Title: The Roman Empire in the Light of Prophecy

Author: W.E. Vine

Release date: January 31, 2012 [eBook #38721]

Most recently updated: January 8, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Julia Neufeld and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

THE

ROMAN

EMPIRE

IN

PROPHECY.

W. E. VINE, M.A.

"Regarded as an historical manual it is of no little value, and the author's summaries of the rise and progress of Rome are quite masterly in their way."

—Glasgow Citizen.

CÆSAR AUGUSTUS, first Roman Emperor, born 63 B.C. Grand-nephew and heir of Julius Cæsar Octavianus. Obtained supreme power over Roman dominions by victory over Anthony at Actium, 31 B.C. Proclaimed Emperor, 27 B.C., by the Roman Senate, which conferred on him the title Augustus. Died 19th August, A.D. 14, in his 76th year.

BY

Author of "B.C. and A.D.; or, How the World was prepared for the

Gospel"; "The Scriptures and How to Use Them," etc.

PICKERING & INGLIS

Printers and Publishers, 14 Paternoster Row, London, E.C.4

229 Bothwell Street, Glasgow; 75 Princes Street, Edinburgh

London: Pickering & Inglis, 14 Paternoster Row, E.C.4.

Glasgow: Pickering & Inglis, 229 Bothwell Street.

Edinburgh: Pickering & Inglis, 75 Princes Street.

Manchester: The Tract Society, 135 Deansgate.

Liverpool: Wm. T. Jaye, 18 Slater Street.

Newcastle: Northern Counties Depot, 63a Blackett Street.

Birmingham: P. H. Hulbert, 315 Broad Street (Corner).

Bath: H. W. & H. R. Griffiths, 35 Milton Avenue.

Bristol: W. B. W. Sarsfield, 78 Park Street.

Weston-super-Mare: Western Bible Depot, 12 Waterloo Street.

Cardiff: H. J. Lear, 17 Royal Arcade.

Dublin: R. Stewart, 10 D'Olier Street, and 2 Nassau Street.

Belfast: R. M'Clay, 44 Ann Street.

Dundee: R. H. Lundie, 35 Reform Street.

New York: Gospel Publishing House, 318 West 39th Street.

Chicago: Wm. Norton, Bible Institute Assoc., 826 North La Salle St.

Buffalo, N.Y.: Sword and Shield Tract Society, 1247 Niagara St.

Swengel, Pa.: I. C. Herenden, Bible Truth Depot.

Los Angeles, Cal.: Geo. Ray, 8508 So. Vermont Avenue.

Boston: Hamilton Bros., 120 Tremont Street.

Philadelphia: Glad Tidings Publishing Co., 5863 Christian St.

Dallas, Texas: J. T. Dean, 2613 Pennsylvania Avenue.

Windsor, Ont.: C. J. Stowe, 23 Martin Street.

Toronto: Upper Canada Tract Society, 2 Richmond Street, E.

Orillia, Ontario: S. W. Benner, Bible and Tract Depot.

Winnipeg: N. W. Bible Depot, 580 Main Street.

Buenos Aires: W. C. K. Torre, Casilla 5.

Melbourne: E. W. Cole, Book Arcade.

Sydney: Bible, Book, and Tract Depot, 373 Elizabeth Street.

Sydney: Christian Workers Depot, 170 Elizabeth Street.

Brisbane: W. R. Smith & Co., Bible Repository, Albert Street.

Auckland, N.Z.: H. L. Thatcher, 135 Symonds Street.

Dunedin: H. J. Bates, Otago Bible House, 38 George Street.

Palmerston North: James G. Harvey, Main Street.

Christchurch: G. W. Plimsoll, 84 Manchester Street.

Belgaum, India: W. C. Irvine, Christian Literature Depot.

Bangalore: A. M'D. Redwood, Frasertown Book Depot.

Switzerland: Jas. Hunter, Clarens.

Cairo: The Nile Press, Bulag.

Hong-Kong: A. Young, Bible Depot, 2 Wyndham Street.

And through most Booksellers, Colporteurs, and Tract Depots.

Copyright—Pickering & Inglis.

The following pages are the outcome of several conversations with inquirers shortly after the outbreak of the great war, in 1914, and of requests for notes of the views expressed. The subject of these conversations had occupied the earnest if intermittent attention of the writer for over twenty years. The notes were expanded into a series of articles which appeared in The Witness during 1915. These have been revised and somewhat extended for the present volume, especially the last chapter, much of which was previously precluded by limitations of space.

In regard to past history, the outlines of events connected with the Roman and Turkish Empires are given with the hope that the records will prove helpful to those who read the history of Nations in the light of Scripture.

In regard to the future, while there are many events which the Word of God has foretold with absolute clearness, and upon these we may speak unreservedly, yet there are many circumstances concerning which definite prediction has been designedly withheld, and upon which prophecy is therefore obscure. In such matters an effort has been made to avoid dogmatism. Prophecy was not given in order for us to prophesy.

On the other hand, the prophetic Scriptures are not to be neglected. Difficulty in understanding them is no reason for disregarding them. They are part of that Word, the whole[6] of which is declared to be "profitable for doctrine, for reproof, for correction, for instruction in righteousness" (2 Tim. 3. 16). They therefore demand prayerful and patient meditation.

For a speaker to refer to the study of the prophecies in a way which tends to minimise their importance in the minds of his hearers is to dishonour both the sacred Word and Him who inspired it. It is significant that the book of the Revelation opens with a promise of blessing to him who reads (the reference is especially to public reading) and to those who "hear the words of the prophecy, and keep the things which are written therein" (chap. 1. 3), and at the close repeats the blessing for him who keeps its words (chap. 22. 7).

The quotations in the present volume are from the Revised Version, the comparatively greater accuracy of its translations being important for a correct understanding of many of the passages considered.

While the book is published at the request of several friends, the author fulfils such request with the earnest desire that in matters of doctrine that only may be accepted which can be confirmed from the Word of God itself, and that the Lord may graciously own what is in accordance with His mind for the glory of His Name and the profit of the reader.

Bath, 1916.

| CHAPTER I. | PAGE |

| The Times of the Gentiles, | 9 |

| Nebuchadnezzar's Dream, | 11 |

| The Chaldean, Medo-Persian, Grecian Kingdoms, | 12 |

| The Fourth Kingdom, | 13 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| The Roman Dominion, | 15 |

| Rise and Progress of the Roman Empire, | 16 |

| Eastward Extension, | 18 |

| The Empire Completed, | 22 |

| The Crushing of the Nations, | 23 |

| The Twofold Division, | 25 |

| The Tenfold Division, | 27 |

| A Comparison of the Visions, | 29 |

| Testimony of Early Christian Writers, | 32 |

| Processes at Work Since the Twofold Division, | 34 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| The Overthrow in the West—Germanic Invasions, | 35 |

| Disintegration of the Western Half, | 37 |

| Alaric and the Goths, | 37 |

| Attila and the Huns, | 39 |

| Genseric and the Vandals, | 40 |

| Northern Limits of the Empire, | 41 |

| Ten Kingdoms not Formed by Germanic Invasions, | 42 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| The Overthrow in the East—Turkish Empire, | 44 |

| Mohammed and the Khaliphs, | 45 |

| Eastern Empire at End of 10th Century, | 46 |

| The Appearance of the Turks, | 46 |

| The Turks Embrace Mohammedanism, | 47 |

| The Turks Enter Europe, | 48 |

| Constantinople Taken, | 49 |

| A Comparison of the Two Divisions, | 50 |

| Decline of the Turkish Empire, | 51 |

| The Coming Overthrow, | 54 |

| A Blank in Prophecy, | 55 |

| Continuation of the Roman Government, | 56 |

| Roman Imperialism Continued, | 57 |

| [8] | |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Coming Revival of the Roman Empire, | 59 |

| 1. Geographical Considerations, | 59 |

| Review of the Ancient Territories, | 62 |

| Divisions of the Greek Empire, | 63 |

| Other European Territories, | 65 |

| The British Empire, | 67 |

| 2. Political Standpoint, | 69 |

| European Federation, | 69 |

| The Sea Symbolic of National Unrest, | 72 |

| Revolutions and their Issues, | 74 |

| The Iron and the Clay, | 74 |

| Unprecedented Political and Social Upheaval, | 77 |

| 3. The Religious Standpoint, | 77 |

| The Papacy: Its Present Power, | 79 |

| A Reunion of Christendom, | 80 |

| The Doom of Religious Babylon, | 81 |

| Satanic Authority of the Emperor, | 82 |

| The "Superman," | 83 |

| Spiritism—The False Prophet, | 84 |

| Universal System of Commerce, | 87 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| The Everlasting Kingdom, | 88 |

