Title: The Gates of India: Being an Historical Narrative

Author: Sir Thomas Hungerford Holdich

Release date: June 17, 2013 [eBook #42970]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Melissa McDaniel and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

Transcriber's Note:

Obvious typographical errors have been corrected. Inconsistent spelling and hyphenation in the original document have been preserved.

"crank" on page 147 is a possible typo.

"Bamain" on page 213 is a possible typo.

"Semetic" on page 225 is a possible typo.

"Zoroastian" on page 270 is a possible typo.

"Aegospotami" (in index) not found in text.

"Kardos" (in index) not found in text.

Spelling differences between the index and the text were resolved in favor of the text.

MACMILLAN AND CO., Limited

LONDON · BOMBAY · CALCUTTA

MELBOURNE

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

NEW YORK · BOSTON · CHICAGO

ATLANTA · SAN FRANCISCO

THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, Ltd.

TORONTO

BEING

AN HISTORICAL NARRATIVE

BY

COLONEL SIR THOMAS HOLDICH

K.C.M.G., K.C.I.E., C.B., D.Sc.

AUTHOR OF

'THE INDIAN BORDERLAND,' 'INDIA,' 'THE COUNTRIES OF THE KING'S AWARD'

WITH MAPS

MACMILLAN AND CO., LIMITED

ST. MARTIN'S STREET, LONDON

1910

As the world grows older and its composition both physical and human becomes subject to ever-increasing scientific investigation, the close interdependence of its history and its geography becomes more and more definite. It is hardly too much to say that geography has so far shaped history that in unravelling some of the more obscure entanglements of historical record, we may safely appeal to our modern knowledge of the physical environment of the scene of action to decide on the actual course of events. Oriental scholars for many years past have been deeply interested in reshaping the map of Asia to suit their theories of the sequence of historical action in India and on its frontiers. They have identified the position of ancient cities in India, sometimes with marvellous precision, and have been able to assign definite niches in history to historical personages with whose story it would have been most difficult to deal were it not intertwined with marked features of geographical environment. But on the far frontiers of India, beyond the Indus, these geographical conditions have only vi been imperfectly known until recently. It is only within the last thirty years that the geography of the hinterland of India—Tibet, Afghanistan, and Baluchistan—have been in any sense brought under scientific examination, and at the best such examination has been partial and incomplete. It is unfortunate that recent years have added nothing to our knowledge of Afghanistan, and it seems hopeless to wait for detailed information as to some of the more remote (and most interesting) districts of that historic country. As, therefore, in the course of twenty years of official wanderings I have amassed certain notes which may help to throw some light on the ancient highways and cities of those trans-frontier regions which contain the landward gates of India, I have thought it better to make some use of these notes now, and to put together the various theories that I may have formed from time to time bearing on the past history of that country, whilst the opportunity lasts. I have endeavoured to present my own impressions at first hand as far as possible, unbiased by the views already expressed by far more eminent writers than myself, believing that there is a certain value in originality. I have also endeavoured to keep the descriptive geography of such districts as form the theatre of historical incidents on a level with the story itself, so that the one may illustrate the other.

Whilst investigating the methods of early explorers into the hinterland of India it has, of course, vii been necessary to appeal to the original narratives of the explorers themselves so far as possible. Consequently I am indebted to the assistance afforded by quite a host of authors for the basis of this compilation. And I may briefly recount the names of those to whom I am under special obligation. First and foremost are Mr. M'Crindle's admirable series of handy little volumes dealing with the Greek period of Indian history, the perusal of which first prompted an attempt to reconcile some of the apparent discrepancies between classical story and practical geography, with which may be included Sir A. Cunningham's Coins of Alexander's Successors in Kabul. For the Arab phase of commercial exploration I am indebted to Sir William Ouseley's translation, Oriental Geography of Ibn Haukel, and the Géographie d'Edrisi; traduite par P. Aimedée Joubert. For more modern records the official reports of Burnes, Lord, and Leech on Afghanistan; Burnes' Travels into Bokhara, etc.; Cabul, by the same author; Ferrier's Caravan Journeys; Wood's Journey to the Sources of the Oxus; Moorcroft's Travels in the Himalayan Provinces; Vigne's Ghazni, Kabul, and Afghanistan; Henry Pottinger's Travels in Baloochistan and Sinde; and last, but by no means least, Masson's Travels in Afghanistan, Beluchistan, the Panjab, and Kalat, all of which have been largely indented on. To this must be added Mr. Forrest's valuable compilation of Bombay records. It has been indeed one viii of the objects of this book to revive the records of past generations of explorers whose stories have a deep significance even in this day, but which are apt to be overlooked and forgotten as belonging to an ancient and superseded era of research. Because these investigators belong to a past generation it by no means follows that their work, their opinions, or their deductions from original observations are as dead as they are themselves. It is far too readily assumed that the work of the latest explorer must necessarily supersede that of his predecessors. In the difficult art of map compilation perhaps the most difficult problem with which the compiler has to deal is the relative value of evidence dating from different periods. Here, then, we have introduced a variety of opinions and views expressed by men of many minds (but all of one type as explorer), which may be balanced one against another with a fair prospect of eliminating what mathematicians call the "personal equation" and arriving at a sound "mean" value from combined evidence. I have said they are all of one type, regarded as explorers. There is only one word which fitly describes that type—magnificent. We may well ask have we any explorers like them in these days? We know well enough that we have the raw material in plenty for fashioning them, but alas! opportunity is wanting. Exploration in these days is becoming so professional and so scientific that modern methods hardly admit of the dare-devil, face-to-face intermixing with ix savage breeds and races that was such a distinctive feature in the work of these heroes of an older age. We get geographical results with a rapidity and a precision that were undreamt of in the early years (or even in the middle) of the last century. Our instruments are incomparably better, and our equipment is such that we can deal with the hostility of nature in her more savage moods with comparative facility. But we no longer live with the people about whom we set out to write books—we don't wear their clothes, eat their food, fraternize with them in their homes and in the field, learn their language and discuss with them their religion and politics. And the result is that we don't know them half as well, and the ratio of our knowledge (in India at least) is inverse to the official position towards them that we may happen to occupy. The missionary and the police officer may know something of the people; the high-placed political administrator knows less (he cannot help himself), and the parliamentary demagogue knows nothing at all. My excuse for giving so large a place to the American explorer Masson, for instance, is that he was first in the field at a critical period of Indian history. Apart from his extraordinary gifts and power of absorbing and collating information, history has proved that on the whole his judgment both as regards Afghan character and Indian political ineptitude was essentially sound. Of course he was not popular. He is as bitter and sarcastic in his x unsparing criticisms of local political methods in Afghanistan as he is of the methods of the Indian Government behind them; and doubtless his bitterness and undisguised hostility to some extent discounts the value of his opinion. But he knew the Afghan, which we did not: and it is most instructive to note the extraordinary divergence of opinion that existed between him and Sir Alexander Burnes as regards some of the most marked idiosyncrasies of Afghan character. Burnes was as great an explorer as Masson, but whilst in Afghanistan he was the emissary of the Indian Government, and thus it immediately became worth while for the Afghan Sirdar to study his temper and his weaknesses and to make the best use of both. Thus arose Burnes' whole-hearted belief in the simplicity of Afghan methods, whilst Masson, who was more or less behind the scenes, was in no position to act as prompter to him. It was just preceding and during the momentous period of the first Afghan war (1839-41) that European explorers in Afghanistan and Baluchistan were most active. Long before then both countries had been an open book to the Ancients, and both may be said geographically to be an open book to us now. There are, however, certain pages which have not yet been properly read, and something will be said later on as to where these pages occur. xi

| PAGE | ||

| Introduction | 1 | |

| CHAPTER I | ||

| Early Relations between East and West—Greece and Persia and Early Tribal Distributions on the Indian Frontier | 11 | |

