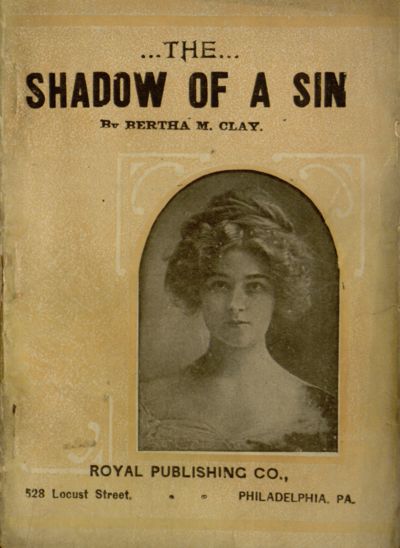

Title: The Shadow of a Sin

Author: Charlotte M. Brame

Release date: March 13, 2013 [eBook #42320]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Demian Katz and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (Images courtesy

of the Digital Library@Villanova University

(http://digital.library.villanova.edu/))

CHAPTER I.

CHAPTER II.

CHAPTER III.

CHAPTER IV.

CHAPTER V.

CHAPTER VI.

CHAPTER VII.

CHAPTER VIII.

CHAPTER IX.

CHAPTER X.

CHAPTER XI.

CHAPTER XII.

CHAPTER XIII.

CHAPTER XIV.

CHAPTER XV.

CHAPTER XVI.

CHAPTER XVII.

CHAPTER XVIII.

CHAPTER XIX.

CHAPTER XX.

CHAPTER XXI.

CHAPTER XXII.

CHAPTER XXIII.

CHAPTER XXIV.

CHAPTER XXV.

CHAPTER XXVI.

CHAPTER XXVII.

CHAPTER XXVIII.

CHAPTER XXIX.

CHAPTER XXX.

CHAPTER XXXI.

CHAPTER XXXII.

CHAPTER XXXIII.

CHAPTER XXXIV.

CHAPTER XXXV.

CHAPTER XXXVI.

CHAPTER XXXVII.

By BERTHA M. CLAY

ROYAL PUBLISHING CO.,

528 Locust Street * * PHILADELPHIA PA.

BY BERTHA M. CLAY

AUTHOR OF

"Thrown on the World," "Lady Damer's Secret,"

"A Passionate Love," "Her Faithful Heart,"

"Shadow of the Past," etc.

ROYAL PUBLISHING COMPANY.

530 Locust Street, Philadelphia

By MICHAEL RYAN, MD.

A GREAT SPECIAL OFFER

A $10.00 BOOK FOR ONLY $1.00

A complete Description of the human system, both Male and Female, and full particulars of Diseases to which each is subject, with Remedies for same. Illustrated with numerous fine, superb, full-page plates.

Fully depicting the mysterious process of Gestation from the time of conception to the period of delivery.

LOVE, COURTSHIP AND MARRIAGE

It tells you of Love and how to obtain its fullest enjoyment; Courtship and its attendant pleasures; Marriage, its joys, pleasures and happiness, and how best to acquire the greater amount of its blessings, with a vast number of wonderful and extraordinary revelations that only those who are married or contemplating marriage should be made acquainted with.

Will be sent, postpaid, securely sealed, to any address, on receipt of $1.00, special price. Address all orders to

ROYAL PUBLISHING COMPANY

No. 530 Locust Street, Philadelphia, Pa.

A rich musical voice trolled out the words, not once, but many times over—carelessly at first, and then the full sense of them seemed to strike the singer.

"'Had it lain for a century dead,'" he repeated slowly. "Ah, me! the difference between poetry and fact—when I have lain for a century dead, the light footfalls of a fair woman will not awaken me. 'Beyond the sun, woman's beauty and woman's love are of small account;' yet here—ah, when will she come?"

The singer, who was growing impatient, was an exceedingly handsome young man—of not more than twenty—with a face that challenged all criticism—bright, careless, defiant, full of humor, yet with a gleam of poetry—a face that girls and women judge instantly, and always like. He did not look capable of wrong, this young lover, who sung his love-song so cheerily, neither did he look capable of wicked thoughts.

That is the way to talk to women," he soliloquized, as the words of the song dropped from his lips. "They can not resist a little flattery judiciously mixed with poetry. I hope I have made no mistake. Cynthy certainly said by the brook in the wood. Here is the brook—but where is my love?"

He grew tired of walking and singing—the evening was[Pg 4] warm—and he sat down on the bank where the wild thyme and heather grew, to wait for the young girl who had promised to meet him when the heat of the day had passed.

He had been singing sweet love-songs; the richest poetry man's hand ever penned or heart imagined had been falling in wild snatches from his lips. Did this great poem of nature touch him—the grand song that echoes through all creation, which began in the faint, gray chaos, when the sea was bounded and the dry land made, and which will go on until it ends in the full harmony of heaven?

He looked very handsome and young and eager; his hair was tinged with gold, his mouth was frank and red; yet he was not quite trustworthy. There was no great depth in his heart or soul, no great chivalry, no grand treasure of manly truth, no touch of heroism.

He took his watch from his pocket and looked at it. "Ten minutes past seven—and she promised to be here at six. I shall not wait much longer."

He spoke the words aloud, and a breath of wind seemed to move the trees to respond; it was as though they said, "He is no true knight to say that."

A hush fell over them, the bees rested on the thyme, the butterflies nestled close to the blue-bells, the little brook ran on as though it were wild with joy. Presently a footstep was heard, and then the long expected one appeared. With something between a sigh and a smile she held out one little white hand to him. "I hardly thought you would wait for me, Claude. You are very patient."

"I would wait twice seven years for only one look at your face," he rejoined.

"Would you?" interrogated the girl wearily. "I would not wait so long even for a fairy prince."

She sat down on the heather-covered bank, and took off her hat. She fanned herself with it for a few minutes, and then flung it carelessly among the flowers.

"You do not seem very enraptured at seeing me, Hyacinth," said the young lover reproachfully. The girl sighed wearily.

"I do not believe I could go into a rapture over any thing in the world," she broke out. "I am so tired of my life—so tired of it, Claude, that I do not believe I could get up an interest in a single thing."

"I hope you feel some little interest in me," he said.

"I—I—I cannot tell. I think even bitterest pain would be better than the dead monotony that is killing me."

She remembered those words in after years, and repented of them when repentance was in vain.

"Surely you might smile now," said Claude. "I hope you do not find sitting by my side on this lovely evening monotonous."

She laughed, but the laugh had no music in it.

"No, I cannot say that I do; but you are going away soon, you tell me, and then the only gleam of sunshine in my life will fade, and all will be darkness again."

"What has depressed you so much?" he asked. "You are not yourself to-day."

"Shall I tell you what my day has been like?" she said. "Shall I describe it from the hour when the first sunbeams woke me this morning until now?" He took both the small white hands in his.

"Yes, tell me; but be merciful, and let me hear that the thought of meeting me has cheered you."

"It has been the only gleam of brightness," she said, so frankly that the very frankness of the words seemed not to displease him. "It was just six when I woke. I could hear the birds singing, and I knew how cool and fresh and dewy everything was. I dressed myself very quickly and went down-stairs. The great house was all darkness and silence. I had forgotten that Lady Vaughan does not allow the front or back doors to be opened until after breakfast. I thought the birds were calling me, and the branches of the trees seemed to beckon me; but I was obliged to go back to my own room, and sit there till the gong sounded for breakfast."

"Poor child!" he said caressingly.

"Nay, do not pity me. Listen. The breakfast-room is dark and gloomy; Lady Vaughan always has the windows closed to keep out the air, and the blinds drawn to keep out the sun; flowers give her the headache, and the birds make too much noise. So, with every beautiful sound and sight most carefully excluded, we sit down to breakfast, when the conversation never varies."

"Of what does it consist?" asked the young lover, beginning to pity the young girl, though amused by her recital.

