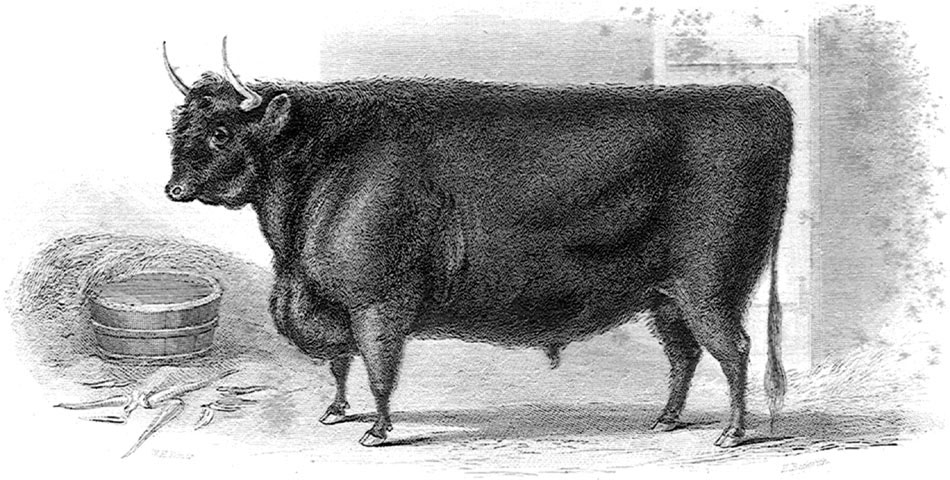

A West Highland Ox

The Property of Mr. Elliott of East Ham Essex.

Title: The American Reformed Cattle Doctor

Author: George H. Dadd

Release date: November 12, 2011 [eBook #37997]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Barbara Kosker, Bryan Ness and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from scans of public domain works at the

University of Michigan\'s Making of America collection.)

| PAGE | ||

| Introduction, | 9 | |

| CATTLE | ||

| Importance of supplying Cattle with pure Water, | 15 | |

| Remarks on feeding Cattle, | 17 | |

| The Barn and Feeding Byre, | 21 | |

| Milking, | 24 | |

| Knowledge of Agricultural and Animal Chemistry important to Farmers, | 25 | |

| On Breeding, | 30 | |

| The Bull, | 34 | |

| Value of different breeds of Cows, | 35 | |

| Method of preparing Rennet, as practised in England, | 36 | |

| Making Cheese, | 37 | |

| Gloucester Cheese, | 38 | |

| Chester Cheese, | 39 | |

| Stilton Cheese, | 40 | |

| Dunlop Cheese, | 41 | |

| Green Cheese, | 42 | |

| Making Butter, | 44 | |

| Washing Butter, | 45 | |

| Coloring Butter, | 46 | |

| Description of the Organs of Digestion in Cattle, | 47 | |

| Respiration and Structure of the Lungs, | 53 | |

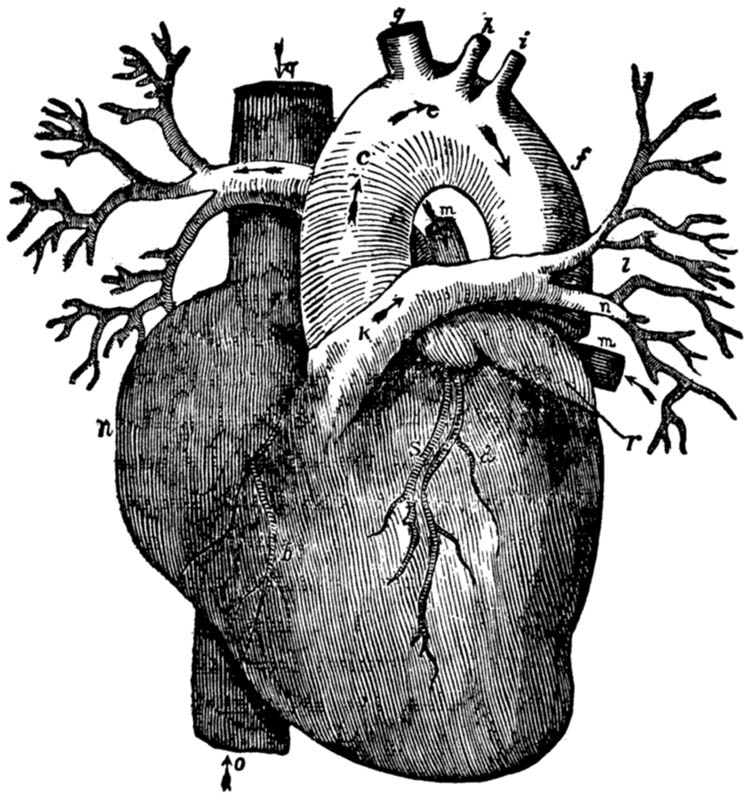

| Circulation of the Blood, | 54 | |

| The Heart viewed externally, | 55 | |

| Remarks on Blood-letting, | 58 | |

| Efforts of Nature to remove Disease, | 67 | |

| Proverbs of the Veterinary Reformers, | 70 | |

| An Inquiry concerning the Souls of Brutes, | 72 | |

| The Reformed Practice—Synoptical View of the Prominent Systems of Medicine, | 75 | |

| Creed of the Reformers, | 79 | |

| True Principles, | 80 | |

| Inflammation, | 88 | |

| Remarks, showing that very little is known of the Nature and Treatment of Disease, | 94 | |

| Nature, Treatment, and Causes of Disease in Cattle, | 105 | |

| Pleuro-Pneumonia, | 107 | |

| Locked-Jaw, | 115 | |

| Inflammatory Diseases, | 121 | |

| Inflammation of the Stomach, (Gastritis,) | 121 | |

| Inflammation of the Lungs, (Pneumonia,) | 122 | |

| Inflammation of the Bowels, (Enteritis.—Inflammation of the Fibro-Muscular Coat of the Intestines,) | 124 | |

| Inflammation of the Peritoneal Coat of the Intestines, (Peritonitis,) | 125 | |