| CHAPTER II | ||

| Assyria and Afghanistan—Ancient Land Routes—Possible Sea Routes | 39 | |

| CHAPTER III | ||

| Greek Exploration—Alexander—Modern Balkh—The Balkh Plain and Baktria | 58 | |

| CHAPTER IV | ||

| Greek Exploration—Alexander—The Kabul Valley Gates | 94 | |

| CHAPTER V | ||

| Greek Exploration—The Western Gates | 135 xii | |

| CHAPTER VI | ||

| Chinese Explorations—The Gates of the North | 169 | |

| CHAPTER VII | ||

| Mediæval Geography—Seistan and Afghanistan | 190 | |

| CHAPTER VIII | ||

| Arab Exploration—The Gates of Makran | 284 | |

| CHAPTER IX | ||

| Earliest English Exploration—Christie and Pottinger | 325 | |

| CHAPTER X | ||

| American Exploration—Masson—The Nearer Gates, Baluchistan and Afghanistan | 344 | |

| CHAPTER XI | ||

| American Exploration—Masson (continued)—The Nearer Gates, Baluchistan and Afghanistan | 390 | |

| CHAPTER XII | ||

| Lord and Wood—The Farther Gates, Badakshan and the Oxus | 411 | |

| CHAPTER XIII | ||

| Across Afghanistan to Bokhara—Moorcroft | 442 xiii | |

| CHAPTER XIV | ||

| Across Afghanistan to Bokhara—Burnes | 451 | |

| CHAPTER XV | ||

| The Gates of Ghazni—Vigne | 462 | |

| CHAPTER XVI | ||

| The Gates of Ghazni—Broadfoot | 470 | |

| CHAPTER XVII | ||

| French Exploration—Ferrier | 476 | |

| CHAPTER XVIII | ||

| Summary | 500 | |

| INDEX | 531 | |

| FACE PAGE | ||

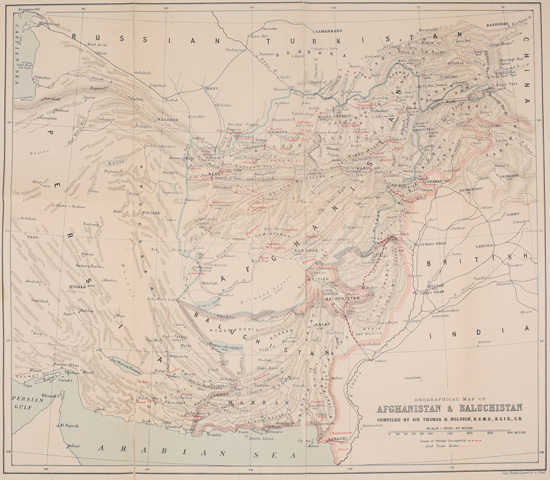

| 1. | General Orographic Map of Afghanistan and Baluchistan, showing Arab trade routes (see page 190 et seq.) | With Introduction |

| 2. | Sketch of Alexander's Route through the Kabul Valley to India | 94 |

| 3. | Greek Retreat from India (Journal of the Society of Arts, April 1901) | 135 |

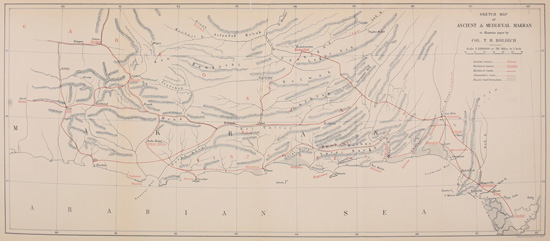

| 4. | The Gates of Makran (Journal of the Royal Geographical Society, April 1906) | 284 |

| 5. | Sketch of the Hindu Kush Passes | 500 |

OROGRAPHICAL MAP OF

AFGHANISTAN & BALUCHISTAN

COMPILED BY SIR THOMAS H. HOLDICH, K.C.M.G., K.C.I.E., C.B.

View larger image

Since the gates of India have become water gates and the way to India has been the way of the sea, very little has been known of those other landward gates which lie to the north and west of the peninsula, through which have poured immigrants from Asia and conquerors from the West from time immemorial. It has taken England a long time to rediscover them, and she is even now doubtful about their strategic value and the possibility of keeping them closed and barred. It is only by an examination of the historical records which concern them, and the geographical conditions which surround them, that any clear appreciation of their value can be attained; and it is only within the last century that such examinations have been rendered possible by the enterprise and activity of a race of explorers (official and otherwise) who have risked their lives in the dangerous field of the Indian trans-frontier. In ancient days the very first (and sometimes the last) thing that was learned about India was the way thither from the North. In our times the process has been reversed, and we 2 seek for information with our backs to the South. We have worked our way northward, having entered India by the southern water gates, and as we have from time to time struggled rather to remain content within narrow borders than to push outward and forward, the drift to the north has been very slow, and there has never been, right from the very beginning, any strenuous haste in the expansion of commercial interests, or any spirit of crusade in the advance of Conquest.

So late as the early years of the sixteenth century England was but a poor country, with less inhabitants than are now crowded within the London area. There was not much to spare, either of money or men, for ventures which could only be regarded in those days as sheer gambling speculations. The splendid records of a successful voyage must have been greatly discounted by the many dismal tales of failure, and nothing but an indomitable impulse, bred of international rivalry, could have led the royal personages and the few wealthy citizens who backed our earliest enterprises to open their purse-strings sufficiently wide to find the necessary means for the equipment of a modest little fleet of square-sailed merchant ships. National tenacity prevailed, however, in the end. The hard-headed Islander finally succeeded where the more impetuous Southerner failed, and England came out finally with most of the honours of a long commercial contest. It was in this way that we 3 reached India, and by degrees we painted India our own conventional colour in patches large enough to give us the preponderating voice in her general administration. But as we progressed northward and north-westward we realized the important fact that India—the peninsula India—was insulated and protected by geographical conformations which formed a natural barrier against outside influences, almost as impassable as the sea barriers of England. On the north-east a vast wilderness of forest-covered mountain ranges and deep lateral valleys barred the way most effectually against irruption from the yellow races of Asia. On the north where the curving serrated ramparts of the north-east gave place to the Himalayan barrier, the huge uplifted highlands of Tibet were equally impassable to the busy pushing hordes of the Mongol; and it was only on the extreme north-west about the hinterland of Kashmir, and beyond the Himalayan system, that any weakness could be found in the chain of defensive works which Nature had sent to the north of India. Here, indeed, in the trans-Indus regions of Kashmir, sterile, rugged, cold, and crowned with gigantic ice-clad peaks, there is a slippery track reaching northward into the depression of Chinese Turkestan, which for all time has been a recognised route connecting India with High Asia. It is called the Karakoram route. Mile upon mile a white thread of a road stretches across the stone-strewn plains, bordered by the bones 4 of the innumerable victims to the long fatigue of a burdensome and ill-fed existence—the ghastly debris of former caravans. It is perhaps the ugliest track to call a trade route in the whole wide world. Not a tree, not a shrub, exists, not even the cold dead beauty which a snow-sheet imparts to highland scenery, for there is no great snowfall in the elevated spaces which back the Himalayas and their offshoots. It is marked, too, by many a sordid tragedy of murder and robbery, but it is nevertheless one of the northern gates of India which we have spent much to preserve, and it does actually serve a very important purpose in the commercial economy of India. At least one army has traversed this route from the north with the prospect before it of conquering Tibet; but it was a Mongol army, and it was worsted in a most unequal contest with Nature.

India (if we include Kashmir) runs to a northern apex about the point where, from the western extension of the giant Muztagh, the Hindu Kush system takes off in continuation of the great Asiatic divide. Here the Pamirs border Kashmir, and here there are also mountain ways which have aforetime let in the irrepressible Chinaman, probably as far as Hunza, but still a very long way from the Indian peninsula. Then the Hindu Kush slopes off to the south-westward and becomes the divide between Afghanistan and Kashmir for a space, till, from north of Chitral, it continues with 5 a sweep right into Central Afghanistan and merges into the mountain chain which reaches to Herat. From this point, north of Chitral, commences the true north-west barrier of India, a barrier which includes nearly the whole width of Afghanistan beyond the formidable wall of the trans-Indus mountains. It is here that the gates of India are to be found, and it is with this outermost region of India, and what lies beyond it, that this book is chiefly concerned.

