The Project Gutenberg eBook of A Maid at King Alfred's Court: A Story for Girls

Title: A Maid at King Alfred's Court: A Story for Girls

Author: Lucy Foster Madison

Illustrator: Ida Waugh

Release date: September 11, 2011 [eBook #37405]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Darleen Dove and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Copyright 1900 by The Penn Publishing Company

CONTENTS

- CHAPTER I—THE MEETING IN THE FOREST

- CHAPTER II—WINCHESTER

- CHAPTER III—A THIEF IN THE NIGHT

- CHAPTER IV—IN THE HALL OF ALFRED

- CHAPTER V—THE DEATH OF A HERO

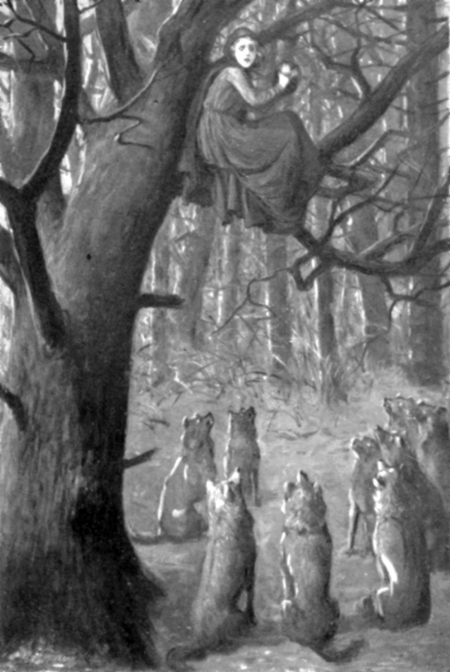

- CHAPTER VI—THE WOLVES’ CONCERT

- CHAPTER VII—THE COMING OF A STRANGER

- CHAPTER VIII—ADIVA GROWS ANGRY

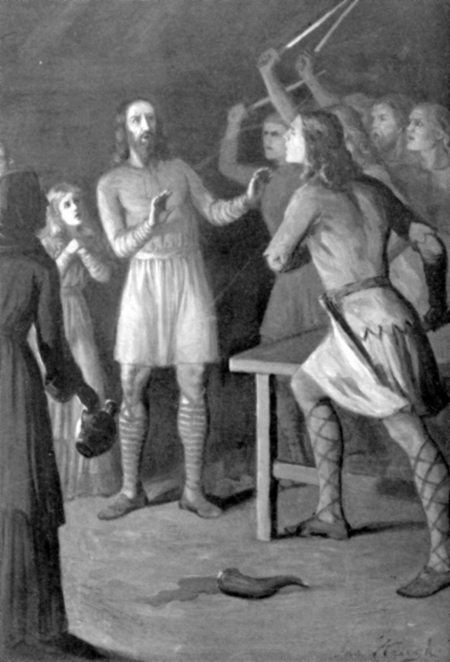

- CHAPTER IX—WOULD YOU STRIKE YOUR KING?

- CHAPTER X—EGWINA GOES AS A MESSENGER

- CHAPTER XI—SOME DANISH TALES

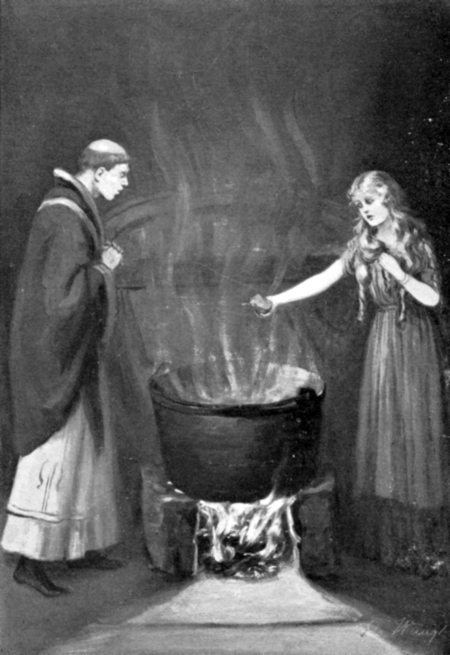

- CHAPTER XII—THE MAGIC SLEEP

- CHAPTER XIII—VICTORY SITS WITH THE SAXONS

- CHAPTER XIV—A PLEASANT SURPRISE

- CHAPTER XV—THE BEGGAR OF ATHELNEY

- CHAPTER XVI—IN THE CAMP OF THE ENEMY

- CHAPTER XVII—THE WINNING OF A BUCKLER

- CHAPTER XVIII—PEACE

- CHAPTER XIX—DARK DAYS

- CHAPTER XX—ÆLFRIC’S REVENGE

- CHAPTER XXI—THE TRIAL OF EGWINA

- CHAPTER XXII—THE ORDEAL

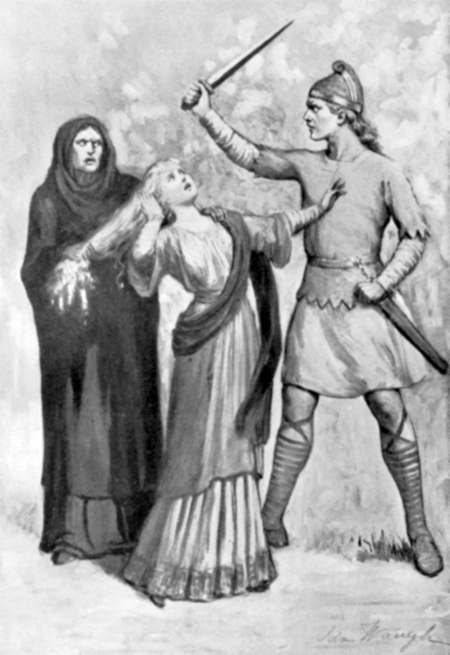

- CHAPTER XXIII—THE DREAD DECREE

- CHAPTER XXIV—ADIVA TAKES MATTERS INTO HER HANDS

- CHAPTER XXV—HILDA AGAIN

- CHAPTER XXVI—THE ECLIPSE

- CHAPTER XXVII—SIEGBERT’S STORY

- CHAPTER XXVIII—AN UNEXPECTED GUEST

- CHAPTER XXIX—BRINGING THE SUMMER HOME

CHAPTER I—THE MEETING IN THE FOREST

Beautiful was the month of October in the year of our Lord 877. That part of merrie England called Wessex was covered, in this ancient time with a vast and extensive wood.

Only where the broad estuary of Southampton Water divided the tangled woodland, and along the river Itchen, was there any break in the forest. Formidable were the wastes of Andred’s weald, and fortunate the traveler whose path lay not apart from the public roads.

Hundreds of wide-spreading, broad-headed oak trees covered the hills and valleys, and flung their gnarled branches over the rich grassy sward beneath. Intermingled with these, sometimes so closely as to hide the rays of the sun, were beeches, hollies, and copsewood of various descriptions.

The great trees were girt round about with mosses or wreaths of ivy that betokened their age, and their foliage was bright with the hues of autumn.

The leaves were falling, but through the openings thus made wider vistas of beauty were revealed. The rich burnished bronze of the oak mingled with the blazing orange of the beech. The gray branches of the graceful ash contrasted with the fir—stately daughter of autumn.

The sunshine streaming through the trees caught and intensified the vivid colorings. Red of many degrees, up to the gaudiest scarlet; every tint of yellow, from the wan gold of the primrose to the deep orange of the tiger lily; purple from lightest lilac to the darkest shade of the pansy, mingled and intermingled, until the whole forest seemed one mass of glowing, riotous color. Ever and anon the antlers of a deer might have been seen as he moved restlessly through the wold, and in the nearer glades the hares and conies came stealing forth to sport or to feed.

In the distance the mellow blasts of a horn could be heard, which grew nearer and more near until presently on the high road which wound through the wastes of forest land from Silchester to Winchester (or Winteceaster, as it was then called) appeared the forms of two people, an old man and a girl.

They moved slowly, the maiden accommodating her steps to those of her companion. Though not really old, for he was not much more than sixty, both the man’s countenance and carriage indicated age. His complexion was fair and his cheeks ruddy; but his visage was deeply furrowed, and his long hair, which escaped from under his bonnet, was white as snow, as was also his large and forked beard. His dark blue woolen mantle was clasped on the shoulder by a broad ouche, or brooch; his leggins were also of blue woolen, cross-gartered by strips of leather. Blue, too, was the under tunic. His right arm encircled a harp.

The girl who accompanied him was somewhere about the age of fourteen. Her form was enveloped in a mantle of scarlet wool, to which was attached a hood of the same material. The face under the hood was wondrously lovely, and had already gained her the appellation of “The Fair.”

“Grandfather, dearest,” she cried as she beheld a log which lay under the overhanging branches of a large oak, “see! here is rest for thy weariness. I wot that thou art tired.”

“Yes, child. The limbs of the old tire quickly, and alack! I am not so young as I was of yore. The way hath seemed long to-day, and we are yet far from Winchester. Prithee, wind the horn no longer, for I weary of its sound; and truly if there be any within hearing, they must know of our coming.”

He sat down as he spake, resting his harp on his knee. The maiden let fall the horn that proclaimed their coming, according to the law of the forest, threw back her hood, unfastened the fibula that closed the mantle, and tossed the garment on the log beside the old man. Thus revealed, she stood forth in all her beauty.