| Inflammation of the Kidneys, (Nephritis,) | 125 | |

| Inflammation of the Bladder, (Cystitis,) | 126 | |

| Inflammation of the Womb, | 126 | |

| Inflammation of the Brain, (Phrenitis,) | 127 | |

| [Pg 6]Inflammation of the Eye, | 128 | |

| Inflammation of the Liver, (Hepatitis,) | 128 | |

| Jaundice, or Yellows, | 130 | |

| Diseases of the Mucous Surface, | 132 | |

| Catarrh, or Hoose, | 133 | |

| Epidemic Catarrh, | 134 | |

| Malignant Epidemic, (Murrain,) | 135 | |

| Diarrhœa, (Looseness of the Bowels,) | 136 | |

| Dysentery, | 138 | |

| Scouring Rot, | 139 | |

| Disease of the Ear, | 140 | |

| Serous Membranes, | 140 | |

| Dropsy, | 141 | |

| Hoove, or "Blasting," | 144 | |

| Joint Murrain, | 147 | |

| Black Quarter, | 149 | |

| Open Joint, | 151 | |

| Swellings of Joints, | 152 | |

| Sprain of the Fetlock, | 153 | |

| Strain of the Hip, | 154 | |

| Foul in the Foot, | 154 | |

| Red Water, | 157 | |

| Black Water, | 160 | |

| Thick Urine, | 160 | |

| Rheumatism, | 161 | |

| Blain, | 162 | |

| Thrush, | 163 | |

| Black Tongue, | 163 | |

| Inflammation of the Throat and its Appendages, | 163 | |

| Bronchitis, | 164 | |

| Inflammation of Glands, | 164 | |

| Loss of Cud, | 166 | |

| Colic, | 166 | |

| Spasmodic Colic, | 167 | |

| Constipation, | 168 | |

| Falling down of the Fundament, | 171 | |

| Calving, | 171 | |

| Embryotomy, | 175 | |

| Falling of the Calf-Bed, or Womb, | 176 | |

| Garget, | 177 | |

| Sore Teats, | 178 | |

| Chapped Teats and Chafed Udder, | 178 | |

| Fever, | 178 | |

| Milk or Puerperal Fever, | 182 | |

| Inflammatory Fever, | 183 | |

| Typhus Fever, | 186 | |

| Horn Ail in Cattle, | 189 | |

| Abortion in Cows, | 191 | |

| Cow-Pox, | 194 | |

| Mange, | 195 | |

| Hide-bound, | 196 | |

| Lice, | 196 | |

| Importance of keeping the Skin of Animals in a Healthy State, | 197 | |

| Spaying Cows, | 201 | |

| Operation of Spaying, | 204 | |

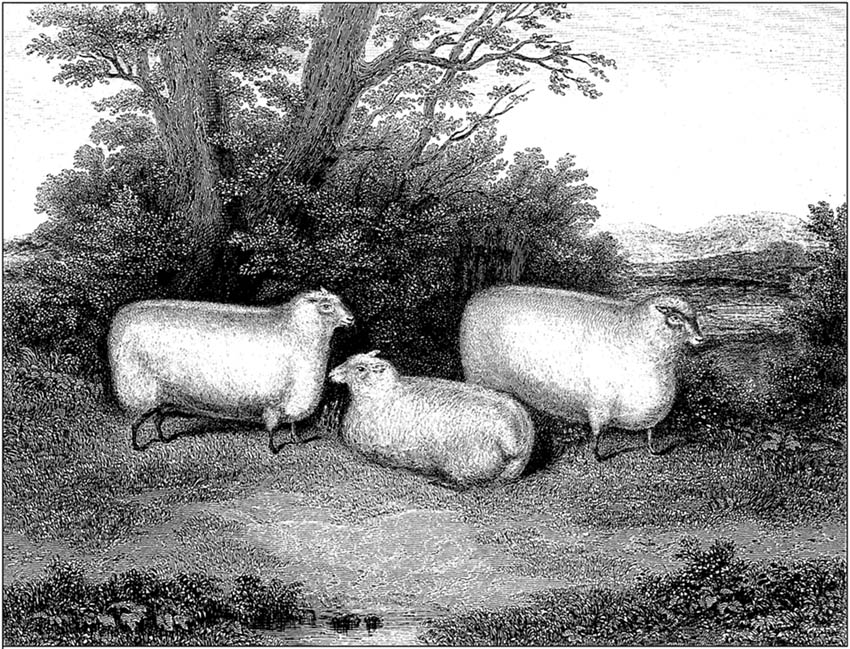

| SHEEP | ||

| Preliminary Remarks, | 209 | |

| Staggers, | 219 | |

| Foot Rot, | 220 | |

| Rot, | 221 | |

| [Pg 7]Epilepsy, | 222 | |

| Red Water, | 223 | |

| Cachexy, or General Debility, | 224 | |

| Loss of Appetite, | 224 | |

| Foundering, (Rheumatism,) | 224 | |

| Ticks, | 225 | |

| Scab, or Itch, | 225 | |

| Diarrhœa, | 227 | |

| Dysentery, | 227 | |

| Constipation, or Stretches, | 228 | |

| Scours, | 230 | |

| Dizziness, | 231 | |

| Jaundice, | 232 | |

| Inflammation of the Kidneys, | 232 | |

| Worms, | 233 | |

| Diseases of the Stomach from eating Poisonous Plants, | 233 | |

| Sore Nipples, | 234 | |

| Fractures, | 234 | |

| Common Catarrh and Epidemic Influenza, | 235 | |

| Castrating Lambs, | 236 | |

| Nature of Sheep, | 237 | |

| The Ram, | 238 | |

| Leaping, | 239 | |

| Argyleshire Breeders, | 239 | |

| Fattening Sheep, | 240 | |

| Improvement in Sheep, | 244 | |

| Description of the Different Breeds of Sheep, | 249 | |

| Teeswater Breed, | 249 | |

| Lincolnshire Breed, | 250 | |

| Dishley Breed, | 250 | |

| Cotswold Breed, | 250 | |

| Romney Marsh Breed, | 251 | |

| Devonshire Breed, | 251 | |

| Dorsetshire Breed, | 251 | |

| Wiltshire Breed, | 252 | |

| South Down Breed, | 252 | |

| Herdwick Breed, | 253 | |

| Cheviot Breed, | 253 | |

| Merino Breed, | 253 | |

| Welsh Sheep, | 254 | |

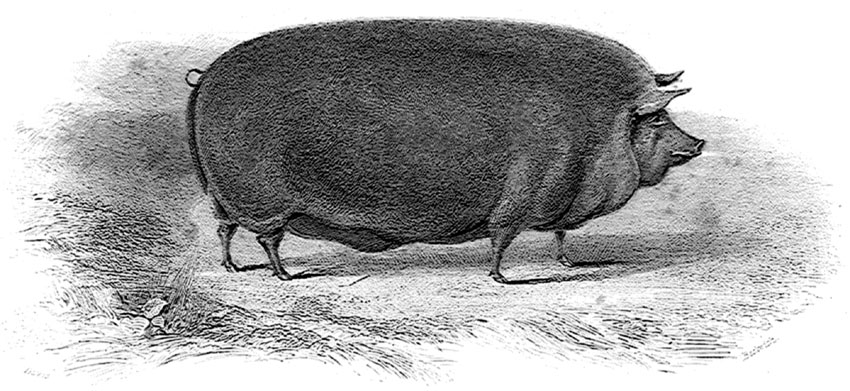

| SWINE. | ||

| Preliminary Remarks, | 255 | |

| Natural History of the Hog, | 259 | |

| Generalities, | 262 | |

| General Debility, or Emaciation, | 263 | |

| Epilepsy, or Fits, | 264 | |

| Rheumatism, | 264 | |

| Measles, | 265 | |

| Ophthalmia, | 266 | |

| Vermin, | 266 | |

| Red Eruption, | 267 | |

| Dropsy, | 267 | |

| Catarrh, | 267 | |

| Colic, | 268 | |

| Diarrhœa, | 268 | |

| Frenzy, | 268 | |

| Jaundice, | 269 | |

| Soreness of the Feet, | 269 | |

| [Pg 8]Spaying, | 270 | |

| Various Breeds of Swine, | 271 | |

| Berkshire Breed, | 271 | |

| Hamphire Breed, | 271 | |

| Shropshire Breed, | 272 | |

| Chinese Breed, | 272 | |

| Boars and Sows for Breeding, | 272 | |

| Rearing Pigs, | 273 | |

| Fattening Hogs, | 275 | |

| Method of Curing Swine's Flesh, | 277 | |

| APPENDIX | ||

| On the Action of Medicines, | 279 | |

| Clysters, | 281 | |

| Forms of Clysters, | 283 | |

| Infusions, | 286 | |

| Antispasmodics, | 287 | |

| Fomentations, | 287 | |

| Mucilages, | 289 | |

| Washes, | 289 | |

| Physic for Cattle, | 290 | |

| Mild Physic for Cattle, | 291 | |

| Poultices, | 292 | |

| Styptics, to arrest Bleeding, | 296 | |

| Absorbents, | 296 | |

| Forms of Absorbents, | 297 | |

| VETERINARY MATERIA MEDICA, embracing a List of the various Remedies used by the Author of this work in the Practice of Medicine on Cattle, Sheep, and Swine, | 299 | |

| General Remarks on Medicines, | 312 | |

| Properties of Plants, | 315 | |

| Potato, | 316 | |

| TREATMENT OF DISEASE IN DOGS—Preliminary Remarks, | 323 | |

| Distemper, | 325 | |

| Fits, | 326 | |

| Worms, | 327 | |

| Mange, | 328 | |

| Internal Abscess of the Ear, | 329 | |

| Ulceration of the Ear, | 329 | |

| Inflammation of the Bowels, | 329 | |

| Inflammation of the Bladder, | 330 | |

| Asthma, | 331 | |

| Piles, | 331 | |

| Dropsy, | 332 | |

| Sore Throat, | 332 | |

| Sore Ears, | 332 | |

| Sore Feet, | 333 | |

| Wounds, | 333 | |

| Sprains, | 333 | |

| Scalds, | 334 | |

| Ophthalmia, | 334 | |

| Weak Eyes, | 335 | |

| Fleas and Vermin, | 335 | |

| Hydrophobia, | 335 | |

| MALIGNANT MILK SICKNESS of the Western States, or Contgious Typhus, | 339 | |

| BONE DISORDER IN COWS, | 351 | |

There is no period in the history of the United States when our domestic animals have ranked so high as at the present time; yet there is no subject on which there is such a lamentable want of knowledge as the proper treatment of their diseases.

Governor Briggs, in a recent letter to the author, says, "You have my thanks, and, in my opinion, are entitled to the thanks of the community, for entering upon this important work. While the subject has engaged the attention of scientific men in other countries, it has been too long neglected in our own. Cruelty and ignorance have marked our treatment to diseased animals. Ignorant himself both of the disease and the remedy, the owner has been in the habit of administering the popular remedy of every neighbor who had no better powers of knowing what should be done than himself, until the poor animal, if the disease would not have proved fatal, is left alone, until death, with a friendly hand, puts a period to his sufferings: he is, however, often destroyed by the amount or destructive character of the remedies, or else by the cruel mode of administering them. I am persuaded that the community will approve of your exertions, and find it to their interest to support and sustain your system."

The author has labored for several years to substitute a safer and a more efficient system of medication in the [Pg 10]treatment of diseased animals, and at the same time to point out to the American people the great benefits they will derive from the diffusion of veterinary education.

That many thousands of our most valuable cattle die under the treatment, which consists of little else than blood-letting, purging, and blistering, no one will deny; and these dangerous and destructive agents are frequently administered by men who are totally unacquainted with the nature of the agents they prescribe. But a better day is dawning; veterinary information is loudly called for—demanded; and the farmers will have it; but it must be a safer and a more efficient system than that heretofore practised.

