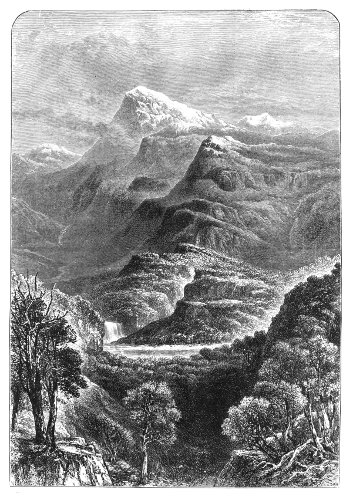

Mount Kosciusko.

From the picture by J. S. Bowman, M.A.

Title: Australian Pictures, Drawn with Pen and Pencil

Author: Howard Willoughby

Release date: April 1, 2012 [eBook #39322]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Nick Wall and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

TRANSCRIBER'S NOTE: A list of changes is detailed at the end of the book.

BY

HOWARD WILLOUGHBY

OF 'THE MELBOURNE ARGUS'

WITH A MAP AND ONE HUNDRED AND SEVEN ILLUSTRATIONS FROM SKETCHES

AND PHOTOGRAPHS, ENGRAVED BY E. WHYMPER AND OTHERS.

LONDON

THE RELIGIOUS TRACT SOCIETY

56 Paternoster Row and 164 Piccadilly

1886

LONDON:

PRINTED BY WILLIAM CLOWES AND SONS, Limited,

STAMFORD STREET AND CHARING CROSS.

In one respect this work differs from its predecessors. The companion volumes were written by travellers to the lands which they described, but Australian Pictures are by an Australian resident. Hence, when praise is required, the author has often preferred to quote some traveller of repute rather than to state his own impressions. Thanks have to be given to the Government of Victoria, which kindly placed all its works at the disposal of the author. The official history of the aborigines compiled by Mr. Brough Smyth is especially a valuable storehouse of facts for future writers. The [Pg 6]proprietors of the Melbourne Argus liberally gave the use of the views and pictures of their illustrated paper, the Australian Sketcher, and the offer was gratefully and largely taken advantage of. Mr. R. Wallen, a President of the Art Union of Victoria, gave permission for the reproduction of any of the works of art published by the society during his term of office. Australia is a large place, and it will be seen that, where the author could not refresh his memory by a personal visit, he has here and there availed himself of the willing aid of literary friends.

| Mount Kosciusko | Frontispiece |

| In the Mountains, Fernshaw | 5 |

| The Scots' Church, Collins Street, Melbourne | 6 |

| A Native Climbing a Tree for Opossum | 12 |

| A Road through an Australian Forest | 13 |

| Coranderrk Station | 16 |

| The Giant Gum-tree | 18 |

| Railroad through the Gippsland Forest | 19 |

| Junction of Murray and Darling Rivers | 20 |

| The National Museum, Melbourne | 26 |

| Statue of Prince Albert in Sydney | 28 |

| The Bower-Bird | 29 |

| The Independent Church, Collins Street, Melbourne | 33 |

| Semi-Civilised Victorian Aborigines | 36 |

| Government House, Melbourne | 37 |

| Melbourne, 1840 | 40 |

| A Railway Pier in Melbourne in 1886 | 41 |

| A Melbourne Suburban House | 44 |

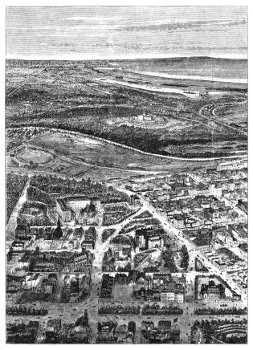

| Bird's-eye View of Melbourne showing Public Office | 46 |

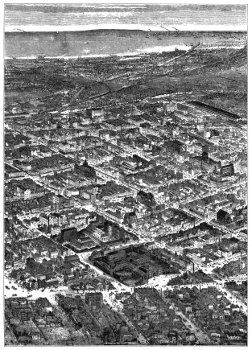

| Bird's-eye View of Melbourne looking Southwards | 47 |

| Bird's-eye View of Central Melbourne | 50 |

| Bourke Street, Melbourne, looking East | 51 |

| University, Melbourne | 52 |

| The Fitzroy Gardens, Melbourne | 53 |

| The Yarra Yarra, near Melbourne | 55 |

| Bird's-eye View of Sandhurst | 58 |

| On Lake Wellington | 63 |

| A Victorian Lake | 65 |

| The Upper Goulbourn, Victoria | 66 |

| Waterfall in the Black Spur | 68 |

| A Victorian Forest | 69 |

| Staging Scenes | 71 |

| A Sharp Corner | 72 |

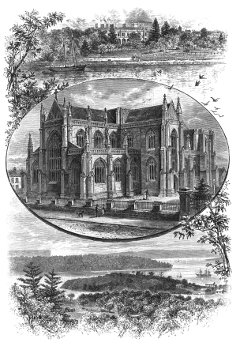

| Views in Sydney: Government House, the Cathedral, and Sydney Heads | 74 |

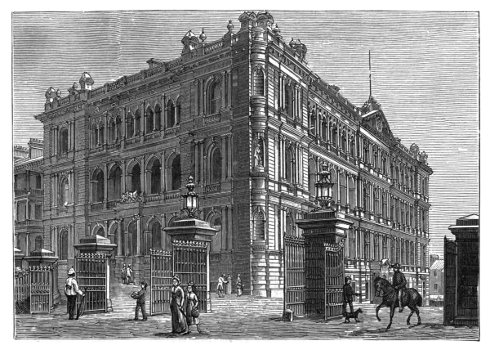

| Government Buildings, Macquarie Street, Sydney | 75 |

| Statue of Captain Cook at Sydney | 77 |

| The Post Office, George Street, Sydney | 80 |

| Sydney Harbour | 82 |

| Macquarie Street, Sydney | 83 |

| The Town Hall, Sydney | 85 |

| Emu Plains | 88 |

| The Valley of the Grose | 89 |

| Zigzag Railway in the Blue Mountains | 91 |

| Fish River Caves | 92 |

| Waterfall at Govett | 93 |

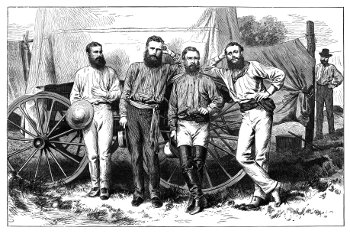

| Overland Telegraph Party | 98 |

| Government House and General Post Office, Adelaide | 99 |

| Waterfall Gully, South Australia | 100 |

| A Murray River Boat | 101 |

| Adelaide in 1837 | 102 |

| King William Street, Adelaide | 104 |

| An Adelaide Public School | 105 |

| Reaping in South Adelaide | 106 |

| Camel Scenes | 108 |

| Peake Overland Telegraph Station | 109 |

| Collingrove Station, South Australia | 111 |

| Sheep in the Shade of a Gum-tree | 112 |

| The Botanical Gardens, Adelaide | 114 |

| Brisbane | 116 |

| A Village on Darling Downs | 117 |

| Valley of the River Brisbane, Queensland | 120 |

| Townsville, North Queensland | 124 |

| Sugar Plantation, Queensland | 127 |

| View of Mount Wellington, Tasmania | 142 |

| Corra Linn, Tasmania | 143 |

| On the South Esk, Tasmania | 145 |

| Views in Tasmania | 147 |

| Launceston | 148 |

| Hell Gate, Tasmania | 149 |

| On the River Derwent | 152 |

| Native Encampment | 154 |

| A New Clearing | 155 |

| Splitters in the Forest | 157 |

| After Stray Cattle | 160 |

| Monument to Burke and Wills in Melbourne | 163 |

| A Corroboree | 166 |

| A Waddy Fight | 167 |

| Civilised Aborigines | 169 |

| A Boomerang | 173 |

| A Native Encampment in Queensland | 174 |

| A Native Tracker | 175 |

| Church, Schoolhouse, and Encampment at Lake Tyers | 176 |

| Australian Tree-Ferns | 180 |

| Dingoes | 181 |

| The Sarcophilus or 'Tasmanian Devil' | 182 |

| Bass River Opossum | 183 |

| A Kangaroo Battue | 184 |

| The Platypus | 186 |

| The Lyre-Bird | 187 |

| The Giant Kingfisher, or Laughing Jackass | 189 |

| The Emu | 190 |

| The Tiger-Snake | 192 |

| Australian Trees | 195 |

| Silver-stem Eucalypts | 198 |

| The Bottle-Tree | 201 |

| Grass-Trees | 202 |

| Driving Cattle | 203 |

| A Merino Sheep | 206 |

| Ring Barking | 209 |

| A Bush Welcome | 213 |

| Before and After the Fire | 216 |

| Found! | 218 |

| A Squatter's Station | 219 |

'Australian Pictures' must necessarily consist of peeps at Australia. It seems presumptuous at first to ask that great island-continent to creep into a single volume. But sketches of parts and bird's-eye views will often reveal more to the stranger than a minute and fatiguing survey of the whole. These pages, though few in number, will, it is hoped, convey to the reader some idea of that vast new world where Saxons and Celts are peacefully building up another Britain.[Pg 14]

