Title: Walks in Rome

Author: Augustus J. C. Hare

Release date: March 29, 2012 [eBook #39308]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This book was

produced from scanned images of public domain material

from the Google Print project.)

WALKS IN ROME

TWO VOLS.

|

Volume I. Contents Volume I. Volume II. Contents Volume II. Index. |

BY AUGUSTUS J. C. HARE

AUTHOR OF "MEMORIALS OF A QUIET LIFE," "WANDERINGS IN SPAIN," ETC.

TWO VOLUMES.—I.

FIFTH EDITION

LONDON

DALDY, ISBISTER & CO.

56, LUDGATE HILL

1875

[All rights reserved]

JOHN CHILDS AND SON, PRINTERS.

TO

HIS DEAR MOTHER

THE CONSTANT COMPANION OF MANY ROMAN WINTERS

These pages are Dedicated

BY THE AUTHOR.

| INTRODUCTORY. | |

| PAGE | |

| THE ARRIVAL IN ROME | 9 |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| DULL-USEFUL INFORMATION | 27 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| THE CORSO AND ITS NEIGHBOURHOOD | 36 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| THE CAPITOLINE | 109 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| THE FORUMS AND THE COLISEUM | 159 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| THE VELABRUM AND THE GHETTO | 221 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| THE PALATINE | 273 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| THE CŒLIAN | 316 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| THE AVENTINE | 348 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| THE VIA APPIA | 372 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| THE QUIRINAL AND VIMINAL | 433 |

"AGAIN this date of Rome; the most solemn and interesting that my hand can ever write, and even now more interesting than when I saw it last," wrote Dr. Arnold to his wife in 1840—and how many thousands before and since have experienced the same feeling, who have looked forward to a visit to Rome as one of the great events of their lives, as the realization of the dreams and longings of many years.

An arrival in Rome is very different to that in any other town of Europe. It is coming to a place new and yet most familiar, strange and yet so well known. When travellers arrive at Verona, for instance, or at Arles, they generally go to the amphitheatres with a curiosity to know what they are like; but when they arrive at Rome and go to the Coliseum, it is to visit an object whose appearance has been familiar to them from childhood, and, long ere it is reached, from the heights of the distant Capitol, they can recognize the well-known form;—and as regards St. Peter's, who is not familiar with the aspect of the dome, of the wide-spreading piazza, and the foaming fountains, for long years before they come to gaze upon the reality?

"My presentiment of the emotions with which I should behold the Roman ruins, has proved quite correct," wrote Niebuhr. "Nothing about them is new to me; as a child I lay so often, for hours together, before their pictures, that their images were, even at that early age, as distinctly impressed upon my mind, as if I had actually seen them."

Yet, in spite of the presence of old friends and landmarks, travellers who pay a hurried visit to Rome, are bewildered by the vast mass of interest before them, by the endless labyrinth of minor objects, which they desire, or, still oftener, feel it a duty, to visit. Their Murray, their Baedeker, and their Bradshaw indicate appalling lists of churches, temples, and villas which ought to be seen, but do not distribute them in a manner which will render their inspection more easy. The promised pleasure seems rapidly to change into an endless vista of labour to be fulfilled and of fatigue to be gone through; henceforward the hours spent at Rome are rather hours of endurance than of pleasure—his cicerone drags the traveller in one direction,—his antiquarian friend, his artistic acquaintance, would fain drag him in others,—he is confused by accumulated misty glimmerings from historical facts once learnt at school, but long since forgotten,—of artistic information, which he feels that he ought to have gleaned from years of society, but which, from want of use, has never made any depth of impression,—by shadowy ideas as to the story of this king and that emperor, of this pope and that saint, which, from insufficient time, and the absence of books of reference, he has no opportunity of clearing up. It is therefore in the hope of aiding some of these bewildered ones, and of rendering their walks in Rome more easy and more interesting, that the following chapters are written. They aim at nothing original, and are only a gathering up of the information of others, and a gleaning from what has been already given to the world in a far better and fuller, but less portable form; while, in their plan, they attempt to guide the traveller in his daily wanderings through the city and its suburbs.

It must not, however, be supposed, that one short residence at Rome will be sufficient to make a foreigner acquainted with all its varied treasures; or even, in most cases, that its attractions will become apparent to the passing stranger. The squalid appearance of its modern streets, the filth of its beggars, the inconveniences of its daily life, will leave an impression which will go far to neutralize the effect of its ancient buildings, and the grandeur of its historic recollections. It is only by returning again and again, by allowing the feeling of Rome to gain upon you, when you have constantly revisited the same view, the same temple, the same picture, that Rome engraves itself upon your heart, and changes from a disagreeable, unwholesome acquaintance, into a dear and intimate friend, seldom long absent from your thoughts. "Whoever," said Chateaubriand, "has nothing else left in life, should come to live in Rome; there he will find for society a land which will nourish his reflections, walks which will always tell him something new. The stone which crumbles under his feet will speak to him, and even the dust which the wind raises under his footsteps will seem to bear with it something of human grandeur."

"When we have once known Rome," wrote Hawthorne, "and left her where she lies, like a long-decaying corpse, retaining a trace of the noble shape it was, but with accumulated dust and a fungous growth overspreading all its more admirable features—left her in utter weariness, no doubt, of her narrow, crooked, intricate streets, so uncomfortably paved with little squares of lava that to tread over them is a penitential pilgrimage; so indescribably ugly, moreover, so cold, so alley-like, into which the sun never falls, and where a chill wind forces its deadly breath into our lungs—left her, tired of the sight of those immense seven-storied, yellow-washed hovels, or call them palaces, where all that is dreary in domestic life seems magnified and multiplied, and weary of climbing those staircases which ascend from a ground-floor of cook-shops, cobblers'-stalls, stables, and regiments of cavalry, to a middle region of princes, cardinals, and ambassadors, and an upper tier of artists, just beneath the unattainable sky,—left her, worn out with shivering at the cheerless and smoky fireside by day, and feasting with our own substance the ravenous population of a Roman bed at night, left her sick at heart of Italian trickery, which has uprooted whatever faith in man's integrity had endured till now, and sick at stomach of sour bread, sour wine, rancid butter, and bad cookery, needlessly bestowed on evil meats,—left her, disgusted with the pretence of holiness and the reality of nastiness, each equally omnipresent,—left her, half lifeless from the languid atmosphere, the vital principle of which has been used up long ago or corrupted by myriads of slaughters,—left her, crushed down in spirit by the desolation of her ruin, and the hopelessness of her future,—left her, in short, hating her with all our might, and adding our individual curse to the infinite anathema which her old crimes have unmistakeably brought down:—when we have left Rome in such mood as this, we are astonished by the discovery, by-and-by, that our heartstrings have mysteriously attached themselves to the Eternal City, and are drawing us thitherward again, as if it were more familiar, more intimately our home, than even the spot where we were born."

This is the attractive and sympathetic power of Rome which Byron so fully appreciated—

The impressiveness of an arrival at the Eternal City was formerly enhanced by the solemn singularity of the country through which it was slowly approached. "Those who arrive at Rome now by the railway," says Mrs. Craven in her 'Anne Severin,' "and rush like a whirlwind into a station, which has nothing in its first aspect to distinguish it from that of one of the most obscure places in the world, cannot imagine the effect which the words 'Ecco Roma' formerly produced, when on arriving at the point in the road from which the Eternal City could be descried for the first time, the postillion stopped his horses, and pointing it out to the traveller in the distance, pronounced them with that Roman accent which is grave and sonorous, as the name of Rome itself."

"How pleasing," says Cardinal Wiseman, "was the usual indication to early travellers, by voice and outstretched whip, embodied in the well-known exclamation of every vetturino, 'Ecco Roma.' To one 'lasso maris et viarum,' like Horace, these words brought the first promise of approaching rest. A few more miles of weary hills, every one of which, from its summit, gave a more swelling and majestic outline to what so far constituted 'Roma,' that is, the great cupola, not of the church, but of the city, its only discernible part, cutting, like a huge peak, into the dear winter sky, and the long journey was ended, and ended by the full realization of well-cherished hopes."

Most travellers, perhaps, in the old days came by sea from Marseilles and arrived from Civita Vecchia, by the dreary road which leads through Palo, and near the base of the hills upon which stands Cervetri, the ancient Cære, from the junction of whose name and customs the word "ceremony" has arisen,—so especially useful in the great neighbouring city. "This road from Civita Vecchia," writes Miss Edwards, the talented authoress of 'Barbara's History,' "lies among shapeless hillocks, shaggy with bush and briar. Far away on one side gleams a line of soft blue sea—on the other lie mountains as blue, but not more distant. Not a sound stirs the stagnant air. Not a tree, not a housetop, breaks the wide monotony. The dust lies beneath the wheels like a carpet, and follows like a cloud. The grass is yellow, the weeds are parched; and where there have been wayside pools, the ground is cracked and dry. Now we pass a crumbling fragment of something that may have been a tomb or temple, centuries ago. Now we come upon a little wide-eyed peasant boy, keeping goats among the ruins, like Giotto of old. Presently a buffalo lifts his black mane above the neighbouring hillock, and rushes away before we can do more than point to the spot on which we saw it. Thus the day attains its noon, and the sun hangs overhead like a brazen shield, brilliant, but cold. Thus, too, we reach the brow of a long and steep ascent, where our driver pulls up to rest his weary beasts. The sea has now faded almost out of sight; the mountains look larger and nearer, with streaks of snow upon their summits, the Campagna reaches on and on and shows no sign of limit or of verdure,—while, in the midst of the clear air, half way, so it would seem, between you and the purple Sabine range, rises one solemn solitary dome. Can it be the dome of St. Peter's?"

