Title: Lancashire Humour

Author: Thomas Newbigging

Illustrator: James Ayton Symington

Release date: June 11, 2012 [eBook #39968]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by sp1nd, Mebyon, Matthew Wheaton and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

First Edition, December 1900

Second Edition, April 1901

All rights reserved

Two Deyghn Layrocks

LANCASHIRE HUMOUR

BY

THOMAS NEWBIGGING

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY

J. AYTON SYMINGTON

LONDON

J. M. DENT & CO.

1901

TO

MY DEAR WIFE

A GRADELY LANCASHIRE LASS

In the present volume I have included a number of Anecdotes and Sketches which I had previously introduced into my History of the Forest of Rossendale, and also a subsequent book of mine, entitled Lancashire Characters and Places. I felt that it was admissible to do this in a volume dealing specifically with the subject of Lancashire Humour, and I am in hopes that readers who already possess copies of the works named will not object to their being reproduced here. They were worth giving in this connection, and, indeed, their omission could scarcely be justified in a book of humorous Lancashire incidents and anecdotes.

There is surely a want of discernment shown by those who object to the use of dialect in literature as occasion offers. A truth, or a stroke of wit, or a touch of humour, can often be conveyed in dialect (rustice loqui) when it would fail of effect in polite English. All language is conventional. Use and wont settles much inx this world. Dialect has its use and wont, and because it differs from something else is surely no reason for passing it by on the other side.

I don't know whether many of my readers have read the poems of T. E. Brown. They are chiefly in the Manx dialect, not Manx as a language—a branch of the Keltic—but Manx dialect English. Here was a man steeped to the eyes in classical learning; a Greek and Latin scholar of the first quality, as his recently published Letters testify. But he was wise as well as learned, and his poetry, not less than his Letters, will give him a place among the immortals, just as the dialect poems of Edwin Waugh will give him a like place. Brown did not shrink from using the speech of the common people around him if haply he could reach their understandings and their hearts.

The proper study of Mankind is man. Not the superfine man, not the cultured man, only, but the man as we encounter him in our daily walk—Hodge in homespun as well as de Vere in velvet.

It will not be disputed that, apart from the use of dialect, there is a substratum of humour in the Lancashire character whichxi evinces itself spontaneously and freely on occasions. There can be no doubt, also, that this humour, whether conscious or unconscious, is usually accentuated or emphasised when the dialect is the conveying medium, because its quaintness is in keeping with the peculiarities of the race. Besides, there is a naturalness, a primitivity, and therefore a special attractiveness in all dialect forms of speech which does not invariably characterise the expression of the same ideas in literary English.

Now, humour is such a desirable ingredient in the potion of our human existence, that it would be nothing less than a dire misfortune to make a point of eschewing the setting which best harmonises with its fullest and fairest presentation, whether it emanates from the man in clogs or from the most cultured of our kind.

Our greatest writers have recognised the worth of dialect as a medium for humour, and hence many of the most memorable and amusing characters in Scott and Dickens—to take the two writers that occur to us most readily by way of illustration—portray themselves in the dialect of their native heath.

These remarks must be taken in a general sense, and not as having any special bearing on the present contribution. The two, else,xii would not be in proportion. My object has simply been to gather up the waifs and strays of humorous incident and anecdote, with a view to enlivening a passing hour.

Some of the stories that I give are related of incidents that are said to have occurred in, or of persons belonging to, both Lancashire and the West Riding. It is difficult to locate all of them so as to be quite certain of their parentage. I have tried, however, to limit myself to such as have a genuine Lancashire origin, without trenching on the domain of our neighbours in Yorkshire.

The present collection by no means exhausts the number of good stories that are to be found on Lancashire soil. It is highly probable that were half-a-dozen writers to devote some time to the subject, they would each be able to present a collection differing from all the rest in the characteristic anecdotes which they would select.

Readers outside of the County Palatine will not have any difficulty in perusing the stories. The dialect in each has been so modified as to admit of its being readily understood by every intelligent reader.

Manchester,

December 10th, 1900.

"Come, Robin, sit deawn, an' aw'll tell thee a tale."

Songs of the Wilsons.

If we would find the unadulterated Lancashire character, we must seek for it on and near to the eastern border of the county, where the latter joins up to the West Riding of Yorkshire.[1] Roughly, a line drawn from Manchester on the south, by way of Bolton and Blackburn and terminating at Clitheroe in the north, will cut a slice out of the county Palatine, 2equal on the eastward side of this line, to about one-third of its whole area; and it is in this portion that the purest breed of Lancashire men and women will be found. A more circumscribed area still, embracing Oldham, Bury, Rochdale, the Rossendale Valley, and the country beyond to Burnley and Colne, contains in large proportion the choicest examples of Lancashire people, and it is within the narrower limit that John Collier ("Tim Bobbin") first of all, then Oliver Ormerod, and, later, Waugh, Brierley, and other writers in the vernacular, have placed the scenes of their Lancashire Stories and Sketches, and found the best and most original of their characters.

[1] In their speech, their employments, their habits and general character, there is much in common between the natives of Lancashire and their neighbours of the West Riding.

The Authors I have specifically named are themselves good examples of that character, Waugh paramountly so—distinguished as they are by a kindly hard-headedness, a droll and often broad wit, which exhibits itself not only in the quality of their writings, but also in their modes of expression, and a blending in their nature of the humorous with the pathetic, lending pungency, naturalness and charm to their best work.

The peculiarities to which I have referred3 are due to what in times past was the retiredness of this belt of the county; its isolation, its comparative inaccessibility, its immunity from invasion. As the coast of any country is approached, the breed of the inhabitants will be found to become more and more mixed, losing to a large extent its distinctive characteristics; and it is only by an incursion into the interior that the unadulterated aborigines are to be found in their native purity. Even here, these conditions no longer exist with anything like the old force, excepting, it may be, in some obscure nook out of sound of the locomotive whistle. Of these there are still a few left, though not many.

The old barriers of time and distance have been obliterated. The means of, and incentives to, migration, have become so easy and great that our "Besom Bens" and "Ab-o' th'-Yates" are grown as scarce as spade guineas, or as the wild roses in our Lancashire hedges, and will ere long exist only in the pages of our native humorists.

The writer of the Introduction to the 1833 edition of John Collier's "Tummus and Meary" makes a wide claim for the antiquity and universality of the Lancashire dialect in England in the past. He says: "Having had occasion, in the course of4 interpreting the following pages, to refer to the ancient English compositions of such as Chaucer, Wycliffe, other poets, historians, etc., I have been led almost to conclude that the present Lancashire dialect was the universal language of the earliest days in England."

Without going quite so far as the writer just quoted, it may be admitted that his contention is not without warrant, as is proved by the very large number of words and phrases of the dialect that are to be found in the Works of Gower, Chaucer, Spenser, Ben Jonson, Shakespeare, and other of our older authors, as well as in the earlier translations of the Bible. The conclusion may certainly be drawn that in the Lancashire dialect as spoken to-day there are more archaic words, both Celtic and Gothic, than are to be found elsewhere in England.

The Rev. W. Gaskell, M.A., in his lectures on the dialect, says with truth that:—"There are many more forms of speech and peculiarities of pronunciation in Lancashire that would yet sound strange, and, to use a Lancashire expression, strangely 'potter' a southern; but these are often not, as some ignorantly suppose, mere vulgar corruptions of modern English,5 but genuine relics of the old mother tongue. They are bits of the old granite, which have perhaps been polished into smoother forms, but lost in the process a good deal of their original strength."[2]

[2] Two Lectures on the Lancashire Dialect, by the Rev. W. Gaskell, M.A., Chapman & Hall, 193 Piccadilly, London, 1854, p. 13.

There have been of recent years many observant gleaners in these fruitful Lancashire fields. Waugh, Brierley, Oliver Ormerod, Samuel Laycock, Miss Lahee, J. T. Staton, Trafford Clegg and other writers have done much to illustrate the character and habits of the people of the County Palatine in their Sketches, Stories and Songs. We owe ungrudging thanks to the writers in the vernacular for the treasures with which, during the last thirty or forty years, they have adorned our Lancashire literature; for the rich legacy they have left us; for having taught us so much of homely wisdom in the quaint tongue of our people, and opened up to us in wider measure than we previously knew, the bright commonsense and humour that are enshrined in their hearts.

