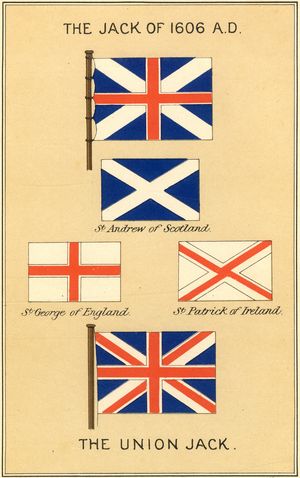

THE JACK OF 1606 A.D.

St. Andrew of Scotland.

St. George of England.

St. Patrick of Ireland.

THE UNION JACK.

Title: Yachting, Vol. 1

Author: Sir Edward Sullivan

Earl Thomas Brassey Brassey

R. T. Pritchett

C. E. Seth-Smith

Watson. G. L.

Release date: February 2, 2013 [eBook #41971]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by StevenGibbs, Christine P. Travers and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

THE JACK OF 1606 A.D.

St. Andrew of Scotland.

St. George of England.

St. Patrick of Ireland.

THE UNION JACK.

THE BADMINTON LIBRARY

OF

SPORTS AND PASTIMES

EDITED BY

HIS GRACE THE DUKE OF BEAUFORT, K.G.

ASSISTED BY ALFRED E. T. WATSON

YACHTING

I.

BY

SIR EDWARD SULLIVAN, BART.

LORD BRASSEY, K.C.B., C. E. SETH-SMITH, C.B., G. L. WATSON

R. T. PRITCHETT

SIR GEORGE LEACH, K.C.B., Vice-President Y.R.A.

'THALASSA'

THE EARL OF PEMBROKE AND MONTGOMERY

E. F. KNIGHT and REV. G. L. BLAKE

IN TWO VOLUMES—VOL. I.

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY R. T. PRITCHETT

AND FROM PHOTOGRAPHS

LONDON

LONGMANS, GREEN, AND CO.

1894

Badminton: May 1885.

Having received permission to dedicate these volumes, the Badminton Library of Sports and Pastimes, to His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales, I do so feeling that I am dedicating them to one of the best and keenest sportsmen of our time. I can say, from personal observation, that there is no man who can extricate himself from a bustling and pushing crowd of horsemen, when a fox breaks covert, more dexterously and quickly than His Royal Highness; and that when hounds run hard over a big country, no man can take a line of his own and live with them better. Also, when the wind has been blowing hard, often have I seen His Royal Highness knocking over driven grouse and partridges and high-rocketing pheasants in first-rate (p. vi) workmanlike style. He is held to be a good yachtsman, and as Commodore of the Royal Yacht Squadron is looked up to by those who love that pleasant and exhilarating pastime. His encouragement of racing is well known, and his attendance at the University, Public School, and other important Matches testifies to his being, like most English gentlemen, fond of all manly sports. I consider it a great privilege to be allowed to dedicate these volumes to so eminent a sportsman as His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales, and I do so with sincere feelings of respect and esteem and loyal devotion.

BEAUFORT.

BADMINTON.

A few lines only are necessary to explain the object with which these volumes are put forth. There is no modern encyclopædia to which the inexperienced man, who seeks guidance in the practice of the various British Sports and Pastimes, can turn for information. Some books there are on Hunting, some on Racing, some on Lawn Tennis, some on Fishing, and so on; but one Library, or succession of volumes, which treats of the Sports and Pastimes indulged in by Englishmen—and women—is wanting. The Badminton Library is offered to supply the want. Of the imperfections which must be found in the execution of such a design we are (p. viii) conscious. Experts often differ. But this we may say, that those who are seeking for knowledge on any of the subjects dealt with will find the results of many years' experience written by men who are in every case adepts at the Sport or Pastime of which they write. It is to point the way to success to those who are ignorant of the sciences they aspire to master, and who have no friend to help or coach them, that these volumes are written.

To those who have worked hard to place simply and clearly before the reader that which he will find within, the best thanks of the Editor are due. That it has been no slight labour to supervise all that has been written, he must acknowledge; but it has been a labour of love, and very much lightened by the courtesy of the Publisher, by the unflinching, indefatigable assistance of the Sub-Editor, and by the intelligent and able arrangement of each subject by the various writers, who are so thoroughly masters of the subjects of which they treat. The reward we all hope to reap is that our work may prove useful to this and future generations.

THE EDITOR.

(Reproduced by J. D. Cooper and Messrs. Walker & Boutall)

FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS

| ARTIST | TO FACE PAGE | |

| Union Jack | Frontispiece | |

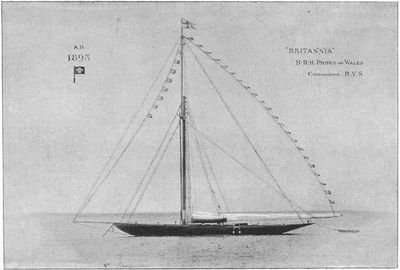

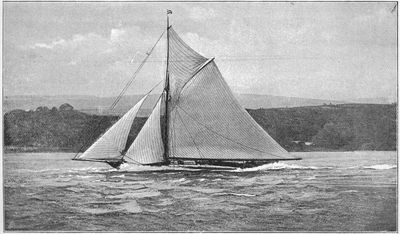

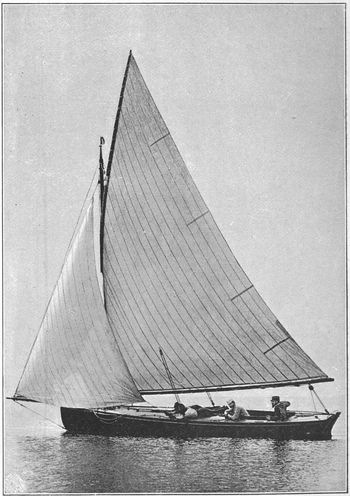

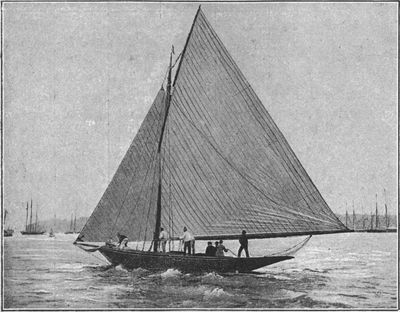

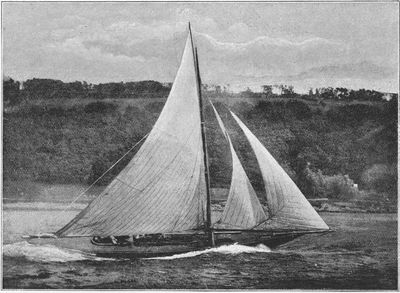

| 'Britannia,' H.R.H. Prince of Wales | From a photograph by Wm. U. Kirk, of Cowes | 50 |

