The Project Gutenberg eBook, Corot, by Sidney Allnutt

MASTERPIECES

IN COLOUR

EDITED BY . .

T. LEMAN HARE

COROT

1796-1875

“Masterpieces in Colour” Series

| Artist. | Author. |

| VELAZQUEZ. | S. L. Bensusan. |

| REYNOLDS. | S. L. Bensusan. |

| TURNER. | C. Lewis Hind. |

| ROMNEY. | C. Lewis Hind. |

| GREUZE. | Alys Eyre Macklin. |

| BOTTICELLI. | Henry B. Binns. |

| ROSSETTI. | Lucien Pissarro. |

| BELLINI. | George Hay. |

| FRA ANGELICO. | James Mason. |

| REMBRANDT. | Josef Israels. |

| LEIGHTON. | A. Lys Baldry. |

| RAPHAEL. | Paul G. Konody. |

| HOLMAN HUNT. | Mary E. Coleridge. |

| TITIAN. | S. L. Bensusan. |

| MILLAIS. | A. Lys Baldry. |

| CARLO DOLCI. | George Hay. |

| GAINSBOROUGH. | Max Rothschild. |

| TINTORETTO. | S. L. Bensusan. |

| LUINI. | James Mason. |

| FRANZ HALS. | Edgcumbe Staley. |

| VAN DYCK. | Percy M. Turner. |

| LEONARDO DA VINCI. | M. W. Brockwell. |

| RUBENS. | S. L. Bensusan. |

| WHISTLER. | T. Martin Wood. |

| HOLBEIN. | S. L. Bensusan. |

| BURNE-JONES. | A. Lys Baldry. |

| VIGÉE LE BRUN. | C. Haldane MacFall. |

| CHARDIN. | Paul G. Konody. |

| FRAGONARD. | C. Haldane MacFall. |

| MEMLINC. | W. H. J. & J. C. Weale. |

| CONSTABLE. | C. Lewis Hind. |

| RAEBURN. | James L. Caw. |

| JOHN S. SARGENT. | T. Martin Wood. |

| LAWRENCE. | S. L. Bensusan. |

| DÜRER. | H. E. A. Furst. |

| MILLET. | Percy M. Turner. |

| WATTEAU. | C. Lewis Hind. |

| HOGARTH. | C. Lewis Hind. |

| MURILLO. | S. L. Bensusan. |

| WATTS. | W. Loftus Hare. |

| INGRES. | A. J. Finberg. |

| COROT. | Sidney Allnutt. |

| DELACROIX. | Paul G. Konody. |

Others in Preparation.

PLATE I.—DANSE DES BERGERS. Frontispiece

The “Danse des Bergers” is the living memorial of a happy mood—one

of those moments of lyrical ecstasy of which Corot experienced

so many, and which, by his genius, those less fortunate are enabled

to share. The “feeling” in the drawing and painting of the trees is

reminiscent of some words spoken by the painter when Paris was

oppressing him—“I need living boughs. I want to see how the

leaves of the willow grow from their branches. I am going to the

country. When I bury my nose in a hazel-bush, I shall be fifteen

years old. It is good; it breathes love!”

Corot

BY SIDNEY ALLNUTT

ILLUSTRATED WITH EIGHT

REPRODUCTIONS IN COLOUR

LONDON: T. C. & E. C. JACK

NEW YORK: FREDERICK A. STOKES CO.

[Pg vii]