Some of the early errors about Australia must have already faded away. Few can now believe that her birds are without voice and her flowers without perfume, and that the continent itself is a desert fringed by a habitable seaboard. Yet it is perhaps hardly realised by the many how grand is the heritage secured in Australia for the British race. The extent of territory is enormous. Twenty-five kingdoms the size of Great Britain and Ireland could be carved out of this giant island and its appendages, and still there would be a remainder. Its total area, 2,983,200 square miles, is only a little less than the area of Europe.

At first it was supposed that only a limited portion of this enormous tract would be available for settlement, but this fear is dying out. The central desert, that bugbear of a past generation, has an existence, but man is pushing it farther and farther back. Where the explorer perished through thirst a few years ago we now have the homestead and the township; water is conserved, flocks are fed, the property, if it has to be offered for sale, is described as 'that valuable and well-known squatting block.' The tales that were first told were true enough, but man, as he advances, subdues the country and ameliorates the climate.

Already Australia exports to the markets of the world the finest wheat, the finest wool, and the finest gold. Her produce in these lines commands the highest prices, and no test of superiority could be more conclusive. In two at least of these items the export could be indefinitely increased, and meat and wine can be added to the list. On such articles as these man subsists, and they are produced here with a minimum of expense and effort.

The total population of Australia is 2,800,000. The settlers have drawn about themselves over 1,100,000 horses, 8,000,000 cattle, and 70,000,000 sheep. But three millions of men and tens of millions of creatures fail to occupy; they do little more than dot the corners of the great lone island. In the north-west of the continent there are tracts of country which the white man has not yet penetrated. Tribes still roam there who may have heard of the European stranger, but who have never seen him. Adventurous spirits are now pushing into these distant regions, but there will be pioneering work for many a long term of years, and after the pioneer has had his day the task of settlement begins. Even in Victoria and New South Wales, the most thickly populated of the colonies, there are many fertile hillsides and valleys as yet untrodden by man. The population has sought the plains, where the least expenditure was required to make the earth bring forth its increase. Some of the richest land in both colonies has yet to be appropriated, the settler having neglected it because it has to be cleared. The giant eucalypt of the uplands frightened the colonist away to the lightly timbered, park-like plains; but now, thanks to the extension of the railways, the mountain ash, the red gum, and the blackwood, with their companions, are found to be sources of wealth. Thus, in the old states and in the new[Pg 15] territories alike, openings exist for the agriculturist and the grazier as favourable as have ever been offered. More fortunes have been made in Australia within the past ten years than have ever been accumulated before. The labourer has put more money than ever into the savings-bank or the building society. The farmer has more rapidly become a comfortable, well-to-do personage; the grazier or squatter has seen his income swell. The value of city property has increased as if by magic. It may be truly said that the chances and prospects of the new arrival are greater to-day, and are likely to be greater for years to come, than they were even in the feverish flush of the gold era.

Australia is for the present divided into six colonies. As time rolls on we may expect six times this number of states. If some of the larger provinces were at all thickly populated they would be absolutely unmanageable for administrative purposes. The states are named Victoria, New South Wales, South Australia, Queensland, Western Australia and Tasmania. They will be noticed in these pages in turn. Victoria, with an area of 87,000 square miles, has a population of a little more than 1,000,000. Thus it is the most densely peopled of the group. Agriculture, gold mining and wool growing are its prominent industries, and it is the colony in which manufactures are most developed. New South Wales has also a population of 1,000,000, with an area of 309,000 square miles. She is a pastoral colony. Queensland, with an area of 668,000 square miles, has less than 350,000 people, a circumstance that shows how little she has been developed. Her industries are pastoral and gold mining; and in the far north sugar plantations have been established under somewhat unhappy auspices. South Australia has an area of 903,000 square miles, and a population under 350,000. Much of her territory is absolutely unexplored. Her little community is clustered about Adelaide, and has relied so far upon the export of wool, copper and, above all, wheat. Last of the continental states comes Western Australia, the Cinderella of the group. Her population is only 35,000, her area is no less than 975,000 square miles, much of it being absolutely unknown, while the greater part has no other occupants than the black man, the emu and the marsupial. Tasmania, the little island colony, has a population of 135,000, and an area of 26,000 square miles.

All the capitals are on the seaboard, and, setting the Western Australian Perth aside, the traveller can proceed from one to the other either by the magnificent liners of the Peninsular and Oriental, the Orient, and the British India Steam Navigation Companies, or he can avail himself of splendid Clyde-built steamers run by local enterprise. Very shortly he will be able to land at either Adelaide or Brisbane, and journey from the one point to the other by rail, as the iron chain is almost continuous now, and missing links are being rapidly completed. Whichever capital he lands at, he will find a network of railways branching into the interior, and seated behind[Pg 16] the locomotive he can visit places where a few years back the explorers perished! Only if he is very ambitious of sight-seeing need he have recourse to coach, horse, or the popular American—but acclimatised—buggy.

So far as the people are concerned, he will find that he is still in the old country. Traveller after traveller, Mr. Archibald Forbes and Lord Rosebery in turn, and a host of others, affirm that the typical Australian is apt to be more English than the Englishman. There is no aristocracy, it is true, and no National Church. Each state is a democracy pure and simple, under the English flag. But the Queen has nowhere more devoted and loyal subjects, and nowhere are the Churches more numerous, more active, and apparently more blessed in results. The traveller meets with English manners, English sympathies, and a frank hospitality which, the compilers of books and the deliverers of lectures affirm, is peculiar to Australia. But he finds the race amid novel surroundings, amid scenery whose peculiarity is vastness, with a distinctive vegetation unlike any other, with seasons which have little resemblance to those of the old country; and the occupations of the people, he discovers, are also often new. When a writer undertakes to sketch the scene, it must be his fault if he has nothing of interest to relate.

[Pg 19]Dimensions of Australia—Mount Kosciusko—The Murray River System—Wind Laws—The Hot Wind—Intense Heat Periods—The Early Explorers—Sturt's Experience—Blacks and Bush Fires—Droughts—Unexplored Australia.

It is not possible to understand Australia without a glance at the physical conditions of the continent. A good angel and a bad, an evil influence and a beneficial, are ever in contention in nature here. From the surrounding sea come cool and grateful clouds; from the heated interior come hot blasts, licking up life and absorbing the watery vapours which would otherwise fall as rain. Sea and land are ever in conflict.

Australia measures from north to south 1700 miles, and from east to west 2400 miles—the total area being somewhat greater than that of the United States of America, and somewhat less than the whole of Europe. The peculiarity is that all its mountain ranges worth taking notice of—all that are factors in the climate—are comparatively near the coast. Thus the main dip is rather inland than outward, and this formation is fatal to great rivers. An interior mountain chain such as the New Zealand Alps would have transformed the country. The enormous coast-line from Spencer's Gulf to King George's Sound is not broken by the mouth of any stream. Such rainfall as there is in this district must drain either into the sea by subterranean channels, or into the inland marshy depressions called Lake Eyre, Lake Gairdner, and Lake Amadeus, which are sometimes extremely shallow sheets of water, sometimes grassy plains, and sometimes desert. The best land is that between the various ranges and the sea, because there most rain falls. And the greatest of the ranges is that which runs from north to south along the east coast of the island, passing through Queensland, New South Wales, and Victoria, and culminating in Mount Kosciusko, whose peak is 7120 feet high, and whose ravines always contain snow. Only at Kosciusko does snow lie all the year round in Australia, though the mountains near it, about 6000 feet high, are also almost always covered. To this range we owe the one river system at all worthy of the continent.[Pg 21] The waters from the western side of the Queensland mountains—there called the Dividing Range—flow down the Warrego into the Darling. Here they are joined by the waters from the higher ranges of New South Wales and Victoria, called the Australian Alps. These waters have been brought down by the Murray, the Murrumbidgee, and the Goulburn, and the united floods fall into the sea, through Lake Alexandrina, between Melbourne and Adelaide.

