Title: The Eulogy of Richard Jefferies

Author: Walter Besant

Release date: May 26, 2011 [eBook #36228]

Most recently updated: January 7, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Malcolm Farmer, Gary Rees and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

| 'I hearing got, who had but ears, | |

| And sight, who has but eyes before; | |

| I moments live, who lived but years, | |

| And truth discern, who knew but learning's lore. | |

| Thoreau. |

In the body of this work I have sufficiently explained the reasons why I was entrusted with the task of writing this memoir of Richard Jefferies. I have only here to express my thanks, first to the publishers, who have given permission to quote from books by Jefferies issued by them, namely: Messrs. Cassell and Co., Messrs. Chapman and Hall, Messrs. Longman and Co., Messrs. Sampson Low and Co., Messrs. Smith and Elder, and Messrs. Tinsley Brothers, and next, to all those who have entrusted me with letters written by Jefferies, and have given permission to use them. These are: Mrs. Harrild, of Sydenham,[Pg vi] Mr. Charles Longman, Mr. J.W. North, and Mr. C.P. Scott. I have also been provided with the note-books filled with Jefferies' notes made in the fields. These have enabled me to understand, and, I hope, to convey to others some understanding of, the writer's methods. I call this book the "Eulogy" of Richard Jefferies, because, in very truth, I can find nothing but admiration, pure and unalloyed, for that later work of his, on which will rest his fame and his abiding memory.

United University Club,

September, 1888.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| COATE FARM | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| SIXTEEN TO TWENTY | 49 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| LETTERS FROM 1866 TO 1872 | 66 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| GLEAMS OF LIGHT | 96 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| FIRST YEARS OF SUCCESS | 108 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| FICTION, EARLY AND LATE | 145[Pg vii] |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| IN FULL CAREER | 163 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| THE LONGMAN LETTERS | 193 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| THE COUNTRY LIFE | 214 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| "THE STORY OF MY HEART" | 269 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| THE CHILD WANDERS IN THE WOOD | 301 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| CONCLUSION | 327 |

| APPENDIX I. | |

| LIST OF JEFFERIES' WORKS | 366 |

| APPENDIX II. | |

| LIST OF PAPERS STILL UNPUBLISHED | 368 |

| APPENDIX III. | |

| LETTER TO THE "TIMES," NOVEMBER, 1872 | 370 |

"Go," said the Voice which dismisses the soul on its way to inhabit an earthly frame. "Go; thy lot shall be to speak of trees, from the cedar even unto the hyssop that springeth out of the wall; and of beasts also, and of fowls, and of fishes. All thy ways shall be ordered for thee, so that thou shalt learn to speak of these things as no man ever spoke before. Thou shalt rise into great honour among men. Many shall love to hear thy[Pg 2] voice above all the voices of those who speak. This is a great gift. Thou shalt also enjoy the tender love of wife and children. Yet the things which men most desire—riches, rank, independence, ease, health, and long life—these are denied to thee. Thou shalt be always poor; thou shalt live in humble places; the goad of necessity shall continually prick thee to work when thou wouldst meditate; to write when thou wouldst walk forth to observe. Thou shalt never be able to sit down to rest; thou shalt be afflicted with grievous plaguy diseases; and thou shalt die when little more than half the allotted life of man is past. Go, therefore. Be happy with what is given, and lament not over what is denied."

Richard Jefferies—christened John Richard, but he was always called by his second name—was born on November 6, 1848, at the farmhouse of Coate—you may pronounce it, if you please, in Wiltshire fashion—Caute. The house stands on the road from Swindon to Marlborough, about two miles and a half from the[Pg 3] former place. It has now lost its old picturesqueness, because the great heavy thatch which formerly served for roof has been removed and replaced by slates. I know not whether any gain in comfort has been achieved by this change, but the effect to outward view has been to reduce what was once a beautiful old house to meanness.

It consists of two rooms on the ground-floor, four on the first floor, and two large garrets in the roof, one of which, as we shall see, has memorable associations. The keeping-room of the family is remarkable for its large square window, built out so as to afford a delightful retreat for reading or working in the summer, or whenever it is not too cold to sit away from the fireplace. The other room, called, I believe, the best parlour, is larger, but it lacks the square window. In the days when the Jefferies family lived here it seems to have been used as a kind of store-room or lumber-room. At the back of the house is a kitchen belonging to a much older house; it is a low room built solidly of stone with timber rafters.[Pg 4]

Beside the kitchen is a large modern room, which was used in Richard's childhood as a chapel of ease, in which service was read every Sunday for the hamlet of Coate.

Between the house and the road is a small flower-garden; at the side of the house is a vegetable-garden, with two or three fruit-trees, and beyond this an orchard. On the other side of the house are the farm buildings. There seems to be little traffic up and down the road, and the hamlet consists of nothing more than half a dozen labourers' cottages.

"I remember," writes one who knew him in boyhood, "every little detail of the house and grounds, even to the delicious scent of the musk underneath the old bay window"—it still springs up afresh every summer between the cobble stones—"the 'grind-stone' apple, the splendid egg-plum which drooped over the roof, the little Siberian crabs, the damsons—I could plant each spot with its own particular tree—the drooping willow, the swing, the quaint little arbour, the fuchsia-bushes, the hedge walks, the little arched gate leading into the road, the delightful scent under the[Pg 5] limes, the little bench by the ha-ha looking towards Swindon and the setting sun. I am actually crying over these delicious memories of my childhood; if ever I loved a spot of this earth, it was Coate House. The scent of the sweet-briar takes me there in a moment; the walnut-trees you recollect, and the old wooden pump, where the villagers came for water; the hazel copse that my uncle planted; the gateway that led to the reservoir; the sitting-room, with its delightful square window; the porch, where the swallows used to build year after year; and the kitchen, with its wide hearth and dark window."

In "Amaryllis at the Fair" the scene is laid at Coate Farm. But, indeed, as we shall see, Coate was never absent from Jefferies' mind for long.

Coate is not, I believe, a large farm. It had, however, been in the possession of the family for many generations. Once—twice—it passed out of their hands, and was afterwards recovered. It was finally lost about twelve years ago. To belong to an old English yeoman stock is, perhaps, good enough[Pg 6] ancestry for anyone, though not, certainly, "showy." Richard Jefferies was a veritable son of the soil: not descended from those who have nothing to show but long centuries of servitude, but with a long line behind him of independent farmers occupying their own land. Field and forest lore were therefore his by right of inheritance.

As for the country round about Coate, I suppose there is no district in the world that has been more minutely examined, explored, and described. Jefferies knew every inch of ground, every tree, every hedge. The land which lies in a circle of ten miles' radius, the centre of which is Coate Farm-house, belongs to the writings of Jefferies. He lived elsewhere, but mostly he wrote of Coate. The "Gamekeeper at Home," the "Amateur Poacher," "Wild Life in a Southern County," "Round about a Great Estate," "Hodge and his Masters," are all written of this small bit of Wiltshire. Nay, in "Wood Magic," in "Amaryllis at the Fair," in "Green Ferne Farm," and in "Bevis," we are still either at Coate Farm itself or on the hills around.[Pg 7]

