Title: Memoirs of Leonora Christina, Daughter of Christian IV. of Denmark

Author: grevinde Leonora Christina Ulfeldt

Translator: F. E. Bunnett

Release date: November 24, 2011 [eBook #38128]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from scanned images of public domain material generously made available by the Google Books Library Project (http://books.google.com/)

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through the the Google Books Library Project. See http://books.google.com/books?vid=MaYBAAAAQAAJ&id |

Obvious word errors have been corrected, but otherwise the original spelling has generally been retained, even where several different spellings have been used to refer to the same person. A list of corrections can be found after the book.

The printed book contained footnotes and endnotes—these have all be placed at the end of the ebook.

Henry S. King & Co., 65, Cornhill

DAUGHTER of CHRISTIAN IV. of DENMARK

WRITTEN DURING HER IMPRISONMENT IN

THE BLUE TOWER AT COPENHAGEN

1663—1685

Translated by F. E. Bunnètt

LONDON

Henry S. King & Co., 65 Cornhill

1872

LONDON: PRINTED BY

SPOTTISWOODE AND CO., NEW-STREET SQUARE

AND PARLIAMENT STREET

All rights reserved

In placing the present translation of Leonora Christina Ulfeldt’s Memoirs before the English reading public, a few words are due from the Publishers, in order to explain the relation between this edition and those which have been brought out in Denmark and in Germany.

The original autograph manuscript of Leonora Christina’s record of her sufferings in her prison, written between the years 1674 and 1685, belongs to her descendant the Austrian Count Joh. Waldstein, and it was discovered only a few years ago. It was then, at the desire of Count Waldstein, brought to Copenhagen by the Danish Minister at Vienna, M. Falbe, in order that its authenticity might be thoroughly verified by comparison with documents preserved in the Danish archives and libraries, and known to be in the hand-writing of the illustrious authoress. When the existence of this interesting historic and literary relic had become known in Denmark, a desire to see it published was naturally expressed on all sides, and to this the noble owner most readily acceded.

Thus the first Danish edition came to light in 1869, promoted in every way by Count Waldstein. The editor was Mr. Sophus Birket-Smith, assistant librarian of the University Library at Copenhagen, who enriched the edition with a historical introduction and copious notes. A second Danish edition appeared a few months later; and in 1871 a German translation of the Memoir was edited by M. Ziegler, with a new introduction and notes, founded partly on the first Danish edition, partly on other printed sources, to which were added extracts from some papers found in the family archives of Count Waldstein, and which were supposed to possess the interest of novelty.

The applause with which this edition was received in Germany suggested the idea of an English version, and it was at first intended merely to translate M. Ziegler’s book into English. During the progress of the work, however, it was found preferable to adopt the second Danish edition as the basis of the English edition. The translation which had been made from M. Ziegler’s German, has been carefully compared with the Danish original, so as to remove any defects arising from the use of the German translation, and give it the same value as a translation made direct from the Danish; a new introduction and notes have been added, for which the Danish editor, Mr. Birket-Smith has supplied the materials; and instead of the fragments of Ulfeldt’s Apology and of an extract from Leonora Christina’s Autobiography found in the German edition, a complete translation of the Autobiography to the point where Leonora’s Memoir of her sufferings in prison takes up the thread of the narrative, has been inserted, made from the original French text, recently published by Mr. S. Birket-Smith. As a matter of course the preface of Count Waldstein, which appears in this edition, is the one prefixed to the Danish edition. The manuscript itself of the record of Leonora Christina’s sufferings in prison was commenced in 1674, and was at first intended to commemorate only what had happened during the preceding ten years of her captivity; it was afterwards extended to embrace the whole period down to 1685, and subjected to a revision which resulted in numerous additions and alterations. As, however, these do not seem to have been properly worked in by the authoress herself, the Memoir is here rendered, as in the Danish edition, in its original, more perfect shape, and the subsequent alterations made the subject of foot notes.

When, in the summer of 1858, I visited the graves of my Danish ancestors of the family of Ulfeldt, in the little village church at Quærndrup, near the Castle of Egeskov, on the island of Fyn, I resolved to honour the memory of my pious ancestress Leonora Christina, and thus fulfil the duty of a descendant by publishing this autograph manuscript which had come to me amongst the heirlooms left by my father.

It is well known that the last male representative of the family of Ulfeldt, the Chancellor of the Court and Realm of Her Majesty the Empress Maria Theresia, had only two daughters. One of them, Elizabeth, married Georg Christian, Count Waldstein, while the younger married Count Thun.

Out of special affection for her younger son Emanuel (my late father), my grandmother bequeathed all that referred to the Ulfeldts to him, and the manuscript which I now—in consequence of requests from various quarters, also from high places—give to publicity by the learned assistance of Mr. Sophus Birket-Smith, thus came to me through direct descent from her father:

‘Corfitz, Count of Ulfeldt of the holy Roman Empire, Lord of the lordships Költz-Jenikau, Hof-Kazof, Brödlich, Odaslowitz, and the fief Zinltsch, Knight of the Golden Vliess, First Treasurer of the hereditary lands in Bohemia, Ambassador at the Ottoman Porte, afterwards Chancellor of the Court and the Empire, sworn Privy Councillor and first Lord Steward of his Imperial and Royal Majesty Carolus VI., as well as of His Imperial Roman and Royal Majesty of Hungary, Bohemia,’ &c.

We add: the highly honoured paternal guide of Her Majesty the Queen Empress Maria Theresia, of glorious memory, during the first year of her government, until the time when the gifted Prince Kaunitz, whose genius sometimes even was too much for this, morally noble lady, became her successor.

I possess more than eleven imposing, closely written folio volumes, which contain the manuscripts of the Chancellor of the Empire, his negociations with the Sublime Porte, afterwards with the States-General of the Netherlands, as well as the ministerial protocols from the whole time that he held the office of Imperial Chancellor; all of which prove his great industry and love of order, while the original letters and annotations of his exalted mistress, which are inserted in these same volumes, testify to the sincere, almost childlike confidence with which she honoured him.

But this steady and circumspect statesman was the direct grandson of the restless and proud

Corfitz, first Count of Ulfeldt of the Roman Empire, High Steward of the Realm in Denmark, &c., and of his devoted and gifted wife Leonora Christina, through their son

Leo, Imperial Count Ulfeldt, Privy Councillor, Field-marshal, and Viceroy in Catalonia of the Emperor Carl VI., and his wife, a born Countess of Zinzendorf.

I preserved, therefore with great care this manuscript, as well as all other relics and little objects which had belonged to my Danish ancestress, whose exalted character and sufferings are so highly calculated to inspire sympathy, interest, and reverence. Amongst these objects are several writings, such as fragments of poems, prayers, needlework executed in prison (some embroidered with hair of a fair colour); a christening robe with cap worked in gold, probably used at the christening of her children; a very fine Amulet of Christian IV. in blue enamel, and many portraits; amongst others the original picture in oil of which a copy precedes the title page, &c. &c.

Considering that the manuscript has been handed down directly from my ancestors from generation to generation in direct line, I could not personally have any doubt as to its genuineness. Nevertheless I yielded to the suggestions of others, in order to have the authenticity of the manuscript thoroughly tested. In what way this was done will be seen from the Introduction of the Editor.

Though the final verdict of history may not yet have been given on Corfitz Ulfeldt, yet—tempus omnia sanat—yon ominous pillar, which was to perpetuate the memory of his crime into eternity, has been put aside as rubbish and left to oblivion. Noble in forgetting and pardoning, the great nation of the North has given a bright example to those who still refuse to grant to Albert, Duke of Friedland—the great general who saved the Empire from the danger that threatened it from the North—the place which this hero ought to occupy in the Walhalla at Vienna.

But as to the fiery temper of Corfitz and the mysterious springs which govern the deeds and thoughts of mankind, it may be permitted to me, his descendant, to cherish the belief, which is almost strengthened into a conviction, that a woman so highly gifted, of so noble sentiments, as Leonora appears to us, would never have been able to cling with a love so true, and so enduring through all the changes of life, to a man who was unworthy of it.

