Title: The Welsh Pony, Described in two letters to a friend

Author: Olive Tilford Dargan

Release date: June 30, 2011 [eBook #36565]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Garcia and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Kentuckiana Digital Library)

THE WELSH PONY

By OLIVE TILFORD DARGAN

BOSTON: PRINTED PRIVATELY

FOR CHARLES A. STONE: 1913

Copyright, 1913, by Charles A. Stone

PINKHAM PRESS, BOSTON

To ANNE WHITNEY

| HERD OF WELSH MOUNTAIN PONIES GRAZING | Frontispiece |

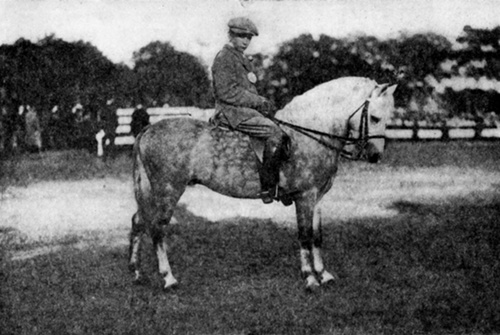

| MY LORD PEMBROKE | xii |

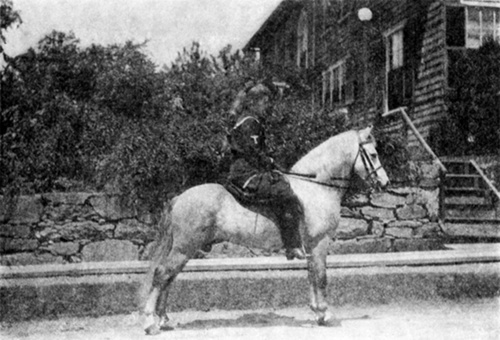

| A MORNING RIDE | xiv |

| IMPORTED WELSH STALLION RAINBOW | 4 |

| SEARCHLIGHT—PONY MARE | 6 |

| THE FAMOUS WELSH STALLION GREYLIGHT | 8 |

| A FULL BROTHER OF DAYLIGHT | 10 |

| LONGMYND FAVORITE AND HER FOAL MANOMET WHITE STAR | 12 |

| MY LORD PEMBROKE WHEN THREE YEARS OLD | 14 |

| LONGMYND ECLIPSE ON A RAINY DAY | 16 |

| A WELSH COB | 18 |

| MARE AND FOAL | 20 |

| LONGMYND | 22 |

| LONGMYND COMMONS | 24 |

| IMPORTED WELSH STALLION MY LORD PEMBROKE | 26 |

| LONGMYND ECLIPSE AND GROVE RAINBOW | 28 |

| LONGMYND CASTOR | 32 |

| LONGMYND ECLIPSE AND MY LORD PEMBROKE | 34 |

| [viii] BRECON | 36 |

| THE BEACONS | 38 |

| LONGMYND POLLOX | 40 |

| FOREST LODGE PASTURES | 42 |

| MY LORD PEMBROKE | 44 |

| KNIGHTON SENSATION, LONGMYND ECLIPSE AND MY LORD PEMBROKE | 46 |

| KNIGHTON SENSATION | 48 |

| MY LORD PEMBROKE IN HARNESS | 50 |

INTRODUCTION

While living in Devon about a year ago, I first became acquainted with the Welsh pony and found great pleasure in riding and driving with my children through the charming lanes and by-ways of Southwestern England.

I was so fortunate as to have at that time an attractive little gray mare which was loaned to me by a friend who was spending the winter in France. This little mare, partly Welsh, was so cheerful and friendly, and seemed so much to enjoy our excursions into the country, that I felt sorry to leave her behind when I left Devon.

The following spring, at the London Horse Show, I saw some splendid specimens of thoroughbred Welsh mountain ponies ridden by children, and my wife and I were so attracted by them that we determined to get four or five and bring them to America. Later during the same season, at the Royal Agricultural Show, which is the best fair of its kind in the world, [xii] I saw many splendid ponies of the Welsh breed, and had an opportunity to find out more particularly about them.

A trip to Wales was then planned with a view of visiting the ponies on their native hills and arranging with some owners and breeders to help me select a small herd for shipment to Boston. On this trip I found the Welsh country so charming and the ponies so attractive and so different from any ponies I had known before, that I spent altogether several weeks in Wales and the border counties selecting a herd which finally amounted to about twenty-five of the best of the true mountain type that I could obtain.

I have been pondering ever since, not only how I might improve and add to my own somewhat superficial knowledge of the remarkable qualities of the Welsh pony, but also how I might bring him to the favorable notice of my countrymen. In this endeavor I was fortunately able to enlist the interest of my cousin, Miss Whitney, whose friend, Mrs. Olive Tilford Dargan, was at that time journeying through England and Wales. Miss Whitney saw the [xv] opportunity that lay before me provided Mrs. Dargan could be won to a study of the pony problem, and promised to set herself at once to the attainment of this object—although she did say that such a call upon her friend was about as nearly related to that lady's real vocation as a yokel's whistle to Pan's pipes. I think, however, that the author of the following letters has shown a true idea of the dignity inherent in the mission to which she was summoned, and has indeed written up to it; responding to the request of her friend with a whole-souled heartiness which makes me her grateful beneficiary.

C. A. S.

December, 1912.

London, England, July 15, 1911.

Dear A——:

Some months ago you asked me to tell you all that I knew or could discover about the Welsh pony. I will tell you if you will stand the listening. For since you bade me I have taken the subject to heart and can talk on it from dawn to dusk. We have travelled—pony and I—from Arabia to the Lybian sands and from Scandanavia to the midland seas; and on my recent journey through Wales—that land, as you know, of old adventure and anguish of endless battle—I kept but half an eye in pursuit of the vanishing skirts of Romance; the other eye and a half swept along the vista in search of the mountain lady who trips so handsomely on her four feet that Sir Phenacodus Primaevus, could he behold her from his fossil retreat, would acknowledge his success as an ancestor, whatever may have been his discouragements in prehistoric society.