"Sir Arthur tells us first of what he dreamed and how he slept. Lady Vaughan follows suit. After that, for one hour by the clock, I must read aloud from Mrs. Hannah More, from a book of meditations for each day of the year, and from Blair's sermons—nothing more lively than[Pg 6] that. Then the books are put away, with solemn reflections from Lady Vaughan, and for the next hour we are busy with needlework. We sit in that dull breakfast-room, Claude, without speaking, until I am ready to cry aloud—I grow so tired of the dull monotony. When we have worked for an hour, I write letters—Lady Vaughan dictates them. Then comes luncheon. We change from the dull breakfast-room to the still more dull dining-room, from which sunshine and fragrance are also carefully excluded. After that comes the greatest trial of all. A closed carriage comes to the door, and for two long, wearisome hours I drive with Sir Arthur and Lady Vaughan. The blinds are drawn at the carriage windows, and the horses creep at a snail's pace. Then we return home. I go to the piano until dinner time. After dinner Lady Vaughan goes to sleep, and I play at chess or backgammon, or something equally stupid, until half-past nine; and then the bell rings for prayers, and the day is done."

"It is not a very exhilarating life, certainly," said Claude Lennox.

"Exhilarating! I tell you, Claude, that sometimes I am frightened at myself—frightened that I shall do something very desperate. I am only just eighteen, and my heart is craving for what every one else has; yet it is denied me. I am eighteen, and I love life—oh, so dearly! I should like to be in the very midst of gayety and pleasure. I should like to dance and sing—to laugh and talk. Yet no one seems to remember that I am young. I never see a young face—I never hear a pleasant voice. If I sing, Lady Vaughan raises her hands to her head, and implores me 'not to make a noise.' Yet I love singing just as the birds do."

"I see only one remedy for such a state of things, Hyacinth," said the young lover, and his eyes brightened as he looked on her beautiful face.

"I am just eighteen," continued the girl, "and I assure you that looking back on my life, I do not remember one happy day in it."

"Perhaps the happiness is all to come," said he quietly.

"I do not know. This is Tuesday; on Thursday we start for Bergheim—a quiet and sleepy little town in Germany—and there we are to meet my fate."

"What is your fate?" he asked.

"You remember the story I told you—Lady Vaughan says I am to marry Adrian Darcy. I suppose he is a[Pg 7] model of perfection—as quiet and as stupid as perfection always is."

"Lady Vaughan cannot force you to marry any one," he cried eagerly.

"No, there will be no forcing in the strict sense of the word—they will only preach to me, and talk at me, until I shall be driven mad, and I shall marry him, or do anything else in sheer desperation."

"Who is he, Hyacinth?" asked her young lover.

"His mother was a cousin of Lady Vaughan's. He is rich, clever, and I should certainly say, as quiet and uninteresting as nearly all the rest of the world. If it were not so, he would not have been reserved for me."

"I do not quite understand," said Claude Lennox. "How it is? Was there a contract between your parents?"

"No," she replied, with a slight tone of scorn in her voice—"there is never anything of that kind except in novels. I am Lady Vaughan's granddaughter, and she has a large fortune to leave; this Adrian Darcy is also her relative, and she says the best thing to be done for us is to marry each other, and then her fortune can come to us."

"Is that all?" he inquired, with a look of great relief. "You need not marry him unless you choose. Have you seen him?"

"No; nor do I wish to see him. Any one whom Lady Vaughan likes cannot possibly suit me. Oh, Claude, how I dread it all!—even the journey to Germany."

"I should have fancied that, longing as you do for change and excitement, the journey would have pleased you," observed Claude.

She looked at him with a half-wistful expression on her beautiful face.

"I must be very wicked," she said; "indeed I know that I am. I should be looking forward to it with rapture, if any one young or amusing were going with me; but to sit in closed carriages with Sir Arthur and Lady Vaughan—to travel, yet see nothing—is dreadful."

"But you are attached to them," he said—"you are fond of them, are you not, Hyacinth?"

"Yes," she replied, piteously; "I should love them very much if they did not make me so miserable. They are over sixty, and I am just eighteen—they have forgotten what it is to be young, and force me to live as they do. I am very unhappy."

She bent her beautiful face over the flowers, and he saw her eyes fill with tears.

"It is a hard lot," he said; "but there is one remedy, and only one. Do you love me, Hyacinth?"

She looked at him with something of childish perplexity in her face.

"I do not know," she replied.

"Yes, you do know, Hyacinth; you know if you love me well enough to marry me."

No blush rose to her face, her eyes did not droop as they met his, the look of perplexity deepened in them.

"I cannot tell," she returned. "In the first place, I am not sure that I know really what love means. Lady Vaughan will not allow such a word in her presence; I have no young girl friends to come to me with their secrets; I am not allowed to read stories or poetry—how can I tell you whether I love you or not?"

"Surely your own heart has a voice, and you know what it says."

"Has it?" she rejoined indifferently. "If it has a voice, that voice has not yet spoken."

"Do not say so, Hyacinth; you know how dearly I love you. I am lingering here when I ought to be far away, hoping almost against hope to win you. Do not tell me that all my love, my devotion, my pleading, my prayers have been in vain."

The look of childish perplexity did not leave her face; the gravity of her beautiful eyes deepened.

"I have no wish to be cruel," she said; "I only desire to say what is true."

"Then just listen to your own heart, and you will soon know whether you love me or not. Are you pleased to see me? Do you look forward to meeting me? Do you think of me when I am not with you?"

"Yes," she replied calmly; "I look with eagerness to the time when I know you are coming; I think of you very often all day, and I—I dream of you all night. In my mind every word that you have ever said to me remains."

"Then you love me," he cried, clasping her little white hands in his, his handsome face growing brighter and more eager—"you love me, my darling, and you must be my wife!"

She did not shrink from him; the words evidently had little meaning for her. He must have been blind indeed[Pg 9] not to see the girl's heart was as void and innocent of all love as the heart of a dreaming child.

"You must be my wife," he repeated. "I love you better than anything else in the wide world."

She did not look particularly happy or delighted.

"You shall go away from this dull gloomy spot," he said; "I will take you to some sunny, far-off city, where the hours have golden wings and are like minutes—where every breath of wind is a fragrant sigh—where the air is filled with music, and the speech of the people is song. You will behold the grandest pictures, the finest statues, the noblest edifices in the world. You shall not know night from day, nor summer from winter, because everything shall be so happy for you."

The indifference and weariness fell from her face as a mask. She clasped her hands in triumph, her eyes brightened, her beautiful face beamed with joy.

"Oh, Claude, that will be delightful! When shall it be?"

"So soon as you are my wife, sweet. Do you not long to come with me and be dressed like a lovely young queen, in flowers, and go to balls that will make you think of fairyland? You shall go to the opera to hear the world's greatest singers; you shall never complain of dulness or weariness again."

The expression of happiness that came over her face was wonderful to see.

"I cannot realize it," she said, with a deep sigh of relief and content. "The sky looks fairer already. I can imagine how bright this world is to those who are happy. You do not know how I have longed for some share of its happiness, Claude. All my heart used to cry out for warmth and love, for youth and life. In that dull, gloomy house I have pined away. See, I am as thirsty to enjoy life as the deer on a hot day is to enjoy a running stream. It would be cruel to catch that little bird swinging on the boughs and singing so sweetly—it would be cruel to catch that bright bird, to put it in a narrow cage, and to place the cage in a dark, dull room, where never a gleam of sunshine could cheer it—but it is a thousand times more cruel to shut me up in that gloomy house like a prison, with people who are too old to understand what youth is like."

"It is cruel," he assented; and then a silence fell over them, broken only by the whispering of the wind.

"Do you know," she went on, after a time, "I have been[Pg 10] so unhappy that I have wished I were like Undine and had no soul?"

Yet, even as she uttered the words, from the books she disliked and found so dreary there came to her floating memories of grand sentences telling of "hearts held in patience," "of endurance that maketh life divine," of aspirations that do not begin and end in earthly happiness. She drove such memories from her.

"Lady Vaughan says 'life is made for duty.' Is that all, Claude? One could do one's duty without the light of the sunshine and the fragrance of flowers. Why need the birds sing so sweetly and the blossoms wear a thousand different colors? If life is meant for nothing but plain, dull duty, we do not need starlit nights and dewy evenings, the calm of green woods and the music of the waves. It seems to me that life is meant as much for beauty as for duty."

Claude looked eagerly into the lovely face.

"You are right," he said, "and yet wrong. Cynthy, life was made for love—nothing else. You are young and beautiful; you ought to enjoy life—and you shall, if you will promise to be my wife."