On paper this river system shows well. The Darling has been navigated up to Walgett, which is 2345 miles from the sea, and this distance entitles the Australian stream to rank third among the rivers of the world, only the Mississippi and the Amazon coming before it. But the facts are not so good as they seem. The Darling depends upon flood waters. Sometimes these flood waters will come down in sufficient volume to enable the stream to run from end to end, and sometimes they fail half-way. The river is never open to navigation all the year round, and frequently it is not open to navigation from year's end to year's end. The occasional failure of the Darling for so long a period upsets all calculations. The colonists will take this stream and the river Murray in hand some day, and will lock both and preserve their storm waters, and the south-eastern corner of the continent will then have a grand river communication. Stores will then be sent up, and wool will be brought down with certainty, where now all is doubt and speculation. Commissions to consider the subject have been appointed both by the Victorian Government and the Government of New South Wales, and conferences are this year (1886) being held upon it and cognate subjects. Unhappily, there are no other streams in Australia that can be so dealt with, though it should be added that the last has not yet been heard of the rivers of Northern Australia. We are ignorant of their capacities, though a good guess can be made about them.

Taking Australia from east to west, we find a high range skirting the coast on the east, and supporting a dense sub-tropical vegetation, and giving rise to an extensive but uncertain river system. Next comes a more sterile interior, composed of desert, of shallow salt lakes, and of higher steppes in unknown proportions. Approaching the west coast we meet ranges again, and rivers and fertile country.

Mr. H. C. Russell, Government Astronomer for New South Wales, in his valuable pamphlet on the 'Physical Geography and Climate of New South Wales,' points out that 'if water flowed over the whole of the Australian continent, the trade wind would then blow steadily over the northern portions from the south-east, and above it the like steady return current would blow to the south-east, while the "brave west winds" and southerly would hold sway over the other half—conditions which now exist a short distance from the coast. Into this system Australia introduces an enormous disturbing element, of which the great interior plains form the most active agency in changing the directions of the wind currents. The[Pg 22] interior, almost treeless and waterless, acts in summer like a great oven with more than tropical heating power, and becomes the great motor force on our winds, by causing an uprush, and consequent inrush on all sides, especially on the north-west, where it has power sufficient to draw the north-east trade over the equator, and into a north-west monsoon, in this way wholly obliterating the south-east trade belonging to the region, and bringing the monsoon with full force on to Australia, where, being warmed, and receiving fresh masses of heated air, it rises and forms part of the great return current from the equator to the south.'

The 'hot winds' of the colonists are produced by the sinking down to the surface of the heated current of air, which in summer is continually passing overhead; and when this wind blows in force upon a clear summer's day things are not pleasant. The thermometer from time to time indicates a degree of heat which is almost incredible. In Southern Melbourne the official record gives a reading of 179 degrees in the sun, and 111 in the shade, and at the inland town of Deniliquin, the official register in the shade is 121 degrees. Man and beast and vegetation suffer on these days. The birds drop dead from the trees, the fruit is scorched and rendered unfit for market. The leaves of the English trees, such as the plane and the elm, drop in profusion, so that in early summer it will seem as if autumn had set in. The sick, especially children, are terribly affected, and the doctors attending an infant sufferer will say that nothing can be done except to pray for a change of wind. Happily, such days as these are rare. The hot blast will not often send the temperature up to more than 100 to 105 degrees, and the duration of the heated wind is limited to three days, and often it prevails during only one, sunset bringing with it a cool southern gale.

A moderate hot wind is relished by many people, for the air is dry and even exhilarating to the strong for a while; and the claim is made that it destroys noxious germs and effluvia. Sometimes the hot wind will gradually die out, but on other occasions a rushing storm will come up from the south, driving the north wind before it, and in that case the welcome conflict will be preceded by whirling and blinding clouds of dust, and will be accompanied by thunder and lightning and torrents of rain. The fall of the temperature will be something marvellous. The thermometer will be standing at 150° in the sun; then the wind will change, rain will fall, and in the evening the register will be 50°, making a difference of 100 degrees in seven or eight hours.

That these days are exceptional is shown by the manner in which vegetation generally flourishes, and by the admiration which each colonist has for the climate of that particular part of Australia in which he resides. 'The Swan Settlements,' says the Western Australian, 'are the pick of the country. No hot winds there.' At Adelaide the visitor is told: 'Yes, we are often hotter by ten degrees in the sun than they are in Melbourne, but[Pg 23] ours is a dry, not a moist heat.' In Melbourne the tale is reversed: 'Sydney is muggy,' it is averred; 'you cannot stand that. A dry heat is the thing, but those poor beggars at Adelaide have it too hot altogether.'

No doubt many mistakes occurred in the descriptions of Australia given by the early explorers. Brave and intelligent as they were, they were 'new chums,' and certainly not born bushmen. Transplanted from a small island, continental features overpowered them. Forests which took weeks to traverse; plains, like the ocean, horizon-bounded; the vast length of our rivers when compared to those of England, often flowing immense distances without change or tributary—now all but dry for hundreds of miles, at other times flooding the countries on their banks to the extent of inland seas—wearied them. Then we know that our cloudless skies, the mirage, the long-sustained high range of the thermometer in the central portion of the continent, troubled them a good deal more than they do us, and helped to make them look on the dark side of things. Hence, as a rule, their reports were unfavourable.

Sturt's account of his detention at Depôt Glen is enough to frighten anybody, and cannot be read to this day without emotion. Here, 'stuck up' by want of water, he dug an underground room, and he and his men passed a terrible summer. The heat was sometimes as high as 130 degrees in the shade, and in the sun it was altogether intolerable. They were unable to write, as the ink dried at once on their pens; their combs split; their nails became brittle and readily broke; and if they touched a piece of metal it blistered their fingers. Month after month passed without a shower of rain. Sometimes they watched the clouds gather, and they could hear the distant roll of thunder, but there fell not a drop to refresh the dry and dusty desert. The party began to grow thin and weak; Mr. Poole, the second in command, became ill with scurvy. At length, when the winter was approaching, a gentle shower moistened the plain; and preparations were being made to send the sick man quickly to the Darling, when Poole died, and the mournful cavalcade returned, leaving a grave in the wilderness. Yet this locality proved in time to be a very good sheep-run, differing in nothing from others around it; and eventually was found to be a gold-field, and was extensively worked. Runs about the spot are commonly advertised in the Melbourne or Sydney papers as carrying immense flocks, and as valued with the stock at from £50,000 to £100,000. The explorer was, in fact, within a few miles of Cooper's Creek.

This process of conquering the interior is still going on. Man modifies all countries, and Australia is no exception to the rule. Even the blacks played their part, and it was a mischievous one. They had an instrument in their hands by which they influenced the whole course of nature. This was the fire-stick. With this implement the aborigines were constantly setting fire to the grass and trees, both accidentally and systematically, for[Pg 24] hunting purposes, and probably in their day almost every part of New Holland was swept over by a fierce fire on an average once in five years. Hence the baked, calcined condition of the ground in many parts of the continent, the character of our vegetation, and the comparative scarcity of animal life. The eucalypts survived the fiery ordeal, because of the hardness of their bark; and, when every other creature perished, or had to abandon its litter, the marsupials leaped over the flames with their young in their pouches. Strange as the assertion may appear in the first instance, it may be doubted whether any section of the human race has exercised a greater influence on the physical condition of a large portion of the globe than the wandering savages of Australia. The white man is working in an entirely opposite direction. By clearing the forest he limits the area of the bush fire. He constructs reservoirs, dams rivers, sinks wells in order to bring subterranean water to the surface, and irrigates land, so that a spot where even the hardiest scrub failed to grow in its natural state, is covered with luxuriant crops. Province after province has been rescued from the wilderness already, and the grand work is likely to go on. Those who look at what has been done in the way of reclaiming territory in Australia will be in no hurry to set bounds as to what man is likely to perform.

