Title: By Wit of Woman

Author: Arthur W. Marchmont

Illustrator: Simon Harmon Vedder

Release date: April 11, 2011 [eBook #35828]

Most recently updated: January 7, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Al Haines

BY WIT OF WOMAN

By

ARTHUR W. MARCHMONT

Author of "When I was Czar" "By Snare of Love"

"A Dash for a Throne" etc etc

ILLUSTRATIONS BY S. H. VEDDER

LONDON

WARD LOCK & CO. LIMITED

1906

CONTENTS

| CHAP. | |

| I | FROM BEYOND THE PALE |

| II | A CHESS OPENING |

| III | MY PLAN OF CAMPAIGN |

| IV | MADAME D'ARTELLE |

| V | A NIGHT ADVENTURE |

| VI | GARETH |

| VII | GARETH'S FATHER |

| VIII | COUNT KARL |

| IX | I COME TO TERMS WITH MADAME |

| X | A DRAMATIC STROKE |

| XI | PLAIN TALK |

| XII | HIS EXCELLENCY AGAIN |

| XIII | GETTING READY |

| XIV | I ELOPE |

| XV | AN EMBARRASSING DRIVE |

| XVI | A WISP OF RIBBON |

| XVII | IN THE DEAD OF NIGHT |

| XVIII | THE COST OF VICTORY |

| XIX | A TRAGI-COMEDY |

| XX | MY ARREST |

| XXI | HIS EXCELLENCY TO THE RESCUE |

| XXII | COLONEL KATONA SPEAKS |

| XXIII | A GREEK GIFT |

| XXIV | WHAT THE DUKE MEANT |

| XXV | ON THE THRESHOLD |

| XXVI | FACE TO FACE |

| XXVII | "THIS IS GARETH" |

| XXVIII | THE COLONEL'S SECRET |

| XXIX | A SINGULAR TRUCE |

| XXX | THE END |

ILLUSTRATIONS

"To John P. Gilmore, Jefferson City, Missouri, U.S.A.

"MY DEAR BROTHER-IN-LAW,—For years you have believed me dead, and I have made no effort to disturb that belief.

"I am dying now, alone in Paris, far from my beloved country; unjustly degraded, dishonoured and defamed. This letter and its enclosure will not be despatched until the grave has closed over me.

"To you I owe a debt of deep gratitude. You have taken and cared for my darling child, Christabel; you have stood between her and the world, and have spared her from the knowledge and burden of her father's unmerited shame. You can yet do something more—give her your name, so that mine with its disgrace may be forgotten; unless—it is a wild thought that has come to me in my last hours, the offspring of my hopeless melancholy—unless she should ever prove to have the strength, the courage, the wit and the will to essay that which I have endeavoured fruitlessly—the clearance of my name and honour.

"When ruin first fell upon me, I made a vow never to reveal myself to her until I had cleared my name and hers from the stain of this disgrace. I have kept the vow—God knows at what sorrow to myself and against what temptation in these last lonely years—and shall keep it now to the end.

"The issue I leave to you. If you deem it best, let her continue to believe that I died years ago. If otherwise, give her the enclosed paper—the story of my cruel wrong—and tell her that during the last years of my life my thoughts were all of her, that my heart yearned for her, and that my last conscious breath will be spent in uttering her name and blessing her.

"Such relics of my once great fortune as I have, I am sending to you for my Christabel.

"Adieu.

"ERNST VON DRESCHLER, COUNT MELNIK."

"To my Daughter, Christabel von Dreschler.

"MY DEAREST CHILD,—If you are ever to read these lines it will be because your uncle believes you are fitted to take up the task of clearing our name, from the stain of crime which the villainy of others has put upon it. But whether you will make the effort must be decided finally by yourself alone. For two years I have tried, with such strength as was left to me by those who did me this foul wrong, and I have failed. Were you a son, I should lay this task upon you as a solemn charge; but you are only a girl, and left in your hands, it would be all but hopeless, because of both its difficulty and probable danger. I leave you free to decide: for the reason that if you have not the personal capacity to make the decision, you will not have in you the power to succeed. One thing only I enjoin upon you. If you cannot clear my name, do not bear it.

"I have not strength to write out in full all the details of the matter, but I give you the main outline here and send in this packet many memoranda which I have made from time to time. These will give you much that you need.

"At the time of your mother's death and your leaving Hungary for the United States I was, as you may remember, a colonel in the Austro-Hungarian army, in possession of my title and estates, and in favour with one of the two most powerful of all the great Slav nobles, Ladislas, Duke of Kremnitz. I continued, as I believed, to enjoy his confidence for two years longer, up to the last, indeed. He was one of the leaders of the Patriots—the great patriotic movement which you will find described in the papers I send you—the other being the Hungarian magnate, Duke Alexinatz of Waitzen. Two of my friends, whose names you must remember, were Major Katona, my intimate associate, and Colonel von Erlanger, whom I knew less well.

"If the Patriots were successful, the Hungarian Throne was to be filled by Duke Alexinatz with reversion to his only son, Count Stephen; and it is necessary for you to understand that this arrangement was expressly made by Duke Ladislas himself.

"So matters stood when, one day, some hot words passed between young Count Stephen and myself, and he insulted me grossly. Two days later, Major Katona came to my house at night in great agitation. He declared that the Count had sworn to shoot me, and that his father had espoused his side in the quarrel and threatened to have me imprisoned; and that Duke Ladislas, unwilling to quarrel with Duke Alexinatz, although taking my part in the affair, desired me to absent myself from Buda-Pesth until the storm had blown over. He pressed me to leave instantly; and, suspecting nothing, I yielded. I had scarcely left my house when the carriage was stopped, I was seized, gagged, and blindfolded, and driven for many hours in this condition, and then imprisoned. I believed that I was in the hands of the agents of Duke Alexinatz; and continued in this belief for six years, during the whole of which time I was kept a close prisoner.

"Then at length I escaped: my strength sapped, my mind impaired and my spirit broken by my captivity; and learned that I had been branded as a murderer with a price set on my head.

"On the night when I had left, the young Count Stephen had been found shot in my house; my flight was accepted as proof of my guilt, and, most infamous of all, a confession of having murdered him had been made public with my signature attached to it.

"That is the mystery, as it stands to-day. The God I am soon to meet face to face knows my heart and that I am innocent; but prove it I cannot. May He give you the strength and means denied to me to solve the mystery.

"With this awful shadow upon me, I could not seek you out, let my heart ache and stab as it would with longing for a sight of your face and a touch of your hand. I thank God I have still been man enough—feeble as my mind is after my imprisonment—to keep away from you.

"This sad story you will never know, unless your uncle deems it for the best.

"That God may keep you happy and bless you is the last prayer of your unhappy father,

"ERNST VON DRESCHLER."

*****

My Uncle Gilmore had been dead three months, having left me his fortune and his name, when, in sorting his old papers to destroy them, I came upon these letters.

They were two years old; and it was evident that while my uncle had intentionally kept them from me, he had at the same time been unwilling to destroy them.

My poor, poor father!

"If your Excellency makes that move I must mate in three moves."

His Excellency's long white fingers were fluttering indecisively above the bishop and were about to close upon it, when I was guilty of so presumptuous a breach of etiquette as to warn him.

He was appropriately shocked. He fidgeted, frowned at me, and then smiled. It was one of those indulgent smiles with which a great man is wont to favour a young woman in his employment.

"Really, I don't think so," he replied; and having been warned by one whose counsel he could not condescend to rank very high, he did what most men would do under the circumstances. He made the move out of doggedness.

I smiled, taking care that he should see it.

The mate was perfectly apparent, but I was in no hurry to move. I had much more in view just then than the mere winning of the game. The time had arrived when I thought the Minister and I ought to come to an understanding.

"Your Excellency does not set enough store by my advice," I said slowly. "But there are reasons this evening. Your thoughts are not on the game."

"Really, Miss Gilmore! I am sorry if I have appeared preoccupied." He accompanied the apology with a graceful, deprecatory wave of his white hand. He was very proud of the whiteness of his hands and the grace of many of his gestures. He studied such things.

