Captain Mayne Reid

"The Young Yagers"

"A Narrative of Hunting Adventures in Southern Africa"

Chapter One.

The Camp of the Young Yägers.

Near the confluence of the two great rivers of Southern Africa—the Yellow and Orange—behold the camp of the “young yägers!”

It stands upon the southern bank of the latter stream, in a grove of Babylonian willows, whose silvery foliage, drooping gracefully to the water’s edge, fringes both shores of the noble river as far as the eye can reach.

A tree of rare beauty is this Salix Babylonica—in gracefulness of form scarce surpassed even by the palms, the “princes of the forest.” In our land, as we look upon it, a tinge of sadness steals over our reflections. We have grown to regard it as the emblem of sorrow. We have named it the “weeping willow,” and draped the tomb with its soft pale fronds, as with a winding-sheet of silver.

Far different are the feelings inspired by the sight of this beautiful tree amid the karoos of Southern Africa. That is a land where springs and streams are “few and far between;” and the weeping willow—sure sign of the presence of water—is no longer the emblem of sorrow, but the symbol of joy.

Joy reigns in the camp under its shade by the banks of the noble Orange River, as is proved by the continuous peals of laughter that ring clear and loud upon the air, and echo from the opposite shores of the stream.

Who are they that laugh so loudly and cheerfully? The young yägers.

And who are the young yägers?

Let us approach their camp and see for ourselves. It is night, but the blaze of the camp-fire will enable us to distinguish all of them, as they are all seated around it. By its light we can take their portraits.

There are six of them—a full “set of six,” and not one appears to be yet twenty years of age. They are all boys between the ages of ten and twenty—though two or three of them, and, maybe, more than that number, think themselves quite men.

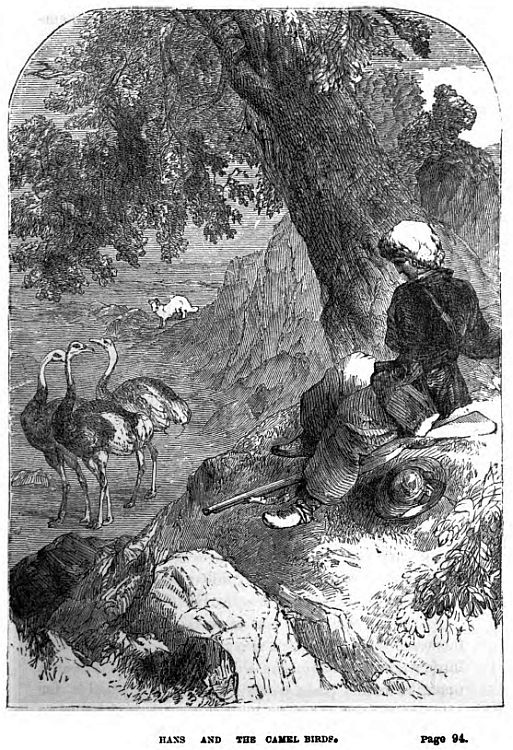

Three of the party you will recognise at a glance as old acquaintances. They are no other than Hans, Hendrik, and Jan, our ci-devant “Bush-boys.”

It is several years since we saw them last, and they have grown a good deal since then; but none of them has yet reached the full stature of manhood. Though no longer “Bush-boys,” they are yet only boys; and Jan, who used to be called “little Jan,” still merits and receives that distinctive appellation. It would stretch Jan to his utmost to square off against a four-foot measuring-stick; and he could only manage it by standing upon the very tips of his toes.

Hans has grown taller, but, perhaps, thinner and paler. For two years he has been at college, where he has been very busy with his books, and has greatly distinguished himself by carrying off the first prizes in everything. Upon Hendrik there is a decided change. He has outgrown his elder brother both in length and breadth, and comes very near looking like a full-grown man. He is yet but eighteen years old, straight as a rush, with a decided military air and gait. The last is not to be wondered at, as Hendrik has now been a cornet in the Cape Mounted Rifles for more than a year, and still holds that commission, as may be learnt by looking at his forage-cap, with its golden embroidery over the peak. So much for our old acquaintances the “Bush-boys!”

But who are the other three that share with them the circle of the camp-fire? Who are their companions? for they are evidently on terms of companionship, and friendship too. Who are they? A word or two will tell that. They are the Van Wyks. The three sons of Diedrik Van Wyk.

And who, then, is Diedrik Van Wyk? That must also be explained. Diedrik is a very rich boor—a “vee-boor”—who every night shuts up within his spacious kraals more than three thousand horses and horned cattle, with five times that number of sheep and goats! In fact, Diedrik Van Wyk is accounted the richest vee-boor, or grazier, in all the Graaf Reinet.

Now the broad plaatz, or farm, of Diedrik Van Wyk lies contiguous to that of our old acquaintance, Hendrik Von Bloom; and it so chances that Hendrik and Diedrik are fast friends and inseparable companions. They see each other once a-day, at the least. Every evening Hendrik rides over to the “kraal” of Diedrik, or Diedrik to that of Hendrik, to enjoy a smoke together out of their ponderous pipes of meerschaum, or a “zoopje” of brandewyn distilled from their own peaches. They are, in fact, a pair of regular old comrades,—for Van Wyk in early life has seen military service as well as Von Bloom,—and, like all old soldiers, they love to repeat their camp stories, and “fight their battles o’er again.”

Under such circumstances it is not to be wondered at, that the children of both should be intimate acquaintances. But, in addition to the friendship of their fathers, there is a tie of relationship between the two families,—the two mothers were cousins,—so that the children are what is usually termed second cousins,—a very interesting sort of affinity. And it is not an unlikely thing that the relationship between the families of Von Bloom and his friend Van Wyk may one day become still closer and more interesting; for the former has for his daughter, as all the world knows, the beautiful flaxen-haired cherry-cheeked Trüey, while the latter is the father of the pretty brunette Wilhelmina—also an only daughter. Now there chance to be three boys in each family; and though both boys and girls are by far too young to think of getting married yet, there are suspicions abroad that the families of Von Bloom and Van Wyk will, at no very distant day, be connected by a double marriage—which would not be displeasing to either of the old comrades, Hendrik and Diedrik.

I have said there are three boys in each family. You already know the Von Blooms, Hans, Hendrik, and Jan. Allow me to introduce you to the Van Wyks. Their names are Willem, Arend, and Klaas.

Willem is the eldest, and, though not yet eighteen, is quite a man in size. Willem is, in fact, a boy of very large dimensions, so large that he has received the sobriquet of “Groot Willem” (Big William) therefrom. All his companions call him “Groot Willem.” But he is strong in proportion to his size,—by far the strongest of the young yägers. He is by no means tidy in his dress. His clothes, consisting of a big jacket of homespun cloth, a check shirt, and an enormously wide pair of leathern trousers, hang loosely about him, and make him look larger than he really is. Even his broad-brimmed felt hat has a slouching set upon his head, and his feldtschoenen are a world too wide for his feet.

And just as easy as his dress is the disposition of the wearer. Though strong as a lion, and conscious of his strength, Groot Willem would not harm a fly, and his kindly and unselfish nature makes him a favourite with all.

Groot Willem is a mighty hunter, carries one of the largest of guns, a regular Dutch “roer,” and also an enormous powder-horn, and pouch full of leaden bullets. An ordinary boy would stagger under such a load, but it is nothing to Groot Willem.

Now it may be remembered that Hendrik Von Bloom is also a “mighty hunter;” and I shall just whisper that a slight feeling of rivalry—I shall not call it jealousy, for they are good friends—exists between these two Nimrods. Hendrik’s favourite gun is a rifle, while the roer of Groot Willem is a “smooth bore;” and between the merits of these two weapons camp-fire discussions are frequent and sharp. They are never carried beyond the limits of gentlemanly feeling, for loose and slovenly as is Groot Willem in outward appearance, he is a gentleman within.

Equally a gentleman, but of far more taste and style, is the second brother of the Van Wyks, Arend. In striking appearance and manly beauty he is quite a match for Hendrik Von Bloom himself, though in complexion and features there is no resemblance between them. Hendrik is fair, while Arend is very dark-skinned, with black eyes and hair. In fact, all the Van Wyks are of the complexion known as “brunette,” for they belong to that section of the inhabitants of Holland sometimes distinguished as “Black Dutch.” But upon Arend’s fine features the hue sits well, and a handsomer youth is not to be seen in all the Graaf Reinet. Some whisper that this is the opinion of the beautiful Gertrude Von Bloom; but that can only be idle gossip, for the fair Trüey is yet but thirteen, and therefore can have no opinion on such a matter. Africa, however, is an early country, and there might be something in it.

Arend’s costume is a tasty one, and becomes him well. It consists of a jacket of dressed antelope-skin,—the skin of the springbok; but this, besides being tastefully cut and sewed, is very prettily embroidered with slashes of beautiful leopard-skin, while broad bands of the same extend along the outside seams of the trousers, from waist to ankle, giving to the whole dress, a very rich and striking effect. Arend’s head-dress is similar to that worn by Hendrik Von Bloom, viz: a military forage-cap, upon the front of which are embroidered in gold bullion a bugle and some letters; and the explanation of that is, that Arend, like his second cousin, is a cornet in the Cape Rifles, and a dashing young soldier he is.

Now the portrait of Klaas in pen and ink.—Klaas is just Jan’s age and Jan’s exact height, but as to circumference therein exists a great difference. Jan, as you all know, is a thin, wiry little fellow, while Klaas, on the contrary, is broad, stout, and burly. In fact, so stout is he, that Jan repeated two and a half times would scarce equal him in diameter!

Both wear cloth roundabouts and trousers, and little broad-brimmed hats; both go to the same school; and, though there is a considerable difference between them in other respects, both are great boys for bird-catching and all that sort of thing. As they only carry small shot-guns, of course they do not aspire to killing antelopes or other large animals; but, small as their guns are, I pity the partridge, guinea-hen, or even bustard, that lets either of them crawl within reach of it.

Now it has been hinted that between the hunters Groot Willem and Hendrik there is a slight feeling of rivalry in regard to matters of venerie. A very similar feeling, spiced perhaps with a little bit of jealousy, has long existed between the bird-catchers, and sometimes leads to a little coolness between them, but that is usually of very short duration.

Hans and Arend have no envious feelings—either of one another or of anybody else. Hans is too much of a philosopher: besides, the accomplishment in which he excels, the knowledge of natural history, is one in which he is without a rival. None of the rest make any pretensions to such knowledge; and the opinion of Hans on any matter of science is always regarded as a final judgment.

As to Arend, he is not particularly proud of any acquirement. Handsome, brave, and generous, he is nevertheless a right modest youth,—a boy to be beloved.

And now you know who are the young yägers.

Chapter Two.

