Title: The Love Affairs of Lord Byron

Author: Francis Henry Gribble

Release date: December 24, 2012 [eBook #41701]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive (http://archive.org)

The Project Gutenberg eBook, The Love Affairs of Lord Byron, by Francis Henry Gribble

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See http://archive.org/details/cu31924013451913 |

Works by the Same Author

MADAME DE STAËL AND HER LOVERS

GEORGE SAND AND HER LOVERS

ROSSEAU AND THE WOMEN HE LOVED

CHATEAUBRIAND AND HIS COURT OF WOMEN

THE PASSIONS OF THE FRENCH ROMANTICS

Lord Byron.

THE LOVE AFFAIRS

OF LORD BYRON

BY FRANCIS GRIBBLE

AUTHOR OF “GEORGE SAND AND HER LOVERS” ETC.

LONDON

EVELEIGH NASH

FAWSIDE HOUSE

1910

Whether a book is called “The Love Affairs of Lord Byron” or “The Life of Lord Byron” can make very little difference to the contents of its pages. Byron’s love affairs were the principal incidents of his life, and almost the only ones. Like Chateaubriand, he might have spoke of “a procession of women” as the great panoramic effect of his career. He differed from Chateaubriand, however, in the first place, in not professing to be very much concerned by the pageant, and, in the second place, in being, in reality, very deeply affected by it. Chateaubriand kept his emotions well in hand, exaggerating them in retrospect for the sake of literary effect, picturing the sensibility of his heart in polished phrases, but never giving the impression of a man who has suffered through his passions, or been swept off his feet by them, or diverted by them from the pursuit of ambition or the serene cult of the all-important ego. In all Chateaubriand’s love affairs, in short, red blood is lacking and self-consciousness prevails. He appears to be equally in love with all the women in the procession; the explanation being that he is more in love with himself than with any of them. In spite of the procession of women, which is admitted[Pg vi] to have been magnificent, it may justly be said of Chateaubriand that love was “of his life a thing apart.”

Of Byron, who coined the phrase (though Madame de Staël had coined it before him) it cannot be said. It may appear to be true of sundry of his incidental love affairs, but it cannot stand as a broad generalisation. His whole life was deflected from its course, and thrown out of gear: first, by his unhappy passion for Mary Chaworth; secondly, by the way in which women of all ranks, flattering his vanity for the gratification of their own, importuned him with the offer of their hearts. Lady Byron herself did so no less than Lady Caroline Lamb, and Jane Clairmont, and the Venetian light o’ loves, though, no doubt, with more delicacy and a better show of maidenly reserve. Fully persuaded in her own mind that he had pined for her for two years, she delicately hinted to him that he need pine no longer. He took the hint and married her, with the catastrophic consequences which we know. Then other women—a long series of other women—did what they could to break his fall and console him. He dallied with them for years, without ever engaging his heart very deeply, until at last he realised that this sort of dalliance was a very futile and enervating occupation, tore himself away from his last entanglement, and crossed the sea to strike a blow for freedom.

That is Byron’s life in a nutshell. His biographer, it is clear, has no way of escape from his[Pg vii] love affairs; while the critic is under an obligation, almost equally compelling, to take note of them. It is not merely that he was continually writing about them, and that the meaning of his enigmatic sentences can, in many cases, only be unravelled by the help of the clue which a knowledge of his love affairs provides. The striking change which we see the tone of his work undergoing as he grows older is the reflection of the history of his heart. Many of his later poems might have been written in mockery of the earlier ones. He had his illusions in his youth. In his middle-age, if he can be said to have reached middle-age, he had none, but wrote, to the distress of the Countess Guiccioli, as a man who delighted to tear aside, with a rude hand, the striped veil of sentiment and hypocrisy which hid the ugly nakedness of truth. The secret of that transformation is written in the record of his love affairs, and can be read nowhere else. His life lacks all unity and all consistency unless the first place in it is given to that record.

Since the appearance of Moore’s Life, and even since the appearance of Cordy Jeaffreson’s “Real Lord Byron,” a good deal of new information has been made available. The biographer has to take cognisance of the various documents brought together in Mr. Murray’s latest edition of Byron’s Writings and Letters; of Hobhouse’s “Account of the Separation”; of the “Confessions,” for whatever they may be worth, elicited from Jane Clairmont and first printed in the Nineteenth Century; of Mr. Richard Edgcumbe’s “Byron: the[Pg viii] Last Phase”; and of the late Lord Lovelace’s privately printed work, “Astarte.”

The importance of each of these authorities will appear when reference is made to it in the text. It will be seen, then, that some of the Murray MSS. give precision to the narrative of Byron’s relations with Lady Caroline Lamb, and that others effectually dispose of Cordy Jeaffreson’s theory that Lady Byron’s mysterious grievance—the grievance which caused her lawyer to declare reconciliation impossible—was her husband’s intimacy with Miss Clairmont. Others of them, again, as effectually confute Cordy Jeaffreson’s amazing doctrine that Byron only brought railing accusations against his wife because he loved her, and that at the time when he denounced her as “the moral Clytemnestra of thy lord,” he was in reality yearning to be recalled to the nuptial bed. Concerning “Astarte” some further remarks may be made.

It is a disgusting and calumnious compilation, designed, apparently, to show that Byron’s descendants accept the worst charges preferred against him by his enemies during his lifetime. Those charges are such that one would have expected a member of the family to hold his tongue about them, even if he were in possession of evidence conclusively demonstrating their truth. That a member of the family should have revived the charges on the strength of evidence which may justly be described as not good enough to hang a dog on almost surpasses belief. Still, the thing has been done, and the biographer’s obligations are[Pg ix] affected accordingly. Unpleasant though the subject is, he must examine the so-called evidence for fear lest he should be supposed to feel himself unable to rebut it; and he is under the stronger compulsion to do so because the mud thrown by Lord Lovelace is not thrown at Byron only, but also at Augusta Leigh, a most worthy and womanly woman, and the best of sisters and wives. It is the hope and belief of the present writer that he has succeeded in definitely clearing her character, together with that of her brother, and demonstrated that the legend of the crime, so industriously inculated by Byron’s grandson, has no shadow of foundation in fact.

Francis Gribble

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Ancestors, Parents, and Hereditary Influences | 1 |

| II. | Childhood and Schooldays at Aberdeen, Dulwich, and Harrow | 10 |

| III. | A Schoolboy’s Love Affairs—Mary Duff, Margaret Parker, and Mary Chaworth | 23 |

| IV. | Life at Cambridge and Flirtations at Southwell | 35 |

| V. | Revelry at Newstead—“English Bards and Scotch Reviewers” | 50 |

| VI. | The Grand Tour—Flirtations in Spain | 63 |

| VII. | Florence Spencer Smith | 75 |

| VIII. | The Maid of Athens—Mrs. Werry—Mrs. Pedley—The Swimming of the Hellespont | 87 |

| IX. | Return to England—Publication of “Childe Harold” | 101 |

| X. | The Secret Orchard | 114 |

| XI. | Lady Caroline Lamb | 127 |

| XII. | The Quarrel with Lady Caroline—Her Character and Subsequent Career | 138 |

| XIII. | Lady Oxford—Byron’s Intention of going Abroad with Her | 148 |

| XIV. | An Emotional Crisis—Thoughts of Marriage, of Foreign Travel, and of Mary Chaworth | 158 |

| XV. | Renewal and Interruption of Relations with Mary Chaworth | 170 |

| [Pg xii]XVI. | Marriage | 182 |

| XVII. | Incompatibility of Temper | 194 |

| XVIII. | Lady Byron’s Demand for a Separation—Rumours that “Gross Charges” might be brought, involving Mrs. Leigh | 208 |

| XIX. | “Gross Charges” Disavowed by Lady Byron—Separation agreed to | 221 |

| XX. | Revival of the Byron Scandal by Mrs. Beecher Stowe and the late Lord Lovelace | 231 |

| XXI. | Inherent Improbability of the Charges against Augusta Leigh—The Allegation that she “Confessed”—The Proof that she did nothing of the kind | 240 |

| XXII. | Byron’s Departure for the Continent—His Acquaintance with Jane Clairmont | 253 |

| XXIII. | Life at Geneva—The Affair with Jane Clairmont | 264 |

| XXIV. | From Geneva to Venice—The Affair with the Draper’s Wife | 277 |

| XXV. | At Venice—The Affair with the Baker’s Wife—Dissolute Proceedings in the Mocenigo Palace—Illness, Recovery and Reformation | 287 |

