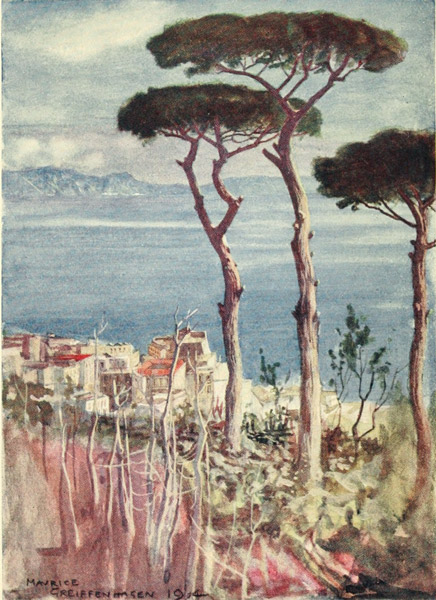

BAY OF NAPLES FROM THE VOMERO.

Title: Naples, Past and Present

Author: Arthur H. Norway

Illustrator: Maurice Grieffenhagen

Release date: March 11, 2012 [eBook #39100]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Melissa McDaniel and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

NAPLES

BY

ARTHUR H. NORWAY

AUTHOR OF "HIGHWAYS AND BYWAYS IN DEVON AND CORNWALL"

"PARSON PETER," ETC.

WITH TWENTY-FIVE ILLUSTRATIONS IN COLOUR

BY MAURICE GRIEFFENHAGEN

SECOND EDITION

METHUEN & CO.

36 ESSEX STREET W.C.

LONDON

First Published May 1901

Second Edition June 1905

TO MY FRIENDS

BARON AND BARONESS MARIO NOLLI

OF NAPLES, AND OF ARI, IN THE ABRUZZI

I DEDICATE THIS BOOK

IN TOKEN THAT THOSE WHO ARE DIVIDED

BY BOTH SEA AND LAND

MAY YET BE UNITED IN THEIR LOVE

FOR ITALY

I have designed this book not as a guide, but as supplementary to a guide. The best of guide-books—even that of Murray or of Gsell-Fels—leaves a whole world of thought and knowledge untouched, being indeed of necessity so full of detail that broad, general views can scarcely be obtained from it.

In this work detail has been sacrificed without hesitation. I have omitted reference to a few well-known places, usually because I could add nothing to the information given in the handbooks, but in one or two cases because the considerations which they raised lay too far from the thread of my discourse.

I have thrown together in the form of an appendix such hints and suggestions as seemed likely to assist anyone who desires wider information than I have given.

A. H. N.

Ealing, 1901

| PAGE | |

| CHAPTER I | |

| The Approach to Naples by the Sea | 1 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| The Ancient Marvels of the Phlegræan Fields | 21 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| The Beauties and Traditions of the Posilipo, with some Observations upon Virgil, the Enchanter | 49 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| The Riviera di Chiaia, and some Strange Things which occurred there | 68 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| The Enchanted Castle of the Egg, and the Succession of the Kings who held it | 85 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| The Barbarities of Ferdinand of Aragon, with certain other subjects which present themselves in strolling round the City | 101 x |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| Chiefly about Churches—with some Saints, but more Sinners | 121 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| A Great Church and two very Noble Tragedies | 143 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| Vesuvius and the Cities which he has Destroyed—Herculaneum, Pompeii, and Stabiæ | 178 |

| CHAPTER X | |

| Castellammare: its Woods, its Folklore, and the Tale of the Madonna of Pozzano | 226 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| Surriento Gentile: its Beauties and Beliefs | 251 |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| Capri | 273 |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

| La Riviera d'Amalfi and its Long-dead Greatness | 299 |

| CHAPTER XIV | |

| The Abbey of Trinità della Cava, Salerno, and the Ruined Majesty of Pæstum | 327 |

| Appendix | 345 |

| Index | 357 |

| Bay of Naples from the Vomero | Frontispiece |

| PAGE | |

| Pozzuoli | 24 |

| Pozzuoli | 32 |

| Columns in the Serapeon, Pozzuoli | 35 |

| Castle of Baiæ | 44 |

| Fishing Stage, Santa Lucia | 54 |

| Strada di Chiaia | 68 |

| Porta Mercantile | 72 |

| Boats at the Mergellina | 76 |

| Gradoni di Chiaia | 78 |

| Naples | 90 |

| Castle of St. Elmo | 97 |

| Old Town | 113 |

| Bay of Naples from San Martino | 116 |

| The Church of the Carmine | 156 |

| In the Strada di Tribunali | 168 |

| Card-players | 188 |

| A Slum | 195 |

| In the Strada di Tribunali | 209 |

| Porta Capuana | 220xii |

| Roof top, Modern Naples | 259 |

| Courtyard in the Old Town | 268 |

| Unloading Boats, Bay of Naples | 284 |

| Naples: on the modern side, looking towards Capri from the Corso Vittorio Emmanuele | 288 |

| Gossip | 334 |

NAPLES

PAST AND PRESENT

On a fine spring morning when the sun, which set last night in gold and purple behind the jagged mountain chain of Corsica, had but just climbed high enough to send out shafts and flashes of soft light across the opalescent sea, I came up on the deck of the great steamer which carried me from Genoa to watch for the first opening of the Bay of Naples. It was so early that the decks were very quiet. There was no sound but the perpetual soft rustle of the wave shed off from the bow of the steamer, which slipped on silently without sense of motion. The Ponza Islands were in sight, desolate and precipitous, showing on their dark cliffs no house nor any sign of life, save here and there a seabird winging its solitary way round the crags and caverns of the coast. Far ahead, in the direction of our course, lay one or two dim, cloudy masses, too faint and shadowy to be detached as yet from the grey skyline which bounded the crystalline sparkles of the sea. And so, having strained my eyes in vain effort to discover the high peak of Ischia, I fell to wondering 2 why any man who is at liberty to choose his route should dream of approaching this Campanian coast otherwise than by the sea.

For Naples is the city of the siren—"Parthenope," sacred to one of those sea nymphs whose marvellous sweet singing floated out across the waves and lured the ancient seamen rowing by in their strange old galleys, shaped after a fashion now long since forgotten, and carrying merchandise from cities which thirty centuries ago and more were "broken by the sea in the depths of the waters" so that "all the company in the midst of them did fail." How many generations had the line of sailors stretched among whom Parthenope wrought havoc before Ulysses sailed by her rock, and saw the heaps of whitening bones, and last of all men heard the wondrous melodies which must have lured him too, but for the tight thongs which bound him to the mast! So Parthenope and her two sisters cast themselves into the sea and perished, as the old prediction said they must when first a mariner went by their rock unscathed. But her drowned body floated over the blue sea till it reached the shore at Naples, and somewhere near the harbour the wondering people built her a shrine which was doubtless rarely lovely, and is mentioned by Strabo, the old Greek geographer, as being shown still in his day, not long after the birth of Christ.

There is now but little navigation on these seas compared with the relative importance of the shipping that came hither in old days. Naples is in our day outstripped by Genoa, and hard run, even for the goods of southern Italy, by Brindisi and Taranto. The trade of Rome goes largely to Leghorn. If Ostia were ever purged of fever and rebuilt, or if the schemes for deepening the Tiber so as to allow 3 large vessels to discharge at Rome were carried out, we might see the port of Naples decline as that of Pozzuoli did for the selfsame reason, the broad facts which govern the course of trade being the same to-day as they were three thousand years ago. Even now it is rather the convenience of passengers and mails than the necessities of merchants which take the great ocean steamers into Naples. It is not easy for men who realise these facts to remember that the waters of the Campanian coast have more than once been ploughed by the chief shipping of the world. Far back in the dawn of history, where nothing certain can be distinguished of the deeds of men or nations, the presence of traders, Phœnician and Greek, can be inferred upon these shores. The antiquity of shipping is immense and measureless. Year by year the spade, trenching on the sites of ancient civilisation, drives back by centuries the date at which man's intellect began to gather science; and no one yet can put his finger on any point of time and say, "within this space man did not understand the use of sail or oar." The earliest seamen of whom we know anything at all were doubtless the successors of many a generation like themselves. It cannot be much less than a thousand years before Christ was born when Greek ships were crossing the sea which washed their western coasts bound for Sicily and the Campanian shores. Yet how many ages must have passed between the days when the Greeks first went afloat and those in which they dared push off toward the night side of the world, where the mariners of the dead went to and fro upon the sea, where the expanse of ocean lay unbroken by the shelter of any friendly island, and both winds and currents beat against them in their course, or even by coasting up and down the Adriatic set that 4 dreaded sea between them and their homes! Superstition, hand in hand with peril, barred their way, yet they broke through! But after what centuries of fearful longing,—curiosity, and love of salt adventure struggling in their hearts with fear of the unknown, till courage gained the mastery and the galleys braved the surf and smoke of the planctæ, the rocks that struck together, "where not even do birds pass by, no, not the timorous doves which carry ambrosia for Zeus, but even of them the sheer rock ever steals one away, and the father sends in another to make up the number."