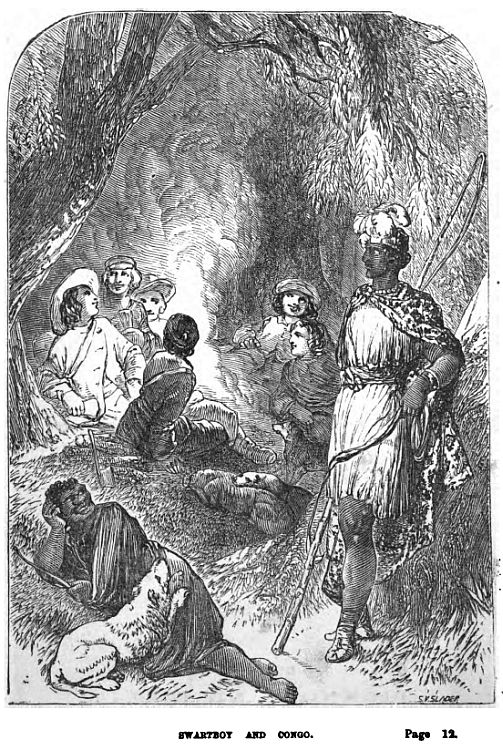

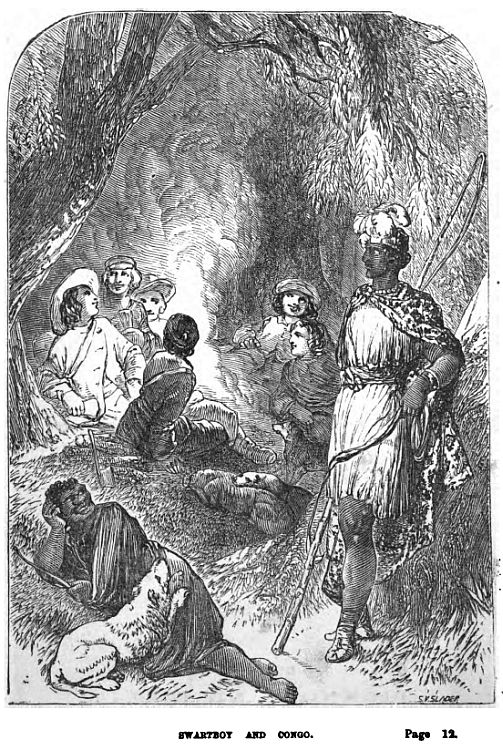

Swartboy the Bushman and Congo the Kaffir.

I have said that the young yägers were encamped on the southern bank of the Great Orange River. What were they doing there? The spot they occupied was many a long day’s journey from their home in the Graaf Reinet, and many a day’s journey beyond the frontier of the Cape Colony. There were no settlements near. No white men ever wandered so far, except an occasional “smouse,” or trader—a class of men who extend their bartering expeditions almost to the central parts of the African Continent. Sometimes, too, the “trek-boor,” or nomade grazier, may have driven his flocks to this remote place, but for all that it could not be considered a settled country. It was still a wilderness.

And what were the young Von Blooms and Van Wyks doing in the wilderness? Jäging to be sure, and nothing else,—they were simply out on a hunting expedition.

It was an expedition that had been long talked of and planned. Since their grand hunt of the elephant, the “Bush-boys” had not followed any game. Hendrik had been with his regiment, and Hans and Jan busy with their respective studies. So with Arend Van Wyk as with Hendrik, and Klaas as with Jan. Groot Willem alone, from time to time, had been jäging springboks and such other game as is to be found among the settlements. But the present was a grand expedition intended to be carried far beyond the settled part of the colony—in fact, as far as they thought fit to go. The boys had received the full sanction of their parents, and had been fitted out in proper style—each having a good horse, and each three a large wagon to carry all their camp utensils, and serve as a tent to sleep in. Each wagon had its driver, and full span of ten long-horned oxen; and these, with a small pack of rough-looking buck-dogs, might be seen in the camp—the oxen tied to the disselbooms of the wagons, and the dogs grouped in various attitudes around the fire. The horses were also fastened some to the wheels, and others to trees that grew near.

Two other objects in the camp are well worthy of a word or two; in fact, they are two individuals of very great importance to the expedition—as without them the wagons would be a troublesome affair. They are the drivers of these vehicles, and each is as proud of his whip-craft as Jehu could possibly have been of his.

In one of these drivers you will recognise an old acquaintance. The large head and high cheek-bones, with the flat spread nostrils between; the small oblique Mongolian eyes; the short curly wool-knots, planted sparsely over the broad skull; the yellow complexion; the thick “chunky” form, scarce four feet in height, and sparely clad in red flannel shirt and brown leathern “crackers;” with all these features and characters before your mind, you cannot fail to recognise an old favourite—the Bushman, Swartboy.

Swartboy it was; and, though several years have rolled over the Bushman’s bare head since we saw him last, there is no visible change observable in Swartboy. The thinly scattered “kinks” of browny black wool still adorn Swartboy’s crown and occiput, but they are no thinner—the same good-natured grin is observed upon his yellow face—he is still the same faithful servant—the same expert driver—the same useful fellow that he ever was. Swartboy, of course, drives the wagon of the Von Blooms.

Now the driver of the Van Wyk vehicle is about as unlike Swartboy as a bear to a bluebottle.

In the first place, he is above a third taller than the Bushman, standing over six feet,—not in his stockings, for he never wears stockings, but in sandals, which he does wear.

His complexion is darker than that of the Hottentot, although it is not black, but rather of a bronze colour; and the hair of his head, although somewhat “woolly,” is longer than Swartboy’s, and less inclined to take root at both ends! Where the line of Swartboy’s nose is concave, that of the other is convex, and the nose itself almost aquiline. A dark piercing eye, a row of white teeth regularly set, lips of moderate thickness, a well-proportioned form, and erect attitude, give to this individual, an aspect of grandeur and gravity, both of which are in complete contrast with the comic picture presented by the short stout body and grinning countenance of the Bushman.

The costume of the tall man has something graceful about it. It consists of a tunic-like skirt suspended around the waist and hanging down to mid-thigh. There is something peculiar in this skirt. It has the appearance of a fringe or drapery of long white hairs, not plaited or woven, but hanging free and full. It is, in fact, the true costume of a savage; and consists simply of a number of antelope’s tails—the white tails of the gnoo—strung together around the waist, and allowed to fall to their full length down the thighs. A sort of “tippet” of the same surrounding the shoulders, with copper rings on the ankles and armlets encircling the wrist, a bunch of ostrich-feathers waving from his crown, and a string of beads around his neck, complete the costume of Congo the Kaffir—for to that nation of romantic savages belonged the wagon-driver of the Van Wyks.

What! a Kaffir the driver of a wagon? you will exclaim. You can hardly realise the idea, that a Kaffir—a warrior, as you may deem him—could be employed in so menial an office as wagon-driving! But it is even so. Many Kaffirs are so engaged in the Cape Colony,—indeed, many thousands; and in offices of a more degrading kind than driving a wagon team—which by the way, is far from being considered an unworthy employment in South Africa, so far that the sons of the wealthiest boors may often be seen mounted upon the voor-kist and handling the long bamboo whip with all the ability of a practised “jarvey.” There is nothing odd about Congo the Kaffir being wagon-driver to the Van Wyks. He was a refugee, who had escaped from the despotic rule of the blood-stained monster Chaaka. Having in some way offended the tyrant, he had been compelled to flee for his life; and, after wandering southward, had found safety and protection among the colonists. Here he had learnt to make himself a useful member of civilised society, though a lingering regard for ancient habits influenced him still to retain the costume of his native country—the country of the Zooloo Kaffir.

No one could have blamed him for this; for, as he stood with his ample leopard-skin kaross suspended togalike from his shoulders, the silvery skirt draping gracefully to his knees, and his metal rings glittering under the blaze of the camp-fire, a noble picture he presented,—a savage but interesting picture. No one could blame Congo for wishing to display his fine form in so becoming a costume.

And no one did. No one was jealous of the handsome savage.

Yes,—one. There was one who did not regard him with the most amiable feelings. There was a rival who could not listen to Congo’s praise with indifference. One who liked not Congo. That rival was Swartboy. Talk of the rivalry that existed between the hunters Hendrik and Groot Willem, of that between Klaas and Jan. Put both into one, and it would still fall far short of the constant struggles for pre-eminence that were exhibited between the rival “whips,” Swartboy the Bushman, and Congo the Kaffir.

Swartboy and Congo were the only servants with the expedition. Cooks or other attendants the young yägers had none. Not but that the rich landdrost,—for it must be remembered that Von Bloom was now chief magistrate of his district,—and the wealthy boor could have easily afforded a score of attendants upon each trio of hunters. But there were no attendants whatever beyond the two drivers. This was not on the score of economy. No such thing. It was simply because the old soldiers, Hendrik Von Bloom and Diedrik Van Wyk, were not the men to pamper their boys with too much luxury.

“If they must go a-hunting, let them rough it,” said they; and so they started them off, giving them a brace of wagons to carry their impedimenta—and their spoils.

But the young yägers needed no attendance. Each knew how to wait upon himself. Even the youngest could skin an antelope and broil its ribs over the fire; and that was about all the cookery they would require till their return. The healthy stomach of the hunter supplies a sauce more appetising than either Harvey or Soyer could concoct with all their culinary skill.

Before arriving at their present camp the young yägers had been out several weeks; but, although they had hunted widely, they had not fallen in with any of the great game, such as giraffes, buffaloes, or elephants; and scarce an adventure worth talking about. A day or two before a grand discussion had taken place as to whether they should cross the great river, and proceed farther northward, in search of the camelopard and elephant, or whether they should continue on the southern side, jäging springboks, hartebeests, and several other kinds of antelopes. This discussion ended in a resolve to continue on to the north, and remain there till their time was up,—the time of course being regulated by the duration of college and school vacations, and leave of absence from the “Corps.”

Groot Willem had been the principal adviser of this course, and Hans his backer. The former was desirous of jäging the elephant, the buffalo, and giraffe,—a sport at which he was still but a novice, as he had never had a fair opportunity of hunting these mighty giants of the wood; while Hans was equally desirous of an exploring expedition that would bring him in contact with new forms of vegetable life.

Strange as it may appear, Arend threw in his vote for returning home; and, stranger still, that the hunter Hendrik should join him in this advice!

But almost every thing can be explained, if we examine it with care and patience; and the odd conduct of the two “cornets” was capable of explanation.

Hans slyly hinted that it was possible that a certain brunette, Wilhelmina, might have something to do with Hendrik’s decision; but Groot Willem, who was a rough plain-spoken fellow, broadly alleged, that it was nothing else than Trüey that was carrying Arend’s thoughts homeward; and the consequence of these hints and assertions was, that neither Hendrik nor Arend offered any further opposition to going northward among the elephants, but, blushing red to the very eyes, both were only too glad to give in their assent and terminate the discussion.

Northward then became the word:—northward for the land of the tall giraffe and the mighty elephant!

The young yägers had arrived on the southern bank of the Orange River, opposite to a well-known “drift,” or crossing-place. There chanced to be a freshet in the river; and they had encamped, and were waiting until the water should fall and the ford become passable.

Chapter Three.

How Congo Crossed a “Drift.”

