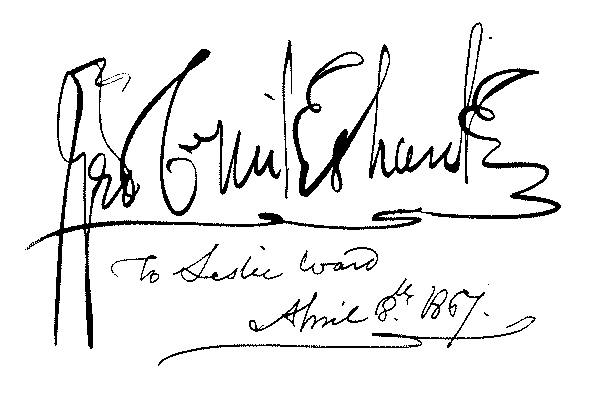

LESLIE WARD.

Title: Forty years of 'Spy'

Author: Sir Leslie Ward

Release date: March 3, 2011 [eBook #35466]

Most recently updated: January 7, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Iona Vaughan, woodie4, Mark Akrigg and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Canada Team at

http://www.pgdpcanada.net

| CONTENTS | |

| CHAPTER I | |

| EARLY DAYS | page |

| I come into the world.—The story of my ancestry.—My mother.—Wilkie Collins.—The Collins family.—Slough and Upton.—The funeral of the Duchess of Kent.—The marriage of the Princess Royal.—Her Majesty Queen Victoria and the Prince Consort.—Their visits to my parents' studios.—The Prince of Wales.—Sir William Ross, R.A.—Westminster Abbey.—My composition.—A visit to Astley's Theatre.—Wilkie Collins and Pigott.—The Panopticon.—The Thames frozen over.—The Comet.—General Sir John Hearsey.—Kent Villa.—My father.—Lady Waterford.—Marcus Stone and Vicat Cole.—The Crystal Palace.—Rev. J. M. Bellew.—Kyrle Bellew.—I go to school.—Wentworth Hope Johnstone. | 1 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| ETON AND AFTER | |

| Eton days.—Windsor Fair.—My Dame.—Fights and Fun.—Boveney Court.—Mr. Hall Say.—Boveney.—Professor and Mrs. Attwell.—I win a useful prize.—Alban Doran.—My father's frescoes.—Battle Abbey.—Gainsborough's Tomb.—Knole.—Our burglar.—Claude Calthrop.—Clayton Calthrop.—The Gardener as Critic.—The Gipsy with an eye for colour.—I attempt sculpture.—The Terry family.—Private theatricals.—Sir John Hare.—Miss Marion Terry.—Miss Ellen Terry.—Miss Kate Terry.—Miss Bateman.—Miss Florence St. John.—Constable.—Sir Howard Vincent.—I dance with Patti.—Lancaster Gate and Meringues.—Prayers and Pantries. | 27 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| MY FATHER'S FRIENDS | |

| My father's friends.—The Pre-Raphaelites.—Plum-box painting.—The Victorians.—The Post-Impressionists.—Maclise.—Sir Edwin Landseer.—Tom Landseer.—Mulready.—Daniel Roberts.—Edward Cooke.—Burgess and Long.—Frith.—Millais.—Stephens and Holman Hunt.—Stanfield.—C. R. Leslie.—Dr. John Doran.—Mr. and Mrs. S. C. Hall.—The Virtues, James and William.—Mr. and Mrs. Tom Taylor.—A story of Tennyson.—Sam Lover.—Moscheles père et fils.—Philip Calderon.—Sir Theodore and Lady Martin.—Garibaldi.—Lord Crewe.—Fechter.—Joachim and Lord Houghton.—Charles Dickens.—Lord Stanhope.—William Hepworth Dixon.—Sir Charles Dilke. | 48 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| WORK AND PLAY | |

| School-days ended.—A trip to Paris.—Versailles and the Morgue.—I enter the office of Sydney Smirke, R.A.—Montagu Williams and Christchurch.—A squall.—Frith as arbitrator.—I nearly lose my life.—William Virtue to the rescue.—The Honourable Mrs. Butler Johnson Munro.—I visit Knebworth.—Lord Lytton.—Spiritualism.—My first picture in the Royal Academy.—A Scotch holiday with my friend Richard Dunlop.—Patrick Adam.—Mr. and Mrs. Arthur Lewis.—Mr. George Fox and Harry Fox.—Sir William Jaffray.—Mr. William Cobbett.—Adventures on and off a horse.—Peter Graham.—Cruikshank.—Mr. Phené Spiers.—Johnston Forbes-Robertson and Irving.—Fred Walker.—Arthur Sullivan.—Sir Henry de Bathe.—Sir Spencer Ponsonby.—Du Maurier.—Arthur Cecil.—Sir Francis Burnand.—The Bennett Benefit. | 67 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| SPY | |

| My coming of age.—The letter.—The Doctor's verdict.—The Doctor's pretty daughter.—Arthur Sullivan.—"Dolly" Storey.—Lord Leven's garden party.—Professor Owen.—Gibson Bowles.—Arthur Lewis.—Carlo Pellegrini.—Paolo Tosti.—Pagani's.—J. J. Tissot.—Vanity Fair.—Some of the Contributors.—Anthony Trollope.—John Stuart Mill.—The World.—Edmund Yates.—Death of Lord Lytton.—Mr. Macquoid.—Luke Fildes.—Small.—Gregory.—Herkomer.—The Graphic.—Gladstone.—Disraeli, etc. | 89 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| CARICATURE | |

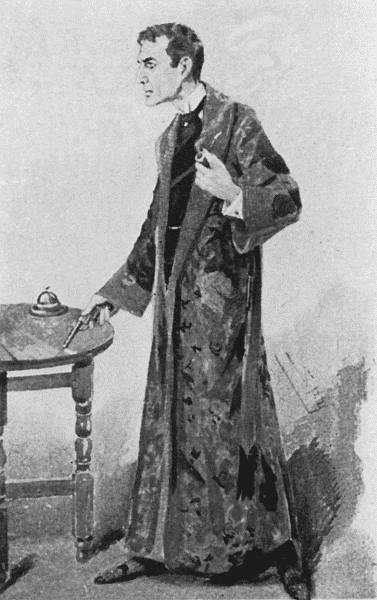

| Cannot be taught.—Where I stalk.—The ugly man.—The handsome man.—Physical defects.—Warts.—Joachim Liszt and Oliver Cromwell.—Pellegrini, Millais and Whistler.—The characteristic portrait.—Taking notes.—Methods.—Photography.—Tattersall's—Lord Lonsdale.—Lord Rocksavage.—William Gillette.—Mr. Bayard.—The bald man.—The humorous sitter.—Tyler.—Profiles.—Cavalry Officers.—The Queen's uniform.—My subjects' wives.—What they think.—Bribery.—Bradlaugh.—The Prince of Wales.—The tailor story.—Sir Watkin Williams Wynn.—Lord Henry Lennox.—Cardinal Newman.—The Rev. Arthur Tooth.—Dr. Spooner.—Comyns Carr.—Pigott.—"Piggy" Palk and "Mr. Spy." | 109 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| PORTRAITURE | |

| Some of my sitters.—Mrs. Tom Caley.—Lady Leucha Warner.—Lady Loudoun.—Colonel Corbett.—Miss Reiss.—The late Mrs. Harry McCalmont.—The Duke of Hamilton.—Sir W. Jaffray.—The Queen of Spain.—Soldier sitters.—Millais.—Sir William Cunliffe Brooks.—Holman Hunt.—George Richmond.—Sir William Richmond.—Sir Luke Fildes.—Lord Leighton.—Sir Laurence Alma Tadema.—Sir George Reid.—Orchardson.—Pettie.—Frank Dicksee.—Augustus Lumley.—"Archie" Stuart Wortley.—John Varley.—John Collier.—Sir Keith Fraser.—Sir Charles Fraser.—Mrs. Langtry.—Mrs. Cornwallis West.—Miss Rousby.—The Prince of Wales.—King George as a boy.—Children's portraits.—Mrs. Weldon.—Christabel Pankhurst. | 140 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| MY CLUBS | |

| The Arts Club.—Mrs. Frith's funeral.—The sympathetic waiter.—Swinburne.—Whistler.—Edmund Yates.—The Orleans Club.—Sir George Wombwell.—"Hughie" Drummond.—"Fatty" Coleman.—Lady Meux.—The Prize Fighter and her nephew.—The Curate.—The Theobald's Tiger.—Whistler and his pictures.—Charles Brookfield.—Mrs. Brookfield.—The Lotus Club.—Kate Vaughan.—Nellie Farren.—The Lyric Club.—The Gallery Club.—Some Members.—The Jockey Club Stand.—My plunge on the turf.—The Beefsteak Club.—Toole and Irving.—The Fielding Club.—Archie Wortley.—Charles Keene.—The Amateur Pantomime.—Some of the caste.—Corney Grain.—A night on Ebury Bridge.—The Punch Bowl Club.—Oliver Wendell Holmes.—Lord Houghton and the herring. | 161 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| THE LAW | |

| The Inspiration of the Courts.—Montagu Williams.—Lefroy.—The De Goncourt case.—Irving.—Sir Frank Lockwood.—Dr. Lampson, the poisoner.—Mr. Justice Hawkins.—The Tichborne case.—Mr. Justice Mellor and Mr. Justice Lush.—The Druce case.—The Countess of Ossington.—The Duke's portrait.—My models.—The Adventuress.—The insolent omnibus conductor.—I win my case.—Sir George Lewis.—The late Lord Grimthorpe.—Sir Charles Hall.—Lord Halsbury.—Sir Alfred Cripps (now Lord Parmoor).—Sir Herbert Cozens-Hardy.—Lord Robert Cecil.—The late Sir Albert de Rutzen.—Mr. Charles Gill.—Sir Charles Matthews.—Lord Alverstone.—Mr. Birrell.—Mr. Plowden.—Mr. Marshall Hall.—Mr. H. C. Biron. | 194 |

| CHAPTER X | |

| THE CHURCH AND THE VARSITIES--PARSONS OF MANY CREEDS AND DENOMINATIONS | |

| Dean Wellesley.—Dr. James Sewell.—Canon Ainger.—Lord Torrington.—Dr. Goodford.—Dr. Welldon.—Dr. Walker.—The Van Beers' Supper.—The Bishop of Lichfield.—Rev. R. J. Campbell.—Cardinal Vaughan.—Dr. Benson, Archbishop of Canterbury.—Dr. Armitage Robinson.—Varsity Athletes.—Etherington-Smith.—John Loraine Baldwin.—Ranjitsinhji.—Mr. Muttlebury.—Mr. "Rudy" Lehmann. | 218 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| IN THE LOBBY | |

| In the House.—Distinguished soldiers.—The main Lobby.—The Irish Party.—Isaac Butt.—Mr. Mitchell Henry.—Parnell and Dillon.—Gladstone and Disraeli.—Lord Arthur Hill.—Lord Alexander Paget.—Viscount Midleton.—Mr. Seely.—Lord Alington's cartoon.—Chaplains of the "House"—Rev. F. E. C. Byng.—Archdeacon Wilberforce.—The "Fourth Party."—Lord Northbrook and Col. Napier Sturt.—Lord Lytton.—The method of Millais.—Lord Londonderry. | 236 |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| VOYAGE ON H.M.S. HERCULES | |

| Sir Reginald Macdonald's caricature.—H.R.H. the Duke of Edinburgh's invitation.—The Lively.—The Hercules.—Admiral Sir William Hewitt.—Irish excursions.—The Channel Squadron.—Fishing party at Loch Brine.—The young Princes arrive on the Bacchante.—Cruise to Vigo.—The "Night Alarm."—The Duke as bon voyageur.—Vigo.—The birthday picnic.—A bear-fight on board the Hercules.—Homeward bound.—Good-bye.—The Duke's visit to my studio. | 252 |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

| YACHTSMEN—FOREIGN RULERS | |

| Lord Charles Beresford.—Cowes.—Lady Cardigan.—Chevalier Martino.—Lord Albemarle.—Harry McCalmont.—Royal Sailors.—King Edward VII.—Queen Alexandra.—Prince Louis of Battenberg.—King of Greece.—Foreign Rulers.—The Prince Imperial.—Don Carlos.—General Ignatieff.—Midhat Pasha.—Sir Salar Jung.—Ras Makounan.—Cetewayo.—Shah of Persia.—Viscount Tadasu Hayashi, etc. | 268 |

