by the schoolchildren throughout Hungary. As a dramatist his fame is extensive; and his "Könyves Kálmán" (Koloman, King of Hungary, surnamed the Book King), "Dózsa György, The Martyr of Szigetvár," "Az Arany Ember" (The Golden Man), and "Fekete[Pg 15] Gyémántok" (Black Diamonds), have been incessantly performed with the greatest success.

As a politician he has made a considerable mark, and no one who has had the privilege of hearing him deliver an oration will forget the music and sonority of his fine voice. What is less generally known is that he is an enthusiastic botanical student and an admirable painter.

These are a few outlines of the life of Hungary's greatest writer, and in the interest of literature let it be hoped that his life may be long spared, and that his remaining years may be spent in the utmost happiness. Such is the fervent wish of all his admirers, who are drawn, not only from this country, but from all civilised peoples, nations, and languages.

Louis Felbermann

(Author of "Hungary and its People").

In the time of the Czar Peter III. a secret society existed at St. Petersburg which bore the title of "The Nameless." Its members used to assemble in the house of a Russian nobleman, Jelagin by name, who alone knew the personality of each visitor, they being, for the most part, unknown to one another. Distinguished men, princes, ladies of the Court, officers of the Guard, Cossack soldiers, young commercial men, musicians, street-singers, actors and actresses, scientific men, clergymen and statesmen, used to meet here. Beauty and talent were alone qualifications for entry into the Society, the members of which were selected by Jelagin. Everyone addressed the other as "thee" and "thou," and they only made use of Christian names such as Anne, Alexandra, Katharine, Olga, Peter, Alexis, and Ivan. And for what purpose did they assemble here? To amuse themselves at their ease. Those who, by the prejudices of caste and rank, were utterly severed, and who occupied the mutual position of master and slave, tore the chains of their barriers asunder, and all met here. It is quite[Pg 18] possible that he with whom the grenadier-private is now playing chess is the very same General who might order him a hundred lashes to-morrow, should he take a step on parade without his command! And now he contends with him to make a queen out of a pawn!

It is also probable that the pretty woman who is singing sportive French songs to the accompaniment of the instrument she strikes with her left hand, is one of the Court ladies of the Czarina, who, as a rule, throws half-roubles out of her carriage to the street-musicians! Perhaps she is a Princess? possibly the wife of the Lord Chamberlain? or even higher in grade than this? Russian society, both high and low, flower and root, met in Jelagin's castle, and while there enjoyed equality in the widest sense of the word. Strange phenomenon! That this should take place in Russia, where so much is thought of aristocratic rank, official garb, and exterior pomp; where an inferior is bound to dismount from his horse upon meeting a superior, where sub-officers take off their coats in token of salute when they meet those of higher rank, and where generals kiss the priests' hands and the highest aristocrats fall on their faces before the Czar! Here they sing and dance and joke together, make fun of the Government, and tell anecdotes of the High Priests, utterly fearless, and dispensing with salutations!

Can this be done for love of novelty? The existence of this secret society was repeatedly divulged to the police, and these cannot be reproached[Pg 19] for not having taken the necessary steps to denounce it; but proceedings, once begun, usually evaporated into thin air, and led to no results. The investigating officer either never discovered suspicious facts, or, if he did, matters were adjourned. Those who were arrested in connection with the affair were in some way set at liberty in peace and quietness; every document relating to the matter was either burnt or vanished, and whole sealed cases of writings were turned into plain white paper. When an influential officer took energetically in hand the prosecution of "The Nameless," he was generally sent to a foreign country on an important mission, from which he did not return for a considerable period. "The Nameless Society" must have had very powerful protectors. At the conclusion of one of these free and easy entertainments, a young Cossack hetman remained behind the crowd of departing guests, and when quite alone with the host he said to him:

"Jelagin, did you see the pretty woman with whom I danced the mazurka to-night?"

"Yes, I saw her. Are you smitten with her, as others have been?"

"That woman I must make my wife."

Jelagin gave the Cossack a blow on the shoulder and looked into his eyes.

"That you will not do! You will not take her as your wife, friend Jemeljan."

"I shall marry her—I have resolved to do so."

"You will not marry her, for she will not go to you."

[Pg 20]"If she does not come I will carry her off against her will."

"You can't marry her, because she has a husband."

"If she has a husband I will carry her off in company with him!"

"You can't carry her off, for she lives in a palace—she is guarded by many soldiers, and accompanied in her carriage by many outriders."

"I will take her away with her palace, her soldiers, and her carriage. I swear it by St. Gregory!"

Jelagin laughed mockingly.

"Good Jemeljan, go home and sleep out your love—that pretty woman is the Czarina!"

The hetman became pale for a moment, his breath stopped; but the next instant, with sparkling eyes, he said to Jelagin:

"In spite of this, what I have said I have said."

Jelagin showed the door to his guest. But, improbable as it may seem, Jemeljan was really not intoxicated, unless it were with the eyes of the pretty woman.

A few years elapsed. The Society of "The Nameless" was dissolved, or changed into one of another form. Katharine had her husband, the Czar, killed, and wore the crown herself. Many people said she had him killed, others took her part. It was urged that she knew what was going to happen, but could not prevent it—that she was compelled to act as she did, and to affect, after a great struggle with her generous heart, complete ignorance of poison being administered to her husband. It was said that she had acted rightly,[Pg 21] and that the Czar's fate was a just one, for he was a wicked man; and finally, it was asserted that the whole statement was untrue, and that no one had killed Czar Peter, who died from intense inflammation of the stomach. He drank too much brandy. The immortal Voltaire is responsible for this last assertion. Whatever may have happened, Czar Peter was buried, and the Czarina Katharine now saw that her late husband belonged to those dead who do not sleep quietly. They rise—rise from their graves—stretch out their hands from their shrouds, and touch with them those who have forgotten them. They turn over in their last resting-place, and the whole earth seems to tremble under the feet of those who walk above them!

Amongst the numerous contradictory stories told, one, difficult to believe, but which the people gladly credited, and which caused much bloodshed before it was wiped out of their memory, was this—that Czar Peter died neither by his own hand, nor by the hands of others, but that he still lived. It was said that a common soldier, with pock-marked face resembling the Czar, was shown in his stead to the public on the death-couch at St. Petersburg, and that the Czar himself had escaped from prison in soldier's clothes, and would return to retake his throne, to vanquish his wife, and behead his enemies! Five Czar pretenders rose one after the other in the wastes of the Russian domains. One followed the other with the motto, "Revenge on the faithless!" The usurpers conquered sometimes a northern, sometimes a southern province, collected[Pg 22] forces, captured towns, drove out all officials, and put new ones in their places, so that it was necessary to send forces against them. If one was subjugated and driven away into the ice deserts, or captured and hung on the next tree, another Czar Peter would rise up in his place and cause rebellion, alarming the Court circle whilst they were enjoying themselves; and so things went on continually and continually. The murdered husband remained unburied, for to-day he might be put in the earth and to-morrow he would rise again one hundred miles off, and exclaim, "I still live!" He might be killed there, but would pop out his head again from the earth, saying, "Still I live." He had a hundred lives! When five of these Peter pretenders went the way of the real Czar a sixth rose, and this one was the most dreaded and most daring of all, whose name will perpetually be inscribed in the chronicles of the Russian people as a dreadful example to all who will not be taught wisdom, and his name is Jemeljan Pugasceff! He was born as an ordinary Cossack in the Don province, and took part in the Prussian campaign, at first as a paid soldier of Prussia, later as an adherent of the Czar. At the bombardment of Bender he had become a Cossack hetman. His extraordinary physical strength, his natural common sense and inventive power, had distinguished him even at this time, but the peace which was concluded barred before him the gate of progress. He was sent with many discharged officers back to the Don. Let them go again and look after their field labours! Pugasceff's head,[Pg 23] however, was full of other ideas than that of again commencing cheese-making, from which occupation he had been called ten years before. He hated the Czarina, and adored her! He hated the proud woman who had no right to tread upon the neck of the Russians, and he adored the beautiful woman who possessed the right to tread upon every Russian's heart! He became possessed with the mad idea that he would tear down that woman from her throne, and take her afterwards into his arms. He had his plans prepared for this. He went along the Volga, where the Roskolniks live—they who oppose the Russian religion, and who were the adherents of the persecuted fanatics whose fathers and grandfathers had been continually extirpated by means of hanging, either on trees or scaffolds, and this only for the sole reason that they crossed themselves downwards, and not upwards, as they do in Moscow!

