The Project Gutenberg eBook of Submarine U93

Title: Submarine U93

Creator: Charles Gilson

Illustrator: George Soper

Release date: March 5, 2012 [eBook #39387]

Most recently updated: April 5, 2012

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Al Haines

――――

CONTENTS

――――

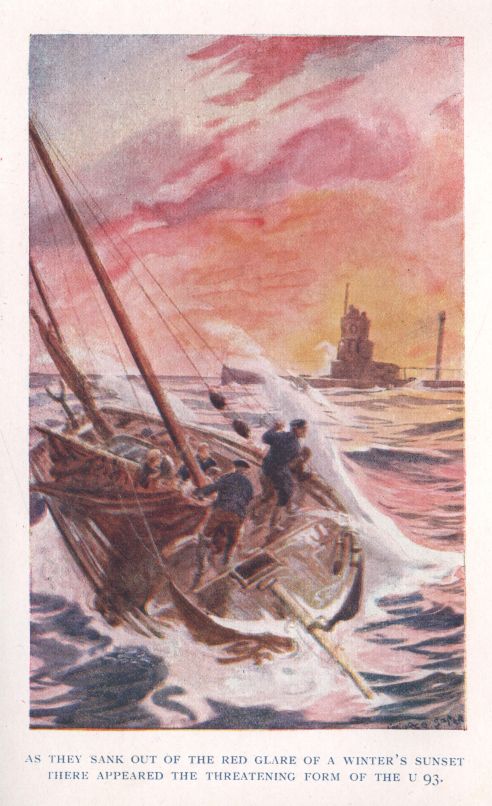

In the following story fact is blended with fiction. The account of the Battle of the North Sea, in which the "Blücher" was sunk, is as historically accurate as is possible with the details at present available. On the other hand, it would be well for the reader to know that the description of the pursuit of the "Dresden" in mid-Atlantic is wholly fictitious. The incident is introduced "for my story's sake," as Robert Louis Stevenson used to say, and also because it is illustrative of the character of the "Sea Affair" in the earlier days of the war.

CHAPTER I--The Admiral's Sixpence

The following incident is well known to those who are acquainted with Naval history, and is mentioned here for the sole benefit of those who are not.

At the time of the Crimean war, and the bombardment of Sebastopol, an officer of the name of Burke commanded H.M.S. "Swiftsure," a ship which at one time approached to within point-blank range of the Russian shore batteries, which it silenced with a series of terrific broadsides. This feat, however, was not accomplished without considerable loss. Several men were struck down on the battery decks in the very act of serving the guns; and the life of the captain--who bellowed his orders from the bridge in a voice that was audible throughout the length and breadth of the ship, despite the roar and thunder of the cannon and the groans of wounded men--was saved as by a miracle.

A round of grape-shot raked the ship from fore to aft as she swung into position; and one of the little leaden pellets struck Burke immediately above the heart. Now, it so happened that he carried, suspended around his neck by a little silver chain, a "lucky" sixpence which he had got from his grandfather, Michael Burke, of the Inner Temple, and which bore the head of His Majesty, King George III.

At the time, Captain Burke was hardly conscious of a wound, which--according to the Fleet Surgeon--came under the official heading of a "severe contusion" not serious in nature. He remained upon the bridge in command of his ship, which he brought safely out of action, to the great credit of himself and the eternal glory of the British Navy.

But his lucky sixpence, which he found that night before he flung himself down upon his bunk, was ever after something of a curiosity--a thing to be talked about and passed from hand to hand in a London club. It was dented so deeply that it was shaped almost like a spoon, and as for the features of His Majesty, the third George, they were so obliterated that he might have been Queen Elizabeth or, for the matter of that, Julius Cæsar or the Cham of Tartary. In short, in plain words, it was a narrow squeak; and ever afterwards, both in the Navy and out of it, this officer, who rose to the rank of admiral and lived to the ripe old age of eighty-six, was known as "Swiftsure Burke." That he and his kind have lived and moved amongst us since the days of Drake and Hawkins is, after all, the best security we have against the invasion of these island shores.

There is a certain irony in the way things happen. No man can say for sure what destiny awaits those whom he loves and cherishes after he himself is gone. There was once--as a fact that can be proved--a man who sang for pennies in the street, whose ancestor, with the rank of colonel in the Army, headed his regiment as it charged at Blenheim. In the year 1914--which is not so long ago--Jimmy Burke, grandson of this same captain of the "Swiftsure," by a series of unmerited misfortunes, found himself, at the age of seventeen, an orphan and alone, in one of the greatest cities in the world. How that came about can be told in a few words. It was certainly through no fault of his own.

"Swiftsure Burke" had a son, whose name was John, who had neither his father's luck nor iron constitution. John Burke married a fair girl who had been thought the fairest in Dublin--that is to say, in the world. They had one son, a boy--the Jimmy Burke with whom these pages are concerned.

For three short years John Burke was happy--more happy, perhaps, than a man has a right to be. And then his wife died quite suddenly, and his frail health broke like a reed.

He was overcome by grief, and for a time his friends even feared for his state of mind. At last, acting on a famous doctor's advice, he realized all the property he possessed, packed up his worldly goods, and accompanied by his little five-year son, betook himself to the great United States, which was about the last place in the world where he had any right to be.

New York City, with all its flare and rush and hurry, was no place for this poor, broken English gentleman. Unsettled and unnerved, he took to speculation, and fell into the hands of a certain firm of financial brokers, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern to wit, famous even in New York for their sharp practices and hardness of heart. They had no more mercy on John Burke than on any other of their clients, and when the poor fellow was well-nigh destitute, he fell into a rapid consumption. Then, knowing that his days were numbered, he called his son to his bedside, and gave Jimmy a dying father's advice.

In the first place, he asked the boy's pardon for the wrong that he had done him. He told Jimmy to try to live honourably and well, and never to forget three things: his duty to God, the example of the mother whom the boy could only just remember, and the fact that he was an English gentleman--the grandson of "Swiftsure Burke."

And after that, John Burke died. The life flickered out of him like a candle in the wind, whilst Jimmy was left kneeling at the bedside, his young frame numbed by a great feeling of weakness that pervaded every limb, and his face all streamed with tears.

The doctor lifted the boy to his feet, and just then something fell from the bed to the floor, which the doctor picked up and gave to Jimmy. It was a little coin--all, indeed, that the boy possessed in the world, all Jimmy Burke's inheritance. It was the "lucky" sixpence of Admiral "Swiftsure Burke."

CHAPTER II--In Defiance of Authority

At the time of his father's death, Jimmy Burke was seventeen years of age. He was a strong lad and tall for his age, fair of complexion, with a direct look in the eyes and a resolute cast of chin that he had got from "Swiftsure Burke."

He had had a hard life, even at that age; and a hard life will either mould a boy or break his heart--more often the latter, unless he be made of the right stuff. But Jimmy came of a fighting race. He soon learnt to hold his own, being in more ways than one far better fitted to succeed in the world than his less robust, unhappy father.

Left alone in a great city like New York, where there are as many rogues as street-cars, and more "toughs" than police, he looked about him for some suitable employment, resolved in spite of everything to earn an honest living. Knowing that good fortune comes only to those that seek it, he presented himself at the offices of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern--the very firm, though he never knew it, that had brought about the ruin of his father--and boldly asked to be taken on as a clerk.

Rosencrantz questioned the boy as to his capacities, sounding him in much the same way as a farmer might prod a fat sheep on a market day, and very soon arrived at the conclusion that Jimmy Burke was the very lad he wanted. He engaged him on the spot, as a kind of combined clerk and office boy, and--what suited Rosencrantz most of all--at a starvation salary, which at the time, however, seemed more than enough to Jimmy.

And thereupon the boy entered upon a phase of his existence in which there was little sunshine and much that would have made him miserable and downcast had he been made of weaker stuff.

Rosencrantz was a bald, clean-shaven man, with a hooked nose, a sallow face, and a domineering manner. It was his habit to browbeat his employees; but it was no more possible to crush the spirit, or blot out the personality of the grandson of "Swiftsure Burke" than it would be to curb the cub of a tiger. The boy remained the same: straightforward, frank and honest. He continued to do his work to the best of his ability, taking his employer's hard words for what they were worth, accepting them as part and parcel of his life, a sort of grim necessity.

As for Guildenstern, he seldom appeared at the office; and when he did so, it was quite evident that he had little or no say in the business. He was a small man, very short-sighted, whose gold-rimmed pince-nez would never stay on his nose. He was always perfectly ready to agree to whatever Rosencrantz said, and if he ever made a suggestion of his own--which was seldom enough--he did so with many apologies, as if he was well aware that he had no right to open his mouth.