| The Jews, | 88 |

| The Seventy Weeks, | 88 |

| The Last "Week," | 89 |

| Fierce Persecution, | 92 |

| Armageddon and After, | 93 |

| The Scene of the Conflict, | 94 |

| The Epiphany of His Parousia, | 97 |

| The Voice of the Lord, | 98 |

| The Treading of the Winepress, | 99 |

| Overthrow of the Man of Sin, | 100 |

| The Scene of Judgment, | 102 |

| The Jews in their Extremity, | 104 |

| Seismic Disturbances, | 104 |

| The King Eternal, | 107 |

| Index to Maps. | |

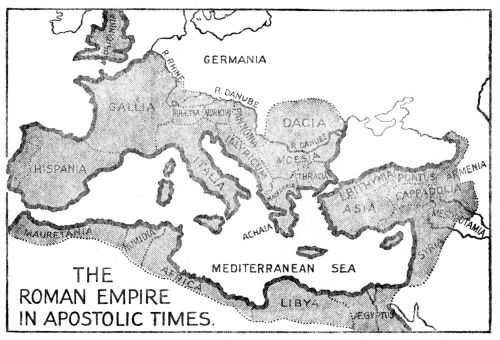

| Roman Empire in Apostolic Times, | 22 |

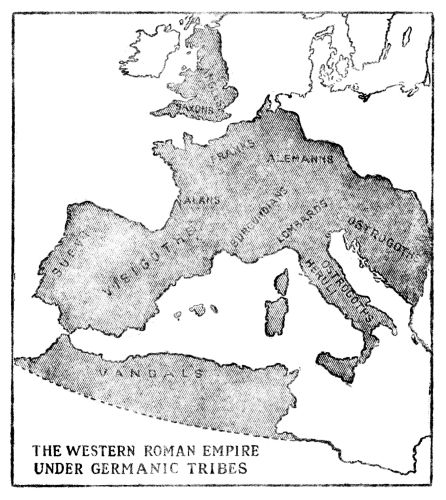

| Western Roman Empire Under Germanic Tribes, | 36 |

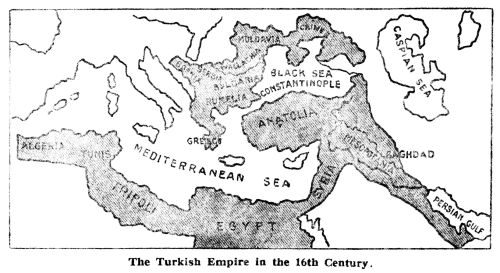

| Turkish Empire in the 16th Century, | 44 |

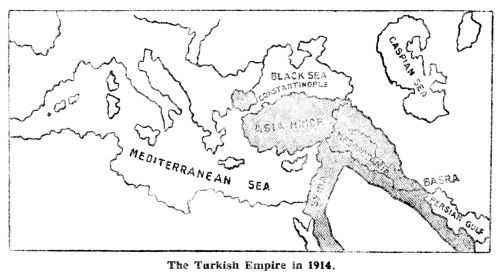

| Turkish Empire in 1914, | 54 |

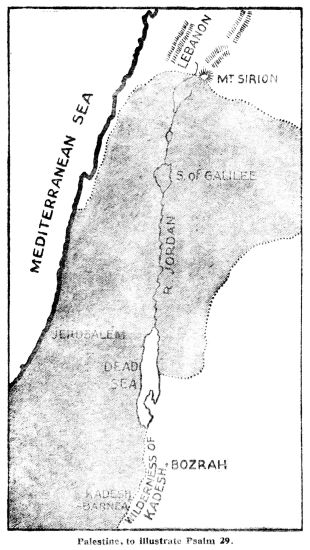

| Palestine To Illustrate Psalm 29, | 88 |

The overthrow of the kingdom of Judah recorded in 2 Kings 24 and 25, and in the opening words of the book of Daniel, was a remarkable crisis in the history of the world. In judgment upon the people of God for their long-continued iniquity, sovereignty was removed from their hands, king and people were led into captivity, and Jerusalem was, in fulfilment of Jeremiah's words, given into the hand of Nebuchadnezzar, the king of Babylon (Jer. 21. 10). The government of their land was thus committed to the Gentiles, and with the Gentiles it has remained from that day till now. These events took place in 606 and 587 B.C.

But Gentile control is not to continue indefinitely. This, which is plain from many Scriptures, was intimated by Christ[10] to His disciples when He said of Jerusalem that the city would "be trodden down of the Gentiles until the times of the Gentiles be fulfilled" (Luke 21. 24). The phrase, "the times of the Gentiles," calls for consideration, and especially as it has to do with Nebuchadnezzar's conquest just mentioned.

There are two words translated "times" in the New Testament; one is chronoi, which is invariably rendered "times;" the other is kairoi, which, when the two are found together, is rendered "seasons." Thus Paul, in writing to the Thessalonian Church, says, "But concerning the times and the seasons, brethren, ye have no need that aught be written unto you" (1 Thess. 5. 1, R.V.; cp. Acts 1.7). We may distinguish "seasons" from "times" in the following way: "times" denotes mere duration, lengths of time; "seasons" implies that these lengths of time have certain events or circumstances associated with them by which they are characterised. Thus the words almost exactly correspond to the terms "periods" and "epochs." Now the word kairoi, "seasons," is used in the phrase translated "the times of the Gentiles," which might accordingly be rendered "the seasons of the Gentiles."[11] We look, then, for some special characteristic of the period or periods thus designated. We have observed that Nebuchadnezzar's overthrow of the kingdom of Judah involved the transference of its sovereignty from Jew to Gentile from that event onward. "The times of the Gentiles," accordingly, is that period, or succession of periods, during which dominion over the Jews and their land is committed to Gentile Powers.

Special significance attaches to the fact that no sooner had the times of the Gentiles begun than God made known the future course of their authority over His people, and the character and doom of that authority, and made it known to the first Gentile conqueror himself. It was in the second year of his reign that Nebuchadnezzar saw in a dream the great image by means of which the purposes of God were to be communicated to him. The description of this, given by Daniel to the troubled monarch, is as follows: "Thou, O king, sawest, and behold a great image. This image, which was mighty, and whose brightness was excellent, stood before thee; and the aspect thereof was terrible. As for[12] this image, his head was of fine gold, his breast and his arms of silver, his belly and his thighs of brass, his legs of iron, his feet part of iron, and part of clay. Thou sawest till that a stone was cut out without hands, which smote the image upon his feet that were of iron and clay, and brake them in pieces. Then was the iron, the clay, the brass, the silver, and the gold, broken in pieces together, and became like the chaff of the summer threshing-floors: and the wind carried them away, that no place was found for them: and the stone that smote the image became a great mountain, and filled the whole earth" (Dan. 2. 31-35).

Interpreting this vision, the prophet identified Nebuchadnezzar, the Chaldean monarch, with the head of gold, and foretold that his kingdom, or empire, would be followed in succession by three others, corresponding respectively to the different parts of the remainder of the image and to the nature of the metals composing them. Of the four kingdoms the last is to engage our chief attention in these papers. Passing from the first, the Chaldean, as specified in Daniel's words to the king, "Thou art this head of gold" (v. 38), we are shown that the second kingdom was[13] that of the Medes and Persians by the prophet's record of the doom of Nebuchadnezzar's successor, Belshazzar: "In that night Belshazzar the Chaldean king was slain. And Darius the Mede received the kingdom" (Dan. 5. 30, 31; cp. v. 28). That the third kingdom was the Grecian we find in the interpretation of part of a vision recorded in the eighth chapter: "The ram which thou sawest that had the two horns, they are the kings of Media and Persia. And the rough he-goat [who was seen to destroy the ram, v. 8] is the king of Greece" (vv. 20, 21; cp. chap. 10. 20).

The name of the fourth kingdom is not mentioned in the Old Testament, but the prediction given in the ninth chapter of Daniel's prophecies sufficiently identifies it. Messiah, it was said, would be cut off, and the people of a coming prince would destroy the city and the sanctuary. Now we know that the perpetrators of this were the Romans. We know, too, that by them the Grecian empire was conquered. The world-wide rule of the first Roman Emperor is indicated in the words of Luke's introduction to his record of the[14] birth of Christ: "Now it came to pass in those days, there went out a decree from Cæsar Augustus, that all the world should be enrolled" (Luke 2. 1).

