Title: Fromentin

Author: Georges Beaume

Editor: Henry Roujon

Translator: Frederic Taber Cooper

Release date: May 29, 2013 [eBook #42838]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by sp1nd, Matthew Wheaton and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

MASTERPIECES

IN COLOUR

EDITED BY - -

M. HENRY ROUJON

FROMENTIN

(1820-1876)

IN THE SAME SERIES

REYNOLDS

VELASQUEZ

GREUZE

TURNER

BOTTICELLI

ROMNEY

REMBRANDT

BELLINI

FRA ANGELICO

ROSSETTI

RAPHAEL

LEIGHTON

HOLMAN HUNT

TITIAN

MILLAIS

LUINI

FRANZ HALS

CARLO DOLCI

GAINSBOROUGH

TINTORETTO

VAN DYCK

DA VINCI

WHISTLER

RUBENS

BOUCHER

HOLBEIN

BURNE-JONES

LE BRUN

CHARDIN

MILLET

RAEBURN

SARGENT

CONSTABLE

MEMLINC

FRAGONARD

DÜRER

LAWRENCE

HOGARTH

WATTEAU

MURILLO

WATTS

INGRES

COROT

DELACROIX

FRA LIPPO LIPPI

PUVIS DE CHAVANNES

MEISSONIER

GÉRÔME

VERONESE

VAN EYCK

FROMENTIN

MANTEGNA

PERUGINO

PLATE I.—A HALT

(Collection of M. Sarlin)

It is hardly necessary to call attention to the art with which Fromentin has succeeded in arranging his masses of colour so as to secure a harmonious distribution of light. Could anything be more perfectly balanced, in point of composition, than this alluring canvas?

TRANSLATED FROM THE FRENCH

BY FREDERIC TABER COOPER

ILLUSTRATED WITH EIGHT

REPRODUCTIONS IN COLOUR

FREDERICK A. STOKES COMPANY

NEW YORK—PUBLISHERS

COPYRIGHT, 1913, BY

FREDERICK A. STOKES COMPANY

Printed in the United States of America

| Page | |

| I.—The First Steps | 11 |

| II.—The Promised Land | 29 |

| III.—An Evolution | 45 |

| IV.—The Master: His Personality and His Destiny | 58 |

| Plate | ||

| I. | Halt of Horsemen | Frontispiece |

| M. Sarlin’s Collection | ||

| II. | The Arab Encampment | 14 |

| Musée du Louvre | ||

| III. | Thirst | 24 |

| M. Jacques Normand’s Collection | ||

| IV. | The Sirocco in the Oasis | 34 |

| Musée du Louvre | ||

| V. | An Arab Fantasia | 40 |

| M. Sarlin’s Collection | ||

| VI. | Egyptian Women on the Bank of the Nile | 50 |

| Musée du Louvre | ||

| VII. | Hunting with the Falcon | 60 |

| Musée du Louvre | ||

| VIII. | Halt of Horsemen | 70 |

| Musée du Louvre |

EUGÈNE-SAMUEL-AUGUSTE FROMENTIN-DUPEUX was born at La Rochelle on the twenty-fourth of October, 1820. His family was a very old one and held in high honour throughout Aunis and Saintonge.

Aunis, one of the ancient provinces of France, glows languidly beneath the caresses of a humid sun, enveloped in a thin veil of ocean mists, and at times she seems to float in the midst of her waves and her sands, beneath a sky bounded by remote and indeterminate horizons, vague and immense, like some vast wreckage overgrown with gardens and oases. For more than a century, she was downtrodden by the English. But if she owes them the pain and humiliation of defeat, they at least inspired her with a passion for commercial greatness and a desire for wealth. Through her shipowners and bankers, she amassed riches that permitted her to devote a goodly share of her days to leisure and festivities, for the betterment of her material welfare and the embellishment of her mind. Thus in the midst of this industrious community, faithful to its duties, jealous of its liberty, there was slowly formed a powerful and cultured bourgeois class, eager for all forms of intellectual improvement.

Eugène Fromentin’s family was, on the father’s side, attached by ancient roots to the soil of Aunis. His ancestors were nearly all of them lawyers and judges, and as far back as they can be traced, even to the beginning of the eighteenth century, formed a part of this bourgeois class, which, in that region of ardent Protestantism, constituted a sort of aristocracy.

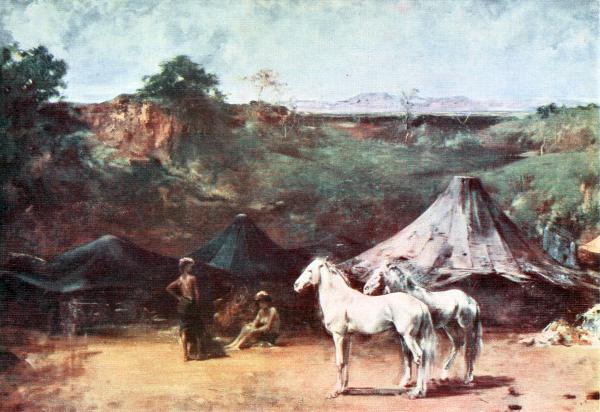

PLATE II.—THE ARAB ENCAMPMENT

(Musée du Louvre)

Against the sombre verdure of the oasis, the whiteness of the tent stands out in sharp relief. The Arabs are resting: meanwhile their horses, untethered, roam at will. This essentially simple scene, undoubtedly drawn straight from life, owes its charm to Fromentin’s admirable art, and his ability to throw some gleam of light even into his densest masses of shade.

His father was a physician of great ability, and for thirty-three years was director of the Lafond insane asylum, which he had founded not far from La Rochelle. He had a reputation for wit, but indecision and suspicion stifled the better impulses of his nature. Fromentin’s mother, whose educational advantages had been slight, had by contrast a sensitive and warmhearted disposition. It was she whom the painter resembled in all the details of his physical nature and in all the qualities of his moral nature, while Charles, his elder brother, practical and taciturn, resembled their father, whose vocation he followed.

The mentality of Eugène Fromentin developed early. At school, he surprised all his instructors by his ability to assimilate knowledge and to think things out for himself, and he was loved by them all. Later on, he confessed that “his childhood had been very lively, almost boisterous.” But somewhere during his fifteenth year, a marked change took place in him. “I had involuntarily formed the habit,” he confessed further, “of reserve and silence, a habit that was often to my disadvantage, and which was respected quite as much through pity as through tolerance. Yet it is to this habit that I owed the chance to develop in accordance with my nature; otherwise, I should have grown up warped and unfit.” And M. Pierre Blanchon, from whose admirably documented volume[1] these details are borrowed, adds further: “His views upon art and poetry clashed with the bourgeois ideas of his environment; the doctor looked upon them as mere nonsense, while his mother feared that they would lead him into temptation.” As a matter of fact, at the very period when he was passing through the moral crisis of adolescence, a romantic attachment shook his soul to its very depths with the emotions of love.