It is a country of downs. Two of them, within sight of the farmhouse, are covered with the grassy mounds and trenches of ancient forts or "castles." There are plantations here and there, and coppices, but the general aspect of the country is treeless; it is also a dry country. In winter there are water-courses which in summer are dry; yet it is not without brooks. Jefferies shows ("Wild Life in a Southern County," p. 29) that in ancient and prehistoric time the whole country must have been covered with forests, of which the most important survival is what is now called Ashbourne Chase. For one who loved solitude and wanderings among the hills, there could be hardly any part of England more delightful. Within a reasonable walk from Coate are Barbury Hill, Liddington Hill, and Ashbourne Chase; there are downs extending as far as Marlborough, over which a man may walk all day long and meet no one. It is a country, moreover, full of ancient monuments; besides the strongholds of Liddington and Barbury, there are everywhere tumuli, barrows, cromlechs, and stone circles. Way[Pg 8]land Smith's Forge is within a walk to the east; another walk, somewhat longer, takes you to Avebury, to Wan's Dyke, to the Grey Wethers of Marlborough, or the ancient forest of Savernake. There are ancient memories or whispers of old wars and prehistoric battles about this country. At Barbury the Britons made a final stand against the Saxons, and were defeated with great slaughter. Wanborough, now a village, was then an important centre where four Roman roads met, so that the chieftain or king who had his seat at Wanborough could communicate rapidly, and call up forces from Sarum, Silchester, Winchester, and the Chilterns. All these things speak nothing to a boy who is careless and incurious. But Richard Jefferies was a boy curious and inquiring. He had, besides, friends who directed his attention to the meaning of the ancient monuments within his reach, and taught him something of the dim and shadowy history of the people who built them. He loved to talk and think of them; in after-years he wrote a book—"After London"—which was inspired by these early[Pg 9] meditations upon prehistoric Britain. He himself discovered—it is an archæological find of very considerable importance—how the garrisons of these hill-top forts provided themselves with water. And as for his special study of creatures and their ways, the wildness of the country is highly favourable, both to their preservation and to opportunities for study. Perhaps no other part of England was better for the development of his genius than the Wiltshire Downs. Do you want to catch the feeling of the air upon these downs? Remember the words which begin "Wild Life in a Southern County."

"The most commanding down is crowned with the grassy mould and trenches of an ancient earthwork, from whence there is a noble view of hill and plain. The inner slope of the green fosse is inclined at an angle pleasant to recline on, with the head just below the edge, in the summer sunshine. A faint sound as of a sea heard in a dream—a sibilant 'sish, sish'—passes along outside, dying away and coming again as a fresh wave of the wind[Pg 10] rushes through the bennets and the dry grass. There is the happy hum of bees—who love the hills—as they speed by laden with their golden harvest, a drowsy warmth, and the delicious odour of wild thyme. Behind the fosse sinks, and the rampart rises high and steep—two butterflies are wheeling in uncertain flight over the summit. It is only necessary to raise the head a little way, and the cool breeze refreshes the cheek—cool at this height while the plains beneath glow under the heat."

All day long the trains from Devon, Cornwall, Somerset and South Wales, from Exeter, Bristol, Bath, Gloucester, and Oxford, run into Swindon and stop there for ten minutes—every one of them—while the passengers get out and crowd into the refreshment rooms.

Swindon to all these travellers is nothing at all but a refreshment-room. It has no other association—nobody takes a ticket to Swindon any more than to Crewe—it is the station where people have ten minutes allowed for eating. As for any village, or town, of Swindon, nobody has ever inquired whether there[Pg 11] be such a place. Swindon is a luncheon-bar; that is all. There is, however, more than a refreshment-room at Swindon. First, there has grown up around the station a new town of twenty thousand people, all employés of the Great Western Railway, all engaged upon the works of the company. This is not by any means a beautiful town, but it is not squalid; on the contrary, it is clean, and looks prosperous and contented, with fewer public-houses (but here one may be mistaken) than are generally found. It is an industrial city—a city of the employed—skilled artisans, skilled engineers, blacksmiths, foremen, and clerks. A mile south of this new town—but there are houses nearly all the way—the old Swindon stands upon a hill, occupying, most likely, the site of a British fortress, such as that of Liddington or Barbury. It is a market town of six or eight thousand people. Formerly there was a settlement of Dutch in the place connected with the wool trade. They have long since gone, but the houses which they built—picturesque old houses presenting two gables to the street—remained after them. Of these[Pg 12] nearly all are now pulled down, so that there is little but red brick to look upon. In fact, it would be difficult to find a town more devoid of beauty. They have pulled down the old church, except the chancel: there was once an old mill—Jefferies' grandfather was the tenant. That is also pulled down, and there is a kind of square or place where there is the corn exchange: I think that there is nothing else to see.

On market-day, however, the town is full of crowd and bustle; at the Goddard Arms you can choose between a hot dinner upstairs and a cold lunch downstairs, and you will find both rooms filled with men who know each other and are interested in lambing and other bucolic matters. The streets are filled with drivers, sheep, and cattle; there is a horse market; in the corn market the farmers, slow of speech, carry their sample-bags in their hands; the carter, whip in hand, stands about on the kerbstone; but in spite of the commotion no one is in a hurry. It is the crowd alone which gives the feeling of busy life.

Looking from Swindon Hill, south and east[Pg 13] and west, there stretches away the great expanse of downs which nobody ever seems to visit; the treasure-land of monuments built by a people passed away—not our ancestors at all. This is the country over which the feet of Richard Jefferies loved to roam, never weary of their wandering. On the slopes of these green hills he has measured the ramparts of the ancient fortress; lying on the turf, he has watched the hawk in the air; among these fields he has sat for hours motionless and patient, until the creatures thought him a statue and played their pranks before him without fear. In these hedges he has peered and searched and watched; in these woods and in these fields and on these hillsides he has seen in a single evening's walk more things of wonder and beauty than one of us poor purblind city creatures can discern in the whole of the six weeks which we yearly give up to Nature and to fresh air. This corner of England must be renamed. As Yorkshire hath its Craven, its Cleveland, its Richmond, and its Holderness, so Wiltshire shall have its Jefferies-land, lying in an irregular oval on[Pg 14] whose circumference stand Swindon, Barbury, Liddington, Ashbourne Chase and Wanborough.

Richard Jefferies was the second of five children, three sons and two daughters. The eldest child, a daughter, was killed by a runaway horse at the age of five. The Swindon people, who are reported to be indifferent to the works of their native author, remember his family very well. They seem to have possessed qualities or eccentricities which cause them to be remembered. His grandfather, for instance, who is without doubt the model for old Iden in "Amaryllis," was at the same time a miller and a confectioner. The mill stood near the west end of the old church; both mill and church are now pulled down. It was worked for the tenant by his brother, a man still more eccentric than the miller. The family seems to have inherited, from father to son, a disposition of reserve, a love of solitude, and a habit of thinking for themselves. No gregarious man, no man who loved to sit among his fellows, could possibly have written even the shortest of Jefferies' papers.[Pg 15]

The household at Coate has been partly—but only partly—described in "Amaryllis at the Fair." It consisted of his parents, himself, his next brother, a year younger than himself, and a brother and sister much younger. Farmer Iden, in "Amaryllis," is, in many characteristics, a portrait of his father. Truly, it is not a portrait to shame any man; and though the lines are strongly drawn, one hopes that the original, who is still living, was not offended at a picture so striking and so original. Jefferies has drawn for us the figure of a man full of wisdom and thought, who speaks now in broad Wiltshire and now in clear, good English; one who meditates aloud; one who roams about his fields watching and remembering; one who brings to the planting of potatoes as much thought and care as if he were writing an immortal poem; yet an unpractical and unsuccessful man, who goes steadily and surely down-hill while those who have not a tenth part of his wisdom and ability climb upwards. A novelist, however, draws his portraits as best suits his purpose; he arranges the lights to fall on this feature[Pg 16] or on that; he conceals some things and exaggerates others, so that even with the picture of Farmer Iden before us, it would be rash to conclude that we know the elder Jefferies. Some of the pictures, however, must be surely drawn from the life. For instance, that of the farmer planting his potatoes:

"Under the wall was a large patch recently dug, beside the patch a grass path, and on the path a wheelbarrow. A man was busy putting in potatoes; he wore the raggedest coat ever seen on a respectable back. As the wind lifted the tails it was apparent that the lining was loose and only hung by threads, the cuffs were worn through, there was a hole beneath each arm, and on each shoulder the nap of the cloth was gone; the colour, which had once been gray, was now a mixture of several soils and numerous kinds of grit. The hat he had on was no better; it might have been made of some hard pasteboard, it was so bare.

"The way in which he was planting potatoes was wonderful; every potato was placed at exactly the right distance apart, and a hole[Pg 17] made for it in the general trench; before it was set it was looked at and turned over, and the thumb rubbed against it to be sure that it was sound, and when finally put in, a little mould was delicately adjusted round to keep it in its right position till the whole row was buried. He carried the potatoes in his coat pocket—those, that is, for the row—and took them out one by one; had he been planting his own children he could not have been more careful. The science, the skill, and the experience brought to this potato-planting you would hardly credit; for all this care was founded upon observation, and arose from very large abilities on the part of the planter, though directed to so humble a purpose at that moment."