Both these men were "hyphenated-Americans" of German descent. Neither, however, had ever been to the Fatherland, nor was Rosencrantz able to speak a single word of what should have been his native language. He had been born in Chicago, and on that account it was his custom to refer to himself as a "freeborn citizen of the great United States."

Whatever else he was, he was first a rascal, and secondly a man of business. The sole object of his life was the making of money, in regard to which he was handicapped by no qualms of conscience. Such ambitions are bound to be debasing; and Herr Rosencrantz was quite incapable of any finer feelings. He took not the least personal interest in the orphan boy whom fate had thrown upon his hands. He experienced no feelings of remorse for having brought John Burke to the brink of ruin and the door of death. Jimmy was just a bright lad who could be put to a good use, who was certainly worth four times the salary he received.

In course of time, the boy so disliked and mistrusted his employer that he had serious thoughts of looking for work elsewhere. One thing, and one thing only, prevented him from doing so. His sole friend in these days was a girl, a little older than himself, whose name was Peggy Wade.

Peggy was an orphan, too. Her parents had died when she was quite a child, since when she had been brought up by an aunt who lived at Hoboken--a true woman, who could give, without thought of recompense, and without reluctance, that love and tender care to which the young should be entitled. She was a mother, in all but name, to Peggy Wade; and Peggy, in a girl's way, was a mother to Jimmy Burke.

She was employed by Rosencrantz as a shorthand-typist; and thus it was that she and Jimmy, constituting the whole office staff, were thrown much in each other's way, and before long they had become inseparable friends. Often, when they were obliged to work long after business hours, smuggling into the office various unwholesome edibles, such as pork-pies, sardines and cakes, they would make cocoa on the stove and revel in what they termed a "picnic."

They would spend their Saturdays together in Central Park, or else go even so far afield as Coney Island, provided one or the other had sufficient money to spend upon the roundabouts and swings. And in the evenings they would return to Hoboken, where Peggy's aunt, with the sweet smile of a loving woman, to whom the happiness of others is a great reward, would listen in patient satisfaction to the whole tale of their adventures. That was how things were during the winter and the early spring of the year 1914--which is a date that will stand forth in scarlet lettering in the History of the World.

It was during the month of April that Rosencrantz began to receive visits from a certain distinguished-looking gentleman, whom Peggy recognized at once by his portrait which had appeared more than once in the New York papers. He was a certain Baron von Essling, a military attaché of the German Embassy in Washington, though never by any chance did he think fit to give his name. He always asked for Rosencrantz, and was admitted without delay, when the two men would remain closeted together sometimes even for hours.

In more ways than one, there was an atmosphere of secrecy about these interviews, which even Jimmy could not fail to observe. In the first place, the Baron's visits invariably took place after dark, when most of the business houses were closed. Rosencrantz, too, never failed to lock his office door after the Baron had entered. He also became more fussy than ever, and more impatient and nervous. He had just discovered that Peggy and Jimmy were in the habit of entering his room after he had left it, for the purpose of converting his office stove into a kitchen range.

This he strictly forbade. He admitted that it was necessary for both of them to have access into the inner office, but cooking he would certainly not permit. There can be small doubt that in his own boyhood (if he had ever had one) the joys of a "picnic" had been quite unknown.

It was also about this time that he purchased a peculiar leather box--which he called his "attaché-case"--of which he himself possessed the only key, and in which he kept certain documents which no one but himself, and apparently the Baron von Essling, was ever permitted to see.

Now, one of the man's peculiarities was that he liked to see his office tidy, whereas he himself was one of the most slovenly people in the world. And as Jimmy was not particularly methodical in such matters, the result was that Peggy was the only one of the three who ever knew where anything was. It was this, as it turned out, that brought about something in the nature of a great calamity, as we shall see.

Von Essling, when he called, was sometimes accompanied by a short, thick-set fellow, who went by the name of Rudolf Stork. Stork was a strange-looking man, with an exceedingly wrinkled face, and a sinister cast of countenance. Peggy, with the unfailing instinct of her sex, mistrusted him from the start.

Stork was evidently a sailor, for he wore a pea-jacket, walked with a rolling gait, and was eternally chewing tobacco, and expectorating with a considerable degree of skill. If Rosencrantz was a scoundrel, Rudolf Stork was something worse. There was that about him that suggested the jail-bird, the man who knows what it means to wear a convict's clothes, to be labelled with a number and pace a prison yard. One evening, Rosencrantz left the office earlier than usual. There had been a sudden bout of cold weather, when it had seemed that the spring was at hand. A bitter wind was blowing through the New York streets, that picked up the dust and drove it in eddies between the great, square-cut, towering buildings. It was wholly characteristic of Rosencrantz that he grudged his clerks a fire, though the stove in his own room had been burning all that day. Peggy and Jimmy had been left at their desks with orders to make up certain arrears of work. The boy sat before an opened ledger; the girl was busy at her typewriter with a sheaf of shorthand notes at her elbow.

Suddenly, she got to her feet, unrolled the last quarto, and placed the cover over the machine.

"I've done," she said, looking across at Jimmy.

The boy, who was still poring over the ledger, ran his fingers through his hair.

"I wish I had," he answered, in a tired voice. "If I can't balance these accounts, I shall hear all about it to-morrow. Say, Peggy," he continued, swinging round in his chair, "what do you say to a picnic?"

Peggy straightened, and shaped her lips as if about to whistle.

"Just fine!" she exclaimed. "But, Jimmy, dare we risk it?"

The boy's face altered; for a moment he looked quite serious.

"No," said he. "It's not good enough. I don't mind for myself, but I'm not going to get you into a row."

Peggy laughed.

"Oh, I don't care," she answered.

"It's not allowed," said Jimmy.

"It wouldn't be half such fun if it was," observed Peggy, with a world of truth. "Besides, he won't come back again to-night. He told me I was to leave the most important letters till to-morrow morning."

Jimmy was on his feet in an instant; the ledger was slammed down upon a shelf.

"Come on," he cried. "We'll have the feast of our lives."

Their cooking utensils consisted of a cheap kettle, a frying-pan, and a few knives, forks and spoons. These Peggy had hidden in a large cupboard in Rosencrantz's room, which was used as a receptacle for old account books and ledgers and all kinds of rubbish, and where their employer never by any chance happened to look. As they rescued these priceless possessions from behind a collection of office brooms and dust-pans, Jimmy noticed that the mysterious leather box--which Rosencrantz called his "attaché-case"--had been placed on the floor of the cupboard.

The recognized preliminary to an office "picnic" was that they should club their money. On this occasion Peggy produced two dollars fifty, whereas Jimmy could contribute no more than seventy cents. When Peggy had filled the kettle, it was arranged that Jimmy should remain in charge, whilst the girl went out to purchase supplies which, it was decided, should include sausages, in regard to the cooking of which Peggy was an acknowledged expert.

Now, an escapade of this sort loses much of its zest when the bold adventurer finds himself alone; and no sooner had Peggy set out upon her errand than Jimmy became conscious of feeling a trifle nervous. Though he was never willing to admit it to himself, he held Rosencrantz in considerable dread; and he did not like to think what the result would be should he and Peggy be caught. In consequence, for the first time in his life, he was really alarmed when suddenly he heard the clashing sound of the brass doors of the elevator, followed by footsteps in the corridor.

Shuffling the knives and forks into his coat pocket, with the kettle in one hand and the frying-pan in the other, he sprang to his feet and stood for a moment irresolute, not knowing what to do. He could not go back to the clerks' office, since there he would meet Rosencrantz, whose voice was audible through the half-opened sliding door in the wall.

It did not take Jimmy long to come to the conclusion that, on such an occasion as this, discretion is the better part of valour. Without a moment's thought, he dashed into the cupboard; tripped over the leather box, so that some of the half-boiling water was spilled from the spout of the kettle, and then closed the door.

He did so only in the nick of time; for, a second later, Rosencrantz himself entered the room, followed by the Baron von Essling and Rudolf Stork.

CHAPTER III--The World Plot

The office door was closed and Jimmy heard the key turn in the lock. Rosencrantz offered his guests chairs, and then apparently seated himself at his writing-desk. Of the conversation that ensued Jimmy could hear every word, for the cupboard door was thin and von Essling, who did most of the talking, had a deep, resounding voice.

The plot that was unfolded, word by word, was amazing and colossal. It was so cold-blooded and terrible, and was intended to be so far-reaching in its results, that the boy could hardly bring himself to believe the evidence of his ears. Time and again, he had to pinch himself, to make sure that the whole thing was not a nightmare from which he would presently awaken.

It must be remembered that at that time the tragedy of Serajevo had not taken place. Europe and, indeed, the whole world--was at peace. Official Germany was even then talking of friendly relations with England.