Next morning, by break of day, our yägers were astir, and the first object upon which they rested their eyes was the river. To their joy it had fallen several feet, as they could tell by the water-mark upon the trees.

The streams of South Africa, like those of most tropical and sub-tropical countries, and especially where the district is mountainous, rise and fall with much greater rapidity than those of temperate climes. Their sudden rise is accounted for by the great quantity of water which in tropical storms is precipitated within a short period of time—the rain falling, not in light sparse drops, but thick and heavy, for several hours together, until the whole surface of the country is saturated, and every rivulet becomes a torrent.

Of these storms we have an exemplification in our summer thunder-showers—with their big rain-drops, when in a few minutes the gutter becomes a rivulet and the rut of the cartwheel a running stream. Fortunately these “sunshiny” showers are of short duration. They “last only half-an-hour,” instead of many hours. Fancy one of them continuing for a whole day or a week! If such were to be the case, we should witness floods as sudden and terrible as those of the tropics.

The quick fall in the streams of South Africa is easily accounted for—the principal reason being that the clouds are their feeders, and not, as with us, springs and lakes. Tropic rivers rarely run from reservoirs; the abrupt cessation of the rain cuts off their supply, and the consequence is the sudden falling of their waters. Evaporation by a hot sun, and large absorption by the dry earth, combine to produce this effect. Now the young yägers saw that the “Gareep” (such is the native name of the Orange River) had fallen many feet during the night; but they knew not whether it was yet fordable. Though the place was a “drift” used by Hottentots, Bechuanas, traders, and occasionally “trek-boors,” yet none of the party knew any thing of its depth, now that the freshet was on. There were no marks to indicate the depth—no means by which they could ascertain it. They could not see the bottom, as the water was of a yellow-brown colour, in consequence of the flood. It might be three feet—it might be six—but as the current was very rapid, it would be a dangerous experiment to wade in and measure its depth in that way.

What were they to do then? They were impatient to effect a crossing. How were they to do so in safety?

Hendrik proposed that one of them should try the ford on horseback. If they could not wade it, they might swim over. He offered to go himself. Groot Willem, not to be outdone by Hendrik in daring, made a similar proposal. But Hans, who was the eldest of the party, and whose prudent counsels were usually regarded by all, gave his advice against this course. The experiment would be too perilous, he said. Should the water prove too deep, the horses would be compelled to swim, and with so rapid a current they might be carried far below the “drift,”—perhaps down to where the banks were high and steep. There they should not be able to climb out, and both horse and rider might perish.

Besides, urged Hans, even should a rider succeed by swimming to reach the opposite side in safety, the oxen and wagons could not get over in that way, and where would be the use of crossing without them? None whatever. Better, therefore, to wait a little longer until they should be certain that the river had subsided to its usual level. That they could ascertain by the water ceasing to fall any further, and another day would decide the point. It would only be the loss of another day.

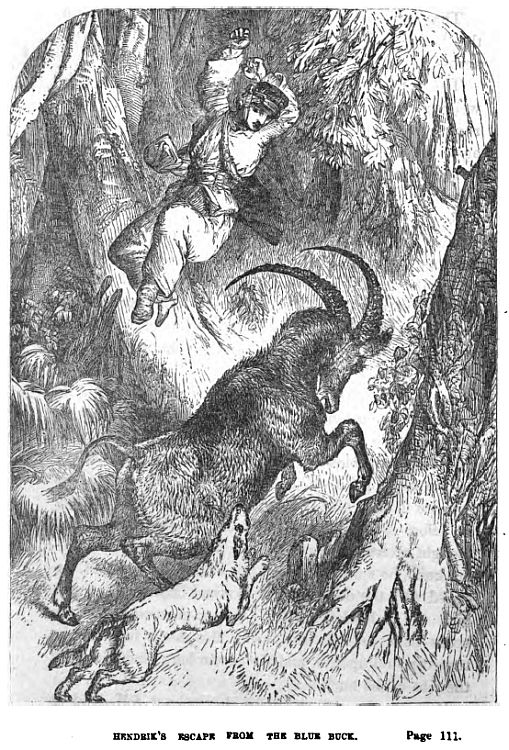

Hans’s reasoning was good, and so was his counsel. Hendrik and Groot Willem acknowledged this, and agreed to act upon it; but for all that, Groot Willem, who was longing to get among the giraffes, buffaloes, and elephants, felt a strong desire to attempt the crossing; and Hendrik, too, was similarly inclined, from the sheer love of adventure—for Hendrik’s fault was that of being over-courageous.

Both would have risked the river—even to swimming it—had it been practicable for the teams to have crossed, but as that was not believed possible, they agreed, though with rather a bad grace, to wait upon the water another day.

But, after all, they were not to wait a day,—scarcely an hour. In an hour from that time they had crossed the drift—wagons, oxen, and all—and were trekking over the plain on the opposite side!

What had led to their so suddenly changing their resolution? How had they ascertained that the drift was fordable? For a knowledge of that fact they were indebted to Congo the Kaffir.

While engaged in their discussion as to the depth of the river, the latter had been observed standing upon the bank and throwing large pebbles into the stream. Thinking it was merely some freak or superstition on the part of the savage, none of them had taken any notice of him, Swartboy excepted. The Bushman was watching the Kaffir, with glances that bespoke a keen interest in his movements.

At length a loud scornful laugh, from Swartboy, accompanying a series of rather rough phrases, directed the attention of the young yägers upon the Kaffir.

“My footy, Congo! ole fool you! b’lieve you tell depth so? tink so, ole skellum? Ha! ha! ha! you bania groot ole humbug! Ha! ha! ha!”

The Kaffir took no notice of this rather insulting apostrophe, but continued to fling his pebbles as before; but the young yägers, who were also watching him, noticed that he was not throwing them carelessly, but in a peculiar manner, and their attention now became fixed upon him.

They saw that each time as the pebble parted from his fingers, he bent suddenly forward, with his ear close to the surface, and in this attitude appeared to listen to the “plunge” of the stone! When the sound died away, he would rise erect again, fling another pebble farther out than the last, and then crouch and listen as before?

“What’s the Kaffir about?” asked Hendrik of Groot Willem and Arend, who, being his masters, were more likely to know.

Neither could tell. Some Zooloo trick, no doubt; Congo knew many a one. But what he meant by his present demonstration neither could tell. Swartboy’s conjecture appeared to be correct, the Kaffir was sounding the depth of the drift.

“Hilloa, there! Congo!” cried Groot Willem. “What are ye after, old boy?”

“Congo find how deep drift be, baas Willem,” was the reply.

“Oh! you can’t tell that way; can you?”

The Kaffir made answer in the affirmative.

“Bah!” ejaculated Swartboy, jealous of the interest his rival was beginning to excite; “da’s all nonsense; ole fool know noffin ’t all ’bout it,—dat he don’t.”

The Kaffir still took no notice of Swartboy’s gibes—though they no doubt nettled him a little—but kept on casting the pebbles, each one, as already stated, being flung so as to fall several feet beyond the one that preceded it. He continued at this, until the last pebble was seen to plunge within a yard or two of the opposite side of the current, here more than a hundred yards wide. Then raising himself erect, and turning his face to the young yägers, he said in firm but respectful tones—

“Mynheeren, you drift may cross—now.”

All regarded him with incredulous glances.

“How deep think you it is?” inquired Hans. The Kaffir made answer by placing his hands upon his hips. It would reach so high.

“My footy!” exclaimed Swartboy, in derision. “It’s twice dar depth. Do you want drown us, ole fool?”

“May drown you—nobody else!” quietly replied the Kaffir, at the same time measuring Swartboy with his eye, and curling his lip in derision of the Bushman’s short stature.

The young yägers burst out into a loud laugh. Swartboy felt the sting, but for some moments was unable to retort.

At length he found words—

“All talk, you ole black, all talk! You make groot show,—you berry wise,—you want wagon sweep off,—you want drown da poor oxen,—you pretend so deep. If tink so, go wade da drift,—go wade yourself! Ha!”

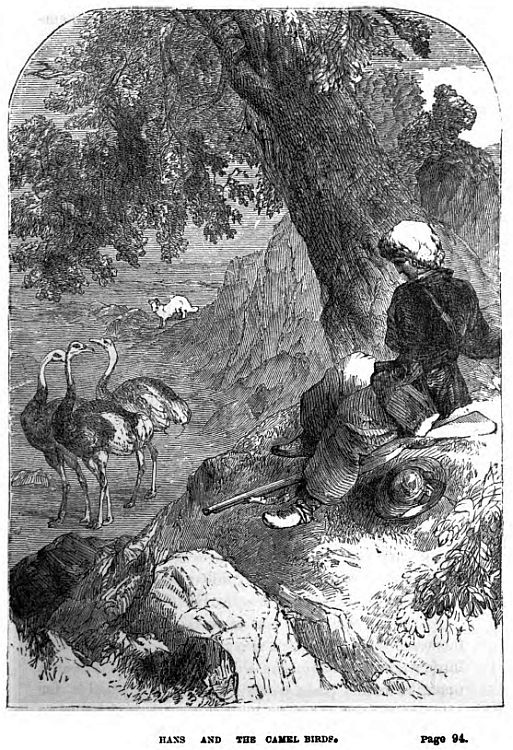

Swartboy thought by this challenge he had put the finisher on the Kaffir. He believed that the latter would not dare to try the ford, in spite of his assertion about its depth. But Swartboy was doomed to disappointment and humiliation.

Scarcely had he uttered the sneering challenge when the Kaffir, having bent a glance upon the rest, and seeing, that they regarded him with looks of expectation, turned round and dashed down the bank to the edge of the water.

All saw that he was bent upon crossing. Several of them uttered cries of warning, and cautioned him to desist.