This book also contains certain references to past family history which show that there had been changes and chances with losses and gains. They may be guessed from the following:

"'The daffodil was your great-uncle's favourite flower.'

"'Richard?' asked Amaryllis.

"'Richard,' repeated Iden. And Amaryllis,[Pg 18] noting how handsome her father's intellectual face looked, wandered in her mind from the flower as he talked, and marvelled how he could be so rough sometimes, and why he talked like the labourers, and wore a ragged coat—he who was so full of wisdom in his other moods, and spoke, and thought, and indeed acted as a perfect gentleman.

"'Richard's favourite flower,' he went on. 'He brought the daffodils down from Luckett's; every one in the garden came from there. He was always reading poetry, and writing, and sketching, and yet he was such a capital man of business; no one could understand that. He built the mill, and saved heaps of money; he bought back the old place at Luckett's, which belonged to us before Queen Elizabeth's days; indeed, he very nearly made up the fortunes Nicholas and the rest of them got rid of. He was, indeed, a man. And now it is all going again—faster than he made it.'"

Everybody knows the Dutch picture of the dinner at the farm—the description of the leg of mutton. Was ever leg of mutton thus glorified?[Pg 19]

"That day they had a leg of mutton—a special occasion—a joint to be looked on reverently. Mr. Iden had walked into the town to choose it himself some days previously, and brought it home on foot in a flag basket. The butcher would have sent it, and if not, there were men on the farm who could have fetched it, but it was much too important to be left to a second person. No one could do it right but Mr. Iden himself. There was a good deal of reason in this personal care of the meat, for it is a certain fact that unless you do look after such things yourself, and that persistently, too, you never get it first-rate. For this cause people in grand villas scarcely ever have anything worth eating on their tables. Their household expenses reach thousands yearly, and yet they rarely have anything eatable, and their dinner-tables can never show meat, vegetables, or fruit equal to Mr. Iden's. The meat was dark-brown, as mutton should be, for if it is the least bit white it is sure to be poor; the grain was short, and ate like bread and butter, firm, and yet almost crumbling to the touch; it was full[Pg 20] of juicy red gravy, and cut pleasantly, the knife went through it nicely; you can tell good meat directly you touch it with the knife. It was cooked to a turn, and had been done at a wood fire on a hearth; no oven taste, no taint of coal gas or carbon; the pure flame of wood had browned it. Such emanations as there may be from burning logs are odorous of the woodland, of the sunshine, of the fields and fresh air; the wood simply gives out as it burns the sweetness it has imbibed through its leaves from the atmosphere which floats above grass and flowers. Essences of this order, if they do penetrate the fibres of the meat, add to its flavour a delicate aroma. Grass-fed meat, cooked at a wood fire, for me."

After the dinner, the great strong man with the massive head, who can never make anything succeed, sits down to sleep alone beside the fire, his head leaning where for thirty years it had daily leaned, against the wainscot, so that there was now a round spot upon it, completely devoid of varnish.

"That panel was in effect a cross on which a heart had been tortured for the third of a century, that is, for the space of time allotted to a generation.

"That mark upon the panel had still a further meaning; it represented the unhappiness, the misfortunes, the Nemesis of two hundred years. This family of Idens had endured already two hundred years of unhappiness and discordance for no original fault of theirs, simply because they had once been fortunate of old time, and therefore they had to work out that hour of sunshine to the utmost depths of shadow.

"The panel of the wainscot upon which that mark had been worn was in effect a cross upon which a human heart had been tortured—and thought can, indeed, torture—for a third of a century. For Iden had learned to know himself, and despaired."

Then the man falls asleep, and Amaryllis steals in on tiptoe to find a book. Then the wife, with a shawl round her shoulders, creeps outside the house and looks in at the window—angry with her unpractical husband.[Pg 22]

"Slight sounds, faint rustlings, began to be audible among the cinders in the fender. The dry cinders were pushed about by something passing between them. After a while a brown mouse peered out at the end of the fender under Iden's chair, looked round a moment, and went back to the grate. In a minute he came again, and ventured somewhat farther across the width of the white hearthstone to the verge of the carpet. This advance was made step by step, but on reaching the carpet the mouse rushed home to cover in one run—like children at 'touch wood,' going out from a place of safety very cautiously, returning swiftly. The next time another mouse followed, and a third appeared at the other end of the fender. By degrees they got under the table, and helped themselves to the crumbs; one mounted a chair and reached the cloth, but soon descended, afraid to stay there. Five or six mice were now busy at their dinner.

"The sleeping man was as still and quiet as if carved.

"A mouse came to the foot, clad in a great rusty-hued iron-shod boot—the foot that[Pg 23] rested on the fender, for he had crossed his knees. His ragged and dingy trouser, full of March dust, and earth-stained by labour, was drawn up somewhat higher than the boot. It took the mouse several trials to reach the trouser, but he succeeded, and audaciously mounted to Iden's knee. Another quickly followed, and there the pair of them feasted on the crumbs of bread and cheese caught in the folds of his trousers.

"One great brown hand was in his pocket, close to them—a mighty hand, beside which they were pigmies indeed in the land of the giants. What would have been the value of their lives between a finger and thumb that could crack a ripe and strong-shelled walnut?

"The size—the mass—the weight of his hand alone was as a hill overshadowing them; his broad frame like the Alps; his head high above as a vast rock that overhung the valley.

"His thumb-nail—widened by labour with spade and axe—his thumb-nail would have covered either of the tiny creatures as his shield covered Ajax.[Pg 24]

"Yet the little things fed in perfect confidence. He was so still, so very still—quiescent—they feared him no more than they did the wall; they could not hear his breathing.

"Had they been gifted with human intelligence, that very fact would have excited their suspicions. Why so very, very still? Strong men, wearied by work, do not sleep quietly; they breathe heavily. Even in firm sleep we move a little now and then, a limb trembles, a muscle quivers, or stretches itself.

"But Iden was so still it was evident he was really wide awake and restraining his breath, and exercising conscious command over his muscles, that this scene might proceed undisturbed.

"Now the strangeness of the thing was in this way: Iden set traps for mice in the cellar and the larder, and slew them there without mercy. He picked up the trap, swung it round, opening the door at the same instant, and the wretched captive was dashed to death upon the stone flags of the floor. So he hated them and persecuted them in one place, and fed them in another.[Pg 25]

"From the merest thin slit, as it were, between his eyelids, Iden watched the mice feed and run about his knees till, having eaten every crumb, they descended his leg to the floor."

This portrait is not true in all its details. For instance, the elder Jefferies had small and shapely hands and feet—not the massive hands described in "Amaryllis."

Another slighter portrait of his father is found in "After London." It is that of the Baron:

"As he pointed to the tree above, the muscles, as the limb moved, displayed themselves in knots, at which the courtier himself could not refrain from glancing. Those mighty arms, had they clasped him about the waist, could have crushed his bending ribs. The heaviest blow that he could have struck upon that broad chest would have produced no more effect than a hollow sound; it would not even have shaken that powerful frame.

"He felt the steel blue eyes, bright as the sky of midsummer, glance into his very mind.[Pg 26] The high forehead bare, for the Baron had his hat in his hand, mocked at him in its humility. The Baron bared his head in honour of the courtier's office and the Prince who had sent him. The beard, though streaked with white, spoke little of age; it rather indicated an abundant, a luxuriant vitality."

And I have before me a letter which contains the following passage concerning the elder Jefferies:

"The garden, the orchard, the hedges of the fields were always his chief delight; he had planted many a tree round and about his farm. Not a single bird that flew but he knew, and could tell its history; if you walked with him, as Dick often did, and as I have occasionally done, through the fields, and heard him expatiate—quietly enough—on the trees and flowers, you would not be surprised at the turn taken by his son's genius."

