GREEK GIRLS PLAYING AT BALL.

GREEK GIRLS PLAYING AT BALL.From the Painting by the late Lord Leighton, P.R.A.

By Permission of the Berlin Photographic Co., Bond Street. W.

Title: The Harmsworth Magazine, Vol. 1, 1898-1899, No. 6

Author: Various

Release date: September 8, 2012 [eBook #40711]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Victorian/Edwardian Pictorial Magazines,

Jonathan Ingram, Nick Wall, Diane Monico, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

| "CHRYSANTHEMUMS CURLED HERE." | 579 |

| "OFF TO KLONDYKE." | 583 |

| LITTLE ROYALTIES. | 590 |

| LONDON'S LATEST LION. | 595 |

| THE HOME OF FOUR O'CLOCK TEA. | 605 |

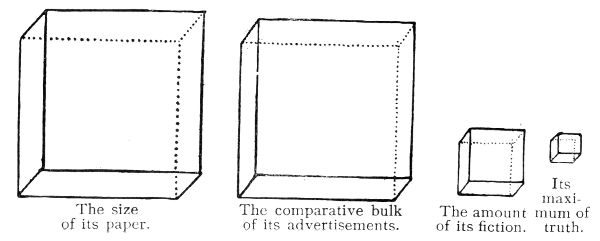

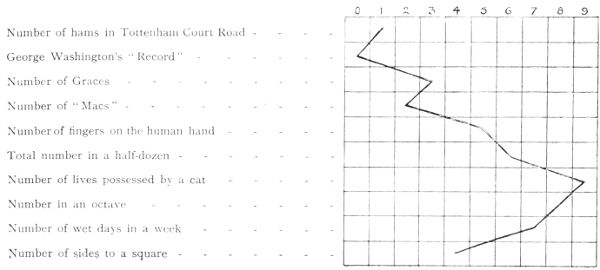

| STATISTICS GONE MAD. | 609 |

| "A PRINCESS IN GREEN AND TAN." | 611 |

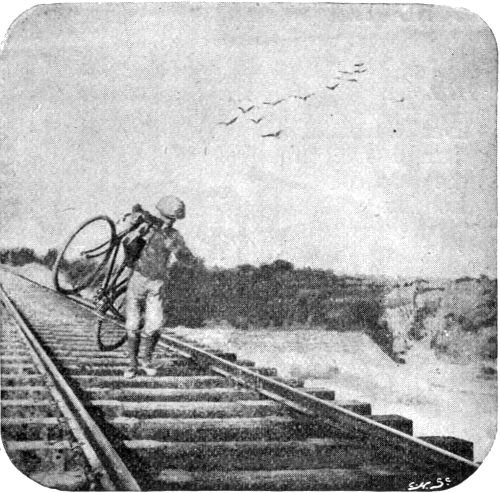

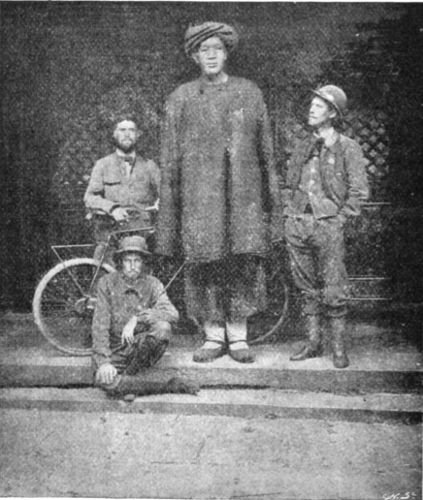

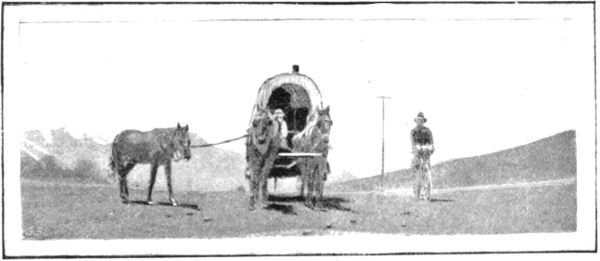

| 3,000 MILES ON RAILWAY SLEEPERS. | 619 |

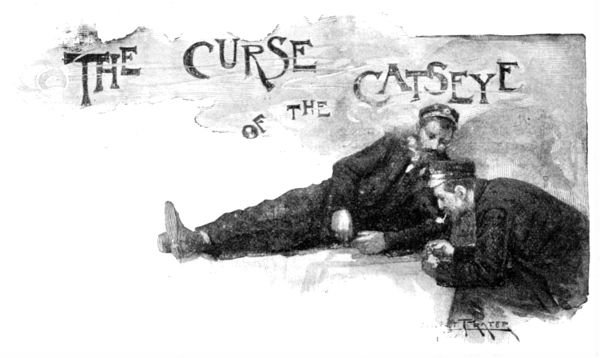

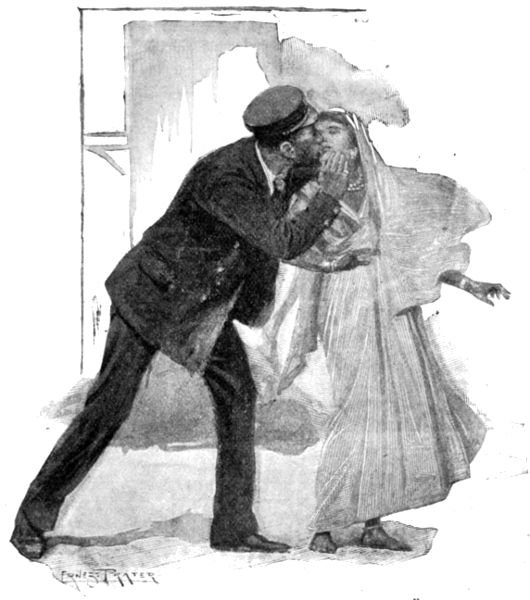

| THE CURSE OF THE CATSEYE. | 623 |

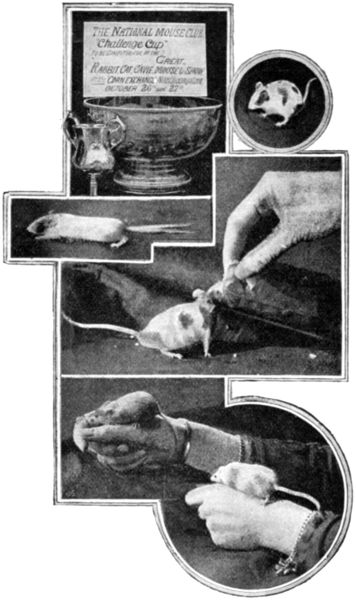

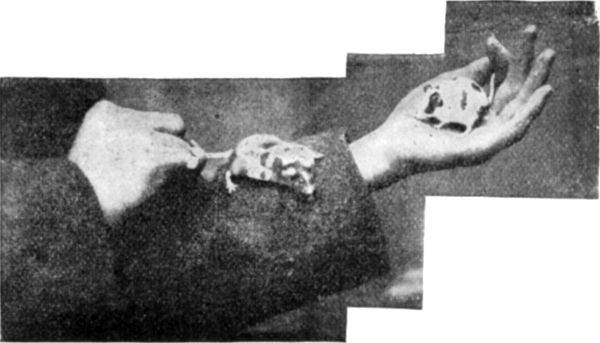

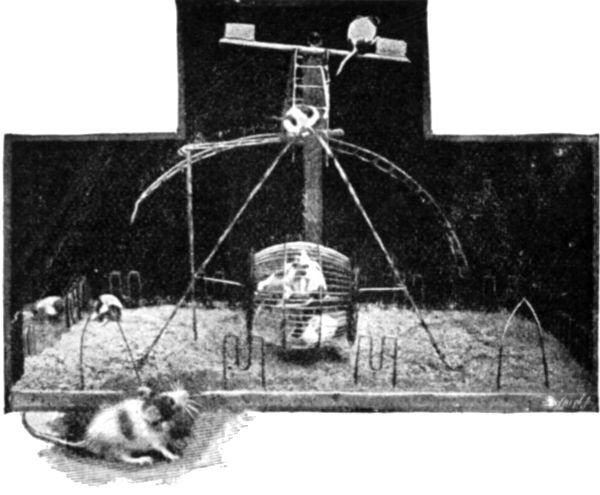

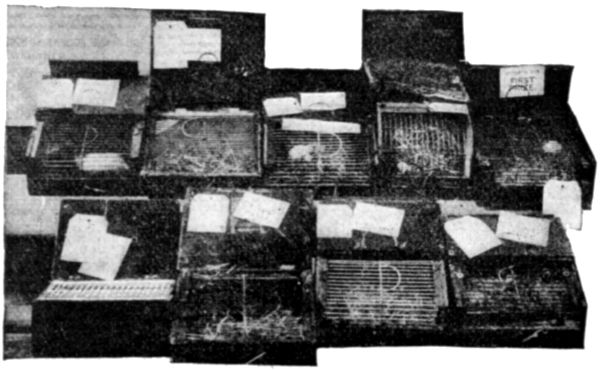

| MICE WORTH THEIR WEIGHT IN GOLD. | 631 |

| A CROWDED HOUR | 634 |

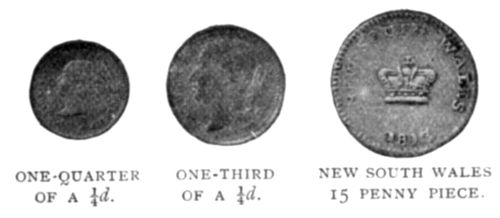

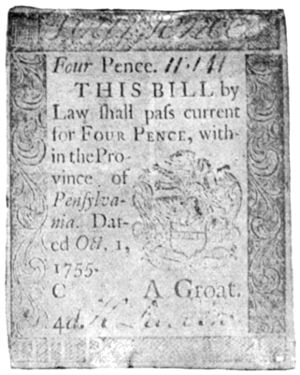

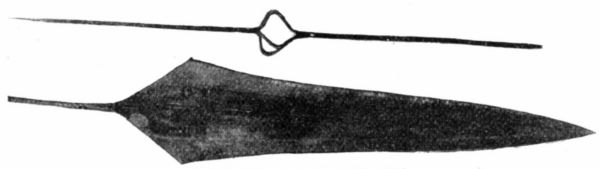

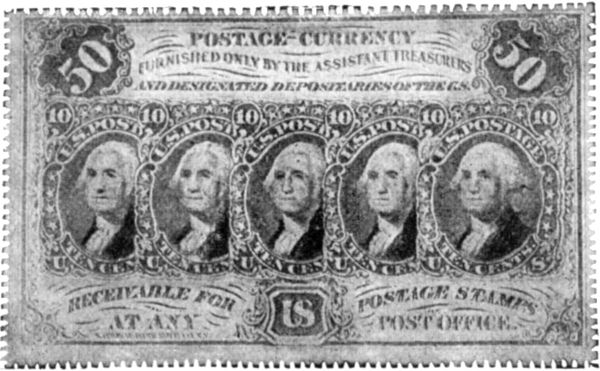

| STRANGE KINDS OF MONEY. | 639 |

| CLEVER MRS. BLADON. | 645 |

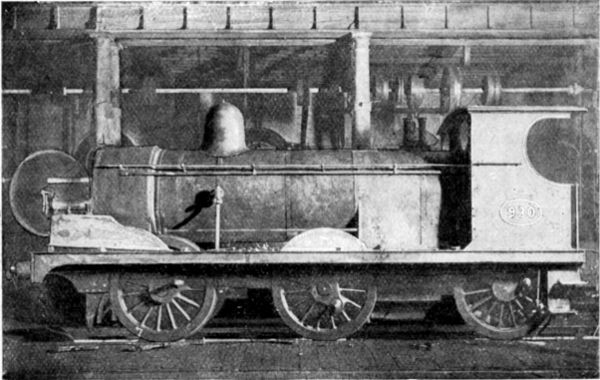

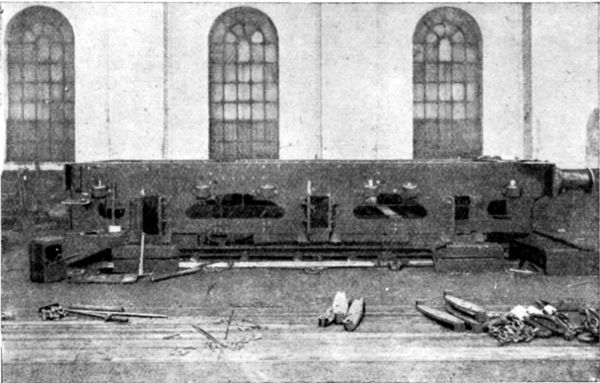

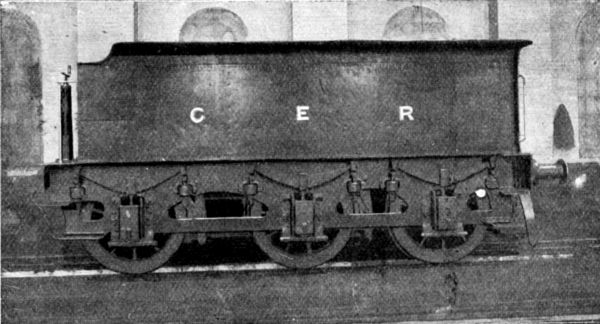

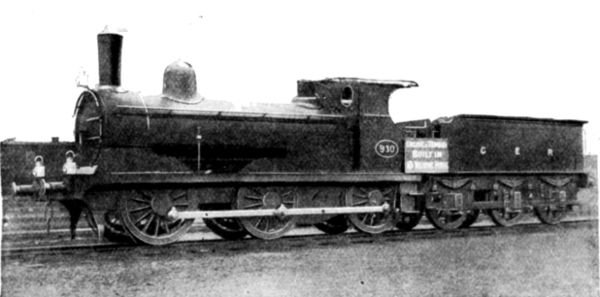

| AN ENGINE MATCH BETWEEN ENGLAND AND AMERICA. | 651 |

| NATURE'S DANGER-SIGNALS. | 656 |

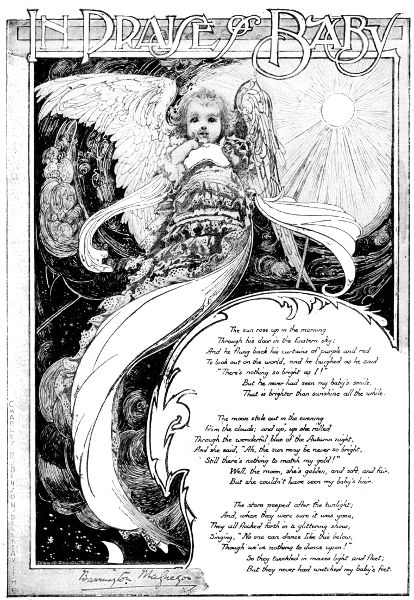

| IN PRAISE OF BABY | 661 |

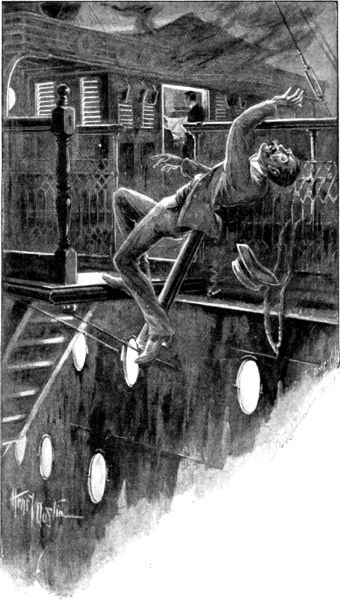

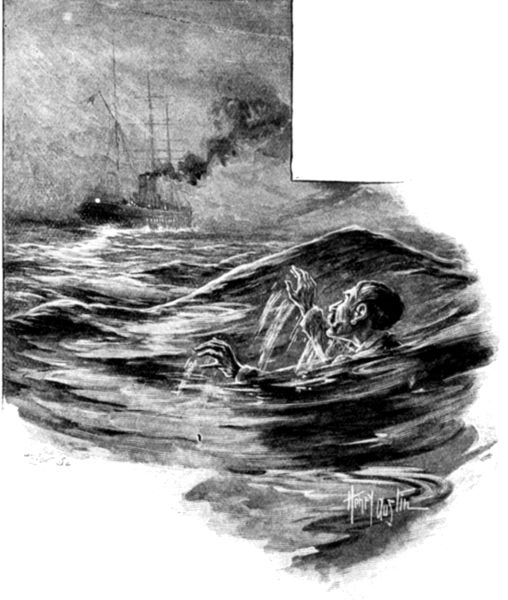

| "MAN OVERBOARD!" | 662 |

| OUR MONTHLY GALLERY OF BEAUTIFUL AND INTERESTING PICTURES. | 665 |

GREEK GIRLS PLAYING AT BALL.

GREEK GIRLS PLAYING AT BALL.A CHAT WITH A FLORAL BARBER.

By Alfred Arkas.

The chrysanthemum is the spoiled and petted darling of the floral world. She is as vain as any society beauty, and quite as much time is spent on her toilet and personal appearance. Though beautiful by nature, she scorns to show herself to her circle of admirers until the arts of the hairdresser and masseur have enhanced her loveliness.

Toilet goes a long way in this world, and many a social star owes half her triumphs to it. Particularly is this true of My Lady Chrysanthemum; for she well repays for any trouble that may be spent upon her.

You cannot paint the lily with any prospect of success, but the number of curls and frills and furbelows you may add to the dainty chrysanthemum bloom, and still leave room for the touch of a titivating hand, is endless.

There are tricks in every trade, and the same is true of most hobbies. Chrysanthemum showing and growing form no exception to the rule. You may have mastered the many little secrets of growing these glorious flowers to the best advantage, and yet be as far from inclusion in the coveted show prize list as though you were but a mere tyro.

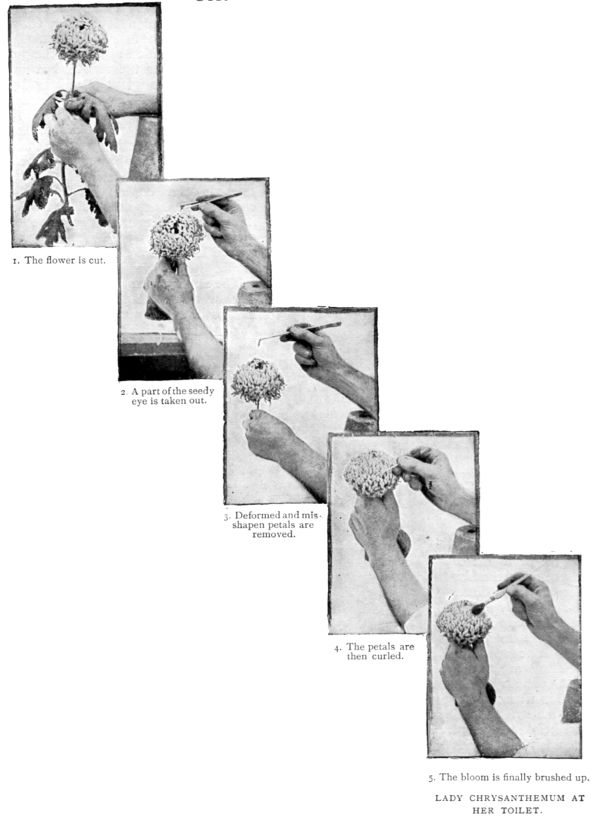

LADY CHRYSANTHEMUM AT HER TOILET.

LADY CHRYSANTHEMUM AT HER TOILET.As a matter of fact the best bloom that ever grew is one thing on the stalk and altogether another in the show box. If you saw some of the magnificent prize-winning and highly commended blossoms which are the feature of the great annual shows before they had been through the deft hands of the floral barber you would fail to recognise them. Glorious they are in their natural state; but, like a beautiful woman, their beauty is only set off the more by a fitting toilet.

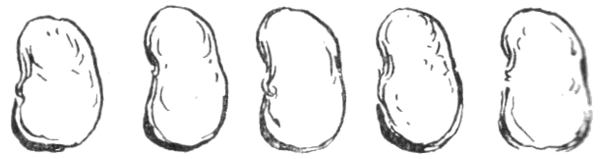

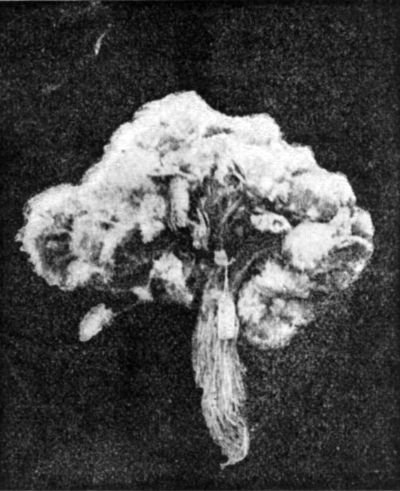