Joh. Count Waldstein.

Cairo: December 8, 1868.

Page

Amongst the women celebrated in history, Leonora Christina, the heroine as well as the authoress of the Memoirs which form the subject of this volume, occupies a conspicuous place, as one of the noblest examples of every womanly virtue and accomplishment, displayed under the most trying vicissitudes of fortune. Born the daughter of a King, married to one of the ablest statesmen of his time, destined, as it seemed, to shine in the undisturbed lustre of position and great qualities, she had to spend nearly twenty-two years in a prison, in the forced company—more cruel to her than solitary confinement—of male and female gaolers of the lowest order, and for a long time deprived of every means of rendering herself independent of these surroundings by intellectual occupation. She had to suffer alone, and innocently, for her husband’s crimes; whatever these were, she had no part in them, and she endured persecution because she would not forsake him in his misfortune. Leonora Christina was the victim of despotism guided by personal animosity, and she submitted with a Christian meekness and forbearance which would be admirable in any, but which her exalted station and her great mental qualities bring out in doubly strong relief.

It is to these circumstances, which render the fate of Leonora so truly tragic, as well as to the fact that we have her own authentic and trustworthy account before us, that the principal charm of this record is due. Besides this, it affords many incidental glimpses of the customs and habits of the time, nor is it without its purely historical interest. Leonora and her husband, Corfits Ulfeldt, were intimately connected with the principal political events in the North of Europe at their time; even the more minute circumstances of their life have, therefore, a certain interest.

No wonder that the history of this illustrious couple has formed, and still forms, the theme both of laborious scientific researches and of poetical compositions. Amongst the latter we may here mention in passing a well-known novel by Rousseau de la Valette,[1] because it has had the undeserved honour of being treated by a modern writer as an historical source, to the great detriment of his composition. Documents which have originated from these two personages are of course of great value. Besides letters and public documents, there exist several accounts written by both Corfits Ulfeldt and Leonora referring to their own life and actions. Ulfeldt published in 1652 a defence of his political conduct, and composed, shortly before his death, another, commonly called the ‘Apology of Ulfeldt,’ which has not yet been printed entirely, but of which an extract was published in 1695 in the supplement of the English edition of Rousseau de la Valette’s book. Some extracts from an incomplete copy discovered by Count Waldstein in 1870, in the family archives at the Castle of Palota, were published with the German edition of Leonora’s Memoir; complete copies exist in Copenhagen and elsewhere. Leonora Christina, who was an accomplished writer, has composed at least four partial accounts of her own life. One of them, referring to a journey in 1656, to be mentioned hereafter, has been printed long ago; of another, which treated of her and Ulfeldt’s imprisonment at Bornholm, no copy has yet been discovered. The third is her Autobiography, carried down to 1673, of which an English version follows this Introduction; it was written in the Blue Tower, in the form of a letter to the Danish antiquarian, Otto Sperling, jun., who wished to make use of it for his work, ‘De feminis doctis.’[2]

About a century ago a so-called Autobiography of Leonora was published in Copenhagen, but it was easily proved to be a forgery; in fact, the original of her own work existed in the Danish archives, and had been described by the historian Andreas Höier. It has now been lost, it is supposed, in the fire which destroyed the Castle of Christiansborg in 1794, but a complete copy exists in Copenhagen, as well as several extracts in Latin; another short extract in French belongs to Count Waldstein. Finally, Leonora Christina wrote the memoir of her sufferings in the prison of the Blue Tower from 1663-1685, of which the existence was unknown until discovered by Count Waldstein, and given to the public in the manner indicated in the Preface.

In introducing these memoirs to the English public, a short sketch of the historical events and the persons to whom they refer may not be unwelcome, particularly as Leonora herself touches only very lightly on them, and principally describes her own personal life.

Leonora Christina was a daughter of King Christian IV. of Denmark and Kirstine Munk. His Queen, Anna Catherine, born a princess of Brandenburg, died in 1612, leaving three princes (four other children died early), and in 1615 the King contracted a morganatic marriage with Kirstine Munk, a lady of an ancient and illustrious noble family. Leonora was born July 18 (new style), 1621, at the Castle of Fredriksborg, so well known to all who have visited Denmark, which the King had built twenty miles north of Copenhagen, in a beautiful part of the country, surrounded by smiling lakes and extensive forests. But little is known of her childhood beyond what she tells herself in her Autobiography. Already in her eighth year she was promised to her future husband, Corfits Ulfeldt, and in 1636 the wedding was celebrated with great splendour, Leonora being then fifteen years old. The family of Ulfeldt has been known since the close of the fourteenth century. Corfits’ father had been Chancellor of the Realm, and somewhat increased the family possessions, though he sold the ancient seat of the family, Ulfeldtsholm, in Fyen, to Lady Ellen Marsvin, Kirstine Munk’s mother. He had seventeen children, of whom Corfits was the seventh; and so far Leonora made only a poor marriage. But her husband’s great talents and greater ambition made up for this defect. Of his youth nothing is known with any certainty, except that he travelled abroad, as other young noblemen of his time, studied at Padua, and acquired considerable proficiency in foreign languages.[3] He became a favourite of Christian IV., at whose Court he had every opportunity for displaying his social talents. At the marriage of the elected successor to the throne, the King’s eldest son, Christian, with the Princess Magdalene Sibylle of Saxony, in 1634, Corfits Ulfeldt acted as maréchal to the special Ambassador Count d’Avaux, whom Louis XIII. had sent to Copenhagen on that occasion, in which situation Ulfeldt won golden opinions,[4] and he was one of the twelve noblemen whom the King on the wedding-day made Knights of the Elephant. After a visit to Paris in 1635, in order to be cured of a wound in the leg which the Danish physicians could not heal, he obtained the sanction of the King for his own marriage with Leonora, which was solemnised at the Castle of Copenhagen, on October 9, 1636, with as much splendour as those of the princes and princesses. Leonora was the favourite daughter of Christian IV., and as far as royal favour could ensure happiness, it might be said to be in store for the newly-married pair.

As we have stated, Ulfeldt was a poor nobleman; and it is characteristic of them both that one of her first acts was to ask him about his debts, which he could not but have incurred living as he had done, and to pay them by selling her jewels and ornaments, to the amount of 36,000 dollars, or more than 7,000l. in English money—then a very large sum. But the King’s favour soon procured him what he wanted; he was made a member of the Great Council, Governor of Copenhagen, and Chancellor of the Exchequer.

He executed several diplomatic missions satisfactorily; and when, in 1641, he was sent to Vienna as special Ambassador, the Emperor of Germany, Ferdinand III., made him a Count of the German Empire. Finally, in 1643, he was made Lord High Steward of Denmark, the highest dignity and most responsible office in the kingdom. He was now at the summit of power and influence, and if he had used his talents and opportunities in the interests of his country, he might have earned the everlasting gratitude of his King and his people.

But he was not a great man, though he was a clever and ambitious man. He accumulated enormous wealth, bought extensive landed estates, spent considerable sums in purchasing jewels and costly furniture, and lived in a splendid style; but it was all at the cost of the country. In order to enrich himself, he struck base coin (which afterwards was officially reduced to its proper value, 8 per cent. below the nominal value), and used probably other unlawful means for this purpose, while the Crown was in the greatest need of money. At the same time he neglected the defences of the country in a shameful manner, and when the Swedish Government, in December 1643, suddenly ordered its army, which then stood in Germany, engaged in the Thirty Years’ War, to attack Denmark without any warning, there were no means of stopping its victorious progress. In vain the veteran King collected a few vessels and compelled the far more numerous Swedish fleet to fly, after a furious battle near Femern, where he himself received twenty-three wounds, and where two of Ulfeldt’s brothers fell fighting at his side; there was no army in the land, because Corfits, at the head of the nobility, had refused the King the necessary supplies. And, although the peace which Ulfeldt concluded with Sweden and Holland at Brömsebro, in 1645, might have been still more disastrous than it was, if the negotiation had been entrusted to less skilful hands, yet there was but too much truth in the reproachful words of the King, when, after ratifying the treaties, he tossed them to Corfits saying, ‘There you have them, such as you have made them!’