The Roskolniks were always ready to plot if they had any pretence and could get a leader. Pugasceff wanted to commence his scheme with these, but he was soon betrayed, and fell into the hands of the police and was carried into a Kasan prison and put into chains. He might thus go on dreaming! Pugasceff dreamt one night that he burst the iron chains from his legs, cut through the wall of the prison, jumped down from the enclosure, swam through the surrounding trench whose depth was filled with sharp spikes, and that he made his way towards the uninhabited plains of the Ural Sorodok, without a crust of bread or a decent[Pg 24] stitch of clothing! The Jakics Cossacks are the only inhabitants of the plains of Uralszk—the most dreaded tribe in Russia—living in one of those border countries only painted in outline on the map, and a people with whom no other on the plains form acquaintanceship. They change locality from year to year. One winter a Cossack band will pay a visit to the land of the Kirghese, and burn down their wooden huts; next year a Kirgizian band will render the same service to the Cossacks! Fighting is pleasanter work in the winter. In the summer everyone lives under the sky, and there are no houses to be destroyed! This people belong to the Roskolnik sect. Just a little while previously they had amused themselves by slaughtering the Russian Commissioner-General Traubenberg, with his suite, who came there to regulate how far they might be allowed to fish in the river Jaik, and with this act they thought they had clearly proved that the Government had nothing to do with their pike! Pugasceff had just taken refuge amongst them at the time when they were dividing the arms of the Russian soldiers, and were scheming as to what they should further do. One lovely autumn night the escaped convict, after a great deal of wandering in the miserable valley of Jeremina Kuriza, situated in the wildest part of the Ural Mountains, and in its yet more miserable town, Jaiczkoi, knocked at the door of the first Cossack habitation he saw and said that he was a refugee. He was received with an open heart, and got plenty of kind words and a little bread. The[Pg 25] house-owner was himself poor; the Kirgizians had driven away his sheep. One of his sons, a priest of the Roskolnik persuasion, had been carried away from him into a lead-mine; the second had been taken to serve as a soldier, and had died; the third was hung because he had been involved in a revolt. Old Kocsenikoff remained at home without sons or family. Pugasceff listened to the grievances of his host, and said:

"These can be remedied."

"Who can raise for me my dead sons?" said the old man bitterly.

"The one who rose himself in order to kill."

"Who can that be?"

"The Czar."

"The murdered Czar?" asked the old soldier, with astonishment.

"He has been killed six times, and yet he lives. On my way here, whenever I met with people, they all asked me, 'Is it true that the Czar is not dead yet, and that he has escaped from prison?' I replied to them, 'It is true. He has found his way here, and ere long he will make his appearance before you.'"

"You say this, but how can the Czar get here?"

"He is already here."

"Where is he?"

"I am he!"

"Very well—very well," replied the old Roskolnik. "I understand what you want with me. I shall be on the spot if you wish it. All is the[Pg 26] same to me as long as I have anyone to lead me. But who will believe that you are the Czar? Hundreds and hundreds have seen him face to face. Everybody knows that the visage of the Czar was dreadfully pockmarked, whilst yours is smooth."

"We can remedy that. Has not someone lately died of black-pox in this district?"

"Every day this happens. Two days ago my last labourer died."

"Well, I shall lay in his bed, and I shall rise from it like Czar Peter."

He did what he said. He lay in the infected bed. Two days later he got the black-pox, and six weeks afterwards he rose with the same wan face as one had seen on the unfortunate Czar.

Kocsenikoff saw that a man who could play so recklessly with his life did not come here to idle away his time. This is a country where out of ten men nine have stored away some revenge of their own for a future time. Amongst the first ten people to whom Kocsenikoff communicated his scheme, he found nine who were ready to assist in the daring undertaking, even at the cost of their lives; but the tenth was a traitor. He disclosed the desperate plot to Colonel Simonoff, the commander of Jaiczkoi, and the commander immediately arrested Kocsenikoff; but Pugasceff escaped on the horse which had been sent out with the Cossack who came to arrest him, and he even carried off the Cossack himself! He jumped into the saddle, patted and spurred the horse, and made his way into the forest.

[Pg 27]History records for the benefit of future generations the name of the Cossack whom Pugasceff carried away with his horse: Csika was the name of this timid individual! This happened on September 15. Two days afterwards Pugasceff came back from the forest to the outskirts of the town Jaiczkoi. Then he had his horse, a scarlet fur-trimmed jacket, and three hundred brave horsemen. As he approached the town he had trumpets blown, and demanded that Colonel Simonoff should surrender and should come and kiss the hand of his rightful master, Czar Peter III.! Simonoff came with 5000 horsemen and 800 Russian regular troops against the rebels, and Pugasceff was in one moment surrounded. At this instant he took a loosely sealed letter from his breast and read out his proclamation in a ringing voice to the opposing troops, in which he appealed to the faithful Cossacks of Peter III. to help him to regain his throne and to aid him to drive away usurpers, threatening with death those traitors who should oppose his command. On hearing this the Cossack troops appeared startled, and the exclamation went from mouth to mouth, "The Czar lives! This is the Czar!" The officers tried to quiet the soldiers, but in vain. They commenced to fight amongst themselves, and the uproar lasted till late at night, with the result that it was not Simonoff who captured Pugasceff, but the latter who captured eleven of his officers; and when he retreated from the field his three hundred men had increased to eight hundred. It was a matter of great difficulty to the Colonel to lead back the rest[Pg 28] into the town. Pugasceff set up his camp outside in the garden of a Russian nobleman, and on his trees he hung up the eleven officers. His opponent was so much alarmed that he did not dare to attack him, but lay wait for him in the trenches, at the mouth of the cannon. Our daring friend was not quite such a lunatic as to go and meet him. He required greater success, more decisive battles, and more guns. He started against the small towns which the Government had built along the Jaik. The Roskolniks received the pseudo-Czar with wild enthusiasm. They believed that he had risen from the dead to humiliate the power of the Moscow priests, and that he intended to adopt, instead of the Court religion, that which had been persecuted. On the third day 1500 men accompanied him to battle. The stronghold of Ileczka was the first halting-place he made. It is situated about seventy versts from Jaiczkoi. He was welcomed with open gates and with acclamation, and the guard of the place went over to his side. Here he found guns and powder, and with these he was able to continue his campaign. Next followed the stronghold of Kazizna. This did not surrender of its own accord, but commenced heroically to defend itself, and Pugasceff was compelled to bombard it. In the heat of the siege the rebel Cossacks shouted out to those in the fort, and they actually turned their guns upon their own patrols. All who opposed them were strung up, and the Colonel was taken a prisoner to Pugasceff, who showed no mercy to anyone who wore his hair long, which was the[Pg 29] fashion at the time amongst the Russian officers, and for this reason the pseudo-Czar hung every officer who fell into his hands. Now, provided with guns, he made his way towards the fort of Nisnàja Osfernàja, which he also captured after a short attack. Those whom he did not kill joined him. Now he led 4000 men, and therefore he could dare attack the stronghold of Talitseva, which was defended by two heroes, Bilof and Jelagin. The Russian authorities took up a firm position in face of the fanatical rebels, and they would have repulsed Pugasceff, if the hay stores in the fort had not been burnt down. This fire gave assistance to the rebels. Bilof and Jelagin were driven out of the fort-gates, and were forced out into the plains, where they were slaughtered. When the pseudo-Czar captured the fort of Nisnàja Osfernàja, a marvellously beautiful woman came to him in the market-place and threw herself at his feet. "Mercy, my master!" The woman was very lovely, and was quite in the power of the conqueror. Her tears and excitement made her still more enchanting.

