The Project Gutenberg eBook of Little Foxes: Stories for Boys and Girls

Title: Little Foxes: Stories for Boys and Girls

Creator: E. A. Henry

Release date: August 2, 2013 [eBook #43387]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Al Haines

LITTLE FOXES

Stories for Boys and Girls

By

E. A. HENRY, D.D.

Pastor, Deer Park Presbyterian Church, Toronto

Introduction by

CHARLES W. GORDON, D.D., LL.D.

(Ralph Connor)

Thomas Allen

366-378 ADELAIDE STREET, WEST

TORONTO

Copyright, 1922, by

FLEMING H. REVELL COMPANY

To the

Girls and Boys of My Ministry

Preface

The following short sermonettes or talks to girls and boys were given as the children's portion at the Sunday morning services.

As a child at church, the author remembers sitting with pins and needles in his feet, which were somewhere between heaven and earth, while he wondered what the preacher was talking about. He determined if the job was ever his, not to neglect the little people.

These are some of his attempts to interest them, and are given out in print because some seemed to think them worth preserving.

If they are, and will help anybody, the author will be content and happy. It has been suggested that the chapters might be used as bedtime stories.

There are some little gems used which are anonymous or whose authors are unknown. They were used in the addresses and are passed on with apologies for not being able to acknowledge authorship.

E.A.H.

Toronto.

Introduction

Winnipeg, 7th July, 1922.

- REV. E. A. HENRY, D.D.,

- Deer Park Presbyterian Church,

Toronto, Ont.

My dear Henry:

I have just looked into your "Little Foxes," and I am delighted to be able to say, with a clear conscience, that you have done a fine bit of work. The book is full of quaint philosophy, and it has the heart touch, too, that will give it wings.

It was a happy inspiration that made you use the vernacular of every-day boy and girl speech without descending to the vulgarity that so often mars the attempt to use vernacular English. The vernacular lends reality to your thought.

Then, too, I wish to congratulate you upon your admirable selection of illustration. Illustration in literature is a very fine art, and you have got the touch in your "Little Foxes." After all, that is the secret of interesting speech—the power of concreting ideas. A Congregation that will drowse or gape over the most logical argument will suddenly wake to alert attention in response to the phrases, "Once on a time," "There was once a boy," "I knew a man."

You have done a real service to the children, but you have also done a real service to Preachers. For many a Preacher who has been forced to confess himself a failure in the art of interesting children in sermons (And how terrible a failure is that!), after reading "Little Foxes," will take new heart because of the suggestions your book will bring.

I venture to say that hosts of people, especially little people and those who think little people worth while, will come to know and love Dr. Henry because of his "Little Foxes."

And so may "Little Foxes" run far and fast.

Yours very truly,

Contents

I

LITTLE THINGS

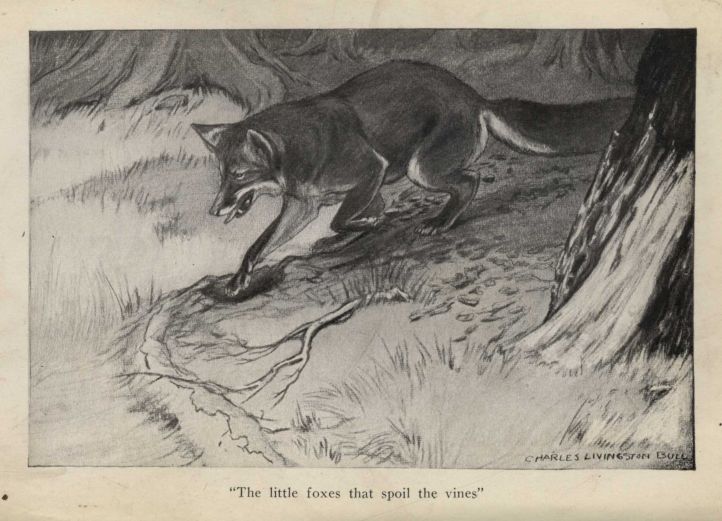

In the second chapter of the Song of Songs and in the fifteenth verse you may read these words: "Take me the little foxes that spoil the vines."

How often you hear people say, "Oh, well, it's so little! What difference will such a little thing make?" And yet—

Every girl and boy knows that the mighty ocean is made up of tiny drops. The great Niagara is, too. Its noise is simply the small patter of drops multiplied into a thunder.

The little drops are made of molecules, which though Science gives them a big name, are so small you cannot see them.

A great castle or a mighty palace is built up of small bricks and stones and pieces of wood and iron, put together with small pegs and pins.

The lovely windows are made of panes of glass; each pane being sand grains heated and fused.

The great Western harvests that cover the plains with gold, and feed the world, come from little grains of seed wheat, any one of which could be lost and never missed. But if all the little seeds were lost, there would be no harvest.

These wonderful bodies of ours, Science says, are built up of cells that are only known through the microscope.

We are now told that the matter that makes our bodies and the great world is a centre of the tiniest bits of revolving force called electric ions, which nobody has ever seen. A pin-head is not very big, but it has a whole system of these revolving little things as wonderful as the way in which the planets roll round the sun.

Across the continent stretches a great road of iron called the C.P.R. or the National R.R., and both never could have been but for littles.

The iron comes from ore in the mines, picked out with small picks, one pick at a time. The ties on which the rails rest are trees that once were little seeds. The gravel of the road bed is made of heaps of sand, shovelled with hand shovels, one shovel at a time.

The engine strength lies in pins that couple, and joints that unite all its wonderful parts. When the fire is started that makes the steam, the fireman builds it with small sticks and pieces of wood and spends his time shovelling little coals out of the tender.

When the train is loaded, it has a mighty weight; but each car was filled with bundles one at a time. The passenger coaches fill up one by one, with persons who travel with a little piece of paper called a ticket, that gives them right of way.

Little, you say! Why, there is nothing real that is little! It only looks little on the surface. Think more deeply and you will see how big all real things are!

So of your character and mine.

A big man is one who has big ideas and plans, and these can never be weighed or measured.

Big events are due to little long continued acts and thoughts, each of which looks small; but taken together make the world go round.

So little kind words, gentle deeds, unselfish acts, make life circles radiant and happy. If we offer nothing because what we have seems small, a lot of happiness is lost to the world.

So, too, little white lies make big black spots in character.

Little bursts of temper start fires that end in murder.

Little wrong words and little nasty deeds make wrong and nasty people.

Dear girls and boys, we are all bundles of habits, good and bad, and they grow from the smallest acts.

Just keep on doing a little deed day by day, and soon you cannot stop, for you have the habit.

A boy puckered his face a little each morning, and now he has a wrinkle he cannot iron out.

A girl puckered her life with an inside squint, and now she has a squint habit in her soul.

For the next few pages we will study some of the little things we need to be careful of.

The verse we have for a motto calls them "little foxes that spoil the vines."

You have all seen a beautiful garden, and can imagine what it would become if little sharp-toothed foxes got inside the fence and bit away leaves and stems and buds. There would soon be no garden.

The names and nature of some of these little foxes appear in the following chapters.

II

"IT'S NO MATTER"

When a girl or boy is slovenly, with tously head and dirty hands; or washes the face and forgets the ears; or leaves a high water mark around the neck, and mother makes a remark on the way things look to her, the girl or boy says, "Oh, it's no matter." And first thing they know, a fox has bitten off a green leaf in their garden.

Or John makes a mistake and the teacher corrects it, and John says, "Oh, it's no matter."

Foolish John!

Say, boy, did you know an architect once made plans for a great building and when he went to work it out, nothing fitted, because away back in the beginning he made a mistake of one inch with his ruler, and it put the whole thing out of joint!

Or Mary, her mother's pride, did not put into her work quite enough time. She fooled over it, and played with it—and when the examination results came out, she failed. And when she saw her mother's sad face, she tried to comfort her by saying, "Oh, it's no matter!"

It seems so dreadful to see a man who has grown up to think things do not matter. His looks—"Oh, well, what's the odds how I look?"