| CHAPTER XIV | |

| MUSICIANS—AUTHORS—ACTORS AND ARTISTS | |

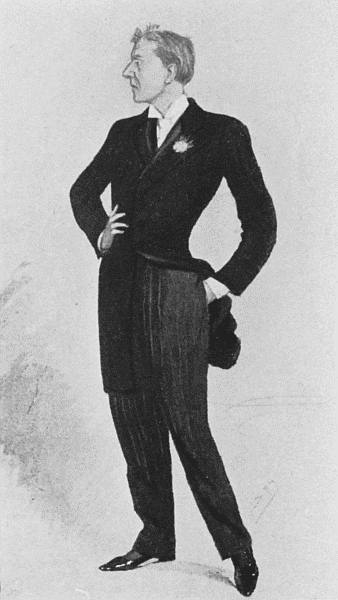

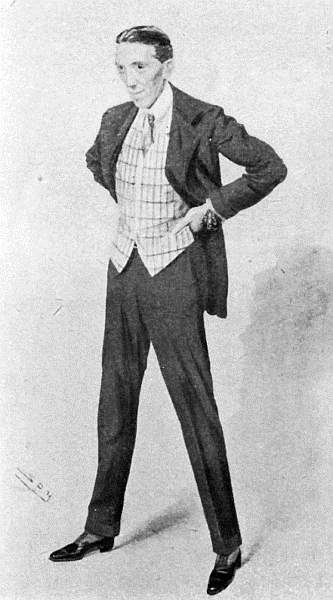

| Wagner.—Richter.—Dan Godfrey.—Arthur Cecil.—Sir Frederick Bridge and bombs.—W. S. Penley.—Sir Herbert Tree.—Max Beerbohm.—Mr. and Mrs. Kendal.—Henry Kemble.—Sir Edgar Boehm.—George Du Maurier.—Rudyard Kipling.—Alfred Austin.—William Black.—Thomas Hardy.—W. E. Henley.—Egerton Castle.—Samuel Smiles.—Farren.—Sir Squire and Lady Bancroft.—Dion Boucicault and his wife.—Sir Charles Wyndham.—Leo Trevor.—Cyril Maude.—William Gillette.—The late Dion Boucicault.—Arthur Bourchier.—Allan Aynesworth.—Charlie Hawtrey.—The Grossmiths.—H. B. Irving.—W. L. Courtney.—Willie Elliot.—"Beau Little."—Henry Arthur Jones.—Gustave Doré.—J. MacNeil Whistler.—Walter Crane.—F. C. G.—Lady Ashburton and her forgetfulness. | 283 |

| CHAPTER XV | |

| NOTABLE PEERS—TANGIER—THE TECKS | |

| Peers of the Period.—My Voyage to Tangier.—Marlborough House and White Lodge. | 303 |

| CHAPTER XVI | |

| MARRIAGE—SOME CLERICS—FAREWELL TO VANITY FAIR | |

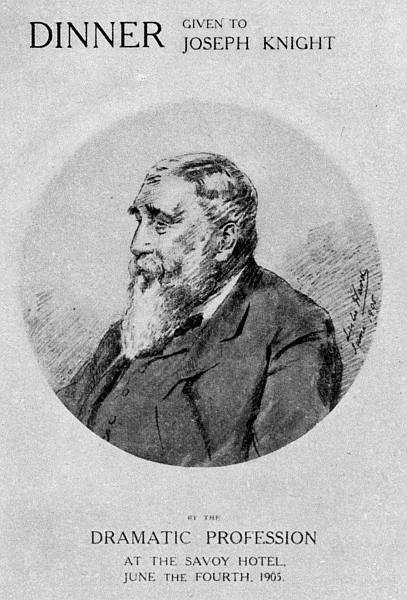

| My engagement and marriage to Miss Topham-Watney.—"Drawl" and the Kruger cartoon.—"The General Group."—Field-Marshal Lord Roberts.—Archbishops Temple and Randall Davidson.—The Bishop of London.—Archbishop of York.—Canon Fleming.—Lord Montagu of Beaulieu.—Lord Salisbury's cartoon.—Mr. Asquith.—Joe Knight.—Lord Newlands.—Four great men in connection with Canada.—The Queen of Spain.—Princess Beatrice of Saxe-Coburg.—General Sir William Francis Butler, G.C.B.—Mr. Witherby.—Farewell to Vanity Fair. | 321 |

| CHAPTER XVII | |

| A HOLIDAY MISFORTUNE—ROYAL PORTRAITS—FAREWELL | |

| Belgium.—Accident at Golf.—Portraits of King George V, the Duke of Connaught, Mr. Roosevelt, Mr. Lloyd George, Mr. Garvin.—Portrait painting of to-day.—Final reflections.—Farewell. | 332 |

| PAGE | |

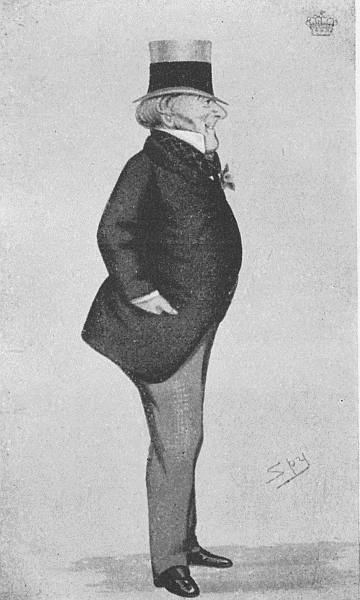

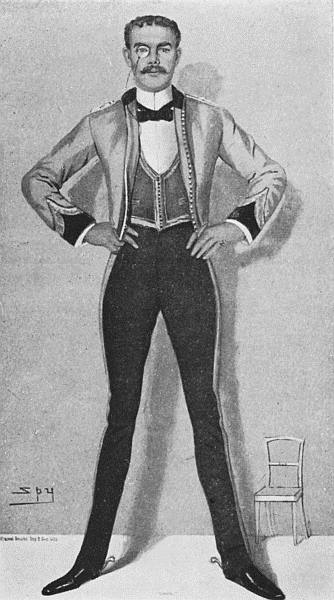

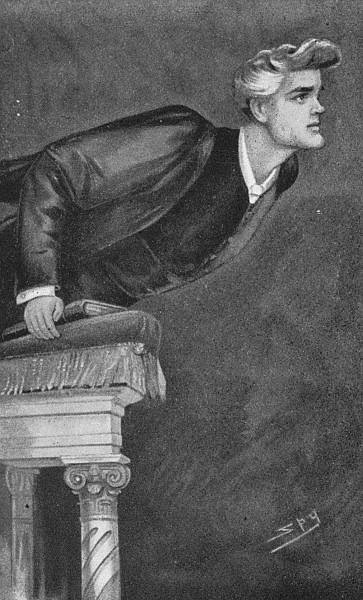

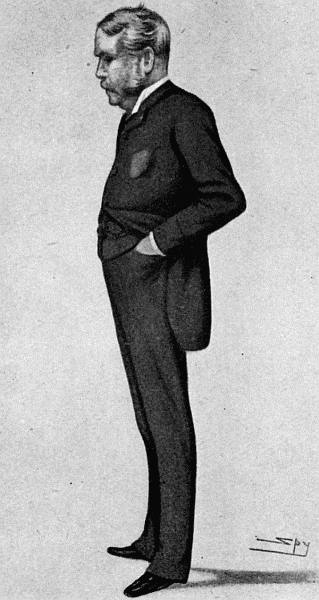

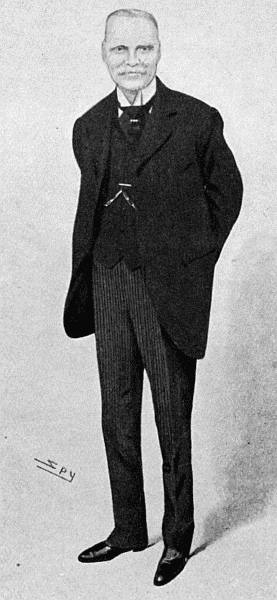

| Mr. Charles Cox (Banker), 1881 | 47 |

| The Marquis of Winchester, 1904 | 61 |

| Sir Alfred Scott-Gatty (Garter King-at-Arms, 1905) | 71 |

| Lord Haldon, 1882 | 138 |

| Admiral Sir Compton Domville, 1906 | 160 |

| Miss Christabel Pankhurst | 160 |

| F. R Spofforth (Demon Bowler), 1878 | 232 |

| Mr. Gladstone, 1887 | 239 |

| Sir Albert Rollit, 1886 | 248 |

| The Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr. Temple, 1902 | 324 |

| The Marquis of Salisbury, 1902 | 326 |

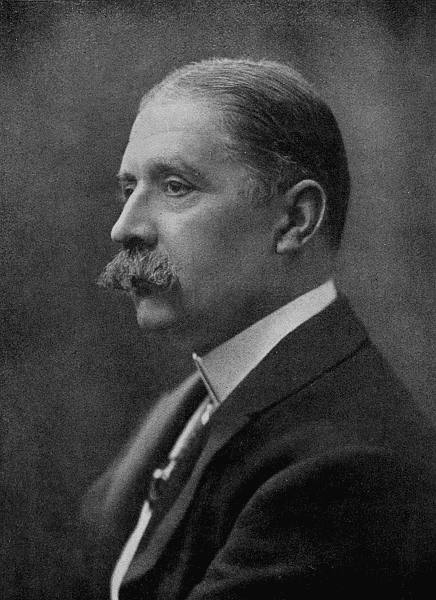

| Leslie Ward | Frontispiece |

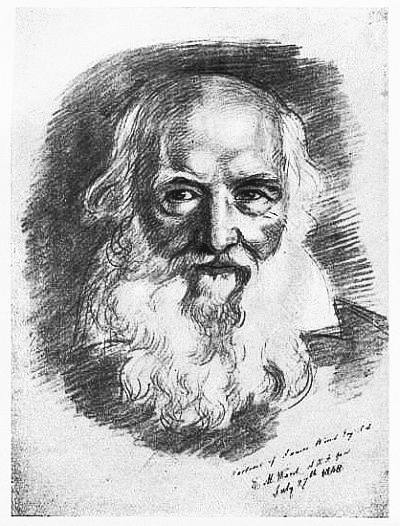

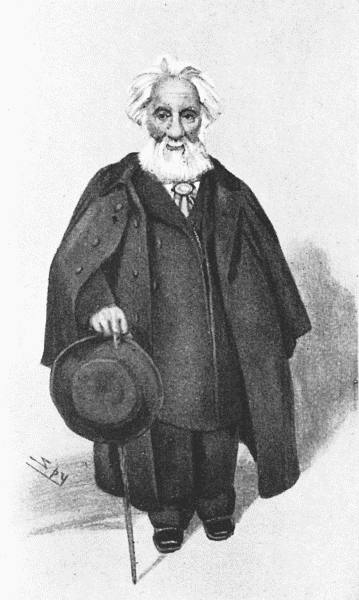

| James Ward, R.A. | 3 |

| James Ward's Mother | 3 |

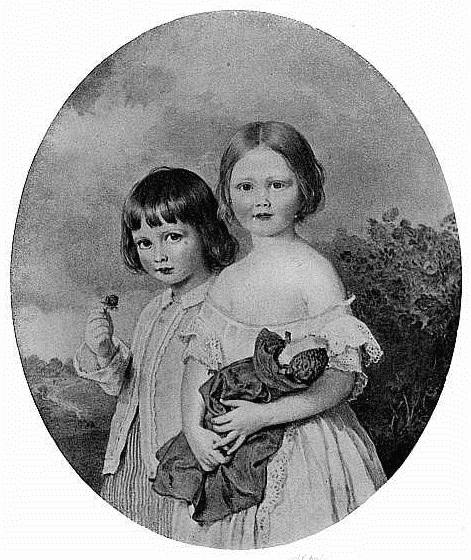

| Miniature of my sister Alice and myself painted by Sir William Ross, R.A. | 12 |

| My Father | 14 |

| My Mother | 14 |

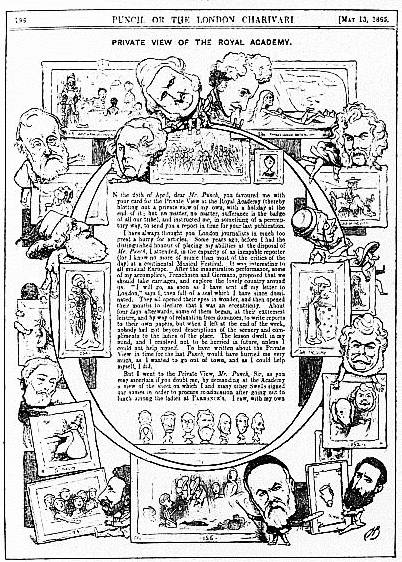

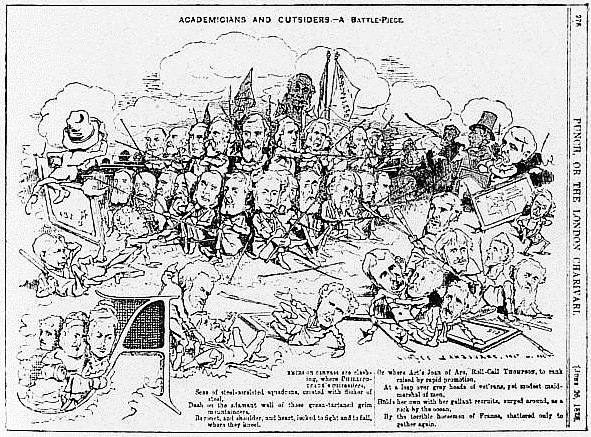

| Cartoons from Punch, 1865 | 22 |

| Sir William Broadbent, 1902 | 31 |

| Sir Thomas Barlow, 1903 | 31 |

| Sir James Paget, Bart., 1876 | 31 |

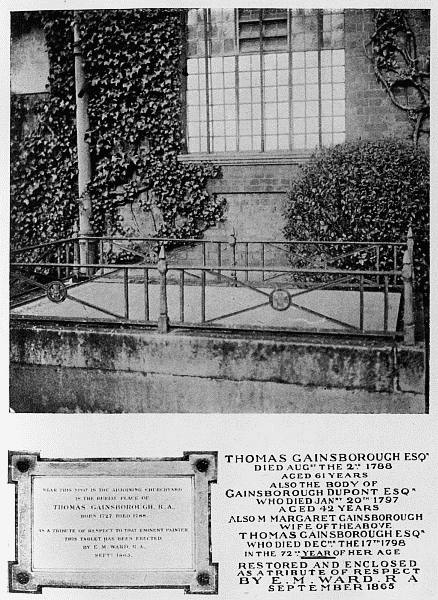

| Gainsborough's Tomb at Kew Churchyard and Tablet to his Memory Inside Church | 35 |

