Title: Turner

Author: W. Cosmo Monkhouse

Release date: September 27, 2012 [eBook #40878]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images available at The Internet Archive)

ILLUSTRATED BIOGRAPHIES OF

THE GREAT ARTISTS.

JOSEPH MALLORD WILLIAM TURNER

ROYAL ACADEMICIAN.

ILLUSTRATED BIOGRAPHIES

OF

THE GREAT ARTISTS.

| TITIAN | From the most recent authorities. |

| By Richard Ford Heath, M.A., Hertford Coll. Oxford. | |

| REMBRANDT | From the Text of C. Vosmaer. |

| By J. W. Mollett, B.A., Brasenose Coll. Oxford. | |

| RAPHAEL | From the Text of J. D. Passavant. |

| By N. D’Anvers, Author of “Elementary History of Art.” | |

| VAN DYCK & HALS | From the most recent authorities. |

| By Percy R. Head, Lincoln Coll. Oxford. | |

| HOLBEIN | From the Text of Dr. Woltmann. |

| By the Editor, Author of “Life and Genius of Rembrandt” | |

| TINTORETTO | From recent investigations. |

| By W. Roscoe Osler, Author of occasional Essays on Art. | |

| TURNER | From the most recent authorities. |

| By Cosmo Monkhouse, Author of “Studies of Sir E. Landseer.” | |

| THE LITTLE MASTERS | From the most recent authorities. |

| By W. B. Scott, Author of “Lectures on the Fine Arts.” | |

| HOGARTH | From recent investigations. |

| By Austin Dobson, Author of “Vignettes in Rhyme,” &c. | |

| RUBENS | From recent investigations. |

| By C. W. Kett, M.A., Hertford Coll. Oxford. | |

| MICHELANGELO | From the most recent authorities. |

| By Charles Clément, Author of “Michel-Ange, Léonard, et Raphael.” | |

| LIONARDO | From recent researches. |

| By Dr. J. Paul Richter, Author of “Die Mosaiken von Ravenna.” | |

| GIOTTO | From recent investigations. |

| By Harry Quilter, M.A., Trinity College, Cambridge. | |

| THE FIGURE PAINTERS OF THE NETHERLANDS. | |

| By Lord Ronald Gower, Author of “Guide to the Galleries of Holland.” | |

| VELAZQUEZ | From the most recent authorities. |

| By Edwin Stowe, B.A., Brasenose Coll. Oxford. | |

| GAINSBOROUGH | From the most recent authorities. |

| By George M. Brock-Arnold, M.A., Hertford Coll. Oxford. | |

| PEUGINO | From recent investigations. |

| By T. Adolphus Trollope, Author of many Essays on Art. | |

| DELAROCHE & VERNET | From the works of CHARLES BLANC. |

| By Mrs. Ruutz Rees, Author of various Essays on Art. | |

JOSEPH MALLORD WILLIAM TURNER.

From a sketch by John Gilbert.

“The whole world without Art would be one great wilderness.”

![]()

BY W. COSMO MONKHOUSE

Author of “Studies of Sir E. Landseer.”

NEW YORK:

SCRIBNER AND WELFORD.

LONDON:

SAMPSON LOW, MARSTON, SEARLE, & RIVINGTON,

1879.

(All rights reserved.)

CHISWICK PRESS:—C. WHITTINGHAM, TOOKS COURT,

CHANCERY LANE.

THE late Mr. Thornbury lost such an opportunity of writing a worthy biography of Turner as will never occur again. How he dealt with the valuable materials which he collected is well known to all who have had to test the accuracy of his statements; and unfortunately many of the channels from which he derived information have since been closed by death. Mr. Ruskin, who might have helped so much, has contributed little to the life of the artist but some brilliant passages of pathetic rhetoric. Overgrown by his luxuriant eloquence, and buried beneath the débris of Thornbury, the ruins of Turner’s Life lay hidden till last year.

Mr. Hamerton’s “Life of Turner” has done much to remove a very serious blot from English literature. Very careful, but very frank, it presents a clear and consistent view of the great painter and his art, and is, moreover, penetrated with that intellectual insight and refined thought which illuminate all its author’s work.

He has, however, left much to be done, and this book will, I hope, help a little in clearing away long-standing errors, and reducing the known facts about Turner to something like order. To these facts I have been able to add a few hitherto unpublished; and it is a pleasant duty to return my thanks to the many kind friends and strangers for the pains which they have taken to supply me with information. To Mr. F. E. Trimmer, of Heston, the son of Turner’s old friend and executor; to Mr. John L. Roget; to Mr. Mayall, and to Mr. J. Beavington Atkinson, my thanks are especially due.

In so small a book upon so large a subject, I have often had much difficulty in deciding what to select and what to reject, and have always preferred those events and stories which seem to me to throw most light upon Turner’s character. On purely technical matters I have touched only when I thought it absolutely necessary. This part of the subject has been already so well and fully treated by Mr. Ruskin in numerous works, too well known to need mention; by Mr. Hamerton in his “Life of Turner,” and “Etching and Etchers;” by Messrs. Redgrave in their “Century of English Painters,” and by Mr. S. Redgrave in his introduction to the collection of water-colours at South Kensington, that I need only refer to these works such few among my readers as are not already acquainted with them. I would also refer them for similar reasons to Mr. Rawlinson’s recent work on the “Liber Studiorum.”

I should have liked to add to this volume accurate lists of Turner’s works and the engravings from them, with information of their possessors, and the extraordinary fluctuation in the prices which they have realized, but this would have entailed great labour and have swelled unduly the bulk of this volume, which is already greater than that of its fellows. Fortunately this information is likely to be soon supplied by Mr. Algernon Graves, whose accurate catalogue of Landseer’s works is sufficient guarantee of the manner in which he will perform this more difficult task.

The edition of Thornbury’s “Life of Turner” referred to throughout these pages, is that of 1877.

W. COSMO MONKHOUSE.

| PART I. | |

| 1775 to 1797. Days of Education and Practice. | |

| CHAPTER I | |

| Page | |

| Introductory | 1 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| Early Days—1775 to 1789 | 6 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| Youth—1789 to 1796 | 20 |

| PART II. | |

| 1797 to 1820. Days of Mastery and Emulation. | |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| Yorkshire and the young Academician—1797 to 1807 | 38 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| The “Liber Studiorum” and the Dragons | 55 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| Harley Street, Devonshire, Hammersmith, and Twickenham | 75 |

| PART III. | |

| 1820 to 1851. Days of Glory and Decline. | |

| CHAPTER VII | |

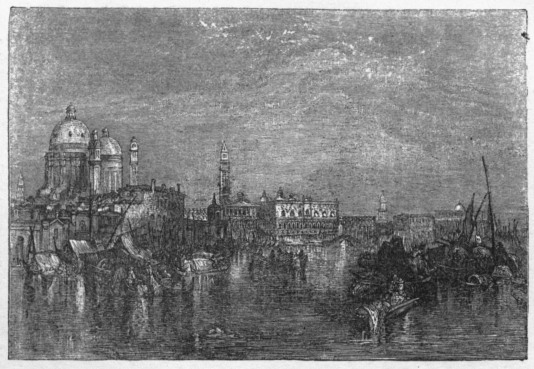

| Italy and France—1820 to 1840 | 92 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| Light and Darkness—1840 to 1851 | 121 |

| Index. | |

| Chronology Of Turner’s Life. | |

THE task of writing a satisfactory life of Turner is one of more than usual difficulty. He hid himself, partly intentionally, partly because he could not express himself except by means of his brush. His secretiveness was so consistent, and commenced so early, that it seems to have been an instinct, or what used to be called by that name. Akin to the most divinely gifted poets by his supreme pictorial imagination, he also seems on the other side to have been related to beings whose reasoning faculty is less than human. When we look at such pictures as Crossing the Brook, The Fighting Téméraire, and Ulysses and Polyphemus, we feel that we are in the presence of a mind as sensitive as Keats’s, as tender as Goldsmith’s, and as penetrative as Shelley’s; when we read of the dirty discomfort of his home and of the difficulty with which his patrons, and even his relations, obtained access to his presence—how even his most intimate friends were not admitted to his confidence—we can only think of a hedgehog, whose offensive powers being limited, is warned by nature to live in a hole and roll itself up into a ball of spikes at the approach of strangers.