At first, aware of my weakness for the equine, I was afraid that I had succumbed to my charmer with regrettable haste, but association only fixed my loyalty and sustained the credentials that he wears on every inch of him. Let me parenthesize here and have done with it, that if I use my genders in hopeless interchange, or am forced to the apologetic "it," you must extricate the sex as best you can, and re-register your old vow to reform the English language. "She" will apply but ludicrously to the gallant entires that were asked to exhibit their best steps before me; and "he" does not come naturally to my pen if I have in mind some of the graceful mares whose acquaintance I made as they drew me through pass and over bryn, almost coquetting with the task laid upon them, yet modest withal, for the Welsh pony, be the pronoun what it may, never forgets manners.

Later, at the Olympia, during the International Horse Show, I spent a fatuously happy time in the stables. Many pony types were exhibited, and nobly they represented their kind, but I found none so love-inspiring as the [5] little conqueror from Cymric, "Shooting Star," owned by Sir Walter Gilbey. He is a dapple-gray, eleven hands high, of perfect shape and brim-full of spirit, not of the self-conscious kind, eager for gratuitous display, but unabashed, careful of the amenities, and avowing with all the grace in him that he will be your friend if you choose to be his. If he has one defect it is a parsimony of tail, though I heard none of his thousands of admirers make that criticism; and he carries it up and out in true Arabian style. In the arena, when all of the horses came in for the general parade—the big Clydesdales first, followed by representatives of nearly every breed in the world, the procession ending with a wee Shetland, whose mistress is the little Princess Juliana of Holland—it was Shooting Star that received the most impulsive greeting—an applause of love evoked by his irresistible dearness, billowing where he passed until he completed the great circuit.

I had the assurance of others who daily haunted the Show that this triumph was a feature of every general parade; and it was then that I began to ask a certain Why? Why [6] is the Welsh pony gifted with a symmetry that subjugates at sight, while his congeners too often show an ensemble whose mild ungainliness must be admitted by their best of friends? Why, with the hardihood of the half-wild forager, and unflagging endurance, does he display the grace and bearing that we associate with carefully tended animals of pedigree? The Exmoor and Dartmoor types only in a moderate degree show signs of high descent, and the ponies of the Fells (though I mind me well of the lovable traits of some of my neighbors among them up in the shires of Cumberland and Westmoreland) are indubitably plebian, while the Welsh pony is a patrician on his wildest hill. Even those who hold a brief for other breeds confess his superiority in points that stamp him "of the blood." Parkinson proclaims him the perfect pony of the kingdom, and Lord Lucas, who for some years has been engaged in improving the New Forest pony, says, after an excursion in search of desirable strains to introduce into the Forest, that he found the best ponies in Wales; and he has confirmed his judgment by the purchase of [7] "Daylight," a young Carmarthenshire pony of prepotent promise, for alliance with the Forest stock.

The breeder of Daylight seems particularly able in adding "lights" to a constellation whose first impulse to shine came from Dyoll Starlight, a sire who cannot be accused of any desire to hide his light under a bushel. It gleams not merely from one hill, but a hundred, and the breeder so happy as to own a bit of this strain rarely fails to advertise his good fortune in the name he gives to his prize. The result is a confusion of Starlights, Greylights—even Skylights!—in repeated series distinguished as Starlight II, III, etc., until the dazzled investigator prays for an eclipse. I take it, however, as a hopeful sign that one of the latest comers to the circle is yclept Radium. But to know these ponies makes one lenient to the pride that clings to the family name. I send you a photograph of Searchlight, a daughter of Dyoll Starlight, and granddaughter of Merlyn Myddfai, who was sold into Australia. She is a sister to Daylight, bought by Lord Lucas, and also to Sunlight, a three-year old pony mare, undoubtedly with a [8] scintillating future, who will be exhibited for the first time at Swansea during the National Pony Show, whither I intend to go just to have sight of some of the exquisite young things that are springing up all over Wales since the recent awakening of Taffy the Thrifty to the fact that the pony is one of the most profitable assets of his country. The photograph of Searchlight is somewhat unfair to her beauty. The slight turn of the head coarsens the nose and widens the lower jaw with an unpatrician suggestion of which there is no hint when she is before you in vivid substance. Her brother, Greylight, poses more successfully, but I send you Searchlight also, partly because she is a lady, and of a more retired life, but mainly because she illustrates, so far as may be in a photograph, that indefinable thing called "pony character," which you will find me dilating on later. Just now I want to get back to my Why.

What in the history of the Welsh pony will explain this union of hardy

wilderness qualities with a form as perfect as that produced in Arabia

after two thousand years of jealous breeding? I asked the question of

dealers and

[9]

breeders and oldest inhabitants. I went to the hills to ask

it of the pony himself; and to the British Museum to ask it of relics

and tomes; following my "Why" to Arabia, to Libya, and back to the

"elephant bed" of the Brighton Pleistocene, where I stopped; for there,

it seemed to me, the Welsh pony began, so far as research permits

him to have a beginning. To follow him beyond neolithic man into the

paleozoic ages, when he was merely an old father Hipparion puzzling

as to whether he should remain in his bog and unenterprisingly evolve

into a tapir, or go into deeper and wetter regions and be a spiritless

rhino, or step bravely onto dry land, turn his five flabby toes into a

fleet and solid hoof, and become the noble equus caballus,—to pursue

him thus far would keep me wandering in a region of timorous conjecture

where he was neither Welsh nor a pony. So I begin with the Brighton

deposit, where was found the skeleton of a small horse supposed,

without successful contradiction, to be an ancestor of a species which

Professor James Cossar Ewart has named the Pony Celticus, and which

once overspread Western Europe.