The great feature of the Civita Vecchia route was that after all the utter desolation and dreariness of many miles of the least interesting part of the Campagna, the traveller was almost stunned by the transition, when on suddenly passing the Porta Cavalleggieri, he found himself in the Piazza, of St. Peter's, with its wide-spreading colonnades, and high-springing fountains; indeed the first building he saw was St. Peter's, the first house that of the Pope, the palace of the Vatican. But the more gradual approach by land from Viterbo and Tuscany possessed equal if not superior interest.

"When we turned the summit above Viterbo," wrote Dr. Arnold, "and opened on the view on the other side, it might be called the first approach to Rome. At the distance of more than forty miles, it was of course impossible to see the town, and besides the distance was hazy; but we were looking on the scene of the Roman history; we were standing on the outward edge of the frame of the great picture, and though the features of it were not to be traced distinctly, yet we had the consciousness that they were before us. Here, too, we first saw the Mediterranean, the Alban hills, I think, in the remote distance, and just beneath us, on the left, Soracte, an outlier of the Apennines, which has got to the right bank of the Tiber, and stands out by itself most magnificently. Close under us in front, was the Ciminian lake, the crater of an extinct volcano, surrounded as they all are, with their basin of wooded hills, and lying like a beautiful mirror stretched out before us. Then there was the grand beauty of Italian scenery, the depth of the valleys, the endless variety of the mountain outline, and the towns perched upon the mountain summits, and this now seen under a mottled sky, which threw an ever-varying light and shadow over the valley beneath, and all the freshness of the young spring. We descended along one of the rims of this lake to Ronciglione, and from thence, still descending on the whole, to Monterosi. Here the famous Campagna begins, and it certainly is one of the most striking tracts of country I ever beheld. It is by no means a perfect flat, except between Rome and the sea; but rather like the Bagshot Heath country, ridges of hills with intermediate valleys, and the road often running between high steep banks, and sometimes crossing sluggish streams sunk in a deep bed. All these banks are overgrown with broom, now in full flower; and the same plant was luxuriant everywhere. There seemed no apparent reason why the country should be so desolate; the grass was growing richly everywhere. There was no marsh anywhere visible, but all looked as fresh and healthy as any of our chalk downs in England. But it is a wide wilderness; no villages, scarcely any houses, and here and there a lonely ruin of a single square tower, which I suppose used to serve as strongholds for men and cattle in the plundering warfare in the middle ages. It was after crowning the top of one of these lines of hills, a little on the Roman side of Baccano, at five minutes after six, according to my watch, that we had the first view of Rome itself. I expected to see St. Peter's rising above the line of the horizon, as York Minster does, but instead of that, it was within the horizon, and so was much less conspicuous, and from the nature of the ground, it looked mean and stumpy. Nothing else marked the site of the city, but the trees of the gardens and a number of white villas specking the opposite bank of the Tiber for some little distance above the town, and then suddenly ceasing. But the whole scene that burst upon our view, when taken in all its parts, was most interesting. Full in front rose the Alban hills, the white villas on their sides distinctly visible, even at that distance, which was more than thirty miles. On the left were the Apennines, and Tivoli was distinctly to be seen on the summit of its mountain, on one of the lowest and nearest parts of the chain. On the right and all before us lay the Campagna, whose perfectly level outline was succeeded by that of the sea, which was scarcely more so. It began now to get dark, and as there is hardly any twilight, it was dark soon after we left La Storta, the last post before you enter Rome. The air blew fresh and cool, and we had a pleasant drive over the remaining part of the Campagna, till we descended into the valley of the Tiber, and crossed it by the Milvian bridge. About two miles further on we reached the walls of Rome, and entered it by the Porta del Popolo."

Niebuhr coming the same way says:—"It was with solemn feelings that this morning from the barren heights of the moory Campagna, I first caught sight of the cupola of St. Peter's, and then of the city from the bridge, where all the majesty of her buildings and her history seems to lie spread out before the eye of the stranger; and afterwards entered by the Porta del Popolo."

Madame de Staël gives us the impression which the same subject would produce on a different type of character:—

"Le comte d'Erfeuil faisait de comiques lamentations sur les environs de Rome. Quoi, disait-il, point de maison de campagne, point de voiture, rien qui annonce le voisinage d'une grande ville! Ah! bon Dieu, quelle tristesse! En approchant de Rome, les postillons s'écrièrent avec transport: Voyez, voyez, c'est la coupole de Saint-Pierre! Les Napolitains montrent aussi le Vésuve; et la mer fait de même l'orgueil des habitans des côtes. On croirait voir le dôme des Invalides, s'écria le comte d'Erfeuil."

It was by this approach that most of its distinguished pilgrims have entered the capital of the Catholic world: monks, who came hither to obtain the foundation of their Orders; saints, who thirsted to worship at the shrines of their predecessors, or who came to receive the crown of martyrdom; priests and bishops from distant lands,—many coming in turn to receive here the highest dignity which Christendom could offer; kings and emperors, to ask coronation at the hands of the reigning pontiff; and among all these, came by this road, in the full fervour of Catholic enthusiasm, Martin Luther, the future enemy of Rome, then its devoted adherent. "When Luther came to Rome," says Ampère, in his 'Portraits de Rome à Divers Ages,' "the future reformer was a young monk, obscure and fervent; he had no presentiment, when he set foot in the great Babylon, that ten years later he would burn the bull of the Pope in the public square of Wittenberg. His heart experienced nothing but pious emotions; he addressed to Rome in salutation the ancient hymn of the pilgrims; he cried, 'I salute thee, O holy Rome, Rome venerable through the blood and the tombs of the martyrs.' But after having prostrated on the threshold, he raised himself, he entered into the temple, he did not find the God he looked for; the city of the saints and martyrs was a city of murderers and prostitutes. The arts which marked this corruption were powerless over the stolid senses, and scandalised the austere spirit of the German monk; he scarcely gave a passing glance at the ruins of pagan Rome;—and inwardly horrified by all that he saw, he quitted Rome in a frame of mind very different from that which he brought with him; he knelt then with the devotion of the pilgrims, now he returned in a disposition like that of the frondeurs of the Middle Ages, but more serious than theirs. This Rome of which he had been the dupe, and concerning which he was disabused, should hear of him again; the day would come when, amid the merry toasts at his table, he would cry three times, 'I would not have missed going to Rome for a thousand florins, for I should always have been uneasy lest I should have been rendering injustice to the Pope.'"

When one is in Rome life seems to be free from many of the petty troubles which beset it in other places; there is no foreign town which offers so many comforts and advantages to its English visitors. The hotels, indeed, are enormously expensive, and the rent of apartments is high; but when the latter is once paid, living is rather cheap than otherwise, especially for those who do not object to dine from a trattoria, and to drive in hackney carriages.

The climate of Rome is very variable. If the sirocco blows, it is mild and very relaxing; but the winters are more apt to be subject to the severe cold of the tramontana, which requires even greater precaution and care than that of an English winter. Nothing can be more mistaken than the impression that those who go to Italy are sure to find there a mild and congenial temperature. The climate of Rome has been subject to severity, even from the earliest times of its history. Dionysius speaks of one year in the time of the republic when the snow at Rome lay seven feet deep, and many men and cattle died of the cold.[1] Another year, the snow lay for forty days, trees perished, and cattle died of hunger.[2] Present times are a great improvement on these: snow seldom lies upon the ground for many hours together, and the beautiful fountains of the city are only hung with icicles long enough to allow the photographers to represent them thus; but still the climate is not to be trifled with, and violent transitions from the hot sunshine to the cold shade of the streets often prove fatal. "No one but dogs and Englishmen," say the Romans, "ever walk in the sun."

The malaria, which is so much dreaded by the natives, lies dormant during the winter months, and seldom affects strangers, unless they are inordinately imprudent in sitting out in the sunset. With the heats of the late summer this insidious ague-fever is apt to follow on the slightest exertion, and particularly to overwhelm those who are employed in field labour. From June to November the Villa Borghese and the Villa Doria are uninhabitable, and the more deserted hills—the Cœlian, the Aventine, and the greater part of the Esquiline,—are a constant prey to fever. The malaria, however, flies before a crowd of human life, and the Ghetto, which teems with inhabitants, is perfectly free from it. In the Campagna,—with the exception of Porto d'Anzio, which has always been healthy,—no town or village is safe after the month of August, and to this cause the utter desolation of so many formerly populous sites (especially those of Veii and Galera) may be attributed:—

Thus wrote Peter Damian in the 10th century, and those who refuse to be on their guard will find it so still.

