Title: The Story of My Life, volumes 4-6

Author: Augustus J. C. Hare

Release date: May 22, 2013 [eBook #42770]

Most recently updated: January 25, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images available at The Internet Archive)

| Every attempt has been made to replicate the original book as printed.

Some typographical errors have been corrected. (a list follows the text.) No attempt has been made to correct or normalize all of the printed accentuation of names or words in French. (etext transcriber’s note) |

BY

AUGUSTUS J. C. HARE

AUTHOR OF “MEMORIALS OF A QUIET LIFE.”

“THE STORY OF TWO NOBLE LIVES.”

ETC. ETC.

VOLUME IV

LONDON

GEORGE ALLEN, 156, CHARING CROSS ROAD

1900

[All rights reserved]

Printed by Ballantyne, Hanson & Co.

At the Ballantyne Press

TABLE OF CONTENTS

| Contents of Volume 4 List of Illustrations Volume 4 Contents of Volume 5 List of Illustrations Volume 5 Contents of Volume 6 List of Illustrations Volume 6 Index to Volumes 4-5: A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, J, K, L, M, N, O, P, Q, R, S, T, U, V, W, Y, Z Footnotes |

WITH the exception of the last two chapters, these three volumes were printed at the same time with the first three volumes of “The Story of my Life” in 1896, therefore many persons are spoken of in them as still living who have since passed away, and others, mentioned as children, have since grown up.

Reviews will doubtless, in general, continue to abuse the book, especially for its great length. But personally, if I am interested in a story, I like it to be a long one; and there is no obligation for any who dislike a long book to read this one: they may look at a page or two here and there, where they seem promising; or, better still, they can leave it quite alone: they really need have nothing to complain of.

In the later volumes I have used letters for my narrative even more than in the former. Many will feel with Dr. Newman that “the true life of a man is in his letters.... Not only for the interest of a biography, but for arriving at the inside of things, the publication of letters is the true method. Biographers varnish, they assign motives, they conjecture feelings, but contemporary letters are facts.”

C. HARE.

| PAGE | |

| IN MY SOLITARY LIFE | 1 |

| LITERARY WORK AT HOME AND ABROAD | 162 |

| LONDON WALKS AND SOCIETY | 352 |

| The illustrations may be viewed enlarged by clicking on them.

In order to ease the flow of reading, some of the illustrations have been moved to before or after the paragraph in which they appeared in the book. (note of etext transcriber) |

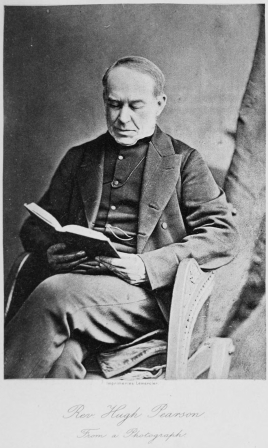

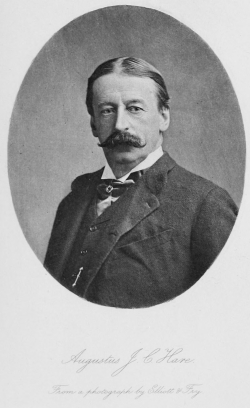

| AUGUSTUS J. C. HARE.From a photograph by Hill and Sounders. (Photogravure) | Frontispiece |

