Title: The Traditional Games of England, Scotland, and Ireland (Vol 2 of 2)

Author: Alice Bertha Gomme

Release date: December 29, 2012 [eBook #41728]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Edwards, Harry Lamé, the Music Team (Anne

Celnik, monkeyclogs, Sarah Thomson and others) and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

(This file was produced from images generously made

available by The Internet Archive)

Please see Transcriber’s Notes at the end of this document.

This is Volume II of a two-volume work. Volume I is available on the Project Gutenberg website here. The hyperlinks to Volume I work when this book is read on the Project Gutenberg website; when read elsewhere or when the files have been downloaded, the hyperlinks to Volume I may not work.

VOL. I.

ACCROSHAY-NUTS IN MAY

Medium 8vo, xix.—424 pp. With numerous Diagrams and Illustrations. Cloth uncut. 12s. 6d. nett.

Some Press Notices

Notes and Queries.—“A work of supreme importance . . . a scholarly, valuable, and delightful work.”

Spectator.—“Interesting and useful to the antiquarian, historian, and philologist, as well as to the student of manners and customs.”

Saturday Review.—“Thorough and conscientious.”

Critic (New York).—“A mine of riches to the student of folk-lore, anthropology, and comparative religion.”

Antiquary.—“The work of collection and comparison has been done with obvious care, and at the same time with a con amore enthusiasm.”

Zeitschrift für vergl. Literaturgeschichte.—“In jeder Beziehung erschöpfend und mustergültig.”

Zeitschrift für Pädagogie.—“Von hoher wissenschaftlicher Bedeutung.”

[All rights reserved]

WITH

TUNES, SINGING-RHYMES, AND METHODS OF PLAYING

ACCORDING TO THE VARIANTS EXTANT AND

RECORDED IN DIFFERENT PARTS

OF THE KINGDOM

COLLECTED AND ANNOTATED BY

ALICE BERTHA GOMME

VOL. II.

OATS AND BEANS-WOULD YOU KNOW

TOGETHER WITH A MEMOIR ON THE STUDY

OF CHILDREN’S GAMES

LONDON

DAVID NUTT, 270-71 STRAND

1898

Printed by Ballantyne, Hanson & Co.

At the Ballantyne Press

The completion of the second volume of my Dictionary has been delayed from several unforeseen circumstances, the most important being the death of my most kind and learned friend the Rev. Dr. Gregor. The loss which folk-lore students as a body sustained by this lamented scholar’s death, was in my own case accentuated, not only by many years of kindly communication, but by the very special help which he generously gave me for this collection.

The second volume completes the collection of games on the lines already laid down. It has taken much more space than I originally intended, and I was compelled to add some important variants to the first volume, sent to me during the compilation of the second. I have explained in the memoir that the two volumes practically contain all that is to be collected, all, that is to say, of real importance.

The memoir seeks to show what important evidence is to be derived from separate study of the Traditional Games of England. That games of all classes are shown to contain evidence of ancient custom and belief is remarkable testimony to the anthropological methods of studying folk-lore, which I have followed. The memoir fills a considerable space, although it contains only the analytical portion of what was to have been a comprehensive study of both the analytical and comparative sides of the questions. Dr. Gregor had kindly promised to help me with the study of foreign[vi] parallels to British Games, but before his death it became apparent that this branch of the subject would almost need a separate treatise, and his death decided me to leave it untouched. I do not underrate its importance, but I am disposed to think that the survey I have given of the British evidence will not be materially shaken by the study of the comparative evidence, which will now be made the easier.

I ought perhaps to add, that the “Memoir” at the end of this volume was read as a paper at the evening meeting of the Folk Lore Society, on March 16th, 1898.

I have again to thank my many kind correspondents for their help in collecting the different versions of the games.

A. B. G.

24 Dorset Square, N.W.

| ENGLAND. | ||

| Bedfordshire— | ||

| Bedford | Mrs. Haddon. | |

| Berkshire— | ||

| Welford | Mrs. S. Batson. | |

| Buckinghamshire— | ||

| Buckingham | Midland Garner. | |

| Cambridgeshire | Halliwell’s Nursery Rhymes. | |

| Barrington, Girton | Dr. A. C. Haddon. | |

| Cambridge | Mrs. Haddon. | |

| Cornwall | Miss I. Barclay. | |

| Derbyshire | Miss Youngman, Long Ago, vol. i. | |

| Devonshire | Miss Chase. | |

| Chudleigh Knighton | Henderson’s Folk-lore of the Northern Counties of England. | |

