Title: Glacier National Park [Montana]

Author: United States. Department of the Interior

Release date: June 19, 2011 [eBook #36463]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Juliet Sutherland, David Garcia and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

American Section WATERTON-GLACIER

INTERNATIONAL PEACE PARK

United States Department of the Interior

Harold L. Ickes, Secretary

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Arno B. Cammerer, Director

UNITED STATES

GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE

WASHINGTON: 1937

The Park Regulations are designed for the protection of the natural beauties as well as for the comfort and convenience of visitors. The complete regulations may be seen at the office of the superintendent and at ranger stations. The following synopsis of the rules and regulations is for the general guidance of visitors, who are requested to assist in the administration of the park by observing them.

Fires.—Fires are the greatest menace to the forests of Glacier National Park. Build camp fires only when necessary and at designated places. Know that they are out before you leave them. Be sure your cigarette, cigar, pipe ashes, and matches are out before you throw them away. During periods of high fire hazard, camp fires are not permitted at nondesignated camp grounds.

Camps.—Camping is restricted to designated campgrounds. Burn all combustible garbage in your camp fire; place tin cans and unburnable residue in garbage cans. There is plenty of pure water; be sure to get it. Visitors must not contaminate water-sheds or water supplies.

Natural features.—The destruction, injury, or disturbance in any way of the trees, flowers, birds, or animals is prohibited. Dead and fallen wood may be used for firewood. Picking wild flowers and removing plants are prohibited.

Bears.—It is prohibited and dangerous to feed the bears. Do not leave foodstuffs in an unattended car or camp, for the bear will break into and damage your car or camp equipment to secure food. Suspend foodstuffs in a box, well out of their reach, or place in the care of the camp tender.

Dogs and cats.—When in the park, dogs and cats must be kept under leash, crated, or under restrictive control of the owner at all times.

Fishing.—No license for fishing in the park is required. Use of live bait is prohibited. Ten fish (none under 6 inches) per day, per person fishing is the usual limit; however, in some lakes the limit is 5 fish per day and in others it is 20. Visitors should contact the nearest district ranger to ascertain the fish limits in the lakes. The possession of more than 2 days' catch by any person at any one time shall be construed as a violation of the regulations.

Traffic.—Speed regulations: 15 miles per hour on sharp curves and through residential districts; 35 miles per hour on the straightaway. Keep gears enmeshed and out of free wheeling on long grades. Keep cutout closed. Drive carefully at all times. Secure automobile permit, fee $1.

Rangers.—The rangers are here to assist and advise you as well as to enforce the regulations. When in doubt consult a ranger.

Forest Fires are a terrible and ever-present menace. There are thousands of acres of burned forests in Glacier National Park. Most of these "ghosts of forests" are hideous proofs of some person's criminal carelessness or ignorance.

Build camp fires only at designated camp sites. At times of high winds or exceptionally dry spell, build no fires outside, except in stoves provided at the free auto camps. At times of extreme hazard, it is necessary to restrict smoking to hotel and camp areas. Guests entering the park are so informed, and prohibitory notices are posted everywhere. Smoking on the highway, on trails, and elsewhere in the park is forbidden at such times. During the dry period, permits to build fires at any camp sites other than in auto camps must be procured in advance from the district ranger.

Be absolutely sure that your camp fire is extinguished before you leave it, even for a few minutes.

Do not rely upon dirt thrown on it for complete extinction.

Drown it completely with water.

Drop that lighted cigar or cigarette on the trail and step on it.

Do the same with every match that is lighted.

Extreme caution is demanded at all times.

Anyone responsible for a forest fire will be prosecuted to the full extent of the law.

If you discover a forest fire, report it to the nearest ranger station or hotel.

The heart of a territory so vast it was measured not in miles but degrees, the site of Glacier National Park was indicated as terra incognita or unexplored on most maps even as late as the dawn of the present century. To its mountain fastness had come first the solitary fur trader, the trapper, and the missionary; after them followed the hunter, the pioneer, and the explorer; in the nineties were drawn the prospector, the miner, and the picturesque trader of our last frontier; today, the region beckons the scientist, the lover of the out-of-doors, and the searcher for beauty. Throughout its days, beginning with the Lewis and Clark Expedition, the Glacier country has been a lodestone for the scientist, attracted from every corner of the earth by the combination of natural wonder and beauty to be found here. A chronological list of important events in the park's history follows:

| 1804–5 | Lewis and Clark Expedition. Meriwether Lewis reached a point 40 miles east of the present park. Chief Mountain was indicated as King Mountain on the expedition map. |

| 1810 | First definitely known crossing of Marias Pass by white man. |

| 1846 | Hugh Monroe, known to the Indians as Rising Wolf, visited and named St. Mary Lake. |

| 1853 | Cutbank Pass over the Continental Divide was crossed by A. W. Tinkham, engineer of exploration party with Isaac I. Stevens, Governor of Washington Territory. Tinkham was in search of the present Marias Pass, described to Governor Stevens by Little Dog, the Blackfeet chieftain. |

| 1854 | James Doty explored the eastern base of the range and camped on lower St. Mary Lake from May 28 to June 6. |

| 1855 | Area now in park east of Continental Divide allotted as hunting grounds to the Blackfeet by treaty. |

| 1872 | International boundary survey authorized which fixed the location of the present north boundary of the park. |

| 1882–83 | Prof. Raphael Pumpelly made explorations in the region. |

| 1885 | George Bird Grinnell made the first of many trips to the region. |

| 1889 | J. F. Stevens explored Marias Pass as location of railroad line. |

| 1891 | Great Northern Railroad built through Marias Pass. |

| 1895 | Purchase of territory east of Continental Divide from the Blackfeet Indians for $1,500,000, to be thrown open to prospectors and miners. |

| 1901 | George Bird Grinnell published an article in Century Magazine which first called attention to the exceptional grandeur and beauty of the region and need for its conservation. |

| 1910 | Bill creating Glacier National Park was signed by President Taft on May 11. Maj. W. R. Logan became first superintendent. |

| 1932 | Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park dedicated. |

| 1933 | Going-to-the-Sun Highway opened to travel throughout its length. |

| 1934 | Franklin D. Roosevelt first President to visit Glacier National Park. |

| Page | |

| International Peace Park | 1 |

| How to Reach Glacier Park | 3 |

| By Rail | 3 |

| By Automobile | 3 |

| By Airplane | 3 |

| Centers of Interest | 3 |

| Glacier Park Station | 3 |

| Two Medicine | 4 |

| Cutbank | 6 |

| Red Eagle | 6 |

| St. Mary and Sun Camp | 6 |

| Many Glacier Region | 8 |

| Belly River Valley, Waterton Lake, and Goathaunt | 11 |

| Flattop Mountain and Granite Park | 13 |

| Logan Pass | 14 |

| Avalanche Camp | 14 |

| Lake McDonald | 15 |

| Sperry Chalets | 16 |

| Belton | 16 |

| What to Do and See | 17 |

| Fishing | 17 |

| Hiking and Mountain Climbing | 18 |

| Popular trails | 21 |

| Swimming | 22 |

| Camping out | 22 |

| Photography | 22 |

| Park Highway System | 22 |

| How to Dress | 23 |

| Accommodations | 24 |

| Saddle-Horse Trips | 25 |

| All-Expense Tours by Bus | 26 |

| Transportation | 27 |

| Launches and Rowboats | 28 |

| Administration | 28 |

| Naturalist Service | 29 |

| Automobile Campgrounds | 29 |

| Post Offices | 29 |

| Miscellaneous | 29 |

| The Park's Geologic Story | 30 |

| Flora and Fauna | 34 |

| Ideal Place to See American Indians | 34 |

| References | 37 |

| Government Publications | 40 |

· SEASON JUNE 15 TO SEPTEMBER 15 ·

Glacier National Park, in the Rocky Mountains of northwestern Montana, established by act of Congress May 11, 1910, contains 981,681 acres, or 1,534 square miles, of the finest mountain country in America. Nestled among the higher peaks are more than 60 glaciers and 200 beautiful lakes. During the summer months it is possible to visit most of the glaciers and many of the lakes with relatively little difficulty. Horseback and foot trails penetrate almost all sections of the park. Conveniently located trail camps, operated at a reasonable cost, make it possible for visitors to enjoy the mountain scenery without having to carry food and camping equipment. Many travelers hike or ride through the mountains for days at a time, resting each evening at one of these high mountain camps. The glaciers found in the park are among the few in the United States which are easily accessible.

The Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park was established in 1932 by Presidential proclamation, as authorized by the Congress of the United States and the Canadian Parliament.

At the dedication exercises in June of that year, the following message from the President of the United States was read:

The dedication of the Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park is a further gesture of the good will that has so long blessed our relations with our Canadian neighbors, and I am gratified by the hope and the faith that it will forever be an appropriate symbol of permanent peace and friendship.

In the administration of these areas each component part of the Peace Park retains its nationality and individuality and functions as it did before the union.