| PAGE | |

| HIGHCLIFFE, THE KING’S ORIEL | 9 |

| FRANCIS GEORGE HARE.(Photogravure) | To Face 20 |

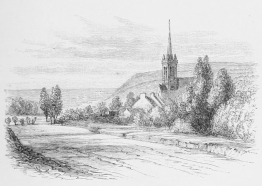

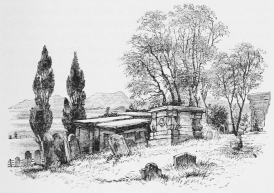

| THE CHURCHYARD AT HURSTMONCEAUX | 15 |

| GIBRALTAR FROM ALGECIRAS.(Full-page woodcut) | To face 34 |

| TOLEDO. (Full-page woodcut) | To face 38 |

| SEGOVIA. (Full-page woodcut) | To face 42 |

| FOUNTAIN OF S. CLOUD | 45 |

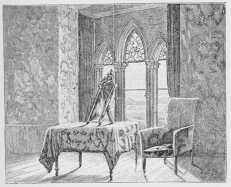

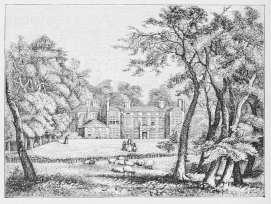

| FROM THE LIBRARY WINDOW, FORD | 52 |

| HATFIELD | 75 |

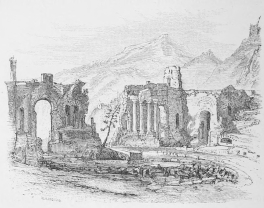

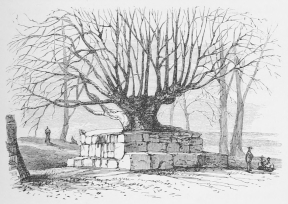

| FIDENAE | 86 |

| VIEW FROM THE TEMPIETTO, ROME | 91 |

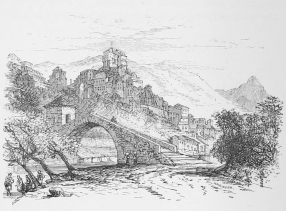

| SUBIACO.(Full-page woodcut) | To face 96 |

| ISOLA FARNESE | 96 |

| PONTE DELL’ ISOLA, VEII | 97 |

| CASTEL FUSANO | 100 |

| CYCLOPEAN GATE OF ALATRI | 104 |

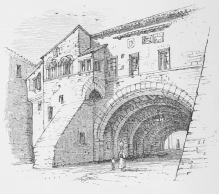

| THE INN AT FERENTINO | 105 |

| PAPAL PALACE, ANAGNI | 106 |

| TEMPLES OF CORI | 107 |

| NINFA | 108 |

| S. ORESTE, FROM SORACTE | 109 |

| CONVENT OF S. SILVESTRO, SUMMIT OF SORACTE | 111 |

| SUTRI | 112 |

| CAPRAROLA | 113 |

| PAPAL PALACE, VITERBO | 114 |

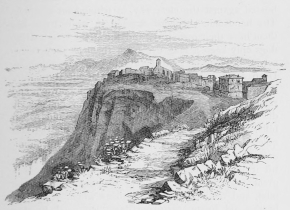

| FROM THE WALLS OF ORVIETO | 115 |

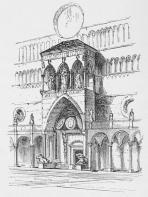

| PORCH OF CREMONA | 120 |

| PIAZZA MAGGIORE, BERGAMO | 121 |

| THE HOSPICE, HOLMHURST | 130 |

| LANGLEY FORD, IN THE CHEVIOTS | 138 |

| RABY CASTLE | 146 |

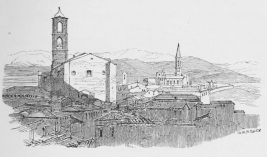

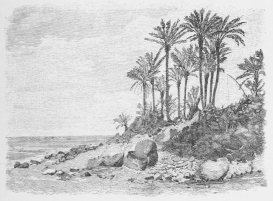

| LAMPEDUSA FROM TAGGIA | 167 |

| STAIRCASE, PALAZZO DELL’ UNIVERSITA, GENOA | 168 |

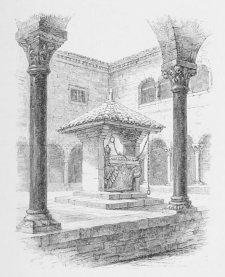

| CLOISTER OF S. MATTEO, GENOA | 169 |

| COLONNA CASTLE, PALESTRINA | 172 |

| GENAZZANO | 173 |

| SUBIACO | 174 |

| SACRO SPECO, SUBIACO | 175 |

| S. MARIA DI COLLEMAGGIO, AQUILA | 176 |

| SOLMONA | 177 |

| HERMITAGE OF PIETRO MURRONE | 178 |

| CASTLE OF AVEZZANO | 179 |

| GATE OF ARPINUM | 180 |

| TRIUMPHAL ARCH, AQUINO | 181 |

| PORTO S. LORENZO, AQUINO | 182 |

| FARFA | 190 |

| GATE OF CASAMARI | 191 |

| LA BADIA DI SETTIMO | 195 |

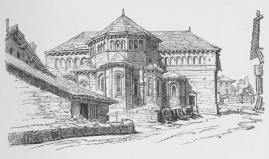

| AT MILAN | 197 |

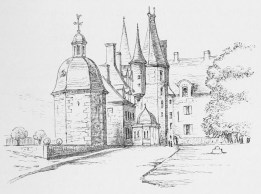

| PARAY LE MONIAL | 198 |

| THE GARDEN TERRACE, HIGHCLIFFE | 210 |

| THE HAVEN HOUSE | 211 |

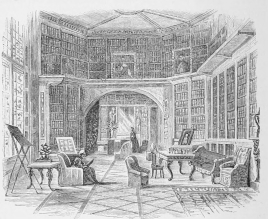

| THE LIBRARY, HIGHCLIFFE | 214 |

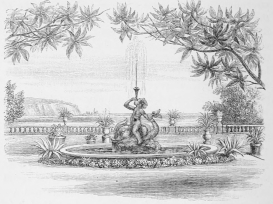

| THE FOUNTAIN, HIGHCLIFFE | 216 |

| GATEWAY, LAMBETH PALACE | 220 |

| THE BLOODY GATE, TOWER OF LONDON | 221 |

| COMPIÈGNE | 225 |

| HOLLAND HOUSE | 227 |

| HOLMHURST, THE ROCK WALK | 229 |

| HOLLAND HOUSE (GENERAL VIEW) | 231 |

| HOLLAND HOUSE, THE LILY GARDEN | 234 |

| COBHAM HALL | 238 |

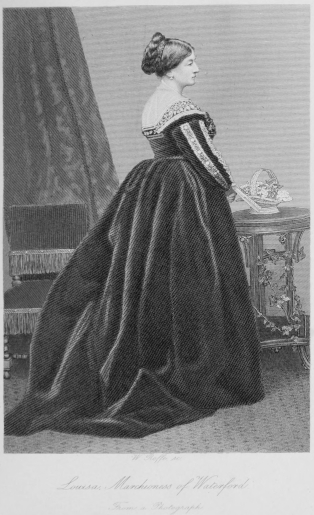

| LOUISA, MARCHIONESS OF WATERFORD. (Line engraving) | To face 256 |

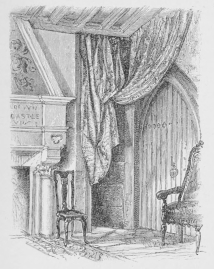

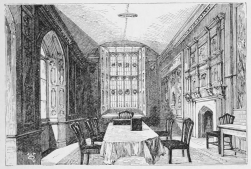

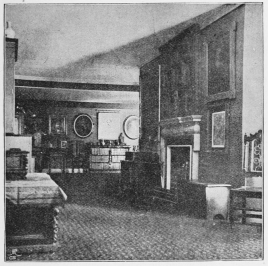

| THE SECRET STAIR, FORD | 257 |

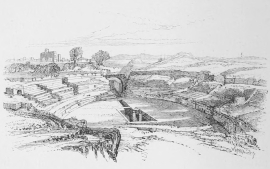

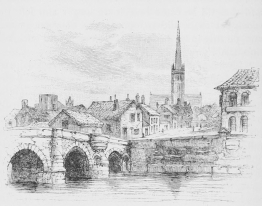

| NORHAM-ON-TWEED | 259 |

| THE KING’S ROOM, FORD | 263 |

| THE PINETA, RAVENNA | 302 |

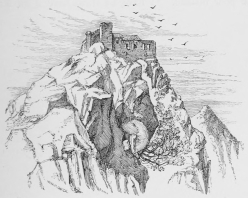

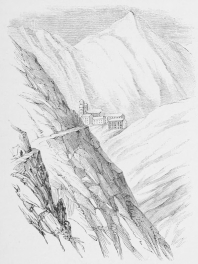

| IL SAGRO DI S. MICHELE | 313 |

| CANOSSA | 314 |

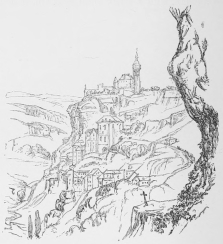

| URBINO | 315 |

| GUBBIO | 316 |

| LA VERNIA | 319 |

| CAMALDOLI | 320 |

| BOBBIO | 321 |

| FRANCES, BARONESS BUNSEN. (Line engraving) | To face 322 |

| LOVERE, LAGO D’ISEO | 322 |

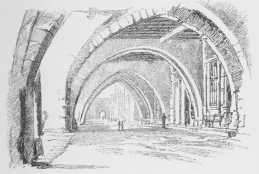

| LAMBETH, INNER COURT | 324 |

| DORCHESTER HOUSE | 332 |

| CROSBY HALL | 337 |

| THE GARDEN PORCH, HIGHCLIFFE | 341 |

| THE SUNDIAL WALK, HIGHCLIFFE | 342 |

| FOUNTAIN COURT, TEMPLE | 361 |

| IN FRONT OF ST. PAUL’S | 364 |

| CHAPEL AND GATEWAY, LINCOLN’S INN | 372 |

| STAPLE INN, HOLBORN | 373 |

| JOHN BUNYAN’S TOMB, BUNHILL FIELDS | 377 |

| TRAITOR’S GATE, TOWER OF LONDON | 378 |

| THE SAVOY CHURCHYARD | 380 |

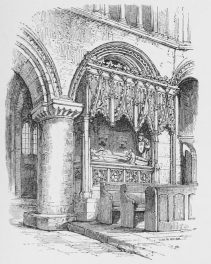

| RAHERE’S TOMB, ST. BARTHOLOMEW’S, SMITHFIELD | 381 |

| THE SLEEPING SISTERS, ST. MARY OVERY | 382 |

| CHARLTON HALL | 389 |

| COURTYARD, FULHAM PALACE | 399 |

| HOLMHURST | 405 |

| LOUISA, MARCHIONESS OF WATERFORD. From a photograph by W.J. Reed. (Photogravure) | To face 406 |

| CHURCHYARD OF ST. ANNE, SOHO | 413 |

| LONDON BRIDGE FROM BILLINGSGATE | 485 |

“Whoever he is that is overrun with solitariness, or crucified with worldly care, I can prescribe him no better remedy than that of study, to compose himself to learning.”—Burton, Anatomy of Melancholy.

“Let us dismiss vain sorrows: it is for the living only that we are called to live. Forward! forward!”—Carlyle.

I SPENT the greater part of the fiercely cold winter of 1870-71 in complete seclusion at Holmhurst, entirely engrossed in the work of the “Memorials,” which had been the last keen interest of my Mother’s life. In calling up the vivid image of long-ago days spent with her, I seemed to live those days over again, and I found constant proof of her loving forethought for the first months of my solitude in the materials which, without my knowledge, and without then the slightest idea of publication, she must have frequently devoted herself to arranging during the last few years of her life. As each day passed, and the work unravelled itself, I was increasingly convinced of the wisdom of her death-bed decision that until the book was quite finished I should give it to none of the family to read. They must judge of it as a whole. Otherwise, in “attempting to please all, I should please none: shocking nobody’s prejudices I should enlist nobody’s sympathies.”

Unfortunately this decision greatly ruffled the sensibilities of my Stanley cousins, especially of Arthur Stanley and his sister Mary, who from the first threatened me with legal proceedings if I gave them the smallest loop-hole for them, by publishing a word of their own mother’s writing without their consent, which from the first, also, they declared they would withhold. They were also “quite certain” that no one would ever read the “Memorials” if they were published, in which I always thought they might be wrong, as people are so apt to be when they are “quite certain.”

My other cousins did not at first approve of the plan of the “Memorials,” but when once completely convinced that it had been their dear aunt’s wish, they withdrew all opposition.

Still the harshness with which I was now continually treated and spoken of by those with whom I had always hitherto lived on terms of the utmost intimacy was a bitter trial. In a time when a single great grief pervades every hour, unreasonable demands, cruel words, and taunting sneers are more difficult to bear than when life is rippling on in an even course. I was by no means blameless: I wrote sharp letters: I made harsh speeches; but that it was my duty to fight in behalf of the fulfilment of the solemn duty which had devolved upon me, I never doubted then, and I have never doubted since. In the fulfilment of that duty I was prepared to sacrifice every friend I had in the world, all the little fortune I had, my very life itself. I felt that I must learn henceforth to act with “Selbständigkeit,” which somehow seems to have a stronger meaning than independence; and I believe I had in mind the maxim of Sœur Rosalie—“Faites le bien, et laissez dire.”

A vivid impression that I had a very short time to live made me more eager about the rapid fulfilment of my task. I thought of the Spanish proverb, “By-and-by is always too late,” and I often worked at the book for twelve hours a day. My Mother had long thought, and latterly often said, that it was impossible I could long survive her: that when two lives were so closely entwined as ours, one could not go on alone. She had often even spoken of “when we die.” But God does not allow people to die of grief, though, when sorrow has once taken possession of one, only hard work, laboriously undertaken, can—not drive it out, but keep it under control. It is as Whittier says:—

“There is nothing better than work for mind or body. It makes the burden of sorrow, which all sooner or later must carry, lighter. I like the wise Chinese proverb: ‘You cannot prevent the birds of sadness from flying over your head, but you may prevent them from stopping to build their nests in your hair.’”[1]

I had felt the gradual separation of death. At first the sense of my Mother’s presence was still quite vivid: then it was less so: at last the day came when I felt “she is nowhere here now.”

It was partly owing to the strong impression in her mind that I could not survive her that my Mother had failed to make the usual arrangements for my future provision. As she had never allowed any money to be placed in my name, I had—being no legal relation to her—to pay a stranger’s duty of £10 per cent on all she possessed, and this amounted to a large sum, when extended to a duty on every picture, even every garden implement, &c.[2] Not only this, but during her lifetime she had been induced by various members of the family to sign away a large portion of her fortune, and in the intricate difficulties which arose I was assured that I should have nothing whatever left to live upon beyond £60 a year, and the rent of Holmhurst (fortunately secured), if it could be let. I was urged by the Stanleys to submit at once to my fate, and to sell Holmhurst; yet I could not help hoping for better days, which came with the publication of “Walks in Rome.”

