Front Cover

Front Cover

Title: The Angel of the Gila: A Tale of Arizona

Author: Cora Marsland

Release date: October 14, 2011 [eBook #37746]

Most recently updated: January 25, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Roberta Staehlin, Jen Haines, David Garcia and

the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images

generously made available by The Internet Archive/American

Libraries.)

Front Cover

Front Cover

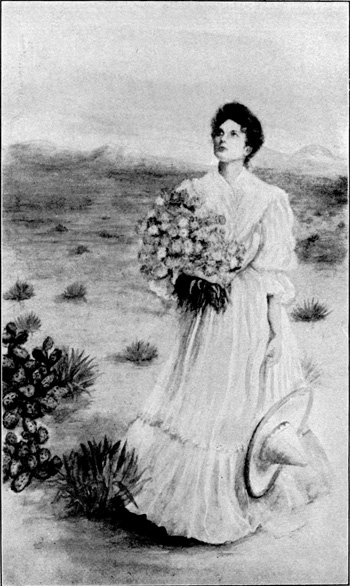

She forgot the flowers in her arms, forgot

the sunset, and stood entranced in prayer.

She forgot the flowers in her arms, forgot

the sunset, and stood entranced in prayer.

Copyright, 1911, by Richard G. Badger

All Rights Reserved

THE GORHAM PRESS, BOSTON, U. S. A.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | The Mining Camp | 11 |

| II | The Dawn of a New Day | 19 |

| III | Clayton Ranch | 30 |

| IV | The Angel of the Gila | 41 |

| V | The Rocky Mountain Ball | 57 |

| VI | A Soul's Awakening | 78 |

| VII | The Gila Club | 89 |

| VIII | The Cow Lasses | 107 |

| IX | A Visit at Murphy Ranch | 117 |

| X | Carla Earle | 132 |

| XI | An Eventful Day | 140 |

| XII | Christmas Day | 154 |

| XIII | The Adoption of a Mother | 167 |

| XIV | The Great Transformation | 182 |

| XV | Some Social Experiences | 194 |

| XVI | Over the Mountains | 205 |

| XVII | The Great Race | 217 |

| XVIII | Night on the Range | 225 |

| XIX | Inasmuch | 238 |

| XX | A Woman's No | 241 |

| XXI | The Valley of the Shadow | 248 |

| XXII | The Greatest of These is Love | 265 |

| XXIII | At Sunset | 271 |

| XXIV | Aftermath | 278 |

It was an October day in Gila,[1] Arizona. The one street of the mining camp wound around the foothills, and led eastward to Line Canyon, which, at that point, divides Arizona from New Mexico. Four saloons, an opium den, a store of general merchandise,—owned and operated by the mining company,—a repair shop, one large, pretentious adobe house,—the headquarters of the company, where superintendent, assayers, and mining engineers boarded,—several small dwelling houses, and many miners' shacks, constituted the town.

A little further to the eastward, around a bend in the foothills, and near Line Canyon, lay Clayton Ranch,—the most historic, as well as the most picturesque spot in that region. Near the dwelling house, but closer to the river than the Clayton home, stood a little adobe schoolhouse.

The town, facing south, overlooked Gila River and its wooded banks. Beyond the Gila, as in every direction, stretched foothills and mountains. Toward the south towered Mt. Graham, the highest peak of the Pinaleno range, blue in the distance, and crowned with snow.

Up a pathway of the foothills, west of the town,[Pg 12] bounding forward as if such a climb were but joy to her, came a slight, girlish figure. She paused now and then to turn her face westward, watching the changing colors of sunset.

At last she reached a bowlder, and, seating herself, leaned against it, removed her sombrero hat, pushed back the moist curls from her forehead, and turned again to the sunset. The sun, for one supreme moment, poised on a mountain peak, then slowly sank, flashing its message of splendor into the majestic dome of the sky, over snow-capped mountains, over gigantic cliffs of red sandstone, over stretches of yellow foothills, and then caught the white-robed figure, leaning against the bowlder, in its rosy glow. The girl lifted her fine, sensitive face. Again she pushed the curls from her forehead. As she lifted her arm, her sleeve slipped back, revealing an arm and hand of exquisite form, and patrician to the tips of the fingers.

She seemed absorbed in the scene before her, unconscious that she was the loveliest part of it. But if she was unconscious of the fact, a horseman who drew rein a short distance away, and who watched her intently a few moments, was not. At last the girl stirred, as though to continue on her way. Instantly the horseman gave his horse a sharp cut with his whip, and went cantering up the ascent before her.

The sudden sound of a horse's hoofs startled her, and she glanced up to see the horseman and his thoroughbred speeding toward the town.

She swung her sombrero hat over her shoulder, and gathered up her flowers; then, with a lingering glance to westward, turned and walked rapidly toward Gila.

By the time she had reached the one long street, many cowboys and miners had already congregated about the[Pg 13] saloons. She dreaded to pass there at this hour, but this she must do in order to reach Clayton Ranch, nearly a mile beyond.

As she drew near one saloon, she heard uproarious laughter. The voices were loud and boisterous. It was impossible for her to escape hearing what was said. It was evident to her that she herself was at that moment the topic of conversation.

"She'll git all the Bible school she wants Sunday afternoon, or my name's not Pete Tompkins," ejaculated a bar-tender as he stepped to the bar of a saloon.

"What're ye goin' ter do, Pete?" asked a young miner. "I'm in f'r y'r game, or my name ain't Bill Hines."

"I?" answered the individual designated as Pete Tompkins, "I mean ter give 'er a reception, Bill, a reception." Here he laughed boisterously. "I repeat it," he said. "I'll give 'er a reception, an' conterive ter let 'er understan' that no sech infernal business as a Bible school 'll be tol'ated in these yere parts o' Arizony. Them as wants ter join me in smashin' this cussed Sunday business step ter the bar. I'll treat the hull blanked lot o' ye."

The girl passing along the street shuddered. The brutal voice went on:

"Set up the glasses o' whiskey, Keith. Here, Jess an' Kate. We want yer ter have a hand in smashin' this devilish Bible school. Another glass fur Jess, Keith, an' one fur Kate."

The pedestrian quickened her pace, but still the voice followed her.

"Here's ter y'r healths, an' ter the smashin' o' the Bible school, an' ter the reception we'll give the new schoolma'am."[Pg 14]

The stranger heard the clink of glasses, mingled with the uproar of laughter. Then she caught the words:

"Ye don't jine us, Hastings. P'r'aps y're too 'ristercratic, or p'r'aps y're gone on the gal! Ha-ha-ha-ha!"

The saloon rang with the laughter of the men and women.

The girl who had just passed quickened her pace, her cheeks tingling with indignation. As she hastened on, the man addressed as Hastings replied haughtily:

"I am a man, and being a man I cannot see insult offered to any woman, especially when that woman is making an effort to do some good in this Godless region."

"He's gone on 'er, sure, Bill. Ha-ha-ha-ha! Imagine me, Pete Tompkins, gone on the schoolma'am! Ha-ha-ha-ha!"

His companions joined in his laughter.

"What'ud she think o' my figger, Bill?" he asked, as he strutted across the saloon. "How 'ud I look by 'er side in Virginny reel, eh? I'm afeared it 'ud be the devil an' angel in comp'ny. Ha-ha-ha!"

"Y're right thar," replied one of the men. "Ye certain are a devil, an' she do look like a angel."

"Say, fellers," said Bill Hines, "me an' Pete an' all o' ye ought ter git some slime from the river, an' throw on them white dresses o' hern. I don't like nobody settin' theirselves up to be better'n we be, even in clo'es, do ye, Jess?"

Jess agreed with him.

"What's all this noise about?" interrupted a new comer.

"Hello, Mark Clifton, is that you? Well, me an' Bill an' Jess an' the other kids is plannin' ter smash[Pg 15] schoolma'am's Bible school, Sunday. We're goin' ter give 'er a reception."

"What do you mean by that?" asked Clifton.

"Ye kin jine the party an' we'll show yer."

"Let me urge you to leave Miss Bright alone. She has not harmed you. Leave the Bible school alone, too, and attend to your own business."

"Oh, he's a saint, ain't he! He is!" sneered Pete Tompkins. "What about this gal as he has with him here? More whiskey! Fill up the glasses, Keith. Come, Jess. Come, Kate Harraday." And the half-intoxicated man swung one woman around and tried to dance a jig, failing in which, he fell to the floor puffing and swearing.