Of course, it is only when he is married or else settled into a grouchy old bachelor he says this. If he is still looking forward—Huh! That makes a difference!

Some young fellows once were lounging about the street corner, when one of them saw a bright young girl coming down the street, and say! he went away so fast his companions wondered what had happened. Well, he did not want her to see him, for he felt it would matter very much for him if she saw his careless street life.

Or his clothes.—Sometimes you can almost tell what he had for dinner by the spots on his vest; and the whole thing started a long time earlier, when as a little boy he said, "It's no matter!"

And it is just the same with the girl. She grows up with a faded character and lopsided gait, and looks as though what she wore had been thrown at her with a pitchfork and sort of lodged on her person.

Sometimes she is real clever and knows a lot, but oh, the pity! She did not think her appearance mattered, and there she is, so that people look at her when she passes, and laugh.

It is very much worse, though, to let that spirit get past your body and your clothes and your outer habits, into the inside of you.

For then, when people see you doing things and saying things you should not,—things that make people look at you—the old habit, started when you were a girl or boy, comes out, and you think it does not matter.

But it does.

It matters whether you are loving or unloving. It matters whether you are kind or ugly in temper. It matters whether you are at the foot of the class or its head. It matters whether you are neat or just a disorderly heap. It matters whether you are a sunbeam or a shadow. It matters whether you are growing up straight or with a lean.

It makes a big difference.

Of course it matters, silly child!

If it didn't matter, God would never have given us so many lessons in nature and history and biography.

Nearly everything in God's great world is telling us that—

"Life is real,Life is earnest."

And it has an end; and it will be a poor end for her or for him who starts by saying, "It's no matter!"

There was a fellow once did that in a great Rugby game. He failed, and the team lost the match and the trophy.

A slip may seem small, but we can slip and fail, and do slovenly work once too often—and lose the game of life!

It does matter! It matters to God! It matters to you, and it matters to all who love you!

III

"I DON'T CARE"

That is one of the worst of all foxes, with a very sharp tooth.

A horse lost a shoe once, and the owner did not care. And some one wrote this verse—

"For want of a shoe a horse was lost,For want of a horse a rider was lost,For want of a rider a battle was lost,And all for want of a shoe."

When I was a student at Toronto University, there took place one February night the great fire that became a college date, and practically helped to end the life of President Sir Daniel Wilson, who saw the building of his life labour go up in smoke.

It was the great social night of the college year. There were no electric lights in those days, and lamps were used. The building was gaily decorated with evergreens and bunting.

A college servant came down the east stair with a tray of lamps, and making a careless step, he stumbled, and the blazing oil started a fire, which, fanned by the air pouring down the great windows, soon destroyed the great building. It all came from a careless step.

Just think of a tailor who goes around with his pants legs down over his heels and the edges all frayed, and a pair of dirty cuffs down over his wrists—what a poor advertisement for his trade and all because he does not care.

And you have a trade, too! Your business is to show every other girl and boy what a girl and boy ought to be; and if you don't care, then you can't show them anything except what they should not be. They should not be like you.

Or think of a girl or boy who is always making a mess of things.

They fail in school, and they grieve their parents, and they are no use to anybody. They get into trouble, and they get others into trouble. They miss the mark and are getting nowhere; and worse than all, they blind their eyes and close their ears. They simply do not care!

A young fellow once went mountain climbing; and I think he thought he was pretty sure-footed. Anyhow, he would take no advice as to dangerous places or how to watch his step, and one careless moment he stepped into a great crack in the ice called a crevasse, and it was twenty years before they found his body, after the slowly moving glacier brought it down to the place where the warmer regions broke off the edges of the ice!

And life has a lot of danger spots too; and it needs care in the step, and to say you don't care may land you sometime in disaster.

In fact, if that spirit stays, I do not see how any one can escape disaster.

"I don't care!"—What does that mean?

It means you would just as soon be bad as good!

It means you would just as soon see things go wrong as right!

It means you would just as soon see things go down as up!

You think it makes no difference. But it does!

It means you shut your eyes and let things go!

Some great preacher tells of the wonders of the eyelids. They act so quickly and they can shut out so much if closed;—all the glory of the heavens; the wonders of the mountains and sea; the books of a library; the great world of people;—all shut out by closing the eyes!

You can shut your eyes if you like—and when you say, "I don't care!" that is what you do. You shut your eyes.

If you keep them shut long enough, you will go blind!

You don't want to be blind, do you? Then do not say, "I don't care!" Instead of that, Care.

Be careful—full of care!

IV

TEMPER

Temper is a fine thing to have.

A horse without any temper nobody wants. A man without temper is no good.

Temper is a word worth study. It comes from a root that means to control and not let get away and run wild. It means to mix up in the right way so that there will not be too much of anything.

And so temper means to give a good form to, by having just enough of what makes that form.

And perhaps because heat is used to mould things and helps in mixing, temper sometimes means heat; and when that heat gets inside us it warms us. And that inside heat is good. A cold heart or mind will not do anything.

Temper is not bad.

We get a lot of good words from temper; like temperament—what your character is like; and temperature—the amount of heat in the air; and temperance—the amount of self-control you have.

Unfortunately, the heat gets often too hot. And then we are people of bad temper. And if you get too much of that, it leads to very serious trouble.

I went once to the gallows with a splendid-looking boy who did not mix things right, and got so much temper that he became a murderer!

Bad temper means lost control. To keep your temper is like riding a high mettled horse.—You have to keep firm hold of the bit.

When the present King George was Duke of York, he came to Western Canada, where I was a young minister. The people of Winnipeg gave him a great reception. The streets were lined, and flags and bunting made gay the city.

It was interesting to see the man who was to become the head later of the greatest empire in history. But I must confess there was a part of the procession that interested me more than even the Prince did.

It was his equerry.—The man who rode by his side on horseback. It was a wonderful sight. He was on the back of a magnificent black charger, with glossy flanks, and flowing mane and tail, and arching neck and prancing feet. Powerfully built, it seemed the ambition of the horse to hurl the driver from his back. The noise of the cheering and the bands added to his restlessness. He curved to this side and that; stood up on his hind legs; tossed his head between his feet; danced and careered around until you would wonder how anybody could stay on his back.

But that rider was a great horseman. He sat there as though he were part of the horse. With a firm hand and soothing voice, and a grip that kept the bit solid in the mouth of his prancing charger, he danced up the street a splendid sight.

And I thought, what a fine illustration of a strong life he was.

The man who can sit on his fiery temper, and hold it in control.

The Bible says: "He that is slow to anger is better than the mighty; and he that ruleth his spirit than he that taketh a city."

I suppose every boy here would envy Foch as he swept back the tide and took trench after trench until he broke the Hindenburg line.

But when you hold the bridle firm on your temper you can be greater than Foch.

Only those who have been West have ever seen a "stampede" where the cowboys undertake to break a wild broncho, or to ride on the back of an untamed steer.

I saw one once at Calgary, where a plunging broncho brought his four feet together, and bucked his back, and lowered his head, and the cowboy was hardly on his back till he was off again, and the broncho wildly galloping down the dusty prairie.

But it was a thrilling sight when, without even reins, just one little piece of rope, the skillful fellow, with his knees dug deep into the broncho's side, mastered him, and came galloping up the track in triumph.

And it is just as fine a sight to see a girl or boy who can use this wonderful gift of temper, and never let it use them—who masters it and are never mastered by it.

Watch your temper, girls and boys. If it is kept under control it is a splendid gift. If it is not, it may ruin you!

V

SELFISHNESS

My, that is a nasty little fox! If it gets into your garden it will spoil it, sure as guns!

Not that you and I are to have no selves. That kind of a person is an empty, silly, shallow body. You want the biggest self you can get. And you need to care for yourself. For if you do not, you will have no self with which to care for any one else.

And you need a true self-love, for if you stop truly loving yourself, you will soon have nothing with which to love any one else.

But selfishness means you cannot see anybody else but yourself.

