Title: By the Barrow River, and Other Stories

Author: Edmund Leamy

Author of introduction, etc.: Katharine Tynan

Release date: April 17, 2013 [eBook #42555]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by eagkw, sp1nd and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

BY THE BARROW RIVER

AND OTHER STORIES

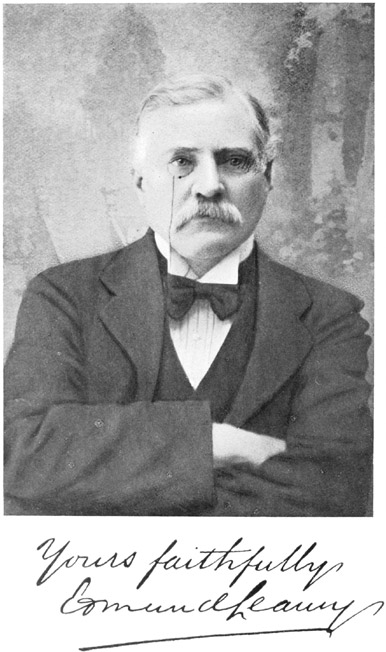

Yours faithfully Edmund Leamy

BY

EDMUND LEAMY

AUTHOR OF “IRISH FAIRY TALES,” ETC.

WITH A FOREWORD BY KATHARINE TYNAN

WITH PORTRAIT

DUBLIN:

SEALY, BRYERS AND WALKER

Middle Abbey Street

1907

PRINTED BY

SEALY, BRYERS AND WALKER,

MIDDLE ABBEY STREET,

DUBLIN.

Edmund Leamy was the beau-ideal of a chivalrous Irish gentleman, patriot, and Christian. During a friendship extending over many years, I never knew him fall short in the slightest particular of the faith I had in him. His nature was poetic and romantic in the highest degree. Through sunny and cloudy day alike he was Ireland’s man, and his faith in her ultimate destiny was never shaken. I have never known a nature more lofty or more lovable. Long years of weak health and suffering, under which most people would have sunk, could not alter his noble nature. He kept his great, loving, true heart to the last. Even if things were sad enough for him, it was happiness if they were well with friends and neighbours. He did not know what it was to have a grudging thought. The experiences which usually make middle-age a period of disillusionment came to him as to other men, yet he was never disillusioned; he had the heart of an innocent and trusting boy till the day he died. To be sure there was one by his hearth who helped to keep his illusions fresh; and his burden of ill-health was lightened for him by God’s mercy through the same bright and devoted companionship. He was Ireland’s man; all he did was for Ireland. He could not[vi] have written a line of verse or prose for the English public, however sure he might be of its suffrage and reward. He wrote a great deal for Ireland, and although, I believe, he reached his highest development as an orator, an orator, alas, sorely hampered by physical weakness, yet his stories and his poems have so much of the personality of the man, the fresh, honest, and sweet personality, that it has been thought well to rescue just a handful from his many writings in Irish journals extending over a number of years. He had not the leisure to make himself exclusively a literary man. He was always in the thick of the fight; it would have broken his heart to be otherwise. But the work he has left, especially his fairy tales and dramatic stories, with their wealth of colour and their imaginativeness, give some earnest of the work he might have done. His book of Irish Fairy Tales, which has long been out of print, has been republished in a worthy form; and I am sure the present volume, which shows his fancy in a different vein, which contains a set of stories that have not been brought together before, will also be welcome to his countrymen. Were I to write his epitaph it would be—“Here lies a white soul!”; and if I had to name the virtue paramount in him it would be Charity, which in him included Faith and Hope.

Katharine Tynan.

St. Patrick’s Day, 1907.

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

| By the Barrow River | 1 |

| “Bendemeer Cottage” | 17 |

| A Night with the Rapparees | 26 |

| “Worse than Cremona” | 39 |

| Maurya Na Gleanna, or Revenged at Last | 50 |

| Story of the Raven | 64 |

| The Spectres of Barcelona | 78 |

| The Black Dog | 103 |

| The Ghost of Garroid Jarla | 112 |

| True to Death | 125 |

| “The Light that Lies in Woman’s Eyes” | 136 |

| Death by Misadventure | 146 |

| A Message from the Dead | 154 |

| A Vision of the Night | 164 |

| The Pretty Quakeress | 175 |

| My First Case | 200 |

| A Vision or a Dream? | 221 |

| From the Jail to the Battlefield | 234 |

| All for a Woman’s Eyes | 241 |

| The Ruse of Madame Martin | 268 |

Amongst the stories here given is the last story the author ever wrote, “The Ruse of Madame Martin.” It was written in France during his last illness and is now for the first time published. It is one of the freshest and raciest in the volume. It has a vivacious sense of actuality as well as delightful humour, and it shows that the author’s talent was at its brightest when death came to extinguish it.

“There are some who see and cannot hear, and some who hear and do not see, and some who neither see nor hear, and you are one of these last, Dermod, son of Carroll.”

The speaker was a man of about forty years, a little above the medium height, of well-knit frame, of a sanguine complexion. His bushy brows, shaded pensive eyes, that one would look for in a poet or a dreamer rather than in a soldier, yet a soldier, Cathal, son of Rory, was, and one of the guards of Cobhthach Cael, the usurper, who reigned over Leinster; it was in the guard-room in the outer wall of the Fortress of Dun Righ that he addressed these words to one of his companions, a stripling of twenty, but of gallant bearing.

“But what did you see or hear, O Cathal?” said another of the guards, who numbered altogether some six or seven. “They say of you, Cathal, that the wise woman of the Sidhe came to you the night you were born and touched your eyes and ears, and that you can see and hear what and when others cannot see or hear.”

“What matters it what I see or hear? What matters it what is seen or heard, Domhnall, son of Eochy, when the king is blind and deaf, and those about him also?” answered Cathal.

“Why say you blind and deaf, O Cathal?”

“Was it not but the last night,” replied Cathal, “when the men of Leinster were gathered at the banquet, and when the King of Offaly rose up and the cry of Slainthe sounded through the hall like the boom of the waves on the shore of Carmen, that the king’s shield groaned on the wall and fell with a mighty clangour, and yet they heard and saw not, and pursued their revelry. But seeing this, and that they had not perceived, I rose and restored the shield to its place on the wall.”

“And what else did you see, O son of Rory?”

“What else did I see? Was I not keeping watch on the ramparts of a night, when the young moon was coming over the woods, and looking at herself in the waters of the Barrow, and did I not see the Lady Edain in her grinan looking out and waving her white arm—whiter than the moon—and did I not hear her moaning, as the wind moans softly on a summer night through the reeds of the river, and, as I listened and watched, did I not see coming to the banks of the river, a woman with a green silken cloak on her shoulders, who sat down opposite the dun, and she was weaving a border, and the lath, or rod, she was weaving with was a sword of bronze?”

“And what do you read from that, O Cathal, son of Rory?”

“What do I read from that? War and destruction I read from that, Domhnall, son of Eochy—war[3] and destruction; for when a king’s shield falls from the wall it means that his house will fall, and the woman weaving with the sword was the long, golden-haired woman of the Sidhe—dangerous to look on is she, Domhnall, son of Eochy, for whiter than the snow of one night, is her form gleaming through her dress, and her grey eyes sparkle like the stars, and red are her lips and thin, and her teeth are like a shower of pearls, and dangerous is she to listen to, Domhnall, for less sweet are the strings of the harp than the sound of her voice; and she comes on the eve of battles, and she weaves the fate of those who will fall; and she sat on the banks of the Barrow, flowing brightly beneath the young moon, and when she will be seen there again it will be red with blood.”

“But the Lady Edain, was she talking to the woman of the Sidhe, Cathal, son of Rory?”

“Evil betide you for your evil tongue, son of Eochy, mention not again the name of the Lady Edain with that of the woman of the Sidhe, or it is against the stone there, at the back of your heart, that the point of my javelin will strike,” and Cathal’s soft eyes blazed with anger.

“Far be it from me to say or think evil of the Lady Edain, Cathal,” said Domhnall, “but you said the Lady Edain was looking from her bower when the green-cloaked woman of the Sidhe came to the Barrow bank?”