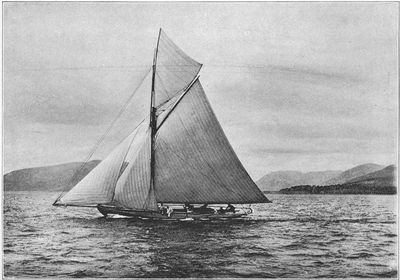

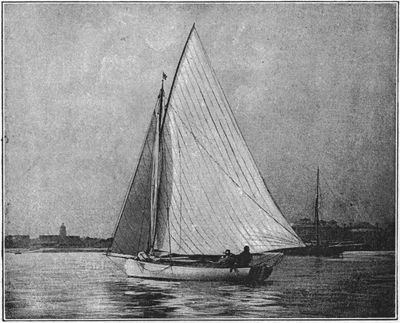

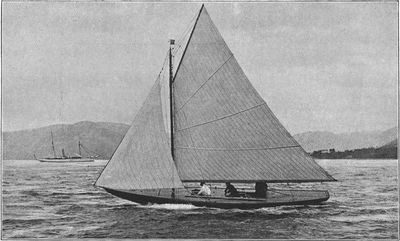

| 'Varuna,' 40-Rater | From a photograph by Adamson, of Rothesay | 54 |

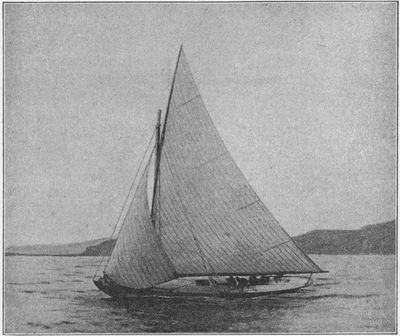

| 'Dora,' 10-Tonner | " | 58 |

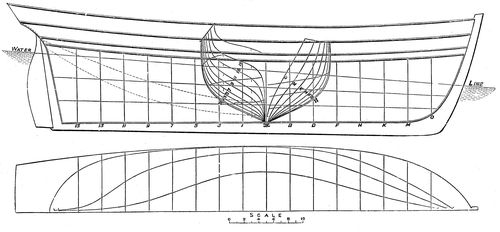

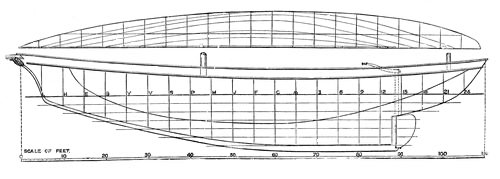

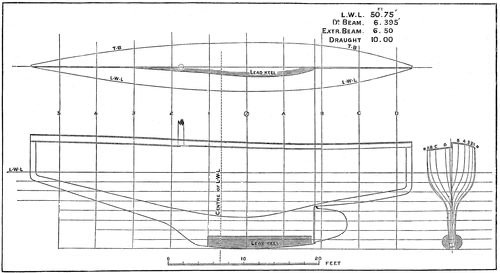

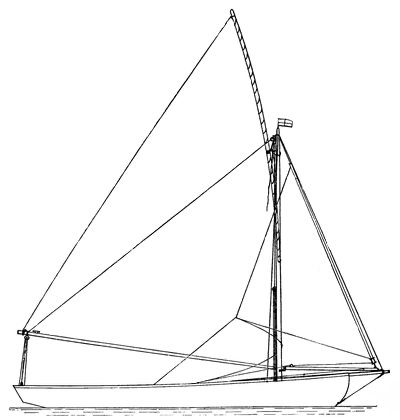

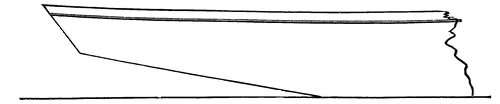

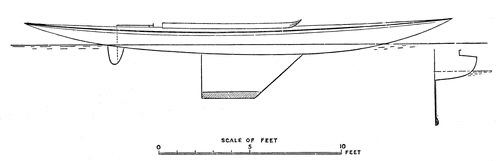

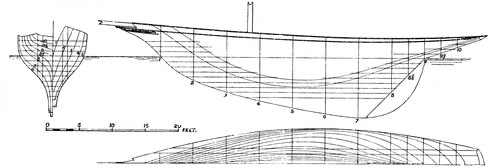

| 'Arrow'—Lines | G. L. Watson | 72 |

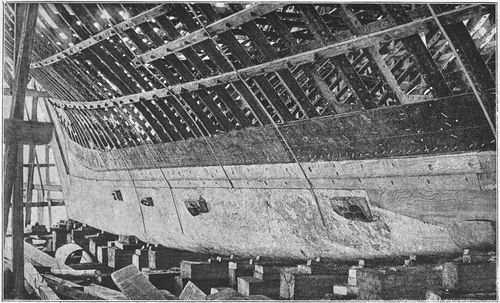

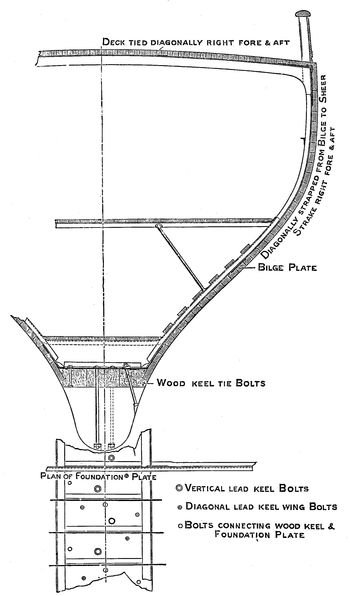

| 'Lethe'—Keel | From a photograph | 78 |

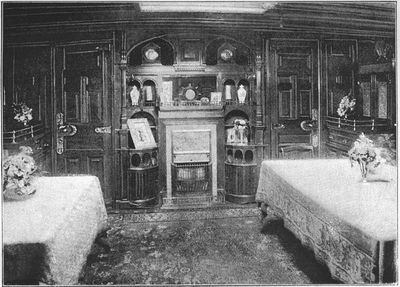

| Saloon of 'Thistle' | " | 82 |

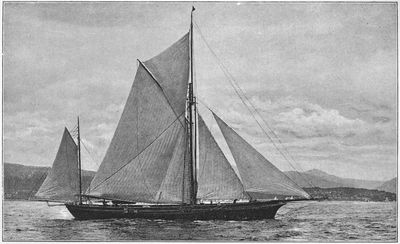

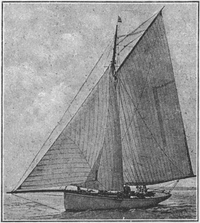

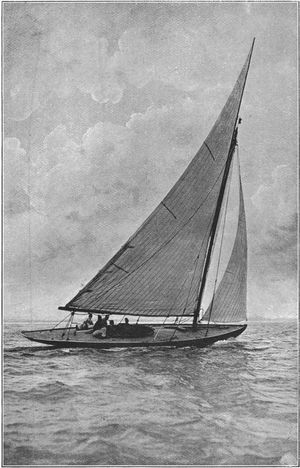

| 'Jullanar' | From a photograph by Adamson, of Rothesay | 88 |

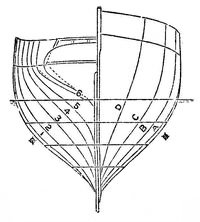

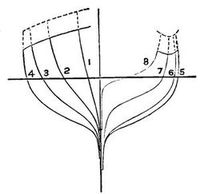

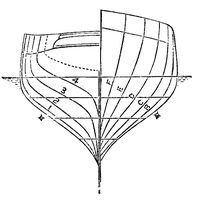

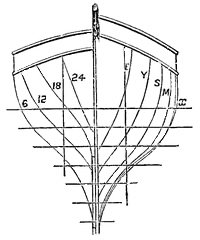

| Midship Sections | J. M. Soper, M.I.N.A. | 102 |

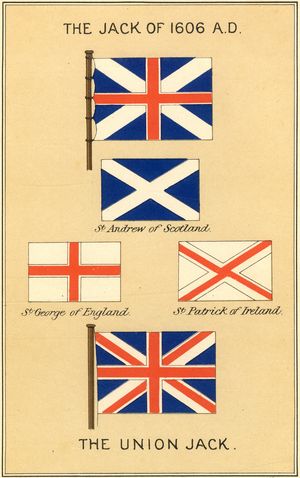

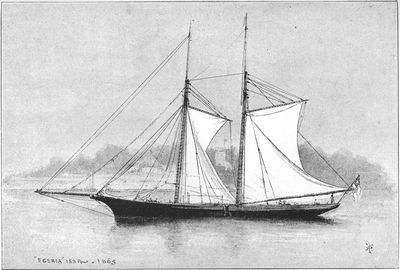

| 'Egeria' | R. T. Pritchett | 114 |

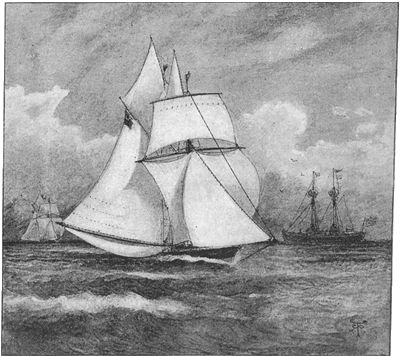

| 'Egeria' and 'Oimara' | " | 134 |

| 'Seabelle' | " | 138 |

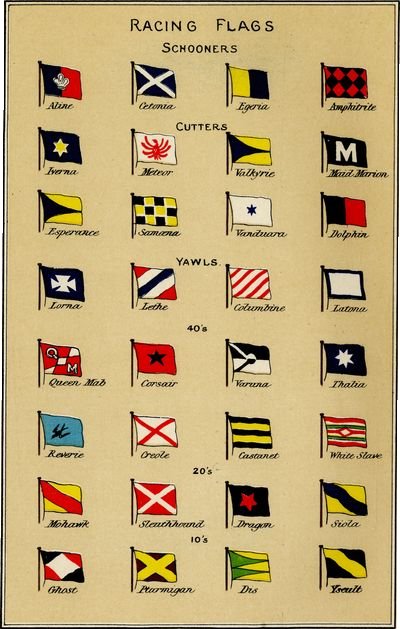

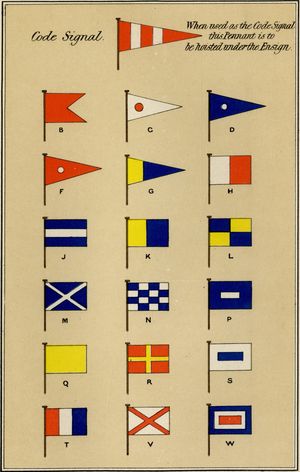

| Racing Flags, Schooners, Cutters, Yawls, &c | 140 | |

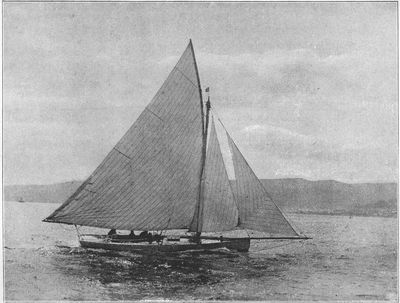

| (p. xii) 'Savourna,' 5-Rater | From a photograph by Adamson, of Rothesay | 244 |

| 'The Babe,' 2½-Rater | From a photograph by Symonds, of Portsmouth | 246 |

| 'Dacia,' 5-Rater | " | 252 |

| Solent Owners' Racing Colours | 276 | |

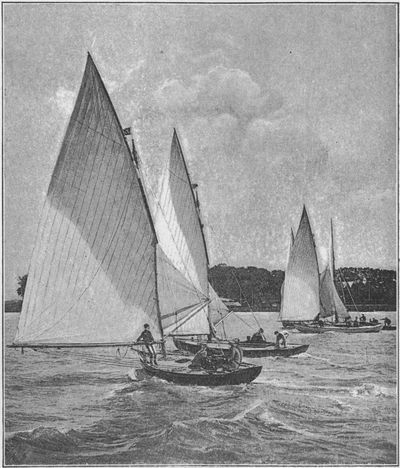

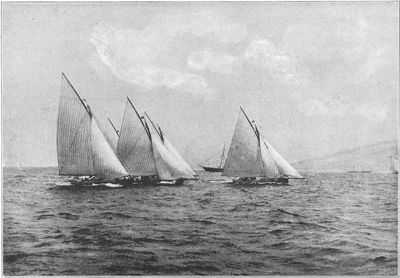

| Start of Small Raters on the Clyde | From a photograph by Adamson, of Rothesay | 354 |