How art may assist nature is admirably shown in the accompanying photographs illustrating My Lady Chrysanthemum in her natural state, and the same bloom dressed and cupped for show purposes. It will probably never have occurred to the majority of people that such dressing is a most important matter in preparing blossoms for exhibition, and it will be news to them that the preparation of this toilet is a matter requiring the greatest skill, and is only to be undertaken with complete success by the horticulturist who has made a special study of chrysanthemum growing and showing.

Such a one is Mr. Southard, who is at present growing prize blooms of all kinds for Mr. Kenyon, of Sutton, Surrey. Mr. Southard is one of the most successful growers in this country of the Japanese national flower. He is an exhibitor whose triumphs in the past are represented by innumerable first, second, and special prizes. And he is generally[Pg 580] recognised as one of the most expert chrysanthemum dressers to be found in a long day's march.

To him we are indebted for our knowledge of the secrets of floral barbering.

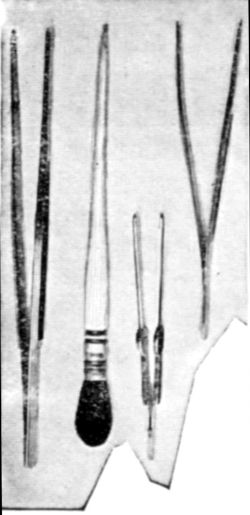

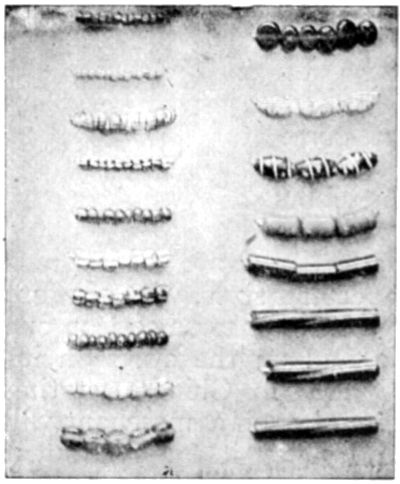

What a science this is may be more readily realised by a glance at our photograph of a set of instruments used for the purpose. These are specially made, and each has a special part to play in dressing the perfect specimen bloom.

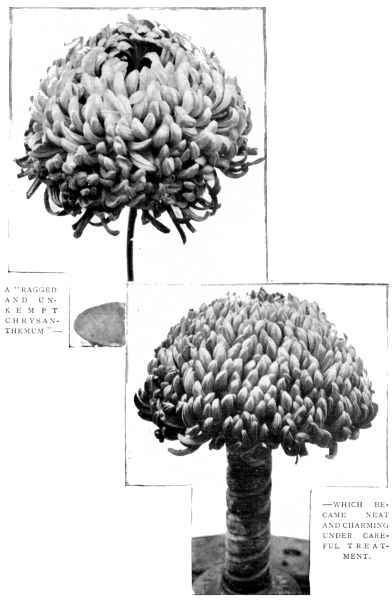

A "RAGGED AND UNKEMPT CHRYSANTHEMUM"—WHICH

BECAME NEAT AND CHARMING UNDER CAREFUL TREATMENT.

A "RAGGED AND UNKEMPT CHRYSANTHEMUM"—WHICH

BECAME NEAT AND CHARMING UNDER CAREFUL TREATMENT.

There are twenty-four varieties of chrysanthemums, but two in particular, the reflex and the incurved, are the subjects of artificial treatment. The accompanying series of photographs show the making of an incurved bloom's toilet from first to last. The first picture illustrates the cutting. To the uninitiated there would not appear to be anything particular about this; but mark one thing. The bloom is cut with a long stalk. This is an important matter: the reason will appear later on. The second photograph of the series illustrates the taking out of a portion of the seedy eye. This is a particularly telling part of the toilet, and goes a long way towards making the bloom show its best.

In the exhibition specimen the petals uniformly cover the flower, but as it appears on the plant it will probably show a considerable amount of centre; unless this is removed it causes an untidy hollow in the middle of the bloom. Portions of the seedy eye are generally removed while the flower is yet on the plant, and the petals then grow naturally towards the centre, and cover the cavity. However, in dressing the bloom it is usual to extract further portions, an operation performed by means of the special instrument shown in the photograph.

The next process is the removing of deformed and misshapen petals. Although not, perhaps, visible to the eye, there are sure to be a few of these lurking beneath the more perfect specimens. They must come out. If visible, they are an eyesore; if invisible, they prevent the others from falling into their natural positions, and so upset the harmony of the whole.

There is a steel forceps provided for this operation. However, the skill is not in using the instrument. Anyone can despoil the plumage of a fine bloom. The art lies in extracting the right petals, so as to give the exterior the best possible shape when finally dressed.

These various processes have taken a great deal of time, yet the bloom looks, if anything, less like a show specimen than it did when on the plant.

However, they are but a means to an end, and their use is soon apparent now that we come to the principal operation of[Pg 581] dressing. In this, order is evolved out of chaos, and in the hands of an expert the bloom immediately begins to assume an altogether different appearance.

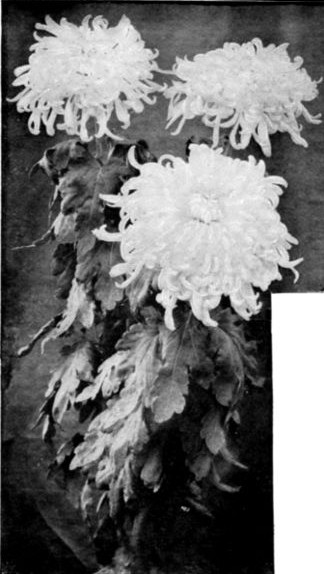

THREE SPECIMEN BLOOMS.

