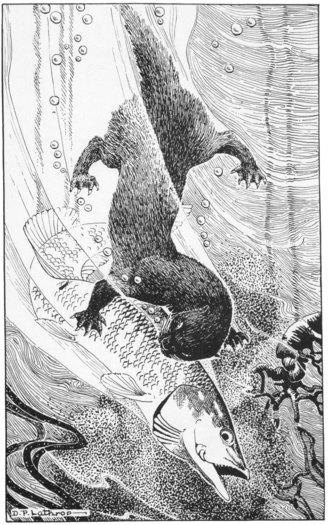

“A wild chase was going on in the depths, and where it passed the rushes bowed their sheaves.”

Title: Grim: The Story of a Pike

Author: Svend Fleuron

Illustrator: Dorothy Pulis Lathrop

Translator: J. Alexander

Jessie Muir

Release date: October 2, 2012 [eBook #40921]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Roger Frank and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

GRIM: THE STORY OF A PIKE

Translated from the Danish of

Svend Fleuron

by J. Muir and J. Alexander

Illustrated by Dorothy P. Lathrop

New York MCMXXI

Alfred A. Knopf

COPYRIGHT, 1919

By SVEND FLEURON

COPYRIGHT, 1921

By ALFRED A. KNOPF, Inc.

Original Title: Grim

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

To devour others and to avoid being devoured oneself,

that is life’s end and aim.

CONTENTS

II: IN THE SHELTER OF THE CREEK

ILLUSTRATIONS

A wild chase was going on in the depths, and where it passed the rushes bowed their sheaves.

With a hiss it curves its neck and turns the foil upwards, snapping and biting at its tormentors.

She snaps eagerly at the nearest “worm,” but it escapes her by adroitly curling up.

Clear running water filled the ditch, but the bottom was dull black, powdery mud. It lay inches deep, layer upon layer of one tiny particle upon another, and so loose and light that a thick, opaque, smoke-like column ascended at the slightest touch.

A monster, with the throat and teeth of a crocodile, a flat, treacherous forehead, and large, dull, malicious eyes, was lying close to the bottom in the wide, sun-warmed cross-dyke that cut its way inland from the level depths of the great lake. The entire monster measured scarcely a finger’s length.

The upspringing water-plants veiled her body and drew waving shadows over her round, slender tail.

When the sun was shining she liked to stay here among the bottom vegetation and imitate a drifting piece of reed. Her reddish-brown colour with the tiger-like transverse stripes made an excellent disguise. She simply was a piece of reed. Even the sharp-eyed heron, which had dropped down unnoticed about a dozen yards off, and was now noiselessly, with slow, cautious steps, wading nearer and nearer, took her at the first glance for a stick.

All the ditch-water life of a summer day was pulsating around the young pike.

Water-spiders went up for air and came down with it between their hind legs, to moor their silvery diving-bells beneath the whorls of the water-moss. One boat-bug after another, with a shining air-bubble on its belly to act as a swimming-bag, and for oars a pair of long legs sticking far out at the sides, darted with great spurts through the water, or rose and sank with the speed of a balloon. The young pike peered upwards, and saw in the shelter of a tuft of rushes a collection of black, boat-shaped whirligigs, showing like dots against the shining surface. The little water-beetles lay and dozed; but all at once a sudden storm seemed to descend upon them and they scattered precipitately, whirling away in wider and wider circles, only to congregate again just as suddenly, like a flock of sheep.

The young pike disappeared from the heron’s view in a cloud of mud, and glided off to some distance, finally coming to anchor on a wide submerged plain in a broad creek, shadowed by a clump of luxuriant marsh marigolds, whose yellow flowers gleamed out from among the clusters of green, heart-shaped leaves.

There was never any peace around her. When one animal was on its way down, another would be on its way up. And the bed of ooze beneath her was in incessant motion. Sticks moved to right and left; hairy balls lay and rolled over one another; there was a twisting and turning of larvae in all directions. The active water-beetles were dredging incessantly, releasing leaves and stalks which slowly and weirdly rose to the surface. Air-bubbles, too, were set free, and ascended quickly with a rotary motion.

Here two large tiger-beetles were fighting with a poor water-bug. The flat-bodied insect stretched out its scorpion-like claws towards its enemies, but the tiger-beetles seized it one at each end, beat off its claws with their strong palpi, and tore its head from its body. It must have been almost a pleasure to find oneself so neatly despatched!

Everything tortured and killed down here, some, indeed, even devoured themselves. To lose arms and legs and flesh from their body was all in the order of the day; and anything resting for but a minute was taken for carrion.

The big horse-leech had wound its rhythmically serpentine way through the water. It was tired now, and had just stretched itself out for a moment’s rest, when the supposed pieces of stick upon which it lay seized it, and voracious heads with sharp jaws attacked its flesh. It was within an ace of being made captive for ever, but at last succeeded in making its escape and pushing off, with two of its tormentors after it.

The young pike watched attentively the flight of the black leech. She saw that to devour others and to avoid being devoured oneself was the end and aim of life.

For a long time she remained quite still, only an undulating movement of the dorsal fin and the malicious glitter of the eyes revealing her vitality. Slowly she opened and closed her small, wide mouth, and let the oxidizing water flow over her blood-red gills.

It was not long before she had forgotten her recent peril, and once more became filled with the cruel passion of the hunter.

From the shadow of the marsh marigolds she darted under the newly unfolded leaf of a water-lily. This was a very favourite lurking-place; she could lie there with her back right up against the under surface of the leaf, and her snout on the very border of its shadow, ready to strike. The silvery flash of small fish twinkled around her, and myriads of tiny shining crustaceans whisked about so close to her nose that at any moment she could have snapped them up by the score into her voracious mouth.

It was especially things that moved that had a magic attraction for Grim. From the time when, but twelve to fifteen days old, she had consumed the contents of her yolksac, and opened her large voracious mouth, everything that flickered, twisted and moved, all that sought to escape, aroused her irresistible desire.

In the innermost depths of her being there was an over-mastering need, expressing itself in an insatiableness, a conviction that she could never have enough, and a fear that others would clear the waters of all that was eatable. An insane greed animated her; and even when she had eaten so much that she could eat no more, she kept swimming about with spoil in her mouth.

On the other hand, anything at rest and quiet possessed little attraction for her; she felt no hunger at sight of it, and no desire to possess it: that she could take at any time.

——Meanwhile, the keen-eyed heron, wading up to its breast in the water, comes softly and silently trawling through the ditch.

Sedately it goes about its business, stalking along with slow, measured steps. Its big, seemingly heavy body sways upon its thin, greenish yellow legs, its short tail almost combing the surface of the water, while its long, round neck is in constant motion, directing the dagger-like beak like a foil into all kinds of attacking positions.

Sea-crows and terns scream around it, and from time to time three or four of them unite in harrying their great rival. Just as the heron has brought its beak close to the surface of the water, ready to seize its prey, the gulls dash upon it from behind. With a hiss it curves its neck and turns the foil upwards, snapping and biting at its tormentors.

An irritating little flock of gulls may go on thus for a long time; and when at last, screaming and mocking, they take their departure, they have spoilt many a chance and wasted many precious minutes of the big, silent, patient fisher’s time.

The gulls once gone, the heron applies itself with redoubled zeal to its business. From various attacking positions its beak darts down into the water, but often without result, and it has to go farther afield; then at last it captures a little eel.

It is not easy, however, to swallow the wriggling captive. The eel twists, and refuses to be swallowed; so the bird has to reduce its liveliness by rolling up and down in its sharp-edged beak. Then it glides down.

This time, too, fortune is disposed to favour the young pike. The heron, coming up behind her, cautiously bends its neck over the drifting piece of reed. It sees there is something suspicious about it, but thinks it is mistaken, and is about to take another step forward. When only half-way, it pauses with its foot in the air; and the next moment the blow falls.

Grim only once moved her tail. Then she was seized, something hard and sharp and strong held her fast, and she passed head foremost down into a warm, narrow channel.

