Title: Fly Fishing in Wonderland

Author: Orange Perry Barnes

Release date: August 31, 2011 [eBook #37278]

Most recently updated: January 8, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Emmy and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

|

This little writing has to do with the streams and the trout therein of that portion of our country extending southward from the southern boundary of Montana to the Teton mountains, and eastward from the eastern boundary of Idaho to the Absaroka range. Lying on both sides of the continental divide, its surface is veined by the courses of a multitude of streams flowing either to the Pacific Ocean or to the Gulf of Mexico, while from the southern rim of this realm of wonders the waters reach the Gulf of California through the mighty canyons carved by the Colorado.

This region has abundant attractions for seekers of outdoor pleasures, and for none more than for the angler. Here, within a space about seventy miles square, nature has placed a bewildering diversity of rivers, mountains, lakes, canyons, geysers and waterfalls not found elsewhere in the world. Fortunately, Congress early reserved the greater part of this domain as a public pleasure ground. Under the wise administration of government officials the natural beauties are protected and made accessible by superb roads. The streams also, many of which were barren of fish, have, by successful plantings and intelligent protection, become all that the sportsman can wish. The angler who wanders through the woods in almost any direction will scarcely fail to find some picturesque lake or swift flowing stream where the best of sport may be had with the rod.[7]

Several years ago I made my first visit to this country, and it has been my privilege to return thither annually on fishing excursions of varying duration. These outings have been so enjoyable and have yielded so much pleasure at the time and afterwards, that I should like to sound the angler's pack-cry, "Good Fishing!" loudly enough to lead others to go also.

The photographs from which the illustrations were made, except where due credit is given to others, were taken with a small hand camera which has hung at my belt in crossing mountains and wading streams, and are mainly of such scenes as one comes upon in out-of-the-way places while following that "most virtuous pastime" of fly-casting.

THE DIM, RED DAWN

THE DIM, RED DAWN

A Leaping Salmon

A Leaping SalmonThere was a time, and this too in comparatively recent geological eras, when the waters of that region now under consideration abounded with fish of many species. The clumsy catfish floundered along the shallows and reedy bayous in company with the solemn red-horse and a long line of other fishes of present and past generations. The lordly salmon found ideal spawning grounds in the gravelly beds of the streams draining to the westward, and doubtless came hither annually in great numbers. It may be that the habit of the Columbia river salmon to return yearly from the Pacific and ascend that stream was bred into the species during the days when its waters ran in an uninterrupted channel from source to sea. It is true that elsewhere salmon manifest this anadromous[10] impulse in as marked a degree as in the Columbia and its tributaries, yet, the conclusion that these heroic pilgrimages are habit resulting from similar movements, accidental at first, but extending over countless years, is natural, and probably correct. When one sees these noble fish congested by thousands at the foot of some waterfall up which not one in a hundred is able to leap, or observes them ascending the brooks in the distant mountains where there is not sufficient water to cover them, gasping, bleeding, dying, but pushing upward with their last breath, the figure of the crusaders in quest of an ancient patrimony arises in the mind, so strong is the simile and so active is your sympathy with the fish.

Mammoth Hot Springs

Mammoth Hot Springs

In those distant days the altitude of this region was not great, nor was the ocean as remote from its borders as now. The forces which already had lifted considerable areas above the sea and fashioned them into an embryo continent were still at work. The earth-shell, yet soft and plastic, was not strong enough to resist the double strain caused by its cooling, shrinking outer crust and the expanding, molten interior. Volcanic eruptions, magnificent in extent, resulted and continued at intervals throughout the Pliocene period. These eruptions were accompanied by prodigious outpours of lava that altered the topography of the entire mountain section. Nowhere else in all creation has such an amount of matter been forced up from the interior of the earth to flow in red-hot rivers to the distant seas as in the western part of the United States. What a panorama of flame it was, and what a sublime impression it must have made on the minds of the primeval men who witnessed it from afar as[11] they paddled their canoes over the troubled waters that reflected the red-litten heavens beneath them! Is it remarkable that the geyser region of the Park is a place of evil repute among the savages and a thing to be passed by on the other side, even to the present day?

Detail from Jupiter Terrace

Detail from Jupiter Terrace

When the elemental forces subsided the waters were fishless, and all aquatic life had been destroyed in the creation of the glories of the Park and its surroundings. Streams that once had their origins in sluggish, lily-laden lagoons, now took their sources from the lofty continental plateaus. In reaching the lower levels these streams, in most instances, fell over cataracts so high as to be impassable to fish, thus precluding their being restocked by natural processes. From this cause the upper Gardiner, the Gibbon and the Firehole rivers and their tributaries—streams oftenest seen by the tourist—were found to contain no trout when man entered upon the scene. From a sportsman's viewpoint the troutless condition of the very choicest waters was fortunate, as it left them free for the planting of such varieties as are best adapted to the food and character of each stream.

The blob or miller's thumb existed in the Gibbon river, and perhaps in other streams, above the falls. Its presence in such places is due to its ability to ascend very precipitous water courses by means of the filamentous algae which usually border such torrents. I once discovered specimens of this odd fish in the algous growth covering the rocky face of the falls of the Des Chutes river, at Tumwater, in the[12] state of Washington, and there is little doubt that they do ascend nearly vertical walls where the conditions are favorable.

Tumwater Falls

Tumwater Falls

The presence of the red-throat trout of the Snake river in the head waters of the Missouri is easily explained by the imperfect character of the water-shed between the Snake and Yellowstone rivers. Atlantic Creek, tributary to the Yellowstone, and Pacific Creek, tributary to the Snake, both rise in the same marshy meadow on the continental divide. From this it is argued that, during the sudden melting of heavy snows in early times, it was possible for specimens to cross from one side to the other, and it is claimed that an interchange of individuals might occur by this route at the present day.[A] Certain it is that these courageous fish exhibit the same disregard for their lives that is spoken of previously as characteristic of their congeners, the salmon. Trout are frequently found lying dead on the grass of a pasture or meadow where they were stranded the night previous in an attempt to explore[13] a rivulet caused by a passing shower. The mortality among fish of this species in irrigated districts is alarming. At each opening of the sluice gates they go out with the current and perish in the fields. Unless there is a more rigid enforcement of the law requiring that the opening into the ditches be screened, trout must soon disappear from the irrigated sections.

The supposition that these fish have crossed the continental divide, as it were, overland, serves the double purpose of explaining the presence of the trout, and the absence of the chub, sucker and white-fish of the Snake River from Yellowstone Lake. The latter are feeble fish at best, and generally display a preference for the quiet waters of the deeper pools where they feed near the bottom and with little exertion. Neither the chub, sucker nor white-fish possesses enough hardihood to undertake so precarious a journey nor sufficient vitality to survive it.

Gibbon Falls

Gibbon Falls

[A] Note—"As already stated, the trout of Yellowstone Lake certainly came into the Missouri basin by way of Two-Ocean Pass from the Upper Snake River basin. One of the present writers has caught them in the very act of going over Two-Ocean Pass from Pacific into Atlantic drainage. The trout of the two sides of the pass cannot be separated, and constitute a single species."