The object of the veterinary art is not only congenial with human medicine, but the very same paths that lead to a knowledge of the diseases of man lead also to a knowledge of those of brutes.

Our domestic animals deserve consideration at our hands. We have tried all manner of experiments on them for the benefit of science; and science and scientific men should do something to repay the debt, by alleviating their sufferings and improving their condition. We are told that physicians of all ages have applied themselves to the dissection of animals, and that it was by analogy that those of Greece and Rome judged of the structure of the human body. For example, the Greeks and Arabians confined themselves to the dissection of apes and other quadrupeds. Galen has given us the anatomy of the ape for that of man; and it is clear that his dissections were restricted to brutes, when he says, that "if learned physicians have been guilty of gross errors, it is because they neglected to dissect animals." We advocate the establishment of veterinary schools, and the cultivation of our reformed system of veterinary medicine, on the broad principles of humanity. These poor animals are as susceptible to pain and suffering as we are. Has not the Almighty given us dominion over them, and placed them under our protection? Have we done our duty by them? Can we render a good account of our stewardship?

[Pg 11]In almost every department of science the spirit of inquiry is abroad, investigation is active; yet, in this department, every thing is left to chance and ignorance. Men of all professions find it for their interest to protect property. The merchant, previous to sending his vessel on a voyage to a distant port, seeks out a skilful navigator to pilot that vessel into her desired haven with safety. He protects his property. We protect our property against the ravages of fire by insurance—we defend our houses from the lightning by conducting that fluid down the sides of the building into the earth. And shall we not protect our animals? Is not property invested in live stock as valuable, in proportion, as that invested in real estate? Can we permit live stock to degenerate and die prematurely from a want of knowledge of the fundamental laws of their being? Can we look on and see their heart's blood drawn from them—their flesh setoned, burned, and blistered—simply because it was the misguided custom of our ancestors?

We appeal to the American people at large. They have great encouragement to educate young men in this important branch of study; for the beneficial results will be, that the diseases of all classes of domestic animals will be better understood, and the great losses which this country sustains will, in a few years, be materially diminished. This is not all. The value of live stock will be increased at least twenty-five per cent!

Look for a moment at the amount of capital invested in live stock; and from these statistics the reader will perceive that not only the farmers, but the whole nation, will be enriched. There are in the United States at least 6,000,000 horses and mules; these, at the rate of $50 per head, amount to $300,000,000. It is also estimated that there are 20,000,000 of neat cattle; reckon these at $25 per head, and we get the snug little sum of $500,000,000. We have also 20,000,000 sheep, worth the same number of dollars. The number of swine have been computed at 24,000,000; and these, at $3 per head, give us $72,000,000. Hence the reader will see that the capital invested in this class of live stock reaches the [Pg 12]enormous sum of $892,000,000. Add the 25 per cent. just alluded to, and we get a clear gain of $223,000,000. This sum would be sufficient to build veterinary schools and colleges capable of affording ample accommodations to every farmer's son in the Union. Hence we entreat the farming community to ponder on these subjects. They have only to say the word, and schools for the dissemination of veterinary information shall spring up in every section of the Union.

Does the reader wish to know how the farmers can accomplish this important object? We answer, there are four millions of men engaged in agricultural pursuits. Their number is three times greater than that of those engaged in navigation, the learned professions, commerce, and manufactures. Hence they have the numerical power to control the government of these United States, and of course can plead their own cause in the halls of congress, and vote their own supplies for educational purposes.

When the author first commenced a warfare against the lancet and other destructive agents, his only hopes of success were based on the coöperation of this mighty host of husbandmen; he well knew that there were many prejudices to be overcome, and none greater than those existing among his brethren of the same profession. The farmers have just begun to see the absurdity of bleeding an animal to death, with a view of saving life; or pouring down their throats powerful and destructive agents, with a view of making one disease to cure another! If the cattle doctors, then, will not reform, they must be reformed through the giant influence of popular opinion. Already the cry is, and it emanates from some of the most influential agriculturists in the country,—"No more blood-letting!" "Use your poisons on yourselves."

To the cattle-rearing interest, at the hands of many of whom the author has received aid and encouragement, the following pages are dedicated; they are intended to furnish them with practical information, with a view of preventing disease, increasing the value of their stock, and restoring them to health when sick.

[Pg 13]In reference to our reformed system of veterinary medication, it will be sufficient, in the present place, just to glance at the fundamental principles. In the succeeding pages these principles will be more fully explained. We contemplate the animal system as a complicated piece of mechanism, subject to the uncompromising and immutable laws of nature, as they are written upon the face of animate nature by the finger of Omnipotence.

All our intentions of cure being in accordance with nature's laws, (viz., promoting the integrity of the living powers,) we have termed our system a physiological one, though it is sometimes termed botanic, in allusion to the fact that most of our remedial agents are derived from the vegetable kingdom. We recognize a conservative or healing power in the animal economy, whose unerring indications we endeavor to follow; considering nature the physician, and the doctor her servant.

Our system proposes, under all circumstances, to restore the diseased organs to a healthy state, by coöperating with the vitality remaining in those organs, by the exhibition of sanative means, and, under all circumstances, to assist, and not oppose, nature in her curative processes. Poisonous substances, blood-letting, or processes of cure that act pathologically, cannot be used by us. The laws of animal life are physiological: they never were, nor ever will be, pathological.

The agents we use are just as we find them in the forest and the field, compounded by the Great Physician. Hence the reader will perceive that our aim is to depart from the popular debilitating and life-destroying practice, and approach as near as possible to the sanative.

G. H. D.

In order to prevent many of the diseases to which cattle are liable, it is important that they be supplied with pure water. Cattle have often been known to turn away from the filthy fluid found in some troughs, which abound in slime and decayed vegetable matter; and, indeed, the common stagnated pond water is no better than the former. Such water has, in former years, proved itself to be a serious cause of disease; and, at the present day, death is running riot among the stock of our western, and also our northern farmers, when, to our certain knowledge, the cause exists, in some cases, under their very noses. The farmers ofttimes see their best stock sicken and die without any apparent cause; and the cattle doctors are running rough-shod through the materia medica, pouring down the throats of the poor brutes salts by the pound, castor oil by the quart; aloes, lard, and a host of kindred trash, follow in rapid succession, converting the stomach into a sort of apothecary's shop; setons are inserted in the "dewlap;" the horns are bored, and sometimes sawed off; and, as a last resort, the animals are blistered and bled. They sometimes recover, in spite of the violence done to the constitution; yet they drag out a low form of vitality, living, [Pg 16]it may be said, yet half dead, until some friendly epidemic puts a period to their sufferings.

The author's attention was first called to this subject on reading an article in an English work, the substance of which is as follows: A number of working oxen were put into a pasture, in which was a pond, considered to abound in good water. Soon after putting them there, they were attacked with scouring, upon which they were immediately removed to another field. The scouring continued. They still, however, drank at the same pond. They were shifted to another piece of very sweet pasture without arresting the disease. The farmer thought it evident that the pastures were not the cause of the disease; and, contrary to the advice of his friends, who affirmed that the spring was always noticed for the excellence of its water, fenced his pond round, so that the cattle could not drink; they were then driven to a distance and watered. The scouring gradually disappeared. The farmer now proceeded to examine the suspected pond; and, on stirring the water, he found it all alive with small creatures. He now stirred into the water a quantity of lime, and soon after an immense number of animalculæ were seen dead on the surface. In a short time, the cattle drank of this water without any injurious results.

There is no doubt but that inferior kinds of water produce derangement of the digestive organs, and subsequently loss of flesh, debility, &c. We have frequently made post mortem examinations of animals that have died from disease induced by debility, and have often found a large number of worms in the stomach and intestines, which, we firmly believe, had their origin either primarily from the water itself, or subsequently from its effects on the digestive function.

All decayed animal and vegetable matter tends to corrupt water, and render it unfit for the purposes of life. Now, if the farmer has the best spring in the world, and the water shall flow from it, as it sometimes does, through whole fields of gutter or dike, abounding in decayed filth, such water will be impregnated with agents that will more or less affect its purity.

Many of the most complicated diseases of cattle originate from the food: for example, it may be given in too large quantities—more than is needed to build up and repair the waste that is constantly going on. The consequence is, the animals get into a state of plethora, which is known by heaviness, dulness, unwillingness to move; there is a disposition to sleep, and they will lie down and often go to sleep in damp places. A chill of the extremities, or collapse of the capillaries, takes place, resulting in diseases of the lungs and pleura. At other times, if driven a short distance, and made to walk fast, they are liable to disease of the brain and other organs, which frequently terminates fatally.

