Title: Notes and Queries, Number 84, June 7, 1851

Author: Various

Editor: George Bell

Release date: September 10, 2011 [eBook #37379]

Most recently updated: January 25, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Charlene Taylor, Jonathan Ingram and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

"When found, make a note of."—CAPTAIN CUTTLE.

VOL. III.—No. 84.

SATURDAY, JUNE 7. 1851.

Price Sixpence. Stamped Edition 7d.

NOTES:—

Edmund Burke, and the "Annual Register," by James Crossley 441

Jews in China 442

The Dutch Martyrology 443

Lady Flora Hastings' Bequest 443

Witchcraft in the Seventeenth Century 444

Indulgences proposed to Benefactors to the Church of St. George the Martyr, Southwark 444

Gray's Plagiarisms, by Henry H. Breen 445

On the Application of the Word "Littus" in the Sense of Ripa, the Bank of a River 446

Minor Notes:—Epigrams by Coulanges and Prior—Brewhouse Antiquities—Joseph of Exeter de Bello Antiocheno—Illustrations of Welsh History 446

QUERIES:—

The Window-tax, Local Mints, and Nobbs of Norwich 447

Minor Queries:—Gillingham—"We hope, and hope, and hope"—What is Champak?—Encorah and Millicent—Diogenes in his Tub—Topical Memory—St. Paul's Clock striking Thirteen—A regular Mull: Origin of the Phrase—Register book of the Parish of Petworth—Going to Old Weston—"As drunk as Chloe"—Mark for a Dollar—Stepony—Longueville MSS.—Carling Sunday—Lion Rampant holding a Crozier—Monumental Symbolism—Ptolemy's Presents to the Seventy-two—Baronette—Meaning of "Hernshaw"—Hogan—"Trepidation talk'd"—Lines on the Temple—Death—Was Stella Swift's Sister? 448

MINOR QUERIES ANSWERED:—John Marwoode—St. Paul—Meaning of Zoll-verein—Crex, the White Bullace 450

REPLIES:—

The Outer Temple, by Edward Foss 451

The Old London Bellman and his Songs or Cries, by Dr. E. F. Rimbault 451

The Travels of Baron Munchausen, and the Author of "The Sabbath" 453

The Penn Family, by Hepworth Dixon 454

On the Word "Prenzie" in "Measure for Measure" by S. W. Singer, S. Hickson, &c. 454

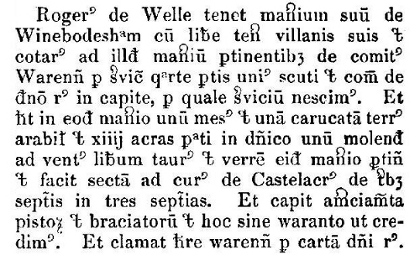

Replies to Minor Queries:—Countess of Pembroke's Epitaph—Court Dress—Ex Pede Herculem—Day of the Accession of Richard III.—Tennyson's "In Memoriam"—Cardinal Azzolin—Babington's Conspiracy—Robert de Welle—Family of Sir John Banks—Charles Lamb's Epitaph—Quebeça and his Epitaph—The Frozen Horn—West Chester—Registry of Dissenters—Poem upon the Grave—Round Robin—Derivation of the Word "Yankee"—Letters on the British Museum—Names of the Ferret—Anonymous Ravennas—The Lion, a Symbol of the Resurrection—Paring the Nails, &c.—Meaning of Gig-Hill—The Mistletoe on the Oak—Spelling of "Britannicus"—T. Gilbert on Clandestine Marriages—Dog's Head in the Pot—Pope Joan—"Nettle in Dock out"—Mind your P's and Q's—Lay of the Last Minstrel—Tingry—Sabbatical and Jubilee Years of the Jews—Luncheon—Prophecy respecting the Discovery or America—Shakespeare's Designation of Cleopatra—Harlequins—Christ's-cross Row, &c. 456

MISCELLANEOUS:—

Notes on Books, Sales, Catalogues, &c. 470

Books and Odd Volumes wanted 470

Notices to Correspondents 471

List of Notes & Queries volumes and pages

[441]That Burke wrote the Annual Registers for Dodsley for some period after its commencement is well known, but no one has yet distinctly stated when his participation in that work ceased. Mr. Prior, in his Life of Burke, places in his list of his writings: "Annual Register, at first the whole work, afterwards only the Historical Article, 1758," &c. He also states that "many of the sketches of contemporary history were written from his immediate dictation for about thirty years," and that "latterly a Mr. Ireland wrote much of it under Mr. Burke's immediate direction." (Life, vol. i. p. 85. edit. 1826.)

In proof of this statement, a fac-simile is given of Burke's receipts to Dodsley for two sums of 50l. each "for the Annual Register of 1761," the originals of which were in Upcott's collection. At the sale of Mr. Wilks's autographs this month, I observe there was another receipt for writing the Annual Register for 1763. I am not aware whether any other receipts from Burke are in existence for the money paid to him for his contributions to this periodical, but for the Annual Registers beginning with 1767, and terminating in 1791, I have the receipts of Thomas English, who appears to have received from Dodsley, first 140l., and subsequently 150l. annually, for writing and compiling the historical portion of the work. Burke's connexion with the publication must therefore have lasted a much shorter period than Mr. Prior appears to have supposed, and apparently was not continued beyond seven or eight years, from 1758 to 1766, after which year, English seems to have taken his place.

Everything relating to Burke is of importance; and if any of your correspondents can afford any further assistance in defining as correctly as possible the limits of his participation in the Annual Register, I feel assured that the information will be gladly received by your readers.

I have not seen it noticed, that the historical articles in the Annual Registers, from 1758 to 1762 inclusive, were collected in an 8vo. vol. under the title of—

[442]"A compleat History of the late War, or Annual Register of its Rise, Progress, and Events in Europe, Asia, Africa, and America, &c." London, 1763.

This work went through more than one edition. My copy, containing 559 pages, is a Dublin edition of the date of 1763, printed by John Exshaw.

As there seems to be no question that what is contained in this volume is the composition of Burke, and as it has never yet been superseded as a spirited history of the stirring period to which it relates, it ought undoubtedly to be attached as a supplement to the 8vo. edition of Burke's Works, with his "Account of the European Settlements in America," his title to which is now placed beyond dispute.

It is greatly to be regretted that some of Burke's early publications are yet undiscovered, amongst which are his poetical translations from the Latin, and his attack upon Henry Brooks, the author of the Fool of Quality.

JAS. CROSSLEY.

The mail which arrived from East India and China about the middle or end of March last, brought news of the discovery of a race of Jews in the interior of the latter country, of which I have seen no notice taken by the English press.

It being a subject in which a number of your readers will probably feel interested, and but comparatively few of them see the China newspapers, I beg to enclose you an account from the Overland China Mail, dated Hong Kong, Jan. 29, 1851.

The existence of a fragment of the family of Abraham in the interior of China has been certainly known for upwards of two hundred years, and surmised much longer. The Jesuit Ricci, during his residence at Peking in the beginning of the seventeenth century, was the means of exciting the attention of foreigners to the Jews of Kai-fung-fú, the ancient capital of Ho-nan province. In 1618 they were visited by Aleni, a follower of Ricci; and a hundred years later, between 1704 and 1723, Fathers Gozani, Domenge, and Gaubil were enabled from personal investigation on the spot to give minute descriptions of the people, their synagogue and sacred books, the latter of which few could even then read, while the former was, with the peculiar institutions of Moses, fast falling to decay. Beyond a few feeble and ineffective efforts on the part of Biblical critics, nothing was subsequently attempted to maintain a communication with this handful of Jews until in 1815 some brethren in London addressed a letter to them in Hebrew, and offered a large reward if any one would bring an answer in the same language. The letter was entrusted to a Chinese bookseller, a native of the province, who is reported to have delivered it, which was doubted, as he brought no written answer.

Recently the Jews' Society in London, encouraged by the munificence of Miss Cook, who placed ample funds at their disposal, instituted enquiries on the subject, and sought the co-operation of the Bishop of Victoria, who having previously opened a correspondence with Dr. Medhurst on the subject, during his Lordship's recent visit to Shanghae, the plan of operations was agreed upon. This was to despatch two Chinese Christians, one of them a literary graduate, the other a young man with a competent knowledge of English, acquired at the London Missionary School. The North China Herald of the 18th January contains an interesting account of their mission, from which we gather the following particulars.

