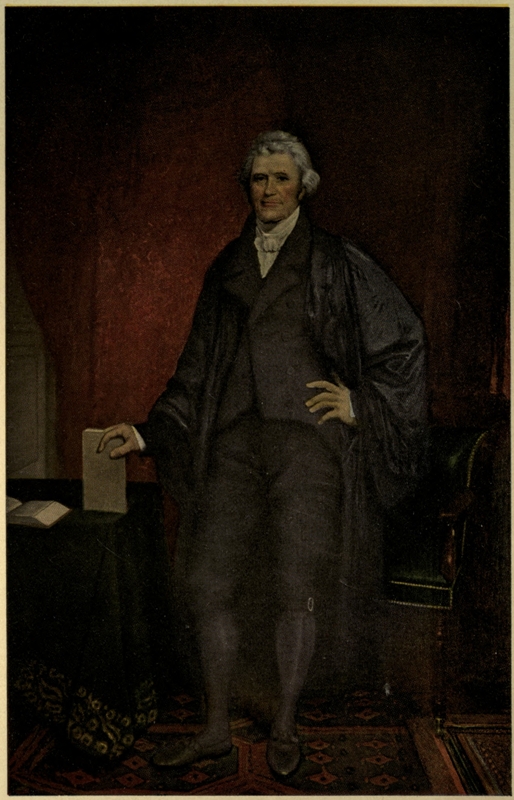

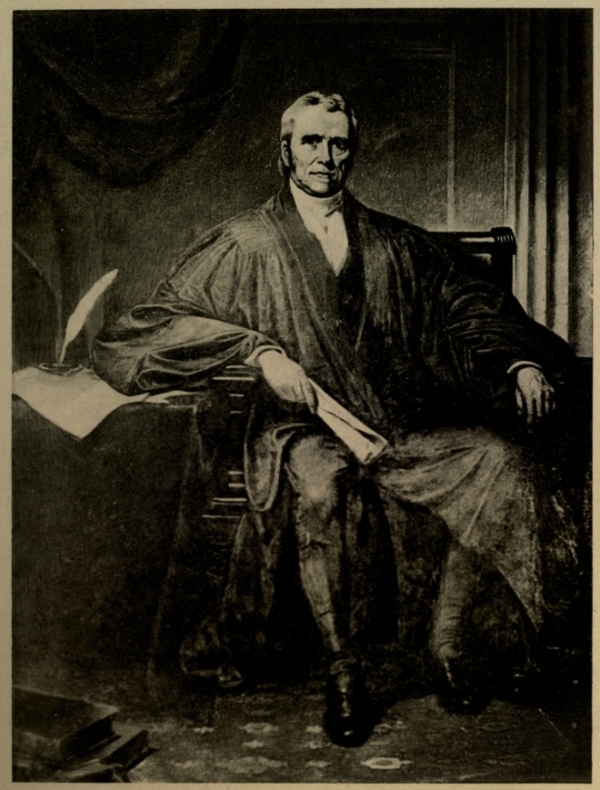

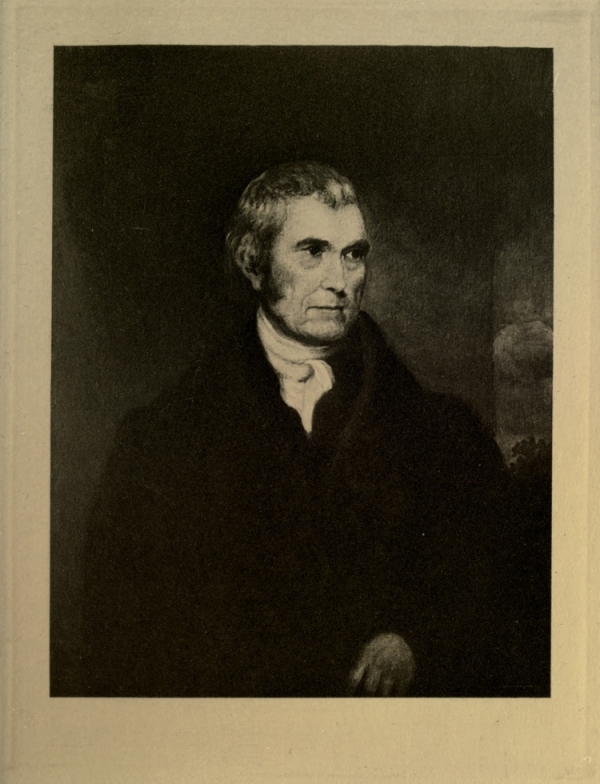

JOHN MARSHALL

JOHN MARSHALLFrom the portrait by Chester Harding

Title: The Life of John Marshall, Volume 3: Conflict and construction, 1800-1815

Author: Albert J. Beveridge

Release date: August 8, 2012 [eBook #40445]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Edwards and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

COPYRIGHT, 1919, BY ALBERT J. BEVERIDGE

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Marshall's great Constitutional opinions grew out of, or were addressed to, serious public conditions, national in extent. In these volumes the effort is made to relate the circumstances that required him to give to the country those marvelous state papers: for Marshall's opinions were nothing less than state papers and of the first rank. In order to understand the full meaning of his deliverances and to estimate the just value of his labors, it is necessary to know the historical sources of his foremost expositions of the Constitution, and the historical purposes they were intended to accomplish. Without such knowledge, Marshall's finest pronouncements become mere legal utterances, important, to be sure, but colorless and unattractive.

It is worthy of repetition, even in a preface, that the history of the times is a part of his greatest opinions; and that, in the treatment of them a résumé of the events that produced them must be given. For example, the decision of Marbury vs. Madison, at the time and in the manner it was rendered, was compelled by the political situation then existing, unless the principle of judicial supremacy over legislation was to be abandoned. The Judiciary Debate of 1802 in Congress—one of the most brilliant as well as most important legislative engagements in parliamentary history—can no more be overlooked by the student of American Constitutional [Pg vi]development, than the opinion of Marshall in Marbury vs. Madison can be disregarded.

Again, in Cohens vs. Virginia, the Chief Justice rises to heights of exalted—almost emotional—eloquence. Yet the case itself was hardly more than a police court controversy. If the trivial fine of itinerant peddlars of lottery tickets were alone involved, Marshall's splendid passages become unnecessary and, indeed, pompous rhetoric. But when the curtains of history are raised, we see the heroic part that Marshall played and realize the meaning of his powerful language. While Marshall's opinion in M'Culloch vs. Maryland, even taken by itself, is a major treatise on constitutional government, it becomes a fascinating chapter in an engaging story, when read in connection with an account of the situation which compelled that outgiving.

The same thing is true of his other historic utterances. Indeed, it may be said that his weightiest opinions were interlocking parts of one great drama.

Much space has been given to the conspiracy and trials of Aaron Burr. The combined story of that adventure and of those prosecutions has not hitherto been told. In the conduct of the Burr trials, Marshall appears in a more intimate and personal fashion than in any other phase of his judicial career; the entire series of events that make up that page of our history is a striking example of the manipulation of public opinion by astute politicians, and is, therefore, useful for the self-guidance of American democracy. Most important of all, the culminating [Pg vii]result of this dramatic episode was the definitive establishment of the American law of treason.

In narrating the work of a jurist, the temptation is very strong to engage in legal discussion, and to cite and comment upon the decisions of other courts and the opinions of other judges. This, however, would be the very negation of biography; nor would it add anything of interest or enlightenment to the reader. Such information and analysis are given fully in the various books on Constitutional law and history, in the annotated reports, and in the encyclopædias of law upon the shelves of every lawyer. Care, therefore, has been taken to avoid making any part of the Life of John Marshall a legal treatise.

The manuscript of these volumes has been read by Professor Edward Channing of Harvard; Professor Max Farrand of Yale; Professor Edward S. Corwin of Princeton; Professor William E. Dodd of Chicago University; Professor Clarence W. Alvord of the University of Illinois; Professor James A. Woodburn of Indiana University; Professor Charles H. Ambler of the University of West Virginia; Professor Archibald Henderson of the University of North Carolina; Professor D. R. Anderson of Richmond (Va.) College; and Dr. H. J. Eckenrode of Richmond, Virginia.

The manuscript of the third volume has been read by Professor Charles A. Beard of New York; Dr. Samuel Eliot Morison of Harvard; and Mr. Harold J. Laski of Harvard. The manuscript of both the third and fourth volumes has been read, from [Pg viii]the lawyer's point of view, by Mr. Arthur Lord of Boston, President of the Massachusetts Bar Association, and by Mr. Charles Martindale of Indianapolis.

The chapters on the Burr conspiracy and trials have been read by Professor Walter Flavius McCaleb of New York; Professor Isaac Joslin Cox of the University of Cincinnati; and Mr. Samuel H. Wandell of New York. Chapter Three of Volume Three (Marbury vs. Madison) has been read by the Honorable Oliver Wendell Holmes, Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States; by the Honorable Philander Chase Knox, United States Senator; and by Mr. James M. Beck of New York. Other special chapters have been read by the Honorable Henry Cabot Lodge, United States Senator; by Professor J. Franklin Jameson of the Department of Historical Research of the Carnegie Institution of Washington; by Professor Charles H. Haskins of Harvard; by Dr. William Draper Lewis of Philadelphia, former Dean of the Law School of the University of Pennsylvania; and by Mr. W. B. Bryan of Washington.

All of these gentlemen have made valuable suggestions of which I have availed myself, and I gratefully acknowledge my indebtedness to them. The responsibility for everything in these volumes, however, is, of course, exclusively mine; and, in stating my appreciation of the comment and criticism with which I have been favored, I do not wish to be relieved of my burden by allowing the inference that any part of it should be assigned to others.

I also owe it to myself again to express my heavy [Pg ix]obligation to Mr. Worthington Chauncey Ford, Editor of the Massachusetts Historical Society. As was the case in the preparation of the first two volumes of this work, Mr. Ford has extended to me the resources of his ripe scholarship; while his wise counsel, steady encouragement, and unselfish assistance, have been invaluable in the prosecution of a long and exacting task.

I also again acknowledge my indebtedness to Mr. Lindsay Swift, Editor of the Boston Public Library, who has read with critical care not only the many drafts of the manuscript, but also the proofs of the entire work. Mr. Swift has given, unstintedly, his rare literary taste and critical accomplishment to the examination of these pages.