[10]

The tribe was gradually driven to the

wall, meaning in this case the sea, and their descendants, certainly

considerably modified, are even now to be found in the outer Hebrides

and the Faroes. They lingered long in North Wales, that little nest of

undisturbed peaks, and it was with the descendants of this species that

the Romans mated their military animals and produced the packhorse so

necessary in rugged West Britain. This packhorse was not the heavy

creature that his name suggests, but a sure-footed, light-bodied

animal, capable, however burdened, of going nimbly up and down the

hills. In East Britain and the midlands there was no incentive to breed

him, as the numerous heavier types sprung from the Forest horse were

more serviceable there. But in Wales at this time we have the first

authentic infiltration of alien blood, and this blood was undoubtedly

of the Orient. The Romans, we know, were patrons of the East in matters

equestrian, and in their files of leadership there could have been

"no lack

Of a proud rider on so proud a back"

[11]

as that of the Arabian courser. But of more importance than such

occasionally distinguished pedigrees was the fact that their army

horses in general were Gallic; and the Gallic horse was of Eastern

origin. So the Romans left to Wales not only a heritage of legendary

stone, such as the old camp, Y Caer Bannau, which is shown you in

Breconshire, but a far more valued legacy which is yet animate in the

veins of the Welsh pony. The invaders were busy in Wales for four

hundred years, during which time the packhorse became a domestic type,

and gradually the acclimated Arabian blood crept up the hills and among

the wildest herds—a slow infusion that left the pony still a pony,

retaining all the hardihood that made life possible on the

scanty-herbaged peaks.

The ponies of the southern moors, no doubt, were also marked by this early cross; and they, too, still held at the time something of their heritage from the Pony Celticus; but their position had left them liable to mixture with the Forest Horse, or what represented him in the low-countries, and it was by just that mixture that the packhorse of Wessex, which [12] was the "gentleman's horse" in Devon down to two hundred years ago, became different from that of Wales. It is very unlikely that the Forest Horse was ever in the Cambrian hills, and the active little Pony Celticus on his remote slopes escaped any alliance with that phlegmatic blood. For this reason, in the Welsh descendants of the species, the Eastern horse found a comparatively unmixed strain which was probably as old as his own. The frequent absence of ergots and callossities (those vestigial signs, near knee and fetlock, of vanished digits) would indicate in the Pony Celticus a development as ancient at least as that of the Libyan ancestors of the Arabian horse. Professor Ridgeway, of Cambridge University, thinks that he may even be a related northern branch of the horse of Libya, and that both the North African species and the Pony Celticus may claim the bones of the small horse found in the Brighton Pleistocene as ancestral. If this be true, then when Roman met Welsh in equine society, the two oldest breeds of the world were united, and, as you know, the older the breed the more ineradicable are its characteristics. [13] If originally congeneric, that too would be in favor of the type produced by such a union, and may be a key to the persistence and potency of the Welsh mountain stock. In the Pony Celticus, wherever his modified posterity is least changed, the dorsal and lateral marks indicating equatorial origin are reproduced with little difficulty.

And we have another reason for suspecting the pony ancestor of our Welsh variety to be of North African kinship rather than allied to the Asiatic horse, with large ergots and heavy callossities, which came by the northern route into Scandinavia. This horse, by tradition and record, was of an intractable disposition. It was in upper Asia that the bit originated, while the Libyan horse was of so gentle a nature that his descendant is yet ridden on the Arabian plains with no more guidance than can be given by a simple noseband. Of this horse Mohammed could say, "God made him of a condensation of the southwest wind"; the consummate simile for fleetness and mildness. But I don't accuse the Asiatic horse of being the first sinner. Though the callossities are against his being as old as [14] the Libyan, he may have originally possessed as gentle a temper, which became lost through association with brutal races (see Herodotus) who insisted on being masters instead of friends. The horse resents mastery, as you know, and resentment is peculiarly poisonous to his character. Make him a comrade or nothing. His ascent may have been more dignified than our own, and in one way at least he prehistorically showed more gentle intentions; 'twas we who kept the claws! But while I leave the question of responsibility open in the case of the Asiatic horse, I am glad to think that our pony did not come by way of his blood, whether corrupted by man or tainted with original sin. Certain it is that the Pony Celticus possessed a docility and fair-mindedness that indicated a blameless descent, and there is no evidence that his Welsh offspring were ever handled by man in a way to warp his character. It is true that in his wild state, after the sheep-dog was introduced into Wales (which was comparatively late), the pony was much harried, and driven to the more barren regions; but whenever brought down to the farms he was at once admitted to family [15] privileges that gave him confidence in humanity. As early as the days of the good king, Howell Dha, laws for his care and protection were recorded, and these seem to have been but a codification of rules that had long been in general practice. We read that if a man borrowed a horse and fretted the hair on his back he was to pay a fine to the owner; but such a law as we find among the ancient statutes of Ireland, "Quhasoever sall be tryet or fund to stow or cut ane uther man's hors tail sall be pwunschit as a thief," seems to have had no call for existence in Welshland.

I have said that there was no danger of invasion by the larger British horse on the eastern side. His big feet would not have been at home on the rocky Welsh passes. On the fen side of England the horses developed a softness of hoof and sponginess of bone whose gradual alteration in later days to a close, dense texture, was one of the difficulties that had to be overcome in the production of the English thoroughbred; but, fortunately, the mountain pony was never troubled by such an inheritance. On the channel side [16] of Wales there was a smaller breed of attractive neighbors, and the question of invasion was different. Just a short space across the water lay a nation of kindred Celts, and that they exchanged horses as well as wives with their Welsh cousins—not always by consent—literature gives us sufficient proof. And the horses of Ireland, happily bred on a soil of limestone formation, developed such compactness, strength, and fineness of bone, that when their hard, clean, flat legs brought them into Welsh camps and pastures they were always welcome to the unseen genius attendant on the mountain pony. The once noted Irish hobbie was often brought into Wales and left his mark there.