"I do promise," she returned. "I am tired to death of that gloomy house and those gloomy people. I am weary of quiet and dull monotony."

His face darkened.

"You must not marry me to escape these evils, Hyacinth, but because you love me."

"Of course. Well, I have told you all my perplexities, Claude, and you have decided that I love you."

He smiled at the childlike simplicity of the words.

"Now, Hyacinth, listen to me. You must be my wife, because I love you so dearly that I cannot live without you and because you have promised. Listen, and I will tell you how it must be."

Hyacinth Vaughan looked up in her lover's face; there was nothing but the simple wonder of a child in hers—nothing but awakened interest—there was not even the shadow of love.

"You say that Lady Vaughan intends starting for Bergheim on Thursday, and that Adrian Darcy is to meet you there; consequently, after Thursday, you have not the least chance of escape. I should imagine the future that lies before you to be more terrible even than the past. Rely upon it, Adrian Darcy will come to live at the Chase[Pg 11] if he marries you; and then you will only sleep through life. You will never know its possibilities, its grand realities."

An expression of terror came over her face.

"Claude," she cried, "I would rather die than live as I have been living!"

"So would I, in your place. Cynthy, your life is in our own hands. If you choose to be foolish and frightened, you will say good-by to me, go to Bergheim, marry Darcy, and drag out the rest of a weary life at the Chase, seeing nothing of brightness, nothing of beauty, and growing in time as stiff and formal as Lady Vaughan is now."

The girl shuddered; the warm young life in her rebelled; the longing for love and pleasure, for life and brightness, was suddenly chilled.

"Now here is another picture for you," resumed Claude. "Do what I wish, and you shall never have another hour's dulness or weariness while you live. Your life shall be all love, warmth, fragrance and song."

"What do you wish?" she asked, her lovely young face growing brighter at each word.

"I want you to meet me to-morrow night at Oakton station; we will take the train for London, and on Thursday, instead of going to Bergheim, we will be married, and then you shall lead an enchanted life."

An expression of doubt appeared on her face; but she was very young and easy to persuade.

"It will be the grandest sensation in all the world," he said. "Imagine an elopement from the Chase—where the goddess of dulness has reigned for years—an elopement, Cynthy, followed by a marriage, a grand reconciliation tableau, and happiness that will last for life afterward."

She repeated the words half-doubtfully.

"An elopement, Claude—would not that be very wrong—wicked almost?"

"Not at all. Lady Helmsdale eloped with her husband, and they are the happiest people in the world; elopements are not so uncommon—they are full of romance, Cynthia."

"But are they right?" she asked, half timidly.

"Well in some cases an elopement is not right, perhaps; in ours it is. Do you think that, hoping as I do to make you my wife, I would ask you to do anything which would afterward be injurious to you? Though you are so young, Cynthia, you must know better than that. To elope is right enough in our case. You are like a captive[Pg 12] princess; I am the knight come to deliver you from the dreariest of prisons—come to open for you the gates of an enchanted land. It will be just like a romance, Cynthy; only instead of reading, we shall act it." And then in his rich cheery-voice, he sung,

"I do not see how I can manage it," said Hyacinth, as the notes of her lover's song died over the flowers. "Lady Vaughan always has the house locked and the keys taken to her at nine."

"It will be very easy," returned Claude. "I know the library at the Chase has long windows that open on to the ground. You can leave one of them unfastened, and close the shutters yourself."

"But I have never been out at night alone," she said, hesitatingly.

"You will not be alone long, if you will only have courage to leave the house. I will meet you at the end of the grounds, and we will walk to the station together. We shall catch a train leaving Oakton soon after midnight, and shall reach London about six in the morning. I have an old aunt living there who will do anything for us. We will drive at once to her house; and then I will get a special license, and we will be married before noon."

"How well you have arranged everything!" she said. "You must have been thinking of this for a long time past."

"I have thought of nothing else, Cynthy. Then, when we are married, we will write at once to Lady Vaughan, telling her of our union; and instead of starting for that dreary Bergheim, we will go at once to sunny France, or fair and fruitful Italy, where the world will be at our feet, my darling. You are so beautiful, you will win all hearts."

"Am I so beautiful?" she asked simply. "Lady Vaughan says good looks are sinful."

"Lady Vaughan is—" The young man paused in time, for those clear, innocent eyes seemed to be penetrating to the very depths of his heart. "Lady Vaughan has forgotten that she was ever young and pretty herself," he said. "Now, Cynthy, tell me—will you do what I wish?"

"Is it not a very serious thing to do?" she asked. "Would not people think ill of me?"

His conscience reproached him a little when he answered "No"—the lovely, trusting face was so like the face of a child.

"I do not expect you to say 'Yes' at once, Hyacinth—think it over. There lies before you happiness with me, or misery without me."

"But, Claude," she inquired eagerly, "why need we elope? Why not ask Lady Vaughan if we can be married? She might say 'Yes.'"

"She would not; I know better than you. She would refuse, and you would be carried off on Thursday, whether you liked it or not. If we are to be married at all we must elope—there is no help for it."

The young girl did not at once consent, although the novelty, the romance, the promised happiness, tempted her as a promised journey pleases a child.

"Think it over to-night," he said, "and let me know to-morrow."

"How can I let you know?" she asked. "I shall be in prison all day; it is not often that I have an hour like this. I shall not be able to see you."

"Perhaps not, but you can give me some signal. You have charge of the flowers in the great western window?"

"Yes, I change them at my pleasure every day."

"Then, if after thinking the matter over, you decide in my favor, and choose a lifetime of happiness, put white roses—nothing but white roses—there; if, on the contrary, you are inclined to follow up a life of unendurable ennui, put crimson flowers there. I shall understand—the white roses will mean 'Yes; I will go;' the crimson flowers will mean 'No; good-by, Claude.' You will not forget, Cynthy."

"It is not likely that I shall forget," she replied.

"You need not have one fear for the future; you will be happy as a queen. I shall love you so dearly; we will enjoy life as it is meant to be enjoyed. It was never intended for you to dream away your existence in one long sleep. Your beautiful face was meant to brighten and gladden men's hearts; your sweet voice to rule them. You are buried alive here."

Then the great selfish love that had conquered him rose in passionate words. How he caressed her! What tender, earnest words he whispered to her! What unalterable devotion he swore—what affection, what love! The girl grew grave and silent as she listened. She wondered why[Pg 14] she felt so quiet—why none of the rapture that lighted up his face and shone in his eyes came to her. She loved him—he said so; and surely he who had had so much experience ought to know. Yet she had imagined love to be something very different from this. She wondered that it gave her so little pleasure.

"How the poets exaggerate it!" she said to herself, while he was pouring out love, passion, and tenderness in burning words. "How great they make it, and how little it is in reality."

She sighed deeply as she said these words to herself, and Claude mistook the sigh.

"You must not be anxious, Hyacinth. You need not be so. You are leaving a life of dull, gloomy monotony for one of happiness, such as you can hardly imagine. You will never repent it, I am sure. Now give me one smile; you look as distant and sad as Lady Vaughan herself. Smile, Cynthy!"

She raised her eyes to his face, and for long years afterward that look remained with him. She tried to smile, but the beautiful lips quivered and the clear eyes fell.

"I must go," she said, rising hurriedly, "Sir Arthur and Lady Vaughan are to be home by eight o'clock."

"You will say 'Yes,' Cynthy?" he said, clasping her hands in his own. "You will say 'Yes,' will you not?"

"I must think first," she replied; and as she turned away the rush of wind through the tall green trees sounded like a long, deep-drawn sigh.

Slowly she retraced her steps through the woods, now dim and shadowy in the sunset light, toward the home that seemed so like a prison to her. And yet the prospect of an immediate escape from that prison did not make her happy. The half-given promise rested upon her heart like a leaden weight, although she was scarce conscious in her innocence why it should thus oppress her. At the entrance to the Hall grounds she paused, and with a gesture of impatience turned her back upon the lofty sombre-looking walls, and stood gazing through an opening in the groves at the gorgeous masses of purple and crimson sky, that marked the path of the now vanished sun.

A very pretty picture she made as the soft light fell upon her fair face and golden hair, but no thought of her young, fresh beauty was in the girl's mind then. The question, "Dare I say—'Yes'?" was ever before her, with Claude's fair face and pleading, loving tones.