And yet, it appeared, from what the Baron had to say, that Germany intended to plunge the whole of Europe into war. By the first of August, the German legions would be on the march, crossing the frontiers of France on the very day that they swept down upon Paris in 1870--forty-four years ago.

France was to be crushed, and would be crushed--according to von Essling--after six weeks of war. Russia would take time to concentrate her forces; and after Paris had fallen, the German armies could be transferred to the east, where the fall of Warsaw would checkmate the Russian armies till the conclusion of the campaign. When peace had been declared, and the German Empire extended to the North Sea and the great port of Antwerp, a fitting moment was to be seized to throttle England and break up the British Empire, once and for all.

This--as the Baron explained--was the main policy of all true Pan-Germans. Not until Great Britain had crumbled to the dust, could Germany realize to the full her dreams of World-Power and World-Dominion. England stood between Germany and the sun.

"I tell you, my friends," von Essling almost shouted; "I tell you, the blow will fall with alarming suddenness. The declaration of war will come like a thunderbolt. We are ready; France and Russia are unprepared; it is impossible that England will dare to interfere."

"That is good," cried Rudolf Stork. "I have no love for the English, who encumber the face of the earth like a plague of flies. None the less, I fail to see why a plain sea-faring man like myself should be taken into your confidence."

"It so happens," said Rosencrantz, "that you are the very man we want. In the first place, though you call yourself a Dutchman, you are German born, as I know very well, and can be trusted. Also, you know the world; you can speak four languages--German, French, English and Dutch. Moreover, you were once an actor; you should know how to disguise yourself, to play several minor parts in this great drama which is about to astonish the world."

Stork gave a grunt of disapproval.

"It seems to me," he said, "you know too much about me."

"I know more than that," said the other. "I know that you are an ex-convict, and even now are wanted by the police. However, you have nothing to fear; I intend to keep my knowledge to myself. The Baron himself will explain exactly what you will be required to do."

Once again, von Essling took up the thread of this ruthless world-wide plot. In order to hasten the decomposition of what he called the already-tottering British Empire, rebellion must be stirred up in the British colonies. The seeds of sedition must be sown broadcast, in India, in South Africa and Egypt.

Here, it appeared, both Rosencrantz and Rudolf Stork could be of the greatest assistance. According to von Essling there was little or no risk, and they might count upon being well paid. "The German Emperor," said the Baron, "does not fail to reward those who serve the Fatherland."

The offices of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern were to be used as a kind of Secret Service Bureau. Whether or not England joined in the conflict, the United States would, in any case, remain neutral. From New York, intelligence could be transmitted direct to Berlin, and vice versa. Von Essling's agents--one of whom was to be Rudolf Stork--acting as spies in the war area, would transmit, or bring personally, the information they gathered to Rosencrantz, who would represent the Baron, who would sift all intelligence, and supervise cyphered telegrams to the Intelligence Department in the Wilhelmstrasse in Berlin. For the present absolute secrecy was to be maintained.

Von Essling ended. There was a brief pause, during which Stork spat upon the floor.

"And may I ask," said he at length, "what guarantee I am to have? I don't, mind you, say that all this is not true; but, still, business is business, and no man takes on board a cargo without a manifest, which is a kind of passport on the sea."

"You are quite right," said the Baron. "I can supply you with credentials which will instantly dispel such doubts. I have already entrusted to Mr. Rosencrantz papers of the utmost value, which will prove to you that we are perfectly sincere, that it will be worth your while to help us."

It was then that Rosencrantz got to his feet, and shuffled about the room.

"It so happens," he observed, "that the papers you mention are in a certain leather box which was given into the charge of my secretary."

Von Essling gave vent to an exclamation of surprise.

"You take grave risks!" said he.

"My dear Baron," replied the other, "the girl can be trusted implicitly. And besides, she is totally ignorant of what the box contains."

Von Essling had something else to say, but Stork took him up.

"What happens if I'm caught?" he asked.

"If you succeed," said the Baron, "you will be amply rewarded. You will be paid according to the value of the information you obtain. But if you fail the misfortune is yours. We wash our hands of you; we know nothing whatsoever about you. That is the principle upon which the Secret Service works."

"I see," said the man. "Whatever I do is at my own risk."

"Precisely," said the Baron.

There was another pause; and then Stork got to his feet.

"I'll do it," said he. "I've every confidence in myself. If you want my candid opinion, I think I'm the very man for the job."

"Good!" said von Essling. "Self-assurance is essential. And now, there are a few questions I would like you to answer. Have you ever been to London? Could you find your own way about in that labyrinth of a city? It will probably be necessary for you to go there."

"I know London well," said Stork, "from Whitechapel to Hammersmith. At one time, I played Iago in Shakespeare's play, in a little theatre which is now pulled down, in the Portobello Road."

"Ah," said the other, "some time in the near future you and I may meet in London. I have never been there. Though I can both speak and write English with ease, I have never set foot in England."

"You are likely to leave New York?" asked Rosencrantz.

"Perhaps; I can say nothing for certain. My post here is merely a blind. I was transferred into the Diplomatic Service from the Secret Service for reasons of convenience. As a military attaché, I have many opportunities for gleaning information."

Jimmy Burke was only a boy, whose experience of the world was necessarily somewhat limited. None the less, he was well able to understand the depth of the perfidy with which he found himself confronted. The whole thing seemed too villainous to be true. He could not believe that the modern civilized world was such a hotbed of treason and deceit--a kind of magnified thieves' kitchen wherein mighty nations played the part of common footpads.

Indignation and excitement left him breathless. In fact, he was so astounded and dismayed that he had forgotten his own danger, when suddenly he was brought back to his senses by the loud slamming of a door. On the instant, as he recognized the truth, it was as if a blow had been struck him: Peggy had returned!

He was told afterwards what actually happened. At the time, shut up in the darkness of the cupboard, fearing to move an inch, almost dreading to breathe, he was able to see nothing of what took place in the room.

Peggy, with cheeks flushed in the wind, and an armful of small paper parcels, came swinging along the corridor, tried to open the office door, and found it locked.

Before she had time to guess what was about to happen, the door was flung wide open, and she found herself confronted by Rosencrantz and his companions.

She stood stock-still, speechless and afraid. Her first inclination was to fly; and the next moment, she found herself wondering what had become of Jimmy.

Rosencrantz, after the manner of a cat who plays with a mouse, with extreme politeness ushered her into the room.

"And may I ask," said he, in a soft, oily voice, "may I ask what those parcels contain?"

Peggy allowed him to take them from her hand. He opened them one by one. The first contained a packet of cocoa; the next (of all iniquities!) a bundle of sausages. There was also bread, butter, sugar and lard.

"I see," said Rosencrantz, "I see. It is not sufficient for me to give orders; it is not sufficient for me to forbid you to turn my office into a kitchen and a common eating-house; but you must leave your work the very moment my back is turned."

"Is this the girl," asked von Essling, "who enjoys a position of trust?"

"I have been mistaken in her," said Rosencrantz. "There can be no doubt as to that. Where is my attaché-case?" he demanded. "Where have you put the leather box?"

At these words, it seemed to Jimmy that his heart ceased to beat. In the ordinary course of events, he would have stepped forth boldly, to share with Peggy the consequence of their joint guilt. As it was, with this colossal secret on his mind, and knowing full well that his right foot was resting on the very leather box in question, he was petrified by fear.

At times of extreme nervous tension, the senses are frequently acute. Though Peggy's frightened voice came in little above a whisper, Jimmy was able to hear her words with terrible distinctness.

"It is here, in the cupboard," she said. "I will get it--now."

CHAPTER IV--Shadowed

Peggy Wade was an American--which is the same thing as saying that she was possessed of considerable presence of mind. In the climax that now took place, she might easily have lost her head, instead of which she did all that was within her power to avert calamity.

She approached the cupboard door and opened it. Fortunately, the hinges were towards the centre of the room, where the three men stood together. Rosencrantz and his companions could neither see into the cupboard nor observe the look of intense alarm that came into the girl's face, the moment she found herself confronted by Jimmy Burke.

She mastered herself in an instant. As quick as thought, Jimmy thrust the leather box into her hand; at which she turned quickly, and closed the door. For the time being, at least, the situation was saved.

"You have not yet told me," said Rosencrantz, in the assured tones of an inveterate bully, "why you dared to disobey my orders?"

Peggy's thoughts were still with Jimmy. Though she knew nothing of the colossal plot which had just come to light, she trembled to think of what the consequences would be, should the boy be discovered. She answered timidly, in a voice so low as to be hardly audible.

"I have no excuse," she said.

Rosencrantz gave vent to a grunt.

"I should think not," said he, with a quick shrug of the shoulders. "And where's that rascal of a boy?"