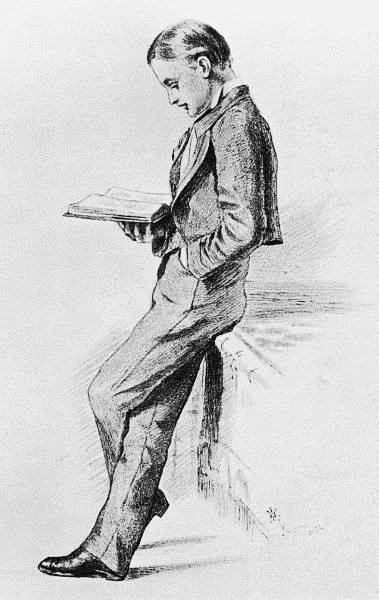

| My Brother, Wriothesley Russell, 1872 | 37 |

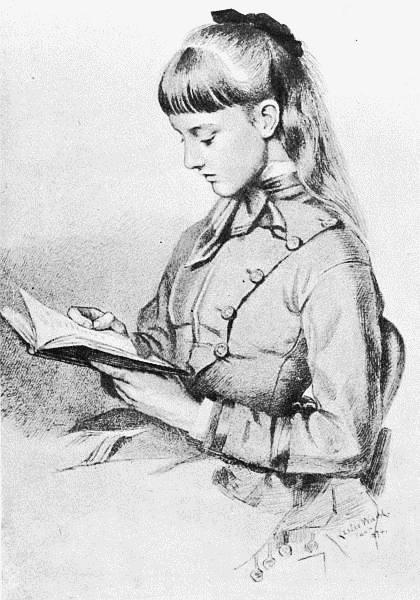

| My Sister, Beatrice, 1874 | 37 |

| Bust of my Brother, Wriothesley Russell, 1867 | 39 |

| My Daughter Sylvia | 39 |

| John Everett Millais, R.A., 1874 | 55 |

| C. R. Leslie, R.A. (my Godfather) | 55 |

| Lord Houghton, 1882 | 66 |

| Fred Archer, 1881 | 66 |

| The Duke of Beaufort, cir. 1895 | 66 |

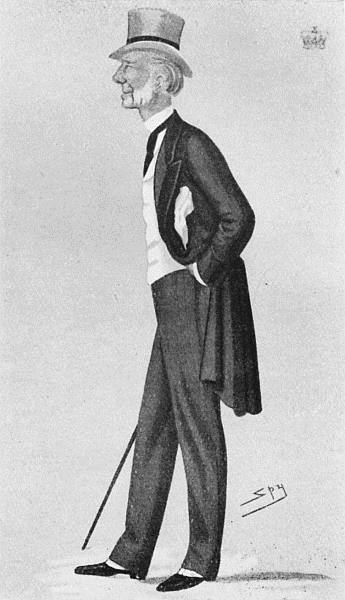

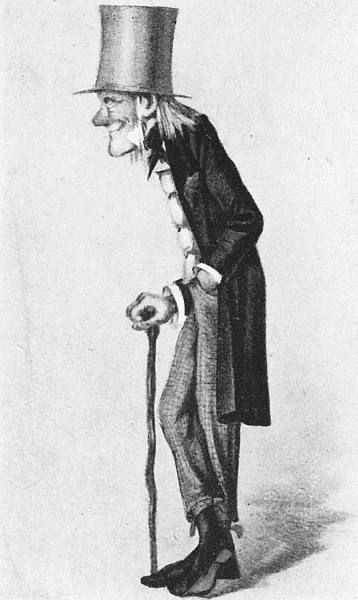

| First Lord Lytton (Bulwer Lytton), 1869 | 77 |

| Mr. George Lane Fox, 1878 | 83 |

| Lord Portman, 1898 | 83 |

| Duke of Grafton, 1886 | 83 |

| Sir William Jaffray, Bart. | 88 |

| Sir William Crookes, 1903 | 93 |

| Sir Oliver Lodge, 1904 | 93 |

| Sir William Huggins, 1903 | 93 |

| Professor Owen, 1873 | 93 |

| Thomas Gibson Bowles, 1905 | 94 |

| Colonel Hall Walker, 1906 | 94 |

| Colonel Fred Burnaby, 1876 | 94 |

| Pellegrini Asleep, etc., cir. 1889 | 99 |

| John Tenniel, 1878 | 105 |

| Anthony Trollope, 1873 | 105 |

| Sir Francis Doyle, Bart., 1877 | 105 |

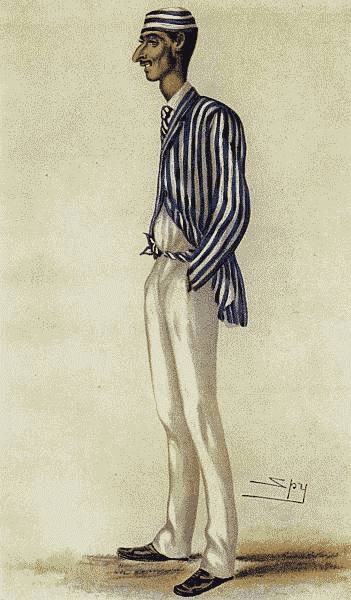

| "Miles Bugglebury," 1867 | 108 |

| J. Redmond, M.P., 1904 | 113 |

| The Speaker (J. W. Lowther, M.P.), 1906 | 113 |

| Bonar Law, M.P., 1905 | 113 |

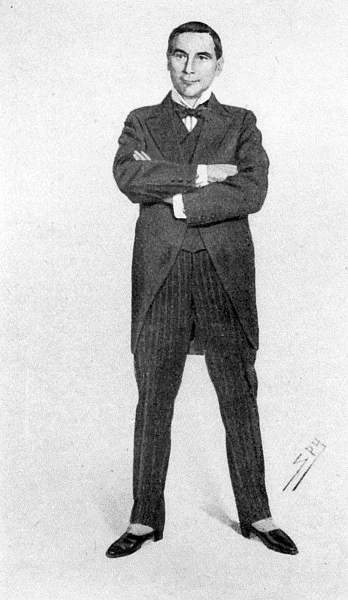

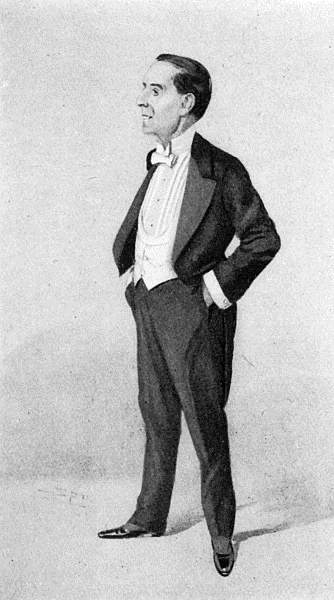

| Henry Kemble, 1907 | 119 |

| H. Beerbohm Tree, 1890 | 119 |

| Gerald du Maurier, 1907 | 119 |

| William Gillette, 1907 | 119 |

| Fifth Earl of Portsmouth, 1876 | 123 |

| Major Oswald Ames (Ozzie), 1896 | 123 |

| Earl of Lonsdale, 1879 | 123 |

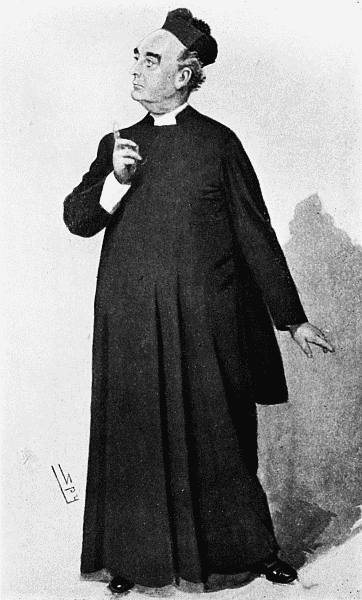

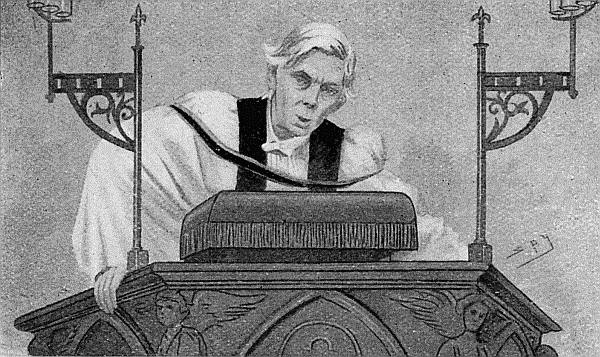

| The Rev. R. J. Campbell, 1904 | 127 |

| Sterling Stuart, 1904 | 127 |

| Father Bernard Vaughan, 1907 | 127 |

| Canon Liddon, 1876 | 133 |

| Cardinal Newman, 1877 | 133 |

| The Dean of Windsor (Wellesley), 1876 | 133 |

| Dr. Jowett, 1876 | 135 |

| Dr. Spooner, 1898 | 135 |

| Professor Robinson Ellis, 1894 | 135 |

| Buckstone, and other Sketches | 140 |

| Mrs. George Rigby Murray | 144 |

| A Study | 144 |

| The Hon. Mrs. Adrian Pollock | 144 |

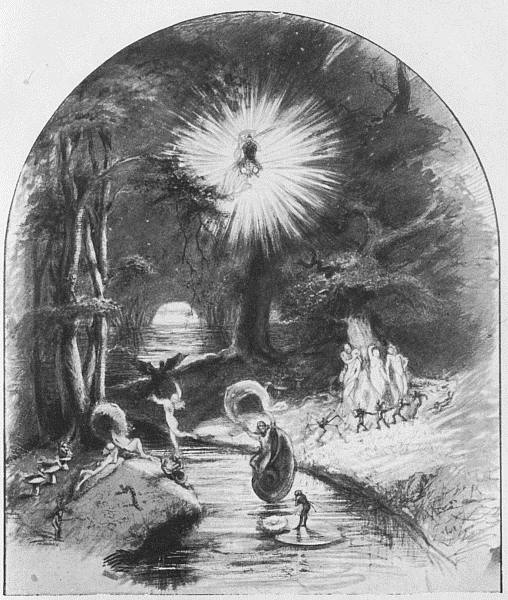

| A Midsummer-Night's Dream | 151 |

| Grand Prix | 151 |

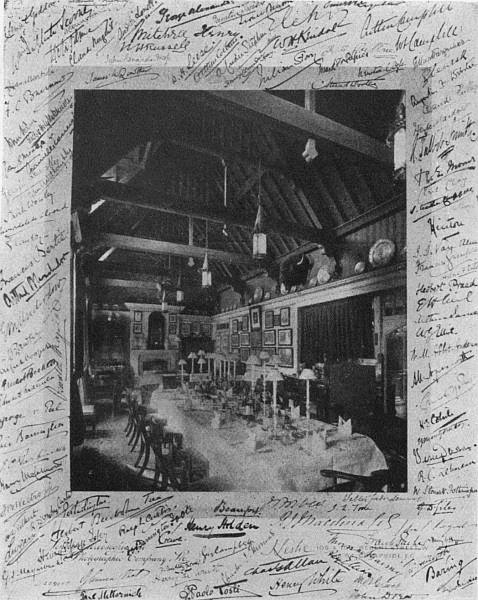

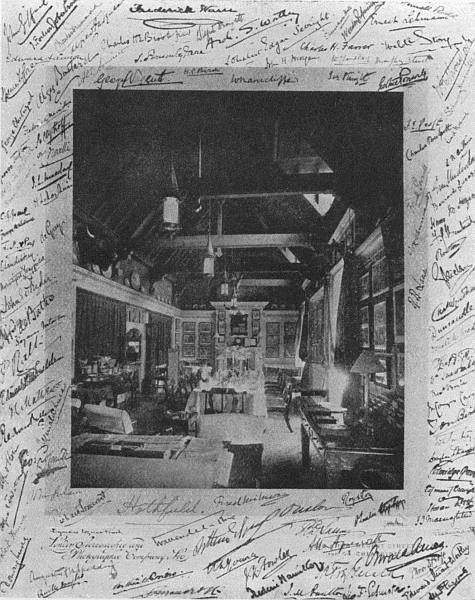

| The Beefsteak Club | 164 |

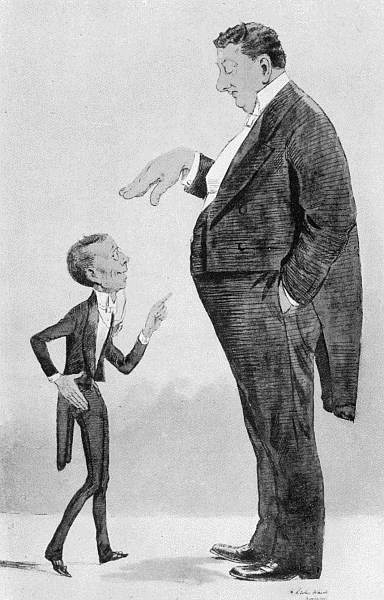

| George Grossmith and Corney Grain, 1888 | 179 |

| C. Birch Crisp, 1911 | 187 |

| Oliver Locker Lampson, M.P., 1911 | 187 |

| Weedon Grossmith, 1905 | 187 |

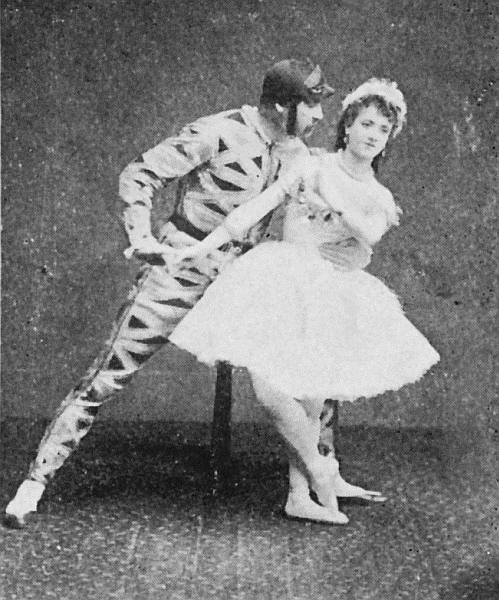