Meanwhile, half distracted by the unsought “advice” which was poured upon me from all sides, and worn-out with the genuine distress of my old servants, I went away in March, just as far as I could, first to visit the Pole Carews in Cornwall, and then to the Land’s End, to Stephen Lawley, who was then living in a cottage by the roadside near Penzance. I was so very miserable and so miserably preoccupied at this time, that I have no distinct recollection of these visits, beyond the image on my mind of the grand chrysoprase seas of Cornwall and the stupendous rocks against which they beat, especially at Tol Pedn Penwith. I felt more in my natural element when, after I had gone to Bournemouth to visit Archie Colquhoun,[3] who was mourning the recent loss of both his parents, I was detained there by his sudden and dangerous illness. While there, also, I was cheered by the first thoughts for a tour in Spain during the next winter.

To Mary Lea Gidman.

“Penzance, March 13, 1871.—I know how much and sadly you will have thought to-day of the last terrible 13th of March, when we were awakened in the night by the dear Mother’s paralytic seizure, and saw her so sadly changed. In all the anguish of looking back upon that time, and the feeling which I constantly have now of all that is bright and happy having perished out of my life with her sweet presence, I have much comfort in thinking that we were able to carry out her last great wish in bringing her home, and in the memory of the three happy months of comparative health which she afterwards enjoyed there. Many people since I left home have read some of the ‘Memorials’ I am writing, and express a sense of never having known before how perfectly beautiful her character was, and that in truth, like Abraham, they ‘entertained an angel unawares.’ Now that dear life, which always seemed to us so perfect, has indeed become perfected, and the heavenly glow which came to the revered features in death is but a very faint image of the heavenly glory which always rests upon them.”

To Miss Wright.

“Stewart’s Hotel, Bournemouth, March 30, 1871.—The discussion of a tour in Spain comes to me as the pleasant dream of a possible future.... It is of course easy for us to see Spain in a way in a few weeks, but if one does not go in a cockney spirit, but really wishing to learn, to open one’s eyes to the glorious past of Spain, the story of Isabella, the Moorish dominion, the boundless wealth of its legends, its proverbs, its poetry—all that makes it different from any other country—we must begin in a different way, and our chief interest will be found in the grand old cities which the English generally do not visit—Leon, Zaragoza, Salamanca; in the wonderful romance which clings around the rocks of Monserrat and the cloisters of Santiago; in the scenes of the Cid, Don Roderick, Cervantes, &c.

“You will be sorry to hear that I am again in my normal condition of day and night nurse, in all the varying anxieties of a sick-room. I came here ten days ago to stay with Archie Colquhoun, whom I had known very little before, but who, having lost both father and mother lately, turned in heart to me and begged me to come to him. On Tuesday he fell with a great crash on the floor in a fit, and was unconscious for many hours.... It was a narrow escape of his life, and he was in a most critical state till the next day, but now he is doing well, though it will long be an anxious case.[4] You will easily understand how much past anguish has come back to me in the night-watches here, and I feel it odd that these duties should, as it were, be perpetually found for me.”

In May I paid the first of many visits to my dear Lady Waterford at Highcliffe, her fairy palace by the sea, on the Hampshire coast, near Christ Church, and though I was still too sad to enter into the full charm of the place and the life, which I have enjoyed so much since, I was greatly refreshed by the mental tonic, and by the kindness and sympathy which I have never failed to receive from Lady Waterford and her friend Lady Jane Ellice. With them, too, I was able to discuss my work in all its aspects, and greatly was I encouraged by all they said.

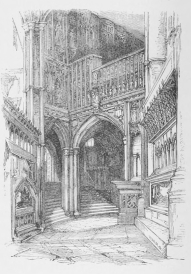

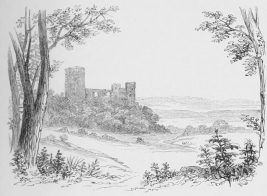

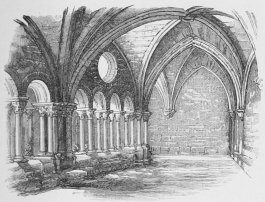

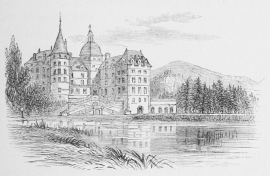

![]()

HIGHCLIFFE, THE KING’S ORIEL.

[5]

For many years after this, Highcliffe was more familiar to me than any other place except my own home, and I am attached to every stone of it. The house was the old Mayor’s house of Les Andelys, removed from Normandy by Lord Stuart de Rothesay, but a drawing shows the building as it was in France, producing a far finer effect than as it was put up in England by Pugin, the really fine parts, especially the great window, being lower down in the building, and more made of. In the room to which that window belonged, Antoyne de Bourbon, King of Navarre, died. The portraits in the present room of the Duchess of Suffolk and her second husband, who was a Bertie, have the old ballad of “The Duchess of Suffolk” inscribed beneath. They fled abroad, and their son Peregrine, born in a church porch, was the progenitor of the present Berties. I have myself always inhabited the same room at Highcliffe—one up a separate stair of its own, adorned with great views of the old Highcliffe and Mount Stuart, and with old French furniture, including a chair worked in blue and red by Queen Marie Amélie and Madame Adelaïde. The original house of Highcliffe was built on land sold to Lord Stuart by a Mr. Penlees, who had had a legacy of bank-notes left him in the case of a cocked-hat—it was quite full of them. Mr. Penlees had built a very ugly house, the present “old rooms,” which Lord Stuart cased over. Then he said that, while Lady Stuart was away, he would add a few rooms. When she came back, to her intense consternation, she found the new palace of Highcliffe: all the ornaments, windows, &c., from Les Andelys having been landed close by upon the coast. I always liked going with Lady Waterford into the old rooms, which were those principally used by Lady Stuart, and contained a wonderful copy of Sir Joshua which Lady Waterford made when she was ten years old. There was also a beautiful copy of the famous picture of Lord Royston, done by Lady Waterford herself long ago; a fine drawing of the leave-taking of Charles I. and his children—Charles with a head like the representations of the Saviour; and a portrait of the old Lady Stuart, “Grannie Stuart,” with all the wrinkles smoothed out. “Oh, if I am like that, I am only fit to die,” she said, when she saw it.[6]

I have put down a few notes from the conversation at Highcliffe this year.

“Mr. M. was remonstrated with because he would not admire Louis Philippe’s régime. He said, ‘No, I cannot; I have known him before so well. I am like the peasant who, when he was remonstrated with because he would not take off his hat to a new wooden cross that was put up, said he couldn’t parceque je l’ai connu poirier.’”

“Some one spoke to old Lady Salisbury[7] of Adam’s words—‘The woman tempted me, and I did eat.’ ‘Shabby fellow,’ she said.”

“Lady Anne Barnard[8] was at a party in France, and her carriage never came to take her away. A certain Duke who was there begged to have the honour of taking her home, and she accepted, but on the way felt rather awkward and thought he was too affectionate and gallant. Suddenly she was horrified to see the Duke on his knees at the bottom of the carriage, and was putting out her hands and warding him off, when he exclaimed, ‘Taisez-vous, Madame, voilà le bon Dieu qui passe.’ It was a great blow to her vanity.”

“Old Lord Malmesbury[9] used to invent the most extraordinary stories and tell them so well; indeed, he told them till he quite believed them. One was called ‘The Bloody Butler,’ and was about a butler who drank the wine and then filled the bottles with the blood of his victims. Another was called ‘The Moth-eaten Clergyman;’ it was about a very poor clergyman, a Roman he was, who had some small parish in Southern Germany, and was a very good man, quite excellent, absolutely devoted to the good of his people. There was, however, one thing which militated against his having all the influence amongst his flock which he ought to have had, and this was that he was constantly observed to steal out of his house in the late evening with two bags in his hand, and to bury the contents in the garden; and yet when people came afterwards by stealth and dug for the treasure, they found nothing at all, and this was thought, well ... not quite canny.

“Now the diocesan of that poor clergyman, who happened to be the Archbishop of Mayence, was much distressed at this, that the influence of so good a man should thus be marred. Soon afterwards he went on his visitation tour, and he stopped at the clergyman’s house for the night. He arrived with outriders, and two postillions, and four fat horses, and four fat pug-dogs, which was not very convenient. However, the poor clergyman received them all very hospitably, and did the best he could for them. But the Archbishop thought it was a great opportunity for putting an end to all the rumours that were about, and with a view to this he gave orders that the doors should be fastened and locked, so that no one should go out.

“When morning came, the windows of the priest’s house were not opened, and no one emerged, and at last the parishioners became alarmed, for there was no sound at all. But when they broke open the doors, volleys upon volleys of moths of every kind and hue poured out; but of the poor clergyman, or of the Archbishop of Mayence, or of the outriders and postillions, or of the four fat horses, or of the four pug-dogs, came out nothing at all, for they were all eaten up. For the fact was that the poor clergyman really had the most dreadful disease which bred myriads of moths; if he could bury their eggs at night, he kept them under, but when he was locked up, and he could do nothing, they were too much for him. Now there is a moral in this story, because if the people and the Archbishop had looked to the fruits of that excellent man’s life, and not attended to foolish reports with which they had no concern whatever, these things would never have happened.

“These were the sort of things Lord Malmesbury used to invent. Canning used to tell them to us.”

“I call the three kinds of Churchism—Attitudinarian, Latitudinarian, and Platitudinarian.”

To Miss Wright.

