Title: St. Nicholas Vol XIII. No. 8 June 1886

Author: Various

Editor: Mary Mapes Dodge

Release date: May 29, 2012 [eBook #39846]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Alex Gam and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Heigh-ho! What frolics we might see,

If it only had happened to you and me

To be born in some beautiful far-off clime,

In the country of Somewhere, once-on-a-time!

Why, once-on-a-time there were mountains of gold,

And cans full of jewels, and treasures untold;

There were birds just waiting to fly before

And show you the way to the magical door.

And, under a tree, there was sure to be

A queer little woman to give you the key;

And a tiny, dancing, good-natured elf,

To say, with his scepter: "Help yourself!"

For millions of dollars grew from a dime

In the country of Somewhere, once-on-a-time.

If we lived in the country of Somewhere, you

Could do whatever you chose to do.

Instead of a boy, with the garden to weed,

You might be a knight, with a sword and a steed.

Instead of a girl, with a towel to hem,

I might be a princess, with robe and gem;

With a gay little page, and a harper old,

Who knew all the stories that ever were told,—

Stories in prose, and stories in rhyme,

That happened somewhere, once-on-a-time.

In the country of Somewhere, no one looks

At maps and blackboards and grammar books;

For all your knowledge just grows and grows,

Like the song in a bird, or the sweet in a rose.

And if ever I chance, on a fortunate day,

To that wonderful region to find my way,

Why then, if the stories all are true,

As quick as I can, I'll come for you,

And we'll row away to its happy shores,

In a silver shallop with golden oars.

Lord Dorincourt had occasion to wear his grim smile many a time as the days passed by. Indeed, as his acquaintance with his grandson progressed, he wore the smile so often that there were moments when it almost lost its grimness. There is no denying that before Lord Fauntleroy had appeared on the scene, the old man had been growing very tired of his loneliness and his gout and his seventy years. After so long a life of excitement and amusement, it was not agreeable to sit alone even in the most splendid room, with one foot on a gout-stool, and with no other diversion than flying into a rage, and shouting at a frightened footman who hated the sight of him. The old Earl was too clever a man not to know perfectly well that his servants detested him, and that even if he had visitors, they did not come for love of him—though some found a sort of amusement in his sharp, sarcastic talk, which spared no one. So long as he had been strong and well, he had gone from one place to another, pretending to amuse himself, though he had not really enjoyed it; and when his health began to fail, he felt tired of everything and shut himself up at Dorincourt, with his gout and his newspapers and his books. But he could not read all the time, and he became more and more "bored," as he called it. He hated the long nights and days, and he grew more and more savage and irritable. And then Fauntleroy came; and when the Earl saw the lad, fortunately for the little fellow, the secret pride of the grandfather was gratified at the outset. If Cedric had been a less handsome little fellow the old man might have taken so strong a dislike to the boy that he would not have given himself the chance to see his grandson's finer qualities. But he chose to think that Cedric's beauty and fearless spirit were the results of the Dorincourt blood and a credit to the Dorincourt rank. And then when he heard the lad talk, and saw what a well bred little fellow he was, notwithstanding his boyish ignorance of all that his new position meant, the old Earl liked his grandson more, and actually began to find himself rather entertained. It had amused him to give into those childish hands the power to bestow a benefit on poor Higgins. My lord cared nothing for poor Higgins, but it pleased him a little to think that his grandson would be talked about by the country people and would begin to be popular with the tenantry, even in his childhood. Then it had gratified him to drive to church with Cedric and to see the excitement and interest caused by the arrival. He knew how the people would speak of the beauty of the little lad; of his fine, strong, straight little body; of his erect bearing, his handsome face, and his bright hair, and how they would say (as the Earl had heard one woman exclaim to another) that the boy was "every inch a lord." My lord of Dorincourt was an arrogant old man, proud of his name, proud of his rank, and therefore proud to show the world that at last the House of Dorincourt had an heir who was worthy of the position he was to fill.

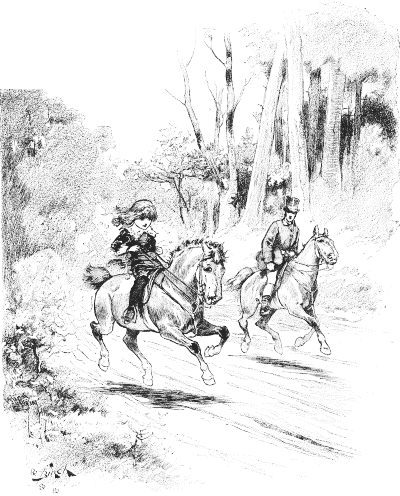

The morning the new pony had been tried, the Earl had been so pleased that he had almost forgotten his gout. When the groom had brought out the pretty creature, which arched its brown, glossy neck and tossed its fine head in the sun, the Earl had sat at the open window of the library and had looked on while Fauntleroy took his first riding lesson. He wondered if the boy would show signs of timidity. It was not a very small pony, and he had often seen children lose courage in making their first essay at riding.

Fauntleroy mounted in great delight. He had never been on a pony before, and he was in the highest spirits. Wilkins, the groom, led the animal by the bridle up and down before the library window.

"He's a well plucked un, he is," Wilkins remarked in the stable afterward with many grins. "It weren't no trouble to put him up. An' a old un wouldn't ha' sat any straighter when he were up. He ses—ses he to me, 'Wilkins,' he ses, 'am I sitting up straight? They sit up straight at the circus,' ses he. An' I ses, 'As straight as a arrer, your lordship!'—an' he laughs, as pleased as could be, an' he ses, 'That's right,' he ses, 'you tell me if I don't sit up straight, Wilkins!'"

But sitting up straight and being led at a walk were not altogether and completely satisfactory. After a few minutes, Fauntleroy spoke to his grandfather—watching him from the window:

"Can't I go by myself?" he asked; "and can't I go faster? The boy on Fifth Avenue used to trot and canter!"

"Do you think you could trot and canter?" said the Earl.

"I should like to try," answered Fauntleroy.

His lordship made a sign to Wilkins, who at the signal brought up his own horse and mounted it and took Fauntleroy's pony by the leading-rein.

"Now," said the Earl, "let him trot."

The next few minutes were rather exciting to the small equestrian. He found that trotting was not so easy as walking, and the faster the pony trotted, the less easy it was.

"It j-jolts a g-goo-good deal—do-doesn't it?" he said to Wilkins. "D-does it j-jolt y-you?"

"WILKINS WAS CARRYING HIS HAT FOR HIM, AND HIS HAIR WAS FLYING, BUT HE CAME BACK AT A BRISK CANTER."

"No, my lord," answered Wilkins. "You'll get used to it in time. Rise in your stirrups."

"I'm ri-rising all the t-time," said Fauntleroy.

He was both rising and falling rather uncomfortably and with many shakes and bounces. He was out of breath and his face grew red, but he held on with all his might, and sat as straight as [Pg 566] he could. The Earl could see that from his window. When the riders came back within speaking distance, after they had been hidden by the trees a few minutes, Fauntleroy's hat was off, his cheeks were like poppies, and his lips were set, but he was still trotting manfully.

"Stop a minute!" said his grandfather. "Where's your hat?"

Wilkins touched his. "It fell off, your lordship," he said, with evident enjoyment. "Wouldn't let me stop to pick it up, my lord."

"Not much afraid, is he?" asked the Earl, dryly.

"Him, your lordship!" exclaimed Wilkins. "I shouldn't say as he knowed what it meant. I've taught young gen'lemen to ride afore, an' I never see one stick on more determin'der."

"Tired?" said the Earl to Fauntleroy. "Want to get off?"

"It jolts you more than you think it will," admitted his young lordship frankly. "And it tires you a little, too; but I don't want to get off. I want to learn how. As soon as I've got my breath I want to go back for the hat."

The cleverest person in the world, if he had undertaken to teach Fauntleroy how to please the old man who watched him, could not have taught him anything which would have succeeded better. As the pony trotted off again toward the avenue, a faint color crept up in the fierce old face, and the eyes, under the shaggy brows, gleamed with a pleasure such as his lordship had scarcely expected to know again. And he sat and watched quite eagerly until the sound of the horses' hoofs returned. When they did come, which was after some time, they came at a faster pace. Fauntleroy's hat was still off; Wilkins was carrying it for him; his cheeks were redder than before, and his hair was flying about his ears, but he came at quite a brisk canter.