| 'Wenonah,' 2½-Rater | " | 360 |

| 'Red Lancer,' 5-Rater | " | 372 |

| Commercial Code of Signals | 394 | |

ILLUSTRATIONS IN TEXT

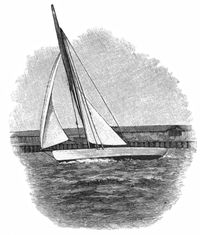

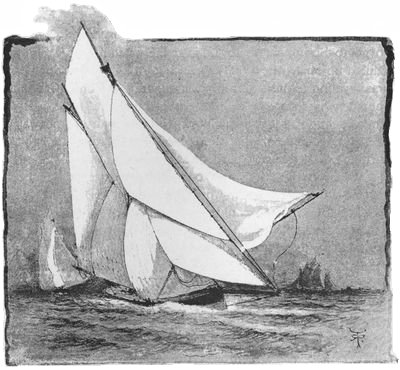

| Before the Start (Vignette) | Title-page | |

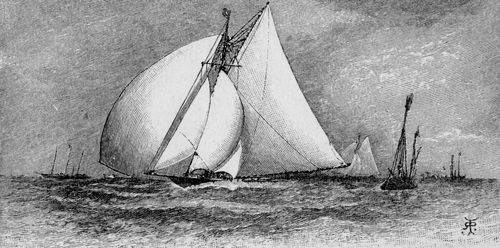

| Victoria Cup, 1893 | R. T. Pritchett | 1 |

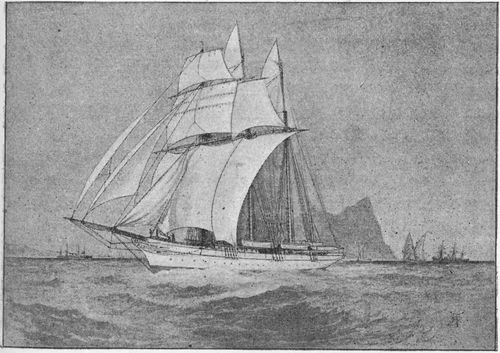

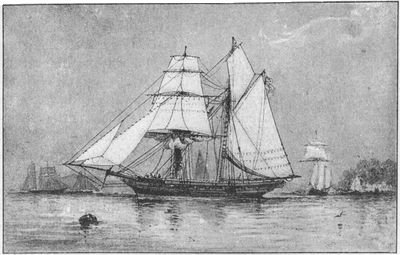

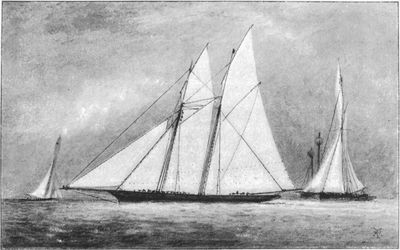

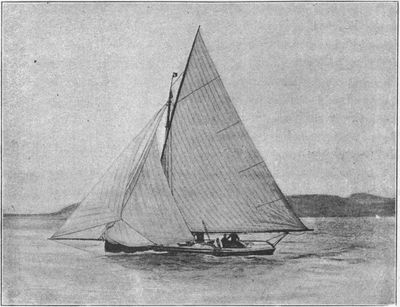

| 'Sunbeam' (R.Y.S), 1874 | " | 19 |

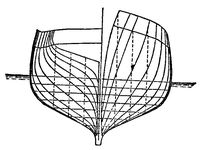

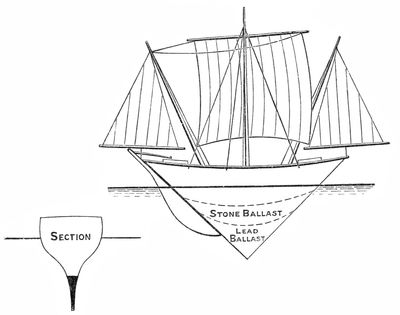

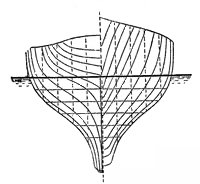

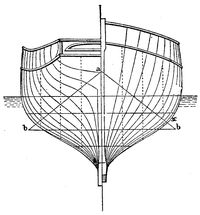

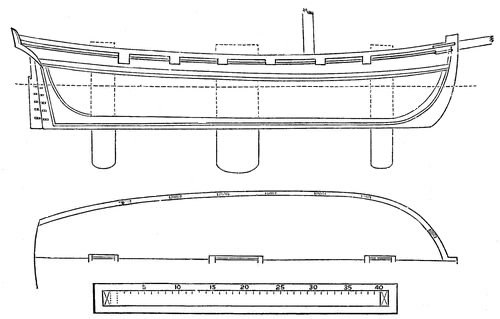

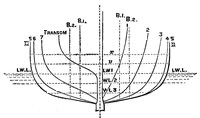

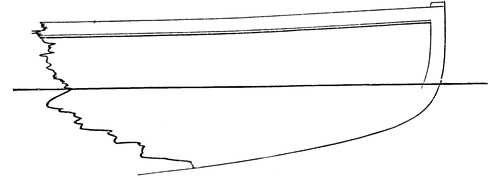

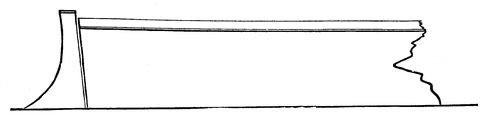

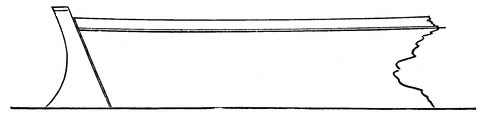

| 'Sunbeam'—Midship Section | St. Clare Byrne, of Liverpool | 24 |

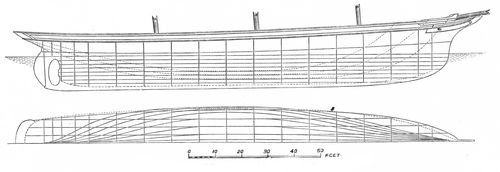

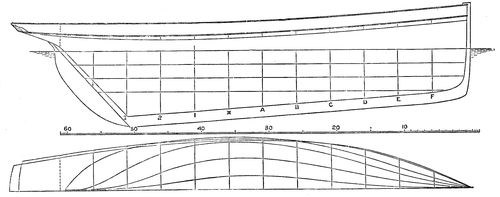

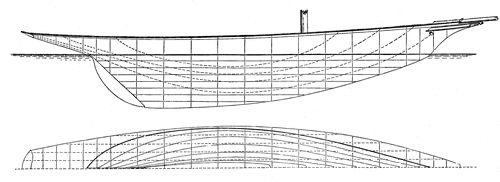

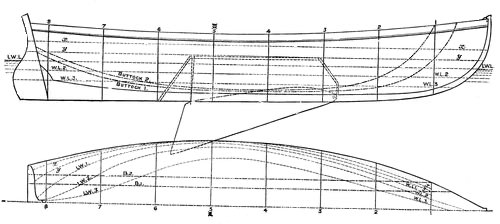

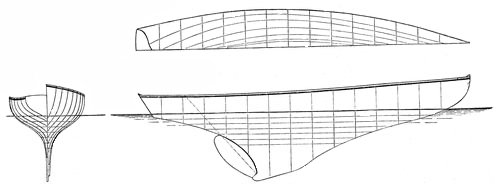

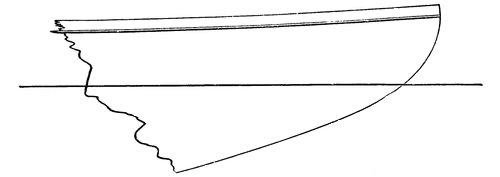

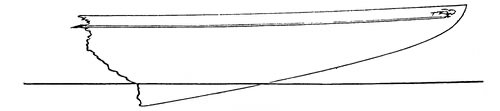

| 'Sunbeam'—Lines | " | 29 |

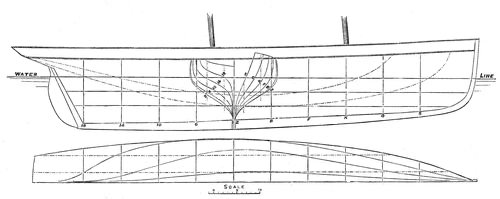

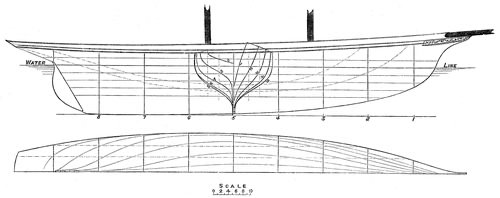

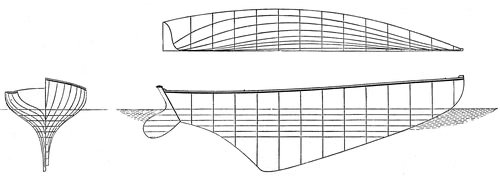

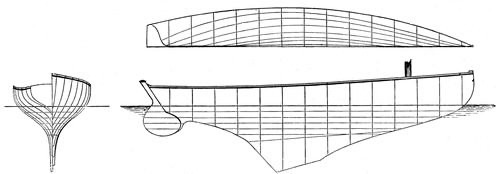

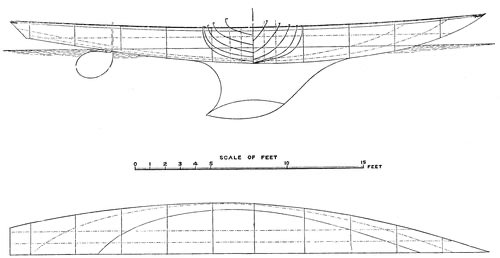

| 'Cygnet,' Cutter, 1846—Lines and Midship Section | G. L. Watson | 54 |

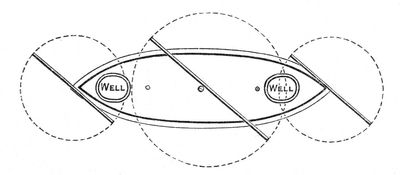

| 'Problem,' 1852—Profile and Deck Plan | Hunt's Magazine | 55 |

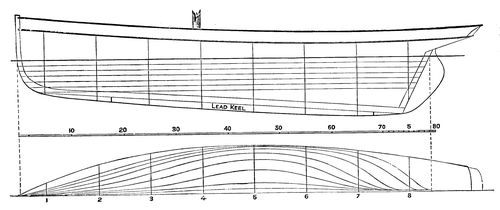

| 'Varuna,' 1892—Profile | G. L. Watson | 55 |

| Vanderdecken's Tonnage Cheater | Hunt's Magazine | 56 |

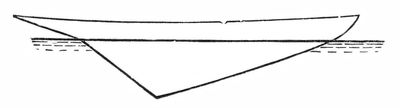

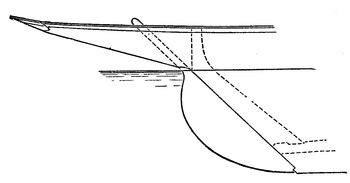

| Dog-legged Sternpost | G. L. Watson | 57 |

| 'Quiraing,' 1877—Immersed Counter | " | 58 |

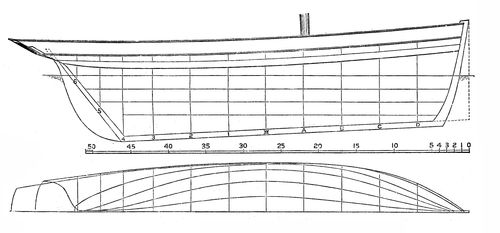

| 'Britannia,' 1893—Cutwater | " | 60 |

| 'Thistle,' 1887—Cutwater | " | 60 |

| (p. xiii) Diagram of Length and Displacement of 5-Tonners | G. L. Watson | 62 |

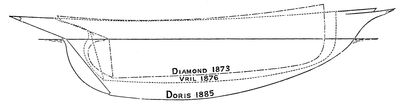

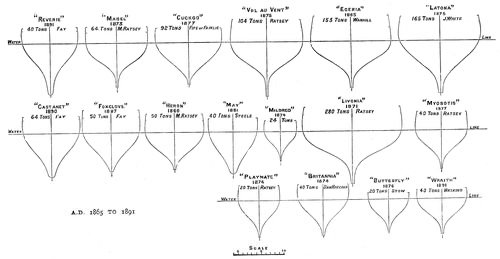

| Profiles of 5-Tonners | " | 63 |

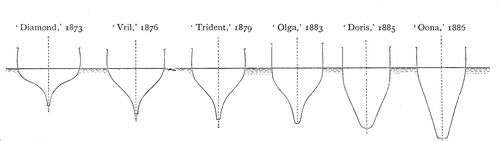

| Sections showing Decrease of Breadth and Increase of Depth in 5-Tonners under 94 and 1730 Rules | " | 63 |

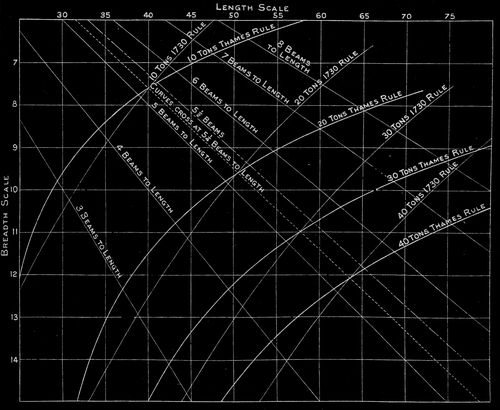

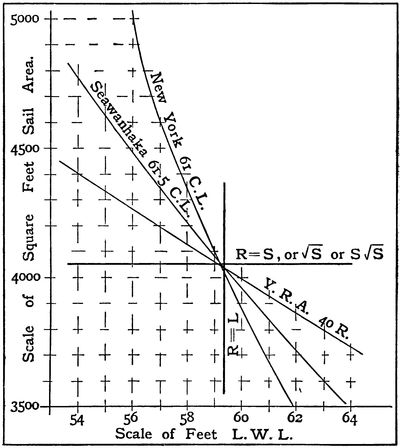

| Diagram of Variation under Different Rules | " | 64 |

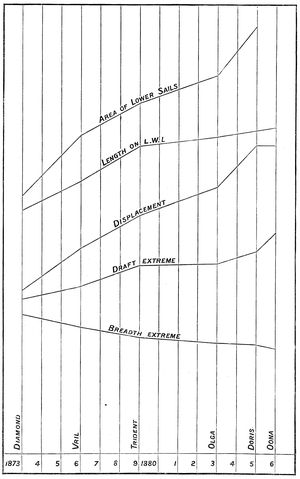

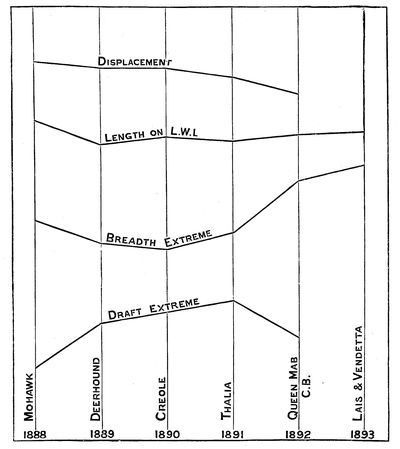

| Diagram showing Variation of Dimensions, &c., with Years; 40-Raters; L. and S.A. Rule. | " | 67 |

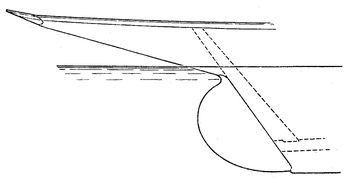

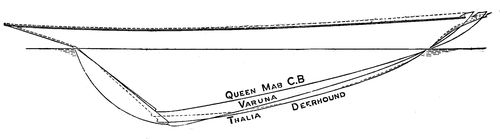

| Profiles of 40-Raters | " | 67 |

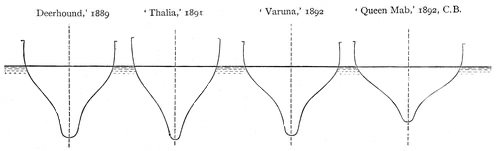

| Midship Sections of 40-Raters | " | 68 |

| 'Leopard,' 1807—Lines and Midship Section | Linn Ratsey, of Cowes | 72 |

| 'Mosquito,' 1848—Lines and Midship Section | T. Waterman | 75 |

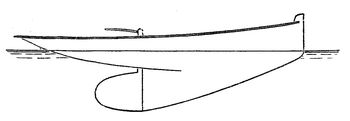

| 'Lethe'—Midship Section | G. L. Watson | 79 |

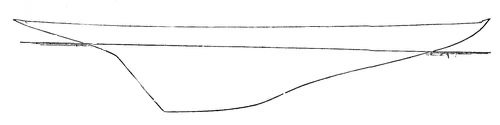

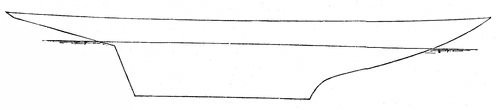

| 'Valkyrie'—Profile | " | 82 |

| 'Vigilant'—Profile | " | 82 |

| 'Britannia' Cutter—General Arrangement Plan | " | 84 |

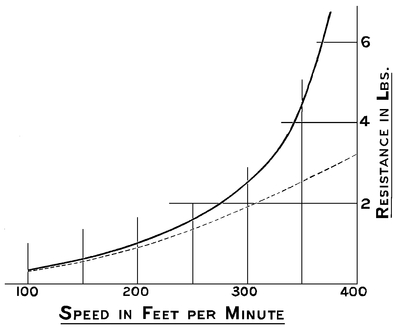

| S.S. 'Merkara'—Resistance Curves | " | 87 |

| 'Jullanar,' Yawl, 1875—Midship Section | E. H. Bentall, Esq. | 89 |

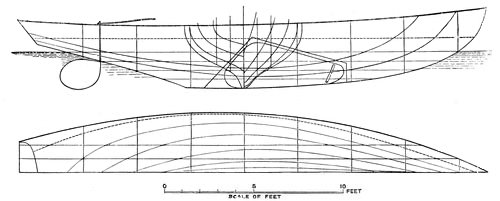

| 'Jullanar,' Yawl—Lines | " | 91 |

| 'Evolution,' 1880—Lines and Midship Section | " | 92 |

| 'Meteor' (late 'Thistle'), 1887—Lines and Midship Section | G. L. Watson | 94 |

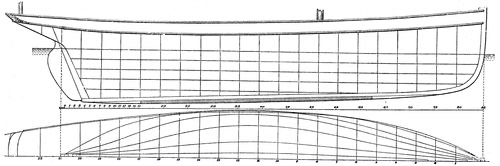

| 'Florinda,' Yawl, 1873—Lines | Camper & Nicholson, of Gosport | 97 |

| (p. xiv) 'Kriemhilda,' 1872—Profile | Michael Ratsey, of Cowes | 98 |

| 'Florinda,' Yawl, 1873—Plans | Camper & Nicholson, of Gosport | 100 |

| 'Florinda,' Yawl, 1873—Midship Section | " | 101 |

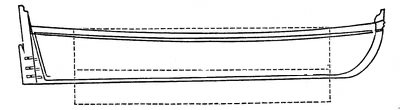

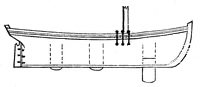

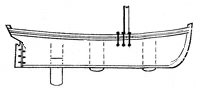

| H.M. Brig 'Lady Nelson,' with three Keels, 1797 | R. T. Pritchett | 102 |

| Diagram of Boat with one Centreboard, 1774 | " | 103 |

| Diagram of Boat with three Sliding Keels, 1789 | " | 103 |

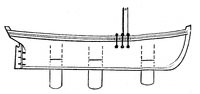

| Diagrams showing use of Three Keels in 'Laying to,' 'on a Wind,' and Scudding | " | 104 |

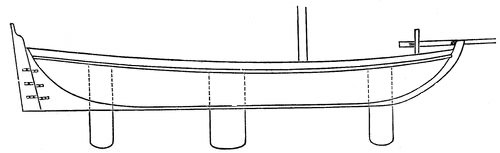

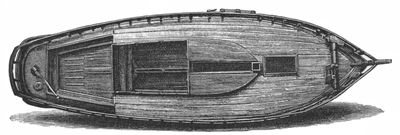

| 'Cumberland,' with Five Sliding Keels | From a model in possession of Taylor family | 105 |

| 'Cumberland,' showing the Five Keels Down | " | 105 |

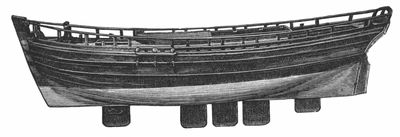

| H.M. 'Trial' Cutter, 1791—Sheer Draught | R. T. Pritchett | 107 |

| 'Kestrel,' Schooner, 1839 | " | 108 |

| 'Pantomime,' Schooner, 1865—Lines and Midship Section | Michael Ratsey, of Cowes | 112 |

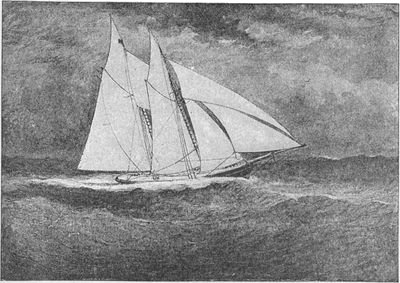

| 'Cambria,' beating 'Dauntless' in 1870 (From picture at R.T.Y.C.) |

R. T. Pritchett | 125 |

| 'Dauntless,' Schooner (N.Y.Y.C.), 1871 | " | 129 |

| 'Cetonia,' Schooner, 1873—Lines and Midship Section | Michael Ratsey, of Cowes | 142 |