Thus, then, the boy was born; in an ancient farmhouse beautiful to look upon, with beautiful fields and gardens round it; in the midst[Pg 27] of a most singular and interesting country, wilder than any other part of England except the Peak and Dartmoor; encouraged by his father to observe and to remember; taught by him to read the Book of Nature. What better beginning could the boy have had? There wanted but one thing to complete his happiness—a little more ease as regards money. I fear that one of the earliest things the boy could remember must have been connected with pecuniary embarrassment.

While still a child, four years of age, he was taken to live under the charge of an aunt, Mrs. Harrild, at Sydenham. He stayed with her for some years, going home to Coate every summer for a month. At Sydenham he went to a preparatory school kept by a lady. He was then at the age of seven, but he had learned to read long before. He does not seem to have gained the character of precocity or exceptional cleverness at school, but Mrs. Harrild remembers that he was always as a child reading and drawing, and would amuse himself for hours at a time over some old volume of "Punch," or the "Illustrated London News,"[Pg 28] or, indeed, anything he could get. He had a splendid memory, was even so early a great observer, and was always a most truthful child, strong in his likes and dislikes. But he possessed a highly nervous and sensitive temperament, was hasty and quick-tempered, impulsive, and, withal, very reserved. All these qualities remained with Richard Jefferies to the end; he was always reserved, always sensitive, always nervous, always quick-tempered. In his case, indeed, the child was truly father to the man. It is pleasant to record that he repaid the kindness of his aunt with the affection of a son, keeping up a constant correspondence with her. His letters, indeed, are sometimes like a diary of his life, as will be seen from the extracts I shall presently make from them.

At the age of nine the boy went home for good. He was then sent to school at Swindon.

A letter from which I have already quoted thus speaks of him at the age of ten:

"There was a summer-house of conical shape in one corner paved with 'kidney'[Pg 29] stones. This was used by the boys as a treasure-house, where darts, bows and arrows, wooden swords, and other instruments used in mimic warfare were kept. Two favourite pastimes were those of living on a desert island, and of waging war with wild Indians. Dick was of a masterful temperament, and though less strong than several of us in a bodily sense, his force of will was such that we had to succumb to whatever plans he chose to dictate, never choosing to be second even in the most trivial thing. His temper was not amiable, but there was always a gentleness about him which saved him from the reproach of wishing to ride rough-shod over the feelings of others. I do not recollect his ever joining in the usual boy's sports—cricket or football—he preferred less athletic, if more adventurous, means of enjoyment. He was a great reader, and I remember a sunny parlour window, almost like a room, where many books of adventure and fairy tales were read by him. Close to his home was the 'Reservoir,' a prettily-situated lake surrounded by trees, and with many romantic nooks on the banks. Here we often[Pg 30] used to go on exploring expeditions in quest of curiosities or wild Indians."

Here we get at the origin of "Bevis." Those who have read that romance—which, if it were better proportioned and shorter, would be the most delightful boy's book in the world—will remember how the lads played and made pretence upon the shores and waters of the lake. Now they are travellers in the jungle of wild Africa; now they come upon a crocodile; now they hear close by the roar of a lion; now they discern traces of savages; now they go into hiding; now they discover a great inland sea; now they build a hut and live upon a desert island. The man at thirty-six recalls every day of his childhood, and makes a story out of it for other children.

One of the things which he did was to make a canoe for himself with which to explore the lake. To make a canoe would be beyond the powers of most boys; but then most boys are brought up in a crowd, and can do nothing except play cricket and football. The shaping of the canoe is described in "After London":[Pg 31]

"He had chosen the black poplar for the canoe because it was the lightest wood, and would float best. To fell so large a tree had been a great labour, for the axes were of poor quality, cut badly, and often required sharpening. He could easily have ordered half a dozen men to throw the tree, and they would have obeyed immediately; but then the individuality and interest of the work would have been lost. Unless he did it himself its importance and value to him would have been diminished. It had now been down some weeks, had been hewn into outward shape, and the larger part of the interior slowly dug away with chisel and gouge.

"He had commenced while the hawthorn was just putting forth its first spray, when the thickets and the trees were yet bare. Now the May bloom scented the air, the forest was green, and his work approached completion. There remained, indeed, but some final shaping and rounding off, and the construction, or rather cutting out, of a secret locker in the stern. This locker was nothing more than a square aperture chiselled out like a mortise,[Pg 32] entering not from above, but parallel with the bottom, and was to be closed with a tight-fitting piece of wood driven in by force of mallet.

"A little paint would then conceal the slight chinks, and the boat might be examined in every possible way without any trace of this hiding-place being observed. The canoe was some eleven feet long, and nearly three feet in the beam; it tapered at either end, so that it might be propelled backwards or forwards without turning, and stem and stern (interchangeable definitions in this case) each rose a few inches higher than the general gunwale. The sides were about two inches thick, the bottom three, so that although dug out from light wood, the canoe was rather heavy."

"As a boy," to quote again from the same letter, "he was no great talker; but if we could get him in the humour, he would tell us racy and blood-curdling romances. There was one particular spot on the Coate road—many years ago a quarry, afterwards deserted—upon which he wove many fancies, with murders and ghosts. Always, in going home after one[Pg 33] of our visits to the farm, we used to think we heard the clanking chains or ringing hoof of the phantom horse careering after us, and we would rush on in full flight from the fateful spot."

His principal companion in boyhood was his next brother, younger than himself by one year only, but very different in manners, appearance, and in tastes. He describes both himself and his brother in "After London." Felix is himself; Oliver is his brother.

This is Felix:

"Independent and determined to the last degree, Felix ran any risk rather than surrender that which he had found, and which he deemed his own. This unbending independence and pride of spirit, together with scarce-concealed contempt for others, had resulted in almost isolating him from the youth of his own age, and had caused him to be regarded with dislike by the elders. He was rarely, if ever, asked to join the chase, and still more rarely invited to the festivities and amusements provided in adjacent houses, or to the grander entertainments of the higher nobles.[Pg 34] Too quick to take offence where none was really intended, he fancied that many bore him ill-will who had scarcely given him a passing thought. He could not forgive the coarse jokes uttered upon his personal appearance by men of heavier build, who despised so slender a stripling.

"He would rather be alone than join their company, and would not compete with them in any of their sports, so that, when his absence from the arena was noticed, it was attributed to weakness or cowardice. These imputations stung him deeply, driving him to brood within himself."

And this is Oliver:

"Oliver's whole delight was in exercise and sport. The boldest rider, the best swimmer, the best at leaping, at hurling the dart or the heavy hammer, ever ready for tilt or tournament, his whole life was spent with horse, sword, and lance. A year younger than Felix, he was at least ten years physically older. He measured several inches more round the chest; his massive shoulders and[Pg 35] immense arms, brown and hairy, his powerful limbs, tower-like neck, and somewhat square jaw were the natural concomitants of enormous physical strength.

"All the blood and bone and thew and sinew of the house seemed to have fallen to his share; all the fiery, restless spirit and defiant temper; all the utter recklessness and warrior's instinct. He stood every inch a man, with dark, curling, short-cut hair, brown cheek and Roman chin, trimmed moustache, brown eye, shaded by long eyelashes and well-marked brows; every inch a natural king of men. That very physical preponderance and animal beauty was perhaps his bane, for his comrades were so many, and his love adventures so innumerable, that they left him no time for serious ambition.

"Between the brothers there was the strangest mixture of affection and repulsion. The elder smiled at the excitement and energy of the younger; the younger openly despised the studious habits and solitary life of the elder. In time of real trouble and difficulty they would have been drawn together; as it was,[Pg 36] there was little communion; the one went his way, and the other his. There was perhaps rather an inclination to detract from each other's achievements than to praise them, a species of jealousy or envy without personal dislike, if that can be understood. They were good friends, and yet kept apart.

"Oliver made friends of all, and thwacked and banged his enemies into respectful silence. Felix made friends of none, and was equally despised by nominal friends and actual enemies. Oliver was open and jovial; Felix reserved and contemptuous, or sarcastic in manner. His slender frame, too tall for his width, was against him; he could neither lift the weights nor undergo the muscular strain readily borne by Oliver. It was easy to see that Felix, although nominally the eldest, had not yet reached his full development. A light complexion, fair hair and eyes, were also against him; where Oliver made conquests, Felix was unregarded. He laughed, but perhaps his secret pride was hurt."