The food may be of such a nature as shall be very difficult of digestion, such as cornstalks, foxgrass, frosted turnips, &c. The clover and grasses may abound in woody fibre, in consequence of being cut too late; they will then require more than the usual amount of gastric fluids to insalivate them, and more time to masticate, and, finally, extract their nutrimental properties. The stomach becomes overworked, producing sympathetic diseases of the brain and nervous structures. The stomach not being able to act on fibrous matter with the same despatch as on softer materials, the former accumulates in its different compartments, distends the viscera, interferes with the motion of the diaphragm, presses on the liver, seriously interfering with the bile-secreting process. In order to prevent the grass and clover from becoming tough and fibrous, it should be mowed early, and while in flower, and should be afterwards almost constantly attended to, if the weather is favorable; the more it is scattered about, the better will it be made, and the more effectually will its fragrance and other good qualities be preserved.

The food may also be deficient in nutriment. The effects of insufficient food are too well known to need much description: debility includes them all; it invades every function of [Pg 18]the animal economy. And as life is the sum of the powers that resist disease, if disease is only the instrument of death, it follows, of course, that whatever enfeebles life, or, in other words, produces debility, must predispose to disease.

Many cattle, during the winter, live on bad hay, which does not appear to contain any of that saccharine and mucilaginous matter which is found in good hay. When the spring comes, they are turned out to grass, and thus regain their flesh. Many, however, die in consequence of the sudden change.

It has been satisfactorily proved that fat cattle, of the best quality, may be produced by feeding them on boiled food.

Dr. Whitlaw says, "On one occasion, a number of cows were selected from a large stock, for the express purpose of making the trial: they were such as appeared to be of the best kind, and those that gave the richest milk. In order to ascertain what particular food would produce the best milk, different species of grass and clover were tried separately, and the quality and flavor of the butter were found to vary very much. But what was of the most importance, many of the grasses were found to be coated with silecia, or decomposed sand, too hard and insoluble for the stomachs of cattle. In consequence of this, the grass was cut and well steamed, and it was found to be readily digested; and the butter, that was made from the milk, much firmer, better flavored, and would keep longer without salt than any other kind. Another circumstance that attended the experiment was that, in all the various grasses and grain that were intended by our Creator as food for man or beast, the various oils that enter into their composition were so powerfully assimilated or combined with the other properties of the farinaceous plants, that the oil partook of the character of essential oil, and was not so easily evaporated as that of poisonous vegetables; and experience has proved that the same quantity of grass, steamed and given to the cattle, will produce more butter than when given in its dry state. This fact being established from numerous experiments, then there must be a great saving and superiority in [Pg 19]this mode of feeding. The meat of such cattle is more wholesome, tender, and better flavored than when fed in the ordinary way." (For process of steaming, see Dadd's work on the Horse, p. 67.)

A mixed diet (boiled) is supposed to be the most economical for fattening cattle. "A Scotchman, who fattens 150 head of Galloway cattle, annually, finds it most profitable to feed with bruised flaxseed, boiled with meal or barley, oats or Indian corn, at the rate of one part flaxseed to three parts meal, by weight,—the cooked compound to be afterwards mixed with cut straw or hay. From four to twelve pounds of the compound are given to each beast per day." The editor of the Albany Cultivator adds, "Would it not be well for some of our farmers, who stall-feed cattle, to try this or a similar mode? We are by no means certain that the ordinary food (meaning, probably, bad hay and cornstalks) would pay the expense of cooking; but flaxseed is known to be highly nutritious, and the cooking would not only facilitate its digestion, but it would serve, by mixing, to render the other food palatable, and, by promoting the appetite and health of the animal, would be likely to hasten its thrift."

Mr. Hutton, who has long been celebrated for producing exceedingly fat cattle at a small cost, estimates that cost as follows:—

| s. d. | |

| "13 lbs. of linseed, bruised, or 2 lbs. per day for six days, and 1 lb. for Sunday, | 1 9 |

| 32 lbs. of ground corn, or 5 lbs. per day for six days, and 2-1/2 lbs. for Sunday, at 1 d. per lb., | 2 8 |

| 35 lbs. of turnips, given twice a day for six days, and thrice on Sunday, | 1 6 |

| Oats, 1-1/2 d.: labor on each beast, 6 d., | 7-1/2 |

| Total cost of each beast per week, | 6 6-1/2 |

"The horses, cows, and young stock are also fed on this food, evidently with great advantage."

Mr. Workington, a successful dairyman, combining cut feed [Pg 20]and oil-cake with different sorts of green food, found that, by giving a middle-sized cow sixteen pounds of green food and two of boiled hay, with two pounds of ground oil cake, (linseed would be preferable,) and eight pounds of cut straw, the daily expense of her keep was only 5-1/2 d., (about ten cents.) The oil-cake he found to be much more productive of milk when given with steamed food, than when employed without it. Varying their food from time to time is found to be of much more advantage to the cow; and this may probably arise from the additional relish with which the animal eats, or from the superior excitement of a new stimulus on the different secretions.

The following table represents the nutritive properties in each article of food:—

| Water. | Husk, or woody fibre. | Starch, gum, and sugar. | Gluten, albumen, &c. | Fatty matter. | Saline matter. | |

| Oats, | 16 | 20 | 45 | 11 | 6 | 2.5 |

| Beans, | 15 | 8 to 11 | 40 | 26 | 2.5 | 3 |

| Pease, | 14 | 9 | 50 | 24 | 2.1 | 3 |

| Indian corn, | 14 | 6 | 70 | 12 | 5 to 9 | 1.5 |

| Barley, | 15 | 14 | 52 | 13.5 | 2 to 3 | 3 |

| Meadow hay, | 14 | 30 | 40 | 7.1 | 2 to 5 | 5 to 10 |

| Clover hay, | 14 | 25 | 40 | 9.3 | 3 to 5 | 9 |

| Pea straw, | 10 to 15 | 25 | 45 | 12.3 | 1.5 | 4 to 5 |

| Oat straw, | 12 | 45 | 35 | 1.3 | 0.8 | 6 |

| Carrots, | 85 | 3 | 10 | 1.5 | 0.4 | 1 to 2 |

| Linseed, | 9.2 | 8 to 9 | 35.3 | 20.3 | 20.0 | 6.3 |

| Bran, | 13.1 | 53.6 | 2 | 19.3 | 4.7 | 7.3 |

The most nutritious grasses are those which abound in sugar, starch, and gluten. Sugar is an essential element in the formation of good milk; hence the sweet-scented grasses are the most profitable to cultivate and feed to milch cows. At the same time, the farmer, if he does not, ought to know that large quantities of saccharine matter are extracted from clover and sweet grasses by the bees. Mr. White tells us that, "on a farm situated a few miles from London, the eldest son of the occupier had the management and profit of the bees given him, which induced him to increase the number of stocks beyond what had ever been kept on the farm before. It so happened that the sheep did not thrive so well as in [Pg 21]former years, and on the farmer complaining at the cause to his man, as they had plenty of keep, the man replied, 'You will never have fat sheep so long as you suffer my young master to keep so many stocks of bees; they suck all the honey from the flowers, so that the clover is not half so nourishing, and does not produce half such good milk.'" Had this man been acquainted with agricultural and animal chemistry, he would have had a clear conception of the seeming absurdity. All our labor or efforts to improve stock or crops will be fruitless, unless guided by chemical science. We must have sugar, starch, gluten, and other materials, to perfect animal organization. The animal may be in good health, the different functions free and unobstructed, and possess the power of reproducing the species; yet, if fed on substances which lack the materials necessary to the composition of bones, blood-vessels, and nerves, sooner or later its health becomes impaired. Reader, if you own cattle, and wish to preserve their health, give them boiled food occasionally; let them have their meals at regular hours, in sufficient quantity, and no more, unless they are intended for the butcher; then, an extra allowance may be given, with a view of fattening. They should be well littered, and the barns well ventilated; finally, keep them clean, avoid undue exposure, and govern them in a spirit of kindness and mercy.

It is well known that the more cleanly and comfortable cattle are kept, and the better the order in which their food is presented to them, the better they will thrive, and the more profitable they will be to the owner. Dr. Gunthier remarks, that "constant confinement to the barn is opposed to the nature of oxen, and becomes the source of numberless diseases. Endeavors are made to promote the lacteal secretion in cows, [Pg 22]and the fattening of oxen, by means of heat: for this purpose, stables [barns] are converted into real stoves, either by not making them sufficiently large, or by crowding them to excess, or by preventing the access of air from without; and all this without recollecting that the skin, thus over-excited, must necessarily fall into a state of atony in a short time. Besides, the moist heat and the emanations of the dung cannot fail to exercise a destructive influence on the lungs and entire system. To these causes if we add the absolute want of exercise and the excess of food, we shall not be surprised at the number of diseases resulting from these different practices, and at the extraordinary forms which they ofttimes assume.

"Persons propose to themselves, by feeding in the barn, to augment the mass of dung; and the beasts are left in their excrement, sometimes up to the very knees. Seldom is there any care taken to cleanse their skin, and still less attention is directed to the feet. What wonder, then, if they exhibit so many forms of disease?"