"There!" he panted, as they drew up, "I c-cantered. I didn't do it as well as the boy on Fifth Avenue, but I did it, and I stayed on!"

He and Wilkins and the pony were close friends after that. Scarcely a day passed in which the country people did not see them out together, cantering gayly on the highroad or through the green lanes. The children in the cottages would run to the door to look at the proud little brown pony with the gallant little figure sitting so straight in the saddle, and the young lord would snatch off his cap and swing it at them, and shout, "Hullo! Good morning!" in a very unlordly manner, though with great heartiness. Sometimes he would stop and talk with the children, and once Wilkins came back to the castle with a story of how Fauntleroy had insisted on dismounting near the village school, so that a boy who was lame and tired might ride home on his pony.

"An' I'm blessed," said Wilkins, in telling the story at the stables,—"I'm blessed if he'd hear of anything else! He wouldn't let me get down, because he said the boy mightn't feel comfortable on a big horse. An' ses he, 'Wilkins,' ses he, 'that boy is lame and I'm not, and I want to talk to him, too.' And up the lad has to get, and my lord trudges alongside of him with his hands in his pockets, and his cap on the back of his head, a-whistling and talking as easy as you please! And when we come to the cottage, an' the boy's mother come out all in a taking to see what's up, he whips off his cap an' ses he, 'I've brought your son home, ma'am,' ses he, 'because his leg hurt him, and I don't think that stick is enough for him to lean on; and I'm going to ask my grandfather to have a pair of crutches made for him.' An' I'm blessed if the woman wasn't struck all of a heap, as well she might be! I thought I should 'a' hex-plodid, myself!"

When the Earl heard the story, he was not angry, as Wilkins had been half afraid that he would be; on the contrary, he laughed outright, and called Fauntleroy up to him, and made him tell all about the matter from beginning to end, and then he laughed again. And actually, a few days later, the Dorincourt carriage stopped in the green lane before the cottage where the lame boy lived, and Fauntleroy jumped out and walked up to the door, carrying a pair of strong, light, new crutches, shouldered like a gun, and presented them to Mrs. Hartle (the lame boy's name was Hartle) with these words: "My grandfather's compliments, and if you please, these are for your boy, and we hope he will get better."

"I said your compliments," he explained to the Earl when he returned to the carriage. "You didn't tell me to, but I thought, perhaps, you forgot. That was right, wasn't it?"

And the Earl laughed again, and did not say it was not. In fact, the two were becoming more intimate every day, and every day Fauntleroy's faith in his lordship's benevolence and virtue increased. He had no doubt whatever that his grandfather was the most amiable and generous of elderly gentlemen. Certainly, he himself found his wishes gratified almost before they were uttered; and such gifts and pleasures were lavished upon him, that he was sometimes almost bewildered by his own possessions. Apparently, he was to have everything he wanted, and to do everything he wished to do. And though this would certainly not have been a very wise plan to pursue with all small boys, his young lordship bore it amazingly well. Perhaps, notwithstanding his sweet nature, he might have been somewhat spoiled by it, if it had not been for the hours he spent with his mother at Court Lodge. That "best [Pg 567] friend" of his watched over him very closely and tenderly. The two had many long talks together, and he never went back to the castle with her kisses on his cheeks without carrying in his heart some simple, pure words worth remembering.

There was one thing, it is true, which puzzled the little fellow very much. He thought over the mystery of it much oftener than any one supposed; even his mother did not know how often he pondered on it; the Earl for a long time never suspected that he did so at all. But being quick to observe, the little boy could not help wondering why it was that his mother and grandfather never seemed to meet. He had noticed that they never did meet. When the Dorincourt carriage stopped at Court Lodge, the Earl never alighted, and on the rare occasions of his lordship's going to church, Fauntleroy was always left to speak to his mother in the porch alone, or perhaps to go home with her. And yet, every day, fruit and flowers were sent to Court Lodge from the hot-houses at the castle. But the one virtuous action of the Earl's which had set him upon the pinnacle of perfection in Cedric's eyes, was what he had done soon after that first Sunday when Mrs. Errol had walked home from church unattended. About a week later, when Cedric was going one day to visit his mother, he found at the door, instead of the large carriage and prancing pair, a pretty little brougham and a handsome bay horse.

"That is a present from you to your mother," the Earl said abruptly. "She can not go walking about the country. She needs a carriage. The man who drives will take charge of it. It is a present from you."

Fauntleroy's delight could but feebly express itself. He could scarcely contain himself until he reached the lodge. His mother was gathering roses in the garden. He flung himself out of the little brougham and flew to her.

"Dearest!" he cried, "could you believe it? This is yours! He says it is a present from me. It is your own carriage to drive everywhere in!"

He was so happy that she did not know what to say. She could not have borne to spoil his pleasure by refusing to accept the gift even though it came from the man who chose to consider himself her enemy. She was obliged to step into the carriage, roses and all, and let herself be taken to drive, while Fauntleroy told her stories of his grandfather's goodness and amiability. They were such innocent stories that sometimes she could not help laughing a little, and then she would draw her little boy closer to her side and kiss him, feeling glad that he could see only good in the old man who had so few friends.

The very next day after that, Fauntleroy wrote to Mr. Hobbs. He wrote quite a long letter, and after the first copy was written, he brought it to his grandfather to be inspected.

"Because," he said, "it's so uncertain about the spelling. And if you'll tell me the mistakes, I'll write it out again."

This was what he had written:

"My dear mr hobbs i want to tell you about my granfarther he is the best earl you ever new it is a mistake about earls being tirents he is not a tirent at all i wish you new him you would be good frends i am sure you would he has the gout in his foot and is a grate sufrer but he is so pashent i love him more every day becaus no one could help loving an earl like that who is kind to every one in this world i wish you could talk to him he knows everything in the world you can ask him any question but he has never plaid base ball he has given me a pony and a cart and my mamma a bewtifle carige and I have three rooms and toys of all kinds it would serprise you you would like the castle and the park it is such a large castle you could lose yourself wilkins tells me wilkins is my groom he says there is a dungon under the castle it is so pretty every thing in the park would serprise you there are such big trees and there are deers and rabbits and games flying about in the cover my granfarther is very rich but he is not proud and orty as you thought earls always were i like to be with him the people are so polite and kind they take of their hats to you and the women make curtsies and sometimes say god bless you i can ride now but at first it shook me when i troted my granfarther let a poor man stay on his farm when he could not pay his rent and mrs mellon went to take wine and things to his sick children i should like to see you and i wish dearest could live at the castle but I am very happy when i dont miss her too much and i love my granfarther every one does plees write soon

"p s no one is in the dungon my granfarther never had any one langwishin in there

"p s he is such a good earl he reminds me of you he is a unerversle favrit"

"Do you miss your mother very much?" asked the Earl when he had finished reading this.

"Yes," said Fauntleroy, "I miss her all the time."

He went and stood before the Earl and put his hand on his knee looking up at him.

"You don't miss her, do you?" he said.

"I don't know her," answered his lordship rather crustily.

"I know that," said Fauntleroy, "and that's what makes me wonder. She told me not to ask you any questions, and—and I wont, but sometimes I can't help thinking, you know, and it makes me all puzzled. But I'm not going to ask any questions. And when I miss her very much, I go and look out of my window to where I see her light shine for me every night through an open place in the trees. It is a long way off, but she puts it in her window as soon as it is dark and I can see it twinkle far away, and I know what it says."

"What does it say?" asked my lord.

"It says, 'Good-night, God keep you all the night!'—just what she used to say when we were together. Every night she used to say that to me, and every morning she said, 'God bless you all the day!' So you see I am quite safe all the time——"

"Quite, I have no doubt," said his lordship dryly. And he drew down his beetling eyebrows and looked at the little boy so fixedly and so long that Fauntleroy wondered what he could be thinking of.

