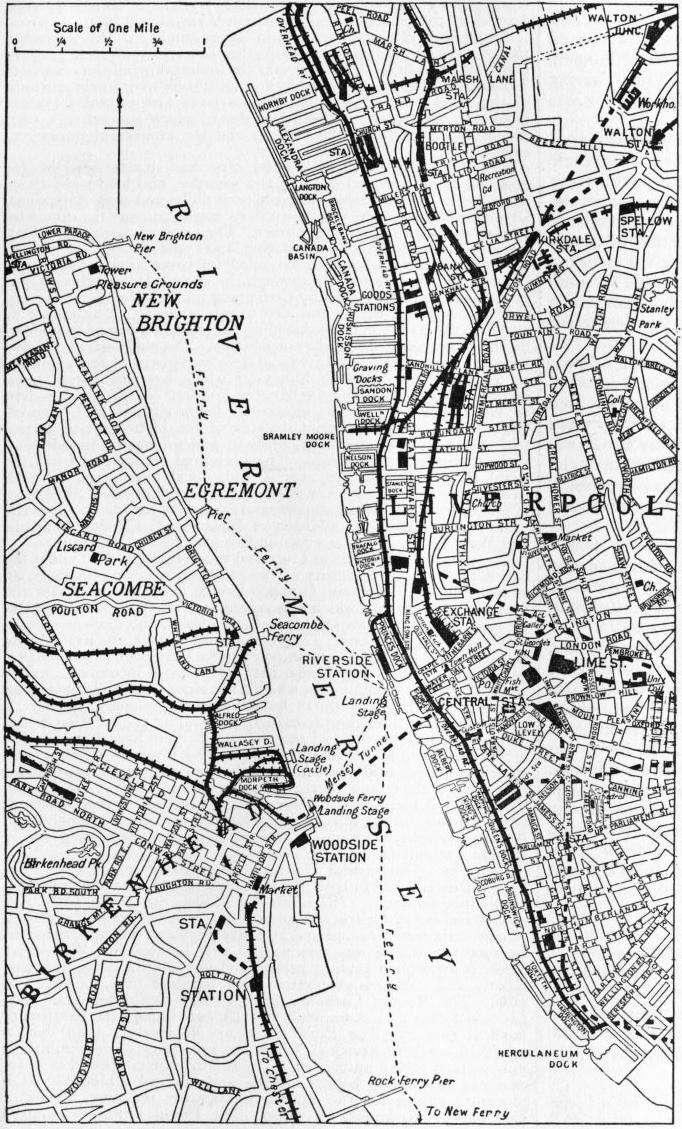

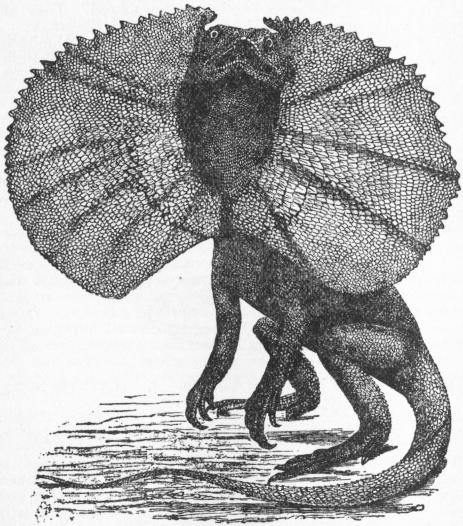

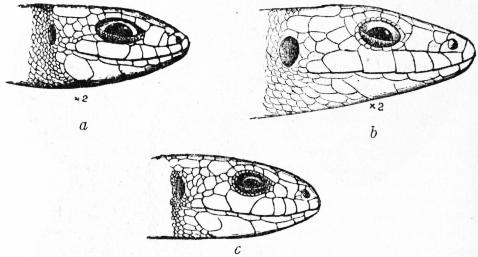

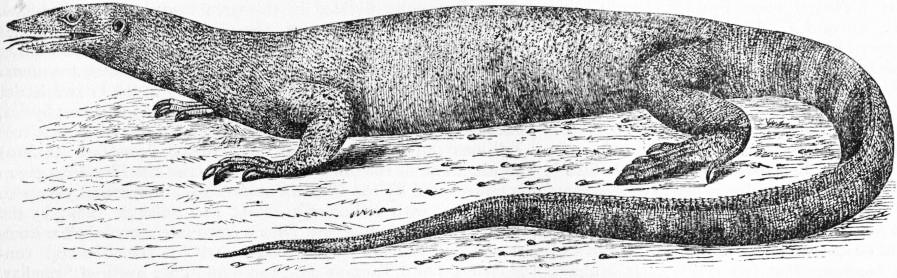

Title: Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th Edition, "Liquid Gases" to "Logar"

Author: Various

Release date: February 23, 2013 [eBook #42173]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Marius Masi, Don Kretz and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

| Transcriber’s note: |

A few typographical errors have been corrected. They

appear in the text like this, and the

explanation will appear when the mouse pointer is moved over the marked

passage. Sections in Greek will yield a transliteration

when the pointer is moved over them, and words using diacritic characters in the

Latin Extended Additional block, which may not display in some fonts or browsers, will

display an unaccented version. Links to other EB articles: Links to articles residing in other EB volumes will be made available when the respective volumes are introduced online. |

Articles in This Slice

LIQUID GASES.1 Though Lavoisier remarked that if the earth were removed to very cold regions of space, such as those of Jupiter or Saturn, its atmosphere, or at least a portion of its aeriform constituents, would return to the state of liquid (Œuvres, ii. 805), the history of the liquefaction of gases may be said to begin with the observation made by John Dalton in his essay “On the Force of Steam or Vapour from Water and various other Liquids” (1801): “There can scarcely be a doubt entertained respecting the reducibility of all elastic fluids of whatever kind into liquids; and we ought not to despair of effecting it in low temperatures and by strong pressures exerted on the unmixed gases.” It was not, however, till 1823 that the question was investigated by systematic experiment. In that year Faraday, at the suggestion of Sir Humphry Davy, exposed hydrate of chlorine to heat under pressure in the laboratories of the Royal Institution. He placed the substance at the end of one arm of a bent glass tube, which was then hermetically sealed, and decomposing it by heating to 100° F., he saw a yellow liquid distil to the end of the other arm. This liquid he surmised to be chlorine separated from the water by the heat and “condensed into a dry fluid by the mere pressure of its own abundant vapour,” and he verified his surmise by compressing chlorine gas, freed 745 from water by exposure to sulphuric acid, to a pressure of about four atmospheres, when the same yellow fluid was produced (Phil. Trans., 1823, 113, pp. 160-165). He proceeded to experiment with a number of other gases subjected in sealed tubes to the pressure caused by their own continuous production by chemical action, and in the course of a few weeks liquefied sulphurous acid, sulphuretted hydrogen, carbonic acid, euchlorine, nitrous acid, cyanogen, ammonia and muriatic acid, the last of which, however, had previously been obtained by Davy. But he failed with hydrogen, oxygen, fluoboric, fluosilicic and phosphuretted hydrogen gases (Phil. Trans., ib. pp. 189-198). Early in the following year he published an “Historical statement respecting the liquefaction of gases” (Quart. Journ. Sci., 1824, 16, pp. 229-240), in which he detailed several recorded cases in which previous experimenters had reduced certain gases to their liquid state.

In 1835 Thilorier, by acting on bicarbonate of soda with sulphuric acid in a closed vessel and evacuating the gas thus obtained under pressure into a second vessel, was able to accumulate large quantities of liquid carbonic acid, and found that when the liquid was suddenly ejected into the air a portion of it was solidified into a snow-like substance (Ann. chim. phys., 1835, 60, pp. 427-432). Four years later J. K. Mitchell in America, by mixing this snow with ether and exhausting it under an air pump, attained a minimum temperature of 146° below zero F., by the aid of which he froze sulphurous acid gas to a solid.

Stimulated by Thilorier’s results and by considerations arising out of the work of J. C. Cagniard de la Tour (Ann. chim. phys., 1822, 21, pp. 127 and 178, and 1823, 22, p. 410), which appeared to him to indicate that gases would pass by some simple law into the liquid state, Faraday returned to the subject about 1844, in the “hope of seeing nitrogen, oxygen and hydrogen either as liquid or solid bodies, and the latter probably as a metal” (Phil. Trans., 1845, 135, pp. 155-157). On the basis of Cagniard de la Tour’s observation that at a certain temperature a liquid under sufficient pressure becomes a vapour or gas having the same bulk as the liquid, he inferred that “at this temperature or one a little higher, it is not likely that any increase of pressure, except perhaps one exceedingly great, would convert the gas into a liquid.” He further surmised that the Cagniard de la Tour condition might have its point of temperature for oxygen, nitrogen, hydrogen, &c., below that belonging to the bath of solid carbonic acid and ether, and he realized that in that case no pressure which any apparatus would be able to bear would be able to bring those gases into the liquid or solid state, which would require a still greater degree of cold. To fulfil this condition he immersed the tubes containing his gases in a bath of solid carbonic acid and ether, the temperature of which was reduced by exhaustion under the air pump to −166° F., or a little lower, and at the same time he subjected the gases to pressures up to 50 atmospheres by the use of two pumps working in series. In this way he added six substances, usually gaseous, to the list of those that could be obtained in the liquid state, and reduced seven, including ammonia, nitrous oxide and sulphuretted hydrogen, into the solid form, at the same time effecting a number of valuable determinations of vapour tensions. But he failed to condense oxygen, nitrogen and hydrogen, the original objects of his pursuit, though he found reason to think that “further diminution of temperature and improved apparatus for pressure may very well be expected to give us these bodies in the liquid or solid state.” His surmise that increased pressure alone would not suffice to bring about change of state in these gases was confirmed by subsequent investigators, such as M. P. E. Berthelot, who in 1850 compressed oxygen to 780 atmospheres (Ann. chim. phys., 1850, 30, p. 237), and Natterer, who a few years later subjected the permanent gases to a pressure of 2790 atmospheres, without result; and in 1869 Thomas Andrews (Phil. Trans., 11) by his researches on carbonic acid finally established the conception of the “critical temperature” as that temperature, differing for different bodies, above which no gas can be made to assume the liquid state, no matter what pressure it be subjected to (see Condensation of Gases).

