OVER THE BORDER

OVER THE BORDER

A NOVEL

BY

HERMAN WHITAKER

AUTHOR OF “THE SETTLER,” “THE PLANTER,” “THE PROBATIONER,” Etc.

NEW YORK

GROSSET & DUNLAP

PUBLISHERS

Published by Arrangement with Harper & Brothers

Books by HERMAN WHITAKER

OVER THE BORDER

THE PROBATIONER

THE SETTLER

THE PLANTER

THE MYSTERY OF THE BARRANCA

CROSS TRAILS

HARPER & BROTHERS NEW YORK

Established 1817

Over The Border

Copyright, 1917, by Harper & Brothers

Printed in the United States of America

Published May, 1917

TO

Jack London

IN MEMORY OF OLD FRIENDSHIP

I: THE THREE BAD MEN OF LAS BOCAS

The Three had chosen their lair wisely.

In the picturesque Spanish phrase, it “situated itself” midway of the desert, the great Mexican desert that is more varied in its heated monotony than a land of woods and fields and streams. Here it runs to sparse grass land under upland piñon; there spreads over wide, clean sands that reflect like burnished brass the intolerable glare of the sun. Now it marches for leagues with the yuccas that fling crazed arms and shrunken limbs like posturing dwarfs; again it is dotted with lonely mesas, monolithic masses that raise orange and vermilion facades out of a violet mirage. A magic land it is, made out of shattered rainbows, girded with crimson-and-gold mountains that wear around their high foreheads cooling bandages of snow; a land of deathless calms, cyclonic storms, torrential rains, peopled only by the vultures that wheel against the sky and the little golden dust-whorls which dance together over its heated face. A country where dwells the very spirit of romance; of which anything might be predicted and come to pass; therefore, as before said, the very place for a lair.

Secondly, the Three had shown a nice discrimination in the selection of a site. Its capacities in the way of offense and defense would have earned the instant commendation of a medieval baron, Mexican bandit, revolutionist, or “movie” director in search of an ideal robber’s roost. Years ago a Yankee “prospector” with more faith than sense and money enough to have left prospecting severely alone, had kept a raft of peones busy for the better part of two years ripping the heart out of a mountain-top in a feverish search for fabulous gold. Rumors that still linger in Sonora jacales tell that the gringo worked under the direction of the spirits—or a spiritualist, which may or may not be quite the same. The results—to wit, a huge gap in the mountain and an abandoned adobe powder house, now serving as a residence for the Three Bad Men—seem to favor the rumor. Spirits were never good miners. But that is neither here nor there, the Three concerning themselves only with the natural fortifications they thus inherited.

The adobe stood well back in a semicircular gap, protected on three sides by the curving walls of the excavation. Behind them, the mountain dropped almost a thousand feet sheer, and the level bench in front of the house could only be gained by a narrow path that fell like a yellow snake down the steep slopes into thick chaparral. From its edge one overlooked the vast reaches of the central Sonora desert, an ashen sea of sage and mimosa shored in by far mountains that loomed dusky purple or stood out stark yellow as they happened to lie to the sun. Since the Yankee went back on his “controls,” or they on him, a sahuaro cactus had raised its fluted barrel within the excavation, captaining a squad of dwarf yuccas that poked grotesque arms in pathetic entreaty out of the rubble. To these natural improvements the Three had added a ramada, broad porch of poles and cornstalks, in the shade of which they took their ease one hot nooning, two playing pedro at a rough wooden table while the third dozed and nodded with stool tilted back against the adobe wall.

It did not require more than a cursory glance to know the Three for members of that sad colony which is doomed by its past to remain on the wrong side of the Mexican border. Beginning with Sliver Smith, the sleeper; his drowsy lids hid blue eyes that were hard as chips of agate and exactly fitted his reckless face. Just now sleep had softened its lines and brought a certain underlying good-nature. But for the mouth and deep creases down each side of the nose, which bespoke passions violent and unrestrained, one would have put him down now for that which he had been—a cowman from the New Mexican ranges.

The other two, however, really looked the “bad man.” “Bull” Perrin, the biggest and eldest, might have been especially cast by nature for the part. Big, burly, black-visaged, and heavy-jowled, excessive drinking had dyed his face out of all relation to the creamy skin the gods had given him. The hot brown eyes under straight bushy brows bespoke a cyclonic temper. But though Bull conveyed the impression of an “ugly customer” at first sight, a physiognomist would have picked Jake Evers, his partner, as a far more dangerous man. The cold, bleak sparks of eyes in his lean, lantern-jawed face scintillated with cunning. But for a certain humor that lurked about the corners of his mouth, his face would have been utterly repulsive.

Yet after granting their “badness,” there was about them no taint of the mean, rat-like wickedness of the city criminal. Their composite was of strong impulses, misdirected forces gone to waste, of men cast by birth in a wrong age. In the councils of a nation in the olden time, their strength, ferocity, would have gained them power and place; here, out in the desert, they exactly fitted their environment. As much as the horned toad in the sand at Bull’s feet, as much as the lizard that coursed swiftly along the adobe wall above the sleeper’s head; as much as the sahuaro and the tormented yucca, they belonged to the land. Its gold glowed in their bronze. It were a safe bet that—horses and cattle not being in question—they would, at a given emergency, live in the letter of its best traditions.

Looking at Bull and Jake as they sat at play, the former might be likened to a grizzly; the latter to a tiger, alert, stealthy, cunning, ferocious; qualities which sprang into evidence with startling suddenness when a shrill burst of woman’s scolding presently disrupted the heated silence.

Apparently the noise issued from a white cloud that hid the doorway; but as this settled and cleared away, a buxom slattern of a Mexican girl stood revealed. While flicking out the last dust of flour from an empty sack she bitterly reviled the Three. Though delivered in Spanish, the substance of her complaint was international and goes easily into English.

“Flojos! Lazy ones! how shall one cook without flour? The coffee, too, is gone—and the sugar. Of lard or grease there is not a smear for the pan. You must go forth, to-day.”

This was merely the text. While she enlarged thereon with copious illustrations to prove their worthlessness as providers, the two men at the table proceeded quietly with their play. It was the third that finally interrupted the harangue with the irascibility of one aroused from pleasant sleep.

“Shut up, Dove!”

In its literal sense the word stands for the most innocent of birds. But she chose to take the opposite meaning of the sarcastic Spanish.

“Si, señor! I am that or I should not be here now, cooking for three beasts.” After a comparison between them and the lower animals that greatly favored the latter, she ran on with increasing heat:

“‘Dove,’ indeed? Then where is my price? Where are they, the fine clothes, the silks and satins and linen, the jewelry and laces you were to gain for me? Was it by this I was bought?” She held out her dirty black skirt. “I, that might be now sitting in the cantina of Ignacio Flores at Las Bocas, selling aguardiente and anisette to his custom? Si, señores, where are they, the velvets, ribands, and neck chains? I—”

It was at this point that Jake displayed his quality. Swinging swiftly around, he threw his knife, so hard and quickly that it stuck quivering in the door lintel close to the girl’s throat before she had time to close her mouth.

“Here! don’t be so careless.” Bull’s bushy brows drew down over his burning eyes in quick reproof. But his next remark proved that the interference was not based on altruism. “If you croak her, who’s to do the cooking? Any corn left, Rosa?”

Whereas Sliver’s rude interruption had merely stimulated her tongue; whereas, also, she had stuck out that member at Jake the instant she made sure the knife had missed, she now caught her breath with a little, frightened gulp. “Si, señor.”

“Then make some tortillas and serve them along with the jerky,” he called after her. “And bring us out a drink.”

At this Sliver, who had resumed his doze, sat up again. His lugubrious exclamation, “Oh, hell!” caused the others to look up a moment later. With an empty demijohn held upside down Rosa stood in the doorway. She did not speak. But her tragic pose, vindictive nod, said quite plainly, “Now will you go?”

Neither did they speak. The situation was beyond revilings. Slowly Jake picked up and pocketed the cards. Sliver rose to his feet. In single file they marched down the path to find their horses. Indeed, they had caught the animals, saddled up at the stable on the flat below and were riding away through the chaparral before they recovered sufficiently to attempt to fix the blame for the shortage.

Sliver—who, by the way, had gained his nickname under the law of opposites because he was short and stout—remembered that he had warned them several times “notter hit it so hard.” But his testimony lost force by reason of certain “lone drinks” in the absorption of which he had, by the others, been caught. Jake, on the other hand, had pleaded for more liquor and less flour the last time they stocked up at Las Bocas. By frank confession, moreover, he reduced the force of Sliver’s charge that he would never be satisfied with less liquor than “he ked swim in.”