A Place to be Remembered

A Place to be Remembered

In a letter to Doctor David Starr Jordan, in September, 1889, Hon. Marshall McDonald, then U. S. Commissioner of Fish and Fisheries, wrote, "I have proposed to undertake to stock these waters with different species of Salmonidae, reserving a distinct river basin for each." Every one will commend the wisdom of the original intent as it existed in the mind of Mr. McDonald. It implied that a[15] careful study would be made of the waters of each basin to determine the volume and character of the current, its temperature, the depth to which it froze during the sub-arctic winters, and the kinds and quantities of fish-food found in each. With this data well established, and knowing, as fish culturists have for centuries, what conditions are favorable to the most desirable kinds of trout, there was a field for experimentation and improvement probably not existing elsewhere.

Willow Park Camp

Willow Park Camp

Klahowya

Klahowya

The commission began its labors in 1889, and the record for that year shows among other plants, the placing of a quantity of Loch Leven trout in the Firehole above the Kepler Cascade. The year following nearly ten thousand German trout fry were planted in Nez Perce Creek, the principal tributary of the Firehole. Either the agents of the commission authorized to make these plants were ignorant of the purpose of the Commissioner at Washington, or they did not know with what immunity fish will pass over the highest falls. Whatever the reason for this error, the die is cast, and the only streams that have a single distinct variety are the upper Gardiner and its tributaries, where the eastern brook trout has the field, or rather the waters, to himself. The first attempt to stock any stream was a transfer of the native trout of another stream to Lava Creek above the falls. I mention this because the presence of the native trout in this locality has led some to believe that they were there from the first, and thus constituted an[16] exception to the rule that no trout were found in streams above vertical waterfalls.

The Little Firehole

The Little Firehole

Many are confused by the variety of names applied to the native trout of the Yellowstone, Salmo lewisi. Red-throat trout, cut-throat trout, black-spotted trout, mountain trout, Rocky Mountain trout, salmon trout, and a host of other less generally known local names have been applied[17] to him. This is in a measure due to the widely different localities and conditions under which he is found, and to the very close resemblance he bears to his first cousins, Salmo clarkii, of the streams flowing into the Pacific from northern California to southern Alaska; and to Salmo mykiss of the Kamchatkan rivers. Perhaps the very abundance of this trout has cheapened the estimate in which he is held by some anglers. Nevertheless, he is a royal fish. In streams with rapid currents he is always a hard fighter, and his meat is high-colored and well-flavored.

The name "black-spotted" trout describes this fish more accurately than any other of his cognomens. The spots are carbon-black and have none of the vermilion and purple colors that characterize the brook trout. The spots are not, however, always uniform in size and number. In some instances they are entirely wanting on the anterior part of the body, but their absence is not sufficiently important to constitute a varietal distinction. The red dash under the throat (inner edge of the mandible) from which the names "cut-throat" and "red-throat" are derived, is never absent in specimens taken here, and, as no other trout of this locality is so marked, it affords the tyro an unfailing means of determining the nature of his catch.

The Path Through the Pines

The Path Through the Pines

If the eastern brook trout, Salvelinus fontinalis, could read and understand but a part of the praises that have been sung of him in prose and verse through all the years, what a pampered princeling and nuisance he would become! But to his credit, he has gone on being the same sensible, shrewd, wary and delightful fish, adapting himself to all sorts of mountain streams, lakes, ponds and rivers, and always giving the largest returns to the angler in the way of health and happiness. The literature concerning the methods employed in his capture alone would make a library in which we should find the names of soldiers, statesmen and sovereigns, and the great of the earth. Aelian, who lived in the second century A. D., describes,[18] in his De Animalium Natura, how the Macedonians took a fish with speckled skin from a certain river by means of a hook tied about with red wool, to which were fitted two feathers from a cock's wattle. More than four hundred years prior to this Theocritus mentioned a method of fishing with a "fallacious bait suspended from a rod," but unfortunately failed to tell us how the fly was made. If by any chance you have never met the brook trout you may know him infallibly from his brethren by the dark olive, worm-like lines, technically called "vermiculations," along the back, as he alone displays these heraldic markings.

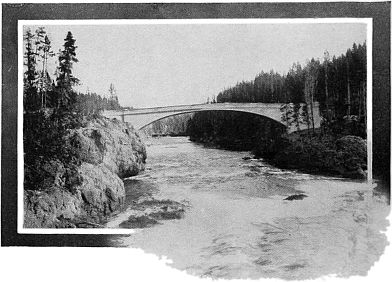

The Melan Bridge

The Melan Bridge

Throughout the northwest the brown trout, Salmo fario, is generally known as the "von Behr" trout, from the name of the German fish-culturist who sent the first shipment of their eggs to this country. This fish may be distinguished at sight by the coarse scales which give his body a dark grayish appearance, slightly resembling a mullet, and by the large dull red spots along the lateral line. There are also three beautiful red spots on the adipose fin.

The Loch Leven trout, Salmo levenensis, comes from a lake of that name in southern Scotland. He is a canny, uncertain fellow, and nothing like as hardy as we might expect from his origin. In the Park waters he has not justified the fame for gameness which he brings from abroad, but there are occasions, particularly in the vicinity of the Lone Star geyser, when he comes on with a very pretty[19] rush. In general appearance he somewhat resembles the von Behr trout, but is a more graceful and finely organized fish than the latter. He is the only trout of this locality that has no red on his body, and its absence is sufficient to distinguish him from all others.

Distant View of Mt. Holmes

Distant View of Mt. Holmes

No one can possibly mistake the rainbow trout, Salmo irideus, for any other species. The large, brilliant spots with which his silvery-bluish body is covered, and that filmy iridescence so admired by every one, will identify him anywhere. There is, however, a marked difference in the brilliance of this iridescence between fish of different ages as well as between stream-raised and hatchery-bred specimens, and even among fish from the upper and lower courses of the same stream.

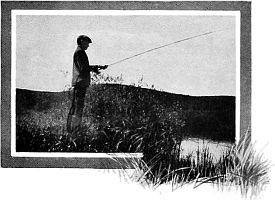

Learning to Cast

Learning to Cast

The question as to which is the more beautiful, the rainbow or the brook trout, has often been debated with much feeling by their respective champions, and will doubtless remain undecided so long as both may be taken from clear-flowing brooks, where sky and landscape blend with the soul of man to make him as supremely happy as it is ever the lot of mortals to become. For it is the joy within and around you that supplies a mingled pleasure far deeper than that afforded by the mere beauty of the fish. You will remember that "Doctor Boteler" said of the strawberry, "Doubtless God could have made a better berry, but[20] doubtless God never did." So, I have said at different times of both brook and rainbow trout, "Doubtless God could have made a more beautiful fish than this, but doubtless God never did."

