Title: The Kingdom of Slender Swords

Author: Hallie Erminie Rives

Illustrator: A. B. Wenzell

Release date: March 29, 2013 [eBook #42427]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Edwards, Ernest Schaal, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

By HALLIE ERMINIE RIVES

(Mrs. Post Wheeler)

SATAN SANDERSON

Illustrated by A. B. WenzellTALES FROM DICKENS

Illustrated by Reginald B. BirchTHE CASTAWAY

Illustrated by Howard Chandler ChristyHEARTS COURAGEOUS

Illustrated by A. B. WenzellA FURNACE OF EARTH

THE BOBBS-MERRILL COMPANY

INDIANAPOLIS

THE KINGDOM OF

SLENDER SWORDS

BY

HALLIE ERMINIE RIVES

(Mrs. Post Wheeler)

With a Foreword by His Excellency Baron Makino

ILLUSTRATIONS BY

A. B. WENZELL

INDIANAPOLIS

THE BOBBS-MERRILL COMPANY

PUBLISHERS

Copyright 1910

The Bobbs-Merrill Company

PRESS OF

BRAUNWORTH & CO.

BOOKBINDERS AND PRINTERS

BROOKLYN, N.Y.

TO

CAROLYN FOSTER STICKNEY

It has been my happy fortune to have made the acquaintance of the gifted author of this book. From time to time she was kind enough to confide to me its progress. When the manuscript was completed I was privileged to go over it, and the hours so spent were of unbroken interest and pleasure.

What especially touched and concerned me was, of course, the Japanese characters depicted, the motives of these actors in their respective roles, and other Japanese incidents connected with the story. I am most agreeably impressed with the remarkable insight into, and the just appreciation of, the Japanese spirit displayed by the author.

While the story itself is her creation, the local coloring, the moral atmosphere called in to weave the thread of the tale, are matters belonging to the domain of facts, and constitute an amount of useful and authentic information. Indeed, she has taken unusual pains to be correctly informed about the people of the country and their customs, and in this she has succeeded to a very eminent degree.

I may mention one or two of the striking characteristics of the work. The sacrifice of the girl Haru may seem unreal, but such is the dominant idea of duty and sacrifice with the Japanese, that in certain emergencies it is not at all unlikely that we should behold her real prototype in life. The description of the Imperial Review at Tokyo and its patriotic significance vividly recalls my own impression of this spectacle.

It gives me great satisfaction to know that by perusing these pages, the vast reading public, who, after all, have the decisive voice in the national government of the greatest republic of the world, and whose good will and friendship we Japanese prize in no uncommon degree, should be correctly informed about ourselves, as far as the scope of this book goes. We attach great importance to a thorough mutual understanding of two foremost peoples on the Pacific, in whose direction and coöperation the future of the East must largely depend. It is, therefore, incumbent upon us all to do our utmost to cultivate such good understanding, not only for those immediately concerned, but for the welfare of the whole human race.

In the chapters of this novel the author seems always to have had such high ideals before her, and the result is that, besides being an exciting and agreeable reading, the book contains elements of serious and instructive consideration, which can not but contribute toward establishing better and healthier knowledge between the East and West of the Pacific.

N. Makino.

Sendagaya, Tokyo, 9th of August, 1909.

CHAPTER PAGE

I Where the Day Begins 1

II "The Roost" 13

III The Land of the Gods 27

IV Under the Red Sunset 42

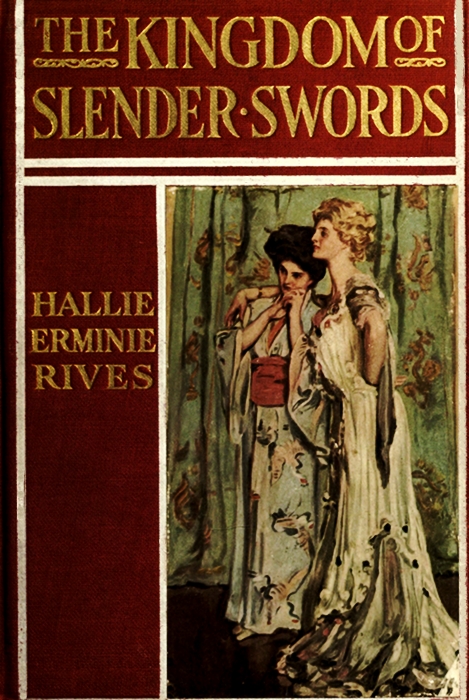

V The Maker of Buddhas 52

VI The Baying of the Wolf-Hound 62

VII Doctor Bersonin 72

VIII "Sally in Our Alley" 78

IX The Web of the Spider 86

X In a Garden of Dreams 92

XI Ishikichi 101

XII In the Street-of-Prayer-to-the-Gods 107

XIII The Whorls of Yellow Dust 113

XIV When Barbara Awoke 119

XV A Face in the Crowd 125

XVI "Banzai Nippon!" 133

XVII A Silent Understanding 142

XVIII In the Bamboo Lane 149

XIX The Bishop Asks a Question 154

XX The Trespasser 160

XXI The Resurrection of the Dead 169

XXII The Dance of the Capital 181

XXIII The Devil Pipes to His Own 194

XXIV A Man Named Ware 198

XXV At the Shrine of the Fox-God 206

XXVI The Nightless City 213

XXVII Like the Whisper of a Bat's Wings 224

XXVIII The Forgotten Man 233

XXIX Daunt Listens to a Song 244

XXX The Island of Enchantment 252

XXXI The Coming of Austen Ware 266

XXXII The Woman of Sorek 276

XXXIII The Flight 284

XXXIV On the Knees of Delilah 288

XXXV When a Woman Dreams 292

XXXVI Behind the Shikiri 297

XXXVII ドント 303

XXXVIII The Lady of the Many-Colored Fires 308

XXXIX The Heart of Barbara 320

XL The Shadow of a To-Morrow 326

XLI Unforgot 334

XLII Phil Makes an Appeal 338

XLIII The Secret the River Kept 345

XLIV The Laying of the Mine 353

XLV The Bishop Answers a Summons 360

XLVI The Golden Crucifix 366

XLVII "If This Be Forgetting" 371

XLVIII While the City Slept 379

XLIX The Alarm 389

L Whom the Gods Destroy 396

LI The Laugh 401

LII The Voice in the Dark 409

LIII A Race with Dawn 414

LIV Into the Sunlight 425

LV Know All Men By These Presents 428

THE KINGDOM

OF SLENDER SWORDS

THE KINGDOM

OF SLENDER SWORDS

Barbara leaned against the palpitant rail, the light air fanning her breeze-cool cheek, her arteries beating like tiny drums, atune with the throb, throb, throb, of the steel deck as the black ocean leviathan swept on toward its harbor resting-place.

All that Japanese April day she had been in a state of tremulous excitement. She had crept from her berth at dawn to see the hazy sun come up in a Rosicrucian flush as weirdly soft as a mirage, to strain her eyes for the first filmy feather of land. Long before the gray-green wisp showed on the horizon, the sight of a lumbering junk with its square sail laced across with white stripes, and its bronze seamen, with white loin-cloth and sweat-band about the forehead, naked and thewed like sculptures, as they swayed from the clumsy tiller, had sent a thrill through her. And as the first far peaks etched themselves on the robin's-egg blue, as impalpable [pg 2] and ethereal as a perfume, she felt warm drops coming with a rush to her eyes.

For Japan, every sight and sound of it, had been woven with the earliest imaginings of Barbara's orphaned life. Her father she had never seen. Her mother she remembered only as a vague, widowed figure. In Japan they two had met and had married, and after a single year her mother had returned to her own place and people broken-hearted and alone. In the month of her return Barbara had been born. A year ago her aunt, to whom she owed the care of her young girlhood, had died, and Barbara had found herself, at twenty-three, mistress of a liberal fortune and of her own future. Japan had always exercised a potent spell over her imagination. She pictured it as a land of strange glowing trees, of queer costumes and weird, fantastic buildings. More than all, it was the land of her mother's life-romance, where her father had loved and died. There was one other tangible tie—her uncle, her mother's brother, was Episcopal bishop of Tokyo. He was returning now from a half year's visit in America, and this fact, coupled with an invitation from Patricia Dandridge, the daughter of the American Ambassador, with whom Barbara had chummed one California winter, had constituted an opportunity wholly alluring. So she found herself, on this April day, the pallid Pacific fuming away behind her, gazing with kindling cheeks on [pg 3] that shadowy background, vaguely intangible in the magical limpidity of the distance.