It is important to note that this fourth kingdom will, in its final condition, be in world-wide authority at the close of the times of the Gentiles, that is, that the Roman power, though in a divided state, will not be finally destroyed until it meets its doom at the hands of the Son of God. This fact, which will receive fuller treatment later, and is borne out by several Scriptures, is plainly indicated in the passage which describes the last state of the fourth kingdom and its destruction. Immediately after showing that it would be a divided kingdom, and describing the nature of that division (vv. 41-43), the prophet says: "And in the days of those kings shall the God of Heaven set up a kingdom, which shall never be destroyed, nor shall the sovereignty thereof be left to another people; but it shall break in pieces and consume all these kingdoms, and it shall stand for ever" (v. 44). Now this indestructible kingdom cannot be other than that of Christ, and by His kingdom the fourth is to be broken in pieces and consumed, thus involving the overthrow of all[15] forms of Gentile authority. Obviously no form of world government will exist between that of the fourth kingdom, in its condition described in verses 42, 43, and the kingdom of Christ which destroys it.

An understanding of the Scriptures does not depend upon access to other books, or reference to historical records outside the limits of the Bible. The Word of God is its own interpreter, and all that is needed for our establishment in the faith is contained in its pages. On the other hand, the Bible throws light upon history not recorded therein, and it is with that in view that we give certain historical outlines in dealing with our subject.

The first part of the prophet's description of the fourth kingdom is as follows: "The fourth kingdom shall be strong as iron: forasmuch as iron breaketh in pieces and subdueth all things: and as iron that crusheth all these, shall it break in pieces and crush" (v. 40). A similar description is given in his account of a subsequent[16] vision, in which he saw four great beasts coming up from the sea. In this vision the Roman kingdom again was undoubtedly symbolised by the fourth beast. This beast he describes as "terrible and powerful, and strong exceedingly; and it had great iron teeth: it devoured and brake in pieces, and stamped the residue with his feet" (7. 7). So, again, in the words of the interpretation: "The fourth beast shall be a fourth kingdom upon earth, which shall be diverse from all the kingdoms, and shall devour the whole earth, and shall tread it down, and break it in pieces" (v. 23). Now all this exactly depicts the Roman power in its subjugation and control of the nations which eventually composed its empire. In the light, then, of these prophecies we give a brief sketch of its rise and conquests.

The Romans, who early in the third century B.C. had become masters of all Italy, save in the extreme north, were drawn into a course of conquest beyond the limits of their own country by the rivalry of the rapidly advancing power of Carthage in North Africa. Carthage, a[17] city founded some centuries earlier by Phœnician colonists from Tyre and Sidon, had at length become the capital of a great North African empire, stretching from Tripoli to the Atlantic Ocean, and embracing settlements elsewhere in countries and islands of the Mediterranean. These settlements included the greater part of Sicily, and that island, situated between the rival nations, became the first bone of contention between them. The precise cause of the struggle must not occupy us here, but the circumstances which decided the Roman Government, in 264 B.C., upon an invasion of Sicily were of the deepest significance in the history of the world. By the year 242 Sicily was subdued. In the following year the island was ceded by Carthage, and the extension of Roman dominion beyond Italy was begun. The war continued intermittently, with many vicissitudes, for a century, but eventually the Carthagians were overwhelmingly defeated by land and sea. "Think you that Carthage or that Rome will be content, after the victory, with its own country and Sicily?" said a Greek orator, while the issues of the struggle in its earliest stage were yet in the balance. Rome's vast ambition, and her abundant means of[18] gratifying it, justified the orator's fears. The islands of Sardinia and Corsica were shortly afterwards seized.

Defeated in Sicily, Carthage extended her dominions in Spain and made that country a base for marching through Gaul to attack the Romans from the north. Though their renowned leader Hannibal met with success, their effort was doomed to failure. Meanwhile Roman armies had pushed into Spain. After a fierce struggle of thirteen years the Carthagians were completely overcome there, and Spain soon became a Roman province. By the decisive battle of Zama, in North Africa, in 202, Carthage and its territories became tributary, and thus all the western Mediterranean passed under the supremacy of Rome. Eventually in 146, as a result of a final war, Carthage was razed to the ground, and its North African kingdom was constituted a Roman province under the name of Africa. War with the Celts in North Italy, commencing the next year, resulted in the extension of the boundary to the Alps, and countries beyond began to feel the terror of the Roman name.

The second century B.C. witnessed the[19] spread of the iron rule eastward. The Grecian Empire of Alexander the Great, the third mentioned in Daniel's interpretation, had embraced all the countries surrounding the eastern half of the Mediterranean and had stretched far beyond the Euphrates. The disintegration of Alexander's empire after his death prepared the way for the Romans. Macedonia, the former seat of that empire, was their first great objective. A pretext for war was soon forthcoming, and war was actually declared in 200 B.C. A series of struggles ensued, and Macedonia was not finally subdued for over thirty years. Meanwhile matters had developed in Greece and Asia Minor. In the latter country Antiochus III., the Great, who had also conquered Syria and Palestine, was seeking to extend his dominions. Cities and states of Asia Minor, however, groaning under the tyranny of Antiochus, appealed to Rome for aid. The Romans declared war against him in 192 B.C. The first conflict occurred in Greece, which was largely under his influence. An early victory secured the submission of the Greek states. Antiochus retreated into Asia Minor, and was finally crushed at Magnesia in 190. The whole of Asia Minor was then surrendered to[20] Rome. Actual possession was postponed and local government was largely granted both there and in Greece. But that policy proved impracticable, and the force of circumstances compelled a forward movement to universal empire. There was no such thing as the balance of power in the ancient world. Once a country became predominant there was nothing for it but the subjugation of its neighbours. The extension of Rome's dominions eastward was a fulfilment of a destiny beyond its own control. The reverent student of Scripture sees in the course of these events the unfolding of God's plans and the fulfilment of His Word.

The final campaign against the Macedonians was opened in 169 B.C., and in the next year they were overwhelmed at the decisive battle of Pydna. Macedonia and the adjacent state of Illyria became tributary, and eventually were reduced to Roman provinces.

The Romans then felt the necessity of definitely annexing Greece. Seventy towns in that country were plundered and 150,000 inhabitants were sold into slavery. Antiochus IV., Epiphanes, was now king of Syria and Palestine, and had possessed himself of almost the[21] whole of Egypt. Such was the effect of the battle of Pydna, however, that he was at once compelled to hand over Egypt to the conquerors, and that country became a Roman protectorate. Syria passed under Roman control at the death of Antiochus Epiphanes, in 164, and by the end of a few decades all the states of Asia Minor had been incorporated.

Thus by the middle of this century the Republic of Rome had gained ascendancy east and west. Its senate was recognised by the civilised world as "the supreme tribunal for kings and nations." Early in the next century Dalmatia and Thrace were subdued, and the latter was incorporated in the province of Macedonia. Wars with Mithradates, King of Pontus, Cappadocia and Armenia, resulted in the conquest of all his territories, and provinces were formed out of the states from thence westward to the Ægean sea.

This century saw the actual interference of Rome in the affairs of Judæa. Syria had been made a province in 65 B.C. by the Roman General Pompey, and from thence he intervened in a strife which had for some time been raging amongst the[22] leaders of the Jews. In 63 he marched an army into Judæa and took Jerusalem. At the final assault upon the Temple 12,000 Jews perished. Judæa thus passed under the iron heel.

As a result of the wars of Cæsar in north-western Europe, in 58-51 B.C., what are now Switzerland, France, and Belgium were subdued and Britain was invaded. By Cæsar also Roman authority in Africa was consolidated across the entire length of the north of the continent. The conquests of Rome as a Republic were complete. The Mediterranean had become a "Roman lake."

In 27 B.C. the purely Republican form of constitution was abolished, and the government of the Roman world was concentrated in the hands of an Emperor, the Cæsar Augustus of Luke 2.1. In his reign were fulfilled the prophecies foretelling the Birth of Christ. When the Prince of Peace was born in Bethlehem the din of strife was hushed throughout the empire, and Rome, under the restraining hand of God, ceased for a time its warring. By Augustus the northern territories of the empire were extended to practically the entire length[23] of the Danube. The greater part of Britain became a province under Claudius. A later Emperor, Trajan, added, at the beginning of the second century A.D., the province of Dacia, covering what are now Transylvania and most of Roumania. Under Marcus Aurelius (161-180) a large part of Mesopotamia was finally annexed.

