Title: Finger-ring lore

historical, legendary, anecdotal

Author: F.S.A. William Jones

Release date: September 13, 2013 [eBook #43707]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images

generously made available by The Internet Archive.)

LONDON: PRINTED BY

SPOTTISWOODE AND CO., NEW-STREET SQUARE

AND PARLIAMENT STREET

FINGER-RING LORE

HISTORICAL, LEGENDARY, ANECDOTAL

BY

WILLIAM JONES, F.S.A.

WITH NUMEROUS ILLUSTRATIONS

London

CHATTO AND WINDUS, PICCADILLY

1877

TO

MY WIFE:

Bon Cœur: Sans Peur.

I had intended to confine my observations exclusively to the subject of ‘ring superstitions,’ but in going through a wide field of olden literature I found so much of interest in connection with rings generally, that I have ventured to give the present work a more varied, and, I trust, a more attractive character.

The importance of this branch of archæology cannot be too highly appreciated, embracing incidents, historic and social, from the earliest times, brought to our notice by invaluable specimens of glyptic art, many of them of the purest taste, beauty, and excellency; elucidating obscure points in the creeds and general usages of the past, types for artistic imitation, besides supplying links to fix particular times and events.

In thus contributing to the extension of knowledge, the subject of ring-lore has a close affinity to that of numismatics, but it possesses the supreme advantage of appealing to our sympathies and affections. So Herrick sings of the wedding-ring:

[Pg viii]

And as this round

Is nowhere found

To flaw, or else to sever,

So let our love

As endless prove,

And pure as gold for ever!

It must be admitted that in many cases of particular rings it is sometimes difficult to arrive at concurrent conclusions respecting their date and authenticity: much has to be left to conjecture, but the pursuit of enquiry into the past is always pleasant and instructive, however unsuccessful in its results. One of our most eminent antiquarians writes to me thus: ‘We must not take for granted that everything in print is correct, for fresh information is from time to time obtained which shows to be incorrect that which was previously written.’

My acknowledgments are due to friends at home and abroad, whose collections of rings have been opened for my inspection with true masonic cordiality.

I have also to thank the publishers of this work for the liberal manner in which they have illustrated the text. Many of the engravings are from drawings taken from the gem-room of the British, and from other museums, and from rare and costly works on the Fine Arts, not easily accessible to the general reader. Descriptions of rings without pictorial representations would (as in the case of coins) materially[Pg ix] lessen their attraction, and would render the book what might be termed ‘a garden without flowers.’

In conclusion I will adopt the valedictory lines of an old author, who writes in homely and deprecatory verse:

FOR HERDE IT IS, A MAN TO ATTAYNE

TO MAKE A THING PERFYTE, AT FIRST SIGHT,

BUT WAN IT IS RED, AND WELL OVER SEYNE

FAUTES MAY BE FOUNDE, THAT NEVER CAME TO LYGHT,

THOUGH THE MAKER DO HIS DILIGENCE AND MIGHT.

PRAYEING THEM TO TAKE IT, AS I HAVE ENTENDED,

AND TO FORGYVE ME, YF THAT I HAVE OFFENDED.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Rings from the Earliest Period | 1 |

| II. | Ring Superstitions | 91 |

| III. | Secular Investiture by the Ring | 177 |

| IV. | Rings in connection with Ecclesiastical Usages | 198 |

| V. | Betrothal and Wedding Rings | 275 |

| VI. | Token Rings | 323 |

| VII. | Memorial and Mortuary Rings | 355 |

| VIII. | Posy, Inscription, and Motto Rings | 390 |

| IX. | Customs and Incidents in connection with Rings | 419 |

| X. | Remarkable Rings | 457 |

| Appendix | 499 |

| PAGE | |

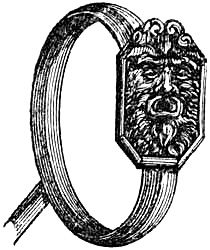

| Egyptian gold signet-ring | 2 |

| Egyptian bronze rings | 4 |

| Egyptian signet-rings | 6 |

| Egyptian porcelain ring | 9 |

| Egyptian mummy, rings on the fingers of an | 10 |

| Egyptian gold ring from Ghizeh | 11 |

| Etruscan ring with chimeræ | 15 |

| Roman-Egyptian ring | 15 |

| Modern Egyptian rings | 17 |

| Modern Egyptian ring with double keepers | 17 |

| Etruscan ring representing the car of Admētus | 19 |

| Etruscan rings with serpents and beetle | 19 |

| Etruscan ring with scarabæus | 20 |

| Etruscan ring with representation of two spirits in combat | 20 |

| Etruscan ring with intaglio | 21 |

| Greek and Roman rings | 22 |

| Late Roman rings | 23 |

| Ring found at Silchester | 24 |

| Ring of a group pattern | 24 |

| Ancient plain rings | 24 |

| Iron ring of a Roman knight | 25 |

| Roman ring, crescent-shaped | 26 |

| Roman ring of coloured paste | 28 |

| Gallo-Roman ring representing a cow or bull | 29 |

| Roman thumb-ring | 29 |

| Roman ring, with a representation of Janus | 32 |

| Roman ring, with figures of Egyptian deities | 32 |

| Roman ring, with busts; from the Musée du Louvre | 33 |

| Roman ring, with head of Regulus | 34 |

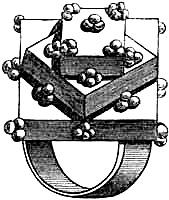

| Roman rings from Montfaucon | 36, 37, 38 |

| Roman ring in the Florentine Cabinet | 39 |

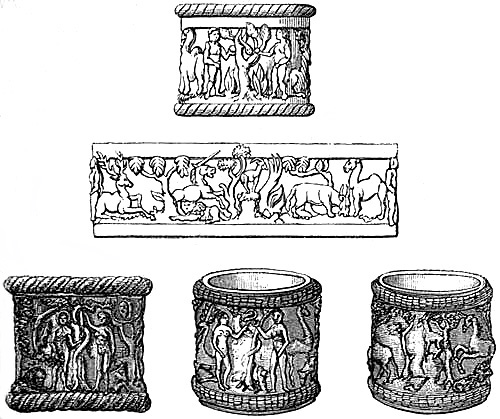

| Roman ‘memorial’ gift-rings | 41 |

| Anglo-Roman | 41 |

| Anglo-Roman and Roman rings | 42 |

| Roman rings found at Lyons | 43 |

| Roman bronze ring of a curious shape | 44 |

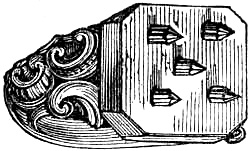

| Roman key-rings | 45 |

| Roman rings, with inscription and monogram | 47 |

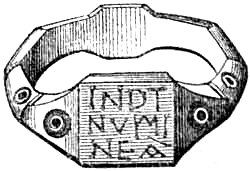

| Roman ‘legionary’ ring | 47 |

| [Pg xiv]Roman ‘legionary’ ring | 48 |

| Roman amber and glass rings | 48 |

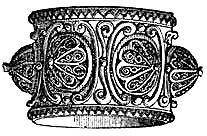

| Byzantine ring, from Montfaucon | 49 |

| Byzantine ring, found at Constantinople | 49 |

| Rings from Herculaneum and Pompeii | 49 |

| Roman bronze ring | 50 |

| Roman ‘trophy’ ring | 50 |

| Roman ring, from the Museum at Mayence | 50 |

| Roman key-rings | 51 |

| Roman, late, from the Waterton Collection | 52 |

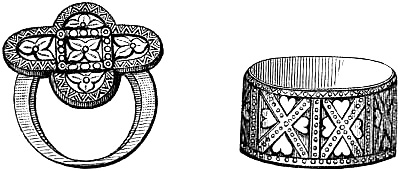

| Anglo-Saxon rings | 53 |

| Early British (?) ring found at Malton | 54 |

| Ring of King Ethelwulf | 54 |

| Anglo-Saxon rings | 58 |

| Early Saxon rings found near Salisbury | 59 |

| South Saxon ring found in the Thames | 60 |

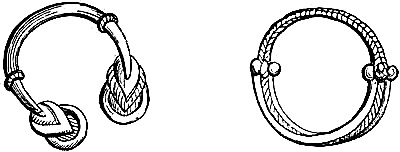

| Ancient Irish rings found near Drogheda | 61 |

| Early Irish gold ring | 62 |

| The ‘Alhstan’ ring | 62 |

| Anglo-Saxon ring found near Bosington | 63 |

| Rings found at Cuerdale, near Preston | 64 |

| Rings in the Royal Irish Academy | 65 |

| Spiral silver ring, found at Lago | 66 |

| Ring found at Flodden Field | 66 |

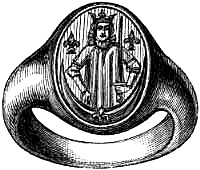

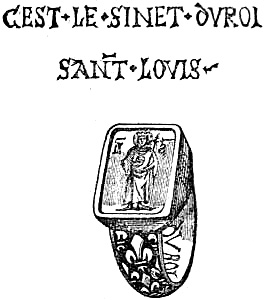

| Figured ring supposed to represent St. Louis | 67 |

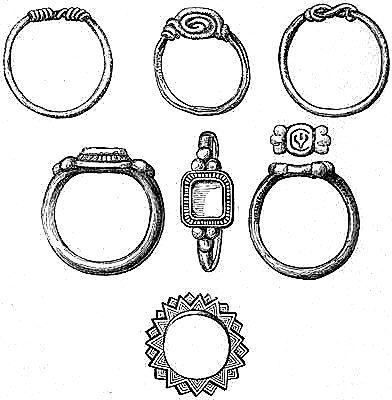

| Rings found in Pagan graves | 68 |

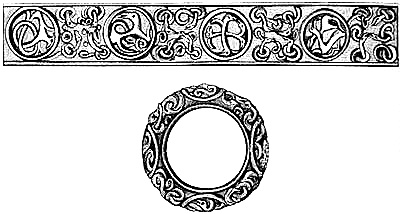

| Rings of the Frankish and Merovingian periods | 69, 70 |

| Gold ‘Middle Age’ ring, from the Louvre | 71 |

| Rings on the effigy of Lady Stafford | 72 |

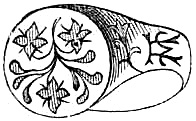

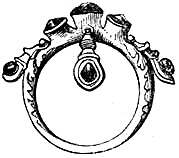

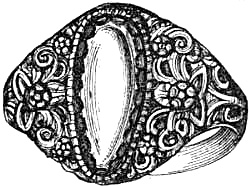

| Enamelled floral ring | 75 |

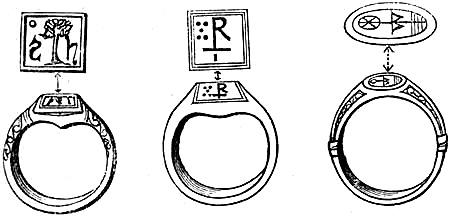

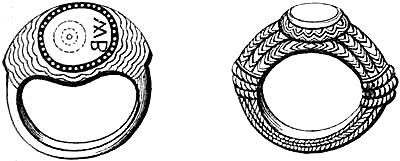

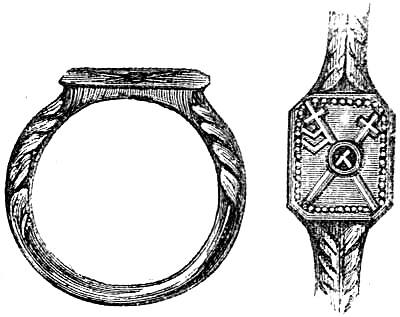

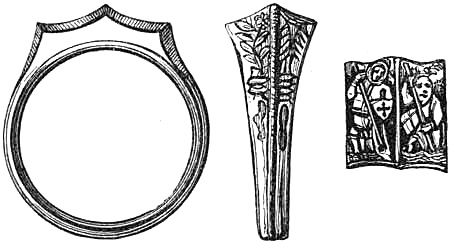

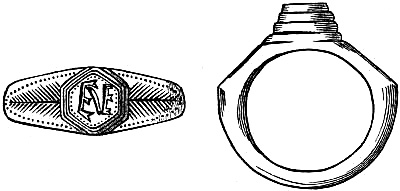

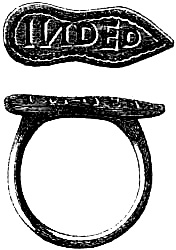

| ‘Merchant’s Mark’ rings | 75, 87 |

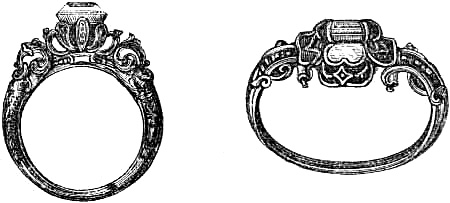

| Ring of the sixteenth century | 76 |

| Ring of Frederic the Great | 76 |

| Venetian ring | 76 |

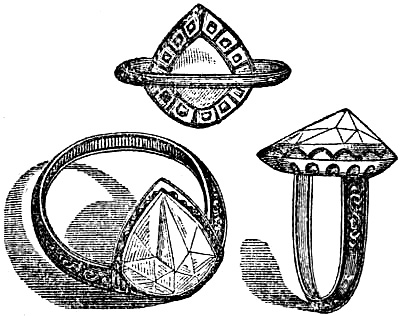

| Italian diamond-pointed ring | 76 |

| Italian symbolical ring | 77 |

| Venetian ring | 78 |

| East Indian ring, with drops of silver | 78 |

| Indian rings | 79 |

| Spanish ring | 79 |

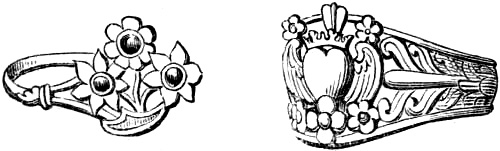

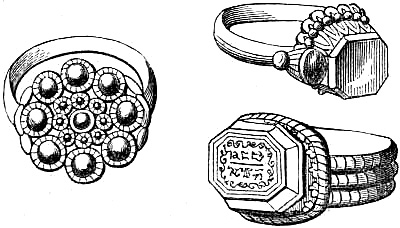

| ‘Giardinetti’ or guard rings | 79 |

| French rings of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries | 80 |