The land was wonderfully nearer now. The hills lay, a clear pile of washed grays and greens, with saffron tinted valleys between, wound in a haze of tender lilac. By imperceptible gradations this unfolded, caught sub-tones, ermine against umbers, of warmer red and flickering emerald, white glints of sun on surf like splashes of silver, till suddenly, spectral and perfect, above a cluster of peaks like purple gentians, glowed forth a phantom mountain, its golden wistaria cone inlaid in the deeper azure. It hung like an inverted morning-glory, mist and mother-of-pearl at the top, shading into porphyry veined with streaks of verd and jade—Fuji-San, the despair of painters, the birthplace of the ancient gods.

The aching beauty of it stung Barbara with a tender, intolerable pang. The little fishing-villages that presently came into sight, tucked into the clefts of the shore, with gray dwellings, elfishly frail, climbing the green slope behind them—the growing rice in patches of cloudy gold on the hillsides—the bluish shadows of bamboo groves—all touched her with an incommunicable delight.

A shadow fell beside her and she turned. It was her uncle. His clean-shaven face beamed at her over his clerical collar.

"Isn't it glorious?" she breathed. "It's better [pg 4] than champagne! It's like pins and needles in the tips of your fingers! There's positively an odor in the air like camelias. And did any one ever see such colors?" She pointed to the shore dead-ahead, now a serrated background of deep tones, swimming in the infinite gold of the tropic afternoon.

Bishop Randolph was a bachelor, past middle age, ruddy and with eyes softened by habitual good-humor. He was the son of a rector of a rich Virginian parish, which on his father's death had sent the son a unanimous call. He had answered, "No; my place is in Japan," without consciousness of sacrifice. For him, in the truest sense, the present voyage was a homeward one.

"Japan gets into the blood," he said musingly. "I often think of the old lady who committed suicide at Nikko. She left a letter which said: 'By favor of the gods, I am too dishonorably old to hope to revisit this jewel-glorious spot, so I prefer augustly to remain here for ever!' I have had something of the same feeling, sometimes. I remember yet the first time I saw the coast. That was twenty-five years ago. We watched it together—your father and I—just as we two are doing now."

She looked at him with sudden eagerness, for of his own accord he had never before spoken to her of her dead father. The latter had always seemed a very real personage, but how little she knew about him! The aunt who had brought her up—her [pg 5] mother's sister—had never talked of him, and her uncle she had seen but twice since she had been old enough to wonder. But, little by little, gleaning a fact here and there, she had constructed a slender history of him. It told of mingled blood, a birthplace on a Mediterranean island and a gipsy childhood. There was a thin sheaf of yellowed manuscript in her possession that had been left among her mother's scanty papers, a fragment of an old diary of his. Many leaves had been ruthlessly cut from it, but in the pages that were left she had found bits of flotsam: broken memory-pictures of his own mother which had strangely touched her, of a bitter youth in England and America overshadowed by the haunting fear of blindness, of quests to West-Indian cities, told in phrases that dripped liquid gold and sunshine. The voyage to Japan had been made on the same vessel that carried her uncle, and they two had thus become comrades. The latter had been an enthusiastic young missionary, one of a few chosen spirits sent to defend a far field-casement thrown forward by the batteries of Christendom. His sister had come out to visit him and a few months later had married his friend.

Such was the story, as Barbara knew it, of her father and mother—a love chapter which had soon closed with a far-away grave by the Inland Sea. Her fancy had made of her father a pathetic figure. As a child, she had dreamed of some day placing a [pg 6] monument to his memory in the Japanese capital. She possessed only one picture of him, a tiny profile photograph which she wore always in a locket engraved with her name. It showed a dark face, clean-shaven, finely chiseled and passionate, with the large, full eye of the dreamer. She had liked to think it looked like the paintings of St. John. Perhaps this thought had caused the projected monument to take the form of a Christian chapel. From a nebulous idea, the plan had become a bundle of blue-prints, which she had sent to her uncle, with the request that he purchase for her a suitable site and begin the building. He had done this before his visit to America and now the Chapel was completed, save in one particular—the memorial window of rich, stained-glass stowed at that moment in the ship's hold. The bishop had not seen it. From some feeling which she had not tried to analyze, Barbara had said nothing to him of the Chapel's especial significance. Now, however, at his unexpected reference, the feeling frayed, and she told him all of her plan.

He gazed at her a moment in a startled fashion, then looked away, his hand shading his eyes. When she finished there was a long pause which made her wonder. She touched his arm.

"You were very fond of father, weren't you?"

"Yes," he said, in a tone oddly restrained.

[pg 7] "And was my mother with you when he fell in love with her?"

"Yes," and after a pause: "I married them."

"Then they went to Nagasaki," she said softly, "and there—he died. You weren't there then?"

"No," he answered in a low voice. His face was still turned away, and she caught an unaccustomed note of feeling in his voice.

He left her abruptly and began to pace up and down the deck, while she stood watching the shoreline sharpen, the tangled blur of harbor resolve and shift into manifold detail. Shapeless dots had become anchored ships, a black pencil a wharf, a long yellow-gray streak a curved shore-front lined with buildings, and the warm green blotch rising behind it a foliaged hill pricked out with soft, gray roofs. There was a rush of passengers to one side, where from a brisk little tug, at whose peak floated a flag bearing a blood-red sun, a handful of spick-and-span Japanese officials were climbing the ship's ladder.

At length the bishop spoke again at her elbow, now in his usual voice: "What are you going to do with that man, Barbara?"

A faint flush rose in her cheek. "With what man?"

"Austen Ware."

She shrugged her shoulders and laughed—a little [pg 8] uneasily. "What can one do with a man when he is ten thousand miles away?"

"He's not the sort to give up a chase."

"Even a wild-goose chase?" she countered.

"When I was a boy in Virginia," he said with a humorous eye, "I used to chase wild geese, and bag 'em, too."

The bishop sauntered away, leaving a frown on Barbara's brow. She had had a swift mental vision of a cool, dark-bearded face and assured bearing that the past year had made familiar. It was a handsome face, if somewhat cold. Its owner was rich, his standing was unquestioned. The fact that he was ten years her senior had but made his attentions the more flattering. He had had no inherited fortune and had been no idler; for this she admired him. If she had not thrilled to his declaration, so far as liking went, she liked him. The week she left New York he had intended a yachting trip to the Mediterranean. When he told her, coolly enough, that he should ask her again in Japan, she had treated it as a jest, though knowing him quite capable of meaning it. From every worldly standpoint he was distinctly eligible. Every one who knew them both confidently expected her to marry Ware. Well, why not?

Yet to-day she did not ask herself the question confidently. It belonged still to the limbo of the future—to the convenient "some day" to which her [pg 9] thought had always banished it. Since she had grown she had never felt for any one the sentiment she had dreamed of in that vivid girlhood of hers, a something mixed of pride and joy, that a sound or touch would thrill with a delight as keen as pain; but unconsciously, perhaps, she had been clinging to old romantic notions.

A passenger leaning near her was whistling Sally in our Alley under his breath and a Japanese steward was emptying over the side a vase of wilted flowers. A breath of rose scent came to her, mixed with a faint smell of tobacco, and these and the whistled air awoke a sudden reminiscence. Her gaze went past the clustered shipping, beyond the gray line of buildings and the masses of foliage, and swam into a tremulous June evening seven years past.

She saw a wide campus of green sward studded with stately elms festooned with electric lights that glowed in the falling twilight. Scattered about were groups of benches each with its freight of dainty frocks, and on one of them she saw herself sitting, a shy girl of sixteen, on her first visit to a great university. Men went by in sober black gown and flat mortar-boards, young, clean-shaven, and boyish, with arms about one another's shoulders. Here and there an orange "blazer" made a vivid splash of color and groups in white-flannels sprawled beneath the trees under the perfumed haze [pg 10] of briar-wood pipes that mingled with the near-by scent of roses. From one of the balconies of the ivied dormitories that faced the green came the mellow tinkle of a mandolin and the sound of a clear tenor:

The groups about her had fallen silent—only one voice had said: "That's 'Duke' Daunt." Then the melody suddenly broke queerly and stopped, and the man who had spoken got up quickly and said: "I'm going in. It's time to dress anyway." And somehow his voice had seemed to break queerly, too.

Duke Daunt! The scene shifted into the next day, when she had met him for a handful of delirious moments. For how long afterward had he remained her childish idol! Time had overlaid the memory, but it started bright now at the sound of that whistled tune.

Her uncle's voice recalled her. He was handing her his binoculars. She took them, chose a spot well forward and glued her eyes to the glass.