| XXVI. | In the Venetian Salons—Introduction to Countess Guiccioli | 300 |

| XXVII. | Byron’s Relations with the Countess Guiccioli and her Husband at Ravenna | 312 |

| XXVIII. | Revolutionary Activities—Removal From Ravenna to Pisa | 324 |

| XXIX. | The Trivial Round at Pisa | 336 |

| XXX. | From Pisa to Genoa | 345 |

| XXXI. | Departure for Greece | 356 |

| XXXII. | Death in a Great Cause | 369 |

| Appendix | 375 | |

| Index | 377 |

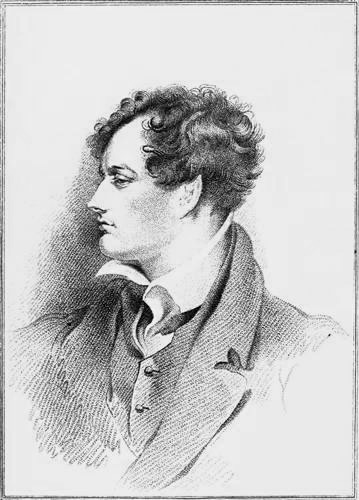

| Lord Byron | Frontispiece | |

| The Maid of Athens | To face page | 88 |

| Lady Caroline Lamb | " | 128 |

| Mary Chaworth | " | 174 |

| Lady Byron | " | 222 |

| Countess Guiccioli | " | 302 |

ANCESTORS, PARENTS, AND HEREDITARY INFLUENCES

The Byrons came over with the Conqueror, helped him to conquer, and were rewarded with a grant of landed estates in Lancashire. Hundreds of years elapsed before they distinguished themselves either for good or evil, or emerged from the ruck of the landed gentry. There were Byrons at Crecy, and at the siege of Calais; and there probably were Byrons among the Crusaders. There is even a legend of a Byron Crusader rescuing a Christian maiden from the Saracens; but neither the maiden nor the Crusader can be identified. The authentic history of the family only begins with the grant of Newstead Abbey, at the time of the dissolution of the monasteries, to Sir John Byron of Clayton, in Lancashire—a reward, apparently, for services rendered by his father at the Battle of Bosworth Field.

Even so, however, the Byrons remained comparatively inconspicuous[1]; and their records only begin to be full and interesting at the time of the war between Charles I. and his Parliament. Seven[Pg 2] Byrons, all brothers, then fought on the King’s side; and the most distinguished of the seven was the eldest, another Sir John Byron of Clayton—a loyal, valiant, and impetuous soldier, with more zeal than discretion. It was his charge that broke Haslerig’s cuirassiers at Roundway Down. It was in his regiment that Falkland was fighting when he fell at Newbury. On the other hand he helped to lose the battle of Marston Moor by charging without orders. “By Lord Byron’s improper charge,” Prince Rupert reported, “much harm hath been done.”

He had been given his peerage—with limitations in default of issue male to his six surviving brothers and the issue male of their bodies—in the midst of the war. After Naseby, he went to Paris, and spent the rest of his life in exile. His first wife being dead, he married a second—a lady concerning whom there is a piquant note in Pepys’ Diary. She was, Pepys tells us, one of Charles II.’s mistresses—his “seventeenth mistress aboard,” who, as the diarist proceeds, “did not leave him till she got him to give her an order for £4000 worth of plate; but, by delays, thanks be to God! she died before she got it.”

This first Lord Byron died childless, and the title passed to his brother Richard, who had also distinguished himself in the war on the King’s side. He was one of the colonels whose gallantry at Edgehill the University of Oxford rewarded with honorary degrees; and he was Governor, successively, of Appleby and Newark. He tried to[Pg 3] seduce his kinsman, Colonel Hutchinson, from his allegiance to the Parliament, but without avail. “Except,” Colonel Hutchinson told him, “he found his own heart prone to such treachery, he might consider that there was, if nothing else, so much of a Byron’s blood in him that he should very much scorn to betray or quit a trust he had undertaken.”

The third Lord, Richard’s son William, succeeded to the title in 1679. His marriage with Elizabeth, daughter of Viscount Chaworth, brings the name of the heroine of the poet’s first and last love into the story; and he is also notable as the first Byron who had a taste, if not actually a turn, for literature. Thomas Shipman, the royalist singer whose songs indicate, according to Mr. Thomas Seccombe’s criticism in the “Dictionary of National Biography,” that “the severe morals of the Roundheads were even less to his taste than their politics,” was his intimate friend; and Shipman’s “Carolina” contains a set of verses from his pen:

“My whole ambition only does extend

To gain the name of Shipman’s faithful friend;

And though I cannot amply speak your praise,

I’ll wear the myrtle, tho’ you wear the bays.”

That is a fair specimen of the third Lord Byron’s poetical style; and it is clear that his descendant did not need to be a great poet in order to improve upon it. Of his son, the fourth Lord, who died in 1736, there is nothing to be said; but[Pg 4] his grandson, the fifth Lord, lives in history and tradition as “the wicked Lord Byron.” The report of his arraignment before his fellow peers on the charge of murdering his relative, Mr. William Chaworth, in 1765, may be read in the Nineteenth Volume of State Trials, though the most careful reading is likely to leave the rights of the case obscure.

The tragedy, whatever the rights of it, occurred after one of the weekly dinners of the Nottinghamshire County Club, at the Star and Garter Tavern in Pall Mall. The quarrel arose out of a heated discussion on the subject of preserving game—a topic which country gentlemen are particularly liable to discuss with heat. Lord Byron is said to have advocated leniency, and Mr. Chaworth severity, towards poachers. The argument led to a wager; and the two men went upstairs together—apparently for the purpose of arranging the terms of the wager—and entered a room lighted only by a dull fire and a single candle. As soon as the door was closed, they drew their swords and fought, and Lord Byron ran Mr. Chaworth through the body.

Those are the only points on which all the depositions agree. Lord Byron said that Chaworth, who was the better swordsman of the two, challenged him to fight, and that the fight was conducted fairly. The case for the prosecution was that Chaworth did not mean to fight, and that Lord Byron attacked him unawares. Chaworth, though he lingered for some hours, and was questioned on the subject, said nothing to[Pg 5] exonerate his assailant. That, broadly speaking, was the evidence on which the peers had to come to their decision; and they found Lord Byron not guilty of murder but guilty of manslaughter. Pleading his privilege as a peer, he was released on payment of the fees.

Society, however, inclined to the view that he had not fought fairly. Two years before he had been Master of the Stag-hounds. Now he was cut by the county, and relapsed into misanthropic debauchery. He quarrelled with his son, the Honorable William Byron, sometime M.P. for Morpeth, for contracting a marriage of which he disapproved. He drove his wife away from Newstead by his brutality, and consorted with a low-born “Lady Betty.” The stories of his shooting his coachman and trying to drown his wife were untrue, but his neighbours believed them, and behaved accordingly; and an unpleasant picture of his retirement may be found in Horace Walpole’s Letters.

“The present Lord,” Horace Walpole writes, “hath lost large sums, and paid part in old oaks; five thousand pounds worth have been cut down near the house. En revanche, he has built two baby forts to pay his country in castles for the damage done to the Navy, and planted a handful of Scotch firs that look like plough-boys dressed in old family liveries for a public day.”

Playing at naval battles and bombardments, with toy ships, on the little lakes in his park, was,[Pg 6] indeed, the favourite, if not the only, recreation of the wicked lord’s old age. It is said that his chief purpose in cutting down the timber was to spite and embarrass his heirs; and he did, at any rate, involve his heir in a law suit almost as long as the famous case of Jarndyce versus Jarndyce by means of an improper sale of the Byron property at Rochdale.

His heir, however, was not to be either his son or his grandson. They both predeceased him—the latter dying in Corsica in 1794—and the title and estates passed to the issue of his brother John, known to the Navy List as Admiral Byron, and to the navy as “foul weather Jack.”

The Admiral had been round the world with Anson, had been wrecked on the coast of Chili, and had published a narrative—“my granddad’s narrative”—of his hardships and adventures. He had later been sent round the world on a voyage of discovery on his own account, but had discovered nothing in particular. Finally he had fought, not too successfully, against d’Estaing in the West Indies, and had withdrawn to misanthropic isolation. His son, Captain Byron, of the Guards, known to his contemporaries as “Mad Jack Byron,” was a handsome youth of worthless character, but very fascinating to women. His elopement, while still a minor, with the Marchioness of Carmarthen, was one of the sensational events of a London season.