I also tender my hearty thanks to Dr. Gardner Weld Allen of Boston, who has generously directed the preparation of the bibliography and personally revised it.

Mr. David Maydole Matteson of Cambridge, Massachusetts, has made the index of these volumes as he made that of the first two volumes, and has combined both indexes into one. In rendering this service, Mr. Matteson has also searched for points where text and notes could be made more accurate; and I wish to express my appreciation of his kindness.

My thanks are also owing to the staff of The Riverside Press, and particularly to Mr. Lanius D. Evans, to whose keen interest and watchful care in the production of this work I am indebted for much of whatever exactitude it may possess.

The manuscript sources have been acknowledged, in all instances, in the footnotes where references to them have been made, except in the case of the letters of Marshall to his relatives, for which I again thank those descendants and connections of the Chief Justice named in the preface to Volumes One and Two. The Hopkinson manuscripts are in the possession of Mr. Edward Hopkinson of Philadelphia, to whom I am indebted for the privilege of inspecting this valuable source and for furnishing me with copies of important letters.

In preparing these volumes, Mr. A. P. C. Griffin, Assistant Librarian, and Mr. John Clement Fitzpatrick, of the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress, have been even more obliging, if possible, than they were in the preparation of the first part of this work. The officers and their assistants of the Boston Public Library, the Boston Athenæum, the Massachusetts State Library, the Massachusetts Historical Society, the Pennsylvania Historical Society, the Virginia State Library, the Indiana State Library, and the Indianapolis City Library, have assisted whole-heartedly in the performance of my labors; and I am glad of the opportunity to thank all of them for their interest and help.

Albert J. Beveridge

| I. | DEMOCRACY JUDICIARY | 1 |

| The National Capital an unsightly "village in the woods"—Difficulty and danger of driving through the streets—Habits of the population—Taverns, shops, and dwellings—Warring interests—A miniature of the country—Meaning of the Republican victory of 1800—Anger, chagrin, and despair of the Federalists—Marshall's views of the political situation—He begins to strengthen the Supreme Court—The Republican programme of demolition—Jefferson's fear and hatred of the National Judiciary—The conduct of the National Judges gives Jefferson his opportunity—Their arrogance, harshness, and partisanship—Political charges to grand juries—Arbitrary application of the common law—Jefferson makes it a political issue—Rigorous execution of the Sedition Law becomes hateful to the people—The picturesque and historic trials that made the National Judiciary unpopular—The trial and conviction of Matthew Lyon; of Thomas Cooper; of John Fries; of Isaac Williams; of James T. Callender; of Thomas and Abijah Adams—Lawyers for Fries and Callender abandon the cases and leave the court-rooms—The famous Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions raise the fundamental question as to the power that can interpret the Constitution—Jefferson plans the assault on the National Judiciary. | ||

| II. | THE ASSAULT ON THE JUDICIARY | 50 |

| The assault on the Judiciary begins—Intense excitement of political parties—Message on the Judiciary that Jefferson sent to Congress—Message he did not send—The Federalists fear the destruction of the National Judiciary—The grave defects of the Ellsworth Judiciary Act of 1789—The excellent Federalist Judiciary Act of 1801—The Republicans determined to repeal it—The great Judiciary debate begins in the Senate—The Federalists assert the exclusive power of the Supreme Court to decide on the constitutionality of acts of Congress—The dramatic language of Senator Gouverneur Morris—The Republican Senators evade the issue—The Federalist Senators press it—Aaron Burr takes his seat as Vice-President—His fateful Judiciary vote—Senator John Breckenridge denies the supervisory power of the Supreme Court over legislation—The debate in the House—Comments of the press—Extravagant speeches—Appearance and characteristics of John Randolph of Roanoke—The Federalists hint resistance—The lamentations of the Federalist newspapers—The Republicans repeal [Pg xii]the Federalist Judiciary act—They also suspend the sessions of the Supreme Court for fourteen months—This done to prevent Marshall from overthrowing the Republican repeal of the Federalist Judiciary Act of 1801—Marshall proposes to his colleagues on the bench that they refuse to sit as Circuit Judges—They reject his proposal—The New England Federalist leaders begin to talk secession—The jubilation of the Republican press: "Huzza for the Washington Judiciary!" | ||

| III. | MARBURY VERSUS MADISON | 101 |

| Power of the Judiciary over legislation the supreme issue—Federalist majorities in State Legislatures assert that Supreme Court can annul acts of Congress—Republican minorities vigorously resist the doctrine of Judiciary supremacy—Republican strength grows rapidly—Critical situation before the decision of Marbury vs. Madison—Power of the Supreme Court must be promptly asserted or permanently abandoned—Marshall confronts a serious dilemma—Escape from it apparently impossible—Republicans expect him to decide against Madison—They threaten impeachment—Marshall delivers his celebrated opinion—His reasoning on the power of the Judiciary merely repeats Federalist arguments in the Judiciary debate—He persuades his associates on the Supreme Bench that Section 13 of the Ellsworth Judiciary Act is unconstitutional—Startling boldness of his conception—History of Section 13—Drawn by framers of the Constitution and never before questioned—Marshall's opinion excites no immediate comment—Jefferson does not attack it until after his reëlection—Republican opposition to the Judiciary apparently subsides—Cause of this—Purchase of Louisiana—Jefferson compelled to take "unconstitutional" action—He counsels secrecy—The New England Federalist secession movement gains strength—Jefferson reëlected—Impeachment the next move. | ||

| IV. | IMPEACHMENT | 157 |

| Republicans plan to subjugate the Judiciary—Federalist Judges to be ousted and Republicans put in their places—Marshall's decision in United States vs. Fisher—The Republican impeachment programme carried out—The trial and the conviction of Judge Addison—The removal of Judge Pickering—The House impeaches Justice Chase of the Supreme Court—Republicans manipulate public opinion—The articles of impeachment—Federalists convinced that Chase is doomed—Marshall the chief object of attack—His alarm—He proposes radical method of reviewing decisions of the Supreme Court—Reason for Marshall's trepidation—The impeachment trial—Burr presides—He is showered with favors by the Administration—Appearance of Chase—His brilliant array of counsel—Luther Martin of Maryland—Examination of witnesses—Marshall testifies—He makes an unfavorable impression: "too much caution; too much fear; too much cunning"—Argu[Pg xiii]ments of counsel—Weakness of the House managers—They are overwhelmed by counsel for Chase—Joseph Hopkinson's brilliant appeal—He captivates the Senate—Nicholson's fatal admission—Rodney's absurd speech—Luther Martin's great argument—Randolph closes for the managers—He apostrophizes Marshall—His pathetic breakdown—The Senate votes—Tense excitement in the Chamber—Chase acquitted—A determinative event in American history—Independence of the National Judiciary saved—Marshall for the first time secure in the office of Chief Justice. | ||

| V. | BIOGRAPHER | 223 |

| Marshall agrees to write the "Life of Washington"—He is unequipped for the task—His grotesque estimate of time, labor, and profits—Jefferson is alarmed—Declares that Marshall is writing for "electioneering purposes"—Postmasters as book agents—They take their cue from Jefferson—Rumor spreads that Marshall's book is to be partisan—Postmasters take few subscriptions—Parson Weems becomes chief solicitor for Marshall's book—His amusing canvass—Marshall is exasperatingly slow—Subscribers are disgusted at delay—First two volumes appear—Public is dissatisfied—Marshall is worried—He writes agitated letters—His publisher becomes disheartened—Marshall resents criticism—The lamentable inadequacy of the first three volumes—Fourth volume an improvement—Marshall's heavy task in the writing of the last volume—He performs it skillfully—Description of the foundation of political parties—Treatment of the policies of Washington's administrations—Jefferson calls Marshall's biography a "five-volume libel" and "a party diatribe"—He seeks an author to answer Marshall—He resolves to publish his "Anas" chiefly as a reply to Marshall—He bitterly attacks him and the biography—Other criticisms of Marshall's work—His lifelong worry over the imperfections of the first edition—He decides to revise it—He devotes nearly twenty years to the task—Work on the Supreme Bench while writing the first edition. | ||

| VI. | THE BURR CONSPIRACY | 274 |

| Remarkable effect on the Senate of Burr's farewell speech—His desperate plight—Stanchness of friends—Jefferson's animosity—Unparalleled combination against Burr—He runs for Governor of New York and is defeated—Hamilton's lifelong pursuit of Burr—The historic duel—Dismemberment of the Union long and generally discussed—Washington's apprehensions in 1784—Jefferson in 1803 approves separation of Western country "if it be for their good"—The New England secessionists ask British Minister for support—He promises his aid—Loyalty of the West—War with Spain imminent—People anxious to "liberate" Mexico—Invasion of that country Burr's long-cherished dream—He tries to get money from Great Britain—He promises British Minister to divide the Republic—His first Western journey[Pg xiv]—The people receive him cordially—He is given remarkable ovation at Nashville—Andrew Jackson's ardent friendship—Burr enthusiastically welcomed at New Orleans—War with Spain seemingly inevitable—Burr plans to lead attack upon Mexico when hostilities begin—Spanish agents start rumors against him—Eastern papers print sensational stories—Burr returns to the Capital—Universal demand for war with Spain—Burr intrigues in Washington—He again starts for the West—He sends his famous cipher dispatch to Wilkinson—Blennerhassett joins Burr—They purchase four hundred thousand acres of land on the Washita River—Plan to settle this land if war not declared—Wilkinson's eagerness for war—Burr arraigned in the Kentucky courts—He is discharged—Cheered by the people—Wilkinson determines to betray Burr—He writes mysterious letters to the President—Jefferson issues his Proclamation—Wilkinson's reign of military lawlessness in New Orleans—Arrest of Burr's agents, Bollmann and Swartwout—Arrest of Adair—Prisoners sent under guard by ship to Washington—The capital filled with wild rumors—Jefferson's slight mention of the Burr conspiracy in his Annual Message—Congress demands explanation—Jefferson sends Special Message denouncing Burr: his "guilt is placed beyond question"—Effect upon the public mind—Burr already convicted in popular opinion. | ||