A sigh of ecstasy came from her lips, for it brought the land almost at arm's length—the stone hatoba crowded with brown Japanese faces, pricked out here and there by the white Panama hat or pith-helmet of the foreigner; at one side a bouquet of gay [pg 11] muslin dresses and beribboned parasols flanked by a phalanx of waiting rick'sha,—the little flotilla of crimson sails at the yacht anchorage—the stately, columned front of the club on the Bund with its cool terrace of round tables—the kimono'd figures squatting under the grotesquely bent pines along the water-front, where a motor-car flashed like a brilliant mailed beetle—farther away tiny shop-fronts hung with waving figured blue and beyond them a gray billowing of tiled roofs, and long, bright, yellow-chequered streets sauntering toward a mass of glowing green from which cherry blooms soared like pink balloons. Arching over all the enormous height of the spring-time blue, and the dreamy soft witchery of the declining sun. It unfolded before her like a panorama—all the basking, many-hued, polyglot, half-tropical life—a colorful medley, queer and mysterious!

Nearer, nearer yet, the ship drew on, till there came to meet it two curved arms of breakwater, a miniature lighthouse at each side. The captain on the bridge lifted his hand, and a cheer rose from the group of male passengers below him as the anchor-chain snored through the hawse-holes.

Barbara lowered the glass from her eyes. The slow swinging of the vessel to the anchor had brought a dazzling bulk between her gaze and the shore, perilously near. She saw it now in its proper perspective—a trim steam yacht, painted white, with [pg 12] a rakish air of speed and tautness, the sun glinting from its polished brass fittings. It lay there, graceful and light, a sharp, clean contrast to the gray and yellow junk and grotesque sampan, a disdainful swan amid a noisy flock of teal and mallard.

Adjusting the focus Barbara looked. A man in naval uniform who had boarded the ship at Quarantine was pointing out the yacht to a passenger, and Barbara caught crisp bits of sentences: "You see the patches of green?—they're decorations for the Squadron that's due to-morrow. Look just beyond them. Prettiest craft I've ever seen east of the Straits.... Came in this morning. Owner's in Nara now, doing the temples.... Has a younger brother who's been out here for a year, going the pace.... They won't let private yachts lie any closer in or they'd go high and dry on empty champagne bottles."

Barbara was feeling a strange sensation of familiarity. Puzzled, she withdrew her gaze, then looked once more.

Suddenly she dropped the glass with a startled exclamation. "What are you going to do with that man?"—her uncle's query seemed to echo satirically about her. For the white yacht was Austen Ware's, and there, on the gleaming bows, in polished golden letters, was the name

BARBARA

The day had been sluggish with the promise of summer, but the failing afternoon had brought a soft suspiration from the broad bosom of the Pacific laden with a refreshing coolness. Along the Bund, however, there was little stir. A few blocks away the foreign dive-quarter was drowsing, and only a single samisen twanged in Hep Goon's saloon, where sailors of a dozen nationalities spent their wages while in port. At the curbing, under the telegraph poles, the chattering rick'sha coolies squatted, playing Go with flat stones on a square scratched with a pointed stick in the hard, beaten ground. On the spotless mats behind their paper shoji the curio-merchants sat on their gaudy wadded cushions, while, over the glowing fire-bowls of charcoal in the inner rooms, their wives cooked the rice for the early evening meal. The office of the Grand Hotel was quiet; only a handful of loungers gossiped at the bar, and the last young lady tourist had finished her flirtation on the terrace and retired to the comfort of a stayless kimono. In the deep foliage of the "Bluff" the slanting sunlight [pg 14] caught and quivered till the green mole seemed a mighty beryl, and in its hedge-shaded lanes, dreamy as those of an English village, the clear air was pungent with tropic blooms.

On one of these fragrant byways, its front looking out across the bay, stood a small bungalow which bore over its gateway the dubious appellation "The Roost." From its enclosed piazza, over which a wistaria vine hung pale pendants, a twisted stair led to the roof, half of which was flat. This space was surrounded by a balustrade and shaded by a rounded gaily striped awning. From this airy retreat the water, far below, looked like a violet shawl edged with shimmering quicksilver and embroidered with fairy fishing junk and sampan; and the subdued voices of the street mingled, vague and undefined, with a rich dank smell of foliage, that moved silently, heavy with the odor of plum-blossoms, a gliding ghost of perfume. Thin blue-and-white Tientsin rugs and green wicker settees gave an impression of coolness and comfort; a pair of ornate temple brasses gleamed on a smoking-stand, and a rich Satsuma bowl did duty for a tobacco jar.

Under the striped awning three men were grouped about a miniature roulette table; a fourth, middle-aged and of huge bulk, with a cynical, Semitic face, from a wide arm-chair was lazily peering through the fleecy curdle of a Turkish cigarette. A fifth stood leaning against the balustrade, watching.

[pg 15] The last was tall, clean-cut and smooth-shaven, with comely head well set on broad shoulders, and gray eyes keen and alert. Possibly no one of the foreign colony (where a Secretary of Embassy was by no means a rara avis) was better liked than Duke Daunt, even by those who never attempted to be sufficiently familiar with him to call him by the nickname, which a characteristic manner had earned him in his salad days.

At intervals a player muttered an impatient exclamation or gave a monosyllabic order to the stolid Japanese servant who passed noiselessly, deftly replenishing glasses. Through all ran the droning buzz of bees in the wistaria, the recurrent rustle of the metal wheel, the nervous click of the rolling marble and the shuffle and thud of the ivory disks on the green baize. All at once the marble blundered into its compartment and one of the gamesters burst into a boisterous laugh of triumph.

As the sudden discord jangled across the silence, the big man in the arm-chair started half round, his lips twitched and a spasm of something like fright crossed his face. The glass at his elbow was empty, but he raised it and drained air, while the ice in it tinkled and clinked. He set it down and wiped his lips with a half-furtive glance about him, but the curious agitation had apparently been unnoted, and presently his face had once more regained its speculative, slightly sardonic expression.

[pg 16] Suddenly a distant gun boomed the hour of sunset. At the same instant the marble ceased its erratic career, the wheel stilled and the youngest of the gaming trio and the master of the place—Philip Ware, a graceful, shapely fellow of twenty-three, with a flushed face and nervous manner—pushed the scattered counters across the table with shaking fingers.

"My limit to-day," he said with sullen petulance, and flipping the marble angrily into the garden below, crossed to a table and poured out a brandy-and-soda.

Daunt's gray eyes had been looking at him steadily, a little curiously. He had known him seven years before at college, though the other had been in a lower class than himself. But those intervening years had left their baleful marks. At home Phil had stood only for loose habit, daring fad, and flaunting mannerism—milestones of a career as completely dissolute as a consistent disregard of conventional moral thoroughfares could well make it. To Yokohama he was rapidly coming to be, in the eyes of the censorious, an example for well-meaning youth to avoid, an incorrigible flanêur, a purposeless idler on the primrose paths.

"Better luck next time," said one of the others lightly. "Come along, Larry; we'll be off to the club."

The older man rose to depart more deliberately, [pg 17] his great size becoming apparent. He was framed like a wrestler, abnormal width of shoulder and massive head giving an effect of weight which contrasted oddly with aquiline features in which was a touch of the accipitrine, something ironic and sinister, like a vulture. His eyes were dappled yellow and deep-set and had a peculiar expression of cold, untroubled regard. He crossed to the farther side and looked down.

"What a height!" he said. "The whole harbor is laid out like a checker-board." He spoke in a tone curiously dead and lacking in timbre. His English was perfect, with a trace of accent.

"Pretty fair," assented Phil morosely. "It ought to be a good place to view the Squadron, when it comes in to-morrow morning. It must have cost the Japanese navy department a pretty penny to build those temporary wharves along the Bund. They must be using a thousand incandescents! By the decorations you'd think the Dreadnaughts were Japan's long lost brothers, instead of battle-ships of a country that's likely to have a row on with her almost any minute. I wonder where they will anchor."

The yellowish eyes had been gazing with an odd, intent glitter, and into the heavy, pallid face, turned away, had sprung sharp, evil lines, that seemed the shadows of some monstrous reflection on which the mind had fed. Its sudden, wicked vitality was in [pg 18] strange contrast to the toneless voice, which now said: "They will lie just opposite this point."

"So far in?" The young man leaning on the balustrade spoke interestedly.

"It seems as though from here one could almost shoot a pea aboard any one of them."

"You might send me up some sticks of Shimosé, Doctor," said Phil with satiric humor, "and I'll practise. I'll begin by shying a few at this forsaken town; it needs it!"

The big man smiled faintly as he withdrew his eyes, and held out his hand to the remaining visitor. The degrading lines had faded from his face.

