Title: Signal in the Dark

Author: Mildred A. Wirt

Release date: January 4, 2011 [eBook #34850]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Stephen Hutcheson, Charlie Howard, and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

By

MILDRED A. WIRT

Author of

MILDRED A. WIRT MYSTERY STORIES

TRAILER STORIES FOR GIRLS

Illustrated

CUPPLES AND LEON COMPANY

Publishers

NEW YORK

PENNY PARKER

MYSTERY STORIES

Large 12 mo. Cloth Illustrated

TALE OF THE WITCH DOLL

THE VANISHING HOUSEBOAT

DANGER AT THE DRAWBRIDGE

BEHIND THE GREEN DOOR

CLUE OF THE SILKEN LADDER

THE SECRET PACT

THE CLOCK STRIKES THIRTEEN

THE WISHING WELL

SABOTEURS ON THE RIVER

GHOST BEYOND THE GATE

HOOFBEATS ON THE TURNPIKE

VOICE FROM THE CAVE

GUILT OF THE BRASS THIEVES

SIGNAL IN THE DARK

WHISPERING WALLS

SWAMP ISLAND

THE CRY AT MIDNIGHT

COPYRIGHT, 1946, BY CUPPLES AND LEON CO.

Signal in the Dark

PRINTED IN U. S. A.

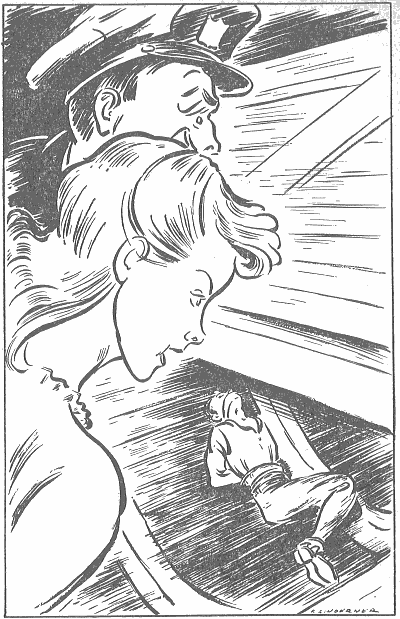

PENNY UTTERED A LITTLE CRY

“Signal in the Dark” (See Page 195)

“The situation is getting worse instead of better, Penny. Three of our reporters are sick, and we’re trying to run the paper with only a third of our normal editorial staff.” Anthony Parker, publisher of the Riverview Star, whirled around in the swivel chair to face his daughter who sat opposite him in the private office of the newspaper. “Frankly, I’m up against it,” he added gloomily.

Penny, a slim girl with deep, intelligent blue eyes, uncurled herself from the window ledge. Carefully, she dusted her brown wool skirt which had picked up a cobweb and streaks of dirt.

“You could use a janitor around here too,” she hinted teasingly. “How about hiring me?”

“As queen of the dustmop brigade?”

“As a reporter,” Penny corrected. “I’m serious, Dad. You’re desperate for employes. I’m desperate for spending money. I have three weeks school vacation coming up, so why not strike a bargain?”

“The paper needs experienced workers, Penny.”

“Precisely.”

“You’re a very good writer,” Mr. Parker admitted. “In fact, in months past you turned in some of the best feature stories the Star ever printed. But always they were special assignments. We must have a reporter who can work a daily, eight-hour grind and be depended upon to handle routine stories with speed, accuracy and efficiency.”

“And you think I am not what the doctor ordered?”

“I think,” corrected Mr. Parker, “that you would blow your pretty little top by the end of the second day. For instance, it’s not easy nor pleasant to write obituaries. Yet it must be done, and accurately. On this paper, a new reporter is expected to do rewrites and other tedious work. You wouldn’t like it, Penny.”

“I’d take it neatly in my stride, Dad. Why not try me and see?”

Mr. Parker shook his head and began to read the three-star edition of the paper, its ink still damp from the press.

“Give me one sound, logical reason for turning me down,” Penny persisted.

“Very well. You are my daughter. Our editors might feel that they were compelled to treat you with special consideration—give you the best assignments—handle you with kid gloves.”

“You could take care of that matter easily enough.”

“If they took my instructions seriously, you might not like it,” the newspaper owner warned. “A reporter learns hard and bitter lessons. Mr. DeWitt, for instance, is a fine editor—our best, but he has a temper and—”

The frosted glass door swung open and an elderly, slightly bald man in shirt sleeves slouched in. Seeing Penny, he would have retreated, had not Mr. Parker called him back.

“What’s on your mind, DeWitt?”

“Trouble,” growled the editor. “That no-good, addle-brained boy we hired as night police reporter, just blew up! Said it was too confining to sit in a police station all night waiting for something to happen! So he gets himself a job in a canning factory! Now we’re another employee short.”

“Dad, let me take over the night police job!” Penny pleaded.

Both her father and Mr. DeWitt smiled as if suffering from intense pain. “Penny,” Mr. Parker explained gently. “Night police work isn’t suitable for a girl. Furthermore, it is one of the most undesirable jobs on a paper.”

“But I want to work somewhere, and you’re so stubborn!”

Mr. DeWitt studied Penny with concentrated interest. Hope flickered in his eyes. Turning abruptly to Mr. Parker he asked: “Why not, Chief? We could use her on the desk for rewrite. We’re mighty hard up, and that’s a fact.”

“What about the personnel problem?” Mr. Parker frowned. “How would the staff take it?”

“Some of the reporters might not like it,” Mr. DeWitt admitted, “but who’s running this paper anyhow?”

“I often wonder,” sighed Mr. Parker.

Detecting signs of a weakening, Penny appealed to Mr. DeWitt. “Wouldn’t I be a help to you if I were on the staff?” she urged.

“Why, sure,” he agreed cautiously.

“There, you see, Dad! Mr. DeWitt wants me!”

“Penny, it’s a personnel problem,” her father explained with growing impatience. “The other reporters might not consider you a welcome addition to the staff. You would expect favors.”

“I never would!”

“We need her,” said Mr. DeWitt significantly. “We really do.”

With two against him, Mr. Parker suddenly gave in.

“All right,” he agreed. “Penny, we’ll put you on as a cub reporter. That means you’ll start as a beginner with a beginner’s salary and do routine work until you’ve proved your merit. You’ll expect no special consideration. Is that understood?”

“Perfectly!” Grinning from ear to ear, Penny would have agreed to anything.

“Furthermore, if the work gets you down, I won’t have you coming to me asking for a change.”

“I’ll never darken your office door, Dad. Just one question. How much money does a beginner get?”

“Twenty-five dollars.”

Penny’s face was a blank.

“It will be more than you are worth the first few weeks,” Mr. Parker said.

“I’ll take it,” Penny declared hastily. “When do I start?”

“Right now,” decided her father. “DeWitt, introduce her to the staff, and put her to work.”

Feeling highly elated but a trifle self-conscious, Penny followed Editor DeWitt past the photography studio and the A.P. wire room to the main newsroom where reporters were tapping at their typewriters.

“Gang,” said Mr. DeWitt in an all inclusive introduction. “This is Penny Parker. She’ll be working here for a few weeks.”

Heads lifted and appraising eyes focused upon her. Nearly everyone nodded and smiled, but one girl who sat at the far end of a long typewriter table regarded her with an intent, almost hostile stare. And as luck would have it, Mr. DeWitt assigned Penny to the typewriter adjoining hers.

“This is Elda Hunt,” he introduced her. “Show Penny the ropes, will you?”

The girl, a blonde, with heavily-rouged cheeks, patted the rigid rolls of her hair into place. Staring at Mr. DeWitt, she answered not a word.

“I’ll have a lot to learn,” Penny said, trying to make friendly conversation.

Elda shrugged. “You’re the publisher’s daughter, aren’t you?” she inquired.

“Yes.”

“Then I don’t think you’ll have too hard a time,” the girl drawled.

Penny started to reply, but thought better of it. Seating herself beside Elda, she unhooded the typewriter, rolled a sheet of copy paper into it, and experimented with the keys.

The main newsroom was a confusion of sound. Although work was being handled with dispatch, there was an air of tension, for press time on the five-star edition was drawing close. Telephones were ringing, and Editor DeWitt, who sat at the head of the big rectangular desk, tersely assigned reporters to take the incoming calls. Not far from Penny’s ear, the police shortwave radio blared. Copy boys ran to and fro.

Benny Jewell, the assistant editor, tossed her a handful of typewritten sheets.

“Take these handouts and make ’em into shorts,” he instructed briefly.

“Handouts?” Penny asked in bewilderment. “Shorts?”

“Cut the stories to a paragraph or two each.”

