Title: With the World's Great Travellers, Volume 4

Editor: Charles Morris

Oliver Herbrand Gordon Leigh

Release date: September 16, 2013 [eBook #43745]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by D Alexander, Ralph Carmichael and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

THE COLOGNE CATHEDRAL

THE COLOGNE CATHEDRAL

Painting by W.Witthoft

SPECIAL EDITION

WITH THE WORLD’S

GREAT TRAVELLERS

EDITED BY CHARLES MORRIS

AND OLIVER H. G. LEIGH

Vol. IV

CHICAGO

UNION BOOK COMPANY

1901

Copyright 1896 and 1897

BY

J. B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY

Copyright 1901

E. R. DuMONT

| SUBJECT. | AUTHOR. | PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Paris, Amsterdam | Oliver H. G. Leigh | 5 |

| Florence and its Art Treasures | Sarah J. Lippincott | 16 |

| The Lake Region of Italy | Robert A. McLeod | 26 |

| A Day in Rome | Bayard Taylor | 37 |

| Pompeii and its Destroyer | Alfred E. Lee | 48 |

| Mount Etna in Eruption | Bayard Taylor | 61 |

| Plebeian Life in Venice | Horace St. John | 70 |

| Athens and its Temples | J. L. T. Phillips | 79 |

| The Isles of Greece | Henry M. Field | 89 |

| The Seraglio on the Golden Horn | Edward Daniel Clarke | 100 |

| Zermatt and its Scenery | Stanley Hope | 112 |

| Alpine Mountain Climbing | Edward Whymper | 121 |

| A Typical Dutch City | Edmondo de Amicis | 131 |

| Antwerp and its People | Rose G. Kingsley | 140 |

| Art Museums of Dresden | Elizabeth Peake | 147 |

| The Students of Heidelberg | Bayard Taylor | 158 |

| The Streets of Berlin | Matthew Woods | 165 |

| A Ramble in Prussia | Stephen Powers | 176 |

| The Salt-Mines of Wieliczka | J. Ross Browne | 183 |

| The Jumping Procession of Echternach | M. Ogle | 193 |

| The Capital of Austria | John Russell | 201 |

| The Esterházy Palaces | John Paget | 210 |

| From Hamburg to Stockholm | Mrs. Andrew Crosse | 221 |

| The Midnight Sun | Langley Coleridge | 229 |

| In the Russian Capital | Samuel S. Cox | 236 |

| A Visit to Finland | David Ker | 246 |

| Moscow in 1800 | Edward Daniel Clarke | 257 |

| A Russian Sleigh Journey | Frederick Burnaby | 267 |

VOLUME IV

| The Cologne Cathedral | Frontispiece |

| Louvre Museum, Apollo Gallery | 12 |

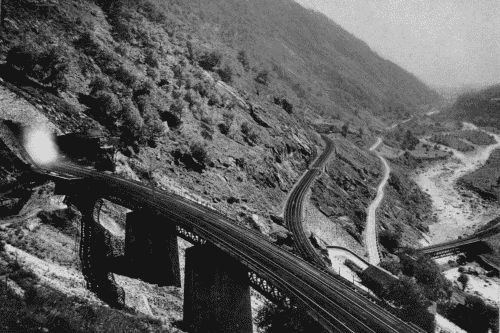

| St. Gotthard Railway (Viaduct and Tunnel) | 28 |

| Arch of Titus, Rome | 38 |

| The Famous Bridge of the Rialto, Venice | 46 |

| The Church of St. Mark, Venice | 74 |

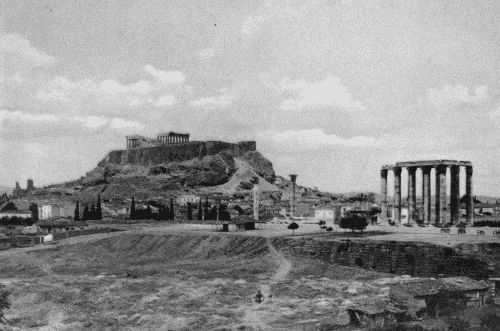

| Acropolis at Athens, Greece | 84 |

| Corinth, Greece | 96 |

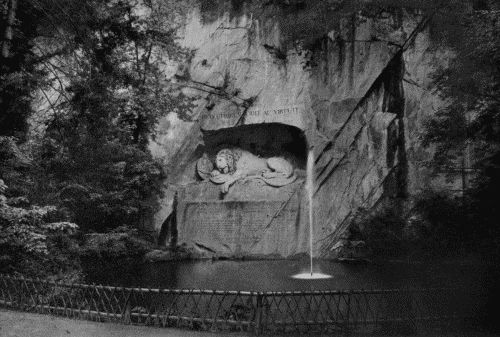

| The Lion Monument, Lucerne | 114 |

| Kleine Scheidegg (The Jungfrau) | 124 |

| A Typical Dutch Windmill | 134 |

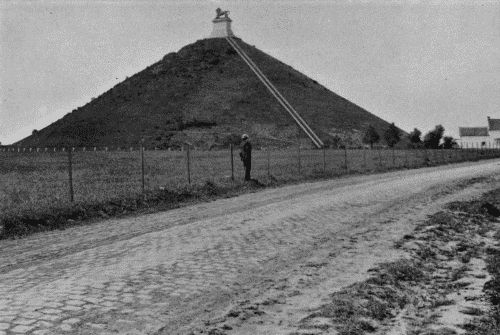

| The Waterloo Pyramid | 144 |

| The Town and Castle of Heidelberg | 160 |

| Innsbruck, Theresa Street | 186 |

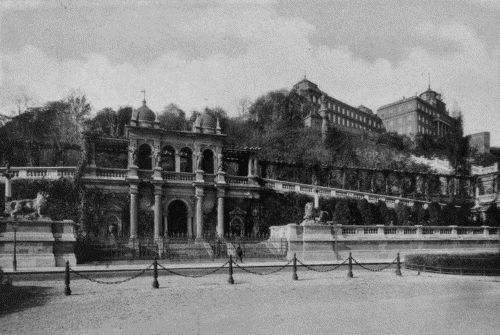

| Budapest | 212 |

| Moscow | 258 |

Paris, pleasure capital of the world, the ideal cosmopolitan city, a thousand different delights for a thousand different tastes, is as fascinating to the scholar and bookworm as to the tourist and the belle of fashion. The weary old world would die of melancholy if the light of gay Paris were to go out. Lutetia, as the Romans called the ancient town, is still the merry child in the family of nations. Fortune gave it favors without stint. Emperors and kings delighted to adorn it with a lavishness equalled by the lasting splendor of their gifts. Art and learning, the genius of ecclesiasticism and the desire for popular enjoyment, contributed the venerable edifices and their priceless treasures, and dowered the modern city with the heirlooms of many centuries. Notre Dame rose eight hundred years ago from the ruins of a fourth-century church. A few years ago were discovered the foundations of an amphitheatre capable of seating ten thousand people as far back as the year 350, when the city’s population must have been at least twice that number. No wonder all the world gathers periodically at this natural centre of everything that can make a city a miniature world[Pg 6] in itself, for in the Paris of to-day stand side by side monuments and memorials of antiquity, and the grandest triumphs of latter-day genius in a profusion that bewilders the eye and the mind. It is as though the genii of all time and all peoples had conspired to shower their fairest gifts upon the favored spot of earth round which the drama of the ages has enacted its tremendous tableaux.

A run through its history must be the first item in the programme of the traveller who wishes to take with him his best pair of eyes. Then he will find the old gray stones turn into glass to let him see into the hidden glory behind. The lesser charms of the pretty city are palpable to any child. Yet it is impossible to look at the building or monument that first catches the eye without a flash-light of mere newspaper lore casting a momentary shadow, or glare, over it. It is not so long ago that the flames lit by the Commune brought the beautiful city nearer to ruin than all the storms of centuries had effected. In its long day Paris has suffered most of the ills that civic life is heir to. Its people have been subject to political maladies from time to time, that have endangered its very existence. A strange career, a blend of demoniac fury and light-hearted gaiety, yesterday its streets flowing with citizen and royal blood, to-day they echo with jubilant laughter, to-morrow—? The wheel is more likely to revolve than to stand long still. Paris alone among the great capitals of the world prefers change to stability, which is only another expression of her happy, mercurial temperament. France is sedate, plodding, content with present conditions until sure they can be bettered. Paris must gallop even if it costs a fall or two, which makes it the most interesting of all places.