"For whom do you want pardon?"

"For my husband, who is wounded in fighting against you."

"What is the name of your husband?"

"Captain Chalof, who commanded this fort."

A noble-hearted hero no doubt would have set at liberty both husband and wife, let them be happy, and love one another. A base man would have hung the husband and kept the wife. Pugasceff[Pg 30] killed them both! He knew very well that there were still many living who remembered that Czar Peter III. was not a man who found pleasure in women's love, and he remained true to his adopted character even in its worst extremes.

The rebels appeared to have wings. After the capture of Talicseva followed that of Csernojecsinszkaja, where the commander took flight on the approach of the rebel leader, and entrusted the defence of the fort to Captain Nilsajeff, who surrendered without firing a shot. Pugasceff, without saying "Thank you," had him hanged. He did not believe in officers who went over to the enemy. He only kept the common soldiers, and he had their hair cut short, so that in the event of their escaping he should know them again! Next morning the last stronghold in the country, Precsisztenszka, situated in the vicinity of the capital, Orenburg, surrendered to the rebels, and in the evening the mock Czar stood before the walls of Orenburg with thirty cannon and a well-equipped army! All this happened in fifteen days.

Since the moment when he carried off the Cossack who had been sent to capture him, and met Kocsenikoff, he had occupied six forts, entirely annihilated a regiment, and created another, with which he now besieged the capital of the province.

The towns of the Russian Empire are divided by great distances, and before things were decided at St. Petersburg, Marquis Pugasceff might almost have occupied half the country. It was Katharine herself who nicknamed Pugasceff Marquis, and she[Pg 31] laughed very heartily and often in the Court circles about her extraordinary husband, who was preparing to reconquer his wife, the Czarina. The nuptial bed awaited him—it was the scaffold!

On the news of Pugasceff's approach, Reinsburg, the Governor of Orenburg, sent, under the command of Colonel Bilof, a portion of his troops to attack the rebel. Bilof started on the chase, but he shared the fate of many lion-hunters. The pursued animal ate him up, and of his entire force not one man returned to Orenburg. Instead of this, Pugasceff's forces appeared before its gates.

Reinsburg did not wish to await the bombardment, and he sent his most trusted regiment, under the command of Major Naumoff, to attack the rebels. The mock-Czar allowed it to approach the slopes of the mountains outside Orenburg, and there, with masked guns, he opened such a disastrous fire upon them that the Russians were compelled to retire to their fort utterly demoralised. Pugasceff then descended into the plains and pitched his camp before the town. The two opponents both began with the idea of tiring each other out by waiting. Pugasceff was encamped on the snow-fields. The plains of Russia are no longer green in October, and instead of tents he had huts made of branches of oak. The one force was attacked by frost—the other by starvation. Finally starvation proved the more powerful. Naumoff sallied from the fort, and turned his attention towards occupying those heights whence his forces had been fired upon a short time[Pg 32] previously. He succeeded in making an onslaught with his infantry upon the rebel lines, but Pugasceff, all of a sudden, changed his plan of battle, and attacked with his Cossacks the cavalry of his opponent, who took to flight. The victory fell from the grasp of Naumoff, and he was compelled to fly with his cannon, breaking his way, sword in hand, through the lines of the Cossacks. Then Pugasceff attacked in his turn. He had forty-eight guns, with which he commenced a fierce bombardment of the walls, which continued until November 9th, when he ordered his troops to storm the town. The onslaught did not succeed, for the Russians bravely defended themselves. Pugasceff, therefore, had to make up his mind to starve out his opponents. The broad plains and valleys were white with snow, the forests sparkled with icicles, as though made of silver, and during the long nights the cold reflection of the moon alone brightened the desolate wastes where the audacious dream of a daring man kept awake the spirits of his men. The dream was this: That he should be the husband of the Czarina of All the Russias.

Katharine II. was passionately fond of playing tarok, and she particularly liked that variety of the game which was later on named, after a celebrated Russian general, "Paskevics," and required four players. In addition to the Czarina, Princess Daskoff, Prince Orloff, and General Karr sat at her table. The latter was a distinguished[Pg 33] leader of troops—in petto—and as a tarok-player without equal. He rose from the table semper victor! No one ever saw him pay, and for this reason he was a particular favourite with the Czarina. She said if she could only once succeed in winning a rouble from Karr she would have a ring welded to it and wear it suspended from her neck. It is very likely that the mistakes of his opponents aided General Karr's continual success. The two noble ladies were too much occupied with Orloff's fine eyes to be able to fix their attention wholly upon the game, whilst Orloff was so lucky in love that it would have been the greatest injustice on earth if he had been equally successful at play. Once, whilst shuffling the cards, some one casually remarked that it was a scandalous shame that an escaped Cossack like Pugasceff should be in a position to conquer a fourth of Russia in Europe, to disgrace the Russian troops time after time, to condemn the finest Russian officers to a degrading death, and now even to bombard Orenburg like a real potentate.

"I know the dandy, I know him very well," said Karr. "During the life of His Majesty I used to play cards with him at Oranienbaum. He is a stupid youngster. Whenever I called carreau, he used to give cœur."

"It appears that he plays even worse now," said the Czarina; "now he throws pique after cœur!"

It was the fashion at this time at the Russian Court to throw in every now and then a French[Pg 34] word, and cœur in French means heart, and piquer means to sting and prick.

"Yes, because our commanders have been inactive. Were I only there!"

"Won't you have the kindness to go there?" asked Orloff mockingly.

"If Her Majesty commands me, I am ready."

"Ah! this tarok-party would suffer a too great loss in you," said Katharine, jokingly.

"Well, your Majesty might have hunting-parties at Peterhof," he said, consolingly, to the Czarina.

This was a pleasant suggestion to Katharine, for at Peterhof she had spent her brightest days, and there she had made the acquaintance of Orloff. With a smile full of grace, she nodded to General Karr.

"I don't mind, then; but in two weeks you must be back."