The greatest risk at Rome is incurred by those who, coming out of the hot sunshine, spend long hours in the Vatican and the other galleries, which are filled with a deadly chill during the winter months. As March comes on this chill wears away, and in April and May the temperature of the galleries is delightful, and it is impossible to find a more agreeable retreat. It is in the hope of inducing strangers to spend more time in the study of these wonderful museums, and of giving additional interest to the hours which are passed there, that so much is said about their contents in these volumes. As far as possible it has been desired to evade any mere catalogue of their collections,—so that no mention has been made of objects which possess inferior artistic or historical interest; while by introducing anecdotes connected with those to which attention is drawn, or by quoting the opinion of some good authority concerning them, an endeavour has been made to fix them in the recollection.

So much has been written about Rome, that in quoting from the remarks of others the great difficulty has been selection,—and the rule has been followed that the most learned books are not always the most instructive or the most interesting. No endeavour has been made to enter into deep archæological questions,—to define the exact limits of the Walls of Servius Tullius,—or to hazard a fresh opinion as to how the earth accumulated in the Roman Forum, or whence the pottery came, out of which the Monte Testaccio has arisen; but it has rather been sought to gather up and present to the reader such a succession of word pictures from various authors, as may not only make the scenes of Rome more interesting at the time, but may deepen their impression afterwards. This was the work which the late illustrious M. Ampère intended to carry out, and which he would have done so much better and more fully.

From the experience of many years the writer can truly say that the more intimately these scenes become known, the more deeply they become engraven upon the inmost affections. Rome, as Goethe truly says, "is a world, and it takes years to find oneself at home in it." It is not a hurried visit to the Coliseum, with guide book and cicerone, which will enable one to drink in the fulness of its beauty; but a long and familiar friendship with its solemn walls, in the ever-varying grandeur of golden sunlight and grey shadow—till, after many days' companionship, its stones become dear as those of no other building ever can be;—and it is not a rapid inspection of the huge cheerless basilicas and churches, with their gaudy marbles and gilded ceilings and ill-suited monuments, which arouses your sympathy; but the long investigation of their precious fragments of ancient cloister, and sculptured fountain,—of mouldering fresco, and mediæval tomb,—of mosaic-crowned gateway, and palm-shadowed garden;—and the gradually-acquired knowledge of the wondrous story which clings around each of these ancient things, and which tells how each has a motive and meaning entirely unsuspected and unseen by the passing eye.

The immense extent of Rome, and the wide distances to be traversed between its different ruins and churches, is in itself a sufficient reason for devoting more time to it than to the other cities of Italy. Surprise will doubtless be felt that so few pagan ruins remain, considering the enormous number which are known to have existed even down to a comparatively late period. A monumental record of A.D. 540, published by Cardinal Mai, mentions 324 streets, 2 capitols—the Tarpeian and that on the Quirinal,—80 gilt statues of the gods (only the Hercules remains), 66 ivory statues of the gods, 46,608 houses, 17,097 palaces, 13,052 fountains, 3785 statues of emperors and generals in bronze, 22 great equestrian statues of bronze (only Marcus Aurelius remains), 2 colossi (Marcus Aurelius and Trajan), 9026 baths, 31 theatres, and 8 amphitheatres!

It is impossible to speak too highly of the facilities afforded to strangers for seeing and enjoying everything, especially by the Roman nobility. The beautiful grounds of the Villa Borghese and the Villa Doria appear to be kept up at an enormous expense, solely for the use and pleasure of the public, and almost all the palaces and collections are thrown open on fixed days with unequalled liberality. In almost all these galleries, museums, and gardens the stranger is permitted to wander about and linger as he pleases, entirely unmolested by officious servants and ignorant ciceroni.

Those will enjoy Rome most who have studied it thoroughly before leaving their own homes. In the multiplicity of engagements in which a foreigner is soon involved, there is little time for historical research, and few are able to do more than "read up their Murray," so that half the pleasure and all the advantage of a visit to Rome are thrown away: while those who arrive with the foundation already prepared, easily and naturally acquire, amid the scenes around which the history of the world revolved, an amount of information which will be astonishing even to themselves. "People out of Rome," says Goethe, "have no idea how one is schooled there;" but then, as the author of 'Vera' remarks, "that is true of Rome, which Madame Swetchine said of life, viz. that you find exactly what you put into it."

The pagan monuments of Rome have been written of and discussed ever since they were built, and the catacombs have lately found historians and guides both able and willing,—about the later Christian monuments far less has hitherto been said. In English, except in the immense collection of interest which is imbedded in the works of Hemans, and in the few beautiful notices of some of the early martyrs by Mrs. Jameson, very little has been written; in French there is far more. There is a natural shrinking in the English Protestant mind from all that is connected with the story of the saints,—especially the later saints of the Roman Catholic Church. Many believe, with Addison, "that the Christian antiquities are so embroiled in fable and legend, that one derives but little satisfaction from searching into them." And yet, as Mrs. Jameson observes, when all that the controversialist can desire is taken away from the reminiscences of those, who to the Roman Catholic mind have consecrated the homes of their earthly life, how much remains!—"so much to awaken, to elevate, to touch the heart;—so much that will not fade from the memory, so much that may make a part of our after-life."

No attempt has been made in these pages to describe the country round Rome, beyond a few of the most ordinary drives and excursions outside the walls. The opening of the railways to Naples and Civita Vecchia have now brought a vast variety of new excursions within the range of a day's expedition—and the papal citadel of Anagni, the temples of Cori, the cyclopean remains of Segni, Alatri, Norba, Cervetri, and Corneto, and the wild heights of Soracte, will probably ere long become as well known as the oft-visited Tivoli, Ostia, and Albano. It is intended to supplement these "Walks in Rome" by a similar volume of "Excursions round Rome."

Hotels.—For passing travellers or bachelors, the best are: Hotel d'Angleterre, Bocca di Leone; Hotel de Rome, Corso. For families, or for a long residence: Hotel des Iles Britanniques, Piazza del Popolo; Hotel de Russie (close to the last), Via Babuino; Hotel de Londres, and Hotel Europa, Piazza di Spagna; Hotel Costanzi, Via S. Nicolo in Tolentino, in a high airy situation towards the railway-station, and very comfortable and well managed, but further from the sights of Rome. Less expensive, are: Hotel d'Allemagne, Via Condotti; Hotel Vittoria, Via Due Macelli; Hotel d'Italie, Via Quattro Fontane; Hotel della Pace, 8 Via Felice; Hotel Minerva, Piazza della Minerva, very near the Pantheon. A large new hotel is the "Quirinale," in the Via Nazionale.

Pensions are much wanted in Rome. The best are those of Miss Smith and Madame Tellenbach, in the Piazza di Spagna; Pension Suez, Via S. Nicolo in Tolentino; and the small Hotel du Sud, in the Capo le Case.

Apartments have lately greatly increased in price. An apartment for a very small family in one of the best situations can seldom be obtained for less than 300 to 500 francs a month. The English almost all prefer to reside in the neighbourhood of the Piazza di Spagna. The best situations are the sunny side of the Piazza itself, the Trinità de' Monti, the Via Gregoriana, and Via Sistina. Less good situations are, the Corso, Via Condotti, Via Due Macelli, Via Frattina, Capo le Case, Via Felice, Via Quattro Fontane, Via Babuino, and Via delle Croce,—in which last, however, are many very good apartments. On the other side of the Corso suites of rooms are much less expensive, but they are less convenient for persons who make a short residence in Rome. In many of the palaces are large apartments which are let by the year.

Trattorie (Restaurants) send out dinners to families in apartments in a tin box with a stove, for which the bearer calls the next morning. A dinner for six francs ought to be amply sufficient for three persons, and to leave enough for luncheon the next day. Restaurants where luncheons or dinners may be obtained upon the spot, are those of Bedeau, Via della Croce, and Nazzari, Piazza di Spagna. Those who wish for a real Roman dinner of Porcupine, Hedgehog, and other such delicacies, find it at the Falcone, where Ariosto used to lodge when in Rome.

English Church.—Just outside the Porta del Popolo, on the left. Services at 9 A.M., 11 A.M., and 3 P.M. on Sundays; daily service twice on week-days. The American Church is in the same building, with an entrance further on.

Post Office.—In the Piazza Colonna. The English mail leaves daily at 8 P.M.

Telegraph Office.—121 Piazza Monte-Citorio. A telegraph of 20 words to England, including name and address, costs 11 francs.

Bankers.—Hooker, 20 Piazza di Spagna; Macbean, 378 Corso; Plowden, 50 Via Mercede; Spada and Flamini, 20 Via Condotti.

For sending Boxes to England.—Welby, Strada Papala. (His agents in London, Messrs. Scott, 11 King William St.)

English Doctors.—Dr. Grigor, 3 Pa di Spagna; Dr. Small, 56 Via Babuino; Dr. Gason, 82 Via della Croce. German: Dr. Taussig, 144 Via Babuino. American: Dr. Gould, 107 Via Babuino. Italian: Dr. Valeri, 138 Via Babuino.

Homœopathic Doctor.—Dr. Liberali, 69 Via della Frezza.

Dentist.—Dr. Parmby, 93 Piazza di Spagna.