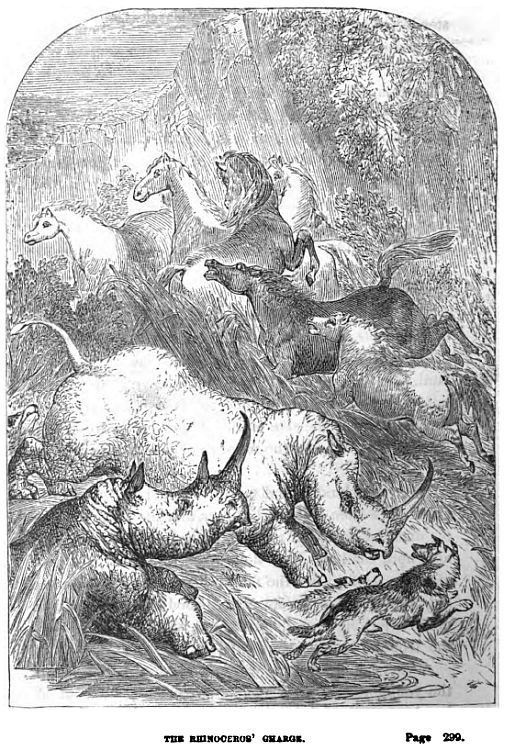

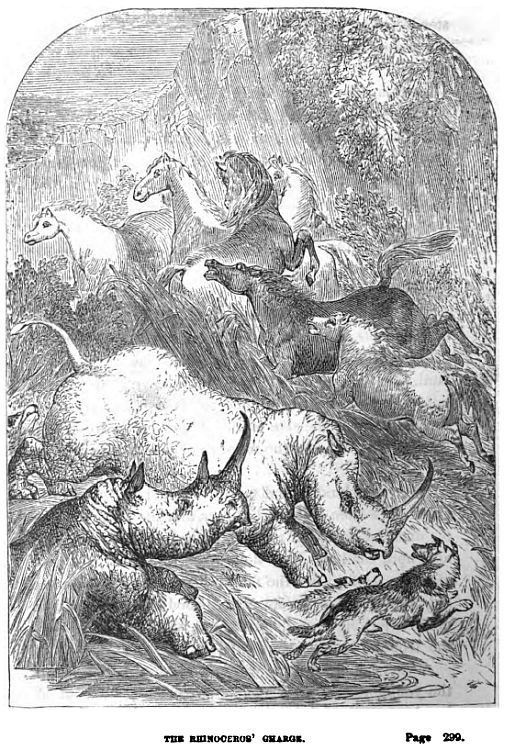

But the Zooloo spirit was roused, and the savage did not heed the warning cries. He did not hurry madly into the current, however; but set about the business with caution and design. They saw him stoop down by the edge of the water, and the next moment rise erect again, holding in his hands a large stone that could not have weighed much less than a hundredweight. This, to the astonishment of all, he raised upon the crown of his head, and, holding it in that position, marched boldly into the water!

All saw the object of his carrying the stone,—which was, of course, to enable him by its additional weight to stem the strong current! In this he was quite successful, for although the water at certain places rose quite to his waist, in less than five minutes he stood high and dry on the opposite bank.

A cheer greeted him, in which all but Swartboy joined, and another received him on his return; and then the oxen were inspanned, and the horses saddled and mounted, and wagons, oxen, dogs, horses, and yägers, all crossed safely over, and continued their route northward.

Chapter Four.

A Brace of “Black Manes.”

If the young yägers had met with but few adventures south of the Gareep, they were not long north of it before they fell in with one of sufficient interest to be chronicled. It occurred at their very first camp after crossing.

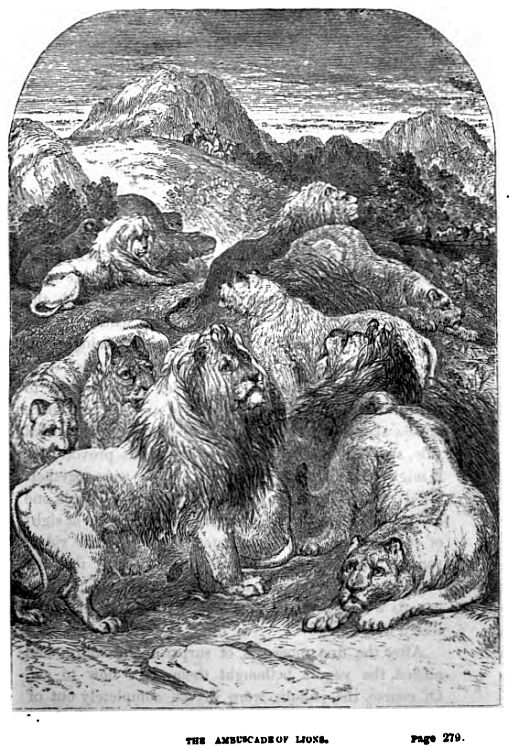

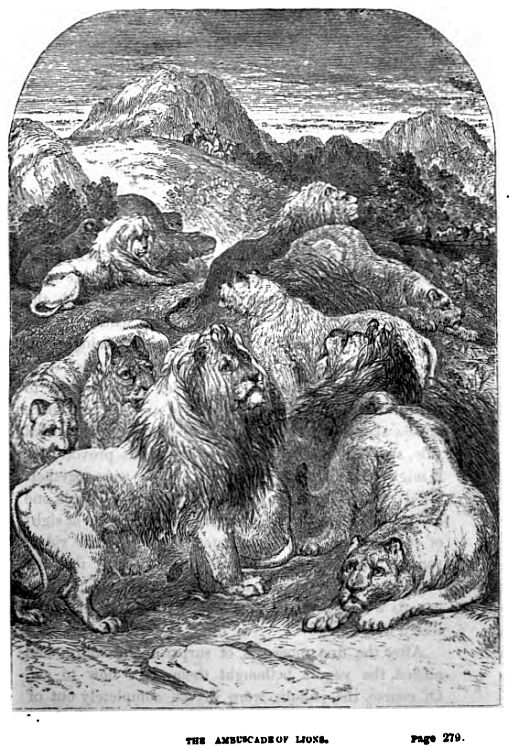

They had chosen for their camp the side of a “vley,” in the midst of a wide plain, where there chanced to be both grass and water, though both of a rather indifferent kind. The plain was tolerably open, though here and there grew clumps of low bushes, and between these stood at intervals the dome-shaped houses of white ants—those of the Termes mordax—rising to the height of several feet above the surface.

They had just outspanned and permitted their oxen to wander upon the grass, when the voice of Swartboy was heard exclaiming—

“De leuw! de leuw!”

All looked where Swartboy pointed. There, sure enough, was a lion,—a large “schwart-fore-life,” or black-maned one,—right out upon the plain, and beyond the place where the oxen were browsing.

There was a clump of “bosch” just behind the lion. Out of this he had come at sight of the oxen; and, having advanced a few yards, he had lain down among the grass, and was now watching the animals as a cat would a mouse, or a spider the unconscious fly.

They had scarcely set their eyes upon him when another was seen issuing from the “bosch,” and, with stealthy trot, running up to the side of her companion. Her companion, I say, because the second was a lioness, as the absence of a mane and the tiger-like form testified. She was scarcely inferior in size to the lion, and not a bit less fierce and dangerous in any encounter she might chance to fall in with.

Having joined the lion, she squatted beside him; and both now sat upon their tails, like two gigantic cats, with full front towards the camp, and evidently eyeing the oxen with hungry looks.

Horses, hunters, drivers, and dogs, were all in sight; but what cared the lions for that? The tempting prey was before them, and they evidently meditated an attack,—if not just then, whenever the opportunity offered. Most certainly they contemplated supping either upon ox-beef or horse-flesh.

Now these were the first lions that had been encountered upon the expedition. “Spoor” had been seen several times, and the terrible roar had been heard once or twice around the night-camp; but the “king of beasts” now appeared for the first time in propria persona, with his queen along with him, and of course his presence was productive of no small excitement in the yäger camp. It must not be denied that this excitement partook largely of the nature of a “panic.”

The first fear of the hunters was for their own skins, and in this both Bushman and Kaffir equally shared. After a time, however, this feeling subsided. The lions would not attack the camp. They do so only on very rare occasions. It was the camp animals they were after, and so long as these were present, they would not spring upon their owners. So far there was no danger, and our yägers recovered their self-possession.

But it would not do to let the carnivorous brutes destroy their oxen,—that would not do. Something must be done to secure them. A kraal must be made at once, and the animals driven into it. The lions lay quietly on the plain, though still in a menacing attitude. But they were a good way off—full five hundred yards—and were not likely to attack the oxen so close to the camp. The huge wagons—strange sight to them—no doubt had the effect of restraining them for the present. They either waited until the oxen should browse nearer, or till night would enable them to approach the latter unobserved.

As soon, then, as it was perceived that they were not bent upon an immediate attack, Groot Willem and Hendrik mounted their horses, rode cautiously out beyond the oxen, and quietly drove the latter to the other side of the vley. There they were herded by Klaas and Jan; while all the rest, Swartboy and Congo included, went to work with axe and bill-hook in the nearest thicket of “wait-a-bit” thorns. In less than half-an-hour a sufficient number of bushes were cut to form, with the help of the wagons, a strong kraal; and inside this, both horses and oxen were driven,—the former made fast to the wheel-spokes, while the latter were clumped up loosely within the enclosure.

The hunters now felt secure. They had kindled a large fire on each side of the kraal, though they knew that this will not always keep lions off. But they trusted to their guns; and as they would sleep inside the canvass tents of their wagons, closing both “voor” and “achter-claps,” they had nothing to fear. It would be a hungry lion, indeed, that would have attempted to break the strong kraal they had made; and no lion, however hungry, would ever think of charging into a wagon.

Having made all secure, therefore, they seated themselves around one of their fires, and set about cooking their dinner, or rather dinner-supper, for it was to include both meals. Their journey prevented them from dining earlier.

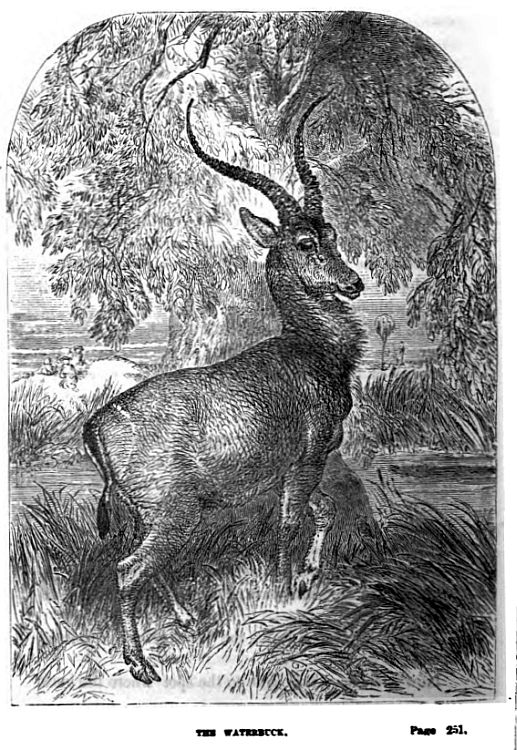

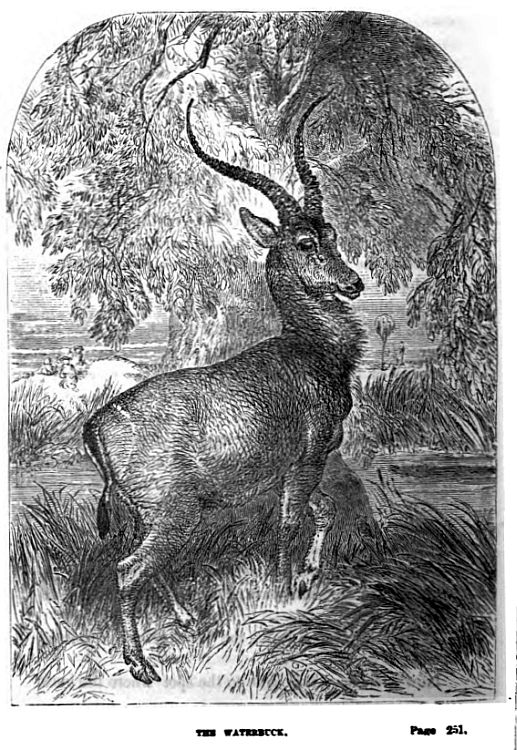

They chanced to have little else than biltong, or dried meat, to cook. The long wait by the drift had consumed their stock of fine springbok venison, which they had laid in some days before. It is true they had venison in camp, but it was that of the “reitbok,” or reed-buck—so called from its habit of frequenting the long reeds by the banks of rivers; and it was while they were journeying through a belt of these after crossing the drift, that this one had been shot by Hendrik. A small antelope the reitbok is—the Antilope eleotragus of naturalists. It stands less than three feet in height, formed much like the springbok, but with a rougher coat of hair, of an ashy grey colour, and silver white underneath. Its horns, however, are not lyrate, as in the springbok, but rise first in the plane of its forehead, and then curve boldly forward to the tips. They are about twelve inches in length, wrinkled at the base, prominently ringed in the middle, and smooth near the points. The reitbok, as its name implies, inhabits the reedy bottoms by the margins of streams and rivers, and its food consists of plants growing in humid and marshy situations. Hence its flesh is inferior to that of most South African antelopes, and it was not a favourite with the young yägers. Although it had been brought along, they preferred even the dry biltong, and it was left to the less delicate appetites of Swartboy and Congo.