THREE SPECIMEN BLOOMS.

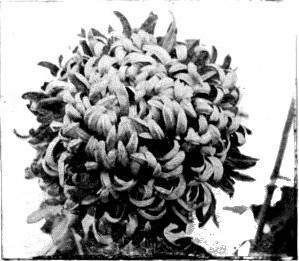

THIS "EDWARD MOLYNEUX" WAS NINE INCHES ACROSS.

THIS "EDWARD MOLYNEUX" WAS NINE INCHES ACROSS.

THE BLOOM HERE PHOTOGRAPHED—"MUTUAL FRIEND"—WAS TEN

INCHES IN DIAMETER.

THE BLOOM HERE PHOTOGRAPHED—"MUTUAL FRIEND"—WAS TEN

INCHES IN DIAMETER.

First it undergoes the operation of cupping. The cups are made of zinc, and vary in design according to the shape of the flower. The upper part closely resembles the socket of a candlestick. The outside is threaded, and screws into a cylindrical case containing water.

Now the reason of the long stalk is apparent. It is passed through the hollow till the lower petals of the bloom are pressed firmly on the plate, then the outer case is screwed on, and the flower is held as rigidly as though in a vice. The screw cup performs three functions: It waters the bloom, keeps it in position, and by pressing the under petals upwards accentuates its shape and size. The operation of dressing brings another instrument into use. It seems a simple matter to take hold of a ragged bloom and pat and stroke it into shape, curling a petal here, twisting another there. In reality it is a matter of great delicacy, and some years of experience are required before one may hope to obtain the best possible results, and even then some three hours may easily be spent in dressing a bloom.

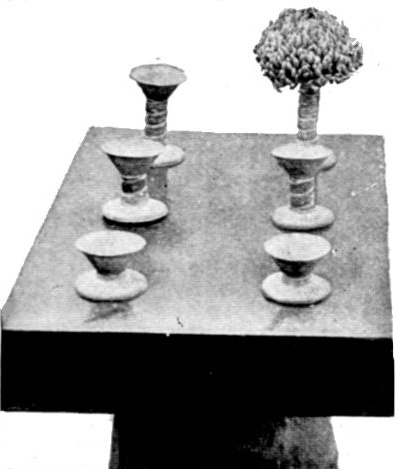

MY LADY CHRYSANTHEMUM'S TOILET TABLE.

MY LADY CHRYSANTHEMUM'S TOILET TABLE.

The imperfect petals underneath having gone, those outside readily respond to the touch of the instrument and spring into regular formation, while those at the top of the bloom are carefully curled to a common centre and effectively conceal all that was left of the seedy eye.

Under the deft touches of the master hand, the ragged bloom rapidly develops into a thing of greatest beauty. Each curl marks a great improvement, and when it is finished one readily realises how much there is in this as in other things for the amateur to learn.

A final brush up is now all that is necessary. A specially made camel-hair brush accompanies the set of instruments; with this the grower gently brushes the leaves till no speck dims their fair loveliness.

SOME USEFUL ARTICLES ON HER DRESSING-TABLE.

SOME USEFUL ARTICLES ON HER DRESSING-TABLE.

My lady's toilet is now completed, and she is forthwith placed in the show box, which is designed to hold six cupped blooms. This box consists of a slanting platform containing six holes, in which the cups are placed. The two at the top are partially unscrewed, the middle pair not quite so much so, while those at the bottom are screwed in tightly. This is called[Pg 582] setting-up, and is an art of itself. It arranges the flowers in tiers, so that those in front do not hide the blooms behind.

Skilled setting-up is worth several points, as it enables the blooms to show themselves off to the best possible effect, and at the same time favourably impresses the judge's eye.

The blooms are shown in specified numbers; generally, thirty-six, twenty-four, or twelve are required from each exhibitor. Nowadays, chrysanthemum blooms attain enormous sizes. We show two specimen blossoms. That known as "Mutual Friend," shown on the previous page, is ten inches in diameter; the other, "Edward Molyneux," at the left hand foot of the same page, is nine inches across. This is about the diameter of an ordinary plate.

Notable sizes are also attained in the plants themselves, and in preparing these for show there are divers little secrets.

In the illustration below Mr. Southard is standing between two specimen plants. Notice the difference in the general appearance of the twain. That on the left is ragged and unkempt, though it is in every way a show specimen. Compare it with the neat, charming effect of the plant to the right of the picture. Here is an instance of what a little show preparation will do for the plant itself. In the latter case, each bloom and stalk is trained up to a stick, and as a consequence perfect harmony is gained, and the plant shows at its best. In many cases these stalks have to be trained round corners, and describe wonderful curves in order to take up the places assigned to them. The space under the blooms and foliage is a forest of sticks, all engaged in carrying the long, pliable stalks to their rightful places.

THE FLORAL BARBER AT HIS WORK. CONTRAST THE TWO PLANTS.

THE FLORAL BARBER AT HIS WORK. CONTRAST THE TWO PLANTS.

The untied plant on the left is a wonderful specimen. It measures over four feet across the top, grows from one stalk, and yet only occupies a twelve-inch pot.

Blooms from some of the choice plants are worth from three to five shillings apiece, while even cuttings will fetch the latter figure.

One of the great fascinations of show-chrysanthemum growing is the possibility of producing new blooms. Out of twelve exhibited flowers shown me at a recent show, nine were entirely new specimens. Like the orchid grower, the chrysanthemum lover is ever seeking floral novelties. In the ordinary way it takes some years to produce and fix a new flower. Endless patience, experiment, and knowledge are necessary to success; but here, as in most branches of floriculture, there is a strong element of luck, and the raw amateur sometimes purchases a cutting which turns out to be an extraordinarily fine specimen of a new variety.

This element of uncertainty undoubtedly constitutes one of the great charms of horticulture.

A STORY TO BE READ TO CHILDREN.

By Geo. A. Best.

Illustrated with novel Photographs from life by Arthur Ullyett,

Ilford.

"Wake up, Lessels!" said Stanley, in a hoarse whisper, shaking his younger brother as he spoke. "I've got a grand idea!"

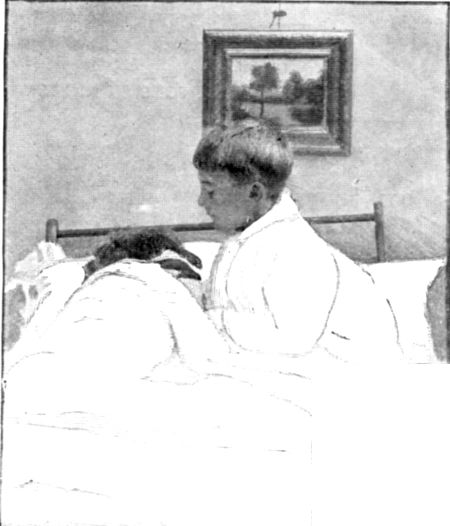

"'WAKE UP, LESSELS! I'VE GOT A GRAND IDEA!'"

"'WAKE UP, LESSELS! I'VE GOT A GRAND IDEA!'"

"'I'M OFF TO KLONDYKE, AND YOU'VE GOT TO BE MY PARD.'"

"'I'M OFF TO KLONDYKE, AND YOU'VE GOT TO BE MY PARD.'"

"Gimme a little bit then," answered Lessels, drowsily. "You had some of my chocolate cweam last night."

"You goose! Don't you know what an idea is?" retorted the elder boy, disdainfully. "It isn't anything to eat. It's a notion."

"Then you can have it all yourself," remarked Lessels, indifferently.

"Would you like a thousand pounds to spend on caramels and chocolate?" asked Stanley. "And a golden guinea to put in the bank till you are a man?"

"I'd like the chocolate," answered Lessels, with some show on interest. "An' I'd like a boxful of caramels; an' a barley-sugar lion; an' a real engine which would go by itself an' wun into things. An' I'd like a toy fire-engine, so that I could set fire to Madge's dolls' house an' put it out; an' a bucketful of ice cream, an'——"

"Don't speak so loud, you little duffer, or you'll get nothing at all!" interrupted the elder boy. "Just get out of bed at once, and dress yourself without dropping anything. We're off to Klondyke!"

"Off to what?"

"Klondyke—a place where you dig money out of the ground like coals. Big lumps of solid gold, what'll buy a whole shopful of toys, and tons of best London mixture and marzipan. See?"

"What about washin' our faces an' bweakfast?"

"Miners never wash themselves, silly; and they don't have proper breakfasts till they've made their pile."

"What's a miner, an' who's a pile?" asked Lessels, chasing himself across the room backwards to attach his braces to a rear button which was apparently running away.

"A miner's a man who digs gold up and washes it in a cinder-sifter," explained Stanley. "And he shoots everybody who comes near him except his pard. I'm off to Klondyke to be a miner before dada awakes, and you've got to be my pard."

"Who'll I shoot?" asked Lessels, with a defiant glare.

"Everybody but me," answered Stanley, condescendingly. "We'll want my best sixpence-ha'penny gun; several sticks of lead pencil to shoot; two spades; a cinder-sifter; an umberrellar to sleep under; our nightshirts; a loaf of bread, and a big knife."

"Shall we take Desmond in the mail cart?" asked the four-year-old "pard," innocently. "Desmond, an' a packet of sherbet, an' my toy engine, an' a chair to sit on, an' the kitchen lamp,[Pg 584] an' our bed, an' a few other fings to eat?"

"Babies and toys must be left at home," snapped the miner. "And how do you think we can carry a bed along? We must hunt for crabs to eat with our bread, and shoot birds and catch fish. Our Klondyke is really the beach, for I heard dada say last night that Southend was a regular Klondyke, as gold had been found on the sands. What a good job we live close to Southend, isn't it?"

"Hadn't we better tell dad we're going, an' get a penny to spend?" suggested the long-headed Lessels, ignoring his brother's question.

"A penny to spend!" echoed the elder boy, scornfully. "We'll have fifty thousand golden sovereigns to spend before this day week; and dad will forget to whack us when we buy him a new house, and a carriage with two horses and a footman, and an ounce of tobacco. And mamma shall have four splendid servants, and a sealskin jacket, and a bottle of scent, and a bicycle, and a new box of hairpins! I'm quite ready now, are you?"

Lessels answered with a somewhat doubtful nod, and the children crept silently downstairs. The kitchen door was successfully unbolted after a table and chair had been mounted by the intrepid Stanley, and the necessary materials for the outfit were rapidly collected from the neighbourhood of the washhouse.

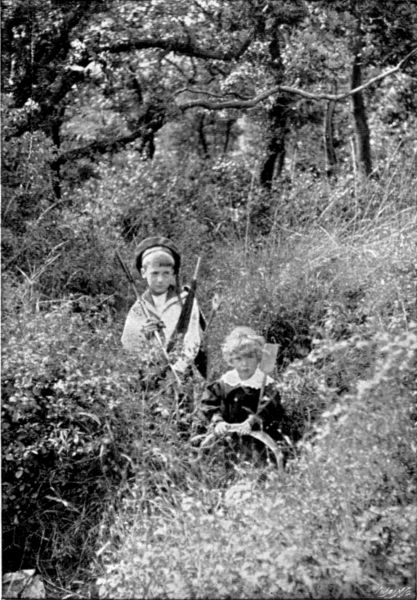

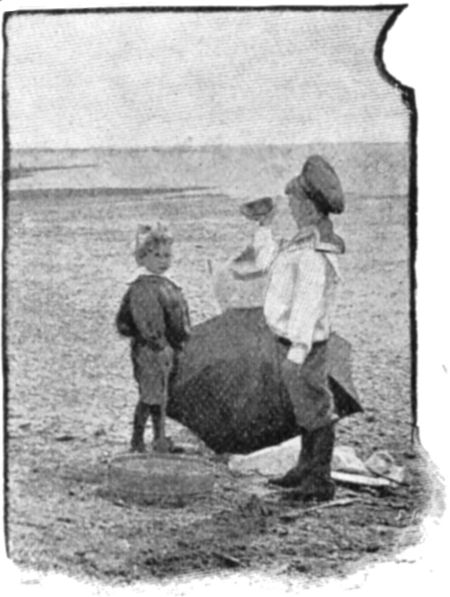

STANLEY AND LESSELS START FOR KLONDYKE.

STANLEY AND LESSELS START FOR KLONDYKE.

"I'll carry the umberellar, gun, and knife," whispered Stanley. "You can fetch along the cinder-sifter and the other things."

"I don't like to touch the shinder-sifter: it's got nasty worms and snails on," protested Lessels, whimpering. "An' if I can't carry the gun I shan't go, so there!"

"I've a great mind to put a lead pencil through you, you great baby!" hissed the miner, furiously. "You're a nice pard for a man to have, to be sure! Don't forget that my gun is loaded, and I'm not going to stand any nonsense, so just do as you're told. If you're afraid of a worm, what are you going to do when conger eels, sea serpents, and octopussys attack us?"

"Fight 'em to deaf!" answered the "pard," growing suddenly cheerful at the prospect of encountering large game. "Is the octopussy like other cats?"

THEY MARCH THROUGH A DENSE JUNGLE.

THEY MARCH THROUGH A DENSE JUNGLE.

