Title: A Philadelphia Lawyer in the London Courts

Author: Thomas Leaming

Release date: October 12, 2012 [eBook #41034]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images

generously made available by The Internet Archive/American

Libraries.)

SECOND EDITION, REVISED

Copyright, 1911,

BY

HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY

Published May, 1911

The nucleus of this volume was an address delivered before the Pennsylvania State Bar Association which, finding its way into various newspapers in the United States and England, received a degree of favorable notice that seemed to warrant further pursuit of a subject heretofore apparently overlooked. Successive holiday visits to England were utilized for this purpose.

As our institutions are largely derived from England, it is natural that the discussion of public questions and the glimpses of important trials afforded by the daily papers—usually murder trials or divorce cases—should more or less familiarize Americans with the English point of view in legal matters. American lawyers, indeed, must keep themselves in close touch with the actual decisions which are collected in the reports to be found in every library and which are frequently cited in our courts.

Nothing in print is available, however, from which much can be learned concerning the barristers, the judges, or the solicitors, themselves, [vi] whose labors establish these precedents. They seem to have escaped the anthropologist, so curious about most vertebrates, and they must be studied in their habitat—the Inns of Court, the musty chambers and the courts themselves.

The more these almost unknown creatures are investigated, the more will the pioneer appreciate the difficulty of penetrating the highly specialized professional life of England, of mastering the many peculiar customs and the elaborate etiquette by which it is governed and of reproducing the atmosphere of it all. He will find that he can do little but record his observations.

It was not unknown to him that some lawyers in England are called barristers, some solicitors, and he had a vague impression that the former, only, are advocates, whose functions and activities differ from those of the solicitor; but he was hardly conscious that the two callings are as unlike as those of a physician and an apothecary. It requires personal observation to see that the barristers, belonging to a limited and somewhat aristocratic corps, less than 800 of whom monopolize the litigation of the entire Kingdom, have little in common with the solicitors, scattered all over England. The former are grouped together in their chambers in the Inns, their clients [vii] are solicitors only, they have no contact, perhaps not even an acquaintance, with the actual litigants and a cause to them is like an abstract proposition to be scientifically presented. The solicitors, on the other hand, constitute the men of law-business, whose clients are the public, but who can not themselves appear as advocates and must retain the barristers for that purpose.

Again, it is difficult to grasp fully the influence exercised through life by the barrister's Inn—that curious institution, with its five hundred years of tradition—voluntarily joined by him when a youth; where he has received his training; by which he has been called to the Bar and may be disbarred for cause, and upon the Benchers of which Inn he must naturally look as his exemplars, although the Lord Chancellor may be the nominal creator of King's Counsel and the donor of judge-ships. The impulse of these Inns is still felt at the American Bar, despite more than a century's separation, for, about the time of the Revolution, over a hundred American law students were in attendance, not only acquiring, for use in the new country, a sound legal training, but absorbing the spirit of the profession which has been transmitted to posterity, although its source may be forgotten.

[viii] Nor will anything he has read prepare the American for the abyss which separates the common law barrister, who spends his days in jury trials, from the chancery man, who knows nothing but equity courts; nor for the complete ignorance, if not contempt, with which they seem to regard each other.

K. C.'s, indeed, are afforded their title in the reports—even in the newspapers—but nowhere does it appear that "Leaders" are appointed by the judge of a particular equity court to "take their seats" and practice before him exclusively, being associated in each case with "Juniors," who in turn have "Devils" to prepare their cases; or that a leader may sever this relation and thereafter "go special"; yet all these, and many other peculiar and inviolable customs, are handed down from one generation to another to be followed as if by instinct: and the profession would no more trouble the busy world with such matters than a dog would feel it necessary to explain that he turns thrice before lying down, simply because his wolfish ancestor did so in order to make a bed in the grass.

In this environment of ancient custom, however, the American is surprised to find the most up-to-date courts in the world and an administration [ix] of law which is so prompt, so colloquial, so simple, so free from formality and so thoroughly in touch with the ordinary man's every-day life, as to provoke a blush for the tribunals of the vaunted New World, still lagging in their archaic conventionality and their diffuse and dilatory methods.

At home, the American has been perplexed by the threadbare assertion that we have as many judges in a large city as has all England, but he shortly learns that such comparison considers only the few judges of the High Court, and ignores the others and the officials performing judicial functions, so numerous that the little Island fairly teems with its justiciary and that the implied criticism is due to ignorance of the facts.

The trials, both civil and criminal, will reveal the complete triumph of common sense and the Englishman will appear at his best in his court, for there he leads the world. The hearty good humor, alacrity and crispness of the proceedings, the absence of declamation but the avoidance of monotony by the proper distribution of emphasis, all combine to delight the practised observer.

The disciplining of the profession by means of [x] a body to whom may be privately submitted questions of morals and manners, mostly solved by gentle admonition and rarely by severe action, will suggest that our single punishment—disbarment—is so drastic as rarely to be invoked and hence largely fails as a corrective.

From the "bobby" in the street, to the Lord Chancellor on the Woolsack, from a hearing by a registrar to collect a petty debt, to the donning of the black cap in order to sentence a murderer; all will prove suggestive to the alert American who will nevertheless depart with a feeling that, while there is room for improvement at home, yet, upon the whole, there is much of which to be proud in our administration of the sound old law of our ancestors.

The kindly aid of a number of English judges, barristers and solicitors, by way of suggestion and criticism, is gratefully acknowledged.

The occasional illustrations are photographic reproductions of original oil sketches.

Philadelphia, April, 1911.

In accordance with the kind suggestions of a well-known barrister, a number of corrections have been adopted in the text of this edition. Some of them it had been the intention of the Author to make before his death and others have seemed necessary in order to secure greater accuracy and to preserve the value of the book for purposes of reference.

May 18, 1912.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | First Impressions | 1 |

| The Law Courts Building on the Strand.—A Court Room.—Participants in a Trial.—Wigs and Gowns.—Colloquial Methods.—Agreeable Voices.— Similarity to American Trials. | ||

| II. | The Making of Lawyers | 9 |

| Classes from which Barristers and Solicitors are Drawn.—The Inns of Court.—Inns of Chancery.— American Students at Period of Revolution.—A Barrister's Chambers.—Training of Barristers in an Inn.—Being Called to the Bar.—Training of Solicitors. | ||

| III. | Barristers | 29 |

| Waiting for Solicitors as Clients. "Devilling."— Juniors.—Conduct of a Trial.—"Taking Silk."— Becoming a K. C.—Active Practice.—The Small Number of Barristers. | ||

| IV. | Barristers—The Common Law and Chancery Bars | 39 |

| Bar Divided into Two Parts. No Distinction Between Criminal and Civil Practice.—Leaders.—"Taking His Seat" in a Particular Court.—"Going Special."— List of Specials and Leaders.—Significance of [xiv] Gowns and "Weepers." "Bands."—"Court Coats."— Wigs in the House of Lords.—Barristers' Bags, Blue and Red. | ||

| V. | Solicitors | 49 |

| Line Which Separates Them from the Bar.—Solicitor a Business Man.—Family Solicitors.—Great City Firms of Solicitors.—The Number of Solicitors in England and Wales.—Tendency Toward Abolishing the Distinction Between Barrister and Solicitor.— Solicitors Wear no Distinctive Dress Except in County Courts.—Solicitors' Bags. | ||

| VI. | Business and Fees | 57 |

| Influential Friends of Barrister.—Junior's and Leader's Brief Fees.—Fees of Common Law and Chancery Barristers.—Barrister Partnerships not Allowed.—English Litigation Less Important than American.—Clerks of Barristers and Solicitors Haggle over Fees.—Solicitors' Fees. | ||

| VII. | Discipline of the Bar and of Solicitors | 67 |

| The General Council of the Bar.—The Statutory Committee of the Incorporated Law Society.— Rulings on Various Matters.—Lapses from Correct Standards. | ||

| VIII. | The Civil Courts | 87 |

| The General System.—Different Courts.—Rules of Practice Made by Lord Chancellor.—Juries, Common and Special.—Judges and How Appointed.—Judges' Pay.—Costs. Court Notes.—Some Differences in English and American Methods. | ||

| IX. | Courts of Appeal | 107 [xv] |

| The Court of Appeal.—House of Lords.—Divisional Court.—Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. | ||