Her long yellow hair, bound only by a golden band, was parted smoothly and hung in ringlets on her shoulders. Her complexion was dazzling in its fairness; her cheeks rosy; her eyes sparkling, and blue as periwinkles. She wore a tunic of blue woolen, falling to her ankles, and bordered by a band of needlework, for which the Anglo-Saxon women were famous. Over this was worn a short gonna of scarlet, the sleeves of which, reaching in long, loose folds to the wrists, were confined there by bracelets. The slenderness of her waist was disclosed by a girdle, and over her shoulders hung a chain, from which was suspended a pair of cymbals and the horn. A picturesque figure she made as she stood there, and one fair to look upon. The old man’s eyes rested upon her fondly, and then he spake:

“Art thou not cold, Egwina? The Wyn (October) month hath bright sunshine, but his breezes carry also the chill that foretokens the coming of winter. Heaven forfend that thou shouldst become ill.”

The girl laughed merrily.

“Be not irked, grandfather. The mantle was wearisome, and I did but cast it aside for a time. See! Lest thou shouldst needlessly fret thy mind, I will put on the garment again, and thou shalt tell me whither we go after Winchester.”

Donning the mantle she sat down beside him. The grandfather looked at her tenderly.

“Egwina The Fair art thou called,” said he, “but Egwina The Good art thou also. From Winchester, dear child, and its market, we will wend our way to the royal vill at Chippenham, where the king is to winter.”

“Why to Chippenham?” asked the girl. “It is not often, grandfather, that thou carest to follow the king.”

“True, child; for Alfred hath scops of his own in his court, and needeth not the glee of Wulfhere, the harper. But even as yon oak hath gathered the moss of years, so have sorrows come to me, and fain am I to lay down their burthen. Of bards there are many; but few glee maidens there be who sing as thou dost. For thy sake do I hope that the king will take us under his hand.”

“But if he will not, then whither?” asked the maiden.

“He will,” answered Wulfhere positively. “The meanest wayfarer hath the right to bed and board for a day and a night in any house. Thinkest, then, that Alfred will not give shelter and food to a gleeman and maiden? I trow that he will.”

“Will not the court be hindrance to thee?” questioned the girl gently. “Dear grandfather, thou hast been so free always, I fear me much that thou wilt mislike to be housed with one lord.”

“Were he younger, child, Wulfhere would have nought of it. I, and my father, and his father’s father have always thus lived, wandering from shire to shire; from burgh to burgh; from mead hall to mead hall, with harp and song and story; and none were so welcome as they. Many lords have bestowed gifts upon them, and fain would have kept them to sing of their bold deeds. But all of us, from father to son, liked better to tell of the daring of many than the prowess of one. The song of a harp of one string becometh in time irksome both to hearer and singer. In sooth, ’tis a merry life and a free. Alack and a day that ’tis past! The Dane is abroad in the land. For a short time hath he left us in quiet, and now winter will still further stay his hand. Guthrum the old is bold, and I fear that the Northmen await only the bringing home of the summer ere falling upon Wessex.”

“The saints forfend!” ejaculated the girl devoutly.

“So it is for thy weal, Egwina, that we seek the king. I would not have thee die as did thy brother, Siegbert. God wots how they could kill the pretty lad.”

“Tell me of it,” coaxed the maiden well knowing the tale, but thus did the old man ease his sorrow.

“Thou wert too young to mind thee now that it was seven years this harvest when Ubbo and Oskitul with the tearful Danes fell upon the abbey of Croyland. To the monks had I sent Siegbert, for the abbot had heard his singing and was pleased with his beauty. ‘He shall be a second Cynewulf,’ said he, ‘when he shall have become learned.’ I wotted not that I was sending the boy to his death. But even while the abbot and the priests, together with the choir, performed the mass and were singing the Psalter, the pagans swooped down upon them, and none were there left to tell the tale. So little do these heathen care for our holy religion. In sooth, meseems that it glads their hearts to destroy our minsters and abbeys. They cared neither for the helplessness of the old nor the harmlessness of childhood. Bright and beautiful as that Baldur whom they worship, methinks they would have spared him. But hearken! was not that a call?”

Both listened intently, and through the clear, crisp air there came a cry for help.

“Some mishap hath befallen a wayfarer!” exclaimed Wulfhere rising quickly to his feet, his weariness vanishing instantly. “Come, Egwina, wind thy horn that he may know that help is near.”

The maiden blew a long, loud blast and then they hastened in the direction whence the cry had come. Soon a turn of the road brought them in sight of the figures of a youth and a maiden. The girl was lying prone upon the sward. The youth bent over her anxiously stroking her hands. Both were clothed in the bright-colored garments of which the Saxons were so fond. The embroidery and richness of adornment of their dress proclaimed them to be of noble rank. A falcon hovered disconsolately near them, and a spear lay on the ground.

As soon as the lad caught sight of Wulfhere and Egwina, he uttered an exclamation of joy.

“Be of good heart, Ethelfleda,” he cried; “here comes a gleeman and his daughter. I wot that they will help us.”

“Son, wherefore thy call?” queried the bard, approaching.

“My sister hath wrenched her foot against a stone,” replied the youth. “We stole away to try my new falcon with the lure, and all would have been well had not this befallen us. Wilt thou not, good harper, hasten into Winchester and bespeak for us a palfrey?”

“Edward,” spoke the maiden quickly, “seest thou not that the gleeman is old? Do thou go, my brother, and leave me with them.”

“Truly hast thou spoken, Ethelfleda,” returned the youth, rising. “I crave forgiveness, bard, that I saw not thy years. Quickly will I go and as quickly come again. Irk not thyself while I am gone, my sister.” With a bow to Wulfhere and Egwina, and a salute for his sister the youth hurried away.

“I hear the ripling of a rill,” remarked Egwina. “Cooling will its waters feel to thy foot.”

“But how canst thou bring the water?” asked the maiden, curiously. “Thou hast no bowl either of horn or wood.”

“Nay; but I have these,” and Egwina touched her cymbals. “Though they be shallow, yet enough will they hold for thy ankle.”

She unloosened the shoe of the maiden as she spoke and removed the silken leggins, marveling much at their richness as she did so.

“There!” she said, after she had laved the foot in the cold water. “Doth it not feel better!”

“It doth,” answered the maiden; “so well that methinks I can stand upon it. How Edward will wonder!”

“Do not so!” ejaculated Wulfhere, but the girl was up before he had spoken. Only for a moment, however. She reeled, and would have fallen had not the gleeman caught her.

“Thou wert o’er rash,” he chided, gently stroking her brow while Egwina fetched more water and again bathed the ankle. The maiden was white from the pain, but she bravely repressed the moans that rose to her lips.

“Witless was I,” she murmured. “Now will I lie still until help comes. O’er rashness is as bad, I ween, as not enough boldness.”

“True,” said Wulfhere. “Thou art young, maiden, and fearless is thy spirit. Thou hast yet to learn that valor is not all in the doing of brave deeds. To bear well is also valorous.”

“Methinks that thou dost speak truly,” she returned. “Thou needst bathe the foot no longer, maiden, for now doth it feel better. Wilt thou not, ministrel, out of thy good pleasure beguile the time by story?”

“What likest thou best to hear?” asked he, well pleased, for the scop delighted in his art.

“Of the deeds of our forefathers,” she replied, quickly. “Well do I love to hear of them.”

“Then will I tell thee of how Hengist gained the land for his castle. Hast heard it?”

“Nay; say on.”

“After Hengist had driven the Picts back to the marches,” began Wulfhere, “he came to Vortigern the king, and asked for a city or town that he might be held in the same honor that he was held among his own countrymen; but Vortigern answered that he could not, as it would be displeasing to his people. ‘Then,’ said Hengist, ‘give me only so much ground as I can encircle by a leather thong.’ To this Vortigern readily yielded, disdaining that which could be enclosed within a thong. Hengist, taking a bull’s hide, made one thong of the whole, with which he did encircle much ground, so that he built a fortress upon it, to which he could go should need require. Vortigern was wroth at being so outwitted, but Hengist called the strong place Thancastre,” which is to say “Thong Castle.”

Ethelfleda laughed.

“Of merry humor was Hengist,” she said. “It is pleasing to hear such things! Wittest thou aught else of him?”

“Wottest thou, maiden, how Vortigern was taken captive by Rowena?”

“Yea; but even as wine groweth better by standing, so do old tales gather wit in oft telling. Say on.”

“When Hengist had made an end of building his strong place he bade Vortigern come to see it. The king was disquieted at the strength of the castle, and, unknown to Hengist, sought to list the men to himself. When they had feasted and the mead glowed in the bowl, Rowena, daughter of Hengist, came forth from her bower bearing a golden cup full of wine which, kneeling, she presented to the king. ‘Lord king,’ she cried, ‘wacht heil!’ ‘What doth she mean?’ asked the king of Hengist. ‘She but offers to drink thy health,’ was the answer. ‘Thou shouldst say, ‘Drink heil!’’ The king did as he was told, and when the maiden drank kissed her, and then drank also. Then so stirred was he by her beauty that he gave to Hengist all of Kent for her hand. Thus through a maiden did the Saxons first get a share of Britain for their own.”