Mark Clifton's face darkened. He grasped a chair and stepped forward, as if to strike the speaker. He hesitated. As he did so, a handsome cowboy entered, followed by a little Indian boy of perhaps six years of age.

"What's the row, Hastings?" asked the cowboy in a low voice.

"Pete Tompkins and Bill Hines and their ilk are planning to give Miss Bright, the new teacher, some trouble when she attempts to start a Bible school to-morrow afternoon. Clifton remonstrated, and they taunted him about Carla Earle. That enraged him."

"What do they plan ter do?"

"I fancy they'll do every blackguard thing they can think of. They are drunk now, but when they are sober they may reconsider. At any rate, the decent men of the camp ought to be on the spot to protect that girl, Harding."

"I'll be there fur one, Hastings. Have yer seen 'er?"[Pg 16]

"Yes. As I rode into camp just now I passed someone I took to be Miss Bright."

"Pretty as a picter, ain't she?" said Jack Harding.

"Look, there she goes around the bend of the road towards Claytons'. There goes y'r teacher, Wathemah."

The Indian child bounded to the door.

"Me teacher, me teacher," he said over and over to himself, as he watched the receding figure.

"Your teacher, eh, sonny," said Kenneth Hastings smiling. He laid his hand on the child's head.

"Yes, me teacher," said the boy proudly.

His remark was overheard by Pete Tompkins.

"Lookee here, boys! There goes Wathemah's teacher. Now's y'r chance, my hearties. See the nat'ral cur'osity as is to start a religion shop, an' grind us fellers inter angels. Are my wings sproutin'?"

As he spoke the words, he flapped his elbows up and down. Kenneth Hastings and Jack Harding exchanged glances. Mark Clifton had gone.

Pete Tompkins hereupon stepped to the door and called out:

"Three cheers fur the angel o' the Gila, my hearties. One, two, three! Now! That's it. Now! Death to the Bible school!"

"Death to the Bible school!" shouted they in unison.

The little Indian heard their words. He knew that insult and, possibly, injury threatened his teacher, and, stepping up to Pete Tompkins, he kicked his shins with all his childish strength, uttering oaths that drew forth hilarious laughter from the men.

"Y're a good un," said one.

"Give 'im a trounce in the air," added another.

[Pg 17] In a moment, the child was tossed from one to another, his passionate cries and curses mingling with their ribald laughter. At last he was caught by John Harding, who held him in his arms.

"Never mind, Wathemah," he said soothingly.

Hoarse with rage, the child shrieked, "You blankety blanked devils! You blankety blanked devils!"

A ruffian cursed him.

He was wild. He struggled to free himself, to return to the fray, but Jack Harding held him fast.

"You devils, devils, devils!" he shrieked again. His little frame trembled with anger, and he burst into tears.

"Never mind, little chap," said his captor, drawing him closer, "ye go with me."

For once John Harding left the saloon without touching liquor. The Indian child was clasped in his arms. When he reached a place beyond the sound of the men's voices, he set the little lad on his feet. He patted him on the head, and looked down compassionately into the tear-stained face.

"Poor little chap," he said, "poor little chap. Y're like me, ain't ye? Ye ain't got nobody in the world. Let's be pards, Wathemah!"

"Pards?" repeated the child between sobs.

"Yes, pards, sonny. That's what I said."

Wathemah clasped his arms about Jack's knees.

"Me teacher pard too?" he asked, trying bravely to stop crying.

"Yourn, not mine, sonny," answered Harding, smiling. Then hand in hand, they strolled toward Clayton Ranch. And this was the strengthening of the comradeship between the two, which was as loyal as it was tender.

Kenneth Hastings overtook them, then passed them.[Pg 18] He reached Clayton Ranch, hesitated a moment, then walked rapidly toward Line Canyon.

For some indefinable reason he did not call that evening at Clayton Ranch as was his custom, nor did he knock at that door for many days. On the following Monday, he was called to a distant mining camp, where he was detained by business. So it happened that he was one of the last to meet the new teacher whose coming was to mean so much to his life and to the people of Gila.[Pg 19]

For many days, public attention had been centered upon Esther Bright, the new teacher in Gila. Her grasp of the conditions of the school, her power to cope with the lawless element there, and her absolute mastery of the situation had now become matters of local history. Her advent in Gila had been a nine days' wonder to the Gilaites; now, her presence there had come to be regarded as a matter of course.

Every new feature introduced into the school life, every new acquaintance made, deepened her hold upon the better life of the community. Moreover, her vital interest in the people awakened in them a responsive interest in her.

Fearlessly she tramped the foothills and canyons, returning laden with flowers and geological specimens. Learning her interest in these things, many people of the camp began to contribute to her collections.

Here in the Rockies, Nature pours out her treasures with lavish hand. White men had long dwelt in the midst of her marvelous wealth of scenic beauty, amazingly ignorant of any values there save that which had a purchasing power and could be counted in dollars and cents.

The mountains were ministering to the soul life of Esther Bright. The strength of the hills became hers. Nature's pages of history lay open before her; but more[Pg 20] interesting to her than cell or crystal, or tree or flower, or the shining company of the stars, were the human beings she found fettered by ignorance and sin. The human element made demands upon her mind and heart. Here was something for her to do. If they had been a colony of blind folk or cripples, their condition could not have appealed more strongly to her sympathy. Profanity, gambling, drunkenness and immorality were about her everywhere. The vices of the adults had long been imitated as play by the children. So one of Esther Bright's first innovations in school work was to organize play and teach games, and be in the midst of children at play. She was philosopher enough to realize that evil habits of years could not be uprooted at once; but she did such heroic weeding that the playground soon became comparatively decent. How to save the children, and how to help the older people of the community were absorbing questions to her. She was a resourceful woman, and began at once to plan wisely, and methodically carried out her plans. In her conferences with Mr. Clayton, her school trustee, she repeatedly expressed her conviction that the greatest work before them was to bring this great human need into vital relation with God. So it came about very naturally that a movement to organize a Bible school began in Gila.

Into every home, far and near, went Esther Bright, always sympathetic, earnest and enthusiastic. Her enthusiasm proved contagious. There had been days of this house to house visitation, and now the day of the organization of the Bible school was at hand.

In the morning, Esther went to the schoolhouse to see that all was in readiness. She paused, as she so often did, to wonder at the glory of the scene. The[Pg 21] schoolhouse itself was a part of the picture. It was built of huge blocks of reddish brown adobe, crumbled at the corners. The red tile roof added a picturesque bit of color to the landscape. Just above the roof, at the right, rose an ample chimney. At the left, and a little back of the schoolhouse, towered two giant cactuses. To the north, stretched great barren foothills, like vast sand dunes by the sea, the dreariness of their gray-white, or reddish soil relieved only by occasional bunches of gray-green sage, mesquite bushes, cacti and the Spanish dagger, with its sword-like foliage, and tall spikes of seed-pods.

Beyond the foothills, miles away, though seeming near, towered rugged, cathedral-like masses of snow-capped mountains. The shadows flitted over the earth, now darkening the mountain country, now leaving floods of light.

All along the valley of the Gila River, stretched great fields of green alfalfa. Here and there, above the green, towered feathery pampas plumes.

The river, near the schoolhouse, made a bend northward. Along its banks were cottonwood trees, aspen, and sycamore, covered with green mistletoe, and tangles of vines. No wonder Esther paused to drink in the beauty. It was a veritable garden of the gods.

At last she entered the schoolhouse. She carried with her Bibles, hymn books, and lesson leaves, all contributions from her grandfather. Already, the room was decorated with mountain asters of brilliant colors. She looked around with apparent satisfaction, for the room had been made beautiful with the flowers. She passed out, locked the door, and returned to the Clayton home.

In the saloons, all that morning, the subject of gossip had been the Bible school. John Harding and Kenneth Hastings, [Pg 22] occasionally sauntering in, gathered that serious trouble was brewing for the young teacher.

The hour for the meeting drew near. As Esther approached the schoolhouse, she found perhaps forty people, men, women and children, grouped near the door. Some of the children ran to meet her, Wathemah, the little Indian, outrunning all of them. He trudged along proudly by his teacher's side.

Esther Bright heard groans and hisses. As she looked at the faces before her, two stood out with peculiar distinctness,—one, a proud, high-bred face; the other, a handsome, though dissipated one.