We are used to having our idols broken; but we still fashion them with a persistency which seems to argue it a necessity of our nature, that we should think of the life and character of gifted men as being the outward and visible sign of the inward and spiritual grace we perceive in their works. It is this habit which makes any attempt to write a life of Turner pre-eminently unsatisfactory, for his refined sense of the most ethereal of natural phenomena is not relieved by any refinement in his manners, his supreme feeling for the splendour of the sun is unmatched by any light or brilliance in his social life; his extreme sensibility, a sensibility not only artistic but human, to all the emotional influences of nature, stands for ever as a contrast to his self-absorbed, suspicious individuality. There is of course no reason why a landscape painter should be refined in manner or choice in his habits. There is no necessary connection between the subjects of such an artist and himself, except his hand and eye. He lives a life of visions that may come and go without affecting his life or even his thought, as we generally use that word. The most tremendous phenomena of nature may be seen and studied, and reproduced with such power as to strike terror into those who see the picture, and yet leave the artist unaltered in demeanour and taste. Even those men of genius who, instead of employing their imagination upon nature’s inanimate works, devote themselves to the study of man himself, socially and morally, do not by any means show that relation between themselves and their finest work that we appear naturally to expect.

But all this, though it may explain much, still leaves unsatisfactory the task of writing the life of a man of whom such passages as the following could be sincerely written:—

“Glorious in conception—unfathomable in knowledge—solitary in power—with the elements waiting upon his will, and the night and morning obedient to his call, sent as a prophet of God to reveal to men the mysteries of the universe, standing, like the great angel of the Apocalypse, clothed with a cloud, and with a rainbow upon his head, and with the sun and stars given into his hand.”—Modern Painters (1843), p. 92.

“Towards the end of his career he would often, I am assured on the best authority, paint hard all the week till Saturday night; and he would then put by his work, slip a five-pound note into his pocket, button it securely up there, and set off to some low sailor’s house in Wapping or Rotherhithe, to wallow till Monday morning summoned him to mope through another week.”—THORNBURY’S Life of Turner (1877), pp. 313, 314.

The contrast is too great to make the picture pleasant, the facts are too few to make it perfect; to make it one or the other, it would be necessary to do as Turner did, and rightly did, with his perfect drawings—suppress facts that jarred with his scheme of form and colour, and insert figures or mountains or clouds that were necessary to complete it; but a biography is nothing if not real—it belongs to the other side of art. The task would be rendered lighter, if not more agreeable, if we were frankly to accept the principle of a dual nature, and cutting up our subject into halves, treat Turner the artist and Turner the man as two separate beings; and there would, at first sight, seem to be no more convincing proof of this duality than is afforded by Turner. He had an exquisitely sensitive apprehension of all physical phenomena, and was able to hoard away his impressions by the thousand in that wonderful brain-store of his, until they were wanted for pictures. He stored them with his eye, he reproduced them with his hand and memory. These three were all of the finest, and seemed to act without that process which is necessary to most of us before we can make use of our impressions, viz., the translation of them into words. This process is as necessary for the nourishment of most minds as digestion for the nourishment of the body, but to him it appears to have been almost entirely denied. He had grasp enough of his impressions without it, to enable him to analyze them and compose them pictorially; but he could not give any account of them or of his method of composition, and they had no sensible effect on his conversation.

He thus lived in two worlds—one the pictorial sight-world, in which he was a profound scholar and a poet, the other the articulate, moral, social word-world in which he was a dunce and underbred. In the one he was great and happy, in the other he was small and miserable; for what philosophy he had was fatalist. The riddle of life was too hard for his uncultivated intellect and starved heart to contemplate with any hope; he was only at rest in his dreamland. When he came down into this world of ours from his own clouds, he brought some of his glory with him, but without any cheerful effect; for it came but as a foil to ruined castles, the vice of mortals and the decay of nations.

Yet, while at a first view this distinction between Turner as a man and Turner as an artist seems complete, further study shows that the man had a great and often a fatal influence on the artist, and that this was not without reaction both serious and deep, and so we find that his art and himself are no more to be divided in any human view of him than were his body and his soul when he was yet alive. For these reasons we shall keep as close together as possible the histories of his life and his art, a task always difficult and sometimes impossible on account of the scantiness of trustworthy data for the one and the almost infinite material for the other.

THE appearance of Turner’s genius in this world is not to be accounted for by any known facts. Given his father and his mother, his grandfather and grandmother, on the father’s side, which is all we know of his ancestry, given the date of his birth, even though that was the 23rd April (St. George’s day, as has been so childishly insisted on), 1775, there seems to be positively no reason why William Turner, barber, of 26, Maiden Lane, opposite the Cider Cellar, in the parish of St. Paul’s, Covent Garden, and Mary Turner, née Marshall, his wife, should have produced an artist, still less, one of the greatest artists that the world has yet seen. There is only one fact, and that a very sad one, which might be held to have some connection with his genius. “Great wits are sure to madness near allied,” sang Dryden,[1] and poor Mrs. Turner became insane “towards the end of her days.” This, however, will in no way account for the special quality of Turner’s genius. He arose like many other great men in those days to help in opening the eyes of England to the beauties of nature, one of the large and illustrious constellation of men of genius that lit the end of the last and the beginning of the present century, and with that truth we must be content.

The earliest fact that we have on record which had any influence on Turner is that his paternal grandfather and grandmother spent all their lives at South Molton in Devonshire. Although he is not known to have visited Devonshire till he was thirty-seven years of age;[2] he appears to have been proud of his connection with the county, and to have asserted that he was a Devonshire man. This is, as far as we know, the solitary effect of Turner’s ancestry upon him. Of his father and mother the influence was necessarily great. From his father he undoubtedly obtained his extraordinary habits of economy, that spirit of a petty tradesman, which was one of his most unlovely characteristics, and, be it added, his honesty and industry also. Of his father we have several descriptions by persons who knew him; of his mother, one only, and that, unfortunately, not so authentic. We will give the lady the first place, and it must be remembered that this unfavourable picture is drawn by Mr. Thornbury from information derived from the Rev. Henry Syer Trimmer, the son of Turner’s old friend and executor, the Rev. Henry Scott Trimmer, of Heston, who obtained it from Hannah Danby, Turner’s housekeeper in Queen Anne Street, who got it from Turner’s father.

“In an unfinished portrait of her by her son, which was one of his first attempts, my informant perceived no mark of promise; and he extended the same remark to Turner’s first essays at landscape. The portrait was not wanting in force or decision of touch, but the drawing was defective. There was a strong likeness to Turner about the nose and eyes; her eyes being represented as blue, of a lighter hue than her son’s; her nose aquiline, and the nether lip having a slight fall. Her hair was well frizzed—for which she might have been indebted to her husband’s professional skill—and it was surmounted by a cap with large flappers. Her posture therein (sic) was erect, and her aspect masculine, not to say fierce; and this impression of her character was confirmed by report, which proclaimed her to have been a person of ungovernable temper, and to have led her husband a sad life. Like her son, her stature was below the average.”

This as the result of a painted portrait by her son, and verbal description by her husband, is not too flattering, and it is all we know of the character and appearance of poor Mary Turner. Of her belongings we know still less. She is said to have been sister to Mr. Marshall, a butcher, of Brentford, and first cousin to the grandmother of Dr. Shaw, author of “Gallops in the Antipodes,” and to have been related to the Marshalls, formerly of Shelford Manor House, near Nottingham.[3] We are able to add to this scanty information that she was the younger sister of Mrs. Harpur, the wife of the curate of Islington, who was grandfather of Mr. Henry Harpur, one of Turner’s executors. He (the grandfather) fell in love with his future wife when at Oxford, and their marriage brought her sister to London. We are also informed that the hard-featured woman crooning over the smoke, in an early drawing by Turner in the National Gallery (An Interior, No. 15), is Turner’s mother, and the kitchen in which she is sitting, the kitchen in Maiden Lane. We have also ascertained that one Mary Turner, from St. Paul’s, Covent Garden, was admitted into Bethlehem Hospital on Dec. 27th, 1800, one of whose sponsors for removal was “Richard Twenlow, Peruke Maker.” This unfortunate lady, whether Turner’s mother or not, was discharged uncured in the following year. Altogether what we know about Turner’s mother does not inspire curiosity, and we fear that she was never destined to figure in an edition of “The Mothers of Great Men.” The “sad life” which she is said to have led her husband could scarcely have been sadder than her own.

Of his father we have fuller information.

“Mr. Trimmer’s description of the painter’s parent, the result of close knowledge of him, is that he was about the height of his son, spare and muscular, with a head below the average standards” (whatever that may mean) “small blue eyes, parrot nose, projecting chin, and a fresh complexion indicative of health, which he apparently enjoyed to the full. He was a chatty old fellow, and talked fast, and his words acquired a peculiar transatlantic twang from his nasal enunciation. His cheerfulness was greater than that of his son, and a smile was always on his countenance.”