"O, I cannot decide now," she thought wearily, "I must think longer about it," and with a sigh she turned from the sunset-light, and walked up the long avenue that led to her stately home.

How her decision—though speedily repented of and corrected—yet cast the shadow of a sin over her fair young life; how her sublimely heroic devotion to the right saved the life of an innocent man, yet drove her into exile from home and friends, and how at last the bright sunshine drove away the shadows and restored her to home and friends, all she had lost and more, remains for our story to tell.

Sir Arthur and Lady Vaughan lived at Queen's Chase in Derbyshire, a beautiful and picturesque place, known to artists, poets, and lovers of quaint old architecture. Queen's Chase had been originally built by good Queen Elizabeth of York, and was perhaps one of the few indulgences which that not too happy queen allowed herself. It was large, and the rooms were all lofty. The building was in the old Tudor style, and one of its peculiarities was that every part of it was laden with ornament: it seemed to have been the great ambition of the architect who designed it to introduce as much carving as possible about it. Heads of fauns and satyrs, fruit and flowers—every variety of carving was there; no matter where the spectator turned, the sculptor's work was visible.

To Hyacinth Vaughan, dreamy and romantic, it seemed as though the Chase were peopled by these dull, silent, dark figures. Elizabeth of York did not enjoy much pleasure in the retreat she had built for herself. It was there she first heard of and rejoiced in the betrothal of her fair young daughter Marguerite, to James IV. of Scotland. A few years afterward she died, and the Chase was sold. Sir Dunstan Vaughan purchased it, and it had remained in the family ever since. It was now their principal residence—the Vaughans of Queen's Chase never quitted it.

Though it was picturesque it was not the most cheerful place in the world. The rooms were dark by reason of the huge carvings of the window frames and the shade of the trees, which last, perhaps, grew too near the house. The[Pg 16] edifice contained no light, cheerful, sunny rooms, no wide large windows; the taste of the days in which it was built, led more toward magnificence than cheerfulness. Some additions had been made; the western wing of the building had been enlarged; but the principal apartments had remained unaltered; the stately, gloomy rooms in which the fair young princess had received and read the royal love-letters were almost untouched. The tall, spreading trees grew almost to the Hall door; they made the whole house dark and perhaps unhealthy. But no Vaughan ventured to cut them down; such an action would have seemed like a sacrilege.

From father to son Queen's Chase had descended in regular succession. Sir Arthur, the present owner, succeeded when he was quite young. He was by no means of the genial order of men: he had always been cold, silent, and reserved. He married a lady more proud, more silent, more reserved than himself—a narrow-minded, narrow-hearted woman whose life was bounded by rigid law and formal courtesies, who never knew a warm or generous impulse, who lived quite outside the beautiful fairyland of love and poetry.

Sir Arthur and Lady Vaughan had but one son, and though each idolized him, they could not change their nature; warm, sweet impulses never came to them. The mother kissed her boy by rule—at stated times; everything was measured, dated, and weighed.

The boy himself was, strange to say, of a most hopeful, ardent, sanguine temperament; generous, high-spirited, slightly inclined to romance and sentiment. He loved and honored his father and mother, but the rigid formality of home was terrible to him; it was almost like death in life. Partly to escape it and partly because he really liked the life, he insisted on joining the army—much against Lady Vaughan's wishes.

"Why could he not be content at home, as his father had been before him?" she asked.

Captain Randall Vaughan enjoyed his brief military career. As a matter of course he fell in love, but far more sensibly than might have been imagined. He married the pretty, delicate Clare Brandon. She was an orphan, not very rich—in fact had only a moderate fortune—but her birth atoned for all. She was a lineal descendant of the famous Brandon, Duke of Suffolk, whom the fair young ex-queen of France had married.

Lady Vaughan was delighted. A little more money might have been acceptable, but the Vaughans had plenty, and there was no young lady in England better born and better bred than Clare Brandon. So the young captain married her and Sir Arthur made them a very handsome allowance. For one whole year they lived in perpetual sunshine, as happy as they could possibly be, and then came an outbreak in our Eastern possessions, and the captain's regiment was ordered abroad.

It was like a deathblow to them. Despite all danger, Mrs. Vaughan would have gone with her husband, but for the state of her health, which absolutely forbade it. Her despair was almost terrible; it seemed as if she had a presentiment of the coming cloud. If the war had not been a dangerous one the young captain would most certainly have sold out; but to do so when every efficient soldier was required, would have been to show the white feather, and that no Vaughan could do—the motto of the house was "Loyal even to death." He tried all possible means to console his wife, but she only clung to him with passionate cries, saying she would never see him again.

It was impossible to leave her alone and she had no near relatives. Then Lady Vaughan came to the rescue. The heir of the Vaughans, she declared, must be born at Queen's Chase: therefore her son's wife had better remain with her. Randall Vaughan thankfully accepted his mother's offer, and took his wife to the old ancestral home. It was arranged that she should remain there until his return.

"You will try for my sake to be well and happy," he said to her, "so that when I come back you will be strong and able to travel with me, should I have to go abroad, again."

But she clasped her tender arms around him and hid her weeping face on his breast.

"I shall never see you again, my darling," she said, "never again!"

They called the unconsciousness that came over her merciful. She remembered nothing after those words. When she opened her eyes again he was gone.

How the certainty of her doom seemed to grow upon her! How her sweet face grew paler, and the frail remnant of vitality grew less! He had been her life—the very sun and centre of her existence. How could she exist without him? Lady Vaughan, in her kind, formal way,[Pg 18] tried to cheer her, and begged of her to make an effort for Randall's sake; and for Randall's sake the poor lady tried to live.

They were disappointed in one respect; it was not an heir that was born to the noble old race, but a lovely, smiling baby girl—so lovely that Lady Vaughan, who was seldom guilty of sentiment, declared that it resembled nothing so much as a budding flower, and after a flower, she said it must be named. They suggested Rose, Violet, Lily—none of them pleased her; but looking one day through the family record, she saw the name of Lily Hyacinth Vaughan. Hyacinth it must be. The poor, fragile mother smiled a feeble assent, and the lovely baby received its name. Glowing accounts were sent to the young captain.

The news was not long in reaching England. When Lady Vaughan read it she knew it was Clare's death-warrant. They tried to break it to her very gently, but her keen, quick perception soon told her what was wrong.

"He is dead," she said; "I knew that I should never see him again."

Clare Vaughan's heart was broken; she hardly spoke after she heard the fatal words; she was very quiet, very patient, but the light on her face was not of this world. She lay one day with little Hyacinth in her arms, and Lady Vaughan, going into her room, said,

"You look better to-day, Clare."

"I have been dreaming of Randall," she said smiling; "I shall soon see him again."

An hour afterward they went to take the little one from her—the tender arms had relaxed their hold, and she lay dead, with a smile on her face.

They buried her in Ashton churchyard. People called her illness by all kinds of different names, but Lady Vaughan knew she had died of a broken heart. The care of little Hyacinth devolved upon her grandmother. It was a dreary home for a child: the rooms were always shaded by trees, and the sombre carvings, the satyr heads, the laughing fauns, all in stone, frightened her. She never saw any young persons; Sir Arthur's servants were all old—they[Pg 19] had entered the service in their youth, and remained in it ever since.

Sir Arthur and Lady Vaughan felt their son's death very keenly; all their hopes died with him; all their interest in life was gone. They became more dull, more formal, more cold every day. They loved the child, yet the sight of her was always painful to them, reminding them so forcibly of what they had lost. They reared her in the same precise, formal manner in which their only son had been reared. She rose at a stated time; she retired at a certain hour, never varying by one minute; she studied, she read, she practiced her music—all by rule.

The neighborhood round Queen's Chase was not a very populous one. Among the friends whom the Vaughans visited, and who visited them in return, there was not one young person, not one child. It never seemed to enter their minds that Hyacinth, being a child, longed for the society of children. At certain times she was gravely told to play. She had a doll and a Noah's ark; and with these she amused herself alone for long hours. As for the graces, the fancies, the wants, the requirements of childhood, its thousand wordless dreams and wordless wants, no one seemed to understand them at all. They treated the child as if she were a little old woman, crushing back with remorseless hand all the quick fancies and bright dreams natural to youth.