They have illustrated for us the various phases, both in speech and thought, of a virile and otherwise important section of the people that go to make up the inhabitants of this Island of ours. They have exhibited the genuine homeliness and simplicity of the people of the county, as well as their native shrewdness a6nd strength of character; their kindliness of heart, their natural insight and aptitude; their characteristic humour—for the gracious gift of humour is theirs in a remarkable degree—their flashes of wit and repartee; their peccadilloes and graver faults, as well as their many admirable virtues; their strenuous working lives, and their abandonment to play as occasion serves—for it is a marked feature of Lancashire people that they work hard and play hard.

They have shown us, also, how rich in resource is the dialect of the county, compacting and crystallizing its phrases and proverbs, and have proved how capable it is of giving expression to the natural affections. It is only of comparatively recent years that we have been able to appreciate the wealth of the dialect in these respects. All the material was in existence before, but it needed the cunning hand of the master to make literature of it; to weave up the warp and woof, 7and present them to us in an embodied form.

A good deal of the humour of our Lancashire writers is of the rollicking kind, no doubt. It does not always belong to the school of high culture. But, on the other hand, we have got the characters true to the life, and he is a fastidious critic, or worse, who would prefer a counterfeit presentment to the genuine portrait.

The subject of Lancashire character, or, indeed, of any peculiarities of local and provincial character in general, with its manifestations either of pathos or humour, may not be one of very great profundity. That is not any part of the claim we make. It may even be considered trivial by some. Those, however, who take such a view, if there be any such, are surely lacking in breadth of vision. To do what we propose is to come nearer to the hearts of the people and their ways of thinking than is possible in the higher and broader flights of the more general historian. And, indeed, the work of the humble gleaner often assists the more ambitious and dignified chronicler in his labours to depict the greater personages and events in the history of his country. The ways of thinking of the people, and also the subject-matter of their thoughts, may be good, or they may be commonplace, or they may be mean, but8 to enter into their thoughts so as to get at their spirit, helps at least to an understanding of them.

Admitting for a moment the triviality of the subject, we cannot always be sitting like Jove on the heights of Olympus; and even when in loftier mood we do emulate the high emprizes of the gods, we are fain to descend at times—and there is true wisdom in so descending—to refresh ourselves with a touch of Mother Earth—to seek in the vale below that necessary relaxation from the strain and stress of high thinking.

When all is said that can be said, a collection of this kind is a contribution to an important branch of folk-lore and folkspeech, and in that respect, if in no other, should be widely acceptable.

It is not, of course, pretended that all the anecdotes here given are new. Some of them are "chestnuts" I am aware—though chestnuts are generally good or they would not deserve to be chestnuts—but they illustrate certain traits of character, and that is a sufficient reason for reproducing them. Neither are we prepared to vouch for the absolute truth of all the stories. Some of them, either in whole or in part, are probably due to an eff9ort of the imagination. In that sense they are true, and certainly they are each characteristic of individuals whom we all know, and who, from our experience of their eccentricities, might safely be set down as the actors in them.

Notwithstanding all that has been done by the writers already named, there is great abundance of good things still ungarnered, in the way of racy anecdotes, wise apothegms, and striking sayings, all too good to be lost—as indeed may be their fate unless pains are taken to record them in permanent form. Even the ludicrous conclusions and remarks of the half-witted—those of whom it is said in the vernacular that "they have a slate off and one slithering,"—are often sufficiently striking or amusing to be worth putting on record.

"The clouted shoe hath oft-times craft in't," as says the rustic proverb.

We have it on the authority of Shakespeare that a jest's prosperity lies in the ear of him that hears it. This is generally so, and especially in those instances where the jest, or the story, is clothed in dialect, and depends for a full appreciation on a knowledge by the listener of the peculiar characteristics of those from whom it10 emanates. For this reason it is doubtful whether, say, the people of the southern portion of our Island are able to enter into, so as to fully enjoy, our more northerly humour; just as we of the north may not be able to thoroughly enjoy theirs. Antipathy, also, to a particular form and mode of spelling and pronunciation intervenes to prevent full enjoyment on both sides. For this reason the writers in dialect are placed at a disadvantage as regards the extent of their audience. Most of their best things are caviere to the general, or, rather, to the particular.

In a letter to a Rossendale friend, John Collier has an interesting reference to the dialect and the extent to which it is used. In this letter the writer offers an apology for, or rather a defence of, his "Tummus and Meary" against certain strictures that had been passed upon it on account of its broad Lancashire speech.

He says: "I am obliged to you for a peep at your friend Mr Heape's ingenious letter. When you write, please to return him my compliments, and thanks for his kind remembrance of me; and hint to him that I do not think our country exposed at all by my view of the Lancashire Dialect: but think it commendable, rather than a11 defect, that Lancashire in general, and Rossendale in particular, retain so much of the speech of their ancestors. For why should the people of Saxony, and the Silesians be commended for speaking the Teutonic or old German, and the Welsh be so proud (and by many authors commended too) for retaining so much of their old British, and we in these parts laughed at for adhering to the speech of our ancestors? For my part I do not see any reason for it, but think it praiseworthy: and am always well pleased when I think at the Rossendale man's answer, who being asked where he wunned, said, 'I wun at th' riggin o' th' Woard, at th' riggin o' th' Woard, for th' Weter o' th' tone Yeeosing faws into th' Yeeost, on th' tother into th' West Seeo.'"

Curiously enough, the dialect in "Tim Bobbin's" day was considered as too plebeian in character to deserve notice. It was looked upon simply as the vulgar speech of the common people, and altogether unworthy of attention and study by better-instructed mortals. Even well into the present century, dialect in general was not held in estimation for any useful purpose, and it is only in comparatively recent years that its value as an aid to 12the study of racial history has been recognised.

It may be admitted that Collier, in his celebrated sketch, is sometimes so broadly coarse as to shock even a taste which is not fastidious; but allowances must be made for him in his efforts at the truthful portraiture of the characters as he knew or conceived them.

In the fifties, when I was a young fellow of twenty or thereabouts, I was personally acquainted with Oliver Ormerod, the author of "A Rachde Felley's Visit to th' Greyt Eggshibishun." He was a smart, dapper, hard-headed Lancashire business man, of medium height, inclining to be stout; clean and bright in appearance, and gentlemanly in his manners. At that time he had written and published his "Rachde Felley," but though we often conversed on the characteristics of the people of East and South Lancashire—a subject with which he was well familiar—he never mentioned to me the circumstance of his being the author of the amusing sketch, which was published anonymously. I rather think that it was but few even of his intimate friends in his native town of Rochdale who knew or suspected at first that he was the author of that clever and amusing brochure.

Possibly he feared that to have associate13d his name with the work would have injured him in his business. For, however erroneous the notion may be, it was at one time held that business and the occasional excursion into the by-paths of literature were incompatible. His case, I am glad to say, was an instance in point refuting the too common belief that the practice of one's pen in vagrant literary work—outside business pure and simple—is a drawback to success, for his record as a man of business was one of the best.

Of the sterling excellence of Oliver Ormerod's little work, "Th' Rachde Felley" there cannot be two opinions. It is original in its conception and in the way it is carried out; full of humour, and racy of the soil of Lancashire. The popularity of the book was immediate and great. It rapidly went through several editions, and it has since had many imitators. Its success led Mr Ormerod to write a second similar work, giving the "Rachde Felley's Okeawnt o wat he and his Mistris seede un yerd wi' gooin to th' Greyte Eggshibishun e London e 1862." This, like most other sequels, is not equal to the original, though if it had been the first to appear it would still have been noteworthy.

The following from "A Rachde Fel14ley" is a good example of his humour:

"Aw seed a plaze koed Hyde Park Cornur, whure th' Duke o' Wellington lives, him as lethurt Boneypart; 'e's gettin an owd felley neaw. Aw bin towd as one neet, when 'e wor at a party as th' Queen gan, as th' owd felley dropt asleep in his cheer, an when the Queen seed 'im, hoo went an tikelt his face whol 'e wakent. Eh! heaw aw shud o' stayrt iv hoo'd o dun it bi me. Th' owd chap drest knots off Boney, dident 'e? But aw'm off wi' feightin; aw'm o fur Kobden an' thame as wantin' fur to do away wi' it otogethur, fur ther wod'nt be hauve as mony kilt i' ther wur no feightin. O'er anent th' Duke's heawse, at th' top o' wot they koen Constitution Hill, aw seed a kast iron likeness ov 'im oppo horseback, as big as loife an bigger. He'd a cloak on an' a rowlur pin i' one hond, saime as wimmen usen wen they maen mowfins. Aw' nevur noed afore wat 'e wor koed th' Iron Duke for.