“Holmhurst, June 12, 1871.—In a few days’ solitude what a quantity of work I have gone through; and work which carries one back over a wide extent of the far long-ago always stretches out the hours, but how interesting it makes them! I quite feel that I should not have lived through the first year of my desolation without the companionship of this work of the ‘Memorials,’ which my darling so wisely foresaw and prepared for me. Daily I miss her more. Now that the flowers are blooming around, and the sun shining on the lawn, and the leaves out on the ash-tree in the shade of which she used to sit, it seems impossible not to think that the suffering present must be a dream and that she is only ‘not yet come out;’ and what the empty room, the unused pillow are, whence the sunshine of my life came, I cannot say. On Thursday I am going for one day to Hurstmonceaux, to our sacred spot. The cross is to be put up then. It is very beautiful, and is only inscribed:—

MARIA HARE,

Nov. 22, 1798. Nov. 13, 1870.

Until the Daybreak.

No other words are needed there; all the rest is written in the hearts of the people who loved her.

![]()

THE CHURCHYARD AT HURSTMONCEAUX.

“I have been thinking lately how all my life hitherto has been down a highway. There was no doubt as to where the duties were; there could be no doubt whence the pleasures, certainly whence the sorrows would come. Now there seem endless byways to diverge upon. But all the interest of life must be on its highway: the byways may be beautiful and attractive, but never interesting.”

“Sept. 26.—I much enjoyed my Peakirk visit to charming people (Mr. and Mrs. James) and a curious place—an oasis in the Fens, the home of St. Pega (sister of St. Guthlac), whose hermitage with its battered but beautiful cross still remains. I saw Burleigh, like a Genoese palace inside; and yesterday made a fatiguing but worth while pilgrimage, for love of Mary Queen of Scots, to Fotheringhay. One stone, but only one, remains of the castle which was the scene of her sufferings; so people wondered at my going so far. ‘Why cannot you let bygones be bygones?’ said young W. to me. However, the church is very curious, and contains inscriptions to a whole party of Plantagenets—Richard, Earl of Cornwall; Cicely, Duchess of York; Edward, father of Edward IV.—for Fotheringhay, now a hamlet in the fen, was once an important place: the death of Mary wrought the curse which became its ruin.”

I have said little for many years of the George Sheffield who was the dearest friend of my boyhood. He had been attaché at Munich, Washington, Constantinople, and was now at Paris as secretary to Lord Lyons. In this my first desolate year he also had a sorrow, which wonderfully reunited us, and we became perhaps greater friends than we had been before. Another of whom I saw much at this time was Charlie Dalison. A younger son of a Kentish squire of good family, he went—like the young men of olden time—to London to seek his fortunes, and simply by his good looks, winning manners, and incomparable self-reliance became the most popular young man in party-giving London society; but he had many higher qualities.

I needed all the support my friends could give me, for the family feud about the “Memorials” was not the only trouble that pressed upon me at this time.

It will be recollected that, in my sister’s death-bed will, she had bequeathed to me her claims to a portrait by Sir Joshua Reynolds. It was the very fact of this bequest which in 1871 made my poor Aunt Eleanor (Miss Paul) set up a counter-claim to the picture, which was valued at £2000.

Five-and-twenty years before, the picture had been entrusted for a time to Sir John Paul, who unfortunately, from some small vanity, allowed it to be exhibited in his own name instead of that of the owner. But I never remember the time when it was not at Hurstmonceaux after 1845, when it was sent there. Sir Joshua Reynolds, who was an intimate family friend, painted it in the house of Bishop Shipley, when my father was two and a half years old. It was painted for my great-aunt Lady Jones, widow of the famous Orientalist. Lady Jones adopted her nephew Augustus Hare, and brought him up as her own son, but, as she died intestate, her personalty passed, not to him, but to her only surviving sister, Louisa Shipley. Miss Shipley lived many years, and bequeathed the portrait to her youngest nephew, Marcus Hare. But Marcus gave up his legacy to my Uncle Julius, who always possessed the picture in my boyhood, when it hung over the dining-room chimney-piece at Hurstmonceaux Rectory. Uncle Julius bequeathed the portrait, with all else he possessed, to his widow, who transferred the picture at once to my adopted mother, as being the widow of the adopted son of Lady Jones.

The claim of the opposite party to the picture was that Mrs. Hare (“Italima”) had said that Lady Jones in her lifetime had promised to give her the picture, a promise which was never fulfilled; and that my sister, after her mother’s death, had said at Holmhurst, “If every one had their rights, that picture would belong to me, as my mother’s representative, for Lady Jones promised it to my mother,” also that she proved her belief in having a claim to it by bequeathing that claim to me. But the strongest point against us was that somehow or other, how no one could explain, the picture had been allowed to remain for more than a year in the hands of Sir John Paul, and he had exhibited it. Though the impending trial about the picture question was very different from that at Guildford, the violent animosity displayed by my poor aunt made it most painful, in addition to the knowledge that she (who had inherited everything belonging to my father, mother, and sister, and had dispersed their property to the four winds of heaven, whilst I possessed nothing which had belonged to them) was now trying to seize property to which she could have no possible moral right, though English law is so uncertain that one never felt sure to the last whether the fact of the picture having been exhibited in Sir John Paul’s name might not weigh fatally with both judge and jury.

For the whole month of November I was in London, expecting the trial every day, but it was not till the evening of the 6th of December that I heard that it was to be the next morning in the law-court off Westminster Hall. The court was crowded. My counsel, Mr. Pollock, began his speech with a tremendous exordium. “Gentlemen of the jury, in a neighbouring court the world is sitting silent before the stupendous excitement of the Tichborne trial: gentlemen of the jury, that case pales into insignificance—pales into the most utter insignificance before the thrilling interest of the present occasion. On the narrow stage of this domestic drama, all the historic characters of the last century and all the literary personages of the present seem to be marching in a solemn procession.” And he proceeded to tell the really romantic history of the picture—how Benjamin Franklin saw it painted, &c. I was called into the witness-box and examined and cross-examined for an hour by Mr. H. James. As long as I was in the region of my great-uncles and aunts, I was perfectly at home, and nothing in the cross-examination could the least confuse me. Then the counsel for the opposition said, “Mr. Hare, on the 20th of April 1866 you wrote a letter, &c.: what was in that letter?” Of course I said I could not tell. “What do you think was in that letter?” So I said something, and of course it was exactly opposite to the fact.

![]()

Francis George Hare

(Photogravure)

As witnesses to the fact of the picture having been at the Rectory at the time of the marriage of my Uncle Julius, I had subpœnaed the whole surviving family of Mrs. Julius Hare, who could witness to it better than any one else, as they had half-lived at Hurstmonceaux Rectory after their sister’s marriage. Her two sisters, Mrs. Powell and Mrs. Plumptre, took to their beds, and remained there for a week to avoid the trial, but Dr. Plumptre[10] and Mr. (F. D.) Maurice had to appear, and gave evidence as to the picture having been at Hurstmonceaux Rectory at the time of their sister’s marriage in 1845,[11] and having remained there afterwards during the whole of Julius Hare’s life. Mr. George Paul was then called, and took an oath that, till he went to America in 1852, the picture had remained at Sir John Paul’s; but such is the inattention and ignorance of their business which I have always observed in lawyers, that this discrepancy passed absolutely unnoticed.

The trial continued for several hours, yet when the court adjourned for luncheon I believed all was going well. It was a terrible moment when afterwards Judge Mellor summed up dead against us. Being ignorant, during my mother’s lifetime, of the clause in Miss Shipley’s will leaving the picture to Marcus Hare, and being anxious to ward off from her the agitation of a lawsuit in her feeble health, I had made admissions which I had really previously forgotten, but which were most dangerous, as to the difficulty which I then felt in establishing our claim to the picture. These weighed with Judge Mellor, and, if the jury had followed his lead, our cause would have been ruined. The jury demanded to retire, and were absent for some time. Miss Paul, who was in the area of the court, received the congratulations of all her friends, and I was so certain that my case was lost, that I went to the solicitor of Miss Paul and said that I had had the picture brought to Sir John Lefevre’s house in Spring Gardens, and that I wished to give it up as soon as ever the verdict was declared, as if any injury happened to it afterwards, a claim might be made against me for £2000.

Then the jury came back and gave a verdict for ... the defendant!

It took everybody by surprise, and it was the most triumphant moment I ever remember. All the Pauls sank down as if they were shot. My friends flocked round me with congratulations.

The trial took the whole day, the court sitting longer than usual on account of it. The enemy immediately applied for a new trial, which caused us much anxiety, but this time I was not required to appear in person. The second trial took place on the 16th of January 1872, before the Lord Chief Justice, Judge Blackburn, Judge Mellor, and Judge Hannen, and, after a long discussion, was given triumphantly in my favour, Judge Mellor withdrawing his speech made at the former trial, and stating that, after reconsideration of all the facts, he rejoiced at the decision of the jury.

As both trials were gained by me, the enemy had nominally to pay all the costs, but still the expenses were most heavy. It was just at the time when I was poorest, when my adopted mother’s will was still in abeyance. There were also other aspirants for the picture, in the shape of the creditors of my brother Francis, who claimed as representing my father (not my mother). It was therefore thought wiser by all that I should assent to the portrait being sold, and be content to retain only in its place a beautiful copy which had been made for me by the kindness of my cousin Madeleine Shaw-Lefevre. The portrait by Sir Joshua Reynolds was sold at Christie’s in the summer of 1872 for £2200, and is now in the National Gallery of America at New York.