Some children would have grown up wicked, hardened, unlovely and unloving under such tuition; but Hyacinth Vaughan was saved from this by her peculiar disposition. The child was all poetry. Lady Vaughan never wearied of trying to correct her. She carefully pruned, as she imagined, all the excess of imagination and romance. She might as well have tried to prevent the roses from blooming, the dew from falling, or the leaves from springing. All that she succeeded in was in making the child keep her thoughts and fancies to herself. She talked to the trees as though they were grave, living friends, full of wise counsel; she talked to the flowers as though they were familiar and dear playfellows. The imagination so sternly repressed ran riot in a hundred different ways.

It was most unfortunate for the child. If she had been as other children—if her imagination, instead of being cruelly repressed, had been trained and put to some useful purpose—if her love of romance had been wisely guarded—if her great love of poetry and beauty, her great love of ideality,[Pg 20] had been watched and allowed for—the one great error that darkened her life would never have been committed. But none of this was done. She was literally afraid to speak of that which filled her thoughts and was really part of her life. If she asked any uncommon question Lady Vaughan scolded her, and Sir Arthur, his hands shaking nervously, would say, "The child is going wrong—going wrong."

It was without exception the dullest and saddest life any child could lead. At thirteen there came two breaks in the monotony—she had a music-master come from Oakton, and she found a key that fitted the library door. How often had she stood against the library windows, looking through them, and longing to open one of those precious volumes; but when she asked Sir Arthur for a book, he told her she could not understand them—she must be content to play with her doll.

There were hundreds of suitable books that might have been provided for the child; she was refused any—consequently she read whatever came in her way. She found this key that fitted the library door, and used it. She would quietly unlock it, and take one of the books nearest to her without fear of its being missed, for Sir Arthur seldom entered the room. In this fashion she read many books that were valuable, instructive, and amusing. She also read many that would have been much better left alone. Her innocence, however, saved her from harm. She knew so little of life that what would have perhaps injured another was not even noticed by her.

In this manner she educated herself, and the result was exactly what was to be expected. She had in her mind the most curious collection of poetry and romance, the most curious notions of right and wrong, the most unreal ideas it was possible to imagine. Then, as she grew older, life began to unroll itself before her eyes.

She saw that outside this dull world of Oakton there was another world so fair and bright that it dazzled her. There was a world full of music and song, where people danced and made merry, where they rode and drove and enjoyed themselves, where there was no dulness and no gloom—a world of which the very thought was so beautiful, so bewildering, that her pulse thrilled and her heart beat as she dreamed of it. Would she ever find her way into that dazzling world, or would she be obliged to live here always, shut up with these old, formal people, amid the quaint carvings and giant trees? And then when she[Pg 21] was seventeen, she began to dream of the other world women find so fair—the fairyland of hope and love. Her ideas of love were nearly all taken from poetry: it was something very magnificent, very beautiful, taking one quite out of commonplace affairs. Would it ever come to her?

She thought life had begun and ended too, for her, when one day Lady Vaughan told her to come into her room—she wished to talk to her. The girl followed her with a weary, hopeless expression on her face. "I am going to have a lecture," she thought; "I have said a word too little or a word too much."

But, wonderful to say, Lady Vaughan was not prepared with a lecture. She sat down in her great easy-chair and pointed to a footstool. Hyacinth took it, wondering very much what was coming.

"My dear Hyacinth," she began; "you are growing up now; you will be quite a woman soon; and it is time you knew what Sir Arthur and I have planned for you."

She did not feel much interest in learning what it was—something intolerably dull it was sure to be.

"You know," continued Lady Vaughan, "there has never been the least deception used toward you. You are the only child of our only son; but it has never been understood that you were to be heiress of the Chase."

"I should not like to have the Chase," said Hyacinth timidly. "I should not know what to do with it."

Lady Vaughan waved her hand in very significant fashion.

"That is not the question. We have not brought you up as our heiress because both Sir Arthur and I think that the head of our house must be a gentleman. Of course you will have a dowry. I have money of my own, which I intend to leave you. Mr. Adrian Darcy, of whom you have heard me speak, will succeed to Queen's Chase—that is, if no other arrangement takes him from us; should he have other views in life, the property will perhaps be left differently. I cannot say. Sir Arthur and I wish very much that you should marry Mr. Darcy."

The girl looked up at the cold, formal face, with wonder in her own. Was this to be her romance? Was this to be the end of all her dreams? Instead of passing into a fairer, brighter world, was she to live always in this?

"How can I marry him?" she asked quickly. "I have never seen him."

"Do not be so impetuous, Hyacinth. You should always repress all exhibition of feeling. I know that you have never seen him. Mr. Darcy is travelling now upon the Continent, and Sir Arthur thinks a short residence abroad would be very pleasant for us. Adrian Darcy always shows us the greatest respect. You will be sure to like him—he is so like us; we are to meet him at Bergheim, and spend a month together, and then we shall see if he likes you."

"Does he know what you intend?" she asked half shyly.

"Not yet. Of course, in families like our own, marriages are not conducted as with the plebeian classes; with us they are affairs of state, and require no little diplomacy and tact."

"Was my father's a diplomatic marriage?" she asked.

"No," replied Lady Vaughan, "your father pleased himself; but then, remember, he was in a position to do so. He was an only son, and heir of Queen's Chase."

"And am I to be taken to this gentleman; if he likes me he is to marry me; if not, what then?"

The scornful sarcasm of her voice was quite lost on Lady Vaughan.

"There is no need for impatience. Even then some other plan will suggest itself to us. But I think there is no fear of failure—Mr. Darcy will be sure to like you. You are very good-looking, you have the true Vaughan face, and, thanks to the care with which you have been educated, your mind is not full of nonsense, as is the case with some girls. I thought it better to tell you of this arrangement, so that you may accustom your mind to the thought of it. Everything being favorable, we shall start for Bergheim in the middle of August, and then I shall hope to see matters brought to a sensible conclusion."

"It will not be of any consequence whether I like this Mr. Darcy or not—will it, Lady Vaughan?"

"You must try to cultivate a kindly liking for him, my dear. All the nonsense of love and romance may be dispensed with. Well brought up as you have been, you will find no difficulty in carrying out our wishes. Now, draw that blind a little closer, my love, and leave me—I am sleepy. Do not waste your time—go at once to the piano."

Having acquainted her young relative with the prospective arrangements she had made for her, Lady Vaughan composed herself to sleep, and Hyacinth quietly left the room. She dared not stop to think until she was outside the door, in the free, fresh air; the walls of the old house seemed to stifle her. Her young soul was awakened, but it rose in a hot glow of rebellion against this new device of fate. She to be taken abroad and offered meekly to this gentleman! If he liked her they were to be married; if not, with the sense of failure upon her, she would have to return to the Chase. The thought was intolerable.

Was this the promised romance of her life? "It is not fair," cried the girl passionately, as she paced the narrow garden paths—"it is not just. Everything has liberty, love, and happiness—why should not I? The birds love each other, the flowers are happy in the sun—why must I live without love or happiness, or brightness? I protest against my fate."

Were all the thousand tender and beautiful longings of her life to be thus rudely treated? Was all the poetry and romance she had dreamed of to end in "cultivating a kindly liking" and a diplomatic marriage? Oh, no, it could not be! She shed passionate tears. She prayed, in her wild fashion, passionate prayers. Better for her a thousand times had she been commonplace, unromantic, prosaic—better that the flush of youth and the sweet longings of life had not been hers. Then a break came in the clouds—a change that was to be most fatal to her. One of the families with whom Sir Arthur and Lady Vaughan were most intimate was that of old Colonel Lennox, of Oakton Park.

Colonel Lennox and his wife were both old; but one day they received a letter from Mrs. Lennox, their sister-in-law, who resided in London, saying how very pleased she should be to pay them a visit with her son Claude. Mrs. Lennox was very rich. Claude was heir to a large fortune. Still she thought Oakton Park would be a handsome addition, and it would be just as well to cultivate the affection of the childless uncle.

Mrs. Lennox and Claude came to Oakton. Solemn dinner-parties, at which the young man with difficulty concealed[Pg 24] his annoyance, were given in their honor, and at one of these entertainments Hyacinth and Claude met. He fell in love with her.