[1] Eugène Fromentin, Lettres de Jeunesse.

About half a league from town, just before entering the village of Saint-Maurice, the Fromentins owned a country place. The country roundabout is nothing but a level plain, fertile and bare, stretching away to the coast, where the sea, harnessed by Richelieu, loses, among its encroaching capes and islands, all its grandeur and poetry. Among their country neighbours there happened to be a certain Madame X., left, at the age of forty-three, the widow of a captain in the merchant marine. She spent her winters at La Rochelle and her summers at Saint-Maurice. She had a daughter, born at Port Louis, in the island of Martinique, in 1817, and consequently three years older than Eugène Fromentin. Madeleine—let us, from a feeling of pious respect, refer to her only by the name she bears in Dominique—Madeleine, being of Creole blood on her mother’s side, had the darkest of hair and eyes, combined with a fair and almost colourless complexion. We know next to nothing about her. He had conceived for her a violent attachment. Brusquely, she was snatched from the heaven in which the secret hopes and dreams of his fifteen years had framed her. She became the wife of an assistant collector of taxes. Fromentin suffered impotently from jealousy, and all the more because his passion was sincere and ingenuous. His light-heartedness vanished, together with his self-assurance; he mistrusted his own sentiments, he probed and analyzed his thoughts. To retire to the comforting privacy of his fireside and bury himself in literary work, poetry, critical essays, fragments of drama, such was his way of healing his wounds.

Some of these productions of his adolescence reveal him as a student well grounded in rhetoric, very serious-minded and painstaking, nurtured on the solid substance of the best classics, and possessed of an uneasy spirit, in which there had already awakened a taste for big, fundamental ideas, together with a goading ambition to achieve, through his own unaided efforts, some creative work of beauty. Furthermore, these early efforts show a great facility of expression, an abundant and substantial eloquence that seeks distinction, not by affecting strange mannerisms, but by frankly employing the simplest of methods.

Having completed his college course, Fromentin lived for a year somewhat at haphazard. His literary efforts became known in La Rochelle, and before long won him the esteem of the numerous men of letters who, in those days, to us the legendary days of the post-chaise and stage-coach, were drawn to a city where the social life was so distinctive and so intense. From time to time, he would steal out in the evening and furtively slip a manuscript in prose or verse into the letter-box of the Journal de La Rochelle. The next morning the poem or story or critical paragraph would appear, without signature, in the columns of the journal. But everyone who read it would, without hesitation, mentally sign the name of Fromentin.

He was now beginning to sketch and paint. The morose doctor, his father, who was himself an amateur artist of no mean ability, initiated him into the rudiments of the craft. The hour had come, however, for choosing some serious career for the lad. Charles was in Paris, studying medicine. Eugène was piloted in the direction of the law. He left La Rochelle in November, 1839, not without some pangs, for he was leaving behind him, perhaps forever, the woman whom he had worshipped with all his soul; and, sensitive and nervous as he was, he experienced a genuine dread of invading unknown territory, the huge city of Paris, so far away from his own kindly province, which had been so indulgent to his early efforts, so tender to the first dreams of his heart. At this time, his figure was slender and well proportioned, save that he was somewhat too short in the leg. His head was comparatively a trifle large. His pale complexion was at times tinged with a faint flush. His long brown hair fell upon his shoulders. His cheeks were full, the contour of his face formed a fine, elongated oval. His lips, surmounted by a budding moustache, were heavy; his forehead high and rounded and very handsome. His nose, which in later years filled out and assumed an aquiline form, was at that time perfectly straight. His eyes, beneath well-formed eyebrows, were brown, and perhaps somewhat too large, but very attractive and very gentle, far more so than they were later on; in moments of enthusiasm, which in those days were fairly frequent, or when under the influence of astonishment or sadness, he would raise them towards heaven with an expression of profundity.

In Paris, he lived at first by himself and in seclusion. His aversion to vulgarity and extravagances of speech or manners was ridiculed by some of his comrades, who nicknamed him “little Monsieur Comme-il-faut.” He followed the courses in the law school only halfheartedly, but was assiduous in his attendance at the lectures of Michelet, Quinet, and Sainte-Beuve, in the Sorbonne.

As a connoisseur of the beautiful in human handiwork, Fromentin soon learned to love Paris and to appreciate, in her environs, Versailles, Saint-Germain, Montmorency, those picturesque landscapes that combine the charm of nature with the glorious high-lights of history. Although without a teacher, he spent more and more time in sketching the changing forms of life, and strove, so far as it lay in him, to retain in his drawings the secret tremors of the soul. “These are his first stumbling utterances as a landscape painter,” wrote M. Louis Gonse in his extensive and admirable work, critical as well as biographical, in which he has reproduced the earliest known sketch by Fromentin, a scene from Chatterton, drawn the morning after a performance of De Vigny’s drama at the Théâtre Française. This pen-and-ink sketch, dated April 2, 1841, shows facility, sureness of touch, and a certain felicity in composition.

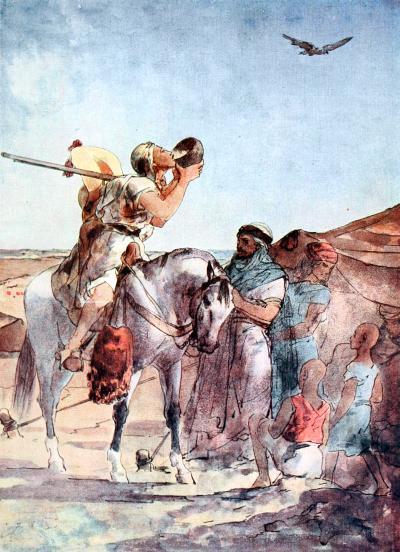

PLATE III.—THIRST

(Collection of M. Jacques Normand)

Fromentin, who was a precise observer as well as a brilliant artist, noted all the picturesque scenes of the desert. How many times he must have witnessed such halts as this beneath the burning African sun, which parches the throat! It is worth while to note the truth of the native’s attitude as he greedily drinks the water of the oasis. One should also notice the art with which the painter has grouped his figures and garments in this unfinished work, in such a way as to fling a violent and joyous note across the sombre monotony of the desert.