There were more hisses and then muttered insults. There was no mistaking the sounds or meaning. The Indian child sprang forward, transformed into a fury. He shook his little fist at the men, as he shouted, "Ye Wathemah teacher hurt, Wathemah kill ye blankety blanked devils."

A coarse laugh arose from several men.

"What're yer givin' us, kid?" said one man, staggering forward.

"Wathemah show ye, ye blankety blanked devil," shrieked he again.

Wild with rage, the child rushed forward, uttering oaths that made his teacher shudder. She too stepped rapidly forward, and clasped her arms about him. He fought desperately for release, but she held him, speaking to him in low, firm tones, apparently trying to quiet him. At last, he burst into tears of anger.

For a moment, the mutterings and hisses ceased, but they burst forth again with greater strength. The child sprang from his teacher, leaped like a squirrel to the back of one of the ruffians, climbed to his shoulder, and dealt lightning blows upon his eyes and nose and [Pg 23] mouth. The man grasped him and hurled him with terrific force to the ground. The little fellow lay in a helpless heap where he had fallen. Esther rushed to the child and bent over him. All the brute seemed roused in the drunken man. He lunged toward her with menacing fists, and a torrent of oaths.

"Blank yer!" he said, "Yer needn't interfere with me. Blank y'r hide. Yer'll git out o' Gila ter-morrer, blank yer!"

But he did not observe the three stern faces at the right and left of Esther Bright and the prostrate child. Three men with guns drawn protected them.

The men who had come to insult and annoy knew well that if they offered further violence to the young teacher and the unconscious child, they would have to reckon with John Clayton, Kenneth Hastings and John Harding. Wordless messages were telegraphed from eye to eye, and one by one the ruffians disappeared.

Esther still knelt by Wathemah. He had been stunned by the fall. Water revived him; and after a time, he was able to walk into the schoolhouse.

Oh, little child of the Open, so many years misunderstood, how generously you respond with love to a little human kindness! How bitterly you resent a wrong!

Afterwards, in describing what Miss Bright did during this trying ordeal, a Scotch miner said:

"The lass's smile fair warmed the heart. It was na muckle, but when she comforted the Indian bairn I could na be her enemy."

As Esther entered the door, she saw two middle-aged Scotch women clasp hands and exchange words of greeting. She did not dream then, nor did she know until months after, how each of these longed for her old home [Pg 24] in Scotland; nor did she know, at that time, how the heart of each one of them had warmed towards her.

Several women and children and a few men followed the teacher into the schoolroom. All looked around curiously.

Esther looked into the faces before her, some dull, others hard; some worn by toil and exposure; others disfigured by dissipation. They were to her, above everything else, human beings to be helped; and ministration to their needs became of supreme interest to her.

There were several Scotch people in the audience. As the books and lesson leaves were passed, Esther gave out a hymn the children knew, and which she fancied might be familiar to the Scotch people present,—"My Ain Countrie."

She lifted her guitar, played a few opening chords, and sang,

At first a few children sang with her, but finding their elders did not sing, they, too, stopped to listen.

The two Scotch women, who sat side by side, listened intently. One reached out and clasped the hand of the other; and then, over the cheeks furrowed by toil, privation and heart-hunger, tears found their unaccustomed way.

The singer sang to the close of the stanza, then urged all to sing with her. A sturdy Scotchman, after clearing his throat, spoke up:

"Please, Miss, an' will ye sing it all through y'rsel? It reminds me o' hame."[Pg 25]

Applause followed. The singer smiled, then lifting her guitar, sang in a musical voice, the remaining stanzas.

When she prayed, the room grew still. The low, tender voice was speaking as to a loving, compassionate Father. One miner lifted his head to see the Being she addressed, and whose presence seemed to fill the room. All he saw was the shining face of the teacher. Months later, he said confidentially to a companion that he would acknowledge that though he had never believed in "such rot as a God an' all them things," yet when the teacher prayed that day, he somehow felt that there was a God, and that he was right there in that room. And he added:

"I felt mighty queer. I reckon I wasn't quite ready ter have Him look me through an' through."

From similar testimony given by others at various times, it is clear that many that day heard themselves prayed for for the first time in their lives. And they did not resent it.

The prayer ended. A hush followed. Then the lesson of the day was taught, and the school was organized. At the close, the teacher asked all who wished to help in the Bible school to remain a few moments.

Many came to express their good will. One Scotch woman said, "I dinna wonder the bairns love ye. Yir talk the day was as gude as the sermons i' the Free Kirk at hame."

Then another Scotch woman took both of Esther Bright's hands in her own, and assured her it was a long day since she had listened to the Word.

"But," she added, "whatever Jane Carmichael can dae tae help ye, Lassie, she'll dae wi' a' her heart."[Pg 26]

The first of the two stepped forward, saying apologetically, "I forgot tae say as I am Mistress Burns, mither o' Marget an' Jamesie."

"And I," added the other, "am the mither o' Donald."

Mr. Clayton, elected superintendent at the organization of the Bible school, now joined the group about the teacher. At last the workers only remained, and after a brief business meeting, they went their several ways. Evidently they were thinking new thoughts.

Mrs. Burns overtook Mrs. Carmichael and remarked to her, "I dinna ken why the Almighty came sae near my heart the day, for I hae wandered. God be thankit, that He has sent the lassie amang us."

"Aye," responded Mrs. Carmichael, "let us be thankfu', an' come back hame tae God."

Esther Bright was the last to leave the schoolhouse. As she strolled along slowly, deep in thought over the events of the day, she was arrested by the magnificence of the sunset. She stopped and stood looking into the crystal clearness of the sky, so deep, so illimitable. Across the heavens, which were suddenly aflame with crimson and gold, floated delicate, fleecy clouds. Soon, all the colors of the rainbow were caught and softened by these swift-winged messengers of the sky. Away on the mountains, the snow glowed as if on fire. Slowly the colors faded. Still she stood, with face uplifted. Then she turned, her face shining, as though she had stood in the very presence of God.

Suddenly, in her path, stepped the little Indian, his arms full of goldenrod. He waited for her, saying as he offered the flowers:[Pg 27]

"Flowers, me teacher."

She stooped, drew him to her, and kissed his dirty face, saying as she did so, "Flowers? How lovely!"

He clasped her hand, and they walked on together.

The life story of the little Indian had deeply touched her. It was now three years since he had been found, a baby of three, up in Line Canyon. That was just after one of the Apache raids. It was believed that he was the child of Geronimo. When the babe was discovered by the white men who pursued the Indians, he was blinking in the sun. A cowboy, one Jack Harding, had insisted upon taking the child back to the camp with them. Then the boy had found a sort of home in Keith's saloon, where he had since lived. There he had been teased and petted, and cuffed and beaten, and cursed by turns, and being a child of unusually bright mind, and the constant companion of rough men, he had learned every form of evil a child can possibly know. His naturally winsome nature had been changed by teasing and abuse until he seemed to deserve the sobriquet they gave him,—"little savage." Now at the age of perhaps six years, he had been sent to the Gila school; and there Esther Bright found him. The teacher was at once attracted to the child.

Many years after, when Wathemah had become a distinguished man, he would tell how his life began when a lovely New England girl, a remarkable teacher, found him in that little school in Gila. He never failed to add that all that he was or might become, he owed entirely to her.

The Indian child's devotion to the teacher began that first day at school, and was so marked it drew upon him persecution from the other children. Never could[Pg 28] they make him ashamed. When the teacher was present, he ignored their comments and glances, and carried himself as proudly as a prince of the realm; but when she was absent, many a boy, often a boy larger than himself, staggered under his furious attacks. The child had splendid physical courage. Take him for all in all, he was no easy problem to solve. The teacher studied him, listened to him, reasoned with him, loved him; and from the first, he seemed to know intuitively that she was to be trusted and obeyed.

On this day, he was especially happy as he trudged along, his hand in that of his Beloved.

"Did you see how beautiful the sunset is, Wathemah?" asked the teacher, looking down at the picturesque urchin by her side. He gave a little grunt, and looked into the sky.

"Flowers in sky," he said, his face full of delight. "God canyon put flowers, he Wathemah love?"

"Yes, dear. God put flowers in the canyon because he loves you."

They stopped, and both looked up into the sky. Then, after a moment, she continued:

"You are like the flowers of the canyon, Wathemah. God put you here for me to find and love."

"Love Wathemah?"

"Yes."

Then she stooped and gathered him into her arms. He nestled to her.