The park entrances are on the main transcontinental line of the Great Northern Railway. Glacier Park Station, Mont., the eastern entrance, is 1,081 miles west of St. Paul, a ride of 30 hours. Belton, Mont., the western entrance, is 637 miles east of Seattle, a ride of 20 hours.

For information regarding railroad fares, service, etc., apply to railroad ticket agents or address A. J. Dickinson, passenger-traffic manager, Great Northern Railway, St. Paul, Minn.

A regular bus schedule is maintained by the Glacier Park Transport Co. to accommodate persons arriving by rail.

Glacier National Park may be reached by motorists over a number of well-marked automobile roads. The park approach roads connect with several transcontinental highways. From both the east and west sides automobile roads run north and connect with the road system in Canada, and motorists may continue over these roads to the Canadian national parks. Glacier National Park is the western terminus of the Custer Battlefield Highway.

A fee of $1 is charged for a permit to operate an automobile in Glacier Park. This permit allows reentry into the park at any time during the current season. Maximum speed limit in the park is 30 miles per hour. On mountain climbs and winding roads, utmost care in driving is demanded. All cautionary signs must be observed.

Fast de luxe airplane service is available by Northwest Airlines to Missoula, Mont., and Spokane, Wash., as is transportation via United Air Lines, from the east and west coasts to Spokane. National Park Airlines has a service from Salt Lake City, Utah, to Great Falls, Mont.

Glacier Park on the Great Northern Railway is the eastern entrance to the park. It is located on the Great Plains, near the base of Glacier's Rockies. It is on U S 2, which traverses from the east through northern Montana along the southern boundary of the park to Belton, the western entrance, and on to the Pacific coast. Glacier Park is also the southern [pg 4] terminus of the Blackfeet Highway which parallels the eastern boundary of the park and connects with the Alberta highway system. It is the southern end of the Inside Trail to Two Medicine, Cutbank, Red Eagle, and Sun Camp.

The commodious Glacier Park Hotel, several lesser hotels, auto camps, stores, an auxiliary park office, a Government fish hatchery, a post office and other structures are located here. The village gives a fine touch of western life, with Indians, cowboys, and picturesque characters contributing to its color. An encampment of Blackfeet is on Midvale Creek; these Indians sing, dance, and tell stories every evening at the hotel.

Two Medicine presents a turquoise mountain lake surrounded by majestic forest-covered peaks separated by deep glaciated valleys. A road leads into it from the Blackfeet Highway and ends at the chalets near the foot of Two Medicine Lake. Across the water rises Sinopah Mountain, while to the north sweep upward the gray-green slopes of Rising Wolf to terminate in purple-red argillites and snow banks. One of the most inviting camp sites of the park is immediately below the outlet of the lake, not far from the chalets. From it, one looks across a smaller lake, banked with gnarled and twisted limber pines, to the superb mountain scenery in every direction.

The cirques and broad mountain valleys above timberline are studded with cobalt blue lakes, and carpeted with multicolored beds of flowers. Mountain goats and sheep are frequently seen in these higher regions. Beaver colonies are located at the outlet of Two Medicine Lake and elsewhere around it, making this one of the best regions in the park to study these interesting mammals. An abundance of brook and rainbow trout in Two Medicine waters makes it a favorite spot for fishermen.

A campfire entertainment with a short popular talk is conducted every evening in the campfire circle of the auto camp by a resident ranger naturalist. Both chalet and campground guests avail themselves of the opportunity to meet for pleasure and instruction under the stars. Trails for hikers and saddle-horse parties radiate to adjacent points of interest: to Glacier Park via Scenic Point and Mount Henry, to Upper Two Medicine Lake and Dawson Pass, to Two Medicine Pass and Paradise Park, and up the Dry Fork to Cutbank Pass and Valley. A daily afternoon launch trip across Two Medicine Lake brings the visitor to the foot of Sinopah, from which there is a short, delightful path through dense evergreen forest to the foot of Twin Falls. Trick Falls, near the highway bridge across Two [pg 6] Medicine River, 2 miles below the lake, is more readily accessible and should be visited by everyone entering the valley. A great portion of its water issues from a cave beneath its brink. In the early season it appears a very proper waterfall, paneled by lofty spruce with the purple, snow-crowned Rising Wolf Mountain in the background. In late season water issues from the cave alone, with the dry fall over its yawning opening.

Cutbank is a primitive, densely wooded valley with a singing mountain stream. Six miles above the Blackfeet Highway are a quiet chalet, a ranger station, and a small grove for auto campers. A spur lane, leaving the highway at Cutbank Bridge, 4 miles north of the Browning Wye, brings the autoist to this terminus. A more popular means of approach is on horseback, over Cutbank Pass from Two Medicine or over Triple Divide Pass from Red Eagle. Cutbank is a favorite site for stream fishermen. At the head of the valley above Triple Divide Pass is the Triple Divide Peak (8,001 feet) which parts its waters between the three oceans surrounding North America, i. e., its drainage is through the Missouri-Mississippi system to the Gulf of Mexico (Atlantic), through the Saskatchewan system to Hudson Bay (Arctic), and through the Columbia system to the Pacific.

Red Eagle Lake in Red Eagle Valley is reached by trail only from Cutbank over Triple Divide Pass or from St. Mary Chalets or Sun Camp via the Many Falls Trail. From the lake rise imposing Split, Almost-a-Dog, and Red Eagle Mountains. On its sloping forested sides reposes Red Eagle Camp, which furnishes rest and shelter. It is a stopping place for travelers on the Inside Trail from Sun Camp or St. Mary to Glacier Park, and is a favorite spot for fishermen, as large, gamey, cutthroat trout abound in the waters of the lake. Reached by a secondary, picturesque trail that winds through magnificent forests, the head of Red Eagle Creek originates in a broad, grassy area almost as high as the Continental Divide. This bears Red Eagle Glacier and a number of small unnamed lakes, and is hemmed in by imposing rock walls and serrate peaks.

To many people Upper St. Mary Lake is the most sublime of all mountain lakes of the world. From its foot roll the plains northeastward to Hudson Bay and the Arctic. Its long and slender surface is deep emerald green, nestled in a salient in the Front Range, with peaks rising majestically [pg 7] a mile sheer over three of its sides. These for the most part possess names of Indian origin: Going-to-the-Sun, Piegan, Little Chief, Mahtotopa Red Eagle, and Curley Bear.

St. Mary Chalet at the lower end of the lake, Going-to-the-Sun Chalets (Sun Camp) near the upper end, Roes Creek Camp Grounds on the north shore, and a hikers' camp at the outlet of Baring Creek furnish ample accommodations for all classes of visitors.

The celebrated Going-to-the-Sun Highway from St. Mary Junction over Logan Pass to Lake McDonald runs along the north shore of St. Mary Lake past Roes Creek Camp. Spurs connect the chalets. Trails centering at Sun Camp lead everywhere: Along the south shore (the Many Falls Trail) to Red Eagle and St. Mary Chalets; up St. Mary Valley to Blackfeet Glacier, Gunsight Lake, and over Gunsight Pass to Lake Ellen Wilson, Sperry Chalets, and Lake McDonald; up Reynolds Creek over Logan Pass [pg 8] and along the Garden Wall to Granite Park; a spur from the trail up the same creek turns right and joins at Preston Meadows, high on Going-to-the-Sun Mountain, with another trail from Sun Camp which leads up Baring Creek past Sexton Glacier and over Siyeh Pass; from Preston Meadows over Piegan Pass and down Cataract Canyon to Many Glacier; up Roes Creek to Roes Basin; up Mount Reynolds to a fire look-out.

A ranger naturalist is stationed at Sun Camp who conducts field trips daily, lectures each evening in the chalet lobby, and maintains a cut-flower exhibit there. Small stores are maintained at both chalets; gasoline is obtainable at each. Scenic twilight launch rides on the lake are featured when the waters are calm. The ranger-naturalist generally accompanies these trips to impart interesting information about the lake and mountains.

Walks and hikes are popular at Sun Camp—to Baring, St. Mary, Florence, and Virginia Falls; to Roes and Baring Basins; to Sexton and Blackfeet Glaciers; to the summit of Goat Mountain. Sunrift Gorge, 100 feet north of the highway at Baring Creek Bridge, should be seen by everyone. It can be reached by trail from Sun Camp.

For many Swiftcurrent Lake is the hub of points of interest, to be surpassed by no other spot in the park. From it branch many deep and interesting glacial valleys. Fishing, boating, swimming, hiking, photographing, mountain climbing, horseback riding, and nature study are to be enjoyed at their best here. It is reached by an excellent spur road from the Blackfeet Highway at Babb, or by trail from Sun Camp, Granite Park, and Waterton Lakes.

Many Glacier Hotel, the largest hotel in the park, is located on Swiftcurrent Lake. Just beyond the hotel is an excellent auto camp and a group of auto housekeeping cabins. The hotel has telegraph and telephone services, an information desk, curio shop, a grill room and soda fountain, swimming pool, barber and shoe-shining shop, photograph shop, a first-aid medical establishment, and other services. A garage is situated near the hotel. A store with an ample line of campers' needs, including fresh meat, bread, butter, and eggs, is located in the auto campground.