The byre recommended by Mr. Lawson consists of two apartments—an inner apartment, or byre for feeding the cattle, and an outer apartment, or barn for containing the fodder. The byre is constructed at right angles with the barn, as follows: "At the distance of about three feet and a half from the side of the building, within, there are constructed, on the ground, in a straight line, a trough, having ten partitions for feeding ten animals. The troughs are so constructed, that there is a small and gradual declivity from the first or innermost to the last or outermost one; and the partitions separating them being made with a small arch at the bottom, a bucket of water, poured in at the uppermost, runs out at the last one through a spout in the wall; and a sweep of the broom carries off the whole remains of the food, rendering all the troughs quite clean and sweet. The whole food of the cattle is thus kept perfectly clean at all times.

"In a line with the feeding troughs, and immediately over them, runs a strong beam of wood, from one end of the byre [Pg 23]to the other; which is strengthened by two strong upright supporters to the roof, placed at equal distances from the ends of the byre; and the main beam is again subdivided by the cattle stakes and chains, so as to keep each of the ten oxen opposite to his own feeding trough and stall.

"The three and a half feet of space between the troughs and outer wall, lighted by a glazed window, is the cattle feeder's walk, who passes along it in front of the cattle, and, with a basket, deposits before each of the cattle the food into the feeding trough of each. To prevent any of the cattle from choking on small pieces of turnips, &c., as they are very apt to do, the chains at the stakes are contrived of such a length, that no ox can raise his head too high when eating; for in this way, it is observed, cattle are generally choked.

"At the distance of about six feet eight inches from the feeding troughs, and parallel to them, is a dung grove and urine gutter. Here too, like the trough, there is a gradual declivity; so that the moment the urine passes from the cattle, it runs to the lowest end of the gutter, whence it is conveyed through the outer wall, in a spout, and deposited in the urinarium outside of the building. At this place is a large enclosed space, occupied as a compost dung-court. Here all sorts of stuff are collected for increasing the manure, such as fat, earth, cleanings of roads, ditches, ponds, rotten vegetables, &c.; and the urine from the byre, being caused to run over all these collected together, which is done very easily by a couple of wooden spouts, moved backwards and forwards to the urinarium at pleasure, renders the whole mass, in a short time, a rich compost dunghill; and this is done by the urine alone, which, in general, is totally lost. The dung of the byre, again, is cleared several times each day, and deposited in the dung-court. Along the edge of the dung-court a few low sheds are constructed, in which swine are kept, and these consume the refuse of the food.

"In the side wall of the byre, and opposite to the heads of the cattle, are constructed three ventilators; these are placed at the distance of about two feet four inches from the [Pg 24]ground, in the inside of the byre, and pass out just under the roof. The inside openings of these are about thirteen inches in length, seven in breadth, and nine in depth; and they serve two good purposes. The breath of cattle being superficially lighter than atmospheric air, the consequence is, that in some byres the cattle are kept in a constant heat and sweat, because their breath and heat have no way to escape; whereas, by means of the ventilators, the air of the barn is kept in proper circulation, which conduces as much to the health of the cattle as to the preservation of the walls and timber of the byre, by drying up the moisture produced from the breath and sweat of the cattle, which is found to injure those parts of the building."

The operation of milking should, if possible, always be performed by the same person, and in the most gentle manner; the violent tugging at the teats by an inexperienced hand is apt to make the animal irritable and uneasy during the operation, and unwilling to be milked. Many of the diseases of the teats and udder can be traced to violence done to the parts under the operation of milking. Young animals are often unwilling to be milked: here a little patience and kindness will perform wonders.

It is not the quantity of milk that gives value to the dairy cow; for the milk of one good cow will make more butter than that of two poor ones, each giving the same quantity of milk. Its most abundant principles are cream, caseous matter or curd, and whey. In these are also contained a saccharine matter, (sugar of milk,) muriate and phosphate of potassa, phosphate of lime, acetic acid, acetate of potassa, and a trace of acetate of iron. The three principal constituents (cream, curd, and whey) can easily be separated: thus the cream rises to the surface, and the curd and whey will separate if [Pg 25]the milk becomes sour, or a little rennet is poured into it. When milk is intended to be made into cheese, no part of the cream should be separated. Good cheese is, consequently, rarely produced in those dairies where much butter is made; the former being robbed for the sake of the latter.

Sir J. Sinclair says, "If a few spoonfuls of milk are left in the udder of the cow at milking; if any of the implements used in the dairy are allowed to be tainted by neglect; if the dairy-house be kept dirty, or out of order; if the milk is either too hot or too cold at coagulation; if too much or too little rennet is put into the milk; if the whey is not speedily taken off; if too much or too little salt is applied; if butter is too slowly or too hastily churned; or if other minute attentions are neglected, the milk will be in a great measure lost. If these nice operations occurred once a month, or once a week, they might be easily guarded against; but as they require to be observed during every stage of the process, and almost every hour of the day, the most vigilant attention must be kept up during the whole season."

It is a well-known fact that plants require for their germination and growth different constituents of soil, and that animals require different forms of food to build up the waste, and promote the living integrity—the vital powers.

Its order to supply the materials necessary for animal and vegetable nutrition, we require alternate changes—the former in the diet, and the latter in the soil. Experience has proved that the cultivation of a plant for several successive years on the same soil impoverishes it, or the plant degenerates. On the contrary, if a piece of land be suffered to lie uncultivated for a short time, it will yield, in spite of the loss of time, a [Pg 26]greater quantity of grain; for, during the interval of rest, the soil regains its original equilibrium. It has been satisfactorily demonstrated that a fruit-tree cannot be made to grow and bring forth good fruit on the same spot where another of the same species has stood; at least not until a lapse of years. This is a fact worth knowing, for it applies more or less to all forms of vegetation. Another fact of experience is, that some plants thrive on the same soil only after a lapse of years, while others may be cultivated in close succession, provided the soil is kept in equilibrium by artificial means; these are subsoiling, &c. Some kinds of plants improve the sod, while others impoverish or exhaust it. Professor Liebig tells us, "turnips, cabbages, beets, oats, and rye are considered to belong to the class which impoverish the soil; while by wheat, hops, madder, hemp, and poppies, it is supposed to be entirely exhausted." Many of our farmers expend large sums of money in the purchase of manure, with a view of improving the soil; and they suppose that their crops will be abundant in proportion to the amount of manure; yet many have discovered that, in spite of the extra expense and labor, the produce of their farms decreased.

The alternation of crops seems destined to effect a great change in agriculture. A French chemist informs us that the roots of plants imbibe matter of every kind from the soil, and thus necessarily abstract a number of substances, which are not adapted to the purposes of nutrition, and that they are ultimately expelled by the excretory vessels, and return to the soil as excrement. The excrementitious portion of the food also returns to the soil. Now, as excrement cannot be assimilated by the same animal or plant that ejected it, without danger to the organs of digestion or eliminations, it follows that the more vegetable excrement the soil contains, the more unfitted must it be for plants of the same species; yet these excrementitious matters may, however, still be capable of assimilation by another kind of plant, which would absorb them from the soil, and render it again fertile for the first. In connection with this, it has been observed that several [Pg 27]plants will flourish when growing beside each other; but it is not good policy to sow two kinds of seed together: on the other hand, some plants mutually prevent each other's development. The same happens if young cattle are suffered to graze and sleep in the barn together; the one lives at the expense of the other, which soon shows evidences of disease. The injurious effects of permitting young children to sleep with aged relatives are known to many of our readers; yet some parents see their children sicken and die without knowing the why or wherefore. From such facts as these,—which we might multiply to an indefinite extent, were it necessary,—we learn that nature's laws are immutable and uncompromising; and woe be to the man that transgresses them: they are a part of the divine law, which cannot be set at nought with impunity.

Ignorance on these important subjects has existed too long: yet we perceive in the distant horizon a ray of intellectual light, streaming through our schools and agricultural societies. The result will be, that succeeding generations will be better acquainted with nature's laws, from which shall flow untold blessings. Chemistry teaches us that animals and vegetables are composed of a vast number of different compounds, which are nearly all produced by the same elementary principles. Vegetables consist of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen; and the same substances, with the addition of nitrogen, are the principal constituents of the animal economy. In a word, all the constituents of animal creation have actually been discovered in vegetables: this has, we presume, led to the conclusion that "all flesh is grass."