About 1877 the problem of liquefying the permanent gases was taken up by L. P. Cailletet and R. P. Pictet, working almost simultaneously though independently. The former relied on the cold produced by the sudden expansion of the gases at high compression. By means of a specially designed pump he compressed about 100 cc. of oxygen in a narrow glass tube to about 200 atmospheres, at the same time cooling it to about −29° C., and on suddenly releasing the pressure he saw momentarily in the interior of the tube a mist (brouillard), from which he inferred the presence of a vapour very near its point of liquefaction. A few days later he repeated the experiment with hydrogen, using a pressure of nearly 300 atmospheres, and observed in his tube an exceedingly fine and subtle fog which vanished almost instantaneously. At the time when these experiments were carried out it was generally accepted that the mist or fog consisted of minute drops of the liquefied gases. Even had this been the case, the problem would not have been completely solved, for Cailletet was unable to collect the drops in the form of a true stable liquid, and at the best obtained a “dynamic” not a “static” liquid, the gas being reduced to a form that bears the same relation to a true liquid that the partially condensed steam issuing from the funnel of a locomotive bears to water standing in a tumbler. But subsequent knowledge showed that even this proximate liquefaction could not have taken place, and that the fog could not have consisted of drops of liquid hydrogen, because the cooling produced by the adiabatic expansion would give a temperature of only 44° abs., which is certainly above the critical temperature of hydrogen. Pictet again announced that on opening the tap of a vessel containing hydrogen at a pressure of 650 atmospheres and cooled by the cascade method (see Condensation of Gases) to −140° C., he saw issuing from the orifice an opaque jet which he assumed to consist of hydrogen in the liquid form or in the liquid and solid forms mixed. But he was no more successful than Cailletet in collecting any of the liquid, which—whatever else it may have been, whether ordinary air or impurities associated with the hydrogen—cannot have been hydrogen because the means he employed were insufficient to reduce the gas to what has subsequently been ascertained to be its critical point, below which of course liquefaction is impossible. It need scarcely be added that if the liquefaction of hydrogen be rejected a fortiori Pictet’s claim to have effected its solidification falls to the ground.

After Cailletet and Pictet, the next important names in the history of the liquefaction of gases are those of Z. F. Wroblewski and K. S. Olszewski, who for some years worked together at Cracow. In April 1883 the former announced to the French Academy that he had obtained oxygen in a completely liquid state and (a few days later) that nitrogen at a temperature of −136° C., reduced suddenly from a pressure of 150 atmospheres to one of 50, had been seen as a liquid which showed a true meniscus, but disappeared in a few seconds. But with hydrogen treated in the same way he failed to obtain even the mist reported by Cailletet. At the beginning of 1884 he performed a more satisfactory experiment. Cooling hydrogen in a capillary glass tube to the temperature of liquid oxygen, he expanded it quickly from 100 atmospheres to one, and obtained the appearance of an instantaneous ebullition. Olszewski confirmed this result by expanding from a pressure of 190 atmospheres the gas cooled by liquid oxygen and nitrogen boiling under reduced pressure, and even announced that he saw it running down the walls of the tube as a colourless liquid.

Wroblewski, however, was unable to observe this phenomenon, and Olszewski himself, when seven years later he repeated the experiment in the more favourable conditions afforded by a larger apparatus, was unable to produce again the colourless drops he had previously reported: the phenomenon of the appearance of sudden ebullition indeed lasted longer, but he failed to perceive any meniscus such as would have been a certain indication of the presence of a true liquid. Still, though neither of these investigators succeeded in reaching the goal at which they aimed, their work was of great value in elucidating the conditions of the problem and in perfecting the details of the 746 apparatus employed. Wroblewski in particular devoted the closing years of his life to a most valuable investigation of the isothermals of hydrogen at low temperatures. From the data thus obtained he constructed a van der Waals equation which enabled him to calculate the critical temperature, pressure and density of hydrogen with very much greater certainty than had previously been possible. Liquid oxygen, liquid nitrogen and liquid air—the last was first made by Wroblewski in 1885—became something more than mere curiosities of the laboratory, and by the year 1891 were produced in such quantities as to be available for the purposes of scientific research. Still, nothing was added to the general principles upon which the work of Cailletet and Pictet was based, and the “cascade” method, together with adiabatic expansion from high compression (see Condensation of Gases), remained the only means of procedure at the disposal of experimenters in this branch of physics.

In some quarters a certain amount of doubt appears to have arisen as to the sufficiency of these methods for the liquefaction of hydrogen. Olszewski, for example, in 1895 pointed out that the succession of less and less condensible gases necessary for the cascade method breaks down between nitrogen and hydrogen, and he gave as a reason for hydrogen not having been reduced to the condition of a static liquid the non-existence of a gas intermediate in volatility between those two. By 1894 attempts had been made in the Royal Institution laboratories to manufacture an artificial gas of this nature by adding a small proportion of air to the hydrogen, so as to get a mixture with a critical point of about −200° C. When such a mixture was cooled to that temperature and expanded from a high degree of compression into a vacuum vessel, the result was a white mass of solid air together with a clear liquid of very low density. This was in all probability hydrogen in the true liquid state, but it was not found possible to collect it owing to its extreme volatility. Whether this artificial gas might ultimately have enabled liquid hydrogen to be collected in open vessels we cannot say, for experiments with it were abandoned in favour of other measures, which led finally to a more assured success.

Vacuum Vessels.—The problem involved in the liquefaction of hydrogen was in reality a double one. In the first place, the gas had to be cooled to such a temperature that the change to the liquid state was rendered possible. In the second, means had to be discovered for protecting it, when so cooled, from the influx of external heat, and since the rate at which heat is transferred from one body to another increases very rapidly with the difference between their temperatures, the question of efficient heat insulation became at once more difficult and more urgent in proportion to the degree of cold attained. The second part of the problem was in fact solved first. Of course packing with non-conducting materials was an obvious expedient when it was not necessary that the contents of the apparatus should be visible to the eye, but in the numerous instances when this was not the case such measures were out of the question. Attempts were made to secure the desired end by surrounding the vessel that contained the cooled or liquid gas with a succession of other vessels, through which was conducted the vapour given off from the interior one. Such devices involved awkward complications in the arrangement of the apparatus, and besides were not as a rule very efficient, although some workers, e.g. Dr Kamerlingh Onnes, of Leiden, reported some success with their use. In 1892 it occurred to Dewar that the principle of an arrangement he had used nearly twenty years before for some calorimetric experiments on the physical constants of hydrogenium, which was a natural deduction from the work of Dulong and Petit on radiation, might be employed with advantage as well to protect cold substances from heat as hot ones from cold. He therefore tried the effect of surrounding his liquefied gas with a highly exhausted space. The result was entirely successful. Experiment showed that liquid air contained in a glass vessel with two walls, the space between which was a high vacuum, evaporated at only one fifth the rate it did when in an ordinary vessel surrounded with air at atmospheric pressure, the convective transference of heat by means of the gas particles being enormously reduced owing to the vacuum. But in addition these vessels lent themselves to an arrangement by which radiant heat could still further be cut off, since it was found that when the inner wall was coated with a bright deposit of silver, the influx of heat was diminished to one-sixth of the amount existing without the metallic coating. The total effect, therefore, of the high vacuum and silvering is to reduce the in-going heat to one-thirtieth part. In making such vessels a mercurial vacuum has been found very satisfactory. The vessel in which the vacuum is to be produced is provided with a small subsidiary vessel joined by a narrow tube with the main vessel, and connected with a powerful air-pump. A quantity of mercury having been placed in it, it is heated in an oil- or air-bath to about 200° C., so as to volatilize the mercury, the vapour of which is removed by the pump. After the process has gone on for some time, the pipe leading to the pump is sealed off, the vessel immediately removed from the bath, and the small subsidiary part immersed in some cooling agent such as solid carbonic acid or liquid air, whereby the mercury vapour is condensed in the small vessel and a vacuum of enormous tenuity left in the large one. The final step is to seal off the tube connecting the two. In this way a vacuum may be produced having a vapour pressure of about the hundred-millionth of an atmosphere at 0° C. If, however, some liquid mercury be left in the space in which the vacuum is produced, and the containing part of the vessel be filled with liquid air, the bright mirror of mercury which is deposited on the inside wall of the bulb is still more effective than silver in protecting the chamber from the influx of heat, owing to the high refractive index, which involves great reflecting power, and the bad heat-conducting powers of mercury.

|

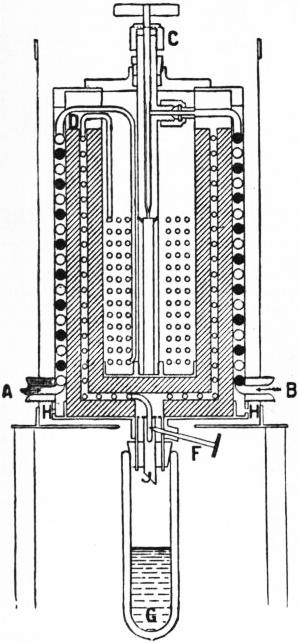

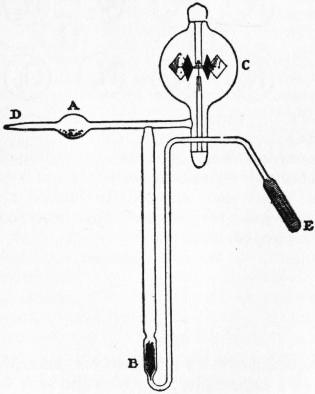

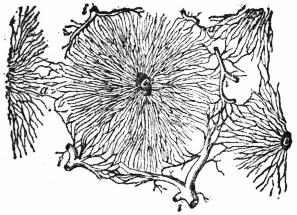

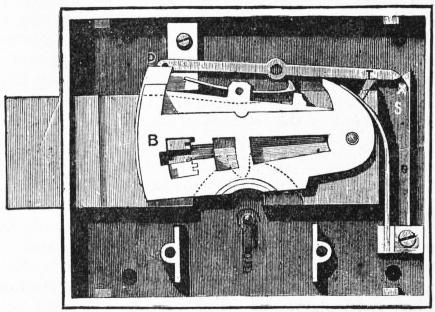

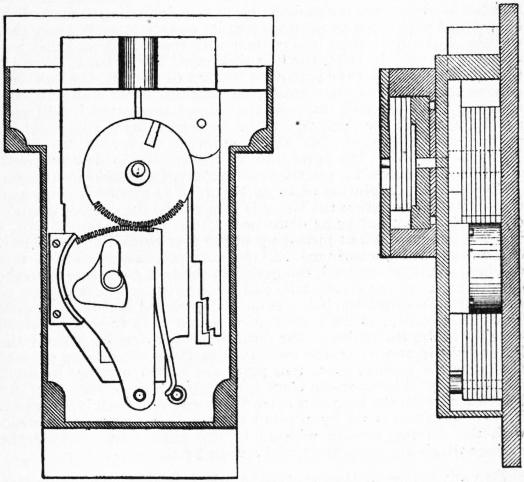

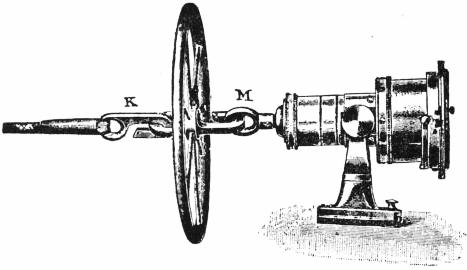

| Fig. 1.—Metallic Vacuum Vessel. |

With the discovery of the remarkable power of gas absorption possessed by charcoal cooled to a low temperature (see below), it became possible to make these vessels of metal. Previously this could not be done with success, because gas occluded in the metal gradually escaped and vitiated the vacuum; but now any stray gas may be absorbed by means of charcoal so placed in a pocket within the vacuous space that it is cooled by the liquid in the interior of the vessel. Metal vacuum vessels (fig. 1), of a capacity of from 2 to 20 litres, may be formed of brass, copper, nickel or tinned iron, with necks of some alloy that is a bad conductor of heat, silvered glass vacuum cylinders being fitted as stoppers. Such flasks, when properly constructed, have an efficiency equal to that of the chemically-silvered glass vacuum vessels now commonly used in low temperature investigations, and they are obviously better adapted for transport. The principle of the Dewar vessel is utilized in the Thermos flasks which are now extensively manufactured and employed for keeping liquids warm in hospitals, &c.