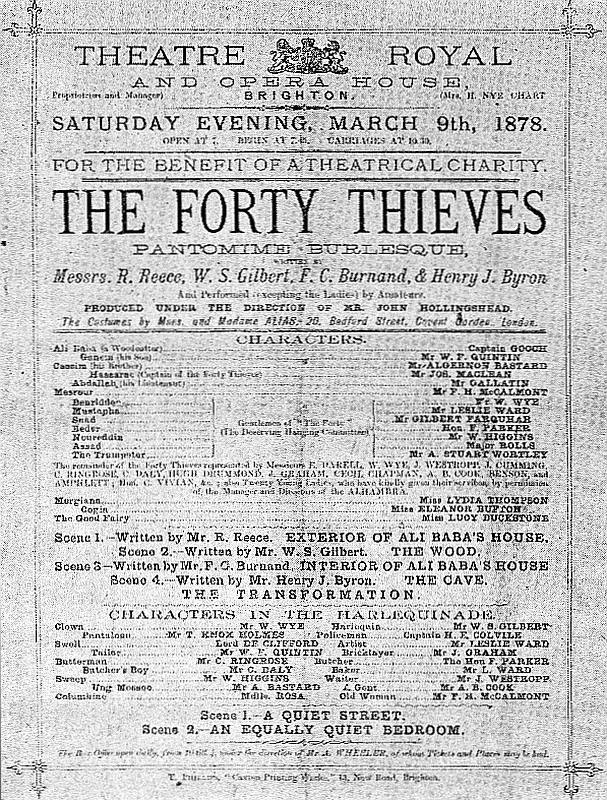

| The Forty Thieves: programme and photographs | 189 |

| Johnny Giffard; Alfred Thompson; Corney Grain; "Tom" Bird; Corney Grain at Datchet; Pellegrini | 191 |

| Augustus Helder, M.P.; Madame Rachel; Lord Ranelagh; Beal, M.P.; Barnum; First Lord Cowley; Sir H. Cozens-Hardy; The Dean of Christchurch; Sir Roderick Murcheson | 199 |

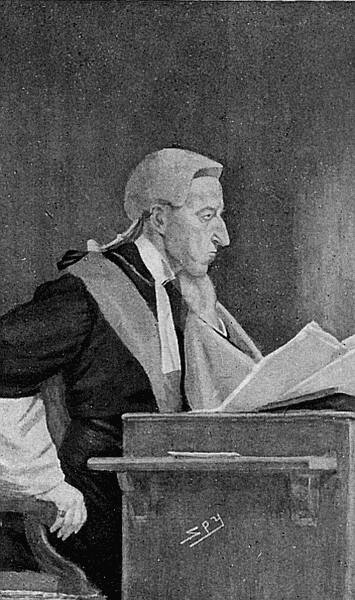

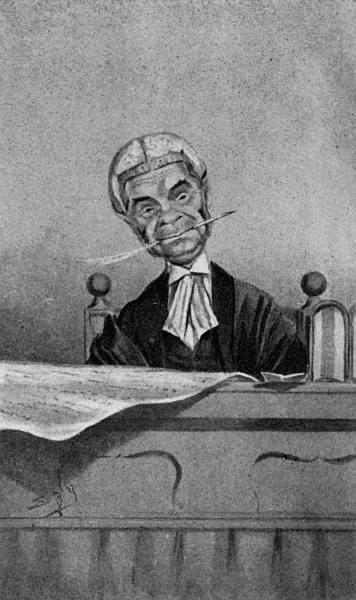

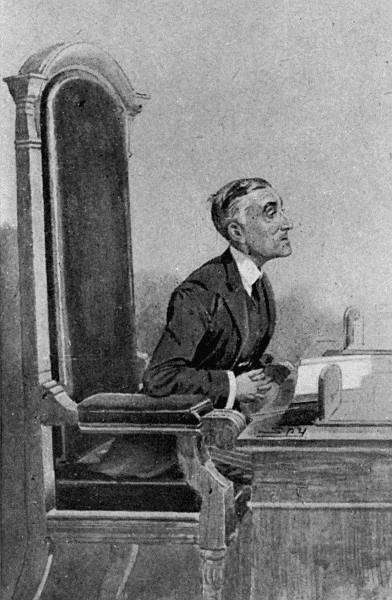

| Lord Coleridge, 1870 | 211 |

| Mr. Justice Cozens-Hardy, 1893 | 211 |

| H. C. Biron, 1907 | 211 |

| E. S. Fordham, 1908 | 211 |

| Charles Williams-Wynn, M.P., 1879 | 215 |

| Sir James Ingham, 1886 | 215 |

| Lord Vivian (Hook and Eye), 1876 | 215 |

| Sir Albert de Rutzen, 1909 | 217 |

| Mr. Plowden, 1910 | 217 |

| Canon Ainger, 1892 | 222 |

| 16th Marquis of Winchester, 1904 | 222 |

| Archdeacon Wilberforce, 1909 | 222 |

| Rev. J. L. Joynes, 1887 | 225 |

| Dr. Warre Cornish, 1901 | 225 |

| Dr. Goodford, 1876 | 225 |

| Rev. R. J. Campbell, 1904 | 231 |

| Sam Loates, 1896 | 234 |

| Arthur Coventry, 1881 | 234 |

| Frank Wootton, 1909 | 234 |

| Fordham, 1882 | 234 |

| "Dizzy" and "Monty" Corry (Lord Rowton), 1880 | 241 |

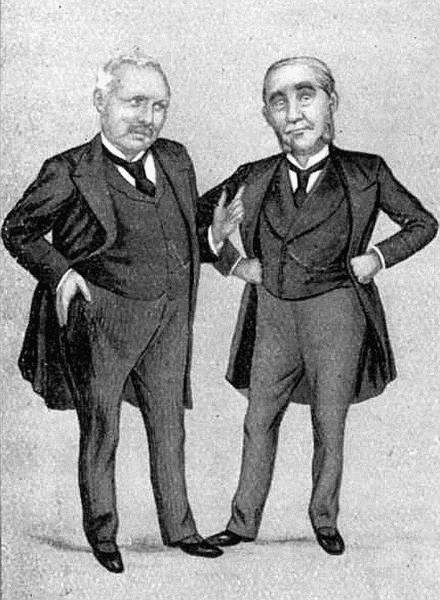

| Campbell-Bannerman and Fowler, 1892 | 247 |

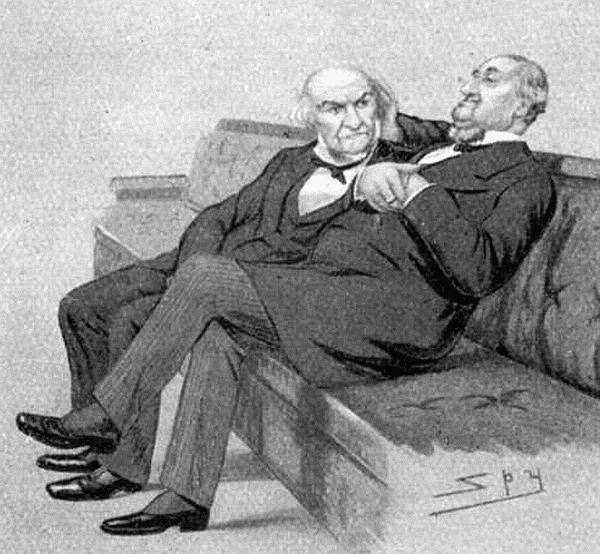

| Gladstone and Harcourt, 1892 | 247 |

| Lords Spencer and Ripon, 1892 | 247 |

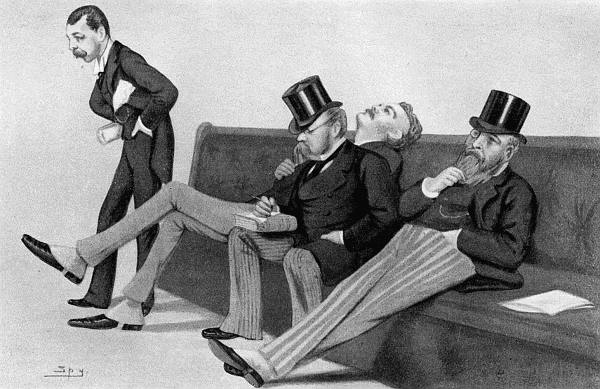

| The Fourth Party, 1881 | 251 |

| Baron Deichmann, 1903 | 253 |

| W. Bramston Beach, M.P., 1895 | 253 |

| "Sam" Smith, M.P., 1904 | 253 |

| Percy Thornton, M.P., 1900 | 253 |

| Seventh Earl of Bessborough, 1888 | 261 |

| Rev. F. H. Gillingham, 1906 | 261 |

| Archdeacon Benjamin Harrison, 1885 | 261 |

| "Charlie" Beresford, 1876 | 268 |

| Admiral Sir John Fisher, 1902 | 268 |

| Admiral Sir Regd. Macdonald, 1880 | 268 |

| Captain Jellicoe, 1906 | 268 |

| King Edward VII, 1902 | 270 |

| Sir John Astley | 276 |

| "Jim" Lowther, M.P., 1877 | 276 |

| Peter Gilpin, 1908 | 276 |

| Earl of Macclesfield, 1881 | 276 |

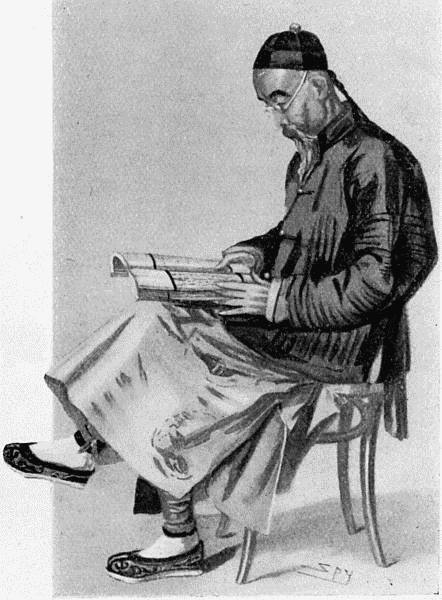

| Chinese Ambassador (Kuo Sung Tuo), 1877 | 280 |

| Ras Makonnen, 1903 | 280 |

| Chinese Ambassador (Chang Ta Jen), 1903 | 280 |

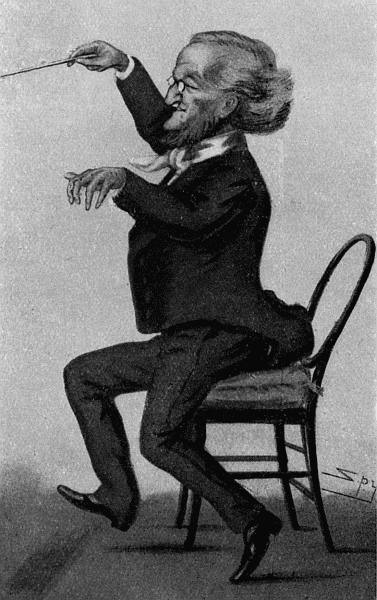

| Richard Wagner, 1877 | 285 |

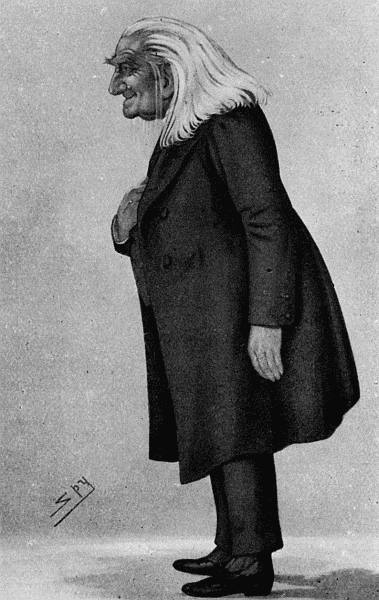

| The Abbé Liszt, 1886 | 285 |

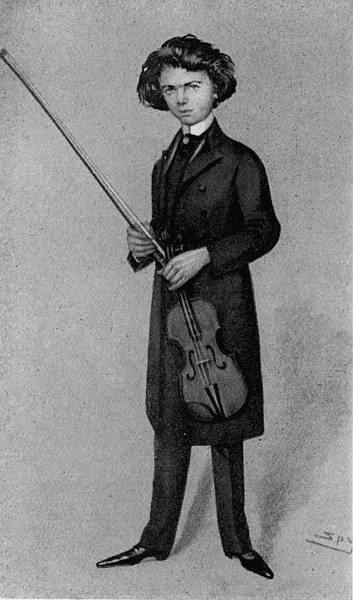

| Kubelik, 1903 | 286 |

| Sir Frederick Bridge, 1904 | 286 |

| Paderewski, 1899 | 286 |

| Sir Edgar Boehm, Bart., R.A., 1884; and the brass on Sir Edgar Boehm's Tomb | 290 |