| VII. | THE CAPTURE AND ARRAIGNMENT | 343 |

| Bollmann and Swartwout arrive at Washington and are imprisoned—Adair and Alexander released by the court at Baltimore for want of proof—Eaton's affidavit against Burr—Bollmann and Swartwout apply to Supreme Court for writ of habeas corpus—Senate passes bill suspending the privilege of that writ—The House indignantly rejects the Senate Bill—Marshall delivers the first of his series of opinions on treason—No evidence against Bollmann and Swartwout, and Marshall discharges them—Violent debate in the House—Burr, ignorant of all, starts down the Cumberland and Mississippi with nine boats and a hundred men—First learns in Mississippi of the proceedings against him—Voluntarily surrenders to the civil authorities—The Mississippi grand jury refuses to indict Burr, asserting that he is guilty of no offense—Court refuses to discharge him—Wilkinson's frantic efforts to seize or kill him—He goes into hiding—Court forfeits his bond—He escapes—He is captured in Alabama and confined to Fort Stoddert—Becomes popular with both officers and men—Taken under military guard for a thousand miles through the wilderness—Arrives at Richmond—Marshall issues warrant for his delivery to the civil authorities—The first hearing before the Chief Justice—Shall Burr be committed for treason—The argument—Marshall's opinion—Probable cause to suspect Burr guilty of attempt to attack Mexico; no evidence upon which to commit Burr for treason—Marshall indirectly criticizes Jefferson—Burr's letters to his daughter—Popular demand for Burr's con[Pg xv]viction and execution—Jefferson writes bitterly of Marshall—Administration scours country for evidence against Burr—Expenditure of public money for this purpose—Burr gains friends in Richmond—His attorneys become devoted to him—Marshall attends the famous dinner at the house of John Wickham, not knowing that Burr is to be a guest—He is denounced for doing so—His state of mind. | ||

| VIII. | ADMINISTRATION VERSUS COURT | 398 |

| Richmond thronged with visitors—Court opens in the House of Delegates—The hall packed—Dress, appearance, and manner of spectators—Dangerous state of the public temper—Andrew Jackson arrives and publicly denounces Jefferson—He declares trial a "political persecution"—Winfield Scott's opinion: the President the real prosecutor—Grand jury formed and instructed—Believe Burr guilty—Burr's passionate reply to George Hay, the District Attorney—Hay reports to Jefferson—Burr's counsel denounce the Administration's efforts to excite the public against him—Attorneys on both sides speak to the public—Hay moves to commit Burr for treason—Marshall's difficult and dangerous situation—Jefferson instructs Hay—Government offers testimony to support its motion—Luther Martin arrives—Hay again reports to Jefferson, who showers the District Attorney with orders—Burr asks that the court grant a writ of subpœna duces tecum directed to Jefferson—Martin boldly attacks the President—Wirt's clever rejoinder—Jefferson calls Martin that "Federal bulldog"—Wants Martin indicted—Marshall's opinion on Burr's motion for a subpœna duces tecum—He grants the writ—Hay writes Jefferson, who makes able and dignified reply—Wilkinson arrives—Washington Irving's description of him—Testimony before the grand jury—Burr and Blennerhassett indicted for treason and misdemeanor—Violent altercations between counsel. | ||

| IX. | WHAT IS TREASON? | 470 |

| Burr becomes popular with Richmond society—Swartwout challenges Wilkinson to a duel—Marshall sets the trial for August 3—The prisoner's life in the penitentiary—Burr's letters to his daughter—Marshall asks his associates on the Supreme Bench for their opinions—Trial begins—Difficulty of selecting a jury—Everybody convinced of Burr's guilt—Hay writes Jefferson that Marshall favors Burr—At last jury is formed—The testimony—No overt act proven—Burr's counsel move that collateral testimony shall not be received—Counsel on both sides make powerful and brilliant arguments—Marshall delivers his famous opinion on the law of constructive treason—Jury returns verdict of not guilty—Jefferson declares Marshall is trying to keep evidence from the public—He directs Hay to press trial on indictment for misdemeanor—Burr demands letters called for in the subpœna duces tecum to Jefferson—President attempts to arrange a truce with the Chief Jus[Pg xvi]tice—Hay despairs of convicting Burr for misdemeanor—Trial on this charge begins—Many witnesses examined—Prosecution collapses—Jury returns a verdict of not guilty—Hay moves to hold Burr and his associates for treason committed in Ohio—On this motion Marshall throws the door wide open to all testimony—He delivers his last opinion in the Burr trials—Refuses to hold Burr for treason, but commits him for misdemeanor alleged to have been committed in Ohio—Marshall adjourns court and hurries to the Blue Ridge—He writes Judge Peters of his situation during the trial—Jefferson denounces Marshall in Message he prepares for Congress—Cabinet induces him to strike out the most emphatic language—Marshall scathingly assailed in the press—The mob at Baltimore—Marshall is hanged in effigy—The attempt to expel Senator John Smith of Ohio from the Senate—In his report on Smith case, John Quincy Adams attacks Marshall's rulings and opinion in the Burr trials—Grave foreign complications probably save Marshall from impeachment. | ||

| X. | FRAUD AND CONTRACT | 546 |

| The corrupting of the Georgia Legislature in the winter of 1794-95—The methods of bribery—Prominent men involved—Law passed selling thirty-five million acres of land for less than one and one half cents an acre—Land companies pay purchase price and receive deeds—Merits of the transaction—Poverty of Georgia and power of the Indians—Invention of the cotton gin increases land values—Period of mad land speculation—The origin of the contract clause in the Constitution—Wrath of the people of Georgia on learning of the corrupt land legislation—They demand that the venal act be repealed—James Jackson leads the revolt—A new Legislature elected—It "rescinds" the land sale law—Records of the transaction publicly burned—John Randolph visits Georgia—Land companies sell millions of acres to innocent purchasers—Citizens of Boston purchase heavily—The news of Georgia's repeal of the land sale act reaches New England—War of the pamphlets—Georgia cedes to the Nation her claims to the disputed domain—Five million acres are reserved to satisfy claimants—The New England investors petition Congress for relief—Jefferson's commissioners report in favor of the investors—John Randolph's furious assault on the relief bill—He attacks Gideon Granger, Jefferson's Postmaster-General, for lobbying on the floor of the House—The origin of the suit Fletcher vs. Peck—The nature of this litigation—The case is taken to the Supreme Court—Marshall delivers his opinion—Legislation cannot be annulled merely because legislators voting for it were corrupted—"Great principles of justice protect innocent purchasers"—The Georgia land sale act, having been accepted, is a contract—The repeal of that act by the Georgia Legislature is a violation of the contract clause of the Constitution—Justice Johnson dissents—He intimates that Fletcher vs. Peck "is a mere feigned case"—Meaning, purpose, and effect of Marshall's opinion—In Congress, Randolph and Troup of Georgia merci[Pg xvii]lessly assail Marshall and the Supreme Court—The fight for the passage of a bill to relieve the New England investors is renewed—Marshall's opinion and the decision of the court influential in securing the final passage of the measure. | ||

| APPENDIX | ||

| A. | The Paragraph Omitted from the Final Draft of Jefferson's Message to Congress, December 8, 1801 | 605 |

| B. | Letter of John Taylor "of Caroline" to John Breckenridge containing Arguments for the Repeal of the Federalist National Judiciary Act of 1801 | 607 |

| C. | Cases of which Chief Justice Marshall may have heard before he delivered his Opinion in Marbury vs. Madison | 611 |

| D. | Text, as generally accepted, of the Cipher Letter of Aaron Burr to James Wilkinson, dated July 29, 1806 | 614 |

| E. | Excerpt from Speech of William Wirt at the Trial of Aaron Burr | 616 |

| F. | Essential Part of Marshall's Opinion on Constructive Treason delivered at the Trial of Aaron Burr, on Monday, August 31, 1807 | 619 |

| WORKS CITED IN THIS VOLUME | 627 | |

| JOHN MARSHALL | Colored Frontispiece |

| From a portrait by Chester Harding painted in Washington in 1828 for the Boston Athenæum and still in the possession of that institution. | |

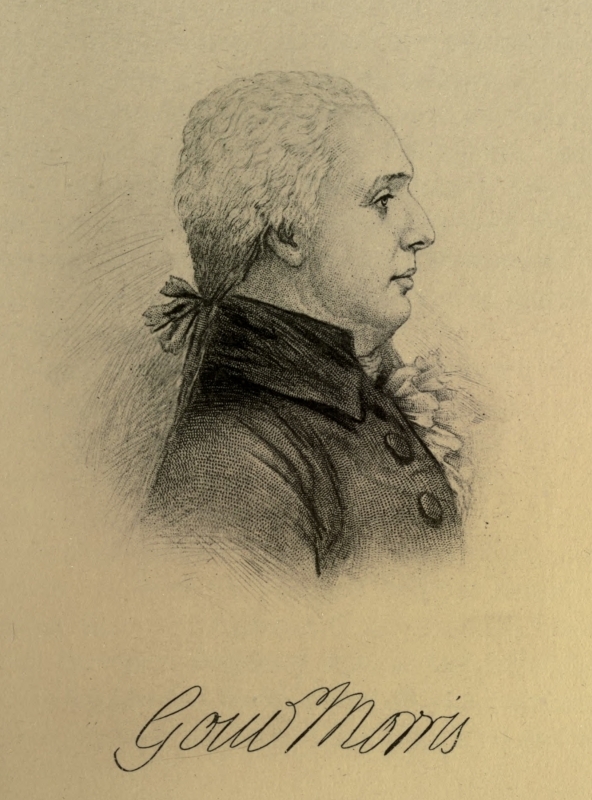

| GOUVERNEUR MORRIS | 60 |

| After a drawing by Quenedey made in Paris, 1789 or 1790, in possession of his granddaughter, Mrs. Alfred Maudslay. By permission of Messrs. Charles Scribner's Sons. | |

| ASSOCIATE JUSTICES SITTING WITH MARSHALL IN THE CASE OF MARBURY VERSUS MADISON: WILLIAM CUSHING, WILLIAM PATERSON, SAMUEL CHASE, BUSHROD WASHINGTON, ALFRED MOORE | 128 |

| Reproduced from etchings by Max and Albert Rosenthal in Hampton L. Carson's history of The Supreme Court of the United States, by the courtesy of the Lawyers' Coöperative Publishing Company, Rochester, New York. The etchings were made from originals as follows: Cushing, from a pastel by Sharpless, Philadelphia, 1799, in the possession of the family; Paterson, from a painting in the possession of the family; Chase, from a painting by Charles Wilson Peale in Independence Hall, Philadelphia; Washington, from a painting by Chester Harding in the possession of the family; Moore, from a miniature in the possession of Mr. Alfred Moore Waddell, of Wilmington, North Carolina. | |