| Dorsetshire— | ||

| Broadwinsor | Folk-lore Journal, vol. vii. | |

| Gloucestershire | Northall’s English Folk Rhymes. | |

| Hampshire— | ||

| Gambledown | Mrs. Pinsent. | |

| Hertfordshire— | ||

| Harpenden, Stevenage | Mrs. Lloyd. | |

| Huntingdonshire— | ||

| St. Neots | Miss Lumley. | |

| Kent | Miss L. Broadwood. | |

| Lancashire— | ||

| Manchester | Miss Dendy. | |

| Liverpool | Mrs. Harley. | |

| Leicestershire | Leicestershire County Folk-lore. | |

| Lincolnshire— | ||

| Brigg | Miss J. Barker. | |

| Spilsby | Rev. R. Cracroft. | |

| London | Dr. Haddon, A. Nutt, Mrs. Gomme. | |

| Blackheath | Mr. M. L. Rouse. | |

| Hoxton | Rev. S. D. Headlam. | |

| Marylebone | Mrs. Gomme. | |

| Middlesex | Mrs. Pocklington-Coltman. | |

| Norfolk[viii] | Mrs. Haddon. | |

| Hemsby | Mrs. Haddon. | |

| Northumberland | Hon. J. Abercromby. | |

| Oxfordshire | Miss L. Broadwood. | |

| Staffordshire | Halliwell’s Nursery Rhymes. | |

| Wolstanton | Miss Bush. | |

| Suffolk | Mrs. Haddon. | |

| Woolpit, near Haughley | Mr. M. L. Rouse. | |

| Surrey— | ||

| Ash | Mrs. Gomme. | |

| Sussex— | ||

| Lewes | Miss Kimber. | |

| Worcestershire— | ||

| Upton on Severn | Miss. L. Broadwood. | |

| Yorkshire | Miss E. Cadman. | |

| SCOTLAND. | ||

| Notes and Queries. Pennant’s Voyage to the Hebrides. | ||

| Aberdeenshire— | ||

| Aberdeen | Mr. M. L. Rouse. | |

| Aberdeen Training College | Rev. Dr. Gregor. | |

| Corgarff, Fraserburgh, Meiklefolla, Rosehearty, Tyrie |

Rev. Dr. Gregor. | |

| Argyllshire— | ||

| Connell Ferry, near Oban | Miss Harrison. | |

| Banffshire— | ||

| Cullen, Macduff | Rev. Dr. Gregor. | |

| Berwickshire | A. M. Bell (Antiquary, vol. xxx.). | |

| Elgin and Nairn— | ||

| Dyke | Rev. Dr. Gregor. | |

| Strichen | ||

| Forfarshire— | ||

| Forfar | Rev. Dr. Gregor. | |

| Kincardineshire— | ||

| Banchory | Rev. Dr. Gregor. | |

| Kircudbrightshire— | ||

| Auchencairn | Miss M. Haddon. | |

| Dr. A. C. Haddon. | ||

| Crossmichael | Rev. Dr. Gregor. | |

| Galloway | Mr. J. G. Carter. | |

| Dalry | ||

| Kirkcudbright | Mr. J. Lawson. | |

| Laurieston | ||

| New Galloway | Rev. Dr. Gregor. | |

| Linlithgowshire— | ||

| Linlithgow | Mrs. Jamieson. | |

| Perthshire— | ||

| Auchterarder | Miss E. S. Haldane. | |

| Perth | Rev. Dr. Gregor. | |

| Ross-shire[ix] | Rev. Dr. Gregor. | |

| Wigtonshire— | ||

| Port William School | Rev. Dr. Gregor. | |

| IRELAND. | ||

| Carleton’s Stories of Irish Peasantry. | ||

| Cork— | ||

| Cork | Mr. I. J. Dennachy. | |

| Down— | ||

| St. Andrews | Miss H. E. Harvey. | |

| Dublin— | ||

| Dublin | Mrs. Coffey. | |

| Howth | Miss H. E. Harvey. | |

| Kerry— | ||

| Kerry | I. J. Dennachy. | |

| Waterville | Mrs. B. B. Green. | |

| Leitrim— | ||

| Kiltubbrid | Mr. L. L. Duncan. | |

| Waterford— | ||

| Waterford | Miss H. E. Harvey. | |

| WALES. | ||

| Roberts’ Cambrian Popular Antiquities. | ||

Children’s games, a definite branch of folk-lore—Nature of material for the study—Games fall into one of two sections—Classification of the games—Under customs contained in them—Under implements of play—Skill and chance games—Importance of classification—Early custom contained in skill and chance games—In diagram games—Tabu in game of “Touch”—Methods of playing the games—Characteristics of line form—Of circle forms—Of individual form—Of the arch forms—Of winding-up form—Contest games—War-cry used in contest games—Early marriage customs in games of line form—Marriage by capture—By purchase—Without love or courtship—Games formerly played at weddings—Disguising the bride—Hiring servants game—Marriage customs in circle games—Courtship precedes marriage—Marriage connected with water custom—“Crying for a young man” announcing a want—Marriage formula—Approval of friends necessary—Housewifely duties mentioned—Eating of food by bride and bridegroom necessary—Young man’s necessity for a wife—Kiss in the ring—Harvest customs in games—Occupations in games—Funeral customs in games—Use of rushes in games—Sneezing action in game—Connection of spirit of dead person with trees—Perambulation of boundaries—Animals represented—Ballads sung to a dance—Individual form games—Hearth worship—Objection to giving light from a fire—Child-stealing by witch—Obstacles in path when pursuing witch—Contest between animals—Ghosts in games—Arch form of game—Contest between leaders of parties—Foundation sacrifice in games—Encircling a church—Well worship in games—Tug-of-war games—Alarm bell ringing—Passing under a yoke—Creeping through holed stones in games—Under earth sods—Customs in “winding up” games—Tree worship in games—Awaking the earth spirit—Serpentine dances—Burial of maiden—Guessing, a primitive element in games—Dramatic classification—Controlling force which has preserved custom in games—Dramatic faculty in mankind—Child’s faculty for dramatic action—Observation of detail—Children’s games formerly an amusement of adults—Dramatic power in savages—Dramatic dances among the savage and semi-civilised—Summary and conclusion.

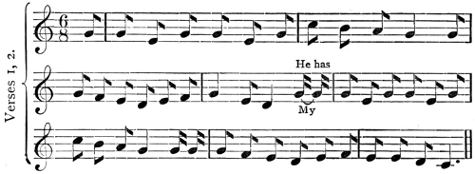

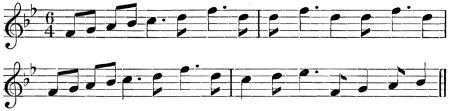

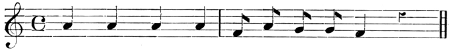

[Play]

—Northants Notes and Queries, ii. 161 (R. S. Baker)

[Play]

—Sporle, Norfolk (Miss Matthews).

—Much Wenlock (Burne’s Shropshire Folklore, p. 508).

—Monton, Lancashire (Miss Dendy).

—Raunds (Northants Notes and Queries, i. 163).

—East Kirkby, Lincolnshire (Miss K. Maughan).

—Winterton (Miss Fowler).

—Tean, North Staffs. (Miss Keary).

—Brigg, Lincolnshire (Miss Barker).

—Nottingham (Miss E. A. Winfield).

—Isle of Man (A. W. Moore).

—Spilsby, N. Lincs. (Rev. R. Cracroft).

—Hampshire (Miss Mendham).

—Cowes, Isle of Wight (Miss E. Smith).

—Long Eaton, Nottinghamshire (Miss Youngman).

—Sporle, Norfolk (Miss Matthews).

—Earls Heaton, Yorks. (H. Hardy).

—Boston, Lincs. (Notes and Queries, 7th series, xii. 493).

—Aberdeen Training College (Rev. W. Gregor).

—Wakefield, Yorks. (Miss Fowler).

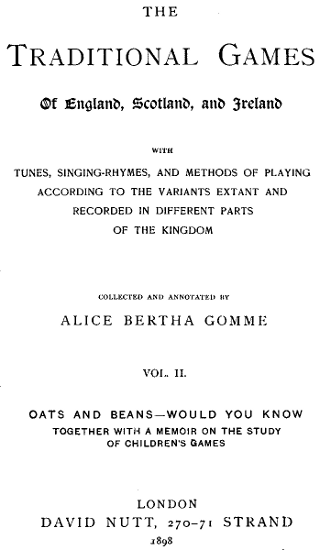

(c) The players form a ring by joining hands, with one child, usually a boy, standing in the centre. The ring walks round, singing the first four lines. At the fifth line the ring stands still, and each child suits her actions to the words sung. At “the farmer sows his seed,” each player pretends to scatter seed, then they all fold their arms and “stand at ease,” “stamp their feet,” and “clap their hands” together in order, and finally each child turns herself round. Then they again clasp hands and move round the centre child, who at the words “open the ring and take one in” chooses and takes into the ring with him one player from it. These two stand together while the ring sings the marriage formula. At the end the child first in the centre joins the ring; the second child remaining in the centre, and in her turn choosing another from the ring.

This is the (Much Wenlock) way of playing. Among the variants there are some slight differences. In the Wakefield version (Miss Fowler), a little boy is placed in the centre of the ring first, he chooses a girl out of the ring at the singing of the third line and kisses her. They stand hand in hand while the others sing the next verse. In the Tean version (Miss Keary), the children turn round with their backs to the one[10] in the centre, and stand still when singing “Waiting for a partner.” In the Hampshire (Miss Mendham), Brigg (Miss Barker), and Winterton (Miss Peacock) versions, the children dance round instead of walking. The Rev. Mr. Roberts, in a version from Kirkby-on-the-Bain (N.W. Lincolnshire), says: “There is no proper commencement of this song. The children begin with ‘A waitin’ fur a pardner,’ or ‘Oats and beans,’ just as the spirit moves them, but I think ‘A waitin’’ is the usual beginning here.” In a Sheffield version sent by Mr. S. O. Addy, four young men stand in the middle of the ring with their hands joined. These four dance round singing the first lines. After “views his lands” these four choose sweethearts, or partners, from the ring. The eight join hands and sing the remaining four lines. The four young men then join the larger ring, and the four girls remain in the centre and choose partners next time. The words of this version are almost identical with those of Shropshire. In the Isle of Man version (A. W. Moore), when the kiss is given all the children forming the ring clap their hands. There is no kissing in the Shropshire and many other versions of this game, and the centre child does not in all cases sing the words.

(d) Other versions have been sent from Winterton, Leadenham, and Lincoln, by Miss Peacock, and from Brigg, while the Northamptonshire Notes and Queries, ii. 161, gives another by Mr. R. S. Baker. The words are practically the same as the versions printed above from Lincolnshire and Northants. The words of the Madeley version are the same as the Much Wenlock (No. 1). The Nottingham tune (Miss Youngman), and three others sent with the words, are the same as the Madeley tune printed above.

(e) This interesting game is essentially of rural origin, and probably it is for this reason that Mr. Newell did not obtain any version from England for his Games and Songs of American Children, but his note that it “seems, strangely enough, to be unknown in Great Britain” (p. 80), is effectually disproved by the examples I have collected. There is no need in this case for an analysis of the rhymes. The variants fall into three[11] categories: (1) the questioning form of the words, (2) the affirming form, and (3) the indiscriminate form, as in Nos. xvi. to xviii., and of these I am disposed to consider the first to represent the earliest idea of the game.

If the crops mentioned in the verses be considered, it will be found that the following table represents the different localities:—

| North- ants. |

Lanca- shire. |

Lin- coln- shire. |

Shrop- shire. |

Staf- ford- shire. |

Not- ting- ham. |

Isle of Man. |

Hants. | Isle of Wight. |

Nor- folk. |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oats | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ... | ... |

| Beans | + | + | + | + | ... | + | + | + | ... | + |

| Barley | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Wheat | ... | ... | ... | ... | + | ... | ... | ... | + | ... |

| Groats | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| Hop | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | + | ... | ... | + |

The first three are the more constant words, but it is curious that Norfolk, not a hop county, should have adopted that grain into the game. Hops are grown there on rare occasions, and it is probable that the game may have been introduced from a hop county.

In Northants Notes and Queries, i. 163-164, Mr. R. S. Baker gives a most interesting account of the game (No. iii.) as follows:—“Having been recently invited to join the Annual Christmas Entertainment of the Raunds Church Choir, I noticed that a very favourite pastime of the evening was one which I shall call ‘Choosing Partners.’ The game is played thus: The young men and maidens join hands indiscriminately, and form a ring; within the ring stand a lad and a lass; then they all step round the way the sun goes, to a plain tune. During the singing of the two last lines [of the first part] they all disjoin hands, stop and stamp their feet and clap their hands and turn right round . . . then join hands [while singing the second verse]. The two in the middle at [‘Open the ring’] choose each of them a partner of the opposite sex, which they do by pointing to the one chosen; then they continue round, to the words [sang in next verse], the two pairs of partners crossing hands, first right and then left, and revolving[12] opposite ways alternately. The march round is temporarily suspended for choosing partners. The partners salute [at ‘Now you’re married’], or, rather, each lad kisses his chosen lass; the first two partners go out, the game continues as before, and every one in the ring has chosen and been chosen, and every lad has saluted every lass. The antiquity of the pastime is evidenced by its not mentioning wheat; wheat was in remote times an exceptional crop—the village people lived on oatmeal and barley bread. It also points, possibly, to a period when most of the land lay in grass. Portions of the open fields were cultivated, and after a few years of merciless cropping were laid down again to recuperate. ‘Helping to chop the wood’ recalls the time when coal was not known as fuel. I am indebted for the correct words of the above to a Raunds maiden, Miss B. Finding, a native of the village, who kindly wrote them down for me.” Mr. Baker does not say how Miss Finding got the peculiar spelling of this version. It would be interesting to know whether this form of spelling was used as indicative of the pronunciation of the children, or of the supposed antiquity of the game. The Rev. W. D. Sweeting, also writes at the same reference, “The same game is played at the school feast at Maxey; but the words, as I have taken them down, vary from those given above. We have no mention of any crop except barley, which is largely grown in the district; and the refrain, repeated after the second and sixth lines, is ‘waiting for the harvest.’ A lady suggested to me that the two first lines of the conclusion are addressed to the bride of the game, and the two last, which in our version run, ‘You must be kind and very good,’ apply to the happy swain.”