After his return from Sydenham the boy, as I have said, went to school for a year or two[Pg 37] at Swindon. Then he presently began to read. He had always delighted in books, especially in illustrated books; now he began to read everything that he could get.

The boy who reads everything, the boy who takes out his younger brothers and his cousins and makes them all pretend as he pleases, see what he orders them to see, and shudder at his bidding and at the creatures of his own imagination—what sort of future is in store for that boy? And think of what his life might have become had he been forced into clerkery or into trade: how crippled, miserable, and cramped! It is indeed miserable to think of the thousands designed for a life of art, of letters, of open air, or of science, wasted and thrown away in labouring at the useless desk or the hateful counter.

This boy therefore read everything. Presently, when he had read all that there was at Coate, and all that his grandfather had to lend him, he began to borrow of everybody and to buy. It is perfectly wonderful, as everybody knows, how a boy who never seems to get any money manages to buy books. The fact is that[Pg 38] all boys get money, but the boy who wants books saves his pennies. For twopence you can very often pick up a book that you want; for sixpence you can have a choice; a shilling will tempt a second-hand bookseller to part with what seems a really valuable book; half-a-crown—but such a boy never even sees a half-crown piece. Richard Jefferies differed in one respect from most boys who read everything. They live in the world of books; the outer world does not exist for them; the birds sing, the lambs spring, the flowers blossom, but they heed them not; they grow short-sighted over the small print; they become more and more enamoured of phrase, captivated by words, charmed by style, so that they forget the things around them. When they go abroad they enact the fable of "Eyes and No Eyes," playing the less desirable part. Jefferies, on the other hand, was preserved from this danger. His father, the reserved and meditative man, took him into the fields and turned over page after page with him of the book of Nature, expounding, teaching, showing him how to use his eyes, and con[Pg 39]tinually reading to him out of that great book.

So a strange thing came to pass. Most of us who go away from our native place forget it, or we only remember it from time to time; the memory grows dim; when we go back we are astonished to find how much we have forgotten, and how distorted are the memories which remain. Richard Jefferies, however, who presently left Coate, never forgot the old place. It remained with him—every tree, every field, every hill, every patch of wild thyme—all through his life, clear and distinct, as if he had left it but an hour before. In almost everything he wrote Coate is in his mind. Even in his book of "Wild Life Round London" the reader thinks sometimes that he is on the wild Wiltshire Downs, while the wind whistles in his ears, and the lark is singing in the sky, and far, far away the sheep-bells tinkle.

Why, in the very last paper which he ever wrote—it appeared in Longman's Magazine two months after his death—his memory goes back to the hamlet where he was born. He[Pg 40] recalls the cottage where John Brown lived—you can see it still, close to Coate—as well as that where Job lived who kept the shop and was always buying and selling; and of the water-bailiff who looked after the great pond:

"There were one or two old boats, and he used to leave the oars leaning against a wall at the side of the house. These oars looked like fragments of a wreck, broken and irregular. The right-hand scull was heavy as if made of ironwood, the blade broad and spoon-shaped, so as to have a most powerful grip of the water. The left-hand scull was light and slender, with a narrow blade like a marrow-scoop; so when you had the punt, you had to pull very hard with your left hand and gently with the right to get the forces equal. The punt had a list of its own, and no matter how you rowed, it would still make leeway. Those who did not know its character were perpetually trying to get this crooked wake straight, and consequently went round and round exactly like the whirligig beetle. Those who knew used to let the leeway proceed a good[Pg 41] way and then alter it, so as to act in the other direction like an elongated zigzag. These sculls the old fellow would bring you as if they were great treasures, and watch you off in the punt as if he was parting with his dearest. At that date it was no little matter to coax him round to unchain his vessel. You had to take an interest in the garden, in the baits, and the weather, and be very humble; then perhaps he would tell you he did not want it for the trimmers, or the withy, or the flags, and you might have it for an hour as far as he could see; 'did not think my lord's steward would come over that morning; of course, if he did you must come in,' and so on; and if the stars were propitious, by-the-bye, the punt was got afloat."

Then the writer—he was a dying man—sings his song of lament because the past is past—and dead. All that is past, and that we shall never see again, is dead. The brook that used to leap and run and chatter—it is dead. The trees that used to put on new leaves every spring—they are dead. All is[Pg 42] dead and swept away, hamlet and cottage, hillside and coppice, field and hedge.

"I think I have heard that the oaks are down. They may be standing or down, it matters nothing to me; the leaves I last saw upon them are gone for evermore, nor shall I ever see them come there again ruddy in spring. I would not see them again even if I could; they could never look again as they used to do. There are too many memories there. The happiest days become the saddest afterwards; let us never go back, lest we too die. There are no such oaks anywhere else, none so tall and straight, and with such massive heads, on which the sun used to shine as if on the globe of the earth, one side in shadow, the other in bright light. How often I have looked at oaks since, and yet have never been able to get the same effect from them! Like an old author printed in other type, the words are the same, but the sentiment is different. The brooks have ceased to run. There is no music now at the old hatch where we used to sit in danger of our lives, happy as kings, on[Pg 43] the narrow bar over the deep water. The barred pike that used to come up in such numbers are no more among the flags. The perch used to drift down the stream, and then bring up again. The sun shone there for a very long time, and the water rippled and sang, and it always seemed to me that I could feel the rippling and the singing and the sparkling back through the centuries. The brook is dead, for when man goes nature ends. I dare say there is water there still, but it is not the brook; the brook is gone like John Brown's soul. There used to be clouds over the fields, white clouds in blue summer skies. I have lived a good deal on clouds; they have been meat to me often; they bring something to the spirit which even the trees do not. I see clouds now sometimes when the iron grip of hell permits for a minute or two; they are very different clouds, and speak differently. I long for some of the old clouds that had no memories. There were nights in those times over those fields, not darkness, but Night, full of glowing suns and glowing richness of life that sprang up to meet them. The nights are[Pg 44] there still; they are everywhere, nothing local in the night; but it is not the Night to me seen through the window."

Nobody believes him, he says. People ask him if such a village ever existed—of course, it never existed. What beautiful picture ever really existed save in the sunrise and in the sunset sky? Those living in the place about which these wonderful things are written look at each other in amazement, and ask what they mean. All this about Coate? Why, here are only half a dozen cottages, mean and squalid, with thatched roofs; and beyond the hedge are only fields with a great pond and bare hills beyond. "No one else," says Jefferies, "seems to have seen the sparkle on the brook, or heard the music at the hatch, or to have felt back through the centuries; and when I try to describe these things to them they look at me with stolid incredulity. No one seems to understand how I got food from the clouds, nor what there was in the night, nor why it is not so good to look out of window. They turn their faces away from[Pg 45] me, so that perhaps, after all, I was mistaken, and there never was any such place, or any such meadows, and I was never there. And perhaps in course of time I shall find out also, when I pass away physically, that as a matter of fact there never was any earth." That, indeed, will be the most curious discovery possible in the after-world. No earth—then no Coate; no "Wild Life in a Southern County," and no "Gamekeeper at Home," because there has never been any home for any gamekeeper.

I have dwelt at some length upon these early years of Jefferies' life because they are all-important. They explain the whole of his after-life; they show how the book of Nature was laid open to this man in a way that it was never before presented to any man who had also the divine gift of utterance, namely, by a man who, though steeped in the wisdom of the field and forest—though he had read indeed in the book—could not read it aloud for all to hear.