The two emissaries started on the 15th November last, and after an absence of fifty-five days, returned to Shanghae, the distance between the two cities being about six hundred miles.[1] Arrived at their destination, they found in the decayed city of Kai-fung-fú, both Mohamedans and Jews, the latter poverty-stricken and degraded, their synagogue in a state of dilapidation, and the distinguishing symbols of their religion nearly extinct. The books of the Law, written in a small square character on sheepskin, are however still preserved, although it would seem for many years they have been seen by no one able to read them.

[1] Kai-fung-fú, according to Williams's map, is situated about a league from the southern bank of the Hwang-ho, or Yellow River, in 34° 55´ N. Lat., and 114° 40´ E. Long.

The Jesuits mention the existence of the sacred books, but were not suffered to copy or even to inspect them; but the Chinese Christians encountered no such scruples; so that, besides taking copies of inscriptions on the stone tablets, they were enabled to bring away eight Hebrew manuscripts, six of them containing portions of the Old Testament, and two of the Hebrew liturgy. The correspondent of the North China Herald states that—

"The portions of Scripture are from the 1st to the 6th chapters of Exodus, from the 38th to the 40th chapters of the same book, Leviticus 19th and 20th chapters, Numbers 13th, 14th, and 15th chapters, Deuteronomy from the 11th to the 16th chapters, with the 32nd chapter of that book. Various portions of the Pentateuch, Psalms, and Hagiographa occur in the books of prayers, which have not yet been definitely fixed. The character in which these portions are written is an antique form of the Hebrew, with points.[2] They are written on thick paper, evidently by means of a style, and the material employed, as well as the silk in which the books are bound, exhibit marks of a foreign origin. Two Israelitish gentlemen, to whom they have been shown in Shanghae, say that they have seen such books in Aden; and the occurrence here and [443]there of Persian words, written with Hebrew letters, in the notes appended, seem to indicate that the books in question came originally from the western part of Asia, perhaps Persia or Arabia. There is no trace whatever of the Chinese character about them, and they must have been manufactured entirely by foreigners residing in China, or who have come from a foreign country. Regarding their age, it would be difficult to hazard even a conjecture."

[2] The Jesuits state expressly that the Hebrew was without points.

The result of this mission has been such that it cannot be doubted another will be sent, and we trust the attempt at least will be made by some discreet foreigner—a Jew, or at all events a Hebrew scholar—to penetrate to Kai-fung-fú; for although the proofs brought away on the present occasion are so far satisfactory, yet in the account given, on the authority of the Chinese emissaries, we presume, there are several things that might otherwise excite incredulity.

SALOPIAN.

[The Jewish Intelligencer for May, 1851, contains a long article on the "Present State of the Jews at Kai-fung-fú;" also a fac-simile of the Hebrew MS. found in the synagogue at that place, and a map of the eastern coast of China.]

Wall, in his History of Infant Baptism, frequently mentions a book called The Dutch Martyrology as quoted by Danvers. He appears never to have seen it, and if I mistake not (although I cannot just now find the passage) he somewhere throws out a hint that no such book ever existed. Archdeacon Cotton, in his valuable edition of Wall's book, says (vol. ii. p. 131. note m.):

"Danvers cites this work as 'The Dutch Martyrology called The bloody Theatre; a most elaborate and worthy collection: written in Dutch, by M. J. Van Braght.' I have never seen it."

A very fine copy of this curious and very important work is in the Fagel collection in the library of Trinity College, Dublin. It is on large paper, with the exception of some few leaves in different parts of the volume, which have been mounted to match the rest. It is full of beautiful engravings by Jan Luyken, representing the sufferings of the martyrs; some of them, indeed all, possessing very great artistic merit. The first in the volume, a crucifixion, representing Our Lord in the very act of being nailed to the cross, is a most striking picture: and I may also mention another, at p. 385., representing a party in a boat reading the Bible, having put out to sea to escape observation.

The book is a large folio in 2 vols.: the first consisting of 450, the second of 840 pages; and contains a most important collection of original documents, which are indispensable to the history of the Reformation, and many of them are intimately connected with the English Reformation. The history of the martyrs begins with Our Saviour's crucifixion (for He is represented as the first Anabaptist martyr!), and ends with the year 1660. The Dublin copy is the second edition, and its full title is as follows:—

"Het Bloedig Tooneel, of Martelaers Spiegel der Doops-gesinde of Weerloose Christenen, die om't getuygenis van JESUS naren Selighmaker, geleden hebben, ende gedood zijn, van CHRISTI tijd af tot desen tijd toe. Versamelt uyt verscheyde geloofweerdige Chronijken, Memorien, en Getuygenissen. Door T. J. V. Braght [or, as he is called on the engraved title-page, Tileman Van Braght]. Den Tweeden Druk, Bysonder vermeerdert met veele Autentijke Stucken, en over de hondert curieuse Konstplaten. Amsterdam. 1685."

Since writing the above, I see that the Bodleian Library has a copy; procured, however, it is right (for Dr. Cotton's sake) to say, since the publication of his edition of Wall's History of Infant Baptism.

J. H. T.

Trin. Coll., Dub.

All who reverence and love the memory of Lady Flora Hastings,—all who have had the happiness of a personal acquaintance with that gentle and gifted being,—who have mourned over her hapless fate,—who have read her poems, so full of beauty and promise, will receive her "Last Bequest" with feelings of deep interest.

This poem has never before been published.

ERZA.

Oh, let the kindred circle,

Far in our northern land,

From heart to heart draw closer

Affection's strength'ning hand:

To fill my place long vacant,

Soon may our loved ones learn;

For to our pleasant dwelling

I never shall return.

Peace to each heart that troubled

My course of happy years;

Peace to each angry spirit

That quench'd my life in tears!

Let not the thought of vengeance

Be mingled with regret;

Forgive my wrongs, dear mother!

Seek even to forget.

Give to the friend, the stranger,

Whatever once was mine;

Nor keep the smallest token

To wake fresh tears of thine,—

Save one, one loved memorial,

With thee I fain would leave;

'Tis one that will not teach thee

Yet more for me to grieve.

'Twas mine when early childhood

Turn'd to its sacred page,

The gay, the thoughtless glances

'Twas mine thro' days yet brighter,

The joyous years of youth,

When never had affliction

Bow'd down mine ear to truth.

'Twas mine when deep devotion

Hung breathless on each line

Of pardon, peace, and promise,

Till I could call them mine;

Till o'er my soul's awakening

The gift of Heavenly love,

The spirit of adoption,

Descended from above.

Unmark'd, unhelp'd, unheeded,

In heart I've walk'd alone;

Unknown the prayers I've utter'd,

The hopes I held, unknown;

Till in the hour of trial,

Upon the mighty train,

With strength and succour laden,

To bear the weight of pain.

Sir Roger Twysden, with all his learning, could not rise above the credulity of his age; and was, to the last, as firm a believer in palmistry and witchcraft, and all the illusions of magic, as the generality of his cotemporaries. His commonplace-books furnish numerous instances of the childlike simplicity with which he gave credence to any tale of superstition for which the slightest shadow of authenticity could be discovered.

The following amusing instance of this almost infantine credulity, I have extracted from one of his note-books; merely premising that his wife Isabella was daughter of Sir Nicholas Saunders, the narrator of the tale:—

"The 24th September, 1632, Sir Nicholas Saunders told me hee herd my lady of Arundall, widow of Phylip who dyed in ye Tower 1595, a virtuous and religious lady in her way, tell the ensuing relation of a Cat her Lord had. Her Lord's butler on a tyme, lost a cuppe or bowle of sylver, or at least of yt prise he was much troubled for, and knowing no other way, he went to a wyzard or Conjurer to know what was become of it, who told him he could tell him where he might see the bowle if he durst take it. The servant sayd he would venture to take it if he could see it, bee it where it would. The wyzard then told hym in such a wood there was a bare place, where if he hyed himself for a tyme he appoynted, behind a tree late in the night he should see ye Cuppe brought in, but wth all advised him if he stept in to take it, he should make hast away wth it as fast as myght bee. The servant observed what he was commanded by ye Conjurer, and about Mydnyght he saw his Lord's Cat bring in the cup was myst, and divers other creatures bring in severall other things; hee stept in, went, and felt ye Cuppe, and hyde home: where when he came he told his fellow servants this tale, so yt at ye last it was caryed to my Lord of Arundel's eare; who, when his Cat came to him, purring about his leggs as they used to doo, began jestingly to speake to her of it. The Cat presently upon his speech flewe in his face, at his throat, so yt wthout ye help of company he had not escaped wthout hurt, it was wth such violence: and after my lord being rescued got away, unknown how, and never after seene.

"There is just such a tale told of a cat a Lord Willoughby had, but this former coming from so good hands I cannot but believe.—R. T."

