Captain Mayne Reid

"The Bandolero"

"A Marriage among the Mountains"

Chapter One.

A City of Angels.

La Puebla de los Angeles is peculiar, even among the cities of modern Mexico; peculiar in the fact, that two-thirds of its population are composed of priests, pelados, poblanas, pickpockets, and incarones of a bolder type.

Perhaps I have been too liberal in allowing a third to the “gente de bueno,” or respectable people. There are travellers who have altogether denied their existence; but this may be an exaggeration on the other side.

Trusting to my own souvenirs, I think I can remember having met with honest men—and women too—in the City of the Angels. But I shall not be positive about their proportion to the rest of the population. It may be less than a third—certainly it is not more!

Equally certain is it: that every tenth man you meet in the streets of Puebla is either a priest, or in some way connected with the holy fraternity—and that every tenth woman is far from being an angel!

Curas in robes of black silk serge, stockings of the finest texture, and “coal-scuttle” hats, full three feet in length; friars of all orders and colours—black and white, blue, brown, and grey—with shaven crowns and sandalled feet, are encountered, not only at every corner, but almost at every step you take.

If monks were immaculate, Puebla might deserve the sanctified appellation it has received—the City of the Angels. As it is, the City of the Devils would be a more appropriate title for it!

“The nearer the church, the farther from God.”

The adage is strikingly illustrated in Puebla, where the Church is not only present—in all its outward symbols—but paramount. It governs the place. It owns it. Almost every house in the city, as almost every acre of land in the vast plain that surrounds it, is the property of the Church, in fee simple, or by mortgage deed!

As you pass through the streets you see painted over the door-heads—three out of every four of them—the phrases, “Casa de San Augustin,” “Casa de San Francisco,” “Casa de Jesus,” and the like.

If a stranger inquire the object of this black lettering, he is told that the houses so designated are the property of the respective convents whose names appear above the doors. In short, you see the Church above, before, and around you, all-powerful over the bodies as well as the souls of the Poblanos; and you have not ceased to be a stranger, ere you discover its all-pervading villainy and corruptness.

Otherwise, Puebla might be termed a terrestrial paradise. Situated in the centre of an immense plain—whose fertility suggested to Cortez and his conquistadores the title “La vega” (the farm)—surrounded by an amphitheatre of magnificent mountains, in grandeur unsurpassed upon earth—with a climate of ever-spring, truly might it be deemed an abiding place for angels; as truly as it is the home of a host of infamous men, and not less infamous women.

Despite its moral character, there is a grand picturesqueness about La Puebla de los Angeles—both in its present aspect and its past history. Both are redolent of romance.

Standing upon the site of an ancient Aztecan town, within view of Cholula, the Indian Athens—with Tlascala, their Sparta, on the other side of the mountain Malinché—what heart would not be touched by the historic souvenirs of such a spot? And though the sages of Cholula and the warriors of Tlascala are no longer to be recognised in their degenerate descendants, there, still, are the grand objects from which they must have drawn their inspirations. On all sides tower up the Cordilleras of the Andes. Sublime, against the eastern sky, rises the “Star mountain;” matched upon the west by the rival cone of Popocatepec. Still in solemn silence reclines the “White Sister” under her cold coverlet of snow.

Well do I remember the impression produced on my own mind when, after passing through the mal pais of Peroté, I first came within view of the domes and spires of La Puebla. It was an impression, grand, mystical, romantic; in interest exceeding even that I afterwards experienced, when gazing for the first time on the valley of Tenochtitlan. It was a coup de coeur never to be forgotten!

As my entry into the “City of the Angels” was not of an ordinary kind,—and, moreover, had much to do with the events about to be related—it will be necessary to give some account of it. I transcribe from the tablets of my memory, where it is recorded with a vividness that makes the transcript easy. I can answer for its being truthful.

I was one of three thousand invaders; all travel stained; many footsore, from long marches over the lava rocks of Las Vigas, and the desert plains of Peroté; some scathed in the skirmish with Santa Anna’s lancers along the foot hills of the mountain Malinché; but all aweary unto death.

Fatigue was forgotten, dust and scars disregarded, as we came within sight of the sanctified city, and with beating drums and braying bugles marched on to take possession of it.

It needed no warlike ardour on our part. Outside the gates we were met by the Alcalde Mayor and his magistrates; who, with fair speech on their lips, but foul thought in their hearts, reluctantly bestowed upon us the “freedom of the city!”

Who could wonder at the reluctance? We only wondered at the soft speeches, instead of the hard blows we had been led to expect from them. All along the route, Puebla had been proclaimed as the point where we were to be brought to bay. There we should have to encounter the sons of the tierra templada; and our laurels, cheaply gathered at Vera Cruz and Cerro Gordo, from the enervated children of the tierra caliente, would be snatched from our brows by the “valientes” of La Puebla. The saints of the “holy city” had been promised a hecatomb; and we expected, at least something in the shape of a fight.

We were disappointed—I will not say disagreeably: for, after all, fighting is not the most desirable duty to be performed in a campaign—especially on the eve of entering into some grand town of the enemy. In my opinion, it is far pleasanter to find the streets clear of obstructions, the pavement without blood spots—although they may be those of the foe—the shops and restaurants open, especially the latter—and the windows filled with fair forms and smiling faces.

After this fashion were we received in the City of the Angels. There were no barricades—no street fighting—no obstructions of any kind. The fair forms were there, seen in shadow behind the iron rejas, or standing in full light in the balcons above. Many of the faces, too, were fair; though I shall not go so far as to assert, that any of them were smiling. It would be nearer the truth to say that most, if not all of them, looked frowningly upon us.

It was a cold reception: but the wonder was that we were received at all, or not more warmly welcomed—in a different sense. Horse and foot all told, we counted scarce three thousand weary warriors—stirred for the moment into a spasmodic activity by the sound of our drums, the thought of being conquerors, and perhaps a little by the battery of bright eyes before which we were paraded. We were marching through the streets of a city of more than sixty thousand inhabitants, with houses enough to hold twice the number; grand massive dwellings with frescoed fronts, that rose frowningly above us—each capable of being converted into a fortress. A city lately guarded by choice troops, and whose own fighting men outnumbered us ten to one!

Its women alone might have overwhelmed us, had each but pitched a projectile—her cigarito or slipper—upon our heads. They looked as if they would have annihilated us!

And yet we did not run the gauntlet altogether unscathed—not all of us. Some received wounds in the course of that triumphal entry, that rankled long after.

They were wounds of the heart, inflicted by those soft love-speaking eyes, for which the Poblana is peculiar.

I can testify to one heart thus sweetly scathed.

The fatigued Foot grounded arms in the Piazza Grande. The detached squadrons of cavalry scoured the deserted streets in search of soldiers’ quarters.

Guided by the displaced authorities, the cuartels were soon discovered; and, before night, a new régime ruled the City of the Angels. The priest had given place to the soldier!

Chapter Two.

A City of Devils.

Our conquering army thus easily admitted into the City of the Angels, soon discovered it to be deserving of a far different appellation; and before we were a week within its walls there were few of our fellows who would not have preferred taking the chance of “quarters in Timbuctoo.” Notwithstanding our antipathy to the place, we were forced to remain in it for a period of several months, as it was not deemed prudent to advance directly upon the capital.

Between the “Vega” of Puebla and the “Valle” of Mexico extends a vast wall—the main “cordillera” of the Mexican Andes. It affords several points capable of easy defence, against a force far superior to that of the defenders. It was reported that one or other of these points would be fortified and sustained.

Moreover, the city of Mexico was not to be considered in the same light as the many others in that Imperial Republic, already surrendered to us with such facile freedom—Puebla among the number. The latter was but an outlying post; the former the heart and centre of a nation—up to this time unvisited by foreign foe—for three centuries untainted by the stranger’s footstep.

Around it would be gathered the chivalry of the land, ready to lay down its life in the defence of the modern city; as its Aztec owners freely did, when it was the ancient Tenochtitlan.

Labouring under this romantic delusion, our timid commander-in-chief decreed that we should stay for a time in the City of the Angels.

It was a stay that cost us several thousands of brave men; for, as it afterwards proved, we might have continued our triumphant march into the capital without hostile obstruction.

Fate, or Scott, ruling it, we remained in La Puebla.

If a city inhabited by real angels be not a pleasanter place of abode than that of the sham sort at Puebla, I fancy there are few of my old comrades would care to be quartered in it.

It is true we were in an enemy’s town, with no great claim to hospitality. The people from the first stayed strictly within doors—that is, those of them who could afford to live without exposing their persons upon the street. Of the tradesmen we had enough; and, at their prices, something more.

But the women—those windows full of dark-eyed donçellas we had seen upon our first entry, and but rarely afterwards—appeared to have been suddenly spirited away; and, with some exceptions, we never set eyes on them again!

We fancied that they had their eyes upon us, from behind the deep shadowy rejas: and we had reason to believe they were only restrained from shewing their fair faces by the jealous interference of their men.