This description is of him when an old man, but he must have been not very different from this when about one year and eighteen months after his marriage, which took place on August 29th, 1773, the little William was born. He was not a man likely to alter much in habit or appearance. He was always stingy, if we may judge by the story of his following a customer down Maiden Lane to recover a halfpenny which he omitted to charge for soap, and from his son’s statement that his “Dad” never praised him for anything but saving a halfpenny. As barbers are proverbially talkative, and as persons do not generally develop cheerfulness in later life, we may consider Mr. Trimmer’s portrait of the old man to be essentially correct of him when young, especially as we find that Turner the younger was always “old looking,” a peculiarity which is generally hereditary.

The house (now pulled down) in which Turner was born, and in which, for at least some time after, father, mother, and son resided together, is thus described by Mr. Ruskin: “Near the south-west corner of Covent Garden, a square brick pit or well is formed by a close-set block of houses, to the back windows of which it admits a few rays of light. Access to the bottom of it is obtained out of Maiden Lane, through a low archway and an iron gate; and if you stand long enough under the archway to accustom your eyes to the darkness, you may see, on the left hand, a narrow door, which formerly gave access to a respectable barber’s shop, of which the front window, looking into Maiden Lane, is still extant.” Maiden Lane is not a very brilliant thoroughfare, and was still narrower and darker at this time, but still this picture, though doubtless accurate, seems to make it still darker, and in the engraving of the house in Thornbury’s life of Turner, even the front window that looked into Maiden Lane is rendered ominously black by the shadow of a watchman thrown up by his low-held lantern. To us it seems that there is plenty of dark in Turner’s life without thus unduly heightening the gloom of his first dwelling-place. A barber cannot do his work without light, and we have no doubt that whatever sorrow fell upon Turner in his life was in no way deepened by his having to pass through a low archway and an iron gate in order to get to his father’s shop.

The house in Maiden Lane would have been a cheerful enough and a wholesome enough nest for little William[4] if it had contained a happy family presided over by a sweetly smiling mother. This want is the real dark porch and iron gateway of his life, the want which could never be supplied. In that wonderful memory of his, so faithful, by all accounts, to all places where he had once been happy, there was no chamber stored with sweet pictures of the home of his youth; no exhaustless reservoir of tender, healthy sentiment, such as most of us have, however poor. Here is a note of pathos on which we might dwell long and strongly without fear of dispute or charge of false sentiment. Children, indeed, do not miss what they have not: present sorrows did not probably affect his appetite, future forebodings did not dim his hopes; but then, and for ever afterwards, he was terribly handicapped in the struggle for peace and happiness on earth, in his desire after right thinking and right doing, in his aims at self-development, in his chance of wholesome fellowship with his kind, in his capacity for understanding others and making himself understood, for all these things are more difficult of attainment to one who never has known by personal experience the charm of what we mean by “home.”

This want in his life runs through his art, full as it is of feeling for his fellow-creatures, their daily labour, their merry-makings, their fateful lives and deaths; there is at least one note missing in his gamut of human circumstance—that of domesticity. He shows us men at work in the fields, on the seas, in the mines, in the battle, bargaining in the market, and carousing at the fair, but never at home. This is one of the principal reasons why his art has never been truly popular in home-loving domestic England.

It is not good for man, still less for a boy, to be alone, and we do not think we can be wrong in thinking that he was a solitary boy. How soon he became so we do not know. We may hope that in his earliest years at least he was tenderly cared for by his mother, and petted by his father. There is no reason why we may not draw a bright picture of his childhood, and fancy him walking on Sundays with his father and mother in the Mall of St. James’s Park, wearing a short flat-crowned hat with a broad brim over his curly brown hair, with snowy ruffles round his neck and wrists, and a gay sash tied round his waist, concealing the junction between his jacket-waistcoat and his pantaloons; but this bright period cannot have lasted long. Soon he must have been driven upon himself for his amusement, and fortunate it was for him that nature provided him with one wholesome and endless.

It is known that one artist, Stothard, was a customer of his father, and it is probable that as there was an academy in St. Martin’s Lane, and the Society of Artists at the Lyceum, and many artists resided about Covent Garden, the little boy’s emulation may have been excited by hearing of them, and perhaps chatting with them and seeing their sketches.

He certainly began very early. We are told that he first showed his talent by drawing with his finger in milk spilt on the teatray, and the story of his sketching a coat-of-arms from a set of castors at Mr. Tomkison’s the jeweller, and father of the celebrated pianoforte maker, must belong to a very early age.[5] The earliest known drawing by him of a building is one of Margate Church, when he was nine years old, shortly before he went to his uncle’s at New Brentford for change of air. There he went to his first school and drew cocks and hens on the walls, and birds, flowers, and trees from the school-room windows, and it is added that “his schoolfellows, sympathizing with his taste, often did his sums for him, while he pursued the bent of his compelling genius.” Very soon after this, if not before, he began to make drawings, some of these copies of engravings coloured, which were exhibited in his father’s shop window at the price of a few shillings, and he drew portraits of his father and mother, and of himself at an early age. It is said that his father intended him to be a barber at first,[6] but struck with his talent for drawing soon determined that he should follow his bent and be a painter. He is said to have delighted in going into the fields and down the river to sketch, but all the very early drawings we have seen, including those purchased at his father’s shop, are drawings of buildings, mostly in London. Of these there is one of the interior of Westminster Abbey, in Mr. Crowle’s edition of “Pennant’s London,” now in the print room of the British Museum. There is nothing to distinguish these from the work of any clever boy, but this drawing and one in the National Gallery, of a scene near Oxford, both probably copied from prints, show a sense not only of light but colour. We have also seen a copy of Boswell’s “Antiquities of England and Wales,” with about seventy of the plates very cleverly coloured by him when a boy at Brentford.

Whatever defects Turner, the barber, may have had as a father, neglect of his son’s talents was not one of them, and, though very careful for the pence, he showed that he could make a pecuniary sacrifice when he had a chance of furthering his son’s prospects, for he refused to allow him to become the apprentice of one architect who offered to take him for nothing, and paid the whole of a legacy he had been left to place him with another, and we may presume a better one.

The information given by Mr. Thornbury about his early training, scholastic and professional, is very meagre, inconsecutive, and puzzling. According to him it was in 1785 that Turner, having been previously taught reading, but not writing, by his father, went to his first school, which was kept by Mr. John White, at New Brentford; in 1786 or 1787, by which time at least his destination for an artist’s career appears to have been settled, he was sent to “Mr. Palice, a floral drawing-master,” at an Academy in Soho, and in 1788, to a school kept by a Mr. Coleman at Margate; at some time before 1789, to Mr. Thomas Malton, a perspective draughtsman, who kept a school in Long Acre, and in this year to Mr. Hardwick, the architect, and to the school of the Royal Academy. He also went to Paul Sandby’s drawing school in St. Martin’s Lane. During all, or nearly all this time, he was, according to Mr. Thornbury, employed: 1. In making drawings at home to sell. 2. In colouring prints for John Raphael Smith, the engraver, printseller, and miniature painter. 3. Out sketching with Girtin. 4. Making drawings of an evening at Dr. Monro’s[7] in the Adelphi. 5. Washing in backgrounds for Mr. Porden. If he was really employed in this way from 1785 to 1789, and could only read and not write when he began this extraordinary course of training, it is no wonder that he remained illiterate all his life, or that his mind was utterly incapacitated for taking in and assimilating knowledge in the usual way. Spending a few months at a day school, and a few more at a “floral drawing master,” then a few more at school at Margate, making drawings for sale, colouring prints, fruitlessly studying perspective, bandied about from school master to drawing master, and from drawing master to architect—such a life for a young mind from ten to fourteen years of age is enough to spoil the finest intellectual digestion.

One fact, however, comes clear out of all this confusion, that of regular and ordinary schooling he had little or none, and there is no reason to suppose that it was because of the peculiar quality of his mind that he always spoke and wrote like a dunce. He never had a fair chance of acquiring in his youth more than a traveller’s knowledge of his own language, and so his mind had a very small outlet through the ordinary channels of speech. On the other hand, faculties of drawing and composition were trained to the utmost, and this compensated him in a measure. His mind had only one entrance, his eye, and only one exit, his hand; but they were both exceptional, and cultivated exceptionally.