"I am not surprised," I said. "The solution of the mystery of those lost ducal jewels must naturally be disturbing."

His involuntary start was sufficiently energetic to shake the table on which the board was placed, and to disturb one or two of the pieces. He looked intently at me, and during the stare I put the pieces upon their squares with unnecessary deliberation. Then I lifted my eyes and returned his look with one equally intent.

Some of the family jewels of the Duke Ladislas of Kremnitz had been stolen a few days before, and the theft had completely baffled the officials of the Government from His Excellency, General von Erlanger, downwards. It had been kept absolutely secret, but—well, I had made it my business to know things.

"It has been a very awkward affair," I added, when he did not speak.

"Shall we resume our game, Miss Gilmore?" The tone was stiff. He intended me to understand that such matters were not for me to discuss.

I made the first move toward the mate and then said—

"Chess is a very tell-tale game, your Excellency. The theft occurred seven days ago, and for six of them you have been so preoccupied that I have won every game. To-night you have been alternately smiling and depressed; it is an easy inference, therefore, that the solution of the mystery is even more troublesome than the mystery itself. In point of fact, I was sure it would be."

Instead of studying his move, he began to fidget again; and presently looked across the board at me with another of his condescending, patronizing smiles.

"The loss you may have heard spoken of, but you cannot know anything more. What, pray, do you think the solution is?" It never entered his clever head that I could possibly know anything about it.

"I think you have been an unconscionable time in discovering what was palpably obvious from the outset."

He frowned. He liked this reply no better than I intended. Then the frown changed to a sneer, masked with a bantering smile, but all the same unmistakable.

"It is a serious matter for our Government to fall under your censure, Miss Gilmore."

"I don't think it is more stupid than other Governments," I retorted with intentional flippancy. I was not in the least awed by his eminent position, while he himself was, and found it difficult therefore to understand me. This was as I wished.

"Americans are very shrewd, I know, especially American ladies, who are also beautiful. But such matters as this——" and he waved his white hand again loftily; as though the problem would have baffled the wisdom of the world—any wisdom, indeed, but his.

Now this was just the opening I was seeking. I had only become governess to his two girls in order to make an opportunity for myself. I used the opening promptly.

"Will your Excellency send for your daughter, Charlotte?"

He started as if I had stuck a pin in him. If you wish to interest a man, you must of course mystify him.

"For what purpose?"

"That you may see there is no collusion."

"I don't understand you," he replied. I knew that as clearly as I saw he was now interested enough to wish me to do so. I let my fingers dawdle among the chessmen during a pause intended to whet his curiosity, and then replied:

"I wish you to ask her to bring you a sealed envelope which I gave her six days ago, the day after the jewels disappeared."

"It is very unusual," he murmured, wrinkling his brows and pursing his lips.

"I am perhaps, not quite a usual person," I admitted, with a shrug.

He sat thinking, and presently I saw he would humour me. His brows straightened out, and his pursed lips relaxed into the indulgent smile once more.

"You are a charming woman, Miss Gilmore, if a little unusual, as you say;" and he rang the bell.

"You have not moved, I think," I reminded him; but he sat back, not looking at the board and not speaking until his daughter came. I understood this to signify that I was on my trial.

"Miss Gilmore gave you a sealed envelope some days ago, Charlotte," he said to her. "She wishes you to bring it to me. Has it really any connexion with this case?" he asked, as soon as she had left to fetch it.

I laughed.

"How could it, your Excellency? What could a girl in my position, here only a few weeks, possibly know about such a thing?"

As this was the thought obviously running in his own mind, he had no difficulty in assenting to it politely.

"Then what does this mean?" he asked, with a little fretful frown of inquisitiveness.

"I am only proving my self-diagnosis as a somewhat unusual person. Will you move now?"

He bent forward and scanned the pieces; but his thoughts were not following his eyes, and with an impatient gesture he leaned back again. I continued to study the board as though the game were all in all to me.

"You are pleased to be mysterious, Miss Gilmore;" he said, his tone a mingling of severity, sarcasm and irritation. I was to understand that a man of his exalted importance was not to be trifled with. "I appreciate greatly your valuable services, but I do not like mysteries."

I raised my eyes from the board as if reluctantly.

"I am unlike your Excellency in that. They have a distinct attraction for me. This has." I indicated the mate problem with my hand, but my eyes contradicted the gesture. He believed the eyes, and again moved uneasily in his chair. "It is naturally an attractive problem. I have moved, you know."

He was a very legible man for all his diplomatic experience; and the little struggle between his sense of dignity and piqued curiosity was quite amusing. But I was careful not to show my amusement. Nothing more was said until the envelope had been brought and Charlotte sent away again.

He toyed with it, trying to appear as if it were part of some silly childish game to which he had been induced to condescend in order to please me.

"What shall I do with this?"

"Suppose you open it?" I said, blandly.

He shrugged his shoulders, waved his white hand, lifted his eyebrows and smiled, obviously excusing himself to himself for his participation in anything so puerile; and then opened it slowly.

But the moment he read the contents his manner changed completely. His clear-cut features set, his expression grew suddenly tense with astonishment, his lips were pressed close together to check the exclamation of surprise that rose to them; even his colour changed slightly, and his eyes were like two steel flints for hardness as he looked up from the paper and across the chessmen at me.

I enjoyed my moment of triumph.

"It is your Excellency's move," I said again, lightly. "It is a most interesting position. This knight——"

He waved the game out of consideration impatiently.

"What does this mean?" he asked, almost sternly.

"Oh, that!" I said, with a note of disappointment, which I changed to one of somewhat simpering stupidity. "I was trying my hand at adapting the French proverb. I think I put it 'Cherchez le Comte Karl el la Comtesse d'Artelle,' didn't I?"

"Miss Gilmore!" he exclaimed, very sharply.

I made a carefully calculated pause and then replied, choosing my words with deliberation: "It is the answer to your Excellency's question as to my opinion of the solution. If you have followed my formula, you have of course found the jewels. The Count was the thief."

"In God's name!" he cried, glancing round as though the very furniture must not hear such a word so applied.

"It was so obvious," I observed, with a carelessness more affected than real.

He sat in silence for some moments as he fingered the paper, and then striking a match burnt it with great deliberation, watching it jealously until every stroke of my writing was consumed.

"You say Charlotte has had this nearly a week?"

"The date was on it. I am always methodical," I replied, slowly. "I meant to prove to you that I can read things."

His eyes were even harder than before and his face very stern as he paused before replying with well-weighed significance:

"I fear you are too clever a young woman to have further charge of my two daughters, Miss Gilmore. I will consider and speak to you later."

"I agree with you, of course. But why later? Why not now? My object in coming here was not to be governess to your children, but to enter the service of the Government. This is the evidence of my capacity; and it is all part of my purpose. I am not a good teacher, I know; but I can do better than teach."

He listened to me attentively, his white finger-tips pressed together, and his lips pursed; and when I finished he frowned—not in anger but in thought. Presently a slight smile, very slight and rather grim, drew down the corners of his mouth. And then I knew that I had matriculated as an agent of the Government.

"Shall we finish the game, your Excellency?"

"Which?" he asked laconically, a twinkle in the hard eyes.

"It is of course for your Excellency to decide."

"You are a good player, Miss Gilmore. Where did you learn?"

"I have always been fond of problems."

"And good at guessing?"

"It is not all guessing—at chess," I replied, meaningly. "One has to see two or three moves ahead and to anticipate your opponent's moves."

A short laugh slipped out. "Let us play this out. You may have made a miscalculation," he said, and bent over the board.

"Not in this game, your Excellency."

"You are very confident."

"Because I am sure of winning."

He grunted another laugh and after studying the position, made a move.

"I foresaw your Excellency's move. It is my chance. Check now, of course, and mate, next move."

"I know when I am outplayed," he said, with a glance. "I resign. And now we will talk. You play a good game and a bold one, Miss Gilmore, but chess is not politics."

"True. Politics require less brains, the stakes are worth winning, and men bar women from competing."

"It is rare to find girls of your age wishing to compete."

"I am twenty-three," I interjected.