As for the latter, we were not long in discovering their proclivity. In a town of sixty thousand inhabitants—with house-room (as already stated) for twice or three times the number—a small corps d’armée, such as ours was, could scarce be discovered in the crowd. On days of general drill, or grand parade, we looked formidable enough—at least to overawe the ruffianism around us.

But when the troops were distributed into their respective cuartels, widely separated from one another, the thing was quite different; and a sky-blue soldier tramping it through the streets might have been likened to a single honest man, moving in the midst of a thousand thieves!

The consequence was that the Poblanos became “muy valiente,” and began to believe, that they had too easily surrendered their city.

And the consequence of this belief, or hallucination on their part, was an attitude of hostility towards our soldiers—resulting in rude badinage, broils, and, not unfrequently, in blood.

The mere mob of “leperos” was not alone guilty of this misconception. The “swells” of the place took part in it—directing their hostility against our subaltern officers—among them some good-natured fellows, who, quite unconscious of the intent, had for a time misconstrued it.

It resulted in a rumour—a repute I should rather call it—which became current throughout the country. The people themselves said, and affected to believe it, that the Americanos, though brave in battle—or, at all events, hitherto successful—were individually afraid of their foes, and shirked the personal encounter!

This idea the jeunesse doré propagated among their female acquaintances; and for a time it obtained credit.

Well do I remember the night when it was first made known to those who were sufferers by the slander.

There were twelve of us busied over a basket of champagne—better I never drank than that we discovered in the cellars of La Puebla.

There is always good wine in the proximity of a convent.

Some one joining our party reported: that he had been jostled while passing through the streets; not by a mob of pelados, but by men who were known as the “young bloods” of the place.

Several others had like experiences to relate—if not of that night, as having occurred within the week.

The Monroe doctrine was touched; and along with it the Yankee “dander.”

We rose to a man; and sallied forth into the street.

It was still early. The pavement was crowded with pedestrians.

I can only justify what followed, by stating that there had been terrible provocation. I had been myself more than once the victim of verbal insult—incredulous that it could have been so meant.

One and all of us were ripe for retaliation.

We proceeded to take it.

Scores of citizens—including the swells, that had hitherto disputed the path—went rapidly to the wall: many of them to the gutter; and next day the banquette was left clear to any one wearing the uniform of “Uncle Sam.”

The lesson, followed by good results, had also some evil ones. Our “rank and file,” taking the hint from their officers, began to knock the Poblanos about like “old boots;” while the leperos finding them alone, and in solitary places, freely retaliated—on several occasions shortening the count of their messes.

The game continuing, soon became perilous to an extreme degree. In daylight we might go where we pleased; but after nightfall—especially if it chanced to be a dark night—it was dangerous to set foot upon the streets. If a single officer—or even two or three—had to dine at the quarters of any remote regiment, he must needs stay all night with his hosts, or take the chance of being waylaid on his way home!

In time the lex talionis became thoroughly established; and a stringent order had to be issued from head-quarters: that neither soldier nor officer should go out upon the streets, without special permission from the commander of the regiment, troop, or detachment.

A revolt of the “angels,” whom we had by this time discovered to be very “devils,” was anticipated. Hence the motive for the precautionary measure.

From that time we were prohibited all out-door exercise, except such as was connected with our drill duties and parade. We were in reality undergoing a sort of mild siege!

Safe sorties could only be made during the day; then only through streets proximate to the respective cuartels. Stragglers to remote suburbs were assaulted sub Jove; while after night it was not safe anywhere, beyond hail of our own sentries!

A pretty pass had things come to in the City of the Angels!

Chapter Three.

The Lady in the Balcon.

Notwithstanding the disagreeables above enumerated, and some others, I was not among those who would have preferred quarters in Timbuctoo.

One’s liking for a place often depends upon a trivial circumstance; and just such a circumstance had given me a penchant for Puebla.

The human heart is capable of a sentiment that can turn dirt into diamonds, or darkness to light,—at least in imagination. Under its influence the peasant’s hut becomes transformed into a princely palace; and the cottage girl assumes the semblance of a queen.

Possessed by this sentiment, I thought Puebla a paradise; for I knew that it contained, if not an angel, one “fair as the first that fell of womankind.” As yet only on one occasion had I seen her; then only at a distance, and for a time scarce counting threescore seconds.

It was during the ceremonial of our entry into the place, already described. As the van of our columns debouched into the Piazza Grande a halt had been ordered, necessarily extending to the regiments in the rear. The spot where my own troop had need to pull up was overlooked by a large two-story house, of somewhat imposing appearance, with frescoed front, balcons, and portales. Of course there were windows; and it was not likely that so situated I should feel shy about looking at, or even into them. There are times and circumstances when a man may be permitted to dispense with the strictest observance of etiquette; and, though it may be quite unchivalric, the conqueror claims, on the occasion of making entry into a conquered city, the right to peep into the windows.

No better than the rest of my fellows, I availed myself of the saucy privilege, by glancing toward the windows of the house, before which we had halted.

In those below there was nobody or nothing—only the red iron bars and the black emptiness behind them.

On turning my eyes upwards, I saw something very different—something that rivetted my gaze, in spite of every effort to avert it. There was a window with balcony in front, and green Venetians inside. Half standing on the sill, and holding the jalousies back, was a woman—I had almost said an angel!

Certainly was she the fairest thing I had ever seen, or in fancy conceived; and my reflection at the time was—I well remember making it—if there be two of her sort in Puebla, the place is appropriately named—La Puebla de los Angeles!

She was not of the fair-haired kind, so fashionable in late days; but dark, with deep dreamy eyes; a mass of black hair, surmounted by a large tortoise-shell comb; eyebrows so pretty as to appear painted; with a corresponding tracery upon the upper lip—the bigotite that tells of Andalusian stock, and descent from the children of the Cid.

While gazing upon her—no doubt rudely enough—I saw that she returned the glance. At first I thought kindly; but then with a serious air, as if resenting my rudeness. I would have given anything I possessed to appease her—the horse I was riding, or aught else. I would have given much for a flower to fling at her feet—knowing the effect of such little flatteries on the Mexican “muchacha;” but, unfortunately, there was no flower near.

In default of one, I bethought me of a substitute—my sword-knot!

The gold tassel was instantly detached from the guard, and fell into the balcony at her feet.

I did not see her take it up. The bugle at that moment sounded the advance; and I was forced to ride forward at the head of my troop.

On glancing back, as we turned out of the street, I saw that she was still outside; and fancied there was something glittering between her fingers in addition to the jewelled rings that encircled them.

I noted the name of the street. It was the Calle del Obispo.

In my heart I registered a vow: that, ere long, I should be back in the Calle del Obispo.

I was not slow in the fulfilment of that vow. The very next day, after being released from morning parade, I repaired to the place in which the fair apparition had made itself manifest.

I had no difficulty in recognising the house. It was one of the largest in the street, easily distinguished by its frescoed front, windows with “balcons,” and jalousies inside. A grand gate entrance piercing the centre told that carriages were kept. In short, everything betokened the residence of a “rico.”

I remembered the very window—so carefully had I made my mental memoranda.

It looked different now. There was but the frame; the picture was no longer in it.

I glanced to the other windows of the dwelling. They were all alike empty. The blinds were drawn down. No one inside appeared to take any interest in what was passing in the street.

I had my walk for nothing. A score of turns, up and down; three cigars smoked while making them; some sober reflections that admonished me I was doing a very ridiculous thing; and I strolled back to my quarters with a humiliating sense of having made a fool of myself, and a resolve not to repeat the performance.

Chapter Four.

A Pair of Counterparts.

It was but a half-heart resolve, and failed me on the following day.

Again did I traverse the Calle del Obispo; again scrutinise the windows of the stuccoed mansion.

As on the day before, the jalousies were down, and my surveillance was once more doomed to disappointment. There was no face, no form, not even so much as a finger, to be seen through the screening lattice.

Shall I go again?

This was the question I asked myself on the third day.

I had almost answered it in the negative: for I was by this time getting tired of the profitless rôle I had been playing.

It was perilous too. There was a chance of becoming involved in a maze, from which escape might not be so easy. I felt sure I could love the woman I had seen in the window. The powerful impression her eyes had made upon me, in twenty seconds of time, was earnest of what might follow from a prolonged observation of them. I could not calculate on escaping without becoming inspired by a passion.

And what if it should not be reciprocated? It was sheer vanity, to have even the slightest hope that it might be!

Better to give it up—to go no more through the street where the fair vision had shewn itself—to try and forget that I had seen it.

Such were my reflections on the morning of the third day, after my arrival in the Angelic city.

Only in the morning. Before twilight there was a change. The twilight had something to do in producing it. On the two previous occasions I had mistaken the hour when beauty is accustomed to display itself in the balconies of La Puebla. Hence, perhaps, my failing to obtain a view of her who had so interested me.

I determined to try again.

Just as the sun’s rays were turning rose-coloured upon the snow-crowned summit of Orizava, I was once more wending my way towards the Calle del Obispo.

A third disappointment; but this time of a kind entirely different from the other two.

I had hit the hour. The donçella—of whom for three days I had been thinking—three nights dreaming—was in the window where I had first seen her.

One glance and I was completely disenchanted!