Ranger-naturalist service is available at Many Glacier. This includes daily field walks; a nightly lecture augmented by motion pictures and slides in the Convention Hall in the basement of the hotel; an evening campfire entertainment in the auto camp; a cut-flower and geological exhibit in the hotel lobby and in the auto camp; a small museum on the opposite shore [pg 9] of the lake from the hotel, on the road leading to the campground; a self-guiding trail around Swiftcurrent Lake; information service in the museum; a naturalist-accompanied launch trip on Swiftcurrent and Josephine Lakes in the afternoon. In addition to this last-named, several other launch trips are taken daily on these lakes. This service may be used to shorten hikers' distance to Grinnell Lake and Glacier.

Many Glacier is a center for fishermen, as there are a dozen good fishing lakes in the vicinity. Rainbow, brook, and cutthroat trout abound in Swiftcurrent, Josephine, and Grinnell Lakes, and the lakes of the Upper Swiftcurrent Valley. Wall-eyed pike are plentiful in Lake Sherburne, the only body of water in the park in which these fish are found.

There are many excellent trails in the Swiftcurrent region. Cracker Lake, Morning Eagle Falls, Cataract Falls, Grinnell Lake, Grinnell Glacier, Iceberg Lake, and Ptarmigan Lake are all reached by oiled horseback trails. Good footpaths lead around Swiftcurrent and Josephine Lakes to the summit of Mount Altyn and to Appekunny Falls and Cirque.

The possibility of seeing and studying wildlife is best in the Many Glacier region. Except during midsummer, mountain sheep are commonly seen at close range around the chalets or in the flats above Lake Sherburne. [pg 11] Throughout summer they are high on the slopes of Mount Altyn or Henkel. Mountain goats are often seen clinging to the precipitous Pinnacle Wall on the way to Iceberg Lake, or on Grinnell Mountain while en route to Grinnell Glacier, or on the trail to Cracker Lake. Black bears and grizzlies occasionally visit the grounds near the hotel. Conies are to be heard bleating among the rock slides back of the ranger station along the trail to Iceberg Lake, or near the footpath across the lake from the hotel. Early in the morning, or at twilight, beavers are frequently seen swimming in the lake. Marmots are common in many valleys near the hotel and auto camp. Deer infrequently visit the region. Hikers, horseback riders, and rangers have reported seeing such rare animals as foxes, wolves, and lynxes. Without moving from one's comfortable chair on the veranda of the hotel one may watch the ospreys soaring back and forth over the lake in quest of fish. These graceful and interesting birds have their huge nest on top of a dead tree across the lake from the hotel. The pair of birds return annually to the same nest. Beside Swiftcurrent Falls, two families of nesting water ouzels may be studied at close range.

Though much like Swiftcurrent Valley in topographical make-up, the Belly River district is much wilder and more heavily forested. It is accessible by trail only from Many Glacier over Ptarmigan Wall or from Waterton Lake over Indian Pass. These, with spur trails to Helen and Margaret Lakes, make up the principal trail system. The Glacier Park Saddle Horse Co. maintains a comfortable mountain camp on Crossley Lake, where food and lodging are available at reasonable rates. Fishing is good in the lakes of the Belly River country. The 33-mile trip from Many Glacier to Waterton is one of the finest to be taken in the park. Crossley Lake Camp is approximately midway.

The International Waterton Lake and the northern boundary line of Glacier National Park mutually bisect each other at right angles. Mount Cleveland rises 6,300 feet sheer above the head of the lake. Waterton Lake townsite, Alberta, is located at the foot. It is reached by highway from Glacier Park, Babb, Cardston, Lethbridge, Calgary, and points in the Canadian Rockies. The modern Prince of Wales Hotel, several other hostelries, cabin camps, garages, stores, and other conveniences are in the settlement. A 12-mile spur highway leads to Cameron Lake, another international body of water on whose northern (Canadian) shore is a fine example of a sphagnum bog. Another winding road leads to a colorful canyon known as "Red Rock."

A picturesque cut-off highway over aspen-covered foothills around the very base of majestic Chief Mountain, and beginning at a point 4 miles north of Babb, leads to Waterton Lakes Park in Canada.

Trails lead from the village to principal points of interest in the Canadian Park as well as up the west shore to the head of the lake at which are situated the Government ranger station and Goathaunt Camp. The head of the lake is more readily reached by the daily launch service from Waterton Village, or over trail from Many Glacier by Crossley Lake Camp, or by Granite Park and Flattop Mountain. A scenic trail leads to Rainbow Falls and up Olson Valley to Browns Pass, Bowman Lake, Hole-in-the-Wall Falls, Boulder Pass, and Kintla Lake in the northwest corner of the park. There are no hotel or camp accommodations at Bowman or Kintla Lakes.

Game is varied and abundant at Waterton Lake. Moose are sometimes seen in the swampy lakes along Upper Waterton River. Later in the season, bull elk are heard bugling their challenge through the night. Deer are seen both at Waterton Lake Village and Goathaunt Camp. Sheep and goats live on neighboring slopes. One does not have to leave the trail [pg 13] to see evidence of the work of the beaver. The trail down Waterton Valley has had to be relocated from time to time, as these industrious workers flooded the right-of-way. A colony lives at the mouth of the creek opposite Goathaunt Camp. Otters have been seen in the lakes in the evening. Marten have bobbed up irregularly at the ranger station.

Bird life is abundant in this district, because of the variety of cover. Waterfowl are frequently seen on the lake. A pair of ospreys nest near the mouth of Olson Creek. Pine grosbeaks, warblers, vireos, kinglets, and smaller birds abound in the hawthorne and cottonwood trees, and in the alder thickets.

Glacier Park has within its boundary two parallel mountain ranges. The eastern, or front range, extends from the Canadian boundary almost without a break to New Mexico. The western, or Livingston Range, rises at the head of Lake McDonald, becomes the front range beyond the international line, and runs northwestward to Alaska. Between these two ranges in the center of the park is a broad swell which carries the Continental Divide from one to the other. This is Flattop Mountain, whose groves of trees are open and parklike, wholly unlike the dense forests of the lowlands with which every park visitor is well acquainted.

A trail leads south from Waterton over Flattop to the tent camp called "Fifty Mountain" and to Granite Park, where a comfortable high-mountain chalet is located. Here is exposed a great mass of lava, which once welled up from the interior of the earth and spread over the region which was then the bottom of a sea. The chalets command a fine view of the majestic grouping of mountains around Logan Pass, of the noble summits of the Livingston Range, and of systems far to the south and west of the park. Extending in the near foreground are gentle slopes covered with sparse clumps of stunted vegetation. In early July open spaces are gold-carpeted with glacier lillies and bizarrely streaked with lingering snow patches. Beyond are the deep, heavy forests of Upper McDonald Valley.

The chalets may also be reached from Sun Camp and Logan Pass over a trail along the Garden Wall, from the highway 2 miles above the western switchback by a 4-mile trail, from Avalanche Camp and Lake McDonald over the McDonald Valley trail, and from Many Glacier by the beautiful trail over Swiftcurrent Pass. A short distance from the chalets a spur from the trail to the Waterton Lake leads to Ahern Pass, from which there is an unexcelled view of Ahern Glacier, Mount Merritt, Helen and Elizabeth Lakes, and the South Fork of the Belly River. This spur is only a mile [pg 14] from the chalets. At Fifty Mountain Camp, half-way between Granite Park and Waterton, a second spur, a quarter of a mile long, takes one above Flattop Mountain to the summit of the knife-edge. From here there is a fine panorama of Mount Cleveland, Sue Lake, and Middle Fork of Belly River.

A foot trail 1 mile long leads from the Granite Park chalet to the summit of Swiftcurrent Mountain upon which a fire lookout is located. For the small amount of effort required to make this ascent of 1,000 feet, no more liberal reward of mountain scenery could be possible. Another foot trail leads from the chalets to the rim of the Garden Wall, from which there are splendid views of Grinnell Glacier and the Swiftcurrent region.

Animal life is varied and easily studied at Granite Park. Bear and deer are common in this section. Mountain goats are frequently seen above Flattop Mountain or near Ahern Pass. Mountain sheep graze on the slopes of the Garden Wall. Ptarmigan should be looked for, especially above Swiftcurrent Pass.

Granite Park is a paradise for lovers of alpine flowers. On the Garden Wall, the connoisseur should seek for the rare, heavenly blue alpine columbine. Here are expanses of dryads, globe flowers, alpine firewood, and a wealth of others. Early July is the best time for floral beauty.

Logan Pass lies between the headwaters of Logan and Reynolds Creeks. It crosses the Continental Divide and carries the Going-to-the-Sun Highway from Lake McDonald to Upper St. Mary Lake and the trail from Sun Camp to Granite Park.