This interesting note not only suggests, as Mr. Baker and Mr. Sweeting say, the antiquity of the game and its connection with harvest at a time when the farms were all laid in open fields, but it points further to the custom of courtship and marriage being the outcome of village festivals and dances held after spring sowing and harvest gatherings. It seems in Northamptonshire not to have quite reached the stage of the pure children’s game before it was taken note of by[13] Mr. Baker, and this is an important illustration of the descent of children’s games from customs. As soon as it has become a child’s game, however, the process of decadence sets in. Thus, besides verbal alterations, the lines relating to farming have dropped out of the Wakefield version. It is abundantly clear from the more perfect game-rhymes that the waiting for a partner is an episode in the harvest customs, as if, when the outdoor business of the season was finished, the domestic element becomes the next important transaction in the year’s proceedings. The curious four-lined formula applicable to the duties of married life may indeed be a relic of those rhythmical formulæ which are found throughout all early legal ceremonies. A reference to Mr. Ralston’s section on marriage songs, in his Songs of the Russian People, makes it clear that marriages in Russia were contracted at the gatherings called Besyedas (p. 264), which were social gatherings held during October after the completion of the harvest; and the practice is, of course, not confined to Russia.

It is also probable that this game may have preserved the tradition of a formula sung at the sowing of grain, in order to propitiate the earth goddess to promote and quicken the growth of the crops. Turning around or bowing to fields and lands and pantomimic actions in imitation of those actually required, are very general in the history of sympathetic magic among primitive peoples, as reference to Mr. Frazer’s Golden Bough will prove; and taking the rhyming formula together with the imitative action, I am inclined to believe that in this game we may have the last relics of a very ancient agricultural rite.

The players stand in a row. The child at the head of the row says, “My son Obadiah is going to be married, twiddle your thumbs,” suiting the action to the word by clasping the fingers of both hands together, and rapidly “twiddling” the thumbs. The next child repeats both words and actions, and so on all along the row, all the players continuing the “twiddling.” The top child repeats the words, adding (very gravely), “Fall on one knee,” the whole row follows suit as before (still[14] twiddling their thumbs). The top child repeats from the beginning, adding, “Do as you see me,” and the rest of the children follow suit, as before. Just as the last child repeats the words, the top child falls on the child next to her, and all go down like a row of ninepins. The whole is said in a sing-song way. This game was, so far as I can ascertain, truly East Anglian. I have never been able to hear of it in other parts of England or Wales.—Bexley Heath (Miss Morris). Also played in London.

See “Solomon.”

A boys’ game, played with buttons, marbles, and halfpence. Peacock’s Manley and Corringham Glossary; also mentioned in Brogden’s Provincial Words (Lincolnshire). Mr. Patterson says (Antrim and Down Glossary)—A boy shuts up a few small objects, such as marbles, in one hand, and asks his opponent to guess if the number is odd or even. He then either pays or receives one, according as the guess is right or wrong. Strutt describes this game in the same way, and says it was played in ancient Greece and Rome. Newell (Games, p. 147) also mentions it.

See “Prickie and Jockie.”

A game played with coins. Brogden’s Provincial Words, Lincolnshire.

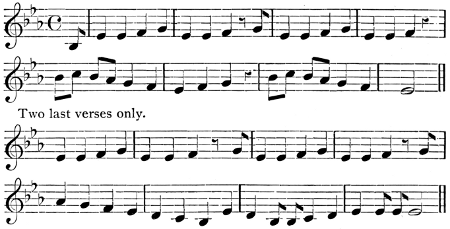

[This is repeated until the old woman says, “It’s eleven, and you’ll be hanged at twelve.”]

—Yorkshire (Miss E. Cadman).

[And so on until “eleven going for twelve” is said, then the following:—]

—Halliwell, Nursery Rhymes, p. 229.

(b) One child sits upon a little stool. The others march round her in single file, taking hold of each other’s frocks. They say in a sing-song manner the first two lines, and the old woman answers by telling them the hour. The questions and answers are repeated until the old woman says, “It’s eleven, and you’ll be hanged at twelve.” Then the children all run off in different directions and the old woman runs after them. Whoever she catches becomes old woman, and the game is continued.—Yorkshire (Miss E. Cadman). In the version given from Halliwell there is a further dialogue, it will be seen, before the old woman chases.

(c) The use of the Yorkshire word “beck” (“stream”) in the first variant suggests that this may be the original version from which the “Beccles” version has been adapted, a particular place being substituted for the general. The game somewhat resembles “Fox and Goose.”

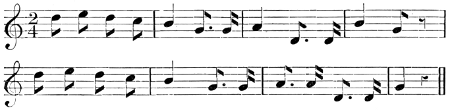

[Play]

[Play]

[Play]

—Earls Heaton, Yorks. (Herbert Hardy).

—Hanbury, Staffs. (Miss Edith Hollis).

—Ordsall, Nottinghamshire (Miss Matthews).

—Brigg, Lincolnshire (Miss J. Barker).

—Tong, Shropshire (Miss Burne).

—Sporle, Norfolk (Miss Matthews).

—Deptford, Kent (Miss Chase).

—Bath, from a Nursemaid (A. B. Gomme).

—Derbyshire (Folk-lore Journal, i. 385).

—Newark, Nottinghamshire (S. O. Addy).

—Belfast (W. H. Patterson).

—Sporle, Norfolk (Miss Matthews).

(b) A ring is formed by children joining hands; one child, who represents Sir Roger, lays down on the ground in the centre of the ring with his head covered with a handkerchief. The ring stands still and sings the verses. When the second verse is begun, a child from the ring goes into the centre and stands by Sir Roger, to represent the apple tree. At the fourth verse another child goes into the ring, and pretends to pick up the fallen apples. Then the child personating Sir Roger jumps up and knocks the child personating the old woman, beating her out of the ring. She goes off hobbling on one foot, and pretending to be hurt. In the Ordsall game the children dance round when singing the verses instead of standing still, the action of the game being the same. In the Tong version, the action seems to be done by the ring. Miss Burne says the children go through various movements, finally all limping round. The Newark (Notts), and Bath versions are played as first described, Poor Roger being covered with a cloak, or an apron, and laying down in the middle of the ring. A Southampton version has additional features—the ring of children keep their arms crossed, and lay their hands on their chests, bending their heads and bodies backwards and forwards, in a mourning attitude, while they sing; in addition to which, in the Bath version, the child who personates the apple tree during the singing of the third verse raises her arms above her head, and then lets them drop to her sides to show the falling apples.

(c) Various as the game-rhymes are in word detail, they[23] are practically the same in incident. One remarkable feature stands out particularly, namely, the planting a tree over the head of the dead, and the spirit-connection which this tree has with the dead. The robbery of the fruit brings back the dead Sir Roger to protect it, and this must be his ghost or spirit. In popular superstition this incident is not uncommon. Thus Aubrey in his Remains of Gentilisme, notes that “in the parish of Ockley some graves have rose trees planted at the head and feet,” and then proceeds to say, “They planted a tree or a flower on the grave of their friend, and they thought the soule of the party deceased went into the tree or plant” (p. 155). In Scotland a branch falling from an oak, the Edgewell tree, standing near Dalhousie Castle, portended mortality to the family (Dalyell, Darker Superstitions, p. 504). Compare with this a similar superstition noted in Carew’s History of Cornwall, p. 325, and Mr. Keary’s treatment of this cult in his Outlines of Primitive Belief, pp. 66-67. In folk-tales this incident also appears; the spirit of the dead enters the tree and resents robbery of its fruit, possession of which gives power over the soul or spirit of the dead.

The game is, therefore, not merely the acting of a funeral, but more particularly shows the belief that a dead person is cognisant of actions done by the living, and capable of resenting personal wrongs and desecration of the grave. It shows clearly the sacredness of the grave; but what, perhaps to us, is the most interesting feature, is the way in which the game is played. This clearly shows a survival of the method of portraying old plays. The ring of children act the part of “chorus,” and relate the incidents of the play. The three actors say nothing, only act their several parts in dumb show. The raising and lowering of the arms on the part of the child who plays “apple tree,” the quiet of “Old Roger” until he has to jump up, certainly show the early method of actors when details were presented by action instead of words. Children see no absurdity in being a “tree,” or a “wall,” “apple,” or animal. They simply are these things if the game demands it, and they think nothing of incongruities.