"Still, only a girl: and a girl at your age is generally looking for a lover instead of nursing ambitions."

"I have known men of your Excellency's age busy at the same sport," said I. "Besides, I may have been a girl," I added, demurely; taking care to infuse the suggestion with sufficient sentiment.

"And now?" he asked, bluntly.

"I am still a girl, I hope—but with a difference."

"You are not thinking of making a confidant of an old widower like me, are you?"

"No, I am merely laying before you my qualifications."

"You know there is no room for heart in political intrigue? Tell me, then, plainly, what do you wish to do?"

"To lend my woman's wit to your Excellency's Government for a fair recompense."

"What could you do?"

There was a return to his former indulgent superiority in the question which nettled me.

"I could use opportunities as your agents cannot."

"How? By other clever guesses?"

"It was no guess. I have seen the jewels in Madame d'Artelle's possession."

He tried not to appear surprised, but the effort was a failure.

"I have been entertaining a somewhat dangerous young woman in my house, it seems," he said.

"It was ridiculously easy, of course."

"Perhaps you will explain it to me."

"A conjuror does not usually give away his methods, your Excellency. But I will tell this one. Feeling confident that Count Karl had stolen the jewels, and that his object would only be to give them to the Countess, I had only to gain access to her house to find them. I found a pretext therefore, and went to her, and—but you can probably guess the rest."

"Indeed, I cannot."

It was my turn now to indulge in a smile of superiority.

"I am surprised; but I will make it plainer. I succeeded in interesting her so that she kept me in the house some hours. I was able to amuse her; and when I had discovered where she kept her chief treasures, the rest was easy."

"You looked for yourself?"

"You do me less than justice. I am not so crude and inartistic in my methods. She showed them to me herself."

"Miss Gilmore!" Disbelief of the statement cried aloud in his exclamation.

"Why not say outright that you find that impossible of credence? Yet it is true. I mean that I led her to speak of matters which necessitated her going to that hiding-place, and interested her until she forgot that I had eyes in my head, so that, in searching for something else, she let me see the jewels themselves."

"Could you get them back?" he asked, eagerly.

I drew myself up and answered very coldly.

"I have failed to make your Excellency understand me or my motives, I fear. I could do so, of course, if I were also—a thief!"

"I beg your pardon, Miss Gilmore," he exclaimed quickly, adding with a touch of malice. "But you so interested me that I forgot who you were."

"It was only an experiment on my part; and so far successful that I won the Countess' confidence and she has pressed me to go to her."

"You didn't refer her to me for your credentials, I suppose?" he said, his eyes lighting with sly enjoyment.

"She asked for no credentials."

"Do you mean that you talked her into wanting you so badly as to take you into her house without knowing anything about you?"

"May I remind your Excellency that I was honoured by even your confidence in giving me my present position without any credentials."

He threw up his hands.

"You have made me forget that in the excellent discretion with which you have since justified my confidence. I have indeed done you less than justice."

"The Countess thinks that, together, we should make a strong combination."

"You must not go to her, Miss Gilmore—unless at least——"

He paused, but I had no difficulty in completing his sentence.

"That is my view, also—unless at least I come to an understanding with you beforehand. It will help that understanding if I tell you that I am in no way dependent upon my work for my living. I am an American, as I have told you, but not a poor one; and my motive in all this has no sort of connexion with money. As money is reckoned here, I am already a sufficiently rich woman."

"You continue to surprise me. Yet you spoke of—of a recompense for your services?"

"I am a volunteer—for the present. I shall no doubt seek a return some time; but as yet, it will be enough for me to work for your Government; to go my own way, to use my own methods, and to rely only upon you where I may need the machinery at your disposal. My success shall be my own. If I succeed, the benefits will be yours; if I fail, you will be at liberty to disavow all connexion between us."

He sat thinking over these unusual terms so long that I had to dig in the spur.

"The Countess d'Artelle is a more dangerous woman than you seem at present to appreciate. She is the secret agent of her Government. She has not told me that, or I should not tell it to you; but I know it. Should I serve your Government or hers? The choice is open to me."

He drew a deep breath.

"I have half suspected it," he murmured; then bluntly: "You must not serve hers."

"That is the decision I was sure you would make, General. We will take it as final."

"You are a very remarkable young woman, Miss Gilmore."

"And now, a somewhat fatigued one. I will bid you good-night. I am no longer your daughter's governess, but will remain until you have found my successor."

"You will always be a welcome guest in my house," and he bade me good-night with such new consideration as showed me I had impressed him quite as deeply as I could have wished. Perhaps rather too deeply, I thought afterwards, when I recalled his glances as we parted.

When my talk with General von Erlanger over the chess board took place, I had but recently decided to plunge into the maelstrom whose gloomy undercurrent depths concealed the proofs of my father's innocence and the dark secret of his cruel wrongs.

My motive in coming to Pesth was rather a desire to gauge for myself at first hand the possibility of success, should I undertake the task, than the definitely formed intention to attempt it.

I had studied all my father's papers closely, and in the light of them had pushed such inquiries as I could. I had at first taken a small house, and as a reason for my residence in the city had entered as a student of the university.

I was soon familiar with the surface position of matters. Duke Alexinatz was dead: his son's death was said to have broken his heart; and Duke Ladislas of Kremnitz was the acknowledged head of the Slavs. Major Katona was now Colonel Katona, and lived a life of seclusion in a house in a suburb of the city. Colonel von Erlanger had risen to be General, and was one of the chief Executive Ministers of the local Hungarian Government—a very great personage indeed.

The Duke had two sons, Karl the elder, his heir, and Gustav. Karl was a disappointment; and gossip was very free with his name as that of a morose, dissipated libertine, whose notorious excesses had culminated in an attachment for Madame d'Artelle, a very beautiful Frenchwoman who had come recently to the city.

Of Gustav, the younger, no one could speak too highly. He was all that his brother was not. As clever as he was handsome and as good as he was clever, "Gustav of the laughing eyes," as he was called, was a favourite with every one, men and women alike, from his father downwards. He was such a paragon, indeed, that the very praises of him started a prejudice in my mind against him.

I did not believe in paragons—men paragons, that is. Cynicism this, if you like, unworthy of a girl of three and twenty; but the result of a bitter experience which I had better relate here, as it will account for many things, and had close bearing upon what was to follow.

As I told General von Erlanger, I am not a "usual person;" and the cause is to be looked for, partly in my natural disposition and partly in my upbringing.

My uncle Gilmore was a man who had made his own "pile," and had "raised" me, as they say in the South, pretty much as he would have "raised" a boy had I been of that sex. His wife died almost directly after I was taken to Jefferson City; but not before my sharp young eyes had seen that the two were on the worst of terms. His nature was that rare combination of dogged will and kind heart; and his wife perpetually crossed him in small matters and was a veritable shrew of shrews. He was "taking no more risks with females," he told me often enough, with special reference to matrimony; and at first was almost disposed to send me back to Pesth because of my sex. That inclination soon changed, however; and all the love that was in his big heart was devoted to my small self.

But he treated me much more like a boy than a girl. I had my own way in everything; nothing was too good for me. In a word, I was spoiled to a degree which only American parents understand.

"Old Gilmore's heiress" was somebody in Jefferson City, I can assure you; and if I gave myself ridiculous airs in consequence, the fault was not wholly my own. I am afraid I had a very high opinion of myself. I did what I liked, had what I wished, went where I pleased, and thought myself a great deal prettier than I was. I was in short "riding for a fall;" and I got it—and fell far; being badly hurt in the process.

The trouble came in New York where I went when I was eighteen; setting out with the elated conviction that I was going to make a sort of triumphal social progress over the bodies of many discomfited and outclassed rivals.

But I found that in New York I was just one among many girls, most of them richer and much prettier than I: a nobody with provincial mannerisms among heaps of somebodies with an air and manner which I at first despised, then envied, and soon set to work at ninety miles an hour speed to imitate.

I had all but completed this self-education when my trouble came—a love trouble, of course. I became conscious of a great change in myself. Up to that point I had held a pretty cheap opinion of men in general, and especially of those with whom I had flirted. But I realized, all suddenly, the wrongfulness of flirting. That was, I think the first coherent symptom. The next was the painful doubt whether a very handsome Austrian, the Count von Ostelen, was merely flirting with me.