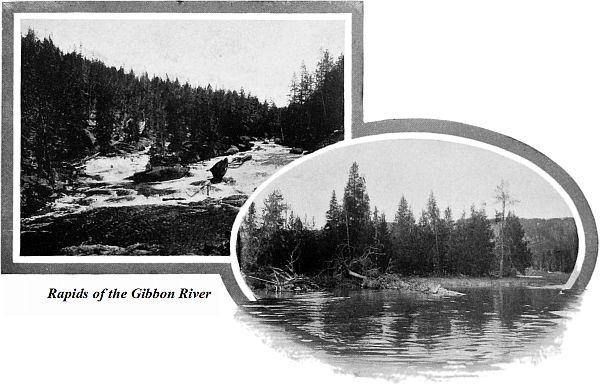

Scene on the Gibbon River

Scene on the Gibbon River

Above Kepler Cascade

Above Kepler Cascade

During a recent trip through the Rocky Mountains I remained over night in a town of considerable mining importance. In the evening I walked up the main street passing an almost unbroken line of saloons, gambling houses and dance halls, then crossed the street to return, and found the same conditions on that side, except that, if possible, the crowds were noisier. Just before reaching the hotel, I came upon a small restaurant in the window of which was an aquarium containing a number of rainbow trout. One beautiful fish rested quivering, pulsating, resplendent, poised apparently in mid air, while the rays from an electric light within were so refracted that they formed an aureola about the fish, seemingly transfiguring it. I paused long in meditation on the scene, till aroused from my revery by the blare of a graphophone from a resort across the street. It sang:

I made the sign of Calvary in the vapor on the glass and departed into the night pondering of many things.

"No man is in perfect condition to enjoy scenery unless he has a fly-rod in his hand and a fly-hook in his pocket."

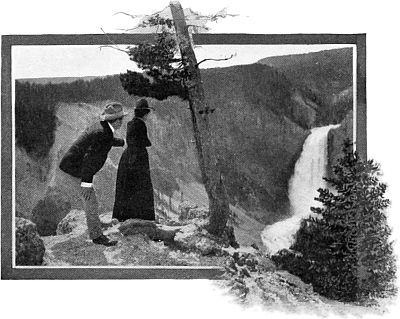

Lower Falls of the Yellowstone

Lower Falls of the Yellowstone

We shall never know and name all the hot springs and geysers of this wonderland, but we may become acquainted with the voice of a stream and know it as the speech of a friend. We may establish fairly intimate relations with the creatures of the wood and be admitted to some sort of brotherhood with them if we conduct ourselves becomingly. The timid grouse will acknowledge the caress of our bamboo with an arching of the neck, and the beaver will bring for our inspection his freight of willow or alder, and will at times swim confidently between our legs when we are wading in deep water.

The Black Giant Geyser

The Black Giant Geyser

The author of "Little Rivers" draws this pleasing picture of the delights of fishing: "You never get so close to the birds as when you are wading quietly down a little river, casting your fly deftly under the branches for the wary trout, but ever on the lookout for all the pleasant things that nature has to bestow upon you. Here you shall come upon the catbird at her morning bath, and hear her sing, in a clump of pussy-willows, that low, tender, confidential song which she keeps for the hours of domestic intimacy. The spotted sand-piper will run along the stones before you, crying, 'wet-feet, wet-feet!' and bowing and teetering in the friendliest manner, as if to show you the best pools." Surely, if this invitation move you not, no voice of mine will serve to stir your laggard legs.

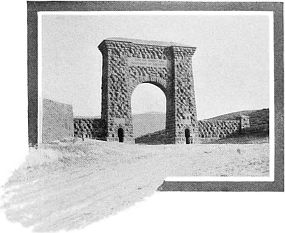

One should not, however, go to the wilderness and expect it to receive him at once with open arms. It was there before him and will remain long after he is forgotten. But approach it humbly and its asperities will soften and in time become akin to affection. As one looks for the first time through the black, basaltic archway at the entrance to the Park, the nearby[23] mountains have an air of distance and unfriendliness, nor do they speedily assume a more sympathetic relation toward the visitor. A region in which the world's formative forces linger ten thousand years after they have disappeared elsewhere will make no hasty alliance with strangers. The heavy foot of time treads so slowly here that one must come often and with observant eye to note the advance from season to season and to feel that he has any part or interest in it.

Park Gateway

Park Gateway

When we can judge correctly from the height of the up-springing vegetation whether the forest fire that blackened this hillside raged one year ago or ten; when we have noted that the bowl of this terrace, increasing in height by the insensible deposit of carbonate of lime from the overflowing waters, appears to outstrip from year to year the growth of the neighboring cedars; when these and a multitude of kindred phenomena are comprehended, how interested we become!

Nothing said here is intended to encourage undue familiarity with the wild game. "Shinny on your own side," is a good motto with any game, and more than one can testify of sudden and unexpected trouble brought on themselves by meddlesomeness. In following an elk trail through the woods one afternoon, I found a pine tree had fallen across the path making a barrier about hip-high. While looking about to see whether any elk had gone over the trail since the tree fell, and, if so, whether they had leaped the barrier or had passed around it by way of the root or top, a squirrel with a pine cone in his teeth, sprang on the butt of the tree and came jauntily along the log. Some twenty feet away he spied me, and suddenly his whole manner and bearing changed. He dropped the cone and came on with a bow-legged, swaggering air, the very embodiment of insolent proprietorship. The top of my rod[24] extended over the log, and as he came under it I gave him a smart switch across the back. Now, there had been nothing in my previous acquaintance with squirrels to lead me to think them other than most timid animals. But the slight blow of the rod-tip transformed this one into a Fury. With a peculiar half-bark, half-scream, he leaped at my face and slashed at my neck and ears with his powerful jaws. So strong was he that I could not drag him loose when his teeth were buried in my coat collar. I finally choked him till he loosened his hold and flung him ten feet away. Back he came to the attack with the speed of a wild cat. It was either retreat for me or death to the squirrel, and I retreated. Never before had I witnessed such an exhibition of diabolical malevolence, and, though I have laughed over it since, I was too much upset for an hour afterward to see the funny side of the encounter.

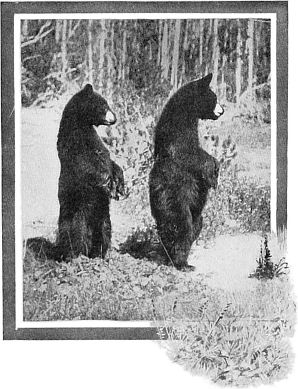

Bear Cubs

Bear CubsThe ways of the wilderness have ever been pleasant to my feet, and whether it was taking the ouananiche in Canada or the Beardslee trout in the shadow of the Olympics, it has all been good. Without detracting from the sport afforded by any other locality, I honestly believe that, taking into consideration climate, comfort, scenery, environment, and the opportunities for observing wild life, this region has no equal for trout fishing under the sun. I am aware that he who praises the fishing on any stream will ever have two classes of critics—the unthinking and the unsuccessful. To these I would say, "Whether your success shall[25] be greater or less than mine will depend upon the conditions of weather and stream and on your own skill, and none of these do I control." In that splendid book, "Fly-Rods and Fly-Tackle," Mr. Henry P. Wells relates an instance in which he and his guide took an angler to a distant lake with the certain promise and expectation of fine fishing. After recording the keen disappointment he felt that not a single trout would show itself, he says, "Then I vowed a vow, which I commend to the careful consideration of all anglers, old and new alike—never again, under any circumstances, will I recommend any fishing locality in terms substantially stronger than these 'At that place I have done so and so; under like conditions it is believed that you can repeat it.' We are apt to speak of a place and the sport it affords as we found it, whereas reflection and experience should teach us that it is seldom exactly the same, even for two successive days."