"Ah! what is two weeks?" returned Karr; "if your Majesty commands it, I will seat myself this very hour upon a sledge, and in three days and nights I shall be in Bugulminszka. On the fourth day I shall arrange my cards, and on the fifth I shall send word to this dandy that I am the challenger. On the sixth day I shall give 'Volat'[1] to the rascal, and the seventh and eighth days I shall have him as Pagato ultimo,[2] bound in chains, and bring him to your Majesty's feet!"

[1] "Volat" is an expression used in tarok to denote that no tricks have been made by an opponent.

[2] This is another term in the game, when the player announces beforehand that he will make the last trick with the Ace of Trumps.

[Pg 35]The Czarina burst out laughing at the funny technical expressions used by the General, and entrusted Orloff to provide the celebrated Pagato-catching General with every necessity. The matter was taken seriously, and Orloff promulgated the imperial ukase, according to which Karr was entrusted with the control of the South Russian troops, and at the same time he announced to him what forces he would have at his command. At Bugulminszka was General Freymann with 20,000 infantry, 2000 cavalry, and thirty-two guns, and he would be reinforced by Colonel Csernicseff, the Governor of Szinbirszk, who had at his command 15,000 horsemen, and twelve guns; while on his way he would meet Colonel Naumann with two detachments of the Body Guard. He was in particular to attach the latter to him, for they were the very flower of the army. Karr left that night. His chief tactics in campaigning consisted in speediness, but it seems that he studied this point badly, for his great predecessors, Alexander the Great, Frederick the Great, Hannibal, &c., also travelled quickly, but in company with an army, whilst Karr thought it quite sufficient if he went alone. He judged it impossible to travel faster than he did, sleighing merrily along to Bugulminszka; but it was possible. A Cossack horseman who started the same time as he did from St. Petersburg, arrived thirty-six hours before him, informed Pugasceff of the coming of General Karr, and acquainted him as to the position of his troops. Pugasceff despatched about 2000 Cossacks to fall[Pg 36] upon the rear of the General, and prevent his junction with the Body Guard.

Karr did not consult any one at Bugulminszka. He pushed aside his colleague Freymann in order to be left alone to settle the affair. He said it was not a question of fighting but of chasing. He must be caught alive—this wild animal. Csernicseff was already on the way with 1200 horsemen and twelve guns, as he had received instructions from Karr to cross the river Szakmara and prevent Pugasceff from retreating, while he himself should, with the pick of the regiment, attack him in front and thus catch him between two fires. Csernicseff thought he had to do with clever superiors, and as an ordinary divisional leader he did not dare to think his General to be so ignorant as to allow him to be attacked by the magnificent force of his opponent, nor did he think that Pugasceff would possess such want of tactics as, whilst he saw before him a strong force, to turn with all his troops to annihilate a small detachment. Both these things happened. Pugasceff quietly allowed his opponents to cross over the frozen river. Then he rushed upon them from both sides. He had the ice broken in their rear, and thus destroyed the entire force, capturing twelve guns. Csernicseff himself, with thirty-five officers, was taken prisoner, and Pugasceff had them all hanged on the trees along the roadway. Then, drunk with victory, he moved with his entire forces against Karr. He, too, was approaching hurriedly, and, thirty-six miles from Bugulminszka, the two forces met in a Cossack village. General Karr was[Pg 37] quite astonished to find, instead of an imagined mob, a disciplined army divided into proper detachments, and provided with guns. Freymann advised him, as he had sent away the trusted squadron of Csernicseff, not to commence operations now with the cavalry, to take the village as the basis of his operations, and to use his infantry against the rebels. A series of surprises then befell Karr. He saw the despised rowdy crowd approaching with drawn sabres, he saw the coolness with which they came on in the face of the fiercest musketry fire. He saw the headlong desperation with which they rushed upon his secure position. He recognised that he had found here heroes, instead of thieves. But what annoyed him most was that this rabble knew so well how to handle their cannon; for in St. Petersburg, out of precaution, Cossacks are not enlisted in the artillery, in order that no one should teach them how to serve guns. And here this ignorant people handled the guns, stolen but yesterday, as though accustomed to them all their lifetime, and their shells had already set fire to villages in many different places. The General ordered his entire line to advance with a rush, while with the reserve he sharply attacked the enemy in flank, totally defeating them. His cavalry started with drawn swords towards the fire-spurting space. Amongst the 1500 horsemen there were only 300 Cossacks, and in the heat of battle these deserted to the enemy. Immediately General Karr saw this, he became so alarmed that he set his soldiers the example of flight. All discipline at an end, they[Pg 38] abandoned their comrades in front, and escaped as best they could.

Pugasceff's Cossacks pursued the Russians for a distance of thirty miles, but did not succeed in overtaking the General. Fear lent him wings. Arrived at Bugulminszka, he learnt that Csernicseff's horsemen had been destroyed, that the Body Guard in his own rear had been taken prisoners, and that twenty-one guns had fallen into the hands of the rebels. Upon hearing this bad news he was seized with such a bad attack of the grippe that they wrapped him up in pillows and sent him home by sledge to St. Petersburg, where the four-handed card-party awaited him, and that very night he had the misfortune to lose his XXI.[3]; upon which the Czarina made the bon mot that Karr allowed himself twice to lose his XXI. (referring to twenty-one guns), which bon mot caused great merriment at the Russian Court.

[3] The card next to the highest in tarok.

After this victory, Pugasceff's star (if a demon may be said to possess one) attained its meridian. Perhaps it might have risen yet higher had he remained faithful to his gigantic missions, and had he not forgotten the two passions which had led him on with such astonishing rapidity—the one being to make the Czarina his wife, the other, to crush the Russian aristocracy. Which of these two ideas was the boldest? He was only separated from their realisation by a transparent film.

After Karr's defeat he had an open road to Moscow, where his appearance was awaited by[Pg 39] 100,000 serfs burning to shake off the yoke of the aristocracy, and form a new Russian empire. Forty million helots awaited their liberator in the rebel leader. Then, of a sudden, he cast away from him the common sense he had possessed until now—for the sake of a pair of beautiful eyes!

After the victory of Bugulminszka a large number of envoyés from the leaders of the Baskirs appeared before him, and brought him, together with their allegiance, a pretty girl to be his wife.

The name of the maiden was Ulijanka, and she stole the heart of Pugasceff from the Czarina. At that time the adventurer believed so fully in his star that he did not behave with his usual severity. Ulijanka became his favourite, and the adventurous chief appointed Salavatké, her father, to be the ruling Prince of Baskirk. Then he commenced to surround himself with Counts and Princes. Out of the booty of plundered castles he clothed himself in magnificent Court costumes, and loaded his companions with decorations taken from the heroic Russian officers. He nominated them Generals, Colonels, Counts, and Princes. The Cossack, Csika, his first soldier, was appointed Generalissimus, and to him he entrusted half his army. He also issued roubles with his portrait under the name of Czar Peter III., and sent out a circular note with the words, "Redevivus et ultor." As he had no silver mines, he struck the roubles out of copper, of which there was plenty about. This good example was also followed by the Russians, who issued roubles to[Pg 40] the amount of millions and millions, and made payments with them generously. Pugasceff now turned the romance of the insurrection into the parody of a reign. Instead of advancing against the unprotected cities of the Russian Empire, he attacked the defended strongholds, and, in the place of pursuing the fairy picture of his dreams which had led him thus far, he laid himself down in the mud by the side of a common woman!