The fact was, his lordship the Earl of Dorincourt thought in those days, of many things of which he had never thought before, and all his thoughts were in one way or another connected with his grandson. His pride was the strongest part of his nature, and the boy gratified it at every point. Through this pride he began to find a new interest in life. He began to take pleasure in showing his heir to the world. The world had known of his disappointment in his sons; so there was an agreeable touch of triumph in exhibiting this new Lord Fauntleroy, who could disappoint no one. He wished the child to appreciate his own power and to understand the splendor of his position; he wished that others should realize it too. He made plans for his future. Sometimes in secret he actually found himself wishing that his own past life had been a better one, and that there had been less in it that this pure, childish heart would shrink from if it knew the truth. It was not agreeable to think how the beautiful, innocent face would look if its owner should be made by any chance to understand that his grandfather had been called for many a year "the wicked Earl of Dorincourt." The thought even made him feel a trifle nervous. He did not wish the boy to find it out. Sometimes in this new interest he forgot his gout, and after a while his doctor was surprised to find his noble patient's health growing better than he had expected it ever would be again. Perhaps the Earl grew better because the time did not pass so slowly for him, and he had something to think of beside his pains and infirmities.

One fine morning, people were amazed to see little Lord Fauntleroy riding his pony with another companion than Wilkins. This new companion rode a tall, powerful gray horse, and was no other than the Earl himself. It was, in fact, Fauntleroy who had suggested this plan. As he had been on the point of mounting his pony he had said rather wistfully to his grandfather:

"I wish you were going with me. When I go away I feel lonely because you are left all by yourself in such a big castle. I wish you could ride too."

And the greatest excitement had been aroused in the stables a few minutes later by the arrival of an order that Selim was to be saddled for the Earl. After that, Selim was saddled almost every day; and the people became accustomed to the sight of the tall gray horse carrying the tall gray old man, with his handsome, fierce, eagle face, by the side of the brown pony which bore little Lord Fauntleroy. And in their rides together through the green lanes and pretty country roads, the two riders became more intimate than ever. And gradually the old man heard a great deal about "Dearest" and her life. As Fauntleroy trotted by the big horse he chatted gayly. There could not well have been a brighter little comrade, his nature was so happy. It was he who talked the most. The Earl often was silent, listening and watching the joyous, glowing face. Sometimes he would tell his young companion to set the pony off at a gallop, and when the little fellow dashed off, sitting so straight and fearless, he would watch the boy with a gleam of pride and pleasure in his eyes; and Fauntleroy, when, after such a dash, he came back waving his cap with a laughing shout, always felt that he and his grandfather were very good friends indeed.

One thing that the Earl discovered was that his son's wife did not lead an idle life. It was not long before he learned that the poor people knew her very well indeed. When there was sickness or sorrow or poverty in any house, the little brougham often stood before the door.

"Do you know," said Fauntleroy once, "they all say, 'God bless you'! when they see her, and the children are glad. There are some who go to her house to be taught to sew. She says she feels so rich now that she wants to help the poor ones."

It had not displeased the Earl to find that the mother of his heir had a beautiful young face and looked as much like a lady as if she had been a duchess, and in one way it did not displease him to know that she was popular and beloved by the poor. And yet he was often conscious of a hard, jealous pang when he saw how she filled her child's heart and how the boy clung to her as his best beloved. The old man would have desired to stand first himself and have no rival.

That same morning he drew up his horse on an elevated point of the moor over which they rode, and made a gesture with his whip, over the broad, beautiful landscape spread before them.

"Do you know that all that land belongs to me?" he said to Fauntleroy.

"Does it?" answered Fauntleroy. "How much it is to belong to one person, and how beautiful!"

"Do you know that some day it will all belong to you—that and a great deal more?"

"To me!" exclaimed Fauntleroy in rather an awe-stricken voice. "When?"

"When I am dead," his grandfather answered.

"Then I don't want it," said Fauntleroy; "I want you to live always."

"That's kind," answered the Earl in his dry [Pg 569] way; "nevertheless, some day it will all be yours—some day you will be the Earl of Dorincourt."

Little Lord Fauntleroy sat very still in his saddle for a few moments. He looked over the broad moors, the green farms, the beautiful copses, the cottages in the lanes, the pretty village, and over the trees to where the turrets of the great castle rose, gray and stately. Then he gave a queer little sigh.

"What are you thinking of?" asked the Earl.

"I am thinking," replied Fauntleroy, "what a little boy I am! and of what Dearest said to me."

"What was it?" inquired the Earl.

"She said that perhaps it was not so easy to be very rich; that if any one had so many things always, one might sometimes forget that every one else was not so fortunate, and that one who is rich should always be careful and try to remember. I was talking to her about how good you were, and she said that was such a good thing, because an earl had so much power, and if he cared only about his own pleasure and never thought about the [Pg 570] people who lived on his lands, they might have trouble that he could help—and there were so many people, and it would be such a hard thing. And I was just looking at all those houses, and thinking how I should have to find out about the people, when I was an earl. How did you find out about them?"

As his lordship's knowledge of his tenantry consisted in finding out which of them paid their rent promptly, and in turning out those who did not, this was rather a hard question. "Newick finds out for me," he said, and he pulled his great gray mustache, and looked at his small questioner rather uneasily. "We will go home now," he added; "and when you are an earl, see to it that you are a better one than I have been!"

He was very silent as they rode home. He felt it to be almost incredible that he, who had never really loved any one in his life, should find himself growing so fond of this little fellow,—as without doubt he was. At first he had only been pleased and proud of Cedric's beauty and bravery, but there was something more than pride in his feeling now. He laughed a grim, dry laugh all to himself sometimes, when he thought how he liked to have the boy near him, how he liked to hear his voice, and how in secret he really wished to be liked and thought well of by his small grandson.

"I'm an old fellow in my dotage, and I have nothing else to think of," he would say to himself; and yet he knew it was not that altogether. And if he had allowed himself to admit the truth, he would perhaps have found himself obliged to own that the very things which attracted him, in spite of himself, were the qualities he had never possessed—the frank, true, kindly nature, the affectionate trustfulness which could never think evil.

It was only about a week after that ride when, after a visit to his mother, Fauntleroy came into the library with a troubled, thoughtful face. He sat down in that high-backed chair in which he had sat on the evening of his arrival, and for a while he looked at the embers on the hearth. The Earl watched him in silence, wondering what was coming. It was evident that Cedric had something on his mind. At last he looked up. "Does Newick know all about the people?" he asked.

"It is his business to know about them," said his lordship. "Been neglecting it—has he?"

Contradictory as it may seem, there was nothing which entertained and edified him more than the little fellow's interest in his tenantry. He had never taken any interest in them himself, but it pleased him well enough that, with all his childish habits of thought and in the midst of all his childish amusements and high spirits, there should be such a quaint seriousness working in the curly head.

"There is a place," said Fauntleroy, looking up at him with wide-open, horror-stricken eyes—"Dearest has seen it; it is at the other end of the village. The houses are close together, and almost falling down; you can scarcely breathe; and the people are so poor, and everything is dreadful! Often they have fever, and the children die; and it makes them wicked to live like that, and be so poor and miserable! It is worse than Michael and Bridget! The rain comes in at the roof! Dearest went to see a poor woman who lived there. She would not let me come near her until she had changed all her things. The tears ran down her cheeks when she told me about it!"

The tears had come into his own eyes, but he smiled through them.

"I told her you didn't know, and I would tell you," he said. He jumped down and came and leaned against the Earl's chair. "You can make it all right," he said, "just as you made it all right for Higgins. You always make it all right for everybody. I told her you would, and that Newick must have forgotten to tell you."

The Earl looked down at the hand on his knee. Newick had not forgotten to tell him; in fact, Newick had spoken to him more than once of the desperate condition of the end of the village known as Earl's Court. He knew all about the tumble-down, miserable cottages, and the bad drainage, and the damp walls and broken windows and leaking roofs, and all about the poverty, the fever, and the misery. Mr. Mordaunt had painted it all to him in the strongest words he could use, and his lordship had used violent language in response; and, when his gout had been at the worst, he had said that the sooner the people of Earl's Court died and were buried by the parish the better it would be,—and there was an end of the matter. And yet, as he looked at the small hand on his knee, and from the small hand to the honest, earnest, frank-eyed face, he was actually a little ashamed both of Earl's Court and of himself.