“That’s right. I never really seen at one time more whisky than I felt I c’d drink.”

From this he went on with invectives against the wave of reform which, by its sudden flooding of the “Territ’ries”—as he still called the States of Arizona and New Mexico—might be held indirectly responsible for his present thirst. “For a cowman, like Sliver here, it don’t matter so much, him being used to dry spells out on the range. But for a man that’s dealt faro in a s’loon for a spell of years with two fingers of bourbon allus under his nose, it comes some bitter. Them was the golden days. What a man made in beef cattle or gold was his’n to plank down on a bar or place on a card. Till them pinch-faces from the Middle West descended like locusts upon the lan’, drought was unknown save by a few fool prospectors that got themselves lost in the desert. Locusts? I wrong ’em! A locust does live up to its natural instincts. Locusts is a blessing compared to pinch-faces. Why—” But certain lengthy reflections that established the place of the “Middle-Wester” beneath even the lowly bedbug in the scale of creation, must give place to his conclusion. “Si, señores! ’twas them druv’ me to rustling. But for them I’d still be living honest, dealing straight faro to all comers with on’y an occasional turn from the bottom of the box for the good of the house.”

“Pity for you!”

Bull’s pithy comment was enlarged upon by Sliver.

“An’ you-all needn’t to be howling so loud, either, about them dry spells on the ranges. We allus had it in the bunk-houses an’ ’twas a poor cook that couldn’t hide a keg in the chuck-wagon. As for your faro—’twas to play the odd card you wolves dealt from the bottom that I med my first rustle. But for you I’d be taking my copa right now out of the cook’s keg instead of dying of thirst in this lousy desert.”

There was real heat in the accusation, but the ex-gambler’s lean, leathery face merely split in a dry grin.

“If your mother bred you a fool, don’t blame me. The flea bit the dog, the dog bit me; I kicked the dog an’ killed the flea. Take a drink of water, Sliver; it all works out in the end. You next, Bull. Which was it—water, wine, or weemen?”

“None of ’em.” The big rustler shook his head. “Early piety did for me. Prayers morning, noon, an’ night; grace before meals; two long sermons on Sundays, an’ two hours, Sabbath-school, and what would you expect? I was so well brought up I jest had to go wrong. But if we don’t jog along we won’t make Las Bocas to-night.”

As Bull spurred on ahead, Sliver looked at Jake. “Say, he ain’t exactly what you-all ’d call frank in his conversings. If there’s a thing he don’t know about us—well, ’tain’t our fault. But him? When you come to think of it did you ever hear him say how he kem to take up rustling?”

The gambler shook his head. “In a gen’ral way—so gen’ral that I couldn’t tell jest how I got it—I’ve sorter gathered that he once croaked a man. But whether ’twas before or after he took up the profesh I couldn’t say. In the natural order of things, a rustler’s bound, sooner or later, to down some prying fool. There’s so many that try to mix in his business. But if it was before, Bull done it—I’ll bet you the gent had it coming.”

II: OVER THE BORDER

That night the Three put up at the cantina in the little adobe town of Las Bocas, where, by reason of occasional largesses to the leader of the revolutionary faction that happened to be on top, a welcome was always certain. Just now it was more particularly so because the present jefe-politico, a Carranzista, varied his political activities by acting as “fence” in the disposal of their plunder.

In accordance with his advice, the following afternoon found them approaching the American border at a point far west of their usual sphere of operations. While they journeyed the sun slid down its western slant till it hung like a smoky lamp in the far dust of the desert. Behind them the sea of sage still ran off to distant mountains, but the sunset glow washed its dust away, draping the land in a royal robe. Ahead the grade was rising imperceptibly but steadily to a sparse grass country where the sage, palo verde, and yucca gave place to huge sahuaros that strewed the plain with their fluted barrels like the jade columns of some vast ruin. Among them roamed the flocks and herds of a pink-walled hacienda that nestled in a grove of lordly cottonwoods. As they rode past, the Three noted with appraising glances the sleek hides of a fine bunch of steers.

“Dress a thousand pounds of beef apiece,” Jake opined.

“Worth eighty pesos, gold, on the hoof, in El Paso,” Sliver yearningly added.

But their interest went no further—for reasons that appeared when, at sundown, they rode past the concrete pillar that marked the international boundary. Rustler that he was, drunkard and gambler, utterly worthless if the reports current on the New Mexican ranges were to be believed, Sliver’s eye nevertheless lit up at the sight of it; the glow on his hard face was not all sunset reflection.

“The good old U.S.,” he commented. “Some country!”

“He wasn’t talking that way las’ time we crossed.” Jake winked at Bull.

“Guess not. He was cussing Cristobel Columbo for ever having discovered it.”

“That’s right,” Sliver admitted. “But I was what you-all might call in a bit of a hurry with a squad of rangers streaking at my heels. Other things being ekal—”

“Which they ain’t,” Jake interrupted. “Mexico’s good enough for me. Mexico an’ revolution! For I tell you right now that if Porfirio Diaz was still boss, his rurales would have taken right holt where the rangers left off. Instead of dangling from a pine on the American side, we’d hev’ finished with a fusillado on this. But with the government switching every five minutes between Orozco, Villa, Huerta, Carranza, an’ the jefe-politicos an’ governors slaughtering each other between-whiles, it’s nobody’s business to look after us. We make our little sneaks across the border an’ return in peace an’ quiet. So ‘Viva la revolucion!’ That reminds me—where’re you heading, Bull?”

“Livingstone rancho on the Little Stoney.”

“Say, but that’s horses! Don’t they run ’em into the corrals at night?”

The big rustler nodded. “All the easier to find, an’ after you once get them moving it don’t take three days to run ’em over the line. Besides, Don Manuel tol’ me at Las Bocas yesterday that the Carranzistas are needing heavy horses for their artillery over on the Coast. He’ll pay fifty pesos apiece an’ take his chance on a five-thousand-per-cent profit after the old gentleman grabs the presidential chair.” He emphatically concluded, “Horses, you bet!”

“Some risky, cutting ’em out?” Sliver, too, looked dubious.

“Not as much as you think. Did you never have some flea-bitten son of a gun rub down the bars while you slept plumb up against the corral an’ wake next morning to find nary a head in sight? A horse don’t like a corral any more’n a man loves prison. The bars once down, you kin trust ’em to soft-foot it out to the open. Why”—his grin at the remembrance set a flash of good-nature in his hard face—“why, I’ve seen an old nag look back at a colt that kicked the bars passing out just like he was saying, ‘You damn young fool! now you’ve upset the soup!’ Leave it to me. I’ll work ’em out on foot while you sit tight an’ hold my horse. Moon’s going to be jest about right, too. She’ll be taking her first peep about the time we get ’em out in the clear. It’ll be a pipe, then, to saddle up fresh beasts an’ shoot ’em over the border.”

The rancho for which they were heading lay still two hours away, and while they rode the sahuaro pillars gave place in turn to piñon and juniper thinly strewn over rolling grassland. Before night settled down, the wandering cattle-trails they had followed drew into the twin ruts of a wagon-road. Their going was timed by the moon. But it stole out from behind a low hill a trifle ahead of schedule. By its first dim radiance they made out the dark mass of the rancho buildings, house, corrals, stables, in a swale between two hills. It was, however, dark enough for their purpose, and, leaving his horse with the others, Bull went forward on foot.

It was nervous work, sitting there watching the buildings take form under the waxing moon. Their strained senses took every sound, smell, and sight; a dog’s bark, click of horns as a steer scratched his forehead on the top rail of a corral, the impatient pawing of a horse, the warm cattle odor that floated on the night breeze. Dim, uncertain shapes seemed to form and fade in the nearer gloom. They were nervous as cats by the time a gun suddenly flashed under the dark porch of the house.

The croupy cough of a child plus the nervous fears of its mother did it. Not that the woman saw Bull when she drew the curtain and peeped out. But these days, with a new revolution breaking, as Jake put it, “every five minutes” over the border, the American ranchers along the international line slept always with an eye open for possible raids. So far as Bull was concerned, her whisper was just as fatal as though she had seen him.

“Pa! get up! I’m sure there’s some one out there!”