“But she did not see her, Domhnall. No! no![4] she did not see the green-cloaked woman, for who so sees her weaving spells, his hour is come. No no! my little cluster of nuts did not see her, Domhnall, and if she were moaning ’twas moaning she was for the youth that is gone away from her—for the young hero, Ebor, who is away with Prince Labbraidh, that is king by right, although you and I, are the guards of King Cobhthach Cael here to-night. Oh, no, Domhnall, son of Eochy, my little cluster of nuts did not see the woman of the Sidhe, for her life is young and it is before her. I remember well, Domhnall, son of Eochy, the night the dun was attacked, when I was as young as Dermod, the son of Carroll, sitting there beside you, and when I caught the little girsha from the flames, and she lay on the hollow of my shield—this very shield against the wall here, Domhnall, and did it not gleam like gold, ay, like the golden boss on the king’s own shield, because of the golden ringlets, softer than silk, that were dancing like sunbeams round her little face, and did she not look up at me and smile, Domhnall, son of Eochy, and the dun all one blaze. And, since then, wasn’t she to me dearer than my own, and have I not watched over her, and do you tell me now that she saw the woman of the Sidhe?”

“Not so, Cathal, not so, son of my heart,” said Domhnall, “but you saw the woman of the Sidhe,” said he, “and what does it mean for you?”

“Death,” said Cathal, “death, Domhnall, did I not tell you it means death for whosoever see her![5] But I am a soldier as you are, Domhnall, and my father before me, and his father, and his father again died in the battle; and why should not I, and no man can avoid his fate, Domhnall? But the colleen of the tresses!—why should she die now, Domhnall, why should she die now?” and Cathal spoke fiercely, “but woe that she should be here to-night, where she has been for many a year like a bird in a cage—and sure never bird had a voice so sweet—and ruin and destruction coming as swift as the blue March wind comes across the hills.”

“The king will keep her here, Domhnall,” he went on, answering himself; “for did not the Druid Dubthach, dead and gone now—and evil follow him and sorrow feed on his heart wherever he is—tell him that so long as the Lady Edain was kept a prisoner—ay, a prisoner, that’s what she is in the grinan—and so long as she remained unwedded, the dun would be secure against all assault; but love found its way into the grinan, Domhnall, and the Lady Edain gave her heart to Ebor, son of Cailté, though never a word she spoke to him; but he is gone, gone away with the exiled prince—gone, he who should be here to-night when the black ruin is marching towards the dun! But she did not see the woman of the Sidhe, Domhnall. No! no! don’t say she saw the woman of the Sidhe!” and Cathal bent his head down on his hands, and for a moment there was silence.

Then he started:

“Do you not hear, Domhnall—do you not hear?” and all the guards strained their ears.

In through the bare stone wall of the guardroom, a sound stole almost as soft as a sigh; then it increased, and a melody as lulling as falling waters in the heart of the deep woods fell on their ears, and, one by one, the listeners closed their eyes, and, leaning back on the rude stone benches, were falling into a pleasant slumber. Suddenly a brazen clangour roused them. Cathal’s shield had fallen from the wall on to the stone floor. The bewitching music had ceased, and they were startled to find that the “candle upon the candlestick,” which gave light to the room, had burned down half an inch. They must have been asleep for at least half-an-hour. Cathal started up, and, bidding his comrades stuff their ears if they heard the music again, he went out and mounted to the rampart. Within it all was silent, and silent all without. The midsummer moon, with her train of stars, poured down a flood of light almost as bright as that of day. The Barrow River shone like a silver mirror, and flowed so slowly that one might almost doubt its motion, and there was not air enough stirring to make the smallest dimple upon its surface. Cathal followed its course until it was lost in the forest that some distance below stretched away for miles on either side of the river. Between the forest and the dun, close to the latter, was the little town, or burgh, with its thatched[7] houses, in which dwelt the artificers of the king. There too, all was silent, and as far as Cathal’s eye could see there was nothing stirring in any direction. He made the circuit of the rampart, pausing only when he came to the grinan of the Lady Edain. It was on such another night, only then the moon was not so full, he had seen her at her open casement—on just such another night he had seen sitting on the Barrow banks, the woman of the Sidhe. The casement was closed, and there was no sign of the Lady Edain. But coming from the woods along the bank, what was that gleaming figure? Cathal did not need to ask himself. It was that of the woman of the Sidhe, and now she sits upon the bank, and begins her task of weaving, and he notes the sparkle of the points of the sword as she plies it in her work. And as he looks, he sees, or thinks he saw, the Barrow river change to a crimson hue; but the moon still shone from a cloudless sky, and he knows that he is the victim of his imagination, and that its waters are silver bright.

But he knew also that this second coming of the woman of the Sidhe betokens that before the moon rise again—perhaps before this moon set—the river would be crimson with the blood of heroes, and yet King Cobhthach sleeps, fancying himself secure, in his dun, and there is no one to pay heed to Cathal’s warnings or visions, except, perhaps, some of his comrades in[8] the guard-room. And when the moon arose again what would have been the fate of the Lady Edain—his little cluster of nuts. A groan escaped the lips of Cathal as the question framed itself in his thought. He could touch with his spear the casement within which she lay sleeping, dreaming, perhaps, of the young lover far away. For a moment the thought leaped to his mind that he should scale the grinan, force open the casement, and carry out the Lady Edain anywhere from the doomed dun; but her maids, sleeping next her, would be terrified, and cry out and spoil his plot, and the Lady Edain might see the woman of the Sidhe, and nothing then could save her. With a heavy heart he retraced his steps, and, coming over the guard-house, he descended and entered the guard-room. His companions were fast asleep. He strove to rouse them, but failed. Some spell had fallen on them, and even while making the effort he himself was smitten with the desire of sleep. The lids closed on his eyes as if weighted with lead. He sank down on the stone bench beside Domhnall, the son of Eochy, and faintly conscious of weird music in his ears, he, too, fell into a deep slumber.

The Lady Edain, even at the very moment when Cathal was looking towards her casement, was tossing uneasily on her embroidered couch. Her maids lay sleeping around her. She had been dreaming—dreaming that she was wandering with her lover through a mossy pathway, lit with[9] moonlight, in the heart of the woods. And when her heart was full of happiness listening, as she thought, to the music of his voice, suddenly through the wood burst out on the pathway an armed band, and Ebor had barely time to poise his spear when he fell pierced to the heart. She awoke with a scream. There was light enough coming through the slits in the casement to permit her to see that her maids were sleeping peacefully. Yet, she was only half satisfied that she had been dreaming. She rose from her couch, and, flinging a green mantle over her, fastening it with a silver brooch, stepped softly to the casement, and, opening it, leaned out. Her golden tresses fell to her feet, some adown her breast, others over her shoulders, and as she sat there, in the full splendour of the moon, one might well believe that it was the beautiful golden-haired, green-robed woman of the Sidhe that had seated herself in the maiden’s bower. The soft influence of the moon descended upon the heart of Lady Edain, and subdued its tumult. She glanced at the lucent waters of the silent river, and along its verduous banks, but she saw no vision of the woman of the Sidhe, for love had blinded her eyes to all such sights; else she was doomed. Then she looked up at the moon, now slowly sailing across the edge of the forest, and the thought came to her heart, which has come to the lover of all ages and all countries, that the same moon was looking down on him who was far away, and, perhaps,[10] even at that moment he, too, was gazing at it, and thinking how it shone on the Barrow river; then her eyes rested on the line which divided the forest from the fields that lay between it and the dun, and she saw the track over which her lover had passed out into the forest on that fatal day when he set out with Prince Labraidh into banishment.

And even as she watched she thought she saw something emerge from the forest and come in the direction of the dun. After a while she caught the glint of weapons, and saw it was a horseman approaching—some warrior, doubtless, seeking the hospitality of Dun Righ. She watched as they came along, horse and man, casting their shadows on the grass. They came right up under the rampart of the dun farthest from where she was, and near to the door that led past the guardroom.

While she was idly speculating whom he might be, she heard a strain of music that seemed to creep along the rampart like a slow wind across the surface of a river. She looked in the direction from which it seemed to come, and then she saw a muffled figure somewhat bent, and saw gleaming in his hands a small harp, while over his shoulder were two spears.

Immediately the thought of the harper, Craiftine, who had gone away with the banished prince, came to her mind. Perhaps he had come back, sent by her lover to bring a message!