Many horticulturists complain that certain fruits and seeds have "run out," or degenerated. Has the stately oak, the elm, or the cedar degenerated? No. Each has preserved its identity, and will continue so to do, at least just as the Divine Artist intended they should, unless man, by his fancied improvements, interferes; and here, reader, permit us to ask if you ever knew a piece of nature's mechanism improved by human agency. Can we make a light better adapted to the [Pg 28]wants of animate and inanimate creation than that which the sun, moon, and stars afford? Whenever we attempt to improve on immutable laws, as they are written on the face of creation, that moment we prevent the full and free play of these laws. Hence the practice of grafting scions of delicious fruit-trees on stock of an inferior order compromises its identity; and successive crops will show unmistakable evidences of encroachment. A son of the lamented Mr. Phinney tells us that he had some very fine sows, that he was desirous of breeding from, with a view of making "improvements." He bred in a close degree of relationship: in a short time, to use his own expression, "their sides appeared like two boards nailed together." Does the farmer wish to know how to prevent seeds and fruit "running out"? Let him study chemistry. Chemistry furnishes the information; it also teaches the husbandman the fact, that to put a plant, composed of certain essential elements, on a soil destitute of those elements,—or to graft a scion, requiring a certain amount of sap or juice, on a stock destitute of such sap or juice, expecting that they will germinate, grow to perfection, and preserve their identity,—would be just as absurd as to expect that a dry sow would nourish a sucking pig.

Agriculture being based on the equilibrium of the soils, a knowledge of chemistry is indispensable to every one who is desirous of keeping pace with the reforms of the age; for it is through the medium of that science alone that we are enabled to ascertain with certainty how this equilibrium is disturbed by the growth of vegetation. Then is it not a matter of deep interest to the farmer to know how this equilibrium is restored?

Does the farmer wish to know what kind of soil is necessary to nourish and mature a plant? Chemistry solves the problem. Does the farmer wish to know how to improve the soil? Let him refer to chemistry. Chemistry will teach the farmer how to analyze the soil; by that means he will learn which of the constituent elements of the plants and soil are constant, and which are changeable. By making an analysis [Pg 29]of the soil at different periods, through the process of germination, growth, and maturity, we are enabled to ascertain the amount of excretory elements given out. Bergman tells us that he found, by analysis, in "100 parts of fertile soil, coarse silex 30 parts, silecia 30 parts, carbonate of lime 30 parts:" hence the fertility of the soil diminishes in proportion as one or the other of these elements predominates.

Ashes of wheat contain, among other elementary substances, 48 parts of silecia. Now, what farmer could expect to raise a good crop of wheat from a soil destitute of silecious earth, since this earth constitutes a large amount of the earthy part of wheat? There is no barrier to agricultural improvement so effectual as for farmers to continue their old customs purely because their forefathers did so. But prejudices are fast dying away before the rays of intellectual illumination; the farmers are fast seceding from the supposed infallibles of their forefathers, and will soon become "book" as well as practical husbandmen. "Book farming," assisted by practical knowledge, teaches that manures require admixture of milder materials to mitigate their force; for some of them communicate a disgusting or offensive quality to vegetables. They are charged with imparting a biting and acrimonious taste to radishes and turnips. Potatoes and grapes are known to borrow the foul taint of the ground. Millers observe a strong, disagreeable odor in the meal of wheat that grew upon land highly charged with the rotten recrements of cities. Stable dung is known to impart a disagreeable flavor to vegetables.

The same effects may be illustrated in the animal kingdom. Ducks are rendered so ill tasted from stuffing down garbage as sometimes to be offensive to the palate when cooked. The quality of pork is known by the food of the swine, and the peculiar flavor of water-fowl is rationally traced to the fish they devour. Thus a portion of the elements of manure and nutrimental matter passes into the living bodies without being entirely subdued. For example, we can alter the color of the cow's milk by mixing madder or [Pg 30]saffron in the food; the odor may be influenced by garlic; the flavor may be altered by pine and wormwood; and lastly, the medicinal effect may be influenced.

In the cultivation of grass the farmer will find it to his advantage to cultivate none but the best kinds; the whole pasture lands will then be filled with valuable grass seeds. The number of grass seeds worth cultivating is but few, and these should be sown separately. It is bad policy to sow different kinds of grass seed together—just as bad as to sow wheat, oats, turnips, and corn promiscuously.

The reason why the farmers, as a community, will be benefited by sowing none but the best seed is, because grass seeds are distributed through neighboring pastures by the winds, and there take root. Now, if the neighboring pastures abound in inferior grasses, the fields will soon be filled with useless plants, which are very difficult to be got rid of. We refer those of our readers who desire to make themselves acquainted with animal chemistry to Professor Liebig's work on that science.

Large sums of money have, from time to time, been expended with a view of improving stock, and many superior cattle have been introduced into this country; yet, after a few generations, the beautiful form and superior qualities of the originals are nearly lost, and the importer finds to his cost that the produce is no better than that of his neighbors. What are the causes of this deterioration? We are told—and experience confirms the fact—that "like produces like." Good qualities and perfect organization are perpetuated by a union of animals possessing those properties: of course it follows, that malformation, hereditary taints, and vices are transmitted and aggravated.

The destructive practice of breeding "in and in," or, in [Pg 31]other words, selecting animals of the same family, is one of the first causes of degeneracy; and this destructive practice has proved equally unfortunate in the human family. Physical defects are the result of the intermarriage of near relatives. In Spain, the deformed and feeble state of the aristocracy arises from their alliances being confined to the same class of relatives through successive generations. But we need not go to Spain to verify such facts. Go into our churchyards, and read on the tombstones the names of thousands of infants,—gems withered in the bud,—young men, and maidens, cut down and consigned to a premature grave; and then prove, if you can, that early marriages and near alliances are not the chief causes of this great mortality.

Mr. Colman, in an article on live stock, says, "There seems to be a limit beyond which no person can go. The particular breed may be altered and improved, but an entirely new breed cannot be produced; and in every departure from the original there is a constant tendency to revert back to it. The stock of the improved Durham cattle seems to establish this fact. If we have the true history of it, it is a cross of a Teeswater bull with a Galloway cow. The Teeswater or Yorkshire stock are a large, coarse-boned animal: the object of this cross was to get a smaller bone and greater compactness. By attempting to carry this improvement, if I may so call it, still further by breeding continually in and in, that is, with members of the same family, in a close degree of affinity, the power of continuing the species seems to become extinct; at least it approximates to such a result. On the other hand, by wholly neglecting all selection, and without an occasional good cross with an animal of some foreign blood, there appears a tendency to revert back to the large-boned, long-legged animal, from which the improvement began.

"There are, however, several instances of superior animals bred in the closest affinity; whilst, in a very great majority of cases, the failure has been excessive."

Overtaxing the generative powers of the male is another cause of deterioration. The reader is probably aware of the [Pg 32]woful results attending too frequent sexual intercourse. If he has not given this subject the attention it demands, then let him read the records of our lunatic asylums: they tell a sad tale of woe, and prove to demonstration that, before the blast of this dire tornado, sexual excess, lofty minds, the suns and stars of our intellectual world, are suddenly blotted out. It spares neither age, sex, profession, nor kind. Dr. White relates a case which substantiates the truth of our position. "The Prince of Wales, who afterwards became George the Fourth, had a stud horse of very superior qualities. His highness caused a few of his own mares to be bred to this stallion, and the produce proved every way worthy of the sire. This horse was kept at Windsor for public covering without charge, except the customary groom's fee of half a guinea. The groom, anxious to pocket as many half guineas as possible, persuaded all he could to avail themselves of the prince's liberality. The result was, that, being kept in a stable without sufficient exercise, and covering nearly one hundred mares yearly, the stock, although tolerably promising in their early age, shot up into lank, weakly, awkward, good-for-nothing creatures, to the entire ruin of the horse's character and sire. Some gentlemen, aware of the cause, took pains to explain it, proving the correctness of their statement by reference to the first of the horses got, which were among the best horses in England."

There is no doubt but that brutes are often endowed with extraordinary powers for sexual indulgence; yet, when kept for the purpose alluded to, without sufficient muscular exercise,—breathing impure air, and living on the fat of the farm,—his services in constant requisition,—then it is no wonder, that if, under these circumstances, the offspring are weak and inefficient.

Professor Youatt recommends that "valuable qualities once established, which it is desirable to keep up, should thereafter be preserved by occasional crosses with the best animals to be had of the same breed, but of a different family. This is the great secret which has maintained the blood horse in his great superiority."