L. B. L.

Witchcraft. In the 13th year of the reign of King William the Third—

"One Hathaway, a most notorious rogue, feigned himself bewitched and deprived of his sight, and pretended to have fasted nine weeks together; and continuing, as he pretended, under this evil influence, he was advised, in order to discover the person supposed to have bewitched him, to boil his own water in a glass bottle till the bottle should break, and the first that came into the house after, should be the witch; and that if he scratched the body of that person till he fetched blood, it would cure him; which being done, and a poor old woman coming by chance into the house, she was seized on as the witch, and obliged to submit to be scratched till the blood came, whereupon the fellow pretended to find present ease. The poor woman hereupon was indicted for witchcraft, and tried and acquitted at Surrey assizes, before Holt, chief justice, a man of no great faith in these things; and the fellow persisting in his wicked contrivance, pretended still to be ill, and the poor woman, notwithstanding the acquittal, forced by the mob to suffer herself to be scratched by him. And this being discovered to be all imposition, an information was filed against him."—Modern Reports, vol. xii. p. 556.

Q. D.

As I believe little is known of the early history of this church, which was dependent upon the Abbey and Convent of Bermondsey, the following curious hand-bill or affiche, printed in black letter (which must have been promulgated previous to the disgrace of Cardinal Wolsey, and the suppression of religious houses in the reign of Henry VIII.), seems worthy of preservation. It was part of the [445]lining of an old cover of a book, and thus escaped destruction. It is surmounted, at the left hand corner, by a small woodcut representing St. George slaying the dragon, and on the right, by a shield, which, with part of the margin, has been cut away by the bookbinder. But few words are wanting, which are supplied by conjecture in Italics.

It appears from Staveley's History of Churches in England, p. 99., that the monks were sent up and down the country, with briefs of a similar character, to gather contributions of the people on these occasions, and that the king's letter was sometimes obtained, in order that they might prove more effectual.

It is most probable that the collectors were authorised to grant special indulgences proportionate to the value of the contribution. No comment is necessary upon these proceedings, from which at least the Reformation relieved the people, and placed pious benefactions upon purer and better motives.

MISO-DOLOS.

"Unto all maner and synguler Cristen people beholdynge or herynge these present letters shall come gretynge.

"Our holy Fathers, xii. Cardynallys of Rome chosen by the mercy of Almighty God and by the Auctorite of these appostles Peter and Paule, to all and synguler cristen people of eyther kynde, trewely penytent and confessyd, and deuoutly gyue to the churche of oure lady and Seynt George the martyr in Sowthwerke, protector and defender of this Realme of Englande, any thyng or helpe with any parte of theyr goodes to the Reparacions or maynteyninge of the seruyce of almighty God done in ye same place, as gyuynge any boke, belle, or lyght, or any other churchly Ornamentis, they shall haue of eche of us Cardinallys syngulerly aforesayd a C. dayes of pardon. ¶ Also there is founded in the same parysshe churche aforesayd, iii. Chauntre preestis perpetually to praye in the sayd churche for the Bretherne and Systers of the same Fraternyte, and for the soules of them that be departed, and for all cristen soules. And also iiii. tymes by the yere Placebo and Dirige, with xiiii. preestis and clerkes, with iii. solempne Masses, one of our Lady, another of Seynt George, with a Masse of Requiem. ¶ Moreouer our holy Fathers, Cardynallys of Rome aforesayd, hathe graunted the pardons followethe to all theym that be Bretherne and Systers of the same Fraternyte at euery of the dayes followynge, that is to say, the firste sonday after the feest of Seynt Johannes Baptyst, on the whiche the same churche was halowed, xii. C. dayes of pardon. ¶ Also the feest of Seynt Mychael ye Archangell, xii. C. dayes of pardon. ¶ Also the second sonday in Lent, xii. C. dayes of pardon. ¶ Also good Frydaye, the whiche daye Criste sufferyd his passion, xii. C. dayes of pardon. ¶ Also Tewisday in the wytson weke, xii. C. dayes of pardon. ¶ And also at euery feeste of our lorde Criste syngulerly by himselfe, from the firste euynsonge to the seconde euynsonge inclusyuely, xii. C. dayes of pardon. ¶ Also my lorde Cardynall and Chaunceller of Englande hathe gyuen a C. dayes of pardon.

"¶ The summe of the masses that is sayd and songe within the same Parysshe Churche of Seynt George, is a m. and xliiii.

"¶ God Saue the Kynge."

Your correspondent VARRO (Vol. iii., p. 206.) rejects as a plagiarism in Gray the instance quoted by me from a note in Byron (Vol. iii., p. 35.), on the ground that Gray has himself expressly stated that the passage was "an imitation" of the one in Dante. I always thought that in literature, as in other things, some thefts were acknowledged and others unacknowledged, and that the only difference between them was, that, while the acknowledgment went to extenuate the offence, it the more completely established the fact of the appropriation. A great many actual borrowings, but for such acknowledgment, might pass for coincidences. "On peut se rencontrer," as the Chevalier Ramsay said on a similar occasion.

The object, however, of this Note is not to shake VARRO'S belief in the impeccability of Gray, for whose genius I entertain the highest admiration and respect, but to show your readers that the imputation of plagiarism against that poet is not wholly unfounded. First, we have the well-known line in his poem of The Bard,—

"Give ample room and verge enough,"—

which is shown to have been appropriated from the following passage in Dryden's tragedy of Don Sebastian:

"Let fortune empty her whole quiver on me;

I have a soul that, like an ample shield,

Can take in all, and verge enough for more."

To this I shall add the famous apothegm at the close of the following stanzas, in his Ode On a Prospect of Eton College:

"Yet, ah! why should they know their fate,

Since sorrow never comes too late,

And happiness too swiftly flies;

... ... Where ignorance is bliss,

'Tis folly to be wise."

The same thought is expressed by Sir W. Davenant in the lines:

"Then ask not bodies doom'd to die

To what abode they go:

Since knowledge is but sorrow's spy,

'Tis better not to know."

But the source of Gray's apothegm is still more obviously traceable to these lines in Prior:

"Seeing aright we see our woes;

Then what avails us to have eyes?

From ignorance our comfort flows,

The only wretched are the wise."

A third sample in Gray is borrowed from Milton. The latter, in speaking of the Deity, has this beautiful image:

"Dark with excessive light thy skirts appear."

[446]And Gray, with true poetic feeling, has applied this image to Milton himself in those forceful lines in the Progress of Poesy, in which he alludes to the poet's blindness:

"The living throne, the sapphire blaze,

Where angels tremble while they gaze,

He saw; but, blasted with excess of light,

Closed his eyes in endless night."

There is a passage in Longinus which appears to me to have furnished Milton with the germ of this thought. The Greek rhetorician is commenting on the use of figurative language, and, after illustrating his views by a quotation from Demosthenes, he adds: "In what has the orator here concealed the figure? plainly in its own lustre." In this passage Longinus elucidates one figure by another,—a not unusual practice with that elegant writer.

HENRY H. BREEN.

St. Lucia, April, 1851.

The late Marquis Wellesley, towards the close of his long and glorious life, wrote the beautiful copy of Latin verses upon the theme "Salix Babylonica," which is printed among his Reliquiæ.

In this copy of verses is to be found the line,—

"At tu, pulchra Salix, Thamesini littoris hospes."

Certain critics object to this word "littoris," used here in the sense of "ripa." The question is, whether such an application can be borne out by ancient authorities. To be sure, the substitution of "marginis" for "littoris" would obviate all controversy; but as the objection has been started, and urged with some pertinacity, it may be worth while to consider it. The ordinary meaning of littus is undoubtedly the sea-shore; but it seems quite certain that it is used occasionally in the sense of "ripa."

In the 2d Ode of Horace, book 1st, we find:

"Vidimus flavum Tiberim, retortis

Littore Etrusco violenter undis,

Ire dejectum monumenta regis,

Templaque Vestæ;

Iliæ dum se nimium querenti

Jactat ultorem; vagus et sinistrâ

Labitur ripâ."

—meaning, as I conceive, that the waters of the Tiber were thrown back from the Etruscan shore, or right bank, which was the steep side, so as to flood the left bank, and do all the mischief. If this interpretation be correct, which Gesner supports by the following note, the question is settled by this single passage:

"Quod fere malim propter ea quæ sequuntur, littus ipsius Tiberis dextrum, quod spectat Etruriam: unde retortis undis sinistrâ ripâ Romam alluente, labitur."

Thus, at all events, I have the authority of Gesner's scholarship for "littus ipsius Tiberis."