There was a fearful crush of fish in the channel, and much elbowing with fins and twisting of tails. Something behind her was pushing, but the throng in front blocked the way: she could get no farther.

And yet she glided on! Very slowly the thick slimy water in the channel bore the living, muddy tangle that surrounded her along; she felt the corners of her mouth rub against the sides of the channel; she could scarcely breathe.

In the meantime the heron was flying homewards to its young, carrying Grim and the rest of the catch. Out on the lake lay a boat in which a man sat fishing. Experience told the bird it was a fisherman, but here the bird was wrong. The man had a gun in the boat, and as the bird sailed upwards a shot was fired which compelled it to relinquish a part of its booty in order to escape more quickly.

Grim was among the fortunate ones. Suddenly the crush in the long, dark channel grew less, and the sluggish stream of mud that was bearing her along changed its course. A little later the stream gathered furious pace and carried her with it; she saw light and felt space round her; she was able to move her fins.

Then she fell from the heron’s beak, from a height of about twenty yards. She had time to notice how suffocatingly dry the other world was. It seemed to draw out her entrails, and all her efforts to right herself were in vain.

Then she regained her native element; water covered her gills, and she could begin to swim.

Grim was a year old when her scales began to grow.

In her early youth, when she could only eat small creatures, she had lived exclusively upon water-insects and larvae; but from now onwards she had no respect for any flesh but that which clothed her own ribs.

She attacked any fish that was not big enough to swallow her, and devoured bleak and small roach with peculiar satisfaction. Now she took her revenge on the voracious small fry that had offended her when she was still in an embryo state.

She had not been hatched artificially, or come into the world in a wooden box with running water passing through it. No, the whole thing had taken place in the most natural manner.

In the flickering sunshine of a March day, her mother, surrounded by three equally ardent wooers, had spawned, and the eggs had dropped and attached themselves to some tufts of grass at the edge of the lake. The very next day, however, little fish had begun to gather about those tufts; one day more, and there were swarms of them. Eagerly they searched the tufts and devoured all the eggs they could find; and so thoroughly did they go about their business, that of the thousands upon thousands of the mother’s eggs, only two that had fallen into the heart of a grass-stalk were left.

Out of one of these Grim had come. The sun had looked after her, hatched her out, and taught her to seize whatever came in her way. Now she was avenging the injuries to her tribe.

She possessed a remarkable power of placing herself, and knew how to choose her position so as to disappear, as it were, in the water. The stalks of the reeds threw their shadows across her body in all directions; water-grass and drifting duck-weed veiled her; the silly roach and other restless little fish flitted about her, sometimes so close to her mouth that she could feel the waves made by their tail-fins. Some would almost run right into her; but when they saw her, then how the water flashed with starry gleams, and how quickly they all made off!

She liked best to hide where the water-lilies floated in islands of green, for there the treacherous shadows--her best friends--fell clearly through the water; absorbed her, as it were, and made capture easy for her. If she found herself discovered, she would retreat with as little haste as possible; for that sort of thing aroused too much attention, and created widespread disturbance in the fishy world.

If she lay on the surface, for instance, and suspected that she was being watched from above, she became, as it were, more and more indistinct and one with the dark water, letting herself sink imperceptibly, at the same time beginning to work all her fins. In ample folds they softly crept round the long stick that her body now resembled, fringed and veiled it and bore it away.

And just as she knew how to place herself, so did she know how to move--cautiously and discreetly.

Formerly she had measured only a finger’s length, and now she was already about a foot long; her voraciousness had increased in a corresponding degree. She could eat every hour of the day. She would fill herself right up to the neck, and even have half a fish sticking out beyond. It was quite a common sight to see a little flapping fish-tail for which her digestive organs had not room as yet, sticking out of her mouth like a lively tongue. She would swim about delightedly, sucking it as a boy would suck a stick of candy.

One day she was gliding slowly through a clump of rushes, as lifeless and dead as any stick. Her eyes seemed to be on stalks and spied eagerly round, but her body exhibited the least possible movement and eagerness.

She turned, but even then holding herself stiff, and playing her new part of a drifting stick in a masterly manner. As she did so she discovered her brother, as promising a specimen of a young pike as herself, with all the distinguishing marks of the race.

Although cold-blooded, she was of a fiery temperament, and as she was also hungry, she stared greedily and with cannibal feelings at the apparition. Her appetite grew in immeasurable units of time. The food was at hand, it stared her in the face; she forgot relationship and resemblance, and bending in the middle so that head and tail met, she seized her brother with a lightning movement.

He was quite as big as she, struggled until he was unable to move a fin; but the stroke was successful.

She began to understand things, and grew ever fiercer and more violent and voracious. Her teeth were doubled, and as they grew they were sharpened by the continual suction of the water through the gills. It was as if she understood their value, too, for she would often take up her position on the bottom and stir up grains of fine, hard sand, thus improving the grinding process considerably.

It was mostly in the half-light that she now went hunting, in the early dawn or at dusk. Her sharp eyes could see in the dark like those of the owl and the cat. When the shadows lengthened, and the red glow from the sky spread over the water, she felt how favourable her surroundings were, and she became one with the power in her mighty nature.

But in the daytime, she lay peacefully drowsing.

The creek in which she lived had low-lying banks.

Among the short, thick grass, orchids and marsh marigolds bloomed side by side, and the ragged robin unfolded its frayed, deep pink flowers upon a stiff, dark brown stalk, that always had a mass of frothy wetness about its head.

Farther out, the muddy water and horsetails began, and beyond them the tall, waving reeds, which stretched away in great clumps as far as it was possible for them to reach the bottom.

Where they left off, the round-stalked olive-green bog rushes began, wading farther and farther out, until in midstream they gathered in low clumps and groves, inhabited by an abundant insect life.

Beautiful butterflies danced their bridal dance out there, some bright yellow with black borders, others with the sunset glow upon their wings. Dragon-flies and water-nymphs by the score refracted the sun’s rays as they turned with a flash of all the colours of the rainbow. Black whirligigs lay in clusters and slept; and on the india rubber-like leaves of the water-lily, flies and wasps crawled about dry-shop, and refreshed themselves with the water.

In the still, early morning the reeds sigh and tremble. The little yellowish grey sedge-warbler comes out suddenly from its hiding place, seizes the largest of the butterflies by the body, and as suddenly disappears again. A little later it begins its soft little sawing song, which blends so well with the perpetual, monotonous whispering of the reeds.

Grim, down among the vegetation, only faintly catches the subdued tones; she is occupied with an event that is developing with great rapidity.

A moth has fallen suddenly into the clear water. It tries to rise, but cannot, so darts rapidly across the surface of the water, dragging its tawny wings behind it. It puts forth its greatest speed, making in a straight line for the shore.

But the whirligigs have seen the shipwreck, and dart out on their water-ski to tear the thing to pieces. They advance with the speed of a torpedo-boat, and in peculiar spiral windings. A wedge-shaped furrow stands out from the bow of each little pirate, and a tiny cascade in his wake.

The poor moth becomes wetter and wetter, and less and less of his body remains visible as he exerts himself to reach the safety of the reeds, where he can climb up into a horse-tail and escape, just as a cat climbs into a tree to escape from a dog.

Unfortunately he does not succeed; he is in a sinking condition, and one of the whirligigs fastens voraciously upon his hind quarters.

The successful captor, however, is given no peace in which to devour his prey. He has to let it go, and seize it, and let it go again; and now a little fish--a bleak--begins to take a part in the play.

The fluttering chase continues noiselessly across the surface of the water, and urged on by the whirligigs above and the bleak beneath, the moth approaches the reeds.

With muscles relaxed and dorsal fin laid flat, Grim lies motionless at its edge, whence again and again she catches a glimpse of the little silvery fish.

Its delicate body is fat outside and in, plump and well nourished, and to the eyes of the fratricide is an irresistible temptation, making her hunger creep out to the very tips of her teeth.