This completes the actual conquests of the Romans. We will now note certain characteristics of their method of subjugation, viewed in the light of Daniel's prophecy concerning the fourth kingdom, that, like iron, it would "break in pieces and crush."

The crushing process was evidenced in many ways, and especially by the establishment of a general system of slavery, which almost everywhere supplanted free labour. Slave-hunting and slave-dealing became a profession. To such an extent were they carried on at one period that certain provinces were well nigh depopulated. We are told that at the great slave-market in the island of Delos, off Greece, as many as ten thousand slaves were disembarked in the morning and[24] bought up before the evening of the same day. Chained gangs worked under overseers and were confined in prison at night. To take an instance of the extreme rigour of the laws regulating the traffic, it is recorded by the historian Tacitus, that once, when the Prefect of Rome had been killed by one of his slaves, of whom he owned a vast number, the whole of his slaves, many of them women and children, were executed together, in accordance with an ancient law. That event took place about the time, apparently, at which the Apostle Paul arrived at Rome.

But not only were the nations ground down by slavery, the pages of Roman history abound in records of wholesale massacre and butchery. We may note, for instance, Luke's statement of Pilate's slaughter of Galilæans while they were sacrificing (Luke 13. 1). Records abound, too, of grossly burdensome taxation and financial exactions, in which the Romans outdid all tyrants that had preceded them. Usury flourished in the last century as it had never done before. Four per cent. per month was an ordinary exaction for a loan to a community. On one occasion a Roman banker, who had a claim on the municipality of Salamis, in Cyprus,[25] kept its council blockaded until five of its members died of hunger.

By these methods the provinces of the empire were at one period reduced to a condition of unsurpassed misery. Nothing could more vividly describe the course of such a kingdom and the control exercised by it than the words of Daniel quoted above.

This fourth kingdom was destined to be divided; and in two respects, territorial and constitutional. The territorial division was indicated by the symbolism of the legs and feet of the image of Nebuchadnezzar's vision; the constitutional division was declared in Daniel's interpretation concerning the iron and clay (v. 40). The former of these divisions claims our consideration first. Territorially the kingdom would be first divided into two parts corresponding with the legs of the image. This actually took place in the fourth century of the present era.

The Roman Empire had continued in a more or less united condition for over three centuries after the accession of its first Emperor, Augustus, in 27 B.C., though various signs of a coming division manifested themselves. It was not unusual,[26] for instance, for an emperor to appoint an associate with himself in the imperial rank, and on one occasion Maximian, who thus became associated with Diocletian in A.D. 288, actually established his seat of government at Nicomedia, in Asia Minor. Constantine (323-337) united the empire under his sole rule, but paved the way for the final separation of east from west by founding, in 328, the city of Constantinople as a second Rome, after his own name, and establishing it as an eastern centre of government with its own legislative institutions. This arrangement was favoured by several conditions, national and otherwise, which characterised the countries of the eastern half as distinct from those of the western.

At the death of Constantine, in 337, his dominions were divided among his three sons, a division, however, which lasted but a brief time. The empire was in 353 again united under Constantius, the survivor of the three. The long impending division into two parts took place under Valentinian I., in the year of his accession, 364. Yielding to the wish of his soldiers that he should associate a colleague with himself, he placed his brother Valens in power in the east, with headquarters at[27] Constantinople, he himself retaining control over the west.

Prophetic Scriptures show that the Roman Empire would be further divided. Now while the ten toes of the image in Nebuchadnezzar's dream have not improperly been regarded as indicative of a tenfold division, the fact that the image had ten toes would be insufficient of itself to signify this, for the toes are naturally essential to a complete human figure. Moreover, the hands and their fingers, equally essential parts, have no territorial significance attached to them. The conclusion regarding the toes is, however, justified when we find the tenfold division abundantly confirmed by other Scriptures.

Thus the fourth beast in the vision in chapter 7, which, as we have seen, likewise symbolised the Roman kingdom, is described as having ten horns (v. 7). The interpretation clearly tells us what these are: "And as for the ten horns, out of the kingdom (the fourth) shall ten kings arise" (v. 24). The Apocalypse gives us further information regarding this division, unfolding with increasing clearness the details connected with it. In one of the[28] visions given to the apostle John, he sees "a great red dragon, having seven heads and ten horns" (Rev. 12. 3). The meaning of the ten horns is not there explained. We are told that the great dragon is "the old serpent, he that is called the Devil and Satan, the deceiver of the whole world" (v. 9). Turning now to the next chapter, we find another vision recorded, giving a fresh view of the same subject. A beast was seen "coming up out of the sea, having ten horns and seven heads, and on his horns ten diadems, and upon his heads names of blasphemy" (chap. 13. 1). Again an explanation of the ten horns is withheld, but that they are identical with those of the twelfth chapter is undeniable. The Apostle receives, however, a further vision, recorded in chapter 17: "I saw a woman sitting upon a scarlet-coloured beast, full of names of blasphemy, having seven heads and ten horns" (chap. 17. 3). And now the symbolism of the horns is explained: "the ten horns that thou sawest are ten kings, which have received no kingdom as yet; but they receive authority as kings, with the beast, for one hour. These have one mind, and they give their power and authority unto the beast" (vv. 12, 13).

[29]We are now concerned, of course, solely with the tenfold division of the empire; other details of the visions just referred to remain for later consideration. We cannot fail to see that what is symbolised by the ten toes of the image, and by the ten horns of the fourth beast as revealed to Daniel, is identical with what is symbolised by the ten horns of the dragon and of the beast seen by John, namely, the Roman kingdom in its ultimately divided condition.

The following points are noteworthy in comparing these visions relatively to the tenfold division. First, there is a parallelism in the order of the revelations given to the two seers, Daniel and John. A preliminary vision is given to each—more than one in the case of John—in which, in the matter of this territorial partition, symbols occur without explanation. Each then receives a further vision, in the interpretation of which the eventual division into ten kingdoms is plainly disclosed. To Daniel it is said: "As for the ten horns, out of the kingdom shall ten kings arise;" and to John: "The ten horns that thou sawest are ten kings, ...[30] which receive authority as kings with the beast for one hour."

Second, the ten kingdoms are seen to be contemporaneous, as is indicated by the co-existence of the ten horns of the beast, and further, by the fact that the ten kings mutually agree to a certain line of policy in handing over their authority to a supreme potentate (Rev. 17. 12, 13).

Third, it is evident that the fourth kingdom is the last of the Gentile world-powers, and that it will exist in its tenfold state at the end of the times of the Gentiles. We observed this above in the case of the image, from the fact that the stone, symbolising the kingdom of Christ, smote the image upon its toes. So now, in the vision of the four beasts, it is the fourth beast that is slain, his body destroyed, and given to be burned (Dan. 7. 11). The Personal Agent of this destruction is here made known: "I saw in the night visions, and, behold, there came with the clouds of Heaven One like unto a son of man, and He came even to the Ancient of Days, ... and there was given Him dominion, and glory, and a kingdom, that all the peoples, nations, and languages should serve Him: His dominion is an everlasting dominion, which shall not pass away, and His kingdom[31] that which shall not be destroyed" (vv. 13, 14). The finality of the fourth kingdom is clearer still from the interpretation given in the remainder of the chapter. The final world-ruler is, of course, prominent in this vision; in his destruction is involved the destruction of his kingdom; his power and aggression are terminated when the Ancient of Days comes (v. 22); then it is that "the judgment shall sit, and they shall take away his dominion, to consume and to destroy it unto the end. And the kingdom and the dominion, and the greatness of the kingdoms under the whole heaven, shall be given to the people of the saints of the Most High: His kingdom is an everlasting kingdom, and all dominions shall serve and obey Him" (vv. 26, 27). Similarly, again, in Revelation 13 and 17, in the corresponding visions of the beast and its ten horns, the ten kings and their federal head, ruling at the time of the end, "shall war against the Lamb, and the Lamb shall overcome them, for He is Lord of lords, and King of kings; and they also shall overcome that are with Him, called and chosen and faithful" (Rev. 17. 14).

The crushing of the image by the stone, the slaying of the fourth beast before the[32] Ancient of Days, and the conquest of the ten kings and their chief by the Lamb, are therefore different views of the same event. The tenfold division of the fourth kingdom is obviously still future, and marks the condition of the world-government at the close of the times of the Gentiles, and immediately prior to the kingdom of Christ.

That the Roman Empire would in its final form be divided into ten kingdoms was held by Christian writers of the earliest post-apostolic times. Their opinions are here given, not as forming any basis of exposition, but as expressions of early Christian conception of the Scriptures under consideration.