| X. | Masters—the Time Savers | 117 |

| Current Hearings.—Minor Issues Threshed out. | ||

| XI. | The Police Courts | 125 |

| Current Hearings. | ||

| XII. | The Central Criminal Court—The Old Bailey | 131 |

| Current Trials | ||

| XIII. | An Important Murder Trial | 145 |

| XIV. | Litigation Arising Outside of London | 169 |

| Local Solicitors.—Solicitors' "Agency Business."— The Circuits and Assizes.—Local Barristers.—The County Courts.—The Registrar's Court. | ||

| XV. | General Observations and Conclusion | 177 |

| Index | 195 | |

| The Corridors of the Courts | Frontispiece | |

| FACING PAGE | ||

| Crossing the Strand from Temple to Court | 36 | |

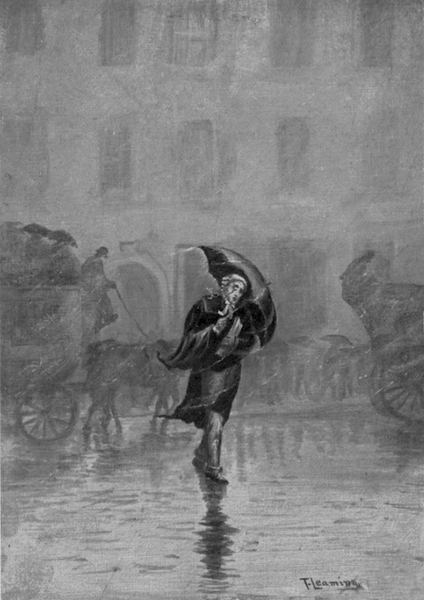

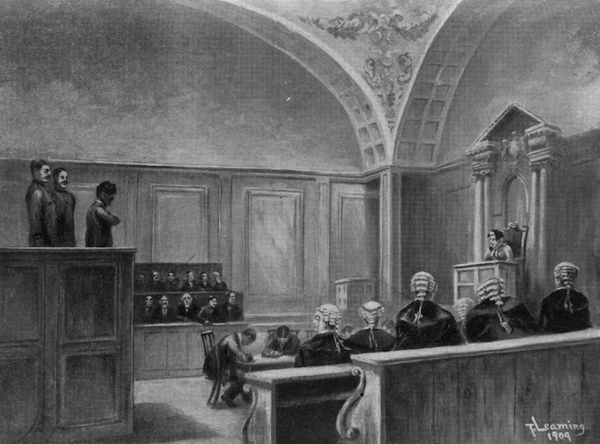

| A Jury Trial | 100 | |

| A Subject for the Police Court | 128 | |

| The Sentencing of Dhingra | 156 | |

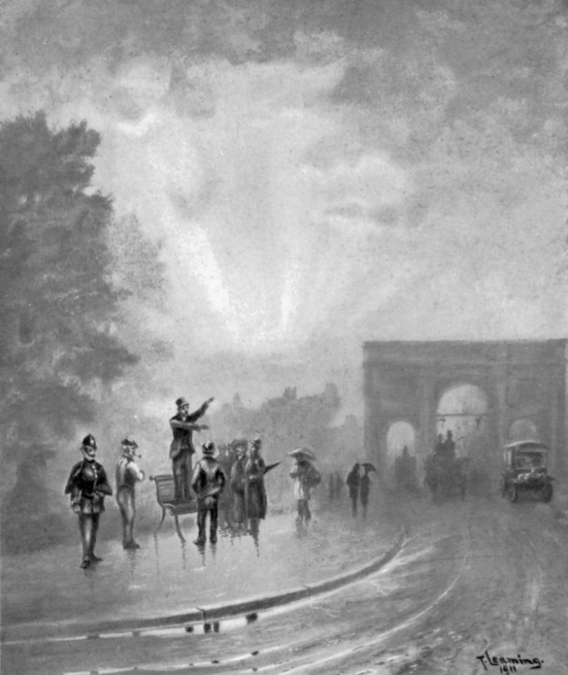

| Sidewalk Socialism—Hyde Park | 178 |

THE LAW COURTS BUILDING ON THE STRAND—A COURT ROOM—PARTICIPANTS IN A TRIAL—WIGS AND GOWNS—COLLOQUIAL METHODS—AGREEABLE VOICES—SIMILARITY TO AMERICAN TRIALS.

Leaving the busy Strand at Temple Bar and entering the Law Courts Building, one plunges into that teeming hive where the disputes of millions of British subjects are settled by law. Here the whole kingdom begins and ends its legal battles—except the cases on circuit, those minor matters which go to the County Courts, and the very few which reach the House of Lords.

The visitor, strolling through the lofty Gothic hall and ascending one of the stair-cases to the second floor, finds himself in a long, vaulted corridor, sombre and quiet, which runs around the building. There are no idle crowds and there is no smoking, but, curiously enough, frequent refreshment [2] bars occupy corners, where drink as well as food is dispensed by vivacious bar-maids.[A] Here and there, a uniformed officer guards a curtained door through which may be had a glimpse of a court room; but no sound escapes, because of a second door of glass, also draped with curtains. Groups of litigants and witnesses await their turns or emerge with flushed faces and discuss their recent experiences before returning to the roar of London. Barristers pace up and down in wig and gown, or retire to a window-seat for conference with their respective solicitors.

A mere sight-seer, having thus visited the courts, passes on his way, but as the administration of law, from the Lord Chancellor to the "bobby," is the thing best done in England and commands the admiration and imitation of the world, the courts deserve more than a casual visit.

Passing the officer and the double-curtained doors, one enters the court-room, which is usually small and lofty, with gray stone walls panelled in oak, subdued in color and well lighted from above. The admirable arrangement of seats sloping steeply upward on all sides, instead [3] of resting upon a level floor, brings the heads of speakers and auditors near together; and the bright colors of the judges' robes—scarlet with a blue sash over the shoulder in the case of the Lord Chief Justice, and blue with a scarlet sash in the case of most of the others, together with various modifications of broad yellow cuffs—first strike the eye.

The judge's bewigged head, as he sits behind his desk, is about twelve feet above the floor. On his left, at the same level, stands the witness, who has reached the box by a small stairway. At the judge's right are the jury, seated in a box of either two rows of six or three rows of four, the back row being nearly on a level with the judge. In front of the judge, but so much lower as to oblige him to stand on his chair when whispering to his lordship, sits his "associate," a barrister in wig and gown, whom we should designate as the clerk of the court.

Facing the associate is the "solicitors' well," at the floor level, where, on the front row of benches, sit the solicitors in ordinary street dress. Then come the barristers—all in wig and gown—seated on wooden benches, each row with a narrow desk which forms the back of the seat in front. The desks are supplied with ink wells, [4] and with the inevitable quill pen. The barristers keep their places until their cases are reached and then try them from the same seats, so that there is always a considerable professional audience. For the public there is little accommodation—usually only a few benches back of the barristers and a meagre gallery above.

The solicitor, whose client may be the plaintiff or the defendant, has prepared the case and knows its ins and outs as well as the personal peculiarities of the parties and witnesses who will be called, but he is unable to take any part in the trial and can only whisper an occasional suggestion to the barristers he has retained, by craning his neck backward to the leader behind him. This leader is a newcomer into the case. He is a K. C. (King's Counsel) who has been "retained" by the solicitor upon payment of a guinea followed by a large "agreed fee," and he leaves the "opening of the pleadings" to the junior immediately back of him, while the latter, in turn, has handed over the preparation to his "devil" who is seated behind him.

Thus, the four men engaged on a side, instead of being grouped around a counsel table, as in America, are seated one in front of the other at different levels, rendering a general consultation [5] difficult when questions suddenly arise. The two men on each side of the case who know most about it have no voice in court, for the devil is necessarily as mum as the solicitor, and the name of the former does not even appear in the subsequent report of the trial. How this comes about requires some acquaintance with the different fields of activity of barristers and solicitors, which will be referred to later.