"I'm distinctly glad to have seen you, Mr. Daunt," he said. "I've watched your trials with your aëroplane more than once lately at the parade-ground. I saw the elder Wright at Paris last year and I believe your flight will prove as well sustained as his. It's a pity you can't compete for some of the European prizes."

"I'm afraid that would take me out of the amateur class," was the answer. "It's purely an amusement with me—a fad, if you like."

"A very useful one," said the other, "unless you break your neck at it. I wonder we haven't met before in Tokyo. I have an appointment to-night, by the way, with your Ambassador. Come in to see me soon," he said, turning to Phil. "I'm at home most of the time. Come and dine with me again. [pg 19] I've only an indifferent cook, as you have discovered, I'm afraid, but my new boy Ishida can make a famous cup of coffee and I can always promise you a good cigar."

"Doctor Bersonin's the real thing!" said Phil, when the other had disappeared. "He's a scientist—the biggest in his line—but he's no prig. He believes in enjoying life. You ought to see his villa at Kisaraz on the Chiba Road. He's worth a million, they say, and he must make no end of money as a government expert." He paused, then added: "You seem mighty quiet to-night! How does he strike you?"

Daunt was silent. He had seen that strange look that had shot across the expert's face—at the sound of a laugh! He was wondering, too, what attraction could exist between this middle-aged scientist with his cold eyes and emotionless voice and Phil, sparkling and irresponsible black-sheep and ne'er-do-well, who thought of nothing but his own coarse pleasures. Frequently, of late, he had seen them together, at theater or tea-house, and once in Bersonin's motor-car in Shiba Park in Tokyo.

"You don't like him! I can see that well enough," went on Phil aggressively. "Why not? He's a lot above any man I know, and I'm proud to have him for a friend of mine."

"There's no accounting for tastes," returned Daunt dryly. "At any rate, I don't imagine it matters [pg 20] particularly whether I like Doctor Bersonin or not. There's another thing that's more apropos." He pointed to the decanter in the other's hands. "You've had enough of that to-night, I should think."

Phil reddened. "I've had no more than I can carry, if it comes to that," he retorted. "And I guess I'm able to take care of myself."

Daunt hesitated a moment. To-day's call had been a part of his consistent effort, steadily growing more irksome, to keep alive for the sake of the old college name, the quasi friendship between them and to invoke whatever influence he might once have possessed.

"I'm thinking of your brother," he said quietly. "You say his yacht came into harbor from Kobe to-day. He'll scarcely be more than a week in the temple cities, and any train may bring him after that. You'll want all the time you've got to straighten out. You'll need to put your best foot forward."

A look that was not pleasant shot across Phil's face. "I suppose I shall," he said savagely. "A pretty brother he is! He wrote me from home that if he found I'd been playing, he'd cut his allowance to me to twenty dollars a week. I'd like to knock that smile of his down his throat—the cold-blooded fish! He spends enough!"

"He's earned it, I understand," said Daunt.

[pg 21] "So will I, perhaps, after I've had my fling. I'm in no hurry, and I won't take orders always from him! I've had to knuckle down to him all my life, and I'm precious tired of it, I can tell you."

Daunt's eyes had turned to the broad expanse below, where the white sails of vagrant sampan drifted. In the road he could hear the sharp tap-tap of a blind amma—adept in the Japanese massage which coaxes soreness from the body—as he passed slowly along, feeling his way with his stick and from time to time sounding on his metal flute his characteristic double note. Across the moment's silence the sound came clear and bird-like, very shrill and sweet.

"What business is it of his," Phil added, "if I choose to stay out here in the East?"

Daunt withdrew his gaze. "Take his advice, Phil," he said. "The East isn't doing you any good. You're doing nothing but dissipate. And—it doesn't pay."

Phil gave a short, sneering laugh. "Why shouldn't I stay abroad if I can have more fun here than I can at home?" he returned. "If I had my way, I'd never want to see the United States again! This country suits me at present. When I get tired, I'll leave—if I can raise enough to get out of town."

A flush had risen to Daunt's forehead, but he turned away without reply. At the stair, however, he spoke again:

[pg 22] "Look here, Phil," he said, coming slowly back. "Why not come up to Tokyo for a while? It's—quieter, and it will be a change. I have a little Japanese house in Aoyama that I leased as a place to work on my Glider models, but I don't use it now, and it's fairly well furnished. The caretaker is an excellent cook, too." He took a key from its ring and laid it on the table. "Let me leave this anyway—the address is on the label—and do as you like about it."

Phil looked at him an instant with narrowing eyes, then laughed. "Tokyo as a gentle sedative, eh? And pastoral visitations every other day!"

"You needn't be afraid of that," replied Daunt. "I'll not come to lecture you. I haven't set foot in the place for a month, and probably shan't for a month to come. Go up and try it, anyway. Drop the Bund and the races for a little while and get a grip on things!"

Phil looked away. A sudden memory came to him of a face he had seen in Tokyo—at one of the matsuri or ward-festivals—a girl's face, oval and pensive and with a smile like a flash of sunlight. Her kimono had been all of holiday colors, and he had tried desperately to pick acquaintance, with poor success. A second time he had seen her, on the beach at Kamakura. Then she had worn a kimono of rich brown, soft and clinging, and an obi stamped with yellow maple leaves and fastened with a little [pg 23] silver clasp in the shape of a firefly. She was with a party of girls bent on frolic; they had discarded the white cleft tabi and clog and were splashing through the surf bare-kneed. He could see yet the foam on the perfect naked feet, and below the lifted kimono and red petticoat, the gleam of the white skin that is the dream of Japanese women. A flush crept over Phil's face as he remembered. He had had better success that time. She had dropped her swinging clog and he had rescued it, and won a word of thanks and a smile from her dark eyes. She herself had unbent little, but the girls with her were full of frolic and the handsome foreigner was an adventure. He had discovered that she spoke English and lived in Tokyo, in the ward of the matsuri. But though he had strolled through that district a score of times since, he had not seen her again.

"You're not a bad sort, Daunt," he said. "I don't know but I—will."

"Good," said Daunt. "I'll send a chit to my caretaker the first thing in the morning, and I'll put your name on the visitors' list at the Tokyo Club. Well, I must be off."

Phil saw him cross the fragrant close to the gate with a growing sneer. Then he threw himself on a chair and gazed moodily out across the deepening haze to where, just inside the harbor breakwater, [pg 24] lay the white yacht of whose coming Daunt had spoken.

A bitter scowl was on his face. Far below, at a little wharf, he could see a tiny red triangle; it marked his sail-boat, the Fatted-Calf, so christened at a tea-house on the river where he and other choice spirits maintained the club whose geisha suppers had become notorious. Japan, to his way of life, had proven expensive. He had drawn on every available resource and had borrowed more than he liked to remember, but still his debts had grown. And now, with the coming of the white yacht, he saw a lowering danger to the allowance on which he abjectly depended. He knew his brother for one whom no plea could sway from a determination, who on occasion could hew to the line with merciless exactitude. Suppose he should cut off his allowance altogether. An ugly passion stole over his countenance. He sprang up, filled a glass from the decanter and drank it thirstily. With the instant glow of the liquor his mood relaxed. He picked up the key from the table and stood thoughtfully swinging it a moment by its wooden label. Then he put it in his pocket and, looking at his watch, caught up a straw hat and went briskly down to the street.

He swung down the steep, twisting, ravine-like road to the Bund with less of ill-humor. He had no thought of the dark blue sky arching over, soft with [pg 25] vapors like a smoke of gold, or of the glimpses of the sea that came in sharp bursts of light between the curving walls that towered on either side. He sniffed the thick, Eastern smells as a cat sniffs catnip, his eye searching the stream of brown, shouting coolies and toiling rick'sha, to linger on a satiny oval face under a shining head-dress, or the powdered cheek of a gold-brocaded geisha on her way to some noble's feast.

At the foot of the hill, stood a sign-board on which was pasted a large bill in yellow:

AT THE GAIETY THEATER

LIMITED ENGAGEMENT OF

THE POPULAR HARDMANN COMIC OPERA COMPANY

WITH

MISS CISSY CLIFFORD

He paused in front of this a moment, then passed to the Bund. At its upper end, near the hotel front, great floating wharves had been built out into the water. They were gaily trimmed with bunting and electric lights in geometrical designs, and were flanked by arches covered with twigs of ground-pine. A small army of workmen were still busied on them, for the European Squadron in whose honor they had been erected would arrive at dawn the next morning. Just beyond the arches, under a row of twisted pines, were a number of park benches, [pg 26] and from one of these a girl with a beribboned parasol greeted him.

"You're a half hour late, Phil," she complained. "I've been waiting here till I'm tired to death." She made place for him with a rustle of flounces. She was showily dressed, her cheeks bore the marks of habitual grease-paint and the fingers of one over-ringed hand were slightly yellowed from cigarette smoke.