In order to read this book aright, one must live apart from one's fellow-men and remain[Pg 46] a stranger to their ambitions, ignorant of their crooked ways, their bickerings, and their pleasures. One must have quick and observant eyes, trained to watch and mark the infinite changes and variations in Nature, day by day; one must go to Nature's school from infancy in order to get this power. Nay; one must never cease to exercise this power, or it will be lost; it must be continually nourished and strengthened by being exercised. If one who has this power should go to live in the city, his eyes would grow as sluggish and as dim as ours; his ear would be blunted by the rolling of the carts, and his mind disturbed by the rush and the activity of the crowd. Again, if one who had this power should abandon the simple life, and should deaden his senses with luxury, sloth, and vice, he would quickly lose it. He must live apart from men; all day long the sun must burn his cheek, the wind must blow upon it, the rain must beat upon it; he must never be out of reach of the fragrant wild flowers and the call and cry of the birds. Of such men literature can show but two or three—Gilbert White, Thoreau,[Pg 47] and Jefferies—but the greatest of them all is Jefferies. No one before him has so lived among the fields; no one has heard so clearly the song of the flowers and the weeds and the blades of grass. The million million blades of grass spoke to Jefferies as the Oak of Dodona spoke through its thousand leaves. When he went home he sat down and was inspired to translate that language, and to tell the world what the grass says and sings to him who can hear.

He who met the great God Pan face to face fell down dead. Still, even in these days, he who communes with the Sylvan Spirit presently dies to the ways of men, while his senses are opened to see the hidden things of hedge and meadow; while his soul is uplifted by the beauty and the variety and the order of the world; by the wondrous lives of the creatures, so full of peril, and so full of joy. Then, if he be permitted to reveal these things, what can we who receive this revelation give in exchange? What words of praise and gratitude can we find in return for this unfolding of the Book of Fleeting Life?[Pg 48]

As for us, we listened to the voice of this master for ten years; we shall hear no more of his discourses; but the old ones remain; we can go back to them again and again. It is the quality of truthful work that it never grows old or stale; one can return to it again and again; there is always something fresh in it, something new. In a great poem the lines always bring some new thought to the mind; in great music, the harmonies always call forth some fresh emotion, and inspire some new thought; in a true book there is always some new truth to be discovered. If all the rest of the literature of this day prove ephemeral and is doomed to swift oblivion, the work of Jefferies shall not perish. Our fashions change, and the things of which we write become old and pass away. But the everlasting hills abide, and the meadows still lie green and flowery, and the roses and wild honeysuckle still blossom in the hedge. And those who have written of these are so few, and their words are so precious, that they shall not pass away, so long as their tongue endureth to be spoken and to be read.

At the age of sixteen, Richard Jefferies had an adventure—almost the only adventure of his quiet life. It was an adventure which could only happen to a youth of strong imagination, capable of seeing no difficulties or dangers, and refusing to accept the word "impossible."

At this time he was a long and loose-limbed lad, regarded by his own family as at least an uncommon youth and a subject of anxiety as to his future, a boy who talked eagerly of things far beyond the limits of the farm, who was self-willed and masterful, whose ideas astonished and even irritated those whose thoughts were accustomed to move in a narrow, unchanging groove. He was also a boy, as[Pg 50] we have seen, who had the power of imposing his own imagination upon others, even those of sluggish temperament—as Don Quixote overpowered the slow brain of Sancho Panza.

Richard Jefferies then, at the age of sixteen, conceived a magnificent scheme, the like of which never before entered a boy's brain. Above all things he wanted to see foreign countries. He therefore proposed to another lad nothing less than to undertake a walk through the whole of Europe, as far as Moscow and back again. The project was discussed and debated long and seriously. At last it was referred to the decision of the dog as to an oracle. In this way: if the dog wagged his tail within a certain time, they would go; if the dog's tail remained quiet, it should be taken as a warning or premonition against the journey. Reliance should never, as a matter of fact, be placed in the oracle of the dog's tail; but this the lads were too young to understand. The tail wagged. The boys ran away. It was on November 11, in the year 1864. Now, here, certain details of the story are wanting. The novelist is never happy unless the whole[Pg 51] machinery of his tale is clear in his own mind. And I confess that I know not how the two boys raised the money with which to pay their preliminary expenses. You may support yourself, as Oliver Goldsmith did, by a flute or a fiddle, you may depend upon the benefactions of unknown kind hearts in a strange land, but the steamship company and the railway company must be always paid beforehand. Where did the passage-money come from? Nay, as you will learn presently, there must have been quite a large bag of money to start with. Where did it come from? The other boy—the unknown—the innominatus—doubtless found that bag of gold.

They got to Dover and they crossed the Channel, and they actually began their journey. But I know not how far they got, nor how long a time, exactly, they spent in France—about a week, it would seem. They very quickly, however, made the humiliating discovery that they could not understand a word that was said to them, nor could they, save by signs, make themselves understood. Therefore they relinquished the idea of walking to[Pg 52] Moscow, and reluctantly returned. But they would not go home; perhaps, because they were still athirst for adventure; perhaps, because they were ashamed. They then saw an advertisement in a newspaper which fired their imaginations again. The advertiser undertook, for an absurdly small sum, to take them across to New York. The amount named was just within the compass of their money. They resolved to see America instead of Russia; they called at the agent's office and paid their fares. Their tickets took them free to Liverpool, whither they repaired. Unfortunately, when they reached Liverpool, they learned that the tickets did not include bedding of any kind, or provisions, so that if they went on board they would certainly be frozen and starved. What was to be done? They had no more money. They could not get their money returned. They were helpless. They resolved therefore to give up the whole project, and to go home again. Jefferies undertook to pawn their watches in order to get the money for the railway ticket. His appearance and manner, for some reason or other—pawning[Pg 53] being doubtless a new thing with him—roused so much suspicion in the mind of the pawnbroker that he actually gave the lad into custody. Happily, the superintendent of police believed his story—probably a telegram to Swindon strengthened his faith; he himself advanced them the money, keeping the watches as security, and sent them home after an expedition which lasted a fortnight altogether. There is no doubt as to the facts of the case. The boys did actually start, with intent to march all the way across Europe as far as Russia and back again. But how they began, how they raised the money to pay the preliminary expenses, wants more light. Also, there is no record as to their reception after they got home again. One suspects somehow that on this occasion the fatted calf was allowed to go on growing.

It must have been about this time that the lad began to have his bookish learning remarked and respected, if not encouraged. One of the upper rooms of the farmhouse—the other was the cheese-room—was set apart for him alone. Here he had his books, his table, his desk, and[Pg 54] his bed. This room was sacred. Here he read; here he spent all his leisure time in reading. He read during this period an immense quantity. Shakespeare, Chaucer, Scott, Byron, Dryden, Voltaire, Goethe—he was never tired of reading Faust—and it is said, but I think it must have been in translation, that he read most of the Greek and Latin masters. It is evident from his writings that he had read a great deal, yet he lacks the touch of the trained scholar. That cannot be attained by solitary and desultory reading, however omnivorous. His chief literary adviser in those days was Mr. William Morris, of Swindon, proprietor and editor of the North Wilts Advertiser. Mr. Morris is himself the author of several works, among others a "History of Swindon," and, as becomes a literary man with such surroundings, he is a well-known local antiquary. Mr. Morris allowed the boy, who was at school with his own son, the run of his own library; he lent him books, and he talked with him on subjects which, one can easily understand, were not topics of conversation at Coate. Afterwards, when Jefferies had already[Pg 55] become reporter for the local press, it was the perusal of a descriptive paper by Mr. Morris, on the "Lakes of Killarney," which decided the lad upon seriously attempting the literary career.

What inclined the lad to become a journalist? First of all, the narrow family circumstances prevented his being brought up to one of the ordinary professions: he might have become a clerk; he might have gone to London, where he had friends in the printing business; he might have emigrated, as his brother afterwards did; he might have gone into some kind of trade. As for farming, he had no taste for it; the idea of becoming a farmer never seems to have occurred to him as possible. But he could not bear the indoor life; to be chained all day long to a desk would have been intolerable to him; it would have killed him; he needed such a life as would give him a great deal of time in the open air. Such he found in journalism. His friend, Mr. Morris, gave him the first start by printing for him certain sketches and descriptive papers. And he had the courage to learn shorthand.[Pg 56]

He had already before this begun to write.

"I remember"—I quote from a letter which has already furnished information about these early days—"that he once showed his brother a roll of manuscript which he said 'meant money' some day." It was necessary in that house to think of money first.