Though there are no overnight stopping places on the pass, its accessibility by automobile makes it a starting place for several delightful walks, chiefly to Hidden Lake, which occupies a basin only recently evacuated by ice, and tiny Clements Glacier, which sends its water to both the Arctic and Pacific Oceans, and which has been termed "Museum Glacier" because it encompasses in its few hundred acres of surficial area all of the principal features of a major glacier.

Ranger-naturalist services, including short field trips, are available daily throughout summer on the pass.

Avalanche auto camp is located in a grove of cedars and cottonwoods on a picturesque flat at the mouth of Avalanche Creek. It is equipped with modern toilets, showers, and laundry, but has no stores or gasoline station. [pg 15] A Government ranger naturalist and a camp tender serve the camp, which is on Going-to-the-Sun Highway.

Near the upper end of the camp, Avalanche Creek has cut a deep, narrow gorge through brilliant red argillite. It is filled with potholes scoured out by stones swirled in the foaming torrent. Drooping hemlocks, festooned with goatsbeard lichen, keep the spot in cool, somber gloom even on the hottest midday. This gorge is the home of the water ouzel, which is often seen flying back and forth in the spray.

From the gorge, a self-guiding trail leads 2 miles to Avalanche Basin, a semicircular amphitheater with walls over 2,000 feet high over which plunge a half dozen snowy waterfalls. A dense forest and calm lake repose on the floor of the cirque. Fishing is good in the lake. The narrow canyon through which the trail leads from the camp offers fine views of Heaven's Peak, Mount Cannon, Bearhat Mountain, Gunsight Mountain with the cirque bearing Sperry Glacier, and the canyon in which Hidden Lake reposes. In the early season the walls of the basin and canyon are draped with countless waterfalls. The sides of Cannon and Bearhat offer one of the most opportune places for seeing mountain goats. In late season huckleberries are abundant.

A ranger naturalist conducts an entertainment every evening in the campfire circle in the auto camp.

Lake McDonald is the largest lake in the park, being 10 miles long and a mile wide. Its shores are heavily forested with cedar, hemlock, white pine, and larch. At its head, impressive, rocky summits rise to elevations 6,000 feet above its waters. The Going-to-the-Sun Highway runs along its southeastern shore. Its outlet is 2 miles above Belton station.

Lake McDonald Hotel is on the highway near the upper end of the lake. It has a store for general supplies, a gasoline station, curio shop, and all modern conveniences. Its dining room, facing the lake, is one of the most appropriate and charming in the park. Its lobby is filled with well-mounted animals and birds of the region. It is the focal point for trails to Sperry Chalet and Gunsight Pass, Upper McDonald Valley, the summit of Mount Brown, and Arrow Lake. There is good fishing in Arrow and Snyder Lakes.

Private cabin camps are located at the head and foot of the lake. A general store and gasoline filling station are located at the foot of the lake. A well-equipped public auto campground is at Sprague Creek, near Lake McDonald Hotel.

Ranger-naturalist services are available at the hotel. Lectures on popular natural history are delivered each evening in the hotel lobby and at the Sprague Creek campfire circle. A cut wild-flower exhibit is also placed in the hotel. Self-guiding trails lead to Fish and Johns Lakes, short distances from the hotel.

Sperry Chalets are located in a picturesque high-mountain cirque, with precipitous, highly colored Edwards, Gunsight, and Lincoln Peaks hemming it in on three sides. It is reached by trail only from Lake McDonald and from Sun Camp via Gunsight and Lincoln Passes.

Mountain climbing, exploring Sperry Glacier, fishing in nearby Lake Ellen Wilson, and meeting mountain goats are the chief diversions of this entrancing spot, located at timberline. During late afternoons goats are to be seen perched against the cirque walls. Practically every evening they start down for the chalets, to reach there after midnight and fill expectant visitors with joy. Besides these, deer, marmots, conies, and Clark nutcrackers and other wildlife are abundant.

Belton, on the Great Northern Railway, is the entrance to the west side of the park. It has stores, hotel, chalet, and a cabin camp to accommodate the visitor.

The waters of Glacier National Park abound in fish. All popular species of trout have been planted. They have thrived owing to the abundant natural fish foods and the nearly constant temperature of the waters the year around. Cutthroat, eastern brook, and rainbow, are the most abundant. Fly fishing is the greatest sport, but spinners and the ever-abundant grasshopper may be used successfully by those not skilled in the use of the fly. In the larger lakes a Mackinaw or Dolly Varden weighing 40 pounds is a possibility. All fishing must be in conformity with the park regulations.

Two Medicine Chalets.—Two Medicine Lake has become well known for its eastern brook and rainbow trout. Good fishing is also found in the Two Medicine River below Trick Falls. This lake and stream are probably better stocked than any in the park, because of the proximity to the hatchery at the eastern entrance.

Cut Bank Chalets.—This camp is located on the banks of the North Fork of Cut Bank Creek, which may be fished both ways from the camp for a distance of from 3 to 5 miles. Cutthroat and eastern brook inhabit this section, and the fisherman who takes the center of the stream and fishes with skill is sure of a well-filled creel. The South Fork at Cut Bank Creek is a wild little stream, well stocked, but little known.

St. Mary Chalets.—St. Mary Lake is the home of the Mackinaw trout, as well as cutthroat and rainbow trout. Numerous streams empty into this lake from which a goodly toll may be taken with fly or spinner. Red Eagle Lake, easily reached by trail from St. Mary Chalets, is one of the best fishing spots in the park. There is also good fishing in Red Eagle Creek.

Going-to-the-Sun Chalets.—The lakes in Roes Creek Basin will furnish excellent sport. For the large Mackinaw trout the upper end of St. Mary Lake is a good place. Gunsight Lake, 9 miles distant, is well stocked with rainbow trout.

Many Glacier Hotel.—Lake Sherburne contains pike, Lake Superior whitefish, and rainbow and cutthroat trout. Pike, and often a cutthroat, are readily taken with the troll. Swiftcurrent River affords good stream fishing for the fly caster. Swiftcurrent, Grinnell, Josephine, and Ptarmigan Lakes are famous for cutthroat, eastern brook, and rainbow trout. The small lakes along the Swiftcurrent Pass Trail abound in eastern brook and rainbow trout. Cracker Lake is always ready to fill the creel with a small black-spotted trout.

The North and South Forks of Kennedy Creek are excellent for fishing. Cutthroats are abundant in them and in Slide Lake. Lower Kennedy Lake on the South Fork abounds in grayling.

Lake McDonald Hotel.—Fishing in Lake McDonald is good but there is unusually good trout fishing in Fish Lake (2 miles), Avalanche Lake (9 miles), Snyder Lake (5 miles), and Lincoln Lake (11 miles). Trout Lake (7 miles) and Arrow Lake (11 miles), as well as McDonald Creek, also furnish a good day's sport.

There is a good automobile road to within 3 miles of Avalanche Lake.

Red Eagle Tent Camp.—Red Eagle Lake and Red Eagle Creek, both above and below the lake, abound in large cutthroat trout, some attaining the weight of 7 pounds.

Crossley Lake Tent Camp.—Crossley and other lakes on the Middle Fork of the Belly River furnish excellent sport. Cutthroat and Mackinaw trout are found here. Large rainbow trout and grayling abound in Elizabeth Lake. In the Belly River proper, rainbow and cutthroat trout and grayling are plentiful.

Goathaunt Tent Camp.—Large Mackinaw and cutthroat trout are found in Waterton Lake; eastern brook trout are numerous in Waterton River; Lake Francis on Olson Creek abounds in rainbow trout.

The park is a paradise for hikers and mountain climbers. There are numerous places of interest near all hotels and chalets which can be visited by easy walks. Or trips can be made to occupy one or more days, stops being planned at various hostelries or camping sites en route.

Space does not permit giving detailed information regarding points of interest along the trails, but this can be secured from Elrod's Guidebook and the United States topographic map. Directional signs are posted at all trail junctions. There is not the slightest danger of hikers getting lost if they stay on the trails. It is safe to travel any of these trails alone. Unless wild animals in the park are molested or are protecting their young they never attack human beings.

Hikers should secure a topographic map of the park which shows all streams, lakes, glaciers, mountains, and other principal features in their proper positions. With a little practice it can be read easily. The official map can be purchased for 25 cents at the superintendent's office at Belton, the administration office at Glacier Park Station, the hotels, and all registration stations at the park entrances.

The trip should not be ruined by attempting too much. An average of 2 or 3 miles per hour is good hiking time in the rough park country. One thousand feet of climb per hour is satisfactory progress over average trails. In this rugged country hikes of 15 miles or more should be attempted only by those who are accustomed to long, hard trips. An attempt at mountain climbing or "stunts" should not be made alone unless one is thoroughly acquainted with the nature of Glacier's mountains and weather. Too often "stunts" result in serious body injuries, or even death, as well as much arduous work for rangers and others. Hikers should consult a ranger naturalist or information ranger before venturing on a hazardous, novel, or new undertaking. No one but an experienced mountaineer should attempt to spend a night in the open. Shelter cabins, for free use by parties overtaken by a storm, have been erected by the Government on Indian, Piegan, and Gunsight Passes. They are equipped with flagstone floors, stoves, and a limited supply of fuel wood. Mountain etiquette demands that they not be left in a disorderly state, that no more fuel be consumed than is absolutely necessary, and that their privileges and advantages not be abused.