Lady Carmarthen’s husband having divorced her, Mad Jack married her in 1778. They lived[Pg 7] together in Paris and at Chantilly—prosperously, for the bride had £4000 a year in her own right. A child was born—Augusta, who subsequently married Colonel Leigh; but, in 1784, his wife died, and Captain Byron, heavily in debt, was once more thrown on his own resources. He returned to England to look for an heiress, and he found one in the person of Miss Gordon of Gight, whom he met and married at Bath in 1786.

The fortune, when the landed estates had been realised, amounted to about £23,000; and Captain Byron’s clamorous creditors took most of it. A considerable portion of what was left was quickly squandered in riotous living on the Continent. The ultimate income consisted of the interest (subject to an annuity to Mrs. Byron’s grandmother) on the sum of £4200; and that lamentable financial position had already been reached when Captain and Mrs. Byron came back to England and took a furnished house in Holles Street, where George Noel Gordon, sixth Lord Byron, was born on January 22, 1788.

There we have, in brief outline, all that is essential of the little that is known of Byron’s heredity. If it is not precisely common-place, it is at least undistinguished. No one can ever have generalised from it and said that the Byrons were brilliant, or even—in spite of the third Lord’s conscientious attempts at versification—that they were “literary.” A far more likely generalisation would have been that the Byrons were mad.

They were not quite that, of course, though[Pg 8] some of them were eccentric; and those who were eccentric had the courage of their eccentricity. But they were, at least so far as we know them, impetuous and reckless men—men who went through life in the spirit of a bull charging a gate, doing what they chose to do because they chose to do it, with a defiant air of “damn the consequences.” We find that note alike in the first Lord’s “improper charge” on Marston Moor, and the fifth Lord’s improvised duel in the dark room of the Pall Mall tavern, and in Captain Byron’s dashing elopement with a noble neighbour’s wife. We shall catch it again, and more than once, in our survey of the career of the one Byron who has been famous; and we shall see how much his fame owed to his pride, his determined indifference, in spite of his prickly sensitiveness, to public opinion, and his clear-cut, haughty character.

Legh Richmond, the popular evangelical preacher, once said that, if Byron had been as bad a poet as he was a man, his poetry would have done but little harm, but that criticism is almost an inversion of the truth. Byron, in fact, imposed himself far less because his poetry was good than because his personality was strong. He never saw as far into the heart of things as Wordsworth. When he tried to do so, at Shelley’s instigation, he only saw what Wordsworth had already shown; and there are many passages in his work which might fairly be described as being “like Wordsworth only less so.” None of his shorter pieces are fit to stand beside “The world is too much with us,” and he never[Pg 9] wrote a line so wonderfully inspired as Wordsworth’s “still, sad music of humanity.”

But he had one advantage over Wordsworth. He spoke out; he was not afraid of saying things. His genius had all the hard riding, neck-or-nothing temper of the earlier, undistinguished Byrons behind it. He was “dowered with the hate of hate, the scorn of scorn,”—and he damned the consequences with the haphazard blasphemy of an aristocrat who feels sure of himself, and has no need to pick his words. He was quite ready to damn them in the presence of ladies, and in the face of kings; and he damned them as one having authority, and not as the democratic upstarts; so that the world listened attentively, wondering what he would say next, and even Shelley, observing how easily he compelled a hearing, was fully persuaded that Byron was a greater poet than himself.

That, in the main, it would seem, was how heredity affected him. The hereditary influences, however, were, in their turn modified by the strange circumstances of his upbringing; and it is time to glance at them, and see how far they help to account for the loneliness and aloofness of Byron’s temperament, for the sensitiveness already referred to, and for the ultimate attitude known as the Byronic pose.

CHILDHOOD AND SCHOOLDAYS AT ABERDEEN, DULWICH, AND HARROW

Captain and Mrs. Byron, finding themselves impoverished, left Holles Street, and retired to Aberdeen, to live on an income of £150 a year. Augusta having been taken off their hands by her grandmother, Lady Holderness, they were alone together, with the baby and the nurse, in cheap and gloomy lodgings; and they soon began to wrangle. It was the old story, no doubt, of poverty coming in at the door and love flying out of the window, leaving only incompatibility of temper behind.

The husband, though inclined to be amiable as long as things went well, was, in modern phrase, a “waster.” The wife, though shrewd and possessed of some domestic virtues, was, in the language of all time, a scold. He wanted to run into debt in order to keep up appearances; she to disregard appearances in order to live within her income. Dinners of many courses and wines of approved vintages seemed to her the superfluities but to him the necessaries of life. He probably did not mince words in expressing his view of the matter; she certainly minced none in expressing hers. There is a strong presumption, too, that she [Pg 11]complained of him to her neighbours; for it is well attested in her son’s letters to his sister that she was that sort of woman. So the day came when Captain Byron walked out of the house, vowing that he would live with his wife no longer.

For a time he lived in a separate lodging in the same street. Presently, scraping some money together—borrowing it, that is to say, without any intention of repaying it—he went to France to amuse himself; and in January 1791, at the age of thirty-five, he died at Valenciennes. It has been suggested that he committed suicide, but nothing is known for certain. One of Byron’s earliest recollections was of his mother’s weeping at the news of her husband’s death, and of his own astonishment at her tears. She had continually nagged at him, and heaped abuse on him, while he lived; yet now her distracted shrieks filled the house and disturbed the neighbourhood. That was the child’s earliest lesson in the unaccountable ways of women. He was only three at the time—yet old enough to wonder, though not to understand.

His stay at Aberdeen was to last for seven more years. He was to go to school there, and to be accounted a dunce, though not a fool. He was to learn religion there from his nurse, who taught him the dark, alarming Calvinistic doctrine; and he was to develop some of the traits and characteristics which were afterwards to be pronounced. On the whole, indeed, in spite of alleviations, he had a gloomy childhood, by a sense, however imperfectly comprehended, of the contrast[Pg 12] between life as it was and life as it ought to have been.

He had been born proud, inheriting quite as much pride from his mother’s as from his father’s family. He soon came to know that there were such things as old families, and that the Byron family was one of the oldest of them. It was borne in upon him by what he saw and heard that the proper place for a baron was a baronial hall; and he could see that the apartment in which he was growing up was neither a hall nor baronial. The first apartment occupied by his mother was, in fact, as has already been said, a lodging, and the second was an “upper part,” the furniture of which, when it ultimately came to be sold, fetched exactly £74 17s. 7d.

The boy must have felt—we may depend upon it that his mother told him—that there was something wrong about that; that his school companions were make-shift associates, not really worthy of him; that he was, as it were, a child born in exile, and unjustly kept out of his rights. The feeling must have grown stronger—we may be quite sure that his mother stimulated it—when the unexpected death of his cousin made him the direct heir to the title and estates; and, indeed, it was a feeling to some extent justified by the facts. His great-uncle, the wicked Lord Byron, ought then, as everybody said, to have shown signs of recognition, and to have offered an allowance.

He made no sign, however, and he offered no allowance. Instead of doing so, he went on felling timber, and effected the illegal sale of the Rochdale[Pg 13] property already referred too; and for four more years—from the age of six, roughly speaking, to the age of ten—the heir apparent to the barony was living poorly in an Aberdeen “upper part,” while the actual baron was living in luxury and state at Newstead. There were good grounds for bitterness and resentment there; and Mrs. Byron, with her unruly tongue, was the woman to make the most of them. Family pride grew apace under her influence; and there was no other influence to check or counteract it. The boy learnt to be as proud of his birth as a parvenu would like to be—a characteristic of which we shall presently note some examples.

If he was proud, however, he was also sensitive: and it may well have been that his pride was, to some extent, a shield of protection which his sensitiveness threw up. He was sensitive, not only because he was poor when he ought to be rich and insignificant when he ought to be important, but also because he was lame. An injury done at birth to his Achilles tendons prevented him from planting his heels firmly on the ground. He had to trot on the ball of his foot instead of walking; he could not even trot for more than a mile or so at a time. A physical defect of that sort is always a haunting grief to a child—especially so, perhaps, to a child with a dawning consciousness of great mental gifts. It appears to such a child as an irreparable wrong done—a wrong which can never be either righted or avenged—an irremovable mark of inferiority, inviting taunts and gibes.