Thermal Transparency at Low Temperatures.—The proposition, once enunciated by Pictet, that at low temperatures all substances have practically the same thermal transparency, and are equally ineffective as non-conductors of heat, is based on erroneous observations. It is true that if the space between the two walls of a double-walled vessel is packed with substances like carbon, magnesia, or silica, liquid air placed in the interior will boil off even more quickly than it will when the space merely contains air at atmospheric pressure; but in such cases it is not so much the carbon, &c., that bring about the transference of heat, as the air contained in their interstices. If this air be pumped out such substances are seen to exert a very considerable influence in stopping the influx of heat, and a vacuum vessel which has the space between its two walls filled with a non-conducting material of this kind preserves a liquid gas even better than one in which that space is simply exhausted of air. In experiments on this point double-walled glass tubes, as nearly identical in shape and size as possible, were mounted in sets of three on a common stem which communicated with an air-pump, so that the degree of exhaustion in each was equal. In two of each three the space between the double walls was filled with the powdered material it was desired to test, the third being left empty and used as the standard. The time required for a certain quantity of liquid 747 air to evaporate from the interior of this empty bulb being called 1, in each of the eight sets of triple tubes, the times required for the same quantity to boil off from the other pairs of tubes were as follows:—

| Charcoal | 5 | Lampblack | 5 |

| Magnesia | 2 | Silica | 4 |

| Graphite | 1.3 | Lampblack | 4 |

| Alumina | 3.3 | Lycopodium | 2.5 |

| Calcium carbonate | 2.5 | Barium carbonate | 1.3 |

| Calcium fluoride | 1.25 | Calcium phosphate | 2.7 |

| Phosphorus (amorphous) | 1 | Lead oxide | 2 |

| Mercuric iodide | 1.5 | Bismuth oxide | 6 |

Other experiments of the same kind made—(a) with similar vacuum vessels, but with the powders replaced by metallic and other septa; and (b) with vacuum vessels having their walls silvered, yielded the following results:—

| (a) | Vacuum space empty | 1 |

| Three turns silver paper, bright surface inside | 4 | |

| Three turns silver paper, bright surfaceoutside | 4 | |

| Vacuum space empty | 1 | |

| Three turns black paper, black outside | 3 | |

| Three turns black paper, black inside | 3 | |

| Vacuum space empty | 1 | |

| Three turns gold paper, gold outside | 4 | |

| Some pieces of goldleaf put in so as to make contact between walls of vacuum-tube | 0.3 | |

| Vacuum space empty | 1 | |

| Three turns, not touching, of sheet lead | 4 | |

| Three turns, not touching, of sheet aluminium | 4 | |

| (b) | Vacuum space empty, silvered on inside surfaces | 1 |

| Silica in silvered vacuum space | 1.1 | |

| Empty silvered vacuum | 1 | |

| Charcoal in silvered vacuum | 1.25 |

It appears from these experiments that silica, charcoal, lampblack, and oxide of bismuth all increase the heat insulations to four, five and six times that of the empty vacuum space. As the chief communication of heat through an exhausted space is by molecular bombardment, the fine powders must shorten the free path of the gaseous molecules, and the slow conduction of heat through the porous mass must make the conveyance of heat-energy more difficult than when the gas molecules can impinge upon the relatively hot outer glass surface, and then directly on the cold one without interruption. (See Proc. Roy. Inst. xv. 821-826.)

Density of Solids and Coefficients of Expansion at Low Temperatures.—The facility with which liquid gases, like oxygen or nitrogen, can be guarded from evaporation by the proper use of vacuum vessels (now called Dewar vessels), naturally suggests that the specific gravities of solid bodies can be got by direct weighing when immersed in such fluids. If the density of the liquid gas is accurately known, then the loss of weight by fluid displacement gives the specific gravity compared to water. The metals and alloys, or substances that can be got in large crystals, are the easiest to manipulate. If the body is only to be had in small crystals, then it must be compressed under strong hydraulic pressure into coherent blocks weighing about 40 to 50 grammes. Such an amount of material gives a very accurate density of the body about the boiling point of air, and a similar density taken in a suitable liquid at the ordinary temperature enables the mean coefficient of expansion between +15° C. and −185° C. to be determined. One of the most interesting results is that the density of ice at the boiling point of air is not more than 0.93, the mean coefficient of expansion being therefore 0.000081. As the value of the same coefficient between 0° C. and −27° C. is 0.000155, it is clear the rate of contraction is diminished to about one-half of what it was above the melting point of the ice. This suggests that by no possible cooling at our command is it likely we could ever make ice as dense as water at 0° C., far less 4° C. In other words, the volume of ice at the zero of temperature would not be the minimum volume of the water molecule, though we have every reason to believe it would be so in the case of the majority of known substances. Another substance of special interest is solid carbonic acid. This body has a density of 1.53 at −78° C. and 1.633 at −185° C., thus giving a mean coefficient of expansion between these temperatures of 0.00057. This value is only about 1⁄6 of the coefficient of expansion of the liquid carbonic acid gas just above its melting point, but it is still much greater at the low temperature than that of highly expansive solids like sulphur, which at 40° C. has a value of 0.00019. The following table gives the densities at the temperature of boiling liquid air (−185° C.) and at ordinary temperatures (17° C.), together with the mean coefficient of expansion between those temperatures, in the case of a number of hydrated salts and other substances:

Table I.

| Density at −185° C. | Density at +17° C. |

Mean coefficient of expansion between −185° C. and +17° C. | |

| Aluminium sulphate (18)* | 1.7194 | 1.6913 | 0.0000811 |

| Sodium biborate (10) | 1.7284 | 1.6937 | 0.0001000 |

| Calcium chloride (6) | 1.7187 | 1.6775 | 0.0001191 |

| Magnesium chloride (6) | 1.6039 | 1.5693 | 0.0001072 |

| Potash alum (24) | 1.6414 | 1.6144 | 0.0000813 |

| Chrome alum (24) | 1.7842 | 1.7669 | 0.0000478 |

| Sodium carbonate (10) | 1.4926 | 1.4460 | 0.0001563 |

| Sodium phosphate (12) | 1.5446 | 1.5200 | 0.0000787 |

| Sodium thiosulphate (5) | 1.7635 | 1.7290 | 0.0000969 |

| Potassium ferrocyanide (3) | 1.8988 | 1.8533 | 0.0001195 |

| Potassium ferricyanide | 1.8944 | 1.8109 | 0.0002244 |

| Sodium nitro-prusside (4) | 1.7196 | 1.6803 | 0.0001138 |

| Ammonium chloride | 1.5757 | 1.5188 | 0.0001820 |

| Oxalic acid (2) | 1.7024 | 1.6145 | 0.0002643 |

| Methyl oxalate | 1.5278 | 1.4260 | 0.0003482 |

| Paraffin | 0.9770 | 0.9103 | 0.0003567 |

| Naphthalene | 1.2355 | 1.1589 | 0.0003200 |

| Chloral hydrate | 1.9744 | 1.9151 | 0.0001482 |

| Urea | 1.3617 | 1.3190 | 0.0001579 |

| Iodoform | 4.4459 | 4.1955 | 0.0002930 |

| Iodine | 4.8943 | 4.6631 | 0.0002510 |

| Sulphur | 2.0989 | 2.0522 | 0.0001152 |

| Mercury | 14.382 | .. | 0.0000881** |

| Sodium | 1.0056 | 0.972 | 0.0001810 |

| Graphite (Cumberland) | 2.1302 | 2.0990 | 0.0000733 |

| * The figures within parentheses refer to the number of molecules of water of crystallization. | |||

| ** −189° to −38.85° C. | |||

It will be seen from this table that, with the exception of carbonate of soda and chrome alum, the hydrated salts have a coefficient of expansion that does not differ greatly from that of ice at low temperatures. Iodoform is a highly expansive body like iodine, and oxalate of methyl has nearly as great a coefficient as paraffin, which is a very expansive solid, as are naphthalene and oxalic acid. The coefficient of solid mercury is about half that of the liquid metal, while that of sodium is about the value of mercury at ordinary temperatures. Further details on the subject can be found in the Proc. Roy. Inst. (1895), and Proc. Roy. Soc. (1902).

Density of Gases at Low Temperatures.—The ordinary mode of determining the density of gases may be followed, provided that the glass flask, with its carefully ground stop-cock sealed on, can stand an internal pressure of about five atmospheres, and that all the necessary corrections for change of volume are made. All that is necessary is to immerse the exhausted flask in boiling oxygen, and then to allow the second gas to enter from a gasometer by opening the stop-cock until the pressure is equalized. The stop-cock being closed, the flask is now taken out of the liquid oxygen and left in the balance-room until its temperature is equalized. It is then weighed against a similar flask used as a counterpoise. Following such a method, it has been found that the weight of 1 litre of oxygen vapour at its boiling point of 90.5° absolute is 4.420 grammes, and therefore the specific volume is 226.25 cc. According to the ordinary gaseous laws, the litre ought to weigh 4.313 grammes, and the specific volume should be 231.82 cc. In other words, the product of pressure and volume at the boiling point is diminished by 2.46%. In a similar way the weight of a litre of nitrogen vapour at the boiling point of oxygen was found to be 3.90, and the inferred value for 78° absolute, or its own boiling point, would be 4.51, giving a specific volume of 221.3.