In those days she was beautiful as the fairest dream of poet or artist. In the fresh spring-tide of her young loveliness, she was something to see and remember. She was tall, her figure slender and girlish, full of graceful lines and curves that gave promise of magnificent womanhood. Her face was of oval shape; the features were exquisite, the eyes of the darkest blue, with long lashes; her lips were fresh and sweet; her mouth was the most beautiful feature in her beautiful face—it was sweet and sensitive, yet at times slightly scornful; the teeth were white and regular; the chin was faultless, with a pretty dimple in it.

It was not merely the physical beauty, the exquisite features and glorious coloring that attracted; there were poetry, eloquence, and passion within these. Looking at her, one knew instinctively that she was not of the common order—that something of the poet and genius was there. Her brow was fair and rounded at the temples, giving a great expression of ideality to her face; her fair hair, soft and shining, seemed to crown the graceful head like a golden diadem.

Claude Lennox, in his half-selfish, half-chivalrous way, fell in love with her. He said something to Lady Vaughan about her one day, and she gave him to understand that her granddaughter was engaged. She did not tell him to whom, nor did she say much about it; but the few words piqued Claude, who had never been thwarted in his life.

On the first day they met, his mother had warned him not to fall in love with the beautiful girl, who might be an heiress or might have nothing—to remember that in his position he could marry whom he would, and not to throw himself away.

Lady Vaughan, too, on her side, seemed much disposed to forbid him even to speak to Hyacinth. If he proposed calling at Queen's Chase, she either deferred his visit or took good care that Hyacinth should not be in the way; and all this she did, as she believed, unperceived. It was evident that Sir Arthur also was not pleased; though the old gentleman was too courtly and polished to betray his feeling openly in the matter. He did not like Claude Lennox, and the young man felt it. One day he met the two young people together in a sequestered part of the Chase grounds, and though he did not utter his displeasure,[Pg 25] the stern, angry look that he gave Claude, fully betrayed it. Hyacinth, whose glance had fallen to the ground in a sudden accession of shyness that she scarce understood, at her grandfather's approach, did not see his set, stern face. Nor did Sir Arthur speak to her of the matter. On talking it over to Lady Vaughan, the two old people concluded that a show of open opposition might awaken a favor toward Claude in the young girl's heart to which it was yet a stranger, and they contented themselves with throwing every possible obstacle in the way of the young people's intercourse. This was, in this case, mistaken policy. If the old gentleman had spoken, he might have saved Hyacinth from unspeakable misery, and his proud old name from the painful shadow of disgrace that a childish folly was to bring upon it. The young girl stood greatly in awe of her grandfather, but she respected him, and in a way loved him, through her fears. And she was now being led, step by step, into folly, through her own ignorance of its nature.

Claude Lennox was piqued. He was young, rich, and handsome; he had been eagerly sought by fashionable mothers. He knew that he could marry Lady Constance Granville any day that he liked; he had more than a suspicion that the pretty, coquettish, fashionable young widow, Mrs. Delamere, liked him; Lady Crown Harley had almost offered him her daughter. Was he to be defied and set at naught in this way—he, a Lennox, come of a race who had never failed in love or war? No, it should never be; he would win Hyacinth in spite of all. He disarmed suspicion by ceasing, when they met, to pay her any particular attention. His lady-mother congratulated herself; she retired to London, leaving her son at Oakton Park. He said his visit was so pleasant that he could not bring it to a close. The colonel, delighted with his nephew, entreated him to stay, and Claude said, smiling to himself, that he had a fair field and all to himself.

His love for Hyacinth was half-selfish, half-chivalrous. It was pique and something like resentment that made him first of all determined to woo her, but he soon became so interested, that he believed his life depended on winning her. She was so different from other girls. She was child, poet, and woman. She had the brightest and fairest of fancies. She spoke as he had never heard any one else speak—as though her lips had been touched with divine fire.

Fortune favored him. He went one morning to the[Pg 26] Chase, and found Sir Arthur and Lady Vaughan at home—alone. He did not mention Hyacinth's name; but as he was going out, he gave one of the footmen a sovereign and learned from him that Miss Vaughan was walking alone in the wood. She had complained of headache, and "my lady" had sent her out into the fresh air.

Of course he followed her and found her. He made such good use of the hour that succeeded, that she promised to meet him again. He was very careful to keep her attention fixed on the poetry of such meetings; he never hinted at the wrong of concealment, the dishonor of any thing clandestine, the beauty of obedience; he talked to her only of love, and of how he loved her and longed to make her his wife. She was very young, very impressionable, very romantic; he succeeded completely in blinding her to the harm and wrong she was doing; but he could not win from her any acknowledgement of her love. She enjoyed the break in the dull monotony of her life. She enjoyed the excitement of having to find time to meet him. She liked listening to him; she liked to hear him praise her beauty, and rave about his devotion to her. But did she love him? Not if what the poets wrote was true—not if love be such as they describe.

So for three or four weeks of the beautiful summer, this little love story went on. Claude Lennox was au fait as to all the pretty wiles and arts of love, he made a post-office of the trunk of a grand old oak-tree—a trunk that was covered with ivy; he used to place letters there every day, and Hyacinth would fetch and answer them. These letters won her more than any spoken words; they were eloquently written and full of poetry. She could read them and muse over them; their poetry remained with her.

When she was talking to him a sense of unreality used to come over her—a vague, uncertain, dreamy kind of conviction that in some way he was not true; that he was saying more than he meant, or that he had said the same things before and knew them all by heart. His letters won her. She answered them, and in those answers found[Pg 27] some vent for the romance and imagination that had never had an outlet before. Claude Lennox, as he read them, wondered at her.

"The girl is a genius," he said; "if she were to take to writing, she would make the world talk of her. I have read all the poetry of the day, but I have never read anything like these lines."

Claude Lennox had been a successful man. He had not been brought up to any profession—there was no need for it; he was to inherit a large fortune from his mother, and he had already one of his own. He had lived in the very heart of society; he had been courted, admired and flattered as long as he could remember. Bright-eyed girls had smiled on him, and fair faces grown the fairer for his coming. He had had many loves, but none of them had been in earnest. He liked Hyacinth Vaughan better than any one he had ever met. If her friends had smiled upon him and everything had been couleur de rose, he would have loved lightly, have laughed lightly, and have ridden away. But because, for the first time in his life, he was opposed and thwarted, frowned upon instead of being met with eagerness, he vowed that he would win her. No one should say Claude Lennox had loved in vain.

He was a strange mixture of vanity and generosity, of selfishness and chivalry. He loved her as much as it was in his nature to love any one. He felt for her; the descriptions she gave him of her life, its dull monotony, its dreary gloom, touched his heart. Then, too, his vanity was gratified; he knew that if he took such a peerlessly beautiful girl to London as his wife, she would be one of the most brilliant queens of society. He knew that she would create an almost unrivalled sensation. So love, vanity, generosity, selfishness, chivalry, all combined, made him resolve to win her.

He knew that if he were to go to Queen's Chase and ask permission to woo her, it would be refused him—she would be kept away from him and hurried away to Germany. That was the honest, honorable course, but he felt sure it was hopeless to pursue it. Man of the world as he was, the first idea of an elopement startled him; then he became accustomed to it, and began at last to think an elopement would be quite a romance and a sensation. So, by degrees he broke it to her. She was startled at first, and then, after a time, became accustomed to it. It would be very easy, soon over, and when they were once married[Pg 28] his mother would say nothing; if the Vaughans were wise, they too would be willing to forgive and say nothing.

He found Hyacinth so simple, so innocent and credulous, that he had no great difficulty in persuading her. If any thought of remorse came to him—that, as the stronger of the two he was betraying his trust—he quickly put the disagreeable reflection away—he intended to be very kind to her after they were married, and to make her very happy.

So he waited in some anxiety for the signal. It was not a matter of life or death with him; neither did he consider it as such; but he was very anxious, and hoped she would consent. The library window could be seen from the park; he had but to walk across it, and then he could see. Claude Lennox was almost ashamed to find how his heart beat, and how nervously his eyes sought the window.

"I did not think I could care about anything so much," he said to himself; "I begin to respect myself for being capable of such devotion."