“Oh,” said Penny, catching on. “You want me to rewrite them.”

At her elbow, Elda openly snickered.

Color stained Penny’s cheeks, but she quietly read the first sheet, which was an account of a meeting to be held the following week. Picking out the most important facts, she boiled the story down to two short paragraphs, and dropped the finished copy into the editor’s wire basket.

Only then did Elda speak. “You’re supposed to make two carbons of every story you write,” she said pityingly.

The girl might have told her sooner, Penny thought. However, she thanked her politely, and finding carbon paper, rewrote the story. In her nervousness she inserted one of the carbons upside down, ruining the impression. As she removed the sheets from the machine, she saw what she had done. Elda saw too, and smiled in a superior way.

“She dislikes me intensely,” Penny thought. “I wonder why? I’ve not done a thing to her.”

Aware that she had wasted paper and valuable time, Penny recopied the story a third time and turned it in to the editor. After that, she rewrote the additional stories with fairly good speed. By watching other reporters she learned that the carbon copies were speared on spindles which at intervals a copy boy collected and carried away.

A telephone rang, and this time, Mr. DeWitt, looking straight at Penny, said: “An obituary. Will you take it?”

She went to the phone and copied down the facts carefully, knowing that while death notices were routine, they were of vital interest to readers of the paper. Any mistake of fact could prove serious.

Returning to her typewriter, she wrote the item. But after she had turned it in, Mr. DeWitt called her to his desk. He was pleasant but firm.

“What day are services to be held?” he asked. “Who are the survivors? Where did the woman die? Furthermore, we never use the word ‘Funeral Home’. Instead, we say ‘mortuary’.”

Penny telephoned for more information, and finally after rewriting the notice twice more, succeeded in getting it past Mr. DeWitt. But as he tossed the story to a copy reader, she saw that he had pencilled several changes.

“There’s more to writing routine stories than I thought,” she reflected. “I’ll really have to dig in unless I want to disgrace Dad.”

Penny was given another obituary to write which proved nearly as difficult as the first. Hopelessly discouraged, she started for the rest room to get a drink and wash her hands.

As she entered the lounge, voices reached her ears, and instantly she realized that Elda Hunt was talking to another girl reporter about her.

“The publisher’s daughter!” she heard her say scathingly. “As if we aren’t having a hard enough time here, without having to coddle her along!”

“I didn’t think she seemed so bad,” the other replied. “She’ll catch on.”

“She’ll be promoted over all our heads if that’s what you mean!” Elda retorted bitterly. “I know for a fact, she’s starting at fifty a week, and no experience! If you ask me, it’s unfair! We should walk out of here, and see how those fine editors would like that!”

Penny’s first thought was to accost the two girls and correct the misstatements. But sober reflection convinced her she could make no graver mistake. Far better, she reasoned, to ignore the entire matter.

She quickly washed her hands, purposely making enough noise to draw attention to her presence. Elda and her friend became silent. A moment later, coming through the inner door of the powder room, they saw her, but offered no comment. Penny hastily returned to the newsroom.

For the remainder of the day she worked with deep concentration, only dimly aware of what went on about her. Seemingly there were endless numbers of obituaries to write. Telephones rang constantly. Work was never finished, for as soon as one edition was off the press, another was in the making.

Now and then Penny caught herself glancing toward an empty desk at the far corner of the room. Jerry Livingston had sat there until a year ago when he had been granted a leave of absence to join the Army Air Force. Unquestionably the Star’s most talented reporter, he had been Penny’s best friend.

“I wish Jerry were here,” she thought wistfully. “But if he were, he’d tell me to buckle down and not let this job lick me! Dad warned me it would be hard, monotonous work.”

Penny worked with renewed energy. After awhile she began to feel that she was making definite progress. Mr. Jewell, the assistant editor, made fewer corrections as he read over her copy, and now and then she actually saw him nod approvingly. Once when she turned in a rewritten “hand-out”—a publicity story which had been sent to the paper in unusable form—he praised her for giving it a fresh touch.

“Good lead,” he commented. “You’re coming along all right.”

Elda heard the praise and her eyes snapped angrily. At her typewriter, she slammed the carriage. No one noticed except Penny. A moment later, Mr. DeWitt called Elda to his desk, saying severely:

“Watch the spelling of names, Elda. This is the third one we’ve checked you on today. Don’t you ever consult the city directory?”

“Of course I do!” Elda was indignant.

“Well, watch it,” Mr. DeWitt said again. “We must have accuracy.”

With a swish of skirts, Elda went back to her desk. Her face was as dark as a thunder cloud. Deliberately she dawdled over her next piece of copy. After she had turned it in, she returned to the editor’s desk to take it from the wire basket and make additional corrections.

“Just being extra careful of names,” she said arrogantly as the assistant editor shot her a quick, inquiring glance.

Thinking no more of the incident, Penny kept on with her own work. She took special care with names, even looking up in the city directory those of which she was almost certain. When she turned in a piece of copy, she was satisfied that not a name or fact was inaccurate.

Late in the afternoon, she noticed that Mr. DeWitt and Mr. Jewell appeared displeased about a story they had found in the Five Star edition of the paper. After reading it, they talked together, and then sorted through a roll of discarded copy, evidently searching for the original. Finally, Mr. DeWitt called:

“Miss Parker!”

Wondering what she had done wrong, Penny went quickly to his desk.

“You wrote this story?” he asked, jabbing a pencil at one of the printed obituaries.

“Why, yes,” Penny acknowledged. “Is anything wrong with it?”

“Only that you’ve buried the wrong man,” DeWitt said sarcastically. “Where did you get that name?”

Penny felt actually sick, and her skin prickled with heat. She stared at the story in print. It said that John Gorman had died that morning in Mercy Hospital.

“The man who died was John Borman,” DeWitt said grimly. “It happens that John Gorman is one of the city’s most prominent industrialists. We’ve made the correction, but it was too late to catch two-thirds of the papers.”

Penny stared again at the name, her mind working slowly.

“But Mr. DeWitt,” she protested. “I don’t think I wrote it that way. I knew the correct name was Borman. I’m sure that was how I turned it in.”

“Maybe you hit a wrong letter on the typewriter,” the editor said less severely. “That’s why one always should read over a story after it’s written.”

“But I did that too,” Penny said, and then bit her lip, because she realized she was arguing about the matter.

“We’ll look at the carbons,” decided Mr. DeWitt.

They had been taken from the spindles by copy boys, but the editor ordered the entire day’s work returned to his desk. Pawing through the sheets, he came to the one Penny had written. Swiftly he compared it with the original copy.

“You’re right!” he exclaimed in amazement. “The carbons show you wrote the name John Borman, not Gorman.”

“I knew I did!”

“But the copy that was turned into the basket said John Gorman. Didn’t you change it on the first sheet?”

“Indeed I didn’t, Mr. DeWitt.”

Scowling, the editor compared the two copies. Obviously on the original sheet, a neat erasure had been made, and a typewritten letter G had been substituted for B.

“There’s something funny about this,” Mr. DeWitt said. “Mighty funny!” His gaze roved about the typewriter table, focusing for an instant upon Elda who had been listening intently to the conversation. “Never mind,” he added to Penny. “We’ll look into this.”

Later, she saw him showing the copy sheets to the assistant editor. Seemingly, the two men were deeply puzzled as to how the error had been made. Penny had her own opinion.

“Elda did it,” she thought resentfully. “I’ll wager she removed the sheet from the wire basket when she pretended to be making a correction on her own story!”

Having no proof, Penny wisely kept her thoughts to herself. But she knew that in the future she must take double precautions to guard against other tricks to discredit her.

At the end of the day, the newsroom rapidly emptied. One by one, reporters covered their typewriters and left the building. A few of the girls remained, among them, Penny and Elda. Editor DeWitt was putting on his hat when the telephone rang.

Absently he reached for it and then straightened to alert attention. Grabbing a sheet of copy paper, he scrawled a few words. Eyes focused upon him, for instinctively everyone knew that something important had happened.

DeWitt hung up the receiver, his eyes staring into space for an instant. Then he seized the telephone again and called the composing room.

“Hold the paper!” he ordered tersely. “We’re making over the front page!”

The news was electrifying, for only a story of the greatest importance would bring an order to stop the thundering presses once they had started to roll.

Calling the photography room, DeWitt demanded: “Is Salt Sommers still there? Tell him to grab his camera and get over to the Conway Steel Plant in double-quick time! There’s been a big explosion! They think it’s sabotage!”

The editor’s harassed gaze then wandered over the little group of remaining reporters. Elda pushed toward the desk.

“You want me to go over there, Chief?” she demanded eagerly.

DeWitt did not appear to hear her. Seizing the telephone once more, he tried without success to get two of the men reporters who had left the office only a few minutes earlier.