| ‘Escutcheon’ ring, French | 81 |

| French rings | 81, 82, 83 |

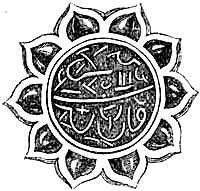

| Moorish rings | 82 |

| Bavarian peasant’s ring | 84 |

| Thumb-rings | 89, 90, 139 |

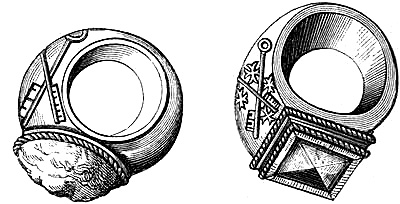

| Divination-rings | 101, 102 |

| Roman amulet-rings | 104, 105, 107 |

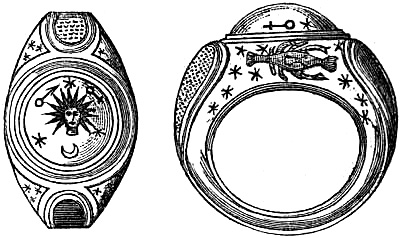

| Astrological ring | 108 |

| Zodiacal ring | 110 |

| Amulet rings | 126, 138, 141, 151, 152 |

| Charm-rings | 133, 153 |

| Talismanic rings | 134, 135, 136 |

| Cabalistic rings | 139, 147 |

| Mystical rings | 140 |

| Rings of the Magi | 143 |

| Rings with mottoes, worn as medicaments | 148 |

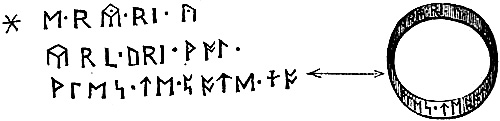

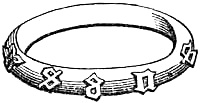

| [Pg xv]Rings, Runic | 150 |

| Toadstone rings | 157, 158 |

| Cramp rings | 163, 165 |

| Serjeant’s ring | 190 |

| Ring of the ‘Beef Steak’ Club | 193 |

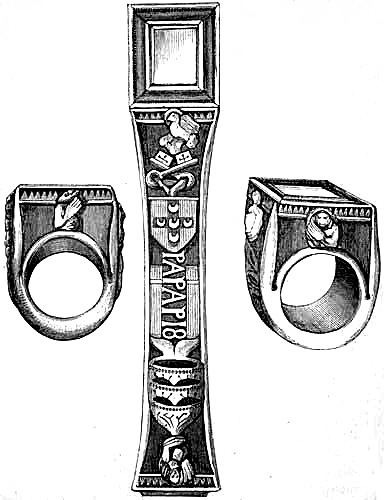

| The Fisherman’s Ring | 199 |

| Ring of Thierry, Bishop of Verdun | 204 |

| Ring of Pope Pius II. | 206 |

| Papal rings | 208 |

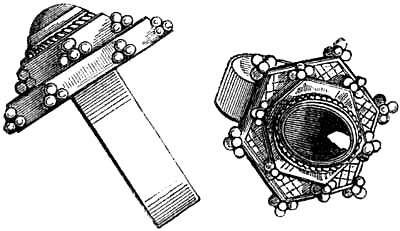

| Episcopal rings | 217, 226, 230, 231 |

| Episcopal thumb-ring | 219 |

| Ring of Archbishop Sewall | 225 |

| Ring of Archbishop Greenfield | 225 |

| Ring of Bishop Stanbery | 226 |

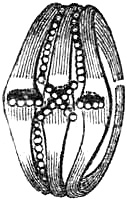

| Decade ring with figure of St. Catherine (?) | 249 |

| Decade thumb-ring | 249 |

| Silver decade ring | 250 |

| Decade ring found near Croydon | 250 |

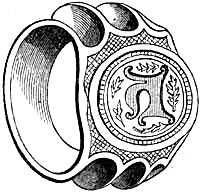

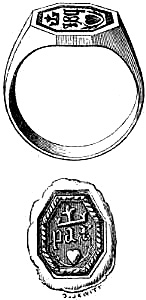

| Decade signet-ring | 251 |

| Decade rings | 251, 252 |

| Decade ring of Delhi work | 253 |

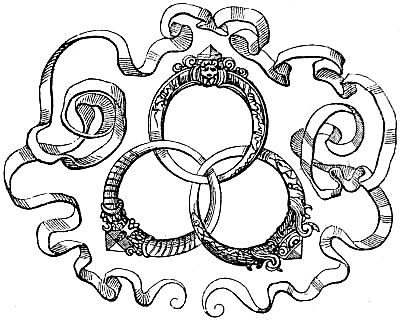

| Trinity ring | 254 |

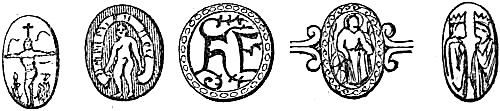

| Religious rings | 254, 255, 256, 260, 261, 262, 263 |

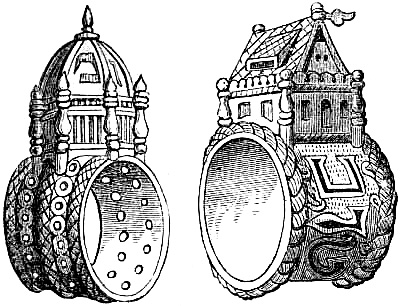

| ‘Paradise’ rings | 257 |

| Reliquary ring | 257 |

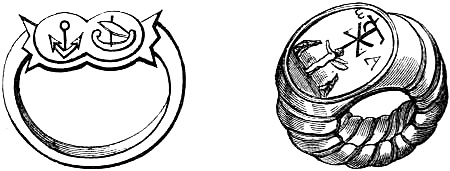

| Early Christian rings | 258, 259, 268, 269, 270, 271, 272, 273 |

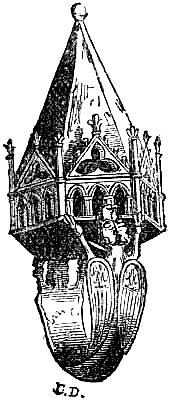

| Ecclesiastical ring | 264 |

| Pilgrim ring | 264 |

| Roman key-rings | 294 |

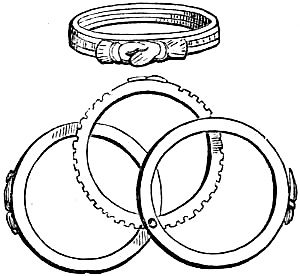

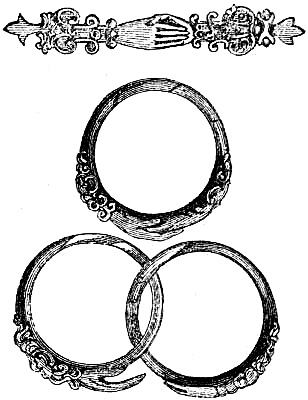

| Hebrew marriage and betrothal rings | 299, 300, 302 |

| Byzantine ring | 304 |

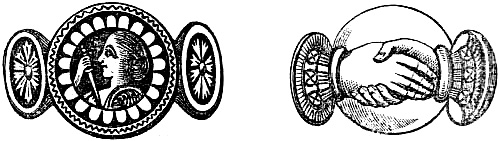

| Betrothal ring | 307 |

| Half of broken betrothal ring | 309 |

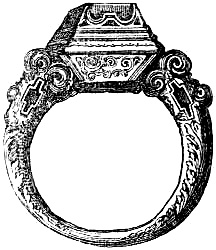

| Jointed betrothal ring | 314 |

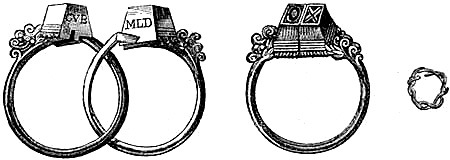

| Gemmel ring, found at Horselydown | 316 |

| Ring with representation of Lucretia | 318 |

| Wedding-ring of Sir Thomas Gresham | 319 |

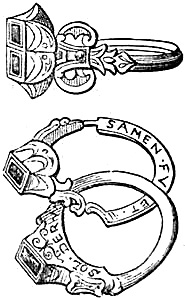

| Gemmel ring | 319 |

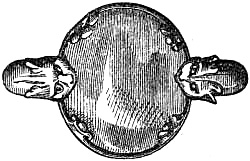

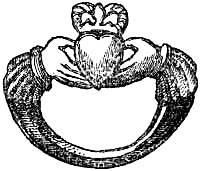

| ‘Claddugh’ ring | 320 |

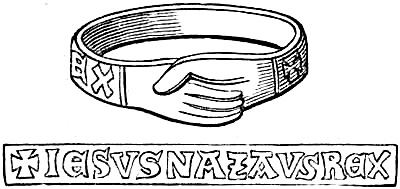

| Betrothal ring with sacred inscription | 321 |

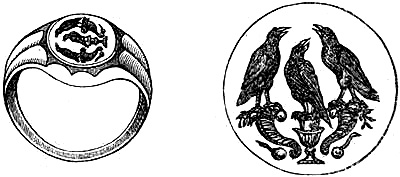

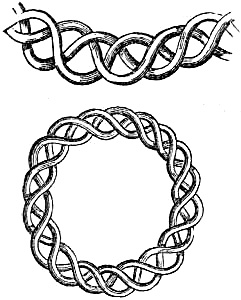

| Devices on wedding rings | 322 |

| The ‘Devereux’ ring | 338 |

| The ‘Essex’ ring | 342 |

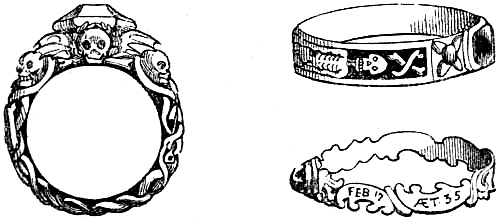

| Old mourning ring | 360 |

| Memorial rings, Charles I. | 366, 367, 370 |

| Royalist memorial ring | 370 |

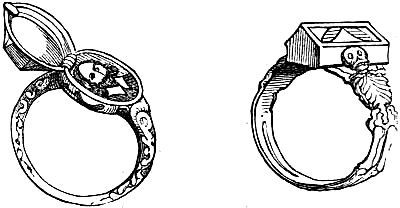

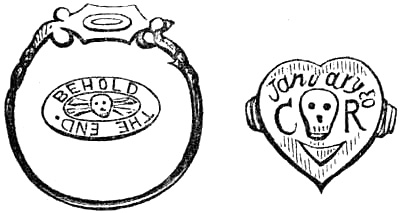

| Memorial and mortuary rings | 373 |

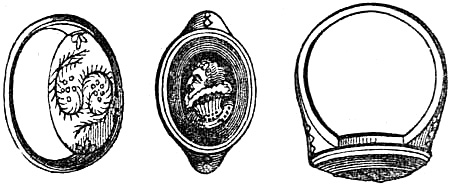

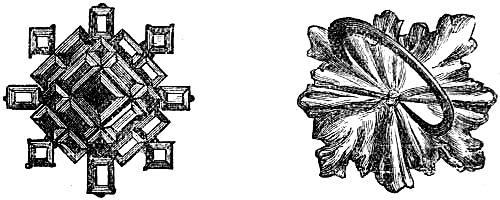

| Squared-work diamond ring found in Ireland | 380 |

| Mortuary rings at Mayence | 381, 382 |

| Gold rings from Etruscan sepulchres | 383 |

| Ring found at Amiens | 383 |

| Ring found in the tomb of William Rufus, Winchester Cathedral | 385 |

| Ring discovered in Winchester Cathedral | 385 |

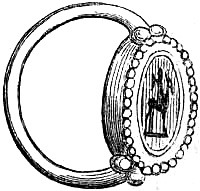

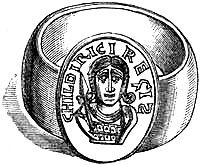

| Ring of Childeric | 386 |

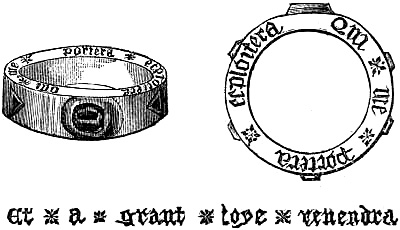

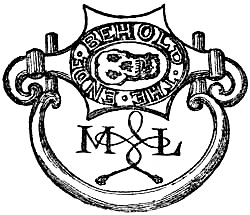

| Motto and device rings | 390, 406 |

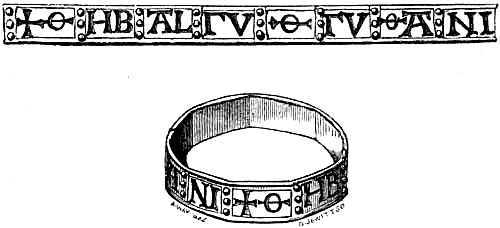

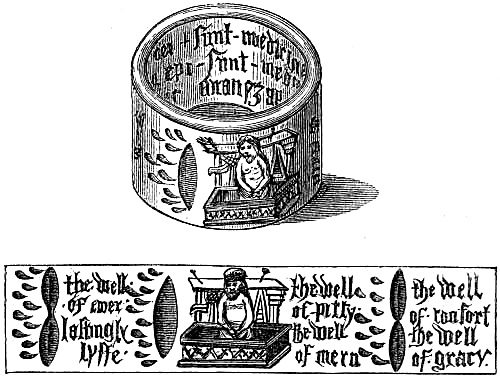

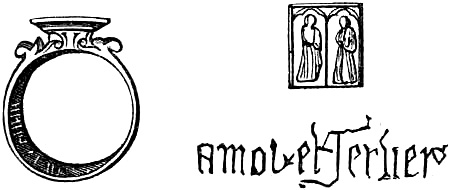

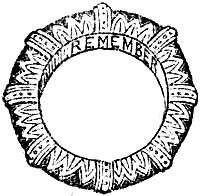

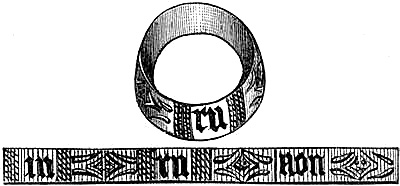

| Posy-ring | 391, 417 |

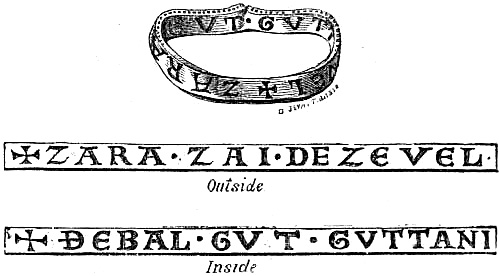

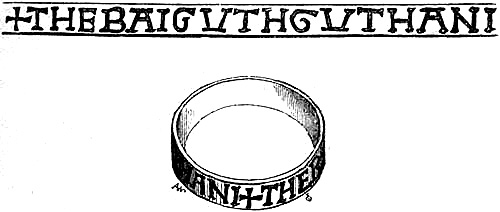

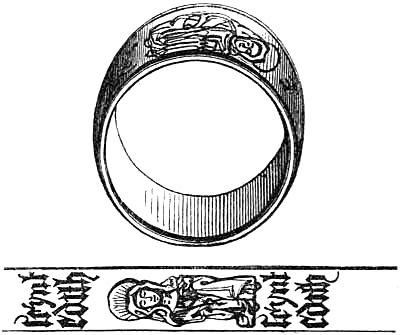

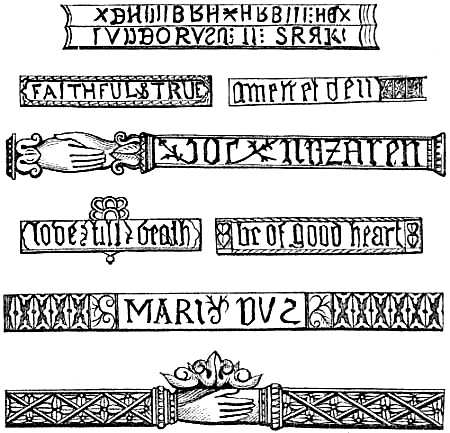

| Inscription rings | 410, 411, 412, 417 |

| New Year’s gift ring | 421, 422 |

| Poison-rings | 433 |

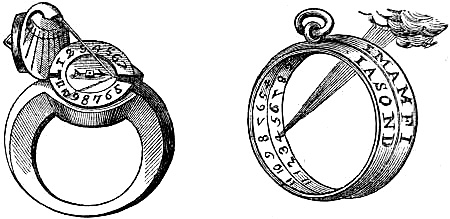

| Dial-rings | 452, 453 |

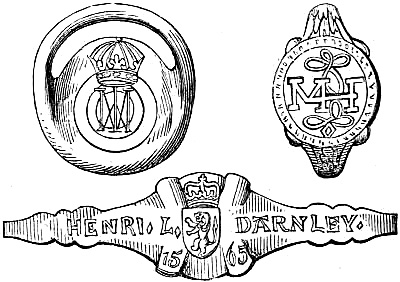

| Signet-ring of Mary, Queen of Scots, and the Darnley ring | 460 |

| [Pg xvi]Supposed ring of Roger, King of Sicily | 465 |

| The Worsley seal-ring | 467 |

| Ring of Saint Louis | 469 |

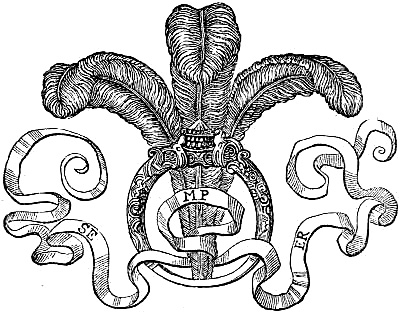

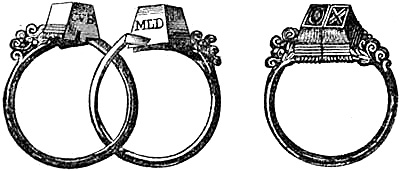

| Ring-devices of the Medici family | 472, 473 |

| Ring found at Kenilworth Castle | 474 |

| Heraldic ring | 481 |

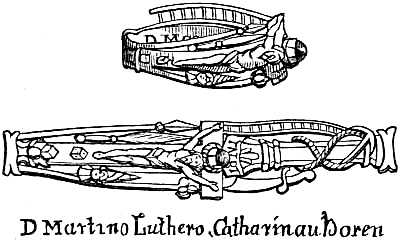

| Martin Luther’s betrothal and marriage rings | 481, 482, 483 |

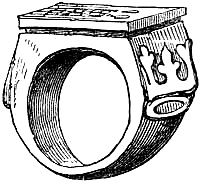

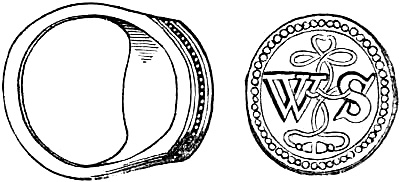

| Shakspeare’s ring (?) | 484 |

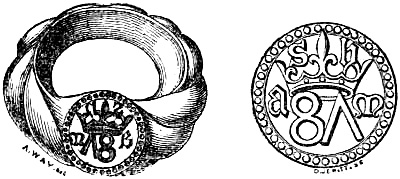

| Initials of Sir Thomas Lucy, at Charlecote Hall | 486 |

| Ivory-turned rings | 488 |

| Squirt ring | 494 |

FINGER-RING LORE.

RINGS FROM THE EARLIEST PERIOD.

The use of signet-rings as symbols of great respect and authority is mentioned in several parts of the Holy Scriptures, from which it would seem that they were then common among persons of rank. They were sometimes wholly of metal, but frequently the inscription was borne on a stone, set in gold or silver. The impression from the signet-ring of a monarch gave the force of a royal decree to any instrument to which it was attached. Hence the delivery or transfer of it gave the power of using the royal name, and created the highest office in the State. In Genesis (xli. 42) we find that Joseph had conferred upon him the royal signet as an insignia of authority.[1] Thus Ahasuerus transferred his[Pg 2] authority to Haman (Esther iii. 12). The ring was also used as a pledge for the performance of a promise: Judah[Pg 3] promised to send Tamar, his daughter-in-law, a kid from his flock, and for fulfilment left with her (at her desire) his signet, his bracelet, and his staff (Genesis xxxviii. 17, 18).