From this time the King began to lose his confidence in Ulfeldt, though the latter still retained his important offices. In the following year he went to Holland and to France on a diplomatic mission, on which occasion he was accompanied by Leonora. Everywhere their personal qualities, their relationship to the sovereign, and the splendour of their appearance, procured them the greatest attention and the most flattering reception. While at the Hague Leonora gave birth to a son, whom the States-General offered to grant a pension for life of a thousand florins, which, however, Ulfeldt wisely refused. In Paris they were loaded with presents; and in the Memoirs of Madame Langloise de Motteville on the history of Anna of Austria (ed. of Amsterdam, 1783, ii. 19-22) there is a striking récit of the appearance and reception of Ulfeldt and Leonora at the French Court. On their way home Leonora took an opportunity of making a short trip to London, which capital she wished to see, while her husband waited for her in the Netherlands.

If, however, this journey brought Ulfeldt and his wife honours and presents on the part of foreigners, it did not give satisfaction at home. The diplomatic results of the mission were not what the King had hoped, and he even refused to receive Ulfeldt on his return. Soon the turning-point in his career arrived. In 1648 King Christian IV. died, under circumstances which for a short time concentrated extraordinary power in Ulfeldt’s hands, but of which he did not make a wise use.

Denmark was then still an elective monarchy, and the nobles had availed themselves of this and other circumstances to free themselves from all burdens, and at the same time to deprive both the Crown and the other Estates of their constitutional rights to a very great extent. All political power was virtually vested in the Council of the Realm, which consisted exclusively of nobles, and there remained for the king next to nothing, except a general supervision of the administration, and the nomination of the ministers. Every successive king had been obliged to purchase his election by fresh concessions to the nobles, and the sovereign was little more than the president of an aristocratic republic. Christian IV. had caused his eldest son Christian to be elected successor in his own lifetime; but this prince died in 1647, and when the King himself died in 1648, the throne was vacant.

As Lord High Steward, Ulfeldt became president of the regency, and could exercise great influence on the election. He did not exert himself to bring this about very quickly, but there is no ground for believing that he meditated the election either of himself or of his brother-in-law, Count Valdemar, as some have suggested. The children of Kirstine Munk being the offspring of a morganatic marriage, had not of course equal rank with princes and princesses; but in Christian IV.’s lifetime they received the same honours, and Ulfeldt made use of the interregnum to obtain the passage of a decree by the Council, according them rank and honours equal with the princes of the royal house.

But as the nobles were in nowise bound to choose a prince of the same family, or even a prince at all, this decree cannot be interpreted as evidence of a design to promote the election of Count Valdemar. The overtures of the Duke of Gottorp, who attempted to bribe Ulfeldt to support his candidature, were refused by him, at least according to his own statement. But Ulfeldt did make use of his position to extort a more complete surrender of the royal power into the hands of the nobility than any king had yet submitted to, and the new King, Fredrik III., was compelled to promise, amongst other things, to fill up any vacancy amongst the ministers with one out of three candidates proposed by the Council of the Realm. The new King, Fredrik III., Christian IV.’s second son, had never been friendly to Ulfeldt. This last action of the High Steward did not improve the feelings with which he regarded him, and when the coronation had taken place (for which Ulfeldt advanced the money), he expressed his thoughts at the banquet in these words: ‘Corfitz, you have to-day bound my hands; who knows, who can bind yours in return?’ The new Queen, a Saxon princess, hated Ulfeldt and the children of Kirstine Munk on account of their pretensions, but particularly Leonora Christina, whose beauty and talents she heartily envied.

Nevertheless Ulfeldt retained his high offices for some time, and in 1649 he went again to Holland on a diplomatic mission, accompanied by his wife. It is remarkable that the question which formed the principal subject of the negotiation on that occasion was one which has found its proper solution only in our days—namely, that of a redemption of the Sound dues. This impost, levied by the Danish Crown on all vessels passing the Sound, weighed heavily on the shipping interest, and frequently caused disagreement between Denmark and the governments mostly interested in the Baltic trade, particularly Sweden and the Dutch republic.

It was with especial regard to the Sound dues that the Dutch Government was constantly interfering in the politics of the North, with a view of preventing Denmark becoming too powerful; for which purpose it always fomented discord between Denmark and Sweden, siding now with the one, now with the other, but rather favouring the design of Sweden to conquer the ancient Danish provinces, Skaane, &c., which were east of the Sound, and which now actually belong to Sweden. Corfits Ulfeldt calculated that, if the Dutch could be satisfied on the point of the Sound dues, their unfavourable interference might be got rid of; and for this purpose he proposed to substitute an annual payment by the Dutch Government for the payment of the dues by the individual ships. Christian IV. had never assented to this idea, and of course the better course would have been the one adopted in 1857—namely, the redemption of the dues by all States at once for a proportionate consideration paid once for all. Still the leading thought was true, and worthy of a great statesman.

Ulfeldt concluded a treaty with Holland according to his views, but it met with no favour at Copenhagen, and on his return he found that in his absence measures had been taken to restrict his great power; his conduct of affairs was freely criticised, and his enemies had even caused the nomination of a committee to investigate his past administration, more particularly his financial measures.

At the same time the new Court refused Leonora Christina and the other children of Kirstine Munk the princely honours which they had hitherto enjoyed. Amongst other marks of distinction, Christian IV. had granted his wife and her children the title of Counts and Countesses of Slesvig and Holstein, but Fredrik III. declined to acknowledge it, although it could have no political importance, being nothing but an empty title, as neither Kirstine Munk nor her children had anything whatever to do with either of these principalities. Ulfeldt would not suffer himself to be as it were driven from his high position by these indications of disfavour on the part of the King and the Queen (the latter was really the moving spring in all this), but he resolved to show his annoyance by not going to Court, where his wife did not now receive the usual honours.

This conduct only served to embolden those who desired to oust him from his lucrative offices, not because they were better patriots, but because they hoped to succeed him. For this purpose a false accusation was brought against Ulfeldt and Leonora Christina, to the effect that they had the intention of poisoning the King and the Queen. Information on this plot was given to the Queen personally, by a certain Dina Vinhowers, a widow of questionable reputation, who declared that she had an illicit connection with Ulfeldt, and that she had heard a conversation on the subject between Corfits Ulfeldt and Leonora, when on a clandestine visit in the High Steward’s house. She was prompted by a certain Walter, originally a son of a wheelwright, who by bravery in the war had risen from the ranks to the position of a colonel, and who in his turn was evidently a tool in the hands of other parties. The information was graciously received at Court; but Dina, who, as it seems, was a person of weak or unsound mind, secretly, without the knowledge of her employers, warned Ulfeldt and Leonora Christina of some impending danger, thus creating a seemingly inextricable confusion.

At length Ulfeldt demanded a judicial investigation, which was at once set on foot, but in which, of course, he occupied the position of a defendant on account of Dina’s information. In the end Dina was condemned to death and Walter was exiled. But the statements of the different persons implicated, and particularly of Dina herself at different times, were so conflicting, that the matter was really never entirely cleared up, and though Ulfeldt was absolved of all guilt, his enemies did their best in order that some suspicion might remain. If Ulfeldt had been wise, he might probably have turned this whole affair to his own advantage; but he missed the opportunity. Utterly absurd as the accusation was, he seems to have felt very keenly the change of his position, and on the advice of Leonora, who did not doubt that some other expedient would be tried by his enemies, perhaps with more success, he resolved to leave Denmark altogether.