Peggy could not answer. For a moment, she thought it was best to tell a deliberate lie, and have done with it; and then, she found she could not. She just stood quite still and silent, unable to lift her eyes from the floor--a very figure of guilt.

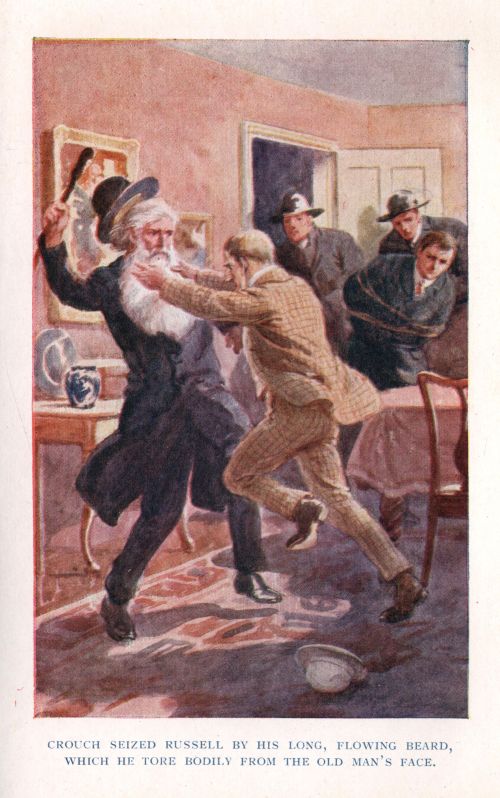

Rudolf Stork was a man upon whom little or nothing was lost. He had the eyes of a lynx. He was one whose very liberty, perhaps, depended upon his powers of observation, his memory and his wits. Without a word, he turned upon his heel, in three strides crossed the room, and flung wide open the cupboard door.

And there stood Jimmy Burke, his head half lowered, his face white as a sheet. He took two slow steps forward towards the centre of the room where the three men stood regarding him in amazement, and then stopped dead, apparently afraid to look about him.

Rosencrantz drew in a deep breath, as a man does who is about to take a plunge into ice-cold water. Von Essling let out an oath in his own language, as he drummed with his fingers upon the silver knob of a stout malacca cane. As for Stork, his hand went quickly to his hip-pocket, and a small nickel-plated revolver glittered in the light.

"Eavesdropping!" cried Rosencrantz. "An eavesdropper--by all that's wonderful!"

"Do you realize what this means?" exclaimed the Baron, gesticulating wildly with a hand. "There's danger here! This boy must have overheard every word we said. The result may be disastrous."

Stork crouched like a tiger. The expression upon the man's face was terrible. Slowly, he raised his revolver at arm's length, directing the muzzle straight at Jimmy's heart.

"There's only one way," said he. "It's not pleasant, but I'll do it."

Beyond doubt, he would have fired, had not the Baron seized his wrist.

"Do nothing foolish!" he exclaimed. "You forget the girl. There's a witness--in the girl!"

Stork lowered his revolver, turned slowly, and stared hard at Peggy, who quailed before the ferocity of those pale, cat-like eyes.

Rosencrantz, who was a coward at heart, had no desire to see murder done on his own premises; he had never bargained for that. Since matters had already gone too far, and seeing some explanation was necessary, he did his best to laugh it off.

"Enough, my friend!" he cried. "That is enough. You desired to frighten him, and have done so. See, the boy is trembling. It will teach him a lesson to the very end of his life."

This was not true; but, still, it was good enough to pass, to act as a shield for Rudolf Stork. Von Essling had not yet recovered his presence of mind; indeed, he was still so put out he could not stand still, but, tucking his malacca cane under his arm, set to pacing backwards and forwards in the room.

"This is serious," he muttered; "terribly serious." Then he pulled up suddenly in front of Jimmy, whom he regarded steadfastly, looking the boy up and down, from head to foot.

"It may be all right," said he at last, with something that was not far from a sigh of relief. "Fortunately the boy is young. And yet," he added, "I cannot think why he hid himself. It is all a mystery."

"I think," said Rosencrantz, "I can explain. He was there by chance. He did not know that I intended to return to the office, and having deliberately disobeyed my orders, he had a natural desire to avoid me."

The Baron von Essling shrugged his shoulders. Rosencrantz turned sharply upon Jimmy and the girl, who now stood side by side.

"You will both leave this place at once," said he, "and you will not return. Understand, I never wish to see your faces again."

At that, he went to the door and threw it open, making a motion of the hand for them to go.

They were about to leave, when Stork seized Jimmy roughly by a shoulder. He was a strong man, as the boy could tell from the iron grip that held him as if he were in a vice.

"Wait a bit," said he. "Easy now. We'd be blind fools to let you go like that. Listen here, my boy, and let what I've got to say sink into your memory. Breathe so much as a single word to any living soul of what you've heard to-night, and I'll find it out. You may set your mind at rest on that. I'm not a mild man, nor a plaster saint; some folk might say that sometimes I'm a little quick of temper. At any rate, I tell you this: I'll stick at nothing, if you neglect the advice I give you gratis. So, just beware, take warning; mum's the word."

And at that, he sent Jimmy flying headlong through the doorway.

As the boy recovered his balance--and indeed, he only just saved himself from stretching his length upon the floor--he found Peggy at his side, with a white face and trembling lips, and her hands clasped together.

"Oh, come," she cried, "we must go away from here. Jimmy, I never knew that I could be so frightened." Somehow she was breathless.

Very quickly, side by side, they ran down flight after flight of steps, until, at last, they found themselves upon the sidewalk of the famous street that traverses New York from end to end. A little after, they stood together at the corner of Fourth Avenue and Broadway.

It was night, and the great city was alive. The people were thronging to the theatres; the street-cars were crowded, their bells clanging incessantly; news-boys raced across the street. Broadway was a blaze of light; thousands of advertisements, brilliantly illumined with all the colours of the rainbow, caught the eye in all directions. Peggy drew near to Jimmy, and took his arm and pressed it.

"Whatever happened, Jimmy?" she asked. "I'm kind of dazed. I don't really understand."

"I don't know that I do," said the boy. "Even now, I can't believe that it wasn't all a dream."

For a little time, they walked along in silence. It was Peggy who spoke again.

"You had better come back with me," she said. "I must tell Aunt Marion I've been dismissed. Somehow I don't think we ought to leave each other now."

There was another pause; and then Peggy gave a shudder.

"That man was terrible," she said. "I can see him now. Do you know, Jimmy, he meant to kill you."

The boy laughed. Now that he was quit of the atmosphere of that room wherein had been disclosed the terrible, almost overpowering plot that was to shake to its very foundations the whole civilized world, it was easy enough to laugh. For all that, his boyish confidence in himself had not yet wholly returned. Quite apart from the fact that his life had been threatened, he had received a shock from which he was not likely to recover for some time to come.

It was quite late when they arrived at Peggy's home in Hoboken, where they found Peggy's aunt, Miss Daintree, laying the table for supper.

In a few brief words, Peggy told her aunt as much as she knew of what had happened; whereat Aunt Marion expressed neither surprise nor disappointment. She listened with a sweet smile, and rewarded Peggy with a kiss, saying that she was more glad than sorry, since the firm of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern had never been to her liking. Besides, as she pointed out, Peggy was worth a great deal more than they paid her. There were thousands of chances for a good stenographer in New York, so after all Peggy had no cause to despair.

Jimmy stayed to supper; but, despite the fact that both he and Peggy had been deprived of the illicit joys of a "picnic," he had neither any appetite nor any wish to talk, but remained pensive and grave as a judge.

Afterwards, seated before the fire with those two women, one on either side, he told the whole truth, in defiance of Rudolf Stork. And that was surely a strange audience to listen to a story of such world-wide dimensions, fraught with such unheard-of possibilities. The one was a woman who had already reached middle age, whose hair was touched with grey, whose life had been spent for the most part in those simple, sunlit joys which are God's gift to the really good. And the other was a girl who might still have been at school.

They listened in still amazement, finding it all not easy to believe. And when Jimmy had come to the end of his narrative, and his face was flushed and his eyes bright, he looked to Aunt Marion, as the eldest--and presumedly the wisest--for some practical advice. But that kind-hearted, loving lady knew, perhaps, even less of the world than he.

She thought at first that it would be best to go at once to the police; but, when Jimmy suggested that the New York police were notoriously corrupt, she agreed that, perhaps, the British consul was a more suitable person. Accordingly, after a long discussion, it was arranged that Jimmy and Peggy should go together to that gentleman's office the following day.

That night, the boy slept on a sofa; but Aunt Marion had made him promise that he would remain with them, as their guest, until he had obtained some new employment. There was a box-room which she could easily convert into a bedroom. She knew Jimmy well, and loved the boy; she even knew the story of "Swiftsure Burke." She knew that Jimmy was quite penniless, and would have to make his own way in the world; and she was anxious to do all she could to help him.