Slamming down the receiver, his gloomy gaze focused upon Elda for an instant. But he passed her by.

“Miss Parker!”

Penny was beside him in a flash.

“Ride with Salt Sommers to the Conway Plant!” he ordered tersely. “Two men have been reported killed in the explosion! Get everything you can and hold on until relieved!”

Seizing hat and purse, Penny made a dash for the stairway. No need for DeWitt to tell her that this was a big story! Because all the other reporters except Elda were gone, she had been given the assignment! But could she make good?

“This is my chance!” she thought jubilantly. “DeWitt probably thinks I’ll fold up, but I’ll prove to him I can get the facts as well as one of his seasoned reporters.”

Penny was well acquainted with Salt Sommers, who next to Jerry Livingston was her best friend. Reaching the ground floor, she saw his battered car starting away from the curb.

“Salt!” she shouted. “Wait!”

The photographer halted and swung open the car door. She slid in beside him.

“What are you doing here, Penny?” he demanded, shifting gears.

“I’m your little assistant,” Penny broke the news gently. “I just started to work on the paper.”

“And DeWitt assigned you to this story?”

“He couldn’t help himself. Nearly everyone else had left the office.”

The car whirled around a corner and raced through a traffic light just as it turned amber. Suddenly from far away, there came a dull explosion which rocked the pavement. Salt and Penny stared at each other with alert comprehension.

“That was at the Conway Plant!” the photographer exclaimed, pushing his foot hard on the gas pedal. “Penny, we’ve got a real assignment ahead of us!”

Darkness shrouded the streets as the press car careened toward the outskirts of the city where the Conway Steel Plant was situated. Rattling over the river bridge, Salt and Penny caught their first glimpse of the factory.

Flames were shooting high into the sky from one of the buildings, and employes poured in panic through the main gate. No policemen were yet in evidence, nor had the fire department arrived.

Pulling up at the curb, Salt seized his camera and stuffed a handful of flashbulbs into his pockets. Grabbing Penny’s elbow, he steered her toward the gate. To get through the barrier, they fought their way past the outsurging, panic-stricken tide of fleeing employes.

“Scared?” Salt asked as they paused to stare at the shooting flames.

“A little,” Penny admitted truthfully. “Will there be any more explosions?”

“That’s the chance we’re taking. DeWitt shouldn’t have sent you on this assignment!”

“He couldn’t know there would be other explosions,” Penny replied. “Besides, someone had to cover the story, and no one else was there. I can handle it.”

“I think you can too,” said Salt quietly. “But you’ll have to work alone. My job is to take pictures.”

“I’ll meet you at the car,” Penny threw over her shoulder as she left him.

Scarcely knowing how or where to begin, she ran toward the burning building. One of the smaller storage structures of the factory, it was not connected with the main office. The larger building remained intact. Workmen with an inadequate hose were making a frantic effort to keep the flames from spreading to the other structures.

Penny ran up to one of the men, plucking at his sleeve to command attention.

“What set off the explosion?” she shouted in his ear.

“Don’t know,” he replied above the roar of the flames.

“Anyone killed?”

“Two workmen. They’re over there.” The man waved his hand vaguely toward another building.

Unable to gain more information, Penny ran toward the nearby structure. The wind, she noted, was carrying flames in the opposite direction. Unless there were further explosions, danger of the fire spreading was not great.

Entering the building, she met several men who appeared to be officials of the company.

“I’m looking for Mr. Conway!” she accosted them. “Is he here?”

“Who are you?” one of the men asked bluntly.

“I’m Penny Parker from the Star.”

“My name is Conway. What do you want to know?”

“How many killed and injured?”

“Two killed. Three or four injured. Perhaps more. We don’t know yet.”

Penny asked for names which were given her. But when she inquired how the explosion had occurred, Mr. Conway suddenly became uncommunicative.

“I have no statement to make,” he said curtly. “We don’t know what caused the trouble.”

As if fearing that Penny would ask questions he did not wish to answer, the factory owner eluded her and disappeared into the darkness.

Running back to the burning building, Penny caught a glimpse of Salt taking a picture. From another workman she sought to glean additional details of the disaster.

“I was in the foundry when the first blast went off!” he revealed. “Just a minute before the explosion, I seen a man in a light overcoat and a dark hat, run from the building.”

“Who was he?”

“No one I ever saw workin’ at this plant. But I’ll warrant, he touched off that explosion!”

“Then you think he was a saboteur?”

“Sure.”

Penny did not place too much stock in the story, but as she wandered about among the excited employes, she heard others saying that they too had seen the strange man running from the building. No one knew his name nor could they provide an accurate description.

Sirens screamed, proclaiming the arrival of fire engines. As the ladders went up, and streams of water began to play on the blazing structure, Salt snapped several more pictures. His hat was gone, and his face had become streaked with soot.

“I got some good shots!” he told Penny enthusiastically as he sought her at the fringe of the crowd. “What luck you having?”

Penny told him everything she had learned.

“We’ll talk with the Fire Chief and then let’s head for a telephone and call the office,” Salt declared.

As they started toward the fire lines, a strange sound accosted their ears. Hearing it, Salt stopped short to listen. From the gates outside the factory came the rumbling murmur of an angry crowd.

“A mob must be forming!” Salt exclaimed. “Something’s up!”

He started for the gate with Penny hard at his heels.

At first they could not see what had caused the commotion. But as the group of angry employes swept nearer the gate, a man in a light overcoat who apparently was fleeing for his life, leaped into a car which waited at the curb.

“Quick!” Penny cried. “Take a picture!”

Salt already had his camera into position. As the car started up, the flash bulb went off.

“Got it!” Salt exclaimed triumphantly.

Penny tried to note the license number of the automobile, but the plate was so covered with mud she could not read a single figure. The car whirled around a corner and was lost to view.

“Salt, that man may have been the one who set off the explosion!” Penny cried. “The mob is of that opinion at least!”

Angry employes now were bearing directly toward Penny and Salt. Suddenly a woman in the crowd pointed toward the photographer, shouting: “There he is! Get him!”

Dismayed, Penny saw then that Salt wore a light overcoat which bore a striking resemblance to the garment of the fleeing stranger. Their builds too were somewhat similar, for both were thin and angular. In the darkness, the mob had failed to see the car roll away, and had mistaken Salt for the saboteur.

“Let’s get out of here!” Salt muttered. “One thing you can’t do is argue with a mob!”

He and Penny started in the opposite direction, only to be faced by a smaller group of workmen who had swarmed from another factory gate. Escape was cut off.

“Tell them we’re from the Star!” Penny urged, but as she beheld the angry faces, she realized how futile were her words.

“They’ll wreck my equipment before I can explain anything!” Salt said swiftly. He thrust the camera into her hands. “Here, take this and try to keep it safe! And these plates!”

Empty-handed, Salt turned to face the mob. Not knowing what to do, Penny tried to cut across the street. But the crowd evidently had taken her for a companion of the saboteur, and was determined she should not escape.

“Don’t let her get away!” shouted a woman in slacks, her voice shrill with excitement. “Get her!”

A car was coming slowly down the street. Its driver, a woman, was watching the flaming building, and had rolled down the window glass to see better. The window of the rear seat also was halfway down.

As the women of the mob bore down upon Penny, she acted impulsively to save Salt’s camera and the precious plates. Without thinking of the ultimate consequence, she tossed them through the open rear window onto the back seat of the moving car.

The driver, her attention focused upon the blazing factory, apparently did not observe the act, for she continued slowly on down the street.

“D F 3005,” Penny noted the license number. “If only I can remember!”

The factory women were upon the girl, seizing her roughly by the shoulders and shouting accusations. Penny’s jacket was ripped as she jerked free.

“I’m a reporter for the Star!” she cried desperately. “Sent here to cover the story!”

The words made not the slightest impression upon the women. But before they could lay hands upon her again, she fled across the street. The women did not pursue her, for just then two police cars rolled up to the curb.

Penny, greatly relieved, ran to summon help.

“Quick!” she urged the policemen. “That crazy mob has mistaken a reporter for one of the saboteurs who escaped in a car!”

With drawn clubs, the policemen battled their way through the crowd. Already Salt had been roughly handled. But arrival of the police saved him from further mistreatment, and fearful of arrest, the mob began to scatter. In another moment the photographer was free, although a bit battered. His coat had been torn to shreds, one eye had been blackened, and blood trickled from a cut on his lower lip.

“Are you all right?” he asked anxiously as Penny rushed to him.

“Oh, yes! But you’re a sight, Salt. They half killed you!”

“I’m okay,” Salt insisted. “The important thing is we’ve got a whale of a story, and we saved the camera and pictures.”