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

| Plate |

| I. | Danse des Bergers | Frontispiece |

| | Page |

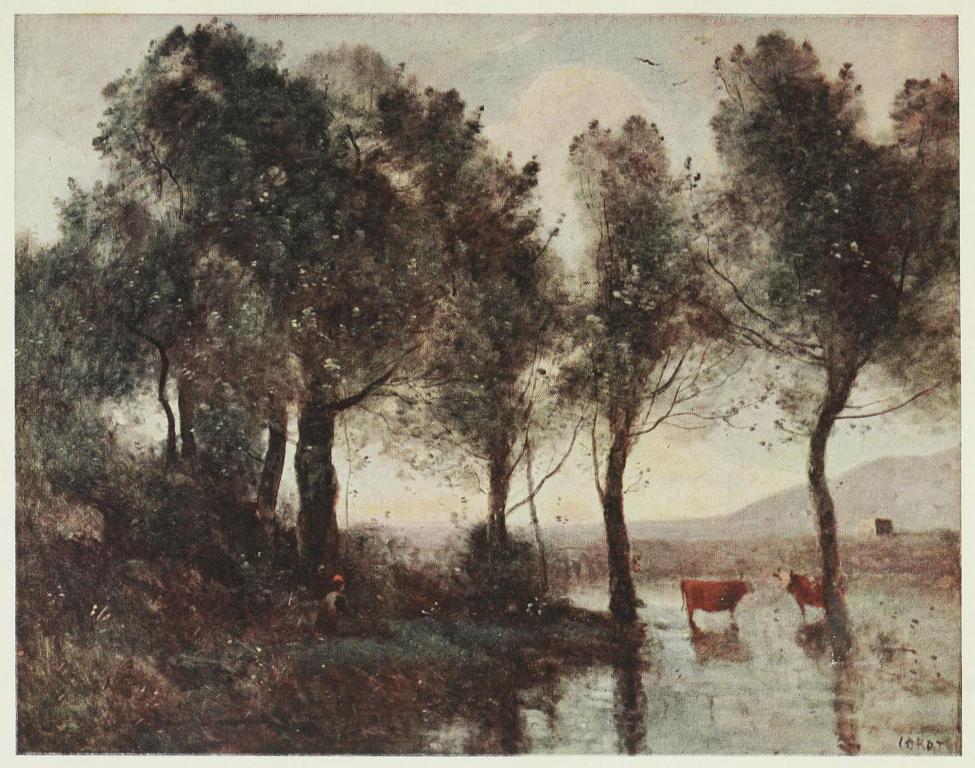

| II. | L’Etang | 14 |

| III. | Les Chaumières | 24 |

| IV. | Le Soir | 34 |

| V. | Paysage | 40 |

| VI. | Le Vallon | 50 |

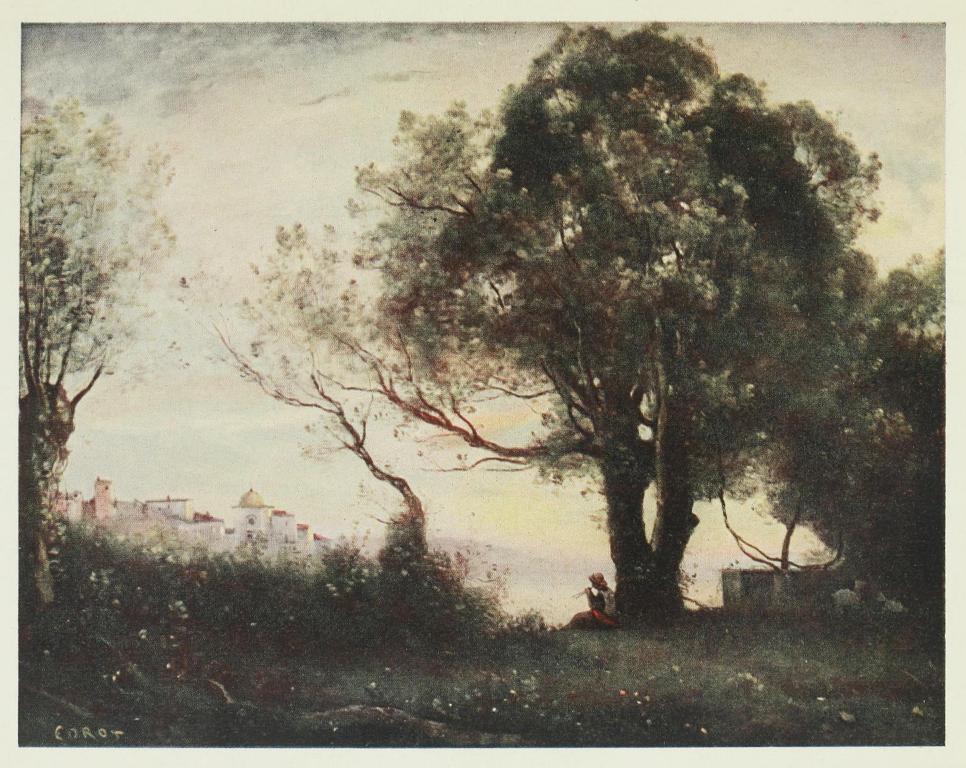

| VII. | Souvenir d’Italie | 60 |

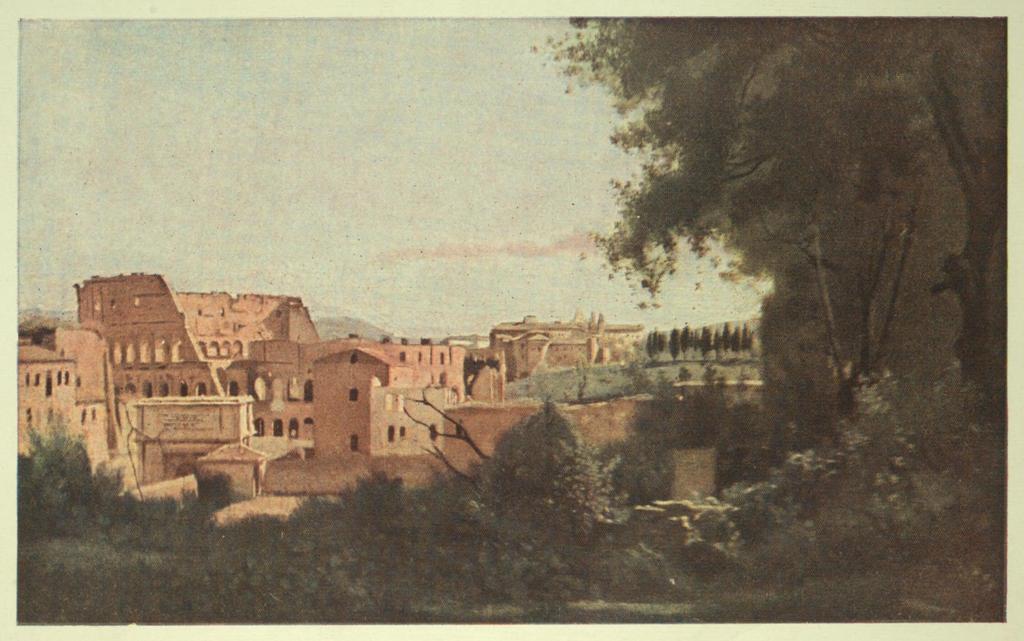

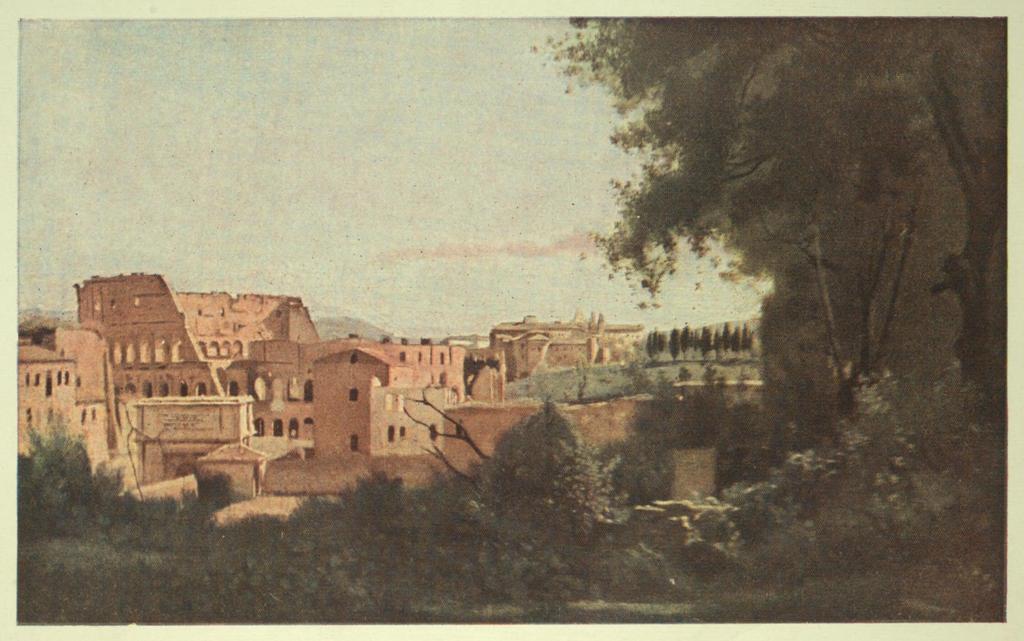

| VIII. | Vue du Colisée | 70 |

|

All the illustrations are taken from the Louvre, Paris |

[Pg 9]

The work of Jean Baptiste Camille

Corot has been steadily rising in the

estimation of the instructed ever since he

won his first notable successes in 1840.

During the greater part of the artist’s life-time

the rise was very gradual, and he

would have been astonished indeed if he

[Pg 10]could have known how rapid it was to be

after his death. It is by no means only a

rise in the selling prices of such of his

works as come into the market—a Corot

has something more than a collector’s value;

but figures are in their way eloquent, and

when we find a work (“Le Lac de Garde”)

for which the painter was glad to get 800

francs selling for 231,000 francs within thirty

years of his death, the rapid growth in the

fame of the painter is materially evidenced.

There are fashions in art as in everything

else: for reasons which the dealers

could often disclose if they would, this or

that artist’s work is suddenly boomed, and

for a time commands absurdly big prices

in the auction rooms, only to find its proper

level again when it is no longer to anybody’s

interest to maintain an artificial

valuation. But it is difficult to believe that

the passing of years will do anything to

diminish the fame of Corot, or lessen the[Pg 11]

prices which connoisseurs are willing to pay

for the possession of his work. Rather will

both increase, there is reason to think, as

under the winnowing of Time’s wings the

chaff is separated from the grain, and many

a painter hailed as a master to-day is

scorned if not forgotten. For whatever may

happen, it is impossible to believe that

the work of Corot will ever become old-fashioned.

There is in it something that

does not belong to one time, but to all

times; not to one place, but to all places.

It is elemental and universal, and instinct

with a vitality and youth that unnumbered

to-morrows can have no power to destroy.

Even those critics who most strongly

opposed the canons Corot professed—and

there were many of them—were often unable

to condemn a heresy in which faith was so

justified by works: coming to curse, like

Balaam, they remained to bless. A far more

trying ordeal the artist had to undergo in[Pg 12]

the intemperate rhapsodies of enthusiastic

admirers. But neither censure or praise,

the scepticism of his own people, or the

indifference of the picture-buying public,

could tempt him to deviate from the path

that for him was the right one. “Vive la

conscience, vive la simplicité!” he used to

say. His creed was in the words, and he

lived up to it.