"What!" he said; "you want to make a builder of model cottages of me, do you?" And he positively put his own hand upon the childish one and stroked it.

"Those must be pulled down," said Fauntleroy, with great eagerness. "Dearest says so. Let us—let us go and have them pulled down tomorrow. The people will be so glad when they see you! They'll know you have come to help them!" And his eyes shone like stars in his glowing face.

The Earl rose from his chair and put his hand on the child's shoulder. "Let us go out and take our walk on the terrace," he said, with a short laugh; "and we can talk it over."

And though he laughed two or three times again, as they walked to and fro on the broad stone terrace, where they walked together almost every fine evening, he seemed to be thinking of something which did not displease him, and still he kept his hand on his small companion's shoulder.

(To be continued.)

Oh, gold-green wings, and bronze-green wings,

And rose-tinged wings, that down the breeze

Come sailing from the maple-trees!

You showering things, you shimmering things,

That June-time always brings!

Oh, are you seeds that seek the earth,

The shade of lovely leaves to spread?

Or shining angels, that had birth

When kindly words were said?

Oh, downy dandelion-wings,

Wild-floating wings, like silver spun,

That dance and glisten in the sun!

You airy things, you elfin things,

That June-time always brings!

Oh, are you seeds that seek the earth,

The light of laughing flowers to spread?

Or flitting fairies, that had birth

When merry words were said?

We have already been in Paris, but we saw very little of it, as we were merely passing through the city on our way to the south of France; and my young companions should not go home without forming an acquaintance with a city which, on account of its importance and unrivaled attractiveness, may be called the queen city of the world, just as London, with its wealth, its size, and its influence, which is felt all over our globe, is the king of cities. In Rome, and in other cities of Italy, we have seen what Europe used to be, both in ancient times and in the Middle Ages; but there is no one place which will show us so well what Europe is to-day, as Paris.

It is an immense city, being surrounded by ramparts twenty-one miles long, and is full of broad and handsome streets, magnificent buildings, grand open spaces with fountains and statues, great public gardens and parks free to everybody, and (what is more attractive to some people than anything else) it has miles and miles of stores and shops, which are filled with the most beautiful and interesting things that are made or found in any part of the world. All these articles are arranged and displayed so artistically, that people buy things in Paris which they would never think of buying anywhere else, simply because they had never before noticed how desirable such things were. But, even if we do not wish to spend any money, we can still enjoy the rare and beautiful objects for which Paris is famous; they are nearly all in the shop windows, and we can walk about and admire them for nothing and as much as we please.

In many respects Paris is as lively as Naples; as grand as Rome; as beautiful, but in a different way, as Venice; almost as rich in remains of the Middle Ages as Florence; and yet, after all, it will remind you of none of those cities.

Before we visit any particular place in Paris, we shall start out to explore the city as a whole; although I do not mean to say that we shall go over the whole of the city. Those of us who choose will walk, and that is the best way to see Paris, for we are continually meeting with something that we wish to stop and look at; but such as do not wish to take so long a walk may ride in the voitures, or public carriages, which abound in the streets of Paris. In fine weather, these are convenient little open vehicles, intended to carry two persons, though more can be sometimes accommodated. They can be hired for two francs (about forty cents) an hour, with the addition of a small sum called pour-boire to which the driver is by custom entitled. Nearly everywhere we may see empty voitures, their drivers looking out for customers. When we want one, we do not call for it, nor do we stand on the curbstone and whistle, as if we were stopping a Fifth Avenue stage: If no driver sees us so that we can beckon to him, we follow the Parisian custom, and going to the edge of the pavement, give a strong hiss between our closed teeth. Instantly the nearest cocher, or driver, pulls up his horse and looks about him to see where that hiss comes from, and when he sees us, he comes around with a sweep in front of us.

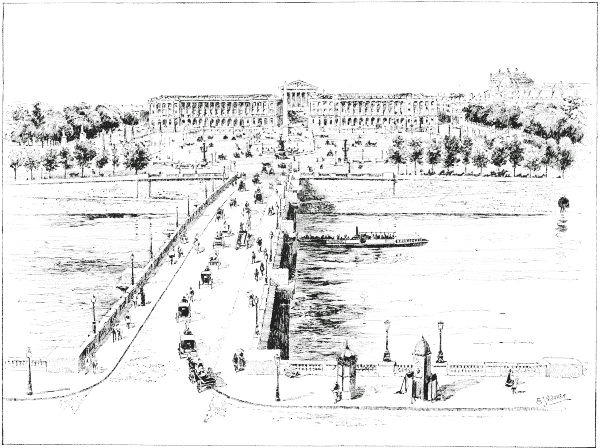

The river Seine runs through Paris, and winds and doubles so much that there are seven miles of it within the city walls. It is crossed by twenty-seven bridges, and from one of these, the Pont de la Concorde, we shall start on our tour through Paris. The upper part of this bridge is built of stones taken from the Bastille prison after its destruction by the enraged people. Thus the Parisians can feel, when they cross this bridge, that they are treading under foot a portion of the building they so greatly abhorred. The view up and down the river is very fine, and gives us a good idea of the city we are about to explore. As we cross to the northern side of the Seine, on which lies the most important part of Paris, we have directly in front of us, the great Place de la Concorde, a fine open square, in the center of which rises an obelisk brought from Egypt. Here are magnificent fountains, handsome statuary on tall pedestals, and crowds of vehicles and foot-passengers crossing it in every direction, making a picturesque and lively scene. This was not always as pleasant a place as it is now, for during the great French Revolution the guillotine stood in this square, and here were executed two thousand eight hundred persons, among whom were Queen Marie Antoinette and her husband, Louis XVI. To the east of this square extends for a long distance the beautiful garden of the Tuileries, which belonged to the royal palace of that name, before it was destroyed. This garden is shaded by long lines of trees, and adorned with fountains and statues. On its southern side is an elevated walk, or terrace, very broad and [Pg 573] handsome, and about half a mile long. In the reign of the Emperor Napoleon the Third, this walk was appropriated to the daily exercise of the Prince Imperial. Here the young fellow could walk up and down without being interfered with by the people below; and underneath was a covered passage in which he could take long walks in rainy weather.

ONE OF THE BRIDGES ACROSS THE SEINE,—SHOWING THE PLACE DE LA CONCORDE AND THE TUILERIES IN THE DISTANCE.

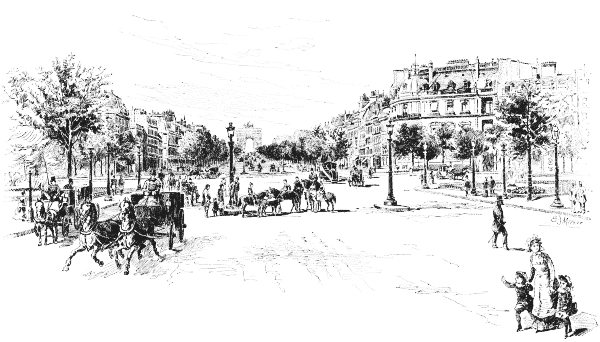

On the other side of the great square extends a broad and magnificent street, a mile and a third in length, called the Avenue des Champs Elysées. On each side, for nearly half a mile, this street is bordered by pleasure-grounds, beautifully laid out and planted with trees; and for the rest of the way it runs between two double rows of trees to the great Arch of Triumph, built by Napoleon Bonaparte to commemorate his victories. This arch is like those erected by the Roman emperors, and is covered with inscriptions and sculptures recording the glorious achievements of the great Napoleon. When Paris was taken by the Prussians in the war of 1871, the German army marched into the city through this arch of triumph; and if they wished to humiliate the French people, they could not have thought of a better plan. But the French people whom we now see here on fine afternoons do not look at all humiliated. They walk about under the trees; they sit upon the thousands of prettily painted iron chairs which are hired out at two cents apiece for a whole day; they drive up and down in the finest carriages that money can buy; and, so far as we can discover by looking at them, they are as well content and have as good an opinion of themselves as any people in the world. The pavement of the street and that of the great square is as smooth as a floor, and kept very neat and clean. This is the case indeed in nearly all the principal streets of Paris, and it is a pleasure to drive over their smooth and even pavements. But after a rain it is not so agreeable to walk across these streets, which are then covered with a coating of very sticky white mud.