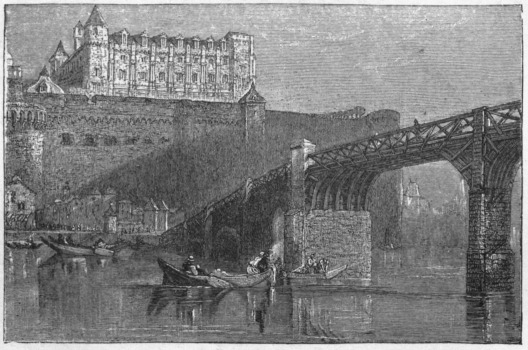

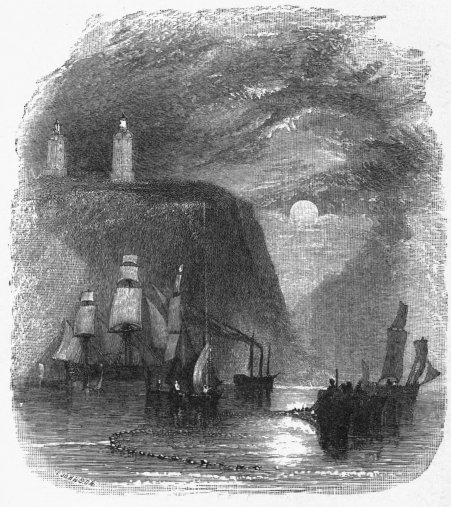

CHATEAU D’AMBOISE.

From “Rivers of France.”

There was, however, much of pleasure in this life for a boy like Turner, for though he evidently worked hard, he liked work and the work he had to do was especially congenial to him. He met friends and encouragers on all sides; from his father to his school-fellows. However much reason he may have had for disappointment in later years, there was none in his early life. He was “found out” in his childhood. Encouraged by his father, with his drawings finding a ready sale to such men as Mr. Henderson, Mr. Crowle, and Mr. Tomkison, with plenty of employment in no slavish mean work for such a youngster, such as colouring prints and putting in backgrounds to drawings, with Mr. Porden generously offering to take him as an apprentice for nothing, with a kind friend like Dr. Monro always willing to give him a supper and half-a-crown for sketches of the country near his residence at Bushey, or the result of an evening’s copying of the then best attainable water colours; his life was far more agreeable, far more tended to make him think well of the world and of the people in it than has been usually represented, and probably as good as he could have had for attaining early proficiency in his art. London at that time was not a bad place for a landscape artist. It was neither so clouded nor so sooty as it is now; there were healthier trees in it, and more of them, a more picturesque and a purer river, and within less than half an hour’s walk from Maiden Lane there were green fields, for north of the British Museum the country was still open.

But he was not entirely dependent upon his art and his employers for enjoyment, or for forming his opinion of the human race. There were houses at which he visited and where he was received warmly. When at school at Margate he got an “introduction to the pleasant family of a favourite school-fellow;” at Bristol there was Mr. Narraway,[8] a fellmonger in Broadmead, and an old friend of his father, at whose house he drew two of the children and his own portrait; and at the house of Mr. William Frederick Wells, the artist, he was evidently one of the family, as is proved by the charmingly tender reminiscences of Mrs. Wheeler.

“In early life my father’s house was his second home, a haven of rest from many domestic trials too sacred to touch upon. Turner loved my father with a son’s affection; and to me he was as an elder brother. Many are the times I have gone out sketching with him. I remember his scrambling up a tree to obtain a better view, and then he made a coloured sketch, I handing up his colours as he wanted them. Of course, at that time, I was quite a young girl. He was a firm affectionate friend to the end of his life; his feelings were seldom seen on the surface, but they were deep and enduring. No one would have imagined, under that rather rough and cold exterior, how very strong were the affections which lay hidden beneath. I have more than once seen him weep bitterly, particularly at the death of my own dear father,[9] which took him by surprise, for he was blind to the coming event, which he dreaded. He came immediately to my house in an agony of tears. Sobbing like a child, he said, ‘Oh, Clara, Clara! these are iron tears. I have lost the best friend I ever had in my life.’ Oh! what a different man would Turner have been if all the good and kindly feelings of his great mind had been called into action; but they lay dormant, and were known to so very few. He was by nature suspicious, and no tender hand had wiped away early prejudices, the inevitable consequence of a defective education. Of all the light-hearted merry creatures I ever knew, Turner was the most so; and the laughter and fun that abounded when he was an inmate of our cottage was inconceivable, particularly with the juvenile members of the family.”—THORNBURY’S Life of Turner (1877), pp. 235, 236.

A man who knew this lady for sixty years, and about whom so kind a heart could have thus written, could not have been driven to a life of morbid seclusion because the world had treated him so badly in his youth. His home may have been, and probably was a cheerless one, and we may well pity him on that account. The rest of our pity we had better reserve for his want of education, and the secretive, suspicious disposition which nature gave him, and which he allowed to master his more genial propensities.

THE only rebuff with which the young artist appears to have met was from Tom Malton, the perspective draughtsman, who sent him back to his father as a boy to whom it was impossible to teach geometrical perspective. As Mr. Hamerton observes, “There is nothing in this which need surprise us in the least. Scientific perspective is a pursuit which may amuse or occupy a mathematician, but the stronger the artistic faculty in a painter the less he is likely to take to it, for it exercises other faculties than his. Besides this, he feels instinctively that he can do very well without it.” No doubt he did feel this, and the feeling very much lessened the disappointment at being “sent back,” and he did very well without it, so well that he was appointed Professor of Perspective to the Royal Academy without it, and not unfrequently exhibited pictures on its walls, which showed how very much “without it” he was.

Otherwise he met with no rebuffs in his art. We have seen that he got plenty of employment, and have expressed an opinion that that employment—colouring engravings, and putting in backgrounds and foregrounds and skies for architectural drawings—was no mean employment for a youngster. He himself, when pitied in later years for this supposed degradation and slavery, replied, “Well, and what could be better practice!” and it was this and more. It not only taught him to work neatly, to lay flat washes smoothly and accurately, but it taught him to exercise his ingenuity and artistic taste. He probably succeeded so well, because it gave him an opportunity of displaying his artistic faculty. Every sketch that he had thus to beautify presented an artistic problem, how best to light and decorate and make a picture of the bare bones of an architectural design. It gave him a sense of power and importance thus to be the converter of topography into art; it taught him the value of light and shade, and the decorative capacities of trees and sky. His success gave him self-reliance. It also, and this was perhaps a more doubtful advantage, taught him to consider drawing as a skill in beautifying. He got the habit of treating buildings as objects less valuable as objects of art in themselves, than for the breaking of sunbeams, and as straight lines to contrast with the endless curves of nature; and also the habit of using trees as he wanted them, of bending their boughs and moulding their contours in harmony with the poem-picture of his imagination. To this early treatment of architectural drawings may be traced his great power of composition, and also much of his mannerism.

That he soon knew his power, and had his secrets of manipulation, may be one reason for his early secretiveness about his art; for though there is little in these early works of his to prefigure his coming greatness, he, when a youth, attained a proficiency equal to that of the best water-colour artists of his day, and, with his friend Girtin, soon surpassed all except Cozens; and he could not have done this without a sense of superiority and many private experiments; or, on the other hand, he may, like many men, have required complete solitude to work at all, though this was not the case in later life, as he often painted almost the whole of his pictures on the Academy walls. At all events, the degree of his secretiveness is extraordinary. “I knew him,” says an old architect, “when a boy, and have often paid him a guinea for putting backgrounds to my architectural drawings, calling upon him for this purpose at his father’s shop in Maiden Lane, Covent Garden. He never would suffer me to see him draw, but concealed, as I understood, all that he did in his bedroom.” When in this bedroom one morning, the door suddenly opened, and Mr. Britton entered.[10] In an instant Turner covered up his drawings and ran to bar the crafty intruder’s progress. “I’ve come to see the drawings for the Earl.”[11] “You shan’t see ’em,” was the reply. “Is that the answer I am to take back to his lordship?” “Yes; and mind that next time you come through the shop, and not up the back way.” When Mr. Newby Lowson accompanied him on a tour on the continent he “did not show his companion a single sketch.” Similar stories could be added to show how this habit continued through his life.

The dates of these two early stories are not given by Mr. Thornbury, nor the name of the “old architect,” but they show that he was early employed by a nobleman, and that he got a guinea a piece for his backgrounds, not only “good practice,” but good pay for a youth; he was, in fact, better employed and better paid than any young artist whose history we can remember. Nor does it seem to have been the fault of Providence if he did not enjoy the crowning happiness of life, a friend of suitable tastes, for Girtin was sent to him, a youth of his own age endowed with similar gifts, and of a most sociable disposition; nor did he want a capable mentor, for he had Dr. Monro, “his true master,” as Mr. Ruskin calls him.

It was at Raphael Smith’s that he formed an intimacy with Girtin, says Mr. Alaric Watts.[12] “His son, Mr. Calvert Girtin, described his father and young Turner as associated in a friendly rivalry, under the hospitable roof and superintendence of that lover of art, Dr. Monro (then residing in the Adelphi). Nor was Turner forgetful of the Doctor’s kindness, for on referring to that period of his career, in a conversation with Mr. David Roberts, he said, ‘There,’ pointing to Harrow, ‘Girtin and I have often walked to Bushey and back, to make drawings for good Dr. Monro, at half-a-crown apiece and a supper.’”