Perhaps the rancher did see. Educated in objects moving through dusk, his plainsman’s eye may have noticed movement. Or perhaps he shot on chance. In either case he was quickly informed by the roar and clatter of hoofs that followed, for though Bull did not expect, now, to get away with a single head, pursuit would be blinded and divided by stampeding the beasts. Dropping the bars while the gun continued to flash its staccato warnings, he started the animals out, leaped on the back of one; as soon as it cleared the huddle, went shooting down the trail, guiding the animal with the swing of his body.

Unfortunately, the whim that governs a stampede moved the other beasts to follow. So when the rancher and his men—in shirts and trousers, but not one without a gun—pulled their mounts out of the stables, their pursuit was guided by the distant thunder of hoofs. Neither did Bull’s quick change to his own beast divert the stampede. When the Three galloped on, the scared animals still followed like dogs at their heels.

“First time my prey ever chased me!” Jake laughed harshly, looking back at the band. “If old man Livingstone don’t follow too close we’ll get ’em yet!”

Bull shook his head. “Not with the moon sailing up to her full an’ the critters leaving a trail broad as a pike road. Listen to that!”

A sharp report punctuated the thud and clatter of the stampede; the first shot of a fusillade that grew hotter and hotter as the horses trailed off right and left, leaving the rustlers more exposed. As yet they were running in the shadow of a long hill where the light was poor. But half a mile ahead lay an open plain unbroken by cover.

“They’ll shoot the lights outen us there!” Sliver prophesied. “Better make a stan’ while we can.”

“They are getting sassy,” Jake agreed, as a bullet whizzed under his chin. “We’ll have to teach ’em this ain’t no turkey-shoot.”

The deciding word came, as usual, from Bull. “They’d surround an’ hold us for the posse. You ride on while I check ’em. If they try to round me it’ll be up to you to take ’em from the rear. Get behind so’s they don’t see me turn.”

In the faint light his sudden whirl behind a bush went unnoticed. He had already unshipped his rifle from the saddle slings, and through the upper branches he took careful aim. A hundred yards away Livingstone was coming at full gallop, about the same distance ahead of his men. Bull waited till he could see the old fellow’s hair, silver in the moonlight, framing his angry red face. Once the sights lined up level between the eyes. But muttering, “I ked sure spoil your beauty, but—I won’t,” Bull lowered them to the horse’s chest and fired.

With the report the beast plunged forward, head and neck doubled under, throwing his rider out in the clear. Though badly shaken, the old man was up the next instant, and as he ran for cover his sudden change of expression from anger to flustered surprise drew from Bull a grin.

“Teach you not to get so fresh.”

At the crack of the rifle the others had also darted for cover, and as their guns began to spit and flash from the chaparral along the hillside, Bull laughed outright. “Not a rifle among ’em. Easy going! Hasta luego, señores! Some other time!”

One or two bolder spirits emerged from the chaparral as Bull rode out in the open. But they scuttled back like rabbits as he swung in the saddle with leveled rifle. Though they followed till the boundary pillar stood out, two hours later, a shining silver shaft under the brilliant moon, they preserved always a safe distance, and Bull denied Sliver’s suggestion to “chuck a volley” into the dim mass.

“Kain’t you leave your Uncle Samuel sleep? He ain’t a-going to be moved off his ‘watchful waiting’ by the loss of no horse, but if we go to killing folks, he’s sure going to take time to catch our goat b’twixt revolutions.”

“To-morrow morning,” Jake commented, grinning, “the morning papers will be running scareheads an inch high about the ‘Latest Border Outrage!’ Meanwhile we’ll be jogging home—”

“—without the horses,” Bull dryly finished.

“An’ Rosa, back at the roost,” Sliver added, “howling for coffee an’ flour an’ grease.”

Which reminded Jake of their former argument: “I told you we orter ha’ bought more whisky. Nothing left but to ride back to Las Bocas an’ hit Don Miguel for credit.”

III: EVEN A RUSTLER HAS HIS TROUBLES

Las Bocas was slowly stewing in its native filth when the Three sighted it again at noon next day.

In all the world nothing reflects its environment more faithfully than a Mexican town. Southward, the great cities of Mexico and Guadalajara testify with their stately cathedrals, ornate public buildings, theaters, parks, and plazas, the flowering patios of lovely and luxurious homes, first to the richness of the central Mexican plateau, secondly to the fact that in normal times all the wealth of the republic drains to them. Oppositely, the northern towns with their squalid adobe streets, overrun with a plague of dirty children, dogs, vultures, pigs; desiccated by fierce heat, drowned by torrential rains; these in their place and turn are eminently characteristic of the arid desert. Save that it was a little smaller, a little dirtier, perhaps a little richer in the variety of its stenches, Las Bocas might serve as the type of all Mexican frontier towns.

As the wind blew their way, the Three smelled it from afar. But usage breeds indifference even to evil odors. If not actually homesome, the fetor bespoke a possible drink.

A quarter mile before entering the town they crossed the arroyo that gave it drink. Its waters also furnished an open-air laundry for two brown girls who knelt by its edge, pounding their soiled linen on flat boulders. These days of rampant revolution, a good girl had needs be careful, and at sight of the Three, dusty, unkempt, bearded, and gaunt from tire and travel, gringos at that, the two leaped up and fled toward the town.

Grinning at their fright, Bull and Sliver would have ridden on, but Jake, who never missed a trick, reined in his beast and began to examine the laundry with the eye of a connoisseur. Though the remainder of her be clad in rags, the humblest peona will have her lace petticoat, and the dozen or so pieces that were already spread out to dry on the neighboring bushes were really very fine.

“D’you allow to turn lady’s maid?” Sliver spoke, as Jake bent to stuff the lingerie into his saddle-bags.

“Not till Rosa’s had the refusal of it. This orter keep her satisfied for at least a month.”

Grinning, the pair of rascals spurred their jaded beasts and overtook Bull as he entered a narrow gut of a street that followed the meanderings of the original cow-path to the jefe’s house, a plastered adobe, limewashed in purple and gold, that faced the inevitable military barracks across a sorry attempt at a plaza.

If the small traders and artisans who constituted the bulk of the population had been addicted to such flights of imagination, they might have pictured the jefatura’s yawning gates as a huge gullet through which, in normal times, their substance drained in taxes, fines, and imposts to Mexico City, the nation’s stomach, there to be consumed by a hungry tribe of official hookworms. Now, of course, it was being deflected into the private pocket of the dominant revolutionary chief. Lacking the imagination, they cursed beneath their breath and waited patiently till the next revolution should bring a new tyrant to avenge them on the present oppressor.

The latest incumbent was at lunch under the peppertree in the patio when the Three dismounted at the gates. Fat and sleek and brown, his generally gross appearance was accentuated by pouched beady eyes, waxed mustache, unhealthy, erupted skin. As he sat there, shoveling in frijoles and chile, even a peon’s slack imaginings could have easily established a resemblance—if not between him and a hookworm, at least, to some greedy parasite. The irritability, blind individualism, offensive conceit, treachery, too common to Mexicans, lay hidden under the usual veneer of Spanish courtesy. The embraces, backpattings, effusive greetings with which he welcomed the Three would have graced the reception of a favorite son.

“Enter, amigos!” His welcome buzzed through the patio. “Sit down and eat. Afterward we shall look over the horses. You have bestowed them—where?”

But when he learned of their failure, the scorpion showed through the glaze of courtesy like a fly in amber. “Carambar-r-r-aa, señores!” His read wagged in a nasty way. “I had counted on the horses—to save your alive. On my desk lies a requisition from your gringo border police, demanding your bodies. Que desgracia!” The spite that scintillated in his beads of eyes gave his words sinister significance. “One would dislike to do it, if ’twere only through hate of your Government. But one has to account to his chiefs. Already they have inquired for you, and always I made answer, ‘These are good hombres, useful to our cause.’ But deeds count more than words. Horses for their artilleria would have proved your worth. But now—” a second nasty wag told that their failure left them as other gringos, to be despised, hated, persecuted. Having given the impression time to sink in, he suggested, “But there must be others? You will try again?”

“No use.” Bull’s gloom emphasized the denial. “This is the second time in a month that we’ve been chased across the border. They’re looking for us all along the line.”

“Si? Then must you go elsewhere. What of”—pausing, he looked cautiously around—“what of this side? In central Chihuahua there are many horse-ranchos, gringo ranches with fine blooded stock.”