I do not, of course, suggest that children have preserved in[24] this game an old play, but I consider that in this and similar games they have preserved methods of acting and detail (now styled traditional), as given in an early or childish period of the drama, as for example in the mumming plays. Traditional methods of acting are discussed by Mr. Ordish, Folk-lore, ii. 334.

One player personates an old soldier, and begs of all the other players in turn for left-off garments, or anything else he chooses. The formula still used at Barnes by children is, “Here comes an old soldier from the wars [or from town], pray what can you give him?” Another version is—

—Liverpool (C. C. Bell).

The questioned child replying must be careful to avoid using the words, Yes! No! Nay! and Black, White, or Grey. These words are tabooed, and a forfeit is exacted every time one or other is used. The old soldier walks lame, and carries a stick. He is allowed to ask as many questions, talk as much as he pleases, and to account for his destitute condition.

(c) Some years ago when colours were more limited in number, it was difficult to promise garments for a man’s wear which were neither of these colours tabooed. Miss Burne (Shropshire Folk-lore, p. 526), in describing this game says, “The words Red or Blue are sometimes forbidden, as well as Yes or No,” and adds that “This favourite old game gives scope for great ingenuity on the part of the beggar, and ‘it seems not improbable’ (to use a time-honoured antiquarian phrase!) that the expression ‘To come the old soldier over a person’ may allude to it.” Halliwell (Nursery Rhymes, p. 224) describes the game as above.

—Berrington (Burne’s Shropshire Folk-lore, p. 508).

(b) The children form a ring and move round, singing the first two lines. Then they curtsey, or “douk down,” all together; the one who is last has to tell her sweetheart’s name. The other lines are then sung and the game is continued. The children’s names are mentioned as each one names his or her sweetheart.

This is apparently the game of which “All the Boys,” “Down in the Valley,” and “Mary Mixed a Pudding up,” are also portions.

The words “Cowardy, cowardy custard” are repeated by children playing at this game when they advance towards the one who is selected to catch them, and dare or provoke her to capture them. Ray, Localisms, gives Costard, the head; a kind of opprobrious word used by way of contempt. Bailey gives Costead-head, a blockhead; thus elucidating this exclamation which may be interpreted, “You cowardly blockhead, catch me if you dare” (Baker’s Northamptonshire Glossary).

The words used were, as far as I remember,

To compel a person to “eat” something disagreeable is a well-known form of expressing contempt. The rhyme was supposed to be very efficacious in rousing an indifferent or lazy player when playing “touch” (A. B. Gomme).

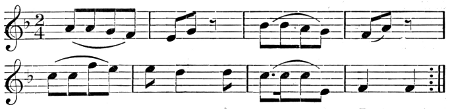

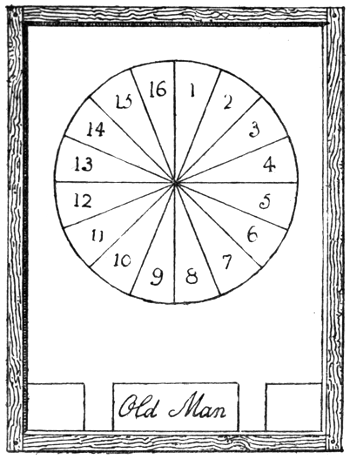

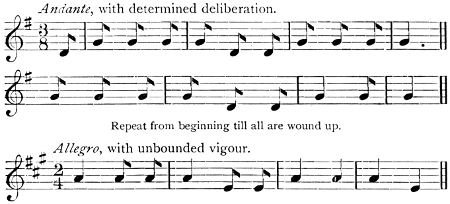

[Play]

[26]An older and more general version of the last five bars (the tail piece) is as follows:—

[Play]

[Play]

[Play]

—London (A. B. Gomme).

—Winterton and Leadenham, Lincolnshire; also Nottinghamshire (Miss M. Peacock).

—Derbyshire (Folk-lore Journal, i. 386).

—Middlesex (Miss Winfield).

—Sporle, Norfolk (Miss Matthews).

—Brigg (from a Lincolnshire friend of Miss Barker).

—Symondsbury, Dorset (Folk-lore Journal, vii. 216).

—Broadwinsor, Dorset (Folk-lore Journal, vii. 217).

—Earls Heaton, Yorks. (Herbert Hardy).

—Earls Heaton (Herbert Hardy, as told him by A. K.).

—Hersham, Surrey (Folk-lore Record, v. 86).

—Eckington, Derbyshire (S. O. Addy).

—Settle, Yorks. (Rev. W. E. Sykes).

—Suffolk (Mrs. Haddon).

—Perth (Rev. W. Gregor).

—Northamptonshire (Baker’s Words and Phrases).

(c) This game is generally played as follows:—

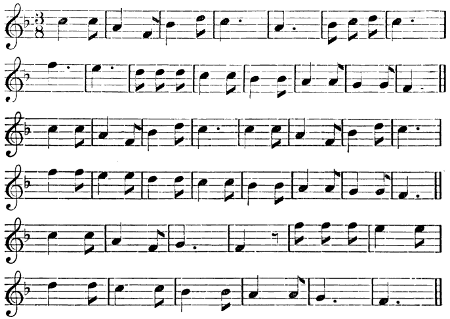

Two of the taller children stand facing each other, holding up their clasped hands. One is named Orange and the other Lemon. The other players, grasping one another’s dresses, run underneath the raised arms and round Orange, and then under the arms again and round Lemon, while singing the verses. The three concluding lines are sung by “Orange” and “Lemon” in a slow emphatic manner, and at the word “head” they drop their arms over one of the children passing between them, and ask her secretly whether she will be orange or lemon. The captive chooses her side, and stands behind whichever leader she selects, placing her arms round her waist. The game continues till every one engaged in it has ranged herself behind one or other of the chiefs. When the two parties are ranged a “tug of war” takes place until one of the parties breaks down, or is pulled over a given mark.

[33]In the Middlesex version (Miss Winfield) the children form a ring and go round singing the verses, and apparently there is neither catching the “last man” nor the “tug.” Mr. Emslie says he has seen and played the game in Middlesex, and it always terminated with the cutting off the last man’s head. In the Symondsbury version the players drop their hands when they say “Sunday.” No tug is mentioned in the first Earls Heaton version of the game (Mr. Hardy). In the second version he says bells are represented by children. They should have in their hands, bells, or some article to represent them. All stand in a row. First, second, and third bells stand out in turn to sing. All rush for bells to sing chorus. Miss Barclay writes: The children of the Fernham and Longcot choir, playing on Christmas Eve, 1891, pulled across a handkerchief. In Monton, Lancashire, Miss Dendy says the game is played as elsewhere, but without words. In a Swaffham version (Miss Matthews), the girls sometimes call themselves “Plum pudding and roast beef,” or whatever fancy may suggest, instead of oranges and lemons. They join hands high enough for the others to pass under, which they do to a call of “Ducky, Ducky,” presently the hands come down and catch one, who is asked in confidence which she likes best. The game then proceeds in the usual way, one side trying to pull the other over a marked line. Oranges and lemons at Bocking, Essex, is an abbreviated variant of the rhyme printed by Halliwell (Folk-lore Record, iii., part II., 171). In Nottinghamshire, Miss Peacock says it is sometimes called “Tarts and Cheesecakes.” Moor (Suffolk Words) mentions “Oranges and Lemons” as played by both girls and boys, and adds, “I believe it is nearly the same as ‘Plum Pudding and Roast Beef.’” In the Suffolk version sent by Mrs. Haddon a new word is introduced, “carwoo.” This is the signal for one of the line to be caught. Miss Eddleston, Gainford, Durham, says this game is called—

Mr. Halliwell (Nursery Rhymes, No. cclxxxi.) adopts the verses entitled, “The Merry Bells of London,” from Gammer[34] Gurton’s Garland, 1783, as the origin of this game. In Aberdeen, Mr. M. L. Rouse tells me he has heard Scotch children apparently playing the same game, “Oranges and Lemons, ask, Which would you have, ‘A sack of corn or a sack of coals?’”

(d) This game indicates a contest between two opposing parties, and a punishment, and although in the game the sequence of events is not at all clear, the contest taking place after the supposed execution, these two events stand out very clearly as the chief factors. In the endeavour to ascertain who the contending parties were, one cannot but be struck with the significance of the bells having different saint’s names. Now the only places where it would be probable for bells to be associated with more than one saint’s name within the circuit of a small area are the old parish units of cities and boroughs. Bells were rung on occasions when it was necessary or advisable to call the people together. At the ringing of the “alarm bell” the market places were quickly filled by crowds of citizens; and by turning to the customs of these places in England, it will be found that contest games between parishes, and between the wards of parishes, were very frequent (see Gomme’s Village Community, pp. 241-243). These contests were generally conducted by the aid of the football, and in one or two cases, such as at Ludlow, the contest was with a rope, and, in the case of Derby, it is specially stated that the victors were announced by the joyful ringing of their parish bells. Indeed, Halliwell has preserved the “song on the bells of Derby on football morning” (No. clxix.) as follows:—

This custom is quite sufficient to have originated the game, and the parallel which it supplies is evidence of the connection between the two. Oranges and lemons were, in all probability,[35] originally intended to mean the colours of the two contesting parties, and not fruits of those names. In contests between the people of a town and the authority of baron or earl, the adherents of each side ranged themselves under and wore the colours of their chiefs, as is now done by political partizans.