It is not wonderful that the first inquiry of the practical settler should be as to the rainfall of the country he proposes to occupy. The map most eagerly scanned in Australia is the 'rainfall' map, prepared by the Government, and issued by the leading weekly papers. A glance at this production reveals the tale which it tells. The coast-line is shown in a dark blue, to indicate the heavy rainfall of from thirty to seventy inches. A pleasant blue represents a moderate rainfall on the interior belt of plains, averaging from fifteen to twenty-five inches. Then comes a faint tint spread over what is called the 'never, never' country, where the rainfall is five or ten inches per annum, and where the rain will descend at once, or for two years there will be none, and then the whole average supply will drop from the clouds in one rushing downpour. Under such circumstances it will be readily imagined that the terror of the Australian settler is a drought. Even in the moments of his utmost prosperity he has his anxieties about the next season. A district which has been rainless for a year or two years is a pitiful spectacle of desolation. The grass disappears; the wind carries with it whirling columns of dust; the trees of the dreary plain become more sombre and mournful than ever. If there is a little water left in any dam or reservoir, it is rendered putrid by the carcases of sheep and cattle, for the wretched animals become so weak that, once they fall or stick, they are unable to rise or to extricate themselves. The sun rises in heat, sails through a cloudless sky, and sets a ball of fire. The nights are dewless. The moon only renders more ghastly the depressing panorama.

[Pg 25]Mr. Russell complains that pictures of the drought are usually exaggerated, and it may be well therefore to quote official figures. In two years, according to Mr. Dibbs, Treasurer and Premier of New South Wales (November 1885), the drought in New South Wales has killed 200,000 horses, 1,500,000 head of cattle, and 13,500,000 sheep. A loss which is estimated at from £10,000,000 to £15,000,000 has fallen upon a single colony, and a single industry in that colony! But this drought was felt with equal severity in parts of South Australia and of Queensland, and it would be no exaggeration therefore to double the figures communicated to Parliament by Mr. Dibbs. And when 400,000 horses, 3,000,000 cattle, and 27,000,000 sheep die miserably of hunger and thirst, it is certain that scenes must occur the gloom and wretchedness of which can hardly be over-painted. One squatting company in the north lost 150,000 sheep out of 250,000 in the drought in question, and the survivors were kept alive with difficulty. Scrub was cut down for them. The living gnawed the bones of the dead. The company's shares went down to two shillings in the pound, and other squatting property similarly situated was equally depreciated, when one January morning, 1886, the Melbourne, Sydney, Brisbane, and Adelaide papers gave prominence to the welcome news of the break-up of the drought. From this place, that place, and the other, all down the line, came telegrams of the fall of three inches, four inches, five inches, and six inches of rain, the water saturating the ground, filling the dams, and sending the price of pastoral property up as though by magic.

The drought disaster, of course, is most felt in the newly taken-up country. Here a state of nature obtains, while, as time rolls on, and profits are made, water is conserved, and the run is practically made drought-proof. A minimum quantity of stock can be kept, and the remainder can be travelled to a district which is not smitten. The recuperative powers of the country are enormous; and if the squatter is afflicted one year he holds on, with the consciousness that with three or four good seasons in succession he is a made man.

How little we yet know of Australia as a whole has been brought under the popular notice by an address delivered by Mr. Ernest Favenc at a meeting of the Australian Geographical Society, held at Sydney in January 1886. South Australia alone has an area of 250,000 square miles unexplored, and Western Australia has an enormous tract of 500,000 square miles, which has been just rushed through, and no more, by three explorers, Messrs. Forrest, Giles, and Warburton. Here is a total of unknown area equivalent to the heart of Europe—say to Germany, France, Switzerland, Austria, and Hungary, with Italy thrown in. Of course the country to the west of the Overland Telegraph Line, being for the most part unknown, is all described as hopeless desert, but Mr. Favenc doubts the story, and no one is better qualified to express an opinion upon the subject than this gentle[Pg 26]man. He stands in the first rank of practical pioneers. The facts that go to support the idea of the existence of large belts of rich prairie land in this huge area are these: In the far interior the transition from barren desert country to rolling downs is sudden and abrupt; without warning, you step from one to the other. The good and the bad country lie very much in bands; and an explorer making an easterly and westerly track might travel in a bad band continuously, if he had the misfortune to strike one.

Mr. Favenc's suggestion is that a well-supplied party should start from a station on the Overland Telegraph Line, and should strike for Perth, making, however, extensive excursions on both sides of their route. The bee-line business is almost useless. It would be well if the Australian Geographical Society could take up the idea, for it is somewhat of a reproach to the three millions of inhabitants that Australia should be less mapped out than Africa; and there is pleasure also in reducing to its narrowest limits that bugbear of the youth of the colonies, the great fiery untamed Central Desert.

If, however, no more exploration be resolved upon, the work will only be postponed, and not abandoned. As one coral insect builds over the other, or as one wave on a rising tide overlaps its predecessor on the shore, so the last outlying pastoral station is speedily passed by one just beyond it. In this way settlement creeps on. Progress, though slow and unsensational, is sure.

[Pg 29]Australian Democracies—The Federal Movement—Immigration—Current Wages—Cost of Living—Absence of an Established Church—Religion in the Rural Districts—A Typical Service—Sunday Observance—Mission Work—Church Building.

The Australian colonies are, one and all, democracies of the most advanced type. Annual Parliaments have been advocated, though at present triennial legislatures are the rule. Payment of members, it should be added, is not adopted by all the states, but the principle seems to be spreading. Two Houses are established in each colony, a Legislative Assembly and a Legislative Council. The former is always elected by manhood suffrage; the latter, as in Victoria and South Australia, may be an elected body, or, as in New South Wales and Queensland, it may be composed of members nominated by the Crown. How the second chamber should be constituted is one of the problems of the day. Every now and then one or the other of the colonies is treated to 'a deadlock' between the two bodies; and more than once in Victoria public payments have been suspended in consequence, and popular passion has run high.

The Australian democracy has worked well upon the whole, and has[Pg 30] given security to life and property. The best proof of this is the rapid rise of colonial securities in the public favour. When New South Wales, South Australia, and Victoria commenced to build their national railways in 1857-1860, they were glad to sell six per cent. debentures at par in London, and now they float four per cent. loans at a premium.

The colony of Victoria is altogether protectionist, and South Australia has given in a partial adherence to the system. To the author the policy seems to be wrong in theory and practice, but the belief is widespread that, even if sacrifices are made, the resources of the colony are thus developed.

Twenty years back the populations of the various colonies did not touch each other: each colony spread from its own centre; but now this isolation has disappeared. Settlement is contiguous with settlement, and trade and intercourse are accelerated accordingly. The colonies can no longer ignore each other, and hence the movement for federation has gathered strength.

The first Federal Council met in Hobart in January 1886, but unfortunately jealousies had crept in, and the new body was shorn of its fair proportions. Federalists cannot help feeling greatly disappointed that the results hitherto have been so small, and yet probably there is much more to rejoice over than to be downcast about.

Victoria, Queensland, Tasmania and Western Australia were represented at the Council, and such laws as it can pass will thus affect three-fifths of the area of the continent. The absence of South Australia is understood to be accidental. She is really one of the parties to the federal bond, having agreed to the terms, and having invited the Imperial Parliament to pass the Enabling Act, and her early adhesion is expected with confidence. No continental state will then remain outside except New South Wales, and it is fairly to be presumed that she will not be insensible to the pressure of public opinion, both in Australia and throughout the Empire, especially as care is being taken to soothe the local susceptibilities that are now offended. The Federal Council meets for the present at Hobart, the chief town of Tasmania, and this town may, for the present, be called the 'federal capital.'