Not that she could be called plain, or otherwise than pretty. She was more than passably so, but still only pretty.

Where was the resplendent beauty that had so strangely, suddenly, impressed me?

She might have deemed me ill-mannered, as I stood scanning her features to discover it; for I was no longer in awe—such as I expected her presence would have produced. I could now look upon her, without fear of that possibly perilous future I had been picturing to myself.

After all, the thing was easy of explanation. For six weeks we had been among the hills—in cantonment—so far from Jalapa, that it was only upon rare occasions we had an opportunity of refreshing our eyes with a sight of the fair Jalapenas. We had been accustomed to see only the peasant girls of Banderilla and San Miguel Soldado, with here and there along the route the coarse unkempt squaws of Azteca. Compared with these, she of the Calle del Obispo was indeed an angel. It was the contrast that had misled me?

Well, it would be a lesson of caution not to be too quick at falling in love. I had often listened to the allegement, that circumstances have much to do in producing the tender passion. This seemed to confirm it.

I was not without regret, on discovering that the angel of my imagination was no more than a pretty woman,—a regret strengthened by the remembrance of three distinct promenades made for the express purpose of seeing her—to say nothing of the innumerable vagaries of pleasant conjecture, all exerted in vain.

I felt a little vexed at having thrown away my sword-knot!

I was scarce consoled by the reflection, that my peace of mind was no longer in peril; for I was now almost indifferent to the opinion which the lady might entertain of me. I no longer cared a straw about the reciprocity of a passion the possibility of which had been troubling me. There would be none to reciprocate.

Thus chagrined, and a little by the same thought consoled, I had ceased to stare at the señorita; who certainly stared at me in surprise, and as I fancied, with some degree of indignation.

My rudeness had given her reason; and I could not help perceiving it.

I was about to make the best apology in my power, by hastening away from the spot—my eyes turned to the ground in a look of humiliation—when curiosity, more than aught else, prompted me to raise them once more to the window. I was desirous to know whether my repentance had been understood and acknowledged.

I intended it only for a transitory glance. It became fixed.

Fixed and fascinated! The woman that but six seconds before appeared only pretty—that three days before I had supposed supremely beautiful—was again the angel I had deemed her,—certainly the most beautiful woman I ever beheld!

What could have caused this change? Was it an illusion—some deception my senses were practising upon me?

If the lady saw reason to think me rude before, she had double cause now. I stood transfixed to the spot, gazing upon her with my eyes, my soul—my every thought concentrated in the glance.

And yet she seemed less frowning than before: for I was sure that she had frowned. I could not explain this, any more than I could account for the other transformation. Enough that I was gratified with the thought of having, not idly, bestowed my sword-knot.

For some time I remained under the spell of a speechless surprise.

It was broken—not by words, but by a new tableau suddenly presented to my view. Two women were at the window! One was the pretty prude who had well nigh chased me out of the street; the other, the lovely being who had attracted me into it!

At a glance I saw that they were sisters.

They were remarkably alike, both in form and features. Even the expression upon their countenances was similar—that similarity that may be seen between two individuals in the same family, known as a “family likeness.”

Both were of a clear olive complexion—the tint of the Moriseo-Spaniard—with large imperious eyes, and masses of black hair clustering around their necks. Both were tall, of full form, and shaped as if from the same mould; while in age—so far as appearance went—they might have been twins.

And yet, despite these many points of personal similarity, in the degree of loveliness they were vastly different. She who had been offended by my behaviour was a handsome woman, and only that—a thing of Earth; while her sister had the seeming of some divine creature whose home might be in Heaven!

Chapter Five.

A Nocturnal Sortie.

From that day, each return of twilight’s gentle hour saw me in the Calle del Obispo. The sun was not more certain to set behind the snow-crowned Cordilleras, than I to traverse the street where dwelt Mercedes Villa-Señor.

Her name and condition had been easily ascertained. Any stray passenger encountered in the street could tell, who lived in the grand casa with the frescoed front.

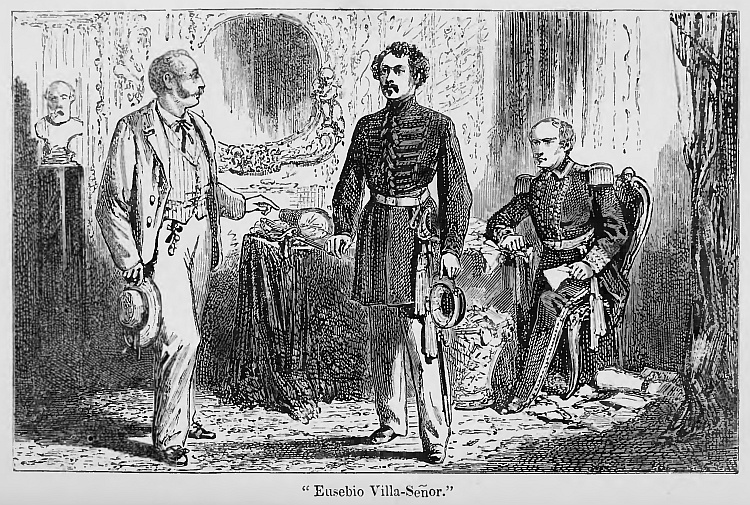

“Don Eusebio Villa-Señor—un rico—with two daughters, muchachas muy lindas!” was the reply of him, to whom I addressed the inquiry.

I was further informed, that Don Eusebio was of Spanish descent, though a Mexican by birth; that in the veins of his daughters flowed only the Andalusian blood—the pure sangre azul. His was one of the familias principales of Puebla.

There was nothing in this knowledge to check my incipient admiration of Don Eusebio’s daughter. Quite the contrary.

As I had predicted, I was soon in the vortex of an impetuous passion; and without ever having spoken to her who inspired it!

There was no chance to hold converse with her. We were permitted no correspondence with the familias principales, beyond the dry formalities which occasionally occurred in official intercourse. But this was confined to the men. The señoritas were closely kept within doors, and as jealously concealed from us as if every house had been a harem.

My admiration was too earnest to be restrained by such trifling obstructions; and I succeeded in obtaining an occasional, though distant, view of her who had so interested me.

My glances—given with all the fervour of a persistent passion—with all its audacity—could scarce be misconstrued.

I had the vanity to think they were not; and that they were returned with looks that meant more than kindness.

I was full of hope and joy. My love affair appeared to be progressing towards a favourable issue; when that change, already recorded, came over the inhabitants of Puebla—causing them to assume towards us the attitude of hostility.

It is scarce necessary to say that the new state of things was not to my individual liking. My twilight saunterings had, of necessity, to be discontinued; and upon rare occasions, when I found a chance of resuming them, I no longer saw aught of Mercedes Villa-Señor!

She, too, had no doubt been terrified into that hermitical retirement—among the señoritas now universal.

Before this terrible time came about, my passion had proceeded too far to be restrained by any ideas of danger. My hopes had grown in proportion; and stimulated by these, I lost no opportunity of stealing out of quarters, and seeking the Calle del Obispo.

I was alike indifferent to danger in the streets, and the standing order to keep out of them. For a stray glance at her to whom I had surrendered my sword-knot, I would have given up my commission; and to obtain the former, almost daily did I risk losing the latter!

It was all to no purpose. Mercedes was no more to be seen.

Uncertainty about her soon became a torture; I could endure it no longer. I resolved to seek some mode of communication.

How fortunate for lovers that their thoughts can be symbolised upon paper! I thought so as I indited a letter, and addressed it to the “Dona Mercedes Villa-Señor.”

How to get it conveyed to her, was a more difficult problem.

There were men servants who came and went through the great gateway of the mansion. Which of them was the one least likely to betray me?

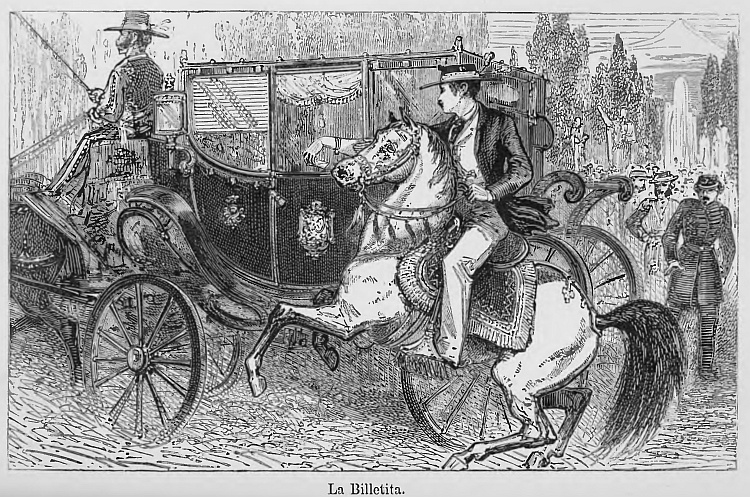

I soon fixed my reflections upon the cochero—a tall fellow in velveteens, whom I had seen taking out the sleek carriage horses. There was enough of the “picaro” in his countenance, to inspire me with confidence that he could be suborned for my purpose.

I determined on making trial of him. If a doubloon should prove sufficient bribe, my letter would be delivered.