Darius sealed with his ring the mouth of the den of lions (Daniel vi. 17). Queen Jezebel, to destroy Naboth, made use of the ring of Ahab, King of the Israelites, her husband, to seal the counterfeit letters ordering the death of that unfortunate man.

The Scriptures tell us that, when Judith arrayed herself to meet Holofernes, among other rich decorations she wore bracelets, ear-rings, and rings.

The earliest materials of which rings were made was of pure gold, and the metal usually very thin. The Israelitish people wore not only rings on their fingers, but also in their nostrils[2] and ears. Josephus, in the third book of his ‘Antiquities,’ states that they had the use of them after passing the Red Sea, because Moses, on his return from Sinai, found that the men had made the golden calf from their wives’ rings and other ornaments.

Moses permitted the use of gold rings to the priests whom he had established. The nomad people called Midianites, who were conquered by Moses, and eventually overthrown[Pg 4] by Gideon (Numbers xxxi.), possessed large numbers of rings among their personal ornaments.

The Jews wore the signet-ring on the right hand, as appears from a passage in Jeremiah (xxii. 24). The words of the Lord are uttered against Zedekiah: ‘though Coniah the son of Jehoiakim, King of Judah, were the signet on my right hand, yet would I pluck thee thence.’

We are not to assume, however, that all ancient seals, being signets, were rings intended to be worn on the hand. ‘One of the largest Egyptian signets I have seen,’ remarks Sir J. G. Wilkinson, ‘was in possession of a French gentleman of Cairo, which contained twenty pounds’ worth of gold. It consisted of a massive ring, half an inch in its largest diameter, bearing an oblong plinth, on which the devices were engraved, 1 inch long, 6⁄10ths in its greatest, and 4⁄10ths in its smallest, breadth. On one side was the name of a king, the successor of Amunoph III., who lived about fourteen hundred years before Christ; on the other a lion, with the legend “Lord of Strength,” referring to the monarch. On one side a scorpion, and on the other a crocodile.’

This ring passed into the Waterton Dactyliotheca, and is now the property of the South Kensington Museum.

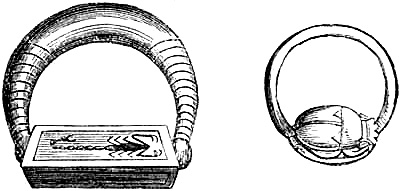

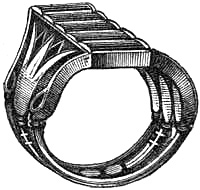

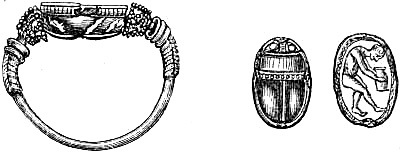

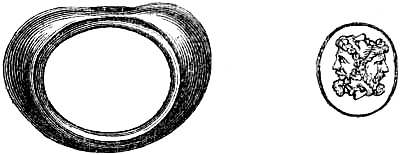

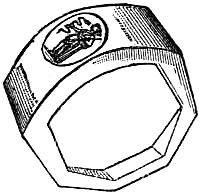

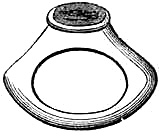

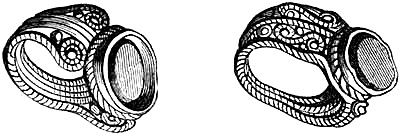

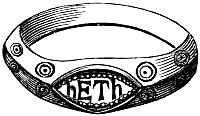

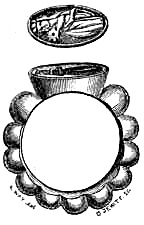

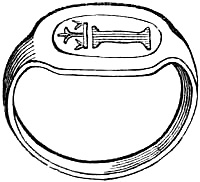

Egyptian Bronze Rings.

Rings of inferior metal, engraved with the king’s name, may, probably, have been worn by officials of the court. In the Londesborough collection is a bronze ring, bearing on[Pg 5] the oval face the name of Amunoph III., the same monarch known to the Greeks as ‘Memnon.’ The other ring, also of bronze, has engraved on the face a scarabæus. Such rings were worn by the Egyptian soldiers.

In the British Museum are some interesting specimens of Egyptian rings with representations of the scarabæus,[3] or beetle. These rings generally bear the name of the wearer,[Pg 6] the name of the monarch in whose reign he lived, and also the emblems of certain deities; they were so set in the gold ring as to allow the scarabæus to revolve on its centre, it being pierced for that purpose.

Colonel Barnet possesses an Egyptian signet-ring formed by a scarabæus set in gold. It was found on the little finger of a splendid gilded mummy at Thebes. In all probability the wearer of the ring had been a royal scribe, as by his side was found a writing-tablet of stone. On the breast was a large scarabæus of green porphyry, set in gold.

The Rev. Henry Mackenzie, of Yarmouth, possesses an Egyptian scarabæus, a signet-ring, set with an intaglio, on cornelian, found in the bed of a deserted branch of the Euphrates, in the district of Hamadân in Persia. The engraving is unfinished, the work is polished in the intaglio, and the date has therefore been supposed not later than the time of the Greeks in Persia, circa 325 B.C.

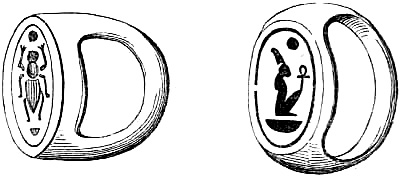

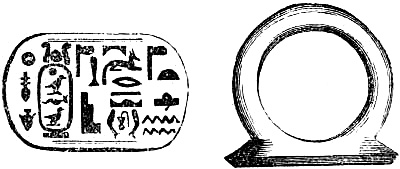

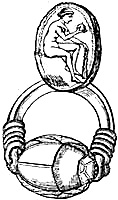

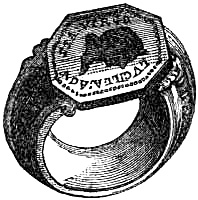

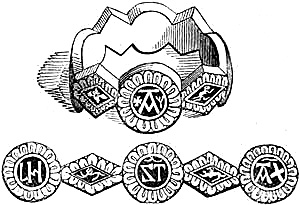

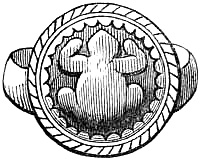

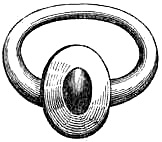

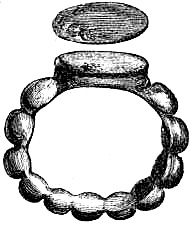

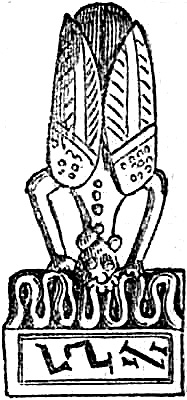

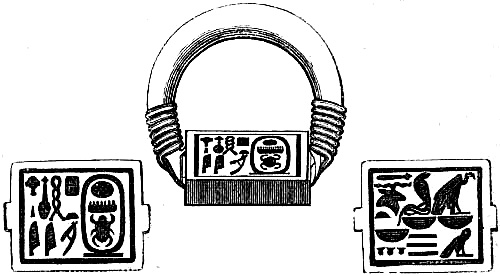

Egyptian Signet-rings.

The representations here given illustrate the large and massive Egyptian signet-ring, and also a lighter kind of hooped signet, ‘as generally worn at a somewhat more recent period in Egypt. The gold loop passes through a small figure of the sacred beetle, the flat under-side being engraved with the device of a crab.’

[Pg 7]In the British Museum, in the first Egyptian Room, is the signet-ring of Queen Sebek-nefru (Sciemiophris). ‘Sebek’ was a popular component of proper names after the twelfth dynasty, probably because this queen was beloved by the people. On Assyrian sculptures are found armlets and bracelets; rings do not appear to have been generally worn.

At a meeting of the Society of Biblical Archæology, in June 1873, Dr. H. F. Talbot, F.R.S., read an interesting paper on the legend of ‘Ishtar descending to Hades,’ in which he translated from the tablets the goddess’s voluntary descent into the Assyrian Inferno. In the cuneiform it is called ‘the land of no return.’ Ishtar passes successively through the seven gates, compelled to surrender her jewels, viz. her crown, ear-rings, head-jewels, frontlets, girdle, finger- and toe-rings, and necklace. A cup full of the Waters of Life is given to her, whereby she returns to the upper world, receiving at each gate of Hades the jewels she had been deprived of in her descent.