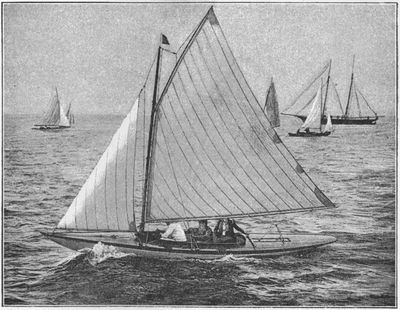

| The Start | From a photograph by Debenham, of Cowes | 148 |

| Chart of the Royal Southampton Yacht Club (Brambles and Lepe Course) | 161 | |

| (p. xv) Diagram of Sail Curves, 40-Rating Class | 'Thalassa' | 173 |

| Whales | R. T. Pritchett | 189 |

| The Swoop of the Gannet | " | 192 |

| 'Black Pearl's' Cutter—Midship Section | " | 200 |

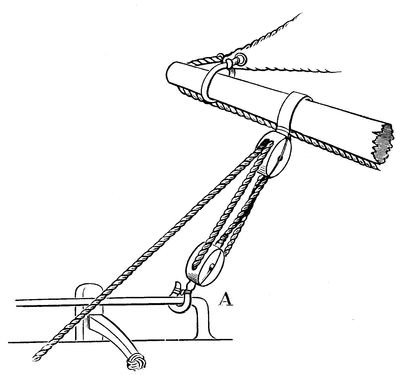

| Main Sheet on Iron Horse | 202 | |

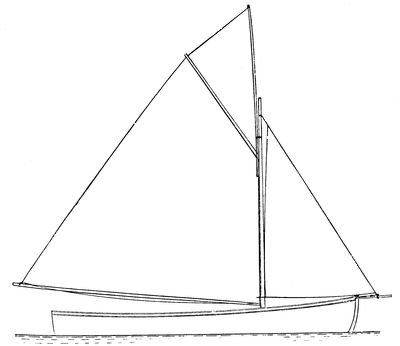

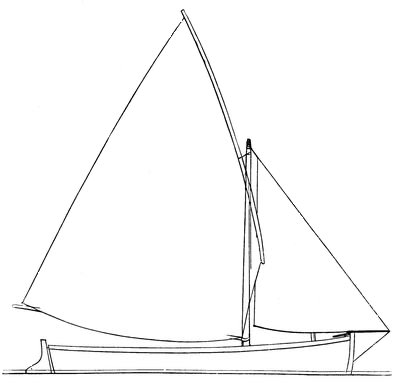

| 'Black Pearl's' Cutter—Sail Plan | Richard Perry & Co. | 203 |

| S.S. 'Aline's' Cutter | 205 | |

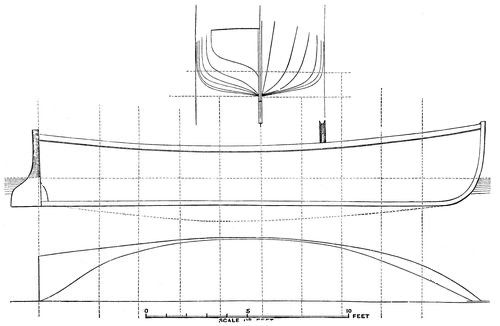

| S.S. 'Aline's' Cutter—Lines and Midship Section | Earl of Pembroke | 207 |

| 'Black Pearl's' Cutter—Lines | " | 209 |

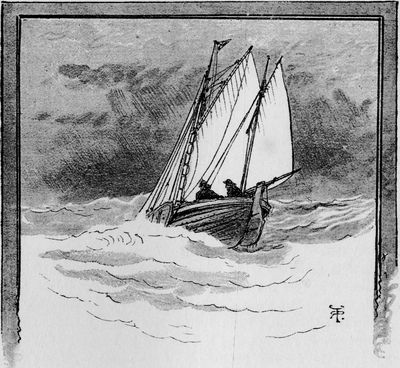

| The Squall in Loch Scavaig, Skye | R. T. Pritchett | 217 |

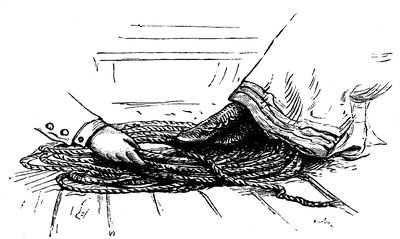

| 'Excuse Me' | " | 218 |

| Self-unmoored | " | 219 |

| Never 'Moon' | " | 220 |

| There is no Place like Home | " | 221 |

| 'Cock-a-whoop,' 1889—Lines and Midship Section | A. E. Payne | 234 |

| 'Humming Bird,' 1889 | A. E. Payne, from a photograph by Symonds | 236 |

| 'Quinque,' 5-Rater; Lt.-Col. Bucknill, R.E. | From a photograph by Symonds, of Portsmouth | 242 |

| 'The Babe,' 1890—Lines and Midship Section | A. E. Payne | 244 |

| 'Mosquito,' 1892, with Roll Foresail | J. M. Soper | 249 |

| 'Doreen,' 1892 | From a photograph by Debenham, of Cowes | 252 |

| 'Cyane,' 1892 | From a private Kodak | 253 |

| 'Windfall,' 1891 | From a photograph by Adamson, of Rothesay | 254 |

| 'Faugh-a-Ballagh,' 1892—Lines and Midship Section | A. E. Payne | 256 |

| (p. xvi) Diagrams showing Improvements in Fore Sections of 2½ Raters | J. M. Soper | 257 |

| Diagrams showing Improvements in Aft Sections of 2½ Raters | " | 258 |

| Design for 1-Rater by J. M. Soper, 1892 | " | 260 |

| Design for a Centreboard 1-Rater by J. M. Soper, 1892 | " | 262 |

| 'Wee Winn,' 1892 | From a photograph by Debenham, of Cowes | 265 |

| 'Wee Winn'—Lines | J. M. Soper | 266 |

| 'Daisy,' 1892—Lines | " | 266 |

| Chart of the Royal Southampton Yacht Club, 'Brambles Course' | 283 | |

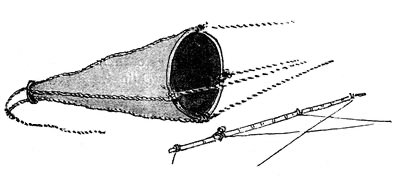

| The Drogue off the Kullen Head | R. T. Pritchett | 308 |

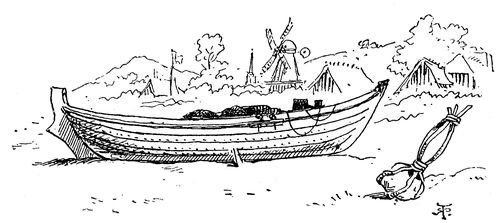

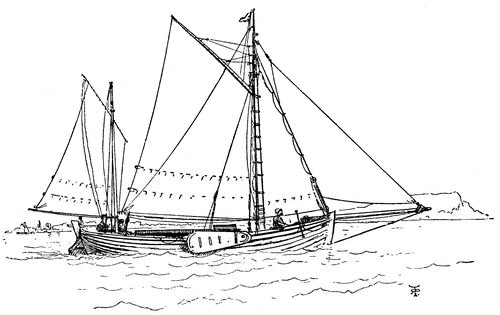

| Danske Fishing-boat and Anchor | " | 311 |

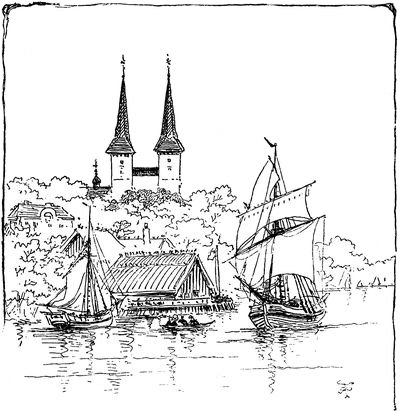

| Roskilde from the Fiord | " | 313 |

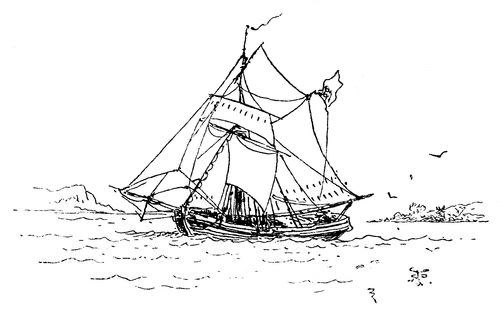

| A Danske Craft | " | 315 |

| A Good Craft for the Baltic | " | 317 |

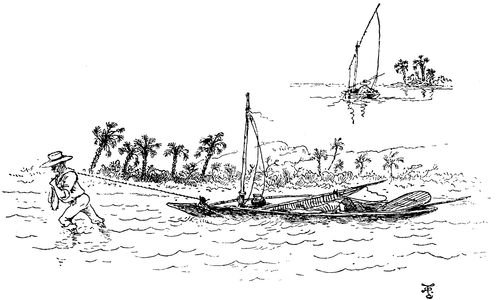

| Towing Head to Wind | " | 319 |

| A Drogue | " | 321 |

| Chart of the Dublin, Kingstown, and Mersey Course | 327 | |

| 'Freda' | R. T. Pritchett | 336 |

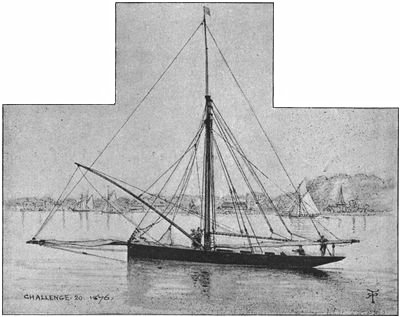

| 'Challenge,' 1876 | " | 339 |

| 'Minerva,' 1888—Lines and Midship Section | Fife of Fairlie | 368 |

| 'Natica,' 1892 | From a photograph by Adamson, of Rothesay | 374 |

| In the Channel | R. T. Pritchett | 406 |

Victoria Cup. 1893.

It is related that Chrysippus, a cynic, killed himself in order that he might sooner enjoy the delights of Paradise. Philosophers do queer things sometimes. Many who are not philosophers kill themselves in order to avoid the miseries of this world; but, as far as I know, this is the only case on record of a man killing himself from impatience to enjoy the pleasures of the next.

(p. 2) Ideas of Paradise are exceedingly various. To the ancients Paradise meant a dolce far niente in the Elysian Fields; to the North American Indians it means happy hunting grounds and plenty of fat buffalo. The Scythians believed in a Paradise of immortal drunkenness and drinking blood out of the skulls of their enemies, and the Paradise that to-day influences the belief of one-fourth of the human race is contained in Chapter X. of the Koran. To Madame de Chevreuse it meant chatting with her friends in the next world. To one friend of mine it was galloping for ever over a grass country without gates. To another it meant driving four horses, with Tim Carter seated at his side. To some, I believe, Paradise means yachting, and for my own part, I think a 200-ton schooner, a ten-knot breeze, and a summer sea hard to beat. Whether yachting approaches one's conception of Paradise or not, I think there are very few of us who, if they do not suffer from that hopeless affection the mal de mer, do not more or less enjoy a life on the ocean wave; it is so fresh and life-giving and so various. 'A home on the stormy deep' we won't say so much about. I have seen two or three storms at sea, but I have never found them pleasant; very much the contrary. There is grandeur, if you like, but there is also terror and horror.

As black as night she turned to white,

And cast against the cloud

A snowy sheet as if each surge

Upturned a sailor's shroud.

This is poetry; but it is true. You look to windward, and you look to leeward; you look ahead, and you look astern, and you feel that, if you are not already engulfed, you probably may be in the next minute.

Dr. Johnson said the pleasure of going to sea was getting ashore again; certainly the pleasure of a storm is getting into smooth water again.

The ideas of pleasure as connected with yachting vary as much as the ideas of Paradise; to one it means steaming at (p. 3) full speed from one port to another; but this becomes monotonous. A friend of mine used to write a letter at Cowes, address it to himself at Guernsey, and then steam, hard all, to Guernsey to get his letter. When he got it he would write to himself at Plymouth, then steam away, hard all again, to get that, and so on; even in steaming you must have an object of some kind, you know.

To another dowagering up and down the Solent, lunching on board, and then hurrying back to dine and sleep ashore are pleasure; to another, sailing with the wind, or against the wind, or drifting when there is no wind, is the ideal of yachting. Certainly that is mine. I have tried both. I have had a steamer and I have had sailing vessels, and if I lived to the age of the Hyperboreans and owned several gold mines I should never keep a steamer for pleasure. In sailing, the interest never flags; the rigging, the sails, the anchors, the cables, the boats, the decks, all have their separate interest; every puff of wind, every catspaw, is a source of entertainment, and when the breeze comes, and, with everything drawing below and aloft, you tear along ten or twelve knots an hour, the sensation of pleasure is complete—if you are not sick.

I can never allow that steaming, under any conditions, can give the same pleasure as sailing—nor a hundredth part of it. If you are in a hurry, steam by all means—steam, steam, steam, pile on the coal, blacken sea and sky with your filthy smoke, and get into your port; but that is the pleasure of locomotion, not of yachting. Even as regards locomotion, there are occasions when a fine sailing vessel will go by a steamer as if she were standing still.

Years ago I sailed from Plymouth to Lisbon in four days, and from Lisbon to Cowes in four days, and passed all the steamers on the way! Atque haec olim meminisse juvabit. These are the happy moments, like forty minutes across a grass country, that fond memory brings back to us, and which Time's effacing fingers will never touch. Can steam at its best afford such delight as this? No; of course not. But, although this (p. 4) is my opinion of the relative pleasure of sailing and steaming, it is not by any means the general one; the race of steam versus canvas has been run, and alas! steam has won easily, hands down. I say alas! for I think that, from every point of view, yachting has suffered from the general employment of steam.