“Only Craiftine,” she said to herself, “could win from strings such music as she now was listening to,” and while she listened a soft languor crept through her frame, and, leaning her head upon her hand, felt as if she were falling asleep, but the music at once changed, and it breathed now like the wind blowing over the fountain of tears on the island of the Queen of Sorrow in the far western seas, and sorrow filled her heart, and the tears, welling up into her eyes, banished sleep from them, and, raising herself up, she looked straight at the harper approaching.

Yes, it was Craiftine! His bent head and stooping shoulders betrayed him and his bardic cloak. He came on, still playing, until he stood on the rampart facing the casement.

Then the cloak was flung off. The stooping figure became erect, and in the shining moonlight Edain beheld her warrior-lover, Ebor!

Making a gesture to her to draw back, he placed his two spear shafts against the casement, and in a second he was in the room, and the Lady Edain was in his arms.

He looked around him and saw the sleeping maidens.

“We need not fear their awakening,” he said softly. “All in the dun, even the guards, are under the spell of the strain of slumber. Craiftine came hither a while ago, and reduced all to sleep, save Cathal, son of Rory, the captain of the guard, but[12] he, too, now is under its spell. He lent me his harp, which, even in my hands, retains some of its power. But we have no time to spare. Array yourself quickly. My horse is below the rampart; we have not a moment to lose.”

Edain needed no word to urge her. In a second she was ready. In another Ebor was carrying her in his arms across the spear shafts to the rampart.

Letting himself down and then standing on the horse’s back, he caught her descending, placed her on the steed before him, and swifter than light galloped off to the shelter of the forest.

But, alas, for Ebor, as they rode away he glanced towards the banks of the shining river, and he saw the woman of the Sidhe weaving her fateful spells.

The pathways of the silent forest were well known to Ebor, and he rode on with his charge over pleasant mossy ways, reminding Edain of those which she had seen in her dream. They had gone not more than a quarter of a mile when she, who had been prattling merrily to Ebor, uttered a frightened cry:

“Oh, Ebor, look; there are armed men!”

“They are friends, Edain,” he replied, “friends, and now my bonnie bride is safe at last.”

They had come to a wide glade. It was crowded with warriors, and through the trees wherever the moonlight fell, Edain caught a glimpse of figures and the glint of arms. Ebor jumped from his horse, and taking the Lady Edain in his arms lifted her gently down. A warrior, of stately mien and[13] wearing the golden helmet of a king, advanced towards them.

“A hundred thousand welcomes, Edain,” he cried, as he clasped her in his arms.

It was her kinsman, Labraidh, the rightful King of Leinster, who had come back to claim his own. Labraidh had been across the seas seeking allies. On his return, he landed at the mouth of the Slaney, and, by forced marches through the woods, had come hither. Unwilling to risk his cousin’s life by making an assault on the dun while she was still in it, he easily yielded to the entreaties of his harper, Craiftine, and of Ebor to allow them to undertake the task of effecting the escape of Edain. He had known of old the skill of Craiftine and the courage and address of Ebor, and did not doubt their success. And now that Edain was free he determined to push on at once, and try the hazard of an assault on the dun. But first he led the Lady Edain to his tent, where his wife, the Lady Moriadh and her women were, and entrusting her to Moriadh’s care, he returned and put himself at the head of his troops, and gave them their orders to push on as quickly as possible until they came to the edge of the forest, within view of the dun. Ebor was at the prince’s side, happy in the knowledge that the Lady Edain was safe, and too full of the desire of battle to give even a moment’s thought to the vision of the woman of the Sidhe. When they arrived at the edge of the forest they halted for a while. They[14] could see the ramparts plainly, and that no one was moving on them. The moon had by this time gone down over the forest, and in the east there was the first faint grey streak of dawn. Then the prince drew out his forces into three battalions. The centre he commanded in person, that to the right was under Ebor, and it was to move along the river bank and make the assault in that direction. The third battalion was to push round the fortress to the left. Orders were given that no trumpets were to be sounded and no shout raised until the troops were face to face with the foe.

The garrison not dreaming of the near approach of Labraidh, who was not known to be in Erin, was buried in sleep almost as deep as that which sealed the lids of Cathal and his comrades in the guard-room. The ramparts were scaled without much difficulty, and it was not until they had passed within the inner wall and had surrounded the house of the usurper that their presence was discovered, and then only when they began to batter in the door. The noise was followed by the cry, “to arms!” which rang through the whole fortress. It was heard by the warriors in the other houses, who, hastily arming themselves, burst out. A desperate hand-to-hand struggle took place, but surprise had given complete advantage to the assailants. They hemmed round the now desperate garrison with a ring of steel, growing ever narrower as their ranks were thinning. Soon the cry of fire[15] was raised. The king’s house was ablaze. He in front of it was fighting desperately, but one by one his men were falling round him. The roar of the flames, which had now spread to the other houses, mingled with the cries of the warriors and the clangour of stricken shields. Prince Labriadh again and again pressed forward to engage Cobhthach, but the tide of battle swept them apart. To save the dun had become impossible, and Cobhthach determined if he could to cut his way out. By desperate efforts he drove those who were in front of him back against the inner rampart, and before they could recover succeeded in leaping on it. He was perceived by Ebor, who, guessing his design, leaped, by the aid of the handles of his spears, on the rampart, and called on Cobhthach to turn and fight like a warrior and not run like a coward, and he launched a javelin against him which glanced off the helmet of Cobhthach. But Cobhthach stayed not, and Ebor launched the second with a surer aim, which, striking Cobhthach through the back, pierced his heart as he was endeavouring to spring to the outer wall, and the usurper fell dead in the intervening ditch. Ebor was on the point of again descending into the dun when his eye caught the sight of a figure on the river bank. It was the woman of the Sidhe, no longer weaving, but dabbling her hands in the waters of the river that were now running red with blood. A cold chill seized his heart, for he thought of the Lady[16] Edain, and he knew that his hour had come. But he would die fighting. He turned round, and coming against him along the rampart was Cathal, son of Rory. The latter hurled his spear, to which Ebor presented his shield, but it had been hurled with such force that it pierced the shield, and entered into the vitals of Ebor. His only weapon now was his sword, and as Cathal, son of Rory, pressed on him, he, with all his remaining strength, drove it into Cathal’s side; but the effort exhausted his last strength, and he fell back dead, and Cathal, son of Rory, fell dead beside him, and the woman of the Sidhe still continued dabbling her hands in the crimson waters of the Barrow river.

Some years ago I was on a visit with a friend in the county of Wicklow, whose house was situated in one of the most delightful valleys of “the garden of Ireland.” It was when the lilac and the laburnum were in full bloom and the air was sweet with scent. The weather was delightful, and I spent most of my time out of doors, taking long walks over the hills and through the hedgerows, musical with the songs of birds and soon to be laden with the perfume of the hawthorn.

In the course of my rambles I chanced one day to pass a rusty iron gate fastened by an equally rusty chain, the base of which was partially concealed by tall, rank grass, showing that it had not been opened for a long time. The gate was hung upon two stone piers covered with lichen. On the top of one was a stone globe. That which had surmounted the other had been removed, or had fallen off through the action of time and weather. From the gate a pathway once gravelled, but now almost overgrown with grass, led up through a fair-sized lawn to a long, one-storied cottage, stoutly built, the windows and door of which were faced with stone, which, like that of the piers, was also stained with lichen. The grass, pushed itself high over the threshold of the door and almost reached the windowsills. The slates on the roof appeared to be nearly all perfect, but[18] were covered with brown or grey patches of moss or lichen. A few of the slates had fallen away and exposed part of a rafter. On the lawn, as doubtless was the case when the cottage was inhabited, a number of sheep were browsing. In the centre of it was a nearly circular piece of water, fenced by a wire railing. Towards this pond the ground dipped gently, both from the roadside and from the side immediately fronting the cottage. The gate pierced a long, high hedgerow, and this it was, perhaps, that caused me stop to look over it to see what lay beyond. The silent, almost grim desolation of the cottage was a curious and striking contrast to the cheerful aspect of all the others which I had seen in the neighbourhood, and this it was that tempted me to cross a stile that was close to the gate and stroll up to the cottage. The windows had been barred up with timber that was giving way in some places. The door, which was of oak, was firm and well secured, and over it I noticed a stone on which were carved some words, of which at first, owing to the incrustation of lichen, I was able only to distinguish the letters “ottage.” By the aid of the ferule of my walking stick I succeeded in clearing off the lichen so as to enable me to decipher the inscription. It was “Bendemeer Cottage.” The name brought to my mind the familiar and delightfully melodious lines of Moore:—

And even while the echo of the melody was floating in my memory, my ear caught the faint whisper of gliding water. I passed round the cottage and saw a gentle stream close to a hedgerow, and between the cottage, and near the stream, were a mass of tangled rose-bushes, which had long ceased to flower, and were pushing forth only a few weak leaves.