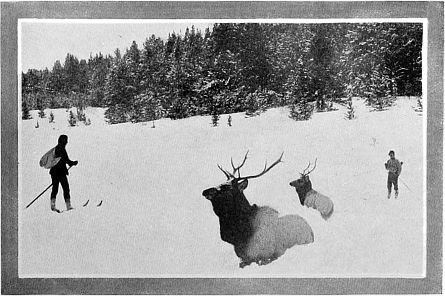

Elk In Winter

Elk In WinterThere is a large number of fly-fishermen in the east who sincerely believe that the best sport cannot be had in the streams of the Rocky Mountains, and this belief has a grain of truth when the fishing is confined solely to native trout and to streams of indifferent interest. But when the waters flow through such picturesque surroundings as are found in the Yellowstone National Park, when from among these waters one may select the stream that shall furnish[26] the trout he loves most to take, the objection is most fully answered. The writer can attest how difficult it was to outgrow the conviction that a certain brook of the Alleghanies had no equal, but he now gladly concedes that there are streams in the west just as prolific of fish and as pleasant to look upon as the one he followed in boyhood. It is proper enough to maintain that: "The fields are greenest where our childish feet have strayed," but when we permit a mere sentiment to prevent the fullest enjoyment of the later opportunities of life, your beautiful sentiment becomes a harmful prejudice.

Having Eaten and Drunk

Having Eaten and Drunk

When the prophet required Naaman to go down and bathe in the river Jordan, Naaman was exceeding wroth, and exclaimed, "Are not Abana and Pharpar, rivers of Damascus, better than any in Israel?" The record hath it that Naaman went and bathed in the Jordan, and that his body was healed of its leprosy and his mind of its conceit. So, when my angling friend from New Brunswick inquires whether I have fished the Waskahegan or have tried the lower pools of the Assametaquaghan for salmon, I am compelled to answer no. But there comes a longing to give him a day's outing on Hell-Roaring Creek or to see him a-foul of a five-pound von Behr trout amid the steam of the Riverside Geyser. The streams of Maine and Canada are delightful and possess a charm that lingers in the mind like the minor chords of almost forgotten music, but they cannot be compared with the full-throated torrents of the Absarokas. As well liken a fugue with flute and cymbals to an oratorio with bombardon and sky-rockets!

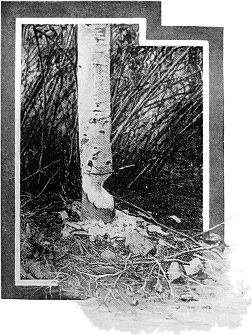

Who Hath Seen the Beaver Busied?

Who Hath Seen the Beaver Busied?"Thyse ben xij. flyes wyth whytch ye shall angle to ye trought and graylling, and dubbe lyke as ye shall now hear me tell."

Water is the Master Mason

Water is the Master Mason

The angler should strive to attain an intelligent understanding of the principal features of the artificial fly and how a change in the form and color of these features affects the behavior of the fish for which he angles. In studying this matter men have gone down in diving suits that they might better see the fly as it appeared when presented to the fish, and there is nothing in their reports to encourage extremely fine niceties in fly-dressing. One may know a great deal of artists and their work and yet truly know but little of the value of art itself; or have been a great reader of economics, and yet have little practical knowledge of that complex product of society called civilization. So, I had rather possess the knowledge a dear friend of mine has of Dickens, Shakespeare, and the Bible alone than to be able to discuss "literature" in general before clubs and societies.

Several years of angling experience in the far west have convinced the writer that flies of full bodies and positive colors are the most killing, and that the palmers are slightly better than the hackles. Of the standard patterns of flies the most successful are the coachman, royal coachman, black hackle, Parmacheene Belle, with the silver doctor for lake fishing, in the order named. The trout here, with the exception of those in Lake Yellowstone, are fairly vigorous fighters, and it is important that your tackle should be strong and sure rather than elegant.

At the Head of the Meadow

At the Head of the Meadow

With a view of determining whether it were possible to make a fly that would answer nearly all the needs of the mountain fisherman, I began, in 1897, a series of experiments in fly-tying that continued over a period of five years. The result is the production of what is widely known in the west as the Pitcher fly. As before indicated, this fly did not spring full panoplied into being, but was evolved from standard types by gradual modifications. The body is a furnace hackle, tied palmer; tail of barred wood-duck feather; wing snow-white, to which is added a blue cheek. The name, "Pitcher," was given to it as a compliment to Major John Pitcher, who, as acting superintendent of the Yellowstone National Park, has done much to improve the quality of the fishing in these streams.

From a dozen states anglers have written testifying to the killing qualities of the Pitcher Fly, and[30] the extracts following show that its success is not confined to any locality nor to any single species of trout:

"The Pitcher flies you gave me have aided me in filling my twenty-pound basket three times in the last three weeks. Have had the best sport this season I have ever enjoyed on the Coeur d'Alene waters, and I can truthfully say I owe it all to the Pitcher fly and its designer."

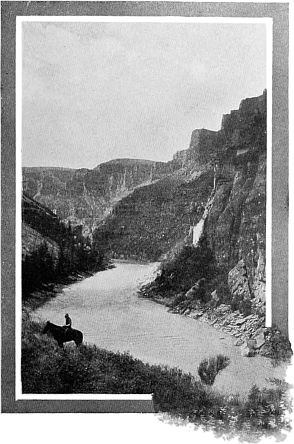

The Tongue River

The Tongue River"One afternoon I had put up my rod and strolled down to the river where one of our party was whipping a pool of the Big Hole, trying to induce a fish to strike. He said: 'There's an old villain in there; he wants to strike but can't make up his mind to do it.' I said: 'I have a fly that will make him strike,' and as I had my book in my pocket I handed him a No. 8 Pitcher. He made two casts and hooked a beautiful trout, that weighed nineteen ounces, down. I regard the Pitcher as the best killer in my book."