It was early on Wednesday morning, but he had not been able to sleep. Would she go, or would she refuse? How many hours of suspense must he pass before he knew? The sun was shining gayly, the dew lay on the grass—it was useless to imagine that she would be thinking of her flowers; yet he could not leave the place—he must know.

At one moment his hopes were raised to the highest point—it was not likely that she would refuse. She would never be so foolish as to choose a life of gloom and wretchedness instead of the golden future he had offered her. Then again his heart sunk. An elopement! It was such a desperate step; she would surely hesitate before taking it. He walked to the end of the park, and then he returned. His heart beat so violently when he raised his eyes that it seemed to him as if he could hear it—a dull red flush rose to his face, his lips quivered. He had won—the white flowers were there!

There was no one to see him, but he raised his Glengarry cap from his head and waved it in the air.

"I have won," he said to himself; "now for my arrangements."

He went back to Oakton Park in a fever of anxiety; he telegraphed from Oakton Station to the kind old aunt who had never refused him a favor, asking her, for particular reasons which he would explain afterward, to meet him at Euston Square at 6 a.m. on Thursday.

"There is some one coming with me whom I wish to put under your charge," he wrote; and he knew she would comply with his request.

He had resolved to be very careful—there should be no imprudence besides the elopement; his aunt should meet them at the station, Hyacinth should go home with her and remain with her until the hour fixed for the wedding.

Hyacinth had taken her life into her own hands, and the balance had fallen. She had decided to go; this gray, dull, gloomy life she could bear no longer; and the thought of a long, dull residence in a sleepy German town with a relative of Lady Vaughan's positively frightened her.

Claude had dazzled her imagination with glowing pictures of the future. She did not think much of the right or wrong of her present behavior; the romance with which she was filled enthralled her. If any one had in plain words pointed out to her that she was acting badly, dishonorably, deceitfully, she would have recoiled in dread and horror; but she did not see things in their true colors.

All that day Lady Vaughan thought her granddaughter very strange and restless. She seemed unable to attend to her work; she read as one who does not understand. If she was asked a question, her vacant face indicated absence of mind.

"Are you ill, Hyacinth?" asked Lady Vaughan at last. "You do not appear to be paying the least attention to what you are doing."

The girl's beautiful face flushed crimson.

"I do not feel quite myself," she replied.

Lady Vaughan was not well pleased with the answer. Ill-health or nervousness in young people was, as she said, quite unendurable—she had no sympathy with either. She looked very sternly at the sweet crimsoned face.

"You do not have enough to do, Hyacinth," she said gravely; "I must find more employment for you. Miss Pinnock called the other day about the clothing club; you had better write and offer your services."

"As though life was not dreary enough," thought the girl, "without having to sew endless seams by the hour!"

Then, with a sudden thrill of joy, she remembered that her freedom was coming. After this one day there would be no more gloom, no more tedious hours, no more wearisome lectures, no more dull monotony; after this one day all was to be sunshine, beauty, and warmth. How the day passed she never knew—it was like a long dream to her.[Pg 30] Yet something like fear took possession of her when Lady Vaughan said:

"It is growing late, Hyacinth; it is past nine."

She went up to her and kissed the stern old face.

"Good-night," she said simply with her lips, and in her heart she added "good-by."

She kissed Sir Arthur, who had never been quite so harsh with her and as she closed the drawing-room door, she said to herself,

"So I leave my old life behind."

A beautiful night—not clear with the light of the moon, but solemn and still under the pale, pure stars; there was a fitful breeze that murmured among the trees, rippling the green leaves and stirring the sleeping flowers. The lilies gleamed like pale spectres, the roses were wet with dew; the deer lay under the trees in the park; there was hardly a sound to break the holy calm.

Queen's Chase lay in dark shadow under the starlight, the windows and doors all fastened except one, the inmates all sleeping save one. The great clock in the turret struck ten. Had any been watching, they would have seen a faint light in the room where Hyacinth Vaughan slept; it glimmered there only for a minute or two, and then disappeared. Soon afterward there appeared at the library window a pale, sweet, frightened face; the window slowly opened and a tall, slender figure, closely wrapped in a dark gray cloak, issued forth from the safe shelter of home, under the solemn stars, to take the false step that was to darken her life for so many years.

She stole along in the darkness and silence, between the trees, till Claude came to her; and her heart gave a great bound at his approach, while a crimson flush rose to her face.

"My darling," he said, clasping her hand in his, "how am I to thank you?"

Then she began to realize in some faint degree what she had done. She looked up at Claude's handsome, careless face, and began to understand that she had given up all the world for him—all the world.

"You are frightened, Hyacinth," he said, "but there is no need. Your hand trembles, and your face is so pale that I notice it even by starlight."

"I am frightened," she confessed. "I have never been out at night before. Oh, Claude, do you think I have done right?"

He spoke cheerily: "That you have, my darling. Such gloomy cages were never made for bright birds like you; let me see you smile before you go one step further."

It was almost midnight when they reached Oakton station; the few lamps glimmered fitfully and there was no one about but the sleepy porters.

"Keep your veil well drawn over your face, Hyacinth," he whispered; "I will get the tickets. Sit down here and no one need see you."

She obeyed him, trembling in every limb. She sat down on the little wooden bench, her veil closely drawn over her face; her cloak wrapped round her; and then, after what seemed to be but a moment of time, yet was in reality over ten minutes, the train ran steaming into the station. One or two passengers alighted. Claude took her hand and placed her in a first-class carriage—no one had either seen or noticed her—he sprang in after her, the door was shut, the whistle sounded, and the train was off.

"It is done!" she gasped, her face growing deadly white, and the color fading even from her lips. She laid her head back on the cushion. "It is done!" she repeated, faintly.

"And you will see, my darling, that all is for the best."

He would not allow her time to think or to grow dull. He talked to her till the color returned to her face and the brightness to her eyes. They looked together from the carriage windows, watching the shining stars and the darkened earth, wondering at the beautiful, holy silence of night, until the faint gray dawn broke in the skies. Then a mishap occurred.

The train had proceeded on its way safely enough until a station called Leybridge had been reached. There the passengers for London leave it, and await the arrival of the mail train. Hyacinth and Claude left the carriage; the train they had travelled by went on.

"We have not long to wait for the mail train," said Claude, "and then, thank goodness, there will be no more changing until we reach London."

The faint gray dawn of the morning was just breaking[Pg 32] into rose and gold. Hyacinth looked pale and cold; the excitement, the fatigue, and the night travelling were rapidly becoming too much for her.

They walked up and down the platform for a few minutes. A quarter of an hour passed—half an hour—and then Claude, still true to his determination that Hyacinth should not be seen, bade her to sit down again while he went to inquire at the office the cause of delay. There were several other passengers, for Leybridge Junction was no inconsiderable one.

Suddenly there seemed to arise a scene of confusion in the station. The station master came out with a disturbed face; the porters were no longer sleepy, but anxious. Then the rumor, whispered first with bated breath, grew—"An accident to the mail train below Lewes. Thirty passengers seriously injured and half as many killed. Traffic on the line impossible."

Claude heard the sad news with a sorrowful heart. He did not wish Hyacinth to know it—it would seem like an omen of misfortune to her. "When will the next train start for London?" he asked one of the porters.

"There is none between now and seven o'clock," the man replied.

"Was there ever anything so unfortunate?" muttered Claude to himself.

Leybridge was only twenty miles from Oakton.

"I should not like any one to see me about the station," he thought; "and Hyacinth is sure to be known here. How unfortunate that we should be detained so near home!" He went out to her: "You must not lose patience, Hyacinth," he said; "the mail train is delayed, and we have to wait here until seven."

She looked up at him, alarmed and perplexed. "Seven," she repeated—"and now it is only three. What shall we do, Claude?"

"If you are willing, we will go for a walk through the fields. I fancy we shall be recognized if we stop here."

"I am sure we shall—I have often been to Leybridge with Lady Vaughan."

They went out of the station and down the quiet street; they saw an opening that led to the fields.

"You will like the fields better than anywhere else," said Claude, and she assented.

They crossed a stile that led into the fertile clover meadows. It seemed as though the beauty and fragrance[Pg 33] of the summer morning broke into full glow to welcome them; the rosy clouds parted, and the sun shone in the full lustre of its golden light; the trees, the hedges, the clover, were all impearled with dew—the drops lay thick, shining and bright, on the grass; there was a faint twitter of birds, as though they were just awakening; the trees seemed to stir with new life and vigor.