|

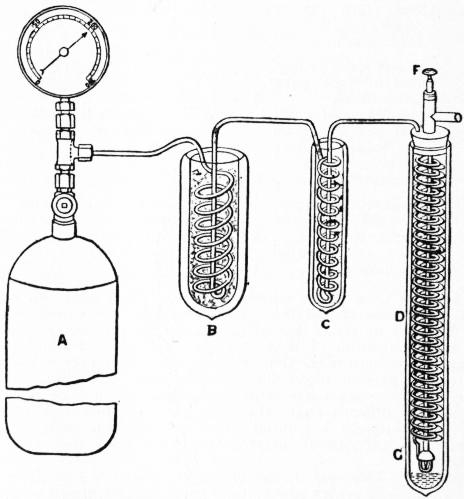

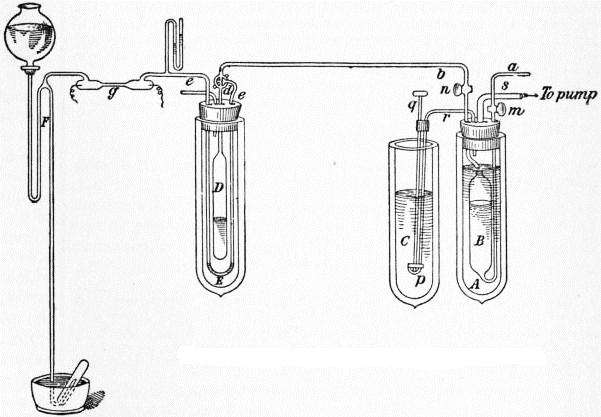

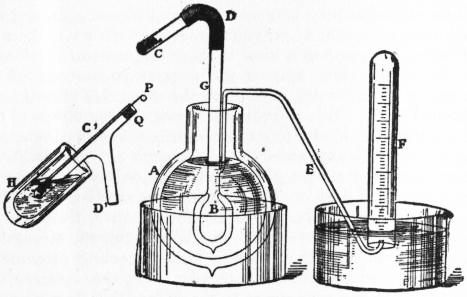

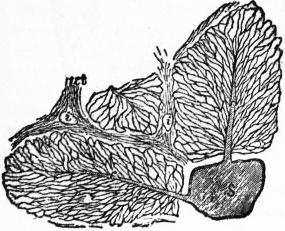

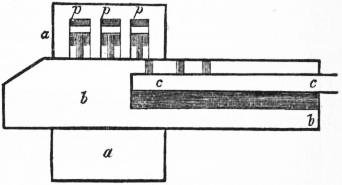

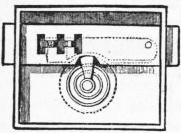

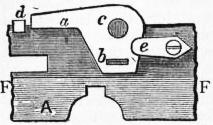

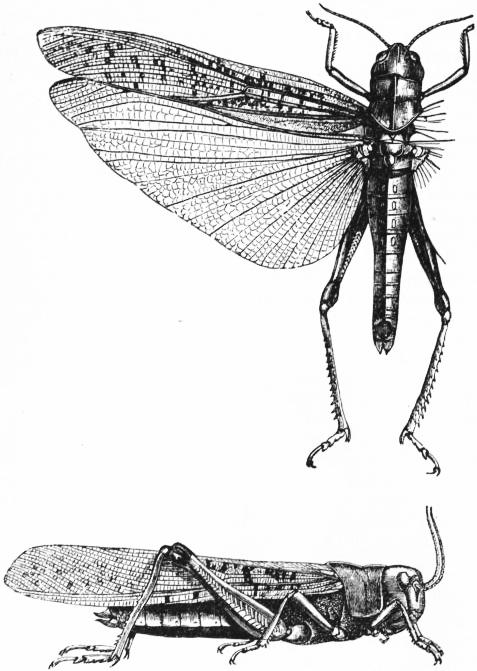

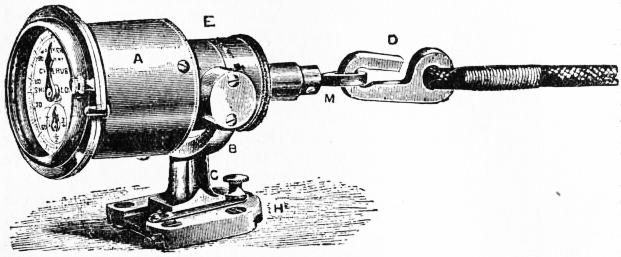

| Fig. 2.—Laboratory Liquid Air Machine. |

A, Air or oxygen inlet. B, Carbon dioxide inlet. C, Carbon dioxide valve. D, Regenerator coils. F, Air or oxygen expansion valve. G, Vacuum vessel with liquid air or oxygen. H, Carbon dioxide and air outlet. O, Air coil. O, Carbon dioxide coil. |

Regenerative Cooling.—One part of the problem being thus solved and a satisfactory device discovered for warding off heat in such vacuum vessels, it remained to arrange some practically efficient method for reducing hydrogen to a temperature sufficiently low for liquefaction. To gain that end, the idea naturally occurred of using adiabatic expansion, not intermittently, as when gas is allowed to expand suddenly from a high compression, but in a continuous process, and an obvious way of attempting to carry out this condition was to enclose the orifice at which expansion takes place in a tube, so as to obtain a constant stream of cooled gas passing over it. But further consideration of this plan showed that although the gas jet would be cooled near the point of expansion owing to the conversion of a portion of its sensible heat into dynamical energy of the moving gas, yet the heat it thus lost would be restored to it almost 748 immediately by the destruction of this mechanical energy through friction and its consequent reconversion into heat. Thus the net result would be nil so far as change of temperature through the performance of external work was concerned. But the conditions in such an arrangement resemble that in the experiments of Thomson and Joule on the thermal changes which occur in a gas when it is forced under pressure through a porous plug or narrow orifice, and those experimenters found, as the former of them had predicted, that a change of temperature does take place, owing to internal work being done by the attraction of the gas molecules. Hence the effective result obtainable in practice by such an attempt at continuous adiabatic expansion as that suggested above is to be measured by the amount of the “Thomson-Joule effect,” which depends entirely on the internal, not the external, work done by the gas. To Linde belongs the credit of having first seen the essential importance of this effect in connexion with the liquefaction of gases by adiabatic expansion, and he was, further, the first to construct an industrial plant for the production of liquid air based on the application of this principle.

The change of temperature due to the Thomson-Joule effect varies in amount with different gases, or rather with the temperature at which the operation is conducted. At ordinary temperatures oxygen and carbonic acid are cooled, while hydrogen is slightly heated. But hydrogen also is cooled if before being passed through the nozzle or plug it is brought into a thermal condition comparable to that of other gases at ordinary temperatures—that is to say, when it is initially cooled to a temperature having the same ratio to its critical point as their temperatures have to their critical points—and similarly the more condensible gases would be heated, and not cooled, by passing through a nozzle or plug if they were employed at a temperature sufficiently above their critical points. Each gas has therefore a point of inversion of the Thomson-Joule effect, and this temperature is, according to the theory of van der Waals, about 6.75 times the critical temperature of the body. Olszewski has determined the inversion-point in the case of hydrogen, and finds it to be 192.5° absolute, the theoretical critical point being thus about 28.5° absolute. The cooling effect obtained is small, being for air about ¼° C. per atmosphere difference of pressure at ordinary temperatures. But the decrement of temperature is proportional to the difference of pressure and inversely as the absolute temperature, so that the Thomson-Joule effect increases rapidly by the combined use of a lower temperature and greater difference of gas pressure. By means of the “regenerative” method of working, which was described by C. W. Siemens in 1857, developed and extended by Ernest Solvay in 1885, and subsequently utilized by numerous experimenters in the construction of low temperature apparatus, a practicable liquid air plant was constructed by Linde. The gas which has passed the orifice and is therefore cooled is made to flow backwards round the tube that leads to the nozzle; hence that portion of the gas that is just about to pass through the nozzle has some of its heat abstracted, and in consequence on expansion is cooled to a lower temperature than the first portion. In its turn it cools a third portion in the same way, and so the reduction of temperature goes on progressively until ultimately a portion of the gas is liquefied. Apparatus based on this principle has been employed not only by Linde in Germany, but also by Tripler in America and by Hampson and Dewar in England. The last-named experimenter exhibited in December 1895 a laboratory machine of this kind (fig. 2), which when supplied with oxygen initially cooled to −79° C., and at a pressure of 100-150 atmospheres, began to yield liquid in about a quarter of an hour after starting. The initial cooling is not necessary, but it has the advantage of reducing the time required for the operation. The efficiency of the Linde process is small, but it is easily conducted and only requires plenty of cheap power. When we can work turbines or other engines at low temperatures, so as to effect cooling through the performance of external work, then the economy in the production of liquid air and hydrogen will be greatly increased.

|

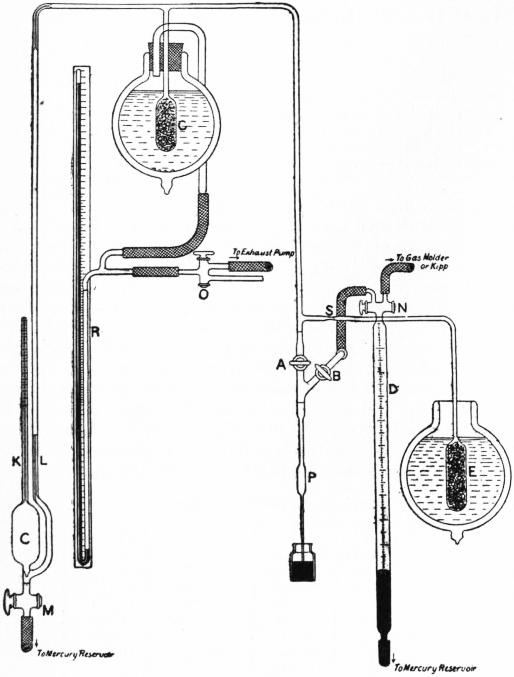

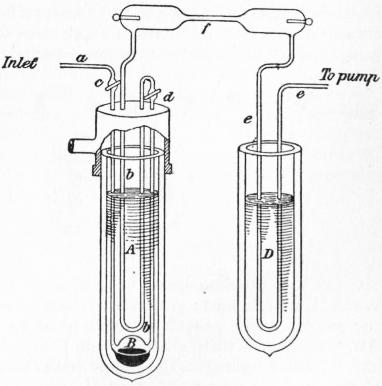

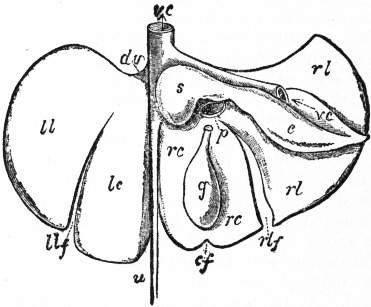

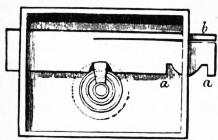

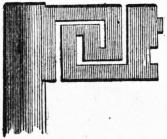

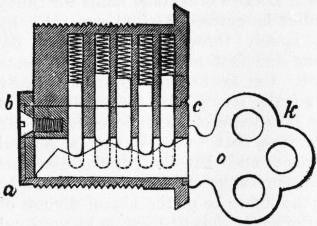

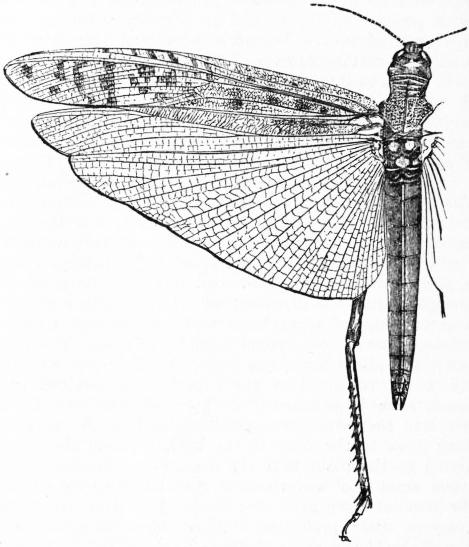

| Fig. 3.—Hydrogen Jet Apparatus. A, Cylinder containing compressed hydrogen. B and C, Vacuum vessels containing carbonic acid under exhaustion and liquid air respectively. D, Regenerating coil in vacuum vessel. F, Valve. G, Pin-hole nozzle. |