As the history of India under British occupation grew and expanded and the painting red process gradually developed, whilst men were ever reaching north-westward with their eyes set on these frontier hills, the countries which lay beyond came to be regarded as the "ultima thule" of Indian exploration, and Afghanistan and Baluchistan were reckoned in English as the hinterland of India, only to be reached by the efforts of English adventurers from the plains of the peninsula. And that is the way in which those countries are still regarded. It is Afghanistan in its relations to India, political, commercial, or strategic, as the case may be, that fills the minds of our soldiers and statesmen of to-day; and the way to Afghanistan is still by the way of ships—across the ocean first, and then by climbing upward from the plains of India to the continental plateau land of Asia. It was not so twenty-five centuries ago. One can imagine the laughter that would echo through the courts and 6 palaces of Nineveh at the idea of reaching Afghanistan by a sea route! Think of Tiglath Pilesur, the founder of the Second Assyrian Empire, seated, curled, and anointed, surrounded by his Court and flanked by the sculptured art of his period (already losing some of the freshness and vigour of First Empire design) in the pillared halls of Nineveh, and counting the value of his Eastern satrapies in Sagartia, Ariana, and Arachosia, with outlying provinces in Northern India, whilst meditating yet further conquests to add to his almost illimitable Empire! No shadow of Babylon had stretched northward then. No premonition of a yet larger and later Empire overshadowed him or his successors, Shalmaneser and Sargon. Northern Afghanistan was to these Assyrian kings the dumping ground of unconsidered companies of conquered slaves, a bourne from whence no captive was ever likely to return. No record is left of the passing of those bands of colonists from West to East. We can only gather from the writings of subsequent historians in classical times that for centuries they must have drifted eastward from Syria, Armenia, and Greece, carrying with them the rudiments of the arts and industries of the land they had left for ever, and providing India with the germs of an art system entirely imitative in design, colour, and relief. The Aryan was before them in India. Already the foundations were laid for historic dynasties, and 7 Rajput families were dating their origin from the sun and moon, whilst somewhere from beneath the shadow of the Himalayas in the foothills of Nipal was soon to arise the daystar of a new faith, a "light of Asia" for all centuries to come.

It is impossible to set a limit to the number and variety of the people who, in these early centuries, either migrated, or were deported, from West to East through Persia to Northern Afghanistan, or who drifted southwards into Baluchistan. Not until the ethnography of these frontier lands of India is exhaustively studied shall we be able to unravel the influence of Assyrian, Median, Persian, Arab, or Greek migrations in the strange conglomeration of humanity which peoples those countries. Baktra (Balkh), in Northern Afghanistan, must have been a city of consequence in days when Nineveh was young. Farah, a city of Arachosia in Western Afghanistan on the borders of Seistan, must have been a centre from whence Assyrian arts and industries were passed on to India for ages; for Farah lies directly on the route which connects Seistan with the southern passes into the Indus valley. The Indus itself seems to have been the boundary which limited the efforts of migration and exploration. Beyond the Indus were deserts in the south and wide unproductive plains of the Punjab in the north, and it is the deserts of the world's geography which, far more than any other feature, have always determined the extent of the 8 human tidal waves and influenced their direction. They are as the promontories and capes of the world's land perimeter to the tides of the ocean. Beyond these parched and waterless tracts, where now the maximum temperatures of sun-heat in India are registered, were vague uncertainties and mythical wonders, the tales of which in ancient literature are in strange contrast to the exact information which was obtained of geographical conditions and tribal distributions in the basins of the Kabul or Swat rivers, or within the narrow valleys of Makran.

A recent writer (Mr. Ellsworth Huntington) has expressed in picturesque and convincing language the nature of the relationship which has ever existed between man and his physical environments in Asia, and has illustrated the effect of certain pulsations of climate in the movement of Asiatic history. The changing conditions of the climate of High Asia, periods of desiccation and deprivation of natural water-supply alternating with periods of cold and rainfall, acting in slow progression through centuries and never ceasing in their operation, have set "men in nations" moving over the face of that continent since the beginning of time, and left a legacy of buried history, to be unearthed by explorers of the type of Stein, such as will eventually give us the key to many important problems in race distribution. But more important even than climatic influence is the direct influence of physical 9 geography, the actual shaping of mountain and valley, as a factor in directing the footsteps of early migration. Nowadays men cross the seas in thousands from continent to continent, but in the days of Egyptian and Assyrian empire it was that straight high-road which crossed the fewest passes and tapped the best natural resources of wood and water which was absolutely the determining factor in the direction of the great human processions; and although change of climate may have set the nomadic peoples of High Asia moving with a purpose more extensive than an annual search for pasturage, and have led to the peopling of India with successive nations of Central Asiatic origin, it was the knowledge that by certain routes between Mesopotamia and Northern Afghanistan lay no inhospitable desert, and no impassable mountain barrier, that determined the intermittent flow from the west, which received fresh impulse with every conquest achieved, with every band of captives available for colonizing distant satrapies. To put it shortly, there was an easy high-road from Mesopotamia through Persia to Northern Afghanistan, or even to Seistan, and not a very difficult one to Makran; and so it came about that migratory movements, either compulsory or voluntary, continued through centuries, ever extending their scope till checked by the deserts of the Indian frontier or the highlands of the Pamirs and Tibet, or the cold wild wastes of Siberia. 10

Thus Afghanistan and Baluchistan, the countries with which we are more immediately concerned, were probably far better known to Assyrian and Persian kings than they were to the British Intelligence Office (or its equivalent) of a century ago. The first landward explorations of these countries are lost in pre-historic mists, but we find that the first scientific mission of which we have any record (that which was led by Alexander the Great) was well supplied with fairly accurate geographical information regarding the main route to be followed and the main objectives to be gained.

In tracing out, therefore, or rather in sketching, the gradual progress of exploration in Afghanistan and Baluchistan, and the gradual evolution of those countries into a proper appanage of British India, we will begin (as history began) from the north and west rather than from the south and the plains of Hindustan. 11

EARLY RELATIONS BETWEEN EAST AND WEST. GREECE AND PERSIA AND EARLY TRIBAL DISTRIBUTIONS ON THE INDIAN FRONTIER.

It is unfortunately most difficult to trace the conditions under which Europe was first introduced to Asia, or the gradual ripening of early acquaintance into inter-commercial relationship. Although the eastern world was possessed of a sound literature in the time of Moses, and although long before the days of Solomon there was "no end" to the "making of books," it is remarkable how little has been left of these archaic records, and it is only by inference gathered from tags and ends of oriental script that we gradually realize how unimportant to old-world thinkers was the daily course of their own national history. India is full of ancient literature, but there is no ancient history. To the Brahmans there was no need for it. To them the world and all that it contains was "illusion," and it was worse than idle—it was impious—to perpetuate the record of its varied phases as they appeared to 12 pass in unreal pageantry before their eyes. We know that from under the veil of extravagant epic a certain amount of historical truth has been dragged into daylight. The "Mahabharata" and the "Ramayana" contain in allegorical outline the story of early conflicts which ended in the foundation of mighty Rajput houses, or which established the distribution of various races of the Indian peninsula. Without an intimate knowledge of the language in which these great epics are written it is impossible to estimate fully the nature of the allegory which overlies an interesting historical record, but it has always appeared to be sufficiently vague to warrant some uncertainty as to the accuracy of the deductions which have hitherto been evolved therefrom. Nevertheless it is from these early poems of the East that we derive all that there is to be known about ancient India, and when we turn from the East to the West strangely enough we find much the same early literary conditions confronting us.