Her dorsal fin opens out and is cautiously raised, while her eyes greedily watch the movements of the nimble little fish.

Flash follows flash, each bigger and brighter than the other.

Grim feels the excitement and ecstasy of the spoiler rush over her--all that immediately precedes possession of the spoil--and delights in the sensation. She begins to change from her stick-like attitude, and imperceptibly to bend in the middle.

The plump little fish is too much engrossed in its moth-hunt. Unconcernedly it lets its back display a vivid, bright green lake-hue, while with its silvery belly it reflects all the rainbow colours of the water.

Another couple of seconds and the prey is near.

Then Grim makes her first real leap. It is successful. Ever since she was the length of a darning-needle, she had dreamt of this leap, dreamt that it would be successful.

The sedge-warbler in the reedy island heard the splash, and the closing snap of the jaws. They closed with such firmness that the bird could feel, as it were, the helpless sigh of the victim, and the grateful satisfaction of the promising young pirate.

She was the tiger of the water. She would take her prey by cunning and by craft, and by treacherous attack. She was seldom able to swim straight up to her food. How could she chase the nimble antelopes of the lake when, timid and easily startled, they were grazing on the plains of the deep waters; they discovered her before she got near them and could begin her leap!

Huge herds were there for her pleasure. She had no need to exert herself, but could choose her quarry in ease and comfort. The larger its size, and the greater the hunger and lust for murder that she felt within her, the more violence and energy did she put into the leap. But just as the falcon may miss its aim, so might she, and it made her ashamed, like any other beast of prey; she did not repeat the leap, but only hastened away.

But when her prey was struggling in her hundred-toothed jaws and slapping her on the mouth with its quivering tail-fin, then slowly, and with a peculiar, lingering enjoyment, she straightened herself out from her bent leaping posture. If she was hungry, she immediately swallowed her captive, but if not, she was fond, like the cat, of playing with her victim, swimming about with it in her mouth, twisting and turning it over, and chewing it for hours before she could make up her mind to swallow it.

She ate, she stuffed herself; and with much eating she waxed great.

In the creek where she lived among rushes and reeds, a shoal of perch had their abode. They were scarcely as big as she, but much thicker and older. Their leader in particular, by whose movements the whole flock were guided, was a broad bellied high-backed fellow, who knew the value of the weapon of defence he possessed in his strong, spiny dorsal fin.

He had a peculiar power of varying his colour so that it always suited the light in the water and on the bottom. There were days when he looked an emerald green, without any brassy tinge; at other times he let the black flickerings along his sides stand out like the stripes on a zebra’s skin, and gave a brilliancy to his belly like that of the harvest moon. That was for fine weather. There was life in the water then!

But common to them all were the rough, rasping scales that grew close up round the carroty-red fins, and the round yellow eyes with coal-black pupils, which seemed to rest on cushions and roll outside the head so that the fish could see both up and down.

The perch were quite as rapacious as Grim herself; they poached upon her small-fish preserves, and often disturbed her in the chase. Had she only been equal to it, she would gladly have devoured some of them, too.

One evening when she was so hungry that she under-estimated everything, she saw her chance of attacking their dark-hued leader, but Rasper, becoming aware of his dilemma, defended himself with the energy of a bulldog. The combat was on the point of turning in his favour, when Grim disappeared from view by taking a bold salmon-leap high into the air. After that they always swam scowling past one another at a respectful distance; but Grim was well aware that the striped swimmer had no friendly feeling towards her.

As she grew bigger, and felt herself more and more the powerful despot, whose dental armature had been provided simply and solely for the purpose of biting others, her hatred of the high-backed one instinctively became greater. They were of such widely different natures!

Grim was passionate, fierce, and reckless in her attacks, and gave herself up to the intoxicating pleasure of the chase until she grew dizzy. She ventured all, and lost herself in rapacious lust. The cunning perch seldom made a false step, but looked carefully ahead, and was always cool and self-restrained in his behaviour; and yet he was always ready--quite as ready as she--to attack, but had a masterly perception of the chances of success. He would frequently dart towards her, then suddenly stop and consider, and stand sniffing at her like a dog.

She was still only a hobbledehoy, flabby and loose-jointed, and not quick enough in emergencies. She had only just found out where the great ones of her own species liked to post themselves, and where it behoved her, therefore, to be on her guard; but beyond this she was not burdened with much experience.

As a young fish she had never been out into deep water, but wisely kept to the quiet parts--the channels and the broad waters of the creek, where her strength was proportionate to the exigencies of her surroundings, and where she instinctively felt that her great enemies would run aground if they pursued her. Here she found shelter among the reeds and the rushes.

But there was something beyond; something great and strong, something always disquieting; and this attracted her.

She began to go farther and farther afield, and one day, when the water was especially bright and clear, she set out on a journey from one end of the lake to the other.

The bottom of the creek was fertile, hilly country. Long slopes, clothed with water-lily plants, and laden with yard-high, round-stalked grass, ran out in parallel chains, framing, as it were, a corresponding stretch of broad, deep valleys. Here and there were steep narrows, passes through which the shoals of fish had to venture when going from one pasture to another.

She swam just below the surface of the water, and looked with interest at the varied scenery of the bottom and all the unfamiliar and strange things that presented themselves. How delightful it was to let herself go and give her fins free play!

She reached a rocky reef, and swam over a group of high, wild mountains that rose steeply out of the black bottom ooze with rugged sides, wooded in parts, and in others barren and naked. The mountains were full of deep ravines, the ice of centuries of winters’ freezing of the bottom had furrowed them with crests and clefts, planed off the points of the summits, and formed rounded tops or plateaux.

Here and there in this rocky land with its numerous winding inlets and sharp corners, a conspicuous stump stuck up. Several of them had a ring at one end, and from a few waved a bit of rope. In the course of time they had dropped down from the other world. They were lost boat-hooks and anchors that had become hopelessly fixed; for the rocky reef was a good fishing-ground.

There were many crayfish in the lake, and Grim, as she swam, had a bird’s-eye view of them walking about, swarming over the bottom of the lake in all directions, laboriously measuring out the kilometres in crayfish steps.

In several places there were whole towns of them, and in the perpendicular cliffs on the deep side of the reef, there was a large crayfish population. Here she noticed certain specimens, larger than she cared about. They lay in wait among the rocks or in the depths of the primeval forest, and caught what fish they could in their deadly claws. Or they ran backwards through the water with claws and feelers extended, step by step and with a beat of the tail; if the waves they set up had not warned her in time, they might have run into her at any moment.

From the reef she passed on over a great sandy desert, where the worms lay in rings, and the fresh-water mussels in colonies. She came upon some unpretending and not very luxuriant plants with swinging stalks that could turn with the current and the waves; but what struck her most, and broke the monotony more than anything else, was the skeleton remains of animals, boats, and a few human beings, that lay scattered about.

Where the substratum of the rocky reef still extended under the sand without disappearing altogether, she saw these slowly-perishing remains of the meteors from the air-world, lying scoured and clean as on a tray. In the eyeholes of the skulls the crayfish sheltered when they rested on their long journey over these perilous wastes, and perch lurked in the shadow of the ribs.

Farther out, where current and drifting sand alternately had the mastery, things were incessantly being uncovered and reburied; and in the middle of the desert waste, where there were quicksands, sometimes an arm would project from the sand-dunes, sometimes a leg, or the frontal bone of a skull bearing a huge pair of horns, or the prow of a boat. Finally, the desert ended in a whole skeleton reef--the remains of a drove of animals that a dozen years before had lost their way in the drifting snow and the dark, taken a short cut over the ice, and fallen through.

Once beyond this, the fertile bottom, with black soil, plants and little fish, began again. Then came a new, high-lying land, not stony and rough like the first, but rich and luxuriant. It lay outside a projecting point of land, of which it formed the natural continuation under the water.

On each side of the point a long creek stretched far inland, the scenery under the water being a repetition of that above. A luxuriance and fertility was visible on all sides; the water-grass waved in stretches like corn in the fields, and the giant growths of the water-forests were like the shady trees on land.