| Sir Henry Lucy, 1909 | 292 |

| W. S. Gilbert, 1881 | 292 |

| W. E. Henley, 1892 | 292 |

| Rudyard Kipling, 1894 | 292 |

| From Nursery Rhyme Sketches; Rt. Hon. "Bobby" Low; Mr. Justice Lawrence; Danckwerts, K.C.; the late Lord Chief Justice Cockburn; a Smile from Nature; Henry Irving | 297 |

| Lord Newlands, 1909 | 306 |

| Count de Soveral, 1898 | 306 |

| M. Gennadius, 1888 | 306 |

| General Sir H. Smith Dorrien, 1911 | 313 |

| Lord Roberts, 1900 | 313 |

| Lord Kitchener, 1899 | 313 |

| Lloyd George, 1911 | 318 |

| Asquith, 1904 | 318 |

| Rufus Isaacs, 1904 | 318 |

| My Daughter | 322 |

| My Wife | 322 |

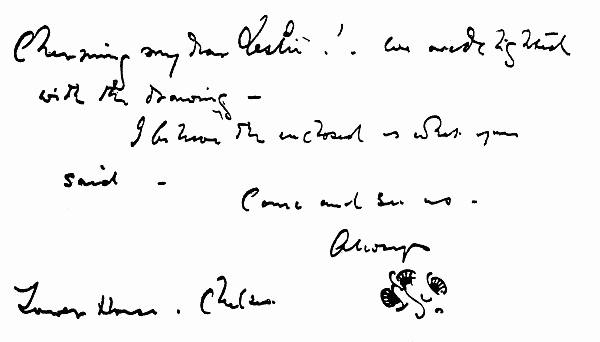

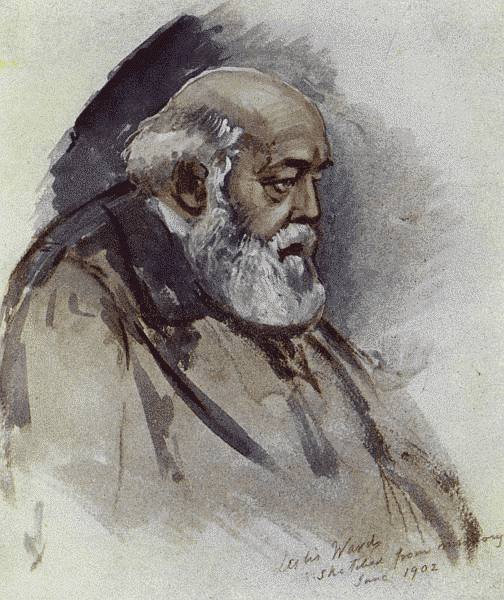

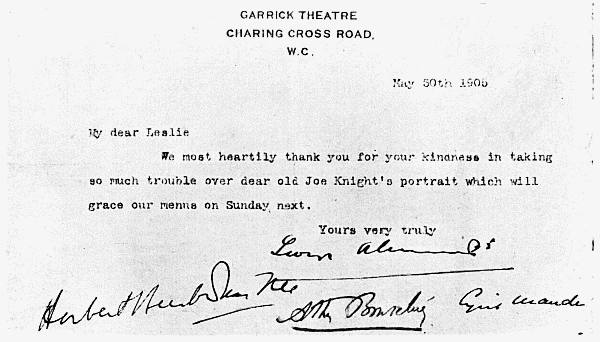

| Joseph Knight, and a facsimile letter | 326 |

| Princess Ena of Battenberg, 1906 | 330 |

| Sketches drawn in September, 1899, by Mr. A. G. Witherby | 332 |

| M. P. Grace, Esq., Battle Abbey | 340 |

I come into the world.—The story of my ancestry.—My mother.—Wilkie Collins.—The Collins family.—Slough and Upton.—The funeral of the Duchess of Kent.—The marriage of the Princess Royal.—Her Majesty Queen Victoria and the Prince Consort.—Their visits to my parents' studios.—The Prince of Wales.—Sir William Ross, R.A.—Westminster Abbey.—My composition.—A visit to Astley's Theatre.—Wilkie Collins and Pigott.—The Panopticon.—The Thames frozen over.—The Comet.—General Sir John Hearsey.—Kent Villa.—My father.—Lady Waterford.—Marcus Stone and Vicat Cole.—The Crystal Palace.—Rev. J. M. Bellew.—Kyrle Bellew.—I go to school.—Wentworth Hope Johnstone.

In the course of our lives the monotonous repetition of daily routine and the similarity of the types we meet make our minds less and less susceptible to impressions, with the result that important events and interesting rencontres of last year—or even of last week—pass from our recollection far more readily than the trifling occurrences and casual acquaintanceships of early days. The deep indentations which everything makes upon the memory when the brain is young and receptive, when everything is novel and comes as a surprise, remain with most men and women throughout their lives. I am no exception to this rule; I remember, with extraordinary clearness of vision, innumerable incidents, trivial perhaps in themselves, but infinitely dear to me. They shine back across the years with a vivid outline, the clearer for a background of forgotten and perhaps important events now lost in shadow.

I was born at Harewood Square, London, on[2] November 21st, 1851, and I was named after my godfather, C. R. Leslie, R.A., the father of George Leslie, R.A.

My father, E. M. Ward, R.A., the only professional artist of his

family, and the nephew by marriage of Horace Smith (the joint author

with James Smith of "The Rejected Addresses"), fell in love with Miss

Henrietta Ward (who, although of the same name, was no relation), and

married her when she was just sixteen. My mother came of a long line

of artists. Her father, George Raphael Ward, a mezzotint engraver and

miniature painter, also married an artist who was an extremely clever

miniature painter. John Jackson, R.A., the portrait painter in

ordinary to William IV., was my mother's great-uncle, and George

Morland became related to her by his marriage with pretty Anne Ward,

whose life he wrecked by his drunken profligacy. His treatment of his

wife, in fact, alienated from Morland men who were his friends, and

amongst them my great-grandfather, James Ward (who, like my father,

married a Miss Ward, an artist and a namesake). James Ward, R.A., was

a most interesting character and an artist of great versatility. As

landscape, animal, and portrait painter, engraver, lithographer, and

modeller, his work shows extraordinary ability. In his early days

poverty threatened to wreck his career, but although misfortune

hindered his progress, he surmounted every obstacle with magnificent

courage and tenacity of purpose. On the subject of theology, his

artistic temperament was curiously intermingled with his faith, but

when he wished to embody his mysticism and ideals in paint, he failed.

On the other hand, we have some gigantic masterpieces in the Tate and

National Galleries which I[3] think will bear the test of time in their

power and excellence. "Power," to quote a contemporary account of

James' life, "was the keynote of his work, he loved to paint mighty

bulls and fiery stallions, picturing their brutal strength as no one

has done before or since." He ground his colours and manufactured his

own paints, made experiments in pigments of all kinds, and "Gordale

Scar" is a proof of the excellence of pure medium. The picture was

painted for the late Lord Ribblesdale, and when it proved to be too

large to hang on his walls, the canvas was rolled and stored in the

cellars of the British Museum. At the rise and fall of the Thames,

water flooded the picture; but after several years' oblivion it was

discovered, rescued from damp and mildew, and after restoration was

found to have lost none of its freshness and colour.

My great grandfather on my mother's side,

My great grandfather on my mother's side, JAMES WARD'S MOTHER,

JAMES WARD'S MOTHER,As an engraver alone James Ward was famous, but the attraction of colour, following upon his accidental discovery—that he could paint—made while he was repairing an oil painting, encouraged him to abandon his engraving and take up the brush. This he eventually did, in spite of the great opposition from artists of the day, Hoppner amongst them, who all wished to retain his services as a clever engraver of their own work. William Ward, the mezzotint engraver, whose works are fetching great sums to-day, encouraged his younger brother, and James held to his decision. He eventually proved his talent, but his triumph was not achieved without great vicissitude and discouragement. He became animal painter to the King, and died at the great age of ninety, leaving a large number of works of a widely different character, many of which are in the possession of the Hon. John Ward, M.V.O.[4]

The following letters from Sir Edwin Landseer, Mulready, and Holman Hunt to my father, show in some degree the regard in which other great artists held both him and his pictures:—

November 21st, 1859.

My dear Sir,

... I beg to assure you that not amongst the large group of mourners that regret him will you find one friend who so appreciated his genius or respected him more as a good man.

Believe me,

Yours sincerely,

E. Landseer.

Linden Grove,

Notting Hill,

June 1st, 1862.

Dear Sir,

I agree with my brother artists in their admiration of your wife's grandfather's pictures of Cattle, now in the International Exhibition, and I believe its being permanently placed in our National Gallery would be useful in our school and an honour to our country.

I am, Dear Sir,

Yours faithfully,

W. Mulready.

June 26th, 1862.

My dear Sir,

... It is many years now since I saw Mrs. Ward's Grandfather's famous picture of the "Bull, Cow, and Calf." I have not been able to go and see it in the International Exhibition. My memory of it is, however, quite clear enough to[5] allow me to express my very great admiration for the qualities of drawing, composition, and colour for which it is distinguished. In the two last particulars it will always be especially interesting as one of the earliest attempts to liberate the art of this century from the conventionalities of the last....

Yours very truly,

W. Holman Hunt.

My mother's versatile talent has ably upheld the reputation of her artistic predecessors; she paints besides figure-subjects delightful interiors, charming little bits of country life, and inherits the gift of painting dogs, which she represents with remarkable facility.

Although both my parents were historical painters, my mother's style was in no way similar to my father's. Her quality of painting is of a distinctive kind. This was especially marked in the painting of "Mrs. Fry visiting Newgate," one of the most remarkable of her pictures. The picture was hung on the line in the Royal Academy, and after a very successful reception was engraved. Afterwards, both painting and engraving were stolen by the man to whom they were entrusted for exhibition round the country; this man lived on the proceeds and pawned the picture. Eventually the painting was recovered and bought for America, and it is still perhaps the most widely known of the many works of my mother purchased for public galleries.

It is not surprising, therefore, that I should have inherited some of the inclinations of my artistic progenitors.

My earliest recollection is of a sea-trip at the age[6] of four, when I remember tasting my first acidulated drop, presented me by an old lady whose appearance I can recollect perfectly, together with the remembrance of my pleasure and the novelty of the strange sweet.

My mother tells me my first caricatures were of soldiers at Calais. I am afraid that—youthful as I then was—they could hardly have been anything but caricatures.

Wilkie Collins came into my life even earlier than this. I was going to say I remember him at my christening, but I am afraid my words would be discredited even in these days of exaggeration. The well-known novelist, who was a great friend of my parents, was then at the height of his fame. He had what I knew afterwards to be an unfortunate "cast" in one eye, which troubled me very much as a child, for when telling an anecdote or making an observation to my father, I frequently thought he was addressing me, and I invariably grew embarrassed because I did not understand, and was therefore unable to reply.

Other members of the Collins family visited us. There was old Mrs. Collins, the widow of William Collins, R.A.; a quaint old lady who wore her kid boots carefully down on one side and then reversed them and wore them down on the other. She had a horror of Highlanders because they wore kilts, which she considered scandalous.

Charles Collins, one of the original pre-Raphaelite brotherhood, her son, and Wilkie's brother, paid frequent week-end visits to our house, and the memory of Charles is surrounded by a halo of mystery and wonder, for he possessed a magic snuff-box made of gold inset with jewels, and at a word of[7] command a little bird appeared on it, which disappeared in the same wonderful manner. But what was even more wonderful, Mr. Collins persuaded me that the bird flew all round the room singing until it returned to the box and fascinated me all over again. In after years I remember seeing a similar box and discovering the deception and mechanism. My disappointment for my shattered ideal was very hard to bear.

My imagination as a small child, although it endowed me with happy hours, was sometimes rather too much for me. On being presented with a sword, I invented a lion to kill with it, and grew so frightened finally of the creature of my own invention that at the last moment, preparatory to a triumphant rush intended to culminate in victory, I was obliged to retreat in terror behind my mother's skirts, my clutch becoming so frantic that she had to release herself from my grasp.

On leaving Harewood Square, my parents went to live at Upton Park, Slough, where I spent some of the happiest days of my life. Always a charming little place, it was then to me very beautiful. I remember the old church, delightfully situated by the roadside, the little gate by the low wall, and the long line of dark green yews bordering the flagged paths, where the stately people walked into church, followed by small Page boys in livery carrying big bags containing the prayer-books. Leech has depicted those quaint children in many a humorous drawing. There were two ladies whom I recollect as far from stately. I wish I could meet them now. Such subjects for a caricature one rarely has the opportunity of seeing. Quite six feet, ungainly, gawky, with odd clothes and queer faces, not unlike[8] those of birds, they always inspired me with the utmost curiosity and astonishment. These ladies bore the name of "Trumper," and I remember they called upon us one day. The servant—perhaps embarrassed by their strange appearance—announced them as the "Miss Trumpeters," and the accidental name labelled them for ever. Even now I think of them as "the Trumpeters." The eccentricity of the Miss Trumpers was evidently hereditary, for on the occasion of a dinner-party given at their house, old Mrs. Trumper startled her guests at an early stage of the meal by bending a little too far over her plate, and causing her wig and cap to fall with a splash into her soup.