The records left by the admirers of this animal are pleasant reading. Says old Blundevill: "These are tender-mouthed, nimble, light, pleasant, apt to be taught, and for the most part they be amblers and therefore verie meete for the saddle and to travel by the way." And this desirable creature was produced by a union of the Spanish-Arabian horse with the Irish pony, the descendant of the yet prevailing [17] Celticus; for the Irish isle, as the Welsh hills, was one of his last strongholds. But long before the introduction of Spanish stallions into Ireland, this pony had become modified by the Gallic breed—the same Eastern strain that the Romans brought into Wales. In the three horse skulls with finely preserved Arabian features, recently discovered in a peat-buried crannog, Professor Ridgeway finds proof that the Eastern horse was in Ireland possibly as early as the sixth century; and the description of the horses in the oldest Irish saga support the claim that the warhorse and charger of the Irishman in his epic days were of Eastern importation. Breton was an open way of the Gallic horse to Ireland, for there was much compliment, combat, and barter, between the Irish and Breton Celts. And the horse of Breton was particularly suitable for union with Irish stock, the Arabian in him being already modified by a hardy breed of the hills. Now let me get back to Wales, taking with me this augmentation of the Arabian strain, pony-diluted, through the Irish port—another infusion most happily chosen by the beneficence [18] that seems to have guided the Welsh pony in his evolution. Not too much of this visiting blood either; for there were always wild herds that kept much to themselves; "companys of beesties" content to come only occasionally to the valleys, when they would lure away some gallant or coquette of the lowlands, glad to sniff the air of a fuller freedom. It was the slowness of these infusions, filtering through centuries, and always the same inexpungeable strain, that has made the cross so lastingly successful.

Now to rush down to the modern period. As population grew, the making of roads, reclamation of slopes, and increase in local valley traffic, made the larger horse more attractive to the eyes of the Welshman; and some praiseworthy types, notably the Cob, were produced by the introduction of well-bred English sires. But there were unwelcome by-products in the process, and the importations from the Shires were often ill-judged and indiscreet. The light, graceful-bodied carthorse, of miraculous endurance, the descendant of the early packhorse, and very different from the clumsy, sluggish [19] carthorse of the Shires, has suffered deterioration in beauty, bone and spirit. As a sage of Radnorshire puts it, there is a touch too little of the Arab and a touch too much of Flanders. And as I cannot claim that all the good blood brought into Wales made its way to the pony on the hills, while all the bad blood staid below, I must admit that he has been affected by these later introductions; but in far less degree, for time has not been left to have its final way, nor is the coarser strain of Eastern potency. We must also remember that two centuries ago, when these adventures in breeding began, the English had commenced those prudent experiments with the Arab cross which has fixed the thoroughbred in his sovereign place. There had been occasional importations of the Arab ever since the Roman days, but the English horses were of such numerous and diffused types, and so unlike the Eastern horse in build and nature, that such spasmodic introductions had no permanent effect. The great improvement came with the determined enthusiasm and patience of the eighteenth century breeders; and it seems providential again that as the ways [20] of breeding between England and Wales became promiscuously open, the Eastern blood was becoming prevalent in England.

From this source the Welsh breeders began renewing the beneficent strain in the slow, best manner. Merlin, a descendant of the Brierly Turk, after his brilliant years on the turf, was brought to Wales and turned out with the ponies on the Ruabon hills to become the founder of a famous and prolific line. Mr. Richard Crashaw secured for his county the Arab sire of Cymro Llwd; and in Merioneithshire, the half-Arab, Apricot, of multiple progeny, became an imperishable tradition. Seventy or eighty years ago, Mr. Morgan Williams put Arab sires with his droves on the hills behind Aberpergwm; and it was in this region that in recent years Moonlight was discovered, roving and unshod, by Mr. Meuric Lloyd, and this dam of certain Arabian descent gave Wales her Dyoll Starlight, to whose paternity I have referred.

Notwithstanding this reinforcement of his aristocracy, there were too many doors left carelessly open. The larger pony of the lower lands was becoming mixed with the Cardinganshire [21] cob; and some owners were guilty of letting half-bred Shire colts have the run of the hills. In time the only safe place for the mountain pony would have been the topmost crests, but for an event of happy effect upon his destiny. This was the organization of the Welsh-Pony- and Cob-Society in the Royal Show Yard at Cardiff one springtime eleven years ago. Lord Tredegar was the first president, and after him the Earl of Powys. King George became a patron, and the society acquired an impetus that proved it had not been born too soon. Not only are all the Shires of Wales represented in its council, but also the border counties of Monmouth, Shropshire and Hereford. The formation of a Stud Book was the initial practical business of the Society, and its first volumes derive special value from the fact that Wales has always tended to the patriarchial system, and her traditions, whether of horses or families, can be relied upon. There have always been wise and prudent breeders in the land; men who could, in some degree, counteract indifference and hold to ideal aim.

The Society went to its work with "ears laid [22] back"; but I will mention only two of its achievements. One of these, which will affect the pony's future, so long as ponies be, was an Act of Parliament that enables breeders to clear the Commons of all stallions which a competent committee decides are undesirable. The Common Lands of Wales are so extensive, and comprise so many tracts, that improvement by selection other than nature's is a farce so long as the pasturage is free to any and all. Nature long ago accomplished her best for the Welsh pony, and while he was practically an isolated type it was easy to maintain her standard. But with multifarious breeds and half-breeds in proximity, the carelessness of man was beginning to undo her work, and Wales might have followed Ireland in the deterioration of her pony stock and the loss of a fixed type, if the Society had not actively intervened. The struggle over the Act was discouragingly prolonged, for Taffy is sometimes stubborn, and he could not see that the right to use the Commons would still be a right if it were limited by consideration for one's neighbors. His beast might be as poor a thing as he pleased—sickle-hocked, [23] goose-rumped, tucked up in the brisket, as some of the larger valley-bred ponies were, and, alas, are—but if it could successfully beguile the feminine portion of his neighbor's carefully sorted drove, the helpless neighbor, injured in heart and pocket, had no redress. Finally, after many difficulties, unwearying effort, and a constant display of good nature, the committee secured the passage of the Act and put an end to what one of the overworked members, exasperated to humor, termed the "unlimited liability sire system."