There are two other passages in Horace's Odes where "littus" seems to bear a different sense from the sea-shore. The first, book iii. ode 4.:

"Insanientem navita Bosporum

Tentabo, et arentes arenas

Littoris Assyrii viator."

The next, book iii. ode 17.:

"Qui Formiarum mœnia dicitur

Princeps, et innantem Maricæ

Littoribus tenuisse Lirim."

Upon which latter Gesner says, that as Marica was a nymph from whom the river received its name,—

"Hinc patet Lirim atque Maricam fuisse duo unius fluminis nomina."

But I will not insist upon these examples even with the support of Gesner, because Marica may have been a district situate on the sea-shore, and because, in the former passage, "littus Assyrium" may mean the Syrian coast, which is washed by the Mediterranean.

But to go to another author, in book x. of Lucan's Pharsalia will be found (line 244.):

"Vel quod aquas toties rumpentis littora Nili

Assiduè[3] feriunt, coguntque resistere flatus."

This seems to be a clear case of the Nile breaking its banks, and is conclusive. Again, in book viii. l. 641.:

"Et prior in Nili pervenit littora Cæsar."

[3] Sc. Zephyri.

And again, "littore Niliaco," book ix. l. 135.

Lastly, in Scheller's Dictionary, the same meaning is given from the 8th book of Virgil's Æneid:

"Viridique in littore conspicitur sus;"

where, beyond a doubt, is meant "littore" fluviali.

It appears, then, from these examples that Lord Wellesley is justified in his application of the word "littus" to the adjective "Thamesinus."

Q. E. D. (A Borderer.)

—Has the following coincidence been noticed between an epigram of M. de Coulanges and some verses by Mat. Prior?

"L'Origine de la Noblesse.

"D'Adam nous sommes tous enfants,

La preuve en est connue,

Et que tous nos premiers parents

Ont mené la charrue.

"Mais, las de cultiver enfin

La terre labourée,

L'une a dételé le matin,

L'autre l'après-dinée."

"The Old Gentry.

"That all from Adam first begun,

None but ungodly Woolston doubts,

And that his son, and his son's sons

Were all but ploughmen, clowns and louts.

C. P. PH***.

—In Forth and others versus Stanton, Trinity Term, 20 Charles II., Timothy Alsopp and others sue for 100l. for cost of beer, sold by them to defendant's late husband. Can this Timothy Alsopp be a lineal predecessor of the present eminent firm of Samuel Alsopp and Sons? We are told that Child's is the oldest banking-house—which may be the oldest brewing establishment?

J. H. S.

—Joseph of Exeter, or Iscanus, was the author of two poems: 1st, De Bello Trojano; 2dly, De Bello Antiocheno. The first has been printed and published. The second was only known by fragments to Leland. See his work De Scrip. Brit. p. 239. Mr. Warton, in his History of English Poetry (1774), affirms, that Mr. Wise, the Radcliffe librarian, had informed him that a MS. copy of the latter was in the library of the Duke of Chandos at Canons. Query, where is it? It was not at Stowe. It is not in Lord Ashburnham's collection, nor in the British Museum; nor in the Bodleian Library, nor in the archives of Sir Thomas Phillipps. For the honour of the nation, we earnestly hope that it may be discovered and committed to the press.

EXONIENSIS.

—In Madox's Collections in the British Museum (Add. MSS. No. 4565., vol. lxxxviii. p. 387.) are the annexed references to two interesting incidents in the history of Wales, noticed in a MS. Chronicle of John De Malverne, in the library of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge. The references are sent for insertion in "NOTES AND QUERIES," in the hope that some member of the University may be induced to favour the readers of "NOTES AND QUERIES" with the passages referred to by Madox.

"Per idem tempus David Princeps Norwalliæ ad alas papalis protectionis confugere proponens, terram suam optulit ei ab ipso tenere, reddendo inde sibi quingentas marcas, cui perhibetur D. Papa favorem præbuisse in magnum regni Angliæ præjudicium: novit enim mundus Principem Walliæ ab antiquo vassallum Regis Angliæ extitisse. Ex eod. Chron. [MS. Joh. de Malverne, M. 14.] A. Dom. 1244."

"Griff. fil. Lewel. Princeps Norwalliæ, being in the Tower of London, fell down as he tryed to make his escape out of a window, and dyed. Ib. ad. Ann. 1244."

JOHN AP WILLIAM AP JOHN.

In a MS. chronicle, now before me, of remarkable events which occurred, in connexion with the history of the city of Norwich, from the earliest period to the year 1716, compiled by an inhabitant of the place named Nobbs, of whom a word or two at the end of this note, occurs the following passage:

"This year (1695) the parliament made an act for remedying the coin of the nation, which was generally debased by counterfeits, and diminished by clipping, and laid a tax upon glass windows, to make good the deficiency when it should be taken in. And, for the speedy supply of money to the subjects, upon calling in of the old money, there were mints set up in York, Bristol, Chester, Exeter, and Norwich. The mint in Norwich began to work in Sept. 1696. Coined there 259,371l. The amount of plate and coin brought into this mint was 17,709 ounces."

These quantities are identical with those given by Blomefield (History of Norwich, fol., 1741, p. 300.).

1. The duties chargeable on windows, as now collected, were regulated by Sched. A. of 48 Geo. III. c. 55.; but, assuming the correctness of Nobbs' statement, is it generally known that this tax originated in the year, and under the circumstances, above recorded?

Bishop Burnet (Hist. Own Time, 8vo., 1833, vol. iv. pp. 252. 258.), describing the proceedings taken by parliament for rectifying the state of the coinage, without telling us by what means the money was raised, says (p. 290.):

"Twelve thousand pounds was given to supply the deficiency of the bad and clipped money."

Is this sum the amount of the proceeds of the tax laid, as our chronicle records, upon glass windows? If so, or from whatever source obtained, it may, in passing, be remarked, that it appears to be ridiculously inadequate to meet the requirements of the case; for, according to the Bishop, in another place (p. 316.):

"About five millions of clipped money was brought into the exchequer, and the loss that the nation suffered, by the recoining of the money, amounted to two millions and two hundred thousand pounds."

The window duties have of late provoked much discussion, and it would prove of some interest, if, through the medium of your pages, any of your correspondents would take the trouble to investigate a little further the subject of this note. It very easily admits of confirmation or denial.

2. The principal reason, however, for now writing, is to request answers to the two following Queries: 1. What amount of money was respectively coined during 1696, and the following year, in the cities of York, Bristol, Chester, and Exeter? [448]and 2. In what parish of each of these places, including Norwich, was the mint situated?

And now let me add a sentence or two respecting the compiler of the above-named chronicle, which I am induced to do, as his name is closely connected with that of one of the most celebrated controversial writers of the Augustan age of Anne and George I., the friend of Whiston, of Newton, and of Hoadley, and the subject of Pope's sarcastic allusion:

"We nobly take the high priori road,

And reason downwards till we doubt of God."

It appears, on the authority of a MS. letter before me, dated Aylsham, Norfolk, Jan. 25, 1755, and addressed to Mr. Nehemiah Lodge, town clerk of Norwich, by Mr. Thos. Johnson, who was speaker of the common council of that city from 1731 to 1736, that Nobbs

"Was many years clerk of St. Gregory's parish in Norwich, where he kept a school, and was so good a scholar as to fit youths for the university, amongst whom were the great Dr. Samuel Clarke, and his brother, the Dean of Salisbury."

The old man's MS. is very neatly written, and arranged with much method. It was made great use of, frequently without acknowledgment, by Blomefield, in the compilation of his history; and besides the chronicle of events immediately connected with the city, there are interspersed through its pages notices of earthquakes, great famines, blazing stars, dry summers, long frosts, and other similar unusual occurrences. The simplicity, and grave unhesitating credulity, with which some of the more astonishing marvels, culled, I suppose, from the pages "of Holinshed or Stow," are recorded, is very amusing. I cannot refrain from offering you a couple of examples, and with them I will bring this heterogeneous "note" to a close.

"In the eighth year of this king's reign (E. II.) it was ordained by parliament, that an ox fatted with grass should be sold for 15s., fatted with corn 20s., the best cow for 12s.; a fat hog of two years 3s. 4d.; a fat sheep shorn 14d., and with fleece 20d.; a fat capon 2d., a fat hen 1d., four pigeons 1d. And whosoever sold for more, should forfeit his ware to the king. But this order was soon revoked, by reason of the scarcity that after followed. For, in the year following, 1315, there was so great a dearth, that continued three years, and therewith a mortality, that the living were not sufficient to bury the dead; horses, dogs, and children were eaten in that famine, and thieves in prison plucked in pieces those that were newly brought in, and eat them half alive."