Mr. Greene, F.S.A., has an Egyptian gold ring, formerly in the possession of the late Mr. Salt, belonging to the nineteenth dynasty, probably from the Lower Country, below Memphis. It is engraved with a representation of the goddess Nephthis, or Neith. Another gold ring of a later period, from the Upper Country, dates, probably, from the time of Psammitichus, B.C. 671 to 617.

In the collection of Egyptian antiquities formed by the late R. Hay, Esq., of Limplum, N.B., were two Græco-Egyptian gold rings, found, it is conjectured, in the Aasa-seef, near Thebes. One of these is of the usual signet form, but without an inscription; the other is of an Etruscan pattern, and is composed of a spiral wire, whose extremities[Pg 8] end in a twisted loop, with knob-like intersections. Both these objects are of fine workmanship, and are wrought in very pure gold. Sir J. G. Wilkinson, in ‘Manners and Customs of the Ancient Egyptians,’ remarks: ‘The rings were mostly of gold, and this metal seems always to have been preferred to silver for rings and other articles of jewellery. Silver rings are, however, occasionally to be met with, and two in my possession, which were accidentally found in a temple at Thebes, are engraved with hieroglyphics, containing the name of the royal city. Bronze was seldom used for rings; some have been discovered of brass and iron (of a Roman time), but ivory and blue porcelain were the materials of which those worn by the lower classes were usually made.’

The Rev. C. W. King observes: ‘I have seen finger-rings of ivory of the Egyptian period, their heads engraved with sphinxes and figures of eyes cut in low relief as camei, and originally coloured.’

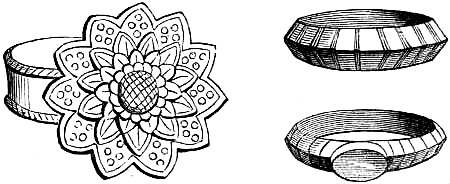

The porcelain finger-rings of ancient Egypt are extremely beautiful, the band of the ring being seldom above one eighth of an inch in thickness. Some have a plate in which in bas-relief is the god Baal, full-faced, playing on the tambourine, as the inventor of music; others have their plates in the shape of the right symbolical eye, the emblem of the sun, of a fish of the perch species, or of a scarabæus. Some few represent flowers. Those which have elliptical plates with hieroglyphical inscriptions bear the names of Amen-Ra, and of other gods and monarchs, as Amenophis III., Amenophis IV., and Amenmest of the eighteenth and nineteenth dynasties. One of these rings has a little bugle on each side, as if it had been strung on the beaded work of a mummy, instead of being placed on the finger.[Pg 9] Blue is the prevalent colour, but a few white and yellow rings, and some even ornamented with red and purple colours, have been discovered. It is scarcely credible that these rings, of a substance finer and more fragile than glass, were worn during life, and it seems hardly likely that they were worn by the poorer classes, for the use of the king’s name on sepulchral objects seems to have been restricted to functionaries of state. Some larger rings of porcelain of about an inch in diameter, seven-eighths of an inch broad, and one-sixteenth of an inch thick, made in open work, represents the constantly-repeated lotus-flowers, and the god Ra, or the sun, seated and floating through the heavens in his boat.

At the Winchester meeting of the Archæological Institute in 1845 a curious swivel-ring of blue porcelain was exhibited, found at Abydus in Upper Egypt; setting modern. It has a double impression: on the one side is the king making an offering to the gods, with the emblems of life and purity; on the other side the name of the monarch in the usual ‘cartouche,’ one that is well known, being that of Thothmes III., whom Wilkinson supposes to have been the Pharaoh of Exodus. It is worthy of remark that this cartouche is ‘supported’ by asps, which are usually considered to be the attributes of royalty.

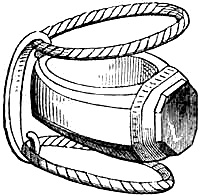

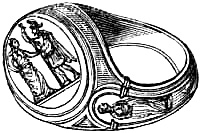

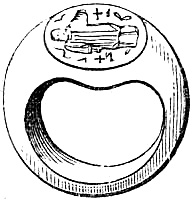

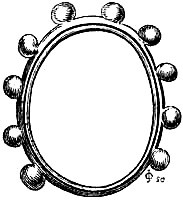

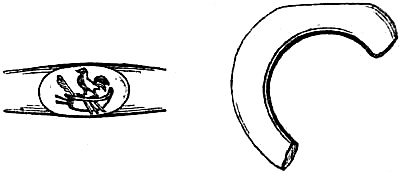

Egyptian Porcelain Ring.

The annexed engraving represents an Egyptian ring, en pâte céramique, from M. Dieulafait’s ‘Diamants et Pierres Précieuses.’

The signet of Sennacherib in the British Museum is made of Amazon stone, one of the hardest stones known to the lapidary, and bears an intaglio ‘which,’ observes the[Pg 10] Rev. C. W. King, ‘by its extreme minuteness, and the precision of the drawing, displays the excellence to which the art had already attained.’

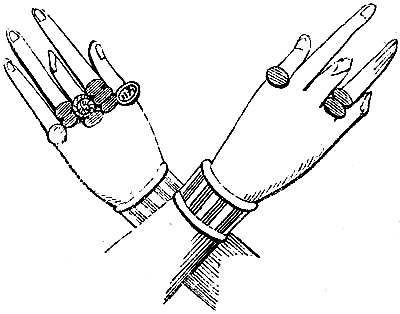

On a mummy-case in the British Museum is a representation of a woman with crossed hands, covered with rings; the left hand is most loaded. Upon the thumb is a signet with hieroglyphics on the surface, three rings on the forefinger, two on the second, one formed like a snail shell, the same number on the next, and one on the little finger. The right hand carries only a thumb ring, and two upon the third finger.

Rings on the fingers of a Mummy.

Sir J. G. Wilkinson observes: ‘The left was considered the hand peculiarly privileged to bear these ornaments; and it is remarkable that its third finger was decorated with a greater number than any other, and was considered by them, as by us, par excellence, the ring-finger, though there is no evidence of its having been so honoured at the marriage ceremony.’

The same author mentions that rings were a favourite decoration among the Egyptians; women wore sometimes[Pg 11] two or three on the same finger. They were frequently worn on the thumb. Some were simple, others had an engraved stone, and frequently bore the name of the owner; others the monarch in whose time he lived, and they were occasionally in the form of a snail, a knot, a snake, or some fancy device. A cat—emblem of the goddess Bast, or Pasht, the Egyptian Diana—was a favourite subject for ladies’ rings.

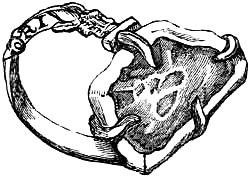

Egyptian Gold Ring, from Ghizeh.

One of the oldest, if not the most ancient ring known, is supposed to be that in the collection of Dr. Abbot, of Cairo, now preserved with his other Egyptian antiquities at New York. It is thus described by him:—‘This remarkable piece of antiquity is in the highest state of preservation, and was found at Ghizeh, in a tomb near the excavation of Colonel Vyse, called Campbell’s tomb. It is of fine gold, and weighs nearly three sovereigns. The style of the hieroglyphics within the oval make the name of that Pharaoh (Cheops, Shofo) of whom the pyramid was the tomb. The details are minutely accurate and beautifully executed. The heaven is engraved with stars; the fox or jackal has significant lines within its contour; the hatchets have their handles bound with thongs, as is usual in the sculptures; the volumes have the strings which bind them hanging below the roll—differing in this respect from any[Pg 12] example in sculptured or painted hieroglyphics. The determinative for country is studded with dots, representing the land of the mountains at the margin of the valley of Egypt. The instrument, as in the larger hieroglyphics, has the tongue and semi-lunar mark of the sculptured examples; as is the case also with the heart-shaped vase. The name is surmounted with the globe and feathers, decorated in the usual manner; and the ring of the cartouche is engraved with marks representing a rope, never seen in the sculptures; and the only instance of a royal name similarly encircled is a porcelain example in this collection, inclosing the name of the father of Sesostris. The O in the name is placed as in the examples sculptured in the tombs, not in the axis of the cartouche; the chickens have their unfledged wings; the cerastes its horns, now only to be seen with a magnifying glass.’

In a lecture to the deaf and dumb in St. Saviour’s Hall, Oxford Street, London (October 1875), on ‘Eastern Manners and Customs,’ amongst various relics exhibited was the hand of a female mummy, on one finger of which was a gold ring, with the signet of one of the Pharaohs.

A gold ring exhibited at the exhibition of antiquities at the Ironmongers’ Hall, in 1861, had hieroglyphics meaning ‘protected by the living goddess Mu.’

Among some interesting specimens of Egyptian rings exhibited at the South Kensington Loan Exhibition of 1872 I may mention an antique ring of pale gold, with a long oval bezel chased in intaglio, with representation of a sistrum (timbrel, used by the Egyptians in their religious ceremonies), the property of Viscount Hawarden; an antique ring of pale gold (belonging to Lady Ashburton), formed of a slender wire, the ends twisted round the[Pg 13] shoulders, upon which is strung a signet, in form of a cat, made of greenish-blue glazed earthenware.

From the collection of R. H. Soden Smith, Esq. F.S.A., an ancient pale gold ring, with revolving cylinders of lapis-lazuli, engraved with hieroglyphics; the shoulders of the hoop wrapped round with wire ornament.

The Waterton Collection contains Egyptian rings of various descriptions: one of silver, with revolving bezel of cornelian representing the symbolical right eye. Several rings of glazed earthenware; one of gold, very massive, with revolving scarab of glazed earthenware, partially encased in gold. A gold ring, the hoop of close-corded work, revolving bezel with blood-stone scarab, engraved with Hathor and child. The same engraving is on a gold signet-ring, with vesica-shaped bezel, and upon a white-metal ring, where the figures are surrounded by lotus-flowers. Another gold signet-ring is engraved with the figure of Amen-ra; a probably Egyptian white-metal ring, with narrow oblong bezel, engraved with a frieze of figures, and winged Genii, divided by candelabra.

Several of the Egyptian rings in the Museum of the Louvre at Paris date from the reign of King Mœris. One of the oldest rings extant is that of Cheops, the founder of the Great Pyramid, which was found in a tomb there. It is of gold, with hieroglyphics.

The Egyptian glass-workers produced small mosaics of the most minute and delicate finish, and sufficiently small to be worn on rings.

Dr. Birch, in a very interesting paper communicated to the Society of Antiquaries, at the meeting of November 17, 1870, observes, with regard to the scarabæi and signet-rings of the ancient Egyptians, that the use of these curious[Pg 14] objects (the exhibition comprising upwards of five hundred scarabs from the collection of Egyptian antiquities formed by the late R. Hay, Esq., of Sinplum, N.B., to which I have alluded) dates back from a remote period of Egyptian history. ‘As it is well known, they were not merely made in porcelain, but also in steatite, or stea-schist, and the various semi-precious stones suitable for engraving, such as cornelian, sard, and such-like.’ In the time of the twelfth dynasty the cylindrical ring, also found in use among the Assyrians and Babylonians, came into vogue. The hard stones and gems were of later introduction, probably under the influence of Greek art, for the ancient Egyptians themselves do not appear to have possessed the method of cutting such hard substances. A few, however, exist, which are clearly of great antiquity—as, for example, a specimen in yellow jasper now in the British Museum.

The principal purpose to which these scarabs were applied was to form the revolving bezel of a signet-ring, the substance in which the impression was taken being a soft clay, with which a letter was sealed.

It is singular that some of these objects have been found in rings fixed with the plane engraved side inwards, rendering them unfit for the purposes of sealing. It is well known that the use of these scarabs was so extensive as to have prevailed beyond Egypt, being adopted by the Phœnicians and the Etruscans.

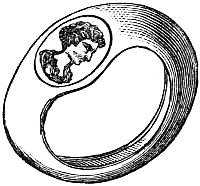

On this subject the Rev. C. W. King remarks that gold rings, even of the Etruscan period, are very rare, the signets of that nation still retaining the form of scarabæi. ‘The most magnificent Etruscan ring known, belonging once to the Prince de Canino, and now in the matchless collection of antique gems in the British Museum, is formed of the[Pg 15] fore-parts of two lions, whose bodies compose the shank, whilst their heads and fore-paws support the signet—a small sand scarab, engraved with a lion regardant, and set in an elegant bezel of filagree-work. The two lions are beaten up in full relief of thin gold plate, in a stiff archaic style, but very carefully finished.’

The Waterton Collection contains a gold ring of Etruscan workmanship, of singular beauty. It is described by Padre Geruchi, of the Sacred College, as a betrothal or nuptial ring. It has figures of Hercules and Juno placed back to back on the hoop, having their arms raised above their heads. Hercules is covered with the skin of a lion, Juno with that of a goat.

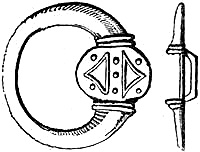

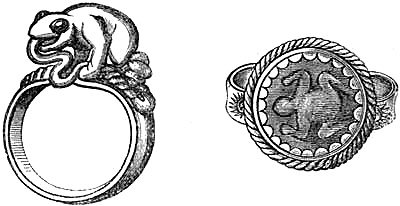

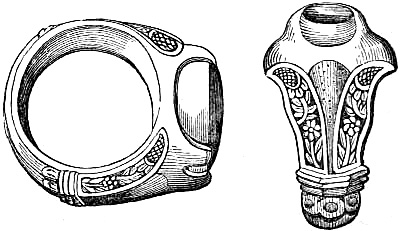

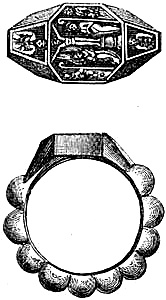

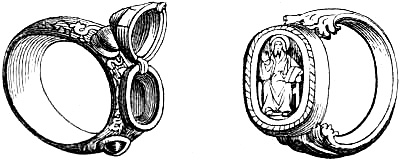

|

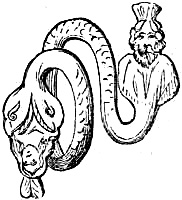

| |

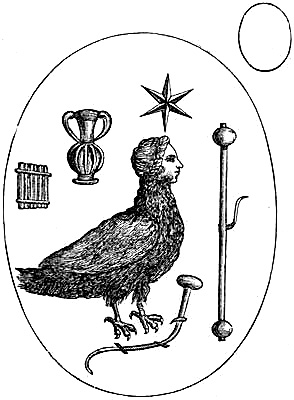

| Etruscan, with Chimeræ. | Roman-Egyptian. |

Fairholt, in ‘Rambles of an Archæologist,’ describes an ancient Etruscan ring in the British Museum, with chimeræ on it opposing each other. The style and treatment partake largely of ancient Eastern art. There is also in the same collection a remarkable ring having the convolutions of a serpent, the head of Serapis at one extremity and of Isis at the other; by this arrangement one or other of them would always be correctly posited; it has, also, the further advantage of being flexible, owing to the great sweep of its curve. Silver rings are rarer than those of gold in[Pg 16] the tombs of Etruria, and iron and bronze examples are gilt.