Generalissimus Csika was instructed to occupy the fort Ufa, with the troops who were entrusted to his care. The time was January, 1774, and it was so terribly cold that nothing like it had been recorded in Russian chronicles. The trees of the forest split with a noise as though a battle were proceeding, and the wild fowl fell to the ground along the roads.

To carry on a siege under such circumstances was impossible. The hardened earth would not permit the digging of trenches, and it was impossible to camp on the frozen ground.

The two rebel chiefs occupied the neighbouring towns, and so cut off all supplies from the neighbouring forests. In Orenburg they had already eaten up the horses belonging to the garrison, and a certain Kicskoff, the commissary, invented the idea of boiling the skins of the slaughtered animals, cutting them into small slices and mixing them with paste, which food was distributed amongst the soldiers, and gave rise to the breaking out of a scorbutic disease in the fort which rendered half the garrison incapable of work. On January the[Pg 41] 13th, Colonel Vallenstierna tried to break his way through the rebel lines with 2500 men, but he returned with hardly seventy. The remainder, about 2000 men, remained on the field. At any rate, they no longer asked for food! A few hundred hussars, however, cut their way through and carried to St. Petersburg the news of what Czar Peter III. (who had now risen for the seventh time from his grave) was doing! The Czarina commenced to get tired of her adorer's conquests, so she called together her faithful generals, and asked which of them thought it possible to undertake a campaign in the depth of the Russian winter into the interior of the Russian snow deserts. This did not mean playing at war, nor a triumphal procession. It meant a battle with a furious people who, in forty years' time, would trample upon the most powerful European troops. There were four who replied that in Russia everything was possible which ought to be done. The names of these four gentlemen were: Prince Galiczin, General Bibikoff, Colonel Larionoff, and Michelson, a Swedish officer. Their number, however, was soon reduced to two at the very commencement. Larionoff returned home after the first battle of Bozal, where the rebels proved victorious, whilst Bibikoff died from the hardships of the winter campaign.

Galiczin and Michelson alone remained. The Swede had already gained fame in the Turkish campaign from his swift and daring deeds, and when he started from the Fort of Bozal against the rebels his sole troops consisted of 400 hussars and[Pg 42] 600 infantry, with four guns. With this small force he started to the relief of the Fort of Ufa. Quickly as he proceeded, Csika's spies were quicker still, and the rebel leader was informed of the approach of the small body of the enemy. As he expected that they only intended to reinforce the garrison of Ufa, he merely sent against them 3000 men, with nine guns, to occupy the mountain passes through which they would march on their way to Ufa. But Michelson did not go to Ufa as was expected. He seated his men on sledges, and flew along the plains to Csika's splendid camp. So unexpected, so daring, so little to be credited was this move of his, that when he fell on Csika's vanguard at one o'clock one morning nobody opposed him. The alarmed rebels hurried headlong to the camp, and left two guns in the hands of Michelson. The Swedish hero knew well enough that the 3000 men of the enemy who occupied the mountain pass would at once appear in answer to the sound of the guns, and that he would thus be caught between two fires; so he hastily directed his men to entrench themselves beneath their sledges in the road, and left two hundred infantry with two guns to defend them, whilst with the remaining troops he made his way towards the town of Csernakuka, whither Csika's troops had fled. Michelson saw that he had no time to lose. He placed himself at the head of his hussars, sounded the charge, and attacked the bulk of his opponents. For this they were not prepared. The bold attack caused confusion amongst them,[Pg 43] and in a few moments the centre of the camp was cut through, and the first battery captured. He then immediately turned his attention to the two wings of the camp. After this, flight became general, and Csika's troops were dispersed like a cloud of mosquitos, leaving behind them forty-eight cannon and eight small guns. The victor now returned with his small body of troops to the sledges they had left behind, and he then entirely surrounded the 3000 rebels. Those who were not slaughtered were captured. The victorious hero sent word to the commander of the Ufa garrison that the road was clear, and that the cannon taken from his opponents should be drawn thither. A hundred and twenty versts from Ufa he reached the flying Csika. The Generalissimus then had only forty-two officers, whilst his privates had disappeared in every direction of the wind. Michelson got hold of them all, and if he did not hang them it was only because on the six days' desert march not a single tree was to be found. In the meantime, Prince Galiczin, whose troops consisted of 6000 men, went in pursuit of Pugasceff. On this miserable route he did not encounter the mock Czar until the beginning of March. Pugasceff waited for his opponent in the forest of Taticseva. This so-called stronghold had only wooden walls, a kind of ancient fencing. It was good enough to protect the sheep from the pillaging Baskirs, but it was not suitable for war. The genius of the rebel leader did not desert him, and he was well able to look after himself. Round[Pg 44] the fences he dug trenches, where he piled up the snow, on which he poured water. This, after being frozen, turned almost into stone, and was, at the same time, so slippery that no one could climb over it. Here he awaited Galiczin with a portion of his troops, while the remainder occupied Orenburg. The Russian general approached the hiding-place of the mock Czar cautiously. The thick fog was of service to him, and the two opponents only perceived one another when they were standing at firing distance. A furious hand-to-hand fight ensued. The best of the rebel troops were there. Pugasceff was always in the front and where the danger was greatest, but finally the Russians climbed the ice-bulwarks, captured his guns, and drove him out of the forest. This victory cost the life of 1000 heroic Russians, but it was a complete one! Pugasceff abandoned the field with 4000 men and seven guns; but what was a greater loss still than his army and his guns, was that of the superstitious glamour which had surrounded him until now. The belief in his incapability of defeat, that was lost too! The revengeful Czar who had but yesterday commenced his campaign, now had to fly to the desert, which promised him no refuge. It was only then that the real horrors of the campaign commenced. It was a war such as can be imagined in Russia only, where in the thousands and thousands of square miles of borderless desert scantily distributed hordes wander about, all hating Russian supremacy, and all born gun in hand. Pugasceff took refuge amongst these people. Once[Pg 45] again he turned on Galiczin at Kargozki. He was again defeated, and lost his last gun. His sweetheart, Ulijanka, was also taken captive—that is, if she did not betray him! From here he escaped precipitately with his cavalry across the river Mjaes.

Here Siberia commences, and here Russia has no longer villages, but only military settlements which are divided from each other by a day's march, across plains and the ancient forests, along the ranges of the Ural Mountains—the so-called factories.

The Woszkrezenszki factory, situated one day's walk into the desert, is divided by uncut forests from the Szimszki factory, in both of which cinnamon and tin paints are made, and here are to be seen the powder factory of Usiska and the bomb factory of Szatkin, where the exiled Russian convicts work. At the meeting of the rivers are the small towns of Stepnàja, Troiczka Uszt, Magitnàja, Petroluskàja, Kojelga, guarded by native Cossacks, whilst others are garrisoned by disgraced battalions. Hither came Pugasceff with the remnants of his army. Galiczin pursued him for some time, but finally came to the conclusion that in this uninhabited country, where the solitary road is only indicated by snow-covered trenches, he could not, with his regular troops, reach an opponent whose tactics were to run away, as far and as fast as possible.

Pugasceff rallied to him all the tribes along the Ural district, who deserted their homesteads and followed him.