On the dividing-line between these fertile regions and the sterile tracts where, on stormy days when the waves ran deep, the drifting sand laid bare old, fish-gnawed skeletons, or covered up new ones, there was a big slough, which formed the beginning of a low-lying, wide-spreading bog, in which the sources of the lake had their origin.

There was always movement in the vegetation here. The mud rose and fell as if waves were passing beneath it. Now and then the surface opened, and jets of water as thick as tree-trunks shot into the air. There were high and low jets, forming, as it were, trees and bushes of water, which sometimes burst into bloom with large, strange-hued, fantastic blossoms of foam and bubbles.

In this slough lived the hermit of the lake, the giant sheat-fish Oa, a scaleless, dark, slimy monster, which only on rare occasions, generally in stormy weather, rose from her mudbed and revealed herself to human eyes. Generally, she moved about on the bottom, living her lonely life of plunder where the law of gravitation ultimately brought everything that was no longer able to swim or float about.

Centuries earlier, pious men had brought her progenitor, wrapped in wet grass, here to the lake, and planted the family of Silurus outside their cloister walls, so that its oily, digestible flesh could serve them as a good dish for fast-days.

The experiment was only moderately successful, and this hardy old fish was the last of her race.

Oa had the body of an eel, but was as long and thick as a boa constrictor. If she were ever caught, and placed upon a wagon, her tail would hang out beyond even the longest wagon-perch.

Her head was large and squat, with a huge shark’s mouth and small, blinking eyes. Six long, worm-like barbels, whose ends curled and twisted, hung from the corners of her mouth; she felt her way with them as she sedately crawled over the muddy bottom. She had neither neck nor breast, but her capacious stomach hung down immediately behind her gullet, like that of an old sow. It was always distended, and apparently so heavy that its owner’s back was quite bent.

Oa was a sinister-looking skulker in dark places, a terror to every poor fish that had been injured and could no longer swim nimbly about.

Like a moss-grown tree-stump she lies buried in the mud when the still inexperienced Grim swims in among the bottom springs, and again and again unwittingly passes over her scaleless, dull green body. She is quite invisible, only the two longest of her barbels projecting from the mud, and incessantly curling and bending like two earth-worms hastily making for the bottom at the approach of an enemy.

Grim, who is always in want of food and cannot resist delicacies, swoops down like a falcon at sight of the “worms,” without noticing the watchful gleam in the two little amber-coloured stones that lie quivering on the muddy bottom. She snaps eagerly at the nearest “worm,” but it escapes her by adroitly rolling itself up.

The active little pike is still too far off the big pirate’s teeth; it must be enticed nearer, so that she can be certain when she strikes.

Grim does not respond to the invitation, however, but prefers to try the other “worm,” and when that, too, with a rapidity unusual in a worm, curls up into a ball and goes to the bottom, she instinctively grows suspicious, and sets her tail-screw going, just as the cunning water-hyena throws off its mask of mud, and makes a wild dash at her.

Grim flees precipitately--so terrified that her cold blood almost stiffens--and darts out of the black cloud that Oa in her eagerness has raised.

The entire hollow seems alive now; everything is gliding and rocking, everything is moving beneath her; she seems to be swimming in black darkness with an angry, gaping, sucking mouth close behind her. She has to keep up full speed with her tail, and to paddle with all her fins, fore and aft, to avoid being drawn in.

When the water begins to clear, and daylight returns, she finds herself in the middle of a shoal of gay little fish, which, at her sudden appearance among them, scatter like a flock of starlings at the dart of a sparrow-hawk down among them. She feels the seething and boiling from the quick flapping of tiny tails; and involuntarily she goes with them, swimming away as quickly as the most nimble of the shoal, to a large, wide-spreading island of reeds.

Here Grim remained for a month, during which time she calmed down, and came to a full understanding of her own cruel, voracious nature.

One day, when she was proceeding along the border of her new beat, she came upon some precipitous cliffs, standing stone upon stone straight up from the bottom, full of holes and openings. She swam into large, slimy-green caverns and lofty grottos. It was the ruin of the old monastery she had found.

For the present she dared not venture back across the lake. The encounter with Oa had given her a feeling that dangers lurked out in the deep water, to which she was by no means equal. She turned into the nearest creek, and lost herself in a series of large reed-forests. Through them she went on into the bay until the world around her grew narrower and narrower, the surface of the water and the bottom approached one another, and the dreaded element in which she could not breathe made known its superior force by many loud sounds.

Here a great fringe of forest encircled the lake, and Grim turned headlong back.

Borne on a gentle breeze, a large crane-fly comes sailing out of the wood. It likes to cool its long legs, as it flies, by trailing them along the surface of the water. The whirligigs are after it, but it easily avoids them. Then comes a sudden surprise: a fish pops up its mouth, and closes its scissor-jaws with a snap on the insect’s legs, and it disappears in the centre of a rocking series of rings.

The lake is perfectly calm, its green-black surface smooth and shining, and full of drifting summer clouds. The reeds are reflected in it and look double their height, and the trees mirror their branches there, seeming twice as leafy; and a red house with a white flagstaff on one of the banks becomes quite a little submarine palace.

More crane-flies arrive, and circle after circle breaks the stillness of the water, just as mole-hills break the uniform smoothness of the meadow, as fishes’ mouths dart up by the score side by side.

It is in one of the valleys in the submarine mountainous region that this shoal of thousands of bleak lies. It covers the area of a market-place, and makes the water alive for fathoms down.

On the one side rises the forest of weed, like a fir-forest on a Norwegian mountain; on the other the thick green water-grass waves and bends like the corn on some fertile plain in Hungary. In front and behind, the valley winds on between the hill-sides until it widens out and finally loses itself in the barren, sandy desert.

Suddenly, at the end of the neighbouring valley, the water seethes and foams. It is cleft incessantly from bottom to surface, bubbles rise and whirlpools are formed, and a long strip of lake foams and spurts.

It is not like a single large animal darting forward with rapidly twisting tail, and leaving a wake and waves behind it; but a general effervescence that makes the depths gleam with millions of scales.

It is the perch, the marauders of the lake, on a hunting expedition!

They go together in a large company, like soldiers in an army, rows of them above, beside, and behind one another. There are hundreds upon hundreds of them, and yet a single unit.

With their uppermost layer only a couple of inches below the surface of the water they hasten on. Then all turn at once, changing from the long, narrow marching column into compact formation. A fresh signal, inaudible, imperceptible to all but themselves, and once more, in a trice, the narrow, smoothly-gliding hunting-column is reformed.

Just as they twist and turn in the horizontal plane, so do they in the vertical. They go suddenly and headlong from the surface to the depths, spinning out from their compact mass a long, living thread.

And the thread becomes longer and longer, and thinner and thinner, while they pass through one of the narrows in the submarine mountainous region.

It is the shoal of bleak they are after. Now they are in the valley where it lies.

The lively little freshwater herring as yet suspect no danger; they are in constant motion, occupied in snapping up the fallen, half-drowned insects. Noses are pushed up, and little thimble-like mouths open; the water streams in, and with it the food. An eager interchange from bottom to surface goes on; for when the upper layer is satiated, it likes to enjoy its feeling of well-being in peace, until voracity once more makes them all rivals.

The splash of the waves on the surface lifts the gluttons up and down, while the ground-swell rocks the satiated to rest.

The perch have quickened their pace; involuntarily the speed is increased; they already scent their prey.

Foremost of the company, with a dark-golden, high-backed leader at their head, swim a couple of hundred of the finest perch. They are at their strongest age, and in best possible condition, suffering neither from too great a weight of fatness, nor from the nervous lassitude of insufficient nourishment. They lead, and with frolicsome eagerness push past one another, so as to be the first to arrive.

After them comes the great mass of the horde, big, heavily-laden craft, their round backs and swelling bellies testifying to their success in their toil for material needs. There are perch among them of half an arm’s-length, and the thickness of the biggest of wrists. Sheaves of silvery-gleaming rays flicker far out in their wake.