The immigration into Australia is about eighty thousand men and women yearly. If double or treble that number came, they could well be accommodated. The labourer of to-day is the employer of to-morrow; and as soon as a man acquires landed property his chief complaint is the paucity of hands to improve his holding.

A few specimens of wages may be taken from the official list of Mr. H. H. Hayter, Government Statist of Victoria. On the whole, labour is more in request in Victoria than in most of the sister states, and the figures may be taken as representing fair average rates for Australia generally. Servants, with board, coachmen, and grooms, 20s. to 30s. per week; female cooks, £40 to £65 per annum; laundresses, £35 to £52 per annum; general servants, 10s. to 14s. per week (these figures are for 1884, and there has[Pg 31] been a heavy rise in 1885-6); ploughmen, 25s. per week and board; black-smiths, 10s. to 14s. per day; boiler-makers, 10s. to 14s. per day; plumbers, £3 to £3 10s. per week; lumpers, 10s. to 12s. per day; masons, carpenters, bricklayers and plasterers, 10s. to 12s. per day.

On the other hand, the necessaries of life are cheap. Bread is 6d. the 4lb. loaf, and beef and mutton are retailed at from 3d. to 8d. per lb.; butter varies from 9d. to 1s. 6d. according to the season; milk is 4d. to 6d. per quart; potatoes 2s. 6d. to 4s. per cwt.; tea 1s. 6d. to 2s. 6d. per lb.; rabbits are sold at 1s. per pair, and hares at 2s. each.

In the Australian colonies there is neither an Established Church, nor is any aid given by the State to the cause of religion. The denominations are now entirely dependent upon the voluntary exertions of their members for support. A strong feeling has grown up both among politicians and the people in Australia that the State ought not to interfere in ecclesiastical matters upon any pretext. The Churches, therefore, are simply corporations empowered to hold property upon certain conditions, and at liberty to manage their own affairs as they think fit.

There are, however, great difficulties in the way of maintaining religious services regularly. In many of the country districts the population is sparse and scattered; and, however willing the people may be, the paucity of their numbers renders it hard for them to support a church. Only a mere handful can be gathered together, most of whom have a hard struggle in their private lives; for, although they own the land which they cultivate, they have to wait until it is cleared for the expected return. The difficulty is enhanced by the fact that each denomination wishes to have a footing in every village, in order to meet the wants of its own people. In many townships where there is room for one strong and self-supporting Protestant congregation, there are three or four, each of which is embarrassed by its own weakness. Some attempt has been made to prevent the weaknesses of disunion by co-operation among the Churches. The Episcopalians and the Presbyterians combine to support a society which is intended to supply the religious wants of the rural population. The money that is thus raised is spent principally in the erection of buildings, which are used alternately by clergymen of each denomination, so that the preferences of the people for their own form of service are gratified at the least cost, and without any rivalry.

By such means the Churches have spread their network well over the land. There is not a township of any importance that cannot boast of two or three neat and substantial edifices dedicated to the service of God. There is not a district that is not visited at intervals by ministers or agents of the different denominations, some of whom have to ride long distances in order to overtake every part. The vast plains that stretch between the rivers Darling and Murray are traversed by clergymen who visit from station to station. The deep forests of Gippsland and the Otway ranges, inhabited by a[Pg 32] hardy race of farmers whose lives are spent in clearing the jungle, are not left unprovided for. Though everything is not done that could be desired, it may be said with perfect truth that the Churches strive earnestly to keep pace with the continual migration of the people towards the backwoods of the country.

It is a pleasant thing to attend a rural service on a typical Australian day, when the sun is hot and the sky cloudless, and the whole landscape steeped in peace and quiet. Driving along the road, we see the sheep couched in the grass, or we pass a clearing where wheat and oats are growing among the blackened stumps of fallen trees; and nothing disturbs the stillness of the scene save, perhaps, the lazy motion of a crow, or the rush of a startled native bear, a sleepy, gentle, little animal, an enlarged edition of the opossum. The church stands a little apart from the few houses that form the infant township. It is generally built of wood, and surrounded by tall gum-trees, which, however, afford a very scanty shade from the burning heat. Here is gathered on the Sunday morning a collection of buggies and horses, for the people come long distances, and it is necessary in Australia to drive or ride. The congregation stand in groups before the door, chatting over the week's news, and waiting for the clergyman to arrive. The Day of Rest is the only day in the week in which they have an opportunity of meeting, and many come early and loiter with their neighbours till the service begins. They are all browned and tanned by scorching suns, but they speak with the self-same accent that they learnt at home. There are Scotchmen of whom, to judge by their speech and appearance, it is hard to believe that they have not very recently left their native glens, and Irishmen whose brogue is wholly uncorrupted by change of climate. Most of them, however, have been settled for many years on the land, retaining their old customs in the solitude of the bush, and among the rest a due regard for the worship of God. The children have caught, to some extent, the tone of their parents, and one could almost imagine oneself in a remote parish of Britain. The service itself heightens the illusion. The hymn-tunes are old and familiar, and sung very slowly to the accompaniment of a harmonium. The exhortation of the preacher is brief, telling the old and yet ever new story of the Saviour's love, and it is listened to with evident attention. One hour suffices for the whole worship, and the audience contentedly disperse, and turn their faces towards their lonely homes.

In the towns the organisation of the different Churches is effective. Their agencies are at work in the poorer quarters of the large cities, where the evils that exist in the Old World are showing themselves on a smaller scale. They have stood out strenuously for the observance of the Lord's Day, and with marked success. Sunday observance, if not so strict as it is in Scotland, is more general than in England. There is no postal delivery.[Pg 33] Trains are not run on the main lines, and a limited suburban traffic is alone allowed. All movements for restricting labour on the Sunday meet with cordial sympathy and practical support.

Though now independent in their government of the Churches in England by which they were originally founded, and which they continue to represent, the colonial Churches maintain a close relationship with the mother-country. Bishops, and the best preachers, are still brought from home to the colonies. All the important congregations send to England for a minister when there[Pg 34] happens to be a vacancy, and all the men who have made a deep impression on the community have been trained there. The whole religious and spiritual life of the colonies is inspired and stimulated by that of England, both in the sense that they naturally lean upon the stronger thought of English writers, and that they are guided by ministers who have studied in British universities. There are colleges connected with the more important denominations, which, it is hoped, will gradually grow till they rival those of other lands. As yet they are incompletely equipped, and one or two men have to bear the brunt of work that is usually divided among four or five.

In a new country, which attracts to itself all sorts and conditions of men, nearly every form of belief is represented. Many of the sects, however, are very small, and may be said to be practically confined to the metropolitan cities. The Catholic Apostolic Church, the Swedenborgians, Lutherans, Moravians, Unitarians, and various bodies of unattached Protestants, are thus limited. The Episcopalians, the Roman Catholics, the Presbyterians and Methodists have by far the largest hold on the people, while Independents and Baptists are fairly numerous and influential. Altogether, the Churches provide accommodation for more than one-half of the people, and the ordinary attendance at their principal weekly service amounts to fully one-third.

Sunday-schools flourish in every part of the country. The total number of children attending them is returned in Victoria as 73½ per cent. of the whole who are at the school age, and the average is not much less in any other colony. When allowance is made for the children who are kept at home by parents that prefer to give their own instruction, and for those in the country who cannot well attend a Sunday-school, it is evident that there are comparatively few who receive no religious education at all.

The love of church building, which every nation has displayed, is by no means wanting among the Australians. In every town the ecclesiastical edifices are the chief features, and in the larger cities some of them are imposing structures. Cathedrals are gradually rising in different places. Even the Churches which are not usually credited with paying much respect to outward appearance are inclined to beautify their buildings.

It would be too much to expect that the denominations could lay aside their differences and unite. But a very kindly feeling exists for the most part between them, whether it be due to their equality, or to the novel circumstances in which they were placed when they began their work. That it may continue and tend to further co-operation is the earnest wish of all.

Statistics, giving the most recent facts about the condition of the various Churches in the colonies, will be found in the Appendix.

