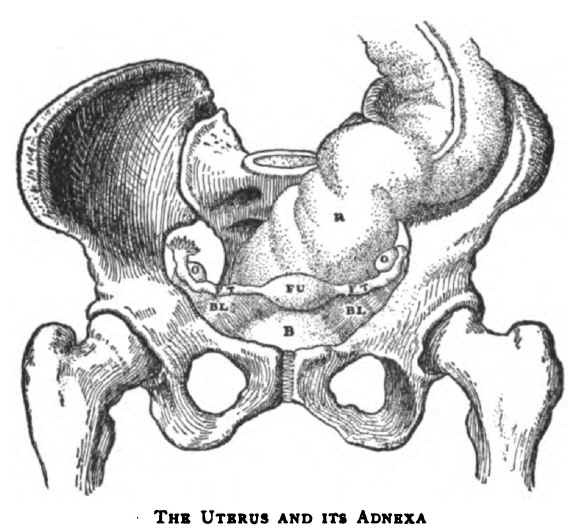

The Uterus and its Adnexa

F U, Fundus or Base of the Uterus. F T, P T, Fallopian Tubes. On the left of the reader the Fimbriated Extremity of the tube is lifted up to show it. O, O, Ovaries. B L, B L, Broad Ligament. R, Rectum. B, Bladder.

Title: Essays In Pastoral Medicine

Author: Austin O'Malley

James J. Walsh

Release date: March 3, 2012 [eBook #39036]

Most recently updated: January 8, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Don Kostuch

[Transcriber's notes]

This is derived from the Internet Archive:

http://www.archive.org/details/essaysinpastora00walsgoog

Page numbers in this book are indicated by numbers enclosed in curly

braces, e.g. {99}. They have been located where page breaks occurred

in the original book.

Obvious spelling errors have been corrected but "inventive" and

inconsistent spelling is left unchanged.

[End Transcriber's notes]

LONGMANS, GREEN, AND CO.

91 AND 93 FIFTH AVENUE, NEW YORK

LONDON AND BOMBAY

1906

Copyright, 1906

By Longmans, Green, and Co.

All rights reserved.

THE UNIVERSITY PRESS, CAMBRIDGE, U. S. A.

The term Pastoral Medicine is somewhat difficult to define because it comprises unrelated material ranging from disinfection to foeticide. It presents that part of medicine which is of import to a pastor in his cure, and those divisions of ethics and moral theology which concern a physician in his practice. It sets forth facts and principles whereby the physician himself or his pastor may direct the operator's conscience whenever medicine takes on a moral quality, and it also explains to the pastor, who must often minister to a mind diseased, certain medical truths which will soften harsh judgments, and other facts, which may be indifferent morally but which assist him in the proper conduct of his work, especially as an educator. Pastoral medicine is not to be confused with the code of rules commonly called medical ethics.

The material of pastoral medicine requires constantly renewed discussion, because medicine in general is progressive enough frequently to devise better methods of diagnosis and treatment, and thus the postulates of the moral questions involved are changed. This discussion, however, is not easily made. The facts upon which the ethical part of pastoral medicine rests are furnished by the physician for the consideration and judgment of the moralist—the physician educated after modern methods knows little or nothing of ethics and can not himself make accurate moral decisions. The moralist, on the other hand, is commonly a poor counsellor to the physician, because long training in medicine is needed before the physical data of the moral decisions is comprehended. The physician, therefore, is at a loss to determine what he may or may not do in {vi} cases that involve the greatest moral responsibility, and the priest is a hesitating guide because the moral theologies do not convincingly present the doctrine in these cases.

Now and then such subjects have been proposed for discussion to a group of physicians and moralists, but usually no practical conclusion has been reached because one side did not understand the other. In 1898 there was a series of articles on ectopic gestation in the American Ecclesiastical Review, in which moralists like Lehmkuhl, Sabetti, Aertnys, and Holaind, and some of the leading gynaecologists of America considered the questions but arrived at no decision. The physicians did not understand certain questions, other questions were on obsolete medical practice, essential questions were omitted, and from the data the moralists came to opposed conclusions.

We find also in moral theologies deductions drawn from false medical sources. Reasons are given, for example, to justify the use of a large quantity of alcoholic liquor at a dose in cases of great pain, typhoid fever, snake-poisoning, and other diseases, in the supposition that such doses will benefit or cure the patient, whereas the physician that would follow that treatment would be guilty of malpractice. There was recently in America a discussion on the relation of öophorectomy to the impedimentum impotentiae. One side held that a lack of ovaries constitutes impotence; the other side, that it does not. The discussion was useful because it incidentally gathered the full doctrine of the moralists on this subject, but from the medical point of view there is no connection whatever between these conditions.

A small number of books on pastoral medicine have been written by clergymen that were not physicians, and a few German books by physicians that were also moralists. Those by the physicians draw conclusions from antiquated medical practice, or they are mere popular treatises on hygiene; those by the clergymen have some value on the ethical side, but they are incomplete because the authors had not the necessary medical knowledge. The essays offered in this book by no {vii} means cover the entire field of pastoral medicine, but as far as they go we have endeavoured to offer the medical doctrine of the present day on the questions considered, and that as completely as is necessary to draw the moral inferences.

Since, then, so many of the questions of pastoral medicine are not defined, physicians are likely to follow the doctrine of the standard medical books, which without exception advise them to take the life of a dangerous foetus almost as unconcernedly as they might prescribe an active drug, or in any case to put utility before justice. There is, therefore, an urgent necessity that competent men fix that shifting part of ethics and moral theology called pastoral medicine, and these essays are presented as a temporary bridge to serve in crossing a corner of the bog until better engineers lay down a permanent causeway.

Some may think that the authors are inclined toward an exaggerated charity in suggesting the measure of responsibility for many human actions, but the physician that is brought much in contact with those suffering from mental defects of various kinds soon learns how easily complete responsibility becomes marred. Responsibility is dependent entirely upon free will; and while the great principle of free will remains solid in truth, no two men are free in exactly the same manner. Physical conditions have not a little to do with modifications of freedom of the will. To point out this fact to the clergyman and the physician has been our intention, for a proper appreciation of it will widen the bounds of charity and save many that are more sinned against than sinning from the injury of grievous misjudgment. It is better to run the risk of exculpating a few individuals whose responsibility is not entirely clear when the application of the same principles lifts many others above the rash judgment of those that can be of most help to them.

The Authorship of the respective Essays is indicated by the signature at the end of each Essay.

| Chapter | Page | |

| I. | Ectopic Gestation | 1 |

| II. | Pelvic Tumours in Pregnancy | 40 |

| III. | Abortion, Miscarriage, and Premature Labour | 48 |

| IV. | The Caesarean Section and Craniotomy | 55 |

| V. | Maternal Impressions | 60 |

| VI. | Human Terata and the Sacraments | 69 |

| VII. | Social Medicine | 88 |

| VIII. | Some Aspects of Intoxication | 105 |

| IX. | Heredity, Physical Disease, and Moral Weakness | 120 |

| X. | Hypnotism, Suggestion, and Crime | 129 |

| XI. | Unexpected Death | 135 |

| XII. | Unexpected Death in Special Diseases | 150 |

| XIII. | The Moment of Death | 164 |

| XIV. | The Priest in Infectious Diseases | 168 |

| XV. | Infectious Diseases in Schools | 187 |

| XVI. | School Hygiene | 202 |

| XVII. | Mental Diseases and Spiritual Direction | 211 |

| XVIII. | Neurasthenia | 230 |

| XIX. | Hysteria | 235 |

| XX. | Menstrual Diseases | 240 |

| XXI. | Chronic Disease and Responsibility | 245 |

| {x} | ||

| XXII. | Epilepsy and Responsibility | 251 |

| XXIII. | Psychic Epilepsy and Secondary Personality | 259 |

| XXIV. | Impulse and Responsibility | 266 |

| XXV. | Criminology and the Habitual Criminal | 271 |

| XXVI. | Paranoia, a Study in Cranks | 282 |

| XXVII. | Suicides | 306 |

| XXVIII. | Venereal Diseases and Marriage | 311 |

| XXIX. | Social Diseases | 317 |

| XXX. | De Impedimento Matrimonii Dirimente Impotentia | 326 |

| APPENDIX. | Bloody Sweat | 347 |

| INDEX | 357 |

Ectopic gestation is gestation in the uterine adnexa, the peritoneal cavity, or the horn of an abnormal or rudimentary uterus. It is opposed to natural uterine gestation, and, since it includes pregnancy in an abnormal uterus, it is a more comprehensive term than extrauterine pregnancy.