Then the rowers saw the rock of Scylla and her ravening heads thrust forth to prey on them, while beneath the fig tree on the opposite crag Charybdis sucked down the black seawater awfully, and cast it forth again in showers of foam and spray. These fabled dangers passed, there remained the Island of the Sirens, which legend placed near Capri, where Ulysses passed it when he sailed south again; and so the wonderful tradition of the Sirens dominates the ancient traffic of mankind upon these waters, and the harbour where the shrine of Parthenope was reflected in the blue sea claims a lofty place in the realms whether of imagination or of that scholarship which cares rather for the deeds of men than for the verbal emendations of a text.

The shrine has gone. The memory remains only as a fable, whose dim meaning rests on the vast duration of the ages through which men have gone to and fro upon these waters. But here, still unchanged, is the pathway to the shrine—the Tyrrhene Sea, bearing still the selfsame aspect as in the days when the galleys of Æneas beat up the coast from Troy, and Palinurus watched the wind rise out of the blackening west. Since those old 5 times the surface of the land has changed as often almost as the summer clouds have swept across it. Volcanic outbursts and the caprice of many masters have wrought together in destruction; so that he who now desires to see what Virgil saw must cheat his eyes at every moment and keep his imagination ever on the stretch. Even the city of mediæval days, the capital of Anjou and Aragon, is so far lost and hidden that a man must seek diligently before he cuts the network of old streets, unsavoury and crowded, in which he can discover the lanes and courtyards where Boccaccio sought Fiammetta, or the walls on which Giotto painted.

But here, upon the silent sea, at every moment fresh objects are coming into sight which have lain unchanged under dawn and dusk in every generation. Already the volcanic cone of Monte Epomeo towers out of Ischia, a menace of destruction which not twenty years ago fulfilled itself and shook the town of Casamicciola in a few seconds into a mere rubble heap. It is a sad thing still to stroll round that once smiling town. Ruins project on every side. The cathedral lies shattered and untouched; there is not enough money in the island to rebuild it. The visitors, to whom most of the old prosperity was due, have not yet recovered from the attack of nerves brought on by the earthquake. But there remains wonderful beauty at Casamicciola and elsewhere on Ischia; the "Piccola Sentinella" is an excellent hotel; some day, surely, the lost ground will be recovered, and prosperity return.

The new town lies gleaming on the flat at the foot of the great mountain. Far away towards my right Capri, loveliest of islands, floats upon the sea touched with blue haze; and there, stretching landwards, is the mountain promontory of Sorrento, Monte St. 6 Angelo towering over Monte Faito, and the whole mass dropping by swift, steep slopes to the Punta di Campanella, the headland of the bell, whence in the old days of corsairs the warning toll swung out across the sea as often as the galleys of Dragut or of Barbarossa hove in sight, echoing from Torre del Greco, Torre Annunziata, and many another watchtower of that fair and wealthy coast, while the artillery of the old castle of Ischia, answering with three shots, gave warning of the coming peril. Even now I can see that ancient castle, standing nobly on a rock that seems an island, though, in fact, it is united with the land by a low causeway; and it comes into my mind how Vittoria Colonna took refuge from her sorrows there, spending her widowhood behind the battlements on which she had played with her husband as a child. Doubtless the two children listened awestruck on many a day to the cannon-shots which warned the fishers. Perhaps Vittoria may even have been pacing there when, as Brantôme writes, a party of French knights of Malta came sailing by with much treasure on their ship, and hearing the three shots took them arrogantly for a salute in honour of their flag, and so, thinking of nothing but their dignity, made a courteous salute in answer, and kept on their way. Whereupon the spider Dragut, who at that moment was sacking Castellammare, just where the peninsula joins the mainland, driving off as captive all those men or women who had not fled up into the wooded hills in time, swooped out with half a dozen galleys, and added the poor knights and their treasure to his piles of plunder.

Many tales are told about that castle, so near and safe a refuge from the turbulence of Naples. But already it is dropping astern, and the lower land of Procida usurps its place, an island which in the 7 days of Juvenal was a byword of desolation, though populous and fertile in our own. The widening strait of water between the low shore and the craggy one played its part in a tale as passionate, though not so famous, as that of Hero and Leander. For Boccaccio tells us that Gianni di Procida, nephew and namesake of a man whose loyalty popular tradition will extol until the end of time, loved one Restituta Bolgaro, daughter of a gentleman of Ischia; and often when his love for her burnt so hotly that he could not sleep, used to rise and go down to the water, and if he found no boat would plunge into the black sea, swim the channel, and lie beneath the walls of Restituta's house all night, swimming back happy in the morning if he had but seen the roof which sheltered her. But one day when Restituta was alone upon the shore she was carried off by pirates out of Sicily, who, wondering at her beauty, took her to Palermo and showed her to King Federigo, who straightway loved her, and gave her rooms in his palace, and waited till a day might come when she would love him. But Gianni armed a ship and followed swiftly on the traces of the captors, and found at last that Restituta was in Palermo. Then, led by love, he scaled the palace wall by night and crossed the garden in the dark and gained the poor girl's chamber, and might have borne her off in safety had not the King, suspecting that all was not well, come with torches in the darkness and discovered Gianni and cast him into prison, where he lay till he was sentenced to be taken out and burned at the stake in the Piazza of Palermo together with the girl who had dared to flout the affection of a king. And burned they would have been had not the great Admiral Ruggiero di Loria chanced to pass that way as 8 they stood together at the stake and known Gianni as the nephew of that great plotter who conceived the massacre of the Sicilian Vespers, whereby the crown of Sicily was set upon the head of Aragon. Straightway he hastened to the King, who forthwith released Gianni and gave him Restituta, and sent both home laden with rich gifts to Ischia, where they lived happy for many a year, till they were overcome at last by no worse fate than that which is reserved for all humanity whether glad or sorry.

No man can prove this story true; but it is at least so happily conceived as to be worth credence, like others told us by the same immortal writer, who, though a Florentine, knew Naples well, and doubtless wove into the Decameron many an anecdote picked up in the taverns which survives now in no other form. For there was no Brantôme to collect for us the gossip of the days when Anjou drove out Hohenstaufen from this kingdom; and if we would know what happened on the coast in those tragic and far-distant times we must take the tales set down by Boccaccio for what they may be worth.

I am not sure that Gianni, the hot-passioned lad who used to swim this strait by night, does not emerge out of the darkness of the centuries more clearly than his greater uncle—that mighty plotter who, using craft and guile where he had no strength, is fabled to have built up a conspiracy and engineered a massacre which has no parallel save in the St. Bartholomew. Yet it is not to be judged without excuse like that foul act of cold-blooded treachery, but was in some measure an expiation of intolerable wrongs, as may be discovered even now by anyone who will study the plentiful traditions of that March night when eight thousand French 9 of every age and either sex perished in two hours, slain at the signal of the vesper bell ringing in Palermo. That bloodshed split the kingdom of the two Sicilies in twain. It did more: it scored men's minds with a memory so deep that even now there is no child in Sicily who could not tell how the massacre began. To men then living it appeared a cataclysm so tremendous that they must needs date time from it, as from the birth of Christ or the foundation of the world. In documents written full four centuries later the passage of the years is reckoned thus; and in Palermo to this day the nuns of the Pietà sing a litany on the Monday after Easter in memory of the souls of the French who perished on that night of woe. So memorable was the deed ascribed by tradition to the plotter, Giovanni di Procida, lord of that little island which is already slipping past me out of sight.