If a saying quoted by T. Miller in his “Memoirs of Turner and Girtin” may be trusted,[13] Turner may have met Gainsborough and other eminent painters of the day at Dr. Monro’s. Speaking of Dr. Monro’s conversaziones, “Old Pine, of ‘Wine and Walnuts’ celebrity, used to say, ‘What a glorious coterie there was, when Wilson, Marlow, Gainsborough, Paul, and Tom Sandby, Rooker, Hearne, and Cozins (sic) used to meet, and you, old Jack,’ turning to Varley, ‘were a boy in a pinafore, with Turner, Girtin, and Edridge as bigwigs, on whom you used to look as something beyond the usual amount of clay.’” As Gainsborough died in 1788, when Turner was thirteen years old, and Turner was only two years the senior of John Varley, this shows how early he began to have a reputation.

The acquaintance between Turner and Girtin is one of the most interesting facts in Turner’s Life. Being more than two years Turner’s senior (Girtin was born on February 18th, 1773) and having at least equal talent as a boy, it is probable that he was “ahead” of Turner at first, and that Turner learnt much from him. We may therefore accept as true his reputed sayings, “Had Tom Girtin lived, I should have starved;”[14] and (of one of Girtin’s “yellow” drawings), “I never in my whole life could make a drawing like that, I would at any time have given one of my little fingers to have made such a one.”[14] With regard to their mutual studies and their respective talents we have information in the studies and drawings themselves, but with regard to their human relationship we have very little. Turner always spoke of him as “Poor Tom,” and proposed to, and possibly did, put up a tablet to his memory; but there are no letters or anecdotes to show that what we all mean by “friendship” ever existed between them.

We are equally ignorant as to the amount of intimacy between him and Dr. Monro, for though the latter did not die till 1833, there is nothing to show that they ever met after Turner’s student days were over.

It may, however, be fairly assumed that we should have known more about his intimacy with his Achates and his Mæcenas if it had been great and continuous. The absence of documents or rumours on the subject are all in favour of his having kept himself to himself, of his absorption in his art from an early date, neglecting the social advantages that were open to him, neglecting intellectual intercourse with his artistic peers, neglecting everything except the pursuit of his art, and the road to wealth and fame. This self-absorption, this concentration of all his time and power to this one but triple object, the trinity of his desire, may have arisen from a natural cause, the strength of impelling genius over which he had no control; it may have arisen from secretiveness, suspicion, selfishness, and ambition, which he could have controlled but would not; but whatever its cause, there is no doubt that it existed, and that with every external facility for becoming a social and cultivated being, he took the solitary path which led him to greatness (not perhaps greater than he might have otherwise attained), but a greatness accompanied with mental isolation and ignorance of all but what he could gather from unaided observation, and an uncultivated intellect.

The education of Turner may be summed up as follows: he learnt reading from his father, writing and probably little else at his schools at Brentford and Margate, perspective (imperfectly) from T. Malton, architecture (imperfectly and classical only) from Mr. Hardwick, water-colour drawing from Dr. Monro, and perhaps some hints as to painting in oils from Sir Joshua Reynolds, in whose house he studied for a while. The rest of his power he cultivated himself, being much helped by the early companionship of Girtin. Nearly all, if not all, this education except that mentioned in the last paragraph was over in 1789, when Sir Joshua laid down his brush, conscious of failing sight, and young Turner became a student of the Royal Academy.

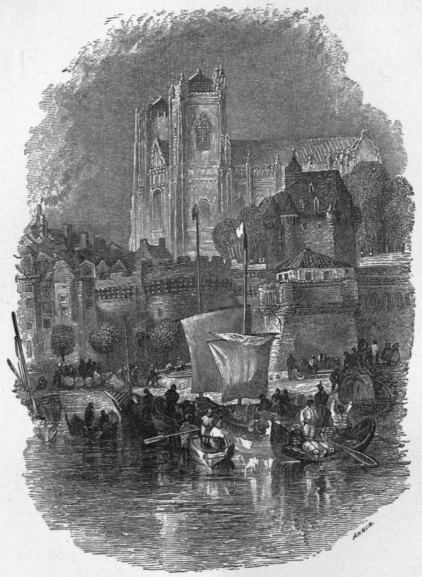

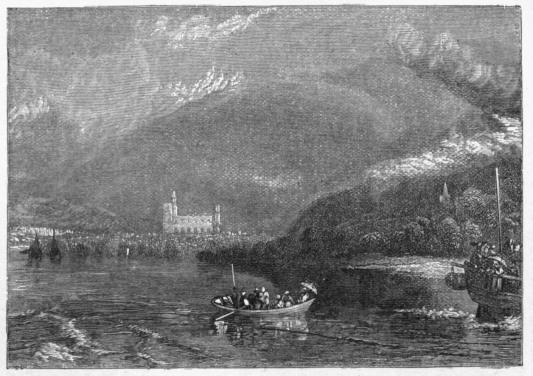

NANTES.

From “Rivers of France.”

These were his principal living instructors, but he learnt more from the dead—from Claude and Vandevelde, from Titian and Canaletto, from Cuyp and Wilson. He learnt most of all from nature, but in the beginning of his career his studies from art are more apparent in his works. There is scarcely one of his predecessors or contemporaries of any character in water-colour painting that he did not copy, whose style and method he did not study, and in part adopt. We have within the last few years only been able to study at ease the works of the early water-colour painters of England, and the result of the interesting collections now at South Kensington and the British Museum, bequests of Mr. and Mrs. Ellison, Mr. Towshend, Mr. William Smith, and Mr. Henderson, has been on the one hand to increase our opinion of their merit, and on the other to show how far Turner outstripped them. We can now see how true and delicate were the lightly-washed monochrome water scenes of Hearne; how robust the studies of Sandby; that Daniell and Dayes could not only draw architecture well, but could warm their buildings with sun, and surround them with space and air; that Cozens could conceive a landscape-poem, and execute it in delicate harmonies of green and silver; that Girtin could invest the simplest study with the feeling of the pathos of ruin and solemnity of evening; the first of water-colour painters to feel and paint the soft penetrative influence of sunlight, subduing all things with its golden charm. In looking at one of his drawings now at South Kensington, a View of the Wharfe, and comparing it with the works around, one cannot help being struck with this difference, that it is complete as far as it goes, the realization of one thought, the perfect rendering of an impression, harmonious to a touch. Broad and almost rough as it is, it is yet finished in the true sense as no English work of the kind ever was before. There are more elaborate drawings around, plenty of struggle after effects of brighter colour, much cleverness, much skill, but nowhere a picture so completely at peace with itself. In looking at it we can realize what Turner meant when he said that he could never make drawings like Girtin. Equal harmony of tone, far greater and more splendid harmonies of colour, miracles of delicate drawing, triumphs over the most difficult effects, dreams of ineffable loveliness, very many things unattempted by Girtin he could achieve, but never this simple sweet gravity, never this perfection of spiritual peace.

But in spite of this, the great fact in comparing Turner with the other water-colour painters of his own time—and we are speaking now of his early works—is this, that whereas each of the best of the others is remarkable for one or two special beauties of style or effect, he is remarkable for all. He could reach near, if not quite, to the golden simplicity of Girtin, to the silver sweetness of Cozens; he could draw trees with the delicate dexterity of Edridge, and equal the beautiful distances of Glover; he could use the poor body-colours of the day, or the simple wash of sepia, with equal cleverness. He was not only technically the equal, if not master of them all, but he comprehended them, almost without exception.

Such mastery was not attained without extraordinary diligence in the study of pictures. At Dr. Monro’s he could study all the best modern men, including Gainsborough, Morland, Wilson, and De Loutherbourg, and he could also study Salvator Rosa, Rembrandt, Claude, and Vandevelde. One day looking over some prints with Mr. Trimmer,[15] he took up a Vandevelde and said, “That made me a painter.” And Dayes (Girtin’s master) wrote in 1804:—“The way he acquired his professional powers was by borrowing where he could a drawing or a picture to copy from, or by making a sketch of any one in the Exhibition[16] early in the morning, and finishing it at home.” The character of his early works is sufficient of itself to prove the extent of his study of pictures, and we are inclined to think that most of his early practice was from works of art, and not from nature. The spirit of rivalry commenced in him very early; it was the only test of his powers, and he seems to have pitted himself in the beginning of his career against all his contemporaries, from Mr. Henderson to Girtin, and many of the old masters, and never to have entirely relinquished the habit. When we think of the number of years he spent in doing little but topographical drawings, a castle here, a town there, an abbey there, with appropriate figures in the foreground, using only sober browns and blues for colours, his progress seems to have been very slow; but when we see most of the artists of his time doing exactly the same, and that the old landscape painters whom he principally studied were almost as limited in the colours they employed, especially in their drawings, we do not see how he could well have progressed more quickly; and when we further consider the enormous distance which he travelled—from the very bottom to the very height of his art—that he should have accomplished it all in one short life appears miraculous. The milestones of his journey are not shown plainly in his early work, that is all.