A week after the trial, on the 13th of December, I left England for Spain. It had at first been intended that a party of five should pass the winter there together, but one after another fell off, till none remained except Miss Wright—“Aunt Sophy”—who joined me in Paris. The story of our Spanish tour is fully told in my book “Wanderings in Spain,” which appeared first as articles in Good Words. These were easily written and pleasant and amusing to write, but have none of the real value of the articles which I afterwards contributed on “Days near Rome.” I will only give here, to carry on the story, some extracts from my letters.

To Miss Leycester.

“Paris, Dec. 14, 1871.—How different France and England! At Holmhurst I left a green garden bright with chrysanthemums and everlastings: here, a pathless waste of snow up to the tops of the hedges became so deep near Creil that, as day broke, we remained fixed for an hour and a half in the midst of a forest, neither able to move backwards or forwards. And by the side of the rail were remains of a frightful accident of yesterday—engine smashed to bits, carriages cut in half, the linings hanging in rags, cushions lying about, &c. The guard was not encouraging—‘Oui, il y avait des victimes, pas beaucoup, mais il y a toujours des victimes.’ ... The state of Paris is unspeakably wretched, hillocks of snow, uncarted away and as high as your shoulder, filling the sides of the streets, with a pond in the intervening space. The Tuileries (after the Commune) looks far worse than I expected—restorable, but for the present it has lost all its form and character. We went inside this morning, but were soon warned out on account of the falling walls weakened by the frost.”

“Pau, Dec. 20.—I was glad to seize the opportunity of Aunt Sophy’s wishing for a few days’ rest before encountering Spain to pay a visit to the Taylors.[12] ... This morning I have walked on the terrace of the park, and lived over again many of those suffering scenes when we were here before. Truly here I have no feeling but one of thankfulness for the Mother’s release from the suffering body which was so great a burden to her. I went to the Hotel Victoria, and looked up at the windows of the rooms where, for the first time, we passed together through the valley of the Shadow of Death.”

To Mary Lea Gidman,

“Jan. 2.—You will imagine how the long-ago came back to me at Pau—the terrible time when we were hourly expecting the blow which has now fallen, and which we both, I know, feel daily and hourly. But I think it was in mercy that God spared us then: we were better prepared for our great desolation when it really came, and in the years for which our beloved one was given back to us, she was not only our most precious comfort and blessing, for her also they were filled with comfort, in spite of sickness, by the love with which she was ever surrounded. When I think of what the great blank is, life seems quite too desolate; but when I think of her now, and how her earthly life must have been one of increasing infirmity, instead of the perfected state from which I believe she can still look down upon us, I am satisfied.

“Do you still keep flowers or something green in her room? I hope so.”

To Miss Leycester.

“Convent of Montserrat, in Catalonia, Jan. 4, 1872.—At the best of times you would never have been able to travel in Spain, for great as is the delight of this unspeakably glorious place, I must confess we paid dear for it in the sufferings of the way. The first day introduced us to plenty of small hardships, as, a train being taken off al improviso, we had to wade through muddy lanes—and the Navarre mud is such mud—in pitch darkness, to a wretched hovel, where we passed the night with a number of others, in fierce cold, no fires or comforts of any kind. From thence (Alasua) we got on to Pamplona, our first picturesque Spanish town, where we spent part of Christmas Day, and then went on to Tudela, where we had another wretched posada; no fires; milk, coffee, and butter quite unknown, and the meat stewed in oil and garlic; and this has been the case everywhere except here, with other and worse in-conveniences.

“At Zaragoza we were first a little repaid by the wonderful beauty of the Moorish architecture—like lace in brick and stone, and the people as well as the place made a new world for us; but oh! the cold!—blocks of ice in the streets and the fiercest of winds raging.... No words certainly can describe the awful, the hideous ugliness of the railway the whole way here: not a tree, not a blade of grass to be seen, but ceaseless wind-stricken swamps of brown mud—featureless, hopeless, utterly uncultivated. However, Manresa is glorious, a sort of mixture of Tivoli (without the waterfall) and Subiaco, and thence we first gazed upon the magnificent Monserrat.

“We have been four days in the convent. I never saw anything anywhere so beautiful or so astonishing as this place, where we are miles and miles above every living thing except the monks, amid the most stupendous precipices of 3000 feet perpendicular, and yet in such a wealth of loveliness in arbutus, box, lentisc, smilax, and jessamine, as you can scarcely imagine. Though it is so high, and we have no fires or even brasieros, we scarcely feel the cold, the air is so still and the situation so sheltered, and on the sunlit terraces, which overlook the whole of Catalonia like a map, it is really too hot. The monks give us lodging and we have excellent food at a fonda within the convent walls, and are quite comfortable, though it must be confessed that my room is so narrow a cell, that when I go in it is impossible to turn round, and I have to hoist myself on the little bed sideways.

“It has been a strange beginning of the New Year. We breakfast at eight, and all day draw or follow the inexhaustibly lovely paths along the edges of the precipices. Yesterday we ascended the highest peak of the range, and were away nine hours—Aunt Sophy, the maid, and I; and nothing can describe the sublimity of the views across so glorious a foreground, to the whole snowy Pyrenean ranges and the expanse of blue sea.

“I act regular courier, and do all the work at inns, stations, &c., and Miss Wright is very easy to do for, and though very piano in misfortunes, is most kind and unselfish. The small stock of Spanish which I acquired in lonely evenings at Holmhurst enables me to get on quite easily—in fact, we never have a difficulty; and the kindness, civility, and helpfulness of the Spanish people compensates for all other annoyances. No one cheats, nor does it seem to occur to them. All prices are fixed, and so reasonable that my week’s expenses have been less than I paid for two dismal rooms and breakfast only in Half-Moon Street.”

“Barcelona, Jan. 9.—We arrived here on the evening of the Befana—a picturesque sight. It was coming into perfect summer, people out walking in the beautiful Rambla till past 12 P.M., ladies without bonnets and shawls. It is a very interesting place, full of lovely architecture, with palms, huge orange-trees, and terraces, and such a deep blue sea.”

To Mary Lea Gidman.

“Barcelona, Jan. 17.—We have good rooms now, but everywhere the food is shocking. At the table-d’hôte one of the favourite dishes is snail-soup, and as the snails are cooked in their shells, it does not look very tempting. If the food were improved, this coast would be better for invalids in winter than the Riviera, as it is such a splendid climate—almost too dry, as it scarcely ever rains for more than fifty days out of the 365. The late Queen ordered every tree in the whole of Spain which did not bear fruit to be cut down, so the whole country is quite bare, and so parched and rocky that often for fifty miles you do not see a shrub, but in some places there are palms, olives, oranges, and caroubas.

“We are very thankful for the tea which Miss Wright’s maid makes for us in a saucepan.”

To Miss Leycester.

“Tarragona, Jan. 19.—We delighted in Barcelona, and wondered it did not bring people to this coast instead of to the south of France.... We get on famously with the Spaniards. I talk as much as I can, and if I cannot, smile and look pleased, and everybody seems devoted to us, and we are made much of and helped wherever we go. It is quite different from Italy: and we are learning such good manners from the incessant bowing and complimenting which is required.”

“Cordova, Feb. 6.—We broke the dreadful journey from Valencia to Alicante by sleeping at Xativa, a lovely city of palms and rushing fountains with a mountain background, but the inn so disgusting we could not stay. Alicante, on the other hand, had no attraction except its excellent hotel, with dry sheets, bearable smells, no garlic, and butter. The whole district is burnt, tawny, and desolate beyond words—houses, walls, and castle alike dust-colour, but the climate is delicious, and a long palm avenue fringes the sea, with scarlet geraniums in flower. With Elche we were perfectly enraptured—the forests of palms quite glorious, many sixty feet high and laden with golden dates; the whole place so Moorish, and the people with perfectly Oriental hospitality and manners. We spent four days there, and were out drawing from eight in the morning to five in the afternoon; such subjects—but I lamented not being able to draw the wonderful figures—copper-coloured with long black hair; the men in blue velvet, with mantas of crimson and gold and large black sombreros.

“It was twenty-three hours’ journey here, and no possible stopping-place or buffet. But as for Miss Wright, she never seems the worse for anything, and is always equally kind and amiable. She is, however, very piano in spirits, so that I should be thankful for a little pleasant society for her, as it must have been fearfully dull having no one but me for so long.

“We were disappointed with Murcia, though its figures reach a climax of grotesque magnificence, every plough-boy in the colours of Solomon’s temple. But though we had expected to find Cordova only very interesting, it is also most beautiful—the immense court before the mosque filled with fountains and old orange-trees laden with fruit, and the mosque itself, with its forest of pillars, as solemn as it is picturesque.”

To Mary Lea Gidman.

“Seville, Feb. 10.—The dirt and discomfort of the railway journey to Cordova was quite indescribable, but the mosque is glorious. It is so large that you would certainly lose your way in it, as it has more than a thousand pillars, and twenty-nine different aisles of immense length, all just like one another. We made a large drawing in the court with its grove of oranges, cypresses, and palms, and you would have been quite aghast at the horrible beggars who crowded round us—people with two fingers and people with none; people with no legs and people with no noses, or people with their eyes and mouths quite in the wrong place.

“The present King (Amadeo) is much disliked and not likely to reign long. Here at Seville, in the Carnival, they made a little image of him, which bowed and nodded its head, as kings do, when it was carried through the street, and all the great people went out to meet it and bring it into the town in mockery; and yesterday it was strangled like a common criminal on a scaffold in the public square; and to-day tens of thousands of people are come into the town to attend its funeral.