Selfishness means putting yourself in the centre and expecting everybody and everything to dance to your music.

A little boy said to his sister, "Mary, there would be more room for me on this sofa if one of us were to get off!"

Was he not a selfish boy? Who would want to have that kind of child around—that expects the whole house to get out of his way so he could blow himself?

Some one tells a story of the sweetness of the unselfish life of a little ragged bootblack, who sold his kit to get a quarter to pay for a notice in the paper of the death of his little brother. When the kind newspaper man asked if it was his little brother, with a quivering chin he said, "I had to sell my kit to do it, b-but he had his arms aroun' my neck when he d-died!"

The news went round and that same day at evening, he found his kit on the doorstep, with a bunch of flowers bought with pennies by his chums, who were touched by his unselfish act.

There is something very attractive about a girl or boy who thinks of others and forgets self.

I have read of the wonderful St. Bernard dogs in the mountains of Switzerland.

There is a house called a hospice, 8,000 feet above sea level, where the monks live who keep the dogs to watch for lost travellers who may perish in the snow.

The dogs have baskets strapped on their backs, which contain food for lost men. They are trained so that they will find people and guide them to the place of safety.

The story that interested me was of an Englishman who wanted to see the dogs at work.

The monks told him that the best dog had been out for some time and they were becoming worried over his absence.

In a few moments, in the dog came, looking completely discouraged. He seemed to have no spirit, although all his companions were barking and jumping around him. The old dog paid no attention, but went and lay down in a sort of hopeless way, without even wagging his tail—like all good dogs do that are pleased with themselves.

The explanation of the monks made me think.

They told the Englishman that that was the way the dog always acted whenever he had failed to help any traveller.

Just think, girls and boys, of the instinct of a well-trained dog—so deeply set on helping, that failure, even when he was not to blame for it, made him ashamed and sad!

Surely we will at least be equal to a trained St. Bernard.

Surely we should far surpass him, by voluntarily, of our own loving choice, seeking to help in a life of shining unselfishness.

I do not know any one who should be better able than a girl or boy to put into their lives the spirit of this little poem, whose author I do not know, but which I give to you:

LITTLE THINGS THAT CHEER

Just to bring to those who needThe little word of cheer;Just to lift the drooping headAnd check the falling tear;Just to smooth a furrow fromA tired brow a while;Just to help dispel a cloud,Just to bring a smile—Oh, the kindly little deeds,As on through life we go,How they bring the sunshine,Only those who do them know.Just to do the best we can,As o'er life's path each day,With other pilgrims homeward bound,We take our steady way;Just to give a helping handSome weary weight to bear,And lend a heart of sympathySome neighbour's grief to share—Oh, those kindly little deeds,Our dear Lord notes each one,And sheds His blessings o'er our wayToward life's setting sun.

VI

IMPURITY

Once in California I visited the beautiful gardens of San Francisco and saw a very lovely flower.

Its petals were white, and when you opened up the heart, away down at the very centre was a shape made by the base of the pistil that looked exactly like a dove. It was a flower with a white dove at its heart. They called it the Holy Ghost plant of South America.

It is a fine thing when a girl or boy carries within them a white heart!

There is no sin that leaves a worse stain than the sin of impurity.

It comes by unclean thoughts and words and deeds; and when it comes, it is next to impossible to wash it out.

A man once looked at a dirty picture, and years after he had not forgotten it! It made for him a lifelong fight!

It is almost like putting nails in a post. You may draw them out, but you can never quite fill out the holes left. A growing tree may fill them and a growing life may, but there is always a scar left where the nail entered.

Some boys like to tell nasty stories, and if the boys to whom I talk want to have white souls they should turn from nasty story-tellers the way they would from drinking poison.

It is awful the way a dirty story sticks. It is so hard to get rid of its memory. It is like indelible ink that you use when you want some writing not to wear out.

The great General Grant, the United States hero of the Civil War, was once at a party where one of those men were who think it smart to tell such stories. Looking around, the man said, "I have a story to tell you. There are no ladies present, are there?" "No," said Grant, "but there are some gentlemen."

That story was never told.

Dear girls and boys, when any evil breath like that is around, think of your dear mother or your beautiful sister, and tell your heart you must be true to them.

"I must be true, for there are those who love me,I must be pure, for there are those who care."

A newspaper published these verses that I think are so good. I would like you to learn them.

While walking through a crowded down-town street the other day,I heard a little urchin to his comrade turn and say:"Say, Jimmy, let me tell youse, I'd be happy as a clamIf I only was de feller dat me mudder t'inks I am.She just t'inks dat I'm a wonder, and she knows her little ladCould never mix wid nothin' dat was ugly, mean or bad.Lots er times I sits and t'inks how nice 'twould be, gee whiz,If a feller was de feller dat his mudder t'inks he is!"My friends, be yours a life of toil or undiluted joy,You still can learn a lesson from this small unlettered boy.Don't aim to be an earthly saint with eyes fixed on a star;Just try to be the fellow that your mother thinks you are.

And how can we keep the life straight, and in a true direction?

You remember the story of Ulysses and the Sirens—how he kept himself and his sailors from the influence of the enticing music when the sirens played on the dangerous rocks, by filling their ears with wax; and having himself tied to the mast till they passed in safety.

That is one way—the way of stiff stern duty and obedience to law. But there is a better way!

A boy once was trying to make a straight track in the snow. And he did. While the other boys left wriggling marks, his pressed straight on. When they asked him how he did it, he said he fixed his eye on a tree on the other side of the field and walked to the tree without looking to right or left. That is the way always to make a straight trail. Look at something ahead and go to it.

And we have that chance, for this is a splendid text for a girl or boy, or man or woman—"Run with patience the race set before us, looking unto Jesus."

The eye fixed on Him and the feet moving toward Him will help make a straight life.

VII

"I CAN'T"

No girl or boy ever says this about anything they love to do!

No matter how hard it is, if they like it, they try at least to do it. In fact, the harder it is, the more they try.

Who ever cares how many bumps he gets when learning to skate?

I saw a fellow once who was trying to vault over a pole. His chums laughed and jeered. "You can't!" they called out. Do you suppose he stopped? No! He kept right at it until he did.

Edison, the wizard of electricity, wanted to get a jewel point hard enough to be the right kind of an end for a phonograph needle. When it was suggested he could not get one, he just looked at the one who said it, and went right on and found it!

Every girl and boy should be like the man who refused to let that word appear in his dictionary.

When I was a little boy, I was brought up in a church where they would not sing anything but psalms. They called all others "man-made hymns" and one member of the church had sewed up all the paraphrases at the back for fear he might open them by mistake. That was a very foolish, narrow way to act; but if you have anywhere in your book of life the words, "I can't!" just sew those leaves together so you will never see them!

For you can—if you will, and if you want to!

And if you can't, it is only because you won't!

I do not know who wrote these verses and will apologize for using them, but would like to pass them on to girls and boys:

IT CAN BE DONE

"Somebody said that it couldn't be done;But he, with a chuckle, repliedThat maybe it couldn't, but he would be oneWho wouldn't say so till he'd tried.So he buckled right in, with the trace of a grinOn his face; if he worried, he hid it.He started to sing as he tackled the thingThat couldn't be done—and he did it."Somebody scoffed: 'Oh, you'll never do that;At least, no one has ever done it.'But he took off his coat, and he took off his hat,And the first thing we knew he'd begun it.With a lift of his chin and a bit of a grin;Without any doubting or quiddit,He started to sing as he tackled the thingThat couldn't be done—and he did it."There are thousands to tell you it cannot be done;There are thousands to prophesy failure;There are thousands to point out to you, one by one,The dangers that wait to assail you.But just buckle in with a bit of a grin,Then take off your coat and go to it.Just start in to sing, as you tackle the thingThat 'cannot be done'—and you'll do it."

VIII

"I FORGOT"

Oh, how much trouble this little fox causes!

Out West near Fort William, once occurred a serious collision—all because an engineer forgot to watch the safety signals! A great train was wrecked and a whole railway district held up for hours; and some lives were lost—because a brakeman forgot to guard an open switch!