A stricken look came over Penny’s face.

“Salt—” she stammered. “Your camera—”

“It was smashed?”

“No, I tossed it into a car, but the car went on down the street. How we’ll ever find it again I don’t know!”

Salt did not criticise Penny when he learned exactly what had happened.

“I’d rather lose a dozen pictures than have my camera smashed,” he declared to cheer her. “Anyway, we may be able to trace the car and get everything back. Remember the license number?”

“D F 3005,” Penny said promptly, and wrote it down lest she forget.

“Let’s call the license bureau and get the owner’s name,” the photographer proposed, steering her toward a corner drugstore. “Gosh, it’s late!” he added, noticing a clock in a store window. “And they’re holding the paper for our story and pictures!”

“I certainly messed everything up,” Penny said dismally. “At the moment, it seemed the thing to do. When those women started for me, I thought it was the only way to save the camera.”

“Don’t worry about it,” Salt comforted. “I’ll get the camera back.”

“But how will we catch the edition with your pictures?”

“That’s a horse of a different color,” Salt admitted ruefully. “Anyway, it’s my funeral. I’ll tell DeWitt something.”

“I’ll tell him myself,” Penny said firmly. “I lost the pictures, and I expect to take responsibility for it.”

“Let’s not worry ahead. Maybe we can trace that car if we have luck.”

Entering the drugstore, Penny immediately telephoned Editor DeWitt at the Star, reporting all the facts she had picked up.

“Okay, that’s fine,” he praised. “One of our men reporters, Art Bailey, is on his way out there now. He’ll take over. Tell Salt Sommers to get in here fast with his pictures!”

“He’ll call you in just a minute or two,” Penny said weakly.

From another phone, Salt had been in touch with the license bureau. As Penny left the booth to join him, she saw by the look of his face that he had had no luck.

“Couldn’t you get the name of the owner?” she asked.

“It’s worse than that, Penny. The license was made out to a man by the name of A. B. Bettenridge. He lives at Silbus City.”

“Silbus City! At the far end of the state!”

“That’s the size of it.”

“But how did the car happen to be in Riverview?”

“The man or his wife probably is visiting relatives here, or possibly just passing through the city.”

“And there’s no way to trace them,” Penny said, aghast. “Oh, Salt, I’ve not only lost your pictures, but your camera as well!”

“Cheer up,” Salt said brusquely. “It’s not that bad. We’re sunk on the pictures, that’s sure. But unless the people are dishonest, I’ll get the camera again. I’ll write a letter to Silbus City, or if necessary, go there myself.”

Penny had little to say as she rode back to the Star office with the photographer. Editor DeWitt was not in the newsroom when they returned, but they found him in the composing room, shouting at the printers who were “making up the paper” to include the explosion story.

Seeing Penny and Salt, he whirled around to face them. “Get any good pictures?” he demanded.

“We lost all of ’em,” Salt confessed, his face long.

“You what?”

“Lost the pictures. The mob tore into us, and we were lucky to get back alive.”

DeWitt’s stony gaze fastened briefly upon Salt’s scratched face and torn clothing, “One of the biggest stories of the year, and you lose the pictures!” he commented.

“It was my fault,” Penny broke in. “I tossed the camera and plates into a passing car. I was trying to save them, but it didn’t work out that way.”

DeWitt’s eyebrows jerked upward and he listened without comment as Penny told the story. Then he said grimly: “That’s fine! That’s just dandy!” and stalked out of the composing room.

Penny gazed despairingly at Salt.

“If you hadn’t told him it was your fault, he’d have taken it okay,” Salt sighed. “Oh, well, it was the only thing to do. Anyway, there’s one consolation. He can’t fire you.”

“I wish he would. Salt, I feel worse than a worm.”

“Oh, buck up, Penny! Things like this happen. One has to learn to take the breaks.”

“Nothing like this ever happened before—I’m sure of that,” Penny said dismally. “What ought I to do, Salt?”

“Not a thing,” he assured her. “Just show up for work tomorrow the same as ever and don’t think any more about it. I’ll get the camera back, and by tomorrow DeWitt will have forgotten everything.”

“You’re very optimistic,” Penny returned. “Very optimistic indeed.”

Not wishing to return through the newsroom, she slipped down the back stairs and took a bus home. The Parker house stood on a knoll high above the winding river and was situated in a lovely district of Riverview. Only a few blocks away lived Louise Sidell, who was Penny’s closest friend.

Reluctant to face her father, Penny lingered for a while in the dark garden, snipping a few roses. But presently a kitchen window flew up, and Mrs. Maude Weems, the family housekeeper called impatiently:

“Penny Parker, is that you prowling around out there? We had our dinner three hours ago. Will you please come in and explain what kept you so long?”

Penny drew a deep sigh and went in out of the night. Mrs. Weems stared at her in dismay as she entered the kitchen.

“Why, what have you done to yourself!” she exclaimed.

“Nothing.”

“You look dreadful! Your hair isn’t combed—your face is dirty—and your clothes! Why, they smell of smoke!”

“Didn’t Dad tell you I started to work for the Star today?” Penny inquired innocently.

“The very idea of you coming home three hours late, and looking as if you had gone through the rollers of my washing machine! I’ll tell your father a thing or two!”

Mrs. Weems had cared for Penny since the death of Mrs. Parker many years before. Although employed as a housekeeper, salary was no consideration, and she loved the girl as her own child. Penny and Mr. Parker regarded Mrs. Weems almost as a member of the family.

“Where is Dad?” Penny asked uneasily.

“In the study.”

“Let’s not disturb him now, Mrs. Weems. I’ll just have a bite to eat and slip off to bed.”

“So you don’t want to see your father?” the housekeeper demanded alertly. “Why, may I ask? Is there more to this little escapade than meets the eye?”

“Maybe,” Penny admitted. Then she added earnestly: “Believe me, Mrs. Weems, I’ve had a wretched day. Tomorrow I’ll tell you everything. Tonight I just want to get a hot bath and go to bed.”

Mrs. Weems instantly became solicitous. “You poor thing,” she murmured sympathetically. “I’ll get you some hot food right away.”

Without asking another question, the housekeeper scurried about the kitchen, preparing supper. When it was set before her, Penny discovered she was not as hungry as she had thought. But because Mrs. Weems was watching her anxiously, she ate as much as she could.

After she had finished, she started upstairs. In passing her father’s study, she saw his eyes upon her. Before she could move on up the steps, he came to the doorway, noting her disheveled appearance.

“A hard day at the office?” he inquired evenly.

Penny could not know how much her father already had learned, but from the twinkle of his eyes she suspected that DeWitt had telephoned him the details of her disgrace.

“Oh, just a little overtime work,” she flung carelessly over her shoulder. “See you in the morning.”

Penny took a hot bath and climbed into bed. Then she climbed out again and carefully set the clock alarm for eight o’clock. Snuggling down once more, she went almost instantly to sleep.

It seemed that she scarcely had closed her eyes when the alarm jangled in her ear. Drowsily, Penny reached and turned it off. She rolled over to go to sleep again, then suddenly realized she was a working woman and leaped from bed.

She dressed hurriedly and joined her father at the breakfast table. He had two papers spread before him, the Star, and its rival, the Daily Times. Penny knew from her father’s expression that he had been comparing the explosion stories of the two papers, and was not pleased.

“Any news this morning?” she inquired a bit too innocently.

Her father shot back a quick, quizzical look, but gave no further indication that he suspected she might have had any connection with the Conway Steel Plant story.

“Oh, they did a little dynamiting last night,” he replied, shoving the papers toward her. “The Times had very good pictures.”

Penny scanned the front pages. The story in the Star was well written, with her own facts used, and a great many more supplied by other reporters. But in comparison to the Times, the story seemed colorless. Pictures, she realized, made the difference. The Times had published two of them which half covered the page.

“Can’t see how DeWitt slipped up,” Mr. Parker said, shaking his head sadly. “He should have sent one of our photographers out there.”

“Dad—”

Mr. Parker, who had finished his breakfast, hastily shoved back his chair. “Well, I must be getting to the office,” he said. “Don’t be late, Penny.”

“Dad, about that story last night—”

“No time now,” he interposed. “On a newspaper, yesterday’s stories are best forgotten.”

Penny understood then that her father already knew all the details of her downfall. Relieved that there was no need to explain, she grinned and hurriedly ate her breakfast.

Because her father had taken the car and gone on, she was compelled to battle the crowd on the bus. The trip took longer than she had expected. Determined not to be late for work, she ran most of the way from the bus stop to the office. By the time she had climbed the stairs to the newsroom, she was almost breathless.