“The Duchesse de Montpensier, who lives here, does a great deal of good, but she is very superstitious, and, when her daughter was ill, she walked barefoot through all the streets of Seville: the child died notwithstanding. She and all the great ladies of Seville wear low dresses and flowers in their hair when they are out walking on the promenade, but at large evening parties they wear high dresses, which is rather contrary to English fashions. Miss Wright’s bonnet made her so stared at and followed about, that now she, and her maid also, have been obliged to get mantillas to wear on their heads instead, which does much better, and prevents their attracting any attention. No ladies ever think of wearing anything but black, and gentlemen are expected to wear it too if they pay a visit.

“I often feel as if I must be in another state of existence from my old life of so many years of wandering with the sweet Mother and you, but that life is always present to me as the reality—this as a dream. There is one walk here which the dear Mother would have enjoyed and which always recalls her—a broad sunny terrace by the river-side edged with marble, which ends after a time in a wild path, where pileworts are coming into bloom under the willows. I always wonder how much she knows of us now; but if she can be invisibly present, I am sure it is mostly with me, and then with you, and in her own room at Holmhurst, whence the holy prayers and thoughts of so many years of faith and love ascended.”

To Miss Leycester.

“Seville, Feb. 13.—Ever since we entered Andalusia it has poured in torrents, but even in fine weather I think we must have been disappointed with Seville. With such a grand cathedral interior and such beautiful pictures, it seems hard to complain, but there never was anything less picturesque than the narrow streets of whitewashed houses, uglier than the exterior of the cathedral, or duller than the surrounding country. Being Carnival, the streets are full of masks, many of them not very civil to the clergy—the Pope being led along by a devil with a long tail, &c. Every one speaks of the Italian King (Amadeo) as thoroughly despised and disliked, and his reign (in spite of the tirades in his favour in English newspapers) must now be limited to weeks; then it must be either a Republic, Montpensier, or Alfonso. Here, where they live, the Montpensiers are very popular, and they do an immense deal of good amongst the poor, the institutions, and in encouraging art. Their palace of San Telmo is beautiful, with a great palm-garden. When we first came, we actually engaged lodgings in the Alcazar, the great palace of the Moorish kings, but, partly from the mosquitoes and partly from the ghosts, soon gave them up again.”

“Algeciras, Feb. 25.—Though we constantly asked one another what people admired so much in Seville, its sights took us just a fortnight. Our pleasantest afternoon was spent in a drive to the Roman ruins in Italica, and we took Miss Butcher with us, who devotes her life to teaching the children in the Protestant school, for which she gets well denounced from the same cathedral pulpit whence the autos-da-fé were proclaimed, in which 34,611 people were burnt alive in Seville alone!

“What a dull place Cadiz is. Nothing to make a feature but the general distant effect of the dazzling white lines of houses rising above a sapphire sea. We had a twelve hours’ voyage to Gibraltar. I was very miserable at first, but revived in time to sketch Trafalgar and to make two views in Africa as we coasted along. At last Gibraltar rose out of the sea like an island, and very fine it is, far more so than I expected, though we have not seen the precipice side of the rock yet. As we turned into the bay of Algeciras, numbers of little boats put out to take us on shore, and we are so enchanted with this place that we shall remain a few days in the primitive hotel. Our sitting-room opens by large glass doors on a balcony. Close below is the pretty beach with its groups of brilliant figures—Moors in white burnooses, sailors, peasants in sombreros and fajas. Across the blue bay, calm as glass, with white sails flitting over it, rises the grand mass of the Rock, with the town of Gibraltar at its foot. All around are endless little walks along the shore and cliffs, through labyrinths of palmito and prickly pear, or into the wild green moorlands which rise immediately behind, and beyond which is a purple chain of mountains. It is the only place I have yet seen in Spain which I think the dear Mother would have cared to stay long at, and I can almost fancy I see her walking up the little paths which she would have so delighted in, or sitting on her camp-stool amongst the rocks.”

“Gibraltar, March 2.—It was strange, when we crossed from Algeciras, to come suddenly in among an English-talking, pipe-smoking, beer-drinking community in this swarming place, where 5000 soldiers are quartered in addition to the crowded English and Spanish population. The main street of the town might be a slice cut out of the ugliest part of Dover, if it were not for the numbers of Moors stalking about in turbans, yellow slippers, and blue or white burnooses. Between the town and Europa Point, at the African end of the promontory, is the beautiful Alameda, walks winding through a mass of geraniums, coronillas, ixias, and aloes, all in gorgeous flower: for already the heat is most intense, and the sun is so grilling that before May the flowers are all withered up.

“I am afraid we shall not be allowed to go to Ronda. Mr. Layard has sent word from Madrid to the Governor to prevent any one going, as the famous brigand chief Don Diego is there with his crew. We had hoped to get up a sufficiently large armed party, but so many stories have come, that Aunt Sophy and her maid, Mrs. Jarvis, are getting into an agony about losing their noses and ears.

“The Governor, Sir Fenwick Williams, has been excessively civil to us, but our principal acquaintance here is quite romantic. The first day when we went down to the table-d’hôte, there were only two others present, a Scotch commercial traveller, and, below him, a rather well-looking Spaniard, evidently a gentleman, but with an odd short figure and squeaky voice. He bowed very civilly as we came in, and we returned it. In the middle of dinner a band of Scotch bagpipers came playing under the window, and I was seized with a desire to jump up and look at them. Involuntarily I looked across the table to see what the others were going to do, when the unknown gave a strange bow and wave of permission! With that wave came back to my mind a picture in the Duchesse de Montpensier’s bedroom at Seville: it was her brother-in-law, Don Francisco d’Assise, ex-King of Spain! Since then we have breakfasted and dined with him every day, and seen him constantly besides. This afternoon I sat out with him in the gardens, and we have had endless talk—the result of which is that I certainly do not believe a word of the stories against him, and think that, though not clever and rather eccentric, he is by no means an idiot, but a very kind-hearted, well-intentioned person. He is kept here waiting for a steamer to take him to Marseilles, as he cannot land at any of the Spanish ports. He calls himself the Comte de Balsaño, and is quite alone here, and evidently quite separated from Queen Isabella. He never mentions her or Spain, but talks quite openly of his youth in Portugal and his visits to France, England, Ireland, &c.

“I have remained with him while Miss Wright is gone to Tangiers with her real nephew, Major Howard Irby. This beginning of March always brings with it many sad recollections, the date—always nearing March 4—of all our greatest anxieties, at Pau, Piazza di Spagna, Via Babuino, Via Gregoriana. It is almost as incredible to me now as a year and a half ago to feel that it is all over—the agony of suspense so often endured, and that life is now a dead calm without either sunshine or storm to look forward to.

“The King says that of all the things which astonish him in England, that which astonishes him most is that the Anglo-Catholics (so called), who are free to do as they please, are seeking to have confession—‘the bane of the Roman Catholic religion, which has brought misery and disunion into so many Spanish homes.’ One felt sure he was thinking of Father Claret and the Queen, but he never mentioned them.”

“March 6.—The poor King left yesterday for Southampton—a most affectionate leave-taking. He says he will come to Holmhurst: how odd if he does!”

“Malaga, March 17.—Our pleasantest acquaintances at Gibraltar were the Augustus Phillimores, with whom we spent our last day—in such a lovely garden on the side of the Rock, filled with gigantic daturas, daphnes, oranges, and gorgeous creeping Bougainvillias. Admiral Phillimore’s boat took us on board the Lisbon, where we got through the voyage very well, huddled up under cloaks on deck through the long night. There is nothing to see at Malaga—a dismal, dusty, ugly place.”

“Hôtel Siete Suelos, Granada, March 19.—We had a dreadful journey here—rail to Las Salinas and then the most extraordinary diligence journey, in a carriage drawn by eight mules, at midnight, over no road, but rocks, marshes, and along the edge of precipices—quite frightful. Why we were not overturned I cannot imagine. I could get no place except at the top, and held on with the greatest difficulty in the fearful lunges. We reached Granada about 3½ A.M., seeing nothing that night, but wearily conscious of the long ascent to the Siete Suelos.

“How lovely was the morning awakening! our rooms looking down long arcades of high arching elms, with fountains foaming in the openings of the woods, birds singing, and violets scenting the whole air. It is indeed alike the paradise of nature and art. Through the first day I never entered the Alhambra, but sat restfully satisfied with the absorbing loveliness of the surrounding gorges, and sketched the venerable Gate of Justice, glowing in gorgeous golden light. This morning we went early to the Moorish palace. It is beyond all imagination of beauty. As you cross the threshold you pass out of fact into fairyland. I sat six hours drawing the Court of Blessing without moving, and then we climbed the heights of S. Nicolas and overlooked the whole palace, with the grand snow peaks of Sierra Nevada rising behind.”

“Granada, April 1—Easter Sunday.—To-day especially I do not feel as if I was at Granada, but in the churchyard at Hurstmonceaux. I am sure Mrs. Medhurst and other loving hands will have decorated our most dear spot with flowers. Aunt Sophy is most kind, only too kind and indulgent always, but the thought of the one for and through whom alone I could really enjoy anything is never absent from me. I feel as if I lived in a life which was not mine—beautiful often, but only a beautiful moonlight: the sunlight has faded.”