The ivy mantled tower was claimed very jealously in those days by the natives of Upton to be the tower of Gray's "Elegy," but it was in Stoke Poges churchyard that Gray wrote his exquisite poem, and it is there by the east wall of the old church that "the poet sleeps his last sleep."

In the meadow by the chancel window stands the cenotaph raised to his memory by John Penn, who, although the Pennsylvanians will assure you he rests safely in their native town, is buried in a village called Penn not far distant.

The churchyard always impresses me with its atmosphere of romantic associations; the fine old elm tree, and the pines, and the two ancient yews casting their dark shade—

all add to the poetic feeling that is still so completely preserved.

When one enters the church the impression gained outside is somewhat impaired by some startlingly[9] ugly stained glass windows, which to my mind are a blot on the church. There is one which is so crushingly obvious as to be positively painful to the eye. It must be remembered, of course, that these drawbacks are comparatively modern, and a few of the windows are very quaint. One very old one reveals an anticipatory gentleman riding a wooden bicycle.

The Reverend Hammond Tooke was then Rector of Upton Church, and a friend of my people. Mrs. Tooke was interested in me, and gave me my first Bible, which I still possess, but which, I am afraid, is not opened as often as it used to be. My excuse lies in my fear lest it should fall to pieces if I touched it. On the way to and from church we used to pass the old Rectory House (in after days the residence of George Augustus Sala), then owned by an admiral of whom I have not the slightest recollection. The admiral's garden was a source of unfailing interest, for there, on the surface of a small pond, floated a miniature man-o'-war.

Another scene of happy hours was Herschel House, which belonged to an old lady whom we frequently visited. On her lawn stood the famous telescope, which was so gigantically constructed that—in search of science!—it enabled me to my delight to run up and down it. Sir William Herschel made most of his great discoveries at this house, including that of the planet Uranus.

Living so near Windsor we naturally witnessed a great number of incidents, interesting and spectacular. From our roof we saw the funeral procession of the Duchess of Kent, winding along the Slough road, and from a shop window in Windsor watched the bridal carriage of the Princess Royal (on the[10] occasion of her marriage to the Crown Prince of Prussia) being dragged up Windsor Hill by the Eton boys. I can also recall an opportunity being given us of witnessing from the platform of Slough station, gaily decorated for the occasion, the entry of a train which was conveying Victor Emmanuel, then King of Sardinia, to Windsor Castle. If I remember rightly, the Mayor—with the inevitable Corporation—read an address, and it was then that I saw the robust monarch in his smart green and gold uniform, with a plumed hat: his round features and enormous moustache are not easily forgotten.

The station-master at Slough was an extraordinary character, and full of importance, with an appearance in keeping. He must have weighed quite twenty-two stone. He used to walk down the platform heralding the approaching train with a penetrating voice that resounded through the station. There is a story told of how he went to his grandson's christening, and, missing his accustomed position of supreme importance and prominence, he grew bored, fell asleep in a comfortable pew ... and snored until the roof vibrated! When the officiating clergyman attempted to rouse him by asking the portly sponsor the name of his godchild, he awoke suddenly and replied loudly, "Slough—Slough—change for Windsor!"

During the progress of my father's commissioned pictures, "The Visit of Queen Victoria to the Tomb of Napoleon I." and "The Investiture of Napoleon III. with the Order of the Garter" (both of which, I believe, still hang in Buckingham Palace), the Queen and Prince Consort made frequent visits to my father's studio. On one of these visits of inspection, the Queen was attracted by some little pictures[11] done by my mother of her children, with which she was so much pleased that she asked her to paint one of Princess Beatrice (then a baby of ten months old). Before the departure of the Royal family on this occasion, we children were sent for, and upon entering the room made our bow and curtsey as we had been taught to do by our governess. My youngest sister, however, being a mere baby, toddled in after us with an air of indifference which she continued to show. I suppose the gold and scarlet liveries of the Royal servants were more attractive to her than the quiet presence of the Royal people. When the Queen departed, we hurried to the nursery windows. To my delight, I saw the Prince of Wales waving his mother's sunshade to us, and in return I kept waving my hand to him until the carriage was out of sight.

In after years my father told me with some amusement, how the Prince Consort (who was growing stouter) reduced the size of the painted figure of himself in my father's picture by drawing a chalk line, and remarking, "That's where my waist should be!"

I sat to my parents very often, and my father occasionally gave me sixpence as a reward for the agonies I considered I endured, standing in awkward attitudes, impatiently awaiting my freedom. In my mother's charming picture called "God save the Queen," which represents her sitting at the piano, her fingers on the keys, her face framed by soft curls is turned to a small group representing her children who are singing the National Anthem. Here I figure with sword, trumpet, and helmet, looking as if I would die for my Queen and my country, while my sisters watch with wide interested eyes.[12]

My sisters and I often played about my mother's studio while she painted. She never seemed to find our presence troublesome, although I believe we were sometimes a nuisance, whereas my father was obliged to limit his attentions to us when work was finished for the day.

I loved to draw, and on Sundays the subject had to be Biblical, as to draw anything of an everyday nature on the Sabbath was in those days considered, even for a child, highly reprehensible (at all events, by my parents).

Even then I was determined to be an artist. I remember that one day my oldest friend, Edward Nash (whose parents were neighbours of ours) and I were watching the Seaforth Highlanders go by, and, roused perhaps by this inspiring sight, we fell to discussing our futures.

"I'm going to be an artist," I announced. "What are you?"

"I'm going to be a Scotchman," he replied gravely. In after life he distinguished himself as a great athlete, played football for Rugby in the school "twenty," and was one of the founders of the Hockey Club. He is now a successful solicitor and the father of athletic sons.

Miniature of my sister Alice and myself painted by

Miniature of my sister Alice and myself painted byA very interesting personality crossed my path at this period in the shape of Sir William Ross, R.A., the last really great miniature painter of his time. He was a most courteous old gentleman, and there was nothing of the artist in his appearance—at least according to the accepted view of the appearance of an artist. In fact, he was more like a benevolent old doctor than anything else. When my sister Alice and I knew that we were to sit to him for our portraits, we rather liked, instead of resenting, the[13] idea (as perhaps would have been natural), for he looked so kind. After our first sitting he told me to eat the strawberry I had held so patiently. I obediently did as he suggested, and after each sitting I was rewarded in this way. The miniature turned out to be a chef d'œuvre. It is so beautiful in its extreme delicacy and manipulation that it delights me always. My mother values it so much that in order to retain its freshness she keeps it locked up and shows it only to those who she knows will appreciate its exquisite qualities. Queen Victoria said when it was shown to her, "I have many fine miniatures by Ross, but none to equal that one."

We visited many artists' studios with our parents. I am told I was an observant child and consequently had to be warned against making too outspoken criticisms on the pictures and their painters. On one occasion a Mr. Bell was coming to dine; we were allowed in the drawing-room after dinner, and as his appearance was likely to excite our interest, we were warned by our governess against remarking on Mr. Bell's nose. This warning resulted in our anticipation rising to something like excitement, and the moment I entered the room, my gaze went straight to his nose and stayed there. I recollect searching my brain for a comparison, and coming to the conclusion that it resembled a bunch of grapes.

My father was a very keen student of archæology; and I think he must have known the history of every building in London inside and out! I remember that once he took us to Westminster Abbey, there, as usual, to make known to us, I have no doubt, many interesting facts. Afterwards we went to St. James' Park, where my father pointed out the ornamental lake where King Charles the Second fed[14] his ducks, and told our governess that he thought it would be an excellent idea if when we returned we were to write a description of our adventures. The next day, accordingly, we sat down to write our compositions; and although my sister's proves to have been not so bad, mine, as will be seen, was shocking. The reader will observe that in speaking of St. James' Park, I have gone so far as to say "King Charles fed his duchess by the lake," which seems to imply a knowledge of that gay monarch beyond my years.

MY FATHER.

MY FATHER. MY MOTHER.

MY MOTHER."Thhe other day you were so kinnd as to take us to Westminster Abbey we went in a cab and we got out of the cab at poets corner and then went in Westminster Abbey and we saw the tombe of queen Eleanor and then we saw the tomb of queen Elizabeth and Mary and the tomb of Henry VII and his wife lying by him and the tomb of Henry's mother, then we came to the tow little children of James II and in the middle the two little Princes that were smothered in the tower and there bones were found there and and bort to Westminster Abbey and berryd there. We saw the sword which was corrade in the procession after the battle of Cressy and we then saw the two coronation Chairs were the kings and queens were crowned and onder one of the Chairs a large stone under it that Edward brought with hin And we saw the tomb of Gorge II who was the last man who was berried there. Then we went to a bakers shop and we had some buns and wen we had done papa said to the woman three buns one barth bun and ane biscuit and papa forgot his gluves and i said they were in the shop and papa said silly boy why did you not tell me and then to the cloysters were three monks were berried then the senkuary[15] were the duke of York was taken and then the jeruclam chamber and then to Marlborough house were Marlborough lived and then Westminster hall and then judge Gerfys house and the inclosid at S' james park were Charles II fed his duchess and then we came home and had our tee and then went to bed."

A visit to London, which made a far greater impression on me, was made later, when I went to Astley's Theatre. Originally a circus in the Westminster Bridge Road, started by Philip Astley, who had been a light horseman in the army, the theatre was celebrated for equestrian performances. "Astley's," as it was called, formed the subject of one of the "Sketches by Boz." "It was not a Royal Amphitheatre," wrote Dickens, "in those days, nor had Duncan arisen to shed the light of classic taste and portable gas over the sawdust of the circus; but the whole character of the place was the same, the clown's jokes were the same, the riding masters were equally grand ... the tragedians equally hoarse.... Astley's has changed for the better ... we have changed for the worse."

Thackeray mentions the theatre in "The Newcomes." "Who was it," he writes, "that took the children to Astley's but Uncle Newcome?"

Mr. Wilkie Collins and Mr. Pigott (afterwards Examiner of Plays) took us; we had a large box, and the play—Garibaldi—was most enthralling. I was overwhelmed with grief at Signora Garibaldi's death scene. There were horses, of course, in the great battle, and one of these was especially intelligent; limping from an imaginary wound, he took between his teeth from his helpless rider a handkerchief, dipped it in a pool of water, and returned[16]—still limping—to lay the cool linen upon the heated brow of his dying master.

Thrilling with excitement and fear, it never occurred to me that the battle, the wounds, and the deaths following were anything but real; but all my grief did not prevent me from enjoying between the acts my never-to-be-forgotten first strawberry ice.

The Panopticon was another place of amusement, long forgotten, I suppose, except by the very few. The building, now changed and known as the Alhambra, was a place where music and dancing were features of attraction. It was opened in 1852 and bore the name of the Royal Panopticon of Science and Art. I believe it was financed by philanthropic people, but it failed. I remember it because in the centre, where the stalls are now, rose a great fountain with coloured lights playing upon it. There were savages, too, and I shook hands with a Red Indian, with all his war paint gleaming, the scalp locks to awe me, and the feathers standing fiercely erect. He impressed me enormously, and in consequence of my seeing the savages, I became nervously imaginative. I had heard of burglars, and often reviewed in my mind my possible behaviour if I discovered one under my bed, where I looked every night in a sort of fearsome expectation. Religion had been early instilled into me; and, knowing the ultimate fate of wicked sinners, I resolved to tell him he would have to go to hell if he harmed me, and was so consoled with the idea that I went to sleep quite contentedly. A burglar might have been rather astonished had he heard such sentiments from my young lips.

In that strange "chancy" way in which remembrances of odd bizarre happenings jostle irrelevantly[17] one against another, I recall another experience. Once I was going to a very juvenile party; I forget where, but I was ready and waiting for the nurse to finish dressing my sisters. Resplendent in a perfectly new suit of brown velvet, and full of expectation of pleasures to come, I was rather excited and consequently restless. My nurse told me not to fidget. Casual reprimands had no effect. Growing angry, she commanded me loudly and suddenly to sit down, which I did ... but in the bath!... falling backwards with a splash and with my feet waving in the air. My arrival at the party eventually in my old suit did not in any way interfere with my enjoyment.

About this time my mother visited Paris, and we looked forward to the letters she wrote to us. One letter mentions the interesting but afterwards ill-fated Prince Imperial.

"I again saw," she wrote, "the little baby Emperor; he is lovely and wore a large hat with blue feathers, I should like to paint him."

In 1857 the Thames was frozen over, and at Eton an ox was roasted upon the ice. I remember it well. Another time on the occasion of one of our many visits to Brighton, we saw the great comet, and a new brother arrived:—all three very wonderful events to me.

The brilliance of the "star with a tail" aroused my sister and me to leave our beds and open the window to gaze curiously upon this phenomenon. Simultaneously a carriage drove up to the door, and my mother (who had just arrived from Slough) alighted, and after her the nurse with a baby in her arms. We were reprimanded severely for our temerity in being out of bed, but we could not[18] return until we had had a glimpse of the new baby, who became one of the most beautiful children imaginable.

In Brighton we visited some relations of my father's, the Misses Smith, daughters of Horace Smith, one of the authors of "The Rejected Addresses." Of the two sisters, Miss Tysie was considered the most interesting, and although Miss Rosie was beautiful, her sister was considered the principal object of attraction by the innumerable people they knew. Everybody worth knowing in the world of art and especially of literature came to see the "Recamier" of Brighton; Thackeray was counted amongst her intimates, and we may possibly know her again in a character in one of his books. I remember being impressed with these ladies as they were very kind to us. Miss Tysie died only comparatively recently.

