Title: The Traditional Games of England, Scotland, and Ireland (Vol 1 of 2)

Author: Alice Bertha Gomme

Release date: December 29, 2012 [eBook #41727]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Edwards, Harry Lamé, the Music Team (Anne

Celnik, monkeyclogs, Sarah Thomson and others) and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

(This file was produced from images generously made

available by The Internet Archive)

Please see Transcriber’s Notes at the end of this document.

This is Volume I of a two-volume work. Volume II (including the Addenda) is available on the Project Gutenberg website here. The hyperlinks to Volume II work when this book is read on the Project Gutenberg website; when read elsewhere or when the files have been downloaded, the hyperlinks to Volume II may not work.

A DICTIONARY

OF

BRITISH FOLK-LORE

EDITED BY

G. LAURENCE GOMME, Esq., F.S.A.

PRESIDENT OF THE FOLK-LORE SOCIETY, ETC.

PART I.

TRADITIONAL GAMES

BY THE SAME EDITOR.

Small 4to. In Specially Designed Cover.

ENGLISH SINGING GAMES.

A Collection of the best Traditional Children’s Singing Games, with their Traditional Music harmonised, and Directions for Playing. Each Game, Text and Music, is written out and set within a Decorative Border by Winifred Smith, who has also designed Full-page Illustrations to each Game, and Initials and Decorative Border to the playing directions.

[All rights reserved.]

WITH

TUNES, SINGING-RHYMES, AND METHODS OF PLAYING

ACCORDING TO THE VARIANTS EXTANT AND

RECORDED IN DIFFERENT PARTS

OF THE KINGDOM

COLLECTED AND ANNOTATED BY

ALICE BERTHA GOMME

VOL. I.

ACCROSHAY-NUTS IN MAY

LONDON

DAVID NUTT, 270-71 STRAND

1894

TO

MY HUSBAND

Soon after the formation of the Folk-lore Society in 1878 my husband planned, and has ever since been collecting for, the compilation of a dictionary of British Folk-lore. A great deal of the material has been put in form for publication, but at this stage the extent of the work presented an unexpected obstacle to its completion.

To print the whole in one alphabet would be more than could be accomplished except by the active co-operation of a willing band of workers, and then the time required for such an undertaking, together with the cost, almost seemed to debar the hope of ever completing arrangements for its publication. Nevertheless, unless we have a scientific arrangement of the enormously scattered material and a close comparison of the details of each item of folk-lore, it is next to impossible to expect that the full truth which lies hidden in these remnants of the past may be revealed.

During my preparation of a book of games for children it occurred to me that to separate the whole of the games from the general body of folk-lore and to make them a section of the proposed dictionary would be an advantageous step, as by arranging the larger groups of folk-lore in independent sections the possibility of publishing the contemplated dictionary again seemed to revive. Accordingly, the original plan has been so far modified that these volumes will form the first section of the dictionary, which, instead of being issued in one alphabet[viii] throughout, will now be issued in sections, each section being arranged alphabetically.

The games included in this collection bear the important qualification of being nearly all Children’s Games: that is to say, they were either originally children’s games since developed into games for adults, or they were the more serious avocations of adults, which have since become children’s games only. In both cases the transition is due to traditional circumstances, and not to any formal arrangements. All invented games of skill are therefore excluded from this collection, but it includes both indoor and outdoor games, and those played by both girls and boys.

The bulk of the collection has been made by myself, greatly through the kindness of many correspondents, to whom I cannot be sufficiently grateful. In every case I have acknowledged my indebtedness, which, besides being an act of justice, is a guarantee of the genuineness of the collection. I have appended to this preface a list of the collectors, together with the counties to which the games belong; but I must particularly thank the Rev. W. Gregor, Mr. S. O. Addy, and Miss Fowler, who very generously placed collections at my disposal, which had been prepared before they knew of my project; also Miss Burne, Miss L. E. Broadwood, and others, for kindly obtaining variants and tunes I should not otherwise have received. To the many versions now printed for the first time I have added either a complete transcript of, where necessary, or a reference to, where that was sufficient, printed versions of games to be found in the well-known collections of Halliwell and Chambers, the publications of the Folk-lore and Dialect Societies, Jamieson’s, Nares’, and Halliwell’s Dictionaries, and other printed sources of information. When quoting from a printed authority, I have as far as possible given the exact[ix] words, and have always given the reference. I had hoped to have covered in my collection the whole field of games as played by children in the United Kingdom, but it will be seen that many counties in each country are still unrepresented; and I shall be greatly indebted for any games from other places, which would help to make this collection more complete. The tunes of the games have been taken down, as sung by the children, either by myself or correspondents (except where otherwise stated), and are unaltered.

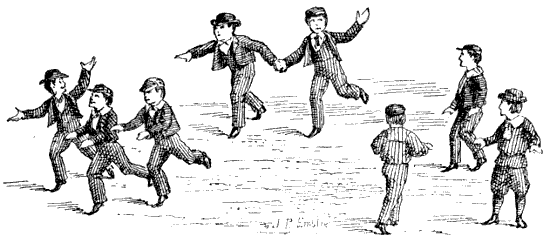

The games consist of two main divisions, which may be called descriptive, and singing or choral. The descriptive games are arranged so as to give the most perfect type, and, where they occur, variable types in succession, followed, where possible, by any suggestions I have to make as to the possible origin of the game. The singing games are arranged so as to give, first, the tunes; secondly, the different versions of the game-rhymes; thirdly, the method of playing; fourthly, an analysis of the game-rhymes on a plan arranged by my husband, and which is an entirely novel feature in discussing the history of games; fifthly, a discussion of the results of the analysis of the rhymes so far as the different versions allow; and sixthly, an attempt to deduce from the evidence thus collected suggestions as to the probable origin of the game, together with such references to early authorities and other facts bearing upon the subject as help to elucidate the views expressed. Where the method of playing the game is involved, or where there are several changes in the forms, diagrams or illustrations, which have been drawn by Mr. J. P. Emslie, are inserted in order to assist the reader to understand the different actions, and in one or two instances I have been able to give a facsimile reproduction of representations of the games from early MSS. in the Bodleian and British Museum Libraries.

[x]Although none of the versions of the games now collected together are in their original form, but are more or less fragmentary, it cannot, I think, fail to be noticed how extremely interesting these games are, not only from the point of view of the means of amusement (and under this head there can be no question of their interest), but as a means of obtaining an insight into many of the customs and beliefs of our ancestors. Children do not invent, but they imitate or mimic very largely, and in many of these games we have, there is little doubt, unconscious folk-dramas of events and customs which were at one time being enacted as a part of the serious concerns of life before the eyes of children many generations ago. As to the many points of interest under this and other heads there is no occasion to dwell at length here, because the second volume will contain an appendix giving a complete analysis of the incidents mentioned in the games, and an attempt to tell the story of their origin and development, together with a comparison with the games of children of foreign countries.

The intense pleasure which the collection of these games has given me has been considerably enhanced by the many expressions of the same kind of pleasure from correspondents who have helped me, it not being an infrequent case for me to be thanked for reviving some of the keenest pleasures experienced by the collector since childhood; and I cannot help thinking that, if these traditional games have the power of thus imparting pleasure after the lapse of many years, they must contain the power of giving an equal pleasure to those who may now learn them for the first time.

ALICE BERTHA GOMME.

Barnes Common, S.W.,

Jan. 1894.

| ENGLAND. | ||

| Halliwell’s Nursery Rhymes. | ||

| Halliwell’s Dictionary, ed. 1889. | ||

| Holloway’s Dictionary, ed. 1838. | ||

| Strutt’s Sports and Pastimes, ed. 1831. | ||

| Brand’s Popular Antiquities, ed. 1875. | ||

| Nares’ Glossary, ed. 1872. | ||

| Grose’s Dictionary, 1823. | ||

| Notes and Queries. | ||

| Reliquary. | ||

| English Dialect Society Publications. | ||

| Folk-lore Society Publications, 1878-1892. | ||

| Bedfordshire— | ||

| Luton | Mrs. Ashdown. | |

| Roxton | Miss Lumley. | |

| Berkshire | Lowsley’s Glossary. | |

| Enborne | Miss Kimber. | |

| Fernham, Longcot | Miss I. Barclay. | |

| Newbury | Mrs. S. Batson, Miss Kimber. | |

| Sulhampstead | Miss Thoyts (Antiquary, vol. xxvii.) | |

| Cambridgeshire— | ||

| Cambridge | Mrs. Haddon. | |

| Cheshire | Darlington’s, Holland’s, Leigh’s, and Wilbraham’s Glossaries. | |

| Congleton | Miss A. E. Twemlow. | |

| Cornwall | Folk-lore Journal, v., Courtney’s Glossary. | |

| Penzance | Miss Courtney, Mrs. Mabbott. | |

| Cumberland | Dickinson’s Glossary. | |

| Derbyshire | Folk-lore Journal, vol. i., Mrs. Harley, Mr. S. O. Addy. | |

| Dronfield, Eckington, Egan | Mr. S. O. Addy. | |

| Devonshire | Halliwell’s Dictionary. | |

| Dorsetshire | Barnes’ Glossary, Folk-lore Journal, vol. vii. | |

| Durham | Brockett’s North Country Words, ed. 1846. | |

| Gainford | Miss Eddleston. | |

| South Shields | Miss Blair. | |

| Essex— | ||

| Bocking | Folk-lore Record, vol. iii. pt. 2. | |

| Colchester | Miss G. M. Francis. | |

| Gloucestershire | Holloway’s Dictionary, Midland Garner. | |

| Shepscombe, Cheltenham | Miss Mendham. | |

| Forest of Dean | Miss Matthews. | |

| Hampshire | Cope’s Glossary, Miss Mendham. | |

| Bitterne | Mrs. Byford. | |

| Liphook | Miss Fowler. | |

| Hampshire[xii]— | ||

| Hartley, Winchfield, Witney | Mr. H. S. May. | |

| Southampton | Mrs. W. R. Carse. | |

| Isle of Man | Mr. A. W. Moore. | |

| Isle of Wight— | ||

| Cowes | Miss E. Smith. | |

| Kent | Pegge’s Alphabet of Kenticisms. | |

| Bexley Heath | Miss Morris. | |

| Crockham Hill, Deptford | Miss Chase. | |

| Platt | Miss Burne. | |

| Wrotham | Miss D. Kimball. | |

| Lancashire | Nodal and Milner’s Glossary, Harland and Wilkinson’s Folk-lore, ed. 1882, Mrs. Harley. | |