|

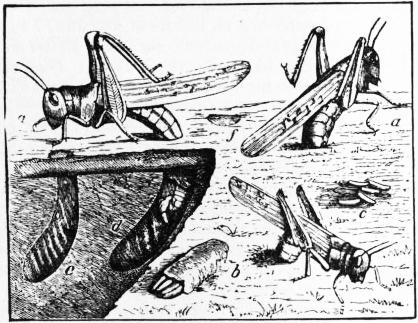

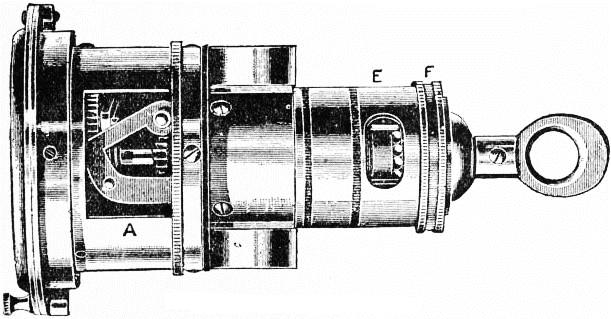

| Fig. 4.—Bottom of Vacuum Vessel. |

This treatment was next extended to hydrogen. For the reason already explained, it would have been futile to experiment with this substance at ordinary temperatures, and therefore as a preliminary it was cooled to the temperature of boiling liquid air, about −190° C. At this temperature it is still 2½ times above its critical temperature, and therefore its liquefaction in these circumstances would be comparable to that of air, taken at +60° C., in an apparatus like that just described. Dewar showed in 1896 that hydrogen cooled in this way and expanded in a regenerative coil from a pressure of 200 atmospheres was rapidly reduced in temperature to such an extent that after the apparatus had been working a few minutes the issuing jet was seen to contain liquid, which was sufficiently proved to be liquid hydrogen by the fact that it was so cold as to freeze liquid air and oxygen into hard white solids. Though with this apparatus, a diagrammatic representation of which is shown in fig. 3, it was now found possible at the time to collect the 749 liquid in an open vessel, owing to its low specific gravity and the rapidity of the gas-current, still the general type of the arrangement seemed so promising that in the next two years there was laid down in the laboratories of the Royal Institution a large plant—it weighs 2 tons and contains 3000 ft. of pipe—which is designed on precisely the same principles, although its construction is far more elaborate. The one important novelty, without which it is practically impossible to succeed, is the provision of a device to surmount the difficulty of withdrawing the liquefied hydrogen after it has been made. The desideratum is really a means of forming an aperture in the bottom of a vacuum vessel by which the contained liquid may be run out. For this purpose the lower part of the vacuum vessel (D in fig. 3) containing the jet is modified as shown in fig. 4; the inner vessel is prolonged in a fine tube, coiled spirally, which passes through the outer wall of the vacuum vessel, and thus sufficient elasticity is obtained to enable the tube to withstand without fracture the great contraction consequent on the extreme cold to which it is subjected. Such peculiarly shaped vacuum vessels were made by Dewar’s directions in Germany, and have subsequently been supplied to and employed by other experimenters.

With the liquefying plant above referred to liquid hydrogen was for the first time collected in an open vessel on the 10th of May 1898. The gas at a pressure of 180 atmospheres was cooled to −205° C. by means of liquid air boiling in vacuo, and was then passed through the nozzle of the regenerative coil, which was enclosed in vacuum vessels in such a way as to exclude external heat as perfectly as possible. In this way some 20 cc. of the liquid had been collected when the experiment came to a premature end, owing to the nozzle of the apparatus becoming blocked by a dense solid—air-ice resulting from the congelation of the air which was present to a minute extent as an impurity in the hydrogen. This accident exemplifies what is a serious trouble encountered in the production of liquid hydrogen, the extreme difficulty of obtaining the gas in a state of sufficient purity, for the presence of 1% of foreign matters, such as air or oxygen, which are more condensible than hydrogen, is sufficient to cause complete stoppage, unless the nozzle valve and jet arrangement is of special construction. In subsequent experiments the liquid was obtained in larger quantities—on the 13th of June 1901 five litres of it were successfully conveyed through the streets of London from the laboratory of the Royal Institution to the rooms of the Royal Society—and it may be said that it is now possible to produce it in any desired amount, subject only to the limitations entailed by expense. Finally, the reduction of hydrogen to a solid state was successfully undertaken in 1899. A portion of the liquid carefully isolated in vacuum-jacketed vessels was suddenly transformed into a white mass resembling frozen foam, when evaporated under an air-pump at a pressure of 30 or 40 mm., and subsequently hydrogen was obtained as a clear transparent ice by immersing a tube containing the liquid in this solid foam.

Liquefaction of Helium.—The subjection of hydrogen completed the experimental proof that all gases can be reduced to the liquid and solid states by the aid of pressure and low temperature, at least so far as regards those in the hands of the chemist at the beginning of the last decade of the 19th century. But a year or so before hydrogen was obtained in the liquid form, a substance known to exist in the sun from spectroscopic researches carried out by Sir Edward Frankland and Sir J. Norman Lockyer was shown by Sir William Ramsay to exist on the earth in small quantities. Helium (q.v.), as this substance was named, was found by experiment to be a gas much less condensable than hydrogen. Dewar in 1901 expanded it from a pressure of 80-100 atmospheres at the temperature of solid hydrogen without perceiving the least indication of liquefaction. Olszewski repeated the experiment in 1905, using the still higher initial compression of 180 atmospheres, but he equally failed to find any evidence of liquefaction, and in consequence was inclined to doubt whether the gas was liquefiable at all, whether in fact it was not a truly “permanent” gas. Other investigators, however, took a different and more hopeful view of the matter. Dewar, for instance (Pres. Address Brit. Assoc., 1902), basing his deductions on the laws established by van der Waals and others from the study of phenomena at much higher temperatures, anticipated that the boiling-point of the substance would be about 5° absolute, so that the liquid would be about four times more volatile than liquid hydrogen, just as liquid hydrogen is four times more volatile than liquid air; and he expressed the opinion that the gas would succumb on being subjected to the process that had succeeded with hydrogen, except that liquid hydrogen, instead of liquid air, evaporating under exhaustion must be employed as the primary cooling agent, and must also be used to surround the vacuum vessel in which the liquid was collected.

Various circumstances combined to prevent Dewar from actually carrying out the operation thus foreshadowed, but his anticipations were justified and the sufficiency of the method he indicated practically proved by Dr H. Kamerlingh Onnes, who, working with the splendid resources of the Leiden cryogenic laboratory, succeeded in obtaining helium in the liquid state on the 10th of July 1908. Having prepared 200 litres of the gas (160 litres in reserve) from monazite sand,2 he cooled it with exhausted liquid hydrogen to a temperature of 15 or 16° abs., and expanded it through a regenerative coil under a pressure of 50 to 100 atmospheres, making use of the most elaborate precautions to prevent influx of heat and securing the absence of less volatile gases that might freeze and block the tubes of the apparatus by including in the helium circuit charcoal cooled to the temperature of liquid air. Operations began at 5.45 in the morning with the preparation of the necessary liquid hydrogen, of which 20 litres were ready by 1.30. The circulation of the helium was started at 4.30 in the afternoon and was continued until the gas had been pumped round the circuit twenty times; but it was not till 7.30, when the last bottle of liquid hydrogen had been brought into requisition, that the surface of the liquid was seen, by reflection of light from below, standing out sharply like the edge of a knife against the glass wall of the vacuum vessel. Its boiling-point has been determined as being 4° abs., its critical temperature 5°, and its critical pressure not more than three atmospheres. The density of the liquid is found to be 0.015 or about twice that of liquid hydrogen. It could not be solidified even when exhausted under a pressure of 2 mm., which in all probability corresponds to a temperature of 2° abs. (see Communications from the physical laboratory at the University of Leiden, 1908-1909).

The following are brief details respecting some of the more important liquid gases that have become available for study within recent years. (For argon, neon, krypton, &c., see Argon.)

Oxygen.—Liquid oxygen is a mobile transparent-liquid, possessing a faint blue colour. At atmospheric pressure it boils at −181.5° C.; under a reduced pressure of 1 cm. of mercury its temperature falls to −210° C. At the boiling point it has a density of 1.124 according to Olszewski, or of 1.168 according to Wroblewski; Dewar obtained the value 1.1375 as the mean of twenty observations by weighing a number of solid substances in liquid oxygen, noting the apparent relative density of the liquid, and thence calculating its real density, Fizeau’s values for the coefficients of expansion of the solids being employed. The capillarity of liquid oxygen is about one-sixth that of water; it is a non-conductor of electricity, and is strongly magnetic. By its own evaporation it cannot be reduced to the solid state, but exposed to the temperature of liquid hydrogen it is frozen 750 into a solid mass, having a pale bluish tint, showing by reflection all the absorption bands of the liquid. It is remarkable that the same absorption bands occur in the compressed gas. Dewar gives the melting-point as 38° absolute, and the density at the boiling-point of hydrogen as 1.4526. The refractive index of the liquid for the D sodium ray is 1.2236.

Ozone.—This gas is easily liquefied by the use of liquid air. The liquid obtained is intensely blue, and on allowing the temperature to rise, boils and explodes about −120° C. About this temperature it may be dissolved in bisulphide of carbon to a faint blue solution. The liquid ozone seems to be more magnetic than liquid oxygen.

Nitrogen forms a transparent colourless liquid, having a density of 0.8042 at its boiling-point, which is −195.5° C. The refractive index for the D line is 1.2053. Evaporated under diminished pressure the liquid becomes solid at a temperature of −215° C., melting under a pressure of 90 mm. The density of the solid at the boiling-point of hydrogen is 1.0265.

Air.—Seeing that the boiling-points of nitrogen and oxygen are different, it might be expected that on the liquefaction of atmospheric air the two elements would appear as two separate liquids. Such, however, is not the case; they come down simultaneously as one homogeneous liquid. Prepared on a large scale, liquid air may contain as much as 50% of oxygen when collected in open vacuum-vessels, but since nitrogen is the more volatile it boils off first, and as the liquid gradually becomes richer in oxygen the temperature at which it boils rises from about −192° C. to about −182° C. At the former temperature it has a density of about 0.910. It is a non-conductor of electricity. Properly protected from external heat, and subjected to high exhaustion, liquid air becomes a stiff transparent jelly-like mass, a magma of solid nitrogen containing liquid oxygen, which may indeed be extracted from it by means of a magnet, or by rapid rotation of the vacuum vessel in imitation of a centrifugal machine. The temperature of this solid under a vacuum of about 14 mm. is −216°. At the still lower temperatures attainable by the aid of liquid hydrogen it becomes a white solid, having, like solid oxygen, a faint blue tint. The refractive index of liquid air is 1.2068.