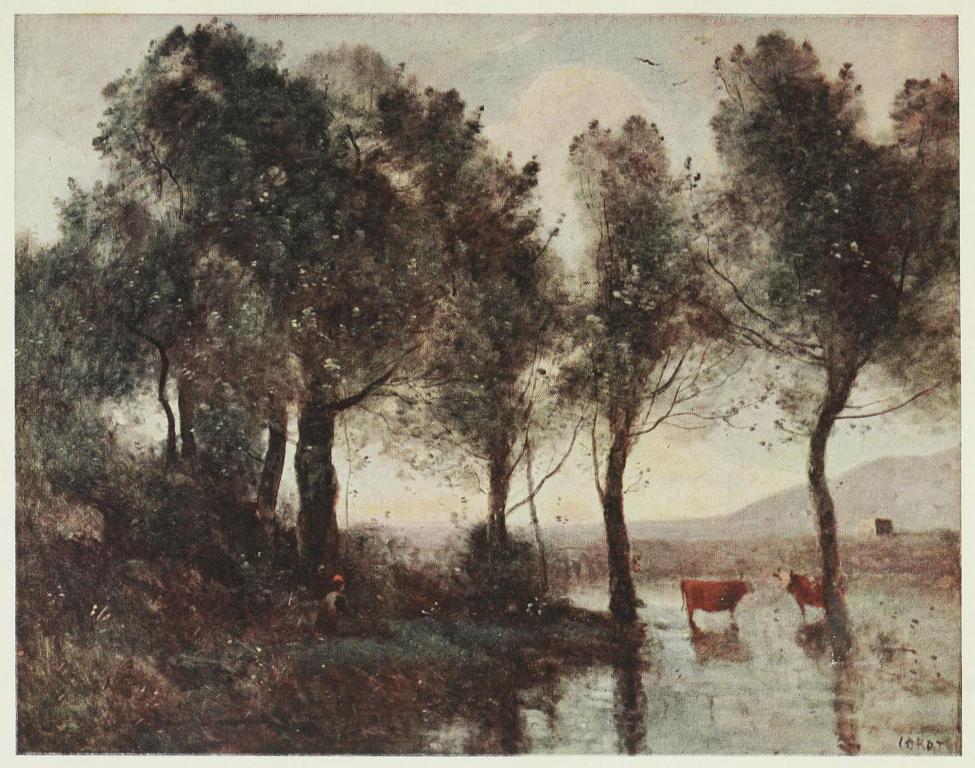

PLATE II.—L’ETANG.

“Beauty in art is truth bathed in the impression, the emotion that

is received from nature.... Seek truth and exactitude, but with

the envelope of sentiment which you felt at first. If you have been

sincere in your emotion you will be able to pass it on to others.”

So said Corot to a pupil, and “L’Etang” would in itself be sufficient

to prove that he knew how to practise what he preached. It is a

variant on a simple motive that he was never weary of, and that he

knew how to invest with new beauties every time it came to him.

He claimed for the artist an entire independence.

“You must interpret nature

with entire simplicity, and according to

your personal sentiment, altogether detaching

yourself from what you know of the

old masters or of contemporaries. Only in

this way will you do work of real feeling.

I know gifted people who will not avail

themselves of their power. Such people

seem to me like a billiard-player, whose

adversary is constantly giving him good

openings, but who makes no use of them.

I think that if I were playing with that

[Pg 15]

man, I would say, ‘Very well, then, I will

give you no more.’ If I were to sit in

judgment, I would punish the miserable

creatures who squander their natural gifts,

and I would turn their hearts to cork.”

Again he says—“Follow your convictions.

It is better not to exist than to be the

echo of other painters. As the wise man

says, if one follows, one is behind.” And

again—“Art should be an individual expression

of the verities, an ardour that

concedes nothing.”

It is on the face of it rather a hopeless

task to attempt to trace the artistic pedigree

of a painter who, at all costs, will be individual

with “an ardour that concedes nothing”;

and it would not help much towards an

understanding of him. At the same time, it

would be a mistake to suppose that Corot

was quite so independent of the influences

around as, perhaps, he imagined himself to

be. “Artists,” says Shelley in a notable[Pg 16]

utterance, “cannot escape from subjection

to a common influence which arises out of

an infinite combination of circumstances belonging

to the times in which they live,

though each is in a degree the author of

the very influence by which his being is

thus pervaded.”

Thus Corot took his part in the revolt

against classicism in France, with which the

name of the little village of Barbizon is so

inseparably associated. He coloured it, and

was coloured by it—so much was inevitable;

but his intense individuality none the less

preserved him in an aloofness from what I

may be permitted to call the broad path of

the movement. And as he grew older, so

far from becoming more affected by his contemporaries,

he only seemed more and more

to discover himself.

Before all things Corot was an idealist—a

painter of ideas rather than of actualities;

which, of course, does not in any way dis[Pg 17]count

his simple sincerity. His landscapes

give the idea of a place or an effect rather

than its exterior appearance. The rendering

of a beautiful passage of colour, of a gracious

form, or a delicate play of light and shade,

was never held to be sufficient. Within

the body of phenomena he saw the throbbing

heart and luminous soul of Nature

revealed; and it was the very heart and

soul of his subject that he strove to

prison in his pigments. At the same time,

dreamer as he was, there was always in

him a healthiness and sanity rare indeed

amongst those who are given to seeing

visions.

I remember a studio gathering at which

Corot was discussed. I wish the master,

who always loved to be praised by those

who could understand and were sincere,

could have heard what was said of him. At

length some one said, “Corot was a great

artist. It is true that he also happened to[Pg 18]

be a great painter.” The words seemed to

me to have meanings.

A painter is a man who does something;

an artist one who is something. The statement

may not be new, but it is true; and

what it involves is, I think, too often forgotten.

In considering what a painter has done

it is natural enough to be preoccupied with

his method, to become immersed in an

analysis of his technique. There will be an

attempt to determine whether he is faithfully

obedient to the accepted canons, or

modifying and adapting, if not it may be

defying them. In the latter case an endeavour

must be made to find a solution for

the question whether these progressive or

revolutionary activities are justified in their

result.

It is criticism of this sort that fills innumerable

studios with a jargon unintelligible

to all but those who are, so to[Pg 19]

say, “in the trade” in one way or another,

and can speak with a craftsman knowledge—of

technical terms if of nothing

else. Such talk is often futile enough,

a breaking of butterfly nothings upon a

ponderous wheel of words; though it can,

on occasion, be useful enough. In any

case only a few, comparatively speaking,

are likely to be either interested or benefited.

It is altogether another matter when an

artist is approached. How he conveys his

message is of much less importance than

what is conveyed. He may be poet, painter,

or musician, but the need for understanding

what he does is infinitely less than that

of learning what he is. This is not to say

that, in the case of the artist, technique is

beneath consideration; but it is to say that

it must not be considered first. Trembling

script sometimes give the authentic gospel

its birth in words, and a true vision may[Pg 20]

be recorded by an uncertain hand. To

lose sight of the artist in contemplating

the technique of the work by which he

reveals himself is to sacrifice the substance

for the shadow.

Corot was a great artist. To him his

art was not a trade or an amusement, still

less a trick, but a religion. He worshipped

with an unceasing diligence and intensity

before the chosen altar of his adoration.

Less than his best he dared not offer there.

Nothing that was not wholly honest and

true could be acceptable. What a magnificent

character he gives to himself, all unconsciously,

in confessing to M. Chardin

an artistic sin! “One day I allowed myself

to do something chic; I did some

ornamental thing, letting my brush wander

at will. When it was done I was seized

with remorse; I could not close my eyes

all night. As soon as it was day, I ran to

my canvas, and furiously scratched out all[Pg 21]

the work of the previous evening. As my

flourishes disappeared, I felt my conscience

grow calmer, and once the sacrifice was

accomplished I breathed freely, for I felt

myself rehabilitated in my own sight.”

What would some of our painters say

to a conscience so tyrannous?

It is, for me, impossible to look at

Corot’s work without feeling that his was,

if I may put it so, a monastic nature.

Here is a serene and cloistered art, something

secluded from the traffic of the

everyday world, a vision intense rather than

wide. I think of Corot as a priest at the

altar of one of Nature’s innermost sanctuaries

celebrating sacramental mysteries.

Every picture that came from him is an

elevation of the Host.

This is the quality in his work, much

more than a fastidious refinement nearer

the surface, that gives it so high a distinction.