I knew German thoroughly, having spoken it in my childhood; and I had ample opportunities of speaking it now with the Count. We both made the most of them, indeed; until I found—I was only eighteen, remember—that the world was all brightness and sunshine; the people all good and true; and the Count the embodiment of all that a girl's hero should be.

I was warned against the Count, of course: one's intimate friends always see to that; but the warnings acted as intelligent persons will readily understand—they made me his champion, and plunged me deeper than ever into love's wild, entrancing, ecstatic maze. To me he became not only the personification of manly beauty and strength, but the very type of human nobility, honour, and virtue.

To think such rubbish about any man, one must of course have the fever very badly; and I had it so intensely that, when he paid me attentions which made other girls tremble with anger and envy, I was so happy that I even forgot to exult over them. I must have been very love sick for that.

I came to laugh at it afterwards—or almost laugh—and to realize that it was an excellent discipline for my silly child's pride: but to learn the lesson I had to pass through the ordeal of fire and passion and hot scalding tears that go to the hardening of a young heart.

He had been merely amusing himself at the expense of a "raw miss from the West;" and the knowledge came to me as suddenly as the squall will strike a yacht, all sails standing, and strew the proud white canvas a wreck on the waves.

At a ball one night we had danced together as often as usual, and when, as we sat out a waltz, he had asked me for a ribbon or a flower, I had been child enough to let him see all my heart as I gave them to him. Love was in my eyes; and was answered by words and looks from him which set me in a very seventh heaven of ecstatic delight.

Then, the next day, crash came the dream-skies all about me.

I was riding in the Central Park and he joined me. I saw at once he was changed; and my glad smile died away at his constrained formal greeting. He struck the blow at once, with scarcely a word of preamble.

"I am leaving for Europe to-morrow, Miss von Dreschler," he said. "I have enjoyed New York immensely."

The chill of dismay was too deadly to be concealed. I gripped the pommel of the saddle with twitching, strenuous fingers.

"You have been called away suddenly?" I asked; my instinct being thus to defend him even against himself.

He paused, as if hesitating to use the excuse I offered.

"No," he answered. "It has been arranged for weeks. These things have to be with us, you know."

In a flash his baseness was laid bare to me; and the first sensation of numbing pain dumbed me. I had not then acquired the art of masking my feelings. But anger came to my relief, as I realized how he had intentionally played with me. I knew what a silly trusting fool I had been; and knew too that had I been a man, I would have struck him first and killed him afterwards for his dastardly treachery. I was like a little wild beast in my sudden fury.

He saw something of this; for his eyes changed. "I am so sorry," he said. As if a lip apology were sufficient anæsthetic for the stabbing pain in my heart.

"For what, Count von Ostelen?" I asked, lifting my head and looking him squarely in the eyes. The question disconcerted him.

"I did not know——" he stammered, and stopped in confusion.

"Did not know what?" I asked; and he was again so embarrassed by the direct challenge that he kept silent. His embarrassment helped me; and I added: "I think your going is the best thing for all concerned, Count, except perhaps for the unfortunate country to which you go. Bon voyage!" And with that I wheeled my horse round and rode away.

It was months before the wound healed; months of sorrow, self-discipline and rigidly suppressed suffering. I took it fighting, as our Missouri men say. No one saw any difference in me. My moods were as changeable, my manner as frivolous, my words as light and my smiles as frequent as before; and I was as careful not to over-act the frivolous part as I was to hide the truth. It was a period of as hard labour as ever a convict endured in Sing-Sing prison.

But I won. Not a soul even suspected the canker in my heart which had changed the point of view of all things in life for me. I came in the end to be glad of the stern self-discipline which had made me a woman before my girlhood had fully opened. I learnt the lesson thoroughly, and never again would I be tempted to trust myself to any man's untender mercies.

I grew very tired of a girl's humdrum routine life. I longed for activity and adventure. I wanted to be doing something earnest and real, to pit myself against men on equal terms; and for this I sought to qualify myself both physically and mentally. I travelled through the States alone; meeting more than once with adventures that tested my nerve and courage.

I made a trip to Europe; and when my uncle insisted upon sending a good placid dame to chaperone me, I found occasion to quarrel with her on the voyage out so that I might even sample Europe by myself.

Unconsciously, I was fitting myself for the work which my father's letters were to lay upon me; and when in Paris on that trip I had an adventure destined to prove of vital import to that task.

The big hotel in which I was staying caught fire one night, and the visitors, most of them women and elderly men, were half mad with panic. I was escaping when I found crouching in one of the corridors, fear-stricken, helpless, and hysterical, a very beautiful woman whom I had seen at the dinner table, the laughing centre of a noisy and admiring crowd of men. I first shook some particles of sense into her and then got her out.

It was a perfectly easy thing to do without any risk to me; but she said I had saved her life. Probably I had: for she might have lain there till she was suffocated by the smoke; and she insisted upon showering much hysterical gratitude upon me; and then wished to make me her close friend. She was a Madame Constans; and, as I can be cautious enough upon occasion, I had some inquiries made about her from our Embassy. The caution was justified. She was a secret Government agent; a police spy with a past.

I parted from her therefore amid vivid evidences of affection from her and vehement protestations that, if ever she could return the obligation, her life would willingly be at my disposal. I accepted her declarations at their verbal worth and expected never to see her again.

But the Fates had arranged otherwise; and it was with genuine astonishment that when Madame d'Artelle was pointed out to me one day driving in the Stadwalchen of Pesth, I recognized her as Madame Constans.

This fact set me thinking. What could she be doing in Buda Pesth? Why was she coiling the net of intrigue round the young Count—the future Duke? Was she still a secret Government agent promoted to an international position? Who was behind her in it all? These and other questions of the kind were started.

Then came the mysterious theft of the ducal jewels; and through my instinct, or intuition, call it by what term you may, that which was a mystery to so many became my key to the whole problem. Count Karl was in the toils of the lovely French-woman; he was one of the very few persons who had access to the jewels; he was admittedly a man of dissipated habits; and it was an easy deduction that she had instigated the robbery; more to test the extent of her power over him, perhaps, than because she coveted the jewels. There was much more than mere vulgar theft in it; that was but one of the coils she threw round him. She was in the Hungarian capital because others had sent her to find out secrets; and she was drawing the net about his feet to ruin him for other and greater purposes.

Here then was my course ready shaped for me. I had entered the Minister's household to win his confidence as a possible means to the end I had in view; but the study of my father's papers had shown me that the General might have had a hand in the grim drama, and in such an event I might find my way blocked.

But if I took the field against Madame d'Artelle and cut the meshes of the net of ruin being woven round Count Karl, I should have on my side the future Duke, the man with the power in his hands, and himself quite innocent of all connexion with my father's fate. Success might easily lie that way.

I acted promptly. I went to Madame d'Artelle's; and the interview was one which would have greatly interested his Excellency. I posed as the student and governess with my own way to make in the world; and the Frenchwoman, eager to buy my silence and wishing to separate me from the Minister, urged me to trust to her to advance my interests, and to live with her in the meantime.

I consented, of course; and it was then I spoke out to General von Erlanger. Thus with one stroke I established close relations with two sides in the intrigue.

It was with a feeling of some inward satisfaction at the progress I was making that I went to stay in Madame d'Artelle's house; and, as I had not yet seen the man whom I planned to deliver from her hands, I looked forward with much curiosity and interest to meeting him. I should need to study him very closely; for I was fully alive to the infinite difficulties of what I had undertaken to do.

But those difficulties were to prove a hundred-fold greater than I had even anticipated; and my embarrassment and perplexity were at first so great, that I was all but tempted to abandon the whole scheme.

I was sitting with Madame d'Artelle one afternoon reading—I kept up the pretence of studying—when Count Karl was announced. I rose at once to leave the room.

"Don't go," she said. "I wish to present you to the Count."

"Just as you please," I agreed, glad of the chance, and resumed my seat.

He was shown in, and as I saw him I caught my breath, my heart gave a great leap, and I felt a momentary chill of dismay.