In my twilight strolls, often prolonged to a late hour, I had noticed that this domestic sallied forth: as if, having done his day’s duty, he had permission to spend his evenings at the pulqueria. The plan would be to waylay him, on one of his nocturnal sorties; and this was what I determined on doing.

On the night of that same day on which I indited the epistle, the Officer of the Guard chanced to be my particular friend. It was not chance either: since I had chosen the occasion. I had no difficulty, therefore, in giving the countersign; and, wrapped in a cloth cloak—intended less as a protection against the cold than to conceal my uniform—I proceeded onward upon my errand of intrigue.

I was favoured by the complexion of the night. It was dark as coal tar—the sky shrouded with a thick stratum of thunder clouds.

It was not yet late enough for the citizens to have forsaken the streets. There were hundreds of them, strolling to and fro, all natives of the place—most of them men of the lower classes—with a large proportion of “leperos.”

There was not a soldier to be seen—except here and there the solitary sentry, whose presence betokened the entrance to some military cuartel.

The troops were all inside—in obedience to the standing order. There were not even the usual squads of drunken stragglers in uniform. The fear of assault and assassination was stronger than the propensity for “raking”—even among regiments whose rank and file was almost entirely composed of the countrymen of Saint Patrick.

A stranger passing through the place could scarce have suspected that the city was under American occupation. There was but slight sign of such control. The Poblanos appeared to have the place to themselves.

They were gay and noisy—some half intoxicated with pulque, and inclined to be quarrelsome. The leperos, no longer in awe of their own national authorities, were demeaning themselves with a degree of licence allowed by the abnormal character of the times.

In my progress along the pavement I was several times accosted in a coarse bantering mariner; not on account of my American uniform—for my cloak concealed this—but because I wore a cloak! I was taken for a native “aristocrat.”

Better that it was so: since the insults were only verbal, and offered in a spirit of rude badinage. Had my real character been known, they might have been accompanied by personal violence.

I had not gone far before becoming aware of this; and that I had started upon a rash, not to say perilous, enterprise.

It was of that nature, however, that I could not give it up; even had I been threatened with ten times the danger.

I continued on, holding my cloak in such a fashion, that it might not flap open.

By good luck I had taken the precaution to cover my head with a Mexican sombrero, instead of the military cap; and as for the gold stripes on my trowsers, they were but the fashion of the Mexican majo.

A walk of twenty minutes brought me into the Calle del Obispo.

Compared with some of the streets, through which I had been passing, it seemed deserted. Only two or three solitary pedestrians could be seen traversing it, under the dim light of half a dozen oil lamps set at long distances apart.

One of these was in front of the Casa Villa-Señor. More than once it had been my beacon before, and it guided me now.

On the opposite side of the street there was another grand house with a portico. Under the shadow of this I took my stand, to await the coming forth of the cochero.

Chapter Six.

“Va Con Dios!”

Though I had already made myself acquainted with his usual hour of repairing to the pulqueria, I had not timed it neatly.

For twenty minutes I stood with the billetita in my hand, and the doubloon in my pocket, both ready to be entrusted to him. No cochero came forth.

The house rose three stories from the street—its massive mason work giving it a look of solemn grandeur. The great gaol-like gate—knobbed all over like the hide of an Indian rhinoceros—was shut and secured by strong locks and double bolting. There was no light in the sagnan behind it; and not a ray shone through the jalousies above.

Not remembering that in Mexican mansions there are many spacious apartments without street windows, I might have imagined that the Casa Villa-Señor was either uninhabited, or that the inmates had retired to rest. The latter was not likely: it wanted twenty minutes to ten.

What had become of my cochero? Half-past nine was the hour I had usually observed him strolling forth; and I had now been upon the spot since a quarter past eight. Something must be keeping him indoors—an extra scouring of his plated harness or grooming of his frisones?

This thought kept me patient, as I paced to and fro under the portico of Don Eusebio’s “opposite neighbour.”

Ten o’clock! The sonorous campaña of the Cathedral was striking the noted hour—erst celebrated in song. A score of clocks in church-steeples, that tower thickly over the City of the Angels, had taken up the cue; and the air of the night vibrated melodiously under the music of bell metal.

To kill time—and another bird with the same stone—I took out my repeater, with the intention of regulating it. I knew it was not the most correct of chronometers. The oil lamp on the opposite side enabled me to note the position of the hands upon the dial. Its dimness, however, caused delay; and I may have been engaged some minutes in the act.

After returning the watch to its fob, I once more glanced towards the entrance of Don Eusebio’s dwelling—at a wicket in the great gate, through which I expected the cochero to come.

The gate was still close shut; but, to my surprise, the man was standing outside of it! Either he, or some one else?

I had heard no noise—no shooting of bolts, nor creaking of hinges. Surely it could not be the cochero?

I soon perceived that it was not; nor anything that in the least degree resembled him.

My vis-à-vis on the opposite side of the street was, like myself, enveloped in a cloak, and wearing a black sombrero.

Despite the disguise, and the dim light afforded by the lard, there was no mistaking him for either domestic, tradesman, or lepero. His air and attitude—his well-knit figure, gracefully outlined underneath the loose folds of the broadcloth—above all, the lineaments of a handsome face—at once proclaimed the “cavallero.”

In appearance he was a man of about my own age: twenty-five, not more. Otherwise he may have had the advantage of me; for, as I gazed on his features—ill lit as they were by the feebly glimmering lamp—I fancied I had never looked on finer.

A pair of black moustaches curled away from the corners of a mouth, that exhibited twin rows of white regular teeth. They were set in a pleasing smile.

Why that pain shooting through my heart, as I beheld it?

I was disappointed that he was not the cochero for whom I had been keeping watch. But it was not this. Far different was the sentiment with which I regarded him. Instead of the “go-between” I had expected to employ, I felt a suspicion, that I was looking upon a rival!

A successful one, too, I could not doubt. His splendid appearance gave earnest of that.

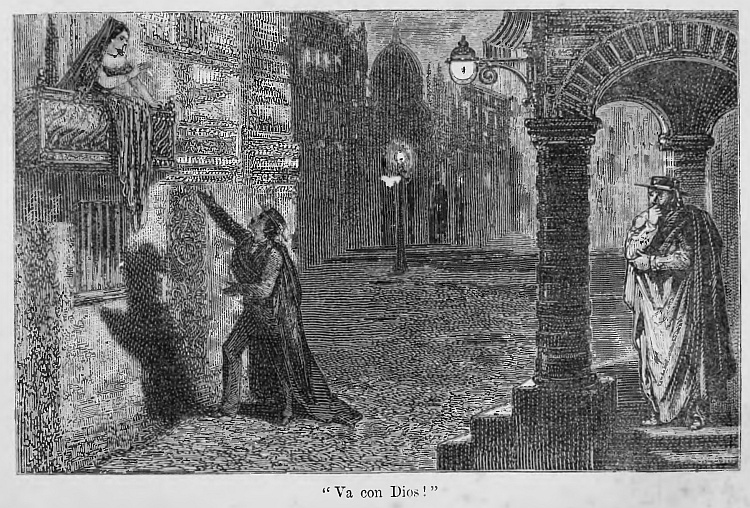

He had not paused in front of the Casa Villa-Señor without a purpose—as was evident from the way in which he paced the banquette beneath, while glancing at the balcon above. I could see that his eyes were fixed on that very window—by my own oft passionately explored!

His look and bearing—both full of confidence—told that he had been there before—often before; and that he was now at the spot—not like myself on an errand of doubtful speculation, but by appointment!

I could tell, that he had not come to avail himself of the services of the cochero. His eyes did not turn towards the grand entrance-gate, but remained fixed upon the balcony above—where he evidently expected some one to make appearance.

Shadowed by the portal, I was not seen by him; though I cared not a straw about that. My remaining in concealment was a mere mechanical act—an instinct, if you prefer the phrase. From the first I felt satisfied, that my own “game was up,” and that I had no longer any business with the domestic of Don Eusebio Villa-Señor. His daughter was already engaged!

Of course I thought only of Mercedes. It would have been absurd to suppose that the man I saw before me could be after the other. The idea did not enter my brain—reeling at the sight of my successful rival.

Unlike me, he was not kept long in suspense. Ten o’clock had evidently been the hour of appointment. The cathedral was to give the time; and, as the tolling commenced, the cloaked cavalier had entered the street, and hastened forward to the place.

As the last strokes were reverberating upon the still night air, I saw the blind silently drawn aside; while a face—too often outlined in my dreams—now, in dim but dread reality, appeared within the embayment of the window.

The instant after, and a form, robed in dark habiliments, stepped silently out into the balcony; a white arm was stretched over the balusters; something still whiter, appearing at the tips of tapering fingers, fell noiselessly into the street, accompanied by the softly whispered words:

“Querido Francisco; va con Dios!” (God be with you, dear Francis!)

Before the billet-doux could be picked up from the pavement, the fair whisperer disappeared within the window; the jalousie was once more drawn: and both house and street relapsed into sombre silence.