Hung in a gallery among other[Pg 22]

pictures, a Corot does not clamour for

notice. It is much too quiet in matter and

manner for that; but, after awhile, it draws

the eye, and when it has done so its hold

is secure. The surrounding canvases almost

invariably begin to look a little vulgar in

its neighbourhood. And this not only because

rioting colour might well look blatant

by the side of the tender greys and greens

and rose flushes that the artist loved so

well, but because the spirituality of which

those tones are merely the expression places

the Corot upon another and a higher plane.

PLATE III.—LES CHAUMIÈRES

Luminous and almost uncannily true in tone, “Les Chaumières”

takes high rank among the finest productions of Corot’s maturer years.

It is the work of a man who “knows,” who is able to take hold of

essentials, and let non-essentials go, with a certainty of discrimination.

Profound knowledge, so thoroughly assimilated as to be

instinctive in its application, can alone account for both the completeness

and simplicity of the landscape, the result achieved with

apparently so absolute a lack of effort.

To come upon a Corot in a gallery is

like stepping out of the noisy glare of the

market-place into the cool stillness of a

church. Market-places are good things,

and the noisy crowd is perhaps only noisy

because it is doing its appointed work in

a right hearty fashion; but the Presence

seems nearer in the silence of the church.

The silence is not dead, but quick with

[Pg 25]

soundless speech. So with a Corot picture;

its quietness is the very antipodes of stagnation.

It seems to spread far beyond the

limits of the frame in ever-widening waves,

until everything around is subdued.

The only other works of art which have

ever given me quite the same impression

in this direction are one or two of those

dreaming Buddhas that, wherever they may

be, seem to be shrined in a stillness emanating

from themselves.

From first to last Corot was as independent

as he was industrious. He strove

always to see Nature with his own eyes,

and to keep his vision clear and simple.

Whether or not other painters had a

grander or nobler vision was nothing to

him. It mattered only that he should be

true to the grace that was his own. “I

pray God every day,” he said, “that He

will keep me a child; that is to say, that

He will enable me to see and draw with[Pg 26]

the eye of a child.” That prayer was surely

answered, for never did an artist look out

upon the world with a more direct simplicity,

or with eyes more delicately sensitive

to the appeal of beauty.

It was seldom the obviously picturesque

that appealed to him. He seemed instantly

to apprehend the most elusive of the

beauties in the scene before him. That

death-bed utterance of Daubigny is significant:

“Adieu; I go above to see if friend

Corot has found me new landscapes to

paint.” That was it: Corot never failed to

find new landscapes to paint, for his eye

was keen enough to pierce through what

seemed commonplace, and discover the

underlying beauty. Starting off on one

of his innumerable sketching excursions, he

remarks to a friend that he has heard bad

accounts from painters of the country for

which he is bound, but adds that he has no

doubt he will find pictures there. And, of[Pg 27]

course, he found them. The pictures are

always there, though the faculty of seeing

them is rare.

No one ever worked more constantly and

faithfully from Nature, or became more

intimately acquainted with the subtle outward

expressions of her innermost moods;

but the profound knowledge thus gained

was only treated as the poet treats a wide

vocabulary; as a means of expression, not

as in itself worth exploitation. The scene

before him was not recorded as a collection

of facts, but as it had stirred his emotions,

and as it was, in a sense, transformed by

his vivid imagination. The resulting picture

is the record of an adventure of the soul;

the outward reality is not lost, but rather

realised in a strange intensity. “See,” said

Corot, pointing to one of his landscapes,

“see the shepherdess leaning against the

trunk of that tree. See, she turns suddenly.

She hears a field-mouse stirring in the grass.[Pg 28]”

Of how the artist went to work when he

had “found” a new landscape some notion

may be gained from M. Silvestre’s description.

“If Corot sees two clouds that at

first sight appear to be equally dark, he

will, before building up the whole harmony

of his picture on one or other of them, apply

himself to discover the difference he knows

must exist. Then, when he has decided on

the darkest as well as the lightest tone in

the scene before him, the intermediate

values readily take their places, and subdivide

themselves indefinitely before his discerning

eyes. These values, from the most

positive to the most vague, call to one

another and give answer, like echo and

voice. When the artist sees he can divide

the principal values of the landscape before

him into four, he does so by numbering the

different parts of his rough sketch from 1 to

4, 4 standing for the darkest and 1 for the

lightest patch, while the intermediate tones[Pg 29]

are represented by 2 and 3. This method

enables Corot, with the help of any old

pencil and any scrap of paper, to make

records of the most transitory effects seen

upon a journey. Corot was not a man to

make an inventory of his sentiments, and

the fact that he made such records proves

that they were sufficient for his own purposes.

As a rule he first of all puts in his

sky, then the more important masses in the

middle of the composition, then those to

the left and to the right; he then picks out

the forms of the reflections in the water, if

there is water, and so establishes the planes

of his picture, his masses falling in one

behind the other while one watches him.

Sometimes he proceeds in a less orderly

way; for it goes without saying that his

methods are the methods of freedom, and

not the invariable recipes of a pedant. He

runs an unquiet eye over every part of the

canvas before putting a touch in place, sure[Pg 30]

that it does no violence to the general

effect. If he makes haste he may become

clumsy and rough, leaving here and there

inequalities of impasto. These he afterwards

removes with a razor, as if he were

shaving his landscape, and leaving himself

free to profit by such accidents of surface

as are happy in effect.”

The picture of Corot sketching in shorthand

shows him when the long and close

study of Nature had enabled him to generalise

with confidence, and when a memory, always

retentive, had been trained to a pitch that

made it far more reliable than any sketchbook

memoranda. Although he always

expressed impatience with the idea that

anything worth doing could be done merely

by taking pains, Corot was the least apt

of men to spare any pains that were essential

to his purpose; and nothing could be

farther from the truth than the suggestion

sometimes made, that he was wanting in[Pg 31]

this respect. To generalise as he generalised

is not to be careless of detail, but the very

reverse: it implies a knowledge so complete

of every element in a landscape that those

belonging to a particular view of it can be

selected with an unerring judgment, and

what is non-essential eliminated. “Put in

as much as you like at first, and afterwards

efface the superfluity,” is a bit of advice

that comes from Corot himself. It was not

a strikingly original remark, but it could

not have been made by other than a conscientious

worker.

It is certainly a mistake to suppose that

Corot was careless of details in the sense

that he did not give them due consideration;

but he always realised that details

were details after all. “I never hurry to

the details of a picture,” he said; “its

masses and general character interest me

before anything else. When those are well

established, I search out the subtleties of[Pg 32]

form and colour. Incessantly and without

system I return to any and every part of

my canvas.”

There is a note in Mr. George Moore’s

Modern Painting that seems to throw

some illumination upon Corot’s manner of

looking at his subject. Mr. Moore came

upon the artist, an old man then, “in front

of his easel in a pleasant glade. After admiring

his work, I ventured to say: ‘What

you are doing is lovely, but I cannot

find your composition in the landscape

before us.’ He said, ‘My foreground is

a long way ahead.’ And sure enough,

nearly two hundred yards away, his picture

rose out of the dimness of the dell,

stretching a little beyond the vista into the

meadow.”

I think Corot’s foreground had a habit

of being a considerable way ahead.

PLATE IV.—LE SOIR

“My ‘Soir,’ I love it, I love it! It is so firm,” said Corot, standing

before his picture in the exhibition gallery in company with an

appreciative friend. It is “firm” enough beyond question, and the

sky especially is a marvel of delicate, palpitating colour. But it is

much more, a moment of magic beauty, evanescent as the reflected

picture on a bubble-bell, seized and made permanent; an emotion of

pleasure cast into a material shape.

