"That will help you remember where your mouth is"

"That will help you remember where your mouth is"

Title: The Sick-a-Bed Lady

Author: Eleanor Hallowell Abbott

Release date: January 3, 2011 [eBook #34829]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Suzanne Shell and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive/American Libraries (http://www.archive.org/details/americana)

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive/American Libraries. See http://www.archive.org/details/sickabedlady00abborich |

"That will help you remember where your mouth is"

"That will help you remember where your mouth is"

| page | |

| The Sick-a-Bed Lady | 3 |

| Hickory Dock | 33 |

| The Very Tired Girl | 57 |

| The Happy-Day | 89 |

| The Runaway Road | 127 |

| Something that Happened in October | 161 |

| The Amateur Lover | 195 |

| Heart of the City | 253 |

| The Pink Sash | 291 |

| Woman's Only Business | 331 |

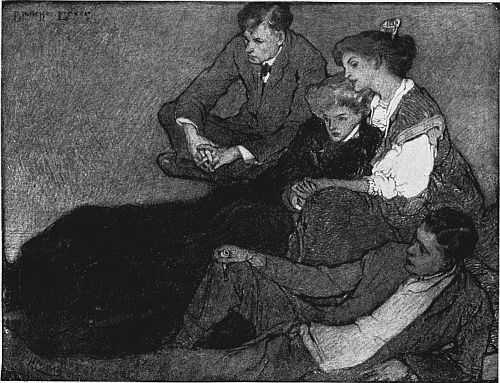

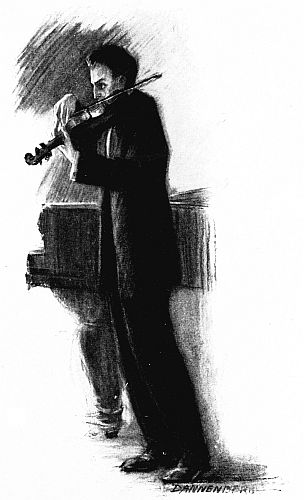

| "That will help you remember where your mouth is" | Frontispiece |

| facing page | |

| With no other object, except to get home | 58 |

| The blue ocean was the most wonderful thing of all | 96 |

| Instinctively she clasped it to her | 146 |

| The four of us who remained huddled very close around the fire | 164 |

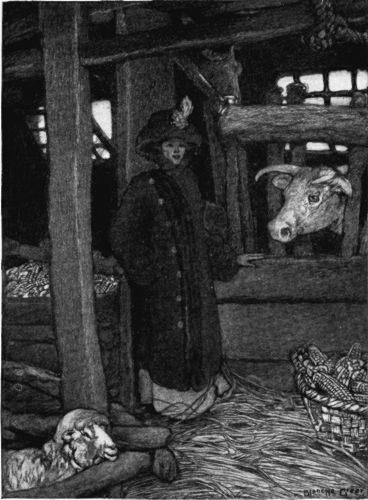

| "Hello, all you animals!" she cried | 244 |

| The lone, accentuated figure of a boy violinist | 256 |

| "Is—a—pink—sash—exactly a—a—passion?" | 298 |

| "Oh, I wish I had a sister," fretted the boy | 364 |

The Sick-A-Bed Lady, herself, was as old as twenty, but she did not look more than fifteen with her little wistful white face against the creamy pillows and her soft brown hair braided in two thick pigtails and tied with great pink bows behind each ear.[4]

When the Sick-A-Bed Lady felt like sitting up high against her pillows, she could look out across the footboard through her opposite window. Now through that opposite window was a marvelous vista—an old-fashioned garden, millions of miles of ocean, and then—France! And when the wind was in just the right direction there was a perfectly wonderful smell to be smelled—part of it was Cinnamon Pink and part of it was Salt-Sea-Weed, but most of it, of course, was—France. There were days and days, too, when any one with sense could feel that the waves beat perkily against the shore with a very strong French accent, and that all one's French verbs, particularly "J'aime, Tu aimes, Il aime," were coming home to rest. What else was there to think about in bed but funny things like that?

It was the Old Doctor who had brought the Sick-A-Bed Lady to the big white house at the edge of the Ocean, and placed her in the cool, quaint room with its front windows quizzing dreamily out to sea, and its side windows cuddled close to the curving village street. It was a long, tiresome, dangerous journey, and the Sick-A-Bed Lady in feverish fancy had moaned: "I shall die, I shall die, I shall die," every step of the way, but, after all, it was the Old Doctor who did the dying! Just like a snap of the finger he went at the end of two weeks, and the[5] Sick-A-Bed Lady rallied to the shock with a plaintive: "Seems to me he was in an awful hurry," and fell back on her soft bed into days of unconsciousness that were broken only by riotous visions day and night of an old man rushing frantically up to a great white throne yelling: "One, two, three, for Myself!"

Out of this trouble the Sick-A-Bed Lady woke one day to find herself quite alone and quite alive. She had often felt alone before, but it was a long time since she had felt alive. The world seemed very pleasant. The flowers on the wall-paper were still unwilted, and the green paper birds hung airily without fatigue. The room was full of the most enticing odor of cinnamon pinks, and by raising herself up in bed the merest trifle she could get a smell of good salt, a smell which somehow you couldn't get unless you actually saw the Ocean, but just as she was laboriously tugging herself up an atom higher, trying to find the teeniest, weeniest sniff of France, everything went suddenly black and silver before her eyes, and she fell down, down, down, as much as forty miles into Nothing At All.

When she woke up again all limp and wappsy there was a Young Man's Face on the Footboard of the bed; just an isolated, unconnected sort of face that might have blossomed from the footboard, or might have been merely a mirage on the horizon.[6] Whatever it was, though, it kept staring at her fixedly, balancing itself all the while most perfectly on its chin. It was a funny sight, and while the Sick-A-Bed Lady was puckering her forehead trying to think out what it all meant the Young Man's Face smiled at her and said "Boo!" and the Sick-A-Bed Lady tiptilted her chin weakly and said—"Boo yourself!" Then the Sick-A-Bed Lady fell into her fearful stupor again, and the Young Man's Face ran home as fast as it could to tell its Best Friend that the Sick-A-Bed Lady had spoken her first sane word for five weeks. He thought it was a splendid victory, but when he tried to explain it to his friend, he found that "Boo yourself!" seemed a fatuous proof of so startling a truth, and was obliged to compromise with considerable dignity on the statement: "Well, of course, it wasn't so much what she said as the way she said it."

For days and days that followed, the Sick-A-Bed Lady was conscious of nothing except the Young Man's Face on the footboard of the bed. It never seemed to wabble, it never seemed to waver, but just stayed there perfectly balanced on the point of its chin, watching her gravely with its blue, blue eyes. There was a cleft in its chin, too, that you could have stroked with your finger if—you could have. Of course, there were some times when she went to[7] sleep, and some times when she just seemed to go out like a candle, but whenever she came back from anything there was always the Young Man's Face for comfort.

The Sick-A-Bed Lady was so sick that she thought all over her body instead of in her head, so that it was very hard to concentrate any particular thought in her mouth, but at last one afternoon with a mighty struggle she opened her half-closed eyes, looked right in the Young Man's Face and said: "Got any arms?"

The Young Man's Face nodded perfectly politely, and smiled as he raised two strong, lean hands to the edge of the footboard, and hunched his shoulders obligingly across the sky line.

"How do you feel?" he asked very gently.

Then the Sick-A-Bed Lady knew at once that it was the Young Doctor, and wondered why she hadn't thought of it before.

"Am I pretty sick?" she whispered deferentially.

"Yes—I think you are very pretty—sick," said the Young Doctor, and he towered up to a terrible, leggy height and laughed joyously, though there was almost no sound to his laugh. Then he went over to the window and began to jingle small bottles, and the Sick-A-Bed Lady lay and watched him furtively and thought about his compliment, and wondered why when she wanted to smile and say "Thank[8] you" her mouth should shut tight and her left foot wiggle, instead.

When the Young Doctor had finished jingling bottles, he came and sat down beside her and fed her something wet out of a cool spoon, which she swallowed and swallowed and swallowed, feeling all the while like a very sick brown-eyed dog that couldn't wag anything but the far-away tip of its tail. When she got through swallowing she wanted very much to stand up and make a low bow, but instead she touched the warm little end of her tongue to the Young Doctor's hand. After that, though, for quite a few minutes her brain felt clean and tidy, and she talked quite pleasantly to the Young Doctor: "Have you got any bones in your arms?" she asked wistfully.

"Why, yes, indeed," said the Young Doctor, "rather more than the usual number of bones. Why?"