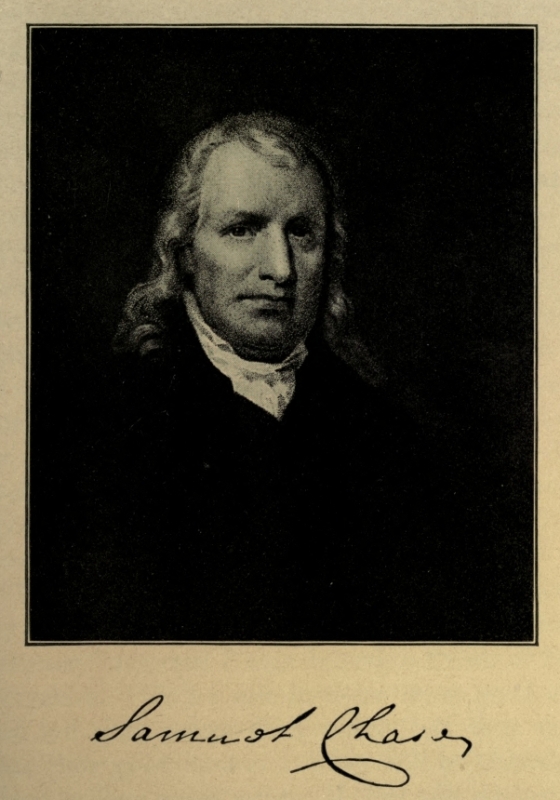

| SAMUEL CHASE | 160 |

| From Sanderson's Biography of the Signers to the Declaration of Independence, after a painting by Jarvis. | |

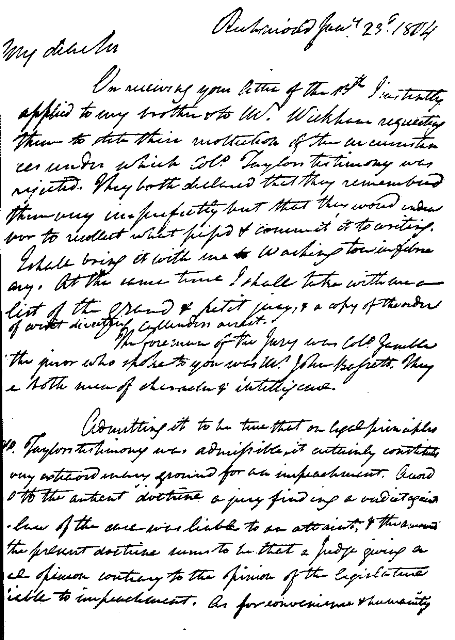

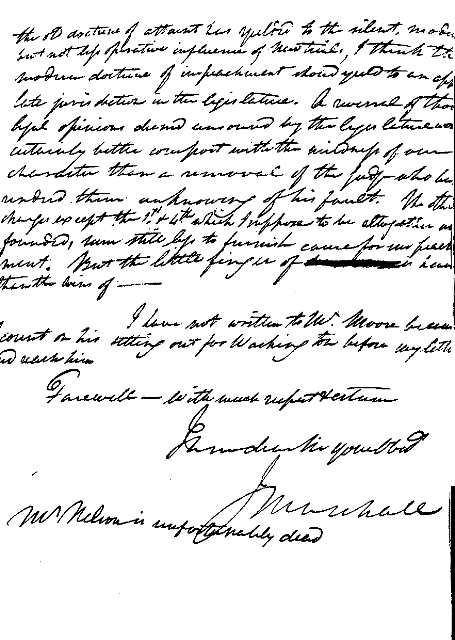

| FACSIMILE OF A LETTER FROM JOHN MARSHALL TO JUSTICE SAMUEL CHASE DATED JANUARY 23, 1804, ADVOCATING APPELLATE JURISDICTION IN THE LEGISLATURE | 176 |

| JOHN RANDOLPH | 188 |

| From the painting by Chester Harding in the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. | |

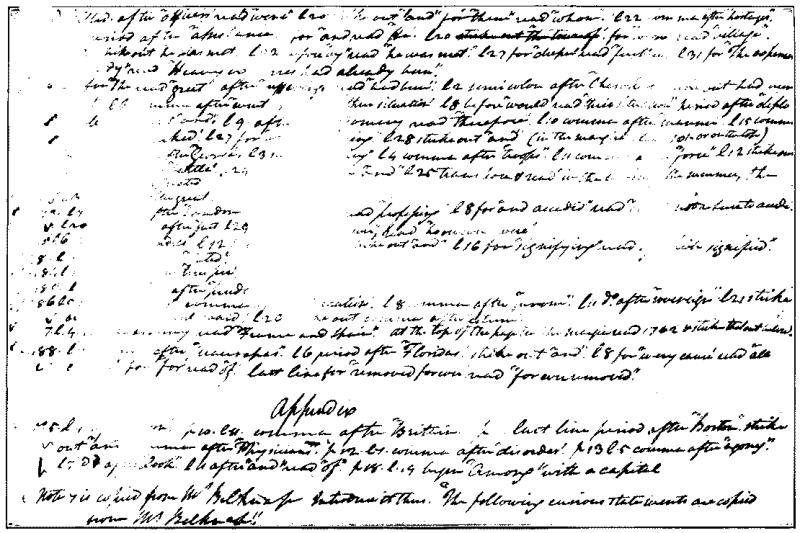

| FACSIMILE OF A PART OF MARSHALL'S LIST OF CORRECTIONS FOR HIS LIFE OF WASHINGTON | 240 |

| [Pg xx] | |

| AARON BURR | 276 |

| From a portrait by John Vanderlyn in the possession of Mr. Pierrepont Edwards, of Elizabeth, New Jersey. | |

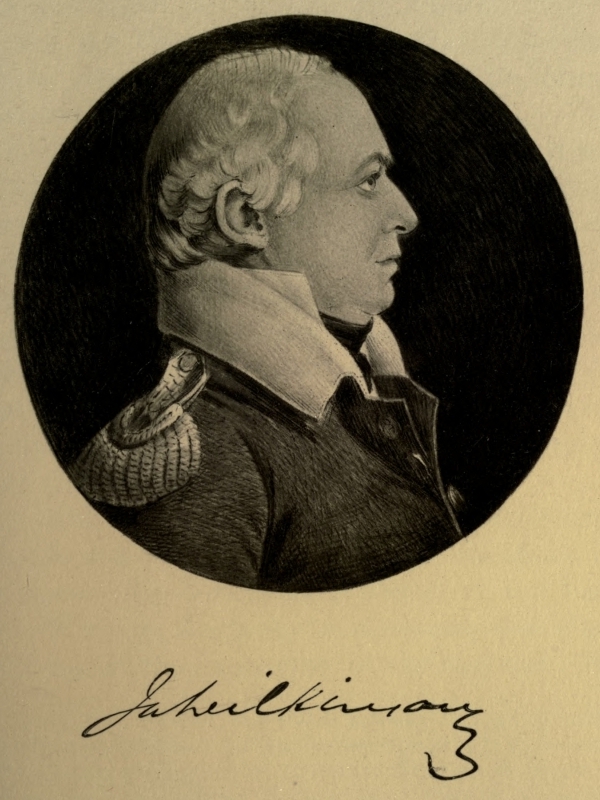

| JAMES WILKINSON | 290 |

| After a print presented to the Library of Harvard University by Lucien Carr, Esq., from a plate in the possession of Colonel John Mason Brown, of Louisville, Kentucky, and now inserted in the Library's copy of Wilkinson's Memoirs, Philadelphia, 1816, vol. 1. | |

| JOHN MARSHALL | 350 |

| From a painting by Richard N. Brooke, on the Gallery Floor of the House of Representatives at the Capitol, Washington, D.C. | |

| THE STATE CAPITOL, RICHMOND, VIRGINIA | 400 |

| From an old photograph showing its appearance at the time of the Burr trial. It was not then stuccoed, and its bare brick walls were exposed between the columns or pilasters, giving it the appearance of a barnlike structure. | |

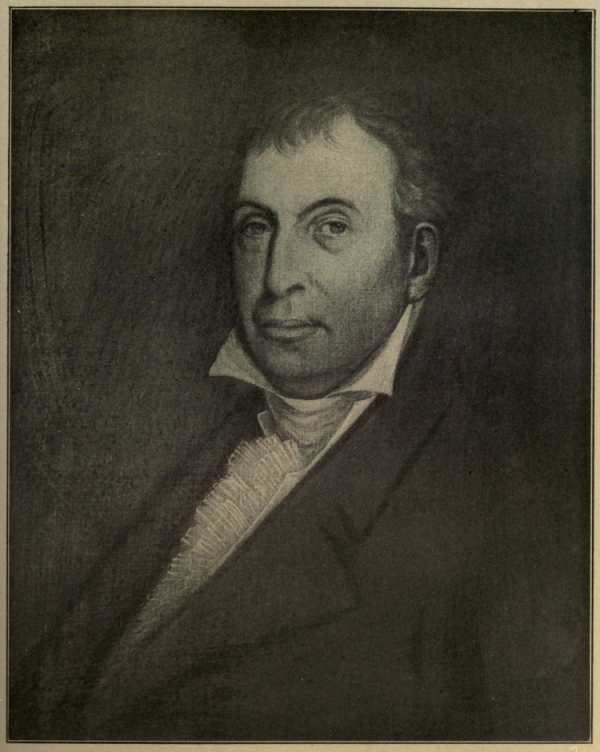

| LUTHER MARTIN | 428 |

| From a portrait in Independence Hall, Philadelphia. | |

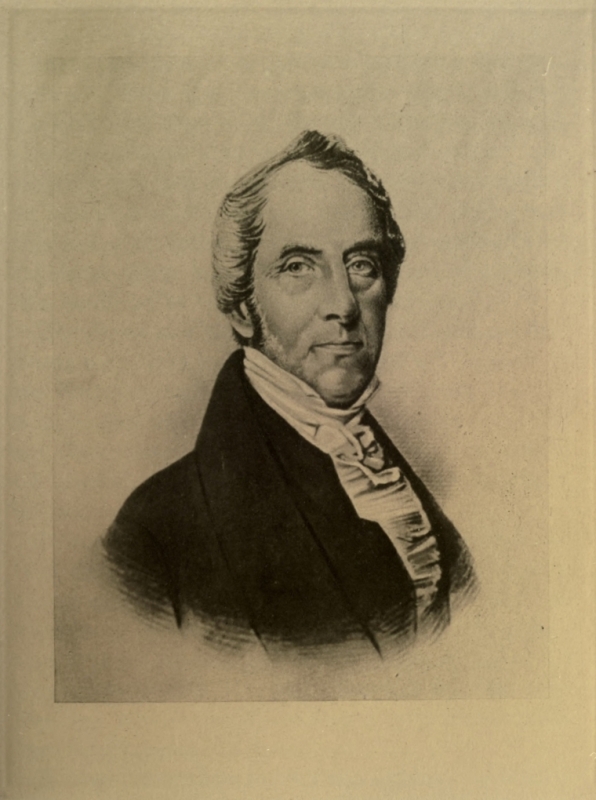

| JOHN WICKHAM | 492 |

| From a portrait in the possession of Henry T. Wickham, Esq., of Richmond, Virginia. | |

| JOHN MARSHALL | 516 |

| From the portrait by Robert Matthew Sully, a nephew and pupil of Thomas Sully, in the possession of the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. |