All the Hindoo Mogul divinities of antiquity had rings; the statues of the gods at Elephanta, supposed to be of the highest antiquity, had finger-rings.

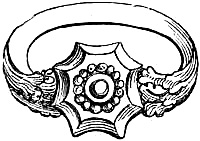

The Rev. C. W. King describes a ring in the Waterton collection, of remarkable interest—apparently dating from the Lower Empire, for the head is much thrown up, and has the sides pierced into a pattern, the ‘interrasile opus, so much in fashion during those times. It is set with two diamonds of (probably) a carat each: one a perfect octahedron of considerable lustre, the other duller and irregularly crystallised. Another such example might be sought for in vain throughout the largest cabinets of Europe.’

After the conquest of Asia Alexander the Great used the signet-ring of Darius to seal his edicts to the Persians; his own signet he used for those addressed to the Greeks.

Xerxes, King of Persia, was a great gem-fancier, but his chief signet was a portrait, either of himself, or of Cyrus, the founder of the monarchy. He also wore a ring with the figure of Anaitis, the Babylonian Venus, upon it. Thucydides says that the Persian kings honoured their subjects by giving them rings with the likenesses of Darius and Cyrus.

The late Mr. Fairholt purchased in Cairo a ring worn by an Egyptian lady of the higher class. It is a simple hoop of twisted gold, to which hangs a series of pendant ornaments, consisting of small beads of coral, and thin plates of gold, cut to represent the leaves of a plant. As the hands move, these ornaments play about the finger, and a very brilliant effect might be produced if diamonds were used in the pendants.

[Pg 17]The rings worn by the middle class of Egyptian men are usually of silver, set with mineral stones, and are valued as the work of the silversmiths of Mecca, that sacred city being supposed to exert a holy influence on all the works it originates.

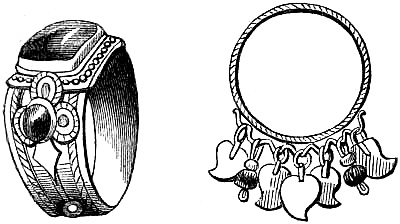

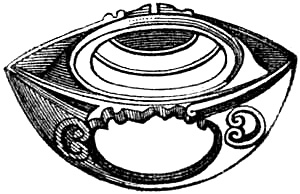

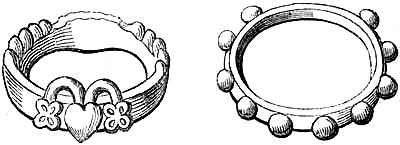

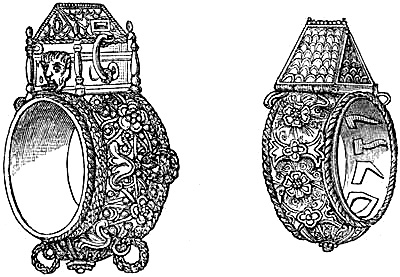

Modern Egyptian Rings.

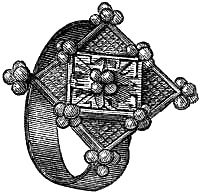

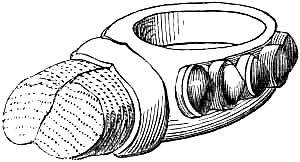

A curious ring with a double keeper is worn by Egyptian men. It is composed entirely of common cast silver, set with mineral stone. The lowermost keeper, of twisted wire, is first put on the finger, then follows the ring. The second keeper is then brought down upon it: the two being held by a brace which passes at the back of the ring, and gives security to the whole.

Modern Egyptian Ring,

with Double Keepers.

Tavernier states in his ‘Travels’ that the Persians did not make gold rings, their religion forbidding the wearing of any article of that metal during prayers, it would have been too troublesome to take them off every time they performed their devotions. The gems mounted in gold rings, sold by Tavernier to the King, were reset in silver by native workmen.

[Pg 18]The custom of wearing rings may have been introduced into Greece from Asia, and into Italy from Greece. They served the twofold purpose, ornamental and useful, being employed as a seal, which was called sphragis, a name given to the gem or stone on which figures were engraved. The Homeric poems make mention of ear-rings only, but in the later Greek legends the ancient heroes are represented as wearing finger-rings. Counterfeit stones in rings are mentioned in the time of Solon. Transparent stones when extracted from the remains of the original iron-rings of the ancients are sometimes found backed by a leaf of red gold as a foil.[4] The use of coloured foils was merely to deceive and impose upon the unwary, by giving to a very inferior jewel the finest colour. Solon made a law prohibiting sellers of rings from keeping the model of a ring they had sold.

The Lacedæmonians, according to the laws of Lycurgus, had only iron rings, despising those of gold; either that the King devised thereby to retrench luxury, or not to permit the use of them.

The Etruscans and the Sabines wore rings at the period of the foundation of Rome, 753 B.C.

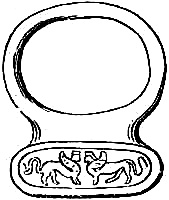

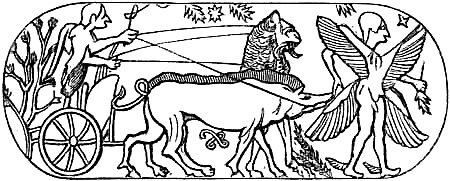

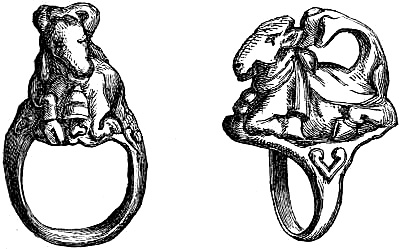

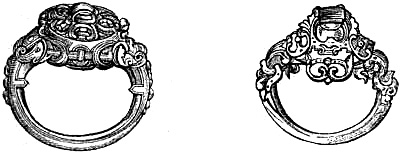

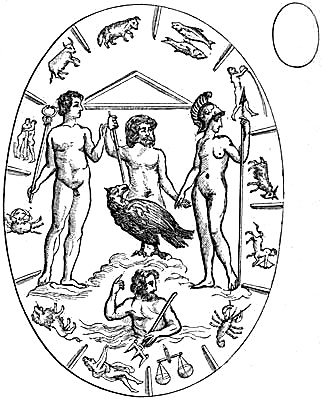

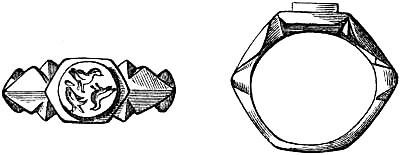

The Etruscans made rings of great value. They have been found of every variety—with precious stones, of massive gold, very solid, with engraved stones of remarkable beauty. Among Etruscan rings in the Musée Nap. III. the table of one offers a representation, enlarged, of the story of Admētus, the King of Pheræ in Thessaly. He took part in the expedition of the Argonauts, and sued for the hand of Alcestis, the daughter of Pelias, who promised him to her on condition that he should come to her in a chariot drawn[Pg 19] by lions and boars. This feat Admētus performed by the assistance of Apollo, who served him, according to some accounts, out of attachment to him, or, according to others, because he was obliged to serve a mortal for one year, for having slain the Cyclops.

Etruscan (Admētus).

Representation of Admētus.

Etrusca.

Among rings taken out of the tombs there are some in the form of a knot or of a serpent. They are frequently found with shields of gold, and of that form which we call Gothic, that is elliptical and pointed, called by foreigners ogive, with raised subjects chiselled on the gold, or with onyxs of the same form, but polished and surrounded with gold.[Pg 20] There are some particular rings which appear more adapted to be used as seals than rings, and they have on the shields, relievos of much more arched, and almost Egyptian, form.[5]

Etruscan.

Etruscan.

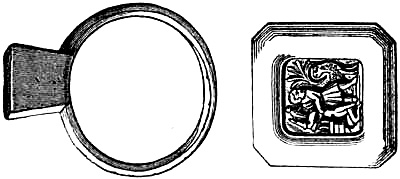

Among the antique jewels at the Bibliothèque Nationale at Paris are two fine specimens of Etruscan rings. One is of gold, on which is a scarabæus in cornelian; the stomach of the scarabæus is engraved hollow and represents a naked man holding a vase. The other is a gold ring found in a tomb at Etruria, of which the bezel, sculptured in relief, could not serve as a seal. The subject is a divinity combating with two spirits, a representation of the eastern idea of the struggles between the two principles of good and evil, such as are found on numerous cylinders that come from the borders of the Euphrates and the Tigris. This analogy between the religious ideas of the Etruscans and those of the most ancient monuments of the East is not[Pg 21] astonishing when it is shown that the Etruscans, the ancient inhabitants of Italy, were originally from Asia. The following engraving represents an intaglio on a scarabæus ring, of fine workmanship, preserved in Vienna.

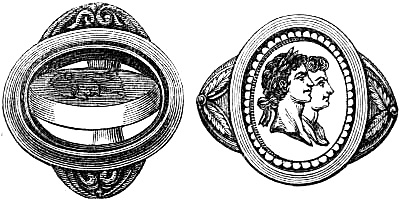

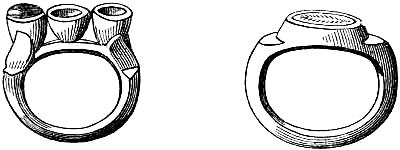

At a meeting of the Archæological Institute (May 3, 1850) the Dowager Duchess of Cleveland exhibited a curious Roman ring of pure gold (weight 182 grains), of which an illustration is given in the Journal of the Institute (vol. vii. p. 190). ‘It was found, with other remains, at Pierse Bridge (Ad Tisam), county of Durham, where the vestiges of a rectangular encampment may be distinctly traced. The hoop, wrought by the hammer, is joined by welding the extremities together; to this is attached an oval facet, the metal engraved in intaglio, the impress being two human heads respectant, probably male and female—the prototype of the numerous “love seals” of a later period. The device on the ring is somewhat effaced, but evidently represented two persons gazing at each other. This is not the first Roman example of the kind found in England. The device appears on a ring, apparently of that period, found on Stanmore Common in 1781. On the mediæval seals alluded to, the heads are usually accompanied by the motto “Love me, and I thee,” to which, also, a counterpart is found among relics of a more remote age. Galeotti, in his curious illustrations of the “Gemmæ Antiquæ Litteratæ,” in the collection of Ficoroni, gives an intaglio engraved with the words “Amo te, ama me.”’

Etruscan.

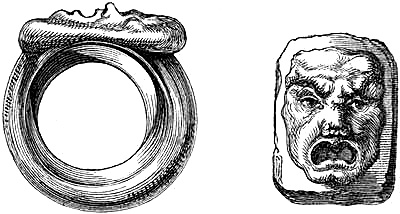

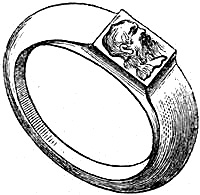

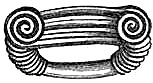

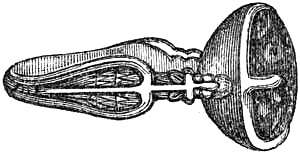

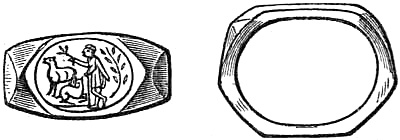

[Pg 22]The following engravings represent: A ring in the Musée du Louvre, with a lion sculptured by a Greek artist, in an oriental cornelian; the reverse has an intaglio of a lion couchant. The second, from the Webb Collection, is that of an ancient Greek ring, of solid gold, with the representation of a comic mask in high relief. The other, a gold ring with a bearded mask, Roman, in the Waterton Collection at the South Kensington Museum—also in high relief—has the shoulders thickened with fillets, engraved with stars.

|

|

| ||

| Greek. | Greek. | Roman. |

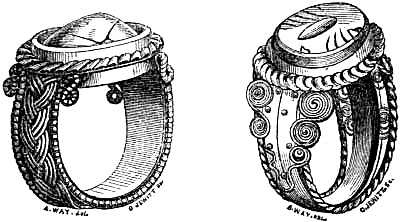

A singular discovery of Roman relics was made in 1824 at Terling Place, near Witham, Essex, by some workmen forming a new road; the earth being soaked by heavy rains the cart-wheels sank up to their naves. The driver of the cart saw some white spots upon the mud adhering to the wheels, which proved to be coins. On further search a small vase was discovered in which had been deposited with some coins, two gold rings, which are interesting examples of late Roman work; and representations of these, by Lord Rayleigh’s permission, were given in the ‘Journal of the Archæological Institute’ (vol. iii. p. 163) and are here shown. One of the rings is set with a colourless crackly crystal, or pasta, uncut and en cabochon; the other with a paste formed of two layers, the upper being of a dull smalt colour, the[Pg 23] lower dark brown. The device is apparently an ear of corn.

Late Roman.

The Hertz Collection contained a well-formed octahedral diamond, about a carat in weight, set open in a Roman ring of unquestionable authenticity.

At the Loan Exhibition of Ancient and Modern Jewellery at the South Kensington Museum, in 1872, John Evans Esq., F.S.A., contributed a series of seven rings, gold and silver, Roman, set with antique stones; one very massive, of silver and gold, set with intaglio on nicolo onyx; one with an angular hoop, and another with beaded ornaments.