“And this was their bower of roses,” said I, “in the days long gone; and where are they who enjoyed its fragrance? Whither have they departed, and why has the blight fallen on the bloom?”

It was an idle question for there was none to answer it. I passed round the cottage again and again. A few moments before I was unaware of its existence, and already it had begun to exercise a fascination on me.

“Is there,” said I, “anyone in a far away land asking his heart ‘Are the roses still bright by the Bendemeer?’” for I doubted not that the name was given to the stream as well as to the cottage.

I turned home slowly and thoughtfully, and scarcely heard the blackbirds trolling out their rich notes in the silence of the evening. The sight of a ruined homestead—a sight, alas! so frequent in many parts of Ireland, has always had a deep effect on me, for I cannot help conjuring up the crackling fire upon the hearthstone lighting the faces of happy children, and of speculating on the fate which[20] awaited them when its light was quenched and they were scattered far and wide across the seas. But this desolate cottage whose name was so suggestive of youth and bloom, and love and happiness, was like a ruined tombstone raised over dead hopes—a mockery of their vanity.

That evening I questioned my friend as to its history. He knew nothing of it, though he had lived twenty years not far from it, and he rallied me on my sentimental mood, and suggested that its former inhabitants had got tired of it, that probably they had found some thorns amongst its roses.

“They were sentimental people like yourself,” he said. “Probably town bred, and that’s what made them give it such an absurd name, and they soon tired of love in a cottage.”

My friend was an extremely good-hearted, generous fellow, ever ready to help another in distress; but he was prone to regard any one who would sorrow over what he called imaginary woes as little better than a simpleton. I saw there was no information to be gained from him, and I could hardly look for any sympathy from him with my desire to procure it. But the desire, instead of abating, increased, and I found myself again and again taking the direction of the lonely cottage. But day after day I saw only the sheep browsing on the lawn, and heard only the murmur of the stream; and I was about giving up all hope of learning its history, when it chanced that one evening I fell in with an old shepherd, who, as[21] I was crossing the stile on to the road, was coming towards it. He saluted me in the friendly way so common until recently with people of his class. I acknowledged his salute with equal friendliness. He remarked on the fineness of the weather, and seeing that he was inclined to be communicative, I resolved to continue the conversation. I thought he was about to cross the stile, but instead he pursued the road leading to my friends’ house.

“That’s a lonely cottage over there,” said I tentatively.

“Oh, then, you may well call it lonely,” said he, “but I mind the time when it was one of the brightest cottages ye’d see in a day’s walk in the whole of the county Wicklow.”

“That must have been a long time ago,” I rejoined.

“Ay, thin, it is. It’s fifty years ago or more. ’Twas about the time that poor Boney was bet at Waterloo. Sure I mind it well. I was only a gorsoon then, yer honour, but ’twas often and often I did a hand’s turn for the lady, and sure ’twas the rale illegant lady she was, yer honour, with her eyes that wor as blue as the sky above us this blessed and holy evenin’, and her smile was as light and as bright as the sunbeams, and her voice was sweeter nor the blackbird that’s singin’ this minit in the elm beyant there, only twice as low.”

“And how long was she living there, and was she married?”

“Troth thin, she was married, or at laste the poor crater thought she was, and her husband was an illegant man, too. He was taller nor yer honour, but twice as dark. He was a foreigner of some kind, but his name was English, or sounded like it. It was Duran. And sure ’twas happy enough they seemed to be, although there were no childre, and they wor livin’ there more nor three years, your honour, and you couldn’t tell which of thim was fonder of the other. And the cottage, yer honour, t’was all covered with roses, and sure, ’tis myself that many a time trimmed the rosebushes that ye might see up by the strame at the back of the cottage, where the summer-house was. And did ye mind the pond in front of it, yer honour?”

“I did,” I replied.

“Well then ’twasn’t a pond at all, yer honour but a quarry hole, and nothing would do the young mistress but that a lake should be made out of it, and didn’t myself help to dam up the strame to let the water run into the hollow ye see in the field, and a purty little lake it made, to be sure. Ay, sure, ’tis I mind it well, for a few days after ’twas finished, the news kem in that Boney was bet.”

“And did they live there long after that?” I asked.

“Little more nor two years, yer honour, for the lake was made the first year they wor there. But sure, ’tis the quare story it was, but no one minds it about here now but myself. The neighbours’ childre, that wor childre wud me are all dead and[23] gone, and sure they were foreigners, and they didn’t mix nor make with anyone outside their own two selves, and till the cross kem they were as happy as the day’s long.”

“And what was the cross?”

“Oh, then, meself doesn’t rightly know the ins and outs of it, yer honour; but ye see the way it was—one day when the master was away in Dublin, there drove up to the door a dark woman, that was more like a gipsy than anything else, and with big goold rings in her ears, and myself chanced to be in the garden behind the house trimmin’ them same rose bushes, an’ I only heard an odd word or two. But as far as I could hear, the dark woman, she was saying that the poor darlin’ lady had no right to call herself Mrs. Duran at all, for that he was ayther promised to marry her, or was married to her, meself didn’t rightly know till after, for I was only a gorsoon then, yer honour, and didn’t know much about it; but when the strange woman went away, and I went into the cottage to ask the mistress if she had any more for me to do, she was as white as a ghost, she, that used always to be bloomin’ like one of the roses ye’d see in them hedges there in the month of June. Well, yer honour, she told me she wouldn’t want anythin’ till mornin’, and sure meself never set eyes on her alive again.”

“Why, what happened?”

“What happened is it, yer honour? Sure there never was a mournfuller story. The master kem[24] home that night, but there was no sign of the poor mistress. I heard long after that she had left a letter, but I never heard tell of what was in it. Well, sure, he was nearly out of his mind, and then when there was no sign of her comin’ back he went away to foreign parts, and myself thought he’d never come back ayther, but he came home one mornin’ and he went on livin’ in the cottage as he did before when they wor together. The only one, barrin’ an old woman of a servant, that he ever let about the house, was myself, for ye see, yer honour, he knew the poor young mistress had a likin’ for me, and he used to employ me in lookin’ after the roses and keepin’ the summer house in order, where I often saw himself and herself sitting together, and often it was he sat there lookin’ as lonesome as a churchyard in the night, yer honour, and sure ’twas hardly a word he ever spoke. And then I knew that he was as fond as ever of the poor mistress, and that ’twas thinkin’ of her all the time he was. And didn’t myself see her picture in his bedroom, and ye’d think ’twas smilin’ at ye she was out o’ the frame, and then I knew the strange woman had wronged her and him.”

“And how long did he live there alone?”

“Sure, that’s the quarest part of the story, yer honour. Ye see, when the poor mistress was gone he didn’t mind the lake, and the water began to sink into the ground, and then there kem one dry summer when all the strames in the country ran dry. It was the driest summer I ever remember, and the[25] grass was as thin and as brown as my old coat, and as little nourishin’, and sure one mornin’ we noticed somethin’ under the shallow water of the lake, and what was it but the body of the poor mistress? And after that when we buried her in the churchyard beyond the hill there, the poor master left the place and the cottage was shut up, for no one would live in it, and the fields around it were tuk by Mr. Toole that had a farm next to it, and ’tis in the hollow where you might see the sheep browsin’ this minnit the poor lady was found.”

(From the Memoirs of an Officer of the Irish Brigade.)