In thus glancing at an English court, an American's attention is sure to be arrested by the wig. The barrister's wig, for his ordinary practice in the High Court, has a mass of white hair standing straight up from the forehead, as a German brushes his; above the ears are three horizontal, stiff curls, and, back of the ears, four more, while behind there are five, finished by the queue which is divided into tails, reaching below the collar of the gown. There are bright, shiny, well-curled wigs; wigs old, musty, tangled and out of curl; some are worn jauntily, producing a smart and sporty effect, others look like extinguishers. So grotesque is the effect that it is difficult to realize that these men are not mummers in some pageant of modern London, but that they are serious participants in grave proceedings.

[6] Not only the eye, but the ear will convey novel and favorable impressions to the observer. He will be struck by the cheerful alacrity and promptness of the witnesses, by the quickness and fulness of their responses, by a certain atmosphere of complete understanding between court, counsel, witnesses and jury, and more than all, by the marked courtesy, combined with an absence of all restraint, and a perfectly colloquial and good-humored interchange of thought. It is hard to define this, but it certainly differs from the air of an American tribunal where the participants seem almost sulky by comparison. The Englishman in his court is evidently in his native element and appears at his best.

The voices, too, are most agreeable, although many barristers acquire the high-pitched, thin tone usually associated with literary and ecclesiastical surroundings. Besides superior modulation, the chief merit is in the admirable distribution of emphasis. In this respect both the dialogue and monologue in an English court room are far less monotonous than in an American.

Passing the superficial impression and coming to the underlying substance, there is extraordinarily little difference between law courts on both sides of the Atlantic. Not only is the common [7] law the same, and the legislation of the two countries largely parallel, but the method of law-thought—the manner of approaching the consideration of questions—is precisely identical, so that, upon the whole, the diversity is no greater than that which may exist between any two of the forty-six states. Indeed, so complete is the similarity that an American lawyer feels that he might step into the barristers' benches and conduct a current case without causing the slightest hitch in the proceedings, provided he could manage the wig and that the difference of accent—not very marked in men of the profession—should not attract too much attention.

That the law emanating from the little Island, which could be tucked away in a corner of some of our States, should have spread over the vast territory of America and control such an enormous population with its many foreign strains, and that, as the decades roll on, it should thrive, improve, and successfully grapple with problems never dreamed of in its origin, indicates its surprising vitality and stimulates interest in the methods now in vogue in its native land.

[A] Very recently these bars have been moved to restaurants on the lower floor.

CLASSES FROM WHICH BARRISTERS AND SOLICITORS ARE DRAWN—THE INNS OF COURT—INNS OF CHANCERY—STUDENTS AT PERIOD OF REVOLUTION—A BARRISTER'S CHAMBERS—TRAINING OF BARRISTERS IN AN INN—BEING CALLED TO THE BAR—TRAINING OF SOLICITORS.

To young Englishmen possessing neither fortune nor influence, the profession of the law has long been an open road to advancement in a country notable for orderly and constitutional methods, where the ultimate appeal is always to reason. Perhaps the worship of money, which characterizes modern England, has somewhat lessened the prestige of success at the Bar there, as it has done in America, where a millionaire, upon urging his son to enter the profession, was met by the young hopeful's reply: "Pooh, father, we can hire lawyers." Nevertheless, the law still draws its recruits from the flower of the youth of both countries and, in England, it appeals to two types of men: to those who would become barristers, [10] and to those whose ambition soars no higher than the solicitor's calling; moreover the classes from which the candidates are generally drawn, differ as do their training and the future functions.

Traditionally, indeed, the sons of gentlemen and the younger sons of peers were restricted, when seeking an occupation, to the Army, the Navy, the Church and the Bar. They never became solicitors, for that branch, like the profession of medicine, was somewhat arbitrarily excluded from possible callings, but this tradition, as is the case with many others, has been gradually losing its force of late years. It must always have been a little hazy in its application, owing to the difficulty of ascertaining accurately the status of the parent, if not a peer; and Sir Thomas Smith who, more than three centuries ago, after describing the various higher titles, attempted a definition of the word "gentleman," could formulate nothing more definite than the following: "As for gentlemen they be made good cheap in this kingdom; for whosoever studieth the laws of the realm, who studieth in the universities, who professeth the liberal sciences, and, to be short, who can live idly and without manual labor, and will bear the port, [11] charge and countenance of a gentleman, he shall be called master and shall be taken for a gentleman." The ancient books, too, afford a glimpse of a struggle on the part of the Bar to demand a certain aristocratic deference, for an old case is reported where the court refused to hear an affidavit because a barrister named in it was not called an "Esquire."

That the struggle was not in vain, is evidenced by the reply of an old-time Lord Chancellor, who, when asked how he made his selection from the ranks of the barristers when obliged to name a new judge, answered: "I always appoint a gentleman and if he knows a little law, so much the better."

Naturally, the solicitor (who was formerly styled an attorney, except when practicing in an equity court) was sensitive about his own position, for the passage of a now-forgotten Act of Parliament was once procured, decreeing that attorneys should thereafter be denominated as "gentlemen."

But times have changed in the law, as in other fields of activity, and sons of good families, as well as those of less degree, now enter both branches of the profession. Hence, representatives of the best names in England are to be [12] found on the barristers' benches side by side with self-made men, some of whom have become ornaments of the Bar, and with men of divers races, such as swarthy East Indians, and Dutch South Africans. One or two barristers may even be found, who, although members of the Bar and necessarily of one of the Inns, nevertheless, remain, as born, American citizens. The Bar, in short, although a jealously close and exclusive organization, has become a less aristocratic body and is now a real republic where brains and character count.

The same diversity of origin exists amongst the solicitors, for, as has been stated, they are now, in part, recruited from those who formerly would have condescended to nothing less than the Bar. A constant improvement in training, too, in the promulgation of rules of professional conduct, in the enforcement of a firm discipline and in the nursing of traditions, all tend to raise and maintain a higher standard and a better tone than formerly existed in the ranks of the solicitors. Thus, the modern tendency is that there should be less difference in the personnel of those entering either branch of the profession.

Candidates for the Bar are mostly University men, more mature in years, perhaps, than our [13] graduates—for boys commence and end their college courses late in England—and they are, as a rule, more broadly cultivated than those who intend to become solicitors. Some, indeed, take a full course of theoretical law at Oxford or Cambridge before beginning practical training as a student in one of the Inns of Court, which are peculiarly British institutions, having no counterpart elsewhere.

Physically, an Inn of Court is not a single edifice, nor even an enclosure. It is rather an ill-defined district in which graceful but dingy buildings of diverse pattern and of various degrees of antiquity, are closely grouped together and through which wind crooked lanes, mostly closed to traffic, but available for pedestrians. Unexpected open squares, refreshed by fountains, delight the eye, the whole affording the most peaceful quietude, despite the nearness of the roar of surrounding London. The four Inns of Court (as distinguished from the Inns of Chancery and Serjeants' Inn, all of which have ceased to exist) are, the Middle Temple, the Inner Temple, Lincoln's Inn and Gray's Inn, but the last is of minor importance in these modern days, having fallen out of fashion.

The Middle Temple and the Inner Temple [14] acquired, by lease in the XIV Century, and by actual purchase in 1609, the lands of the Knights Templar, consisting of many broad acres situated on the south side of the Strand and Fleet Street, opposite the present Law Courts Building, and the whole space is now occupied by an intricate mass of structures—the great Halls, the Libraries, the quaint barristers' chambers—and by the beautiful Temple Gardens, sloping to the Thames, adorned with bright flowers and shaded by fine trees. There is no line of demarcation between the two Temples—one simply melts into the other. They own in common the Temple Church, part of which dates from 1185, with its recumbent black marble figures of Knights in full armor and, in the churchyard, its tomb of Oliver Goldsmith.

The wonderful Hall of the Middle Temple, where the benchers, barristers and students still eat their stated dinners, was built about 1572, and is celebrated for its interior, especially for the open-work ceiling of ancient oak. Shakespeare's comedy, Twelfth Night, was performed in the Hall in 1601, and it is believed that one of the actors was the author himself. The Library is a great one, but an American [15] lawyer may be surprised at the incompleteness of the collection of American authorities. The Hall of the Inner Temple, on the other hand, is quite modern, although most imposing and in the best of taste.