The rest of the fierce horde are large and small mingled--hundreds of perch of half-a-pound’s weight, and rank upon rank of others well over two pounds.

For the present the whole flock keeps to the bottom, darting along with dorsal fin erect, the stiff spines bristling menacingly. It is as well to have bayonets fixed in case of the sudden appearance of a pike.

All at once the van slips away from the rest, and the latter have to exert themselves to catch up, twisting and turning their tails, and unfurling the stiff sail of their dorsal fin. There must be nothing now to check their speed; fair-weather sailing is over, and the privateering expedition has begun.

The certainty of booty fills them all.

The vanguard has led the marauders well; they have come under their prey, and now shoot up among the unfortunate, unsuspecting bleak. All order among the assailants instantly ceases, and each member thinks only of its own mouth, and cares for nothing but getting it filled.

Like yellow flashes of water-lightning the perch dart into the shoal of little fish, and like grain among a flock of chickens, masses of bleak disappear into their mouths. They kill and devour--and it will be still worse when the rear-guard comes up.

Now they arrive, and the alarm in the swarm of bleak below spreads with magical swiftness to the upper layers, where the bewildered little creatures make off at full speed. Gleam after gleam flashes up as the little shining fish, uncertain of their way, twist and turn about. Each makes itself as long and thin as it can, so as to show as little as possible, and disappear, as it were, in the water.

But now the fierce horde becomes still fiercer. The rear-guard overtakes the fugitives and cuts off their retreat; and smack after smack is heard after their charge.

The swarm of bleak scatters in wild panic. Thousands of them, in their terror, make for the surface, leaping into the air like jets from a fountain. They tumble over one another and try in their bewilderment which can leap highest and farthest. They rise like flying-fish out of the water with a flash, and once more disappear with a splash into the water. There is a splash when they rise, and a splash when they again reach the surface of the water; making a sound like the falling of torrents of rain.

Hell is beneath them in the water! The yellow devils not only menace them from the side; they come upon them from all directions. When they descend in crowds from their flight into the air, they grow stiff with terror on finding themselves face to face with great, amber eyes that seem starting out of their sockets to go greedily hunting on their own account. Then a mouth opens, shoots out a pair of concertina-like lips, and changes into a funnel; and the poor little fish disappear into a chasm, like threads into a vacuum cleaner.

Above the spot a cloud of terns is circling. They fly low with half-extended legs and drooping wings, ready to dart down. Sometimes they make a catch, sometimes miss their aim, but have the good fortune to take a fish that inadvertently appears close by; indeed the bleak often leap straight into the birds’ open beak. The birds hold them at all sorts of angles in their beak, and fly away with them, shrieking and screaming, pursued by their fellows.

Poor little bleak! they were so pretty to look at. An emerald green colour extended from the back right over the head and nose; and the rims of their eyes when they blinked could sparkle and shine like the gem itself. Their shining breast was whiter than a swan’s, and their plump sides gleamed and sparkled like ice under a wintry moon.

But from the time they left their Creator’s hand they were intended to serve as food for others.

A boat lay anchored a few hundred yards off. In it was an elderly man.

An angler this. He had been out since early morning, and had a delightful day.

Not a single bite. But what did that matter?

He was lying now at the bottom of the boat, dreaming.

He was a regular visitor to the lake. His ancestors’ love of a free, out-of-door life had entered into his blood.

It is well known that it takes three generations to make a gentleman; but it would take three times as many to create, out of a race that ever since the morning of time had lived out of doors, a generation that did not care to handle either gun or rod.

In his youth his gun had been his best friend; but the chase demands much of legs and muscles and heart. When a man is no longer in his prime, he should beware of paying ardent court to Dame Diana. In her suite--it is useless to deny it--the old man is seldom looked upon with favour: he has had his day. But Father Neptune clasps him rapturously in his wet embrace, and sets the fish around his boat leaping and playing.

It was thus in his later years that his fishing rod had become the old man’s joy and companion.

Season after season he made his weekly journey from town by rail, and then drove out to the lake. He fished in the good old-fashioned way, talked very little, and was always alone in the boat.

The weather to-day, from a fisherman’s point of view, is the worst possible. The July sun is shining hotly, and sends its beams deep down into the water.

The lake slumbers. There is a bottle-green hue above the deep water, and a lilac shade in the shallows; but over the sandy bottom the colour is drab. Far off a flock of wild ducks rising raise some little, gentle waves, that look so blue, so blue!

The angler, who is a big, sturdy man with large, black-rimmed spectacles upon his voluminous nose, is in his customary fishing-dress--an old straw hat with an elastic under the chin, his coat off, and no collar, on his legs a pair of thick, yellowish brown moleskin trousers, his feet in a pair of felt shoes, lined with straw.

He generally stays all day, and it is still far from evening.

He is now lying outstretched in midday drowsiness, enjoying the great peace that rests on the lake. He has wound the ends of his lines round his wrist; he waits patiently, and if towards evening he is fortunate enough to haul in a pike, he will be filled with a quiet, intense joy.

Suddenly he awakes with a start. He hears a rushing sound like that of the paddles of a distant steamer striking and tearing the water; he sees the terns flocking, and the surface of the water broken again and again by bleak leaping high into the air. He takes up his anchor, and rows up until he hears the smack, smack of the greedy perch all round him, and knows he is in the middle of the whirlpool of fish.

He gets four lines clear, and has enough to do in throwing them out and pulling them in. He throws off his hat and waistcoat, and loosens his belt--but even then he is drenched with perspiration.

At last he can do no more, and drops exhausted on to a thwart.

In less than twenty minutes he has caught more than fifty perch, weighing from one to three pounds apiece; they are lying in a brassy heap in the boat.

Then he opens his wallet, takes out the bottle containing clear liquid, and takes a nip. This he is accustomed to do every time he catches a fish of any importance. He drinks to the health of the lake, the lake with the fresh waves and the clear, bright water--the lake that treasures his dearest memories.

Between a cloudy sky and rough water the wind tore through reeds and rushes.

Grim was lurking at the edge of the bottom vegetation; she had not seen fish-food since the previous evening.

There is a splash in front of her, a broad foot is pushed obliquely down into the water and forces a large, heavy “swimming-bird” past her.

A little later there is a sudden gleam. A small fugitive of a fish darts past as though taking advantage of the wake of the big bird, from one reedy shelter to another.

Grim has already eaten so many bleak and roach that they are beginning to be everyday fare; and now, there goes a new kind of food, a fish that shines all red and green and blue and black, with large, glittering, beady eyes!

At a distance she follows the tit-bit that swims through the water like no other fish, turning incessantly round and round on its own axis.

How hard it works! there is a bright starry light all round it, and its tail-fin quivers behind in a long thick trail.

She cannot look at it unmoved. “After it!” say her eyes; “after it!” echoes her empty stomach.

She does not succeed in seizing it across as she generally does, but has to swim up and swallow it from behind in one mouthful.

It is a curiously sharp-spined little fish! Now that she has it in her mouth, it is not nearly so tempting to her palate as it was before her eyes. Well, she has taken the trouble to catch it, so down it shall go!

She cannot get it to move in her mouth; it will not stir! She takes a firmer hold, turns with it, and hastens back into her hiding place.

Then it begins to bite her in the throat! And now--she becomes quite uneasy--her throat suddenly tries to go the opposite way to her tail! What can be the matter?

She forcibly sets her teeth into her refractory captive, when suddenly she is pulled over.

How strange! The simple little pearly fish takes the form of a master, and drags her after it through the water; no matter how much she tries to back, no matter what powerful strokes she makes to force it to obey her will, she is obliged to yield and go with it. Her brain is bursting; she cannot comprehend this powerlessness: the fish is in her mouth and on its way down her throat, and yet it is dragging her along with it.

No! No! And she sets to work and lashes the water into foam with her tail; but the little pearly fish is inexorable; it is too strong for her.