When a city is little else than “sights” there is monotony in naming them. Paris itself commands first attention.[Pg 7] The grandeur of its design, its famous boulevards, avenues and streets, and many of its ornamental features, must be credited to the last emperor, Napoleon III., whose dynasty came to grief at Sedan. Modern Paris owes more to his reign, and modern travellers more of their pleasure, than is ordinarily acknowledged. He bade Haussmann replace the old streets with the noble avenues that give inexhaustible sensations of delight at every turn and vista. A happy thought was that which perpetuates the great names of France in these street names; even literature is not forgotten, but reflects the honor it receives from tablets naming avenues after Montaigne, Voltaire, Hugo and others.

The three-mile walk from the Place de la Concorde to the site of the old Bastille yields the ideal of city magnificence and personal delight. There is no disappointment of even extravagant expectation. This unrivalled Place is in itself a grand intellectual as well as artistic feast. The Luxor obelisk brings into mind Egypt’s six thousand years of strangest history, its Pyramids, its Sphinx, and Napoleon. Close to it the Revolution guillotined a king and queen, and an old aristocracy. Heroic sculptures range around the Place, symbolizing eight great cities of France, that of lost Strasburg veiled in mourning. From the Place and the twelve streets radiating from the Arc de Triomphe, it is not possible to go far without coming upon some striking feature.

The Church of the Madeleine is accounted the most exquisite building in the city, though it is modelled on the art of ancient Greece. There are many triumphs of later styles, each grand, but yielding the palm to this Temple of Glory, as Napoleon intended it to be. It is three hundred and thirty feet long, one hundred and thirty[Pg 8] wide, and one hundred high, without windows, and surrounded by Corinthian columns.

The Arc de Triomphe is the stateliest arch ever built, perfect in every respect. It was copied from the imperial arches of old Rome, with grander massiveness. It commemorates the triumphs of Napoleon.

Notre Dame is not a modern imitation. The great cathedral stands on the little Ile de la Cité which was the beginning of Paris, inhabited two thousand years ago by the Parisii, a Celtic tribe whose name survives. For eight centuries it has been a Christian church. The west front is rich in statues of the kings of France. The originals were destroyed in the Revolution, but have been replaced. The cathedral itself was turned into the mockery of a Temple of Reason, with a woman of the town enthroned as its deity. Napoleon’s wise statesmanship restored the church to its rightful usages. The Commune once more made free with the old shrine, using it as barracks. Among its relics is the robe Archbishop Darboy wore when the Communists put him to death. The churches of Paris have weird stories to tell. The sacred spot where Genevieve, the patron saint of Paris, was buried, in the sixth century, was a place of worship until the Revolution changed it into a Pantheon. It became a church once more in 1851, though in its crypt lie Voltaire, Rousseau, and other famous writers. The tomb of Napoleon is beneath the Dome of the Church of the Invalides, attached to the home for veterans founded by Louis XIV.

The famous palace of the Tuileries was built in the sixteenth century for Catherine de’ Medici. It was the home of emperors and kings, and the shrine of precious treasures of art from that time down to the fall of the second empire, when the Communists destroyed it beyond repair. The politics of spite never yet inspired its votaries [Pg 9] to create a thing of beauty for posterity to enjoy. Opposite the blank left by this vandal outrage stands the Louvre, perhaps the greatest jewel casket of art in existence, certainly beyond human power to replace if destroyed. Yet even the Louvre was, in 1870, undermined by the mob in power, who longed to blow it into nothingness—in their pious enthusiasm for enlightened progress. This two-hundred-year old palace is a wonder of architectural beauty. Its museums are famous for the statuary and paintings by the great masters. The Venus of Melos stands as the chief feature of one gallery. Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, Titian and others of their rank are represented here among the two thousand pictures, besides innumerable masterpieces in various arts. The gallery of Apollo passes description as a chamber, were it empty. Its contents have almost fabulous value.

The Luxembourg Palace was built in 1620. It has known strange experiences—first royal habitation, then a prison during the Revolution, again a palace under the Directory and Consulate, and at last the house of the Republic’s Senate. The Palais Royal was built for Cardinal Richelieu. After his death it had a king for its master, to-day its grand arcades echo to the chatter of bargain-seeking shoppers, despite the firebrands of the Communists. Adjoining it is the national playhouse, the Comédie Française, which also had a narrow escape from the caresses of the reformers. Molière managed this theatre for a while, for which, and because he gave the world immortal plays, he was denied Christian burial. His statue, however, makes amends. A greater theatre as to size and gorgeousness is the Grand Opera House. Three acres of central ground were cleared of ordinary buildings and streets to make room for this imposing[Pg 10] structure, which is the most ornate of its kind in the world. The mere pictures of its staircase and foyer are bewildering in magnificence.

After weariness of city sights it is good to make for the Bois de Boulogne, the main park of Paris. Its twenty-three hundred acres are connected with the Champs-Élysées by several avenues, of which the finest is the Avenue du Bois de Boulogne, three hundred and fifteen feet wide and forty-two hundred long. The drive round the lake is the rendezvous of fashion every afternoon. The zoological garden, model dairy, the avenue of acacias, the field of Longchamps, where races and reviews take place, are among the showplaces. At the opposite, the east, side of the city is the spacious Bois de Vincennes, a favorite park with many attractions. The monuments of Paris are familiar to the average reader who stays at home. The July Column replaces the Bastille, the Vendôme Column, with its statue of Napoleon as Cæsar, was pulled down by the Commune and has risen again. Arches, fountains and statuary abound on all sides. Père la Chaise cemetery is the favorite field of oratory, many eulogies of the dead being political harangues of extreme types. Here are buried enough celebrities to immortalize a monumentless city, Abélard and Héloïse, Chopin, Rossini, Bellini, Cherubini, Alfred de Musset, Bernardin de St.-Pierre, Beaumarchais, Béranger, Talma, Racine, Molière, Lafontaine, Balzac, and many national statesmen. In Montmartre cemetery lie Heine, Murger, Halévy, Gautier, Troyon. Lafayette and many of the old nobility who perished in the Revolution, repose in the Picpus burial-ground.

There are many attractive places near Paris, such as Versailles, which must be counted among the city sights. This old town has grown up around the palace built by Louis XIV. It has not been inhabited by royalty since the[Pg 11] Revolution, but is a museum devoted “to all the glories of France.” The halls are thronged with statues and portraits of the great men of history and her victorious battles. The bedroom of the Grand Monarch, the halls of the kings and marshals, the Queen’s Chamber, and every corner of the building are rich in historical memories. The great park and famous fountains, the royal coaches, the Grand Trianon villa which was the home of Madame de Maintenon, and the Petit Trianon, the cosy country cottage of Marie Antoinette, all have their fascinations. So might we notice St. Cloud, the favorite residence of the last emperor, and St. Denis, with its ancient cathedral, where the kings of France during eleven centuries were buried. The Revolutionists dug up the royal bones and flung them into a ditch, whence they were afterwards borne back into the crypt of St. Denis. The region of Paris teems with associations, grown sacred by age and sentiment, yet its citizens rarely appear to be in the serious vein. Their mode of life conduces to rapidity of thought and quick passing of emotions. Over a simple glass of sweetened water grave-looking men will vivaciously enact a dialogue which a stranger to the country might suppose was the prelude to a tragedy, when it is only a comparison of views on last night’s ballet. The outdoor gatherings in front of the innumerable cafés is one of the charms of the gay capital. The habit is Parisian to the core. They sit and quiz the human menagerie as it parades for their delectation; at least this is the complacent view taken of the moving crowd by the true Parisian. The great streets are made for grand informal parades; there is elbow room for hundreds of thousands and each avenue has a park-like aspect. The French are gifted with the instinct of perfect taste in most things, and this shows nowhere more effectively than in their planning and[Pg 12] using a city for artistic ends. Every street stall and lamppost is made part of the general scheme of adornment.

The first few explorations of Paris will fill the mind with wonder and admiration. Then comes the irrepressible desire to know what all its magnificence, its historic object-lessons, all its inexhaustible resources of art and invention, will lead to. A hopeless question, yet the past piques curiosity about the future. So stupendous a monument to human achievement of every order surely betokens an abiding greatness. A people capable of creating a Paris must be destined to a millennium of happy peace and unbroken prosperity. National temperament rarely changes, but bitter experience cannot forget the consequences of former laxity in managing the helm of state. Paris owes it to modern civilization and to posterity to conserve its remaining treasures, at whatever cost.