All references here are to the List of Authorities at the end of this volume

Adams: U.S. See Adams, Henry. History of the United States.

Ames. See Ames, Fisher. Works.

Channing: Jeff. System. See Channing, Edward. Jeffersonian System, 1801-11.

Channing: U.S. See Channing, Edward. History of the United States.

Chase Trial. See Chase, Samuel. Trial.

Corwin. See Corwin, Edward Samuel. Doctrine of Judicial Review.

Cutler. See Cutler, William Parker, and Julia Perkins. Life, Journals, and Correspondence of Manasseh Cutler.

Dillon. See Marshall, John. Life, Character, and Judicial Services. Edited by John Forrest Dillon.

Eaton: Prentiss. See Eaton, William. Life.

Jay: Johnston. See Jay, John. Correspondence and Public Papers.

Jefferson Writings: Washington. See Jefferson, Thomas, Writings. Edited by Henry Augustine Washington.

King. See King, Rufus. Life and Correspondence.

McCaleb. See McCaleb, Walter Flavius. Aaron Burr Conspiracy.

McMaster: U.S. See McMaster, John Bach. History of the People of the United States.

Marshall. See Marshall, John. Life of George Washington.

Memoirs, J. Q. A.: Adams. See Adams, John Quincy. Memoirs.

Morris. See Morris, Gouverneur. Diary and Letters.

N.E. Federalism: Adams. See New-England Federalism, 1800-1815, Documents relating to. Edited by Henry Adams.

Plumer. See Plumer, William. Life.

Priv. Corres.: Colton. See Clay, Henry. Private Correspondence. Edited by Calvin Colton.

Records Fed. Conv.: Farrand. See Records of the Federal Convention of 1787.

Story. See Story, Joseph. Life and Letters.

Trials of Smith and Ogden. See Smith, William Steuben, and Ogden, Samuel Gouverneur. Trials for Misdemeanors.

Wharton: Social Life. See Wharton, Anne Hollingsworth. Social Life in the Early Republic.

Wharton: State Trials. See Wharton, Francis. State Trials of the United States during the Administrations of Washington and Adams.

Wilkinson: Memoirs. See Wilkinson, James. Memoirs of My Own Times.

Works: Colton. See Clay, Henry. Works.

Works: Ford. See Jefferson, Thomas. Works. Federal Edition. Edited by Paul Leicester Ford.

Writings, J. Q. A.: Ford. See Adams, John Quincy. Writings. Edited by Worthington Chauncey Ford.

Rigorous law is often rigorous injustice. (Terence.)

The Federalists have retired into the Judiciary as a stronghold, and from that battery all the works of republicanism are to be battered down. (Jefferson.)

There will be neither justice nor stability in any system, if some material parts of it are not independent of popular control. (George Cabot.)

A strange sight met the eye of the traveler who, aboard one of the little river sailboats of the time, reached the stretches of the sleepy Potomac separating Alexandria and Georgetown. A wide swamp extended inland from a modest hill on the east to a still lower elevation of land about a mile to the west.[1] Between the river and morass a long flat tract bore clumps of great trees, mostly tulip poplars, giving, when seen from a distance, the appearance of "a fine park."[2]

Upon the hill stood a partly constructed white stone building, mammoth in plan. The slight elevation north of the wide slough was the site of an apparently finished edifice of the same material, noble in its dimensions and with beautiful, simple lines,[3] but "surrounded with a rough rail fence 5 or 6 feet high unfit for a decent barnyard."[4] From the river[Pg 2] nothing could be seen beyond the groves near the banks of the stream except the two great buildings and the splendid trees which thickened into a seemingly dense forest upon the higher ground to the northward.[5]

On landing and making one's way through the underbrush to the foot of the eastern hill, and up the gullies that seamed its sides thick with trees and tangled wild grapevines,[6] one finally reached the immense unfinished structure that attracted attention from the river. Upon its walls laborers were languidly at work.

Clustered around it were fifteen or sixteen wooden houses. Seven or eight of these were boarding-houses, each having as many as ten or a dozen rooms all told. The others were little affairs of rough lumber, some of them hardly better than shanties. One was a tailor shop; in another a shoemaker plied his trade; a third contained a printer with his hand press and types, while a washerwoman occupied another; and in the others there was a grocery shop, a pamphlets-and-stationery shop, a little dry-goods shop, and an oyster shop. No other human habitation of any kind appeared for three quarters of a mile.[7]

A broad and perfectly straight clearing had been made across the swamp between the eastern hill and the big white house more than a mile away to the westward. In the middle of this long opening ran a roadway, full of stumps, broken by deep mud holes in the rainy season, and almost equally deep with[Pg 3] dust when the days were dry. On either border was a path or "walk" made firm at places by pieces of stone; though even this "extended but a little way." Alder bushes grew in the unused spaces of this thoroughfare, and in the depressions stagnant water stood in malarial pools, breeding myriads of mosquitoes. A sluggish stream meandered across this avenue and broadened into the marsh.[8]

A few small houses, some of brick and some of wood, stood on the edge of this long, broad embryo street. Near the large stone building at its western end were four or five structures of red brick, looking much like ungainly warehouses. Farther westward on the Potomac hills was a small but pretentious town with its many capacious brick and stone residences, some of them excellent in their architecture and erected solidly by skilled workmen.[9]

Other openings in the forest had been cut at various places in the wide area east of the main highway that connected the two principal structures already described. Along these forest avenues were scattered houses of various materials, some finished and some in the process of erection.[10] Here and there unsightly gravel pits and an occasional brick kiln added to the raw unloveliness of the whole.

Such was the City of Washington, with Georgetown near by, when Thomas Jefferson became President and John Marshall Chief Justice of the United States—the Capitol, Pennsylvania Avenue, the[Pg 4] "Executive Mansion" or "President's Palace," the department buildings near it, the residences, shops, hostelries, and streets. It was a picture of sprawling aimlessness, confusion, inconvenience, and utter discomfort.

When considering the events that took place in the National Capital as narrated in these volumes,—the debates in Congress, the proclamations of Presidents, the opinions of judges, the intrigues of politicians,—when witnessing the scenes in which Marshall and Jefferson and Randolph and Burr and Pinckney and Webster were actors, we must think of Washington as a dismal place, where few and unattractive houses were scattered along muddy openings in the forests.

There was on paper a harmonious plan of a splendid city, but the realization of that plan had scarcely begun. As a situation for living, the Capital of the new Nation was, declared Gallatin, a "hateful place."[11] Most of the houses were "small miserable huts" which, as Wolcott informed his wife, "present an awful contrast to the public buildings."[12]

Aside from an increase in the number of residences and shops, the "Federal City" remained in this state for many years. "The Chuck holes were not bad," wrote Otis of a journey out of Washington in 1815; "that is to say they were none of them much deeper than the Hubs of the hinder wheels. They were however exceedingly frequent."[13] Pennsylvania[Pg 5] Avenue was, at this time, merely a stretch of "yellow, tenacious mud,"[14] or dust so deep and fine that, when stirred by the wind, it made near-by objects invisible.[15] And so this street remained for decades. Long after the National Government was removed to Washington, the carriage of a diplomat became mired up to the axles in the sticky clay within four blocks of the President's residence and its occupant had to abandon the vehicle.

John Quincy Adams records in his diary, April 4, 1818, that on returning from a dinner the street was in such condition that "our carriage in coming for us ... was overset, the harness broken. We got home with difficulty, twice being on the point of oversetting, and at the Treasury Office corner we were both obliged to get out ... in the mud.... It was a mercy that we all got home with whole bones."[16][Pg 6]

Fever and other malarial ills were universal at certain seasons of the year.[17] "No one, from the North or from the high country of the South, can pass the months of August and September there without intermittent or bilious fever," records King in 1803.[18] Provisions were scarce and Alexandria, across the river, was the principal source of supplies.[19] "My God! What have I done to reside in such a city," exclaimed a French diplomat.[20] Some months after the Chase impeachment[21] Senator Plumer described Washington as "a little village in the midst of the woods."[22] "Here I am in the wilderness of Washington," wrote Joseph Story in 1808.[23]

Except a small Catholic chapel there was only one church building in the entire city, and this tiny wooden sanctuary was attended by a congregation which seldom exceeded twenty persons.[24] This absence of churches was entirely in keeping with the[Pg 7] inclination of people of fashion. The first Republican administration came, testifies Winfield Scott, in "the spring tide of infidelity.... At school and college, most bright boys, of that day, affected to regard religion as base superstition or gross hypocricy."[25]

Most of the Senators and Representatives of the early Congresses were crowded into the boarding-houses adjacent to the Capitol, two and sometimes more men sharing the same bedroom. At Conrad and McMunn's boarding-house, where Gallatin lived when he was in the House, and where Jefferson boarded up to the time of his inauguration, the charge was fifteen dollars a week, which included service, "wood, candles and liquors."[26] Board at the Indian Queen cost one dollar and fifty cents a day, "brandy and whisky being free."[27] In some such inn the new Chief Justice of the United States, John Marshall, at first, found lodging.