What is known as "The Epistle of Barnabas," probably written early in the second century A.D., quotes from Daniel concerning the ten kingdoms to show that they would exist at the consummation of the present age. Irenæus (circa A.D. 120-202), a disciple of Polycarp, who had been a companion of the apostle John, observes that "the ten toes are ten kings, among whom the kingdom[33] will be divided." Tertullian, a contemporary of Irenæus, remarks that "the disintegration and dispersion of the Roman State among the ten kings will produce Antichrist, and then shall be revealed that Wicked One, whom the Lord Jesus shall slay with the breath of His mouth and destroy by the brightness of His manifestation." Hippolytus, who was a follower of Irenæus, and flourished in the first half of the third century, makes similar reference to the ultimate division. Lactantius, of the latter half of the third and the early part of the fourth centuries, writes as follows: "The Empire will be sub-divided, and the powers of government, after being frittered away and shared among many, will be undermined. Civil discords will then ensue, nor will there be respite from destructive wars, until ten kings arise at once, who will divide the world among themselves to consume rather than to govern it." Cyril (circa 315-386), who became bishop of Jerusalem in 350, quoting from Daniel, and speaking of the Empire and its future division, implies that teaching on the subject was customary in the churches. Jerome (342-420) observes that "at the end of the world, when the kingdom of the[34] Romans is to be destroyed, there will be ten kings to divide the Roman world among themselves." Similarly writes Theodoret in the fifth century, and others of that time make more or less direct reference to the subject. While the views of these writers differ considerably on other points of detail, all are unanimous as to the eventual division of the Empire among ten contemporaneous potentates.

The mediæval and modern history of the lands originally constituting the Roman Empire is a history of the formation of independent states in such a way as to point to the eventual revival of the Empire in the tenfold division we have been considering. The process has been a long and involved one, for the counsels of God have had a far wider range than the mere shaping of national destiny. It has been the Divine pleasure, for instance, that the Gospel should be spread among all nations for the purpose of taking out from among them a people for the Name of Christ, and for the formation thereby of His Church. In contradistinction to this, and from the standpoint of the world[35] itself, which, though under God's control, remains in alienation from Him, there has been a gradual development of the political, social, and religious principles which are ultimately to permeate the nations.

In the interpretation of his vision of the beast, John is told of its rise, temporary removal, and reappearance: "The beast that thou sawest was, and is not; and is about to come up out of the abyss, and to go into perdition" (Rev. 17. 8). Here the Roman world-power, the imperial dominion, is in view. In verse 11 the final king himself is similarly described. The symbol of the beast is thus employed to describe first the dominion and then its imperial head. This symbolic association of locality and ruler is found elsewhere in Scripture, and is illustrated in this very chapter. The seven heads of the beast, for example, are interpreted in both ways: "The seven heads are seven mountains, ... and they are seven kings" (v. 9, R.V. ) The distinction between verses 8 and 11[36] may be observed in this way: in the first part of the chapter, verses 1-8, the beast is viewed as a whole, indicating world-wide government; in verse 11 the scope of the symbol is limited, the beast is a person, and is identified with one of the seven heads, or kings, he is "himself also an eighth, and is of the seven." With this individual we shall be occupied later.

A striking illustration of the symbolic use of the word "beast" to denote both a kingdom and the ruler over it is to be found in Dan. 7, where the following statements are made: "These great beasts, which are four, are four kings" (v. 17), and "The fourth beast shall be the fourth kingdom" (v. 23).

The statement of verse 8 seems, then, undoubtedly to refer to the Empire; it did exist, it ceased to be, and it will reappear. The assertion that it "is not" must not be taken to mean that the beast had ceased to exist in John's time. The present tense is to be regarded as prophetic. The verb "to be" often has the force of continuance of existence. The whole statement implies a past existence, a discontinuance of that existence, a future reappearance. In the vision recorded in the thirteenth chapter, John saw one of the heads of the[37] beast "as though it had been smitten unto death." If, as seems probable, this head is imperialism, then the overthrow of imperial Rome is likewise indicated in that passage.

In the light, then, of the words: "The beast that thou sawest was, and is not," we may now consider how the Roman Empire was overthrown.

We have seen that, at the accession of the Emperor Valentinian I. in A.D. 364, the Empire was divided into two parts. The succeeding century witnessed the disintegration of the western half. The cause was primarily from within. Augustus, the first Emperor, had instituted a policy of settling colonies of "barbarians" from northern Europe within the frontiers of the Empire. Later Emperors adopted the policy more generally. The significance of this lies in the fact that by the barbarians who had already been thus established in the Empire, the attacks were commenced which resulted in the dismemberment of its western provinces.

At the close of the fourth century hordes[38] of Gothic tribes from north-eastern and eastern Germany set out, under Alaric their chief, in quest of new lands. Settlements of these very Goths had already been established south of the Danube by the Imperial Government as allies of the Romans. After an excursion into Italy, in which they were temporarily checked, they poured, in 406, into defenceless Gaul. From thence Alaric returned to invade Italy, and three times in three years besieged Rome (408-410), eventually sacking the city. After his death, in 410, the Goths retired from Italy, entered Gaul, and permanently occupied the southern part of that country and a large part of Spain, where they were known as Visigoths (i.e., Western Goths).

Other Germanic tribes also streamed into Gaul. Of these, the Franks (whence the name France) issued from districts around the middle and lower Rhine and occupied northern Gaul; the Suevi, from north and north-west Germany, passed through into Spain; the Alani, formerly from eastern Europe, settled in west France and Spain; the Burgundians, from eastern Germany, seized that part of Gaul which eventually was named after them, Burgundy. The Vandals, from[39] northern and central Germany, after being defeated by the Franks, crossed into Spain under their leader Genseric, and from thence established themselves in the province of Africa, in 429. This occupation of Gaul and Spain was soon perforce recognised by the Emperor at Rome. At the death of the Emperor Honorius, in 423, Rome exercised little more than a nominal authority over the greater part of the west.

From Britain the Roman troops were withdrawn by Honorius, in 409, though the final abandonment of the island province did not take place till 436. Teutonic tribes from North Europe were soon engaged in invading this part of the Empire. The Jutes, from Jutland, landed in 449, the Saxons in 477, and about the same time the Angles.

Toward the close of the reign of Valentinian III. (433-455), Gaul and Italy were invaded by the Huns under Attila. The Huns originally inhabited a large part of central and northern Asia. In the latter part of the fourth century they moved west into Scythia and Germany, driving the Goths before them. Attila's dominions[40] thereafter extended over a vast area of eastern, central, and northern Europe, and he was regarded as of equal standing with the Emperors at Constantinople and Rome. After a gigantic but futile incursion into Gaul, in 451, the Huns rushed into Italy, ravaging its northern plains. An embassy from Rome and an immense ransom saved the situation. Attila died in 453, and Italy was evacuated. The Huns eventually settled in south-eastern Europe, and their dominion dwindled away. A trace of their name may be found in the word Hungary.

In North Africa Genseric the Vandal established a powerful dominion, and set about preparing an invasion of Italy by sea. In 455 (the last year of the reign of Valentinian III.) his army of Vandals and Moors attacked Rome, which was again given over to pillage. Its wealth and treasures were transported to Carthage, and with them the vessels of the temple at Jerusalem; these had been brought to Rome in A.D. 70 by Titus, the conqueror of Jerusalem. For twenty years after Genseric's achievement Roman Emperors existed in little else than name, the real[41] power being in the hands of a barbarian officer. In 476 the last Emperor was deposed by Odoacer, the king of the Heruli, a tribe which, issuing from the shores of the Baltic, made successful inroads into Italy and occupied much of the country. Odoacer was, at the request of the Roman Senate, given the reins of government by the eastern Emperor Zeno, and news was despatched to the court at Constantinople that no longer was there an Emperor of the west. Subsequently, in 493, Odoacer was slain by Theodoric, the king of the Ostrogoths, who then became predominant in the Italian peninsula. The Ostrogoths (i.e., Eastern Goths) had broken off from the main body of their nation, and after settling south of the Danube moved into the province of Dalmatia.

Other Germanic tribes, in addition to those named above, firmly established themselves within the northern limits of the Empire. Of these, two are worthy of mention, the Alemanni, who occupied most of what is now Switzerland and districts northward, and the Lombards, who settled in north Italy and the territory north-east of it.