That there was much conscious restraint on his part in the use of colours, that he of wise purpose devoted himself to perfection of his technical power before he endeavoured to show his strength to the world, we see no reason to believe. He could not well have done otherwise, and for such an original mind one marvels to observe how throughout his career he was led in the chains of circumstance. The poet-painter, the dumb-poet, as he has well been called, shows little eccentricity of genius in his youth. There was the strong inclination to draw, but no strong inclination to draw anything in particular, or anything very beautiful. On the contrary, he drew the most uninteresting and prosaic of things, copied bad topographical prints and ugly buildings. When it was proposed to make him an architect he did not rebel; when it was afterwards proposed to make him a portrait-painter he did not murmur. It was Mr. Hardwick, not himself, that insisted on his going to the Royal Academy. His first essay in oils was due to another’s instigation. Whatever work came to him, he did; that which he could do best, that which he had special genius for, the painting of pure landscape, he scarcely attempted at all for years. Almost every artist of that day went about England drawing abbeys, seats, and castles for topographical works. What others did, he did. What others did not do, he did not do. No doubt it was the only profitable employment he could get, and he very properly took it, and worked hard at it; he was borne along the stream of circumstance as everybody else is, but he, unlike most men of strong genius, seems never to have attempted to stem its tide, or get out of its way. His genius was a growth to which every event and accident of his life added its contribution of nourishment. Though stirred with unusual power, he was probably almost as unconscious as to what it tended as a seed in the ground; he had a dim perception of a light towards which he was growing; he was conscious that he put forth leaves, and that he should some day flower, but when, and with what special bloom he was destined to surprise the world, we doubt if he had any prophetic glimpse. His development was extraordinary, and could only have been produced by special careful training, but this training was mainly due to circumstances over which he had no control. Nature came to his assistance in a thousand different ways, and in nothing more than giving him a quiet temperament, like that of Coleridge’s child, “that always finds, and never seeks.” He was not fastidious, except with regard to his own work, and about that, more as to the arrangement and finish of it than the subject. He had an excellent constitution, early inured to rough it, and his comforts were very simple and easily obtained. He was not particular, even about his materials and tools; any scrap of paper would do for a sketch on an emergency. He was always able to work, and to work swiftly and well. No fidgeting about for hours and days because he was not in the mood; no sacrifice of sketch after sketch because they did not please him; none of that nervous restlessness which so often attends imaginative workers; and his work was imaginative from the first—if not in conception, in execution. Solitude seems to have been the only necessary condition for the free exercise of his powers, which were as happily employed in “making a picture” of one thing as of another, and when he wanted something to put in it to get it “right,” he never had much trouble in finding it. He said, “If when out sketching you felt a loss, you have only to turn round, or walk a few paces further, and you had what you wanted before you.” His physical powers were also great, and his mind was active in receiving impressions. Mr. Lovell Reeve, as quoted by Mr. Alaric Watts, says:—“His religious study of nature was such that he would walk through portions of England, twenty to twenty-five miles a day, with his little modicum of baggage at the end of a stick, sketching rapidly on his way all striking pieces of composition, and marking effects with a power that daguerreotyped them in his mind. There were few moving phenomena in clouds and shadows that he did not fix indelibly in his memory, though he might not call them into requisition for years afterwards.” He was not tied to any particular method, or bound to any particular habit; when he found that his way of sketching was too minute and slow to enable him to make his drawings pay their expenses, he changed his style to a broader, swifter one. So, without going quite to the length of Mr. Hamerton, who appears to think that everything in Turner’s youth (including ugliness and bandy legs) happened for the best in the best of possible worlds, we may safely affirm that he could scarcely have been gifted with a temperament better suited for steady progress, or one which was more calculated to make him happy, for it enabled him to exercise his body and mind at the same time, to earn his living and to lay up stores of pictorial beauty in his memory, to do whatever task was set him, and yet get artistic pleasure out of even the most commonplace study by embellishing it with his imagination.

In 1789 he became a student of the Royal Academy, and in the year after he exhibited a View of the Archbishop’s Palace at Lambeth. In 1791, 2, and 3 he exhibited several topographical drawings, but down to this time he seems to have made no sketching tours of any length. He drew in the neighbourhood of London, and his journeys to stay with friends at Margate and Bristol will account for his drawings of Malmesbury, Canterbury, and Bristol. But about 1792 he received a commission from Mr. J. Walker, the engraver (who also afterwards employed Girtin), to make drawings for his “Copper-plate Magazine.” This was the beginning of the long series of engravings from his works, and it may have been one of the reasons which decided him to set up a studio for himself, which he did in Hand Court, Maiden Lane, close to his father, where he remained till he was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy in 1800, when he removed to 64, Harley Street. A year or so after his employment by Walker he got similar commissions from Mr. Harrison for his “Pocket Magazine.” These commissions sent him on his travels over England referred to by Mr. Lovell Reeve. The copper-plates of the sketches for Walker, including some after Girtin, were found about sixty years afterwards by Mr. T. Miller, who republished them in 1854, in a volume called “Turner and Girtin’s Picturesque Views, sixty years since.” These drawings mark his first tour to Wales, on which he set forth on a pony lent by Mr. Narraway. The first public results of this tour were the drawing of Chepstow in “Walker’s Magazine” for November, 1794, and three drawings in the Royal Academy for that year. By the next year’s engravings and pictures we trace him to “Nottingham,” “Bridgnorth,” “Matlock,” “Birmingham,” “Cambridge,” “Lincoln,” “Wrexham,” “Peterborough,” and “Shrewsbury,” and by those of 1796 and 1797 to “Chester,” “Neath,” “Tunbridge,” “Bath,” “Staines,” “Wallingford,” “Windsor,” “Ely,” “Flint,” “Hampton Court, Herefordshire,” “Salisbury,” “Wolverhampton,” “Llandilo,” “The Isle of Wight,” “Llandaff,” “Waltham,” and “Ewenny (Glamorgan),” not including drawings of places he had been to before.

His furthest point north was Lincoln, his farthest west (in England) Bristol. The only parts in which he reached the coast were in Wales and the Isle of Wight. Lancashire and the Lakes, Yorkshire and its waterfalls, were yet to come, and nearly all coast scenery, except that of Kent.

The drawings for the Magazines were not remarkable for any poetry or originality of treatment perceptible in the engravings, the cathedrals being generally taken from an unpicturesque point of view, more with the object of showing their length and size than their beauty, to which he appears to have been somewhat insensible always; they show a great love of bridges and anglers—there is scarcely one without a bridge, and some have two; a desire to tell as much about the place as possible by the introduction of figures; they show his habit of taking his scenes from a distance, generally from very high ground, and his delight in putting as much in a small space as possible, and his power of drawing masses of houses, as in the Birmingham and the Chester.

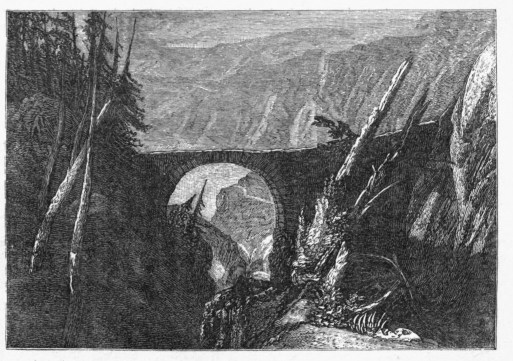

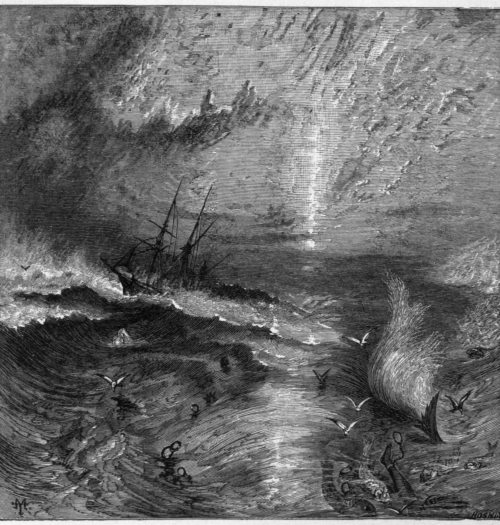

The result of these tours may be said to have been the perfection of his technical skill, the partial displacement of traditional notions of composition, and the storing of his memory with infinite effects of nature. It was as good and thorough discipline in the study of nature, as his former life had been in the study of art, and though his visit to Yorkshire in the next year (1797) seemed necessary to bring thoroughly to the surface all the knowledge and power he had acquired, it was not without present fruit. Rather of necessity than choice, we may observe, he confined his powers mainly to the drawing of views of places supposed to be of interest to the subscribers of the Magazines, but his individual inclinations in the choice of subject, and his tendency to purer landscape and sea-view, showed themselves now and then. First in his drawing of The Pantheon, the Morning after the Fire, exhibited in 1792; next in 1793, in his View on the River Avon, near St. Vincent’s Rocks, Bristol, and the Rising Squall, Hot Wells,[17] from the same place; then in 1794, Second Fall of the River Monach, Devil’s Bridge; in 1795, View near the Devil’s Bridge, Cardiganshire, with the River Ryddol; in 1796, Fishermen at Sea; and in 1797, Fishermen coming Ashore at Sunset, previous to a Gale, and Moonlight: a study in Milbank,[18] now in the National Gallery.