| Monton | Miss Dendy. | |

| Leicestershire | Evan’s Glossary. | |

| Leicester | Miss Ellis. | |

| Lincolnshire | Peacock’s, Cole’s, and Brogden’s Glossaries, Rev. —— Roberts. | |

| Anderby, Botterford, Brigg, Frodingham, Horncastle, North Kelsey, Stixwould, Winterton | Miss Peacock. | |

| East Kirkby | Miss K. Maughan. | |

| Metheringham | Mr. C. C. Bell. | |

| Middlesex | Miss Collyer. | |

| Hanwell | Mrs. G. L. Gomme. | |

| London | Miss Chase, Miss F. D. Richardson, Mr. G. L. Gomme, Mrs. G. L. Gomme, Mr. J. P. Emslie, Miss Dendy, Mr. J. T. Micklethwaite (Archæological Journal, vol. xlix.), Strand Magazine, vol. ii. | |

| Norfolk | Forby’s Vocabulary, Spurden’s Vocabulary, Mr. J. Doe. | |

| Sporle, Swaffham | Miss Matthews. | |

| Northamptonshire | Baker’s Glossary, Northants Notes and Queries, Revue Celtique, vol. iv., Rev. W. D. Sweeting. | |

| Maxey | Rev. W. D. Sweeting. | |

| Northumberland | Brockett’s Provincial Words, ed. 1846. | |

| Hexham | Miss J. Barker. | |

| Nottinghamshire | Miss Peacock. | |

| Long Eaton | Miss Youngman. | |

| Nottingham | Miss Winfield, Miss Peacock. | |

| Ordsall | Miss Matthews. | |

| Oxfordshire | Aubrey’s Remains, ed. 1880. | |

| Oxford | Miss Fowler. | |

| Summertown | Midland Garner, vol. ii. | |

| Shropshire | Burne’s Shropshire Folk-lore. | |

| Madeley, Middleton | Miss Burne. | |

| Tong | Miss R. Harley. | |

| Somersetshire[xiii] | Elworthy’s Dialect, Somerset and Dorset Notes and Queries, Holloway’s Dictionary. | |

| Bath | Miss Large. | |

| Staffordshire— | ||

| Hanbury | Miss E. Hollis. | |

| Cheadle | Miss Burne. | |

| Tean, North Staffordshire Potteries | Miss Keary, Miss Burne, Mrs. T. Lawton. | |

| Wolstanton | Miss Keary. | |

| Suffolk | Moor’s Suffolk Words, Forby’s Vocabulary, Lady C. Gurdon’s Suffolk County Folk-lore. | |

| Surrey— | ||

| Barnes | Mrs. G. L. Gomme. | |

| Clapham | Miss F. D. Richardson. | |

| Hersham | Folk-lore Record, vol. v. | |

| Redhill | Miss G. Hope. | |

| Sussex | Parish’s Dialect, Holloway’s Dictionary, Toone’s Dictionary. | |

| Hurstmonceux | Miss Chase. | |

| Shipley, Horsham, West Grinstead | Miss R. H. Busk (Notes and Queries). | |

| Ninfield | Mr. C. Wise. | |

| Warwickshire | Northall’s Folk Rhymes, Notes and Queries, Northants Notes and Queries, Mr. C. C. Bell. | |

| Wiltshire— | ||

| Marlborough, Manton, Ogbourne | Mr. H. S. May. | |

| Worcestershire | Chamberlain’s Glossary. | |

| Upton-on-Severn | Lawson’s Glossary. | |

| Yorkshire | Atkinson’s, Addy’s, Easther’s, Hunter’s, Robinson’s, Ross and Stead’s Glossaries, Henderson’s Folk-lore, ed. 1879. | |

| Almondbury | Easther’s Glossary. | |

| Epworth, Lossiemouth | Mr. C. C. Bell. | |

| Earls Heaton, Haydon, Holmfirth | Mr. H. Hardy. | |

| Settle | Rev. W. S. Sykes. | |

| Sharleston | Miss Fowler, Rev. G. T. Royds. | |

| Sheffield | Mr. S. O. Addy, Miss Lucy Garnett. | |

| Wakefield | Miss Fowler. | |

| SCOTLAND. | ||

| Chambers’ Popular Rhymes, ed. 1870. | ||

| Mactaggart’s Gallovidian Encyclopædia, ed. 1871. | ||

| Jamieson’s Etymological Dictionary, ed. 1872-1889. | ||

| Folk-lore Society Publications. | ||

| Aberdeen— | ||

| Pitsligo | Rev. W. Gregor. | |

| Banffshire—[xiv] | ||

| Duthil, Keith, Strathspey | Rev. W. Gregor. | |

| Elgin— | ||

| Fochabers | Rev. W. Gregor. | |

| Kirkcudbright— | ||

| Auchencairn | Prof. A. C. Haddon. | |

| Lanarkshire— | ||

| Biggar | Mr. Wm. Ballantyne. | |

| Lanark | Mr. W. G. Black. | |

| Nairn— | ||

| Nairn | Rev. W. Gregor. | |

| IRELAND. | ||

| Folk-lore Society Publications. | ||

| Notes and Queries. | ||

| Antrim and Down | Patterson’s Glossary. | |

| Clare— | ||

| Kilkee | G. H. Kinahan (Folk-lore Journal, vol. ii.) | |

| Cork— | ||

| Cork | Mrs. B. B. Green, Miss Keane. | |

| Down— | ||

| Ballynascaw | Miss C. N. Patterson. | |

| Belfast | Mr. W. H. Patterson. | |

| Holywood | Miss C. N. Patterson. | |

| Dublin— | ||

| Dublin | Mrs. Lincoln. | |

| Louth— | ||

| Annaverna, Ravendale | Miss R. Stephen. | |

| Queen’s County— | ||

| Portarlington | G. H. Kinahan (Folk-lore Journal, vol. ii.) | |

| Waterford— | ||

| Lismore | Miss Keane. | |

| WALES. | ||

| Byegones. | ||

| Folk-lore Society Publications. | ||

| Carmarthenshire— | ||

| Beddgelert | Mrs. Williams. | |

On page 15, line 12, for “Eggatt” read “Hats in Holes.”

On pp. 24, 49, 64, 112, for “Folk-lore Journal, vol. vi.” read “vol. vii.”

On page 62, last line, insert “vol. xix.” after “Journ. Anthrop. Inst.”

On page 66, line 4, delete “Move All.”

On page 224, fig. 3 of “Hopscotch” should be reversed.

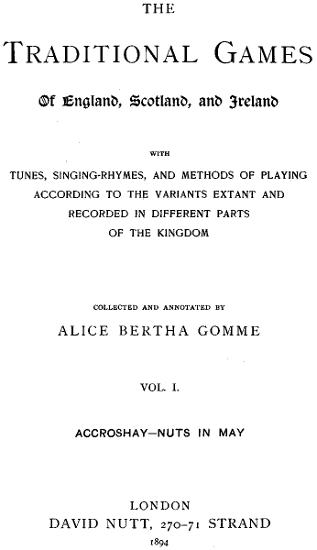

On page 332, diagram of “London” omitted.

A cap or small article is placed on the back of a stooping boy by other boys as each in turn jumps over him. The first as he jumps says “Accroshay,” the second “Ashotay,” the third “Assheflay,” and the last “Lament, lament, Leleeman’s (or Leleena’s) war.” The boy who in jumping knocks off either of the things has to take the place of the stooper.—Cornwall (Folk-lore Journal, v. 58).

See “Leap-frog.”

“A meere children’s pastime” (A Curtaine Lecture, 1637, p. 206). This is no doubt the game of “Hide and Seek,” though Cotgrave apparently makes it synonymous with “Hoodman Blind.” See Halliwell’s Dictionary. It is alluded to in Dekker’s Satiromastix, “Our unhansomed-fac’d Poet does play at Bo-peepes with your Grace, and cryes All-hidde, as boyes doe.” Tourneur, Rev. Trag., III., v. 82, “A lady can at such Al-hid beguile a wiser man,” is quoted in Murray’s Dictionary as the first reference.

—Northall’s English Folk Rhymes, p. 386.

This is a marching game for very little children, who follow each other in a row.

(b) Halliwell gives the first two lines only (Nursery Rhymes, No. dxv., p. 101), and there is apparently no other record of[2] this game. It is probably ancient, and formerly of some significance. It refers to days of bows and arrows, and the allusion to the killing of the wren may have reference to the Manx and Irish custom of hunting that bird.

A juvenile game in Newcastle and the neighbourhood. A circle is made, about eight inches in diameter, termed the well, in the centre of which is placed a wooden peg four inches long, with a button balanced on the top. Those desirous of playing give buttons, marbles, or anything else, according to agreement, for the privilege of throwing a short stick, with which they are furnished, at the peg. Should the button fly out of the ring, the player is entitled to double the stipulated value of what he gives for the stick. The game is also practised at the Newcastle Races and other places of amusement in the North with three pegs, which are put into three circular holes made in the ground about two feet apart, and forming a triangle. In this case each hole contains a peg about nine inches long, upon which are deposited either a small knife or some copper. The person playing gives so much for each stick, and gets all the articles that are thrown off so as to fall on the outside of the holes.—Northumberland (Brockett’s North Country Glossary).