"You be Wathemah's mother?" he questioned.

She put her cheek against the little dirty one. The child felt tears. As he patted her cheek with his dirty hand, he repeated anxiously:

"Me teacher be Wathemah mother?"

"Yes," she answered, as though making a sacred[Pg 29] covenant, "I, Wathemah's teacher, promise to be Wathemah's mother, so help me God."

The child was coming into his birthright, the birthright of every child born into the world,—a mother's love. Who shall measure its power in the development of a child's life?

They had reached the Clayton home. Wathemah turned reluctantly, lingering and drawing figures in the road with his bare feet, a picture one would long remember.

He was a slender child, full of sinuous grace. His large, lustrous dark eyes, as well as his features, showed a strain of Spanish blood. He was dressed in cowboy fashion, but with more color than one sees in the cowboy costume. His trousers were of brown corduroy, slightly ragged. He wore a blue and white striped blouse, almost new. Around his neck, tied jauntily in front, was a red silk handkerchief, a gift from a cowboy. He smoothed it caressingly, as though he delighted in it. His straight, glossy black hair, except where cut short over the forehead, fell to his shoulders. Large loop-like ear-rings dangled from his ears; but the crowning feature of his costume, and his especial pride, was a new sombrero hat, trimmed with a scarlet ribbon and a white quill. He suddenly looked at his teacher, his face lighting with a radiant smile, and said:

"Mother, me mother."

"Tell me, Wathemah," she said, "what you learned to-day in the Bible school."

He turned and said softly:

"Jesus love."

Then the little child of the Open walked back to the camp, repeating softly to himself:

"Jesus love! Mother love!"[Pg 30]

Early traders knew Clayton Ranch well, for it was on the old stage route from Santa Fe to the Pacific coast.

The house faced south, overlooking Gila River, and commanded a magnificent view of mountains and foothills and valleys. To the northeast, rose a distant mountain peak always streaked with snow.

The ranch house, built of blocks of adobe, was of a creamy cement color resembling the soil of the surrounding foothills. The building was long and low, in the Spanish style of a rectangle, opening on a central court at the rear. The red tile roof slanted in a shallow curve from the peak of the house, out over the veranda, which extended across the front. Around the pillars that supported the roof of the veranda, vines grew luxuriantly, and hung in profusion from the strong wire stretched high from pillar to pillar. The windows and doors were spacious, giving the place an atmosphere of generous hospitality. Northeast of the house, was a picturesque windmill, which explained the abundant water supply for the ranch, and the freshness of the vines along the irrigating ditch that bordered the veranda. The dooryard was separated from the highway by a low adobe wall the color of the house. In the yard, palms and cacti gave a semi-tropical setting to this attractive old building. Port-holes on two[Pg 31] sides of the house bore evidence of its having been built as a place of defense. Here, women and children had fled for safety when the Apache raids filled everyone with terror. Here they had remained for days, with few to protect them, while the men of the region drove off the Indians.

Senor Matéo, the builder and first owner of the house, had been slain by the Apaches. On the foothills, just north of the house, ten lonely graves bore silent witness to that fatal day.

Up the road to Clayton Ranch, late one November afternoon, came Esther Bright with bounding step, accompanied, as usual, by a bevy of children. She heard one gallant observe to another that their teacher was "just a daisy."

Although this and similar compliments were interspersed with miners' and cowboys' slang, they were none the less respectful and hearty, and served to express the high esteem in which the new teacher was held by the little citizens of Gila.

As the company neared the door of the Clayton home, one little girl suddenly burst forth:

"My maw says she won't let her childern go ter Bible school ter be learned 'ligion by a Gentile. Me an' Mike an' Pat an' Brigham wanted ter go, but maw said, maw did, that she'd learn us Brigham Young's 'ligion, an' no sech trash as them Gentiles tells about; 'n' that the womern as doesn't have childern'll never go ter Heaven, maw says. My maw's got ten childern. My maw's Mormon."

Here little Katie Black paused for breath. She was a stocky, pug-nosed, freckle-faced little creature, with red hair, braided in four short pugnacious pigtails, tied with white rags.[Pg 32]

"So your mother is a Mormon?" said the teacher to Katie.

"Yep."

"Suppose I come to see your mother, Katie, and tell her all about it. She might let you come. Shall I?"

Her question was overheard by one of Katie's brothers, who said heartily:

"Sure! I'll come fur yer. Maw said yer was too stuck up ter come, but I said I knowed better."

"Naw," said Brigham, "she ain't stuck up; be yer?"

"Not a bit." The teacher's answer seemed to give entire satisfaction to the company.

The children gathered about her as they reached the door of Clayton Ranch. Esther Bright placed her hand on Brigham's head. It was a loving touch, and her "Good night, laddie," sent the child on his way happy.

Within the house, all was cheer and welcome. The great living room was ablaze with light. A large open fireplace occupied the greater part of the space on one side. There, a fire of dry mesquite wood snapped and crackled, furnishing both light and heat this chill November evening.

The floor of the living room was covered with an English three-ply carpet. The oak chairs were both substantial and comfortable. On the walls, hung three oil paintings of English scenes. Here and there were bookcases, filled with standard works. On a round table near the fireplace, were strewn magazines and papers. A comfortable low couch, piled with sofa pillows, occupied one side of the room near the firelight. Here, resting from a long and fatiguing journey, was stretched John Clayton, the owner of the house.

As Esther Bright entered the room, he rose and[Pg 33] greeted her cordially. His manner indicated the well-bred man of the world. He was tall and muscular, his face, bronzed from the Arizona sun. There was something very genial about the man that made him a delightful host.

"Late home, Miss Bright!" he said in playful reproof. "This is a rough country, you know."

"So I hear, mine host," she said, bowing low in mock gravity, "and that is why we have been scared to death at your long absence. I feared the Indians had carried you off."

"I was detained unwillingly," he responded. "But, really, Miss Bright, I am not joking. It is perilous for you to tramp these mountain roads as you do, and especially near nightfall. You are tempting Providence." He nodded his head warningly.

"But I am not afraid," she persisted.

"I know that. More's the pity. But you ought to be. Some day you may be captured and carried off, and no one in camp to rescue you."

"How romantic!" she answered, a smile lurking in her eyes and about her mouth.

She seated herself on a stool near the fire.

"Why didn't you ask me why I was so late? I have an excellent excuse."

"Why, prisoner at the bar?"

"Please, y'r honor, we've been making ready for Christmas." She assumed the air of a culprit, and looked so demurely funny he laughed outright.

Here Mrs. Clayton and Edith, her fifteen-year-old daughter, entered the room.

"What's the fun?" questioned Edith.

"Miss Bright is pleading guilty to working more hours than she should."[Pg 34]

"Oh, no, I didn't, Edith," she said merrily. "I said we had been making ready for Christmas."

Edith sat on a stool at her teacher's side. She, too, was ready for a tilt.

"You're not to pronounce sentence, Mr. Judge, until you see what we have been doing. It's to be a great surprise." And Edith looked wise and mysterious.

Then Esther withdrew, returning a little later, gowned in an old-rose house dress of some soft wool stuff. She again sat near the fire.

"Papa," said Edith, "I have been telling Miss Bright about the annual Rocky Mountain ball, and that she must surely go."

John Clayton looked amused.

"I'm afraid Edith couldn't do justice to that social function. I am quite sure you never saw anything like it. It is the most primitive sort of a party, made up of a motley crowd,—cowboys, cowlassies, miners and their families, and ranchmen and theirs. They come early, have a hearty supper, and dance all night; and as many of them imbibe pretty freely, they sometimes come to blows."

He seemed amused at the consternation in Esther's face.

"You don't mean that I shall be expected to go to such a party?" she protested.

"Why not?" he asked, smiling.

"It seems dreadful," she hastened to say, "and besides that, I never go to dances. I do not dance."

"It's not as bad as it sounds," explained John Clayton. "You see these people are human. Their solitary lives are barren of pleasure. They crave intercourse with their kind; and so this annual party offers this opportunity."[Pg 35]

"And is this the extent of their social life? Have they nothing better?"

"Nothing better," he said seriously, "but some things much worse."

"I don't see how anything could be worse."

"Oh, yes," he said, "it could be worse. But to return to the ball. It is unquestionably a company of publicans and sinners. If you wish to do settlement work here, to study these people in their native haunts, here they are. You will have an opportunity to meet some poor creatures you would not otherwise meet. Besides, this party is given for the benefit of the school. The proceeds of the supper help support the school."