I have mentioned two sections where this system had been brought to a close some years before the passage of the Act. One of these is the Longmynd Range, lying back of Church Stretton, in Shropshire. Though beyond the March, it is practically Welsh in all that concerns its pony interests. The Range covers about seventy square miles, and at the top is a plateau, two thousand feet high, which was a stronghold of the pony before England began to write her history. Deep gullies cut the slopes and widen into ravines, then into valleys. There are crags to climb, and boggy dongas to be avoided. The heather in places is girth-deep, and altogether [24] it is a typical breeding spot of the wild mountain pony. Here we understand how he came by his agility and hardiness, and realize how persistent must be the qualities bred into him by centuries of such environment. In this region it has been the custom for the last twenty-five years to have an annual drive and round-up, when all the ponies are brought down, selected, sorted, the undesirables cast out, and the others, excepting those picked for market, or exchanged for ponies of another run, sent back to freedom. The ponies are not eager to leave their heights, and they give the riders that bring them down an anxious as well as exhilarating time. The "drives" take place in September, and I hope to be at the next one, but whether for the sake of poetry or ponies I don't yet know. I am beginning to believe that they are not unrelatable.

The other section where practically the same system was adopted years ago, is Gower Common, on the Peninsula near Swansea. In this region, as in Longmynd, the standard has been raised in a manner very attractive to the contemplative purchaser; but I would not sound [25] the merits of their ponies above all others, for here and there throughout Wales are breeders who, with difficulty and expense, have individually practiced a system of sorting; and now that the Commons Act has been passed, every one, be he breeder or pony, will have an opportunity to do his best for his country.

The Society's other achievement which I wish to note connects itself with the United States and the mystifying evolution of a new order regulating the certification of those recognized breeds to be accorded exemption from import duty "on and after January 1, 1911." The only thing clear to me in regard to the international reactions involved, is that without the establishment of a Stud Book, and the vigorous registrative activity of the Society's Council, the new order, which recognizes the Welsh pony as a pure breed exempt from duty, would not be in existence, and the same mysterious "rules" and "exceptions" that bewildered breeders previous to 1911 would still be a discouragement to exportation. Whereas all is now plain sailing.

And here is the end of my prologizing. Having finished with his history, I shall be ready [26] in my next to tell you something of the pony himself. In this letter I have only tried to uncover some of the influences that have made him what he is to-day—in beauty an Arab, in constitution an original pony. There was, first, his early purity of type as a descendant of the true pony that homed in these lands. It has been said that when Henry the Eighth passed his law for the extermination of all horses below an approved stature, some of the lowland ponies, scenting danger and led by equine Tells and Winkelrieds, retreated to the mountain fastnesses, defied the throne of England, and became the Welsh mountain pony. This is a mistake. The ponies scattered through the Shires were weedy stunts of horse breeds from which all trace of the Pony Celticus had long disappeared; and if any of the persecuted beasts gained the regions of safety that lay cupped in the lofty hollows of the Welsh slopes, they found native occupants before them. But I cannot believe that the mountain stock ever received this dreggy mixture from the Shires. In spite of his ancient and resisting lineage, such adulteration would have left its mark on [27] the pony's conformation, as, for instance, the large ears of the Dartmoor, or the coarse heads of the Fell ponies. Doctor Johnson suggested (not confidently, I admit) that the word "pony" came from "puny," and was applied to the creatures so stigmatized because they were puny degenerates of a nobler breed. Though he was wrong philologically, we have no reason to doubt that he knew the lowland pony of his times; and when I come across the implication that these "degenerates" escaped hostile hands, scaled unaccustomed heights, and became the ancestors of the Welsh pony, with all his invincibilities, it simply puts my back up.

But I was recapitulating. The second salient factor in the production of our pony was the manner in which the Eastern blood was introduced—those repeated infusions from the earliest times in a form most favorable for mingling with his own. And a third influence was his remote, mountain home. Perhaps this ought to be put first, as it made possible the other two. It kept him a Pony Celticus long after the species in other parts of Britain had become mixed with the Forest tribe; and it [28] prevented the rapid introduction of alien blood which, even when it is of the best, will if too liberally applied turn the hardy and valuable pony into an indifferent small horse.

These are the influences which, working together for seventeen hundred years (from the first to the eighteenth centuries), produced the precious and unexcelled foundation pony-stock of the Welsh mountains.

I suspect that this compression into stark outlines of my delectable wanderings after facts and conclusions has made me too prosy for your patience,—but if I make any apology it will be to the pony; remembering, as I do, one Sunday morning in Brecon, when I sallied out unmoved by the church-bells, which chime so indefatigably in Welshland, and climbed the highest, craggiest hill in sight.

On the top of it I found a small herd of ponies, living without bluff or boast the simple life. There were several mares with young foals, and some colts of poetic promise, which led me to press for entrance into the family circle; but with retreating dignity they let me know that I was a mere inquisitive bounder, and I was [29] reduced to the old trick that used to work so successfully with the cows in the high meadow above the red cottage in Shelburne. I laid myself down, my hands over my eyes and my fingers craftily windowed, and in a few moments was surrounded by a group investigating me with scientific detachment. Then I found myself looking into eyes, very different from unimaginative Bossy's. Through their unguarded limpidity I was admitted to a realm where it seemed for the moment, at least, that

"beast, as man, had dreams,

And sought his stars."

Cardinal Newman said that we knew less of animals than of angels. A severer modicum of knowledge could not be imputed to mortals. But we must admit the truth of the maxim. Such then and so bottomless being the depth of our ignorance, how can we bestow his just dues upon our "brother without hands," the creature that Huxley called the finest piece of animal mechanism in existence?

O. T. D.

London, England, August 1, 1912.

Dear A——:

I have just returned from a day in Epping Forest, whither I was drawn by a rumor of primeval beeches to be seen there. And I found them—groves of the great trees, each as large as the largest oak of my memory. But my interest was soon divided, for our pony was there too—very lovely and very Welsh—tripping along the forest roads and drawing the mind away from a reverie of the old Saxon days, for it was in these very woods that the pious Confessor impartially exercised his two passions for praying and hunting, and here that his devotions were so disturbed by the multitudinous nightingales that he besought God to banish them; and history records that the birds had to go. But I suspect that the arrows of Edward's obedient henchmen assisted a too complaisant deity in the work of banishment. This, too, is the forest through which the mourning Githa brought the body of "Haroldus infelix" to be interred in the [32] abbey founded by him in the woods he had loved. But such faded memories yielded to the modern picture as soon as I saw that my little gallant from the Welsh hills formed a lively part of it. He was there in numbers, attached to carts full of children, to ladies' traps, and sometimes to a more ambitious vehicle. I saw one noble fellow, barely eleven hands high, drawing two fat men, each weighing, to my indignant eyes, at least seventeen stone. In my first rashness I should have protested, but the men were lolling back in such a haze of bliss, pipes in their mouths, and beaming with contentment, that I felt it would be irreverent to disturb a happiness so rare in this rough world. I also saw that the little Welsher was in good fettle and would probably be the first to resent a protest involving an impeachment of his powers.