Everybody ate at one long table. At Conrad and McMunn's more than thirty men would sit down at the same time, and Jefferson, who lived there while he was Vice-President, had the coldest and lowest place at the table; nor was a better seat offered him[Pg 8] on the day when he took the oath of office as Chief Magistrate of the Republic.[28] Those who had to rent houses and maintain establishments were in distressing case.[29] So lacking were the most ordinary conveniences of life that a proposal was made in Congress, toward the close of Jefferson's first administration, to remove the Capital to Baltimore.[30] An alternative suggestion was that the White House should be occupied by Congress and a cheaper building erected for the Presidential residence.[31]

More than three thousand people drawn hither by the establishment of the seat of government managed to exist in "this desert city."[32] One fifth of these were negro slaves.[33] The population was made up of people from distant States and foreign countries[34]—the adventurous, the curious, the restless, the improvident. The "city" had more than the usual proportion of the poor and vagrant who, "so far as I can judge," said Wolcott, "live like fishes[Pg 9] by eating each other."[35] The sight of Washington filled Thomas Moore, the British poet, with contempt.

"This embryo capital, where Fancy sees

Squares in morasses, obelisks in trees;

Where second-sighted seers, even now, adorn

With shrines unbuilt and heroes yet unborn,

Though nought but woods and Jefferson they see,

Where streets should run and sages ought to be."[36]

Yet some officials managed to distill pleasure from materials which one would not expect to find in so crude a situation. Champagne, it appears, was plentiful. When Jefferson became President, that connoisseur of liquid delights[37] took good care that the "Executive Mansion" was well supplied with the choicest brands of this and many other wines.[38] Senator Plumer testifies that, at one of Jefferson's dinners, "the wine was the best I ever drank, particularly the champagne which was indeed delicious."[39] In fact, repasts where champagne was served seem to have been a favorite source of enjoyment and relaxation.[40][Pg 10]

Scattered, unformed, uncouth as Washington was, and unhappy and intolerable as were the conditions of living there, the government of the city was torn by warring interests. One would have thought that the very difficulties of their situation would have compelled some harmony of action to bring about needed improvements. Instead of this, each little section of the city fought for itself and was antagonistic to the others. That part which lay near the White House[41] strove exclusively for its own advantage. The same was true of those who lived or owned property about Capitol Hill. There was, too, an "Alexandria interest" and a "Georgetown interest." These were constantly quarreling and each was irreconcilable with the other.[42]

In all respects the Capital during the first decades of the nineteenth century was a representation in miniature of the embryo Nation itself. Physical conditions throughout the country were practically the same as at the time of the adoption of the Constitution; and popular knowledge and habits of thought had improved but slightly.[43]

A greater number of newspapers, however, had profoundly affected public sentiment, and demo[Pg 11]cratic views and conduct had become riotously dominant. The defeated and despairing Federalists viewed the situation with anger and foreboding. Of all Federalists John Marshall and George Cabot were the calmest and wisest. Yet even they looked with gloom upon the future. "There are some appearances which surprize me," wrote Marshall on the morning of Jefferson's inauguration to his intimate friend, Charles Cotesworth Pinckney.

"I wish, however, more than I hope that the public prosperity & happiness will sustain no diminution under Democratic guidance. The Democrats are divided into speculative theorists & absolute terrorists. With the latter I am disposed to class Mr. Jefferson. If he ranges himself with them it is not difficult to foresee that much difficulty is in store for our country—if he does not, they will soon become his enemies and calumniators."[44]

After Jefferson had been President for four months, Cabot thus interpreted the Republican victory of 1800: "We are doomed to suffer all the evils of excessive democracy through the United States.... Maratists and Robespierrians everywhere raise their heads.... There will be neither justice nor stability in any system, if some material parts of it are not independent of popular control"[45]—an opinion[Pg 12] which Marshall, speaking for the Supreme Court of the Nation, was soon to announce.

Joseph Hale wrote to King that Jefferson's election meant the triumph of "the wild principles of uproar & misrule" which would produce "anarchy."[46] Sedgwick advised our Minister at London: "The aristocracy of virtue is destroyed."[47] In the course of a characteristic Federalist speech Theodore Dwight exclaimed: "The great object of Jacobinism is ... to force mankind back into a savage state.... We have a country governed by blockheads and knaves; our wives and daughters are thrown into the stews.... Can the imagination paint anything more dreadful this side of hell."[48]

The keen-eyed and thoughtful John Quincy Adams was of the opinion that "the basis of it all is democratic popularity.... There never was a system of measures [Federalist] more completely and irrevocably abandoned and rejected by the popular voice.... Its restoration would be as absurd as to undertake the resurrection of a carcass seven years in its grave."[49] A Federalist in the Commercial Gazette of Boston,[50] in an article entitled "Calm Reflections," mildly stated that "democracy teems with fanati[Pg 13]cism." Democrats "love liberty ... and, like other lovers, they try their utmost to debauch ... their mistress."

There was among the people a sort of diffused egotism which appears to have been the one characteristic common to Americans of that period. The most ignorant and degraded American felt himself far superior to the most enlightened European. "Behold the universe," wrote the chronicler of Congress in 1802. "See its four quarters filled with savages or slaves. Out of nine hundred millions of human beings but four millions [Americans] are free."[51]

William Wirt describes the contrast of fact to pretension: "Here and there a stately aristocratick palace, with all its appurtenances, strikes the view: while all around for many miles, no other buildings are to be seen but the little smoky huts and log cabins of poor, laborious, ignorant tenants. And what is very ridiculous, these tenants, while they approach the great house, cap in hand, with all the fearful trembling submission of the lowest feudal vassals, boast in their court-yards, with obstreperous exultation, that they live in a land of freemen, a land of equal liberty and equal rights."[52][Pg 14]

Conservatives believed that the youthful Republic was doomed; they could see only confusion, destruction, and decline. Nor did any nation of the Old World at that particular time present an example of composure and constructive organization. All Europe was in a state of strained suspense during the interval of the artificial peace so soon to end. "I consider the whole civilized world as metal thrown back into the furnace to be melted over again," wrote Fisher Ames after the inevitable resumption of the war between France and Great Britain.[53] "Tremendous times in Europe!" exclaimed Jefferson when cannon again were thundering in every country of the Old World. "How mighty this battle of lions & tygers! With what sensations should the common herd of cattle look upon it? With no partialities, certainly!"[54]

Jefferson interpreted the black forebodings of the defeated conservatives as those of men who had been thwarted in the prosecution of evil designs: "The[Pg 15] clergy, who have missed their union with the State, the Anglo men, who have missed their union with England, the political adventurers who have lost the chance of swindling & plunder in the waste of public money, will never cease to bawl, on the breaking up of their sanctuary."[55]

Of all the leading Federalists, John Marshall was the only one who refused to "bawl," at least in the public ear; and yet, as we have seen and shall again find, he entertained the gloomy views of his political associates. Also, he held more firmly than any prominent man in America to the old-time Federalist principle of Nationalism—a principle which with despair he watched his party abandon.[56] His whole being was fixed immovably upon the maintenance of order and constitutional authority. Except for his letter to Pinckney, Marshall was silent amidst the clamor. All that now went forward passed before his regretful vision, and much of it he was making ready to meet and overcome with the affirmative opinions of constructive judicial statesmanship.

Meanwhile he discharged his duties—then very light—as Chief Justice. But in doing so, he quietly began to strengthen the Supreme Court. He did[Pg 16] this by one of those acts of audacity that later marked the assumptions of power which rendered his career historic. For the first time the Chief Justice disregarded the custom of the delivery of opinions by the Justices seriatim, and, instead, calmly assumed the function of announcing, himself, the views of that tribunal. Thus Marshall took the first step in impressing the country with the unity of the highest court of the Nation. He began this practice in Talbot vs. Seeman, familiarly known as the case of the Amelia,[57] the first decided by the Supreme Court after he became Chief Justice.

During our naval war with France an armed merchant ship, the Amelia, owned by one Chapeau Rouge of Hamburg, while homeward bound from Calcutta, was taken by the French corvette, La Diligente. The Amelia's papers, officers, and crew were removed to the French vessel, a French crew placed in charge, and the captured ship was sent to St. Domingo as a prize. On the way to that French port, she was recaptured by the American frigate, Constitution, Captain Silas Talbot, and ordered to New York for adjudication. The owner demanded ship and cargo without payment of the salvage claimed by Talbot for his rescue. The case finally reached the Supreme Court.

In the course of a long and careful opinion the Chief Justice held that, although there had been no formal declaration of war on France, yet particular acts of Congress had authorized American warships to capture certain French vessels and had provided[Pg 17] for the payment of salvage to the captors. Virtually, then, we were at war with France. While the Amelia was not a French craft, she was, when captured by Captain Talbot, "an armed vessel commanded and manned by Frenchmen," and there was "probable cause to believe" that she was French. So her capture was lawful.

Still, the Amelia was not, in fact, a French vessel, but the property of a neutral; and in taking her from the French, Talbot had, in reality, rescued the ship and rendered a benefit to her owners for which he was entitled to salvage. For a decree of the French Republic made it "extremely probable" that the Amelia would be condemned by the French courts in St. Domingo; and that decree, having been "promulgated" by the American Government, must be considered by American courts "as an authenticated copy of a public law of France interesting to all nations." This, said Marshall, was "the real and only question in the case." The first opinion delivered by Marshall as Chief Justice announced, therefore, an important rule of international law and is of permanent value.

Marshall's next case[58] involved complicated questions concerning lands in Kentucky. Like nearly all of his opinions, the one in this case is of no historical importance except that in it he announced for the second time the views of the court. In United States vs. Schooner Peggy,[59] Marshall declared that, since the Constitution makes a treaty a "supreme law of the land," courts are as much bound by it as[Pg 18] by an act of Congress. This was the first time that principle was stated by the Supreme Court. Another case[60] concerned the law of practice and of evidence. This was the last case in which Marshall delivered an opinion before the Republican assault on the Judiciary was made—the causes of which assault we are now to examine.