The rhymes are probably corrupted, but whether from some early cries or calls of the different parishes, or from sentences which the bells were supposed to have said or sung when tolled, it is impossible to say. The “clemming” of the bells in the Norfolk version (No. 5) may have originated “St. Clements,” and the other saints have been added at different times. On the other hand, the general similarity of the rhymes indicates the influence of some particular place, and, judging by the parish names, London seems to be that place. If this is so, the main incident of the rhymes may perhaps be due to the too frequent distribution of a traitor’s head and limbs among different towns who had taken up his cause. The exhibitions of this nature at London were more frequent than at any other place. The procession of a criminal to execution was generally accompanied by the tolling of bells, and by torches. It is not unlikely that the monotonous chant of the last lines, “Here comes a light to light you to bed,” &c., indicates this.[Addendum]

A boy (A) kneels with his face in another’s (B) lap; the other players standing in the background. They step forward one by one at a signal from B, who says to each in turn—

A then designates a place for each one. When all are despatched A removes his face from B’s knees, and standing up exclaims, “Hot! Hot! Hot!” The others then run to him, and the laggard is blinded instead of A.—Warwickshire (Northall’s Folk Rhymes, p. 402).

This is probably the same game as “Hot Cockles,” although it apparently lacks the hitting or buffeting the blinded wizard.

The name for the game of “Warner” in Oxfordshire. They have a song used in the game commencing—

—Halliwell’s Dictionary.

See “Stag Warning.”

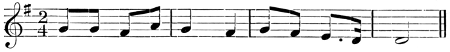

[Play]

—Long Eaton, Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire borders (Miss Youngman).

(c) The children form a ring, and hold in their hands a string tied at the ends, and on which a ring is strung. They pass the ring from one to another, backwards and forwards. One child stands in the centre, who tries to find the holder of the ring. Whoever is discovered holding it takes the place of the child in the centre.

(d) This game is similar to “Find the Ring.” The verse is, no doubt, modern, though the action and the string and ring are borrowed from an older game. Another verse used for the same game at Earl’s Heaton (Mr. Hardy) is—

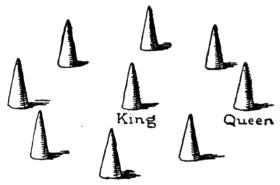

Three cherry stones are placed together, and another above them. These are all called a castle. The player takes aim with a cherry stone, and when he overturns the castle he claims the spoil.—Jamieson. See “Cob Nut.”

A Scottish name for “Hop Scotch.”—Jamieson.

See “Hop Scotch.”

A child’s name for the simple game of throwing a ball from one to another.—Lowsley’s Berkshire Glossary.

A boys’ game, somewhat similar to “Duckstone.” Each boy, when he threw his stone, had to say “Pay-swad,” or he had to go down himself.—Holland’s Cheshire Glossary.

See “Duckstone.”

A game played with pins: also called “Pinny Ninny,” “Pedna-a mean,” “Heads and Tails,” a game of pins.—Courtenay’s West Cornwall Glossary.

The game of “Hide and Seek.” When the object is hidden the word “Peesie-weet” is called out.—Fraserburgh, Aberdeenshire (Rev. W. Gregor).

See “Hide and Seek (2).”

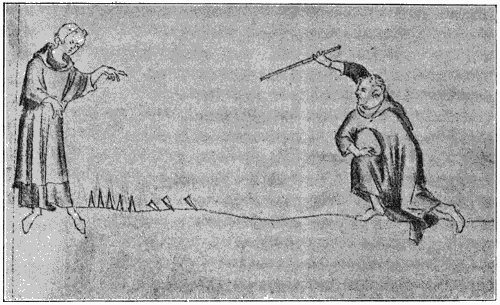

The players provide themselves with short, stout sticks, and a peg (a piece of wood sharpened at one or both ends). A ring is made, and the peg is placed on the ground so as to balance. One boy then strikes it with his stick to make it spring or bounce up into the air; while in the air he strikes it with his stick, and sends it as far as he possibly can. His opponent declares the number of leaps in which the striker is to cover the distance the peg has gone. If successful, he counts the number of leaps to his score. If he fails, his opponent leaps, and, if successful, the number of leaps count to his score. He strikes the next time, and the same process is gone through.—Earls Heaton, Yorks. (Herbert Hardy).

See “Tip-cat.”

A west country game. The performers in this game are each furnished with a sharp-pointed stake. One of them then strikes it into the ground, and the others, throwing their sticks across it, endeavour to dislodge it. When a stick falls, the owner has to run to a prescribed distance and back, while the rest, placing the stick upright, endeavour to beat it into the ground up to the very top.—Halliwell’s Dictionary.

A boyish game with nuts.—Dickinson’s Cumberland Glossary.

A game of “Peg-top.” The object of this game is to spin the top within a certain circle marked out, in which the top is to exhaust itself without once overstepping the bounds prescribed (Halliwell’s Dict. Provincialisms). Holloway (Dictionary) says, “When boys play at ‘Peg-top,’ a ring is formed on the ground, within which each boy is to spin his top. If the top, when it has ceased spinning, does not roll without the circle, it must remain in the ring to be pegged at by the other boys, or he redeems it by putting in an inferior one, which is called a ‘Mull.’ When the top does not roll out, it is said to be ‘mulled.’” Mr. Emslie writes: “When the top fell within the ring the boys cried, ‘One a penny!’ When two had fallen within the ring it was, ‘Two a penny!’ When three, ‘Three a penny, good as any!’ The aim of each spinner was to do what was called ‘drawing,’ i.e., bring his top down into the ring, and at the same time draw the string so as to make the top spin within the ring, and yet come towards the player and out of the ring so as to fall without.”

See “Tops.”

One of the players, chosen by lot, spins his top. The other players endeavour to strike this top with the pegs of their own tops as they fling them down to spin. If any one fails to spin his top in due form, he has to lay his top on the ground for the others to strike at when spinning. The object of each[39] spinner is to split the top which is being aimed at, so as to release the peg, and the boy whose top has succeeded in splitting the other top obtains the peg as his trophy of victory. It is a matter of ambition to obtain as many pegs in this manner as possible.—London (G. L. Gomme).

See “Peg-in-the-Ring,” “Tops.”

A game played with round flat stones, about four or six inches across, being similar to the game of quoits; sometimes played with pennies when the hobs are a deal higher. It was not played with pennies in 1810.—Easther’s Almondbury Glossary. In an article in Blackwood’s Magazine, August 1821, p. 35, dealing with children’s games, the writer says, Pennystanes are played much in the same manner as the quoits or discus of the ancient Romans, to which warlike people the idle tradesmen of Edinburgh probably owe this favourite game.

See “Penny Prick.”

A rude dance, which formerly took place in the common taverns of Sheffield, usually held after the bull-baiting.—Wilson’s Notes to Mather’s Songs, p. 74, cited by Addy, Sheffield Glossary.

“A game consisting of casting oblong pieces of iron at a mark.”—Hunter’s Hallamsh. Gloss., p. 71. Grose explains it, “Throwing at halfpence placed on sticks which are called hobs.”

—Scots’ Philomythie, 1616.

Halliwell gives these references in his Dictionary; Addy, Sheffield Glossary, describes it as above; adding, “An old game once played by people of fashion.”

See “Penny Cast.”

See “Penny Cast.”

The name of a dance mentioned in an old nursery rhyme. A correspondent gave Halliwell the following lines of a very old song, the only ones he recollected:—

—Halliwell’s Dictionary.

These words are somewhat of the same character as those of “Auntie Loomie,” and are evidently the accompaniment of an old dance.

See “Lubin.”

The game of “Pitch and Toss.”—Brogden’s Provincial Words, Lincolnshire. It is called Pickenhotch in Peacock’s Manley and Corringham Glossary.

A game in which one half of the players are supposed to keep a castle, while the others go out as a foraging or marauding party. When the latter are all gone out, one of them cries Pee-ku, which is a signal to those within to be on the alert. Then those who are without attempt to get in. If any one of them gets in without being seized by the holders of the castle, he cries to his companions, The hole’s won; and those who are within must yield the fortress. If one of the assailants be taken before getting in he is obliged to change sides and to guard the castle. Sometimes the guards are successful in making prisoners of all the assailants. Also the name given to the game of Hide and Seek.—Jamieson.

A boy’s game [undescribed].—Patterson’s Antrim and Down Glossary.

A game at marbles where a ring is made about four feet in diameter, and boys “shoot” in turn from any point in the[41] circumference, keeping such marbles as they may knock out of the ring, but loosing their own “taw” if it should stop within.—Lowsley’s Berkshire Glossary. See “Ring Taw.”