"Hello, Cissy," he said carelessly, and sat down beside her. In his mind was still the picture of that oval Japanese face suffused with pink, those pretty bare feet splashing through the foam, and he looked sidewise at his companion with an instant's sullen distaste.

"I had another row with the manager to-day," she continued. "I told him he must think his company was a kindergarten!"

"Trust you to set him right in that," he answered satirically.

"My word!" she exclaimed. "How glum you are to-day! Same old poverty, I suppose." She rose and shook out her skirts. "Come," she said. "There's no play to-night. I'm in for a lark. Let's go to the Jewel-Fountain Tea-House. They've got a new juggler there."

In the first touch of the shore, where the Ambassador's pretty daughter waited, Barbara's problem had been swept away. Patricia had rushed to meet her, embraced her, with a moist, ecstatic kiss on her cheek, rescued the bishop from his ordeal of hand-shaking and carried him off to find their trunks, leaving Barbara borne down by a Babel of sound and scent whose newness made her breathless, and to whose manifold sensations she was as keenly alive as a photographic plate to color.

A half-dozen gnarled, unshaven porters in excessively shabby jackets and straw sandals carried her hand-baggage into the hideously modern, red-brick custom-house, over whose entrance a huge golden conventionalized chrysanthemum shone in the sunlight, and as she watched them, a dapper youth in European dress, with a shining brown derby, a bright purple neck-tie, a silver-mounted cane and teeth eloquent of gold bridge-work, slid into her hand a card whose type proclaimed that Mr. Y. Nakajima "did the guiding for foreign ladies and gentlemans." The air was fragrant with the mild [pg 28] aroma from tiny Japanese pipes and a-flutter with moving fans. A group of elderly men in hot frock-coats and tiles of not too modern vintage were welcoming a returning official, and sedate gentlemen in sad-colored houri and spotless cleft foot-wear, bowed double in stately ceremonial, with the sucking-in of breath which in the old-fashioned Japanese etiquette means "respectful awe bordering on terror."

Barbara had found herself singularly conscious of a feeling of universal good-nature. It came to her even in the posture of the resting coolies, stretched at the side of the quay, lazily sunning themselves, with whiffs of the omnipresent little pipe, and in the faces of the bare-legged rick'sha men, with round hats like bobbing mushrooms, arms and chests glistening with sweat, and thin towels printed in black and blue designs tucked in their girdles. She smiled at them, and they smiled back at her with that unvarying smile which the Japanese of every caste wears to wedding and to funeral. She even caught herself patting the tonsured head of a preternaturally solemn baby swaddled in a variegated kimono and strapped to the back of a five-year-old boy.

The rick'sha ride to the stenshun (for so the Japanese has adapted the English word "station") was a moving panorama of strange high lights and shades, of savory odors from bake-ovens, of open [pg 29] shop-fronts hung with gaudy figured crape, or piled with saffron biwa, warty purple melons, ebony eggplant, shriveled yellow peppers and red Hokkaido apples, of weighted carts drawn by chanting half-naked coolies, and swiftly gliding victorias of Europeans. From a hundred houses in the long, narrow streets hung huge gilded sign-boards, painted with idiographs of black and red. At intervals the tall stone front of a foreign business building looked down on its neighbors, or a tea-house towered three stories high, showing gay little verandas on which stood pots of flowers and dwarf trees; between were smaller houses of frame and of cement, and thick-walled go-downs for storing goods against fire.

Here and there, from behind a gateway of unpainted wood, showing a delicate grain, a pine thrust up its needled clump of green, or a cherry-tree flung its pink pyrotechnics against the sky's flood of dimming blue and gold. At a crossing a deformed beggar with distorted face and the featureless look of the leper, waved a crutch and wheedled from the roadside, and a child in dun-colored rags, unbelievably agile and dirty, ran ahead of Barbara's rick'sha, prostrating himself again and again in the dust, holding out grimy hands and whining for a sen. In the side streets Barbara could catch glimpses of bare-breasted women sitting in shop doors nursing babies, and [pg 30] children of a larger growth playing Japanese hopscotch or tossing "diavolo," the latest foreign toy.

When the rick'sha set them down at the station she felt bewildered, yet full of exhilaration. As they drew up at its stone front, a porter with red cap and brass buttons emerged and began to ring a heavy bell, swinging it back and forth in both hands. The bishop bought their tickets at a little barred window bearing over it the sign: "Your baggages will be sent freely in every direction."

Making their way along the platform, crowded with Japanese, mostly in native dress, and filled with the aroma of cigarettes and the thin ringing of innumerable wooden clogs on stone flags, Barbara was conscious for the first time of a studious surveillance. A young Japanese passed her carrying his bent and wizened mother on his back; the old woman, clutching him tightly about the neck, turned her shaven head to watch. Children in startling rainbow tinted kimono stared from the platform with round, serious eyes. A peasant woman, with teeth brilliantly blackened, peered from a car window, and a group of young men turned bodily and regarded her with gravely observant gaze, in a prolonged, unwinking scrutiny that seemed as innocent of courtesy as of any intent to offend. In European cities she had felt the gaze of other races, but this was different. It was not the curious study of a phenomenon, of an enduring puzzle of far origins, [pg 31] nor the expression of the ignorant, vacantly amused by what they do not understand; it was a deeper look of inner placidity, that held no wonder and no awe, and somehow suggested thoughts as ancient as the world. A curious sense began to possess Barbara of having left behind her all familiar every-day things, of being face to face with some new wonder, some brooding mystery which she could not grasp.

They entered the car just behind an ample lady who had been among the ship's passengers—a good-natured, voluble Cook's tourist who, the second day out, had confided to Barbara her certainty of an invitation to the Imperial Cherry-Blossom party, as her husband had "a friend in the litigation." She wore a painted-muslin, and the husband of influential acquaintance and substantial, red-bearded person showed now a gleaming expanse of white waistcoat crossed by a gold watch-chain that might have restrained a tiger. The lady nodded and smiled beamingly.

"Isn't it all perfectly splendid!" she cried. "There was a baby on the platform that was too sweet!—for all the world like the Japanese dolls we buy at home, with their hair shingled and a little round spot shaved right in the crown! My husband tried to give it a silver dollar, but the mother just smiled and bowed and went away and left it lying on the bench." She found a seat and fanned herself [pg 32] vigorously with a handkerchief. "I just thought I never would get through that car door," she added. "It's only two feet across!"

The road was narrow gage and the seats ran the length of the car on either side. Hardly had its occupants settled themselves when, to the shrill piping of a horn, the train started.

"Goodness, this is a relief!" sighed Patricia, as the bishop opened the first Japanese newspaper he had seen for many months. "I hate rick'sha—they're such unsociable things! I haven't said ten words to you, Barbara, and I've got oceans to talk about. But I'll be merciful till I get you home. What a good-looking youth that is in the corner!"

The young man referred to had a light skin and long, almond-shaped eyes. He wore a suit of gray merino underwear, and between the end of the drawers and the white, cleft sock, an inch of polished skin was visible. His hat was a modish felt. His houri, which bore a woven crest on breast and sleeves, swung jauntily open and above his left ear was coquettishly disposed an unlighted cigarette. Next him, under a brass rack piled with bright-patterned carpet-bags, an old lady in dove-colored silk was placidly inflating a rubber air-cushion. Her face had an artificial delicacy of nuance that was a triumph of rice-powder and rouge. Beside her was a girl of perhaps eighteen, in a kimono of dark blue and an obi of gold brocade. The latter wore white [pg 33] silk "mits" with bright metal trimming and on one slender finger was a diamond ring. Her hands were delicately artistic and expressive, and her complexion as soft as the white wing of a miller. She gazed steadfastly away, but now and then her sloe-black eyes returned to study Barbara's foreign gown and hat with surreptitious attention.

"What complexions!" whispered Patricia. "The old lady made hers this morning, sitting flat on a white mat in front of a camphor-wood dressing-chest about two feet high, with twenty drawers and a round steel mirror on top. It beats a hare's-foot, doesn't it! The daughter's is natural. If I had been born with a skin like that, it would have changed my whole disposition!"

Having settled her air-cushion, the old lady drew from her girdle a lacquer case and produced a pipe—a thin reed with a tiny silver bowl at its end. A flat box yielded a pinch of tobacco as fine as snuff. This she rolled between her fingers into a ball the size of a small pea, placed it carefully in the bowl and began to smoke. Each puff she inhaled with a lingering inspiration and emitted it slowly, in a thin curdled cloud, from her nostrils. Three puffs, and the tiny coal was exhausted. She tapped the pipe gently against the edge of the seat, put it back into the case and replaced the latter in her girdle. Then, tucking up her feet under her on the plush seat, she turned her back to the aisle and went to sleep.