Count Karl was no other than the Count von Ostelen—the man whose treatment of me five years before in New York had all but broken my heart and spoilt my life.

Here was a development indeed.

For a moment the situation oppressed me, but the next I had mastered it and regained my self-possession. I was not recognized. Karl threw a formal glance at me as Madame d'Artelle mentioned my name, and his eyes came toward me again when she explained that I was an American. I was careful to keep my face from the light and to let him see as little of my features as possible. But I need not have taken even that trouble. He did not give me another thought; and I sat for some minutes turning over the pages of my book, observing him, trying to analyze my own feelings, and speculating how this unexpected development was likely to affect my course.

My first sensation was one which filled me with mortification. I was angry that he had not recognized me. I told myself over and over again that this was all for the best; that it made everything easier for me; that I had no right to care five cents whether he knew me or not; and that it was altogether unworthy of me. Yet my pride was touched: I suppose it was my pride; anyway, it embittered my resentment against him.

It was an insult which aggravated and magnified his former injury; and I sat, outwardly calm, but fuming inwardly, as I piled epithet upon epithet in indignant condemnation of him until my old contempt quickened into hot and fierce hatred. I felt that, come what might, I would not stir a finger to save him from any fate to which others were luring him.

But I began to cool after a while. I was engaged in too serious a conflict to allow myself to be swayed by any emotions. I could obey only one guide—my judgment. Here was the man who of all others would be able by and by to help me most effectively: and if I was not to fail in my purpose I must have his help, let the cost be what it might.

It was surely the quaintest of the turns of Fate's wheel that had brought me to Pesth to save him of all men from ruin; but I never break my head against Fate's decrees, and I would not now. So I accepted the position and began to watch the two closely.

Karl was changed indeed. He looked not five, but fifteen, years older than when we had parted that morning in the Central Park. His face was lined; his features heavy, his eyes dull and spiritless, and his air listless and almost preoccupied. He smiled very rarely indeed, and seemed scarcely even to listen to Madame d'Artelle as she chattered and laughed and gestured gaily.

The reason for some of the change was soon made plain. Wine was brought; and when her back was toward him I saw him look round swiftly and stealthily and pour into his glass something from a small bottle which he took from his pocket.

I perceived something else, too. Madame d'Artelle had turned her back intentionally so as to give him the opportunity to do this; for I saw that she watched him in a mirror, and was scrupulous not to turn to him again until the little phial was safely back in his pocket.

So this was one of the secrets—opium. His dulness and semi-stupor were due to the fact that the previous dose was wearing off; and she knew it, and gave him an opportunity for the fresh dose.

I waited long enough to notice the first effects. His eyes began to brighten, his manner changed, he commenced to talk briskly, and his spirits rose fast. I feared that under the spur of the drug his memory might recall me, and I deemed it prudent to leave the room.

I had purposely held my tongue lest he should recognize my voice—the most tell-tale of all things in a woman—but now I rose and made some trivial excuse to Madame d'Artelle.

As I spoke I noticed him start, glance quickly at me, and pass his hand across his forehead; but before he could say anything, I was out of the room. I had accomplished two things. I had let him familiarize himself with the sight of me without associating me with our former relations; and I had found out one of the secrets of Madame's influence over him—her encouragement of his drug-taking.

But why should she encourage it? It seemed both reasonless and unaccountable. Did she care for him? I had my reasons for believing she did. Yet if so, why seek to weaken his mind as well as destroy his reputation? I thought this over carefully and could see but one answer—she must be acting in obedience to some powerful compelling influence from outside. Who had that influence, and what was its nature?

When I knew that Karl had gone I went down stairs and had another surprise. I found Madame d'Artelle plunged apparently in the deepest grief. She was a creature of almost hysterical changes of mood.

"What is the matter?" I asked, with sparse sympathy. "Don't cry. Tears spell ruin to the complexion."

"I am the most miserable woman in the world," she wailed.

"Then you are at the bottom of a very large class. Tears don't suit you, either. They make your eyes red and puffy. A luxury even you cannot afford, beautiful as you are."

"You are hateful," she cried, angrily; and immediately dried her eyes and sat up to glare at me.

I smiled. "I have stopped your crying at any rate."

"I wish to be alone."

"I think you ought to be very grateful to me. Look at yourself;" and I held a hand mirror in front of her face.

She snatched it from me and flung it down on the sofa pillow with a little French oath.

"Be careful. To break a mirror means a year's ill luck. A serious misfortune for even a pretty woman."

"I don't believe you have a grain of sympathy in your whole heart. It must be as hard as a stone."

"My dear Henriette, the heart has nothing to do with sympathy or any other emotion. It is just the blood pump. I have not read much physiology but...."

"Nom de Dieu, spare me your science," she cried, excitedly.

I laughed again without restraint. "We'll drop physiology, then. But I know other things, and now that I have brought you out of the tear stage, we'll talk about them if you like. I agree with you that it is most exasperating and bitterly disappointing."

Her face was a mask of bewilderment as she turned to me swiftly. "What do you mean?" The question came after a pause.

"It is so ridiculously easy. I mean what you were thinking about when the passion of tears came along. What are you going to do about it?"

I had seated myself and taken up a book, and was turning over the leaves as I put the question. She jumped up excitedly and came and stood over me, her features almost fiercely set as she stared down.

"What do you mean? You shall say what you mean. You shall."

"Not while you stand there threatening me with a sort of wild glare in your eyes. I don't think it's fair to be angry with me just because you can't do what you wish."

She stretched out her hands as if she would shake me in her exasperation. Then she laughed, a little wildly, and went back to her seat on the couch.

"What was in my thoughts then?"

"At the foundation—the inconvenience of your religious convictions as a member of the Roman Catholic Church."

"You are mad," she cried, with a toss of her shapely head and a ringing laugh. But as the laugh died away her eyes filled with sobering perplexity. "At the foundation," she said slowly, repeating my words. "You are a poor thought-reader. What else was I thinking of?"

I paused to give due significance to my next words, and looked at her fixedly as I spoke. "Of your marriage with M. Constans; and that in your church, marriage is a sacrament."

"You are a devil," she exclaimed, with fresh excitement, almost with fury indeed. "Say what you mean and don't torment me."

"The Count has been urging you to marry him of course, and——"

"You have been listening. You spy." The last vestige of her self-control was lost as she flung the words at me.

I paused. I never act impetuously with hysterical people. With studied deliberation I closed my book, having carefully laid a marker between the pages, and looked round as if for anything that might belong to me. Then I rose. Her eyes watched me with growing doubt and anxiety.

"I shall be ready to leave the house in about an hour, Madame," I said icily, and walked toward the door.

She let me get close to it. "What are you going to do?"

My answer was a cold smile, in which I contrived to convey a threat. I knew how to frighten her.

She jumped up and rushed to the door and stood with her back against it—as an angry, over-teased child will do. "You shall not go. You mean to try and ruin me." I had known before that she was afraid of me; but she had never shown it so openly.

"Yes, I shall do my best." I spoke so calmly and looked her so firmly in the face that she was convinced of my earnestness.

"I didn't mean what I said," she declared.

"It is too late for that," I replied, with a sneer of obvious distrust and disbelief. She had very little courage and was a poor fighter. Her only weapon was her beauty; and it was useless of course against me.

Her eyes began to show a scared, hunted expression. "Don't go. Forgive me, Christabel. I didn't mean it. I swear I didn't. You angered me, and you know how impetuous I am."

"I am surprised you should plead thus to—a spy, Madame."

"But I tell you I didn't mean it. Christabel, dear Christabel, I know you are not a spy. Don't make so much of an angry word. Come, let us talk it over. Do, do"; and she put her arm in mine to lead me back to my chair.

I let her prevail with me, but with obvious reluctance. "Why are you so afraid of me?" I asked.

"I am not afraid of you; but I want you to stay and help me."

I sat down then as a concession and a sign that I was willing to talk things over; and she sat near me, taking care to place her chair between me and the door.

"If that is so, it is time that we understood one another. Perhaps I had better begin. You cannot marry Count Karl."