After having sent away the most valuable part of his furniture and movable property, and placed abroad his amassed capital, he left Copenhagen secretly and at night, on July 14, 1651, three days after the execution of Dina. The gates of the fortress were closed at a certain hour every evening, but he had a key made for the eastern gate, and ere sunrise he and Leonora, who was disguised as a valet, were on board a vessel on their way to Holland. The consequences of this impolitic flight were most disastrous. He had not laid down his high offices, much less rendered an account of his administration; nothing was more natural than to suppose that he wished to avoid an investigation. A few weeks later a royal summons was issued, calling upon him to appear at the next meeting of the Diet, and answer for his conduct; his offices, and the fiefs with which he had been beneficed, were given to others, and an embargo was laid on his landed estates.

Leonora Christina describes in her Autobiography how Ulfeldt meanwhile first went to Holland, and thence to Sweden, where Queen Christina, who certainly was not favourably disposed to Denmark, received Ulfeldt with marked distinction, and promised him her protection. But she does not tell how Ulfeldt here used every opportunity for stirring up enmity against Denmark, both in Sweden itself and in other countries, whose ambassadors he tried to bring over to his ideas. On this painful subject there can be no doubt after the publication of so many authentic State Papers of that time, amongst which we may mention the reports of Whitelock, the envoy of Cromwell, to whom Ulfeldt represented that Denmark was too weak to resist an attack, and that the British Government might easily obtain the abolition of the Sound dues by war.

It seems, however, as if Ulfeldt did all this merely to terrify the Danish King into a reconciliation with him on terms honourable and advantageous to the voluntarily exiled magnate. Representations were several times made with such a view by the Swedish Government, and in 1656 Leonora Christina herself undertook a journey to Copenhagen, in order to arrange the matter. But the Danish Government was inaccessible to all such attempts.

This attitude was intelligible enough, for not only had Ulfeldt left Denmark in the most unceremonious manner, but in 1652 he published in Stralsund a defence against the accusations of which he had been the subject, full of gross insults against the King; and in the following year he had issued an insolent protest against the royal summons to appear and defend himself before the Diet, declaring himself a Swedish subject. But, above all, the influence of the Queen was too great to allow of any arrangement with Ulfeldt. The King was entirely led by her; she, from her German home, was filled with the most extravagant ideas of absolute despotism, and hated the free speech and the independent spirit prevailing among the Danish nobility, of which Ulfeldt in that respect was a true type. Leonora Christina was compelled to return in 1656, without even seeing the King, and as a fugitive. It is of this journey that she has given a Danish account, besides the description in the Autobiography.

It may be questioned whether it would not have been wise, if possible, to conciliate this dangerous man; but at any rate it was not done, and Ulfeldt was, no doubt, still more exasperated. Queen Christina had then resigned, and her successor, Carl Gustav, shortly after engaged in a war in Poland. The Danish Government, foolishly overrating its strength, took the opportunity for declaring war against Sweden, in the hope of regaining some of the territory lost in 1645. But Carl Gustav, well knowing that the Poles could not carry the war into Sweden, immediately turned his whole force against Denmark, where he met with next to no resistance. Ulfeldt was then living at Barth, in Pommerania, an estate which he held in mortgage for large sums of money advanced to the Swedish Government. Carl Gustav summoned Ulfeldt to follow him, and Ulfeldt obeyed the summons against the advice of Leonora Christina, who certainly did not desire her native country to be punished for the wrongs, if such they were, inflicted upon her by the Court.

The war had been declared on June 1, 1657; in August Ulfeldt issued a proclamation to the nobility in Jutland, calling on them to transfer their allegiance to the Swedish King. In the subsequent winter a most unusually severe frost enabled the Swedish army to cross the Sounds and Belts on the ice, Ulfeldt assisting its progress by persuading the commander of the fortress of Nakskov to surrender without resistance; and in February the Danish Government had to accept such conditions of peace as could be obtained from the Swedish King, who had halted a couple of days’ march from Copenhagen. By this peace Denmark surrendered all her provinces to the east of the Sound (Skaane, &c.), which constituted one-third of the ancient Danish territory, and which have ever since belonged to Sweden, besides her fleet, &c.

But the greatest humiliation was that the negotiation on the Swedish side was entrusted to Ulfeldt, who did not fail to extort from the Danish Crown the utmost that the neutral powers would allow. For himself he obtained restitution of his estates, freedom to live in Denmark unmolested, and a large indemnity for loss of income of his estates since his flight in 1651. The King of Sweden also rewarded him with the title of a Count of Sölvitsborg and with considerable estates in the provinces recently wrested from Denmark. Ulfeldt himself went to reside at Malmö, the principal town in Skaane, situated on the Sound, just opposite Copenhagen, and here he was joined by Leonora Christina.

In her Autobiography Leonora does not touch on the incidents of the war, but she describes how her anxiety for her husband’s safety did not allow her to remain quietly at Barth, and how she was afterwards called to her mother’s sick-bed, which she had to leave in order to nurse her husband, who fell ill at Malmö. We may here state that Kirstine Munk had fallen into disgrace, when Leonora was still a child, on account of her flagrant infidelity to the King, her paramour being a German Count of Solms. Kirstine Munk left the Court voluntarily in 1629,[5] shortly after the birth of a child, whom the King would not acknowledge as his own; and after having stayed with her mother for a short time, she took up her residence at the old manor of Boller, in North Jutland, where she remained until her death in 1658.

Various attempts were made to reconcile Christian IV. to her, but he steadily refused, and with very good reason: he was doubtless well aware that Kirstine Munk, as recently published diplomatic documents prove, had betrayed his political secrets to Gustav Adolf, the King of Sweden, and he considered her presence at Court very dangerous. Her son-in-law was now openly in the service of another Swedish king, but the friendship between them was not of long duration. Ulfeldt first incurred the displeasure of Carl Gustav by heading the opposition of the nobility in the newly acquired provinces against certain imposts laid on them by the Swedish King, to which they had not been liable under Danish rule. Then other causes of disagreement arose. Carl Gustav, regretting that he had concluded a peace, when in all probability he might have conquered the whole of Denmark, recommenced the war, and laid siege to Copenhagen. But the Danish people now rose as one man; foreign assistance was obtained; the Swedes were everywhere beaten; and if the Dutch, who were bound by treaty to assist Denmark, had not refused their co-operation in transferring the Danish troops across the Sound, all the lost provinces might easily have been regained.

The inhabitants in some of these provinces also rose against their new rulers. Amongst others, the citizens of Malmö, where Ulfeldt at the time resided, entered into a conspiracy to throw off the Swedish dominion; but it was betrayed, and Ulfeldt was indicated as one of the principal instigators, although he himself had accepted their forced homage to the Swedish King, as his deputy. Very probably he had thought that, if he took a part in the rising, he might, if this were successful, return to Denmark, having as it were thus wiped out his former crimes, but having also shown his countrymen what a terrible foe he could be. As it was, Denmark was prevented by her own allies from regaining her losses, and Ulfeldt was placed in custody in Malmö, by order of Carl Gustav, in order that his conduct might be subjected to a rigorous examination.

Ulfeldt was then apparently seized with a remarkable malady, a kind of apoplexy, depriving him of speech, and Leonora Christina conducted his defence. She wrote three lengthy, vigorous, and skilful replies to the charges, which still exist in the originals. He was acquitted, or rather escaped by a verdict of Not Proven; but as conscience makes cowards, he contrived to escape before the verdict was given. Leonora Christina describes all this in her Autobiography, according to which Ulfeldt was to go to Lubeck, while she would go to Copenhagen, and try to put matters straight there. Ulfeldt, however, changed his plan without her knowledge, and also repaired to Copenhagen, where they were both arrested and sent to the Castle of Hammershuus, on the island of Bornholm in the Baltic, an ancient fortress, now a most picturesque ruin, perched at the edge of perpendicular rocks, overhanging the sea, and almost surrounded by it.