One of the objects of the Royal Yacht Squadron, when it was originally founded, was to encourage seamanship, and, as steam was supposed to destroy seamanship, steamers were not admitted into the Club; and the Royal Yacht Squadron was right. Steam does destroy seamanship; a steamship hand is certainly not half a sailor. Now more than half the tonnage of the Club is in steamers. I think it is a pity, and they are such steamers too! 800 tons, 1,000 tons, 1,500 tons. I do not see where they are to stop; but, I believe that in this, as in most things, we have run into excess. I cannot believe that the largest steam yacht afloat, with all the luxury and cost that upholsterers and cabinet-makers can devise, will ever give a man who is fond of the sea and seafaring matters a tithe of the gratification that a 100-ton sailing vessel will afford; one is a floating hotel, the other is a floating cottage. I prefer the cottage.

The worry of maintaining discipline in a crew of forty or fifty men, amongst whom there is sure to be one or two black sheep, the smoke, the smell of oil, the vibration, the noise, even the monotony, destroy pleasure. Personally, the game seems to me not worth the candle.

Thirty or forty years ago, yachting men with their sixty or hundred tonners went on year after year, fitting out, and cruising about the coast, as part of their yearly life. When their vessel was wearing out, they would sell her, and buy or build another; they seldom parted with her for any other reason. Now a man builds a floating palace or hotel at a fabulous cost; but as a general rule in about two years he wants to sell her and to retire from yachting life.

A sailing vessel and a steamer are different articles; you (p. 5) get attached to a sailing vessel as you do to anything animate, to your horse, or your dog; but I defy anyone to get attached to a smoky, oily steamer. There is an individuality about the sailing vessel; none about the steamer.

When the seven wise men of Greece delivered the oracular dictum that there were only two beautiful things in the world, women and roses, and only two good things, women and wine, they spoke according to their limited experience—they had never seen the new type of racing yacht under sail. Of course the perfection of animate beauty is represented by women, but certainly inanimate nature can show nothing more beautiful than 'Britannia,' 'Navahoe,' 'Valkyrie,' 'Satanita,' their sails well filled, the sun shining on them, streaking along twelve or thirteen knots an hour, apparently without an effort, scarcely raising a ripple. And then a yacht is so exceedingly feminine in her ways. One day everything goes right with her—she will not only do all she is asked to do, but a great deal more than her greatest admirers ever thought she could do: the next day everything goes wrong with her—she will not do anything she is asked, and indeed will not do what her admirers know she can do without an effort.

Some women—I speak it with all respect—bear being 'squeezed' and 'pinched,' they almost seem to like it, at any rate they don't cry out; whereas others will cry out immediately and vigorously. So will yachts.

The more you squeeze one vessel, the more you pinch her, the more she seems to enjoy it. Squeeze another, pinch her into the wind, and she lies down and calls out at once. The difference between vessels in this respect is quite funny, and essentially feminine.

Curiously enough, extremes meet; that is to say, if the pendulum of taste or fashion goes very much over to one side, it is sure to go over just as far on the other. Sailing yachts of 100, 200, 300 tons have gone out of fashion, and leviathan steamers of 800, 1,000, 1,500 tons have taken their place; but at the same time that a taste for immense steamers has (p. 6) driven moderate-sized sailing vessels out of the field, a taste for small boats, 5-raters, 3-raters, ½-raters—I don't quite understand their rating—has sprung up, and promises almost to supplant the big steamers themselves.

I believe the increasing popularity of these swallows of the seas—for turning, wheeling, skimming, doubling, as they do, I can compare them to nothing else—is a very good omen for yachting; they are expensive for their size and tonnage, certainly, but, after all, their cost may be counted in hundreds instead of tens of thousands. They have brought scientific boat sailing and racing within the reach of hundreds who cannot afford big racing yachts; and, moreover, the ladies join in these exciting contests, and of course very often win. In endurance, and courage, and nerve, and quickness, they are quite the equals of the other sex; and if they are occasionally a little too pertinacious, a little too eager to win, and don't always 'go about' exactly when the rules of the road require, what does it signify? Who grudges them their little victory?

A flight of these sea swallows skimming over the course at Calshot Castle, on a fine day with a good working breeze, is one of the prettiest sights in the world.

Independently of the health-giving and invigorating influences both to mind and body of a yachting life, it has advantages that in my opinion raise it above any other sport, if sport it is to be called. There is neither cruelty nor professionalism in yachting, except when certain foolish snobs in sheer wantonness shoot the too-confiding gulls that hover round the sterns of their yachts. There is no professional element in yachting, I repeat, not even in yacht racing, at least not enough to speak of, and it is an enormous advantage in its favour that it brings one into contact with what I believe is without doubt the best of our working population; for are not the toilers of the sea workers in the very fullest sense of the word?

Yacht sailors, as a rule, are sober, honest, obliging, good-tempered, (p. 7) original. During the many years I have yachted, I have had crews from north, east, west, and south, and I have almost without exception found them the same. A man must be hard to please indeed, if, after a three or four months' cruise, he does not part from his crew with regret, and with a sincere wish that they may meet again.

Amongst yachting skippers, I have come across some of the most honourable, trustworthy, honest men I have met in any class of life, men who know their duty, and are always willing and anxious to do it.

The chief peculiarity of all the seafaring class that I have been brought into contact with is their entire freedom from vulgarity. They are obliging to the utmost of their power, but never cringing or vulgar. The winter half of their lives is spent in fishing-boats, or coasters, or sea voyages where they have to face dangers and hardships that must be experienced to be realised. As a rule, they are religious; and their preparations for the Sabbath, their washings and soapings and brushings, show with what pleasure they welcome its recurrence. Yacht minstrelsy, with its accordion, its songs of twenty verses, its never-ending choruses, its pathos, is a thing of itself. Some day perhaps some Albert Chevalier will make it fashionable. Such as they are, I know no class of Englishmen superior, if any be equal, to the sailors who man our yachts. Of course there are sharks, or at any rate dog-fish, in all waters; but where the good so immensely outnumber the bad, that man must be a fool indeed who gets into wrong hands.

To say there is no vulgarity in yachting is not true; there is; but it is not amongst the men or among the skippers. And, after all, the vulgarity one sometimes sees amongst yacht-owners does not go for much; it amuses them and hurts nobody. If the amateur sailor wishes to be thought more of a sailor than the sailor born, he soon finds out his mistake, and when he gets into a good club subsides into his proper position.

To those who are fond of the sea and of yachting, the (p. 8) yacht is the most 'homey' of residences; everything is cosy, and comfortable, and within reach; and the sensation of carrying your house and all its comforts about with you is unique.

The internal economy of a yacht constitutes one of its greatest charms. Your cook, with only a little stove for which a shore cook would scarcely find any use, will send you up an excellent dinner cooked to perfection for any number of guests; and the steward! who can describe the work of a yacht's steward? I doubt whether Briareus with his hundred hands could do more than a steward does with two. At seven in the morning he is ashore for the milk, and the breakfast, and the letters, and the flowers; he valets half a dozen people, prepares half a dozen baths, brushes heaven knows how many clothes, gets the breakfast, makes the beds, cleans the plate, tidies the cabin, provides luncheon, five-o'clock tea, dinner, is always cheerful, obliging, painstaking, and more than repaid if occasionally he gets a petit mot of compliment or congratulation. When he ever sleeps, or eats, I never can tell; and, far from grumbling at his work, he often resents the assistance of any shore-going servant.

The introduction of steam launches has added very much to the pleasures of yachting, and to my mind has greatly lessened the advantages, if any, that steamers possess over sailing vessels. Every vessel of 100 tons and over can now carry a steam launch, big or small, at the davits, or on deck. You sail from port to port, or loch to loch, in your sailing vessel, and when you have found snug anchorage, you 'out kettle' and puff away for as long as you like, enjoying the pleasure of exploring the rivers and creeks and neighbouring objects of interest. Everywhere this is delightful, at Plymouth, at Dartmouth, at Falmouth, the Scilly Isles, at St. Malo, and perhaps especially in Scotland.

To my mind, the West Coast of Scotland is, par excellence, the happy cruising grounds of yachtsmen. I know of none like it—the number and variety of the lochs, the wild grandeur (p. 9) of some, the soft beauty of others, the mountains, the rocks, the islands, the solitude, the forests, the trees.

Oh! the Oak and the Ash, and the bonny Ivy tree,

They flourish best at home in the North Countrie.

The heather, especially the white, the ferns, the mosses, the wild flowers, the innumerable birds and fish, the occasional seals and whales, the wildness of the surroundings, all combine to give it a charm that is indescribable. I have seen on the coast of Skye a whale, thirty or forty feet long, jump clean out of the water three or four times, like a salmon. Anchored close under a cliff in Loch Hourn, and happening to look up, I met the wondering eyes of a hind craning over the edge of the cliffs, and staring right down on the yacht. Go the world over, you will nowhere find so much varied beauty, above or below, on land or sea, as on the West Coast of Scotland.

Nobody can explore or appreciate the beauty of the Scotch lochs without a 'kettle.' It spoils one's pleasure to keep a boat's crew pulling for eight or ten hours in a hot sun, and therefore, if you have no steam launch, many expeditions that promise much interest and pleasure are abandoned; but with your kettle and a man, or a man and a boy, you don't care how long you are out or how far you go. This to my mind is the most enjoyable combination of sails and steam—a comfortable sailing vessel, schooner or ketch for choice, to carry you from port to port, and a steam launch for exploration when you get there.

The accommodation of a sailing vessel is, on a rough calculation, double the accommodation of a steamer of the same tonnage. The Earl of Wilton, Commodore of the Royal Yacht Squadron, had a schooner of 200 tons, and after sailing in her many years he decided, as so many others have done, to give up sailing and take to steam. To obtain exactly the same accommodation that he had on board his 200-ton schooner, he had to build a steamer, the 'Palatine,' of 400 tons. Of course in an iron steamer of 400 tons the height between (p. 10) decks is very much greater than in a wooden schooner of 200 tons. Also the cabins are larger, but there are no more of them.

I think many people have erroneous ideas of the cost of yachting. Yacht racing, especially in the modern cutters of 150 or 170 tons, is very expensive. The wear and tear of spars and gear is incredible. I believe that in the yachting season of 1893 H.R.H. the Prince of Wales's vessel the 'Britannia' sprang or carried away three masts; and some of his competitors were not more lucky. Then racing wages are very heavy: 10s. per man when you lose, and 20s. when you win, with unlimited beef, and beer, &c., mount up when you have a great many hands, and the new type of racer, with booms 90 feet long, requires an unlimited number; when you look at these boats racing, they seem actually swarming with men. In addition to 10s. or 20s. to each man, the skipper gets 5 per cent. or 10 per cent. of the value of the prize, or its equivalent.

So that a modern racing yacht with a crew of 30 men may, if successful, easily knock a hole in 1,000l. for racing wages alone, to say nothing of cost of spars, and sails, and gear, &c. Of course, in comparison with keeping a pack of hounds, or a deer forest, or a good grouse moor, or to pheasant preserving on a very large scale, the expense of yacht racing even at its worst is modest; but still in these days 1,000l. or 1,500l. is an item.

But yachting for pleasure, yacht cruising in fact, is not an expensive amusement. The wages of a 100- to a 200-ton cutter or schooner will vary from 50l. to 100l. a month at the outside, and the wear and tear, if the vessel and gear are in good order, is very moderate; and undoubtedly the living on board a yacht is infinitely cheaper than living ashore.

Thirty to forty pounds, or as much as fifty pounds, a week may easily go in hotel bills if there is a largish party. Half the sum will keep a 100- or 150-ton yacht going, wages, wear and tear, food, &c., included, if you are afloat for three or four months. Certainly for a party of four or five yachting is (p. 11) cheaper than travelling on the Continent with a courier and going to first-class hotels. Travelling on the Continent under the best conditions often becomes a bore; the carriages are stuffy and dusty, the trains are late, the officials are uncivil or at least indifferent, the hotels are full, the kitchen is bad, and you come to the conclusion that you would be better at home. Now, on board a yacht you are never stuffy or dusty, the accommodation is always good, everyone about you is always civil, anxious for your comfort, the kitchen is never bad, and you cannot come to the conclusion that you would be better at home, for you are at home—the most cosy and comfortable of homes!

The yachting season of 1893 will always be a memorable one. The victory of H.I.M. the German Emperor's 'Meteor' for the Queen's Cup at Cowes; the victorious career of H.R.H. the Prince of Wales's 'Britannia' and the 'Valkyrie'; the series of international contests between the 'Britannia' and 'Navahoe,' with the unexpected victory of the latter over the cross-Channel course; and, finally, the gallant attempt of Lord Dunraven to bring back the cup from America, make a total of yachting incidents, and indeed surprises, that will last for a very long time. The victory of the 'Meteor' in the Queen's Cup was a surprise: it was more than a surprise when the 'Navahoe' beat 'Britannia' to Cherbourg and back in a gale of wind. I don't know that it was a matter of surprise that the Americans kept the Cup; I think, indeed, it was almost a foregone conclusion. In yachting, as in everything else, possession is nine points of the law, and a vessel sailing in her own waters, with pilots accustomed to the local currents and atmospheric movements, will always have an advantage. Whether the 'Vigilant' is a better boat than the 'Valkyrie,' whether she was better sailed, whether her centreboard had anything to do with her victory, I cannot say. But there is the result: that the 'Vigilant' won by seven minutes, which, at the rate they were sailing, means about a mile.

It would appear that the Americans are still slightly ahead of us in designing yachts for speed, but they are not nearly as (p. 12) far ahead of us as they were forty years ago. I remember the first time the 'America' sailed at Cowes in 1851. I could not believe my eyes. It was blowing a stiff breeze, and whilst all the other schooners were laying over ten or twelve degrees, she was sailing perfectly upright, and going five knots to their four. It was a revelation—how does she do it? was in everybody's mouth. Now we are much more on an equality. The 'Navahoe,' a beautiful vessel, one of the best, comes to England and is worsted: the 'Valkyrie,' a beautiful vessel, also one of the best, goes over to America and is worsted.