“Toledo, April 11.—We had twelve hours’ diligence from Granada, saw Jaen Cathedral on the way, and joined the railroad at the little station of Mengibar. Next morning found us at Aranjuez, a sort of Spanish Hampton Court, rather quaint and pleasant, four-fifths of the place being taken up by the palace and its belongings, so much beloved by Isabella (II.), but since deserted. We went to bed for four hours, and spent the rest of the day in surveying half-furnished palaces, unkempt gardens, and dried-up fountains, yet pleasant from the winding Tagus, lilacs and Judas-trees in full bloom, and birds singing. It was a nice primitive little inn, and the landlord sat on the wooden gallery in the evening and played the guitar, and all his men and maids sang round him in patriarchal family fashion.

“On the whole, I feel a little disappointed at present with this curious, desolate old city: the cathedral and everything else looks so small after one’s expectations, and the guide-books exaggerate so tremendously all over Spain.

“My last day at Granada was saddened by your mention of what is really a great loss to me—dear old Mr. Liddell’s death,[13] so kind to me ever since I was a little boy, and endeared by the many associations of most happy visits at Bamborough and Easington. I had also sad news from Holmhurst in the death of dear sweet Romo, the Mother’s own little dog, which no other can ever be.”

“Madrid, April 20.—We like Madrid better than we expected. It is a poor miniature of Paris, the Prado like the Champs Elysées, the Museo answering to the Louvre, though all on the smallest possible scale. It has been everything to us having our kind friends Don Juan and Doña Emilia de Riaño here, and we have seen a great deal of them. They have a beautiful house, full of books and pictures, and every day she has come to take us out, and has gone with us everywhere, taking us to visit all the interesting literary and artistic people, showing us all the political characters on the Prado, escorting us to galleries, &c., and in herself a mine of information of the most beautiful and delightful kind—a sort of younger Lady Waterford. She gives a dreadful picture of the immorality of society in Madrid under the Italian King, the want of law, the hopelessness of redress; that everything is gained by influence in high places, nothing by right. A revolution is expected any day, and then the King must go. The aristocratic Madrilenians all speak of him as ‘the little Italian wretch,’ though they pity his pretty amiable Queen. All seem to want to get rid of him, and, whatever is said by English newspapers, we have never seen any one in Spain who was not hankering after the Bourbons and the handsome young Prince of Asturias, who is sure to be king soon.

“The pleasantest of all the people Madame de Riaño has taken us to visit are the splendid artist Don Juan de Madraza and his most lovely wife.[14]

“The Layards have been very civil. At a party there we met no end of Spanish grandees. The Queen’s lady-in-waiting (she has only two who will consent to take office), Marqueza d’Almena, was quite lovely in white satin and pearls—like an old picture.”

“Segovia, April 28.—I was quite ill at Madrid with severe sore throat and cough, and this in spite of the care I was always taking of myself, having been so afraid of falling ill. But it is the most treacherous climate, and, from burning heat, changes to fierce ice-laden winds from the Guadarama and torrents of cold rain. I was shut up five days, but cheered by visits from Madame de Riaño, young Arthur Seymour an attaché, and the last day, to my great delight, the well-known Holmhurst faces of Mr. and Mrs. Scrivens (Hastings banker), brimming with Sussex news. Mr. Layard was evidently very anxious to get us and all other travelling English safe out of Spain, but we preferred the alternative, suggested by the Riaños, of coming to this ‘muy pacifico’ place, and waiting till the storm was a little blown over. Madrid was certainly in a most uncomfortable state, the Italian King feeling the days of his rule quite numbered, houses being entered night and day, and arrests going on everywhere. I do not know what English papers tell, but the Spanish accounts are alarming of the whole of the north as overrun by Carlists, and that they have taken Vittoria and stopped the tunnel on the main line.

“It was a dreadful journey here. The road was cut through the snow, but there was fifteen feet of it on either side the way on the top of the Guadarama. However, our ten mules dragged us safely along. Segovia is gloriously picturesque, and the hotel a very tolerable—pothouse.”

“Salamanca, May 5.—One day at the Segovia table-d’hôte we had the most unusual sight of a pleasing young Englishman, who rambled about and drew with us all afternoon, and then turned out to be—the Duchess of Cleveland’s younger son, Everard Primrose.[15]

“May-day we spent at La Granja, one of the many royal palaces, and one which would quite enchant you. It is a quaint old French château in lovely woods full of fountains and waterfalls, quite close under the snow mountains; and the high peaks, one glittering mass of snow, rise through the trees before the windows. The inhabitants were longing there to have the Bourbons back, and only spoke of the present King as ‘the inoffensive Italian.’ Even Cristina and Isabella will be cordially welcomed if they return with the young Alfonso.

“On May 2nd we left Segovia and went for one night to the Escurial—such a gigantic place, no beauty, but very curious, and the relics of the truly religious though cruelly bigoted Philip II. very interesting. Then we were a day at Avila, at an English inn kept by Mr. John Smith and his daughter—kindly, hearty people. Avila is a paradise for artists, and has remains in plenty of Ferdinand and Isabella, in whose intimate companionship one seems to live during one’s whole tour in Spain. It was a most fatiguing night-journey of ten hours to Salamanca, a place I have especially wished to see—not beautiful, but very curious, and we have introductions to all the great people of the place.

“I shall be very glad now to get home again. It is such an immense separation from every one one has ever seen or heard of, and such a long time to be so excessively uncomfortable as one must be at even the best places in Spain. Five-o’clock tea, which we occasionally cook in a saucepan—without milk of course—is a prime luxury, and is to be indulged in to-day as it is Sunday.”

“Biarritz, May 12.—We are thankful to be safe here, having seen Zamora, Valladolid, and Burgos since we left Salamanca. The stations were in an excited state, the platforms crowded with people waiting for news or giving it, but we met with no difficulties. I cannot say with what a thrill of pleasure I crossed the Bidassoa and left the great discomforts of Spain behind. What a luxury this morning to see once more tea! butter!! cow’s milk!!!”

“Paris, May 20.—Most lovely does France look after Spain—the flowers, the grass, the rich luxuriant green, of which there is more to be seen from the ugliest French station than in the whole of the Spanish peninsula after you leave the Pyrenees. I have spent the greater part of three days at the Embassy, where George Sheffield is most affectionate and kind—no brother could be more so. We have been about everywhere together, and it is certainly most charming to be with a friend who is always the same, and associated with nineteen years of one’s intimate past.”

“Dover Station, May 23.—On Monday George drove me in one of the open carriages of the Embassy through the Bois de Boulogne to S. Cloud, and I thought the woods rather improved by the war injuries than otherwise, the bits cut down sprouting up so quickly in bright green acacia, and forming a pleasant contrast with the darker groves beyond. We strolled round the ruined château, and George showed the room whither he went to meet the council, and offer British interference just before war was declared, in vain, and now it is a heap of ruins—blackened walls, broken caryatides.[16] What a lovely view it is of Paris from the terrace: I had never seen it before. Pretty young French ladies were begging at all the park gates for the dishoused poor of the place, as they do at the Exhibition for the payment of the Prussian debt. George was as delightful as only he can be when he likes, and we were perfectly happy together. At 7 P.M. I went again to the Embassy. All the lower rooms were lighted and full of flowers, the corridors all pink geraniums with a mist of white spirea over them. The Duchesse de la Tremouille was there, as hideous as people of historic name usually are. Little fat Lord Lyons was most amiable, but his figure is like a pumpkin with an apple on the top. It is difficult to believe he is as clever as he is supposed to be. He is sometimes amusing, however. Of his diplomatic relations with the Pope he says, ‘It is so difficult to deal diplomatically with the Holy Spirit.’ He boasts that he arrived at the Embassy with all he wanted contained in a single portmanteau, and that if he were called upon to leave it for ever to-day, the same would suffice. He has collected and acquired—nothing! He evidently adores George, and I don’t wonder!”

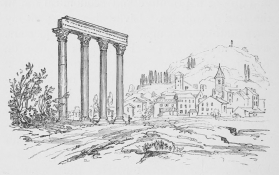

![]()

FOUNTAIN OF S. CLOUD.

[17]

To Miss Wright.

“Holmhurst, May 24, 1872.—You will like to know I am safe here. I found fat John Gidman waiting at the Hastings station, and drove up through the flowery lanes to receive dear Lea’s welcome—most tearfully joyous. The little home looks very lovely, and I cannot be thankful enough—though its sunshine is always mixed with shadow—to have a home in which everything is a precious memorial of my sacred past, where every shrub in the garden has been touched by my mother’s hand, every little walk trodden by her footsteps, and where I can bring up mental pictures of her in every room. In all that remains I can trace the sweet wisdom which for years laid up so much to comfort me, which sought to buy this place when she did, in order to give sufficient association to make it precious to me; above all, which urged her to the supreme effort of returning here in order to leave it for me with the last sacred recollections of her life. In the work of gathering up the fragments from that dear life I am again already engrossed, and Spain and its interests are passing into the far away; yet I look back upon them with much gratitude, and especially upon your long unvaried kindness and your patience with my many faults.”

“May 26.—To-night it blows a hurricane, and the wind moans sadly. A howling wind, I think, is the most melancholy natural accompaniment which can come to a solitary life. After this, I must give you—to meditate on—a beautiful passage I have been reading in Mrs. Somerville—‘At a very small height above the surface of the earth the noise of the tempest ceases, and the thunder is heard no more in those boundless regions where the heavenly bodies accomplish their periods in eternal and sublime silence.’”