[pg 34] Three students in the uniform of some lower school with foreign jackets of blue-black cloth set off with brass buttons, sat in a row on the opposite side. Each had a cap like a cadet's, with a gilt cherry-blossom on its front, and all watched Barbara movelessly. The man nearest her wore a round straw hat and horn spectacles. He was reading a vernacular newspaper, intoning under his breath with a monotonous sing-song, like the humming of a bumblebee. Between them a little boy sat on the edge of the seat, his clogs hanging from the thong between his bare toes, the sleeves of his kimono bulging with bundles. He stared as if hypnotized at a curl of Barbara's bronze hair which lay against the cushion. Once he stretched out a hand furtively to touch it, but drew it back hastily.

"If I could only talk to him!" Barbara exclaimed. "I want to know the language. Tell me, Patsy—how long did it take you to learn?"

"I?" cried Patricia in comical amazement. "Heavens and earth, I haven't learned it! I only know enough to badger the servants. You have to turn yourself inside out to think Japanese, and then stand on your head to talk it."

"Never mind, Barbara," said the bishop, looking up from his newspaper. "You can learn it if you insist on it. Haru would be a capital teacher—bless my soul, I believe I forgot to tell you about her!"

"Who is Haru?" asked Barbara.

[pg 35] "She's a young Japanese girl, the daughter of the old samurai who sold us the land for the Chapel. The family is a fine old one, but of frayed fortune. I was greatly interested in her, chiefly, perhaps, because she is a Christian. She became so with her father's consent, though he is a Buddhist. She isn't of the servant class, of course, but I thought—if you liked—she would make an ideal companion for you while you are learning Tokyo."

"I know Haru," said Patricia. "She's a dear! She's as pretty as a picture, and her English is too quaint!"

"It would be lovely to have her," Barbara answered. "You're a very thoughtful man, Uncle Arthur. Are you sure she'll want to?"

"I'll send her a note and ask her to come to you at the Embassy this evening. Then—all aboard for the Japanese lessons!"

"No such wisdom for me, thank you," said Patricia. "I prefer to take mine in through the pores. All the Japanese officials speak English anyway, just as much as the diplomatic corps. By the way, there's Count Voynich, the Servian Chargé." She nodded toward the farther end of the carriage where a bored-looking European plaintively regarded the landscape through a monocle. "He's nice," she added reflectively, "but he's a dyspeptic. I caught him one night at a dinner dropping a capsule into his soup. He has a cabinet with three [pg 36] hundred Japanese nets'kés—they're the little ivory carvings on the strings of tobacco-pouches. He didn't speak to me for a month once because I said it looked like a dental exhibition. Almost every secretary has a fad, and that's his. Ours has an aëroplane. He practises on it nearly every day on the parade-ground. The pudgy woman in the other corner with a cockatoo in her hat is Mrs. Sturgis, the wife of the big exporter. She wears red French heels and calls her husband 'papa'."

Barbara's laughter was infectious. It caught the bishop. It reflected itself even on the demure face of the Japanese girl, and the serious youths opposite giggled openly in sympathy.

"I do envy you your first impressions!" exclaimed Patricia. "I've been here so long that I've forgotten mine. It seems perfectly natural now for people to live in houses made of bird-cages and paper napkins, and travel about in grown-up baby-buggies, and to see men walking around with bare legs and oil-skin umbrellas. It's like the sea-shore at home, I suppose—you get used to it."

The train had stopped at a suburb and guards went by proclaiming its name in a musical guttural, their voices dwelling insistently on the long-drawn, last syllable. The next carriage was a third-class one with bare floors and wooden benches, set crosswise. Through the opened door Barbara could see its crowd of brown faces, keen and saturnine. On [pg 37] its front seat a heavy-featured, lumpish coolie woman was nursing a three-year-old baby, holding it to her bared breast with red and roughened hands. Just outside the station's white-washed fence, a clump of factory chimneys spouted pitchy smoke into the dimming sky, and the descending sun glistened from a monster gas-tank. Farther away, beyond clipped hedges, lay thatched roofs, looking as soft as mole-skin, with wild flowers growing on the ridges, and bamboo clumps soaring above them, like pale green ostrich-feathers yellow at the tips. Through the open window came the treble note of a girl singing.

A man passed hastily through the carriage leaving a trail of small pamphlets bound in green paper with gold lettering—an advertisement of a health resort, printed in English for the tourist. Barbara opened one curiously. She looked up with a merry eye.

"Here's a paragraph for you, Uncle Arthur," she said. "Listen:

"'This place has other modern monuments, first and second-class hotels and many sea-scapes. In one quarter are a number of missionaries, but they can easily be avoided.'"

"Do let us credit that to difficulties of the language," he protested. "I'm sure that must have been meant complimentarily."

[pg 38] "But what a contradiction!" put in Patricia wickedly.

"Well," he retorted. "My baker has a sign on his wagon, 'The biggest loafer in Tokyo.' He means that well, too."

A shrill whistle, a slamming of doors, and now the gray roofs fell away. On one side the steel road all but dipped in the bay. Wild ducks drew startled wakes across the rippleless lagoon. On a sand-bar a flock of gray and white gulls disported, looking at a distance like pied bathers; and about an anchored fishing boat, a dozen naked urchins were splashing with shrill cries. Far across the inlet, hazy, vapory, visionary, Barbara could make out a farther shore, an outline in violets and opalines, coifed with lilac cloud, and in the mid-azure a high-pooped junk swam by, a shape of misty gold, palely drawn in wan, blue light.

On the other side the train was rounding grassy hills, terraced to the very tops. Laid against their steep sides, or standing upright on wooden framework, were occasional huge advertisements in red or white—Chinese characters or pictures—while flowering camelia trees and small green-yellow shrubs drew lengthening blue shadows. A high tressle spanned acres of orchard where continuous trellis made a carpet of growing fruit, across which Barbara saw far away the bold outline of bluish hills.

[pg 39] They were crossing flooded rice-fields now, like gigantic crazy checker-boards, and the air was musical with the low, chirring chorus of frogs. Shades of orange light played over the marshes, bars of rape braided them with vivid yellow, and on the narrow, curving partitions between the burnished squares, round stacks of garnered straw stood like crawfish chimneys. Amid them peasants worked with broad-bladed mattocks, knee-deep in mud. They were blue clad, with white cloths bound about their heads, and some had sashes of crimson. Here and there, naked to the thighs, a boy trod a water-wheel between the terraced levels. At intervals a refractory rock-hillock served as excuse for a single twisted pine-tree shading a carved tablet to some Shinto divinity, or a steep bluff sheltered a tiny shrine of unpainted wood; and all along the way, shining canals drew silver ribbons through the paddy-fields, and little arrowy flights of birds darted hither and thither.

Occasionally they passed small, neat stations, each with its white sign-boards bearing long liquid names in English, and queer Japanese characters. Opposite one, on a sloping hill that was a mass of deep glowing green, Patricia pointed out the peaked roofs of a cluster of temples, the shrine of some century-dead Buddhist saint. Barbara began to realize that these fields through which this modern train was gliding were old Japan, that in those blue hills [pg 40] had been nurtured the ancient legends she had read, of famous two-sworded samurai, of swaggering bandits and pleasure-loving shogun, and of tea-house geisha who danced their way into daimyo's palaces. The spell of the land, whose sheer beauty had thrilled her on the ship, drew her closer with the threads of memories almost forgotten.

Its contrasts were wonderful. They spoke of primary and unmixed emotions, that lisped themselves through the fading golden sunlight, the moist, dreamy air, the graceful outlines of roof and tree. In the west the sun was declining toward a range of hills jagged as the teeth of a bear. Their tops were pale as cloud and their bases melted into an ebony line of forest. The plain below was a winey purple, with slashes of red earth gorges like fresh wounds, and one side had the cloudy color of raspberries crushed in curdled milk. The farther range seemed a part of a far-off painted curtain, tinted in pastels, and high above a milky cloud floated, curling like a lace scarf about the opal crest of Fuji, mysteriously blue and dim as an Arctic summer sea.

Barbara glimpsed it, the very spirit of beauty, between the whirling shadows of pine and camphor trees, between tiled walls guarding thatched temples, flights of gray pigeons and spurts of pink cherry-blossom. As she leaned out, and the pines bowed rhythmically, and the water-wheels turned [pg 41] in the furrows, and the yellow-green of the bamboo, the purple-indigo of the hills and the golden-pink of the cherries lifting, above the hedges, went by like raveling skeins of a tapestry—that majestic Presence, ghostly and splendid above the wild contour of hill and mountain, seemed to call to her.