"I'd give my life," said the Sick-A-Bed Lady, "if there were bones in my silky pillows." She faltered a moment and then continued bravely: "Would you mind—holding me up stiff and strong for a second? There's no bottom to my bed, there's no top to my brain, and if I can't find a hard edge to something I shall topple right off the earth. So would you mind holding me like an edge for a moment—that is—if there's no lady to care?[9] I'm not a little girl," she added conscientiously—"I'm twenty years old."

So the Young Doctor slipped over gently behind her and lifted her limp form up into the lean, solid curve of his arm and shoulder. It wasn't exactly a sumptuous corner like silken pillows, but it felt as glad as the first rock you strike on a life-swim for shore, and the Sick-A-Bed Lady dropped right off to sleep sitting bolt upright, wondering vaguely how she happened to have two hearts, one that fluttered in the usual place, and one that pounded rather noisily in her back somewhere between her shoulder-blades.

On his way home that day the Young Doctor stopped for a long while at his Best Friend's house to discuss some curious features of the Case.

"Anything new turned up?" asked the Best Friend.

"Nothing," said the Young Doctor, pulling moodily at his cigar.

"Well, it certainly beats me," exclaimed the Best Friend, "how any long-headed, shrewd old fellow like the Old Doctor could have brought a raving fever patient here and installed her in his own house under that clumsy Old Housekeeper without once mentioning to any one who the girl was, or where to communicate with her people. Great Heavens, the Old Doctor knew what a poor 'risk' he was.[10] He knew absolutely that that heart of his would burst some day like a firecracker."

"The Old Doctor never was very communicative," mused the Young Doctor, with a slight grimace that might have suggested professional memories not strictly pleasant. "But I'll surely never forget him as long as ether exists," he added whimsically. "Why, you'd have thought the old chap invented ether—you'd have thought he ate it, drank it, bathed in it. I hope the smell of my profession will never be the only part of it I'm willing to share."

"That's all right," said the Best Friend, "that's all right. If he wanted to go off every Winter to the States and work in the Hospitals, and come back every Spring smelling like a Surgical Ward, with a lot of wonderful information which he kept to himself, why, that was his own business. He was a plucky old fellow anyway to go at all. But what I'm kicking at is his wicked carelessness in bringing this young girl here in a critical illness without taking a single soul into his confidence. Here he's dead and buried for weeks, and the Girl's people are probably worrying themselves crazy about not hearing from her. But why don't they write? Why in thunder don't they write?"

"Don't ask me!" cried the Young Doctor nervously. "I don't know! I don't know anything[11] about it. Why, I don't even know whether the Girl is going to live. I don't even know whether she'll ever be sane again. How can I stop to quiz about her name and her home, when, perhaps, her whole life and reason rests in my foolish hands that have never done anything yet much more vital than usher a perfectly willing baby into life, or tinker with croup in some chunky throat? There's only one thing in the case that I'm sure of, and that is that she doesn't know herself who she is, and the effort to remember might snap her utterly. She's just a thread.

"I have an idea—" the Young Doctor shook his shoulders as though to shake off his more somber thoughts—"I have an idea that the Old Doctor rather counted on building up a sort of informal sanitarium here. He was daft, you know, about the climate on this particular stretch of coast. You remember that he brought home some athlete last Summer—pretty bad case of breakdown, too, but the Old Doctor cured him like a magician; and the Spring before that there was a little lad with epilepsy, wasn't there? The Old Doctor let me look at him once just to tease me. And before that—I can count up half-a-dozen people of that sort, people whom you would have said were 'gone-ers,' too. Oh, the Old Doctor would have brought home a dead man to cure if any one had 'stumped' him.[12] And I guess this present case was a 'stump' fast enough. Why, she was raging like a prairie fire when they brought her here. No other man would have dared to travel. And they put her down in a great silk bed like a fairy-story, and the Old Doctor sat and watched her night and day studying her like a fiend, and she got better after a while: not keen, you know, but funny like a child, cooing and crooning over her pretty room, and tickled to pieces with the ocean, and vain as a kitten over her pink ribbons—the Old Doctor wouldn't let them cut her hair—and everything went on like that, till in a horrid flash the Old Doctor dropped dead that morning at the breakfast table, the little girl went loony again, and every possible clew to her identity was wiped off the earth!"

"No baggage?" suggested the Best Friend.

"Why, of course, there was baggage!" the Young Doctor exclaimed, "a great trunk. Haven't the Housekeeper and I rummaged and rummaged it till I can feel the tickle of lace across my wrists even in my sleep? Why, man alive! she's a rich girl. There never were such clothes in our town before. She's no free hospital pauper whom the Old Doctor obligingly took off their hands. That is, I don't see how she can be!

"Oh, well," he continued bitterly, "everybody in town calls her just the Sick-A-Bed Lady, and pretty[13] soon it will be the Death-Bed Lady, and then it will be the Dead-and-Buried Lady—and that's all we'll ever know about it." He shivered clammily as he finished and reached for a scorching glass of whisky on the table.

But the Young Doctor did not feel so lugubrious the next day and the next and the next, when he found the Sick-A-Bed Lady rallying slowly but surely to the skill of his head and hands. To be frank, she still lay for hours at a time in a sort of gentle daze watching the world go by without her, but little by little her body strengthened as a wilted flower freshens in water, and little by little she struggled harder for words that even then did not always match her thoughts.

The village continued to speculate about her lost identity, but the Young Doctor seemed to worry less and less about it as time went on. If the sweetest little girl you ever saw knew perfectly whom you meant when you said "Dear," what was the use of hunting up such prosy names as May or Alice? And as to her funny speeches, was there anything in the world more piquant than to be called a "beautiful horse," when she meant a "kind doctor"? Was there anything dearer than her absurd wrath over her blunders, or the way she shook her head like an angry little heifer, when she occasionally forgot altogether how to talk? It was at one[14] of these latter times that the Young Doctor, watching her desperate struggle to focus her speech, forgot all about her twenty years and stooped down suddenly and kissed her square on her mouth.

"There," he laughed, "that will help you remember where your mouth is!" But it was astonishing after that how many times he had to remind her.

He couldn't help loving her. No man could have helped loving her. She was so little and dear and gentle and—lost.

The Sick-A-Bed Lady herself didn't know who she was, but she would have perished with fright if she had realized that no one in the village, and not even the Young Doctor himself, could guess her identity.

The Young Doctor knew everything else in the world; why shouldn't he know who she was? He knew all about France being directly opposite the house; he had known it ever since he was a boy, and had been glad about it. He stopped her trying to count the green birds on the wall-paper because he "knew positively" that there were four hundred and seventeen whole birds, and nineteen half birds cut off by the wainscoting. He never laughed at her when she slid down the side of her bed by the village street window, and went to sleep with her curly head pillowed on the hard, white sill. He never laughed, because he understood perfectly that[15] if you hung one white arm down over the sidewalk when you went to sleep, sometimes little children would come and put flowers in your hand, or, more wonderful still, perhaps, a yellow collie dog would come and lick your fingers.

Nothing could surprise the Young Doctor. Sometimes the Sick-A-Bed Lady took thoughts she did have and mixed them up with thoughts she didn't have, and sprung them on the poor Young Doctor, but he always said, "Why, of course," as simply as possible.

But more than all the other wise things he knew was the wise one about smelly things. He knew that when you were very, very, very sick, nothing pleased you so much as nice, smelly things. He brought wild strawberries, for instance, not so much to eat as to smell, but when he wasn't looking she gobbled them down as fast as she could. And he brought her all kinds of flowers, one or two at a time, and seemed so disappointed when she just sniffed them and smiled; but one day he brought her a spray of yellow jasmine, and she snatched it up and kissed it and cried "Home," and the Young Doctor was so pleased that he wrote it right down in a little book and ran away to study up something. He let her smell the fresh green bank-notes in his pocketbook. Oh, they were good to smell, and after a while she said "Shops." He brought her[16] a tiny phial of gasoline from his neighbor's automobile, and she crinkled up her nose in disgust and called it "gloves" and slapped it playfully out of his hand. But when he brought her his riding-coat she rubbed her cheek against it and whispered some funny chirruppy things. His pipe, though, was the most confusing symbol of all. It was his best pipe, too, and she snuggled it up to her nose and cried "You, y-o-u!" and hid it under her pillow and wouldn't give it back to him, and though he tried her a dozen times about it, she never acknowledged any association except that joyous, "Y-o-u!"

So day by day she gained in consecutive thought till at last she grew so reasonable as to ask: "Why do you call me Dear?"

And the Young Doctor forgot all about his earliest reason and answered perfectly simply: "Because I love you."