Now the hunters, Hendrik and Groot Willem, would have gone out to look for a springbok, or some other game, but the presence of the lions prevented that; and so the boys were obliged to content themselves with a slice of the biltong; and each, having cut him a short stick for a spit, set about broiling his piece over the coals.

During all this time the lion and lioness kept the position they had taken on the plain, scarce once having changed their attitude. They were waiting patiently the approach of night.

Groot Willem and Hendrik had both advised making an attack upon them; but in this case they again gave way to the more prudent counsel of Hans, strengthened, perhaps, by his reminding them of the instructions they had received from both their fathers at setting out. These instructions were,—never to attack a lion without good reason for so doing, but always to give the “ole leuw” a wide berth when it was possible to do so. It is well known that the lion will rarely attack man when not first assailed; and therefore the advice given to the young yägers was sound and prudent? and they followed it.

It wanted yet an hour or two of sunset. The lions still sat squatted on the grass, closely observed by the hunters.

All at once the eyes of the latter became directed upon a new object. Slowly approaching over the distant plain, appeared two strange animals, similar in form, and nearly so in size and colour. Each was about the size of an ass, and not unlike one in colour,—especially that variety of the ass which is of a buff or fulvous tint. Their forms, however, were more graceful than that of the ass, though they were far from being light or slender. On the contrary, they were of a full, round, bold outline. They were singularly marked about the head and face. The ground colour of these parts was white, but four dark bands were so disposed over them as to give the animals the appearance of wearing a headstall of black leather. The first of these bands descended in a streak down the forehead; another passed through the eyes to the corners of the mouth; a third embraced the nose; while a fourth ran from the base of the ears passing under the throat—a regular throat-strap—thus completing the resemblance to the stall-halter.

A reversed mane, a dark list down the back, and a long black bushy tail reaching to the ground, were also characters to be observed. But what rendered these animals easily to be distinguished from all others was the splendid pair of horns which each carried. These horns were straight, slender, pointing backwards almost horizontally. They were regularly ringed till within a few inches of their tips, which were as sharp as steel spits. In both they were of a deep jet colour, shining like ebony, and full three feet in length. But what was rather singular, the horns of the smaller animal—for there was some difference in their size—were longer than those of the larger one! The former was the female, the latter the male, therefore the horns of the female were more developed than those of the male—an anomaly among animals of the antelope tribe, for antelopes they were. The young yägers had no difficulty in distinguishing their kind. At the first glance they all recognised the beautiful “oryx,” one of the loveliest animals of Africa, one of the fairest creatures in the world.

Chapter Five.

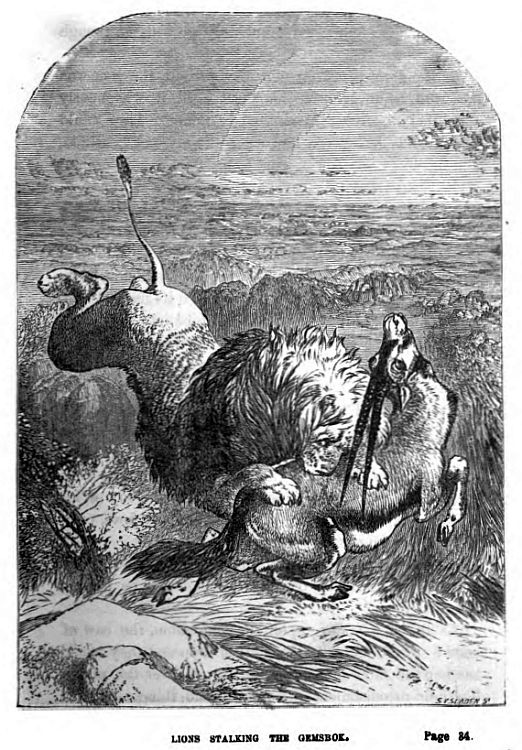

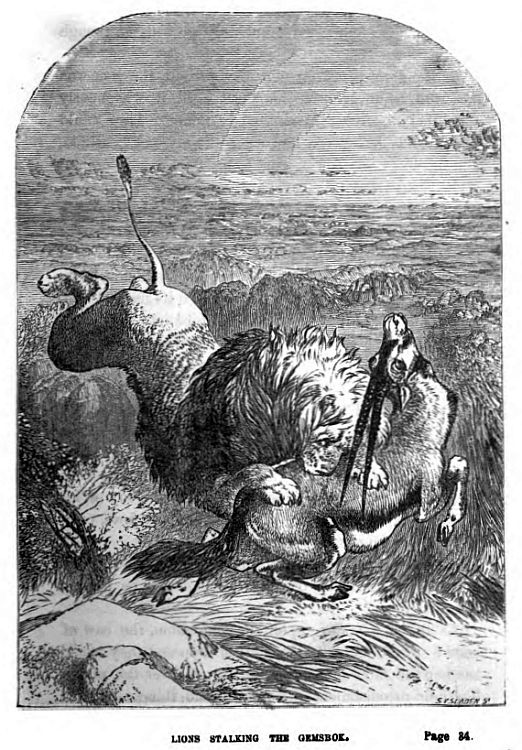

Lions Stalking the Gemsbok.

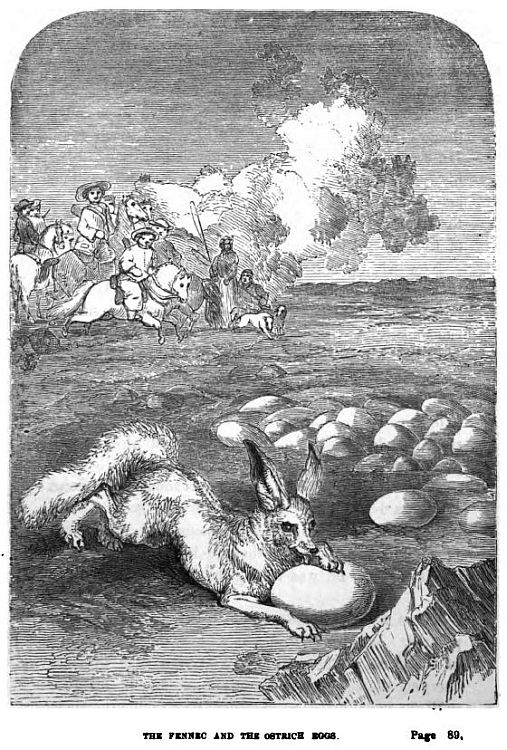

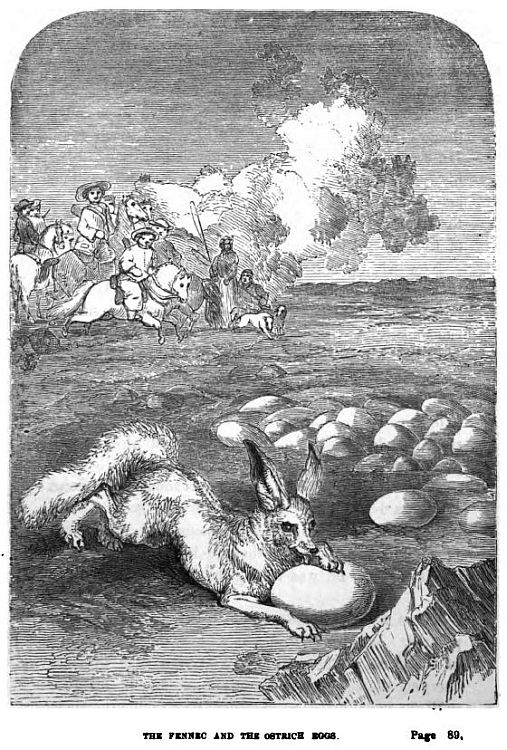

On seeing the “gemsbok”—for by such name is the oryx known to the Cape colonists—the first thought of the young yägers was how they should kill or capture one of them. Beautiful as these creatures looked upon the plain, our hunters would have fancied them better on the spit—for they well knew that the venison of the gemsbok is delicious eating—not surpassed by that of any other antelope, the eland perhaps excepted.

The first thought of the yägers, then, was a steak of gemsbok venison for dinner. It might throw their dinner a little later, but it would be so much of a better one than dry biltong, that they were willing to wait.

The slices of jerked meat, already half-broiled, were at once put aside, and guns were grasped in the place of roasting-sticks.

What was the best course to be pursued? That was the next question.

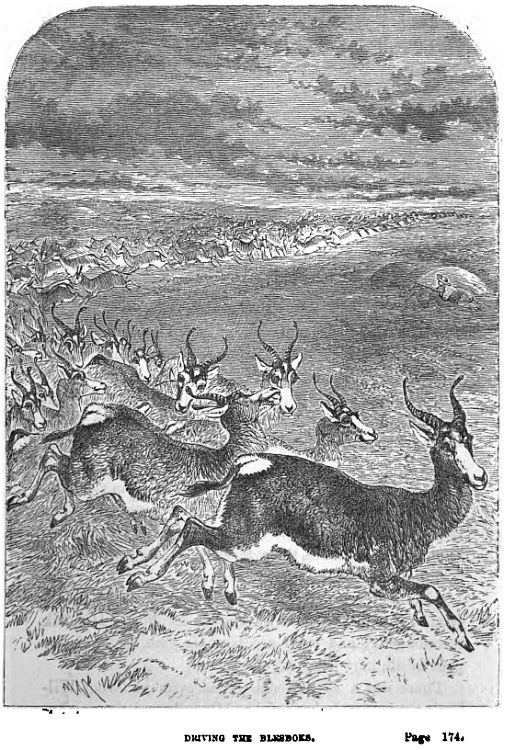

It would scarce be possible to stalk the gemsboks. They are among the most wary of antelopes. They rarely approach near any cover that might shelter an enemy; and when alarmed they strike off in a straight line, and make for the open desert plains—their natural home. To stalk them, is a most difficult thing, and rarely attempted by the hunter. They can only be captured by a swift horse, and after a severe chase. Even from the swiftest horse they often make their escape; for in the first burst of a mile or two they can run like the wind. A good horse, however, has more “bottom” than they, and if well managed will in time overtake them.