To most, Corot is “the man of greys,”

the painter of the twilight. Without for a

[Pg 35]

moment suggesting that this is true in so

far as it seems to hint that his art had

very narrow limitations, I am certainly inclined

to believe that the general eye has

fixed itself upon his most characteristic and

most valuable work. The two dawns, as

the old Egyptians called them, Isis and

Nephthys, the dawn of day and the dawn

of night, revealed themselves to Corot

with a fulness to be measured only perhaps

in part by the manner in which he

has revealed them to us. The stillness,

the freshness, the indescribable tremor of

awakening life, the curious sense of a remoteness

in familiar things, the expectancy

as of some momentous revelation, all that

goes to make the mystery and magic of

the dawn, he knew how to translate into

subtle yet easily understandable terms of

form, and tone, and colour. It was a miracle

to which he seemed to have found the key—perhaps

by means of that prayer to be[Pg 36]

“kept a child.” Over and over again he

invoked the dawn to appear upon his

canvas, and never in vain. In ever-varying

robes of loveliness, but the same in all of

them, the dawn responded to his call.

Grey dawn! The words had a cold and

gloomy sound until Corot interpreted them,

taking the gloom away and leaving of the

cold only the delicious shiver of the morning

freshness. Beautiful almost as the

dawn itself—born of it as they were—are

those wonderful pearly greys of his. His

palette seemed to hold an infinite range

of them, each pure and perfect in itself,

and each in a true harmonic relation to

the others.

And if the painted dawns are beautiful,

they are also true; they carry instant

conviction of their absolute verity. There is

only one thing that can make a painted

canvas do this, and that is truth of tone,

and of tone-values Corot made himself a[Pg 37]

master, mainly because he never ceased to

be a student. He retained the eye of a

child, but his mind became stored with the

accumulated experience of many long hours

that were only not laborious because the

work was a delight. And great as the

store grew in process of time, he was adding

to it up to the last.

Here is a picture by Albert Wolff of the

artist at the age of 79, when the hand of

Death was already stretched out towards

him. “An old man, come to the completion

of a long life, clothed in a blouse, sheltered

under a parasol, his white hair aureoled in

reflections, attentive as a scholar, trying to

surprise some secret of nature that had

escaped him for seventy years, smiling at the

chatter of the birds, and every now and again

throwing them the bar of a song, as happy

to live and enjoy the poetry of the fields

as he had been at twenty. Old as he was,

this great artist still hoped to be learning.[Pg 38]”

It is altogether an important thing about

Corot that he was always singing—in season

and out of season I was about to say, when

I remembered that he would probably have

declared that it was always singing-time.

He went to his work carolling like a lark,

though with a somewhat robuster organ,

and snatches of song punctuated his brush

strokes. The day’s work done, he broke

out into melody in earnest, and sang to

himself, to his friends, at home or abroad,

with equal vigour and enjoyment. We are

told that on one occasion his irrepressible

song broke out at an official reception,

doubtless to the confusion of dignities and

the shocking of many most respectable

people.

PLATE V.—PAYSAGE

The play of light filtering through foliage has never been more

beautifully rendered upon canvas, or with a closer approximation to

the truth of Nature, than in the “Paysage,” reproduced here. The

manner in which the tree has been portrayed, the body and soul of

it, is not less astonishing. The landscape is a masterpiece among

masterpieces, and an impressive witness to Corot’s amazingly sensitive

faculty of apprehending what was in front of him, both with eye

and mind.

I cannot but think that something of

music found its way into Corot’s pictures.

They look as if they could have been done

in music as well as they were done in paint.

In a way they were: if there was always a

[Pg 41]

song on his lips, surely there was also a

song at his heart. One may say that his

paintings were built to music like the walls

of Thebes. They are haunted by sweet

harmonies, and seem charged with hidden

melodies that tremble on the verge of

sound.

Many of those who read may shake their

heads at this attempt to make a confusion

of two arts, but my apology shall take the

form of a quotation from Corot himself.

Moved to sudden emotion by a magnificent

view, he exclaimed, “What harmony!

What grandeur! It is like Gluck!” I

think the man who said that may possibly

have painted a little music, without caring

for a moment whether he was confusing

the arts or not. Perhaps he felt that

painting and music were more nearly

related than a certain school of critics can

allow itself to admit. But that is by the

way.[Pg 42]

When in Paris he was frequent in his

attendances at concerts and the opera, and

indeed music always drew him with a power

only second to that of his chosen mistress—painting.

As the twig is bent the tree will

grow—it may be that had the accidents of

his early environment been other than they

were, his name would be famous as that of

a great composer instead of a great painter.

Fortunately we do not know what we may

have missed, while we are fully conscious

of what we have gained.

The father of Corot the painter was

Louis Jacques Corot, who, if he escaped

being altogether a hairdresser, only did so

by a narrow margin. One would rather like

to imagine him as another “Carrousel, the

barber of Meridian Street.”

“Such was his art, he could with ease

Curl wit into the dullest face;

Or to a goddess of old Greece

[Pg 43]Lend a new wonder and a grace.

The curling irons in his hand

Almost grew quick enough to speak;

The razor was a magic wand

That understood the softest cheek.”

Such was Carrousel, according to Aubrey

Beardsley’s ballad, and such Louis Jacques

Corot should surely have been, if only to

make his son more easily explainable; but,

as a matter of fact, he appears at an early

age to have forsaken the high art of hairdressing

for more strictly commercial pursuits.

He became a clerk, and his wife’s

assistant manager.

For Madame Corot was a business

woman—very much so. She was a native

of Switzerland, and evidently of the practical

nature that so often distinguishes the Swiss

people. A woman of property in a moderate

way, and two years older than her

husband, as well as a capable manager, she

does not appear by any means to have

allowed marriage to submerge her own per[Pg 44]sonality.

As a marchande de modes she

was a distinct success. Fashion found its

way to her establishment in the Rue du Bac,

and the name Corot became a hall-mark

of elegance.

Perhaps her son owed more to his

mother than has sometimes been suspected.

Corot himself remarked that a skill equal

to that of the painter was often shown by

the costumier in the blending of colours—indeed

he went farther, and said as much

of a certain flower-seller of his acquaintance

and her bouquet-making. Really, when one

comes to think of it, he may be said to

come of artists on both sides, for if his

father was scarcely as much of a hairdresser

as we should like him to be, his

paternal grandfather’s claim to the description

is beyond criticism.

Under these circumstances it is a little

sad that, when he had completed his

educational career without winning any[Pg 45]

considerable distinction, it was decided to

make a draper of him. There is every

evidence that, in so far as the attempt went,

he made a very bad draper indeed. I do

not know how long it took him to come to

the conclusion that he would never make

a good one—not very long, I should say—but

after a trial of six years or so, it would

seem that his father had arrived at the

same conclusion. When his son declared

his intention of abandoning drapery and

of becoming a painter, Corot père did not

offer any strenuous objection. He thought

that the young man was a fool, and said

so, with possibly a little bitterness, but on

the whole with resignation. What was

more to the point, he made a small provision,

so that his son might live while

“amusing himself.”

The provision in question was certainly

a small one—1500 francs a year—but it

prevented Corot from ever knowing the[Pg 46]

extremities of poverty to which some of

his brilliant contemporaries were reduced.

As he said, he could always count on “shoes

and soup”—and shoes and soup, if not

much in themselves, can often bridge the

gulf that lies between hope, or even content,

and despair. Moreover, Corot’s wants were

few. Throughout his life he had the simplest

tastes, and his only extravagance was

a charity that gave without measure and

never thought about return.

However, figure to yourself Corot fully

embarked on his career as a painter. He

is, roughly, twenty-five years of age, and for

stock-in-trade has glowing health, a certain

familiarity with pencil and brush already

acquired, an unquenchable enthusiasm, and

so many francs a year. On the whole it

is the outfit of a very happy and fortunate

young man.

Once emancipated from the compulsions

of drapery he lost no time in setting to[Pg 47]

work. He went straight to Nature, and

even at this time produced work that bore

a hall-mark as distinctive as that of his

later years. He worked also in the studios

of Michallon and of Bertin, and if they did

him no good (and there is little reason to

suppose such a thing), they at least did

him no harm. Already he was too keenly

engaged upon a line of his own.