Talking It Over

Talking It Over

"I determined to follow the stream up into the mountains, but as I neared the woods at the upper end of the meadow I stopped to cast into a long, straight reach of the river where the breeze from the ocean was rippling the surface of the stream. The grassy bank rose steep behind me and only a little fringe of wild roses partly concealed me from the water. I cast the Pitcher flies you gave me well out on the rough water, allowed them to sink a hand-breadth, and at the first movement of the line I saw that heart-expanding flash of a broad silver side gleaming from the clear depths. The trout fastened on savagely, and as he was coming my way, I assisted his momentum with all the spring of the rod, and he came flying out into the clean, fresh grass of the meadow behind me. It was a half-pound[32] speckled brook trout. I did not stop to pouch him, but cast again. In a moment I was fast to another such, and again I sprung him bodily out, glistening like a silver ingot, to where his brother lay. In my first twelve casts I took ten such fish, all from ten to twelve inches long, mostly without any playing. I took twenty-two fine fish without missing one strike, and landed every one safely. I was not an hour in taking the lot. Then oddly enough, I whipped the water for fifty yards without another rise. Satisfied that the circus was over, I climbed up into the meadow and gathered the spoils into my basket. Nearly all were brook trout, but two or three silvery salmon trout among them had struck quite as gamely. I had such a weight of fish as I never took before on the Nekanicum in our most fortunate fishing."

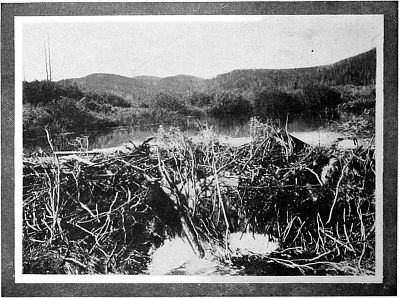

Beaver Dam and Reservoir

Beaver Dam and Reservoir

"Walking back along the trail, I came again to the long[33] reach where I had my luck an hour before, and cast again to see if there might be another fish. Two silver glints shone up through the waves in the same instant. I struck one of the two fish, though I might have had both if I had left the flies unmoved the fraction of a second. Three times I refused such doublets, for I had not changed an inch of tackle, and scarcely even looked the casting line over. It was no time to allow two good fish to go raking that populous pool. However I did take chances with one doublet. So out of the same lucky spot on my return, I took ten more fish each about a foot long. I brought nearly every one flying out as I struck him, and I never put such a merciless strain on a rod before.

"That Populous Pool"

"That Populous Pool""I had concluded again that the new tenantry had all been evicted, and was casting 'most extended' trying the powers of the rod and reaching, I should say, sixty feet out. As the flies came half-way in and I was just about snatching them out for a long back cast, the father of the family soared after them in a gleaming arc. He missed by not three inches and bored his way straight down into the depths of the clear green water. 'My heart went out to him,' as our friend[34] Wells said, but coaxing was in vain. I tried them above and below, sinking the flies deeply, or dropping them airily upon the waves, but to no purpose. I had the comforting thought that we may pick him up when you are here this summer."

Note—I am indebted to Mrs. Mary Orvis Marbury, author of "Favorite Flies," for copies of "Hey for Coquet," and "Farewell to Coquet," from the former of which the foregoing are extracts.[35]

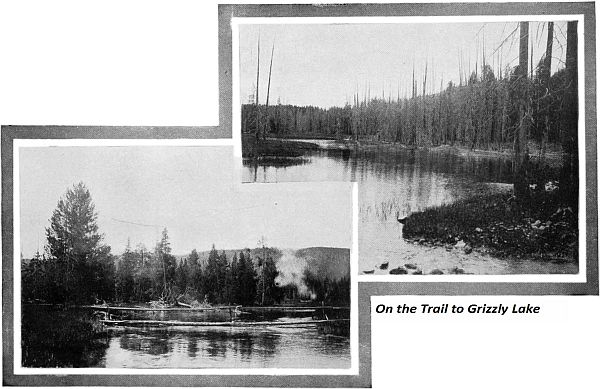

Grizzly Lake

Grizzly Lake

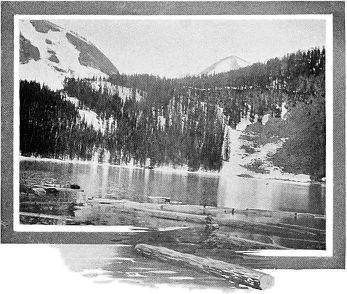

Lake Rose

Lake Rose

In order to reach this location conveniently, I, early in 1902, constructed a light raft of dry pine logs, about six by ten feet, well spiked together with drift bolts; since which time other parties have added a substantial row boat. Both the boat and the raft may be found at the lower end of the lake, just where the trail brings you to it. The canvas boat that was set up on the lake earlier, was destroyed the first winter by bears, but the boat and raft now there will probably hold their own against the beasts of the field for some time. If you use either of them you will, of course, return it to the outlet of the lake, that he who cometh after may also enjoy.

The route to Grizzly Lake follows very closely the Bannock Indian trail from the point where Straight Creek enters the meadows of Willow Park to the outlet of the lake. The trail itself is interesting. It was the great Indian thoroughfare between Idaho and the Big Horn Basin in Wyoming, and was doubtless an ancient one at the time the Romans dominated Britain. How plainly the record tells you that it was made by an aboriginal people. Up hill and down hill, across marsh or meadow, it is always a single trail, trodden into furrow-like distinctness by moccasined feet. Nowhere does it permit the going abreast of the beasts of draft or burden. At no place does it suggest the side-by-side travel of the white man for companionship's sake, nor the[37] hand-in-hand converse of mother and child, lover and maid. Ease your pony a moment here and dream. Here comes the silent procession on its way to barter in the land of the stranger, and here again it will return in the autumn, as it has done for a thousand years. In the van are the blanketed braves, brimful of in-toeing, painful dignity. Behind these follow the ponies drawing the lodge-poles and camp outfit, and then come the squaws and the children. Just there is a bend in the trail and the lodge-poles have abraded the tree in the angle till it is worn half through. A little further on, in an open glade, they camped for the night. Decades have come and gone since the last Indian party passed this way, yet a cycle hence the trail will be distinct at intervals.

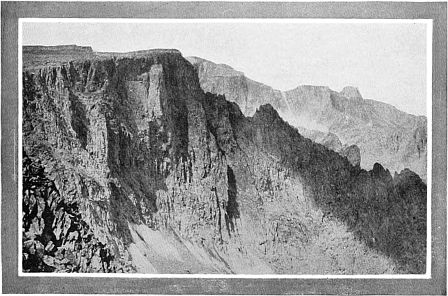

The Bighorn Range Photo by N. H. Darton

The Bighorn Range Photo by N. H. Darton

By turning to the west at Winter Creek and passing over the sharp hills that border that stream you will come, at the end of a nine-mile journey, to Lake Rose. The way is upward through groves of pane, thickets of aspen, and steep open glades surrounded by silver fir trees that would be the delight of a landscape gardener if he could cause them to grow in our city parks as they do here. Elk are everywhere. We ride through and around bands of them, male, female, and odd-shapen calves with[38] wobbly legs and luminous, questioning eyes. As you pause now and then to contemplate some new view of the wilderness unfolding before you, the beauty, and freedom and serenity of it are irresistible, and you comprehend for the first time the spirit of the Argonauts of '49 and the nobility of the pæan they chanted to express their exalted brotherhood:

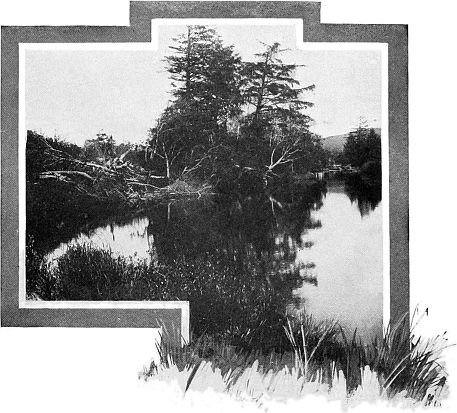

A Wooded Islet

A Wooded Islet

Suddenly the ground slopes away before us and Lake Rose lies at our feet, like an amethyst in a chalice of jade-green onyx. The surroundings are picturesque. The mountains descend abruptly to the water's edge and the snow never quite disappears from its banks in the longest summer. Here in June may be seen that incredible thing, the wild strawberry blossoming bravely above the slush-snow that still hides the plant below, and the bitter-root putting forth buds in the lee of a snow bank. A small stream enters the lake at the northwest, and here the trout are most abundant. They rise eagerly to the silver doctor fly, a half dozen often breaking at once, any one of which is a weight for a rod. Probably not more than a score of anglers have ever cast a fly from this point, and a word of caution may for this reason be pardoned. The low temperature of the water retards the spawning season till midsummer, consequently trout should not be taken here earlier than the third week of July. Again, nature has given to every true sportsman the good sense to stop when he has enough, and as this unwritten law is practically his only restraint, he should feel that its observance is in safe hands and that the sportsman's limit will be strictly observed.

Bear Up!

Bear Up!

The Boy and the von Behr

The Boy and the von Behr

Along Iron Creek

Along Iron Creek

Stealthily drop the fly just over the edge of the bank, as though some witless insect had lost his hold above and fallen!—Right Honorable Dean of the Guild, I read the other day an article in which you stated that the brown trout never leaps on a slack line.[42] Surely you are right, and this is not a trout after all, but a flying fish, for he went down stream in three mighty and unexpected leaps that wrecked your theory and the top joint of the rod before the line could be retrieved. Then the fly comes limply home and nothing remains of the sproat hook but the shank.

Divinity and Infinity

Divinity and Infinity

These things happened to a friend in less time than is taken in the telling. When he had recovered from the shock he remarked, smilingly, "That wasn't half bad for a Dutchman, now, was it?" As he is a sensible fellow and has no "tendency toward effeminate attenuation" in tackle, he graciously accepted and used the proffered cast of Pitcher flies tied on number six O'Shaughnessy hooks.

Having ventured this much concerning what the writer considers proper tackle, he would like to go further and record here his disapproval of the individual who turns up his nose at any rod of over five ounces in weight, and who tells you with an air from which you are expected to infer much, that fly fishing is really the only honorable and gentlemanly manner of taking trout. In the language of one who was a master of concise and forceful phrase, "This is one of the deplorable fishing affectations and pretences which the rank and file of the fraternity ought openly to expose and repudiate. Our irritation is greatly increased when we recall the fact that every one of these super-refined fly-casting dictators, when he fails to allure trout by his most scientific casts, will chase grasshoppers to the point of profuse perspiration, and turn over logs and stones with feverish anxiety in quest of worms and grubs, if haply he can with[43] these save himself from empty-handedness."[B] Fly fishing as a recreation justifies all good that has been written of it, but it is a tell-tale sport that infallibly informs your associates what manner of being you are. It is self-purifying like the limpid mountain stream its followers love, and no wrong-minded individual nor set of individuals can ever pollute it. It is too cosmopolitan a pleasure to belong to the exclusive, and too robust in sentiment to be confined to gossamer gut leaders and midge hooks.

Virginia Cascade

Virginia Cascade

Much, in fact everything, of your success in taking fish in Iron Creek depends on the time of your visit. For three hundred, thirty days of the year it is profitless water. Then come the days when the German trout begin their annual auswanderung. No one need be told that these trout do not live in this creek throughout the year. For trout are brook-wise or river-wise according as they have been reared, and the habits, attitudes and behavior of the one are as different from the other as are those of the boys and girls reared in the country from the city-bred. If one of these river-bred fish breaks from the hook here he does not immediately bore up stream into deep water and disappear beneath a sheltering log, bank or submerged tree-top as one would having a claim on these waters, but heading down-stream, he stays not for brake and he stops not for stone till the river is reached. In his headlong haste to escape he reminds one of a country boy going for a doctor.

It is one of the unexplained phenomena of trout life and habit, why these fish leap as they do here at this season, when hooked. In no other stream and at no other time have I known them to exhibit this quality. It is one of those problems of trout activity for which apparently no reason can be given further than the one which is said to control the fair sex;

"I'm wrapped up in my plaid, and lyin' a' my length on a bit green platform, fit for the fairies' feet, wi' a craig hangin' ower me a thousand feet high, yet bright and balmy a' the way up wi' flowers and briars, and broom and birks, and mosses maist beautiful to behold wi' half shut e'e, and through aneath ane's arm guardin' the face frae the cloudless sunshine; and perhaps a bit bonny butterfly is resting wi' faulded wings on a gowan, no a yard frae your cheek; and noo waukening out o' a simmer dream floats awa' in its wavering beauty, but, as if unwilling to leave its place of mid-day sleep, comin' back and back, and roun' and roun' on this side and that side, and ettlin in its capricious happiness to fasten again on some brighter floweret, till the same breath o' wund that lifts up your hair so refreshingly catches the airy voyager and wafts her away into some other nook of her ephemeral paradise."

[B] Hon. Grover Cleveland in The Saturday Evening Post.

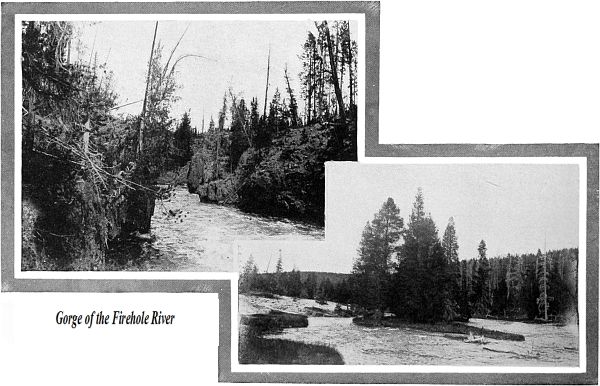

First View of the Firehole

First View of the Firehole

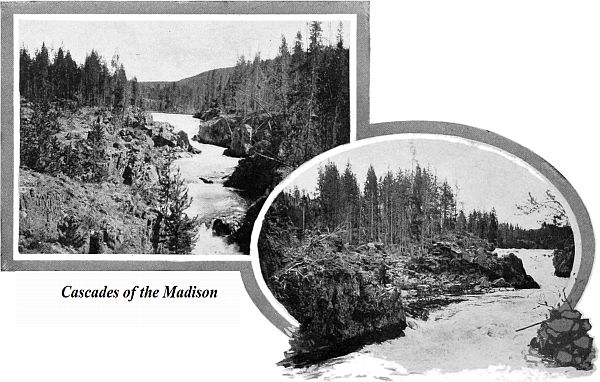

Below the Cascades

Below the Cascades

During the restful period following the noon-hour, when there is a truce between fisherman and fish, we lie in the shadow of the pines and read "Our Lady's Tumbler," till, in the drowsy mind fancy plays an interlude with fact. The ripple of the distant stream[47] becomes the patter of priestly feet down dim corridors, and the whisper of the pines the rustle of sacerdotal robes. Through half-shut lids we see the clouds drift across the slopes of a distant mountain, double as it were, cloud and snow bank vying with each other in whiteness.