The hunters having seized their guns, next thought of their horses. Should they saddle and ride out after the gemsboks? That would have been their course at once, and without further consideration, had they not observed that the antelopes were coming directly towards them. If they continued in the same course much longer, they, the yägers, need not stir from the spot. The game would approach within shot and save them the trouble of a chase. This would be very agreeable, as the hunters were hungry, and their horses tired after a hard day’s journeying.

There was some probability that the gemsboks would give them the chance they wished for. The camp was well hidden among the bushes. The smoke of the fire alone showed its situation, but the antelopes might not perceive this, or if so, might not regard it as a thing to be feared. Besides, as Groot Willem and Hendrik observed, the vley was close by, and both believed the antelopes were on their way to the water. The student Hans, however, corrected them in this belief, by telling them that the oryx is an animal that never drinks,—that it is quite independent of springs, streams, or vleys,—one of those creatures which Nature has formed to dwell in the desert, where no water exists! It was not likely then that the gemsboks were coming to the vley. The hunters need make no calculation on that.

At all events, they were certainly approaching the camp. They were heading straight for it, and were already less than a thousand yards from the spot. There would scare be time to saddle before they should come within shot, or else start off alarmed at the appearance of the smoke. The hunters, therefore, gave up all thoughts of a chase; and, crouching forward to the outer edge of the grove, they knelt down behind the bushes to await the approach of the antelopes.

The latter still kept steadily on, apparently unconscious of danger. Surely they had not yet perceived the smoke, else they would have shown symptoms either of curiosity or alarm! The wind was blowing in the same direction in which they marched, or their keen sense of smell would have warned them of the dangerous proximity of the hunter’s camp. But it did not; and they continued with slow but unaltered pace to approach the spot, where no less than six dark muzzles—a full battery of small arms—were waiting to give them a volley.

It was not the destiny of either of the gemsboks to die by a leaden bullet. Death, sudden and violent awaited them, though not from the hand of man. It was to come from a different quarter.

As the yägers lay watching the approach of the antelopes, their eyes had wandered for a moment from the lions; but a movement on the part of these again drew attention to them. Up to a certain period they had remained in an upright attitude, squatted upon their tails, but all at once they were observed to crouch flat down, as if to conceal themselves under the grass, while their heads were turned in a new direction. They were turned towards the gemsboks. They had caught sight of the latter as they approached over the plain; and it was evident that they contemplated an attack upon them.

Now if the antelopes continued on in the same course, it would carry them quite clear of the lions, so that the latter would have no advantage. A gemsbok can soon scour off from a lion, as the latter is at best but a poor runner, and secures his prey by a sudden spring or two, or else not at all. Unless, therefore, the lions could obtain the advantage of getting within bounding distance of the antelopes without being seen by them, their chances of making a capture would be poor enough.

They knew this, and to effect that purpose—that of getting near—now appeared to be their design. The lion was observed to crawl off from the spot in a direction that would enable him to get upon the path of the gemsboks, between them and the camp. By a series of manoeuvres,—now crawling flat along the grass, like a cat after a partridge; now pausing behind a bush or an ant-heap to survey the game; then trotting lightly on to the next,—he at length reached a large ant-hill that stood right by the path in which the antelopes were advancing. He seemed to be satisfied of this, for he stopped here and placed himself close in to the base of the hill, so that only a small portion of his head projected on the side towards the game. His whole body, however, and every movement he made, were visible to the hunters from their ambush in the grove.

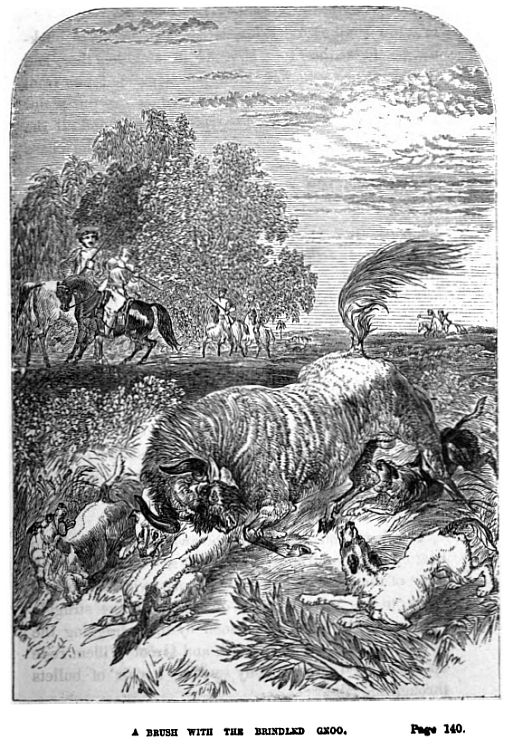

But where was the lioness? She was no longer by the bosch where first seen. Where had she gone? Not with the lion? No. On the contrary, she had gone in a direction nearly opposite to that taken by him. Their eyes had been busy with his movements, and they had not noticed hers. Now, however, that the lion had come to a halt, they looked abroad for his mate, and saw her far out upon the plain. They saw that she was progressing in the same way the lion had done,—now crawling among the grass, now trotting swiftly from bush to bush, and pausing a moment behind each, but evidently bending her course so as to arrive in the rear of the antelopes!

The “strategy” of the lions was now perceived. They had evidently planned it before separating. The lion was to place himself in ambush upon the path, while the lioness swept round to the rear and forced the antelopes forward; or should the latter become alarmed and retreat, the lion could then show himself in pursuit, and run the frightened game back into the clutches of the lioness.

The thing was well calculated, and although it was likely to rob the hunters of their game, they had grown so interested in the movements of the carnivora and their intended victims, that they thought only of watching the spectacle to its end.

The ambuscade was well planned, and in a few minutes its success was no longer doubtful. The gemsboks advanced steadily towards the ant-hill, occasionally switching about their black bushy tails; but that was to rid their flanks of the flies, and not from any apprehension of danger.

The lioness had completed the great détour she had made, and was now seen crouching after them, though still far to the rear.

As the antelopes drew near the ant-hill, the lion was observed to draw back his head until it was nearly concealed under his black shaggy mane. They could not possibly have seen him where he lay, nor he them, and he now appeared to trust to his ears to inform him of their approach.

He waited till both were opposite, and broadside toward him, at the distance of less than twenty paces from the hill. Then his tail was seen to vibrate with one or two quick jerks, his head shot suddenly forth, his body spread out apparently to twice its natural size, and the next moment he rose like a bird into the air!

With one bound he cleared the wide space that separated him from the nearest of the gemsboks, alighting on the hind-quarters of the terrified animal. A single blow of his powerful paw brought the antelope on its haunches; and another, delivered almost at the same instant, stretched its body lifeless on the plain!

Without looking after the other, or seeming to care further about it, the lion sprang upon the body of his victim, and, clutching its throat between his jaws, commenced drinking its warm blood.

It was the bull gemsbok which the lion had pulled down, as this was the one that happened to be nearest the hill.

As the lion sprang upon her companion, the cow of course started with affright, and all supposed they would see her the next moment scouring off over the plains. To their astonishment she did no such thing. Such is not the nature of the noble oryx. On the contrary, as soon as she recovered from the first moments of alarm, she wheeled round towards the enemy; and, lowering her head to the very ground, so that her long horns projected horizontally in front, she rushed with all her strength upon the lion! The latter, in full enjoyment of his red draught, saw nothing of this manoeuvre. The first intimation he had of it was to feel a pair of spears pierced right through his ribs, and it is not likely he felt much more.

For some moments a confused struggling was observed, in which both lion and oryx seemed to take part; but the attitudes of both appeared so odd, and changed so rapidly, that the spectators could not tell in what manner they were combating. The roar of the lion however had ceased, and was now succeeded by the more shrill tones of the lioness, who, bounding forward upon the spot, mixed at once in the mêlée.

A single touch of her claws brought the cow oryx to the earth, and ended the strife; and the lioness now stood over the victims screaming her note of triumph.

Was it a note of triumph? There was something odd in its tone—something singular in the movements of the creature that uttered it—something strange about the whole thing. Why was the lion silent? His roar had ceased, and he lay embracing the carcass of the bull gemsbok, and apparently drinking its blood. Yet he was perfectly without motion, not a muscle could be seen to move, not a quiver of his tawny hide betokened that he breathed or lived! Was he dead?

Chapter Six.

An Angry Lioness.

Certainly there was something mysterious about the matter. The lion still kept his position; no motion could be observed, no sound escaped him; whereas the lioness uttered incessantly her shrill growling, at the same time pacing to and fro, round and round, the confused heap of bodies! She made no attempt to feed, though her prey lay bleeding before her. Surely her lord was not the cause of her abstinence! Did he insist upon having both the carcasses to himself?

Sometimes it is so. Sometimes an old male plays the selfish tyrant, and keeps the younger and weaker members of his family off, till he has gorged himself, permitting them to make a “second table” of his leavings.

In the present instance this was not likely. There were two whole carcasses,—large fat carcasses,—enough for both. Besides, the lioness was evidently the lion’s own mate—his wife. It was scarcely probable he would treat her so. Among human beings instances of such selfishness,—such a gross want of gallantry, are, I regret to say, by no means rare; but the young yägers could not believe the lion guilty of such shabby conduct—the lion, Buffon’s type of nobility! No such thing. But how was it? The lioness still growled and paced about, ever and anon stooping near the head of her partner, which was not visible from the camp, and placing her snout in contact with his as if kissing him. Still there was no sign of any response, no motion on his part; and, after watching for a good while without perceiving any, the hunters at length became satisfied that the lion was dead.

He was dead—as Julius Caesar or a door-nail, and so, too, was the brace of gemsboks. The lioness was the only living thing left from that sanguinary conflict!

As soon as the hunters became satisfied of this, they began to deliberate among themselves what was best to be done. They wished to get possession of the venison, but there was no hope of their being able to do so, as long as the lioness remained upon the ground.

To have attempted to drive her off at that moment would have been a most perilous undertaking. She was evidently excited to madness, and would have charged upon any creature that had shown itself in her neighbourhood. The frenzied manner in which she paced about, and lashed her sides with her tail, her fierce and determined look, and deep angry growl, all told the furious rage she was in. There was menace in her every movement. The hunters saw this, and prudently withdrew themselves—so as to be near the wagons in case she might come that way.

They thought that by waiting awhile she would go off, and then they could drag the antelopes up to camp.

But after waiting a good while, they observed no change in the conduct of the fierce brute. She still paced around as before, and abstained from touching the carcasses. As one of the yägers observed, she continued to “play the dog in the manger,”—would neither eat herself, nor suffer anybody else to eat.