There must be some strange witchcraft about it all!

Instead of her swimming away with it, here it goes swimming away with her, and on they go, nearer and nearer up towards the light and the surface, which she instinctively shuns. All at once the pearly fish leaps into the air with her. She wants to let go, to spit it out, but she is too late; for the moment she is not quite conscious.

Her eyes ache; she feels as if they would jump out of her head. Her sight is gone, and a bright red mist surrounds her. She tries to swim, but cannot get her balance; she tries to strike with her tail in order to escape, but the water round her offers no resistance.

A suffocating feeling seems suddenly to contract her gills; she cannot open them far enough. She opens her mouth to let water in, but only swallows dry wind.

The next moment she is lying floundering in a boat, and then a human hand takes her up.

“A pickerel! undersized!” mutters the angler. And he carefully takes out the revolving bait and weighs the fish in his hand. Alas! not even a miserable two pounds!

He takes out his sheath-knife and marks her dorsal fin; and then, in the hope of finding favour with the gods on account of his magnanimity, and catching the fish again at some future time, he tosses her over the side of the boat, and Grim is given back to life.

It was much the same feeling as when she was ejected from the heron’s throat; her intestines seem bursting, and her breath to be leaving her. Then she reaches the water, where she lies floating on her side, and slowly wakens as though from a long fit of unconsciousness.

And in a trice she has disappeared into the depths.

Her suspicion was aroused. The world was full of villainies, more than those that she herself committed!

Twilight was falling.

The sun’s fiery columns, that stood obliquely over the lake, suddenly separated and flowed out, their glowing fragments lying like burning oil upon the surface of the water. Then they were gradually extinguished; the darkness of evening shed its deep blue tones over them.

Long and black, the shadows crept out from the banks; the little fish made their way in to the shelter of the reeds, and the pursuing pike went to rest. And while the surface still sparkled with a peculiar mother-of-pearl brilliancy, the darkness of night already brooded closely beneath the water.

As quietly as a snail, a little crayfish was crawling over the bottom; but it was more watchful than a polecat, and listened and felt its way carefully. It came out from the rocky reef, and was now on its way over the sandy plain in to the nearest bank.

Nipper was a robber, encased in coat of mail; he spared nothing that he thought he was big enough to overcome. A sharp, serrated dagger projected above his jaws, and the pincers of his large claws were half-open, ready to fasten upon the unwary prey.

He was a young crayfish, no longer than the span of a child’s hand, and with a tail no broader than a finger. His eyes were stalked, and the long, wide-straddling feeling carefully searched the bottom for more than a body’s length in advance. The half-closed claws scraped over rocks and water-lily roots in their efforts to drag the mailed body along.

Suddenly there was a shock to his feelers. Nipper suspected danger, and struck with his tail; and at once beginning to go backwards, he hastily, with his front claws, stirred up a cloud of mud all round him. Step by step, long and rapid, he hastened, without changing his direction, back through the water.

It was only a false alarm, however; there was no otter or water-rat--its worst enemies--close to the tips of it claws. It might take things quietly, and safely set about its search for nocturnal prey again. It stopped beating the water with its tail, and with extended claws and tail outspread, it let itself sink slowly through the water.

Sedately and circumspectly, and with extreme caution, he felt his way before advancing over the bottom of the lake on his clawed legs.

Nipper was descended from an old “backslider” that had been a monster of the order of Decapoda, and had at last become so fat and heavy that she could hardly swim, and preferred to crawl about. Like the rest of her species, she had espoused a new male crayfish every other year; the wedding generally took place in November, when out-of-door pleasures were few, and everything, even the water, was cold and grey.

When the happy honeymoon was over, she always suddenly broke off all relations with her spouse, and withdrew into one of the roomiest of the numerous deep, dark, basement flats through the winter, waiting for the sun and the white water-lilies to bring out her little children.

And they came!

Next summer a swarm of little creatures crept out of the eggs that adhered in scores to her tail. From their birth they had tiny claws, a tiny rostrum, and tiny feelers; and they were all an exact copy of him. Holding fast with one claw to their mother’s poorly-developed caudal legs, they hung as to a strap, while with the other claw they fought among themselves as much as possible.

It was a little world of malice, cannibal cruelty, and good, healthy egoism that the old monster thereafter dragged about with her, and she defended it--to her praise it must be said--on every occasion against the violence and malice of the outside world, by interposing her own body.

Half without will of her own and unconsciously, she kept life in her young. Every time she required food and drew it forward under her body, the baby crayfish got a bit of it. On such occasions they let go of one another, and struck out with his free claw, and hastily transferred the morsel to his mouth.

Nipper had hung to one of the outside “straps” and he was with his mother on the night she went into a crayfish trap. He let go the strap in order to cram himself with both hands, and he did succeed in producing a feeling of extraordinary satiety; but when the trap was suddenly hauled up, he was not quick enough in taking hold again; the water drew him with it, and washed him out through the wide-meshed net. In this way he lost the shelter that in the natural order of things he could still have reckoned on beneath the caudal fan of his great parent; but fate had nevertheless been kind to him. While old Madam Nipper, boiled red like a lobster and with lettuce round her tail, lay that evening curled up on a dish, her little nipper was surrounded with all the wonders of life; and he went at them with greedy claws and flapping tail. It was not for nothing that he had been born with the art of going backwards.

He had now lived through three winters, and was therefore not altogether lacking in experience of life. He had successfully passed the age in which his growth of no more than a few weeks made each jacket-sleeve and trouser-leg too short, and had gone through nearly a score of those dreadful “metamorphoses.” They were terrible bouts, real illnesses that cost both toil and suffering. The last was still fresh in his memory. He had suddenly become uneasy, could not even rest in his hole. It was the same with them all; the same unrest seized upon all the inhabitants of the crayfish-town that extended over the rocky reef. None of them any longer ventured out at sunset; they remained indoors. Then the illness began with an irresistible desire to scrape and rub oneself. It was impossible to hold out against it; one had to let it go its way and follow a certain system.

The “system” commenced with some wild movements of arms and legs. Resting on the carapace and the big claws, the hind part of the body was raised, and the tail spread, and then the thighs, legs, and ankles were worked until a hole was made in the old, armour-like skin, and it split up length-wise.

The transformation took days, so one had to sleep now and then, and rest often. Food there was none.

One started up out of sleep, unable to rest for fear of being left in the old skin and dying of starvation. Nothing for it but to go on, and try to get over this most unpleasant process of moulting as quickly as possible.

Nipper, who was endowed with all the courage and impatience of youth, was one of the most eager to push on the business. He quickly got rid of the armour-plates on his legs, and was now working to get out of his tight coat-of-mail, throwing himself on his back, and rubbing himself backwards and forwards upon the floor.

The coat-of-mail has already come away from the trouser-band, and he can raise it from his body; he presses its stiff edges against a stone, while he works himself backwards out of the old crayfish-case. First he carefully releases both his stalked eyes, then come the feelers, and then the big claws. Oh, but it hurts! And he shakes and twists himself, sweating with exertion and anxiety. After all, it is going confoundedly fast! Suppose a limb got into a tangle, or a joint refused to move! Then it would break, as he very well knows: that kind of thing is a part of the crayfish system!

At last the whole thing was accomplished, and he felt stronger and freer than ever. This evening he would kill! This evening he would eat his fill!

The darkness grew deeper The sinister shadows were already darkening the banks, and the deep water, which before had shone with gleaming mother-of-pearl, seemed now leaden-grey. There was not a water-lily leaf to be seen on the surface; it was impossible to distinguish a single green stalk.

Down on the soft mud, beneath a rotten, wrinkled tree-stump, sat a fresh-water mussel with its shells half-open. As the round feelers of the crayfish came gliding tentatively round its foot, it became aware of the approach of an enemy, and had already almost closed its broadly-gaping shells when Nipper, at the last moment, managed to introduce the end of one of his broad pincers, like the heel of a boot in a door. The mussel worked its hardest, straining till its shells creaked and splinters actually broke off in its efforts to crush the hard armour-plating of the claw.