“Quotha! that is good!” exclaimed Ethelfleda. “I thought not of that before, and full oft have I heard the tale. Pleasing are thy stories! I would hear more of them. Tell on, harper.”

Thus entreated, Wulfhere told his choicest tales of folklore and legends, and so well was the maiden entertained that the time did not seem long until Edward returned with attendants and a palfrey for her use.

“Kind have ye been to me,” said the noble damsel, “and much do I thank ye for it. Prithee take this ring, maiden. It is not only a ward against the wiles of the wicca (witch), but betokeneth purity also. Take it to keep thee in mind of Ethelfleda.”

When she had thus spoken, her brother lifted her before him on the palfrey, and with many thanks for their courtesy, rode off with their servitors.

“Sawest thou, granther, how rich were their garments?” asked Egwina when the turn in the road hid them from their sight.

“Yea; they are gentlefolk,” answered Wulfhere. “Of good blood comes the maiden for she moaned not but bore well the pain of the wrench, though she was white from the hurt of it.”

“And the youth! How proud in bearing he was!”

“Yea; noble was his port. Yet methinks it would have been more seemly to have given us the name of their father. Now we wot not who or what they be save that they be gentle. Marry! I misdoubt not that the father is a thegn. Mayhap, one of the king’s.”

“But how kind of heart the maiden was!” mused Egwina. “How beautiful the ring which she gave me!” She looked at it admiringly.

“It is a sapphire, and of great worth,” said the gleeman examining it. “Now, child, let us hasten to Winchester there to find some mead hall; for where there is wassail, there is welcome for the gleeman. Hasten, Egwina.”

The two started off at a brisk walk, and were soon lost to view in the forest.

CHAPTER II—WINCHESTER

Under Æthelwulf, Alfred’s father, Winchester had become the chief city of England; for while the other kingdoms went down before the Northern pirates, Wessex still stood its ground. It was farther off from the main points of attack, and had the incalculable advantage of a succession of capable kings: Egbert, Æthelwulf, and—at the time of our story—Alfred.

As the Danish invasion pressed more and more, Wessex grew to be the champion of all the other kingdoms of England. For the ruin of the north made it the sole remaining home of the civilized life of the land. Happily for Wessex and for England, the greatest of English kings succeeded to the throne at the most critical moment.

The six years that Alfred had sat upon the throne had been troubled and restless. During the first year, nine pitched battles were fought with the Danes. Then Alfred was forced to pay to the Northmen money for peace, for the invaders occupied all of Northumbria, Mercia, and East Anglia, and the West Saxons, deeming the struggle hopeless, and fearful of being brought under their rule, responded no longer to the call to battle.

For a short time Wessex was left undisturbed. During this interval the indefatigable Alfred builded ships and met the pirates upon the sea, defeating them on their own element. In 876 the peace was broken with that facility which characterized the breaking of Danish oaths, and it was not until the beginning of the year 877, the time of our story, that peace was again restored.

In that forest, before spoken of, just beyond a circular chalk down later called St. Catherine’s hill—where the valley was at the narrowest and the downs sloped gently to the little river of Ichen, stood Winchester. In the time of the Roman, a main thoroughfare, still the High Street of the city, bisected it from East Gate to West Gate. At right angles with that street ran a main intersecting road from South Gate to North Gate. The West Saxon kings did but follow the lead of the Roman in retaining this division of the town, and, up the rising ground towards the west on either side of the ancient Roman road from the eastward gate, the houses of the citizens were clustered into a street; with here and there a stone-built dwelling, and the rest of “wattle and dab” construction. In the southeastern part of the town stood the minster of St. Swithen strongly inclosed, and protected on the north by the river and marsh lands. Near this convent stood the royal vill, from which place emanated all those plans against the encroachments of the Danes, the school of justice and learning, and the bulwark of England’s defense. Near the palace were the dwellings of the bishop and his clergy; the residence of the wicgerefa, which was near the site of the courts of justice, and in the centre of the town was the market with its cross.

The day after the one on which the events narrated in the last chapter had taken place, a busy scene was presented in the market. Merchandise of all sorts was exposed for sale. Stalwart Saxons, called reeves, with the badge of the king’s authority upon them, had charge of the steelyards, yard measures, and bushels, and were kept busy weighing and measuring that each might receive his just due, and the sale be legal according to the doom of the land. It was the endeavor on the part of the authorities to confine all bargaining as much as possible to towns and walled places, so that the people might be assured of fair dealing, and a warranty of what the Saxon laws called unlying witnesses.

Yet not all the citizens were occupied in trade, nor was all the market given up to traffic. On one side, quite away from the stalls, two circular spaces were set apart; one for bear, the other for bull baiting. Closer to the stalls, yet not so near as to detract from the business of the mart, some gleemen were exercising their art. One dexterous juggler threw three knives and three balls alternately in the air, catching them one by one as they fell.

Another, a short distance from the juggler, was gravely leading a great bear to dance on its hind legs, while his coadjutor kept time on the flageolet. Around each of these amusements was gathered the crowd that in every clime or age such things attract.

The merriment was at its height when from the upper end of the market appeared two figures that quietly stationed themselves near one of the stalls. It was Egwina and her grandfather. During a momentary lull the old gleeman struck his harp, and together he and his grandchild lifted up their voices in song.

The excellence of the music, for Wulfhere was a skillful harper, the sweetness of the song, and above all the wonderful beauty of the maiden, drew all eyes in that direction. There was a murmur of approval, and the crowd surged toward them, and gathered round the two, leaving the coarser attractions of baiting and juggling for the more refined ones of melody and beauty.

“Marry!” ejaculated the juggler in disgust as he found himself forsaken. “’Twere unmannerly thus to make one forego his craft.”

“Be not disheartened, friend,” said he with the dancing bear as he chained the animal, and quietly stretched himself out on some straw. “Fickle is the mind of man. Make use of thy leisure while thou mayst. ’Twill be but a short time ere they will come again.”

“Quotha! but the gifts will be showered upon the maiden. And, fair though she be, Ælfric would gather them to his own hoard.” And he gazed moodily at the crowd which surrounded the harper and the maiden.

Song followed song in quick succession, for the Saxons loved to hear of the brave deeds of the heroes of old, until at last Wulfhere declared himself unable to sing longer, and, laden with gifts, the two slowly wended their way from the city. Vainly did the juggler await the return of an audience. The balls and knives seemed to have lost their charm for the people, and, muttering anathemas upon the ministrel and his daughter, he, too, left Winchester, but in disgust.

“Well have we done, Egwina,” said Wulfhere, pausing when they were some little distance from the town, to conceal the gold and other gifts about his person. “Truly, Winchester is worthily called the first city of the Saxons. Kingly hath it proven itself to be. Were it not that I fear the Dane, beshrew me if I would ask aught better than to dwell therein.”

“But why could we not, grandfather? Then might it be that we could behold again the youth and the maiden whom we met in the forest. Didst thou see aught of them?”

“No, child; and let not thy heart dwell upon them. Not long are nobles mindful of their words. Whilst thou may be in favor to-day, the morrow doth full oft bring unkindness.”

“But the maiden, Ethelfleda, her brother called her, seemed not like one to forget,” and Egwina twirled the sapphire ring upon her finger. “She spake as though there were truth and well-meaning in her words.”

“And so there were for the time,” answered Wulfhere; “but well-a-day! she is young, and the young learn easily the lesson of forgetfulness.”

“Why could we not live in Winchester?” asked the girl after a moment’s silence. “Methinks that we could find some thegn to take us under his mund. Why, grandfather, is not that the city where the king abideth?”

She stopped short, and half turned as though to return to the town. Wulfhere smiled.

“The king hath already sought the palace at Chippenham,” he said. “Wottest thou not that by the doom of the witan he cannot dwell all the year in one burgh only? And I wish not to seek the protection of any lord but him in these troublesome times. Alfred hath shown himself able to cope with the invader, and there is surety nowhere else for life and limb. ’Tis for thy weal, child, that I fear, and to none but him will I commend thee. Besides, to whom but the king doth the protection of the wanderer belong?”

Egwina turned with a half sigh, for deep down in her heart lurked the wish to see again the noble maiden and the youth who had spoken so kindly to them the day before, and in leaving Winchester she felt that she left also the probability of seeing them once more. But unquestioned obedience from child to parent was the rule in those days, and so without further remark she trudged on, varying the monotony of the journey by frequent blasts of the horn. Presently the mellow notes of another horn floated to their ears. Wulfhere glanced back over his shoulder.

“Behold, another cometh,” he said. “Stop, Egwina! If he choose to bear us company, the way will not seem so long.”

They waited for him, and soon the juggler came up with them.

“Whither away, my merry man?” cried Wulfhere heartily, as the gleeman approached. “Brothers we be of the same craft. Therefore, if it seems good to thee, let us bear each other company.”

The juggler hesitated a moment, and then answered:

“Willing am I for a short while at least; if it so be that the girl will wind the horn while thou and I talk by the way.”

“With right good-will will she do so,” answered the harper. “’Tis as easily wound for three as for two, and always doth she wind it to save me the toil. Wulfhere is not what he once was!”