Around Ville d’Avray, where his father

had bought a house, he found numberless

subjects ready to his hand, subjects of

which nothing that he saw in his wide

wanderings could ever make him tired. He

also had an experience in Morvan. I shall

venture to quote from Mr. Everard Meynell’s

“Corot and his Friends,” concerning it. “He

went, presently, to the little hamlet of

Morvan, whose blacksmith gave him hospitality.

As a member of a farrier’s numerous

family, with the forge for sitting-room, and

its fires to assuage the cold of mortals and[Pg 48]

of metals, and soup for fuel, and the blue

smock of the country for raiment, Corot

saved money. He saved money out of the

1200 francs of his allowance; even the cost

of canvas and paints did not bring his expenditure

to three francs a day. His

austerity meant Rome, but it was not a

hard road for him to follow. Never was a

man less provoked to any of the pampered

ways of living.”

PLATE VI.—LE VALLON

“Le Vallon” is probably one of the best-known and most universally

admired of Corot’s works. It does not record one of those

tender twilight effects in which, as may be believed, the painter found

his keenest pleasure, but the quiet glory of a golden afternoon. The

simple landscape is bathed in the most wonderful of painted sunshine,

and possesses an extraordinary verity. The material essentials

of the scene are set down with an unerring regard for truth, but it is

in interpreting its “sentiment” that the most notable success has

been achieved.

“It was in Morvan that Corot picked up

with the peasant, and found in him many

things fit to be learned. He learnt about

soups, and pipes, and blouses, and the habit

of the sunrise; and nothing that he learned

did he forget. Soups, and pipes, and blouses,

and the sunrise lasted him till the end of

his life. These things, like the honest

humour and good-comradeship of a man

afield, were in his blood; but Morvan and

Morvan’s blacksmith, and daily things done

with the Morvan peasantry, developed the

[Pg 51]

peasant in the painter. Corot’s was nearer

to the peasant’s character than Millet’s

even; for the emotional gloom of Millet’s

outlook, his sense of the price paid for life,

his sense of death and toil, of the significance

of the seed and the scythe, made

him a person too great and dreadful to be

familiar with those for whom he thought

and felt. Corot’s laugh and song, his raillery

and content, were things to be friends

with.”

I think that in the foregoing passage

the influence upon Corot of the Morvan

visit, though it may well have been a

memorable one, has been perhaps a trifle

exaggerated. Surely he must have “picked

up” with the peasant long before, and found

out how much he had in common with the

dweller on the soil. And will the comparison

with Millet fully bear examination? I doubt

it. The extraordinary delicacy and refinement

of Corot’s vision is at least a thing as[Pg 52]

foreign to the peasant as the tense

emotionalism of Millet; and I suspect that

the deep-rooted content of the one was as

much removed as the implicit revolt of the

other from the people with whom in their

several ways they were both so much in

sympathy. That in personal relations Corot

got nearer than Millet to his peasant

friends is more than probable. If not more

understandable in reality, he seemed so in

daily intercourse with those as simple and

direct as himself. There was nothing in

him to repel. His gay and expansive

nature invited a confidence that was seldom

withheld, except by those too distrustful

and secretive themselves to understand it.

The first visit to Italy, undertaken in 1825,

marks an epoch in the life of Corot, as in

that of many another painter. But though

it widened his outlook, and taught him

much that otherwise he might never have

learned, it did not tempt him to any de[Pg 53]viation

from the simple principles that all

through his life guided him in the practice

of his art. All the inducements which Italy

could offer were not sufficient to make

him incline to use other eyes than his

own when painting. He seems to have

treated the Masters in an unusually cavalier

manner. Nature in Italy interested him

much more than Art in Italy: he was more

concerned with sunsets than with Michael

Angelo.

As was his custom, Corot was always at

work in Italy, “sitting down” with his

usual happy knack in finding the right spot,

and painting what he saw as he saw it,

with careful fidelity to his own beautiful

way of looking at things. Sometimes he

worked from models in his room, but whether

indoors or out, day after day found him painting,

painting with unabated enthusiasm and

ever-fresh delight.

And he made friends, as always—among[Pg 54]

them d’Aligny, who was the first to take the

true measure of the then somewhat awkward

young man. “D’Aligny,” says Mr. Everard

Meynell, “was the discoverer of his genius

and its advertiser; for having found Corot

at work on the ‘Vue du Colisée,’ now hanging

in the Louvre, he made a formal statement

of his admiration at ‘Il Lepre’ (a café

in Rome much frequented by painters) that

night. ‘Corot, who sings songs to you, and

to whom you listen or call out your ribald

chaff,’ said he, ‘might be master of you all!’”

The friendship lasted until the death of

d’Aligny in 1874, and Corot never forgot

the generous praise that had so encouraged

him during those early days in Rome.

In 1827 Corot exhibited for the first time

in the Salon. The two pictures which bore

his name were not unnoticed, but no one

was sufficiently interested to purchase them.

It was indeed fortunate on the whole that

he was assured of “shoes and soup” from[Pg 55]

other sources than his art, for it was not

until 1840 that it brought him any monetary

reward worth mentioning. But it would be

beside the mark to say that he had to endure

any remarkable period of neglect. It

must be remembered that his career as a

painter did not seriously begin until he

was of an age when many artists have

already secured something of a position for

themselves. His work, too, was not of such

a description as to make any sensational

impact upon the attention of the art-loving

public.

Before he returned from his first visit

to Rome he had, however, made his mark

in some measure, had been hailed by a few

discerning critics as one of the elect. The

enthusiastic testimony of d’Aligny and one

or two others had been endorsed with signatures

that carried some weight—only at

home was he still held to be an amateur.

His right to a place among the more notable[Pg 56]

artists of his time was no more questioned,

except by those whom ignorance or prejudice

had rendered incapable of sane

judgment.

Once more, and again, he visited Italy,

painting as he went, and what was much

more to the purpose, filling with magic

pictures the tablets of his mind: but I

doubt if these subsequent visits carried him

far beyond the point he had arrived at

during the first. Each day he was gaining

more knowledge and greater dexterity, but

his point of view was never seriously modified.

Italy gave to his delicacy some of

its strength, invested the most tender-hearted

of painters with the touch of sternness

that could alone save his work from

becoming invertebrate: but it could not

materially alter his habit of vision, or turn

into dramatic shape an inherently lyrical

gift. He saw Nature as a song in France

first of all and last of all; Italy only helped[Pg 57]

him to give the song a more severe metrical

basis than it might otherwise have possessed.

Much that was sweet in Corot it

would seem that the relentless landscapes

and pitiless skies of Italy helped to make

strong.

From 1840 onwards one may say that

Corot was steadily growing into fame. In

that year two of his pictures were bought

by public authorities, and thus, for the first

time, an official imprimatur was set upon

his increasing reputation. He never knew

the feverish delight of awaking one morning

to find himself famous. The value of his

work was only very slowly recognised, and

as his paintings attracted more and more

notice a heavy fire of hostile criticism was

opened upon them: with no more effect

than to make him smile as he went upon

his way.

Some of these egregious criticisms are

so utterly beside the mark that it is difficult[Pg 58]

to believe them anything but the result of

a wilful misapprehension on the part of

the critics. They seem to be inspired by

venom and spite when read to-day: but in

their own time they probably fairly represented

the serious opinions of many who

thought they were defending legitimate art

against a spreading anarchy. It is even

possible that such as Nieuwerkerke, who,

as Mr. Meynell records, was “overheard

describing Corot as a miserable creature

who smeared canvases with a sponge dipped

in mud,” honestly believed that he was

administering a well-deserved castigation

to a charlatan. It is more than likely that

many of us are making mistakes almost as

serious to-day, so we need not find such an

attitude incredible.