As she came hurriedly through the swinging door, Elda Hunt, cool and serene, looked up from her typewriter.

“Why the rush?” she drawled, but in a voice which carried clearly to everyone in the room. “Are you going to another fire?”

Ignoring the thrust, Penny hung up her hat and coat and went to work. Neither Editor DeWitt nor his assistant, Mr. Jewell, made any reference to the explosion story of the previous day.

Another reporter had written the “follow-up” on it which Penny read with interest. Cause of the explosion, responsible for more than $40,000 damages, had not yet been determined. However, Fire Chief Schirr had stated that there was evidence the explosion had not been accidental. Several witnesses had reported seeing a man in light overcoat flee from the building only a few minutes before the disaster.

“He must have been the fellow who leaped into that waiting car and escaped!” Penny thought. “And to think, Salt’s picture might actually be evidence in the case, if I hadn’t thrown it away!”

She was staring glumly at the story when DeWitt motioned for her to take a telephone call. It was another obituary.

“After muffing a good story, I’ll probably be assigned to these things for the rest of my time on the paper,” Penny thought as she mechanically scribbled notes.

All morning the obituaries kept coming in, and then there were the hospitals to call for accident reports, and the weather bureau. After lunch, a reporter was needed to interview a famous actress who had arrived in Riverview for a personal appearance. It was just the story Penny wanted to try. She knew she could do it well, for in months past, she frequently had contributed special feature stories to the paper.

Mr. DeWitt’s gaze focused upon her for an instant, but he passed her by.

“Elda,” he said, and she went quickly to his desk to receive instructions.

Elda was gone a long while on the assignment. When she returned in the afternoon, she spent nearly two hours typing the interview. Several times Editor DeWitt glanced impatiently at her, and finally he said: “Let’s have a start on that story, Elda. You’ve been fussing with it long enough.”

She gave it to him. As Mr. DeWitt read, he used his pencil to mark out large blocks of what had been written. But as he gave the story to a copy reader who would write the headline, he said: “Give her a byline.”

Elda heard and grinned from ear to ear. A byline meant that a caption directly under the headline would proclaim: “By Elda Hunt.”

Penny, who also heard, could not know that Mr. DeWitt had granted the byline only because it was customary with a personal interview story. She felt even more depressed than before.

“See if you can find a picture of this actress in the photography room,” DeWitt instructed Elda. “Salt Sommers took one this morning, but it hasn’t come up yet.”

With a swishing of skirts, for she now was in a fine mood, Elda disappeared down the corridor. Fifteen minutes elapsed. Penny, busy writing hand-outs and obituaries, had forgotten about her entirely, until Mr. DeWitt summoned her to his desk.

“See if you can find out what became of Elda,” he said in exasperation. “Tell her we’d like to have that picture for today’s paper.”

Penny went quickly toward the photography room. The door was closed. As she opened it, she was startled half out of her wits by hearing a shrill scream. The cry unmistakably came from an inner room of the photography studio and was Elda’s voice. At the same instant, a gust of cool air struck Penny’s face.

“Elda!” she called in alarm.

“Here,” came the girl’s muffled voice from the inner room.

Fearing the worst, Penny darted through the doorway. Elda had collapsed in a chair, her face white with terror. Wordlessly, she pointed toward the ceiling.

Penny gazed up but could see nothing amiss. Warm sunshine was pouring through the closed skylight which covered half the ceiling area.

“What ails you, Elda?” she asked. “Why did you scream?”

“The skylight!”

“What about the skylight?” Penny demanded with increasing impatience. “I can’t see anything wrong with it.”

“Only a moment ago I saw a shadow there,” Elda whispered in awe.

“A shadow!” Penny was tempted to laugh. “What sort of shadow?”

“I—I can’t describe it. But it must have been a human shadow. I think a man was crouching there.”

“Nonsense, you must have imagined it.”

“But I didn’t,” Elda insisted indignantly. “I saw it just before you opened the door.”

“Did the skylight open?”

“Not that I saw.”

Recalling the cool gust of wind that had struck her face, Penny took thought. Was it possible that Elda actually had seen someone crouching on the skylight? However, the idea seemed fantastic. She could think of no reason why any person would hide on the roof above the photography room.

“Oh, snap out of it, Elda,” she said carelessly. “Even if you did see a shadow, what of it?”

“It was a man, I tell you!”

“A workman perhaps. Mr. DeWitt sent me to tell you he was in a hurry for that picture.”

“Oh, tell Mr. DeWitt to jump in an ink well!” Elda retorted angrily. “He’s always in a hurry.”

“You haven’t been watching a shadow all this time, I judge,” Penny commented.

“Of course not. I went downstairs to get a candy bar.”

With a sigh, Elda pulled herself from the chair. She really did look as if she had undergone a bad fright, Penny observed. Feeling a trifle sorry for the girl, she helped her find the photograph, and they started with it to the newsroom.

“I’d not say anything about the shadow if I were you, Elda,” Penny remarked.

“Why not, pray?”

“Well, it sounds rather silly.”

“Oh, so I’m silly, am I?”

“I didn’t say that, Elda. I said the idea of a shadow on the skylight struck me that way. Of course, if you want to be teased about it, why tell everyone.”

“At least I didn’t make a mess of an important story,” Elda retorted, tossing her head.

“Elda, why do you dislike me?” Penny demanded suddenly.

The question was so unexpected that it threw the girl off guard. “Did I say I did?” she countered.

“It’s obvious that you do.”

“I’ll tell you what I dislike,” Elda said sharply. “The rest of us here have to work for our promotions. You’ll get yours without even turning a hair—just because you’re Mr. Parker’s one and only daughter.”

“But that’s not true, Elda. I’m expected to earn my way the same as you. I’m working at a beginner’s salary.”

“You can’t expect me to believe that!”

“Was it because you thought I was making more money than you, that you changed the name on the Borman obituary?”

Elda stopped short. She tried to register indignation, but instead, only looked frightened. Penny was certain of her guilt.

“I haven’t told Mr. DeWitt, and I don’t intend to,” she said quietly. “But I’m warning you! If anything like that happens again, you’ll answer for it!”

“Well, of all the nerve!” Elda exploded, but her voice lacked fire. “Of all the nerve!”

Penny deliberately walked away from her.

The day dragged on. At five-thirty Penny covered her typewriter and telephoned Mrs. Weems.

“I’ll be late coming home tonight,” she said apologetically. “I thought I might get dinner downtown and perhaps go to a show.”

“Another hard day?” the housekeeper asked sympathetically.

“Much easier than yesterday,” Penny said, making her voice sound cheerful. “Don’t worry about me. I’ll be home no later than nine.”

Though she would not have confessed it even to herself, Penny was reluctant to meet her father at dinner time. He might not ask questions, but his all-knowing, all-seeing eyes would read her secrets. At a glance he could tell that newspaper work was not going well for her, and that she disliked it.

“I certainly won’t give him an opportunity to even think, ‘I told you so,’” she reflected. “Even if it kills me, I’ll stick here, and I’ll pretend to like it too!”

Because it was too early to dine, Penny walked aimlessly toward the river. She paused at a dock to watch two boys fishing, and then sauntered on toward the passenger wharves.

A young man in an unpressed suit, and shoes badly in need of a shine, leaned against one of the freight buildings. Seeing Penny, he pulled his hat low over his eyes, and became engrossed in lighting a cigarette.

She would have passed him by without a second glance, save that he deliberately turned his back to shield his face. The hunch of his shoulders struck her as strangely familiar.

Involuntarily, she exclaimed: “Ben! Ben Bartell!”

He turned then and she saw that she had not been mistaken. The young man indeed was a former reporter for the Riverview Mirror, a news magazine published weekly. Ben had not shaved that day, and he looked years older than when she last had seen him.

“Hello, Penny,” he said uncomfortably.

“Ben, what has happened to you?” she asked. “Why were you trying to avoid me?”

Ben did not reply for a moment. Then he said quietly: “Why should I want to see any of my old friends now? Just look at me and you have your answer.”

“Why, Ben! You were one of the best reporters the Mirror ever had!”

“Were is right,” returned Ben with a grim smile. “Haven’t worked there for six months now. The truth is, I’m down and out.”

“Why, that’s ridiculous, Ben! Nearly every paper in town needs a good man.”

“They don’t need me.”

“Ben, you sound so bitter! What has happened to you?”

“It’s a long story, sister, and not for your dainty little ears.”

Penny now was deeply troubled, for she had known Ben well and liked him.

“Ben, you must tell me,” she urged, taking his arm. “We’re going into a restaurant, and while we have dinner together, you must explain why you left the Mirror.”

Ben held back.

“Thanks,” he said uncomfortably, “but I think I ought to be moving on.”