“Wulfhere is thy name?” questioned the other, fixing his glittering eyes upon the maiden with such a look that she shrank from it, and crept close to the side of her grandsire. “Ælfric am I called in East Anglia, which is my home; but the Danes have driven us from our houses, or pressed into slavery our people, and I fled into Wessex for safety.”

“Brothers we be in craft, and sibbe also in the fact that we flee from the Dane,” remarked Wulfhere. “Fearful is the pirate who hath so ruthlessly destroyed the homes and laid waste the land of our people.”

“Whither art thou going?” queried Ælfric.

“North into Berkshire and from thence into Wiltshire,” answered the old man.

“Then together can we journey but a short distance, for on the morrow our paths must be sundered, as I go into Kent. But while our roads are one tell me of the deeds which the Northmen have done of which thou thyself wottest, and I in turn will tell thee that which hath happened to me.”

Then, with emotion, did Wulfhere tell of his grief in the death of his grandson, Siegbert.

“And I,” said Ælfric, after he had expressed his sympathy, “abode in Thetford of East Anglia at the house of Eldred the thegn, and was the chief of his gleemen. None was so honored as I, and the heart of my lord clave unto me with love. Alack! the Northman fell upon us, and I wot not whether my lord be living or dead. I fled from the foe. When I was far distant, I looked back, and behold the manor was in flames.”

“Didst thou not fight for thy lord?” queried Wulfhere in amazement.

“Nay; why should I risk life in vain? Naught would it have availed him. I myself would have been slain, so I fled.”

“It was not the old custom,” remarked the elder Saxon, “thus to abandon one’s lord. ’Twere shame to live were he slain.”

“Times are not as they once were,” returned Ælfric hastily, avoiding the glance of the harper. “Custom hath changed, and, I trow, for the better. Beautiful is thy ring, maiden! Where gottest thou it?”

“’Twas a gift,” returned Egwina, as she allowed the man to examine the jewel, shrinking from his touch as she did so, for she liked not his appearance.

“A gift? I’ll warrant that thou and thy grandfather have many such?” And there was envy and avarice in the juggler’s look.

“There be many—” began Egwina, when Wulfhere interrupted her:

“Wind thy horn, child, a little distance from us that our talk be not disturbed by the sound.”

Obediently the girl ran ahead a little, and Wulfhere resumed the conversation with Ælfric concerning the atrocities committed by the Danes. The shades of evening were falling when at last the ministrel called to the girl:

“Child, is not that a monastery that looms in the distance?”

“Yes, granther,” and Egwina ran to his side.

“Then there will we abide. Long have we wayfared, and wearied am I by the journey. Though the priests may not hearken to song, or story, or glee-beam, yet will they shelter us for the night.”

Quickening their steps they entered the courtyard of the convent, which was a low building of timber, fortified by a wall.

The dwellings of the Anglo-Saxons with the exception of a few great nobles, were simple in the extreme. Yet simple as were their abodes, the monasteries were handsome, and great wealth and possessions were held by the church. Despite all this, learning was at the very lowest ebb, so much so that when Alfred was atheling, and desired to learn Latin, he could find no one in all his father’s kingdom capable of teaching him. There were no inns in England at this time, and all travelers, whether on business or pleasure, were entertained by the convents.

Wulfhere, Ælfric, and Egwina were welcomed by the monks and refreshed by the bath, for the Saxons were a cleanly people, and fond of bathing; then were they called into a long, low hall, the refectory or dining-room, and invited to partake of supper. Cakes of barley, fish, swine flesh, milk, eggs, and cheese, with plenty of mead to wash it down, constituted the repast; for even the priests of this hardy race were hearty eaters and fond of good cheer.

The meat was passed round on spits, and each one cut a portion for himself with his knife, and then ate it, using the fingers to convey the food to the mouth, as there were no forks.

After the meal, all gathered round the fire which was built in the centre of the room, the smoke escaping through a hole or cover in the roof.

“It is forbidden us to listen to the songs of the people,” said the abbot addressing Wulfhere, “but mayhap thou canst sing to us the songs of the Church.”

“Nay, good father,” answered Wulfhere, “I am not skilled in sacred song.”

“Cannot thy daughter sing them?” asked the abbot. “Truly it were ill if so fair a flower should know naught of the songs of the Faith.”

“I know not,” replied Wulfhere in perplexity.

“There is one that I know,” interrupted Egwina, softly. “It was one that my mother sang.”

“Let us hear it, daughter,” said the abbot.

Without hesitation, Egwina then sang the “Crist” of Cynewulf.

“It was well sung,” commented the abbot, after Egwina had concluded. “Sweet is it to Him when the voice of youth sounds His praises. Knowest thou no more, my child?”

“Nay, I know none other,” answered Egwina.

“Thou must not think ill of us, father,” spoke the harper hastily, “that we wot not of these things. Our aim is to please the people, and the mead hall cares but for the song of the warrior or of glory.”

“True,” answered the abbot, “yet Aldhelm used thy art to advantage. Hast thou not heard how the good priest stood on the bridge of Malmesbury, where the ministrels were wont to stand, because the people would not come to worship, and there did he sing of war and the heroes, until attracted by the sweetness of his voice, he had gained their attention? Then did he change the words, and sing to them of the Holy One and the blessed Virgin. In which manner many were instructed in our sacred religion and brought to the Church.”

“Sayest thou so, good father?” broke in Ælfric, the juggler. “Marry! but well would it please me to hear such songs! Canst thou or thy monks sing for us any of the songs that he sang?”

“There is one, brother, which is food for reflection. That we will sing thee, and then after the Te Deum. Then shall ye tell us if aught hath happened recently from the Dane.”

Without further ado, the monks began singing the following dismal dirge, the brief metre sounding abruptly on the ear with a measured stroke like the passing bell:

“For thee was a house built ere thou wert born,For thee was a mold shapen ere thou of thy mother camest.Its height is not determined, nor its depth measured;Nor is it closed up, however long it may be, until I thee bring where thou shalt remain;Until I shall measure thee, and the sod of the earth.Thy house is not highly built; it is not unhigh and low.When thou art in it, the heel ways are low, the side ways unhigh.The roof is built thy breast full high;So thou shalt in earth dwell full cold, dim, and dark.Doorless is that house, and dark it is within.There thou art fast detained, and Death holds the key.Loathly is that earth house, and grim to dwell in.There thou shalt dwell, and worms shall share thee.Thus thou art laid, and leavest thy friends.Thou hast no friend that will come to thee,Who will ever inquire how that house liketh thee.Who shall ever open for thee the door, and seek thee;For soon thou becomest loathly and hateful to look upon.”

“The saints guard us!” ejaculated Ælfric, crossing himself devoutly. “I like not thy song, father, and if it were with songs like that, it marvels me much how thy Aldhelm should draw the people to hear him. Quotha! my flesh creepeth to think of it! Doth not thine, Friend Harper?”

Wulfhere’s face was inscrutable, and he made no reply for, Saxon-like, he scorned to show that the picture held any dread for him.

“It is indeed gloomy to think upon, son,” said the abbot, “if that were all of death; but the religion of our Saviour hath robbed the grave of its terrors. We know that the soul is beyond, and what matters the body?”

“A truce to such talk,” cried Ælfric. “Give us the Te Deum, priest. I like not to think on such things.”

“It shall be as thou wishest, though much I mislike to leave the subject as I perceive that thou art ungodly.”

Then all joined in the sublime, unmetrical Te Deum.

“Did thy priest but sing that,” burst from the juggler, “I would wonder not at the people listening to him.”

The abbot smiled, well pleased.

“Thy heart is not altogether hardened, son, if it be touched by the hymn,” he said. “Mayhap thou wilt be willing yet to talk with me.”

After more singing, the conversation turned upon the Danes, and the probability of a fresh outbreak discussed. The hour was late when the abbot, noting that Egwina’s eyes were heavy and that it was with difficulty she kept awake, arose.

“To bed! to bed! See ye not that the maiden is aweary?”

So saying he conducted them to the guest house, a building in the courtyard but without the convent proper, and soon quiet reigned over the monastery.

CHAPTER III—A THIEF IN THE NIGHT

Soft and downy was the bed in the bower chamber to which Egwina had been assigned, and grateful was it to the weary maiden, who was soon fast asleep.

It seemed to her that she had slept but a short time when something awakened her. She lay quite still trying to determine what it could be, and hearing only the soughing of the wind.

Suddenly, she felt her hand taken softly, and the sapphire ring which Ethelfleda had given her was gently withdrawn from her finger. For a moment the girl thought that she must be dreaming, and quickly clasped her right hand over the left. The ring was in truth gone. She grew numb with fear as the fact dawned upon her. There was a thief in the room.

Her heart almost stopped its beating, and then began to throb fast. Was it one of the monks? No, no; they were too good, too kind for that! It must be, it was Ælfric the juggler, who had joined them on their journey. Had he not looked covetously upon the jewel? At this moment she heard the thief moving quietly toward the door. The sound broke the spell that held her. It was too dark for her to see anything, but she sprang from the bed shrieking:

“Grandfather! grandfather! Awake! awake!”

There was a muttered ejaculation from the intruder. He turned, bounded back toward her and felled her, with a blow; then, as Wulfhere ran into the room, dashed from the house.

“Egwina! Egwina!” called the harper in alarm. “What is it? What hath befallen thee?”