The moral I think is 'race at home in your own waters.' I do not believe much in international contests of any kind, gravely doubting whether they do much to promote international amity.

It is a familiar sight to see H.R.H. the Prince of Wales taking part in yacht racing, but 1893 was the first occasion, in an English yacht race at any rate, that the Kaiser donned his flannels and joined personally in the contest. I suppose there is no monarch who is so dosed with ceremony and etiquette as the Emperor of Germany. What a relief, therefore, it must be to him to put aside the cares of monarchy for a whole week, and sit for hours in two or three inches of water, hauling away at the mainsheet as if his life depended on it, happy as the traditional king, if, when he has gone about, he finds he has gained six feet on his rival!

But beyond all this—the heartiness, the equality, the good feeling, the absorbing interest that attends yacht racing and yacht cruising—there are some very interesting questions that suggest themselves in connection with the great increase of speed lately developed by the new type of racing yachts.

There is no doubt whatever that whereas the Pleasure Fleet of England is progressing and improving every year, and is a subject of congratulation to everyone concerned with it—designers, builders, and sailors—the Business Fleet, the Royal Navy, is the very reverse: not only has it not improved, but it appears to have been going steadily the wrong (p. 13) road; and instead of being a joy to designers and sailors, it is confusion to the former, and something very like dismay to the latter.

In James I.'s time the fleet was not held in very high estimation. It was said of it that 'first it went to Gravesend, then to Land's End, and then to No End,' and really that appears to be its condition now. Whilst yachts are developing all the perfections of the sailing ship, our ironclads seem to be developing most of the imperfections of the steamship.

Whilst our yachts can do anything but speak, our ironclads can do anything but float. Of course this is an exaggeration; but exaggeration is excusable at times, at least if we are to be guided by the debates in Parliament. At any rate, it is no exaggeration to say they are very disappointing. If they go slow, they won't steer. If they go fast, they won't stop. If they collide in quite a friendly way, they go down. One sinks in twelve minutes, and the other with difficulty keeps afloat. In half a gale of wind, if the crew remain on deck, they are nearly drowned; if they go below, they are nearly asphyxiated.

They have neither stability nor buoyancy. But this does not apply to English ironclads alone. French, German, Italian, American, are all the same. Some of these monsters are fitted with machinery as delicate and complicated as a watch that strikes the hours, and minutes, and seconds, tells the months, weeks, and days, the phases of the moon, &c. &c. Some of them have no fewer than thirty to thirty-five different engines on board. If the vessel containing all this wonderful and elaborate machinery never left the Thames or Portsmouth Harbour, all well and good, very likely the machinery would continue to work; but to send such a complex arrangement across the Atlantic or the Bay in winter seems to me contrary to common sense.

The biggest ironclad afloat, a monster of 13,000 tons, in mid ocean is, after all, only as 'a flea on the mountain'; it is (p. 14) nothing; it is tossed about, and rolled about, and struck by the seas and washed by them, just as if it were a pilot boat of 60 tons. It is certain that the concussion of the sea will throw many of these delicate bits of machinery out of gear: in the 'Resolution' in a moderate gale the engine that supplied air below decks broke down; the blow that sank the unfortunate 'Victoria' threw the steering apparatus out of gear, so that if she had not gone down she would not have steered; more recently still the water in the hydraulic steering apparatus in a ship off Sheerness froze, so that she could not put to sea. If such accidents can happen in time of peace, when vessels are only manœuvring, or going from port to port, what would happen if two 13,000-ton ships rammed each other at full speed? Is it not almost certain that the whole thirty-five engines would stop work?

We have, I suppose, nearly reached the maximum of speed attainable by steam; have we nearly reached the maximum attainable by sails? By no means. When Anacharsis the younger was asked which was the best ship, he said the ship that had arrived safe in port; but even the ancients were not always infallible. The 'Resolution' did not prove she was the best ship by coming into port; on the contrary, she would have proved herself a much better ship if she had been able to continue her voyage. What we want in a man-of-war, as far as I understand the common-sense view of the question, is buoyancy, speed, handiness, and the power of keeping the seas for long periods.

Racing cutters of 150 to 170 tons are now built to sail at a speed that two years ago was not dreamt of. Where a short time since the best of them used to take minutes to go about, they now go about in as many seconds. The racing vessels of the present day will reach thirteen or fourteen knots an hour, and sail ten knots on a wind; with hardly any wind at all they creep along eight knots. They do not appear to be able to go less than eight knots; double their size, and their speed would be immensely increased.

(p. 15) Now if thirteen and fourteen knots can be got out of a vessel of 170 tons, and seventeen knots out of one double her size, what speed might you fairly expect to get out of a racing vessel of 10,000 tons? Rather a startling suggestion certainly; but, if carefully examined, not without reason.

We have nothing to guide us as to the probable speed of a racing vessel of that size. Time allowance becomes lost in the immensity of the question.

I see no reason why a vessel of 10,000 tons, built entirely for speed, should not, on several points of sailing, go as fast as any torpedo boat, certainly much faster than any ironclad. Her speed, reaching in a strong breeze, would be terrific; and if 'Britannia,' 'Navahoe,' 'Valkyrie,' 'Vigilant,' and vessels of that class can sail ten knots on a wind, why should not she sail fifteen? She would have to be fore and aft rigged, with an immense spread of canvas, very high masts, and very long booms; single sticks would be nowhere; but iron sticks and iron booms can be built up of any length and any strength, and with wire rigging I see no limit to size. Such a vessel amply provided with torpedoes of all descriptions, and all the modern diabolisms for destroying life, would be so dangerous a customer that no ironclad would attack her with impunity. Of course there would occasionally be conditions under which she would be at a disadvantage with ironclads; but, on the other hand, there are many conditions under which ironclads, even the best of them, would be under enormous disadvantages with her. She could circumnavigate the globe without stopping. I believe her passages would be phenomenal, life on board would be bright and healthy, she would be seaworthy, able to keep the seas in all weathers, easily handled, no complicated machinery to fail you at the moment when you were most dependent on it; and then what a beauty she would be! Why, a fleet of such vessels would be a sight for gods and men. We have sailing vessels of 3,000 and 4,000 tons, four-masted, square-rigged; they are built for carrying, not for speed, but even they make passages that (p. 16) to the merchant seaman of a hundred years ago would appear incredible.

I probably shall not live to see the clumsy, unwieldy, complicated, unseaworthy machines called ironclads cast aside, wondered at by succeeding generations, as we now wonder at the models of antediluvian monsters at the Crystal Palace; but that such will be their fate I have no doubt whatever. For our battleships we have gone back to the times of knights in armour, when men were so loaded with iron that where they fell there they remained, on their backs or their stomachs, till their squires came to put them on their legs again. I am certain that neither the public, nor the naval authorities of the world, realise what an ironclad in time of war means—positively they will never be safe out of near reach of a coaling station. Suppose—and this is tolerably certain to happen—that when they reach a coaling station they find no coal, or very possibly find it in the hands of the enemy. What are they to do? Without coal to steam back again, or to reach another station, they will be as helpless as any derelict on the ocean: a balloon without gas, a locomotive without steam, a 100-ton gun without powder, would not be so useless as an ironclad without coal.

But what has all this to do with yachting? it may be asked. Well, it is the logical and practical result of the recent development of speed in sailing vessels. It positively becomes the question whether racing sails and racing hulls may not, in speed even, give results almost as satisfactory as steam, and in many other matters results far more favourable.

Of course the model of the racing yacht would have to be altered for the vessel of 10,000 tons. Vessels must get their stability from beam and from the scientific adjustment of weights, not merely from depth of keel—the Channel would not be deep enough for a vessel that drew twenty fathoms; but this change of design need not affect their speed or their stability very much.

In the introduction to the Badminton Library volumes on Yachting, a great deal might be expected about the national (p. 17) importance of the pastime as a nursery for sailors, a school for daring, and all that sort of thing. But I think all this 'jumps to the eyes'; those who run may read it. I have preferred to treat the question of yachting more as one of personal pleasure and amusement than of national policy; and besides, I am sure that I may safely leave the more serious aspects of the sport to the writers whose names are attached to the volumes.

For myself, after yachting for nearly a quarter of a century, I can safely say that it has afforded me more unmixed pleasure than any other sport or amusement I have ever tried. Everything about it has been a source of delight to me—the vessels, the skippers, the crews, the cruises. I do not think I have ever felt dull or bored on a yacht, and even now, in the evening of life, I would willingly contract to spend my remaining summers on board a 200-ton schooner.

I fear that I can scarcely hope to contribute to the present volume of the admirable Badminton Series anything that is very new or original. Although my voyages have extended over a long period, and have carried me into nearly every navigable sea, I have for the most part followed well-known tracks. The seamanship, as practised in the 'Sunbeam,' has been in conformity with established rule; the navigation has been that of the master-ordinary.

It would be hardly fair to fill the pages of a general treatise with autobiography. As an introduction, however, to the remarks which follow, my career as a yachtsman may be summarised in the most condensed form.

Twelve voyages to the Mediterranean; the furthest points reached being Constantinople, 1874 and 1878; Cyprus, 1878; Egypt, 1882.

Three circumnavigations of Great Britain.

One circumnavigation of Great Britain and the Shetland Islands, in 1881.

Two circumnavigations of Ireland.

Cruises with the fleets during manœuvres, in 1885, 1888, and 1889.

Voyages to Norway, in 1856, 1874, and 1885. In the (p. 19) latter year Mr. Gladstone and his family were honoured and charming guests.

Voyages to Holland, in 1858 and 1863.

Round the World, 1876-77.

India, Straits Settlements, Borneo, Macassar, Australia, Cape of Good Hope, 1886-87.

England to Calcutta, 1893.

Two voyages to the West Indies, 1883 and 1892, the latter including visits to the Chesapeake and Washington.

'Sunbeam,' R.Y.S. (Lord Brassey).

Canada and the United States, 1872.

The Baltic, 1860.

In 1889 the 'Sunbeam' was lent to Lord Tennyson, for a short cruise in the Channel. The owner deeply regrets that he was prevented by Parliamentary duties from taking charge of his vessel with a passenger so illustrious on board.

The distances covered in the course of the various cruises enumerated may be approximately given:—

(p. 20) Distances sailed: compiled from Log Books

| Year | Knots | Year | Knots | Year | Knots | Year | Knots |

| 1854 | 150 | 1864 | 1,000 | 1874 | 12,747 | 1884 | 3,087 |

| 1855 | 250 | 1865 | 2,626 | 1875 | 4,370 | 1885 | 6,344 |

| 1856 | 2,000 | 1866 | 4,400 | 1876 | 37,000 | 1886 | 36,466 |

| 1857 | 1,500 | 1867 | 3,000 | 1877 | 1887 | ||

| 1858 | 2,500 | 1868 | 1,000 | 1878 | 9,038 | 1888 | 1,175 |

| 1859 | 2,300 | 1869 | 1,900 | 1879 | 5,627 | 1889 | 8,785 |

| 1860 | 1,000 | 1870 | 1,400 | 1880 | 5,415 | 1890 | 8,287 |

| 1861 | 800 | 1871 | 5,234 | 1881 | 5,435 | 1891 | 1,133 |

| 1862 | 3,200 | 1872 | 9,152 | 1882 | 3,345 | 1892 | 11,992 |

| 1863 | 900 | 1873 | 2,079 | 1883 | 13,545 | 1893 | 8,500 |

Total, 1854-1893, 228,682 knots.

I turn from the voyages to the yachts in which they were performed, observing that no later possession filled its owner with more pride than was felt in the smart little 8-tonner which heads the list.

| Date | Name of yacht | Rig | Tonnage | — |

| 1854-58 | Spray of the Ocean | Cutter | 8 | — |

| 1853 | Cymba (winner of Queen's Cup in the Mersey, 1857) | " | 50 | Fife of Fairlie's favourite |

| 1859-60 | Albatross | 118 | — | |

| 1863-71 | Meteor | Auxiliary schooner | 164 | — |

| 1871-72 | Muriel | Cutter | 60 | Dan Hatcher's favourite |

| 1872 | Eothen | S.S. | 340 | — |

| 1874-93 | Sunbeam | Auxiliary schooner | 532 | — |

| 1882-83 | Norman | Cutter | 40 | Dan Hatcher |

| 1891 | Lorna | " | 90 | Camper and Nicholson (1881) |

| 1892-93 | Zarita | Yawl | 115 | Fife of Fairlie (1875) |

| Yachts hired | ||||

| 1885 | Lillah | Cutter | 20 | — |

| 1863 | Eulalie | " | 18 | — |

| 1873 | Livonia | Schooner | 240 | Ratsey (1871) |

The variety of craft in the foregoing list naturally affords (p. 21) opportunity for comparison. I shall be glad if such practical lessons as I have learned can be of service to my brother yachtsmen. And, first, as to the class of vessel suitable for ocean cruising. As might be expected, our home-keeping craft are generally too small for long voyages. Rajah Brooke did some memorable work in the 'Royalist' schooner, 45 tons; but a vessel of 400 tons is not too large to keep the sea and to make a fair passage in all weathers, while giving space enough for privacy and comfort to the owner, his friends, and the crew. Such vessels as the truly noble 'St. George,' 871 tons, the 'Valhalla,' 1,400 tons, and Mr. Vanderbilt's 'Valiant,' of 2,350 tons (Mr. St. Clare Byrne's latest production), cannot be discussed as examples of a type which can be repeated in ordinary practice. Yachtsmen have been deterred from going to sufficient tonnage by considerations of expense. When providing a floating home of possibly many years, first cost is a less serious question than the annual outlay in maintaining and working.