Far from relinquishing his literary efforts, Fromentin applied himself, from this time onward, with increased ardour, and, throwing off the trammels of romanticism, produced poems, critical studies, and even a comedy, written in collaboration with his friend, Emile Deltrémieux.

From this time onward, Fromentin held firmly to a conviction on which all his efforts as painter and author were destined to be based: namely, that an artist, instead of imitating the masters, should draw his inspiration solely from himself, from his own emotions and memories, and that, if he aspires to speak sincerely, in a new and original language, he ought to belong to some one country, to reflect its image and to repeat its accent. As a matter of fact, he himself was not, excepting in appearance, uprooted from his native soil. In the depths of his inmost consciousness, there always resounded the echo of his province.

But for the time being, while he amused himself in studying the reasons for things and administering to himself doses of his own keen analysis, he suffered from that curious affliction of dual personality which, twenty-five years later, he described in Dominique: “That cruel gift of being able to look on at one’s own life as at a performance given by someone else. Sensibility is an admirable gift; in the order of creation it may become a rare power, but on one condition: namely, that one does not turn it against oneself.”

Having taken his licentiate’s degree, Fromentin pursued his studies for the doctorate. He entered the law office of M. Denormandie. There he met, as fellow clerks, the future lawyer, M. Nicolet, and Forcade de la Roquette, destined later to become minister. Here Fromentin spent his time chiefly in drawing sketches on the desk pads, the margins of legal pleadings, and even the panels of the doors. One day he descended into the courtyard and covered the coach-house, stable, and party-wall with his artistic efforts. He paid long and frequent visits to the Louvre. The Italian school left him wellnigh indifferent. In the French school he ranked Chardin above all the rest. But already his chief enthusiasm was reserved for the Dutch. The Ford, by Wynauts, with figures by Berchem, and Ruysdaël’s Sunstroke and Dyke beaten by the Sea fascinated him. At times, he conceived a fine passion for Rubens. Rembrandt, however, from first to last, was very nearly, if not quite, incomprehensible to him. “He reproached Ingres,” records M. Louis Gonse, “for being an imitator of Raphael; nevertheless, he declared, after seeing one of Ingres’ sketches, that he was a sculptor of the first order. As regards music, he knew Mozart and Beethoven only by reputation; he loved Bellini, Donizetti, etc., and the entire sensualistic school of Rossini.”

Apparently Fromentin was now hesitating between two paths, that of the fine arts and that of belles-lettres. It is my own deep conviction that his choice had already been made. He knew that literature, worthily conceived and liberally practised, cannot become a career capable of supporting the man who follows it. He saw daily, with his wise and prudent judgment, that painting, on the contrary, can guarantee bread and fuel to an artist of real talent, respectful of his art and loyal in his efforts. Accordingly, he wrote henceforth in his leisure hours, and when the mood was on him, economizing his strength and hoping only that the art of his written word might attract attention and perhaps awaken sympathy.

At last, unable to endure any longer the legal dust of M. Denormandie’s office, he boldly confided to a friend of the family his horror of judicial procedure, and confessed his desire to devote himself wholly to painting. This friend, Charles Michel, promptly went to La Rochelle, to open negotiations with Dr. Fromentin; and the latter, after a vigorous protest, ended by yielding. But, priding himself on his knowledge of such matters, he insisted upon choosing Eugène’s instructor, and selected the painter Rémond, who at that time represented the academic school of landscape painting. Fortunately for him, Eugène did not remain long in Rémond’s studio, but left it to enter that of Cabat. A correct and careful artist, and one of the best, next to Dupré and Rousseau, Cabat had opened a new path for landscape painting—a path in which it would not be very hard to discover the influence which this celebrated master of the landscape exerted over the earlier manner of his pupil, through his sympathetic understanding of his subjects and the grace and distinction of his art.

In the month of March, 1846, Fortune suddenly smiled upon Eugène Fromentin. His friend, Charles Labbé, the orientalist-painter, was starting to attend his sister’s wedding at Blidah. Fromentin, in whom an ardent curiosity regarding the lands of sunshine had been awakened by an exhibition of aquarelles, brought back from the East by Labbé himself, by Delacroix, Decamps, and notably by Marilhat, enthusiastically accepted his friend’s invitation to accompany him. Had he some intuition that a new world of sensations and of colours awaited him in Algeria? He set forth, without even notifying his family, light of pocketbook, but buoyant with hope and faith. To his dazzled eyes, to his soul seething with ambition, it proved to be literally the promised land. Within two days after his arrival at Blidah, he wrote: “Everything here interests me. The more I study nature here, the more convinced I am that, in spite of Marilhat and Decamps, the Orient is still waiting to be painted. To speak only of the people, those that have been given us in the past are merely bourgeois. The real Arabs, clothed in tatters and swarming with vermin, with their wretched and mangy donkeys, their ragged, sun-ravaged camels, silhouetted darkly against those splendid horizons; the stateliness of their attitudes, the antique beauty of the draping of all those rags—that is the side which has remained unknown.... In short, from the point of view of my work, I have nothing to complain of, and at the rate at which I am progressing, I can promise you that I shall bring back a fairly interesting sketch-book.”

He was especially appreciative of Marilhat and Decamps; the absolutely new brilliance of their works haunted him constantly, in the midst of his own labours. “That talented pair, Marilhat and Decamps, so Théophile Gautier writes me, are oddly close neighbours, yet they do not trespass on each other’s ground; where the one has the advantage in fantasy, the other offsets it in character.”

Reinstalled in Paris, Fromentin painted with desperate zeal, lacking the gift, so he said, of inventing what he had not seen. He forced himself to escape from that spirit of imitation which is at once a pleasure and a danger, and up to the present he had accomplished nothing save to rid himself of those borrowed qualities which he had acquired, without succeeding in gaining others which he could call his own. He had, however, learned—and this knowledge is an essential virtue of every artist—that the real masters have never attempted to reproduce any object actually, but only the spirit which animates it to the point of rendering it a treasury of life and of beauty; he learned, day by day, more thoroughly, that poetry is everywhere, like the spark in the flint; that the artist must study technique from the masters and truth from nature, but that he can find nowhere, except within himself, the innate image of beauty. In 1847, he sent to the Salon, which at that time was held in the Louvre, three little pictures, which were unanimously accepted: A Farm in the Outskirts of La Rochelle, A Mosque near Algiers, The Gorges of Chiffa. “The first of the pictures,” says M. Gonse, “is characteristic of Fromentin’s earliest manner. Looked at only from the surface, it is heavy and pasty. It was a timid work, but in nowise silly or vulgar. The Gorges of Chiffa forms the curtain-raiser to Fromentin’s Algeria.” But Fromentin was exercising more and more his power of self-analysis; he knew that his paintings were nothing more than a certain equilibrium of secondary qualities, approximately correct in design and agreeable in colour, but destitute of motive power. He had also learned the cause of alteration in certain tones; the colours which he had been employing were not susceptible of combination. “He had learned that mineral blue and indian yellow, combined with white, especially with white of lead, turned black and produced a leaden tone ... also that paint was less enduring on white canvas than on canvas already prepared with a ground colour.”