In this article the morality involved in the surgical treatment of ectopic gestation is considered; and to have the data requisite for judgment it is necessary to describe in outline the anatomy of the uterine adnexa and the growth of the foetus; to explain the varieties, effects, diagnosis, and treatment of ectopic gestation; to present the cases of this condition, or rather this disease, as they occur in medical practice; to set forth some of the moral principles or laws that govern medical practice, especially where there is question of life and death; and finally to apply these principles to the cases offered for investigation.

The uterus is in the pelvic cavity, between the bladder and the rectum and above the vagina, into which it opens. It is a hollow, pear-shaped, muscular organ, somewhat flattened, and about three inches long, two inches broad, and one inch thick. The base or fundus is upward, and the neck is downward. Passing out horizontally from the corners or horns of the uterus, which are at its base, are the two Fallopian Tubes, one on either side. These are about five inches in length and somewhat convoluted. They are true tubes, opening into the uterus, and they are about one-sixteenth of an inch in diameter along the greater part of their extent The ends farthest {2} from the uterus are fringed and funnel-shaped; and this funnel-end, called the Infundibulum or the Fimbriated Extremity, opens into the abdominal or peritoneal cavity. Near the Fimbriated Extremity of each tube is an Ovary,—an oval body about one and a half inches long by three-quarters of an inch in width.

The Uterus and its Adnexa

F U, Fundus or Base of the Uterus. F T, P T, Fallopian Tubes. On

the left of the reader the Fimbriated Extremity of the tube is

lifted up to show it. O, O, Ovaries. B L, B L, Broad Ligament.

R, Rectum. B, Bladder.

For convenience in description, each tube is divided into four parts: (1) the Uterine Portion, which is that part included in the wall of the uterus itself; it extends from the outer end of the horn into the upper angle of the uterine cavity, and its lumen is so small it will admit only a very fine probe; (2) the Isthmus, or the narrow part of the tube which lies nearest the uterus; it gradually opens into the wider part called (3) the Ampulla; (4) the Infundibulum, or the funnel-shaped end of the Ampulla. This part is fimbriated, as has been said, and one of the fimbriae—the Fimbria Ovarica—which is longer than the others, forms a shallow gutter which extends to the ovary.

The uterus, tubes, and ovaries lie in a septum which reaches across the pelvis from hip to hip. This septum is called the Broad Ligament. If a man's soft felt hat, of the kind called a "Fedora" hat, is held crown downward with one hand at the front and the other at the back of the rim, it will represent the pelvic cavity, and the fold along the crown of the hat coming up into this cavity is very like the Broad Ligament. As the crown is held downward, the uterus would be in the middle, its fundus upward, and, of course, altogether outside the hat, but in the crown fold. The tubes and ovaries would also be outside the hat and in the crown fold, and the fimbriated extremities would open by holes into the hat's interior.

The ovum breaks through the surface of the ovary, passes, probably on a capillary layer of fluid, into the fimbriated extremity of the tube, and then is moved along slowly through the tube into the uterus. Ovulation and menstruation occur about the same time, but often one antedates the other a few days. In exceptional cases they may occur independently.

If the ovum produced is not fecundated, it gradually shrivels up, and passes off through the uterus and the vagina. Fecundation of the ovum rarely occurs in the uterus, but ordinarily in the Fallopian tube, according to the general opinion of physiologists. After fecundation the ovum is pushed on into the uterus in from five to seven days, where it fastens to the wall and develops. Hyrtl (Kollmann's Lehrbuch der Entwickelungsgeschichte des Menschen, Jena, 1898) speaks of a case in which the ovum appeared to reach the uterus in three days. If the fecundated ovum is blocked or held in the Fallopian tube, the embryo grows where the ovum stops, and we have a case of Ectopic Gestation.

The average time of normal human gestation is ten lunar months or forty weeks. At the moment the pronucleus of the spermatozoon fuses with the pronucleus of the ovum in the Fallopian tube and makes the segmentation nucleus, in my opinion, the soul of the child enters, and personality exists as absolutely as it does in a child after birth. It is as much a murder, as such, to unjustly destroy this microscopic fecundated ovum as it is to kill the child after birth. This is the opinion of every embryologist I have consulted on the {4} subject, with the exception of one who said he did not know when the soul enters.

Technically the product of conception is called the Ovum for the first two weeks of pregnancy; during the third and fourth weeks it is called the Embryo, and after the fifth week the Foetus. During the fourth week the embryo begins to draw nourishment from the maternal blood through its umbilical vessels, but before that time it obtains nourishment by osmosis.

The foetus at the end of the eighth week is about one inch in length; at the end of the fourth lunar month it is from four to six inches long, and its sex may be distinguished. At the end of twenty-four weeks, if the normal foetus is born it will attempt to breathe and to move its limbs, but it dies in a short time. At the end of twenty-eight weeks of gestation if it is born it moves its limbs freely and cries weakly. It is nearly fifteen inches in length and weighs about three pounds. Such an infant might be deemed viable, but its chances for life are extremely precarious, even in most expert hands and with the help of an incubator. At the end of thirty-two weeks of gestation a foetus if born may be raised with skilful care, but the chances are not promising. It is viable. At the end of forty weeks the child is at term.

In 1876 Parry collected 500 cases of extrauterine pregnancy from medical literature, but when Tait in 1883 first operated on a case of ruptured tubal pregnancy attention was called to the subject. It was better understood as coeliotomies (opening the abdomen) became common, and in 1892 Schrenck collected 610 cases that had been reported during the preceding five years. Küstner alone has operated on 105 cases in five years.

There has been much discussion among physicians as to the causes that arrest the fertilized ovum in the tube, but whatever these causes may be they do not affect the moral questions which come up in this article. There may be mechanical obstruction from peritoneal adhesions, or abnormal conditions resulting from inflammatory diseases of the tubes, ovaries, and the pelvic peritoneum, but no general cause that will explain all cases can be ascribed.

Tait denied the possibility of Ovarian Pregnancy, or a pregnancy where the ovum fastened to the ovary itself and developed there, but five fully established cases of this kind have been reported. Dr. J. Whitridge Williams, professor of Obstetrics at the Johns Hopkins University, in his textbook on Obstetrics (New York, 1903), collects twenty-five cases of ovarian pregnancy, where five cases are certain diagnoses, thirteen highly probable, and seven fairly probable. In these twenty-five cases ten foetuses reached full term, but four of the five certain cases ruptured at early periods.

It was formerly thought that primary abdominal pregnancy is quite common; that is, that the ovum is implanted on some organ within the abdomen itself, apart from the uterine adnexa. This is now looked upon as very doubtful, and such cases are probably secondary; that is, secondary to a pre-existing tubal pregnancy which has ruptured without great maternal hemorrhage and let the foetus grow within the peritoneal cavity.

The common form of extrauterine pregnancy is the Tubal Pregnancy. The ovum may be stopped in any one of the three parts of the tube, and we find Interstitial, Isthmic, or Ampullar Pregnancy. From these primary types, by rupture, secondary forms sometimes arise,—Tubo-abdominal, Tubo-ovarian, and Broad-ligament Pregnancy.

The interstitial form, that is, where the ovum is arrested in that part of the tube which passes through the wall of the uterus itself, is the rarest of the tubal pregnancies. Rosenthal (Ein Fall intranturaler Schwangerschaft. Centralbl. f. Gyn. 1297-1305) found it in only three per centum of 1324 cases of tubal pregnancy. Some deem the Isthmic variety the commonest. Dr. Howard Kelly (Operative Gynaecology) says he never met a case of Interstitial or Ovarian pregnancy in his practice. The interstitial form is especially liable to rupture with suddenly fatal hemorrhage.