About 950 years before Christ, two of the most perfect epic poems were written that ever delighted the world, the Iliad and Odyssey of Homer. The first begins with Achilles and ends with the funeral of Hector. The second recounts the voyages and adventures of Ulysses after the destruction of Troy. With our modern intimate knowledge of the coasts of the Mediterranean it is not difficult to detect, amidst the fabulous accounts of heroic adventures, 13 many references to geographical facts which must have been known generally to the Greeks of the Homeric period, dealing chiefly with the coasts and islands of the Western sea. There is but little reference to the East, although many centuries before Homer's day there was a sea-going trade between India and the West which brought ivory, apes, and peacocks to the ports of Syria. The obvious inference to be derived from the general absence of reference to the mysteries of Eastern geography is that there was no through traffic. Ships from the East traded only along the coast-lines that they knew, and ventured no farther than the point where an interchange of commodities could be established with the slow crawling craft of the West, the navigation of the period being confined to hugging the coast-line and making for the nearest shelter when times were bad. The interchange of commodities between the rough sailor people of those days did not tend to an interchange of geographical information. Probably the language difficulty stood in the way. If there was no end to the making of books it was not the illiterate and rough sailor men who made them. Nor do sailors, as a rule, make them now. It is left to the intelligent traveller uninterested in trade, and the journalistic seeker after sensation, to make modern geographical records; and there were no such travellers in the days of Homer, even if the art of writing had been a general accomplishment. In days much later than 14 Homer we can detect sailors' yarns embodied in what purport to be authentic geographical records, but none so early. We have a reference to certain Skythic nomads who lived on mare's milk, and who had wandered from the Asiatic highlands into the regions north of the Euxine, which is in itself deeply interesting as it indicates that as early as the ninth century B.C. Milesian Greek colonies had started settlements on the shores of the Black Sea. As the centuries rolled on these settlements expanded into powerful colonies, and with enterprising people such as the early Greeks there can be little doubt that there was an intermittent interchange of commerce with the tribes beyond the Euxine, and that gradually a considerable, if inaccurate, knowledge of Asia, even beyond the Taurus, was acquired. The world, for them, was still a flat circular disc with a broad tidal ocean flowing around its edge, encompassing the habitable portions about the centre.

Africa extended southward to the land of Ethiop and no farther, but Asia was a recognised geographical entity, less vague and nebulous even than the western isles from whence the Phœnicians brought their tin. There were certain fables current among the Greeks touching the one-eyed Arimaspians, the gold-guarding griffins, and the Hyperboreans, which in the middle of the sixth century were still credited, and almost indicate an indefinite geographical conception of northern 15 Asiatic regions. But it is probable that much more was known of Asiatic geography in these early years than can be gathered from the poems and fables of Greek writers before the days of Herodotus and of professional geography. There were no means of recording knowledge ready to the hand of the colonist and commercial traveller then; even the few literary men who later travelled for the sake of gaining knowledge were dependent largely on information obtained scantily and with difficulty from others, and the expression of their knowledge is crude and imperfect. But what should we expect even in present times if we proceeded to compile a geographical treatise from the works of Milton and Shakespere? What indeed would be the result of a careful analysis of parliamentary utterances on geographical subjects within, say, the last half century? Would they present to future generations anything approaching to an accurate epitome of the knowledge really possessed (though possibly not expressed) by those who have within that period almost exhausted the world's store of geographical record? The analogy is a perfectly fair one. Geographers and explorers are not always writers even in these days, and as we work backwards into the archives of history nothing is more astonishing than the indications which may be found of vast stores of accurate information of the earth's physiography lost to the world for want of expression. 16

It was between the sixth century B.C. and the days of Herodotus that Miletus was destroyed, and captive Greeks were transported by Darius Hystaspes from the Lybian Barké to Baktria, where we find traces of them again under their original Greek name in the northern regions of Afghanistan. It was long ere the days of Darius that the hosts of Assyria beat down the walls of Samaria and scattered the remnants of Israel through the highlands of Western Asia. Where did they drift to, these ten despairing tribes? Possibly we may find something to remind us of them also in the northern Afghan hills.

It was probably about the same era that some pre-Hellenic race, led (so it is written) by the mythical hero Dionysos, trod the weary route from the Euxine to the Caspian, and from the southern shores of the Caspian to the borderland of modern Indian frontier, where their descendants welcomed Alexander on his arrival as men of his own faith and kin, and were recognised as such by the great conqueror. Now all this points to an acquaintance with the geographical links between East and West which appears nowhere in any written record. Nowhere can we find any clear statement of the actual routes by which these pilgrims were supposed to have made their long and toilsome journeys. Just the bare facts are recorded, and we are left to guess the means by which they were accomplished. But it is clear that the old-world overland connection 17 between India and the Black Sea is a very old connection indeed, and further, it is clear that what the Greeks may not have known the Persians certainly did know. When Herodotus first set solidly to work on a geographical treatise which was to embrace the existing knowledge of the whole world, he undoubtedly derived a great deal of that knowledge from official Persian sources; and it may be added that the early Persian department for geographical intelligence has been proved by this last century's scientific investigations to have collected information of which the accuracy is certainly astonishing. It is only quite recently, during the process of surveys carried on by the Government of India through the highlands and coast regions of Baluchistan and Eastern Persia, that anything like a modern gazetteer of the tribes occupying those districts has been rendered possible. Twenty-five years ago our military information concerning ethnographic distributions in districts lying immediately beyond the north-western frontier was no better than that which is contained in the lists of the Persian satrapies, given to the world by Herodotus nearly 500 years before the Christian era. Twenty-five years ago we did not know of the existence of some of the tribes and peoples mentioned by him, and we were unable to identify others. Now, however, we are at last aware that through twenty-four centuries most of them have clung to their old habitat in a part of the Eastern 18 world where material wealth and climatic attractions have never been sufficient to lead to annihilation by conquest. Oppressed and harried by successive Persian dynasties, overrun by the floatsam and jetsam of hosts of migratory Asiatic peoples from the North, those tribes have mostly survived to bear a much more valuable testimony to the knowledge of the East entertained by the West in the days of Herodotus than any which can be gathered from written documents.

The Milesian colonies founded on the southern and western shores of the Euxine in the sixth and seventh centuries B.C., whilst retaining their trade connection with the parent city of Miletus (where sprang that carpet-making industry for which this corner of Asia has been famous ever since), found no open road to the further eastern trade through the mountain regions that lie south of the Black Sea. Half a century after Herodotus we find Xenophon struggling in almost helpless entanglement amongst these wild mountains comparatively close to the Greek colonies; and it was there that he encountered the fiercest opposition from the native tribes-people that he met with during his famous retreat from Persia. It is always so. Our most active opponents on the Indian frontier are the mountaineers of the immediate borderland—the people who know us best, and therefore fear us most. It was chiefly through Miletus and the Cilician gates that Greek trade 19 with Persia and Babylon was maintained. There were no Greek colonies on the rugged eastern coasts of the Black Sea—sufficient indication that no open trade route existed direct to the Caspian by any line analogous to that of the modern railway that connects Batum with Baku. On the north of the Euxine, however, there were great and flourishing colonies (of which Olbia at the mouth of the Borysthenes, or Dnieper, was the most famous) which undoubtedly traded with the Skythic peoples north and west of the Caspian. From these sources came the legends of Hyperboreans and Griffins and other similar tales, all flavoured with the glamour of northern mystery, but none of them pointing to an eastern origin. Recent investigations into the ethnography of certain tribes in Afghanistan, however, seem to prove conclusively that even if there was no recognised trade between Greece and India before Miletus was destroyed by Darius Hystaspes, and Greek settlers were transported by the Persian conqueror to the borders of the modern Badakshan, yet there must have been Greek pioneers in colonial enterprise who had made their way to the Far East and stayed there. For instance, we have that strange record of settlements under Dionysos amongst the spurs and foothills of the Hindu Kush, which were clearly of Greek origin, although Arrian in his history of Alexander's progress through Asia is unable to explain the meaning of them.