But, again, sub ann. 1349:

"This year dyed in Norwich of the plague, from the first of January to the last of June, 57,374 persons, besides religious people and beggars; and in Yarmouth, 7053. This plague began November the first, 1348, and continued to 1357, and it hath been observed that they that were born after this had but twenty-eight teeth, whereas before they had thirty-two."

This latter notice refers to the first of those three destructive epidemics which visited Europe during the reign of our Edw. III., and are so frequently mentioned in ancient records. It is styled the "Pestilencia Prima et Magna, Anno Domini 1349, a festo Stæ. Petronillæ usque ad festum Sti. Michaelis." (Nicolas, Chron. of Hist., p. 345.)

COWGILL.

—Can you, or any of your correspondents, furnish me with any historical or local data that may tend to identify the place where that memorable council was convened, by which the succession to the English crown was transferred from the Danish to the Saxon line? Hutchins, in his History of Dorset (Edw. II., 1813, vol. iii. p. 196.), says:

"Malmsbury[4] mentions a council held at Gillingham, in which Edward the Confessor was chosen king. It was really a grand council of the realm; but the generality of our historians place it with more probability at London, or in the environs thereof."

[4] Book ii. c. 12. p. 45.

I am not aware of anything else that can be advanced in support of the claims of the Dorset shire Gillingham to be the scene of this event except it be the fact that a royal palace or hunting-seat there was the occasional residence of the English kings early in the twelfth century, and subsequently. I do not know whether its existence can be traced prior to the Conquest; and unless that can be done, it is obviously of no importance in the present inquiry. Now it had occurred to me that, after all, Gillingham, near Chatham in Kent, may be the true locality; but, unfortunately, my knowledge of that place is limited to the fact, that our London letters, when directed without the addition of "Dorset," are usually sent to rusticate there for a day or two. Perhaps one of your Kentish correspondents will favour me with some more pertinent information.

QUIDAM.

—I wish to discover the author (a disappointed courtier, I believe) of a poem ending thus:

"We hope, and hope, and hope, then sum

The total up—Despair!"

C. P. PH***.

—In Shelley's "Lines to an Indian Air," I read—"The Champak odours fail." Is it connected with the spice-bearing regions of Champava, or Tsiampa, in Siam?

C. P. PH***.

—These are very common baptismal names for females in this parish, and I should be very much obliged to any one [449]who could refer me to the origin and meaning of either or both of them. The former is also spelt Anchōra and Enchōra.

J. EASTWOOD.

Ecclesfield.

—It may be hypercritical, but is there any authority for placing Diogenes in the tub at the time of his interview with Alexander, which took place at Corinth, as Landseer has done in his celebrated dog-picture?

A. A. D.

—Where can I find the subject of "topical memory" treated of? Cic. de Orat. i. 34. alludes to it.

A. A. D.

—Will you allow me on this subject to put to men of science, and to watchmakers, the à priori question—Is the alleged fact mechanically possible?

AVENA.

—"You have made a regular mull of it," meaning a complete failure. This expression I have often heard, from my school days even to the present time. Can you give me the origin of it? In reading a very clever and interesting paper communicated by J. M. Kemble, Esq., to the Archæological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland in the volume of their proceedings for 1845, entitled, "The Names, Surnames, and Nicnames of the Anglo-Saxons," I found the following paragraph:

"Two among the early kings of Wessex are worthy of peculiar attention, viz., the celebrated sons of Cênberht, Cædwealha and his brother Mûl. Of the former it is known, that after a short and brilliant career of victory, he voluntarily relinquished the power he had won, became a convert to Christianity, and having retired to Rome, was there baptised by the name Petrus, and died while yet in the Albs, a few days after the ceremony. His brother Mûl, during their wars in Kent, suffered himself to be surprised by the country-people and was burnt to death, together with twelve comrades, in a house where they had taken refuge."

This "Note," I think, answers my Query. Do you know of any other explanation?

W. E. W.

—Can any reader of "NOTES AND QUERIES" assist in discovering a document which was formerly quoted by this title? Heylin used it for the reign of Edward VI., but his learned editor (Mr. Robertson) appears to have searched for it in vain.

C. H.

St. Catharine's Hall, Cambridge.

—When a Huntingdonshire man is asked "If he has ever been to Old Weston," and replies in the negative, he is invariably told, "You must go before you die." Old Weston is an out-of-the-way village in the county, and until within a few years was almost inapproachable by carriages in winter; but in what the point of the remark lies, I do not know.

ARUN.

—Who was Chloe, and what gave rise to the expression?

J. N. C.

—What is the origin of the mark for a dollar, $?

T. C.

—If not too stale by this time, may I put a Query to any Worcestershire reader on the possible connexion of Stepony ale with a well-known country inn in that county, which must have startled many a traveller with strange hippophagous apprehensions, viz., Stew-poney?

B.

Lincoln.

—Was the collection of MSS. possessed by Henry Viscount Longueville, and catalogued in Cat. Lib. MSS. Angliæ, 1697, dispersed; or, if not, where is it to be found?

E. T. B.

York, May 13.

—Carling Sunday, occurring nowabouts, is observed on the north coast of England by the custom of frying dry peas; and much augury attends the process, as indicated by the different effect of the bounding peas on the hot plate. Is any solution to be given? The writer has heard that the practice originated in the loss of a ship (freighted with peas) on the coast of Northumberland. Carling is the foundation beam of a ship, or the main beam on the keel.

X.

—I met with this crest some time since on a private seal, and should be glad to ascertain whether the device was borne by chancellors and archbishops who exercised these functions contemporaneously, the last of whom was the Archbishop of York, who was also Lord Keeper from 1621 to Nov. 1625. The motto on the seal is—

"Malentour."

To this I cannot trace any meaning. Perhaps some of your heraldic antiquaries can favour me with a solution of the above device of the motto?

F. E. M.

—On a monument dated 1600, or thereabouts, erected to a member of an ancient Roman Catholic family in Leicestershire, there are effigies of his children sculptured. Two of the sons are represented in a kneeling posture, with their hands clasped and upraised; while all the others are standing, some cased in armour, or otherwise. Can you, from knowledge of heraldry, or any other source, decide confidently what is the reason of the difference of posture, or rather what it is intended to denote?

READER.

—Josephus (Ant. b. xii. ch. ii. sect. 15.) mentions, as among the presents bestowed by Ptolemy on the Seventy-two elders, "the furniture of the room in which [450]they were entertained." Was this a usual custom of antiquity?

H. J.

—In an extract from a statute temp. Hen. IV., it is stated that "dukes, earls, barons, and baronettes might use livery of our lord the king, or his collar," &c. Query the meaning of the term baronette, in the reign of Henry IV.?

B. DE M.

—Hernshaw occurs in Hamlet, II. 2. Query, What is the derivation of it? It means, I believe, a young heron. Chaucer ("Squire's Tale," l. 90.) spells it "heronsewe." As sewe signifies a dish (whence the word sewer, he who serves up the dinner), this word applied to heron may mean one fit for eating, young and tender.

J. H. C.

Adelaide, South Australia.

"For your reputation we keep to ourselves your not hunting nor drinking hogan, either of which here would be sufficient to lay your honor in the dust."

This passage occurs in a letter from Gray to Horace Walpole in 1737. Can any subscriber state what "hogan" was, the not drinking of which was "to lay your honor in the dust?"

HENRY CAMPKIN.

—What mean the following words in Milton, Paradise Lost, book iii. line 481?

"They pass the planets seven, and pass the fixed,

And that crystalline sphere whose balance weighs

The trepidation TALK'D, and that first moved."

By the last three words we may easily understand the primum mobile of the Ptolemaic astronomy; and trepidation is thus explained in the Imperial Dictionary:

"In the old astr. a libration of the eighth sphere, or a motion which the Ptolemaic system ascribes to the firmament, to account for the changes and motion of the axis of the world."

Newton, in his edition of Milton, is silent. Bentley says in a note:

"Foolish ostentation, in a thing that a child may be taught in a map of these imaginary spheres. Talk'd, not good English, for called, styled, named."

Paterson, in his Commentary on Paradise Lost, 1744, for the sight of which I am indebted to the courtesy of the librarian of the Chetham Library, says:

"Trepidation, Lat., an astronomical T., a trembling, a passing. Here, two imagined motions of those spheres. Therefore Milton justly ridicules those wild notions."

Granting that trepidation and whose balance weighs are understood, can any of your readers explain the phrase trepidation talk'd?

W. B. H.

Manchester.