I wonder what that manuscript was. Perhaps poetry—a clever lad's first attempt at verse; there is never a clever lad who does not try his hand at verse. Perhaps it was a story—we shall see that he wrote many stories. At that time his handwriting was so bad that when he began to feed the press, the compositors bought him a copybook and a penholder and begged him to use it. He did use it, and his handwriting presently became legible at least, but it remained to the end a bad handwriting. His note-books especially are very hard to read.

He was left by his father perfectly free and uncontrolled. He was allowed to do what he pleased or what he could find to do. This liberty of action made him self-reliant. It also, perhaps, increased his habit of solitude[Pg 57] and reserve. In those days he used to draw a great deal, and is said to have acquired considerable power in pen-and-ink sketches, but I have never seen any of them.

At this period he was careless as to his dress and appearance; he suffered his hair to grow long until it reached his coat collar. "This," says one who knew him then, "with his bent form and long, rapid stride, made him an object of wonder in the town of Swindon. But he was perfectly unconscious of this, or indifferent to it."

Later on, he understood better the necessity of paying attention to personal appearance, and in his advice to the young journalist he points out that he should be quietly but well dressed, and that he should study genial manners.

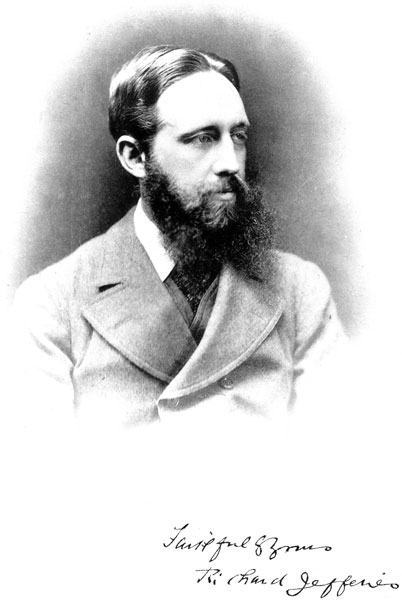

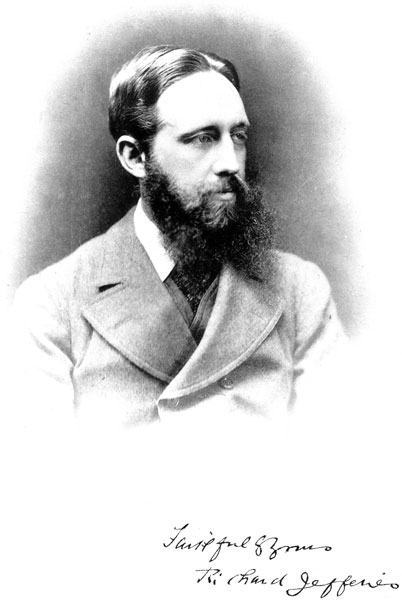

In appearance Richard Jefferies was very tall—over six feet. He was always thin. At the age of seventeen his friends feared that he would go into a decline, which was happily averted—perhaps through his love for the open air. His hair was dark-brown; his beard was brown, with a shade of auburn; his forehead both high and broad; his features strongly marked; his nose long, clear, and straight;[Pg 58] his lower lip thick; his eyebrows distinguished by the meditative droop; his complexion was fair, with very little colour. The most remarkable feature in his face was his large and clear blue eye; it was so full that it ought to have been short-sighted, yet his sight was far as well as keen. His face was full of thought; he walked with somewhat noiseless tread and a rapid stride. He never carried an umbrella or wore a great-coat, nor, except in very cold weather, did he wear gloves. He had great powers of endurance in walking, but his physical strength was never great. In manner, as has been already stated, he was always reserved; at this time so much so as to appear morose to those who knew him but slightly. He made few friends. Indeed, all through life he made fewer friends than any other man. This was really because, for choice, he always lived as much in the country as possible, and partly because he had no sympathy with the ordinary pursuits of men. Such a man as Richard Jefferies could never be clubable. What would he talk about at the club? The theatre? He never went there. Literature[Pg 59] of the day? He seldom read it. Politics? He belonged to the people, and cursed either party. That once said, he had nothing more to say. Art? He had ideas of his own on painting, and they were unconventional. Gossip and scandal? He never heard any. Wine? He knew nothing about wine. Yet to those whom he knew and trusted he was neither reserved nor morose. An eremite would be driven mad by chatter if he left his hermitage and came back to his native town; so this roamer among the hills could not endure the profitless talk of man, while Nature was willing to break her silence for him alone among the hills and in the woods.

He became, then, a journalist. It is a profession which leaves large gaps in the day, and sometimes whole days of leisure. The work, to such a lad as Jefferies, was easy; he had to attend meetings and report them; to write descriptive papers; to furnish and dress up paragraphs of news; to look about the town and pick up everything that was said or done; to attend the police courts, inquests, county courts, auctions, markets, and every[Pg 60]thing. The life of a country journalist is busy, but it is in great measure an out-door life.

Although Mr. Morris was his first literary friend and adviser, Jefferies was never attached to his paper as reporter. Perhaps there was no vacancy at the time. He obtained work on the North Wilts Herald, and afterwards became in addition the Swindon correspondent of the Wilts and Gloucestershire Standard, published at Cirencester. The editor of the North Wilts Herald was a Mr. Piper, who died two years ago. Of him Jefferies always spoke with the greatest respect, calling him his old master. But in what sense he himself was a pupil I know not. Nor can I gather that Jefferies, who acquired his literary style much later, and after, as will be seen, the production of much work which has deservedly fallen into oblivion, learned anything as a writer from anybody. In the line which he afterwards struck out for himself—that of observations of nature—his master, as regards the subject-matter, was his father; as regards his style he had no master.

He filled these posts and occupied himself[Pg 61] in this kind of work between the years 1865 and 1877.

But he did other things as well, showing that he never intended to sit down in ignoble obscurity as the reporter of a country newspaper.

I have before me a little book called "Reporting, Editing, and Authorship," published without date at Swindon, and by John Snow and Co., Ivy Lane, London. I think it appeared in the year 1872, when he was in his twenty-fourth year. It is, however, the work of a very young man; the kind of work at which you must not laugh, although it amuses you, because it is so very much in earnest, and at the same time so very elementary. You see before you in these pages the ideal reporter—Jefferies was always zealous to do everything that he had to do as well as it could be done. It is divided into three chapters, but the latter two are vague and tentative, compared with the first. The little book should have been called, "He would be an Author."

"Let the aspirant," he says, "begin with[Pg 62] acquiring a special knowledge of his own district. The power and habit of doing this may subsequently stand him in good stead as a war-correspondent. Let him next study the trade and industries peculiar to the place. If he is able to write of these graphically, he will acquire a certain connection and good-will among the masters. He will strengthen himself if he contributes papers upon these subjects to the daily papers or to the magazines; thus he will grow to be regarded as a representative man. Next, he should study everywhere the topography, antiquities, traditions, and general characteristics of the country wherever he goes; he should visit the churches, and write about them. He may go on to write a local history, or he may take a local tradition and weave a story round about it—things which local papers readily publish. Afterwards he may write more important tales for country newspapers, and so by easy stages rise to the grandeur of writing tales for the monthly magazines." Observe that so far the ambition of the writer is wholly in the direction of novels.[Pg 63]

One piece of advice contrasts strongly with the description of him given by his cousin. He has found out that eccentricity of appearance and manner does not advance a man. Therefore he writes:

"A good personal manner greatly conduces to the success of the reporter. He should be pleasant and genial, but not loud: inquiring without being inquisitive: bold, but not presumptuous: and above all respectful. The reporter should be able to talk on all subjects with all men. He should dress well, because it obtains him immediate attention: but should be careful to avoid anything 'horsey' or fast. The more gentlemanly his appearance and tone, the better he will be received."