A sport among children in Fife. An egg, an unfledged bird, or a whole nest is placed on a convenient spot. He who has what is called the first pill, retires a few paces, and being provided with a cowt or rung, is blindfolded, or gives his promise to wink hard (whence he is called Winkie), and moves forward in the direction of the object, as he supposes, striking the ground with the stick all the way. He must not shuffle the stick along the ground, but always strike perpendicularly. If he touches the nest without destroying it, or the egg without breaking it, he loses his vice or turn. The same mode is observed by those who succeed him. When one of the party breaks an egg he is entitled to all the rest as his property, or to some other reward that has been previously agreed on. Every art is employed, without removing the nest or egg, to mislead the blindfolded player, who is also called the Pinkie.—Jamieson. See “Blind Man’s Stan.”

The game of “Pitch-Halfpenny,” or “Pitch and Hustle.”—Halliwell’s Dictionary. Addy (Sheffield Glossary) says this game consists of pitching halfpence at a mark.

See “Penny Cast,” “Penny Prick.”

A child’s peep-show. The charge for a peep is a pin, and, under extraordinary circumstances of novelty, two pins.

I remember well being shown how to make a peep or poppet-show. It was made by arranging combinations of colours from flowers under a piece of glass, and then framing it with paper in such a way that a cover was left over the front, which could be raised when any one paid a pin to peep. The following words were said, or rather sung, in a sing-song manner:—

—(A. B. Gomme).

Pansies or other flowers are pressed beneath a piece of glass, which is laid upon a piece of paper, a hole or opening, which can be shut at pleasure, being cut in the paper. The charge for looking at the show is a pin. The children say, “A pin to look at a pippy-show.” They also say—

—Addy’s Sheffield Glossary.

In Perth (Rev. W. Gregor) the rhyme is—

Described also in Holland’s Cheshire Glossary, and Lowsley’s Berkshire Glossary. Atkinson’s Cleveland Glossary describes it as having coloured pictures pasted inside, and an eye-hole at one of the ends. The Leed’s Glossary gives the rhyme as—

Northall (English Folk-rhymes, p. 357), also gives a rhyme.

On the 1st of January the children beg for some pins, using the words, “Please pay Nab’s New Year’s gift.” They then play “a very childish game,” but I have not succeeded in getting a description of it.—Yorkshire.

See “Prickie and Jockie.”

A game played by boys, “and the name demonstrates that it is a native one, for it would require a page of close writing to make it intelligible to an Englishman.” The rhyme used at this play is—

—Blackwood’s Magazine, August 1821, p. 37.

The rhyme suggests comparison with the game of “Hot Cockles.”

A game played with pennies, or other round discs. The object is to pitch the penny into a hole in the ground from a certain point.—Elworthy, West Somerset Words.

Probably “Pick and Hotch,” mentioned in an article in Blackwood’s Mag., Aug. 1821, p. 35. Common in London streets.

“Chuck-Farthing.” The game of “Pitch and Toss” is very common, being merely the throwing up of halfpence, the result depending on a guess of heads or tails.—Halliwell’s Dictionary.

This game was played by two or more players with “pitchers”—the stakes being buttons. The ordinary bone button, or “scroggy,” being the unit of value. The “pitcher” was made of lead, circular in form, from one and a half inch to two inches in diameter, and about a quarter of an inch thick, with an “H” to stand for “Heads” cut on one side, and a “T” for “Tails” on the other side. An old-fashioned penny was sometimes used, and an old “two-penny” piece I have by me bears the marks of much service in the same cause. A mark having been set up—generally a stone—and the order of play having been fixed, the first player, A, threw his “pitcher” to the mark, from a point six or seven yards distant. If he thought he lay sufficiently near the mark to make it probable that he would be the nearest after the others had thrown, he said he would “lie.” The effect of that was that the players who followed had to lie also, whatever the character of their throw. If A’s throw was a poor one he took up his “pitcher.” B then threw, if he threw well he “lay,” if not he took up his pitcher, in hope of making a better throw, as A had done. C then played in the same manner. D followed and “lay.” E played his pitcher,[44] and had no choice but to lie. F followed in the same way. These being all the players, A threw again, and though his second might have been worse than his first, he has to lie like the others. B and C followed. All the pitchers have been thrown, and are lying round the mark, in the following order of proximity—for that regulates the subsequent play—B’s is nearest, then D’s follows, in order by A, C, F, E. B takes the pitchers, and piles them up one above the other, and tosses them into the air. Three (let us say) fall head up, D’s, A’s, and F’s. These three B keeps in his hand. D, who was next nearest the mark, takes the three remaining pitchers, and in the same manner tosses them into the air. B’s and C’s fall head up, and are retained by D. A, who comes third, takes the remaining pitcher, E’s, and throws it up. If it falls a head he keeps it, and the game is finished except the reckoning; if it falls a tail it passes on to the next player, C, who throws it up. If it falls a head he keeps it, if a tail, it is passed on to F, and from him to E, and on to B, till it turns up a head. Let us suppose that happens when F throws it up. The game is now finished, and the reckoning takes place—

| B | has | three | pitchers, | D’s, A’s, and F’s. | |

| D | „ | two | „ | B’s and C’s. | |

| F | „ | one | „ | E’s. | |

| A, C, and E have none. | |||||

Strictly speaking, D, A, and F should each pay a button to B. B and C should each pay one to D. E should pay one to F. But in practice it was simpler, F holding one pitcher had, in the language of the game, “freed himself.” D had “freed himself,” and was in addition one to the good. B had “freed himself,” and was two to the good. A, C, and E, not having “freed themselves,” were liable for the one D had won and the two B had won, and settled with D and B, without regard to the actual hand that held the respective pitchers. It simplified the reckoning, though theoretically the reckoning should have followed the more roundabout method. Afterwards the game was begun de novo. E, who was last, having first pitch—the advantage of that place being meant to compensate him[45] in a measure for his ill luck in the former game. The stakes were the plain horn or bone buttons—buttons with nicks were more valuable—a plain one being valued at two “scroggies,” or “scrogs,” the fancy ones, and especially livery buttons, commanding a higher price.—Rev. W. Gregor. See “Buttons.”

A game played by boys, who roll counters in a small hole. The exact description I have not been able to get.—Halliwell’s Dictionary.

A game at marbles. The favourite recreation with the young fishermen in West Cornwall. Forty years ago “Pits” and “Towns” were the common games, but the latter only is now played. Boys who hit their nails are looked on with great contempt, and are said “to fire Kibby.” When two are partners, and one in playing accidentally hits the other’s marble, he cries out, “No custance,” meaning that he has a right to put back the marble struck; should he fail to do so, he would be considered “out.”—Folk-lore Journal, v. 60. There is no description of the method of playing. It may be the same as “Cherry Pits,” played with marbles instead of cherry stones (vol. i. p. 66). Mr. Newell, Games and Songs of American Children, p. 187, says “The pits are thrown over the palm; they must fall so far apart that the fingers can be passed between them. Then with a fillip of the thumb the player makes his pit strike the enemy’s and wins both.”

Sides are picked; as, for example, six on one side and six on the other, and three or four marks or tuts are fixed in a field. Six go out to field, as in cricket, and one of these throws the ball to one of those who remain “at home,” and the one “at home” strikes or pizes it with his hand. After pizing it he runs to one of the “tuts,” but if before he can get to the “tut” he is struck with the ball by one of those in the field, he is said to be burnt, or out. In that case the other side go out to field.—Addy’s Sheffield Glossary.

See “Rounders.”

A game at marbles of two or more boys. Each puts an equal number of marbles in a row close together, a mark is made at some little distance called taw; the distance is varied according to the number of marbles in a row. The first boy tosses at the row in such a way as to pitch just on the marbles, and so strike as many as he can out of the line; all that he strikes out he takes; the rest are put close together again, and two other players take their turn in the same manner, till all the marbles are struck out of the line, when they all stake afresh and the game begins again.—Baker’s Northamptonshire Glossary.

Mentioned by Moor, Suffolk Words and Phrases, as the name of a game. Undescribed, but nearly the same as French and English.

A small mark is made on the wall. The one to point out the point, who must not know what is intended, is blindfolded, and is then sent to put the finger on the point or mark. Another player has taken a place in front of the point, and bites the finger of the blindfolded pointer.—Fraserburgh, Aberdeenshire (Rev. W. Gregor).

Name of a girl’s game the same as Cheeses.—Holland’s Cheshire Glossary. See “Turn Cheeses, Turn.”

An old game mentioned in Taylor’s Motto, sig. D, iv. London, 1622.

—Barnes, Surrey (A. B. Gomme).

—Upton-on-Severn, Worcestershire (Miss Broadwood).

—Dorsetshire (Folk-lore Journal, vii. 209).

—Sporle, Norfolk (Miss Matthews).

—Colchester (Miss G. M. Frances).

—(Suffolk County Folk-lore, pp. 66, 67.)

—Berkshire (Miss Thoyts, Antiquary, xxvii. 254).

—Winterton and Lincoln (Miss M. Peacock).

—Hanbury, Staffs. (Miss E. Hollis).

—Forest of Dean, Gloucestershire (Miss Matthews).

—Enborne School, Newbury, Berks. (Miss M. Kimber).

—Liphook, Hants. (Miss Fowler).