"At tis present toime it started o' raynin', an' so aw thrutch'd mi road as fast as aw cud goo in a greyt creawd o'15 foke, an' as aw wor gooin' on, a homnibus koome past, an' a chap as stoode at th' bak soide on't bekont on me fur to get in. Thinks aw to mesel 'e's a gud naturt chap; aw gues 'e sees as aw'm gettin mi sunday clewus deetud. 'E koed o' th' droiver fur to stop, an' ax'd me iv aw wur fur th' Greyt Eggshibishun, an' aw sed, ah, an' wi' that 'e towd me fur to get in, an' in aw geet. We soon koome to th' Krystil Palus. Eh! wat a rook o' foke ther wor theere, aw never seed nawt loike it afore, never! Aw geet eawt o' th' homnibus, an' aw sed to th' felley as leet me ride: Aw'm very mich obleeght to yo aw'm shure, an' aw con but thank yo, an' aw wur turnin' reawnd fur to goo into th' Palus, wen 'e turn'd on me as savidge as iv he'd a hetten me, an' ax'd me fur forepenze. Forepenze, aw sed, what for? An' 'e made onsur, for ridin', to be shure, Sur. Waw, aw sed, didn't theaw koe on me fur to get in? But o' as aw cud say wor o' no mak o' use watsumever, an' th' powsement sed as iv aw didn't pay theere an' then, he'd koe a poleese as16 wor at th' other side o' th' road, an', bi th' mon, wen aw yerd that, aw deawn wi' mi brass in a minnit. Aw seed as aw wor ta'en in; same toime, it wor a deyle bettur fur to sattle wi' th' powsedurt, nur get into th' New Bailey so fur fro whome. Thinks aw ti mesel', iv aw'm done ogen i' this rode aw'm a Dutchmun."

Ormerod, like that other genial humorist, Artemus Ward, affected a peculiar spelling, or rather mis-spelling, of his words, which, in my opinion, was a mistake. There was no necessity for this. It does not enhance the humour of his sketches in any special degree, but only renders him more difficult to read. Dialectical spelling need not necessarily be bad English.

As a writer of Lancashire stories, Waugh is unsurpassed. His pages overflow with a humour which is irresistible and almost cloys by its exuberance. But even about his drollest characters there is a pathetic tenderness which touches the heart. It is not easy, for example, to read some parts of "Besom Ben" and "The Old Fiddler" without a lump in one's throat, so much akin are laughter and tears in the hands of this master. If it were not that his themes are principally the work-a-day Lancashire17 folk, and that the dialect limits and muffles his fame, Waugh would be ranked (as he is ranked by those who know him) as one of the first humorists of the century.

Waugh is incomparable in his curious ideas and touches and turns of expression, ludicrous enough many of them, but all rich in Lancashire humour and well calculated to excite the risible faculty. Speaking of a toper in one of his sketches he says:

"Owd Jack's throttle wur as drufty as a lime brunner's clog."

Again: "Some folk are never content; if they'd o' th' world gan to 'em, they'd yammer for th' lower shop to put their rubbish in!"

Oatmeal he calls "porritch powder."

Again: "Rondle o' th' Nab had a cat that squinted—it catched two mice at one go."

Addressing his donkey, Besom Ben said: "Iv thae'd been reet done to, thae met ha' bin a carriage horse bi neaw!"

"Robin o' Sceawter's feyther went by th' name o' 'Coud an' Hungry'; he're a quarryman by trade; a long, hard, brown-looking felley, wi' 'een like gig-lamps, an' yure as strung as a horse's mane. He looked as if he'd bin made out o' owd18 dur-latches an' reawsty nails. Robin th' carrier is his owdest lad; an' he favours a chap at's bin brought up o' yirth-bobs an' scaplins."

These are of course the merest example of the many curious sayings and comparisons that are lavishly scattered through Waugh's pages.

Ben Brierley was an adept at telling a short Lancashire story. In giving expression to the drollest figures of speech he maintained a mock gravity which greatly enhanced the presentment, whilst the peculiar puckering of the corners of his mouth and the merry twinkle in his eye told how thoroughly he entered into the spirit of the characters he portrayed. His "Ab' o' th' Yate" in London bubbles over with humour, and it is a true, if somewhat grotesque, account of what would be likely to arrest the attention of a denizen of that out-of-the-way village of "Walmsley Fowt" on a visit to the great metropolis.

Some years ago I attended a meeting held at Blackley where Ben gave a number of racy Lancashire anecdotes, told in his own inimitable way. I may quote one or two of these which are not given in the collected 19edition of his writings.

"Long Jammie wur a brid stuffer, an' it used to be his boast ut he'd every fithert animal, or like it, ut ever flew on wing, or hung on a wall. He'd everything fro' a hummabee to a flying jackass, an' he'd ha' a pair o' thoose last if Billy o' Bobs would alleaw hissel' to be stuffed."

"Theau'rt one thing short," Billy said one day as he're looking reaund Jammie's Musaum, as he co'd his collection.

"What's that?" Jammie ax'd.

"It's a very skase brid," Billy said, "Co'd a sond brid."

"Ay, it mun be skase or else I should ha' had a speciment i' my musaum," Jammie said. "But what is it like?"

"It's like o' th' bit-bat gender," Billy said. "It's a yead like a cat, and feet like a duck, an' when it flies it uses its feet like paddles to guide itsel'."

"But why dun they co' it a sond brid?"

"Well, theau sees, it's a native o' th' Great Desert o' Sara, an' when it's windy, it flies tail first to keep th' sond eaut o' its een."

Billy Kay had had a lot of his hens stown, an' he never could find eawt who th' thief wur. He'd set a trap, but someheaw it didno20' act. Shus heaw, it never catch't nowt.

Bill had a parrot ut wur a bit gan to leavin' th' cage an' potterin' abeaut th' hencote when th' hens wur eaut. But as it had bin brought up to a soart o' alehouse life, it wanted company. It had learnt to crow so natural ut th' owd cock wur curious to know what breed it belonged to. So he invited Pol to spend a neet wi' him an' th' family, an' gie' th' cote a rooser. Th' parrot went, and they'd a merry time on't. It wur late when they went to roost, an' they'd hardly had a wink o' sleep when Pol yerd summat oppen th' cote dur. Then ther a hont lifted to the peearch, an' one after another o' th' hens wur snigged off, till it coome to th' owd cock. Pol thowt it wur gettin' warm, so hoo says to th' owd rooster, "Hutch up, owd lad, it's your turn next!" Ther no moore hens stown!

"Owd Neddy Fitton's Visit to the Earl o' Derby" is one of the finest sketches in the vernacular; giving, as it does, a realistic picture of the old-time Lancashire farmer. It is bright with humour, not wanting in pathetic touches, and with that warm human interest that lends charm and distinction to the homeliest story.

Miss Lahee, the writer, was Irish both by21 birth and up-bringing. Coming to Rochdale, where she lived for many years, the character of the Lancashire people and their idiom won her sympathy, and she studied both to such purpose as to produce not only the story in question, but a number of other sketches and stories in the dialect. It is no disparagement to these latter to say that none of them is equal to her sketch of "Neddy Fitton." This has long been popular in the county Palatine, and its intrinsic merit is such that it deserves a still wider circle of readers.

Lancashire has from time immemorial been famous for its mathematicians, botanists, and naturalists among the humbler ranks, and Crabtree as an Astronomer has his niche in the temple of fame. There was another worthy of rather a different stamp who professed acquaintance with that sublime science, Astronomy, though his credentials will hardly be considered sufficient to justify the claim. Jim Walton was a well-known character, at one time living at Levenshulme. Modest enough when sober, when he had imbibed a few glasses of beer Jim professed to b22e great in the mysteries of "ass-tronomy." The names of the planets, their positions and motions in the heavens were as familiar to him as the dominoes on the tap-room table, and he knew all the different groups of stars and their relative positions. One night Jim was drinking in the village "Pub" with a number of boon companions, topers like himself—and the conversation, as was usual when he was present, got on to the stars and other heavenly bodies, on which Jim expatiated at length. A mischievous doubt, however, was expressed by one of the company, whether, after all, Jim really knew as much about astronomy as he professed to do. So, to maintain his reputation by proving his knowledge, Jim made a bet of glasses round with his opponent that the moon would rise at a quarter past nine o'clock that night.

Accordingly, about ten minutes before the time named, the company all staggered out into the backyard to see the moon rise as predicted.