It is partly the relief I experienced after Spain and the animation of ever-changing society which make me look back upon the summer of 1872 as one of the happiest I have spent at Holmhurst. A constant succession of guests filled our little chambers, every one was pleased, and the weather was glorious. I was away also for several short but very pleasant glimpses of London, and began to feel how little the virulence of some of my family signified when there was still so much friendship and affection left to me.

To Miss Wright.

“Holmhurst, June 21, 1872.—I am feeling ungrateful for never having written since my happy fortnight with you came to a close, a time which I enjoyed more than I ever expected to enjoy anything again, and which made me feel there might still be something worth living on for, so much kindness and affection did I receive from so many. It is pleasant too to think of your comfortable home, which rises before me in a gallery of happy pictures, and I know it all so well now, from the parrot in Mrs. Jarvis’s room to the red geraniums in your window. I have had Mrs. and Miss Kuper here, and now I am alone, no voice but that of the guinea-fowls shrieking ‘Come back’ in the garden. I miss all my London friends very much, but suppose one would not enjoy it if it went on always, and certainly solitude is the time for work: I did eleven hours of it yesterday. As regards my books, I feel more and more with Arnold that a man is only fit to teach as long as he is himself learning daily.”

“Holmhurst, June 25.—‘Poor Aunt Sophy’ would not have thought she had done nothing to cheer me, could she have seen the interest with which I read her letter and returned to it over and over again. Such a letter is quite delightful, and here has the effect of one reaching Robinson Crusoe in Juan Fernandez, so complete is the silence and solitude when no one is staying here.

“How I delight in knowing all that the delightful human beings are about, of whom I think now as living in another hemisphere. I should like to see more of people—perhaps another year I may not be so busy: that is, I long for the cream which I enjoyed with you, but I should not care for the milk and water of a country neighbourhood. If one has too much people-seeing, however, even of the London best, one feels that it is ‘a withering world,’[19] and that if—

“I have been made very ill-tempered all day because Murray, during my absence in Spain, has published a second edition of my Oxfordshire Handbook, greatly altered, without consulting me, and it seems to me utterly spoilt and vulgarised. He is obliged by his contract to give me £40, but I would a great deal rather have seen the book uninjured and received nothing.”

To Miss Leycester (after a long visit from her at Holmhurst).

“Holmhurst, August 18, 1872.—There seems quite a chaos of things already to be said to the dear cousin who has so long shared our quiet life, and who has so much care for the simple interests of this little home. Much have I missed her—in her chair, with her crotchet; sitting on the terrace; and especially in the early morning walk yesterday, when the garden was in its richest beauty, all the crimson and blue flowers twinkling through a veil of dewdrops, and when ‘the gentleness of Heaven was on the sea,’ as Wordsworth would say. I am grieved to think of you in London, instead of in your country home.

“Our visit to Hurstmonceaux was thoroughly enjoyed by Mr. and Mrs. Pile.[21] For myself, I shall always feel such short visits produce such extreme tension of conflicting feelings that they are scarcely a pleasure. Most lovely was the drive for miles through Ashburnham beech and pine woods and by its old timber-yard. At Lime Cross we saw Mrs. Isted at her familiar window, and the dear woman sat there all the afternoon to have another glimpse on our return. We drove to the foot of the hill and walked up to the church. Our sacred spot looked most peaceful, its double hedge of fuchsia in full flower, and the turf as smooth as velvet. We had luncheon in the church porch, and then went to the castle, and back through the park uplands, high with fern, to Hurstmonceaux Place. How often, at Hurstmonceaux especially, I now feel the force of Wordsworth’s lines:

To Miss Wright.

“Holmhurst, Sept. 6, 1872.—If my many guests of the last weeks have liked their visits, I have most entirely enjoyed having them and the pleasant influx of new life and new ideas. Dear old Mrs. Robert Hare is now very happy here, and most grateful for the very small kindness I am able to show. I have pressed her to make a long visit, as it is a real delight to give so much pleasure, though humbling to think that, when one can do it so easily, one does not do it oftener. She is quite stone-deaf, so we sit opposite one another and correspond on a slate.[22] On Tuesday I fetched Marcus Hare from Battle. He also is intensely happy here; but his aunts, the Miss Stanleys, have written to refuse to see him again or allow him to visit them, because he has been to see the author of the ‘Memorials.’ I took him to Hurstmonceaux yesterday, and lovely was the first flush of autumn on our dear woods, while the castle looked most grand in the solemn stillness of its misty hollow. Next week I shall have George Sheffield here.”

![]()

FROM THE LIBRARY WINDOW, FORD.

[24]

In September I paid a pleasant visit to my cousin Edward Liddell, whom I found married to his sweet wife (Christina Fraser Tytler) and living in the Rectory in Wimpole Park in Cambridgeshire, close to the great house of our cousin Lord Hardwicke, which is very ugly, though it contains many fine pictures.[23] In the beginning of October I was at Ford with Lady Waterford, meeting the Ellices, Lady Marion Alford, and Lady Herbert of Lea, who had much to tell of La Palma, the estatica of Brindisi, who had the stigmata, and could tell wonderful truths to people about their past and future. Lady Herbert had been to America, Trinidad, Africa—in fact, everywhere, and in each country had, or thought she had, the most astounding adventures—living with bandits in a cave, overturned on a precipice, &c. She had travelled in Spain and was brimful of its delights. She had armed herself with a Papal permit to enter all monasteries and convents. She had annexed the Bishop of Salamanca and driven in his coach to Alva, the scene of S. Teresa’s later life. The nuns refused to let her come in, and the abbess declared it was unheard of; but when Lady Herbert produced the bishop and the Papal brief, she got in, and the nuns were so captivated that they not only showed her S. Teresa’s dead body, but dressed her up in all S. Teresa’s clothes, and set her in S. Teresa’s arm-chair, and gave her her supper out of S. Teresa’s porringer and platter. “Can you see Lady Jane Ellice’s face,” I read in a letter from Ford to Miss Leycester, “as Lady Herbert ‘goes on’ about the Blessed Paul of the Cross, the holy shift of S. Teresa, and the saintly privileges of a hermit’s life?” The first evening she was at Ford Lady Herbert said:—

“Did you never hear the story of ‘La Jolie Jambe’? Well, then, I will tell it you. Robert, my brother-in-law, told me. He knew the old lady it was all about in Paris, and had very often gone to sit with her.

“It was an old lady who lived at ‘le pavillon dans le jardin.’ The great house in the Faubourg was given up to the son, you know, and she lived in the pavillon. It was a very small house, only five or six rooms, and was magnificently furnished, for the old lady was very rich indeed, and had a great many jewels and other valuable things. She lived quite alone in the pavillon with her maid, but it was considered quite safe in that high-terraced garden, raised above everything else, and which could only be approached through the house.

“However, one morning the old lady was found murdered, and all her jewels and valuables were gone. Of course suspicion fell upon the maid, for who else could it be? She was taken up and tried. The evidence was insufficient to convict her, and she was released, but every one believed her guilty. Of course she could get no other place, and she was so shunned and pointed at as a murderess that her life was a burden to her.

“One day, eleven years after, the maid was walking down a street when she met a man, who, as she passed, looked suddenly at her and exclaimed, ‘Oh, la jolie jambe!’ She immediately rushed up to a sergeant-de-ville and exclaimed, ‘Arrêtez-moi cet homme.’ The man was confused and hesitated, but she continued in an agony, ‘Arrêtez-le, je vous dis: je l’accuse, je l’accuse du meurtre de ma maîtresse.’ Meanwhile the man had made off, but he was pursued and taken.

“The maid said at the trial, that, on the night of the murder, the windows of the pavilion had been open down to the ground; that they were so when she was going to bed; that as she was getting into bed she sat for a minute on its edge to admire her legs, looked at them, patted one of them complacently, and exclaimed, ‘Oh, la jolie jambe!’

“The man then confessed that while he had been hidden in the bushes of the garden waiting to commit his crime, he had seen the maid and heard her, and that, when he met her in the street, the scene and the words rushed back upon his mind so suddenly, that, as if under an irresistible impulse, his lips framed the words ‘Oh, la jolie jambe.’ The man was executed.”

Lady Herbert also told us that—

“Hogg, the Ettrick Shepherd, had a sheep-dog to which he was quite devoted, and which used to go out and collect his sheep. One day in winter a thick snow came on, and Hogg was in the greatest anxiety about his flocks. He called his dog and explained all the matter to him, telling him how he was going all round one side of the moors himself to drive in his sheep, and that he was to go the other way and collect. The dog understood perfectly. Late in the evening the Shepherd returned perfectly exhausted, bringing in his flock through the deep snow, but the dog had not come back. Hour after hour passed and the dog did not return. The Shepherd, who was devoted to his dog, was very anxious about it, when at last he heard a whining and scratching at the door, and going out, found the dog bringing all his sheep safe, and in its mouth a little puppy, which it laid at its master’s feet, and instantly darted off through the snow to seek another and bring it in. The poor thing had puppied in the snow, but would not on that account neglect one iota of its duty. It brought in its second puppy, laid it in its master’s lap, looked up wistfully in his face as if beseeching him to take care of it, and—died.”

Lady Marion Alford is a real grande dame. Some one, Miss Mary Boyle, I think, wrote a little book called the “Court of Queen Marion,” descriptive of her and her intimate circle. At Ford she talked much of the pleasure of Azeglio’s Ricordi, how he was the first Italian writer who had got out of the ‘conciosiachè style,’ and she was delightful with her reminiscences of Italy:—