Lincoln's Inn became possessed about 1312 of what was once the country-seat of the Earl of Lincoln, which, running along Chancery Lane, adjoins the modern Law Courts Building on the north and consists of two large, open squares surrounded by rows of ancient dwellings, long since converted into barristers' chambers, and shady walks leading to a fine Hall of no great antiquity, however. An old gateway, with the arms of the Lincolns and a date, A. D. 1518, is considered a good example of red brick-work of a Gothic type—probably the only one left in London. The Library, which has been growing for over four hundred years, contains the most complete collection of books upon law and kindred subjects in England, numbering upward of 40,000 volumes.

These three Inns of Court are the active institutions; the fourth, Gray's Inn, which probably took its name from the Greys of Wilton who formerly owned its site, has long since ceased to be of much importance, although the [16] old Hall and the classic architecture of some of the Chambers, still attracts the eye. It happens, however, that a Philadelphia student, who attended this ancient Inn nearly two hundred years ago, was responsible for the phrase still proverbial on both sides of the Atlantic, "that's a case for a Philadelphia lawyer." The unpopular Royal judges of the Province of New York had, in 1734, indicted a newspaper publisher for libel in criticising the court and they threatened to disbar any lawyer of the Province who might venture to defend him. But, from the then distant little town on the Delaware, the former student of Gray's Inn, although an old man at the time, journeyed to Albany and, by his skill and vehemence, actually procured a verdict of acquittal from the jury under the very noses of the obnoxious court; the fame of which achievement spread throughout not only the Colonies but the mother-country itself.

Names great in the law, in literature, in statecraft and in war are linked with each of these venerable establishments, to record which would mean to review much of the history of England as well as of America; for, besides the early Colonial students, a large number were entered in the different Inns during the period immediately [17] preceding the Revolution. Of these, South Carolina sent forty-seven, Virginia twenty-one, Maryland sixteen, Pennsylvania eleven, New York five and New England two. The names of many of them are later to be found amongst the leaders of the Bar of the new country, on the bench as Chief Justices and even as signers of the Declaration of Independence.

The Halls of the Inns were once the scenes of masques and revels, triumphs and other mad orgies, in which the benchers, barristers and students took part; including, as mentioned, the production of Shakespeare's plays during his lifetime.

In these halls also occur the stated dinners—to which, in the Temple, at least, the porter's horn still summons. The members and students of the Inn, arrayed in gowns, attend in procession and, entering the hall, seat themselves on long benches before oaken tables; the governing body—the benchers—being placed at one end where the floor is elevated. It is pleasant to record that, during the last year or two, the daily contact of the barrister with his Inn has been increased by the innovation of a luncheon which is served in the hall at the hour when the courts take a recess. On this occasion the most [18] noted English advocates may be seen, strolling in without removing their silk hats, sometimes without even having dispensed with wig and gown, when, seating themselves on the uncompromising oak, they call for a chop and beer and relax into jolly sociability.

At one time barristers actually lived in the Inns of Court, but this practically ceased about the time of the reign of Elizabeth. All of them now have their "chambers" in the obsolete little dwelling houses, facing upon the open squares or narrow lanes of the Inns, which are merely offices, but very unlike those of an American lawyer in one of our "skyscrapers."

Entering the front door by a low step, or climbing two or three flights of a rickety staircase in one of these houses, the visitor finds a door on which, or on a tin sign, are painted the names of one or more gentlemen, without stating their occupations, which would be superfluous in this small world of barristers. A summons by means of the old iron knocker, discloses the barrister's clerk, whose habitat is an outer room, and whose business it is to receive visitors—perchance the clerks of solicitors with briefs and fees.

Ushered into the barrister's sanctum, one finds [19] a meagrely furnished room, the walls masked with rows of books, the table, chairs and window-sills littered with papers. Amidst all this, a modern telephone looks quite out of place, and the American tries to avoid detection when his eye unconsciously steals to a wig hanging on a hook back of the barrister's chair and to a round tin box, lying on the floor, which is for the transportation of the tonsorial armor when its owner travels on circuit. The otherwise uninviting aspect of the place is redeemed, however, by a cheerful fire blazing on the hearth and by a restful outlook upon a shady garden, and a splashing fountain, where the sparrows sip the water and take their dainty baths. Here the barrister remains when not in court; but when the day's work is done, if he be prosperous, his motor car whisks him to the more elegant surroundings of a home in the West End, or, perhaps a humble bus and suburban train carry him far from town.

The Inns of Court began their existence about 1400, nearly cotemporaneously with the Trade Guilds, and both, doubtless, took their rise from the instinct of men engaged in a common occupation to combine for mutual protection. All lawyers were once men in holy orders and the [20] judges were bishops, abbots and other Church dignitaries, but in the XIII Century the clergy were forbidden to act in the courts and, thereupon, the students of the law gathered together and formed the Inns. Much concerning their origin is obscure, but the nucleus of each was doubtless the gravitation of scholars to some ancient hostelry, there to profit by the teachings of a master lawyer of the day—just as the modern London club had its beginning in the convivialities of a casual coffee house. In time these loose aggregations developed into strong and elaborate organizations which acquired extensive real property, now of enormous value, and have long wielded a powerful influence.

In order to enjoy the quiet of what was then the country, and yet to retain the advantage of the city's protection at a time when rural localities were far from safe, the Inns were mostly located close to the west wall of the City, although the Inner Temple, as its name implies, is just within the line of that vanished wall, and thus they were convenient to Westminster, where the courts were permanently located by a provision of Magna Charta. During the present generation, however, the principal courts (except the House of Lords and the Judicial Committee [21] of the Privy Council) have returned to a situation actually contiguous to the old Inns, whilst the vast town, during the centuries, has not only engulfed Westminster but has spread miles beyond it. Thus, all the Inns were grouped in a section, perhaps a square mile in extent, bounded on the east by Chancery Lane, which roughly follows the old City wall and between the Thames on the south, and the district called Holborn on the north.

Looking now to the functions of these ancient institutions, an Inn of Court may be defined as an unincorporated society of barristers, which, originating about the end of the XIII Century, possesses by immemorial custom the exclusive privilege of calling candidates to the Bar, and of disciplining, or when necessary, of disbarring barristers.

The governing body is composed of the benchers, who are either Judges or King's Counsel and prominent junior barristers, but it is usual to invite a member to join the benchers of his Inn when, and only when, a vacancy occurs. The executive officer is the treasurer, who is selected annually, and the members consist of the barristers and students.

All the Inns are alike in authority, and in [22] the privileges which they enjoy and the regulations of each, governing the admission, education and examination of students and the calling to the Bar of those who are qualified, are precisely uniform; any differences which may have existed having been abolished by the adoption in 1875 of a code of rules known as the "Consolidated Regulations." While there is thus complete equality and no official precedence, yet each Inn has its own history, traditions and ancient customs. The choice of which Inn to enter, thus becomes a matter of individual preference, depending upon sentiment, or upon family or social surroundings.

The former Inns of Chancery should also be mentioned before leaving the subject, although they have no present interest for the modern lawyer. Their origin, too, is buried in obscurity, but they arose about the same time as the Inns of Court, with one of which each was connected, and were at first places of preparatory training for young students later to be admitted to the particular Inn. These youthful apprentices, however, were gradually ousted by the attorneys and solicitors—who have always been excluded from the Inns of Court—whereupon the Inns of Chancery fell out of fashion and deteriorated, [23] so that by the middle of the Eighteenth Century they had disappeared and their names are now mere memories. During the period of activity of the Inns of Chancery, Staple Inn (perhaps the best known) and Barnard's Inn, were attached to Gray's Inn; Clifford's Inn, Clement's Inn and Lyon's Inn were intimately related to the Inner Temple; Furnival's Inn and Thavie's Inn to Lincoln's Inn; the New Inn and Strand Inn to the Middle Temple. One block only of quaint Elizabethan buildings, with gables of cross timber and plaster, still overhangs the great thoroughfare of Holborn and marks what is left of Staple Inn.

Likewise Serjeants' Inn vanished in 1876, when its valuable realty was sold—for Serjeants-at-law had long ceased to be created—and the proceeds were divided amongst the few survivors; a proceeding much criticized at the time, although one of them gave his share to charity. The serjeants-at-law were once a class of barristers who had in some manner acquired the exclusive right of audience in the Court of Common Pleas and had also secured a monopoly of the then profitable art of pleading. Upon attaining this degree, a serjeant severed his relations with his Inn of Court and attached himself [24] to the Serjeants' Inn. After having occupied several sites since the Sixteenth Century, Serjeants' Inn was finally located on Chancery Lane, and to it belonged all of the Serjeants, and all of the judges of the Common Law Courts, for they, necessarily, had been serjeants before being elevated to the bench. The buildings, which are small and have no pretensions to architectural beauty, have for many years been occupied as offices, chiefly those of solicitors.