"Now then, chaps, look here!" cried Jim, "Let's have a fair understondin'. Recolect, it's on th' owd original moon 'at awm betting, noan o' yer d—— d new ones!"

Needless to say this was a poser for23 their bemuddled brains, and with sundry expletives at Jim and the qualification he had announced, they all staggered back to their places in the more comfortable tap-room.

Jim's idea of "th' owd original moon," and his thorough contempt for quarter and half moons, strikes us as irresistibly funny. We can imagine the new, vague light that would dawn on the minds of the half-fuddled roysterers as he announced his reservation in favour of the whole or none.

However prejudiced, as a rule, the British workman may be against the introduction of labour-saving appliances in the way of automatic machinery, circumstances sometimes arise when he can fully appreciate their value and advantages. This will appear by the following characteristic anecdote:—

An Oldham chap, who, for some misdemeanour, had found his way into Preston House of Correction, was put on to the tread-mill. After working at it for some time till his back and legs ached with the unwonted exercise, he at length exclaimed:

"Biguy! if this devil had been i' Owdham, they'24d a had it turned bi pawer afore now!"

Another good story of an "Owdham" man is the following: At one of the Old Trafford County Cricket matches we overheard a conversation that took place between two Owdhamers. A pickpocket, plying his avocation, had been caught in the act of taking a purse, and quite a commotion was created in that corner of the field as the thief was collared by a detective and hauled away to the police station. Says the Oldham man to his friend who was seated next him:

"Sharp as thoose chaps are, they'd have a job to ta' my brass. Aw'll tell thi what aw do, Jack, when aw comes to a place o' this sooart; aw sticks mi brass reet down at th' bottom o' mi treawsers pocket, and then aw puts abeaut hauf a pint o' nuts at top on't; it tae's some scrawpin out, aw can tell thi, when tha does that!"

Pigeon fancying and flying is an absorbing pursuit with many of the Wigan colliers. Men otherwise ignorant (save of their daily work in the mine), are profoundly versed in the different breeds and capabilities of the birds. The training of them to fly long distances on their return to their lofts and within a comparatively brief space of time,25 is a passion which absorbs all their thoughts.

One such enthusiastic pigeon flyer was lying sick unto death, with no prospect of recovery. The parson paid him a visit and endeavoured to turn his thoughts to his approaching end. The casual mention by the parson of heaven and the angels interested the dying man. He had seen angels depicted in the picture books with wings on their shoulders. An idea struck him and he enquired:

"Will aw ha' wings, parson, when aw get to heaven?"

"Yes, indeed," replied the parson, willing to humour and console him as best he might.

"An' will yo ha' wings too when yo get theer?"

"Oh yes, I'll have wings too, we'll both have wings."

"Well, aw tell thi what," said the dying pigeon fancier, his eye brightening as he spoke, "Aw tell thi what, parson, when tha comes up yon, aw'll flee yo for a sovereign!" A striking example of the ruling passion strong in death!

It is well known that an admiration for dogs of a high quality, not less than for pigeons, is a weakness of the Lancashire collier, who will spend a small fortun26e to gratify his taste in this direction. A Tyldesley collier had a favourite bull-pup. This canine fancier with his dog and a friend were out for a ramble in the fields, and to make a short cut to get into the lane, his friend began scrambling through a hole in the hedge. The dog, unable, it may be presumed, to resist the sudden temptation, seized the calf of the disappearing leg with a grip which caused the owner of the said leg to shriek with pain. Despite his frantic wriggles and yells the brute held fast, and its master, appreciating the situation, clapped his hands in enthusiastic admiration, at the same time calling out to his beleaguered companion:

"Thole it, Bill! Thole it, mon! Thole it! It'll be th' makin' o' th' pup!"

Another such on returning home and finding that the day's milk had disappeared from the milk basin, angrily enquired what had become of it, and receiving for answe27r from his better-half that she had "gan it to th' childer for supper!" exclaimed: "Childer, be hang'd! thae should ha' gan it to th' bull pup!"

Some years ago there appeared in Punch sundry sketches of incidents in the mining districts. These may not all be true in the sense that the occurrences represented actually took place. But there is a spirit of truth in them, in that they illustrate a phase of the rudeness that often accompanies untutored tastes and undesirable habits.

The appearance of a stranger in the mining village, especially if he happens to wear a black cloth coat, is sometimes resented by the denizens of the place.

The new curate, a meek-looking individual, had arrived, and passing the corner of a street where a group of colliers had assembled, one of them asked:

"Bill, who's yon mon staring about him like a lost cat?"

"Nay, I doan't know," replied the other, "a stranger belike."

"Stranger, is he?" responded the first, "then hey've a hauve brick at 'im!"

The same, accosting one of his flock r28esting on a gate, and wishing to make himself agreeable, tried to open a conversation with the remark:

"A fine morning, my friend," was pulled up with the reply:

"Did aw say it war'nt?—dun yo' want to hargue?"

It is surprising how a person of regular habits feels the lack of any little comforts and companionships to which he has been accustomed. A Lancashire collier had lost a favourite dog by death, that, on Saturday afternoons or Sundays, he had been in the habit of taking with him for a stroll. An acquaintance sitting on a gate saw the bereaved collier coming along the road trundling a wheelbarrow.

"What's up wi' thee, Bob—what ar' t' doin' wi' th' wheelbarrow, and on good Sunday too?"

"Well, thae sees," replied Bob, "aw've lost mi dog, an' a fellow feels gradely lonesome bout company, so aw've brought mi wheelbarrow out for a bit of a ramble."

These stories go to prove that the Lancashire collier is a simple unsophisticated being, and the following[3] is still further evidence of the fact:

[3] Quoted from an article on "Quacks" by Mr R. J. Hampson 29in the East Lancashire Review for November 1899.

"Many interesting anecdotes could be given of the methods adopted by travelling Quacks. I will relate one respecting the oldest and best known now on the road, who lately visited a colliery village near Manchester. He had a very gorgeous show, a large gilded chariot with four cream-coloured smart horses, and four Highland pipers. He 'made a pitch' on some land on the main Manchester road side. There was a severe struggle on at the time between the miners and the colliery owners. This Quack was asked if he would allow the miner's agent, then Mr Thomas Halliday, to address the men from his chariot, and he consented on condition that he (the Dr) should speak before the men dispersed. This was readily agreed to. He was a man of fine physique, handsome and smartly dressed. He began:

"'Aye, I have longed for this day when I should have the honour and privilege of speaking to a large assemblage of Lancashire colliers. I left my comfortable mansion and park to come and encourage you in this fight of right against might. Yes, men, what could we do without colliers? Who was it that found out the puffing-billy? Was it a king? Was it a lord? Was it a32 squire? No, my dear men, it was a collier—George Stephenson!' (loud cheers, during which the learned doctor opened a large case and brought out a small round box). He continued: 'Men, they cannot do without colliers. The colliers move the world' (and holding up the box of pills, shouted) 'and these pills will move the colliers! They are sixpence a box. My Pipers will hand a few out!' Something moved the colliers, for he sold 278 boxes of pills, and he moved away before morning."

The Rev. Robert Lamb in his "Free Thoughts by a Manchester Man"[4] relates several good clerical stories. He remarks, that, in ordinary discourse with the poor, it is safest to avoid all flights of metaphor. We heard of a young clergyman not long ago being suddenly pulled down in his soarings of fancy.

[4] In two volumes published anonymously in 1866, but they were known to have been written by Mr Lamb, sometime Rector of St Paul's, Manchester. They consist of a number of Essays and Sketches which had been contributed by him to Fraser's Magazine and they deal chiefly with Lancashire subjects.

"I fear, my friend," he said to a poor weaver, to whose bedside he had been summoned, "I fear I must address you in the language that was addressed to King Hezekiah, 'Set thine house in order for thou shalt die and not live.'"

"Well," was the man's reply, as he rose languidly on his elbow, and pointed with his finger, "I think it's o' reet, but for a brick as is out behint that cupboard."

Sometimes from this species of misconception a ludicrous idea is suggested to the clergyman's mind, when he least wishes one to intrude.

"Resign yourself under your affliction, Ma'am," one of our friends not long ago said to a sick parishioner, "be patient and trustful; you are in the hands of the good Physician, you know."

"Aye, sir," she replied innocently, "Dr Jackson is said to be a skilfu' man."