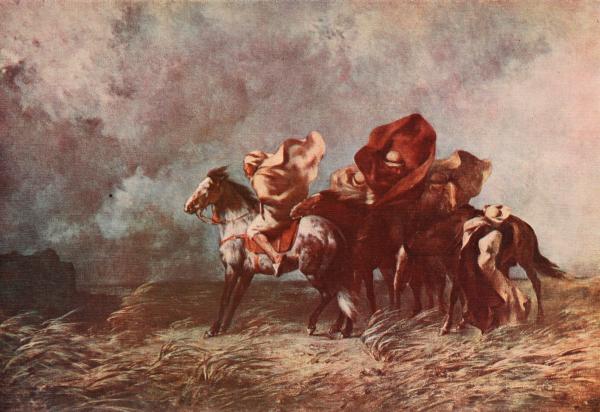

PLATE IV.—THE SIROCCO IN THE OASIS

(Musée du Louvre)

Fromentin was not only a past-master of colour. The Sirocco proves, by the prodigious cataclysm that it represents, how supple and varied was this painter’s talent. And one must marvel at such evidence of power in the author of so many works of exquisite and lyric charm.

Algeria had won him once and forever. It was decreed by fate that he should understand that African land which offered certain points of resemblance with the land of Aunis and of Saintonge. The same flat, level stretch, abandoned to the rages of the sun, or lashed by the fury of the tempests, or shivering beneath the shadow of clouds; the same voice of silence and of solitude to which he had so often listened with beating heart in the habitually melancholy fields surrounding La Rochelle, he heard again in these desolate reaches of the desert, across the burning sands, whose infinite extent is rendered almost sad by the excessive ardour of the light of heaven. Africa became the second land which he wished to cherish with all his heart and which belonged to him: he made it his own by the right of his genius, through the works of his brush and the works of his pen. From a new journey which he undertook in 1852, a wedding journey, radiant with every promise of happiness—since he had just wedded the sister of his friend, Dumesnil, who understood him and whom he loved—he brought back two volumes, A Summer in the Sahara and An Army in Sahel. The first of these appeared in the Revue de Paris and the second in the Revue des Deux Mondes. In the world of letters these two works produced a great sensation. With what finished and majestic simplicity Fromentin painted his white page with colours which his poet’s eyes had unerringly retained! “The weather is magnificent. The heat is augmenting rapidly, but so far its effect upon me has been stimulating rather than exhausting. For the past eight days not a cloud has appeared on any part of the horizon. The sky is an ardent and sterile blue that gives promise of a long period of drought. The wind, fixed in the east and almost as hot as the air at rest, blows intermittently, morning and evening, but always very lightly, and as if only for the purpose of keeping up a gentle swaying of the palm trees, similar to that of the Hindoo panwa dance. For a long time past, everyone has worn the thinnest of clothing and broad-brimmed hats, and no one ventures out of the shade. I cannot, however, bring myself to adopt the siesta.”

Thus, through two masterpieces, a new writer, of strong and pure French stock, suddenly revealed himself. The most distinguished novelists and critics of the day, George Sand, Théophile Gautier, Sainte-Beuve, sent him their heartiest congratulations and sought his friendship. In both of these books, Fromentin showed himself to be not only a curious and close observer, but a subtle and trained psychologist. He studied not only the outward forms of people and of things, he probed the depths as well, the underlying spirit; and having found it, he revealed it to others with keen and original discernment. What he saw in those tribes and peoples, as new to him as they are to us, was not merely the picturesqueness of their attitudes and the exuberant brilliance of their land, but the whole predestined history of the race from its origins, as revealed in the practice of their strange customs and the passionate intensity of their instincts. For Fromentin was not one of those who find satisfaction solely in the contemplation of beauty. He was above all one of the kind that wants to understand the meaning and the cause of beauty, in order to enjoy more keenly its possession.

It is interesting to compare with Fromentin the painter, who paints best of all with his pen, a poet of the highest rank, who came later than he in this same region of Saintonge: Pierre Loti. Roving, restless, concerned solely with the misery of his own soul and the beauty of the world, Loti carries his dreams with him to the remotest shores, and in order to distract his thoughts from life which bores him, he has gathered together extraordinary colours, the brilliant dust of picturesque ruins, and has created for himself a capricious and sensual world, in which nothing, perhaps, is real excepting his own melancholy, yet which amuses and enchants him with its prodigious fund of poetry. Like Loti, Fromentin also had an eye for rich and dazzling hues and knew how to render them with his pen. But being less feverish, more self-controlled in heart and mind, he did not write merely for the sake of depicting faces and backgrounds; he developed his robust and harmonious phrases for the purpose of interpreting, and preferably in their most vivid aspects, the dominant impulse of a race, the art with which a picture is composed, the design of a landscape, the emotion of an hour, or the spirit of an epoch.

PLATE V.—AN ARAB FANTASIA

(M. Sarlin’s Collection)

Movement, life, colour, an eddying cloud of brilliant fabrics, beneath the luminous vault of an African sky: such are the ingredients of this magnificent composition, as beautiful and as vigorous as any that the artist ever produced.

“To Fromentin,” writes Gabriel Trarieux, “the function of an adjective is to appeal, not to the eye or ear, but to the moral sense. Nature, to this psychologist, is not an inert colour, but an inner voice. He shows us Africa, and more especially his own heart. Is such conscientiousness, such self-revelation, a distinctive mark of the native of Charente? For my part, I think it is.”