Fluorine, prepared in the free state by Moissan’s method of electrolysing a solution of potassium fluoride in anhydrous hydrofluoric acid, was liquefied in the laboratories of the Royal Institution, London, in 1897. Exposed to the temperature of quietly-boiling liquid oxygen, the gas did not change its state, though it lost much of its chemical activity, and ceased to attack glass. But a very small vacuum formed over the oxygen was sufficient to determine liquefaction, a result which was also obtained by cooling the gas to the temperature of freshly-made liquid air boiling at atmospheric pressure. Hence the boiling-point is fixed at about −187° C. The liquid is of a clear yellow colour, possessing great mobility. Its density is 1.14, and its capillarity rather less than that of liquid oxygen. The liquid, when examined in a thickness of 1 cm., does not show any absorption bands, and it is not attracted by a magnet. Cooled in liquid hydrogen it is frozen to a white solid, melting at about 40° abs.

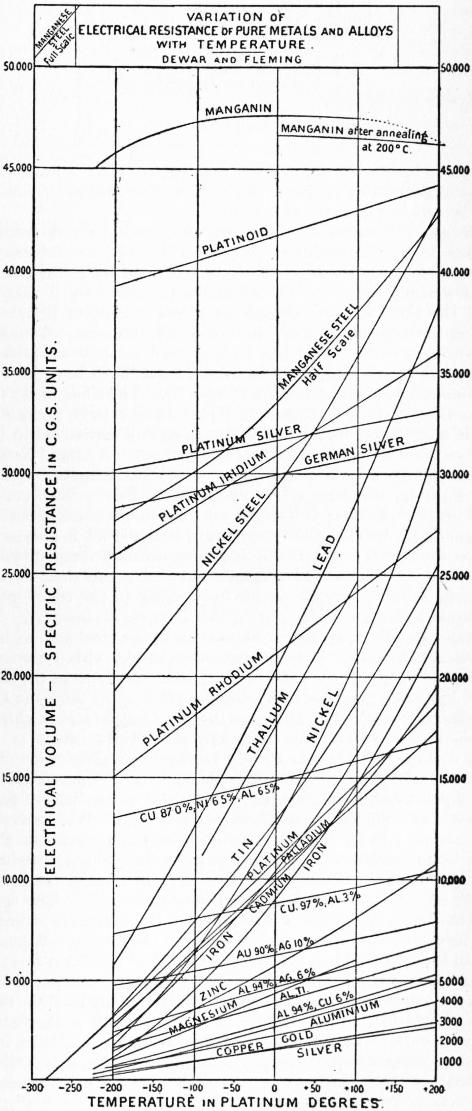

Hydrogen.—Liquid hydrogen is the lightest liquid known to the chemist, having a density slightly less than 0.07 as compared with water, and being six times lighter than liquid marsh-gas, which is next in order of lightness. One litre weighs only 70 grammes, and 1 gramme occupies a volume of 14-15 cc. In spite of its extreme lightness, however, it is easily seen, has a well-defined meniscus and drops well. At its boiling-point the liquid is only 55 times denser than the vapour it is giving off, whereas liquid oxygen in similar condition is 258 times denser than its vapour, and nitrogen 177 times. Its atomic volume is about 14.3, that of liquid oxygen being 13.7, and that of liquid nitrogen 16.6, at their respective boiling-points. Its latent heat of vaporization about the boiling-point is about 121 gramme-calories, and the latent heat of fluidity cannot exceed 16 units, but may be less. Hydrogen appears to have the same specific heat in the liquid as in the gaseous state, about 3.4. Its surface tension is exceedingly low, about one-fifth that of liquid air at its boiling-point, or one-thirty-fifth that of water at ordinary temperatures, and this is the reason that bubbles formed in the liquid are so small as to give it an opalescent appearance during ebullition. The liquid is without colour, and gives no absorption spectrum. Electric sparks taken in the liquid between platinum poles give a spectrum showing the hydrogen lines C and F bright on a background of continuous spectrum. Its refractive index at the boiling-point has theoretically the value 1.11. It was measured by determining the relative difference of focus for a parallel beam of light sent through a spherical vacuum vessel filled successively with water, liquid oxygen and liquid hydrogen; the result obtained was 1.12. Liquid hydrogen is a non-conductor of electricity. The precise determination of its boiling-point is a matter of some difficulty. The first results obtained from the use of a platinum resistance thermometer gave −238° C., while a similar thermometer made with an alloy of rhodium-platinum indicated a value 8 degrees lower. Later, a gold thermometer indicated about −249° C., while with an iron one the result was only −210° C. It was thus evident that electrical resistance thermometers are not to be trusted at these low temperatures, since the laws correlating resistance and temperature are not known for temperatures at and below the boiling-point of hydrogen, though they are certainly not the same as those which hold good higher up the thermometric scale. The same remarks apply to the use of thermo-electric junctions at such exceptional temperatures. Recourse was therefore had to a constant-volume hydrogen thermometer, working under reduced pressure, experiments having shown that such a thermometer, filled with either a simple or a compound gas (e.g. oxygen or carbonic acid) at an initial pressure somewhat less than one atmosphere, may be relied upon to determine temperatures down to the respective boiling-points of the gases with which they are filled. The result obtained was −252° C. Subsequently various other determinations were carried out in thermometers filled with hydrogen derived from different sources, and also with helium, the average value given by the experiments being −252.5° C. (See “The Boiling Point of Liquid Hydrogen determined by Hydrogen and Helium Gas Thermometers,” Proc. Roy. Soc., 7th February 1901.) The critical temperature is about 30° absolute (−243° C.), and the critical pressure about 15 atmospheres. Hydrogen has not only the lowest critical temperature of all the old permanent gases, but it has the lowest critical pressure. Given a sufficiently low temperature, therefore, it is the easiest gas to liquefy so far as pressure is concerned. Solid hydrogen has a temperature about 4° less. By exhaustion under reduced pressure a still lower depth of cold may be attained, and a steady temperature reached less than 16° above the zero of absolute temperature. By the use of high exhaustion, and the most stringent precautions to prevent the influx of heat, a temperature of 13° absolute (−260° C.) may be reached. This is the lowest steady temperature which can be maintained by the evaporation of solid hydrogen. At this temperature the solid has a density of about 0.077. Solid hydrogen presents no metallic characteristics, such as were predicted for it by Faraday, Dumas, Graham and other chemists and neither it nor the liquid is magnetic.

The Approach to the Absolute Zero.—The achievement of Kamerlingh Onnes has brought about the realization of a temperature removed only 3° from the absolute zero, and the question naturally suggests itself whether there is any probability of a still closer approach to that point. The answer is that if, as is not impossible, there exists a gas, as yet unisolated, which has an atomic weight one-half that of helium, that gas, liquefied in turn by the aid of liquid helium, would render that approach possible, though the experimental difficulties of the operation would be enormous and perhaps prohibitive. The results of experiments bearing on this question and of theory based on them are shown in table II. The third column shows the critical temperature of the gas which can be liquefied by continuous expansion through a regenerative cooling apparatus, the operation being started from the initial temperature shown in the second column, while the fourth column gives the temperature of the resulting liquid. It will be seen that by the use of liquid or solid hydrogen as a cooling agent, it should be possible to liquefy a body having a critical temperature of about 6° to 8° on the absolute scale, and a boiling point of about 4° or 5°, while with the aid of liquid helium at an initial temperature of 5° we could liquefy a body having a critical temperature of 2° and a boiling point of 1°.

Table II.

| Substance. | Initial Temperature. Abs. Degrees. | Critical Temperature. Abs. Degrees. | Boiling Points. Abs. Degrees. |

| (Low red heat) | 760 | 304 | 195 (CO2) |

| (52° C.) | 325 | 130 | 86 (Air) |

| Liquid air under exhaustion | 75 | 30 | 20 (H) |

| Liquid hydrogen | 20 | 8 | 5 (He) |

| Solid hydrogen | 15 | 6 | 4 |

| Liquid helium | 5 | 2 | 1 |

It is to be remarked, however, that even so the physicist would not have attained the absolute zero, and he can scarcely hope ever to do so. It is true he would only be a very short distance from it, but it must be remembered that in a thermodynamic sense one degree low down the scale, say at 10° absolute, is equivalent to 30° at the ordinary temperature, and as the experimenter gets to lower and lower temperatures, the difficulties of further advance increase, not in arithmetical but in geometrical progression. Thus the step between the liquefaction of air and that of hydrogen is, thermodynamically and practically, greater than that between the liquefaction of chlorine and that of air, but the number of degrees of temperature that separates 751 the boiling-points of the first pair of substances is less than half what it is in the case of the second pair. But the ratio of the absolute boiling-points in the first pair of substances is as 1 to 4, whereas in the second pair it is only 1 to 3, and it is this value that expresses the difficulty of the transition.

But though Ultima Thule may continue to mock the physicist’s efforts, he will long find ample scope for his energies in the investigation of the properties of matter at the temperatures placed at his command by liquid air and liquid and solid hydrogen. Indeed, great as is the sentimental interest attached to the liquefaction of these refractory gases, the importance of the achievement lies rather in the fact that it opens out new fields of research and enormously widens the horizon of physical science, enabling the natural philosopher to study the properties and behaviour of matter under entirely novel conditions. We propose to indicate briefly the general directions in which such inquiries have so far been carried on, but before doing so will call attention to the power of absorbing gases possessed by cooled charcoal, which has on that account proved itself a most valuable agent in low temperature research.