“But—”

The jefe’s shrug anticipated the objection. “Si, si! ’tis Mexico. That is what I have always told my chief—‘these hombres bother only the gringo pigs.’” With a covert grin at the safe insult, he continued, “But a gringo is a gringo, whether here or in your United States. If they be despoiled, we shall not shed many tears. There will be a complaint, of course, to and from your Government, and much writing between departments. In the mean time we have the horses. So—”

“But that’s Valles’s country, isn’t it?” Jake put in. “He’s a bad hombre to fool with!”

The jefe turned on him his evil grin. “What if the gringo ranchers had caught you last night? Hanging, amigo, is a dog’s death. I would prefer the fusilado of Valles’s men.”

“What if he kicks to your people? Puts in a claim for our heads? You’re working together, ain’t you?”

Once again the jefe looked around. “Listen, amigos! Between friends one may show the truth. Already there is a cloud, a little cloud, no bigger than a child’s hand arisen between us and Valles. If the horses are taken from a gringo rancho in Valles’s country, my chiefs will be the better pleased. What they have Valles cannot get in the days when the cloud grows big and black and bursts.”

Sliver, who understood more Spanish than he could speak, here nudged Bull. “Ask him if he’ll grub-stake the deal.”

“Ask nothing!” Bull’s hot eyes shot brown fire. “You heard him rubbing it into us, didn’t you? If it wasn’t that we need him I’d wring the little brown adder’s neck.” He went on, suavely, in Spanish, “My amigo questions me of the price. It will be the same—fifty pesos apiece, señor?”

Nodding, the jefe glanced impatiently back at his lunch. He appeared to have forgotten his invitation. Pleading an engagement, he bowed them out through the gates, then returned to his gorging while, hungrier, and even still thirstier, the Three rode down the street.

Usually they were not averse to an exchange of glances, or a flirtation—if the hombre was not in sight—with the brown girls who watched them from their doorways. But now their glances sought only the cantinas, whose open bars displayed a tempting array of bottles. While they looked their progress grew constantly slower, finally stopped in front of one whose owner was taking his siesta stretched out on the bar.

Jake looked from the sleeper to his companions, then at the bottles of anisette and tequila on the rough wooden shelves. “If he was drunk it ’u’d be easy—” As the Mexican disposed of the doubt, just then, by opening one excessively sober eye, Jake desperately concluded, “Say, kain’t we raise the price among us?”

Bull tapped his empty pockets.

Sliver mourned, “All I’ve got is a Confederate five some one slipped me during my last toot in El Paso. I’ve carried it sence for a lucky piece.”

“An’ lucky it is!” Jake extended an eager hand. “After this revolutionary currency that’s run off by the million on a newspaper press, these greasers are crazy for gringo bills. What if it has got Jeff Davis’s picter on it? This fellow don’t know him from Abe Lincoln. All gringo bills look alike to him. He’ll never know the diff.”

Neither did he. The note, when thrown with elaborate carelessness on the bar, brought in exchange at current ratios thirty-two pesos and some centavos, along with three stiff copas. Deceived by the size of the roll, the Three now proceeded to order from the tienda behind the bar coffee, sugar, maize, the grease of Rosa’s desire, and other necessaries. With half a dozen bottles of tequila, it made a goodly pile on the counter, but the offer of the roll brought a second lesson in finance—to wit, that cheap money buys few goods. After segregating the tequila from the groceries, the merchant explained with a bow and shrug that the thirty-two dollars and some centavos aforesaid represented the value of either.

From the groceries, the glances of the Three passed to the tequila; then, with one accord, their hands went out and each closed on the neck of a bottle. They were already outside when, looking back, Sliver happened to catch the merchant’s eye.

He grinned, answering Sliver’s wink. “Si, señores, this time you shall drink with me.”

That which followed was quite accidental. While the Mexican was setting out three glasses, Jake drew a pack of cards from his pocket and began to throw two kings and an ace in the “three-card trick.” So deftly he did it that Sliver, who was really trying to pick the ace, failed half a dozen times in succession. Their backs being turned, only Bull noticed the Mexican’s interest in the performance. Fascinated, he watched the flying cards.

“Looks easy, don’t it?” Bull suggested. “Here, Sliver, give this hombre a chance.”

Of course he succeeded, and, being Mexican, his conceit prodded him on to try again. He could do it! He’d bet his sombrero, his horse, his store, that he could do it every time! The Three being possessed of no other stake, he finally wagered the pile of goods, which still stood on the counter, against their bottles of tequila—and lost! In the course of the next half-hour, being judiciously led on by occasional winnings, there were added to the groceries six other bottles, the original thirty-two pesos and some centavos, a bolt of lace and linen for Rosa; but for a large, greasy, and infuriated brown woman who charged them suddenly from the rear of the store he would undoubtedly have lost his all. Further acquisitions being balked by her unreasonable interference with the course of nature as applied to fools, the Three packed their winnings in the saddle-bags and rode on their way.

As a rule a certain fairness is inherent in the externally masculine. Even a Mexican expects to pay his losings, and, of his own impulse, the comerciante would probably have let things go with a shrug. But not so his woman! The eternally feminine is ever a poor loser—perhaps because she has usually no hand in the game—and as the Three rode off she let loose an outcry that brought a gendarme running from around the corner.

“It is that honest Mexicans are robbed by gringo thieves while thou art lost in a siesta!” she assailed him. “After them, lazy one, and recover our goods!”

By her violence she might have lost her case. With an answer that was quite ungentlemanly the gendarme had already turned to go, when the two girls whom Jake had robbed of their lingerie came tearing up the street and added their outcries to the woman’s clamor. And now the Three were surely out of luck. It chanced that for a week past this very gendarme had been making sheep’s eyes at the larger of the two girls, and now the saints had sent this chance for him to gain her favor.

“They stole thy—” Delicacy gave him pause; then, his natural indignation increased by the nature of the robbery, he hot-footed it up the street and overtook the Three.

Ordinarily the arrest would have been accomplished with lofty Spanish punctilio, but in his heat the gendarme allowed his zeal to exceed his discretion, and thereby invited disaster. For as he seized Bull’s bridle, the rustler reached over, spread his huge hand flat over the man’s angry face, and sent him toppling backward into the kennel. He was up, the next second, long gun in hand. But in that second Jake’s bleak eyes squinted along his gun, Sliver had him covered, Bull’s rifle was aimed from the hip.

To give the Mexican policeman his due, he does not easily give up. If one man cannot bring in a prisoner, ten may. If they fail, perhaps a company can—or a regiment. The man’s shrill whistle was really far more dangerous than his absurd long gun. Instantly it was taken up on the next street and the next; went echoing through the town till it finally brought from the carcel a squad on the run.

By that time the Three had backed up against a wall and stood with rifles leveled across the backs of their beasts. Every particle of human kindness, humor, that had showed in their dealings with one another was gone. Jake’s long teeth were bared in a wolf grin. Sliver’s reckless face had frozen in stone. Bull’s head and huge shoulders rose above his breast, his face dark, imperturbable, fierce. Grim, silent, ferocious as trapped wolves, they faced the squad which took cover while messengers brought an officer and company from the barracks.

Now it was really dangerous. The tragedy that lurks behind all Mexican comedy might break at any moment. In its uniform, that ragged soldiery set forth the history of three revolutions. The silver and gray of Porfirio Diaz’s famed rurales, the blue and red stripes or fatigue linen of the Federal Army, even the charro suits of Orozco’s Colorados, were all represented. But in spite of their motley the men were all fighters, tried by years of guerrilla warfare. Their dark brown faces showed only eager savagery. If it had depended on them, tragedy would have burst forth there and then. But the word had to come from the officer, who found himself looking down the barrels of three leveled rifles. It took him just five seconds to make up his mind on this fundamental truth—whoever else survived, he would die. The game was not worth the candle! Very politely he addressed Bull.

“Did I not see you, señor, at the jefatura just now?”

With Bull’s nod tragedy resolved into comedy. Swinging round on the comerciante and his woman, the officer pronounced on their complaint. “They that gamble must expect to lose. Off, fool! before I throw thee in carcel.”

Having driven in the moral with the flat of his saber across the merchant’s back, he next took up the complaint of the girls. “How know ye that these be they that stole your garments? Only that they passed while you were at the wash? Then back, doves, to your cotes! These be friends of the jefe and no stealers of women’s fripperies.”

Stiffly saluting the Three, he marched his ragged soldiery away.

Five seconds thereafter the Three were again on their way—to the cantina where they usually put up.

“All we’ve gotter do now,” Sliver chuckled as they rode on down the street, “is to rope a stray calf or a pig on the way home, an’ Rosa’ll be fixed for a month.”