Two years later, I met a real hero, a general of six feet four inches, who seemed to me like a brilliant personage from the pages of a romantic drama.

General Sir John Hearsey, then just returned from India, where he had taken a conspicuous part in quelling the Mutiny, came to stay with us at Upton Park with his wife, dazzling my wondering eyes with curiosities and strange toys, embroideries, and queer things such as I had never seen or heard of before. Their two children were in charge of a dark-eyed ayah, whose native dress and beringed ears and nose created no little stir in sleepy Upton.

I could never have dreamt of a finer soldier than the General, and I shall never forget the awe I felt when he showed me the wounds all about his neck, caused by sabre-cuts, and so deep I could put my fingers in them. My father painted a splendid[19] portrait of him in native uniform and another of the beautiful Lady Hearsey in a gorgeous Indian dress of red and silver.

Another friend of my childhood was the late Mr. Birch, the sculptor; he was assisting my father at that time by modelling some of the groups for his pictures, and he used to encourage me to try and model, both in wax and clay. Some thirty years later, we met at a public dinner, and I realised the then famous sculptor and A.R.A. was none other than the Mr. Birch of my childhood.

When I was quite a small boy, we left Upton Park and came to Kent Villa. The house (which became afterwards the residence of Orchardson, the painter), was built for my father, who went to live at Kensington Park chiefly through Dr. Doran, a great friend of his (of whom I have more to say later on).

There were two big studios, one above the other, for my parents. The house, which was covered with creepers, was large and roomy. It was approached by a carriage drive, the iron gates to which were a special feature. There was a garden at the back where we used frequently to dine in a tent until the long-legged spiders grew too numerous; but we often received our friends there when the weather was summery.

There was a ladies' school next door, and I recollect in later years my father's consternation when the girls, getting to know by some means or other (I think by the back stairs), of the Prince of Wales' intended visit, formed a guard of honour at our gate to receive him, which caused annoyance to my father and natural surprise to His Royal Highness.

My parents were very regular in their habits,[20] for no matter how late the hour of retiring, they always began to work by nine. At four my father would take a glass of sherry and a sandwich before he went his usual long walk with my mother to the West End, and from there they wandered into the neighbourhood of Drury Lane, and lingered at the old curiosity shops. They were connoisseurs of old furniture and bought with discretion. As great believers in exercise, this walk was a regular pastime; on their return they dined about seven and often read to one another afterwards. My father's insatiable love of history and of the past led him to seek with undying interest any new light upon old events.

J. H. Edge, K.C., in his novel, "The Quicksands of Life," writes of my father: "The artist was then and probably will be for all time the head of his school. He was a big, burly, genial man, with a large mind, a larger heart, and a large brain. He was a splendid historian, with an unfailing memory, untiring energy and industry, and at the same time, like all true artists, men who appreciate shades of colour and shades of character—highly strung and morbidly sensitive, but not to true criticism which he never feared." Highly religious and intensely conscientious in every way and yet so very forgetful that his friends sometimes dubbed him the "Casual Ward." Brilliant conversational powers combined with a strong sense of humour, made him a delightful companion. His love of children was extraordinary. He never failed to visit our nursery twice a day, when we were tiny, and I have often seen him in later years, when bending was not easy, on his knees playing games with the youngest children. His voice was very penetrating, and they used to say[21] at Windsor that one might hear him from the beginning of the Long Walk to the Statue. In church he frequently disturbed other worshippers by loudly repeating (to himself, as he thought) the service from beginning to end. I remember that on Sundays when the weather did not permit of our venturing to church, my father would read the service at home out of a very old Prayer-book, and when he came to the prayer for the safety of George IV., we children used to laugh before the time came, in expectation of his customary mistake. His powers of mimicry were extraordinary; I have seen him keeping a party of friends helpless with laughter over his imitations of old-fashioned ballet-dancers. His burlesque of Taglioni was side-splitting, especially as he grew stouter. Although a painter of historical subjects, he was extraordinarily fond of landscape, and among those of other places of interest there are some charming sketches of Rome, which he made while studying there in the company of his friend George Richmond, R.A. Among his drawings in the library at Windsor Castle, which were purchased after his death, are some remarkably interesting studies of many of the important people who sat to him for the pictures of Royal ceremonies. For the studies of the Peeresses' robes in "The Investiture of Napoleon III. with the Order of the Garter," my father was indebted to Lady Waterford (then Mistress of the Robes), whose detailed sketches were extraordinarily clever and very useful. This lady was a remarkable artist, her colour and execution being brilliant, so much so that when she was complaining of her lack of training in art, Watts told her no one who was an artist ever wished to see any of her work different from what it was ... and he[22] meant it. My father had an equally high opinion of her gift.

Perhaps the "South Sea Bubble" is one of the most widely known of my father's pictures. Removed from the National Gallery to the Tate not very long ago, this splendid example of a painter-historian's talent remains as fresh as the day it was painted, and its undoubted worth, although unrecognised by a section of intolerant modernists, will, I think, stand the test of time.

I recollect many well-known people who came to our house in those days; some, of course, I knew intimately, and amongst those, Marcus Stone and Vicat Cole, who calling together one evening, were announced by the servant as "The Marquis Stone and Viscount Cole."

Gambert, the great art dealer, afterwards consul at Nice, is always connected in my mind with the Crystal Palace, where he invited my parents to a dinner-party in the saloon, and we were told to wait outside. My sister and I walked about, quite engrossed with sight-seeing. The evening drew on and the people left, the stall-holders packed up their goods and departed, while we sat on one of the seats and huddled ourselves in a corner. As the dusk grew deeper we thought of the tragic fate of the "Babes in the Wood." Up above, the great roof loomed mysteriously, and as fear grew into terror, we resolved as a last resort to pray. Our prayer ended, a stall-keeper, interested, no doubt, came to the rescue, and on hearing our story, stayed with us until our parents came.

My father is represented with Millais on the left hand

top of the cartoon. 1865.

My father is represented with Millais on the left hand

top of the cartoon. 1865.

My mother is represented in the centre of the trio of

My mother is represented in the centre of the trio ofWe loved the Crystal Palace none the less for our misadventure, and the happiest day of the year, to me at least, was my mother's birthday, on the[23] first of June, when we annually hired a private omnibus, packed a delicious lunch, and drove to the Palace, where we visited our favourite amusements, or rambled in the spacious grounds. Sims Reeves, Carlotta Patti, Grisi, Adelina Patti, sang there to distinguished audiences. Blondin astonished us with remarkable feats, and Stead, the "Perfect Cure," aroused our laughter with his eccentric dancing. A great source of attraction to me were the life-like models of fierce-looking African tribes, standing spear and shield in hand, in the doorways of their kralls. A pictorial description of how the Victoria Cross was won was another fascination, for in those days I had all the small boy's love of battle. When we were at home I loved to go to Regent's Park to see the panorama of the earthquake at Lisbon, and I would gaze enthralled at the scene, which was as actual to me as the "Battle of Prague," a piece played by our governess upon the piano, a descriptive affair full of musical fireworks, the thundering of cavalry and the rattle of shots.

On Sundays we were accustomed to walk to St. Mark's, St. John's Wood, to hear the Rev. J. M. Bellew, whose sermons to children were famous. We had to walk, I remember, a considerable distance to the church. I can't recall ever being bored by him. He was a very remarkable man, and his manner took enormously with children; he had a magnificent head and silvery curls, which made a picturesque frame to his face, and offered an effective contrast to his grey eyes. This, combined with a very powerful sweep of chin, an expressive mouth, wide as orators' mouths usually are, and an attractive voice, made him a very fascinating personality. He taught elocution to Fechter, the great actor, and[24] afterwards—when he had retired from the Protestant Church and become a Roman Catholic—he gave superb readings of Shakespeare. At all these readings, as at his sermons, an old lady, whose infatuation for Bellew was well known, was always a conspicuous member of the audience; for no matter what part of the country he was to be heard, she would appear in a front seat with a wreath of white roses upon her head. Bellew never became acquainted with her beyond acknowledging her presence by raising his hat.

I used to take Latin lessons with Evelyn and Harold Bellew (afterwards known as Kyrle Bellew, the actor). Sometimes I stayed with them at Riverside House at Maidenhead where their father, being very fond of children, frequently gave parties, and I remember his entertaining us. Here Mr. Bellew nearly blew off his arm in letting off fireworks from the island. In those days there were few trees on this island, and it was an ideal place for a display, though this affair nearly ended disastrously.

The advantage of "archæological research" was very early impressed upon me by my father, and I was taken to see all that was interesting and instructive. We used to go for walks together, and as we went he would tell me histories of the buildings we passed, and on my return journey I was supposed to remember and repeat all he had said.

"Come now," he would say, pausing in Whitehall. "What happened there?"

"Oh—er——" I would reply nervously. "Oliver Cromwell had his head cut off—and said, 'Remember'!"

I used to dread these walks together, much as I loved him, and I was so nervous I never ceased to[25] answer unsatisfactorily; so my father, over-looking the possibility of my lack of interest in his observations, and the fact that life was a spectacle to me, for what I saw interested me far more than what I heard, decided I needed the rousing influence of school life, and after a little preparation, sent me to Chase's School at Salt Hill.

Salt Hill was so called from the ceremony of collecting salt in very ancient days by monks as a toll; and in later times by the Eton boys, who collected not "salt"—but money, to form a purse for the captain of the school on commencing his University studies at King's College, Cambridge. Soon after sunrise on the morning of "Montem," as it was called, the Eton boys, dressed in a variety of quaint or amusing costumes, started from the college to extort contributions from all they came across. "They roved as far as Staines Bridge, Hounslow, and Maidenhead, and when 'salt' or money had been collected, the contributors would be presented with a ticket inscribed with the words, 'Nos pro lege,' which he would fix in his hat, or in some conspicuous part of his dress, and thus secure exemption from all future calls upon his good nature and his purse."

"Montem" is now a matter of history, and was discontinued in 1846, when the Queen turned a deaf ear to her "faithful subjects'" petition for its survival.

Amongst my school friends at Salt Hill, Wentworth Hope-Johnstone stands out as an attractive figure, as does that of Mark Wood (now Colonel Lockwood, M.P.). The former became in later life one of the first gentlemen riders of the day. At school he was always upon a horse if he could get[26] one, and he would arrange plays and battle pieces in which we, his schoolfellows, were relegated to the inferior position of the army, while he was aide-de-camp, or figured as the equestrian hero performing marvellous feats of horsemanship. He became a steeple-chase rider, and coming to my studio many years after, I remember him telling me with the greatest satisfaction that he had never yet had an accident—ominously enough, for within the week he fell from his horse and sustained severe injuries.

I did not stay long at my school at Salt Hill, for the school was broken up owing to the ill-health of the principal. My preparation thus coming to an end rather too soon, I was sent to Eton much earlier than I otherwise should have been, and my pleasant childhood days began to merge into the wider sphere of a big school and all its unknown possibilities.

Eton days.—Windsor Fair.—My Dame.—Fights and Fun.—Boveney Court.—Mr. Hall Say.—Boveney.—Professor and Mrs. Attwell.—I win a useful prize.—Alban Doran.—My father's frescoes.—Battle Abbey.—Gainsborough's Tomb.—Knole.—Our burglar.—Claude Calthrop.—Clayton Calthrop.—The Gardener as Critic.—The Gipsy with an eye for colour.—I attempt sculpture.—The Terry family.—Private Theatricals.—Sir John Hare.—Miss Marion Terry.—Miss Ellen Terry.—Miss Kate Terry.—Miss Bateman.—Miss Florence St. John.—Constable.—Sir Howard Vincent.—I dance with Patti.—Lancaster Gate and Meringues.—Prayers and Pantries.

I have the liveliest recollection of my first day at Eton, when I was accompanied by my mother, who wished to see me safely installed. In her anxiety to make my room comfortable (it was afterwards, by the way, Lord Randolph Churchill's room), she bought small framed and coloured prints of sacred subjects to hang upon the walls, to give it, as she thought, a more homely aspect. These were very soon replaced, on the advice of Tuck, my fag-master (and wicket-keeper in the eleven), by racehorses and bulldogs by Herring.

Next I remember my youthful digestion being put to test by a big boy who "stood me," against my will, "bumpers" of shandy-gaff; and for my first smoke a cheroot of no choice blend, the inevitable results succeeding.

Shortly afterwards I was initiated into the mysteries of school life; I had to collect cockroaches to let loose during prayers; and of course the usual[28] fate of a new boy befell me. I was asked the old formula: or something to this effect—

If your reply did not give satisfaction, you were promptly "bonneted," and, in Eton phraseology, your new "topper" telescoped over your nose.

I was at first made the victim of a great deal of unpleasant "ragging" by a bully, who on one occasion playing a game he called "Running Deer!" made me a target for needle darts, one of which lodged tightly in the bone just above my eye; but he was caught in the act by Tuck, who punished the offender by making him hold a pot of boiling tea at arm's length, and each time a drop was spilled, my champion took a running kick at him.

I learned a variety of useful things. Besides catching cockroaches, I became an adept in the art of cooking sausages without bursting their skins: if I forgot to prick them before cooking, I was severely reprimanded by my fag-master, and I considered his anger perfectly justifiable; my resentment only existing where unjustifiable bullying was concerned.