"Then I must attend?"

"I believe so. With your desire to help these people, I believe it wise for you to go with us to the ball. You remember how a great Teacher long ago ate with publicans and sinners."

"Yes, I was just thinking of it. Christ studied people as he found them; helped them where he found them." She sat with bent head, thoughtful.

"Yes," John Clayton spoke gently, "Christ studied them as he found them, helped them where he found them."

He sometimes smiled at her girlish eagerness, while more and more he marveled at her wisdom and ability. She had set him to thinking; and as he thought, he saw new duties shaping before him.

It may have been an hour later, as they were reading aloud from a new book, they heard a firm, quick step on the veranda, followed by a light knock.

"It's Kenneth," exclaimed John Clayton in a brisk, cheery tone, as he hastened to open the door. The newcomer was evidently a valued friend. Esther[Pg 36] recognized in the distinguished looking visitor one of the men who had protected her the day of the organization of the Bible school.

John Clayton rallied him on his prolonged absence. Mrs. Clayton told him how they had missed him, and Edith chattered merrily of what had happened since his last visit.

When he was presented to Esther Bright, she rose, and at that moment, a flame leaped from the burning mesquite, and lighted up her face and form. She was lovely. The heat of the fire had brought a slight color to her cheeks, and this was accentuated by her rose-colored gown. Kenneth Hastings bowed low, lower than his wont to women. For a moment his eyes met hers. His glance was keen and searching. She met it calmly, frankly. Then her lashes swept her cheeks, and her color deepened.

They gathered about the hearth. Fresh sticks of grease woods, and pine cones, thrown on the fire, sent red and yellow and violet flames leaping up the chimney. The fire grew hotter, and they were obliged to widen their circle.

What better than an open fire to unlock the treasures of the mind and heart, when friend converses with friend? The glow of the embers seems to kindle the imagination, until the tongue forgets the commonplaces of daily life and grows eloquent with the thoughts that lie hidden in the deeps of the soul.

Such converse as this held this group of friends in thrall. Kenneth Hastings talked well, exceedingly well. All the best stops in his nature were out. Esther listened, at first taking little part in the conversation. She was a good listener, an appreciative listener, and therein lay some of her charm. When he[Pg 37] addressed a remark to her, she noticed that he had fine eyes, wonderful eyes, such eyes as belonged to Lincoln and Webster.

One would have guessed Kenneth Hastings' age to be about thirty. He was tall, rather slender and sinewy, with broad, strong shoulders. He had a fine head, proudly poised, and an intelligent, though stern face. He was not a handsome man; there was, however, an air of distinction about him, and he had a voice of rare quality, rich and musical. Esther Bright had noticed this.

The visitor began to talk to her. His power to draw other people out and make them shine was a fine art with him. His words were like a spark to tinder. Esther's mind kindled. She grew brilliant, and said things with a freshness and sparkle that fascinated everyone. And Kenneth Hastings listened with deepening interest.

His call had been prolonged beyond his usual hour for leave-taking, when John Clayton brought Esther's guitar, that happened to be in the room, and begged her for a song. She blushed and hesitated.

"Do sing," urged the guest.

"I am not a trained musician," she protested.

But her host assured his friend that she surely could sing. Then all clamored for a song.

Esther sat thrumming the strings.

"What shall I sing?"

"'Who is Sylvia,'" suggested Mrs. Clayton.

This she sang in a full, sweet voice. Her tone was true.

"More, more," they insisted, clapping their hands.

"Just one more song," pleaded Edith.

"Do you sing, 'Drink to me only with thine eyes'?"[Pg 38] asked Kenneth. For answer, she struck the chords, and sang; then she laid down the guitar.

"Please sing one of your American ballads. Sing 'Home, Sweet Home,'" he suggested.

She had been homesick all day, so there was a home-sigh in her voice as she sang. Kenneth moved his chair into the shadow, and watched her.

At last he rose to go; and with promises of an early return, he withdrew.

Not to the saloon did he go that night, as had been his custom since coming to the mining camp. He walked on and on, out into the vast aloneness of the mountains. Once in a while he stopped, and looked down towards Clayton Ranch. At intervals he whistled softly.—The strain was "Home, Sweet Home."

John Clayton and his wife sat long before the fire after Esther and Edith had retired. Mary Clayton was a gentle being, with a fair, sweet English face. And she adored her husband. They had been talking earnestly.

"Any way, Mary," John Clayton was saying, "I believe Miss Bright could make an unusually fine man of Kenneth. I believe she could make him a better man, too."

"That might be, John," she responded, "but you wouldn't want so rare a soul as she is to marry him to reform him, would you? She's like a snow-drop."

"No, like a rose," he suggested, "all sweet at the heart. I'd really like to see her marry Kenneth. In fact, I'd like to help along a little."

"Oh, my dear! How could you?" And she looked at him reproachfully.

"Why not?" he asked. "Tell me honestly." He[Pg 39] lifted her face and looked into it with lover-like tenderness. "You like Kenneth, don't you? And we are always glad to welcome him in our home."

"Y-e-s," she responded hesitatingly, "but—"

"But what?"

"I fear he frequents the saloons, and is sometimes in company totally unworthy of him. In fact, I fear he isn't good enough for Miss Bright. I can't bear to think of her marrying any man less pure and noble than she is herself."

He took his wife's hand in both of his.

"You forget, Mary," he said, "that Miss Bright is a very unusual woman. There are few men, possibly, who are her peers. Don't condemn Kenneth because he isn't exactly like her. He's not perfect, I admit, any more than the rest of us. But he's a fine, manly fellow, with a good mind and noble traits of character. If the right woman gets hold of him, she'll make him a good man, and possibly a great one."

"That may be," she said, "but I don't want Miss Bright to be that woman."

"Suppose he were your son, would you feel he was so unworthy of her?"

"Probably not," came her hesitating answer.

"Mary, dear," he said, "I fear you are too severe in your judgment of men. I wish you had more compassion. You see, it is this way: many who seem evil have gone astray because they have not had the influence of a good mother or sister or wife." He bent his head and kissed her.

A moment later, he leaned back and burst into a hearty laugh.

"Why, what's the matter?" she asked. "I don't think it's a laughing matter."[Pg 40]

"It's so ridiculous, Mary. Here we've been concerning ourselves about the possible marriage of Kenneth and Miss Bright, when they have only just met, and it isn't likely they'll ever care for each other, anyway. Let's leave them alone."

And the curtain went down on a vital introductory scene in the drama of life.[Pg 41]

Days came and went. The Bible school of Gila had ceased to be an experiment. It was a fact patent to all that the adobe schoolhouse had become the social center of the community, and that the soul of that center was Esther Bright. She had studied sociology in college and abroad. She had theorized, as many do, about life; now, life itself, in its bald reality, was appealing to her heart and brain. She did not stop to analyze her fitness for the work. She indulged in no morbid introspection. It was enough for her that she had found great human need. She was now to cope, almost single handed, with the forces that drag men down. She saw the need, she realized the opportunity. She worked with the quiet, unfailing patience of a great soul, leaving the fruitage to God.

Sometimes the seriousness in Esther's face would deepen. Then she would go out into the Open. On one of these occasions, she strayed to her favorite haunt in the timber along the river, and seated herself on the trunk of a dead cottonwood tree, lying near the river bank. Trees, covered with green mistletoe, towered above her. Tremulous aspens sparkled in the sunshine. The air was crystal clear; the vast dome of the sky, of the deepest blue. She sat for a long time with face lifted, apparently forgetful of the open letter in her hand. At last she turned to it, and read as follows:[Pg 42]

Lynn, Mass., Tenth Month, Fifth Day, 1888.

My Beloved Granddaughter:

Thy letter reached me Second Day. Truly thou hast found a field that needs a worker, and I do not question that the Lord's hand led thee to Gila. What thou art doing and dost plan to do, interest me deeply; but it will tax thy strength. I am thankful that thou hast felt a deepening sense of God's nearness. His world is full of Him, only men's eyes are holden that they do not know. All who gain strength to lead and inspire their fellows, learn this surely at last:—that the soul of man finds God most surely in the Open. If men would help their fellows, they must seek inspiration and strength in communion with God.