At the time of his inauguration, Jefferson apparently meant to carry out the bargain[61] by which his election was made possible. "We are all Republicans, we are all Federalists," were the reassuring words with which he sought to quiet those who already were beginning to regret that they had yielded to his promises.[62] Even Marshall was almost favorably impressed by the inaugural address. "I have administered the oath to the Presdt.," he writes Pinckney immediately after Jefferson had been inducted into office. "His inauguration speech ... is in general well judged and conciliatory. It is in direct terms giving the lie to the violent party declamation which has elected him, but it is strongly characteristic of the general cast of this political theory."[63]

It is likely that, for the moment, the President intended to keep faith with the Federalist leaders. But the Republican multitude demanded the spoils of victory; and the Republican leaders were not slow or soft-spoken in telling their chieftain that he must take those measures, the assurance of which[Pg 19] had captivated the popular heart and given "the party of the people" a majority in both House and Senate.

Thus the Republican programme of demolition was begun. Federalist taxes were, of course, to be abolished; the Federalist mint dismantled; the Federalist army disbanded; the Federalist navy beached. Above all, the Federalist system of National courts was to be altered, the newly appointed Federalist National judges ousted and their places given to Republicans; and if this could not be accomplished, at least the National Judiciary must be humbled and cowed. Yet every step must be taken with circumspection—the cautious politician at the head of the Government would see to that. No atom of party popularity[64] must be jeopardized; on the contrary, Republican strength must be increased at any cost, even at the temporary sacrifice of principle.[65] Unless these facts are borne in mind, the curious blending of fury and moderation—of violent attack and sudden quiescence—in the Re[Pg 20]publican tactics during the first years of Jefferson's Administration are inexplicable.

Jefferson determined to strike first at the National Judiciary. He hated it more than any other of the "abominations" of Federalism. It was the only department of the Government not yet under his control. His early distrust of executive authority, his suspicion of legislative power when his political opponents held it, were now combined against the National courts which he did not control.

Impotent and little respected as the Supreme Court had been and still was, Jefferson nevertheless entertained an especial fear of it; and this feeling had been made personal by the thwarting of his cherished plan of appointing his lieutenant, Spencer Roane of Virginia, Chief Justice of the United States.[66] The elevation of his particular aversion, John Marshall, to that office, had, he felt, wickedly robbed him of the opportunity to make the new regime harmonious; and, what was far worse, it had placed in that station of potential, if as yet undeveloped, power, one who, as Jefferson had finally come to think, might make the high court of the Nation a mighty force in the Government, retard fundamental Republican reforms, and even bring to naught measures dear to the Republican heart.

It seems probable that, at this time, Jefferson was the only man who had taken Marshall's measure correctly. His gentle manner, his friendliness and conviviality, no longer concealed from Jefferson the[Pg 21] courage and determination of his great relative; and Jefferson doubtless saw that Marshall, with his universally conceded ability, would find means to vitalize the National Judiciary, and with his fearlessness, would employ those means.

"The Federalists," wrote Jefferson, "have retired into the judiciary as a stronghold ... and from that battery all the works of republicanism are to be beaten down and erased."[67] Therefore that stronghold must be taken. Never was a military plan more carefully devised than was the Republican method of capturing it. Jefferson would forthwith remove all Federalist United States marshals and attorneys;[68] he would get rid of the National judges whom Adams had appointed under the Judiciary Act of 1801.[69] If this did not make those who remained on the National Bench sufficiently tractable, the sword of impeachment would be held over their obstinate heads until terror of removal and disgrace should render them pliable to the dominant political will.[Pg 22] Thus by progressive stages the Supreme Court would be brought beneath the blade of the executioner and the obnoxious Marshall decapitated or compelled to submit.

To this agreeable course, so well adapted to his purposes, the President was hotly urged by the foremost leaders of his party. Within two weeks after Jefferson's inauguration, the able and determined William Branch Giles of Virginia, faithfully interpreting the general Republican sentiment, demanded "the removal of all its [the Judiciary's] executive officers indiscriminately." This would get rid of the Federalist marshals and clerks of the National courts; they had been and were, avowed Giles, "the humble echoes" of the "vicious schemes" of the National judges, who had been "the most unblushing violators of constitutional restrictions."[70] Again Giles expressed the will of his party: "The revolution [Republican success in 1800] is incomplete so long as that strong fortress [the Judiciary] is in possession of the enemy." He therefore insisted upon "the absolute repeal of the whole judiciary system."[71]

The Federalist leaders quickly divined the first part of the Republican purpose: "There is nothing which the [Republican] party more anxiously wish than the destruction of the judicial arrangements made during the last session," wrote Sedgwick.[72] And Hale, with dreary sarcasm, observed that "the independence of our Judiciary is to be confirmed[Pg 23] by being made wholly subservient to the will of the legislature & the caprice of Executive visions."[73]

The judges themselves had invited the attack so soon to be made upon them.[74] Immediately after the Government was established under the Constitution, they took a position which disturbed a large part of the general public, and also awakened apprehensions in many serious minds. Persons were haled before the National courts charged with offenses unknown to the National statutes and unnamed in the Constitution; nevertheless, the National judges held that these were indictable and punishable under the common law of England.[75]

This was a substantial assumption of power. The Judiciary avowed its right to pick and choose among the myriad of precedents which made up the common law, and to enforce such of them as, in the opinion of the National judges, ought to govern American citizens. In a manner that touched directly the lives and liberties of the people, therefore, the judges[Pg 24] became law-givers as well as law-expounders. Not without reason did the Republicans of Boston drink with loud cheers this toast: "The Common Law of England! May wholesome statutes soon root out this engine of oppression from America."[76]

The occasions that called forth this exercise of judicial authority were the violation of Washington's Neutrality Proclamation, the violation of the Treaty of Peace with Great Britain, and the numberless threats to disregard both. From a strictly legal point of view, these indeed furnished the National courts with plausible reasons for the position they took. Certainly the judges were earnestly patriotic and sincere in their belief that, although Congress had not authorized it, nevertheless, that accumulation of British decisions, usages, and customs called "the common law" was a part of American National jurisprudence; and that, of a surety, the assertion of it in the National tribunals was indispensable to the suppression of crimes against the United States. In charging the National grand jury at Richmond, May 22, 1793, Chief Justice John Jay first announced this doctrine, although not specifically naming the common law.[77] Two months later, Justice James Wilson claimed the same inclusive power in his address to the grand jury at Philadelphia.[78]

In 1793, Joseph Ravara, consul for Genoa, was in[Pg 25]dicted in the United States District Court of Pennsylvania for sending an anonymous and threatening letter to the British Minister and to other persons in order to extort money from them. There was not a word in any act of Congress that referred even indirectly to such a misdemeanor, yet Justices Wilson and Iredell of the Supreme Court, with Judge Peters of the District Court, held that the court had jurisdiction,[79] and at the trial Chief Justice Jay and District Judge Peters held that the rash Genoese could be tried and punished under the common law of England.[80]

Three months later Gideon Henfield was brought to trial for the violation of the Neutrality Proclamation. The accused, a sailor from Salem, Massachusetts, had enlisted at Charleston, South Carolina, on a French privateer and was given a commission as an officer of the French Republic. As such he preyed upon the vessels of the enemies of France. One morning in May, 1793, Captain Henfield sailed into the port of Philadelphia in charge of a British prize captured by the French privateer which he commanded.

Upon demand of the British Minister, Henfield was seized, indicted, and tried in the United States Circuit Court for the District of Pennsylvania.[81] In the absence of any National legislation covering the[Pg 26] subject, Justice Wilson instructed the grand jury that Henfield could, and should, be indicted and punished under British precedents.[82] When the case was heard the charge of the court to the trial jury was to the same effect.[83]

The jury refused to convict.[84] The verdict was "celebrated with extravagant marks of joy and exultation," records Marshall in his account of this memorable trial. "It was universally asked," he says, "what law had been offended, and under what statute was the indictment supported? Were the American people already prepared to give to a proclamation the force of a legislative act, and to subject themselves to the will of the executive? But if they were already sunk to such a state of degradation, were they to be punished for violating a proclamation which had not been published when the offense was committed, if indeed it could be termed an offense to engage with France, combating for liberty against the combined despots of Europe?"[85]

In this wise, political passions were made to strengthen the general protest against riveting the common law of England upon the American people by judicial fiat and without authorization by the National Legislature.

Isaac Williams was indicted and tried in 1799, in the United States Circuit Court for the District of[Pg 27] Connecticut, for violating our treaty with Great Britain by serving as a French naval officer. Williams proved that he had for years been a citizen of France, having been "duly naturalized" in France, "renouncing his allegiance to all other countries, particularly to America, and taking an oath of allegiance to the Republic of France." Although these facts were admitted by counsel for the Government, and although Congress had not passed any statute covering such cases, Chief Justice Oliver Ellsworth practically instructed the jury that under the British common law Williams must be found guilty.

No American could cease to be a citizen of his own country and become a citizen or subject of another country, he said, "without the consent ... of the community."[86] The Chief Justice announced as American law the doctrine then enforced by European nations—"born a subject, always a subject."[87] So the defendant was convicted and sentenced "to pay a fine of a thousand dollars and to suffer four months imprisonment."[88]

These are examples of the application by the National courts of the common law of England in cases[Pg 28] where Congress had failed or refused to act. Crime must be punished, said the judges; if Congress would not make the necessary laws, the courts would act without statutory authority. Until 1812, when the Supreme Court put an end to this doctrine,[89] the National courts, with one exception,[90] continued to apply the common law to crimes and offenses which Congress had refused to recognize as such, and for which American statutes made no provision.

Practically all of the National and many of the State judges were highly learned in the law, and, of course, drew their inspiration from British precedents and the British bench. Indeed, some of them were more British than they were American.[91] "Let a stranger go into our courts," wrote Tyler, "and he[Pg 29] would almost believe himself in the Court of the King's Bench."[92]

This conduct of the National Judiciary furnished Jefferson with another of those "issues" of which that astute politician knew how to make such effective use. He quickly seized upon it, and with characteristic fervency of phrase used it as a powerful weapon against the Federalist Party. All the evil things accomplished by that organization of "monocrats," "aristocrats," and "monarchists"—the bank, the treaty, the Sedition Act, even the army and the navy—"have been solitary, inconsequential, timid things," avowed Jefferson, "in comparison with the audacious, barefaced and sweeping pretension to a system of law for the U.S. without the adoption of their legislature, and so infinitely beyond their power to adopt."[93]

But if the National judges had caused alarm by treating the common law as though it were a statute of the United States without waiting for an act of Congress to make it so, their manners and methods in the enforcement of the Sedition Act[94] aroused against them an ever-increasing hostility.