The winter suddenly disappeared, and those mild,[Pg 46] short April days commenced which one can only realise in Siberia, when at night the water freezes, while in the daytime the melting snow covers the expanse of waste, every mountain stream becomes a torrent, and the traveller finds in the place of every brook a vast sea. The runaway might still proceed by sledge, but the pursuer would only find before him fathomless morasses. Only one leader had the courage to pursue Pugasceff even into this land—this was Michelson. Just as the Siberian wolf who has tasted the blood of the wild boar does not swerve from the track, but pursues him even amongst reeds and morasses, so the daring leader chased his opponent from plain to plain. He never had more than 1000 men, cavalry, artillery, and gunners all told. Every one had to carry provisions for two weeks, and 100 cartridges. The cavalry had guns as well as sabres, so that they might also fight on foot, and the artillery were supplied with axes, so that, if necessary, they might serve as carpenters, and all prepared to swim should the necessity arise. With this small force Michelson followed Pugasceff amid the horde of insurrectionary tribes, surrounded on every side by people upon whose mercy he could not count, whose language he did not understand, and whose motto was death. Yet he went amongst them in cold blood, as the sailor braves the terrors of the ocean. On the 7th of May he was attacked by the father of the pretty Ulijanka, near the Szimszki factory, with 2000 Baskirs, who were about to join Pugasceff. Michelson dispersed them, captured their guns, and dis[Pg 47]covered from the Baskir captives that Beloborodoff, one of the dukes created by Pugasceff, was approaching with a large force of renegade Russian soldiers. Michelson caught up with them near the Jeresen stream, and drove them into the Szatkin factory. Riding all by himself, so close to them that his voice could be heard, he commenced by admonishing them to rejoin the standard of the Czarina. He was fired at more than 2000 times from the windows of the factory, but when they saw that he was invulnerable they suddenly threw open the gates and joined his forces. From them he discovered the whereabouts of the mock Czar, who had at the time once more recovered himself, had captured three strongholds, Magitnàja, Stepnàja, and Petroluskàja, and was just then besieging Troiczka. This place he took before the arrival of Michelson, who found in lieu of a stronghold nothing but ruins, dead bodies, and Russian officers hanging from the trees. Pugasceff heard of the approach of his opponent, and, with savage cunning, laid a snare to capture the daring pursuer. He dressed his soldiers in the uniforms of the dead Russian soldiers, and sent messengers to Michelson in the name of Colonel Colon that he should join him beyond Varlamora. Michelson only perceived the trick when his vanguard was attacked and two of his guns captured.

Although surrounded, he immediately fell upon the flower of Pugasceff's guard, and cut his way through just where the enemy was strongest. The net was torn asunder. It was not strong enough.[Pg 48] Pugasceff fled before Michelson, and, with a few hundred followers, escaped into the interior of Siberia, near the lake of Arga. All of a sudden Michelson found Szalavatka at his rear with Baskir troops who had already captured the Szatkin factory, and put to the sword men, women, and children. Michelson turned back suddenly, and found the Baskir camp strongly intrenched near the river Aj. The enemy had destroyed the bridges over the river, and confidently awaited the Imperial troops. At daybreak Michelson ordered up forty horsemen and placed a rifleman behind the saddle of each, telling them to swim the river and defend themselves until the remainder of the troops joined them. His commands were carried out to the letter amidst the most furious firing of the enemy, and the Russians gained the other side of the river without a bridge, drawing with them their cannon bound to trees. The Baskirs were dispersed and fled, but whilst Michelson was pursuing them with his cavalry he received news that his artillery was attacked by a fresh force, and he had to return to their aid. Pugasceff himself, who again was the aggressor, stood with a regular army on the plains. The battle lasted till late at night in the forest. Finally the rebels retreated, and Michelson discovered that his opponents meant to take by surprise the Fort of Ufa. He speedily cut his way through the forest, and when Pugasceff thought himself a day's distance from his opponent, he found him face to face outside the Fort of Ufa. Michelson proved again[Pg 49] victorious, but by this time his soldiers had not a decent piece of clothing left, nor a wearable shoe, and each man had not more than two charges. He therefore had to retreat to Ufa for fresh ammunition. It appears that Michelson was just such a dreaded opponent to Pugasceff as the man not born of a woman was to Macbeth. Immediately he disappeared from the horizon, he arose anew, and at each encounter with the pretender beat him right and left. When Michelson drove him away from Ufa, Pugasceff totally defeated the Russian leaders approaching from other directions, London, Melgunoff, Duve, and Jacubovics were swept away before him, and he burnt before their very eyes the town of Birszk. With drawn sword he occupied the stronghold of Ossa, where he acquired guns, and, advancing with lightning rapidity, he stood before Kazan, which is one of the most noted towns of the province; it is the seat of an Archbishop, and there is kept the crown which the Russian Czars use at their coronation. This crown was required by the mock Czar. If he could get hold of it, and the Archbishop of Kazan would place it on his head, who could deny that he was the anointed Czar? Generals Brand and Banner had but 1500 musketry for the defence of Kazan, but the citizens of the town took also to the guns to defend themselves from within their ancient walls. The day before the bombardment, General Potemkin, accompanied by General Larionoff, arrived at Kazan. The Imperialists had as many generals and colonels in their camp as Pugasceff had corporals who had[Pg 50] deserted their colours, yet the horde led by the rebel stormed the stronghold of the generals. Pugasceff was the first to scale the wall, standard in hand, upon which the generals took refuge in the citadel. Larionoff fled, and on his flight to Nijni Novgorod did not once look back.

Pugasceff captured the town of Kazan, and gave it up to pillage. The Archbishop of Kazan received him before the cathedral, bestowed upon him gold to the value of half-a-million roubles, and promised that he would place the crown on his head immediately he procured it; it being in the citadel. Pugasceff set fire to the town in all directions, as he wanted to effect the surrender of the citadel garrison by that means. Just at this moment Michelson was on his way. The heroic General hardly allowed his troops time for rest, but again started in pursuit of Pugasceff. No news of him was heard, his footsteps alone could be traced. At Burnova he was attacked by a gang of rebels, whom he dispersed, but they were not the troops of Pugasceff. At Brajevana he came upon a detachment, but this also was not the one he was looking for. He then turned towards the Fort of Ossa, where he found a group of Baskir horsemen, whom he dispersed, capturing many others, from whom he learnt that Pugasceff had crossed the river Kuma; and he knew that he would find the rebel at Kazan. He hastened after him, meeting right and left with camps and troops belonging to his adventurous opponent. He found no boats on the river Kuma, so he swam it. Two other rivers lay in his way,[Pg 51] but neither of these prevented his progress, and when he arrived at Arksz he heard firing in the direction of Kazan. Allowing but one hour's repose to his troops, he marched through the night, and at daybreak the thick dark smoke on the horizon told him that Kazan was in flames. Pugasceff's patrols communicated to their leader that Michelson was again at hand. The mock Czar cursed upon hearing the news. Was it a devil who was again at his heels, when he believed him 300 miles off? He decided that this must not be known to the garrison, who had been forced into the citadel. He collected from his troops those whom he could spare, and stationed them in the town of Taziczin, seven miles from Kazan, to prevent the advance of the dreaded enemy. Just as he was proclaiming himself Czar Peter III. in the market-place of Taziczin, a miserable-looking woman rushed in, and fell at his feet, embracing him, and covering him with kisses. This woman was Pugasceff's wife, who thought her husband lost long ago. They had been married very young, and Pugasceff himself believed her no longer living, but the poor woman recognised him by his voice. Pugasceff did not lose his presence of mind, but, gently lifting the woman up, he said to his officers:—"Look after this woman; her husband was a great friend of mine and I owe him much." But every one knew that the sham-Czar was no other than the husband of Marianka, and no doubt the appearance of the peasant woman told on the spirits of the insurgent troops. The most[Pg 52] bitter and decisive battle of the insurrection awaited them. The night divided the two armies, and it was only in the morning that Michelson could force his way into the town, whence he sent word to the people of Kazan to come to his assistance. Pugasceff again attacked him with embittered fury, and as he could not dislodge him he withdrew the remainder of his troops from Kazan and encamped on the plain. The third day of the battle, fortune turned to the side of Pugasceff. They fought for four hours, and Michelson was already surrounded, when the hero put himself at the head of his small army and made a desperate rush upon Pugasceff.