No one passing the mansion of Don Eusebio Villa-Señor could have told, that his daughter had been committing an indiscretion. That secret was in the keeping of two individuals; one to whom it had, no doubt, imparted supreme happiness; the other to whom it had certainly given a moment of misery!

Chapter Seven.

Brigandage in New Spain.

Accustomed to live under a strong government, with its well-organised system of police, we in England have a difficulty in comprehending how a regular band of robbers can maintain itself in the midst of a civilised nation.

We know that we have gangs of burglars, and fraternities of thieves, whose sole profession is to plunder. The footpad is not quite extinct; and although he occasionally enacts the rôle of the highwayman, and demands “your money or your life,” neither in dress nor personal appearance is he to be distinguished from the ordinary tradesman, or labourer. More often is he like the latter.

Moreover, he does not bid open defiance to the law. He breaks it in a sneaking, surreptitious fashion; and if by chance he resists its execution, his resistance is inspired by the fear of capture and its consequences—the scaffold, or penitentiary.

This defiance rarely goes further than an attempt to escape from the policeman, with a bull’s-eye in one hand and a truncheon in the other.

The idea of a band of brigands showing fight, not only to a posse of sheriffs’ officers, but to a detachment, perhaps half a regiment, of soldiers—a band armed with swords, carbines, and pistols; costumed and equipped in a style characteristic of their calling—is one, to comprehend which we must fancy ourselves transported to the mountains of Italy, or the rugged ravines of the Spanish sierras. We even wonder at the existence of such a state of things there; and, until very lately, were loth to believe in it. Your London shopkeeper would not credit the stories of travellers being captured, and retained in captivity until ransomed by their friends—or if they had no friends, shot!

Surely the government of the country could rescue them? This was the query usually put by the incredulous.

There is now a clearer understanding of such things. The experience of an humble English artist has established the fact: that the whole power of Italy—backed by that of England—has been compelled to make terms with a robber-chief, and pay him the sum of four thousand pounds for the surrender of his painter-prisoner!

The shopkeeper, as he sits in the theatre pit, or gazes down from the second tier of boxes, will now take a stronger interest in “Fra Diavolo” than he ever did before. He knows that the devil’s brother is a reality, and Mazzaroni something more than a romantic conceit of the author’s imagination.

But there is a robber of still more picturesque style to which the Englishman cannot give his credibility—a bandit not only armed, costumed, and equipped like the Fra Diavolos and Mazzaronis, but who follows his profession on horseback!

And not alone—like the Turpins and Claude Duvals of our own past times—but trooped along with twenty, fifty, and often a hundred of his fellows!

For this equestrian freebooter—the true type of the highwayman—you must seek, in modern times, among the mountains, and upon the plains, of Mexico. There you will find him in full fanfar; plying his craft with as much earnestness, and industry, as if it were the most respectable of professions!

In the city and its suburbs, brigandage exists in the shape of the picaron-à-pied—or “robber on foot”—in short, the footpad. In the country it assumes a far more exalted standard—being there elevated to the rank of a regular calling; its practitioners not going in little groups, and afoot—after the fashion of our thieves and garotters—but acting in large organised bands, mounted on magnificent horses, with a discipline almost military!

These are the true “bandoleros,” sometimes styled salteadores del camino grande—“robbers of the great road”—in other words, highwaymen.

You may meet them on the camino grande leading from Vera Cruz to the capital—by either of the routes of Jalapa or Orizava; on that between the capital and the Pacific port of Acapulco; on the northern routes to Queretaro, Guanaxuato, and San Luis Potosi; on the western, to Guadalaxara and Michoacan; in short, everywhere that offers them the chance of stripping a traveller.

Not only may you meet them, but will, if you make but three successive excursions over any one of the above named highways. You will see the “salteador” on a horse much finer than that you are yourself riding; in a suit of clothes thrice the value of your own—sparkling with silver studs, and buttons of pearl or gold; his shoulders covered with a serapé, or perhaps a splendid manga of finest broadcloth—blue, purple, or scarlet.

You will see him, and feel him too—if you don’t fall upon your face at his stern summons “A tierra!” and afterwards deliver up to him every article of value you have been so imprudent as to transport upon your person.

Refuse the demand, and you will get the contents of carbine, escopeta, or blunderbuss in your body, or it may be a lance-blade intruded into your chest!

Yield graceful compliance, and he will as gracefully give you permission to continue your journey—with, perhaps, an apology for having interrupted it!

I know it is difficult to believe in such a state of things, in a country called civilised—difficult to you. To me they are but remembrances of many an actual experience.

Their existence is easily explained. You will have a clue to it, if you can imagine a land, where, for a period of over fifty years, peace has scarcely ever been known to continue for as many days; where all this time anarchy has been the chronic condition; a land full of disappointed spirits—unsatisfied aspirants to military fame, also unpaid; a land of vast lonely plains and stupendous hills, whose shaggy sides form impenetrable fastnesses—where the feeble pursued may bid defiance to the strong pursuer.

And such is the land of Anahuac. Even within sight of its grandest cities there are places of concealment—harbours of refuge—alike free to the political patriot, and the outlawed picaro.

Like other strangers to New Spain, before setting foot upon its shores, I was incredulous about this peculiarity of its social condition. It was too abnormal to be true. I had read and heard tales of its brigandage, and believed them to be tinged with exaggeration. A diligencia stopped every other day, often when accompanied by an escort of dragoons—twenty to fifty in number; the passengers maltreated, at times murdered—and these not always common people, but often officers of rank in the army, representatives of the Congresa, senators of the State, and even high dignitaries of the Church!

Afterwards I had reason to believe in the wholesale despoliation. I was witness to more than one living illustration of it.

But, in truth, it is not so very different from what is daily, hourly, occurring among ourselves. It is dishonesty under a different garb and guise—a little bolder than that of our burglar—a little more picturesque than that practised by the fustian-clad garotter of our streets.

And let it be remembered, in favour of Mexican morality—that, for one daring bandolero upon the road, we have a hundred sneaking thieves of the attorney type—stock-jobbers—promoters of swindling speculations—trade and skittle sharpers—to say nothing of our grand Government swindle of over-taxation—all of which are known only exceptionally in the land of Moctezuma.

In point of immorality—on one side stripping it of its picturesqueness, on the other of its abominable plebbishness—I very much doubt, whether the much-abused people of Mexico need fear comparison with the much-bepraised people of England.

For my part, I most decidedly prefer the robber of the road, to him of the robe; and I have had some experience of both.

This digression has been caused by my recalling an encounter with the former, that occurred to me in La Puebla—on that same night when I found myself forestalled.

Chapter Eight.

A Rival Tracked to his Roof-Tree.

That I was forestalled, there could be no mistake.

There was no ambiguity about the meaning of the phrase: “God be with you, dear Francis!” The coldest heart could not fail to interpret it—coupled with the act to which it had been an accompaniment.

My heart was on fire. There was jealousy in it; and, more: there was anger.

I believed, or fancied, that I had cause. If ever woman had given me encouragement—by looks and smiles—that woman was Mercedes Villa-Señor.

All done to delude me—perhaps but to gratify the slightest whim of her woman’s vanity? She had shown unmistakeable signs of having noted my glances of admiration. They were too earnest to have been misunderstood. Perhaps she may have been a little flattered by them? But, whether or no, I was confident of having received encouragement.

Once, indeed, a flower had been dropped from the balcon. It had the air of an accident—with just enough design to make the act difficult of interpretation. With the wish father to the thought, I accepted it as a challenge; and, hastening along the pavement, I stooped, and picked the flower up.

What I then saw was surely an approving smile—one that seemed to say: “in return for your sword-knot.” I thought so at the time; and fancied I could see the tassel, protruding from a plait in the bodice of the lady’s dress—shown for an instant, and then adroitly concealed.

This sweet chapter of incidents occurred upon the occasion of my tenth stroll through the Calle del Obispo. It was the last time I had the chance of seeing Mercedes by twilight. After that came the irksome interval of seclusiveness,—now to be succeeded by a prolonged period of chagrin: for the dropping of the billet-doux, and the endearing speech, had put an end to my hopes—as effectually as if I had seen Mercedes enfolded in Francisco’s arms.

Along with my chagrin I felt spite. I was under the impression that I had been played with.

Upon whom should I expend it? On the Señorita?

There was no chance. She had retired from the balcony. I might never see her again—there, or elsewhere? Who then? The man who had been before me in her affections?

Should I cross over the street—confront—pick a quarrel with him, and finish it at my sword’s point? An individual whom I had never seen, and who, in all probability, had never set eyes upon me!

Absurd as it may appear—absolutely unjust as it would have been—this was actually my impulse!

It was succeeded by a gentler thought. Francisco’s face was favourable to him. I saw it more distinctly, as he leant forward under the lamp to decipher the contents of the note. It was such a countenance as one could not take offence at, without good cause; and a moment’s reflection convinced me that mine was not sufficient. He was not only innocent of the grief his rivalry had given me, but in all likelihood ignorant of my existence.

From that time forward he was likely to remain so.