—Cambridge (Mrs. Haddon).

—Ogbourne, Wilts. (H. S. May).

—Manton, Marlborough, Wilts. (H. S. May).

—South Devon (Notes and Queries, 8th Series, i. 249, Miss R. H. Busk).

—Earls Heaton (Herbert Hardy).

—(Rev. W. Gregor).

—Berwickshire (A. M. Bell, Antiquary, xxx. 16).

| No. | Barnes. | En- borne. |

Dorset- shire. |

Upton. | Sporle. | Col- chester. |

Winter- ton. |

Forest of Dean. | Lip- hook. |

Earls Heaton. | Suf- folk. |

Berk- shire. |

Staf- ford- shire. |

New- bury. |

South Devon. | Cam- bridge. |

Og- bourne. |

Manton. | Ber- wick- shire. |

Scot- land. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Poor Mary sits a-weeping. | Poor Mary sits a-weeping. | — | Poor Mary is weeping. | Poor [ ] sat a-weeping. | Poor Mary sat a-weeping. | Mary sits a-weeping. | — | Poor Sarah’s a-weeping. | — | Poor Mary sits a-weeping. | Poor Mary sits a-weeping. | Poor Mary sits a-weeping. | Poor Mary sits a-weeping. | Poor Mary is a-weeping. | Poor Mary is a-weeping. | Poor Mary is a-weeping. | Poor Sally is a-weeping. | What is Jennie weeping for? | Poor Mary is a-weeping. |

| 2. | Pray, Mary, what are you weeping for? | Pray, what are you a-weeping for? | Pray, Sally, what are you weeping for? | Pray, tell me what you’re weeping for. | — | — | Mary, what are you weep’ng for? | Oh! what is Nellie weeping for? | Oh, what is she a-weeping for? | Poor Mary, what are you weeping for? | What is she weeping for? | — | — | Pray what are you weeping for? | What is she weeping for? | — | Pray what is she weeping for? | Pray tell me what you’re weeping for. | — | Pray tell me what you’re weeping for. |

| 3. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | Pray tell us what you are weeping for? | — | Pray tell me what she is weeping for? | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 4. | I’m weeping for a sweetheart. | She’s weeping for a lover. | I’m weeping for a sweetheart. | I am weeping for my true love. | I’m weeping for a sweetheart. | — | I’m weeping for a sweetheart. | I’m weeping for my sweetheart. | I’m weeping for a sweetheart. | — | She’s weeping for a sweetheart. | I’m weeping for a sweetheart. | She’s weeping for her lover. | She’s weeping for a lover. | She’s weeping for her lover. | — | I’m weeping for my true love. | I’m weeping for my sweetheart. | I’m weeping for my own true love. | — |

| 5. | On a bright summer’s day. | This bright summer’s day. | On a bright shiny day. | On a bright summer’s day. | On a bright summer’s day. | — | — | — | This bright summer’s day. | On a bright summer’s day. | On a fine summer’s day. | On a bright summer’s day. | On a bright summer’s day. | This bright summer’s day. | On a fine summer’s day. | — | On a bright summer’s day. | — | All on this summer’s day. | On a fine summer’s day. |

| 6. | — | — | — | — | — | By the side of the river. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 7. | — | — | — | — | — | She sat down and cried. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 8. | — | — | — | — | — | — | Close by the sea side. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | [See No. 41.] | — | — | Down by the seaside. | — | — |

| 9. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | On a cold and sunshine day. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 10. | Pray, Mary, choose your lover. | Rise up and choose your lover. | — | Stand up and choose your lover. | Pray, get up and choose one. | Pray, get up and choose one. | Pray, get up and choose one. | Now stand up and choose one. | Rise up and choose your lover. | — | Pray get up and choose one. | — | Stand up and choose your lover. | Rise up and choose your lover. | — | Stand up upon your feet and show the one you love so sweet. | Stand up and choose your true love. | — | — | Stand up and choose your love. |

| 11. | — | — | Pray, Sally, go and get one. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 12. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | She shall have a sweetheart. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | Rise up and choose another love. | — |

| 13. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | On the carpet she shall kneel till the grass grows on the field. | — | — | — | — |

| 14. | Now you’re married, I wish you joy. | Now Mary she is married. | — | — | — | Now you’re married, I wish you joy. | — | — | — | — | Now you’re married, we wish you joy. | — | — | Now Mary she is married. | — | Now you’re married I wish you joy. | — | — | — | — |

| 15. | First a girl, then a boy. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | First a girl and second a boy. | — | — | — | — |

| 16. | Seven years after, son and daughter. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 17. | — | — | Pray, Sally, now you’ve got one. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 18. | — | — | — | — | Now you’re married you must obey. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 19. | — | — | — | — | You must be true to all you say. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 20. | — | — | — | — | You must be kind and good. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 21. | — | — | — | — | Help wife to chop wood. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 22. | — | — | — | — | — | Father and mother you must obey. | — | — | — | — | Father and mother you must obey. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 23. | — | — | — | — | — | Love one another like sister and brother. | — | — | — | — | Love one another like brother and sister. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 24. | Pray, young couple, come kiss together. | — | — | — | — | Pray, young couple, come kiss together. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 25. | — | — | One kiss will never part you. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 26. | — | — | — | Go to church with your lover. | — | — | — | — | Go to church, love. | — | Pray go to church, love. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 27. | — | — | — | Be happy in a ring, love. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 28. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | Say your prayers, love. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 29. | Kiss her once, twice, kiss three times over. | — | — | Kiss both together, love. | — | — | — | — | Kiss your lovers. | — | — | — | — | — | — | If one don’t kiss, the other must. | — | — | — | — |

| 30. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | My father he is dead, sir. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | Because my father’s dead and gone. |

| 31. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | She’s kneeling by her father’s grave. |

| 32. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | Pray put the ring on. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 33. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | Pray come back, love. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 34. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | Now it’s time to go away. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 35. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | Mary’s got a shepherd’s cross. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 36. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | Now she’s got a lover. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 37. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | Who is her lover? | — | — | — | — | — |

| 38. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | I. O. is her lover. | — | — | — | — | — |

| 39. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | Where is her lover? | — | — | — | — | — |

| 40. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | Her lover is sleeping. | — | — | — | — | — |

| 41. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | At the bottom of the sea. | — | — | — | — | — |

| 42. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | Ring a ring o’ roses a pocketful of posies. | A ring of roses a pocketful of posies. | — | — |

| 43. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | We all tumble down. | — | — |

| No. | Barnes. | Enborne. | Dorsetshire. | Upton. | Sporle. | Colchester. | Winterton. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Poor Mary sits a-weeping. | Poor Mary sits a-weeping. | — | Poor Mary is weeping. | Poor [ ] sat a-weeping. | Poor Mary sat a-weeping. | Mary sits a-weeping. |

| 2. | Pray, Mary, what are you weeping for? | Pray, what are you a-weeping for? | Pray, Sally, what are you weeping for? | Pray, tell me what you’re weeping for. | — | — | Mary, what are you weep’ng for? |

| 3. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 4. | I’m weeping for a sweetheart. | She’s weeping for a lover. | I’m weeping for a sweetheart. | I am weeping for my true love. | I’m weeping for a sweetheart. | — | I’m weeping for a sweetheart. |

| 5. | On a bright summer’s day. | This bright summer’s day. | On a bright shiny day. | On a bright summer’s day. | On a bright summer’s day. | — | — |

| 6. | — | — | — | — | — | By the side of the river. | — |

| 7. | — | — | — | — | — | She sat down and cried. | — |

| 8. | — | — | — | — | — | — | Close by the sea side. |

| 9. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 10. | Pray, Mary, choose your lover. | Rise up and choose your lover. | — | Stand up and choose your lover. | Pray, get up and choose one. | Pray, get up and choose one. | Pray, get up and choose one. |

| 11. | — | — | Pray, Sally, go and get one. | — | — | — | — |

| 12. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 13. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 14. | Now you’re married, I wish you joy. | Now Mary she is married. | — | — | — | Now you’re married, I wish you joy. | — |

| 15. | First a girl, then a boy. | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 16. | Seven years after, son and daughter. | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 17. | — | — | Pray, Sally, now you’ve got one. | — | — | — | — |

| 18. | — | — | — | — | Now you’re married you must obey. | — | — |

| 19. | — | — | — | — | You must be true to all you say. | — | — |

| 20. | — | — | — | — | You must be kind and good. | — | — |

| 21. | — | — | — | — | Help wife to chop wood. | — | — |

| 22. | — | — | — | — | — | Father and mother you must obey. | — |

| 23. | — | — | — | — | — | Love one another like sister and brother. | — |

| 24. | Pray, young couple, come kiss together. | — | — | — | — | Pray, young couple, come kiss together. | — |

| 25. | — | — | One kiss will never part you. | — | — | — | — |

| 26. | — | — | — | Go to church with your lover. | — | — | — |

| 27. | — | — | — | Be happy in a ring, love. | — | — | — |

| 28. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 29. | Kiss her once, twice, kiss three times over. | — | — | Kiss both together, love. | — | — | — |