"I love him, Christabel."

"And Monsieur Constans—your husband?"

"Don't, don't. He deserted me. He is a villain, a false scoundrel. Don't speak of him in the same breath with—with the man I love."

"He is your husband, Madame." She moaned and waved her arms despairingly.

"I am the most wretched woman on earth. I love him so."

"And therefore encourage him to take opium. I do not understand that kind of love. Had you not better tell me the truth?"

"I shall save him. You don't understand. My God, you don't understand at all. The only way I can save him is to do what he asks."

"Who is it that is forcing your hand?"

She winced at the question, as if it were a lancet thrust. "You frighten me, Christabel, and mystify me."

"No, no. It is only that you are trying to mystify me, and are frightened lest I should guess your secret. Let us be fair to one another. I have an object here which you cannot guess and I shall not tell you. You have an object which I can see plainly. You have been brought here to involve Count Karl in a way which threatens him with ruin, and you have fallen in love with him—or think you have. You are now anxious to please your employer and also secure the man you love from the ruin which threatens him. He has asked you to marry him; and a crisis has arisen which you have neither the nerve to face nor the wit to solve."

"Nom de Dieu, how you read things!" she exclaimed under her breath, her eyes dilated with wonder and fear.

"But for my presence you would marry him; and trust to Fate to avoid the discovery being made that M. Constans is still alive. To yourself you would justify this by the pretence that if you were once the Count's wife you could check instead of encourage his opium habit and so save him. Who then is it with the power to drive you into this reckless crime?"

She was too astounded to reply at once, but sat staring at me open mouthed. Suddenly she changed, and her look grew fierce and tense. "Who are you, and what is your motive in forcing yourself upon me here?"

"I depend on my wits to make a way for me in the world, Madame; and I take care to keep them in good condition. But I am not forcing myself upon you. I am ready to go at this moment—if you prefer that—and if you think it safer to have me against you."

"Mon Dieu, I believe I am really afraid of you."

"Of me, no. Of the knowledge I have, yes. And you will do well to give that fear due weight. You have been already induced to make one very foolish move. To receive stolen jewels is a crime, even when the thief is——"

"How dare you say that!"

"You forget. The day I came first to you you had occasion to go to the secret drawer in the old bureau in your boudoir, and I saw them there. You are a very poor player, Madame, in such a game as this."

The colour left her cheeks, and hate as well as fear was in her eyes as she stared helplessly at me.

"It is all your imagination," she said, weakly.

I smiled.

"It can remain that—if you wish. It is for you to decide."

"What do you mean?"

"You had better trust me. You can begin by telling me what and whose is this evil influence behind you?"

A servant interrupted us at that moment.

"His Excellency Count Gustav is asking for you, Madame."

She gave a quick start, and flashed a look at me.

"I will go to him," she answered.

I had another intuition then. I smiled and rose.

"So that is the answer to my question. You may wish to consult him, Madame. I will see you afterwards; and will use the interval to have my trunks packed in readiness to leave the house should he deem it best."

"I am right. You are a devil," she cried, with another burst of impetuous, uncontrollable temper.

I turned as I reached the door.

"Should he decide that I stay, Madame, and wish to see me, I shall be quite prepared."

I went out then without waiting for any reply.

I felt completely satisfied with the result of my conversation with Madame d'Artelle. I had had some qualms about the manner in which I had entered her house; feeling, it must be confessed, something like a spy. But our relations would now be changed. It would be at most an alliance of hostility. I should only remain because she would deem it more dangerous for me to leave; she would trust me no further than she dared; and as I had openly acknowledged that I had an object of my own in view, I need no longer have any scruples about staying.

I had made excellent use of my opportunities, moreover; and if my last shaft had really hit the bull's-eye—that the influence behind her was that of Karl's brother—the discovery would be of the utmost value.

Could it be Count Gustav? Instead of packing my trunks I sat trying to answer that question and the others which flowed from it. I had always heard him spoken of not only as a man of high capacity and integrity but as a staunch friend to his brother Karl. Yet he was a man; and he might be as false as any other. I would take no man's good faith for granted.

There was the crucial fact, too, that Karl's ruin meant Gustav's advantage. Every one expressed regret that Karl and not Gustav was to be the future Duke; and if others felt this, was Gustav himself likely to hold a different opinion? From such an opinion it was no doubt a far cry to form a deliberate plot to secure the dukedom; but Gustav was no more than a man; and men had done such things before.

I hoped they would send for me, that I might judge for myself. I could understand how my interference with such a scheme, if he had formed it, would rouse his resentment; and the difficulty it would present. To send me out of the house would in his view be tantamount to giving away the whole scheme at once to General von Erlanger; and I settled it with myself therefore that, if he was really at the back of the plot, he would be as eager to see me as I was to see him.

An hour passed and I was beginning to think I was wrong, when Madame's French maid came to my room, saying that her mistress would very much like to speak to me.

"Where is she, Ernestine?"

"In the salon, mademoiselle."

"Alone?"

"M. le Comte Gustav is with her."

"I will go to her," I said; and as she closed the door I laughed. I was not wrong, it seemed, but very much right; and I went down to meet them with the confidence borne of the feeling that I knew their object while they were in ignorance of mine.

People did the Count no less than justice in describing him as a handsome man. He had one of the handsomest faces I had ever looked upon; eyes of the frankest blue, a most engaging air, and a smile that was almost irresistibly winning.

He held out his hand when Madame presented him, and spoke in that ingratiating tone which is sometimes termed caressing.

"I have desired so much to know Madame d'Artelle's new friend, Miss Gilmore. I trust you will count me also among your friends."

"You are very kind, Count. You know we Americans have a weakness for titles. You flatter me." I was intensely American for the moment, and almost put a touch of the Western twang in my accent.

"You are really American, then?"

"You bet. From Missouri, Jefferson City: as fine a town in as fine a State as anywhere in the world. Not that I run down these old-world places in Europe. Have you been in the States?"

"To my regret, no."

"Ah, then you haven't seen what a city should be. Fine broad straight streets, plenty of air space, and handsome buildings."

"I know that American women are handsome," he replied, with a look intended to put the compliment on me. But I was not taking any.

"I guess we reckon looks by the dollar measure, Count. You should see our girls at home."

"You must regret living away from your country."

"Every man must whittle his own stick, you know, and every woman too. Which means, I have to make my own way."

"You are more than capable, I am sure."

"I can try to plough my own furrow, sure."

"You have come to Pesth for that purpose?"

"Yes—out of the crowd."

"What furrow do you think of ploughing here?"

"Well, just at present I'm in Madame's hands, you see. And I think we're getting to understand one another, some. Though whether we're going to continue to pull in the same team much longer seems considerably doubtful."

"I am very anxious to help you, Christabel, dear," put in Madame d'Artelle; and I knew from that "dear," pretty much what was coming.

"It would give me much pleasure to place what influence I have at your disposal, Miss Gilmore."

"I must say I find everybody's real kind," I answered, demurely. "There is General von Erlanger saying very much the same thing."

"You speak German with an excellent idiom," said the Count, with a pretty sharp look. "One is tempted to think you have been in Europe often before."

I laughed. "I was putting a little American into the accent, Count, as a matter of fact. I have a knack for languages. I know Magyar just as well. And French, and Italian, and a bit of Russian. I'm a student of comparative folk lore, you know; and I'm getting up Turkish and Servian and Greek."

"But surely you have been much in Europe?"

"I was in Paris three years ago;" and at that Madame d'Artelle looked away.

"So Madame told me," he said, suggestively. "It was there you met, of course. It was there you made your mistake about her, I think."

"What mistake was that?"

"That Madame's husband was still alive."

So he was a scoundrel after all, and this was to be the line of tactics.

"Oh, that is to be taken as a mistake, is it?" I said this just as though I were ready to fall in with the suggestion.

"Not taken as a mistake, Miss Gilmore. It is a mistake. We have the proofs of his death."

"'We'?" I rapped back so sharply that he winced.

"Madame has confided in me," he replied.

"Well, from all accounts she has not lost much; and must be glad to be free to marry again."

His eyes smiled. "You are very quick, Miss Gilmore."