[Pg 14]Byron was sensitive on the subject, fearing that it made him ridiculous, throughout his life, alike when he was the darling and when he was the outcast of society; and various stories show how the deformity embittered his childhood.

“What a pretty boy Byron is! What a pity he has such a leg!” he, one day, heard a lady say to his nurse.

“Dinna speak of it,” he screamed, stamping his foot, and slashing at her with his toy whip.

And then there is the story of his mother who, in one of her fits of passion, called him “a lame brat.”

He drew himself up, and, with a restraint and a concentrated scorn beyond his years, replied in the word which he afterwards put into “The Hunchback”:

“I was born so, mother.”

That was one of the passionate scenes that passed between them—but only one among many; and it was only in the case of this one affront which cut him to the quick, that the child displayed such precocious self-control. More often he answered rage with rage and violence with violence. In one fit of fury he tore his new frock to shreds; in another he tried to stab himself, at table, with a dinner knife. Exactly why he did it, or what he resented, he probably did not know either at the time, or afterwards; but he vaguely felt, no doubt, that something was wrong with the world, and instinct impelled him to kick against the pricks and damn the whole nature of things.

[Pg 15]Then, in 1798, came the sudden change of fortune. The wicked Lord Byron was dead at last; and the child of ten was a peer of the realm and the heir to great, though heavily mortgaged estates. He could not take possession of them yet—the embarrassed property needed to be delicately nursed—but still, subject to the charges, they were his. He was taken to look at them, and then, a tenant having been found for Newstead, Mrs. Byron settled, first at Nottingham, and then in London, and her son was sent to school—first to a preparatory school at Dulwich, and then to Harrow.

Even so, however, there remained something strange, abnormal, and uncomfortable about his position. On the one hand, Mrs. Byron, not understanding, or trying to understand, him, nagged and scolded until he lost almost all his natural affection for her. On the other hand, his father’s relatives, whether because they felt that “Mad Jack” had disgraced the family, or because they objected to Mrs. Byron—who, in truth, in spite of her good birth, was extremely provincial in her style, and of loquacious, mischief-making propensities—were very far from cordial. They had not even troubled to communicate with her when the death of her son’s cousin made him the direct heir, but had left her to learn the news accidentally from strangers. Lord Carlisle, the son of his grandfather’s sister, Isabella Byron, consented to act as his guardian, but abstained from making friendly overtures.

The fault in that case, however, was almost[Pg 16] entirely Mrs. Byron’s. There was some dispute between her and Dr. Glennie, her son’s Dulwich headmaster—a dispute which culminated in a fit of hysterics in Dr. Glennie’s study. Lord Carlisle was appealed to, and the result of his attempt at mediation was that Mrs. Byron practically ordered him out of the house. Byron, of course, could not help that; but, equally of course, he suffered from it. He was neglected, and he was sensible of the neglect. He had come into a world in which he had every right to move, only to be made to feel that he was not wanted there. Born in exile, and having returned from exile, he was cold-shouldered by kinsmen who seemed to think that he would have done better to remain in exile.

Very likely he was, at that age, somewhat of a lout, shy, ill at ease, and unprepossessing. Genius does not necessarily reflect itself in polished behaviour. Aberdeen is not as good a school of manners as Eton, and Mrs. Byron was but an indifferent teacher of deportment. But his pride, it seems clear, was not the less but the greater because of his inability to express it in strict accordance with the rules of the best society. He was a Byron—a peer of the realm—the senior representative of an ancient house. He knew that respect, and even homage, were due to him; and he felt that he must assert himself—if not in one way, then in another. So, when the Earl of Portsmouth—a peer of comparatively recent creation—presumed to give his ear a friendly pinch, he asserted himself by picking up a sea-shell and throwing it at the[Pg 17] Earl of Portsmouth’s head. That would teach the Earl, he said, not to take liberties with other members of the aristocracy.

At this date, too, when writing to his mother, he addressed her as “the Honorable Mrs. Byron,” a designation to which, of course, she had no shadow of a right; and he earned the nickname of “the old English Baron” by his habit of boasting to his schoolfellows of the amazing antiquity of his lineage. Lord Carlisle may well have thought that it was high time for his ward to go to Harrow to be licked or kicked into shape. He went there in 1803, at the age of thirteen and a half.

Dr. Drury, of Harrow, was the first man who saw in Byron the promise of future distinction. “He has talents, my lord,” he soon assured his guardian, “which will add lustre to his rank.” Whereat Lord Carlisle merely shrugged his shoulders and said, “Indeed!”—whether because his ward’s talents were a matter of indifference to him, or because he considered that rank could dispense with the lustre which talents bestow.

According to his own recollections, Byron was quick but indolent. He could run level in the class-room with Sir Robert Peel, who afterwards took a sensational double-first at Oxford, when he chose; but, as a rule, he did not choose. He absorbed a good deal of scholarship, without ever becoming a good scholar in the technical sense, and his declamations on the speech-days were[Pg 18] much applauded. There are records to the effect that he was bullied. A specially offensive insult directed at him in later life drew from him the retort that he had not passed through a public school without learning that he was deformed; and Leigh Hunt has related that sometimes “he would wake and find his leg in a tub of water.” But he was not an easy boy to bully, for he was ready to fight on small provocation; and he won all his fights except one. He did credit to his religious training by punching Lord Calthorpe’s head for calling him an atheist, though it is possible that his objections to the obnoxious epithet were as much social as theological, for an atheist, among schoolboys is, by implication, an “outsider.”

“I was a most unpopular boy,” he told Moore, “but led latterly.” The latter statement has been generally accepted by his biographers; but not all the stories told in support of it stand the test of inquiry. There is the story, for instance, accepted even by Cordy Jeaffreson, that he led the revolt against Butler’s appointment to the headmastership, but prevented his followers from burning down one of the class-rooms by reminding them that the names of their ancestors were carved upon the desks. “I can certify,” wrote the late Dean Merivale of Ely, “that just such a story was told in my early days of Sir John Richardson;” so that Byron seems here to have got the credit for another hero’s exploits.

There are the stories, too, of his connection with[Pg 19] the first Eton and Harrow cricket match. Cordy Jeaffreson goes so far as to express doubt whether he took part in the match at all; but that is exaggerated scepticism, which research would have confuted. The score is printed in Lillywhite’s “Cricket Scores and Biographies of celebrated Cricketers;” and it appears therefrom that Byron scored seven runs in the first innings and two in the second, and also bowled one wicket; but even on that subject the Dean of Ely, who went to Harrow in 1818, has something to say.

“It is clear,” the Dean writes, “that he was never a leader.... On the contrary, awkward, sentimental, and addicted to dreaming and tombstones, he seems to have been held in little estimation among our spirited athletes. The remark was once made to me by Mr. John Arthur Lloyd (of Salop), a well-known Harrovian, who had been captain of the school in the year of the first match with Eton (1805): ‘Yes,’ he said, ‘Byron played in the match, and very badly too. He should never have been in the eleven if my counsel had been taken.’”

And the Dean goes on, picturing Byron’s awkwardness:

“Mrs. Drury was once heard to say of him: ‘There goes Byron’ (Birron she called him) ‘straggling up the hill, like a ship in a storm without rudder or compass.’”

[Pg 20]Byron’s influence at Harrow, in short, was exercised over his juniors rather than his contemporaries. It pleased him, when he was big enough, to protect small boys from school tyrants. One catches his feudal spirit again in his appeal to a bully not to lick Lord Delawarr “because he is a fellow peer”; but he was also ready to intervene in other cases in which that plea could not be urged; and he had the reward that might be expected. He once offered to take a licking for one of the Peels; and he became a hero with hero-worshippers—titled hero-worshippers for the most part—sitting at his feet. Lord Delawarr, Lord Clare, the Duke of Dorset, the Honorable John Wingfield, were the most conspicuous among them. It was from their adulation that he got his first taste of the incense which was, in later years, to be burnt to him so lavishly.

He described his school friendships, when he looked back on them, as “passions”; and there is no denying that the language of the letters which he wrote to his friends was inordinately passionate for a schoolboy addressing schoolfellows. “Dearest” is a more frequent introduction to them than “dear,” and the word “sweet” also occurs. It is not the happiest of signs to find a schoolboy writing such letters; and it is not altogether impossible that unfounded apprehensions caused by them account for the suggestion made by Drury—though the fact is not mentioned in the biographies—that Byron should be quietly removed from the school on the ground that his conduct was causing “much trouble and uneasiness.”