The insurrectionary forces were broken asunder. They left 3000 men on the battlefield, and 5000 captives fell into the hands of the victors.

Kazan was free, but the Russian empire was not so yet.

Pugasceff, trodden a hundred times to the ground, rose once more. After his defeat at Kazan, he fled, not towards the interior of Siberia, but straight towards the heart of the Russian empire—towards Moscow. Out of his army which was split asunder at Kazan he formed 100 battalions, and with a small number of these, crossed the Volga. Immediately he appeared on the opposite banks of the river, the entire province was enkindled: the peasantry rose in revolt against the aristocracy. Within a district of 100 miles every castle was destroyed, and one town after the other opened its gates to the mock Czar. The further he advanced the more his army increased and the faster his insurrectionary red flag[Pg 53] travelled towards the gates of Moscow. On their way the rebels occupied forts, pillaged and destroyed the towns, and the troops which were sent against them were captured. Before the Fort of Zariczin an Imperial force challenged their advance. In the ensuing battle, every Russian officer fell, and the entire force was captured. Again Pugasceff had 25,000 men and a large number of guns, and his road would have been clear to Moscow if the ubiquitous Michelson had not been at his back! This wonderful hero did not dread his opponents, however numerous, and like the panther which drives before him the herd of buffaloes, so he drove with his small body Pugasceff's tremendous army. The rebel felt that this man had a magic power over him, and that he was in league with fate. Finally, he found a convenient place outside Sarepta, and here he awaited his opponent. It is a height which a steep mountain footpath divides, and this path is intersected by another. Pugasceff placed a portion of his best troops on the ascending path, whilst to the riff-raff he entrusted his two wings. If Michelson had caught the bull by the horns with his ordinary tactics, he ought to have cut through the little footpath leading to the steep road, and if he had succeeded then, the troops which were at the point of intersection would have fallen between two fires, from which they could not have escaped. But Michelson changed his system of attack. Whilst the bombardment was going on, he, together with Colonel Melin, rushed upon the wings of the opposing forces. Pugasceff saw himself fall into the pit[Pg 54] he had dug for others. The rebel army, terror-struck, rushed towards his camp. The forces that flew to his rescue fell at the mouth of his guns, and he had to cut his way through his own troops in order to escape from the trap. This was his last battle! He escaped with sixty men, crossed the Volga, and hid amongst the bushes of an uninhabited plain.

The Russian troops surrounded the plain, whence Pugasceff and his men could not escape. And yet he still dreamt of future glory! Amidst the great desert his old ambition came back to him—he pictured the golden dome of the Kremlin, and the conquered Czarina. And with these dreams he suffered the tortures of hunger. For days and days he had no nourishment but horse-flesh roasted on the reeds, which was made palatable by meadow-grass in place of salt. One night, as he was sitting over the fire and roasting his meagre dinner on a wooden spit, one of the three Cossacks who formed his body-guard said to him, "You have played your comedy long enough, Pugasceff!" The adventurer sprang up from his place.

"Slave, I am your Czar!" and whilst saying this he slew the speaker. The two others made a rush at him, struck him to the ground, bound him, tied him to a horse, and thus took him to Ural Sorodok and delivered him to General Szuvarof. It was the very same Ural Sorodok whence he had started upon his bold undertaking. From here he was taken to Moscow. The sentence passed upon him was that he should be cut up alive into small[Pg 55] pieces. The Czarina confirmed the sentence, though her beautiful eyes had had great share of responsibility for the sinner's fate. The hangman was more merciful. It was not specified in the sentence where he should commence the work of slaughter, so he began at once with the head, and for this oversight he was sent to Siberia! Katharine about this time changed her favourite. Instead of Orloff, Potemkin, a fine fellow, was chosen.

All around, as far as eye could range, not a palm, nor a plant, nor a blade of grass was to be seen. From one end of the horizon to the other, nothing on which the rising sun could cast a shadow! There was only a small hillock in the centre of this desert, and against this a man was resting, spreading out his hands upon the square stone which stood upon it. He had either just risen from sleep or from the recital of prayer, and, kneeling, he greeted the rising sun. His dress was similar to that of an Eastern mendicant, for he was covered with a long woollen cloak, and one could see through his wide-hanging sleeves the wounds on his arms which had been scorched by the sun. He was short, and lame with a crippled foot, and, although his hair and beard were already white, his face, which was ruddy and youthful, belied his age, for on his forehead no wrinkles were to be seen, and his eyes were bright and sparkling. The expression of his face was as grave and gentle as that of a philosopher or a pilgrim.

[Pg 58]To the eastern horizon of the desert, along the stony plain of Szivasz, a red pyramid arrested the sun's rays, and appeared through the morning mists like a red shadow, whilst westward, a long black streak of cloud seemed to hover, which the morning breeze was powerless to agitate and the light of dawn could not kindle into colour. Throughout the whole extent of the plains not a human voice was to be heard, but in the melancholy quietude some continuous and dismal sounds attracted the ear, proceeding apparently from the interior of the earth. Far and wide as the waste extended were these heartrending and distressing noises to be heard. It seemed as though the earth were sobbing, or as though one could recognise the sighs and groans ascending from lost souls in purgatory, numbed into faint echoes in their transit from the depths below. Or even as though the air were filled with the loud screams of evil spirits, coming and going one knew not whence or whither. On the face of the lonely wanderer no expression of fear was visible. He did not shrink shudderingly from the phantom of the plain, nor from the desolate picture spread before him. If he could pass the night alone amidst these ghostly surroundings, was it likely that he would be afraid in the sunlight?

He knelt once again upon the hillock, touching the stone with his forehead, speaking in low murmurs as though into the sand:

"Oh! Wisdom beyond all wisdoms! grant to me to acquire thy knowledge that I may wander[Pg 59] throughout the world, and accomplish what Thou hast left unfinished."

Whilst saying this he rose, and, with dignified mien, gazed around the expanse of plain. These plains were the blessed soil of Irán. But yesterday it was the fourth paradise of Asia, while to-day it is a desert.

The little hillock was the sepulchre of Abu Mozlim who killed half a million of people in his fierce and continuous fights.

The philosopher, wanderer, and mendicant who rested upon it was Timur (the man of the iron sword), nicknamed also Timur Lenk (the lame), who in the language of flatterers was called Gurgan (the high and mighty lord), Szabil Kirán (the master of all time), or Djeihangir (the conqueror of the world)—one of the greatest of all conquerors. On his head rested the crowns of twenty-seven countries, and from the Indus to the Volga twenty-seven nationalities groaned under his yoke.

It was he himself, the dreaded Tamerlan. The red pyramid to the east was a pyramid of skulls, which had been piled up from the heads of 90,000 soldiers captured during the war, whilst the immovable cloud towards the west was the smoke rising from Szivasz, which only two days ago was inhabited by 100,000 people and to-day held as many graves!