This remark, which was made by little Jan, elicited a round of laughter that sounded in strange contrast with the melancholy howl of the lioness, which still continued to terrify the animals of the camp. Even the dogs cowered among the wheels of the wagons, or kept close to the heels of their masters. It is true that many of these faithful brutes, had they been set on, would have manfully battled with the lioness, big as she was. But the young yägers well knew that dogs before the paws of an angry lion are like mice under the claws of a cat. They did not think of setting them on, unless they had themselves made an attack; and that, the advice of Hans, coupled with the counsels they had received before leaving home, prevented them from doing. They had no intention of meddling with the lioness; and hoped she would soon retire, and leave the game, or part of it, on the ground.

After waiting a long while, and seeing that the lioness showed no symptoms of leaving the spot, they despaired of dining on oryx venison, and once more set to broiling their slices of biltong.

They had not yet commenced eating, when they perceived a new arrival upon the scene of the late struggle. Half-a-dozen hyenas appeared upon the ground; and although these had not yet touched the carcasses, but were standing a little way off—through fear of the lioness—their hungry looks told plainly what their intention was in coming there.

Now the presence of these hideous brutes was a new point for consideration. If the lioness should allow them to begin their feast upon the antelopes, in a very short while scarce a morsel of either would remain. The yägers, although they had resigned all hope of dining on the gemsbok venison, nevertheless looked forward to making their supper of it; but if the hyenas were permitted to step in, they would be disappointed.

How were the brutes to be kept off?

To drive them off would be just as perilous an undertaking as to drive off the lioness herself.

Once more Groot Willem and Hendrik talked about attacking the latter; but, as before, were opposed by Hans, who had to use all his influence with his companions before he could induce them to abandon the rash project.

At this moment an unexpected proposal put an end to their discussion.

The proposal came from Congo the Kaffir. It was neither less nor more than that he himself should go forth and do battle with the lioness!

“What! alone?”

“Alone.”

“You are mad, Congo. You would be torn to pieces!”

“No fear, Mynheeren. Congo the leuw kill without getting scratch. You see, young masters.”

“What! without arms? without a gun?”

“Congo not know how use one,” replied the Kaffir, “you see how I do ’im,” he continued. “All Congo ask you not come in way. Young masters, here stay and Congo leave to himself. No danger. Mynheeren, Congo fear if go yonder help him—leuw very mad. Congo not care for that—so much mad, so much better—leuw no run away.”

“But what do you intend to do, Congo?”

“Mynheeren soon all see—see how Congo kill lion.”

The hunters were disposed to look upon the Kaffir as about to make a reckless exposure of his life. Swartboy would have treated the proposal as a boast, and laughed thereat, but Swartboy remembered the humiliation he had had in the morning on account of similar conduct; and though he feared to be farther outstripped in hunter-craft by his rival, he had the prudence upon this occasion to conceal his envy. He bit his thick lips, and remained silent. Some of the boys, and especially Hans, would have dissuaded Congo from his purpose; but Groot Willem was inclined to let him have his way. Groot Willem knew the Kaffir better than any of the others. He knew, moreover, that savage as he was, he was not going to act any foolish part for the mere sake of braggadocio. He could be trusted. So said Groot Willem.

This argument, combined with a desire to eat gemsbok venison for supper, had its effect. Arend and Hans gave in.

Congo had full permission to battle with the lioness.

Chapter Seven.

How Congo the Kaffir killed a Lioness.

Congo had now become an object of as great interest as in the morning. Greater in fact, for the new danger he was about to undergo—a combat with an enraged lioness—was accounted still greater than that of fording the Gareep, and the interest was in proportion. With eager eyes the young yägers stood watching him as he prepared himself for the encounter.

He was but a short while in getting ready. He was seen to enter the Van Wyk wagon, and in less than three minutes come out again fully armed and equipped. The lioness would not have long to wait for her assailant.

The equipment of the Kaffir must needs be described.

It was simple enough, though odd to a stranger’s eye. It was neither more nor less than the equipment of a Zooloo warrior.

In his right hand he held a bunch of assegais,—in all six of them.

What is an “assegai?”

It is a straight lance or spear, though not to be used as one. It is smaller than either of these weapons, shorter and more slender in the shaft, but like them armed with an iron head of arrow shape. In battle it is not retained in the hand, but flung at the enemy, often from a considerable distance. It is, in short, a “javelin,” or “dart,”—such as was used in Europe before fire-arms became known, and such as at present forms the war weapon of all the savage tribes of Southern Africa, but especially those of the Kaffir nations. And well know they how to project this dangerous missile. At the distance of a hundred yards they will send it with a force as great, and an aim as unerring, as either bullet or arrow! The assegai is flung by a single arm.

Of these javelins Congo carried six, spanning their slender shafts with his long muscular fingers.

The assegais were not the oddest part of his equipment. That was a remarkable thing which he bore on his left arm. It was of oval form, full six feet in length by about three in width, concave on the side towards his body, and equally convex on the opposite. More than any thing else did it resemble a small boat or canoe made of skins stretched over a framework of wood, and of such materials was it constructed. It was, in fact, a shield,—a Zooloo shield—though of somewhat larger dimensions than those used in war. Notwithstanding its great size it was far from clumsy, but light, tight, and firm,—so much so that arrow, assegai, or bullet, striking it upon the convex side, would have glanced off as from a plate of steel.

A pair of strong bands fastened inside along the bottom enabled the wearer to move it about at will; and placed upright, with its lower end resting upon the ground, it would have sheltered the body of the tallest man. It sheltered that of Congo, and Congo was no dwarf.

Without another word he walked out, the huge carapace on his left arm, five of the assegais clutched in his left hand, while one that he had chosen for the first throw he held in his right. This one was grasped near the middle, and carried upon the balance.

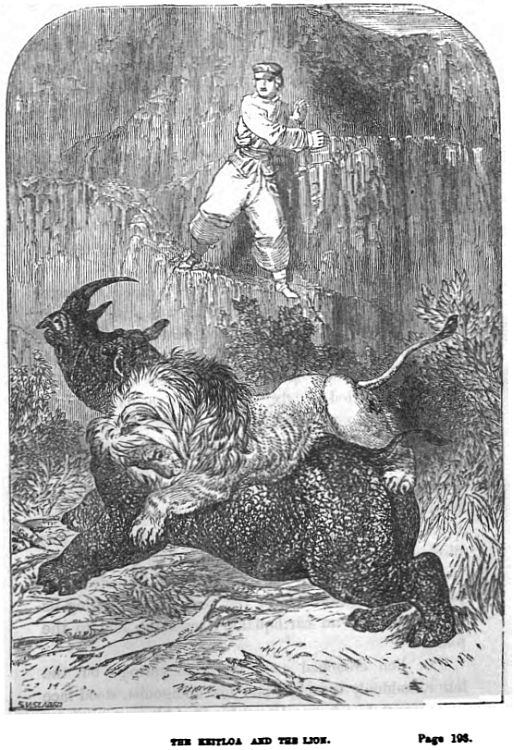

No change had taken place in the situation of affairs out upon the plain. In fact, there had not been much time for any. Scarce five minutes had elapsed from the time the Kaffir stated his purpose, until he went forth to execute it. The lioness was still roaming about, uttering her frightful screams. The hyenas were still there. The moment the Kaffir was seen approaching, the cowardly hyenas fled with a howl, and soon disappeared under the bosch.

Far different with the lioness. She seemed to pay no regard to the approach of the hunter. She neither turned her head, nor looked in the direction he was coming. Her whole attention was absorbed by the mass of bodies upon the plain. She yelled her savage notes as she regarded them. She was no doubt lamenting the fate of her grim and swarthy partner, that lay dead before her eyes. At all events, she did not seem to notice the hunter, until he had got within twenty paces of the spot!

At that distance the Kaffir halted, rested his huge shield upon the ground—still holding it erect—poised the assegai a moment in his right hand, and then sent it whizzing through the air.

It pierced the side of the tawny brute, and hung quivering between her ribs. Only for a moment. The fierce animal doubled round upon herself, caught the shaft in her teeth, and broke it off as if it had been a straw!

The blade of the assegai still remained in the flesh, but the lioness waited no longer. She had now perceived her enemy; and, uttering a vengeful scream, she sprang towards him. With one tremendous bound she cleared three-fourths of the space that lay between them, and a second would have carried her upon the shoulders of the Kaffir; but the latter was prepared to receive her, and, as she rose to her second leap, he disappeared suddenly from the scene! As if by magic he had vanished; and had not the boys been watching his every movement, they would have been at a loss to know what had become of him. But they knew that under that oval convex form, whose edges rested upon the earth, lay Congo the Kaffir. There lay he, like a tortoise in its shell, clutching the straps with all his might, and pressing his carapace firmly against the ground!

The lioness was more astonished than the spectators. At the second leap she pitched right down upon the shield, but the drum-like noise made by her weight, and the hard firm substance encountered by her claws, quite disconcerted her, and springing aside she stood gazing at the odd object with looks of alarm!

She stood but for a moment, and then, uttering a savage growl of disappointment, turned tail upon it, and trotted off!

This growl guided Congo. The shield was raised from the ground—only on one side, and but a very little way at first—just enough to enable the hunter to see the stern of the retreating lioness.

Then the Kaffir rose quickly to his feet, and, holding the shield erect, prepared for the casting of a second assegai.

This was quickly thrown and pierced the animal in the flank, where shaft and all remained sticking in the flesh. The lioness turned with redoubled fury, once more charged upon her assailant, and, as before, was met by the hard convex surface of the shield. This time she did not immediately retreat, but stood menacing the strange object, striking it with her clawed hoofs, and endeavouring to turn it over.

Now was the moment of peril for Congo. Had the lioness succeeded in making a capsize, it would have been all up with him, poor fellow! But he knew the danger, and with one hand clutching the leathern straps, and the other bearing upon the edge of the frame, he was able to hold firm and close,—closer even “than a barnacle to a ship’s copper.”

After venting her rage in several impotent attempts to break or overturn the carapace, the lioness at length went growling away towards her former position.

Her growls, as before, guided the actions of Congo. He was soon upon his feet, another assegai whistled through the air, and pierced through the neck of the lioness.

But, as before, the wound was not fatal, and the animal, now enraged to a frenzy, charged once more upon her assailant. So rapid was her advance that it was with great difficulty Congo got under cover. A moment later, and his ruse would have failed, for the claws of the lion rattled upon the shield as it descended.

He succeeded, however, in planting himself firmly, and was once more safe under the thick buffalo hide. The lioness now howled with disappointed rage; and after spending some minutes in fruitless endeavours to upset the shield, she once more desisted. This time, however, instead of going away, the angry brute kept pacing round and round, and at length lay down within three feet of the spot. Congo was besieged!

The boys saw at a glance that Congo was a captive. The look of the lioness told them this. Though she was several hundred yards off, they could see that she wore an air of determination, and was not likely to depart from the spot without having her revenge. There could be no question about it,—the Kaffir was in “a scrape.”

Should the lioness remain, how was he to get out of it? He could not escape by any means. To raise the shield would be to tempt the fierce brute upon him. Nothing could be plainer than that. The boys shouted aloud to warn him of his danger. They feared that he might not be aware of the close proximity of his enemy.