To keep well, one must keep his mind calm and cheerful. So I urge thee not to allow the sorrowfulness of life about thee to depress thee. Thou canst not do thy most effective work if thy heart is always bowed down. The great sympathy of thy nature will lead thee to sorrow for others more than is well for thee. Joy is necessary to all of us. So, Beloved, cultivate joyousness, and teach others to do so. It keeps us sane, and strong and helpful.

I know that the conditions thou hast found shock and distress thee, as they do all godly men and women; but I beg thee to remember, Esther, that our Lord had compassion on such as these, on the sinful as well as on the good, and that He offers salvation to all. How to have compassion! Ah, my child, men are so slow in learning that. Love,—compassion, is the key of Christ's philosophy.

I am often lonely without thee; but do not think I would call thee back while the Lord hath need of thee.

Thy Uncle and Aunt are well, and send their love to thee.

I have just been reading John Whittier's 'Our Master.' Read it on next First Day, as my message to thee.

God bless thee.

Thy faithful grandfather,

David Bright.

As she read, her eyes filled.

In the veins of Esther Bright flowed the blood of honorable, God-fearing people; but to none of these, had humanity's needs called more insistently than to her. Her grandfather had early recognized and fostered[Pg 43] her passion for service; and from childhood up, he had frequently taken her with him on his errands of mercy, that she might understand the condition and the needs of the unfortunate. Between the two there existed an unusual bond.

After reading the letter, Esther sat absorbed in thought. The present had slipped away, and it seemed as though her spirit had absented itself from her body and gone on a far journey. She was aroused to a consciousness of the present by a quick step. In a moment Kenneth Hastings was before her; then, seated at her side.

"Well!" he began. "How fortunate I am! Here I was on my way to call on you to give you these flowers. I've been up on the mountains for them."

"What beautiful mountain asters!" was her response, her face lighting with pleasure. "How exquisite in color! And how kind of you!"

"Yes, they're lovely." He looked into her face with undisguised admiration. Something within her shrank from it.

Three weeks had now passed since the meeting of Kenneth Hastings and Esther Bright. During this time, he had become an almost daily caller at Clayton Ranch. When he made apologies for the frequency of his calls, the Claytons always assured him of the pleasure his presence gave them, saying he was to them a younger brother, and as welcome.

It was evident to them that Kenneth's transformation had begun. John Clayton knew that important changes were taking place in his daily life; that all his social life was spent in their home; that he had ceased to enter a saloon; and that he had suddenly become fastidious about his toilet.[Pg 44]

If Esther noted any changes in him, she did not express it. She was singularly reticent in regard to him.

At this moment, she sat listening to him as he told her of the mountain flora.

"Wait till you see the cactus blossoms in the spring and summer." He seemed very enthusiastic. "They make a glorious mass of color against the soft gray of the dry grass, or soil."

"I'd love to see them." She lifted the bunch of asters admiringly.

"I have some water colors of cacti I made a year ago. I'd like to show them to you, Miss Bright, if you are interested."

She assured him she was.

"I was out in the region of Colorado River a year ago. It is a wonderful region no white man has yet explored. Only the Indians know of its greatness. I have an idea that when that region is explored by some scientist, he will discover that canyon to be the greatest marvel of the world. What I saw was on a stupendous, magnificent scale."

"How it must have impressed you!"

"Wonderfully! I'll show you a sketch I made of a bit of what I found. It may suggest the magnificence of the coloring to you."

"How did you happen to have sketching materials with you?"

"I agreed to write a series of articles for an English magazine, and wished illustrations for one of the articles."

"How accomplished you are!" she exclaimed. "A mining engineer, a painter, an author—"

"Don't!" he protested, raising a deprecatory hand.

Having launched on the natural wonders of Arizona,[Pg 45] he grew more and more eloquent, till Esther's imagination made a daring leap, and she looked down the gigantic gorge he pictured to her, over great acres of massive rock formation, like the splendor of successive day-dawns hardened into stone, and saw gigantic forms chiseled by ages of erosion.

"Do you ride horseback, Miss Bright?" he asked, suddenly changing the conversation.

"I am sorry to say that I do not. I do not even know how to mount."

"Let me teach you to ride," he said, with sudden interest.

"You would find me an awkward pupil," she responded, rising.

"I am willing to wager that I should not. When may I have the pleasure of giving you the first lesson?"

"Any time convenient for you when I am not teaching." She began to gather up her flowers and hat.

Then and there, a day was set for the first lesson in horsemanship.

"Sit down, please," said Kenneth. "I want you to enlighten me. I am painfully dense."

She seated herself on the tree trunk again, saying as she did so:

"I had not observed any conspicuous signs of density on your part, Mr. Hastings, save that you think I could be metamorphosed into a horsewoman. Some women are born to the saddle. I was not. I am not an Englishwoman, you see."

"But decidedly English," he retorted. "I wish you would tell me your story."

Her face flushed.

"I beg your pardon," he hastened to say. "I did [Pg 46] not mean to be rude. You interest me deeply. Anything you think or do, anything that has made you what you are, is of deep interest to me."

"There is nothing to tell," she said simply. "Just a few pages, with here and there an entry; a few birthdays; graduation from college; foreign travel; work in Gila; a life spent in companionship with a wonderfully lovely and lovable grandfather; work at his side, and life's history in the making. That is all."

"All?" he repeated. "But that is rich in suggestion. I have studied you almost exclusively for three weeks, and I know you."

She looked up. The expression in his eyes nettled her. Her spinal column stiffened.

"Indeed! Know a woman in three weeks! You do well, better than most of your sex. Most men, I am told, find woman an unsolvable problem, and when they think they know her, they find they don't."

This was interesting to him. He liked the flash in her eye.

"Some life purpose brings you to Gila, to work so unselfishly for a lot of common, ignorant people."

"What is that to you?"

Her question sounded harsh in her own ears, and then she begged his pardon.

"No apology is necessary on your part," he said, changing from banter to a tone of seriousness. "My words roused your resentment. I am at fault. The coming of a delicately nurtured girl like you into such a place of degradation is like the coming of an angel of light down to the bottomless pit. I beg forgiveness for saying this; but, Miss Bright, a mining camp, in these days, is a hotbed of vice."

"All the more reason why people of intelligence and character should try to make the life here clean. I[Pg 47] believe we can crowd out evil by cultivating the good."

"You are a decided optimist," he said; "and I, by force of circumstances, have become a confirmed pessimist."

"You will not continue to be a pessimist," she said, prophetically, seeing in her mind's eye what he would be in the years to come. "You will come to know deep human sympathy; you will believe in the possibility of better and better things for your fellows. You will use your strength, your intellect, your fine education, for the best service of the world about you."

Somehow that prophecy went home to him.

"By George!" he exclaimed, "you make a fellow feel he must be just what you want him to be, and what he ought to be."

The man studied the woman before him, with deep and increasing interest. She possessed a strength, he was sure, of which no one in Gila had yet dreamed. He continued:

"Would you mind telling me the humanitarian notions that made you willing to bury yourself in this godless place?"

She hesitated. The catechism evidently annoyed her, for it seemed to savor of impertinent curiosity. But at last she answered:

"I believe my grandfather is responsible for the humanitarian notions. It is a long story."

She hesitated.

"I am interested in what he has done, and what you are doing. Please tell me about it."

"Well, it goes back to my childhood. I was my grandfather's constant companion until I went to college. He is a well-known philanthropist of New England, interested in the poor, in convicts in prison and[Pg 48] out, in temperance work, in the enfranchisement of woman, in education, and in everything that makes for righteousness."

She paused.

"And he discussed great questions with you?"

"Yes, as though in counsel. He would tell me certain conditions, and ask me what I thought we had better do."

"An ideal preparation for philanthropic service." He was serious now.

"There awoke within me, very early, the purpose to serve my fellow men in the largest possible way. Grandfather fostered this; and when the time came for me to go to college, he helped me plan my course of study." She looked far away.

"You followed it out?"

"Very nearly. You see, Mr. Hastings, service is no accident with me. It dates back generations. It is in my blood."

"Your blood is of the finest sort. Surely service does not mean living in close touch with immoral, disreputable people."

Her eyes kindled, grew dark in color.

"What does it mean, then? The strong, the pure, the godly should live among men, teach by precept and example how to live, and show the loveliness of pure living just as Jesus did. I have visited prisons with grandfather, have prayed with and for criminals, and have sung in the prisons. Is it not worth while to help these wretched creatures look away from themselves to God?"