It was towards the end of October in the year before the Battle of Fontenoy, and a few months before I joined one of the flocks of “the Wild Geese” in their flight to France, that I fell in with the experience which I am now about to relate. I had been staying for a few days with a friend in the west of the County of Cork, and I had started for home in full time, as I had hoped, to reach it before nightfall. My shortest way, about five miles, lay across the mountains. It was familiar to me since I was a child, and I felt sure I could make it out in dark as well as in daylight. When I started a light wind was blowing. Some dark clouds were in the sky, but the wind was not from a rainy point, and I was confident that the weather would keep up. When, however, I had traversed half the way, the wind changed suddenly and a light rain began to fall. I pushed on more quickly, yet without misgiving, but before I had gone a half-mile further the mountain was suddenly enveloped in mist that became denser at every step. I could scarcely see my hand when I stretched it out before me. The mossy sheep-track beneath my feet was scarcely[27] distinguishable, and now and again I was almost tripped up by the heather and bracken that grew high at either side.

I found it necessary to move cautiously and very slowly; yet, notwithstanding my caution, I frequently got tangled in the heather, but succeeded in regaining the path. I continued on until I judged that I had made another half-mile from the spot in which I was first surrounded by the mist. How long I had been making this progress it was difficult for me to estimate, but I became aware that the night had fallen, and I was no longer able to distinguish anything even at my feet. I began to doubt whether I was on the proper path, for sheep tracks traversed the mountain in all directions. It occurred to me to turn into the bracken and try to make the best shelter I could. The bracken here grew to a height of nearly three feet, and some of the stalks were thick and strong. I had often amused myself when a child twining the stalks together, and making them into a cosy house, and often escaped thereby from a heavy summer shower. The mere recollection of my childish efforts lightened my heart, though I was conscious enough that the experiment I was about to make was not likely to be very successful. But I set to, and tore up some of the bracken, and began to twist it around the standing clumps so as to form a roof, but when I had gone on a few feet from the track I felt the ground slipping from my feet. I[28] caught hold of a clump of bracken only to pull it from the roots, and to find myself sliding down I knew not whither. Stones were rumbling by my side, but fortunately none of them touched me, and quicker than I can tell it I was lying prone on the earth. I stretched out my hands, and found level ground as far as I could reach on either side. I struggled till I regained my feet. I was dazed for a while, but when I fully recovered myself I was utterly perplexed as to what I was to do. After the experience which I had had I was afraid to move either to the right or left. I stood still, and I am not ashamed to say that I could distinctly hear the beating of my heart. The mist still enveloped me, so I was unable to see anything. Suddenly I thought I heard the sound of voices, but set that down to my imagination, for I knew there was no house within miles of me. I listened, however, with the utmost eagerness, and again I heard the voices.

I was about to shout when the mist a little in advance of me was brightened, as if a light were thrown on it. Instinctively I advanced in the direction of the luminous haze, when I felt myself caught by the neck by a firm grasp, and I was flung forward. My feet slipped on some projection, and I fell headlong.

When I managed to raise myself I saw I was in a dwelling of some kind, partially lighted by the blaze of a turf fire. Several men were present, and I distinctly saw the flash of firearms. There was at[29] once a confusion of voices, and I was pulled to my feet by one of the men, who presented a horse-pistol at my head.

“Shoot him! He is a Sassenach spy!” came in a hoarse chorus from the men around the fire.

“No Sassenach am I,” I answered back, endeavouring to shake myself free from the grip of the man who held me.

“And who are you? And whence come you?” he asked, fiercely.

“Frank O’Mahony,” I said, “the son of Shaun O’Mahony, of the Glen.”

“Let me look at him,” cried an old woman, whom I had not previously noticed, and she shook off the grip of my captor and brought me towards the fire.

With a corner of her shawl she rubbed my face, and then she caught me in her arms.

“Ah, then, ’tis Frank—Frank O’Mahony,” said she. “Shure I nursed your mother, avourneen, on my knee. But ’tis no wondher the boys didn’t know you, for your own mother wouldn’t know you with the wet clay of the mountain plastered over your face, and ’tis you are welcome, Frank avourneen, in daylight or in dark, and shure no true Rapparee need close the doore again your father’s son.”

When the old woman had done speaking, the man who had seized me clasped my hand.

“Frank, my boy,” said he, “you’re welcome—welcome as the flowers of May. Make room for him[30] there, comrades; don’t you see the boy is cowld and wet.”

And they made a place for me, and the old woman brewed a steaming jug of poteen, and she said to the others that I wasn’t to be asked a question until I had taken some of her mountain medicine.

Hardly had I taken the medicine when I felt pretty comfortable, and then when I got time to look about me I saw I was in something like a cave of large dimensions, half of which was in shadow owing to the imperfect light.

About half-a-dozen men came in shortly after my arrival, and then the whole force numbered thirty.

When all who had been expected had come, the captain, who was the man who had seized me said—addressing me:—

“Help and comfort we always got from your father, Frank O’Mahony. Ah, and if the truth were known, my boy, he spent many a night on the hills with the Rapparees. May Heaven be his bed to-night. You are over young yet, but still not too young to strike a blow for Ireland. There isn’t a man here who wouldn’t die for you if necessary.”

“I hope to strike a blow for Ireland,” I said, “but word has come from my uncle, Colonel O’Mahony, that he wishes me to go to France and join him.” “God bless the Colonel, wherever he is,” said the captain, “he’ll never miss the chance, but would to God he was with us at home. The best—the best and the bravest have gone away from us.”

“What are you saying, man,” said the old woman, suddenly confronting him. “There’s not a colonel nor a general in the whole French army a bit boulder or braver than our own Rapparees.”

“We do our best, Moira asthoreen,” said the captain, laying his hand on her shoulder, “but the men who are gone away are winning fame for the old land, God bless them all. For sure their thoughts are always with poor Ireland, and every blow they strike they strike for her, and their pride in the hour of victory is because their own old land hears of it.”

“Ay, and every blow the Rapparees strike, they strike for her, too,” said Moira, “and ’tis no living there would be no living at all at all for poor people here at home if it weren’t for the boys, and—come there now, Jem Mullooney, and give us a stave about my bowld Rapparees. Yes, you can do it when you like, and I bet Master Frank here never heard it.”

I admitted I never had, and I cordially joined in the chorus which followed, and endorsed Moira’s demand.

Moira, apparently delighted to hear me backing up her demand, said:

“Musha, good luck to the mist that brought you here, Master Frank,” said she, “and sure that same mist has often proved a great friend to the Rapparees.”

The men had seated themselves around the cave as best they could, some on bunches of heather, some[32] on sods of turf, some on roots of trees roughly shaped into a seat. The captain, a few others and myself, were sitting close to the fire.

Jem Mullooney was nearly opposite me. The firelight flashing in his direction, enabled me to catch a full view of his face, and a fine face it was, though a little too long. You knew at a glance you could trust your life with him, but he looked like a pleased boy when he was importuned to give us the song.

Clearing his throat with the least taste of Moira’s medicine, he struck out in a rich voice, to a rattling air, accompanying himself occasionally with dramatic gestures, the following song:—

“THE RAPPAREES.

The applause which followed the song had barely ceased, when a low whistle was heard from outside.

“Open!” cried the captain of the Rapparees.

The barrier closing the entrance to the cave was removed, and a man covered with perspiration, and almost fainting for want of breath, rushed in.

“Two troops of infantry left Adamstown Barracks three hours ago. Shaun-na-cappal was with them.”

“Shaun-na-cappal!”

“Yes! They made for the red lanes, and ought to be in the glen by this.”

Another low whistle was heard, when the door was again opened, and a lad burst in.

“The sojers are in the glen, captain, and the clouds are going and the moon is coming.”

“Well, my lads,” said the captain, “our retreat is discovered. They think they will catch us here like rats in a trap. Perhaps we can set one for them. Bar the entrance. Pile up everything; make it as firm as you can.”

The men set to work with a will, and their task was soon completed. The captain, having surveyed it, said:

“That will do, men. They won’t burst in that in a hurry. We have a means of escape, which I have hitherto kept to myself. Get a few picks and loosen the hearth stone. That will do. Lift it up now, boys, and leave it in the centre of the floor.”

The men did as they were bidden, and when the stone had been set down, the captain, catching up one of the flaming brands, held it over the opening discovered by the removal of the hearth stone. It was large enough to allow a man to go down through it.

“Nine or ten steps,” said the captain, “lead to a narrow passage, through which by stooping a man can make his way. It is not more than fifty yards long. The outlet is blocked by a bank of earth; but just there the passage is wide and high enough to allow two men to stand abreast and erect. A hole can easily be cut or dug through this bank.