About one-fourth of the cases of tubal pregnancy end within the first twelve weeks by rupture of the Fallopian tube. If the embryo is implanted in the interstitial end of the tube, the rupture (into the uterus, or into the abdominal cavity, or into the broad ligament) takes place later,—about the fourth month, or even considerably after that time. The reason for {6} the delay here is that the uterus grows with the foetus. If the foetus breaks into the uterus (a very rare occurrence), it is either expelled through the vagina almost immediately or it goes on like a normal pregnancy.

Tait was of the opinion that every case of tubal pregnancy results in a rupture of the tube not later than the twelfth week, but this opinion is no longer held. Very rarely a tubal pregnancy goes on without rupture to full term, as in the cases reported by Williams, Saxtorph, Spiegelberg, Chiari, and a few others.

Three-fourths, about seventy-eight per centum, of the cases of tubal pregnancy result in what is technically called "tubal abortion" instead of rupture. In tubal abortion the connection between the embryo and the tube-wall is broken by effusion of blood. If the separation is complete the effused blood pushes the embryo out through the fimbriated end of the tube into the abdominal cavity, and then the hemorrhage of the mother commonly ceases. Such an extrusion of the foetus is called a complete tubal abortion. If the connection between the foetus and the tube-wall is only partly severed, the ovum remains in the tube, and the maternal hemorrhage goes on. This is called incomplete tubal abortion.

In incomplete tubal abortion the maternal blood may slowly trickle from the fimbriated extremity of the tube into the abdominal cavity, become encapsulated, and thus form an haematocele. If the fimbriated extremity of the tube is blocked, the blood accumulates in the tube and makes an haematosalpynx.

In complete tubal abortion the foetus dies; in incomplete tubal abortion the viability might depend on the injury done the placenta, but in almost every case of even incomplete tubal abortion the foetus dies as a result of its separation from the tubal wall, or from compression after the bleeding.

In cases of rupture of the tube in extrauterine pregnancy, if the foetus with its attachments is expelled from the tube into the peritoneal cavity or into the broad ligament, the embryo dies.

If the foetus or embryo itself alone is expelled into the abdominal cavity and the placenta remains attached to the wall of the tube and communicates with the foetus by the umbilical cord which runs through the tear in the tube, the foetus may {7} possibly live, provided the mother does not die from hemorrhage. If the foetus goes on growing in this case, we have an abdominal pregnancy. One such case is reported by Both where a fully developed foetus was found in the abdominal cavity even lacking all its membranes, which had been left in the tube, but a foetus will not live apart from its membranes within the maternal body.

When an embryo or foetus ruptures the tube and goes into the broad ligament, it may live or die according to the injury done its attachments to the tubal wall, but it ordinarily dies. Sometimes such a broad-ligament pregnancy ruptures again into the abdominal cavity. Because the bleeding is more likely to be confined within the folds of the broad ligament, the immediate danger of maternal death from hemorrhage is less in this than in other forms of rupture.

Concerning tubo-abdominal pregnancy the only remark to be made is that, owing to adhesions, it is often surgically difficult to remove such a growth.

If the foetus is expelled after rupture into the peritoneal cavity it dies, and if the hemorrhage does not kill the mother the dead foetus if small is absorbed; if large it becomes mummified, or it hardens into a lithopoedion, or it turns into a yellowish greasy mass called adipocere, or it putrefies. A lithopoedion may be carried for years. There are more than thirty cases reported which were carried from twenty to thirty years in the abdomen, and one case where a lithopoedion was carried for fifty years.

If the foetus putrefies it causes fatal septicaemia in the mother, or a perforating abscess, unless it is successfully removed.

There are various abnormalities of the uterus, and in these pregnancy resembles in effect extrauterine pregnancy. An abnormal uterus may be unicornis, didelphys, pseudodidelphys, bicornis duplex, bicornis septus, bicornis subseptus, bicornis unicollis, or bicornis unicollis with a rudimentary horn. The impregnated ovum may fasten in the rudimentary horn and be blocked there; then the usual result is rupture within the first four months, with fatal hemorrhage unless the bleeding is immediately checked by coeliotomy and ligation.

As to diagnosis in Ectopic Gestation, Williams (op. cit.), one of the authorities at present on the subject, says: "A positive diagnosis is occasionally made before rupture, but in the vast majority of cases the condition escapes recognition until symptoms of collapse point to the probability of rupture or abortion. In advanced cases careful examination will usually disclose the real condition of affairs, and when full term has been passed the history is so characteristic that mistakes should hardly occur."

In the American Ecclesiastical Review for January, 1898 (vol. ix., n. i), Father René I. Holaind, S. J., published the answers of many physicians to six questions concerning extrauterine pregnancy. Among these physicians were Thomas Addis Emmet, Barton Cooke Hirst, Howard A. Kelly, W. T. Lusk, T. Galliard Thomas, Mordecai Price and his brother Joseph Price, William Goodell, and Lawson Tait,—all eminent authorities on this subject. The second question submitted was: "During pregnancy, at what time and by what means can a differential diagnosis be made between intra and extra-uterine pregnancy, and between abnormal gestation and pelvic or other tumour?"

In answer to this question Dr. Emmet said: "There can be no absolute certainty as to the existence of pregnancy in any case until the pulsation of the foetal heart can be detected. [After the eighteenth or twentieth week of gestation.] … A diagnosis is difficult in all cases of abnormal pregnancy, but an expert can, within a reasonable degree of certainty, arrive at a knowledge of the existing conditions between the second and third month."

Dr. Hirst said: "In almost all cases of advanced gestation the differential diagnosis can be made. In early cases it is not always possible unless conditions be favourable."

Dr. Howard A. Kelly said: "The differential diagnosis between intra and extrauterine pregnancy can usually be made from the sixth week up to the end of pregnancy. It is more easily made from the tenth to the twelfth week on." Writing in the American Text Book of Obstetrics (Philadelphia, 1896), he says: "In the atypical cases, on the contrary, a positive diagnosis is often difficult or even impossible. … {9} The diagnosis of ectopic gestation after the death of the foetus is largely dependent upon the clinical history; if this be deficient, the diagnosis is frequently impossible."

Dr. Lusk said: " … The frequent discovery of the dead ovum in a tube when there has been no suspicion of pregnancy shows the difficulty of a diagnosis." In his text-book (The Science and Art of Midwifery, New York, 1890) is this remark: "Sometimes the diagnosis can only be decided by the introduction of the sound or a finger into the uterus, the physician assuming the risk of premature labour, should he find his supposition of extrauterine pregnancy an error." This means that sometimes the diagnosis is impossible without running the risk of causing abortion of a normal uterine pregnancy.

Dr. Thomas said, "After the second month the diagnosis is perfectly possible." This was also the opinion of Dr. Mordecai Price; and Dr. Joseph Price holds that the diagnosis can be made "after the third month, by exclusion." Dr. John F. Roderer, quoting Lawson Tait, says that "the diagnosis between intra and extrauterine pregnancy can not be made with certainty before rupture, nor can it be determined exactly whether an enlargement of the tube is either an ectopic pregnancy or some form of tumour."

Dr. Goodell's opinion was, "A differential diagnosis can rarely be made positively at any stage of extrauterine pregnancy."

The diagnosis, then, is difficult; and for the ordinary practitioner, the average physician, who does perhaps ninety-five per centum of the medical work of the world, the diagnosis is often impossible. There is no greater expert than Dr. Thomas Addis Emmet, and he says the diagnosis is difficult. Others hold that the diagnosis can be clearly made, and they speak truly as regards themselves, but ordinary skill finds the diagnosis almost impossible in many cases. Mordecai Price (The Pennsylvania Medical Journal, vol. viii. p. 223) in one year saw four cases which he and other physicians diagnosed as ectopic pregnancies with rupture of the tube. When the abdomen had been opened, uterine pregnancy was discovered with a ruptured tube in each case, and all the women died.

The first positive diagnosis of unruptured tubal pregnancy was made by Veit in 1883, and the first one made in America was by Janvrin in 1886, eight years before Father Holaind's article was written. Before 1883, only eleven years in advance of the same article, when Lawson Tait performed the first coeliotomy for the purpose of checking hemorrhage from a ruptured tubal gestation, extrauterine pregnancy was as mysterious as the old "inflammation of the bowels," which turned out afterward to be appendicitis. Hence common skill in the difficult diagnosis of ectopic gestation can not be looked for.