We are assured that the following incident occurred to a Manchester clergyman in one of his visits to an old woman in her sickness. He had been to Oldham and afterwards called on his patient. She was a person on whom he could make no impression whatever, but remained uninterested and impassive under all his efforts to rouse and instruct her. A thought suddenly came into his mind that he would try a new method with her; so, after stating that he had been at Oldham and thus detained a short time, he began by giving her the m34ost glowing description of the new Jerusalem as portrayed by St John in the Apocalypse; when at length she seemed to be aroused, and looking earnestly at him, she said with a degree of emotion never before exhibited by her,—

"Eh, for sure, an' dud yo see o' that at Owdham? Laacks, but it mon ha' been grand! Aw wish aw'd bin wi' yo'!"

The late esteemed Bishop of Manchester, Dr Fraser, whose genial and kindly disposition was well known and appreciated, was one day walking along one of the poorer streets in Ancoats, and seeing two little gutter boys sitting on the edge of the pavement busy putting the finishing touches to a mud house they had made, stopped, and speaking kindly to the urchins asked them what they were doing.

"We've been makin' a church," replied one of them.

"A church!" responded the Bishop, much interested, as he stooped over the youthful architect's work. "Ah, yes, I see. That, I suppose, is the entrance door" (pointing with his stick). "This is the nave, these are the aisles, there the pews, and you have even got the pulpit! Very good, my boy35s, very good. But where is the parson?"

"We ha'not gettin' muck enough to mak' a parson!" was the reply.

The answer was one which the good Bishop would much enjoy, for he had a happy sense of humour. Patting the heads of the urchins he bade them be good boys and gave them each a coin. As he strode along the street the unconscious humour of the artists in mud must have greatly tickled him.

Yet another clerical anecdote:

In her charming little volume of "Lancashire Memories,"[5] Mrs Potter gives a racy story of the new vicar of a Lancashire Parish in an encounter with one of the natives. She remarks: "There is a quaint simplicity about the country people in Lancashire, that wants a name in our vocabulary of manners, as far removed from the vulgarity of the lower orders in the town on the one hand, as from the polished conversationalisms of the higher classes on the other; a simplicity that asserts itself because of its simplicity, and that never heard, and if it did, never understood 'who's who.' Imagine the surprise of 36the new vicar of the parish, fresh from Emmanuel College, Cambridge, in all the dignity of the shovel hat and garments of a rigidly clerical orthodoxy, accustomed to an agricultural population that smoothed down its forelocks in deference to the vicar, but never dreamed of bandying words with him: imagine him losing his way in one of his distant parochial excursions, and inquiring, in a dainty south-country accent, from a lubberly boy weeding turnips in a field, 'Pray, my boy, can you tell me the way to Bolton?'

[5] "Lancashire Memories," by Louise Potter. Macmillan & Co., London, 1879.

"'Ay,' replied the boy. 'Yo' mun go across yon bleach croft and into th' loan, and yo'll get to Doffcocker, and then yo're i' th' high road, and yo' can go straight on.'

"'Thank you,' said the vicar, 'perhaps I can find it. And now, my boy, will you tell me what you do for a livelihood?'

"'I clear up th' shippon, pills potatoes, or does oddin; and if I may be so bou'd, win yo' tell me what yo' do?'

"'Oh, I am a minister of the Gospel; I preach the Word of God.'

"'But what dun yo' do?' persisted the boy.

"'I teach you the way of salvation; I show you the road to heaven.'

"'Nay, nay,' said the lad; 'dunnot yo' pretend to teach me th' road to heaven, and doesn't know th' road to Bow'ton.'"

Certain shrewd remarks are sometimes made which imply a good deal more than they express. The following will illustrate what I mean. As justifying the regrettable fact that men who have risen from the ranks, and, having attained to opulence, are often found to change their politics, we have heard a "Radical" defined as "a Tory beawt brass." This is akin to John Stuart Mill's specious saying, that some men were Radicals because they were not Lords.

Alluding to the recent death of a person of wealth whose character was not of the best, a Lancashire man remarked:

"Well, if he took his brass wi' him, it's melted by this time!"

Waugh used to tell the story of a man having run to catch a train, and was just in time to see it leaving the railway station, puff, puff, puff. He stood looking at it for a second or two, and then gave vent to his injured feelings by exclaiming: "Go on, tha greyt puffin' foo, go on! aw con wait!"

The girl at the Christmas Soirée was38 pressed to take some preserves to her tea and bread and butter: "No, thank yo'," she responded, "aw works wheer they maks it."[6]

[6] "The image-maker does not worship Buddha; he knows too much about the idol."—Chinese saying.

Old stingy Eccles was talking one day to his coachman, who he was trying to impress with his own super-excellent quality, though he had never used his old Jehu over-well in the matter of wages.

"John," he said, "there's two sorts of Eccleses; there's Eccleses that are angels, and Eccleses that are devils."

"Ay, maister," responded John, "an' th' angels ha' been deod for mony a yer!"

A temperance meeting was being held in a Lancashire village, and one of the speakers, waxing eloquent, not to say pathetic, exclaimed:

"How pleased my poor dead father must be, looking down on me, his son, advocating teetotalism from this platform!"

One of the audience, interrupting him, rose and interjected:

"Nay, nay, that'll do noan, mon; if aw know'd thi feythur reet when he're alive, he's moar like lookin' up than deawn!"

I was amused with the answer given by a working man to an acquaintance. He was hurrying to the railway station with a small hand-bag on "Wakes Monday morning."

"Wheer ar't beawn, Jack?"

"Aw'm fur th' Isle o' Man."

"Heaw long ar't stayin'?"

"Thirty bob," was the laconic reply, meaning that the length of his stay would depend on the time his money might last.

Lancashire Proverbs are numerous and much to the point, and they generally inculcate their lesson with a touch of dry humour.

An expressive saying is that: "He hangs th' fiddle at th' dur sneck" applied to a person who is all life and gaiety when with his boon companions, but sullen and sour of temper at home.

Another proverb has it that "There's most thrutching where there's least room." Hence, probably, the Lancashire fable: "The flea and the elephant were passing into the Ark together, said the flea to his big brother: 'Now then, maister! no thrutching!'"

There is quaint wisdom in the saying, "It costs a deal more playing than working."

"Th' quiet sow eats o' t' draff," is another Lancashire proverb of deep significance as applied to any one who speaks40 little, but appears to take in all that he hears, and uses it to his own advantage.

When one gets married "he larns wot meyl is a pound."

The safe rule as to food for children, is, "rough and enough."

In choosing a wife the swain is warned that "Fine faces fill no butteries, an' fou uns rob no cubbarts."

The Lancashire farmer says that, "A daisy year is a lazy year," because when daisies are plentiful in the fields the crop of grass is usually light.

Other proverbs tell us that "An honest mon an' a west wind alus go to bed at neet," and "Fleet at meyt fleet at wark." "The first cock of hay drives the cuckoo away."

Attempting to cross a busy thoroughfare in front of a moving omnibus with an impetuous friend, the cautious Lancashire man will say: "Nay, howd on! There's as mitch room behint as before." And in response to one who is exaggerating in his language:—"Come! tha's said enough, thou'rt over doing it, owd lad; there's a difference between scrattin' yor head and pullin th' hair off!"

When disputation waxes high and hot, the same humorist will say: "Come, come lads! no wranglin', let's go in for a bit o' peace and 41quietness, as Billy Butterworth said when he put his mother-in-law behint th' fire."

Of any one whose nasal organ is unusually prominent, in other words, when it is large enough to afford a handle for ridicule, it is said that "he was n't behint th' door when noses were gan out!"

The etiquette of mourning for lost relations has its ludicrous side. Many of the working-classes in Lancashire, especially in out-of-the-way villages, take pride in the style of their funerals. On such occasions it is usual to have a "spread" in the shape of a "thick tay" on returning to the house after the "burying," when the relations and friends assemble and talk over the virtues of the dear departed. To omit such a provision is looked upon as a neglect of duty not to be passed over without comment. A ham, boiled whole, and served cold along with the tea, is the favourite "thickening" on those occasions.

One matron was much scandalized that her next door neighbour had made no further provision for the funeral guests than a "sawp o' lemonade" and a few sweet cakes.

"Aw 've laid mi husband an' three childer i' th' churchyard," remarked this42 censor of her neighbour's conduct, "an', thank the Lord, aw buried 'em o' wi' 'am!"

My next story must not be taken as fairly exemplifying the Lancashire female character, which, indeed is usually of a very different complexion. It is, however, related as a fact that a poor old fellow as he lay dying, and who, in an interval of reviving consciousness, detected the smell of certain savoury viands that were being prepared, managed in his weakness to say to his better-half who was busy near the fireplace:

"Aw think aw could like a taste o' that yo've gettin i' th' pot, Betty."