Nipper lay as though petrified in front of his victim, and let the mussel exhaust itself while he watched his opportunity to drive his unimpressionable wedge farther and farther in. He had the patience of Job, and knew that he only had to wait.

It was not long before he had succeeded in making room for his other claw, and now he was cutting and picking at the body of the poor mussel, one claw holding the pearly shells sufficiently wide apart for the other to convey dainty pieces of mussel-flesh to his mouth.

At last the poor mussel’s strength is quite exhausted. It gives up, and Nipper’s head and the front part of his body disappear inside the shell.

Nipper remained there the first part of the night, cramming himself, but at last could not help regretting that a mussel went such a little way. He took a short rest, and then towards morning set out confidently in search of more.

Unfortunately there were no sleepy, unprepared mussels to surprise; but behind some stones in one of the deep, submarine mountain passes stood a solitary fish, which had apparently got out of its course.

The quiet little Nipper had not much experience regarding the way in which a crayfish catches fish; he was more accustomed to snails and mussels. He could also seize a younger comrade in his claws, and suck him dry, leaving nothing but his coat and trousers; but the finned animal, with fans on back, belly, and tail, the nimblest of all--how did one catch it?

He slyly pushes through a crack at the bottom of the cave, raises himself on the points of his closed claws, and blinks with his diverging eyes. He has turned back his feelers so that they shall not betray him while he is investigating his immediate surroundings.

Grim is standing motionless with her head towards the current, leaving her forked tail to keep her, with slight movements, on the same spot. She is tired and exhausted after her long struggle with the pearly fish, and feeling rather languid and out of sorts. Her lacerated mouth hurts every time she opens it to rinse it with fresh water. She has, therefore, sought shelter in the rocky cave to compose herself and recover.

Something quivers along her breast and cautiously pricks her sides and belly. It must be a waving grass-stalk!

Then a gradually-increasing, continuous pressure is suddenly felt round the thick part of her tail.

With a sudden movement of her body she tries to shake off the supposed reed, but at the same moment the pressure is felt like a bite from the hard, sharp-edged beak of a heron. She struggles and writhes, and warps herself out of the cave; and now she flies, fin-winged, through the water.

Nipper is hanging to her stern. He has only hold with one claw, but hopes to get the other, which he is waving about, also applied. His tail-fan works incessantly.

Grim drags at full speed over stock and stone, and swings him out of one gyration into another; through reed-beds and undergrowth, and far, far into the forest of water-weed; but he hangs on still!

He feels, however, that his prize is rather more than he can manage. There is no time left for him to pick at the fish’s flesh with his other claw; he was growing quite dizzy, for he was not accustomed to going forward at such a pace!

Then he stretches out his free claw to seize hold of a root, and thus try to chain his captive to the bottom.

But the trick does not succeed. The jerk that follows is so violent that he loses his claw!

He has now lost his chance, and lets go.

Grim feeling herself relieved of his weight, and free in her movements, darts away with the speed of a run-away engine. In addition to the soreness of her mouth, she now has a pain in her tail. She will need some time to recover from both.

Things had gone against her, and to tell the truth she did not think there was much fun in being a fish; but then she had to learn her lesson, and once bitten, twice shy, both in and above the water.

The recollection of the strange little pearly fish long remained in her memory. Its stiff body, and continual turning about its own dorsal fin, without a single stroke of the tail, were long imprinted on her mind; and whenever afterwards the “tit-bit” appeared, her wounded mouth assured her voracious stomach that it was wiser to refrain.

Years went by; and Grim grew into a splendid fish. Her long, flat forehead was now continued straight into the strong duck-like beak of the upper jaw. A hollow in the middle enabled it, as it were, to project in canopies that hung down over her eyes, which thus acquired an expression even more cruel and scowling.

The cheeks stood perpendicularly on each side of the forehead, and enclosed the cranium as between walls; it was as though she had had a dent on both sides of her head. The back of her neck swelled up like that of a bull, for here the muscles lay over the cranium in large, thick curves, until down by the neck, they gave place each to its branchial cleft, which was as large as a barn door.

And what a mouth! It opened up far past the eyes! Generally, it only stood ajar; but to look into it when it opened wide was like looking into a barrel studded with nails.

In the front of the lower jaw, the teeth stood thick as pins in a pincushion. They were small and pointed, and sloped backwards, so that they served as barbs. In along the sides came the long, widely-separated incisors, whose purpose was to enter into and hold fast the prey. They were more than half an inch in length, rounded and blunt, and resembled the teeth of a rake.

The upper jaw was provided with a far more terrible armature. Whole rows of harrow-like teeth stood out, making a diabolical grater of the palate. They continued far down the throat, and even came forward over the tongue. Woe to the body that became jammed here! It was only released as mince-meat.

But the throat that swallowed the victim was by far the most horrible contrivance.

It resembled the drawn-up mouth of a sack. Down through it lay great rolls of swallowing-muscles, studded with grasping protuberances. In the midst of them the œsophagus was discernible, its aperture incessantly opening and closing with a suction that inexorably drew everything down with it.

And her external equipment corresponded to her internal. The wonderful, dark colours of the shallows drew a broad stripe along her great back. About the forehead and along the back of the neck, the water-grasses had laid a ground-wash of their own deep green; and her sides were veiled by the flickering streaks of the reed-beds. Patches of gold, like the sunshine falling through the glassy surface of the water, shone out between the transverse stripes on her sides; and over the branchial arch and the belly lay the pure whiteness of the water-lily.

Yes, she was adorned in all her splendour. Her scales gleamed with the rays of the sun and moon; and when, with the rapidity of lightning, she made a dart, it seemed like the twinkling of stars in the dark night of the deep waters.

From this time onwards, her voracity knew no bounds. The desire for food, which she had possessed from her earliest days, and which had lain like a germ in the very heart of her nature, was given free play by means of the terrible weapons that Nature had placed at her disposal. No one else should now get a bite; she would be alone in clearing the waters of food.

She now as readily seized her prey lengthwise as cross-wise; indeed, she even preferred, when hungry, to make straight for the head; by so doing, she wasted no time in turning it, but could swallow it at once.

By nature she was very reserved, and had no desire for companionship; but her mental abilities were by no means small, and she was well able to make various observations, and profit by their lessons. Nor was she deficient in memory, as she distinctly showed every spring when going to spawn; she always found her way up the brook to the wide fen.

She was very sensitive to every movement in the water, and in a way heard with ease the boats, “the big birds.” They always splashed so much with their oar-feet, or whisked their tail round in the water. She had often wondered at them! She had discovered that, like the grebe, they carried their young on their back; and, like all the other fish in the lake, she supposed them to be a part of the unrest up on the surface.

Long before they came near her, she was distinctly aware of their approach.

If she were high in the water, and the bird suddenly rushed down towards her, she darted to one side and hastened out of the way. It was different when the boat came slowly gliding along; then she only moved so as not to be run down.

But it was many a day before she came to understand that it was they especially who wanted to harm her.

One evening the old angler was rowing home late from his fishing-ground. The moon had risen, and shed her silvery light around his oars. They dipped down rhythmically, and came up with the silver dripping from them. Suddenly he noticed that one of them struck something, and the shock passed through the oar up into his arm. He was dragging something heavy, and could not bring the oar forward; and then he pulled the head of a pike up above the water. At the same moment the fish dropped, and the oar was free; but Grim was wiser after that.

As the years passed she developed into a powerful ruler, and increasingly felt herself to be the divinely-favoured inmate of the lake. She was not one of the rabble! She hunted large and small, and lorded it over the inhabitants of the lake as far as she possibly could.

By more frequent and longer expeditions, she increased her knowledge of the lake, and learned the routes to all the reefs, creeks and banks; and she ascertained that in certain directions her world was immense. It was only the surface that she shunned, and the deepest depths; for there were great crayfish--to whom the Creator had been so good as to set their maxillary half at the end of a pair of long, jointed claws--and there, too, lived Oa, the dreaded fish-monster.