"Oh, Miss Bright," he protested, "it is dreadful for a young girl like you even to hear of the wickedness of men."[Pg 49]

"Women are wicked, too," she responded seriously, "but I never lose hope for any one."

"Some day hope will die out in your heart," he said discouragingly.

"God forbid!" she spoke solemnly. In a moment she continued:

"I am sure you do not realize how many poor creatures never have had a chance to be decent. Just think how many are born of sinful, ignorant parents, into an environment of sin and ignorance. They live in it, they die in it. I, by no will or merit of my own, received a blessed heritage. My ancestors for generations have been intelligent, godly people, many of them people of distinction. I was born into an atmosphere of love, of intelligence, of spirituality, and of refinement. I have lived in that atmosphere all my life. My good impulses have been fostered, my wrong ones checked."

"I'll wager you were painfully conscientious," he said.

"Why should I have been given so much," she continued, "and these poor creatures so little, unless it was that I should minister to their needs?"

"You may be right." He seemed unconvinced. "But I am sure of one thing. If I had been your grandfather, and you my grandchild, I never would have let you leave me."

He was smiling.

"You should know my grandfather, and then you would understand."

"How did you happen to come to Gila?" he asked.

"I met Mr. and Mrs. Clayton in the home of one of their friends in England. We were house guests there at the same time. We returned to America on the same steamer. Mrs. Clayton knew I was to do settlement[Pg 50] work, and urged me to come to Gila a while instead. So I came."

How much her coming was beginning to mean to him, to others! Both were silent a while. Then it was Kenneth who spoke.

"Do you know, Miss Bright, it never occurred to me before you came, that I had any obligations to these people? Now I know I have. I was indifferent to the fact that I had a soul myself until you came."

She looked up questioningly.

"Yes, I mean it," he said. "To all intents and purposes I had no soul. A man forgets he has a soul when he lives in the midst of vice, and no one cares whether he goes to the devil or not."

"Is it the environment, or the feeling that no one cares?" she asked.

"Both." He buried his face in his hands.

"Did you feel that no one cared? I'm sure your mother cared."

She had touched a sore spot.

"My mother?" he said, bitterly. "My mother is a woman of the world." Here he lifted his head. "She is engrossed in society. She has no interest whatever in me, and never did have, although I am her only child."

"Perhaps you are mistaken," she said softly. "I am sure you must be mistaken."

"When a mother lets year after year go by without writing to her son, do you think she cares?"

"You don't mean to say that you never receive a letter from your mother?"

"My mother has not written to me since I came to America. Suppose your mother did not write to you. Would you think she had a very deep affection for you?"[Pg 51]

Esther's face grew wistful.

"Perhaps you do not know," she answered, "I have no living mother. She died when I was born."

"Forgive my thoughtless question," he said. "I did not know you had lost your mother. I was selfish."

"Oh, no," she said, "not selfish. You didn't know, that was all. We sometimes make mistakes, all of us, when we do not know. I lost my father when I was a very little child."

"And your grandfather reared you?"

"Yes, grandfather, assisted by my uncle and auntie."

"Tell me about your grandfather, I like to hear."

"He was my first playfellow, and a fine one he was, too."

"How I envy him!"

"You mustn't interrupt me," she said demurely.

"I am penitent. Do proceed."

Then she told him, in brief, the story of her life, simple and sweet in the telling. She told him of the work done by her grandfather.

"He preaches, you tell me."

"Yes," she said, rambling on, "he is a graduate of Yale, and prepared to be a physician. But his heart drew him into the ministry, the place where he felt the Great Physician would have him be. Grandfather is a Friend, you know, a Quaker."

"So I understood."

"He had a liberal income, so it was possible for him to devote his entire time to the poor and distressed. He has been deeply interested in the Negro and American Indian, and in fact, in every one who is oppressed by his stronger brother."

"An unusual man."

"Very."[Pg 52]

"How could you leave him? Did you not feel that your first duty was to him?"

"It was hard to leave him," she said, while her eyes were brimming with tears; "but grandfather and I believe that opportunity to serve means obligation to serve. Besides, love is such a spiritual thing we can never be separated."

"Love is such a spiritual thing—" he repeated, and again, "Spiritual."

He was silent a moment, then he spoke abruptly.

"You have already been the salvation of at least one soul. I owe my soul to you."

"Oh, no, not to me," she protested. "That was God's gift to you from the beginning. It may have slumbered, but you had it all the while."

"What did your grandfather say to your coming to Gila?"

"When I told him of the call to come here, told him that within a radius of sixty miles there was no place of religious worship, he made no response, but sat with his head bowed. At last he looked up with the most beautiful smile you ever saw, and said, 'Go, my child, the Lord hath need of thee.'" Her voice trembled a little.

"He was right," said Kenneth earnestly. "The Lord has need of such as you everywhere. I have need of you. The people here have need of you. Help us to make something of our lives yet, Miss Bright." There was no doubting his sincerity.

She had again risen to go.

"Don't go," he said. "I would like to tell you my story, if you care to hear."

"I shall be glad to hear your story. I know it will not be as meager as mine."[Pg 53]

"I wish," he said earnestly, "that I might measure up to your ideal of what a man should be. I cannot do that. But I can be honest and tell you the truth about myself.

"I belong to a proud, high-strung race of people. My father is like his forbears. He is a graduate of Cambridge; has marked literary ability.

"My mother is a society woman, once noted as a beauty at court. She craves admiration and must have it. That is all she cares for. She has never shown any affection for my father or me.

"I left England when I was twenty-two,—my senior year at Cambridge. I've been in America eight years, and during that time I have received but two letters from home, and those were from my father."

"You must have felt starved."

"That's it," he said, "starved! I did feel starved. You see, Miss Bright, a fellow's home has much to do with his life and character. What is done there influences him. Wine was served on our table. My parents partook freely of it; so did our guests. I have seen some guests intoxicated. We played cards, as all society people do. We played for stakes, also. You call that gambling. My mother's men admirers were mush-headed fools."

"Such conditions obtain in certain circles in this country, too. They are a menace to the American home," she said gravely.

"I was sent to Cambridge," he continued, "as my father and his father, and father's father before him, had been sent. I was a natural student and always did well in my work. But my drinking and gambling finally got me into trouble. I was fired. My father was so incensed at my dismissal he told me never to[Pg 54] darken his doors again. He gave me money, and told me to leave at once for America.

"I went to my mother's room to bid her good-by. She stood before a mirror while her maid was giving the final touches to her toilet. She looked regal and beautiful as she stood there, and I felt proud of her. I told her what had happened, and that I had come to bid her good-by. She turned upon me pettishly, and asked me how I could mar her pleasure just as she was going to a ball. Her last words to me were, 'I hate to be disturbed with family matters!'"

"Did she bid you good-by?"

"No."

"Forget it," she urged. "All women are not like that. I hope you will find some rare woman who will be as a mother to you."

"Forget it!" he repeated bitterly. "I can't."

"But you will sometime. You came to America. What next?"

"Then I entered the School of Mines at Columbia, and took my degree the following year, after which I joined Mr. Clayton here. That was seven years ago."

"Did you know him in England?"

"Yes. During these intervening years I have frequented the saloons. I have drank some, gambled some, as I did at home. And I have mingled with disreputable men here, but not to lift them up. I have not cared, chiefly because I knew no one else cared."

His companion was silent.

"You despise me, Miss Bright," he continued. "I deserve your contempt, I know. But I would do anything in the power of man to do now, if I could undo the past, and have a life as blameless as your own."[Pg 55]

He glanced at his companion.

"What a brute I have been," he exclaimed, "to pour my ugly story into your ears!"

"I am glad you told me," she assured him. She looked up with new sympathy and understanding. "You are going to live down your past now, Mr. Hastings. We'll begin here and now. You will not speak of this again unless it may be a relief to you. The matter will not cross my lips."

She flashed upon him a radiant smile. She believed in him. He could hardly comprehend it.

"You do not despise me? You forgive my past?" He looked into her face.

"It is God who forgives. Why should I despise whom God forgives?"

"If ever I find my way to God," he said in a low voice, "it will be through you."

She quoted softly:

"'Though your sins be as scarlet, they shall be as white as snow; though they be red as crimson, they shall be as wool.'" Then she added, "I must go home now."

They walked on to Clayton Ranch. After a few commonplaces, Kenneth lifted his hat, and turning, walked swiftly toward the company's headquarters.