Jimmy spent the following morning bringing the few worldly goods he possessed from his old lodgings in New York itself to the other side of the harbour. He had enough money at home to pay the week's rent he owed, and the cab fare and the ferry-boat. And when he had done that, he found himself with nothing in the world--but "Swiftsure Burke's" lucky, dented sixpence.

At about three o'clock in the afternoon, the boy and girl sallied forth together, to interview the British consul. They had an exceedingly vague notion of what they were going to say to that all-important personage when they met him; they had not even a very exact idea as to what the duties of a consul were. None the less, they were quite convinced that he would explain the whole affair.

As it turned out, the consul was on a holiday--as his Britannic Majesty's consuls frequently are. However, they were shown into the presence of a certain Mr. Ridgeway, who introduced himself as the consul's private secretary.

This Mr. Ridgeway listened to the boy's story with an expression of mingled astonishment and disgust. At one moment, he was really alarmed; at the next, he was perfectly convinced that the whole thing was a hoax. But, towards the end, when Jimmy became very excited, and Peggy wrung her hands, he could scarcely fail to see that the boy was terribly in earnest. Moreover, he knew the Baron von Essling by reputation--which reputation was certainly not of the best. Still, he could hardly bring himself to believe either that such a cold-blooded, deliberate plot really did exist, or that a military attaché could so abuse a position of the greatest trust.

He promised, however, to tell the whole story to the consul when he returned, and pointed out that in due course, no doubt, the Foreign Office would be informed. In the meantime, Jimmy was to keep his eyes open and his mouth shut. On no account whatsoever was he to say a word to any one of what he knew.

The boy was determined to remember this advice, which--strangely enough--coincided with that of Rudolf Stork. As he came down the front doorsteps of the consulate, though he was out of work and practically a pauper, though he was conscious of the fact that he was living on the charity of others who could not afford to support him and upon whom he had no claim, he walked with a lighter tread than ever in his life before. He could not but feel proud of the fact that, for some mysterious reason, he was, indeed, a person of importance.

A man was leaning against the railings, both hands thrust deep in his trousers pockets, a battered hat jammed over his eyes--one of the inevitable loafers who are to be found in the streets of every city in the world. As Jimmy reached the bottom step, this man looked at him sharply from over his shoulder, and then slouched away.

The boy stood stock still, staring after the man with the battered hat, with parted lips and widely opened eyes. He did not speak or move, until Peggy suddenly touched his arm.

"Did you see that man?" he whispered.

"What is it?" Peggy exclaimed. "What's the matter, Jimmy?"

Jimmy pointed to the receding figure which just then disappeared quite suddenly round a corner.

"That man," said he, "was Rudolf Stork. And he knows I saw him."

CHAPTER V--Dropping the Pilot

If we put away ghosts and such like--in which nobody nowadays believes--there is, perhaps, no more unpleasant experience in the world than to be shadowed. The fact that one's footsteps are dogged eternally, that at every sudden corner or darkened by-way a hidden foe may lurk, is the kind of thing that is well calculated to test the strongest nerves.

Stork, in his own words, was a man who would stick at nothing--a desperate blade who, no doubt, had already more than one crime upon his conscience. Peggy was terrified; and though Jimmy did his best to show a bold front, his heart was filled with misgivings.

Determined to get back to Hoboken as soon as possible, they quickened their footsteps, crossing the great avenues that traverse the entire length of this most wonderful of modern cities.

As all Yankees know, the offices of an exceedingly influential newspaper are situated in Fifth Avenue, which is the main thoroughfare of New York; and as the boy and girl passed the entrance to this enormous block of buildings, they were almost swept from the pavement by a crowd of news-boys who came rushing round a corner, shouting themselves hoarse, like a party of dancing Dervishes or Bashi-bazouks. In point of fact, they made so much noise among themselves that it was quite impossible to understand a single word they said, though it was manifest that some news had just come to hand of startling importance.

At that moment, a poster was pasted up in one of the windows on the ground floor, which contained the following announcement--

Peggy and Jimmy stopped to read the notice, which--it must be confessed--conveyed little or nothing to either of them. They could not in any way associate the murder of the heir to the throne of Austria with the colossal plot that von Essling had disclosed in the presence of Rosencrantz and Rudolf Stork. They did not realize that this was the spark that was destined to spread, within the space of a few short weeks, into an almost universal conflagration; that the curtain had been rung up upon the greatest drama the world had ever known.

It was during the next few weeks that it gradually became apparent to the ordinary man in the street that the situation was serious. Nearly all that time Jimmy was looking about him for some new employment. Peggy had been almost immediately successful. She had secured quite a well-paid position with a large firm of shipping agents: Jason, Stileman and May, a British company whose house-flag is to be found on every ocean in the world.

Jimmy, on the other hand, had no such luck; and indeed, he had not Peggy's qualifications. Week after week, he roamed the streets of New York, looking for work, and every night returned to Hoboken, crestfallen and disappointed. Though he had come to regard Peggy and Aunt Marion as his own relations, he was still the grandson of "Swiftsure Burke," and found his position in one sense insupportable. Though he was treated with the utmost kindness, he was never quite able to forget that he was living upon the charity of those who were pressed for money themselves. Finally, he resolved to work with his hands; and seeing a notice to the effect that stevedores and dock-labourers were wanted, he applied for work in the docks, and was engaged on the spot, at a rate of pay which--to his surprise--greatly exceeded that which he had received from Rosencrantz.

Neither was his work particularly hard or uncongenial. All he had to do was to manipulate a large hydraulic crane, by means of which cargo was hoisted into the ships. For a week or so, he was happier than he had ever been in his life. He continued to live with Peggy and Aunt Marion, whom he had persuaded to accept payment for his board and lodging. Indeed, he soon came to regard them as mother and sister; Peggy and he were greater inseparables than ever. Also, he was man enough not to be ashamed of his canvas working suit and oily hands. He was earning an honest living; his work kept him out in the open air, and the ships which went forth every day to all the seven seas, that flew the ensigns of every country in the world, appealed to his imagination and carried his thoughts back to the land of his birth which he could only just remember.

And then, the War broke out; Europe burst suddenly into flame. For days the tension had been extreme. Austria, in spite of the protestations of every country in Europe, with the sole exception of the German Empire, was determined to carry out a kind of punitive expedition against Servia.

It was not only the sacred duty of the Czar to protect Slav interests, it was of vital importance to Russia that no Germanic power should gain control of the Dardanelles; and hence, as a purely precautionary measure Russia was forced to mobilize.

At that the German Empire gathered its armies together, which made it incumbent upon France to hold to her alliance, to be prepared to stand side by side with her great Eastern ally. Germany knew quite well what the result would be, when she urged Austria to take reprisals. It is unbelievable that Austria would have acted without the assurance of German support. Germany was resolved that a purely local question, relating to the independence of the Kingdom of Servia, which might easily have been settled in a friendly manner, should be made the excuse for a trial of her own gigantic strength, for an attempt to realize "World-Power."

She wanted this for three reasons: Firstly, she recognized that she could not maintain indefinitely the continued cost of her armaments and fleet without internal troubles sooner or later arising; secondly, she had supreme confidence in herself, she knew that she was prepared, and that no other nation was; and thirdly, it was only by conquest that she could gain the opportunities for national expansion she desired. If any further proof be needed that the guilt of the Great War lies upon the rulers of the German Empire, it is to be found in the fact that when--mainly through the efforts of His Majesty King George, the Czar of Russia and Sir Edward Grey--both Austria and Russia were ready to do their best to come to some agreement, Germany bluntly replied that the matter had gone too far, that the die was cast, and her troops--already on the march--could not be called back. The great machinery of War had been set in motion.

And as if this had not been in itself a sufficient outrage upon the claims of civilization, the German armies, without warning or excuse, swept down upon poor, unhappy Belgium, and the whole world stood aghast at atrocities which put to shame even the campaigns of Tamerlane and Jenghiz Khan. In such circumstances as these, if England had stood apart, the British Empire would have crumbled to the dust. There would not have been a right-thinking, honest roan, worthy of the name of Briton, who would not have disowned his Motherland for very shame. In defence of Belgium, in defence of the sacred right of treaties, in defence of our own honour, our homes and the land we love, we took up the sword--which shall not be laid down until Belgium is avenged, and a great and growing menace to the peace and prosperity of Europe has been blotted out, once and for all.

These things were understood by the majority of people in America, as in every other neutral state in the world--with the possible exception of Sweden.

As for Jimmy Burke, working a good ten hours a day in the New York docks, he yearned to board one of the many steamers flying the red ensign of England, to sail to his native land. As the grandson of "Swiftsure Burke" he longed to fight for England--a longing that was almost irresistible during the first weeks of the War, when it seemed that nothing could save Paris from the fate of '70.