There was no response, and in trying to reach the couch, he stumbled over the body of the girl.

“My child! My child!” broke from his lips in agonized accents as he recognized Egwina’s form by the feel of her garments and hair. “What hath happened to thee, little one?”

Still there came no reply, and almost crazed by the darkness and the silence, Wulfhere ran across the courtyard and began to pound with all his might upon the portals of the convent, calling upon the abbot as he did so.

“What hath happened?” cried the abbot from within in response to the clamor. “Why rouse ye reverend men from needed slumber?”

“Because,” cried Wulfhere, frantically, “something hath befallen my child. I know not what evil hath been wrought, but only that she lieth dead or in a swoon. For the love of heaven, good father, open unto me!”

There was a rattle of chains, and then the door swung back, and the old man was surrounded by the monks.

“What is it, son?” demanded the abbot.

“I know not,” cried Wulfhere, “save only that Egwina cried out to me in terror. Now lies she there, and whether she be quick or dead I wot not. Come!”

The abbot was quick to act.

“A leech and herbs,” he commanded. Without further parley, he ran rapidly with Wulfhere to the guest-house, the monks following.

Egwina still lay unconscious on the floor. The abbot and Wulfhere stroked her hands while the leech applied various restoratives. Soon the maiden showed signs of returning consciousness, and the leech gave her a drink which he prepared from the herbs. In a short time she had so far recovered as to be able to tell her story.

“And see, granther,” she concluded, “the ring that the maiden gave me hath been taken.”

Wulfhere uttered an exclamation as a sudden thought struck him, and he sprang to his feet. “Ælfric! Where is Ælfric?”

Several of the monks started in search of him, but no juggler could be found.

“’Tis he who hath done this!” cried Wulfhere.

“Hast thou lost aught of other treasure?” asked the abbot. “If his purpose were robbery, methinks that he would have deprived thee also of booty.”

Wulfhere drew from under his tunic the pouch that he always carried strapped about his waist, and from it took a bag.

“By the bones of the holy Cuthbert,” he exclaimed, “it is empty!”

And so, indeed, it proved. The gold, silver, and copper coins, and gems which had been given him, were all gone. With a groan the old man let the bag fall to the floor.

“Courage, man!” cried the abbot. “Thou hast not time to moan. Already hath the first cock crowed for sun-rising. ’Twill be but a short time ere morning dawns, and then we will seek the niddering. We will loose the hounds upon his track, and though he have a few hours the best of us, natheless we shall o’ertake him.”

So, in the early morning, Wulfhere and a small party of monks on palfreys set forth from the convent. Hounds of the best English breed so famed at this time were let loose upon the trail. It was not until late in the afternoon that the man-hunt was brought to a close.

Then the hounds gathered round some alders in which Ælfric lay concealed. He was soon dislodged from his covert, and, seeing that resistance was useless, suffered himself to be led back to the monastery.

“Brother,” said Wulfhere to him, more in sorrow than in anger, “I knew not before that a gleeman would deal with another as a pagan might.” But Ælfric answered not a word.

A report of the matter was laid before the sciregerefa, the reeve or sheriff of the county, and Wulfhere, Egwina, the abbot, and such of the monks that knew of the affair, were summoned before him.

In the presence of this man, the bishop, and the ealdorman, Wulfhere accused the juggler of the theft.

“In the Lord,” said he, “do I urge this accusation with full right, and without fiction, deceit, or any fraud; so from me was stolen the gold and gems which my craft had brought me, and of this do I complain. Also from my granddaughter was taken a ring. These things were found again with Ælfric the juggler.”

Then the gerefa proceeded to examine the several persons. Ælfric looked upon Egwina with aversion as the maiden gave her simple account of the loss of her ring and the subsequent occurrences.

“I know no more,” concluded she, “for when I called aloud to my grandfather, the man did strike me, and I fell into a swound.”

“And this is the man?” inquired the gerefa. “Marry! Is it thus that a Saxon demeans himself?”

“Nay,” said Egwina, sweetly, “I would not take oath that it was he, good gerefa; for it was dark, and I could not see. Mayhap he meant only to affright me.”

The gerefa, the ealdorman, and even the bishop smiled at this artless attempt to shield the fellow.

“He doth not deserve thy pity, maiden,” said the sheriff gently. “I misdoubt not that he is the man sith the booty was found upon him. Thou needst say no more.”

Egwina sat down by her grandfather while the abbot and the monks deposed. Then the reeve turned to the juggler:

“Ælfric, by these witnesses thou hast been proven to have taken the ring belonging to the maiden, and the coin and gems of the bard. Hast thou aught to answer for thyself? Why didst thou this thing? Is it not enow for the Northmen to pillage our people that they must prey upon each other?”

Ælfric was silent for a moment, and then raised his head defiantly.

“Naught can be gained by saying that I did it not, for ye have proved it. Ælfric did rob the old man of his gold, and the girl of her ring. Will ye know why? They were mine by right. Ye have dooms by which a man must pay bot if he wrong his neighbor by theft or feud; but no weregeld must he pay that takes from another his trade. Yet is not that an injury? This then have the scop and the maiden done to me: ’twas in the market at Winchester that I played with my balls and knives. The people cried up the act for they were pleased. Then, before it was time for the giving of the gifts, did this harper and his daughter come. They sang, and the throng left me. Have they not robbed me? I took that which was mine own. Had they but waited until the distribution of gifts, naught would have befallen them. I have said.”

He sat down as he spake, and a silence fell upon the company. Such a plea was unusual. There was a puzzled look upon the faces of the ealdorman and the bishop. Soon the gerefa spake:

“Natheless, Ælfric, the mulct must be paid. Little did the harper and his daughter reck that they took gifts from thee. It was but a whim of fortune, and doth not condone thy fault. Thou knowest the doom. Canst pay thy weregeld?”

Ælfric shook his head sullenly.

“Then hast thou kindred who will pay it for thee?”

But the juggler clasped his hands.

“There is none,” cried he, “that is sibbe to me. Do to me as ye will for none is there to pay the bot.”

“If thou canst not pay thy weregeld,” said the reeve, “and there is no man to pay it for thee, then must thou become a wite theow according to the doom; for thus doth it read: ‘If anyone through conviction of theft forfeit his freedom, and deliver himself up and his kindred forsake him, and he know not who shall make bot for him; let him then be worthy of theowe-work which thereunto appertaineth; and let the were abate from his kindred.’ Thus shalt thou be given unto a lord for his theow, and if any there be who choose to redeem thee, then let him come forward before the year hath passed; else serfdom must be thy portion for life.”

The juggler advanced and laying down his sword and his spear, symbols of the free, took up the bill and the goad, the implements of slavery, and falling on his knees placed his head under the hand of the gerefa.

“Oh!” cried Egwina pityingly, her eyes full of tears. “A theowe! Nay, granther, it must not be! Prithee, give to the reeve the weregeld. I would not that he be made a wite through us. Is he not a gleeman?”

“True;” answered Wulfhere, “and a Saxon also. It is just. He hath committed a crime against the doom of the land; according to the doom let him be judged. Come, child, put on thy ring again, and let us be going. Too long have we tarried already with the good monks. The Wind month cometh on apace, and ere it wanes, I would be in Alfred’s vill. Come!”

He arose as he spake, but, moved by an irresistible impulse, Egwina sprang to the side of Ælfric.

“Sorry am I and grieved,” she said, gently laying her hand on his arm, “that we have brought thee to this pass. Take heart! It may be that grandfather will let me have some of the gifts, and if so I will send them to thee to pay thy were. We knew not in the market that thou hadst received no gifts.”

But Ælfric shook her hand from his arm roughly, and turned on her with hate in his eyes.

“Thinkest thou that thy father alone could have taken them from me? No; it is thou that art to blame! Had it not been for thy fair face Ælfric would have received his gifts. Wulfhere is old! No longer hath he power to charm by his harp and voice, so he uses thy beauty to drive a better man from the field. Wulfhere did it not! It is thou who hath done this!”

Egwina shrank back affrighted. Wulfhere strode forward, his face white with passion.

“What! Tauntest thou a girl? It is best for thy weal an thou art a theow else Wulfhere would make thee pay thy weregeld twice over. Wulfhere may have lost his power as harper, but strong yet is his right arm and mighty its stroke.”

“Marry, son,” interposed the abbot. “Be not wroth with such as he! Thou demeanest thyself.”

“True;” said the harper recovering himself, “what hath Wulfhere to do with a niddering?”

At that term of reproach which no Saxon could hear unmoved, Ælfric sprang forward, his face convulsed with rage, his hand upraised. The gerefa and the abbot seized him before the blow fell.

“Niddering?” he shrieked. “Ælfric niddering! As ye be Saxons let me at him!”

But they would not, and, as they led him away, he called back in a loud voice:

“By all the saints, I swear that Ælfric shall be revenged. As I am now so shall ye be! Look to yourselves, Wulfhere, and thou, daughter of Wulfhere! For every hour spent as theow, ye shall have double. For every task assigned, two shall be your portion. The rod and the lash shall not be wanting. I swear it! Lead on; I have spoken!”

Egwina paled and trembled at the words, but the old man laughed.

“Heed him not,” he said. “Doth not the beast growl when foiled? What harm can befall us if we are in the king’s hand? Come!”