There have been various attempts to identify with the ten prophetic kingdoms the states formed from the western half of the Roman Empire by the Germanic tribes from the north. Such attempts fail from the standpoints both of history and of prophecy. To group the tribes so as to make ten kingdoms out of them is, of course, possible in several ways, for there were at least eighteen such tribes. Accordingly lists put forward differ considerably. But such grouping is manifestly arbitrary. Again, since these invading nations occupied only the western half of the Empire, the above allocation of the ten kingdoms necessarily leaves the eastern half out of consideration, and therefore excludes the land of Palestine from this stage of the prophetic forecast.

Now the prophecies concerning the times of the Gentiles are invariably focussed upon the Jews and their land. The dealings of God with the Jews form the pivot of His dealings with other nations. Thus no scheme of prophetic exposition relative to this subject is to be regarded as Scriptural which excludes Palestine from its[43] scope. To endeavour to make the Word of God square with facts of history is to tamper with Scripture and to run the risk of obscuring its meaning and force.

The idea that the formation of the ten kingdoms took place in the fifth century fails to stand the test of Scripture in other respects. Of the ten kings prophecy foretells that "they receive authority as kings with the beast for one hour," that they "have one mind, and they give their power and authority unto the beast" (Rev. 17. 13, 14). No such tenfold confederacy has existed in Europe; it certainly never existed among the chieftains of the Germanic tribes which invaded the west of the Roman Empire in the fifth century, neither is there any record of such an agreement among them. Nor, again, can it be said that they made war with the Lamb and were overcome by Him (v. 14). These prophecies still await fulfilment. Similar considerations apply to the passage in Daniel 7 in reference to the fourth kingdom. The ten kings, it is said, would arise out of that kingdom, and after them another king who would make war with the saints and prevail against them until the Ancient of Days came (vv. 21, 22, 24).

Again, since the persecution under the[44] king who arises after the others continues until the Ancient of Days comes (v. 22), his war against the saints must have lasted from the fifth century until the present time, if he arose in that century. Moreover, as he was said to be going to subdue three kingdoms (v. 24), the seven kingdoms not so subdued must likewise have continued. This has obviously not been the case. From every point of view it is impossible to assign the tenfold division to any time in the past.

Having narrated the disintegration of the western half of the Empire, we will now recount the events which involved the overthrow of the eastern half. The impoverishment of the imperial power at Rome, and the weakening effect of the Germanic attacks upon it, tended to enhance the power of the Emperor at Constantinople. Indeed the eastern Empire was soon regarded as the more important of the two, and for some time after the barbarian invasions in Italy the Emperors[45] at Constantinople claimed supremacy over the west.

The seventh century saw the ascendency of Mohammed (born A.D. 570) in Arabia, to which country his personal power, temporal and religious, was limited. Upon his death, in 632, his followers determined on the invasion of Persia and the Asiatic dominions of the Emperor at Constantinople. Mohammed's successor, Abubekr, the first of the Khaliphs (i.e., "representatives" of the prophet), at once waged war in both directions. Persia speedily succumbed; Syria and Palestine were subjugated after seven years by the Khaliph Omar. The reduction of Egypt followed, and during the remainder of this century the Saracens, the name by which the followers of Mohammed became termed in Christendom, extended their territory across the entire length of North Africa, and shortly afterwards even into Spain, where they overpowered the then disunited Visigoths.

The Saracen power in Western Asia was distracted during the next century by civil war, and was further weakened by unsuccessful wars against the Greeks. At length, in 750, the seat of government was[46] moved from Damascus to Bagdad. From the eighth century onward, though the religion of Mohammed gained ground, and continues to do so to-day, the empire established by his followers dwindled rapidly, one province after another shaking off its allegiance until at the end of the tenth century its shattered dominions lay open to the nearest invader. The foe appeared in the shape of the formidable Turk.

In view of the entrance of this new enemy we may note the extent of the territory belonging at this time to the eastern branch of the old Roman world, the Byzantine Empire, as it is termed (from Byzantium, the ancient name of Constantinople). The Eastern Emperors had recovered some of their lost ground in Asia, and at the close of the tenth century they held all Asia Minor, Armenia, a part of Syria, a considerable portion of Italy, and all the Balkan Peninsula.

Beyond the north-eastern border of the Saracen dominions lay the country of Turkestan, inhabited by the Turks, a branch of the warlike nation of the Tartars[47] of Central Asia. With them the Saracens, after the establishment of their Government at Bagdad, waged successful warfare for a time, taking numbers of Turks captive and dispersing them over the Empire. This only facilitated the eventual downfall of the Saracen sovereignty. The Turks in Western Asia grew in influence, and at length the Turkish troops, breaking into open revolt, assumed control over the Khaliphate, deposing and nominating the Khaliphs at their will.

Early in the eleventh century the bulk of the Turkish nation, under its leader Tongrol Bek, moving out from Turkestan, swept down upon Persia. The Khaliphate at Bagdad was, however, permitted to remain, and not only so, but Tongrol Bek and all his tribes embraced the Mohammedan religion. The invaders then marched west in vast numbers to make an attack upon Christendom, and in the course of time subdued Armenia and most of Asia Minor. Europe became alarmed, and the Byzantine Emperors eagerly sought the assistance of the nations of the west. Hence arose the Crusades, which had as their chief object the deliverance[48] of Palestine from both Saracens and Turks, and which served to retard, though not to prevent, the advance of the Turkish power in Europe.

Early in the thirteenth century a mighty movement of Mongols south-west from Central Asia, involving the immediate destruction of the Khaliphate at Bagdad, exerted an important influence upon the Turks, in driving those Turkish tribes which had remained east of Armenia westward into Asia Minor. This resulted in the establishment of various Turkish dynasties in that country. At the close of the thirteenth century the paramount power over these was exercised by Osman (or Othman, whence the name Ottoman), who seized all that remained of the ancient Roman world in Asia, and thus practically founded the Ottoman Empire. In the middle of the fourteenth century the way was opened for the Ottomans to advance into Europe. They were invited by one of the rival factions at Constantinople to undertake their cause. The Turks accordingly crossed the Hellespont and seized Gallipoli and the territory in the vicinity of the capital. Constantinople[49] itself was left unattacked for the time. Under Murad I., the grandson of Osman, Roumania and several kingdoms south of the Danube, including Bulgaria, were subdued. The kings of Hungary, Bosnia and Serbia rose against the invader, but were severely defeated, and by the decisive victory of Kosovo, in 1389, Serbia and Bosnia were annexed.

Constantinople was temporarily saved by another advance of the Mongol Tartars upon the Turkish dominions in Asia, where, in 1402, the Ottomans suffered a severe defeat. From this check they recovered, and during the first part of the fifteenth century were at war with the Hungarians and neighbouring races, whom they eventually overthrew. In 1451 Mohammed II. ascended the Ottoman throne, and in 1453 led an immense army against Constantinople. The city was taken by storm, the last of the Roman Emperors of the east died fighting, and Mohammed II. rode in triumph to the cathedral of St. Sophia, where he established the Moslem worship.

For over a hundred years after this the Turkish Empire continued to extend.[50] Egypt was annexed in 1517, and in the middle of this century Tripoli and Algeria were added, as well as considerable districts in Europe and Asia. The Turks were now at the zenith of their power.

Recapitulating, we may compare the two divisions of the Roman Empire since their overthrow, from the prophetic, religious and political standpoints. From the prophetic point of view our interest in the west has thus far centred in the fact that the ten kingdoms were not formed by the fifth century invasions; our interest in the east centres chiefly in the land of Palestine, wrenched, as we have seen, from the eastern Emperor by the Saracens, and then occupied by the Turks, who still possess it. From the religious standpoint, the Germanic tribes in the west accepted Roman Catholicism, hence its progress in that part of Europe; in the east the Turks had accepted Mohammedanism when invading the Empire of the Khaliphs, hence the establishment of Islamism throughout the Turkish dominions. Politically, the western invasion in the fifth century, and the consequent amalgamation of the Teutonic tribes with the peoples formerly[51] under Roman control, led eventually to the formation of the various mediaeval monarchies of Western Europe which are to-day either kingdoms or republics. Affairs in the eastern half of the Roman world have moved more slowly in this respect, owing to the prolonged existence of the Ottoman Empire. The slow decay of the Turkish power from the middle of the sixteenth century onward has already resulted in the formation of some Eastern States, and the process still continues.