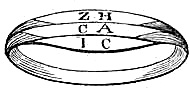

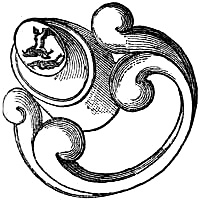

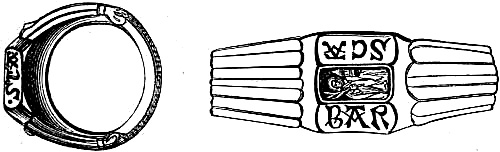

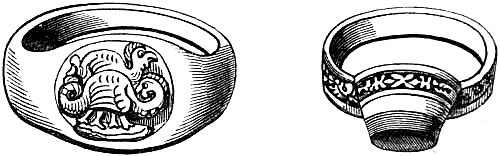

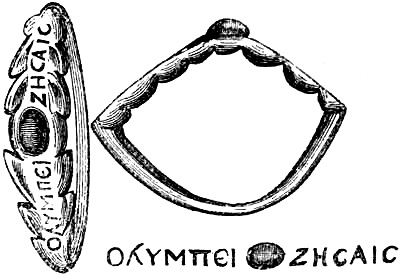

‘Though,’ remarks Mr. Fairholt, ‘a great variety of form and detail was adopted by Greek and Roman goldsmiths for the rings they so largely manufactured, the most general and lasting resembled a Roman ring, probably of the time of Hadrian, which is said to have been found in the Roman camp at Silchester, Berkshire. The gold of the ring is massive at the face, making a strong setting for the cornelian, which is engraved with the figure of a female bearing corn and fruit. By far the greater majority of Roman rings exhumed at home and abroad are of this fashion, which recommends itself by a dignified simplicity, telling by quantity and quality of metal and stone its true value,[Pg 24] without any obtrusive aid.’ Sometimes a single ring was constructed to appear like a group of two or three upon the finger. Mr. Charles Edwards, of New York, in his ‘History and Poetry of Finger Rings,’ has given an example of this kind of ring. Upon the wide part of each are two letters, the whole forming ‘ZHCAIC,’ mayst thou live!

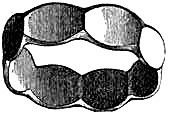

|

| |

| Ring found at Silchester. | Group Pattern. |

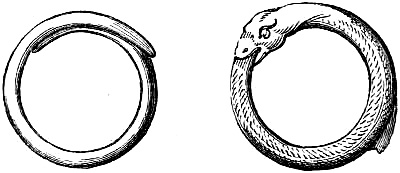

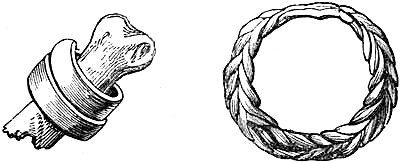

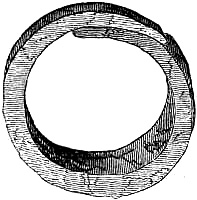

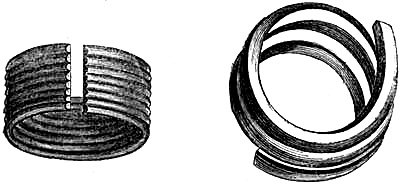

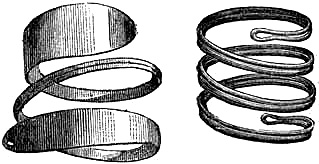

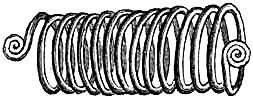

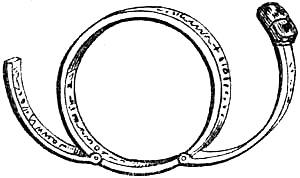

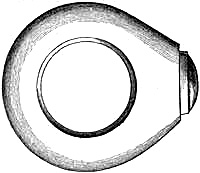

‘The simplest and most useful form of rings, and that by consequence adopted by people of all early nations, was the plain elastic hoop. Cheap in construction and convenient in wear, it may be safely said to have been generally patronised from the most ancient to the most modern times.’ An engraving by Mr. Fairholt represents ‘the old form of a ring made in the shape of a coiled serpent, equally ancient, equally far-spread in the old world, and which has had a very large sale among ourselves as a decided novelty. In fact, it has been the most successful design our ring-makers have produced of late years.’

Ancient Plain Rings.

The statues of Numa and Servius Tullius were represented with rings, while those of the other Kings had none;[Pg 25] which would induce the belief that the use of rings was little known in the early days of Rome. Pliny[6] states that the first date in Roman history in which he could trace any general use of rings was in A.U.C. 449, in the time of Cneius Flavius, the son of Annius. Less than a century before Christ, Mithridates, the famous King of Pontus, possessed a museum of signet-rings; later, Scaurus, the stepson of the Dictator, Sylla, had a collection of signet-rings, but inferior to that of Mithridates, which, having become the spoil of Pompey, was presented by him to the Capitol.

In Rome every freeman had the right to use the iron ring, which was worn to the last period of the Republic, by such men as loved the simplicity of the good old times. Among these was Marius, who, as Pliny tells us, wore an iron ring in his triumph after the subjugation of Jugurtha. In the early days of the Empire the jus annuli seems to have elevated the wearer to the equestrian order. Those who committed any crime forfeited the distinction, and this shows us the estimation in which the ring, as an emblem of honour, was regarded.

Iron Ring of a

Roman Knight.

We are told of Cæsar that when addressing his soldiers after the passage of the Rubicon he often held up the little finger of his left hand, protesting that he would pledge even to his ring to satisfy the claims of those who defended his cause. The soldiers of the furthest ranks, who could see but not hear him, mistaking the gesture, imagined that he was promising to each man the dignity of a Roman Knight.

Gold rings appear to have been first worn by ambassadors[Pg 26] to a foreign State, but only during a diplomatic mission; in private they wore their iron ones.

In the course of time it became customary for all the senators, chief magistrates, and the equites to wear a gold seal-ring. This practice, which was subsequently termed the jus annuli aurei, or the jus annulorum, remained for several centuries at Rome their exclusive privilege, while others continued to wear the iron ring. In Plutarch’s Life of Caius Marius he mentions that the slaves of Cornutus concealed their master at home, and hanging up by the neck the body of some obscure person, and putting a gold ring on his finger, they showed him to the guards of Marius, and then wrapping up the body as if it were their master’s, they interred it.

Magistrates and governors of provinces seem to have possessed the privilege of conferring upon inferior officers, or such persons as had distinguished themselves, the right of wearing a gold ring. Verres thus presented his secretary with a gold ring in the assembly at Syracuse.

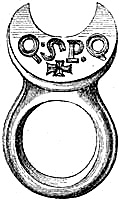

Roman.

Montfaucon mentions in his ‘Antiquity Explained’ (English Edition, 1722, vol. iii. p. 146), a Greek seal-ring, which has the shape of a crescent. An illustration is here given of a similarly-formed Roman ring, with the letters Q. S. P. Q., Quintanus Senatus Populusque, from the ‘Gemmæ Antiquæ Litteratæ.’

Some wore rings of gold, covered with a plate of iron. Trimalchion wore two rings, one upon the little finger of his left hand, which was a large gilt one, and the other of gold, set with stars of iron upon the middle of the ring-finger.[Pg 27] Some rings were hollow, and others solid. The Flamines Diales could only wear the former.

During the Empire the right of granting the privilege of a gold ring belonged to the emperors, and some were not very scrupulous in conferring this distinction.

Severus and Aurelian granted this privilege to all Roman soldiers; Justinian allowed all citizens of the empire to wear such rings.

But there always seems to have been a difficulty in restricting the use of the gold ring. Tiberius (A.D. 22) allowed its use to all whose fathers and grandfathers had property of the value of 400,000 sestertia (3,230l.). The restriction, however, was of little avail, and the ambition for the annulus aureus became greater than it had ever been before.

Juvenal, in his eleventh ‘Satire,’ alludes to a spendthrift who, after consuming his estate, has nothing but his ring:—

At length, when nought remains a meal to bring,

The last poor shift, off comes the Knightly ring,

And sad Sir Pollio begs his daily fare,

With undistinguished hands, and fingers bare.

Martial attacks a person under the name of Zoilus, who had been raised from a state of servitude to Knighthood, and was determined to make the ring, the badge of his new honour, sufficiently conspicuous:—

Zoile, quid tota gemmam præcingere libra

Te juvat, et miserum perdire sardonycha?

Annulus iste tuus fuerat modo cruribus aptus;

Non eadem digitis pondera conveniunt.

The keeping of the imperial ring (cura annuli) was confided to a state keeper, as the Great Seal with us is placed in custody of the Lord Chancellor.

[Pg 28]With the increasing love of luxury and show, the Romans, as well as the Greeks, covered their fingers with rings, and some wore different ones for summer and winter, immoderate both in number and size.[7] The accompanying illustrations represent a huge ring of coloured paste, all of one piece, blue colour—one of the rings of inexpensive manufacture in popular use among the lower classes. It is smaller on one side, to occupy less space on the index or little finger.

Roman.

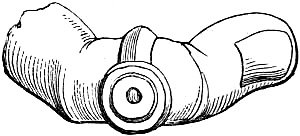

The following illustrates a supposed Gallo-Roman ring of outrageous proportions, similar to those complained of by Livy (xxxiii., see Appendix), for their extravagant size. It is of bronze, and supposed to represent a cow or bull seated, with a bell round the neck.

Heavy rings of gold of a sharp triangular outline were worn on the little finger in the later time of the Empire. A thumb-ring[Pg 29] of unusual magnitude and of costly material is represented in Montfaucon. It bears the bust in high relief of the Empress Plotina, the consort of Trajan: she is[Pg 30] represented with the imperial diadem. It is supposed to have decorated the hand of some member of the imperial family. The Rev. C. W. King mentions a ring in the Fould Collection (dispersed by auction in 1860), the weight of which, although intended for the little finger, was three ounces. It was set with a large Oriental onyx, not engraved.

Supposed Gallo-Roman.

Roman Thumb-ring.

Juvenal alludes to the ‘season’ rings:—

Charged with light summer rings his fingers sweat,

Unable to support a gem of weight.

The custom of wearing numerous rings must have been at a comparatively early period: it is alluded to both by Plato and Aristophanes. According to Martial, one Clarinus wore daily no less than sixty rings: ‘Senos Clarinus omnibus digitis gerit,’ and, what is more remarkable, he loved to sleep wearing them, ‘nec nocte ponit annulos.’ Quintilian notices the custom of wearing numerous rings: ‘The hand must not be overloaded with rings, especially with such as do not pass over the middle joints of the finger.’ Demosthenes wore many rings and he was stigmatised as unbecomingly vain for doing so in the troubled times of the State.

Seneca, describing the luxury and ostentation of the time, says: ‘We adorn our fingers with rings, and a jewel is displayed on every joint.’

As a proof of the universality of gold rings as ornaments in ancient times, we are told that three bushels of them were gathered out of the spoils after Hannibal’s victory at Cannæ. This was after the second Punic war.

According to Mr. Waterton it is believed that gems were not mounted in rings prior to the LXII. Olympiad.

Nero, we are informed, during his choral exhibitions in[Pg 31] the circus, was attended by children, each of whom wore a gold ring. Galba’s guard, of the Equites, had gold rings as a distinguishing badge.

Rock crystal appears to have been much in use among the Romans for making solid finger-rings carved out of one single piece, the face engraved with some intaglio serving for a signet.

‘All those known to me,’ remarks the Rev. C. W. King in ‘Precious Stones,’ &c., ‘have the shank moulded into a twisted cable; one example bore for device the Christian monogram, which indicates the date of the fashion. It would seem that these rings superseded and answered the same purpose as the balls of crystal carried at an earlier period by ladies in their hands for the sake of the delicious coolness during the summer heat.’

Stone rings were in common use, formed chiefly of chalcedony. ‘It is most probable,’ remarks the Rev. C. W. King, ‘that the first ideas of these stone rings were borrowed by the Romans from the Persian conical and hemispherical seals in the same material. Some of these latter have their sides flattened, and ornamented with divers patterns, and thus assume the form of a finger-ring, with an enormously massy shank and very small opening, sufficient, however, to admit the little finger. And this theory of their origin is corroborated by the circumstance that all these Lower Roman examples belong to the times of the Empire, none being ever met with of an early date.’

Silver rings were common: Pliny relates that Arellius Fuscus, when expelled from the equestrian order, and thus deprived of the right of wearing a gold ring, appeared in public with silver rings on his fingers.

Among the ancient jewels in the Bibliothèque Nationale[Pg 32] at Paris is a fine Roman ring, of which the bezel, a cornelian graved hollow, represents a Janus with four faces.

Roman.

Another Roman ring, also of gold, is attributed to the epoch of the Emperor Hadrian. The three golden figures represented on it are those of Egyptian deities, which have suffered under the hands of a Roman jeweller. It is, however, possible to distinguish them as one of the most important of the Egyptian Pantheon; that is to say, Horus, Isis, and Nephtys. Isis-Hathor is shown with cow’s ears; she has near her Horus-Harpocrates, her son, who is crowned with the schent; the mother and child rise from a lotus flower: on the left is Nephtys, crowned with a hieroglyphic emblem, accidentally incomplete, but the signification of which is the name even of this divinity, ‘the lady of this house.’

Roman.

Montfaucon, in his ‘L’Antiquité Expliquée,’ describes a ring with a gem engraved representing Bellerophon, Pegasus, and the Chimæra. The hero, riding on his famous horse, in the air, throws a dart at the monster below, whose first head is that of a lion, the goat’s head appears on her back, and her tail terminates in a large head of a serpent. This ring was found on the road to Tivoli, among some ashes of a dead body.

Representation of a ring

ornamented with busts

of divinities. From the

Musée du Louvre.

Montfaucon gives the contents of a Roman lady’s jewel box cut upon the pedestal supporting a statue of Isis, and amongst other rich articles for female decoration are, for her little finger, two rings with diamonds; on the next finger a ring with many gems (polypsephus), emeralds, and one pearl. On the top joint of the same finger, a ring with an emerald. The Roman ladies were prodigal in their display of rings: we read that Faustina spent 40,000l. of our money, and Domitia 60,000l. for single rings. Greek women wore chiefly ivory and amber rings, and these were less costly and numerous than those used by men.