Then some of the evenings grew to be almost sweetheart evenings, though the Sick-A-Bed Lady's fragile childishness keyed the Young Doctor into an almost uncanny tenderness and restraint.

Those were wonderful evenings, though, after the Sick-A-Bed Lady began to get better and better. A good deal of the Young Doctor's practice was scattered up and down the coast, and after the dust and sweat and glare and rumble of his long day he would come back to the sleepy village in the early[17] evening, plunge for a freshening swim into the salt water, don his white clothes and saunter round to the quaint old house at the edge of the ocean. Here in the breezy kitchen he often sat for as long as an hour, talking with the Old Housekeeper, till the Sick-A-Bed Lady's tiny silver bell rang out with absurd peremptoriness. Then for as much time as seemed wise he went and sat with the Sick-A-Bed Lady.

One night, one full-moon night, he came back from his day's work extraordinarily tired and fretted after a series of strident experiences, and hurried to the old house as to a veritable Haven of Refuge. The Housekeeper was busy with village company, so he postponed her report and went at once to the Sick-A-Bed Lady's room.

Only fools lit lights on such a night as that, and he threw himself down in the big chair by the bedside, and fairly basked in peacefulness and moonlight and content, while the Sick-A-Bed Lady leaned over and stroked his hair with her little white fingers, crooning some pleasant, childish thing about "nice, smoky Boy." There was no fret or fuss or even sound in the room, except the drowsy murmur of voices in the Garden, and the churky splash of little waves against the shore.

"Hear the French Verbs," said the Sick-A-Bed Lady, at last, with deliberate mischief. Then she[18] shut her lips tight and waved her hands distractedly after a manner she had when she wished to imply that she was suddenly stricken dumb. The Young Doctor laughed and reached over and kissed her.

"J'aime," he said.

"J'aime," the Sick-A-Bed Lady repeated.

"Tu aimes," he persisted.

"Tu aimes," she echoed on his lips.

—Then—"There'll be no 'he loves' to our story," he cried suddenly, and caught her so fiercely to his breast that she gave a little quick gasp of pain and struggled back on her pillows, and the Young Doctor jumped up in bitter, stinging contrition and strode out of the room. Just across the threshold he met the Old Housekeeper with a clattering tray of dishes.

"I'm going down to the Library to smoke," he said huskily to her. "Come there when you've finished. I want to talk with you."

His thoughts of himself were not kind as he wandered into the library and settled down in the first big chair that struck his fancy.

Then he fell to wondering whether there was anything gross about his love, because it took no heed of mental qualifications. He thought of at least three houses in the village where that very night he would have found lights and laughter and clever talk, and the prodding sympathy of earnest women[19] who made the sternest happening of the day seem nothing more than a dress rehearsal for the evening's narration of it. Then he thought again of the big, quiet room upstairs, with its unquestioning peace and love and restfulness and content. What was the best thing after all that a woman could bring to a man? Yet a year ago he had bragged of the blatant braininess of his best woman friend! He began to laugh at himself.

Slowly the incongruities of the whole situation bore in upon him, and he sat and smoked and smiled in moody silence, staring with skeptical interest at the dimly lighted room around him. It was certainly the Old Doctor's private study, and realization of just what that meant came over him ironically.

The Old Doctor had been very stingy with his house and his books and his knowledge and his patients. It was natural perhaps under the professional circumstances of waning Age and waxing Youth. Yet the fact remained. Never before in five years of village association had the Young Doctor crossed the threshold of the Old Doctor's home, yet now he came and went like the Man of the House. Here he sat at this instant in the Old Doctor's private study, in the Old Doctor's chair, his feet upon the Old Doctor's table, and the whole great room with its tier after tier of bookcases, and[20] its drawer after drawer of probable memoranda free before him. He could imagine the Old Doctor's impotent wrath over such a contingency, yet he felt no sentimental mawkishness over his own position. As far as he knew the Dead were dead.

Sitting there in the Old Doctor's study, he conjured up scene after scene of the Old Doctor's irascibility and exclusiveness. Even as late as the Sick-A-Bed Lady's arrival, the Old Doctor had snubbed him unmercifully before a crowd of people. It was at the station when the little sick stranger was being taken off the car and put into a carriage, and the Old Doctor had hailed the Younger with unwonted friendliness.

"I've got a case in there that would make you famous if you could master it," he said.

The Young Doctor remembered perfectly how he had walked into the trap.

"What is it?" he had cried eagerly.

"That's none of your business," chuckled the Old Doctor, and drove away with all the platform loafers shouting with delight.

Well, it seemed to be the Young Doctor's business now, and he got up, turned the lamp higher and began to hunt through the Old Doctor's rarest books for some light on certain curious developments in the Sick-A-Bed Lady's case.

He was just in the midst of this hunt when the[21] Old Housekeeper glided in like a ghost and startled him.

"Sit down," he said absent-mindedly, and went on with his reading. He had almost forgotten her presence when she coughed and said: "Excuse me, sir, but I've something very special to say to you."

The Young Doctor looked up in surprise and saw that the Woman's face was ashy white.

"I—don't—think—you quite—understand the case," she stammered. "I think the little lady upstairs is going to be a Mother!"

The Young Doctor put his hand up to his face, and his face felt like parchment. He put his hand down to the book again, and the book cover quivered like flesh.

"What do you m-e-a-n?" he asked.

"I'll tell you what I mean," said the Old Housekeeper, and led him back to the sick room.

Two hours later the Young Doctor staggered into his Best Friend's house clutching a sheet of letter paper in his hand. His shoulders dragged as though under a pack, and every trace of boyishness was wrung like a rag out of his face.

"For Heaven's sake, what's the matter?" cried his friend, starting up.

"Nothing," muttered the Young Doctor, "except the Sick-A-Bed Lady."

"When did she die? What happened?"[22]

The Young Doctor made a gesture of dissent and crawled into a chair and began to fumble with the paper in his hand. Then he shivered and stared his Best Friend straight in the face.

"You might say," he stammered, "that I have just heard from the Sick-A-Bed Lady's Husband—" he choked at the word, and his Friend sat up with astonishment: "You heard me say I had heard from the Sick-A-Bed Lady's Husband?" he persisted. "You heard me say it, mind you. You heard me say that her Husband is sick in Japan—detained indefinitely—so we are afraid he won't get here in time for her confinement—"

The sweat broke out in great drops on his forehead, and his hand that held the sheet of paper shook like a hand that has strained its muscles with heavy weights.

The Best Friend took a scathing glance at the scribbled words on the paper and laughed mirthlessly.

"You're a good fool," he said, "a good fool, and I'll publish your blessed lie to the whole stupid village, if that's what you want."

But the Young Doctor sat oblivious with his head in his hands, muttering: "Blind fool, blind fool, how could I have been such a blind fool?"

"What is it to you?" asked his Best Friend abruptly.[23]

The Young Doctor jumped to his feet and squared his shoulders.

"It's this to me," he cried, "that I wanted her for my own! I could have cured her. I tell you I could have cured her. I wanted her for my own!"

"She's only a waif," said the Best Friend tersely.

"Waif?" cried the Young Doctor, "waif? No woman whom I love is a waif!" His face blazed furiously. "The woman I love—that little gentle girl—a waif?—without a home?—I would make a cool home for her out of Hell itself, if it was necessary! Damn, damn, damn the brute that deserted her, but home is all around her now! Do I think the Old Doctor guessed about it? N-o! Nobody could have guessed about it. Nobody could have known about it much before this. You say again she isn't anybody's? I'll prove to you as soon as it's decent that she's mine."

His Best Friend took him by the shoulder and shook him roughly.

"It is no time," he said, "for you to be courting a woman."

"I'll court my Sweetheart when and where I choose!" the Young Doctor answered defiantly, and left the house.

The night seemed a thousand miles long to him,[24] but when he slept at last and woke again, the air was fresh and hopeful with a new day. He dressed quickly and hurried off to the scene of last night's tragedy, where he found the Old Housekeeper arguing in the doorway with a small boy. She turned to the Doctor complacently. "He's begging for the postage stamp off the Japanese letter," she exclaimed, "and I'm just telling him I sent it to my Sister's boy in Montreal."

There was no slightest trace of self-consciousness in her manner, and the Young Doctor could not help but smile as he beckoned her into the house and shut the door.

Then, "Have you told her?" he asked eagerly.