Aunt Marion and Peggy were no less anxious to help; there are noble parts for women to play in war. It so happened that at one time Miss Daintree had been a hospital nurse; and she was now resolved to return to her old profession. Peggy, too, began to attend evening classes at a hospital, and very soon displayed a natural aptitude for nursing--a combination of quickness, sympathy and presence of mind.

In all probability, Jimmy would have eventually worked his way to Canada, and joined the loyal and splendid forces of the Dominion, but for the incident narrated below, which altered the course of his life in a very unexpected and violent manner. There is no question as to the motive that led to the outrage: the boy was in possession of extremely valuable information; and besides, he had deliberately neglected Stork's advice.

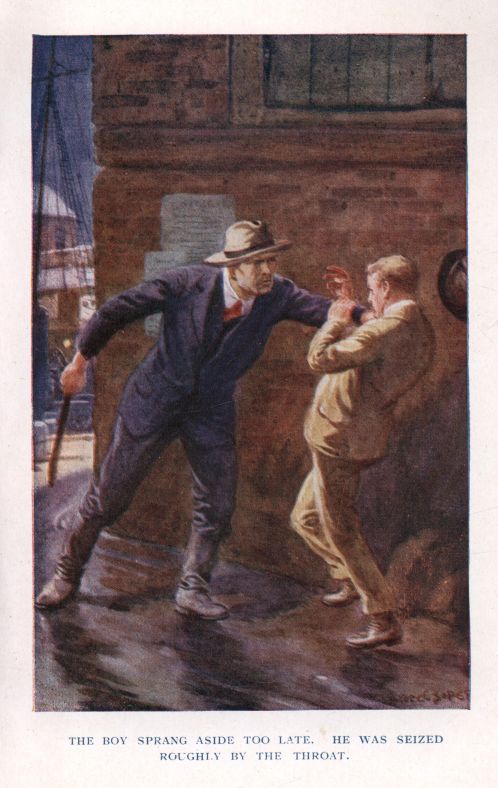

One night, when a ship, timed to sail at daybreak, had not taken on all her cargo until past ten o'clock, and Jimmy was on his way home through a narrow, and somewhat darkened street, he suddenly became conscious of footsteps close behind him.

There was that in the sound that made him start and look back in haste. Some one was coming upon him rapidly and with stealth--some one who was wearing india-rubber shoes.

The boy sprang aside--too late. He was seized roughly by the throat, and held at arm's length, whilst a gruff voice let out, "I've got you!"

Looking up, he recognized in the dim light the face of Rudolf Stork, an expression of extreme ferocity stamped upon every feature.

Afterwards, Jimmy remembered the man's words quite well, just as clearly as one often remembers on waking one's last thoughts before falling asleep.

"You defy me!" he muttered. "You'll not live to do it again."

At that, he raised his right hand, in which was something like a bar of iron, and Jimmy Burke remembered nothing more; the conscious part of him vanished, as in a flash, and left him in a weird world of darkness, nothingness and silence.

When he came to his senses, he was in bed; Aunt Marion was bending over him, and Peggy was near at hand. There were bandages about his head. Also, something was the matter with his eyes; for, before he could remember where he was, or who Peggy and Aunt Marion were, his eyes began to ache, and he was obliged to close them.

According to the doctor, it was a miracle that Jimmy had escaped with his life. He had been dealt a shattering blow with some blunt instrument; he had not been found for three hours, when he was picked up by a labouring man on his way to his work in the small hours of the morning. Since there was no hospital near at hand this man had carried the unconscious boy to his own address which he had found in a note-book in the pocket of Jimmy's coat.

Peggy had immediately hastened for a doctor; and the police were informed of the identity of Rudolf Stork. For days Jimmy was delirious; and had it not been for good nursing, he could never have pulled through.

Those critical days, when the boy's life was in danger and his mind adrift, were followed by weeks of convalescence. And finally, when he was quite well again, he was so reduced in strength that it was altogether out of the question that he should think of returning to work.

And when he did try to go back to his former employment at the docks, he found that his place had been filled by another. Since the outbreak of the war, trade had been on the ebb, and work was harder than ever to find.

There followed another period of enforced idleness. And it was now winter; and grey, sunless skies, bitter winds, and constant rain and sleet, have, at the best of times, a sombre effect upon the spirits.

The boy became utterly depressed. He felt that he had no right to go on living with Aunt Marion and Peggy, though both repeatedly assured him that there was no need for him to worry. He felt that he was approaching manhood, and it was a man's duty to work. This inactivity was all the harder to bear, because the Great War was still raging with unabated fury.

At last, one evening, as he was wending his way home through Central Park, after another unsuccessful day, he decided to take his destiny into his own hands, to take a plunge into the future, which might be fortunate or fatal, but which in any case would be decisive.

He knew quite well that what he proposed to do was wrong. He had often prayed to God for help, but that night he prayed to be forgiven.

That evening he opened a small box of tools which his father had given him years ago, and taking out a steel file, set to work on "Swiftsure Burke's" lucky sixpence, which he deliberately filed in half.

That took him the best part of half an hour; and it was almost as great a business to punch a hole through each separate half. He was not quite sure where he had heard of the old, time-worn superstition of dividing a lucky sixpence. Perhaps his father and mother had done something of the kind, in the days when they were young.

He wrapped up a few of his most necessary belongings in a towel; and when he had done that he went downstairs and found Peggy in the sitting-room. Aunt Marion had gone to bed.

"Peggy," said he, "I'm going away."

"Going away!" she repeated. "Where?"

"I'm going right away. I can't stay here idle any longer. I'm going to try to do my duty."

She came towards him, and a little nervously laid a hand upon his arm.

"Jimmy," she said, "you're not serious, are you?"

It took him quite a long time to convince her that he was really in earnest; then, without another word, she gave him what he asked for--a bottle of water and a loaf of bread. This he put into his bundle; and then it was that he produced the two halves of the dented, lucky sixpence, which had saved the life of the Admiral.

What he had to say he said altogether clumsily, and even blushed as he said it. He explained that he wanted to give her something by which she would always remember him, and he thought half his lucky sixpence might meet the case; indeed, it was all he had. Before he had finished speaking there were tears in Peggy's eyes.

She did not endeavour to dissuade him from going. But she told him that Aunt Marion would never forget it, if he went away without seeing her. Jimmy, however, felt that he had not sufficient moral courage to resist further persuasions, and in this case it was kinder to be cruel.

It was very late when he let himself out, and set off walking rapidly in the direction of the docks. Peggy did not sleep that night; hour after hour, she lay awake, her pillow wetted with tears, gripping tightly in her hand her half of the Admiral's sixpence.

Jimmy knew his way about New York harbour. He knew where the ships were moored, and how to elude the night-watchmen and the dockyard police. He had tried, time and again, to work his way to England, as a cabin boy or a steerage hand, and had failed. There was no other way but this.

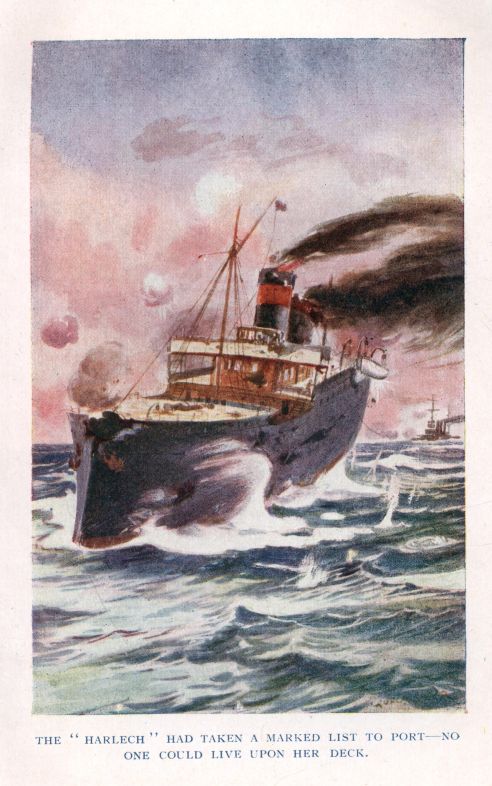

Stealthily, he made his way along the wharves, creeping in and out among bales and boxes of cargo. A large tramp steamer, the "Harlech," which belonged to Jason, Stileman and May, was under steam, bound for Portsmouth, due to sail some time the following day.

From behind a great crane, similar to that at which he himself had once been wont to work, Jimmy took stock of the "Harlech." Her after-gangway was lowered, a lantern suspended at the top. The night-watchman patrolled the main deck, pausing now and again to relight his pipe. Presently, the man went forward to the forecastle; and Jimmy seizing his opportunity, slipped up the gangway, crossed the after-well deck, and tumbled down the hatch.