The steamer slips on noiselessly as ever. Procida falls away into the background, with its old brown town clinging to the seaward face of a precipitous cliff; and I can look down the Bay of Baiæ, where in old Roman days every woman who went in a Penelope came out a Helen, and almost catch a glance at Cumæ, where Dædalus put off his weary wings after that great flight from Crete which no man since has contrived to imitate. There lies the Gate of Hell down which Æneas plunged in company with the Sibyl; and round it all the land of the Phlegræan fields, heaving and steaming with volcanic fires. There too is the headland of Posilipo, where Virgil dwelt and where he wrought those enchantments concerning which I shall have much to say hereafter; for though Virgil is a poet to the world at large, he is a magician in the memory of the Neapolitans. And who shall say their tradition is not true? 10

Next, sweeping round towards my right hand in a perfect curve, comes the shore of the Riviera di Chiaia, once a pleasant sandy beach, broken midway by the jutting rock and island on which stood the church and monastery of San Lionardo. It is long since church and island disappeared, and few of those gay Neapolitans who throng the Via Caracciolo, that fine parade which now usurps the whole seafront from horn to horn of the bay, could even point out where it stood. In these days the whole shore is embowered in trees and gardens skirting the fine roadway; and there stands the wonderful aquarium, which has no equal in the world, and where the wise will spend many afternoons and yet leave its marvels unexhausted.

My eyes have travelled on to the other horn of this fine bay, and are arrested by what is surely the most picturesque object in all Naples. For at this point the spine or backbone of land which breaks the present city into two, leaving on the right the ancient town and on the left the modern, built along the pretty shore of which I have just spoken,—at this point the ridge sweeps down precipitously from the Castle of St. Elmo on the height, breaks off abruptly in the sheer cliff of the Pizzo-Falcone, "The Falcon's Beak," and then sends jutting out into the sea a small craggy island which bears an old hoary castle low down by the water's edge. On this grey morning the sea breaks heavily about the black reef on which the castle stands, and the walls, darkened almost to the colour of the rock itself, assume a curious aspect of vast age, such as disposes one to seek within their girth for some at least among the secrets of old Naples. Nor will the search be vain; for this hoary fortress is Castel dell'Uovo, "The Castle of the Egg," so called, if we may lend an ear to Neapolitan tradition, because Virgil the Enchanter built it on an egg, 11 on which it stands unto this hour, and shall stand until the egg is broken. Others again say that the islet is egg-shaped, which it is not, unless my eyes deceive me; and of other explanations I know none at all, so that any man who can content himself with neither of these may resign himself to contemplate an unsolved puzzle for as long as he may stay in Naples.

Apart, however, from the wizard Virgil and the idle tale of the enchanted egg, there is something so arresting in the sight of this ancient castle thrust out into the sea that I cannot choose but see in it the heart of the interest of Naples. It is by far the oldest castle which Naples owns, and as its day came earliest so it passed the first. Castel Nuovo robbed it of its consequence, both as a royal dwelling and a place of arms; and now the noisy, feverish tide of life that beats so restlessly from east to west through the great city finds scarce an echo on the silent battlements of the Egg Castle, where Norman monarchs met their barons and royal prisoners languished in the dungeons. Inside the walls there is nothing to attract a visitor but memories. Yet those gather thick and fast as soon as one has crossed the drawbridge, and there is scarce one other spot in Naples where a man who cares for the past of the old tragic city can lose himself more easily in dreams.

But again the steamer turns her course a little, and suddenly the Castel dell'Uovo slips out of sight, the old brown city passes across my line of vision like a picture on the screen of a camera oscura when the lens is moved, and I am gazing out beyond the houses across the wide rich plain out of which the vast bulk of Vesuvius rears itself dark and tremendous, towering near the sea. There are other mountains far 12 away, encircling the plain like the walls of some great amphitheatre, but they are beyond the range of volcanic catastrophe, and stood unmoved while the peaks of Vesuvius were piled up and blown away into a thousand shapes, sometimes green and fertile, the haunt of wild boars and grazing cattle, at others rent by fire and subterranean convulsion so as to give reality to the most awful visions which the imagination of mankind has conceived concerning the destruction which befell the sinful cities of the plain.

The plain is the Campagna Felice, a happy country, notwithstanding the perpetual menace of the smoking mountain, which time after time has convulsed the fields, altered the outline of the coast, and overwhelmed cities, villages, and churches. Throughout the last eighteen hundred years a destruction like to that which befell the cities of Herculaneum and Pompeii has been overtaking hamlets and buildings of less note. The country is a palimpsest. What is now written on its surface is not a tithe of what was once inscribed there. In 1861 an earthquake at Torre del Greco made a fissure in the main street. Those who dared descend it found themselves in a church, long since buried and forgotten. So it is in every direction throughout the Campagna Felice. The works of man are overwhelmed in countless numbers by the ejections from Vesuvius, and the green fields of beans and lupins which stretch so pleasantly across the wide spaces between the Sarno and the Sebeto cover the ruins of innumerable homes.

It seems strange that a land exposed to such great and constant perils should be densely populated. The coast is lined with towns, all shining in the sun, and the first graceful slopes of Vesuvius itself are studded with white buildings, planted here and there in apparent oblivion of the floods of red-hot 13 lava which have so often forced their way down the inclines towards the sea. There must be many dwellers in those towns who saw the lava break out from new vents in 1861 among the cultivated fields. Yet the fields are cultivated still, and in time of eruption the peasants will continue working in the vineyards within a few hundred yards of the crawling stream, knowing well how often its progress is arrested by the cooling of the fiery mass. There is, moreover, the power of the saints to be considered. How often has not San Gennaro arrested the outbreaks, and brought peace to the frightened city! On the Ponte della Maddalena he stands unto this day, his outstretched arm, pointing to the mountain with a gesture drawn from the mimic language of the people, bids it "Halt!" And then the fertility of the volcanic soil! Vesuvius, if a rough friend, is a kindly one. He may drive the people to their prayers from time to time, which is no great harm! but, if a balance be struck, his benefits are as many as his injuries, and the peasants, looking up, as they hoe their fields, at the coiling wreaths of copper-coloured smoke which issue from the cone, are content to take their chance that death may some day meet them too in a cloud of scorching ashes as it did those who dwelt in Pompeii so very long ago.

The great steamer is already near her moorings. The western or newer half of Naples is hidden by the hill, and I have before my eyes only the densely peopled ancient city, a rabbit warren of tortuous and narrow streets, unsavoury and not too safe, yet full of interest if not of beauty, and possessing a picturesqueness which is all their own. One salient feature only arrests the eye wandering over this intricate mass of balconies and house-fronts—the handsome steeple of the Carmine, a church sorely 14 injured and defaced, but still abounding in romance. For there lies the boy-king Conradin, slaughtered by Charles of Anjou in the market-place just outside; and there, too, the fisherman Masaniello met his end, after a trick of fortune had made him ruler of Naples for eight days. There is no church in all the city so full of tragedies as this, which was founded by hermits fleeing from Mount Carmel twelve hundred years ago, and which ever since has been close to the heart of the passionate and fierce-tempered people dwelling round its walls.