The Autobiography relates circumstantially, and no doubt truthfully, the cruel treatment to which they were here subjected by the governor, a Major-General Fuchs. After a desperate attempt at escape, they were still more rigorously guarded, and at length they had to purchase their liberty by surrendering the whole of their property, excepting one estate in Fyen. Ulfeldt had to make the most humble apologies, and to promise not to leave the island of Fyen, where this estate was situated, without special permission. He was also compelled to renounce on the part of his wife the title of a Countess of Slesvig-Holstein, which Fredrik III. had never acknowledged. She never made use of that title afterwards, nor is she generally known by it in history. Corfits Ulfeldt being a Count of the German Empire, of course Leonora and her children were, and remained, Counts and Countesses of Ulfeldt. This compromise was effected in 1661.

Having been conveyed to Copenhagen, Ulfeldt could not obtain an audience of the King, and he was obliged, kneeling, to tender renewed oath of allegiance before the King’s deputies, Count Rantzow, General Hans Schack, the Chancellor Redtz, and the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Christofer Gabel, all of whom are mentioned in Leonora’s account of her subsequent prison life.

A few days after, Corfits Ulfeldt and Leonora Christina left Copenhagen, which he was never to see again, she only as a prisoner. They retired to the estate of Ellensborg, in Fyen, which they had still retained. This was the ancient seat of the Ulfeldts, which Corfits’ father had sold to Ellen Marsvin, Leonora Christina’s grandmother, and which had come to Leonora through her mother. In the meanwhile it had been renamed and rebuilt such as it stands to this day, a picturesque pile of buildings in the Elizabethan style. Here Ulfeldt might have ended his stormy life in quiet, but his thirst for revenge left him no peace. Besides this, a great change had taken place in Denmark. The national revival which followed the renewal of the war by Carl Gustav in 1658 led to a total change in the form of government.

It was indisputable that the selfishness of the nobles, who refused to undertake any burden for the defence of the country, was the main cause of the great disasters that had befallen Denmark. The abolition of their power was loudly called for, and the Queen so cleverly turned this feeling to account, that the remedy adopted was not the restoration of the other classes of the population to their legitimate constitutional influence, but the entire abolition of the constitution itself, and the introduction of hereditary, unlimited despotism. The title ‘hereditary king,’ which so often occurs in Danish documents and writings from that time, also in Leonora’s Memoir, has reference to this change. Undoubtedly this was very little to Ulfeldt’s taste. Already, in the next year after his release, 1662, he obtained leave to go abroad for his health. But, instead of going to Spaa, as he had pretended, he went to Amsterdam, Bruges, and Paris, where he sought interviews with Louis XIV. and the French ministers; he also placed himself in communication with the Elector of Brandenburg, with a view of raising up enemies against his native country. The Elector gave information to the Danish Government, whilst apparently lending an ear to Ulfeldt’s propositions.

When a sufficient body of evidence had been collected, it was laid before the High Court of Appeal in Copenhagen, and judgment given in his absence, whereby he was condemned to an ignominious death as a traitor, his property confiscated, his descendants for ever exiled from Denmark, and a large reward offered for his apprehension. The sentence is dated July 24, 1663. Meanwhile Ulfeldt had been staying with his family at Bruges. One day one of his sons, Christian, saw General Fuchs, who had treated his parents so badly at Hammershuus, driving through the city in a carriage; immediately he leaped on to the carriage and killed Fuchs on the spot. Christian Ulfeldt had to fly, but the parents remained in Bruges, where they had many friends.

It was in the following spring, on May 24, 1663, that Leonora Christina, much against her own inclination, left her husband—as it proved, not to see him again alive. Ulfeldt had on many occasions used his wealth in order to gain friends, by lending them money—probably the very worst method of all. It is proved that at his death he still held bonds for more than 500,000 dollars, or 100,000l., which he had lent to various princes and noblemen, and which were never paid. Amongst others he had lent the Pretender, afterwards Charles II., a large sum, about 20,000 patacoons, which at the time he had raised with some difficulty. He doubted not that the King of England, now that he was able to do it, would recognise the debt and repay it; and he desired Leonora, who, through her father, was cousin of Charles II., once removed, to go to England and claim it. She describes this journey in her Autobiography.

The Danish Government, hearing of her presence in England, thought that Ulfeldt was there too, or hoped at any rate to obtain possession of important documents by arresting her, and demanded her extradition. The British Government ostensibly refused, but underhand it gave the Danish minister, Petcum, every assistance. Leonora was arrested in Dover, where she had arrived on her way back, disappointed in the object of her journey. She had obtained enough and to spare of fair promises, but no money; and by secretly giving her up to the Danish Government, Charles II. in an easy way quitted himself of the debt, at the same time that he pleased the King of Denmark, without publicly violating political propriety. Leonora’s account of the whole affair is confirmed in every way by the light which other documents throw upon the matter, particularly by the extracts contained in the Calendar of State Papers, Domestic Series, of the reign of Charles II., 1663-64.

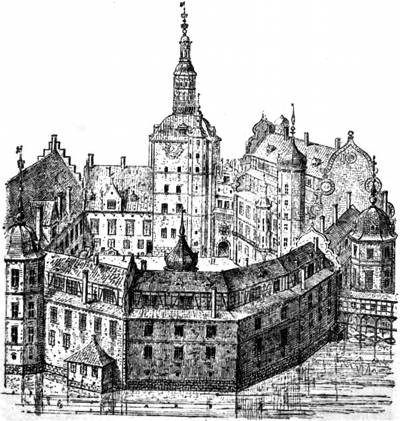

Leonora was now conducted to Copenhagen, where she was confined in the Blue Tower—a square tower surmounted by a blue spire, which stood in the court of the royal castle, and was used as a prison for grave offenders (see the engraving). At this point the Memoir of her sufferings in the prison takes up the thread of her history, and we need not here dwell upon its contents.

As soon as Ulfeldt heard that the Brandenburg Government had betrayed him, and that sentence had been passed on him in Copenhagen, he left Bruges. No doubt the arrest of Leonora in England was a still greater blow to him. The Spanish Government would probably have surrendered him to the Danish authorities, and he had to flee from place to place, pursued by Danish agents demanding his extradition, and men anxious to earn the reward offered for his apprehension, dead or alive. His last abode was Basle, where he passed under a feigned name, until a quarrel between one of his sons and a stranger caused the discovery of their secret. Not feeling himself safe, Ulfeldt left Basle, alone, at night, in a boat descending the Rhine; but he never reached his destination. He was labouring under a violent attack on the chest, and the night air killed him. He breathed his last in the boat, on February 20, 1664. The boatmen, concluding from the gold and jewels which they found on him that he was a person of consequence, brought the body on shore, and made the matter known in Basle, from whence his sons came and buried him under a tree in a field—no one knows the spot.

Meanwhile the punishment of beheading and quartering had been executed on a wooden effigy in Copenhagen. His palace was demolished, and the site laid out in a public square, on which a pillar of sandstone was erected as an everlasting monument of his crimes. This pillar was taken away in 1842, and the name was changed from Ulfeldt Square to Greyfriars Square, as an indication of the forgetting and forgiving spirit of the time, or perhaps rather because the treason of Ulfeldt was closely connected with the ancient jealousy between Danes and Swedes, of which the present generation is so anxious to efface the traces.

His children had to seek new homes elsewhere. Christian, who killed Fuchs, became a Roman Catholic and died as an abbé; and none of them continued the name, except the youngest son Leo, who went into the service of the German Emperor, and rose to the highest dignities. His son Corfits likewise filled important offices under Charles VI. and Maria Theresa, but left no sons. His two daughters married respectively a Count Waldstein and a Count Thun, whose descendants therefore now represent the family of Ulfeldt.

Leonora Christina remained in prison for twenty-two years—that is, until the death of Sophia Amalia, the Queen of Fredrik III. This King, as well as his son Christian V., would willingly have set her at liberty; but the influence of the Queen over her husband and son was so strong that only her death, which occurred in 1685, released Leonora.