—Can any of your readers inform me if these lines, said to be the impromptu production of some passer-by struck with the horse and lamb over the Temple gates, have ever been in print, and where?

"As by the Templars holds you go,

The Horse and Lamb display'd

In emblematic figures show,

The merits of their trade.

"That travellers may infer from hence

How just is their profession;

The lamb sets forth their innocence,

The horse their expedition.

"Oh! happy Britons! happy isle,

May wondering nations say,

There you get justice without guile,

And law without delay."

J. S.

—I am making a collection, for a literary purpose, of the forms or similitudes under which the idea of Death has been embodied in different ages, and among different nations, and shall be highly obliged by any additions which your numerous learned and intelligent correspondents may be able to make to my stock of materials. References to manuscripts, books, coins, paintings, and sculptures, will be highly acceptable. I must confess that it has not yet been in my power to trace satisfactorily the origin, or the earliest pictorial example, of the current representation of Death as a skeleton, with hour-glass and scythe.

S. T. D.

—Being last week on a visit to Dublin, I went to see St. Patrick's Cathedral there, when, contemplating the monuments of the Dean and Stella, the verger's boy informed me, that after the death of the latter, the Dean discovered that she was his own sister, which occasioned him to go mad. Is there any foundation for this?

J. H. S.

—A house in the town of Honiton, Devon, has the following inscription carved above the dining-room mantelpiece:

"John . Marwoode . Gēt . Phiſition . Bridget . Wife . Buylded."

From a marble tablet in the porch, J. M. appears to have been "Gentleman Physician" to Queen Elizabeth. Any information respecting him will be acceptable to

C. P. PH***.

[Dr. Thomas Marwood, of Honiton, was a physician of the first eminence in the West of England, and succeeded in effecting a cure in a diseased foot of the Earl of Essex, for which he received from Queen Elizabeth, as a reward for his professional skill, an estate near Honiton. From an inscription on his tomb in the parish church, it appears that "he died the 18th Sept., 1617, aged above 105." The house [451]mentioned by our correspondent was erected in 1619 by John Marwood, who was also a physician, and by Bridget his wife. For further particulars respecting the family of the Marwoods, see Gentleman's Magazine, vols. lxi. p. 608.; lxiii. 113.; lxxix. 3.; lxxx. pt. i. 429.; lxxx. pt. ii. 320.]

—I shall be obliged if you will allow me the opportunity of asking your correspondents for a reference to the fullest and most reliable life of St. Paul the apostle?

EMUN.

[Our correspondent is referred to The Life and Epistles of St. Paul, comprising a complete Biography of the Apostle and a paraphrastic Translation of his Epistles, inserted in Chronological Order, now in course of publication by Messrs. Longman, under the editorship of the Rev. W. J. Conybeare, M.A., and the Rev. J. S. Howson. The work is copiously illustrated with maps plans, views, &c.]

—Should a one-shilling visitor to the Crystal Palace ask a question of a holder of a season ticket touching the exact meaning and history of the word Zoll-verein, I wonder what he would tell him?

CORDEROY.

[Zoll-Verein, i. e. Customs Union.—An union of smaller states with Prussia for the purposes of Customs uniformity, first commenced in 1819 by the union of Schwarzburg-Sondershausen, and which now includes Prussia, Saxony, Bavaria, Wirtemburg, Baden, Hesse-Cassel, Brunswick, and Mecklenburg-Strelitz, and all intermediate principalities. For the purposes of trade and customs these different kingdoms and principalities act as one empire.]

—Will you insert a Query from a new correspondent but old subscriber? Crex is the ordinary name with Cambridgeshire folk for the White Bullace. I cannot answer for the orthography, as neither Dictionary nor Provincial Glossary acknowledges the word. Can any of your correspondents enlighten me?

CHARLES THIRIOLD.

St. Dunstan.

[This Cambridgeshire name for the White Bullace is clearly connected with the Dutch name for Cherry, Kriecke. See Killian, s. v., where we find KRIECKE, Cerasum, and the several kinds of cherry, described as Swarte Kriecke, Spaensche Kriecke, Roode Kriecke, &c.]

While I thank MR. PETER CUNNINGHAM for his ready compliance with my request, I am sorry to say that I cannot concur in the reliance which he expresses on the authority of Sir George Buc. The passage quoted from that writer contains so palpable a blunder in that part of the history of the Temple of which we have authentic records, that I look with much suspicion on that portion of the relation, with regard to which no documentary evidence has been found.

He makes "Hugh Spencer, Earle of Glocester," the next successor of the Earl of Lancaster in the possession of the Temple after the suppression, and places "Andomare de Valence" in the house after the execution of Spencer for treason: an account which receives a somewhat significant contradiction in the fact, that Valence died in 1323, and Spencer was beheaded in 1326.

With reference to Buc's assertion, that "the other third part, called the Outward Temple, Doctor Stapleton, Bishop of Exceter, had gotten in the raign of the former king, Edward the Second, and conuerted it to a house for him and his successors, Bishops of Exceter," I can only say that no such grant has ever been discovered, and that every fact on which we have any information in relation to the Templars' possessions in London, contradicts the presumption that any part of them was disposed of to the bishop. He was raised to his see in 1307. The Templars were suppressed in 1309. Their lands and tenements in London were then placed in the hands of custodes appointed by the king, who in 1311 transferred them into the custody of the sheriffs of London, with directions to account for the rents into the Exchequer. In both of these documents, and in the grants to the Earls of Lancaster and Pembroke, ALL the property that belonged to the Templars in London and its suburbs is expressly included; without excepting any part of it as having been previously granted to the bishop; which, had any such been made, would inevitably have been specially noticed. And I have already shown in my former communication (p. 325.) that the grant by the Hospitallers themselves to Hugh le Despenser in 1324 is of the whole of their house called the New Temple, and that the bishop's mansion is therein stated to be its western boundary.

All these particulars confirm me in my opinion, that the bishop's house never formed any part of the New Temple.

EDWARD FOSS.

The songs of the old bellman are interesting relics of the manners and customs of "London in the olden time;" but they must not be confounded with the more modern "copies of verses" which, until lately, were annually handed about at Christmas time by that all-important functionary the "Parish Beadle." The history of the old London bellman may be gleaned from a series of tracts from the pen of those two prolific writers—Thomas Dekker and Samuel Rowlands. The first of these in the order of date is The Belman of London. Bringing to light the most notorious Villanies that are now practised in the Kingdome. Profitable for Gentlemen, Lawyers, Merchants, Citizens, Farmers, [452] Masters of Households, and all sortes of Servants to marke, and delightfull for all Men to Reade. Printed at London for Nathaniel Butler, 4to. 1608. The author of this tract was Thomas Dekker. Its popularity was so great that it passed through three editions in the course of one year. The title-page above given is that of the first impression. It is adorned with an interesting woodcut of the bellman with bell, lantern, and halberd, followed by his dog. In the following year the same author printed his Lanthorne and Candle-light, or the Bellman's second Nights-walke. In which he brings to light a Brood of more strange Villanies then ever were till this yeare discovered, &c. London, printed for John Busbie, 4to. 1609. The success of the Bellman of London, which Dekker published anonymously, induced him to write this second part, to the dedication of which "to Maister Francis Mustian of Peckham" he puts his name, while he also admits the authorship of the first part. This is the second edition of Lanthorne and Candle-light, but it came out originally in the same year. On the title-page of this tract the bellman is represented in a night-cap, without his dog, and with a "brown bill" on his shoulder. Three years later Dekker produced his O per se O, or a New Cryer of Lanthorne and Candle-light. Being an Addition, or Lengthening of the Bellman's Second Night-walke, &c. Printed at London for John Busbie, 4to. 1612. Previous to the year 1648, this production went through no fewer than nine distinct editions, varying only in a slight degree from each other. One of these editions, now before me, has for its title English Villanies Eight severall times Prest to Death by the Printers, 4to. 1648. The author in this calls the bellman "the childe of darkeness, a common night-walker, a man that hath no man to wait upon him, but onely a dogge; one that was a disordered person, and at midnight would beat at men's doores bidding them (in meere mockerie) to looke to their candles, when they themselves were in their dead sleepes." The following verses are at the back of the title-page, preceded by a woodcut of a bellman. The same lines are also given, "with additions," in the earlier editions of the Villanies, but they are too indecent to quote:

"THE BELL-MAN'S CRY.

"Men and children, maids and wives,

'Tis not too late to mend your lives:

Midnight feastings are great wasters,

Servants' riots undoe masters.

When you heare this ringing bell,

Thinke it is your latest knell:

Foure a clock, the cock is crowing,

I must to my home be going:

When all other men doe rise,

Then must I shut up mine eyes."