The chapter on Editing gives a tolerably complete account of the conduct of a country-town newspaper. The chapter on Authorship is daring, because the writer as yet knew nothing whatever of the subject. Among other mistakes is the very common one of supposing that a young man can help himself on by publishing at his own expense a manu[Pg 64]script which all the respectable publishing houses have refused. He himself subsequently acted upon this mistake, and lost his money without in the least advancing his reputation. The young writer can seldom be made to understand that all publishers are continually on the look-out for good work; that good work is almost certain (though mistakes have been made) to be taken up by the first publisher to whom it is offered; that if it is refused by good Houses, the reason is that it is not good work, and that paying for publication will not turn bad work into good. Jefferies concludes his little book by so shocking a charge against the general public that it shall be quoted just to show what this country lad of nineteen or twenty thought was the right and knowing thing to say about them:

"The public will read any commonplace clap-trap if only a well-known name be attached to it. Hence any amount of expenditure is justified with this object. It is better at once to realize the fact, however unpleasant it may be to the taste, and instead of trying[Pg 65] to win the good-will of the public by laborious work, treat literature as a trade, which, like other trades, requires an immense amount of advertising."

This is Jefferies' own ideal of a journalist. In March, 1866, being then eighteen years of age, he began his work on the North Wilts Herald.

The principal sources of information concerning the period of early manhood are the letters—a large number of these are happily preserved—which he wrote to his aunt, Mrs. Harrild. In these letters, which are naturally all about himself, his work, his hopes, and his disappointments, he writes with perfect freedom and from his heart. It is still a boyish heart, young and innocent. "I always feel dull," he says, "when I leave you. I am happier with you than at home, because you enter into my prospects with interest and are always kind.... I wish I could have got something to do in the neighbourhood of Sydenham, which would have enabled me to live with you."

The letters reveal a youth taken too soon from school, but passionately fond of reading[Pg 67]—of industry and application intense and unwearied; he confesses his ambitions—they are for success; he knows that he has the power of success within him; he tries for success continually, and is as often beaten back, because, though this he cannot understand, in the way he tries success is impossible for him. Let us run through this bundle of letters.

One thing to him who reads the whole becomes immediately apparent, though it is not so clear from the extracts alone. It is the self-consciousness of the writer as regards style. That is because he is intended by nature to become a writer. He thinks how he may put things to the best advantage; he understands the importance of phrase; he wants not only to say a thing, but to say it in a striking and uncommon manner. Later on, when he has gotten a style to himself, he becomes more familiar and chatty. Thus, for instance, the boy speaks of the great organ at the Crystal Palace: "To me music is like a spring of fresh water in the midst of the desert to a wearied Arab." He was genuinely and truly fond of good music, and yet this phrase has in[Pg 68] it a note of unreality. Again, he is speaking of one of his aunt's friends, and says, as if he was the author of "Evelina": "How is Mr. A.? I remember him as a pleasant gentleman, anxious not to give trouble, and the result is ..." and so forth. When one understands that these letters were written by the immature writer, such little things, with which they abound, are pleasing.

In March, 1866, he describes the commencement of his work on the North Wilts Herald; he speaks of the kindness of his chief and the pleasant nature of his work. In December of the same year he sends a story which he wants his uncle to submit to a London magazine. In June, 1867, he writes that he has completed his "History of Swindon" and its neighbourhood. This probably appeared in the pages of his newspaper.

In the same year he says that he has finished a story called "Malmesbury."

"Here I have no books—no old monkish records to assist me—everything must be hunted out upon the spot. I visit every place I have to refer to, copy inscriptions, listen to[Pg 69] legends, examine antiquities, measure this, estimate that; and a thousand other employments essential to a correct account take up my time. The walking I can do is something beyond belief. To give an instance. There is a book published some twenty years ago founded on a local legend. This I wanted, and have actually been to ten different houses in search of it; that is, have had a good fifty miles' walk, and as yet all in vain. However, I think I am on the right scent now, and believe I shall get it.

"This neighbourhood is a mine for an antiquary. I was given to understand at school that in ancient days Britain was a waste—uninhabited, rude and savage. I find this is a mistake. I see traces of former habitation, and former generations, in all directions. There, Roman coins; here, British arrowheads, tumuli, camps—in short, the country, if I may use the expression, seems alive with the dead. I am inclined to believe that this part of North Wilts, at least, was as thickly inhabited of yore as it is now, the difference being only in the spots inhabited having been exchanged for[Pg 70] others more adapted to the wants of the times. I do not believe these sweeping assertions as to the barbarous state of our ancestors. The more I study the matter the more absurd and unfounded appear the notions popularly received."

"The spiders have been more disturbed in the last few days than for twelve months past. I detest this cruelty to spiders. I admire these ingenious insects. One individual has taken possession of a box of mine. This fellow I call Cæsar Borgia, because he has such an affection for blood. You will call him a monster, which is praise, since his size shows the number of flies he has destroyed. Why not keep a spider as well as a cat? They are both useful in their way, and a spider has this advantage, that he will spin you a web which will do instead of tapestry."

Between July 21st and September 2nd of this year he writes of a bad illness which sent him to bed and kept him there, until he became as thin as a skeleton. As soon as he was able to get out of bed he wrote to his aunt; his eyes were weak, and he could read[Pg 71] but little, which was a dreadful privation for him. And he was most anxious lest he should lose his post on the paper.

Later on he tells the good news that Mr. Piper will give him another fortnight so that he may get a change of air and a visit to Sydenham.

He goes back to Swindon apparently strengthened and in his former health and energy. Besides his journal work he reports himself engaged upon an "Essay on Instinct." This is the first hint of his finding out his own line, which, however, he would not really discover for a long time yet.

"The country," he says, little thinking what the country was going to do for him, "is very quiet and monotonous. There is a sublime sameness in Coate that reminds you of the stars that rise and set regularly just as we go to bed down here."

His grandfather—old Iden of "Amaryllis"—died in April, 1868.

He speaks in June of his own uncertain prospects.

"My father," he says, "will neither tell me[Pg 72] what he would like done or anything else, so that I go my own way and ask nobody...." The letters are full of the little familiar gossip concerning this person and that, but he can never resist the temptation of telling his aunt—who "enters into his prospects"—all that he is doing. He has now spent two months over a novel—this young man thinks that two months is a prodigiously long time to give to a novel. "I have taken great pains with it," he says, "and flatter myself that I have produced a tale of a very different class to those sensational stories I wrote some time ago. I have attempted to make my story lifelike by delineating character rather than by sensational incidents. My characters are many of them drawn from life, and some of my incidents actually took place." This is taking a step in the right direction. One wonders what this story was. But alas! there were so many in those days, and the end of all was the same. And yet the poor young author took such pains, such infinite pains, and all to no purpose, for he was still groping blindly in the dark, feeling for himself.[Pg 73]

His health, however, gave way again. He tells his aunt that he has been fainting in church; that he finds his work too exciting; that his walking powers seem to have left him—everybody knows the symptoms when a young man outgrows his strength; he would like some quiet place; such a Haven of Repose or Castle of Indolence, for instance, as the Civil Service. All young men yearn at times for some place where there will be no work to do, and it speaks volumes for the happy administration of this realm that every young man in his yearning fondly turns his eyes to the Civil Service.

He has hopes, he says, of getting on to the reporting staff of the Daily News, ignorant of the truth that a single year of work on a great London paper would probably have finished him off for good. Merciful, indeed, are the gods, who grant to mankind, of all their prayers, so few.

In July he was prostrated by a terrible illness, aggravated by the great heat of that summer. This illness threatened to turn into consumption—a danger happily averted. But[Pg 74] it was many months before he could sit up and write to his aunt in pencil. He was at this time greatly under the influence of religion, and his letters are full of a boyish, simple piety. The hand of God is directing him, guiding him, punishing him. His heart is soft in thinking over the many consolations which his prayers have brought him, and of the increased benefit which he has derived from reading the Bible. He has passed through, he confesses, a period of scepticism, but that, he is happy to say, is now gone, never to return again.

He is able to get out of bed at last; he can read a little, though his eyes are weak; he can once more return to his old habits, and drinks his tea again as sweet as he can make it; he is able presently to seize his pen again. And then ... then ... is he not going to be a great author? And who knows in what direction? ... then he begins a tragedy called "Cæsar Borgia; or, The King of Crime."

He is touched by the thoughtfulness of the cottagers. They have all called to ask after him; they have brought him honey. He resolves to cultivate the poor people more.[Pg 75]