The Rev. C. W. King remarks of Roman rings that if of early date, and set with good intagli, they are almost invariably hollow and light, and consequently are easily crushed. Cicero relates of L. Piso, that ‘while prætor in Spain he was going through the military exercises, when the gold ring which he wore was, by some accident, broken and crushed. Wishing to have another ring made for himself, he ordered a goldsmith to be summoned to the forum at Cordova, in front of his own judgment-seat, and weighed out the gold to him in public. He ordered the man to set down his bench in the forum, and make the ring for him in the presence of all, to prove that he had not employed the gold of the public treasury, but had made use only of his broken ring.’

The signs engraved on rings were very various, including portraits of friends and ancestors, and subjects connected with mythology and religion. In the reign of Claudius no[Pg 34] ring was to bear the portrait of the emperor without a special licence, but Vespasian, some time after, issued an edict, permitting the imperial image to be engraven on rings and brooches. Besides the figures of great personages, there were also representations of popular events: thus, on Pompey’s ring, like that of Sylla, were three trophies, emblems of his three victories in Europe, Asia, and Africa. After the murder of this great general, his seal-ring, as Plutarch tells us, was brought to Cæsar, who shed tears on receiving it. The Roman senate refused to credit the news of the death of Pompey, until Cæsar produced before them his seal-ring.

Head of Regulus,

between cornucopiæ.

On the ring of Julius Cæsar was a representation of an armed Venus, as he claimed to be a descendant of the goddess. This device was adopted by his partisans; on that of Augustus, first a sphinx; afterwards the image of Alexander the Great, and at last, his own portrait, which succeeding emperors continued to use.[8]

Among the ancients the figures engraved on rings were not hereditary, and each assumed that which pleased him. Numa had made a law prohibiting representations of the[Pg 35] gods, but custom abrogated the ordinance, and the Romans had engraved in their rings not only figures of their own deities, but those of other countries, especially of the Egyptians. The physician Asclepiades had a ring with Urania represented upon it. Scipio the African had a sphinx; Cornelius Scipio Africanus, younger son of the great Africanus, wore the portrait of his father, but as his conduct was unworthy of the character of his illustrious sire the people expressed their disgust by depriving him of the ring. Sylla had a Jugurtha; the Epicureans, a head of Epicurus; Commodus, an Amazon, the portrait of his mistress Martia; Aristomenes, an Agathocles, King of Sicily; Callicrates, a Ulysses; the Greeks, Helen; the Trojans, Pergamus; the inhabitants of Heraclia, a Hercules; the Athenians, Solon; the Lacedæmonians, Lycurgus; the Alexandrians, an Alexander; the Seleucians, Seleucus; Mæcenas, a frog; Pompey, a dog on the prow of a ship; the Kings of Sparta, an eagle holding a serpent in its claws; Darius, the son of Hystaspes, a horse; the infamous Sperus, the rape of Proserpine; the Locrians, Hesperus, or the evening star; Polycrates, a lyre; Seleucus, an anchor.

The Rev. C. W. King, in ‘Antique Gems,’ informs us that ‘the earliest mention of a ring-stone in relief occurs in Seneca, who, in a curious anecdote which he tells (“De Beneficiis,” iii. 26) concerning the informer Maro and a certain Paulus, speaks of the latter as having had on his finger on that occasion a portrait of Tiberius in relief upon a projecting gem, “Tiberii Cæsaris imaginem ectypam atque eminente gemma.” This periphrasis would seem to prove that such a representation was not very common at the time, or else a technical term would have been used to express that particular kind of gem-engraving.’

[Pg 36]Among the discoveries made during some excavations at Canterbury in 1868 was a Roman ring of exceedingly pure gold, the stone being a very fine and highly-polished onyx, engraved with a Ganymede.

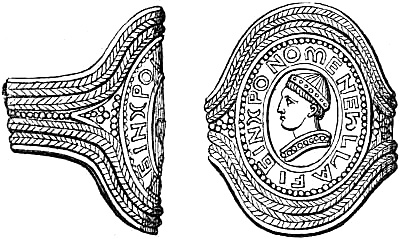

At a meeting of the Archæological Institute at Norwich in 1847 a fine gold Roman ring found at Caistor was exhibited, set with an intaglio on onyx, the subject being the Genius of Victory. The following illustrations of engraved Roman rings are taken from Montfaucon’s ‘L’Antiquité Expliquée’:—

|

| |

| Gold ring, with head of Trajan, radiated. |

Silver ring, with head of the Empress Crispina. | |

|

| |

| Head of the Emperor Gordian III. | Iron ring, with head of Socrates. | |

|

| |

| Gold ring, with name, Vibianæ. | Iron ring, representing a shepherd and goat. | |

| [Pg 37] | ||

|

| |

| Jupiter Serapis. | Galba. | |

|

| |

| Pan and Goat. | Hygeia. | |

|

| |

| Mercury. | Bust, with inscription ‘Lucilla Acv. Sta. Virgo,’ formerly in the collection of St. Geneviève; added to the splendid Cabinet of Antiquities at Paris in 1796. |

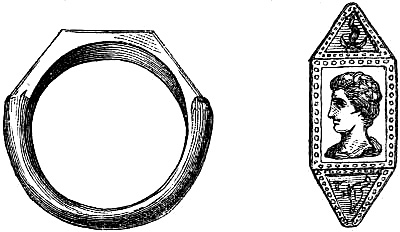

The following engraving (from Gorlæus) refers to the story of Masinissa and Sophonisba, well known to classical readers. She was betrothed at a very early age to the Numidian prince, but was afterwards married to Syphax, B.C. 206. This warrior, in a battle with Masinissa, was conquered, and Sophonisba became a prisoner to the Numidian[Pg 38] prince, who, won by her charms, married her. Scipio, fearing her influence, persisted in his immediate surrender of the princess, and Masinissa, to spare her the humility of captivity, sent her a bowl of poison, which she drank without hesitation, and thus perished.

Ring with figures of

Masinissa and Sophonisba.

The portraits of Caligula and Drusilla, in an iron ring, made to turn from one side to the other (Gorlæus):—

Caligula and Drusilla.

A representation of Victory, suspending a shield to a palm-tree (Gorlæus):—

Roman ring of ‘Victory.’

With regard to the engraved representations on rings,[Pg 39] Clemens Alexandrinus gives some advice to the Christians of the second century: ‘Let the engraving upon the stone be either a pigeon, or a fish, or a ship running before the wind, or a musical lyre, which was the device used by Polycrates; or a ship’s anchor, which Seleucus had cut upon his signet; and if it represents a man fishing, the wearer will be put in mind of the Apostle, and of the little children drawn up out of the water. For we must not engrave on them images of idols, which we are forbidden even to look at; nor a sword, nor a bow, being the followers of peace, nor drinking goblets, being sober men.’ (See Chapter IV., ‘Rings in connexion with ecclesiastical usages,’ religious rings.) The Rev. C. W. King remarks that ‘the practice of engraving licentious subjects on rings was very prevalent in Ancient Rome. Ateius Capito, a famous lawyer of the Republic, highly censured the practice of wearing figures of deities on rings, on account of the profanation to which they were exposed.’

Roman.

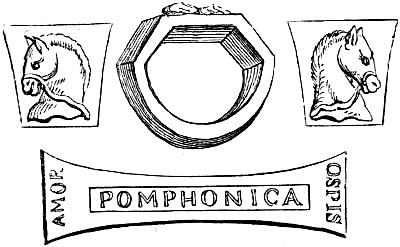

The same distinguished writer mentions an antique gold ring now in the Florentine Cabinet, set with a cameo, which evidently shows that it belonged to some Roman sporting gentleman, who, as the poet says, ‘held his wife a[Pg 40] little higher than his horse,’ for it is set with a cameo-head of a lady, of tolerable work in garnet, and on the shoulders of the ring are intaglio busts of his two favourite steeds; also a garnet with their names cut in the gold on each side—Amor and Ospis. On the outside of the shank is the legend Pomphonica, ‘success to thee, Pomphius,’ very neatly engraved on the gold.

In the possession of Captain Spratt is a remarkably fine specimen of early Greek work, a large ring of thin gold, set with an intaglio on very fine red sard, oval, of most unusual size, representing a figure of Abundantia beside an altar; the edge of the setting slightly bended; the stone held in its position by thin points of gold. This most important gem is in its original gold setting, and was purchased in June 1845 at Milo, where it had been found the previous year, within a short distance of the theatre, near the position in which the Venus of Milo had been discovered about thirty years previously.

Such was the value attached by the Romans to the setting of gems in rings, that Nonius, a senator, is said to have been proscribed by Antony, for the sake of a precious opal, valued at 20,000l. of our money, which he would not relinquish.

The taste for engraved gems, ‘grew,’ observes the Rev. C. W. King, ‘into an ungovernable passion, and was pushed by its noble votaries to the last degree of extravagance. Pliny seriously attributes to nothing else the ultimate downfall of the Republic; for it was in a quarrel about a ring at a certain auction that the feud originated between the famous demagogue Drusus, and the chief senator Cæpio, which led to the breaking out of the Social War, and to all its fatal consequences.’

[Pg 41]In the Braybrooke Collection is a gold Roman finger-ring, with two hands clasping a turquoise in token of concord: this device, a favourite one in mediæval times, has thus an early origin. In the same collection is a beautiful Romano-British gold ring, chased to imitate the scales of a serpent, which it resembles in form: the eyelet-holes have been set with some coloured gem, or paste, now lost.

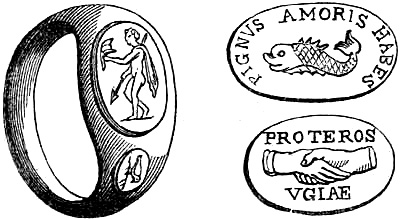

Sometimes the decoration of a ring was not confined to a single gem. Valerian speaks of the annulus bigemmis, and Gorlæus gives specimens; one, the larger gem of which has cut upon it the figure of Mars, holding a spear and helmet, but wearing only the chlamys; the smaller gem is incised with a dove and myrtle-branch. Engraved are two examples of the emblematic devices and inscriptions adopted for classic rings when used as memorial gifts. The first is inscribed,—‘You have a love-pledge,’ the second,—‘Proteros (to) Ugiæ,’ between conjoined hands.

Roman ‘memorial’ gift-rings.

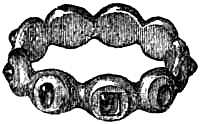

The annexed illustration represents a jewelled ring of gold, considered to be of Roman work. It is formed with[Pg 42] nine little bosses, set with uncut gems, emeralds, garnets, and a sapphire: one only, supposed to be a blue spinel, is cut in pyramidal fashion.

Anglo-Roman.

A similar ring, of gold, found in Barton, Oxfordshire, may, probably, be ascribed to the same period of the Roman rule in Britain. Weight 3 dwts. 16 grains. (‘Archæological Journal,’ vol. vi. p. 290.)

|

| |

| Anglo-Roman. | Roman. |

The Roman ring here given must have been inconvenient to the wearer from its form, but may have been used as a signet. Rings were chiefly used by the Romans for sealing letters and papers; also cellars, chests, casks, &c.[9] They were affixed to certain signs, or symbols, used for tokens, like what we call tallies, or tally-sticks, and given in contracts instead of a bill, or bond, or for any sign. Rings were also given by those who agreed to club for an entertainment, to the person commissioned to bespeak it, from symbola, a reckoning; hence, symbolam dare, to pay his reckoning. Rings were also given as votive offerings to the gods.

In 1841 a curious discovery was made at Lyons of the[Pg 43] jewel-case of a Roman lady containing a complete trousseau, including rings: one is of gold, the hoop slightly ovular, and curving upward to a double leaf, supporting three cup-shaped settings, one still retaining its stone, an Arabian emerald. Another is also remarkable for its general form, and still more so for its inscription, ‘Veneri et Tvtele Votvm,’ explained by M. Comarmond as a dedication to Venus, and the local goddess Tutela, who was believed to be the protector of the navigators of the Rhine; hence he infers these jewels to have belonged to the wife of one of those rich traders in the reign of Severus.

Roman rings, found at Lyons.

Boeckh’s Inscriptions (dating from the Peloponnesian War) enumerate in the Treasury of the Parthenon, among other sacred jewels, the following rings: an onyx set in a gold ring; ditto in a silver ring; a jasper set in a gold ring; a jasper seal, enclosed in gold, seemingly a mounted scarabæus; a signet in a gold ring, dedicated by Dexilla (the two last were evidently cut in the gold itself); two gem signets set in one gold ring; two signets in silver rings, one plated with gold; seven signets of coloured glass plated with gold (i.e. their settings); eight silver rings, and one gold piece, fine (probably a Daric), a gold ring of 1½ drs. offered by Axiothea, wife of Socles; a gold ring with one gold piece, fine, tied to it, offered by Phryniscus, the Thessalian; a[Pg 44] plain gold ring weighing ½ dr. offered by Pletho of Ægina (a widow’s mite).

Fabia Fabiana, a Roman lady, offered in honour of her granddaughter Avita, amongst other costly gifts, two rings on her little finger with diamonds, on the next finger a ring with many gems, emeralds and one pearl; on the top joint of the same ring, a ring with an emerald. ‘The notice of the two diamond-rings and the emerald-ring on the top joint of the ring-finger are,’ remarks the Rev. C. W. King, ‘very curious. The pious old lady had evidently offered the entire set of jewels belonging to her deceased grandchild for the repose of her soul.’

Roman.

The annexed engraving represents a remarkably fine Roman bronze ring of a curious shape. The parts nearest the collet are flat and resemble a triangle from which the summit has been cut. The peculiarity of the ring is an intaglio, here represented, cut out of the material itself, representing a youthful head. The two triangular portions which start from the table of the ring are filled with ornaments, also engraved hollow. Upon it is the word Vivas, or Mayest thou live; probably a gift of affection, or votive offering.