I do not doubt there was a time when travellers, arriving at Naples by sea, found themselves greeted by persons of aspect more pleasing than those who accost the astonished pilgrim of to-day. There was surely an age when the lazzaroni were really picturesque, when they lay on the warm sand in the sunshine, while the bay resounded with the chant of fishermen, the light-hearted people beguiling their unbounded leisure with the tuneful strains of "Drunghe, drunghete," of "Tiritomba," or even the too familiar "Santa Lucia." It cannot be that travellers lied when they wrote of the amazing picturesqueness of the Neapolitans, that they painted brown purple, and put on their spectacles of rose as they approached the land! I wish I had those spectacles; for indeed the aspect of the quays and wharves of Naples is not attractive, while the people who throng the boats now pushing off towards the steamer are just such a crowd of expectant barterers as one may see wherever a great steamer touches. In the stern of the first stands a naked boy, brown and lithe. His accomplishment is to dive for pence, which he does with singular dexterity, cramming all the coins as he catches them into his mouth, which yet is not so full as to impede his bellowing like a bull in the effort to 15 attract more custom. Did I complain of the lack of music? I was hasty; for there comes a second boat, carrying two nymphs whose devotion to the art has caused them to forget the use of water, unless it be internally. One has a hoarse voice, the other a shrill one; and with smiles and antics they pipe out the cheapest of modern melodies, chanting the eternal "Funicoli, Funicola," till one wishes the writer of that most paltry song could be keelhauled, or taught by some other process of similar asperity how grave is the offence of him who casts one more jingle into the hoarse throats of the street musicians of to-day. If I flee to the further side of the steamer and stop my ears from the cacophony, my face is tickled by the foliage of huge nosegays thrust up on the ends of poles from a boat so low in the water that I cannot see it. The salt air grows heavy with the scent of violets and roses. None of my senses is at peace.

But in another hour the landing was happily accomplished. The recollection of the mob through which one struggled to the quay, the noise, the extortion, and the smells had faded away into the limbo of bad dreams, and I was free to go whither I would in the small portion of the day remaining and taste whichever sight of Naples pleased me first. There is nothing more bewildering to a stranger than to be turned loose in a great city with which he is imperfectly acquainted. I looked east towards the Carmine; but the handsome campanile lay far from the centre of the city. I gazed before me, up a long straight street which cleft the older city with a course as straight as any bow shot, the house fronts intricate with countless balconies and climbing plants. It is the Strada del Duomo; but I knew it to be new through all its lower length, and it leads into the 16 very heart of the dense old town, where, lost in a maze of vicoli, I could never grasp the broad and general aspect of this metropolis of many kings.

At that moment I remembered the hill on which the Castle of St. Elmo stood; and turning westwards along the street which borders the quays, I came out in no great distance on the Piazza del Municipio, bordered on the further side by the walls and towers of Castel Nuovo, that old royal castle of Anjou and Aragon, which saw so many tragedies wrought within its walls, and holds some still, as I shall tell in time, for the better persuasion of any who may be disposed to set down the accusations of history as distant and vague charges, which cannot nowadays be brought to the test of sight. Before my eyes rises the white priory of San Martino topping the hillside high above the town, and it is to that point that I am hastening ere the gold light of the afternoon fades off the bay, and the grey shades of the early dusk rob the islands of their sunset colours. It is a long climb up to the belvedere of the low white building. The Neapolitans believed in days not long distant that vast caverns of almost immeasurable extent branched out laterally from the dungeons of St. Elmo and ran down beneath the city even to Castel Nuovo, making a secret communication between the garrisons of the two fortresses on which the security of Naples most depended. The story is not true. The vaults of St. Elmo do not reach so far, and are not more extensive than the circuit of the castle. But indeed these hillsides on which Naples lies are pierced so frequently by caverns, so many tales are told of grottoes known and unknown in every spine of rock, that the wildest stories of mysterious passages have found ready credence; and there are doubtless many 17 children, old and young, in Naples who believe that one may walk beneath the earth from St. Elmo to Castel Nuovo no less firmly than they credit the existence of vast caverns filled with gold and jewels lying underneath Castel dell'Uovo, guarded for ever from the sight of man by the chafing of the waves.

Naples presents us with a strange blend of romance and common sense—the modern spirit, practical and useful, setting itself with something like the energy of the old Italian genius towards the gigantic task of acquiring the arts of government, and turning a people enslaved for centuries into one which can wield the hammer of its own great destinies. "L'Italia è fatta," said Massimo d'Azeglio, "ma chi farà ora gli Italiani?" It was the question of a patriot, and it may be that it is not wholly answered yet. The most careless of observers can see that some things still go wrong in Italy, that the Italians are not yet wholly made, and it is the easiest as it is the stupidest of tasks to demonstrate that thirty years of freedom have not taught the youngest nation what the oldest took eight centuries to learn. It galls me to hear the supercilious remarks dropped by strangers coming from a country where serious difficulties of government have not existed in the memory of man, the casual wisdom of critics who look around too carelessly to note the energy with which one by one the roots of evil are plucked up, and the refuse of the long tyranny cleared away. I am not writing a political tract; but I say once for all that the recent history of Italy can show more triumphs than its failures; and the day will surely come when the indomitable courage of her rulers shall purge the country of those cankers which for centuries ate out her manhood. 18

"We do not serve the dead—the past is past.

God lives, and lifts his glorious mornings up

Before the eyes of men awake at last,

Who put away the meats they used to sup,

And down upon the dust of earth outcast

The dregs remaining of the ancient cup,

Then turn to wakeful prayer and worthy act."

Dear prophetess and poet, who once from Casa Guidi sang so bravely of the future, kindling the love of Italy in many a heart where it has since grown into a passion,—it is coming true! It may be that fulfilment loiters, but Heaven does not disappoint mankind of hopes so great as these. They are of the sort with which God keeps troth. The child who went by singing "O bella libertà, o bella!" does not flute so sweetly now he is a man, but his hands have taken hold, and his heart is set on the greatness of his motherland.

The sun lies thick and hot in the Toledo, that long and crowded street which is the chief thoroughfare of Naples. It is hotter still when, having toiled as far as the museum, I turn off along the Corso Vittorio Emmanuele, which winds along the hillside, giving at each turn grand views across the town and harbour towards Capri shining in the west. A little way down the Corso is a flight of steps, long, tortuous and steep, yet forming much the pleasantest approach to the white priory whither every visitor to Naples goes once at least towards the hour of sunset. As one mounts, the city drops away, and the long semicircle of hills behind it rises into sight, green rounded hills, bearing on their summits palms which stand out sharp and dark against the sky. With every convolution of the stairs one sees more and more of the great plain out of which Vesuvius rises,—the Campagna Felice, a purple flat, stretching from the base of the 19 volcano as far as that mountain chain which marks the limit of its power. Out of the mountains comes a fresh cool wind, and all the city sparkles in the sun.

So I went up among the housetops till at length I reached an open space bounded by a rampart whence one looked down upon the town. On the further side a gateway gave admission to a courtyard, and that again to a corridor of the old priory, through which a guide led me with vain pointings toward the chamber containing the "Presepe," a vast model of the scene of the Nativity. Mary sits upon a height under a fragment of an old Greek building; while all the valleys are filled with the procession of the kings. Their goods are being unloaded from the troops of asses which bore them. In the meadows sheep are grazing, cows are being milked; and the sky is filled with choirs of angels. It is an ingenious, theatrical toy, but not half so pretty as the sunset, which I came to see. So, with some indignation of my guide, I pressed on through an exquisitely cool arcaded courtyard of white marble, its centre occupied by a garden wherein palms and roses grew almost profuse enough to hide the ancient draw well, with its chain and bucket lying as if they waited for some brother told off by the Prior to draw water for the rest. In one corner of this courtyard a doorway gives admission to the belvedere, a little chamber with two windows, whereof one looks towards the plain behind Vesuvius, and the other gives upon Posilipo.

As I stepped out on the belvedere the sun was dropping fast towards Posilipo, and wide flashes of gold were spreading over all the cup-shaped bay. Far out at sea, between the two horns of the gulf, the dark peaks of Capri caught the light, and presently 20 the glow blazed more brightly in the west, and all the shores where Sorrento lies began to quiver softly in the sunset. Vesuvius was grim and black; a pillar of dark smoke mounted slowly from its summit, and stretched across the paling sky like a banner floating defiantly from some tall citadel. Deep down beneath me lay the white city, a forest of domes and house-fronts which seemed at first impenetrable. But ere long the royal palace detached itself from the other buildings, and I could distinguish Castel Nuovo, with its old round towers, looking very dark and grim, while on the left a forest of domes and spires rose out of the densely crowded streets which have known so many masters and have allured conquerors from lands so very far away. A faint brown haze crept down from the hilltops, the first touch of evening chilled the air, but the seaward sky was marvellously clear, and the wide bay gleamed with gold and purple lights.