Undine Falls

Undine Falls

Neither the companionship of man nor that of a boisterous stream will accord with our present mood. So, with rod in hand, we ford the stream above the island and lie down amid the wild flowers in the shadow of the western hill. For wild flowers, like patriotism, seemingly reach their highest perfection amid conditions of soil and climate that are apparently most uncongenial. Here almost in reach of hand, are a variety and profusion of flowers rarely found in the most favored spots; columbines, gentians, forget-me-nots, asters and larkspurs, are all in bloom at the same moment, for the summer is short and nature has trained them to thrust forth their leaves beneath the very heel of winter and to bear bud, flower, and fruit within the compass of fifty days.

I strongly urge every tourist, angling or otherwise, to carry with him both a camera and a herbarium. With these he may preserve invaluable records of his outing; one to remind him of the lavish panorama of beauty of mountain, lake and waterfall; the other to hold within its leaves the delicately colored flowers that delight the senses. A great deal is said about the cheap tourist nowadays, with the emphasis so placed on the word "cheap" as to create a wrong impression. With the manner of your travel, whether in Pullman cars, Concord coaches, buck-board wagons, or on foot, this adjective has nothing to do. It does, however, describe pretty accurately a quality of mind too often found among visitors to such places—a mind that looks only to the present and passing events, and that between intervals of geyser-chasing, is busied with inconsequential gabble, with no thought of selecting the abiding, permanent things as treasures for the storehouse of memory.[48]

What fisherman is there who has not in his fly-book a dozen or more flies that are perennial reminders of great piscatorial events? And what angler is there who does not love to go over them at times, one by one, and recall the incidents surrounding the history of each?

The whole field of angling literature contains nothing more exquisite than the following description of the last days of Christopher North, as written by his daughter:[49]

"It was an affecting sight to see him busy, nay, quite absorbed with the fishing tackle scattered about the bed, propped up with pillows—his noble head, yet glorious with its flowing locks, carefully combed by attentive hands, and falling on each side of his unfaded face. How neatly he picked out each elegantly dressed fly from its little bunch, drawing it out with trembling hand along the white coverlet, and then replacing it in his pocket-book, he would tell ever and anon of the streams he used to fish in of old."

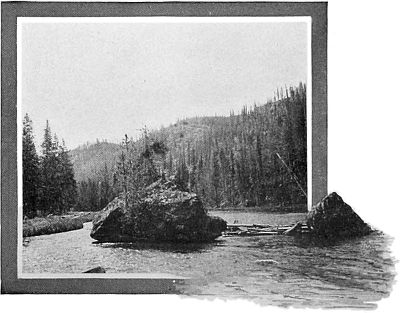

Picturesque Rocks in River

Picturesque Rocks in River

By four o'clock the stream is hidden from the sun and the shadow of the wooded summit at your back has crossed the roadway and is climbing the heights beyond. As if moved by some signal unheard by the listener, the trout begin to feed all along the surface of the water. Leap follows or accompanies leap as far as the eye can discern up stream, and down stream to where the water breaks to the downpull of the gorge below. Select a clear space for your back-cast, wait till a cloud obscures the sun. * * * * The trout took the fly from below and with a momentum that carried him full-length into the air. But there was no turning of the body in the arc that artists love to picture. He dropped straight down as he arose and the waters closed over him with a "plop" which you learn afterward is characteristic of the rise and strike of the German trout. All this may not be observed at first, for if he is one of the big fellows, he will cut out some busy-work for you to prevent his going under the top of that submerged tree which you had not noticed before. As it was, you brought him clear by[50] a scant hand's breadth, only to have him dive for another similar one with greater energy.

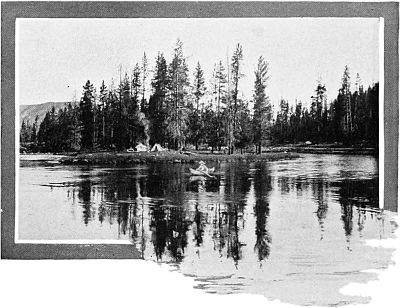

"That Delectable Island"

"That Delectable Island"

Well, it's the same old story over again, but one that never becomes altogether tedious to the angler. And the profitable part of this tale is that it may be re-enacted here on any summer afternoon.

Some day a canoe will float down the river and land on the gravelly beach at the upper end of that delectable island, just where the trees are mirrored in the water so picturesquely. Then a tent will be set up and two shall possess that island for a whole, happy week. If you are coming by that road then, give the "Hallo" of the fellow craft and you shall have a loaf and as many fish as you like, and be sent on your way as becomes a man and brother.

Yancey's

Yancey's

The government has recently completed a road from the canyon of the Yellowstone, over Mt. Washburn, down the valley near Yancey's, and reaching Mammoth Hot Springs by way of Lava Creek. This has added another day to the itinerary of the Park as planned by the transportation companies, and one[52] which for scenic interest surpasses any other day of the tour. A mere category of the places of interest that may be seen in this region would be lengthy.

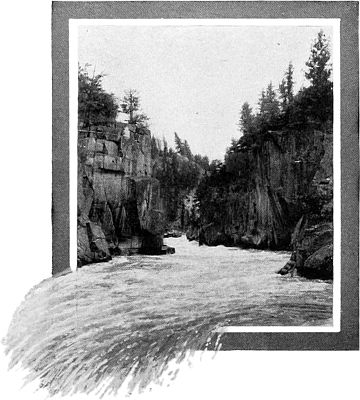

The lower canyon of the Yellowstone with its overhanging walls five hundred feet high, with pillars of columnar basalt reaching more than half-way from base to summit, the petrified trees, lofty cliffs, and romantic waterfalls, will delight and charm the visitor.