A cruise on the eastern seaboard of North America, where the business of coasting has been brought to the highest perfection, would materially alter the prevailing view as to the complements necessary for handling a schooner of the tonnage recommended. The coasting trade of the United States is carried on in large schooners, rigged with three to five masts. All the sails are fore and aft. In tacking, a couple of hands attend the headsheets, and these, with a man at the wheel, are sufficient to do the work of a watch, even in narrow channels, working short boards. The anchor is weighed and the large sails are hoisted by steam-power. The crews of the American fore-and-aft schooners scarcely exceed the proportion of one man to every hundred tons of cargo carried. For a three-masted schooner of 400 tons, a crew of twelve working hands would be ample, even where the requirements of a yacht have to be provided for. In point of safety, comfort, speed in blowing weather, and general ability to keep the sea and make passages, the 400-ton schooner would offer most desirable advantages (p. 22) over schooner yachts of half the tonnage, although manned with the same number of hands.

It is not within the scope of my present remarks to treat of naval architecture. The volumes will contain contributions from such able men as Messrs. G. L. Watson, who designed the 'Britannia' and 'Valkyrie,' and Lewis Herreshoff, whose 'Navahoe' and 'Vigilant' have recently attracted so much attention. I may, however, say that my personal experience leads me to admire the American models, in which broad beam and good sheer are always found. In 1886, I had the opportunity of seeing the International Race for the America Cup, when the English cutter 'Galatea' (Lieut. Henn, R.N.), with a sail-area of 7,146 feet, and 81 tons of ballast, sailed against the American sloop 'Puritan,' with 9,000 square feet of sail-area and 48 tons of ballast. On this occasion, the advantages of great beam, combined with a shallow middle body and a deep keel, were conspicuously illustrated. The Americans, while satisfied with their type, do not consider their sloops as seaworthy as our cutters. The development which seems desirable in our English building was indicated in a letter addressed to the 'Times' from Chicago in September 1886:—

Avoiding exaggerations on both sides, we may build up on the solid keel of an English cutter a hull not widely differing in form from that of the typical American sloop. It can be done, and pride and prejudice should not be suffered to bar the way of improvement. The yachtsmen of a past generation, led by Mr. Weld of Lulworth, the owner of the famous 'Alarm,' were not slow to learn a lesson from the contests with the 'America' in 1851. We may improve our cutters, as we formerly improved our schooners, by adaptations and modifications, which need not be servile imitations of the fine sloops our champion vessels have encountered on the other side of the Atlantic.

After the lapse of seven years, we find ourselves, in 1893, at the termination of a very remarkable year's yachting. The new construction has included H.R.H. the Prince of Wales's yacht, (p. 23) the 'Britannia,' with 23 feet beam, Lord Dunraven's 'Valkyrie,' Mr. Clarke's 'Satanita,' and the Clyde champion 'Calluna,' all conspicuous for development of beam, combined with the deep, fine keel which is our English substitute for the American centreboard. These vessels have proved doughty antagonists of the 'Navahoe,' brought over by that spirited yacht-owner, Mr. Caryll, to challenge all comers in British waters.

Thus far as to sailing yachts. Though the fashion of the hour has set strongly towards steam-propelled vessels, the beautiful white canvas, and the easy motion when under sail, will long retain their fascination for all pleasure voyaging. It is pleasant to be free from the thud of engines, the smell of oil, and the horrors of the inevitable coaling. Owners who have no love for sailing, and to whom a yacht is essentially a means of conveyance from port to port and a floating home, do well to go for steam. The most efficient and cheapest steam yacht is one in which the masts are reduced to two signal-poles, on which jib-headed trysails may be set to prevent rolling. As to tonnage, the remarks already offered on the advantages of large size apply to steamers even more than to sailing yachts. When space must be given to machinery, boilers, and bunkers, the tonnage must be ample to give the required accommodation. The cost of building and manning, and the horse-power of the engines, do not increase in proportion to the increase of size. The building of steamers for the work of tramps has now been brought down to 7l. per ton. I would strongly urge yacht-owners contemplating ocean cruising to build vessels of not less than 600 tons. Let the fittings be as simple and inexpensive as possible, but let the tonnage be large enough to secure a powerful sea-boat, with coal endurance equal to 3,000 knots, at ten knots, capable of keeping up a fair speed against a stiff head wind, and habitable and secure in all weathers.

Deck-houses are a great amenity at sea, but the conventional yacht skipper loves a roomy deck, white as snow, truly a marvel of scrubbing. Considerations of habitability at sea are totally disregarded by one who feels no need for an airy place of retirement (p. 24) for reading and writing. The owner, seeking to make life afloat pass pleasantly, will consider deck cabins indispensable.

There remains a third and very important type for ocean cruising, that of the sailing yacht with auxiliary steam-power. The 'Firefly,' owned by Sir Henry Oglander, the pioneer in this class, suggested to the present writer a debased imitation in the 'Meteor,' 164 tons. About the same date somewhat similar vessels were brought out, amongst others by Lord Dufferin, whose earliest experiences under sail had been given to the world in 'Letters from High Latitudes.' All will remember the never-varying announcement by a not too cheering steward, on calling his owner, in response to the inquiry, 'How is the wind?' 'Dead ahead, my lord, dead ahead!'

'Sunbeam'—midship section.

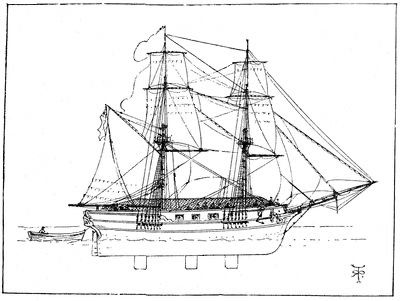

The 'Sunbeam' was launched in 1874; following in her wake, the 'Chazalie,' 1875, 'Czarina,' 1877, and the 'Lancashire Witch,' 1878, appeared in rapid succession. The 'Lancashire Witch' was bought by the Admiralty for a surveying vessel, as being especially adapted to the requirements of that particular service. The 'St. George,' 831 tons, launched 1890, is an enlargement and improvement on her predecessors already named. She does credit to her owner, Mr. Wythes; the designer, Mr. Storey; and the builders, Messrs. Ramage. The 'Sunbeam,' as the first of this class, has been a great success. She was designed by Mr. St. Clare Byrne, M.I.N.A., as a composite three-masted topsail-yard screw schooner, constructed at Birkenhead, and launched in 1874. The following table gives the leading details:—

Dimensions of Spars

| — | Length | Diam. |

| Fore | ft. | in. |

| Foremast, from deck to masthead | 69½ | — |

| Below deck | 14½ | — |

| Total | 84 | 19½ |

| Top and topgallant-mast | 45 | 12 |

| Fore-yard | 50½ | 12 |

| Topsail-yard | 42½ | 9 |

| Topgallant-yard | 33 | 7 |

| Fore-gaff | 29½ | 7 |

| Fore-boom | 33¾ | 9 |

| Main | ||

| Mainmast from deck to masthead | 74 | — |

| Below deck | 14½ | — |

| Total | 88½ | 19 |

| Main-topmast | 422/3 | 9½ |

| Main-gaff | 29¾ | 7½ |

| Main-boom | 35½ | 8¾ |

| Mizen | ||

| Mizenmast from deck to masthead | 78½ | — |

| Below deck | 7½ | — |

| Total | 86 | 18½ |

| Mizen-topmast | 43½ | 9½ |

| Mizen-gaff | 33 | 9 |

| Mizen-boom | 52¾ | 13½ |

| Jibboom, length 49 ft. 9 in., diameter 9½ inches | ||

| Bowsprit " 21 ft. 9 in. " 17½ inches (outside knighthead) | ||

(p. 26) It may be interesting to give some general account of the 'Sunbeam's' performances at sea.

In making the voyage round the world in 1876-77 the total distances covered were 15,000 knots under sail and 12,800 knots under steam. The best run under steam alone was 230 knots. The most successful continuous performance was on the passage from Penang to Galle, when 1,451 knots were steamed in a week, with a daily consumption of 4-¼ tons of coal. The best runs under sail, from noon to noon, were 298 and 299 knots respectively. The first was on the passage from Honolulu to Yokohama, sailing along the 16th parallel of north latitude, and between 163° and 168° 15' east. The second was in the Formosa Channel. The highest speed ever attained under sail was 15 knots, in a squall in the North Pacific. On 28 days the distance under sail alone has exceeded, and often considerably exceeded, 200 knots. The best consecutive runs under sail only were:—

1. Week ending August 13, South Atlantic, in the south-east trades, wind abeam, force 5, 1,456 knots.

2. Week ending November 19, South Pacific, south-east trades, wind aft, force 5, 1,360 knots.

3. Four days, January 15 to 18, North Pacific, north-east trades, wind on the quarter, force 5 to 9, 1,027 knots. The average speed in this case was 10.7 knots an hour.

The following were the average speeds of the longer passages:—

| —— | Days at sea | Total Distance | Distance under steam | Daily average |

| miles | miles | miles | ||

| 1. Cape Verdes to Rio | 18 | 3,336 | 689 | 185 |

| 2. Valparaiso to Yokohama | 72 | 12,333 | 2,108 | 171 |

| 3. Simonosaki to Aden | 37 | 6,93 | 4,577 | 187 |

On a later voyage to Australia, the total distance covered was 36,709 knots, 25,808 under sail and 10,901 under steam. The runs under sail included thirty-nine days over 200 knots, fifteen (p. 27) days over 240, seven days over 260, and three days over 270. The best day was 282 knots. Between Port Darwin and the Cape the distance covered was 1,047 knots under steam, and 5,622 knots under sail. The average speed under steam and sail was exactly eight knots. In the fortnight, October 13 to 27, 1887, 3,073 knots, giving an average speed of nine knots an hour, were covered under sail alone, with winds of moderate strength. Balloon canvas was freely used.

On returning from the voyage just referred to, the boilers of the 'Sunbeam' (which are still at work, after nineteen years' service) required such extensive repairs that it was recommended to remove them and to replace with new. Hesitating to take this step, we went through two seasons under sail alone, the propeller being temporarily removed and the aperture closed. In 1889 a voyage was accomplished to the Mediterranean under these conditions. Making the passage from Portsmouth to Naples, in the month of February, we covered a total distance of 2,303 miles from port to port in ten days and four hours. The same good luck with the winds followed us in subsequent passages to Messina, Zante, Patras, and Brindisi, during which we steadily maintained the high average of ten knots. On the return voyage down the Mediterranean, the results were very different. As this novel experiment in running an auxiliary steam yacht under sail alone may be of interest, a few further details may be added.

The average rate of speed for the distance sailed through the water was approximately 6.4 knots. The total number of days at sea was 44. On 23 days the winds were contrary. On 21 days favourable winds were experienced. With much contrary wind and frequent calms the distances made good on the shortest route from port to port averaged 123 miles per day.

For the total distance of 3,020 miles from Portsmouth to Brindisi, touching at Naples, Messina, Taormina, Zante, and Patras, with fresh and favourable breezes, the distances made good on the shortest route averaged 201 miles per day.

On the passage down the Mediterranean, from Brindisi to (p. 28) Gibraltar, calling at Palermo and Cagliari, against persistent head winds, and with 60 hours of calm, the distance made good from port to port was reduced to 67 miles a day.

Homewards, from Gibraltar, against a fresh Portuguese trade, the distance made good rose to an average of 122 miles through the water per day, the average rate of sailing being 6-¼ knots. From a position 230 miles nearly due west of Cape St. Vincent to Spithead, the 'Sunbeam' covered the distance of 990 miles in six days, being for the most part close-hauled.

| —— | Total distances port to port | Distances sailed | Time under way | Fair winds | Calms | ||

| miles | miles | days | hrs. | days | hrs. | hours | |

| Portsmouth to Naples | 2,200 | 2,303 | 10 | 4 | 9 | 0 | 11 |

| Naples to Brindisi (calling at Messina, Taormina, Zante, and Patras) | 820 | 841 | 5 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 16 |

| Brindisi to Palermo | 400 | 638 | 5 | 6 | 0 | 7 | 13 |

| Palermo to Cagliari | 224 | 353 | 3 | 19 | — | 11 | |

| Cagliari to Gibraltar | 730 | 1,188 | 10 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 37 |

| Gibraltar to Portsmouth | 1,175 | 1,457 | 9 | 16 | 6 | 0 | 8 |

| Total | 5,549 | 6,780 | 44 | 2 | 21 | 9 | 96 |

In the course of the voyage numerous gales of wind were experienced, viz.: on February 12, a severe mistral, on the passage from Minorca towards Naples; March 28, heavy gale from westward off Stromboli; April 9 and 10, gale from S.W. at the mouth of the Adriatic; April 17, gale from S., off south coast of Sardinia; April 29 and 30, gale from W., off Almeria.

On the days of light winds and calms, balloon topmast staysails, a jib-topsail, and an extra large lower studsail, were found most valuable in maintaining the rate of sailing.

In ordinary cruising I find that, as a general rule, one-third of the distance is covered under steam, and that upon the average we make passages at the rate of 1,000 miles a week. (p. 29) The consumption of coal is very moderate. For a voyage round the world, of 36,000 miles, the coal consumed was only 325 tons.