It's a bad fox, girls and boys!

It makes your character ragged and slovenly. It wastes people's time. It causes endless confusion. It holds up plans. Somebody forgets to do his duty and that upsets all some one else has to do; and so it goes on and around, until things become a regular mix-up.

There is a place for a good forgetter!

It is just to forget your worries and to forget yourself; and to forget the nasty things people do to you; and to forget your mistakes, if you are sorry for them; and to forget that you were not invited to somebody's party; and to forget that you fell down yesterday, if you got up again and are still on your feet!

But it is important to have a good memory too.

A little girl forgot to post her mother's letter, and it stopped the chance of a pleasant holiday for her grandmother, who was waiting for directions.

A little boy forgot to close the door of the nursery when he was told, and the baby nearly died of pneumonia.

In the days of the great war so recently closed, they had to spend millions of dollars on making shells. They had to be very carefully made. If a shell was more than 3/1000 of an inch more in diameter than was called for, it was sent back. It was important not to forget this. In fact, they had to watch against fuzz getting on the shell from the gloves worn by the workers.

One day an inspector found a shell that would not fit. Some one forgot to watch against the fine lint and sent in the shell which was at once sent back.

And surely if it was so important to remember all these fine points about a death-dealing shell, it is just as important not to forget the little things of life, that may spoil the whole day.

A bridge-builder made out all his plans and set the men to work, and when it was put together it was seventeen feet too short, because the plan-maker forgot one little measure that knocked the whole work out.

I read a rather strange thing that occurred across the line among our Southern neighbours.

A bill was passed, allowing certain goods to come in free of paying duty. Among them were what was called foreign fruit-plants. You know what that stroke between the two words is. It is a hyphen that joins the words and makes them one. A clerk was copying the bill and forgot all about the hyphen, and made the bill read "fruit, plants," etc., and for a whole year, until their parliament met, all foreign fruit came in free; and they say the government lost nearly $2,500,000, all because a clerk forgot a hyphen and put in a comma instead.

But it is not only the mistake that costs, but if we will just think that it is the memories that store up our thoughts. It is the things marked in memory that we use for all our mind's growth.

A girl or boy who is always forgetting will some day find the life grown up and full of emptiness; for it is what you remember that makes the furniture in your soul's living-rooms; and if you keep on forgetting, your soul will have bare walls, and bare floors, and all you will hear will be echoes.

Be alert. Keep your eyes open. Attend to business. Put your mind on things. Do not say, "I forgot!" Be ashamed to! You have no right to forget!

You can pardon an old man whose teeth are all out and whose hair is all off, and who is bent with age, but you have no excuse.

Your forgetter has no right to be working at all.

Stop forgetting!—Remember!

IX

"BY-AND-BY"

"Oh, dear me! What a child that is! Johnny, will you please do that errand for me?"

"Yes, Mother, by-and-by!"'

"Mary, will you pick up your things and tidy your room? It looks as though a storm had struck it!"

"Oh, yes, I will, by-and-by!"

When are you going to do your home work? By-and-by!

When are you going to start that job you wanted to do? By-and-by!

When are you going to be useful? By-and-by!

When are you going to bed? By-and-by!

When are you going to get up? By-and-by!

When? When? When?—By-and-by! By-and-by! By-and-by!

"By-and-by is a very bad boy,Shun him at once and forever;For he that goes with By-and-bySoon comes to the town of Never!"

They say that Rothschild, one of the wealthiest men of the world, made the beginning of his fortune by acting at the moment. He was in Brussels and heard the report of the battle, and spurred his horse and paid a large sum to be ferried across a river; and got to London early in the morning before the news was abroad; and laid the foundations of his wealth in a few hours.

That is one of the roads to success—being prompt.

The dilly-dallying, shirking, waiting girl or boy will always be at the tail-end of things, and will never catch up enough to catch on.

Do you want to catch on?

Then do it now—not by-and-by!

There is a little poem printed in Messenger for the Children. I want to repeat it to you:

PUT-OFF TOWN

Did you ever go to Put-Off town,Where the houses are old and tumble-down,And everything tarries and everything drags,With dirty streets and people in rags?On the street of Slow lives Old Man Wait,And his two little boys named Linger and Late;With unclean hands and tousled hair,And a naughty little sister named Don't Care.Grandmother Growl lives in this town,With her two little daughters called Fret and Frown;And Old Man Lazy lives all aloneAround the corner on Street Postpone.Did you ever go to Put-Off townTo play with the little girls, Fret and Frown,Or to the home of Old Man Wait,And whistle for his boys to come to the gate?To play all day in Tarry Street,Leaving your errands for other feet?To stop or shirk, or linger, or frown,Is the nearest way to this old town.

X

BOLDNESS

There is a splendid kind of boldness.

One day, years ago, sometime after the death of Jesus, two of His disciples, Peter and John, were arrested and brought before their bitter enemies who were ready and able to kill them. And Peter, the noble soul, stood up without a pang of fear and just told them face to face what he thought; and then the New Testament story says: "When they saw the boldness of Peter and John they marvelled."

It is a fine thing to see men and women and girls and boys who are not afraid to do and stand for the right.

Listen to this story which I will give you just as I got it:

He was small for his age, worked in a signal box, and booked the trains. One day the men were chaffing him about being so small. One of them said:

"You will never amount to much. You will never be able to pull these levers; you are too small."

The little fellow looked at them.

"Well," said he, "as small as I am, I can do something which none of you can do."

"Ah! what is that?" they all said.

"I don't know that I ought to tell you," he replied.

But they were anxious to know, and urged him to tell what he could do that none of them were able to do. Said one of the men:

"What is it, boy?"

"I can keep from swearing and drinking!" replied the little fellow.

There were blushes on the men's faces, and they didn't seem anxious for any further information on the subject.

Was not he the right kind of a bold boy?

Or what do you think of a lot of officers at a dinner, drinking and telling unclean tales.

Everybody had to tell a story or sing a song.

One young, shy fellow said, "I cannot sing but I will give a toast in water." And the toast he gave was "Our Mothers."

The rest were so touched by his splendid courage that they shook his hand and thanked him, and the Colonel said it was one of the bravest acts he ever saw.

A great Scotch preacher was so brave that it was said, "he never feared the face of man."

Every girl and boy should be bold in that way—fearless, heroic, full of courage and with a stiff, brave heart.

Some day you will read and study Shakespeare, and he will give you this message:

"What's brave, what's noble, let's do it, andmake death proud to take us."

Another writer, whose name I do not know, is quoted as saying:

"We make way for the man who boldly pushes past us."

Dear girls and boys, was it not a great moment for Canada when a little handful of Canadians stood at Ypres, in the first poison gas attack and dare to face it, and stand fast? Their boldness helped to stem the tide, and that first stand was the beginning of the events that won the war for the Allies.

That sort of a bold person makes history, and makes the history of their country.

The poet Emerson puts it this way:

"Not gold, but only men can makeA people great and strong.Men who for truth and honour's sakeStand fast and suffer long.Brave men who work while others sleep,Who dare while others fly—They build a nation's pillars deepAnd lift them to the sky."

But there is a boldness that acts on life like foxes in a garden.

It is seen in the rude, rough, saucy, forward girl or boy.

The boy who becomes a "smart Alec." Sometimes other boys call him "Smarty."

Or the girl who does not know how to blush; with no sense of shame. You can always tell them. She dresses loud, and laughs loud, and makes a fool of herself on the street; and he stares at you and acts impudently, and thinks he is manly.

They like to be looked at, and stare back.

They lack gentle, quiet refinement, and if that spirit grows, it will ruin the character and make the girl or boy disliked by everybody who cares for a gentleman or a lady; and in later years they will be ashamed.

Take a dictionary if you have one, and see the two uses of the word.

Bold—heroic, brave, gallant, courageous, fearless.Bold—rude, without shame, impudent.

Which are you going to be?