The decline of the power of the Turks set in during the latter half of the sixteenth century, when their dominions passed under incapable rulers. In the reign of Selim II. (1566-1574) occurred the first conflict between the Turks and Russians, the former being driven back from Astrakkan. In 1593, during a war between Turkey and Austria, the provinces of Transylvania, Moldavia, and Wallachia rose in revolt. As the result of intermittent wars in the latter half of the seventeenth century Austria acquired almost the whole of Hungary. In 1770 Russia occupied Moldavia and Wallachia, which though nominally for a time under Turkey were[52] practically Russian protectorates. During the next few years Russia regained the Crimea and all the neighbouring district north of the Black Sea. At the commencement of the nineteenth century the Ottoman Empire was in a perilous condition. Napoleon had plans for its partition. Provincial governors were everywhere acting independently of the Sultan. In 1804 Serbia revolted, and after a few years of persistent struggle obtained its autonomy. Greece revolted in 1820, and, though subdued for a time, gained its independence in 1829 through the intervention of England, France, and Russia, and chiefly as the result of the naval battle of Navarino, in which the Turco-Egyptian fleet was annihilated. In the same year Algeria was annexed by the French. European rivalries prevented for a time any rapid diminution of the Empire.

The Crimean War of 1854-5 had important consequences for the Balkan peoples. It gave them, under the slackening grasp of the Porte, twenty years of comparatively quiet national development. In 1860 Wallachia and Moldavia formed themselves into the single state of Roumania. In 1866 the Pasha of Egypt assumed the title of Khedive (i.e., king), thereby securing a[53] measure of independence for the country. In 1875 the misrule of the Sultan led to the insurrection of Bosnia, Herzegovina, and Bulgaria. Serbia and Montenegro then took up arms. In 1877 a war with Russia saw Turkey without an ally. A complete Russian victory in 1878 issued in the treaties first of San Stefano and then of Berlin, by which Turkey yielded to Russia the state of Bessarabia and districts south of the Caucasus, the independence of Serbia, Montenegro, and Roumania were recognised by the Porte, Bulgaria was constituted an autonomous state, Bosnia and Herzegovina were ceded to Austria, Thessaly to Greece, and Cyprus to Britain. In 1885, as the result of a revolution, Eastern Roumelia became united to Bulgaria. Shortly after that date German influence began to gain ascendancy at the court of the Sultan, and, among other affairs, largely dominated the granting of railway concessions in Western Asia. The effects of that influence have been evidenced in the present war. In 1912 Italy annexed Tripoli after a brief war. In 1913 a short but sanguinary war with the Balkan States deprived Turkey of all her European dominions save for a small piece of territory in the vicinity[54] of Constantinople. Egypt, which has been chiefly under British control for a considerable period, has in 1915 been practically annexed by Britain as a protectorate, the Khedive being deposed and a nominee of the British Government being placed in authority. Britain has likewise annexed a district north of the Persian Gulf.

The continual decrease of the Turkish Empire, and more especially during the past hundred years, affords ground, apart from other considerations, for the expectation of its overthrow and the eventual cession of Palestine to the Jews, perhaps by a general agreement among the European Powers, events which seem not far distant. National jealousies would not permit the permanent annexation of Palestine by any one of these Powers, in whatever way the remaining Asiatic Turkish dominions may be divided. A proposal has already been put forward for its annexation to Egypt. Such an arrangement would in any case be merely temporary. To the Jews the land belongs, and by Divine decree the Jews are to possess it again.

It should be observed, in passing, that Scripture is apparently silent concerning the occupation of Palestine by the Saracens and Turks. Such silence is noticeable when we remember how definitely the occupation by the other Gentile powers, the Chaldean, Medo-Persian, Greek, and Roman, and the order and character of their rule, were predicted. The cause of the silence is not difficult to ascertain. The four Gentile powers just mentioned had to do with the Jews as the recognised possessors of Palestine, either by way of removing them from their country or restoring them to it, or during such time as they were permitted to remain in it with liberty to continue their temple worship and sacrifice. The Chaldeans removed the Jews from the land, the Medo-Persians repatriated them, the Greeks permitted their continuance in it, the Romans did so too, until A.D. 70, when they crushed them. When, however, the Saracens and the Turks seized the land the Jews had been scattered, nor have they received national recognition while under them. Gentile occupation of Palestine during such times as the Jews remain[56] in their present condition seems therefore to receive no direct notice in prophecy.

The restoration of Palestine to the Jews is closely connected with the revival of the Roman Empire in its tenfold form. Prior to considering the manner of this revival we must notice how during the period between the overthrow of that Empire and its coming resuscitation, its dominions and their government have remained Roman in character, thus affording a further proof that the coming and final world-power will not be entirely a new one, but will be a revival of the ancient Roman or fourth empire indicated in the prophecies of Daniel.

Such was the prestige of the Roman name and authority that the chieftains of the Germanic tribes which in the fifth century subdued the western half of the Empire governed the conquered territories, not so much as tribal chiefs, but as successors to, and in continuation of, the imperial rule; they introduced no radical changes in the provincial and municipal forms of government of their predecessors. Civil organisation remained distinctly Roman, and has continued so; upon it are[57] based some of the chief municipal institutions of modern life. Indeed Roman civil law still remains the foundation of modern jurisprudence.

In south-eastern Europe, too, countries which were for centuries under the power of the Turk retained, in their municipal institutions and organisation, the impress of Roman authority. It should be remembered that though the eastern or Byzantine portion of the ancient Roman Empire was distinct from the western, its emperors being designated as Grecian in contrast to the Roman, yet its legislative foundations were laid in the Roman Empire prior to the division of the east from the west. Byzantine imperialism was therefore really Roman under an eastern title. According as the states in the east have become freed from the Turkish yoke, so the character of their government and legislation has conformed in a large degree to those of the west. The further diminution of the Turkish Empire will doubtless see a corresponding revival of western conditions and methods.

It is important also to observe that notwithstanding the passing away of the[58] Roman Empire as such, the principle of imperialism remained, and, amidst the vicissitudes of national government in Europe, has continued to the present time. The imperial power in the west was not abolished when in 476 the last Roman Emperor was deposed. On the contrary, there was a kind of reunion imperially of the west with the east. For a considerable time the tribal kings of the west received recognition from the eastern emperors, and were regarded as their associates in imperial control. This was the case even with the Saxon kings in Britain, and on Saxon coins may be seen to-day the same title, basileus (i.e., king), as was borne by the emperors at Constantinople. Italy itself was wrested from the Teutons by the eastern Emperor Justinian in the sixth century, and remained under the Byzantine Caesars till 731.

Meanwhile the Roman Senate continued to exercise its authority, and in 800 chose the Frankish king Charlemagne as their sovereign. He was already ruling over the greater part of Western Europe, and was now crowned as Emperor at Rome by the Pope. Though his empire fell to pieces after his death, his dominions retained, and have since retained, their Roman character.

[59]Consideration of space forbids our tracing here the further continuance of imperialism as a factor in European politics. Recent history and present-day events indicate how rapidly we are approaching its final development at the close of the times of the Gentiles. The coming confederacy of European states will not result in the formation of a new empire, but will be the revival of the Roman in an altered form.

(1) The Geographical Standpoint.

The coming revival of the Roman Empire will for our present purpose be best considered from the geographical, political, and religious standpoints.

Any forecast of the exact delimitations of the ten kingdoms constituting the reconstructed Empire must necessarily be largely conjectural. That their aggregate area will precisely conform to that of the ancient Roman Empire does not necessarily follow from the fact of its revival,[60] and cannot be definitely concluded from Scripture. An extension of the territories of the Empire in its resuscitated form would be quite consistent with the retention of its identity. Moreover, if Roman imperialism may be considered to have continued in the hands of Teutonic monarchs after the fall of the western part of the Empire in 476, if, for instance, Charles the Great, of whom we have spoken (p. 58), ruled as a Roman Emperor, despite the passing away of the actual Empire itself, then the dominions which were under the rule of these later monarchs may yet be found incorporated in the Empire, and so form parts of the ten kingdoms. In that case Germany and Holland would be included. Possibly, too, the Empire will embrace all the territories which belonged to the three which preceded it, the Grecian, Medo-Persian, and Chaldean. Certainly when the stone fell on the toes of the image, the whole image, representing these former three as well as the fourth, was demolished. Suggestive also in this respect is the fact that the beast in the vision recorded in Revelation 13. 2 was possessed of features of the leopard, the bear, and the lion, the same beasts which represented in Daniel's vision the Grecian, Medo-Persian, and[61] Chaldean kingdoms (Dan. 7. 4-6), the order in Revelation 13 being inverted. While political characteristics are doubtless chiefly in view in these symbols, there may at the same time be an indication of the eventual incorporation of the first three empires in the fourth. It must be remembered, too, that the authority of the federal head of the ten kingdoms is to be world-wide: "There was given to him authority over every tribe and people and tongue and nation" (Rev. 13. 7). It is probable, therefore, that while the ten kingdoms will occupy a well defined area, their dependencies and the countries which are allied with them will embrace practically the remainder of the world.