Amsterdam after Paris may suggest water after wine. A watery city it is and water is excellent at times, if not always. The water streets of the Dutch capital are, sometimes, if not always, inky, and ink of an odor best described by prefixing a couple of consonants. Yet old Amsterdam is full of charm, though not of the Parisian kinds. Its quaint houses have a general look of being turned end-on to the street, their ornamental gables make a sky-line suggestive of a lady’s lace collar. Many of them have a projecting crane with rope and pulley, giving a warehouse appearance to private dwellings. They are still used to save dirtying the stairs when goods are delivered. Cleanliness is the prevailing vice of Amsterdam dames. From bedroom to kitchen every room, and everything in every room, is painfully clean. Between six and eight in the morning every good housewife swills the front of her home from the roof to the curbstone, whether it needs it or not.

LOUVRE MUSEUM, APOLLO GALLERY

LOUVRE MUSEUM, APOLLO GALLERY

The capital, as Erasmus of Rotterdam once remarked, is a place where the people dwell on the tops of trees, like birds. Amsterdam is built on three million piles, driven deep into the swampy soil. Half of its streets are canals. A large population lives in canal-boats the year round. The city is divided by large and small canals into about a hundred islands, with three hundred bridges. The inhabitants feel secure on their timber foundation, though buildings have sunk, occasionally. While the wood-worms are few and feeble and the piles keep wet there is little danger.

The river Amstel passes through the city and gives it its name from the great system of embankments which dam the ever-threatening tide from the arm of the Zuyder Zee on which Amstel-dam stands. This arm is called the Y, spelled Ij in Dutch, and will form a ship-channel, fifty miles long, to the North Sea when fully completed. A large shipping trade is done in the spacious docks, where coffee, tobacco, and sugar come in vast quantities from the Dutch East Indies. One of the industries peculiar to Amsterdam is diamond-cutting. It is not difficult to get access to one of the workshops, and the operation is exceedingly interesting. On market-days and holidays there is a chance to see the old-time picturesque costumes still worn in country parts. The metal helmets, sometimes of silver and gold, with curious ear ornaments have a fine antique air. On Sunday evenings the working folk take their pleasures in the parks, of which swinging is with many the favorite joy. A plump damsel or plumper matron stands facing the lover or husband, and they can swing almost level with the treetop before they tire, or tumble. They take no harm by a fall.

The churches are large, cold and gloomy. The Oude Kerk dates from about 1300. The stained windows are[Pg 14] interesting and the organ, two or three stories high, is powerful and mellow. Instead of the pews covering the floor, they occupy a raised platform in the centre, enclosed by a fence with locked doors. Near by may be seen a pile of boxes like stools, which are charcoal stoves to warm the worshippers in winter. The psalmody is so slow that the organ fills up the intervals between words and lines with rolling chords. Near the palace in the centre of the city is the Niewe Kerk, a more ornate and interesting church, built in 1408, in which the sovereigns are crowned. Its monuments to Admiral de Ruyter and Vondel, the national poet, are fine art-works, as also are the carved pulpit and the bronzes in the choir.

The royal palace, on the central square called the Dam, was built in 1648. It stands on thirteen thousand piles. It was originally the State House. Opposite is the Beurs, or Exchange. The Dutch school of painting has qualities not excelled by the finest productions of other nations. Its painters developed a marvellous proficiency in detail-work, a literalness of interpretation, a realism which is undoubtedly imitative, but in its mastery of execution compels enthusiastic admiration. The flatness of their country afforded no chance for painting fine landscapes. What they saw was the sky and the sea in the distance, and people, cattle and household goods at close range. No painters among the old masters equal the Dutchmen in cloud-scapes and sea-pieces, in fidelity to nature and delicate touch. Similarly, there are few, if any, portraits as strong as these wonderful canvases of the Dutch school. No other artists had the genius to see the possible triumphs awaiting the brush that could counterfeit the dewdrop on a rose, the glisten of the copper stew-pan or the satin gown, or the fluffy texture of a beggar’s coat. Now that two generations have learned these things by patient imitation of[Pg 15] the old Dutchmen this art has become familiar, but no copyist of our time has approached the marvellous beauty and skill that mark the old Dutch masterpieces. The traveller will enjoy himself to the full in the famous galleries of Amsterdam, and the other towns that lie within easy reach. There are four hundred paintings in the Trippenhuis museum, of which the most famous is Rembrandt’s great picture, “The Night Watch.” Still more impressive to many is the magnificent work of Vander Helst, “The Banquet of the Civic Guard,” an immense canvas, showing a band of men in armor carousing around a table loaded with gold and silver plate, glasses, flagons, etc., affording an opportunity for the painter to show Dutch art at its highest. There are great treats in these galleries for the lover of pictures and for the student of manners. Some of the old painters either lacked poetical imagination or indulged their whimsical humor to the verge of the shocking, in certain subjects. They had at least the merit of being faithful to life as they saw it, which satisfies the average man better, on the whole, than impressionism run to seed.

Eight hundred years ago Amsterdam was a fishing village. In the fifteenth century it became the most important commercial city in the Netherlands. Peter the Great learned the art of ship-building in the little village of Zaandam near the capital. A modern building encloses the cottage in which he lived. The people are rightly proud of their city and its history. They have not of late had opportunities to test their old supremacy as sea-warriors, but they exhibit all their sturdy characteristics in fighting the sea itself, repelling its ceaseless attempts at invasion. The women may be expected to uphold the national reputation for energy in any emergency, to judge by the stolid contentment with which so many of them do men’s work. They act as railway signal men, boatmen, market porters,[Pg 16] and do not object to being harnessed with dogs as wagon teams. Yet they seem happy if not exactly gay. In the cities less of this is noticeable. The capital is not behind in artistic and literary culture. Scholarship has always distinguished its people. Its old bookstores are a delightful temptation. The zoological garden is one of the finest anywhere. English is spoken in all the principal stores. The public charities are on an extensive scale. The foreigner is occasionally embarrassed at being politely saluted by members of the Exchange if he chances to pass as they are coming out, and in many such ways he is impressed by the courtesies shown him on all hands. One would not rush to Amsterdam for Parisian excitements, but for nervous systems needing the tone best secured by moderate activity in surroundings that are novel and uniquely interesting, a visit to Amsterdam will prove as great a pleasure as a benefit.

[Mrs. Sarah J. Lippincott (“Grace Greenwood”), in her popular “Haps and Mishaps of a Tour in Europe,” has given a well-written and appreciative account of Florence and its objects of art and interest, which we here reproduce. Our extract begins with a railway journey from Leghorn.]

The railway, which is a very good one, runs through a pleasant country cultivated like a garden, which grows more and more lovely till you reach Florence. The station is near Cascine, the fashionable drive and promenade lying just beyond the city walls, along the Arno; so that our[Pg 17] first lookout was upon a gay and beautiful scene,—those noble grounds thronged with equestrians, and pedestrians, and elegant equipages. From that moment I have been charmed with Florence beyond all expectation and precedent. Every picturing of fancy, every dream of romance, has been met and surpassed. It is a city of enchantment, rich in incomparable treasures for the lover of poetry and art. In merely driving from the station to our hotel, on the Arno, near the Ponte Vecchio, I was struck by the noble style of architecture; uniform in solidity, and in a sort of antique solemnity, yet not monotonously gloomy or curiously quaint. But when we drove about in the brightness of a lovely morning, and saw the grand and ponderous old palaces, the noble churches, the beautiful towers, the graceful bridges,—when we caught, at almost every turn, natural pictures which art could never approach,—I could only express by broken sentences and exclamations, childishly repeated, the rare and glowing pleasure I enjoyed.

O pictures of beauty, O visions of brightness, how must ye fade under my leaden pencil! It is strange, but I never feel so poor in expression as when my very soul is staggering under the weight of new treasures of thought and feeling.

One of our first visits was to the Royal Gallery, in the Uffizi. Through several rooms and corridors, making little pause in any, we passed to the Tribune,—for its size, doubtless the richest room in the world in great works of art. In the centre stands the Venus de Medici, “the wondrous statue that enchants the world,” says the poet; but as for me, I bow not before it with any heartiness of adoration. Exquisite, tender, and delicate beyond my fairest fancy, I found the form; graceful to the last point of perfection seemed to me the attitude and action; but the smallness[Pg 18] and the insignificant character of the head, and the simpering senselessness of the face, place it without my Olympus. I deny its divinity in toto, and bear my offerings to other shrines. Yet the Venus de Medici does not strike me as a voluptuous figure; it certainly is not powerfully and perilously so, wanting, as it does, all strength of passion and noble development of soul; for, paradoxical as it may seem, a soul of wild depths and passionate intensity must lie beneath the alluring warmth and brightness of a refined and perfect sensuality.