| 30. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 31. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 32. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 33. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 34. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 35. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 36. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 37. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 38. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 39. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 40. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 41. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 42. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 43. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| No. | Forest of Dean. | Liphook. | Earls Heaton. | Suffolk. | Berkshire. | Staffordshire. | Newbury. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | — | Poor Sarah’s a-weeping. | — | Poor Mary sits a-weeping. | Poor Mary sits a-weeping. | Poor Mary sits a-weeping. | Poor Mary sits a-weeping. |

| 2. | Oh! what is Nellie weeping for? | Oh, what is she a-weeping for? | Poor Mary, what are you weeping for? | What is she weeping for? | — | — | Pray what are you weeping for? |

| 3. | — | — | Pray tell us what you are weeping for? | — | Pray tell me what she is weeping for? | — | — |

| 4. | I’m weeping for my sweetheart. | I’m weeping for a sweetheart. | — | She’s weeping for a sweetheart. | I’m weeping for a sweetheart. | She’s weeping for her lover. | She’s weeping for a lover. |

| 5. | — | This bright summer’s day. | On a bright summer’s day. | On a fine summer’s day. | On a bright summer’s day. | On a bright summer’s day. | This bright summer’s day. |

| 6. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 7. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 8. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 9. | On a cold and sunshine day. | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 10. | Now stand up and choose one. | Rise up and choose your lover. | — | Pray get up and choose one. | — | Stand up and choose your lover. | Rise up and choose your lover. |

| 11. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 12. | — | She shall have a sweetheart. | — | — | — | — | — |

| 13. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 14. | — | — | — | Now you’re married, we wish you joy. | — | — | Now Mary she is married. |

| 15. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 16. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 17. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 18. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 19. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 20. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 21. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 22. | — | — | — | Father and mother you must obey. | — | — | — |

| 23. | — | — | — | Love one another like brother and sister. | — | — | — |

| 24. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 25. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 26. | — | Go to church, love. | — | Pray go to church, love. | — | — | — |

| 27. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 28. | — | Say your prayers, love. | — | — | — | — | — |

| 29. | — | Kiss your lovers. | — | — | — | — | — |

| 30. | — | — | My father he is dead, sir. | — | — | — | — |

| 31. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 32. | — | — | — | Pray put the ring on. | — | — | — |

| 33. | — | — | — | Pray come back, love. | — | — | — |

| 34. | — | — | — | Now it’s time to go away. | — | — | — |

| 35. | — | — | — | — | Mary’s got a shepherd’s cross. | — | — |

| 36. | — | — | — | — | — | Now she’s got a lover. | — |

| 37. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 38. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 39. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 40. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 41. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 42. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 43. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| No. | South Devon. | Cambridge. | Ogbourne. | Manton. | Berwickshire. | Scotland. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Poor Mary is a-weeping. | Poor Mary is a-weeping. | Poor Mary is a-weeping. | Poor Sally is a-weeping. | What is Jennie weeping for? | Poor Mary is a-weeping. |

| 2. | What is she weeping for? | — | Pray what is she weeping for? | Pray tell me what you’re weeping for. | — | Pray tell me what you’re weeping for. |

| 3. | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 4. | She’s weeping for her lover. | — | I’m weeping for my true love. | I’m weeping for my sweetheart. | I’m weeping for my own true love. | — |

| 5. | On a fine summer’s day. | — | On a bright summer’s day. | — | All on this summer’s day. | On a fine summer’s day. |

| 6. | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 7. | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 8. | [See No. 41.] | — | — | Down by the seaside. | — | — |

| 9. | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 10. | — | Stand up upon your feet and show the one you love so sweet. | Stand up and choose your true love. | — | — | Stand up and choose your love. |

| 11. | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 12. | — | — | — | — | Rise up and choose another love. | — |

| 13. | — | On the carpet she shall kneel till the grass grows on the field. | — | — | — | — |

| 14. | — | Now you’re married I wish you joy. | — | — | — | — |

| 15. | — | First a girl and second a boy. | — | — | — | — |

| 16. | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 17. | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 18. | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 19. | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 20. | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 21. | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 22. | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 23. | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 24. | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 25. | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 26. | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 27. | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 28. | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 29. | — | If one don’t kiss, the other must. | — | — | — | — |

| 30. | — | — | — | — | — | Because my father’s dead and gone. |

| 31. | — | — | — | — | — | She’s kneeling by her father’s grave. |

| 32. | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 33. | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 34. | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 35. | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 36. | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 37. | Who is her lover? | — | — | — | — | — |

| 38. | I. O. is her lover. | — | — | — | — | — |

| 39. | Where is her lover? | — | — | — | — | — |

| 40. | Her lover is sleeping. | — | — | — | — | — |

| 41. | At the bottom of the sea. | — | — | — | — | — |

| 42. | — | — | Ring a ring o’ roses a pocketful of posies. | A ring of roses a pocketful of posies. | — | — |

| 43. | — | — | — | We all tumble down. | — | — |

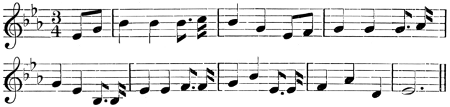

[61](b) A ring is formed by the children joining hands. One child kneels in the centre, covering her face with her hands. The ring dances round, and sings the first two verses. The kneeling child then takes her hands from her face and sings the next verse, still kneeling. While the ring sings the next verse, she rises and chooses one child out of the ring. They stand together, holding hands while the others sing the marriage formula, and kiss each other at the command. The ring of children dance round quickly while singing this. When finished the first “Mary” takes a place in the ring, and the other child kneels down (Barnes and other places). At Enborne school, Newbury (Miss Kimber), this game is played by boys and girls. All the children in the ring sing the first two verses. Then the boys alone in the ring sing the next verse; all the ring singing the fourth. While singing this the kneeling child rises and holds out her hand to any boy she prefers, who goes into the ring with her. When he is left in the ring at the commencement of the game again, a boy’s name is substituted for that of “Mary.” There appears to be no kissing. In the Liphook version (Miss Fowler), after the girl has chosen her sweetheart the ring breaks, and the two walk out and then kneel down, returning to the ring and kissing each other. A version identical with that of Barnes is played by the girls of Clapham High School. All tunes sent me were similar to that given.

(c) The analysis of the game rhymes is on pp. 56-60.

This analysis shows that the incidents expressed by the rhymes are practically the same in all the versions. In the majority of the cases the weeping is depicted as part of a ceremony, by which it is known that a girl desires a lover; she is enabled then to choose one, and to be married. The marriage formula is the usual one in the Barnes’ version, but follows another set of words in three other versions. In the cases[62] where the marriage is neither expressed by a formula, nor implied by other means (Winterton and Forest of Dean), the versions are evidently fragments only, and probably at one time ended, as in the other cases, with marriage. But in three other cases the ending is not with marriage. The Earls Heaton and Scottish versions represent the cause of weeping as the death of a father, the Berkshire version introduces the apparently unmeaning incident of Mary bearing a shepherd’s cross, and the South Devon version represents the cause of weeping the death of a lover at sea. It is obvious that at places where sailors abound, the incident of weeping for a sailor-lover who is dead would get inserted, and the fact of this change only occurring once in the versions I have collected, tells all the more strongly in favour of the original version having represented marriage and love, and not death, but it does not follow that the marriage formula belongs to the oldest or original form of the game. I am inclined to think this has been added since marriage was thought to be the natural and proper result of choosing a sweetheart.

(d) The change in some of the verses, as in the Cambridge version, is due to corruption and the marked decadence now occurring in these games. No. 13 in the analysis is from the game “Pretty little girl of mine,” and Nos. 42-3 “Ring o’ Roses.”

I.

—Belfast (W. H. Patterson).

II.

—Belfast (W. H. Patterson).

III.

—Nairn (Rev. W. Gregor).

(b) One child is chosen to act the part of the widow. The players join hands and form a circle. The widow takes her stand in the centre of the circle in a posture indicating sorrow. The girls in the circle trip round and round, and sing the first five lines. The widow then chooses one of the ring. The ring then sings the marriage formula, the two kiss each other, and the game is continued, the one chosen to be the mate of the first widow becoming the widow in turn (Nairn).

(c) This game is probably the same as “Silly Old Man.” Two separate versions may have arisen by girls playing by themselves without boys.[Addendum]

[1] Sometimes “pray,” but “pree” seems to be the Scotch for taste:—“pree her moo” = taste her mouth = to kiss.

—Earls Heaton (Herbert Hardy).

[64](b) Children stand in two rows facing each other, they sing while moving backwards and forwards. At the close one from each side selects a partner, and then, all having partners, they whirl round and round.

(c) An additional verse is sometimes sung with or in place of the above in London.

—(A. Nutt).

Mr. Nutt writes: “The Eagle was (and may be still) a well-known tavern and dancing saloon.”

A game in which two, each putting down a pin on the crown of a hat or bonnet, alternately pop on the bonnet till one of the pins crosses the other; then he at whose pop or tap this takes place, lifts the stakes.—Teviotdale (Jamieson). The same game is now played by boys with steel pens or nibs.

See “Hattie.”

See “Pinny Show.”