The Old Housekeeper humped her shoulders against the door and folded her arms sumptuously. "No, I haven't told her," she said, "and I'm not going to. I don't dar'st! I help you out about your business same as I helped the Old Doctor out about his business. That's all right. That's as it should be. And I'll go skipping up those stairs to tell the little lady any highfaluting, pleasant yarn that you can invent, but I don't budge one single step to tell that poor, innocent, loony Lamb—the truth. It isn't ugliness, Doctor. I haven't got the strength, that's all!"

Just then the little silver bell tinkled, and the Doctor went heavily up the few steps that swung the[25] Sick-A-Bed Lady's room just out of line of real upstairs or downstairs.

The Sick-A-Bed Lady was lying in glorious state, arrayed in a wonderful pale green kimono with shimmering silver birds on it.

"You stayed too long downstairs," she asserted and went on trying to cut out pictures from a magazine.

The Young Doctor stood at the window looking out to sea as long as his legs would hold him, and then he came back and sat down on the edge of the bed.

"What's your name, Honey?" he asked with a forced smile.

"Why, 'Dear,' of course," she answered and dropped her scissors in surprise.

"What's my name?" he continued, fencing for time.

"Just 'Boy,'" she said with sweet, contented positiveness.

The Young Doctor shivered and got up and started to leave the room, but at the threshold he stopped resolutely and came back and sat down again.

This time he took his Mother's wedding ring from his little finger and twirled it with apparent aimlessness in his hands.

Its glint caught the Sick-A-Bed Lady's eye, and[26] she took it daintily in her fingers and examined it carefully. Then, as though it recalled some vague memory, she crinkled up her forehead and started to get out of bed. The Young Doctor watched her with agonized interest. She went direct to her bureau and began to search diligently through all the drawers, but when she reached the lower drawer and found some bright-colored ribbons she forgot her original quest, whatever it was, and brought all the ribbons back to bed with her.

The Young Doctor started to leave her again, this time with a little gesture which she took to be anger, but he had not gone further than the head of the stairs before she called him back in a voice that was startlingly mature and reasonable.

"Oh, Boy, come back," she cried. "I'll be good. What do you want?"

The Young Doctor came doubtfully.

"Do you understand me to-day?" he asked in a voice that sent an ominous chill to her heart. "Can you think pretty clearly to-day?"

She nodded her head. "Yes," she answered; "it's a good day."

"Do you know what marriage is?" he asked abruptly.

"Oh, yes," she said, but her face clouded perceptibly.

Then he took her in his arms and told her plainly,[27] brutally, clumsily, without preface, without comment: "Honey, you are going to have a child."

For a second her mind wavered before him. He could actually see the totter in her eyes, and braced himself for the final hopeless crash, but suddenly all her being focused to the realization of his words, and she pushed at him with her hands and cried: "No—No—Oh, my God—n-o!" and fainted in his arms.

When she woke up again the little-girl look was all gone from her face, and though the Young Doctor smiled and smiled and smiled, he could not smile it back again. She just lay and watched him questioningly.

"Sweetheart," he whispered at last, "do you remember what I told you?"

"Yes," she answered gravely, "I remember that, but I don't remember what it means. Is it all right? Is it all right to you?"

"Yes," said the Young Doctor, "it's—all—right to—me."

Then the Sick-A-Bed Lady turned her little face wearily away on her pillow and went back to those dreams of hers which no one could fathom.

For all the dragging weeks and months that followed she lay in her bed or groped her way round her room in a sort of timid stupor. Whenever the Young Doctor was there she clung to him desperately[28] and seemed to find her only comfort in his presence, but when she talked to him it was babbling talk of things and places he could not understand. All the village feared for the imminent tragedy in the great white house, and mourned the pathetic absence of the young husband, and the Young Doctor went his sorrowful way cursing that other "boy" who had wrought this final disaster on a girl's life.

But when the Sick-A-Bed Lady's hour of trial came and some one held the merciful cone of ether to her face, the Sick-A-Bed Lady took one deep, heedless breath, then gave suddenly a great gasp, snatched the cone from her face, struggled up and stretched out her arms and cried, "Boy—Boy!"

The Young Doctor came running to her and saw that her eyes were big and startled and sharp with terror:

"Oh, Boy—Boy," she cried, "the Ether!—I remember everything now—I—was his wife—the Old Doctor's Wife!"

The Young Doctor tried to replace the cone, but she beat at him furiously with her hands, crying:

"No, No, No!—If you give me Ether I shall die thinking of him!—Oh, no!—n-o!"

The Young Doctor's face was like chalk. His knees shook under him.

"My God!" he said, "what can I give you!"

The Sick-A-Bed Lady looked up at him and[29] smiled a tortured, gallant smile. "Give me something to keep me here," she gasped! "Give me a token of you! Give me your little briarwood pipe to smell—and give it to me—quickly!"

Hickory Dock was a clock, and, of course, the Man, being a man, called it a clock, but the Girl, being a girl, called it a Hickory Dock for no more legitimate reason than that once upon a time

The Man and the Girl were very busy collecting a Home—in one room. They were just as poor as Art and Music could make them, but poverty does not matter much to lovers. The Man had collected the Girl, a wee diamond ring, a big Morris chair, two or three green and rose rugs, a shiny chafing-dish, and various incidentals. The Girl was no less discriminating. She had accumulated the Man, a Bagdad couch-cover, half-a-dozen pictures, a huge gilt mirror, three or four bits of fine china and silver,[34] and a fair-sized boxful of lace and ruffles that idled under the couch until the Wedding-Day. The room was strikingly homelike, masculinely homelike, in all its features, but it was by no means home—yet. No place is home until two people have latch-keys. The Girl wore her key ostentatiously on a long, fine chain round her neck, but its mate hung high and dusty on a brass hook over the fireplace, and the sight of it teased the Man more than anything else that had ever happened to him in his life. The Girl was easily mistress of the situation, but the Man, you see, was not yet Master.

It was tacitly understood that if the Wedding-Day ever arrived, the Girl should slip the extra key into her husband's hand the very first second that the Minister closed his eyes for the blessing. She would have chosen to do this openly in exchange for her ring, but the Man contended that it might not be legal to be married with a latch-key—some ministers are so particular. It was a joke, anyway—everything except the Wedding-Day itself. Meanwhile Hickory Dock kept track of the passing hours.

When the Man first brought Hickory Dock to the Girl, in a mysteriously pulsating tissue-paper package, the Girl pretended at once that she thought it was a dynamite bomb, and dropped it precipitously on the table and sought immediate refuge in the[35] Man's arms, from which propitious haven she ventured forth at last and picked up the package gingerly, and rubbed her cheek against it—after the manner of girls with bombs. Then she began to tug at the string and tear at the paper.

"Why, it's a Hickory Dock!" she exclaimed with delight,—"a real, live Hickory Dock!" and brandished the gift on high to the imminent peril of time and chance, and then fled back to the Man's arms with no excuse whatsoever. She was a bold little lover.

"But it's a c-l-o-c-k," remonstrated the Man with whimsical impatience. He had spent half his month's earnings on the gift. "Why can't you call it a clock? Why can't you ever call things by their right names?"

Then the Girl dimpled and blushed and burrowed her head in his shoulder, and whispered humbly, "Right name? Right names? Call things by their right names? Would you rather I called you by your right name—Mr. James Herbert Humphrey Jason?"

That settled the matter—settled it so hard that the Girl had to whisper the Man's wrong name seven times in his ear before he was satisfied. No man is practical about everything.

There are a good many things to do when you are in love, but the Girl did not mean that the Art of[36] Conversation should be altogether lost, so she plunged for a topic.

"I think it was beautiful of you to give me a Hickory Dock," she ventured at last.

The Man shifted a trifle uneasily and laughed. "I thought perhaps it would please you," he stammered. "You see, now I have given you all my time."

The Girl chuckled with amused delight. "Yes—all your time. And it's nice to have a Hickory Dock that says 'Till he comes! Till he comes! Till he comes!'"

"Till he comes to—stay," persisted the Man. There was no sparkle in his sentiment. He said things very plainly, but his words drove the Girl across the room to the window with her face flaming. He jumped and followed her, and caught her almost roughly by the shoulder and turned her round.

"Rosalie, Rosalie," he demanded, "will you love me till the end of time?" There was no gallantry in his face but a great, dogged persistency that frightened the Girl into a flippant answer. She brushed her fluff of hair across his face and struggled away from him.

"I will love you," she teased, "until—the clock stops."

Then the Man burst out laughing, suddenly and[37] unexpectedly, like a boy, and romped her back again across the room, and snatched up the clock and stole away the key.

"Hickory Dock shall never stop!" he cried triumphantly. "I will wind it till I die. And no one else must ever meddle with it."

"But suppose you forget?" the Girl suggested half wistfully.