The carts that pleased me most were those that overflowed with chirruppy, glowing children. They usually took the by-ways denied to the motors, and as they bubbled out of sight into a leafy world, I felt renewedly grateful to the gentle servitor that makes such intimacy [33] between childhood and woodland possible. Little feet cannot get far unassisted, but give them such a helper as the pony and their explorations need hardly be limited. The ideal creature for this purpose is the mountain pony of about eleven hands. Sagacious and docile, he is the safest of companions, and is just as happy under saddle as in harness. The Welsh-Pony- and Cob-Society recognizes two classes of the pony, one this smaller animal of the mountains, not exceeding twelve hands in height, and the larger pony, usually lowland bred, which may be as high as thirteen hands. But the mountain pony is held to be the foundation stock of all the ponies of Wales; furnishing the indestructible material from which is bred the little hunter, saddler and harness pony, or the dear, obliging factotum who will equably plough your garden in the morning and high-step in the park in the afternoon. Whatever his family leanings, toward the Arab, thoroughbred, or more cobby-built type, you will find his "pony character" unaffected. I have already alluded to this attribute, so evident in the pony and so elusive in definition. It is a [34] quality made up of so many others that a full description would be mere endless analysis. Even the all-charitable word, "temperament," will not shelter inadequacy here. To know it one must know the pony. A hint of it is found in his warm, quick sympathy. The horse, however faithful, can at times be cold and judicial in friendship. The pony accepts you without reserving his judgment. He must love wholly, by virtue of the romance that is in him—a tinge of imagination that enables him to idealize rather than criticise, and not an inferior mentality as some students of horse psychology would mistakenly have it. But, though the latchstring of welcome is always out, he will never toss it in your face, for he, too, has a dignity that awaits approach. He serves you, but he is not your underling. If you are so cruel as to be simply the master, ignoring the higher calls of companionship, he does not retreat into indifference, as the horse will, but remains hopeful, expectant, until he wins an understanding or breaks his heart. I do not exaggerate. Wait till you know him; and then you will not more than feebly doubt the story of the [35] pony who came to his aged master, Saint Columba, on the day he was to die, and foremourned their parting.

"Character" is also found in the way the pony uses his eye—the manner of his outlook on the world. In the horse's eye one may sometimes read a slight suggestion of boredom. He is disillusioned. But the pony does not confess to a finished experience; there may be surprises ahead. He is blithely ready for the unusual; and this brings us to another element of "character" which is peculiarly the pony's; that is, a shrewd understanding which gets him out of a difficulty while the horse is still pondering. The latter has had his nose in the mangers of civilization so long that he has lost the mental independence which his pre-domestic life fostered. Unstimulating, derivative knowledge he has in plenty from his association with man; but the Welsh pony of the hilltops, to this day pressed by the necessity of looking out for himself, has a capable initiative which the horse does not possess. Through ages on his sequestered peaks he fought for life against an enemy armed with sleet and snows and dearth, [36] and the record of his struggle is writ in his fibre. He knows where he may climb and where he may not, the slopes that will let him live and the steeps where starvation waits. The colt, though he has never been in a bog, will avoid its treachery, and needs no warning where the gully is ugly, the pool deep, or the ice too thin to bear him. And there has been much hiding and flying, for the sheep-dogs of Wales have been merciless to the pony. Some call here, you see, for a usable mind!

I must mention one more ingredient of this composite "character"—his

indomitable spirit. Match him against a horse of equal strength and the

latter will be out of heart while the pony is confidently forging on.

At Forest Lodge, the home of a gentleman who owns the largest herd

in Wales, I saw a mare of less than twelve hands just after she had

taken four men down the long hills to Brecon and up again—fourteen

miles—and she was not drooping apart waiting to be washed and rubbed

down, but frisking over the yard as if she were quite ready to be off

again. This spirit that unconsciously believes in itself is an unfailing

mark of the

[37]

mountain ponies. If ever they are guilty of jibbing, or like

"poor jades

Lob down their heads,"

investigation is sure to reveal an injudicious cross too recent to be

obliterated by the persistent pony strain.

Of this blitheness of spirit I will give another instance. So far as I am involved I do not look back upon the incident with pride, but the pony in the case shall have his due. At Beddgelert I slept late, and was not fully dressed when informed that the coach was at the door. Being anxious to get to Port Madoc in time for the Dolgelly train, I rushed down and out, leapt to a seat, and was off before I realized that the "coach" was a sort of trap drawn by a single pony. There was a cross seat for the driver, and behind it two lengthwise seats arranged so that the occupants must sit facing, with frequent personal collision. We started six in all, and a snug fit we were. I would have descended and tried to secure a private conveyance, in the hope of saving the pony my own weight at least, but we were fairly out of the village before I [38] was fully awake—and there was my train to be caught! However, I soon found that the pony would not have profited by any tenderness on my part, for all along the road there were would-be passengers waiting to be "taken on." The first we met was helped up and made a third in the driver's seat, and the second pinned himself somehow into the seat opposite me. I was congratulating myself on the Welsh courtesy that had left me, a stranger, unmolested, when we rounded a curve and I saw that the gentle consideration had been unavailing. A man stood by the way signaling—a man of unqualified depth and breadth. I thought that he alone might fill the cart. As that astounding driver halted and the man approached my instinct for self-preservation came basely uppermost. I had observed the middle passenger on the other seat to be quiet, elderly and lean. I coveted a seat beside him, and hastily, on the pretext of being a stranger, desiring a better view of the landscape, asked an exchange of seats with the opposite end, which was courteously granted—all to no purpose. My lean neighbor, all at once, took on alarming latitude. [39] I had reckoned without disestablishment. It seemed the man was a bitter opponent of Lloyd George. If some one dropped a word of advocacy he was straightway a tempest of opposition. His shoulders threatened, his elbows flung dissent, his fingers snapped, his arms, compassing the visible area, were not dodgeable, as he defied the world, the bill and the devil in the shape of the Chancellor of the Exchequer—ah well, there was nothing left for me but resignation and nine in a donkey cart.