The Memoir of her life in prison terminates with this event, and her after-life does not offer any very remarkable incidents. Nevertheless, a few details, chiefly drawn from a MS. in the Royal Library at Copenhagen, recently published by Mr. Birket Smith, may serve to complete the historical image of this illustrious lady. The MS. in question is from the hand of a Miss Urne, of an ancient Danish family, who managed the household of Leonora from 1685 to her death in 1698. A royal manor, formerly a convent, at Maribo, on the island of Laaland, was granted to Leonora shortly after her release from the Blue Tower, together with a sufficient pension for a moderate establishment.

‘The first occupation of the Countess,’ says Miss Urne, ‘was devotion; for which purpose her household was assembled in a room outside her bed-chamber. In her daily morning prayer there was this passage: “May the Lord help all prisoners, console the guilty, and save the innocent!” After that she remained the whole forenoon in her bedchamber, occupied in reading and writing. She composed a book entitled the “Ornament of Heroines,” which Countess A. C. Ulfeldt and Count Leon took away with them, together with many other rare writings. Her handiwork is almost indescribable, and without an equal; such as embroidering in silk, gold embroidery, and turning in amber and ivory.’

It will be seen from Leonora’s own Memoir that needlework was one of her principal occupations in her prison. Count Waldstein still possesses some of her work; in the Church of Maribo an altar-cloth embroidered by her existed still some time ago; and at the Castle of Rosenborg, in Copenhagen, there is a portrait of Christian V. worked by Leonora in silk, in return for which present the King increased her annual pension. Miss Urne says that she sent all her work to Elizabeth Bek, a granddaughter of Leonora, who lived with her for some years. But she refused to send her Leonora’s Postille, or manual of daily devotion, which had been given Leonora on New Year’s Day, in the last year of her captivity, by the castellan, Torslev, who is mentioned in Leonora’s Memoir, and who had taught her to turn ivory, &c. This book has disappeared; but amongst the relics of Leonora Christina, the Royal Library at Copenhagen preserves some leaves which had been bound up with it, and contain verses, &c., by Leonora, and other interesting matter.

Her MS. works were taken to Vienna after her death. It is not known what has become of some of them. A copy of the first part of the book on heroines exists in Copenhagen. Miss Urne says that she possessed fragments of a play composed by her and acted at Maribo Kloster; also the younger Sperling speaks of such a composition in Danish verse; but the MS. seems to be lost now.

Several of Leonora’s relations stayed with her from time to time at Maribo; amongst them the above-mentioned Elizabeth Bek, whose mother, Leonora Sophie, famous for her beauty, had married Lave Bek, the head of an ancient Danish family in Skaane. After Ulfeldt’s death Lave Bek demanded of the Swedish Government the estates which Carl Gustav had given to Ulfeldt in 1658, but which the Swedish Government had afterwards confiscated, without any legal ground. Leonora Christina herself memorialised the Swedish King on the subject, and at least one of her memorials on the subject, dated May 23, 1693, still exists; but it was not till 1735 that these estates were given up to Lave Bek’s sons. Leonora’s eldest daughter, Anne Catherina, lived with her mother at Maribo for several years, and was present at her death. She had married Casetta, a Spanish nobleman, mentioned by Leonora Christina in her Memoir, who was with her in England when she was arrested. After the death of Casetta and their children, Anne Catherina Ulfeldt came to live with her mother. She followed her brother to Vienna, where she died. It was she who transmitted the MS. of Leonora’s Memoir of her life in the Blue Tower to the brother, with the following letter, which is still preserved with the MS.:—

‘This book treats of what has happened to our late lady mother in her prison. I have not been able to persuade myself to burn it, although the reading of it has given me little pleasure, inasmuch as all those events concern her miserable state. After all, it is not without its use to know how she has been treated; but it is not needful that it should come into the hands of strangers, for it might happen to give pleasure to those of our enemies who still remain.’

The letter is addressed ‘A Monsieur, Monsieur le Comte d’Ulfeldt,’ &c., but without date or signature. The handwriting is, however, that of Anne Catherina Ulfeldt, and she had probably sent it off to Vienna for safety immediately after her mother’s death, before she knew that her brother would come to Maribo himself. Miss Urne says, in the MS. referred to, that the King had ordered that he was to be informed immediately of Leonora’s demise, in order that she might be buried according to her rank and descent; but she had beforehand requested that her funeral might be quite plain. Her coffin, as well as those of three children who had died young, and whose coffins had been provisionally placed in a church at Copenhagen, was immured in a vault in the church of Maribo; but when this was opened some forty years ago, no trace of Leonora’s mortal remains could be found, though those of the children were there: from which it is concluded that a popular report, to the effect that the body had been secretly carried abroad, contains more truth than was formerly supposed. Count Waldstein states that in the family vault at Leitsmischl, there is one metal coffin without any inscription, and which may be hers. If so, Leonora has, as it were, after her death followed her husband into exile. At any rate, the final resting-place of neither of them is known with certainty.

Sir,[6]—To satisfy your curiosity, I will give you a short account of the life of her about whom you desire to be informed. She was born at Fredericksborg, in the year 1621, on June 11.[7] When she was six weeks old her grandmother took her with her to Dalum, where she remained until the age of four years; her first master there being Mr. Envolt, afterward a priest at Roeskild. About six months after her return to the Court, her father sent her to Holland to his cousin, a Duchess of Brunswick, who had married Count Ernest of Nassau, and lived at Lewarden.

Her sister Sophia, who was two years and a half older than herself, and her brother, who was a year younger, had gone to the aforesaid Duchess nearly a year before. I must not forget to mention the first mischances that befell her at her setting out. She went by sea in one of the royal ships of war; having been two days and a night at sea, at midnight such a furious tempest arose that they all had given up any hope of escaping. Her tutor, Wichmann Hassebart (afterwards Bishop of Fyn), who attended her, woke her and took her in his arms, saying, with tears, that they should both die together, for he loved her tenderly. He told her of the danger, that God was angry, and that they would all be drowned. She caressed him, treating him like a father (after her usual wont), and begged him not to grieve; she was assured that God was not angry, that He would see they would not be drowned, beseeching him again and again to believe her. Wichmann shed tears at her simplicity, and prayed to God to save the rest for her sake, and for the sake of the hope that she, an innocent girl, reposed in Him. God heard him, and after having lost the two mainmasts, they entered at dawn of day the harbour of Fleckeröe,[8] where they remained for six weeks.

Having received orders to proceed by sea, they pursued their route and arrived safely. Her sister being informed of her arrival, and being told that she had come with a different retinue to herself—with a suite of gentlemen, lady preceptor, servants and attendants, &c.—she burst into tears, and said that she was not surprised that this sister always insinuated herself and made herself a favourite, and that she would be treated there too as such. M. Sophia was not mistaken in this; for her sister was in greater favour with the Duchess, with her governess, and with many others, than she was herself. Count Ernest alone took the side of M. Sophia, and this rather for the sake of provoking his wife, who liked dispute; for M. Sophia exhibited her obstinacy even towards himself. She did all the mischief she could to her sister, and persuaded her brother to do the same.

To amuse you I will tell you of her first innocent predilections. Count Ernest had a son of about eleven or twelve years of age; he conceived an affection for her, and having persuaded her that he loved her, and that she would one day be his wife, but that this must be kept secret, she fancied herself already secretly his wife. He knew a little drawing, and by stealth he instructed her; he even taught her some Latin words. They never missed an opportunity of retiring from company and conversing with each other.

This enjoyment was of short duration for her; for a little more than a year afterwards she fell ill of small-pox, and as his elder brother, William, who had always ridiculed these affections, urged him to see his well-beloved in the condition in which she was, in order to disgust him with the sight, he came one day to the door to see her, and was so startled that he immediately became ill, and died on the ninth day following. His death was kept concealed from her. When she was better she asked after him, and she was made to believe that he was gone away with his mother (who was at this time at Brunswick), attending the funeral of her mother. His body had been embalmed, and had been placed in a glass case. One day her preceptor made her go into the hall where his body lay, to see if she recognised it; he raised her in his arms to enable her to see it better. She knew her dear Moritz at once, and was seized with such a shock that she fell fainting to the ground. Wichmann in consequence carried her hastily out of the hall to recover her, and as the dead boy wore a garland of rosemary, she never saw these flowers without crying, and had an aversion to their smell, which she still retains.