XI

REVENGE

This is a fox whose bite brings blood.

It represents a very bad spirit.

It means, "I am going to pay him back." "I am going to get even." "You just see, I'll catch him and make him sorry!"

It does make him sorry, not in the sense of being penitent and wishing he had not done it, or longing to undo it; but sorry because of the blow he gets in return.

It is a bitter heart that takes revenge. It goes with a hard, unforgiving spirit.

It is an awful way for girls and boys to act, because they should be so bright and smiling. They are so fresh and sunny. They are so young they should not grow hard like an old shell.

They ought to be all mercy, forgiveness, kindness, because they have so much of it shown to them.

I hate to see a kiddie who is always looking for a chance to hit some one who happened to hit him.

Johnny Pay-him-back once was hurt when he was playing with a schoolmate, and instead of turning up a rosy face and laughing it off, the way the sun does when a piece of mud flies up in the face of the sky, he opened the door of his heart and this little fox began to chew away all his finer feelings. As the fox chewed, Johnny chewed on his hurt, just the way he was chewing a wad of gum in his mouth. The more he chewed the hotter he grew under his collar.

You see, in your heart there is a cooling plant called Love, but the pesky little fox chewed it all up, and he got so hot that he paid the boy back and sent him to bed for a whole month to suffer pain; simply because he wanted revenge.

I read of a man once who was injured by another man of high rank in society, and he said to a friend, "Would it not be manly to resent it?" The friend answered, "Yes, but it would be God-like to forgive!"

It is not easy to forgive. It takes a real man to do it, but it makes you very much like God, who forgives us so much day after day!

And the gentle, forgiving spirit does so much to make the world bright, while the revengeful spirit adds so much to its gloom. Put that in a house or a school, and you pull down all the blinds and stop all the music of life.

Part of the horrors of the war were bred of revenge.

Germany had piled up all she could on France in 1870. France could not forget it, and the terrible thing about revenge is it burns so long. It may be that even now after victory, sparks of that old fire are still burning in the heart of France. If it should blaze up nobody can tell how awful the results would be.

Brighten up your hearts by keeping them sweet with mercy.

Instead of making yourself dark with the desire to pay back—just shine up a little. Keep the air fresh, and polish off your windows and put the flowers of kindness on the sills and hand out mercy to those who pass by.

Jesus said, "Blessed are the merciful for they shall obtain mercy." And if you and I can't forgive, how can we hope to be forgiven?

Oh, there is nothing like the sunny life to cast out the shadows of hate.

It was the radiant sunshine of Pollyanna that changed a whole community and brought two people together who had not spoken for years; so

Smile, don't frown. Love, don't hate.

"Are you feeling cross to-day?Stop and smile.And of course, if you feel gay,Why, you'll smile.You will find that it will payIf everywhere and every dayAt your work or at your playYou will smile. Just smile."

It was a piece of fine advice one gave another. It was this:

"Smile a while,And while you smileAnother smiles!And soon there will be milesAnd milesOf smiles.And life's worth whileBecause you smile."

May I add:

Don't frown and groanOr throw your stone.But pile up highYes, just sky-highYour joy and love.Then by-and-byDown from aboveThe holy doveWill come and moveOur world with love.

XII

UNTRUTHFULNESS

"Oh, what do you want to talk so much about that?" said a boy to his mother. "It was only a white lie!"

And the poor little silly thought that you got your opinion of a lie by its colour!

A bad man may be white, or brown, or black, or yellow, but he is a bad man all the same! The colour does not matter; and so is a lie a bad thing, whether it is little or big, or white or black. I'll tell you why, girls and boys!

1. White lies give you a habit of telling lies, and when you get the habit you become a liar! In fact, white lies are almost the worse of the two, because a big black lie would scare you, but the little white lie eats into you without you knowing it.

2. White lies are like that awful disease called Cancer.

We hear a lot about it to-day, and the doctors are puzzled because they do not know how to trace it. But it eats and eats away until some of us have seen most loathsome forms of it consuming the poor body, while the life is still there, often in very intense suffering. And the doctors say, "Take care of the first pimple and have it cut out." Cancer often starts in a tiny spot or the smallest growth.

Now, the liar is just the same. He starts with lie pimples—just little white spots on his language tongue, but they grow until they eat away his best life.

In the East there is a dread disease called Leprosy.

It often begins with a little white spot, which grows and grows until the body gets rotten, and the poor fellow who has the disease has to be sent away by himself. And white lies grow and grow until the man becomes an evil one, who sometimes has to be sent off by himself in a jail, and the boy is sent off to some industrial home to keep him away so he cannot hurt others, until he has learned a better way of talking and living.

Be afraid of a lie!

3. They make people whom you cannot trust, and almost anything else I would wish for you than to be one who cannot be trusted.

You can't rely on a liar. Not only one who lies with his tongue, but who acts lies. He gets by-and-by so full of lies that if you try to lean on him, down you go!

Out in the West, one of the great wheat elevators at Fort William suddenly slid down into the river, because the foundation was too weak to hold it up.

And a liar is like that! He is a bad foundation for home or school or society!

He caves in if any weight is put on him.

Let the girls and boys who study about these foxes watch this bad one, and be straight and true and upright and strong, so people can be sure of them.

I like the story I read once of a Scottish schoolboy who was called "Little Scotch Granite." When the boys were supposed to tell how often they had whispered in school—and if they had not at all, got a perfect mark called "Ten"—they got the habit of saying "Ten," even when they had broken the school rule. Little Scotty came, and although he was bright and full of fun he would not say "Ten"—although his record got very low.

But he changed the whole school.

He was always a good sport, but he never would tell a lie to save himself.

At the close of the term he was away down on the list, but when the teacher said he had decided to give a special medal to the most faithful boy in the school and asked to whom he would give it—forty voices called out together, "Little Scotch Granite!"

XIII

"I CAN'T BE BOTHERED!"

Did you ever hear any girl or boy say that?

"Sonny, go and do that little job, will you?" "Oh, I can't be bothered!"

"Johnny, your sister Mary is having a hard time with her home work. Go and see if you can help her." "Oh, I can't be bothered!"

A load of firewood was dumped at the back gate and Billy, who was lying kicking up his heels on the porch in the sun, was asked to go and pile some of it in the cellar. "Oh, I can't be bothered! Wait till Dad comes home, he'll do it!"

The next door neighbour had a sick baby and Nellie was asked to go to the drug store for something. Now, Nellie really loved babies and she was a good little kiddie usually; but she was busy on some ribbons she was fixing for herself—so busy she forgot to shut the garden gate and that fox came in and bit one of the flowers off her soul, and she said, "Oh, don't bother me!"

My, girls and boys, you let that fox loose in your garden, and he'll make an awful mess of it! He'll chew up the loveliest thing and leave a wreck!

If he gets abroad in the home or the church or the city, or society, he'll ruin things without a doubt.

Because:

1. If everybody said that nothing ever would be done to help anybody, this poor old world would be left so that none of us would want to live in it.

Of course, I know there is a lot of "bother" that we should not bother with—the "bother" that your mother means when she says, "Stop bothering the baby!"—the "bother" that means teasing, and vexing and annoying, and making yourself a nuisance.

But think where you would have been if your mother and father had never bothered over you.

Think of where the world would have been if all men and women had refused to be bothered about its history. It would have had no heroes, no authors, and no leaders, and what we call history would have been a perfect mess!

It is because savages do not bother that we have the dark places where the missionary goes and bothers his soul to help; and if he did not, there would be no progress; and if he never had gone, you and I would still be savages!

Whenever you are tempted to say, "Don't bother me!"—just remember and be glad that it was bothering about things gave you home and friends and school and all that makes your life worth while!

There is another queer thing about bothering.

A lot of girls and boys never think it half as much a bother to bother about some people outside as they do to bother about people in their own homes. Some boys, and girls too, can be as sweet as an all-day sucker when some other lady asks them to go a message, and as sour as a dose of vinegar when their own mother wants something done!