On the northern side of the square is a handsome street of moderate length, called the Rue Royale. It is filled with fine shops, and is very animated [Pg 574] and lively. At its upper end stands the beautiful church of the Madeleine, fashioned like a Grecian temple. We go up this street, and when we reach the broad space about the Madeleine, part of which is occupied as a flower-market, with long lines of booths crowded with many varieties of blossoms and plants, we find ourselves at the beginning of the magnificent line of streets, which are called the boulevards of Paris. The word boulevards means ramparts or bulwarks, and this long line of streets is built where the old ramparts of Paris used to stand. Of late, however, the word has been applied to many of the other broad and splendid streets for which Paris is famous. This crowded, lively, and interesting thoroughfare is over two miles long, and is, in fact, but one great street, although it is divided into eleven sections, called the Boulevard de la Madeleine, Boulevard des Capucines, Boulevard des Italiens, etc. These boulevards do not extend in a straight line, but make a great sweep to the north, and come down again to within a short distance of the river.

THE AVENUE DES CHAMPS ELYSÉES. (SEE PAGE 573.)

On each side of this wide line of streets are splendid shops and stores, cafés, restaurants, and handsome hotels; and before we have gone very far we shall see, standing back in an open space, the Grand Opera House of Paris. It is a magnificent building both inside and out; it is the largest theater in the world, and covers three acres of ground.

But although the fine buildings and the dazzling show-windows full of beautiful objects will continually attract our attention, they can not keep our eyes from the wonderful life and activity of the streets. The broad sidewalks, of course, are crowded with people, though no more than we often meet on Broadway, in New York, but the throng is peculiar because it is made up of such a variety of people who seem to be doing so many different things: ladies and gentlemen dressed in the latest fashions; working men in blue blouses; working women, always without any head-covering; boys and men with wooden shoes; gentlemen, and often ladies, sitting at little tables placed on the sidewalk in front of cafés, drinking coffee, or taking some other refreshment; soldier-policemen marching up and down, and looking very inoffensive; now and then a priest in long black clothes, and a broad felt hat. But yet among this multitude of people we seldom meet any one who is dashing along as if he were trying to catch a train or a boat, or to do something else for which he is afraid there is not time enough. Here and there we see, standing close to the curbstone, a little round wooden house, prettily ornamented, inside of which a woman sits selling newspapers which are displayed at the open window. These houses are called kiosks, and they take the place of the newspaper stands in our country. As far as possible, the French like to make their useful things ornamental, and these kiosks add very much to the appearance of the streets.

Occasionally we come to the opening of a covered arcade, extending a long distance back from the street, and crowded on both sides with shops, the pavement in the center being occupied only by foot-passengers. These arcades are called passages, and are among the most interesting features of Paris. The shops here are generally small, but they display their goods in a very enticing way. Some of the passages contain cafés and restaurants, and one of them is almost entirely devoted to the sale of toys and presents for children.

In another passage we shall find a very wonderful wax-work show, which, although it is not so large as the famous exhibition of Madame Tussaud in London, is, in many respects, much more interesting. There are figures here of all kinds, many of celebrated people, but instead of being set up stiffly around a room, they are arranged in groups in separate compartments, and in natural positions, as if they were saying or doing something. In the center of the room is a studio, in which the artist, who looks as natural as life, is painting a picture of a girl standing at a little distance from him, while behind him another girl is peeping over his shoulder to see how he is getting on, and she looks so life-like that we can almost expect to hear her say what she thinks about it. Near by, some ladies and gentlemen are looking over portfolios of drawings, other visitors are talking together and examining the pictures on the walls, while a servant is bringing in wax refreshments which look quite good enough to eat and drink. This scene will give us an excellent idea of life in the studio of a French artist. There are all kinds of scenes represented here, and some, especially in the basement, are of a gloomy and somber kind. One of these represents a body of policemen bursting into a room occupied by a band of counterfeiters engaged in making false money. The dismay of the counterfeiters, disturbed in their work, and the desperate fight that has already begun, are very startling and real, and we almost feel that we ought to move out of the way.

The roadway of the boulevards is filled with vehicles of every kind, and among these we particularly notice the great omnibuses, much larger than any we have, and each drawn by three powerful horses, generally white. These omnibuses have seats on top as well as inside, and a very good way to see the city is to take a ride upon one of those upper seats. The omnibuses are almost always well filled, but never crowded, no one being taken on after every seat is occupied, and a fixed number are standing on the outside platform. They stop at regular stations, not very far apart, and the people who wait here for them are provided with numbered tickets, which they procure from the agent at the station, so that when the omnibus comes, as many as can be accommodated take their seats in regular order, according to the number of their tickets. In this way, there is no crowding and pushing to get in, and those who are left behind have the best chance at the next omnibus.

In other parts of the city of Paris, there are street [Pg 576] railways, called here tramways, which are managed very much in the same manner as the omnibuses. These vehicles are convenient and cheap, but not very agreeable, and it is much pleasanter to walk and pay nothing, or to take a voiture and pay thirty cents for two people for a drive from one end of the city to another.

And thus we go on along the boulevards, passing the celebrated gateways, Porte St. Martin and Porte St. Denis, until we come to the great open space once occupied by the Bastille, in which now rises a tall, sculptured column surmounted by a figure of Liberty. Those who have studied and remembered modern French history will take a great interest in this spot, where so many important events occurred.

Here end the boulevards. We now turn toward the river, and soon reach a wide street called the Rue de Rivoli, one side of which is lined with shops under arcades, which, in some respects, are more attractive than any we have yet seen. At many of these, photographs are sold; and their windows are crowded with pictures. All sorts of useful and cheap things are to be found here, and a walk through this street is like a visit to a museum. On the other side of the street is the great Palace of the Louvre, which extends for some distance, and after that, we come to the Garden of the Tuileries. When we have walked through this magnificent pleasure-ground, we shall reach the point from which we started on our tour.

We shall take many other walks and drives through the streets of Paris, and wherever we go, we shall find in each an interest of a different sort. On the southern side of the river, is the Latin Quarter, where there are some celebrated schools and academies, which, for centuries, have been the resort of students. Here we shall find narrow streets, crowded footways, and shops full of all sorts of antiquarian articles, and odds and ends of every kind, some of which seem to have no other value than that they are old, while other things are very valuable, and often very cheap.

Here, too, we find book shops, and shops where prints and engravings are sold, and all with their windows and even their outside walls crowded with the best things they have to offer. Along the river front are rows of stalls covered with second-hand books at very low prices, and those of us who are collectors of old coins can find them here by the peck or bushel. In this quarter, also, are some immense dry-goods and variety stores, which are worth going to see. One of them is so large, and there is so much to see in it, that, at three o'clock every day, a guide who can speak English sets out to conduct visitors through the establishment and to explain its various details.

In nearly every quarter of Paris, on either side of the river, we shall find shops, shops, shops; people, people, people; life, activity, and bustle of every sort. Splendid buildings meet our eyes at every turn,—churches, private residences, places of business, and public edifices. In the western portion of the city, near the Arc de Triomphe, there are fewer shops, these streets being generally occupied by fine private residences. But there is very little monotony in Paris; no quarter is entirely given up to any one thing. We can not walk far in any direction without soon coming upon some object of interest. The parks, palaces, public monuments, gardens, grand and beautiful churches, fountains of various designs, great market-places, squares, and buildings of historic interest or architectural beauty, are sometimes collected in groups, but, as a rule, they are scattered all over the city.