If, on the other hand, the Roman Empire is to be reconstructed in exact conformity territorially with its ancient boundaries—such a reconstruction is, of course, not inconceivable—we must consider what period of the conquests of the ancient Empire to take, whether under the first emperor, Augustus, or during the Apostolic Age, or later. We may, perhaps, be helped by the facts already mentioned, that prophecy relating to Gentile dominion is focussed upon the Jews and Palestine, and has especially in view the presence of[62] the nation in their land. Now, shortly after their overthrow, in A.D. 70, their national recognition as possessors of the land ceased. This period, moreover, corresponds broadly to the close of the Apostolic Age. The dispersion of the Jews among the nations was completed by Adrian in the next century. He desolated the whole of Palestine, expelling all the remaining Jewish inhabitants.

We will therefore now review the limits of the Empire and of some of its provinces at that time, noticing certain circumstances of past and present history suggestive of future issues. In doing so we are not predicting that the boundaries of the revived Empire will be those of the ancient.

Commencing with North Africa, it will be observed, on referring to the map, that practically the same strip of territory which belonged to the Roman Empire in the times of the apostles has passed directly under the government of countries which were themselves then within the Empire. For Spain rules over Morocco, France over Algeria and Tunis, Italy recently seized Tripoli, and Britain has, since Turkey's entrance into the great war, virtually[63] taken possession of Egypt. It seems not a little significant that no country which was outside the limits of the Empire at the time under consideration has been permitted by God to annex these North African territories since the Saracens and the Turks were dispossessed of them.

Passing now to Asia, the territory in that continent which belonged to Rome in the first century is approximately what remained to Turkey immediately prior to the present war. Mesopotamia and most of Armenia were included. The war has already seen Turkey dispossessed of portions of these. The downfall of the Turkish Empire would almost certainly involve territorial rearrangements of deepest import in the light of prophecy, especially as regards Palestine.

The 8th chapter of Daniel apparently indicates that the Asiatic territories of the Empire will be divided much as they were under the Greeks after the death of Alexander the Great. He was obviously symbolised by the great horn (v. 22). The four horns which came up in its place (v. 8) are clearly, too, the four generals who[64] succeeded Alexander, and among whom his dominions were divided, Cassander ruling over Macedonia and Greece, Lysimachus over part of Asia Minor and Thrace (the extent of the latter province was almost exactly what now belongs to Turkey in Europe), Seleucus over most of Syria, Palestine, Mesopotamia, and the east, and Ptolemy over Egypt. Next follows a prediction carrying us to events which are evidently yet future. It is said, for instance, that these events will take place "in the latter time of their kingdom (not, it will be observed, in the time of the four kings themselves who succeeded Alexander, but of the kingdoms over which they ruled), when the transgressors are come to the full" (v. 23). The expressions in this chapter, "the time of the end" (v. 17), "the latter time of the indignation," "the appointed time of the end" (v. 19), and "the latter time of their kingdom" (v. 23), all point to a period still future, namely, to the close of the present age. Again, in reference to the "king of fierce countenance," while much of the prophecy can be applied to Antiochus Epiphanes in the second century B.C., yet no man has hitherto arisen whose character and acts have been precisely those related in[65] verses 9-12 and 23-25. We may also compare what is said of "the transgression that maketh desolate" (v. 13) with the Lord's prophecy concerning the abomination of desolation (Matt. 24. 15-22), a prophecy which also manifestly awaits fulfilment.

Possibly, therefore, these Asiatic territories will be similarly divided in the coming time. In regard to the first of the above-mentioned four divisions, the recent extension of Greece to include the ancient province of Macedonia is remarkable. This was an outcome of the Balkan War of 1912. The boundaries of Greece are now approximately what they were under Cassander in the time of the Grecian Empire, what they were also later as the provinces of Macedonia and Achaia in the Roman Empire. There has lately, therefore, been a significant reversion to ancient conditions in this respect.

Coming now to the dual-monarchy of Austria-Hungary, reference to the map of the Roman Empire in the Apostolic Age will show that what are now Hungary, Transylvania, Bessarabia, and other states of the present monarchy were without the[66] Roman boundaries, while Pannonia, or what is now Austria west of the Danube, was within; even when in the next century Dacia (now Transylvania, Bessarabia, &c.) was annexed, the two parts of the present dual kingdom were separate. The separation of Hungary from Austria has for a considerable time been a practical question of European politics, and may be hastened by present events.

The northern and north-eastern boundaries of Italy embraced the Trentino and the peninsula of Istria. Noticeable, therefore, are the present efforts of Italy to acquire these very districts, efforts which seem likely to achieve success. Roman states north of Italy covered what are now Baden, Wurtemberg, Luxemberg, and a large part of Bavaria. The possibility of an eventual severance of these from Prussian domination has been much discussed of late.

The Rhenish provinces of Alsace and Lorraine, originally portions of the Roman province of Gallia (now France), were snatched from France by Germany in the Franco-Prussian war of 1870-71. Their recovery is a supreme object of the efforts of the French in the present war, and not without hope of success.

As to Britain, at the time under consideration the greater part of the island was definitely included in the Roman Empire. Ireland and most of Scotland were never conquered by the Romans. Should Britain form one of the ten kingdoms, there is nothing to show that Ireland or any other part of the British Empire must of necessity be absolutely separated from it. Self-government may yet be possessed by those territories which have not yet received it, and it is significant that Ireland has now practically obtained it. That the lands which are linked with Britain as dependencies, or as in possession of self-government, should remain as integral parts of the Empire is but consistent with the coming world-wide authority of the potentate who will be the federal head of the ten kingdoms. And that each state in the British Empire should have its own local government is, on the other hand, consistent with the establishment of a closer and complete confederacy of ten kingdoms, the area of which may correspond largely to that of the ancient Roman Empire. In contrast to the self-government of the other countries of the world at[68] the coming period, the ten united kingdoms will eventually be absolutely under the control of the final emperor just mentioned, for the ten kings over these states, who receive authority as kings with him, will be of one mind to give their power and authority and their kingdom to him (Rev. 17. 12, 13, 17).

What has been said of the British Empire may be true also of others of the ten kingdoms which have colonies or dependencies, and thus, while the ten kingdoms will themselves constitute an Empire, their alliances and treaties with other countries of the world will apparently involve an extension of the authority of the controlling despot "over every tribe and people and tongue and nation" (Rev. 13. 7). If, for instance, the United States of America were at that time in alliance with Britain (quite a possible contingency), their joint influence would probably extend to the whole of the American continents, which would thereby acknowledge his authority.

We may observe, too, the way in which the continent of Africa has come under certain European influences in modern times. The mention of this is simply suggestive. That the Scripture will be[69] absolutely fulfilled is beyond doubt; the exact mode of its accomplishment is known to God.

(2) The Political Standpoint.

Agencies are already at work for the establishment of a confederacy of European States—not the least significant of the many signs that the end of the age is approaching. The movement towards confederacy is doubtless receiving an impetus from the great upheaval in Europe. A circular issued in December, 1914, and distributed far and wide, announced the formation of a committee of influential men with the object of promoting a "European Federation." The circular says: "In sight of the present situation of ruin it ought to be the general opinion that a firmer economical and political tie is of utmost importance for all nations without exception, and that particularly for Europe the narrower bond of a federation, based on equality and interior independence of all partaking states, is of urgent necessity, which public opinion ought to demand."

A pamphlet published by the Committee recommends that the union of states shall[70] be economical, political, and legal, with an international army as a common guarantee, and that European Federation should become the principal and most urgent political battle-cry for the masses of all European nations, and declares that "when the Governments are willing, when the public opinion of all peoples forces them to be willing, there is no doubt but that a reasonable and practical union of nations will prove to be as possible and natural as is at present a union of provinces, cantons, territories, whose populations often show more difference of race and character than those of nations now at hostilities." The Committee calls upon the peoples of Europe to suffer the diplomatists no longer to dispose of them like slaves and by militarism to lash them to fury against each other. It calls upon them to see to it that never and nowhere should a member of any body or Government be elected who is not an advocate of the Federation, and that the trade union, society, or club to which any individual belongs should express sympathy with the movement in meetings and in votes. "The people," it is said, "have it now in their power, more than ever before, to control the Powers."