"It isn't a cat at all; it's a fish like a large spring onion with eyes in, and hundreds of roots which are all alive," explained[Pg 585] Stanley, as the expedition moved slowly across the first field.

After a long and painful march over a plain covered with thistles and long grass, succeeded by a dense jungle, the heavily laden "prospectors" reached the beach at a lonely spot some miles to the westward of Southend pier. Here the umbrella tent was erected, the gun reloaded, and the mining utensils carefully unpacked. The loaf was thoughtfully wrapped up in a nightshirt to preserve it from the effect of sun and salt water.

"We must stake out our claim at once," said Stanley, producing four clothes pegs from his pocket, and sticking one at each corner of a four-sided diagram hastily scratched on the sand with a spade. "All miners have to do this before they've been in Klondyke five minutes. And we must put up a notice that this claim belongs to us, so as to keep other gold hunters off. See?"

"Then we shan't have nobody to shoot," protested Lessels, in a disappointed tone.

"Dig up some sand, pard, and fling it into the cinder-sifter while I write out the caution in blue pencil," said Stanley. "And when all the sand has run through call me to pick out the gold."

And after seeing the first spadeful of sand fall into the sieve, the elder miner rapidly produced a notice worded as follows:—

"This is our clame. Tresspasers will be persecuted and shot. Vissitors are requested not to tuch the nugets."

"Anybody reading that warning won't dare to come within a mile of us," remarked the author, proudly, as he attached the notice to the ferrule of his "tent." "Any luck, pard?"

"Any what, Stan?"

"Luck—I mean have you found anything?"

"I've got a kwab, an' a cockle shell, an' an old shoe, an' a ginger-beer bottle," replied Lessels, with a yawn. "The bottle's got some beer left in, an' I'm very thirsty. Shall we have a dwop?"

"That isn't ginger-beer, it's sea water!" cried Stanley, warningly. "If you drink ever so little you'll go mad, and smash things and shoot yourself! Then I shall have to bury you in the sand, and put a wooden cross over your head, so that I can show dada where I left you."

"My head aches, an' I'm getting thirsty," protested the hard-working pard.

THEY DIG FOR GOLD, AND FLING THE SAND INTO THE

CINDER-SIFTER.

THEY DIG FOR GOLD, AND FLING THE SAND INTO THE

CINDER-SIFTER.

A BIG NUGGET IS DISCOVERED.

A BIG NUGGET IS DISCOVERED.

"You 'ave got gold fever, that's all!" said Stanley, impatiently. "All miners suffer from gold fever, but it doesn't often kill 'em. If we both work hard for a few minutes p'r'aps we'll find a tiny nugget that we can change for real ginger-beer and buns at the store. We'll have a splendid evening at the store after our day's work is done. All the boys will be there, and we'll drink more than is good for us, and fight and play poker."

"We haven't got any pokers to play with," argued the matter-of-fact Lessels. "An' there isn't any boys but us about;[Pg 586] an' there's no store where we can spend our nuggets, an' fight in. If you tell stories like that, Stan, you'll never get to——"

"The worst of you is you're so silly!" interrupted the elder boy, shaking the cinder-sifter vigorously as he spoke. "You never think anything's real that you can't see. When people get to know that there's millions of pounds under these sands there'll be cheap two-and-sixpenny excursion trains, full of wild miners, arriving here every few minutes."

"Will there be anything to eat an' dwink?" demanded the hot and thirsty pard, anxiously.

"Tons of it!" answered the senior digger, enthusiastically. "We shall use sweets an' sugar sticks for bullets, an' wash ourselves in real ginger beer. Miners always spend their money like that. They waste what they can't eat, and wash their faces in drink when they've had more than is good for them. It's a splendid life, isn't it, Lessels?"

"Which?" asked the pard, doubtfully.

"What's the use of explaining things to a fellow like you?" snapped Stanley. "Haven't I told you all about it?"

Lessels retired to the shelter of the tent without attempting to reply to either of these questions, and slowly divested himself of his shoes and socks.

"Now what are you going to do?" demanded the miner, angrily.

"Paggle," replied Lessels, pointing to the incoming tide, which was rapidly approaching the camp.

"Paddle!" echoed Stanley. "What sense is there in paddling before we've found a single ha'porth of gold? Hallo! Come here, quick!" he continued, excitedly, as something large and hard rolled from side to side of the sieve. "Oh, Lessels! I've found a monster nugget! Come and help me lift it out. Hurrah!"

"Wait till I get my sock off," replied Lessels, indifferently. "Is it weal gold?"

"Of course it is, you little duffer! Never mind your sock!" roared the excited miner. "It's a large, square nugget—yellow, and broken in two. I wonder who's stole the other half."

"Looks like a bwick," remarked the pard, suspiciously, after carefully surveying the find. "An' it isn't clean an' bwight like weal money."

"I tell you it's a nugget," replied the lucky miner, in a tone which was intended to put an end to all argument on the subject. "Keep the gun loaded; I guess we'll have some robbers along presently."

"Where can we spend it?" asked Lessels, anxiously.

"There's a stall where they sell ginger-beer and ice-cream, about half a mile along the beach," replied Stanley; "you can just see it in the distance. If you like, you can walk over there and bring back half a dozen of beer, three gipsy cakes, and about twenty sovereigns' worth of change. But don't let the storekeeper cheat you."

"I'll go!" declared Lessels, delighted by the prospect of obtaining some very necessary refreshment. "I'll go, Stan, and you can dig out plenty big nuggets, an' save 'em up till I come back. I'd better take the gun, so's I can shoot the man if he tries to cheat me."

"Don't forget the change!" cried Stanley, as he watched his little brother run rapidly away in the direction of the stall.

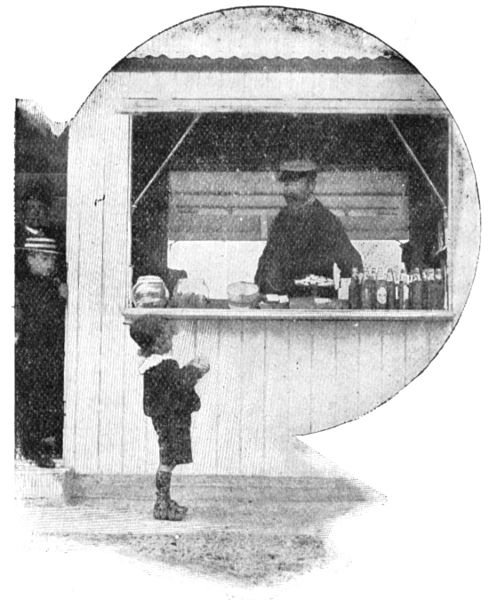

In ten minutes' time, a flushed and weary-looking little miner, hugging a piece of wave-worn brick, presented himself to the storekeeper, who was just in the act of[Pg 587] taking down the shutters of his timber-built shop.

"Well, my little man, what can I do for you?" asked the shopkeeper, cheerily.

"Half a dozen of ginger-beer, three gipsy cakes, and twenty sovereigns in change!" demanded the miner, breathlessly.

LESSELS TRIES TO CASH HIS NUGGET.

LESSELS TRIES TO CASH HIS NUGGET.

"Twenty sovereigns change!" echoed the man. "What do you mean, little one? Where's your money?"

"Here it is!" replied Lessels, boldly, laying the precious "nugget" on a plate of puff pastry, and assuming an attitude of defence. "Half a dozen of ginger cakes, three bottles of gipsy——"

"I can't give you all that for a brick," interrupted the shopkeeper, shaking his head. "You'd better run away and play."

"It isn't a bwick—it's a weal nugget," said the miner, with a scowl. "An' if you try to cheat me, Stanley said I must shoot you dead!"

"Here's a bottle of pop and your nugget for nothing," said the kind-hearted shopkeeper, with a laugh. "But don't bring any more brick ends or rubbish over here. Where are you going to take it to?"

"The camp."

"Where's the camp?"

"In Klondyke."

"Where's Klondyke?"

"On the beach, wight over there where Stanley is."

"Who's Stanley?"

"Stan's a miner, an' I'm his pard. We're diggin' up nuggets to spend in sweets, an' carriages, an' other fings for dada and mamma."

The tide had nearly reached the camp when Lessels returned.

"I haven't found any more nuggets, Lessels," said Stanley, despondingly. "Did you get the change all right?"

"No: I brought the gold back with me, 'cos the man said it was only a bwick!"

"Only a brick!" echoed Stan, with a dry sob. "I'm so thirsty and tired, Les."

"You've got gold fever, like I had," said Lessels, sympathetically. "Lie down an' west a bit while I dwink up the ginger-beer which the man gave me for nothing."

"All right, greedy!"

"I'm not gweedy, Stan, only thirsty. You can have a little dwop when I've cut the string an' shot the cork off. Then we'll go home to bweakfast, won't we?"

"It's nearly dinner time now, Lessels," said Stanley, sadly. "And we can't go home without a single nugget to buy presents with, or dada'll be sure to whack us."

"'I DON'T LIKE KLONDYKE.'"

"'I DON'T LIKE KLONDYKE.'"

"I don't like Klondyke! I don't like Klondyke!" sobbed poor Lessels, a moment afterwards when[Pg 588] the ginger-beer cork flew skywards with a loud report, causing the bold miner to drop the bottle in dismay.

"You're a pretty pard to send on an errand!" cried the disappointed Stanley, as the greedy sand quickly absorbed the contents of the bottle. "Frightened of a ginger-beer cork! I wouldn't be such a cowardy custard! Here I am nearly dying of gold fever, and there's nothing to drink or eat but sea-water and dry bread."

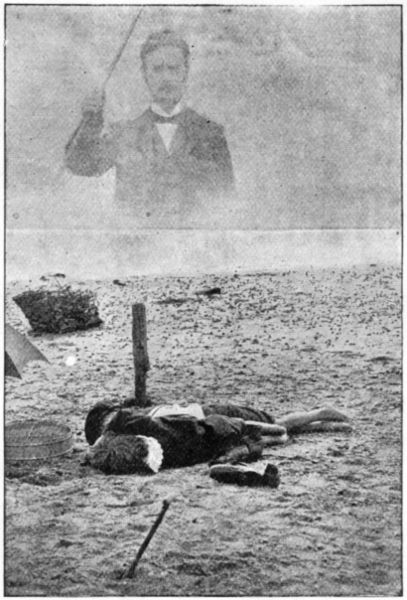

"Poor old Stan!" said Lessels, with genuine concern. "Don't die an' leave me to find my way home all by myself. Let's lie down an' go to sleep a bit. Then we'll forget how hungwy an' thirsty we are, an' how dada'll whack us when we get home!"

"Dear old pard!" said Stanley, sleepily. "It was my fault bringing you here, and I ought to have all dada's smacks."

"Not all; nearly all," answered the loyal pard, with sublime condescension. "You can have all the biggest ones. I'm not gweedy! S'pose the tide comes up an' drownds us, what'll mamma say?"

"It serves us right," was the drowsy reply.

"An' dada?"

"Dada'll say he'll teach us to get drownded again!"

"An' baby Desmond?"

"Desmond'll say 'cuckoo'—he doesn't know any other words."

"An' the dog?"

The last question remained unanswered.

"Poor old Stanny's asleep," soliloquised Lessels. "I'll just cover him over with the nightshirts, an' the nugget bag what hasn't any nuggets in, so's he won't catch a cough an' keep me awake at nights. Then I'll lie down close to him, as I do in bed, an' have a west. I wish mamma was here to kiss me, an' I hope dad won't beat me harder than he can help!"

And in another moment absolute silence reigned in the camp, while the tide crept noiselessly and stealthily around the higher bank of sand which formed the children's Klondyke. The summer sun shone lovingly on a pair of still forms; and the warning to trespassers fluttered gently in the warm breeze.

THE MINERS' DREAM OF HOME.

THE MINERS' DREAM OF HOME.

When a wave, bolder than the rest, broke against the bare feet of the younger miner, he awoke with a cry of alarm.

"Wake up, Stan! We're both drownded!"

"What's the matter?" demanded Stanley, sitting up and rubbing his eyes.

"We're in the miggle of the sea!" was the startling answer. "Our camp's all wet an' miserable, an' we can't shwim home, an' it's no use shoutin', cos there's nobody on the beach!"

"Lessels, we shall have to leave dada's umberellar, and the gold, and everything else, and fly for our lives," said Stanley, impressively, glancing anxiously towards the distant beach as he spoke.

"I can't fly," whimpered Lessels. "Let's call dada."

"He wouldn't hear us!"

"Dad heard me shout when I fell in a bucket of water at home," argued Lessels.

"This isn't a bucket of water, and we're not home now," replied the elder boy, irritably. "I believe I could swim all the distance to the beach—with one foot on the bottom. Then I could walk to the village and get a boat to bring you off; or[Pg 589] run home and get dada and the clothes line; or fetch one of the life-buoys from the end of Southend pier."

"I'll come and get a live boy, too!" exclaimed Lessels, clinging frantically to his brother, as a wave broke over his knees. "Don't leave me, Stanny; I'se so frightened!"

"I can't swim if you hold me like that!" said Stanley, rolling up his shirt sleeves with sudden determination. "You'll have to let me tow you to land by the hair of your head. Drowning people have to stun each other sometimes to keep one another quiet while they are rescued," he added, darkly.