Sick-nurses.—Mrs. Meyer, 44 Via delle Carozze; the Nuns of the Bon-Secours at the convent in the Via del Banchi.

Chemists.—English Pharmacy, 498 Corso; Sininberghi, 134 Via Frattina; and Borioni, Via Babuino, are those usually employed by the English; but the chemists' shops in the Corso are as good, and much less expensive.

English House Agent.—Shea, 11 Piazza di Spagna.

English Livery Stables.—Jarrett, 3 Piazza del Popolo; Ranucci, Vicolo Aliberti.

Circulating Library.—Piale, 1, 2, Piazza di Spagna.

Booksellers.—Monaldini, Piazza di Spagna; Spithover, Piazza di Spagna; Bocca, 216 Corso; Loesther, 346 Corso.

Italian Masters.—Vannini, 31 Via Condotti (in the summer at the Bagni di Lucca); Monachesi (a Roman), 8 Via S. Sebastianello; Gordini, 374 Corso; N. Lucantini, 17 Via della Stamperia.

Photographers.—For views of Rome.—Watson, Via Babuino; Macpherson, 12 Vicolo Aliberti; Mang, 104 Via Felice; Anderson (his photographs sold at Spithover's); Joseph Phelps, 169 Via Babuino; Maggi, 329 Corso. For Artistic Bits, very much to be recommended, De Bonis, 11 Via Felice. For Portraits.—Suscipi, 48 Via Condotti (the best for medallions); Alessandri, 12 Corso (excellent for Cartes de Visite); Lais, 57 Via del Campo-Marzo; Ferretti, 50 Via Sta. Maria in Via.

Drawing Materials.—Dovizelli, 136 Via Babuino; Corteselli, 150 Via Felice. For commoner articles and stationery, the "Cartoleria," 214 Corso, opposite the Piazza Colonna.

Engravings.—At the Stamperia Nazionale (fixed prices), 6 Via della Stamperia, near the fountain of Trevi.

Antiquities.—Depoletti, 31 Via Fontanella Borghese; Innocenti, 118 Via Frattina; Santelli, 141 Via Frattina; Capobianchi, 152 Via Babuino.

Bronzes.—Röhrich, 104 Via Sistina; Chiapanelli, 92 Via Babuino; Dressler, 17 Via Due Macelli.

Cameos.—Saulini, 96 Via Babuino; Neri, 72 Via Babuino.

Mosaics.—Rinaldi, 125 Via Babuino; Boschetti, 74 Via Condotti.

Jewellers.—Castellani, 88 Via Poli (closed from 12 to 1), very beautiful, but very expensive; Pierret, 20 Piazza di Spagna; Innocenti, 33 Piazza Trinità de' Monti.

Roman Pearls.—Rey, 122 Via Babuino; Lacchini, 70 Via Condotti.

Bookbinder.—Olivieri, 1 Via Frattina.

Engraver.—(For visiting cards, &c.), Martelli, 139 Via Frattina.

Tailors.—Mattina (the "Poole" of Rome), Corso, opposite S. Carlo, entrance 2 Via delle Carozze; Vai, 60 Piazza di Spagna; Reanda, 61 Piazza. S. Apostoli; Evert, 77 Piazza Borghese.

Shoemakers.—Rubini, 223 Corso (none good).

Dressmaker.—Clarisse, 166 Corso.

Shops for Ladies' Dress.—Massoni, Palazzo Simonetti; the Ville de Lyon, 48 Via dei Prefetti (behind S. Lorenzo in Lucina); Sebastiani, 8 Via del Campo-Marzo; Giovannetti, 50 to 53 Campo-Marzo.

Roman Ribbons and Shawls.—Arvotti, 66 Piazza Madama (fixed prices); Bianchi, 82 Via della Minerva.

Gloves.—Cremonesi, 420 Corso; 4 Piazza S. Lorenzo in Lucina.

Carpets and small Household Articles.—Cagiati, 250 Corso.

German Baker.—Colalucci, 88 Via della Croce (excellent).

English Grocer.—Lowe, 76 Piazza di Spagna.

Italian Grocer and Wine Merchant.—Giacosa, Via della Maddalena.

Oil, Candles and Wood, &c.—Luigioni, 70 Piazza di Spagna.

English Dairy.—Palmegiani, 66 Piazza di Spagna.

Artists' Studios.—

Benonville, 61 Via Babuino,—landscapes.

Brennan, 76 Via Borghetto.

Coleman, 16 Via dei Zucchelli,—very good for animals.

Corrodi, 25 Angelo-Custode,—water-colour landscapes, very highly finished.

Desoulavy, 33 Via Margutta,—landscapes.

Fattorini, Via Margutta,—a very beautiful copyist.

Flatz, 3 Mario di Fiori,—sacred subjects.

Haseltine, J. H., 59 Via Babuino.

*Joris, 33 Via Margutta,—quite first-rate for figure subjects in water-colour.

Garelli, 217 Ripetta,—an admirable copyist, generally to be found in the Capitoline Gallery.

*Glennie, 17 Piazza Margana,—water-colour, first-rate.

Knebel, 33 Via Margutta,—oil landscapes.

Maes, 33 Via Margutta.

*Marianecci, 53 Via Margutta,—the prince of copyists.

Muller, 60 Piazza Barberini,—water-colour landscapes.

Podesti, 55 Via Margutta,—oil: large historical and sacred subjects.

Poingdestre, 36 Vicolo dei Greci—oil: landscapes.

Buchanan Read, 55 Via Margutta.

*Rivière, 36 Vicolo dei Greci,—water-colour.

De Sanctis, 33 Via Margutta.

Strutt (Arthur), 81 Via della Croce,—landscapes and figures, both oil and water-colour.

Tapiro (Spanish), 72 Sistina,—admirable for figures.

Tilton, 20 Via S. Basilio,—remarkable for his drawings of the Nile.

Vertunni, 53 Via Margutta.

Wedder, 55A Via Margutta.

*Penry Williams, 12 Piazza Mignanelli.

Sculptors' Studios.—

D'Epinay, 57 Via Sistina.

Fabj-Altini, 4 S. Nicolo in Tolentino.

Miss Foley, 53 Via Margutta,—admirable for medallion portraits and

busts, also the author of a beautiful fountain.

*Miss Hosmer, 118 Via Margutta—(Gibson's studio).

Miss Lewis, 8 Via S. Nicolo in Tolentino.

Macdonald, 7 Piazza Barberini.

Rosetti, 55 Via Margutta.

Story, 2 Via S. Nicolo in Tolentino.

Tadolini, 150A Via Babuino.

Wood (Shakspeare), 504 Corso,—excels in medallion portraits.

Wood (Warrington), 7 Piazza Trinità de' Monti.

It is impossible for a traveller who spends only a week or ten days in Rome to see a tenth part of the sights which it contains. Perhaps the most important objects are:

Churches.—S. Peter's, S. John Lateran, Sta. Maria Maggiore, S. Lorenzo fuori Mura, S. Paoli fuori Mura, S. Agnese fuori Mura, Ara Cœli, S. Clemente, S. Pietro in Montorio, S. Pietro in Vincoli, Sta. Sabina, Sta. Prassede and Sta. Pudentiana, S. Gregorio, S. Stefano Rotondo, Sta. Maria sopra Minerva, Sta. Maria del Popolo.

Palaces.—Vatican, Capitol, Borghese, Barberini (and, if possible, Corsini, Colonna, Sciarra, Rospigliosi, and Spada).

Villas.—Albani, Doria, Borghese, Wolkonski, and, though less important, Ludovisi.

Ruins.—Palace of the Cæsars, Temples in Forum, Coliseum, and, if possible, the ruins in the Ghetto, and the Baths of Caracalla.

It is desirable for the traveller who is pressed for time to apply at once to his Banker for orders for any of the villas for which they are necessary. The following scheme will give a good general idea of Rome and its neighbourhood in a few days. The sights printed in italics can only be seen on the days to which they are ascribed:—

Monday.—General view of Capitol, Gallery of Sculpture, Ara Cœli, General view of Forum, Coliseum, St. John Lateran (with cloisters), and drive out to the Via Latina and the aqueducts at Tavolato.

Tuesday.—Morning: St. Peter's and the Vatican Stanze. Afternoon: Villa Albani, St. Agnese, and drive to the Ponte Nomentana.

Wednesday.—Go to Tivoli (the Cascades, Cascatelle, and Villa d'Este).

Thursday.—Morning: Palace of the Cæsars. Afternoon: drive on the Via Appia as far as Torre Mezzo Strada; in returning, see the Baths of Caracalla.

Friday.—Morning: Palazzo Borghese, Palazzo Spada, The Ghetto, The Temple of Vesta, cross the Ponte Rotto to Sta. Cecilia; and end in the afternoon at St. Pietro in Montorio and the Villa Doria (or on Monday).

Saturday.—Frascati and Albano. Drive to Frascati early, take donkeys, by Rocca di Papa to Mte. Cavo; take luncheon at the Temple, and return by Palazzuolo and the upper and lower Galleries to Albano, whither the carriage should be sent on to await you at the Hotel de Russie. Drive back to Rome in the evening.