"I shall never forget," said the Man. "I will wind Hickory Dock every week as long as I live. I p-r-o-m-i-s-e!" His lips shut almost defiantly.

"But it isn't fair," the Girl insisted. "It isn't fair for me to let you make such a long promise. You—might—stop—loving me." Her eyes filled quickly with tears. "Promise me just for one year,"—she stamped her foot,—"I won't take any other promise."

So, half provoked and half amused, the Man bound himself then and there for the paltry term of a year. But to fulfil his own sincerity and seriousness he took the clock and stopped it for a moment that he might start it up again with the Girl close in his arms. A half-frightened, half-willing captive, she stood in her prison and looked with furtive eyes into the little, potential face of Hickory Dock.

"You—and I—for—all time," whispered the Man solemnly as he started the little mechanism throbbing once more on its way, and he stooped[38] down to seal the pledge with a kiss, but once more the significance of his word and act startled the Girl, and she clutched at the clock and ran across the room with it, and set it down very hard on her desk beside the Man's picture. Then, half ashamed of her flight, she stooped down suddenly and patted the little, ticking surface of ebony and glass and silver.

"It's a wonderful little Hickory Dock," she mused softly. "I never saw one just like it before."

The Man hesitated for a second and drew his mouth into a funny twist. "I don't believe there is another one like it in all the world," he acknowledged, half laughingly,—"that is, not just like it. I've had it fixed so that it won't strike eleven. I'm utterly tired of having you say 'There! it's eleven o'clock and you've got to go home.' Now, after ten o'clock nothing can strike till twelve, and that gives me two whole hours to use my own judgment in."

The Girl took one eager step towards him, when suddenly over the city roofs and across the square came the hateful, strident chime of midnight. Midnight? Midnight? The Girl rushed frantically to her closet and pulled the Man's coat out from among her fluffy dresses and thrust it into his hands, and he fled distractedly for his train without "Good-by."[39]

That was the trouble with having a lover who lived so far away and was so busy that he could come only one evening a week. Long as you could make that one evening, something always got crowded out. If you made love, there was no time to talk. If you talked, there was no time to make love. If you spent a great time in greetings, it curtailed your good-by. If you began your good-by any earlier, why, it cut your evening right in two. So the Girl sat and sulked a sad little while over the general misery of the situation, until at last, to comfort herself with the only means at hand, she went over to the closet and opened the door just wide enough to stick her nose in and sniff ecstatically.

"Oh! O—h!" she crooned. "O—h! What a nice, smoky smell."

Then she took Hickory Dock and went to bed. This method of bunking was nice for her, but it played sad havoc with Hickory Dock, who lay on his back and whizzed and whirred and spun around at such a rate that when morning came he was minutes and hours, not to say days, ahead of time.

This gain in time seemed rather an advantage to the Girl. She felt that it was a good omen and must in some manner hasten the Wedding-Day, but when she confided the same to the Man at his next visit he viewed the fact with righteous scorn, though[40] the fancy itself pleased him mightily. The Girl learned that night, however, to eschew Hickory Dock as a rag doll. She did not learn this, though, through any particular solicitude for Hickory Dock, but rather because she had to stand by respectfully a whole precious hour and watch the Man's lean, clever fingers tinker with the little, jeweled mechanism. It was a fearful waste of time. "You are so kind to little things," she whispered at last, with a catch in her voice that made the Man drop his work suddenly and give all his attention to big things. And another evening went, while Hickory Dock stood up like a hero and refused to strike eleven.

So every Sunday night throughout the Winter and the Spring and the Summer, the Man came joyously climbing up the long stairs to the Girl's room, and every Sunday night Hickory Dock was started off on a fresh round of Time and Love.

Hickory Dock, indeed, became a very precious object, for both Man and Girl had reached that particular stage of love where they craved the wonderful sensation of owning some vital thing together. But they were so busy loving that they did not recognize the instinct. The man looked upon Hickory Dock as an exceedingly blessed toy. The Girl grew gradually to cherish the little clock with a certain tender superstition and tingling reverence that sent[41] her heart pounding every time the Man's fingers turned to any casual tinkering.

And the Girl grew so exquisitely dear that the Man thought all women were like her. And the Man grew so sturdily precious that the Girl knew positively there was no person on earth to be compared with him. Over this happiness Hickory Dock presided throbbingly, and though he balked sometimes and bolted or lagged, he never stopped, and he never struck eleven.

Thus things went on in the customary way that things do go on with men and girls—until the Chronic Quarrel happened. The Chronic Quarrel was a trouble quite distinct from any ordinary lovers' disturbance, and it was a very silly little thing like this: The Girl had a nature that was emotionally apprehensive. She was always looking, as it were, for "dead men in the woods." She was always saying, "Suppose you get tired of me?" "Suppose I died?" "Suppose I found out that you had a wife living?" "Suppose you lost all your legs and arms in a railroad accident when you were coming here some Sunday night?"

And one day the Man had snapped her short with "Suppose? Suppose? What arrant nonsense! Suppose?—Suppose I fall in love with the Girl in the Office?"

It seemed to him the most extravagant supposition[42] that he could possibly imagine, and he was perfectly delighted with its effect on his Sweetheart. She grew silent at once and very wistful.

After that he met all her apprehensions with "Suppose?—Suppose I fall in love with the Girl in the Office!"

And one day the Girl looked up at him with hot tears in her eyes and said tersely, "Well, why don't you fall in love with her if you want to?"

That, of course, made a little trouble, but it was delicious fun making up, and the "Girl in the Office" became gradually one of those irresistibly dangerous jokes that always begin with laughter and end just as invariably with tears. When the Girl was sad or blue the Man was clumsy enough to try and cheer her with facetious allusions to the "Girl in the Office," and when the Girl was supremely, radiantly happy she used to boast, "Why, I'm so happy I don't care a rap about your old 'Girl in the Office.'" But whatever way the joke began, it always ended disastrously, with bitterness and tears, yet neither Man nor Girl could bear to formally taboo the subject lest it should look like the first shirking of their perfect intimacy and freedom of speech. The Man felt that in love like theirs he ought to be able to say anything he wanted to, so he kept on saying it, while the Girl claimed an equal if more caustic liberty of expression, and[43] the Chronic Quarrel began to fester a little round its edges.

One night in November, when Hickory Dock was nearly a year old in love, the Chronic Quarrel came to a climax. The Man was very listless that evening, and absent-minded, and altogether inadequate. The Girl accused him of indifference. He accused her in return of a shrewish temper. She suggested that perhaps he regretted his visit. He failed to contradict her. Then the Girl drew herself up to an absurd height for so small a creature and said stiffly,—

"You don't have to come next Sunday night if you don't want to."

At her scathing words the Man straightened up very suddenly in his chair and gazed over at the little clock in a startled sort of way.

"Why, of course I shall come," he retorted impulsively, "Hickory Dock needs me, if you don't."

"Oh, come and wind the clock by all means," flared the Girl. "I'm glad something needs you!"

Then the Man followed his own judgment and went home, though it was only ten o'clock.

"I'm not going to write to him this week," sobbed poor Rosalie. "I think he's very disagreeable."

But when the next Sunday came and the Man[44] was late, it seemed as though an Eternity had been tacked onto a hundred years. It was fully quarter-past eight before he came climbing up the stairs.

The Girl looked scornfully at the clock. Her throat ached like a bruise. "You didn't hurry yourself much, did you?" she asked spitefully.

The Man looked up quickly and bit his lip. "The train was late," he replied briefly. He did not stop to take off his coat, but walked over to the table and wound Hickory Dock. Then he hesitated the smallest possible fraction of a moment, but the Girl made no move, so he picked up his hat and started for the door.

The Girl's heart sank, but her pride rose proportionally. "Is that all you came for?" she flushed. "Good! I am very tired to-night."

Then the Man went away. She counted every footfall on the stairs. In the little hush at the street doorway she felt that he must surely turn and come running back again, breathless and eager, with outstretched arms and all the kisses she was starving for. But when she heard the front door slam with a vicious finality she went and threw herself, sobbing on the couch. "Fifty miles just to wind a clock!" she raged in grief and chagrin. "I'll punish him for it if that's all he comes for."

So the next Sunday night she took Hickory Dock[45] with a cruel jerk, and put him on the floor just outside her door, and left a candle burning so that the Man could not possibly fail to see what was intended. "If all he comes for is to wind the clock, just because he promised, there's no earthly use of his coming in," she reasoned, and went into her room and shut and locked her door, waiting nervously with clutched hands for the footfall on the stairs. "He loves some one else! He loves some one else!" she kept prodding herself.