“Have you had your dinner?” Penny asked.

“Not yet.”

“Then do come with me, Ben. Or don’t you want to tell me what happened at the Mirror?”

“It’s not that, Penny. The truth is—well—”

“You haven’t the price of a dinner?” Penny supplied. “Is that it, Ben?”

“I’m practically broke,” he acknowledged ruefully. “Sounds screwy in a day and age like this, but I’m not strong enough for factory work. Was rejected from the Army on account of my health. Tomorrow I guess I’ll take a desk job somewhere, but I’ve held off, not wanting to get stuck on it.”

“You’re a newspaper man, Ben. Reporting is all you’ve ever done, isn’t it?”

“Yes, but I’m finished now. Can’t get a job anywhere.” The young man started to move away, but Penny caught his arm again.

“Ben, you are having dinner with me,” she insisted. “I have plenty of money, and this is my treat. I really want to talk to you.”

“I can’t let you pay for my dinner,” Ben protested, though with less vigor.

“Silly! You can take me somewhere as soon as you get your job.”

“Well, if you put it that way,” Ben agreed, falling willingly into step. “There’s a place here on the waterfront that serves good meals, but it’s not stylish.”

“All the better. Lead on, Ben.”

He took her to a small, crowded little restaurant only a block away. In the front window, a revolving spit upon which were impaled several roasting chickens, captured all eyes. Ben’s glands began to work as he watched the birds browning over the charcoal.

“Ben, how long has it been since you’ve had a real meal?” Penny asked, picking up the menu.

“Oh, a week. I’ve mostly kept going on pancakes. But it’s my own funeral. I could have had jobs of a sort if I had been willing to take them.”

Penny gave her order to the waitress, taking double what she really wanted so that her companion would not feel backward about placing a similar order. Then she said:

“Ben, you remarked awhile ago that you can’t get a newspaper job anywhere.”

“That’s true. I’m blacklisted.”

“Did you try my father’s paper, the Star?”

“I did. I couldn’t even get past his secretary.”

“That’s not like Dad,” Penny said with troubled eyes. “Did you really do something dreadful?”

“It was Jason Cordell who put the bee on me.”

“Jason Cordell?” Penny repeated thoughtfully. “He’s the editor of the Mirror, and has an office in the building adjoining the Star.”

“Right. Well, he fired me.”

“Lots of reporters are discharged, Ben, but they aren’t necessarily blacklisted.”

Ben squirmed uncomfortably in his chair.

“You needn’t tell me if you don’t wish,” Penny said kindly. “I don’t mean to pry into your personal affairs. I only thought that I might be able to help you.”

“I want to tell you, Penny. I really do. But I don’t dare reveal some of the facts, because I haven’t sufficient proof. I’ll tell you this much. I stumbled into a story—a big one—and it discredited Jason Cordell.”

“You didn’t publish it?”

“Naturally not.” Ben laughed shortly. “I doubt if any newspaper would touch it with a ten-foot pole. Cordell is supposed to be one of our substantial, respectable citizens.”

“Actually?”

“He’s as dishonorable as they come.”

Knowing that Ben was bitter because of his discharge, Penny discredited some of the remarks, but she waited expectantly for him to continue. A waitress brought the dinner, and for awhile, as the reporter ate ravenously, he had little to say.

“You’ll have to excuse me,” he finally apologized. “I haven’t tasted such fine food in a year! Now what is it you want to know, Penny? I’m in a mood to tell almost anything.”

“What was this scandal you uncovered about Mr. Cordell?”

“That’s the one thing I can’t reveal, but it concerned the owner of the Conway Steel Plant. They’re bitter enemies you know.”

Penny had not known, and the information interested her greatly.

“Did you talk it over with Mr. Cordell?” she asked.

“That was the mistake I made.” Ben slowly stirred his coffee. “Cordell didn’t have much to say, but the next thing I knew, I was out of a job and on the street.”

“Are you sure that was why he discharged you?”

“What else?”

Penny hesitated, not wishing to hurt Ben’s feelings. There were several things she had heard about him—that he was undependable and that he drank heavily.

“Most of the things you’ve been told about me aren’t true,” Ben said quietly, reading her thoughts. “Jason Cordell started a lot of stories intended to discredit me. He told editors that I had walked off a job and left an important story uncovered. He pictured me as a drunkard and a trouble maker.”

“I’ll talk to my father,” Penny promised. “As short as the Star is of employes, I’m sure there must be a place for you.”

“You’re swell,” Ben said feelingly. “But I’m not asking for charity. I’ll get along.”

Refusing to talk longer about himself, he told Penny of amusing happenings along the waterfront. After dessert had been finished, she slipped a bill into his hand, and they left the restaurant.

Outside, the streets were dark, for in this section of the city, lights were few and far between. Ben offered to escort Penny back to the Star office or wherever she wished to go.

“This isn’t too safe a part of the city for a girl,” he declared. “Especially after night.”

“All the same, to me the waterfront is the most fascinating part of Riverview,” Penny declared. “You seem to know this part of town well, Ben.”

“I should. I’ve lived here for the past six months.”

“You have a room?”

“I’ll show you where I live,” Ben offered. “Wait until we reach the next corner.”

They walked on along the river docks, passing warehouses and vessels tied up at the wharves. Twice they passed guards who gazed at them with intent scrutiny. However, Ben was recognized, and with a friendly salute, the men allowed him to pass unchallenged.

“The waterfront is strictly guarded now,” the reporter told Penny. “Even so, plenty goes on here that shouldn’t.”

“Meaning?”

Ben did not answer for they had reached the corner. Beyond, on a vacant lot which Penny suspected might also be a dumping ground, stood three or four dilapidated shacks.

“See the third one,” Ben indicated. “Well, that’s my little mansion.”

“Oh, Ben!”

“It’s not bad inside. A little cold when the wind blows through the chinks, but otherwise, fairly comfortable.”

“Ben, haven’t you any friends or relatives?”

“Not here. I thought I had a few friends, but they dropped me like a hot potato when I ran into trouble.”

“This is no life for you, Ben. I’ll certainly talk to my father tomorrow.”

Ben smiled and said nothing. From his silence, Penny gathered that he had no faith she would be able to do anything for him.

They walked on, and as they approached a small freighter tied up at the wharf, Ben pointed it out.

“That’s the Snark,” he informed her.

The name meant nothing to Penny. “Who owns her?” she inquired carelessly.

“I wish I knew, Penny. There’s plenty goes on aboard that vessel, but it’s strictly hush-hush. I have my suspicions that—”

Ben suddenly broke off, for several men had appeared on the deck of the Snark. The vessel was some distance away, and in the darkness only shadowy forms were visible.

Seizing Penny’s arm, Ben pulled her flat against a warehouse.

Amazed by his action, she started to protest. Then she understood. Aboard the Snark there was some sort of disturbance or disagreement. The men, although speaking in low, almost inaudible tones, were arguing. Penny caught only one phrase: “Heave him overboard!”

“Ben, what’s happening there?” she whispered anxiously.

“Don’t know!” he answered. “But nothing good.”

“Where are the guards?”

“Probably at the far end of their beats.”

Aboard the Snark, there was a brief scuffle, as someone was dragged across the deck to the rail.

“That’ll teach you!” they heard one of the men mutter.

Then the helpless victim was raised and dropped over the rail. Shrieking in terror, he fell with a great splash into the inky waters. Frantically, he began to struggle.

“Those fiends!” Penny cried. “They deliberately threw the man overboard, and he can’t swim!”

Penny and Ben ran to the edge of the dock, peering into the dark, oily waters. On the deck of the Snark there was a murmur of voices, then silence.

Casting a quick glance upward, Penny was angered to see that the men who had been standing there had vanished into a cabin or companionway. Obviously, they had no intention of trying to aid the unfortunate man.

“There he is!” Ben exclaimed, suddenly catching another glimpse of the bobbing head. “About done in too!”

Kicking off his shoes and stripping off his coat, the reporter dived from the dock. He struck the water with an awkward splash, but Penny was relieved to see that he really could swim well. He struck out for the drowning man, but before he could reach him, the fellow slipped quietly beneath the surface.

Close by were two barges lashed together, and the current would take a body in that direction. Ben jack-knifed and went down into the inky waters in a surface dive. Unable to find the man, he came up, filled his lungs in a noisy gulp, and went down again. He was under such a long time that Penny became frantic with anxiety.

She decided to turn in an alarm for the city rescue squad. But before she could act, Ben surfaced again, and this time she saw that he held the other man by the hair.

As Ben slowly towed the fellow toward the dock, Penny realized that she must find some way to get them both out of the river. She could expect no help from anyone aboard the Snark. Gazing upward again, she thought she saw a man watching her from the vessel’s bow, but as her gaze focused upon him, he retreated into deeper shadow, beyond view.