It is a morning of alternate sun and shadow. The clouds are flying low across the city, so that now one dome and now another flashes into light and the orange groves shine green and gold among the square white houses. All the high range of the Sorrento mountains lies in shadow, but on the sea the colours are glowing warm and bright, here a tender blue, there deepening into grey, and again, nearer into shore, a marvellous rich tint which has no name, but is azure and emerald in a single moment. Away across the crescent of the gulf a crowd of fishing boats are putting forth from Torre del Greco or Torre dell' Annunziata. Even at this distance one can see how they set their huge triangular sails and scatter, some one way, some another, searching each perhaps for his favourite volcanic shoal; for the largest fish lurk always in the hollows of those lava reefs which have from time to time burst out of the bottom of the bay. Some, perhaps, are sailing for the coral fishery upon the coast of Africa, to which great numbers go still in this month of April out of all the harbours beneath Vesuvius, though the profits are not what they were, and the trade is falling upon evil days. As for the mountain, he has cleared himself of clouds, and from his summit a heavy coil of smoke uncurls itself lazily 22 and spreads like a pennant stretching far across the sky.

All these things and more I have time to notice while I trudge along above the housetops of the city, those flat roofs named astrici which are such pleasant lounges on the summer evenings when the blue bay is dotted over with white sails and the shadows deepen on the flanks of Vesuvius or the distant line of the Sorrento coast. At length the road approaching the ridge of hill whose point forms the headland of Posilipo drops swiftly, and I find myself in face of a short ascent leading to the mouth of the very ancient grotto by which, these two thousand years and more, those who fared from Naples unto Pozzuoli have saved themselves the trouble of the hill.

It is absolutely necessary to pause and consider this hill, to which so much of the rare beauty of Naples is to be attributed. For the moment I set aside its legends and traditions, and turn my attention to the eminence itself. It is a cliff of yellow rock, whose consistency somewhat resembles sandstone, evidently worked without much difficulty, since it has been quarried out into vast cavities. The rock is tufa. It is a volcanic product, and forms the staple not only of the headland, but also of all the site of Naples and the rising ground behind it up to the base of the blue Apennines, which are seen continually towering in the distance beyond Vesuvius.

Thus at Naples one may distinguish between the eternal hills and those which have no title to the name. Of the latter is Posilipo, formed as I said out of volcanic ash. That ash was ejected underneath the sea, and having been compacted into rock by the action of the water was upreared by some convulsion long since forgotten. It is an intrusion on the landscape—a very ancient one, certainly—but it has 23 nothing to do with the great mountain-chain which hems in the Neapolitan Campagna and ends at last in the Sorrento peninsula and Capri. All the most fertile plain which lies within that barrier was once beneath the sea, which flowed up to the bases of the mountains. There is no doubt about it. The rock of Posilipo contains shells of fish now living in the bay. From Gaeta to Castellammare stretched one wide inlet of the sea. But underneath the water volcanic ash was being cast out, as it is still at certain spots within the bay; the heaps of ash and pumice stone grew into shoals and reefs, were uplifted into hills, the sea flowed back from its uptilted bed, and the coasts of Naples and of Baiæ assumed some outline roughly similar to that which they possess at present.

Of course all this is very ancient history, far beyond the ken of written records, or even the faintest whisper of tradition, unless, indeed, in the awe with which ancient writers alluded to the Phlegræan fields, fabled in old time to be the gate of hell, we may detect some lingering memory of the horrible convulsion which drove back the sea, and out of its deserted bed reared up this wilderness of ash and craters. But speculations of this kind are rather idle. We had better turn towards the grottoes, which are, at least in part, the work of men whose doings on this earth are known to history. The one, of course, is wholly modern, a construction of our own age for the accommodation of the steam tramway; but the other, through which one walks or drives, is certainly as old as the Emperor Augustus, and has sometimes been supposed to possess an antiquity far greater than that.

It seems remarkable that the Romans should have esteemed it easier to bore through the cliff than to 24 make a road across the headland. Indeed, there were villas on Posilipo, and there must surely have been a road of some sort from very early times, though it must be admitted that the founders of Naples did not go to Pozzuoli by the coast as we do. The old road climbed up directly from the city to Antignano, in the direction of Camaldoli, and kept along the ridge as far as possible. The coast road began to be used when the tunnel had been made. Still there must have been at least a track across the headland, and one wonders why the Romans did not improve it, in preference to boring underground. The ease with which the soft stone can be worked may account partially for their choice; but it is not to be forgotten that numberless caves, whether natural or artificial, exist in the cliffs at Posilipo and Pizzofalcone, giving occasion to the quick fancy of the Neapolitans to devise wild tales of buried treasure and of strange fierce beasts which guard it from the greed of men. The old legends of the Cimmerians who dwelt in dark caverns of the Phlegræan fields present themselves to mind in this connection, and without following out this mysterious subject further into the mists which envelope it, we may recognise the possibility that some among these caverns are far older than is commonly believed. Of course the preference of the Romans for tunnelling is explained at once, if we may suppose that by enlarging existing caverns they found their tunnel already partly made.

"I do not know," cries Capaccio, an ancient topographer who may yet be read with pleasure, though the grapes have ripened three hundred times above his tomb, "I do not know whether the Posilipo is more adorned by the grotto or the grotto by Posilipo." I really cannot guess what he meant. It sounds like the despairing observation of a writer 25 at a loss for matter. We will leave him to resolve his own puzzle and go on through the darkness of the ill-lighted grotto—no pleasanter now than when Seneca grumbled at its dust and darkness—sparing some thought for that great festival which on the 7th of September every year turns this dark highway into a pandemonium of noise and riot. The festival of Piedigrotta is held as much within the tunnel as on the open space outside, where stands the church whose Madonna furnishes a devotional pretext for all the racket. Indeed it is almost more wild and whirling within than without; for one need not become a boy again to understand that the joys of rushing up and down, wearing a fantastic paper cap, blowing shrieks upon a catcall, and brandishing a Chinese lantern, must be infinitely greater in the bowels of the hill than in the open air. Of course it is not only, nor even chiefly, a feast for children. All the lower classes rejoice at Piedigrotta, and often with the best of cause; for it happens not infrequently that the sky, which for many weeks has been pitiless and brazen, clouds and breaks about that time, the welcome rain falls, the streets grow cool again, and laughter rises from end to end of the reviving city.

Of Fuorigrotta, the unpleasing village at the further end of the grotto, I have nothing to say, unless it be to express the wish that Giacomo Leopardi, who lies in the church of San Vitale, lay elsewhere. That superb poet and fine scholar whose verses upon Italy not yet reborn rank by their majesty and fire next after those of Dante, and who yet could produce a poem rendering so nobly the solitude of contemplation as that which commences—

"Che fai tu luna in ciel, dimmi, che fai,

Silenziosa luna!"

this man should have lain upon some mountain-top, among the scent of rosemary and of fragrant myrtle, rather than in such a reeking dirty village as Fuorigrotta.

But I forget!—the compelling interest of this day's journey is not literary. A short walk from Fuorigrotta brings me to a point where the road turns slightly upward to the right, leading me to the brow of a hill, over which I look into a wooded hollow—none other than the Lago d'Agnano, once a crater, then a volcanic lake. Oddly enough, it is not mentioned as a lake by any ancient writer. Pliny describes the Grotta del Cane, which we are about to visit, but says not a word of any lake. This fact, with some others, suggests that the water appeared in this old crater only in the Middle Ages; though it really does not matter much, for it is gone now. The bottom has been reft from the fishes and converted into fertile soil. The sloping heights which wall the basin have a waste and somewhat blasted aspect; but I was not granted time to muse on these appearances before a smiling but determined brigand, belonging to the class of guides, sauntered up with a small cur running at his heels and made me aware that I had reached the entrance of the Dog Grotto.