But, alas for Rosa! After they had stabled their horses and eaten, followed one of those debauches that occur when men with natural “thirsts” turn loose after a period of deprivation. During its course they spent first the thirty-two pesos and some centavos, drank up their own tequila, finally bartered the groceries to buy still more liquor for the rabble of peones and brown girls that flocked to the cantina like buzzards to carrion.

The “drunk” went through the customary stages from boisterous conviviality, singing, loud boasting, quarreling, fighting. Three times Sliver and Jake locked and rolled on the floor, tearing like tigers at each other’s throats, nor let go till pried apart by Bull. Worse, because really terrible, was it to see the giant rustler, after the other two had lapsed into sottish sleep, sitting with his broad shoulders against the adobe wall, huge hands squeezing an imaginary throat, while his drink-crazed brain rehearsed the details of some past tragedy. Shortly thereafter he also rolled over in drunken sleep.

As they lay there, crumpled, limp, breathing stertorously, there was nothing edifying in the spectacle. It would be unfair to hint at a likeness between them and the swine that snored in the kennel outside; unfair to the swine, which never descend through drink from their natural estate. Drunkards and outlaws, they were probably as low, at that moment, as human beings ever go. Yet when they awoke, sans groceries, sans tequila, sans money, but plus three splitting headaches, they faced the situation with saving humor.

“Tough on Rosa,” Jake said, with a rueful grin.

“If she’s still there,” Sliver doubted. “An’ I’ll bet a peppercorn to a toothpick she ain’t.”

“Chihuahua, now, or starve,” Bull succinctly summed the situation. He added, grinning, “Anyway, we’ll travel light.”

IV: THE TRAIL OF THE COLORADOS

Five days later the Three looked down from a mountain shoulder upon the first and greatest of the Chihuahua haciendas.

Far beyond the limit of sight its level ranges ran. From the crest of the blue range in the distance, their glances would still have traveled on less than half-way to the eastern limit. The Mexican Central train, then running southward in the trough between two ranges thirty miles away, had been speeding all day across lands whose ownership was vested in one man. The half-score of towns, hundred villages, in its environs were there only by his consent. Until the bursting of the first revolution had sent him flying into El Paso with other northern overlords, their thousands of inhabitants, shopkeepers, muleteers, artisans, peones, drew by his grace the very breath of life.

“Seems foolish even to think that one could own all that.”

Jake’s glance wandered over the desert that laid off its shining distances to the horizon. Here and there flat-topped mesas uplifted their chrome and vermilion façades from the dead flat. Very far away, one huge fellow raised phantom battlements from the ghostly waters of a mirage. It was altogether unlike their own Sonora desert. In place of the familiar seas of sage, cactus and spiky yucca were thinly strewn over a land whose unmitigated drought was accentuated by the parched windings of waterless streams. Gold! gold! its shimmer was everywhere; burned in the sand; in the dust whorls that danced with the little winds; in the air that flowed like wine around the royal purple of distant ranges. Lifeless, without sign of human tenancy, its solitary reaches were infinite as the ocean. Yet man and his works were not so very far away. Certain black specks that hovered or wheeled against the blue of the sky a mile away served as a sign-post.

“Vultures,” Sliver pointed. “Must be something dead over there.”

“Or dying?” Bull questioned. “Otherwise the birds ’u’d settle. These days it’s as likely to be human as horse. We might ride down that way.”

And human it proved to be when, half an hour later, they rode out of encircling cactus into an open space around a giant sahuaro. Head fallen back so that his face was turned up to the torrid sun; relaxed, limp as a rag, a man hung by his wrists that had been tied at the full stretch of his arms around the sahuaro’s barrel. During the sixty hours he had hung there without food or water the skin had shrunk till it lay like scorched parchment on the bones of his face. In addition to the vultures that hovered above, others hopped or fluttered over the hot sands, or perched, patient as death itself, on the surrounding cactus. Now and then a bolder scavenger hopped upon his shoulder. But a slow roll of the head, sudden hiss of dry breath, would drive it away. At the approach of the Three the evil creatures rose in a black cloud, filling the air with the beat and swish of coffin wings.

“He’s white! a gringo!” Bull cried it while he hacked at the cords.

“The poor devil!” Sliver spoke softly as he lifted and laid the poor, limp body on his outspread coat.

While he laved the shrunken face and Bull poured water, drop by drop, on the man’s swollen tongue, Jake carefully parted the swollen flesh of the wrists and cut away the cords.

If old man Livingstone, or other of the border ranchers who had suffered through their raids, could have seen them at their merciful work, have noted their gentleness, heard their sympathetic comment, they would probably have refused the evidence of their own eyes. Though still too weak to even raise his head, they brought the man in an hour to the point where he was able, in whispers, to give an account of himself.

He was a miner and his claim lay on a natural bench that jutted out from the sheer wall of a great gulch in the mountains about a mile away. His house, a hut of corrugated iron, stood with a few rough work buildings up there. If he could only get to it, he’d be all right.

And he soon did. Lifted by the others to the saddle in front of Bull and cradled like a child in the rustler’s great arms, he scarcely felt the journey. Viewed as he hung on the sahuaro, dirty, bruised, shrunken by fever and thirst, he might have been any age. But when laid on his bed, washed, fed with a quick soup compounded by Sliver out of pounded jerky and some pea meal he found on a shelf, he proved to be a typical American miner of middle age—short gray beard, hawk profile, high cheek-bones, eyes blue and hard as agate. By the time they had cooked for themselves—for even if his condition had permitted, it was now too late to go on—he had recovered his voice and told them all.

“It was the ‘Colorados’ that tied me up. I knew them by the ‘red hearts’ on the breasts of their charro jackets.”

Even up into their far corner of Sonora had penetrated something of the terror associated with the name. Originally the “Colorados” had been Orozco’s soldiers. But when dispersed by the collapse of his revolution against Madero they had split up into bands and overrun the northern Mexican states. Because of their frightful cruelties they were shot by the Carranzistas whenever caught. But though the spread of the latter power was driving them farther south, they still made occasional raids.

“But I was lucky to get off with that,” he said, after describing the beating that had preceded the tying-up. “They cut the soles off the feet of two of my peones, then drove them, stark-naked, through spiky chollas. When the poor devils fell, exhausted, they beat them to death where they lay on the ground. Surely I was lucky, for if it hadn’t been that they thought I had money, and tied me up to make me confess, I’d have got the same. They left me to raid some rancho, but swore they’d come back.”

Riding in, they had passed the dead peones, and, bad man that he was, Jake shuddered at the memory. “But why do you stay here, with that kind of people running loose?”

“Why do I stay?” The miner repeated the question, with heat. “The American consul in Chihuahua is always asking that. Why does any man stay anywhere? Because his living is there. We came here under treaties that guaranteed our rights in the time of Diaz when this country had been at peace for thirty years. Every cent I had was put into this mine, and I’d worked it along to the point where it would pay big capital to come in when that fanatic, Madero, turned hell loose.

“At first we naturally expected that Uncle Sam would look after our rights. But did he? Yes, by ordering us to get out—we that had invested a thousand million dollars in opening up markets for a hundred million dollars’ worth a year of his manufactured products. Get out and have it all go up in smoke the minute our backs were turned!

“Luckily for me, I had no women folk to complicate the situation. But most of the others had. We’d thought, of course, that the mistreatment of one American woman would bring intervention, and so did the Mexicans till the thing had been done again and again. Since then—know what that Colorado leader replied when I threatened him with the vengeance of our Government?”

“‘Your Government!’ he sneered. ‘We have killed your men, we have ravished your women, we have exterminated your brats; will you tell me what else we can do to make your Government fight?’”

He concluded, with bitter sadness, “I was brought up to love and revere the flag; to believe that an American citizen was safe wherever it floated. But, men! I’ve seen it trampled in the mire, spat upon, defiled by filthy peones, then spread in mockery over the dead bodies of Americans who believed in its power to save.”

In Sonora and on the west coast, so far, foreigners had suffered principally in their goods. But rumors and reports of excesses in the central states had found their way westward; enough of them for the Three to find all the miner had said quite easy of belief.

“It sure puts Uncle Sam in rather a poor light,” Jake agreed. “He don’t seem a bit like the old fellow that sent General Scott right through to Mexico City.”

Bull’s big head moved in an emphatic nod through a thick cloud of tobacco smoke. “Looks like the old gent had lost his pep sence he put the Apaches outer the scalping business an’ got through spanking Johnny Reb.”