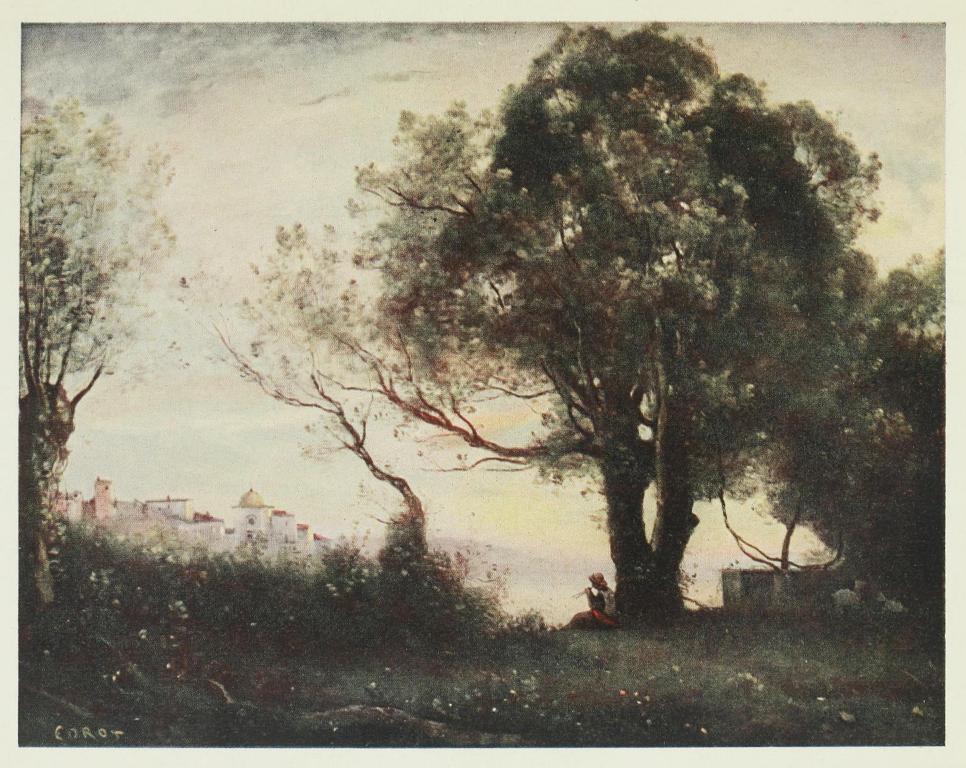

PLATE VII.—SOUVENIR D’ITALIE

Corot at the height of his powers is seen in the “Souvenir d’Italie.”

The thousand subtle nuances of exquisite colour in the luminous

sky, the refined drawing and firm painting of the trees, and the

happy confidence revealed by every brush mark upon the canvas,

make it one of the most delightful and, we may say, most “lovable”

of its creator’s works.

There were other critics at this same

period who were less hampered by preconceived

notions, and came to a very different

conclusion than those who were able to

[Pg 61]

dismiss the whole Nature school with contempt

as “pampered humbugs.” Delacroix

could see that Corot was not “only a man

of landscapes” but “a rare genius,” and he

was not alone. Every year, as one masterpiece

after another appeared at the Salon

from the “mud-dauber’s” brush, the general

body of artists and art-lovers were more

disposed to give him the rank that was

his due.

In 1848 Corot was elected one of the

judges for the annual exhibition by his

fellow-artists. He himself sent nine pictures,

and one of them, a “Site d’Italie,” was

purchased by the State. The following

year Corot was again one of the judges,

and in 1850 he was elected a member of

the “Jury de Peinture.” He had become a

personage in the art-world of France.

Already in 1846 he had been decorated with

the Cross of the Legion of Honour, to the

astonishment of his worthy father, who[Pg 62]

could not in the least understand on what

grounds such an honour had been done to

his failure of a son.

The history of Corot’s following years

there is no necessity to follow in detail.

Like the years which had gone before, they

were fulfilled with happy labour. He

journeyed through the length and breadth

of France, to Switzerland, and elsewhere,

“finding landscapes” with that apprehensive

eye of his, and recording them on canvas

or on paper, or storing them in the pigeon-holes

of a memory that in such matters

never failed him. For the rest the record is

one of a continually increasing appreciation

of his work. It started in a very small

circle, extending thence in ever-widening

ripples. Almost imperceptibly his fame

increased until he became an acknowledged

master.

In view of the sums paid for many of

them since, the prices he obtained for his[Pg 63]

pictures seem ridiculously small, but there is

no reason to suppose that he was anything

but well content with such material rewards

as came his way. Indeed, so much to the

contrary, for some time he looked upon the

increasing prices which purchasers were

willing to pay with a mild astonishment

and a kind of humorous fear that it was

too good to be true.

The slighting of his earlier work and the

laudation excited by the later had precisely

the same effect upon him—that is none at

all. If one had asked him, I think he would

have said both alike were out of perspective.

And he would have spoken without any

taint of bitterness: for, from the very first,

he was both confident and humble.

Of the man Corot there are many portraits

both in pen and pencil, that help to

give an outward shape to the more intimate

revelation of personality to be found in his

work.[Pg 64]

One of the most interesting is a portrait

by the artist of himself as a young man.

He is sitting, a burly, broad-shouldered

figure, before his easel. The face looks out

from the canvas square and strong, but the

full-lipped mouth is sensitive, almost tremulous,

and betrays the nature of the man

even more surely than the alert eyes;

though these eyes, on the pounce, one may

say, and the forehead drawn in the intense

endeavour to see—these also tell their own

story.

A pen-portrait of later date by Silvestre

describes the artist as “of short but Herculean

build; his chest and shoulders are

solid as an iron chest; his large and powerful

hands could throw the ordinary strong

man out of the window. Attacked once,

when with Marilhat, by a band of peasants

of the Midi, he knocked down the most

energetic of them with a single blow, and

afterwards, gentle again and sorry, he said,[Pg 65]

‘It is astonishing; I did not know I was

so strong.’ He is very full-blooded, and

his face of a high colour. This, with the

bourgeois cut of his clothes and the plebeian

shape of his shoes, gives him at first sight

a look which disappears in a conversation

that is nearly always full of point, of wit,

and matter. He explains his principles with

great ease, and illustrates the method of

his art with anything at hand; and that

generally is his pipe. He so loves to talk

about his practices in painting that, a student

told me, he will talk in his shorts and with

bare feet for two hours at a stretch without

being once distracted by the cold.”

Many photographs are in existence to

present to us Corot in his autumn time.

Says M. Gustave Geffroy, examining one

of these: “The features are clearly marked.

The brow, high and bare, crowned with hair

in the coup de vent style, is furrowed with

lines. His glance goes clear, keen, direct,[Pg 66]

from beneath the heavy eyelids. The nose,

short and fleshy, is attached to the cheeks

by two strongly marked creases. There is

a smile on the lips, of which the lower is

very thick—altogether a good, intelligent,

witty face.” In general appearance, I may

add, these later portraits of Corot always

remind me of the late Mr. Lionel Brough.

To my mind there is something more

in these photographs than M. Geffroy has

called attention to. They are the portraits

of a very happy man. A deep spiritual happiness

and content make the old, wrinkled

face a beautiful one. It is the face of one

who, to use a lovely old phrase, “walked

with God,” and of whom it was said, “c’est

le Saint Vincent de Paul de la peinture.”

As one of his friends said, Corot was

“adorably good.” He was a good son, for

all that he found himself unable to fall in

with his father’s desire to make him a successful

draper: and the fact that “at home[Pg 67]”

his outstanding abilities were never recognised,

could not in the least abate the

warmth of his family affections. And he

was a good friend. He never forgot a

kindness done to him either in word or

deed, although his memory seemed to be

singularly incapable of retaining a record

of anything done to his hurt. It has been

said, and the argument could be powerfully

supported, that the same qualities that go

to the making of a good friend make a

bad enemy. Very likely it is true in ninety-nine

cases out of a hundred: if so the case

of Corot was the hundredth. He seemed

to have a natural incapacity to bear malice

or retain a sense of injury. Perhaps he

was too simple or too wise; or, maybe,

both.