Grim’s territory lay half-way between these.

In the pure light of early dawn, when the night flies and moths, drowsy and intoxicated with their nocturnal visits to the flowers, fell by hundreds into the water on their way home; when the swallows relieved the bats, and the whirligigs in the sheltered nooks began their noiseless scurrying over the water, beneath which the water-plants were beginning to appear in green, yellow and rust-red colours; when the day dawned down where Grim had her home, and the wide surface above her was filled with light and radiance--then she hunted most keenly, and felt most voracious, and then there was terror in her splash and snap.

One morning early, a breeze is ruffling the surface of the lake, and winding, white-foamed currents are eating their way out among black shallows. The terns are diving down after small fish, and along the rush-bordered banks the rising sun is treading the water.

Grim is abroad, pushing herself forward like a shadow along the bottom. Her cunning crocodile eyes are turned up so that they project from her head.

A number of roach are thronging about a clump of rushes, examining leaves and stalks just as long-tailed tits search tree-tops and bark; they are inside it and outside it, sucking up the water-snails and insects.

Grim stops with a jerk. She scarcely moves her ventral fins, and breathes very gently. At each breath she cautiously opens her mouth and draws back her tongue, thus filling the spiked barrel with water; then she carefully closes it again, shoots her tongue forward, and emits the water through her gills.

The little fish gambol unwittingly close to her mouth. Her upturned eyes look still higher, and see the gleam of their white-scaled bellies.

Now she is ready to spring.

There is just a movement of the extreme tip of the tail. Only the shifting shadow-lines that the reeds cast over her body indicate that she is moving forward. She peers about continually, peevishly, and evilly. Only one thing troubles her; she can never decide which fish out of the swarming multitude she will take. True, she has made a special study of the way to direct her attack--as the ardent hunter his aim--where the throng is thickest; but the roach are nimble, and she seldom gets more than one at a stroke.

Slowly and imperceptibly she rises, while all the fin-tips wag and wave in lingering enjoyment.

Suddenly a little scarlet roach-eye discovers her black back, which up to the present had looked just like part of the bottom, and they fly away from her in a panic of terror. In one moment the rushy margin is empty.

An accident that may happen even to the best of us! And Grim has to move on to fresh hunting-grounds.

Among the floating forests of green feather-foil go big, broad-scaled bream. They follow close in one another’s wake, and lie on the surface, letting the sunlight play upon their golden scales. Their fat bellies with the lobster-red fins, and their large, cod-like mouths, give an impression of simpleness. Yet they are cunning enough, and very cautious in all their behaviour.

Several of them are covered with cuts and wounds on the back and sides, and it is evident they have already made acquaintance with a pike’s mouth. The body of one of them is still bloody, and threads of flesh and torn scales make it look quite woolly as it moves through the water.

They come from deep down at the bottom, and shine with mud and slime and water-moss. They whisk along with much movement and many strokes of the tail. Reeds and rushes swing and sway as they stop for a moment to rub themselves against them. As they pass through the open water, between the masses of vegetation, where the sun suddenly shines upon their amber scales, Grim hastily conceals herself in the forest of weed.

The pliant water-plants, with their long stalks, accommodate themselves to the current, hanging westwards for an hour, only to turn just as unresistingly the opposite way the next. Stiff collars of leaves, like life-belts, hold up the naked stalks, and form a close, flickering thicket about the lurking lynx. Without the slime on her body, she would never get through.

Soon the fat-bellies are before her; they are slouching along in little companies, with a thick, greenish, juicy rim to the corners of their fat mouths.

Her purpose strengthens, her powers are doubled, but she is able to restrain herself: the moment has not yet come.

Not until the last “water-cow” is straight in front of her does she reveal herself; and the water flashes and bubbles as Grim twists and turns in her efforts to come up with her prey.

The flank attack, however, does not come altogether as a surprise to the “cow”; it has been prepared for it in this narrow passage, and therefore kept close to the bottom. As a stone bores its way into the ground, so does it plunge into the mud, stirring up the water, and digging itself in, so that Grim gets only mud and grains of sand between her teeth.

Another accident which only sharpened her appetite and made her ungovernably fierce; and just then a little roach swam past.

Grim started. Her embarrassment at her failure almost disappeared, and she involuntarily stiffened as she stood. She could see with half an eye that the little roach, which was limping along without any frolicsome jumps and twists, would be an easy prey.

What luck! Roach were generally lively little fish, and not easily got hold of; and although they formed part of her daily fare, she had to use all her powers and unfold all her energy in order to catch two or three, at the most five, a day. It was only in May, when they lay in bundles among the rushes, amorously flicking their tails, that she had her fill of them, taking as many as a score in the day.

Now only patience, a little more time to wait; for this time she would make sure of her fish!

Just then there is a movement in one of the clumps of weed. The dusky-hued perch with the high back forestalls her. Right before her nose he darts like an arrow after the fugitive, but hesitates at the very moment of striking, stops, and sniffs.

“Oh! so he daren’t! He wants to have the whole company with him!”

Grim’s eyes are alight with the eagerness of the hunter, and her stiff tongue quivers in her mouth as, with widely opened jaws, she springs upon her prey.

The roach is good enough! It wriggles between her teeth and tickles her cheeks and chin with slaps of its little tail; and yet ... it has an inexplicable strength like that of a little pearly fish that she dimly remembers.

She grows angry. Is an insignificant little fish like this going to resist her will? The silly little thing is ready to go any way but the one she wants it to go; she can hardly get from one thicket of weeds to the other. She becomes so angry that she feels the blood burning in the back of her neck, and with a sudden vigorous effort, she gives the roach a violent tug.

That helps; the fish becomes manageable, its strength vanishes. She is triumphant. Yes, she knew, of course, how it would be!

Grim had been fortunate in her misadventure. True, it was a man-roach that she had bitten into, but she had fortunately broken the line, and now went off with a long trace dragging after her. She had swallowed the bait, but what made her horribly uncomfortable was that in doing so she had got a long, thorny water-plant fixed to her upper lip.

They were the barbs of the triple hook that she took for thorns!

At that moment she sees another little roach shining. It is just as languid as the previous one, and makes the same tempting impression. Instantly she makes a dash at it.

The same comedy was gone through, the same incomprehensible strength in a puny roach, and the same work to get the refractory fish into her power.

Well, she managed it at last; at last she had her mouthful.

This one she swallowed too, but once more she had to spit out something sharp and prickly that hung to her upper lip on the opposite side.

It was a long time before Grim managed to wear away the two triple hooks from the corners of her mouth, and in the meantime she swam about with the rusty things like an extra set of monster eye-teeth sticking out of her mouth. The pieces of line that trailed behind her often caught in things and chained her in an incomprehensible manner to reeds and rushes; but at last she pulled out one, and a little later the other, and a hard, gristly, leather-like skin formed where they had been.

She gained some experience from this incident; henceforward, she regarded solitary, sickly-looking roach with keen suspicion. She would still take with confident voracity large roach and small; but she very reluctantly took a halting, languid fish like those that had pricked her so horribly that morning. Their drooping fins and heavy, wriggling flight had fixed themselves clearly in her mind’s eye.

Her peaceful youth, in which she had only had the heron and the crayfish and her own kind to fight with, had long since passed, and henceforth she was to see more and more of the angler’s implements.

But the old sportsman, whose tackle was wearing out, had to overhaul and renew his stock. It irritated him beyond endurance, and for a long time he felt ashamed of himself. From the resistance it had offered he felt quite convinced that the pike he had lost was at least worth a bronze medal. He would not tell anyone where it lay, but would take it himself when he had the opportunity.

The horde of marauders were chasing through the lake again, and behind them came the pike. These last did not go together, like the perch, in serried ranks at a furious hunting pace, but slunk along one by one from stone to stone, and from weedy clump to weedy clump.