“You, O’Donovan,” he said, turning sharply to one of the Rapparees, “will know, once you are outside, where you are—close to the stream that runs down to the glen. Take a dozen men with you, turn to the left, and five minutes will bring you to the heathery height above the left of the track leading to this cave. And you, Mullooney,” said the captain to the singer of “The Rapparees,”[35] “take a score of men with you, and make for the right. You’ll have a bit of climbing at first, but in ten minutes you should be able to get down to the right bank of the track. Be all of you as wary as foxes, and let not a sound escape from any of you, even if you see the enemy coming right up to the door of the cave, and none of you are to fire a shot until you see a flaming brand flung out by us who will remain here to defend the cave against assault, but when you see the lighted brand, blaze away! If they waver, down on them like thunderbolts. When you beat them off, you will find us here, if not, we shall be at the sally gap two hours from this. Now go!”

“Would you like to go or stay, Frank?” said the captain, turning to me.

“I should like to go,” I replied.

“All right, my lad. Look to him, O’Donnell, and take this Frank,” said he, handing me a musket, “it has never missed fire.”

The two bodies of men descended in single file. The air of the passage was remarkably pure, and we made our way without difficulty. Then there was a halt of a few minutes while the foremost men were forcing a passage. One by one we passed out, and found ourselves knee-deep in the heather. A brawling stream ran down a few feet below us. O’Donovan and his men crept along by the stream. We, with O’Donnell at our head, clambered up through the heather, and in about ten minutes we[36] were lying snugly concealed within fifteen yards of the rock in which was the cave entrance.

We were lying at right angles to it, and about twelve feet above the open space in front of the rock. It was from this very height I had fallen an hour before. Opposite us the ground was about the same elevation as ours, and in the cover of the heather which crowned it, O’Donovan and his men were to ensconce themselves.

The moon was shining, and for about twenty yards we had a full view of the pathway leading to the cave. At that distance it took a sharp turn. I had barely time to make these observations, when we saw the moonlight glint on the level arms of the advancing troops. In a few seconds they were against the face of the rock. With the soldiers was a tall, wiry-looking man, dressed in a long frieze coat that went to his heels.

“Where is the entrance?” cried the captain of the troops. “I can find none.”

“There,” came the answer in a hoarse whisper.

“There, behind those furze bushes.”

“Come, my lads,” said the captain, “clear away those bushes.”

The soldiers began to work. Our fingers were impatient. The desire to fire grew upon me, when suddenly from the cave came a flash, a report, and the tall man in the frieze coat fell without a moan. Another shot and another and two soldiers were struck down.

“Quick, my lads, quick! Bring a canister, and we’ll blow the door in or out.”

The soldiers advanced with the canister, and were about to set it down at the cave’s mouth. Only then was hurled out the red brand, the signal for firing.

We poured a volley into their midst, O’Donovan’s men firing at the same time, while single firing was kept up from the cave.

The troops were staggered; their captain was shot dead. They paused for a moment; then, as they turned to run, a second volley laid low more than half their number.

“Down on them!” cried O’Donnell.

We hurled ourselves down into the path. O’Donovan’s men as eager, but with a view to cutting off all hope of retreat, had rushed down on the other side so as to meet them retreating. Caught between the two forces, the soldiers clubbed their muskets and fought desperately. Not more than four or five escaped. Desisting from the pursuit, we returned to the cave.

Our captain and the men with him had, in the meantime, removed the barrier and were standing outside. We were all curious to see the opening through which the captain fired, and through which he threw the lighted brand. No one except himself had known of it. It was a fissure in the rock which had been closed up with clay and moss, and which the captain, when we left the cave, dug out with a bayonet.

In the meantime some of our men were examining the fallen enemy, and found five that were wounded only. These were borne into the cave and placed under the charge of the old woman, the captain saying that a large body of troops were sure to come out next day who would take them away.

There was one object that attracted universal attention—the corpse of Shaun-na-cappal. He had fallen on his back; a bullet had pierced his throat; from the round hole the blood was still flowing. His mouth grinned horribly, and we felt it a relief when a dark cloud covered the moon, which had been shining down on the upturned face and open eyes. The captain having given his orders, and having arranged for the next meeting with his followers they dispersed, and he, having given some instructions to Moira with regard to the wounded, set out, taking me along with him. We found shelter that night in a little shebeen about two miles away from the cave.

And that is the story of my first night with the Rapparees.

(A Story of the days of the Irish Brigade.)

Towards the end of October, in the year 1704, a man of middling height, with a face rather thin and long, was seated at a table on which were spread some military maps. Over these he had been poring for some time. When he looked up from them, his dark, eager eyes revealed a nature alert, resourceful and vigorous. One glance at him, as he looked straight before him, was sufficient to convince every observer that here was a man accustomed to command by the right of genius. The military costume in which he was dressed betrayed no evidence of high rank. It was, it must be confessed, plain almost to the verge of sloveliness, and the breast of his doublet was stained with snuff. Beside him on the table was a golden snuff-box, on the lid of which, set in brilliants, was a portrait of the Emperor Leopold I. of Austria, and to this he frequently had recourse, even while studying the maps most carefully.

He was alone. The room in which he was sitting looked in the direction of the camp of the allies, then besieging Landau, and from it a good view could be had of the fortress. The siege had[40] lasted longer than had been anticipated, and no one chafed more at the delay than the subject of our sketch. His one desire was to be for ever rushing from battlefield to battlefield. Rapid in action as in decision, he found the time hang heavily on his hands. While the siege was in progress he had been considering the possibility of engaging in some other enterprise which might redound to the honour of his Emperor, and at the same time add to his own glory.

He pushed the maps away from him, rose from his chair, and taking a large pinch of snuff, moved towards the window and stood a while watching the operations of the siege. A knock at the door attracted his attention.

“Enter!”

“The Governor of Freiburg awaits the pleasure of your Highness,” said the person who entered, evidently an officer of rank, who was, in fact, an aide-de-camp to his Highness.

“I am ready to see him,” was the reply.

His Highness took another heavy pinch of snuff.

A tall, military looking man, somewhat over middle age, and of resolute countenance, entered. He made a low bow and then drew himself erect.

“Be seated,” said his Highness, as he himself resumed his chair. The Governor of Freiburg obeyed.

“You bring news of Brissach, Governor?”

“Yes, your Highness.”

“Your informant?”

“My valet, your Highness. He has been a soldier, and possesses a keen power of observation. He succeeded in getting into the Old Town several times on the pretence of purchasing wines. The French are busy strengthening the fortifications, but discipline is lax, and as there are over twelve hundred labourers employed in the works there is considerable disorder in the town.”

“Good. What is the strength of the garrison?”

“Only four battalions, your Highness, and six independent companies.”

“Any Irish among them?” and his Highness again had recourse to his snuff-box.

“None, sir.”

“Sure?”

“Certain, your Highness.”

“So much the better. Those fighting devils upset the best laid plans, as I learned to my cost at Cremona. And pardieu, they can fight!” And Prince Eugene of Savoy, for it was he, shook his head, causing some of the snuff he was taking to fall down, and increase the stain on his doublet.

“But, let me see. Four battalions and six independent companies. What time are the gates open in the morning?”

“At daybreak, your Highness. Many of the labourers live outside the town.”

Prince Eugene remained silent for a few moments.

“Then,” he said, as he rapped the lid of his snuff-box, “you should be able to surprise Brissach Old Town. We may also make an attempt on the New Town. You will command the expedition—” a slight flush of pleasure exhibited itself on the Governors face—“I shall place at your disposal 4,000 picked men from the German and Swiss infantry, and 100 cavalry; with that force you should be able to possess yourself of Old Brissach and hold it.”

The Governor of Freiburg bowed as if in assent, but could not help remembering that only the year before, King Louis of France had employed 40,000 men and 160 guns in the reduction of the two Brissachs.

“You shall have under you,” continued the Prince, dabbing at the same time his nostrils with snuff, “some capable officers, including the Lieutenant-Colonel of the Regiment of Bayreuth and the Lieutenant-Colonel of the Regiment of Osnabruck, who shall be Governor of the town.”

“He regards it as good as taken,” thought the Governor, and he did not feel too happy at the thought. There is so much chance in war.