Port Phillip—Early Settlement and Abandonment—The Pioneers Henty, Batman and Fawkner—Size of Victoria—Melbourne—Its Appearance—Public Buildings—Streets—Reserves—Pride of its People—Unearned Increment—Sandhurst—Ballarat—The Capital of the Interior—Geelong—The Western District—View of the Lakes—Portland—The Wheat Plains—Shepperton—The Mallee—Gippsland—Mountain Ranges—School System—Cobb's Coaches—Facts and Figures.

It is strange that Victoria should be one of the youngest of the colonies, for Port Phillip was amongst the places first noticed by the early settlers of the continent. Lieutenant Grant, commanding the little brig Lady Nelson, observed the inlet in the year 1800, when en route for Sydney. In 1802[Pg 38] Governor King, of New South Wales, dispatched the Lady Nelson, under Lieutenant Murray, to explore and report. The account given was most favourable of the extent of the bay, the security of its anchorages, and the beauty and apparent fertility of its shores. The result was that it was decided to establish a convict settlement on the shores of the gulf, and in 1803 Colonel Collins and a party of prisoners, with their guards, landed at the site of the now fashionable seaside resort, which has been called Sorrento at the instance of Sir Charles Gavan Duffy, one of the first landowners there. To the lover of beauty the scene, gazing from Sorrento down Capel Sound, is fair; the blue sea ripples at your feet; the high hills around Dromana, draped with the rich ultramarine blue not to be found outside of Australia, form a charming background on which one can gaze and gaze again. But the prose of the situation for Governor Collins was that he was landed on a well-nigh waterless sand-spit, the most sterile portion of the district, the resort to-day of the admirers of loveliness, but shunned even to-day by the practical settler. The citizen in his Sorrento villa is lulled by the roar of the league-long surf which ever breaks on the rocky ocean beach, scarcely a mile away. But circumstances alter human views, and the historian of the expedition reports that the monotonous booming of the breakers irritated and depressed both soldiers and convicts, and made a miserable company still more wretched. A search was made for water that was not brackish, but the right places were missed, and at last, happily for all concerned, the settlement was abandoned in favour of the Hobart colony. Governor Collins rejoiced to get away from the spot, the soldiers rejoiced, and the convicts also, and posterity will never leave off rejoicing that Victoria was left to be a 'free colony' from its inception.

The bad name given to the Port Phillip district clung to it for nearly a generation. The great central desert was supposed to extend to the sea-coast in this direction; but gradually the real district was discovered by 'overlanders' from New South Wales, and at last, in 1824, Hovell and Hume crossed the Murray river, skirted the Australian Alps, and struck the shores of Port Phillip between Geelong and Melbourne. Later on the Messrs. Henty, crossing from Tasmania, established a whaling-station in Portland Bay, and began cultivation also. So the new land was more and more talked about in the existing settlements, just as the new country in North-western Australia is being talked of in Sydney and Melbourne to-day. Tasmania sent the first batch of colonists, an association, with Mr. John Batman at its head, being formed to take up land there. In one sense Batman did take up land on an enormous scale. He landed in May, 1835. He says in a despatch to the Governor of Tasmania: 'After some time and full explanation, I found eight chiefs amongst them who possessed the whole of the territory near Port Phillip. Three brothers, all of the same name, were the principal chiefs, and two of them, men six feet high, very good-looking; the other not so tall,[Pg 39] but stouter. The chiefs were fine men. After explanation of what my object was, I purchased five large tracts of land from them—about 600,000 acres, more or less—and delivered over to them blankets, knives, looking-glasses, tomahawks, beads, scissors, flour, &c., as payment for the land; and also agreed to give them a tribute or rent yearly. The parchment the eight chiefs signed this afternoon, delivering to me some of the soil, each of them, as giving me full possession of the tracts of land.' How the blacks could sign a parchment is somewhat of a mystery. Batman seems to have recognised that a performance of this kind would be laughed at, and so he goes on to describe another signing away which took place. He travelled about with the natives, marking boundary trees.

Batman was a hardy bushman, and acquired great fame in Tasmania by his courage in capturing a notorious convict desperado; but if he imagined that these deeds and purchases would ever be recognised, he was as simple as the blacks themselves. As a matter of fact, no one ever took any notice of them. Within a few weeks after the transaction, the second or Fawkner party of settlers were on the river Yarra, had landed in the gully now called Elizabeth Street, Melbourne, and the future capital had been founded. When the deeds were shown to the new arrivals, they laughed and declined to move on, but proceeded to clear away the site of the city. Batman died from the effects of a severe cold in 1839, and 'Batman's Hill,' where he built his hut, has been cleared away to make room for the great Spencer Street railway station. John Batman would probably have become a rich man had he lived, but his estate was frittered away, and his grandchildren are now working in the mass for their living. Quite recently, a subscription having been organised for the purpose, a suitable monument was placed over the grave of the pioneer in the old Melbourne cemetery. The blacks would certainly have very much liked the terms which Batman made with them to have been respected, for Batman spoke of a yearly rent, and no one afterwards ever dreamed of such a provision.

The rival pioneer was much more fortunate. John Pascoe Fawkner lived to a ripe old age, became a member of the Legislative Council, and 'Fawkner's Park,' a handsome city reserve, perpetuates his name; while his portrait is in the Victorian National Gallery. The last time the author met the shrewd old man was in 1870, when he had stopped his carriage on the Eastern Hill to gaze wistfully at the scene, and was ready to talk with animation about the changes that had passed over it. Those changes had been great indeed. On the whole, the lieutenant of the convoy ship Calcutta was not exactly happy in his prophecy, when he wrote as he sailed away: 'The kangaroo now reigns undisturbed lord of the Port Phillip soil, and he is likely to retain his dominion for ages.' Sir Thomas Mitchell was more felicitous when, being commissioned by the Sydney Government to explore and report on the country to the south of the Murray, he wrote back[Pg 40] in 1836-7: 'A land more favourable for colonisation could not be found. This is Australia Felix.'

The surface of this south-eastern corner of Australia is strangely diversified, and hence its charm. Its own south-eastern region is occupied by the Australian Alps. Hundreds of peaks rising from 4000 to 7000 feet in height secure here an abundant rainfall, and in the sheltered gullies a noble vegetation is to be found; then come the uplands sloping down to the Murray plains. And back from the western seaboard stretches the beautiful so-called Western District, composed of open rolling plains studded with lakes, and with the isolated cones of extinct volcanoes. A grand and terrible sight they must have presented when these agents were at work sending forth fire, ashes and water, but, happily for man, their powers have departed long, long ago. Mount Franklin shows no sign of becoming a second Vesuvius, and the volcanic deposit has secured for the west a wonderful luxuriance of growth—such a growth as the grazier dearly loves. The beauty of the eastern district of Victoria is of the kind that delights the artist; the pleasant western [Pg 43]spectacle is grateful to the banker. The capitalist will build a cottage home in the one, but he will advance money freely on the acres of the other. The gold-fields are the least picturesque of any portion of the Austral region, though as gold-fields they possess a romance of their own.

But, turning from the country to the town, we have first and foremost that special pride of Victoria, the great city of Melbourne. Batman proclaimed the site 'a good spot for a village,' and the village has become a metropolis. We give an engraving showing what Melbourne was like in 1840, and as a contrast, one of a railway pier in the same city forty-six years later. Its population of over 350,000 puts Melbourne into the rank of the first score of the cities of the empire. And if area were considered as the test, the city would not easily be surpassed, except by London itself, for a ten miles' radius from the Post Office is required to cover it all. There is much filling in to be done, of course, but Brighton, Oakleigh, Surrey Hills, and other of the long distance suburbs have not only been built up to, but are being passed by the spreading population. The city itself is a compact mass of about a mile and a half square, encircled by large parks and gardens, all the property of the people, and permanently reserved for their use. Built upon a cluster of small rolling hills, the views of Melbourne are pleasantly interrupted, and yet it is possible to obtain frequent glimpses from commanding points, either of the whole or of parts of the whole. You will turn a corner and come upon a panoramic peep of streets, of sea and of spires that takes one's breath away. Near Bishopscourt you have one of these 'coigns of vantage.' You see the busy town below, and hear its hum. On the one side are the suburbs where artisan and clerk and small tradesman have their long rows of cottages and houses, costing from £200 to £2,000 each, while on the other side are the high lands of Malvern and Toorak, where the successful squatter, speculator, and storekeeper have erected mansions, standing in at present prices from £5,000 to £50,000. Government House, the residence of His Excellency, the representative of the Crown, is a conspicuous object to the south; to the north is the handsome Exhibition Building, in which the gathering of 1880 was held. Numerous places of amusement speak of a pleasure-loving people. The two or three spires upon every hill proclaim a Christian community not averse to spending money and making sacrifices for its religion. There is no veneer. The cottage is usually of brick; the public buildings, from the twin cathedrals of the Roman and Anglican Churches downwards, are of stone, which is costly here. The mushroom Melbourne of 1857 has been exchanged for Mr. G. A. Sala's 'Marvellous Melbourne' of the present year of grace, 1886.