"Eh! give o'er talkin' that way, Jone," was the response, "thae cannot ha' noan o' this; it's th' 'am, mon, as aw'm gettin ready for th' buryin!"

There is sarcastic humour in the remark made by one to his friend who had just buried his uncle, the latter when alive having been something of a rip:

"I've known worse men, John, than your uncle."

"Oh, I'm glad to hear you speak so well of my uncle," was the response of the other, with just a touch of surprise in his look.

"Ay," continued the firs43t speaker, "I've known worse men than your uncle, John, but not so d—— d many!"

The Lancashire artizan, like others in higher station who should, but do not always, set him a better example, is prone to the occasional use of an oath, generally a petty oath, to emphasize his speech. It is an objectionable habit, doubtless, even when no irreverence is intended. Curiously enough, instead of being employed to express aversion to the object to which it is applied, the expletive is often used as a term of endearment. For example, we sometimes hear the expression: "He's a clever little devil!" applied by a father in admiration of the budding intelligence of his own little boy. An anecdote will best exhibit this peculiar turn of speech.

Some time ago, I had occasion to stay at Stalybridge over night, and after dinner I left my hotel and took a turn along one of the streets leading towards the outskirts of the town. It was a fine evening and the lamps were lighted. At a short distance before me I observed three working men, as I judged by their speech and gait, dressed in their best black toggery, and with each a tall silk hat on his head. Evidently they were returning from a funeral. They were stepping leisurely44 along, and, as I neared them from behind, I overheard part of their conversation. One of them, as he approached a lamp post, took his hat off, and began expatiating to the others on its quality.

"Ay," he said, holding the hat at arm's length that it might catch the rays from the gas lamp overhead, "Ay, aw guv ten bob for this when it wur new!" (looking at his two friends to note if they expressed surprise and admiration), "that's mooar than ten years sin'. Ay" (stroking it with his arm and again admiringly holding it out t45ill it twinkled in the lamp rays), "Ay, an' th' devul shines like a raven yet!"

Another incident in illustration of the same peculiarity is said to have occurred in the experience of a well-known actor, who, with his company, while starring it in the provinces, was playing for a few nights at Wigan. During the daytime Mr —— took a turn into the country, and, feeling tired with his walk, called to rest and refresh at a way-side "Public." As he entered the hostelry he observed in the sanded drinking room to the left of the passage, two colliers sitting each with a pot of ale before him on the table. So, instead of taking the room to the right, which was the more luxurious parlour fitted for guests of his quality, he turned into that where the colliers sat conversing, hoping, as he was a student of human nature, to add something to his store of observation in that respect. He was not disappointed.

One of the men was evidently overcome with grief at some mischance that had befallen him. It turned out that he had just lost by death a favourite son of tender years to whom he had been fondly attached. The sorrowing parent leaned with his elbows on the table; and occasionally stroking his fo46rehead with his hands, or resting his chin upon them, he would look vacantly into space and sigh deeply. His friend was endeavouring to comfort him.

"It's hard to bear, aw know, Jack; but cheer up, mon, an' ma' th' best ov a bad job."

"Ah! he wur a fine little lad wur our Jamie! It breaks mi heart to part wi' him."

"That's true enough, Jack," responded his companion. "But, what mon! he's goown and tha connot mend it! Cheer up and do th' best tha con."

"Ay, ay, aw connot mend it. That's th' misfortun on't. But he wur a rare bit of a lad wur our Jim!"

"Well, come, bear't as weel as tha con," patting his friend on the shoulder. "We's o' ha' to dee some time, keep thi heart up an' ma' th' best on't. Tha knows tha connot bring 'im back."

The other buried his face in his hands and remained silent for a time. Then, suddenly stretching himself up, he struck his hard fist on the table as he exclaimed:

"Aw tell thi what, Sam. If it wurn't for th' law, aw'd ha' th' little devul stuffed!"

The Rifle Volunteer movement, with its47 excellent motto, "Defence, not Defiance," has stood the test of time, having proved itself to be not only an ornamental but a useful and even necessary arm of defence, where, in this free country, a levy by conscription would not be tolerated. In its earlier stages, however, it encountered much opposition from many persons, who treated it with ridicule, and took every opportunity of speaking contemptuously of the "Saturday afternoon soldiers." This is well illustrated in a good story told by the late Mr John Bright. Speaking to an old fellow-townsman in Rochdale about the movement at the time of its inception, when corps were being formed throughout the country and enrolment was proceeding briskly:

"Yea," said the old Lancashire man to Mr Bright, "I always knew there wur a lot o' foo's i' this world, but I never knew how to pyke 'em out before!"

Mr Bright himself had a fund of Lancashire humour which came out at times in his speeches. He was also quick at repartee, not always without a touch of acrimony. On one occasion when he was dining with a well-known Manchester citizen the conversation turned on the subject of the growth and development of the United States.

"I should like," said his host, who is an48 enthusiastic admirer of the great Republic, "I should like to come back fifty years after my death to see what a fine country America has become.'"

"I believe you will be glad of any excuse to come back," was Mr Bright's wicked remark.

One of Disraeli's admirers, in speaking of him to Mr Bright, said:

"You ought to give him credit for what he has accomplished, as he is a self-made man."

"I know he is," retorted Mr Bright, "and he adores his maker."

In a recent number of the Spectator, a writer remarks that "after reading the drawn-out platitudes of some politicians, how refreshing it is to find that 'a voice' in the gallery so often puts the whole case in a nutshell, and performs for the audience and the country what the orator was unable to do."[7] The remark is much to the point. Political meetings are often the occasion of a good deal of spontaneous wit or humour on the part of the audience. A Lancashire audience excels in repartee at such gatherings, and when the speaker of the moment is himself good at the game, the encounter is 49provocative of mirth.

[7] "The Use and Abuse of Epigram," Spectator, Nov. 4th, 1899.

Sir William Bailey gives what he asserts is an unfailing recipe for silencing a hesitating and tiresome speaker. This is for a person in the audience to shout at the moment of one of the orator's pauses: "Thou'rt short o' bobbins!" The roar of laughter which follows this sally effectually covers the orator with ridicule, and any attempt on his part to take up the thread of his discourse is useless. The reference to "bobbins" is well understood by a Lancashire audience. The spinning frames in the cotton factories are fed from bobbins filled with roved cotton, and when these fail from any cause the machinery has to stand.

On the other hand, the worthy knight himself silenced a noisy and persistent meeting-disturber in a very effective way. Sir William, in the course of delivering a political speech was greatly annoyed by a person in front of the platform uttering noisy ejaculations with the object of interrupting the argument. As it happened, the fellow had an enormous mouth, as well as an unruly tongue and great strength of lungs. Sir William, suddenly stopping and pointing with his finger at the dist50urber, exclaimed: "If that man with the big mouth doesn't keep it shut, I'll jump down his throat—aw con do!" at the same time setting himself as if to take a spring. This had the desired effect and he continued his speech without further interruption. The real fun was in the final three words: "Aw con do!" The threat of jumping down the fellow's throat was not a mere idle threat; his mouth was big enough to allow of the threat being carried out.

At election times some of the drollest questions are put to the candidates in the "heckling" that takes place after the speech, where the audience is allowed to interrogate the aspirant for parliamentary honours. The following occurred in my own experience. A Socialist candidate was stumping a wide outlying division in North-East Lancashire, and in the course of a stirring address in the village school-room he expatiated on the heavy cost with which, as he asserted, the country was saddled in the up-keeping of royalty. Amongst other items of expenditure he enumerated the number of horses that had to be maintained for the royal use, and made a calculation of the huge quantity of oats, beans, hay an51d other fodder which the animals consumed every week throughout the year, with the heavy cost which these entailed, and he concluded by pathetically pointing out how many working men's families might be maintained in comfort with the money.

Questions being invited, an old farmer, who had been intently listening to the harangue, rose and said:

"Maister Chairman, aw have been very much interested wi' the speech o' th' candidate, and mooar especially wi' that part on't where he towd us abeaut th' royal horses, an' th' greyt quantity ov oats, beans and hay ut they aiten every week, an' th' heavy taxes we han to pay for th' uphowd o' thoose. But there's one thing, maister Chairman, ut he has missed out o' his speech, an' aw wish to put a question: Aw wud like if th' candidate wod now tell us heaw much they gettin every week for th' horse mook!"