There is more to be said about these settlements 20 later. The first actual record of settlement of Greeks in Baktria is that of Herodotus, to which we have referred as being affected by Darius Hystaspes in the sixth century before Christ, and the descendants of these settlers are undoubtedly the people referred to by Arrian as "Kyreneans", who could be no other than the Greek captives from the Lybian Barke. Their existence two centuries later than Herodotus is attested by Arrian, and they were apparently in possession of the Kaoshan pass over the Hindu Kush at the time of Alexander's expedition. Another body of Greeks is recorded by Arrian to have been settled in the Baktrian country by Xerxes after his flight from Greece. These were the Brankhidai of Milesia, whose posterity are said to have been exterminated by Alexander in punishment for the crimes of their grandfather Didymus. The name Barang, or Farang, is frequently repeated in the mountain districts of Northern Afghanistan and Badakshan, and careful inquiry would no doubt reveal the fact that surviving Greek affinities are still far more widely spread through that part of Asia than is generally known. All these settlements were antecedent to Alexander, but beyond these recorded instances of Greek occupation there can be little doubt that (as pointed out by Bellew in his Ethnography of Afghanistan and supported by later observations) the Greek element had been diffused through the wide extent of the Persian sovereignty for centuries before the birth of 21 Alexander the Great. It is probable that each of the four great divisions of the ancient Greeks had contributed for a thousand years before to the establishment of colonies in Asia Minor, and from these colonies bands of emigrants had penetrated to the far east of the Persian dominions, either as free men or captives. Amongst the clans and tribal sections of Afghans and Pathans are to be found to this day names that are clearly indicative of this pre-historic Greek connection.

Persia at her greatest maintained a considerable overland trade with India, and Indian tribute formed a large part of her revenues. All Afghanistan was Persian; all Baluchistan, and the Indian frontier to the Indus. The underlying Persian element is strong in all these regions still, the dominant language of the country, the speech of the people, whether Baluch or Pathan, is of Persian stock, whilst the polite tongue of Court officials, if not the Persian of Tehran or Shiraz, is at least an imitation of it. It is hardly strange that the Greek language should have absolutely disappeared. We have the statement of Seneca (referred to by Bellew in his Inquiry) that the Greek language was spoken in the Indus valley as late as the middle of the first century after Christ; "if indeed it did not continue to be the colloquial in some parts of the valley to a considerably later period." As this is nearly two centuries after the overthrow of Greek dominion in Afghanistan, it at least indicates that the Greek 22 settlements established four centuries earlier must have continued to exist, and to be reinforced by Greek women (for children speak their mother's tongue) to a comparatively late period; and that the triumph of the Jat over the Greek did not by any means efface the influence of the Greek in India for centuries after it occurred. It is probable that when the importation of Greek women (who were often employed in the households of Indian chiefs and nobles at a time when Greek ladies married Indian Princes) ceased, then the Greek language ceased to exist also. The retinue and followers of Alexander's expedition took the women of the country to wife, and it is not, as is so often supposed, to the results of that expedition so much as to the long existence of Greek colonies and settlements that we must attribute the undoubted influence of Greek art on the early art of India.

Thus we have a wide field before us for inquiry into the early history of ethnographical movement in Asia, as it affected the relation between Europe and Afghanistan. Afghanistan (which is a modern political development) has ever held the landward gates of India. We cannot understand India without a study of that wide hinterland (Afghan, Persian, and Baluch) through which the great restless human tide has ever been on the move: now a weeping nation of captives led by tear-sodden routes to a land of exile; now a band of merchants reaching forward to the land of golden promise; or perchance 23 an army of pilgrims marching with their feet treading deep into narrow footways to the shrines of forgotten saints; or perchance an armed host seeking an uncertain fate; a ceaseless, waveless tide, as persistent, as enterprising, and infinitely more complicated in its developments than the process of modern emigration, albeit modern emigration may spread more widely.

Living as we do in fixed habitations and hedged in not merely by narrow seas but by the conventionalities of civilized existence, we fail to realize the conditions of nomadic life which were so familiar to our Asiatic ancestors. Something of its nature may be gathered to-day from the Kalmuk and Kirghiz nomads of Central Asia. A day's march is not a day's march to them—it is a day's normal occupation. The yearly shift in search of fresh pasture is not a flitting on a holiday tour; it is as much a part of the year's life as the change of raiment between summer to winter. Everything moves; the home is not left behind; every man, woman, and child of the family has a recognised share in the general shift. Perhaps that of the Kirghiz man is the easiest. He smokes a lazy pipe in the bright sunshine and watches his boys strip off the felt covering of his wicker-built "kibitka," whilst his wife with floating bands of her white headdress fluttering in the breeze, and her quilted coat turned up to give more freedom to her booted legs, gets together the household traps in compact bundles for 24 the great hairy camel to carry. Her efforts are not inartistic; long experience has taught her exactly where every household god can be stowed to the best advantage. Meanwhile the happy, good-looking Kirghiz girls are racing over the grass country after sheep, and ere long the little party is making its slow but sure way over the breezy steppes to the passes of the blue mountains, which look down from afar on to the warmer plains. And who has the best of it? The free-roving, untrammelled child of the plain, quite godless, and taking no thought for the morrow, or the carefully cultured and tight-fitted product of civilization to whom the motor and the railway represent the only thinkable method of progression? That, however, is not the point. What we wish to emphasize is the apparent inability on the part of many writers on the subject of ancient history and geography to realize the essential difference between then and now as regards human migratory movement.

There is often an apparent misconception that there is more movement in these days of railways and steamers and motors than existed ten centuries before Christ. The difference lies not in the comparative amount of movement but in the method of it. In one sense only is there more movement—there are more people to travel; but in a broader sense there is much less movement. Whole nations are no longer shifted at the will of the conqueror 25 across a continent, trade seekers no longer devote their lives to the personal conduct of caravans; armies swelled to prodigious size by a tagrag following no longer (except in China) move slowly over the face of the land, devouring, like a swarm of locusts, all that comes in their way. Colonial emigration perhaps alone works on a larger scale now than in those early times; but taking it "bye and large," the circulation of the human race, unrestricted by political boundaries, was certainly more constant in the unsettled days of nomadic existence than in these later days of overgrown cities and electric traffic. If little or nothing is recorded of many of the most important migrations which have changed the ethnographic conditions of Asia, whilst at the same time we have volumes of ancient philosophy and mythology, it is because such changes were regarded as normal, and the current of contemporary history as an ephemeral phenomenon not worth the labour of close inquiry or a manuscript record.

Such a gazetteer as that presented to us by Herodotus would not have been possible had there not been free and frequent access to the countries and the people with whom it deals. It is impossible to conceive that so much accuracy of detail could have been acquired without the assistance of personal inquiry on the spot. If this is so, then the Persians at any rate knew their way well about Asia as far east as Tibet and India, and the Greeks 26 undoubtedly derived their knowledge from Persia. When Alexander of Macedon first planned his expedition to Central Asia he had probably more certain knowledge of the way thither than Lord Napier of Magdala possessed when he set out to find the capital of Theodore's kingdom in Abyssinia, and it is most interesting to note the information which was possessed by the Greek authorities a century and a half before Alexander's time.

One notable occurrence pointing to a fairly comprehensive knowledge of geography of the Indian border by the Persians, was the voyage of the Greek Scylax of Caryanda down the Indus, and from its mouth to the Arabian Gulf, which was regarded by Herodotus as establishing the fact of a continuous sea. This voyage, or mission, which was undertaken by order of Darius who wished to know where the Indus had its outlet and "sent some ships" on a voyage of discovery, is most instructive. It is true that the accounts of it are most meagre, but such details as are given establish beyond a doubt that the expedition was practical and real. The Persian dominions then extended to the Indus, but there is no evidence that they ever extended beyond that river into the peninsula of India. The Indus of the Persian age was not the Indus of to-day, and its outlet to the sea presumably did not differ materially from that of the subsequent days of Alexander and Nearkos. 27 Thanks to the careful investigations of the Bombay Survey Department, and the close attention which has been given to ancient landmarks by General Haig during the progress of his surveys, we know pretty certainly where the course of the Lower Indus must have been, and where both Scylax and Nearkos emerged into the Arabian Sea. The Indus delta of to-day covers an area of 10,000 square miles with 125 miles of coast-line, and it presents to us a huge alluvial tract which is everywhere furrowed by ancient river channels. Some of these are continuous through the delta, and can be traced far above it; others are traceable for only short distances. Without entering into details of the rate of progression in the formation of Delta (which can be gathered not only from the abandoned sites of towns once known as coast ports, but from actual observation from year to year), it may be safely assumed that the Indus of Alexander and Scylax emptied itself into the Ran of Kach, far to the south of its present debouchment. The volume of its waters was then augmented by at least one important river (the Saraswati), which, flowing from the Himalayas through what is now known as the Rajputana desert, was the source of widespread wealth and fertility to thousands of square miles where now there is nothing to be met with but sandy waste. As far as the Indus the Persian Empire is known to have extended, but no farther; and it was important to the military advisers of 28 Darius that something should be known of the character of this boundary river.