Thus, of the many Inns of Chancery, of the Serjeants' Inn (and the once powerful societies which they housed), there remain none but the four great Inns of Court, through one of which must pass every barrister called to the English Bar.

This brief sketch may convey some idea of the extent to which the young law student unconsciously absorbs tradition, and is moulded, when plastic, by the pressure of centuries of custom and etiquette. Whatever may have been his forebears, he is more than likely, when turned out as a full-fledged barrister, to answer pretty nearly to the old definition, for he has, indeed, been one "who studieth the laws of the realm" and he is apt to "bear the port, charge and countenance of a gentleman."

[25] To the embryo barrister, however, the existing Inns possess interests far livelier than those referred to, for he must enter one of them, and not only thus gain access to the Bar, but must ally himself to his choice unless he elects, by going through certain formalities, to emigrate to another Inn. Formerly he had only to attend a single function—a dinner—during each term and, having "eaten twelve dinners," he, ipso facto, became entitled to be called to the Bar, no matter how inadequate might be his knowledge of the law. In these less aristocratic and more prosaic days, however, he is obliged diligently to apply himself to study, and to pass, from time to time, regular and strict examinations, prescribed by the Council of Legal Education, so that his equipment is no longer left to chance, but is really measured with cold accuracy. The term of study is not less than three years, and twelve terms, four in each year, must be "kept" at the Inn, the evidence of which is still the fact of dining in the hall six days during each term, although members of the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge need dine but three days in each term.

An English student's reading is much like that pursued in one of our own law schools, the [26] chief difference being that he devotes more time to mastering general principles than to the consideration of reported cases from which our students are presumed to extract the underlying principle. Much has been said in favor of each method, and the true course probably lies between the extremes, but the average result of an English law training, superimposed upon a generally superior prior education, is perhaps somewhat better than the average American result, while, as to the few on both sides of the water destined to attain real eminence, no superiority could fairly be claimed by either.

The total fees payable by a student amount to about £140. and women, be it observed by progressive ladies, are not eligible for the Bar in England.

Having passed the necessary examinations, the young barrister is finally "called to the Bar," a ceremony which takes place in the Hall of his Inn, at the close of dinner on "Grand Day," which is the day appointed for a banquet, to which a score or more of distinguished guests are invited by the "Treasurer and the Masters of the Bench." The Students, wearing gowns over evening dress, are grouped together, below the dais on which the benchers' table stands. The [27] Steward of the Inn calls out the names in order of seniority. Each Student, as his name is called, advances to the high table and halts there, facing the Treasurer, who, standing up, says to him: "Mr. ——, by the authority and on behalf of the Masters of the Bench, I publish you a barrister of this Honorable Society." Then the Treasurer shakes hands with the new barrister and the latter walks away to join his comrades.

Solicitors are created by entirely different methods, as there are no Inns nor any similar organizations for students. There is a preliminary examination to determine whether the boy who desires to become a solicitor, has sufficient general education. If so, he is apprenticed, for a period of five years, to some practitioner, for which privilege he pays a sum of money, say from 100 to 400 guineas; the amount chiefly depending upon the solicitor's standing. There are official fees, too, amounting to about £130, so that, as he receives no compensation during his five years' apprenticeship, and meantime must be supported by his people, the cost of entering the solicitor's calling is not inconsiderable. He begins by copying papers and performing minor [28] services in the public offices and, at the same time, pursues his legal studies, which have steadily become more arduous. His progress as a law student is ascertained by an intermediate examination, held under the direction of the Solicitors' Incorporated Law Society, and a final one determines whether he has acquired sufficient knowledge of the law to be admitted to practice. If shown to be qualified, he is admitted by the courts, and is thereafter subject to the discipline of the Society and to that of the courts themselves, usually prompted by the Society. The marked difference, therefore, that distinguishes the solicitor's training from that of the barrister, is the absence of any Inn of Court—with its esprit de corps—as a commanding influence in shaping his development and governing his whole career. Nevertheless, while the whole body of solicitors is, perhaps, not as liberally educated nor as polished as the Bar, the higher grade of solicitors are lawyers quite as well equipped, and gentlemen equally accomplished, as members of the Bar itself.

Some glimpses of the separate roads which the barrister and the solicitor travel after their student days, will be reserved for later chapters.

WAITING FOR SOLICITORS AS CLIENTS—"DEVILLING"—JUNIORS—CONDUCT OF A TRIAL—"TAKING SILK"—BECOMING A K. C.—ACTIVE PRACTICE—THE SMALL NUMBER OF BARRISTERS.

Having been called to the Bar, the question first confronting the young barrister is whether he really intends to practice. He may have read law as an education, meaning to devote himself to literature, to politics or to some other pursuit, or he may have embraced the profession in deference to the wishes of his family and to fill in the time while awaiting the inheritance of property. Supposing him, however, to be one of the minority determined to rise in the profession, he is confronted with formidable obstacles, for he can not look to his friends to furnish him with briefs. He can never be consulted nor retained by the litigants themselves. The only clients he can ever have are solicitors, whose clients, in turn, are the public. He never goes beyond his [30] dingy chambers in the Inns of Court, where, guarded by his clerk, he either wearily waits for solicitors with briefs and fees, or, more likely still, gives it up and goes fishing, shooting or hunting. And this furnishes the market for the alluring placards one sees at the old wig-makers' shops in the Inns of Court: "Name up and letters forwarded for £5 per annum."

The early ambition of the young barrister is to become a "devil" to some junior barrister, who always has recourse to such an understudy, and, if the junior is making over £1,000 a year, he continuously employs the same devil. This term is not applied in a jocular sense, but is the regular and serious appellation of a young barrister who, in wig and gown, thus serves without compensation and without fame—for his name never appears—often for from five to seven years. The devil studies the case, sees the witnesses, looks up the law and generally masters all the details, in order to supply the junior with ammunition.

Before the trial the junior has one or more "conferences" with the solicitor, all paid for at so many guineas; occasionally he even sees the party he is to represent, and, more rarely, an important witness or two. The devil is sometimes [31] present, although his existence is, as a rule, decorously concealed from the solicitor.

If the solicitor, or the litigating party, grows nervous, or hears that the other side has employed more distinguished counsel, the solicitor retains a K. C. as leader. Then a "consultation" ensues at the leader's chambers between the leader, junior, solicitor, and, occasionally, the devil.

At the trial, the junior merely "opens the pleadings" by stating in the fewest possible words, what the action is about—that it is, perhaps, a suit for breach of promise of marriage between Smith and Jones, or to recover upon an insurance policy for a loss by fire—and then resumes his seat, whereupon the leader—the great K. C.—really opens the case, at considerable length and with much more detail and argument than would be good form in an American court. He states his side's contention with particularity, reads documents and correspondence (none of which have to be proved unless their authenticity is disputed—points which the solicitors have long ago threshed out) and he even indicates the position of the other side, while, at the same time, arguing its fallacy. Having done this, he leaves it to the junior to call the witnesses—more often [32] he departs from the court room to begin another case elsewhere, and returns only to cross-examine an important witness on the other side, or to make the closing speech to the jury. In this way a busy leader may have several trials going on at once. The junior then proceeds to examine the witnesses with the help of an occasional whispered suggestion from the solicitor, who is more than ever isolated by the departure of the leader, and the devil is proud when the junior audibly refers to him for some detail.

If the leader is absent, which frequently happens notwithstanding his fee has been paid, inasmuch as no case is deferred by reason of counsel's absence, the junior takes his place, while the solicitor grumbles and more devolves upon the devil.

Occasionally, indeed, both leader and junior may be elsewhere and then is the glorious opportunity of the poor devil, who hungers for such an accident, for he may open, examine, and cross-examine, and, if neither his junior nor his august leader appear, he may even close to the jury. The solicitor will be white with rage and chagrin, wondering how he shall explain to the litigant the absence of the counsel whose fees he has paid, but the devil may win and so [33] please the solicitor that the next time he may himself be briefed as junior. This is one of the things he has read of in the Lives of the Lord Chancellors.