Whether the question was put ironically or in sober earnest it is difficult to say, for the questioner maintained the gravity of a judge even in the midst of the roar of laughter that ensued. Probably he was quite in earnest, and considered that the "tale" was not complete u52ntil credit had been given on the other side of the account for the residual product.

During the Home-Secretaryship of the Right Hon. Sir Richard (now Lord) Cross, the mode of executing criminals was widely discussed in the newspapers, and created some considerable difference of opinion. At one of his election meetings in South-West Lancashire, a person in the audience asked leave to say a word, and convulsed the meeting by putting this question: "Aw want to know," he said, "an' aw could like to have a straight answer: is the honourable candidate in favour of a six-foot drop?"

A Member, representing one of the Lancashire divisions, who had for some reason or other made himself unpopular with his constituents, was seeking a renewal of their confidence at the general election. He was giving an account of his stewardship at a crowded meeting, pointing out how he had devoted his time to the interests of the division; how he had attended to his Parliamentary duties during the long session, sitting up night after night recording his votes, when he was interrupted in his harangue by "A voice from the gallery":

"We'll ma' thae sit up, devil, before we ha' done wi' thae!"

Another M.P., dilating on the services he had rendered to "the Borough which he had the honour to represent," asked, with a flourish of his arms towards the assembled electors and non-electors, "Now, what do you think your Member has recently been doing in London?"

"Aye! there's no telling!" was the response of an honest dame, suspiciously shaking her head as she sat near to the platform listening to the orator.

Barristers, as becomes their calling, are usually sharp-witted and often sharp-tongued. At the recent general election the candidates in the Eccles (Lancashire) division were Mr O. Leigh Clare, Q.C., Conservative, and Mr J. Pease Fry, Liberal. Mr Clare had finished addressing one of his meetings when an elector rose and put the following conundrum: "Mr Fry at his meeting last night stated that Mr Chamberlain was the cause of the Boer War, and Dr Quayle, one of his supporters, declared that the war might have been averted by a little careful diplomacy; will the Conservative candidate give us his opinion on the statements of these two gentlemen?"

"Yes," was Mr Leigh Clare's reply, "I54 shall be only too happy. In my opinion Dr Quayle should be left to Fry, and Mr Fry should be left to Quayle!" Judging by the manner in which the sally was received by the meeting, the answer was eminently satisfactory.

The Lancashire dialect occasionally finds its way into the British Houses of Parliament to point a moral or adorn a tale. Recently Mr Duckworth, M.P. for Middleton, told with effect the anecdote about Sam Brooks, and his advice to his brother John, on the latter being asked to stand as a City Councillor.[8]

[8] Post, page 94.

Lord Derby ("the Rupert of debate"), many years before, related the following story in the House, greatly to the amusement of their lordships. In the neighbourhood of Rochdale a big, hulking collier had an extremely diminutive wife, who, it was currently reported, was in the habit of thrashing her husband.

"John," said his master to him one day, "they really say that your wife beats you. Is it true?"

"Ay, aw believe it is," drawled John, with provoking coolness.

"Ay! you believe it is!" responded the master; "what do you mean, you lout? A great thumping fellow like you, as strong 55as an elephant, to let a little woman like your wife thrash you?"

"Whaw," was the patient answer, "it ple-ases hur, maister, an' it does me no hurt!"

Lancashire humour, though hilarious, is largely unconscious. The unconsciousness resting with the originator and the hilarity with the auditory. In this respect it is allied to Irish more than to Scotch humour, the former having a rollicking and blundering quality, the latter being more subdued, pawky, and intentional. The following were not intended as humorous sallies, and, indeed, they are only humorous from the point of view of the intelligent observer or listener; that is to say, the jest's prosperity lay in the ear of him who heard it, not in the tongue of him that made it.

During the recent great strike of the Lancashire colliers, coal was scarce and dear, and those who had anything of a stock in their backyards had to keep an eye on it to prevent its being depleted by hands other than their own. One, more fortunate than his neighbours, had reason to suspect that somebody was helping him56self to what wasn't his own—for the reserve of the precious fuel was evidently being tampered with. Accordingly, one night he determined to sit up in the back-kitchen and find out, if possible, whether his suspicions were justified. Shortly he heard a rustling in the coalbunk in the yard, and putting his head half out of the window, which he had left partly open, called out to the depredator:

"You're pykin' 'em out, aw see!"

"Nay, thou'rt a liar, owd mon," was the ready response, "Aw'm ta'en 'em as they come."

The thievish neighbour resented the imputation that he was "picking and choosing" instead of "playing fairation" by taking the small and the cobs together. Clearly he was not lost to all sense of honour. It would hardly have been fair to be picking and choosing under the circumstances. Beggars, much less thieves, have no right to be choosers.

"Owd Sam," a well-known Bury character, was tired of being domiciled in the Workhouse and thought he would try and get a living outside if he could. Passing by the "Derby" he saw Mr Handley, the landlord, standing on the front steps. Seeing Owd Sam coming hobbling up the street:

"Hello!" said Handley, "You're out o'57 th' Workhouse again, Sam, I see!"

"Ay, maister Handley, aw am for sure, aw'm tiert o' yon shop, an' aw've been round to co' on some o' mi friends, and they've promised to buy me a donkey; but aw'm short of a cart; and, maister Handley, if yo' lend me as much as wod buy me a cart, aw'd pay yo back again as soon as ever aw could; aw want to begin sellin' sond and rubbin' stones, an' things o' that mak, just to mak' a bit ov a livin', fur aw'm gradely tiert o' yon shop."

"Well, well, Sam, but what security can you give me if I lend you the money?"

"Aw just thowt yo'd ax mi that," responded Sam, "an aw've been thinkin' abeawt it, an' aw'll tell yo what aw'll do, maister Handley, if yo'll lend mi th' bit o' brass, thae shall ha' thi name painted up o' th' cart."

To fully realise the ludicrous nature of Owd Sam's proposal, it should be noted58 that Mr Handley was a smart, dapper, well-dressed personage, a man of substance withal, who knew his importance as the landlord of the "Derby," the chief hotel in the town.

A tramp between Bolton and Bury accosted an old stonebreaker by the road side, and asked him how far it was to the latter place.

"There's a milestone down theer, thae con look for thi' sel'," was the reply.

"But aw connot read," pleaded the interrogator.

"Well, then, that milestone 'll just suit thee, owd lad. It has nought on it. Th' reading 's gettin' o' wesht off. Go look for thi' sel'. If thae connot read, that milestone 'll just suit thee."

A would-be "feighter again th' Boers" enlisted in one of the Lancashire regiments, but, before final acceptance, was sent up to undergo medical examination for fitness. Being rejected by the doctor on account of the bad state of his teeth, he expressed his disgust and astonishment by remarking: "Aw thowt as aw'd ha' to shoot th' Boers! aw didn't know as aw'd ha' to worry 'em!"

Socialistic ideas have not taken very deep root among the masses in Lancashire. Such ideas, indeed, were more prevalently discussed ten years ago than they are to-day. Admirable as the propagandism is in many respects, and desirable in every sense as is the amelioration of the lot of working people, there is a tendency to drifting away from the saner precepts of its earnest advocates towards the levelling notions that engage the minds of the more ignorant and unthinking of its disciples. One of these had read, or been told, that if all the wealth of England were divided equally amongst the people, the interest on each person's share would yield an income of thirty shillings a week for life. Our Lancashire Socialist friend, expatiating upon the theme to some of his working-men comrades, began to speculate how he would occupy his spare time when in the enviable position of having thirty shillings per week without working. One thing he would do; he would save something out of his allowance and make a trip by train to London at least once a year to feast his eyes on the sights of the Metropolis. One of the listeners, however, demurred to the views expressed, suggesting that the train would have to be drawn by an engine, that this would require a60 driver and a stoker; a guard also would be necessary to manage the train, with others to attend to his comfort on arrival at his destination. These would be as little inclined to work, possibly, as himself. This view of the matter had not struck our leveller, but it was now brought home to him. So, after ruminating for a moment, and scratching his head to assist at the solution of the difficulty, he responded: "Well, it seems that some devils would ha' to work, but aw wouldn't!" That chap had evidently made up his mind.

The genuine Lancashire native is noted for his aptness in conveying the idea he wishes to express. Referring to a mild and open winter one of them remarked, speaking to a friend, "I'm a good deal older than thee, Jim, and I've known now and then for a Summer to miss, but I've never known a Winter to miss afore." Another, winding up a wrangle with a relative who possessed more of this world's goods than himself and assumed airs in consequence, said, "We are akin, yo' cannot scrat that out!"[9]

Another, quaintly and cautiously expressing his opinion as to the stage of inebriation reached by his friend, said that "He 61wasn't exactly drunk, but one or two o' th' glasses he'd had should ha' been left o'er till to-morrow."