His offerings to the Salon continued uninterruptedly, year after year. Only the more famous need be mentioned: The Moorish Burial (1850); The Negro Boatmen (1859); Horsemen returning from a Fantasia, Couriers from the Land of the Ouled Naïls (1861); The Arab Bivouac at Daybreak, The Arab Falconer, Hunting with the Falcon in Algeria, The Quarry (1863); Windstorm in the Plains of Algiers (1864); Heron Hunting, Thieves of the Night (1865); A Tribe on the March through the Pasture Lands of Tell, A Pool in an Oasis (1866); Arabs attacked by a Lioness (1868); Halt of the Muleteers (1869); and his last five pictures, The Grand Canal and The Breakwater (1872); The Ravine (1874); The Nile and View of Esneh (1876).

With the second picture that he exhibited, The Place of the Breach in Constantine, the talent of the painter was officially recognized by the bestowal of a Second Class Medal. Fromentin, nevertheless, knew his weaknesses. What distressed him the most was that he still saw what was pretty, rather than what was great; a defect of instinct which is particularly conspicuous in The Moorish Burial (1850) and The Gazelle Hunt (1859). He strove, by consulting nature ceaselessly, to rid himself of this almost-but-not quite tendency, of which he could never have been cured by mere studio work. He soon began, as a matter of fact, to acquire a truer and broader vision. He grasped this singular fact, peculiar to tropical lands: namely, that, howsoever discordant the details of a landscape may be, they form a sum total that is always simple and easy to transcribe upon a canvas. Since he never played false, either with himself or with nature, he mirrored back accurately, through the crystal clearness of his mind, the form and colour of the objects before him. Looking to-day at such pictures as An Audience before the Caliph, The Negro Boatmen, and a host of others, we breathe in, just as we do in reading his books, that indefinable odour of the Orient which comes from the smoke of the camp fires and the tobacco, from the orange trees and from the persons of the natives themselves; we delight our eyes with the venerable olive trees of the sacred grove at Blidah, with the plain bounded on the north by the long chain of the hills of Sahel, low-lying, gray in the morning, ruddy at noon, with just one white spot toward the northeast, at Coléah, where there is a vast gap, formed by the course of the Mazapan River, through which we get a glimpse of the sea.

The entire series of sketches and notes which, from Constantine to Biskra, by way of Lambessa, Fromentin collected during his journey into the heart of Algeria, he was destined to make use of later on, to guard himself from ever falsifying. And if the colours of his paintings are often timid, it is precisely for the reason that in the seclusion of his studio, remote from Africa, he lacked that pulsation of generous light, with which he needed to be enveloped, in order to kindle his palette to the required glow.

Eugène Fromentin will be remembered as the painter of Algeria, or at least as one of the first who revealed it in such a way as to make it beloved. Not the Algeria of the South, lost amid a furnace of sunshine and of sand, but the Algeria which is accessible to all, that of the Arabs, with peaceful cities set in the midst of ruins, and grateful palm groves forgotten, like baskets after a festival, on the border of the desert; the Algeria of ceremonious and brilliant fantasias, of mosques, of battle-fields still smoking, and of vagabond tribes. It may be regretted that he contented himself with seeing the Arab exclusively outside his tent, in the open light of sand and sky, and that, instead of confining his studies to external phases of life, he never ventured to penetrate to his hearthstone, in the intimacy of his family life. Yet who would reproach the artist for his scrupulous delicacy and discretion?

Jules Claretie was quite right in declaring that Marilhat brought back from the Orient landscapes imbued with profound melancholy, Decamps scenes distinguished for their dazzling brilliance, Delacroix spectacles of majestic grandeur, and that Fromentin in his turn discovered in that land of light a personal note which his predecessors would have sought in vain, since he carried it within himself. The colour scale of Fromentin is a subdued one; his favourite shades are the half-tones.

In the presence of that brilliant land, ennobled by centuries of history, Fromentin remained, nevertheless, a Parisian of the purest stock. His Arabs are all keenly alert, down to the very folds of their burnooses. He could not bear to behold ugliness; he transformed it through the golden warp of his imagination. Although his pictures lack the harsh vibration of the desert and a sense of its far-reaching monotony, the desert nevertheless loses nothing of its grandeur; because his poet’s understanding, more infinite than the expanses of the dunes, passed of its own accord beyond the bounds of a horizon which, unlike that of the sea, is not void save for the passerby who is incapable of emotion and comprehension. Beneath his sober brush, the Arabs retain all their strange attractions, which he amply indicates by a single dash of light, just as in his books he evokes a landscape or an individual by a single word. His eyes took in the outward form of things as completely as his mind penetrated the minds of others. His unwearied power of observation neglected nothing that pertained to light; consequently the accuracy of his paintings, comparable to that of historic documents, is attested by every traveller.

The Fantasia, for example, gives an admirable presentment of the open country around Algiers and of one aspect of Arab manners and customs. It shows us a numerous cavalcade galloping at headlong speed, with clamorous shouts and discharge of guns, across a broad plain toward a knoll on which the mounted emir sits in judgment. This mingling of motley garments and of horses galloping in all directions produces a scene of extraordinary animation and a liveliness of tone that contrasts sharply with the bare immensity of the plain and the uniformity of the sky.

Suddenly, in 1861, Fromentin’s manner was marked by a complete evolution. Not that he abandoned the fine and delicate methods habitual with him, the methods of a poet seeking to interpret his visions and his sentiments through his skill in animated composition. Nothing of his originality was sacrificed. His power, on the contrary, was increased, because he had learned, in regard to the inspiration of his works, how to see reality more truly, and in regard to the resources of his art, how to understand better the superior methods of his compeers and his masters. But he had seen Corot, and his admiration of him increased day by day; it was the influence of the painter of The Farm Wagon that induced him to render the value of colour tones in accordance with their harmonies rather than their contrasts.

PLATE VI.—EGYPTIAN WOMEN ON THE BANK OF THE NILE

(Musée du Louvre)

In this attractive, verdant nook, lighted by a luminous patch of brilliant fabrics, the artist has harmoniously placed a group of women. While some of them, stretched at length beneath the shade, gossip together while they rest, two of their number are standing, and watch the flow of the sacred river, the mysterious Nile, witness of so many things, contemporaneous with so many illustrious civilizations. This picture is a masterpiece of composition and colour.