When we have satisfied ourselves with what Paris itself is, although we have not seen anything like the whole of it, we shall set about visiting some of its especial attractions. And the first place we shall go to will be the great palace of the Louvre. This palace, with its courts and buildings, covers some twenty acres. Here have lived kings, queens, and princes; but now the palace has been made into a museum for the people, and its grand halls and galleries are filled with paintings, statuary, and other works of art, ancient and modern, from all parts of the world. It would take many, many visits even to give one look at every painting and statue in the Louvre; but if we have not much time to spare, it is possible to see the best things without walking ourselves to death through the never-ending galleries. Some of the finest paintings of Raphael, Da Vinci, Murillo, and other great masters, are collected in one room, which many persons would think well worth coming to Paris to see, if they saw nothing else. The original statue of the noble Venus de Milo is in the sculpture galleries; and in the Egyptian museum, which is so full that the history of Egypt may be studied here almost as well as in that land itself, we shall see a large stone sphinx which once [Pg 57] belonged to that king of Egypt from whom the children of Israel fled, and the inscriptions on it show that it must have been a pretty old sphinx even when Pharaoh had it. In another part of the museum are three life-size figures in stone, which are portraits of persons who lived before the great pyramids were built, about 4000 years before the Christian era.

Altogether, the collections of the Louvre are among the finest and most extensive in the world, and they have a great advantage over the galleries of the Vatican at Rome: In the Vatican some of the galleries are open on one day and some on another, some requiring one kind of order of admission, some another, and others yet another, and these permits are sometimes troublesome to obtain;—but the galleries of the Louvre are free to all, rich or poor, who may choose to walk into them on any day of the week except Monday, which is always reserved for cleaning, dusting, and putting things in order.

In the old palace of the Luxembourg, a very much smaller building, there is another valuable collection of paintings, but all by French artists; and the Hotel de Cluny, not far away, is a small palace of the Middle Ages, and is one of the quaintest, queerest, pleasantest, and most home-like palaces we are likely to meet with. It is now a museum, containing over ten thousand interesting objects, mostly relating to mediæval times. Here, among the other old-time things, we can see the very carriages and sleighs in which the great people of the seventeenth century used to ride. Those of us who suppose that we have now left the Romans for good must not fail to visit some large baths adjoining this palace, built about the end of the third century, when the Romans had possession of Gaul. They then had a palace on this spot, and felt bound, as the ancient Romans always did, to make themselves comfortable with baths and everything of the kind. There are other museums and art exhibitions in Paris, but those we have seen are the most important; and it is very pleasant to find that they are greatly frequented by the poorer classes of the city, who are just as orderly and well behaved while walking about these noble palaces as if they belonged [Pg 579] to the highest families of the land. In the great garden of the Tuileries, in the courts and gardens attached to the Louvre, the Luxembourg, the Palais Royal, and in all the pleasure-grounds of the city, we find the poor people enjoying themselves; and in some cases they seem to get more good out of these places than do the rich. The old women sit knitting in the shade of the trees; the little babies with their funny caps toddle about on the walks; the boys and girls have their games in the great open spaces around the fountains, and while those who have a cent or two to spare can hire little chairs and put them where they like, there are always benches for those who have no pennies to spend. The convenience of resting one's self in the open air is one of the comforts of Paris. In many places along the principal streets, there are benches on the sidewalk, where weary passers-by may rest shaded by the trees. In one part of the city, chiefly inhabited by the poor and the working people, a fine park has been laid out entirely for their accommodation. In very many ways the French government offers opportunities to the poor people to enjoy themselves, and it is pleasant to see how neat, orderly, and quiet these people are. It is very necessary that they should be kept in good humor, for when the lower classes of Paris become thoroughly dissatisfied, they are apt to rise in fierce rebellion, and then down go kings, governments, and palaces.

On the southern side of the river rises a great gilded dome which glistens in the sun, and may be seen from all parts of Paris. This dome belongs to the church attached to the Hotel des Invalides, or hospital for invalid soldiers, and it covers the tomb of Napoleon Bonaparte. This tomb, which is very magnificent and imposing, is some distance below the floor of the church, and we look down upon it over a circular railing. There we see the handsome sarcophagus, made of a single block of granite weighing sixty-seven tons, which contains the remains of a man who once conquered the greater part of Europe.

Paris is full of churches, some old and some new, and many grand or beautiful, but no one of them is so interesting as the famous cathedral of Notre Dame, which stands on an island in the Seine, called La Cité, or the Island of the City, because here the original Paris was built. This great church is not so attractive in appearance as some that we have seen elsewhere, but it is connected with so many events in the history of France, that as we wander about under its vaulted arches and through its pillared aisles, and as we look upon the strange and sometimes startling sculptures in the chapels, the curious wood carvings about the choir, the immense circular window of gorgeously stained glass in the transept, which sends its brightness into the solemn duskiness of the church, we shall do so with a degree of interest increased by what we have read about this old and famous building.

Another church which we shall wish to see is Sainte-Chapelle, or Holy Chapel, built in 1245 by King Louis IX., who was known as St. Louis. It stands on the same island as Notre Dame, and near the Palace of Justice, a great pile of buildings containing the law courts. This church or chapel is small, but it is, perhaps, the most beautiful of the kind in the world. The walls of the upper story, in which the royal court used to worship, are almost entirely of exquisitely colored glass. These walls are formed of windows nearly fifty feet high, and the light shining through every side of this gorgeous temple of stained glass produces a remarkable and beautiful effect.

The present Palace of Justice is for the most part a modern building, but portions of the old edifice of the same name which used to stand upon this spot still remain. In one of these we shall visit the old Conciergerie, which is famous as a French state prison. Here we shall see the little room with a brick floor, in which the beautiful Marie Antoinette, the wife of Louis XVI., was imprisoned for two months before her execution. Here is the very arm-chair in which she sat. Thus we bring to mind the events of the great French revolution, and can easily recall the sorrowful things which took place in the halls and rooms of that gloomy Conciergerie.

Another celebrated Parisian church is the Pantheon, an immense edifice. This building was intended as a burial-place for illustrious men of France.

We have all heard of the famous cemetery of Père-Lachaise. It lies within the city, and will be interesting to us, not only because of its great size and beauty, and because it contains the graves of so many persons famous in art, science, literature, and war, but because it is so different from any graveyard to which we are accustomed. It has more than twenty thousand monuments, and many of these are like little houses standing side by side as if they were dwellings on a street. Each vault generally belongs to a family, and the little buildings are almost always decorated with a profusion of flowers and wreaths, and often with [Pg 581] pictures and hanging lamps. Here, as in other French cemeteries, it is not uncommon to place a framed photograph of a deceased person over his grave.

There are small steamboats which run up and down the Seine like omnibuses, and the charge to passengers is about two cents apiece. These little boats are called by the Parisians mouches, or flies, and as they are often very convenient for city trips, we shall take one of them and go to the Jardin des Plantes, a very extensive and famous zoölogical and botanical garden. Here we may ramble for hours, and see animals from all parts of the world in cages, and houses, and in little yards, where they can enjoy the open air.

At the other end of the city, outside the walls, is the Jardin d' Acclimatation, that contains a great number of foreign animals and plants, many of which have been naturalized so as to feel at home in the climate of France. In one house here, we may see all kinds of silk-worms, with the plants they feed upon growing near by. In another part of the grounds we shall find trained zebras and ostriches harnessed to little carriages, in which children may take a ride; and we shall see some very gentle elephants and camels, on which we may mount and get an idea of how people travel in the East. We shall here perhaps call to mind the account of this place which was published in St. Nicholas more than ten years ago,—in June, 1874.

The Bois de Boulogne, adjoining this garden, is a very large park, where we can see the fashionable people of Paris in their carriages on fine afternoons.

There are certain goods sold in Paris known under the name of "articles de Paris." These consist of all sorts of pretty things, generally very tasteful but not very expensive, among which are jewelry and trinkets of many kinds, and a great variety of useful and ornamental little objects made in the most attractive fashion. These goods, of course, can be bought in other cities, but Paris has made a specialty of their manufacture, and many shops are entirely given up to their sale. A great number of such shops is to be found in the Palais Royal. This is a vast palace built for Cardinal Richelieu, in 1625, and is in the form of a hollow square, surrounding the garden of the Palais Royal. Around the four sides of the palace, under long colonnades and facing the garden, are rows of shops, their windows filled with all sorts of sparkling and beautiful things in gold, silver, precious stones, bronze, brass, and every other material that pretty things can be made of. By night or by day the colonnades of the Palais Royal [Pg 582] are very attractive places, and as all visitors go to them, so do we. Even if we do not buy anything, we shall be interested in the endless display in the windows.