Table III.—Gas Absorption by Charcoal.

| Volume absorbed at 0° Cent. | Volume absorbed at −185° Cent. | |

| Helium | 2 cc. | 15 cc. |

| Hydrogen | 4 | 135 |

| Electrolytic gas | 12 | 150 |

| Argon | 12 | 175 |

| Nitrogen | 15 | 155 |

| Oxygen | 18 | 230 |

| Carbonic oxide | 21 | 190 |

| Carbonic oxide and oxygen | 30 | 195 |

Gas Absorption by Charcoal.—Felix Fontana was apparently the first to discover that hot charcoal has the power of absorbing gases, and his observations were confirmed about 1770 by Joseph Priestley, to whom he had communicated them. A generation later Theodore de Saussure made a number of experiments on the subject, and noted that at ordinary temperatures the absorption is accompanied with considerable evolution of heat. Among subsequent investigators were Thomas Graham and Stenhouse, Faure and Silberman, and Hunter, the last-named showing that charcoal made from coco-nut exhibits greater absorptive powers than other varieties. In 1874 Tait and Dewar for the first time employed charcoal for the production of high vacua, by using it, heated to a red heat, to absorb the mercury vapour in a tube exhausted by a mercury pump; and thirty years afterwards it occurred to the latter investigator to try how its absorbing powers are affected by cooling it, with the result that he found them to be greatly enhanced. Some of his earlier observations are given in table III., but it must be pointed out that much larger absorptions were obtained subsequently when it was found that the quality of the charcoal was greatly influenced by the mode in which it was prepared, the absorptive power being increased by carbonizing the coco-nut shell slowly at a gradually increasing temperature. The results in the table were all obtained with the same specimen of charcoal, and the volumes of the gases absorbed, both at ordinary and at low temperatures, were measured under standard conditions—at 0° C., and 760 mm. pressure. It appears that at the lower temperature there is a remarkable increase of absorption for every gas, but that the increase is in general smaller as the boiling-points of the various gases are lower. Helium is conspicuous for the fact that it is absorbed to a comparatively slight extent at both the higher and the lower temperature, but in this connexion it must be remembered that, being the most volatile gas known, it is being treated at a temperature which is relatively much higher than the other gases. At −185° (= 88° abs.), while hydrogen is at about 4½ times its boiling-point (20° abs.), helium is at about 20 times its boiling-point (4.5° abs.), and it might, therefore, be expected that if it were taken at a temperature corresponding to that of the hydrogen, i.e. at 4 or 5 times its boiling-point, or say 20° abs., it would undergo much greater absorption. This expectation is borne out by the results shown in table IV., and it may be inferred that charcoal cooled in liquid helium would absorb helium as freely as charcoal cooled in liquid hydrogen absorbs hydrogen. It is found that a given specimen of charcoal cooled in liquid oxygen, nitrogen and hydrogen absorbs about equal volumes of those three gases (about 260 cc. per gramme); and, as the relation between volume and temperature is nearly lineal at the lowest portions of either the hydrogen or the helium absorption, it is a legitimate inference that at a temperature of 5° to 6° abs. helium would be as freely absorbed by charcoal as hydrogen is at its boiling-point and that the boiling-point of helium lies at about 5° abs.

Table IV.—Gas Absorption by Charcoal at Low Temperatures.

| Temperature. | Helium. Vols. of Carbon. | Hydrogen. Vols. of Carbon. |

| −185° C. (boiling-point of liquid air) | 2½ | 137 |

| −210° C. (liquid air under exhaustion) | 5 | 180 |

| −252° C. (boiling-point of liquid hydrogen) | 160 | 258 |

| −258° C. (solid hydrogen) | 195 | .. |

The rapidity with which air is absorbed by charcoal at −185° C. and under small pressures is illustrated by table V., which shows the reductions of pressure effected in a tube of 2000 cc. capacity by means of 20 grammes of charcoal cooled in liquid air.

Table V.—Velocity of Absorption.

| Time of Exhaustion. | Pressure in mm. | Time of Exhaustion. | Pressure in mm. |

| 0 sec. | 2.190 | 60 sec. | 0.347 |

| 10 ” | 1.271 | 2 min. | 0.153 |

| 20 ” | 0.869 | 5 ” | 0.0274 |

| 30 ” | 0.632 | 10 ” | 0.00205 |

| 40 ” | 0.543 | 19 ” | 0.00025 |

| 50 ” | 0.435 | .. | .. |

Table VI.

| Volume of Gas absorbed. | Occlusion Hydrogen Pressure. | Occlusion Nitrogen Pressure. |

| cc. | mm. | mm. |

| 0 | 0.00003 | 0.00005 |

| 5 | 0.0228 | .. |

| 10 | 0.0455 | .. |

| 15 | 0.0645 | .. |

| 20 | 0.0861 | .. |

| 25 | 0.1105 | .. |

| 30 | 0.1339 | 0.00031 |

| 35 | 0.1623 | .. |

| 40 | 0.1870 | .. |

| 130 | .. | 0.00110 |

| 500 | .. | 0.00314 |

| 1000 | .. | 0.01756 |

| 1500 | .. | 0.02920 |

| 2500 | .. | 0.06172 |

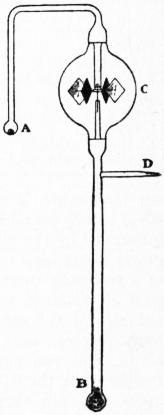

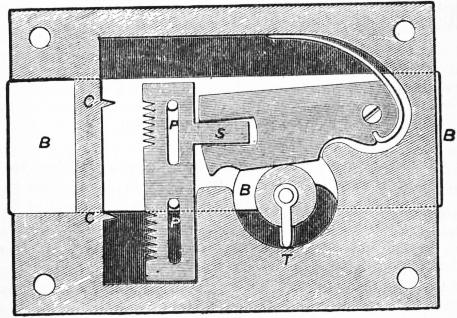

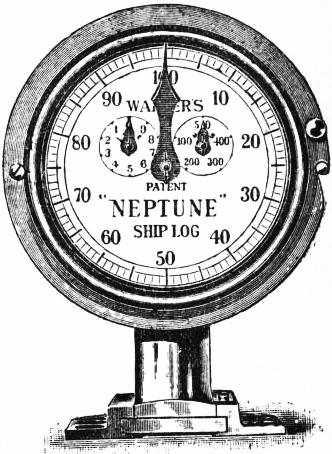

Charcoal Occlusion Pressures.—For measuring the gas concentration, pressure and temperature, use may be made of an apparatus of the type shown in fig. 5. A mass of charcoal, E, immersed in liquid air, is employed for the preliminary exhaustion of the McLeod gauge G and of the charcoal C, which is to be used in the actual experiments, and is then sealed off at S. The bulb C is then placed in a large spherical vacuum vessel containing liquid oxygen which can be made to boil at any definite temperature under diminished pressure which is measured by the manometer R. The volume of gas admitted into the charcoal is determined by the burette D and the pipette P, and the corresponding occlusion pressure at any concentration and any temperature below 90° abs. by the gauge G. In presence of charcoal, and for small concentrations, great variations are shown in the relation between the pressure and the concentration of different gases, all at the same temperature. Table VI. gives the comparison between hydrogen and nitrogen at the temperature of liquid air, 25 grammes of charcoal being employed. It is seen that 15 cc. of hydrogen produce nearly the same pressure (0.0645 mm.) as 2500 cc. of nitrogen (0.06172 mm.). This result shows how 752 enormously greater, at the temperature of liquid air, is the volatility of hydrogen as compared with that of nitrogen. In the same way the concentrations, for the same pressure, vary greatly with temperature, as is exemplified by table VII., even though the pressures are not quite constant. The temperatures employed were the boiling-points of hydrogen, oxygen and carbon dioxide.

|

| Fig. 5. |

Table VII.

| Gas. | Concentration in cc. per grm. of Charcoal. | Pressure in mm. | Temperature Absolute. |

| Helium | 97 | 2.2 | 20° |

| Hydrogen | 397 | 2.2 | 20° |

| Hydrogen | 15 | 2.1 | 90° |

| Nitrogen | 250 | 1.6 | 90° |

| Oxygen | 300 | 1.0 | 90° |

| Carbon dioxide | 90 | 3.6 | 195° |

Table VIII.

| Gas. | Concentration cc. per grm. | Molecular Latent Heat. | Mean Temperature. Absolute. |

| Helium | 97 | 483.0 | 18° |

| Hydrogen | 390 | 524.4 | 18° |

| Hydrogen | 20 | 2005.6 | 78° |

| Nitrogen | 250 | 3059.0 | 82° |

| Oxygen | 300 | 3146.4 | 82° |

| Carbon dioxide | 90 | 6099.6 | 180° |

Heat of Occlusion.—In every case when gases are condensed to the liquid state there is evolution of heat, and during the absorption of a gas in charcoal or any other occluding body, as hydrogen in palladium, the amount of heat evolved exceeds that of direct liquefaction. From the relation between occlusion-pressure and temperature at the same concentration, the reaction being reversible, it is possible to calculate this heat evolution. Table VIII. gives the mean molecular latent heats of occlusion resulting from Dewar’s experiments for a number of gases, having concentrations in the charcoal as shown. The concentrations were so regulated as to start with an initial pressure not exceeding 3 mm. at the respective boiling-points of hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen and carbon dioxide.

|

| Fig. 6. |

Production of High Vacua.—Exceedingly high vacua can be obtained by the aid of liquid gases, with or without charcoal. If a vessel containing liquid hydrogen be freely exposed to the atmosphere, a rain of snow (solid air) at once begins to fall upon the surface of the liquid; similarly, if one end of a sealed tube containing ordinary air be immersed in the liquid, the same thing happens, but since there is now no new supply to take the place of the air that has been solidified and has accumulated in the cooled portion of the tube, the pressure is quickly reduced to something like one-millionth of an atmosphere, and a vacuum is formed of such tenuity that the electric discharge can be made to pass only with difficulty. Liquid air can be employed in the same manner if the tube, before sealing, is filled with some less volatile gas or vapour, such as sulphurous acid, benzol or water vapour. But if a charcoal condenser be used in conjunction with the liquid air it becomes possible to obtain a high vacuum when the tube contains air initially. For instance, in one experiment, with a bulb having a capacity of 300 cc. and filled with air at a pressure of about 1.7 mm. and at a temperature of 15° C., when an attached condenser with 5 grammes of charcoal was cooled in liquid air, the pressure was reduced to 0.0545 mm. of mercury in five minutes, to 0.01032 mm. in ten minutes, to 0.000139 mm. in thirty minutes, and to 0.000047 mm. in sixty minutes. The condenser then being cooled in liquid hydrogen the pressure fell to 0.0000154 mm. in ten minutes, and to 0.0000058 mm. in a further ten minutes when solid hydrogen was employed as the cooling agent, and no doubt, had it not been for the presence of hydrogen and helium in the air, an even greater reduction could have been effected. Another illustration of the power of cooled charcoal to produce high vacua is afforded by a Crookes radiometer. If the instrument be filled with helium at atmospheric pressure and a charcoal bulb attached to it be cooled in liquid air, the vanes remain motionless even when exposed to the concentrated beam of an electric arc lamp; but if liquid hydrogen be substituted for the liquid air rapid rotation at once sets in. When a similar radiometer was filled with hydrogen and the attached charcoal bulb was cooled in liquid air rotation took place, because sufficient of the gas was absorbed to permit motion. But when the charcoal was cooled in liquid hydrogen instead of in liquid air, the absorption increased and consequently the rarefaction became so high that there was no motion when the light from the arc was directed on the vanes. These experiments again permit of an inference as to the boiling-point of helium. A fall of 75% in the temperature of the charcoal bulb, from the boiling-point of air to the boiling-point of hydrogen, reduced the vanes to rest in the case of the radiometer filled with hydrogen; hence it might be inferred that a fall of like amount from the boiling-point of hydrogen would reduce the vanes of the helium radiometer to rest, and consequently that the boiling-point of helium would be about 5° abs.