Of another, and a far more dangerous character, I should say, is the Venus of Titian, which hangs near it. Here is voluptuousness, gorgeous, undisguised, yet subtle, and in a certain sense poetic and refined. She is neither innocent nor unconscious, yet not bold, nor coarse, nor meretricious. She proudly and quietly revels in her own marvellous beauties, if not like a goddess who knows herself every inch divine, at least like a woman by character and position quite as free from the obligations of morality and purity. For all the wonderful beauty of this great picture, I cannot like it, cannot even tolerate it; but, with an inexpressible feeling of relief, turn from it to the Bella Donna and the Flora of the same artist. The latter is to me the most fascinating and delicious picture I have ever beheld; the richness, the fulness, the golden splendor of its beauty, flood my soul with a strange and passionate delight. There is no high peculiar sentiment about it, though it is grand in its pure simplicity; yet its soft, sunny, luxurious loveliness alone brings tears to my eyes,—tears which I dash away jealously, lest they hide for one instant the transcendent vision.

In the Tribune are several of the finest paintings of Raphael,—the Fornarina, a rich, glowing picture, but a face I cannot like; the young St. John, a glorious figure, and[Pg 19] the Madonna del Cardellino, one of the loveliest of his holy families. There is also a great picture by Andrea del Sarto, which impressed me much; the Adoration of the Magi, by Albert Dürer, the heads full of a simple grandeur peculiar to that noble artist; and an exquisite little Virgin and Child, by Correggio. In another room, after looking at a bewildering number of pictures, most of which have already passed from my mind, I came upon a head of Medusa, by Leonardo da Vinci, which I fear will haunt me to my dying day. It is surely the most terrible painting I have ever beheld.

In the magnificent Pitti palace, among many glorious pictures, I saw two before which my heart bowed in most living adoration—the Madonna della Seggiola of Raphael, and a Virgin and Child of Murillo. The former is surely the sweetest group by the divine painter; and the last, if not of a very elevated character, pure and tender, and surpassingly lovely. In this gallery are Titian’s Bella Donna, Magdalene, and Marriage of St. Catharine. The first of these, which is a portrait, seems to me far the finest. The more I see of them the more am I impressed with the conviction that there is nothing in all his grand and varied works displaying such profound and pre-eminent genius, such subtle, masterly, miraculous power, as the portraits of Titian.

In this palace we saw Canova’s Venus, which I liked no better than I expected. There is about the head, attitude, and figure an affected, fine-ladyish air, dainty, and conscious, and passionless, which is worse than the absolute voluptuousness which would be in character at least with the earthly Venus.

I am more and more convinced that there is in sculpture but one divine mother of pure Love,—the grand and majestic Venus of Milo.

To-day we have driven out to Fiesole, and seen the massive walls of the ancient Etruscan city. These ramparts, which are called “Cyclopean constructions,” are said to be at least three thousand years old, and yet look as though they might endure to the end of time. From a hill above the town we had a large and lovely view of the beautiful valley of the Arno, and looked down upon Florence, lapped in its midst, small, compact, yet beautiful and stately. I never beheld a more enchanting picture than the broad and bright one there spread before me: the blue mountains, the gleaming river, the green and smiling valley; hills covered with olives and myrtles; roads winding between hedges of roses to innumerable villas, nestled in flowery nooks, or crowning breezy heights. Oh, this was enchantment of fairy-land, no dream of poetry; it was in very truth a paradise on earth.

On our return we visited the house of Michael Angelo, which is reverently kept by his descendants, as nearly as possible, in the same state in which he left it. It is a handsome, quaint old house, quiet, shadowy, and somewhat sombre, still pervaded with the awe-inspiring atmosphere of the colossal genius of that Titanic artist.

As I stood in his studio, or in the little cabinet where he used to write, and saw before me the many objects once familiar to his eye and hand, I felt that it was but yesterday that he was borne forth from his beloved home, and that it was the first funereal stillness and sadness which pervaded it now.

We afterwards drove to “Dante’s stone,” a slab of marble by the side of the way, on which he used to sit in the long summer evenings, rapt in mournful meditations, and dreaming his immortal dreams. It is now as sacred to his memory as the stone above his grave.

For the past two afternoons we have driven in the Cascine,[Pg 21] by far the most delightful drive and place of reunion I have ever seen. It is much smaller and, of course, less magnificent than Hyde Park, but pleasanter, I think, in having portions more sheltered, wild, and quiet for riders and promenaders. In the centre of the grounds, opposite the Grand Duke’s farm-house, is an open space where the band is stationed, and the carriages come together to exchange compliments and hear music. Here are always to be seen many splendid turnouts, open carriages filled with elegantly-dressed ladies; gallant officers and gay dames on horseback; flower-girls, bearing about the most delicious lilies and roses, pinks and lilacs, mignonette and heliotrope, freighting the golden evening air with their intoxicating fragrance and amazing you with their paradisian profusion,—altogether a cheering and charming scene, colored and animated by the very soul of innocent pleasure.

This afternoon we met Charles Lever, riding with his wife and two daughters. They are all fine riders, were well mounted, and looked a very happy family party. Mr. Lever is much such a man as you would look to see in the author of Charles O’Malley,—hale and hearty, careless, merry, and a little dashing in his air.

This evening I have spent with the Brownings, to whom I brought letters. They live in that Casa Guidi which Mrs. Browning has already immortalized by the grandest poem ever penned by woman....

Mr. and Mrs. Browning have taken up their residence in Florence, a place in every way congenial to them. I know that thousands of her unknown friends across the water will rejoice to hear that the health of Mrs. Browning improves with every year spent in Italy. Yet she is still very delicate,—but a frail flower, ceaselessly requiring all the sheltering and fostering care, all the wealth and watchfulness of love, which is round about her....

Yesterday I saw, for the first time, the grand, antique group of Niobe and her children. Of these wonderful figures, by far the most noble and pathetic are those of the mother and the young daughter she is seeking to shield. Oh, the proud anguish, the wild, hopeless, maternal agony, of that face haunts me, and will haunt me forever.

I afterwards saw the Mercury of John of Bologna,—a marvel of beauty, grace, and lightness. We visited the treasure-room of the Pitti palace, and saw all the Grand Duke’s plate, among which are several magnificent articles by Benvenuto Cellini. In the evening we drove in the Cascine, and to the Hill of Bellosguardo, from whence we had an enchanting view of Florence and the Val d’Arno,—and so the day ended. To-day we have made the tour of the churches. In the solemn old cathedral, whose wonderful dome was the admiration and study of Michael Angelo, there were extraordinary religious ceremonies, on the occasion of some great festa. Some archbishop or other officiated in very gorgeous robes, of course,—in capital condition, and looking indolent, proud, and stupid, as another matter of course. The court came in great state and pomp, with much trumpeting and beating of the drum. The Grand Duke was accompanied by the Grand Duchess and his household, by the Guardia Nobile, and by numerous ladies and gentlemen of high rank, all in full dress. Those ball costumes of the courtly dames—gay silks and lace, diamonds, flowers, and plumes—looked strange enough after the uniform and decent sombreness of the dress prescribed for the “functions” of St. Peter’s.

The Grand Duke is a man of ordinary size, and appears not far from seventy years of age, though it is said he is hardly sixty. His hair and moustaches are nearly white, and he wears the white coat of the Austrian uniform, and so looks more miller-like than majestic. There was a[Pg 23] sort of sullen sadness in his air, which I confess I was rather gratified to remark,—remembering all the treachery of the past, and beholding all the degradation of the present. The Grand Duchess is a dignified-looking woman enough, but the ladies in attendance on her to-day dazzled alone with their diamonds.

After hearing some fine music, we went to the Santa Croce, the Westminster Abbey of Florence, where are the tombs of its most illustrious dead. Of these, the noblest is that of Michael Angelo, and the poorest, yet more pretentious, that of Dante. Canova has here a monument to Alfieri, which is affected and sentimental, like nearly all his works; and the tombs of Galileo and Machiavelli are anything but pleasing and imposing. Infinitely better were the most simple slabs than such pompous piles.

At the San Lorenzo we saw that marvellous mausoleum, the Medicean Chapel,—the richest yet plainest structure of the kind in the world. There is here a peculiar assumption and ostentation of simplicity,—your eye, accustomed to the crowded ornament and vivid gorgeousness of ordinary princely chapels, is shocked and cheated at the first glance by the sombre magnificence, the sumptuous bareness, of this singular structure; but right soon is disappointment changed to admiration and amazement, as you see that all those lofty walls, from floor to roof, are composed of the most rare and beautiful marbles and precious stones, wrought into exquisite mosaics. Then you see the stupendous and beautiful cenotaphs, and the solemn dark statues of the Medici, and, at length, fully realize all their royal waste of wealth over this mausoleum, all their princely pomp of death.