"Oh, yes, dear Mrs. Smith, it will be no trouble at all to take that letter to the post. I'll gladly go!"

"Oh, confound it, Mother! I can't do that! I wanted to go down to the pond to skate!"

Girls and boys! Don't say, "I can't be bothered!"

Bothering for others is the bliss of life!

If you want to be happy, aid some one to-day!

XIV

THANKLESSNESS

Don't you love to hear the gentle voice of a child say, "Thank you!"?

Don't you like to see a girl or boy that feels and shows gratitude?

Everything in Nature seems to have it!

The birds twittering in the tree-tops always seem to be chirping, "Thanks." The flowers bordering the green lawn breathe out a fragrance that makes you so glad, it must be the odour of thanks! The sun is so glorious and scatters its rays so brightly, I think if you could hear it speaking as it shines, you would hear it saying, "Oh, I am so thankful I have all this power of sifting down these drops of sunlight!" When the rain sees the brown-burnt grass starting up into bright greenness, how thankful it must feel for its ability to refresh! I think even the wind is glad it can shake things up and scatter nasty germs and clean the air that people breathe!

"All things bright and beautiful,All creatures great and small,All things wise and wonderful,The Lord God made them all."

And I really believe there is not one that is not glad and thankful for being and doing!

There is no spirit so dark, unhappy and unattractive as the one that is thankless.

Shakespeare says:

"Ingratitude, thou marble-hearted fiendMore hideous in a childThan the sea monster."

And again he says:

"How sharper is it than a serpent's toothTo have a thankless child."

Once Jesus cured ten lepers, and you know leprosy was a dreadful disease that little by little ate away the body and turned it into a rotting sore; and of the ten who were healed of that frightful trouble, only one came back to say, "I thank you!"

Isn't it a lovely sight to see the sweet spirit of a thankful heart saying it—to find people who appreciate what you do—that is, who think it is worth something, for appreciation just means putting a value on, and they say so!

The Bible says, "Let the redeemed of the Lord say so."

Don't keep it to yourself. Say so! Pass it on! Tell some one you are glad they did something for you!

Everybody dislikes a girl or boy who is like a sponge, always soaking in!

I saw a lovely flower once. At first it was only a dirty-looking bulb. But it was put in nice clean water, in a glass, and soon beautiful white rootlets began to fill up the bottle; and one day the bulb was so glad that it was no longer a nasty earthy-looking brown bulb, but had graceful white roots, and a bud shooting out that it burst in a splendid poem of thanks; only the poem was called a flower, and its name was Hyacinth!

We all love to see a thankful life—At home it makes the atmosphere so soft and helpful—At school it straightens wrinkles off the teacher and fills the room with light—With one another it acts like good oil in an automobile. It makes things run smoother.

And girls and boys, God likes it too!

There is a fable of a lion that lay hot and tired, trying to sleep, when some field mice ran over his body and made him so mad he clapped down his paw and was going to tear it when the little mouse pled for mercy in such a way that the lion set him free.

Sometime later he heard a great roaring and found it was the lion caught by hunters in a great net. He remembered the mercy of the lion, and telling him not to fear, he set to work with his little sharp teeth and gnawed away at the cords and knots of the trap and set the lion free.

It is fine to be thankful.

It is even finer to prove it by doing things that make others thankful.

Be thankful for home, and school, for church and gospel.

Be thankful you are not children in a heathen land.

Be thankful for your happy girl and boy life.

Be thankful God cares for you.

A minister once told a bishop of a wonderful escape he had from a burning ship. He called it a "great providence of God."

"Yes," said the bishop, "but I know a greater. I know a ship where nothing happened and it arrived safely." That was God's providence too, for which he was thankful.

And all your life God is working over you.

Are you thankful?

And do you show it by helping others and being kind to those who are kind to you?

There is a legend from Norway, that wonderful sea-washed land in Europe, so full of tales that girls and boys like. It is called the legend of the "Gertrude Bird."

It is a woodpecker that is said to have been a woman once, who was making bread, when two men passed by who happened to be Christ and His disciple Peter, although she did not know.

They asked for some of the dough, for they had had a long walk and fast; and she pinched a piece off when lo, it grew till it filled the bake box. So she said, "No, that is too much," and pinched a piece off it, when the same thing happened! Three times it happened, and each time she got more selfish and hard and stingy. At last, as she saw how much dough she was getting, she said to the two strangers, "I cannot give you any. Go on, you can't stop here!"

They passed on and then she knew them; and oh, she got humble and sorry, and fell down asking for pardon, and the Christ said, "I gave you much, but you had no thanks. Now I'll try poverty. After this you must get your food between the bark and the tree. But because you are sorry, when your clothing is all black with your sorrow, it will stop, because then you will have learnt to be thankful!"

And so she was punished for a while by becoming a woodpecker, picking her food between the bark and the tree, until as she grew older her back and wings all got black; and then God turned them all white again!

Dear girls and boys, God loves you and me to be thankful!

XV

CRUELTY

There are two ways you can get a bad bite from the fox called Cruelty.

(1) By being cruel to people. Of course, most normal girls and boys would hardly like to be called cruel; and yet how often you can be without just knowing its name.

A boy that is a bully is a cruel boy. At school he likes to lord it over other boys, especially if they are smaller than he is.

I knew a boy once in a school in Toronto, who at recess was knocked down by a bigger boy who pushed his face into a snow bank and sat on him until he was in an agony of suffocation. I don't suppose the boy realized what he was doing, but he was a bully just the same.

He is the fellow who likes to see smaller fellows afraid of him, and likes to strut around with the feeling that he is cock of the walk!

I was going to a funeral one day, and saw a large boy on the street, seated on a small boy who was lying helpless on his back and enduring all kinds of nasty actions by the young bully. If I had not been at the head of the funeral, I would have stopped and gone and spanked him!

How boys hate a bully. He is a coward, you know, at heart. A real brave boy will never take advantage of some one weaker and smaller than himself. A real brave hero protects others. The boy who hurts some one who can't defend himself is a mean coward. It does not matter how big his breast is or how far it sticks out, his inside heart is small, and narrow and hard. Now, don't you be like that!

(2) You can be cruel to animals—torturing them—loving to hurt them, just for the fun of killing. It is so strange the way some people think they are having no sport unless something is suffering.

"It's a fine day," some one is reported as saying, "let us go out and kill something."

We live in a day when Children's Aid Societies and Humane Societies are telling us of the beauty of a kind life, and that even animals are God's creatures and should be treated with reverence, or at least with the gentleness that will not cause unnecessary pain.

The cruel spirit hardens us. It takes away what learned men call sensitiveness; i.e., it makes us so we do not feel. It makes our hearts like our hands sometimes get when not cared for—it makes callous marks; and when fine feeling is lost, we are less than we ought to be.

A little Indian girl, the educated daughter of a chief, said she could never forget the first time she ever heard God's name.

In her play she found a wounded bird by her tent and picked it up and said, "This is mine." One of the men who saw her said, "What have you?" "A bird," she said, "it's mine."

He looked at it and said, "No, it's not yours. You must not hurt it." "Not mine," she said, "then whose is it?" "It's God's," he said. "He can care for it. Give it back to Him." She felt scared and awed. "Who is God? Where is God? How will I give it back?" "Go and lay it down near its nest," he said, "and tell God there is His bird."

She went very softly back and laid it down and said, "God, there is your bird."—And she never forgot!

Be kind to all things, girls and boys.

"There's nothing so kingly as kindnessAnd nothing so royal as truth."

And watch carefully that you may not be a cruel girl or boy to any person or to any of God's creatures.

XVI

COWARDLINESS

If there is any one in the world that a boy or a girl admires, it is a hero. You are all hero-worshippers.

You know how big you feel if you ever get a chance to shake hands with a great man who had made a name for himself, and if he is a great national hero and he speaks to you, why you never forget it; and you blow about it to all your chums!

When the Prince of Wales was in Vancouver, a little girl presented a bouquet to him, and I fancy she felt so big that her dress-waist grew very tight as she swelled up.