Only Sliver, the optimist, stood by the accused. “Jest wait! D’you-all know what’s going to happen one o’ these days? That same Uncle Sam, he’s mighty patient an’ he’s been handed a heap o’ bad counsel; but one of these days he’s a-going to get mad. When he does—listen! he’s a-going to walk down to the Mexican line an’ take a look at it with his nose all crinkled up like he smelled something bad. ‘Things ain’t quite right here!’ he’ll say, ca’m an’ deliberate, that-a-way. Then he’ll stoop an’ pick up that line, an’ when he sots it down again—it ’ull be south of Panama. Jest you-all wait an’ see!”

“‘Wait? Wait?’” the miner sarcastically repeated. “Seems as though I’d heard that before. Wait all you want. As for me—one thing I know. Unless your Uncle Samuel crinkles his nose pretty soon, there’ll be darned few of us gringos left to see.”

“Why not watch from the other side?”

“Watch hell!” The sudden firing of the hard agate eyes showed that, despite his wounds and torture, his just grievance, sorrow, and indignation over his fellows’ wrongs, that despite all the indomitable American spirit, the spirit that dared Indian massacres in the conquest of the plains, the spirit of the Alamo which added Texas and California to the Union, the spirit that preserved the Union itself from disintegration, the fine old spirit of ’76, still burned under all. “Watch hell! As I told you, we came here under treaties that guaranteed protection. We have a right to stay, and by God! we’re going to stay! To-morrow I’ll get together my peones and go right to it again; only”—he observed a significant pause—“the next time the Colorados come there’ll be a machine-gun trained on ’em from up here on the bench. All I ask is that the Lord sends me the same bunch again.”

In this stout frame of mind and recovered sufficiently to move about, the Three left him next morning. Looking back from the mouth of the gorge, they got a last glimpse of him between the towering walls, a solitary figure on the edge of the bench. A wave of the hand and he passed out of their lives—in person, but not in other ways. His was one of the stray figures that stroll casually across the course of a life and, in passing, deflect its course into alien channels. Not for nothing had he suffered torture. That and his talk last night had sown in Bull, at least, a certain leaven; the first fruits whereof showed in the sudden, vicious thump with which he brought his big fist down on the pommel as they rode along.

“I was thinking of what that fellow said las’ night,” he replied to Jake’s questioning look. “To think, after that, we’re out to rob our own countrymen for the benefit of a rotten little greaser.”

“That’s so.” Sliver accepted the new point of view with his accustomed alacrity. “Damned if I seen it that way afore.”

But Jake, always practical, sterilized this absurd sentimentality with a sudden injection of rustler’s sense. “Aw, come off! You fellows may be out for Mexicans, but I’m for myself. We robbed our countrymen on the other side of the line, an’ what’s wrong with robbing them on this? I kain’t see the diff. Business is business; we’ve gotter eat.”

“That’s right, too.” Sliver caught the sense of it. “We’ve sure gotter eat.”

But Bull’s face grew blacker. The Colorado’s boast, “We’ve raped your women, exterminated your brats,” had aroused in him instincts older than the race; the instinct that set the gorilla-like caveman with bristling hair, grinning teeth, in the mouth of his cave; that sent the Saxon hind at the throat of the Norse rover; the instinct that has animated the entire line of men through eons of time to rise in defense of the tribal women.

He felt their soul agony, these tribeswomen of his, condemned to become a prey of peon bandits; and while the feeling swelled within him, his black brow drew down over narrowed hot eyes. His huge frame quivered with indignation as righteous as ever animated the best of the race in the defense of a common cause. And yet—

Business was business, they had to eat! The feeling left untouched their evil habit of life; compelled no immediate change of plan.

About midway of the afternoon the Three sighted the poles of the Mexican Central Railway, a gray line of sticks running off in the distance. As they drew nearer, a certain dark blur on the embankment resolved into the rusted ironwork of a burned train. The line here ran almost due east to round a mountain spur, and as they followed along it the rack and ruin of three revolutions passed under their eyes.

Linking burned trains, that occurred every few miles, long lines of twisted rails writhed and squirmed in the ditch. The desiccated carcasses of dead horses, small twig crosses that marked the graves of their wild riders, ran continuously with the telegraph poles. Far beyond their view they ran, those twisted rails, wrecks, carcasses, and crosses, for ten thousand miles throughout the ramifications of the Nacional railroads, to the uttermost corners of Mexico; and typical of the vast destruction was the burned station they came on at sundown. Topping a black hill that rose abruptly from the plain behind it, a huge wooden cross stood blackly out against the smoldering reds of the evening sky, futile emblem of the simple faith that had relied upon it to save the station.

While the Three sat their horses and gazed at the ruin, a whistle sounded, and out from the north steamed a troop-train, first of a dozen, whose glaring headlights spaced off the dusk which was now falling like a dusty brown blanket over the desert.

As the first rolled past Jake swore softly and Sliver exclaimed in surprise, for never before was seen such a sight. On it were packed some thousand peon soldiers, part of Valles’s army on its way south to pursue the merry trade that had wrought the prevailing destruction. Unlike any other army, its guns, horses, munitions, and supplies were loaded inside, while the soldiers rode with their women on top of box-cars.

In their motley uniforms, regulation khaki or linen alternating with tight charro suits and peon cottons, they were exceedingly picturesque, and not a man of them but was belted or bandoliered with at least fifteen pounds of shining brass cartridges.

Under shelters of cottonwood boughs or serapes stretched on poles, their brown women crouched by clay cooking-pots, set over fires built on earthen hearths within a ring of stones; so while the frijoles and chile simmered and sent forth grateful odors, their lords gambled, smoked, or slept.

Nor did they lack music. On every car careless fellows sat with legs dangling precariously over the edge, while they chanted in a high nasal drone to the tinkling of a guitar. Ablaze with vivid color, scarlets, violets, blues, yellows of the women’s dresses and serapes, wreathed in the faint blue smoke of cooking-fires, the trains flashed out of and passed on into the brown dusk, while the guitar tinkled a subdued minor to their roar and rattle.

As the last rolled by a tall Texan rose alongside a machine-gun that was set up on the car roof and yelled to the Three: “Come on, fellows! We’re going to belt hell out of the Federals at Torreon!”

It was the trumpet call of adventure; Adventure, the mistress of men, she who was largely responsible for their “rustlings,” investing it, as she did, with the fireglows of romance. Subtract the long rides through hot dusks, sudden swoop on drowsy herds, the thunder of the stampede, the fight, pursuit, take away all this and reduce the business to its essence, plain thievery, and not one of the Three but would have turned from it in disgust.

If the train had stopped—perhaps their lives would have been deflected into those roaring, revolutionary channels that led on to death in the trenches outside Torreon. But it rolled on into the dusk, and as it vanished their eyes went to a light that burst like a golden flower in the window of a hut built of railroad ties. Five minutes thereafter they were in full enjoyment of that hospitality which, such as it is, may be had all over Mexico for “a cigarette and a smile.”

While eating they extracted from their host, a simple peon, all the information necessary for the horse raid. To avoid “requisitions” payable in revolutionary currency wet from the nearest newspaper press, the gringos hacendados had driven their animals into the mountain pastures three-quarters of a day’s ride east of the tracks. But omitting the details of the long ride next day over plains where the scant grass ran in sunlit waves ahead of the wind to the horizon, the history of the raid may proceed from the moment the Three sighted the first horses in the hollow of a shallow valley late the following afternoon.

Even at the distance, almost a quarter-mile, they could see the difference in size and condition between them and the common Mexican scrubs. After long study through powerful binoculars that played about the same part in their operations as a “jimmy” in those of a burglar, Bull exclaimed his admiration, “Some horses!”

“But—” Jake indicated five Mexicans who were herding the animals at a fast trot down the valley, “we’re out of luck.”

“Oh, I don’t know.” Bull handed him the glasses. “See what you make of ’em.”

“Colorados!” Jake spied at once the dreaded ensign, the red heart on the blue charro jacket. “It’s the same outfit that tied up the miner, too. Remember how he described the leader? ‘About twice as tall as a common Mexican’? That fellow’s six-foot-two if he’s an inch.”

“The gall of him,” Sliver snorted. “What do you think o’ that? After our horses! Well, they ’ain’t got ’em yet. We’ll jest ride along behind the hill here an’—”

But Jake, who was still gazing through the glasses, dryly interrupted. “No, you bet he hain’t. I’ve a hunch that the gent coming over the hill, there, is the man that owns ’em.”