[Pg 21]That, however, is uncertain, and one must not insist. All that the so-called “passions”—occasionally detrimental though they may have been to school discipline—demonstrate is Byron’s enjoyment of flattery, and his proneness to sentiment and gush. He liked, as he grew older, to accept flattery, while professing to be superior to it; to enjoy sentiment, and then to laugh at it; to gush with the most gushing, and then suddenly to turn round and “say ‘damn’ instead.” But the cynicism which was afterwards to alternate with the sentimentalism had not developed yet. He did not yet say “damn”—at all events in that connection.

One must think of him as a boy with a great capacity for passionate affection, and a precocious tendency to gush, deprived of the most natural outlets for his emotions. He could not love his mother because she was a virago; he hardly ever saw his sister; his guardian kept him coldly at a distance. Consequently his feelings, dammed in one direction, broke out with almost ludicrous intensity in another; and his friendships were sentimental to a degree unusual, though not, of course, unknown or unprecedented, among schoolboys. He wrote sentimental verses to his friends.

But not to them alone. “Hours of Idleness,” first published when he was a Cambridge undergraduate, is the idealised record of his school friendships; but it is also the idealised record of other, and very different, excursions into sentiment. It introduces us to Mary Duff, to Margaret Parker,[Pg 22] to Mary Chaworth,—and also to some other Maries of less importance; and we will turn back and glance, in quick succession at their stories before following Byron to Cambridge.

A SCHOOLBOY’S LOVE AFFAIRS—MARY DUFF, MARGARET PARKER, AND MARY CHAWORTH

First on the list of early loves comes little Mary Duff of Aberdeen. She was one of Byron’s Scotch cousins, though a very distant one; and there is hardly anything else to be said, except that he was a child and she was a child in their kingdom by the sea. Only no wind blew out of a cloud chilling her. Her mother made a second marriage—described by Byron as a “faux pas” because it was socially disadvantageous—and left the city; and the two children never met again.

It was of no importance, of course. They were only a little more than seven when they were separated. But Byron was proud of his precocity, and liked to recall it, and to wonder if any other lover had ever been equally precocious. “I have been thinking lately a good deal of Mary Duff,” he wrote in a fragment of a diary at the age of twenty-five; and he reminded himself how he used to lie awake, picturing her, and how he urged his nurse to write her a love letter on his behalf, and how they sat together—“gravely making love in our way”—while Mary expressed pity for her[Pg 24] younger sister Helen, for not having an admirer too. Above all, he reminded himself of the shock which he felt, years afterwards, when the sudden communication of a piece of news revived the recollection of the idyll.

“My mother,” he proceeded, “used always to rally me about this childish amour; and, at last, many years after, when I was sixteen, she told me, one day, ‘Oh, Byron, I have had a letter from Edinburgh, from Miss Abercromby, and your old sweetheart Mary Duff is married to a Mr. C——.’ And what was my answer? I really cannot explain or account for my feelings at that moment; but they nearly threw me into convulsions, and alarmed my mother so much that, after I grew better, she generally avoided the subject—to me—and contented herself with telling it to all her acquaintance.”

And then again:

“My misery, my love for that girl were so violent that I sometimes doubt if I have ever been really attached since. Be that as it may, hearing of her marriage several years after was like a thunder stroke—it nearly choked me—to the horror of my mother and the astonishment and almost incredulity of nearly everybody.”

It is a well-known story, and one can add nothing to it beyond the fact that Mary Duff’s husband was Mr. Cockburn, the wine merchant, and that she lived quite happily with him, and that we are[Pg 25] entitled to think of her whenever we drink a glass of Cockburn’s port. But we may also doubt, perhaps, whether Byron is, in this case, quite a faithful reporter of his own emotions, and whether his grief was not artistically blended with other and later regrets, and other and later perceptions of the fickleness of the female heart and the mutability of human things. For when we come to look at the dates, we find that the date of Mary Duff’s marriage was also the date of Byron’s desperate passion for Mary Chaworth.

Between Mary Duff and Mary Chaworth, however, Margaret Parker had intervened. She was another cousin, descended from Admiral Byron’s daughter Augusta. The first letter that Byron ever wrote was addressed to her mother. “Dear Madam,” it began, “My Mamma being unable to write herself desires I will let you know that the potatoes are now ready and you are welcome to them whenever you please.” For the rest, one can only quote Byron’s brief reminiscence:

“My first dash into poetry was as early as 1800. It was the ebullition of a passion for my first cousin Margaret Parker, one of the most beautiful of evanescent beings. I have long forgotten the verses, but it would be difficult for me to forget her—her dark eyes—her long eyelashes—her completely Greek cast of face and figure! I was then about twelve—she rather older, perhaps a year. She died about a year or two afterwards in consequence of a fall which injured her spine and[Pg 26] induced consumption.... My sister told me that, when she went to see her, shortly before her death, upon accidentally mentioning my name, Margaret coloured through the paleness of mortality to the eyes.... I knew nothing of her illness, being at Harrow and in the country, till she was gone. Some years after I made an attempt at an elegy—a very dull one.”

And then Byron speaks of his cousin’s “transparent” beauty—“she looked as if she had been made out of a rainbow”—and concludes:

“My passion had its usual effect upon me—I could not eat—I could not sleep—I could not rest; and although I had reason to know that she loved me, it was the texture of my life to think of the time that must elapse before we could meet again, being usually about twelve hours of separation! But I was a fool then, and am not much wiser now.”

The elegy is included in the collected works. Special indulgence is asked for it on the ground that it was “composed at the age of fourteen.” It is very youthful in tone—quite on the conventional lines—as one would expect. A single quatrain may be given—not to be criticised, but merely to show that Byron, as a boy, was still looking at life pretty much as his pastors and masters told him to look at it:

“And shall presumptuous mortals Heaven arraign!

And, madly, Godlike Providence accuse!

[Pg 27]Ah! no, far fly from me attempts so vain;—

I’ll ne’er submission to my God refuse.”

We are still a long way here from the intense, the cynical, the defiant, or even the posturing Byron of later years. The gift of personal expression has not yet come to him; and he is still in literary fetters, weeping, on paper, according to the rules. Intensity and the personal note only begin with his sudden love for Mary Chaworth; cynicism and defiance only begin after that love affair has ended in failure.

Mary Chaworth was the heir of the Annesley property, adjoining Newstead, and she was the grand-niece of the Chaworth whom the wicked Lord Byron ran through the body in the upper chamber of the Pall Mall tavern; so that their marriage, if they could have been married, would, as Byron says, “have healed feuds in which blood had been shed by our fathers.” But Byron was not yet the Byron who had only to come, and to be seen, in order to conquer. He was a schoolboy of fifteen, which is an awkward age. He had achieved no triumphs in any field which could give him self-assurance. He was not yet a leader, even among his schoolfellows; and he was not only lame, but also fat. How shall a fat boy hope, whatever fires of genius burn within him, to enter the lists against his elders and bear away the belle from county balls? Byron, at any rate, failed signally in the attempt to do so.

[Pg 28]Newstead having been let to Lord Grey de Ruthen, Mrs. Byron was, at the time, lodging at Nottingham; and Byron had various reasons for preferring to see as little of her as possible. She was never sympathetic; she was often quarrelsome; it was her pleasant habit, when annoyed, to rattle the fire-irons and throw the tongs at him. So he often availed himself of his tenant’s invitation to visit Newstead, whenever he liked; and from Newstead it was the most natural thing in the world that he should go over to Annesley, where Miss Chaworth, with whom he already had a slight acquaintance, was living with her mother, Mrs. Clarke.

He was always welcome there. There was as little desire on his cousin’s side as on his to revive the recollection of the feud. When he came to call, he was pressed to stay and sleep. At first he refused, most probably from shyness, though he professed a superstitious fear of the family portraits. They had “taken a grudge to him,” he said, on account of the duel; they would “come down from their frames at night to haunt him.” But presently his fears, or his shyness, were conquered. He had seen a ghost, he said, in the park; and if he must see ghosts he might just as well see them in the house; so, if it was all the same to his hosts, he would like to stay.