That his genius was perceptible even in these early days is evident from the notice taken in a contemporary review of his drawings in 1794, when he was nineteen.

“388. Christchurch Gate, Canterbury. W. Turner. This deserving picture, with Nos. 333 and 336, are amongst the best in the present exhibition. They are the productions of a very young artist, and give strong indications of first-rate ability; the character of Gothic architecture is most happily preserved, and its profusion of minute parts massed with judgment and tinctured with truth and fidelity. This young artist should beware of contemporary imitations. His present effort evinces an eye for nature, which should scorn to look to any other source.”

Again in 1796, the “Companion to the Exhibition,” with regard to his first sea-piece contains this paradoxical sentence, attempting to express his peculiar power of giving a distinct impression of ill-defined objects, which was apparently evident even in this early work.

“Colouring natural, figures masterly, not too distinct—obscure perception of the objects distinctly seen—through the obscurity of the night—partially illumined.”

Again in 1797, we have this testimony as to the extraordinary (for that time) character of his work, from an entry in the diary of Thomas Greene, of Ipswich, about the Fishermen of 1797.

“June 2, 1797. Visited the Royal Academy Exhibition. Particularly struck with a sea-view by Turner; fishing vessels coming in, with a heavy swell, in apprehension of tempest gathering in the distance, and casting, as it advances, a night of shade, while a parting glow is spread with fine effect upon the shore. The whole composition bold in design and masterly in execution. I am entirely unacquainted with the artist; but if he proceeds as he has begun, he cannot fail to become the first in his department.”

Here, then, before Turner’s visit to Yorkshire, we have evidence that not only was the superiority of his work apparent, but that one or two of the special qualities which were to mark it in the future were already perceived, and publicly praised.

After looking carefully at all the ascertainable facts of Turner’s youth, we can only come to the conclusion that it was not the fault of nature or mankind that he grew into a solitary and disappointed man.

Secretiveness on his own part and want of trust in his fellow-creatures seem to have been bred in him, and to have resisted all the many proofs which the friends of his youth, and we may say of his life, afforded, that there were kind and unselfish persons in the world whom he could trust, and who would trust him. There is no proof that he ever had confidential relations with any human being, not even Girtin. That he should have willingly cut himself adrift from human fellowship we are loath to believe, in spite of the many facts which seem to support it. It seems more natural, and on the whole (sad as even this is) more pleasant, to believe that he met with a severe blow to his confidence; that, though naturally suspicious, the many kindnesses he received were not without a gracious effect, but that his budding trust was killed by a sudden unexpected frost. For these reasons we are inclined to believe in the story of his early love; although it, as told by Mr. Thornbury, is not without inconsistencies.

Turner is said to have plighted vows with the sister of his school friend at Margate; he left on a tour, giving her his portrait, the letters between them were intercepted, and after waiting two years she accepted another. When he reappeared she was on the eve of her marriage, and thinking her honour involved, refused to return to her old love.

Such in short is the story which we wish to believe, and as it came to Mr. Thornbury from one who heard it from relatives of the lady, to whom she told it, there is probably some truth in it. It is, however, almost impossible to believe that Turner, whose tours never extended to two years, and whose power of locomotion was extraordinary, should allow that time to elapse without going to see one whom he really loved. If he did not get any letters he would have been desperate; if he did get letters they would have shown him that she had not received his, which would have made him, if possible, more desperate still. As the name of the lady is not given, it is next to impossible to find out the truth. Our faith, however, as a balance of probability, still remains that Turner was jilted, and that the effect of it was to confirm for ever his want of confidence in his fellow-creatures.

FHE the facts of the foregoing chapter it may be fairly presumed that although Turner’s election as Associate in 1799 followed quickly after his fine display of pictures from the northern counties in 1798, he was before this a marked man, whose superiority over all then living landscape painters was visible to critics and lovers of art, and could not have been disguised from the eyes of the artists of the Royal Academy. It did not require a genius like that of Turner to distance competitors on the Academy walls in those days. England was almost at its lowest point both in literature and art. The great men of the earlier part of the eighteenth century, Pope, Thomson, Gray, Collins, Swift, Fielding, Sterne and Richardson, had long been dead, and of the later brilliant, but small circle of artists and men of letters of which Dr. Johnson was the centre (Goldsmith and Burke, Garrick and Reynolds, Hume and Gibbon), Reynolds only was left, and he was moribund. Of other artists with any title to fame there was none left but De Loutherbourg and Morland; Hogarth had died in 1764, Wilson in 1782, Gainsborough in 1788. The new generation of men of genius were born; some were growing up, some in their cradles. A few had already shown signs. Wordsworth and Coleridge had just put forth their “Lyrical Ballads” at Bristol, Burns was famous in Scotland, Charles Lamb had written “Rosamund Gray,” but Scott the “Great Unknown,” was as yet “unknown” only, though five years older than Turner; Byron had not gone to Harrow, and the united ages of Keats and Shelley did not amount to ten years; the only living poets of deserved repute were Cowper and Crabbe. Della Crusca in poetry, and West in art, were the bright particular stars of this gloomy period. The landscape painters who were Academicians were such men as Sir William Beechey, Sir Francis Bourgeois, Garvey, Farington, and Paul Sandby, and among the Associates, Turner had no more important rival than Philip Reinagle. Girtin and De Loutherbourg alone of all the then exhibitors were anything like a match for him, and Girtin spoilt (till 1801) any chance he might otherwise have had of Academic honours by not exhibiting pictures in oil; he died in 1802, leaving Turner undisputed master of the field. It is not greatly therefore to be wondered at that Turner was elected Associate in 1799, and a full Academician in 1802. It was, however, much to the credit of the Academy that they recognized his talent so soon and welcomed him as an honour to their body, instead of keeping him out from jealous motives. Turner never forgot what he owed to the Academy, and whether it taught him nothing, as Mr. Ruskin says, or a great deal, as Mr. Hamerton thinks, does not much matter—it taught him all it knew, and gave him ungrudgingly every honour in its gift. But its claims on his gratitude did not stop here, for it was his school in more than one branch of learning; from its catalogues he derived the subjects of most of his pictures, they directed him to the poems which set flame to his imagination, and helped (unfortunately), with their queer spelling and grammar and truncated quotations, to form what literary style he had; but the greatest boon which the Academy afforded was the opportunity of fame, a field for that ambition which was one of the ruling powers of his nature.

But his tour in the North in 1797 was before his days of Academic rivalries and glories. He was only two-and-twenty, and seems to have been actuated by no motive but to paint as well and truly as he could the beautiful scenery through which he passed. The effect upon him of the fells and vales of Yorkshire and Cumberland seems to have been much the same as that of Scotland upon Landseer; it braced all his powers, developed manhood of art, turned him from a toilsome student into a triumphant master. Mr. Ruskin writes more eloquently than truly about this first visit. “For the first time the silence of nature around him, her freedom sealed to him, her glory opened to him. Peace at last, and freedom at last, and loveliness at last; it is here then, among the deserted vales—not among men; those pale, poverty-struck, or cruel faces—that multitudinous marred humanity—are not the only things which God has made.” These are fine words, but what a picture, if true! Can this young man who has travelled through all these many counties in England and Wales, which we have already enumerated, never have known the “silence of nature,” or “freedom,” or “peace,” or “loveliness?” Can his experience of mankind, of Dr. Monro, of Girtin, of Mr. Hardwick, of Sir Joshua Reynolds, of Mr. Henderson, have left upon him such an impression of the failure of God’s handiwork in making men, that a mountain seems to him in comparison as a revelation of unexpected success? If Turner had been cooped in a garret of the foulest alley in London since his birth, and had only escaped now and then from the hardest drudgery to read the works of Mr. Carlyle, this picture might be near the truth, but we doubt even then if it could escape the charge of being over-coloured.