Wherever the ships sent by Darius may have gone it is quite clear that they did not sail up the Indus, or there would have been no objective for an expedition which was organised to determine where the Indus met the sea by the process of sailing down that river. Moreover, the voyage up the Indus would have been tedious and slow, and could only have been undertaken in the cold weather with the assistance of native pilots acquainted with the ever-shifting bed of the river, which, so far as its liability to change of channel is concerned, must have been much the same in the days of Darius as it is at present. The possibility, therefore, is that Scylax made his way to the Upper Indus overland, for we are told that the expedition started from the city of Carpatyra in the Pactyan country. This in itself is exceedingly instructive, indicating that the Pactyans, or Pathans, or Pukhtu speaking peoples have occupied the districts of the Upper Indus for four-and-twenty centuries at least; and coincident with them we learn that the Aprytæ or Afridi shared the honour of being resident landowners. Nor need we suppose that the beginning of this history was the beginning of their existence. The Afridi may have rejoiced in his native hills ten or twenty centuries before he was written about by Herodotus. We need not stay to identify the site of Carpatyra. The Upper Indus valley is full of 29 ancient sites. A century and a half later Taxilla was the recognized capital of the Upper Punjab, and Carpatyra meanwhile may have disappeared. Anyhow we hear of Carpatyra no more, nor has the ingenuity of modern research thrown any certain light on its position. It is, however, probably near Attok that we must look for it. Scylax made his way down the Indus in native craft that from long before his day to the present have retained their primitive form, a form which was not unlike that of the coast crawling "ships" of Darius. He proved the existence of an open water-way from the Upper Punjab to the Persian Gulf, and incidentally his expedition shows us that the chief lines of communication through the width of the Persian Empire were well known, and that the road from Susa to the Upper Indus was open. The outlying satrapies of the Persian Empire could never have been added one by one to that mighty power without definite knowledge of the way to reach them. It was not merely a spasmodic expedition, such as that of Scylax, which pointed the way to the conquests of the Far East; it was the gathered information of years of experience, and it was on the basis of this experience (unwritten and unrecorded so far as we know) that Alexander founded his plans of campaign.

The detailed list of peoples included in the satrapies of the Persian Empire, whilst it is more ethnographical than geographical in its character, 30 is sufficient proof in itself of the existence of constant movement between Persia and the borderland of Afghanistan, which assuredly included commercial traffic. This enumeration has been compared with a catalogue of tribal contingents which swelled the great army of Xerxes, an independent statement, and therefore a valuable test to the general accuracy of Herodotus; and it is still further confirmed by the list of nations subject to the Persian king found in the inscriptions of Darius at Behistan and Persepolis. We are not immediately concerned with the satrapies included in Western Asia and Egypt, but when Herodotus makes a sudden departure from his rule of geographical sequence and introduces a satrapy on the remotest east of the Persian Empire, we immediately recognize that he touches the Indian frontier.

The second satrapy most probably corresponds with that part of Central Afghanistan south of the Kabul River, which lies west of the Suliman Hills and north of the Kwaja Amran or Khojak. Every name mentioned by Herodotus certainly has its counterpart in one or other of the tribes to be found there to this day, excepting the Lydoi (whose history as Ludi is fairly well known) and the Lasonoi, who have emigrated, the former into India and the latter to Baluchistan.

The seventh satrapy, again, comprised the Sattagydai, the Gandarioi, the Dadikai, and the Aparytai ("joined together"), an association of 31 names too remarkable to be mistaken. The Sattag or Khattak, the Gandhari, the Dadi, and the Afridi are all trans-Indus people, and without insisting too strongly on the exact habitat of each, originally there can be little doubt that the seventh satrapy included a great part of the Indus valley.

The eleventh satrapy is also probably a district of the Indian trans-frontier, although Bunbury associates the name Kaspioi with the Caspian Sea. It is far more likely that the Kaspioi of Herodotus are to be recognized as the people of the ancient Kaspira or Kasmira, and the Daritæ as the Daraddesa (Dards) of the contiguous mountains. All Kashmir, even to the borders of Tibet (whence came the story of the gold-digging ants), was well enough known to the Persians and through them to Herodotus.

The twelfth satrapy comprised Balkh and Badakshan—what is now known as Afghan Turkistan. It was here that, generations before Alexander's campaign, those Greek settlements were founded by Darius and Xerxes which have left to this day living traces of their existence in the places originally allotted to them. In Afghan Turkistan also was founded the centre of Greek dominion in this part of Asia after the conquest of Persia, and it is impossible to avoid the conviction that there was a connection between these two events. The Greeks took the country from the Bakhi; but there are no people of this name left in these provinces now. 32 They may (as Bellew suggests) be recognized again in the Bakhtyari of Southern Persia, but it seems unlikely; and it is far more probable that they were obliterated by Alexander as his most active opponents after he passed Aria (Herat) and Drangia (Seistan).

The sixteenth satrapy was north of the Oxus, and included Sogdia and Aria (Herat). South of Aria was the fourteenth satrapy, represented by Seistan and Western Makran, with "the islands of the sea in which the King settles transported convicts"; and east of this again was the seventeenth satrapy covering Southern Baluchistan and Eastern Makran. It is only during the last twenty-five years that an accurate geographical knowledge of these uninviting regions has been attained. The gradual extension of the red line of the Indian border, with the necessity for preserving peace and security, has gradually enveloped Makran and Persian Baluchistan, the Gadrosia and Karmania of the Greeks, and has brought to light many strange secrets which have been dormant (for they were no secrets to the traveller of the Middle Ages) for a few centuries prior to the arrival of the British flag in Western India. It is an inhospitable country which is thus included. "Mostly desert," as one ancient writer says; marvellously furrowed and partitioned by bands of sun-scorched rocky hills, all narrow and sharp where they follow each other in parallel waves facing the Arabian Sea, or massed 33 into enormous square-faced blocks of impassable mountain barrier whenever the uniform regularity of structure is lost. And yet it is a country full not only of interest historical and ethnographical, such as might be expected of the environment of a series of narrow passages leading to the western gates of India, but of incident also. There are amongst these strange knife-backed volcanic ridges and scarped clay hills valleys of great beauty, where the date-palms mass their feathery heads into a forest of green, and below them the fertile soil is moist and lush with cultured vegetation. But we have described elsewhere this strangely mixed land, and we have now only to deal with the aspect of it as known to the Greeks before the days of Alexander. That knowledge was ethnographical in its quality and exceedingly slight in quantity. Herodotus mentions the Sagartoi, Zarangai, Thamanai, Uxoi, and Mykoi. These are Seistan tribes. The Sagartoi were nomads of Seistan, mentioned both amongst tribes paying tribute and those who were exempt. The Zarangai were the inhabitants of Drangia (Seistan), where their ancient capital fills one of the most remarkable of all historic sites. The Zarangai are said to be recognizable in the Afghan Durani. No Afghan Durani would admit this. He claims a very different origin (as will be explained), and in the absence of authoritative history it is never wise to set aside the traditions of a people about 34 themselves, especially of a people so advanced as the Duranis. More probable is it that the ancient geographical appellation Zarangai covers the historic Kaiani of Seistan supposed to be the same as the Kakaya of Sanscrit.