To drop the aspirate is a common failing of half-educated Lancashire people (though this special weakness is by no means peculiar to Lancashire folk), and sometimes gives a ludicrous turn to a remark.

Speaking with a working-man friend of mine about the desirability of everyone cultivating some pursuit or hobby outside of one's daily employment: "Ah!" replied my friend, "a man with an 'obby is an 'appy man!" to which sensible expression of opinion I assented with a smile. The same person, curiously enough, would put in the aspirate where it was not required. Looking at the picture of an ancient mansion, he asked: "Is that a hold habbey?" I have even heard a fairly well-educated person speak of the "Hodes of Orrace."

Jack Smith was a well-known Blackburn character in his day. He began life as a quarryman, rose to be a quarrymaster, and became Mayor of his native town. Mr62 Abram, the historian of Blackburn, relates that "when in February 1869, Justice Willes came down to Blackburn to hear the petition against the return of Messrs Hornby and Fielden at the Parliamentary election in the November preceding, Mayor Smith attained the height of his grandeur and importance. On the morning of the opening of the Court, the room was thronged with counsel, solicitors, witnesses and active politicians interested in the trial on one side or the other. The Mayor, Jack Smith, took his seat on the Bench by the side of Justice Willes, who found the air of the Court rather too close for him. He was seen to say a few words in an undertone to the Mayor, who nodded assent, and rising, shouted in his heavy voice, pointing to the windows at the side of the Court: "Heigh, policemen, hoppen them winders, an' let some hair in." As he reseated himself, Jack added, chidingly, addressing the group of constables in attendance: "Do summat for yor brass!" Few of the audience could resist a laugh at the quaint idiom of the Right Worshipful, and even the Judge's severe features for a moment relaxed into a half smile.

An incident in Punch has reference to the same failing. The Inspector had been visiting a school, in which a Lancashire magnate63 took great interest, being something of an enthusiast in the educational movement. In commenting upon the progress of the pupils in care of the schoolmistress, the Inspector, on leaving, remarked to the patron of the school:

"It strikes me that teacher of yours retains little or no grasp upon the attention of the children—not hold enough, you know—not hold enough."

"Not hold enough!" exclaimed the magnate in surprise. "Lor' bless yer—if she ever sees forty again, I'll eat my 'at!"

To fully convey the humour of the incident, Charles Keene's picture (for it is one of his) should accompany the recital.

At one of the political meetings of the Eccles division, during the recent general election contest, a working man who occupied the chair, and prodigal of his aitches, in introducing Mr O. L. Clare, Q.C., the Conservative candidate, convulsed the audience by strenuously aspirating the two initials of the honourable candidate's name.

Some illiterate men, again, are fond of using or misusing big words. They are content, following the example of Mrs Malaprop, that the sound shall serve just as well as the sense. For example: you will sometimes hea64r an old gardener remark that the soil wouldn't be any the worse of some "manœuvre." One that I knew used to talk of "consecrating" the footpaths. He meant concreting.

An old mechanic of my acquaintance, who is learned in the mysteries of steam raising and steam pressure, is wont to dilate on his favourite subject, and will persist in holding forth on what he describes as "Th' expression up o' th' steawm." Truly, a nice "derangement of epitaphs."

The same, speaking of Lord Roberts' generalship in outflanking the Boer armies, remarked, "Ay, he's a surprising mon, for sure, is General Roberts, an' he does it o' wi' his clever tictacs."

And again: "Aw nobbut wish he could get how'd o' owd Krooger, and send him to keep Cronje company at St Helens."

A confusion of ideas sometimes extends to other subjects. Another simple friend of mine, relating the treatment he had been subjected to by a ferocious tramp in a lonely neighbourhood, declared that the would-be highwayman "Clapped a pistol to mi bally, and swore he'd blow mi brains out if aw didn't hand over mi money!" Possibly the thief 65knew better where his brains lay than my friend did himself.

An equally ludicrous confusion of ideas is shown in the next example. Owd Pooter, the odd man who tidied up the stable yard and pottered about the garden, was troubled with a neighbour's hens getting into the meadow and treading down the young grass. So, speaking to his master one day, he said,

"Maister, I durn't know what we maun do if thoose hens are to keep comin' scratt, scrattin' i' th' meadow when they liken; we'st ha'e no grass woth mentionin."

"Put a notice up," suggested his employer.

"Put a notice up!" responded Pooter, looking as wise as a barn owl. "Eh! maister, if aw did put a notice up there isn't one hen in a 66hundred as could read it!"

Another hen story is worth relating. A poultry farmer calling on a grocer one day was told by the latter that he must be prepared to give him more than fourteen eggs for a shilling. "The grocers have had a meeting," said his customer, "and they have come to the conclusion that there must be at least sixteen eggs for a shilling." The poultry farmer listened but said nothing. Next time he called he counted out his eggs—sixteen for a shilling—but they were all very small—pullet eggs in fact.

"Hello! what does this mean? How comes it that your eggs are so small?" asked the grocer.

"Well, yo see," was the reply, "th' hens have had a meetin' and they have coom to th' conclusion that they connot lay ony bigger than thur at sixteen for a shillin!" Evidently the shrewd farmer had profited by the knowledge that the animal creation, as Æsop has taught us, can hold converse and come to as sensible decisions as their betters.

The same owd Pooter, already mentioned, being much out of sorts, consulted the doctor on his state of health, who, after hearing his story and making the necessary examination of the patient, recommended him to eat plentifully of animal foo67d. Pooter, looking somewhat askance, said he would do his best to follow the doctor's advice, but he feared his "grinders wur noan o' th' best for food o' that mak." "Try it for a week," said the doctor, "and then call and see me again." At the expiration of a week Pooter repeated the visit. "Have you done what I recommended?" asked the physician. "Aw've done mi best," replied Pooter, "aw have for sure, an' as lung as aw stuck to th' oats an' beans, aw geet on meterley; but aw wur gradely lickt when aw coom to th' choppins!" Pooter's idea of "animal food" was the horse's diet of oats, beans and choppings.

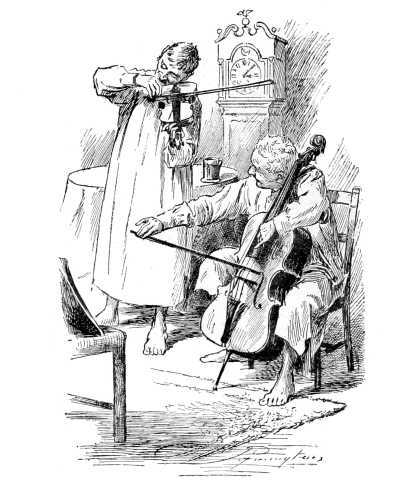

Among the ridiculous stories that are told, are the three following, which are more imaginative than true in their details. The fact of their invention, however, is a proof that the author possessed a considerable share of happy humour. The old fellow who went to see "Elijah," the Oratorio of that name, on being asked if he had seen the prophet, replied: "Yea, aw did." "Well, what was he like?" "Wha, he stood theer at th' back o' th' crowd up o' th' platform, an' he kept rubbin a stick across his bally, an' he groant, and groant—yo could yer 'im all o'er th' place!" He took the double-bass 'cello-player to 68be Elijah.

The Wardens of the church at Belmont determined to move the structure a few yards to make room for a gravel path, so, laying their coats on the ground to mark the exact distance, they went round to the opposite side and pushed with all their might. Whilst they were thus engaged a thief stole the coats. Coming back again to observe the effect of their exertions, and being unable to find their stolen garments, "Devilskins!" they exclaimed, "we have pushed too far!"

Mother, to her hopeful son standing at the door one night:

"Come in an' shut th' door, John, what ar't doin' theer?"

"Aw'm lookin' at th' moon."

"Lookin' at th' moon! Come in aw tell thae, an' let th' moon alone."

"Who's touching th' moon?"

The Municipal Authorities of a Lancashire town, in laying out a public park which had been presented by a wealthy citizen, added to its other attractions a large ornamental lake, formed by damming up a stream that ran through the grounds.69 One of the park committee, in the course of a speech extolling the beauty of the lake, suggested that they might put a gondola upon it. Another of his confreres on the Council, thinking that a swan or other aquatic fowl was meant, responded: "What's th' use o' having only one gondola? let's ha' two and then they con breed."