Melbourne streets are wide—a chain and a half or ninety-nine feet in all—and they are busy. The shops seem 'squat' to most visitors from the Old World, for two stories high was the rule until within the last few years; but as the price of land goes up, so does the height of the buildings. Nothing would [Pg 44]be built in the city now under four or five stories, and there are tradesmen's places and stores and 'coffee palaces' that run up to six and seven stories, and are more than a hundred feet above the level of the roadway. Thus the complaint of squatness will speedily disappear. Not only are the streets wide, but they are also regular. Some run north and south; others east and west. Thus the city is something of a gridiron, or rather, giants could play games of chess upon its plan. Usually towns have been built on the tracks of the cows of the first inhabitants, but Melbourne is a surveyor's city. All the streets are straight, and none would be narrow but that lanes intended by the original designers as back entrances for the residents of the main roads have been eagerly seized upon, and are utilised as business frontages. The importers of 'soft goods'—that is, of articles of apparel—have taken possession of one of these streets, Flinders Lane, and as 'the lane' it is known everywhere throughout Australia, without the need of any distinctive affix. Further north, dilapidated buildings in another 'lane,' with their shutters up and a profuse [Pg 49]display of blue banners with golden hieroglyphics, proclaim that Little Bourke Street has been converted into a Chinese quarter. The main streets run their mile and more east and west. They are five in number, with four lanes, while nine broad streets run north and south. Of the five, Flinders Street is adjacent to the wharves and great warehouses, and is commercial in character.

Bird's-Eye View of Melbourne, Showing Public Offices and Gardens: St. Kilda in the Distance. |

Bird's-Eye View of Melbourne, Looking Southwards to the Sea. |

Collins Street runs from the public offices in the east to the country railway-station in the west. The one end is given up to the fashionable doctors and the favoured dentists, handsome churches and prosperous chemists filling in the interstices. From the Town Hall corner, Collins Street is gay with carriages and with pedestrians who come to see or to shop. Farther on we enter the region of the banks, the exchange, the offices of barristers and solicitors, and the rooms of the auctioneers. Here men of business are hurrying about. The flutter about the tall building on the left tells of some mining excitement. Farther on, a bearded, sun-burned, but well-dressed group will attract attention. 'Scott's' is the squatters' hotel, and it has been selected as the place for submitting to auction those 'well-known and extensive pastoral properties entitled the "Billabong Blocks," within easy distance of market (say eight hundred miles), together with all improvements and stock.' The conversation is whether the station will bring £300,000 or not—for it is a large property; whether a better sale could have been effected in Sydney, and so on; and next day you read in your Argus that 'the biddings reached £290,000, when the lot was passed in, and was subsequently sold at a satisfactory price, withheld.' Last of all, in Collins Street come Assurance Companies' offices, the buildings of merchants, and great wool stores.

In Bourke Street, commencing again at the west, where the new Houses of Parliament stand, we have first shops, hotels, and theatres, then hotels and mews, and finally a region of hotels (now less frequent), and of offices and stores. Lonsdale Street is in a transitive condition. La Trobe Street is not recognised. Standing on the midway flat you see two hills: the western hill is commercial, the eastern hill is social. After six o'clock Flinders Street and Collins Street are deserted. In place of busy scenes of life there is gloom and solitude, while Eastern Bourke Street, where the theatres and concert halls are, is lit up and is thronged. Leisured people who can promenade in the daytime use Collins Street as their lounge; the toiling multitude, who must promenade in the evening or not at all, patronise Bourke Street. On Saturday nights the Bourke Street block is great; the footways will not accommodate the crowds.

Another Melbourne feature is the rush from the city from four to six o'clock P.M., and the inrush from eight to ten o'clock in the morning. It is enormous, but it is easily met. There is an extensive suburban railway system, the property of the Government—as all railways in Victoria are. Omnibuses and waggonettes are numerous, the latter taking the place of the London cab; and now there are gliding through the streets the successful and popular[Pg 50] cable trams, a company having obtained a concession to put down fifty miles of these costly roadways. Let a heavy shower of rain fall at or about six P.M., however, and the rush is too great for the accommodation, and those 'too late' have to wait for return vehicles, and to bewail their misfortune.

In public buildings Melbourne would be really great, if all that have been begun were finished. But few are. The citizens are not running up miserable flimsy structures, but are building for posterity. Final contracts have been [Pg 51]taken for the Houses of Parliament, which are to be finished with a newly-discovered stone of a beautiful whiteness, but expensive to work. From first to last half a million of money will be spent on these halls of legislation. They will crown the eastern hill. The Law Courts, which cost nearly £300,000, are finished, and constitute a handsome pile on the western hill. St. Patrick's Cathedral, on the eastern hill, will be a marvel, and it is slowly creeping on. The Anglican Cathedral, founded by Bishop Moorhouse, is in the heart of the city, and is making more rapid progress. The Public Library is a noble institution, containing 150,000 volumes, and is open without restraint to all comers. So is a National Picture Gallery which is attached, and which contains specimens of the work of many of the best modern masters. There is a National Museum, in which the Australian fauna is admirably represented,[Pg 52] and the Melbourne University is near at hand. This institution, beautifully situated and handsomely endowed, grants degrees which are recognised throughout the Empire, and its doors are open to male and to female students alike. Ladies have taken B.A. and M.A. degrees already, and the number of the softer sex entering is on the increase. Not a ladies' school of repute but has its matriculation class. The Town Hall, where 2,000 people can sit to listen to the organ—one of the world's great organs—is not to be passed over. The Botanic Gardens are another show spot. They are well within the civic bounds, and by visiting them you obtain a series of lovely views, and become acquainted with the flora of the Australian continent, for everything that can be coaxed to grow here has been provided by the director, Mr. Guilfoyle, with a suitable home. There is a gully for the graceful Gippsland ferns, a spot for the gorgeous Illawarra flame-tree, a guarded receptacle for the great northern nettle-bush, which is here twelve or fifteen feet in height, and which no one would presume to handle. Cycads, palms, and palm lilies represent Queensland in one division; a mass of foliage of a bright metallic green speaks of New Zealand in another. Of no place is the Melbournite more proud than of the Gardens, which Mr. Guilfoyle has only had in hand about twelve years, but which he has transformed from a waste into a Paradise.

Melbourne has a grand system of water supply. The river Plenty, a tributary of the Yarra, is dammed twenty miles away, and the huge reservoir when full contains nearly a two years' supply. The reticulation allows of a[Pg 53] supply of eighty gallons per head to each consumer; but in hot days the demand for baths and for the Garden are so great that this quantity is not found to be half enough, and improvements are to be effected. The Yan Yean system has cost £2,000,000, and now the Watts River is to be brought in, and as the engineers speak of £750,000 being necessary, the presumption is that £1,000,000 will be required. It is a grand spectacle to see a full head of Yan Yean turned on to a fire, say at night, when there is no strain to abate the maximum pressure. The flames are not so much put out as they are smashed out of existence. On a wooden building the jet will act like a battering-ram, sending everything flying. No engine is required in these cases; the hose is wound on a light big-wheeled reel, and the instant an alarm is given a brigade can start off at racing speed and come into action on the moment of arrival.

As to industries, a list would be wearisome. A hundred tall chimneys make known to the observer the fact that Melbourne is becoming a great manufacturing centre.