The doctrine given in all the leading medical works at present concerning the treatment of extrauterine pregnancy is this:

1. As soon as an extrauterine pregnancy is discovered remove the

foetus through an opening made in the mother's abdominal wall. Do

not use electricity or the injection of poisons into the foetal sac,

or the incandescent knife. Emmet and a few others approved of the

use of electricity at times, but this is against the teaching of the

great majority of writers at present. The reason for removing the

foetus at once is that it is apt at any moment to cause rupture and

fatal hemorrhage before surgical aid can be effective.

2. In a case of rupture with free hemorrhage and collapse the only

operation advised is an immediate coeliotomy to stop the bleeding by

ligatures. The rupture should not be approached through the vaginal

wall according to the common doctrine, but through the abdominal

wall.

3. If there is a rupture in which the bleeding is confined and there

is no collapse, do not operate at once unless the haematocele

increases steadily or shows signs of suppuration. Sometimes

evacuation of the haematocele through the vaginal wall is possible.

4. In the later months of an extrauterine pregnancy, whether the

case is intraligamentous or abdominal, perform coeliotomy as soon as

the diagnosis has been made, and remove the foetus, because there is

always danger of sudden and fatal hemorrhage before the surgeon can

reach the source of the bleeding. What is to be done in a case where

the surgeon is certain before operating that the foetus is {11}

dead, has interest only for the physician, and it involves no moral

question.

Operating for extrauterine pregnancy maybe a simple coeliotomy, if any coeliotomy is really simple, but it commonly is the most dangerous operation for the mother that the gynaecologist is called upon to perform.

The discussion of the moral questions that arise in cases of ectopic gestation which began in volume ix. of the American Ecclesiastical Review was very valuable, but as the moralists had not full data to work on their decision as a whole is not satisfactory. The original cases presented are in part obsolete in the medical practice of to-day, and important physical conditions were not disclosed in some of the other parts of the cases. Father Holaind tentatively agreed with Father Lehmkuhl in one decision, Fathers Eschbach and Sabetti directly attacked Father Lehmkuhl's reasons, and Father Aertnys indirectly opposed Father Sabetti's chief argument. These men are all eminent authorities, but as each, except Father Holaind, was dissatisfied with the arguments advanced by the others, and as their data were incomplete, we can not rest the case on their decision.

In Father Holaind's fifth question, if I understand it correctly, he seemed to think it possible to baptize a foetus through the opening in the mother's abdominal wall while it lies in the abdominal cavity before surgical removal. He mentions antiseptic precautions in the baptism, which would have no meaning if the foetus were out of the abdomen.

Baptism would not be possible in that case: the priest could not get at the foetus, he ordinarily could not even see it, and certainly no surgeon would permit the attempt. There would be no time for the attempt in a rupture case, even if the foetus could be seen; and there would be no advantage gained by baptizing the foetus in the abdominal cavity where the conditions gave time to do so. If it is alive it will live long enough for baptism after removal from the abdomen, provided, of course, it is baptized immediately in the operating room. That it does not breathe is no proof of immediate death. It is not unusual for a full-term child not to breathe for even an hour or longer after birth.

If Father Holaind had not in view baptism within the abdominal cavity, the question has this meaning: What is the most effective method after the foetus has been removed from the abdomen to open its enveloping membranes so as to give it a chance for a life lasting long enough to allow baptism?

The best method is to slit the membranes with a scalpel or scissors as quickly as possible. The envelopes, cord, and placenta are essential parts of the foetus itself, and they grow from itself, not from the mother. They take the place of the lungs and the alimentary tract, which do not come into action until after normal birth. It would be worth discussing whether a baptism on the intact foetal envelopes is valid, were it not that we may not apply probabilism in such a case. The remaining matter brought out in Father Holaind's questions will be considered in the course of this article.

Before presenting the cases of ectopic gestation that occur in medical practice, the fundamental ethical principles that are to be applied in judging the morality of the surgeon's interference should be given.

The morality of any action is determined, (1) by the object of the action; (2) by the circumstances that accompany the action; (3) by the end the agent had in view.

1. The term object has various meanings, but here it means the deed

performed in the action, the thing which the will chooses. That deed

by its very nature may be good, or it may be bad, or it may be

indifferent morally. In themselves to help the afflicted is a good

action, to blaspheme is a bad action, to walk is an indifferent

action. Some bad actions are absolutely bad, they never can become

good or indifferent (blasphemy or adultery, for example); others, as

stealing, are evil because of a lack of right in the agent: these

may become good by acquiring the missing right. Others are evil

because of the danger necessarily connected with their

performance,—the danger of sin connected with them, or the

unnecessary peril to life. An action to have the moral quality must

be voluntary, deliberate; and mere repugnance in doing an act does

not in itself make the act involuntary.

2. Circumstances sometimes, though not always, can add a {13} new

element of good or evil to an action. The circumstances of an action

are the agent, the object, the place in which the action is done,

the means used, the end in view, the method observed in using the

means, the time in which the deed is done. If a judge in his

official position tells a sheriff to hang a criminal, and a private

citizen gives the same command, the actions are very different

morally because of the circumstances of the agent giving the

command. The object—it changes the morality of the deed if a man

steals a cent or a thousand dollars. The place—what might be merely

a filthy action in a house might be a sacrilege in a church. The

means—to support a family by labour or by thievery. The end in

view—to give alms in obedience to divine command or to give them

to buy votes. The method observed in using means—kindly, say, or

cruelly. The time—to do manual labour on Sunday or on Monday. Some

circumstances aggravate the evil in a deed, some extenuate it.

Others may so colour a deed that they specify the deed, make the

action some special virtue or vice. The circumstance that a murderer

is the son of the man he kills specifies the deed as parricide.

The end also determines the morality of an action (see St Thomas, Sum. Theol. I. 2., q. xviii., a. 4 and 7). Since the end is the first thing in the intention of the agent, he passes from the object wished for in the end to choosing the means for obtaining it. Without the end the means can not exist as such. There are occasions when an end is only a circumstance: for example, if it is a concomitant end. When an end is a, finis extrinsecus operantis, when it is in keeping with right reason or discordant thereto, it may become a determinant of morality.

In every voluntary, or human, act there is an interior and an exterior act of the will, and each of these acts has its own object. The end is the proper object of the interior act of the will; the exterior object acted upon is the object of the exterior act of the will; and as this exterior act specifies the morality, so does the interior object—which is the end—specify it, and even more importantly than the exterior object does.

The will uses the body as an instrument on the external {14} object, and the action of the body is connected with morality only through the will. We judge the morality of a blow, not by the physical stroke, but from the intention of the striker. The exterior object of the will is, in a way, the matter of the morality, and the interior object of the will, or the end, is the form. Aristotle (Ethics, lib. v., cap. 2) says: "He that steals that he may commit adultery, is, absolutely speaking, more an adulterer than a thief." The thievery is a means to the principal end, and it is this principal end that chiefly specifies or informs the action.

The means used to obtain an end are very important in a consideration of the morality of an act. There are four classes of means,—the good, the bad, the indifferent, and the excusable.

Good means may be absolutely good, but commonly they are liable to become vitiated by circumstances,—almsgiving is an example. Some means are bad always and inexcusable,—lying, for example. The excusable means are those which are bad, but justifiable through circumstances. To save a man's life by cutting off his leg is an excusable means.

The existence of excusable means whereby some good actions are effected does not establish the assertion that the end justifies the means. The end sometimes may incriminate or sanctify indifferent means, but it does not in itself justify all means. The means, like other circumstances, are accidents of an action, but they are in an action just as much as colour is in a man. Colour is not of a man's essence, but you can not have a man without colour.

The effect of an action, the result or product of an effective cause or agency, may in itself be an end or an object or a circumstance, and it has influence in the determination of morality. Sometimes an act has two effects, one good and the other bad; and that such an action be lawful it is necessary (1) that the action itself be good or indifferent; (2) that the good effect be intended and the evil effect be not intended (chosen) but only reluctantly permitted; (3) that the evil effect be not a means to secure the good effect; (4) that there be present a motive sufficiently grave to excuse or counterbalance the bad effect. {15} St. Thomas (Sum. Theol. 2. 2. q. 64, a. 7) Speaking of killing a man in self-defence, says: "Nihil prohibet unius actus esse duos effectus, quorum alter solum sit in intentione, alius vero sit praeter intentionem. Morales autem actus recipiunt speciem secundum id quod intenditur, non autem ab eo quod est praeter intentionem, cum sit per accidens."