Beginning with The Verge of an Oasis during the Sirocco, one can see how Corot’s dexterous and delightful gray came to life again under Fromentin’s brush. “It was a rare distinction,” writes M. Louis Gonse, “in that period of ardent romanticism, to have realized instinctively the value of gray, its caressing softness, its modest yet insistent appeal. Silver gray, amethystine and turquoise gray, these were the tones of which Fromentin was soon vaunting the delicate and tender charm. I remember an interview which I had with him one morning, in his studio, regarding the painter of that unique masterpiece, a Souvenir of Marissal. Fromentin was in fine good humour and buoyant spirits. All that he said to me about Corot, his place in art, his daring innovations, his inimitable feeling for light, his exquisite sense of the exact tone, was well worth remembering. It was a marvellous offhand estimate, the substance of which summed up deep-seated convictions. Beneath that flashing, swift-winged flight of words, I felt the earnestness of opinions born of long reflection.”

From 1861 onward, Fromentin deserted the Sahara in favour of Sahel, exchanged the consuming heat of summer for a milder sunshine. “He sought,” recorded Louis Gonse, “to paint in lighter, fresher colours: his instinct counselled him to avoid black as a mortal enemy—that black which certain painters deliberately affect, thinking that in this way they are imitating the old masters. All those soft grays, which are luminous half-tones of white, appeared imperceptibly beneath his brush. After having won distinction as a colourist, he became and remained to the end a master of tonal harmony in the subtlest sense. According to the opinion of Sainte-Beuve, ‘he attained his greatest effects by combining the simplest methods in a marvellous manner.’ And since his ambition was of steady growth, his progress in his craft was uninterrupted.”

Among Fromentin’s productions of this period are: The Shepherds on the High Plateaus of Kabylia, an austere spectacle witnessed on the road from Medéah to Boghar; The Bed of the Oued Mzi; and the charming canvas of Turkish Houses in Mustapha-in-Algiers. In 1863, he produced The Arab Bivouac at Daybreak, which, by its presentment of salient details and its sympathetic understanding of the slightest gesture, sets before us the impressive melancholy of the nomad life; he produced further The Arab Falconer, one of the most brilliant of his smaller works; and lastly, Hunting with the Falcon in Algeria, which many of his admirers regard as his masterpiece, and which, at all events, is his most famous painting. It may now be seen in the collection in the Louvre.

Fromentin repeatedly duplicated, in crayon, in aquarelle, and in oil, this scene which represents two Arab chiefs hunting, accompanied by their attendants. The horseman in the middle of the picture, an old man holding a falcon, resembles, on his motionless horse, an equestrian statue. The second horseman, the one in the foreground, is undoubtedly his son; he is as attractive as a pretty girl and young like the horse he rides, a white horse, of a beautiful, silvery white, the lower part of the legs shading off into an exquisite rose tint. The rider is clad in blue, white, and gray, while a saddle of turquoise blue, enriched with trimmings of glazed vermillion, adorns the courser, which is distinguished by a luxuriant mane, an ample, flowing tail tinged with ochre and amber, and a black eye, profound and full of life. Two Arabs, kneeling in the pathway, have taken possession of a hare which the falcons have just killed. The whole effect is that of extreme distinction, marred perhaps by too much embellishment.

In 1870, Fromentin found his way to Venice. At the first rumours of war, however, he returned precipitately to France, to join his wife and daughter in Paris and take them to Saint-Maurice, his beloved village adjacent to La Rochelle. From Venice, he brought back The Grand Canal and The Breakwater, two canvases somewhat leaden in tone, which some critics class in the number of Fromentin’s blunders. The reason may be that they failed to recognize in them the Venice of their dreams, the Venice of tradition, flamboyant and enchanted. But there is another, a tranquillized Venice, which at times allows her fireworks to burn out. Fromentin was not a romantic painter; it was in their hours of repose that he beheld the Grand Canal, the Breakwater, the houses leaning over the water’s brink; and he expressed what he really saw in the midst of a silence that contains a special poetry as well as truth. Fromentin exhibited for the last time in the Salon of 1876—two canvases brought back from Egypt, The Nile and A Souvenir of Esneh, canvases distinguished for their “cold, dull colouring, ranging through a neutral scale of violet lights.”

The masterpiece of Fromentin, the picture in which his qualities of composition, drawing, and colour are most clearly revealed, is, in the opinion of all artists—who are alone capable of simultaneously appreciating the art and the craftsmanship of a painting—Crossing the Ford. This picture is now in the possession of Mme. Isaac Péreire. Across a canvas measuring little more than two yards, a group of horsemen are journeying through a waste of sand, stretching away in long, pallid dunes, broken here and there by clumps of sombre growth; a swarm of women surrounds them, as light of foot as bees upon the wing. A stream, bordered on the right by tamarinds with sharp, narrow leafage, displays its slender, mirror-like surface. Some of the horses are reserved for the chiefs, while others are laden with burdens of clothing and provisions. The sky, partly clear and partly overcast, occupies the greater portion of the canvas: in the far distance, the swelling curve of the horizon conveys a strong impression of infinity and solitude. The central figures are drawn upon a scale hardly exceeding eight inches in height. The horses, fired with that generous pride which this painter always attributes to them, seem to know their way even better than their riders. They proceed without haste, enjoying the gentle breeze stirring fitfully across the vast expanse, and the time of day, which is growing late. The colour scheme of the picture is bold and conveys an exquisite savour of gold and gray, flickering flames vanishing behind the leafage, as well as along the horizon, as the dusk shuts down. In this picture, Fromentin has produced, with the simplest and most adaptable resources of his palette, a work in which, underneath all the surface charm, the melancholy which abides in the heart of man, and above all in the heart of the Arab, blends harmoniously with the beauty of the world.

One of the masters of to-day, of a generous and impulsive nature, who does not wish to be quoted by name, but whose works may be admired in the Luxembourg, consented to give me some information regarding Fromentin, whose pupil he once was. I should like, as a conclusion to this study, to be able to transcribe literally what he told; but at least I shall draw a pious inspiration from his words.

Fromentin laid on his colours very thickly. His solid grounds were always most carefully prepared and his composition calculated in advance down to the smallest detail. At the start, he came under the influence of Decamps, Marilhat, and more especially Delacroix, and in consequence neglected line work, devoting himself solely to the distribution of colours. Delacroix and the romantic school of his time did not interpret Algeria well, because they failed to see it well. They saw it through the black holes of windows, in all the violence of its whites and reds, in the picturesqueness of its costumes and the long stretches of its dusty streets. But Fromentin had visited Italy, and during his excursions across this museum of diverse aspects he made a special study of the effects of sunshine upon the handiwork of man. It was while still saturated with the brilliance and with the art treasures of Italy that he first saw the land of Africa, or rather that he first conceived the desire to learn to know its secrets. Fromentin never put upon his canvases the Africa of the desert, in which there is nothing but the white of the burnoose and the gray of the dune, but Algeria the Fair, Algeria already civilized. He was enraptured by the sight of it and by the penetrating conception, full of eager curiosity, which he had already formed of it. For Fromentin does not command by the audacity of his colours; he commands by the charm of his apportionment of light and shadow, and by the precision of a style which seeks, irrespective of form, to show us the soul of people and of things. He sees with the eyes of a poet, he expresses himself in the manner of a philosopher, he forces us to reflect. He detests all that is vulgar, superfluous, and extravagant. All that pertains to reality has for him a significance, of which he seeks the cause, and for which he frequently discovers a definitive expression.