No guards were anywhere near, and the entire waterfront seemed deserted. Penny’s eyes fastened upon a rope which hung loosely over a dock post. It was long enough to serve her purpose, and finding it unattached, she hurled one end toward Ben.

He caught it on the second try and made a loop fast about the body of the man he towed. Penny then pulled them both to the dock.

“You can’t haul us up,” Ben instructed from below. “Just hold on, and I think I can get out of here by myself.”

He swam off in the darkness and was lost to view. Penny clung desperately to the rope, knowing that if she relaxed for an instant, the man, already half drowned, would submerge for good. Her arms began to ache. It seemed to her she could not hold on another instant.

Then Ben, his clothes plastered to his thin body, came running across the planks.

Without a word he seized the rope, and together they raised the man to the dock. In the darkness Penny saw only that he was slender, and in civilian clothes.

Stretching him out on the dock boards, they prepared to give artificial resuscitation. But it was unnecessary. For at the first pressure on his back, the man rolled over and muttered: “Cut it out. I’m okay.”

Then he lay still, exhausted, but breathing evenly.

“You were lucky to get him, Ben,” Penny said as she knelt beside the stranger. “If the current had carried him beneath those barges, he never would have been taken out alive.”

“I had to dive deep,” Ben admitted. “Found him plastered right against the side of the first barge. Yeah, I was lucky, and so is he.”

The man stirred again, and sat up. Penny tried to support him, but he moved away, revealing that he wanted no help.

“Who pushed you overboard?” Ben asked.

The man stared at him and did not answer.

Observing that Ben was shivering from cold, and that the stranger too was severely chilled, Penny proposed calling either the rescue squad or an ambulance.

“Not on your life,” muttered the rescued man, trying to get up. “I’m okay, and I’m getting out of here.”

With Ben’s help, he managed to struggle to his feet, but they buckled under him when he tried to walk.

The man looked surprised.

“We’ll have to call the rescue squad,” Penny decided firmly.

“I have a better idea,” Ben supplied. “We can take him to my shack.”

Penny thought that the man should have hospital treatment. However, he sided with Ben, insisting he could walk to the nearby shack.

“I’m okay,” he repeated again. “All I need is some dry clothes.”

Supported on either side, the man managed to walk to the shack. Ben unlatched the door and hastily lighting an oil lamp, helped the fellow to the bed where he collapsed.

“Ben, I think we should have a doctor—” Penny began again, but Ben silenced her with a quick look.

Drawing her to the door he whispered: “Let him have his way. He’s not badly off, and he has reason for not wanting anyone to know what happened. If we call the rescue squad or a doctor, he’ll have to answer to a lot of questions.”

“There are some things I’d like to know myself.”

“We’ll get the answers if we’re patient. Now stay outside for a minute or two until I can get his clothes changed, and into dry ones myself.”

Penny stepped outside the shack. A chill wind blew from the direction of the river, but with its freshness was blended the disagreeable odor of factory smoke, fish houses and dumpings of refuse.

“Poor Ben!” she thought. “He never should be living in such a place as this! No matter what he’s done, he deserves another chance.”

Exactly what she believed about the reporter, Penny could not have said. His courageous act had aroused her deep admiration. On the other hand, she was aware that his story regarding Jason Cordell might have been highly colored to cover his own shortcomings.

Within a few minutes Ben opened the door to let her in again. The stranger had been put to bed in a pair of the reporter’s pajamas which were much too small for him. In the dim light from the oil lamp, she saw that he had a large, square-shaped face, with a tiny scar above his right eye. It was not a pleasant face. Gazing at him, Penny felt a tiny chill pass over her.

Ben also had changed his clothes. He busied himself starting a fire in the rusty old stove, and once he had a feeble blaze, hung up all the garments to dry.

The room was so barren that Penny tried not to give an appearance of noticing. There was only a table, one chair, the sagging bed, and a shelf with a few cracked dishes.

“I’ll get along with him all right,” Ben said, obviously expecting Penny to leave.

She refused to take the hint. Instead she said: “This man will either have to go to a hospital or stay here all night. He’s in no condition to walk anywhere.”

“He can have my bed tonight,” Ben said. “I’ll manage.”

The stranger’s intent eyes fastened first upon Penny and then Ben. But not a word of gratitude did he speak.

“You’ll need more blankets and food,” Penny said, thinking aloud. “I can get them from Mrs. Weems.”

“Please don’t bother,” Ben said stiffly. “We’ll get along.”

Though rebuffed, Penny went over to the bedside. Instantly she saw a bruise on the stranger’s forehead and a sizeable swollen place.

“Why, he must have struck his head!” she exclaimed, then corrected herself. “But he didn’t strike anything that we saw. Ben, he must have been slugged while aboard the Snark!”

The stranger turned so that he looked directly into the girl’s clear blue eyes. “Nuts!” he said emphatically.

“Our guest doesn’t seem to care to discuss the little affair,” Ben commented dryly. “I wonder why? He escaped drowning by only a few breaths.”

“Listen,” said the stranger, hitching up on an elbow. “You fished me out of the water, but that don’t give you no right to put me through the third degree. My business is my business—see!”

“Who are you?” demanded Penny.

She thought he would refuse to answer, but after a moment he said curtly: “James Webster.”

Both Penny and Ben were certain that the man had given a fictitious name.

“You work aboard the Snark?” Ben resumed the questioning.

“No.”

“Then what were you doing there?”

“And why were you pushed overboard?” Penny demanded as the man failed to answer the first question.

“I wasn’t pushed,” he said sullenly.

“Then how did you get into the water?” Penny pursued the subject ruthlessly.

“I tripped and fell.”

Penny and Ben looked at each other, and the latter shrugged, indicating that it would do no good to question the man. Determined to keep the truth from them, he would tell only lies.

“You can’t expect us to believe that,” Penny said coldly. “We happened to see you when you went overboard. There was a scuffle. Then the men who threw you in, disappeared. For the life of me, I can’t see why you would wish to protect them.”

“There are a lot of things you can’t see, sister,” he retorted. “Now will you go away, and let me sleep?”

“Better go,” Ben urged in a low tone. “Anyone as savage as this egg, doesn’t need a doctor. I’ll let him stay here tonight, then send him on his way tomorrow morning.”

“You really think that is best?”

“Yes, I do, Penny. We could call the police, but how far would we get? This bird would deny he was pushed off the boat, and we would look silly. We couldn’t prove a thing.”

“I suppose you’re right,” Penny sighed. “Well, I hope everything goes well tonight.”

Moving to the door, she paused there, for some reason reluctant to leave.

“I’ll take you home,” Ben offered.

“No, stay here,” Penny said firmly. “I’m not afraid to go alone. I only hope you get along all right with your guest.”

Ben followed her outside the shack.

“Don’t worry,” he said, once beyond hearing of the stranger. “This fellow is a tough hombre, but I know how to handle him. If he tries to get rough, I’ll heave him out.”

“I never saw such ingratitude, Ben. After you risked your life to save him—”

“He’s just a dock rat,” the reporter said carelessly.

“Even so, why should he refuse to answer questions?”

“Obviously, he’s mixed up in some mess and doesn’t dare talk, Penny. I’ve always had my suspicions about the Snark and her owners.”

“What do you mean, Ben?”

Before the reporter could answer, there came a thumping from inside the shack. Welcoming the interruption, Ben turned quickly to re-enter.

“Can’t tell you now,” he said hurriedly. “We’ll talk some other time. So long, and don’t worry about anything.”

Firmly, he closed the door.

Penny stood there a moment until satisfied that there was no further disturbance inside the shack. Then with a puzzled shake of her head, she crossed the vacant lot to the docks.

“Those men aboard the Snark should be arrested,” she thought indignantly. “I wish I could learn more about them.”

She stood for a moment lost in deep reflection. Then with sudden decision, she turned and walked toward the Snark.

Approaching the Snark, Penny saw several men moving about on the unlighted decks. But as she drew nearer, their forms melted into the darkness. When she reached the dock, the vessel appeared deserted.

Yet, peering upward at the towering vessel, the girl had a feeling that she was being watched. She was satisfied that the rescue of the man who called himself James Webster had been observed. She was equally certain that those aboard the Snark were aware of her presence now.

“Ahoy, the Snark!” she called impulsively.

There was no answer from aboard the tied-up vessel, but footsteps pounded down the dock. Penny whirled around to find herself the target for a flashlight. Momentarily blinded, she could see nothing. Then, the light shifted away from her face, and she recognized a wharf guard.

“What you doing here?” he demanded gruffly.