Whether Turner had any special object in this journey to the North in 1797 is not clear, but it is at least probable that Girtin’s success at the Exhibition of this year with his drawings from Yorkshire and Scotland may have influenced him, and that he may have already received a commission from Dr. Whitaker to make drawings for the “Parish of Whalley,” published three years afterwards. He must at all events have had much leisure from other employment in order to produce the important pictures in oil and water-colour which he exhibited the next year. Of these we only know Morning on the Coniston Fells and Buttermere Lake, now in the National Gallery. Another, whether water or oils we do not know, was Norham Castle on the Tweed—Summer’s Morn, the first of several pictures of the same subject, which was a favourite of his for a good reason. Many years after (probably about 1824 or 1825), when making sketches for “Provincial Antiquities and Picturesque Scenery of Scotland, with descriptive illustrations by Sir Walter Scott, 1826,” he took off his hat to Norham Castle, and Cadell the publisher, who was with him, expressed surprise. “Oh,” was the reply, “I made a drawing or painting of Norham several years since. It took; and from that day to this I have had as much to do as my hands could execute.” If the Castle was treated in the same way in this first as in the subsequent pictures of Norham, with the hill and ruin in the middle distance set against a brightly illumined sky, the effect was sufficiently new and striking to make the reputation of any painter in those days. It was an effect which as far as we know had never been attempted before, this casting of the whole shadow of hill and castle straight at the spectator, so that, in spite of the bright reflections in the watery foreground, he seems to be within it, and to see through the soft shadowy air, the solemn bulk of mound and ruin, with their outlines blurred with light, grand and indistinct against the burning sky.

The pictures of 1797-99 confirmed beyond any doubt that a great artist had arisen, who was not only a painter but a poet—a poet, not so much of the pathos of ruin, though so many of his pictures had ruins in them, nor of the chequered fate of mankind, though there is something of the “Fallacies of Hope” indicated in the quotations to his pictures—as of the mystery and beauty of light, of the power of nature, her inexhaustible variety and energy, her infinite complexity and fulness. No one can look upon his splendid drawing of Warkworth Castle, exhibited in 1799, and now at South Kensington, with its rich glow of sunset and transparent shadow, and its wonderful masses of clouds, without feeling that such work as this was a revelation in those days. Sparing and not very pleasant in colour, it is yet in this respect a great advance upon the former work of others and of his own; such colour as there is penetrates the shade and is complete in harmony and tone, while the sky has no blank space and is part of the picture, the vivifying uniting power of the composition, with more interest and feeling in one roll of its truly-studied masses of cloud-form than could be found in the whole of any sky of his contemporaries.

Altogether it is difficult to over-estimate the influence of this first journey to the North upon Turner’s mind and art, although he had almost perfected his skill and shown unmistakable signs of genius before. But these tours had other gifts not less important, though in a different way, for his introductions to Dr. Whitaker, the local historian, to Mr. Basire, the engraver, to Mr. Fawkes of Farnley, to Lord Harewood, and to Sir John Leicester (afterwards (1826) Lord de Tabley), through Mr. Lister-Parker of Browsholme Hall, his guardian, may all be said to have resulted from this tour.

Dr. Whitaker was the vicar of the parish of Whalley, and was writing a book upon it in the manner of those days, giving descriptions of the local antiquities, the churches, the ruins, the crosses, and an account of the county families, with their pedigrees and engravings of their ancestral seats. Not only each county, but almost every parish had such a historian in those days, and although the spirit of these works is archaeological rather than artistic, engaged with genealogy rather than history, and with pride of family and county rather than of the people and nation, they did a great deal of valuable work. Dr. Whitaker’s work is no exception to this rule, and he was in many ways a typical writer of the kind, for he himself, though he “chose” the Church as his profession, was a man of property and county importance. Valuable as artists were in those days to the writers of these works, they were yet considered of very secondary rank. They were indeed not called “artists” but “draftsmen,” and notwithstanding that Dr. Whitaker recognized Turner’s genius, he did not think it necessary in this “Parish of Whalley” to mention in the preface the existence of such a person, although the names of all the gentlemen of the county who had furnished him with drawings or information are carefully acknowledged therein; but nothing will show better the relations between the two men than an extract from a letter from the reverend bookmaker to one of his county friends, Mr. Wilson, of Clitheroe, dated Feb. 8th, 1800.

“I have just had a ludicrous dispute to settle between Mr. Townley” (Charles Townley, Esq. of Townley), “myself and Turner, the draftsman. Mr. Townley it seems has found out an old and very bad painting of Gawthorpe at Mr. Shuttleworth’s house in London, as it stood in the last century, with all its contemporary accompaniments of clipped yews, parterres, &c.: this he insisted would be more characteristic than Turner’s own sketch, which he desired him to lay aside, and copy the other. Turner, abhorring the landscape and contemning the execution of it, refused to comply, and wrote to me very tragically on the subject. Next arrived a letter from Mr. Townley, recommending it to me to allow Turner to take his own way, but while he wrote, his mind (which is not unfrequent) veered about, and he concluded with desiring me to urge Turner to the performance of his requisition, as from myself. I have, however, attempted something of a compromise, which I fear will not succeed, as Turner has all the irritability of youthful genius.”[19]

The “compromise” was handing over the task of drawing from the objectionable picture to Mr. J. Basire the engraver.

We should like to see Turner’s “tragical” letter, and also his rejected drawing; we should also like to have seen Dr. Whitaker’s face if he had been told that not many years after a book would have been published of drawings by Turner, the draftsman, with “descriptions by the Rev. Dr. Whitaker.”

Of Mr. Fawkes, of whose hall at Farnley Turner made a drawing for the “Parish of Whalley,” but with whom he is said by Thornbury to have become acquainted about 1802, it may be said that he was one of Turner’s longest and staunchest friends. The number of drawings (still at Farnley) which he made when visiting Mr. Fawkes between 1803 and 1820 (including as they do studies of birds shot while he was there, of the outhouses, porches, and gateways on the property, of the old places in the vicinity, and of the rooms in Farnley Hall) attest the frequency of his visits and his affection for the place and its occupants, while the splendid series of drawings in England, Switzerland, Italy, and on the Rhine, and the few precious oil pictures purchased by Mr. Fawkes, show him to have been not only a true friend, but a warm and sympathizing admirer of his genius. He indeed was a friend such as few are permitted to know—one of a goodly number who in Turner’s youth and manhood should have made the world to him specially pleasant and sociable, frank and healthy. If he could not or would not have it so, it was not from insensibility, for his feeling was deep and his heart was sound. “He could not make up his mind to visit Farnley after his old friend’s death,” and he could not speak of the shore of the Wharfe (on which Farnley Hall looks down) “but his voice faltered.” Dayes wrote of him in 1804, “This man must be loved for his works, for his person is not striking, nor his conversation brilliant.” At Farnley, as at Mr. Wells’ cottage, Turner was made at home, but that he did not escape good-humoured ridicule even at Farnley is plain from a caricature by Mr. Fawkes, “which is thought by old friends to be very like. It shows us a little Jewish-nosed man in an ill-cut brown tail coat, striped waistcoat, and enormous frilled shirt, with feet and hands notably small, sketching on a small piece of paper, held down almost level with his waist.”[20] It is evident that at this time, in spite of his clear little blue eyes, and his small hands and feet, his appearance was not one likely to prepossess women, or to inspire consideration among men, and that one of the ills from which his painting room afforded a refuge may have often been a wounded vanity. There can be nothing more constantly galling to a sensitive man of genius than to feel that his appearance does not inspire the respect he feels due to him. If he has eloquence sufficient to command attention, this will not matter so much; but if he has not even that (and Turner had not), his natural refuge is solitude, his one absorbing occupation is his art, his only worldly ambition is to show what is in him, and to compel respect to his genius through his works.

From the time that Turner became an Associate his struggles, if he can ever be said to have had any, were over, and many changes took place in his life and art. He ceased almost entirely from making topographical drawings for the engravers, limiting his efforts to a heading to the “Oxford Almanack,” and a few drawings for “Britannia Depicta,” “Mawman’s Tour,” and some other books, until the commencement of the “Southern Coast” in 1814. He had in effect emancipated himself from “hackwork,” and could turn his attention to more congenial and ambitious labour. The “draftsman” had become the artist, and he showed the improvement in his position by moving from Hand Court, Maiden Lane, to 64, Harley Street.