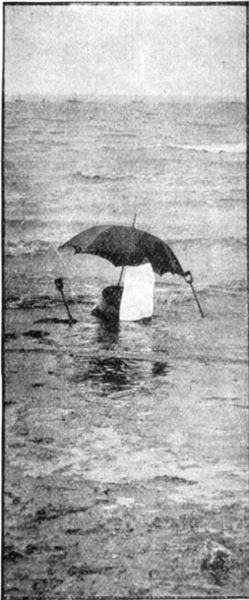

THE RESCUE OF THE MINERS.

THE RESCUE OF THE MINERS.

At this distressing moment a well-known form appeared on the beach, and the terrified miners shouted and waved their caps simultaneously.

"It's dada!" shrieked Lessels; "I knew he'd come. Look! he's walking in the sea, with all his clothes on; an' he's laughing; an' he hasn't got a shtick after all."

"What is all this about, boys?" asked the welcome visitor, pointing, as he spoke, to the fast disappearing camp.

"It's Klondyke, dada, that's all!" answered Lessels. "We digged for gold all day to buy you a lot of horses and tobacco, but we haven't found anything at all 'cept a bad nugget!"

"You're not the first miner who has done that, Lessels," was the comforting reply.

"I had a horrid dream about you, dad, when I was tired and fell asleep on the sand," said Stanley. "Guess what it was."

"Perhaps I was injured by one of the fine horses you were going to buy?"

"No, dad, it was much worse than that," was the earnest reply. "In my dream you were looking for us with a great stick in your hand."

"Dear old dad!" whispered Stanley, as he was being carried into safety, upside down, a few minutes later. "Dear old dad! You aren't very cross because we have lost your umberellar, and haven't got any nuggets, are you? And you won't turn nasty and spank us after we've made you laugh so?"

THE LAST OF THE CAMP.

THE LAST OF THE CAMP.

"Please don't, dada!" added Lessels, brokenly.

And dada only kissed the weary little faces of the supplicants, and laughed again until the tears ran down his cheeks.

"I believe dad's crying," said Lessels, in a stage whisper—"cryin' inside, an' laughin' outside!"

"Keep quiet, you little muff!" whispered Stanley, hoarsely. "Father looked like that when the doctor told him that I wasn't likely to die of fever after all. It's a laugh that stops crying."

"And one which is worth more than all the ordinary laughs of a lifetime, my boys," added the listener, quietly.

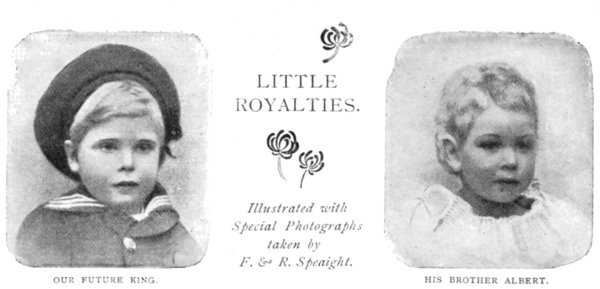

OUR FUTURE KING. | HIS BROTHER ALBERT.

OUR FUTURE KING. | HIS BROTHER ALBERT.

Illustrated with

Special Photographs

taken by

F. & R. Speaight.

Even in the days when the Queen's children formed a charming group of young people, high-spirited, intelligent, and enjoying, according to many passages in the late Princess Alice's letters, an ideally happy childhood, British Royal Nurseries were not better filled than they are at present, for in the immediate Court circle there are many young people, not one of whom can be considered in any sense grown up.

PRINCESS VICTORIA OF YORK, HIS SISTER.

PRINCESS VICTORIA OF YORK, HIS SISTER.

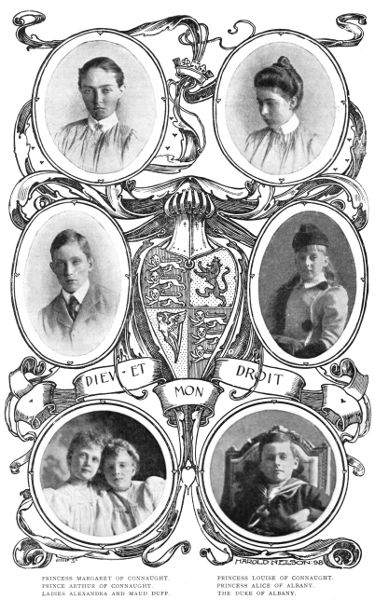

Prince Arthur of Connaught and his two sisters form the eldest group, being severally fifteen, sixteen, and twelve. The three children of the Duke of Connaught, though they are half German, for their mother was the daughter of the Red Prince, have received an entirely English form of education, Prince Arthur having been the first British Prince sent to Eton, and the two Princesses, Margaret and Louise, being educated at home, partly under their parents and partly under the Queen's supervision, for during the Duke and Duchess' stay in India their children remained in England, and so their short lives have been divided between Aldershot, Bagshot Park, and Windsor Castle.

To the same group of the Queen's British grandchildren may be said to belong the children of the late Duke of Albany and of Princess Henry of Battenberg. In each case they are much younger than Her Majesty's other grandchildren.

There is something very pathetic in the position of the Duchess of Albany: left a widow within two years of her marriage, and obliged, by the circumstances of her position, to remain in a foreign country, finding her only solace and interest in her two children, to whom she has proved a model mother. Till last year, when the Prince entered Mr. Benson's popular house at Eton,[Pg 591] Princess Alice and her young brother had never been separated for a single day. In this connection it may be stated that the Royal Princes when at school lead exactly the same lives as do other Eton boys. They are addressed by their masters and by their school-fellows as "Connaught" and "Albany," and though, as is natural, they generally spend any half-holidays at Windsor Castle, the Queen is most particular never to ask them out of hours, or to treat them in a way calculated to make them feel themselves favoured above the other boys.

PRINCESS MARGARET OF CONNAUGHT.

PRINCESS MARGARET OF CONNAUGHT.The portraits of the Prince and Princesses of Connaught were specially taken by Mr. R. Speaight for this article, and most of the others taken by the same photographer are published by special permission of the Royal parents.

Princess Alice of Albany's great friend is her first cousin, the young Queen of Holland, and this in spite of the fact that she is three years younger than the girl-monarch. The Duchess of Albany has remained on very intimate terms with her sister, the Queen-mother of the Netherlands, and there has always been a constant interchange of visits between Claremont and the Dutch Court; indeed, the Duke and Princess Alice of Albany are the only members of the British Royal Family who can speak Dutch fluently, that language having been taught them by their Queen-cousin.

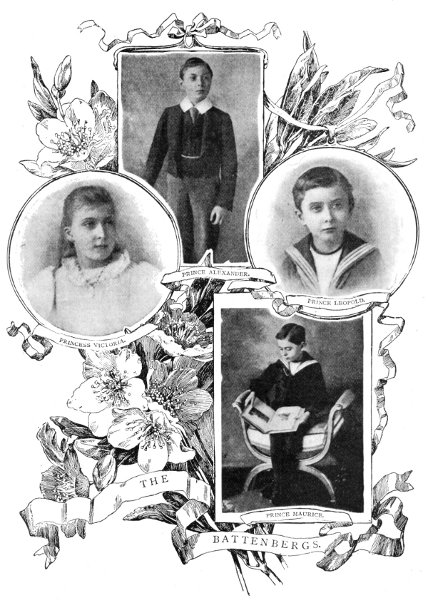

The four children of Princess Henry of Battenberg have had their childhood sadly shadowed by the death of their father, to whom they were all devotedly attached. In one matter their position differs very much from that of the other Royal children: that is, they have been thrown into peculiarly close relations with their venerable grandmother, and it is perhaps owing to this fact that the only girl among them, Princess Victoria Eugénie, is, although only eleven years old, said to be exceptionally intelligent and grown-up for her age.

Of Princess Beatrice's three sons, the eldest, Prince Alexander Albert, who is just twelve years old, is at school at Lyndhurst, but next year he will join the Britannia, for, like his uncle Prince Louis of Battenberg, he is very fond of the sea and wishes to enter the British Navy. Prince Leopold and Prince Maurice are too young for it to have been yet decided what career they will follow, but they will each enter a profession, for their position is a somewhat peculiar one. Unlike the young Duke of Albany, who was a peer from the moment of his birth, the children of Princess Beatrice have no legal rank, and their father, the late Prince Henry, was even desirous that they should not be habitually given the title of "Prince" or "Princess."

PRINCE GEORGE OF TECK.

PRINCE GEORGE OF TECK.

In this matter, however, the Queen overruled his objection, though, curiously enough, Her Majesty did not seem desirous of doing so in the case of the children of the Duke and Duchess of Fife, notwithstanding the fact that when the elder, Lady Alexandra, was born she was considerably nearer the throne than had been Queen Victoria herself at the moment of her birth. The question of whether the eldest grandchild of the Prince and Princess of Wales should or should not be given the title of "Royal Highness" was actually discussed at some length, but as both the Duke and Duchess of Fife were very anxious that their child should only bear the title and have the precedence accorded to a Duke's daughter, the matter was arranged that way. Subsequent events—that is, the birth of the Duke and Duchess of York's three children—have proved how wisely the parents of Lady Alexandra Duff acted in this matter. As it is, the Ladies Alexandra and Maud Duff are in the happy position of having all the privileges and none of the responsibility of Royal birth. They are so far the only younger members of the Royal Family who have never been out of the United Kingdom, their lives having been spent between London, Norfolk, and Scotland. They are being brought up in the very simplest fashion compatible with their rank; indeed, the only public appearance, since her birth, made by Lady Alexandra was when she acted as bridesmaid to her aunt Princess Maud of Wales.

Of course, from many points of view, by far the most important group of Royal children is that composed of the two little sons and of the baby daughter of the heir-presumptive.[Pg 593] Owing to the sad death of the Duke of Clarence there are only three lives between little Prince Edward of York and the throne, and far more care has been bestowed upon his education and general upbringing than is generally the case even with Royal children of so tender an age, for our King to be will not be five years old until the 23rd of next June.

THE BATTENBERGS.

THE BATTENBERGS.As his names, Edward, Andrew, Patrick, and David, indicate, his grandparents and parents were anxious that the Prince should, from his birth, belong rather to the nation than to his family. It was seriously[Pg 594] proposed that he should share the Queen's carriage on Diamond Jubilee Day, but the idea was given up when it was realised that the long slow drive through the streets of London would be a terrible ordeal for a three-year-old baby; thus, although little Prince Edward's Jubilee clothes were actually prepared, he only wore them at home, to the disappointment of his young mother, who would have liked her son to have gone down in history as having taken part in so great and noteworthy a pageant.

The Duke of York's second son, Prince Albert Frederick Arthur George, was born on the anniversary of the deaths of the Prince Consort and of Princess Alice, and so was three years old on the 14th of last December. Two years younger is Princess Victoria Alexandra Alice Mary, the youngest but not the least of Her Majesty's British great-grandchildren.

The child of Prince Adolphus of Teck—whose wife, it will be remembered, was Lady Margaret Grosvenor, a daughter of the Duke of Westminster—is Royal in the same sense as are the Ladies Alexandra and Maud Duff, and it is rather interesting to note that the three children all stand in the same intimate relationship to the future King of England, though even Prince Edward of York was not legally entitled to the name of "Royal Highness" until a special decree was passed in favour of all the children of the Duke of York.

A word on Royal children from the photographer's point of view.

Mr. Richard Speaight of Regent Street, who took all our photographs except those of the Duke of Albany and his sister Princess Alice of Albany, which were taken by Messrs. Gunn and Stuart of Richmond, speaks enthusiastically of them—and he is now quite a connoisseur of children.

He says he is always struck by the natural and careful way in which the children are brought up. The younger ones are always most obedient to their nurses, and they, on the other hand, are very jealous in guarding their Royal charges. They do not even allow them to sit to be photographed without hiding behind to hold them in case they should fall.

The photographs of the Duke of York's children were taken at Sandringham. They took great delight in the musical and clockwork toys which Mr. Speaight took with him; and when the operation was finished, Prince Edward, shaking hands with his photographer, thanked him for the trouble he had taken.

THE COVER FOR BINDING OUR FIRST VOLUME.

Order at once.

Here is a small facsimile of the charming cover which has been designed for binding the first volume of The Harmsworth Magazine, which is completed with the issue of this number.

The colour of the cover is a very pretty pale green, and the ornamentation is very dainty in gold and black.

The design is copyright, and any local bookbinder infringing it will be prosecuted. The initials of Harmsworth Bros., "H. B.," will be found on the back and side of every genuine cover, and none should be accepted without them.

THIS IS A SKETCH OF THE PRETTY COVER FOR BINDING OUR

FIRST VOLUME.

THIS IS A SKETCH OF THE PRETTY COVER FOR BINDING OUR

FIRST VOLUME.

This cover can be obtained from any bookseller or newsman, price 1s. 3d., or it will be sent, post free, on receipt of 1s. 6d., on application to the Publisher, Harmsworth Bros., Ltd., 24, Tudor Street, E.C.

An Index to the volume is also now ready, price threepence.

Everyone should bind the six numbers of The Harmsworth Magazine, for they make a most delightful, attractive, and interesting volume.