In the Sagrestia Nuova, built by Michael Angelo, are the statues of Lorenzo and Julian de Medici, with their attendant groups, the Morn and Night, Evening and Day, and[Pg 24] the Virgin and Child,—surely the noblest works of that mighty artist. I instinctively bowed in awe before the gloomy grandeur of Lorenzo; and there was something in his still frown which shook my soul more than the warlike air and almost startling action of Julian. The unfinished group of the Virgin and Child has much tenderness and sweetness with all its force and grandeur; but, as a general thing, I must think that Michael Angelo’s female figures are far more remarkable for gigantic proportions and muscular development than for grace, beauty, or any fine spiritual character. This Virgin is majestic almost to sublimity, yet truly gentle, lovable, divinely maternal....

In what was the refectory of an old monastery, but which was afterwards used as a carriage-house, has been found, within a few years past, a noble fresco by Raphael,—a Last Supper. This we went to see, and I felt it to be one of the purest and most touching creations of that angelic painter. In this picture, the “beloved disciple” seems to have fallen asleep on the breast of the Master, and to have bowed his head lower and lower, till it lies upon the table, while the hand of Jesus is laid caressingly upon his shoulder. There is something so exquisitely sweet and sad, so divinely pitiful, yet humanely tender, in the action, that the very memory of it blinds my eyes with tears.

After dinner we drove in the Cascine, where we met all the world. As it was an exceedingly beautiful sunset, and the evening of a festa, the band continued to play, and the brilliant crowd remained long. I revelled in the delicious air and the cheerful scene as fully as was possible, with the intrusive consciousness that I was breathing the one and beholding the other for the last time—probably forever—certainly for many years.

Mrs. H. and I here took leave of a brace of charming[Pg 25] young nobles, in whom, I fear, we had become too deeply interested. These were two beautiful Russian boys, brothers, of the ages of nine and seven, with whom we voyaged on the Mediterranean and formed an acquaintance which has been continued in Florence. In all my life I never saw such enchanting little fellows,—simple, natural, frank, and free, yet perfect gentlemen in air and expression, displaying, with the utmost ease, grace and polish of manner, tact, wit, and savoir-faire truly astonishing. They always came to our carriage at the Cascine, and, lounging on the steps, chatted to us in French between the pieces of music. To-night, as the youngest was describing to me, very graphically, the different countries through which he had travelled and the cities which he had visited, I advised him to go next to England, and assured him that he would be greatly interested and amused by the sights and pleasures of London. With the slightest possible shrug, he replied, “Oui, madame, c’est une grande ville, sans doute; mais pour tous les amusements il n’y a qu’une ville dans le monde,—c’est Paris.” ...

As I looked back upon Florence for the last time, when I could distinguish only the battlemented Palazzo Vecchio, with its fine old tower, and that incomparable group, the Duomo, the Campanile, and the Baptistery, and a slender, shining line, which I knew for the Arno, I suddenly felt my sight struggling through tears,—real hearty tears. Ah, Bella Firenze, I went from you reluctantly, almost rebelliously; I grieved to leave those glorious galleries, through which I seemed to have merely run; I grieved to leave the Cascine, with its delicious drives and walks, its music and gayety; but I “sorrowed most of all” at parting, so soon, with my friends the Brownings. My friends, how rich I feel in being able to write these words!

I think I must venture to say a little more of them, as,[Pg 26] after writing of my first evening at Casa Guidi, I was so happy as to enjoy much of their society. Robert Browning is a brilliant talker, and more—a pleasant, suggestive conversationist and a sympathetic listener. He has a fine humor, a keen sense of the ridiculous, which he indulges, at times, with the hearty abandon of a boy. In the gentle stream of Elizabeth Browning’s familiar talk shine deep and soft the high thoughts and star-bright imaginations of her rare poetic nature. The two have oneness of spirit, with distinct individuality; they are mated, not merged together.

In the atmosphere of so much learning and genius, you naturally expect to perceive some mustiness of old folios, some uncomfortable brooding of solemn thought; to feel about you somewhat of the stretch and struggle of grand aspiration and noble effort, or the exhausted stillness of a brief suspension of the “toil divine.” But in this household all is simple, cheerful, and reposeful; here is neither lore nor logic to appall one; here is not enough din of mental machinery to drown the faintest heart-throb; here one breathes freely, acts naturally, and speaks honestly.

[The lakes of northern Italy have a world-wide fame, alike for their natural beauty and for the charms of architecture and scenic art which surround them. We give here a brief description of these renowned places of pilgrimage for lovers of the beautiful.]

It was towards the end of last October that I strolled away from my occupations in the French capital to spend a fortnight on the Italian lakes. Of the many routes which[Pg 27] from time immemorial have served for the invasion of Italy by the barbarian and the tourist, I chose on this occasion the Brenner. Apart from the pleasing views it offers, this Alpine pass is interesting as being the first over which the Romans ventured to lead their legions, and the first upon which a railway was constructed. I halted at Trent, and it was several days before I could free myself from the charm of the Etruscan city and plan my departure.

One afternoon I was making inquiries at the office of the diligence which runs to Riva on the Lake of Garda, when a newly-married German couple offered to share with me a private carriage which they had just hired for the same journey. I accepted at once, and in an hour we were off. The sober gray suit trimmed with green in which Hans was attired contrasted oddly with the brilliant purple travelling-dress of his fair-haired Gretchen. I wondered at first that they should have been willing to embarrass themselves with a stranger, until I perceived that my presence was no hinderance at all to their demonstrations of affection. We climbed up by a steep and winding road to a narrow defile which the impetuous Vella almost fills. One day, when St. Vigilius was too much pressed for time to walk over the mountain, he wrenched it apart and made this passage. The imprint of his holy hand is still to be seen on the rock. Passing under the cyclopean eyes of scores of Austrian cannon which now defend this important military position, we began to descend the valley of the Sarca. It is a wild region, where every hamlet has a ruined castle and a legend of knight or robber, saint or fairy. The picturesque remains of the Madruzzo Castle bring to mind the celebrated portraits which Titian painted of members of this noble family. The artist’s colors have survived the last of a long line, and will doubtless outlive as well the crumbling stones of their stronghold. As we[Pg 28] skirted the little Lake of Dobling its still waters reflected rocks and trees, sky and mountain, in an enchanting manner.

“Lovely!” I exclaimed.

“Lovely!” echoed Gretchen, without taking her eyes off Hans.

“Lovely!” answered Hans, still watching the beautiful things reflected in her eyes.

After crossing the rapid Sarca and traversing a desolate tract where rocks of every size, fallen from the overhanging mountain, lie strewn about in chaotic confusion, we reached Arco. This sunny village nestles at the foot of an immense detached boulder whose dizzy summit is crowned by mediæval battlements and towers. Home fit only for birds of prey, this castle was long the nest of a family of robbers. Scarcely had we lost in the distance this greatest wonder of the valley when a sharp turn of the road brought Riva and the Lake of Garda full in view. It was a prospect of singular beauty. The sun had already set except on the highest peaks, and a part of the lake was wrapped in purple shadows. Another part, however, was as clear and light as the sky above it, and all aglow with the images of crimson and orange-tinted clouds. A shrill cry—of delight, I thought—burst from Gretchen’s lips. I was mistaken. Hans had pulled off too rudely a ring from her finger, and the fair one was in tears....

ST. GOTTHARD RAILWAY

(Viaduct and Tunnel)

ST. GOTTHARD RAILWAY

(Viaduct and Tunnel)

In the afternoon I take the famous walk to the Ponale waterfall. The road thither ascends continually. It has been skilfully led along the ledges of a precipitous cliff which borders the lake to the west of Riva, and occasionally pierces the mountain by short tunnels. After passing through the third tunnel I come to a wooden bridge, under which the Ponale dashes just before taking its final leap into the lake. The frail structure on which I stand trembles and is wet with spray, and the air is full of the roar and gurgle of the waters. But for me the main charm of the walk is not the sight of this noisy torrent, but the superb view of Riva that I get on my way back upon issuing from one of the tunnels. The eye, accustomed for a moment to the darkness, is all the more sensitive to the rich soft light which bathes the mountains and the town. A gentle breeze ripples the lake, and the brightly-painted houses that fringe the beach are seen indistinctly in the water, where they look like a line of waving banners. Half a dozen steeples and bell-towers rise gracefully from among the roofs, and their presence explains the surprising frequency with which the hours of the night are struck. From this height I can distinguish the low walls which surround the town and compress its four thousand inhabitants into the area of a small quadrilateral. But Riva, though still fortified, has a thorough look of peaceful commercial prosperity, and has quite laid aside the warlike air she wore in the Middle Ages. In those troubled times this town saw countless wars and sustained many sieges; belonged now to Venice, now to Milan, now to Austria; and at times was independent and able to defy even a bull of the pope or a rescript of the emperor....