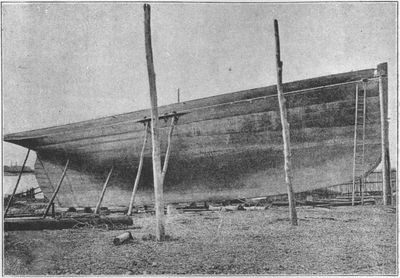

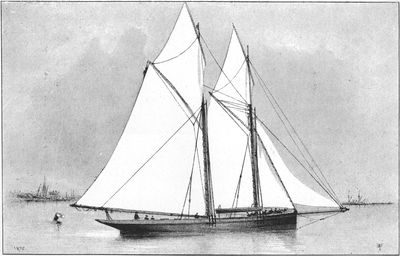

'Sunbeam,' R.Y.S. Designed by St. Clare Byrne, 1874.

If I were dealing with the question of rig, with the long experience gained on the 'Sunbeam,' I should decidedly adopt the barque rig. In confirmation of this opinion, it may be interesting to note that when H.M. brig 'Beagle' was under the command of Captain FitzRoy, R.N., for a lengthened service in the Straits of Magellan and the coasts of South America, the mizenmast was stuck through the skylight of the captain's cabin, an arrangement which, while of service to the ship, was not unnaturally a source of discomfort to the captain. In making passages in the Trades, with light winds on the quarter and the usual swell, fore-and-aft sails are constantly lifting, while sails set on (p. 30) fixed yards keep asleep. They draw better, and there is no chafe. I have found great advantage from the use of large studding-sails, made of light duck. This material was highly esteemed when it was first brought out. In modern practice a combination of silk and hemp furnishes a greatly superior material for the huge spinnakers, of 4,000 square feet, carried by the 'Navahoe' and 'Valkyrie.' The new balloon sails can no longer be called canvas. They may more accurately be described as muslin.

I will not attempt a recital of nautical adventures in the present chapter; but a few experiences may be briefly described. The worst passage I ever made was in the 'Eothen,' s.s., 340 tons, in 1872, from Queenstown to Quebec, touching at St. John's, Newfoundland. On August 14 we put to sea deeply laden, with bunkers full, and 15 tons of coal in bags on deck. In this condition we had 2 ft. 9 in. of freeboard. On the second day out we encountered a summer gale. Shortly after it came on, we shipped a sea, which broke over the bow and filled us up to the rail. At the same time the engineer put his head above the engine-room hatch, and announced that, the bearings having become heated, he must stop the engines. For a short time we were in danger of falling off into the trough of the sea. It was a great relief when the engines once more slowly turned ahead. In the mid-Atlantic, we encountered a cyclone, passing through the calm but ominous centre into a violent gale from the north-west, which lasted twenty-four hours. We were battened down and suffered considerable discomfort. Fortunately, no heavy sea broke on board as we lay to under double-reefed main storm-trysail, the engines slowly turning ahead. Two days later we encountered another sharp gale, in which the barometer fell to 29.14°. Happily it soon passed over. After this third gale we had a change of wind to the eastward, and, pushing on, with all sail set, we reached St. John's in thirteen days from Queenstown, with four inches of water in the tanks, two tons of coal in the bunkers, the decks leaking in every seam, cabins in utter (p. 31) disarray, and a perfect wreck aloft and on deck. After leaving St. John's, where we had confidently hoped that the worst was over, we encountered a hurricane off Cape Race, which exceeded in violence anything that had been experienced in these waters for many years. We lay to for three days, and when the storm abated put into the French island St. Pierre, almost exhausted. It was an unspeakable relief when we entered the St. Lawrence.

The lesson to be drawn from my voyage in the 'Eothen' is obvious. It is a great mistake to attempt to cross the stormiest ocean in the world in a steam yacht of such small size. For ocean steaming much more tonnage and power are necessary.

The heaviest gale ever experienced by the 'Sunbeam' was off Flamborough Head, in 1881. I embarked at Middlesbrough on the evening of October 13, intending to sail for Portsmouth at daybreak on the following morning; but, finding the wind from the south and the barometer depressed, our departure was deferred. At 9 a.m. the barometer had fallen to 28.87°, but as the wind had changed to W.N.W., and was off shore from a favourable quarter, I determined to proceed to sea. We were towed down the Tees, and as we descended the river I conferred with the pilot as to what we might anticipate from the remarkable depression in the barometer. He was of opinion that a severe gale was at hand, that it would blow from the north-west, and that there was no reason for remaining in port. The tug was accordingly cast off at the mouth of the Tees, and we made sail. Foreseeing a storm, topmasts were housed, boats were secured on deck, and we kept under close-reefed canvas, setting the main and mizen jib-headed trysails, double-reefed foresail and forestay-sail, and reefed standing jib. As the day advanced no change took place in the weather. The wind blew strongly, but not with the force of a gale, and the sea was comparatively smooth. Meanwhile the barometer continued to descend rapidly, and at 2 p.m. had fallen to 28.45°. As nothing had yet occurred to account for this depression, my sailing-master remarked that it (p. 32) must have been caused by the heavy showers of rain which had fallen in the course of the morning. I knew from former experiences that it was not the rain, but the coming storm, that was indicated by the barometer. It had needed some resolution to quit the mouth of the Tees in the morning, and at mid-day, when we were off Whitby, a still greater effort was required to resist the temptation to make for a harbour. No further incidents occurred until 3 p.m., when we were nearing Flamborough Head. Here we were at last overtaken by the long impending storm. Looking back to the north-west, over the starboard quarter, we saw that the sea had suddenly been lashed into a mass of white foam. The hurricane was rushing forward with a velocity and a force which must have seemed terrible to the fleet of coasting vessels around us. Before the gale struck the 'Sunbeam' our canvas had been reduced to main and mizen trysails and reefed standing-jib; but even with the small spread of sail, and luffed up close to the wind, our powerful little vessel careened over to the fury of the blast until the lee-rail completely disappeared under water—an incident which had never previously occurred during all the extensive voyages we had undertaken. Such was the force of the wind that a sailing vessel near us lost all her sails, and our large gig was stove in from the tremendous pressure of the gunwale against the davits. We took in the jib and the mizen-trysail, and, with our canvas reduced to a jib-headed main-trysail, were soon relieved of water on deck. For an hour and a half we lay-to on the starboard tack, standing in for the land below Burlington Bay. We were battened down, and felt ourselves secure from all risks except collision. The fury of the wind so filled the air with spoon-drift that we could not see a ship's length ahead, and in such crowded waters a collision was a far from impossible contingency. At 6 p.m. we thought it prudent to wear, so as to gain an offing during the night, and gradually drew out of the line of traffic along the coast. At 9 p.m. the extreme violence of the hurricane had abated, and we could see, through occasional openings in the mist, the (p. 33) masthead lights of several steamers standing, like ourselves, off the land for the night. At midnight the barometer was rising rapidly, and the wind gradually settled down into a clear hard gale, accompanied by a heavy sea, running down the coast from the north.

At 6 a.m. we carefully examined the dead reckoning, and, having fixed on an approximate position, we determined to bear away, steering to pass in mid-channel between the Outer Dowsing and the Dudgeon, through a passage about ten miles in width. We were under easy sail; but, under the main-trysail, double-reefed foresail, staysail, fore-topsail, and reefed jib, we scudded at the rate of eleven knots. A constant look-out had been kept from aloft, and at 10 a.m., having nearly run the distance down from our assumed position when we bore away to the north end of the Outer Dowsing, I established myself in the crosstrees until we should succeed in making something. After a short interval we saw broken water nearly ahead on the port bow. We at once hauled to the wind, steering to the south-west, and set the mizen-trysail. The lead showed a depth of three fathoms, and we were therefore assured that we had been standing too near to the Outer Dowsing. The indications afforded by the lead were confirmed by sights, somewhat roughly taken, and by the circumstance of our having shortly before passed through a fleet of trawlers evidently making for the Spurn. In less than an hour after we had hauled to the wind we found ourselves in the track of several steamers. At 3 p.m. we made the land near Cromer, and at 5.30 we brought up in the Yarmouth Roads, thankful to have gained a secure shelter from the gale.

In connection with this experience, it may be remarked that, as a general rule, our pleasure fleet is over-masted. We are advised in these matters by sailmakers, who look to the Solent and its sheltered water as the normal condition with which yachtsmen have to deal. When we venture forth from that smooth and too-much frequented arm of the sea into open waters, our vessels have to pass a far more severe ordeal, and (p. 34) they do not always come out of it to our satisfaction. Many are compelled to stay in harbour when a passage might have been made in a snugly rigged yacht.

One of the longest gales experienced in the 'Sunbeam' was on the passage from Nassau to Bermuda, in November 1883. The gale struck us south of Cape Hatteras, on November 25, in latitude 31.54° N. The north-east wind gradually subsided, and we pushed on, under steam, for Bermuda at 7 knots. The head sea increased, but no change took place in the force or direction of the wind from 8 p.m. on the 25th till 4 a.m. on the 27th. Meanwhile, the barometer had gradually fallen to 29.82°, giving warning for a heavy gale, which commenced at north-by-east, and ended on November 30, at 4 p.m., with the wind at north-west. We lay-to on the 27th, under treble-reefed foresail and double-reefed mainsail, shipping no water, but driving to the south-east at the rate of at least one knot an hour. On the 28th we decided to try the 'Sunbeam' under treble-reefed foresail and mainsail, double-reefed fore-staysail and reefed mizen-trysail. With this increased spread of canvas we were able to make two knots an hour on the direct course to Bermuda, and to keep sufficient steerage way to luff up to an ugly sea. The behaviour of the vessel elicited the unqualified approval of our most experienced hands. Bad weather quickly brings out the qualities of seamen. Our four best men relieved each other at the wheel, and it was due in no small degree to their skill that, in a gale lasting three days, no heavy sea broke on board. I need not say that all deck openings were secured, especially at night, by means of planks and canvas. Our situation might perhaps excite sympathy, but we had no cause to complain. Meals could not be served in the usual manner, but by placing every movable thing on the floor of the cabins and on the lee side, and by fixing ourselves against supports, or in a recumbent position, we were secured against any further effects of the force of gravity, and did our best to enjoy the novelty of the situation. On the 30th the wind veered to the north-west, and the weather rapidly improved. The sea turned (p. 35) gradually with the wind, but for many hours we met a heavy swell from the north-east.

An acquaintance with the law of storms had proved invaluable on this occasion. There is no situation in which knowledge is more truly power, none in which, under a due sense of the providential care of Heaven, it gives a nobler confidence to man, than at sea, amid the raging of a hurricane. Mr. Emerson has truly said, 'They can conquer who believe they can. The sailor loses fear as fast as he acquires command of sails, and spars, and steam. To the sailor's experience, every new circumstance suggests what he must do. The terrific chances which make the hours and minutes long to the mere passenger, he whiles away by incessant application of expedients and repairs. To him a leak, a hurricane, a waterspout, is so much work, and no more. Courage is equality to the problem, in affairs, in science, in trade, in council, or in action. Courage consists in the conviction that the agents with which you contend are not superior in strength, or resources, or spirit, to you.'

As a specimen of a dirty night at sea, I give another extract from the log-book. During our voyage round the world in 1876-77, after leaving Honolulu for Japan, as we approached Osima, on January 26, we were struck by a tremendous squall of wind and rain. We at once took in the flying square-sail, stowed the topgallant-sail and topsail, reefed the foresail and mizen, and set mainsail. At 6 p.m., the wind still blowing a moderate gale, the mizen was double-reefed. We pursued our way through a confused sea, but without shipping any water. All seemed to be going well, when, at 8 p.m., shortly after I had taken the wheel, a sudden squall heeled us over to the starboard side, where the gig was hung from the davits outboard. At the same time a long mountainous wave, rolling up from the leeward, struck the keel of the gig and lifted it up, unshipping the fore davit, and causing the boat to fall into the boiling sea, which threatened at every instant to dash it to pieces. We at once brought to. A brave fellow (p. 36) jumped into the boat and secured a tackle to the bows, and the gig was hoisted on board and secured on deck intact. It was a very seaman-like achievement. A heavy gale continued during the night, and at 2 a.m., on the 27th, we met with another accident. The boatswain, a man of great skill and experience, was at the wheel, when a steep wave suddenly engulfed the jibboom, and the 'Sunbeam,' gallantly springing up, as if to leap over instead of cleaving through the wave, carried away the spar at the cap. This brought down the topgallant-mast. The jibboom was a splendid Oregon spar, 54 feet long, projecting 28 feet beyond the bowsprit. It was rigged with wire rope, and the martingale was sawn through with the greatest difficulty.

The record of personal experiences must not be further prolonged. To the writer yachting has been to some extent part of a public life, mainly devoted to the maritime interests of the country. To conduct the navigation and pilotage of his vessel seemed fitting and even necessary, if the voyages undertaken were to be regarded in any sense as professional. There is something pleasant in any work which affords the opportunity for encountering and overcoming difficulties. It is satisfactory to make a headland or a light with precision after a long run across the ocean, diversified perhaps by a heavy gale. To be able to thread the channels of the West Coast of Scotland, the Straits of Magellan, the Eastern Archipelago, the labyrinths of the Malawalle Channel of North-East Borneo, or the Great Barrier Reef of Australia, without a pilot is an accomplishment in which an amateur may perhaps take legitimate pleasure.

To the yachtsman who truly loves the sea, it will never be satisfactory to remain ignorant of navigation. Practice of the art is not a relaxation. It demands constant attention, and is an interruption to regular reading. It may imply a considerable amount of night-work. On the other hand, the owner who is a navigator can take his proper place as the commander of his own ship. All that goes on around him when at sea becomes more interesting. He is better able to appreciate the professional (p. 37) skill of others. The confidence which grows with experience cannot be expected in the beginning. The writer first took charge of navigation in 1866, on a voyage up the Baltic. It was a chequered experiment. In the Great Belt we ran ashore twice in one day. In making Stockholm we had to appeal to a Swedish frigate, which most kindly clewed up her sails, and answered our anxious enquiries by writing the course on a black-board. On the return voyage to England we struck the coast some sixty miles north of our reckoning. Such a history does not repeat itself now.