Not less characteristic of Corot than

his manner of going about always with a

song on his lips, was his incurable habit

of giving. The wonder is that he ever[Pg 68]

had anything at all left for himself, that

even shoes and soup did not follow after

francs. And very reprehensibly, of course,

he gave to almost every one who had recourse

to him, as well as to many who did not. His

generosity was all but indiscriminate, and

conducted in a manner that, it may be

supposed, would drive a charity organisation

society to distraction. He was victimised

often and knew it, but the knowledge

never dulled the edge of an insatiable

appetite. To give was at once a luxury

and a necessity to him, as appears, and

he was never so gay as when he had been

indulging himself in this direction rather

more recklessly than usual. “He would

paint” (I quote from Meynell), “saying to

himself, ‘Now I am making twice what

I have just given.’ Or, again, having just

emptied his cash drawer, he would take

up his easel, saying: ‘Now we will paint

great pictures. Now we will surprise the

[Pg 71]

nations.’” Rather a foolish fellow evidently:

but “one of God’s fools,” as I heard an

old priest say of a somewhat similar example.

PLATE VIII.—VUE DU COLISÉE

The “Vue du Colisée” is a reminiscence of Corot’s first visit to

Rome. It plainly shows that even in those early days he had

obtained a great mastery of his medium, and could set down with

distinction what he so clearly saw. Though the subject is a big one,

it is handled in such a fashion that simple dignity is its outstanding

characteristic. The “Vue du Colisée” was one of the paintings that

first gained for Corot the high consideration of the more discerning

among his artist friends.

Notwithstanding the love that made the

keynote of his character, all the investigations

of the curious have not discovered

an “affair of the heart” in Corot’s life story.

It is a story to all intents and purposes

without a woman in it: or, if that is saying

too much, certainly without a heroine.

There has been some attempt to exalt his

relations with “Mademoiselle Rose” to

the level of a romance, but it has failed

completely for want of materials. Mademoiselle

Rose was one of his mother’s

work girls, and in those early days, when

he was but newly emancipated from the

bondage of drapery, she used to come to

see him at his painter-work. She never

married, and thirty-five years later Corot

still counted her among his friends, and[Pg 72]

she visited him from time to time. It is

a little romance of friendship, if you like,

it may have been on the part of Mademoiselle

Rose something more—who knows?—but

it cannot count as a Corot love-affair

on the evidence that is available.

As far as is known this is the nearest

approach to a “love interest” in the life of

the artist. It may have been that he

looked upon women too much with the

eye of an artist ever to be able to see

them merely as a man; more probably it

was the element of austerity in him that

kept him immune from passion.

With all his intense delight in life and

in living, Corot was always detached; always

preserved, as by a religious habit, from

actual contact with the world around him.

Through the midst of the follies, the extravagances,

and the vices of Romanticist

circles in Paris of the thirties, he passed

without coming to any harm, and character[Pg 73]istically

enough, without losing his regard

for some of the wildest of a wild company.

He took part in much of the “fun” that

was going on, but though often in the set

he was never of it, and so far as can be

judged it did not influence him, or colour

his outlook upon life, in the slightest

degree.

I think it was this temperamental detachment,

and possibly a sense, unexpressed

even to himself, of being vowed to one particular

service, that prevented Corot from

ever “falling in love,” as the phrase goes.

Or, to put it another way, his life was so full

of his art, that there was no room within its

limits for another dominating interest.

Simple and single-minded, happily pursuing

the occupation that of all others he

would have chosen, he made his life a work

of art more lovely than the most beautiful

of his paintings. No one can live in such

a world as this for the allotted span and[Pg 74]

more without becoming acquainted with

grief, but Corot knew none of those searing

sorrows which scorch their way into

heart and brain, until they make existence

a burden hardly to be borne. His faith in

“the good God,” to whom he looked up with

so childlike a confidence, was so complete

that sorrow for him could hold no bitterness;

nor, deeply sympathetic as he was,

had it power over an impregnable content

and an unfailing serenity.

And he died as he had lived. A few

days before his death it is recorded “that

he told one of his friends how in a dream

he had seen ‘a landscape with a sky all

roses, and clouds all roses too. It was

delicious,’ he said; ‘I can remember it quite

well. It will be an admirable thing to paint.’

The morning of the day he died, the 22nd

of February, 1875, he said to the woman

servant who brought him some nourishment,

‘Le père Corot is lunching up there to-day.[Pg 75]’”

“It will be hard to replace the artist;

the man can never be replaced,” was one

fine tribute to his memory; and another,

“Death might have had pity and paused

before cutting short so sweet a life-work.”

A sale of some 600 of Corot’s works took

place in the May and June following his

death. It realised nearly two million francs,

or £80,000. This is, of course, not a fraction

of the sum that would be realised were the

same pictures to be put up to auction to-day;

but it shows that his achievement was

beginning to be estimated at something

approaching its true value.

Corot’s work, of which at one time he

was able to boast he had a “complete collection,”

is now scattered to the four corners of

the earth. Paris possesses some splendid

examples at the Louvre, and there are many

not less admirable distributed among the

provincial galleries of France. America

holds a large number in public and private[Pg 76]

galleries, and there are in private ownership

in this country Corots sufficient to

make a magnificent collection. Lately the

National Gallery has been enriched, by the

Salting bequest, with seven fine paintings

from the master’s hand, eloquent witnesses

alike to his individuality and variety.

To me it is an added joy, when I stand

before a Corot picture, to think of the

gracious personality of its creator. It is

almost as if his eager, happy voice were

pointing out the manifold beauties of the

miraculously bedaubed canvas, and recalling

the “moment,” so certainly made permanent

there.

It is always a “moment” that is seized

in Corot’s paintings, with the exception of

some of the earliest. Nature is surprised

with her fairest charms unveiled, in a passing

emotion, of laughter or of tears. There

is life, movement, the tremble of being, in

everything set down. The air is palpitant[Pg 77]

with colour, rainbows are dissolved in an

atmosphere that clothes everything in magic

and mystery.

Beneath the gay confidence of the painting,

subserving the emotion of the moment,

what knowledge is shown in these pictures!

These tree forms, bold and delicate, with

such wonderful subtleties of drawing in

them, give more than externals. They

reveal a very psychology of trees, the soul

that the artist so plainly saw in everything

around him. He was concerned to set down

far more than the details of the scene before

him, not in the least satisfied to be but a

reporter. The higher, or, if you like, deeper

verities were what he strove for, and the

universal verdict to-day is that he did not

strive in vain.

The figure-painting of Corot is comparatively

little known, and it is a subject

of too much importance to attempt to deal

with adequately in small space. An en[Pg 78]thusiastic

critic claims that it includes the

artist’s “absolute masterpieces,” but I doubt

if many would agree, beautiful as some of

these figures are. They show the same

faculty of apprehending a sudden revelation

of beauty as is shown by the more familiar

landscapes, the same exquisite sense of

graces in form and colour, which elude the

eyes of most of us. But it is still in landscape

that Corot is supreme.

I have already stated my conviction that

he was not greatly influenced by other

artists, his predecessors, or contemporaries.

Perhaps Constable, to mention but one name,

helped to open his eyes, but once open he

used them as his own. Again, the classicism

which surrounded him in his youth left

gentle memories that in his age were never

quite forgotten; but it was worn as sometimes

an elderly gentleman wears a bunch

of seals, and had about as much to do with

the essential personality of the wearer.[Pg 79]

He was always true to himself. His

equipment was simple faith, definite purpose,

and unflagging zeal. A clear eye, a dream-haunted

brain, and a great loving heart—that

was Corot.

The plates are printed by Bemrose & Sons, Ltd., Derby and London

The text at the Ballantyne Press, Edinburgh