As the wars between Germany and the King of Denmark had been the cause of the removal of his aforesaid children, they were recalled to Denmark when peace was concluded. At the age of seven years and two months she was affianced to a gentleman of the King’s Chamber. She began very early to suffer for his sake. Her governess was at this time Mistress Anne Lycke, Qvitzow’s mother. Her daughter, who was maid of honour, had imagined that this gentleman made his frequent visits for love of her. Seeing herself deceived, she did not know in what manner to produce estrangement between the lovers; she spoke, and made M. Sophia speak, of the gentleman’s poverty, and amused herself with ridiculing the number of children in the family. She regarded all this with indifference, only declaring once that she loved him, poor as he was, better than she loved her rich gallant.[9]

At last they grew weary of this, and found another opportunity for troubling her—namely, the illness of her betrothed, resulting from a complaint in his leg; they presented her with plaisters, ointments, and such like things, and talked together of the pleasure of being married to a man who had his feet diseased, &c. She did not answer a word either for good or bad, so they grew weary of this also. A year and a half after they had another governess, Catharina Sehestedt, sister of Hannibal.[10] M. Sophia thus lost her second, and her sister had a little repose in this quarter.

When our lady was about twelve years old, Francis Albert, Duke of Saxony,[11] came to Kolding to demand her in marriage. The King replied that she was no longer free, that she was already betrothed; but the Duke was not satisfied with this, and spoke to herself, and said a hundred fine things to her: that a Duke was far different to a gentleman. She told him she always obeyed the King, and since it had pleased the King to promise her to a gentleman, she was well satisfied. The Duke employed the governess to persuade her, and the governess introduced him to her brother Hannibal, then at the Court, and Hannibal went with post-horses to Möen, where her betrothed was, who did not linger long on the road in coming to her. This was the beginning of the friendship between Monsieur and Hannibal, which afterwards caused so much injury to Monsieur. But he had not needed to trouble himself, for the Duke never could draw from her the declaration that she would be ready to give up her betrothed if the King ordered her to do so. She told him she hoped the King would not retract from his first promise. The Duke departed ill satisfied, on the very day the evening of which the betrothed arrived. (Four years afterwards they quarrelled on this subject in the presence of the King, who appeased them with his authority.)

It happened the following winter at Skanderborg that the governess had a quarrel with the language-master, Alexandre de Cuqvelson, who taught our lady and her sisters the French language, writing, arithmetic, and dancing. M. Sophia was not studious; moreover, she had very little memory; for her heart was too much devoted to her dolls, and as she perceived that the governess did not punish her when Alexandre complained of her, she neglected everything, and took no trouble about her studies. Our lady imagined she knew enough when she knew as much as her sister. As this had lasted some time, the governess thought she could entrap Alexandre; she accused him to the King, said that he treated the children badly, rapped their fingers, struck them on the hand, called them bad names, &c., and with all this they could not even read, much less speak, the French language. Besides this, she wrote the same accusations to the betrothed of our lady. The betrothed sent his servant Wolff to Skanderborg, with menaces to Alexandre. At the same time Alexandre was warned that the King had sent for the prince,[12] to examine his children, since the father-confessor was not acquainted with the language.

The tutor was in some dismay; he flattered our lady, implored her to save him, which she could easily do, since she had a good memory, so that he could prove by her that it was not his fault that M. Sophia was not more advanced. Our lady did not yield readily, but called to his remembrance how one day, about half a year ago, she had begged him not to accuse her to the governess, but that he had paid no attention to her tears, though he knew that the governess treated them shamefully. He begged her for the love of Jesus, wept like a child, said that he should be ruined for ever, that it was an act of mercy, that he would never accuse her, and that from henceforth she should do nothing but what she wished. At length she consented, said she would be diligent, and since she had yet three weeks before her, she learnt a good deal by heart.[13] Alexandre told her one day, towards the time of the examination, that there was still a great favour she could render him: if she would not repeat the little things which had passed at school-time; for he could not always pay attention to every word that he said when M. Sophia irritated him, and if he had once taken the rod to hit her fingers when she had not struck her sister strongly enough, he begged her for the love of God to pardon it. (It should be mentioned that he wished the one to strike the other when they committed faults, and the one who corrected the other had to beat her, and if she did not do so strongly enough, he took the office upon himself; thus he had often beaten our lady.)

She made excuses, said that she did not dare to tell a lie if they asked her, but that she would not accuse him of herself. This promise did not wholly satisfy him; he continued his entreaties, and assured her that a falsehood employed to extricate a friend from danger was not a sin, but was agreeable to God; moreover, it was not necessary for her to say anything, only not to confess what she had seen and heard. She said that the governess would treat her ill; so he replied that she should have no occasion to do so, for that he would never complain to her. Our lady replied that the governess would find pretext enough, since she was inclined to ill-treat the children; and anyhow, the other master who taught them German was a rude man, and an old man who taught them the spinette was a torment, therefore she had sufficient reason for fear. He did not give way, but so persisted in his persuasion that she promised everything.

When the prince arrived the governess did not forget to besiege him with her complaints, and to beg him to use his influence that the tutor might be dismissed. At length the day of the examination having come, the governess told her young ladies an hour before that they were to say how villanously he had treated them, beaten them, &c. The prince came into the apartments of the ladies accompanied by the King’s father-confessor (at that time Dr. Ch(r)estien Sar); the governess was present the whole time.

They were first examined in German. M. Sophia acquitted herself very indifferently, not being able to read fluently. The master Christoffre excused her, saying that she was timid. When it came to Alexandre’s turn to show what his pupils could do, M. Sophia could read little or nothing. When she stammered in reading, the governess looked at the prince and laughed aloud. There was no difference in the gospel, psalms, proverbs, or suchlike things. The governess was very glad, and would have liked that the other should not have been examined. But when it came to her turn to read in the Bible, and she did not hesitate, the governess could no longer restrain herself, and said, ‘Perhaps it is a passage she knows by heart that you have made her read.’ Alexandre begged the governess herself to give the lady another passage to read. The governess was angry at this also, and said, ‘He is ridiculing me because I do not know French.’ The prince then opened the Bible and made her read other passages, which she did as fluently as before. In things by heart she showed such proficiency that the prince was too impatient to listen to all.

It was then Alexandre’s turn to speak, and to say that he hoped His Highness would graciously consider that it was not his fault that M. Sophia was not more advanced. The governess interrupted him saying, ‘You are truly the cause of it, for you treat her ill!’ and she began a torrent of accusations, asking M. Sophia if they were not true. She answered in the affirmative, and that she could not conscientiously deny them. Then she asked our lady if they were not true. She replied that she had never heard nor seen anything of the kind. The governess, in a rage, said to the Prince, ‘Your highness must make her speak the truth; she dares not do so, for Alexandre’s sake.’

The Prince asked her if Alexandre had never called her bad names—if he had never beaten her. She replied, ‘Never.’ He asked again if she had not seen nor heard that he had ill-treated her sister. She replied, ‘No, she had never either heard or seen it.’ At this the governess became furious; she spoke to the prince in a low voice; the prince replied aloud, ‘What do you wish me to do? I have no order from the King to constrain her to anything.’ Well, Alexandre gained his cause; the governess could not dislodge him, and our lady gained more than she had imagined in possessing the affection of the King, the goodwill of the Prince, of the priest, and of all those who knew her. But the governess from that moment took every opportunity of revenging herself on our lady.