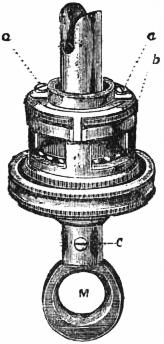

The vacua obtainable by means of cooled charcoal are so high that it is difficult to determine the pressures by the McLeod gauge, and the radiometer experiments referred to above suggested the possibility of another means of ascertaining such pressures, by determining the pressures below which the radiometer would not spin. The following experiment shows how the limit of pressure can be ascertained by reference to the pressures of mercury vapour which have been very accurately determined through a wide range of temperature. To a radiometer (fig. 6) with attached charcoal bulb B was sealed a tube ending in a small bulb A containing a globule of mercury. The radiometer and bulb B were heated, exhausted and repeatedly washed out with pure oxygen gas, and then the mercury was allowed to distil 753 for some time into the charcoal cooled in liquid air. On exposure to the electric beam the vanes began to spin, but soon ceased when the bulb A was cooled in liquid air. When, however, the mercury was warmed by placing the bulb in liquid water, the vanes began to move again, and in the particular radiometer used this was found to happen when the temperature of the mercury had risen to −23° C. corresponding to a pressure of about one fifty-millionth of an atmosphere.

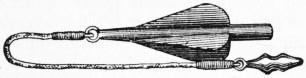

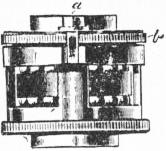

For washing out the radiometer with oxygen the arrangement shown in fig. 7 is convenient. Here A is a bulb containing perchlorate of potash, which when heated gives off pure oxygen; C is again the radiometer and B the charcoal bulb. The side tube E is for the purpose of examining the gas given off by minerals like thorianite or the gaseous products of the transformation of radioactive bodies.

|

| Fig. 7. |

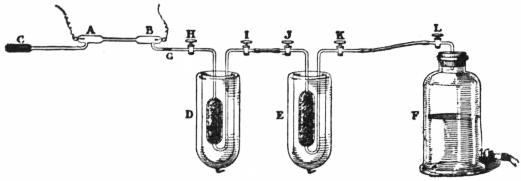

Analytic Uses.—Another important use of liquid gases is as analytic agents, and for this purpose liquid air is becoming an almost essential laboratory reagent. It is one of the most convenient agents for drying gases and for their purification. If a mixture of gases be subjected to the temperature of liquid air, it is obvious that all the constituents that are more condensable than air will be reduced to liquid, while those that are less condensable will either remain as a gaseous residue or be dissolved in the liquid obtained. The bodies present in the latter may be separated by fractional distillation, while the contents of the gaseous residue may be further differentiated by the air of still lower temperatures, such as are obtainable by liquid hydrogen. An apparatus such as the following can be used to separate both the less and the more volatile gases of the atmosphere, the former being obtained from their solution in liquid air by fractional distillation at low pressure and separation of the condensable part of the distillate by cooling in liquid hydrogen, while the latter are extracted from the residue of liquid air, after the distillation of the first fraction, by allowing it to evaporate gradually at a temperature rising only very slowly.

In fig. 8, A represents a vacuum-jacketed vessel, containing liquid air; this can be made to boil at reduced pressure and therefore be lowered in temperature by means of an air-pump, which is in communication with the vessel through the pipe s. The liquid boiled away is replenished when necessary from the reservoir C, p being a valve, worked by handle q, by which the flow along r is regulated. The vessel B, immersed in the liquid air of A, communicates with the atmosphere by a; hence when the temperature of A falls under exhaustion below that of liquid air, the contents of B condense, and if the stop-cock m is kept open, and n shut, air from the outside is continuously sucked in until B is full of liquid, which contains in solution the whole of the most volatile gases of the atmosphere which have passed in through a. At this stage of the operation m is closed and n opened, a passage thus being opened along b from A to the remainder of the apparatus seen on the left side of the figure. Here E is a vacuum vessel containing liquid hydrogen, and d a three-way cock by which communication can be established either between b and D, between b and e, the tube leading to the sparking-tube g, or between D and e. If now d is arranged so that there is a free passage from b to D, and the stop-cock n also opened, the gas dissolved in the liquid in B, together with some of the most volatile part of that liquid, quickly distils over into D, which is at a much lower temperature than B, and some of it condenses there in the solid state. When a small fraction of the contents of B has thus distilled over, d is turned so as to close the passage between D and b and open that between D and e, with the result that the gas in D is pumped out by the mercury-pump, shown diagrammatically at F, along the tube e (which is immersed in the liquid hydrogen in order that any more condensable gas carried along by the current may be frozen out) to the sparking-tube or tubes g, where it can be examined spectroscopically. When the apparatus is used to separate the least volatile part of the gases in the atmosphere, the vessel E and its contents are omitted, and the tube b made to communicate with the pump through a number of sparking-tubes which can be sealed off successively. The nitrogen and oxygen which make up the bulk of the liquid in B are allowed to evaporate gradually, the temperature being kept low so as to check the evaporation of gases less volatile than oxygen. When most of the oxygen and nitrogen have thus been removed, the stop-cock n is closed, and the tubes partially exhausted by the pump; spectroscopic examination is made of the gases they contain, and repeated from time to time as more gas is allowed to evaporate from B. The general sequence of spectra, apart from those of nitrogen, oxygen and carbon compounds, which are never eliminated by the process of distillation alone, is as follows: The spectrum of argon first appears, followed by the brightest (green and yellow) rays of krypton. Then the intensity of the argon spectrum wanes and it gives way to that of krypton, until, as Runge observed, when a Leyden jar is in the circuit, the capillary part of the sparking-tube has a magnificent blue colour, while the wide ends are bright pale yellow. Without a jar the tube is nearly white in the middle and yellow about the poles. As distillation proceeds, the temperature of the vessel containing the residue of liquid air being allowed to rise slowly, the brightest (green) rays of xenon begin to appear, and the krypton rays soon die out, being superseded by those of xenon. At this stage the capillary part of the sparking-tube is, with a jar in circuit, a brilliant green, and it remains green, though less brilliant, if the jar is removed.

|

| Fig. 8.—Apparatus for Fractional Distillation. |

|

| Fig. 9.—Apparatus for continuous Spectroscopic Examination. |

An improved form of apparatus for the fractionation is represented in fig. 9. The gases to be separated, that is, the least volatile part of atmospheric air, enter the bulb B from a gasholder by the tube a with stop-cock c. B, which is maintained at a low temperature by being immersed in liquid hydrogen, A, boiling under reduced pressure, in turn communicates through the tube b and stop-cock d with a sparking-tube or tubes f, and so on through e with a mercurial pump. To 754 use the apparatus, stop-cock d is closed and c opened, and gas allowed to pass from the gasholder into B, where it is condensed in the solid form. Stop-cock c then being closed and d opened, gas passes into the exhausted tube f, where it is examined with the spectroscope. The vessel D contains liquid air, in which the tube e is immersed in order to condense vapour of mercury which would otherwise pass from the pump into the sparking-tube. The success of the operation of separating all the gases which occur in air and which boil at different temperatures, depends on keeping the temperature of B as low as possible, as will be understood from the following consideration:—

The pressure p, of a gas G, above the same material in the liquid state, at temperature T, is given approximately by the formula

| log p = A − | B | , |

| T |

where A and B are constants for the same material. For some other gas G′ the formula will be

| log p1 = A1 − | B1 | , |

| T |

and

| log | p | = A − A1 + | B1 − B | , |

| p1 | T |

Now for argon, krypton and xenon respectively the values of A are 6.782, 6.972 and 6.963, and those of B are 339, 496.3 and 669.2; so that for these substances and many others A − A1 is always a small quantity, while (B1 − B)/T is considerable and increases as T diminishes. Hence the ratio of p to p1 increases rapidly as T diminishes, and by evaporating all the gases from the solid state, and keeping the solid at as low a temperature as possible, the gas that is taken off by the mercurial pump first consists mainly of the substance which has the lowest boiling point, in this case nitrogen, and is succeeded with comparative abruptness by the gas which has the next higher boiling point. Examination of the spectrum in the sparking-tube easily reveals the change from one gas to another, and when that is observed the reservoirs into which the gases are pumped can be changed and the fractions stored separately. Or several sparking-tubes may be arranged so as to form parallel communications between b and e, and can be successively sealed off at the desired stages of fractionation.

|

| Fig. 10. |

Analytical operations can often be performed still more conveniently with the help of charcoal, taking advantage of the selective character of its absorption, the general law of which is that the more volatile the gas the less is it absorbed at a given temperature. The following are some examples of its employment for this purpose. If it be required to separate the helium which is often found in the gases given off by a thermal spring, they are subjected to the action of charcoal cooled with liquid air. The result is the absorption of the less volatile constituents, i.e. all except hydrogen and helium. The gaseous residue, with the addition of oxygen, is then sparked, and the water thus formed is removed together with the excess of oxygen, when helium alone remains. Or the separation may be effected by a method of fractionation as described above. To separate the most volatile constituents of the atmosphere an apparatus such as that shown in fig. 10 may be employed. In one experiment with this, when 200 c.c. was supplied from the graduated gas-holder F to the vessel D, containing 15 grammes of charcoal cooled in liquid air, the residue which passed on unabsorbed to the sparking-tube AB, which had a small charcoal bulb C attached, showed the C and F lines of hydrogen, the yellow and some of the orange lines of neon and the yellow and green of helium. By using a second charcoal vessel E, with stop-cocks at H, I, J, K and L to facilitate manipulation, considerable quantities of the most volatile gases can be collected. After the charcoal in E has been saturated, the stop-cock K is closed and I and J are opened for a short time, to allow the less condensable gas in E to be sucked into the second condenser D along with some portion of air. The condenser E is then taken out of the liquid air, heated quickly to 15° C. to expel the occluded air and replaced. More air is then passed in, and by repeating the operation several times 50 litres of air can be treated in a short time, supplying sparking-tubes which will show the complete spectra of the volatile constituents of the air.

The less volatile constituents of the atmosphere, krypton and xenon, may be obtained by leading a current of air, purified by passage through a series of tubes cooled in liquid air, through a charcoal condenser also cooled in liquid air. The condenser is then removed and placed in solid carbon dioxide at −78° C. The gas that comes off is allowed to escape, but what remains in the charcoal is got out by heating and exhaustion, the carbon compounds and oxygen are removed and the residue, consisting of nitrogen with krypton and xenon, is separated into its constituents by condensation and fractionation. Another method is to cover a few hundred grammes of charcoal with old liquid air, which is allowed to evaporate slowly in a silvered vacuum vessel; the gases remaining in the charcoal are then treated in the manner described above.

|

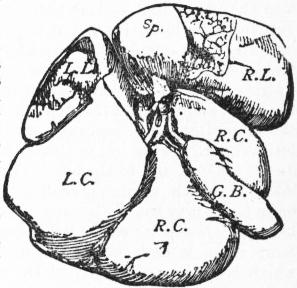

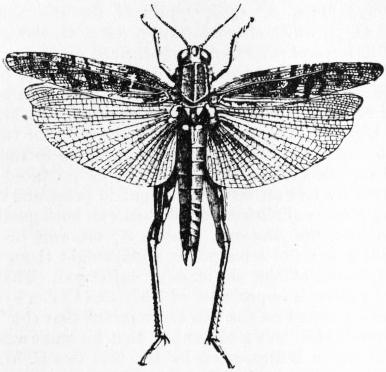

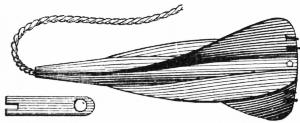

| Fig. 11. Fig. 12. |