That an act, therefore, be morally good, or justifiable, (a) the whole train of the tendency of the will must be good; that is, (1) the object, (2) the end, (3) and the circumstances must be good; or (b) the intention should be good, and the remaining elements in the train of will-tendency are to be indifferent. That an act be morally bad it is enough that the object, the end, or the circumstances be inexcusably bad.

There may be honest doubt as to the existence of evil in the circumstances or the end, and here enters the matter of probability; but apart from this, some general rules of morality that govern all cases may be formulated:

1. An intention or end which is gravely evil always makes the entire

action evil and unjustifiable.

2. An intention or end which is slightly evil, if it is the entire

end of an action, makes the whole action evil but not gravely

evil—makes it, say, a venial sin and not a mortal sin.

3. If an intention or end which is venially evil accompanies

secondarily a good intention or end, and is rather a motive than the

real effective agent in attracting the will, this venial evil does

not vitiate the whole goodness or righteousness of the main action.

Compare the remarks made above in discussing an action that has a

double effect, partly good and partly bad.

4. Circumstances that are gravely evil practically vitiate the

entire action, but circumstances which are venially evil do not

always vitiate the entire action.

Much might be said here concerning conscience as a judge of the morality in an act, but this discussion is not necessary for our present purpose. Like other men, physicians often confuse conscience with inclination, or at best with unfounded opinion. When conscience is to be a rule of action it must {16} have at the least moral certitude; or, what is different but practically the same thing, the opinion of conscience must be at the least genuinely probable. The term "probable" is used here in a technical sense, and it will be so used throughout the remainder of this article.

The doctrine of Probabilism is connected with the promulgation of law. A law, according to St. Thomas (op. cit. I. 2., q. 90, a. 4) is: "Ordinatio rationis ad bonum commune ab eo qui curam habet communitatis promulgata." Sometimes it is not evident whether or not a law binds in a particular case, and in such a condition, that is, in which there is question solely of the existence, interpretation, or application of a law, we may follow a probable opinion which assures us the act is licit, although the opinion which says the act is illicit may be just as probable or even more probable. This is the fundamental proposition of Probabilism, which is the doctrine especially of St. Alphonsus Liguori, but it was held centuries before his time. As the church has never condemned this doctrine, but rather tacitly approved of it, Catholics may safely follow it, and those that are not Catholics will find it very reasonable.

A law which is doubtful after honest and capable investigation has not been sufficiently promulgated, and therefore it can not impose a certain obligation because it lacks an essential element of a law. When we have used such moral diligence of inquiry as the gravity of a matter calls for, but still the applicability of the law is doubtful in the action in view, the law does not bind; and what a law does not forbid it leaves open.

Probabilism is not permissible when there is question of the worth of an action as compared with another, or of issues like the physical consequences of an act. If a physician knows a remedy for a disease that is certainly efficacious and another that is probably efficacious, he may not choose the probable cure, at the least in a grave illness. Probabilism has to do with the existence, interpretation, or applicability of a law, as I said, not with the differentiation of actions.

The term probable means provable, not guessed at, or jumped at without reason. There must be sound reason {17} adduced to constitute probability. The doubt must be founded on a positive opinion against the existence, interpretation, or application of the law. It must be more than mere negative doubt, more than ignorance, more than vague suspicion, especially must it be more than a sentimental impression. There is a mental condition, which easily passes over into disease, wherein a man habitually can not make up his mind. This flabbiness has nothing to do with Probabilism. The opinion against a law to constitute Probabilism must be solid. It must rest upon an intrinsic reason from the nature of the case, or an extrinsic reason from authority,—always supposing the authority cited is really an authority. Many men sitting upon the supreme bench in the Court of Science and called authorities by friends and newspapers, are only fools in good company.

The probability must also be comparative. What seems to be a very good reason when standing alone may be very weak when compared with a reason on the other side. When we have weighed the arguments on both sides, and we still have good reason left for standing by our opinion, our opinion is probable. The probability is, moreover, to be practical. It must have considered all the circumstances of the case.

The principles presented here have been arranged, as we said, with a view toward application in judging the morality of actions that may occur in cases of ectopic gestation, and we shall apply the doctrine of probabilism in the question, does the commandment "Thou shalt not kill" bind in certain cases of ectopic pregnancy? It is also necessary to add the principles underlying our duty to preserve human life.

1. It is never lawful directly or indirectly to kill an innocent

man. "Insontem et justum non occides" (Exod. xxiii. 7). An

innocent man is one that has not by any human act done harm to

another man or to society commensurate with the loss of his life.

Directly means to kill either as an end, say, for revenge, or as a

means toward an end.

A man is a person, an intelligent being, therefore free, and

autocentric; he belongs to no one except to God, who made {18} him;

he is by that very fact distinguished from brutes or things which

may belong to another. Now, if you kill a man, you destroy his human

nature by separating his soul and body, you subordinate and

sacrifice him wholly to yourself, make him entirely yours, which is

unjust. Even the state has no right to kill an innocent man. A

foetus in the womb, only a few hours old, is as much a human being

as a man fifty years of age, and this natural law holds for the

foetus as for the man.

2. It is, however, lawful indirectly to kill a man provided this

man is an unjust aggressor. Cardinal de Lugo (De Just. et Jure,

10, 149) and others hold you may even directly kill an unjust

aggressor. Indirectly here means incidentally. An effect happens

indirectly when it is neither intended as an end nor a means, but

happens as a circumstance unavoidably attached to the end or means

intended.

We may not, however, kill an innocent man even indirectly, because no end is proportionate to the sacrifice of an innocent man's life, but the case of an unjust aggressor differs from that of an innocent man. By an unjust aggressor is meant some one that outside the due course of law threatens your life or the equivalent of your life, or the life of some one you should or may protect. You may stop such an aggressor, and if you happen to kill him while trying to stop him, there is no moral wrong involved. This aggressor may be formally or only materially unjust: he may be a normal man with a formal intention to kill you or your ward, or a murderous lunatic that tries to kill you or your ward, but he must be unjust either formally or materially.

It is natural for every being to maintain itself in existence, to resist destruction. This is a primary law of nature. As Father Holaind well said (Amer. Eccl. Rev., January, 1894): "The ethical foundation of self-defence is this: Justice requires a sort of moral equation, and if a right prevails it must be superior to the right which it holds in abeyance. At the outset both the aggressor and his intended victim have equal rights to life, but the fact of the former using his own life for the destruction of a fellow man places him in a condition of juridic inferiority with regard to the latter. If we may be {19} allowed so to express it, the moral power of the aggressor is equal to his inborn right to life, less the unrighteous use which he makes of it, whilst the moral power of the intended victim remains in its integrity and has consequently a higher juridic value. When the person assailed cannot defend himself, his right can and sometimes must be exercised by those who are bound in justice or charity to protect the innocent. At the dawn of human life the physician or surgeon stands as the natural protector both of the mother and of the child; he is beholden to both.

"The right of self-defence is not annulled by the fact that the aggressor is irresponsible. The absence of knowledge saves him from moral guilt, but it does not alter the character of the act, considered objectively and in itself; it is yet an unjust aggression, and in the conflict, the life assailed has yet a superior juridic value. The right of killing in self-defence is not based on the ill will of the aggressor but on the illegitimate character of the aggression. Now, an aggressor is at least materially unjust whenever he perpetrates an act destructive of the right of another."

Mark the words "right of another," at the end of the quotation. In a case of pregnancy at term in a woman with a contracted pelvis the foetus would be a contributing instrument of death to the mother, supposing there were no artificial means of delivering her, but such a child is not an aggressor even materially unjust. The child itself is normal, it has a natural right to be where it is, it did not put itself where it is; the mother's contracting uterus crushing the child against her narrow pelvic arch is the direct agency that kills the woman, and the child is only an inert instrument used by the contracting uterus. In such a case the mother might be considered an aggressor materially unjust against the life of the child rather than that the child is the aggressor.