A Suffolk game, not described (Moor’s Suffolk Glossary). Jamieson also gives it without description. Compare the rhyme in the game “Fool, fool, come to School,” “Little Dog, I call you.”[Addendum]

—Hampshire (from friend of Miss Mendham).

—Deptford (Miss Chase).

—Belfast (W. H. Patterson).

—Earls Heaton (Herbert Hardy).

(b) A full description of this game could not be obtained in each case. The Earls Heaton game is played by forming a ring, one child standing in the centre. After the first verse is sung, a child from the ring goes to the one in the centre. Then the rest of the verses are sung. The action to suit the words of the verses does not seem to have been kept up. In the Hampshire version, after the line “As a bird upon a tree,” the two children named pair off like sweethearts while the rest of the verse is being sung.

(c) The analysis of the game rhymes is as follows:—

| Hants. | Deptford (Kent). | Belfast. | Earls Heaton (Yorks.). | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Village life. | Village life. | Hunting life. | Roving life. |

| 2. | All the boys happy. | All the boys happy. | All lusty bachelors. | — |

| 3. | Except [ ], who wants a wife. | Except [ ], who wants a wife. | Except [ ], who courts [ ]. | — |

| 4. | He shall court [ ]. | He shall court [ ]. | He courted [ ]. | Seeks for a bride. |

| 5. | Huddles and cuddles, and sits on his knee. | Kisses and cuddles, and sits on his knee. | Huggled and guggled, and took on his knee. | — |

| 6. | — | — | — | Catch the bride. |

| 7. | Mutual expressions of love. | Mutual expressions of love. | — | — |

| 8. | — | — | Asking to marry. | — |

| 9. | Wife makes a pudding. | Girl makes a pudding. | Girl makes a pudding. | Girl makes a pudding. |

| 10. | Husband cuts a slice. | Boy cuts a slice. | Asks boy to taste. | Asks boy to taste. |

| 11. | Fixing of wedding day. | Fixing of wedding day. | Fixing of wedding day. | Fixing of wedding day. |

| 12. | Wife in carriage, husband in cart. | Wife with domestic utensils. | Bride with rings on fingers and bells on toes. | — |

| 13. | — | Grief if wife should die. | — | — |

| 14. | — | — | Bride with a baby. | — |

| 15. | — | Doctor, cat, and devil. | — | — |

| 16. | — | — | Applause for the bride. | Applause for bride. |

It appears by the analysis that all the incidents of the Hants version of this game occur in one or other of the versions, and these incidents therefore may probably be typical of the game. This view would exclude the important incidents of bride capture in the Earls Heaton version; the bride having a baby in the Belfast version, and the two minor incidents in the Deptford version (Nos. 13 and 15 in the analysis), which are obviously supplemental. Chambers, in his Popular Rhymes of Scotland, pp. 119, 137, gives two versions of a courtship dance which are not unlike the words of this game, though they do not contain the principal incidents. Northall, in his English Folk Rhymes, p. 363, has some verses of a similar import, but not those of the game. W. Allingham seems to have used this rhyme as the commencement of one of his ballads, “Up the airy mountain.”

(d) The game is clearly a marriage game. It introduces two important details in the betrothal ceremony, inasmuch as the “huddling and cuddling” is typical of the rude customs at marriage ceremonies once prevalent in Yorkshire, the northern counties, and Wales, while the making of the pudding by the bride and the subsequent eating together, are clearly analogies to the bridal-cake ceremony. In Wales, the custom known as “bundling” allowed the betrothing parties to go to bed in their clothes (Brand, ii. 98). In Yorkshire, the bridal cake was always made by the bride. The rudeness of the dialogue seems to be remarkably noticeable in this game.

See “Mary mixed a Pudding up,” “Oliver, Oliver, follow the King.”[Addendum] [Addendum]

[1] Miss Chase says, “I think the order of verses is right; the children hesitated a little.”

[2] Mr. Hardy says, “This was sung to me by a girl at Earls Heaton or Soothill Nether. Another version commences with the last verse, continues with the first, and concludes with the second. The last two lines inserted here belong to that version.”

A Suffolk game, not described.—Moor’s Suffolk Glossary. See “Fool, fool, come to School,” “Little Dog, I call you.”

—Sporle, Norfolk (Miss Matthews).

[7]The children form into a ring and sing the above words. They “bop down” at the close of the verse. To “bop” means in the Suffolk dialect “to stoop or bow the head.”—Moor.

A little amusing game played by young girls at country schools. The same as “Drop Handkerchief,” except that the penalty for not following exactly the course of the child pursued is to “stand in the circle, face out, all the game afterwards; if she succeed in catching the one, the one caught must so stand, and the other take up the cap and go round as before” (Mactaggart’s Gallovidian Encyclopædia). No explanation is given of the name of this game.

See “Drop Handkerchief.”

I.

—Middleton (Burne’s Shropshire Folk-lore, p. 523).

II.

—Shepscombe, Gloucestershire (Miss Mendham).

III.

—Warwickshire (Northall’s Folk Rhymes, p. 394).

IV.

—Hersham, Surrey (Folk-lore Record, v. 87).

V.

—Halliwell’s Nursery Rhymes, p. 121.

(b) The children form pairs, one pair following the other, with their arms linked behind. While the first four lines are repeated by all, they skip forward, and then skip back again. At the end of the last line they turn themselves about without loosing hands.

(c) Miss Burne includes this among obscure and archaic games, and Halliwell-Phillips mentions it as a marching game. The three first versions have something of the nature of an incantation, while the fourth and fifth versions may probably belong to another game altogether. It is not clear from the great variation in the verses to which class the game belongs.

An old English game undescribed.—Useful Transactions in Philosophy, 1709, p. 43.

One child is called the “Angel,” another child the “Devil,” and a third child the “Minder.” The children are given the names of colours by the Minder. Then the Angel comes over and knocks, when the following dialogue takes place.

Minder: “Who’s there?”

Answer: “Angel.”

Minder: “What do you want?”

Angel: “Ribbons.”

Minder: “What colour?”

Angel: “Red.”

Minder retorts, if no child is so named, “Go and learn your A B C.” If the guess is right the child is led away. The Devil then knocks, and the dialogue and action are repeated.—Deptford, Kent (Miss Chase).

See “Fool, fool, come to School.”

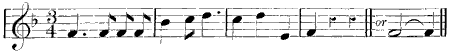

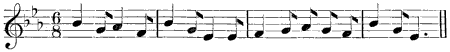

The children join hands, and dance in a circle, “with a front step, a back step, and a side step, round an invisible May-pole,” singing—

Then follows kissing.—Brigg, Lincolnshire (Miss Peacock).

[Play]

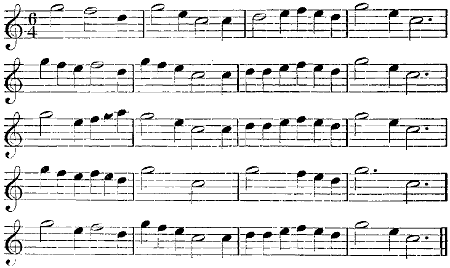

—Biggar (Wm. Ballantyne).

—Biggar (W. H. Ballantyne).

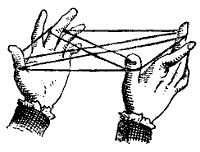

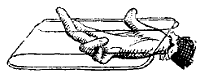

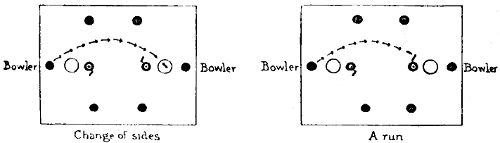

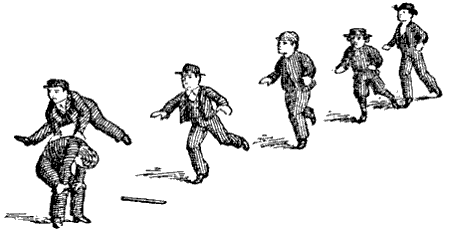

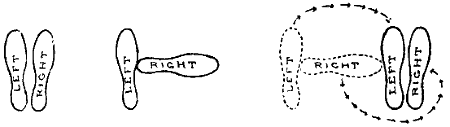

[10](b) Mr. Ballantyne describes the dance as taking place at the end of a country ball. The lads all sat on one side and the girls on the other. It began with a boy taking a handkerchief and dancing before the girls, singing the first verse (fig. 1). Selecting one of the girls, he threw the handkerchief into her lap, or put it round her neck, holding both ends himself. Some spread the handkerchief on the floor at the feet of the girl. The object in either case was to secure a kiss, which, however, was not given without a struggle, the girls cheering their companion at every unsuccessful attempt which the boy made (fig. 2). A girl then took the handkerchief, singing the next verse (fig. 3), and having thrown the handkerchief to one of the boys, she went off to her own side among the girls, and was pursued by the chosen boy (fig. 4). When all were thus paired, they formed into line, facing each other, and danced somewhat like the country dance of Sir Roger.

(c) Chambers’ Popular Rhymes, p. 36, gives a slightly different version of the verses, and says they were sung by children at their sports in Glasgow. Mactaggart alludes to this game as “‘Bumpkin Brawly,’ an old dance, the dance which always ends balls; the same with the ‘Cushion’ almost.”

The tune of this song is always played to the dance, says Mactaggart, but he does not record the tune. To bab, in Lowland Scottish, is defined by Jamieson to mean “to play backward and forward loosely; to dance.” Hence he adds, “Bab at the bowster, or Bab wi’ the bowster, a very old Scottish dance, now almost out of use; formerly the last dance at weddings and merry-makings.” Mr. Ballantyne says that a bolster or pillow was at one time always used. One correspondent of N. and Q., ii. 518, says it is now (1850) danced with a handkerchief instead of a cushion as formerly, and no words are used, but later correspondents contradict this. See also N. and Q., iii. 282.