“These mornings lend themselves to such an enterprise,” continued the Prince, again resorting to the snuff-box, for it had become a habit with him to punctuate, as it were, his sentences with a pinch of snuff. “The fog lies low upon the river until some hours after sunrise.”

“He thinks of everything,” said the Governor to himself.

“And,” added the Prince, “you will hear from me by to-morrow as to the time for your attempt.”

The Governor of Freiburg accepted this as a dismissal, and saluting Prince Eugene, passed from the room.

The morning of the 10th of November was fixed for the attempt on the town. That day had been selected because it had come to the ears of the Governor of Freiburg, whom we know was to command the expedition, that a large quantity of hay requiring many carts to convey it, was to be brought into the magazine at Brissach. The hay was to be coming from a considerable distance, and the carters in charge would travel all night, and endeavour to arrive at the town as soon as, if not earlier than, the gates would be opened.

That this was their intention the Governor, who was well served by his spies, had also learned. The opportunity was too good to be lost. Over 50 waggons had been requisitioned, and each would be attended by at least two peasants. The entering of so many waggons into the town would necessarily cause some distraction, and if it were possible, under the cover of darkness, to follow close on them, the Germans and Swiss, might hope to pour in after them without let or hindrance of any kind, as discipline had become very much relaxed.

When the day came, fortune proved even kinder than the Governor of Freiburg had hoped. A thick, dark fog was over the river, and hung like a pall over the two Brissachs, so that those in the new town, on the French bank of the Rhine, could not see their neighbours on the German bank, nor could their neighbours see them. And it was through this fog, that what might be called the advance guard of the waggons made their way into the town.

It was then eight o’clock in the morning. The reveille had sounded long before. The garrison were preparing for breakfast, and the labourers had gone to work in the fortifications. There were, however, owing to the thick fog, but few people about the streets, and the sentries at the gate were watching, with no very keen interest, the lumbering hay waggons passing in.

Several of the peasants who had followed them, other than the drivers, stood inside the gates in an aimless fashion as if their task had been completed.

Attracted by the rumble of the carts, the Overseer of the workmen on the fortifications, a tall, brawny looking fellow, came towards the gate, and seeing the group of idle peasants mistook them for some of his labourers, and asked them why they were not at work. He received no answer. He then addressed himself particularly to one who was a little in advance of the others, and who had a keen eye and appeared to be a man of intelligence.

“Why are you not at work?”

The man accosted, did not at once answer, and the Overseer had to step back and make way for an incoming waggon.

“Why are you not at work, I say?” he repeated angrily.

Still no answer, and the Overseer thought he detected in the faces of the other peasants something like a grin. His temper at the best was not angelic, and this suspicion proved too much for him.

“By G——, I’ll teach you how to talk,” and before the astonished peasant could lift a hand to defend himself, down came the blackthorn on his shoulders with a rapidity that showed that the Overseer was well versed in the argumentum baculinum. Instead of answering, the peasant rushed to the nearest hay waggon, and crying out some word in German, thrust his hand into the hay, drew out a loaded musket, aimed at the Overseer, fired point blank and missed. A blow of the blackthorn sent the peasant down. In the meantime others of the peasants had crowded round the Overseer, who, while with every blow he felled an assailant, kept crying, “To arms, to arms!”

But suddenly the hay was swept from the waggons, and from each a number of armed men sprang out. The Overseer, unable to withstand so many foes, having succeeded in getting round one of the carts, made a rush for the sedge on the river.

The enemy, in an excess of folly, fired at the sedge, and the bullets whizzed through it, cutting it just above his head, but the report of the muskets was heard through the town, and the whole garrison turned out. A rush was made for the gate, inside of which there were now some hundreds of the enemy. The Overseer, seeing the troops coming out, quitted his retreat and joined them, and threw himself into the midst of the desperate hand-to-hand conflict, in which both sides were at once engaged. Many a stout German went down with a cracked skull before the wielder of the blackthorn. At length, after a stubborn resistance, the enemy were driven out and pursued some distance, the Governor of Freiburg covering their retreat with the cavalry. They left behind them nearly two hundred dead, including the Lieutenant-Colonel of the regiment of Osanbruch and the Lieutenant-Colonel of the regiment of Bayreuth, and several majors and captains.

Bad news travels fast, but the Governor of Freiburg determined that he himself would be the bearer of it to the Prince. It was an unpleasant task, but he thought it better that he should be the first to carry it, so that rumour might have no time to make out a worse case against him than his conduct of the affair warranted.

On the following day he found the Prince alone, as on the former occasion, and in the same apartment.

“You have taken Brissach?” said the Prince, with an eager glance.

The Governor flushed.

“After a stubborn fight we were driven out, your Highness.”

“You were inside the gate?”

“Yes.”

“Details. Briefly!” And the Prince rapped the lid of his snuff-box sharply.

The Governor told what the reader has already learned.

Several times during the brief narrative the Prince’s thumb, dipped into the box, and small showers of snuff fell on his doublet.

“How many were inside the gate when the rascal with the stick came up?”

“About forty, your Highness.”

“And they were unable to disarm him, or take him without firing and raising the garrison?”

The Governor did not reply.

“Who was the idiot who fired the first shot?”

“The Lieutenant-Colonel of the regiment of Bayreuth.”

The Prince looked hard at the Governor, who almost shrank before the fierce gaze.

“Where is he?”

“Dead, your Highness. He fell fighting.”

“The fate was too good for him.”

The Prince made a gesture of dismissal. The Governor bowed, and was on the point of withdrawing.

“Stay,” said the Prince. “Did you chance to hear the name of the prodigy whose single blackthorn foiled the attempt made by four thousand of the best troops in the Imperial service?”

“He is called, your Highness, the Sieur O’Byrne.”

“O’Byrne! O’Byrne! an Irishman!” exclaimed the Prince.

The Governor bowed.

“But you told me there were no Irishmen in Brissach.”

“There was only one.”

“Only one!” The Prince arrested his thumb as he was lifting up a pinch of snuff. He made a gesture of dismissal and the Governor retired.

“Only one,” the Prince repeated when he was alone. “If there had been a hundred it is more than probable the Governor of Freiburg would never have found his way back from Brissach.”

The Prince made up for his interrupted pinch, and dabbed at both nostrils as he moved to the window. The cannonade, which had been going on for some hours, had ceased, but a puff of smoke from the trenches, followed by a report, showed that the firing was kept up in a desultory fashion. The Prince’s eyes rested for a second on the portrait of the Emperor on his snuff-box. “The loss of Brissach,” he said half aloud, “was a severe blow to the Emperor. I had recovered it for him if it were not for that infernal Irishman with his blackthorn. Pardieu, but it is worse than Cremona!”[49] And the Prince, of whom it has been written that his “passion was for glory and his appetite for snuff,” flicking up the lid of the precious box, scooped up between finger and thumb what was left, and as he sniffed the fragrant but strong powder, “I must get more snuff,” he said.

Or Revenged at Last.

During the year of the ’98 Centennial celebrations, it chanced that I was staying on a short visit with a friend in the county of ——, whose residence was not far from one of the battlefields of the rebellion. Our talk turned one day upon ’98, and I asked him if he knew if any stories of the period were still current in the neighbourhood. He said he was not himself familiar with any. He was not belonging to the county, and had been residing in it only a few years. But he promised to find out if any of the servants or workpeople could give me any information. That evening he informed me there was an old man helping in the garden, now almost past his work, who was at one time a schoolmaster, and had originally come from the county of Antrim, and who had some stories of the rising in the North. The next day I made the old man’s acquaintance, and from him took down the story of Maurya na Gleanna:—

“I wasn’t more nor nine or ten years old when I first saw Maurya na Gleanna, and although I’m over seventy years now I can see her face just as if she was standing there foreninst me. She would have been very tall if it were not for a stoop in her shoulders. Her face was rather long, her cheeks[51] shrunken and almost yellow. Her hair (and there was plenty of it) was tied up in a wisp at the back of her head, and was gray almost to whiteness, while her eyebrows were as dark as the night. Her lips were full and might have once been red, but the colour had left them and they looked dry and blanched. Her eyes were as black as a coal with a red heart that would blaze up for a moment and then become dull.