It was a sheer drop of ten feet at least. Luckily for the boy, he fell upon soft bags of oats. Scrambling to his feet, he passed onward, stumbling repeatedly, for the hold was so dark he could not see a yard before him.

More by good luck than by good management, he came upon the lower hatchway, which connected with the hold beneath. Lowering himself with the utmost care, he found a firm footing upon a great pile of boxes; and passing over these, he found a place where he could sit down and where there was little chance that he would be discovered. There, he waited nearly twenty-four hours, during which time he had nothing to eat but his loaf of bread, whilst he ran a great risk of his presence being detected, for the time of sailing was put off until late on the following night.

There were rats in the hold, but he did not mind them in the least. All that he cared about was that he should remain undiscovered until the ship was well out at sea. He had no wish to be put ashore at Cape Race or Halifax.

Soon after sunrise, he heard the feet of men moving on the deck above, and this continued throughout the day, whilst the winches rattled and groaned. Fortunately for him, they were working on the forward holds, and though the after-hatches were still open, there was apparently no more cargo for that part of the ship. All this time the engines were throbbing violently. There was a kind of continuous vibration throughout the length and breadth of the ship which continued far into the night. It must have been almost ten o'clock, when suddenly a voice rang out--the voice of a man whom Jimmy was destined to know, whom he was to learn to honour and admire. It was the voice of Captain Crouch.

"Mr. Dawes," came the voice, "all hands aboard?"

"All aboard, sir."

"Then man the windlass, and let her go. We're mighty late as it is."

A moment later, Jimmy heard the bell ring in the engine-room and the "Harlech" was under way.

She steamed slowly out of New York harbour, passing Liberty Island and the forts. Jimmy--though he could see nothing but the outline of great packing-cases and boxes, dimly visible in the half-light that crept down through the open hatchway--pictured in his imagination the great sky-scrapers around Wall Street, and the towering buildings in Madison Square, fading gradually out of sight in the bright moonshine that flooded New York harbour.

From time to time, the bell rang in the engine-room; and then, the "Harlech" slowed down to drop the pilot. And Jimmy Burke knew that he, too, had dropped the pilot on the long voyage of life.

His heart was beating rapidly in excitement and vague anticipation. The Past had not been altogether happy. The Future was in the clouds.

And then, once again, came the voice of Captain Crouch.

"Mr. Dawes, close that after-hatch."

Jimmy heard the men at work under the boatswain on the deck above; and then, all was utter darkness and silence. The hatch had been battened down.

A little after, the "Harlech" took on a roll, as she struck the broad Atlantic, and took up her course for the Fastnet on the south coast of Ireland, nearly three thousand miles away. The grandson of "Swiftsure Burke" was bound for the shores of the Motherland which he could only just remember, and the Great War that thundered in the East.

CHAPTER VI--Captain Crouch

At about ten o'clock in the morning of the day the "Harlech" sailed, whilst Jimmy Burke lay in hiding in the hold among the packing-cases and boxes of cargo, Captain Crouch was ushered into the offices of Jason, Stileman and May.

Now, those who know nothing of Captain Crouch are unacquainted with one of the most singular personalities it were possible to imagine. He knew the world as few men know it, from Yokohama to Valparaiso, from Hudson Bay to Hobart. Indeed, his strange and varied experiences would fill a book, which could certainly never be published at less than a guinea net.

As a boy, he had sold newspapers in the crowded streets of London. From that he had risen to command a merchant ship. He had been shipwrecked time and again. He had been shot in the right eye with a poisoned arrow, somewhere at the back-of-beyond on the West Coast of Africa, which is called "The White Man's Grave." He had had a foot bitten off by a shark in the Bay of Fernando Po. And yet, in spite of his cork foot and his glass eye, he was more than a match for most men. Though he was not much more than five feet four in height, he was as wiry as a ferret, and as quick in all his movements. He feared no man, and was a rifle and revolver shot who seldom missed his mark. He had a threefold reputation: he was one of the most intrepid explorers in the world; he had shot tigers in the Sunderbunds and rogue-elephants in the forests of the Congo. As a master mariner, he had sailed the seven seas for the greater part of his life, was a skilful navigator, and one who could keep his head in an emergency.

Such a man was Crouch. Those who have read of his doings elsewhere know that, on a former occasion, he penetrated to the reaches of the Hidden River, in the unexplored valley of the Kasai, and there unearthed both a modern slave-trader and a ruby mine. It was also Captain Crouch who ventured into the trackless region of the Aruwimi, in search of Edward Harden, the lost explorer, of whom nothing had been heard for four years; and how he succeeded in his quest, and all the adventures that befell him, have been written of elsewhere.

In fact, Crouch was a man to whom adventure was as the very breath of his nostrils; the spirit of adventure flowed in the blood of his veins. He sought perilous enterprises because his idea of life was danger, because he understood that in this world the main duty of man was to accomplish. And Crouch accomplished much. He was one of the pioneers of civilization, one of those who go before the flag that trade is said to follow. He was as much out of his element in a comfortable armchair before a winter's fireside, as a backwoodsman in a boudoir. He belonged to the life of the open air, of the free and rolling sea. Indeed, it may even be said that his little, shrunk and wizened figure was a kind of stormy petrel: his very presence was a certain signal that danger and adventure were at hand.

And thus, it is hardly likely, on the face of things, that at the outbreak of the Great War such a man would remain idle for long. Even had he not sought employment of his own free will, there were those who knew of him by reputation, who were only too eager to enlist his services.

He had been found in London, at the Explorers' Club in Bond Street, which is a great place of a winter's evening, where you may hear tales which are as wonderful as they are true. He had been asked to leave at once for New York, on a certain dangerous mission. He had been given five minutes in which to make up his mind; and that was exactly four minutes and fifty-nine seconds longer than he required.

He arrived in New York in a sailor's jacket, with brass buttons which would have been none the worse for a polish. He wore a flaming red tie, and gum boots such as seamen wear when the decks are running with salt water and the funnels white with foam. His face was as wrinkled as a date, the colour of tan, beaten for years by sun and wind and rain. His nose was large, and hooked like an eagle's. He had a small moustache, and beneath his underlip a little imperial beard, which he was wont to tug whenever he was vexed or deep in thought. As he entered the spacious offices of Jason, Stileman and May, he carried in his right hand a seaman's kit-bag, and in the other, a small mahogany box about six inches long.

He was greeted by Peggy Wade.

"Captain Crouch?" she asked.

"Miss," said he, "the same."

"Mr. Jason is expecting you," said Peggy. "Will you be so good as to wait?"

Crouch regarded Peggy. The girl--whose own custom it was to look people straight in the face--found the penetrating and unflinching stare of Captain Crouch a somewhat trying ordeal.

"You're a well-spoken lass," said he, at last, "and well looking, too. Come, stay there a bit," he added, seeing that Peggy made as if to go; "stay there a bit, my girl. I'll polish up the glass eye, and have a better look at you."

And at that, to Peggy's horror and consternation, Crouch slipped out his glass eye, threw it up in the air and caught it, as though it had been a marble, and then proceeded to polish it violently on the shiny sleeve of his coat.

That done, he put it back again in the socket, and looked at Peggy even harder than before.

"Seems fair," said he. "You're a lass after my own heart; neat, trim and ship-shape. I've half a mind to adopt you."

Peggy could not restrain a smile.

"I don't know," she said, "that I ever exactly wished to be adopted."

Crouch looked thoroughly amazed.

"Why, my girl," said he, quite slowly, shaking his head in a doleful manner, "you've no right notion what kind of man I am. I could tell you stories that would make that curly hair of yours stand right up on end, like the bristles on the neck of a pig. And maybe, some day, p'raps, you'd learn to love me--like a father."

To speak the truth, Peggy was by now a little frightened. In all of her somewhat limited experience, she had never come across such an extraordinary and eccentric individual. She knew nothing then of Crouch's iron will and dauntless courage; she knew nothing of his deeds upon the Congo or Aruwimi. She had more than a suspicion that the little sea-captain was not quite right in the head.

"I think," she said, "I had better tell Mr. Jason you are here."

"No haste," said Crouch. "My cargo won't be aboard till daybreak to-morrow morning, and I reckon all he has got to say to me won't take above ten minutes."

None the less, Peggy thought it advisable to announce the little sea-captain's arrival to Mr. Jason, Junior, the New York agent, and a nephew of the senior partner of the firm. Mr. Jason, who just then was busy at the telephone, replied that he would see Captain Crouch in a minute, and Peggy returned to the waiting-room.