Long before daybreak the next morning the great red and green eyes of two small steamers are looking around for passengers, and their whistles screeching that it is time to get up. I have chosen the boat which skirts the western bank. It starts an hour later than the other, but it is not yet sunrise when we push off. The after-deck is thinly peopled, chiefly by tourists, but the fore-deck, where the seats are cheaper, is crowded. We pass by the tumbling and roaring Ponale, and before many minutes we cross the invisible boundary-line between Austria and Italy. The motion of the boat is hardly felt, for we are sailing with a[Pg 30] strong current. The high peaks to the north have already caught the first rays of the sun: masses of white vapor which have been sleeping in the mountain-hollows are roused up and put on a rosy tint. The sky is without a cloud, the lake without a ripple: we seem to be floating in mid-air.

Limone, the first stopping-place, is quite given up to the culture of the fruit from which it takes its name. A row of cypresses gives a gloomy air to the village and awakens a melancholy recollection. It was here that, in 1810, Andreas Hofer, the Tyrolese patriot, was arrested by order of Napoleon. A boat conveyed him to the prison of Peschiera, and he was soon afterwards shot in the citadel of Mantua.

We next stop before Tremosine, a village perched high up on a rock, and to which no visible road leads. On the other side of the lake, which is here narrow, the white houses of Malcesine cluster around the base of an imposing castle. This stronghold of the Middle Ages, one of the few in this neighborhood which Time has not been suffered to destroy, was built by Charlemagne, and was formerly the boundary between Austria and the Venetian territory; but it is chiefly interesting from an adventure which here befell Goethe. He had sat down in the court-yard, and was sketching one of the quaint old towers, when the crowd that had gathered around him, taking him for a spy, fell on him, tore his drawings to pieces and sent for the authorities to arrest him. Fortunately, there was in the village a man who had worked in Frankfort and knew the poet by sight, and through his influence Goethe was set free.

[From Lake Garda the traveller proceeded to the more famous Lake Como, passing localities where songful Catullus dwelt, and Virgil and Dante loved to visit.]

On the map the Lake of Como looks like an inverted and somewhat irregular Y, or, still more, like a child’s first attempt to draw a man, who without arms and with unequal legs is running off to the left. Just at the moment his picture is taken he has one foot on Lecco and the other on the town of Como. The hilly district between the two southern branches of the lake is known as the Brianza, and is noted for its bracing air, its fertile soil, and the coolness of its springs. The Brianza ends at the middle of the lake in a dolomite promontory several hundred feet high, on whose western slope lies the village of Bellaggio. This point commands the finest views in every direction: it is near the most interesting of those villas which are open to the public, and it abounds in good hotels. To visit Bellaggio is therefore the aim of every tourist who passes this way. My journey thither it is best to pass over in silence, for I see nothing, and what I feel is indescribable. I am shut up during a furious storm of wind and rain in the cabin of a little steamer which is as nervous and uneasy as if on the Atlantic. I am told, however, that in this part of the lake the banks are lofty and steep, and frequently barren, and that there are marble-quarries to be seen, and cascades and houses and villages crowning the cliffs.

On arriving at Bellaggio, I take lodging in the Villa Serbelloni, one of the many magnificent residences which poverty has induced the Italian nobles to put into the hands of hotel-keepers. The house stands high up on the very end of the promontory, and adjoining it is an extensive park, on which the ruins of a robber’s castle look down. The panorama which on a fine day spreads itself out before one who walks in these grounds is of singular beauty. The northern arm of the lake, wider and more regular than the others, opens up a long vista of headlands and bays[Pg 32] and red-roofed villages as far as where Domaso peeps out from a grove of giant elms. Beyond, the view is bounded by the snow-covered Alps. Close at hand, near Varenna, the Fiume di Latte, a milk-white waterfall, leaps down from a height of a thousand feet. Towards Lecco huge walls of barren rock arise and wrap everything near them in sombre shadows. Towards Como the tranquil water is shut in by hills and low mountains, whose flowing lines blend gracefully together. Some of these slopes are dark with pines, some are gray with the olive, some are garlanded with vines which hang from tree to tree, while others are clothed in a rich green foliage, amid which glistens the golden fruit of the orange and the lemon. The banks are lined with bright gardens and noble parks and villas, whose lawns run down to the water’s edge and are adorned with fountains, statues, masses of brilliant flowers and clumps of tall trees. Above is a sky of Italian blue, and below is a crystal mirror in which every charm of the landscape is repeated. The impression made by all this loveliness is increased by the air of happiness that pervades the spot. It is the haunt of the rich, the gay, the newly-married: music and song, laughter and mirthful talk, are the most familiar sounds. The smile of Nature seems here to warm men’s hearts and drive away the cares they have brought with them.

It is on this site that Pliny the Younger is believed to have had the villa which he called Cothurnus or “Tragedy.” The present building is several centuries old. Tradition relates that a certain countess, one of its first occupants, had a habit of throwing her lovers down the cliff when she was tired of them. Making this delightful abode my head-quarters, I spend a week, partly in agreeable sight-seeing and partly in still more agreeable idleness. I visit villas, towers, fossil-beds, and waterfalls,—in short, everything[Pg 33] interesting and accessible,—now going on foot, now borne from point to point in one of the sharp-prowed row-boats which are in use here, and now taking the steamer up to Colico or down to Como and back....

Across the lake from here is the Villa Carlotta, called after its former owner, the princess Charlotte of Prussia. Stepping out of his boat, the visitor ascends the marble stairs which lead up from the shore. After a few steps across the garden he reaches the villa, passes through a porch fragrant with jasmine, and is at once ushered into a small room where are some of the finest works of modern sculpture. Canova’s Mars and Venus and Palamedes are here, and they are most admirable, but they are surpassed in charm by the famous group in which Psyche is reclining and Cupid bending fondly over her. The best piece of the collection is the frieze that runs round the room. It is from the chisel of Thorwaldsen, and represents Alexander the Great’s triumphal entry into Babylon. Full of the beauty of youth, the conqueror advances in his chariot; Victory comes to meet him; vanquished nations bring presents; while behind him follow his brave Greeks on horse and on foot, dragging along with them the prisoners and the booty. The subject was suggested by Napoleon, who intended the work for the Quirinal. It is in high relief, and in general effect resembles strongly the frieze with which Phidias encircled the Parthenon. It is a pity that these masterpieces are shown first, for after seeing them one does not fully enjoy the statues and paintings in the other rooms.

Two hours may be delightfully spent in making the journey by steamboat from Bellaggio to Como. Here the lake is so narrow and winding that it seems to be a river. At every moment bold mountain-spurs project into the water appearing to bar all passage, and one’s curiosity is[Pg 34] continually excited to find the outlet. The views shift and change with surprising quickness, for the boat stops at a dozen little towns on the way, and for this purpose keeps crossing and recrossing from shore to shore.

[Passing next to Lake Maggiore, the traveller takes a row-boat down the latter in preference to waiting for the steamer.]

The four islands that we have passed on the way are known as the Borromean Islands, because they belong for the most part to the rich and powerful Borromeo family. The rare beauty of one of them makes it the wonder of the lake. It was towards the middle of the seventeenth century that Count Vitaliano Borromeo, finding himself the possessor of almost the whole of this island, which was then a barren rock, resolved to make it his residence, and to surround himself with gardens that should rival those of Armida. For more than twenty years architects, gardeners, sculptors, and painters labored to give material form to the count’s fancies. A spacious palace was erected on one end of the island; on the other ten lofty terraces rose one above the other, like the hanging-gardens of Babylon. The rock was covered with good soil, and the choicest trees and shrubs were brought from every land. Only evergreens, however, were admitted into this Eden, for the count would have about him no sign of winter or death. In 1671 the work was finished. The island was called Isabella, after the count’s mother,—a name which has since, by a happy corruption, become changed to Isola Bella.