He stayed, and was entranced with Mary Chaworth’s singing. He rode with her, and practiced pistol shooting on the terrace—more than a little pleased, one conjectures, to show off his[Pg 29] marksmanship. He went with her—and with others, including a chaperon—on an excursion to Matlock and Castleton. A note, written long afterwards, preserves a memory of the trip:

“It happened that, in a cavern in Derbyshire, I had to cross in a boat (in which two people only could lie down) a stream which flows under a rock, with the rock so close upon the water as to admit the boat only to be pushed on by a ferryman (a sort of Charon) who wades at the stern, stooping all the time. The companion of my transit was M.A.C., with whom I had long been in love, and never told it, though she had discovered it without. I recollect my sensations, but cannot describe them, and it is as well.”

And no doubt Mary Chaworth encouraged the boy, amused at his raptures, enjoying the visible proof of her power, prepared to snub him, in the end, if necessary, but scarcely expecting that there would be any need for her to do so. She was seventeen, and a girl of seventeen always feels capable of reminding a boy of fifteen that the prayer book forbids him to marry his grandmother. Moreover, she was engaged, though the engagement had not yet been announced, to Mr. John Musters—a grown man and a Philistine—a handsome, rather dissipated, hard-riding and hard-drinking country squire. The dreamy, limping, fat boy from Harrow had no shadow of a chance against his athletic rival. It was impossible for[Pg 30] Mary Chaworth to divine the genius that lurked beneath the fat. One has no right to expect such powers of divination from girls of seventeen.

No doubt she thought the fat boy, as she would have said, “good fun.” No doubt she was amused when, as a demonstration that he was not too young to be loved, he showed her the locket which Margaret Parker had given him, three years before, when he was twelve. Unquestionably she flirted with him—or, at least, let him flirt with her. She even gave him a ring, and the gift must have raised high hopes, though it was the cause of the discovery which brought the flirtation to an end.

Squire Musters discovered the ring among Byron’s clothes one day when he and the boy were bathing together in the Trent. He recognised it, picked it up, and put it in his pocket. Byron claimed it, and Musters declined to give it up; and then, to quote the Countess Guiccioli, who is the authority for the story:

“High words were exchanged. On returning to the house, Musters jumped on a horse and galloped off to ask an explanation from Miss Chaworth, who, being forced to confess that Lord Byron wore the ring with her consent, felt obliged to make amends to Musters by promising to declare immediately her engagement with him.”

Such is the story, as one gets it, through the Countess and through Moore, from Byron himself; but we also get a side glimpse at it in a letter,[Pg 31] recently published,[2] from Mrs. Byron to Hanson, the family solicitor. From this we gather that Byron, in order to make love, had absented himself from school; that Drury had inquired the reason of his absence; and that his mother was making strenuous, but unavailing, efforts to induce him to return. Nothing was the matter with him but love—“desperate love, the worst of all maladies in my opinion.” He had hardly been to see his mother at all, but had been spending all his time at Annesley. “It is the last of all connexions,” she added, “that I should wish to take place”; and she begged Mr. Hanson to make arrangements for her son to spend his next holidays elsewhere. Expense was no object; and it would suit her very well if Dr. Drury could be induced to detain him at Harrow.

And Byron himself, meanwhile, was writing to his mother, alternately using lofty language about his right to choose his own friends, and pleading for one more day in order that he might take leave.

He took it; but there is more than one version of the story.

“Do you think,” he overheard Mary Chaworth say to her maid, “that I could care anything for that lame boy?” And, having heard that, “he instantly darted out of the house, and, scarcely knowing whither he ran, never stopped till he found himself at Newstead.” That is what Moore tells us; but the picture drawn in “The Dream,”—the[Pg 32] most obviously and deliberately autobiographical of Byron’s poems—is different.

“She loved,” he writes:

“Another: even now she loved another,

And on the summit of that hill she stood

Looking afar as if her lover’s steed

Kept pace with her expectancy, and flew.”

She was waiting, that is to say, for Squire Musters to ride up the lane, while listening to Byron’s declaration. That is the first picture; and then there follows the picture of the boy who “within an antique oratory stood,” and to whom, presently, “the lady of his love re-entered”:

“She was serene and smiling then, and yet

She knew she was by him beloved—she knew,

For quickly comes such knowledge, that his heart

Was darkened with her shadow, and she saw

That he was wretched, but she saw not all.

He rose, and with a cold and gentle grasp

He took her hand; a moment o’er his face

A tablet of unutterable thoughts

Was traced, and then it faded, as it came;

He dropped the hand he held, and with slow steps

Retired, but not as bidding her adieu,

For they did part with mutual smiles; he passed

From out the massy gate of that old Hall,

And mounting on his steed he went his way;

And ne’er repassed that hoary threshold more.”

[Pg 33]There we have the Mary Chaworth legend as it has been handed down from one generation of biographers to another. Byron, according to that legend, saw Mary once after her marriage, but once only. He was on the point of visiting her at a later date, but was dissuaded by his sister. “If you go,” Augusta said, “you will fall in love again, and then there will be a scene; one step will lead to another, et cela fera un éclat.” He agreed that the reasoning was sound, and did as he was advised. He tells that story himself, and adds: “Shortly after, I married.”

And yet—the legend continues—this hopeless love, which touched his heart at the age of fifteen, was the dominating influence of his life. Mary Chaworth, though always absent, was yet always present. He never loved any other woman, though he tried to love, and indeed seemed to love, several. The vision of her face always came between him and them. His later love affairs were only concessions, or attempts to escape from himself and his memories—unavailing attempts, for this memory continued to haunt him until the end.

It sounds incredible. The thoughts of youth may be long, long thoughts; but the memories of youth are short, and the dreams of youth are dreams from which we never fail to wake. And yet Byron insists, quite as much as biographers have insisted. He insists in “The Dream,” which was written more than a decade after the parting. He insists in later poems, the inner meaning of[Pg 34] which is hardly to be questioned. So that speculation is challenged, and, when pursued, leads us inevitably to a dilemma.

For of two things, one: Either Byron was posing—posing not only to the world but to himself; or else the story, as all the biographers from Moore to Cordy Jeaffreson have told it, is incomplete, and after an interlude, had a sequel.

To search for such a sequel will be our task presently. Unless we can find one, the development of the personal note in Byron’s work will have to be left unexplained. The impression which we get, if we read the more personal poems in quick succession, is of a man who first awakes from the dream of love—and remains very wide awake for a season—and then relapses and dreams it all over again. Unless the story which first set him dreaming had had a sequel, that would hardly be. So we will seek for the sequel in due course, though we must first gather up the incidents of the interlude.

LIFE AT CAMBRIDGE AND FLIRTATIONS AT SOUTHWELL

Baffled in love, Byron returned to Harrow, after a term’s absence, in January 1804, and remained there for another eighteen months. This eighteen months is the period during which he describes himself as having been happy at school. It is also the period during which he haunted the Harrow churchyard, indulging his day dreams as he looked down from the hillside on the wide, green valley of the Thames. Those dreams, it is hardly to be doubted, were chiefly of Mary Chaworth; and we may picture the poet’s secret sorrow as giving him, fat though he was, a sense of superiority over other boys who had no secret sorrows. Apparently, too, casting about for an explanation of his failure, he realised that, in the rivalries of love, the victory is far less likely to rest with the fat than with the lame; and so, presently,—though not until after an interval of reflection—he set himself the task of compelling his too solid flesh to melt.

He has been laughed at, and charged with vanity for doing so; but he was right. He would also have been ridiculed, and with more justice, if he had resigned himself to be overwhelmed by the[Pg 36] rising tide of superabundant tissue. Fatness is not merely a grotesque condition. It is a condition incompatible with fitness; and it is far nobler to resist it with systematic heroism than to cultivate it and call heaven and earth to witness that one is the fattest person going; and the fact that Byron, by dint of exercises which made him perspire, a careful diet, and a persistent use of Epsom salts, reduced his weight from fourteen stone six to twelve stone seven, is no small achievement to be passed over lightly. It is, on the contrary, one of the most memorable incidents in his development—the greatest of all the feats performed by him at Trinity College, Cambridge,[3] where he began to reside in October 1805.