The following incident--though of little value in itself--goes a long way to prove that Captain Crouch was both an observant man upon whom little or nothing was lost, whose single eye was as good as most men's two, and one who was by no means devoid of sentiment and consideration for others.

"My lass," said he, the moment Peggy entered, "a halved sixpence is a lover's token. Who gave it you?"

At first, Peggy was inclined to resent this blunt allusion, which she regarded as a little too personal. Only the night before, she had bade farewell to Jimmy, and even then tears were not so far from her eyes. She had hung her half of the lucky sixpence around her neck on a little chain; and she saw no reason why she should confide her innermost feelings to Captain Crouch, who, after all, was a stranger.

Now, this--as we have said--to the everlasting credit of the little, wizened captain: somewhere beneath his hardened visage, his rough manners and his almost violent way of talking, there was a heart as soft as a woman's. He saw, at once, that Peggy's feelings had been hurt, that he had touched a tender chord, and he did his best to make amends. When he spoke again, it was in a voice quite different, much softer and full of sympathy.

"I've no wish, my lass," said he, "to pry into your secrets. I only asked, because I took a kind of fancy to you, the moment I saw you; and that, as a general rule, is not my way with women. I'm a single man. I've never married for two reasons: first, no one wanted to marry me; second, I never wanted to. I can only remember two women in my life with whom--as I might say--I was ever on speaking terms. One was my landlady in Pimlico, who thought she knew more about cooking than I did; and the other was an old negress, black as a lump of charcoal, who did my washing at Sierra Leone. She weighed seventeen stone, and was about as broad as an oil-tank steamer in the Bosphorus. So if I've hurt your feelings, miss, you must forgive a rough sea-faring man, who has had his port-light put out by a poisoned arrow, and who doesn't know any better."

And at that, he held out a hand so eagerly and frankly that Peggy could not refrain from taking it.

She experienced then, for the first time, what manner of a man was Captain Crouch--if a shake of the hand counts for anything, as it is generally thought to do. Indeed, he gripped her hand so tightly that she was obliged to wince; and noticing that, he forthwith apologized, by telling her once again that he was an old sea-dog more used to marling-spikes than lassies.

"I'm sorry," said Peggy, "I was so foolish as to think you too inquisitive."

"Say no more," said Crouch.

"But, I will," she took him up. "There's no reason why you shouldn't know, for this sixpence once belonged to a sailor."

"I know the breed," said Crouch, "and just because he was a sailor, I guarantee he never kept it long."

Peggy laughed aloud, and shook her head.

"He kept it many years," she answered, "for this lucky sixpence once saved his life. You can see for yourself," she went on, "it is dented and covered with lead from a bullet. It belonged to an Admiral, whose name was 'Swiftsure Burke.'"

Captain Crouch drove the fist of one hand into the palm of the other.

"Known throughout the Navy," he exclaimed, "and to every right-thinking sailor that ever sailed the ocean who takes a pride in the job! Admiral 'Swiftsure Burke' of Sebastopol. Lass, you've got a jewel in that lucky sixpence that I wouldn't exchange for a diamond as big as a monkey-nut. Stick to it, and you'll come to no harm. It's what, in a manner of speaking, you might call a talisman. It'll protect you from fire, shipwreck, sudden death and the Income Tax. You're in luck's way, my girl."

Now Captain Crouch was a man who knew that God alone could give good fortune, or permit evil to fall upon one, but he had all a sailor's superstition and belief in omens and talismans, and was quite sincere in what he said to Peggy.

It was then that the door of the inner office was thrown open, and Mr. Jason, Junior, entered the room. He was a man who could not have been more than thirty-four years of age, clean-shaven and a little prematurely bald. He was immaculately dressed, a small orchid in his buttonhole and a pair of exceedingly shiny patent leather boots making him look as if he had just come out of a bandbox.

"Captain Crouch," said he, coming forward, and holding out a hand, "I'm delighted to see you. I have a very important matter to discuss. Miss Wade," he added, turning to Peggy, "if any one else calls, you will say I am engaged."

At that, he conducted Captain Crouch into his office, and was careful to close the door.

Crouch seated himself in a comfortable chair. As for Mr. Jason, he walked backwards and forwards from the hearthrug to the writing-desk, with the restless activity of a man who has something on his mind.

"Captain Crouch," he repeated, speaking abruptly, "I can scarcely exaggerate the extremely perilous nature of the task I have undertaken. I sent for you, because I know no other man to whom I would care to entrust so great a responsibility."

Crouch yawned, and thrusting a hand into one of his coat pockets, produced a tobacco-pouch, made of snake-skin, and about as large as a letter-case.

"Mr. Jason," said he, "with your permission, I'll light a pipe. Maybe, you've no objection to Bull's Eye Shag. There's some people that don't hold with it, but I don't suppose that would apply to you."

Now, Mr. Jason knew Crouch's tobacco of old, and he knew that it was powerful and pungent enough to fumigate anything from an isolation hospital to a greenhouse. It was a brand of tobacco--if the truth be told--for which there was no great demand, since he who smoked it required the digestive organs of an ostrich. Its aroma would cling to a bare room for days. The path of Captain Crouch through this populous and sinful world was strewn with dead flies, wasps and beetles which had been poisoned by the fumes of his tobacco.

Accordingly, Mr. Jason--though he gave Crouch full permission to light his pipe--took the double precaution of opening the window and lighting one of his strongest cigars. Then, still pacing the room, he fired at the little sea-captain a series of questions in a quick, nervous voice.

"When will the 'Harlech' be loaded?"

"To-night, sir. Soon after nine."

"With what kind of cargo?"

"You should know that as well as I," said Crouch. "There's a few tons of oats, a certain amount of machinery, and several cases of rifles."

"Ah," said Mr. Jason.

"I said so," said the other, looking hard at the agent, whose conduct was rather strange. Mr. Jason repeated over and over again, as if to himself, the one word "rifles," and was then silent for more than a minute, puffing vigorously at his cigar.

"I suppose you've heard," said he, at last, "that several German cruisers and commerce destroyers are abroad on the Atlantic?"

"I've heard tell of it," said Crouch, quite unmoved.

"Exactly. There is the 'Kronprinz Wilhelm' and the 'Königsberg,' and moreover, the 'Karlsruhe' and the 'Dresden.' Also--as, perhaps, you know--the English Channel and the Irish Sea are said to be swarming with enemy submarines, sent out from Wilhelmshaven and Kiel. You realize all that, of course?"

"Seems fair," said Crouch. "I'm ready to take my chance."

"You'll take a greater chance than you think," said Mr. Jason.

"How so, sir?"

"The fact is," said the agent, drawing nearer to the captain, and speaking in a voice that was little above a whisper; "the fact is, that although the cases are not marked, there is some reason to suppose that German agents in New York suspect that the 'Harlech' has a cargo of small-arms for the British Government."

Crouch whistled softly to himself.

"You mean," said he, "there's a chance that the secret has leaked out. This place teems with spies."

"I can say no more," said Mr. Jason, "than that we suspect; but, these times, we can be sure of nothing. It is quite possible that the German commerce destroyers may be warned, and you will be run down in mid-ocean. There may even be spies on board."

"If I find one," said Crouch, "I'll know how to deal with him."

"That's not the point," said the other. "Are you willing to take the risk?"

Captain Crouch got to his feet, carefully knocked out his pipe in the fire-grate, and then thrust his peaked sailor's cap on to the side of his head.

"Why not?" said he, at last.

Mr. Jason smiled.

"I thought you wouldn't hesitate."

"Why not?" repeated Crouch. "If those are my orders, I'll do my best to carry them out, and I'll sight the Needles and take on a pilot in the Solent, if a sound knowledge of navigation and steam coal can do it."

Mr. Jason held out a hand.

"I'm glad I sent for you," said he. "You will start to-night?"

"We'll be under way," said Crouch, "before eleven, at the latest."

"Then, good-bye--and the best of fortune."

A few minutes later, Captain Crouch, who had just taken an almost affectionate farewell of Peggy Wade, was stumping on his cork foot along the Fifth Avenue as if he owned New York.

CHAPTER VII--In the Hold

We know already that Crouch went on board that night, shortly before ten o'clock, and took over the command of the "Harlech" from Mr. Dawes, the Chief Officer--a blunt, plain-spoken Yorkshireman, who had run away to sea at the age of fourteen, and who, like Crouch himself, had worked his way from the forecastle to the bridge.

Now, Captain Crouch encircled by the atrocious perfume of his famous Bull's Eye Shag, holding forth upon the subject of his experiences in various parts of the world, and Captain Crouch upon the bridge or in the chart-room of the ship that he commanded, were two very different men. Once he set foot upon the main deck--even the very moment he grasped the gangway hand-rope--Crouch took upon himself the character of a martinet. In the very tones of his voice, one was led to understand that his word was law.