Sunday.—Morning: Sta. Maria del Popolo on way to English Church. Afternoon: St. Peter's again; drive to Monte Mario (Villa Mellini), or in the Villa Borghese, and end with the Pincio.

2d Monday.—Morning: Sta. Prassede, Sta. Pudentiana, Sta. Maria Maggiore. Afternoon: Sta. Sabina, Priorato Garden, English Cemetery, S. Paolo, and the Tre Fontane.

2d Tuesday.—Morning: Vatican Sculptures. Afternoon: S. Gregorio, S. Stefano Rotondo, S. Clemente, S. Pietro in Vincoli, Sta. Maria degli Angeli, S. Lorenzo fuori Mura, and drive out to the Torre dei Schiavi, returning by the Porta Maggiore.

2d Wednesday.—Morning: Palazzo Barberini, Palazzo Rospigliosi, (and on Saturdays) Vatican Pictures. Afternoon: Forum in detail, SS. Cosmo and Damian, and ascend the Coliseum.

The following list may be useful as a guide to some of the best subjects for artists who wish to draw at Rome, and have not much time to search for themselves:—

Morning Light:

Temple of Vesta with the fountain.

Arch of Constantine from the Coliseum (early).

Coliseum from behind Sta. Francesca Romana (early).

Temples in the Forum from the School of Xanthus.

View from the Garden of the Rupe Tarpeia.

In the Garden of S. Giovanni e Paolo.

In the Garden of S. Buonaventura.

In the Garden of the S. Bartolomeo in Isola.

In the Garden of S. Onofrio.

On the Tiber from Poussin's Walk.

From the door of the Villa Medici.

At S. Cosimato.

At the back entrance of Ara Cœli.

At the Portico of Octavia.

Looking to the Arch of Titus up the Via Sacra.

In the Cloister of the Lateran.

In the Cloister of the Certosa.

Near the Temple of Bacchus.

On the Via Appia, beyond Cecilia Metella.

Torre Mezza Strada on the Via Appia.

Torre Nomentana, looking to the mountains.

Ponte Nomentana, looking to the Mons Sacer.

Torre dei Schiavi, looking towards Tivoli.

Aqueducts at Tavolato.

Evening Light:

From St. John Lateran.

From the Ponte Rotto.

From the Terrace of the Villa Doria (St. Peter's).

Palace of the Cæsars—Roman side—looking to Sta. Balbina.

Palace of the Cæsars—French side—looking to the Coliseum.

Apse of S. Giovanni e Paolo.

Near the Navicella.

Garden of the Villa Mattei.

Garden of the Villa Wolkonski.

Garden of the Priorato.

Porta S. Lorenzo.

Torre dei Schiavi, looking towards Rome.

Via Latina, looking towards the Aqueducts.

Via Latina, looking towards Rome.

The months of November and December are the best for drawing. The colouring is then magnificent; it is enhanced by the tints of the decaying vegetation, and the shadows are strong and clear. January is generally cold for sitting out, and February wet; and before the end of March the vegetation is often so far advanced that the Alban Hills, which have retained glorious sapphire and amethyst tints all winter, change into commonplace green English downs; while the Campagna, from the crimson and gold of its dying thistles and fenochii, becomes a lovely green plain waving with flowers.

Foreigners are much too apt to follow the native custom of driving constantly in the Villa Borghese, the Villa Doria, and on the Pincio, and getting out to walk there during their drives. For those who do not care always to see the human world, a delightful variety of drives can be found; and it is a most agreeable plan for invalids, without carriages of their own, to take a "course to the Parco di San Gregorio," or to the sunny avenues near the Lateran, and walk there instead of on the Pincio. A carriage for the return may almost always be found in the Forum or at the Lateran.

The Piazza del Popolo—Obelisk—Sta. Maria del Popolo—(The Pincio—Villa Medici—Trinità de' Monti) (Via Babuino—Via Margutta—Piazza di Spagna—Propaganda) (Via Ripetta—SS. Rocco e Martino—S. Girolamo degli Schiavoni)—S. Giacomo degli Incurabili—Via Vittoria—Mausoleum of Augustus—S. Carlo in Corso—Via Condotti—Palazzo Borghese—Palazzo Ruspoli—S. Lorenzo in Lucina—S. Sylvestro in Capite—S. Andrea delle Fratte—Palazzo Chigi—Piazza Colonna—Palace and Obelisk of Monte-Citorio—Temple of Neptune—Fountain of Trevi—Palazzo Poli—Palazzo Sciarra—The Caravita—S. Ignazio—S. Marcello—Sta. Maria in Via Lata—Palazzo Doria Pamfili—Palazzo Salviati—Palazzo Odescalchi—Palazzo Colonna—Church of SS. Apostoli—Palazzo Savorelli—Palazzo Buonaparte—Palazzo di Venezia—Palazzo Torlonia—Ripresa dei Barberi—S. Marco—Church of Il Gesu—Palazzo Altieri.

THE first object of every traveller will naturally be to reach the Capitol, and look down thence upon ancient Rome; but as he will go down to the Corso to do this, and must daily pass most of its surrounding buildings, we will first speak of those objects which will, ere long, become the most familiar.

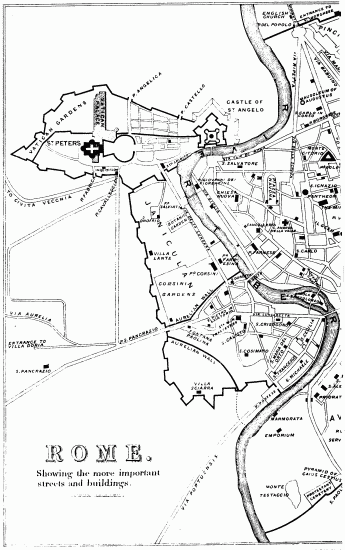

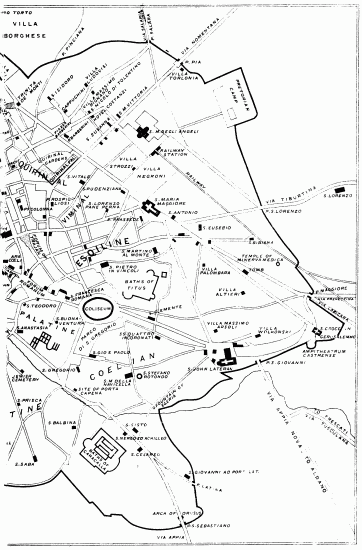

A stranger's first lesson in Roman geography should be learnt standing in the Piazza del Popolo, whence three streets branch off—the Corso, in the centre, leading towards the Capitol, beyond which lies ancient Rome; the Babuino, on the left, leading to the Piazza di Spagna and the English quarter; the Ripetta, on the right, leading to the Castle of St. Angelo and St. Peter's. The scene is one well known from pictures and engravings. The space between the streets is occupied by twin churches, erected by Cardinal Gastaldi.

"Les deux églises élevées au Place du Peuple par le Cardinal Gastaldi à l'entrée du Corso, sont d'un effet médiocre. Comment un cardinal n'a-t-il pas senti qu'il ne faut pas élever une église pour faire pendant à quelque chose? C'est ravaler la majesté divine." Stendhal, i. 172.

It is in the church on the left that sermons are preached every winter on Sunday afternoons by some of the best Roman Catholic controversialists, just at the right moment for catching the Protestant congregations as they emerge from their chapels outside the Porta del Popolo.

These churches are believed to occupy the site of the magnificent tomb of Sylla, who died at Puteoli B.C. 82, but was honoured at Rome with a public funeral, at which the patrician ladies burnt masses of incense and perfumes on his funeral pyre.

The Obelisk of the Piazza del Popolo was placed on this site by Sixtus V. in 1589, but was originally brought to Rome and erected in honour of Apollo by the Emperor Augustus.

"Apollo was the patron of the spot which had given a name to the great victory of Actium; Apollo himself, it was proclaimed, had fought for Rome and for Octavius on that auspicious day; the same Apollo, the Sun-god, had shuddered in his bright career at the murder of the Dictator, and terrified the nations by the eclipse of his divine countenance." ... Therefore, "besides building a temple to Apollo on the Palatine hill, the Emperor Augustus sought to honour him by transplanting to the Circus Maximus, the sports of which were under his special protection, an obelisk from Heliopolis, in Egypt. This flame-shaped column was a symbol of the sun, and originally bore a blazing orb upon its summit. It is interesting to trace an intelligible motive for the first introduction into Europe of these grotesque and unsightly monuments of eastern superstition."—Merivale, Hist. of the Romans.

"This red granite obelisk, oldest of things, even in Rome, rises in the centre of the piazza, with a four-fold fountain at its base. All Roman works and ruins (whether of the empire, the far-off republic, or the still more distant kings) assume a transient, visionary, and impalpable character, when we think that this indestructible monument supplied one of the recollections which Moses and the Israelites bore from Egypt into the desert. Perchance, on beholding the cloudy pillar and fiery column, they whispered awe-stricken to one another, 'In its shape it is like that old obelisk which we and our fathers have so often seen on the borders of the Nile.' And now that very obelisk, with hardly a trace of decay upon it, is the first thing that the modern traveller sees after entering the Flaminian Gate."—Hawthorne's Transformation.