When I was a little boy, I had a very learned and eloquent minister; and I used to watch him, and made up my mind to be just like him, and to wear a gray silk hat some day. He was my hero.

It is a fine thing to be a hero and to love a hero; and one of the things we all believe our heroes possess is bravery.

No girl or boy would ever knowingly worship a coward.

The very fact that we have heroes that always stand to us for big, brave, noble people, should make us anxious to be big, brave and noble ourselves.

Everybody admires Scott who died in the search for the South Pole; and Shackleton who died on his way to explore that part of the earth. Everybody has learned to think highly of the fearless John Knox, who was not afraid to talk back to the Queen when she did wrong; or Luther, who defied the Emperor and the whole Empire because he knew he was right. It was one of the greatest moments in history when the little monk stood straight up and looked his enemies in the eye, and said, "I will not retract. I can do no other. Here I stand!"

When you think of people like that, how it makes us ashamed of ourselves when fear grips our heart.

And yet, cowardice is not quite the same as fear.

Wellington, England's great general, once in a battle ordered a young officer to a dangerous spot. The young fellow turned deadly pale, but put spurs to his horse and went straight to duty. And General Wellington said, "There goes a courageous man. He is afraid, but he only thinks of duty!"

Nor is physical courage the highest kind. That is a matter of physical nerve and sometimes of health. But moral courage is still higher—the very highest kind.

A poet once wrote:

"One dared to die, a swift moment's paceFell in war's forefront, laughter on his face,Bronze tells the tale in many a market-place."One dared to live the whole day through,Felt his life blood ooze like morning dew,And smiled for duty's sake, and no one knew."

Neither were cowards, but I think the second was the braver, don't you?

Now, there are different ways of being cowards and of being brave. If you can't stand sneers when you are right, but give in because of laughs, you are a coward at heart. If you are afraid to do right, you are a coward, but if you can do it even when you are afraid, you are a brave hero.

If you can stand against a crowd when the crowd is wrong, and stand there even if you are the only one, you are brave and will never have the coward heart!

The coward spirit, especially the spirit of a moral coward, eats the power out of your life, and the only way to avoid it is to dare to do right, and dare to be true.

Sometimes it takes a lot out of you, but it is worth while.

The boys who stood the trenches and braved bullets and shells and mud stains and never faltered, were courageous. Those who funked were always despised cowards; and the girl or boy who stands strong wherever duty calls is a brave life, and will never be bitten by the fox called Coward.

XVII

DISHONESTY

Did you ever really hear in your heart and believe in your very soul that "An honest man's the noblest work of God"?

What is honesty?

It is the quality of your character that always rings true.

You can always tell when a bell has a crack in it. It does not ring true.

And you can tell when a girl or boy has a crack somewhere in his character. He or she does not give a clear ringing sound. One of the worst kind of cracks is dishonesty.

You can't trust that kind of person. He always has to be watched.

What a horrid kind of child that is, from whom you dare never take your eyes!

But when you see a real honest girl or boy, how you admire the sight.

They will not cheat. They play fair. They are true sports. They won't take advantage of you when your back is turned.

You know how even in school games you like a real sport, who plays the game and obeys the rules of the game.

You can't have a game with any other kind. He spoils everything and you can't have real life with a cheat. He spoils the school and disgraces a house.

More than that, an honest person will not take what does not belong to them. A lot of girls and boys forget the difference between "mine" and "thine."

Then when they grow up they spoil society, and if they go far enough, they become that awful thing, "a thief."

An honest girl and boy is one with honour bright.

A looking-glass always shines when it is polished bright.

A pool of water is very beautiful when you can look right down into it and see clear through it—

And so is a boy and girl who has no mud in the eye or in the soul.

It is simply great to be a life on the square, aboveboard, with nothing to conceal; what is called transparent, so that the light shines throughout, with no pretending to be what it is not; no scamping work and trying to get things without paying for them. You can't anyhow! You always get in the end what you pay for.

Did you ever hear some one described as "four square"—standing true, upright, facing everywhere with a clear eye and an undimmed soul?

It is a fine thing to have a life with no spots in it, and one of the very worst spots is to be false and dishonest—

And it always comes home some day—

A wonderful book called "Silas Marner" tells of a young man who stole the money that old Silas had gathered and kept under the boards of his cottage floor.

For many years no one ever knew where it went.

It nearly broke the heart of Silas, only in hunting for it he found the golden curls of a little child who helped to save him and make a good man of him.

Near by was an old pit, full of water, and some years later in draining off the water, they found a skeleton with a bag of gold beside him. It was the bones of the young fellow who stole it, and who had fallen in, years before, and been drowned.

But there at last, it was all seen, and his dishonesty was published to the whole district.

And dishonesty does come out, and even if the dishonest act is never known in itself, it comes out in the life that has lost its truth and beauty and grown mean and unworthy, so that nobody believes in it.

It leaves a bad black stain wherever any one is dishonest.

Therefore, dear girls and boys, be honest.

"Be true, little laddie, be true,From your cap to the toe of your shoe."

XVIII

"LIMPY LATE"

There are some people who are like a cow's tail—they are always behind.

They go to bed late and they get up late. They go to school late and to church. The only thing they are never late for is their meals, and if their mothers were like them their meals would be late too.

You sometimes read in the papers of "the late Mr. So and So," which means they are dead and are no longer Mr. So and So that used to be.

But there are some who do not have to wait till they die to be called "the late Johnny" and "the late Mary." They come strolling along after everything is started.

I taught school once, and had a scholar who came in any old time. He was a most trying sort of a boy. He always missed his lessons, and I did not know what to do with him. He loitered on the way and was absent-minded; and spoiled his class; and took up my time, for I always had to say a thing all over again for him.

One day I saw him coming and met him at the door with a very big welcome and offered to shake hands, and told him how glad we all were to see him; and he was so ashamed he cried and was never late again. He did not want any more such greetings.

Even big people are like that.

If a Committee meets, they come in when it is partly through and waste everybody's time by asking what was done, and it has to be said all over again, and is very hard on one's temper.

They are not often late for a party, or for anything that is going to give them fun, but for real earnest things, they are never early.

They are like the Irishman who came panting to the station just in time to see the train moving away up the yard, and cried out, "Hie, there! There's a man aboard left behind!"—And girls and boys, if you practice the habit of being late, you'll be left behind too, and life's train will go off without you.

It's a very bad habit. It makes you slovenly. It puts ragged edges in your work. Nothing is ever done. You are always trying to catch up. You knock everybody's plans in pieces. It makes a nuisance of you; for who wants girls and boys who are always running up when they should be running ahead?

It puts a limp into you, and you stay at the tail-end instead of being what every bright smart girl and boy ought to be—up in the van, right at the front.

You don't want to be a tail-ender, I am sure—a kind of "might-have-been."

You should have some business get-up to you.—

"Alert and at the prowOf life's broad deckTo seize the passing moment big with fateFrom opportunity's extended hand."

Take care of being Limpy Late, for if you let that spirit grow, some day you will be "Too late" and that makes two of the saddest words in the language.

XIX

"SISSY SLOW"

I really believe some people are so slow they could not catch a cold.

If they ever get one, they really do not get it,—it gets them.

They are like molasses in winter—there is no run to it.—And the worst is, they do not think it is very important.

But it is.

I know all about the old proverb, "Slow and steady wins the race." But I think the real word of value there is "steady" and the proverb was never meant to tell any one to tie up their feet and crawl along. It was meant to tell you to keep at it. Even if you are not clever and brilliant you can get there just the same. And so you can.

Lots of girls and boys have had bright brains and great gifts, but they do not use them, and somebody who has less gifts passes them, because they work hard, and stick to it.

They are like postage stamps. They stick!

Their perseverance conquers difficulties, and keeping at it steadily, readily, constantly, they arrive at the goal, while the more gifted ones, trusting to what they think is their inspiration, forget the need of perspiration, and never get anywhere.

That is all true, but it is a mistake just the same to be slow.