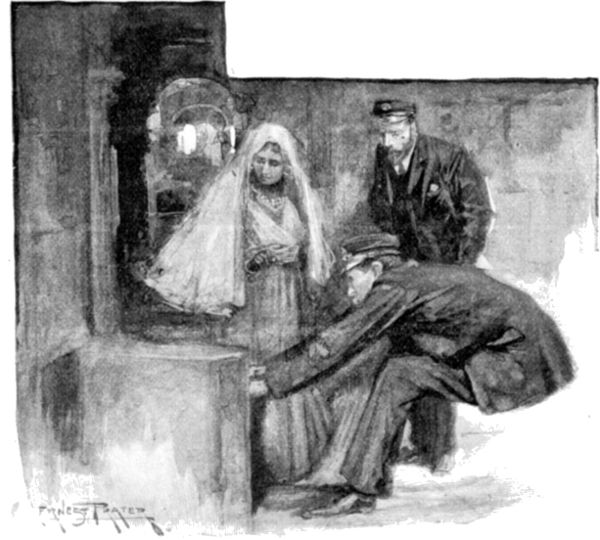

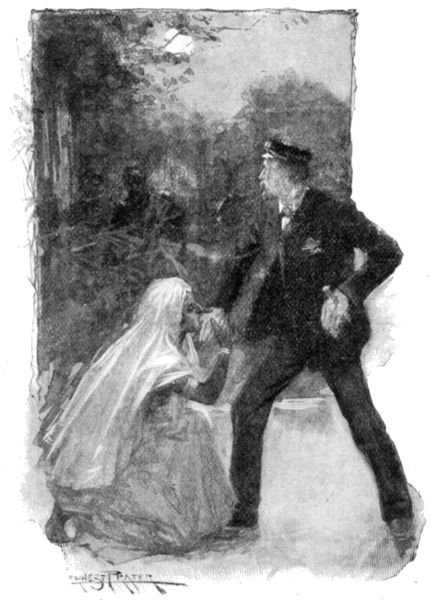

AN EMPIRE MAKER'S LOVE STORY.

By Gilbert Dayle.

Illustrated by Fred Pegram.

It was dusk on a summer evening, as a tall broad-shouldered man made his way down a path that led through the Vicarage garden at Winchmere.

Reaching the roadway, he turned and, with one arm resting on the gate, gazed at the rambling house with its clustering ivy and old-fashioned windows.

"To all appearances just the same," he said, musingly, "yet how different it is—strange faces, strange voices! A short eight years, and I return to find my old friend dead, almost forgotten, and She vanished—swallowed up by the world!"

He sighed heavily, then turned and set out down the country road in the direction of the railway station.

"It's the bitterest disappointment I could have met with!" he went on; "but—I shall find her. Yes, I shall find her!" And as he spoke the step of the tall bronzed man quickened into a resolute stride.

Halton Towers, the country residence of Earl Kenwell, was a magnificent place, situated in the heart of Berkshire. On a certain morning in July, a governess and her two charges were sitting at a table in the schoolroom. The governess, a pretty girl of about twenty-four, was attempting to instil some elementary ideas of geography into the head of her eldest pupil, a boy some six years old.

Presently the door opened, and a party of people trooped into the room. Their leader, Lady Dorothy Kenwell, looked smilingly at the governess. She was young, and considered to be one of the most beautiful women in the country.

"You don't mind us coming in just for a minute, Miss Grahame?" she asked. "These absurd people declared that nothing would satisfy them but seeing the children."

Lord Scaife (to his intimates he was known as "Bobbie") stepped forward and laid a hand on the boy's shoulder, whilst his cousin, Miss Julia Crofton, put her arm round the little girl's neck and kissed her impulsively. A few feet away in the background stood the remaining member of the party, Count Morlot. He was a slimly built man of foreign appearance. A slight smile hovered round his lips as he watched the scene.

"'NOTHING WOULD SATISFY THESE ABSURD PEOPLE BUT SEEING

THE CHILDREN,' SAID LADY DOROTHY."

"'NOTHING WOULD SATISFY THESE ABSURD PEOPLE BUT SEEING

THE CHILDREN,' SAID LADY DOROTHY."

"Well, Jim, my lad," began Lord Bobbie, cheerfully, "what has Miss[Pg 596] Grahame been driving into your precious young head this morning?"

"Jogruffy," replied Master Jim.

Lord Bobbie bent down over the atlas that was open on the table.

"Africa, eh? Well, it's a great country, particularly the southern part of it. It's where the millionaires come from."

Lady Dorothy took hold of Jim's hand and guided it to a certain part of the map.

"Look, Jim, dear, this map is not up to date, and this piece I'm showing you should be coloured red—British, you know. The country is now——"

"British Kafangaland!" put in little Jim, eagerly.

"Bravo, youngster! Who told you that?" asked Bobbie.

"Miss Grahame," answered Jim, "and she said that it had nearly all been done by one man—a very good man."

Lady Dorothy shot a smile at Miss Grahame, then bent over her little cousin again.

"Yes, Jim, and he is coming here, this very morning. What do you think of that?"

Jim turned open-mouthed in his chair.

"Shall I see him," he gasped, "the man who has turned this big patch red?"

"Yes, my boy," laughed Lord Bobbie, "you'll see him, our most modern Empire-maker, the uncrowned King of British Kafangaland—London's latest lion——" He paused.

"Anything more, Bobbie?" queried Julia Crofton.

"No, I don't think so. I was wondering what qualities he possessed to have put him so far ahead of the other pioneers out there."

Count Morlot drew a little nearer to the group.

"In buccaneering circles," he remarked, with a smile, "the man who is most unscrupulous is the man who wins. Probably this fact accounts for Mr. Winn's marvellous successes."

Lady Dorothy drew herself up, and, swinging round, faced the Count. There was a touch of crimson on her cheeks.

"You have evidently never met Alan Winn, Count Morlot," she said, with flashing eyes. "He is the soul of honesty—and a true man!"

Without waiting for any reply, she moved quickly towards the door, and swept out of the room. There was a dead silence. All eyes were fixed on the Count. He gave a barely perceptible shrug of the shoulders, as he glanced at the door through which Lady Dorothy had made her retreat.

Julia Crofton was the first to speak.

"Come along, Bobbie," she said, "you promised to take me to see the fruit-garden."

"Certainly," replied Lord Bobbie, with alacrity. He crossed the room and opened the door.

"See you presently, Count," he said. "Good morning, Miss Grahame; ta-ta, Jim, don't be too much of a nuisance."

The Count waited a few seconds after the couple had disappeared, then bowed to the governess and took his departure.

Olive Grahame did not immediately return to the children. She stood staring absently into the middle of the room. There was still a picture before her, of a woman supremely beautiful, standing with lifted head, her glorious eyes flashing indignantly, as she defended the character of Alan Winn. She sighed softly.

"He cannot help loving her!" she whispered to herself. "It is better for him not to see me!"

She was roused from her reflections by a touch on the hand. Master Jim had slipped down from his seat and crossed to her.

"Miss Grahame," he said, pleadingly, "may I get my paint-box and put in that piece of red on the map. I shouldn't like the man who did it all to see my atlas, and then find it not there. May I?"

Olive Grahame bent down and kissed the eager young face.

"Yes, dear," she said, softly.

Meanwhile Julia Crofton and Lord Bobbie had found a pleasant seat in the garden. They were two young people who found enjoyment in discussing together the affairs of others, and incidentally their own. They did not love one another, and had not the slightest intention of doing so. They were simply, as Julia put it, "good pals." Lord Bobbie described his cousin, who was sportively inclined, not at all pretty, and addicted to the occasional use of slang, as a "brick"; and Julia returned the compliment by declaring that Bobbie was an "awfully good sort, with no nonsense to speak of about him."

Lord Bobbie lighted a cigarette.

"I'm hanged if I like that Frenchman!" he exclaimed. "Who is he, and how on earth did he get into Kenwell's house?"

"He is a protégé of old Lady Steele, and she had him invited here. She says that[Pg 597] he has such charming manners, and she trots him about everywhere with her."

"Wouldn't mind betting he's an adventurer," growled Bobbie. "He has got the cut of a Monte Carlo sharp. Didn't Dolly look fine as she snubbed him? If ever there was a case of a woman openly showing her admiration for a man, this is one. She positively adores Winn. Confound him!" he added, with an air of disgust.

"Poor old Bobbie!" said Julia, sympathetically. "It's a bit rough on you."

"And I was getting on so well with her," he continued, with a sigh. "I believe that in another week I should have won her. And then this Winn must needs turn up. I ought to hate him as a rival; I should like to, but, 'pon my word, I can't. He's such a good sort.

"Jove! how these fellows get on! Here we have a man, I don't believe he's touched thirty yet, been working like a nigger in some place or other, starts a new country, becomes the right-hand man of the company formed to run it, and in a few years he returns to his native land, pleasantly near to being a millionaire. I don't know how they do it!" he finished, despairingly.

"'WOULDN'T GERMANY GIVE SOMETHING FOR THE CONTENTS OF

THAT WALLET!'"

"'WOULDN'T GERMANY GIVE SOMETHING FOR THE CONTENTS OF

THAT WALLET!'"

Miss Crofton glanced at her cousin's good-natured though somewhat indolent-looking face.

"I believe," she said, calmly, "the possession of a quality termed 'grit' frequently explains the mystery."

"And now," went on Bobbie, concernedly, "the beggar has the chance of marrying the loveliest girl in society. Anyone can see that Dolly idolises him, and that he has but to say the word, and she is his. Oh! it's disgusting!"

"Perhaps he won't say it," said Miss Crofton.

"Of course he will," replied Bobbie, warmly. "There is no man on earth who could possibly be such a fool as to refuse the chance. Why, Kenwell is Chairman of the Chartered Company of Kafangaland, and is dead set on the match himself. Oh! he couldn't be such a fool!" he added, shaking his head with an air of conviction.

Miss Crofton rose to her feet.

"Have you noticed, Bobbie, that a man never prizes that which he can have for the asking?" She paused. "I'll tell you what I'll do: I'll bet you a hundred cigarettes that Winn doesn't make this easy conquest."

"You're throwing your money away," said Bobbie, warningly.

"Are you taking it?" asked Miss Crofton, coolly.

"Oh," said Bobbie, with a shrug, "if you're set on it, certainly."

She glanced at the watch on her wrist.

"The Lion will be here by now. We had better be going in to see him. By the way, old man, you remember my preference for Turkish?"

"Oh, yes," replied Bobbie, smiling grimly; "but there will be no occasion to[Pg 598] tax my memory, I assure you. It's a 'cert' for me, worse luck!" he added, mournfully.

He rose from the seat, and together they strolled towards the house.

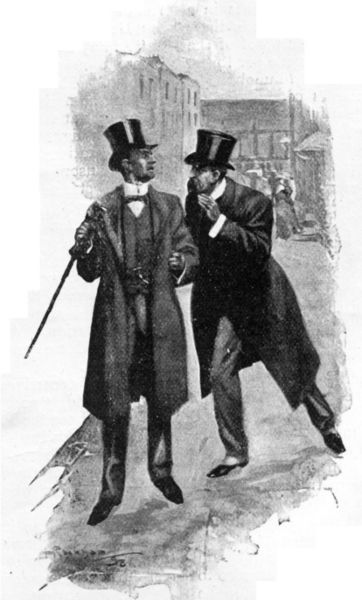

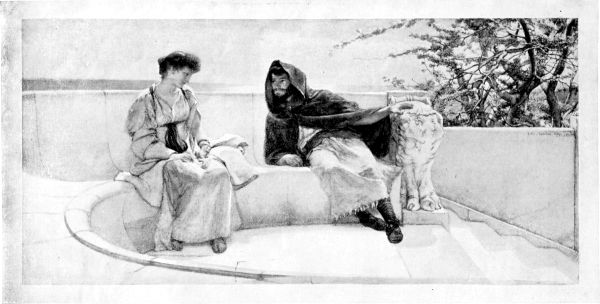

Alan Winn had arrived half an hour ago, and was now strolling on the terrace with Earl Kenwell, engaged in talking over business matters. A casual observer would have taken the pair for father and son. The Earl, although approaching his fifty-third year, was still erect, his complexion fresh, his eyes keen. Winn was perhaps a trifle the taller of the two; he had well-cut features, a determined-looking chin, and a pair of grey eyes that gazed steadily from their depths. From the other end of the terrace, Lady Dorothy, who was reading a newspaper to old Lady Steele, paused now and again to shoot a glance at the broad-shouldered man walking by her father's side.

"My dear," she heard Lady Steele's voice say, "I am deeply interested in what you are reading, but might I suggest that we proceed to the next paragraph? You have read that one three times."

Lady Dorothy blushed, and hurriedly turned her attention to the paper.

"I beg your pardon," she said, with an air of confusion, "I was——"

"In a day dream, I fancy, in which admiration for another person figured prominently," retorted the old lady. "I think I shall have to get the dear Count to read to me; he has such a charming voice. By the way, where can he be? I haven't seen him since breakfast time."

At the present moment, the Count was comfortably ensconced in a chair behind the library windows, and intent on perusing a recently arrived copy of the Figaro.

The library faced the terrace, and as the Earl passed with Winn he glanced casually into the long dark room. It appeared to be empty, for the window curtains effectually concealed the Count from view. The Earl caught hold of two chairs, and placed them in the shade.

"So you really think the scheme has a good chance?" he asked, anxiously.