(d) Two important suggestions occur as to this game. First, that the dance was originally the indication at a marriage ceremony for the bride and bridegroom to retire with “the bowster” to the nuptial couch. Secondly, that it has degenerated in Southern Britain to the ordinary “Drop Handkerchief” games of kiss in the ring. The preservation of this “Bab at the Bowster” example gives the clue both to the origin of the present game in an obsolete marriage custom, and to the descent of the game to its latest form. See “Cushion Dance.”

A rude kind of “Cricket,” played with a bat and a ball, usually with wall toppings for wickets. “Bad” seems to be the pronunciation or variation of “Bat.” Halliwell says it was a rude game, formerly common in Yorkshire, and probably resembling the game of “Cat.” There is such a game played now, but it is called “Pig.”—Easther’s Almondbury Glossary.

The game of “Hockey” in Cheshire.—Holland’s Glossary.

A rough game, sometimes seen in the country. The boy who personates the Bear performs his part on his hands and knees, and is prevented from getting away by a string. It is the part of another boy, his Keeper, to defend him from the attacks of the others.—Halliwell’s Dictionary.

This is a boys’ game, and is called “Buffet the Bear.” It may be taken part in by any number. One boy—the Bear—goes down on all fours, and lowers his head towards his breast as much as possible. Into his hand is placed one end of a piece of cord, and another boy, called the Keeper, takes hold of the other end in one hand, while he has in the other his cap. The other boys stand round, some with their caps in hand, and others with their neckties or pocket-handkerchiefs, and on a given signal they rush on the Bear and pelt him, trying specially to buffet him about the ears and face, whilst the Keeper does his best to protect his charge. If he happens to strike a boy, that boy becomes the Bear, and the former Bear becomes the Keeper, and so on the game goes.—Keith, Banffshire (Rev. W. Gregor).

I saw this game played on Barnes Green, Surrey, on 25th August 1892. The boys, instead of using their hats, had pieces of leather tied to a string, with which they struck the Bear on the back. They could only begin when the Keeper cried, “My Bear is free.” If they struck at any other time, the striker became the Bear. It is called “Baste the Bear.”—A. B. Gomme.

Chambers (Popular Rhymes, p. 128) describes this game under the title of “The Craw.” It was played precisely in the same way as the Barnes game. The boy who holds the end of the long strap has also a hard twisted handkerchief, called the cout; with this cout he defends the Craw against the attacks of the other boys, who also have similar couts. Before beginning, the Guard of the Craw must call out—

[13]The first one he strikes becomes the Craw. When the Guard wants a respite, he calls out—

(b) Jamieson defines “Badger-reeshil” as a severe blow; borrowed, it is supposed, from the hunting of the badger, or from the old game of “Beating the Badger.”

—MS. Poem.

Mr. Emslie says he knows it under the name of “Baste the Bear” in London, and Patterson (Antrim and Down Glossary) mentions a game similarly named. It is played at Marlborough under the name of “Tom Tuff.”—H. S. May.

See “Doncaster Cherries.”

—Northall’s English Folk Rhymes, p. 394.

Two children stand back to back, linked near the armpits, and weigh each other as they repeat these lines.

See “Weigh the Butter.”

I.

—Chambers’ Pop. Rhymes of Scotland, p. 115.

II.

—Burne’s Shropshire Folk-lore, p. 530.

(b) Children throw a ball in the air, repeating the rhyme, and divine the length of their lives by the number of times they can catch it again. In some places this game is played with a cowslip ball, thence called a “tissy-ball.”

(c) I have heard other rhymes added to this, to determine whether the players shall marry or not, the future husband’s calling, dress to be worn, method of going to church, &c. (A. B.[14] Gomme). Strutt describes a handball game played during the Easter holidays for Tansy cakes (Sports, p. 94). Halliwell gives rhymes for ball divination (Popular Rhymes, p. 298) to determine the number of years before marriage will arrive. Miss Baker (Northamptonshire Glossary) says, “The May garland is suspended by ropes from the school-house to an opposite tree, and the Mayers amuse themselves by throwing balls over it. A native of Fotheringay, Mr. C. W. Peach,” says Miss Baker, “has supplied me with the reminiscences of his own youth. He says the May garland was hung in the centre of the street, on a rope stretched from house to house. Then was made the trial of skill in tossing balls (small white leather ones) through the framework of the garland, to effect which was a triumph.”

See “Cuck Ball,” “Keppy Ball,” “Monday.”

This is a boys’ game. The players may be of any number. They place their caps or bonnets in a row. One of the boys takes a ball, and from a fixed point, at a few yards’ distance from the bonnets, tries to throw it into one of the caps (fig. 1). If the ball falls into the cap, all the boys, except the one into whose cap the ball has fallen, run off. The boy into whose cap the ball has been thrown goes up to it, lifts the ball from it, and calls out “Stop!” The other boys stop. The boy with[15] the ball tries to strike one of the other boys (fig. 2). If he does so, a small stone is put into the cap of the boy struck. If he misses, a stone is put into his own cap. If the boy who is to pitch the ball into the cap misses, a stone is put into his own cap, and he makes another trial. The game goes on till six stones are put into one cap. The boy in whose cap are the six stones has to place his hand against a wall, when he receives a certain number of blows with the ball thrown with force by one of the players. The blows go by the name of “buns.” The game may go on in the same way till each player gets his “buns.”—Nairn (Rev. W. Gregor).

See “Hats in Holes.”

A row of boys’ caps is set by a wall. One boy throws a ball into one of the caps. The owner of the cap runs away, and is chased by all the others till caught. He then throws the ball.—Dublin (Mrs. Lincoln).

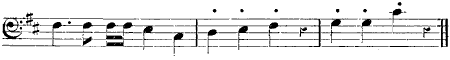

[Play]

—Epworth, Doncaster; and Lossiemouth, Yorkshire (Charles C. Bell).

(b) The children form a ring, joining hands, and dance round singing the two first lines. Then loosing hands, they waltz in couples, singing as a refrain the last line. The game is continued, different coloured ribbons being named each time.

(c) This game was played in 1869, so cannot have arisen from the political movement.

A game played with an inflated ball of strong leather, the ball being struck by the arm, which was defended by a bracer of wood.—Brand’s Pop. Antiq., ii. 394.

(b) It is spelt “balloo” in Ben Jonson, iii. 216, and “baloome” in Randolph’s Poems, 1643, p. 105. It is also mentioned in Middleton’s Works, iv. 342, and by Donne.

—Donne’s Poems, p. 133.

Toone (Etymological Dict.) says it is a game rather for exercise than contention; it was well known and practised in England in the fourteenth century, and is mentioned as one of the sports of Prince Henry, son of James I., in 1610. Strutt (Sports and Pastimes, p. 96) gives two illustrations of what he considers to be baloon ball play, from fourteenth century MSS.

A game played with sticks called “bandies,” bent and round at one end, and a small wooden ball, which each party endeavours to drive to opposite fixed points. Northbrooke in 1577 mentions it as a favourite game in Devonshire (Halliwell’s Dict. of Provincialisms). Strutt says the bat-stick was called a “bandy” on account of its being bent, and gives a drawing from a fourteenth century MS. book of prayers belonging to Mr. Francis Douce (Sports, p. 102). The bats in this drawing are nearly identical with modern golf-sticks, and “Golf” seems to be derived from this game. Peacock mentions it in his Glossary of Manley and Corringham Words. Forby has an interesting note in his Vocabulary of East Anglia, i. 14. He says, “The bandy was made of very tough wood, or shod with metal, or with the point of the horn or the hoof of some animal. The ball is a knob or gnarl from the trunk of a tree, carefully formed into a globular shape. The adverse parties strive to beat it with their bandies through one or other of the goals.”

A game played with a nurr and crooked stick, also called “Shinty,” and much the same as the “Hockey” of the South of England. “Cad” is the same as “cat” in the game of “Tip-cat;” it simply means a cut piece of wood.—Nodal and Milner’s Lancashire Glossary.

A game at ball common in Norfolk, and played in a similar manner to “Bandy” (Halliwell’s Dictionary). Toone (Etymological Dictionary) says it is also played in Suffolk, and in West Sussex is called “Hawky.”

The game of “Cricket,” played with a bandy instead of a bat (Halliwell’s Dictionary). Toone mentions it as played in Norfolk (Dict.), and Moor as played in Suffolk with bricks usually, or, in their absence, with bats in place of bails or stumps (Suffolk Words).

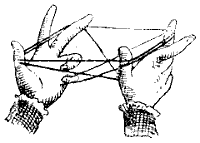

Each boy provides himself with a button. One of the boys lays his button on the ground, near a wall. The other boys snap their buttons in turn against the wall. If the button drops within one span or hand-reach of the button laid down, it counts two (fig. 2); if within two spans, it counts one. When it hits the button and bounces within one span, it counts four (fig. 1); within two spans, three; and above three spans, one. Each player snaps in turn for an agreed number; the first to score this number wins the game.—Deptford, Kent, and generally in London streets (Miss Chase).

This game is known in America as “Spans.”—Newell, p. 188.

To play at “Bar,” a species of game anciently used in Scotland.—Jamieson.

This game had in ancient times in England been simply denominated “Bars,” or, as in an Act of James IV., 1491, edit. 1814, p. 227: “That na induellare within burgh . . . play at bar,” “playing at Bars.”

See “Prisoner’s Base.”

—Deptford, Kent (Miss Chase).

—Clapham, Surrey (Miss F. D. Richardson).

—Lady Camilla Gurdon’s Suffolk County Folk-lore, p. 63.

—Penzance (Mrs. Mabbott).