"Is this the morning?" said Hyacinth, looking round. "Why, Claude, it is a thousand times more beautiful than the fulness of day!"

Hyacinth and Claude stood together leaning against the stile. Something in the calm beauty of the summer morning awoke the brightest and purest emotions in him; something in the early song of the birds and in the shining dewdrops made Hyacinth think more seriously than she had yet done.

"I wonder," she said, turning suddenly to her lover, "if we shall ever look back to this hour and repent what we have done?"

"I do not think so. It will rather afford subject for pleasant reflection."

"Claude," she cried suddenly, "what is that lying over there by the hedge? It—it looks so strange."

He glanced carelessly in the direction indicated. "I can see nothing," he replied. "My eyes are not so bright as yours."

"Look again, Claude. It is something living, moving—something human I am sure! What can it be?"

He did look again, shading his eyes from the sun. "There is something," he said slowly, "but I cannot tell what it is."

"Let us see, Claude; it may be some one ill. Who could it be in the fields at this time of the morning?"

"I would rather you did not go," said Claude; "you do not know who it may be. Let me go alone."

But she would not agree to it; and as they stood there, they heard a faint moan.

"Claude," cried the girl, in deep distress, "some one is ill or hurt; let us go and render assistance."

He saw that she was bent upon it and held out his[Pg 34] hand to help her over the stile. Then when they were in the meadow, and under the hedge, screened from sight by rich, trailing woodbines, they saw the figure of a woman.

"It is a woman, Claude!" cried Hyacinth; and then a faint moan fell on their ears.

Hastening to the spot, she pushed aside the trailing eglantines. There lay a girl, apparently not much older than herself, fair of face, with a profusion of beautiful fair hair lying tangled on the ground. Hyacinth bent over her.

"Are you ill?" she asked. But no answer came from the white lips. "Claude," cried Hyacinth, "she is dying! Make haste; get some help for her!"

"Let us see what is the matter first," he said.

The sound of voices roused the prostrate girl. She sat up, looking wildly around her, and flinging her hair from her face; then she turned to the young girl, who was looking at her with such gentle, wistful compassion.

"Are you ill?" repeated Hyacinth. "Can we do any thing to help you?"

The girl seemed to gather herself together with a convulsive shudder, as though mortal cold had seized her.

"No, I thank you," she said. "I am not ill. I am only dying by inches—dying of misery and bad treatment."

It was such a weary young face that was raised to them. It looked so ghastly, so wretched, in the morning sunlight, that Hyacinth and Claude were both inexpressibly touched. Though she was poorly clad, and her thin, shabby clothes were wet with dew, and stained by the damp grass, still there was something about the girl that spoke of gentle culture.

Claude bent down, looking kindly on the dreary young face.

"There is a remedy for every evil and every wrong," he said; "perhaps we could find one for you."

"There is no remedy and no help for me," she replied; "my troubles will end only when I die."

"Have you been sleeping under this hedge all night?" asked Hyacinth.

"Yes. I have no home, no money, no food. Something seemed to draw me here. I had a notion that I should die here."

Hyacinth's face grew pale; there was something unutterably sad in the contrast between the bright morning and the crouching figure underneath the hedge.

"Are you married?" asked Claude, after a short pause.

"Yes, worse luck for me!" she replied, raising her eyes, with their expression of guilt and misery, to his, "I am married."

"Is your husband ill, or away from you? or what is wrong?" he pursued.

"It is only the same tale thousands have to tell," she replied. "My husband is not ill; he simply drinks all day and all night—drinks every shilling he earns—and when he has drunk himself mad he beats me."

"What a fate!" said Claude. "But there is a remedy—the law interferes to protect wives from such brutality."

"The law cannot do much; it cannot change a man's heart or his nature; it can only imprison him. And then, when he comes out, he is worse than before. Wise women leave the law alone."

"Why not go away from him and leave him?"

"Ah, why not? Only that I have chosen my lot and must abide by it. Though he beats me and ill-treats me, I love him. I could not leave him."

"It was an unfortunate marriage for you, I should suppose," said Hyacinth soothingly. The careworn sufferer looked with her dull, wistful eyes into the girl's beautiful face.

"I was a pretty girl years ago," she said, "fresh, and bright, and pleasing. I lived alone with my mother, and this man who is now my husband came to our town to work. He was tall, handsome, and strong—he pleased my eyes; he was a good mechanic, and made plenty of money—but he drank even then. When he came and asked me to be his wife, my mother said I had better dig my grave with my own hands, and jump into it alive, than marry a man who drank."

She caught her breath with a deep sob.

"I pleased myself," she continued, with a deep sigh; "I had my own way. My mother was not willing for me to marry him, so I ran away with him."

Hyacinth Vaughan's face grew paler.

"You did what?" she asked gently.

"I ran away with him," repeated the woman; "and, if I could speak now with a voice that all the world could hear, I would advise all girls to take warning by me, and rather break their hearts at home than run away from it."

Paler and paler grew the beautiful young face; and then Hyacinth suddenly noticed that one of the woman's[Pg 36] hands lay almost useless on the grass. She raised it gently and saw that it was terribly wounded and bruised. Her heart ached at the sight.

"Does it pain you much?" she inquired.

The woman laughed—a laugh more terrible by far than any words could have been.

"I am used to pain," she said. "I put that hand on my husband's shoulder last night to beg him to stay at home and not to drink any more. He took a thick-knotted stick and beat it; and yet, poor hand, it was not harming him." Hyacinth shuddered. The woman went on, "We had a terrible quarrel last night. He vowed that he would come back in the morning and murder me."

"Then why not go away? Why not seek a safe refuge?"

She laughed again—the terrible, dreary laugh. "He would find me; he will kill me some day. I know it; but I do not care. I should not have run away from him."

"Why not go home again?" asked Hyacinth.

"Ah, no—there is no returning—no undoing—no going back."

Hyacinth raised the poor bruised hand.

"I am afraid it is broken," she said gently. "Let me bind it for you."

She took out her handkerchief; it was a gossamer trifle—fine cambric and lace—quite useless for the purpose required. She turned to Claude and asked for his. The request was a small one, but the whole afterpart of her life was affected by it. She did not notice that Claude's handkerchief was marked with his name in full—"Claude Lennox." She bound carefully the wounded hand.

"Now," she said, "be advised by us; go away—don't let your husband find you."

"Go to London," cried Claude eagerly; "there is always work to be done and money to be earned there. See—I will give you my address. You can write to me; and I will ask my aunt or my mother to give you employment."

He tore a leaf from his pocket-book and wrote on it; "Claude Lennox, 200 Belgrave Square, London."

He looked very handsome, very generous and noble, as he gave the folded note to the woman, with two sovereigns inside it.

"Remember," he said, "that I promise my mother will find you some work if you will apply to us."

She thanked him, but no ray of hope came to her poor[Pg 37] face. She did not seem to think it strange that they were there—that it was unusual at that early hour to see such as they were out in the fields.

"Heaven bless you!" she said gratefully. "A dying woman's blessing will not hurt you."

"You will not die," said Claude cheerily; "you will be all right in time. Do you belong to this part?"

"No," she replied; "we are quite strangers here. I do not even know the name of the place. We were going to walk to Liverpool; my husband thought he should get better wages there."

"Take my advice," said Claude earnestly—"leave him; let him go his own road. Travel to London, and get a decent living for yourself there."

"I will think of it," she said wearily; and then a vague unconsciousness began to steal over her face.

"You are tired," said Hyacinth gently; "lie down and sleep again. Good-by." The birds were singing gayly when they turned to leave her.

"Stay," said Claude; "what is your name?"

"Anna Barratt," she replied; and only Heaven knows whether those were the last words she spoke.

The woman laid her weary head down again as one who would fain rest, and they walked away from her.

"We have done a good deed," said Claude thoughtfully; "saved that poor woman from being murdered, perhaps. I hope she will do what I advised—start for London. If my mother should take a fancy to her, she could easily put her in the way of getting her living."

To his surprise, Hyacinth suddenly took her hand from his, and broke out into a wild fit of weeping.