Winn puffed a cloud of smoke from his cigar, as he dropped into a chair.

"Yes," he said at length, "I am confident that we shall succeed. I do not think it possible that anyone can have the least suspicion of my discoveries in the Vaarg Valley, or of what we contemplate doing there. We shall be first in the field."

Behind the curtains, the Figaro dropped slowly in the Count's hands. An alert look came into his eyes, and he moved his head nearer to the window.

"It's going to be the biggest coup ever effected in South Africa," continued the calm, confident voice. "I believe that in the Vaarg Valley we have another Kafangaland, although, of course, on a smaller scale."

"As good as that!" exclaimed the Earl.

"Yes, I believe so. I spent the whole of yesterday at the Colonial Office; the railway concessions have been granted, and practically everything is settled. Not one of our rivals dreams that we are making any move. Like myself, they are now all holiday-making. Even old Vorenbeck is in London staying at the Victoria."

"And what have you arranged?"

"Forster will leave on Saturday in the Tantallon Castle, with full authority to act on our behalf. In this wallet are all the plans, complete to the minutest detail, and also his instructions as to how to proceed."

"By Jove!" put in the Earl, "wouldn't old Vorenbeck, or rather Germany, give something for the contents of that wallet!"

"Vorenbeck, the old scoundrel," replied Winn, with a laugh, "would give anything up to twenty thousand pounds for the contents of that wallet, provided they were in his hands by to-morrow evening. But that contingency need not be entertained, for it will not leave my person until I hand it myself to Forster on Saturday."

Inside the library, the Figaro had slipped quietly to the ground, and the Count was staring hard in front of him, a curious expression in his eyes, as he pulled thoughtfully with one hand at his moustache.

There was a clatter of feet on the terrace, and the children ran up to their uncle. They were followed by Lady Dorothy, who shot a playfully reproachful glance at Winn. She had been dismissed by old Lady Steele as an incompetent reader.

"Kafanga, toujours Kafanga!" she said, with a smile.

"But it was really necessary," he replied; "there shall be no more of it to-day, on my word of honour."

She stooped and laid a hand on Jim's curly head.

"This is my little cousin, Jim," she said.

Master Jim was staring open-mouthed[Pg 599] at Winn. Under his arm he held a book of some kind.

"Jim," continued Lady Dorothy, "this gentleman is——"

"I know," blurted out Jim, without waiting for the introduction to be finished. He hastily opened the book and turned over the leaves with feverish impatience. Finally he selected a page and held it out for Winn's inspection.

"I know," he went on, his finger pointing to a red daub at the bottom, "you're the man who did this."

Winn looked, and saw that a map of South Africa was before his eyes. He laughed as he grasped the compliment.

"Yes, it's British now, right enough," he said.

Jim nodded. His gaze was fixed wonderingly on the bronzed face of the tall man. Then a sudden eager look spread over his face.

"Well," asked Winn, with a smile, as he noticed the pleading glance, "what is it?"

Jim hesitated shyly for a moment, then burst out in his childish treble—

"I want to know how you did it?"

Winn laughed again, and caught the boy up and placed him on his shoulder.

"Come, that's not a fair question," he said; "it's a State secret."

"And, like most State secrets, everyone knows it, and is proud of it," put in Lady Dorothy, with a smile at Winn.

Her glance drifted up to Master Jim, who looked supremely happy in his lofty position.

"You'll understand one day, Jim," she added, "how these things are done, when you're grown up."

"When I'm grown up," retorted Master Jim, confidently, "I'm going to do the same myself."

"If we go on at our present rate, there won't be any of South Africa left for him by that time," said the Earl. "We shall have to discover a new field for him to operate upon. But there is no immediate hurry. What do you say to our visiting the kennels in the meantime?"

"Delighted," said Winn, and the whole party moved off slowly down the terrace.

"MISS GRAHAME BURIED HER FACE IN HER HANDS—SHE WAS

CRYING."

"MISS GRAHAME BURIED HER FACE IN HER HANDS—SHE WAS

CRYING."

As soon as they were out of earshot, the Count got up leisurely from his seat. Producing his case, he lighted a cigarette. He puffed at it reflectively.

"Twenty thousand pounds," he said, softly; "yes, Vorenbeck would certainly give that for the Vaarg Valley plans—" he paused—"and it happens that I am a poor man."

He moved across the room towards a heavily-curtained doorway.

"But how," he muttered, "how is it to be done?"

He pulled the drapery aside, then started back in surprise. Miss Grahame was standing in the space between the curtains and the door. In one hand she was holding a book.

He looked at her suspiciously. He noticed that the door was closed behind her. How long had she been there? What had she heard?

She returned his gaze almost defiantly.

"I came to replace this book," she said, simply, then stepped forward.

He bowed to her in silence, and passed out of the room. She stood for a moment with her eyes fixed on the door through which he had disappeared.

"Oh!" she exclaimed, "if I could only warn him!"

She stood for some minutes staring absently out of the window. Suddenly the sound of voices caught her ear, and she turned her head. She drew back quickly behind the curtain, as round the corner of the terrace Lady Dorothy appeared with Winn. He was smiling, and she was laughing happily into his face. It would have been difficult to picture a more perfect pair.

Olive Grahame stood for a few moments immovable, her eyes fixed on Winn. Then, as they came to within a few feet of the library window, she turned with a quick movement and hurried away. She made her way upstairs, and, gaining her room, shut the door. On the opposite side by the window stood a table, on which was an old-fashioned leather-covered desk. She crossed to this, and, unlocking it, began to turn over some papers. Presently she came upon a photograph. She held this before her and gazed at it steadily for some seconds. Suddenly it dropped from her grasp, and, sinking into a chair by the table, she leant forward and buried her face between her hands. Miss Grahame was crying.

The day passed pleasantly enough for Earl Kenwell's guests. They lunched, played tennis, drove, and after dinner there had been some music. Lady Dorothy sang, and Julia Crofton whistled—she was an accomplished amateur siffleuse. The ladies having retired, Lord Bobbie volunteered to play billiards with the Count. After one game, however, Bobbie, who had been yawning a good deal, remarked that he was extremely tired, and suggested that they should go to bed. The Count assented, and together they made their way upstairs.

Winn and the Earl had repaired to the latter's study with the intention of talking business. For an hour they discussed the Vaarg Valley scheme in all its bearings.

"Well, we have done everything we can," said the Earl, as a concluding remark, "the rest we must leave to Providence."

There was silence for a few moments. Winn puffed at his cigar, his eyes idly following the rings of smoke. From the other side of the room the Earl was subjecting him to a close and critical observation. He had no son of his own; as he noted Winn's splendid proportions, the look of indomitable resolution in his face, he felt that had he been blessed with one, he would have wished him to be like this man.

Then he thought of his daughter, Dorothy. He was not blind, and had been quick to observe the state of her feelings. He loved his daughter, he liked Winn. He had given the matter his close consideration, and had arrived at a decision. It was this decision which prompted him to speak now. He intended to hint to Winn that his engagement with Lady Dorothy would be entirely to his satisfaction.

"You say you will be returning to Kafanga in September?" he began.

Winn roused himself from his reverie.

"That was my intention," he replied; "but I have something to accomplish first, something——" He paused.

The Earl had his keen eyes fixed on him.

"Forgive me, Winn," he said, quietly, "I am not asking out of sheer curiosity, but the 'something'—is it a question of marriage?"

Winn looked straight across at the Earl.

"Yes," he said, simply.

The Earl rose from his seat and stood with his back to the mantelpiece.

"My dear Winn," he said, "I think I am right in saying that there is no one who wishes more to see you happily married than myself." The Earl paused. "And surely," he added, "with your reputation there should be no difficulty in achieving this end."

Winn shook his head slowly. The Earl[Pg 601] glanced across at him, and for a moment their eyes met.

"Why not tell me?" said the Earl, gently.

Winn appeared to hesitate for a moment.

"You are very kind," he said at length. "It began when we were boy and girl——" He stopped, for the Earl's cigar dropped through his fingers to the ground, and he stooped to pick it up.

"Yes?" said the Earl, in a low tone. He was thinking of the disappointment in store for his daughter.

"She was the daughter of a country vicar under whose care I had been placed," continued Winn. "Then, I was suddenly thrown on my own resources, and there came the chance of my going to South Africa. We parted, and I vowed that I would come back to claim her.

"The day after I returned," he went on, speaking slowly, "I made my way down to the old place. I found the vicar dead—and she gone. I have searched everywhere, but can find no trace of her."

He rose to his feet.

"But I shall find her, I shall find her!" he said, and his voice had the same confident ring as when he uttered the words that night at Winchmere.

The Earl did not speak for a moment or so; then he stepped forward and held out his hand.

"I sincerely hope you will," he said; "if ever a man deserved a good wife, you are he."

THE COUNT HELD A HEAVY STICK IN HIS HAND, BUT THE WALLET

SLIPPED TO THE GROUND.

THE COUNT HELD A HEAVY STICK IN HIS HAND, BUT THE WALLET

SLIPPED TO THE GROUND.

Winn grasped the proffered hand.

"Thank you," he replied, simply.

"By Jove," continued the Earl, with a glance at the clock, "I didn't notice that it was so late! Shall we be going to bed?"

Winn had turned to the window and drawn aside the curtains. He passed a hand restlessly over his forehead.

"I think, if you don't mind, I will smoke a last cigar on the terrace. I don't feel sleepy, and the air will do me good. But please go on yourself. I know my way about perfectly."

The Earl demurred.

"I insist," said Winn, smilingly. "If you do not go, I shall have to give up my stroll."

"Well, if you're determined, that settles it," said the Earl, with a good-humoured laugh. "I have my recollections of the firmness of your decisions. Good-night."

Left alone, Winn lighted another cigar, then unfastened the French windows and stepped on to the terrace. He walked to the end, and stood at the top of the steps leading to the front entrance. He descended these, and started to stroll down the avenue of trees that stretched for half a mile to the park gates.

He did not know that from a window he was being watched by a pair of eyes—eyes that were shining with the eagerness that proclaims but one feeling in a woman. Olive Grahame, fully dressed—she had not the slightest inclination for sleep—was sitting at an open window, her gaze riveted on the tall figure that was fast disappearing from her view. Suddenly she gave a slight start, then strained eagerly forward. There was a brilliant moon, and across a small piece of turf she had seen a dark shadow move quickly. She looked intently. There was no mistake. She saw the shadow move again, then finally vanish into the blackness of the trees.

She got up quickly, her hand trembling with excitement. Someone was following Winn, hiding from him behind the trees! She stood for a moment in the middle of the room, thinking. One fact was clear before her: Alan Winn was in danger, and she was the only person who knew of it. Without a second's hesitation, she crossed her room, opened the door, and crept along the passage until she reached a staircase. She was well acquainted with the house, and knew a way by which she could gain the terrace. She reached the library, and found the window half open. Someone else had evidently used this means of exit. She guessed who.

In another minute, she had crossed the terrace, run down the steps, and was speeding quickly down the avenue. She had gone barely a dozen paces when her eye caught sight of a tiny patch of white ahead of her. It grew bigger, and she realised that it was coming towards her. A few yards more and she almost ran into the arms of the Count. He was in evening dress, and in one hand held a short, heavy-looking stick. With the other he was attempting to slip something into his pocket as he ran. As he met Olive, he drew back with a nervous start, and it slipped through his fingers to the ground. She pounced on it; it was a leather wallet.

Recovering from his surprise, he caught hold of her wrist. His face grew livid with rage.

"Give that to me, you little fool," he said, breathing heavily.

"What have you done to Mr. Winn?" she panted; "tell me, else I'll scream for help."

He glared at her savagely. Then, letting go her wrist, he drew back a step and raised the stick, as if about to strike her.

"Will you give that——?" he began, threateningly, then broke off with an oath.

Olive had seen her opportunity, and darted off down the avenue. He did not dare to follow her. She ran on for some fifty yards, then caught sight of a dark heap lying on the ground. In a moment she was kneeling by his side, peering eagerly into his face.

Winn uttered a groan, then slowly opened his eyes. His head was tough, and it took a heavier blow than the one which the Count had dealt him to effectually lay him low.

"Where am I?" he said, in a dazed tone, raising himself on one elbow. His hand flew to his pocket. "The wallet?" he cried.

She pressed it into his hand. He clasped it, and his eyes travelled up to her face. For a moment he stared at her in absolute wonderment.

"Olive!" he gasped, "is it really you, my darling?"

She was trembling, but looked into his face with smiling eyes.

"Really me," she said.

Slowly and unsteadily he rose to his feet.

"It is bewildering," he said. "I am knocked on the head in some mysterious fashion, and the plans are stolen. I regain consciousness, and find you by my side with the wallet. What does it all mean?"

She told him what had happened.

"Wonderful!" he cried at the conclusion, catching hold of her hand, "to think that you, of all people, should come to my aid in this fashion! Do you know, Olive, I have thought of you every day during the last eight years; and now——" He paused and looked into her face.

"Ah! now," she said, falteringly, "our positions are so different. Remember, I am only a gov——"

"You are the woman I love," he interrupted; "and do you think I can let you go—after this? Olive, you cannot—you must not ask it of me! My dearest, you——?"

He stopped and looked into her eyes for the answer. Then, satisfied by what he saw there, he drew her gently to him.