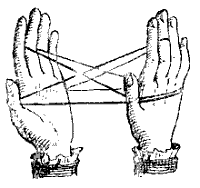

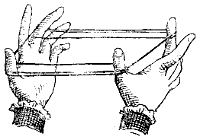

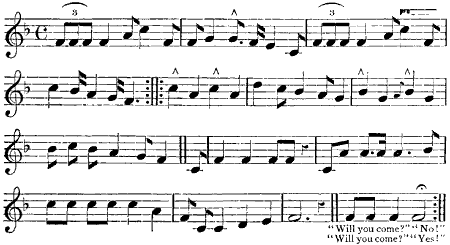

(b) Two children stand together joining hands tightly, to personate a fortress; one child stands at a distance from these to personate the King of Barbarie, with other children standing behind to personate the soldiers (fig. 1). Some of the soldiers[20] go to the fortress and surround it, singing the first verse (fig. 2). The children in the fortress reply, the four first verses being thus sung alternately. The soldiers then go to the King singing the fifth verse (fig. 3), the remaining verses being thus sung alternately. One of the soldiers then goes to the fortress and endeavours by throwing herself on the clasped hands of the children forming the fortress to break down the guard (fig. 4). All the soldiers try to do this, one after the other; finally the King comes, who breaks down the guard. The whole troop of soldiers then burst through the parted arms (fig. 5).

This is the Deptford version. The Clapham version is almost identical; the children take hold of each others’ skirts and make a long line. If the brave soldier is not able to break the clasped hands he goes to the end of the line of soldiers.[21] The soldiers do not surround the fortress. In the Suffolk version the soldiers try to break through the girls’ hands. If they do they have the tower. The Cornwall version is not so completely an illustration of the capture of a fortress.

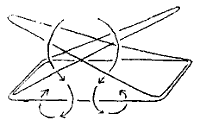

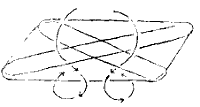

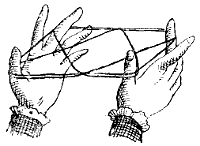

Barley-break, or the Last Couple in Hell, was a game played by six people, three of each sex, who were coupled by lot. A piece of ground was then chosen, and divided into three compartments, of which the middle one was called Hell. It was the object of the couple condemned to this division to catch the others who advanced from the two extremities (figs. 1, 2), in which case a change of situation took place, and Hell was filled by the couple who were excluded by pre-occupation from the other place (fig. 3). In this catching, however, there was some difficulty, as by the regulations of the game the middle couple were not to separate before they had succeeded, while the others might break hands whenever they found themselves hard pressed. When all had been taken in turn, the last couple was said to be “in Hell,” and the game ended.—Dekker’s Works, iv. 434.

[22]Jamieson calls this “a game generally played by young people in a corn-yard. Hence called barla-bracks about the stacks, S. B.” (i. e., in the North of Scotland). “One stack is fixed on as the dule or goal; and one person is appointed to catch the rest of the company, who run out from the dule. He does not leave it till they are all out of sight. Then he sets off to catch them. Any one who is taken cannot run out again with his former associates, being accounted a prisoner; but is obliged to assist his captor in pursuing the rest. When all are taken the game is finished; and he who was first taken is bound to act as catcher in the next game. This innocent sport seems to be almost entirely forgotten in the South of Scotland. It is also falling into desuetude in the North.”

(b) The following description of Barley-break, written by Sir Philip Sidney, is taken from the song of Lamon, in the first volume of the Arcadia, where he relates the passion of Claius and Strephon for the beautiful Urania:—

[23]Sir John Suckling also has given a description of this pastime with allegorical personages, which is quoted by Brand. In Holiday’s play of the Marriages of the Arts, 1618, this sport is introduced, and also by Herrick (Hesperides, p. 44). Barley-break is several times alluded to in Massinger’s plays: see the Dramatic Works of Philip Massinger, 1779, i. 167. “We’ll run at barley-break first, and you shall be in hell” (Dekker’s The Honest Whore). “Hee’s at barli-break, and the last couple are now in hell” (Dekker’s The Virgin Martir). See Gifford’s Massinger, i. 104, edit. 1813. See also Browne’s Britannia’s Pastorals, published in 1614, Book I., Song 3, p. 76.

Randle Holme mentions this game as prevailing in his day in Lancashire. Harland and Wilkinson believe this game to have left its traces in Yorkshire and Lancashire. A couple link hands and sally forth from home, shouting something like

and trying to tick or touch with the free hand any of the boys running about separately. These latter try to slip behind the couple and throw their weight on the joined hands to separate them without being first touched or ticked; and if they sunder the couple, each of the severed ones has to carry one home on his back. Whoever is touched takes the place of the toucher in the linked couple (Legends of Lancashire, p. 138). The modern name of this game is “Prison Bars” (Ibid., p. 141). There is also a description of the game in a little tract called Barley Breake; or, A Warning for Wantons, 1607. It is mentioned in Wilbraham’s Cheshire Glossary as “an old Cheshire game.” Barnes, in his Dorsetshire Glossary, says he has seen it played with one catcher on hands and knees in the small ring (Hell), and the others dancing round the ring crying “Burn the wold witch, you barley breech.” Holland (Cheshire Glossary) also mentions it as an old Cheshire game.

See “Boggle about the Stacks,” “Scots and English.”

—Played about 1850 at Hurstmonceux, Sussex (Miss Chase).

This is probably a forfeit game, imperfectly remembered. See “Old Soldier.”

An undescribed Suffolk game.—Moor’s Suffolk Words. See “Rounders.”

[Play]

—London (A. B. Gomme).

In this game the children all follow one who is styled the “mother,” singing:

The mother presently turns and catches or pretends to beat them.—Dorsetshire (Folk-lore Journal, vii. 231).

—Hersham, Surrey (Folk-lore Record, v. 84).

A version familiar to me is the same as above, but ending with

The mother then chased and beat those children she caught. The idea was, I believe, that the children were imitating or mocking their mother (A. B. G.). In Warwickshire the four[25] lines of the Surrey game are concluded by the additional lines—

When the mother runs after them and buffets them.—Northall’s English Folk Rhymes, p. 393.

See “Shuttlefeather.”

A number of boys agree to play at this game, and sides are picked. Five, for example, play on each side. A square is chalked out on a footpath by the side of a road, which is called the “Den;” five of the boys remain by the side of the Den, one of whom is called the “Tenter;” the Tenter has charge of the Den, and he must always stand with one foot in the Den and the other upon the road; the remaining five boys go out to field, it being agreed beforehand that they shall only be allowed to run within a prescribed area, or in certain roads or streets (fig. 1). As soon as the boys who have gone out to field have reached a certain distance—there is no limit prescribed—they[26] shout “Relievo,” and upon this signal the four boys standing by the side of the Den pursue them, leaving the Tenter in charge of the Den (fig. 2). When a boy is caught he is taken to the Den, where he is obliged to remain, unless the Tenter puts both his feet into the Den, or takes out the one foot which he ought always to keep in the Den. If the Tenter is thus caught tripping, the prisoner can escape from the Den. If during the progress of the game one of the boys out at field runs through the Den shouting “Relievo” without being caught by the Tenter, the prisoner is allowed to escape, and join his comrades at field. If one of the boys out at field is tired, and comes to stand by the side of the Den, he is not allowed to put his foot into the Den. If he does so the prisoner calls out, “There are two Tenters,” and escapes if he can (fig. 3). When all the boys out at field have been caught and put into the Den, the process is reversed—the boys who have been, as it were, hunted, taking the place of the hunters. Sometimes the cry is “Delievo,” and not “Relievo.” One or two variations occur in the playing of this game. Sometimes the Tenter, instead of standing with one foot in the Den, stands as far off the prisoner as the prisoner can spit. The choosing of sides is done by tossing. Two boys are selected to toss. One of them throws up his cap, crying, “Pot!” or “Lid!” which is equivalent to “Heads and Tails.” If, when a prisoner is caught, he cries out “Kings!” or “Kings to rest!” he is allowed to escape. The game is a very rough one.—Addy’s Sheffield Glossary.

Jamieson gives this as the Scottish name for “Hopscotch;” also Brockett, North Country Words.

I.

—Stanton Lacey (Burne’s Shropshire Folk-lore, p. 520).

II.

—Halliwell’s Nursery Rhymes, p. 283.

(b) The children form long trains, standing one behind the other. They march and sing the first four lines, then the fifth line, when they stand and begin again as before.

(c) Miss Burne suggests a connection with the old pack-horses. Mr. Addy (Sheffield Glossary) gives the first two lines as a game. He says, “The first horse in a team conveying lead to be smelted wore bells, and was called the bell-horse.” I remember when a child the two first lines being used to start children a race (A. B. G.). Chambers (Pop. Rhymes, p. 148) gives a similar verse, used for starting a race:—

and these lines are also used for the same purpose in Cheshire (Holland’s Glossary) and Somersetshire (Elworthy’s Glossary). Halliwell, on the strength of the corrupted word “Bellasay,” connects the game with a proverbial saying applied to the family of Bellasis; but there is no evidence of such a connection except the word-corruption. The rhyme occurs in Gammer Gurton’s Garland, 1783, the last words of the second line being “time to away.”

The name for “Blind Man’s Buff” in Upper Clydesdale. As anciently in this game he who was the chief actor was not only hoodwinked, but enveloped in the skin of an animal.—Jamieson.

See “Blind Man’s Buff.”

The name for “Blind Man’s Buff” in Roxburgh, Clydesdale, and other counties of the border. It is probable that the term is the same with “Billy Blynde,” said to be the name of a familiar spirit or good genius somewhat similar to the brownie.—Jamieson.

See “Blind Man’s Buff.”