The exceeding popularity of the Bellman of London induced Samuel Rowlands to bring out his Martin Mark-all, Beadle of Bridewell, his Defence and Answere to the Belman of London, discovering the long-concealed Originall and Regiment of Rogues when they first began to take head, and how they have succeeded, &c. Printed for John Budge, &c., 4to. 1610. The object of this publication was to expose Dekker's Bellman, which Rowlands says was only a "vamp up" of Harman's Caveat or Warening for Common Cursetors; but Harman himself was only a borrower, and the origin of his work is The Fraternitye of Vacabondes, printed prior to 1565. Greene's Ground-work of Coney-catching is another work which may be pointed out as having been taken from the same original. But as these tracts do not contain any "bellman's songs," I need not now dwell upon them.

Among the many curious musical works printed in London at the close of the sixteenth and the beginning of the following century, I can scarcely point out a more desirable volume than one with this title: Melismata, Musical Phansies fitting the Court, City, and Country Humours, to three, four, and five voices:

To all delightful, except to the spiteful;

To none offensive, except to the pensive.

London, printed by William Stansby, &c., 4to. 1611. The work is in five divisions, viz., 1. Court Varieties; 2. Citie Rounds; 3. Citie Conceits; 4. Country Rounds; 5. Country Pastimes. Among the "City Conceits" we have the following:

"A BEL-MAN'S SONG.

"Maides to bed, and cover coale,

Let the mouse out of her hole;

Crickets in the chimney sing,

Whilst the little bell doth ring:

If fast asleepe, who can tell

When the clapper hits the bell."

But perhaps the most curious collection of bellman's songs that has been handed down to us, is a small tract of twelve leaves entitled The Common Calls, Cries, and Sounds of the Bel-Man; or Diverse Verses to put us in minde of our Mortality, 12mo. Printed at London, 1639. This excessively rare and interesting "set of rhymes" is now before me, and from them I have extracted a few specimens of the genuine old songs of the London bellman of past times:—

"THE BEL-MAN'S SOUNDS.

"For Christmas Day.

"Remember all that on this morne,

Our blessed Saviour Christ was borne;

Who issued from a Virgin pure,

Our soules from Satan to secure;

And patronise our feeble spirit,

That we through him may heaven inherit."

"All you that doe the bell-man heere,

The first day of this hopefull yeare;

I doe in love admonish you,

To bid your old sins all adue,

And walk as God's just law requires,

In holy deeds and good desires,

Which if to doe youle doe your best,

God will in Christ forgive the rest."

"COMMON SOUNDS.

"The belman like the wakefull morning cocke,

Doth warne you to be vigilant and wise:

Looke to youre fire, your candle, and your locke,

Prevent what may through negligence arise:

So may you sleepe with peace and wake with joy,

And no mischances shall your state annoy."

"All you which in your beds doe lie,

Unto the Lord ye ought to cry,

That he would pardon all your sins;

And thus the bell-man's prayer begins:

Lord, give us grace our sinful life to mend,

And at the last to send a joyfull end:

Having put out your fire and your light,

For to conclude, I bid you all good night."

The collection of Bellman's songs here described is sometimes found appended to a little work entitled Time well Improved, or Some Helps for Weak Heads in their Meditations, 12mo. 1657. The latter publication is a reprint, with a new title-page, of Samuel Rowlands' Heaven's Glory, seeke it; Earth's Vanitie, fly it; Hell's Horror, fere it. But whether the songs in question were written, or merely collected by Rowlands, does not appear.

EDWARD F. RIMBAULT.

The Bellman (Vol. iii., p. 324.).—Your correspondent F. W. T. will find a very amusing sketch of a night-watchman in Gemälde aus dem häuslichen Leben und Erzählungen of G. W. C. Starke: whether it may help his inquiries or not I cannot say. It will at least inform him of the difficulties in which a conscientious and gallant watchman found himself when he attempted to improve on the time-honoured terms in which he had to "cry the hours."

BENBOW.

Birmingham.

1. In answer to the communication of A COLLECTOR, allow me to remark, that although Bruce did not publish his Travels till about seventeen years after his return to Great Britain, various details had got abroad; and, as usually happens, the actual facts, as given by himself, were either intentionally or accidentally misrepresented. Latterly, Bruce, indignant at the persecution he suffered, held his tongue, and patiently awaited the publication of his Travels to silence his accusers. Amongst other teasing occurrences, Paul Jodrell brought him on the stage in a clever after-piece which was acted in the Haymarket in 1779, and was published in 8vo. in 1780. A copy of this piece, which is called A Widow and no Widow, is now before me: and Macfable, a Scotch travelling impostor, was acted by Bannister; and the hits at Bruce cannot be mistaken.

Further, Bruce himself understood that he was the party meant by "Munchausen," and he complained of this and many other attacks to a distant relative of mine, who died a few years since, and who mentioned the circumstances to me; adding, that Bruce uniformly declared that the publication of his work would, he had no doubt, afford a triumphant answer to his calumniators.

Whilst on the subject of Munchausen, I may observe, that the story of the frozen words is to be found in Nugæ venales, or a Complaisant Companion, by Head, the author or compiler of the English Rogue. It occurs among the lies, p. 133.:

"A soldier swore desperately that being in the wars between the Russians and Polemen, there chanced to be a parley between the two generals where a river parted them. At that time it froze so excessive that the words were no sooner out of their mouths but they were frozen, and could not be heard till eleven days after, that a thaw came, when the dissolved words themselves made them audible to all."

As my copy has a MS. title, I should be obliged if any of your readers could furnish me with a correct one.

2. There were not "two James Grahame" cotemporaries. The author of Wallace was the author of The Sabbath, as well as of Poems and Tales, Scotch and English, thin 8vo., Paisley, 1794: a copy of which, as well as of Mary Stewart and Wallace, is in my tolerably extensive dramatic library. The latter is defective, ending at p. 88.; and was saved some years ago from a lot of the drama about to be consigned to the snuff-shop. Probably the same reasons which caused the suppression of a political romance from the same pen, and of which I have reason to believe the only existing copy is in my library, may have induced the non-completion of Wallace. Grahame, like many other young men just emerging at that particular time from the Scotch Universities, had imbibed opinions which in after years his good sense repudiated. He concealed his authorship of the Paisley poems (now very scarce), and the secret only transpired after his death. From the intimacy that subsisted between myself and his amiable nephew and namesake, whose untimely death, in 1817, at the age of twenty, I have never ceased to lament, I had the best means of learning many facts relative to the poet, who was, according to all accounts, one of the most estimable and truly pious men that ever lived. As to the crude opinions of early youth, [454]can we forget that the truly admirable Southey was the author of Wat Tyler?

Whether there were only six copies of Wallace completed, I cannot say; but this much I can assert, that there were a great many printed, and that, as before mentioned, the greater part went to the snuff-shop; probably, because people were not fond of purchasing a drama wanting the title and end.

In concluding, I may mention, that the "Mary Stewart" in the 12mo. edition of the Poems of Grahame, is quite altered from the one printed in 8vo. in 1801.

J. M.

In reply to your correspondent A. N. C., William Penn, eldest son of the famous Quaker, married Mary Jones, by whom he had three children, Gulielma Maria, Springett, and William. The latter had a daughter by his first wife, Miss Fowler, who married a Gaskill, from which marriage the present Penn Gaskills of Rolfe's Hould, Buckinghamshire, are descended. While writing on this subject, allow me to send you two other "notes."

Hugh David, a Welshman, who went out to America in the same vessel with William Penn, used to relate this curious anecdote of the state founder. Penn, he says, after watching a goat gnaw at a broom which lay on deck, called out to him, "Hugh, dost thou observe the goat? See what hardy fellows the Welsh are; how they can feed on a broom! However, Hugh, I am a Welshman myself, and will relate by how strange a circumstance our family lost their name. My grandfather was named John Tudor, and lived on the top of a hill or mountain in Wales. He was generally called John Penmunith, which in English is—John on the top of the hill. He removed from Wales into Ireland, where he acquired considerable property. Upon his return to his own country he was addressed by his friends and neighbours, not in the former way, but as Mr. Penn. He afterwards removed to London, where he continued to reside under the name of John Penn, which has since been the family name." David told this story to a Quaker, who wrote it down in these words, and gave the MS. to Robert Proud, the historian of Pennsylvania. The same David, in a copy of doggrel verses presented to Thomas Penn on a visit to Philadelphia in 1732, made an allusion to this descent. I quote four of the lines:

"For the love of him that now descended be,

I salute his loyal one of three,

That ruleth here in glory so serene,

I branch of Tudor, alias Thomas Penn."