Though tempted to tell the entire story, Penny held her tongue. “Just looking,” she mumbled.

“Didn’t I hear you call out?”

“Yes.”

“Know anyone aboard the Snark?”

“No.”

“Then move along,” the guard ordered curtly.

Penny did not argue. Slipping quietly away, she sought a brightly lighted street which led toward the newspaper office. Midway there, she stopped at a corner drugstore to call home and inquire for her father. Mrs. Weems told her that so far as she knew Mr. Parker had returned to the Star office to do a little extra work.

“Then I’ll catch him there,” Penny declared.

“Is anything wrong?” the housekeeper inquired anxiously.

“Just something in connection with a news story,” Penny reassured her. “I’ll be home soon.”

Hanging up the receiver before the housekeeper could ask any more questions, she walked swiftly on to the Star building. The front door was locked, but Penny had her own key. Letting herself in through the darkened advertising room, she climbed the stairs to the news floor.

A few members of the Sunday staff were working at their desks, but otherwise the room was deserted. Typewriters, like hooded ghosts, stood in rigid ranks.

Pausing to chat for a moment with the Sunday editor, Penny asked if her father were in the building.

“He was in his office a few minutes ago,” the man replied. “I don’t know if he left or not.”

Going on through the long newsroom, Penny saw that her father’s office was dark. The door remained locked.

Disappointed, she started to turn back when she noticed a light burning in the photography room. At this hour she knew no one would be working there, unless Salt Sommers or one of the other photographers had decided to develop and print a few of his own pictures.

“Dad, are you there?” she called.

No one answered, but Penny heard a scurry of footsteps.

“Salt!” she called, thinking it must be one of the photographers.

Again there was no reply, but a gust of wind came suddenly down the corridor. The door of the photography room slammed shut.

Startled, Penny decided to investigate. She pushed open the door. The light was on, but no one was in the room.

“Salt!” she called again, thinking that the photographer might be in the darkroom.

He did not reply. As she started forward to investigate, the swinging chain of the skylight drew her attention. The glass panels were closed and there was no breeze in the room. Yet the brass chain swung back and forth as if it had been agitated only a moment before.

“Queer!” thought Penny, staring upward. “Could anyone have come in here through that skylight?”

The idea seemed fantastic. She could think of no reason why anyone should seek such a difficult means of entering the newspaper office. To her knowledge, nothing of great value was kept in the photography rooms.

Yet, the fact remained that the light was on, the chain was swaying back and forth, and a door had slammed as if from a gust of wind.

Studying the skylight with keen interest, Penny decided that it would be possible and not too difficult for a person on the roof to raise the glass panels, and by means of the chain, drop down to the floor. But could a prowler reverse the process?

Penny would have dismissed the feat as impossible, had not her gaze focused upon an old filing cabinet which stood against the wall, almost directly beneath the skylight. Inspecting it, she was disturbed to find imprints of a man’s shoe on its top surface.

“Someone was in here!” Penny thought. “To get out, he climbed up on this cabinet!”

The brass handles of the cabinet drawers offered convenient steps. As she tried them, the cabinet nearly toppled over, but she reached the top without catastrophe. By standing on tiptoe, her head and shoulders would just pass through the skylight.

Pulling the brass chain, she opened it, and peered out onto the dark roof. No one was in sight. In the adjoining building, lights burned in a number of offices.

Suddenly the door of the photography room opened. Startled, Penny ducked down so fast that she bumped her head.

“Well, for Pete’s sake!” exclaimed a familiar voice. “What are you doing up there?”

Penny was relieved to recognize Salt. She closed the skylight and dropped lightly to the floor.

“Looking for termites?” the photographer asked.

“Two legged ones! Salt, someone has been prowling about in here! Whoever he was, he came in through this skylight.”

“What makes you think so, kitten?” Salt looked mildly amused and not in the least convinced.

Penny told him what had happened and showed him the footprints on the filing cabinet. Only then did the photographer take her seriously.

“Well, this is something!” he exclaimed. “But who would sneak in here and for what reason?”

“Do you have anything valuable in the darkroom?”

“Only our cameras. Let’s see if they’re missing.”

Striding across the room, Salt flung open the door of the inner darkroom, and snapped on a light. One glance assured him that the cameras remained untouched. But several old films were scattered on the floor. Picking them up, he examined them briefly, and tossed them into a paper basket.

“Someone has been here all right,” he said softly. “But what was the fellow after?”

“Films perhaps.”

“We haven’t anything of value here, Penny. If we get a good picture we use it right away.”

Methodically, Salt examined the room, but could find nothing missing.

“Perhaps the person, whoever he was, didn’t get what he was after,” Penny speculated. “I’m inclined to think this isn’t his first visit here.”

Questioned by Salt, she revealed Elda Hunt’s recent experience in the photography room.

“That dizzy dame!” he dismissed the subject. “She wouldn’t know whether she saw anything or not.”

“Something frightened her,” Penny insisted. “It may have been this same man trying to get in. Can’t the skylight be locked?”

“Why, I suppose so,” Salt agreed. “The only trouble is that this room gets pretty stuffy in the daytime. We need the fresh air.”

“At least it should be locked when no one is here.”

“I’ll see that it is,” Salt promised. “But it’s not likely the prowler will come back again—especially as you nearly caught him.”

It was growing late. Convinced that her father had left the Star building, Penny decided to take a bus home. As she turned to leave, she asked Salt carelessly:

“By the way, did you know Ben Bartell?”

“Fairly well,” he returned. “Why?”

“Oh, I met him tonight. He’s had a run of hard luck.”

“So I hear.”

“Salt, what did Ben do, that caused him to be blacklisted with all the newspapers?”

“Well, for one thing, he socked an editor on the jaw.”

“Jason Cordell of the Mirror?”

“Yes, they got into a fight of some sort. Ben was discharged, and he didn’t take it very well.”

“Was he a hard drinker?”

“Ben? Not that I ever heard. I used to think he was a pretty fair reporter, but he made enemies.”

Penny nodded, and without explaining why the information interested her, bade Salt goodnight. Leaving the Star building by the back stairway, she walked slowly toward the bus stop.

As she reached the corner, she heard the scream of a police car siren. Down the street came the ambulance, pulling up only a short distance away. Observing that a crowd had gathered, Penny quickened her step to see who had been injured.

Pushing her way through the throng of curious pedestrians, she saw a heavy-set man lying unconscious on the pavement. Policemen were lifting him onto a stretcher.

“What happened?” Penny asked the man nearest her.

“Just a drunk,” he said with a shrug. “The fellow was weaving all over the street, and finally collapsed. A storekeeper called the ambulance crew.”

Penny nodded and started to move away. Just then, the ambulance men pushed past her, and she caught a clear glimpse of the man on the stretcher. She recognized him as Edward McClusky, a deep water diver for the Evirude Salvage Company. She knew too that under no circumstances did he ever touch intoxicating liquors.

“Wait!” she exclaimed to the startled ambulance crew. “I know that man! Where are you taking him?”

“We’re taking this man to the lockup,” the policemen told Penny. “He’ll be okay as soon as he sobers up.”

“But he’s not drunk,” she protested earnestly. “Edward McClusky is a diver for the Evirude Salvage Co. Whatever ails him must be serious!”

The policeman stared at Penny and then down at the unconscious man on the stretcher. “A deep sea diver!” he exclaimed. “Well, that’s different!”

Deftly he loosened the man’s collar, and at once his hand encountered a small disc of metal fastened on a string about his neck. He bent down to read what was engraved on it.

“Edward McClusky, 125 West Newell street,” he repeated aloud. “In case of illness or unconsciousness, rush this man with all speed to the nearest decompression lock.”

“You see!” cried Penny. “He’s had an attack of the bends!”

“You’re right!” exclaimed the policeman. He consulted his companions. “Where is the nearest decompression chamber?”

“Aboard the Yarmouth in the harbor.”

“Then we’ll rush him there.” The policeman turned again to Penny. “You say you know this man and his family?”

“Not well, but they live only a few blocks from us.”

“Then ride along in the ambulance,” the policeman suggested.

Penny rode in front with the driver, who during the speedy dash to the river, questioned her regarding her knowledge of the unconscious man.

“I don’t know much about him,” she confessed. “Mrs. Weems, our housekeeper, is acquainted with his wife. I’ve heard her say that Mr. McClusky is subject to the bends. Once on an important diving job he stayed under water too long and wasn’t properly put through a decompression lock when he came out. He is supposed to have regular check-ups from a doctor, but he is careless about it.”

“Being careless this time might have cost him his life,” the driver replied. “When a fellow is in his condition, he’ll pass out quick if he isn’t rushed to a lock. A night in jail would have finished him.”