Thus it was I journeyed through the wonderful Pass of Aberglaslyn with its dripping cliffs, walls of crysoprase, and bowlders of shattered dawn—beauty of which I wrote you, with care at the time not to trench upon circumstances here disclosed. And thus I passed by beautiful Tanyrallt, once the home of Shelley, but I did not lift my eyes to the slope where the house stood. I kept them on the roots of the mighty trees that border the foot of the hill, for I felt that if I looked up I should see my poet's passionate apparition confronting me. Such an angel as he was to the poor beasts! How I came back afterwards to make my apology [40] to his spirit need be no part of this letter. When we reached Port Madoc, dissevered, and dropped ourselves out, I crept around to the pony with commiserating intent, and found him to be the only unwilted member of the party. He had lost neither breath nor dignity, and his happy air and the tilt of his lovely head seemed almost an affront to one in my humbled state. He was under thirteen hands, and he had drawn nine of us eight miles over an uneven road at an unflagging trot; and here he was almost laughing in my face, and barely moist under his harness.

It is his sureness of himself that keeps him cool, being neither anxious nor fearful of failure. Of course this confident spirit has its source in his physical hardiness. In mere bodily endurance he is the equal of the pony of Northern Russia, while much his superior in conformation. But I should never use the phrase I so often heard, "You can't tire him out." It is wrong to suppose that he can be pushed without limit, or kept constantly at the edge of his capacity, and be none the worse for it. Too often the pony that might have lived usefully [41] for thirty or forty years is brought to his death at twenty. He will give man his best for little enough. On half the food that a horse must have, he will do that horse's work; and when not in service, all he asks is a nibbling place, barren as may be—no housing, blanketing, coddling. I know of a pony mare who has spent every winter of her life unsheltered on the hills of Radnorshire, and has not missed foaling a single year since she was four years old. The last account I have reports her as forty-one and with her thirty-seventh foal. And I have come across other instances of longevity that make me believe that the pony that dies at twenty dies young and has not been wisely used.

Formerly the ponies on the hills had no help from man, however long the snows lay or the winds lashed; but now, if severe weather persists, they are brought down to the valleys, or rough fodder is taken to them. At Forest Lodge I saw four hundred ponies freshly home from a winter sojourn on the hills near Aberystwyth. They still wore the shaggy hair put on against a pinching February and stinging March [42] under open skies. A little later they would shed these protective coats and be trim and sleek for the summer. I had been repeatedly told that the Welsh pony was remarkably free from unsoundness, but among so many that had not been sorted for the year, and were at the worn end of their hardest season, I expected to find some of the lesser blemishes, if not defects of the more serious kind. But if I did, it was with a rarity that effectually argued against them. And I found this true all through Wales. Occasionally I would see low withers, a water-shoot tail, or drooping quarters. But predominantly the quarters were good, not with the roundness that denies speed, burying the muscles in puffy obscurity, but displaying the strong outline which is a plump suggestion of the gnarled and bossy hip-bone beneath. As for the high withers that are always to be desired, the Welsh pony is better off in this respect than the other breeds of Britain, unless it be the pure Highland type. You who remember Belmont days full of equine significances, need not be told how much the horse is affected in anatomical free play by the [43] withers. If they are high the interlacing fibres attaching the shoulder-bone to the trunk may rise freely, and the shoulder arm be long and sloping—a position which gives easy movement and power to the forearm and the structures below it—the pony moves gracefully, without strain, with good action and sure speed. But low withers limit propulsion from the shoulder, and while there may be good knee action the pony must pay out strength to get it. There is, besides, a strain on the cervical muscles which makes natural grace impossible. Dealers can often persuade buyers that the upright shoulder is stronger for harness work, and here in London parks I have seen horses of this type dash strainingly along, expending their strength in fashionable action, and with the unavoidable pull on the neck "corrected" by the bearing-rein; the average owner not guessing the difficulty of his creatures, or the torture that in years too few will bring them to a coster's cart or the dump-heap. Having seen and mourned such things, I was happy to find high withers the rule in Wales, and to learn that wise breeders [44] were laying stress on this point and breeding for it.

Although, as I have said, there has been some imprudent crossing with heavier breeds, these unsuccessful types are being weeded out, and methods of improving the Welsh pony are now, for the most part, confined to individual selection within his own breed, or to the careful introduction of thoroughbred and Arab blood. Of course the door is not entirely closed to other comers, and I talked with one breeder of thirty years' experience who believed in mating his ponies with any sire of fine type that had the points he was trying for. But this gentleman possesses a sixth sense in regard to horses, and can safely indulge in latitude that might prove disastrous in the case of an equally conscientious but less intelligent breeder. Such a method heightens interest and is an open invitation to adventurous possibilities; but it is just as well, I think, that there are others who go to the opposite extreme and are ready to preach on all occasions against bringing alien blood into the mountains. From the shades of Ephraim a poser was once flung to [45] the world—"Can two walk together unless they be agreed?" In this instance, one might surprise hoary Amos with an affirmative, for these two classes of breeders do walk and work together for the good of the Welsh pony; one a barrier to harmful laxity, the other a protest against overcautious restriction. But while guarding him from invasion on his mountains, the most rigid of the "shut-the-door" advocates will permit him to go forth and conquer where he may. It is partly to strengthen him for these expeditions that they insist on keeping the mountain stock unmixed; and it is true that in recent years he has grown much in favor as a factor in the improvement and modification of other pony breeds.