He did not read for honours. At Oxford he might have done so, and might have figured in the same class list as his Harrow friend, Sir Robert Peel, who took a double-first, and Archbishop Whately, who took a double-second. At Cambridge, however, the pernicious rule prevailed that honours were only for mathematicians. The Classical Tripos was not originated until a good many years afterwards, and Byron had neither talent nor taste for figures. The most notable, though not the highest, wranglers of his year were Adam Sedgwick, the geologist, and Blomfield, Bishop of London. Byron would have had to work very hard to make any show against them.[Pg 37] He did not enter the competition, but let his mind exercise itself on more congenial themes, cherishing the belief—so erroneous and yet so common—that Senior Wranglers never come to any good in after life.

His allowance was £500 a year; and he kept a servant and a horse. His general proceedings, except when he was writing verses were pretty similar to those of the average young nobleman who attends a University, not to instruct but to amuse himself. He rode, and fenced, and boxed, and swam, and dived; he gambled and backed horses; he was alternately guest and host at rather uproarious wine-parties, and was spoken of as a young man “of very tumultuous passions.” The statement has been made—he has made it himself and his biographers have repeated it—that he lived quietly at first, and only latterly got into a dissipated set; but as we find him, in his second term, entreating his sister to back a bill for £800, the statement probably needs to be modified in order to square with the facts.

Apparently Augusta did not comply with his request; but the proofs that he lived beyond his means are ample. Mrs. Byron was as loud in her wail on the subject as the widows of Asher. She complains—this also in the second term—of bills “coming in thick upon me to double the amount I expected”; and she protests, in Byron’s first Easter vacation, against his wanton extravagance in subscribing thirty guineas to Pitt’s statue; while, in the course of the next Easter vacation we find her[Pg 38] consulting the family solicitor as to the propriety of borrowing £1000 to get her son out of the hands of the Jews, and declaring that, during the whole of his Cambridge career he has done “nothing but drink, gamble, and spend money.”

Very similar is the testimony of his own and his sister’s letters. “I was much surprised,” Augusta writes, in the second term, to the solicitor, “to see my brother a week ago at the Play, as I think he ought to be employing his time more profitably at Cambridge.” Byron himself, writing to his intimates, confesses to several departures from sobriety. The first was in celebration of the Eton and Harrow match, which was followed by a convivial scene, foreshadowing those at the Empire on boat-race night, at some place of public entertainment. “How I got home after the play,” Byron says, “God knows. I hardly recollect, as my brain was so much confused by the heat, the row, and the wine I drank, that I could not remember in the morning how I found my way to bed.” Later, in a letter to Miss Elizabeth Bridget Pigot of Southwell, he speaks of his life as “one continual routine of dissipation,” talks of “a bottle of claret in my head,” and concludes with the specific admission: “Sorry to say been drunk every day, and not quite sober yet.”

Possibly he exaggerates a little; but those who know the Universities best will be least likely to suspect him of exaggerating very much. There is always a set which lives in that style at any college frequented by young men of ample means. Their[Pg 39] ways, mutatis mutandis, are faithfully described in the pages of “Verdant Green.” Byron’s career, once more mutatis mutandis, was not unlike the career of Charles Larkyns and Little Mr. Bouncer in Cuthbert Bede’s picture of life at the sister University. He had, at any rate, one foot in such a set as that, though he was in a better set as well, and formed serious friendships with such men as Hobhouse, afterwards Lord Broughton, Charles Skinner Matthews, afterwards Fellow of Downing, Scrope Davies, afterwards Fellow of King’s, and Francis Hodgson, ultimately Provost of Eton. It is not quite clear whether he was, or was not, one of the rowdy spirits who “ragged” Lort Mansell, the Master of Trinity.[4] He certainly annoyed the dons by keeping a bear as a pet, and asserting that he intended the animal to “sit for a fellowship.” But the most characteristic picture, after all, is that which he draws (selecting his solicitor, of all persons in the world, for his confidant) of his mode of reducing his flesh.

“I wear seven waistcoats, and a great Coat, run and play cricket in this Dress, till quite exhausted by excessive perspiration, use the bath daily, eat only a quarter of a pound of Butcher’s Meat in 24 hours.... By these means my ribs display Skin of no great Thickness, and my clothes have been taken in nearly half a yard.”

That is the closing passage of a letter which[Pg 40] begins with the confession that “Wine and women have dished your humble servant.” The two statements, taken in conjunction, furnish two-thirds of the picture. The remaining third of it may be deduced and constructed from the verses which Byron had then written or was then writing.

It might be tempting to see in the period of dissipation a disappointed lover’s desperate attempt to escape from an ineffaceable recollection; and the view might be supported by Byron’s own subsequent declaration that “a violent, though pure, love and passion,” was “the then romance of the most romantic period of my life.” Undergraduate excesses, however, rarely require such recondite explanations; and Byron’s reminiscences had, as we shall see, been coloured by intervening events. All the contemporary evidence that one can gather goes to show that they were inexact; that, though he had been hard hit by Mary Chaworth’s disdainful reception of his suit, he did not mope, but, holding up his head, was in a fair way to live his trouble down; and that his theory of himself, put forward in the well-known lines in “Childe Harold”:

“And I must from this land begone

Because I cannot love but one”

is an after thought entirely inconsistent with his practices as a Cambridge undergraduate.

One would be constrained to suspect that, even if the early poems addressed to Mary Chaworth[Pg 41] stood alone. There are not many of them, and they lack the intensity of passion—the impression of all possible hopes irremediably blighted—which “The Dream” reveals. They strike one as a little stiff and artificial, as though the poet had tried to express, not so much what he actually felt, as what he considered that a man in his position ought to feel. That is particularly the case with the poems of the first period. There are boasts in them which we know to have been quite unwarranted by the circumstances of the case. The poet pictures himself as one who might disturb domestic peace if he chose, but refrains, being merciful as he is strong:

“Perhaps his peace I could destroy,

And spoil the blisses that await him;

Yet let my rival smile in joy,

For thy dear sake, I cannot hate him.”

The boasts there, we see, are the prelude of resignation; and, a line or two further on, resignation is followed by the resolution to forget:

“Then, fare thee well, deceitful Maid,

’Twere vain and fruitless to regret thee;

Nor Hope nor Memory yield their aid,

But Pride may teach me to forget thee.”

That is very conventional—hardly less conventional than the Elegy on Margaret Parker—a sentimental “prelude to life,” one would judge, of quite an ordinary kind. And, as has been said, the sentimental utterance does not stand alone. Other[Pg 42] verses, hardly less sentimental, addressed to several other ladies, were, at the same time, pouring from Byron’s pen.

Burgage Manor, a house which his mother had taken at Southwell, near Nottingham, was his vacation home. He fled from his home, from time to time, because of Mrs. Byron’s incurable habit of rattling the fire-irons in order to draw attention to his faults; but he returned at intervals, and stayed long enough to form a considerable circle of friends—friends, be it noted, who belonged not to “the county” but to the professional society of the town.

The county did not “call” to any appreciable extent. A few of the men called on Byron himself; but none of the women called on Mrs. Byron—whether because her reputation for rattling the fire-irons and hurling the tongs had reached them, or because, on general principles, they did not think her good enough to mix with them. Byron, as was natural, resented their attitude and refused to return visits which implied a slight upon his mother. Whatever his own disputes with her, he would not have her snubbed by the local magnates, or himself enter their doors on sufferance while she was excluded from them. He mixed instead with the clergy, the doctors, the lawyers, the retired colonels, and flirted with their sisters and daughters. In that set he moved as a triton among the minnows, fluttering the dovecotes of Southwell pretty much as, at a later date, Praed, fresh from Eton, fluttered the dovecotes of [Pg 43]Teignmouth. He could not dance, of course, owing to his lameness; but he could distinguish himself in amateur theatricals, and he could write verses.

His success in the Southwell drawing-rooms and boudoirs was the first reward of his success in resisting and repelling the encroachments of the flesh. The struggle was one which he had to renew at intervals throughout his life; but his “crowning mercy” was the victory of this date. He emerged from it slim, elegant, and strikingly handsome. He rejoiced, and the girls of Southwell rejoiced with him. They understood, as well as he did, that it is difficult for a man to be fat and sentimental at one and the same time; that there is something ludicrously incongruous in the picture of a fat boy writing sentimental verses and professing to pine away for love. And they liked him to write sentimental verses to them, and he was quite willing to do so. He was, at this time, the sort of young man who will write verses to any girl who will give him a keepsake—the sort of young man to whom almost every girl will give a keepsake on condition that he will write verses to her.