Shelter is not available in some of the most beautiful sections of the park. To those who are sufficiently sturdy to pack blankets, cooking utensils, and provisions, and are sufficiently versed in woodcraft to take care of themselves overnight, Glacier presents wonderful opportunities. Provisions can be purchased at Glacier Park Station, Belton, and at any hotel or chalet in the park. For fire prevention, it is unlawful to build campfires (or fires of any kind) except at designated places. The location of these sites can be ascertained from park rangers. Unless one is an experienced mountaineer and thoroughly familiar with the park, it is unwise to go far from the regular [pg 20] trails alone. He should not scorn the services of a guide on such trips. Above all, he should not attempt to hike across country from one trail to another. The many sheer cliffs make this extremely dangerous.

If one is a veteran mountaineer and plans to climb peaks or explore trackless country, he should take the precaution to leave an outline of his plans at his hotel, chalet, or camp, giving especially the time he expects to return or reach his next stopping place.

At each ranger station, hotel, chalet, and permanent camp in the park will be found a "Hiker's Register" book. Everyone is urged for his own protection to make use of these registers, entering briefly his name, home address, time of departure, plans, and probability of taking side trips or of changing plans. The hotel clerk should be informed of these at the time of departure. If a ranger is not there, this information should be entered in the register which will be found near the door outside the building, so that when the ranger returns he can report it to the next station or to headquarters. These precautions are to protect the park visitor. In case of injury or loss, rangers will immediately investigate.

In planning hiking trips, the following should also be taken into consideration: At higher elevations one sunburns easily and painfully because of the rarity of the atmosphere and intense brightness of the sun. Hikers should include in their kits amber goggles and cold cream for glacier and high mountain trips.

Footwear is most important. A hike should not be started with shoes or boots that have not been thoroughly broken in. Because feet swell greatly on a long trip, hiking shoes should be at least a half size larger than street shoes. They need not be heavy, awkward shoes—in fact, light shoes are much easier on the feet. Most people are made uncomfortable by high-top boots or shoes which retard the circulation of the calves. Six-or eight-inch tops are sufficient. Soles should be flexible, preferably of some composition which is not slippery when wet. Crepe soles are excellent for mountain climbing and for fishing. Hobnailed shoes are necessary only for grassy slopes or cross-country work. Hungarian nails are much to be preferred to hobs, and only a light studding of soles and heels is most effective. White silk socks should be worn next to the feet, a pair of heavy wool (German) socks over them. Soaking the feet daily in salt or alum solution toughens them. On a hike the feet should be bathed in cold water whenever possible.

Hiking trips with ranger naturalists are described under that service. There are many interesting short side trips from all hotels, chalets, and camps. Short self-guiding trails upon which interesting objects of natural history are fittingly labeled have been established at the following places:

1. Around Swiftcurrent Lake (2-1/2 miles).

2. From Lake McDonald Hotel to Fish Lake (2 miles).

3. From Lake McDonald Hotel to Johns Lake (2 miles).

4. From Avalanche Campground to Avalanche Lake (2 miles).

Lunches may be ordered from hotels and chalets the night before a trip. If an early departure is planned, it should be so stated upon ordering the lunch.

(Figures indicate altitude in feet above sea level)

Glacier Park Hotel (4,796) to Two Medicine Chalets (5,175) via Mount Henry Trail (7,500). Distance, 11 miles.

Two Medicine Chalets to Cut Bank Chalets (5,100) via Cut Bank Pass (7,600), 17-1/2 miles.

Cut Bank Chalets via Triple Divide Pass (7,400) and Triple Divide Peak (8,001) to Red Eagle Camp on Red Eagle Lake (4,702), 16 miles.

Red Eagle Camp to St. Mary Chalets (4,500), 9 miles.

The Many Falls Trail: Red Eagle Camp via the south shore of St. Mary Lake and Virginia Falls to Going-to-the-Sun Chalets (4,500), 11-1/2 miles.

The 2-day trip, St. Mary Chalets to Red Eagle Camp (7 miles) and thence over Many Falls Trail to Going-to-the-Sun Chalets, is excellent.

Going-to-the-Sun Chalets via Sunrift Gorge (4,800), Siyeh (8,100), and Piegan (7,800) Passes to Many Glacier Hotel (4,861), 17-1/2 miles.

Going-to-the-Sun Chalets via Reynolds Creek, Preston Park, and Piegan Pass to Many Glacier Hotel, 19 miles.

Many Glacier Hotel to Granite Park Chalets (6,600) via Swiftcurrent Pass (7,176), 9 miles.

Granite Park Chalets to Lake McDonald Hotel (3,167) via McDonald Creek, 18 miles.

Granite Park Chalets (6,600) via Logan Pass (6,654) to Going-to-the-Sun Chalets (4,500), 18 miles.

Granite Park Chalets to the Going-to-the-Sun Highway (5,200) meeting it 2 miles above the switchback, 4 miles.

Granite Park Chalets to Goathaunt Camp at Waterton Lake (4,200) via Flattop Mountain (6,500), 20 miles. A short side trail leads to Ahern Pass, from which is obtained a splendid view of the valley of the South Fork of Belly River. Another from Flattop Mountain to the Summit of the Continental Divide overlooks Sue Lake and the Middle Fork of the Belly River. Fifty Mountain Camp is midway between Granite Park and Goathaunt Camp.

Goathaunt Camp to Browns Pass (6,450), Boulder Pass (8,200), and Hole-in-the-Wall Falls, 15 miles. One of the most scenic trips in the park. From Boulder Pass a trail leads to Kintla Lake; from Browns Pass a trail to Bowman Lake. A secondary road leads from Kintla to Bowman Lakes, 20 miles.

Goathaunt Camp via Indian Pass (7,400) to Crossley Lake Camp (4,855), 18 miles.

Crossley Lake Camp to Many Glacier Hotel (4,861) via the celebrated Ptarmigan Trail which includes a 183-foot tunnel through Ptarmigan Wall, 17 miles.

Lake McDonald Hotel to Avalanche Camp (3,400), 6-1/2 miles.

Avalanche Camp to Avalanche Lake (3,885), 2 miles.

Lake McDonald Hotel to Sperry Chalets (6,500), 6 miles. From Sperry Chalets to Sperry Glacier, 2-1/2 miles.

Sperry Chalets to Going-to-the-Sun Chalets (4,500) via Lincoln (7,000) and Gunsight (6,900) Passes, 13 miles.

While it is possible for visitors to indulge in lake bathing, it will be found that the water of the lakes, usually just from the melting glaciers, is uncomfortably cold, and for this reason is not enjoyed except by the most hardy. Swimming pools and plunges with warmed water are provided at Glacier Park Hotel and Many Glacier Hotel.

The traveler who is not in a hurry may camp out in the magnificent wilderness of the park, carrying equipment in his automobile and staying as long as he wishes in any of the free Government campgrounds, or he may carry his bed and provisions on his back. With a competent guide and a complete camping outfit the park visitor may set forth upon the trails to wander at will. On such trips one may venture far afield, explore glaciers, climb divides for extraordinary views, linger for the best fishing, or spend idle days in spots of inspirational beauty.

The Glacier Park Saddle Horse Co. provides excellent small sleeping tents and a complete outfitting of comforts for pack trips.

There are several important points to be remembered on such trips:

A Government topographic map should be procured and consulted frequently.

Extreme care should be taken about fires. No fire should be left even for a few minutes unless it is entirely extinguished. It should be drenched completely with water.

Glacier offers exceptional views to delight the photographer. While the scenic attractions are most commonly photographed, the animals, the flowers, and the picturesque Blackfeet Indians provide interesting subjects. Photographic laboratories are maintained at Many Glacier, Lake McDonald, and Glacier Park Hotels, and at Belton village. Expert information regarding exposures and settings is also available at these places.

The Blackfeet Highway, lying along the east side of the park, is an improved highway, leading from Glacier Park Station to the Canadian [pg 23] line via Babb, Mont., and from the line to Waterton Lakes Park and other Canadian points via Cardston, Alberta. There is also an improved picturesque cut-off highway, which branches from this road at Kennedy Creek Junction, 4 miles north of Babb, leading around the base of Chief Mountain to Waterton Lakes Park. Improved highways lead from the Blackfeet Highway to Two Medicine Lake, the Cutbank Chalets, and Many Glacier Hotel on Swiftcurrent Lake.

The Theodore Roosevelt Highway (US 2) follows the southern boundary of the park from Glacier Park Station to Belton, a distance of 58 miles, and a trip over this highway affords views of excellent scenery.