The devil is in no sense an employee or personal associate of the junior—which might look like partnership, a thing too abhorrent to be permitted. On the contrary, he often has his own chambers and may, at any time, be himself retained as a junior, in which event his business takes precedence of his duties as a devil, and he then describes himself as being "on his own."

Having gained some identity, and more or less business "on his own" from the solicitors, a devil gradually begins to shine as a junior, whereupon appears his own satellite in the person of a younger man as devil, while the junior becomes more and more absorbed in the engrossing but ever fascinating activities of regular practice at the Bar.

Reaching a certain degree of prominence, a junior at the common-law Bar may next "take silk;" that is, become a K. C., or King's Counsel, which has its counterpart at the Chancery Bar, as will be explained later when dealing with the division between the law [34] and equity sides of the system. Whether a barrister shall "apply" for silk is optional with himself and the distinction is granted by the Lord Chancellor, at his discretion, to a limited, but not numerically defined, number of distinguished barristers. The phrase is derived from the fact that the K. C.'s gown is made of silk instead of "stuff," or cotton. It has also a broad collar, whereas the stuff gown is suspended from shoulder to shoulder.

Whether or not to "take silk," or to become a "leader," is a critical question in the career of any successful common law or chancery barrister. As a junior, he has acquired a paying practice, as his fee is always two-thirds that of the leader. He has also a comfortable chamber practice in giving opinions, drawing pleadings and the like, but all this must be abandoned—because the etiquette of the Bar does not permit a K. C. or leader to do a junior's work—and he must thereafter hazard the fitful fancy of the solicitors when selecting counsel in important causes. Some have taken silk to their sorrow, and many strong men remain juniors all their lives, trying cases with K. C.'s much younger than themselves as their leaders.

They tell this story in London: A certain [35] Scotch law reporter (recently dead), noted for his shrewdness and good judgment, having been consulted by a barrister whether to "apply for silk," advised him in the negative, but declined to go into particulars. The barrister renewed his inquiry more than once, finally demanding the Scot's reason for his advice. The latter reluctantly explained that the barrister had a good living practice which he would be foolish to give up. Being further pressed, he finally said: "In many years' observation of the Bar I have learned that success is only possible with one or more of three qualifications, that is, a commanding person, a fine voice, or great ability, and I rate their importance in the order named. Now, with your wretched physique, penny-trumpet voice, and mediocre capacity, I think you would surely starve to death." The barrister did not "apply," but never spoke to the Scotchman again.

The anecdote illustrates the crucial nature of the step when taken by any barrister, and even if taken with success, yet there are waves of popularity affecting a leader's vogue. Solicitors get vague notions that the sun of a given K. C. is rising or setting—that the judges are looking at him more kindly or less so, therefore K. C.'s and leaders who were once overwhelmed with business, [36] may sometimes be seen on the front row with few briefs.

A successful K. C. leads a strenuous life, as may well be appreciated if he be so good as to take his American friend about with him in his daily work, seating him with the barristers while he is actually engaged. One very eminent K. C., who is also in Parliament, rises in term time at 4 a.m., and reads his briefs for the day's work until 9, when he breakfasts and drives to chambers. Slipping on wig and gown at chambers and crossing the Strand, or arraying himself in the robing room of the Law Courts, he enters court at 10:30, and takes part in the trial or argument of various cases until 4 o'clock, often having two or three in progress at once, which require him to step from court to court, to open, cross-examine, or close, having relied upon the juniors and solicitors to keep each case going and tell him the situation when he enters to take a hand. From 4 to 6:30 he has consultations at his chambers, at intervals of fifteen minutes, after which he drives to the House of Commons, where he sits until 8:30, when it is time for dinner. If there is an important debate, he returns to the House, but tries to retire at midnight for four hours' sleep. Naturally the Long Vacation alone makes such a life possible for even the strongest man.

Crossing the Strand from Temple to Court

Crossing the Strand from Temple to Court

His success, however, means much, for there lie before him great pecuniary rewards, fame, perhaps a judgeship, or possibly an attorney-generalship, both of which, unlike their prototypes in America, mean very high compensation, to say nothing of the honor and the title which usually accompany such offices.

The English Bar is small and the business very concentrated, but no statistics are available, for many are called who never practice. By considering the estimates of well-informed judges, barristers and solicitors, it seems that the legal business of the Kingdom is handled by so small a number as from 500 to 800 barristers, although the roll of living men who have been called to the Bar now includes 9,970 names.

We have no Bar with which to institute a comparison, for each county of every State has its own and all members of county Bars, practicing in the appellate court of a State, constitute the Bar of that State, which is a complete entity. Great commercial centres have larger ones and have more business than rural localities, but no Bar in America is national like that of London.

It would be interesting, if it were possible, to compare the proportion of the population of [38] England, which pursues the law as a vocation, with that of the United States, but no figures exist for the purpose. The number of barristers includes, as already stated, those who do not practice, while an enumeration of the solicitors' offices would exclude individual solicitors employed by others, as will be explained hereafter. The aggregate of these two uncertain elements, however, would be about 27,000. The legal directories give the names of something like 95,000 lawyers in America of whom about 27,000 appear in fifteen large cities—New York, for example, being credited with over 10,000, Chicago with over 3,500 and San Francisco with about 1,500—leaving about 69,000 in the smaller towns and scattered throughout the land. These tentative, and necessarily vague, suggestions rather indicate that the proportion of lawyers may not be very unequal in the two countries.

BAR DIVIDED INTO TWO PARTS—NO DISTINCTION BETWEEN CRIMINAL AND CIVIL PRACTICE—LEADERS—"TAKING HIS SEAT" IN A PARTICULAR COURT—"GOING SPECIAL"—LIST OF SPECIALS AND LEADERS—SIGNIFICANCE OF GOWNS AND "WEEPERS"—"BANDS"—"COURT COATS"—WIGS IN THE HOUSE OF LORDS—BARRISTERS' BAGS, BLUE AND RED.

The Bar is divided into two separate parts—the Common Law Bar and the Chancery Bar; for a barrister does not try cases of both kinds as in America. The solicitor knows whether he has a law or equity case in hand, and takes it to the appropriate barrister. Common law barristers have their chambers chiefly in the Middle Temple and Inner Temple; chancery men, largely in Lincoln's Inn, and the two kinds of barristers know little of, and seem even to have a kind of contempt for, each other. Thus a common law barrister passes his life in jury trials and appeals; [40] whereas a chancery man knows nothing but courts of equity, unless he follows a will case into a jury trial as a colleague of a common law man to determine an issue of devisavit vel non. And there are further specializations—although the divisions are not so marked—into probate, divorce or admiralty men. Besides, there is what is known as the Parliamentary Bar, practicing entirely before Parliamentary committees, boards and commissions. It is, however, curious that in England no apparent distinction exists between civil and criminal practice and common law barristers accept both kinds of briefs indiscriminately.

At the Chancery Bar there is a peculiar subdivision which has already been mentioned. Having reached a certain degree of success and become a K. C., a barrister may "take his seat" in a particular court as a "leader" by notifying the Judge and informing the other K. C.'s who are already practising there. Thereafter he can never go into another, except as a "special," a term which will be explained presently. For three pence, at any law stationer's, one can buy a list of the leaders in the six chancery courts, varying in number from three to five and aggregating twenty-five, and if a solicitor wishes a [41] leader for his junior in any of these courts he must retain one out of the limited list available or pay the "special" fee. Hence, these gentlemen sit like boys in school at their desks and try the cases in which they have been retained as they are reached in rotation.

But even for a leader at the Chancery Bar, one more step is possible, a step which a barrister may take, or not, as he pleases, and that is: he may go "special." This means that he surrenders his position as a leader in a particular court and is open to accept retainers in any chancery court; but his retainer, in addition to the regular brief fee, must be at least fifty guineas or multiples of that sum, and his subsequent fees in like proportion. The printed list also shows the names of these "specials," at present only five in number. The list of leaders and specials in 1910 reads as follows: [42]

Usually Practicing in the Chancery Division

of the High Court of Justice.