I might have known it; for, in fact, through many centuries up to that recent year when it pleased the Italians to drain the lake, the life of the small dogs dwelling in this neighbourhood has been composed of progresses from grotto to lake and back again, first held up by the heels to be stifled by the poisonous gas, then soused head over ears in the lake with instructions to recover quickly because another carriage was coming down the hill. Thus lake and grotto were twin branches of one establishment, now dissolved. Perhaps the lake was the more important 27 of the two, since it is easier to stifle a dog or man than to revive him; and on many occasions there would have been melancholy accidents had not the cooling waters been at hand. For instance it is related by M. de Villamont, who came this way when the seventeenth century was very young indeed, that M. de Tournon, a few years before, desiring to carry off a bit of the roof of the grotto, was unhappily overcome by the fumes as he stood chipping off the piece he fancied, and tumbled on the floor, as likely to perish as could be wished by the bitterest foe of those who spoil ancient monuments. His friends promptly dragged him out and tossed him into the lake. It is true the cure found so successful with dogs proved somewhat less so with M. de Tournon, for he died a few days later. Yet had the lake been dry, as it is to-day, he would have died in the cave, which would surely have been worse.

The little dog—he was hardly better than a puppy—looked at me and wagged his tail hopefully. I understood him perfectly. He had detected my nationality; and I resolved to be no less humane than a countrywoman of my own who visited this grotto no great while ago, and who, when asked by the brigand whether he should put the dog in, answered hastily, "Certainly not." "Ah!" said the guide, "you are Englees! If you had been American you would have said, 'Why, certainly.'" I made the same condition. The fellow shrugged his shoulders. He did not care, he knew another way of extorting as many francs from me; and accordingly we all went gaily down the hill, preceded by the happy cur, running on with tail erect, till we reached a gate in the wall through which we passed to the Grotta del Cane.

A low entrance, hardly more than a man's height, 28 a long tubular passage of uniform dimensions sloping backwards into the bowels of the hill—such is all one sees on approaching the Dog Grotto. A misty exhalation rises from the floor and maintains its level while the ground slopes downwards. Thus, if a man entered, the whitish vapour would cling at first about his feet. A few steps further would bring it to his knees, then waist high, and in a little more it would rise about his mouth and nostrils and become a shroud indeed; for the gas is carbonic acid, and destroys all human life. King Charles the Eighth of France, who flashed across the sky of Naples as a conqueror, came here in the short space of time before he left it as a fugitive, bringing with him a donkey, on which he tried the effects of the gas. I do not know why he selected that animal; but the poor brute died. So did two slaves, whom Don Pietro di Toledo, one of the early Spanish viceroys, used to decide the question whether any of the virtue had gone out of the gas. That question is settled more humanely now. The guide takes a torch, kindles it to a bright flame, and plunges it into the vapour. It goes out instantly; and when the act has been repeated some half-dozen times the gas, impregnated with smoke, assumes the appearance of a silver sea, flowing in rippling waves against the black walls of the cavern.

With all its curiosity the Dog Grotto is a deadly little hole, in which the world takes much less interest nowadays than it does in many other objects in the neighbourhood of the Siren city, going indeed by preference to see those which are beautiful, whereas not many generations ago it rushed off hastily to see first those which are odd. For that reason many visitors to Naples neglect this region of the Phlegræan fields and are content to wait the natural occasion 29 for visiting the mouth of Styx, over which all created beings must be ferried before they reach the nether world. It is a pity; for, judged from the point of beauty solely, there is enough in the shore of the Bay of Baiæ to content most men. The road mounts upon the ridge which parts the slope of Lago d' Agnano from the sea. One looks down from the spine over a broken land of vineyards to a curved bay, an almost perfect semicircle, bounded on the left by the height of Posilipo, with the high crag of the Island of Nisida, and on the right by Capo Miseno, the point which took its name from the old Trojan trumpeter who made the long perilous voyage with Æneas, but perished as he reached the promised land where at last the wanderers were to find rest. The headland, which, like every other eminence in sight, is purely volcanic, is a lofty mass of tufa, united with the land by a lower tongue, like a mere causeway; and on the nearer side stands the Castle of Baiæ, with the insignificant townlet which bears on its small shoulders the burden of so great a name. Midway in the bay the ancient town of Pozzuoli nestles by the water's edge, deserted this long while by all the trade which brought it into touch with Alexandria and many another city further east, filling its harbour with strange ships, crowding its quays with swarthy sailors, and with silks and spices of the Orient. All that old consequence has gone now like a dream, and no one visits the cluster of old brown houses for any other reason than to see that which is still left of its ancient greatness. But before going down the hill, I turn aside towards a gateway on my right, which admits me to a place of strange and curious interest. It is the Solfatara, and is nothing more or less than the crater of a half-extinct volcano, which, having lain torpid for full seven centuries, is 30 now a striking proof of the fertility of volcanic soil, and the speed with which Nature will haste to spread her lushest vegetation even over a thin crust which covers seething fires. It was so once with the crater of Vesuvius, which, after five centuries of rest, filled itself with oaks and beeches, and covered its slopes with fresh grass up to the very summit.

Indeed, on entering the inclosure of the Solfatara, one receives the impression of treading the winding alleys of a well-kept and lovely park. The path runs through a pretty wood. The trees are scarcely more important than a coppice; but under their green shade there grows a wealth of flowers of every colour, glowing in the soft sunshine which filters through the boughs. There is the white gum-cistus, which is so strangely like the white wild rose of English hedges, and the branching asphodel, with myriads of those exquisite anemones, lilac and purple, which make the woods of Italy in springtime a perpetual joy to us who come from colder climates; and among these, a profusion of smaller blossoms trailing on the ground, crimson, white and orange, making such a mass of colour as the most cunning gardener would seek vainly to produce. One lingers and delays among these woods, doubting whether any sight which may be shown one further on can compensate for the loss of the cool glades.

But already over the green coppice bare grey hillsides have come in sight. They are the walls of the old crater, and here and there a puff of white smoke curling out of a cleft reminds me that the flowers are only here on sufferance, and that the whole hollow is in fact but waiting the moment when its hidden fires will break forth again, and vomit destruction over all the country. A few yards further on the coppice falls away. The flowers persist in carpeting the 31 ground; but in a little way they too cease, the soil grows grey and blasted. Full in front there rises a strange scene of desolation. The wall of the crater is precipitous and black. At its base there are openings and piles of discoloured earth which suggest the débris of some factory of chemicals, an impression which is driven home by the yellow stains of sulphur which lie in every direction on the grey bottom of the crater. From one vast rent in the soil a towering pillar of white smoke pours out with a loud hissing noise, and blows away in wreaths and coils over the dark surface of the cliff.

There is something curiously arresting in this quick passage from a green glade carpeted with flowers to the calcined ash and the grey desolation of this broken hillside. Of vegetation there is almost none, except a stunted heather which creeps hardily towards the blast hole. A little way off, towards the right, lies a level space sunk beneath the surrounding land, not unlike the fashion of an asphalt skating rink, so even in its surface that it resembles the work of man, and one strolls towards it to discover with what purpose anyone had dared to tamper with the soil in a spot where so thin a crust lies over bottomless pits of fire. But when one steps out upon the level flat, it reveals itself at once to be no human work. The guide stamps with his foot, and remarks that the sound is hollow. It is indeed, most unpleasantly so. He jumps upon it, and the surface quivers. You beg him to spare you further demonstrations, and walking gingerly on tiptoe, wishing at each step that you were safe in Regent Street once more, you follow him out towards the middle of this devilish crust, which rocks so easily and covers something which you hope devoutly you may never see. Midway in the expanse the fellow pauses in 32 triumph—he has reached what he is confident will please you. He is standing by a hole, just such an opening as is made in a frozen lake in winter for the watering of animals. From it there emerges a little vapour and a curious low sound, like that which a child will make with pouting lips. The guide grins, crouching by the opening; you, on the other hand, hang back, in doubt whether the crust may not break off and suddenly enlarge the hole. You are encouraged forwards, and at last, peering nervously down the hole, you see with keen and lively interest that the crust appeared to have about the thickness of your walking-stick, at which depth there is a lake of boiling mud. The grey mud stirs and seethes in the round vent-hole, rising and falling, while on its surface the gas collects slowly into a huge bubble, which forms and bursts and then collects again.