[Pg 33]The live stock of our farmers frequently degenerates in a very short space of time. The why and the wherefore is not generally understood; neither will it be, until animal physiology shall be better understood than it is at the present time. Men are daily violating the laws of animal organization in more ways than one, in the breeding, rearing, and general management of all kinds of domestic animals,—until the different breeds are so amalgamated, that, in many cases, it is a difficult task to ascertain, with any degree of certainty, their pedigree. If a farmer has in his possession a bull of a favorite breed, the neighboring stock-raisers avail themselves of his bullship's services by sending as many cows to him as possible: the consequence is, that the offspring got in the latter part of the season are good for nothing. The cow also, at the time of impregnation, may be in a state of debility, owing to some derangement in the organs of digestion; if so, impregnation is very likely to make the matter worse; for great sympathy exists between the organs of generation and those of digestion, and females of every order suffer more or less from a disturbed state of the stomach during the early months of pregnancy. In fact, during the whole stage they should be considered far from a state of health. Add to this the fact that impregnated cows are milked, (not generally, yet we know of such cases:) the fœtus is thus deprived of its due share of nourishment, and the extra nutrimental agents, necessary for its growth and development, must be furnished at the expense of the mother. She, in her turn, soon shows unmistakable evidences of this "robbing Peter to pay Paul" system, by her sunken eye, loss of flesh, &c., and often, before she has seen her sixth month of pregnancy, liberates the fœtus by a premature birth—in short, pays the penalty of disobedience to the immutable law of nature. On the other hand, should such a cow go safely through the whole period of gestation and parturition, the offspring will not be worth keeping, and the milk of the former will lack, in some measure, those constituents which go to make good milk, and without which it is almost worthless for making butter or [Pg 34]cheese. A cow should never be bred from unless she shall be in good health and flesh. If she cannot be fatted, then she may be spayed. (See article Spaying Cows.) By that means, her health will improve, and she will be made a permanent milker. Degeneracy may arise from physical defects on the part of the bull. It is well known that infirmities, faults, and defects are communicated by the sexual congress to the parties as well as their offspring. Hence a bull should never be bred to unless he possesses the requisite qualifications of soundness, form, size, and color. There are a great number of good-for-nothing bulls about the country, whose services can be had for a trifle; under these circumstances, and when they can be procured without the trouble of sending the cow even a short distance, it will be difficult to effect a change.

If the farming community desire to put a stop to this growing evil, let them instruct their representatives to advocate the enactment of a law prohibiting the breeding to bulls or stallions unless they shall possess the necessary qualifications.

THE BULL.

Mr. Lawson gives us the following description of a good bull. It would be difficult to find one corresponding in all its details to this description; yet it will give the reader an idea of what a good bull ought to be. "The head of the bull should be rather long, and muzzle fine; his eyes lively and prominent; his ears long and thin; his horns white; his neck rising with a gentle curve from the shoulders, and small and fine where it joins the head; his shoulders moderately broad at the top, joining full to his chine and chest backwards, and to the neck-vein forwards; his bosom open; breast broad, and projecting well before his legs; his arms or fore thighs muscular, and tapering to his knees; his legs straight, clean, and very fine boned; his chine and chest so full as to leave no hollows behind the shoulders; the plates strong, to keep his belly from sinking below the level of his breast; his back or loin broad, straight, and flat; his ribs rising one above an[Pg 35]other, in such a manner that the last rib shall be rather the highest, leaving only a small space to the hips, the whole forming a round or barrel-like carcass; his hips should be wide placed, round or globular, and a little higher than the back; the quarters (from the hips to the rump) long, and, instead of being square, as recommended by some, they should taper gradually from the hips backwards; rump close to the tail; the tail broad, well haired, and set on so as to be in the same horizontal line with his back."

VALUE OF DIFFERENT BREEDS OF COWS.

Mr. Culley, in speaking of the relative value of long and short horns, says, "The long-horns excel in the thickness and firm texture of the hide, in the length and closeness of the hair, in their beef being finer grained and more mixed and marbled than that of the short-horns, in weighing more in proportion to their size, and in giving richer milk; but they are inferior to the short-horns in giving a less quantity of milk, in weighing less upon the whole, in affording less fat when killed, in being generally slower feeders, in being coarser made, and more leathery or bullish in the under side of the neck. In a few words, the long-horns excel in hide, hair, and quality of beef; the short-horns in the quantity of beef, fat, and milk. Each breed has long had, and probably may have, their particular advocates; but if I may hazard a conjecture, is it not probable that both kinds may have their particular advantages in different situations? Why not the thick, firm hides, and long, closer set hair, of the one kind be a protection and security against tempestuous winds and heavy fogs and rains, while a regular season and mild climate are more suitable to the constitutions of the short-horns? But it has hitherto been the misfortune of the short-horned breeders to seek the largest and biggest boned ones for the best, without considering that those are the best that bring the most money for a given quantity of food. However, the ideas of our short-horned breeders being now more enlarged, and their minds more open to [Pg 36]conviction, we may hope in a few years to see great improvements made in that breed of cattle.

"I would recommend to breeders of cattle to find out which breed is the most profitable, and which are best adapted to the different situations, and endeavor to improve that breed to the utmost, rather than try to unite the particular qualities of two or more distinct breeds by crossing, which is a precarious practice, for we generally find the produce inherit the coarseness of both breeds, and rarely attain the good properties which the pure distinct breeds individually possess.

"Short-horned cows yield much milk; the long-horned give less, but the cream is more abundant and richer. The same quantity of milk also yields a greater proportion of cheese. The Polled or Galloway cows are excellent milkers, and their milk is rich. The Suffolk duns are much esteemed for the abundance of their milk, and the excellence of the butter it produces. Ayrshire or Kyloe cows are much esteemed in Scotland; and in England the improved breed of the long-horned cattle is highly prized in many dairy districts. Every judicious selector, however, will always, in making his choice, keep in view not only the different sons and individuals of the animal, but also the nature of the farm on which the cows are to be put, and the sort of manufactured produce he is anxious to bring to market. The best age for a milch cow is betwixt four, or five, and ten. When old, she will give more milk; but it is of an inferior quality, and she is less easily supported."

Take the calf's maw, or stomach, and having taken out the curd contained therein, wash it clean, and salt it thoroughly, inside and out, leaving a white coat of salt over every part of it. Put it into an earthen jar, or other vessel, and let it stand three or four days; in which time it will have [Pg 37]formed the salt and its own natural juice into a pickle. Take it out of the jar, and hang it up for two or three days, to let the pickle drain from it; resalt it; place it again in the jar; cover it tight down with a paper, pierced with a large pin; and let it remain thus till it is wanted for use. In this state it ought to be kept twelve months; it may, however, in case of necessity, be used a few days after it has received the second salting; but it will not be as strong as if kept a longer time. To prepare the rennet for use, take a handful of the leaves of the sweet-brier, the same quantity of rose and bramble leaves; boil them in a gallon of water, with three or four handfuls of salt, about a quarter of an hour; strain off the liquor, and, having let it stand until perfectly cool, put it into an earthen vessel, and add to it the maw prepared as above. To this add a sound, good lemon, stuck round with about a quarter of an ounce of cloves, which give the rennet an agreeable flavor. The longer the bag remains in the liquor, the stronger, of course, will be the rennet. The amount, therefore, requisite to turn a given quantity of milk, can only be ascertained by daily use and observation. A sort of average may be something less than a half pint of good rennet to fifty gallons of milk. In Gloucestershire, they employ one third of a pint to coagulate the above quantity.

IT is generally admitted that many dairy farmers pay more attention to the quantity than the quality of this article of food; now, as cheese is "a surly elf, digesting every thing but itself," (this of course applies to some of the white oak specimens, which, like the Jew's razors, were made to sell,) it is surely a matter of great importance that they should attend more to the quality, especially if it be intended for exportation. There is no doubt but the home consumption of [Pg 38]good cheese would soon materially increase, for many thousands of our citizens refuse to eat of the miserable stuff "misnamed cheese."

The English have long been celebrated for the superior quality of their cheese; and we have thought that we cannot do a better service to our dairy farmers than to give, in as few words as possible, the various methods of making the different kinds of cheese, for which we are indebted to Mr. Lawson's work on cattle.

"It is to be observed, in general, that cheese varies in quality, according as it has been made of milk of one meal, or two meals, or of skimmed milk; and that the season of the year, the method of milking, the preparation of the rennet, the mode of coagulation, the breaking and gathering of the curd, the management of the cheese in the press, the method of salting, and the management of the cheese-room, are all objects of the highest importance to the cheese manufacturer; and yet, notwithstanding this, the practice, in most of these respects, is still regulated by little else than mere chance or custom, without the direction of enlightened observation or the aid of well-conducted experiment.

GLOUCESTER CHEESE.

"In Gloucestershire, where the manufacture of cheese is perhaps as well understood as in any part of the world, they make the best cheeses of a single meal of milk; and, when this is done in the best manner, the entire meal of milk is used, without any addition from a former meal. But it not unfrequently happens that a portion of the milk is reserved and set by to be skimmed for butter; and at the next milking this proportion is added to the new milk, from which an equal quantity has been taken for a similar purpose. One meal cheeses are principally made here, and go by the name of best making, or simply one meal cheeses. The cheeses are distinguished into thin and thick, or single and double; the last having usually four to the hundred weight, (112 [Pg 39]pounds,) the other about twice that number. The best double Gloucester is always made from new milk.

"The true single Gloucester cheese is thought by many to be the best, in point of flavor, of any we have. The season for making their thin or single cheese is mostly from April to November; but the principal season for the thick or double is confined to May, June, and the early part of July. This is a busy season in the dairy; for at an earlier period the milk is not rich enough, and if the cheese be made later in the summer, they do not acquire sufficient age to be marketable next spring. Very many cheeses, however, can be made even in winter from cows that are well fed. The cows are milked in summer at a very early hour; generally by four o'clock in the morning, before the day becomes hot, and the animals restless and unruly.

CHESTER CHEESE.