Just at eight o'clock the Man came. She heard him very distinctly on the creaky board at the head of the stairs, and her heart beat to suffocation. Then she heard him come close to the door, as though he stooped down, and then he—laughed.

"Oh, very well," thought the Girl. "So he thinks it's funny, does he? He has no business to laugh while I am crying, even if he does love some one else.—I hate him!"

The Man knocked on the door very softly, and the Girl gripped tight hold of her chair for fear she should jump up and let him in. He knocked again, and she heard him give a strange little gasp of surprise. Then he tried the door-handle. It turned fatuously, but the door would not open. He pushed his weight against it,—she could almost feel the soft whirr of his coat on the wood,—but[46] the door would not yield.—Then he turned very suddenly and went away.

The Girl got up with a sort of gloating look, as though she liked her pain. "Next Sunday night is the last Sunday night of his year's promise," she brooded; "then everything will be over. He will see how wise I was not to let him promise forever and ever. I will send Hickory Dock to him by express to save his coming for the final ceremony." Then she went out and got Hickory Dock and brought him in and shook him, but Hickory Dock continued to tick, "Till he comes! Till he comes! Till he comes!"

It was a very tedious week. It is perfectly absurd to measure a week by the fact that seven days make it—some days are longer than others. By Wednesday the Girl's proud little heart had capitulated utterly, and she decided not to send Hickory Dock away by express, but to let things take their natural course. And every time she thought of the "natural course" her heart began to pound with expectation. Of course, she would not acknowledge that she really expected the Man to come after her cruel treatment of him the previous week. "Everything is over. Everything is over," she kept preaching to herself with many gestures and illustrations; but next to God she put her faith in promises, and hadn't the Man promised a great, sacred[47] lover's promise that he would come every Sunday for a year? So when the final Sunday actually came she went to her wedding-box and took out her "second best" of everything, silk and ruffles and laces, and dressed herself up for sheer pride and joy, with tingling thoughts of the night when she should wear her "first best" things. She put on a soft, little, white Summer dress that the Man liked better than anything else, and stuck a pink bow in her hair, and big rosettes on her slippers, and drew the big Morris chair towards the fire, and brought the Man's pipe and tobacco-box from behind the gilt mirror. Then she took Hickory Dock very tenderly and put him outside the door, with two pink candles flaming beside him, and a huge pink rose over his left ear. She thought the Man could smell the rose the second he opened the street door. Then she went back to her room, and left her door a wee crack open, and crouched down on the floor close to it, like a happy, wounded thing, and waited—

But the Man did not come. Eight o'clock, nine o'clock, ten o'clock, eleven o'clock, twelve o'clock, she waited, cramped and cold, hoping against hope, fearing against fear. Every creak on the stairs thrilled her. Every fresh disappointment chilled her right through to her heart. She sat and rocked herself in a huddled heap of pain, she taunted[48] herself with lack of spirit, she goaded herself with intricate remorse—but she never left her bitter vigil until half-past two. Then some clatter of milkmen in the street roused her to the realization of a new day, and she got up dazed and icy, like one in a dream, and limped over to her couch and threw herself down to sleep like a drunken person.

Late the next morning she woke heavily with a vague, dull sense of loss which she could not immediately explain. She lay and looked with astonishment at the wrinkled folds of the white mull dress that bound her limbs like a shroud. She clutched at the tightness of her collar, and fingered with surprise the pink bow in her hair. Then slowly, one by one, the events of the previous night came back to her in all their significance, and with a muffled scream of heartbreak she buried her face in the pillow. She cried till her heart felt like a clenched fist within her, and then, with her passion exhausted, she got up like a little, cold, rumpled ghost and pattered out to the hall in her silk-stockinged feet, and picked up Hickory Dock with his wilted pink rose and brought him in and put him back on her desk. Then she brought in the mussy, pink-smooched candlesticks and stowed them far away in her closet behind everything else. The faintest possible scent of tobacco-smoke came to her from the closet depths, and as she reached instinctively[49] to take a sad little whiff she became suddenly conscious that there was a strange, uncanny hush in the room, as though a soul had left its body. She turned back quickly and cried out with a smothered cry. Hickory Dock had stopped!

"Until—the—end—of—Time," she gasped, and staggered hard against the closet-door. Then in a flash she burst out laughing stridently, and rushed for Hickory Dock and grabbed him by his little silver handle, opened the window with a bang, and threw him with all her might and main down into the brick alley four stories below, where he fell with a sickening crash among a wee handful of scattered rose petals.

—The days that followed were like horrid dreams, the nights, like hideous realities. The fire would not burn. The sun and moon would not shine, and life itself settled down like a pall. Every detail of that Sunday night stamped and re stamped itself upon her mind. Back of her outraged love was the crueller pain of her outraged faith. The Man of his own free will had made a sacred promise and broken it! She realized now for the first time in her life why men went to the devil because women had failed them—not disappointed them, but failed them! She could even imagine how poor mothers felt when fathers shirked their fatherhood. She tasted in one[50] week's imagination all possible woman sorrows of the world.

At the end of the second week she began to realize the depth of isolation into which her engagement had thrown her. For a year and a half she had thought nothing, dreamed nothing, cared for nothing except the Man. Now, with the Man swept away, there was no place to turn either for comfort or amusement.

At the end of the third week, when no word came, she began to gather together all the Man's little personal effects, and consigned them to a box out of sight—the pipe and tobacco, a favorite book, his soft Turkish slippers, his best gloves, and even a little poem which he had written for her to set to music. It was a pretty little love-song that they had made together, but as she hummed it over now for the last time she wondered if, after all, woman's music did not do more than man's words to make love Singable.

When a month was up she began to strip the room of everything that the Man had brought towards the making of their Home. It was like stripping tendons. She had never realized before how thoroughly the Man's personality had dominated her room as well as her life. When she had crowded his books, his pictures, his college trophies, his Morris chair, his rugs, into one corner of her[51] room and covered them with two big sheets, her little, paltry, feminine possessions looked like chiffon in a desert.

While she was pondering what to do next her rent fell due. The month's idling had completely emptied her pewter savings-bank that she had been keeping as a sort of precious joke for the Honeymoon. The rent-bill startled her into spasmodic efforts at composition. She had been quite busy for a year writing songs for some Educational people, but how could one make harmony with a heart full of discord and all life off the key. A single week convinced her of the utter futility of these efforts. In one high-strung, wakeful night she decided all at once to give up the whole struggle and go back to her little country village, where at least she would find free food and shelter until she could get her grip again.

For three days she struggled heroically with burlap and packing-boxes. She felt as though every nail she pounded was hurting the Man as well as herself, and she pounded just as hard as she possibly could.

When the room was stripped of every atom of personality except her couch, and the duplicate latch-key, which still hung high and dusty, a deliciously cruel thought came to the Girl, and the irony of it set her eyes flashing. On the night before[52] her intended departure she took the key and put it into a pretty little box and sent it to the Man.

"He'll know by that token," she said, "that there's no more 'Home' for him and me. He will get his furniture a few days later, and then he will see that everything is scattered and shattered. Even if he's married by this time, the key will hurt him, for his wife will want to know what it means, and he never can tell her."

Then she cried so hard that her overwrought, half-starved little body collapsed, and she crept into her bed and was sick all night and all the next day, so that there was no possible thought or chance of packing or traveling. But towards the second evening she struggled up to get herself a taste of food and wine from her cupboard, and, wrapping herself in her pink kimono, huddled over the fire to try and find a little blaze and cheer.

Just as the flames commenced to flush her cheeks the lock clicked. She started up in alarm. The door opened abruptly, and the Man strode in with a very determined, husbandly look on his haggard face. For the fraction of a second he stood and looked at her pitifully frightened and disheveled little figure.

"Forgive me," he cried, "but I had to come like this." Then he took one mighty stride and[53] caught her up in his arms and carried her back to her open bed and tucked her in like a child while she clung to his neck laughing and sobbing and crying as though her brain was turned. He smoothed her hair, he kissed her eyes, he rubbed his rough cheek confidently against her soft one, and finally, when her convulsive tremors quieted a little, he reached down into his great overcoat pocket and took out poor, battered, mutilated Hickory Dock.

"I found him down in the Janitor's office just now," he explained, and his mouth twitched just the merest trifle at the corners.

"Don't smile," said the Girl, sitting up suddenly very straight and stiff. "Don't smile till you know the whole truth. I broke Hickory Dock. I threw him purposely four stories down into the brick alley!"

The Man began to examine Hickory Dock very carefully.