The hollow murmuring from the centre of the earth was caused by the cries of 4000 Armenians, whom the victorious conqueror had caused to be buried alive in one vast timber-lined grave, so that their screams could be heard for some time. It[Pg 60] was their moans which came from beneath the earth, whilst the cripple rested on his club, made from the horn of the buffalo, and gazed with a satisfied air around the desert wastes which, yesterday a paradise, had been battered down by his horses' hoofs into a dismal plain. What he saw and heard was delight to his heart. The air of the desert mourned, and the earth moaned in concert.

Timur's camp was always full of learned men, poets, and lute singers. When he devastated a country or uprooted a town, there was never a living soul left behind his track—not the sound of a child's cry, the bark of a dog, or the crow of a cock—everything was destroyed!

But he spared learned men and poets. On the day of destruction his camp was a place of refuge to them, and they were guarded by his soldiers in order that no evil might befall them; and when he moved onwards he carried with him not only the treasures of the dead—silver, gold, and jewels, but also those of the living—art and science. His camp was swarming with astronomers, magicians, singers, poets, painters, gymnasts, engineers, doctors, conjurers, monkey-trainers, and such like. Timur caused them to be elegantly dressed and well fed, and paid them handsomely. He carried them about everywhere with him, in order that they might amuse all but himself. Why should he trouble his[Pg 61] head with astronomy when he knew no star so sparkling as himself? Why should he learn history, when he was the one to make it; or listen to verses which were sung in praise of love, when he distributed captive maidens to his soldiers as a portion of their pay? If he had scientific men in his camp it was in order that they should exert their power over his people. Let them hear the poet's stories, and the recital of heroic deeds, and let the chroniclers write on their parchment what he dictated. Let comedians amuse the crowd, so long as it was acknowledged that all the amusement was owing to him.

It was 830 in the Hedjir year, and the countries of two great conquerors adjoined one another. One was Timur, another was Bajazet, whose surname was Djildirim (the lightning). This latter name is also inscribed in letters of blood in the chronicles of other unfortunate nations, and a people who yet cannot fail to remember his name are still called Magyars. Bajazet was the victorious hero of Nicapol. Where two sword-blades touch there is sure to be fighting, and how could two conquerors of the world find room close to one another? Bajazet conquered three provinces which were in vassalage to Timur, and drove away the Khans of Taherten, Szarnchan and Aidin. The last he took captive, together with his wife. Timur, with whom the Khan of Aidin was a favourite, sent envoys to the Sultan, asking him to restore their provinces to his protégés, and to set the Khan of Aidin and his wife at liberty. The Sultan was inclined to[Pg 62] slay these envoys, but was dissuaded from doing so by his advisers, who said, "Timur, the son of the desert, never causes the envoys sent by his opponents to be killed." However, he ordered them to be scourged through the streets with camel-hide whips, and thrust them into prison, whilst to Timur he sent word that if he dared to say another word on behalf of the Khan of Aidin he would send him back to him cut into two pieces.

Timur kept silent and prepared for war, and he inspired and humoured his troops by the aid of his dervishes, poets, and acrobats.

One day Shacheddin, Timur's historian, interrupted him whilst plunged in thought, "Master of the world, deign to be gracious! A magician wishes to appear before you."

"For what purpose? If he wants money he can have it without seeing me."

"He does not want money; he only asks to be received into your favour."

"If he does not gain that, then, he will have stolen my time, and time is life; therefore, he will have deprived me of life, and will have to be considered a regicide!"

Such thoughts as those were frequent utterances from Timur's lips, and it is a fact that he often had people killed for a mere trifle, and spared their lives as a sort of good joke.

Shacheddin did not relinquish his request, and a few minutes afterwards Timur's guards hastened to bring the magician before their master. It was a mark of respect that all should enter hurriedly into[Pg 63] the presence of this mighty man, and that they should throw themselves upon their faces on the ground. To walk slowly was considered a mark of haughty conduct by him.

The magician was attired in grey robes, and on his head he wore a tall, silk cap. His beard was painted yellow, and his eyebrows blue, whilst on his face were inscribed Tallic words in green and red.

"Magician," said Timur, with mocking condescension, "where have you learnt your art? Amongst the idiots of Almanzor, or in the company of Chinese clowns? Do you understand how to charm people back to this country from another, or vice versâ? Say, do you understand that?"

"I understand that," answered the magician, bowing down to the ground.

"If, indeed, you understand that, then command that in one moment my beloved servant, the Khan of Aidin, shall stand before me; and, if you cannot do this, perhaps you will manage to transplant yourself at least a thousand miles from me, for my hands can reach even to that extent, and may possibly cause your death!"

"It shall be as you command," said the magician. "Will you please to order your slaves to bring a vat of water before me?"

"Shacheddin has tried that," said Timur, with cold irony. "Bring water to the magician!"

A vat filled with water was placed before the magician, and he jumped into it, still wearing his clothes.

[Pg 64]Timur gazed upon him with doubting condescension, thinking to himself at the same time what kind of death he should bestow upon this deceitful mortal. All at once the water was divided and in place of the magician a fine, tall young man, with hanging locks, stood before him.

It was the Khan of Aidin himself!

Timur rose hastily from his seat, and flew to him as a lioness who discovers her lost cubs. He embraced the young fellow and carried him in his arms to a panther skin, where he told him to be seated before him.

"How did you get here?"

"As an acrobat," replied the Khan of Aidin, with a smile. "I escaped disguised as a rope-dancer from your enemy's country!"

A Prince as an acrobat! Could there be a greater humiliation? Could there be anything in existence calling for more bitter revenge?

"Which way did you come, and what towns did you touch?" asked Timur of the Khan, who was seated at his feet.

"From Smyrna I escaped as a running footman. The people praised my running to such an extent that I felt compelled to prove how far I could go by running away altogether! In Aleppo I was a monkey-trainer! In Bagdad I turned somersaults! In Damascus I climbed by a rope to the[Pg 65] Tower of Minarch! At Angora I put sharp swords into my throat; whilst in Szivasz I swallowed burning coals before the son of the Sultan!"

Timur Lenk counted on his fingers the names of the towns as the Khan of Aidin recapitulated them; Smyrna, Aleppo, Damascus, Bagdad, Angora, Szivasz—not one stone of them should remain! And the people who had been so amused by the acrobatic performances of a prince should bitterly deplore this! Little time should be given them to lament!

"And your children?" asked Timur of his protégé.

The Khan gave a sigh.

"They are kissing the whips of Bajazet's slaves."

"They shall not do so long!"

Timur called Shacheddin before him, and had another letter written to the Sultan, taking care that every time his name was mentioned it should appear in a line with his in quite as large-sized letters, and not in different ink; whilst, in accordance with his usual custom, he signed his name at the top, not the bottom, of the page. The contents of the missive were not couched in angry terms, though they were written in a haughty manner.

"Do you not know that the greater portion of Asia is submissive to my sword and my laws? Do you not know that my army reaches from one sea to another, and that the world's rulers stand humbly at my doors imploring to be heard! What is your boast to me? A victory over the Christians? You have been victorious over them because the swords[Pg 66] of the prophet—blessed be Allah!—were in your hands. But who will defend you against me? Your only protector is the Koran, whose commands I obey as you do. Be wise! Do not despise your opponent because he was once insignificant. When the locust grows up, and its wings become red, it attacks the very birds who wished to consume it before!"