Windsor Fair was an attraction in those days, especially for the small boys, as it was "out of bounds," and therefore forbidden. I remember once being "told off" to go to the fair and bring as many musical and noisy toys as I could carry; which were to be instrumental in a plot against our "dame" ... (the Reverend Dr. Frewer) ... On the great occasion, the boys secreted themselves in their lock-up beds. The rest hid in the housemaid's cupboard, and we started a series of hideous discords upon the[29] whistles and mouth organs from the fair. Presently our "dame" appeared, roused by the concert, and at the door received the water from the "booby trap" all over his head, and then, drenched to the skin and looking like a drowned rat, he proceeded to rout us. We were all innocence with a carefully concocted excuse to the effect that the reception had been intended for Anderson, one of the boys in the house. Notwithstanding that expulsion was threatening us, we were all called to his room next morning, severely reprimanded, but ... forgiven.

Old Etonians will remember Jobie, who sold buns and jam; and Levy, who tried to cheat us over our "tuck," and was held under the college pump in consequence; and old Silly-Billy, who used to curse the Pope, and, considering himself the head of the Church, was always first in the Chapel at Eton. Then there was the very fat old lady who sold fruit under the archway, and had a face like an apple herself. She sold an apple called a lemon-pippin, that was quite unlike anything I have tasted since, and looked like a lemon.

At "Sixpenny" the mills took place, and there differences were settled. A "Shinning-match," which was only resorted to by small boys, was a most serious and carefully managed affair; we shook hands in real duel fashion, and then we proceeded to exchange kicks on one another's shins until one of us gave in.

I remember having a "shinning-match" to settle some dispute with one of my greatest friends, but we were discovered, taken into Hawtrey's during dinner, and there talked to in serious manner. Our wise lecturer ended his speech with the time-honoured, "'Tis dogs delight to bark and bite," etc.[30]

In 1861 I recollect very well the Queen and Prince Consort reviewing the Eton College Volunteer Corps in the grounds immediately surrounding the Castle, while we boys were permitted to look on from the Terrace.

At the conclusion of the review the volunteers were given luncheon in the orangery, where they were right royally entertained.

Prince Albert, whom I had noticed coughing, retired after the review into the castle, while the Queen and Princess Alice walked together on the slopes.

This was the last time that Prince Albert appeared in public, for he was shortly after seized with an illness from which he never recovered.

From Eton I frequently had "leave" to visit some friends of my parents, the Evans, of Boveney Court, a delightful old country house opposite Surly Hall. Miss Evans married a Mr. Hall-Say, who built Oakley Court, and I was present when he laid the foundation stone.

Mr. Evans, who was a perfectly delightful old man, lent one of his meadows at Boveney (opposite Surly Hall) to the Eton boys for their Fourth of June celebrations. Long tables were spread for them, with every imaginable good thing, including champagne, some bottles of which those in the boats used to secrete for their fags; and in my day small boys would come reeling home, unable to evade the masters, and the next day the "block" was well occupied, and the "swish" busy.

There were certain unwritten laws in those days as regards flogging; a

master was not supposed to give downward strokes, for thus I believe

one deals a more powerful sweep of arm and the stroke becomes torture.

In cricket, also, round arm bowling was[31] always the rule; a ball was

"no ball" unless bowled on a level with the shoulder, but lob-bowling

was, of course, allowed. Nowadays, the bowling has changed. Perhaps

the character of the "swishing" has also altered, but somehow I think

the boys are just the same.

SIR WILLIAM BROADBENT,

SIR WILLIAM BROADBENT, SIR THOMAS BARLOW.

SIR THOMAS BARLOW. SIR JAMES PAGET, BART.

SIR JAMES PAGET, BART.On the occasion of my first holiday, I arrived home from Eton a different boy; imbued with the traditions of my school, I was full of an exaggerated partisanship for everything good or indifferent that existed there. I remember I discovered my sisters in all the glory of Leghorn hats from Paris; they were large with flopping brims as was then the fashion. But to my youthful vision they seemed outrageous, and I refused to go out with the girls in these hats, which I considered, with a small boy's pride in his school, were a disgrace to me ... and consequently to Eton!

My regard for the honour and glory of this time-honoured institution did not prevent me sallying forth on several occasions with a school friend to anticipate the Suffragettes by breaking windows; although I was not the proposer of this scheme, I was an accessory to the act, and my friend (who seemed to have an obsessive love of breaking for its own sake) and I successfully smashed several old (but worthless) windows, both of the Eton Parish Church and also Boveney Church. Although I have made this confession of guilt, I feel safe against the law both of the school and the London magistrates.

In most respects I was the average schoolboy, neither very good, or very bad. Running, jumping, and football I was pretty "nippy" at, until a severe strain prevented (under doctor's orders) the pursuance of any violent exercises for some time.[32]

Previous to this I had won a special prize for my prowess in certain sports when I arrived second in every event. I won a telescope, which seemed a meaningless sort of thing until I went home for the holidays, when I gave an experimental quiz through it from my bedroom window and discovered the infinite possibilities of the girls' school next door. Finally I was noticed by a portly old mistress who complained of my telescopic attentions, never dreaming, from what I could gather, of my undivided interest in other quarters, and my prize was confiscated by my father.

During my enforced rest from all exercise of any importance, I spent my time in compiling a book of autographs and in sketching anything I fancied. My aptitude and love for drawing were not encouraged at school at the request of my father, but I was always caricaturing the masters, and having the result confiscated. It was inevitable, living as I did in an atmosphere of art, loving the profession, and sitting to my parents, that I should grow more and more interested and more determined to become a painter myself, although strangely enough I never had a lesson from either my father or mother.

The boy is indeed the father of the man, for just as I anticipated my future by becoming the school caricaturist, so Alban Doran, one of my schoolfellows (and the son of my father's friend, Dr. Doran), spent the time usually occupied by the average schoolboy in play or sport, in searching for animal-culæ or bottling strange insects, the result of his tedious discoveries. I believe he kept an aquarium even in his nursery, and was more interested in microscopes than cricket. The clever boy became a brilliant man, distinguishing himself at "Bart's,"[33] was joint compiler with Sir James Paget and Dr. Goodhart of the current edition of the Catalogues of the Pathological series in the Museum of the College of Surgeons. His success as a surgeon and a woman's specialist was all the more wonderful, when we remember his nervous shaking hands, which might have been expected to render his touch uncertain; but when an operation demands his skill the nervousness vanishes, and his hand steadies. He is noted for a remarkable collection of the ear-bones from every type of living creature in this country, and especially for his literary contributions to the study of surgery.

When I was at home on my holidays I spent a great deal of my time in a temporary studio erected on the terrace of the House of Lords. Here I watched my father paint his frescoes for the Houses of Parliament. Fresco painting would not endure the humidity of our climate, and several of these historical paintings which hung in the corridor of the House of Commons began to mildew. Other important frescoes were completely destroyed by the damp; but my father restored his works, and they were placed under glass, which preserved them. With his last two or three frescoes he adopted a then new process called "water-glass," which was a decided success.

Another holiday was spent at Hastings, where my father occupied much of his time restoring frescoes which he discovered, half-obliterated, in the old Parish Church at Battle. He intended eventually to complete his task; but on his return to London he found that the great pressure of work and engagements rendered this impossible. The dean of the parish wrote in consequence to say that[34] the restorations looked so patchy that it would be better to whitewash them over!

The Archæological Society met that year at Hastings, and my father, who intended to prepare me for an architectural career, thought it would encourage me if we attended their meetings, at which Planché, the President, presided. We visited all the places of interest near, and I heard many edifying discourses upon their histories, while I watched the members, who were rather antiquities themselves, and thoroughly enjoyed the many excellent luncheons spread for us at our various halting places.

À propos of restoration, my father visited Kew Church in 1865, and found in the churchyard Gainsborough's tomb, which was in a deplorable state of neglect. Near to Gainsborough are buried Zoffany,[1] R.A., Jeremiah Meyer, R.A., miniature painter and enamellist (the former's great friend), and Joshua Kirby, F.S.A., also a contemporary. My father at once took steps to have the tomb restored at his own expense, and as the result of his inquiries and efforts in that direction, received the following letter which is interesting in its quaint diction as well as in reference to the subject.

Petersham, Surrey,

August 24th, 1865.

My Dear Sir,

It is with much pleasure that I learn that one great man is intending to do Honor to the Memory of another. In reply to your note, I beg that you will consider that my Rights, as the Holder of the Freehold, are to be subservient by all means[35] to the laudable object of paying our Honor to the Memory of the great Gainsborough.

I am,

My dear Sir,

Yours very truly,

R.B. Byam, Esq.

Vicar of Kew.

To J. Rigby, Esq., Kew.

To this capital letter my father replied:—

Kent Villa.

Dear and Reverend Sir,

I cannot refrain from expressing to you my warm thanks for the very kind and disinterested manner in which you have been pleased to entertain my humble idea in regard to the restoration of Gainsborough's tomb, and the erection of a tablet to his memory in the church, the duties of which you so ably fulfil, nor can I but wholly appreciate your very kind but far too flattering reference to myself in your letter to our friend Mr. Rigby which coming from such a source is I assure you most truly valued.

Your most obedient and obliged Servant,

E. M. Ward.

The tomb was restored, a new railing placed around it, and a tablet to

the artist's memory was also placed by my father inside the church.

GAINSBOROUGH'S TOMB AT KEW CHURCHYARD AND TABLET TO HIS MEMORY INSIDE

CHURCH.

GAINSBOROUGH'S TOMB AT KEW CHURCHYARD AND TABLET TO HIS MEMORY INSIDE

CHURCH.

Some very pleasant memories are connected with enjoyable summers spent at Sevenoaks, where my father took a house for two years, close to the seven oaks from which the neighbourhood takes its name. Particularly I remember the amusing incident of the burglar. I was awakened from midnight slumbers by my sister knocking at the door and[36] calling in a melodramatic voice "Awake!... awake!... There is a burglar in our room." I promptly rushed to her bedroom, where I found my other sister crouching under the bedclothes in speechless terror. Having satisfied myself as to the utter absence of a burglar in that particular room, I started to search the house—but by this time the whole household was thoroughly roused; the various members appeared with candles, and together we ransacked the establishment from garret to cellar. In the excitement of the moment we had not had time to consider our appearances and the procession was ludicrous in the extreme. My grandfather (in the absence of my father) came first in dressing-gown, a candle in one hand and a stick in the other. My mother came next (in curl papers), and then my eldest sister. It was the day of chignons, when everybody, without exception, wore their hair in that particular style. On this occasion my sister's head was conspicuous by its quaint little hastily bundled up knot. I wore a night-shirt only; but my other sister, who was of a theatrical turn of mind (she who had awakened me), had taken the most trouble, for she wore stockings which, owing to some oversight in the way of garters, were coming down.

After satisfying ourselves about the burglar—who was conspicuous by his absence—we adjourned to our respective rooms, while I went back to see the sister upon whom fright had had such paralyzing effects. There I heard an ominous rattle in the chimney.

"Flora!" said my stage-struck sister, in trembling tones, with one hand raised (à la Lady Macbeth)—and the poor girl under the clothes cowered deeper and deeper.[37]

Two seconds later a large brick rattled down and subsided noisily into the fireplace.

"That is the end of the burglar," said I, and the terrified figure

emerged from the bed, brave and reassured. Retiring to my room I

recollected the procession, and having made a mental note of the

affair went back to bed. Early the next morning I arose and made a

complete caricature of the incident of the burglar, which set our

family (and friends next day) roaring with laughter when they saw it.

MY BROTHER, WRIOTHESLEY RUSSELL.

1872.

MY BROTHER, WRIOTHESLEY RUSSELL.

1872.

MY SISTER, BEATRICE.

1874.

MY SISTER, BEATRICE.

1874.

In those days we used to sketch at Knole House, then in the possession of Lord and Lady Delaware. My mother made some very beautiful little pictures of the interiors there, and several smaller studies. She copied a Teniers so perfectly that one could have mistaken it for the original. The painting was supposed to represent "Peter and the Angels in the Guard Room," and the guards were very conspicuous. On the other hand, as one only discovered a little angel with Peter in the distance, one could almost suppose Teniers had forgotten them until the last minute, and then had finally decided to relegate them to the background. This picture (the original) was sold at Christie's during a sale from Knole several years ago.

Of course the old house was the happy hunting ground of artists; the pictures were mostly fine although some of them were at one time in the hands of a cleaner, by whom they were very much over-restored. A clever artist (and a frequenter of Knole at that time for the purpose of making a series of studies) was Claude Calthrop (brother of Clayton Calthrop the actor and father of the present artist and writer Dion Clayton Calthrop). I was then just[38] beginning to be encouraged to make architectural drawings, and I was making a sketch of the exterior of Knole House when one of the under gardeners came ambling by wheeling a barrow. He paused ... put down the barrow, took off his cap ... scratched his head and said to me, "Er ... why waaste yer toime loike that ... why not taake and worrk loike Oi dew!"

Another time when I was sketching in that neighbourhood, in rather a lonely part, I fell in with a gipsy encampment. One of the tribe, a rough specimen, of whom I did not at all like the look, was most persistently attentive. He asked a multitude of questions, about my brushes, paints, and materials generally—and seemed anxious as to their monetary value. As he did not appear to be about to cut my throat—and I felt sure he harboured no murderous intentions towards my painting—I began to feel more at ease, and when no comments after the style of my critic, the gardener, were forthcoming, it struck me that perhaps I had a vagrant but fellow beauty-lover in my gipsy sentinel. I wish now that I had even suggested (in view of his evident love of colour) his changing his roving career for one in which he could indulge his love of red to the utmost and more or less harmlessly.

When I was about sixteen I turned my attention to modelling, and in

the vacation I started a bust of my young brother Russell. I spent all

my mornings working hard and at length finished it. On the last day of