"I should judge that it was a brick alley," he remarked with an odd twist of his lips, as he tossed the shattered little clock over to the burlap-covered armchair.

Then he took the Girl very quietly and tenderly in his arms again, and gazed down into her eyes with a look that was new to him.

"Rosalie," he whispered, "I will mend Hickory[54] Dock for you if it takes a thousand years,"—his voice choked,—"but I wish to God I could mend my broken promise as easily!"

And Rosalie smiled through her tears and said,—

"Sweetheart-Man, you do love me?"

"With all my heart and soul and body and breath, and past and present and future I love you!" said the Man.

Then Rosalie kissed a little path to his ear, and whispered, oh, so softly,—

"Sweetheart-Man, I love you just that same way."

And Hickory Dock, the Angel, never ticked the passing of a single second, but lay on his back looking straight up to Heaven with his two little battered hands clasped eternally at Love's high noon.[57]

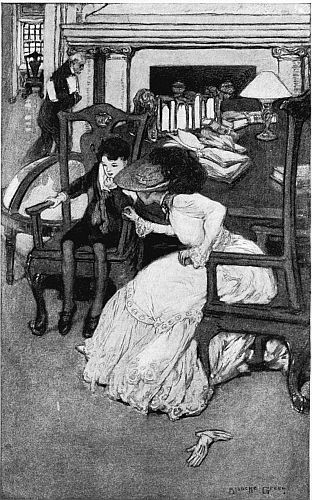

It was supper time, too, somewhere between six and seven, the caved-in hour of the day when the ruddy ghost of Other People's dinners flaunts itself rather grossly in the pallid nostrils of Her Who Lives by the Chafing-Dish.

One of the girls was a Medical Masseuse, trained brain and brawn in the German Hospitals. One was a Public School Teacher with a tickle of chalk dust in her lungs. One was a Cartoon Artist with a heart like chiffon and a wit as accidentally malicious as the jab of a pin in a flirt's belt.

All three of them were silly with fatigue. The[58] writhing city cavorted before them like a sick clown. A lame cab horse went strutting like a mechanical toy. Crape on a door would have plunged them into hysterics. Were you ever as tired as that?

With no other object, except to get home

With no other object, except to get home

It was, in short, the kind of night that rips out every one according to his stitch. Rhoda Hanlan the Masseuse was ostentatiously sewed with double thread and backstitched at that. Even the little Teacher, Ruth MacLaurin, had a physique that was embroidered if not darned across its raveled places. But Noreen Gaudette, the Cartoon Drawer, with her spangled brain and her tissue-paper body, was merely basted together with a single silken thread. It was the knowledge of being only basted that gave Noreen the droll, puckered terror in her eyes whenever Life tugged at her with any specially inordinate strain.

Yet it was Noreen who was popularly supposed to be built with an electric battery instead of a heart.

The boarding-house that welcomed the three was rather tall for beauty, narrow-shouldered, flat-chested, hunched together in the block like a prudish, dour old spinster overcrowded in a street car. To call such a house "Home" was like calling such a spinster "Mother." But the three girls called it "Home" and rather liked the saucy taste of the word in their mouths.[59]

Across the threshold in a final spurt of energy the jaded girls pushed with the joyous realization that there were now only five flights of stairs between themselves and their own attic studio.

On the first floor the usual dreary vision greeted them of a hall table strewn with stale letters—most evidently bills, which no one seemed in a hurry to appropriate.

It was twenty-two stumbling, bundle-dropping steps to the next floor, where the strictly Bachelor Quarters with half-swung doors emitted a pleasant gritty sound of masculine voices, and a sumptuous cloud of cigarette smoke which led the way frowardly up twenty-two more toiling steps to the Old Maid's Floor, buffeted itself naughtily against the sternly shut doors, and then mounted triumphantly like sweet incense to the Romance Floor, where with door alluringly open the Much-Loved Girl and her Mother were frankly and ingenuously preparing for the Monday-Night-Lover's visit.

The vision of the Much-Loved Girl smote like a brutal flashlight upon the three girls in the hall.

Out of curl, out of breath, jaded of face, bedraggled of clothes, they stopped abruptly and stared into the vista.

Before their fretted eyes the room stretched fresh and clean as a newly returned laundry package. The green rugs lay like velvet grass across the floor.[60] The chintz-covered furniture crisped like the crust of a cake. Facing the gilt-bound mirror, the Much-Loved Girl sat joyously in all her lingerie-waisted, lace-paper freshness, while her Mother hovered over her to give one last maternal touch to a particularly rampageous blond curl.

The Much-Loved Girl was a cordial person. Her liquid, mirrored reflection nodded gaily out into the hall. There was no fatigue in the sparkling face. There was no rain or fog. There was no street-corner insult. There was no harried stress of wherewithal. There was just Youth, and Girl, and Cherishing.

She made the Masseuse and the little School Teacher think of a pale-pink rose in a cut-glass vase. But she made Noreen Gaudette feel like a vegetable in a boiled dinner.

With one despairing gasp—half-chuckle and half-sob—the three girls pulled themselves together and dashed up the last flight of stairs to the Trunk-Room Floor, and their own attic studio, where bumping through the darkness they turned a sulky stream of light upon a room more tired-looking than themselves, and then, with almost fierce abandon, collapsed into the nearest resting-places that they could reach.

It was a long time before any one spoke.

Between the treacherous breeze of the open window[61] and a withering blast of furnace heat the wilted muslin curtain swayed back and forth with languid rhythm. Across the damp night air came faintly the yearning, lovery smell of violets, and the far-off, mournful whine of a sick hand-organ.

On the black fur hearth-rug Rhoda, the red-haired, lay prostrated like a broken tiger lily with her long, lithe hands clutched desperately at her temples.

"I am so tired," she said. "I am so tired that I can actually feel my hair fade."

Ruth, the little Public School Teacher, laughed derisively from her pillowed couch where she struggled intermittently with her suffocating collar and the pinchy buckles on her overshoes.

"That's nothing," she asserted wanly. "I am so tired that I would like to build me a pink-wadded silk house, just the shape of a slipper, where I could snuggle down in the toe and go to sleep for a—million years. It isn't to-morrow's early morning that racks me, it's the thought of all the early mornings between now and the Judgment Day. Oh, any sentimental person can cry at night, but when you begin to cry in the morning—to lie awake and cry in the morning—" Her face sickened suddenly. "Did you see that Mother downstairs?" she gasped, "fixing that curl? Think of having a Mother!"[62]

Then Noreen Gaudette opened her great gray eyes and grinned diabolically. She had a funny little manner of cartooning her emotions.

"Think of having a Mother?" she scoffed. "What nonsense!—Think of having a c-u-r-l!

"You talk like Sunday-Paper débutantes," she drawled. "You don't know anything about being tired. Why, I am so tired—I am so tired—that I wish—I wish that the first man who ever proposed to me would come back and ask me—again!"

It was then that the Landlady, knocking at the door, presented a card, "Mr. Ernest T. Dextwood," for Miss Gaudette, and the innocent-looking conversation exploded suddenly like a short-fused firecracker.

Rhoda in an instant was sitting bolt upright with her arms around her knees rocking to and fro in convulsive delight. Ruth much more thoughtfully jumped for Noreen's bureau drawer. But Noreen herself, after one long, hyphenated "Oh, my H-e-a-v-e-n-s!" threw off her damp, wrinkled coat, stalked over to the open window, and knelt down quiveringly where she could smother her blazing face in the inconsequent darkness.

For miles and miles the teasing lights of Other Women's homes stretched out before her. From the window-sill below her rose the persistent purple[63] smell of violets, and the cooing, gauzy laughter of the Much-Loved Girl. Fatigue was in the damp air, surely, but Spring was also there, and Lonesomeness, and worst of all, that desolating sense of patient, dying snow wasting away before one's eyes like Life itself.

When Noreen turned again to her friends her eyelids drooped defiantly across her eyes. Her lips were like a scarlet petal under the bite of her teeth. There in the jetty black and scathing white of her dress she loomed up suddenly like one of her own best drawings—pulseless ink and stale white paper vitalized all in an instant by some miraculous emotional power. A living Cartoon of "Fatigue" she stood there—"Fatigue," as she herself would have drawn it—no flaccid failure of wilted bone and sagging flesh, but Verve—the taut Brain's pitiless rally of the Body that can not afford to rest—the verve of Factory Lights blazing overtime, the verve of the Runner who drops at his goal.

"All the time I am gone," she grinned, "pray over and over, 'Lead Noreen not into temptation.'" Her voice broke suddenly into wistful laughter: "Why to meet again a man who used to love you—it's like offering store-credit to a pauper."