The spectacular Going-to-the-Sun Highway, well known as one of the outstanding scenic roadways of the world, links the east and west sides of the park, crossing the Continental Divide through Logan Pass at an altitude of 6,654 feet, and connects with the Blackfeet Highway at St. Marys Junction, a distance of 51 miles from Belton. East of the divide an improved spur road leads to Going-to-the-Sun Chalets on famous St. Marys Lake. On the west side at Apgar, 2 miles above Belton, a narrow dirt road follows the north fork of the Flathead River to Bowman and Kintla Lakes.

As a rule tourists are inclined to carry too much. There are no unnecessary formalities and no need for formal clothes in Glacier Park, where guests are expected to relax from everyday affairs of living. An inexpensive and simple outfit is required—old clothes and stout shoes are the rule. These, together with toilet articles, can be wrapped into a compact bundle and put into a haversack or bag. For saddle trips, hiking, or idling, both men and women wear riding breeches for greater comfort and freedom. Golf knickers are also satisfactory. "Shorts", such as are worn by Boy Scouts, are not generally feasible in this park. Ordinary cotton khaki breeches will do, although woolen ones are preferable; lightweight woolen underwear and overshirt are advised because of rapid changes of temperature. A sweater or woolen mackinaw jacket, 1 or 2 pairs of cotton gloves, and a raincoat are generally serviceable. Waterproof slickers are furnished free with saddle horses.

Supplies and essential articles of clothing of good quality, including boots, shoes, leggings, socks, haversacks, shirts, slickers, blankets, camping equipment, and provisions, may be purchased at well-stocked commissaries at Glacier Park, Many Glacier, and Lake McDonald Hotels and at the camp store at Many Glacier campground. The Glacier Park Hotel [pg 24] Co., which operates these commissaries, also makes a practice of renting, at a nominal figure, riding outfits, mackinaw coats, and other overgarments. Stores carrying a similar general line of articles most useful in making park trips are located at Belton and at Glacier Park village. There is a store carrying provisions, cigars, tobacco, and fishermen's supplies at the foot of Lake McDonald.

The Glacier Park Hotel Co., under franchise from the Department of the Interior, operates the hotel and chalet system in the park and the Belton Chalets. This system includes the Glacier Park Hotel at Glacier Park Station, an imposing structure built of massive logs, nearly as long as the Capitol at Washington, accommodating 400 guests; the Many Glacier Hotel on Swiftcurrent Lake, accommodating over 500 guests; and the Lake McDonald Hotel on Lake McDonald, with capacity for 100 guests.

The chalet groups are from 10 to 18 miles apart, but within hiking distance of one another or of the hotels, and provide excellent accommodations for trail tourists. They are located at Two Medicine, Cutbank, St. Mary, Sun Camp, Granite Park, Sperry, and Belton. In addition to these, the Glacier Park Saddle Horse Co. maintains tent camps at Red Eagle Lake, Crossley Lake, Goathaunt, and Fifty Mountain.

There are also a few hotels and camps located on the west side, in or adjacent to the park, on private lands. The National Park Service exercises no control over their rates and operations. Private tourist cabins and hotels are operated outside the park at Glacier Park Station, Belton, St. Mary, Babb, and Browning Junction.

The Glacier Park, Many Glacier, and Lake McDonald Hotels are open from June 15 to September 15. The American-plan rates range from $6.50 a day for a room, without bath, to $14 a day for de luxe accommodations for one. Rooms may also be obtained on the European plan. Breakfast and lunch cost $1 each; dinner, $1.50. Children under 8 are charged half rates, and a discount of 10 percent is allowed for stays of a week or longer at any one hotel. Cabins are obtainable at Lake McDonald Hotel at a rate of $5 each, American plan, for 3 persons in 1 room; 2 persons in room, $5.50 each; 1 person, $6.50.

Chalets operated during 1937 will be open from June 15 to September 15, except Sperry and Granite Park, which will open July I and close September 1. Minimum rates are computed on a basis of $4.50 a day per person, special accommodations ranging as high as $7.50. A 10-percent [pg 25] discount is allowed for stays of a week or more at any one chalet group. Tent camp rates are $5 per day, per person, American plan.

The Swiftcurrent auto cabins are located a little more than a mile from Many Glacier Hotel. Here a 2-room cabin for 1 or 2 persons costs $2.50 a day; 3 or 4 persons in a 3-room cabin, $4 a day. Blankets and linen may be rented by the day. The 10 percent discount given at the hotels and chalets also applies to the housekeeping cabins.

Glacier National Park has the distinction of being the foremost trail park. More saddle horses are used than in any other park or like recreational region in this country. The Glacier Park Saddle Horse Co. has available during the season about 800 saddle animals. There are nearly 900 miles of trails in this park.

At Glacier Park, Many Glacier, and Lake McDonald Hotels, Going-to-the-Sun Chalets, and Goathaunt Tent Camp, horses may be engaged or released for trips in the park, including camping trips. At Two Medicine Chalets horses may be engaged or released for local rides only.

A wonderful 3-day excursion is afforded by the Logan Pass Triangle trip. This trip may be started at either the Many Glacier Hotel and Chalets or Going-to-the-Sun Chalets. Beginning at Many Glacier Hotel, the first [pg 26] day's route follows up Swiftcurrent Pass to Granite Park Chalets, where luncheon is served and the overnight stop made. The second day the Garden Wall Trail to Logan Pass is followed, with a box luncheon on the way, and Going-to-the-Sun Chalets is reached in late afternoon in time for dinner. The return to Many Glacier Hotel is made the third day via Piegan Pass, Grinnell Lake, and Josephine Lake.

The South Circle trip requires 5 days to complete and may be started either from Many Glacier, Going-to-the-Sun Chalets, or Lake McDonald Hotel on Lake McDonald. Three of the principal passes are traversed—Swiftcurrent, Gunsight, and Piegan. The North Circle trip is also a 5-day tour via tent camps, crossing Swiftcurrent Pass, Indian Pass, and Ptarmigan Wall. The trip starts from Many Glacier Hotel, Going-to-the-Sun Chalets, or Lake McDonald Hotel.

There is a 4-day inside trail trip from Glacier Park Hotel via Two Medicine, Cut Bank, and Red Eagle to Sun Camp.

Many delightful specially scheduled trips of 1 and 2 days' duration are also available.

Information about saddle-horse trips may be obtained at any of the hotels or other points of concentration. Practically any type of trip desired can be arranged, from short excursions to special points of interest, such as the half-day trip from Glacier Park Hotel to Forty-Mile Creek for $3.50, to pack trips of unlimited duration; the larger the party, the cheaper the rates. For minimum parties of 3 persons, the average rate for 1-day trips is $5 or $6. For parties of 3 or more, the all-expense Fifty Mountain Trail trip of 3 days is $28.50; the 5-day North Circle trip, $50.50. These are specifically mentioned merely to give an idea of the cost; many other fine trips are available at rates computed on a similar basis.

Special arrangements can be made for private camping parties making a trip of 10 days or more at rates amounting to $11 a day each for groups of 7 or more; $12 a day each for 6 persons; $13 for 5; $15 for 4; $16 for 3; $18 for 2; and $27 for 1 person. A guide and cook, are furnished for a party of one or more persons, and extra helpers are added, if the number of persons require it. Private trips of less than 10 days may also be arranged.

Experienced riders may rent horses for use on the floor of the valleys at $1 an hour, $3 for 4 hours, and $5 for 8 hours.

The Glacier Park Transport Co. and the Glacier Park Hotel Co. have jointly arranged some very attractive all-expense tours of 1, 2, 3, and 4 days' duration. These trips are priced reasonably and include auto fare, [pg 27] meals, and hotel lodgings. The trips begin at Glacier Park Station for west-bound passengers and at Belton for east-bound passengers and are made daily during the season.

Trip No. 1.—Logan Pass Detour.—Glacier Park Hotel to Going-to-the-Sun Chalets, Lake McDonald Hotel, and Belton, Mont. Leave Glacier Park Hotel at 2:30 p. m.; arrive Belton the next day, 2:05 p. m. All-expense rate, $15.50.

Trip No. 2.—Glacier Park Hotel to Many Glacier Hotel, Going-to-the-Sun Chalets, Lake McDonald Hotel, and Belton. Leave Glacier Park Hotel 2:30 p. m.; arrive Belton on third day, 2:05 p. m. All-expense rate, $27.75.

Trip No. 3.—Glacier Park Hotel to Two Medicine Lake, Many Glacier Hotel, Going-to-the-Sun Chalets, Lake McDonald, and Belton. Leave Glacier Park Hotel 2 p. m.; arrive Belton on fourth day, 2:05 p. m. All-expense rate, $38.

Trip No. 4.—Same as Trip No. 3, except an extra day at Many Glacier Hotel, and the all-expense rate is $44.50.