PLATE VII.—HUNTING WITH THE FALCON

(Musée du Louvre)

Falconry is an episode of African life which peculiarly attracted Fromentin. He has treated it in a number of different pictures, all equally remarkable. The collection in the Louvre possesses two: the one which we give here is distinguished by the cleverness of its composition, the way in which its component parts are distributed throughout the prospective, in accordance with the desired effect, thus lighting up the gray immensity with joyous and violent tints.

Through his habit of studying the inner workings of the mind of man, he reached a point, toward the end of his life, when he ceased to compose, even in painting, any works other than those of a man of letters. The keenest intellectual alertness was always ceaselessly pulsating within him. Furthermore, he made a sort of religious cult of life in all its forms, even the most humble, and imbued them with an ennobling charm. And for the purpose of understanding the psychology of a race which enwraps itself jealously in a pride of attitude, the works of Fromentin offer testimony that bears the stamp of rare sincerity and clear-sighted sympathy. His mind never wastes time over the eccentricities of a tribe or a people, but bends its whole effort to gathering up, through a choice of typical details, the general idea, the embodiment of a human group.

Fromentin knew, better than anyone else, how great his lack was of elementary training in painting. He knew that no natural gift can replace those initial steps in craftsmanship in any and all forms of production, and that works which are truly beautiful and worthy of being held in honour through the centuries obtain their right to live solely from having obeyed the laws of order and of clearness. These laws, as related to pictorial art, are taught in the studio and the school. A naturally gifted artist may undoubtedly evolve, out of his own personal inspiration, an amusing or interesting work; but that work, if not constructed according to the syntactic rules peculiar to his art, will have merely an ephemeral charm, like the costly baubles of a passing fashion. What proves the necessity of rules of technique is that the masters themselves have not been contented with the possession of genius or talent alone. They have learned their craft down to its profoundest secrets; and the greatest of these masters are the ones who have succeeded best in practising the methods transmitted by past experience, and have even in their turn discovered new laws.

How many times, with touching modesty, Fromentin deplored his total lack of the essential studies of apprenticeship! Beneath the colour of forms and objects, he grasped the course and movement of life. But his restless hands did not succeed completely, to his own satisfaction, in transferring them to his canvas. Nevertheless, his pictures, because imbued with an emotion, the contagion of which was communicated to their colours, far from resembling, as so many others do, a sort of clever and inert photograph, are evocations, and often magnificent ones, of some historic hour, of the destiny of a race, or the soul of a landscape.

Under the influence of the romantic school, as I have already said, Fromentin’s brush sought at first chiefly to dazzle. But one day he awoke to a comprehension of Corot. The inward emotion which he underwent affected him like the discovery of a new light. A transformation followed rapidly, not in his ability to feel, but in his fashion of reproducing what he felt. Yielding joyfully to the authority of Corot, he began to make use of gray, and before long it became his dominant tone. Like a frail cloud interspersed with invisible rays of red and azure, enveloping the atmosphere of his scenes and characters, and blending into his minutely wrought skies, this gray of his, which borrowed something of its hue from each of the primary colours, pleased him by the very discreetness of its opulence. Discreetness is one of the hallmarks of refinement; and Fromentin was nothing, if not refined, in his manners, his thoughts, and his speech. “Just as his painting was never heavy and his writing never dull,” says Emile Montégut, “his physical build was slender, graceful, delicate; yet his slenderness was in no way weakness, nor his delicacy affectation. No objectionable professional mannerism proclaimed the craft he practised; still less did he ape the manners of the man of fashion, in order to hide the fact that he was a man of toil. With all his frankness, he had the good taste to refrain from betraying his intimate personality to the world at large.”

It was precisely this use which he made of gray that enabled him, by its play of half-tones, to explore the mystery of souls. And quite unconsciously he revealed his own, a noble soul, enamoured of all that is great and eternal in civilization and in life. When face to face with an actual scene, he frequently gave up the attempt to transfer it with his brush. It was not until much later, after long reflection over the material conditions of a scene whose beauty had delighted his eye, that he was ready to begin work.

Consequently there are other artists who have more accurately rendered the colour of this African land: there are, for instance, Guillaumet and Regnault. With a somewhat austere, yet precise, touch, after the fashion of an extremely well-informed commentator rather than a deeply moved poet, Guillaumet shows us, in all their picturesque authenticity, the history and architecture of buildings ravaged by the sun, and outlined against them the stately silhouettes of Arabs to whom silence appears to be a sort of religious rite. Yet the sublime poetry of the desert has also touched his painter’s heart in The Evening Meal, now in the collection in the Luxembourg; the thin blue smoke, melting away into the calm atmosphere, is typical of the immobility of the Sahara, the sullen oppressiveness of daytime amid the sands. Henri Regnault, in works that are scarcely more than sketches and have never been exhibited, transcribed, with all the ardour of his age, during too brief a sojourn in Morocco, the symphony of divine colours which exhales from the soil of Africa and from its sky, that burns like living coals.

Fromentin did not always dare to undertake to paint his own conceptions. His timidity is betrayed by the very modesty of his canvases, which scarcely exceed two yards. Nevertheless, the painter whom he loved the most was Rubens: Rubens, the prodigal dispenser of light, who poured his inexhaustible and gorgeous imaginings, like the waters of a mighty river, over canvases without number.

Fromentin did not find it easy to give forth the treasures of his brain, excepting through the medium of writing. He delighted in sumptuousness, and he found it in Rubens, whom he eulogized, in his Masters of Yesterday, in a truly lyric strain. He did not understand Rembrandt and despaired of ever understanding him. He studied him constantly, with a sort of impatience, striving to glimpse, through his veils of half-shadows, the spirit of a genius who was too alien in nature, country, and race.