Lehmkuhl (Compendium Theologiae Moralis, 1891, p. 238) says: "Medicus graviter peccat … si media abortus procurat: nisi quando ad salvandam matrem ex probabili opinione liceat." On page 188 he says: "Ex consulto abortum inducere, etiam liceri videtur in praesenti vitae {20} maternae discrimine, quod per solam foetus immaturi ejectionem avert! possit … Idque videtur applicari posse ad matrem quae tarn arcta est ut tempus praematuri partus exspectare non possit."

By foetus immaturus here he means an unviable foetus, as is evident from the context. If this probabilism of Father Lehmkuhl's stands (but it does not), a decision in most of the cases that occur in ectopic gestation would be easily made, but even he himself would not take responsibility in the matter, and that before the decision of the Holy Office which defined abortion. Since this decision, made July 24, 1895, Lehmkuhl has entirely withdrawn his opinion.

On May 4, 1898, the Holy Office published the following decree, which was approved by the Pope:

BEATISSIME PATER,—Episcopus Sinaloen. ad pedes S. V. provolutus,

humiliter petit resolutionem insequentium dubiorum:

I. Eritne licita partus acceleratio quoties ex mulieris arctitudine

impossibilis evaderet foetus egressio suo naturali tempore?

II. Et si mulieris arctitudo talis sit, ut neque partus prematurus

possibilis censeatur, licebitne abortum provocare aut caesariam suo

tempore perficere operationem?

III. Estne licita laparotomia quando agitur de pregnatione

extra-uterina, seu de ectopicis conceptibus?

Feria iv, die 4 Mali, 1898.

In Congregatione habita, etc … EE. ac RR. Patres rescribendum

censuerunt:

Ad I. Partus accelerationem per se illicitam non esse, duromodo

perficiatur justis de causis et eo tempore ac modis, quibus ex

ordinariis contingentibus matris et foetus vitae consulatur.

Ad II. Quoad primam partem, negative, juxta decretum, Feria iv., 24

Julii, 1895, de abortus illiceitate.—Ad secundam vero quod spectat:

nihil obstare quominus mulier de qua agitur caesareae operationi suo

tempore subjiciatur.

Ad III. Necessitate cogente, licitam esse laparotomiam ad extra-hendos

e sinu matris ectopicos conceptos, dummodo et foetus et matris vitae,

quantum fieri potest, serio et opportune provideatur.

In sequenti Feria vi., die 6 ejusdem mensis et anni … SSmus

responsiones EE. ac RR. Patrum approbavit.

The third question proposed by the bishop is:

"Is laparotomy licit when performed for extrauterine pregnancy or ectopic gestation?"

The approved answer of the Holy Office to this question is:

"In a case of necessity, laparotomy for the purpose of removing an ectopic foetus (conceptus) from the abdomen of the mother is licit, provided the lives of both the foetus and the mother, as far as is possible, are carefully and fitly guarded."

The expression, "dummodo et foetus et matris vitae, quantum fieri potest, serio et opportune provideatur," is capable of various translations and interpretations.

The words might have this meaning: "In a case of necessity you may do laparotomy and remove an ectopic gestation, provided you do not kill either the mother or the foetus." If that is the interpretation, the decree means that we may never remove an unviable ectopic foetus when we know that the foetus is alive, because removal will kill it.

The sentence can also be translated in this sense: "In a case of necessity, you may do laparotomy and remove an ectopic foetus from the mother, provided you take full care to save mother and child if that is possible."

If that is the signification, it is evidently very different from the first interpretation. It would mean: do the laparotomy, remove the foetus, and if you possibly can save both mother and foetus do so, but if you can not, take the best means you can to save one or the other.

If the decree refers only to cases in which the foetus is viable, it would appear to be unnecessary—we need no decree of the Holy Office to let us do a laparotomy to remove a viable foetus. If it does not refer to a viable foetus, it refers to an unviable foetus, but to remove an unviable foetus is to either kill it or to hasten its death.

Génicot (Institutiones Theologiae Moralis, Louvain, 1902, vol. i. p. 358) has this interpretation of the decree:

"In conceptione extra-uterina licebit sane recurrere ad laparotomiam similemve operationem, quando aliqua etiam tenuissima spes affulget salvandi infantem, simul ac mater fere certo liberabitur. … Ubi vero nulla spes hujusmodi {22} affulget, neque in hoc casu licebit abortum directe inducere, etiamsi foetus certo moriturus sit antequam in lucem edatur, et baptismum recipere nequeat. Etenim S. Inqu., dum provocat ad responsum 19 August, 1888, satis indicat abortus inductionem a se haberi tamquam operationem directe occisivam foetus ideoque semper illicitam."

There is no question of an abortion in a laparotomy for extrauterine gestation; abortion is altogether a different operation in method and nature. Secondly, the other decree of the Holy Office to which he refers speaks of a direct killing of the foetus, but there is no direct killing of the foetus in the operation for ectopic gestation, nor is the indirect hastening of the foetus's death a means to an end. The decree on abortion is so clear it leaves no room for doubt.

Cardinal Monaco, in the Epistola ad Archiepiscopum Camarcensem, August 19, 1889, says the Holy Office decreed that "In scholis catholicis tuto doceri non posse licitam esse operationem chirurgicam quam craniotomiam appellant, sicut declaratum fuit die 28 Maii, 1884, et quamcumque chirurgicam operationem directe occisivam foetus vel matris gestantis."

Note the words "directe occisivam." Craniotomy is a direct killing, and a direct killing used as a means to an end; moreover it is an altogether unnecessary killing. Artificial abortion in the case of an unviable foetus is also a direct killing as a means to save the mother's life, but the removal of an unviable ectopic foetus is neither a direct killing, nor is it a means toward any end.

Since the meaning of the decree concerning laparotomy in extrauterine pregnancy is by no means clear, we may discuss the question until the law has been fully promulgated, ready to conform to the real meaning of the decree whenever it is explained. In that spirit we may now consider the cases that occur in ectopic gestation.

Case I. A surgeon is called in to treat a woman and he finds her in a state of collapse. He makes a diagnosis of tubal pregnancy, which has gone on to rupture with hemorrhage, and the bleeding will evidently be fatal to the mother unless it is checked. Practically the only chance of saving the {23} mother's life is coeliotomy and the ligation of her open arteries. Dr. Howard Kelly (Operative Gynaecology, vol. ii. p. 437) says: "When the hemorrhage is sudden and excessive the patient falls in collapse; but, in spite of these alarming symptoms, she may survive a succession of similar attacks and the foetus and sac may continue to develop." This exception complicates the case slightly. If the surgeon were absolutely certain that the only possible chance to save the woman's life is coeliotomy and haemostasis, the case would be somewhat different from one in which there is some chance of escape by spontaneous haemostasis. That chance, however, is so slight, and so far beyond any means we have for forecasting, that it is mere luck, and it is to be neglected. The surgeon may safely consider the patient in the gravest actual danger.

(a) Before he opens the abdomen he can not tell whether the foetus is alive or not; but the stronger probability is that it is not, and the certainty is that it has no chance at all to remain alive more than a few minutes or hours, unless the surgeon is willing to trust to sheer luck in the expectation that he may happen to have one of Dr. Kelly's exceptions before him.

(b) The operation to save the mother is this: as quickly as possible he makes a vertical slit from four to six inches long through the woman's belly-wall. Then commonly the free blood begins to run out, or it may even spurt out some feet into the air. The surgeon can see nothing for the blood and the presence of the entrails. If the blood is not freshly welling up he bails it out with his hands or a ladle; if it is spurting he at once thrusts in his hand, feels for the foetal sac, lifts it up, and puts on clamps near the uterus on one side and near the pelvic brim on the other. This stops the hemorrhage, and he can then work more leisurely, but unfortunately this also stops the flow of blood to the foetus. He can not first examine the foetus and then stop the hemorrhage. He can not back out even if he finds a live foetus without letting the mother die on the table.

(c) If the placenta is already loose from the Fallopian tube the child is dead or it will die in a few seconds or minutes. If it was not loose the lifting out may tear it loose, and this {24} tearing loose will hasten the death of the foetus a few minutes (but give a chance for baptising it).