Then she slammed the door behind her and started downstairs for the bleak, plush parlor, with a chaotic sense of absurdity and bravado.[64]

But when she reached the middle of the bachelor stairway and looked down casually and spied her clumsy arctics butting out from her wet-edged skirt all her nervousness focused instantly in her shaking knees, and she collapsed abruptly on the friendly dark stair and clutching hold of the banister, began to whimper.

In the midst of her stifled tears a door banged hard above her, the floor creaked under a sturdy step, and the tall, narrow form of the Political Economist silhouetted itself against the feeble light of the upper landing.

One step down he came into the darkness—two steps, three steps, four, until at last in choking miserable embarrassment, Noreen cried out hysterically:

"Don't step on me—I'm crying!"

With a gasp of astonishment the young man struck a sputtering match and bent down waving it before him.

"Why, it's you, Miss Gaudette," he exclaimed with relief. "What's the matter? Are you ill? What are you crying about?" and he dropped down beside her and commenced to fan her frantically with his hat.

"What are you crying about?" he persisted helplessly, drugged man-like, by the same embarrassment that mounted like wine to the woman's brain.[65]

Noreen began to laugh snuffingly.

"I'm not crying about anything special," she acknowledged. "I'm just crying. I'm crying partly because I'm tired—and partly because I've got my overshoes on—but mostly"—her voice began to catch again—"but mostly—because there's a man waiting to see me in the parlor."

The Political Economist shifted uneasily in his rain coat and stared into Noreen's eyes.

"Great Heavens!" he stammered. "Do you always cry when men come to see you? Is that why you never invited me to call?"

Noreen shook her head. "I never have men come to see me," she answered quite simply. "I go to see them. I study in their studios. I work on their newspapers. I caricature their enemies. Oh, it isn't men that I'm afraid of," she added blithely, "but this is something particular. This is something really very funny. Did you ever make a wish that something perfectly preposterous would happen?"

"Oh, yes," said the Political Economist reassuringly. "This very day I said that I wished my Stenographer would swallow the telephone."

"But she didn't swallow it, did she?" persisted Noreen triumphantly. "Now I said that I wished some one would swallow the telephone and she did swallow it!"[66]

Then her face in the dusky light flared piteously with harlequined emotions. Her eyes blazed bright with toy excitement. Her lips curved impishly with exaggerated drollery. But when for a second her head drooped back against the banister her jaded small face looked for all the world like a death-mask of a Jester.

The Political Economist's heart crinkled uncomfortably within him.

"Why, you poor little girl," he said. "I didn't know that women got as tired as that. Let me take off your overshoes."

Noreen stood up like a well-trained pony and shed her clumsy footgear.

The Man's voice grew peremptory. "Your skirt is sopping wet. Are you crazy? Didn't have time to get into dry things? Nonsense! Have you had any supper? What? N-o? Wait a minute."

In an instant he was flying up the stairs, and when he came back there was a big glass of cool milk in his hand.

Noreen drank it ravenously, and then started downstairs with abrupt, quick courage.

When she reached the ground floor the Political Economist leaned over the banisters and shouted in a piercing whisper:

"I'll leave your overshoes outside my door where you can get them on your way up later."[67]

Then he laughed teasingly and added: "I—hope—you'll—have—a—good—time."

And Noreen, cleaving for one last second to the outer edge of the banisters, smiled up at him, so strainingly up, that her face, to the man above her, looked like a little flat white plate with a crimson-lipped rose wilting on it.

Then she disappeared into the parlor.

With equal abruptness the Political Economist changed his mind about going out, and went back instead to his own room and plunged himself down in his chair, and smoked and thought, until his friend, the Poet at the big writing-desk, slapped down his manuscript and stared at him inquisitively.

"Lord Almighty! I wish I could draw!" said the Political Economist. It was not so much an exclamation as a reverent entreaty. His eyes narrowed sketchily across the vision that haunted him. "If I could draw," he persisted, "I'd make a picture that would hit the world like a knuckled fist straight between its selfish old eyes. And I'd call that picture 'Talent.' I'd make an ocean chopping white and squally, with black clouds scudding like fury across the sky, and no land in sight except rocks. And I'd fill that ocean full of sharks and things—not showing too much, you know, but just an occasional shimmer of fins through the foam.[68] And I'd make a sailboat scooting along, tipped 'way over on her side toward you, with just a slip of an eager-faced girl in it. And I'd wedge her in there, wind-blown, spray-dashed, foot and back braced to the death, with the tiller in one hand and the sheet in the other, and weather-almighty roaring all around her. And I'd make the riskiest little leak in the bottom of that boat rammed desperately with a box of chocolates, and a bunch of violets, and a large paper compliment in a man's handwriting reading: 'Oh, how clever you are.' And I'd have that girl's face haggard with hunger, starved for sleep, tense with fear, ravished with excitement. But I'd have her chin up, and her eyes open, and the tiniest tilt of a quizzical smile hounding you like mad across the snug, gilt frame. Maybe, too, I'd have a woman's magazine blowing around telling in chaste language how to keep the hair 'smooth' and the hands 'velvety,' and admonishing girls above all things not to be eaten by sharks! Good Heavens, Man!" he finished disjointedly, "a girl doesn't know how to sail a boat anyway!"

"W-h-a-t are you talking about?" moaned the Poet.

The Political Economist began to knock the ashes furiously out of his pipe.

"What am I talking about?" he cried; "I'm talking about girls. I've always said that I'd[69] gladly fall in love if I only could decide what kind of a girl I wanted to fall in love with. Well, I've decided!"

The Poet's face furrowed. "Is it the Much-Loved Girl?" he stammered.

The Political Economist's smoldering temper began to blaze.

"No, it isn't," ejaculated the Political Economist. "The Much-Loved Girl is a sweet enough, airy, fairy sort of girl, but I'm not going to fall in love with just a pretty valentine."

"Going to try a 'Comic'?" the Poet suggested pleasantly.

The Political Economist ignored the impertinence. "I am reasonably well off," he continued meditatively, "and I'm reasonably good-looking, and I've contributed eleven articles on 'Men and Women' to modern economic literature, but it's dawned on me all of a sudden that in spite of all my beauteous theories regarding life in general, I am just one big shirk when it comes to life in particular."

The Poet put down his pen and pushed aside his bottle of rhyming fluid, and began to take notice.

"Whom are you going to fall in love with?" he demanded.

The Political Economist sank back into his chair.

"I don't quite know," he added simply, "but[70] she's going to be some tired girl. Whatever else she may or may not be, she's got to be a tired girl."

"A tired girl?" scoffed the Poet. "That's no kind of a girl to marry. Choose somebody who's all pink and white freshness. That's the kind of a girl to make a man happy."

The Political Economist smiled a bit viciously behind his cigar.

"Half an hour ago," he affirmed, "I was a beast just like you. Good Heavens! Man," he cried out suddenly, "did you ever see a girl cry? Really cry, I mean. Not because her manicure scissors jabbed her thumb, but because her great, strong, tyrant, sexless brain had goaded her poor little woman-body to the very cruelest, last vestige of its strength and spirit. Did you ever see a girl like that Miss Gaudette upstairs—she's the Artist, you know, who did those cartoons last year that played the devil itself with 'Congress Assembled'—did you ever see a girl like that just plain thrown down, tripped in her tracks, sobbing like a hurt, tired child? Your pink and white prettiness can cry like a rampant tragedy-queen all she wants to over a misfitted collar, but my hand is going here and now to the big-brained girl who cries like a child!"

"In short," interrupted the Poet, "you are going to help—Miss Gaudette sail her boat?"[71]

"Y-e-s," said the Political Economist.

"And so," mocked the Poet, "you are going to jump aboard and steer the young lady adroitly to some port of your own choosing?"

The older man's jaws tightened ominously. "No, by the Lord Almighty, that's just what I am not going to do!" he promised. "I'm going to help her sail to the port of her own choosing!"

The Poet began to rummage in his mind for adequate arguments. "Oh, allegorically," he conceded, "your scheme is utterly charming, but from any material, matrimonial point of view I should want to remind myself pretty hard that overwrought brains do not focus very easily on domestic interests, nor do arms which have tugged as you say at 'sheets' and 'tillers' curve very dimplingly around youngsters' shoulders."

The Political Economist blew seven mighty smoke-puffs from his pipe.

"That would be the economic price I deserve to pay for not having arrived earlier on the scene," he said quietly.

The Poet began to chuckle. "You certainly are hard hit," he scoffed.

"It's a rotten rhyme," attested the Political Economist, and strode over to the mantelpiece, where he began to hunt for a long piece of twine.