In fact, the successful people are not slow. They are quick to see the end and march straight at it.

Quick does not necessarily mean galloping. Quick is just another word for alive. The quick girl and boy have life in them.

The slow girl and boy are only half alive. Their step has no spring. Their eyes have no gleam. Their movements have no brightness. They never do anything. It is impossible to do unless you are alive. It is the lively, lifelike people who do things.

Life always is like that.

Wherever you have life, you have action.

And it is so unnatural for you; for if there is anything that should describe a natural normal girl or boy, it is liveliness!

Sometimes, what people call "lively kids" are a trial. They keep you on the run looking after them, but I tell you, if they are guided and controlled, they become splendid men and women.

It is very queer to see a sit-still boy. You feel he must be sick. It used to be thought a very becoming thing for a girl to be a sort of lovely, good-for-nothing sort of wall flower. It was not supposed to be ladylike to be too stirring.

But now we look for the red-blooded, red-cheeked, blooming, alert, bright, breezy girl as much as we do a boy like that. That does not make a girl unladylike.

You can be a lady and still be alive. What's the use of a dead lady?

There was once a boy who came into the office of a big business place, carrying a notice that said, "Boy Wanted." He asked the manager if that was his sign, and the big man said, "Yes, you young monkey. What did you take that off the door for?" And the boy answered, "Well, I'm the boy!" And I think he got the job. He should have, anyway, for he was alive.

Oh, stop your slowness!

What do you want to shuffle along in that snail-like way for? Pick your feet up!

Get a move on!

Quicken your steps!

Opportunity lies just around the corner.—Run after it!

Things do not just happen. You have to seek things.

Jesus once said:

"Ask and it shall be given you,Seek and ye shall find,Knock and it shall be opened unto you."

May I add just one word?

Do you know, girls and boys, the future of the Church is in your hands? We elders are going to drop out soon, and we want you to be ready to take our places.

Do you know, moreover, that you get to a very important age between twelve and sixteen?

You make great choices then. It is called the age of adolescence. You are flowering out; and around those ages the highest of all choices are made—The choice for God and a religious life.

As we grow older we get set, like plaster, and it is hard to change. But you are plaster, like clay, and are being formed now.

If you let these days pass by you may never choose, and if you do not choose the Church, your country will lose what it sorely needs. Therefore, be quick now to make your choice.

Slowness here is fatal.

For you it is literally true,

"Now is the accepted time, and now is the day of salvation."

And if a girl or boy is speeding up religiously, do not let any parent or any older person put anything in their way. Help them make the choice and in the days of youth remember their Creator.

Do not say, "Go slow." Say, "Certainly, 'Go Sure.'"

But let them come with all the sweet swiftness of these lovely, impressionable days, and help them speedily lay their lives at Jesus' feet.

XX

SHAME

It seems queer to call shame a fox, does it not? For a girl or boy without sense of shame would be in a sad state.

But a lot of foxes look at first like something else. I have seen a fox that at a distance looked like a little dog.

There is a real shame that every one should have. But there is another kind just as bad as the vine-spoiling fox. It is the shame of the life that is afraid to show its colours.

You know in the war how proud every loyal person was to wear a little flag in the buttonhole; how we hung flags in our churches so every one could see where we stood. On all our public buildings the nation's flag was flung to the breeze, and even in our schools the girls and boys were proud to stand up and salute, and sing the national anthem.

You will see men everywhere who wear pins or seals or rings that show they belong to some society; and in college, the students hang on the walls the pennants with the names of their home town or their college, and nobody blushes because they are there.

But, oh, how many girls and boys get so different when asked to show where they stand on questions of right and wrong. They blush, and apologize, and look so shy, and feel so queer—with their ears red and the goose-flesh running up and down their backs. They are out and out for some things, and very neutral for others.

Neutral may be a rather big word, but your mother will tell you about it when she goes to the dry-goods store. There are some ribbons whose colour you are not sure of. They are of no outstanding tint, a sort of dull gray with no mark to it. They call them neutral colours.

They may be all right. But girls and boys like that are a terrible sight.—Neither this nor that—ashamed to come out; afraid to say where they stand.

In the war, at one time, there were prominent people who were afraid to have a conviction on Belgian and French outrages, or on the sinking of the Lusitania, and it did not add to public opinion about them. It was called spiritual neutrality; which is just a big learned way of saying it had no character.

That spirit nobody in his heart admires. You girls and boys do not. You love to read about the knights of old, and how they wore their armour and rode their chargers, and carried their spears, and did not blush to let everybody know who they were. Sir Walter Scott describes one in these words:

"Proudly his red-roan charger trode,His helm hung at the saddle-bow;Well by his visage you might knowHe was a stalwart knight and keen,And had in many a battle been.His eyebrow dark, and eye of fire,Showed spirit proud, and prompt to ire;Yet lines of thought upon his cheekDid deep design and counsel speak;His square-turned joints, and strength of limb,Showed him no carpet-knight so trim,But in close fight a champion grim,In camps a leader sage."

Not a single one but threw his boast to the world of his plans and purposes. They were not ashamed. Their hearts were brave and the world saw the brave hearts through noble knightly deeds. They never tried to hide them. What a splendid sight to see one who wears his colours outside, and never lowers his flag!

A lot of soldiers won V.C.'s in the war and deserved the honour. Some who deserved it never got it; and some deserve it in peace as well as in war.

A disaster took place in a mine where eleven men and a boy were working. Ten died, leaving one man and the boy. The man wrapped his overcoat around the boy, covered his own eyes with his sleeve, turned his back on the flames and backed through it all and brought the boy to safety, although his skin was charred.

He was a hero equal to any V.C. He had a brave heart, and was not ashamed to do what it told him.

Do you show your colours? Are you afraid to let people see the real thing in your heart? You want to be kind and good and true. Does anybody know? Do you keep your colours waving?

In the Great War, how we all shouted, "We'll never let the old flag fall." That was fine, and we did not let it fall, and we were not ashamed.

Will you be ashamed to do the right or speak the right? Will you fear the face of some other girl or boy, and slink away from your duty?

If you do, that wretched fox of shame will have given you a bite that will take a long time to cure.

XXI

"A BATTERED WARSHIP"

In the days of the Great War I was a minister in Vancouver. One day I went to Esquimault, which was the station for the Pacific squadron of the British Navy.

There entered the harbour one of the cruisers which had passed through a naval battle. It was H.M.S. Kent. It was a touching spectacle to me. In appearance she showed all the marks of the experience she had gone through.

Painted in the dull gray of the navy, she stood at anchor, scarred and marred by service. The enemy shot had set ablaze her gun cotton; enemy shells had punctured the magazine; and through her funnels the cartridges of hostile ships had plowed their way. Decks were soiled and rigging torn; and her keel was covered with the sea growths that accumulate with long voyages.

She was so different to the spick and span vessels of pre-war days, with their fresh paint and shining spars and burnished brass fixtures and trimmings. But as I looked at her, I will tell you what I thought.

1. I said, "There are the marks of service." And it was a long service, for she was one of the older ships, but they were splendid marks. They showed she was no harbour vessel or a parade ship. She had not dodged the issue or slunk away from storm and conflict. She had watched for the enemy and when sighted, she turned her prow in the direction of the fight.

You see in all our cities and towns the scarred veterans with their wounds and disabled bodies. And when you see them, take your hat off, for you are in the presence of the servants of liberty.

There are some marks that are always a disgrace.

A life marked by sin; a face that shows the sway of selfishness that cannot be hid; a body that carries the signs of living for mere pleasure—these have no honour with them.

The marks of evil always come, until if it continues, the forehead shows the mark of the beast.

But, thank God, marks of goodness are just as sure; and they are seen in the eye, on the face, in the walk, in one's carriage, the way one conducts oneself; and if it goes on, by-and-by the forehead will show the marks of God.

One of the very finest marks is the scar of service.

That grand old ship brought me a lesson to live not to be served, but to serve, so that the world is a little larger, better, stronger place because I have been in it.