Such was my reflection, as I turned to take my departure from the place. There was no longer any reason for my remaining there. The cochero might now come and go, without danger of being accosted by me. His tardiness had lost him the chance of obtaining an onza; and the letter I had been hitherto holding in my hand went crumpled back into my pocket. Its warm words and soft sentiments—contrived with all the skill of which I was capable—should never be read by her for whom they had been indited!

So far as the offering of any further overtures on my part, I had done with the daughter of Don Eusebio Villa-Señor; though I knew I had not done with her in my heart, and that it would be long—long—before I should get quit of her there.

I turned to go back to my quarters—in secret to resign myself to my humiliation. I did not start instantly. Something whispered me to stay a little longer. Perhaps there might be a second act to the episode I had so unwillingly witnessed?

It could hardly be this that induced me to linger. It was evident she did not intend reappearing. Her visit to the balcon had the air of being made by stealth. I noted that once or twice she cast a quick glance over her shoulder—as if watchful eyes were behind her, and she had chosen a chance moment when they were averted.

The manoeuvre had been executed with more than ordinary caution. It was easy to see they were lovers without leave. Ah! too well could I comprehend the clandestine act!

Still standing concealed within the shadow of the portal, I watched Francisco deciphering, or rather devouring, the note. How I envied him those moments of bliss! The words traced upon the tiny sheet must be sweet to him, as the sight was bitter to me.

His face was directly under the lamplight. I could see it was one that woman might well love, and man be jealous of. No wonder he had won the heart of Don Eusebio’s daughter!

He was not long in making himself acquainted with the contents of the epistle. Of course they caused him joy. I could trace it in the pleased expression that made itself manifest in every line of his countenance. Could I have seen my own, I might have looked upon a sad contrast!

The reading came to a close. He folded the note, and with care—as though intending it to be tenderly kept. It disappeared under his cloak; the cloak was drawn closer around him; a fond parting look cast up to the place from which he had received the sweet missive; and then, turning along the pavement, he passed smilingly away.

I followed him.

I can scarce tell why I did so. My first steps were altogether mechanical—without thought or motive.

It might have been an instinct—a fascination—such as often attracts the victim to the very danger it should avoid.

Prudence—experience, had I consulted it—would both have said to me:

“Go the other way. Go, and forget her! Him too—all that has happened. ’Tis not yet too late. You are but upon the edge of the Scylla of passion. You may still shun it. Retire, and save yourself from its Charybdis!”

Prudence and experience—what is either—what are both in the balance against beauty? What were they when weighed against the charms of that Mexican maiden?

Even the slight I had experienced could not turn the scale in their favour! It only maddened me to know more; and perhaps it was this that carried me along the pavement, on the footsteps of Francisco.

If not entertained at first, a design soon shaped itself—a sort of morbid motive. I became curious to ascertain the condition of the man who had supplanted me; or whom I had been myself endeavouring to supplant with such slight success.

He had the air of a gentleman, and the bearing of a true militario—a type I had more than once met with in the land of Anahuac—so long a prey to the rule of the sabre.

There was nothing particularly martial about his habiliments.

As he passed lamp after lamp in his progress along the street, I could note their style and character. A pair of dark grey trousers without stripes; a cloak; a glazed hat—all after a fashion worn by the ordinary commerciantes of the place. I fancied I could perceive a certain shabbiness about them—perhaps not so much that, as a threadbareness—the evidence of long wear: for the materials were of a costly kind. The cloak was of best broadcloth—the fabric of Spain; while the hat was encircled by a bullion band, that, before getting tarnished by the touch of time, must have shone splendidly enough.

These observations were not made without motive. I drew from them a series of deductions. One, that could not be avoided: that my rival, instead of being rich, was in the opposite condition of life—perhaps penniless?

I was confirmed in this conjecture, as I saw him stop before the door of an humble one-storied dwelling, in a street of corresponding pretensions; thoroughly convinced of it as he lifted the latch with a readiness that betokened it to be his home, and, without speaking to any one, stepped inside.

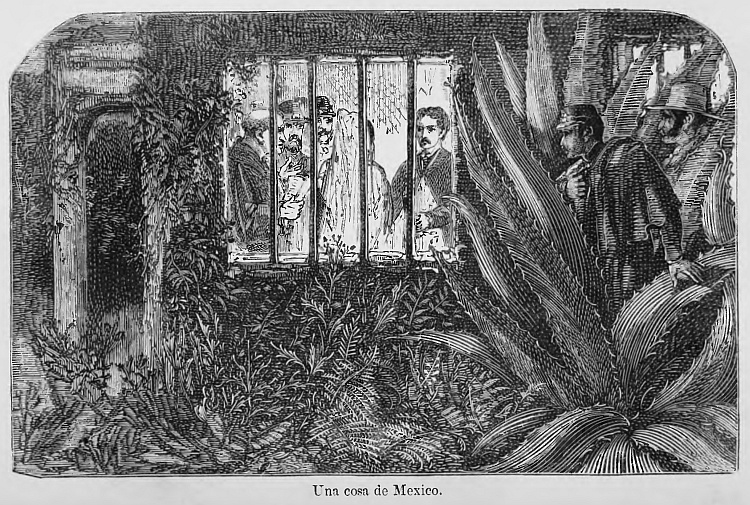

The circumstances were conclusive; he was not one of the “ricos” of the place. It explained the clandestine correspondence, and the caution observed by her who flung down the billetita.

Instead of being solaced by the thought, it only increased my bitterness of spirit. I should have been better pleased to have seen my rival surrounded by splendour. A love unattracted by this must be indeed disinterested—without the possibility of being displaced. No chance to supplant the lover who is loved for himself. I did not harbour a hope.

A slight incident had given me the clue to a romantic tale. Mercedes Villa-Señor, daughter of one of the richest men in the place—inhabiting one of its grandest mansions—in secret correspondence with a man wearing a threadbare coat, having his home in one of the lowliest dwellings to be found in the City of the Angels!

I was not much surprised at the discovery. I knew it to be one of the “Cosas de Mexico.” But the knowledge did not lessen my chagrin.

Chapter Nine.

Muera El Americano!

Like a thief skulking after the unsuspecting pedestrian, on whom he intends to practise his professional skill, so did I follow Francisco.

Absorbed in the earnestness of my purpose, I did not observe three genuine thieves, who were skulking after me.

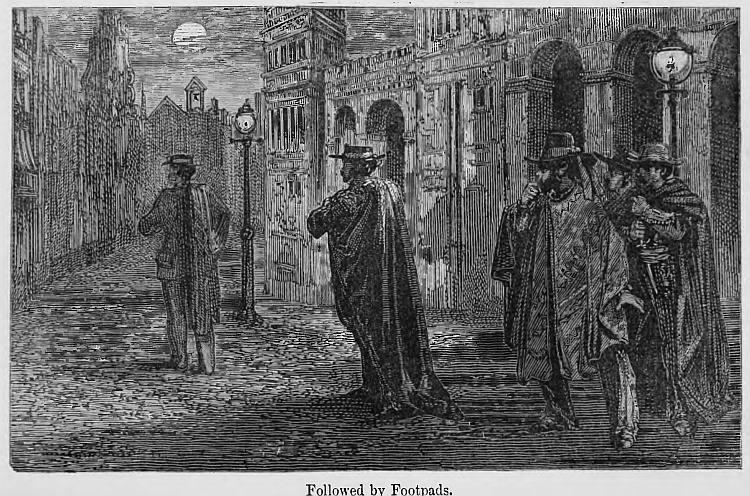

I am scarce exact in my nomenclature. They were not thieves, but picarones-à-pied—footpads.

My first acquaintance with these gentry was now to be made.

As already said, I was not aware that any one was imitating me, in the somewhat disreputable rôle I was playing.

After watching my rival disappear within his doorway, I remained for some seconds in the street—undecided which way to go. I had done with “querido Francisco;” and intended to return to my quarters.

But where were they? Engrossed by my espionage I had made no note of the direction, and was now lost in the streets of La Puebla!

What was to be done? I stood considering.

All of a sudden I felt myself grappled from behind!

Both my arms were seized simultaneously, at the same time that a garota was extended across my throat!

They were strong men who had taken hold of me; but not strong enough to retain it.

I was then in the very vigour of my manhood; and, though it may seem vanity to say so, it was a vigour not easily overcome.

With a quick wrench, I threw off the two flankers; and turning suddenly—so that the garota was diverted from its purpose—I got a blow at the ruffian who held it that sent him face foremost upon the pavement.

Before any of the three could renew their attempt, I had my revolver in hand—ready to deal death to the first who re-assailed me.

The footpads stood aghast. They had not expected such a determined resistance; and, if left to themselves, in all probability, I should have seen no more of them that night.

If left to themselves, I could have dealt with them conveniently enough. In truth, I could have taken the lives of all three, as they stood in their speechless bewilderment.

I held in my hand a Colt’s six-shooter, Number 2; another in my belt; twelve shots in all—sure as the best percussion caps and careful loading could make them. A fourth of the shots would have sufficed: for I had no thought of taking uncertain aim.

Despite the cause given me for excitement, I never felt cooler in my life—that is for a combat. For an hour before, my nerves had been undergoing a strain, that served only to strengthen them.