PLATE VIII.—A HALT AT AN OASIS

(Musée du Louvre)

The weary caravan has halted, tempted by the verdure of the oasis. Faithful to his manner, Fromentin has taken advantage of this picturesque scene to throw a harmony of colour and light over the men and their surroundings. In all its simplicity, this picture is one of its author’s happiest efforts, because of the impression of life which emanates from this group, relatively so few in number.

Among Fromentin’s pupils was Cormon, an intractable pupil with a marked individuality; yet while he ignored his professional authority, he always proclaimed him, and with real feeling, the most intelligent of masters and the most loyal of men. Fromentin did not exactly conduct a regular art-school. He had gathered around him seven or eight young artists, in whom he foresaw a prosperous future: Gervex, extremely brilliant, Thirion, the most temperamental of them all, Lhermitte and Humbert, who was the master’s favourite. Fromentin saw in Humbert a second self, more fortunate in having a chance to learn at the outset the indispensable rules of his craft, and therefore capable later on of achieving works which he himself could never carry out. Without effort, he won the adoration of his pupils. With an eloquence which came from his heart quite as much as from his brain, he preached to them the doctrine of sincere labour, of disinterested ideals, and of reverence for the past because it has produced the present. He had a combative spirit. He never hesitated to express his opinion about works or about men, since the nobility of his character forbade that he should be suspected of maliciousness or envy. Certain works of his time, that are still discussed and that our own age has consecrated, were displeasing to him: Millet’s, for example. He professed a profound esteem for the man, but he did not admit the technical value of the artist nor the importance of his ideas.

For a long time Fromentin’s rank as a painter was disputed. He proceeded peaceably on his way toward fortune and glory. His literary successes confirmed and enhanced his triumphs as a painter. Through his books his pictures became known and admired by the general public. In 1859, he obtained a First Class Medal and the Cross of the Legion of Honor. The emperor, Napoleon III., invited him to Compiègne. In 1869, his election as Officer of the Legion of Honor followed upon his exhibition of the Fantasia in Algeria and The Halt of the Muleteers. In 1868, he exhibited a very strange and disconcerting picture: Male and Female Centaurs practising at Archery. He wished to show by means of this work, which evoked much comment and criticism, that “the equestrian statue is the last word in human statuary.” “Mingle,” he wrote, “man and horse, give to the rest of the body the combined attributes of alertness and vigour, and you have a being which is supremely strong, thinking and acting, brave and swift, free, and yet docile.” Fromentin’s aristocratic instincts extended from men to things, and even to animals. It was he who in a certain sense discovered the horse, the Arab horse, fine and free, poet of the desert and the sun quite as much as his master. When Fromentin shows him to us with his long silvery tail and his mane quivering like waves, one would say that in the swift flight of his course the artist had lent him wings. “Nevertheless,” writes one critic, “in spite of his intimate acquaintance with the form and the varied coat of the Arab horse, it is perhaps in the little inaccuracies of his drawing of this animal that Fromentin betrays most obviously the defectiveness of his early studies.”

What a pity, let us say once again, that he lacked the time to acquire, while still young, that power and technique in painting which he possessed in literature! Each one of his volumes evoked an outburst of admiration and sympathy. He wrote only when he had something definite to say. His novel, Dominique, fired with the spirit of youth, burning with love and sorrow, was, from the date of its publication, in 1862, in the Revue des Deux Mondes, hailed as a masterpiece.

Not everywhere, however. The poets alone, the born writers, those in whom the habit of psychology and criticism had not extinguished that personal flame which burns within the heart, Sainte-Beuve, for example, and George Sand, recognized it as a work of genius. It was much discussed and even disparaged, by professional writers and critics, even in the Revue des Deux Mondes itself. Emile Montégut, who combined absolute frankness with a wide range of knowledge and keen understanding, while not disputing the literary value of Dominique, did not hesitate to affirm that the book was not a novel, but a series of faultily composed scenes and descriptions, confessions, and memories.

At first, and for some time afterward, the public seemed to ratify this opinion. The volume, issued by Hachette, was bought only at rare intervals and out of curiosity. Later, after this initial failure, it took a fresh start, and to-day is a recognized classic. For, while it is true that this prose poem is lacking in intrigue and that its characters are somewhat overwhelmed by the floods of light from its stage-settings, it diffuses such a redolence of the soil teeming with life, such a fragrance of warm and pure tenderness, that every sensitive and ardent soul delights to yield itself to the harmonious flow of its words and colours.

The Masters of Yesterday has become a breviary for painters who are studying the Flemish and Dutch schools. “The Fromentin revealed in The Masters of Yesterday” asserts Emile Montégut, “is a second Taine, minus the defects for which the latter is reproached, and minus that sort of harshness which comes from the exclusive use of crude colours and a disdain of half-tones. There is also this further difference between them: that Taine puts his battalions of ideas and facts through their manoeuvres with the imperiousness of a general-in-chief commanding an action, while Fromentin assembles and reviews his own with the ease of an orchestra leader directing the instruments under his orders by the simple gesture of his bow.... Just one word is applicable, in point of strict definition, to the temperament and talent of Fromentin: that word is perfection. He strove for it all his life. He deserves to be called the classic of that type of picturesque literature, whose ambition, at the outset, looked toward a very different goal from that of gaining this title, and whose enterprises and audacities the classic school of art could not, as a matter of fact, have beheld without alarm.” This book is, without doubt, Fromentin’s best. For, while the majority of art critics are merely amateurs posing as craftsmen and judges, he knew quite well whereof he spoke. While he understood as well as the others, and even better, an author’s purpose, he could also see of what material and by what means the work of this same artist was composed. He was not a dilettante, endowed with a greater or less amount of taste, but a fellow craftsman, who knew how to mix his own colours and to analyze the palette of another.

His literary works entitled him to a seat in the Académie Française considerably sooner than he could have dreamed of the Académie des Beaux-Arts.

As a matter of fact, in 1874, he offered himself, at the urgent entreaty of his friends, as a candidate for the Académie Française, quite suddenly and when it was already too late to bring any influence to bear, while solemn pledges had already been secured by his competitors. In spite of this, the weight of his name secured him thirteen or fourteen votes.

He was preparing a volume of critical studies on the French school and planning another on the Italian school, when death abruptly cut him short, at the age of fifty-five, in the midst of a steady ascension into the light of fame. It was a misfortune for France. In the beauty of his character, as lofty as that of his genius, he offered an example of the most precious qualities of man and artist: uprightness, charity, good taste in what he admired, and sincerity in what he tried to do. The name of Eugène Fromentin grows greater day by day; clouds may pass before him, as before a star, but without ever effacing him.