This is at least curious. But I attach little credit to Mr. David's report. He certainly mistook or ill remembered Penn's words; as his grandfather was Giles Penn, and his ancestors for two generations before Giles are known to have been William.

The second note refers to Penn's descendants, and may claim a corner in your chronicle on more than one ground. William Penn was born in 1644: in 1844 his grandson, Granville Penn, well known as a writer on classical subjects, was still alive! The descendants of his first marriage with Miss Springett, six years ago were in the fifth and sixth generation after him; those by his second wife, Hannah Callowhill, in the second.

HEPWORTH DIXON.

I have read with attention the argument of your correspondent LEGES on the passage in Measure for Measure, in which the word "prenzie" occurs; and to much that he advances I should, like the modest orator who followed Mr. Burke, be contented to say "ditto." Nevertheless, as I cannot agree with him altogether, I beg permission to make a few remarks upon the question. The extent of my agreement with your correspondent will be shown in stating, that I think neither "priestly," "princely," nor "precise" to be the true word. We disagree, however, in the measure of our dislike; for of the three suggested corrections, "princely" is, to my mind, by far the best, and "precise," beyond all measure, the worst. Indeed, but that Mr. Knight has adopted the latter term, as well as Tieck, I should have regarded it as an instance of the difficulty in the way of the best qualified Germans of understanding the niceties of English meaning, or of feeling how far license might be tolerated in English versification. In adopting this term Mr. Knight appears to have forgotten that it has a special application as the Duke (Act I. Sc. 4.) uses it. Taken in connexion with the expressions "stands at a guard" and "scarce confesses," cautiously exact would appear to express the sense in a passage the whole spirit of which shows a scarcely disguised suspicion. The Duke, evidently, would not have been surprised, as Claudio was; and the expression appropriate to a close observer like the one, is a most unlikely epithet to have been chosen by the other. More fatal, however, is the destruction of the measure. Both instances go beyond all bounds of license. And though we may pass over the error in a critic so eminent even as Tieck, we need feel no compunction at exposing "earless on high" an Englishman who has pilloried so often and so mercilessly others for the same offence.

While, however, LEGES has shown good cause against the adoption of either of the above epithets, it does not appear to me that he has succeeded in establishing a case in favour of the [455]word "pensive," which he proposes instead. In the first place, the passages your correspondent quotes, show Angelo to be "strict," "firm," "precise," to be "a man whose blood is very snow-broth," &c., but certainly not "pensive" in the common acceptation of the word. Secondly, he fails to show that, if Shakspeare meant by "pensive" anything more than thoughtful in the passages he cites, he meant anything so strong as religiously melancholy, which would be the sense required to be of any service to him as an epithet to the word "guards."

I will now, with your permission, call attention to what I consider an oversight of enquirers into this subject. The conditions required, as your correspondent well states, are "that the word adopted shall be (1) suitable to the reputed character of Angelo; (2) an appropriate epithet to the word 'guards;' (3) of the proper metre in both places; and (4) similar in appearance to the word 'prenzie.'" Now, it does not appear to have been considered that this similarity was to be sought in manuscript, and not in print; or, if considered, that much more radical errors arise from illegible manuscripts than the critics have allowed for. In his "Introductory Notice," Mr. Knight says the word (prenzie) "appears to have been inserted by the printer in despair of deciphering the author's manuscript." Yet in his note to the text he has printed it, together with three suggested emendations, as though he would call attention to the comparative similarity in print. But if, as all have hitherto assumed, the printer had read the first three or four letters correctly, is it not most probable that the context, with the word recurring within four lines, would have set him right? And his having twice inserted a word having no apparent meaning, is it not as probable that he was misled at the very beginning of the word by some careless combination of letters presenting accidentally the same appearance in the two instances? Having thus shown that the search for the true word may have been too restricted, I will proceed to make a final suggestion.

When Claudio exclaims in surprise—

"The ( ) Angelo!"

it is quite clear that the epithet which has to be supplied is one in total contrast to the character just given of him by Isabella. What is this character?

"This outward-sainted deputy,—

Whose settled visage and deliberate word

Nips youth i' the head, and follies doth emmew,

As falcon doth the fowl,—is yet a devil;

His filth within being cast, he would appear

A pond as deep as hell."

To this it appears to me Claudio would naturally exclaim:

"The saintly Angelo!"

and Isabella, as naturally following up the contrast, would continue—

"O, 'tis the cunning livery of hell,

The damned'st body to invest and cover

In saintly guards!"

My acquaintance with the handwriting of the age is very limited, but I have no doubt there are possible scrawls in which saintlie might be made to look like prenzie. If any one knows a better word, let him propose it; only I beg leave to warn him against pious, which I have already tried, and for various reasons rejected.

SAMUEL HICKSON.

St. John's Wood, May 24. 1851.

"Prenzie" in "Measure for Measure."—It must be gratifying to the correspondents of "NOTES AND QUERIES" to know that their suggestions receive attention and consideration, even though the result be unfavourable to their views. I am therefore induced to express, as an individual opinion, that the reading of the word "prenzie," as proposed by LEGES, does not appear more satisfactory than those already suggested in the various editions.

Of these, "precise" is by far the most consonant with the sense of the context; while "pensive," almost exclusively restricted to the single meaning, contemplative,—action of mind rather than strictness of manner,—is scarcely applicable to the hypocritical safeguard denounced by Isabella.

From the original word, too, the deviation of "precise" is less than that of "pensive." Since the former substitutes e for n, and transposes two letters in immediate proximity, while the latter substitutes v for r, and transposes it from one end of the word to the other.

But "precise" has the immeasurable advantage of repetition by Shakspeare himself, in the same play, applied to the same person, and coupled with the same word "guard," which is undoubtedly used in both instances in the metaphorical sense of defensive covering, and not in that of "countenance or demeanour," nor yet in that of "the formal trimmings of scholastic robes:"

"Lord Angelo is precise;

Stands at a guard with envy—

O, 'tis the cunning livery of hell

The damned'st body to invest and cover

In precise guards."

Therefore, while I cannot quite join with Mr. Knight in understanding "precise" as applicable to the formal cut of Angelo's garments, I nevertheless agree with him, on other grounds, in awarding a decided preference to the reading of the German critic.

A. E. B.

The Obsolete Word "Prenzie."—I agree with your correspondent LEGES, that the several emendations which have been suggested of the word "prenzie," do not "answer all the necessary conditions."[456] LEGES says, "it is universally agreed that the word is a misprint."[5] Now misprinting may be traced to wrong letters being dropped in the boxes into which compositors put the types, and which generally are found to be neighbours (this is hardly intelligible but to the initiated). However, they will at once see that a more unfortunate illustration could hardly have been suggested. An error, made by the printer, often passes "the reader" or corrector, because it is something, in appearance and sound, like what should have been used. But in this word there is no assimilation of either to any one of the words conjectured to have been meant. Moreover, such a word would never have been twice used erroneously in the same piece. May it not rather have been an adaptation from the Norman prisé, or the Latin prenso, signifying assumed, seized, &c.? The sound comes much nearer, the sense would do. I hardly like to venture a suggestion where so many eminent commentators entertain other views; but it seems to me that it is a main excellence of your periodical to encourage such suggestions; and if mine be not too wild, your insertion of it will oblige

B. B.

[5] Old as well as modern typographers need have broad backs. Bale, in his Preface to the Image of both Churches, says, "But ij cruel enemies have my just labours had * * * The printers are the first whose heady hast, negligence, and couetousnesse commonly corrupteth all bokes * * * though they had in their handes ij learned correctours wh take all paynes possyble to preserue them."

P.S. May I end this note by adopting a Query many years since put forth by a highly valued and, alas! deceased friend and coadjutor in antiquarian pursuits,—"What is the date of that edition of the Bible which reads (Psalm cxix. 161.): Printers have persecuted me without a cause?"

On a Passage in "Measure for Measure" (Vol. iii., p. 401.).—One of the very few admissible conjectural emendations on Shakspeare made by the ingenious and gifted poet and critic Tieck, is that which Mr. Knight adopted, and I cannot think your correspondent LEGES happy in proposing to substitute "pensive."

There can be no doubt that "guards" in the passage in question signifies facings, trimmings, ornaments, and that it is used metaphorically for dress, habit, appearance, and not for countenance, demeanour.

The context clearly shows this:

"Claud. The precise Angelo?

"Isab. O, 'tis the cunning livery of hell,

The damned'st body to invest and cover

In prècise guards."

Isabella had before characterised Angelo—