CHAPTER IV—IN THE HALL OF ALFRED

Wulfhere and Egwina journeyed slowly northward over Hampshire, into Berkshire, and thence into Wiltshire, so that it was not until the sixth day of the Wolf month that they arrived at Chippenham.

The landscape was dreary and barren. The wind howled dismally through the branches of the leafless trees. The sedge by the river was silvered over by heavy rime and the frosted flag rushes seemed to cut like swords. The gray clouds hung low in the dull leaden sky until the summits of the hills in the distance were lost among them. The wide-open moors and hedgeless commons showed no sign of any living thing on their desolate wastes.

Without the gates of the city all was chill and drear, but within the sounds of music and revelry could be heard on every hand; for it was the twelfth night, and the feast of the Epiphany. For twelve days the yule log had blazed on every hearth, and as soon as the last of its embers died out life must again take on its work-a-day aspect. So loud rang the mirth and hearty the feast of the last of the holy festival.

Chippenham held one of the strongest of the royal residences. A long, low irregular building, it still towered above the other dwellings of the burgh. It was brilliantly lighted, for night was fast approaching when the wayfarers entered the gates, and Wulfhere and Egwina immediately made their way to it.

A dense throng of poor people waited without the hall for the remnants of the banquet which was going on within. Pushing their way through them, the two paused just outside the portals.

“Now, child,” commanded Wulfhere, “sing as thou hast never sung before. ’Tis Alfred the king who hears thee.”

And with his own nerves tingling, Wulfhere swept the strings of his harp, and they sang softly and tenderly an old ballad. The noise and the glee within ceased with the first few notes of the melody. The sweetness of the girl’s clear soprano blended with the deep bass of the bard, making a pleasing harmony. When they had finished the strain, the portals were flung wide, and the voice of the warder called in ringing tones:

“Now who be ye that bring such music from the harp?”

“Wulfhere, the Gleeman, with his daughter, Egwina the Fair.”

“Enter, Wulfhere, with thy daughter; and for our good cheer give us of thy melody. I wot that none of Alfred’s harpers hath such power of the harp. Enter and welcome!”

Well pleased, the bard and the maiden entered. The hall was a long room whose length was disproportionate to its width, and whose vaulted roof was blackened by the smoke of the fire which burned in its centre. In the upper end was a dais raised a step above the rest of the building. The walls were covered by silken hangings richly embroidered, which served the double purpose of ornamentation and to keep the wind out. For in those days so illy built were even the palaces of the kings that the candles were ofttimes extinguished by the gusts of air which came through the cracks and crevices of the buildings.

Three long tables were ranged down the length of the apartment, filled with Alfred’s gesiths or retainers. In the centre of each table was a large boar’s head with an apple in its mouth. The room was decked with evergreens, conspicuous among them being the mistletoe, to which a traditionary superstition attached.

The floor was covered with rushes and sweet herbs, and a number of dogs lay thereon close to the great fire, watching greedily for some chance tidbit, if any there were so unmannerly as to throw to them. Upon the dais stood an oval-shaped table handsomely carved, above which was a canopy of richly embroidered cloth.

Around this table, reserved for the king’s family and guests of honor, were gathered two ladies and three small children, one boy and two girls. The king’s chair was empty. Behind the ladies stood two youths and a maiden of high rank, who served them with napkins and mead, and with a start of surprise, Egwina saw that the maiden was Ethelfleda and that one of the youths was her brother.

The tables were laden with gold and silver plate, and each person had a knife with a jeweled hilt. Pages served the meat on spits, kneeling, and occasionally passed bowls of water in which the fingers were dipped before drying them on the napkins.

Wulfhere and Egwina were given seats in the lower end of the hall among the other harpers, scops, bards, and gleemen. At their entrance every eye was turned inquiringly toward them. The reeve who had the feast in charge hastened to them.

“Thy music hath enchanted the household. Prithee delight us again. The feast is deepening.”

Nothing loth, Wulfhere complied readily; then, as the song was finished, without waiting for further request, his fingers swept the strings and he half sang, half recited, improvising as he went:

“Here Alfred of the West Saxons king, the giver of the bracelets of the nobles,A lasting glory won by slaughter in battle, with the edges of swords at Ashdown.The wall of shields he cleaved, the noble banners he hewed;Pursuing, he destroyed the Danish people.The field was colored with the warrior’s blood.After that—the sun on high—the greatest starGlided over the earth, God’s candle bright!Till the noble creature hastened to her setting.There lay soldiers many with darts struck down,Northern men over their shields shot.So were the Danes weary of ruddy battles.The screamers of war he left behind; the raven to enjoy,The dismal kite, and the black raven with horned beak, and the hoarse toad;The eagle afterwards to feast on the white flesh;The greedy battle hawk, and the gray beast, the wolf in the wood.He has marched with his bloody sword, and the raven has followed him.Furiously hath he fought, and the Northmen fear his presence.Then did the Dane seek his fleet.And they sang as they coursed gayly along the track of the swans:‘Not here can the Great one harm us.The force of the storm is a help to the arms of our rowers;The hurricane is in our service;It carries us the way we would go.’Then arose the king in his wisdom. Alfred, great of understanding!He the wise builder of ships! The giver of laws, the bestower of bracelets!He spake, and the timbers took shape.Then did the raven shriek on the waters.Red ran the blood of the Northman, as the Dragon of Wessex pursued him.Great, great are the deeds of Alfred! The wonder and glory of men!”

Thunderous applause broke forth from the retainers that shook the very rafters. Wulfhere sat down upon the settle, and glanced toward the dais from which there now advanced the royal cup-bearer.

“Later will the king grace the feast by his presence,” he said. “And then, O minstrel, shalt thou receive fitting guerdon for thy words. Drink hael to Elswitha, the lady” (the correct designation of the queens of that time was “The Lady”) “who sends thee cheer from her own table and in her own cup.”

He presented the cup, a golden goblet, to Wulfhere as he spoke. The old man flushed with delight.

“Wass-hael,” responded he, as he took the cup. “Wass-hael to the Lady Elswitha.”

“She bids thee welcome, thou and the maiden, and wishes ye also to sing for her in her bower later. Meanwhile, partake of the glee and mingle as of our own household among us.”

So saying he returned to his own station on the dais.

“Granther,” whispered Egwina as the youth left, “seest thou not that the maiden, Ethelfleda, serveth the lady Elswitha? The youth also is on the dais.”

“It may be, child,” answered Wulfhere. “They are guests, likely. Methought they were gentles. But didst thou see, Egwina, that the lady hath sent her own cup? Fortune hath favored us in sooth.”

The girl looked at the cup as he wished, but ever and anon stole glances toward the dais where were the youth and the maiden. At this moment from one of the settles where sat the minstrels, a voice exclaimed:

“Tell me, ye wise ones, what is winter?”

“Tell us, Witlaf,” shouted the reeve. “Expect not wisdom at a feast.”

“It is the banishment of summer,” answered the minstrel.

“Good, good! Another! Give us another.”

“What is spring? The painter of the earth. What is the year? The world’s chariot. What is the sun? Quotha! Doltish are ye if none can answer.”

“The splendor of the world, the beauty of heaven, the grace of nature, the honor of day, the distributer of the hours,” spoke up Wulfhere. “Now thou, whom they have called Witlaf, answer this: What is the sea?”

Witlaf thought for a moment ere he replied, “The path of audacity, the boundary of the earth, the receptacle of the rivers, the fountain of showers.”

“Right!” exclaimed the old bard, his spirits high, his blood coursing warmly through his veins, for it was scenes of this kind that he loved. “Right, sir bard! Now prithee read me this riddle. An unknown person, without tongue or voice spoke to me, who never existed before, nor has existed since, nor ever will be again, and whom I neither heard nor knew.”

But Witlaf shook his head.

“Thou wilt have to unravel it thyself,” he said, “I know not that.”

“It is a dream,” answered Wulfhere, and again the rafters shook with applause.

“Now, wanderer, read this for me if thou canst. It is a wonder. I saw a man standing; a dead man walking who never existed,” quoth Witlaf.

“It is an image in the water,” replied Wulfhere quickly.

“He hath thee, Witlaf,” came from the board in a merry shout. “Thou hast met thy match.”

“Nay; here is another,” cried Witlaf on his mettle. “I wot that there be few men that can unravel this: I saw the dead produce the living, and by the living the dead were consumed.”

Wulfhere smiled as sagely and answered:

“From the friction of trees fire was produced, which consumed.”

So, fast and furious grew the fun, every minstrel or bard contributing his quota to the mirth; Witlaf and Wulfhere leading, each striving to outdo the other.

The feast thickened, and mead, pigment, and morat circled round the board, and the tongue of the Saxon was unloosened. Then did the harp pass from hand to hand and each sang. Even the nobles at the king’s board lifted up their voices in song. Again the cup-bearer approached the place where the minstrels sat.

“The lady Elswitha wishes to know if thy daughter sings not alone?” said he, addressing the bard. “Hath she not some simple lay that will charm the ear?”

“She hath,” answered the gleeman, “and gracious is the lady in the asking. Egwina, Elswitha would hear thee sing. Thy sweetest, child! ’Tis the Lady who asks thee.”