The Uxoi may be the modern Hots of Makran—a people who are traditionally reckoned amongst the most ancient of the mixed population which has drifted into the Makran ethnographic cul-de-sac, and who were certainly there in Alexander's time. In eastern Makran, Herodotus mentions only the Parikanoi and the Asiatic Ethiopian. Parikan is the Persian plural form of the Sanscrit Parva-ka, which means "mountaineer." This bears exactly the same meaning as the word Kohistani, or Barohi, and is not a tribal appellation at all, although the latter may possibly have developed into the Brahui, the well-known name of a very important Dravidian people of Southern Baluchistan (highlanders all of them) who are akin to the Dravidian races of Southern India. The Asiatic Ethiopian presents a more difficult problem. During the winter of 1905 careful inquiries were made in Makran for any evidence to support the suggestion that a tribe of Kushite origin still existed in that country. It is of interest in connection with the question whether the earliest immigrants into Mesopotamia (these people who, according to Accadian tradition, brought with them from the South the science of civilization) were a Semitic 35 race or Kushites. It is impossible to ignore the existence of Kushite races in the east as well as the south. We have not only the authority of the earliest Greek writings, but Biblical records also are in support of the fact, and modern interest only centres in the question what has become of them. Bellew suggests that it was after the various Kush or Kach, or Kaj tribes that certain districts in Baluchistan are called Kach Gandava or Kach (Kaj) Makran, and that the chief of these tribes were the Gadara, after whom the country was called Gadrosia. This seems mere conjecture. At any rate the term Kach, sometimes Kachchi, sometimes Katz, is invariably applied to a flat open space, even if it is only the flat terrace above a river intervening between the river and a hill, and is purely geographical in its significance. But it was a matter of interest to discover whether the Gadurs of Las Bela could be the Gadrosii, or whether they exhibited any Ethiopian traits. The Gadurs, however, proved to be a section of the Rajput clan of Lumris, a proud race holding themselves aloof from other clans and never intermarrying with them. There could be no mistake about the Rajput origin of the red-skinned Gadur. He was a Kshatrya of the lunar race, but he might very possibly represent the ancient Gadrosii, even though he is no descendant of Kush. The other Rajput tribes with whom the Gadurs coalesce have apparently held their own in Las from a period 36 quite remote, and must have been there when Alexander passed that way.

Asiatic negroes abound in Makran: some of them fresh importations from Africa, others bred in the slave villages of the Arabian Sea coast, as they have been for centuries. They are a fine, brawny, well-developed race of people, and some of the best of them are to be found as stokers in the P. & O. service; but they do not represent the Asiatic Ethiopian of Herodotus, who could hardly compile a gazetteer for the Greeks which should include all the ethnographical information known to the Persians, any more than our Intelligence Department could compile a complete gazetteer of the whole Russian Empire. To the maritime Greek nation the overwhelming preponderance of the huge Empire which overshadowed them must have created the same feeling of anxious suspicion that the unwieldy size of Russia presents to us, and it is not very likely that military intelligence of a really practical nature was offered gratis to the Greeks by the Persian geographers and military leaders. It is not surprising, therefore, that Herodotus did not know all that existed on the far Persian frontier. There are tribes and peoples about Southern Baluchistan who are as ancient as Herodotus but who are not mentioned. For instance, the ruling tribe in Makran until quite recently (when they were ousted by certain Sikh or Rajput interlopers 37 called Gichki) were the Boledi, and their country was once certainly called Boledistan. The Boledi valley is one of the loveliest in a country which is apt to enhance the loveliness of its narrow bands of luxuriance by their rarety and their narrowness. It is a sweet oasis in the midst of a barren rocky sea, and must always have been an object of envy to dwellers outside, even in days when a fuller water-supply, more widely spread, turned many a valley green which is now deep drifted with sand. Ptolemy mentions the Boledis, so that they can well boast the traditional respectability of age-long ancestry. The Boledis are said to have dispossessed the Persian Kaiani Maliks, who ruled Makran in the seventeenth century, when they headed what is known as the Baluch Confederation. This may be veritable history, but their pride of race and origin, on whatever record it is based, has come to an end now; it has been left to the present generation to see the last of them. A few years ago there was living but one representative of the ruling family of the Boledis, an old lady named Miriam, who was exceedingly cunning in the art of embroidery, and made the most bewitching caps. She was, I believe, dependent on the bounty of the Sultan of Muscat, who possesses a small tract of territory on the Makran coast. Herodotus apparently knew nothing about the Boledis, nor can it be doubted that the Greek knowledge of Makran was exceedingly scanty. 38 Thus, whilst Alexander marched to the Indian frontier, well supplied with information as to the ways thither when once he could make Persia his base, he was almost totally ignorant of the one route out of India which he eventually followed, and which so nearly enveloped his whole force in disaster. 39

ASSYRIA AND AFGHANISTAN—ANCIENT LAND ROUTES—POSSIBLE SEA ROUTES

With the building up of the vast Persian Empire, and the gradual fostering of eastern colonies, and the consequent introduction of the manners and methods of Western Asia into the highlands of Samarkand and Badakshan, other nationalities were concerned besides Persians and Greeks. Captive peoples from Syria had been deported to Assyria seven centuries before Christ. The House of Israel had been broken up (for Samaria had fallen in 721 B.C. before the victorious hosts of Sargon), and some of the Israelitish families had been deported eastwards and northwards to Northern Mesopotamia and Armenia. With the vitality of their indestructible race it is at least possible that a remnant survived as serfs in Assyria, preserving their own customs and institutions—secretly if not openly—intermarrying, trading, and money-making, yet still looking for the final restoration of Israel until the final break-up of the Assyrian Kingdom. 40 They were never absolutely absorbed, and never forgot to recount their historic pedigree to their children.

With the final overthrow of the Assyrian Kingdom we lose sight of the tribes of Israel, who for more than a century had been mingled with the peoples of Northern Mesopotamia and Armenia. At least history holds no record of their further national existence. From time immemorial in Asia it had been customary for the captives taken in war to be transported bodily to another field for purposes of colonization and public labour. When the world was more scantily peopled such methods were natural and effectual; the increase of working power gained thereby being of the utmost importance in days when enormous irrigation canals were excavated, and bricks had to be fashioned for the construction of walled cities.

The extent and magnificence of Assyrian building must have demanded an immense supply of such manual labour for the purpose of brickmaking. All the mighty works of ancient Egypt, Assyria, and Babylon were literally "the work of men's hands." In Mesopotamia was captured labour especially necessary. Stone was indeed available at Nineveh, but the barrenness of the soil which stretches flatly from the rugged hills of Kurdistan across Mesopotamia rendered the country unproductive unless enormous works of irrigation were undertaken for the distribution of water. Mesopotamia is a 41 country of immense possibilities, but the wealth of it is only for those who can distribute the waters of its great rivers over the productive soil. The yearly inundations of the Euphrates and Tigris are but sufficient for the needs of a narrow strip of land on either side the rivers, and the crops of the country undeveloped by canals can only support a scattered and scanty population. Towards the south there is another difficulty. The flat soil becomes water-logged and marshy and runs to waste for want of drainage. There is no stone for building purposes near Babylon. Approaching Babylon over the windy wastes of scrub-powdered plain there is nothing to be seen in the shape of a hill. Long, low, flat-topped mounds stretch athwart the horizon and resolve themselves on nearer approach into deeply scarred and weather-worn accretions of debris, or else they are banks of ancient waterways winding through the steppe, the last remnants of a stupendous system of irrigation. Then there breaks into view the solitary erection which stands in the open plain overlooking a wide vista of marsh and swamp to the west, which represents the ruins called Birs Nimrud, the Ziggurat or temple which, in successive tiers devoted to the powers of heaven, supported the shrine of Mercury. It is by far the most conspicuous object in the Babylonian landscape; huge, dilapidated, and unshapely, it mounts guard over a silent, stagnant, swampy plain. 42