It was on the left of the Piazza, at the foot of what was even then called "the Hill of Gardens," that Nero was buried (A.D. 68).

"When Nero was dead, his nurse Eclaga, with Alexandra, and Acte the famous concubine, having wrapped his remains in rich white stuff, embroidered with gold, deposited them in the Domitian monument, which is seen in the Campus-Martius under the Hill of Gardens. The tomb was of porphyry, having an altar of Luna marble, surrounded by a balustrade of Thasos marble."—Suetonius.

Church tradition tells that from the tomb of Nero afterwards grew a gigantic walnut-tree, which became the resort of innumerable crows,—so numerous as to become quite a pest to the neighbourhood. In the eleventh century, Pope Paschal II. dreamt that these crows were demons, and that the Blessed Virgin commanded him to cut down and burn the tree ("albero malnato"), and build a sanctuary to her honour in its place. A church was then built by means of a collection amongst the common people; hence the name which it still retains of "St. Mary of the People."

Sta. Maria del Popolo was rebuilt by Bacio Pintelli for Sixtus IV. in 1480, and very richly adorned. It was modernized by Bernini for Alexander VII. (Fabio Chigi, 1655-67), of whom it was the family burial-place, but it still retains many fragments of beautiful fifteenth century work (the principal door of the nave is a fine example of this); and its interior is a perfect museum of sculpture and art.

Entering the church by the west door, and following the right aisle, the first chapel (Venuti, formerly Della Rovere[3]) is adorned with exquisite paintings by Pinturicchio. Over the altar is the Nativity—one of the most beautiful frescoes in the city; in the lunettes are scenes from the life of St. Jerome. Cardinal Christoforo della Rovere, who built this chapel and dedicated it to "the Virgin and St. Jerome," is buried on the left, in a grand fifteenth century tomb; on the right is the monument of Cardinal di Castro. Both of these tombs and many others in this church have interesting and greatly varied lunettes of the Virgin and Child.

The second chapel, of the Cibo family, rich in pillars of nero-antico and jasper, has an altarpiece representing the Assumption of the Virgin, by Carlo Maratta. In the cupola is the Almighty, surrounded by the heavenly host.[4]

The third chapel is also painted by Pinturicchio. Over the altar, the Madonna and four saints; above, God the Father, surrounded by angels. In the other lunettes, scenes in the life of the Virgin;—that of the Virgin studying in the Temple, a very rare subject, is especially beautiful. In a frieze round the lower part of the wall, a series of martyrdoms in grisaille. On the right is the tomb of Giovanni della Rovere, ob. 1483. On the left is a fine sleeping bronze figure of a bishop, unknown.

The fourth chapel has a fine fifteenth century altar-relief of St. Catherine between St. Anthony of Padua and St. Vincent. On the right is the tomb of Marc-Antonio Albertoni, ob. 1485; on the left, that of Cardinal Costa, of Lisbon, ob. 1508, erected in his lifetime. In this tomb is an especially beautiful lunette of the Virgin adored by Angels.

Entering the right transept, on the right is the tomb of Cardinal Podocanthorus of Cyprus, a very fine specimen of fifteenth century work. A door near this leads into a cloister, where is preserved, over a door, the Gothic altar-piece of the church of Sixtus IV, representing the Coronation of the Virgin, and two fine tombs—Archbishop Rocca, ob. 1482, and Bishop Gomiel.

The choir (shown when there is no service) has a ceiling by Pinturicchio. In the centre, the Virgin and Saviour, surrounded by the Evangelists and Sibyls; in the corners, the Fathers of the Church—Gregory, Ambrose, Jerome, and Augustine. Beneath are the tombs of Cardinal Ascanio Sforza, and Cardinal Girolamo Basso, nephews of Sixtus IV. (Francesco della Rovere), beautiful works of Andrea di Sansovino. These tombs were erected at the expense of Julius II., himself a Della Rovere, who also gave the windows, painted by Claude and Guillaume de Marseilles, the only good specimens of stained glass in Rome.

The high-altar is surmounted by a miraculous image of the Virgin, inscribed, "In honorificentia populi nostri," which was placed in this church by Gregory IX., and which, having been "successfully invoked" by Gregory XIII., in the great plague of 1578, has ever since been annually adored by the pope of the period, who prostrates himself before it upon the 8th of September. The chapel on the left of this has an Assumption, by Annibale Caracci.

In the left transept is the tomb of Cardinal Bernardino Lonati, with a fine fifteenth century relief of the Resurrection.

Returning by the left aisle, the last chapel but one is that of the Chigi family, in which the famous banker, Agostino Chigi (who built the Farnesina) is buried, and in which Raphael is represented at once as a painter, a sculptor, and an architect. He planned the chapel itself; he drew the strange design of the Mosaic on the ceiling (carried out by Aloisio della Pace), which represents an extraordinary mixture of Paganism and Christianity, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn (as the planets), conducted by angels, being represented with and surrounding Jehovah; and he modelled the beautiful statue of Jonah seated on the whale, which was sculptured in the marble by Lorenzetto. The same artist sculptured the figure of Elijah,—those of Daniel and Habakkuk being by Bernini. The altarpiece, representing the Nativity of the Virgin, is a fine work of Sebastian del Piombo. On the pier adjoining this chapel is the strange monument by Posi (1771) of a Princess Odescalchi Chigi, who died in childbirth, at the age of twenty, erected by her husband, who describes himself, "In solitudine et luctu superstes."

The last chapel contains two fine fifteenth century ciboria, and the tomb of Cardinal Antonio Pallavicini, 1507.

On the left of the principal entrance is the remarkable monument of Gio. Batt. Gislenus, the companion and friend of Casimir I. of Poland (ob. 1670). At the top is his portrait while living, inscribed, "Neque hic vivus"; then a medallion of a chrysalis, "In nidulo meo moriar"; opposite to which is a medallion of a butterfly emerging, "Ut Phœnix multiplicabo dies": below is a hideous skeleton of giallo antico in a white marble winding-sheet, "Neque hic mortuus."

Martin Luther "often spoke of death as the Christian's true birth, and this life as but a growing into the chrysalis-shell in which the spirit lives till its being is developed, and it bursts the shell, casts off the web, struggles into life, spreads its wings, and soars up to God."

The Augustine Convent adjoining this church was the residence of Luther while he was in Rome. Here he celebrated mass immediately on his arrival, after he had prostrated himself upon the earth, saying, "Hail sacred Rome! thrice sacred for the blood of the martyrs shed here!" Here, also, he celebrated mass for the last time before he departed from Rome to become the most terrible of her enemies.

"Lui pauvre écolier, élevé si durement, qui souvent, pendant son enfance, n'avait pour oreiller qu'une dalle froide, il passe devant des temples tout de marbre, devant des colonnes d'albâtre, des gigantesques obélisques de granite, des fontaines jaillissantes, des villas fraîches et embellies de jardins, de fleurs, de cascades et de grottes. Veut-il prier? il entre dans une église qui lui semble un monde véritable, où les diamants scintillent sur l'autel, l'or aux soffites, le marbre aux colonnes, la mosaïque aux chapelles, au lieu d'un de ces temples rustiques qui n'ont dans sa patrie pour tout ornement que quelques roses qu'une main pieuse va déposer sur l'autel le jour du dimanche. Est-il fatigué de la route? il trouve sur son chemin, non plus un modeste banc de bois, mais un siège d'albâtre antique récemment déterré. Cherche-t-il une sainte image? il n'aperçoit que des fantaisies païennes, des divinités olympiques, Apollon, Vénus, Mars, Jupiter, auxquelles travaillent mille mains de sculpteurs. De toutes ces merveilles, il ne comprit rien, il ne vit rien. Aucun rayon de la couronne de Raphaël, de Michel-Ange, n'éblouit ses regards; il resta froid et muet devant tous les trésors de peinture et de sculpture rassemblés dans les églises; son oreille fut fermée aux chants du Dante, que le peuple répétait autour de lui. Il était entré à Rome en pèlerin, il en sort comme Coriolan, et s'écrie avec Bembo: 'Adieu, Rome, que doit fuir quiconque veut vivre saintement! Adieu, ville où tout est permis, excepté d'être homme de bien.'"—Audin, Histoire de Luther, c. ii.

It was in front of this church that the cardinals and magnates of Rome met to receive the apostate Christina of Sweden upon her entrance into the city.

On the left side of the piazza rise the terraces of the Pincio, adorned with rostral-columns, statues, and marble bas-reliefs, interspersed with cypresses and pines. A winding road, lined with mimosas and other flowering shrubs, leads to the upper platform, now laid out in public drives and gardens, but, till twenty years ago, a deserted waste, where the ghost of Nero was believed to wander in the middle ages.