It is on a sunny afternoon that I direct my bark towards the “Beautiful Island.” I look on the landing-place with respect, for it is worn by the footsteps of six generations of travellers. The interior of the palace, which I visit first, is fitted up with princely magnificence and is rich in art-treasures. Mementos of kings and queens who[Pg 35] accepted hospitality here are shown, and a bed in which Bonaparte once slept. There is a chapel where a priest daily says mass; a throne-room, as in the palaces of the Spanish grandees; and a gallery with numerous paintings. A whole suite of rooms is given up to the works of Peter Molyn, a Dutch artist, fitly nicknamed “Sir Tempest.” This erratic man, having killed his wife to marry another woman, was condemned to death. He escaped from prison, however, found an asylum here, and in return for the protection of the Borromeo of that day he adorned his walls with more than fifty landscapes and pastoral scenes.

The garden betrays the epoch at which it was laid out. Prim parterres, where masses of brilliant flowers bloom all the year round, are enclosed by walks along which orange-trees and myrtles have been bent and trimmed into whimsical patterns. There are dark and winding alleys of cedars where at every turn some surprise is planned. Here is a grotto made of shells,—there an obelisk, or a mosaic column, or a horse of bronze, or a fountain of clear water in which the attendant tritons and nymphs would doubtless disport were they not petrified into marble. There is one lovely spot where, at the middle point of a rotunda, a large statue of Hercules stands finely out against a background of dark foliage. Other Olympians keep him company and calmly eye the visitor from their painted niches. Not far from there is a venerable laurel on which Bonaparte cut the word “Battaglia” a few days before the battle of Marengo. The B is still plainly visible.

Pines and firs planted thickly along the northern side of the island defend it from cold winds. In the sunny nooks of the terraces the delicate lemon-tree bears abundant fruit and the oleander grows to a size which it attains nowhere else in Europe. The tea-plant from China, the banana from Africa, and the sugar-cane from Mississippi[Pg 36] flourish side by side; the camphor-tree distils its aromatic essence and the magnolia loads the air with perfume. The cactus and the aloe border walks over which the bamboo bends and throws its grateful shade. Turf and flowerbeds carpet each terrace, and a tapestry of ivy and flowering vines conceals the walls of the structure. From the summit a huge stone unicorn looks down upon his master’s splendid domain. He overlooks also a corner of the island where his master’s authority is not acknowledged. The small patch of land on which the Dolphin Hotel stands has for many centuries descended from father to son in a plebeian family, nor have the Borromeos ever been able to buy it. They have to endure the inn, therefore, as Frederick endured the mill at Sans-Souci and Napoleon the house he could not buy at Paris.

At last the moment comes when I must quit Stresa, not, however, before I have visited the remaining islands and other points of interest. The steamer puts off, and soon separates me from the landscape that has been my delight for three days,—the blue bay with its verdant banks, the softly-shaded hills which enclose it, the snow-covered chain of the Simplon in the background. As we approach the southern end of the lake a colossal bronze statue of San Carlo Borromeo on the summit of a hill near Arona comes into sight. From head to foot the saint measures little less than eighty feet, and the pedestal on which he stands adds to his height half as much more. His face is turned towards Arona, his native town, and one hand is extended to bless it. With my glass I descry a party of liliputian tourists engaged in examining this great Gulliver. Most of them are satisfied when they have reached the top of the pedestal and have ranged themselves in a row on one foot of the statue. Others, more daring, climb up by a ladder to the saint’s knee, where they disappear through[Pg 37] an aperture in the skirt of his robe. From this point the ascent continues inside of the statue, by means of iron bars, to the head, in which four persons can conveniently remain at once.

At Arona the railway-station and the wharf are near each other, and in a few minutes after I have landed an express-train starts and bears me away from the region of the Italian lakes. When we have passed the last houses of Arona and gained the open plain, the statue of the great Borromeo with his outstretched arm comes again for a few moments into view. Perhaps the uncertain light of evening and the jolting of the train deceive me, but I fancy that the good old saint is waving his hand in the familiar Italian way, as much as to say, “A rivederci!”

[The things worth seeing in the Eternal City are so many, and crowd so closely upon each other, that the lover of the antique finds himself almost overwhelmed by the rapid succession of striking objects and historic ruins. It would seem that little could be seen in a day’s walk among these marvels of the past, yet Taylor’s observing eyes managed to take in a long series of interesting objects, his graphic account of which is given below.]

One day’s walk through Rome,—how shall I describe it? The Capitol, the Forum, St. Peter’s, the Coliseum,—what few hours’ ramble ever took in places so hallowed by poetry, history, and art? It was a golden leaf in my calendar of life. In thinking over it now, and drawing out the threads of recollection from the varied woof of thought I have woven to-day, I almost wonder how I dared so much[Pg 38] at once; but within reach of them all, how was it possible to wait? Let me give a sketch of our day’s ramble.

Hearing that it was better to visit the ruins by evening or moonlight (alas! there is no moon now) we started out to hunt St. Peter’s. Going in the direction of the Corso, we passed the ruined front of the magnificent Temple of Antoninus, now used as the Papal Custom-House. We turned to the right on entering the Corso, expecting to have a view of the city from the hill at its southern end. It is a magnificent street, lined with palaces and splendid edifices of every kind, and always filled with crowds of carriages and people. On leaving it, however, we became bewildered among the narrow streets, passed through a market of vegetables, crowded with beggars and contadini, threaded many by-ways between dark old buildings, saw one or two antique fountains and many modern churches, and finally arrived at a hill.

We ascended many steps, and then descending a little towards the other side, saw suddenly below us the Roman Forum! I knew it at once; and those three Corinthian columns that stood near us, what could they be but the remains of the temple of Jupiter Stator? We stood on the Capitoline Hill; at the foot was the Arch of Septimius Severus, brown with age and shattered; near it stood the majestic front of the Temple of Fortune, its pillars of polished granite glistening in the sun as if they had been erected yesterday, while on the left the rank grass was waving from the arches and mighty walls of the palace of the Cæsars! In front ruin upon ruin lined the way for half a mile, where the Coliseum towered grandly through the blue morning mist, at the base of the Esquiline Hill!

ARCH OF TITUS, ROME

ARCH OF TITUS, ROME

Good heavens, what a scene! Grandeur such as the world never saw once rose through that blue atmosphere; splendor inconceivable, the spoils of a world, the triumphs [Pg 39] of a thousand armies had passed over that earth; minds which for ages moved the ancient world had thought there, and words of power and glory from the lips of immortal men had been syllabled on that hallowed air. To call back all this on the very spot, while the wreck of what once was rose mouldering and desolate around, aroused a sublimity of thought and feeling too powerful for words.

Returning at hazard through the streets, we came suddenly upon the Column of Trajan, standing in an excavated square below the level of the city, amid a number of broken granite columns, which formed part of the Forum dedicated to him by Rome after the conquest of Dacia. The column is one hundred and thirty-two feet high, and entirely covered with bas reliefs representing his victories, winding about it in a spiral line to the top. The number of figures is computed at two thousand five hundred, and they were of such excellence that Raphael used many of them for his models. They are now much defaced, and the column is surmounted by a statue of some saint. The inscription on the pedestal has been erased, and the name of Sixtus V. substituted. Nothing can exceed the ridiculous vanity of the old popes in thus mutilating the finest monuments of ancient art. You cannot look upon any relic of antiquity in Rome but your eyes are assailed by the words “Pontifex Maximus,” in staring modern letters. Even the magnificent bronzes of the Pantheon were stripped to make the baldachin under the dome of St. Peter’s.

Finding our way back again, we took a fresh start, happily in the right direction, and after walking some time, came out on the Tiber, at the Bridge of St. Angelo. The river rolled below in his muddy glory, and in front, on the opposite bank, stood “the pile which Hadrian reared on high,” now the Castle of St. Angelo. Knowing that St.[Pg 40] Peter’s was to be seen from this bridge. I looked about in search of it. There was only one dome in sight, large and of beautiful proportions. I said at once, “Surely that cannot be St. Peter’s!” On looking again, however, I saw the top of a massive range of building near it, which corresponded so nearly with the pictures of the Vatican, that I was unwillingly forced to believe the mighty dome was really before me. I recognized it as one of those we saw from the Capitol, but it appeared so much smaller when viewed from a greater distance that I was quite deceived. On considering that we were still three-fourths of a mile from it, and that we could see its minutest parts distinctly, the illusion was explained.

Going directly down the Borgo Vecchio towards it, it seemed a long time before we arrived at the square of St. Peter’s; when at length we stood in front, with the majestic colonnade sweeping around, the fountains on each side sending up their showers of silvery spray, the mighty obelisk of Egyptian granite piercing the sky, and beyond, the great front and dome of the Cathedral, I confessed my unmingled admiration. It recalled to my mind the grandeur of ancient Rome, and mighty as her edifices must have been, I doubt if there were many views more overpowering than this. The facade of St. Peter’s seemed close to us, but it was a third of a mile distant, and the people ascending the steps dwindled to pigmies.