"After the milk has been strained, to free it from any impurities, it is conveyed into a cooler placed upon feet like a table, having a spigot at the bottom for drawing off the milk. This, when sufficiently cooled, is drawn off into pans, and the cooler again filled. In so cases, the cooler is large enough to hold a whole meal's milk at once. The rapid cooling thus produced (which, however, is necessary only in hot weather, and during the summer season) is found to be of essential utility in retarding the process of fermentation, and thereby preventing putridity from commencing in the milk before two meals of it can be put together. Some have thought that the cheese might be improved by cooling the evening's milk still more rapidly, and that this might be effected by repeatedly drawing it off from and returning it into the cistern. When the milk is too cold, a portion of it is warmed over the fire and mixed with the rest.

"The coloring matter, (annatto,) in Cheshire, is added by tying up as much of the substance as is thought sufficient in a linen rag, and putting it into a half pint of warm water, to [Pg 40]stand over night. The whole of this infusion is, in the morning, mixed with the milk in the cheese-tub, and the rag dipped in the milk and rubbed on the palm of the hand as long as any of the coloring matter can be made to come away.

"The next operation is salting; and this is done, either by laying the cheese, immediately after it comes out of the press, on a clean, fine cloth in the vat, immersed in brine, to remain for several days, turning it once every day at least; or by covering the upper surface of the cheese with salt every time it is turned, and repeating the application for three successive days, taking care to change the cloth twice during the time. In each of these methods, the cheese, after being so treated, is taken out of the vat, placed upon the salting bench, and the whole surface of it carefully rubbed with salt daily for eight or ten days. If it be large, a wooden hoop or a fillet of cloth is employed to prevent renting. The cheese is then washed in warm water or whey, dried with a cloth, and laid on what is called the drying bench. It remains there for about a week, and is thence removed to the keeping house. In Cheshire, it is found that the greatest quantity of salt used for a cheese of sixty pounds is about three pounds; but the proportion of this retained in the cheese has not been determined.

"When, after salting and drying, the cheeses are deposited in the cheese-room or store-house, they are smeared all over with fresh butter, and placed on shelves fitted to the purpose, or on the floor. During the first ten or fifteen days, smart rubbing is daily employed, and the smearing with butter repeated. As long, however, as they are kept, they should be every day turned; and the usual practice is to rub them three times a week in summer and twice in winter.

STILTON CHEESE.

"Stilton cheese is made by putting the night's cream into the morning's new milk along with the rennet. When the [Pg 41]curd has come, it is not broken, as in making other cheese, but taken out whole, and put into a sieve to drain gradually. While this is going on, it is gently pressed, and, having become firm and dry, is put into a vat, and kept on a dry board. These cheeses are exceedingly rich and valuable. They are called the Parmesan of England, and weigh from ten to twelve pounds. The manufacture of them is confined almost exclusively to Leicestershire, though not entirely so.

DUNLOP CHEESE.

"In Scotland, a species of cheese is produced, which has long been known and celebrated under the name of Dunlop cheese. The best cheese is made by such as have a dozen or more cows, and consequently can make a cheese every day; one half of the milk being immediately from the cow, and the other of twelve hours' standing. Their method of making it is simple. They endeavor to have the milk as near as may be to the heat of new milk, when they apply the rennet, and whenever coagulation has taken place, (which is generally in ten or twelve minutes,) they stir the curd gently, and the whey, beginning to separate, is taken off as it gathers, till the curd be pretty solid. When this happens, they put it into a drainer with holes, and apply a weight. As soon as this has had its proper effect, the curd is put back again into the cheese-tub, and, by means of a sort of knife with three or four blades, is cut into very small pieces, salted, and carefully mixed by the hand. It is now placed in the vat, and put under the press. This is commonly a large stone of a cubical shape, from half a ton to a ton in weight, fixed in a frame of wood, and raised and lowered by an iron screw. The cheese is frequently taken out, and the cloth changed; and as soon as it has been ascertained that no more whey remains, it is removed, and placed on a dry board or pine floor. It is turned and rubbed frequently with a hard, coarse cloth, to prevent moulding or breeding mites. No coloring matter [Pg 42]is used in making Dunlop cheese, except by such as wish to imitate the English cheese.

GREEN CHEESE.

"Green cheese is made by steeping ever night, in a proper quantity of milk, two parts of sage with one of marigold leaves, and a little parsley, after being bruised, and then mixing the curd of the milk, thus greened, as it is called, with the curd of the white milk. These may be mixed irregularly or fancifully, according to the pleasure of the operator. The management in other respects is the same as for common cheese."

Mr. Colman says, "In conversation with one of the largest wholesale cheesemongers and provision-dealers in the country, he suggested that there were two great faults of the American cheese, which somewhat prejudiced its sale in the English market. He is a person in whose character and experience entire confidence may be placed.

"The first fault was the softness of the rind. It often cracked, and the cheese became spoiled from that circumstance.

"The second fault is the acridness, or peculiar, smart, bitter taste often found in American cheese. He thought this might be due, in part, to some improper preparation or use of the rennet, and, in part, to some kind of feed which the cows found in the pastures.

"The rind may be made of any desired hardness, if the cheese be taken from the press, and allowed to remain in brine, so strong that it will take up no more salt, for four or five hours. There must be great care, however, not to keep it too long in the brine.

"The calf from which the rennet is to be taken should not be allowed to suck on the day on which it is killed. The office of the rennet, or stomach of the calf, is, to supply the [Pg 43]gastric juice by which the curdling of the milk is effected. If it has recently performed that office, it will have become, to a degree, exhausted of its strength. Too much rennet should not be applied. Dairymaids, in general, are anxious to have the curd 'come soon,' and so apply an excessive quantity, to which he thinks much of the acrid taste of the cheese is owing. Only so much should be used as will produce the effect in about fifty minutes. For the reason above given, the rennet should not, he says, be washed in water when taken from the calf, as it exhausts its strength, but be simply salted.

"When any cream is taken from the milk to be made into butter, the buttermilk should be returned to the milk of which the cheese is to be made. The greatest care should be taken in separating the whey from the cheese. When the pressing or handling is too severe, the whey that runs from the curd will appear of a white color. This is owing to its carrying off with it the small creamy particles of the cheese, which are, in fact, the richest part of it. After the curd is cut or broken, therefore, and not squeezed with the hand, and all the whey is allowed to separate from it that can be easily removed, the curd should be taken out of the tub with the greatest care, and laid upon a coarse cloth attached to a frame like a sieve, and there suffered to drain until it becomes quite dry and mealy, before being put into the press. The object of pressing should be, not to express the whey, but to consolidate the cheese. There should be no aim to make whey butter. All the butter extracted from the whey is so much of the proper richness taken from the cheese."

It is a matter of impossibility to make a superior article of butter from the milk of a cow in a diseased state; for if either of the organs of secretion, absorption, digestion, or circulation, be deranged, we cannot expect good blood. The milk being a secretion from the blood, it follows that, in order to have good milk, we must have pure blood. A great deal depends also on the food; certain pastures are more favorable to the production of good milk than others. We know that many vegetables, such as turnips, garlic, dandelions, will impart a disagreeable flavor to the milk. On the other hand, sweet-scented grasses and boiled food improve the quality, and, generally, increase the quantity of the milk, provided, however, the digestive organs are in a physiological state.

The processes of making butter are various in different parts of the United States. We are not prepared, from experience, to discuss the relative merits of the different operations of churning; suffice it to say, that the important improvements that have recently been made in the construction of churns promise to be of great advantage to the dairyman.

The method of churning in England is considered to be favorable to the production of good butter. From twelve to twenty hours in summer, and about twice as long in winter, are permitted to elapse before the milk is skimmed, after it has been put into the milk-pans. If, on applying the tip of the finger to the surface, nothing adheres to it, the cream may be properly taken off; and during the hot summer months, this should always be done in the morning, before the dairy becomes warm. The cream should then be deposited in a deep pan, placed in the coolest part of the dairy, or in a cool cellar, where free air is admitted. In hot weather, churning should be performed, if possible, every other day; but if this is not convenient, the cream should be daily shifted into a clean pan, and the churning should never be less frequent than twice a week. This work should be performed in the [Pg 45]coolest time of the day, and in the coolest part of the house. Cold water should be applied to the churn, first by filling it with this some time before the cream is poured in, or it may be kept cool by the application of a wet cloth. Such means are generally necessary, to prevent the too rapid acidification of the cream, and formation of the butter. We are indebted for much of the poor butter, (cart-grease would be a more suitable name,) in which our large cities abound, to want of due care in churning: it should never be done too hastily, but—like "Billy Gray's" drumming—well done. In winter the churn may be previously heated by first filling it with hot water, the operation to be performed in a moderately warm room.

In churning, a moderate and uninterrupted motion should be kept up during the whole process; for if the motion be too rapid, heat is generated, which will give the butter a rank flavor; and if the motion is relaxed, the butter will go back, as it is termed.

WASHING BUTTER.