Hence the Eternal City is seen spread at our feet, and beyond it the wide-spreading Campagna, till a silver line marks the sea melting into the horizon beyond Ostia. All these churches and tall palace roofs become more than mere names in the course of the winter, but at first all is bewilderment Two great buildings alone arrest the attention:

"Westward, beyond the Tiber, is the Castle of St. Angelo, the immense tomb of a pagan emperor with the archangel on its summit.... Still further off, a mighty pile of buildings, surmounted by a vast dome, which all of us have shaped and swelled outward, like a huge bubble, to the utmost scope of our imaginations, long before we see it floating over the worship of the city. At any nearer view the grandeur of St. Peter's hides itself behind the immensity of its separate parts, so that we only see the front, only the sides, only the pillared length and loftiness of the portico, and not the mighty whole. But at this distance the entire outline of the world's cathedral, as well as that of the palace of the world's chief priest, is taken in at once. In such remoteness, moreover, the imagination is not debarred from rendering its assistance, even while we have the reality before our eyes, and helping the weakness of human sense to do justice to so grand an object. It requires both faith and fancy to enable us to feel, what is nevertheless so true, that yonder, in front of the purple outline of the hills, is the grandest edifice ever built by man, painted against God's loveliest sky."—Hawthorne.

Here the band plays under the great palm-tree every afternoon except Friday. On Sunday afternoons the Pincio is in what Miss Thackeray describes as "a fashionable halo of sunset and pink parasols"—when immense crowds collect, showing every phase of Roman life; and disperse again as the Ave-Maria bell rings from the churches, either to descend into the city, or to hear benediction sung by the nuns in the Trinità de' Monti.

"When the fashionable hour of rendezvous arrives, the same spot, which a few minutes before was immersed in silence and solitude, changes as it were with the rapidity of a scene in a pantomime to an animated panorama. The scene is rendered not a little ludicrous by the miniature representation of the Ring in Hyde Park in a small compass. An entire revolution of the carriage-drive is performed in the short period of three minutes as near as may be, and the perpetual occurrence of the same physiognomies and the same carriages trotting round and round for two successive hours, necessarily reminds one of the proceedings of a country fair, and children whirling in a roundabout."—Sir G. Head's 'Tour in Rome.'

"The Pincian Hill is the favourite promenade of the Roman aristocracy. At the present day, however, like most other Roman possessions, it belongs less to the native inhabitants than to the barbarians from Gaul, Great Britain, and beyond the sea, who have established a peaceful usurpation over all that is enjoyable or memorable in the Eternal City. These foreign guests are indeed ungrateful, if they do not breathe a prayer for Pope Clement, or whatever Holy Father it may have been, who levelled the summit of the mount so skilfully, and bounded it with the parapet of the city wall; who laid out those broad walks and drives, and overhung them with the shade of many kinds of tree; who scattered the flowers of all seasons, and of every clime, abundantly over those smooth, central lawns; who scooped out hollows in fit places, and setting great basons of marble in them, caused ever-gushing fountains to fill them to the brim; who reared up the immemorial obelisk out of the soil that had long hidden it; who placed pedestals along the borders of the avenues, and covered them with busts of that multitude of worthies,—statesmen, heroes, artists, men of letters and of song,—whom the whole world claims as its chief ornaments, though Italy has produced them all. In a word, the Pincian garden is one of the things that reconcile the stranger (since he fully appreciates the enjoyment, and feels nothing of the cost,) to the rule of an irresponsible dynasty of Holy Fathers, who seem to have arrived at making life as agreeable an affair as it can well be.

"In this pleasant spot the red-trousered French soldiers are always to be seen; bearded and grizzled veterans, perhaps, with medals of Algiers or the Crimea on their breasts. To them is assigned the peaceful duty of seeing that children do not trample on the flower-beds, nor any youthful lover rifle them of their fragrant blossoms to stick in his beloved one's hair. Here sits (drooping upon some marble bench, in the treacherous sunshine,) the consumptive girl, whose friends have brought her, for a cure, into a climate that instils poison into its very purest breath. Here, all day, come nursery maids, burdened with rosy English babies, or guiding the footsteps of little travellers from the far western world. Here, in the sunny afternoon, roll and rumble all kinds of carriages, from the Cardinal's old-fashioned and gorgeous purple carriage to the gay barouche of modern date. Here horsemen gallop on thorough-bred steeds. Here, in short, all the transitory population of Rome, the world's great watering-place, rides, drives, or promenades! Here are beautiful sunsets; and here, whichever way you turn your eyes, are scenes as well worth gazing at, both in themselves and for their historical interest, as any that the sun ever rose and set upon. Here, too, on certain afternoons in the week, a French military band flings out rich music over the poor old city, floating her with strains as loud as those of her own echoless triumphs."—Hawthorne.

The garden of the Pincio is very small, but beautifully laid out. At a crossroads is placed an Obelisk, brought from Egypt, and which the late discoveries in hieroglyphics show to have been erected there, in the joint names of Hadrian and his empress Sabina, to their beloved Antinous, who was drowned in the Nile A.D. 131.

From the furthest angle of the garden we look down upon the strange fragment of wall known as the Muro-Torto.

"Le Muro-Torto offre un souvenir curieux. On nomme ainsi un pan de muraille qui, avant de faire partie du rempart d'Honorius, avait servi à soutenir la terrasse du jardin du Domitius, et qui, du temps de Bélisaire, était déjà incliné comme il l'est aujourd'hui. Procope racconte que Bélisaire voulait le rebâtir, mais que les Romains l'en empêchèrent, affirmant que ce point n'était pas exposé, parce que Saint Pierre avait promis de le défendre. Procope ajoute: 'Personne n'a osé réparer ce mur, et il reste encore dans le même état.' Nous pouvons en dire autant que Procope, et le mur, détaché de la colline à laquelle il s'appuyait, reste encore incliné et semble près de tomber. Ce détail du siége de Rome est confirmé par l'aspect singulier du Muro-Torto, qui semble toujours près de tomber, et subsiste dans le même état depuis quatorze siècles, comme s'il était soutenu miraculeusement par la main de Saint Pierre. On ne saurait guère trouver pour l'autorité temporel des papes, un meilleur symbole."—Ampère, Emp. ii. 397.

"At the furthest point of the Pincio, you look down from the parapet upon the Muro-Torto, a massive fragment of the oldest Roman wall, which juts over, as if ready to tumble down by its own weight, yet seems still the most indestructible piece of work that men's hands ever piled together. In the blue distance rise Soracte, and other heights, which have gleamed afar, to our imagination, but look scarcely real to our bodily eyes, because, being dreamed about so much, they have taken the aerial tints which belong only to a dream. These, nevertheless, are the solid framework of hills that shut in Rome, and its broad surrounding Campagna; no land of dreams, but the broadest page of history, crowded so full with memorable events, that one obliterates another, as if Time had crossed and recrossed his own records till they grew illegible."—Hawthorne.

In early imperial times the site of the Pincio garden was occupied by the famous villa of Lucullus, who had gained his enormous wealth as general of the Roman armies in Asia.

"The life of Lucullus was like an ancient comedy, where first we see great actions, both political and military, and afterwards feasts, debauches, races by torchlight, and every kind of frivolous amusement. For among frivolous amusements, I cannot but reckon his sumptuous villas, walks, and baths; and still more so the paintings, statues, and other works of art which he collected at immense expense, idly squandering away upon them the vast fortune he amassed in the wars. Insomuch that now, when luxury is so much advanced, the gardens of Lucullus rank with those of the kings, and are esteemed the most magnificent even of these."—Plutarch.

Here, in his Pincian villa, Lucullus gave his celebrated feast to Cicero and Pompey, merely mentioning to a slave beforehand that he should sup in the hall of Apollo, which was understood as a command to prepare all that was most sumptuous.

After Lucullus—the beautiful Pincian villa belonged to Valerius Asiaticus, and in the reign of Claudius was coveted by his fifth wife, Messalina. She suborned Silius, her son's tutor, to accuse him of a licentious life, and of corrupting the army. Being condemned to death, "Asiaticus declined the counsel of his friends to starve himself, a course which might leave an interval for the chance of pardon; and after the lofty fashion of the ancient Romans, bathed, perfumed, and supped magnificently, and then opened his veins, and let himself bleed to death. Before dying he inspected the pyre prepared for him in his own gardens, and ordered it to be removed to another spot, that an umbrageous plantation which overhung it might not be injured by the flames."

As soon as she heard of his death, Messalina took possession of the villa, and held high revel there with her numerous lovers, with the most favoured of whom, Silius, she had actually gone through the religious rites of marriage in the lifetime of the emperor, who was absent at Ostia. But a conspiracy among the freedmen of the royal household informed the emperor of what was taking place, and at last even Claudius was aroused to a sense of her enormities.

"In her suburban palace, Messalina was abandoning herself to voluptuous transports. The season was mid-autumn, the vintage was in full progress; the wine-press was groaning; the ruddy juice was streaming; women girt with scanty fawnskins danced as drunken Bacchanals around her: while she herself, with her hair loose and disordered, brandished the thyrsus in the midst, and Silius by her side, buskined and crowned with ivy, tossed his head to the flaunting strains of Silenus and the Satyrs. Vettius, one, it seems, of the wanton's less fortunate paramours, attended the ceremony, and climbed in merriment a lofty tree in the garden. When asked what he saw, he replied, 'an awful storm from Ostia'; and whether there was actually such an appearance, or whether the words were spoken at random, they were accepted afterwards as an omen of the catastrophe which quickly followed.