"I am not so quick as Madame," I retorted; "because she has got these proofs within the last hour. It is nothing to me, of course; but I don't think we are getting on so quickly to an understanding as we might."

"You know that I am my brother's friend as well as Madame's in this?"

"What does that mean?"

"In regard to the marriage on which my brother's heart is so deeply set. You are willing to help it also?"

"How can it concern me? What for instance would happen to me if I were not?" I paused and then added, significantly: "And what also if I were?"

"I think we shall arrive at a satisfactory understanding," he answered, with obvious relief. "Those who help my family—a very powerful and influential one, I may remind you—are sure to secure a great measure of our favour."

"I desire nothing more than that," said I, with the earnestness of truth—although the favour which I needed was not perhaps in his thoughts.

"Madame would of course like to know a good deal about all who co-operate with her," he declared, very smoothly and suggestively.

"What do you wish to know about me; and what do you wish me to do?"

"Americans are very direct," he replied, bowing. "She would leave you to tell us what you please, of course, and afford such means as you think best for her to make inquiries."

"Every one in Jefferson City knew my uncle, John P. Gilmore, knows that he educated me, and that what little money he left came to me. My father was a failure in life, and my mother died when I was a little child. I'm afraid I haven't made much history so far. And that's about all there is to it. What matters to me is not the past but the present and, perhaps, the future."

"You have no friends in Pesth?"

"None, unless you count General von Erlanger; I was his children's governess and used to play chess with him."

"And your motive in coming here?" There was a glint in his eyes I did not understand.

"I thought I had told you. I am a student in the University."

"That is all?"

I laughed. "Oh no, indeed it isn't. I am just looking around to shake hands with any opportunity that chances to come my way. I am a soldieress of fortune. That's why I came to Madame d'Artelle. Not to study folk lore."

"In Paris you were not a student?"

"Oh, you mean I was better off then? My uncle Gilmore was alive; and we all thought he was rich."

"Pardon my inquisitiveness yet further. You know New York well?" This was the scent, then.

"I know Fifth Avenue, have walked about Broadway, and once stood in a whirl of amazement on Brooklyn Bridge. But I haven't a friend in the whole city."

"Were you there five years ago?"

I affected to search my memory. "That would be in ninety-five. I was eighteen. I have been about so much in the States that my flying visits to New York are difficult to fix. Was that the year I went to California? If so, I did not go East as well, and yet I fancy I did. No, that was to Chicago and down home through St. Louis."

"I mean for a considerable stay in New York?"

"Oh, I shouldn't forget that. That was three years ago before I started for Paris," I said, laughing lightly. "I had the time of my life then."

"Did you ever meet a Miss Christabel von Dreschler?"

Where was he leading me now? What did he know? I shook my head meditatively. "I have met hundreds of girls but I don't remember her among them."

"She must resemble you closely, Miss Gilmore, just as she has the same Christian name. My brother knew her and declares that you remind him of her."

I laughed lightly and naturally. "I should scarcely have believed he had eyes or thoughts for any woman except Madame d'Artelle."

"Pardon me if I put a very plain question. You have acknowledged to be seeking your fortune here. You are doing so in your own name? You are not Miss von Dreschler?"

I took umbrage at once and showed it. I rose and answered with all the offended dignity I could assume. "When I have cause to hide myself under an alias, Count, it will be time to insult me with the suggestion that I am ashamed of my own name of Gilmore."

He was profuse in his apologies. "Please do not think I intended the slightest insult. Nothing was farther from my thoughts. I was merely speaking out of my hope that that might be the case. I am exceedingly sorry. Pray resume your seat."

I had scored that game, so I consented to be pacified and sat down again. I was curious to see what card he would play next.

He pulled at his fair moustache in some perplexity.

"You expressed a desire just now to have the advantage of my family's influence, Miss Gilmore."

"Am I to remain with Madame, then?" I asked, blandly.

"Of course you are, dear," she answered for herself.

"You are willing to help her and my brother in this important matter?" said the Count.

"How can I help? I am only a stranger. And I should not call it helping any one to connive at a marriage when one of the parties is already married. I would not do that."

The handsome face darkened; and in his impatience of a check he made a bad slip.

"Our influence is powerful to help our friends, Miss Gilmore, and not less powerful to harm our antagonists."

I laughed, disagreeably. "I see. A bribe if I agree, a threat if I do not. And how do you think you could harm an insignificant person like me? I am not in the least afraid of you, Count."

"I did not mean to threaten," he said, rather sullenly, as he saw his mistake. "You can do us neither harm nor good for that matter. You are labouring under a mistake as to Madame d'Artelle's husband—her late husband; and by speaking of the matter might cause some temporary inconvenience and slander. We do not wish you to do so. That is all.

"I have not yet been shown that it is a mistake."

"The proofs shall be given to you." He spoke quite angrily. "In the meantime if you speak of the matter, you will offend and alienate us all."

"It seems a very lame conclusion for all this preamble," I answered, lightly, as I got up. "Produce the proofs and I of course have no more to say. But until they are produced I give no pledge to hold my tongue;" and without troubling myself to wait for a reply, I left the room.

I had obtained the information I needed as to the power behind Madame d'Artelle, and I had something to do. They intended to produce proofs of M. Constan's death, and I resolved to get the proof that he was still living.

Leaving a message for Madame that I had to go to the university for an evening lecture, I drove to the house which I had taken on coming to Pesth.

In passing through Paris I had seen the friend who had formerly given me the information about Madame, and I now telegraphed to him that I must know the whereabouts of M. Constans at once, and that no expense was to be spared in getting the information.

I had brought three servants with me from home, John Perry and his wife and their son, James. The last was a sharp, clever young fellow, and he was now in Paris where I had sent him to get information about Madame d'Artelle. I wired to him also, telling him what further information I needed; and I instructed him to help in the matter and wire me the instant M. Constans had been traced.

That done I set out to return to Madame's. I was not nervous at being out alone at such a time, night prowling having long been a habit with me. I was perfectly able to take care of myself, too; for at home I had been accustomed to carry a revolver, and was an excellent shot. If any one interfered with me, it was not I who was likely to come worse off.

I think it is just nonsense that girls must always be "seen home" in the dark. It is a good excuse for flirtation, possibly; but an extremely undignified admission of inferiority. A humiliation I have never countenanced and never will.

The night was fine and clear, and a bright moon was nearly at the full; so I turned out of my way a little to a very favourite spot of mine—the great Suspension Bridge which constitutes the hyphen between Buda and Pesth. My house was close to the bridge in that part of Pesth known as the "Inner Town;" and I strolled across to a point on the Buda side from which a glorious view can be had of the stately Danube.

I stood there in the deep shadow of the high Suspension Arches, gazing at the dotted lights along the quays, across the flat country on the Pesth side, up the river toward the witching Margaret Island, and away to the old hilly Buda on my left, with the Blocksberg and its citadel keeping its frowning watch and ward over all.

There is not much poetry in my nature; but the most prosaic and commonplace soul must feel a quickening of thought and sentiment at the appeal of that majestic waterway and its romance-filled setting.

I did that night; and stood there, thinking dreamily, until I was roused abruptly by the sound of laughter. I recognized the voice of Count Gustav; and glancing round saw him on the other side of the bridge with a companion. He stooped a second and pointed down the river; and as they walked on, I heard her laugh sweetly in response.

I was considering what to do, when I caught the sound of footsteps, and shrank into the shadow of the deep buttress as two men came slouching past me stealthily; and I heard enough to tell me they were following Count Gustav. I let them pass and then followed in my turn.

The Count and his companion left the bridge, turned to the right, and presently entered the old garden of Buda—a deserted spot enough at such an hour. Presently, as the two reached an open place, I saw the Count hesitate, glance about him, stand a moment, and take off his hat. Then they continued their walk.

I was struck by the action. It looked as though it might have been a signal; for the next moment the two men quickened their pace and closed up to the pair. A momentary scuffle followed; the girl gave a half-smothered cry for help; and then the Count came running past me, making for the bridge at the top of his speed. He had left his companion in the hands of the two men.