The reserves between the city and its suburbs must ever be the greatest charm of Melbourne. To leave Melbourne on the south, you must pass through the mile-long Albert Park, with its ornamental water and its handsome carriage drives, or you must saunter through Fawkner Park or the Domain. Yarra Park and the Botanic Gardens are to the south-east, and they link with the beautiful Fitzroy Gardens. Carlton Gardens crown the[Pg 54] city to the north, and communicate by smaller reserves, such as Lincoln Square, to the 1,000 acre Royal Park, in which, among other attractions, are the well-stocked gardens of the Zoological Society, open to the public on certain days, in consideration of a Government subsidy, free of cost.

The Yarra Park, lying between Melbourne and Richmond, contains the principal cricket grounds of the city. Here the Melbourne Cricket Club has its head-quarters, and much its sward and its grand stand and its pavilion are praised by our cricketing friends from the Old World. In the season the big matches, All England v. Australia, or New South Wales v. Victoria, will draw their tens of thousands of spectators, and on other occasions the area is utilised for moonlight concerts, for flower-shows, and for pyrotechnics.

A jealous eye is kept upon these reserves. Once or twice a minister, eager to increase the land revenue, has made a dash at a city park, and has essayed to sell a slice, but so great has been the uproar that no Government is likely to indulge in the effort again. Indeed, in almost all cases, the alienation has now been rendered impossible except by means of an Act of Parliament, which could never be obtained. The belt of reserves—5,000 acres in all—is secure, and it must grow in beauty yearly, continually adding to the attractions of the town. As it is within a stone's throw of city life, you can wander into cool glens and sequestered shades, and hear the thrush sing, or study the beauties of a fern gully. To the pedestrian the walk to business in the morning or from it in the evening is thus rendered delightful; but if the ordinary Australian can possibly avoid it he never does walk. You meet curious traces in these reserves of that former time when the eucalypts sheltered not the inevitable perambulator and nursemaid at noon, nor the equally inevitable 'young people' at the 'billing and cooing' stage in the evening, but rather the kangaroo and the black fellow. In the Yarra Park an inscription on a green tree calls attention to the fact that a bark canoe has been taken from the trunk. The canoe shape being evident in the stripped portion, and the marks of the stone hatchet being still visible on the stem. The blacks would find their way to the river impeded now by a treble-track railway that runs close to their old camp, carrying passengers to a station which three hundred trains enter and leave daily.

Melbourne has a river. One knows this mostly by crossing the bridges, as otherwise the Yarra plays but a small part in the social arrangements of the community. The lower portion of the stream is being greatly improved. It is to be straightened and deepened, so that the largest liners are to come up to the city, as already do 2000-ton intercolonial steamers. The works, which will cost millions, are now (1886) about half-way through. Near Melbourne the stream is muddy and nasty. Sluicers use the water for gold-washing purposes twenty miles away, and factories were allowed years back to be started upon its banks, and though new tanneries and new fellmongeries are forbidden, the old evil-smelling establishments remain. Few who look upon[Pg 55] the sluggish ditch at Melbourne would imagine that five and forty miles away it is a brisk and sparkling river, parrots and satin birds and kingfishers floating about it, ferns bending over and hiding its waters, and the giant gum rising from its banks to double the height of any city spire. The improvements will make the Yarra below the city a grand stream, bearing the commerce of the world on its bosom, and one may look forward to the time when the city portion itself will be purified, and the river made worthy of its romantic mountain home.

The city has its drawbacks. There is dust in the summer, which the water-carts seek in vain to control; and there is mud in winter, which no raving against the Corporation appears to affect; and the less said on the drainage question the better. Again, as to weather, there are people who protest against the suddenness of the change when the wind in January chops round from north to south, and after panting in the morning you begin to[Pg 56] think of a fire at night. But the three hundred delightful days of the year, when existence is a pleasure, are to be remembered, and not the odd sixty-five when ills have to be endured. A favourable impression is usually made upon visitors by the city with its charm of suburbs, its wealth and reserves, its crowds of well-dressed people, always busy about either their pleasure or their business, always obliging, the poorest showing no signs of poverty, nor yet the lowest of the influence of drink. And if a visitor had ideas of his own he would withhold any adverse dictum until he was away, and would not seek to wound the feelings of his hospitable hosts. With them, at any rate, it is a cardinal principle of faith that their much-loved home is entitled to the proud appellation of the 'Queen City of the South.'

An 'unearned increment,' such as would satisfy the most glowing dreams of the most ardent speculator, has occurred in the capital. One instance may be given. One of the few original half-acre blocks now in possession undisturbed—not cut up—of the family of the original purchaser is situated in a good part of Collins Street. The colonist whose executors are now holding the property gave £20 for it in 1837. To-day the sixty-six feet frontage to Collins Street is worth £1,150 per foot; the Flinders Lane frontage is worth £350 per foot. A little ciphering brings out a sum total of £99,000 as the present value of the original £20 investment. And for decades the income derived from the block has been counted by many thousands per annum. The £20 has by this time earned at least £200,000 in all. In many country places a £5 lot will bring £500 when a decade has passed. But then the place may not become a centre, and your 'unearned increment' will be no more substantial than the evening cloud. There is a reverse to this shield, as to all others.

From Melbourne it is easy to journey to the two great gold-fields of Victoria—Ballarat and Sandhurst. The latter is due north, and is reached by a double-track railway, built in the early days at a cost of £40,000 per mile. Single-track railways, costing £4,000 per mile, are now the order of the day. Sandhurst is the Bendigo of old days. It has had many ups and downs; has been deserted, and has been ruined; but the result is the fine city of to-day, with its broad, tree-lined streets, its splendid buildings, and high degree of commercial activity. As a recent writer puts it: 'What vicissitudes has not the place undergone! From enormous wealth to the verge of bankruptcy, from the pinnacle of prosperity to the direst adversity; from financial soundness to commercial rottenness; and yet, with that wonderful elasticity and buoyancy which characterises our gold-fields, the falling ball has rebounded, the sunken cork has again come to the surface, and Sandhurst, after all her reverses, is perhaps now richer and on a safer basis than ever—a city whose wide, well-watered streets are perfect avenues of trees, bordered by handsome buildings and well-stocked shops, brilliantly lighted by gas; whose hotel accommodation is proverbially good, whose [Pg 59]civic affairs are admirably regulated, whose citizens are busy, hospitable, and prosperous.' There is no mistake about the character of the town. Miles and miles of country before you enter it have been excavated and upturned by the alluvial digger. And there are few more desolate sights to be met with than a worked-out and deserted diggings, for often Nature refuses to lend her assistance, and does not hide the violated tract with trees or verdure. Ugly gravel heaps, staring mounds of 'pipe-clay,' deposits of sludge, a surface filled with holes, broken windlasses, the wrecks of whims, all combine to make a hideous picture as they stand revealed in the pitiless sunshine. Alluvial digging of the shallow type is a curse to the unhappy country operated upon. But alluvial mining has long had its little day, and ceased to be in and about Sandhurst, and the town lives now by deep quartz mining. You come upon the 'poppet-heads' and the batteries everywhere, even in the beautiful reserve which is the centre of the city. Sandhurst contains 30,000 inhabitants, 8,000 of whom are miners, while the value of the mining machinery and plant is three-quarters of a million sterling.

Old Bendigo had busy scenes, but never did it witness such excitement as when a share mania broke out in 1871. Then it was that the richness of the so-called 'saddle reefs' was demonstrated. The old-established companies were paying well, and the Extended Hustlers exhibited one cake of 2,564 ozs. as the result of a crushing of 260 tons. This was just the spark wanted to set the market aflame. From being unduly neglected, Sandhurst was unduly exalted; new companies were projected in every direction where a line of reefs could be imagined; existing 'claims' were subdivided, and in a few months £500,000 was invested in Sandhurst mines. Of course there was a reaction; but though the speculators lost money to sharpers, there really were auriferous reefs in Sandhurst to be honestly worked, and no town seems more likely to hold its own in Victoria than the great quartz city. Foundries and potteries are springing up in its midst, or rather have sprung up; vineyards and orchards are found to be successes in its neighbourhood, and the visitor is grateful for the tree planting in the broad streets, appreciates the water supply, is duly dazed if he enters a battery chamber, and is delighted when 1,500 feet below the surface he is allowed to break off some fragment of glittering quartz.