He wrote lines, for instance, “to a lady who presented to the author a lock of hair braided with his own and appointed a night in December to meet him in the garden.” Nothing is known of her except that her name was Mary, and that she was neither Mary Duff nor Mary Chaworth, but a third Mary “of humble station.” Southwell, when it saw those verses, was shocked. It seemed highly[Pg 44] improper to Southwell that maidens of humble station should be encouraged to presume by such attentions on the part of noblemen. Probably it was on this occasion that the Reverend John Becher, Vicar of Rumpton, Notts, expostulated with the poet for

“Deigning to varnish scenes that shun the day

With guilty lustre and with amorous lay.”

But Byron kept Mary’s lock of hair, and showed it, together with her portrait, to his friends and wrote:

“Thro’ hours, thro’ years, thro’ time ’twill cheer—

My hope in gloomy moments raise;

In life’s last conflict ’twill appear,

And meet my fond, expiring gaze.”

To Mary Chaworth herself Byron could hardly have said more, but he was, in fact, at this time, saying the same sort of thing to all and sundry. Just the same sentiment recurs in the lines addressed “To a lady who presented the author with the velvet band which bound her tresses”:

“Oh! I will wear it next my heart;

’Twill bind my soul in bonds to thee:

From me again ’twill ne’er depart,

But mingle in the grave with me.”

Yet if Byron proposes to be faithful for ever to this un-named lady, he proposes, at the same[Pg 45] time, to be equally faithful to a lady who can be identified as Miss Anne Houson:

“With beauty like yours, oh, how vain the contention!

Thus lowly I sue for forgiveness before you;—

At once to conclude such a fruitless dissension,

Be false, my sweet Anne, when I cease to adore you!”

And then there are other lines—innumerable other lines which would also have to be quoted if the treatment of the subject were to be encyclopædic—lines to Marion, lines to Caroline, lines to a beautiful Quaker, lines to Miss Julia Leacroft, whose brother, the fire-eating Captain John Leacroft remonstrated with Byron, and, according to Moore, even went so far as to challenge him, on account of his pointed attentions to his sister: lines, finally, to M.S.G. who would appear, if verse could be accepted as autobiography, to have offered to yield to Byron, but to have been spared because of his tender regard for her fair fame:

“I will not ease my tortured heart,

By driving dove-ey’d peace from thine;

Rather than such a sting impart,

Each thought presumptuous I resign.

“At least from guilt shalt thou be free,

No matron shall thy shame reprove;

Though cureless pangs may prey on me,

No martyr shalt thou be to love.”

[Pg 46]With that citation we may quit the subject. Not one of the sets of verses—with the single exception of the set addressed to Miss Leacroft—has any discoverable story attached to it. All of them—or nearly all of them—have the air of celebrating some profound attachment from which no escape is to be looked for on this side of the grave. Byron’s later conception of himself as a man who had loved but one had not crept into his poetry yet. He had not even begun to strike the pose of the Childe impelled to “visit scorching climes beyond the sea” because the one he loved “could ne’er be his.”

The idea, indeed, of a man fleeing the country in 1809 because he had loved in vain in 1804 would not, in any case, carry conviction. Even to a poet the idea could hardly have presented itself without some definite renewal of the memories. They were revived, in fact, at a dinner party, in 1808, of which we find an account in one of Byron’s letters to Hodgson:

“I was seated near a woman to whom, when a boy, I was as much attached as boys generally are, and more than a man should be. I knew this before I went, and was determined to be valiant and converse with sang froid; but instead I forgot my valour and my nonchalance, and never opened my lips even to laugh, far less to speak, and the lady was almost as absurd as myself, which made both the object of more observation than if we had conducted ourselves with easy indifference. You[Pg 47] will think all this great nonsense; if you had seen it, you would have thought it still more ridiculous. What fools we are! We cry for a plaything which, like children, we are never satisfied with till we break open, though, like them, we cannot get rid of it by putting it on the fire.”

That is the prose record of the meeting, and there is also a record in verse. There are lines “to a lady on being asked my reason for quitting England in the Spring”; there is the piece beginning, “Well! thou art happy”:

“Mary, adieu! I must away:

While thou art blest I’ll not repine;

But near thee I can never stay;

My heart would soon again be thine.”

And also:

“In flight I shall be surely wise,

Escaping from temptation’s snare;

I cannot view my Paradise

Without the wish of dwelling there.”

Poor stuff, as poetry, it will be agreed. Any one who wrote poetry at all might have written it. The sentiment rendered in it is just the sentiment which any sentimental youth would have felt to be proper to the occasion. We can find in it, at most, only the faint fore-running shadow of the Byronic pose. It rings very insincerely if we set it beside[Pg 48] the lines in which Walter Savage Landor, at about the same period, commemorated a similar moment of emotion:

“Rose Aylmer, whom these waking eyes

May weep but never see;

A night of memories and of sighs

I consecrate to thee.”

In that comparison, most decidedly, all the advantage is with Landor—inevitably, because his were the feelings of a man, whereas Byron’s were the feelings of a boy. He was only twenty, and his age is the explanation of a good deal. It explains his startled timidity, described in the letter to Hodgson, in a novel, romantic situation. It explains his hugging his grief as a precious possession on no account to be let go. It also explains the zest with which, when grief had had its sacred hour, he could turn from it and throw himself into other activities.

He rejoiced in the pose, only outlined as yet, which was presently to make him the most interesting man (to women at all events) in Europe; but he also rejoiced in his youth. He flirted, as we have seen; he took part in amateur theatrical performances; he engaged energetically in most of the sports of the day, fencing with Angelo, boxing with Gentleman Jackson, swimming the Thames from Lambeth to the Tower; he accumulated debts with the fine air of a man heaping Pelion on Ossa; he flung down his[Pg 49] defiant challenge to the literary bigwigs in “English Bards and Scotch Reviewers”; he drew his plans for the grand tour. The world, in short, was just then “so full of a number of things” that Mary Chaworth’s importance in it can easily be, as it has often been, exaggerated.

Presently we shall see Byron exaggerating it; and we shall also see how he came to do so—how the boy’s occasional pose became the determining reality of the man’s life. But before we come to that, we must turn back.

REVELRY AT NEWSTEAD—“ENGLISH BARDS AND SCOTCH REVIEWERS”

One watches the swelling of Byron’s indebtedness with morbid interest. It is like the rapid rising of a Spring tide which threatens to submerge a city. Already, in his second term at Cambridge, as we have seen, he besought his sister to pledge her credit for his loans. At the beginning of his third year, we find him making a confession to his solicitor:

“My debts amount to three thousand, three hundred to Jews, eight hundred to Mrs. B. of Nottingham, to coachmaker and other tradesmen a thousand more, and these must be much increased before they are lessened.”

They were increased before they were lessened—unless the explanation be that Byron only told the truth about them in instalments. Three months later this is his confession to the Reverend John Becher:

“Entre nous, I am cursedly dipped; my debts, everything inclusive, will be nine or ten thousand before I am twenty-one.”

[Pg 51]But, even so, the high-water mark is not yet reached. Towards the end of the same year, when Byron is contemplating his “grand tour,” he once more calls his solicitor into council:

“You honour my debts; they amount to perhaps twelve thousand pounds, and I shall require perhaps three or four thousand at setting out, with credit on a Bengal agent. This you must manage for me.”

A pleasant commission, which seems to have led to a reference to Mrs. Byron, who made a luminous suggestion:

“I wish to God he would exert himself and retrieve his affairs. He must marry a woman of fortune this Spring; love matches is all nonsense. Let him make use of the Talents God has given him. He is an English Peer, and has all the privileges of that situation.”

It was a matter-of-fact proposal, worthy of the canny Scotswoman who made it—a proof that, even when she threw the tongs at her son, she still had his interests at heart; but nothing came of it. Very likely Byron, at this date knew no heiresses; and even his mother was not matter-of-fact enough to expect him to advertise for one, even for the purpose of avoiding the necessity of selling Newstead. There was still the resource of borrowing a little more, and of making the loans go as far as possible by retaining the money for personal[Pg 52] expenses, instead of applying it to the payment of debt; and something of that sort seems to have been done. Scrope Davies lent Byron £4800; and yet Mrs. Byron had occasion to write:

“There is some Trades People at Nottingham that will be completely ruined if he does not pay them, which I would not have happen for a whole world.”