As yet the new-comer was unseen by the Colorados, and as, without pause, he raced after them down the slope, Bull growled his admiration. “He’s sure got his nerve.”

“Mebbe he don’t know they’re Colorados.”

Perhaps Sliver was right. As the raiders’ backs were turned, the daring rider could not see the dreaded ensign. Or he may have thought that the marauders would fly at the sight of him; intended to afford them opportunity when he pulled his gun and fired.

“Here comes his army!” Jake croaked.

“Only a lad.”

Bull, who now held the glasses, made out both the youthful face, white with anxiety, and the lithe swing of the young body in rhythm with the galloping horse. The anxiety was justified, for as he also raced on down the slope the Colorados swung in their saddles, let go a volley from their short carbines, and dropped the first rider and horse in his tracks. At the same moment the lad’s hat, a soft slouch, blew off, loosing a cloud of fair hair on the breeze. If it had not, a shrill scream would still have proclaimed the rider’s sex.

“Hell!” Bull’s astonishment vented itself in a sudden oath. “It’s a woman! a white girl—dressed in man’s riding-togs!”

V: THE “HACIENDA OF THE TREES”

Strange is fate! From two points, perhaps the width of the world apart, two lives begin their flow, and though their mutual currents be deflected hither and thither by the winds of fortune, tides of chance, yet will they eventually meet, coalesce, and roll on together like two drops that join running in down a window-pane.

Now between John Carleton, owner of some hundred thousand broad acres, and the three rapscallions of Las Bocas the only possible relation would appear to be that which could be established by a well-oiled gun. Between them and Lee Carleton, his pretty daughter, any relation whatever would appear still more foreign. Yet—but let it suffice, for the present, that just about the time the Three had gained almost to the hacienda Carleton and his daughter had reined in their horses on the crest of a grassy knoll that overlooked the buildings.

A long pause, during which neither spoke, gives time for her portrait. Rather tall for a girl and slender without thinness, her fine, erect shoulders and the lines of her lithe body lost nothing by her costume; riding-breeches of military cord, yellow knee-boots, man’s cambric shirt with a negligée collar turned down at the neck. Her features were small and delicately cut; the nose piquant, slightly retroussé. Her eyes, large and brown and widely placed under a low broad brow, vividly contrasted with her fair skin and tawny hair. The face, as a whole, was wonderfully mobile and expressive, almost molten in its swift response to lively emotion. Just now, while she sat on gaze, it expressed that curious yearning, half pathetic, that is born of deep feeling.

“Oh, dad, isn’t it beautiful!”

The sweep of her small hand took in the range rolling in long sunlit billows; but her eyes were on the hacienda—Hacienda de los Arboles, named in the sonorous Spanish after the huge cottonwoods that lent it pleasant shade.

Built in a great square, its massive walls, a yard thick and twice the height of a man, formed the back wall of the stables, adobe cottages, storehouses, and granaries on the inner side. It also lent one corner to the house which rose above it to a second story. Pierced for musketry, with a watch-tower rising above its iron-studded gates, it was, in the old days, a real fort. Besides the long row that followed the meanderings of a dry water-course across the landscape, a cluster of giant cottonwoods raised their glossy heads within the compound, shading with checkered leafage the watering wells and house. Set amidst growing fields of corn and wheat at the foot of a range that loomed in violet, crimson, or gold, according to the hour, it was as pleasant a place as ever a man looked upon and called his home.

Carleton smiled as she added, “I’d hate to have been brought up in El Paso or any other prosy American city.”

He might have replied that there were American cities she might find less prosy than El Paso. But he was well content to have her think as she did.

His own gaze, overlooking the prospect, expressed the pride of accomplishment with which men survey their completed work; nor was his satisfaction less because the buildings themselves were not of his creation. Coming here, sixteen years ago, with a nest-egg of two or three thousand dollars, he had leased and let, bought and sold with Yankee shrewdness; added acre to acre, flock to flock, until, at last, he was in position to buy Los Arboles from a “land-poor” Spanish owner.

To a man without imagination the fact that its foundations had been laid almost four centuries ago by one of Cortés’s conquistadores might have meant little. With Carleton it counted more than its broad acreage. From a trove of old papers left by the former owner he had gathered many a story of siege and battle, scandal and intrigue, consummated within its massive walls. Instead of fairy-tales, he had told these to Lee during her childhood, so that medieval atmosphere had penetrated her very being.

They seldom overlooked the hacienda, as now, without making some observations anent its past. As in some vivid pageant, they saw the old Dons, their señoras, señoritas, savage brown retainers, in the midst of their fighting, working, loving, praying. By self-adoption, as it were, Carleton, at least, had allied himself with them, had come to think of himself as belonging to the family.

“Great old fellows they were!” Though he spoke musingly, now, without connection, she instantly caught his meaning, knew he was harking back. “Great old chaps! I was looking into one of our land titles the other day, and the records read in princely fashion. ‘Between the rivers such and such, of a width that a man may ride in one day,’ that was a favorite method of establishing boundaries. No paring of land like cheese rinds; everything done by wholesale; no haggling over a few square leagues.”

“And here comes one of them.” Lee pointed her quirt at a horseman who had just topped the opposite rise. “Doesn’t he look it?”

Surely he did. The charro suit of soft tanned deerskin with its bolero jacket and tight pantaloons braided or laced with silver; the lithe figure under the suit; dark, handsome face, great Spanish eyes that burned in the dusk of a gold-laced sombrero; the fine horse and Mexican saddle heavily chased in solid silver; the gold-hilted machete in its saddle sheath under the rider’s leg, even the rope riata coiled around the solid silver pommel, horse, rider, and trappings belonged in that pageant of the past.

“It is Ramon Icarza,” Carleton nodded. “He hasn’t been here for a long time.” This he repeated in Spanish when the young man rode up.

“Attending to the herds and the horses, señor. As with you, the most of our peones have run away to the wars. We have left only a few ancianos too feeble and stiff to be of much service. Still, with the aid of the women we manage. That last requisition for the”—his shrug was eloquent in its disdain—“cause. You paid it?”

“Had to—or be confiscated.” With a grin comical in its mixture of amusement and anger, Carleton went on, “I raked up five thousand pesos of Valles’s money and took it to him myself. And what do you think he said? ‘I don’t want that stuff. I can print off a million in a minute. You must pay me in gold.’”

Perhaps because humor has no place in the primitive psychology of his race, Ramon received the news with a black frown. “The devil take him! Yet you Americans are better treated than we, his countrymen. With us, he takes all. Those poor Chihuahua comerciantes!” His hands and eyebrows testified to Valles’s scandalous treatment of the merchants. “First he demands a contribution to the cause. Those who refuse are foolish, for first he shoots them as traitors, then confiscates their goods. But the poor devils who contribute, see you, fare little better; for with the money he runs off a newspaper press he buys up the goods they have left. In the old days we used to curse the locusts, señor; but they, at least, left us our beasts and lands. Who would have thought, four years ago, that you and the señorita here and my venerable father would be reduced to become herders of cattle?”

“Oh, but it’s lots of fun!” Lee’s happy laugh bespoke sincerity. “I love it out here. They will never be able to get me back in the house. And that reminds me that we’re almost due there for lunch.”

“You’ll stay, of course, Ramon?” Pointing to a couple of mares with foals they had brought in from a distant part of the range, Carleton added, “There’s still another over in the next valley. If you will take these along, I’ll get her.”

Left to themselves, the young man and girl headed the mares toward the hacienda, riding sufficiently in rear to check the sudden, aimless boltings of the foals. The helplessness of the little creatures touched the girl’s maternal instinct, and though their stilts of legs, wabbly knees, long necks, and big heads were badly out of drawing, she exclaimed like a true mother over their beauty.

“Oh, aren’t they pretty!”

Ramon agreed—as he would had she called upon him to admire a Gila monster. Not that he had always followed her lead. Close neighbors—that is, as neighboring goes in range countries where distance is reckoned by the hundred miles—their childhood had compassed more than the usual number of squabbles. Until the dawn of masculine instinct had bound him slave to her budding beauty, they had upset the peace and dignity of many a ceremonial visit by fighting like cat and dog. Lee knew, of course, his mother and sister, and not until she had extracted the last iota of family gossip did she bestow a sisterly inspection on himself and clothes. Having passed favorably on the material, fit, and trimmings, she reached for his sombrero.