Stories of their performances on the bench in such cases—their tones when speaking to counsel, to accused persons, and even to witnesses, their immoderate language, their sympathy with one of the European nations then at war and their animosity[Pg 30] toward the other, their partisanship in cases on trial before them—tales made up from such material flew from mouth to mouth, until finally the very name and sight of National judges became obnoxious to most Americans. In short, the assaults upon the National Judiciary were made possible chiefly by the conduct of the National judges themselves.[95]

The first man convicted under the Sedition Law was a Representative in Congress, the notorious Matthew Lyon of Vermont. He had charged President Adams with a "continual grasp for power ... an unbounded thirst for ridiculous pomp, foolish adulation and selfish avarice." Also, Lyon had permitted the publication of a letter to him from Joel Barlow, in which the President's address to the Senate and the Senate's response[96] were referred to as "the bullying speech of your President" and "the stupid answer of your Senate"; and expressed wonder "that the answer of both Houses had not[Pg 31] been an order to send him [Adams] to the mad house."[97]

Lyon was indicted under the accusation that he had tried "to stir up sedition and to bring the President and Government of the United States into contempt." He declared that the jury was selected from his enemies.[98] Under the charge of Justice Paterson of the Supreme Court he was convicted. The court sentenced him to four months in jail and the payment of a fine of one thousand dollars.[99]

In the execution of the sentence, United States Marshal Jabez G. Fitch used the prisoner cruelly. On the way to the jail at Vergennes, Vermont, he was repeatedly insulted. He was finally thrown into a filthy, stench-filled cell without a fireplace and with nothing "but the iron bars to keep the cold out." It was "the common receptacle for horse-thieves ... runaway negroes, or any kind of felons." He was subjected to the same kind of treatment that was accorded in those days to the lowest criminals.[100] The people were deeply stirred by the fate of Matthew Lyon. Quick to realize and respond to public feeling, Jefferson wrote: "I know not which mortifies me most, that I should fear to write what I think, or my country bear such a state of things."[101]

One Anthony Haswell, editor of the Vermont Ga[Pg 32]zette published at Bennington, printed an advertisement of a lottery by which friends of Lyon, who was a poor man, hoped to raise enough money to pay his fine. This advertisement was addressed "to the enemies of political persecutions in the western district of Vermont." It was asserted that Lyon "is holden by the oppressive hand of usurped power in a loathsome prison, deprived almost of the right of reason, and suffering all the indignities which can be heaped upon him by a hard-hearted savage, who has, to the disgrace of Federalism, been elevated to a station where he can satiate his barbarity on the misery of his victims."[102] The "savage" referred to was United States Marshal Fitch. In the same paper an excerpt was reprinted from the Aurora which declared that "the administration publically notified that Tories ... were worthy of the confidence of the government."[103]

Haswell was indicted for sedition. In defense he established the brutality with which Lyon had been treated and proposed to prove by two witnesses not then present (General James Drake of Virginia, and James McHenry, President Adams's Secretary of War) that the Government favored the occasional appointment of Tories to office. Justice Paterson ruled that such evidence was inadmissible, and charged the jury that if Haswell's intent was defamatory, he should be found guilty. Thereupon he was convicted and sentenced to two months' imprisonment and the payment of a fine of two hundred dollars.[104][Pg 33]

Dr. Thomas Cooper, editor of the Sunbury and Northumberland Gazette in Pennsylvania, in the course of a political controversy declared in his paper that when, in the beginning of Adams's Administration, he had asked the President for an office, Adams "was hardly in the infancy of political mistake; even those who doubted his capacity thought well of his intentions.... Nor were we yet saddled with the expense of a permanent navy, or threatened ... with the existence of a standing army.... Mr. Adams ... had not yet interfered ... to influence the decisions of a court of justice."[105]

For this "attack" upon the President, Cooper was indicted under the Sedition Law. Conducting his own defense, he pointed out the issues that divided the two great parties, and insisted upon the propriety of such political criticism as that for which he had been indicted.

Cooper was himself learned in the law,[106] and during the trial he applied for a subpœna duces tecum to compel President Adams to attend as a witness, bringing with him certain documents which Cooper alleged to be necessary to his defense. In a rage Justice Samuel Chase of the Supreme Court, before whom, with Judge Richard Peters of the District Court, the case was tried, refused to issue the writ. For this he was denounced by the Republicans. In the trial of Aaron Burr, Marshall was to issue this very writ to President Thomas Jefferson and, for doing so, to be rebuked, denounced, and abused by the very parti[Pg 34]sans who now assailed Justice Chase for refusing to grant it.[107]

Justice Chase charged the jury at intolerable length: "If a man attempts to destroy the confidence of the people in their officers ... he effectually saps the foundation of the government." It was plain that Cooper "intended to provoke" the Administration, for had he not admitted that, although he did not arraign the motives, he did mean "to censure the conduct of the President"? The offending editor's statement that "our credit is so low that we are obliged to borrow money at 8 per cent. in time of peace," especially irritated the Justice. "I cannot," he cried, "suppress my feelings at this gross attack upon the President." Chase then told the jury that the conduct of France had "rendered a loan necessary"; that undoubtedly Cooper had intended "to mislead the ignorant ... and to influence their votes on the next election."

So Cooper was convicted and sentenced "to pay a fine of four hundred dollars, to be imprisoned for six months, and at the end of that period to find surety for his good behavior himself in a thousand, and two sureties in five hundred dollars each."[108]

"Almost every other country" had been "convulsed with ... war," desolated by "every species of vice and disorder" which left innocence without protection and encouraged "the basest crimes." Only in America there was no "grievance to complain of." Yet our Government had been "as[Pg 35] grossly abused as if it had been guilty of the vilest tyranny"—as if real "republicanism" could "only be found in the happy soil of France" where "Liberty, like the religion of Mahomet, is propagated by the sword." In the "bosom" of that nation "a dagger was concealed."[109] In these terms spoke James Iredell, Associate Justice of the Supreme Court, in addressing the grand jury for the District of Pennsylvania. He was delivering the charge that resulted in the indictment for treason of John Fries and others who had resisted the Federalist land tax.[110]

The triumph of France had, of course, nothing whatever to do with the forcible protest of the Pennsylvania farmers against what they felt to be Federalist extortion; nevertheless upon the charge of Justice Iredell as to the law of treason, they were indicted and convicted for that gravest of all offenses. A new trial was granted because one of the jury, John Rhoad, "had declared a prejudice against the prisoner after he was summoned as a juror."[111] On April 29, 1800, the second trial was held. This time Justice Chase presided. The facts were agreed to by counsel. Before the jury had been sworn, Chase threw on the table three papers in writing and announced that these contained the opinion of the judges upon the law of treason—one copy was for the counsel for the Government, one for the defendant's counsel, and one for the jury.

William Lewis, leading attorney for Fries, and one[Pg 36] of the ablest members of the Philadelphia bar,[112] was enraged. He looked upon the paper, flung it from him, declaring that "his hand never should be polluted by a prejudicated opinion," and withdrew from the case, although Chase tried to persuade him to "go on in any manner he liked." Alexander J. Dallas, the other counsel for Fries, also withdrew, and the terrified prisoner was left to defend himself. The court told him that the judges, personally, would see that justice was done him. Again Fries and his accomplices were convicted under the charge of the court. "In an aweful and affecting manner"[113] Chase pronounced the sentence, which was that the condemned men should be "hanged by the neck until dead."[114]

The Republicans furiously assailed this conviction and sentence. President Adams pardoned Fries and his associates, to the disgust and resentment of the Federalist leaders.[115] On both sides the entire proceeding was made a political issue.

On the heels of this "repetition of outrage," as the Republicans promptly labeled the condemnation of Fries, trod the trial of James Thompson Callender for sedition, over which it was again the fate of the unlucky Chase to preside. The Prospect Before Us, written by Callender under the encouragement of Jefferson,[116] contained a characteristically vicious[Pg 37] screed against Adams. His Administration had been "a tempest of malignant passions"; his system had been "a French war, an American navy, a large standing army, an additional load of taxes." He "was a professed aristocrat and he had proved faithful and serviceable to the British interest" by sending Marshall and his associates to France. In the President's speech to Congress,[117] "this hoary headed incendiary ... bawls to arms! then to arms!"

Callender was indicted for libel under the Sedition Law.

Before Judge Chase started for Virginia, Luther Martin had given him a copy of Callender's pamphlet, with the offensive passages underscored. During a session of the National court at Annapolis, Chase, in a "jocular conversation," had said that he would take Callender's book with him to Richmond, and that, "if Virginia was not too depraved" to furnish a jury of respectable men, he would certainly punish Callender. He would teach the lawyers of Virginia the difference between the liberty and the licentiousness of the press.[118] On the road to Richmond, James Triplett boarded the stage that carried the avenging Justice of the Supreme Court. He told Chase that Callender had once been arrested in Virginia as a vagrant. "It is a pity," replied Chase, "that they had not hanged the rascal."[119][Pg 38]

But the people of Virginia, because of their hatred of the Sedition Law, were ardent champions of Callender. Richmond lawyers were hostile to Chase and were the bitter enemies of the statute which they knew he would enforce. Jefferson was anxious that Callender "should be substantially defended, whether in the first stages by public interference or private contributors."[120]

One ambitious young attorney, George Hay, who seven years later was to act as prosecutor in the greatest trial at which John Marshall ever presided,[121] volunteered to defend Callender, animated to this course by devotion to "the cause of the Constitution," in spite of the fact that he "despised" his adopted client.[122] William Wirt was also inspired to offer his services in the interest of free speech. These Virginia attorneys would show this tyrant of the National Judiciary that the Virginia bar could not be borne down.[123] Of all this the hot-spirited Chase[Pg 39] was advised; and he resolved to forestall the passionate young defenders of liberty. He was as witty as he was fearless, and throughout the trial brought down on Hay and Wirt the laughter of the spectators.