I had been in want of something upon which to pour out my gathering wrath; and here was the thing itself. God, or the devil, seemed to have sent the three thieves as a safety-valve to my swollen passion—a sort of target on which to expend it!

Jesting apart, I thought so at the time; and so sure was I of being able to immolate the trio at my leisure, that I only hesitated as to which of them I should shoot down first!

You may be incredulous. I can assure you that the scene I am describing is no mere romance, but the transcript of a real occurrence. So also are the thoughts associated with it.

I stood eyeing my assailants, undecided about the selection.

I had my finger on the trigger; but, before pressing it, a quick reflection came into my mind that restrained me from shooting.

It was still early—not quite ten o’clock—and the pavement was alive with passengers. I had passed several on entering the little street; and, from the place where I stood, I could see a dozen dark forms flitting about, or loitering by the doors of the houses.

They were all leperos of the low quarter.

The report of my pistol would bring a crowd of them around me; and, although I might disembarrass myself of the footpads, I should be in as much, or more, danger from the patriotas!

I was quite sensible of the perilous situation in which I had placed myself by my imprudent promenade.

As the robbers appeared to have given up their design upon my purse, and were making their best speed to get out of reach of my pistol, I thought the wisest way would be to let them go off.

With this design I was about to content myself—only staying to pick up my cloak, that in the struggle had fallen from my shoulders.

Having recovered it, I commenced taking my departure from the place.

I had not gone six paces, when I became half convinced that I had made a mistake, and that it would have been better to have killed the three thieves. After doing so, I might have found time to steal off unobserved.

Allowing them to escape, I had given them the opportunity to return in greater strength, and under a different pretence from that of their former profession.

A cry that all three raised as they ran down the street, was answered by a score of other voices; and, before I had time to make out its meaning, I was surrounded by a circle of faces, scowling upon me with an expression of unmistakeable hostility.

Were they all robbers—associates of the three who had assaulted me?

Had I chanced into one of those streets entirely abandoned to the thieving fraternity—such as may be found in European cities—where the guardians of the night do not dare to shew their faces?

This was my first impression, as I noted the angry looks and hostile attitude of those who came clustering around me.

It became quickly changed, as I listened to the phrase, fiercely vociferated in my ears:

“Dios y Libertad! Muera el Americano!”

The discomfited footpads had returned upon a new tack. They had seen my uniform, as it became uncloaked in the struggle; and, under a pretence of patriotism, were now about to take satisfaction for their discomfiture and disappointment.

By good fortune I was standing upon a spot where there was a tolerable light—thrown upon the street by a couple of lamps suspended near.

Had it been darker, I might have been set upon at once, and cut down, before I could distinguish my antagonists. But the light benefited me in a different way. It exposed to my new assailants a brace of Colt’s revolvers—one held in hand and ready to be discharged; the other ready to be drawn.

The knife was their weapon. I could see a dozen blades bared simultaneously around me; but to get to such close quarters would cost some of them their lives.

They had the sharpness to perceive it; and halting at several paces distance—formed a sort of irregular ring around me.

It was not a complete circle, but only the half: for I had taken my stand against the front of a house, close to its doorway.

It was a lucky thought, or instinct: since it prevented my being assailed from the rear.

“What do you want?” I asked, addressing my antagonists in their own tongue—which by good fortune I spoke with sufficient purity.

“Your life!” was the laconic reply, spoken by a man of sinister aspect, “your life, filibustero! And we mean to have it. So you may as well put up your pistol. If not, we’ll take it from you. Yield, Yankee, if you don’t want to be killed on the spot!”

“You may kill me,” I responded, looking the ruffian full in the face, “but not till after I’ve killed you, worthy sir. You hear me, cavallero! The first that stirs a step towards me, will go down in his tracks. It will be yourself—if you have the courage to come first.”

I cannot describe how I felt at that queer crisis. I only remember that I was as cool, as if rehearsing the scene for amusement—instead of being engaged in a real and true tragedy that must speedily terminate in death!

My coolness, perhaps, sprang from despair, or an instinct that nought else could avail me.

My words, with the gestures that accompanied them, were not without effect. The tall man, who appeared to lead the party, saw that I had selected him for my first shot, and cowered back into the thick of the crowd.

But among his associates there were some of more courage, or greater determination; and the cry, “Muera el Americano!” once more shouted on all sides, gave a fresh stimulus to the passions of the patriotas.

Besides, the crowd was constantly growing greater, through fresh arrivals in the street. I could see that the six-shooter would not much longer keep my assailants at a distance.

There appeared not the slightest chance of escape. A death, certain as cruel—sudden, terrible to contemplate—stared me in the face. I saw no way of avoiding it. I had no thought of there being a possibility to do so—no thought of anything, save selling my life as dearly as I could.

Before falling, I should make a hecatomb of my cowardly assassins.

I saw no pistols or other firearms in their hands—nothing but knives and machetés. They could only reach me from the front; and, before they could close upon me, I felt certain of being able to discharge every chamber of my two revolvers. At least half a dozen of my enemies were doomed to die before me.

I was in a splendid position for defence. The house against which I had been brought to bay was built of adobés, with walls full three feet thick. The door was indented to a depth of at least two. I stood with my back against it, the jambs on both sides protecting me. My position was that of the badger in the barrel attacked by terriers.

How long I might have been permitted to hold it is a question I will not undertake to answer. No doubt it would have depended upon the courage of my assailants, and the stimulus supplied by that patriotic cry still shouted out, “Muera el Americano!”

But none of those who were shouting had reached that climax of recklessness, to rush upon the certain death which I stood ready to deal out.

They obstructed the doorway in front, and in a close threatening phalanx—like a pack of angry hounds holding a stag at bay, the boldest fearing to spring forward.

Despite the knowledge that it was a terrible tragedy, I could not help fancying it a farce: so long and carefully did my assailants keep at arm’s length.

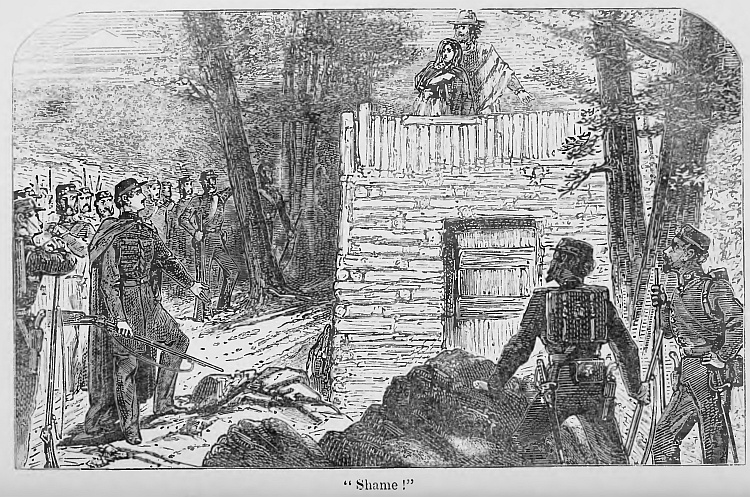

Still more like a burlesque might it have appeared to a spectator, as I fell upon the broad of my back—kicking up my heels upon the door-stoup!

It was neither shot, nor stab, that had caused this sudden change in my attitude; but simply the opening of the door, against which I had been supporting myself.

Some one inside had drawn the bolt, and, by doing so, removed the support from behind me!

Chapter Ten.

The Street of the Sparrows.

As I tottered upon my back, I felt my head and shoulders in contact with the legs of a man. They broke the fall, that might otherwise have stunned me: for the floor was of stone flags.

I lost no time in disentangling myself; but, before I could regain my feet, the man bounded over my body, and stood upon the threshold.

As he passed between me and the light outside, I could see something shining by his side. It was a sword blade. I could see that the hilt was in his hand.

My first impression was that he had sprung into the doorway to intercept my retreat. Of course I classed him among my enemies. How could I expect to find friend, or protector, in such a place?

It could make but little difference. I believed that retreat by the front door was out of the question. Double barring it would make things no worse.

Just then I bethought me of a chance of escape, not before possible. Was there a back door? Or a stair up to the azotea?

My reflections were quick as thought itself; but while making them they lost part of their importance. The man was standing with his back towards me and his face to the crowd upon the street. Their cries had followed me in; and no doubt so would some of themselves, had they been left to their predilections.

But they were not, as I now perceived. He who had opened his door to admit, perhaps, the most unwelcome guest who had ever entered it, seemed not the less determined upon asserting the sacred rights of hospitality.

As he placed himself between the posts, I saw the glint of steel shooting out in front—while he commanded the people to keep back.

The command delivered in a loud authoritative voice, backed by a long toledo, whose blade glittered deathlike under the pale glimmer of the lamp, had the effect of awing the outsiders into a momentary silence. There was an interval in which I heard neither shout nor reply.

He himself broke the stillness, that succeeded his first salutation.

“Leperos!” he cried, in the tone of one who feels himself speaking to inferiors; “What is this disturbance? What are you after?”

“An enemy! A Yankee!”

“Carrambo! I suppose they are synonymous terms. To all appearance you are right,” continued he, catching sight of my uniform, as he turned half round in the doorway. “But what’s the use?” he continued. “What advantage can our country derive from killing a poor devil like this?”