And across the gorgeous landscape, rejoicing from every rift and crevice of its moist soil, in its colors of rich red earth and green foliage, in the grace and vigor of its springing, resilient bamboo groves and the cardinal pride of its flowering camelias, Barbara's heart answered the call.

The slowing of the train awoke Barbara from her reverie. The three boy students got out, casting sidelong glances at her. More Japanese entered, and two foreigners—a bright-faced girl on the arm of a keen-eyed, soldierly man with bristling white hair, a mustache like a walrus, and a military button. The girl's hands were full of cherry-branches, whose bunches of double blossoms, incredibly thick and heavy, filled the car with a delicate fragrance. The bishop folded his newspaper and put it into his pocket.

As he did so the owner of the expansive waistcoat leaned across the aisle and addressed him.

"Say, my friend," he said, "you've lived out here some time, I understand."

"Yes," the bishop replied. "Twenty-five years."

"Well, I take it, then, you ought to know this country right down to the ground; and if you don't mind, I'd like to ask a question or two."

"Do," said the bishop. "I'll be glad to answer if I can."

[pg 43] The other got up and took a seat opposite. "You see," he pursued confidentially, "I came on this trip just for a rest and to settle the bills for the curios my wife"—he indicated the lady, who had now moved up beside him—"thinks she'd like to look at back home. But I've been getting interested by the minute. It's quite some time since I went to school, and I guess there hadn't so much happened then to Japan. I wish you'd run down the scale for me—just to hit the high places. Now there was a big rumpus here, I remember, at the time of our Civil War. They chose a new Emperor, didn't they?"

"No. The dynasty has been unbroken for two thousand years."

"Two thousand years!" cried the lady. "Why, that's before Christ!"

"When our ancestors, Martha, were painting themselves up in yellow ochre and carrying clubs—what was the row about, then?"

"It was something like this. To go back a little, the Emperor was always the nominal ruler and spiritual head, but the temporal power was administered by a self-decreed Viceroy called the shogun. Japan was a closed country and only a little trading was allowed in certain ports."

His questioner nodded. The girl beside the white-haired old soldier had touched the latter's sleeve, and both were listening attentively. "Then Perry [pg 44] came along and kicked open the gate. Bombarded 'em, didn't he?"

The bishop's eyes twinkled. "Only with gifts. He brought a small printing-press, a toy telegraph line and a miniature locomotive and railroad track. He set up these on the beach and showed the officials whom the shogun's government sent to treat with him, how they worked. In the end he made them understand the immense value of the scientific advancement of the western world. The visit was an eye-opener, and the wiser Japanese realized that the nation couldn't exist under the old régime any longer. It must make general treaties and adopt new ideas. Some, on the other hand, wanted things to stay as they were."

"Pulling both ways, eh?"

"Yes. At length the progressists decided on a sweeping measure. Under the shogunate, the daimyos (they were the great landed nobles) had been in a continual state of suppressed insurrection."

"Some wouldn't knuckle down to the shogun, I suppose."

"Exactly. There was no national rallying-point. But they all alike revered their Emperor. In all the bloody civil wars of a thousand years—and the Japanese were always fighting, like Europe in the Middle Ages—no shogun ever laid violent hands on the Emperor. He was half divine, you see, [pg 45] descended from the ancient gods, a living link between them and modern men. So now they proposed to give him complete temporal power, make him ruler in fact, and abolish the shogunate entirely."

"Phew! And the big daimyos came into line on the proposition?"

"They poured out their blood and their money like water for the new cause. The shogun himself voluntarily relinquished his power and retired to private life."

"Splendid!" said the stranger, and the girl clapped her gloved hands. "So that was the 'Restoration,' the beginning of Meiji, whatever that may mean?"

"The 'Era of Enlightenment.' The present Emperor, Mutsuhito, was a boy of sixteen then. They brought him here to Yedo, and renamed it Tokyo——"

"And proceeded to get reeling drunk on western notions," said the man with the military button, smiling grimly. "I was out here in the Seventies."

"True, sir," assented the bishop. "It was so, for a time. And the opposition took refuge in riot, assassination, and suicide. But gradually Japan worked the modernization scheme out. She sent her young statesmen to Europe and America to study western systems of education, jurisprudence and art. She hired an army of experts from all over the world. She sent her cleverest lads to foreign universities. [pg 46] In the end she chose what seemed to her the best from all. Her military ideas come from Germany and her railroad cars from the town of Pullman, Illinois. When the best didn't suit her, she invented a system of her own, as she has done with wireless telegraphy."

"So!" said the other. "I'm greatly obliged to you, sir. I've read plenty in the newspapers, but I never had it put so plain. It strikes me," he added to the old soldier, "that a nation plucky enough to do this in fifty years, in fifty more will make some other nations get a move on." He brought a big fist smashing down in an open palm. "And, by gad! the Japanese deserve all they get! When we go back I guess me and Martha won't march in any anti-Jap torch-light processions, anyway!"

The fields were gone now. The train was rumbling along a canal teeming with laden sampan, level with the paper shoji of frail-looking houses on its opposite bank. Beyond lay a sea of roofs, swelling gray billows of tiling spotted with green foam, from which steel factory chimneys lifted like the black masts of sunken ships. A leafy hill of cryptomeria rose near-by, and an octagonal stone tower peeped above its foliage. Crows were circling about it, black dots against the bronze. The train was entering Tokyo.

A door slammed sharply. From the forward smoking carriage a man had entered. He was an [pg 47] European and Barbara was struck at once by his great size and the absence of color in his leaden face. The bored-looking diplomatist in the corner gathered himself hastily into a bow, which the other acknowledged abstractedly. Seemingly he had been occupied in some intent speculation which spread a kind of glaze over his sharp features. A book drooped carelessly from his heavy fingers.

"That is Doctor Bersonin," said the bishop, as the girls collected their wraps. "He came just before I left, last fall. He is the government expert, and is supposed to be one of the greatest living authorities on explosives."

"Oh, yes," said Patricia, "I know. He invented a dynamo or a torpedo, or something. I saw him once at a reception; he had a foreign decoration as big as a dinner-plate."

The big man made his way slowly along the aisle and, still absorbed, took a dust-coat from a rack. As he ponderously drew it on, the daylight was suddenly eclipsed, and the rumbling reëchoed from metal roofing. They were in Shimbashi Station.

"Isn't he simply odious!" whispered Patricia, as the expert stepped before them on to the long, dusky, asphalt platform. "His eyes are like a cat's and his hands look as if they wanted to crawl, like big white spiders! There is the Embassy betto," she said suddenly, pointing over the turnstile, where stood a Japanese boy in a wide-winged kimono of [pg 48] tea-colored pongee with crimson facings and a crimson mushroom hat. "The carriage is just outside. You'll come, too, of course, Bishop," she added. "Father will expect you."

He shook his head and motioned toward a dense assemblage comprising a half dozen of his own race in clerical black, and a half hundred kimono'd Japanese, whose faces seemed one composite smile of welcome. "There is a part of my flock," he said. "There will be a jubilation at my bachelor palace to-night. I shall see you to-morrow, I hope."

They watched him for a moment, the center of a ceremonious ring of bowing figures, then passed through the station to the steps where the carriage waited.

The station debouched on to a broad open square bordered with canals and lined with ranks of rick'sha, some of which had small red flags with the name of a hotel in white letters, in English. The space was gray and dusty; pedestrians dotted it and across it a bent and sweating street-sprinkler hauled his ugly trickling cart, chanting in a half-tone as he went. A little distance away Barbara caught a glimpse of a busy paved street, lined with ambitious glass shop-fronts and with a double line of clanging trolley-cars passing to and fro beneath a maze of telegraph wires seemingly as fine as pack-thread. Her nostrils twitched with strange odors—from stagnant moats of sticky, black mud, from panniers of dressed [pg 49] fish, from the rice-powder and pomade of women's toilets—all the scents bred in swarming streets by a glowing tropic sun.

At one side waited a handful of foreign carriages. All the drivers of these wore the loose, flapping liveries and the round hats of green or crimson or blue. "They are Embassy turn-outs," explained Patricia. "Each one has its color, you see. Ours is red and you can see it farthest." As they took their seats an open victoria rolled up, with cobalt-blue wheels, and a betto with a kimono of dark cloth trimmed with wide strips of the same hue ran ahead, clearing the way with raucous cries. "There goes the Bulgarian Minister's wife," said Patricia. "She's got the finest pearls in Tokyo."