(d) If the lifting out does not tear loose the supposedly fixed placenta, the foetus either will die anyhow if the mother dies, or it will die if the mother lives, because to save her the surgeon must put ligatures just where the flow of blood will be shut off from the foetus. Commonly there is no time to even look for the foetus until after the maternal arteries have been closed.

(e) The same conditions could exist in the rupture of a pregnancy in a rudimentary uterine horn as in a rupture in tubal gestation.

What is the surgeon to do in a case like this? Fathers Holaind (Amer. Eccl. Rev., January, 1894, in a note on p. 39), Lehmkuhl and Sabetti say: do coeliotomy, ligate the mother's arteries, remove and baptise the foetus.

The analysis of the case is this: (i) The action is the stopping of a fatal hemorrhage in a woman, and possibly, though not certainly, an indirect incidental hastening of a foetus's inevitable death.

(2) The object of the action is the haemostasis, which is good, and the possible indirect hastening of the foetus's death, which is evil, but, as we shall see, excusable evil.

(3) The end of the action is to save the mother's life—a good end.

(4) The circumstances are: (a) that possibly, through mere luck, the woman's condition is not necessarily hopeless: a few women have escaped in this seemingly imminent peril—but that chance of escape is not soundly probable; the stronger probability by far is on the side of a fatal issue; therefore the chance for escape may be neglected, and the woman's case may be regarded as hopeless if operation is foregone.

(b) The quickest possible work on the surgeon's part is necessary, and there is no time or chance to examine the foetus's condition before tying the maternal arteries. Before he opens the mother's abdomen he can tell nothing whatever of the foetus's condition, but the probability is all in favour of the fact that the foetus is already dead or moribund.

(c) The means are coeliotomy, and the ligation of the {25} uterine and ovarian arteries to stop the mother's bleeding. This ligation, in the contingency that the foetus is still attached to the Fallopian tube, will also shut off the blood from the foetus, yet the uncertain shutting off of the foetal blood-supply is not intended by the surgeon as a means toward his end in any degree direct or indirect, but it is an evil circumstance associated with the action which may hasten the foetal death—even here the hastening is uncertain.

(5) The action has two effects,—one, the saving of the mother, is directly intended and evidently good; the other, the possible indirect hastening of the foetus's death, may or may not be evil. The moral centre of the whole case is this possible hastening of the foetus's death. If that possible hastening is licit the whole action is licit; if it is not permissible it will vitiate the entire action.

Suppose that there is no doubt that the ligation of the maternal arteries in this case really hastens the foetus's death some minutes: it would still be an indirect volition. Father Lehmkuhl also calls it indirect and licit. Father Sabetti denied that it is indirect, but he held that it is licit for another reason. Sabetti said (Aner. Eccl. Rev., August, 1894): "It is evidently false to say that a means which is directly adopted for obtaining an end is only indirectly contained in the intention of the agent who so adopts it." That is true, but the minor proposition in a syllogism drawn from that statement is to be emphatically denied. The cutting off of the foetal blood is a fact associated with the means, not a means direct or indirect toward the end, which is to save the mother—the means to save the mother is the stopping of her bleeding.

This is not hair-splitting in the opprobrious sense of that term. The bases of all sins are absolutely abstract principles, and because abstract principles can not be pinched or weighed, they have often little meaning for the opposition in an argument. There is only the width of a hair between Heaven and Hell at many places along the frontier, and there is only the difference between a direct or an indirect volition separating murder and a good deed. The best ethics frequently consists in delicate hair-splitting; and despite the protests of sentimentalists, one of the most valuable benefits of Moral Science is {26} to show us how to handle moral poisons for good purposes, as a physician uses the material poisons, opium and aconite.

If the foetus in this case of rupture in ectopic gestation were a materially unjust aggressor on the mother's life, the indirect hastening of its death would be justifiable according to all moralists, and the direct hastening would be licit according to Cardinal de Lugo, who was, in the opinion of St. Alphonsus, "post D. Thomam inter alios theologos facile princeps" (Th. Mor., lib. 4. n. 552).

Sabetti held that the foetus is a materially unjust aggressor. His reason for this opinion is that the extrauterine foetus is not in a position in which it has a right to be. If it were in the uterus, its natural position, it would have a right to its position. Ectopic gestation is a disease, not a physiological condition.

Father Aertnys (Amer. Eccl, Rev., July, 1893) denies that the foetus is an aggressor materially unjust. He says: "Nequaquam enim mortem intentat matri, sed actione, quam non ipse sed corpus matris producit, conatur ad lucem pervenire, et iste conatus non nisi ex naturali concursu rerum fit matri causa mortis. Infans ergo non est aggressor et multo minus est aggressor injustus. Hinc nego paritatem cum homine mente capto, qui delirans alteri mortem intentat; hic enim agit motus a sua voluntate, licet absque culpa, et ponit actiones in se injustas, utpote ad necandum directe intentas."

In the same periodical (January, 1894) while repeating this statement he says: "Sive in utero existat sive alibi reconditus sit [sc. foetus], nequaquam mortem intentat matri, siquidem non ipse actione propria conatur egredi, sed corpus matris infantem expellit et haec expulsio a matre emanans fit matri causa mortis."

What Father Aertnys says in these two passages is true of an intrauterine foetus, but it is altogether erroneous when applied to an extrauterine foetus, of which alone there is question here. In extrauterine pregnancy the uterus or any other part of the maternal body does not "try to expel" the foetus; the uterus has nothing at all to do with the case—the very name of the condition is extra-uterine pregnancy. If an ectopic gestation {27} goes on to term (a very rare happening), there will be false labour and uterine contractions, and these cease after a time without effect one way or the other; but in all cases of rupture and the like the uterus is outside the question and the mother is passive. There is no attempt by the mother in extrauterine pregnancy at expulsion either before rupture or at any other time unless the dead foetus putrefies, and the maternal tissues "try to expel" it as a foreign body by breaking down into an abscess. The foetus simply grows, and its bulk bursts the tube. If it were in the uterus, the uterus would enlarge synchronously with the foetus and there would be no rupture, but the tube will not give beyond a certain point, therefore it bursts.

In normal uterine pregnancy at term the uterus and other maternal muscles are the active factors in expelling the foetus—the foetus is passive. In ectopic gestation the foetus is active, the mother is passive, and there is no attempt at expulsion from either side. In this case the foetus in the tube through the action of its own vital principle draws nourishment from the mother and grows gradually larger till it bursts the tube (it may even move its arms and legs if advanced), and this rupture tears open arteries wherethrough the mother bleeds, commonly to death. This is evidently material aggression.

Father Aertnys says the foetus differs from the murderous lunatic in this, that the madman is moved by his will, although blamelessly, in doing unjust actions directly intended as homicidal. The fact that the lunatic uses his will has no weight whatever in permitting me to defend my life against him, it is an accidental thing outside the question; but Father Aertnys in mentioning the madman's will means solely, if I understand him, that the madman is really an active aggressor. The foetus, however, is also an active aggressor without using its will. I might fall from a height toward a man and certainly endanger his life while I was not using my will at all, not conscious of the man's presence under me, or even while I was using all the power of my will against the result. In any of these cases I should be a materially unjust aggressor; and if in trying to prevent my body from killing him the man killed me, he would be blameless.

Now, in the first place, the tubal foetus is an aggressor; and since, secondly, its position is unnatural, monstrous, a disease, a thing not intended by nature, it has no right to its position, and it is therefore a materially unjust aggressor. Since it is an aggressor on the very life of the mother in a place where it should not be, the surgeon therefore may at the least stop the fatal bleeding it causes. If the foetus dies as an unwished for, though permitted, consequence of this haemostasis, the surgeon may lament this result, but he is blameless.

The foetus was blocked in its unnatural position through a defect in the mother, nevertheless it remains a materially unjust aggressor. If I by an accidental blow had made a man insane, and later this lunatic tried to kill me, I, or my legitimate protector, might lawfully kill the lunatic in defence of my life. This is an exact parallel to the case of the mother and the extrauterine foetus.