"For now in the midst of these wanton orgies the rumour quickly spread, and swiftly messengers arrived to confirm it, that Claudius knew it all, that Claudius was on his way to Rome, and was coming in anger and vengeance. The lovers part: Silius for the forum and the tribunals; Messalina for the shade of her gardens on the Pincio, the price of the blood of the murdered Asiaticus." Once the empress attempted to go forth to meet Claudius, taking her children with her, and accompanied by Vibidia, the eldest of the vestal virgins, whom she persuaded to intercede for her, but her enemies prevented her gaining access to her husband; Vibidia was satisfied for the moment by vague promises of a later hearing; and upon the arrival of Claudius in Rome, Silius and the other principal lovers of the empress were put to death. "Still Messalina hoped. She had withdrawn again to the gardens of Lucullus, and was there engaged in composing addresses of supplication to her husband, in which her pride and long-accustomed insolence still faintly struggled into her fears. The emperor still paltered with the treason. He had retired to his palace; he had bathed, anointed, and lain down to supper; and, warmed with wine and generous cheer, he had actually despatched a message to the poor creature, as he called her, bidding her come the next day, and plead her cause before him. But her enemy Narcissus, knowing how easy might be the passage from compassion to love, glided from the chamber, and boldly ordered a tribune and some centurions to go and slay his victim. 'Such,' he said, 'was the emperor's command'; and his word was obeyed without hesitation. Under the direction of the freedman Euodus, the armed men sought the outcast in her gardens, where she lay prostrate on the ground, by the side of her mother Lepida. While their fortunes flourished, dissensions had existed between the two; but now, in her last distress, the mother had refused to desert her child, and only strove to nerve her resolution to a voluntary death. 'Life,' she urged, 'is over; nought remains but to look for a decent exit from it.' But the soul of the reprobate was corrupted by her vices; she retained no sense of honour; she continued to weep and groan as if hope still existed; when suddenly the doors were burst open, the tribune and his swordsmen appeared before her, and Euodus assailed her, dumb-stricken as she lay, with contumelious and brutal reproaches. Roused at last to the consciousness of her desperate condition, she took a weapon from one of the men's hands and pressed it trembling against her throat and bosom. Still she wanted resolution to give the thrust, and it was by a blow of the tribune's falchion that the horrid deed was finally accomplished. The death of Asiaticus was avenged on the very spot; the hot blood of the wanton smoked on the pavement of his gardens, and stained with a deeper hue the variegated marbles of Lucullus."—Merivale, Hist. of the Romans under the Empire.

From the garden of the Pincio a terraced road (beneath which are the long-closed catacombs of St. Felix) leads to the Villa Medici, built for Cardinal Ricci da Montepulciano by Annibale Lippi in 1540. Shortly afterwards it passed into the hands of the Medici family, and was greatly enlarged by Cardinal Alessandro de Medici, afterwards Leo XI. In 1801 the Academy for French Art-Students, founded by Louis XIV., was established here. The villa contains a fine collection of casts, open every day except Sunday.

Behind the villa is a beautiful Garden (which can be visited on application to the porter). The terrace, which looks down upon the Villa Borghese, is bordered by ancient sarcophagi, and has a colossal statue of Rome. The garden side of the villa has sometimes been ascribed to Michael Angelo.

"La plus grande coquetterie de la maison, c'est la façade postérieure. Elle tient son rang parmi les chefs-d'œuvre de la Renaissance. On dirait que l'architecte a épuisé une mine de bas-reliefs grecs et romains pour en tapisser son palais. Le jardin est de la même époque: il date du temps où l'aristocratie romaine professait le plus profond dédain pour les fleurs. On n'y voit que des massifs de verdure, alignés avec un soin scrupuleux. Six pelouses, entourées de haies à hauteur d'appui, s'étendent devant la villa et laissent courir la vue jusqu'au mont Soracte, qui ferme l'horizon. A gauche, quatre fois quatre carrés de gazon s'encadrent dans de hautes murailles de lauriers, de buis gigantesques et de chênes verts. Les murailles se rejoignent au-dessus des allées et les enveloppent d'une ombre fraîche et mystérieuse. A droite, une terrasse d'une style noble encadre un bois de chênes verts, tordus et eventrés par le temps. J'y vais quelquefois travailler à l'ombre; et le merle rivalise avec le rossignol au-dessus de ma tête, comme un beau chantre de village peut rivaliser avec Mario ou Roger. Un peu plus loin, une vigne toute rustique s'étend jusqu'à la porte Pinciana, où Belisaire a mendié, dit-on. Les jardins petits et grands sont semés de statues, d'Hermes, et de marbres de toute sorte. L'eau coule dans des sarcophages antiques ou jaillit dans des vasques de marbre: le marbre et l'eau sont les deux luxes de Rome."—About, Rome Contemporaine.

"The grounds of the Villa Medici are laid out in the old fashion of straight paths, with borders of box, which form hedges of great height and density, and are shorn and trimmed to the evenness of a wall of stone, at the top and sides. There are green alleys, with long vistas, overshadowed by ilex-trees; and at each intersection of the paths the visitor finds seats of lichen-covered stone to repose upon, and marble statues that look forlornly at him, regretful of their lost noses. In the more open portions of the garden, before the sculptured front of the villa, you see fountains and flower-beds; and, in their season, a profusion of roses, from which the genial sun of Italy distils a fragrance, to be scattered abroad by the no less genial breeze."—Hawthorne.

A second door will admit to the higher terrace of the Boschetto; a tiny wood of ancient ilexes, from which a steep flight of steps leads to the "Belvidere," whence there is a beautiful view.

"They asked the porter for the key of the Bosco, which was given, and they entered a grove of ilexes, whose gloomy shade effectually shut out the radiant sunshine that still illuminated the western sky. They then ascended a long and exceedingly steep flight of steps, leading up to a high mound covered with ilexes.

"Here both stood still, side by side, gazing silently on the city, where dome and bell-tower stood out against a sky of gold; the desolate Monte Mario and its stone pines rising dark to the right. Behind, close at hand, were sombre ilex woods, amid which rose here and there the spire of a cypress or a ruined arch, and on the highest point, the white Villa Ludovisi; beyond, stretched the Campagna, girdled by hills melting into light under the evening sky."—Mademoiselle Mori.

From the door of the Villa Medici is the scene familiar to artists, of a fountain shaded by ilexes, which frame a distant view of St Peter's.

"Je vois (de la Villa Medici) les quatre cinquièmes de la ville; je compte les sept collines, je parcours les rues régulières qui s'étendent entre le cours et la place d'Espagne, je fais le d'enombrement des palais, des églises, des dômes, et des clochers; je m'égare dans le Ghetto et dans la Trastévère. Je ne vois pas des ruines autant que j'en voudrais: elles sont ramassées là-bas, sur ma gauche, aux environs du Forum. Cependant nous avons tout près de nous la colonne Antonine et la mausolée d'Adrien. La vue est fermée agréablement par les pins de la villa Pamphili, qui reunissent leurs larges parasols et font comme une table à mille pieds pour un repas de géants. L'horizon fuit à gauche à des distances infinies; la plaine est nue, onduleuse et bleue comme la mer. Mais si je vous mettais en présence d'un spectacle si étendu et si divers, en seul objet attirerait vos regards, un seul frapperait votre attention: vous n'auriez des yeux que pour Saint Pierre. Son dôme est moitié dans la ville, moitié dans la ciel. Quand j'ouvre ma fenêtre, vers cinq heures du matin, je vois Rome noyée dans les brouillards de la fièvre: seul, le dôme de Saint-Pierre est coloré par la lumière rose du soleil levant."—About.

The terrace ("La Passeggiata") ends at the Obelisk of the Trinità de' Monti, erected here in 1822 by Pius VII., who found it near the Church of Sta. Croce in Gerusalemme.

"When the Ave Maria sounds, it is time to go to the church of Trinità de' Monti, where French nuns sing; and it is charming to hear them. I declare to heaven that I am become quite tolerant, and listen to bad music with edification; but what can I do? The composition is perfectly ridiculous, the organ-playing even more absurd: but it is twilight, and the whole of the small bright church is filled with persons kneeling, lit up by the sinking sun each time that the door is opened; both the singing nuns have the sweetest voices in the world, quite tender and touching, more especially when one of them sings the responses in her melodious voice, which we are accustomed to hear chaunted by priests in a loud, harsh, monotonous tone. The impression is very singular; moreover, it is well known that no one is permitted to see the fair singers, so this caused me to form a strange resolution. I have composed something to suit their voices, which I have observed very minutely, and I mean to send it to them. It will be pleasant to hear my chaunt performed by persons I never saw, especially as they must in turn sing it to the 'barbaro Tedescho,' whom they also never beheld."—Mendelssohn's Letters.

"In the evenings people go to the Trinità to hear the nuns sing from the organ-gallery. It sounds like the singing of angels. One sees in the choir troops of young scholars, moving with slow and measured steps, with their long white veils, like a flock of spirits."—Frederika Bremer.

The Church of the Trinità de' Monti was built in 1495 by Charles VIII. of France, at the request of S. Francesco di Paola. At the time of the French revolution it was plundered, but was restored by Louis XVIII. in 1817. It contains several interesting paintings.