A boys’ phrase for a slide on a pond when the ice is thin and bends. There is a game on the ice called playing at “Bend-leather.” Whilst the boys are sliding they say “Bend-leather, bend-leather, puff, puff, puff.”—Addy’s Sheffield Glossary.

[Play]

—Kent (J. P. Emslie).

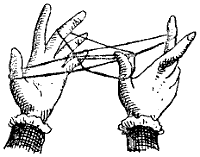

Two children cross their hands in the fashion known as a “sedan chair.” A third child sits on their hands. The two sing the first line. One of them sings, “You’re the lock,” the other sings, “and I’m the key,” and as they sang the words they unclasped their hands and dropped their companion on the ground. Mr. J. P. Emslie writes, “My mother learned this from her mother, who was a native of St. Laurence, in the Isle of Thanet. The game possibly belongs to Kent.”

In Somersetshire the game of “Hide and Seek.” To bik’ee is for the seekers to go and lean their heads against a wall, so as not to see where the others go to hide.—Elworthy’s Dialect.

See “Hide and Seek.”

A Lincolnshire name for “Prisoner’s Base.”—Halliwell’s Dictionary; Peacock’s Manley and Corringham Glossary; Cole’s S. W. Lincolnshire Glossary.

Name for “Blind Man’s Buff.”—Dickinson’s Cumberland Glossary.

The Derbyshire name for “Tip-cat.”—Halliwell’s Dictionary.

A name for “Prisoner’s Base.”—Halliwell’s Dictionary.

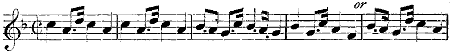

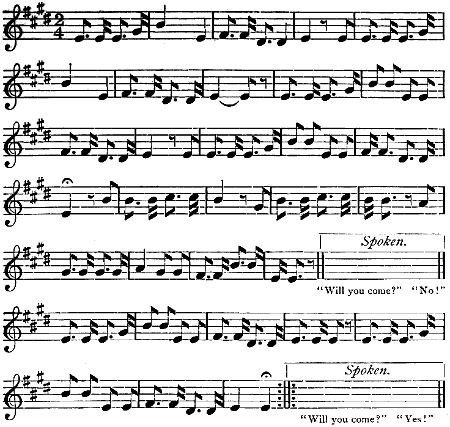

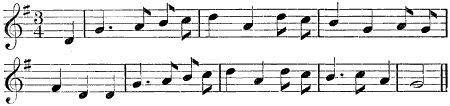

[Play]

[Play]

[Play]

[Play]

[Play]

—Monton, Lancashire (Miss Dendy).

—Market Drayton, Ellesmere, Oswestry (Burne’s Shropshire Folk-lore, p. 513).

—Liphook, Hants; Wakefield, Yorks (Miss Fowler).

—Tean, Staffs.; and North Staffs. Potteries (Miss Keary).

—Nottinghamshire (Miss Winfield).

—Maxey, Northants (Rev. W. D. Sweeting).

—Eckington, Derbyshire (S. O. Addy).

—Enbourne, Berks (Miss Kimber).

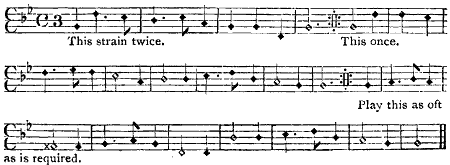

(b) In the Lancashire version, one child represents the Miller. The rest of the children stand round in a circle, with the Miller in the centre. All dance round and sing the verses. When it comes to the spelling part of the rhyme, the Miller points at one child, who must call out the right letter. If the child fails to do this she becomes Miller. In the Shropshire version, a ring is formed with one player in the middle. They dance round and sing the verses. When it comes to the spelling part, the girl in the middle cries B, and signals to another, who says I, the next to her N, the third G, the fourth “O! his name was Bobby Bingo!” Whoever makes a mistake takes the place of the girl in the middle. In the Liphook version, at the fourth line the children stand still and repeat a letter each in turn as quickly as they can, clapping their hands, and at the last line they turn right round, join hands, and begin again. In the Tean version, the one in the centre points, standing still, to some in the ring to say the letters B.I.N.G; the letter O has to be sung; if not, the one who says it goes in the ring, and repeats it all again until the game is given up. In the other Staffordshire version, when they stop, the one in the middle points to five of the others in turn, who have to say the letters forming “Bingo,” while the one to whom O comes has[32] to sing it on the note on which the others left off. Any one who says the wrong letter, or fails to sing the O right, takes the place of the middle one. The Northants version follows the Lancashire version, but if the answers are all made correctly, the last line is sung by the circle, and the game begins again. In the Metheringham version the child in the centre is blindfolded. When the song is over the girls say, “Point with your finger as we go round.” The girl in the centre points accordingly, and whichever of the others happens to be opposite to her when she says “Stop!” is caught. If the blindfolded girl can identify her captive they exchange places, and the game goes on as before. The Forest of Dean and the Earls Heaton versions are played the same as the Lancashire. In the West Cornwall version, as seen played in 1884, a ring is formed, into the middle of which goes a child holding a stick; the others with joined hands run round in a circle, singing the verses. When they have finished singing they cease running, whilst the one in the centre, pointing with his stick, asks them in turn to spell Bingo. If they all spell it correctly they again move round singing; but should either of them make a mistake, he or she has to take the place of the middle man (Folk-lore Journal, v. 58). In the Hexham version they sing a second verse, which is the same as the first with the name spelt backwards. The Berks version is practically the same as the Tean version. The Eckington (Derbyshire) version is played as follows:—A number of young women form a ring. A man stands within the ring, and they sing the words. He then makes choice of a girl, who takes his arm. They both walk round the circle while the others sing the same lines again. The girl who has been chosen makes choice of a young man in the ring, who in his turn chooses another girl, and so on till they have all paired off.

(c) The first verse of the Shropshire version is also sung at Metheringham, near Lincoln (C. C. Bell), and Cowes, I. W. (Miss E. Smith). The Staffordshire version of the words is sung in Forest of Dean, Gloucestershire (Miss Matthews), West Cornwall (Folk-lore Journal, v. 58), Earls Heaton, Yorkshire (H. Hardy), Hexham, Northumberland (Miss Barker),[33] Leicester (Miss Ellis). Miss Peacock says, “A version is known in Lincolnshire.” Tunes have also been sent from Tean, North Staffs. (Miss Keary), and Epworth, Doncaster (Mr. C. C. Bell), which are nearly identical with the Leicester tune; from Market Drayton (Miss Burne), similar to the Derbyshire tune; from Monton, Lancashire (Miss Dendy), which appears to be only the latter part of the tune, and is similar to those given above. The tune given by Rimbault is not the same as those collected above, though there is a certain similarity.

The editor of Northamptonshire Notes and Queries, vol. i. p. 214, says, “Some readers will remember that Byngo is the name of the ‘Franklyn’s dogge’ that Ingoldsby introduces into a few lines described as a portion of a primitive ballad, which has escaped the researches of Ritson and Ellis, but is yet replete with beauties of no common order.” In the Nursery Songs collected by Ed. Rimbault from oral tradition is “Little Bingo.” The words of this are very similar to the Lancashire version of the game sent by Miss Dendy. There is an additional verse in the nursery song.

A row of boys or girls stands parallel with another row opposite. Each of the first row chooses the name of some bird, and a member of the other row then calls out all the names of birds he can think of. If the middle member of the first row has chosen either of them, he calls out “Yes,” and all the guessers immediately run to take the place of the first row, the members of which attempt to catch them. If any succeed, they have the privilege of riding in on their captives’ backs.—Ogbourne, Wilts (H. S. May).

| B | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | h | = | Bullfinch |

| E | × | × | × | × | × | × | t | = | Elephant | |

| S | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | h | = | Swordfish |

This is a slate game, and two or more children play. One writes the initial and final letters of a bird’s, beast’s, or fish’s[34] name, making crosses (×) instead of the intermediate letters of the word, stating whether the name is that of bird, beast, or fish. The other players must guess in turn what the name is. The first one who succeeds takes for himself the same number of marks as there are crosses in the word, and then writes the name of anything he chooses in the same manner. If the players are unsuccessful in guessing the name, the writer takes the number to his own score and writes another. The game is won when one player gains a certain number of marks previously decided upon as “game.”—Barnes (A. B. Gomme).

The Sussex game of “Stoolball.” There is a tradition that this game was originally played by the milkmaids with their milking-stools, which they used for bats; but this word makes it more probable that the stool was the wicket, and that it was defended with the bittle, which would be called the bittle-bat.—Parish’s Sussex Dialect.

See “Stoolball.”

Bishop Kennet (in MS. Lansd. 1033) gives this name as a term for “Prisoner’s Base.”—Halliwell’s Dictionary.

A long rope is tied to a gate or pole, and one of the players holds the end of the rope, and tries to catch another player. When he succeeds in doing so the one captured joins him (by holding hands) and helps to catch the other players. The game is finished when all are caught.—Cork (Miss Keane).

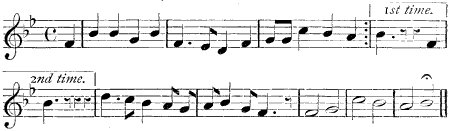

[Play]

—Earls Heaton, Yorks.

—Monton, Lancashire (Miss Dendy).

—Harland and Wilkinson’s Lancashire Folk-lore, p. 150.

—Addy’s Sheffield Glossary.

—Earls Heaton, Yorkshire (Herbert Hardy).

(b) One set of children stand against a wall, another set stand opposite, facing them. The first set sing the first line, the others replying with the second line, and so with the third and fourth lines. The two sides then rush over to each other, and the second set are caught. The child who is caught last becomes one of the first set for another game. This is the Earls Heaton version. The Lancashire game, as described by Miss Dendy, is: One child stands opposite a row of children, and the row run over to the opposite side, when the one child tries to catch them. The prisoners made, join the one child, and assist her in the process of catching the others. The rhyme is repeated in each case until all are caught, the last one out becoming “Blackthorn” for a new game. Harland and Wilkinson describe the game somewhat differently. Each player has a mark, and after the dialogue the players run over to each other’s marks, and if any can be caught before getting home to the opposite mark, he has to carry his captor to the mark, when he takes his place as an additional catcher.