“You are quite the hacendado, now, Ramon, in that magnificent hat. Let me look at it. What a beauty!”

While she turned and twisted it, fingered the rich gold braid, examined it with head slightly askew like a pretty bird, the natural glow intensified in Ramon’s big dark eyes; a wave of color flowed through the gold of his skin. His mouth—too red and womanish for Anglo-Saxon standards—drew into a tender smile.

According to the cañons of fiction, this was wrong. A man with a black or brown skin must reserve his admiration for women of his race. Yet, with singular disregard, for writer’s law, Nature continued to weave for Ramon her potent spells. The sunshine snared in Lee’s hair, rose blush of her skin, her womanly contours, the fine molding of her limbs, the sweetness of youth, all the witcheries of form and color with which Nature lures her creatures to their matings, affected the lad just as powerfully as if he had been born north of the Rio Grande.

On her part Lee ought to have resented his admiration. But here, again, Nature utterly ignored “best seller” conventions. Brought up among Mexicans, counting Ramon’s sister her best friend, Lee felt no racial prejudice. Wherefore, like any other young girl possessed of normal health and spirits, she made the most of the situation. After sufficiently admiring the hat, she tried it on.

“How does it look?”

As she faced him, saucily smiling from under the enormous brim, there was no mistaking the “dare.” Whether or no the custom obtains in Mexico, Ramon caught the implication.

“Pretty enough to—kiss!”

With the word he reached swiftly for her neck, but caught only empty air. Ducking with a touch of the spur, she shot from under his hand.

The next second he was after her. Along the shallow valley for a half-mile she led, then, whirling just as he rode alongside, she shot back along the ridge. At the end he overtook her, and, anticipating her whirl, caught her bridle rein. Leaning back, however, flat on her beast’s back, laughing and panting, she was still out of his reach; and when he began to travel, hand over hand, along the bridle, she leaped down on the opposite side and dodged behind a lone sahuaro.

Sure of her now, he followed. But, dodging like a hare around the sahuaro, she came racing back for the horses; might possibly have gained them and made good her escape, if, glancing back over her shoulder, she had not seen Ramon stumble, stop, then clasp his right ankle.

“Oh, is it sprained?” she cried, running back. Then, as, reaching suddenly, he caught her, she burst out, “Cheat! oh, you miserable cheat!”

That all is fair in love and war, however, goes in all languages, and while she punctuated the struggle with customary objections whereby young maids enhance the value of a kiss, there was no anger in her protests. Wrestling her back and down, he got, at last, the laughing face upturned in the hollow of his arm; had almost reached her lips, when, with force that sent Lee to the ground, he was seized and thrown violently against the horse.

In the excitement of the chase they had completely forgotten Carleton, who had viewed its beginnings from the opposite ridge. By self-adoption he had almost, as before said, identified himself with the Spanish strain that had flowed for centuries through the patios and compound of Los Arboles. He had even come to think in Spanish; in custom and manner was almost Mexican. But in moments of anger habit gives place to instinct. The instinct that first formed and later preserved the tribe, pride of race, overpowered friendship. In one second the young Mexican, whom he had regarded for years almost as a son, was transmuted into the despised “greaser” of the border.

“You—you—” Choking with anger, eyes bits of blue flame, he strode at Ramon, fist bunched to strike.

But the blow did not fall, for, scrambling up again, Lee seized his arm from behind. “Oh, dad! dad!” Despite his struggles, she clung like a cat, defeating his efforts to shake her off. “Oh, dad! It was only a bit of fun! all my fault! I put on his hat! Please don’t!”

If the young fellow had flinched, perhaps Carleton would have struck. But, head erect, he quietly waited, and presently Carleton ceased struggling.

“All right! I’ll let him go—this time. But, remember”—bringing his clenched fist in a heat of passion into the palm of the other hand, he glared at the young man—“remember! when this girl is kissed—it will be by a man of her own breed. Get off my land!” After helping Lee to mount, he vaulted into his own saddle and rode away, driving the mares and foals before them.

In accordance with before-mentioned precedents, Ramon ought to have folded his arms and hissed a threat through gritted teeth. Instead, he stood very quietly, his face less angry than sad, watching them go. His little nod, in its firmness, would have become any young American; went very well with his thought.

“We shall see.”

Mounting, he rode away to the northward, and not till he had covered many miles did he rein in his beast, so suddenly that it fell back on its haunches. His dark face expressed vexation mixed with alarm. “Maldito! I forgot to warn them that Colorados had been seen east of the railroad. I must go back.”

On their part, Lee and her father rode on toward the hacienda. Though he glanced at her from time to time, it was always furtively, for with a man’s dislike of scenes he made no reference to that which had just passed. Nevertheless, it filled his mind. Man-like, he had watched her develop into womanhood with scarcely a thought for her future. If he had given the subject any consideration he would probably have concluded that, sooner or later, she would choose a suitable mate from the hundreds of American miners, railroad men, ranchers, and engineers that had swarmed in the state of Chihuahua before the revolution.

But with the clear vision of after sight he now saw that he had unconsciously depended on the race pride which had just manifested itself in himself to prevent her from contracting a mésalliance. Now, with consternation, he faced the truth that racial pride is masculine; contrary to both the feminine instinct and nature’s scheme of things.

“I was a fool!” he berated himself. “A damned fool! She will have to go north—live in the States for a while.”

These and similar thoughts were whirling through his mind when they came on a band of his horses at pasture under charge of an anciano, a withered old peon, whose age and infirmities had estopped him from joining the exodus to the wars. After cautioning the old fellow not to allow the animals to stray too far, Carleton plunged again into deep meditation.

Had he not been thus preoccupied he would probably have long ago discovered the five horsemen who were following at a distance, using the natural cover afforded by the rolling land; for he always rode with a powerful binocular in his holster, and often swept with it the prospect. Several times the glass would have shown him a row of heads behind the next ridge in rear. As it was, he had ridden to the crest of the rise from which they had looked down on the hacienda before habit asserted itself. He had no sooner leveled the glasses than an exclamation burst from his lips. “My God!”

“What is it, dad?” Lee swung in her saddle, looking back at him.

“Raiders! They are attacking Francisco! He has nothing but his staff! He’s fighting them like an old lion! My God, they’re chopping him with their machetes.” It came out of him in staccato phrases. “Race in and send out Juan, Lerdo, and Prudencia with rifles! Stay there! Don’t dare to follow!”

Digging in his spurs, he galloped away. For a moment the girl hesitated. Her eyes went to the hacienda, still half a mile away, then back to her father racing madly down the slope. There was no time to go for help! Loosening the pistol in her holster, she drove in her spurs and galloped after.

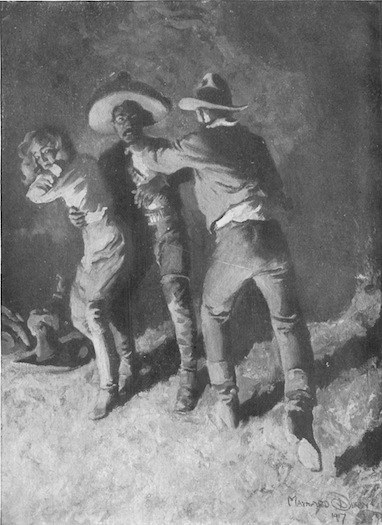

From Carleton’s first appearance till the girl screamed all had passed so quickly that the Three could only sit and gape. From their original intent to rob Carleton it was a far cry to the reconstructed impulse to succor and save him, and it speaks well for them that they accomplished the revolution as soon as they did.

The scream had not passed unnoticed by the Colorados. The leader, who had turned to ride on, swung his beast, looked, then, as the girl dropped from the saddle to her knees beside the wounded man, drove in his spurs and galloped toward her. Heedless of her own danger, Lee was trying to stanch with her handkerchief the bloodflow from Carleton’s chest, so lost in her agonized grief that she did not look up till the Colorado leaped down and seized her.

In this world there are savages who would have respected, for the time at least, her white grief. But this was the man who had tortured the miner and his peones; driven the latter naked through spiky cactus after he had cut the soles off their feet. She sprang up when he seized her, and as she fought bitterly, beating away his black, evil face with her little fists, his strident laughter mingled with her wild sobbing and carried to Bull behind the ridge.

For three days this man’s boast had rung in his brain: “We’ve killed your men, outraged your women!” But though anger blazed within him, his tone was icy cold. “Look after the others. I’ll ’tend to him!”