The extrauterine foetus is not like a foetus in a craniotomy case. Where there might be question of craniotomy the foetus is not an unjust aggressor even materially, as has been said: first, because it is not an aggressor in any manner, it is altogether passive; secondly, it has a perfectly natural right to be where it is. In ectopic gestation with fatal rupture the foetus is, first, an active aggressor; secondly, it has no right to be where it is. In craniotomy the foetus is killed as a direct means toward the end that its head may be reduced and extracted and the mother saved; in extrauterine gestation with fatal rupture the foetus is incidentally killed as a consequence of the haemostasis, and not as a means in any sense of the term. In craniotomy the child is wantonly killed since there are other means of saving the mother; in extrauterine pregnancy with fatal rupture the hastening of the death of the child is unfortunately associated with the only possible means we have to save the mother.

In Case I., therefore, we have an action that has an object partly good and partly, very probably, not evil; the end intended is good; the circumstances are justifiable or indifferent; consequently in Case I. the surgeon may do coeliotomy, tie the uterine and ovarian arteries, and if the foetus {29} happens to be alive he may reluctantly and indirectly permit the hastening of its death after attempting to baptise it.

Case II. The conditions presented in Case I. are the ordinary and most common that the surgeon meets with in treating ectopic gestation, but other conditions may be found.

Suppose the surgeon, before operation, diagnoses a case of ectopic gestation, but that he can not tell whether or not the foetus is alive. The probability leans toward the side that the foetus is alive, because there is no indubitable history, as physicians say, of maternal symptoms that indicate rupture.

Medical authorities tell him to do coeliotomy at once, ligate the uterine and ovarian arteries, and remove the foetus. Would he certainly or probably be justified in following out this medical doctrine?

The mother is in actual, very probable danger of death, but not in actual, certain danger of death. She may possibly escape if operation is deferred; she has a negligible chance of escape if no operation is performed after the death of the foetus; coeliotomy and ligation of the uterine and ovarian arteries give her by far the surest chance of escape, so sure an opportunity for escape when performed early that it can scarcely be called a mere chance.

If operation is deferred the chances for rupture are about 22 per centum, say, one and a half in five chances, and all ruptures are not necessarily fatal. The chances of the mother's death, however, are much higher than that, because death can come in ectopic pregnancy from causes other than rupture. From 63.1 to 68.8 per centum (say, 66.3 per centum) of ectopic gestations treated by the expectant method result in death to the mother—just two-thirds of the women die. A. Martin in a series of 265 cases of ectopic gestation where the expectant treatment was employed found a maternal mortality of 63.1 per centum; Parry in 500 similar cases found a mortality of 67.2 per centum; and Schauta in 241 cases a mortality of 68.8 per centum.

In the 87 years between 1809 and 1896, 77 cases of coeliotomy for the delivery of viable ectopic foetuses were reported {30} in all medical literature with a maternal mortality of about 58.3 per centum. Between 1809 and 1888 there were 37 coeliotomies with a maternal mortality of 86.5 per centum. Between 1889 and 1896 there were 40 such operations, with a maternal mortality reduced to 32.5 per centum by modern surgical methods.

The results as regards the children were almost the same in the two series, and perhaps a little better in the latter series. In the first series the 37 children were alive at delivery: the length of time in which three of these children lived is not given; three more were alive but they did not breathe; the others lived from a few seconds to days, weeks, months or years. One was well at six months, another at one year, another at seven and a half years, another in its fourteenth year, another in its fifteenth year. In the second series the results as regards the children were, as has been said, almost the same. The 40 cases that were reported from 1889 to 1896 are the standard for this phase of ectopic gestation, because they come under the diagnosis and treatment of the present day. They represent closely all such cases that occurred in the entire world between 1889 and 1896, because physicians report these operations to medical societies, and active physicians are almost without exception members of such societies—outside the civilised world these operations do not take place. In the seven years there were annually less than six cases of coeliotomy for ectopic gestation at term in the world, therefore operations at term may be neglected in discussing Case II., and the argument may be confined to the ordinary cases of expectant treatment. Schrenck in 1892 collected 610 cases of ectopic gestation which had been reported between 1887 and 1892; during the same time there were 23 cases (less than 4 per centum) of operations for the delivery of viable foetuses.

If the physician that has made the diagnosis in this Case II. leaves the patient, she may have a fatal hemorrhage at any moment. Dr. Howard Kelly reports (Operative Gynaecology, vol. ii. p. 438) a fatal hemorrhage in two days from rupture where the foetus was only as large as a Lima bean. The hemorrhage may be so suddenly fatal that the woman drops {31} to the floor unconscious just as if she had been shot. Dr. Harris (International Cyclop. of Surgery, vol. vi. p. 784) tells of a case where three of the best obstetricians in Philadelphia met in consultation daily for 16 days expectantly watching development, but the woman died from hemorrhage in thirty minutes before any of these physicians could be called to her aid. Death may be brought about by anaemia after repeated hemorrhages. Some hemorrhages can be mistaken for colic by the physician, and this error will defer until too late the treatment for hemorrhage.

If the woman is living in a hospital where there is a resident surgeon with instruments ready, she has a better chance than if she is in her own house. Even if she has a surgeon within call the outcome of the case for her will depend largely on his skill, his presence of mind, the preparedness of his instruments, the general condition of the patient, and many other circumstances.

The instruments, ligatures, gauzes, solutions, dressing, etc., for coeliotomy are multitudinous, and all must be sterile, or the woman will be killed by septicaemia even if the hemorrhage is stopped. It is almost impossible to keep a set of instruments and the other things used in a coeliotomy always sterile and ready for instant use.

The skin surface of the patient's abdomen must be sterilised, or pus infection will get into the peritoneum through the wound. In all ordinary coeliotomies this surface is carefully sterilised by a long process the night before the operation, a protective dressing is put on, and the sterilisation is repeated the next day just before the operation. This is so important that its voluntary omission is malpractice. In the hurried operation for tubal rupture there would be no time for sterilisation of the abdominal skin surface, and probably no time to sterilise the instruments and other things used, especially the surgeon's hands.

The surgeon to do any coeliotomy needs assistant physicians—one to anaesthetise the patient, and at the least one other to work with him in the operation. He should have three or four physicians and one or two nurses. He can not do a coeliotomy alone. Hence the patient in a ruptured {32} extrauterine pregnancy must have at the very least two physicians within call.

The woman, then, in Case II. before operation has one chance in three of life if no operation is done until the child is viable, and if she remains alive till the child is viable (when she must be operated upon) her chances for life will be no better, judging from modern statistics.

At any moment, therefore, she is in actual peril of death by two chances in three, and probably more if all special circumstances are considered. The foetus is a materially unjust aggressor in this case before rupture or other similar mishap, as it was in Case I., but not to the same extent. In Case II. it is a materially unjust aggressor as two is to three; in Case I. it is a materially unjust aggressor as three is to three.

If a lunatic is just about to fire three cartridges at me, I may know the chances are only two in three, or even only one in three, that he will hit me fatally, nevertheless I may licitly kill him to stop the firing and save my life. The mother in Case II. is in exactly similar danger of life.

The objection that the danger to my life from the action of the lunatic exists hic et nunc and that the danger to the mother's life does not threaten hic et nunc, is not of any weight. She is in actual danger hic et nunc, even while the surgeon is in the room examining her. Moreover, the matter of time here is accidental. If you give a man a poison that may kill him in ten hours, or one that may kill him in ten days, the action is essentially the same.

I am of the opinion that if this second case were proposed to moral theologians many of them would decide that the surgeon should explain the case fully to the patient or her family, and if immediate operation were insisted upon he should withdraw from the case. Nevertheless, as far as I can see, he has sound probabilism on the side that operation is justifiable.

But, it may be objected, in Case I. the surgeon ligated the uterine and ovarian arteries to stop an actual hemorrhage, and he permitted the death of the foetus; in Case II. there is no hemorrhage yet, there may possibly be none at all. I answer {33} that in Case II. if he operates he ties the two arteries to forestall an imminent hemorrhage which might begin within the next hour if it were not securely shut off, and to forestall sepsis by leisurely and proper precautions, and exactly as in the first case he permits the death of the foetus, he indirectly kills an unjust aggressor. If the lunatic is aiming at me I do not have to wait until he begins firing to licitly shoot at him. The sooner I shoot, servato moderamine inculpatae tutelae, the more prudent my action.