At the breakfast table the next morning there was one absentee. The Count had been suddenly called away and had left by the early train.

"Extraordinary!" remarked Bobbie Scaife. "I wonder what was the reason?" he added, looking across at Winn.

Winn gave no reply. His thoughts at that moment were centred on a young person who, in the schoolroom, was continuing her lesson with Master Jim.

Jim had found something wanting in his lesson that morning. He looked up at his governess with a troubled expression.

"You don't seem to be thinking about my jogruffy at all, Miss Grahame," he said, at last, in rather an aggrieved tone.

Jim was a keen observer. Her thoughts had been far away from the consideration of the natural products of Canada. She turned to him now with a smile.

"We'll have to make up for it to-morrow, dear," she said. "See, it is your time for going out."

AN AWKWARD MOMENT—WINN TELLS LADY DOROTHY THAT OLIVE IS

TO BE HIS WIFE.

AN AWKWARD MOMENT—WINN TELLS LADY DOROTHY THAT OLIVE IS

TO BE HIS WIFE.

A few moments afterwards a servant[Pg 604] appeared and took charge of the children.

As the door closed behind them, Olive Grahame strolled to the window and looked out across the park. The sun was shining and everything was tinged with its gold.

"It's wonderful," she murmured, "after all these years!"

There was a tap at the door. She turned and saw Earl Kenwell entering the room; with him was Winn.

The Earl crossed to the window and held out his hand.

"Miss Grahame," he said, with a smile, "will you please accept my congratulations? My friend Winn has been telling me how he has been hunting the country for you, and found you at last under my roof. He has also told me how you pluckily saved the Vaarg Valley plans from our rivals; and after hearing the story, I took the liberty of telling him that he is an exceptionally lucky man to have gained such a woman for his wife."

"You are very kind," murmured Olive, with a blush.

The Earl pushed open the French windows and led the way on to the terrace. Winn linked his arm within Olive's and followed.

"If ever I meet that scoundrel Morlot," remarked the Earl, "I'll——"

There was a rustle of a dress on the terrace, and a second afterwards Lady Dorothy appeared in view. The Earl shot a half-nervous glance at Winn, then turned to meet his daughter.

"Dolly," he said, and his voice was more affectionate than usual, "we have some surprising news for you."

Lady Dorothy had come to a sudden stop, and her eyes were fixed on Olive and Winn, whose arms were still linked.

"It appears," continued the Earl, and his voice grew even softer, "that Miss Grahame and Mr. Winn are old friends—very old friends—" he paused awkwardly, "that is, they knew one another before he went to Africa." Again the Earl paused.

Lady Dorothy was still standing with her gaze riveted on the pair. She saw the whole affair at a glance, and her heart seemed to grow cold within her.

"Yes, Lady Dorothy," said Winn, coming to the Earl's rescue, "Olive and I have loved one another for ten years, although separated most of the time. We have met again, and she has promised to be my wife."

There was a moment's dead silence. Olive glanced up timidly, and her gaze met that of Lady Dorothy. Both women knew that the other loved Alan Winn; but one counted her love by years, the other by days. One had dreamed, hoped, counted on being his wife, and she had lost. The other knew all this, and her heart went out in sympathy to her rival.

Lady Dorothy looked at the pretty flushed face; the grey eyes seemed almost pleading in their wistfulness. She felt she could not hate this girl. With a sudden movement she stepped forward and held out her hands. Olive grasped them eagerly.

"I hope," said Lady Dorothy, and her voice had a slight tremor in it—"I hope you'll be very, very happy."

Then she released her hold of Olive, and, without another word, hurried away. The Earl turned his head and watched his daughter disappear. There was a suspicious moisture about his eyes as he faced Winn again.

"You two would perhaps like to be alone," he said, forcing a smile, "so I'll wish you au revoir for the present," and he too hastened away.

The pair stood silent for a moment. Then she touched him lightly on the arm. He bent his head and looked at her inquiringly.

"What is it, dearest?" he asked.

"I hope," she said, softly, "that some day she will marry someone worthy of her—someone whom she will love as much—" she paused, and looked into his face—"as much as I love you."

He pressed her gently to him and kissed her lips.

"I hope so, too," he said; "she is a good woman."

Events happened as they wished; for, a year later, the engagement of Lady Dorothy to Lord Scaife was announced.

"Awfully glad, old chap," remarked Julia Crofton, as she tendered her congratulations; "you didn't go particularly strong at the start, but you picked up splendidly at the finish. I didn't think you had it in you," she added, candidly.

"Oh," replied Bobbie, with a happy laugh, "as with those successful fellows from South Africa, it's the 'grit' that tells."

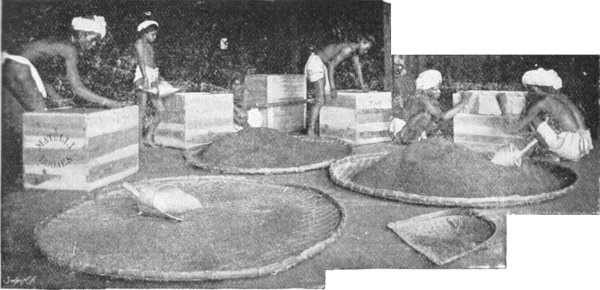

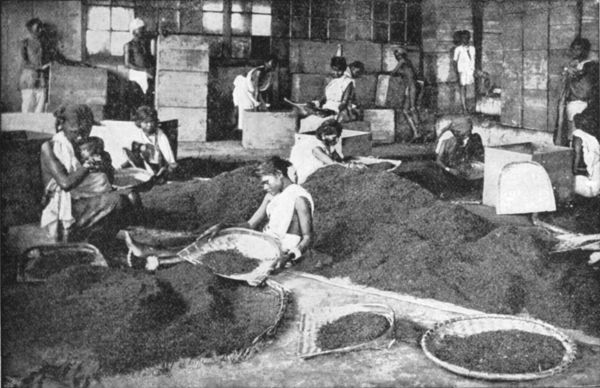

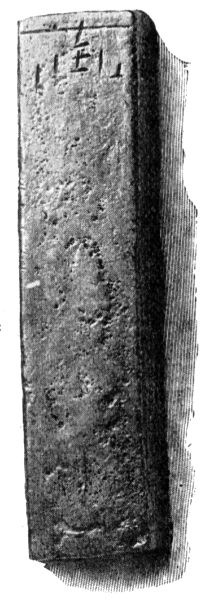

PACKING TEA FOR EXPORT.

PACKING TEA FOR EXPORT.SOME GOSSIP NOT OFTEN HEARD.

Of the millions of people who drink tea, very few seem to know how it is grown or manufactured.

They would hardly believe that there are just on 800,000 acres of land planted under tea in India and Ceylon, employing over one million people—all British subjects. Just imagine employing a fifth of the population of London for the production of one article! Then, again, look at the thousands of people who are employed in the tea trade at home—merchants, dealers, brokers—all dependent on this one article of consumption for their bread-and-butter!

And yet hardly ten per cent. of these know anything about tea manufacture, or have ever given a thought to the one million of people employed in its production.

The duty paid to the Customs during the past twelve months on Indian and Ceylon tea amounted to £3,805,935, to say nothing of the revenue accruing to the Indian and Ceylon Governments in taxes and a hundred and one little charges, all helping to swell the coffers of State, and enabling hundreds of thousands of people to maintain a living.

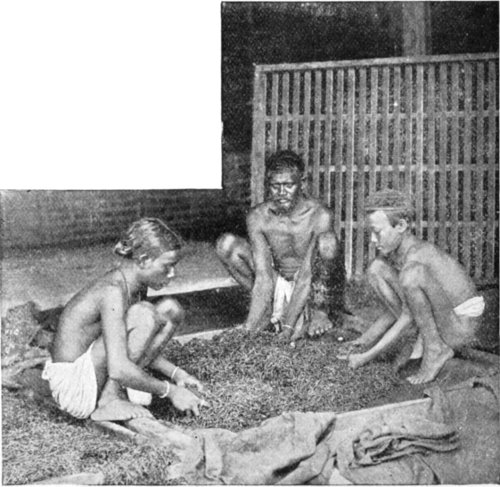

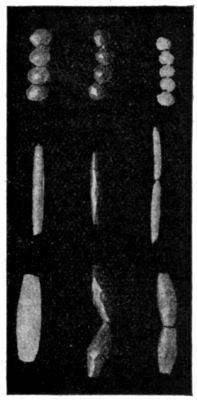

TURNING THE LEAVES FOR FERMENTATION.

TURNING THE LEAVES FOR FERMENTATION.Surely all these things should[Pg 606] induce the patriotic British public to drink only British-grown tea, grown as it were by their own people—for are not India and Ceylon British? and are not the people of Great Britain and India and Ceylon one, under one Sovereign?

The plucking of the tea plant generally commences about the middle of March, and goes on till the end of November, except in Ceylon, where it goes on more or less throughout the twelve months, there being no cold weather to check the "flush" and allow the bushes to lie dormant.

A tea bush is not considered fully ripe for plucking until about five years of age, though a little "tipping" is done on low-lying gardens during the third and fourth years. It is generally carried on by the coolie women and children; the former are rapid and expert workers, and are paid so much for every pound of green leaf plucked. As the leaves are plucked they are thrown into baskets, the contents of which are taken to the factory twice a day for weighing.

There are many ideas as to how plucking should be carried out, and how many leaves should be taken off, but the most general system is to pluck two leaves and a bud, not separately but together.

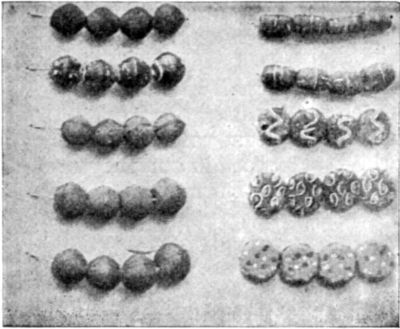

PICKERS HAVING THEIR TEA LEAVES WEIGHED.

PICKERS HAVING THEIR TEA LEAVES WEIGHED.Some planters, who prefer quantity to quality, pluck the half or whole of the third leaf as well.

It must be thoroughly understood that all the leaves are not "ripped" off the bushes, but only the young shoots. It is a very delicate operation, requiring great care and skill, and is usually carried out under the eye of the assistant manager.

It is usual to get round a plantation once in six to eight days, and woe be to him who cannot cope with the leaf, or lets it run away from him, as it will show the result both in the dry leaf and liquor.

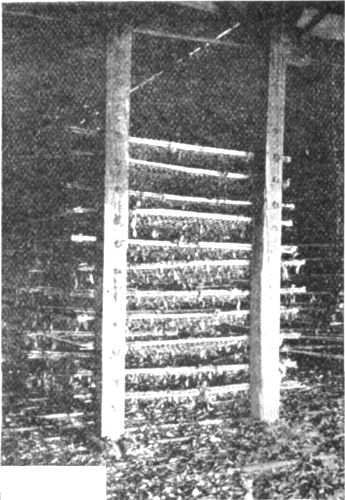

The leaf, when plucked, is brought into the factory, weighed, and put through the following process of manufacture. The first process is called withering. The leaf is thinly spread on wire meshing, stretched from end to end of the loft or withering-house, the object being to allow a certain percentage of moisture to evaporate, and to get the leaf into a pliable condition for rolling, so that it will not break during this process. Properly withered leaf should be as flexible as a soft kid glove.

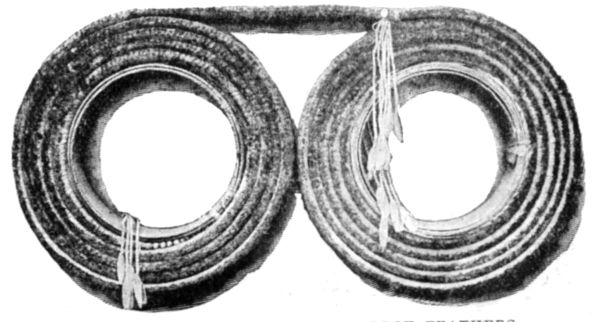

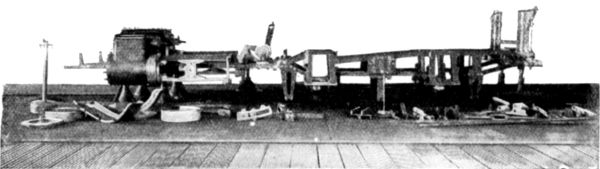

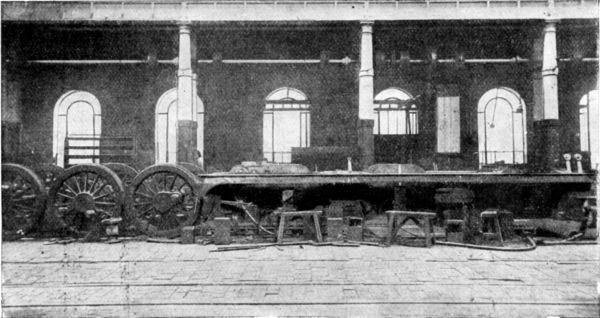

Then comes the rolling, the object of which is to break the cells of the leaf one into the other, so as to free the juice[Pg 607] and to give a "twist" or "roll" to the leaf. Care has to be taken that too much juice is not expressed, which would be detrimental to the liquor when in the household pot.