Notwithstanding the danger there was something ludicrous in the situation in which the Kaffir was placed; and the young hunters, though anxious about the result, could scarce keep from laughter, as they looked forth upon the plain.

There lay the lioness within three feet of the shield, regarding it with fixed and glaring eyes, and at intervals uttering her savage growls. There lay the oval form, with Congo beneath, motionless and silent. A strange pair of adversaries, indeed!

Long time the lioness kept her close vigil, scarce moving her body from its crouching attitude. Her tail only vibrated from side to side, and the muscles of her jaws quivered with subdued rage. The boys shouted repeatedly to warn Congo; though no reply came from the hollow interior of the carapace. They might have spared their breath. The cunning Kaffir knew as well as they the position of his enemy. Her growls, as well as her loud breathing, kept him admonished of her whereabouts; and he well understood how to act under the circumstances.

For a full half-hour this singular scene continued; and as the lioness showed no signs of deserting her post, the young yägers at length determined upon an attack, or, at all events, a feint that would draw her off.

It was close upon sunset, and should night come down what would become of Congo? In the darkness he might be destroyed. He might relax his watchfulness,—he might go to sleep, and then his relentless enemy would have the advantage.

Something must be done to release him from his narrow prison,—and at once.

They had saddled and mounted their horses, and were about to ride forth, when the sharp-eyed Hans noticed that the lioness was much farther off from the shield than when he last looked that way. And yet she had not moved,—at all events, no one had seen her stir—and she was still in the very same attitude! How then?

“Ha! look yonder! the shield is moving!”

As Hans uttered these words the eyes of all turned suddenly upon the carapace.

Sure enough, it was moving. Slowly and gradually it seemed to glide along the ground, like a huge tortoise, though its edges remained close to the surface. Although impelled by no visible power, all understood what this motion meant,—Congo was the moving power!

The yägers held their bridles firm, and sat watching with breathless interest.

In a few minutes more the shield had moved full ten paces from the crouching lioness. The latter seemed not to notice this change in the relative position of herself and her cunning adversary. If she did, she beheld it rather with feelings of curiosity or wonder than otherwise. At all events, she kept her post until the curious object had gone a wide distance from her.

She might not have suffered it to go much farther; but it was now far enough for her adversary’s purpose, for the shield suddenly became erect, and the Kaffir once more sent his assegai whirring from his hand.

It was the fatal shaft. The lioness chanced to be crouching broadside towards the hunter. His aim was true, and the barbed iron pierced through her heart. A sharp growl, that was soon stifled,—a short despairing struggle, that soon ended, and the mighty brute lay motionless in the dust!

A loud “hurrah!” came from the direction of the camp, and the young yägers now galloped forth upon the plain, and congratulated Congo upon the successful result of his perilous conflict.

The group of dead bodies was approached, and there a new surprise awaited the hunters. The lion was dead, as they had long since conjectured,—the sharp horns of the oryx had done the work; but what astonished all of them was, that the horns that had impaled the body of the great lion still remained sticking in his side. The oryx had been unable to extricate them, and would thus have perished along with her victim, even had the lioness not arrived to give the fatal blow!

This, both Congo and Swartboy assured the party, was no uncommon occurrence, and the bodies of the lion and gemsbok are often found upon the plains locked in this fatal embrace!

The cow gemsbok, yielding the more tender venison, was soon skinned and cut up; and as the delicious steaks spurted over the red coals of their camp-fire, the young yägers became very merry, and laughed at the singular incidents of the day.

Chapter Eight.

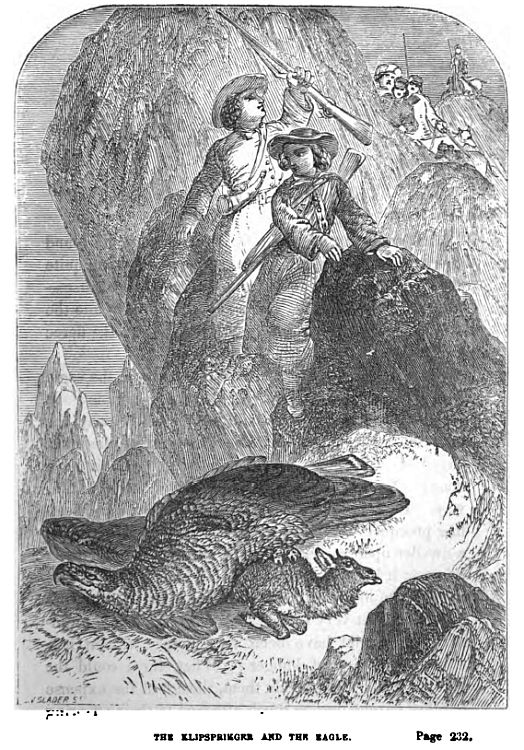

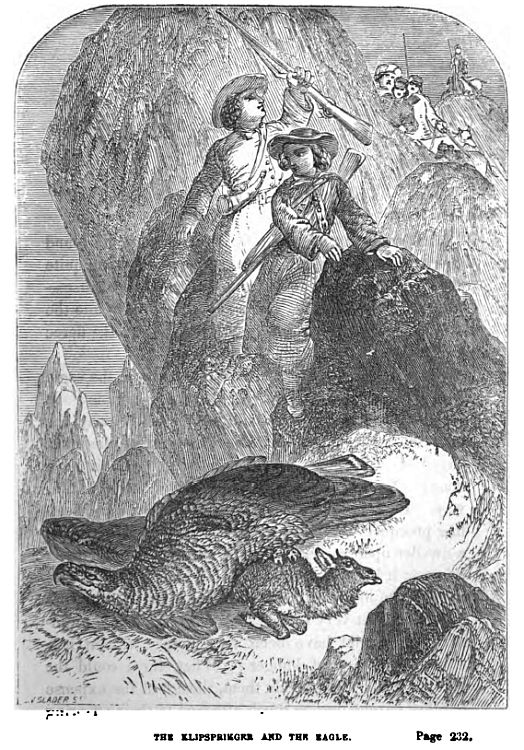

A Short Chat about Lions.

Before going to supper the hunters dragged the carcasses of both lion and lioness close up to the camp-fire. A good pull it was, but they managed it by attaching strong “rheims” of raw hide around the necks of the creatures, and sliding them with the grain of the hair.

Their object in bringing them to the fire was, that they might have light to skin them,—not that they deem the lion-hides of any great value, except as trophies of their expedition—and they were not going to leave such trophies on the plain. Had the lions been permitted to remain all night where they had been killed, the hyenas would have eaten them up before morning,—skins and all. It is a fable which tells that the hyena will not eat the dead lion. The filthy brute will eat anything, even one of his own kind,—perhaps the most unpalatable morsel he could well find.

Of course the oryx were also brought up to the camp to be skinned and cut up. The bull, as large and heavy as a dead ass, gave them a good pull for it. But it afforded Groot Willem an opportunity of exhibiting his enormous strength; and the big boy, seizing the tow-rope, dragged the oryx after him with as much ease as if it had been a kitten at the end of a string of twine.

Both the gemsboks were regularly “butchered” and cut into quarters, to be carried to the next camp, and there dried. They would have dried the meat on the spot, but the water where they had halted was not good, and they did not wish to remain there another day.

The horns of the oryx are also esteemed trophies of the chase, and those of both that were killed being perfect specimens—long, handsomely ringed, and black as ebony—were added to the collection which the young yägers were forming, and stowed safely away in the wagons. The heads, with the skins left on, were carefully cleaned and preserved, at no distant day to become ornaments in the voor-huis, or entrance-hall, either of the Von Bloom or Van Wyk mansions.

All these matters being arranged, the yägers sat down to supper around the camp-fire. The roast ribs and steaks of the gemsbok venison proved delicious, and the whole party, as already stated, were contented and merry. Of course lions were the subject of conversation, and all laughed again and again whenever they thought of Congo and his encounter.

All of them, little Jan and Klaas excepted, had stories to tell of adventures with lions, for these animals were still to be found in the Graaf Reinet, and both Groot Willem and Arend had been present at more than one lion-hunt. Hans and Hendrik had met them in many an encounter during the great elephant expedition, and Swartboy was an old Hottentot lion-hunter.

But Congo seemed to know more of the lion than even Swartboy, though the latter would have gone wild had such a thing been hinted at by any one of the party; and many a rival story of strange interest fell from the lips of both Kaffir and Bushman at that same camp-fire. Some of the party had heard of a mode of lion-hunting practised by the Bechuana tribes, and, indeed, in Congo’s own country. There was nothing very novel about the mode. A number of people,—naked savages they were,—attacked the lion wherever they met him, either in the bush or on the open plain, and there fought him to the death. These people carried for arms only the assegai, and, as a sort of defensive weapon, a mop of black ostrich-feathers fastened upon the end of a slender stick, and somewhat resembling a large fly-brush. The object of this was to disconcert the lion when rushing upon the hunter. By sticking it in the ground at the right moment, the lion mistakes the clump of ostrich-feathers for his real assailant, and, charging upon it, permits the hunter to escape. Such a ruse is far inferior to the trick of the carapace, but that singular mode of defence against the lion was only practised by such cunning hunters as Congo.

Now, as already stated, the plan practised by the Bechuana savages had nothing very novel or strange in it. Any strangeness about it consisted in the fact of the imprudence of such a mode of attack; for it was said that the hunters did not stand off at a distance and cast their assegais, on the contrary, they retained these weapons in their hands, and used them as spears, approaching the lion close enough to thrust them into his body! The consequence was, that in every encounter with their terrible antagonist, several hunters were either killed or badly mangled. This was the thing that appeared strange to our young yägers. They could not understand why any hunters should attack the fierce lion thus boldly and recklessly, when they might avoid the encounter altogether! They could not understand why even savages should be so regardless of life. Was it true that any people hunted the lion in that way? They asked Congo if it was true. He replied that it was.

Now this required explanation,—and Congo was requested to give it, which he did as follows.

The hunters spoken of were not volunteers. They did not attack the lion of their own will and pleasure, but at the command of the tyrant that ruled them. It was so in Congo’s country, where the sanguinary monster, Chaaka, had sway. The whole people of Chaaka were his slaves, and he thought nothing of putting a thousand of them to death in a single morning to gratify some petty spleen or dislike! He had done so on more than one occasion, often adding torture. The tales of horrors practised by these African despots would be incredible were it not for the full clear testimony establishing their truth; and, although it forms no excuse for slavery, the contemplation of such a state of things in Africa lessens our disgust for the system of American bondage. Even the atrocious slave-trade, with all the horrors of the “middle passage,” appears mild in comparison with the sufferings endured by the subjects of such fearful tyrants as Chaaka, Dingaan, or Moselekatse!

Congo related to the young yägers that it was customary for Chaaka’s people to act as the herdsmen of his numerous flocks, and that when any of his cattle were killed by a lion,—a frequent occurrence,—the unfortunate creatures who herded them were commanded to hunt the lion, and bring in his head, or suffer death in case of failure; and this sentence was sure to be carried into effect.

This explained the apparently reckless conduct of the hunters.