I passed the obelisk, went up the long ascent, crossed the portico, pushed aside the heavy leathern curtain at the entrance, and stood in the great nave. I need not describe my feelings at the sight, but I will tell the dimensions, and you may then fancy what they were. Before me was a marble plain six hundred feet long, and under the cross four hundred and seventeen feet wide! One hundred and fifty feet above sprang a glorious arch, dazzling with inlaid[Pg 41] gold, and in the centre of the cross there were four hundred feet of air between me and the top of the dome! The sunbeam stealing through the lofty window at one end of the transept made a bar of light on the blue air, hazy with incense, one-tenth of a mile long before it fell on the mosaics and gilded shrines of the other extremity. The grand cupola alone, including lantern and cross, is two hundred and eighty-five feet high, or sixty feet higher than the Bunker Hill Monument, and the four immense pillars on which it rests are each one hundred and thirty-seven feet in circumference. It seems as if human art had outdone itself in producing this temple,—the grandest which the world ever erected for the worship of the Living God! The awe felt in looking up at the giant arch of marble and gold did not humble me; on the contrary, I felt exalted, ennobled,—beings in the form I wore planned the glorious edifice, and it seemed that in godlike power and perseverance they were indeed but a “little lower than the angels.” I felt that, if fallen, my race was still mighty and immortal.

The Vatican is only open twice a week, on days which are not festas; most fortunately, to-day happened to be one of these, and we took a run through its endless halls. The extent and magnificence of the gallery of sculpture is perfectly amazing. The halls, which are filled to overflowing with the finest works of ancient art, would, if placed side by side, make a row more than two miles in length! You enter at once into a hall of marble, with a magnificent arched ceiling, a third of a mile long; the sides are covered for a great distance with inscriptions of every kind, divided into compartments according to the era of the empire to which they refer. One which I examined appeared to be a kind of index of the roads in Italy, with the towns on them; and we could decipher on that time-worn block the very route I had followed from Florence hither.

Then came the statues, and here I am bewildered how to describe them. Hundreds upon hundreds of figures,—statues of citizens, generals, emperors, and gods; fauns, satyrs, and nymphs, born of the loftiest dreams of grace; fauns on whose faces shone the very soul of humor, and heroes and divinities with an air of majesty worthy the “land of lost gods and godlike men!”

I am lost in astonishment at the perfection of art attained by the Greeks and Romans. There is scarcely a fourth of the beauty that has ever met my eye which is not to be found in this gallery. I should almost despair of such another blaze of glory on the world were it not for my devout belief that what has been done may be done again, and had I not faith that the dawn in which we live will bring another day equally glorious. And why should not America with the experience and added wisdom which three thousand years have slowly yielded to the old world, joined to the giant energy of her youth and freedom, re-bestow on the world the divine creations of art? Let Powers answer!

But let us step on to the hemicycle of the Belvedere, and view some works greater than any we have yet seen or even imagined. The adjoining gallery is filled with masterpieces of sculpture, but we will keep our eyes unwearied and merely glance along the rows. At length we reach a circular court with a fountain flinging up its waters in the centre. Before us is an open cabinet; there is a beautiful manly form within, but you would not for an instant take it for the Apollo. By the Gorgon head it holds aloft we recognize Canova’s Perseus,—he has copied the form and attitude of the Apollo, but he could not breathe into it the same warming fire. It seemed to me particularly lifeless, and I greatly preferred his Boxers, who stand on either side of it. One, who has drawn back in the attitude of striking, looks as if he could fell an ox with a single blow[Pg 43] of his powerful arm. The other is a more lithe and agile figure, and there is a quick fire in his countenance which might overbalance the massive strength of his opponent.

Another cabinet,—this is the far-famed Antinous. A countenance of perfect Grecian beauty, with a form such as we would imagine for one of Homer’s heroes. His features are in repose, and there is something in their calm, settled expression strikingly like life.

Now we look on a scene of the deepest physical agony. Mark how every muscle of old Laocoon’s body is distended to the utmost in the mighty struggle! What intensity of pain in the quivering distorted features! Every nerve which despair can call into action is excited in one giant effort, and a scream of anguish seems first to have quivered on those marble lips. The serpents have rolled their strangling coils around father and sons, but terror has taken away the strength of the latter, and they make but feeble resistance. After looking with indifference on the many casts of this group, I was the more moved by the magnificent original. It deserves all the admiration that has been heaped upon it.

I absolutely trembled on approaching the cabinet of the Apollo. I had built up in fancy a glorious ideal, drawn from all that bards have sung or artists have rhapsodized about its divine beauty,—I feared disappointment,—I dreaded to have my ideal displaced and my faith in the power of human genius overthrown by a form less perfect. However, with a feeling of desperate excitement I entered and looked upon it.

Now, what shall I say of it? How make you comprehend its immortal beauty? To what shall I liken its glorious perfection of form, or the fire that imbues the cold marble with the soul of a god? Not with sculpture, for it stands alone and above all other works of art,—nor with[Pg 44] men, for it has a majesty more than human. I gazed on it, lost in wonder and joy,—joy that I could at last take into my mind a faultless ideal of godlike, exalted manhood. The figure appears actually to possess a spirit, and I looked on it not as on a piece of marble but a being of loftier mould, and half expected to see him step forward when the arrow reached its mark. I would give worlds to feel one moment the sculptor’s mental triumph when his work was completed; that one exulting thrill must have repaid him for every ill he might have suffered on earth! With what divine inspiration has he wrought its faultless lines! There is a spirit in every limb which mere toil could not have given. It must have been caught in those lofty moments

We ran through a series of halls, roofed with golden stars on a deep blue midnight sky, and filled with porphyry vases, black marble gods, and mummies. Some of the statues shone with the matchless polish they had received from a Theban artisan before Athens was founded, and are, apparently, as fresh and perfect as when looked upon by the vassals of Sesostris. Notwithstanding their stiff, rough-hewn limbs, there were some figures of great beauty, and they gave me a much higher idea of Egyptian sculpture. In an adjoining hall, containing colossal busts of the gods, is a vase forty-one feet in circumference, of one solid block of red porphyry.

The “Transfiguration” is truly called the first picture in the world. The same glow of inspiration which created the Belvedere must have been required to paint the Saviour’s aerial form. The three figures hover above the earth in a[Pg 45] blaze of glory, seemingly independent of all material laws. The terrified Apostles on the mount, and the wondering group below, correspond in the grandeur of their expression to the awe and majesty of the scene. The only blemish in the sublime perfection of the picture is the introduction of the two small figures on the left hand, who, by the bye, were Cardinals, inserted there by command. Some travellers say the color is all lost, but I was agreeably surprised to find it well preserved. It is, undoubtedly, somewhat imperfect in this respect, as Raphael died before it was entirely finished; but “take it all in all,” you may search the world in vain to find its equal.

[This ended the day’s tour of observation. On a succeeding day the traveller saw as many objects of interest; among them the graves of Shelley and Keats. These, however, we must pass by, and describe his visit to the ruins of the great Roman amphitheatre.]

Amid the excitement of continually changing scenes I have forgotten to mention our first visit to the Coliseum. The day after our arrival we set out with two English friends to see it by sunset. Passing by the glorious fountain of Trevi, we made our way to the Forum, and from thence took the road to the Coliseum, lined on both sides with remains of splendid edifices. The grass-grown ruins of the palace of the Cæsars stretched along on our right; on our left we passed in succession the granite front of the Temple of Antoninus and Faustina, the three grand arches of the Temple of Peace, and the ruins of the Temple of Venus and Rome. We went under the ruined triumphal arch of Titus, with broken friezes representing the taking of Jerusalem, and the mighty walls of the Coliseum gradually rose before us. They grew in grandeur as we approached them, and when at length we stood in the centre, with the shattered arches and grassy walls rising above[Pg 46] and beyond one another far around us, the red light of sunset giving them a soft and melancholy beauty, I was fain to confess that another form of grandeur had entered my mind of which before I knew not.

A majesty like that of nature clothes this wonderful edifice. Walls rise above walls, and arches above arches, from every side of the grand arena, like a sweep of craggy pinnacled mountains around an oval lake. The two outer circles have almost entirely disappeared, torn away by the rapacious nobles of Rome, during the middle ages, to build their palaces. When entire and filled with its hundred thousand spectators, it must have exceeded any pageant which the world can now produce. No wonder it was said,—

—a prediction which time has not verified. The world is now going forward prouder than ever, and though we thank Rome for the legacy she has left us, we would not wish the dust of her ruin to cumber our path....