Mr. Levett: Mr. Astbury: Mr. Upjohn: Mr. Buckmaster.

| Mr. Justice Joyce Lord Chancellor's Court |

Date of Ap'ointment | Mr. Justice Warrington Chancery Court 2 |

Date of Ap'ointment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mr. T. R. Hughes | 1898 | Mr. Henry Terrell | 1897 |

| Mr. R. F. Norton | 1900 | Mr. T. H. Carson | 1901 |

| Mr. R. Younger | 1900 | Mr. George Cave | 1904 |

| Mr. A. C. Clauson | 1910 | ||

| Mr. Justice Eve | Date of Ap'ointment | Mr. Justice Swinfen Eady Chancery Court 1 |

Date of Ap'ointment |

| Mr. P. O. Lawrence | 1896 | Mr. W. D. Rawlins | 1896 |

| Mr. Ingpen | 1900 | Mr. E. C. Macnaghten | 1897 |

| Mr. Dudley Stewart-Smith | 1902 | Mr. N. Micklem | 1900 |

| Mr. A. H. Jessel | 1906 | Mr. Frank Russell | 1908 |

| Mr. E. Clayton | 1909 | ||

| Mr. Justice Melville | Date of Ap'ointment | Mr. Justice Parker Chancery Court 4 |

[43] Date of Ap'ointment |

| Mr. Bramwell Davis | 1895 | Mr. W. F. Hamilton | 1900 |

| Mr. J. G. Butcher | 1897 | Mr. M. L. Romer | 1906 |

| Mr. C. E. E. Jenkins | 1897 | Mr. E. W. Martelli | 1908 |

| Mr. A. F. Peterson | 1906 | Mr. A. Grant | 1908 |

| Mr. F. Casse | 1906 | Mr. J. Gatey | 1910 |

[44] The dress of barristers is the same for the Common Law Bar as for the Chancery Bar, but the details of both gown and wig signify to the initiated much as to the professional position of the wearer. The difference between the junior's stuff gown and the leader's silk one has already been referred to, but it is not true that a barrister having "taken silk," that is, having become a K. C. or a leader, always wears a silk gown, for, if he be in mourning, he again wears a cotton gown, as he did in his junior days, but, to preserve his distinction, he wears "weepers"—a six-inch deep, white lawn cuff, the name and utility of which originated before handkerchiefs were invented. Moreover, when in mourning his "bands"—the untied white lawn cravat, hanging straight down, which all barristers wear—have three lines of stitching instead of two. Under his gown, a K. C. wears a "court coat," cut not unlike an ordinary morning coat, though with hooks and eyes instead of buttons, while the junior wears the conventional frock coat. On a hot day, a junior wearing a seersucker jacket and carelessly allowing his gown to disclose it, may receive an admonition from the court, whispered in his ear by an officer.

Wigs, which were introduced in the courts in [45] 1670, and have long survived their disappearance in private life, were formerly made of human hair which became heavy and unsanitary with repeated greasing. They required frequent curling and dusting with powder which had a tendency to settle on the gown and clothing. About 1822, a wig-maker, who may be regarded as a benefactor of the profession, invented the modern article, composed of horse hair, in the proportion of five white strands to one black; this is so made as to retain its curl without grease, and with but infrequent recurling, and it requires no powder.

The wig worn by the barrister in his daily practice has already been described, but, when arguing a case in the House of Lords he has recourse to an extraordinary head-dress, which is precisely the shape of a half-bushel basket with the front cut away to afford him light and air. This, hanging below the shoulders, has an advantage over the Lord Chancellor's wig in being more roomy, so that the barrister's hand can steal inside of it if he have occasion to scratch his head at a knotty problem, whereas his Lordship, in executing the same manoeuvre, inevitably sets his awry and thereby adds to its ludicrous effect.

To the unaccustomed eye, the wig, at first, is [46] a complete disguise. Individuality is lost in the overpowering absurdity and similarity of the heads. Then, too, there is an involuntary association of gray hair with years, making the Bar seem composed exclusively of old gentlemen of identical pattern. The observer is somewhat in the position of the Indian chiefs, who, having been taken to a number of eastern cities in order to be impressed with the white man's power, recognized no difference between them—although they could have detected, in the deepest forest, traces of the passage of a single human being—and reported upon returning to their tribes that there was only one town, Washington, and that they were merely trundled around in sleeping cars and repeatedly brought back to the same place.

By degrees, however, differences between individuals emerge from this first impression. Blond hair above a sunburned neck, peeping between the tails of a queue, suggests the trout stream and cricket field; or an ample cheek, not quite masked by the bushel-basket-shaped wig, together with a rotundity hardly concealed by the folds of a gown, remind one that port still passes repeatedly around English tables after dinner. But it must be said that, while the wig may add [47] to the uniformity and perhaps to the dignity—despite a certain grotesqueness—of a court room, yet it largely extinguishes individuality and obliterates to some extent personal appearance as a factor in estimating a man; and this is a factor of no small importance, for every one, in describing another, begins with his appearance—a man's presence, pose, features and dress all go to produce prepossessions which are subject to revision upon further acquaintance. One thing is certain, the wig is an anachronism which will never be imported into America. For the Bar to adopt the gown (as has been largely done by the Bench throughout the country) would be quite another matter and it seems to work well in Canada. This would have the advantage of distinguishing counsel from the crowd in a court room, of covering over inappropriateness of dress and it might promote the impressiveness of the tribunal.

The bag of an English barrister is also an important part of his outfit. It is very large, capable of holding his wig and gown, as well as his briefs, and suggests a clothes bag. It is not carried by the barrister himself, but it is borne by his clerk. Its color has a deep significance. Every young barrister starts with a blue bag and [48] can only acquire a red one under certain conditions. As devil, and as junior, it is not considered infra dig. to carry his own bag and he has ever before him the possibility of possessing a red bag. At last he succeeds in impressing a venerable K. C. by his industry and skill in some case, whereupon one morning the clerk of the K. C. appears at the junior's chambers bearing a red bag with his initials embroidered upon it—a gift from the great K. C. Thereafter he can use that coveted color and he may be pardoned for having his clerk follow him closely for awhile so there may be no mistake as to the ownership. Custom requires him to tip the K. C.'s clerk with a guinea and further exacts that the clerk shall pay for the bag, which costs nine shillings and sixpence, thus, by this curious piece of economy, the clerk nets the sum of eleven shillings and sixpence and the K. C. is at no expense.

LINE WHICH SEPARATES THEM FROM THE BAR—SOLICITOR A BUSINESS MAN—FAMILY SOLICITORS—GREAT CITY FIRMS OF SOLICITORS—THE NUMBER OF SOLICITORS IN ENGLAND AND WALES—TENDENCY TOWARD ABOLISHING THE DISTINCTION BETWEEN BARRISTER AND SOLICITOR—SOLICITORS WEAR NO DISTINCTIVE DRESS EXCEPT IN COUNTY COURTS—SOLICITORS' BAGS.

The line which separates solicitors from the Bar—the barristers—is difficult for an American to fully appreciate, for in our country it does not exist. The solicitor, or attorney, is a man of law business—not an advocate. A person contemplating litigation must first go to a solicitor, who guides his conduct by advice in the preliminary stages, or occasionally retains a barrister to give a written opinion upon a concrete question of law. The solicitor conducts all the negotiations or threats which usually precede a lawsuit and if compromise is impossible he brings a suit and retains [50] a junior barrister by handing him a brief, which consists of a written narrative of the controversy, with copies of all papers and correspondence—in short, the facts of the case—and which states on its back the amount of the barrister's fee. The brief is engrossed or type-written on large-sized paper with very broad margins for notes, and is folded only once and lengthwise so as to make a packet fifteen by four inches.

All Englishmen of substance, and all firms and corporations, have their regular solicitors and the relation is frequently handed down from generation to generation. It is, of course, unusual except in large corporations to have a permanent barrister, because the solicitor selects one from time to time, as the occasion requires, and the client is rarely even consulted in the choice. When an Englishman speaks of his lawyer, he always means his solicitor and if he wishes to impress his auditor with the seriousness of his legal troubles, he adds that his lawyer has been obliged to take the advice of counsel—perhaps of a K. C.

Hence, the solicitor, unlike the barrister, is not ambitious for fame, nor does he worry because he can not become the Attorney-General or a judge; his mind is intent upon the pounds, shillings and pence of his calling. He may seek [51] business, which the barrister can not do, and he is something of a banker, often a promoter. Some solicitors, especially those practicing at Liverpool, are admiralty men, others are adepts in the organization of corporations and in litigation arising concerning them and there are many other specialties. Some are men of the highest grade—particularly those employed by big companies or by families with large estates.