[36](c) Miss Burne’s version (Shropshire Folk-lore, p. 521) is practically the same as the Earls Heaton game, and Easther in his Almondbury Glossary gives a version practically like the Sheffield. Mr. Hardy says it is sometimes called “Black-butt,” when the opposite side cry “Away we cut.” Miss Dendy quotes an old Lancashire rhyme, which curiously refers to the different subjects in the Lancashire game rhyme. It is as follows:—

Another version is given in Notes and Queries, 3rd Series, vii. 285.

(d) This is a dramatic game, in which the children seem to personate animals, and to depict events belonging to the history of the flock. Miss Burne groups it under her “dramatic games.”

A game formerly common in Berwickshire, in which all the players were hoodwinked except the person who was called the Bell. He carried a bell, which he rung, still endeavouring to keep out of the way of his hoodwinked partners in the game. When he was taken, the person who seized him was released from the bandage, and got possession of the bell, the bandage being transferred to him who was laid hold of.—Jamieson.

(b) In “The Modern Playmate,” edited by Rev. J. G. Wood, this game is described under the name of “Jingling.” Mr. Wood says there is a rougher game played at country feasts and fairs in which a pig takes the place of the boy with the bell, but he does not give the locality (p. 7). Strutt also describes it (Sports, p. 317).

In Somersetshire the game of “Blind Man’s Buff.” Also in Cornwall (see Couch’s Polperro, p. 173). Pulman says this means “Blind buck and have ye” (Elworthy’s Dialect).

A name for “Blind Man’s Buff.”—Jamieson.

The Suffolk name for “Blind Man’s Buff.”—Halliwell’s Dictionary; Moor’s Suffolk Glossary.

—Shrewsbury (Burne’s Shropshire Folk-lore, p. 525).

—Deptford (Miss Chase).

—Cornwall (Folk-lore Journal, v. 57, 58).

—Cumberland (Dickinson’s Glossary).

[38](b) In the Deptford version one of the players is blindfolded. The one who blindfolds ascertains that the player cannot see by putting the first question. When the players are satisfied that the blindfolding is complete, the dialogue follows, and the blind man is turned round three times. The game is for him to catch one of the players, who is blindfolded in turn if the blind man succeeds in guessing who he is. Players are allowed to pull, pinch, and buffet the blind man.

(c) This sport is found among the illuminations of an old missal formerly in the possession of John Ives, cited by Strutt in his Manners and Customs. The two illustrations are facsimiles from drawings in one of the Bodleian MSS., and they indicate the complete covering of the head, and also the fact that the game was played by adults. Gay says concerning it—

And another reference is quoted by Brand (ii. 398)—

—The Newe Metamorphosis, 1600, MS.

Other names for this game are “Belly Mantie,” “Billy Blind,” “Blind Bucky Davy,” “Blind Harie,” “Blind Hob,” “Blind Nerry Mopsey,” “Blind Palmie,” “Blind Sim,” “Buck Hid,”[39] “Chacke Blynd Man,” “Hoodle-cum-blind,” “Hoodman Blind,” “Hooper’s Hide,” “Jockie Blind Man.”

(d) There is some reason for believing that this game can be traced up to very ancient rites connected with prehistoric worship. The name “Billy Blind” denoted the person who was blindfolded in the game, as may be seen by an old poem by Lyndsay, quoted by Jamieson:

And also in Clerk’s Advice to Luvaris:

“It is probable,” says Jamieson, “that the term is the same as Billy Blynde, said to be the name of a familiar spirit or good genius somewhat similar to the brownie.” Professor Child identifies it with Odin, the blind deity. Another name in Scotland is also “Blind Harie,” which is not the common Christian name “Harry,” because this was not a name familiar in Scotland. Blind Harie may therefore, Jamieson thinks, arise from the rough or hairy attire worn by the principal actor. Auld Harie is one of the names given to the devil, and also to the spirit Brownie, who is represented as a hairy being. Under “Coolin,” a curious Highland custom is described by Jamieson, which is singularly like the game of “Belly Blind,”[40] and assists in the conclusion that the game has descended from a rite where animal gods were represented. Sporting with animals before sacrificing them was a general feature at these rites. It is known that the Church opposed the people imitating beasts, and in this connection it is curious to note that in South Germany the game is called blind bock, i. e., “blind goat,” and in German blinde kuhe, or “blind cow.” In Scotland, one of the names for the game, according to A. Scott’s poems, was “Blind Buk”:

It may therefore be conjectured that the person who was hoodwinked assumed the appearance of a goat, stag, or cow by putting on the skin of one of those animals.

He who is twice crowned or touched on the head by the taker or him who is hoodwinked, instead of once only, according to the law of the game, is said to be brunt (burned), and regains his liberty.—Jamieson.

A boys’ game, played with the eggs of small birds. The eggs are placed on the ground, and the player who is blindfolded takes a certain number of steps in the direction of the eggs; he then slaps the ground with a stick thrice in the hope of breaking the eggs; then the next player, and so on.—Patterson’s Antrim and Down Glossary.

The Whitby name for “Blind Man’s Buff.”—Robinson’s Glossary.

One of the names given to the game of “Blindman’s Buff.”—Jamieson.

Suffolk name for “Blind Man’s Buff.”—Forby’s Vocabulary of East Anglia.

This is a boys’ game, and requires seven players. One boy, the Block, goes down on all fours; another, the Nail, does the same behind the Block, with his head close to his a posteriori part. A third boy, the Hammer, lies down on his back behind the two. Of the remaining four boys one stations himself at each leg and one at each arm of the Hammer, and he is thus lifted. He is swung backwards and forwards three times in this position by the four, who keep repeating “Once, twice, thrice.” When the word “Thrice” is repeated, the a posteriori part of the Hammer is knocked against the same part of the Nail. Any number of knocks may be given, according to the humour of the players.—Keith (Rev. W. Gregor).

A fellow lies on all fours—this is the Block; one steadies him before—this is the Study; a third is made a Hammer of, and swung by boys against the Block (Mactaggart’s Gallovidian Encyclopædia). Patterson (Antrim and Down Glossary) mentions a game, “Hammer, Block, and Bible,” which is probably the same game.

Strutt considers this to have been a children’s game, played by blowing an arrow through a trunk at certain numbers by way of lottery (Sports, p. 403). Nares says the game was blowing small pins or points against each other, and probably not unlike “Push-pin.” Marmion in his Antiquary, 1641, says: “I have heard of a nobleman that has been drunk with a tinker, and of a magnifico that has played at blow-point.” In the Comedy of Lingua, 1607, act iii., sc. 2, Anamnestes introduces Memory as telling “how he played at blowe-point with Jupiter when he was in his side-coats.” References to this game are also made in Apollo Shroving, 1627, p. 49; and see Hawkins’ English Drama, iii. 243.

See “Dust-Point.”

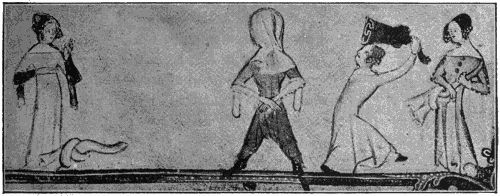

A children’s game, consisting in jumping at cherries above their heads and trying to catch them with their mouths (Halliwell’s Dictionary). It is alluded to in Herrick’s[42] Hesperides as “Chop Cherry.” Major Lowsley describes the game as taking the end of a cherry-stalk between the teeth, and holding the head perfectly level, trying to get the cherry into the mouth without using the hands or moving the head (Berkshire Glossary). It is also mentioned in Peacock’s Manley and Corringham Glossary. Strutt gives a curious illustration of the game in his Sports and Pastimes, which is here reproduced from the original MS. in the British Museum.

The Staffordshire St. Clement Day custom (Poole’s Staffordshire Customs, &c., p. 36) and the northern Hallowe’en custom (Brockett’s North-Country Words) probably indicate the origin of this game from an ancient rite.

A favourite play among young people in the villages, in which one hunts several others (Brockett’s North-Country Words). The game is alluded to in one of the songs given by Ritson (ii. 3), and Jamieson describes it as a Scottish game.

See “Barley-break.”

The child’s play of finding the hidden person in the company.—Robinson’s Whitby Glossary. See “Hide and Seek.”

This is a boys’ game. The players place their bonnets or caps in a pile. They then join hands and stand in a circle round it. They then pull each other, and twist and wriggle round and round and over it, till one overturns it or knocks a bonnet off it. The player who does so is hoisted on the back of another, and pelted by all the others with their bonnets.—Keith, Nairn (Rev. W. Gregor).

[Play]

—Norfolk.

—Norfolk, 1825-30 (J. Doe).

(b) One boy lies down and personates Booman. Other boys form a ring round him, joining hands and alternately raising and lowering them, to imitate bell-pulling, while the girls who play sit down and weep. The boys sing the first verse. The girls seek for daisies or any wild flowers, and join in the singing of the second verse, while the boys raise the prostrate Booman and carry him about. When singing the third verse the boys act digging a grave, and the dead boy is lowered. The girls strew flowers over the body. When finished another boy becomes Booman.

(c) This game is clearly dramatic, to imitate a funeral. Mr. Doe writes, “I have seen somewhere [in Norfolk] a tomb with a crest on it—a leek—and the name Beaumont,” but it does not seem necessary to thus account for the game.