Another place we shall wish to visit is the famous manufactory of Gobelin tapestry. In this factory, which belongs to the Government, are produced large and beautiful woven pictures, and the great merit of the work is that it is done entirely by hand, no machinery being used. The operation is very slow, each workman putting one thread at a time in its place, and faithfully copying a painting in oil or water-colors, which stands near him, as a model. If, in a day, he covers a space as large as his hand, he considers that he has done a very good day's work. These tapestries, which are generally very large and expensive, are used as wall-hangings in palaces and public buildings. It will be an especial delight, I think, to the girls in our company to watch this beautiful work slowly growing under the fingers of the skillful workmen.

Outside of Paris, but not far away, there are some famous places which we must see. First among these are the palace and grounds of Versailles, a magnificent palace, built by Louis XIV. for a summer residence. This gentleman, who liked to be called Le Grand Monarque had so high an idea of the sort of country place he wanted, that he spent upon this palace and its grounds the sum of two hundred millions of dollars.* The whole place is now open to the public, and the grand and magnificent apartments and halls, some of them nearly four hundred feet long, are filled with paintings and statuary, so that the palace is now a great art gallery. The park is splendidly laid out, having in it a wide canal nearly a mile long. The fountains here are considered the finest in the world, and when they play, which is not very often, thousands upon thousands of people come out from Paris to see them. In the grounds are two small palaces, once inhabited by French queens; and one of these, called the little Trianon, was the beautiful home of Marie Antoinette, whose last home on earth was the brick-paved room of the Conciergerie. The private garden attached to this little palace, which is more like a park than a garden, possesses much rural beauty.

Here, on the margin of a lake, we may see the little thatched cottages which Marie Antoinette had built, that she and the ladies of her court might play at being milkmaids. These cottages stand just as they did when those noble ladies dressed themselves up like peasant girls, and milked cows, which, I have no doubt, were very gentle animals, while the royal milkmaids probably tried to make themselves believe that they could have the happiness of real milkmaids as well as that which belonged to their own lives of luxury and state.

At Fontainebleau is another royal palace, to which is attached a magnificent forest of forty-two thousand acres. The kings of France did not like to feel cramped in their houses or grounds, and in this beautiful forest, which measures fifty miles around, there are twelve thousand four hundred miles of roads and foot-paths. On the borders of this forest is the village of Barbizon, where lived the artist, Millet, of whom you have read in St. Nicholas.

Not far from Paris is the old palace of St. Germain, in which many kings have been born, lived, and died, and to which there is a forest of nine thousand acres attached. There is also St. Cloud, with a ruined palace and a lovely park, with statues, fountains, and charming walks; and, near by, the village of Sèvres, where the famous porcelain of that name is made. Also within easy distance of the city, is the old cathedral of St. Denis, where, for over a thousand years, the kings of France were buried. Here, in a crypt or burial-place under the church, we may look through a little barred window into a gloomy vault, and see, standing quite near us, the metal coffin which contains the bones of Marie Antoinette, whose palaces, pleasure-grounds, prison-house, and place of execution we have already seen.

The history of France shows us that Paris has been as rich in historical events as it is now in bright, attractive shops; but, as a rule, it is much more pleasant to see the latter than to remember the former. In our walks through Paris, we will not think too much of the dreadful riots and combats that have taken place in her streets, the blood that has been shed even in her churches, and the executions and murders that have been witnessed in her beautiful open squares. Instead of this, we will give ourselves up to the enjoyment of the Queen of Cities, as she now is, thinking only of the unrivaled pleasures she offers to visitors, and of the kindness and politeness which we almost always meet with from her citizens.

Footnote *: A sketch of the boyhood of this spendthrift monarch was given in the series of "Historic Boys," under the title of "Louis of Bourbon: the Boy King," in St. Nicholas for October, 1884.

|

There are roses that grow on a vine, on a vine, There are roses that grow on a tree; But my little Rose Grows on ten little toes, And she is the rose for me. Come out in the garden, Rosy Posy! Come visit your cousins, child, with me. If you are my grandchild, it stands to reason That Grandpapa Rosebush I must be. Oh! fair is the rose on the vine, on the vine, And fair is the rose on the stalk; But there's only one rose Who has ten little toes, And it's that rose I'll take for a walk. Come put on your calyx, Rosy Posy! Put on your calyx and come with me; For if you are my grandchild, it stands to reason That Grandpapa Rosebush I must be. |

Before Beman's Beach had become the popular summer resort which all tourists know to-day, there lived, a little back from the rocky coast which stretches away from it toward the southwest, a farmer named Elder. He had a large family, which consisted mostly of girls; but there were two boys, who were twins.

The boys were called Moke and Poke. These were not their baptismal names, of course. Moke Elder had been christened Moses, and Poke Elder had received at the same time the respectable appellation of Porter—both after their uncle, Mr. Moses Porter, who lived in the family. But they were so seldom called by those names that most people seemed to have forgotten them. Moke was Moke, and Poke was Poke, the world over.

That is to say, their world, which would not have required a tape measure quite twenty-five thousand miles long to go around it. "Frog-End" was the nickname of the part of the town where they lived,—probably on account of a great marsh which was very noisy in spring,—and they were little known beyond its borders.

But everybody about Frog-End and along the coast knew Moke and Poke. That is to say, they were known as twins, if not as individual, separate boys. They looked so much alike, both being thin-faced and tow-headed, and dressed so much alike, often wearing each other's clothes, that he who, meeting one alone, could always say "Moke," or "Poke," as the case might be,—and feel sure he wasn't calling Moke "Poke" or Poke "Moke,"—must have known them very well indeed.

Of course, only a born Frog-Ender could do that. I am not a Frog-Ender myself, and the only way I could ever tell them apart was by looking closely at their moles.

They had two moles between them, exactly alike, except that Moke wore his on the right cheek, quite close to the right nostril, while Poke hung out his sign on the left cheek, at about an equal distance from the left nostril; as if Nature had had just a pair of moles to throw in with their other personal attractions, and had divided her gift in this impartial way.

Even after people had learned these distinguishing marks, however, they could not always remember, at a moment, which had the right mole and which the left; but they would often say "Poke" to the right mole and "Moke" to the left mole, in a manner that appeared very ridiculous to the boys' seven sisters, who couldn't see that they resembled each other at all.

The twins were nearly always together, whether at work or at play; when one was sent on an errand, as a rule both would go, if it was only to get a pound of board-nails or a spool of thread at the village store. They were about the age of their neighbors and playmates, Oliver Burdeen (commonly called Olly), who, when he was at home, lived two farms away from them, and Percival Bucklin (familiarly known as Perce), who lived still nearer, on the other side.

These four boys are the three heroes of our story,—counting the twins as one,—and they come into it on a certain afternoon late in August, just after a great storm had swept over the New England coast.

Uncle Moses Porter—uncle of the twins on the mother's side, an odd and very shabby old bachelor—comes into it at the same time, but doesn't get in very far. It would be hard to make a hero of him. At about four o'clock that day he stood in Mr. Elder's backyard, barefooted and without his hat, watching the clouds and the wooden fish on the barn, and making up his mind about the weather. That was a subject to which he had given the study of a lifetime. He could tell you as many "signs" as there are letters in the alphabet, and spell out to-morrow's weather very exactly with them; that is to say, what it should be, not always what it actually was—Nature sometimes neglecting in the strangest way her own plain rules. A great deal was said about Uncle Moses's occasional lucky hits, and very little about his frequent misses; and he enjoyed a world-wide reputation (the Frog-End world, again) as a weather-prophet, until "Old Probabilities" at Washington took the wind out of his predictions, and drove him, so to speak, out of the business.

But at the time of which I write he was at the pinnacle of his fame, and nobody ventured to doubt his prognostications. If the weather didn't turn out as he predicted, why, so much the worse for the weather!

"Wind has whipped 'round the right way this time, boys!" he remarked, after long and careful observation. "It's got square into the west, and I predict it's a-go'n' to stay there, and give us fair weather, nex' four-'n'-twenty hours. The's no rain in yon clouds; it's all been squeezed out, or else I never saw a flyin' scud afore!"