For my part I do not deny that the sight fascinated me, but it deprived me of all wish to tread further on that shaking crust, and I sped back as lightly as I might, wishing all the way for wings, to where there was at least sound, green earth for a footing, in place of pumice stone and hardened mud, which some day, surely, will fly into splinters, and leave the seething, steaming lake once more open to the heavens.

From the hillside just beyond the gate of the Solfatara one gazes down on the town of Pozzuoli, brown and ancient, looking, I do not doubt, much the same unto this hour as when the Apostle Paul landed there from the Castor and Pollux, a ship of Alexandria which had wintered in the Island of Melita. But if the town itself, the very houses clustered on the hill, preserve the aspect which they bore twenty centuries ago, so much cannot be said for the sea-front, which is vastly changed. Pozzuoli in those days must have rung with the noise of ships entering or departing. 33 Its quays were clamorous with all the speeches of the East; its great trade in corn needed long warehouses near the water's edge; its amphitheatre was built for the games of a people numbering many thousands. But now the little boats which come and go are too few to break the long silence of the city, and there are scarce any other noises in the place than the shout of children at their games, or the loud crack of the vetturino's whip as the strangers rattle through the streets on their way to Baiæ.

It was the fall of Capua which made the trade of Pozzuoli, and it was the rise of Ostia that destroyed it. Capua, long the first town of Italy by reason of its commerce and its luxury, lost that pre-eminence in the year 211 B.C., when the Romans avenged the adhesion of the city to the cause of Hannibal. That act of punishment made Rome the chief mart of merchants from the East, and the nearest port to the Eternal City being Pozzuoli, the trade flowed thither naturally. Naples no doubt had a finer harbour; but Naples was not in Roman hands, while Pozzuoli was. Ostia, before the days of the Emperor Claudius, who carried out great works there, was a port of smallest consequence. Thus the harbour of Pozzuoli was continually full of ships. They came from Spain, from Sardinia, from Elba, bringing iron, which was wrought into fine tools by cunning workmen of the town; from Africa, from Cyprus, and all the trading ports of Asia Minor and the isles of the Ægean. Thither came also the merchants of Phœnicia, bringing with them all those gorgeous wares which moved the prophet Ezekiel to utter so great a chant of glory and its doom. "Tarshish was thy merchant by reason of the multitude of all kinds of riches; with silver, iron, tin, and lead they traded in thy fairs.... These were thy merchants in all sorts of things, in 34 blue clothes and broidered work and in chests of rich apparel, bound with cords and made of cedar among thy merchandise. The ships of Tarshish did sing of thee in thy market. Thou wast replenished and made very glorious in the midst of the seas." All that most noble description of the commerce of Tyre returns irresistibly upon the mind when one looks back on the greatness of Pozzuoli, where the Tyrians themselves had a mighty factory and all the nations of the East brought their wares for sale. Most of all the town rejoiced when the great fleet hove in sight which came each year from Egypt in the spring. Seneca has left us a description of the stir. The fleet of traders was preceded some way in advance by light, swift sailing ships which heralded its coming. They could be known a long way off, for they sailed through the narrow strait between Capri and the mainland with topsails flying, a privilege allowed to none but ships of Alexandria. Then all the town made ready to hasten to the water's edge, to watch the sailors dancing on the quays, or to gloat over the wonders which had travelled thither from Arabia, India, and perhaps even far Cathay.

Well, all this is an old story now—too old, perhaps, to be of any striking interest—yet here upon the shore is still the vast old Temple of Serapis, the Egyptian deity whom the strangers worshipped. One knows not by what slow stages the Egyptians departed and the ancient temple was deserted. The only certain fact is that at some period the whole inclosure was buried deep beneath the sea, and after long centuries raised up again by some fresh movement of the swaying shore.

Strange as this seems to those who have not watched the perpetual heavings and subsidences of a volcanic land, the testimony of the fact is 35 unmistakably in sight of all. For the sacred inclosure once hallowed to the rite of Serapis is still not allotted to any other purpose; and the visitor who enters it finds many of the ancient columns still erect. It is a vast quadrangle, once paved with squares of marble. There was a covered peristyle, and in the centre another smaller temple. Many of the columns of fine marble which once adorned the abode of the goddess were reft from her in the last century, when the spot was cleared of all the soil and brushwood which had grown up about it; but three huge pillars of cipollino, once forming part of the pronaos, are still erect; and what is singular about them is that, beginning at a height of some twelve feet from the ground and extending some nine feet further up, the marble is honeycombed with holes, drilled in countless numbers deep into the round surface of the columns.

There is no animal in earth or air which will attack stone in this destructive manner; but in the sea there is a little bivalve, called by naturalists "lithodomus," whose only happiness lies in boring. This animal is still found plentifully in the Bay of Baiæ. His shells still lie in the perforations of the columns; and it is thus demonstrated that the ancient temple must have been plunged beneath the sea, that it lay there long ages, till at length some fresh convulsion reared it up once more out of the reach of fish. Surely few buildings have sustained so strange a fate!

The holes drilled by the patient lithodomus, as I have said, do not extend through the whole height of the column, but have a range of about nine feet only, which is thus the measure of the space left for the operations of the busy spoiler. Above the ring of perforations one sees the indications of 36 ordinary weathering, so that the upper edge of the holes doubtless marks the level of high water, and the summit of the columns stood up above the waves. But one does not see readily what protected the lower portion of the marble. Possibly, before the land swayed downwards something fell which covered them.

In the twelfth century the Solfatara broke forth into eruption for the last time. The scoriæ and stones fell thick in Pozzuoli, and they filled the court of the Serapeon to the height of some twelve feet. Probably the sea had then already stolen into the courtyard; and it may be that the earthquakes attending the eruption caused the subsidence which left the lithodomus free to crawl and bore upon the stones which saw the ancient mysteries of Serapis. At any rate it was another volcanic outburst which raised the dripping columns from the sea in 1538, since which time the land has been swaying slowly down once more, so that now if anyone cares to scratch the gravel in the courtyard he will find he has constructed a pool of clear sea water.

It is a strange and terrible thing to realise the existence of hidden forces which can sway the solid earth as lightly as a puff of wind disturbs an awning; none the less terrible because the ground has risen and fallen so very gently that the pillars stand erect upon their bases. Once more, as at the Solfatara, one has the sense of treading over some vast chasm filled with a sleeping power which may awake at any moment. Let us go on beyond the city and see what has happened elsewhere upon this bay, so beautiful and yet so deadly, a strange dwelling-place for men who have but one life to pass on the surface of this earth.

In passing out of Pozzuoli one sees upon the right 37 the vine-clad slopes of Monte Barbaro. That also is a crater, the loftiest in the Phlegræan fields, but long at rest. The peasants believe the mountain to contain vast treasures—statues of kings and queens, all cast of solid gold, with heaps of coin and jewels so immense that great ships would be needed to carry them away. These tales are very old. I sometimes wonder whether they may not have had their source in dim memory of the great hoard of treasure which the Goths stored in the citadel of Cumæ, and which, when their power was utterly broken, they were supposed to have surrendered to the imperial general Narses. Perhaps they did not; perhaps—but what is the use of suppositions? Petrarch heard the stories when he climbed Monte Barbaro in 1343. Many men, his guides told him, had set out to seek the treasure, but had not returned, lost in some horrible abyss in the heart of the mountain. They must have neglected the conditions of success. They should have watched the moon, and learnt how to catch and prison down the ghosts which guard the precious heaps, otherwise the whole mass, even if found, will turn to lumps of coal!

What a wilderness of craters! Small wonder if wild tales exist yet in a district which in old days, and even modern ones, has been encompassed with fear. One volcano is enough to fill the country east of Naples with terror. But here are many—active, doubtless, in very different ages—Monte Barbaro, Monte Cigliano, Monte Campana, Monte Grillo, which hems in the more recent crater of Avernus much as Somma encircles the eruptive crater of Vesuvius. What terrible sights must have been witnessed here in those far-distant days when these and other craters were in action!—"affliction such as 38 was not from the beginning of the creation which God created" until then! But a few miles away across the sea is Monte Epomeo, towering out of Ischia. That was the chief vent of the volcanic forces in Roman times; and then the Phlegræan fields were still. Epomeo has been silent for five centuries; but that proves nothing, and there are people who suggest that the awful earthquake which destroyed Casamicciola may be just such a prelude to the awakening of Epomeo as was the convulsion which shook Pompeii to its foundations sixteen years before its final destruction. Dî avertite omen!