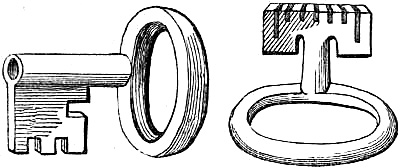

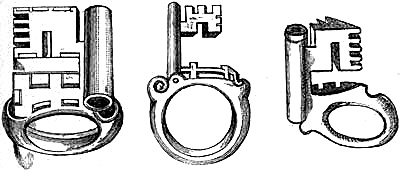

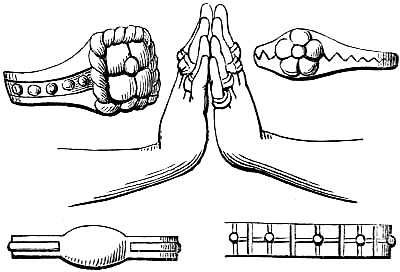

In many of the Roman keys that have been discovered[Pg 45] the ring was actually worn on the finger. The shank disappears, and the wards are at right angles to the ring, or in the direction of the length of the finger.

Roman ‘Key-rings.’

When a person, at the point of death, delivered his ring to anyone, it was esteemed a mark of particular affection. The Romans not only took off the rings from the fingers of the dead, but also from such as fell into a very deep sleep or lethargy. Pliny observes: ‘Gravatis somno aut morientibus religione quadam annuli detrahuntur.’ Some have conjectured that Spartian alludes to this custom where, taking notice in the Life of the Emperor Hadrian of the tokens of his approaching death, he says: ‘Signa mortis hæc habuit: annulus in quo Imago ejus sculpta erat, sponte de digito lapsus est.’ The ring, with his own image on it, fell of itself from his finger. Morestellus thinks they took the rings from the fingers for fear the Pollinctores, or they who prepared the body for the funeral, should take them for themselves, because when the dead body was laid on the pile they put the rings on the fingers again, and burnt them with the corpse.

The custom of burning the dead lasted to the time of Theodosius the Great, as Gothofredus states. Macrobius, who lived under Theodosius the Younger, says the custom of burning the dead had quite ceased in his time.

The Romans commonly wore the rings on the digitus[Pg 46] annularis, the fourth finger, and upon the left hand, but this custom was not always observed. Clemens Alexandrinus remarks that men ought to wear the ring at the bottom of the little finger, that they might have their hand more at liberty. For Pliny’s account of this, and other ring customs, I refer the reader to the Appendix at the end of this volume.

The clients of a Roman lawyer (remarks Fosbroke), usually presented him, as a birthday present, with a ring, which was only used on that occasion.

Rings were given among the Romans on birthdays—generally the most solemn festival among them, when they dressed and ornamented themselves, with as much grandeur as they could afford, to receive their guests. Persius alludes to the natal ring in his first Satire, in which a ring, richly set with precious stones, figures as a part of the ceremonial.

The gladiators often wore heavy rings, a blow from which was sometimes fatal. The ring of the first barbarian chief who entered and sacked Rome was a curious cornelian inscribed ‘Alaricus rex Gothorum.’

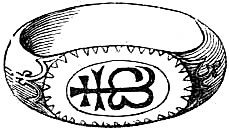

In the famous Castellani Collection of Antiques, now in the British Museum, are some splendid specimens of Roman rings: one with an uncut crystal of diamond, a stone of great rarity, and highly prized; also a minute votive ring set with a cameo, which probably adorned the finger of a statuette; a curious double ring for two fingers. The early Christian rings are very remarkable; one has a crossed ‘P’ in gold, formerly filled with stones or enamel; another has an anchor for device, and one a ship, emblematic of the Church.

Amongst the Greek rings in this superb collection is the most splendid intaglio, on gold, ever discovered; the bust of[Pg 47] some Berenice or Arsinoe side by side with that of Serapis; the ring itself, plain and very massive, is, as the Rev. C. W. King observes, ‘a truly royal signet.’

A ring in the Londesborough Collection bears the Labarum, the oldest monogram of Christianity, derived from the vision in which Constantine believed he saw the sacred emblem, and placed it on his standard with the motto, ‘In hoc signo vinces.’ This ring came from the Roman sepulchre of an early Christian.

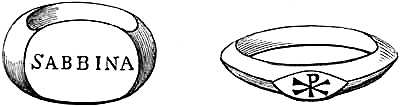

An engraving of another ring in the same collection of massive silver is inscribed Sabbina, most probably a love-gift.

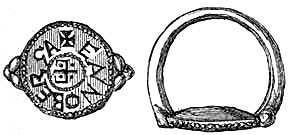

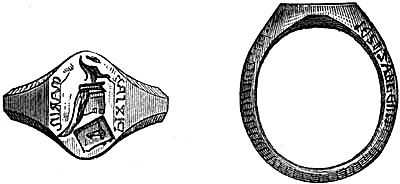

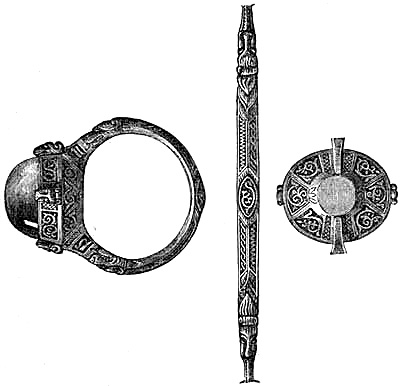

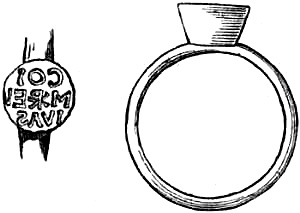

Roman.

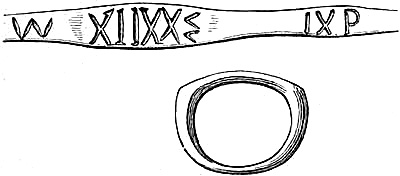

The following represents a bronze ‘legionary’ ring, of oval form, with flattened bezel, supposed to be Early Christian; obtained from Rome (‘Arch. Journal,’ vol. xxvi. p. 146):—

Roman ‘Legionary’ ring.

[Pg 48]Another, of the same description, is more elaborate:—

|

| |

| Roman ‘Legionary’ ring. | Roman. |

The collections of our English antiquaries contain numerous specimens of Roman rings. At Uriconium several have been found of very varied materials. Rings formed of bone, amber,[10] and glass were provided for the poorer people, as was the case in ancient Egypt.

Roman amber and glass rings.

In the later period of the Roman empire a more ostentatious decoration of rings, derived from Byzantium, became common. In Montfaucon we find illustrations of this change from the classical simplicity of earlier times.

[Pg 49]A specimen of this character is given by Montfaucon:—

Byzantine.

The annexed represents a gold ring, probably of the fifth or sixth century, found at Constantinople (‘Arch. Journal,’ vol. xxvi. p. 146):—

Byzantine.

In the Museum at Naples are two fine specimens of rings discovered at Herculaneum and Pompeii, illustrations of which are here given from the work of M. Louis Barré, ‘Herculaneum et Pompeii’ (Paris, 1839-40):—

Rings from Herculaneum and Pompeii.

A bronze ring is curious from having similar ornaments to those of the horse-furniture discovered some years ago at Stanwick, on the estates of the Duke of Northumberland in Yorkshire, and which are analogous in the character of their[Pg 50] design to those found in Roman places of sepulture in Rhenish Germany.

Roman.

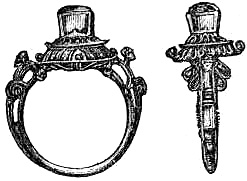

Representation of a ‘trophy’ ring in the Museum of the Hermitage, St. Petersburg; the figure of a lion on the convex; on the reverse a trophy:—

|

| |

| ‘Trophy’ ring. | Roman ring (from the Museum at Mayence). |

In the Waterton Collection are some valuable and curious specimens of Greek and Roman art in ring-manufacture. These are composed of gold, silver, bronze, iron, lead, earthenware, amber, vitreous paste, jet, white cornelian, lapis-lazuli, chrysoprase, &c. Amongst these will be seen some interesting Roman rings for children; one engraved with a rude figure of Victory, found at Rietri, in 1856, diam. 9⁄16 in. In the same collection are bronze ‘legionary’ rings—perhaps the number of a ‘centuria,’ some corps employed about Rome, where all the rings of this character connected with the collection have been found.

[Pg 51]Among the ‘votive’ rings in this collection, is one in the form of a shoe, inscribed Felix, of bronze.

There are also specimens of rings with the key on the hoop, to which I have alluded in the chapter on ‘Betrothal and Wedding Rings.’ One has a fluted pipe; another has a key with two wards; in another the key is riveted on the hoop.

Roman Key-rings.

The earthenware rings are of brown or red. The amber rings are of mottled deep red, set with green paste. Those in vitreous paste are of pale blue, transparent yellowish and transparent brown. A ‘jet’ ring belongs to the late Roman period. A white cornelian ring has a smaller part of the hoop cut down, so as to form an oval bezel, on which is engraved a standing figure of Æsculapius. A gold ring, Roman, set with oval intaglio, on cornelian, of a trophy consisting of a horse’s head bridled, and two Gallic shields crossed, with the name of Q. Cornel Lupi, is the seal of Quintus Cornelius Lupus, commemorating a victory over the Gauls: the setting is modern. Another gold ring, with oval bezel, set with an intaglio on yellow sard, has a youthful bust, full-faced; on one side a spear,[Pg 52] on the other side, in Greek letters, ‘Hermai.’ A gold ring with nicoli onyx is inscribed ‘Vibas Luxuri Homo Bone.’

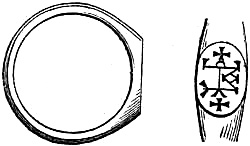

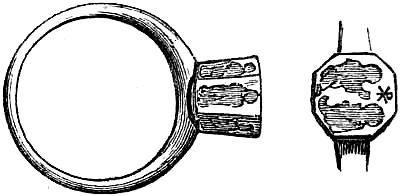

Some of the ‘Early Christian’ rings in the same collection are very interesting. These are of silver, bronze, and lead. One of silver has an octagonal bezel engraved with the Agnus Dei; another, of bronze, has a square bezel inscribed ‘Vivas in Deo’; a bronze ring with oval bezel is chased with a lamb, the shoulders and hoop chased so as to represent a wreath of palms; another, of bronze, has a projecting octagonal bezel, engraved with a dove and a star, the hoop formed so as to resemble a wreath. A massive bronze ring has the bezel engraved with the figure of an orante; on the hoop is also a sigillum engraved with a cross. One ring, of lead, has a flattened bezel rudely incised with a cross.

The following engraving represents the fore-finger, from a bronze statue, of late Roman workmanship, on which a large ring is seen on the second joint. A similar custom prevails in Germany.

Late Roman (from the Waterton Collection).

The latest ‘surprise’ in regard to rings is that in connection with Dr. Schliemann’s discovery of antiquities upon the presumed site of Troy. The Doctor, in June 1873, after indefatigable exertions in excavating, came upon a trouvaille consisting of ancient relics of great rarity, value, and importance, including finger-rings, of which, as I have[Pg 53] mentioned, the Homeric writings make no mention. These were found among a marvellous assemblage of bronze, silver, and gold objects, which lay together in a heap within a small space. This seemed to indicate that they had originally been packed in a chest which had perished in a conflagration (most of the articles having been exposed to the action of fire), a bronze key being found near them. The period to which these objects belong is the subject of much controversy, but their origin must date from a very remote period.

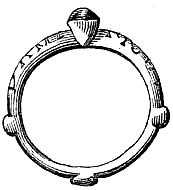

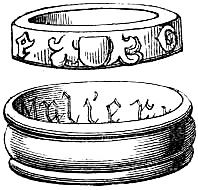

Among our British, Saxon, and Mediæval ancestors, rings were in common use. Pliny (‘Hist. Nat.’ lib. xxxiii. c. 6) mentions, that the Britons wore the ring on the middle finger. In the account of the gold, silver, and jewellery belonging to Edward the First is mentioned ‘a gold ring with a sapphire, the workmanship of St. Dunstan.’ Aldhelm, ‘De Laud. Virg.’, describes a lady with bracelets, necklaces, and rings set with gems on her fingers. Rings are frequently mentioned in the Anglo-Saxon annals. They appear to have been worn then on the finger next to the little finger, and on the right hand—for a Saxon bard calls that the golden finger—and we find recorded that a right hand was once cut off on account of this ornament.

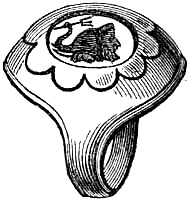

Anglo-Saxon.

Early British (?) ring, found at Malton.

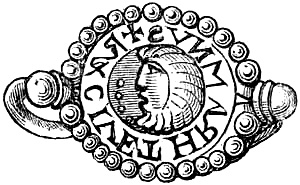

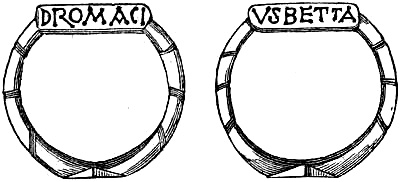

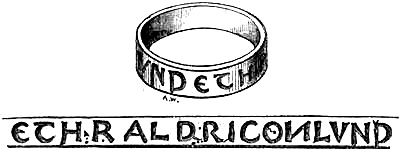

It was not uncommon for Saxon gold rings to have the name of the owner for a legend. Some of the rings of the Anglo-Saxon period which have been discovered would not discredit the workmanship of a modern artificer. One of the most interesting relics of enamelled art which is exhibited in the medal room of the British Museum is the gold ring of Ethelwulf, King of Wessex (A.D. 837-857), the father of Alfred the Great. It was found in the parish of Laverstock, Hampshire, in a cart-rut, where it had become much crushed and defaced. Its weight is 11 dwts. 14 grains. This ring was presented to the British Museum by Lord Radnor, in 1829. Ethelwulf became later in life a monk at Winchester, where he had been educated, and he died there. No[Pg 55] reasonable ground can be alleged for doubting the authenticity of this ring.[11]

Ring of Ethelwulf.

M. de Laborde, in his ‘Notice des Émaux, &c., du Louvre,’ considers the character of the design and ornament to be Saxon; and there is every reason to suppose it was the work of a Saxon artist.

In connexion with this valuable relic is the gold ring of Æthelswith, Queen of Mercia, the property of the Rev. W. Greenwell, F.S.A., by whom it was exhibited at a meeting of the Society of Antiquaries in January 1875. On this occasion, A. W. Franks, Esq., Director of the Society, made the following observations:—‘This ring is one of the most remarkable relics of antiquity that has appeared in our rooms for many years past.