"Swirl and Sweep of the Water"

"Swirl and Sweep of the Water"

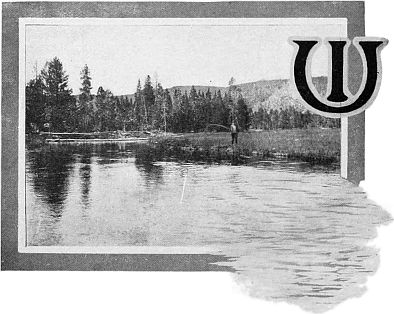

The angler will find the waters of this region as abundantly supplied with trout as any area of like extent anywhere. No amount of fishing will ever exhaust the "Big Eddy" of the Yellowstone, and it is worth a day's journey to witness the swirl and sweep of the water after it emerges from the confining, vertical walls. The velocity of the current at this point is very great, and surely, during a flood, attains a speed of sixteen or more miles an hour. In the eddy itself the trout rise indifferently to the fly, but will come to the red-legged grasshopper as long as the supply lasts.

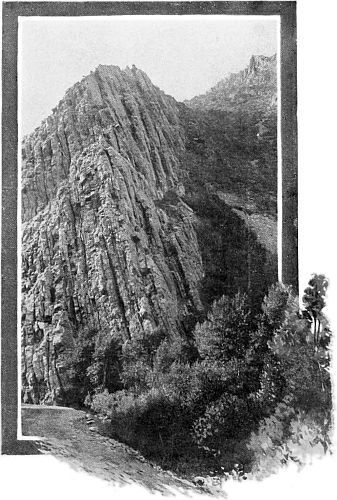

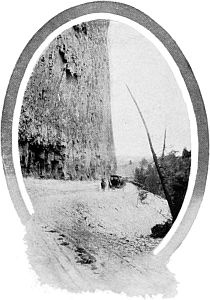

The Palisades

The Palisades

Strange to say, they will not take the grasshopper on the surface of the water. Two bright faced boys who had climbed down into the canyon watched me whip the pool in every direction for a quarter of an hour without taking a single trout. Satisfied that something was wrong, I fastened a good sized Rangeley sinker to the leader about a foot above the hook and pitched the grasshopper into the buffeting currents. An hour later we carried back to camp twenty-five trout which, placed endwise, head to tail, measured twenty-five feet on a tape line.[53]

This use of a sinker under the circumstances was not a great discovery, but it spelled the difference between success and failure at the time. So I have been glad at most times to learn by experience and from others the little things that help make a better day's angling.

Once when I knew more about trout fishing than I have ever convinced myself that I knew since, I visited a famous stream in a wilderness new and unknown to me, fully resolved to show the natives how to do things. Near the end of the third day of almost fruitless fishing, the modest guide volunteered to take me out that evening, if I cared to go. Of course I cared to go, and I shall never forget that moonlight night on Beaver Creek. We returned to camp about ten o'clock with twenty-eight trout, four of which weighed better than three pounds apiece.

A Young Corsair of the Plains

A Young Corsair of the Plains

It may be a severe shock to the sensibilities of the "super-refined fly-caster" to suggest so mean a bait as grasshoppers, yet he may obtain some comfort, as did one aforetime, by labeling the can in which the hoppers are carried:

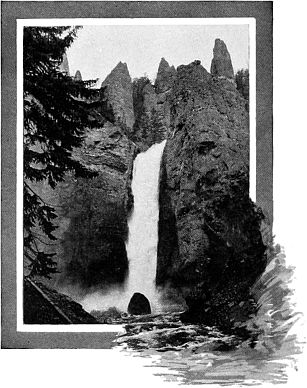

Tower Falls

Tower Falls

Then there are Slough Creek, Hell-Roaring Creek, East Fork, Trout Lake, and a host of other streams and lakes that have been favorite resorts with anglers for years, and in which may be taken the very leviathans of six, seven, eight, and even ten, pounds' weight. He must be difficult to please[54] who finds not a day of days among them. Up to the present time only the red-throat trout inhabit these waters, but plants of other varieties have been made and will doubtless thrive quite as well as the native trout.

Owing probably to the fact that, until recently, the region around Tower Creek and Falls was not accessible by roads, this stream received no attention from the fish commission till the summer of 1903, when a meager plant of 15,000 brook trout fry was made there. The scenery in this neighborhood is unsurpassed, and when the stream becomes well stocked it will, doubtless, be a favorite resort with anglers who delight in mountain fastnesses or in the study of geological records of past ages. The drainage basin of Tower Creek coincides with the limits of the extinct crater of an ancient volcano. As you stand amid the dark forests with which the walls of the crater are clothed and see the evidences on all sides of the Titanic forces once at work here, fancy has but little effort in picturing something of the tremendous scenes once enacted on this spot. Now all is peace and quiet, the quiet of the wilderness, which save for the rush of the torrential stream, is absolutely noiseless. No song of bird gladdens the darkened forests, and in its gloom the wild animals are seldom or never seen. How strikingly the silence and wonder of the scene proclaim that nature has formed the world for the happiness of man.

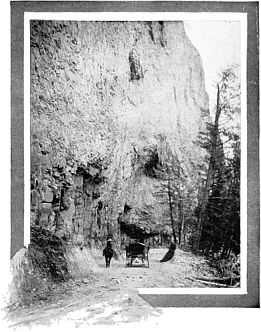

The Shadow of a Cliff

The Shadow of a Cliff

Within two hundred yards of the Yellowstone River, Tower Creek passes over a fall of singular and romantic beauty. Major Chittenden in his book "The Yellowstone"[55] thus describes it: "This waterfall is the most beautiful in the Park, if one takes into consideration all its surroundings. The fall itself is very graceful in form. The deep cavernous basin into which it pours itself is lined with shapely evergreen trees, so that the fall is partially screened from view. Above it stand those peculiar forms of rock characteristic of that locality—detached pinnacles or towers which give rise to the name. The lapse of more than thirty years since Lieutenant Doane saw these falls, has given us nothing descriptive of them that can compare with the simple words of his report penned upon the first inspiration of a new discovery: 'Nothing can be more chastely beautiful than this lovely cascade, hidden away in the dim light of overshadowing rocks and woods, its very voice hushed to a low murmur unheard at the distance of a few hundred yards. Thousands might pass by within half a mile and not dream of its existence; but once seen, it passes to the list of most pleasant memories.'"

If the angler wanders farther into the wilderness than any waters named herein would lead him, he will find other streams to bear him company amid scenes that will live long in his memory and where the trout are ever ready to pay him the compliment of a rise. To the eastward flows Shoshone river with its myriad tributaries, teeming with trout and draining a region far more rugged and lofty than the Park proper. To the south and west are those wonderfully beautiful lakes that form the source of the Snake river. Here, early in the season, the great lake or Macinac trout, Salvelinus namaycush, are occasionally taken with a trolling spoon.[56]

From north to south, from the Absaroka Mountains to the Tetons, on both sides of the continental divide, this peerless pleasuring-ground is netted with a lace-work of streams. Two score lakes and more than one hundred, sixty streams are named on the map of this domain which is forever secured and safeguarded

Good Bye Till Next Year

Good Bye Till Next Year

Obvious punctuation errors repaired.

Page 26, "Whpskehegan" changed to "Waskahegan" (fished the Waskahegan)