“She had come into the glen many years before. She had wandered into it of a wild March morning—a Patrick’s morning, too, it was—when the snow lay deep in the glen, and you could hardly see a bit of green for miles around.

“The snow was in a drift against Jack M’Guinness’s door when she knocked at it just after the break of day. There was hardly one astir in the house at the time, but when the knock was repeated the servant-man got up and went to the door and opened it; before he could question the woman he saw standing outside, she had stepped across the threshold.

“Her hair was then, so they afterwards told me, as white as when I first saw her, but there was some colour in her cheeks, nor had it left her lips. A kerchief covered her head, and a shawl thrown over her shoulders was fastened above her breast by a skewer that had been beaten into the semblance of a pike, and which served to keep in its place a bunch of shamrocks. Her head-dress and shoulders[52] were thickly coated with snow, which clung to her dress that stopped short at her ankles. Her feet were bare.

“The man said afterwards that the blaze of her eyes nearly blinded him, and took the word out of his mouth.

“She laid her left hand upon his shoulder, and touching the shamrock with one of the fingers of her right hand, she whispered in a tone suggestive of mystery:

“‘Is there green upon your cape?’

“’Twas then a few years after the troubles, but the servant boy had been one of the United men, and had fought at Ballinahinch. He knew the words of the rebel song, but as he didn’t reply at once, she whispered again:

“‘Is there green upon your cape?’

“For answer he took her hand, while a strange feeling came over him that she was something ‘uncanny,’ and he gave her the ‘grip’ that showed he was a United man. She returned it.

“‘Who is there?’ cried Jack M’Guinness, who came out of his room into the kitchen, having heard the door open.

“He started back a step when he saw the blazing eyes and tall figure (for the stoop had not fallen on her then).

“‘Is there green upon your cape?’ she asked him eagerly, almost feverishly.

“‘Ah, my poor woman, the day is over I’m[53] afeard,’ he said softly, for, with a keener perception than that of the servant boy, he saw the poor creature was demented.

“‘Over! over!’ she cried, almost hysterically, ‘it will never be over until he—he that you know—sure everybody knows him—until he, Red Michil of the Lodge, comes to his own, his own, you know, the three sticks, two standin’ straight and one across. Red Michil, with the brand of Cain and the curse of God on him. An’ isn’t this a purty posy?’ and she took the bunch of shamrocks from her breast and held it up to Jack M’Guinness.

“‘A purty posy it is, my girl,’ said he, falling in with her humour; ‘but shake the snow from yourself and come near the fire. Blow up the turf, Shane,’ and he turned to the servant boy, ‘and let the girl warm herself.’

“‘Ay, sure enough, it’s the purty posy,’ the girl continued, ‘but hadn’t I trouble enough finding it, with the snow here, there and everywhere, every step I took goin’ deeper than the rest; but I didn’t mind the snow, why should I? Sure his face was colder when I saw it last, and his windin’ sheet was as white.’

“‘Sit down, achorra, and the good woman will be up in a few minutes and will give ye something to warm ye.’

“‘Ay, then! ‘tis cowld ye think I am, and maybe I am cowld, too; an’ I gets tired sometimes; but there’s a fire in my heart always—a fire that’ll niver[54] go out—niver go out, I tell ye, until Michil of the Lodge comes to his own.’ And then the poor thing sat down by the hob, and the boy blew up the turf till the blaze lighted the whole kitchen, and the pewter on the dresser flashed back the ruddy rays. And when the heat began to spread about the room, the head of the poor, tired creature dropped on her breast and she fell into a deep sleep.

“This was the first coming of Maurya to the Glen, and that’s the way the story was told to me. For, as I told you, it was before my time. She was treated kindly by Jack M’Guinness and his wife, who took to the poor girl, and would have kept her with her if she could, but Maurya couldn’t be induced to spend more than a few days in any place.

“Who she was, or why she came to the glen, or where she came from nobody in the glen knew.

“The women said it was love trouble that drove the poor thing wandering, and that her question about the green upon the cape showed that the lover had fallen a victim on the scaffold, or in the field, in the struggle in ’98.

“There wasn’t a family in the glen that hadn’t sent a man to Ballinahinch, and not a few sent more than one, and there wasn’t a hearth in the glen where poor Maurya didn’t find a welcome.

“But she was always roaming. After a night’s rest she went ‘scouting,’ as she used to say, hoping to catch Red Michil to bring him to his own—‘the three sticks.’

“And so in the first light of the morning she used to go out and ramble over the hills, living any way she might, and coming back and seeking hospitality—now in one house, now in another, in the glen.

“‘I didn’t see any signs of him to-day,’ she used to say, on entering the house which she had come to for her night’s lodging. ‘I didn’t see any signs of him to-day, but, please God, I soon will. Red Michil won’t escape me, never fear.’

“And this mode of life Maurya continued for years. The colour faded from the cheeks and from the lips, and the tall form began to stoop, and they noticed that she didn’t ramble so far as she had been wont to do. She had always been very gentle in her manner, but at times, and when she seemed oblivious to everything passing round her, the flame would flash from her eyes, and she would leave her seat by the fire, and despite remonstrance, no matter what the weather or the hour, would start out on her quest for Red Michil. Over and over again, some of her women friends tried to get her story from her, not so much through curiosity as through a belief that it might lighten the burden on her heart if she would confide her sorrow to some one.

“But they could get nothing from her but a denunciation of Red Michil of the Lodge; but who he was, or what he had done, they could not find out from her.

“There was one house in the glen to which she came oftener than to any other, and that was Shane O’Donnell’s, an uncle of mine. I don’t mind saying it now (said the schoolmaster), but Shane had a little shanty upon the hills, beyond the glen, where he carried on, in a small way, the manufacture of the mountain dew. You’d hardly know the hut from the heather. It was in a little dip on the side of a hill, just deep enough for the walls, and until you were almost atop of it you could hardly distinguish the roof from the heather, and no wonder, for it was thatched with scraws, with the heather roots in them. The only thing that betrayed its existence was the occasional smoke from the hole in the roof that was the excuse for the absence of a chimney. Thither Maurya na Gleanna often went, and there she was always welcome. Although her wits were generally wandering, she was always able to lend a hand in household matters, and in the cabin I’ve mentioned she used to boil the potatoes and cabbage, and do other cooking what was necessary.

“The hut itself was little more than an excuse. It covered the descent into a cave, in which was carried on the manufacture of poteen, and this was reached through an opening which was disclosed when the hearthstone was lifted up.

“The smoke from the operations below came up through an aperture close to the hearthstone, and was carried off with that of the fire in the hut, so that anyone who might drop into the hut would[57] not suspect anything. It was a shepherd’s hut and nothing more.

I was occasionally called on to assist in making the poteen, and at this time Maurya na Gleanna had been regularly employed as cook, that is to say, whenever the men were at work Maurya was sure to come there, and boil the potatoes and make the stirabout, and sometimes, too, a bit of mountain mutton found its way into the pot.

Well, it happened one day Maurya was boiling a bit of mutton, and myself was sitting near the fire, when Maurya said:

“It was a quare dhrame I had last night, Shamey.”

“What was it, Maurya?” I asked, for all of us, young and old, used to humour her.

“Well, then,” said she, “do you see them three legs to the pot that’s boilin’ there before you?”

“I do,” said myself, “why wouldn’t I?”

“Well, then, Shamey, and mind you, I didn’t tell this to anyone but yourself, I dreamt last night them three legs to the pot were the three sticks; and rayson that out for me if you can, for I can’t. I think sometimes my poor head is goin’, Shamey.”

I knew what she meant by “the sticks,” but, of course, I couldn’t guess the meaning of her dream.

“I don’t know, Maurya,” said I. “I don’t know what it means.”

“Ah, then, how could you, Shamey?” said she. “Sure you never supped sorrow, and I hope you[58] never will, avick, and ’tis only them that has supped it year after year that could tell poor Maurya what she wants to know.”

And she swung the crane from which the pot was hanging out from the burning turf.

“Do you see the three legs of it, Shamey?” she asked.

“I do, Maurya,” said I.

“They are red now from the fire,” said she. “And he was red—Red Michil, you know—and I dreamt last night that they were the three sticks. But dhrames are foolish, and there’s no use minding them, Shamey. And how could they be the three sticks? Sure, you couldn’t hang a mouse on them, could you, Shamey, let alone Red Michil?”