Esther stood a moment, watching the easy, graceful stride of the young engineer. His words then, and long afterwards, rang in her ears,—"Help us to make something of our lives yet." And as the words echoed in her heart, a voice aged and full of tender love, came to her like an old refrain,—"Go, my child, the Lord hath need of thee."

[Pg 56] She lifted her face and looked into the sky. Suddenly she became conscious of the beauty of the hour. The violet light of evening played about her face and form. She forgot the flowers in her arms, forgot the sunset, and stood absorbed in prayer. [Pg 57]

It was the day of the ball. Parties of mountaineers, some on horseback, some in wagons, started for Jamison Ranch.

In the early evening, a wagon load made up of the members of the Clayton household, Kenneth Hastings and some Scotch neighbors, started for the same destination.

The road skirted the foothills for some distance, then followed the canyon several miles; and then, branching off, led directly to Jamison Ranch. As the twilight deepened into night, Nature took on a solemn and mysterious beauty. The rugged outline of the mountains, the valley and river below,—were all idealized in the softening light. The New England girl sat drinking in the wonder of it all. The mountains were speaking to her good tidings of great joy.

In the midst of merry chatter, some one called out:

"Sing us a song, Miss Bright."

It was Kenneth Hastings. Hearing her name, she roused from her reverie.

"A song?"

"Yes, do sing," urged several.

"Sing 'Oft in the Stilly Night,'" suggested Mrs. Clayton.

"All sing with me," responded Esther.

Then out on the stillness floated the beautiful old Irish song. Other voices joined Esther's. Kenneth[Pg 58] Hastings was one of the singers. His voice blended with hers and enriched it.

Song after song followed, all the company participating to some extent in the singing.

Was it the majesty of the mountain scenery that inspired Esther, that sent such a thrill of gladness into her voice? Or was it perhaps the witchery of the moonlight? Whatever may have been the cause, a new quality appeared in her voice, and stirred the hearts of all who listened to her singing; it was deep and beautiful.

What wonder if Kenneth Hastings came under the spell of the song and the singer? The New England girl was a breath of summer in the hard and wintry coldness of his life.

"Who taught you to sing?" he asked abruptly.

"The birds," she answered, in a joyous, laughing tone.

"I can well believe that," he continued, "but who were your other instructors?"

Then, in brief, she told him of her musical training.

Would she sing one of his favorite arias some day? naming the aria.

She hummed a snatch of it.

"Go on," he urged.

"Not now; some other time."

"Won't you give us an evening recital soon?" asked John Clayton.

And then and there the concert was arranged for.

"Miss Bright," said Mrs. Carmichael, "I am wondering how we ever got on without you."

Esther laughed a light-hearted, merry laugh.

"That's it," Kenneth hastened to say. "We 'got on.' We simply existed. Now we live."

All laughed at this.[Pg 59]

"You are not complimentary to our friends. I protest," said Esther.

"You are growing chivalrous, Kenneth," said Mrs. Clayton. "I'm glad you think as we do. Miss Bright, you have certainly enriched life for all of us."

"Don't embarrass me," said Esther in a tone that betrayed she was a little disconcerted.

But now they were nearing their journey's end. The baying of hounds announced a human habitation. An instant later, the house was in sight, and the dogs came bounding down the road, greeting the party with vociferous barks and growls. Mr. Jamison followed, profuse in words of welcome.

As Kenneth assisted Esther from the wagon, he said:

"Your presence during this drive has given me real pleasure."

Her simple "Thank you" was her only response.

At the door they were met by daughters of the house, buxom lasses, who ushered them into an immense living room. This opened into two other rooms, one of which had been cleared for dancing.

Esther noted every detail,—a new rag carpet on the floor; a bright-colored log-cabin quilt on one of the beds; on the other bed, was a quilt of white, on which was appliqued a menagerie of nondescript animals of red and green calico, capering in all directions. The particular charm of this work of art was its immaculate quilting,—quilting that would have made our great-grandmothers green with envy.

Cheap yellow paper covered the walls of the room. A chromo, "Fast Asleep," framed in heavy black walnut, hung close to the ceiling. A sewing machine stood in one corner.

At first, Esther did not notice the human element in[Pg 60] the room. Suddenly a little bundle at the foot of the bed began to grunt. She lifted it, and found a speck of humanity about three months old. In his efforts to make his wants known, and so secure his rightful attention, he puckered his mouth, doubled up his fists, grew red in the face, and let forth lusty cries.

As she stood trying to soothe the child, the mother rushed in, snatched it from the teacher's arms, and gave it a slap, saying as she did so, "The brat's allus screechin' when I wanter dance!"

She left the babe screaming vociferously, and returned to dance. Four other infants promptly entered into the vocal contest, while their respective parents danced in the adjoining room, oblivious of everything save the pleasure of the hour. Then it was that the New England girl became a self-appointed nurse, patting and soothing first one, then another babe; but it was useless. They had been brought to the party under protest; and offended humanity would not be mollified.

The teacher stepped out into the living room, which was in festive array. Its picturesqueness appealed to her. A large fire crackled on the hearth, and threw its transforming glow over the dingy adobe walls, decorated for the occasion with branches of fragrant silver spruce. Blocks of pine tree-trunks, perhaps two feet in height, stood in the corners of the room. Each of these blocks contained a dozen or more candle sockets, serving the purpose of a candelabrum. Each of the sockets bore a lighted candle, which added to the weirdness of the scene.

The room was a unique background for the men and women gathered there. At least twenty of the mountaineers had already assembled. They had come at late[Pg 61] twilight, and would stay till dawn, for their journey lay over rough mountain roads and through dangerous passes.

The guests gathered rapidly, laughing and talking as they came.

It was a motley crowd,—cowboys, in corduroy, high boots, spurs, slouch hats, and knives at belt, brawny specimens of human kind; cowlasses, who for the time, had discarded their masculine attire of short skirts, blouse, belt and gun, for feminine finery; Scotchmen in Highland costume; Mexicans in picturesque dress; English folk, clad in modest apparel; and Irishmen and Americans resplendent in colors galore.

For a moment, Esther stood studying the novel scene. Mr. Clayton, observing her, presented her to the individuals already assembled. The last introduction was to a shambling, awkward young miner. After shaking the hand of the teacher, which he did with a vigor quite commensurate to his elephantine strength, he blurted out, "Will yez dance a polky wid me?"

She asked to be excused, saying she did not dance.

"Oh, but I can learn yez," he said eagerly. "Yez put one fut so, and the other so," illustrating the step with bovine grace as he spoke.

His efforts were unavailing, so he found a partner among the cowlasses.

Again Esther was alone. She seated herself near one of the improvised pine candelabra, and continued to study the people before her. Here she found primitive life indeed, life close to the soil. How to get at these people, how to learn their natures, how to understand their needs, how to help them,—all these questions pressed upon her. Of this she was sure:—she[Pg 62] must come in touch with them to help them. Men and women older and more experienced than she might well have knit their brows over the problem.

She was roused to a consciousness of present need by a piercing cry from one of the infants in the adjoining room. The helpless cry of a child could never appeal in vain to such a woman as Esther Bright. She returned to the bedroom, lifted the wailing bundle in her arms, seated herself in a rocker, and proceeded to quiet it. Kenneth Hastings stood watching her, while an occasional smile flitted across his face. As John Clayton joined him, the former said in a low tone:

"Do you see Miss Bright's new occupation, John?"

"Yes, by George! What will that girl do next? Who but Miss Bright would bother about other people's crying infants? But it's just like her! She is true woman to the heart. I wish there were more like her."

"So do I, John. I wish I were more like her myself in unselfish interest in people."

"She has done you great good already, Kenneth."

"Yes, I know."

Then a shadow darkened Kenneth's face. He moved toward the outer door that stood open, and looked out into the night.

At last Esther's task was accomplished, the babe was asleep, and she returned to the scene of the dancing. Kenneth sought her and asked her to dance the next waltz with him. She assured him, also, that she did not dance.

"Let me teach you," he urged. But she shook her head.

"You do not approve of dancing?" he asked, lifting his brows.

"I did not say I do not approve of dancing; I said[Pg 63] I do not dance. By the way," she said, changing the subject of the conversation, "my lessons in riding are to begin to-morrow, are they not?"

"To-morrow, if I may have the pleasure. Do you think riding wicked, too?"

This he said with a sly twinkle in his eye.

"Wicked, too?" she echoed. "What's the 'too' mean?"

"Dancing, of course."