A hundred yards from the entrance the Embassy carriage halted abruptly and Barbara caught her companion's arm with a low exclamation. At the side of the square, seated or reclining on the ground was a body of perhaps eighty men dressed in a deadly brownish-yellow, the hue of iron-rust, with coarse hats and rough straw sandals. They were disposed in lines, a handcuff was on each left wrist, and a thin, rattling iron chain linked all together.

"They are convicts," said Patricia; "on their way to the copper mines, I imagine. They will move presently and we can pass."

At the head of the melancholy platoon stood an officer in dark blue cloth uniform and clumsy shoes, [pg 50] a sword by his side. He stood motionless as an idol, his sparse mustaches waxed, his visored cap set square on his crisp, black hair, his bronze face impassive. The prisoners looked on stolidly at the stir of the station, the flying rick'sha, the crowded sampan in the canal, and the noisy trolley-cars passing near-by. Some talked in low tones and pointed here and there, with furtive glances at the officer. Barbara noted their different expressions, some stolid, low-browed and featureless, some with side-looks of sharper cunning, all touched with oriental apathy.

A bell now began to clamor in the train-shed and there came the rasping hoot of an engine. The officer turned, gave a sharp order, and the prisoners rose, with light clanking of their chains. Another order, and they moved, in double lines of single file, into the station.

Patricia heaved a sigh of relief as the halted traffic started. "Hyaku, Tucker," she called to the driver. "Hyaku means quickly," she explained aside. "His name is Taka, but I call him Tucker because it's easier to remember."

As they rolled swiftly on, through the wondrous panorama of teeming Tokyo streets, the sun hung, an elongated globe of deep orange-crimson, streaked with little whips of rosy cloud. Beneath it the mountains lay like coiled, purple dragons, indolent and surfeited. One star twinkled palely in the [pg 51] lemon-colored sky. Yet now to Barbara the splendor of color seemed tragic, the poured-out beauty but a veil, behind which moved, old and apish and gray, the familiar passions of the world. Before her eyes were flowing and mingling a thousand strands of orient life, yet she saw only the red light glowing on the stone entrance of Shimbashi, with those hideous saffron jackets filing perpetually into its yawning mouth, like unholy spectres in a dream.

The setting sun poured a flood of wine-colored light over Reinanzaka—the "Hill-of-the-Spirit"—whose long slope rose behind the American Embassy, whither the Dandridge victoria was rolling. It was a long leafy ridge stippled with drab walls of noble Japanese houses, and striped with narrow streets of the humble; one of the many green knolls that, rising above the gray roofs, make the Japanese capital seem an endless succession of teeming village and restful grove.

Along its crest ran a lane bordered with thorn hedges. A little way inside this stood a huge stone torii, facing a square, ornamented gateway, shaded by cryptomerias. The latter was heavily but chastely carved, and on its ceiling was a painting, in green and white on a gold-leaf ground, of Kwan-on, the All-Pitying. From the gate one looked down across the declivity, where in a walled compound, the rambling buildings of the Embassy showed pallidly amid green foliage. Beyond this were sections of trafficking streets, and still farther a narrow, white road climbed a hill toward a military barracks—a blur of dull, terra-cotta red. In the dying afternoon the lane had an air of placid aloofness. [pg 53] Somewhere in a thoroughfare below a trolley bell sounded, an impudent note of haste and change in a symphony of the intransmutable. Over all was the scent of cherry-blossoms and a faint musk-like odor of incense.

From the gate a mossy pavement, shaded by sacred mochi trees, led to a Buddhist temple-front of the Mon-to sect, before which a flock of fluttering gray-and-white pigeons were pecking grains of rice scattered by a priest, who stood on its upper step, watching them through placid, gold-rimmed spectacles. He wore a long green robe, a stole of gold brocade was around his neck, and his face was seamed with the lines of life's receding tides. At one side of the pavement, worn and grooved by centuries of worshiping feet, was a square stone font and on the other side a graceful bell-tower of red lacquer. Back of this stood a forest of tall bronze lanterns, and beyond them a graveyard, an acre thick with standing stone tablets of quaint, squarish shape, chiseled with deep-cut idiographs. Nearer the graveyard, overshadowed by the greater bulk of the temple, was a long, low nunnery, with clumps of flowers about it. Through its bamboo lattices one caught glimpses of women's figures, clad in slate-color, of placid faces and boyishly shaven heads. About the yard a few little children were playing and a mother, with a baby on her back, looked smilingly on.

The space where the priest stood was connected [pg 54] by a small, curved, elevated bridge with another temple structure standing on the right of the yard, evidently used as a private residence. This was more ornate, far older and touched with decay. Its porch was arcaded, set with oval windows and hung with bronze lanterns green from age. Its entrance doors were beautifully carved, paneled with endless designs in dull colors, and bordered with great gold-lacquer peonies laid on a background of green and vermilion. From their corners jutted snarling heads of grotesque lions and on either side stood gigantic Ni-O—glowering demon-guardians of sacred thresholds. Through the straight-boled trees that grew close about it, came transient gleams of a hedged garden, of burnished green and maroon foliage, where cherry-blooms hung like fluffy balls of pink smoke. The garden had a private entrance—a gate in the outer lane—and over this was a small tablet of unpainted wood:

Which, translated, read:

ALOYSIUS THORN

Maker of Buddhas

[pg 55] Directly opposite stood a small Christian Chapel. It was newly built and still lacked its final decoration—a rose-window, whose empty sashes were stopped now with black cloth. High above the flowering green its slanting roof lifted a cross.

It rose, white and pure, emblem of the Western faith that yet had been born in the East. Over against the ornate pageantry of Buddhist architecture, in a land of another creed, of variant ideals and a passionate devotion to them, it stood, simple, silent, and watchful. The priest on the temple steps was looking at the white cross, regarding it meditatively, as one to whom concrete symbols are badges of spiritual things.

Footsteps grated on the gravel and the occupant of the older temple came slowly through its garden. He was a foreigner, though dressed in Japanese costume. His shoulders were broad and powerful and he moved with a quickness and grace in step and action that had something feline in it. His hair, worn long, was black, touched with gray, and a curved mustache hid his lips. His expression was sensitively delicate and alertly odd—an impression added to by deeply-set eyes, one of which was visibly larger than the other, of the variety known as "pearl," slightly bulbous, though liquid-brown and heavily lashed.

The new-comer ascended the steps and stood a moment silently beside the priest, watching the gluttonous [pg 56] pigeons. As he looked up, he saw the other's gaze fixed on the Chapel cross. A quick shiver ran across his mobile face, and passing, left it hard with a kind of grim defiance.

Presently the priest said in Japanese:

"The Christian temple across the way honorably approaches completion. Assuredly, however, moths have eaten my intelligence. Why does the gloomy hole illustriously elect to remain in its wall?"

"It is for a thing they call a 'window'," said Thorn. "After a time they will put therein an august abomination, representing sublimely hideous cloud-born beings and idiotic-looking saints in colored glass."

The priest nodded his shaven head sagely.

"It will, perhaps, deign to be a gaku of the Christian God. I shall, with deference, study it. I have watered my worthless mind with much arrogant reading of Him. Doubtless He was also Buddha and taught The Way."

An acolyte had come from the temple and approached the red bell-tower. Midway of the huge bronze bell a heavy cedar beam, like a catapult, was suspended from two chains. He swung this till its muffled end struck the metal rim, and the air swelled with a dreamy sob of sound. He swung it again, and the sob became a palpitant moan, like breakers on a far-away beach. Again, and a deep [pg 57] velvety boom throbbed through the stillness like the heart of eternity.

"It is time for the service," said the priest, and turning, went into the temple, from whose interior soon came the woodeny tapping of a mok'gyo—the hollow wooden fish, which is the emblem of the Mon-to sect—and the sound of chanting voices.

Thorn, the man with whom the priest had spoken, crossed the bridge to the other temple with a slow step. He passed between the scowling guardian figures, slid back a paper shoji and entered. The room in which he stood had been the haiden, or room of worship. Around its walls were oblong carvings, marvelously lacquered, of the nine flowers and nine birds of old Japanese art. In one were set six large painted panels; the red seal they bore was that of the great Cho Densu, the Fra Angelico of Japan. In its center, under a brocade canopy, was a raised platform once the seat of the High Priest. It faced a long transept, like a chancel; this ended in a short flight of steps leading, through doors of soft, fretted gold-lacquer, to a huge altar set with carved tables, great tarnished brasses and garish furniture. The walls of the transept were done in red with green ornamentations. From the overhead gloom grotesque phœnix and dragon peered down and in the gathering dimness, shot [pg 58] through with the wan yellow gleam of brass, the place seemed uncanny.