The venerable family solicitor of the novel and stage—that custodian of private estates and secrets who appears in all domestic crises, warning the wayward son, comforting the daughter whose affections are misplaced and succoring the gambling father, is sufficiently familiar. The worldly experience, which this kindly old gentleman brings from his musty office, is invaluable to his clients.

The large City firms of solicitors, on the other hand, occupy spacious suites of offices and maintain elaborate organizations like modern banks, with scores of clerks distributed in many departments, whose duties are so specialized that no one of them has much grasp of the business as a whole. The name of such a firm, appearing as sponsor for an extensive financial project, carries weight in the business world and its heads [52] enjoy generous incomes, besides being men of much importance upon whom the honor of knighthood is sometimes conferred.

In all England and Wales only about 17,000 solicitors took out annual certificates last year. This indicates the number of offices and does not include clerks (many of whom have been admitted to practice as solicitors), nor those who, for one reason or another, do not practice. Instead of being concentrated, like the barristers, in the Inns of Court in London, solicitors are scattered all over the town and throughout the Kingdom itself. Some, especially in the minor towns or poorer quarters of London, are in a small way of business and must earn rather a precarious living. Others are of a still lower class and seek business of a more or less disreputable character by devious methods, but all are supposed to have been carefully educated in the law and are answerable to their Society and to the courts for questionable practices.

The division of the profession between the solicitors and the Bar is no doubt a survival in modern, or socialistic, England of aristocratic conditions which it is the tendency of the times to weaken, if not eventually to abolish. It is somewhat hard upon the solicitor of real ability [53] to be confined to a limited field and to feel that, no matter how great his powers and acquirements, it is impossible to rise to the best position in his profession without abandoning his branch and beginning all over again in the barrister's ranks.

In associating with solicitors, one can not fail to be struck by their attitude towards barristers, as a class, which is hardly flattering to the latter; they frequently allude somewhat lightly to them as though they were useless ornaments and as if such a division of the profession were rather unnecessary. Upon asking whether the distinction exists in America, they receive the information that it does not with evident approval.

The advantages, however, of the separation of the functions of the solicitor from those of the barrister are distinctly felt in the superior skill, as trial lawyers, developed by the restriction of court practice to the limited membership of the Bar, which would hardly exist if the practice were distributed over the whole field of both branches of the profession. Then, too, the small number of persons composing the Bar enables greater control by the benchers over their professional conduct, and helps to maintain a high standard of ethics and the feeling of esprit de corps. Moreover, the Bar is not distracted from [54] the science, by contact with the business, of the law and it is saved from the contaminating effect of participation in the sordid details of litigation. At the same time, this very condition may be calculated to develop in the average barrister, as distinguished from one of real ability, an attitude approaching dilettanteism.

If the division of the profession ever ceases to exist, the change will no doubt come about by the gradual encroachment of the solicitors' branch upon the Bar. Already solicitors possess the right of audience in the county courts, the limit of whose jurisdiction is constantly being increased, with the result of developing a species of solicitor-advocate, whose functions are very similar to those of the barrister. The more this progresses, the greater will be the number of solicitors who will become known as court practitioners, and whose services will be sought by the public and even by other solicitors, providing an existing act forbidding the latter is repealed.

While such is the drift in England, there is at the same time a tendency in America to approach English conditions in the evolution of the law firm composed of lawyers of whom some are known as distinctively trial lawyers, while the other members devote themselves to the business [55] of the law, and indeed one now occasionally hears of such partnerships designating one of their number as "counsel" to the firm—which is, perhaps, an affectation.

Solicitors often become barristers—sometimes eminent ones, for they have an opportunity to study other barristers' methods, and have acquired a knowledge of affairs. Of course they must first retire as solicitors and enter one of the Inns for study. The late Lord Chief Justice of England began his career as an Irish solicitor.

Solicitors wear no distinctive dress (except a gown when in the county court, as will be explained hereafter) but attire themselves in the conventional frock or morning coat and silk hat which is indispensable for all London business men. They all, however, carry long and shallow leather bags, the shape of folded briefs, which are usually made of polished patent leather.

INFLUENTIAL FRIENDS OF BARRISTER—JUNIOR'S AND LEADER'S BRIEF FEES—FEES OF COMMON LAW AND CHANCERY BARRISTERS—BARRISTER PARTNERSHIPS NOT ALLOWED—ENGLISH LITIGATION LESS IMPORTANT THAN AMERICAN—CLERKS OF BARRISTERS AND SOLICITORS HAGGLE OVER FEES—SOLICITORS' FEES.

An American lawyer will be curious concerning two things, about which he will get little reliable information, viz., how legal business comes and what are its rewards.

The barrister supplements his reading, sometimes by practical service for a short time in a solicitor's office and nearly always by the deviling before described, and thus, in theory—and according to the traditions of the Bar—may pass years awaiting recognition. Finally, briefs begin to arrive which are received by his clerk with the accompanying fee, in gold, as to which the barrister is presumed to be quite oblivious. This, however, is not always the experience of the [58] modern barrister, who may have some relative occupying the position of chairman of a railway, or of a large City company, the solicitors of which will be apt to think of this particular man when retaining counsel. In such fashion and other ways, while he can not receive business directly from an influential friend or relative, but only through the medium of a solicitor, yet such connections are often definitely felt in giving the young barrister a start. His eventual success, however, as in every other career, depends upon how well he avails himself of his opportunities.

When briefed as a junior, without a leader, in a small action, his fee may be "3 & 1," meaning three guineas for the trial and one guinea for the "conference" with the solicitor. When briefed with a leader, however, his fee, which is always endorsed on the brief, may read: [59]

| "Mr. J. Jones . . . . | 35 guineas |

| 1 guinea | |

| 36 guineas | |

| "With you Sir J. Black, K. C." |

The leader's brief will be endorsed:

| "Sir J. Black, K. C. . . . . | 50 guineas |

| 2 guineas | |

| 52 guineas | |

| "With you Mr. J. Jones" |

The fee is not always sent by the solicitor with the brief, but a running account, with settlements at intervals, is not uncommon. Contingent fees are absolutely prohibited, the barrister gets his compensation, or is credited with it, irrespective of the result.

All speculation as to professional earnings of a barrister must be vague, for there can be little accurate knowledge on such a subject. Chancery men seem to earn much less than common law barristers and their business is of a quieter and less conspicuous character. At the fireside in chambers in Lincoln's Inn, if the conversation [60] drifts to fees, one may hear a discussion as to how many earn £2,000, and a doubt is expressed whether more than three men average £5,000, but the gossips will add that they do not really know the facts.

The fees of common law men, while larger, are equally a matter of guess-work. One hears of the large earnings of Judah P. Benjamin a generation ago, and R. Barry O'Brien, in his life of Sir Charles Russell, quotes from his fee book yearly showing that the year he was called to the Bar he took only £117, while thirty-five years later—in 1894—just before he was elevated to the bench, his fees for the year were £22,517. For the ten years preceding he had averaged £16,842, and, for the ten years before that, £10,903. The biographer of Sir Frank Lockwood, a successful barrister, relates that he earned £120 his first year and that this increased to £2,000 in his eighth year, but he was glad to accept during his twenty-second year the Solicitor Generalship, paying about £10,000. The Attorney General, who, although his office is a political one, is generally a leading barrister, receives a salary of £7,000 and his fees are about £6,000 more.

The clerk of a one time high judicial officer now dead, is authority for the statement that the [61] year before he went upon the bench his fees aggregated 30,000 guineas. It seems to be the general opinion of those well informed that the most distinguished leader may, at the height of his career, take 20,000 to 25,000 guineas. All such estimates must, however, be received with the greatest reserve, and no one could undertake to vouch for them.

Barristers' fees are, of course, for purely professional services and do not come within the same category as the immense sums one occasionally hears of being received by American lawyers—not, however, as a rule, for real professional services in litigation, but for success in promoting, merging or reorganizing business enterprises. The fees of English barristers are practically all gain, as there are no office expenses worth mentioning. No suit can be brought by a barrister to compel the payment of a fee although the services have been performed, nor is he liable for negligence or incompetence in his professional work.