I felt half indignant at the speech. I recognised in the speaker the handsome youth who had been before me with Mercedes Villa-Señor!

A bitter chance that should have made him my protector!

“Let them come on!” I cried, driven to desperation at the thought; “I need no protection from you, sir—thanks all the same! I hold the lives of at least twelve of these gentlemen in my hands. After that, they shall be welcome to mine. Stand aside, and see how I shall scatter the cowardly rabble. Aside, sir!”

If I was not mad, my protector must have thought me so.

“Carrambo, señor!” he responded, without showing himself in the least chafed by my ungrateful answer. “You are perhaps not aware of the danger you are in. If I but say the word, you are a dead man.”

“You’ll say it, capitano!” shouted one on the outside. “Why not? The Yankee has insulted you. Let’s punish him, if it be only for that!”

“Muera! Muera el Americano!”

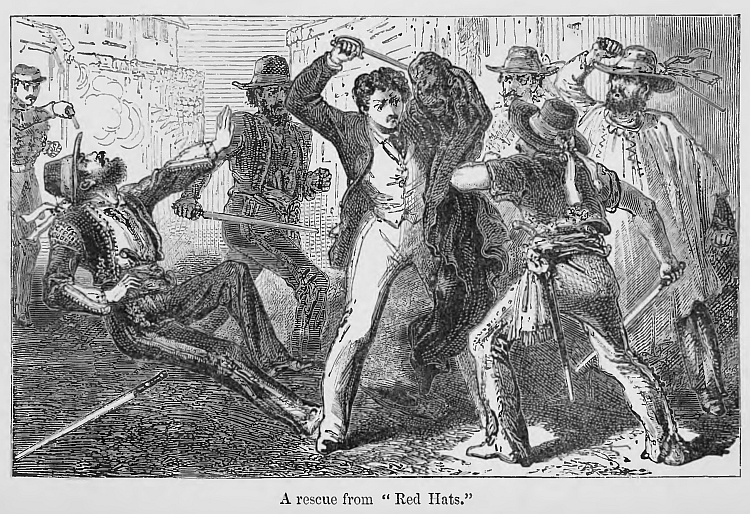

My assailants, freshly excited by these cries, came surging towards the door.

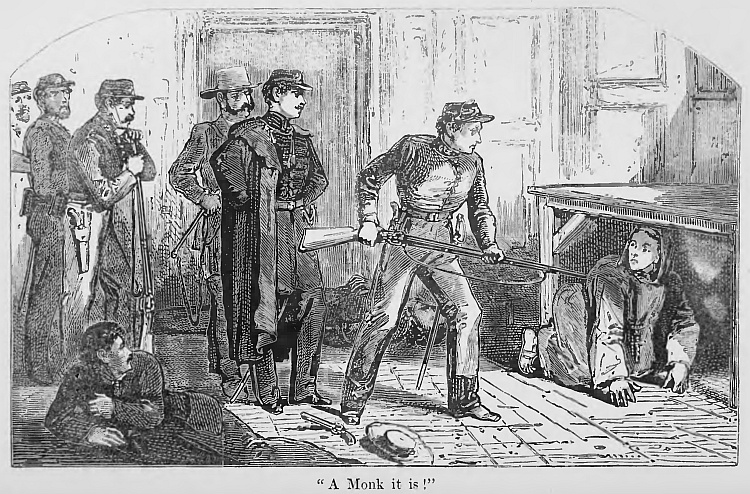

“Al atras, leperos!” shouted my protector. “The first that sets foot over my threshold—humble as it is—I shall spit upon my sword, like a piece of tasajo. You are very brave here in the Callecito de los Pajaros! I doubt whether there’s one among you who has met the enemy—either at Vera Cruz, or Cerro Gordo!”

“You’re mistaken there, capitan Moreno!” answered a tall dark man who stood out in front of his fellows, and whom I recognised as the chief of the trio who had first attacked me, “Here’s one who has been in both the battles you are pleased to speak of; and who has come out of them, not like your noble self—a prisoner upon parole!”

“Captain Carrasco, if I mistake not?” sneeringly retorted my protector. “I can believe that of you. Not likely to be a prisoner of any kind. No doubt you took care to get well out of the way before the time when prisoners were being taken?”

“Carajo!” screamed the swarthy disputant, his face turning livid with rage. “You say that? You have heard it, camarados? Capitan Moreno sets himself up, not only as our judge, but the protector of our accursed invaders! And we must submit to his sublime dictation—we the citizens of Puebla!”

“No—no, we won’t stand it. Muera el Americano! The Yankee must be delivered up!”

“You must take him, then,” coolly responded Moreno, “at the point of my sword.”

“And at the muzzle of my pistol,” I added, springing to the side of my generous host—determined to share with him the defence of his doorway.

This unexpected resistance caused a change in the attitude of Carrasco and his cowardly associates. Though they hailed it with a vengeful shout, it was plain that their impetuosity had received a check; and, instead of advancing to the attack, one and all stood cowed-like and silent.

They seemed to know the temper of my protector as well as his sword; and this no doubt for the time restrained them.

But the true secret of their backwardness was to be sought for in the six-shooters, one of which I now held in each hand. The Mexicans had just become acquainted with the character of this splendid weapon—first used in battle in that same campaign—and its destructive powers, by report exaggerated tenfold, inspired them, as it had done the Prairie Indians, with a fear almost supernatural.

Perhaps to this sentiment was I indebted for my salvation. Brave as my protector was, and skilled as he might be with his toledo—quick and sure as I could have delivered my twelve shots—what would all have availed against a mob of infuriated men, already a hundred strong, and every moment augmenting? One, perhaps both, of us must have fallen before their fury.

It may seem strange to talk of sentiment, in such a crisis as that in which I was placed. You will be incredulous of its existence. And yet, by my honour, it did exist. I felt it, as certainly as I ever did in my life.

I need scarcely say what the sentiment was. It could only be that of profound gratitude—first to Francisco Moreno; and then to God for making such a noble man!

The thought that followed was but a consequence of this reflection. It was to save him who was risking his life to save me.

I was about to appeal to him to stand aside, and leave me to my fate. What good would it do for both to die? for I verily believed that death was at hand.

My purpose was not carried out; though its frustration came not from a craven fear. Very different was the cause that stayed my tongue.

As we stood silent—both defenders and those threatening to attack—a sound was borne upon the breeze, which caused the silence to be prolonged.

There could be no doubt as to the signification of this sound. Any one who has ever witnessed the spectacle of a troop of horse passing along a paved street, will recognise the noises that accompany it:—the continuous tramping of hoofs, the tinkling of curbs, and the occasional clank of a scabbard, as it strikes against spur or stirrup.

Such noises I recognised, as did every individual in the “Street of the Sparrows.”

“La guardia! La patrulla Americana!” (The guard! The American patrol!) was the muttered exclamations that came from the crowd.

My heart bounded with joy, and I was about to spring forth—thinking my assailants would now make way for me.

But no. They stood firm and close as a wall, maintaining their semicircle around the doorway.

Though evidently resolved on keeping their ground they made no noise—with their knives and machetés only demonstrating in silence!

I saw their design. The patrol was passing along one of the principal streets. They knew that the least disturbance would attract it into the Callecito.

If silent, but for ten seconds, they would be safe to renew the attack; and I should then be lost—surely sacrificed!

What was to be done? Fire into their midst, commence the fracas, and, by so doing, summon the patrol to my rescue? Perhaps it would arrive in time to be too late—to take up my mangled corpse, and carry it to the cuartel?

I hesitated to tempt the attack.

Was there no other way, by which I could give warning to my countrymen?

O God! the hoof-trampling seemed gradually growing less distinct! No sound of bit, or spur, stirrup, or steel scabbard. They had passed the end of the Callecito. Ten seconds more, and they would be beyond hearing!

Ha! a happy thought! That night—I now remembered it—my own corps—the Rifle Rangers—constituted the street patrol. My first Serjeant would be at its head. Between him and me had long been established a code of signals—independent of those set for the bugler. By the favour of fortune, I had upon my person the means of making them—a common dog-call, that more than once, during the campaign, had stood me in good stead.

In another instant its shrill echoes resounded through the street, and were heard half-way across the City of the Angels.

If the devil himself had directed the signal, it could not have more effectually paralysed our opponents. They stood speechless—astounded!

Only for a short while did they thus remain. Then, as if some wild panic had suddenly seized upon them, both footpads and citizens ran scattering away!

In the place they had occupied I could see two score of horses, with the same number of men upon their backs—whose dark green uniforms were joyfully recognised.

With a shout I rushed forth to receive them!

After an interlude of confused congratulations I turned to give thanks—far more than thanks—to Francisco Moreno.

My gratitude was doomed to disappointment. He who so well deserved it was no longer to be seen.

The door, through which I had so fortunately fallen, was closed upon my generous protector!

Chapter Eleven.

The Red Hats.

For more than a month after the incidents related, were we of the invading army compelled to endure a semi-seclusion, within cuartels neither very clean nor comfortable.