A game at marbles. Strutt describes it as follows:—“One bowls a marble to any distance that he pleases, which serves as a mark for his antagonist to bowl at, whose business it is to hit the marble first bowled, or lay his own near enough to it for him to span the space between them and touch both the marbles. In either case he wins. If not, his marble remains where it lay, and becomes a mark for the first player, and so alternately until the game be won.”—Sports, p. 384.

The same as “Boss-out.” It is mentioned, but not described, in Baker’s Northamptonshire Glossary.

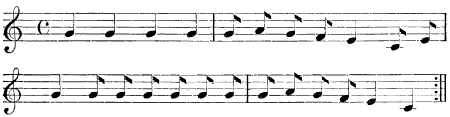

[Play]

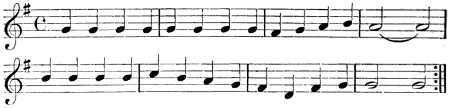

—The Dancing Master, 1728, vol. ii., p. 138.

—Useful Transactions in Philosophy, p. 44.

This rhyme is repeated when it is decided to begin any game, as a general call to the players. The above writer says[45] it occurs in a very ancient MS., but does not give any reference to it. Halliwell quotes the four first lines, the first line reading “Boys and girls,” instead of “Boys, boys,” from a curious ballad written about the year 1720, formerly in the possession of Mr. Crofton Croker (Nursery Rhymes). Chambers also gives this rhyme (Popular Rhymes, p. 152).

A game formerly common at fairs, called also “Hit my Legs and miss my Pegs.”—Dickinson’s Cumberland Glossary.

A game at marbles. The boys have a board a foot long, four inches in depth, and an inch (or so) thick, with squares as in the diagram; any number of holes at the ground edge, numbered irregularly. The board is placed firmly on the ground, and each player bowls at it. He wins the number of marbles denoted by the figure above the opening through which his marble passes. If he misses a hole, his marble is lost to the owner of the Bridgeboard.—Earls Heaton (Herbert Hardy). [The owner or keeper of the Bridgeboard presumably pays those boys who succeed in winning marbles.]

See “Nine Holes.”

A boys’ game, undescribed.—Patterson’s Antrim and Down Glossary.

Ebenezer is sent out of the room, and the remainder choose one of themselves. Two children act in concert, it being understood that the last person speaking when Ebenezer goes out of the room is the person to be chosen. The medium left in the room causes the others to think of this person without letting them know that they are not choosing of their own free will. The medium then says, “Brother Ebenezer, come in,” and asks him in succession, “Was it William, or Jane,” &c., mentioning[46] several names before saying the right one, Ebenezer saying “No!” to all until the one is mentioned who last spoke.—Bitterne, Hants (Mrs. Byford).

A child’s game, undescribed.—Halliwell’s Dictionary.

The name of a game probably the same as “Nine Holes.”—Halliwell’s Dictionary.

A boy stoops so that his arms rest on a table; another boy sits on him as he would on a horse. He then holds up (say) three fingers, and says—

The stooping boy guesses, and if he says a wrong number the other says—

When the stooping boy guesses rightly the other says—

The boy then gets off and stoops for the other one to mount, and the game is played again.—London (J. P. Emslie).

Similar action accompanies the following rhyme:—

—Almondbury (Easther’s Glossary).

A different action occurs in other places. It is played by three boys in the following way:—One stands with his back to a wall; the second stoops down with his head against the stomach of the first boy, “forming a back;” the third jumps on it, and holds up his hand with the fingers distended, saying—

[47]Should the stooper guess correctly, they all change places, and the jumper forms the back. Another and not such a rough way of playing this game is for the guesser to stand with his face towards a wall, keeping his eyes shut.—Cornwall (Folk-lore Journal, v. 59).

In Nairn, Scotland, the game is called Post and Rider. One boy, the Post, takes his stand beside a wall. Another boy stoops down with his head touching the Post’s breast. Several other boys stoop down in the same way behind the first boy, all in line. The Rider then leaps on the back of the boy at the end of the row of stooping boys, and from his back to that of the one in front, and so on from back to back till he reaches the boy next the Post. He then holds up so many fingers, and says—

The boy makes a guess. If the number guessed is wrong, the Rider gives the number guessed as well as the correct number, and again holds up so many, saying—

This goes on till the correct number is guessed, when the guesser becomes the Rider. The game was called “Buck, Buck” at Keith. Three players only took part in the game—the Post, the Buck, and the Rider. The words used by the Rider were—

If the guess was wrong, the Rider gave the Buck as many blows or kicks with the heel as the difference between the correct number and the number guessed. This process went on till the correct number was guessed, when the Rider and the Buck changed places.—Rev. W. Gregor.

(b) Dr. Tylor says: “It is interesting to notice the wide distribution and long permanence of these trifles in history when we read the following passage from Petronius Arbiter, written in the time of Nero:—‘Trimalchio, not to seem moved by the loss, kissed the boy, and bade him get up on his back. Without delay the boy climbed on horseback on him, and slapped him on the shoulders with his hand, laughing and calling out,[48] “Bucca, bucca, quot sunt hic”?’—Petron. Arbitri Satiræ, by Buchler, p. 84 (other readings are buccæ or bucco).”—Primitive Culture, i. 67.

A rude game amongst boys.—Dickinson’s Cumberland Glossary.

“A kind of play used by boys in London streets in Henry VIII.’s time, now disused, and I think forgot” (Blount’s Glossographia, p. 95). Hall mentions this game, temp. Henry VIII., f. 91.

For this the boys divide into sides. One “stops at home,” the other goes off to a certain distance agreed on beforehand and shouts “Buckey-how.” The boys “at home” then give chase, and when they succeed in catching an adversary, they bring him home, and there he stays until all on his side are caught, when they in turn become the chasers.—Cornwall (Folk-lore Journal, v. 60).

—Shropshire (Burne’s Shropshire Folk-lore, p. 526).

Same verses as in Shropshire, except the last, which runs as follows:—

—Cheltenham (Miss E. Mendham).

Same verses as in Shropshire, except the last, which runs as follows:—

—London (J. P. Emslie).

(b) Five or six children stand in a row. Another child comes up to the first of the row, and strikes smartly on the ground with a stick. The child facing him asks the first question, and the one with the stick answers. At “strokes his face” he suits the action to the words, and then thumps with his stick on the ground at the beginning of the last line. The object of all the players is to make Buff smile while going through this absurdity, and if he does he must pay a forfeit.

Another version is for one child to be blindfolded, and stand in the middle of a ring of children, holding a long wand in his hand. The ring dance round to a tune and sing a chorus [which is not given by the writer]. They then stop. Buff extends his wand, and the person to whom it happens to be pointed must step out of the circle to hold the end in his hand. Buff then interrogates the holder of the wand by grunting three times, and is answered in like manner. Buff then guesses who is the holder of the wand. If he guesses rightly, the holder of the stick becomes Buff, and he joins the ring (Winter Evening’s Amusements, p. 6). When I played at this game the ring of children walked in silence three times only round Buff, then stopped and knelt or stooped down on the ground, strict silence being observed. Buff asked three questions (anything he chose) of the child to whom he pointed the stick, who replied by imitating cries of animals or birds (A. B. Gomme).

(c) This is a well-known game. It is also called “Buffy Gruffy,” or “Indian Buff.” The Dorsetshire version in Folk-lore Journal, vii. 238, 239, is the same as the Shropshire version.[50] Halliwell (Nursery Rhymes, cclxxxii.) gives a slight variant. It is also given by Mr. Addy in his Sheffield Glossary, the words being the same except the last two lines, which run—

This seems to be an old name for some game, probably “Blindman’s Buff,” Sw. “Blind-bock,” q. “bock” and “hufwud head” (having the head resembling a goat). The sense, however, would agree better with “Bo-peep” or “Hide and Seek.”—Jamieson.

One child places himself in the centre of a circle of others. He then asks each of the circle in turn, “Where’s the key of the park?” and is answered by every one, except the last, “Ask the next-door neighbour.” The last one answers, “Get out the way you came in.” The centre one then makes a dash at the hands of some of the circle, and continues to do so until he breaks through, when all the others chase him. Whoever catches him is then Bull.—Liphook, Hants (Miss Fowler).

“The Bull in the Barn” is apparently the same game. The players form a ring; one player in the middle called the Bull, one outside called the King.

Bull: “Where is the key of the barn-door?”

Chorus: “Go to the next-door neighbour.”

King: “She left the key in the church-door.”

Bull: “Steel or iron?”

He then forces his way out of the ring, and whoever catches him becomes Bull.—Berrington (Burne’s Shropshire Folk-lore, pp. 519, 520).

Another version is that the child in the centre, whilst the others danced around him in a circle, saying, “Pig in the middle and can’t get out,” replies, “I’ve lost my key but I will get out,” and throws the whole weight of his body suddenly on the clasped hands of a couple, to try and unlock them. When he had succeeded he changed the words to, “I’ve broken your[51] locks, and I have got out.” One of the pair whose hands he had opened took his place, and he joined the ring.—Cornwall (Folk-lore Journal, v. 50).

(b) Mr. S. O. Addy says the following lines are said or sung in a game called “T’ Bull’s i’ t’ Barn,” but he does not know how it is played:—

A play amongst boys, in which, all having joined hands in a line, a boy at one of the ends stands still, and the rest all wind round him. The sport especially consists in an attempt to heeze or throw the whole mass on the ground.—Jamieson.

See “Eller Tree,” “Wind up Jack,” “Wind up the Bush Faggot.”

A play of children. “Bummers—a thin piece of wood swung round by a cord” (Blackwood’s Magazine, Aug. 1821, p. 35). Jamieson says the word is evidently denominated from the booming sound produced.

A hole is scooped out in the ground with the heel in the shape of a small dish, and the game consists in throwing a marble as near to this hole as possible. Sometimes, when several holes are made, the game is called “Holy.”—Addy’s Sheffield Glossary; Notes and Queries, xii. 344.