Convinced now that mischief was on foot, I resolved to see the matter through. I hid myself as the men came hurrying back with the girl, half-leading, half-carrying her; and I noticed that her face was closely muffled.

Near the entrance to the place they halted, and drew back under the shadow of the trees. They stood there some moments, when one of them went out into the road and stood listening. I heard in the distance the sound of wheels, and guessed it was a carriage for which the two were waiting.

Clearly, if I was to make an attempt to save the girl, I must act at once; and to save her and learn her story, I was now determined.

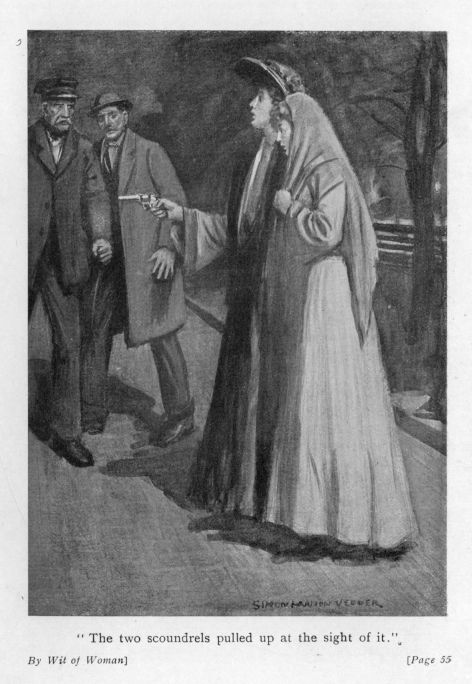

I took a deep breath, as one will when about to plunge into a cold stream, and keeping my hand on my revolver I darted across to where the girl and her one captor stood. It was a point in my favour that the two men were just then separated.

He did not hear my footsteps until I was close to him, and gave a great start of surprise when I spoke.

"Let my friend go at once," I said, in a loud, firm tone.

The man's start was the girl's opportunity. Snatching her arm out of his grasp, she rushed to me, tearing at the wrapper which covered her face.

The man swore and called his companion, who ran swiftly back. A couple of words were exchanged hurriedly between them, and then they came at me, one of them brandishing a heavy stick and threatening me.

The girl uttered a sharp cry of fear.

I whipped out my revolver, and the two scoundrels pulled up at the sight of it.

"If you make me fire I shall not only shoot you," I called, "but bring the police up, and you'll have to explain this to them."

And as we stood thus, the carriage drove up.

I was quite as anxious to avoid police interference as the men themselves could be; but I knew the threat was more likely to drive them off than any other.

To recover the girl, they would have bludgeoned me readily enough, if they could have done it without being discovered; but my weapon made that impossible. Moreover, they liked the look of the business end of the revolver as little as many braver men.

The stick was lowered; they whispered together, and then tried to fool me. They began to edge away from one another, so as to be able to rush in from opposite directions.

"You stand just where you are, or I fire, right now," I called.

They stopped and swore.

"Can't a man take his own daughter home?" growled one of them.

"I am not his daughter," protested the girl.

"I know that. Don't be afraid, I shan't give you up."

"Who are you to interfere with us?" asked the other.

"I'm a man in woman's clothes," I answered, intending this tale to be carried to their employer. "And I'll give you five seconds to clear. You get into that carriage and drive off, the lot of you together, or I'll bring the police about your ears. Now, one, two, if you let me count to five, you'll eat nothing but prison fare for a year or two. Off with you;" and emboldened by my success I made a step toward them.

It was good bluff. They shrank back; then turned tail and scurried to the carriage, swearing copiously, and drove off in the direction of Old Buda.

I watched the vehicle until the darkness swallowed it, and then hurried with my companion in the opposite direction. We recrossed the bridge and made for my house.

When we were near it I stopped, and she began to thank me volubly and with many tears.

"Don't thank me yet. Tell me where you wish to go."

"I have nowhere to go in Pesth, sir," she answered.

I smiled at her mistake. "Let me explain. I said that about my being a man to frighten those ruffians. I am a girl, like yourself, and have a home close by. If you like to come to it, you will be quite safe there."

"I trust you implicitly," she said, simply; and with that I took her to my house.

As we entered I managed to draw out a couple of hairpins, so that when I took off my hat, my hair came tumbling about my shoulders in sufficient length to satisfy her of my sex. She was quick enough to understand my reason; and with a very sweet smile she put her arm round my waist and kissed me on the cheek.

"I did not need any proof, dear," she said. "But you are wonderful. How I wish I were you. So brave and daring."

"You are very pretty, my dear," I answered, as I kissed her. She was; but very pale and so fragile that I felt as if I were petting a child.

"I am so wretched," she murmured, and the tears welled up in her great blue eyes. "If I were only strong like you!"

"You shall tell me your story presently; but first I have something to do. Sit here a moment."

I went out and told Mrs. Perry to get us something to eat and to prepare a bed for my friend; and I wrote a hurried line to Madame d'Artelle that I was staying for the night with a student friend, and sent it by Mr. Perry.

When I went back the girl was sitting in a very despondent attitude, weeping silently; but she started up and tried to smile to me through her tears. Then I made a discovery. She had taken off her gloves, and on her left hand was a wedding ring.

"How can I ever thank you?" she cried.

"First by drying your tears—things might have been much worse with you, you know; think of that; then by having some supper; I am positively famished; and after that, if you like, you can tell me your story, and we will see whether, by putting our heads together, we cannot find a way to help you further."

"I am afraid——" and she broke down again.

With much persuasion I induced her to eat something and take a little wine; and this seemed to cheer her. She dried her eyes and as we sat side by side on a couch, she put her hand in mine and gradually nestled into my arms like a weary wee child.

"I'll begin," I said. "My name is Christabel Gilmore. I'm an American, and a student at the University here;" and I added some details about the States and so on; just talking so as to give her time to gather confidence.

"You haven't told me your name yet," I said, presently.

"I am the Countess von Ostelen. You have heard the name?" she said, quickly, at my start of surprise.

"I was surprised, that is all. Yes. I knew the name years ago in America. I knew the Count von Ostelen."

"He is my husband," she said, very simply. "My Christian name is Gareth. You will call me by that, of course." With a sweet little nervous gesture she slipped her arm away and began to finger her wedding ring.

"I had seen that, my dear."

"Your eyes see everything, Christabel;" and her arm came about me again and her head rested on my shoulder.

I sat silent for a few moments in perplexity. If she were Karl's wife, how came his brother to have been——what a fool I was! Of course the thing was plain. Gustav was the husband, and he had used his brother's name. My heart was stirred, and my intense pity for her found vent in a sigh.

"Why that sigh, Christabel?" Her sweet eyes fastened upon my face nervously, and I kissed her.

"The sigh was for you, child, not for myself. Had you not better tell me everything? Have you your husband's likeness?"

"I had it here in a locket," she said, wistfully, as she drew a chain from her bosom. "But to-day he said the locket was not good enough for me. I wish I had kept it now. You would have said he was the handsomest man you had ever seen. Oh, how selfish I am," she broke off, with a quick cry of distress and sat up.

"What is the matter?"

"I never thought of it. He was with me when those men attacked us. Oh, if he should have been hurt!"

"You can make your mind easy about that," I said, a little drily. "I saw the attack and that he escaped."

"He is so brave. He would have risked his life for me."

"I saw him—get away, dear," I replied. I nearly said run away; but could not yet undeceive her.

"If anything had happened to him, it would have killed me. I would rather have died than that." Then with a change of manner she asked: "Did you see his face, Christabel?"

"Yes, in the moonlight, but he passed me quickly."

"But you saw he was handsome?"

"One of the handsomest men I have ever seen," I assented, to please her.

"Yes, yes. That is just it, and as good as he is handsome."

"I could not see that, of course," I answered; and then was silent. I was growing very anxious as I saw the problem widening and deepening. Poor trustful little soul! How should I ever break the truth to her and not break her heart at the same time?

There was a long pause, which she broke. "Oh, how I hope he has really escaped, as you say."

"How came you to be where I saw you?" I asked. This reminded her, as I intended, that she had told me nothing yet.