We need not, however, go back five centuries for facts that bid men heed what may be passing underground about the shores of this blue bay. Here is one too large to be overlooked, immediately in front of us—no other than the green slope of Monte Nuovo, a hill of aspect both innocent and ancient, ridged with a few pine trees by whose aid the mountain contrives to look as if it had stood there beside the Lucrine Lake as long as any eminence in sight. This is a false pretension. There was no such mountain when Petrarch climbed the neighbouring height, nor for full two centuries afterwards. What Petrarch saw exists no longer. He looked down upon the Lucrine Lake connected with the sea by a deep channel, and formed with Lake Avernus into one wide inlet fit for shipping. This was the Portus Julius, a harbour so large that the whole Roman fleet could manœuvre in it. The canals and piers were in existence less than four centuries ago; and this great work, so remarkable a witness to the sea power of the Romans, would doubtless have lasted unto our day had it not been for the intrusion of Monte Nuovo, which destroyed 39 the channels and reduced the Lucrine Lake to the dimensions of a sedgy duck pond.

The catastrophe is worth describing, for no other in historic times has so greatly changed the aspect of this coast or robbed it of so large a portion of its beauty. For full two years there had been constant earthquakes throughout Campania. Some imprisoned force was heaving and struggling to release itself, and all men began to fear a great convulsion. On the 27th of September, 1538, the earth tremors seemed to concentrate themselves around the town of Pozzuoli. More than twenty shocks struck the town in rapid succession. By noon upon the 28th the sea was retreating visibly from the pleasant shore beside the Lucrine Lake, where stood the ruined villa of the Empress Agrippina, and a more modern villa of the Anjou kings, who were used, like all their predecessors in Campania, to take their ease in summer among the luxuriant vegetation of the hills whose volcanic forces were believed to be lulled in a perpetual sleep.

For three hundred yards the sea fell back, its bottom was exposed, and the peasants came with carts and carried off the fish left dry upon the strand. The whole of the flat ground between Lake Avernus and the sea had been heaved upwards; but at eight o'clock on the following morning it began to sink again, though not as yet with any violence. It fell apparently at one spot only, and to a depth of about thirteen feet, while from the hollow thus formed there burst out a stream of very cold water, which was investigated cautiously by several persons, some of whom found it by no means cold, but tepid and sulphurous. Ere long those who were examining the new spring perceived that the sunken ground was rising awfully. It was upreared so rapidly that by 40 noon the hollow had become a hill, and as the new slopes swelled and rose where never yet had there been a rising ground, the crest burst and fire broke out from the summit.

"About this time," says one Francesco del Nero, who dwelt at Pozzuoli, "about this time fire issued forth and formed the great gulf with such a force, noise, and shining light that I, who was standing in my garden, was seized with great terror. Forty minutes afterwards, though unwell, I got upon a neighbouring height, and by my troth it was a splendid fire, that threw up for a long time much earth and many stones. They fell back again all round the gulf, so that towards the sea they formed a heap in the shape of a crossbow, the bow being a mile and a half and the arrow two-thirds of a mile in dimensions. Towards Pozzuoli it has formed a hill nearly of the height of Monte Morello, and for a distance of seventy miles the earth and trees are covered with ashes. On my own estate I have neither a leaf on the trees nor a blade of grass.... The ashes that fell were soft, sulphurous, and heavy. They not only threw down the trees, but an immense number of birds, hares, and other animals were killed."

Amid such throes and pangs Monte Nuovo was born, and the events of that natal day suggest hesitation before we label any crater of the Phlegræan fields with the word "extinct." It is granted that in the course of geologic ages volcanic forces do expend themselves. The British Isles, for instance, contain many dead volcanoes, once at least as formidable as any in the world. But the exhaustion has been the work of countless ages, and many generations of mankind will come and go upon this planet before the coasts of Baiæ and Misenum are as safe as those of Cumberland. 41

While speaking of these terrors, I have been halting by the wayside at a point, not far beyond the outskirts of Pozzuoli, where two roads unite, the one going inland beneath the slope of Monte Barbaro, the other following the outline of the curved shore on which Baiæ stands. The inland road is the one which goes to Cumæ, and is entitled to respect, if not to veneration, as being among the oldest of Italian highways, the approach to the most ancient Greek settlement in Italy, mother city of Pozzuoli and of Naples, not to mention the mysterious Palæopolis, whose very existence has been disputed by some scholars. Some say it was more than ten centuries before Christ's birth that the bold Greeks of Eubœa came up this coast, where already their kinsmen were known as traders, and having settled first on Ischia moved to the opposite mainland, and built their acropolis upon a crag of trachyte which overhung the sea. Their life was a long warfare. More than once they owed salvation to the aid of their kinsmen from Sicilian cities, yet they made their foundation a mighty power in Italy. With one hand they held back the fierce Samnite mountaineers who coveted their wealth, and gave out with the other more and more freely that noble culture which has had no rival yet.

One must wonder why these strangers coming from the south passed by so many gulfs and harbours shaped out of the enduring rock only to choose a site for their new city at the foot of all these craters. It may be that chance had its part in the matter; in some slight indication of wind or wave they may have seen the guidance of a deity. Indeed, an ancient legend says their ships were guided by Apollo, who sent a dove flying over sea to lead them. But again, the fires of the district were sacred in their eyes. The 42 subterranean gods were near at hand, and on the dark shore of Lake Avernus they recognised the path by which Ulysses sought the shades. The mysteries of religion drew them there, and the cave of the Cumæan sibyl became the most venerated shrine in Italy. Lastly, one may perceive that the volcanic tract, full of terrors for the Etruscan or Samnite mountaineer who looked down upon its fires from afar, must have made attack difficult from the land.

Greek cities, such as Cumæ, studded the coast of southern Italy. "Magna Græcia" they called the country; and Greek it was, in blood, in art, and language. How powerful and how rich is better understood at Pæstum than it can be now at Cumæ, where, with the single exception of the Arco Felice, there remains no dignity of ruin, nothing but waste, crumbling fragments, half buried in the turf of vineyards. Such shattered scraps of masonry may aid a skilful archæologist to imagine what the city was; but in the path of untrained men they are nothing but a hindrance, and anyone who has already in his mind a picture of the greatness of Eubœan Cumæ had better leave it there without attempt to verify its accuracy on the spot.

Observations similar to these apply justly to most of the remaining sights in this much-vaunted district. The guides are perfectly untrustworthy. They give high-sounding names to every broken wall, and there is not a burrow in the ground which they cannot connect with some name that has rung round the world. It is absolutely futile to hope to recapture the magic with which Virgil clothed this country. The cave of the Sibyl under the Acropolis of Cumæ was destroyed by the imperial general Narses when he besieged the Goths. The dark, wet passage on the shore of Lake Avernus, to which the name of 43 the Sibyl is given by the guides, is probably part of an old subterranean road, not devoid of interest, but is certainly not worth the discomfort of a visit. The Lake of Avernus has lost its terrors. It is no longer dark and menacing, and anyone may satisfy himself by a cursory inspection that birds by no means shun it now.

The truth is that this region compares ill in attractions with that upon the other side of Naples. In days not far distant, when brigands still invested all the roads and byways of the Sorrento peninsula, strangers found upon the Bay of Baiæ almost the only excursion which they could make in safety; and imbued as every traveller was with classical tradition, they still discovered on this shore that fabled beauty which it may once have possessed. There is now little to suggest the aspect of the coast when Roman fashion turned it into the most voluptuous abode of pleasure known in any age, and when the shore was fringed with marble palaces whose immense beauty is certainly not to be imagined by contemplating any one of the fragments that stud the hillside, though it may perhaps be realised in some dim way by anyone who will stand within the atrium of some great house at Pompeii, say the house of Pansa, who will note the splendour of the vista through the colonnaded peristyle, and will then remember that the Pompeiian houses were not famed for beauty, while the palaces of Baiæ were.