Now the remarkable feature in all these gigantic remains of antiquity is that they are built of brick. In the wide expanse of Mesopotamia plain around there is not a stone quarry to be found. Of Nineveh, we learn from the masterly records of Xenophon that as he was leading the surviving 10,000 Greeks in their retreat from the disastrous field of Babylon back to the sunny Hellespont, some 200 years after the destruction of Nineveh, he came upon a vast desert city on the Tigris. The wall of it was 25 feet wide, 100 feet high, with a 20-foot basement of stone. This was all that was left of Kalah, one of the Assyrian capitals. A day's march farther north he came on another deserted city with similar walls. These were the dry bones of Nineveh, already forgotten and forsaken. Two centuries had in these early ages been sufficient to blot out the memory of Assyrian greatness so completely that Xenophon knew not of it, nor recognized the place where his foot was treading. Barely seventy years ago was the memory of them restored to man, and tokens of the richness and magnificence of the art which embellished them first given to the world. The mounds representing Nineveh and Babylon are some of them of enormous size. The mound of Mugheir (the ancient Ur) is the ancient platform of an Assyrian palace, which is faced with a wall 10 feet thick of red kiln-dried bricks cemented with bitumen. Some of these platforms were raised 43 from 50 to 60 feet above the plain and protected by massive stone masonry carried to a height exceeding that of the platform. But the Babylonian mound of Birs Nimrud, which rises from the plain level to the blue glazed masonry of the upper tier of the Ziggurat, is altogether a brick construction. The debris of the many-coloured bricks now forms a smooth slope for many feet from its base; but above, where the square blocks of brickwork still hold together in scattered disarray, you may still dig out a foot-square brick with the title and designations of Nebuchadnezzar imprinted on its face. These artificial mounds could only have been built at an enormous cost of labour. The great mound of Koyunjik (the palace of Nineveh) covers an area of 100 acres and reaches up 95 feet at its highest point. It has been calculated that to heap up such a pile would "require the united efforts of 10,000 men for twelve years, or 20,000 men for six years" (Rawlinson, Five Monarchies), and then only the base of the palace is reached; and there are many such mounds, for "it seems to have been a point of honour with the Assyrian Kings that each should build a new palace for himself" (Ragozin, Chaldaea).

Only conquering monarchs with whole nations as prisoners could have compassed such results. This, indeed, was one of the great objectives of war in these early times. It was the amassing of a great population for manual labour and the creation 44 of new centres of civilization and trade. Thus it was that the peoples of Western Asia—Egyptians, Israelites, Jews, Phœnicians, Assyrians, Babylonians, and even Greeks—were transported over vast distances by land, and a movement given to the human race in that part of the world which has infinitely complicated the science of ethnology. The peopling of Canada by the French, of North America by the English, of Brazil by the Portuguese, of Argentina and Chile by Spaniards and Italians, is perhaps a more comprehensive process in the distribution of humanity and more permanent in its character. But ancient compulsory movement, if not as extensive as modern voluntary emigration, was at least wholesale, and it led to the distribution of people in districts which would not naturally have invited them. The first process in the consolidation of a district, or satrapy, was the settlement of inhabitants, sometimes in supercession of a displaced or annihilated people, sometimes as an ethnic variety to the possessors of the soil. Tiglath Pileser was the first Assyrian monarch to consolidate the Empire by its division into satrapies. Henceforward the outlying provinces of the dominions were convenient dumping places for such bodies of captives as were not required for public works at home.

Nothing would be more natural than that Sargon should deport a portion of the Israelitish nation to colonize his eastern possessions towards India, just as 45 Darius Hystaspes later employed the same process to the same ends when he deported Greeks from the Lybian Barke to Baktria. There is nothing more astonishing in the fact that we should find a powerful people claiming descent from Israel in Northern Afghanistan than that we should find another people claiming a Greek origin in the Hindu Kush.

Nor was the importance of peopling waste lands and raising up new nations out of well-planted colonies overlooked ten centuries before Christ any more than it is now. Then it was a matter of transporting them overland and on foot to the farthest eastern limits of these great Asiatic empires. Always east or south they tramped, for nothing was known of the geography of the North and West. Eastwards lay the land of the sun, whence came the Indians who fought in the armies of Darius, and where gold and ivory, apes and peacocks were found to fill Phœnician ships. To-day it is different. The peopling of the world with whites is chiefly a Western process. Emigrants go out in ships, not as captives, but almost equally in compact bodies—the best of our working men to Canada, and many of the best of our much-wanted domestic servants to South Africa. It is a perpetual process in the world's economy, and perhaps the chief factor in the world's history; but in the old, old centuries before the Christian era it was necessarily a land process, and the geographical 46 distribution of the land features determined the direction of the human tide. Some twenty years before the fall of Samaria and the deportation of the ten tribes of Israel, Tiglath Pileser had effected conquests in Asia which carried him so far east that he probably touched the Indus. Why he went no farther, or why Alexander subsequently left the greater part of the Indian peninsula unexplored, is fully explicable on natural grounds, even if other explanations were wanting.

The Indus valley would offer to the military explorers from the West the first taste of the quality of the climate of the India of the plains which they would encounter. The Indus valley in the hot weather would possess little climatic attraction for the Western highlander. Alexander's troops mutinied when they got far beyond the Indus. Any other troops would mutiny under such conditions as governed their outfit and their march. It is more than possible that the great Assyrian conqueror before him encountered much the same difficulty. It is clear, however, historically, that the Assyrian knew and trod the way to Northern Afghanistan (or Baktria), and if we examine the map of Asia with any care we shall see that there is no formidable barrier to the passing of large bodies of people from Nineveh to Herat (Aria), or from Herat to the Indus valley, until we reach the very gates of India on the north-west frontier. Four centuries later than Tiglath Pileser the battle 47 of Arbela was fought to a finish between Alexander and Darius (who possessed both Greek and Indian troops in his army) on a field which is not so very far to the east of Nineveh, and which is probably represented more or less accurately by the modern Persian town of Erbil. The modern town may not be on the exact site of the action, and we know that the ancient town was some sixty miles away from the battlefield. However that may be, we learn that in the general retreat of the Persians which followed the battle, Darius made his way to Ecbatana, the ancient capital of the Medes. There he remained for about a year, but hearing of Alexander's advance from Persepolis in the spring of 330 B.C. he fled to the north-east, with a view to taking refuge with his kinsman Bessos, who was then satrap of Baktria. This gives us the clue to the general line of communication between Northern Mesopotamia and Baktria (or Afghanistan) in ancient days; and the twenty-five centuries which have rolled by since that early period have done little to modify that line.

Until the beginning of the nineteenth century A.D. from the earliest times with which we can come into contact through any human record, this high-road (not the only one, but the chief one) must have been trodden by the feet of thousands of weary pilgrims, captives, emigrants, merchants, or fighting men—an intermittent tide of humanity exceeding in volume any host known to modern 48 days—bringing East into touch with the West to an extent which we can hardly appreciate. It may be said that the straightest road to Baktria did not lie through Ecbatana. It did not; but independently of the fact that Ecbatana was a city of great defensive capacity, and of reasons both political and military which would have impelled Darius to take that route, we shall find if we examine the latest Survey of India map of Western Persia that the geographical distribution of hill and valley make it the easiest, if not the shortest, route. The configuration of Western Persia, like that of Makran and Southern Baluchistan extending to our own north-west frontier, mainly consists of long lines of narrow ridges curving in lines parallel to the coast, rocky and mostly impassable to travellers crossing their difficult ridge and furrow formation transversely, but presenting curiously easy and open roads along the narrow lateral valleys. Ecbatana once stood where the modern Hamadan now stands. The road from Arbil (or Erbil) that carries most traffic follows this trough formation to Kermanshah and then bends north-eastward to Hamadan. From Hamadan to Rhagai and the Caspian gates, which was the route followed by Darius in his flight from Ecbatana, the road was clearly coincident with the present telegraph line to Tehran from Hamadan, which strikes into the great post route eastward to Mashad and Herat, one of the straightest and most uniformly level 49 roads in all Asia. It must always have been so. Remarkable physical changes have occurred in Asia during these twenty-five centuries, but nothing to alter the relative disposition of mountain and plain in this part of Persia, or to change the general character of its ancient highway. All this part of Persia was under the dominion of the Assyrian king when the tribes of Israel left Syria for Armenia. He had but recently traversed the road to India, and he knew the richness of Baktria (of Afghan Turkistan and Badakshan) and could estimate what a colony might become in these eastern fields.