Then timidly the maiden arose. The company hushed the noisy revel, and listened as the sweet voice of the girl sounded through the hall. Her voice quavered slightly when she began, but the maiden on the dais smiled reassuringly at her, and she took courage. It grew stronger and then pealed forth in all its strength and beauty:

“Alone sits the exile,Alone on the plain;And the voice of the south windSpeaks to him in vain.“For back hath his fancyFlown to his lord;When oft he had followed himWith arrow and sword.“Again does he seem to feelAs of old his caresses;The thought is so sweet to him.The awakening distresses.“No friends hath he now,Nor lord for to follow;Long have they been estranged,Life seem but hollow.“Naught doth earth hold for him;No surcease of sorrow:For hunger of heartacheFails comfort to borrow.“Cold, cold is his earth dwelling,Care sits on his brow;Joyless his dark abode,Bereft is he now.“Those he hath loved in lifeThe tomb now is holding;Fain would he join them thereFor rest he is needing.”

The sad little strain produced a few moments of silence, and then again, after vociferous plaudits for the maiden, the uproar broke forth. As Egwina sat down, the maiden Ethelfleda descended from the dais, and came to her.

”Thou art the maiden and this is thy father who were so kind to me in Andred’s Weald,” she said, taking Egwina by the hand. “Often have I wondered about thee, and hoped to see thee again. Now thou shalt stay with me, and thou shalt, if thou wilt, teach me some of thy pretty songs. Sweetly dost thou sing, but it hath made my heart sad to hear thy little plaint.”

”An it please thee, maiden, she shall sing another, merrier and more suited to the feast,” interposed Wulfhere, “I know not why the child chose so sad a theme.”[SYNC]

“It doth please me,” said Ethelfleda. “But come! Before thou dost sing again, thou shalt drink hael with the lady Elswitha.” To the old man’s joy he saw his granddaughter led to the dais where Alfred’s wife sat.

The lady graciously arose to receive the girl. With her own hand she proffered the cup. Just as Egwina was lifting the goblet to her lips, a great noise was heard without. There was the crash of arms, the hoarse shout of battle, and then the portals were flung wide, and the warder shouted:

“The Dane, the Dane!”

CHAPTER V—THE DEATH OF A HERO

Instantly the wildest confusion prevailed. The Saxons, half-dazed by the suddenness of the attack, sprang for their arms which hung upon the walls of the hall. Such a thing as a winter campaign had hitherto been unknown, and they were taken completely by surprise.

Before they could collect themselves or form any plan for defense, the Norsemen were upon them, and then there followed an awful scene of carnage. The clash of steel, the hoarse shouts and cries of the Saxons, the shrieks and groans of the women, mingled with the exultant yells of the Danes. High above all, rose the Norse battle song which contained a covert sneer at the English religion:

“We have sung the mass of the lances.It began at sunrise, and lo! the bright star hath gone to her rest,And the orison is not completed.Odin awaits us in Valhalla!The perennial boar steams upon the festive board!Hela, the death goddess, gnashes her teeth that we escape her!The kite and the raven scream with joy at the feast!Red runs the blood!Fearful the carnage!Guthrum the old hath destroyed the great one.The black Raven with pointed beakHath subdued the Dragon of Wessex.”

On and on it went while the sharp-edged swords did their work. The Saxons made a brave but ineffectual resistance. On every side they fell. The tables were overturned in the strife, and mead and pigment mingled with the blood of those who such a short time before quaffed the cup so gayly.

Through the struggling combatants, Wulfhere made his way somehow to the upper end of the hall where Egwina, Ethelfleda, Elswitha, the lady’s mother, Eadburga, the two youths and the little ones were huddled together, terrified at the sudden onslaught.

“Thou must not stay here,” he cried to the Lady Elswitha. “It is no place for thee, or these others.”

A thegn darted to them at this moment.

“Retire,” he shouted. “Retire, Lady, to thy bower.”

“Retire!” exclaimed the lady, “and leave my lord’s hearthstone to the invader?”

“Thou must,” cried the thegn in anguish. “For the love of the Holy Mary, seek thy bower. We must answer to the king for thy safety.”

Without further remonstrance, the lady turned to flee with her children. It was none too soon. The Northmen pressed furiously toward that end of the hall. The few remaining Saxons threw themselves between the terrible Danes and their beloved lady.

“Go, lads,” commanded the same thegn who had before spoken, pushing the youths who lingered towards the fleeing group; “ye can do naught here, and your duty lies there. Go!” and the boys obeyed him.

As quickly as possible the little party made its way into the bower and barricaded the entrance behind them.

“Now what?” asked the lady of Wulfhere.

“We must not stay here,” answered he. “After the slaughter comes the flame. The Dane will apply the torch as is his wont. Let us to the king.”

“The king! Alack!” Elswitha cried in sudden terror. “Where is he? I fear, oh, I fear that he hath fallen into the hands of Guthrum.”

“Where went he?” asked Wulfhere.

“To Malmesbury to determine the limits of some bocland. Were he living, he would have been here ere this. Oh, I fear, I fear!”

Moaning, she drew her little ones to her while the others looked at her compassionately. At this moment a mighty shout rose from without the castle walls.

“The king! The king!”

The clash of steel, the shouts and cries which now broke forth with renewed vigor, showed that the king had indeed come. Elswitha sprang to her feet, her face transfigured with joy.

“God be praised!” she cried. “It is my lord. Now, my children, ye are in sooth safe. O thank God! Thank God!”

But even as she spoke, the door fell inward with a crash, and the Northmen burst into the room. Wulfhere drew his seax, and threw himself in front of the women and children. The youths—Edward and the cup-bearer—ranged themselves beside him.

“Minstrel, sheathe thy sword,” cried the foremost of the Danes. “Arms and battle are not for thee. It is thine to sing the praises of warriors. Sheathe thy sword.”

“I will, an it please thee, in thy body,” answered Wulfhere. He made a lunge, and the Dane fell pierced through the heart.

The others sprang toward him, but the youths received those in the fore on their swords. Then rose the voice of Guthrum, King of the Danes, and it rang through the hall:

“Whoso brings me the head of Alfred the King, him will I hold dearer than a brother, and great shall be his reward.”

The Northmen turned and ran back towards the hall, shouting as they did so:

“Safe enow art thou, minstrel. Later will our swords drink of thy blood.”

Elswitha started up frantically. “Come,” she cried. “Let us to Alfred. There only is safety.”

“Thou art right. Let us be gone ere others of the pagans come,” said the bard. “Do ye,” to the youths, “lead, and let the women follow. I will bring up the rear.”

The two boys went before. Elswitha and Eadburga came next with the three children. Egwina and Ethelfleda followed, while Wulfhere guarded the rear. Out into the night they went. The wind which had arisen, moaned and sobbed as though bewailing the strife. The din without the castle was fearful. The wailing of women and children mingled with the clash of swords and the cries of battle. Citizens ran to and fro, whither they knew not, seeking loved ones or refuge from the Danes. The darkness of the night was broken only by the torchlights which flitted hither and thither, or were suddenly extinguished as the bearers fell pierced by sword or arrow.

Hesitating only for a moment, the boys turned in the direction of the sound of the conflict. They had gone but a short distance, when there was a great shout, and the Saxons—warriors, citizens, women and children—went flying past them.

“Fly, men of Wessex,” they cried as they ran. “Fly, and save yourselves!”

It was impossible to stem the living current. The little party was obliged to turn and go with the surging, seething mass of humanity.

And now the torch was applied to finish the awful work. Soon the ruddy flames leaped high in the air, lighting up the sky with a lurid glare, and bathing the landscape in a crimson glow.

A wail went up from the fleeing Saxons, for they knew that the light was from their dwellings, and that they were homeless. Full of anguish they redoubled their speed, and ran on, breathless and in terror, for the cries in the rear showed that the Northmen were still in pursuit; still slaying those who were unfortunate enough to fall into their hands.

In every direction ran the fugitives. It was cold, for it was midwinter; but though the chill wind pierced to the very marrow, the people thought only of life for themselves and dear ones, and heeded it not. The terror-stricken inhabitants of the villages into which they fled could afford them no asylum for they knew that but a few short hours must elapse ere they would suffer a like fate. So they, too, joined the fugitives and the crowd became a multitude.

At first our little band had no difficulty in keeping together, but as the numbers were increased, they pressed closer one to another, and called aloud frequently.

It was just the hour before the dawn, when the flames of the burning villages had died down and a thick darkness had settled over the earth, that a cry went up from those in front that the Danes were coming from that direction also. Panic-stricken, the throng knew not which way to turn. They became confused in the darkness and made a sudden dash in opposite directions, shouting and crying as they did so. The party was swept asunder by the rush.

Egwina called frantically to Ethelfleda, but the noise was so great that she could scarcely hear the sound of her own voice. Carried onward by the crowd, she did not know where she was going, or if the Danes had really fallen upon them.

At last morning dawned. With the rising of the sun—the distributor of God’s blessed light—the stricken people revived somewhat from their terrors which the darkness had augmented, and proceeded more quietly. Now, too, each began to search for his relatives. To the girl’s joy, her grandfather was soon found.

“Dost know what became of the others?” he inquired.

“No, granther. The maiden was carried from my side when the shout went up that the Danes were coming. Alack! where can they be?”