All west-bound trips are scheduled to arrive at Belton at 2:05 p. m., in time for the Empire Builder, west. The trips east bound all begin at Belton and close at Glacier Park Station, in time for the Empire Builder, east. The rates for these trips are:

No. 1—$16.50 No. 2—$30.25 No. 3—$36.75 No. 4—$45.00.

All trips, both east and west, are routed over the spectacular Going-to-the-Sun Highway and Logan Pass.

The Glacier Park Transport Co. is operated in the park under franchise from the Department of the Interior. Daily stage service in each direction is maintained between Glacier Park Hotel and St. Mary Chalets, Many Glacier Hotel and Chalets, Waterton, and Going-to-the-Sun Chalets, [pg 28] Lake McDonald Hotel, and Belton Station. A daily bus trip is made from Glacier Park Hotel to Two Medicine Chalets on Two Medicine Lake, allowing sufficient time at the lake to fish or make the launch trip. Regular motorbus service is maintained between Glacier Park Hotel and Belton. On the west side daily bus service is maintained between Belton, the foot of Lake McDonald, and the Lake McDonald Hotel at the head of Lake McDonald, and between this hotel and Logan Pass on the Continental Divide.

The transportation company and launch companies allow each passenger to carry with him 25 pounds of hand baggage without extra charge, which is usually sufficient for shorter trips. Trunks are forwarded at extra expense. Arrangements can be made for caring for trunks left at entrances during tour of park or rechecking them for passengers who enter at one side and leave by the other. Storage charges on baggage at Glacier Park Station and at Belton are waived while tourists are making park trips.

The Glacier Park Hotel Co. operates launch service on Waterton Lake between Goathaunt Camp in Glacier Park, and the Waterton Lake townsite in Alberta, Canada, crossing the international boundary line about half-way up the lake. One-way, the fare is 75 cents; round trip, $1.50.

Twilight launch rides on St. Mary and McDonald Lakes are featured during fair weather.

The J. W. Swanson Boat Co. operates launch service on beautiful Two Medicine Lake, at a charge of 75 cents each for four or more passengers. For a smaller number the minimum charge for the trip around the lake is $3. Trips around Josephine and Swiftcurrent Lakes may be made for $1 each. The Swanson Co. also rents rowboats for 50 cents an hour; $2.50 a day, or $15 a week for use on the following lakes: Two Medicine, St. Mary, Swiftcurrent, Josephine, and McDonald. Outboard motors may also be rented.

This booklet is issued once a year and the rates mentioned herein may have changed slightly since issuance, but the latest rates approved by the Secretary of the Interior are on file with the superintendent and the park operators.

The representative of the National Park Service in immediate charge of the park is the superintendent, E. T. Scoyen, Belton, Mont.

William H. Lindsay is United States commissioner for the park and holds court in all cases involving violations of park regulations.

A daily schedule of popular guided trips afield, all-day hikes, boat trips, campfire entertainments, and illustrated lectures is maintained at Many Glacier, Going-to-the-Sun, Two Medicine, Lake McDonald, Sprague Creek, and Avalanche Auto Campgrounds, the leading tourist centers. Naturalists who conduct local field trips and walks to nearby Hidden Lake and Clements Glacier are stationed at Logan Pass daily from 9 to 4.

A small museum dealing with popular local natural history subjects is maintained throughout July and August at Many Glacier Ranger Station. Cut-flower exhibits are installed at various hotels and chalets, and an exhibit of rock specimens is in the lobby of Many Glacier Hotel.

Requests from special parties desiring ranger naturalist assistance are given every consideration. All park visitors are urged to avail themselves of the services of the naturalists who are there to assist them in learning of the untold wonders that abound everywhere in the park. Acceptance of gratuities for this free service is strictly forbidden.

For complete information on naturalist schedules and types of service offered consult the free pamphlet, Ranger-Naturalist Service, Glacier National Park.

For the use of the motoring public a system of free automobile campgrounds has been developed on both sides of the park. On the east side, these camps are located at Two Medicine, Cutbank, Roes Creek, and Many Glacier. The west side camps are at Bowman Lake, Fish Creek, Avalanche Creek, and Lake McDonald. Pure water, firewood, cookstoves, and sanitary facilities are available, but campers must bring their own equipment.

The United States post offices are located at Glacier Park, Mont., Belton, Mont., Polebridge, Mont., and (during summer season) Lake McDonald, Mont., at Lake McDonald Hotel, and Apgar, at the foot of Lake McDonald. Mail for park visitors should include in the address the name of the stopping place as well as the post office.

Telegraph and express service is available at all points of concentration.

Qualified nurses are in attendance at the hotels and both sides of the park, and there is a resident physician at Glacier Park Hotel.

The mountains of Glacier National Park are made up of many layers of limestone and other rocks formed from sediments deposited under water. The rocks show ripple marks which were made by waves when the rock material was soft sand and mud. Raindrop impressions and sun cracks show that the mud from time to time was exposed to rains and the drying action of the air. These facts indicate that the area now known as "Glacier National Park" was once covered by a shallow sea. At intervals muds were laid down which later became consolidated into rocks known as "shales" and "argillites." Limy or calcareous muds were changed into limestone. The geologist estimates that these depositions were made several hundred million years ago.

In the plains area east of the mountains are other lime and mud formations. These are younger and softer than the rocks which make up the mountains but were undoubtedly formed under much the same conditions. These contain much higher forms of life, such as fish and shells.

When originally laid down all these layers must have been nearly horizontal, just as they are deposited today in bodies of standing water all over the world. Then came a time when the sea slowly but permanently withdrew from the area by an uplift of the land, which since that time has been continuously above sea level. This uplift, one of the greatest in the history of the region, marks the beginning of a long period of erosion which has carved the mountains of Glacier National Park.

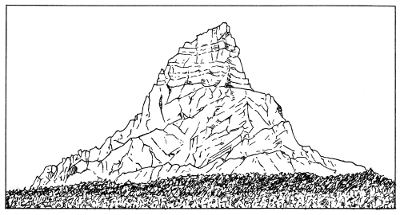

The geologist observes that the rock layers are no longer in the horizontal position in which they were laid down. There are folds in the rocks and many breaks or faults cutting across the layers. Furthermore, the oldest rocks in the region are found to be resting on the younger rocks of the adjacent plains. One of the best examples of this is to be seen at Chief Mountain where the ancient limestone rests directly on the young shale below (fig. 1). The same relationship is visible in Cutbank, St. Mary, and Swiftcurrent Valleys. In these areas, however, the exact contact is not always so easy to locate principally because of the debris of weathered rocks that have buried them. What has happened? How did this peculiar relationship come about? The answers to these questions unravel one of the grandest stories in earth history. Forces deep in the earth slowly gathered energy until finally the stress became so great that the rocky crust began to move.

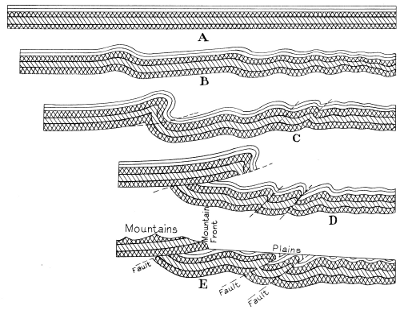

The probable results of the movement in the crust of the earth are shown in the diagram (fig. 2). Section A represents a cross section of the Glacier Park region, as it most likely appeared, immediately following the long [pg 31] period of sedimentation. The rock strata are horizontal. Section B shows the same region after the rock layers have been slightly wrinkled due to the forces from the southwest, which, although slightly relieved by the bending, still persisted and the folds were greatly enlarged as shown in section C. At this stage the folds reached their breaking limit, and the strata broke in a number of places as indicated by dotted lines in the diagram. As a result of this fracturing, the rocks on the west side of the folds were pushed upward and over the rocks on the east, as shown in section D. The mountain rocks (represented by patterns of cross lines) were shoved over the rocks of the plains (represented in white), producing what is known as an "overthrust fault." It has been estimated that the rocks have moved a distance of at least 15 miles.

As the rocks were thrust northeastward and upward they made a greatly elevated region, but did not, however, at any time project into the air, as indicated in section D, because as the rocky mass was being uplifted, streams were wearing it away and cutting deep canyons in its upland portion. The rocks of the mountains, owing to their resistant character, are not worn away as rapidly as the plains formations with the result that great thicknesses of limestone and argillite tower above the plains. Where the older, more massive strata overlie the soft rocks the mountains are terminated by precipitous walls as shown in section E. This explains the absence of foothills that is so conspicuous a feature of this mountain front and one in which it differs from most other ranges.

While the region now known as "Glacier National Park" was being uplifted and faulted, the streams were continually at work. The sand and other abrasive material being swept along on the beds of the streams slowly wore away much of the rock. The uplifting gave the streams life and they consequently cut deep valleys into the mountain area. They cut farther and farther back into the mountain mass until they dissected it, leaving instead of an upland plateau a region of ridges and sharp peaks. This erosional process which has carved the mountains of Glacier Park has produced most of the mountains of the world.