The Polo pony is profiting much by his blood. It seems that the mountain habits practiced by the Welsh pony, in family seclusion and without applause, such as climbing ledges like a fly, turning and twisting himself out of physio-graphical difficulties, not to speak of his leaping powers (his tribe has furnished a champion jumper of the world) and his quick mental reaction upon the unexpected, have produced [46] just the virtues which figure most brilliantly on the polo field. As the game has grown in complexity, the ponies of the plains, Argentine, Arabian, American, have given place to those of hill-bred ancestry. To get the requisite height and weight-bearing power, yet keep the pony qualities, the hardihood, the astuteness, the thought-like instancy of motion—a wit that can almost prophesy—is a problem that is being patiently worked out. I cannot follow the mystical ways which lead to the production of the unparagoned Polo pony; but it is not until the third or fourth generation that the breeder arrives at the nonpareil, the heart's desire of the polo player. In the first generation a thoroughbred cross with the mountain stock is more satisfactory than the Arab, but the advantage is soon lost, as a type with a pedigree covering something over two hundred years cannot compete in persistence with one that has been established for five times that period.

But to get back to the pony on his hill-tops. Careful breeding from the finest of the native stock is now doing more for him than any [47] crossing. While close in-breeding tends to bring out latent defects in any strain, the mountain families are so numerous, and the points to be kept down are so few, that this gives little trouble to breeders. I have spoken of the low withers, which are being eliminated, and sometimes there is a badly set-on head—a more serious matter that, if beauty only were involved—but an angular junction is not often seen, and the head in every case is finely formed, with the large, wide brow of the Arab, tapering face-bones, small, sensitive ears, delicate, silken mouth that needs only a touch in guidance, and roomy underchannel between the branches of the lower jaw. There is never a fiddle-head, heavy jaw, leathered nose, or anything suggestive of the coarse-bred animal in these little creatures that may proudly trample on parchment pedigrees. But now they are to have their parchments too.

I have heard it said that the arching crest is not easy to secure in conjunction with high withers, but the combination is often found in the Welsh pony. As I mentioned in my previous letter, in all points of grace he has more to [48] be thankful for than his neighbors to the north and south of him. Lord Arthur Cecil suggests as an explanation of the ungainliness of Fell ponies, that by long huddling against winter storms on treeless slopes, they have become hunched and heavy, both fore and aft, while their middle shows only a discouraged development. But, though the winds of the Welsh peaks may be less keen, they are keen enough to furnish ample incentive to the huddling spirit; yet the Welsh pony has the head I have described, fine, well-placed shoulders, a deep, round barrel, and quarters that, in general, break no rule of proportion. Therefore, I think the difference is one of origin. The Fell pony is probably a descendant of dwarf horses that escaped to the Pennines during seasons of persecution, and being unestablished as to type was more easily modified by environment. I should like to think this because it supports me in the belief that I have taken the right track in pursuing the Welsh pony's ancestry.

I have not spoken of his adaptiveness to other climates, but he is little affected by transplantation. A breed formed of the two [49] oldest races known, and having in its own type a genealogical history of a thousand years, is apt to persist under any sky, and this is probably why he thrives so well apart from his native heath. I am told that even in Canada he does not object to wintering out; but I should like to interview a pony that has tried it before proffering the information as fact. However, if any ill reports have come back from the numbers shipped to Australia and America, they have been successfully concealed from me. I want you to know that the mountain pony's hocks are a feature not to be passed lightly by. They never fail to bring him commendation from the horseman who knows. The curby hocks sometimes found in the larger type of South Wales are unknown to him. His own are always of the right shape, having plenty of compact bone showing every curve and denture under thin, shining skin, and with clean-cut, powerful back sinews at an unhampered distance from the suspensory tendons. "His hocks do send him along," as one admirer said.

The limbs themselves, whether fore or hind, are handsomely dropped and clear of all blemish—no [50] bubbly knees, soufflets about the ankles, puffy fetlocks, or contracted heels. The pasterns are of the approved gentle obliquity—neither short and upright, betraying stubborn flexors, nor long enough to weaken the elasticity of the support that must here guard the whole body from concussion. The pastern is a debatable point, but I refer all advocates of the "long" and "short" schools to the golden mean which the Welsh pony has evolved for himself in those much-mentioned disciplinary years on his problematic hills.

The hoof is always round, never the suspicious bell shape, and blue, deep and dense. One need not look there for symptoms of sand-crack, seedy-toe, pumice-foot, or any of the pedal ills that too often beset the lowland horse. The centuries of unshod freedom among his crags have given the hoof a resisting density coupled with the diminutive form that agility demands; and this happy union the smithies of man have not yet been able to sever or vitiate. Even the thoroughbred must sometimes find a downward gaze as fatal to vanity as did the peacock of our venerated spelling-book; but not the Welsh [51] pony. He may look to earth as to Heaven with unchastened pride.

And now that the hoof has brought me to the ground I will not mount again. If I have ridden my pony too hard, bethink you who it was that set me upon him. You remember Isaac Walton's caution when instructing an angler how to bait a hook with a live frog:—"And handle the frog as if you loved him." However infelicitously I may have impaled the pony on my pen, I hope you will own that I have done it as if I loved him. Though I am not ready to say that the "earth sings when he touches it," be assured that he will gallantly carry more praise than I have laid upon him.

I have no quarrel with the motor, though it has made me eat dust more than once. As a means of transporting the body when the object is to arrive, I grant it superlative place. But as a medium between man and Nature it is a failure. It will never bring them together. The motor is restricted to the highway, and from the highway one can never get more from Nature than a nod of half recognition. She remains a stranger undivined.

But on a ramble with a pony, adaptive, unobtrusive, all the leisurely ways are open—the deepwood path, or the trail up the exhilarating steep. As self-effacing as you wish, he saves you from weariness and frees the mind for its own adventure. There will be pause for question, and if Nature ever answers at all, you will hear her. There will be the placid hour that is healing-time with her woods, her skies and waters; and that communion with her divinity which means rest and—haply—peace.

O. T. D.

Transcriber's Note: The photo titled "The Beacons" in the list of illustrations is consistently absent in all available copies from multiple sources. Presumably this is the result of a publisher's error where the illustration was omitted from the final version, but not removed from the listings.