At length she found one, which was rather absurd. The old Jean Meinicken, who taught our lady the spinette, one day, in a passion, seized the fingers of our lady and struck them against the instrument; without remembering the presence of her governess, she took his hand and retaliated so strongly that the strings broke. The governess heard with delight the complaints of the old man. She prepared two rods; she used them both, and, not satisfied with that, she turned the thick end of one, and struck our lady on the thigh, the mark of which she bears to the present day. More than two months elapsed before she recovered from the blow; she could not dance, nor could she walk comfortably for weeks after. This governess did her so much injury that at last our lady was obliged to complain to her betrothed, who had a quarrel with the governess at the wedding of M. Sophia, and went straight to the King to accuse her; she was at once dismissed, and the four children, the eldest of which was our lady, went with the princess[14] to Niköping, to pass the winter there, until the king could get another governess. The King, who had a good opinion of the conduct of our lady, who at this time was thirteen years and four months old, wrote to her and ordered her to take care of her sisters. Our lady considered herself half a governess, so she took care not to set them a bad example. As to study, she gave no thought to it at this time; she occupied herself in drawing and arithmetic, of which she was very fond, and the princess, who was seventeen years of age, delighted in her company. Thus this winter passed very agreeably for her.

At the approach of the Diet, which sat eight days after Pentecost, the children came to Copenhagen, with the prince and princess, and had as governess a lady of Mecklenburg of the Blixen family, the mother of Philip Barstorp who is still alive. After the Diet, the king made a journey to Glückstad in two days and a half, and our lady accompanied him; it pleased the King that she was not weary, and that she could bear up against inconveniences and fatigues. She afterwards made several little journeys with the King, and she had the good fortune occasionally to obtain the pardon of some poor criminals, and to be in favour with the king.

Our lady having attained the age of fifteen years and about four months, her betrothed obtained permission for their marriage, which was celebrated (with more pomp than the subsequent weddings of her sisters), on October 9, 1636. The winter after her marriage she was with her husband at Möen, and as she knew that her husband’s father had not left him any wealth, she asked him concerning his debts, and conjured him to conceal nothing from her. He said to her, ‘If I tell you the truth it will perhaps frighten you.’ She declared it would not, and that she would supply what was needful from her ornaments, provided he would assure her that he had told her everything. He did so, and found that she was not afraid to deprive herself of her gold, silver, and jewels, in order to pay a sum of thirty-six thousand rix-dollars. On April 21, 1637, she went with her husband to Copenhagen in obedience to the order of the king, who gave him the post of V.R.[15] He was again obliged to incur debt in purchasing a house and in setting up a larger establishment.

There would be no end were I to tell you all the mischances that befell her during the happy period of her marriage, and of all the small contrarieties which she endured; but since I am assured that this history will not be seen by anyone, and that you will not keep it after having read it, I will tell you a few points which are worthy of attention. Those who were envious of the good fortune of our lady could not bear that she should lead a tranquil life, nor that she should be held in esteem by her father and King; I may call him thus, for the King conferred on her more honours than were due to her from him. Her husband loved and honoured her, enacting the lover more than the husband.

She spent her time in shooting, riding, tennis, in learning drawing in good earnest from Charles v. Mandern, in playing the viol, the flute, the guitar, and she enjoyed a happy life. She knew well that jealousy is a plague, and that it injures the mind which harbours it. Her relations tried to infuse into her head that her husband loved elsewhere, especially M. Elizabet, and subsequently Anna, sister of her husband, who was then in her house. M. Elizabet began by mentioning it as a secret, premising that no one could tell her and warn her, except her who was her sister.

As our lady at first said nothing and only smiled, M. Elis... said: ‘The world says that you know it well, but that you will not appear to do so.’ She replied with a question: ‘Why did she tell her a thing as a secret, which she herself did not believe to be a secret to her? but she would tell her a secret that perhaps she did not know, which was, that she had given her husband permission to spend his time with others, and when she was satisfied the remainder would be for others; that she believed there were no such jealous women as those who were insatiable, but that a wisdom was imputed to her, which she did not possess; she begged her, however, to be wise enough not to interfere with matters which did not concern her, and if she heard others mentioning it (as our lady had reason to believe that this was her own invention) that she would give them a reprimand. M. Elis... was indignant and went away angry, but Anna, Monsieur’s sister, who was in the house, adopted another course. She drew round her the handsomest women in the town, and then played the procuress, spoke to her brother of one particularly, who was a flirt, and who was the handsomest, and offered him opportunities, &c. As she saw that he was proof against it, she told him (to excite him) that his wife was jealous, that she had had him watched where he went when he had been drinking with the King, to know whether he visited this woman; she said that his wife was angry, because the other woman was so beautiful, said that she painted, &c.

The love borne to our lady by her husband made him tell her all, and, moreover, he went but rarely afterwards to his sister’s apartments, from which she could easily understand that the conversation had not been agreeable to him; but our lady betrayed nothing of the matter, visited her more than before, caressed this lady more than any other, and even made her considerable presents. (Anna remained in her house as long as she lived.)

All this is of small consideration compared with the conduct of her own brother. It is well known to you that the Biel... were very intimate in our lady’s house. It happened that her brother made a journey to Muscovy, and that the youngest of the Biel... was in his suite. As this was a very lawless youth, and, to say the truth, badly brought up, he not only at times failed in respect to our lady’s brother, but freely expressed his sentiments to him upon matters which did not concern him; among other things, he spoke ill of the Holstein noblemen, naming especially one, who was then in waiting on the King, who he said had deceived our lady’s brother. The matter rested there for more than a year after their return from this journey. The brother of our lady and Biel... played cards together, and disputed over them; upon this the brother of our lady told the Holstein nobleman what Biel... had said of him more than a year before, which B. did not remember, and swore that he had never said. The Holstein nobleman said insulting things against Biel....

Our lady conversed with her brother upon the affair, and begged him to quiet the storm he had raised, and to consider how it would cause an ill-feeling with regard to him among the nobility, and that it would seem that he could not keep to himself what had been told him in secret; it would be very easy for him to mend the matter. Her brother replied that he could never retract what he had said, and that he should consider the Holstein nobleman as a villain if he did not treat B. as a rogue.

At length the Holstein nobleman behaved in such a manner as to constrain B. to send him a challenge. B. was killed by his adversary with the sword of our lady’s brother, which she did not know till afterwards. At noon of the day on which B. had been killed in the morning, our lady went to the castle to visit her little twin sisters; her brother was there, and came forward, laughing loudly and saying, ‘Do you know that Ran... has killed B...?’ She replied, ‘No, that I did not know, but I knew that you had killed him. Ran... could do nothing less than defend himself, but you placed the sword in his hand.’ Her brother, without answering a word, mounted his horse and went to seek his brother-in-law, who was speaking with our old friend,[16] told him he was the cause of B.’s death, and that he had done so because he had understood that his sister loved him, and that he did not believe that his brother-in-law was so blind as not to have perceived it. The husband of our lady did not receive this speech in the way the other had imagined, and said, ‘If you were not her brother, I would stab you with this poniard,’ showing it to him. ‘What reason have you for speaking thus?’ The good-for-nothing fellow was rather taken aback at this, and knew not what to say, except that B... was too free and had no respect in his demeanour; and that this was a true sign of love. At length, after some discussion on both sides, the brother of our lady requested that not a word might be said to his sister.

As soon as she returned home, her husband told her everything in the presence of our old friend, but ordered her to feign ignorance. This was all the more easy for her, as her husband gave no credence to it, but trusted in her innocence. She let nothing appear, but lived with her brother as before. But some years after, her brother ill-treated his own mother, and her side being taken by our lady, they were in consequence not good friends.

In speaking to you of the occupations of our lady, after having reached the age of twenty-one or thereabouts, I must tell you she had a great desire to learn Latin. She had a very excellent master,[17] whom you know, and who taught her for friendship as well as with good will. But she had so many irons in the fire, and sometimes it was necessary to take a journey, and a yearly accouchement (to the number of ten) prevented her making much progress; she understood a little easy Latin, but attempted nothing difficult; she then learnt a little Italian, which she continued studying whenever an opportunity presented itself.