Following their early erosional history, there came a period of much colder climate during which time heavy snows fell and large ice fields were formed throughout the mountain region. At the same time huge continental ice sheets formed in Canada and also in northern Europe. This period, during which glaciers, sometimes over a mile thick, covered many parts of the world including all of Canada and New England and much of North Central United States, is known as the "Ice Age." Such a tremendous covering of ice had an enduring and pronounced effect upon the relief of the country.

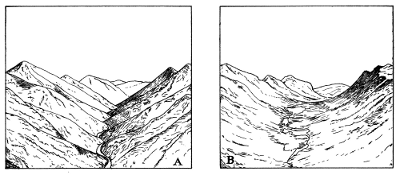

In Glacier National Park some of the ice still remains in the higher portions of the valleys and a study of these ice fields helps in interpreting the history of the park during the Ice Age. It is evident that ice did not cover the entire range, but that the higher peaks stood out above the ice, which probably never reached a thickness of over 3,000 feet in this region. The V-shaped valleys which had been produced by stream erosion were filled with glaciers which moved slowly down the valleys. The ice froze onto all loose rock material and carried it forward, using it as abrasive to gouge out the rock, the valley bottoms, and sides. Gradually the valleys were molded until they had acquired a smooth U-shaped character (fig. 3). There are excellent examples of this work of ice in the park, among which are Two Medicine, Cut Bank, St. Mary, Swiftcurrent, and Belly River Valleys.

In addition to smoothing the valley down which they moved, the glaciers produced many rock basins called cirques. These are the result of ice plucking in the regions where the glaciers formed. Alternate freezing and thawing cause the rock to break and the resulting fragments are carried away by the moving ice mass. In the majority of cases the cirques have lakes on their floors. The park is dotted with these beautiful little lakes scattered throughout the high mountain country.

The valley lakes are usually larger than the cirque lakes and have a different origin. As the glaciers melted they deposited huge loads of sand, mud, and boulders in the valley bottoms called moraines. Debris of this nature has helped to hold in the waters of St. Mary, Lower Two Medicine, McDonald, Bowman, and numerous other lakes in the park.

Glacier National Park is exceptionally rich in many kinds of wildlife. Its rugged wilderness character, enhanced by numerous lakes and almost unlimited natural alpine gardens, combine to offer an unexcelled opportunity to enjoy and study nature.

Glacier is noted for its brilliant floral display which is most striking in early July. Above timber line hardy plants such as mosses and lichens, together with the delicately colored alpine flowers, are found. Lower on the mountains are heather, gentians, wild heliotrope, and stunted trees of alpine fir, white-barked pine, and alpine larch. The valleys on the east bear Engelmann spruce, alpine fir, lodgepole pine, Douglas fir, and limber pine.

The valleys of the west side are within an entirely different plant life zone, typified by dense climax forests. For the most part these forests consist of red cedar and hemlock, with intermediate forests of larch, fir, spruce, and white pine. There are also younger stands of larch and lodgepole pine. Some of the white pines in McDonald Valley have reached huge dimensions. The deficiency of wild flowers found there is in part made up by the presence of sphagnum bogs with a typical fauna and flora of their own.

On the east, at lower elevations, representatives of the Great Plains flora are found, such as the passion flower, carpet pink, shooting star, scarlet paintbrush, red and white geraniums, bronze agoseris, the gaillardia, wild hollyhock, asters, and many other composites. The bear grass is one of the most characteristic plants of Glacier.

Of equal interest is the abundant animal life, including both the larger and smaller forms. Bighorn, mountain goats, moose, wapiti, grizzly and black bear, and western white-tailed and Rocky Mountain mule deer exist in as natural a condition as is possible in an area also utilized by man. Mountain caribou are occasional visitors to the park. Mountain lions, bobcats, and coyotes are present, although the first have been reduced greatly from their original numbers. The beaver, marmot, otter, marten, cony, and a host of smaller mammals are interesting and important members of the fauna. Among the birds, those that attract the greatest interest are the osprey, water ouzel, ptarmigan, Clark nutcracker, thrushes, and sparrows.

With the exception of the Kootenais, few Indians ventured into the fastness of the park mountains before the coming of the white men. Yet so frequently did a large number of tribes use its trails for hunting and [pg 36] warfare, or camp in midsummer along its lakes and streams on the edge of the plains, that the park has an Indian story intertwined with its own that is unsurpassed in interest. Except for a few plateau Indians who had strong plains' characteristics because they once lived on the plains, all tribes were of that most interesting of Indian types, the plains Indian.

The earliest peoples inhabiting the northern Montana plains of which we have any record were apparently Snake Indians of Shoshonean stock. Later Nez Perces, Flatheads, and Kootenais pushed eastward through passes from the headwaters of the Columbia River system. Then came horses and firearms, and the whites themselves to set up an entirely different state of affairs in their hitherto relatively peaceful existence. First, a growing and expounding Siouan race, pressed forward also by an expanding irresistible Algonkian stock, occupied the high plains and pushed back its peoples behind the wall of mountains. These were the Crows from the south, the Assiniboins to the east. Lastly, armed with strategy and Hudson's Bay Co. firearms, and given speed and range with horses, the dauntless Blackfeet came forth from their forests to become the terror of the north. They grew strong on the abundance of food and game on the Great Plains, and pushed the Crows beyond the Yellowstone River, until met by the forces of white soldiery and the tide of civilization.

Today the Blackfeet on the reservation adjoining the park on the east remain a pitiful but picturesque remnant of their former pride and glory. They have laid aside their former intense hostility to the whites and have reconciled themselves to the fate of irrepressible civilization. Dressed in colorful native costume, a few families of braves greet the park visitor at Glacier Park Station and Hotel. Here they sing, dance, and tell stories of their former greatness. In these are reflected in a measure the dignity, the nobility, the haughtiness, and the savagery of one of the highest and most interesting of aboriginal American peoples.

Albright, Horace M., and Taylor, Frank J. Oh, Ranger! About the national parks.

Bowman, I. Forest Physiography. New York, 1911. Illustrated; maps.

Eaton, Walter Pritchard. Boy Scouts in Glacier Park. 1918. 336 pages.

—— Sky-line Camps. 1922. 268 pp., illustrated. A record of wanderings in the Northwestern Mountains from Glacier National Park to Crater Lake National Park in Oregon.

Elrod, Dr. Morton J. Complete Guide to Glacier National Park. 1924. 208 pp.

Faris, John T. Roaming the Rockies. 1930. 333 pp., illustrated. Farrar & Rinehart, New York City, Glacier National Park on pp. 42 to 80.

Holtz, Mathilde Edith, and Bemis, Katherine Isabel. Glacier National Park, Its Trails and Treasures. 1917. 262 pp., illustrated.

Jeffers, Le Roy. The Call of the Mountains. 1922. 282 pp., illustrated. Dodd, Mead & Co. Glacier National Park on pp. 35-39.

Johnson, C. Highways of Rocky Mountains. Mountains and Valleys in Montana, pp. 194-215. Illustrated.

Kane, J. F. Picturesque America. 1935. 256 pp., illustrated. Frederick Gumbrecht, Brooklyn, N. Y. Glacier National Park on pp. 147-169.

Laut, Agnes C. The Blazed Trail of the Old Frontier. Robt. M. McBride & Co., New York, 1926.

—— Enchanted Trails of Glacier Park. Robt. M. McBride & Co., New York. 1926.

Marshall, L. Seeing America. Philadelphia, 1916. Illustrated. Map. Chapter XXIII, Among the American Alps, Glacier National Park, pp. 193-200.

McClintock, W. The Old North Trail. 539 pp., illustrated, maps. Macmillan Co. 1920.

—— Old Indian Trails, Houghton Mifflin Co. 1923.

Mills, Enos A. Your National Parks. 532 pp., illustrated. Houghton Mifflin Co. 1917. Glacier National Park on pp. 148-160, 475-487.

Rinehart, Mary Roberts. Through Glacier Park. The Log of a Trip with Howard Eaton. 1916. 92 pp., illustrated.

—— My Country 'Tis of Thee.

Rolfe, Mary A. Our National Parks, Book Two. A supplementary reader on the national parks for fifth- and sixth-grade students. Benj. H. Sanborn & Co., Chicago. 1928. Glacier National Park on pp. 197-242.

Sanders, H. F. Trails Through Western Woods. 1910. 310 pp., illustrated.

—— History of Montana, vol. 1, 1913. 847 pp. Glacier National Park on pp. 685-689.

—— The White Quiver. 344 pp., illustrated, Duffield & Co., New York. 1913.

Schultze, James Willard. Blackfeet Tales of Glacier National Park. 1916. 242 pp., illustrated.

Steele, David M. Going Abroad Overland. 1917. 198 pp., illustrated. Glacier National Park on pp. 92-101.

Stimson, Henry L. The Ascent of Chief Mountain. In Hunting in Many Lands, edited by Theodore Roosevelt and George B. Grinnell, 1895, pp. 220-237.