He paused as if to relax his mind after the severe strain of this prophecy, and smiled as he came toward the woodshed,—where the twins were standing.

"An' I tell ye what, boys! A heap o' that kelp the storm's hove up, are a-go'n' to land, this tide an' tomorrer mornin's, an' you'd better be on hand to git our share on 't."

Of all the farm-work the twins ever tried, they found going for sea-weed the most delightful. There was a relish of adventure in it; and it took them to the beach, which was always a pleasant change for boys brought up on Frog-End rocks. The kelp was usually hauled up from the shore and left to rot in heaps; after which, it became excellent dressing for the land.

There was no good beach very near Mr. Elder's farm, but he had a right on Beman's Beach, two or three miles down the coast.

Mr. Bucklin, another Frog-End farmer, had a similar right, and he and his son Percival were that same afternoon talking about the expected harvest of kelp. Mr. Bucklin was saying that there was nothing to be gained by starting for the beach till the next morning, and that even then he couldn't go, as being one of the town's selectmen he would have some public business to attend to,—and Percival, a bright, strong, enterprising boy of sixteen, was insisting that their team ought to be on the shore by daylight, and that he would be there with it if he could get anybody to go with him, when the Elder twins came crossing fields and leaping fences, and finally tumbled over the bars into the yard where father and son were talking.

"Uncle Mose says—" began Moke.

"Wind's just right for the kelp," struck in Poke.

"There'll be stacks of it," Moke exclaimed.

"And we're going!" Poke continued.

That was the way they usually did an errand or told a story,—one giving one fragment of a sentence, [Pg 586] and his brother the next, if, indeed, they didn't both speak together.

They ended with a proposition. Their father had gone to Portland with the team; and if Mr. Bucklin would let Perce take his tip-cart and yoke of steers, they would go with him, and all the sea-weed gathered by the three should be shared equally by the two farmers.

"And what we want is——" said Moke.

"To start after an early supper this evening," said Poke.

"Camp to-night at the beach," Moke added.

"And be on hand to begin work——" Poke added, contributing his link to the conversational chain.

"As soon as the tide turns in the morning," rattled both together.

Mr. Bucklin smiled indulgently.

"I think your uncle is right," he said. "And I'm willing Perce should go. Though I don't know about your starting to-night to camp out."

"Oh, yes!" exclaimed Percival, as eager for the adventure as if he had been a third twin and shared the enthusiasm of his two other selves. "That will be all the fun!"

"We'll take some green corn——" said Moke.

"And new potatoes——" said Poke.

"And a sickle to cut grass——" Moke ran on.

"And make a fire of driftwood——" Poke outstripped him.

"For the steers," said Moke, finishing his own sentence, and not Poke's.

"To roast 'em," concluded Poke, referring to the potatoes and green corn, and not to the steers.

"It'll be just grand!" Percival exclaimed. "May we, father? The tide will turn about daylight; we'll have our breakfast on the beach, and be ready to go to work; and we'll haul two big heaps on the shore, one for us and one for them, and leave 'em till they're ready to draw away and spread on the land. May we, father?"

"You're not so sure the kelp'll land," said the cautious farmer. "It's notional about it sometimes."

"But if the wind keeps off shore it will!" said Moke and Poke, two voices for a single thought.

"The wind may chip around again, and the kelp all disappear as clean as if the beach had been swept. But I don't care," added the farmer indulgently. "If you boys want to take the chance, I'll let Perce have the steers. You might gather some driftwood, anyhow. The storm must have driven a good lot of that high up, out of the reach of the common tides."

His easy consent made the boys as happy as if they had been going to a circus; and they immediately began to make preparations for the trip.

Moke and Poke ran home for their suppers, and came running back in an incredibly short time, bringing a basket of provisions, with ears of unhusked corn and bottles of spruce-beer sticking out, a blanket for their bed on the beach, and each a three-tined pitchfork for handling the kelp. These were put into the cart, along with articles furnished by Percival, and a quantity of hay which Mr. Bucklin said they would find comfortable to sleep on that night, even if it didn't come handy to feed the oxen.

The yoked steers were then made fast to the cart, and they set off.

Never king in his coach enjoyed a more exhilarating ride than our three youngsters in the old tip-cart, drawn by the slow cattle along the rough country road. The source of happiness is in our own hearts; and it is wonderful how little it takes to make it run over, in a healthy boy.

A board placed across the cart-box served as a seat; and when one of them tired of riding on that, he would tumble in the hay. Perce wielded the ox-gad at first; but soon the twins wished to drive. Both reached for the whip at once.

"Wait a minute! you can't both have it!" cried Perce. "The oldest first!"

"I'm the oldest," declared Moke.

"So I've heard you say," Perce replied. "But I don't see how anybody ever remembered."

"They looked out for that when they named us," said Moke.

"It was uncle Moses's idea," said Poke. "He told 'em, 'Call the oldest by my first name and the youngest by my last name——'"

"'And that will fix it in folks's minds,'" Moke completed the quotation.

"That was before they discovered the moles," said both together.

"I never thought of that," said Perce. "But whenever anybody asks me which is the oldest, I think of your initials, and run over in my mind—L, M, N, O, P;—M comes before P; then I say, 'Moke's the oldest.' But how could they tell you apart before they saw the moles?"

"They tied a red string around Moke's ankle," said Poke.

"But once the string came off, and Ma thinks it might have been changed," said Moke.

"And to this day she can't say positively but I am Moke, and Moke is me," said Poke.

Perce laughed. "Why didn't you have something besides a couple of teenty-taunty moles to distinguish you?" he asked. "Why didn't one [Pg 587] of you be light-complexioned and the other dark? There'd have been some sense in that."

"We couldn't!" said Poke.

"You didn't try," replied Perce.

"We couldn't if we had tried," said Moke. "Twins are always——"

"The same complexion," struck in Poke. "Just like one person."

"No, they're not; there's no rule about that," said Perce. "And when you talk of one person—have you heard of the man over in Kennebunk?"

"What about him?" asked the twins.

"Why, haven't you heard? One half his face," said Perce, "as if you should draw a line straight down his forehead and nose to the bottom of his chin," he drew his finger down his own face, by way of illustration; "one half—it's the right half, I believe—is as black as a negro's. Yes; I'm sure it's the right half."

"Pshaw!" said Moke.

"Oh, Jiminy!" said Poke.

"I don't believe it!" said both together.

"It's true, I tell you!" Perce insisted. "My father has seen him; and my father wouldn't lie."

"He must have had some disease," said Moke.

"He's what they call a leopard," said Poke.

"You mean a leper?" laughed Perce. "No; he isn't a leper, nor an albino. Why, boys! didn't you ever hear of such a case? It's quite common, and it's easily explained."

"I give it up! How do you explain it?" said the twins.

"Simply enough!" exclaimed Perce. "The other side of his face is black too." And he keeled over backward on the hay.

It was an old joke which he had indeed heard his father tell; but it was new to the twins, who were completely taken in by it.

"Throw him out of the cart!" shrieked Poke, half smothered with laughter, at the same time seizing hold of Perce as if to execute his own order.

"I'll jolt him out!" cried Moke, who was driving; and he began to urge the oxen into a heavy, clumsy trot, which shook up the cart and its contents in a way that was more lively than pleasant.

"Oh, don't do that!" cried Perce, with the jolts in his voice. "You'll break the e-g-g-s in my ba-ask-et!"

"I've had one supper, but I shall want another by the time we get to the beach," said Poke.

"So shall I!" cried Perce. "We'll make a big fire on the shore, and have a jolly time. And, I say, boys, let's call for Olly Burdeen, and make him come down on the beach with us to-night."

"That will be fun, if he isn't too proud to go with country people now," replied Moke.

"Since he's been waiting on city folks, he's as stuck up as if he'd tumbled into a cask of molasses," said Poke.

"Olly is all right," said Perce. "He doesn't put on any airs with me. We'll have him with us, anyhow!"

There was but one boarding-house at Beman's Beach in those days. Originally a farm-house, it stood in not the very best situation, a little distance back from the sea, in a hollow of the hills. It was kept by a farmer's widow, Mrs. Murcher, who, as her business expanded, had built on additions until her house looked as if it had the mumps in one enormously swollen cheek.