“I wot not,” answered Wulfhere moodily. “I fear, child, that this is the end. None know whether Alfred be fallen or taken prisoner. If either be true naught is left for us but loss of life or slavery.”

With the morning the people scattered into the different villages in search of rest and sustenance. Wulfhere and Egwina did likewise. As they were resting in the thatched cottage of a ceorl, there came through the village one riding hotly on a palfrey. He bore an arrow in one hand and a naked sword in the other. When he reached the centre of the hamlet he stopped and called in a loud voice:

“What, ho, Saxons! Listen to the words of the king. Alfred would have aid against the Dane. Let every man that is not niddering, whether in a town or out of a town, leave his house and come.”

Never before had the old national proclamation, which no Saxon capable of bearing arms had ever resisted, been published to such deaf ears. Wulfhere sprang up with a shout: “God be praised! The king lives!”

But the mass of the people responded not but murmured among themselves that resistance was useless. If they submitted, they would be allowed to till the soil, and to live in their homes even as their brethren in Mercia and East Anglia were doing; while opposition meant death, loss of homes and loved ones.

So the message fell upon deaf ears, and the messenger swept on to other villages with the summons. Wulfhere’s shout met no answering one of gladness. The old man sat down amazed and despairing.

“What hath become of the spirit of the Saxons?” he asked fiercely. “Now shall we be conquered by the Dane, even as our forefathers conquered the Britons. The Saxons serfs? Out, I say! To what have the descendents of Woden fallen that they should submit without a blow to the pagan?”

“Friend,” spoke a ceorl near by, “have a care to thy words. The land hath been ravaged by the invader for years. No rest can be obtained either by resistance or by gifts and money. We are weary of strife. Serfdom and life are better than freedom and death. Marry, let us have peace!”

“Come, Egwina,” and Wulfhere rose, his form dilated, his lip curled with scorn. “Theowes already be these men. I would be no more among them. Come!”

Obediently the girl followed him. There were some mutterings from those who heard his words, but they were allowed to depart without molestation. They had not gone far from the village when they saw in the distance a party of Danes approaching on horseback. As the Danes caught sight of the man and the maiden, they spurred their horses and came up to the two on a run.

“A scald and a scald maiden,” cried they in delight. “Now let song and dance be our portion. Weary are we of the fray. Let us have song.”

They flung themselves from their palfreys and surrounded the two. Egwina shrank close to her grandfather.

“No song, even for thy life, girl,” commanded the old man sternly.

“Strike up, old scald! Is thy harp mute that thou dost not sweep it?” spoke the leader.

“A song! A song in praise of Guthrum! Guthrum the bold!”

But Wulfhere folded his arms across his harp and remained silent.

“Silent art thou?” demanded he who seemed to be the chief.

“’Tis fear that whitens his face and makes his tongue cleave to the roof of his mouth,” laughed a youth mockingly.

“Haco, take the harp,” commanded the jarl. “Do thou sing for us. Then will the old man be stirred to obey. He seems to forget that we war not against gleemen.”

The youth stepped toward Wulfhere and reached out his hand for the instrument. Still silent, the bard drew his seax and cut the strings with one blow.

“What!” cried the chief in fury. “What doest thou?”

“No harp of mine shall sing in praise of Guthrum,” responded Wulfhere sternly.

“But thy tongue shall,” declared the other. “Sing, scald, else it shall be torn from the roof of thy mouth, and never shalt thou lift thy voice in praise of any other.”

“Rather than it should sing in praise of the Northmen I would tear it out myself,” declared the bard with energy.

“Bold art thou,” cried the leader, “or it may be that thou believest that we will be niggardly with our gifts. See! Hath the Saxon done so well?”

He tore from his arms some massive gold bracelets which were held in great esteem by the Danes, and cast them at the ministrel’s feet. The gleeman thrust them aside contemptuously with his foot.

“I scorn both your gifts and your threats,” he cried. “But listen! Ye shall hear a song.”

Believing that he was really intimidated despite his words, the Danes stayed their hands and composed themselves to listen, well knowing that there was time enough to avenge the insult to their gifts. Then Wulfhere drew Egwina back from them a little and began:

“What shall the minstrel sing by the fireside?What hero shall he laud to the young?When the nights have grown cold and chill whistles the wind in the tree tops,Close gather they to the fireside.Then call they for the harper.He sings, and he sings of the Northman.Great was the feast of the ravenWhen Guthrum swept over the land.Wild shrieked the kite and the eagle;And hoarse croaked the toad that was hornedUp rose the Dragon of Wessex!Up then rose the Deliverer!Up rose Alfred the wise one!Maker of ships and of laws!Guthrum and Danes floe before him!Guthrum the old and the aged!Guthrum in fear of the great one!”

With cries of fury the Danes set upon him. Wulfhere received the onslaught with a grim smile, and lunging at the nearest one, chanted on:

“Fast flee the Norseman before him.Stark fall they upon their bucklers!Under the clash of the steel of Alfred.Alfred, the great one! The wise one!Maker of ships and of—”

He fell, pierced through and through by their swords.

“Grandfather!” shrieked Egwina, flinging herself down beside him. “Grandfather, speak to me!”

And Wulfhere opening his eyes, smiled, and chanted in a loud voice: “Maker of ships and of laws!” and expired.

With a cry of anguish the girl fell unconscious on the body.

CHAPTER VI—THE WOLVES’ CONCERT

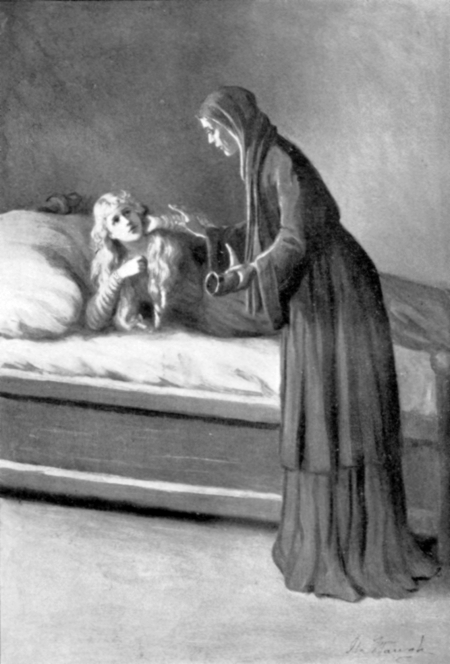

When Egwina recovered consciousness, two priests were bending over her. The Danes were gone, and only the pitying faces of the presbyters were in sight. Half dazed, she stared at them stupidly, and then, as her eyes fell upon the body of Wulfhere, the remembrance of what had happened returned with full force.

“Granther! Oh, granther!” she sobbed. One of the priests leaned over her, and lifted her up gently.

“Daughter, be comforted. He is at rest. No longer is he beset by Dane or foe of any kind. Calm thy grief, and be with us while we give him Christian burial. Our time is short, and we know not how soon the pagans will return. That thou wert left alive is a mercy of God.”

Egwina controlled herself by a great effort. The priests, taking turns, dug a grave with Wulfhere’s seax. Then they approached the remains. With loving hands, the maiden herself re-arranged the garments of the dead man, taking the bag of valuables from his person.

“Take this for the soul sceat,” she said, giving it into the hands of the priests.

“But, daughter, it is too much,” and the priests looked at each other, wondering at the amount. “Keep part for thine own use.”

“I want it not,” answered she, weeping softly. “Let it bring him as many prayers as it will, good fathers.”

Reverently the body was laid within the excavation, and then Egwina brought his harp.

“Bury it with him,” she said.

“Nay, daughter; it savors too much of heathenism,” said one much scandalized. “Do not the pagans so, and the bard was a Christian?”

“True,” said the girl through her tears. “True, good fathers, but granther loved it so. I could not bear that other than he should use it. And if it so be, as ye tell us, that we will sing praises in the heavenly land then will he have need of it.”

The priests were touched, yet still they hesitated. It savored so much of the heathenish custom of the Danes they were loth to consent to the act; yet did they mislike to deprive the maiden of this small comfort.

“See,” said the girl showing them the mutilated strings. “When they would have taken it from him to use it in praise of Guthrum, he cut the strings rather than have it so defiled. If the harp be left, we wot not but that some of the Northmen may find it and use it. Grandfather could not rest if that were to happen. Always it hath been with him. It was his friend, his glee-beam. I know that he will be lonely without it.”

“Brother,” said one to the other, “what sayest thou?”

“Do as the child wisheth,” replied the second one. “It will comfort her, and doth not bewray the church at such a time. Besides ’twere pity that the Northman should get the harp sith the bard hath given his life so nobly.”

So, to Egwina’s relief, the harp was interred with the gleeman. Prayers were said over the grave, and then the priests turned to the girl.

“Now, daughter, respect hath been shown to the dead, and now is our duty to the living. Whither goest thou? Where are thy friends?”

“Alack!” returned she, bravely checking her tears, “I wot not. None but granther did I have.”

“But were ye not under some lord’s hand?”

“Nay, ye know the custom of the wandering gleemen. From mead hall to mead hall did we go, and we have always done so. At Chippenham, we came to put ourselves under the hand of the king for fear of the Danes; but now—”

“Now,” said the elder priest, “thou art like others of people and priests. No friends, no home; thou hast nowhere to go. God help and comfort thee and us in our affliction.”